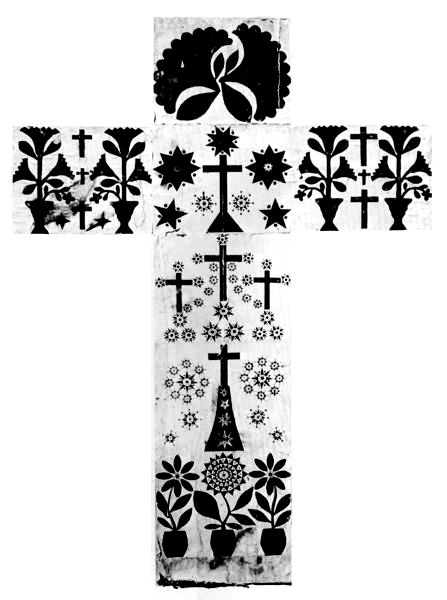

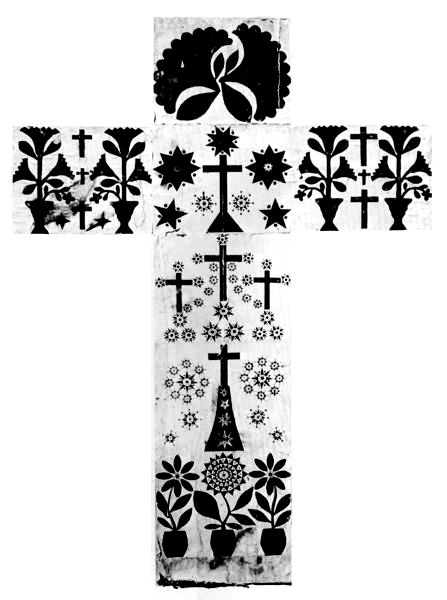

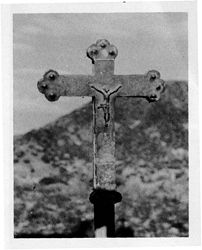

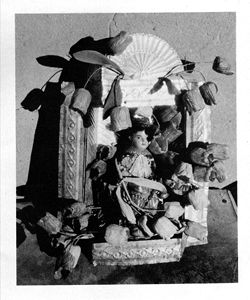

Figure 26. Cross (cruz). Size: 106.7 centimeters high, 73.6 wide. Date: First quarter of 20th century. Origin: Abiquiú; Onésimo Martínez. Location: South morada, center room. Manufacture: Indigo blue designs (stencilled?).

Title: The Penitente Moradas of Abiquiú

Author: Richard E. Ahlborn

Release date: January 15, 2014 [eBook #44678]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Chris Pinfield, Joseph Cooper

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

With the exception of Figure 26, which forms the frontispiece of this work, the individual figures have been shifted next to their first mention in the text.

Apparent typographical errors have been corrected.

Contributions from

The Museum of History

and Technology

Paper 63

The Penitente Moradas of Abiquiú

Richard E. Ahlborn

Introduction

Penitente Organization

Origins of the Penitente Movement

The History of Abiquiú

The Architecture of the Moradas

Interior Space and Artifacts

Summary

Smithsonian Institution

Press

Washington, D.C.

1968

U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1968 0—287-597

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

Washington, D.C. 20402—Price 75 cents

Figure 26. Cross (cruz). Size: 106.7 centimeters high, 73.6 wide. Date: First quarter of 20th century. Origin: Abiquiú; Onésimo Martínez. Location: South morada, center room. Manufacture: Indigo blue designs (stencilled?).

Richard E. Ahlborn

By the early 19th century, Spanish-speaking residents of villages in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado felt the need for a brotherhood that would preserve their traditional social and religious beliefs. Known as "brothers of light," or penitentes, these Spanish-Americans centered their activities in a houselike building, or morada, especially equipped for Holy Week ceremonies.

For the first time, two intact moradas have been fully photographed and described through the cooperation of the penitente brothers of Abiquiú, New Mexico.

The Author: Richard E. Ahlborn is associate curator in the Division of Cultural History in the Smithsonian Institution's Museum of History and Technology.

This study describes two earthern buildings and their special furnishings—humble but unique documents of Spanish-American culture. The two structures are located in Abiquiú, a rural, Spanish-speaking village in northern New Mexico. Known locally as moradas, they serve as meeting houses for members of a flagellant brotherhood, the penitentes.

The penitente brotherhood is characteristic of Spanish culture in New Mexico (herein called Hispano to indicate its derivation from Hispanic traditions in Mexico). Although penitential activities occurred in Spain's former colonies—Mexico, Argentina, and the Philippines—the penitentes in the mountainous region that extends north of Albuquerque into southern Colorado are remarkable for their persistence.

After a century and a half of clerical criticism[1] and extracultural pressures against the movement, physical evidence of penitente activity, although scattered and diminished, still survives. As intact, functioning artifacts, the penitente moradas at Abiquiú are valuable records of an autonomous, socio-religious brotherhood and of its place in the troubled history of Spanish-American culture in the Southwest.

This paper maintains that penitentes are not culturally deviant or aberrant but comprise a movement based firmly in Hispanic traditions as shown by their architecture and equipment found at Abiquiú and by previously established religious and social practices. Also, this paper presents in print for the first time a complete, integrated, and functioning group of penitente artifacts documented, in situ, by photographs.

My indebtedness in this study to local residents is immense: first, for inspiration, from Rosenaldo Salazar of Hernández and his son Regino, who introduced me to penitente members at Abiquiú and four times accompanied me to the moradas. The singular opportunity to measure and to photograph interiors and individual artifacts is due wholly to the understandably wary but proud, penitentes themselves. The task of identifying religious images in the moradas was expertly done by E. Boyd, Curator of the Spanish-Colonial Department in the Museum of New Mexico at Santa Fe. The final responsibility for accuracy and interpretation of data, of course, is mine alone.

[1] Beginning in 1820 with the report of ecclesiastic visitor Niño de Guevara, the Catholic Church has continued to frown upon penitente activities, A modern critical study by a churchman: Father Angélico Chavez, "The Penitentes of New Mexico," New Mexico Historical Review (April 1954), vol. 22, pp. 97-123.

Penitente brotherhoods usually are made up of Spanish-speaking Catholic laymen in rural communities. Although the activities and artifacts vary in specific details, the basic structure, ceremonies, and aims of penitentes as a cultural institution may be generalized. Full membership is open only to adult males. Female relatives may serve penitente chapters as auxiliaries who clean, cook, and join in prayer, as do children on occasion, but men hold all offices and make up the membership-at-large.

Penitente membership comprises two strata distinguishable by title and activity. In his study of Hispano institutional values, Monro Edmonson notes that penitente chapters are divided into these two groups: (1) common members or brothers in discipline, hermanos disciplantes; and (2) officers, called brothers of light, hermanos de luz.

Edmonson names each officer and lists his duties:

The head of the chapter is the hermano mayor. He is assisted in administrative duties by the warden (celador) and the collector (mandatario), and in ceremonial duties by an assistant (coadjutor), reader (secretario), blood-letter (sangredor) and flutist (pitero). An official called the nurse (enfermero) attends the flagellants, and a master of novices (maestro de novios) supervises the training of new members.[2]

In an early and apparently biased account of the penitentes, Reverend Alexandar Darley,[3] a Presbyterian missionary in southern Colorado, provides additional terms for three officers: picador (the blood-letter), regador or rezador (a tenth officer, who led prayers) and mayordomo de la muerte (literally "steward of death"). As host for meetings between penitente chapters, the mayordomo may be a late 19th-century innovation that bears the political overtones of a local leader.[4]

Having less influence than individual officers are the penitente members-at-large, numbering between thirty and fifty in each chapter. Through the Hispano family system of extended bilateral kinship, however, much of the village population is represented in each local penitente group.

Edmonson's study in the Rimrock district demonstrates the deep sense of social responsibility felt by penitentes for members and their extended family circles. "Special assistants were appointed from time to time to visit the sick or perform other community services which the brotherhood may undertake."[5] At other times of need, especially in sickness and death, the general penitente membership renders invaluable service to the afflicted family. In addition, penitente welfare efforts include spiritual as well as physical comfort such as wakes, prayers and rosaries, and the singing of funereal chants (alabados). At Española in November of 1965, I witnessed penitentes contributing such help to respected nonmembers: grave digging, financial aid, and a rosary service with alabados.

These spiritual services, however, are peripheral to the principal religious activity of penitentes—the Lenten observance of the Passion and death of Jesus. During Holy Week, prayer meetings, rosaries, and via crucis processions with religious images are held at the morada and at a site representing Calvary (calvario), usually the local cemetery. On Good Friday, vigils are kept and the morada is darkened for a service known as las tinieblas. The ceremony of "the darkenings" consists of silent prayer broken by violent noise making. Metal sheets and chains, wooden blocks and rattles are manipulated to suggest natural disturbances at the moment of Jesus' death on the cross. This emphatic portrayal of His last hours is recalled also by acts of contrition and flagellation in penitente initiation rites, punishments, and Holy Week processions.

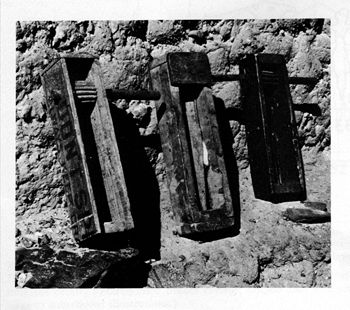

Penitentes use physical discipline and mortification as a dramatic means to intensify their imitation of Jesus' suffering.[6] Heavy timber crosses (maderos) and cactus whips (disciplinas) are used in processions that often include a figure of death in a cart (la carreta de la muerte). Disciplinary and initiatory mortification in the morada makes use of flint or glass blood-letting devices (padernales).[7]

[2] Monro S. Edmonson, Los Manitos: A Study of Institutional Values (Publ. 25, Middle American Research Institute; New Orleans: Tulane University, 1950), p. 43.

[3] Alexander M. Darley, The Passionists of the Southwest (Pueblo, 1893).

[4] E. Boyd, Curator of the Spanish-Colonial Department, Museum of New Mexico, Santa Fe, states that Jesús Trujjillo in 1947 furnished information on other penitente officers, including one man who uses the matraca and one who acts as a sergeant at arms.

[5] Edmonson, loc. cit.

[6] George Wharton James, New Mexico: Land of the Delight Makers (Boston, 1920), lists concisely the Biblical and historical references to religious mortification practiced by New Mexican penitentes.

[7] Darley (op. cit., pp. 8 ff.) gives an exhaustive list of methods of mortification said to be used by penitentes.

By 1833, bodily penance practiced in lay brotherhoods of Hispano Catholics attracted criticism from the Church in New Mexico and resulted in the pejorative name penitentes.[8] Historically, however, within the traditional framework of Hispanic Catholicism, the penitentes had precedents for their religious practices, including flagellation.

Penitente rites were derived from Catholic services already common in colonial New Mexico. Prayers and rosaries said before altars comprised an important part of Hispano religious observances, and processions of Catholics and penitentes alike were announced by bell, drum, and rifle in Hispano villages. In particular, penitentes used via crucis processions to dramatize the Passion, portrayed in every Catholic church by the fourteen Stations of the Cross. Penitentes also maintained Catholic Lenten practices by holding tenebrae services, the tinieblas rites mentioned above, and by flagellation.

These parallels between Catholic and penitente religious observances caused Edmonson to theorize that "the autonomous movement originated within the Church."[9] Variations, however, between the two religious traditions led Edmonson to discover "an important thread of religious independence and even apostasy in New Mexican history."[10] Edmonson's study of 1950 has established the persistence of penitente activity in Hispano culture.

Three and a half centuries earlier, in 1598, Spanish settlers made a courageous thrust into the inhospitable environment of New Mexico. Through the 17th and 18th centuries, Spanish settlement along the upper Rio Grande was a tenuous thread unraveled from a stronger fabric in Mexico. Aridity and extremes in temperatures marked New Mexico's climate. Arable land was scarce and could be extended back from streams only by careful upkeep of the irrigation ditches. Plateaus rose from 1500 to more than 2500 meters in altitude. Building timbers were hard to obtain without roads or navigable rivers.

Finally, distance itself was a challenge, sometimes insurmountable for the supply caravans from Mexico. Outfitted over a thousand miles to the south of Santa Fe, the Mexican caravans brought presidio and mission supplies, but few goods for the common settler. By the end of the 18th century, Spanish authorities thought of the northern colonies (provincias internas) primarily as missionary fields and military buffer zones.[11]

Cultural traditions and an insecure environment caused Spanish colonists to turn to religion for comfort. Again, however, a supply problem arose. Individual ranchos were too scattered for clerical visits, and even settlements that were grouped for greater security, poblaciones or plazas, became visitas on little more than an annual basis, sharing two dozen Franciscan clergy with missions assigned to Indian pueblos and Spanish villages. Before 1800, a shortage of friars prompted the Bishop in Durango to send secular clergy into the Franciscan enclave of New Mexico. In 1821 the Mexican Revolution formalized secularization with a new constitution. In brief, the traditional religious patterns of the Hispanos were threatened. They needed reinforcement if they were to survive.

By 1850, other conditions in New Mexico endangered the status quo of the Spanish-speaking residents. With the growing dominance of Anglo-Americans in the commercial, military, political, and social matters of Santa Fe, Hispanos recognized the threat of Anglo culture to their own traditional way of life. This cultural challenge turned many Hispanos back in upon themselves for physical and social security and for spiritual comfort. By the second quarter of the 19th century, penitentes were common in Hispano villages such as Abiquiú.[12] The immediate origins of penitentism were clearly present in early 19th-century New Mexico.

Despite this evidence, historians of the Spanish Southwest have suggested geographically and culturally remote sources for the penitentes. Dorothy Woodward has pointed out similarities between New Mexican penitentes and Spanish brotherhoods (cofradías) of laymen.[13] Cofradías were not full church orders like the Franciscan Third Order, but they did conduct Lenten processions with flagellation.

Somewhat nearer in miles but culturally more distant from Hispano penitente experience was mortification practiced by Indians in New Spain. In the 16th century, Spanish chroniclers reported incidents ranging from sanguinary ceremonies of central Mexican tribes to whippings witnessed in the northern provinces of Sonora and New Mexico. While of peripheral interest to this study, these activities of American Indians had no direct bearing on Hispano cultural needs in early 19th-century New Mexico.

It is more significant that Hispanos already knew a lay religious institution that very easily could have served as a model for the penitente brotherhood—the Third Order of St. Francis. Established in 13th-century Italy and carried to Spain by the Gray Friars, the Order is recorded in contemporary histories of New Mexico before 1700. Materials in the archives of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe also document the presence of the Franciscan Third Order in New Mexico and suggest to me its influence on penitente activity.[14]

In March 1776, Fray Domínguez, an ecclesiastic visitor, recorded Lenten "exercises" of the Third Order under the supervision of the resident priest at Santa Cruz and, two weeks later, in April, Domínguez visited Abiquiú, where he commended the Franciscan friar, Fray Sebastian Angel Fernández, for "feasts of Our Lady, rosary with the father in church. Fridays of Lent, Via Crucis with the father, and later, after dark, discipline attended by those who came voluntarily."[15] Domínguez, however, described the priest as "not at all obedient to rule"[16] when Father Fernández, acting in an independent manner, proceeded to build missions at Picuris and Sandia without authorization. But in 1777, he again praised Fray Fernández for special Via Crucis devotions and "scourging by the resident missionary and some of the faithful."[17] Domínguez thus documented flagellant practices and tinieblas services at Abiquiú and his approval, as an official Church representative, of these activities.

Father Chavez, O.F.M., protests the theory of penitente origins in the Third Order of St. Francis and counters with the idea that "penitentism" was imported directly from Mexico in the early 1800s.[18] I note, however, that the bishops seated in Santa Fe after 1848 recognized the strength of this lay socio-religious movement and tried to deal with it in terms of the Order. At a synod in 1888, Archbishop Salpointe pleaded for penitentes "to return" to the Third Order. Some degree of direct influence of the Third Order on "penitentism" seems fairly certain.

[8] Angélico Chavez, Archives of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, 1678-1900 (Washington, 1957): "Books of Patentes," 1833: books xi, xii, xix, lxxiii, and lxxxii. (Original documents from archives noted hereinafter as AASF.)

[9] Edmonson, p. 33.

[10] Ibid., p. 18.

[11] H. E. Bolton, "The Spanish Borderlands and the Mission as a Frontier Institution," American Historical Review (Santa Fe, 1917), vol. 23, pp. 42-61, indicates that this policy was developed after 1765 by Charles III of Spain in an attempt to reorganize the administration of his vast colonial empire.

[12] AASF, Patentes, book lxxiii, box 6.

[13] "The Penitentes of the Southwest" (unpublished Ph. D. dissertation, Yale University, 1935).

[14] Chavez, Archives, p. 3 (ftn.).

[15] Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez, The Missions of New Mexico, 1776, transl. and annot. Eleanor B. Adams and Fray Angelico Chavez (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1956), p. 124.

[16] Domínguez, ms., from Biblioteca Nacional de Méjico, leg. 10, no. 46, p. 300.

[17] Ibid., no. 43, p. 321.

[18] Chavez, "Penitentes," p. 100.

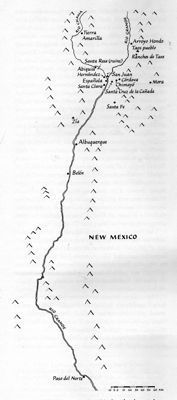

Figure 1. Mid-19th-century New Mexico, showing pertinent geographical features, Indian pueblos (indicated by solid triangles), and Spanish villages cited in text.

About three generations before the first morada was built at Abiquiú, the conditions of settlement mentioned earlier and subsequent historical events resulted in an environment conducive to the development of penitente activity. Shortly after 1740, civil authorities in Santa Fe attempted to settle colonists along the Chama River in order to create a buffer zone between marauding Indians to the northwest and Spanish and Pueblo villages on the Rio Grande (Figure 1). This constant threat of annihilation produced self-reliant and independent-minded settlers.

Unorthodoxy appeared early in the religious history of Abiquiú. By 1744, settlers had installed Santa Rosa de Lima as their patroness in a little riverside plaza near modern Abiquiú. After a decade, several colonists from Santa Rosa were moved to the hilltop plaza of Abiquiú, where the mission of Santo Tomás Apostol had been established. In his 1776 visit to Abiquiú, Domínguez noted, however, a continuing allegiance to the earlier patroness: "... settlers use the name of Santa Rosa, as the lost mission was called in the old days. Therefore, they celebrate the feast of this female saint [August 30th] and not of that masculine saint [St. Thomas the Apostle, December 21]."[19] Loyalty to Saint Rose survived this official protest, and village festivals have persisted in honoring Santa Rosa to this day. It is, therefore, not surprising to find her image in the earlier east morada of Abiquiú.

A disturbing influence in the religious life of Abiquiú were semi-Christianized servants (genízaros), who had been ransomed from the Indians by Spaniards.[20] Often used to establish frontier settlements, genízaros came to be a threat to the cultural stability of Abiquiú. For example, in 1762, two genízaros accused of witchcraft were taken to Santa Cruz for judicial action. After the trial, Governor Cachupín sent a detachment from Santa Fe to Abiquiú to destroy an inscribed stone said to be a relic of black magic.[21] Similar incidents with genízaros during the next generation prolonged the unstable religious pattern at Abiquiú. In 1766, an Indian girl accused a genízaro couple of killing the resident priest, Fray Felix Ordoñez y Machado, by witchcraft.[22] And again in 1782 and 1786, charges of apostasy were entered against Abiquiú genízaros.[23]

Another disturbing element in the religious history of Abiquiú was the disinterest of her settlers in the building and furnishing of Santo Tomás Mission. Although the structure was completed in the first generation of settlement at Abiquiú, 1755 to 1776, Domínguez could report only two contributions from colonists, both loans: "In this room [sacristy] there is an ordinary table with a drawer and key ... a loan from a settler called Juan Pablo Martin ... the chalice is in three pieces, and one of them, for it is a loan by the settlers, is used for a little shrine they have."[24] All mission equipment was supplied by royal funds (sínodos) except some religious articles provided by the resident missionary, Fray Fernández, who finished the structure raised half way by his predecessor, Fray Juan José Toledo. Both Franciscans found settlers busy with everyday problems of survival and resentful when called on to labor for the mission. The settlers not only failed to supply any objects, but when they were required to work at the mission, all tools and equipment had to be supplied to them.[25]

Despite these detrimental influences, the mission at Abiquiú continued to grow. Between 1760 and 1793, the population increased from 733 to 1,363, making Abiquiú the third largest settlement in colonial New Mexico north of Paso del Norte [Ciudad Juarez].[26] (Only Santa Cruz with 1,650 and Santa Fe with 2,419 persons were larger.) In 1795, the pueblo had maintained its size at 1,558, with Indians representing less than 10 percent of the population.[27]

The increase in size brought the mission at Abiquiú more important and longer-term resident missionaries: Fathers José de la Prada, from 1789 to 1806, and Teodoro Alcina de la Borda, from 1806 to 1823. Both men were elected directors (custoses) of the Franciscan mission field in New Mexico, "The Custody of the Conversion of St. Paul." Custoses Prada and Borda backed the Franciscans, who were fighting for a missionary field that they had long considered their own. Official directives (patentes) issued by Custos Prada at Abiquiú warned all settlers against "new ideas of liberty" and asked each friar for his personal concept of governmental rights.[28] In 1802, Fray Prada also complained to the new Custos, Father Sanchez Vergara, about missions that had been neglected under the secular clergy.[29] In this period, Abiquiú's mission was a center of clerical reaction to the revolutionary political ideas and clerical secularization that had resulted from Mexico's recent independence from Spain.

In the year 1820, the strained relations between religious authorities and the laity at Abiquiú clearly reflected the unstable conditions in New Mexico. Eventually, charges of manipulating mission funds and neglect of clerical duties were brought against Father Alcina de la Borda by the citizens of Abiquiú.[30] At the same time, Governor Melgares informed the Alcalde Mayor, Santiago Salazar, that these funds (sínodos) had been reduced and that an oath of loyalty to the Spanish crown would be required.[31] This situation produced a strong reaction in Abiquiú's next generation, which sought to preserve its traditional cultural patterns in the penitente brotherhoods.

The great-grandsons of Abiquiú's first settlers witnessed a significant change in organization of their mission—its secularization in 1826. For three years, Father Borda had shared his mission duties with Franciscans from San Juan and Santa Clara pueblos, giving way in 1823 to the last member of the Order to serve Santo Tomás, Fray Sanchez Vergara. Santo Tomás Mission received its first secular priest in 1823, Cura Leyva y Rosas, who returned to Abiquiú in 1832. Officially the mission at Abiquiú was secularized in 1826, along with those at Belén and Taos.[32]

The first secular priest assigned to Santo Tomás reflected the now traditional and self-sufficient character of Hispano culture at Abiquiú.[33] He was the independent-minded Don Antonio José Martínez. Born in Abiquiú, Don Antonio later became an ambitious spiritual and political leader in Taos, where he fought to preserve traditional Hispano culture from Anglo-American influences.

The mission served by Father Martínez in Taos bore resemblance to that at Abiquiú. Both missions rested on much earlier Indian settlements, but the Taos pueblo was still active. Furthermore, Taos and Abiquiú were buffer settlements on the frontier, where Indian raids as well as trade occurred. In 1827 a census by P. B. Pino listed nearly 3,600 persons at Taos and a similar count at Abiquiú; only Santa Fe with 5,700 and Santa Cruz with 6,500 were larger villages.

At this time, an independent element appeared in the religious activities of the Santa Cruz region. In 1831, Vicar Rascon gave permission to sixty members of the Third Order of St. Francis at Santa Cruz to hold Lenten exercises in Taos, provided that no "abuses" arose to be corrected on his next visit.[34] Apparently this warning proved inadequate, for in 1833 Archbishop Zubiría concluded his visitation at Santa Cruz by ordering that "pastors of this villa ... must never in the future permit such reunions of Penitentes under any pretext whatsoever."[35] We have noted, however, that two generations earlier Fray Domínguez had commended similar observances at Santa Cruz and Abiquiú, and it was not until the visitation of Fray Niño de Guevara, 1817-1820, that Church officials found it necessary to condemn penitential activity in New Mexico.[36]

In little more than two generations, from 1776 to 1833, the Franciscan missions were disrupted by secularization and excessive acts of penance. In the second half of the 19th century, the new, non-Spanish Archbishops, Lamy and Salpointe, saw a relation between the Franciscan Third Order and the brotherhood of penitentes. When J. B. Lamy began signing rule books (arreglos) for the penitente chapters of New Mexico,[37] he hoped to reintegrate them into accepted Church practice as members of the Third Order. And at the end of the century, J. B. Salpointe expressed his belief that the penitente brotherhood had been an outgrowth of the Franciscan tertiaries.[38]

Abiquiú shared in events that marked the religious history of New Mexico in the last three quarters of the 19th century. We have noted the secularization of Santo Tomás Mission in 1826; by 1856 the village had its penitente rule book duly signed by Archbishop Lamy. Entitled Arreglo de la Santa Hermandad de la Sangre de Nuestro Señor Jesucristo, a copy was signed by Abiquiú's priest, Don Pedro Bernal, on April 6, 1867.[39] While officialdom worked out new religious and political relations, villagers struggled to preserve a more familiar tradition.

Occupation of New Mexico in 1846 by United States troops tended to solidify traditional Hispano life in Abiquiú. In that year, Navajo harassments caused an encampment of 180 men under Major Gilpin to be stationed at Abiquiú.[40] Eventually, the Indian raids slackened, and a trading post for the Utes was set up at Abiquiú in 1853.[41] Neither the U.S. Army nor Indian trading posts, however, became integrated into Abiquiú's Hispano way of life, and these extracultural influences soon moved on, leaving only a few commercial artifacts.

With a new generation of inhabitants occupying Abiquiú between 1864 and 1886, the village on the Rio Chama lost its primary function as a buffer settlement against nomadic Indians and settled down into a well-established cultural pattern, which in part was preserved by the penitentes. Kit Carson had rounded up the Navajos at Bosque Redondo, and two decades later, by 1883, the Utes had been moved north. In preparation, the Indian trading post at Abiquiú was closed in 1872 and moved to the new seat of Rio Arriba County, Tierra Amarilla,[42] 65 kilometers northward. Within two generations, Abiquiú's population had fallen to fewer than 800 from a high of nearly 3,600 in 1827.[43] As a result, many Hispanos at Abiquiú withdrew into the penitente organization, which promised to preserve and even intensify their traditional ways of life and beliefs. These attitudes were materialized in the building of the penitente moradas.

[19] Domínguez, Missions, pp. 121 (ftn. 1), 200.

[20] AASF, Patentes, 1700, forbids friars to buy genízaros even under the excuse of Christianizing them since the result would likely be morally dangerous.

[21] H. H. Bancroft, History of Arizona and New Mexico (San Francisco, 1889), p. 258.

[22] Domínguez, Missions, p. 336.

[23] AASF, Loose Documents, Mission, 1782, no. 7.

[24] Domínguez, Missions, p. 122.

[25] Ibid., p. 123.

[26] Bancroft, p. 279.

[27] AASF, Loose Documents, Mission, 1795, no. 13.

[28] Ibid., 1796, nos. 6, 7.

[29] Ibid., 1802, no. 18.

[30] Ibid., 1820, nos. 15, 21, 38; also R. E. Twitchell, The Spanish Archives of New Mexico (Cedar Rapids, 1914), vol. 2, pp. 630, 631.

[31] AASF, Loose Documents, Mission, 1820, nos. 12, 21.

[32] Ibid., 1826, no. 7.

[33] Don Antonio was less than eager to accept his first post; he had to be ordered to report to duty (AASF, Accounts, book lxvi [box 6], April 27, 1826).

[34] AASF, Patentes, 1831, book lxx, box 4, p. 25.

[35] Ibid., book lxxiii, box 7.

[36] AASF, Accounts, book lxii, box 5.

[37] AASF, Loose Documents, Diocesan, 1853, no. 17, for Santuario and Cochiti; other rule books document penitente chapters at Chimayo, El Rito, and Taos.

[38] Jean B. Salpointe, Soldiers of the Cross (Banning, Calif., 1898).

[39] AASF, Loose Documents, Diocesan, 1856, no. 12.

[40] Twitchell, pp. 533-534.

[41] Bancroft, p. 665.

[42] Twitchell, p. 447.

[43] Ibid., p. 449, from P. B. Pino, Notícias históricas (Méjico, 1848); and Ninth U.S. Census (1870). The later figure may represent only the town proper; earlier statistics generally included outlying settlements.

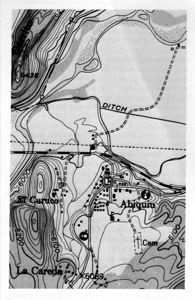

Figure 2. The Abiquiú area, showing the Chama River, U.S. Highway 84, and siting of buildings (the mission of Santo Tomás and the two moradas are circled).

In a modern map (Figure 2), circles enclose the Mission of Abiquiú and its two penitente moradas. The moradas lie 300 meters east and 400 meters south of the main plaza onto which Santo Tomás Mission faces from the north. Between the moradas rests the local burial ground (campo santo), a cemetery that serves penitentes as "Calvary" (calvario) in their Lenten re-enactment of the Passion.

Penitente moradas share a common system of adobe construction with the religious and domestic structures of New Mexico. While the Indians set walls of puddled earth directly on the ground, the Spaniards, following Moorish precedent, laid adobe bricks on stone foundations. Standard house-size adobes average 15 by 30 by 50 centimeters. Adobe bricks are made by packing a mixture of mud, sand, and straw into a wood frame from which the block then is knocked out onto the ground to dry in the sun. Stones set in adobe mortar provide a foundation. The sun-dried bricks, which are also laid in adobe mortar, form exterior, load-bearing walls and interior partitions.

Spanish adobe construction also employs wood. Openings are framed and closed with a lintel that projects well into the wall. These recessed lintel faces often are left exposed after the plastering of adjoining surfaces. Roofs are transverse beams (vigas), which in turn hold small cross branches (savinos) or planks (tablas). A final layer of brush and adobe plaster closes the surface cracks. Plank drains (canales), rectangular in section, lead water from this soft roof surface (Figure 3).

Domestic adobe structures differ from ecclesiastic buildings in scale and in spatial arrangement. Colonial New Mexican churches are relatively large, unicellular spaces. Their simple nave volume often is made cruciform by a transept whose higher roof allows for a clerestory. A choir loft over the entry and a narrowed, elevated sanctuary further articulate the space at each end of the nave. In contrast, Hispano houses consist of several low rooms set in a line or grouped around a court (placita) in which a gate and porch (portal) are placed. Rooms vary in width according to the length of the transverse beams, which usually are from four to six meters long.[44]

The everyday living spaces inside Spanish-New Mexican houses tend to combine domestic activities and to appear similar in space and decor. Inside a Hispano church, however, areas of special useage are marked off clearly within the volume. Celebration of the mass requires a special spatial treatment to indicate the sanctuary. This area is emphasized by an arched entry, lateral pilasters, raised floor, and characteristically convergent side walls. These slanting walls provide better vision for the congregation and easier movement for the celebrants. The convergent wall of sanctuaries is often visible from the exterior. It is noteworthy that both the contracted sanctuary of local churches and the linear arrangement of domestic interiors appear in the penitente moradas of Abiquiú.

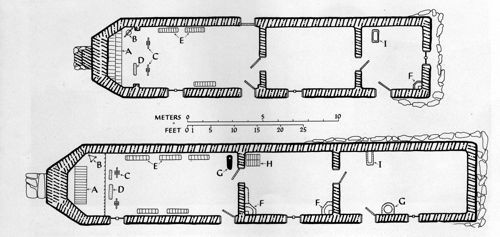

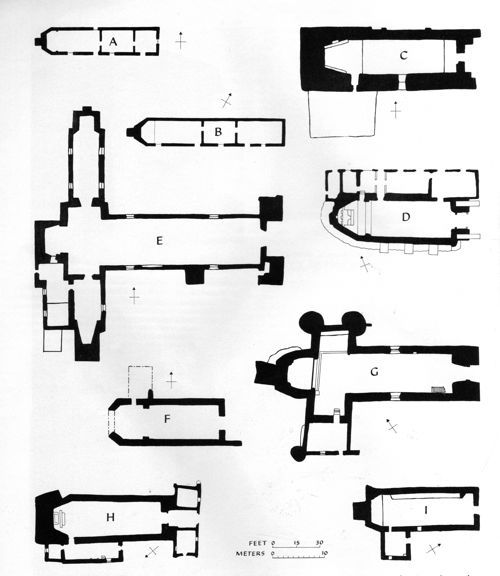

In the plans of the Abiquiú moradas (Figure 4), the identical arrangement of the three rooms reveals an origin in the typical Hispano house form. George Kubler has observed that the design of moradas "is closer to the domestic architecture of New Mexico than to the churches."[45] Bainbridge Bunting confirms the houselike form of moradas but notes their lack of uniformity.[46] In comparison to moradas of the L-plan,[47] and even of the pre-1856 T-plan structure at Arroyo Hondo,[48] the two penitente buildings at Abiquiú preserve a simple | shape with one significant variation—a contracted chancel.

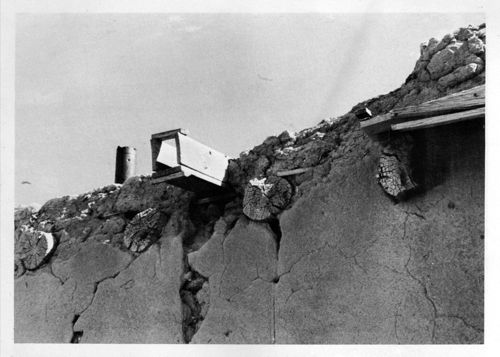

Figure 3. North roofline of east morada, showing exposed ends of ceiling beams (vigas), chimney of oratory stove, and construction of water drain (canal).

Figure 4. Plans of south morada (top) and east morada (bottom): A=altar; B=standard; C=candelabra; D=sandbox; E=benches; F=fireplace; G=stove; H=chest; I=tub.

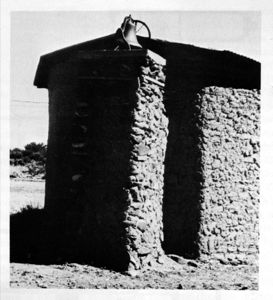

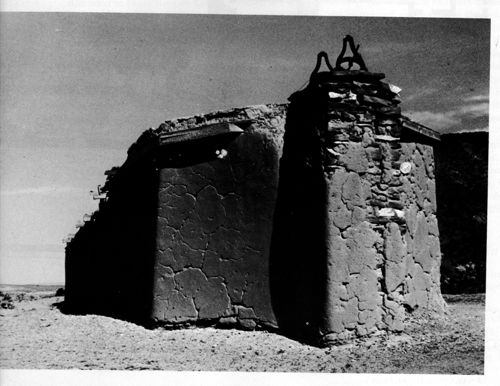

The basic form of the Abiquiú moradas (Figures 5 and 6) is a rectangular box that closely resembles nearby houses. Even the long, windowless north facade of both Abiquiú moradas recalls the unbroken walls of earlier Hispano houses in hostile frontier regions. The Abiquiú moradas, however, possess one exception to the domestic form—a narrowed, accented end. On each morada the west end is blunted and buttressed by a salient bell tower of stones laid in adobe mortar and strengthened by horizontal boards (Figures 7 and 8). This innovation in the form of the Abiquiú moradas appears to be ecclesiastic in origin.

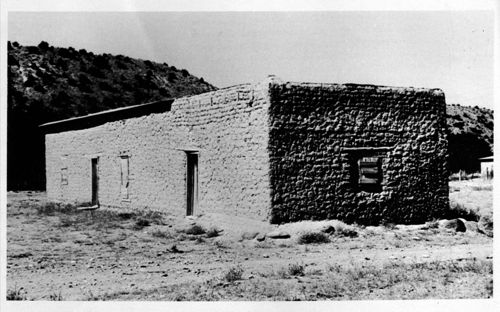

Figure 5. South Morada. Size: 24.02 meters long, 5.41 wide, 3.51 high. Date: About 1900. Location: 400 meters south of Santo Tomás Church in main plaza; seen from southeast corner. Manufacture: Adobe bricks on stone foundation; wood door and window frames.

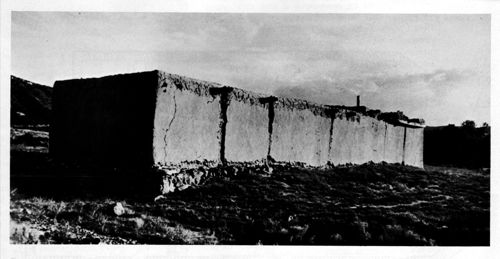

Figure 6. East Morada. Size: 28.82 meters long, 4.88 wide, 3.58 high. Date: 19th century. Location: 300 meters east-southeast of Santo Tomás Church in main plaza; seen from northeast corner. Manufacture: Adobe bricks set on stone foundation; wood drains (canales) and beam (viga) ends at top of wall.

Figure 7. West end of south morada, showing construction of bell tower and contracted sanctuary walls.

Figure 8. Northwest view of east morada, showing limestone slab bell tower on contracted west end.

Plans of churches built close to Abiquiú in time, distance, and orientation could have served as sources for the design of the moradas' west ends (Figure 9). Only five kilometers east of Abiquiú stood the chapel dedicated to Santa Rosa de Lima. As shown in Figure 9f, the sanctuary in its west end had a raised floor and flanking entry pilasters, features found in the east morada's west end. This chapel was dedicated about 1744 and was still active as a visíta from Abiquiú in 1830.[49] Through this period and to the present, the popularity of Saint Rose of Lima has persisted at Abiquiú. Her nearby chapel would have been a likely and logical choice for the design of the morada's sanctuary end.

Figure 9. Plans of two Abiquiú moradas compared to New Mexican churches with contracted sanctuaries: A, south morada, B, east morada; C, Zía Mission; D, San Miguel in Santa Fe; E, Santa Cruz; F, Santa Rosa; G, Ranchos de Taos; H, the santuario at Chimayo; I, Córdova. (From Kubler, Religious Architecture [see ftn. 45]: C=his figure 8; D=28, E=9, F=34, G=13, H=22, I=35.)

A second possible source for the contracted ends of the Abiquiú moradas would be the south transept chapel of the Third Order of St. Francis at Santa Cruz (Figure 9e). It was completed shortly before 1798[50] and served Franciscan tertiaries into the 1830s. Plans compared in Figure 9 indicate that the dimensions of this left transept chapel at Santa Cruz measure only five percent larger than the chapel room of the east morada at Abiquiú, and the plans also reveal contracted chancel walls at both locations.

The concept of a constricted sanctuary as seen in Abiquiú moradas originated in earlier Spanish and Mexican churches. In 1479, architect Juan Guas used a trapezoidal apse plan in San Juan de los Reyes at Toledo and, by 1512, the design found its way into America's first cathedral at Santo Domingo. Within the first century of Spanish colonization, contracted sanctuary walls appeared on the American mainland in Arciniega's revised plan for Mexico City's Cathedral (post-1584)[51] and, again, in New Mexico, where it first appeared at the stone mission of Zía, built about 1614 (Figure 9c). Once established in the Franciscan province, the concept of converging sanctuary walls survived the 1680 Indian revolt and returned with the reconquest of New Mexico in 1693. Spaniards raised and rebuilt missions from the capital at Santa Fe (San Miguel, rebuilt 1710; Figure 9d) north to Taos (San Geronimo, 1706). Throughout the 18th century, in a three-to-one ratio, the churches of New Mexico used the contracted, as opposed to the box, sanctuary.

In the early 19th century, churches at Ranchos de Taos (1805-1815[52]; Figure 9g), Chimayo (about 1810; Figure 9h), and Córdova (after 1830; Figure 9i) continued to employ the trapezoidal sanctuary form. By midcentury, penitente brotherhoods are known to have been active in these villages, and the local ecclesiastic structures could have acted as an influence in the design of the penitente moradas at Abiquiú.

In summary, the moradas at Abiquiú are traditional regional buildings in material and in basic form. The pointed west end of each building, however, is an ecclesiastic innovation in an otherwise typical domestic design. These moradas provide a significant design variant in the history of Spanish-American architecture in New Mexico.

[44] The "Hall of Everyday Life in the American Past" in the Museum of History and Technology (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.) displays an interior typical of a Spanish-New Mexican adobe house of about 1800.

[45] George Kubler, The Religious Architecture of New Mexico (Colorado Springs, 1940), p. viii.

[46] Bainbridge Bunting, Taos Adobes (Santa Fe, 1964), P. 54.

[47] L-plan moradas are pictured by Woodward [see ftn. 13] in a 1925 photograph at San Mateo, a different morada from that illustrated in Charles F. Lummis, Land of Poco Tiempo (New York, 1897), as well as in another Woodward photograph [see ftn. 13] taken on the road to Chimayo. L. B. Prince, Spanish Mission Churches of New Mexico (Cedar Rapids, 1915), shows an L-plan morada near Las Vegas. Was the L-plan house an unconscious recall of the more secure structure that completely enclosed a placita?

[48] Bunting, p. 56. After 1960 the Arroyo Hondo morada became the private residence of Larry Franks.

[49] AASF, Loose Documents, Mission, 1829 (May 27).

[50] Kubler, Religious Architecture, p. 103.

[51] George Kubler and Martin Soria, The Art and Architecture of Spain and Portugal and Their American Dominions, 1500 to 1800 (Baltimore, 1959), pp. 3, 64, 74.

[52] E. Boyd, interview, April 1966. Building date of about 1780 usually is given for the present church. Boyd, however, states that documents in AASF support the tree-ring dates given in Kubler. Religious Architecture, p. 121, as 1816±10.

The plans of the two penitente moradas of Abiquiú (Figure 4) reveal an identical arrangement of interior space. There are three rooms in each morada: (1) the longest is on the west end and, with its constricted sanctuary space, acts as an oratory; (2) the center room serves as a sacristy; and (3) the east room is for storage. The only major difference between the two moradas is the length of the storage room, which is nearly twice as long in the east morada. The remarkable similarities in design suggest that one served as the model for the other; local oral tradition holds that the east morada is older.[53]

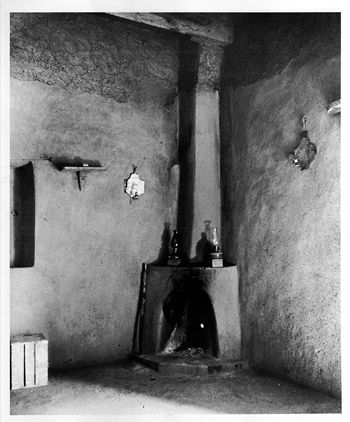

Internal evidence indicates that the east morada is indeed the older one. As shown in Figure 2, the south morada is located farther from the Abiquiú plaza, suggesting it was built at a later date—perhaps nearer 1900, when public and official criticism had prompted greater privacy for Holy Week processions, which were considered spectacles by tourists. In addition, the lesser width of the south morada rooms, the square-milled beams in the oratory, and the fireplace in the east end storage room indicate that it was built after the east morada. In contrast, the two corner fireplaces of the east morada are set in the center room, while another heating arrangement—an oil drum set on a low adobe dais—appears to have been added at a later date.

The east morada was the obvious model for the builders of the later one on the south edge of Abiquiú. Local penitentes admit that there was a division in the original chapter just prior to 1900[54] but deny that the separation was made because of political differences, as suggested by one author.[55] The older members say that the first morada merely had become too large for convenient use of the building.

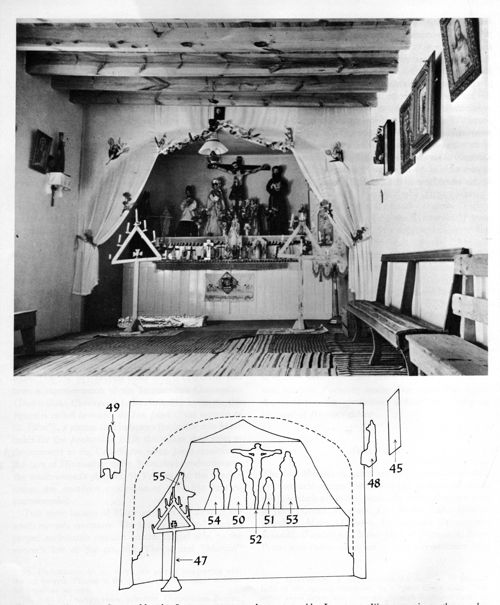

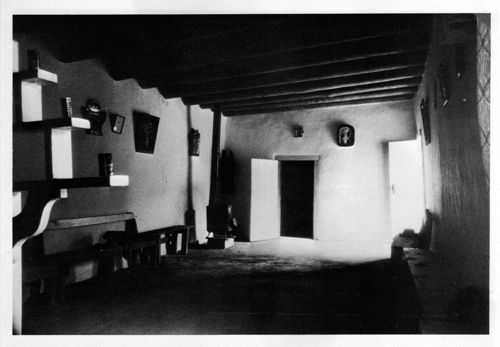

The three rooms in each morada are distinguished by bare, whitewashed walls of adobe plaster, hard-packed dirt floors, two exterior doors, and three windows. A locked door is located off the oratory in the north face of the south morada. Figures 10 and 11 show the sanctuaries in the south and east morada; and Figure 12, the back of the east morada oratory. Its open door leads into the center room, where the members would not remove the boards on the windows for me to take photographs. The east end room in each morada serves for storage of processional and ceremonial equipment.

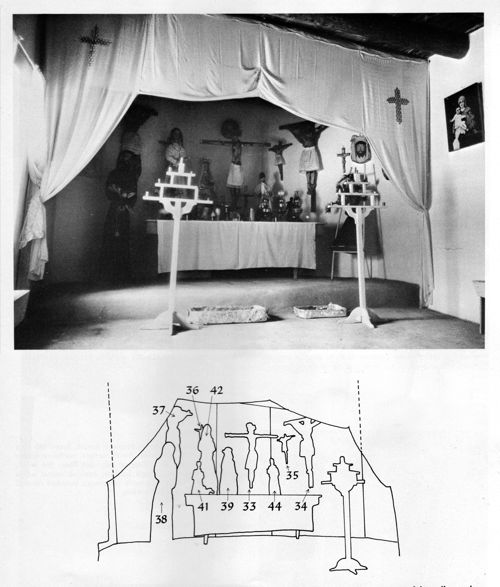

Figure 10. Altar in South Morada. Size: 10.05 meters long, 3.51 wide. Location: West room in south morada. Description: Looking west into sanctuary; dirt floor with cotton rag rugs; side walls lined with benches and hung with religious prints; square-milled timber ceiling; draped arch with candelabra; altar and gradin with religious images. (Numbers refer to subsequent illustrations.)

Figure 11. Altar in East Morada. Description: Looking into sanctuary; dirt floor and convergent adobe walls; sacristy entry marked by drapes and raised floor; candelabra and sand boxes for votive candles; draped altar table supplied with religious images. (Numbers refer to subsequent illustrations.)

Figure 12. Rear of Oratory, East Morada. Size: 10.98 meters long, 4.04 wide. Location: Back of west room in east morada. Description: Looking east, to rear of oratory. Dirt floor, adobe-plastered walls, wooden benches, iron stove, framed religious prints on walls, ceiling of round beams (vigas).

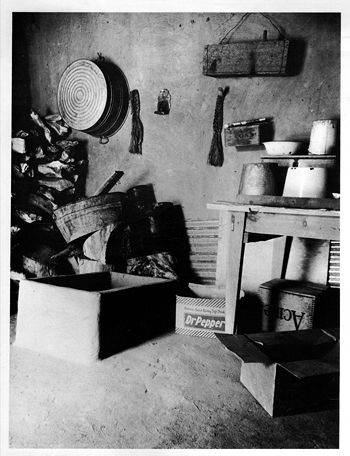

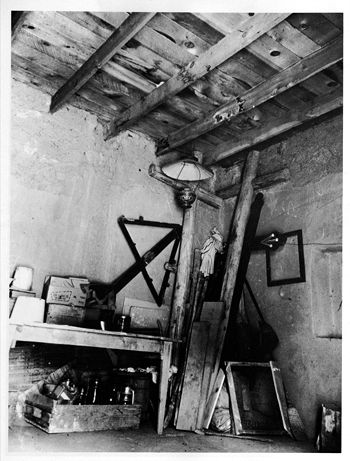

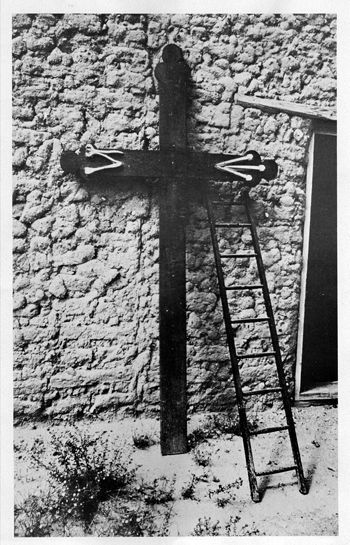

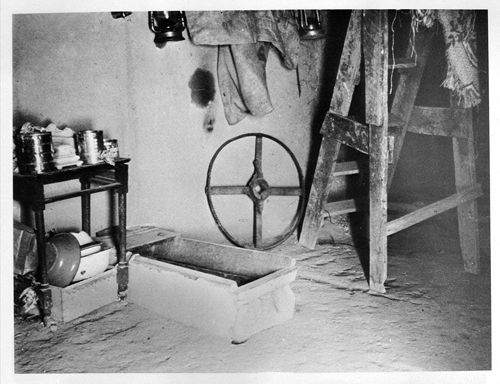

Storage Room in Both Moradas.—In the south morada (Figure 13), there are cactus scourges (disciplinas), corrugated metal sheeting used for roofing, and three rattles (matracas; Figure 14), also used for noise-making in tinieblas services. Situated here also are black Lenten candelabrum, a ladder, a cross with silvered Passion emblems, and massive penitential crosses (maderos; Figure 15). The Lenten ladder and cross are shown next to the exterior entry (Figure 16). A corner fireplace is flanked by locally made tin candle sconces (Figure 17). Two 19th-century kerosene lamps appear on the fireplace mantle, and a tin-shaded lantern with its silver-plated reservoir hangs from the ceiling (Figure 15).

Figure 13. Floor Tub in Storage Room. Size: tub 53.3 centimeters high. Location: South morada, northwest corner of room. Description: Cement tub, dirt floor, fire wood, galvanized tubs, enamelized buckets, braided cactus whips (disciplinas), wooden box rattle (matraca), punched tin wall sconce, corrugated metal roofing.

Figure 14. Rattles (matracas). Size: 26 to 40 centimeters long. Location: South morada storage (east) room. Description: Flexible tongue set at one end of wooden frame, and notched cylinder on handle turning in opposite end.

Figure 15. Penitente Crosses (maderos) in Storage Room. Sizes: black cross 269.2 centimeters high (Figure 16); ceiling boards 2.5 by 15; maderos 345 long. Date: 20th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified carpenter. Location: South morada, northeast corner. Description: black candelabra (tenebrario), kerosene lanterns, tin shades, wooden keg and box under table.

Figure 16. Cross and Ladder (cruz and escalera). Size: cross 269.2 centimeters high. Date: Fourth quarter of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified carpenter. Location: South morada, storage (east) room. Description: Milled and carved wood (painted), black cross and ladder, silvered nails (left arm), hammer and pliers (right arm).

Figure 17. Corner Fireplace in Storage Room. Size: mantel 106.7 centimeters high. Location: South morada, southeast corner. Description: Walls, fireplace, and flue of plastered adobe, kerosene lamps and tin wall sconces, boarded up window to left (east).

In each morada storage area, there is a tub built on the floor that serves to wash off blood after penance. Figure 13 shows the tub in the south morada. In the older, east morada, the tub (Figure 18) is a wood- and tin-lined trough pushed against the north wall and plastered with adobe.

Figure 18. Storage Room, East Morada. Sizes: Tub 112.6 centimeters long, 46 wide, 25.6 high; ladder 175 high. Description: Detail of north wall showing enamelized containers, tub built into the floor for washing after penance, and ladder.

The storage room in the east morada also contains commercially made lamps, such as the plated reservoir with stamped Neo-rococo motifs (Figure 19). Nearby is a processional cross with two metal faces and a small, cast corpus (Figure 20). While kerosene lanterns are evidence of east-west rail commerce after 1880, the cross probably indicates a southern contact, possibly through Parral or Chihuahua, Mexico. Locally made, however, are the woven rag rugs (jergas) hung over a pole (varal)[56] that drops from the ceiling. Also in the east morada storage are two percussion rifles (Figure 21). Craddock Goins, Department of Armed Forces History, the Smithsonian Institution, identifies both as common Indian trade objects from midcentury Europe. These rifles probably were imports for sale to the Utes at the Abiquiú trading post between 1853 and 1874. At the rear of the room (Figure 22) rests a saw-horse table holding an assortment of stocks for these "trade guns," of wooden rattles (matracas), and of heavy crosses (maderos). On the ground stands a large bell, which, in a photograph (Museum of New Mexico, Photo No. 8550) taken by William Lippincott about 1945, appears on the tower of the morada. The silhouette dates the bell as being cast after 1760. Behind the bell rests the morada death cart. Also in the room are a plank ladder and the oil drum stove raised on an adobe dais (Figure 23) to the east of the exterior door.

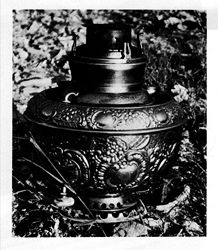

Figure 19. Reservoir for Kerosene Lamp. Size: 25.4 centimeters wide. Date: Second half of 19th century. Origin: Imported to New Mexico. Location: East morada, storage (east) room. Manufacture: Silver-plated metal stamped into Rococco revival decorations.

Figure 20. Processional Cross. Size: 30.5 centimeters high. Date: 19th century. Origin: Imported to New Mexico, probably from Mexico. Location: East morada, storage (east) room. Manufacture: Punched trifoil ends in metal face, cast corpus.

Figure 21. Percussion Rifles. Size: 111.8 centimeters long. Date: Middle of 19th century. Origin: European (Belgian?) exports. Location: East Morada, storage (east) room.

Figure 22. Storage Room, East Morada. Sizes: Bell 64 centimeters wide (diameter), 47.4 high; cart 122 long (frame), 70 wide (frame), 71 between axle centers; wheels 45 high. Description: Detail of east wall showing saw-horse table, corrugated sheeting, bell, and death cart of cottonwood and pine.

Figure 23. Storage Room, East Morada: View next to exterior door showing low adobe dais supporting oil drum stove.

Sacristy in Both Moradas.—While a panelled wooden box in the south morada stands inside the exterior door of the east room, another type of chest, said to hold cooking utensils, rests in the northwest corner of the center room of the east morada. Both storage chests are located in rooms with corner fireplaces. An informant said that these boxes held heating and cooking utensils and ceremonial equipment, including the penitentes' rule book. As noted above, the two fireplaces in the middle room of the east morada suggest that it was built earlier than the south morada, which has a single fireplace in the less active and more convenient rear storage room. Further evidence of this point is that the storage chest in the east morada is better constructed than that in the south morada; the former displays a slanted top and punch-decorated tin reinforcements on its corners. In the center room there are several benches with lathe-turned legs (Figure 24).

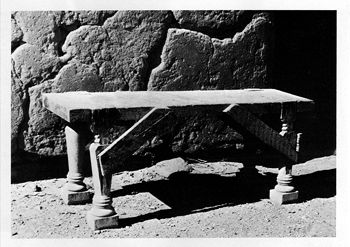

Figure 24. Bench (banco). Size: 108 centimeters long, 51 high, 47 wide. Location: East morada, center room.

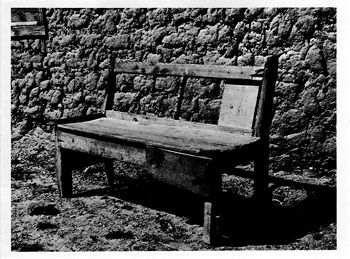

The central room of the south morada also displays a number of benches of an earlier style (Figure 25). Over the rear door appears an unusual cross (Figure 26). The cross consists of two wood planks, 1.6 centimeters thick, notched together and covered with paper. The surface bears carefully drawn, or perhaps stenciled, floral and religious designs in indigo blue: eleven Latin crosses appear among flowering vases, oversize buds, and 4-, 5-, and 8-pointed stars. These motifs probably are the result of copying from weaving or quilt pattern books of the late 19th century. A local penitente leader stated that the cross was made before 1925 by Onésimo Martínez of Abiquiú, when the latter was in his thirties. (The strong religious symbolism of the New Mexican designs reminds one of the stylized motifs on Atlantic Coastal folk drawings and textiles of Germanic origin.)

Figure 25. Bench (banco). Size: 128 centimeters long, 106 high at back, 45 wide. Location: South morada, center room.

(Figure 26 is frontispiece.)

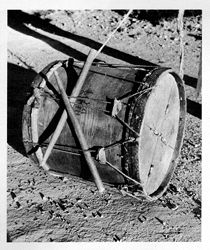

Snare drums appear in the central room of both moradas (Figures 27, 28). The drum in the east morada is mounted on top of a truncated wicker basket. It is interesting to note that rifles and drums commonly are recorded in mission choir lofts in 1776 by Domínguez.[57] In addition to marking significant moments in church ritual, they are used in Indian and Hispano village fiestas.

Figure 27. Snare Drum (tambor). Size: 55.9 centimeters long. Date: 19th century. Origin: Imported to New Mexico. Location: East morada, center room. Manufacture: Commercially made, military type, rope lines with leather drum ears [tighteners].

Figure 28. Snare Drum (tambor). Size: 58.4 centimeters long. Date: 19th century. Origin: Imported to New Mexico. Location: South morada, center room. Manufacture: Commercially made, military type, reddish stain, rope tension lines with rope and leather drum ears [tighteners].

Before describing religious objects in the west end rooms of Abiquiú moradas, a list of similar items in Santo Tomás Mission at an earlier date (1776) is of interest:

a medium-sized bell ... altar table ... gradin ... altar cloth ... a banner ... candleholders ... processional cross ... a painted wooden cross ... ordinary single-leaved door ... image in the round of Our Lady of the [Immaculate] Conception ... a wig ... silver crown ... string of fine seed pearls ... ordinary bouquet ... painting on copper of Our Lady of Sorrows (Dolores) in a black frame ... Via Crucis in small paper prints on their little boards ... a print of the Guadalupe.[58]

Comparable versions of each of these objects occur in Abiquiú's moradas. In fact, virtually all objects found in the penitente moradas of Abiquiú are recorded as typical artifacts by church inventories and house wills of 18th- and 19th-century Spanish New Mexico.[59]

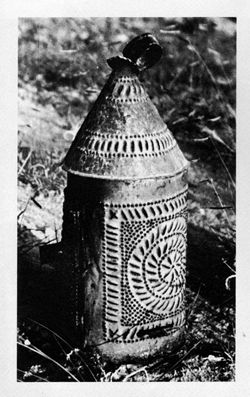

Oratory in the East Morada.—In the rear of the oratory of the older east morada (Figure 12), one sees a stove and lantern on the right. Both are imported, extracultural items. The pierced, tin candle-lantern (Figure 29) is a common artifact found throughout Europe and America.[60]

Figure 29. Candle Lantern. Size: 30.5 centimeters high. Date: 19th century. Origin: Imported to New Mexico. Location: East morada, chapel. Manufacture: Pierced tinwork.

Along the walls of the oratory hang imported religious prints framed in local punch-decorated tinwork. Tin handicraft became more widespread after 1850 when metal U.S. Army containers became available to the Hispanos. Designs seen on three tin frames (Figure 30) include twisted columns, crests, scallops, corner blocks, wings, and a variety of simple repoussé patterns. Paper prints in the tin frame suggest midcentury trade contacts between northern Mexico and the Atlantic Coast. Even the Mexican War (1846-1848) did not discourage American publishers such as Currier from appealing to Mexican religious and national loyalties with lithographs of Our Lady of Guadalupe (much in the same manner as the British, after the Revolution and War of 1812, profited by selling Americans objects that bore images of Yankee ships, eagles, and likenesses of Franklin and Washington). A fourth piece of local tinwork (Figure 31) in the east morada oratory is a niche for a small figure of the Holy Child of Atocha, Santo Niño de Atocha. This advocation of Jesus, like that of His mother in the Guadalupe image, further indicates Mexican influence.[61] The image of the Atocha is a product of local craftsmanship.

Figure 30. Religious Prints in Tin Frames. Size: 52.1 centimeters high (center). Date: First three-quarters of 19th century. Origin: Prints imported to New Mexico; frames from New Mexico, unidentified tinsmiths. Location: East morada, walls in chapel (west) room. Manufacture: Tin frames: cut, repoussé, stamped and soldered into Federal and Victorian designs. Prints: left, Guadalupe, early 19th century, Mexican copperplate engraving; center, Guadalupe, 1847, N. Currier, hand-colored lithograph; right, San Gregorio [Pope St. Gregory], mid-19th-century lithograph.

Figure 31. Niche with Image of the Holy Child of Atocha (nicho and El Santo Niño de Atocha). Size: niche 44.4 centimeters high, image 21.6 high. Date: Second half of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified tinsmith and santero. Location: East morada, wall in chapel room. Manufacture: Tin: cut, repoussé, soldered into fan, shell, and guilloche designs. Image: carved wood, gessoed and painted red and white. Rosary and artificial flowers.

These representations of religious personages are called santos, and their makers, santeros. Flat panel paintings are known locally as retablos, while sculptured forms are bultos. George Kubler, distinguished art historian at Yale, suggests that bultos, because of their greater dimensional realism, are more popular than planar retablos with the Hispanos.[62] Supporting this theory is the fact that bultos in the Abiquiú moradas outnumber prints and retablos two to one.

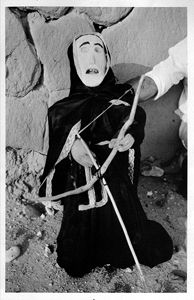

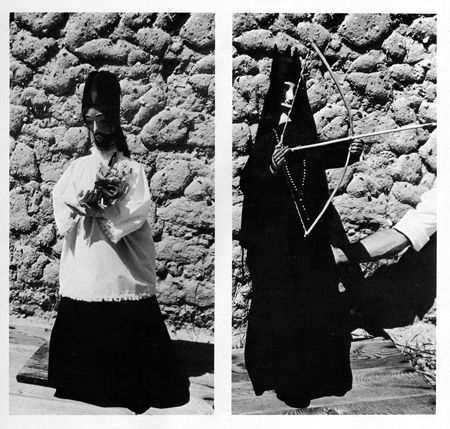

Perhaps the most distinctive three-dimensional image in any morada is not a santo by definition, but a unique figure that represents death (la muerte). Also known as La Doña Sebastiana, her image clearly marks a building as a penitente sanctuary. Personifying death with a sculptured image and dragging her cart to a cemetery called calvario, the penitentes of New Mexico reflect the sense of fate common to Spanish-speaking cultures, the recognition that death is life's one personal certainty.[63] The figure of death in the east morada hangs in the corner at the rear of the oratory. Placed outside for examination, this muerte (Figure 32) presents a flat, oval face with blank eyes. The black gown and bow and arrow are typical of muerte figures.[64] Turning toward the altar (Figure 11), one sees that death is outnumbered by images of hope and compassion: Jesus, His mother, and the saints who intercede for man.

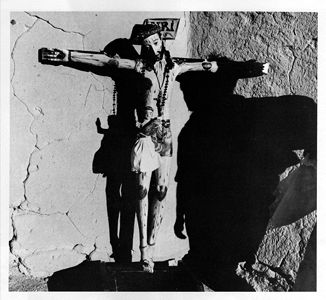

On the lower step of the altar appear a host of small, commercial products, mostly crucifixes, in plaster, plastic, and cheap metal alloys as well as numerous glass cups for candles. Above the upper ledge (gradin) appear five locally made images of Jesus crucified, El Cristo.[65] At the side of this central Cristo (Figure 33) hangs a small angel, angelito, which traditionally held a chalice to catch blood from the spear wound. Other Cristos, at the Taylor Museum in Colorado Springs and at the Museum of New Mexico (McCormick Collection A.7.49-24) in Santa Fe, repeat the weightless corpus and stylized wounds used by the anonymous santero who, after 1850, made these bultos.

Figure 32. Death (la muerte). Size: 76.2 centimeters high. Date: Early 20th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: East morada, back of oratory. Manufacture: Carved and whitewashed wood, glass eyes and wood teeth, dressed in black fabric with white lace border, bow and arrow.

Figure 33. Crucifix with Angel (Cristo and angelito). Size: cross 139.7 centimeters high. Date: Fourth quarter of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: East morada, center of altar. Manufacture: Carved wood gessoed and painted, over-painted in oil; crown of thorns, rosaries, crucifix; wooden plank, H-shape platform; black cross with iNRi plaque; angelito with white cotton skirt.

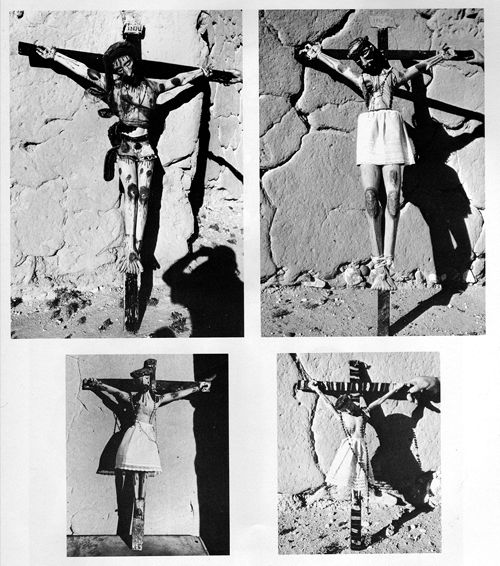

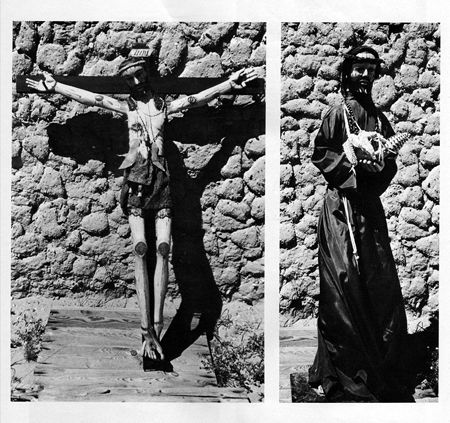

Additional Cristo figures appear on the convergent walls of the east morada sanctuary. There are two pairs, large and small, perhaps dating as late as 1900, one pair to the right (Figures 34, 35), the other, on the Gospel side (plates 36, 37).

top left

Figure 34. Crucifix (Cristo). Size: cross 170.2 centimeters high. Date: Second half of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: East morada, right wall behind altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted, over-painted in oils; black gauze shroud over head; rosary and iNRi plaque.

bottom left

Figure 35. Crucifix (Cristo). Size: cross 64.8 centimeters high. Date: Second half of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: East morada, right wall behind altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; dressed in white skirt with rosary.

top right

Figure 36. Crucifix (Cristo). Size: cross 71.1 centimeters high. Date: Second half of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: East morada, left wall behind altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted, repainted in oil colors, yellow and red strips on black; dressed in white cotton skirt; rosary.

bottom right

Figure 37. Crucifix (Cristo). Size: cross 177.8 centimeters high. Date: Fourth quarter of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: East morada, left wall behind altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; crown of thorns and rosary; dressed in white cotton waist cloth.

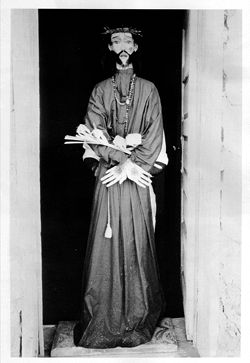

To the far left stands an important image: the scourged Jesus (Figure 38) prominent in penitente activity as "Our Father Jesus the Nazarene" (Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno). By 1918, Alice Corbin Henderson[66] reports, this same figure appeared in penitente Holy Week processions at Abiquiú. She claims it was made originally for the Mission of Santo Tomás. E. Boyd points out stylistic traits shared by this Abiquiú bulto and the retablo figures in the San José de Chama Chapel at nearby Hernández, which was the work of santero Rafael Aragon, active from 1829 to after 1855.[67] Symbolic of man's physical suffering, the image of the Jesus Nazareno is essential to penitente enactments of the Passion.

Figure 38. Man of Sorrows (Ecce Homo, Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno). Size: 1.60 meters high. Date: Second quarter of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, Rafael Aragon, active 1829-55. Location: East morada, to left of altar. Manufacture: Dressed in red fabric gown, palm clusters and rosaries, leather crown of thorns, horsehair wig, bright border painted on platform.

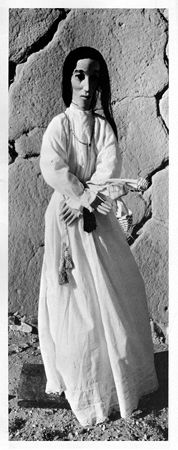

On the left side of the east morada altar, two carved images represent the grieving mother of Jesus as "Our Lady of Sorrows" (Nuestra Señora de los Dolores), one image (Figure 39) in pink equipped with her attribute, a dagger; the other (Figure 40), like many processional figures, has been constructed by draping a pyramidal frame of four sticks with gesso-dipped cloth, which, when dry, is painted to represent a skirt. The apron-like design that appears on the skirt, now hidden under a black dress, indicates that the original identity probably was "Our Lady of Solitude" (Nuestra Señora de la Soledad).[68]

Figure 39. Our Lady of Sorrows (Nuestra Señora de los Dolores). Size: 99.1 centimeters base to crown. Date: Early 20th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: East morada, left side of altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; dressed in pink cotton gown and veil; tin crown and metal dagger; artificial flowers, rosaries.

Figure 40. Our Lady of Sorrows or Solitude (Nuestra Señora de los Dolores or la Soledad). Size: 81.3 centimeters base to crown. Date: Second half of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: East morada, left side of altar. Manufacture: Carved wood head and hands, gessoed, painted, and repainted; body of gesso-wetted cloth, draped on stick frame to dry, painted; dressed in black satin habit with white lace border; tin halo, rosary, artificial flowers.

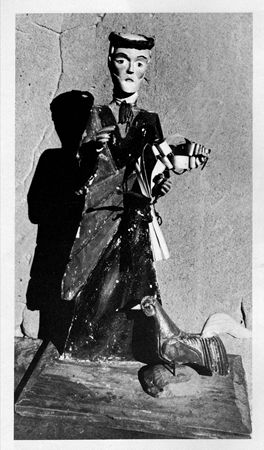

Also on the left side of the east morada altar, there are two male saints (santos) who fill vital roles in the penitente Easter drama. One, St. Peter (San Pedro) with the cock (Figure 41), is a bulto whose frame construction duplicates that of Our Lady (Figure 40). The cock apparently was made by another hand, and, despite its replaced tail, is a fine expression of local art. This group represents Peter's triple denial of Jesus before the cock announced dawn of the day of the Crucifixion. The bulto of San Pedro has special meaning for penitentes who, through their penance, bear witness to "Jesus the Nazarene."

With the other bulto, penitentes have also recalled the crucifixion by representing St. John the Evangelist (San Juan) at the foot of the cross, where Jesus charged the disciple with the care of His mother. The image of John (Figure 42) bears distinctive stylistic features: blunt fingers; protruding forehead, cheek bones, and chin; and a full-lipped, open mouth.

Figure 41. Saint Peter and Cock (San Pedro and Gallo). Size: 61 centimeters high. Date: First quarter of 19th century, and 19th century cock. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: East morada, left side of altar. Manufacture: St. Peter's head (later): carved wood, gessoed and painted. Body: cloth dipped in wet gesso, draped over stick frame to dry, and painted, later over-painted. Blue gown and orange cape. Cock of carved wood, gessoed and painted; orange body with green haunch. Carved wood tail, replacement.

Figure 42. Saint John the Evangelist (San Juan). Size: 137.2 centimeters high. Date: Second half of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, "Abiquiú morada" santero. Location: East morada, left side of altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; black horsehair wig; dressed in white cotton fabric; palm clusters and rosary.

Since these stylistic traits also occur in a Cristo figure in the Taylor Museum collection[69] and in two other bultos—a Cristo and Jesus Nazareno in the south morada at Abiquiú—it seems reasonable to designate the anonymous image-maker as the "Abiquiú morada santero."

A bulto that Alice Henderson identifies as St. Joseph is probably this figure of St. John (Figure 42) now resting in the east morada. She has reported that this image and that of St. Peter were in the mission of Santo Tomás before 1919.[70] The shift in residence for these santos was substantiated by José Espinosa, who stated that several images "were removed to one of the local moradas ... when the old church was torn down."[71]

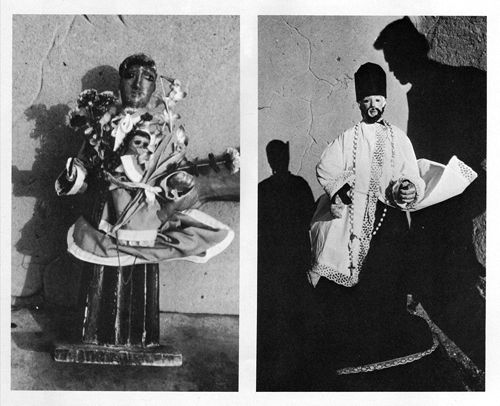

On the right side of the east morada altar, images of two male saints reflect the intense affection felt by penitentes for the Franciscan saints Anthony of Padua and John of Nepomuk. The most popular New Mexican saint, San Antonio (Figure 43), customarily carries the young Jesus, El Santo Niño. This image has been painted dark blue to represent the traditional Franciscan habit of New Mexico before the 1890s.[72]

The 14th-century saint, John of Nepomuk, Bohemia (Figure 44), is known from a legend that states he was killed by King Wenceslaus for refusing to reveal secrets of the Queen, for whom he was confessor. The story notes that, after torture, John was drowned in the Moldau River, but that his body floated all night and, in the morning, was taken to the Church of the Holy Cross of the Penitents in Prague. After the martyred chaplain was canonized in 1729, his cult spread to Rome, then Spain, and, by 1800, into New Mexico.

Figure 43. Saint Anthony of Padua and the Infant Jesus (San Antonio y Niño). Size: 43.2 centimeters high. Date: First half of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: East morada, right side of altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted with repainted head; dark blue habit; dressed in light blue cotton fabric with white border, artificial flowers.

Figure 44. Saint John of Nepomuk (San Juan Nepomuceno). Size: base to hat 78.7 centimeters. Date: Second quarter of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: East morada, right side of altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; dark blue robe with white border; dressed in black hat and robe under white alblike coat; rosary.

Among the Hispanos, local Franciscans promoted this cult of St. John as a prognosticator and as a respecter of secrecy.[73] Due in part to this promotion, San Juan Nepomuceno became a favorite of New Mexican penitentes. E. Boyd suggests that the image of St. John (Figure 44) may have first represented St. Francis or St. Joseph. She also notes a stylistically similar bulto of St. Joseph in Colorado Springs, manufactured not long after 1825.[74]

Oratory in South Morada.—Turning to the south morada chapel, we find numerous parallels to the earlier east morada in santo identities and in religious artifacts. (Figure 10 presents a previously unphotographed view of this active penitente chapel with its fully equipped altar.) The walls of the west chamber of the south morada are lined with benches over which hang religious prints in frames of commercial plaster and local tin work (Figure 45).

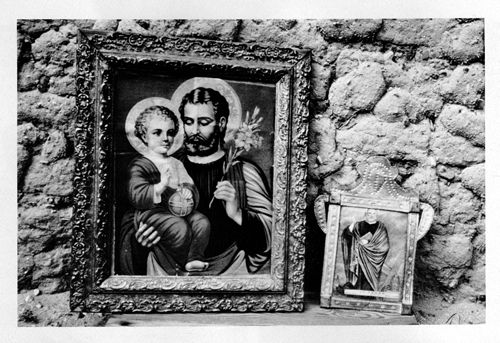

Figure 45. Saint Joseph and Christ Child (San José y el Santo Niño). Size: frame 45.7 centimeters high. Date: Fourth quarter of 19th century. Origin: Imported commercial products. Location: South morada, chapel wall. Manufacture: Plaster frame, molded and gilded. Chromo-lithograph on paper. Saint Peter (San Pedro). Size: frame 25.4 centimeters high. Date: Third quarter of 19th century. Origin: Imported, commercially made print. New Mexico, unidentified tinsmith. Location: South morada, chapel wall. Manufacture: Tin frame: cut, repoussé, stamped, and soldered. Chromo-lithograph on paper.

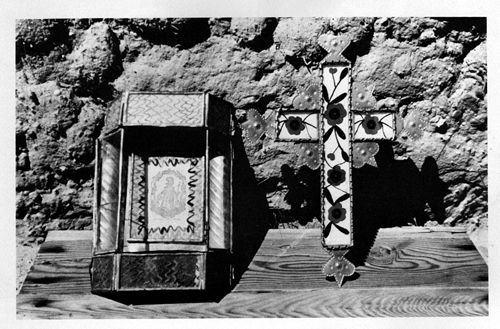

The tin frame for a lithograph of St. Peter reveals repoussé designs found on east morada frames (Figure 30, center). Other examples of local tinwork are seen in Figure 46. On the right is a cross of punched tinwork with pomegranate ends and corner fillers that reflect Moorish characteristics in Spanish arts known as mudéjar. The frame dates from after 1850, as indicated by glass panes painted with floral patterns suggesting Victorian wallpaper. To the left is a niche made of six glass panels painted with wavy lines and an early 19th-century woodcut of the Holy Child of Atocha. Here again, twisted half-columns repeat a motif seen on a tin frame in the east morada chapel. In front of the draped entry to the south morada sanctuary stand two candelabra, one of which is shown in the doorway to the oratory (Figure 47) with tin reflectors and hand-carved sockets.[75] There are also vigil light boxes, kerosene lanterns with varnished tin shades, commercial religious images and ornaments that are similar to items in the east morada sanctuary.

Figure 46. Niche with Print of Christ Child (Nicho and Santo Niño de Atocha). Size: 35.5 centimeters high. Date: Second half of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified tinsmith. Location: South morada, chapel walls. Manufacture: Tin frame: cut, repoussé, and soldered. Glass: cut and painted. Woodcut on paper. Cross (cruz). Size: 43.2 centimeters high. Date: Fourth quarter of 19th century. Origins: New Mexico, unidentified tinsmith. Location: South morada, chapel walls. Manufacture: Tin frame: cut, repoussé, and soldered. Glass: cut and painted.

Figure 47. Candelabrum (candelabro). Size: 157.5 centimeters high. Date: Early 20th century. Location: South morada, in front of altar in oratory. Manufacture: Mill-cut wood stand, hand-carved pegs to hold candles, and hand-worked tin crosses. Painted white. One of a pair.

Embroidered textiles portray the Last Supper, and a chapter banner, made up for the brotherhood after 1925, shows the Crucifixion in oil colors. This banner bears the words "Fraternidad Piadosa D[e] N[uestro] P[adre] J[esus] D[e] Nazareno, Sección No. 12, Abiquiú, New Mexico." The title fraternidad is that assumed by penitente chapters that incorporated in New Mexico around 1930, although the term cofradía often appears in transfers of private land to penitente organizations.[76] A second banner, this one on the left, reads "Sociedad de la Sagrada Familia," which is a Catholic women's organization that often supports penitente groups.

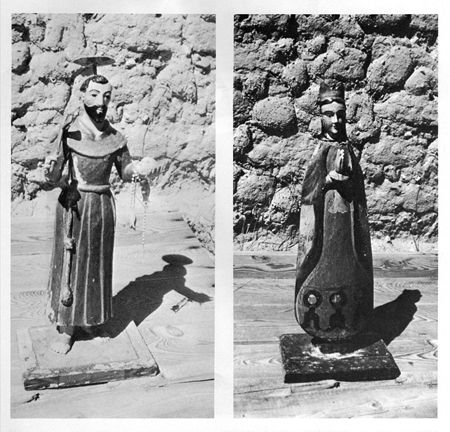

In the oratory of the south morada, locally made images merit special notice. Two carved images flank the entry to the south morada sanctuary. The bulto on the right, St. Francis of Assisi (Figure 48), has a special significance. As we noted in the east morada, many Spanish settlers in New Mexico honored San Francisco as the founder of the Franciscans, the order whose missionaries long had served the region. The second bulto (Figure 49) reveals clues that it originally had been a representation of the Immaculate Conception (Inmaculata Concepción). In Abiquiú, however, this figure is called la mujer de San Juan ("the woman of St. John"), a phrase that indicates the major role Mary holds for the penitentes. With this image they refer to the moment in the Crucifixion when Jesus committed the care of His mother to St. John. As introductions to the south morada chancel, St. Francis and the Marian image are excellent specimens of pre-1850 santero craftsmanship.

Figure 48. Saint Francis of Assisi (San Francisco). Size: 53.3 centimeters high. Date: First half of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: South morada, right wall of chapel. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; blue habit with brown collar; wood cross and skull, tin halo; rosary beads with fish pendants.

Figure 49. The Immaculate Conception (la mujer de San Juan [local name]). Size: 55.9 centimeters high. Date: First half of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: South morada, left wall of chapel. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; oil colors over earlier tempera; red gown and crown; blue cape and base.

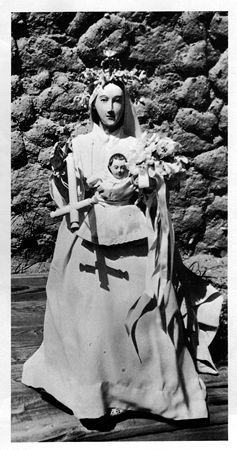

Two more images of Mary occur on the altar of the south morada sanctuary. The first (Figure 50) takes its proper ecclesiastic position on the Gospel side, to the viewer's left of the crucifix. The second "Marian" image (Figure 51) is less orthodox. Not only does this bulto stand on the Epistle side of the crucifix but, like the Marian advocation cited above as la mujer de San Juan, this figure's identity has been changed to suit local taste. Penitentes at Abiquiú refer to the image as Santa Rosa, the traditional patroness of the area following its first settlement by Spaniards.

Figure 50. Our Lady of Sorrows (Nuestra Señora de los Dolores). Size: 104.1 centimeters high. Date: Third quarter of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: South morada, left side of altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; dressed in pink satin; artificial flowers, tin crown.

Figure 51. Virgin and Child or Saint Rita (Santa Rosa de Lima [local name]). Size: 68 centimeters high. Date: Fourth quarter of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: South morada, right side of altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; dressed in pink satin; cross of turned wood; artificial flowers, shell crown.

Between these Marian images there are two large bultos that are examples of the work of the "Abiquiú morada santero" suggested earlier. Both are figures of Jesus. The first, a Cristo (Figure 52), is the central crucifix on the altar. As in the east morada, the focal image is accompanied by an angelito, this time with tin wings.[77] To the right stands the other image of Jesus, the Nazarene, Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno (Figure 53). Along with the nearby crucifix (Figure 52) and the figure of St. John the Evangelist (Figure 42) in the east morada, this representation of the scourged Jesus reflects the style of the "Abiquiú morada santero." This Nazarene bulto embodies the penitente concept of Jesus as a Man of suffering Who must be followed.

Figure 52. Crucifix with Angel (Cristo and angelito). Size: Cross 144.8 centimeters high. Date: Early 20th century. Origin: New Mexico, "Abiquiú morada" santero. Location: South morada, center of altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; purple fabric, waist cloths; tin wings on angelito; black cross with iNRi plaque.

Figure 53. Man of Sorrows (Ecce Homo, Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno). Size: 122 centimeters high. Date: Second half of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, "Abiquiú morada" santero. Location: South morada, right side of altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; black horsehair wig, crown of thorns; purple fabric gown; palm clusters, rosaries.

The special character of the penitente brotherhood is demonstrated also in the last two bultos on the south morada altar. The prominent size and position of St. John of Nepomuk (Figure 54) on the altar indicate again the importance given by the penitentes to San Juan as a keeper of secrets. The other figure is the south morada's personification of death (Figure 55), la muerte, here even more gaunt than the image in the east morada. Probably made after 1900, this figure demonstrates the persistent artistic and religious heritage of Hispano culture.

Figure 54. Saint John of Nepomuk (San Juan Nepomuceno). Size: 90.2 centimeters high. Date: Early 20th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: South morada, left side of altar. Manufacture: Carved wood, gessoed and painted; dressed in black gown and cap; white cotton cassock; artificial flowers; horsehair wig.

Figure 55. Death (la muerte). Size: 111.8 centimeters high. Date: Fourth quarter of 19th century. Origin: New Mexico, unidentified santero. Location: South morada, left side of altar.

[53] Interviews with Abiquiú inhabitants: Delfino Garcia in summer 1963 and Agapita Lopez in fall 1966.

[54] Interviews with penitente members at Abiquiú, summers of 1965 and 1967.

[55] José Espinosa, Saints in the Valley (Albuquerque, 1960), p. 75.

[56] Domínguez, Missions, p. 50 (ftn. 5), defines varal and its customary use.

[57] Ibid., pp. 107, 131 (ftn. 4), 167.

[58] Ibid., pp. 121-123.

[59] AASF, Loose Documents, Mission, 1680-1850, and Accounts, books xxxxv and lxiv. Also in Wills and Hijuelas, State Records Center, and in Twitchell documents, Land Management Bureau, both offices in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

[60] Walter Hough, Collections of Heating and Lighting (Smithsonian Inst. Bull. 141, Washington, D.C., 1928), pl. 28a, no. 3.

[61] Stephen Borhegyi, El Santuario de Chimayo (Santa Fe, 1956); also E. Boyd, Saints and Saint Makers (Santa Fe, 1946), pp. 126-132.

[62] George Kubler, in Santos: An Exhibition of the Religious Folk Art of New Mexico with an Essay by George Kubler (Fort Worth, Tex.: Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, June 1964).

[63] A fuller discussion of the penitente death cart and further illustrations are found in Mitchell A. Wilder and Edgar Breitenbach, Santos: The Religious Folk Art of New Mexico (Colorado Springs, 1943), pl. 30 and text. Relevant to this study is the death cart with immobile wheels recorded by Henderson, p. 32 [see ftn. 64], as having been used in processions before 1919. It is likely that this is the same cart described above in the storage room of the east morada (Figure 22); it is important because its measurements and construction details are nearly identical to the death cart in the collections of the Museum of New Mexico, reputed to have come from Abiquiú.

[64] Alice Corbin Henderson, Brothers of Light (Chicago, 1962), p. 32, describes a muerte figure: chalk-white face, obsidian eyes, black outfit.

[65] E. Boyd, "Crucifix in Santero Art," El Palacio, vol. LX, no. 3 (March 1953), pp. 112-115, indicates the significance of this image form.

[66] Henderson, pp. 13 (red gown, blindfolded, flowing black hair), 26 (red gown, bound hands, made for mission), and 43-46 (tall, almost life size, blindfolded, carried on small platform in procession from lower [east] morada, horsehair rope).

[67] Boyd, in litt., Nov. 13, 1965.

[68] Boyd, loc. cit. Regarding construction, see E. Boyd, "New Mexican Bultos with Hollow Skirts: How They Were Made," El Palacio, vol. LVIII, no. 5 (May, 1951), pp. 145-148.

[69] Wilder and Breitenbach, pls. 24, 25.

[70] Henderson, p. 26.

[71] José Espinosa, op. cit., p. 75.

[72] Domínguez, Missions, p. 264 (ftn. 59). The brown robe worn by Franciscans today is a late 19th-century innovation.

[73] Boyd, Saints, p. 133.