Title: The Library of Work and Play: Home Decoration

Author: Charles Franklin Warner

Release date: January 25, 2014 [eBook #44750]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Chris Jordan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

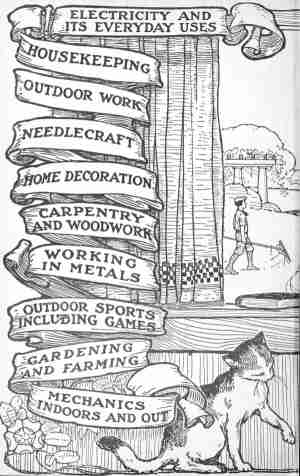

Front Endpaper A

Front Endpaper B

| Carpentry and Woodwork By Edwin W. Foster |

| Electricity and Its Everyday Uses By John F. Woodhull, Ph.D. |

| Gardening and Farming By Ellen Eddy Shaw |

| Home Decoration By Charles Franklin Warner, Sc.D. |

| Housekeeping By Elizabeth Hale Gilman |

| Mechanics, Indoors and Out By Fred T. Hodgson |

| Needlecraft By Effie Archer Archer |

| Outdoor Sports, and Games By Claude H. Miller, Ph.B. |

| Outdoor Work By Mary Rogers Miller |

| Working in Metals By Charles Conrad Sleffel |

HOME DECORATION

BY PROF. CHARLES F. WARNER, Sc.D.

For eight years Master of the Rindge Manual Training School, Mass. Twelve years principal of the Technical High School and Director of the Evening School of Trades, Springfield, Mass.

Garden City New York

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1916

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF TRANSLATION INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES, INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

COPYRIGHT, 1911, BY DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

TO THE BOYS AND GIRLS OF AMERICA

THIS BOOK

WHICH RECORDS WHAT SOME OF THEM HAVE DONE

IS HOPEFULLY DEDICATED

Some pure lovers of art discard the formula, Art for Progress, the Beautiful Useful, fearing lest the useful should deform the beautiful. They tremble to see the drudge's hand attached to the muse's arm. They are solicitous for the sublime if it descends as far as to humanity. Ah! they are in error. The useful, far from circumscribing the sublime, enlarges it.... Is Aurora less splendid, clad less in purple and emerald—suffers she any diminution of majesty and of radiant grace, because, foreseeing an insect's thirst, she carefully secretes in the flower the dewdrop needed by the bee?

This volume is the result of an effort to bring together in close relation with fundamental principles of design a variety of practical problems which are more or less closely connected with the general problem of home decoration and suited to the constructive ability of boys and girls from twelve to eighteen years of age. While the book is mainly a record of the author's experience and observation in this department of educational work, he has received many suggestions from co-workers in the same field. It will be impossible to give credit to all who have directly or indirectly assisted in the preparation of this book: but special acknowledgments are due to Mr. Fred M. Watts, who furnished the material for the chapter on Pottery and several drawings for other parts of the book; to Miss Grace L. Bell for the illustrations and descriptions embodied in the chapter on Block Printing; to Mr. Burton A. Adams for the problems in metal work; to Mr. Edwin A. Finch and Mr. Lewis O. Richardson who contributed many of the specifications for the problems in furniture-making; to Miss Elizabeth M. Morton for specific suggestions pertaining to the subject of dress as related to the principles of decoration; and to Mrs. Ruth B. S. Flower, of Florence, Mass., who supplied several of the photographs and much of the descriptive matter for the chapter on Weaving.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Introductory—The Story of a House | 3 |

| II. | Decorations and Furniture | 34 |

| III. | Pictures | 64 |

| IV. | The Arrangement of Flowers | 81 |

| V. | Decorative Fabrics | 95 |

| VI. | Dress and the Principles of Decoration | 121 |

| VII. | Furniture Making | 129 |

| VIII. | Finishing and Re-finishing | 212 |

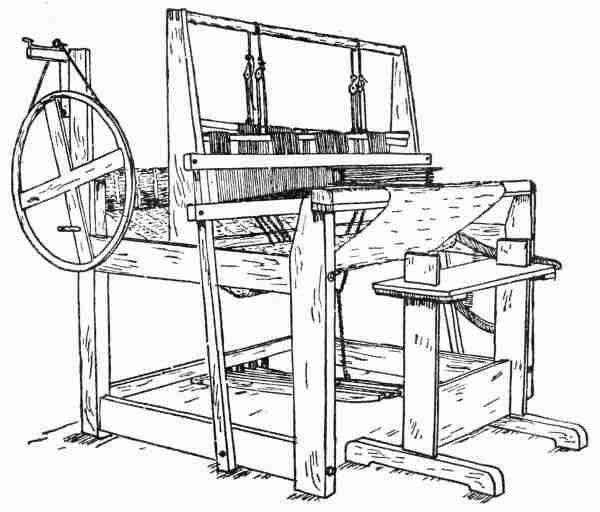

| IX. | Hand Weaving | 244 |

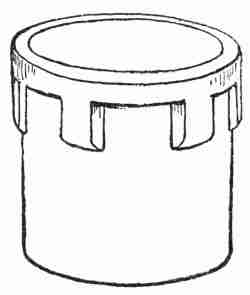

| X. | Pottery | 280 |

| XI. | Decorative Work in Leather, Copper, and Other Materials | 321 |

| XII. | Concluding Suggestions—Country Homes | 366 |

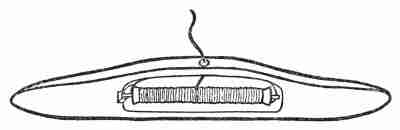

| Hanging a Picture | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| All the Rough Carpentry was Assigned to the Boys of the Woodworking Sections of the Vocational School | 22 |

| The Boys of the Forging Classes of the Technical High School were not Overlooked in the Distribution of the Work on the House | 24 |

| A Table Runner of Russian Crash and Pillow Cover with Geometrical Design | 96 |

| Window Draperies with Stencilled Border | 108 |

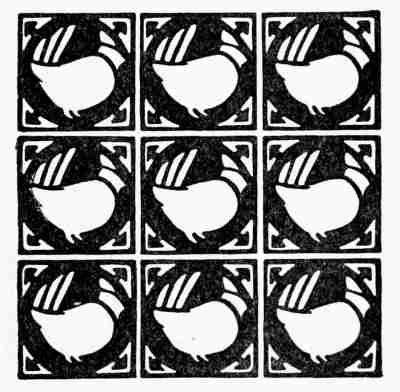

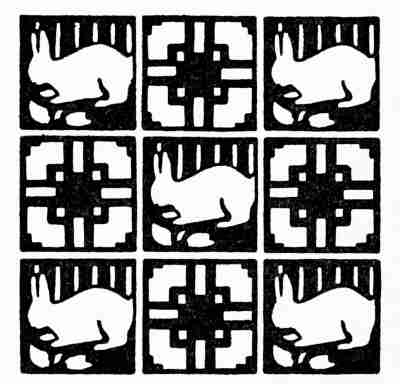

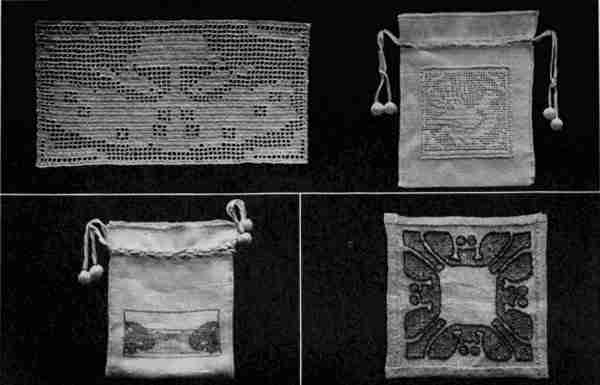

| Crocheted Panels, a Linen Work Bag with Conventional Landscape in Darning Stitch, a Crash Table Mat Embroidered in Darning and Couching Stitch | 118 |

| Finishing a Library Table | 212 |

| Weaving a Rug | 244 |

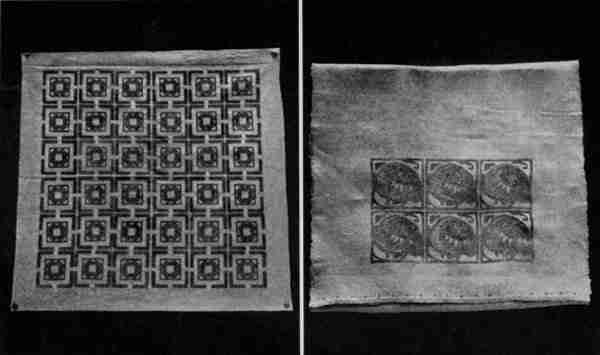

| Hand Made Rugs, Hand Made Towels | 252 |

| An Alcove with Window Draperies, Pillow Covers, Window Seat and Moss Green Rug, All Hand Woven | 262 |

| Hand Woven Window Draperies, Couch Cover, Slumber Rug, and Pillow Covers | 266 |

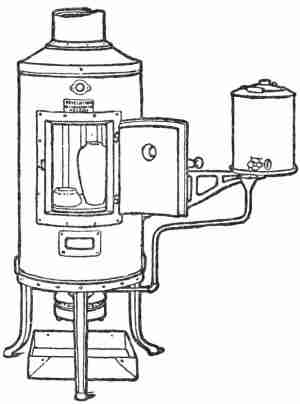

| Girls at Work on Pottery | 280 |

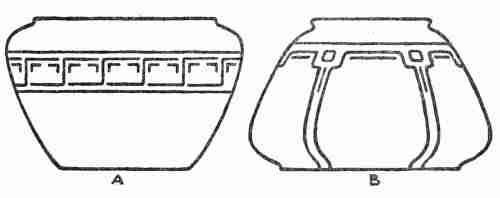

| Bowls | 294 |

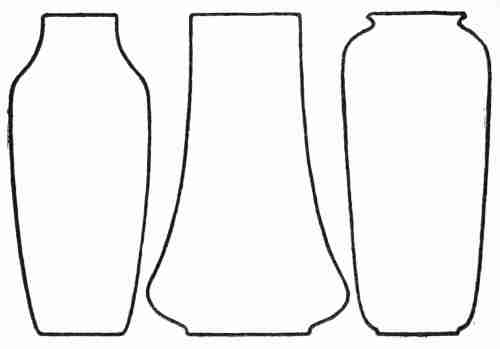

| Vases and Fern Dishes | 312 |

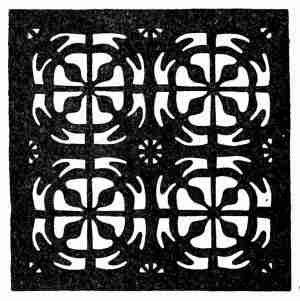

| Tiles | 316 |

| Pottery: Designed and Made by Schoolgirls | 318 |

| Decorative Forgings | 364 |

To design, plan, and build a house is a task that rarely falls to the lot of boys and girls. In fact, it is not the common experience of men and women to build houses without the aid of architects, masons, and carpenters. Such a task, however, was recently offered to certain classes in one of the public schools of a well-known New England city. It was, indeed, a school problem, and yet there was something about it that seemed to suggest larger and more interesting things than are ordinarily dealt with in the school-room. It did not seem at all like some school work. It was more like real life; for all boys and girls must some day have homes of their own, and here was a chance to learn how the house, which is an important part of every home, is planned and built. It is hardly necessary to say that this work—or play, if you like that word better—was undertaken with[4] genuine enthusiasm. It was a task crammed full of the pleasure of interest and of accomplishment—full of the joy of doing something worth while—from the beginning to the end.

The House a Work of Art.—One of the first lessons learned by these young builders—perhaps the most important one of all—was that a great many things have to be thought of in planning a house, if the thing is to be well done. It is not simply a question of deciding how many rooms one will have, arranging them in some conventional order, and building the house around them with whatever external features style or fancy may dictate. Too many houses, it is true, are planned, or at least put up, in this thoughtless fashion; and whatever goes into them in decoration or furniture is generally chosen either for necessary use or for display—not with any thought of the real comfort and satisfaction that come from artistic surroundings. People who are satisfied with such dwellings seem to show less appreciation of art, the highest product of civilization, than those uncivilized tribes who decorated their caves or huts with beautiful rugs of their own weaving and who ornamented their pottery and their utensils and implements with wonderfully conceived and elaborately wrought[5] designs. Modern cave dwellers in apartment houses with all the conveniences of their ready-made surroundings, are in danger of missing that self-expression in their home belongings that encouraged and delighted even the savage. The most extreme example of this form of degeneracy is found in the suggestion of a certain great inventor, that the age of concrete construction, now at hand, means that we are to have concrete houses poured into a standard mould, hardened in twenty-four hours, and finished for occupancy in a day or two.

The boys and girls of this story would not have accepted a machine-made, standardized house if one had been offered them, ready for use. There was a special purpose for which their house was to be planned and built, as there generally is in the case of any real house. No style A, B, or C, chosen from any series of pattern-built or moulded houses, could fulfil such a purpose; and even if it could, would they willingly give up all the fun of planning and building and furnishing? Would they forego the lessons of experience to be learned from all this work? This is always a large part of the satisfaction which comes to any one who builds his own house. In the present instance it was the chief motive, since the boys and girls who were[6] planning this house were not expecting to make their home there.

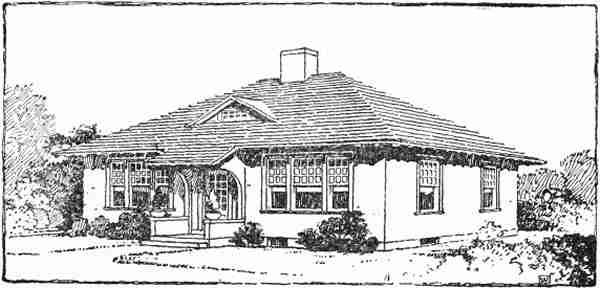

Why the House Was Built.—What, then, was the purpose for which this house was to be built; and what were the specific problems involved in realizing this purpose? It was to be a practice house for the girls of the household technology course. This meant that it should be, so far as possible, a model house; but it must of necessity be a simple one. Economy, always a safe guide, was a most important factor in determining the character of the design. A limited appropriation—about $1000—for building material was available. Economy of space as well as of expense was also important. The only available land was a triangular lot in the corner of the school yard, 665 square feet in area. This limited the dimensions of the floor plan to 24 by 35 feet. It was decided to develop the design within these dimensions, on a rectangular plan, with one story and a hip roof, because such a design would present comparatively easy problems in framing and insure a building of pleasing external proportions.

In attacking the problem of design the method of approach was determined by the fact that school-[7] girls and school-boys were to be the architects and builders. House planning, home decoration, and household management were important subjects of study on the part of the girls and various forms of drawing and constructive work were required of all the boys of this school; so they all felt that they had a right to contribute something out of their study and experience that might be of value in working out this problem. The design must therefore be a composite of the best features of many studies.

A Composite Design.—The rooms required for a house of this character were thought to be a hall, a living room, a dining-room, a kitchen, a pantry, a bedroom with a closet, a bath room, and a linen closet. Nothing short of this outfit of rooms would satisfy the demands of a house to be used to give practical training in all the essentials of plain housekeeping and in the entertainment of guests. With these requirements in mind and with full knowledge of all the limitations of the problem, the girls of the junior and senior classes, who were taking the course in household technology, entered into a lively but friendly competition with each other to produce the most acceptable design and draw the best plan. So many excellent plans resulted from this competition that it was difficult[8] to select the best. It was therefore decided to combine in a new and final plan the best features of several studies that seemed to meet the conditions of the problem with equal success. Two of these were selected as having the greatest number of good points. From these the final floor plan was developed and the necessary modifications made in the original drawings to make the general design of the building fit the plan.

[9] The Hall.—It may be of interest to note how some of the details of the problem of design were worked out for the final plan. Beginning with the hall, it was easily seen that economy of space required that the room should have small dimensions. In fact, it did not need to be a separate room at all. It could easily be a space between the living room and the dining-room, separated from both by means of portières and joined upon occasion with either room or with both, thus making possible a reception room or a dining-room of good size, or one large room. Of course, the central idea of a hall must not be lost sight of in providing for a desirable extension of other rooms. It should suggest a warm welcome to the guest; and here is where the fireplace may fulfil the double function of giving the cheer of the hearth-stone at all times and the comfort of fire when warmth is needed. The absence of a stairway, since none was needed, was a favourable circumstance. Appropriate decoration and furnishing in due time were to add a few distinguishing marks so that the house could retain, without any appreciable sacrifice of space, the dignity of an entrance hall.

The Living Room and the Dining-room.—The relative positions of the living room and the dining-room,[10] as already stated, were determined by the location of the hall. The purpose of each was distinct and self-evident, and determined the features of design that lent themselves most readily to appropriate decoration. In the living room the floor, the wall spaces, and the ceiling needed consideration with regard to their final treatment, to give pleasing proportions and harmonious colouring. The same was true of the dining-room, though its different purpose suggested a different design. An abundance of light was important for both rooms, hence the large, multiple windows. Such windows would also offer a good chance for pleasing drapery effects.

The Kitchen and Its Appointments.—No room demanded so much study as the kitchen. In the first place it was necessary to make provision for a relatively larger kitchen than would ordinarily be needed in a house of this size, because in this case it was designed to be used as a practice kitchen and must therefore be large enough to accommodate a considerable number of girls—at least eight—at one time. This point assumed so much importance in the minds of the young designers that they were constantly tempted to rob other rooms of the space that was due them in order to[Pg 11] get a "nice, big kitchen." But by clever adjustments and combinations the necessary floor dimensions were secured without unduly cramping other features of the plan. The range, laundry tubs, and sink were conveniently located near each other with the tubs at such a height that when not in use the cover was flush with the top of the range, forming a shelf on which kettles and other kitchen utensils could be easily placed as they were moved back and forth from the range. It was thought that it would be very desirable, if not necessary, to have this shelf covered with zinc or some kind of sheet metal.

It will be noted as a possible fault in the plan that the range is very near the door into the passageway leading to the bedroom, the living room, and the hall. This point received due consideration; but in view of the compensating advantages the arrangement was thought allowable, inasmuch as the door into the passageway would be used only occasionally. There seemed to be no more convenient location for the passageway, which was designed to give privacy to bedroom and bath room and, in cases of sickness or any emergency requiring it, easy communication between the kitchen and the bedroom.[12] Special Features.—The pantry was located between the kitchen and the dining-room for obvious reasons—to give easy communication in serving and to confine kitchen odours to their proper place. In place of a kitchen closet a cabinet was provided for as being on the whole the more serviceable of the two. It is always desirable to have an entry or lobby, with a convenient part of it reserved for the refrigerator; but the need of providing as much room as possible in the kitchen itself seemed to justify the omission of the lobby. Another unusual feature—this time not an omission—is to be found in the window of the bedroom closet. Such a window, although not common, was thought to be very desirable on sanitary grounds and as a possible protection against moths.

Early Plans for Decorating and Furnishing.—These were by no means all the features of design that had to be considered. As already suggested, there was much study given to the question of interior decoration and furnishing, even at this early stage. This was simply necessary forethought; for much of the attractiveness, restfulness, and homelike atmosphere of any house is created by the architect, who, in his arrangement of rooms, door-ways, and windows, disposes his wall areas so that they[13] may be divided symmetrically and lend themselves naturally to colour toning, offering tempting spaces for a few choice pictures and opening up beautiful vistas. Such house-planning, begun with clear vision and followed with taste and delicacy in every detail, may often lead to a harmony of effects as pleasing to people of artistic temperament as a symphony is to those who enjoy a fine musical composition. In fact, the parallel between sympathetic gradations of form and colour and harmony of musical tones is a very close one, and the appreciation of it is by no means rare. Any intelligent person, on seeing a suite of rooms designed and arranged by a real artist, though he may not understand why, will be impressed by the rhythm of space divisions, the harmony of colours, the lack of any jarring or discordant notes in the decoration, the simplicity, fitness, and real beauty, not of any particular part, perhaps, but of the whole combination. We often find ourselves using the same language whether we are describing the work of an artist-architect or the work of a musical composer.

Adaptation to Purpose.—Our young architects discovered that there are certain fundamental principles or laws that must be observed at the[14] very beginning, if a really good and true design is to be made. The first of these laws is the law of adaptation to purpose. The application of this law was illustrated in the location of the various rooms in the plan of the house, in the dimensions agreed upon for each, and in the details of arrangement, especially in the kitchen and other rooms connecting with it. But this law is universal in its application. It determines not only the broad features of the plan but the details as well. It does not permit anything useless or superfluous to exist, for that would mean weakness. It aims at efficiency and strength. It dictates the details of construction all along the line, from the framing of the building to its finish and its decoration. It even determines the character of the furniture and the amount of it. Adaptation to purpose is a ruling principle.

Simplicity.—Another great principle that revealed itself as the plans of the house developed may be called the law of simplicity. This is one of the elementary laws of nature transferred to the realm of craftsmanship. It is an axiom of geometry that the straight line is the shortest distance between two points. Not less evident is the fact that when Nature undertakes to do anything she goes[15] about it in the simplest and most direct way. The natural tendency of all motion is along a straight line—so reads the first law of motion. Analyze the most complex forms and processes of nature and we shall find them due to the harmonious combination of the simplest elementary lines and movements. But the same law of simplicity which invariably marks the works of nature gives strength and beauty also to the works of man. Thus, in discussing the various problems that developed as the designing of the house progressed, it was found—as of course it should have been—that the solution which met the test of simplicity, while satisfying the law of adaptation to purpose, was the true one.

Correlation.—A third great fundamental principle that found expression in these studies of the house plans was the principle of correlation. Not only must each part of the design be adapted to its use in the simplest possible manner, but it must support all other parts and receive support in return. It is like cooperation or team-work in play or in the practical affairs of life. Every room in a house bears some natural relation to every other room, and even the objects in the same room or in adjoining rooms must assist each other,[16] whether their purpose be utility or decoration or a combination of both. Only by due attention to the mutual relations of the various elements that must enter into the composition, can the designer produce those pleasing space effects, those blendings of colour tones, those manifest relations between the various objects, useful or decorative, that give order, unity, and sympathetic feeling to a complete design.

The Floor the Foundation.—Almost unconsciously our young architects found themselves under the guidance of these three great fundamental principles of design. When they came to the problem of specifying the finish for the floors and other wood work of the hall, living room, and dining-room, they found that this problem was intimately associated with the larger question of the colour scheme as a whole. The mutual dependence of all the elements concerned could not be overlooked. It was evident that the floor, which is the foundation of the room, should be darker than the walls and ceiling and the general tone of the furnishings, in order to give the suggestion of sufficient weight and firmness for the support of the entire room and all it might contain. The effect of solidity could[17] be produced by staining the floor boards or by providing a liberal supply of dark, rich-toned rugs, large ones as well as small ones. There was no question of carpets. These, of course, are not allowable in a model house. A few rugs were already available, and others could be procured by buying them or by making them. A properly toned floor, however, is desirable, even with a most generous covering of rugs. It was therefore decided to give the floor a coat of stain when it was ready to be finished.

Importance of Colour Schemes.—But what was the colour to be? The designers were thus brought face to face with that difficult but important problem which all who plan houses have to solve before they can hope to bring their work into harmonious adjustment with the various natural and human conditions that must be satisfied in the final product, if it be made a good example of the designer's art. The problem of the colour scheme is fundamental. Upon this depends not only the tone of the floors, the walls, and the ceilings, but also, to a certain extent, as has already been suggested, the kind of woods to be used in the interior finishing, and whether they are to be painted, stained, or left in their natural colours. It will determine the material and the colours of the portières, curtains,[18] cushions, lamp shades, picture frames, vases; in fact, it will largely settle the decorative character of every article placed in the rooms. The consideration of movable objects, however, may be deferred till the more substantial and fixed elements are decided upon.

Southern Exposures and Cool Colours.—In settling the all-important question of the colour scheme the first point to be considered was the location of the rooms with reference to light and to external surroundings. Rooms that have a southern exposure and nothing to interfere with their being flooded with sunlight need to be protected against the glare of too much light. For such rooms dull tones of colour are the best—dull browns, soft gray-greens, certain blue tones, and the medium grays—light, cool colours that counteract the overbrilliancy of direct sunlight and give a positively tempered feeling to the atmosphere of a room. Incidentally, too, perhaps because they are the tints associated with distant views, the cool colours make a room seem larger than it really is.

Northern Exposures and Warm Colours.—Northern rooms, on the other hand, do not generally suffer from excess of sunlight and heat. Warm colours are needed in such rooms. Deep reds, rich yellows,[19] and golden browns will seem to bring sunlight into a sunless room. Our designers noted the fact that many of the rooms in the house they were planning must be comparatively dark. The house was to face the high brick walls of the neighbouring school building, not more than twenty-five feet distant, and its principal rooms had a northern exposure. A warm colour treatment, therefore, was unquestionably needed. Should red, brown, or yellow be the prevailing tone? The deciding point was the location of the hall and its relations to the other rooms. It was, first of all, the hall, the place of welcome for the guest; but it was dark. Its walls must have the sunniest of all colours—a rich golden yellow. The same would serve the needs of the living room, or perhaps a brown with yellow enough in it to be well in tune. The dining-room could safely be darker and more luminous, in pleasing contrast with the golden yellow of the hall; but it must not be decidedly red. The ceilings of these three rooms, whether beamed or not, since they must be lighter than the walls, could have the same or nearly the same tint. This might well be a light corn yellow.

The colouring of the walls of the bedroom, bath room, and kitchen was not so important a question[20] as the decoration of the three front rooms. Utility and sanitary conditions were important things to be considered. Light tints were decided upon, which in the bedroom might be relieved, in the finishing touches, by delicate stenciled figures in some warm tone.

Interior Woodwork.—With the colour scheme settled it was a comparatively easy matter to decide what should be the general tone and character of the interior woodwork. The floors of the three front rooms, since they were to be closely associated, required the same solid colour, which could well be a walnut brown, darker than any of the walls. Fumed oak trimmings were thought desirable for the dining-room and gum wood for the living room, either of which could be extended to the hall; but ivory white for the living room and the hall, leaving the oak for the dining-room, found much favour. It was finally decided, however, to adopt for the three front rooms the combination of natural woods first suggested. The bedroom and bath room, where suggestions of cleanliness are peculiarly appropriate, were specified to be finished in white. Yellow southern pine was decided upon for the kitchen and its accessory rooms.

As soon as the chief features of design were decided upon, preparations were made for carrying them out in the actual work of building; for the house was not to be a "castle in air." The first step was to put these ideas on paper and work out the details of construction in clearly executed and accurately dimensioned drawings. These included, as the first to be used, the working drawings for the framing and other rough woodwork, blue print copies of which were to be put into the hands of the boys of the elementary vocational school, who were to carry out this part of the building plans.

The Working Drawings.—A considerable number of detailed drawings had to be made before the[22] work of construction could be wisely begun. This furnished an interesting set of problems for the mechanical drawing groups of the technical high school. The material for this work consisted of rough sketches in pencil, but with the correct dimensions as determined in the plan accepted as the result of the competition in design. These preliminary sketches required much study on the part of both boys and girls, under proper guidance, in order to find out what the elements of construction should be, what dimensions were required, and how the various parts should be put together. It was an experience of great value to all, but especially to those boys who were looking forward to architectural draughting as a possible vocation. They got an inside view of the importance, on the one hand, of accurate working drawings as a basis for good construction and, on the other hand, a practical illustration of the necessity of a thorough knowledge of constructive principles, in order to make correct working drawings. They saw that the efficient architect must be a builder, acquainted with all the detailed processes employed by the carpenter or mason, informed upon all the conditions to be met, and knowing the best ways of meeting them. They gained impressions which should [23] help them, in studying the work of great architects, to look beyond the exterior, however pleasing it may be, for those elements of strength and beauty that characterize all good workmanship.

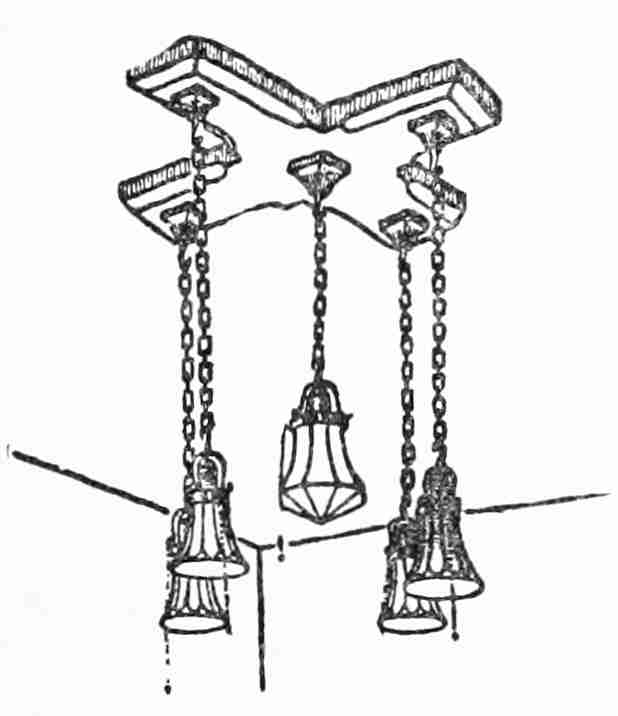

How the Work Was Distributed.—It will be recalled that boys and girls were to be coworkers in the designing, planning, and building of the house. The boys were to be held responsible for the drawings, the decorating after designs made by the girls, and the higher grades of woodwork, including the finishing of the rooms and the making of the furniture. They were to do the wiring for the electric lights, the bells, and the interior telephones; and they were to install all the fixtures in connection with this wiring. Boys from the metal-working sections were to do the necessary piping for gas and water and some of the work of plumbing; but, since the laws regulating plumbing are strict and well enforced, as they should be, it was necessary to keep this most essential feature of the work under charge of licensed plumbers. But this requirement did not remove even the plumbing of the building from the field of public school work; for, fortunately, this city has a well-equipped plumbing school in the trades school department, under the direction of[24] licensed plumbers of high standing, who were glad to have given them, as an exercise for their classes, a practical problem in house plumbing. The boys in the forging classes were not overlooked in the distribution of the work on the house. Many of the fixtures needed for use or ornament were designed to be made in the school forge shop. The girls designed and made rugs, curtains, portières, and cushions as a part of their school work in weaving and stencilling; and they contributed many decorative articles in clay, copper, leather, and other materials. Thus every technical department of the school was brought into service; for in the building of a house there is to be found something to enlist the interest of every boy and girl.

Boy Foremen in Charge.—To bring about the right distribution of the work and to marshal the working forces effectually required the oversight and management of an experienced instructor. But much of the work of direction was delegated to competent boys. The preliminary tool work in the school shops had revealed those who were especially observant and capable as leaders, and those who worked best under specific directions. Thus the twenty boys of the vocational school who set the posts and framed the house worked sometimes [25] in pairs—one being the chief foreman and the other the helper—sometimes in gangs of three or four under a foreman. The plan was varied according to the nature of the work in hand. When leaders of more technical knowledge and skill were needed, as was the case in setting the window frames and directing the shingling, capable boys from the technical high school were placed in charge of groups of younger boys from the vocational school. In this way the work was advanced in several directions at the same time; and the advantage was not all in the advancement of the house construction. It was a delightful and profitable experience for all the boys, not unlike that which some of them will doubtless repeat when school days are over and they take their place in the more serious affairs of life. In after years they may look back upon the first house that they helped to build and recall the part they took, their companions in the work, and the good time they had withal.

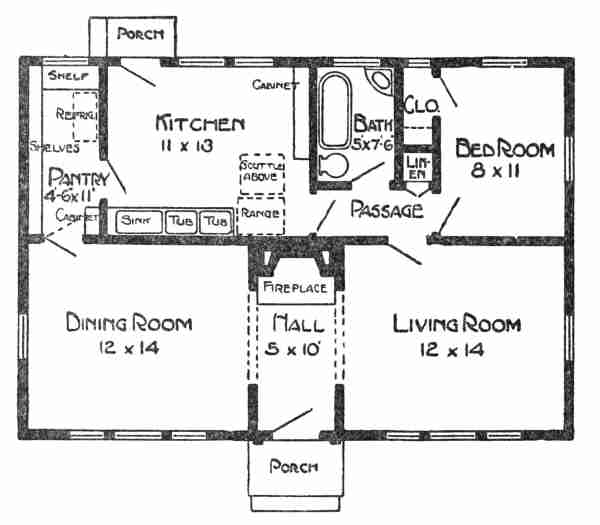

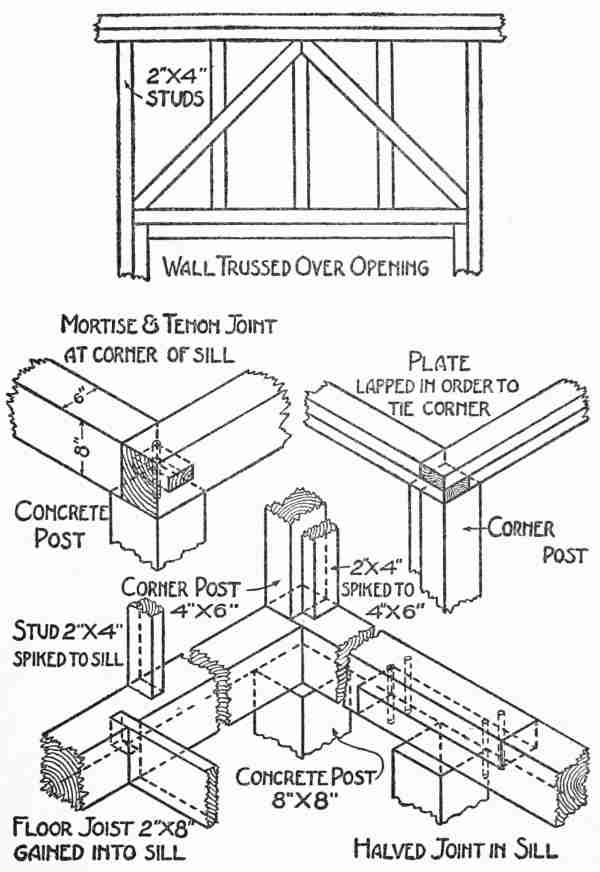

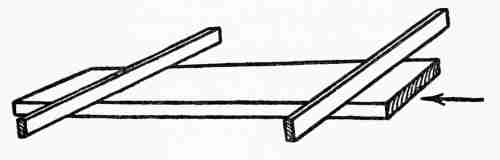

Setting Batter Boards, Posts, and Sills.—The first step in actual construction was to mark off the lot and set the batter boards. These were made by driving three stakes to form a right angle about four feet from the point where each of the four main[26] corners of the house was to be located. Two rough boards, one for each side of each angle, were nailed horizontally to each of the four sets of stakes, with their upper edges all brought to the same level. It is very important to set these batter boards with accuracy, since their function is to carry the lines which mark the dimensions and level of the ground floor. In the present instance their first use was to locate the concrete posts on which the sills of the house were to rest. Twenty-two of these posts, which were 4 feet long and 8 inches square, were put in position by first setting moulds or boxes, the interior dimensions of which were those of the posts, 3 feet deep in the light soil and filling them with a mixture of concrete and crushed rock. It was not thought necessary to remove the moulds after the hardening of the concrete. In fact, the sills were framed and placed in position resting on these boxes before sufficient time had been given for the concrete to harden. The sides of the boxes, however, were scored with a saw cut so that they could be easily broken off just below the ground, exposing the projecting ends of the concrete posts for about one foot. The sills were of 6 by 8-inch first quality spruce. They were set on the 6-inch face, the two long sills being spliced over posts,[27] using a long halved joint. Mortise and tenon joints, draw-bored and pinned, were used at the corners. The floor timbers of 2 by 8-inch spruce were gained into the sills with the top faces flush with the top of the sill and crowning (i. e., bending) upward if at all. The spacing of the floor timbers was taken off at the sill on a strip of furring—spruce, 7⁄8 of an inch thick by 2 inches wide—which was moved out to the centre near the line of bridging and lightly nailed, bringing crooked timbers into line. The bridging was then nailed in, the outside last to prevent springing the sills.

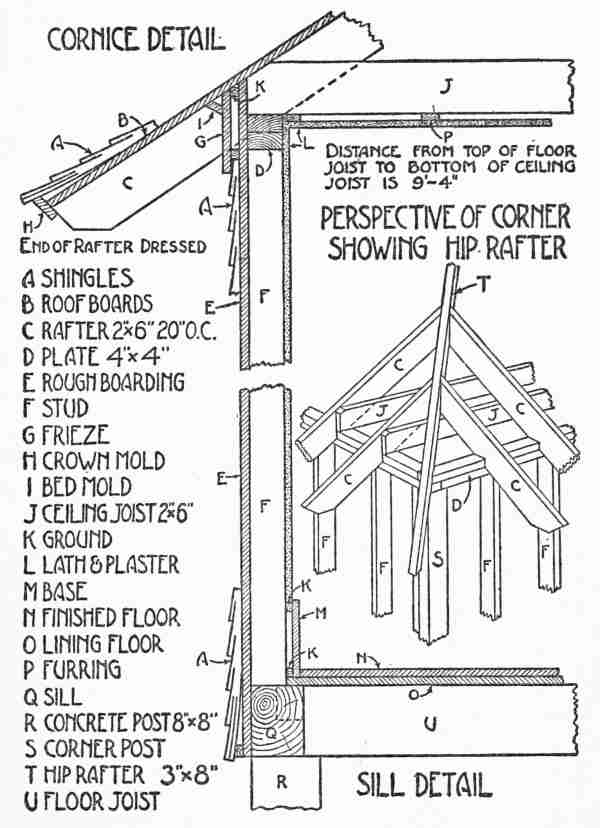

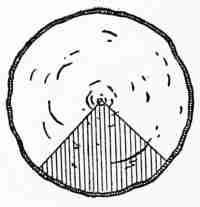

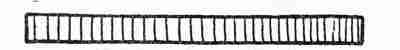

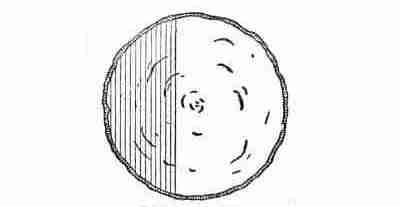

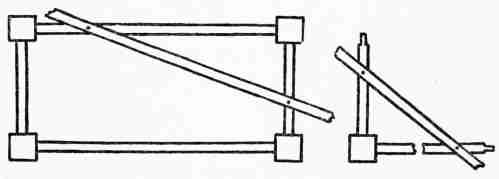

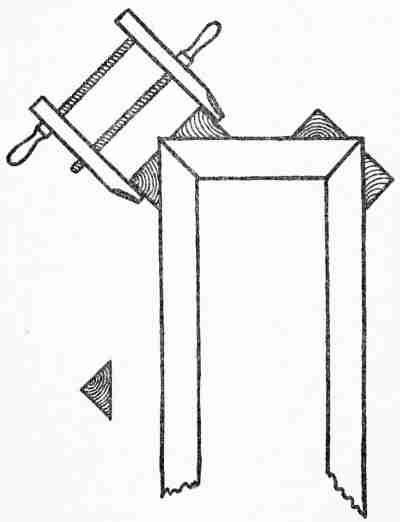

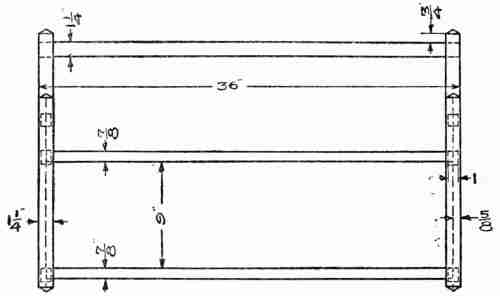

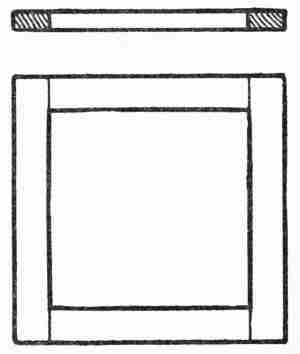

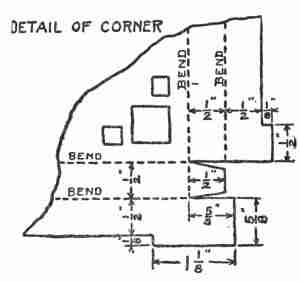

Referring to the accompanying sketch (Plan A) it will be noticed that the corner posts and centres were not mortised into the sills, but were simply butted on and heavily nailed or spiked. There was a time when carpenters would have regarded such a method as altogether wrong; but those were the days of great corner posts and heavy studding, placed two or three times as far apart as is the practice now. It was thought that placing the studs 16 inches on centres, which is the common practice in modern house framing, removed the necessity of mortising into the sill. Mortising is still recognized, however, as a good thing to do and is sometimes practised by first-rate carpenters.[29] Plan A also shows how the outside walls were trussed over openings; and Plan B shows how the corners of the building were tied by the lapping of the double plate, and how the ceiling timbers and rafters were placed on the top of the plate.

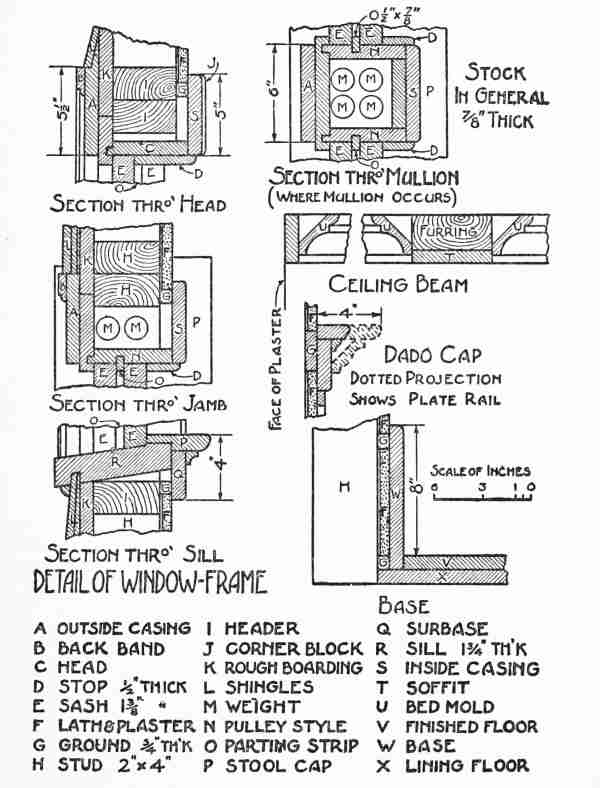

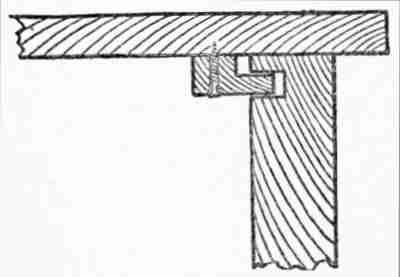

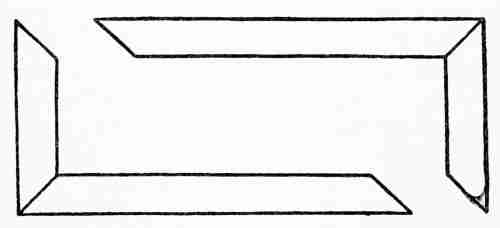

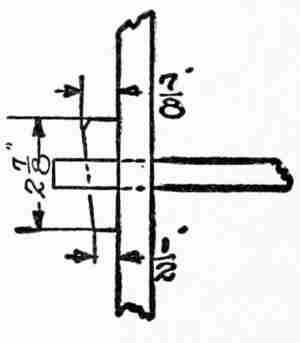

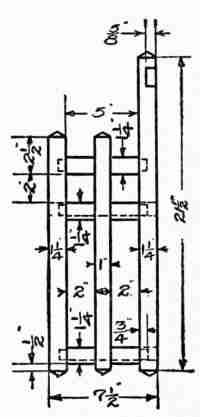

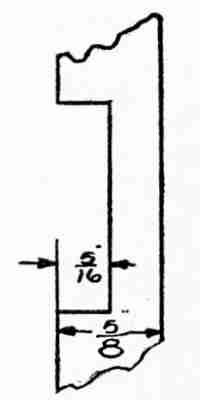

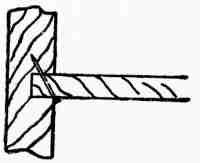

The window frame details are shown in a series of cuts (Plan C) which for the sake of completeness are drawn to show also the interior finish, not usually represented in the framing drawings. A detailed description of these features of construction is unnecessary, since the dimensions and relations of the various elements and the technical terms by which they are known are all clearly indicated in the illustrations.

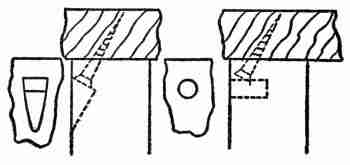

In the same series of cuts a detail of the base is shown which includes the framing, the base board, and the lath and plaster. It should be stated, however, that a substitute for lath and plaster was recommended to the student architects—a new product in paper board especially designed for walls and ceilings, which it was decided to use. The use of this material removed the necessity of the "grounds" shown in the drawings and always needed as a nailing base for the wood trim when the walls and ceilings are lathed and plastered. In the detail of the dado cap, which will be found[31] on the page of construction drawings, the dotted lines show how the cap was to be expanded into a plate rail, requiring the addition of brackets with a bed moulding between, in the finishing of the walls of the dining-room. Among these drawings will also be found a detail showing a section of the beamed ceiling finish.

It will be readily understood that none of the finishing work called for in the detailed drawings was begun until the rough carpentry on the house was practically completed. All the rough work, which included framing, boarding, shingling, laying of the lining floors, and putting up partitions, was assigned to boys of the woodworking sections of the vocational school. This is an elementary industrial or trade school, admitting from the grades below the high school boys who have attained the age of fourteen years and wish to learn some mechanical trade. It represents a new and promising experiment in American education. The building of this house furnished an excellent opportunity for the boys of this school to show the honesty of their purpose in enrolling themselves to learn the fundamentals of a trade and thus prove their right to have the chance.

So the house was built by the combined efforts[33] of the boys and girls of the public schools of this New England city, unassisted by professional architects or paid labourers. How they carried out with their own hands the designs for decorating and furnishing the house is told in the succeeding chapters of this book, which also suggests wider applications of the principles of household decoration as possible to be made in the homes of clever boys and girls throughout the country. To carry out these suggestions will mean work—but work of a kind that gives pleasure to the worker and to many others. It was work for the young designers and builders of whom this story tells, but they said it was "great fun," and there really is no pleasure quite equal to that found in doing with one's own hands an exceptionally good thing. The true craftsmen of all time have found it so. One of these master workmen, Stradivarius, the violin maker, so George Eliot tells us, made his confession thus:

Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful—William Morris

The decorating and furnishing of a house have their true beginning in good architectural design. It is a mistake to proceed upon the theory that decoration necessarily implies something added for its own sake—something beautiful in itself but selected and applied without regard to the lines, spaces, and colours of the room in which it is to be placed and without considering the relation of this room to neighbouring rooms and to more remote surroundings. The truth is, a decorative object may or may not be intrinsically beautiful; but however beautiful it may be in itself, it finds its truest beauty in an appropriate setting. And the decorator who is actuated by the true spirit looks to the architect for inspiration and finds his greatest successes in acknowledging that leadership. To attempt to[35] lead when one should follow is neither good art nor good sense.

There is danger, perhaps, that this truth may be taken too seriously. It would also be a mistake to run to the other extreme and adopt at the outset a rigid plan of decoration and furnishing, specified like contract work to be carried out and completed on a certain date soon after the house is built. The problem is one of growing interest, especially as regards furniture, pictures, and the smaller objects of use or beauty, and for its best and happiest solution requires time and study. Only the broad and fundamental features can be settled in advance. The important thing is to have the main lines, dimensions, space relations, and colour schemes settled with due regard to utility and appropriateness and, as the work of construction proceeds, to keep all details in harmony with this general plan.

Colour Harmony in the Model House.—It will be remembered that the colour scheme of the hall, living room, and dining-room of our model house was settled quite early in the development of the design. Standing near the centre of the living room and looking through the hall into the dining-room,[36] one may see at a glance how some of the details of decoration were worked out in keeping with the general treatment. The walnut brown stain of the floors gives a good foundation of colour. It flows easily into the lighter browns and yellows of all the lower wall spaces. The suggestion of olive green in the frieze of the living room offers a pleasing contrast with the prevailing browns and harmonizes well with the woodwork of this room, which, it will be remembered, was designed to be finished in gum wood. This beautiful wood, when properly treated, presents a surface of satin-like texture and soft colour tone. In the dining-room a corner of which is shown in the frontispiece, the frieze lends a warmth of colour where it is needed and is in keeping with the fumed oak trim. The wide openings into the hall from the rooms on each side of it, together with the long, unbroken lines of the beamed ceilings, give the impression of generous width. The plain wall spaces, though varied in tone and relieved of monotonous spacings by the location of the necessary doors and windows, are of great assistance in increasing the apparent size of the room. Plain walls are also the best of backgrounds for pictures.[37] Redecorating Old Houses.—It is, of course, true that the decorating and furnishing of a house or an apartment cannot always have a new and original architectural design as the basis for the solution of the problems involved. As a matter of fact, in the great majority of cases, the houses in which homes are made are already built and have been previously occupied. Often they are very old houses, presenting difficult and even impossible tasks for the decorator. Sometimes, however, such houses are all the more desirable if they bear the marks of age that suggest a past of dignity and charm. But the spirit which inspires the artist in decorating and furnishing a house already built is the same as that which controls his thought when he can begin with the foundation of a new and original design. His first thought is to discover how beauty may be enhanced and at the same time unity of purpose and harmony of treatment be preserved. His constant care is to avoid incongruous elements, however beautiful they may be in themselves or however appropriate in other houses. His general aim is to use his art to develop the design as it is, if there be any design at all, and make the most of it.

Decoration as a Corrective.—But this does not[38] prevent him from attempting to counteract the blunders of faulty design and bad architecture. Such correction, indeed, forms a large part of the work of decorators and furnishers, both professional and amateur. If the lines and space divisions of a room be not good, the decoration must be planned with a view to giving the needed harmony of proportions, or at least the appearance of it. If the ceiling be too high, it may be made to "look" lower by carrying the ceiling paper or tinting one or two feet down the walls of the room to meet the picture moulding. The effect of reduced height is accentuated by a high base board or by wainscoting. If the ceiling be too low, the depressing effect may be largely overcome by extending the picture moulding along the top of the wall spaces close to the ceiling. This is a desirable thing to do in the living rooms of most modern houses. Striped wall papers of proper tones may be used in low rooms with good effect in increasing their apparent height. Bad wall spacing may also be corrected by enlarging door-ways, substituting portières for the doors, and by arranging the drapery over windows to give the effect either of increasing or of diminishing their height, as the conditions may require.[39] Wall Papers.—Probably no element of decoration furnishes so many pitfalls to ensnare the unwary as wall papers do. It is easy to fall a victim to a captivating design as it appears in the few square feet of wall paper displayed on the dealer's rack. The same interesting figure, spread out in endless repetition on the four walls of the living room, may create an atmosphere of unrest and positive discomfort keenly felt by sensitive persons. A wise choice cannot be made in the absence of all the conditions that should really determine it. After all, it is not the paper which is beautiful in the roll that should be selected, but only that which will become beautiful when hung upon the walls of a certain room. Papers with large figures should be avoided unless there is a special reason for using them. They always have the effect of reducing the apparent size of everything associated with them. They make a small room appear dwarfish and a large one over decorated unless well relieved by plain spaces harmonizing in colour with the large-figured patterns. Strong contrasts in colour values should also be avoided, not only between the designs and the ground colour of the wall paper itself, but also between the paper and other objects of[40] importance in the room. The principle of gradation in colour values, which does not as a general thing allow the placing together of light and dark shades or tints, is almost as important as harmony of colour tones.

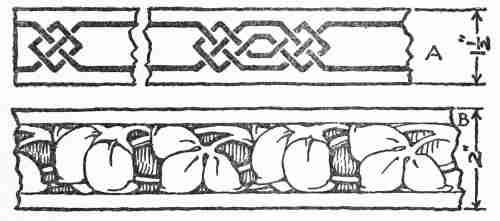

Nature of Decorative Design.—The one fact never to be lost sight of by the decorator is the real nature of true decorative design. It is never a picture. While it may suggest the natural forms of plants or animals, it does not aim to represent them in a naturalistic way. Some of the best decorative designs do not even suggest natural forms; but, whether they do or not, the central idea is the repetition of good combinations of line and form in closely related colours and values on a flat surface. If natural forms are used, they should be more or less highly conventionalized. Anything that destroys the idea of flat surfaces in the same plane is a false note in wall decoration. In the nature of the case, a wall can have but one plane. Clusters of flowers or patterns of any kind that seem to hang in front of this plane, or back of it, are out of place and therefore offend the sense of fitness. Such incongruities are sometimes so pronounced that they positively shock the sensibilities of refined people. Extreme examples[41] have been known to give such pain to sensitive persons as to drive them from the room.

Advantage of Plain Walls.—Decorative designs, however, are not essential in wall papers. The main point in the treatment of walls is to secure and preserve a good background. If one is in doubt as to the kind of figure or pattern to be used, which is often a perplexing question, it is well to leave them out altogether. Plain walls are always good if the colour tone is right; for colour is the main thing in wall decoration. The decorative effects of form may be brought out in the portières and window draperies, which may easily carry more elaborate patterns when associated with plain walls than is desirable with figured wall decorations. In fact, with figured walls plain portières and curtains are much to be preferred. In our model house, as has been explained, the wall decorations were designed to offer a plain background of colour. The figured borders of the portières and curtains, combined with the careful gradation in the colouring of the floors, wall spaces, and ceiling, gave such a variety of tone to this background that nothing further was needed to avoid monotony.

Trial Needed in Doubtful Cases.—It is, indeed,[42] a good rule to omit whatever is unnecessary. To observe this rule wisely is to escape much that is positively bad in decoration. Overwrought designs, too great variety in decorative material, too many decorative objects, however great their individual beauty, too many odd pieces of furniture, too many interesting things in whatever direction one may turn, create an oppressive and disquieting atmosphere and a feeling of unrest which it should always be the aim of home decoration to dispel. And yet it may not always be best to set aside our treasures because they do not seem perfectly suited to the general scheme of decoration or are not apparently needed to complete it. It is, in fact, often very difficult to determine where the line should be drawn between what is needed and what is not needed. The fact that nothing seems to be lacking is not a final test if one has at hand useful or beautiful things that may be introduced into a scheme of decoration already well thought out and be given a trial. Such experimenting will often reveal unsuspected needs or add a new charm that at once proves its right to be retained.

To take a step like this, somewhat out of line with accepted rules as strictly interpreted, is entirely[43] safe if this step is dictated by good taste and does not lead the young decorator too far afield. Exceptional treatment of any kind should show proper restraint, and such restraint, when it is plainly indicated in any work of art, is in itself an attractive feature.

Precise Rules not Always Practicable.—The truth is, the rules of decoration, though founded upon fundamental principles of art, are not rules of precision like those founded upon mathematical principles. In the nature of the case they must in their application yield more or less to circumstances. It is, for example, a good general rule to determine the colour scheme and background first and accommodate other decorative features to these as a foundation; and yet it is possible for a situation to be so exceptional as to justify a complete reversal of this rule. Here is a concrete case. A young artist was the fortunate possessor of a considerable number of Japanese and Chinese embroideries and other Oriental ornaments. He wished to make these the main decorative materials for one of his rooms. The embroidered figures were in yellow and white on a deep, strong blue, the general effect being quite dark. There were in the collection several[44] prints, showing the typical dull reds, dark blues, and yellows of Japanese art. Now the room itself happened to be one that, under the general principle of colour schemes as determined by exposure and other fixed conditions, would demand warm colours on its walls. It would easily support a rich red frieze with appropriate combinations in floor, dado, and ceiling. This would set off well the dark oak trim and the mahogany furniture, but it would rule out the Oriental decorations. One or the other must give way; and, since the value of these decorative materials was beyond question, it was decided to try them, even at the cost of setting aside the general rule. The whole matter resolved itself into selecting a proper background for these beautiful pictures and embroideries; and for these the best colour was a gray blue—the coldest of colours. But when the whole decorative scheme was carried out to completion and the cold background was fully employed in setting off the rich colours and exquisite workmanship of the Oriental prints and draperies, all the circumstances that ordinarily determine the choice of backgrounds were forgotten in the charm of originality. No one thought of the exposure as requiring warm colours, the dark[45] oak trim was not noticed, and the mahogany furniture was still in keeping. The result was so absolutely satisfying that no one who saw it could question the good taste displayed in this very original plan of decoration.

But such exceptional cases should not shake our confidence in the fundamental principles of decoration. It is true that these principles cannot be reduced to formulas to be applied invariably in all cases, and it is unreasonable to assume that any form of treatment is the only one possible in any given case. Modifications in the application of these principles are always possible, but the principles themselves are as unalterable as the Mosaic law. One is, indeed, tempted to summarize them thus as the

Thou shalt have no household gods except those that be beautiful or those that be useful.

Thou shalt not make unto thyself any likeness that is in the heaven above or in the earth beneath, or in the waters under the earth, that does not find an appropriate setting in thine house.

Thou shalt not look in vain upon the creations of the great masters of decorative art.

Remember the colour scheme and keep a good background.

Honour the original design, however old it may be, and make the most of it.[46] Thou shalt not hesitate to correct the blunders of faulty design and bad architecture.

Thou shalt not kill thy neighbours or thy friends with over-decorated wall papers or oppressive decorations of any kind.

Thou shalt not bring together incongruous articles nor permit insane arrangements of anything that is thine.

Thou shalt not permit any false note to mar the harmony of thy decorations.

Thou shalt not imitate thy neighbour's house or anything that is thy neighbour's, for it is the glory of the good decorator to show originality but at the same time to acknowledge his dependence upon those who have preceded him.

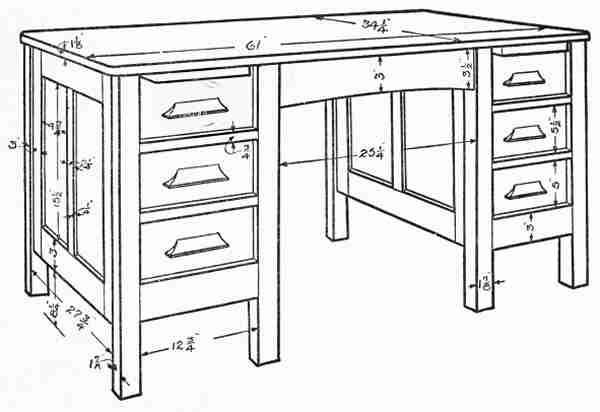

Relation of Furniture to Decoration.—So much for the treatment of floors, walls, and ceilings. We may now turn to the more special consideration of those objects of use or beauty that are to be associated with these backgrounds—furniture, pictures, lamp shades, and small ornaments. That these are closely related to decoration has been implied in all that has been said. They are, in fact, in themselves elements in the decorative scheme and as such must obey the same laws. Their value, however, depends more or less upon their utility, and for this reason they seem to require consideration somewhat apart from their merely decorative functions. This is especially true of furniture, which would have[47] very little reason for being if it were not for its usefulness.

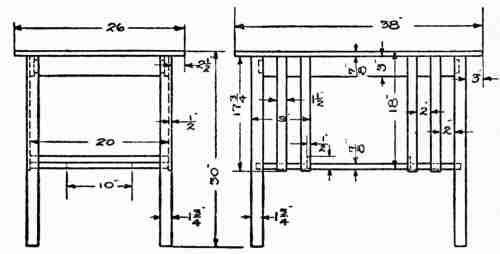

In designing the furniture for the model house the questions that constantly suggested themselves were: What is this piece of furniture under consideration to be used for? What form, construction, and finish will enable it to give the best service? What features of design are needed to render it suited to its surroundings? In considering the furniture for the model house it was most natural to apply these tests to the various rooms in order.

Hall of the Model House.—First, there is the hall. This is the room into which a visitor is first admitted, and from its atmosphere he gets his first impressions. But in this house it is a very small room and designed to serve not merely[48] as a place for the formalities of welcome but also as an expansion of the rooms on either side. Its furniture must consist largely of the fireplace. There is no room for a hall settle nor even for a chair. A mirror, simply but richly framed, might hang on the wall near the front door, balanced by a picture on the opposite wall behind the door. An umbrella rack should stand outside on the porch.

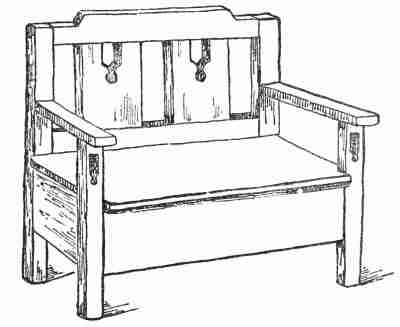

Hall Furniture in General.—The halls of modern houses vary greatly in their relative importance. In some the traditions of the old English manor houses seem partially to survive. In mediæval England the hall was the principal room, if not the only one comfortably furnished. When modern houses combine the living room and[49] library or reception room with the hall, there is need of something more than hall furniture of the formal kind. The requirements of comfort must be met. But, generally speaking, hall furniture is of little real use. Odd chairs, attractive by reason of their oddity, the richness of the materials used in their construction, or some other assertive quality, but not fit to sit in, are suitable or at least excusable in the hall. The hat and coat rack of our fathers has been declared insane and no longer appears in well-regulated houses. In place of it is found the hall settle, which is of real use. It should be designed on simple lines and give the impression of strength and dignity. If the hall is to be used as a waiting room for guests, a few good chairs, conveniently placed, will be needed for[50] their comfort and a choice picture or two on the walls will add greatly to their pleasure.

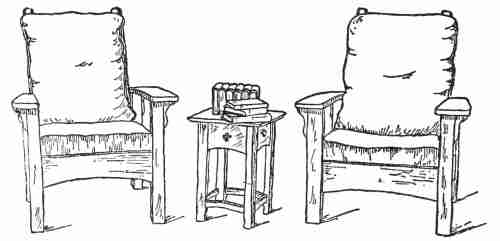

Living Room Furniture.—In furnishing living rooms there is bound to be a wide range for the exercise of good taste because of the variety of needs to be met and the large facilities afforded in the markets for meeting these needs with due regard to artistic requirements. It will be quite impossible to go into detail in discussing so large a topic. The important thing is to keep in mind the central idea of a living room—the place of all places where[51] the freedom, comfort, and protection of home life are to be enjoyed. The very atmosphere of the room should suggest simplicity, sincerity, and good cheer. Every article of furniture should be there to serve a genuine need, and it should be strong enough to do its full duty. Spider-legged, top-heavy tables; light, weak chairs; chairs on casters or rockers; sofas with carved backs or couches with none at all,—these have no place in the living room. The long, straight lines of the craftsman or mission style of furniture are in the right direction; but if these be used at all they must be made quite general, since few other styles harmonize with them. Wicker or reed furniture[52] is a notable exception. When well designed it will fit in almost anywhere.

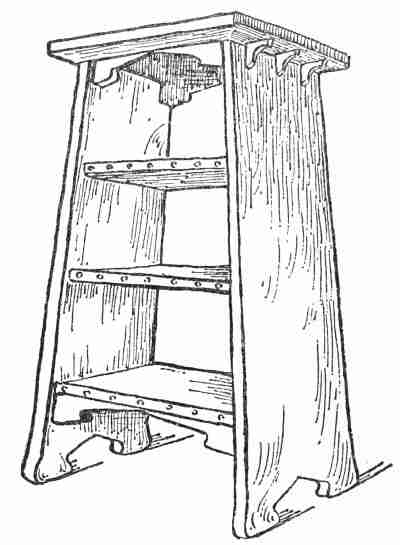

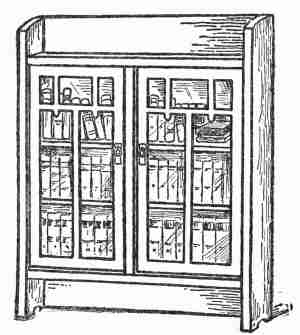

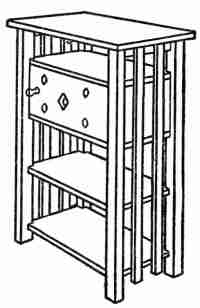

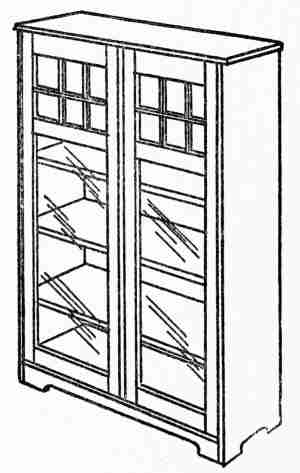

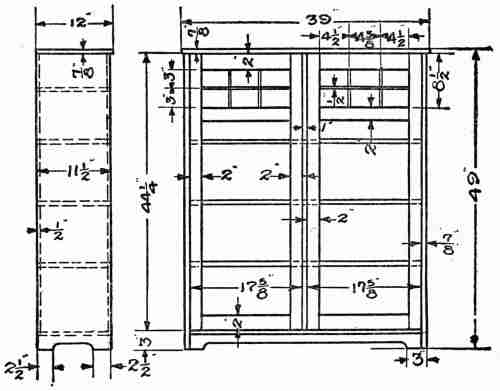

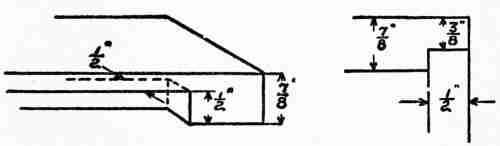

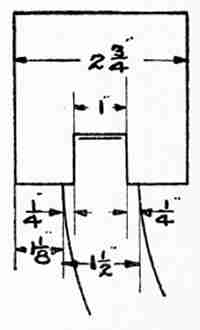

The frequent combination of the library with the living room requires a suitable adjustment of the furniture to this use. A plain, serviceable magazine rack, which may be easily made, will relieve the tables of an accumulation of weeklies and monthlies. Moderately low bookcases, with[53] or without doors, are to be preferred to the more ordinary high ones because this form harmonizes better with the lines of a room, which are generally longer horizontally than vertically. If doors are used, it is well to break up the glare of the glass by heavy sash, the spacing of which may be arranged in a very pleasing manner. Good design in library tables calls for ample size. Firmness and convenience as well as satisfactory proportions should control the choice of a writing desk.

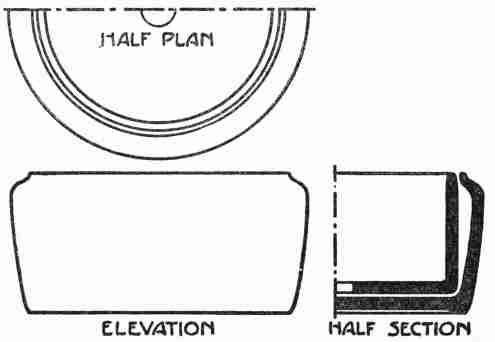

Dining-room Furniture. Only a few elements[54] enter into the design for the furnishing of a dining-room; but they are evident and should have a controlling influence. The table and chairs are for a definite purpose and this should show itself in good design. Heavy construction is permissible since the chairs are to be moved but little and the table is practically stationary. Moreover, weight and generous dimensions are suggestive of bounty and good service. The rectangular extension table is most readily adjusted to varied demands, but the round table is preferable for the family circle; and for a company of twelve or fifteen a large, round, temporary table top, placed on an ordinary extension table, has been found very attractive.

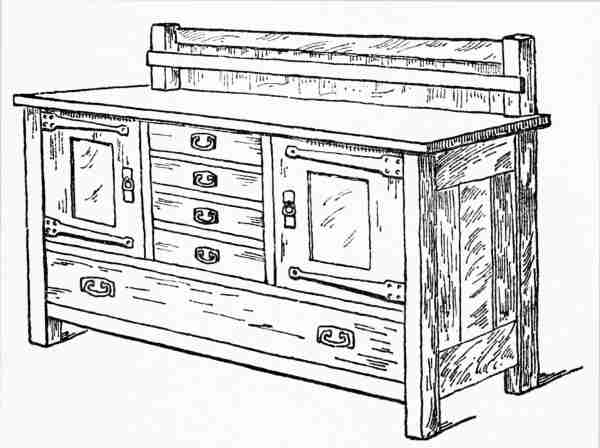

As comfort is the chief result to be obtained in furnishing a living room, so richness, within one's means, is an appropriate aim in furnishing a dining-room. The history of sideboard design might be cited in proof of this statement, if proof were needed. Probably no single article of furniture has been subjected to greater elaboration; but the desirable suggestion of plenty with convenience may be secured without overdoing it. The unique purpose of the sideboard makes it an interesting study for one who wishes to design and[56] construct his own in conformity with the architecture of his dining-room. The buffet or serving table furnishes an equally interesting, though simpler, problem.

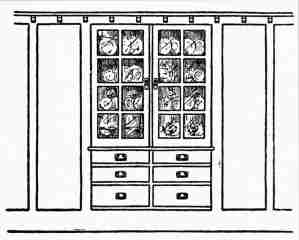

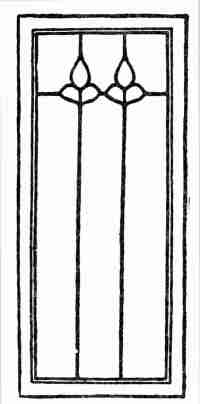

For the care of the china, the built-in cabinet as a feature of the architecture of the room is to be preferred to the movable cabinet designed for this purpose, because of its richer decorative possibilities. Large, glazed doors are desirable in either case, not for the full display of china and glassware but to give a suggestive glimpse of it. As this cabinet is for decoration and not for show, it is well to avoid plain glass doors unbroken by sash. Leaded panes[57] are frequently employed with good effect. The decorative effect of old and odd pieces of china—not too many of them—is most appropriately employed by the use of the plate rail; but it is better to leave the plate rail bare than to load it with commonplace crockery and inappropriate ornaments.

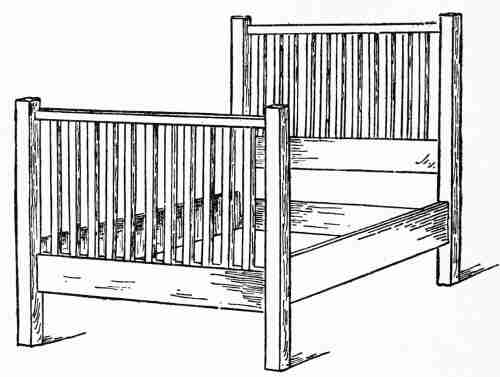

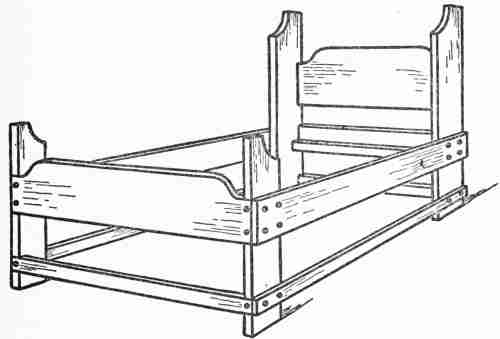

Chamber Furniture.—The bedroom speaks for itself. A dainty freshness in all its appointments is conducive to sleep and rest, which it is the distinctive purpose of this room to provide. The necessary articles of furniture are a bed, a dressing table, a bureau or chiffonier, a few chairs, and, if there be no bath room attached, a commode or wash stand. A couch is an appropriate addition;[58] and here, if anywhere, rocking chairs are allowable. When the bedroom must be used more or less as a living room or sewing room, as it too often unfortunately is, furniture to serve such uses must be provided. In selecting or designing all this furniture, lightness, and simplicity of design, combined with strength, should be allowed a controlling influence. The recognition of this idea has given great popularity to the brass or iron beds; but it is possible to design and construct beds of oak, maple, or other woods that harmonize with the rest of the furniture, carry out the idea of daintiness, and have sufficient strength for service.

Many of these suggestions on furniture design are being carried out in fitting up the model house described in our introductory chapter. A small house like this, limited to one story, does not permit great variety in its furnishings. Certain standard conditions, however, were to be met here, as everywhere else, and the young designers found[59] much pleasure and great profit in working out the furniture problems. Some of the construction details will be given in the later chapters.

Arrangement Follows Selection.—The problem of furnishing a home is not fully settled when the questions of design have been answered and the right selections made. After selection comes arrangement, or, to speak more accurately, after a certain amount of selection a certain amount of arrangement; for, as has already been suggested, there is considerable dependence of one upon the other. It is not wise to drop the arrangement till the selection is complete, for the simple reason that the happiest choices are often the late ones, determined by the disposition of the earlier ones. And yet in the main the order as stated is the true one. It should be noted, too, that in arrangement[60] there is a larger field for the exercise of individuality and taste. While artistic principles still hold sway, they yield more readily to exceptional interpretation by the ruling spirit of the household, to the demands of style, and to the larger number of possibilities for pleasing effects when the question is one of the arrangement of things already well chosen for their usefulness and for their artistic value.

Utility the Controlling Principle.—The problems of arrangement, however, are by no means vague and uncertain. The natural law of adaptation[61] to purpose is not difficult to follow. In some rooms obedience to it has become a settled custom. No one, for example, would think of placing the dining table in any other place than the centre of the dining-room or, if the room be a long one, in the centre of one end. The sideboard, serving table, and china closet likewise fall into their natural places. So also the bedroom and the hall, though perhaps to a less degree, present comparatively easy problems in furniture arrangement when due regard is paid to the purposes for which such rooms are designed.

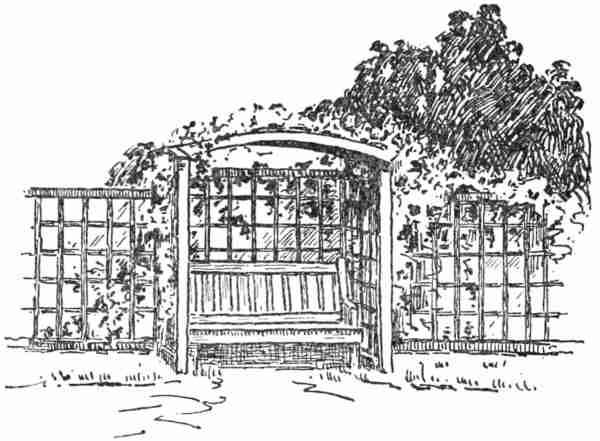

Importance of Appropriateness.—But it is in the library and the living room that we find the most difficult and at the same time the most interesting problems. And this is due to the operation of the same law of adaptation to purpose. It is the variety of uses and the diversity of useful objects that make the problem somewhat complex. However refined and beautiful the different units may be, there must be some arrangement of them into working groups. The important elements should dominate and those of lesser importance should fall naturally into related but subordinate places. The easy corner with its couch, pillows, and its low seats, has a definite function to perform. So[62] also have the piano and the music rack, the bookcases and library table, the Morris chairs and tabourettes, the window seats and screens, the writing desk and its proper lighting by window or lamp, the fireplace and all the accessories of comfort that may belong to it. The various centres of interest should be accentuated by grouping around them the most appropriate furnishings and the most suggestive decorative features. It may be well to add one word of caution, and that is that a proper balance should be maintained between the various centres of arrangement in order that no part of the room may seem neglected and bare.

The Danger of Overcrowding.—Finally, the one great danger to be avoided in meeting the requirements of good arrangement is the temptation to overcrowding. Many otherwise excellently appointed living rooms suffer from an embarrassment of riches. Such overcrowded rooms are worse than an overloaded ship because they cannot topple over and sink as one might well wish them to. To secure the right things and just enough of them, arranged with a proper balance between utility and beauty, is the true aim. It is as true to-day as it ever was in the arrangement and beautifying of the home, and, for that matter, in[63] everything that concerns every-day life—just as true as it was in ancient times when men wrote those famous inscriptions over the doors of the temple at Delphi: over one, know thyself, and over the other, the golden mean of not too much.

I now require this of all pictures, that they domesticate me, not that they dazzle me. Pictures must not be too picturesque. Nothing astonishes men so much as common sense and plain dealing. All great actions have been simple, and all great pictures are.—Ralph Waldo Emerson

The decoration of a room is generally not complete without pictures. There is, of course, great value in good pictures entirely aside from their decorative effect; and too great care cannot be exercised in their selection. But our present purpose is to consider them as decorative features; for, though a decoration is not a picture, pictures themselves are properly regarded as important elements in the general scheme of decoration. And this is especially true as regards matting and framing, the distribution of pictures upon the wall spaces, and the method of hanging them.

Importance of Space Relations.—A picture mat and frame are simply elements of finish, and their function is to give the picture a certain individuality[65] and yet connect it harmoniously with the space in which it hangs. In fact, the wall space is a part of the framing of the picture. The importance of giving some study to the relations of all the spaces involved is evident. The mat and the frame should not be of equal width. Here is a fine opportunity to secure variety in spacing. No definite rules can be given; sometimes the one, sometimes the other should give way. Generally speaking, tall wall spaces require vertical pictures, and spaces longer horizontally demand horizontal pictures. But variation from this rule is possible and even necessary through the grouping of several pictures. In grouping, however, there is danger of being tempted to allow too many pictures. In the houses of the well-to-do, and even in the homes of those of moderate means, too many pictures, rather than too few, are often found. The example of one New England home, known to the author, may be mentioned. The house is new, of generous proportions, and it is the home of an artist. There are few pictures on the walls, but they are distributed with rare artistic effect. There are many good pictures stored in the attic because there is no suitable space in which to hang them.

The Japanese Way.—The Japanese have taught[66] us many valuable lessons in art, and in the matter of the number of pictures to be displayed they have a very interesting lesson to teach. It is their practice to hang a single choice picture for a season in a space where it may be best enjoyed, and then after a time to replace it with another picture, and this, perhaps, by another if circumstances permit. There are many conditions that determine the selection of the picture to be displayed. It may be the preference of a guest, or it may be the season of the year, or, in fact, any occasion that may give a certain picture special significance. There is, in this singular custom, a very definite service which the picture is made to perform, and it is given an individuality which perhaps has no parallel in our own practice.

Grouping of Small, Simple Pictures.—If a considerable number of pictures are grouped together, it is quite essential that all the pictures of the group should be of similar character and tone and similarly framed. It is hardly possible for them to be all of the same size, nor, indeed, is such agreement desirable except in so far as is required to give proper balance to the group. Small pictures in light frames are, of course, the most desirable for such grouping, and if possible there should be[67] an evident reason for the grouping. A series of photographs of a certain locality, for example, might form a group of four or five or even more pictures so that they could be easily seen together and so more thoroughly enjoyed. A collection of photographs in passe-partout bindings, especially if they deal with subjects in any way related, may form an attractive group. But pictures of any considerable size or those having decided individuality are generally not suited to any plan of grouping. They should appear by themselves, in frames and other surroundings which accentuate their peculiar merits.

The Kind of Frame.—The material of the frame, its colour, and the colour of the mat are determined by the tone of the picture. Oil paintings easily support gilt frames and should be hung in good light. Pictures of light values with white mats are well finished in narrow gilt frames. Carbon photographs and other pictures of dull tones, are appropriately framed in wood of dark or medium colour, and appear best when hung against a dark wall. The truth of these statements will hardly be questioned by any one who has a good sense of colour harmony. But there are many other elements that enter into a concrete problem of picture[68] framing that cannot be brought under general rules or formulas. It is generally best to depend largely upon the tests of trial. In framing and hanging pictures, as in many other things, observation and experience are the best teachers. Some suggestions may be found in the following record of two actual framing problems that were satisfactorily solved.

The conditions which had to be met in this problem are plainly shown in the framed picture as it hangs on the wall. The picture itself is a small one, 8 inches wide and 13 inches long. It is interesting because of its representation of a sewing room in one of the high-class homes of the colonial period. The mistress and her two young daughters are engaged in sewing and embroidery. Patterns are displayed upon the wall; the furniture is appropriate and evidently an example of the best of the period. All these details are suggestive of the delightful home life of our grandmothers.

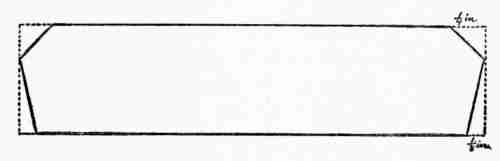

Such a picture needs a mat to give it depth and to properly emphasize its details; and it requires a simple, narrow frame. The mat was accordingly made 21⁄2 inches wide and the frame 1 inch wide. The tone of the mat selected was a light bluish[69] gray, forming a good connecting link between the bright colours of the picture and the gray of the wall against which it was to be placed. Since it was to hang directly over a fine old mahogany table, it was thought fitting to give the frame a mahogany finish, connecting the furniture shown in the picture with that of the room.

The frame was made with mitred corners of perfectly plain, square-edged birch, which readily takes a mahogany finish. The stain was first applied with a brush, rubbed in, and allowed to dry. A surfacing coat of shellac, coloured to match the stain, was next put on, allowed to dry, and then carefully sand-papered, special care being taken to guard against rounding the edges and corners. A coat of varnish was next applied, which, after hardening for one week, was rubbed first with pumice stone and oil and finally with rotten stone and oil. A final coat of thin finishing varnish was then put on, which was lightly rubbed with rotten stone and water to give the half dull effect required to match the antique mahogany table.

The picture is a copy in sepia tones of Murillo's Saint Anthony, 16 inches in height by 20 inches[70] horizontally. The frame is made of quartered oak 3 inches wide, slightly convex but smooth; and it is well joined with mitred corners. A picture of this character needs no mat. Indeed, it would have been the height of presumption to strive to accentuate a masterpiece of such highly idealistic meaning and treatment. It must be left to itself as much as possible. The dimensions of the frame are therefore determined by the size of the picture itself.

The picture hangs against a light gray wall in good light, somewhat apart from other pictures. It was a happy thought thus to recognize its dignity. It was given further distinction by finishing the oak frame so that it should not associate itself with the other woodwork in the room. Since the room in which the picture was to hang has a light ash trim and most of the furniture a mahogany finish, this requirement was easily met.

But there are many ways of finishing a frame to avoid too close association with the commonplace that would have been anything but appropriate to such a picture as this. A gilt surface, a silver-gray tone, or a highly polished golden oak are possible blunders. Nothing should be done to call attention to the frame of any picture, least[71] of all to one of such spiritual feeling as this one. The frame should seem to be a part of the picture, repeating its prevailing tones with a richness in keeping with the composition of the picture itself. The colour should be a rich, dark brown, but not so dark as to obscure the figure of the wood. The finish should be dull, but soft and smooth.

There are several brown stains which, properly applied, would give the desired effect. For the colour it was thought best to rely upon Van Dyke brown, which may be used either with alcohol or turpentine. It is not desirable to use a water stain in a case like this because it would raise the grain, necessitating sand-papering, which should be avoided as much as possible on picture frames in order to keep the edges and corners intact. Ammonia fuming preserves the figure of the wood better than any other form of staining, but it was thought that the oak might not take on a tone dark enough to meet the requirements. It was decided, however, to try the fuming method and to tone up with a thin coat of stain if the effect proved to be not sufficiently dark. The ammonia process resulted in a rich, soft surface, but in a colour too light. A thin Van Dyke brown alcohol stain was therefore[72] applied and when dry this was followed by a very thin coat of shellac—mostly alcohol—coloured to match the stain. This was to fill partially the grain of the wood. Finally, it was thoroughly coated with wax finish and well rubbed to restore the soft, satin-like surface.

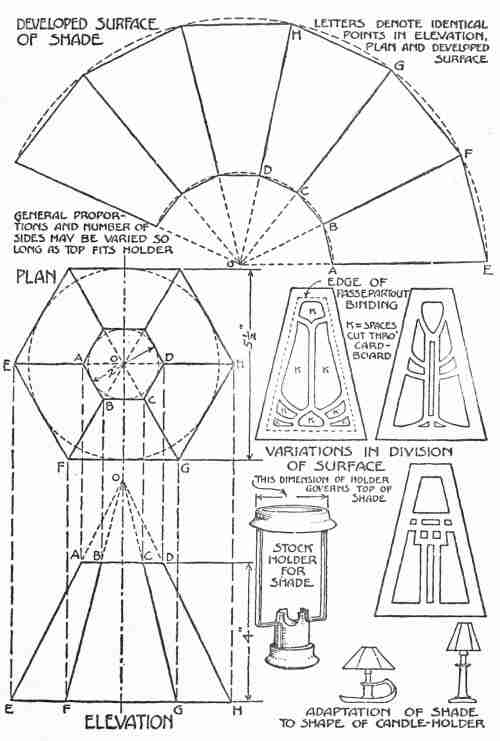

Framing pictures in passe-partout binding is one of the little arts of home decoration, though it is by no means an unimportant one. It is easy to learn and it involves small expense in time and money, but it furnishes a means of preserving many pictures of real worth in themselves or of value to their owners because of pleasant associations; and it is in itself a delightful occupation. It offers the same chances for artistic effects in[73] colour harmony and contrasts, in spacing, and in the arrangements for hanging that the more difficult methods of framing do, with the added advantage that one need not be deterred by the question of expense from discarding an unsuccessful result and trying again.

Varieties of Binding.—Passe-partout binding is made in a great variety of colours. It costs from ten to twenty cents per roll of twelve yards, according to colour and quality, and it may be purchased of dealers in artists' supplies. For general use the ordinary width of binding—7⁄8 of an inch—is required; but extra narrow widths are supplied when it is desired to add a margin of a contrasting colour. For these margins the gold and silver narrow bindings are, with certain pictures, very effective; but white and other light colours are often used for this purpose.

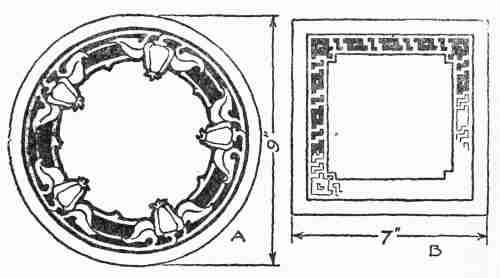

Artistic Colour Effects.—The choice of the colour for the principal binding should be controlled mainly by the tone of the picture, with which, as a general thing, it should blend. If no mat be used, more or less of a contrast in colour between the picture and the binding is permissible; but the most artistic effects are obtained when mats are used. These should, of course, be in harmony with the[74] colour tones and general character of the picture. It may be a harmony of agreement if there is a border of light tone between the picture and the mat, as illustrated in the accompanying drawing. Without such a border it will be necessary to show a pleasing contrast of tone. But in almost all cases when a mat is used the outer binding should repeat the predominant colour or some other prominent characteristic of the picture. For example, if it be a picture of an English hunting scene with mounted sportsmen in red coats, the mat may be of a light greenish hue and the binding red. If it be a landscape photograph in sepia tones, a white or light coffee-coloured mat with a dark brown binding is a good combination. A Scotch scene is appropriately framed in a plaid binding. In this case it is the subject of the picture rather than the colour that suggests the binding. But in all cases opportunity is offered for carefully selecting the colour combinations, planning the spacing, and arranging the grouping of pictures of like character. Thus one of the simplest of decorative processes presents large artistic possibilities.

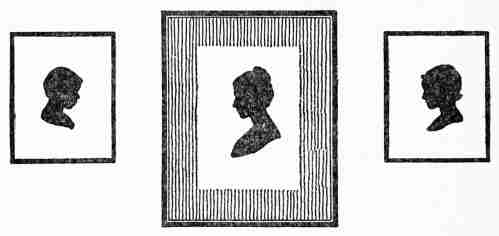

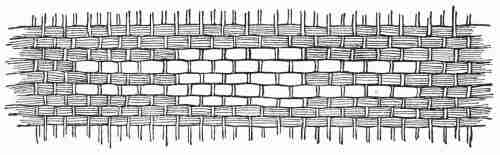

An Actual Problem.—The various steps in the process of framing a picture in passe-partout binding may perhaps be best understood by giving[75] an example of it. The actual problem is to frame a silhouette—an original drawing in black India ink on light gray paper, 8 by 10 inches in size, with the longer dimension vertical.