Title: Fairy Realm: A Collection of the Favourite Old Tales Told in Verse

Author: Tom Hood

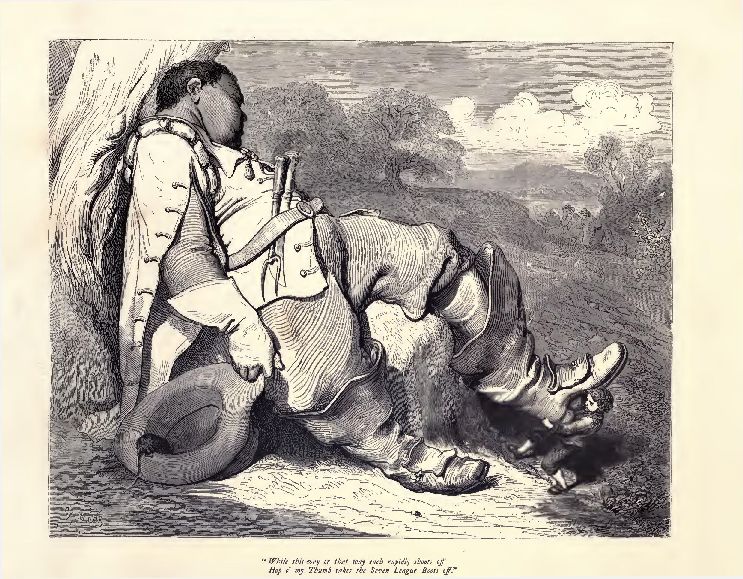

Illustrator: Gustave Doré

Release date: December 16, 2013 [eBook #44447]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

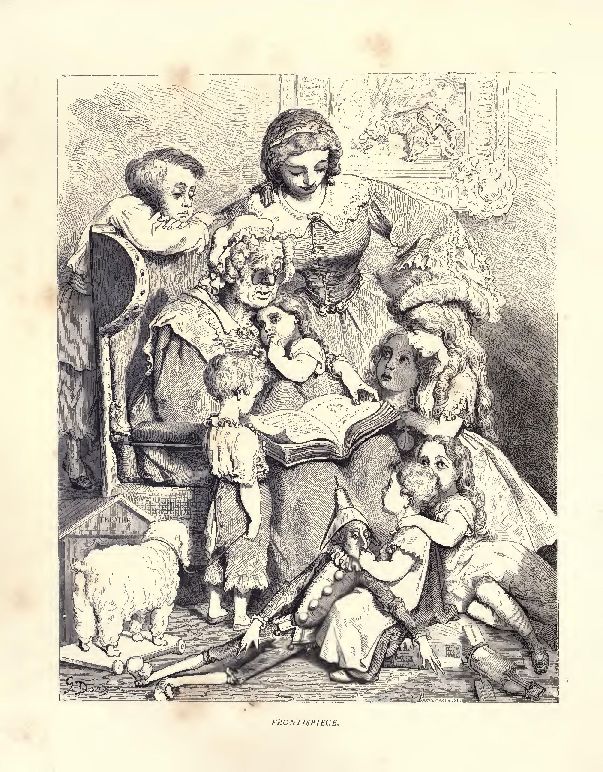

THE five favourite fairy legends which M. Gustave Doré has illustrated are so well known, have been so often told, and in so many different ways, that it was a matter of no small difficulty to determine the best mode of treating them. The plan I have adopted is to give the tales in a simple metre and in the most unpretending manner, going, in short, little if anything beyond mere recital in easy verse. From performing even this plain task as I could have wished I have been prevented by ill health, and I fear that what I have written little deserves the honour of association with works of genius like M. Gustave Dore's pictures. But I have the single satisfaction of knowing that I have done the best I could.

November, 1865.

CONTENTS

IN that strange region, dim and grey,

Which lies so very far away,

Whose chronicles in prose or rhyme

Are dated "Once upon a time,"

There was a land where silence reigned

So deep,—the ear it almost pained

To hear the gnat's shrill clarion blow,—

Though he Sleep's herald is we know.

Scarce would you deem that calm profound,

Unbroken by the ghost of sound,

Had, like a sudden curtain, dropt

Upon a revel, instant stopt,—

That laugh and shout and merry rout

And hunting song had all died out,

Stricken to silence at a touch—

A single touch! It was not much!

I 'll tell you how it came about.

What bevies of pages

Of various ages

Princess Prettipet's christening banquet engages!

They all look as deeply important as sages.

What hundreds of cooks!

To judge by their looks,

They had written the very profoundest of books.

(Of course, books like those by Hobbes, Bacon, or Hooker I

Mean—not mere Kitchener's Essays on Cookery.)

As to the cartes,

From the soups to the tarts,

'T would need to detail them a man of some parts;

While to eat of each item—

To taste—just to bite 'em,

The veracious voracious will own would affright 'em.

If you want to find out

The amount, or about,

Of the salmon, beef, partridges, lobsters, sourcrout,

Maccaroni, potatoes, cream, cutlets, ice, trout,

Lamb, blanc-mange, kippered herring, duck, brocoli sprout,

Sheep's trotters, real turtle, tripe, truffles, swine's snout,

Sole au gratin, snails, birds' nests, Dutch cheese, whiting-pout,

Jelly, plovers' eggs, bitters, liqueurs, ale, wine, stout,

Peas, cheese, fricassées, and ragoût—(say ragout

For the sake of the rhyme)—

And have plenty of time,

And a knowledge of figures (which I call a crime),

Because it's a feat that would puzzle beginners—

Make out and declare

The cube of the square,

Of twice twenty thousand of Lord Mayor's grand dinners.

#####

The invited guests begin to arrive:

With nobles and courtiers the scene is alive.

They hustle,

And bustle,

In rich dresses rustle;

The squeeze for good places is almost a tussle;

Precedence depends not on birth, but on muscle.

But they're none of them able

To reach the high table,

For the grave Major-Domo, perceiving the Babel,

A sufficient space clears

With the King's Musqueteers,

Because he well knows it will cost him his ears

If—when the time comes for the soups and the meats—

The twelve fairy godmothers cannot find seats.

At last there's a bray

Of trumpets, to say

That His Majesty's Majesty's coming this way,

With his Ministers all in their gorgeous array,

And the Lords of his Council, a noble display,

And the Queen, who's as beauteous as blossoms in May,

With her Ladies in Waiting so smiling and gay,

With a great many more

I might briefly run o'er

If at pageants like this I were only au fait.

The glittering procession

Makes stately progression

To the seats that the Musqueteers hold in possession

At the top of the hall;

While the visitors all

Are crowded to death, though the place is not small,

But from wall unto wall

Crammed with short folks and tall,

Who, as chances befall,

And in various degrees

They suffer the squeeze,

bawl, brawl, haul, maul, squall, call, fall, crawl, and sprawl

The King's looking pleasant,

Expecting a present—

Say knives, forks, and spoons that cost many a bezant—

For his daughter and heiress

From each of the fairies;

(A fay for a sponsor in these days quite rare is!)

But fairies, we' know,

Have gifts to bestow

More precious than silver and gold ones—and so

One gives the babe beauty,

Another gives health,

This a strong sense of duty,

That plenty of wealth.

Five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten

Add their presents, but when

Eleven have endowed her, the last of the dozen

Says, "I really don't know what to give her, dear cousin

(Addressing the Queen,)

"But the courses between

I shall hit upon something. I will not be mean;

So pray take your seats, for I'm not such a sinner

As, while I am thinking, to keep you from dinner!"

The King has taken the highest place,

Beside him the Queen in her diamonds and lace.

Each fairy godmother

Sits down by another,

And my lord the Archbishop is just saying grace,

When in comes a cook, with a very white face,

Who cries, as he straight up the hall rushes nimbly,

"Please your Majesty, somebody's fell down the chimbley!

There's silence in the hall

For half a minute,

And not a word doth fall

From those within it;

When, lo!—No!—And yet it is so!

The sound of a foot comes heavy and slow

Up the staircase from down below;

And a figure ill-grown,

Unattended, alone,

Walks straight through the guests to the foot of the throne,

And then with a squeak

Rising into a shriek,

And eyes that with fury are terribly glistening,

Cries, "Pray, sir, why was not I asked to the christening?"

'T was old Fairy Spite,

Whom they did not invite,

Because of her manners, which were not polite.

She led a bad life,

Was addicted to strife,

And besides—worst of all—she ate peas with a knife!

But 'twas really no joke

Her wrath to provoke.

So in hopes to appease her His Majesty spoke,

And said, sore affrighted,

"They both were delighted

To see her that day—

Quite charmed—in fact, they

Couldn't think how it was she had not been invited!

Shrieked Spite, "Silence, gaby!

Let's look at the baby."

The Queen, in a tremble,

Her fears to dissemble,

Said, Here is the darling—papa she'll resemble.

You'd like, p'rhaps, to take her,

But please not to wake her,

She sleeps." "Sleeps!" said Spite, "does she really? I 'll make her

Of sleep, ma'am, have plenty"

(Here—"Chorus "Attente!")*

"If she touches a spindle before she is twenty!

"For if she does, a heavy sleep

Shall over all your palace creep,

And you, with your whole court, shall keep

Buried in leaden fetters deep!"

"Until"—here Fairy Number Twelve,

Who, as we know, was forced to shelve

Her gift because the banquet waited,

Broke in and capped what Spite had stated—

"Until a prince shall come to wake

The Sleeping Beauty, and so break

The spell wherewith old Spite in vain

Would her young life for aye enchain!"

#####

The King sent heralds through the land

Proclaiming spindles contraband,

Pronouncing penalties and pains

'Gainst distaffs, treadles, rocks, and skeins.

And so to spin

Became a sin;

Wheels were bowled out, and looms came in.

No more old women were allowed to meddle

With wheel or treadle;

There were no spinsters left, the fair deceivers

All became weavers;

* The passage I quote in this wild dithyramb you'll

assuredly find in Act I. of "Sonnambula."

The very name and uses of a spindle

To nought did dwindle;

The fashion was, folks said,

Entirely dead,

Expired—past human effort to re-kindle.

Time's wonted pace

Is not a rapid race;

His motto seems to be "Festina lente."

But yet he passed away,

Until at length the day—

Approached on which the Princess would be twenty.

What consultations!

What preparations!

What busy times for people of all stations!

What scouring out of rooms

With mops and brooms!

What scouring to and fro of hurried grooms!

No leisure, not the least,

For man or beast,

Because His Majesty had fixed a feast—

Acres of eatables and seas of ale,

A banquet that should make all others pale,

E'en those of Heliogabalus, deceased—

To celebrate the day his child was quite

Beyond the malice of old Fairy Spite!

It was a scene of bustle and intrusion,

And vast profusion—

Such game, and meat, and fish, and rare confections!

The tables and the chairs

Down- and up-stairs

Were packed away—piled up in all directions,

In chaos, which the master of a house

Whose want of nous

Is such that he allows his wife a soirée,

Discovers round him, when tired out and sorry,

He fain would sleep, but cannot for the din doze—

In short, that plague, "a house turned out of windows."

No wonder the Princess, so meek and quiet,

Should run away from all the dust and riot.

No wonder, I repeat,

When all the suite,

From the Great Seal to her who made the beds,

Were hardly sure if they were on their heads,

Or on their feet!

No wonder the Princess—no soul aware,

Even of those who had her in their care—

Stole from her room, and up a winding stair,

Up to the highest turret's tipmost top,

Without or let or stop,

Went to enjoy the scenery and air!

In a room at the top of the tower that day

Merrily, merrily turned the wheel!

An old dame span, with never a stay,

Merrily, merrily turned the wheel!

The wool was as white as the driven snow,

Merrily, merrily turned the wheel!

And she sang, "Merrily, merrily, oh!

Merrily turn the wheel!"

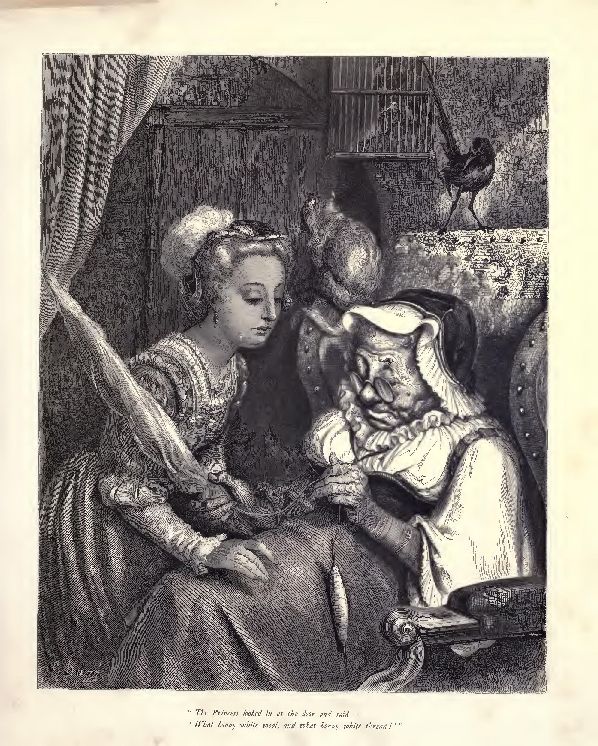

The Princess looked in at the door and said—

Merrily, merrily turned the wheel!—

"What bonny white wool, and what bonny white thread!"

Merrily, merrily turned the wheel!

"Come hither, then, fair one, and make the wheel go!"

Merrily, merrily turned the wheel!

Said ugly old Spite, who sang, "Merrily, oh!

Merrily turn the wheel!"

She turns the wheel and wakes its busy hum,

She twists the white wool with her whiter fingers;

She hears them call her, but she will not come:

Charmed with the toy, in that small room she lingers.

The wheel runs swiftly and the distaff's full,

She takes the spindle—heedless of who calls her.

Two tiny drops of blood fall on the wool,

And all that cruel Spite foretold befalls her!

On one and all

Did sudden slumber fall!

The steed that in the palace courtyard cropt—

The very bird upon the roof that hopt—

The cook who mincemeat for the banquet chopt—?

The gardener who the fruit tree's branches lopt—

The huntsman who his beaded forehead mopt—

The gay young lover who the question popt—

The damsel who thereat her eyelids dropt—

The councillor who fain the state had propt—

The King, his measures anxious to adopt—

The courtier in his new court suit be-fopt—

The toper who his beak in Rhenish sopt—

The scullion wiping up the sauce he slopt—

The chamberlain, as wise as ancient Copt—

The purblind peer who'd in the fountain flopt—

The jester who that fall with mirth had topt—

Stopt!

And over all there came a change;

A silence terrible and strange

Enwrapt the place:

While thickets dense of thorn and brier

Grew round it till the topmost spire

They did efface.

And only agéd crones came nigh

To gather sticks; or, passing by,

Some huntsman bold,

Spying a tower, would ask its tale,

And by the shepherds scared and pale

Would then be told—

How many a prince of noble blood

Had striven to penetrate the wood,

And reach the keep

Where that Princess so passing fair,

With King and Queen and courtiers there,

Lay wrapt in sleep.

But how none ever yet could make

A path through that thick-tangled brake—

And none came back,

But perished miserably there,

And left their bones all bleached and bare

In that dark track!

It was a solemn place, I ween,

Wrapt in its shroud of sombre green,

So hushed and still;

The fall of every leaf you heard,

Nor was there in its shades a bird

To cheep and trill.

No cricket chirped beneath the hedge—

No reed-wren rustled in the sedge—

No skylark soared;

Only at times, where round the keep

Did thickest snaky ivies creep,

A grey owl snored.

The sunlight slumbered on the wall;

The trancéd shadow did not crawl,

Or scarcely crept;

Dreaming the white lake-lilies lay

Above their image, still as they;

The hushed wave slept;

Like hermits dozing in their cells,

Drowsed in the drooping blossom-bells

The murmurous bees;

All languidly the land up-clomb

Around the central palace dome

By slow degrees.

But that embowered pile did seem

A cloud from some fantastic dream—

Some visioned place:

Its towers were clothed in misty sheen,

And slumbering forests seemed to lean

About its base.

The branches nodded, and the breeze

Sighed ceaseless through the sleepy trees,

A long-drawn breath:

Nature's warm pulses here seemed stayed,

Steeped in a trance that all dismayed,

'T was so like death!

Only for ever grew and spread

The sombre branches overhead,

Thick leaf and bloom;

As if to make for Nature's sleep

The brooding silence still more deep—

More deep the gloom!

Into the heart a terror sank:

The vegetation lush and rank

On all sides ran,

And looped and drooped in bine and twine;

And never trace or track or sign

Of living man!

#####

Down by the river that runs through the wood

The horns are gaily winding.

Tra-la-la-la! That music good

Denotes the red deer's finding!

Tra-la-la-la!

La-la! la-la!

The echoes repeat

The music sweet

That tells of the red deer's finding!

Over the river and over the plain,

Through forest, vale, and hollow!

Tra-la-la-la! That note again

Bids all good huntsmen follow.

Tra-la-la-la!

La-la! la-la!

The sweet notes fail

Along the gale,

Then, all good huntsmen, follow!

By many a mile of moorland vast,

By many a mile of forest—

Tra-la-la-la!—the huntsman's blast

Tells where the chase is sorest.

Tra-la-la-la!

La-la! la-la!

Oh, hapless deer,

Thy fate is near,

Which vainly thou deplorest.

In vain the flying quarry seeks

The dark wood's friendly branches:

The chase is done—its race is run,

The dogs are at its haunches.

The Prince looks back. He rides alone,

His suite no longer follow,

And he can hear no friendly cheer

In answer to his holloa!

What a chase!

What a race!

What a terrible pace!

He's outridden his friends. It's a very queer case—

Where can he have got? What's the name of the place

He 'll never be able his steps to retrace!

He pulls up his steed,

Not too early, indeed,

For the poor beast is finished, it shakes like a reed.

If his home lay quite near,

And he knew where to steer,

His horse could not carry him there—that is clear.

Meanwhile each lengthening shadow shows

That day is drawing to a close.

In two more hours the glowing sun

Will down the western heavens run,

And quench its glories manifold

In yon bright sea of molten gold.

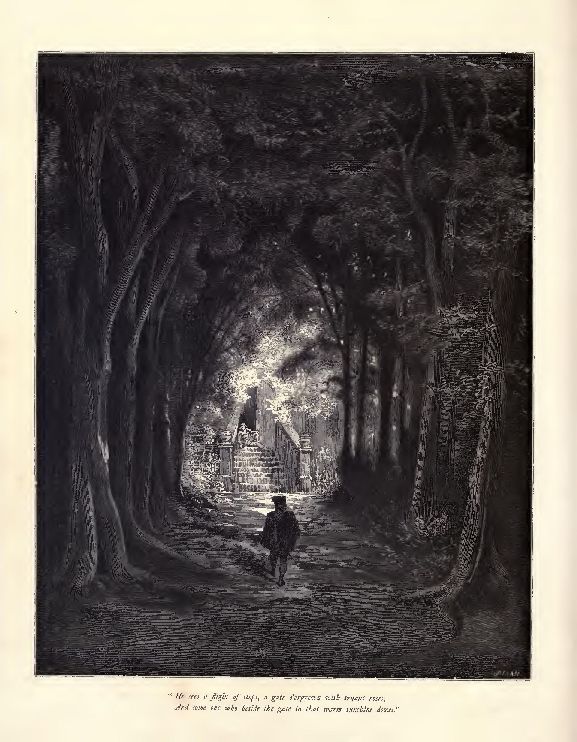

Before him that dense thicket vast and dim

Spreads out its awful silence and seclusion,

And none is near to tell its tale to him

And scare intrusion.

On either side his path a giant bole

Rears its huge form, a rude gigantic column.

That gloomy portal does not fill his soul

With fancies solemn.

His step is light on the luxuriant sod,

From the green blades a thousand dew-drops spurning.

Little he dreams that path has ne'er been trod

By foot returning.

Heedless he views the dark nooks in the glades,

Passing to spots that shafts of sunlight brighten—

Nor knows that human bones within those shades

Are laid to whiten.

For him there is no terror in the spot,

No hint of deaths to which it interest sad owes;

For him no spectres its bright sunshine blot,

Or fill its shadows.

For him the secret of that grove profound

Is locked away—that tragic tale, and tearful.

To him the death-like calm that reigns around

Is strange, not fearful.

So on he fares, through sunshine and through shade,

By paths that ne'er before were trod by mortal,

To where the dusky forest's green arcade

Leads to a portal.

Along that silent avenue the young Prince gaily passes,

'T is carpeted with velvet moss beneath the nodding grasses.

The dreamy sunlight through the boughs upon the green sward streaming,

Sets here and there with radiance rare a lingering dew-drop gleaming.

On either hand rise lofty stems; above, the branches mingle;

And, as a glimpse of blue shuts in the end of some green dingle,

Framed in an arch of greenery where that long alley closes

He sees a flight of steps, a gate o'ergrown with truant roses,

And some one who beside the gate in that warm sunshine dozes.

Was ever there found

A sleeper so sound?

He thumps him and shakes him,

But that never wakes him;

Not kick, tweak, or pinch

Can stir him an inch.

I don't think he'd stir if you gave him a—pig—

An immoderate slice of the coldest "cold pig."

Cried the Prince, leaping o'er

The page, "Qu'il s'endort!"

So he left that inveterate sleeper to snore

While he ventured on farther the place to explore.

"'T is a very fine place

As one clearly may trace—

Though, by Jove," said the Prince, and he made a wry face,

"From the dirt that's about, it don't seem they can muster

So much as a Turk's head, or dust-brush, or duster!

It's quite an inch thick:

Oh, wouldn't I lick

The minions for playing this slovenly trick,

If I were the owner, and had a big stick!

Look! with curtains of velvet and carpets of plush, rooms—

And yet the floor's covered with toadstools and mushrooms!

It's well for the parlour-maid she'd not beside her

This child, when she left that great cobweb and spider.

It's evident cleanliness isn't their hobby!"

With these words the Prince reached the end of the lobby.

From the lobby he passed to the guard-room, and thence

To the courtyard and gardens, which both were immense.

The palace, he sees,

Lies back beyond these,

Apparently rather too darkened by trees—

They're not trees though he finds, bringing closer his peepers,

But ivy and woodbine and other quick creepers,

Which with no interference of gardeners to "worret,"

Have climbed to the roof of the loftiest turret.

How those creepers have turned and twirled,

Twisted, wandered, rambled, and curled!

Such a place, I ween,

Had never been seen—

From basement to roof in such greenery furled—

Throughout the whole inhabited world.

Not even that building, so widely known

For its want of proportion—

That vast abortion,

The Exhibition of 'Sixty-two,

Though quite a monstrosity to the view,

Seemed half so "overgrown."

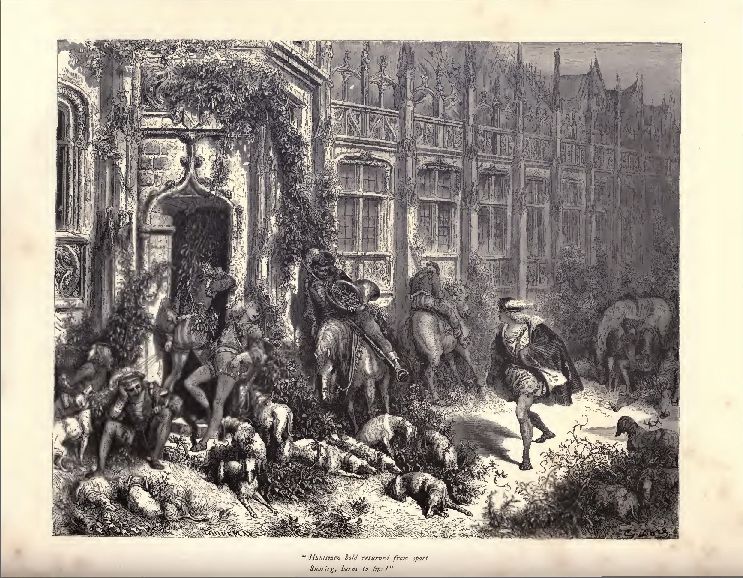

Swift across the court

Now the young Prince trips,

Sees around a sallyport

Hounds asleep in slips;

Huntsmen bold, returned from sport,

All prepared to blow a mort,

Snoring, horns to lips!

There they were becalmed, like ships

Lying with all sail outspread,

Lifeless on an ocean dead.

He draws near: there is no one to bar his way,

E'en the steeds are too sleepy to utter a "nay,"

While each single hound

In the pack, I 'll be bound,

Is so sound there's no chance of his making a sound,

Though not wanting in bark, since he's closely bound round

With branches of creepers;—but then they are boughs

That are not of the sort to be followed by "wows."

One huntsman would have an ugly fall

If he were not upheld by the palace wall,

Whence a stray branch of woodbine, in pitying scorn for him,

Has thrown out a trailer that's winding his horn for him.

Another one, dropt

Off soundly, is propt

By a buttress that stands where his steed by chance stopt.

An odd pillow, I vow;

For you 'll surely allow

That unless of some slumber your need is the utt'rest,

A sleep on a buttress seems anything but rest.

Two men in the doorway

Appear in a poor way,

So closely they're bound

And wound

Around;

Their feet in fetters, their temples crowned

By the snake-like stems in their various inclinings,

That they must appear

To the Prince, I fear,

Sleeping partners in some branch department of Twining's.

Past grooms as unawakened as sad sinners,

Past screws of hunters sound as Derby winners,

Past hounds as fast—no less—

As the express,

Through Bedfordshire into the land of Nod,

The young Prince trod,

And on through corridors and long arcades,

Halls wrapt in sombre shades,

And anterooms wherein had Echo slept

So long, it scarce awakened as he stept

Lightly and swiftly o'er

The dusty floor,

That sadly stood in need of being swept.

And ever and anon,

As he passed on,

In room, in hall, on stair,

Here, there, and everywhere,

He came on sleepers sleeping with the air

Of folks at active work by sleep o'ertaken,

Whom nothing could awaken;

Not even being—like physic with a sediment

That to its being swallowed's an impediment—

Well shaken!

The housemaid, seemingly in fuss and fluster,

Tripping downstairs with feather-broom and duster,

Caught unaware

Upon the bottom stair

By sudden slumber, had quite failed to muster

Sufficient sense to rouse herself to any stir,

And so lay dozing up against the banister.

A lacquey, carrying upstairs the coal-scuttle,

Had fallen napping, and let fall the whole scuttle;

A giddy page

Was, with another youngster of his age,

Playing at fly-the-garter in, the hall

When both asleep did fall—

One

Going to take a run,

Straining to start (as when is trained a pup—any

Pointer or sporting dog—and there gets up any

Partridge or pheasant, in the slip he 'll strain),

The other of the twain

Had fallen asleep while tucking in his twopenny!

Within their barracks several of the guards

Were quarrelling in their slumber over cards;

The butler in the cellar at the tap

Was taking such a nap,

He'd filled his silver flagon o'er and o'er,

And let the wine run all about the floor

Until the cask was drained and held no more.

But he'd continued after that to snore,

Until he was as dusted

And cobwebbed and encrusted

As rare old port, bottled in 'Thirty-four.

All these the Prince passed by with stealthy tread

As on he sped,

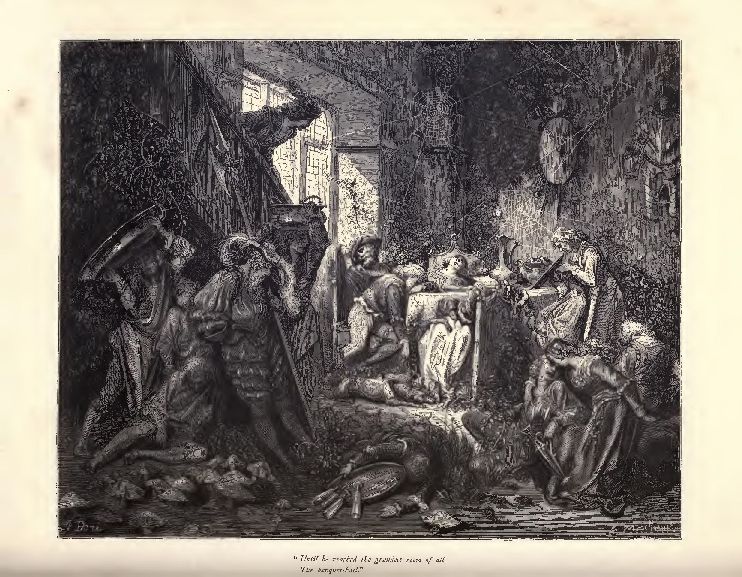

Until he reached the grandest room of all,

The banquet-hall,

Where on the board a mighty feast was spread.

But since the day when first that cloth was laid

Time had strange havoc made

With dish and dainty on the board arrayed;

Had played strange tricks

With those—some five or six—

People of station

Who had been favoured with an invitation

To dinner with the ruler of the nation;

In short, to no conclusion harsh to jump, any

Person of taste

Had thought the King disgraced,

Not only by his room, but by his company.

Vast mushrooms, spawn of hideous dreams,

Had quickened in the rotting seams,

And dusty cobwebs huge,

Wherein did bloated spiders lie,

And feign to sleep, were hung on high;

But there was neither gnat nor fly

To catch by subterfuge.

The very mice had fallen asleep

That ventured in that hall to creep.

And where the sun athwart the gloom

Poured through the pane

A glittering lane

Like Dreamland's golden bridge,

You looked for stir of life in vain,

Because the very midge

Slept in that drowsy room,

As silent as the tomb!

The King—with half-way to his lips the beaker,

And head half turning to the latest speaker—

Presiding o'er his banquet, slumbered there-amid.

Like the first Pharaoh sleeping in his pyramid;

While the Prime Minister, acute and wise,

Still saw what must be done with fast-shut eyes,

And, as behoved him in the royal presence,

Kept nodding to his Sovereign acquiescence.

The Treasurer and Chancellor of Exchequer

Was bolt upright, as trim as a three-decker.

For raising coin and borrowing he was meant,

And nobody could ever say he leant

To right or left,

E'en when of sense bereft.

The Secretary, Foreign and Domestic,

Upright did less stick,

And, being long accustomed to indite,

Inclined to right.

Beside the door a sentry

Stood like the Roman soldier in the entry

Discovered in the ruins of Pompeii,

(Or Herculaneum—which was't? You see, I

Have got no book of reference at all

Here in the country, not e'en what we'll call,

For sake of rhyme, a classical invént'ry.

At any rate, he stood

There like a thing of wood;

And by his side did stand,

Salver in hand,

A servitor whose duty was to cater

With flagons, flasks, and bowls

For all the thirsty souls—

(He's called a buttery-man at Alma Mater)—

Well! There this lad of liquor

Remained a sticker

Against the stair-foot, with his laden tray

Of claret, sherry, Burgundy, Tokay,

And other wines we 'll call et cætera—

Just like a very image or dumb-waiter.

Another 'mid the goblets lay a-sprawl—

It made the young Prince think

Him overcome with drink,

Which really had not been the case 'at all.

O ercome he was there's no denying, but

'T was only sleep; for though the glass was cut,

He was not even blown—

He could have shown

He did not owe to any drop his fall.

Through every tiny crevice, nook, and cranny,

Heaven knows how many

Of every kind of creeping plant had sprouted

And grown and wandered since,

Till the young Prince

If he were in—or out—of doors half doubted.

The clinging tendrils,

Which Nature (as an officer his men drills)

Had taught to turn one way, enwound and bound

The silent sleepers who all slept so sound.

One trailer formed a sort of chain between

The foremost Maid of Honour and the Queen,

As if to say

To those who sleeping lay,

"It's time to rise, good sirs, and go away"—

In short, the very same remark that made is

By stingy hosts who save their wines by dint

Of the discourteous hint,

"Come, don't you think it's time to join the ladies?"

The young Prince gazed

Upon the scene amazed.

He shouted; not a single head was raised—

No single sound upon the silence broke—

Nobody spoke—

All heads alike were bowed.

He shouted loud

As one who wishes to outroar a crowd;

But not a word

He heard—

No creature stirred:

The situation really seemed absurd.

There lay the feast

Untouched for years at least;

And though they'd sat so long,

Not one of all the throng—

Of feeding seemed inclined to be beginner,

And there was the young Prince,

Dropt in some minutes since,

And making such a din

Since he'd come in,

That he became for them another dinner.

At last tired out,

Of vain attempts by shout,

And even shake, to rout

From their deep sleep the slumberers about

The banquet-table,—

Whether he'd be able

Ever to wake them, feeling quite in doubt,

The Prince made up his mind

To leave them all behind,

And see if some one waking he could find,

And so passed on through halls and quiet cloisters,

But everywhere found people mute as oysters

And sound as tops.

But yet he never stops,

Though neither man nor woman, girl nor boy stirs.

All is as still as death,

And not a breath

Stirs the ancestral banners or the arras;

No page's voice or groom's

Heard in the rooms,

No maid's shrill tongue the listener's ear to harass;

No step upon the stair,

No footfall anywhere,

Not e'en on what Jane Housemaid calls the tarrace.

But still the Prince his onward course pursued,

Half fearing to intrude,

As each fresh chamber doubtfully he stept in.

In tiring-rooms he views

The ladies' maids so tired they 're in a snooze.

Then for a change

Through sleeping-rooms he 'll range,

Which by some contradiction very strange

Appear the only rooms that are not slept in.

Yet onward still he strays

All undecided,

And yet his steps are guided;

For round his head on airy pinion plays

A band of Fays,

Who lead him forward still by devious ways,

To where the Sleeping Beauty lies,

O'er whose tender violet eyes

For such years the lids have closed,

On her couch while she reposed.

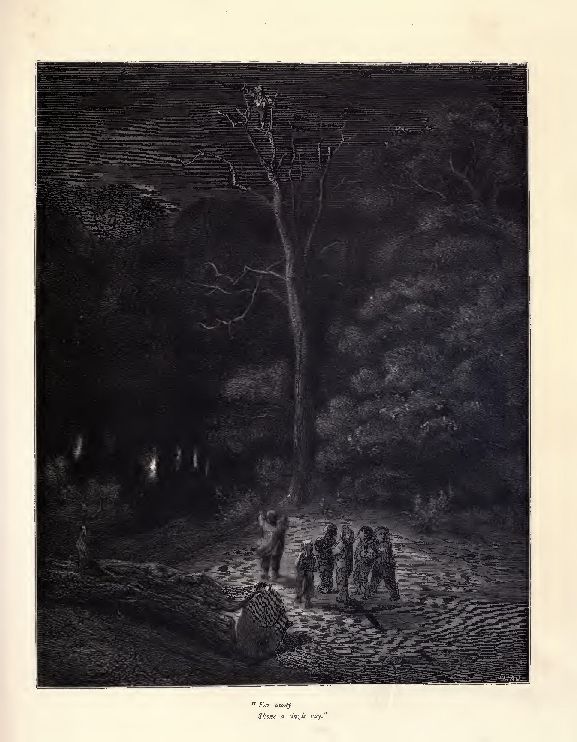

"Come away!" sang each Fay,

"Now we hail the happy day

When the Prince shall break the spell

Spoken by old Spite the fell.

Now sing we merrily,

For the destined one is he!"

Thus all gladly sung the Fays,

Though he could not hear their lays,

Wandering on as in a maze.

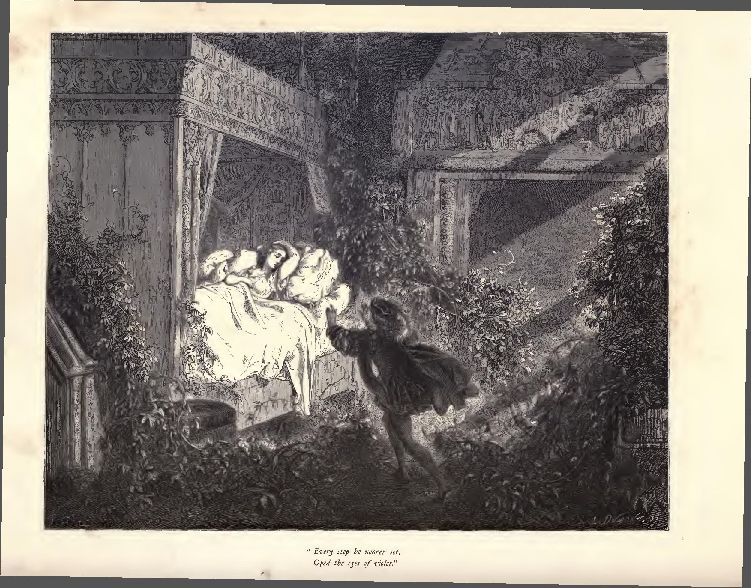

Last he reached a silent chamber,

Where through all the woodbine's clamber,

And the roses' red profusion,

And the jasmine's silver stars,

Glowed the glorious sun's intrusion—

Misty golden bars,

Touching all with amber.

But—or e'er that room he entered

Where the magic all was centred,

For a space, in wonder, dumbly

Gazed he on that figure comely

Sleeping in the snowy bed,

Where the sunshine splendour shed

From the casement's pictured pane

Crimson, blue, and yellow stain

In a variegated rain.

(Not all colours, as we know,

That in painted windows glow

Can the sun contrive to throw—

Primal tints, red, yellow, indigo,

Will, however, through a "windy" go.)

One moment on the threshold—

One moment and no more!

So like a thing of dreams

And Fairyland she seems,

That he must pause till time his breath restore,

And he of life take fresh hold—

One moment and no more—

And then across the room he bounded

To that white bed by clustering bloom surrounded—

Across the startled floor,

Whence foot had been estranged so long before,

The frightened echoes that his step awoke

Seemed shrieking out to hear when silence broke!

In her bed, as white as snow,

Softly had she slumbered,

While old Time with silent flow

Had the long years numbered.

Quiet as the dead she lay,

Sleeping all those years away

On her pillow, woodbine-cumbered,

Wreathed with flowering may.

And her breath so softly slips

Through the rosy-tinted lips,

That the white lace seems to rest

Moveless on her whiter breast—

That it scarce appears to stir

One of all the fluttering motes

That, in love to look at her,

Glitter down the golden lanes

That the sun pours through the panes,

Bright with armour-coats.

Drawn by her sweet lips' perfume,

As a bee to golden broom,

When the braes are all in bloom,

Stole the Prince across the room.

Every step he nearer set,

Oped the eyes of violet—

Oped a little—wider yet!—

Till the white lids, quite asunder,

Showed the beauties hidden under—

Showed the soft eyes, full of wonder,

Opening, towards him turned—

Till their radiance bent upon him

From his trance of marvel won him;

And his bosom burned

With the passion to outpour

All his soul her feet before,

Careless if she spurned,

So that he might only tell

That he loved her—and how well!

Now through the palace woke the stir of life;

Both fork and knife

Were in the banquet-hall with vigour plied,

While far and wide

Awoke so great a riot after the quiet,

It seemed as if the household was at strife.

Girl, woman, boy, and man

Bustled about and ran—

All hurried, not one plodding!

Because, you see,

Each thought that he or she

Had been the only one that had been nodding,

And, fearful of detection,

Was bound to strive and look alive,

In order to escape correction.

Meanwhile the red sun set. And yet

The household did not into order get:

All was surprise and wonder,

Error and blunder.

The fire was out, the cook was in a pet,

The feast was cold, the Queen was in a fret;

The hunters just returned, they thought, from hunting,

Felt it affronting

Their game should get so very high and mite-y;

The housemaid, seeing all the dust and dirt,

Felt hurt,

It drove her almost crazy—at least flighty.

But over all this din and turmoil soon

Uprose the silver moon,

And by its rays shed on the dewy grass,

Forth from the palace that young pair did pass,

And threaded the deep shades

In the arcades

Of sombre forests that around them lay.

And so they took their way

To Fairyland, wherein, as legends say,

'Mid mirth and merry-making, song and laughter,

They married, living happy ever after—

And there, I'm told, they 're living to this day!

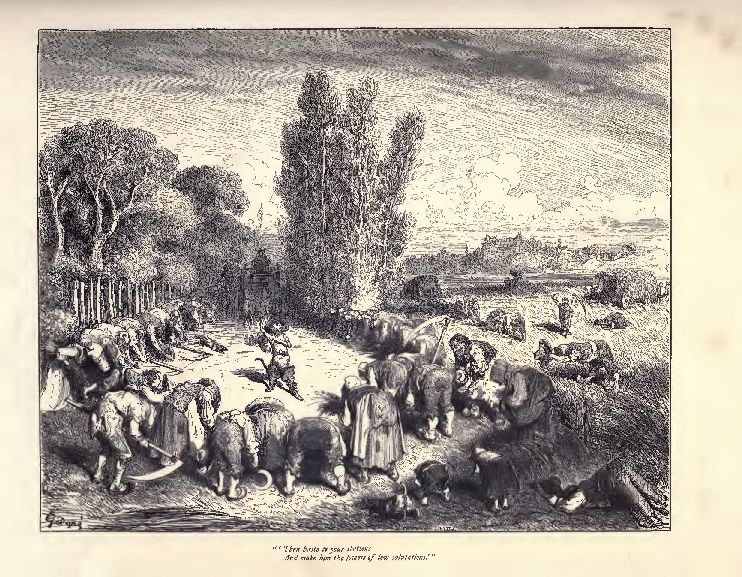

BY the side of a wood

A cottage once stood,

Where a little girl dwelt, who wore a red hood.

Her father of trees in the forest was cutter,

And her mother sold poultry, milk, eggs, cream, and butter.

The little red hood,

It must be understood,

Belonged to a mantle—as pretty and proper a cloak

As e'er you set eyes on:—in short, a red opera cloak.

But operas ne'er, that I am aware,

Had been heard of by any one dwelling round there;

Whereas every dame had a cloak bright as flame

That she wore when out riding (which gave it its name.)

For then in those parts

They'd no chaises, spring-carts,

Gigs, or waggonettes, such as a farmer now starts;

So Hodge, Reuben, or Giles,

Went his eight or ten miles

By the road—or the bridle path, dodging the stiles—

On his nag, grey or brown, to the next market town.

And were you to meet him, I'd bet you a crown

You would certainly find him

(If your sight's not, like mine, dim,)

A-jogging along with the goodwife behind him,

Perched up on the pillion of Dobbin or Dapple,

With a cloak like a poppy and cheeks like an apple:—

A cloak with a hood, that was really some good,

For use, not for ornament—one that you could

(That is, if you would)

Draw over your face quite closely, in case

The sun was too warm or the rain fell apace,—

A both-ears-protecting, eyes-shading, hair-hiding hood.

And that's why they called the child Little Red Riding Hood.

By the side of the cot where Red Riding Hood dwelt

Was a garden, surrounded by trees;

The flowers were the sweetest that ever were smelt,

And were greatly beloved by the bees,

Who led jolly lives

In a couple of hives

Well sheltered from shower and from breeze.

Beyond the small garden, whose flowers were so sweet

Bees wooed them through long summer days,

The woodman had cleared a small patch for the wheat

That, as each year came round, he would raise,

To grind and to bake

For bread and for cake——

Simple wheat, not that wonder, a maize!

Now the sun rises and the world awakes,

For morning—like a careless servant—breaks;

And from house, hut, and cot,

Hind, farmer, or what not,

Each villager his way to labour takes.

Each stride he makes a thousand dew-drops shakes

From off the fresh green grass they were besprinkling,

And makes them wink,

And gleam, and glance, and blink,

Until the peasant in great haste you think

Because he walks the whole way in a twinkling.

Red Riding Hood's father has shouldered his axe,

And is off to the woods again.

At the thwacks and the cracks as the timber he hacks

The echoing shades complain;

But woe to the stem that his steel attacks,

For its murmurs are all in vain.

Red Riding Hood's mother has risen with day,

As soon as the hens were awake,

And down to the kitchen has taken her way,

From the hearth all the embers to rake,

And the butter and flour on the table to lay,

For she's bent upon making a cake.

But little Red Riding Hood's slumbering yet—

She is terribly lazy, I fear;

For little folks up in the morning should get

As soon as the light becomes clear,

And not sleep away

The best time of the day,

Which is six, or about:—as I hear.

When the cake's nice and brown

The young lady comes down,

In her little white apron and little blue gown;

Has for breakfast a bowl of fresh milk from the cow,

And when she has finished, her mother says, "Now,

Just slip on your cloak, dear, as quick as you can; I

Want you to carry some things to your granny!"

Red Riding Hood's drest,

And, looking her best,

Is only awaiting her mother's behest.

On the table is laid

The cake that was made

Ere Red Riding Hood opened her eyes, I'm afraid,

And beside it a pot

Whose equal could not

At Fortnum and Mason's be easily got;

For, as every one tells me, fine fragrant fresh honey

Is not always obtainable, even for money.

There are very few treats in the matter of sweets,

Like the honey one fresh from the honeycomb eats.

But fond as I am of a little fresh honey,

I can't watch the bees in their wanderings sunny

Without a great risk of a painful disaster,

Though I think it would trouble the famous "Beemaster"

(As his real name's a secret, we 'll say Dr. Thingamy)

To explain to a "fellah,"

Qui tam amat viella,

How it is that the bees make an object to sting o' me.)

"Little Red Riding Hood, child of mine,".

Said the mother to her daughter,

"Through the forest of beeches, and larches, and pine,

And down by the pool of water,

And over the fields to your grandmother's cot

With the griddle-cake and the honey-pot,

Go, and tell her what you have brought her.

But—mind what I say—do not delay

To chatter with folks or pick flowers on the way!"

Little Red Riding Hood promised her mother

She'd not stop on the road to do one or the other.

"Such allurements I old enough now to withstand am,

So I 'll carry the honey and cake to my grandam,

And then you shall see how quick I can be.

Good bye, dearest mother!" And off hurried she.

The fields with buttercups are gold,

The hedges white with may;

The woodbine's trumpets manifold

Are bright beside the way;

The foxglove rears its lofty spire

Where hang the purple bells;

In shady quiet nooks retire

The modest pimpernels;

The poppy the green corn-fields decks,

The meads are bright with cowslips.

She loiters on her way, nor recks

How rapidly time now slips.

She enters now a glade,

Dappled with light and shade,

Through which the path is to her grandam's made;

And as she strolls along,

Singing her careless song,

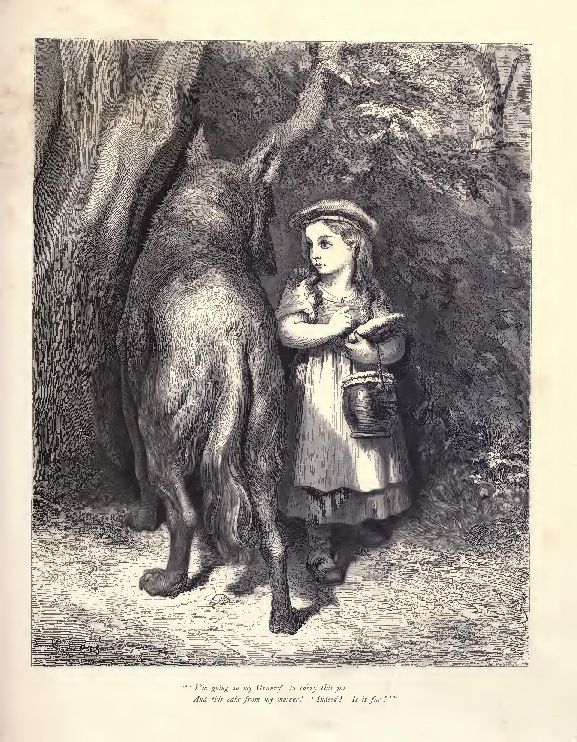

She meets a grim grey wolf. She's not afraid,

Because close by

She hears her father ply

His axe, and knows he'd to the rescue fly

If Master Wolf should any treason try.

And Master Wolf knows too it would not do,

Although it's hard with such a meal in view;

And so most laudably

He makes himself quite pleasant,

For the present,

Albeit his stomach's crying "cupboard" audibly.

"What a nice cloak of scarlet!

How pretty you are! Let

Me carry that cake or that very big jar:—let

Me carry it, pray—are you taking it far? Let

Me see you safe there!" said the wicked old varlet.

Alas! for Little Red Riding Hood,

That she should be naughty instead of good;

That she should let the old wolf flatter,

And allow him to walk

By her side and talk,

When her mother so strictly forbade her to chatter.

"What your name is, my dear," he said, "fain I'd be knowing."

"I'm Little Red Riding Hood." "Where are you going?"

"I am going to my granny's, to carry this jar

And this cake from my mother." "Indeed! Is it far?"

"Oh, you go through the wood, and a little beyond

You 'll see a small cottage that stands by a pond."

"And your granny lives there?" "Yes; but now she's so old

She can't get out of bed and she suffers from cold."

"Poor dear," said the wolf, with a pitying grin;

"But how does she do about letting you in?"

"When I reach granny's cottage I always take care

To knock at the door till she calls out 'Who's there?'

]Your grandchild, who brings you a bite and a sup

From her mother,' say I;

And she's sure to reply,

'If you pull at the bobbin the latch will fly up.'

That's how I get in." "Oh!" said wolf, in a hurry,

"This lane is my way,

So I 'll wish you good day."

And he vanished at once in a terrible scurry;

Said Red Riding Hood, "Doesn't he seem in a flurry!"

Like a shot from a rifle,—or faster a trifle,

Away goes the wolf, and, I 'll wager my life, 'll

Be up to some mischief or other ere long,

For his only delight is in doing what's wrong.

Off through the wood—(he's up to no good),

Hastening still—(bent upon ill),

Round by the pond, to the cottage beyond

(He's after some evil I 'll give you my bond),

Stealing along—(intending a wrong)

Towards the grandam's abode, by the skirts of the road,

(By skirts I don't mean either muslin or calico,)

He sneaks to what Shakespeare has called "miching mallecho."

Rap, tap! at the door.

In the midst of a snore

The old lady woke up with a start, and said, "Lor!

Red Riding Hood ne'er knocked so loudly before.

Oh, deary me, it cannot be she;

I 'll pretend I 'm still sleeping, and then we shall see."

Rap, tap! once more

She heard at the door:

The wolf rapped so hard that his knuckles were sore.

"The old woman sleeps like a top—what a bore!

If she doesn't make haste,

My time I shall waste—

I shall miss that tit-bit who's so much to my taste."

Rap, tap! Tap, rap!

"She must wake from her nap,

Or the child will be here

Before I can clear

Her foolish old grandmother up, every scrap."

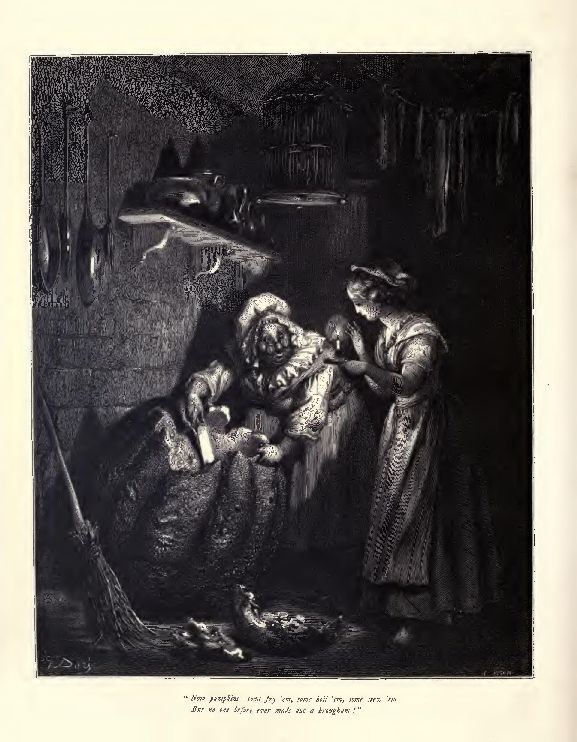

At last said the grandam,

"I rather a hand am

At sleeping, I know,

Very soundly, and so

Perhaps she has waited and knocked there so long

That, in order to wake me, her tap becomes strong.

Who 's there?" then she cried;

Said the wolf from outside,

Disguising his voice the deception to hide,

And whispering low with his mouth to a cranny,

"It's no one but Little Red Riding Hood, granny!

I've brought you some butter, some eggs, and a cake

That mother got up in the morning to make,

And she sends you besides some nice cream in a cup"

"If you pull at the bobbin the latch will fly up!"

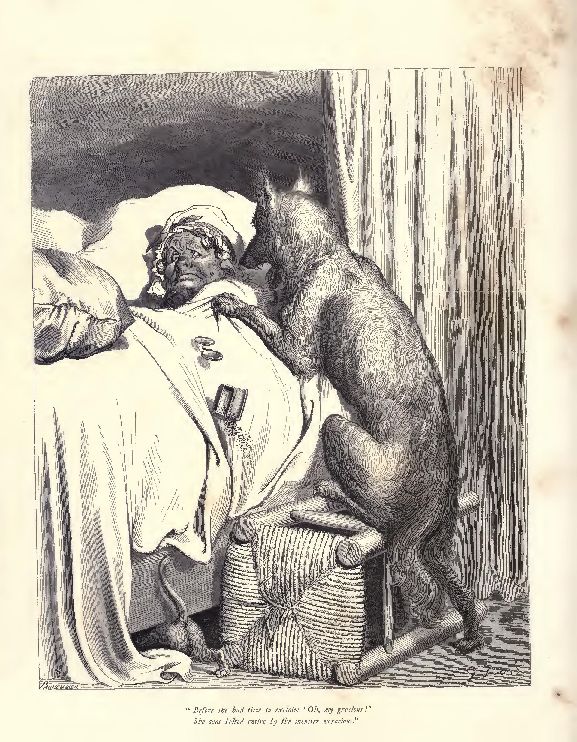

Wolf pulled at the bobbin,

And—what a sad job!—in

He went; but no sooner had thrust his grim knob in

(But for rhyming, instead

Of "knob" I'd say "head")

Than the frightened old lady sat bolt up in bed:

But before she had time to exclaim, "Oh my gracious!"

She was bolted entire by the monster voracious;

Who, though the fierce pangs of his hunger were gratified,

Remarked to himself, with a grumble dissatisfied,

Tough skinny old folks are not nice things to victual one;

However, no matter! Here goes for the little one!"

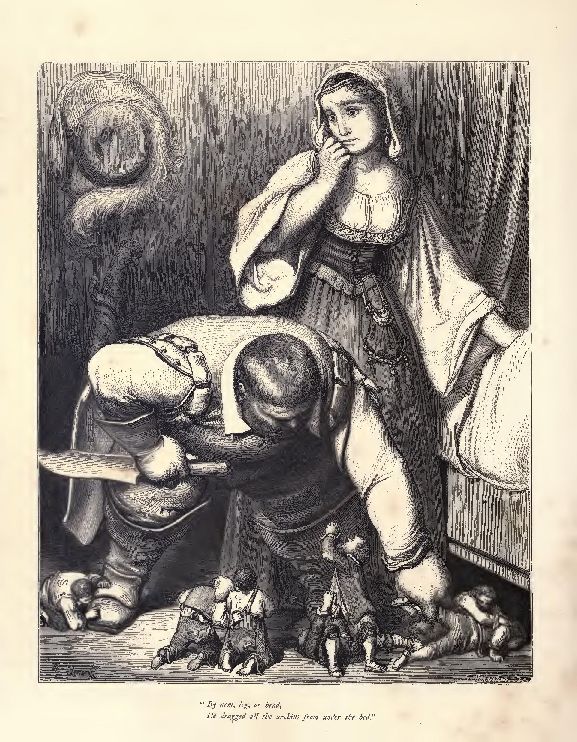

Then he turned down the bed-clothes and quickly jumped in,

And granny's big nightcap tied under his chin:

And he cuddled the clothes

Close up to his nose,

And was speedily off in a very nice doze;

For said he, "For Red Riding Hood if I'd have any

Respectable twist I must first digest granny.

For though at one meal I could eat child, pa, and mamma,

There's a good deal of picking somehow about grandmamma!"

Little Red Riding Hood loitered along,

Stopping to hear while the thrush sang his song,

Or to list in the croft to the blackbird's clear whistle,

Or to follow the feathery down of the thistle—

Or blowing in flocks

The seeds from the "clocks"

Of the bright dandelions, or searching the docks

For the burrs, whose chief trick

Is to catch and to stick

To one's garments, no matter if thin ones or thick:

(Though it matters to you,

Because they come through—

Supposing your clothes are the former—and prick.

Why, foolish butterfly,

Will you skip, flutter, fly

Close by the child? You 're an idiot utter, fly!

She puts down the honey and cake in a trice,

And the latter's immediately stolen by the mice.

But what does the latter at all to her matter:

She's after that butterfly, mad as a hatter.

[It's not clear to me

Why a hatter should be

Proverbially called a fit subject for De

Luncitico—so runs the writ—inquirendo;

But I fancy the hatter this harsh innuendo

Must, in the first place, to a humorous friend owe,

Who fain in the sneer would his gratitude smother

For a man who's invariably felt for another.]

Through pastures and meads as the butterfly leads,

Red Riding Hood follows, and little she heeds

The orders and warning her mother that morning

Had given her, or even her grandmother's needs.

But when she comes back once again to the track,

And finds the cake gone, she grows frightened. "Alack!"

She cries, "what a loss!

Won't granny be cross,

To breakfast off nothing—with honey for sauce?"

Just then a glittering dragon-fly

On gauzy pinion darted by.

Oh, he was clad in burnished mail,

His wing a fairy galley's sail,

And he was twice as big, I ween,

As the biggest butterfly she had seen.

Soon forgotten the honey's;

She off with a run is

Where the dragon-fly glancing so bright in the sun is.

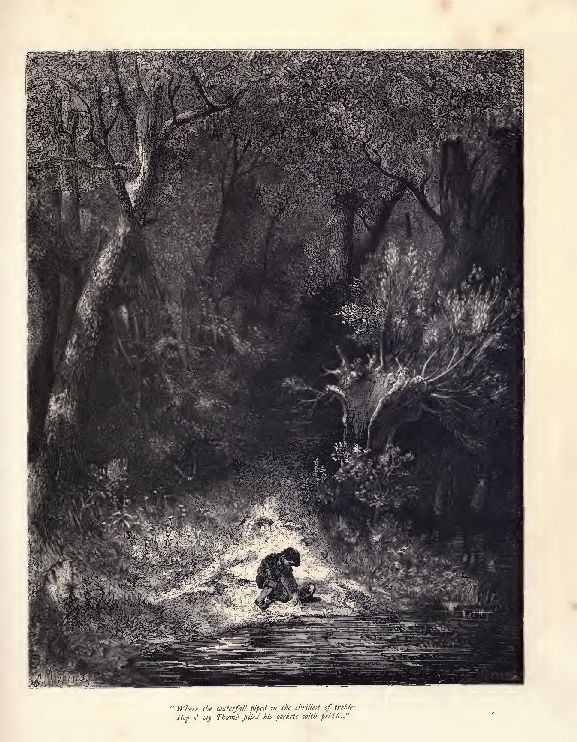

By ditches and hedges, by rushes and sedges,

By ponds full of reeds and all sorts of weeds,

By pools that are stagnant, and brooks full of waterbreaks,

She chases Libellula

Eagerly. [Well, you'll a-

Llow there must some

Awful punishment come

When her mother's commands in this manner a daughter,

But conceive her concern

When, on her return,

She finds that an empty jar's all she can earn.

For the ants had discovered it placed in a sunny spot,

And cleared all the honey, and left but the honey's pot.

Said she, "Lack-a-day!

What will grandmother say?

And shan't I get scolded for stopping to play!

I'd better get on without further delay!"

Resolution how vain! Again and again

She loiters in meadow, wood, highway, and lane—

Strays into the coppice

To pick the bright poppies,

Or climbs up the hedge for the nest that a-top is;

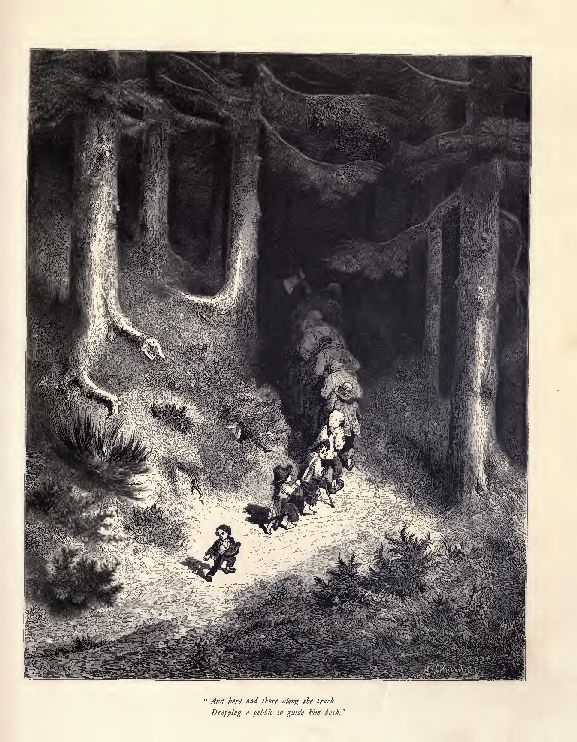

Or else she emerges

Where widely diverges

The forest's long avenues—leafy green arches

Of beeches, of ashes, of elms and of larches,

Which she lingers beneath

To pick for a wreath

A bright trail of ivy, that some lofty stem on is,

Or with bluebells her apron to fill—or anemones;

Or to watch the quaint habits

And ways of the rabbits,

And the plans of the crows,

Who, as every one knows,

Establish their scouts

At certain look-outs,

To warn them of danger whenever they 've doubts.

[As touching these rooks,

Natural History books

Declare that the thing to their greatest éclat's

The fact—which should win them the warmest applause—

That nothing they do is e'er done without caws.]

But now she has passed

Through the forest, and fast

Is approaching her grandmother's cottage at last.

What excuse can she make

For the honey and cake?

At the thought of that scrape she's beginning to quake.

She creeps through the garden,

Attempting to harden

Her heart, and declare she "Don't care a brass farden."

But, in spite of her trying,

She's very near crying,

And asking her granny to grant her a pardon.

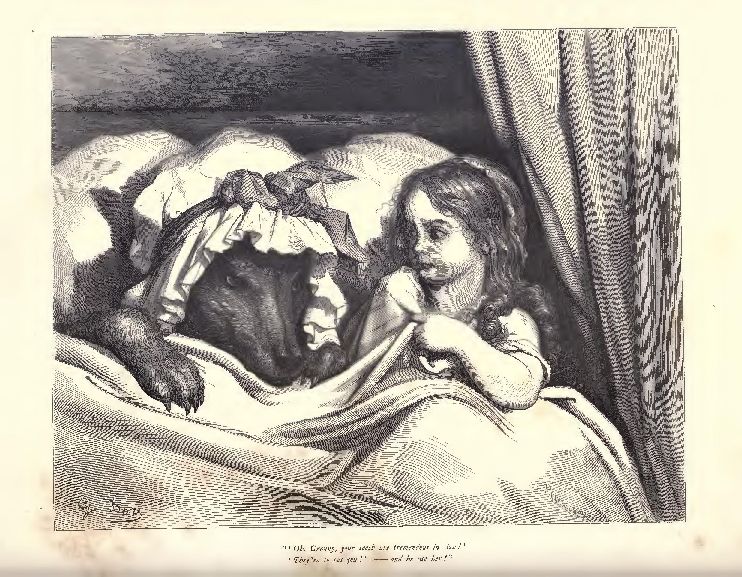

The knock is so faint, that the wolf's scarce aware

That there's any one knocking, but cries out, "Who's there

"Red Riding Hood"—here on her speech broke a sob in—

"Come to see you." Said wolf, "If you pull at the bobbin,

The latch will fly up!" So she opened the door,

And tottered with terrified feet o'er the floor.

Said wolf, "Where's the cake

Mother promised to make?"

"Please, granny, to-day she's not able to bake,

For love or for money."

"Then where is my honey?"

"What makes you expect any, granny? How funny!"

Said Little Red Riding Hood, trying to smile,

Although in a terrible fright all the while.

"To send me no breakfast," said wolf, "she was silly;

I 'm feeling so hungry and faint, I'm quite chilly.

As you 've brought me no food, you must warm me instead;

I 'll take you in place of my breakfast in bed.

So take off your things, and, some help to your gran to be,

Jump into bed, just for once warming-pan to be."

She takes off her clothes,

And into bed goes.

Old wolf keeps the counterpane up to his nose,

But the child sees with fear

That, now she's so near,

Her grandmother's looking remarkably queer.

She trembles with fright, and in sad perturbation,

Commences the following brief conversation:

"Oh, granny, I view your long ears with surprise!"

"They 're to hear all you say to the letter."

"Oh, granny, how fiery and big are your eyes!"

"They 're to see you all the better."

"Oh, granny, your teeth are tremendous in size!"

"They 're to eat you!"

—AND HE ATE HER.

'THERE once was a miller, who lived till he died—

It's been done by a good many people beside;

But this miller, you see,

In particular—he,

On the brink of the grave—"on the banks of the dee,"

As a Scotchman would say (vide song "Annie Laurie;"

It North-country short is

For articula mortis)—

Made a will, whence arises the whole of my story.

Three sons had this miller,

To whom all his "siller," *

Stock, business, premises, goodwill, and "wilier"—

A tenure, in short, not to spin out my verse, on all

Things he died "seised" of, both real and personal,

(Exclusive, of course, of the very bad cough

With which he was seized—and which carried him off)

He had to devise—

And, as you would surmise,

Would divide in accordance with ages and size.

But no!—not a bit!

He hadn't the wit

For such a division—or didn't see fit;

* Though with terms Caledonian this story is filled,

You 'll find it, I hope, only scotched, and not killed.

But made a partition

So strange in condition

That to one 't was a blow—for the others a hit.

It is half after one,

The funeral 's done,

The reading should now of the will be begun.

The youngest is crying,

The others are trying

To think who's most colour for praising the dying;

Their loss doesn't grieve,

Since it does not bereave

Them of all that their father was able to leave.

(Though "where there s a will," says the proverb, you know,

There's always a Way"—there's not always a Woe.)

When the will is recited

They both are delighted,

For it proves their young brother is cruelly slighted.

For joy they with decency scarce can bemean them

When they find that their dad

Every thing that he had

Has left them, the eldest, to own all between them,

Save one thing—and that

Is only the cat,

Which he leaves to the youngest, described as "that brat."

The youngest, poor lad! didn't care what he had,

By the loss of a father, not fortune, made sad.

But as silent he sat, nursing his cat,

And quite at a loss what he next should be at,

Each brother, addressing him sternly as Nemesis,

(Who, the Greeks say, less just and more cruel than Themis is,)

Said, "Now then, young Lazybones! Clear off the premises!''

He asked for some bread and some straw for a bed,

And he'd work like a slave for his brothers, he said.

But they both answered, "No! you'd much better go:

We shall have to assist you along if you're slow!"

So, half broken-hearted, the poor lad departed,

And thus in the world for himself he was started.

'T was a poorish look out,

Of that there's no doubt;

He'd not an idea what he'd best set about.

So, much to be pitied,

The old mill he quitted.

The door gave a slam—

Not one pang was spared for him—

He sat by the dam,

And that nobody cared for him

He could not help feeling—and what was prepared for him!

Thus he sat, while big tear-drops his eyes were suffusing,

Nor speaking a word,

Till he suddenly heard,

As he was a-musing, his cat, too, a mew sing.

"Ah, Puss," he said, "you

Are unfortunate too;

I'm inclined to think yours the more serious disaster

In having a penniless wretch for a master."

Puss, thus addressed, his master caressed,

And then in plain language his feelings expressed.

"Dear master," said he, "just leave it to me;

You shall see, then, I promise, what then you shall see.

I 'll at once undertake

Your fortune to make,

And assist you to wreak your revenge on those brutes;

And all that I want is a new pair of boots!"

The notion was funny:

He hadn't much money,

But as nothing more hopeful appeared to be done, he

Went off to a cobbler, who lived in a stall,

And ordered the boots to be made—rather small.

New boots, too! Not shabby, old, worn-out, and holey 'uns,

But a spick-and-span pair of resplendent Napoleons.

The boots arrived, the bill was paid,

And Pussy an excursion made.

Some snares he prepares,

To take dozens of hares,

And a wire that will grab its

Quantum of rabbits;

Without burning cartridges,

Catches some partridges

And several pheasants;

And bears them as presents

To the court of the King—I can't tell you his name,

But history reports he was partial to game.

Day after day the cat brought his prey

In numbers sufficient to load a big dray,

Or the cart which they call in the Crimea an arabah;

And each single thing

He brought to the King

"With the loyal respects of the Marquis of Carabas."

Said the monarch one day, "Come, tell me, I pray,

Whereabouts is the Marquis's property, eh?

The cat, as requested, the quarter suggested

Where the lands lay whose fee in the Marquis was vested.

Said the monarch, "Hooray!

I'll drive over that way:

Tell the Master of Horse just to bring round the chay."

In a moment at that off went the cat

At what modern slang styles "a terrible bat,"

Faster and faster, till, reaching his master,

He cried, "Of your clothes be at once off a caster,

And jump in the river that runs by the path!"

"In the river—" "Don't talk, sir, but pray go to bath!"

On the bank Pussy stayed, while his master obeyed;

But the Royal procession so long was delayed

That he felt very cold in the stream, I'm afraid.

At last, "Here they come!" cried Pussy: "now, mum

Is the word!" Said his master, "With cold I am numb,

But, while my teeth chatter so, cannot be dumb."

Said the cat, "My young friend, to this warning attend;

If you do, it will all turn out well in the end.

You've good fortune at hand, and the path's very quick to it,

So keep a look-out,

Mind what you 're about,

And whatever I say, say you likewise—and stick to it!"

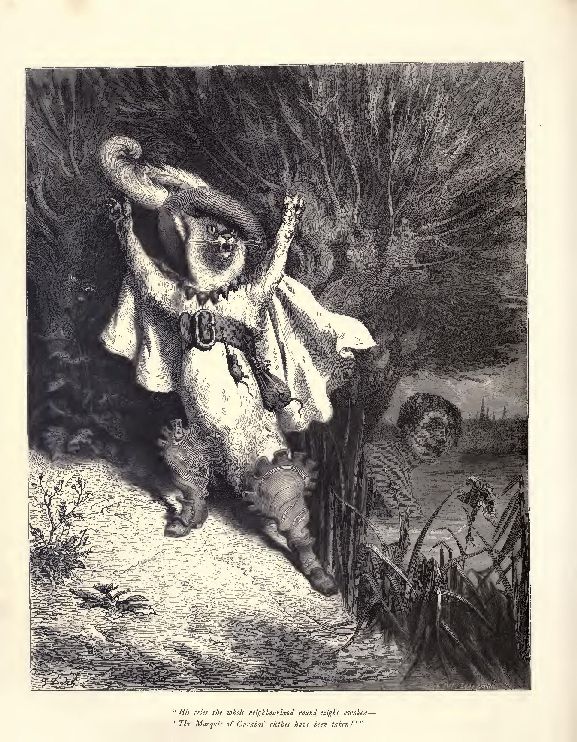

Then crafty Puss goes

And hides all the clothes

With grass and dead leaves; and when he perceives

The royal coach nearing him, loudly calls "Thieves!"

His cries the whole neighbourhood round might awaken—

"The Marquis of Carabas' clothes have been taken!"

Said the King, "Deary me!

What is it I see?

My good friend the cat up a tropical tree?"

Ah," said Puss, "my dear master has had a disaster,

For some one has cut—" "Cut! Oh, here's some court plaster."

"No, sire," said the cat,

"He doesn't want that.

He needs no court plaster, but needs a court suit;

For while he was bathing some mannerless brute,

Who had chosen the reeds and the rushes to lurk in,

Cut away with his hosen, knee-breeches, and jerkin."

"Is that all?" said the King;

"My servants shall bring

Whatever is needful—cloak, stockings, cap, sword, robe,

Gloves, collar, and doublet—in short, a whole wardrobe,

Each thing that he wants,

From castor to pants."

[Of course, you 're aware when a king takes the air

He's provided with changes of clothing to spare—

At least, so this legend would seem to declare.]

The servants produce for the Marquis's use

A rich velvet suit with gold trimmings profuse,

A rich velvet mantle with a lining of satin,

A diamond brooch stuck a point-lace cravat in,

While another the ostrich plume fastened the hat in.

These elegant clothes

Were couleur de rose,

With trimmings of green and with apple-green hose,

With noeuds of ruban, to encase his stout mollets

(For further particulars, please see Le Follet).

Our hero, attired in the garb thus acquired,

By the King's lovely daughter was greatly admired,

Who sat (as before I intended to state) on

The right of her pa in the royal "phe-ayton."

But I'm bound to confess

Our hero no less

Was charmed by her grace and her beauty in turn—

For if she liked his looks, he was ravished with "hern

Said the King, "My dear Marquis, it's really a treat

Thus to fall in with one I 've been dying to meet.

Pray take a seat,

And let me repeat

How much I'm obliged for your numerous presents

Of partridges, rabbits, grouse, woodcocks, and pheasants.

We 're going for a drive—pray enter the carriage.

Here's my daughter—she's yours, if you wish it, in marriage.

Any news? None, I fear:

Bread's still getting dear,

But the weather is fine for the time of the year.

I suppose we are passing here through your estate?"

So the King rattled on,

But the old miller's son,

Unable to answer, sat scratching his pate,

But Pussy cut in with, "Yes! though he's in doubt of it;

And for why? Dash my wig!

Because it's so big

He never can tell if he's in it or out of it.

But your Majesty, p'rhaps,

Will order your chaps

To drive to the castle, which certainly caps

Any castles you'll meet in a long summer day;

And, if you 'll allow me, I'll show them the way."

To Pussy's request the King promptly accedes,

Bids his coachman to follow wherever he leads,

And away the cat sped

A long way ahead

On a road that was bordered by corn-land and meads.

Pussy well knew

That the land they passed through

Belonged to a wizard—a mighty one, too——

Who, besides with the Evil One being "colloguer,"

(Don't think I, in quoting from "Arrah na Pogue," err:

It's what Shaun the Post says to Feeney,—the rogue—urgh!) *

Was that Middle Aged cannibal known as an ogre.

But where'er in the fields, as on they kept going,

They came upon labourers reaping or mowing,

Or ploughing or harrowing, weeding or sowing—

The cat ran before,

And cried out, "Give o'er!

Your master commands!" and the workmen forebore.

Said Puss, "He 'll approach

In a splendid state-coach,

And has sent me before him these tidings to broach,

And to bid you, unless you wish demons to tease you,

If the King, his companion, inquires who employs you,

With one voice in a moment, men, women, and boys, you

Must haste to declare,

With a satisfied air,

'The Marquis of Carabas, sire, an it please you!'

See! The carriage draws near!

Come, haste! Do you hear?

Quit all occupations,

And haste to your stations,

And give him the lowest of low salutations!"

The poor people, afraid,

His orders obeyed.—

The Marquis himself became rather dismayed,

* This expletive, used to express utter loathing,

I scarcely can spell—

One really can't tell

How to put sounds in etymological clothing.

Thinking what was to end all these funny proceedings

Into which he was following Pussy's queer leadings;

But he felt he was sinned against rather than sinning

For Pussy strange fun

With the clothes had begun,

But what would the close be of such a beginning?

Still on Pussy speeds

By pastures and meads,

And the coachman still follows wherever he leads.

"Your estates are enormous—

Pray, Marquis, inform us,

If I may inquire,

Did they come from your sire?

He must really have been a most terrible lord,

Acquiring so much by the right of the sword.

I'm pleased to perceive,

With such riches to leave,

He'd a son of such merit

The wealth to inherit

Of so mighty a conqueror and enemy-killer."

"Yes," said the youth,

"To tell you the truth,

My late father had quite a renown as a miller."

The Princess smiled sweetly,

As if to hint neatly,'

Though she counted the father

A conqueror rather,

She fancied the son

Had a victory won—

In fact, she was sure—as the smile would infer—

About one of his conquests, and that was of her!

For she felt he was lord of her bosom completely.

And now the fields and meads they leave;

To right and left huge mountains rise,

And seem—so much their heights deceive—

With lofty crests to touch the skies.

Pine forests clothe their sombre sides,

Where dark ravines and gorges frown,

And many a mountain torrent glides,

Or bounds from ledge to ledge adown.

Their mighty wings the eagles flap

High up among the summits lone,

Whose peaks the snows eternal cap,

Or where the glacier billows groan.

But in the plain about the base

Of this portentous mountain chain,

The signs of human toil they trace,

And find men labouring again.

Here, turned by some wild torrent's force,

Huge wheels revolve with busy hum;

There some vast chasm stops their course,

Whose depths the eye would vainly plumb;

Or, laden deep on shrieking wheels,

Toil waggons up the steep inclines:

Their load the mystery reveals,—

This region is a place of mines!

As soon as Puss got to this desolate spot,

Addressing the miners, he kept up the plot.

"See your master approach

In the King's grand state-coach;

He has sent me before him, his orders to broach.

"'Then haste to your stations

And make him the lowest of low salutations'"

If you don't wish the gnomes and the kobolds to seize you,

When asked whom you obey,

Be certain to say,

'The Marquis of Carabas, sire, an it please you!'

When His Majesty's Grace

Appears on the place,

You must bow till each one touches earth with his face!"

To every word

That from Pussy they heard

The miners attended—

Low bowed and low bended;

And when the King came,

And asked them the name

Of their master, they answered him all just the same.

And I'd just hint to you

That as thus this whole crew

Of miners obeyed—minors always should do.

But now having passed through this wild tract at last,

They came to a plain greenly wooded and vast,

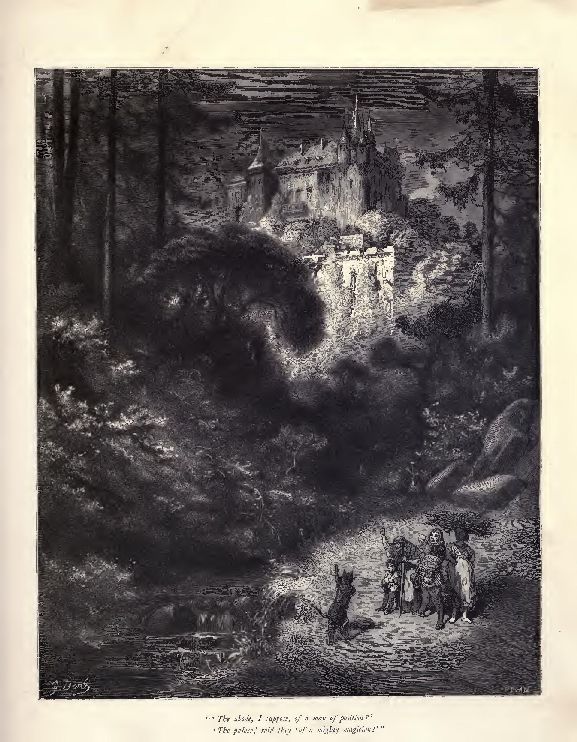

And spied out, half hid

A thick forest amid,

A castle that stood on the crest of a hill,

Or the brow of a rock—you may choose which you will;

For the hill was so steep

The road had to creep

Round and round from the baser

To the gates of the place,

Though Pussy went straight up the side at full chase,

While slowly around

The royal coach wound,

The horses got pretty well tired, I 'll be bound,

For such roads will e'en puzzle a nag that is sound.

Half-way to the top Puss in Boots made a stop

Not because he was tired and quite ready to drop,

But because he encountered a dame and her goodman

And child—by profession the man was a woodman—

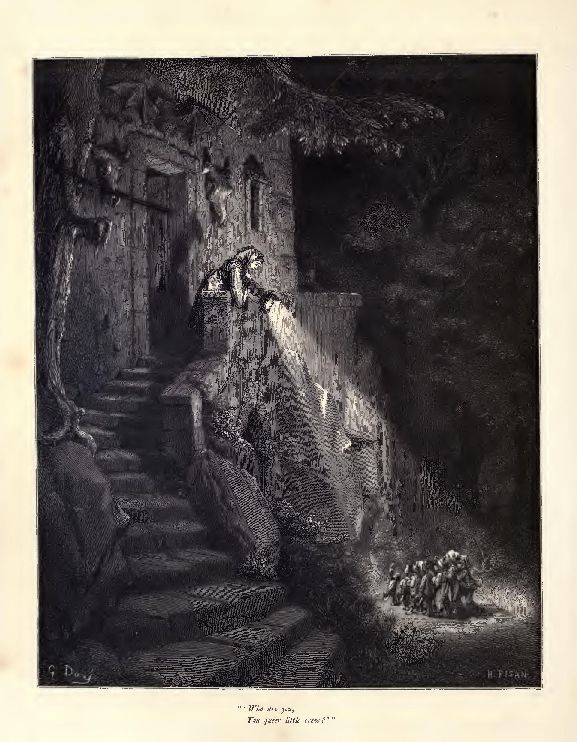

And wished to inquire

Ere he went any higher

If this past all doubt was the castle and dwelling

Of the wizard of whom I have elsewhere been telling.

So, making a bow, he said, "Pray allow

Me to ask you one question that struck me just now—

That castle that rises

To dazzle our eyes is

The abode, I suppose, of a man of position:

"The palace," said they, "of a mighty magician,

So harsh and severe he's regarded with fear

By all the poor people who dwell about here;

The best course, if you asked us, that we'd recommend to you,

Is not to go near him—he may put an end to you."

Said Puss, "Never fear, for I'll persevere

Till the neighbourhood I of this wicked one clear."

So he went on once more, till reaching the door

Of the castle, he gave with the knocker a score

Of such rat-tat-tat-tats, to the blush as would put man-

-Y thundering knocks by a real London footman.

The door was flung wide, and Puss stept inside,

But not an attendant there was to be spied—

Nought but a hand

Bearing a wand,

That pointed the way with a courtesy bland,

By corridors gorgeous, up staircases grand,

Through halls by arched ceilings, all painted, o'erspanned,

Along galleries brilliant with lovely stained windows,

Whose curtains were made

Of that Indian brocade

Which Great Britain, 't is said, to the conquest of Scinde owes;

Though the wizard of course got his curtains by witchcraft,

Not by merchant-ships, P. and O. steamers, or sich craft.

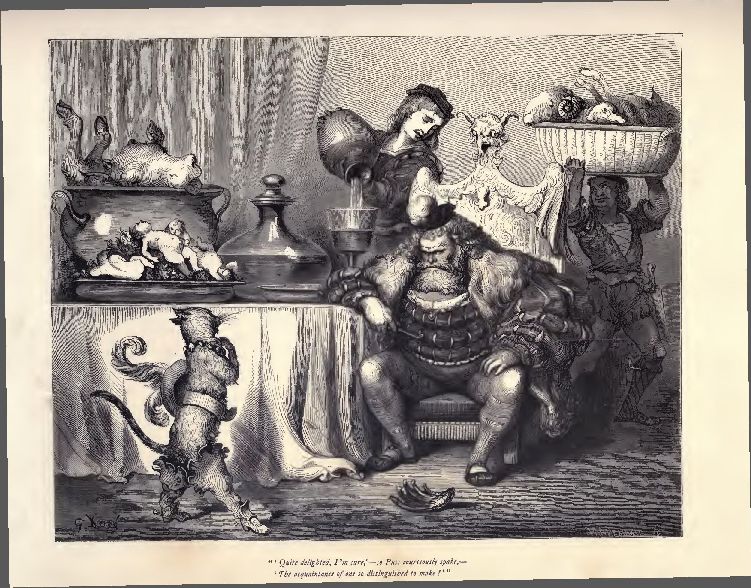

At length doth Puss enter

A hall in whose centre

The Ogre he spies, cui Cyclopius venter.

(Which, translated, would mean "as a matter of taste,

His figure and form ran a good deal to waist."

He has taken his seat,

Preparing to eat

An enormous repast of all manner of meat—

Beef, mutton, and veal, each in separate bowl—

And the different beasts are served up to him whole;

And there's one dish, moreover,

That Puss can discover,

That strikes him with horror and harrows his soul—

Babes of quite slender years (that means tender, not thin, age)

Piled up on a dish (and no gammon), and spinach.*

Puss, nothing daunted

(Although 't will be granted

The sight in some hearts might have terror implanted),

Walked straight to the board

Where the monster abhorred

At the servants attending him bellowed and roared;

And servants sure ne'er on their master attended

With such an unwilling respect as those men did!

"Rascals of mine!

Bring me some wine,

Or I 'll cut you in sunder from head-piece to chine!"

* In thus making spinach

'To rhyme as with Greenwich

I 'm authorised wholly

By Anthony Rowley,

Whose edito princeps (of course it's a foli-

-O) spells the word s.p.i.n.n.a.g.e—

And if any should know how to spell it, 't would be he.

Alarmed at the speaker,

One brought a big beaker

Of wine—one-tenth part had floored any one weaker.

But the Ogre held up the great glass to his eye

In a critical way,

Smacked his lips, just to say

"That 'll do!" and then all at one gulp drained it dry,

And set down the goblet. [I cannot see why

It is called so, and count as a regular puzzle it;

For since it's to drink,

Not to eat from, you'd think

They'd, instead of a "gobble-it," call it a "guzzle-it."]

Drawing near the huge chair with a reverent air,

With knee lowly bent, hand on heart, and head bare,

"Quite delighted, I'm sure," so Puss courteously spake,

"The acquaintance of one so distinguished to make,

For skill that's gigantic in arts necromantic,

Whose fame—not to speak it in terms sycophantic—

Is driving with envy all wizards quite frantic,

European, or Asian, or e'en Transatlantic!"

Here Puss bowed again with a courtier-like antic.

Even wizards, I fear, or so 't would appear,

Cannot always, unmoved, artful flattery hear.

The Ogre said, "Ugh!

Pray who are you?

In return for these compliments what can I do?

For since I'm not vain, it seems pretty plain

You would not tell me this without some hope of gain."

Says Pussy, "Quite right—you 're very polite—

Of your magical powers I'd fain have a sight.

There's one now report says is yours, the which borders

On what is impossible." "Pray give your orders,

And I 'll open your eyes with a little surprise,

And prove that report does not always tell lies."

"Well, since you're so kind—what a wonderful dodge I call

Is the power of assuming all shapes zoological—

Ape, bear, lion, elephant, wolf, hippopotamus

(The latter a beast

Scarcely known in the least

Till the Pacha of Egypt obliging got 'em us),

Tiger, peccary, leopard, gnu, paradoxurus;

Or e'en if you wish

A bird or a fish—

The penguin, for instance, or Buckland's silurus."

Said the Ogre, "He! he!

You quickly shall see—

That's only child's-play to a wizard like me!"

So without more ado, hands and knees on he sunk,

His ears turned to flaps, and his nose to a trunk,

And his form all at once took so quickly to swelling,

He threatened to knock off the roof of his dwelling.

"Bravo!" cried the cat; "that's capital, that!

You 're almost as big as the Heidelberg vat!

But can you now, please, with just as much ease

Into smaller dimensions at once yourself squeeze?

Say, turn from the elephant, big as the house,

Sans any embarrassment, into a mouse?"

Bulk, big legs, and trunk

Immediately shrunk!

In three seconds—no more—

Was a mouse on the floor

Where the elephant stood but an instant before.

At one bound, quick as thought,

That mouse Pussy caught,

And before any aid from his charms could be sought,

Or help could be had from the spirits who followed him,

Had given the magician one grip—and then swallowed him!

Then back to the door

Puss hastened once more,

Just in time to receive the state carriage and four.

He helped to descend

His master and friend,

Who was still in bewilderment how it would end,

And proceeded to bring

The Princess and the King

Through all the grand rooms,

Where pages and grooms—

Who were glad with the Marquis their old situations

To hold in the castle—made low salutations.

To cut my tale short,

They returned to the court,

And, since nobody wished their attachment to thwart,

The young folks were married,

And he his bride carried

To his castle, where happily ever they tarried;

And the cat was provided—

The King so decided—

With a cushion of silk

And a gallon of milk

Every day of his life till the day that he died-ed.

I 've only to add

The fortunate lad

Sent and fetched his two brothers so cruel and bad,

And recalling the past

To their memory, at' last

Told his present good fortune, which made them aghast;

And then, bidding them better in future behave them,

To be nobly revenged on them both—he forgave them!

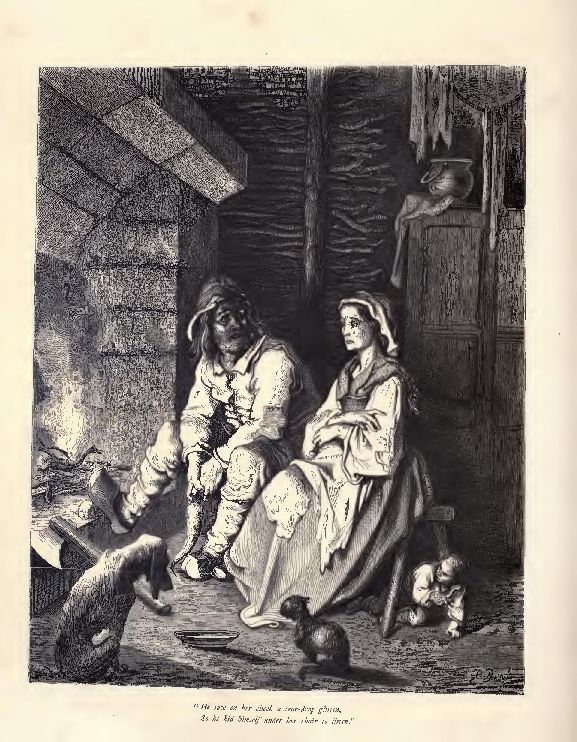

THERE once was a Baron who dwelt at the top

Of a rock by the Rhine,

Whence, whene'er he'd incline,

Upon travellers that way he was ready to drop,

And lighten their purses—

Which brought many curses

On the head of the Baron of Snitherumpopp

For a practice, which now

We shouldn't allow,

And, in fact, the police would immediately stop.

Hard by where the Bar(i)on *

These strange tricks did carry on

There lived a young Prince, who by flourish of clarion

Proclaimed unto all, both great folks and small,

He intended to give a great banquet and ball—

Or, to use modern language, a spread and a hop:—

'T was good news for the daughters of Snitherumpopp.

For the Baron, you see, had daughters three,

The two eldest as ugly as ugly can be,

And prouder than Lucifer—(no! I must scratch

That through. For they'd waited so long for a catch,

It's not true that their pride was above any match)—

But the youngest was fair, with beautiful hair;

Her sisters looked on her with rage and despair;

And that they'd have no chance they declared past a doubt,

If that "forward young minx" was allowed to "come out."

* At this new mode of spelling the word don't feel shy—

I have seen a Baron with more than one eye!

So for fear of her beauty their lovers bewitching,

They compelled her to stop

In that wretched cook's-shop

Which is—by its own denizens—christened the "kitching."

In clothes very mean they compelled her to clean

Pots, kettles, and pans—implements de cuisine.

In her pa's worn-out gloves

She polished the stoves,

Poker, shovel, and tongs, and whatever belongs

To the role of what Stubbs * calls "say po-vers onfongs,"

The General Servants—or Maids-of-All-Work,

Though this last is a name they seem anxious to shirk,

Or at least as a rule in advertisements burke.

Though far from robust, she'd to sweep and to dust,

And to see dinner cooked, when skewered rightly or trussed,

(Though dining herself off a scrap and a crust,

While if aught turned out wrong by her pa she was cussed)

Not to mention, en passant, the fact that she must

Chairs and tables adjust; and, from last unto fust,

See that all things were clean from dirt, mildew, or rust.

(For this last she used paper, which is, unless memory

Deserts this poor brain altogether, called Emery.)

[N.B. Any doubt on the point to enlighten,

I don't mean the actor, although he's a bright 'un.]

When the ball was announced, off the two sisters bounced

To send their best dresses to have them re-flounced,

And soon became clawers from various drawers

Of fans, flowers, gloves (by the shopman styled "strawers"),

Trimmings, ribbons, and laces, to add to the graces

Of their very poor forms and their very poor faces.

* Of scenes continental Poor Stubbs has been viewer

But once, though he speaks of his trip as "mong two-er."

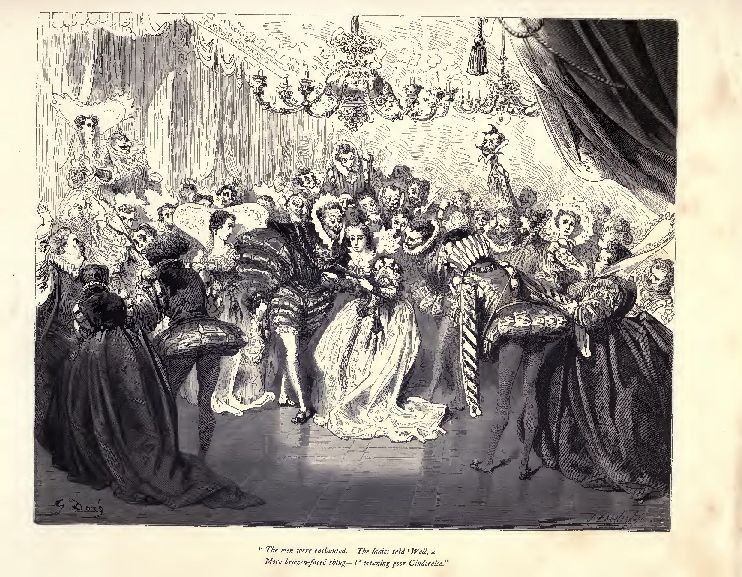

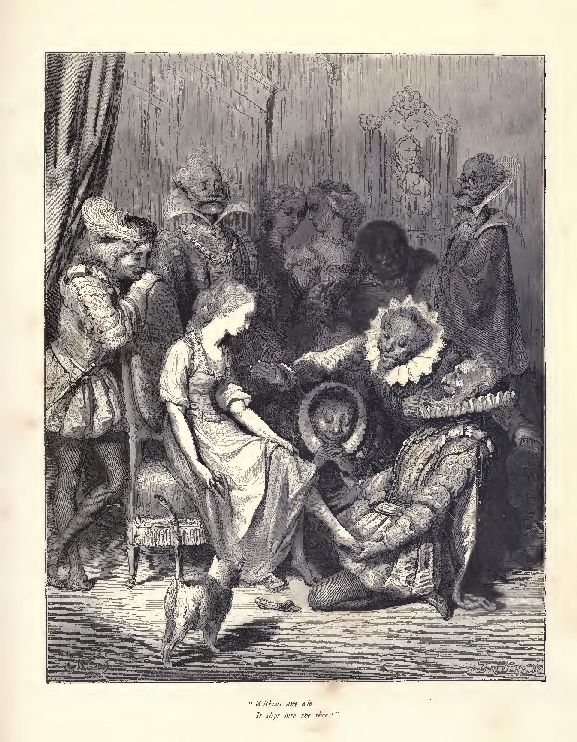

I must own that they were (since plain speaking de rigueur 's)