In Metz there lived a lady named Florentina, whose

husband, Alexander, was going to the Crusades; she presented him, on

his departure, with a miraculous shirt, which would always retain its

purity (a great comfort in a crusade).

The Knight was taken prisoner, and being put to labour, the Sultan

remarked the extraordinary circumstance of a prisoner being always in a

clean shirt, and [51]inquired the reason. Alexander told him it was a

miraculous shirt, which would always remain as spotless as his

wife’s virtue.

The Sultan despatched a cunning man to undermine the lady’s

virtue, as he thought ill of the sex.

The emissary was quite unsuccessful.

Florentina having learnt from the cunning man her husband’s

condition, disguised herself as a pilgrim, and reached the place of his

captivity. She then, by her singing, so charmed the Sultan, that, at

her request, he made her a present of a slave who she selected. This

was her husband; and she gave him his liberty, and received in exchange

from him a piece of the miraculous shirt, he not recognising his

wife.

Florentina hastened back to Metz, but Alexander arrived there first,

and was informed by his friends of his wife’s long absence during

his captivity. When she arrived, he bitterly reproached her (although

the shirt had not become dirty). She explained, and produced the piece

he had given her, thus showing how she had been employed; and so they

lived happily together.

Very quaint is this legend, and we are at a loss to understand the

origin of so curious an invention. The following is a story of the same

date, and, though not belonging to Metz, serves to illustrate this

period:—

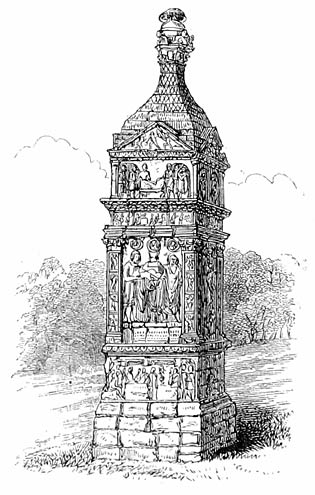

A Thuringian Count, who was married, being taken prisoner in the

East, the Sultan’s daughter fell in love [52]with

him, gave him his liberty, and fled with him to Europe, he promising to

marry her.

On arriving at home he presented her to his Countess, and with the

consent of all parties, and the Pope’s sanction, wedded her also,

and they all three lived very happily together. At Erfurt may be seen

the three effigies, the Count in the centre: the tombs have been

opened, and one of the skulls was found to be like an Asiatic’s,

thus in some measure corroborating the truth of this remarkable

tale.

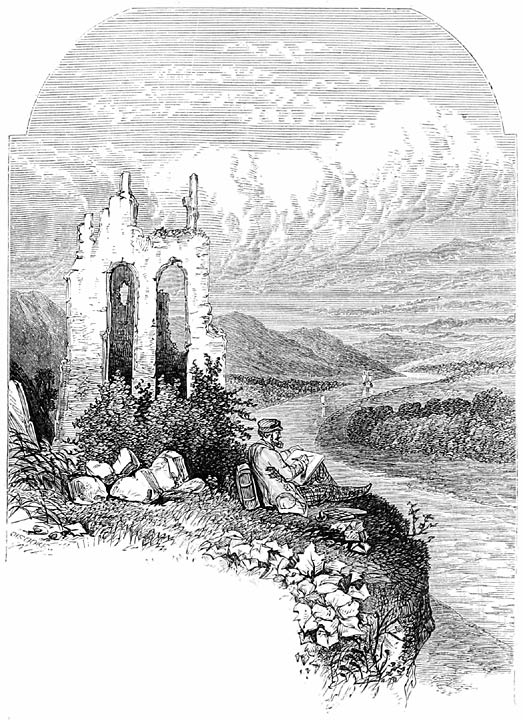

We have now emerged from what may be termed the ancient history of

Metz, and the more detailed accounts of the modern period give us a

series of [53]sieges, battles, and plots, from which we will

select those appearing the most interesting.

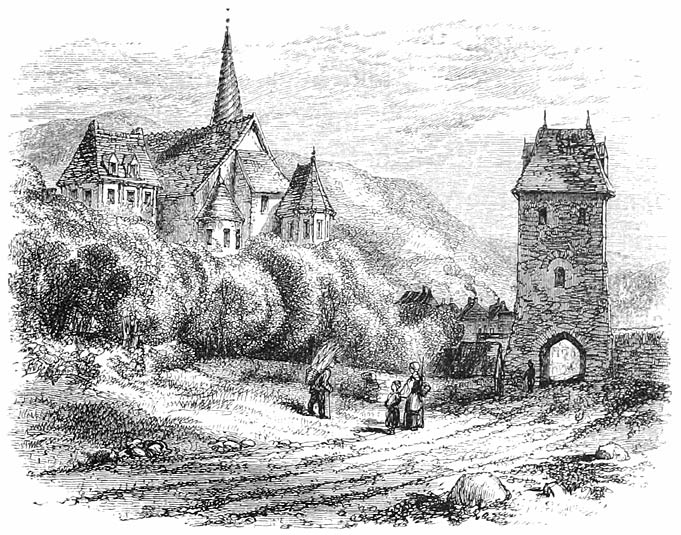

In 1354 the Emperor Charles IV. remained some time at Metz, and

returned there again two years after, when he held a Diet, at which the

Archbishops of Trèves, Cologne, and Mayence, and the four

lay-Electors, were present. At this Diet additions were made to the

celebrated Golden Bull, which was then published, and remained the law

of the Empire until the nineteenth century. Metz was now at the height

of its glory. Now, say the “Annals,” Metz was resplendent

with knights, princes, dukes, and archbishops. The Emperor, clothed

with the imperial ensigns, and surrounded by the great officers of

state, the naked sword in his hand and the crown on his head, attended

service in the Cathedral.

A party in the town wished to raise a tumult, and deliver the city

to the Emperor; but the Cardinal de Piergort representing the infamy of

such treachery, the Emperor sent for the chiefs of the city and gave up

to them the traitors, who, when night-time came, were drowned in the

river. The Emperor departed, and then followed a series of discords

unimportant except to the actors.

In 1365, companies of countrymen, and pillagers set free by the

peace of Bretigny, succeeded each other in attacking Metz, and ravaging

the neighbourhood. With some difficulty they were defeated and

dispersed.

No sooner were these petty wars ended, than a [54]larger

one broke out with the Lorrainese; and the Count de Bar advanced to

Metz and defied the Messins to combat, sending them a bloody gauntlet.

The citizens, however, declined the conflict, and peace was

concluded.

In 1405 an émeute took place in the town,

and the people rising turned out the magistrates, and replaced them

with their own representatives. Soon, however, the ancient rulers

managed to reinstate themselves, and took a bloody vengeance on their

enemies.

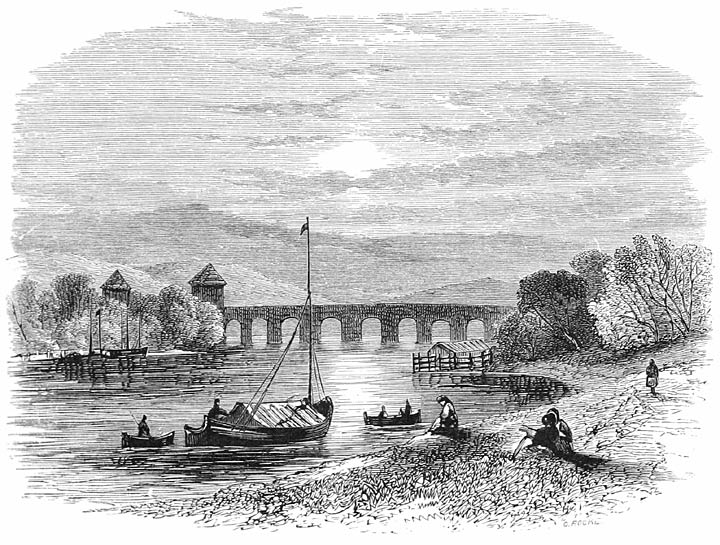

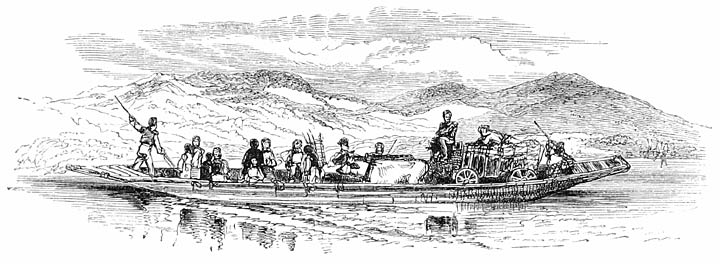

In 1407, the Duke de Bar resolved to take Metz by surprise. He

secretly fitted out a train of boats, filled with arms and munitions of

war, and sent a large body of soldiers, who secreted themselves near

the town. All was prepared, and on the morrow an attack was to be made,

when a sudden panic seized the attacking party, and they fled, leaving

their boats and munitions, by which the Messins learnt the peril they

had escaped.

In 1444, a furious war was waged between the Duke of Lorraine and

the Messins: the Duke was assisted by his brother-in-law, Charles VII.

of France. The quarrel originated in some money claims that the city

had on the Duchess of Lorraine, which claims she refused to satisfy.

The irritated Messins seized on the lady’s baggage between

Pont-à-Mousson and Nancy, as she was performing a pilgrimage to

the former. The Duke, in revenge, besieged the city, and the burghers

ravaged his territories. Much blood was shed on both sides, until at

last peace was made [55]between the belligerents by the King, who

received a sum of money from the Messins. So powerful was this

republic, that it could single-handed wage war with a sovereign

prince.

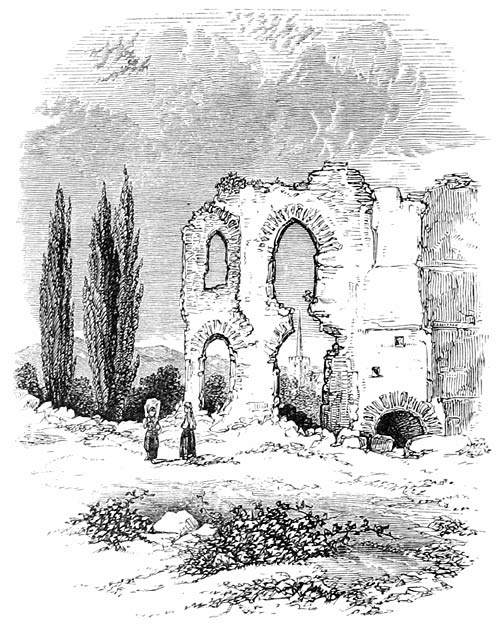

A few years after, when the celebrated War of Investitures took

place, the Messins were called on to fight for Adolphe of Nassau, the

nominee of the Pope. They pleaded their privileges and the late ruinous

wars, and begged to remain neutral. The Pope, in consequence,

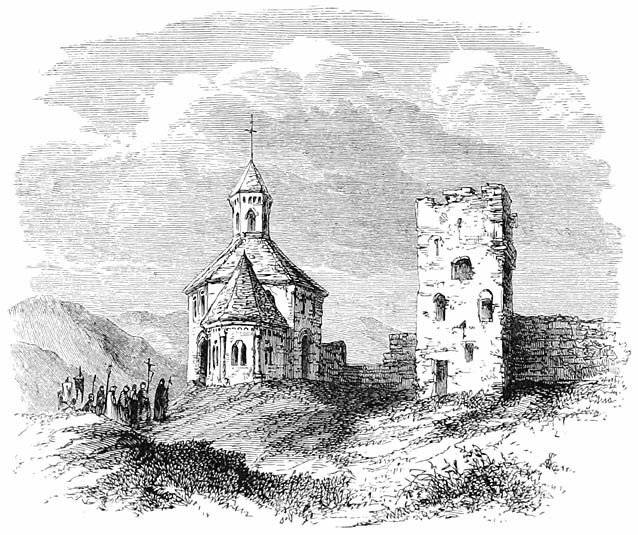

excommunicated the city; a great number of the clergy obeyed the Papal

Bull, and left in procession for Pont-à-Mousson, with the cross

and banners at their head. For three years this extraordinary state of

things lasted, during which time the churches were empty and the dying

unshriven. At length the Pope took off the interdict, and the priests

and canons returned, but the Messins had to pay dearly for their

opposition to ecclesiastical power.

About this period the wily Louis XI. of France thought the time was

come for joining Metz to his dominions; he accordingly wrote a kind,

mild letter to the citizens, suggesting that they should put themselves

under his protection, and thus secure their peace. The citizens wrote

back cautiously, but expressed their surprise at the King’s

proposition; he, fearing to incense and thus throw so powerful a city

into alliance with the noblesse that were taking part against him,

disowned his herald, and denied the letter he had sent.

The next event was an endeavour to take Metz by [56]storm,

on the part of the Duke of Lorraine, and it very nearly succeeded.

Early in the morning of the 9th April, 1473, while the Messins still

slept, ten thousand Lorrainese arrived near the walls from

Pont-à-Mousson, having marched during the night; with them was a

certain Krantz, nicknamed “La Grande Barbe,” who had

constructed a peculiar waggon, filled with casks, which was capable of

sustaining the weight of a portcullis, and thus preventing its closing

when once it had been raised.

Disguised as merchants, Krantz and some of his companions, with a

train of waggons filled with casks, among which was the

peculiarly-constructed one, appeared before the city gates, and were

admitted; the waggons entered, and the particular one was halted

immediately beneath the portcullis, the pretended merchants then rushed

on the guardian of the gate and killed him.

Being joined by a select body of five hundred men, who quickly

entered, La Grande Barbe raised the shout of “Ville

gagnée!” adding, “Slay, slay, women and children;

spare none! Vive Lorraine!”

The awakened burghers rushed in disorder from their beds, knowing

what these sounds portended, and all was lost but for the presence of

mind of a baker named Harelle, who lived near the gate under which the

waggon was stationed. He ran to the house over the gate, and succeeded

in lowering the side portions of the portcullis, so that horsemen could

not enter, and foot soldiers only by creeping under the waggon.

[57]

Then rushing into the streets, Harelle rallied and encouraged the

citizens, and finally routed the Lorrainese, slaying La Grande Barbe

and two hundred of his companions, the rest escaping by flight.

In a few minutes all was over; the assaulters dead or flown, the

gates reclosed, and the assembled Council preparing to prosecute the

war. Thus the clear-headed baker saved the good city of Metz.

In 1473 the Emperor Frederick III. visited the town, and the keys

being presented to him, he promised solemnly to preserve the liberties

of the citizens. He then, accompanied by his son, Maximilian, entered

in state, followed by the Archbishop of Mayence, and other princes and

prelates.

The Messins had been so harassed by attempts at surprise that they

now were ever on their guard against them; and so fearful had they

become, that when the Emperor, in visiting their church, came to the

great bell, and expressed a wish to hear it sound, they declined

respectfully, saying it was an old custom only to sound it thrice in

the year. This they did, fearing it might be meant as a signal of

attack on their hardly-maintained liberties. They also had, during the

Emperor’s visit, 2000 men constantly under arms, ready to obey

the Maître Echevin’s orders at a moment’s notice; and

they kept strict guard over the gates.

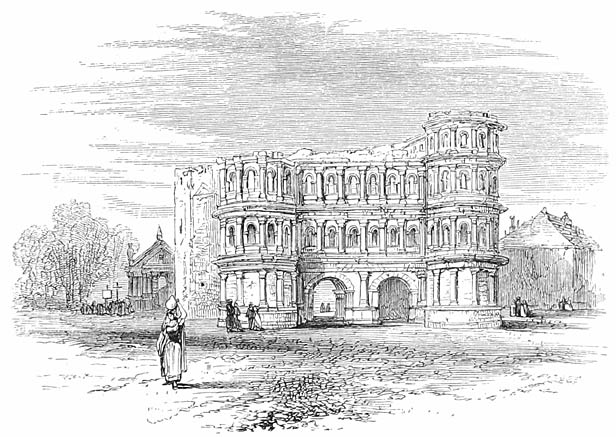

While Frederick was with them the Messins refused to admit Charles

the Bold, with more than five hundred horsemen. He was furious, but the

Emperor agreed to meet him at Trèves instead; and afterwards

Duke [58]Charles had no time or opportunity to revenge

himself on Metz, but rather conciliated that powerful city, and when he

took Nancy sent a present of cannon and other spoil to the Messins, who

were delighted at the misfortune of their old enemies, the

Lorrainese.

In 1491 another attempt was made by the Duke of Lorraine to gain

possession of the town. Surprise and stratagem having previously

failed, he now tried treachery, and secured the services of a certain

Sire Jehan de Landremont, who induced one of the gatekeepers, named

Charles Cauvellet, a Breton by birth, but who had acquired the rights

of citizenship, to join the plot.

All was easily arranged, thanks to Cauvellet, who had the keys of

the city. A day was fixed on, but it turning out so rainy that the

river flooded the approaches to the town, a fresh day was named; in the

meantime Cauvellet’s conscience pricked him, and he confessed the

plot to the Maître Echevin. His life was spared, but the Sire de

Landremont, after his sentence had been read at every cross-street in

the town, he being led about on horseback for this purpose, was

strangled, drawn, and quartered. He died with a smile on his

countenance, saying he only regretted having been unsuccessful.

A peace was soon after patched up between René and the

Messins.

Though so long resisting, the city was doomed eventually to fall by

treachery, and the time at length arrived. [59]

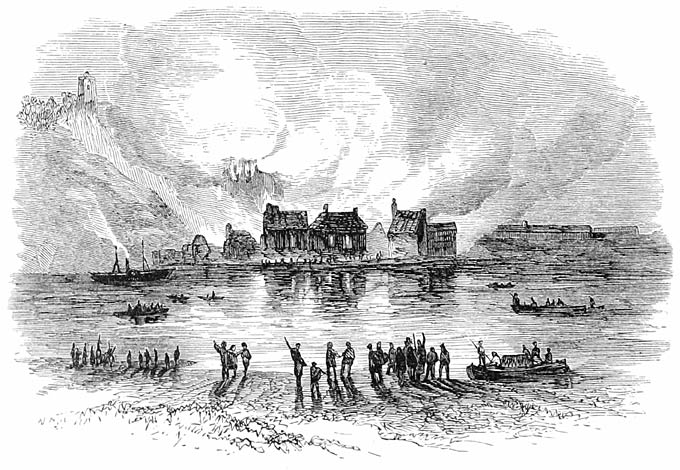

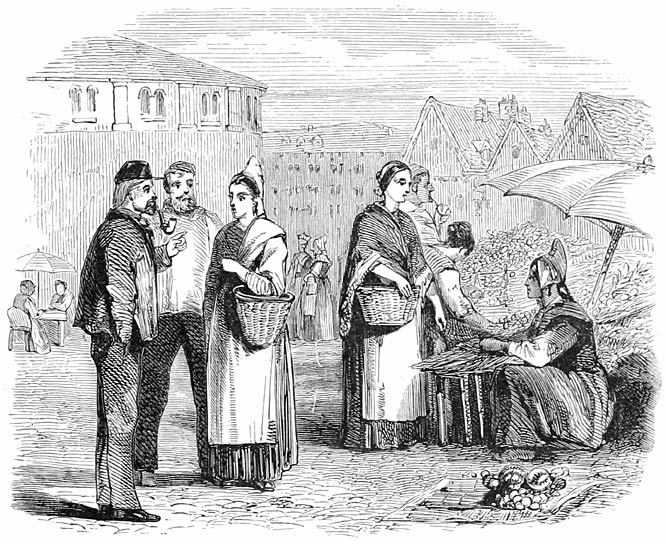

In 1552, Henry II. of France entered Lorraine, and occupied

Pont-à-Mousson. On the 10th of April he presented himself before

the gates of Metz, which is styled in the annals of the day “a

great and rich imperial city, very jealous of its liberties.”

Although Henry had taken the most rigorous measures to suppress

Protestantism in his own dominions, he here appeared as the champion of

that religion, and entered into a secret treaty with the Protestant

Princes, who agreed that he should occupy Metz, Courtrai, Toul, and

Verdun, as Vicar-Imperial. Henry, wishing to gain immediate possession

of Metz, engaged his ally, the Bishop, to bribe the inhabitants of the

“Quartier du Heu,” and raise

dissensions among the garrison. These preparations made, the Sieur de

Tavannes arrived before that quartier, and harangued the people,

telling them that the good King Henry was fighting for their liberties,

and they could not do less than allow him to lodge in their town with

his body-guard of five hundred men. “Surely that was not too much

to grant to their defender?” The people, half-persuaded, allowed

a body of men to approach and commence filing through the gate, but

seeing that instead of five hundred there were nearly five thousand

drawing near, they wished to close the gate; but Tavannes continued to

speak them fair until upwards of seven hundred picked men had entered,

when a Swiss captain, who held the keys for Metz, seeing the number,

threw the keys at Tavannes’ head, exclaiming in the idiom of the

country, “Tout est choué.”

[60]

Thus was Metz taken, kings and nobles thinking any treachery fair

against mere bourgeois. Of course Henry kept it for himself, not the

Protestant interest; and henceforward it remained a portion of the

French dominions.

Before the Emperor Charles V. allowed so important a free city

quietly to revert to France, he sent Alba with a large army to besiege

it, he remaining at Thionville to watch proceedings, his health being

too bad to allow him to prosecute the siege in person.

The town was defended by the young Duke of Guise, who turned out all

the women, old men, and children, and pulled down half the town in

order the better to defend the other half; working himself in the

trenches, he by his example so encouraged his soldiers and citizens,

that they sustained all the assaults of the Imperialists.

Charles V., seeing that the siege did not progress, and that the

breaches were repaired as fast as made; finding also that his own army

was rapidly wasting with cold and sickness, reluctantly ordered Alba to

raise the siege; the Duke retired, leaving his tents and sick, together

with a great quantity of baggage and munitions: to the credit of the

conquerors, they treated the sick with great kindness, contrary to the

usual custom at that period. Charles departed, saying that he perceived

“Fortune, like other women, accorded her favours to the young,

and disdained grey locks.”

In 1555, the people of Metz became exceedingly [61]discontented at the Governor’s taking-away

many of their ancient liberties; this gave rise to the