Title: Harper's Young People, March 1, 1881

Author: Various

Release date: February 17, 2014 [eBook #44943]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| Vol. II.—No. 70. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | Price Four Cents. |

| Tuesday, March 1, 1881. | Copyright, 1881, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

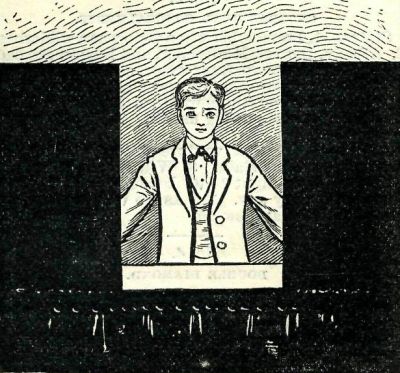

In a little town called Lystra, in Asia Minor, a multitude is gathered in the market-place. Two strangers are the attraction, who have strange tidings to tell. Their story is of one Jesus, a King, who, they say, was born in Judea some fifty years before. They tell of marvellous deeds of mercy which He wrought, and of words as marvellous and as merciful that He spake. They tell that He died on a cross, but that, King of Death, He came back from the grave at His own appointed time. They declare that He did visibly ascend into heaven, and now sitteth there to pardon and to bless all who will believe on Him. And even while the crowd is listening to the words of the chief speaker, whose name is Paul, he looks fixedly upon a poor lame man, a cripple from his birth, who is among his auditors, and cries with a loud voice, "Stand upright on thy feet." Instantly the command is obeyed, and the life-time cripple leaps and walks.

Respectful attention straightway became enthusiasm. The market-place resounds with the shout, "The gods are come down to us in the likeness of men," and the priest who serves in Jupiter's Temple hastens with oxen and garlands to do sacrifice to the miracle-workers, despite their earnest remonstrance that they are but sinful men, come to tell them of the one living God.

But quickly there is interruption as effective as sudden from other strangers of the same distant nation, whose words persuade the fickle populace, and in a little while Paul is being dragged out of the city to all appearance dead. They have stoned the man to whom just now they would do sacrifice!

Among the listeners to the gospel Paul had preached, among the wondering spectators of the lame man's healing, among the on-lookers at the deed of violence, stands a boy, generous and warm-hearted, weeping manly tears over that which is done. His name is Timothy, and of him, as he sits there that day in his native town, his heart all aglow with the new hopes whereof he has heard, and his spirit all aflame with admiration for undaunted courage, and with pity for the innocent sufferer, our artist has given us the portrait. The Sacred Scriptures, which he has known from a child, have gained new meaning. He is reading the ancient writings with the new light which Paul has thrown upon them—the light from the open grave of Jesus.

He is the child from a mixed marriage, his mother a Jewess, but his father a Greek, and therefore he is but ill esteemed by the Hebrews who dwell in his town. The records of his life make no mention of his father, and from this fact it has been inferred that he died while Timothy was yet an infant. And we are plainly told that his education was all given by his mother, Eunice, and his grandmother, Lois, and that "from a child he knew the Holy Scriptures."

The face which the artist has drawn will represent to us what we should expect to be the appearance of a boy thus brought up, and the character which we judge him to have possessed, from the warnings and the advice given to him by his master and teacher, Paul. His piety, while sincere and intense, is yet of a feminine cast; his constitution is far from robust; he shrinks from opposition and responsibility; his tears lie close to their outlet, and are ready to flow and hide the suffering object; he will subject his body to denial greater than its strength will bear, and as the natural counterpart of these characteristics, he is in danger of being carried away by "youthful lusts." Such is Timothy when, after seven years have passed away, and the boy is grown to be a man, Paul, returning to Lystra to confirm and comfort the Christians there, will have him to be the companion of his journeyings and the best-loved friend of his heart.

There is not space in this article to recite the events of the career that followed. Let each of our boy readers search them out for himself, and learn of what doughty deeds a gentle spirit in a feeble frame is capable under the impulse of an earnest faith. Let us learn, moreover, from a life of noble devotion to high purpose so to devote our life, not, it may be of necessity, to proclaim a Gospel, as Timothy did, but surely to labor, not alone for self, but for our race.

He died a confessor of that faith he learned from the preacher at Lystra in his boyhood. "Out of weakness he was made strong." He, the timid, girlish, tearful boy, waxed valiant in the great fight, and is known to the Christian world as a saint of God and as the great Bishop of Ephesus.

You're a beautiful, beautiful dolly,

And dressed like a sweet little queen;

Not to care for you, dear, may seem folly,

When I've but a rag-doll so mean.

I know that its arms are the queerest,

Its head very funny and flat;

Its eyes anything but the clearest;

Yet old friends are best, for all that.

Your hair falls in ringlets so flaxen,

Your eyes are delightfully blue;

Your cheeks they are rosy and waxen,

You're charming, I'll give you your due.

Yet shall I give up Betsy Baker,

Who hasn't a shoe nor a hat,

Because you've a splendid dressmaker?

No! old friends are best, for all that.

You came Christmas morn, in my stocking;

I ought to be proud, I suppose;

And not to be pleased would be shocking:

Do, Betsy dear, turn out your toes.

Oh, you are my every-day dolly!

And this one in silk dress and hat

I'll put on the shelf: call it folly,

Yet old friends are best, for all that.

"We can beat that," said Joe Larkin, contemptuously, as he drew back and began to blow through his red fists. "That isn't any kind of a snow man."

"Like to know why," said Dan Madderley. "He's all right but his ears. We can make them of the same size, easy."

"Yes, but he ain't right anyhow. Everything's just stuck on outside. When I was in the city once, I saw a sculptor chiselling a man out of marble. 'Twasn't much like this thing."

"Well, of course it wasn't. Stone's better'n snow. Everybody knows that, I guess."

"No, it isn't. Not exactly. When you knock off a chunk of marble, you can't stick it on again."

"You might glue it, but I guess it would show the crack."

"Tell you what, boys," exclaimed Joe, with a new idea shining all over his face, "let's make a big snow marble down on the ice, and then let's dig it out into a man, just as the sculptors do."

There was an instant hurrah all around, and not one opposing vote; the half-finished snow man in Deacon Madderley's back yard was left to thaw down all alone, and in ten minutes more the whole crowd of young sculptors was down on the pond.

It was a warm day for winter, and the water was pouring over the dam in a hurry, but the ice was pretty firm up where the boys were, and the soft snow was in just[Pg 275] the condition to pack nicely. At it they went, as if they had a whole marble quarry to make, and were afraid some of their marble might get away from them.

"I say, now, Joe," shouted Burr Whitcomb, as the great white pile came up to his shoulders, "who're we going to sculp out? Anybody in partikler?"

"Julius Cæsar."

"No, we can't. You never saw him, nor we didn't either."

"Yes, I did. I saw a picture of him once, with a brass helmet on his head, and a sword in his hand."

"That'd beat us, then," said Dan Madderley. "We'd better try George Washington."

"He's on horseback," said Joe, "and so is Andrew Jackson. No use for us to try a horse. Snow legs won't hold up. He'd come down all in a heap."

A dozen other great names followed, each bringing with it a chorus of doubts as to how he looked, and whether anything like him could be found in that heap of snow; but the shrill voice of little Billy McCoy settled the matter. He had followed his big brothers down upon the ice, and now he eagerly squeaked:

"Boys, why don't you scoop out Ben Franklin? Make him sitting down."

"Hurrah for you, Billy!" exclaimed Joe Larkin. "Guess we all know Ben. He's just the man."

"Guess he is," chirped Billy. "He's fat, too. You can make him real big."

On piled the snow, after that, until they had to reach up with their shovels. When Joe Larkin began to play sculptor, he had to dig his toes into the snow and climb.

"We'll make his head first," he sagely remarked; "and we'll cut out the rest of him to fit that."

"Dig away, Joe," shouted Burr Whitcomb, from the other side of the quarry. "Let's see which of us'll get in first to where old Ben is."

"We'll set him up with his hands in his lap," said Joe; "and we'll part his hair in the middle."

Pieces of shingle, whittled to a sharp edge, did very well for chisels, and no mallets were called for. It was easy to work that kind of marble, and it was just as Joe Larkin had said about mending it. He had to carve Ben's nose for him over and over again, and the last time he shaved it smooth with his jackknife.

"We'll make his hair long, Burr, and lots of it. That'll help hold his head up stiff, and we won't have to cut out so much coat collar. I say, you've made his arm on that side twice as big as this one."

"I can scrape it down. What'll we do for buttons?"

"Boys," said Joe, "pack a lot of round, hard snow-balls, and cut 'em in two. They wore the biggest kind of buttons when Ben was alive; big as dollars."

"How about his hat?"

"He'll look better bare-headed. You can't make a snow brim stay on—not unless it's three or four inches thick, and that won't do."

Joe was giving special attention just then to the parting of Benjamin Franklin's hair, but in a moment more he sang out, "Look here, boys, he never was as fat as all that."

They had been digging away industriously at their part of the great patriot, but they had carefully put on quite as much snow marble as they had cut away. They had made Ben look more like Daniel Lambert than anybody else; but Joe Larkin came down now, and he speedily effected a wholesome change.

"Looks as if he could lift himself and get up now."

"Well, ye—es," said Burr, doubtfully; "but what about his legs? We haven't left any room for 'em."

"Yes we have. But you see we began at the top."

"What's he a-sitting on, anyhow?"

"On the ice. Tell you what, boys, we'll have to make him cross-legged."

"He wasn't a tailor," squeaked Billy McCoy. "He was the lightning-rod man."

Billy had watched all that work with his round mouth half open, and had seemed to regard the job as in a manner under his supervision. But then he had that way of looking at almost any work, no matter who might be doing it, and he had never been known to make any charge for his advice.

It was too late now for any discussion of the matter, however, and all the boys were proud of the way they crossed Benjamin Franklin's legs for him.

"We'll hide one of his feet under him," said Burr. "Joe, can you cut out the other one like a boot?"

"Of course I can."

He did, but if the hidden foot was as large as the one he fitted at the end of Ben's right leg, he could not have needed a great deal more to sit on.

Billy McCoy himself remarked of it, doubtfully, "It's just the biggest foot I ever saw."

The pegs on the sole of that boot and the heel of it were the last touches required, and the young sculptors stood back, and walked around their great work, again and again, in almost silent admiration. Ben fairly looked warm and comfortable in the flood of noon sunshine that was pouring down upon him.

"He'll thaw out," grumbled Dan Madderley; and just then there came a great shout from the shore.

The sun had been at work as well as the boys, and the thaw he was making had had a day or two the start of them.

The shout came from Billy McCoy's biggest brother, Bob, and they saw him dance up and down with excitement, while he swung his hat and repeated it: "Boys! boys! come in! The ice is breaking away!"

So much trampling and running to and fro, and so much added weight of boys and sculpture, had helped the sun above and the rising water below the ice, and now they all had just about time to hurry ashore. Then the great crack Bob McCoy had noticed grew rapidly wider, and they could hear all the frozen surface of the pond crack and split in every direction.

There was some fun in watching the ice break up, but there was sorrow among the sculptors, for all that.

"It's an awful pity to lose such a snow man as that is."

"He didn't even have time to thaw out."

"We can make another."

"There never was just such a Ben Franklin as that."

Probably not, and now there he was floating out into the middle of the pond on a wide cake of ice, and drifting down toward the dam. The water was rising, for the snow was melting fast, and the cake of ice Ben was on rocked now and then in a way which made him seem to bow to his friends on shore.

"Isn't he polite, though!" said Billy McCoy. "Pity he can't swim."

"Swim!" exclaimed Joe Larkin; "I guess so. There he goes, boys. Just a rod or two more."

Most of them gave vent to their feelings in a volley of snow-balls which fell about half way short of their mark. Then they all stood still, for the swift water seemed to seize Ben's cake of ice with a sudden jerk, and swept it to the edge of the dam. For one short minute the brittle raft stuck on the edge, and then it broke right in two. With a great slushy splash the snow Ben went to pieces, and was carried over the slippery "apron," down among the foaming eddies below.

Every boy that was looking on drew a long breath and held it for a moment, and then there rose a chorus of shouts.

Joe Larkin led off with, "Good-by, Ben!"

And the rest followed with: "Hi! hi! hurrah! Good-by, Ben!"

Burr Whitcomb remarked, a little soberly, as he turned away: "Well, I don't care; he was the best snow man I ever saw. He looked a good deal like Ben Franklin."

"Alice, may I? Say I may. I can do it, dear sister"; and as he spoke, Archie Kirk bent eagerly over his sister's chair.

Three weeks before, he and Alice had been rescued—the only survivors—from a fine ship that had gone to pieces off the coast of the island of St. Kilda, which is a little speck of land in the wide waters of the Atlantic, forming a part of the Hebrides.

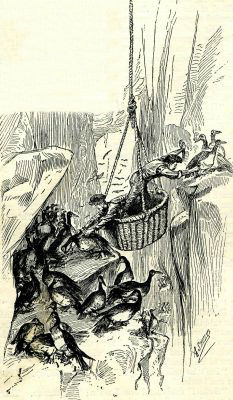

They had been tenderly cared for by the good islanders, and the request which Archie had made of his sister, and which she was very reluctant to grant, was, that he might go with Hakon Bork—the son of the good woman who had given them food and shelter—in search of the eggs and down of puffins, a species of sea-bird upon which these simple people depend mainly for their subsistence.

THE PUFFIN-HUNTERS.

THE PUFFIN-HUNTERS.

"You are so young, and it is such a terrible way to earn your bread," replied Alice, who shudderingly remembered watching Hakon but the day before fasten his rope to a stake, and then lower himself down the awful precipice, with nothing but his firm grip to save him from falling into the foaming, raging sea beneath. "You are too young, Archie."

"Why, Alice, I am ten years old, and boys much younger than I go down all alone. These people are very good to us, but they are also very poor. I feel mean to accept their charity, and do nothing in return, when Hakon says I can help him if I will."

"It is so terrible, Archie, and if I should lose you too!" cried Alice, whose heart was still full of sorrow for her lost parents.

"God is good, my sister," said Hakon, "and I will watch thy brother carefully."

"You are right, Hakon; go, Archie, I will trust you to God's care."

So Archie bravely pulled his bonnet over his brows, and set out with Hakon and another man. After climbing to the summit of the great rocks, Hakon and Archie stepped fearlessly into the basket, and were slowly lowered over the side of the precipice, on whose edge a piece of wood was made fast to prevent the jagged rocks from cutting the rope. Down, down they went, the boiling sea below, the frightful precipices above, but in all the little shelves and fissures the puffins had made their nests. By a separate line they indicated to the man above when they were to be lowered or raised, and thus they labored away cheerily for hours, collecting many eggs and much down.

Archie showed great skill and coolness, and won great praise from Hakon, and after this he went with him on all such excursions, and as time went on was readily trusted down in the basket alone.

So the months slipped away, and Archie had, with Hakon's help, made himself a rope, such as is used for the perilous work of puffin-catching. The mode of making these ropes is as follows: A hide of a sheep and one of a cow are cut into slips, the latter being the broader; each slip of sheep's hide is then plaited to one of cow's, and two of these compound slips are then twisted together, so as to form a rope of about three inches in circumference. The length of these ropes varies from ninety to two hundred feet, and they are so valuable that a single one forms a girl's marriage portion in St. Kilda. Archie prized his very highly, not only because it was in a measure his own making, but because all his friends had denied themselves in some way or other to procure it for him.

Archie's life was very simple and very hard, but he enjoyed it, and for many months he was very useful to Hakon. Then one day the neighbors brought home a mangled body and laid it down on Dame Bork's hearth-stone. No need to tell the wailing mother, or the sorrowful Archie and Alice, poor Hakon's fate. The men went silently out, and the neighbor women spoke such words of comfort as their own losses, or the constant danger of their loved ones, prompted. Tenderly the dead was buried, and then the little household awoke to the duties of the day.

When their humble breakfast was over, Archie took his bonnet and rope, and said to the old dame, as he had said with Hakon many a morning,

"Give me your blessing, mother."

"Oh, Archie," said Alice, "must you go—all alone must you go?"

"I have a brave heart, Alice, which is good company." And then, glancing at Hakon's old mother, he whispered: "For Hakon's sake, as well as for her own kindness, we owe her every duty;" and then kissing Alice, he went off to the rocks.

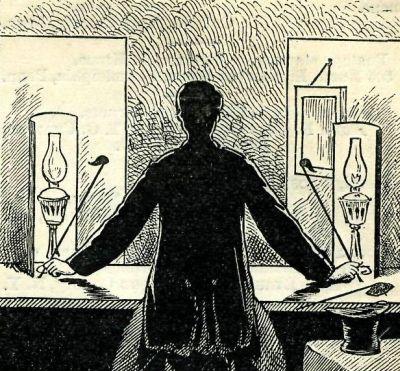

As Archie had not Hakon now to help him, he had to leave his basket at home, and adopt the much less common but much more dangerous practice of reaching the birds' nests by fastening a simple rope to a strong stake securely driven into the earth a short distance from the edge of the precipice, and then gradually lower himself to some projecting cliff likely to contain the eggs and down of which he was in search.

So this morning, having reached the cloud-capped peaks, he secured his rope carefully, and then cautiously lowered himself until he reached a spot where the rocks overhung and sheltered a wide ledge.

He was sure that he would be likely to reap here an ample harvest, and he dexterously swung himself forward and gained a resting-place. As he expected, he found a great number of nests, and was soon eagerly filling the large pockets which are used for this purpose with[Pg 277] the eggs and down, the patient birds scarcely disturbing him by a flutter.

But in his ardor he had forgotten to fasten the rope tightly around his body; it slipped from his grasp, and after swinging backward and forward for some time, but without coming within his reach, at length settled many feet from the spot where he stood. For a moment he stood aghast. The sudden blow almost deprived him of the power of thinking, but gradually he recovered his senses, and began anxiously to look around for some means of escape.

Fearful was the prospect. The rock for hundreds of feet above was smooth as if chiselled by the mason's hand; many hundred feet below, the raging waters burst with terrific noise upon the pointed crags, while the depth to which he had descended, the solitude of the spot, and the roar of the waves, precluded all possibility of making himself heard.

One desperate chance alone remained: by a bold leap he might catch the dangling rope. It was an awful hazard, for if he failed, instant death would be the result. Yet if he remained on the rock, death, though slower, was no less sure. His resolution was taken. He lifted his eyes to heaven with one short strong prayer for help, then like a winged creature sprang forward, and grasped the rope.

Many a year passed before Archie Kirk told his sister and adopted mother of his leap for life on that day, when he, a lad twelve years old, had determined to fill the place of Hakon. He became the most expert bird-catcher and climber in the Hebrides, but he never again forgot to secure his rope. Nor in telling the story did he ever take any credit to himself. "God is good," he used to add, reverently; "the rope was in His hands, or I had not caught it."

The town in which the circus remained over Sunday was a small one, and a brisk walk of ten minutes sufficed to take Toby into a secluded portion of a very thickly grown wood, where he could lie upon the mossy ground, and fairly revel in freedom.

As he lay upon his back, his hands under his head, and his eyes directed to the branches of the trees above, where the birds twittered and sang, and the squirrels played in fearless sport, the monkey enjoyed himself, in his way, by playing all the monkey antics he knew of. He scrambled from tree to tree, swung himself from one branch to the other by the aid of his tail, and amused both himself and his master, until, tired by his exertions, he crept down by Toby's side, and lay there in quiet, restful content.

One of Toby's reasons for wishing to be by himself that afternoon was that he wanted to think over some plan of escape, for he believed that he had nearly money enough to enable him to make a bold stroke for freedom and Uncle Daniel's. Therefore, when the monkey nestled down by his side, he was all ready to confide in him that which had been occupying his busy little brain for the past three days.

"Mr. Stubbs," he said to the monkey, in a solemn tone, "we're goin' to run away in a day or two."

Mr. Stubbs did not seem to be moved in the least at this very startling piece of intelligence, but winked his bright eyes in unconcern, and Toby, seeming to think that everything which he said had been understood by the monkey, continued: "I've got a good deal of money now, an' I guess there's enough for us to start out on. We'll get away some night, an' stay in the woods till they get through hunting for us, an' then we'll go back to Guilford, an' tell Uncle Dan'l if he'll only take us back, we'll never go to sleep in meetin' any more, an' we'll be just as good as we know how. Now let's see how much money we've got."

Toby drew from a pocket, which he had been to a great deal of trouble to make in his shirt, a small bag of silver, and spread it upon the ground where he could count it at his leisure.

The glittering coin instantly attracted the monkey's attention, and he tried by every means to thrust his little black paw into the pile; but Toby would allow nothing of that sort, and pushed him away quite roughly. Then he grew excited, and danced and scolded around Toby's treasure, until the boy had hard work to count it.

He did succeed, however, and as he carefully replaced it in the bag, he said to the monkey: "There's seven dollars an' thirty cents in that bag, an' every cent of it is mine. That ought to take care of us for a good while, Mr. Stubbs, an' by the time we get home we shall be rich men."

The monkey showed his pleasure at this intelligence by putting his hand inside Toby's clothes to find the bag of treasure that he had seen secreted there, and two or three times, to the great delight of both himself and the boy, he[Pg 278] drew forth the bag, which was immediately taken away from him.

The shadows were beginning to lengthen in the woods, and, heeding this warning of the coming night, Toby took the monkey on his arm and started for home, or for the tent, which was the only place he could call home.

As he walked along he tried to talk to his pet in a serious manner, but the monkey, remembering where he had seen the bright coins secreted, tried so hard to get at them, that finally Toby lost all patience, and gave him quite a hard cuff on the ear, which had the effect of keeping him quiet for a time.

That night Toby took supper with the skeleton and his wife, and he enjoyed the meal, even though it was made from what had been left of the turkey that served as the noonday feast, more than he did the state dinner, where he was obliged to pay for what he ate by the torture of making a speech.

There were no guests but Toby present, and Mr. and Mrs. Treat were not only very kind, but so attentive that he was actually afraid he should eat so much as to stand in need of some of the catnip tea which Mrs. Treat had said she gave to her husband when he had been equally foolish. The skeleton would pile his plate high with turkey bones from one side, and the fat lady would heap it up, whenever she could find a chance, with all sorts of food from the other, until Toby pushed back his chair, his appetite completely satisfied if it never had been before.

Toby had discussed the temper of his employer with his host and hostess, and, after some considerable conversation, had confided in them his determination to run away.

"I'd hate awfully to have you go," said Mrs. Treat, reflectively; "but it's a good deal better for you to get away from that Job Lord if you can. It wouldn't do to let him know that you had any idea of goin', for he'd watch you as a cat watches a mouse, an' never let you go so long as he saw a chance to keep you. I heard him tellin' one of the drivers the other day that you sold more goods than any other boy he ever had, an' he was going to keep you with him all summer."

"Be careful in what you do, my boy," said the skeleton, sagely, as he arranged a large cushion in an arm-chair, and proceeded to make ready for his after-dinner nap; "be sure that you're all ready before you start, an' when you do go, get a good ways ahead of him; for if he should ever catch you, the trouncin' you'd get would be awful."

Toby assured his friends that he would use every endeavor to make his escape successful when he did start, and Mrs. Treat, with an eye to the boy's comfort, said, "Let me know the night you're goin', an' I'll fix you up something to eat, so's you won't be hungry before you come to a place where you can buy something."

As these kind-hearted people talked with him, and were ready thus to aid him in every way that lay in their power, Toby thought that he had been very fortunate in thus having made so many kind friends in a place where he was having so much trouble.

It was not until he heard the sounds of preparation for departure that he left the skeleton's tent, and then, with Mr. Stubbs clasped tightly to his breast, he hurried over to the wagon where old Ben was nearly ready to start.

"All right, Toby," said the old driver, as the boy came in sight; "I was afraid you was going to keep me waitin' for the first time. Jump right up on the box, for there hain't no time to lose, an' I guess you'll have to carry the monkey in your arms, for I don't want to stop to open the cage now."

"I'd just as soon carry him, an' a little rather," said Toby, as he clambered up on the high seat, and arranged a comfortable place in his lap for his pet to sit.

In another moment the heavy team had started, and nearly the entire circus was on the move. "Now tell me what you've been doin' since I left you," said old Ben, after they were well clear of the town, and he could trust his horses to follow the team ahead. "I s'pose you've been to see the skeleton an' his mountain of a wife?"

Toby gave a clear account of where he had been and what he had done, and when he concluded, he told old Ben of his determination to run away, and asked his advice on the matter.

"My advice," said Ben, after he had waited some time to give due weight to his words, "is that you clear out from this show just as soon as you can. This hain't no fit place for a boy of your age to be in, an' the sooner you get back where you started from, an' get to school, the better. But Job Lord will do all he can to keep you from goin' if he thinks you have any idea of leavin' him."

Toby assured Ben, as he had assured the skeleton and his wife, that he would be very careful in all he did, and lay his plans with the utmost secrecy; and then he asked whether Ben thought the amount of money which he had would be sufficient to carry him home.

"Wa'al, that depends," said the driver, slowly; "if you go to spreadin' yourself all over creation, as boys are very apt to do, your money won't go very far; but if you look at your money two or three times afore you spend it, you ought to get back and have a dollar or two left."

The two talked, and old Ben offered advice, until Toby could hardly hold his eyes open, and almost before the driver concluded his sage remarks, the boy had stretched himself on the top of the wagon, where he had learned to sleep without being shaken off, and was soon in dreamland.

The monkey, nestled down snug in Toby's bosom, did not appear to be as sleepy as was his master, but popped his head in and out from under the coat, as if watching whether the boy was asleep or not.

MR. STUBBS AND TOBY'S MONEY.

MR. STUBBS AND TOBY'S MONEY.

Toby was awakened by a scratching on his face, as if the monkey was dancing a hornpipe on that portion of his body, and by a shrill, quick chattering, which caused him to assume an upright position instantly.

He was frightened, although he knew not at what, and looked around quickly to discover the cause of the monkey's excitement.

Old Ben was asleep on his box, while the horses jogged along behind the other teams, and Toby failed to see anything whatever which should have caused his pet to become so excited.

"Lie down, an' behave yourself," said Toby, as sternly as possible, and as he spoke he took his pet by the collar to oblige him to obey his command.

The moment that he did this, he saw the monkey throw something out into the road, and the next instant he also saw that he held something tightly clutched in his other paw.

It required some little exertion and active movement on Toby's part to enable him to get hold of that paw, in order to discover what it was which Mr. Stubbs had captured; but the instant he did succeed, there went up from his heart such a cry of sorrow as caused old Ben to start up in alarm, and the monkey to cower and whimper like a whipped dog.

"What is it, Toby? What's the matter?" asked the old driver, as he peered out into the darkness ahead, as if he feared some danger threatened them from that quarter. "I don't see anything. What is it?"

"Mr. Stubbs has thrown all my money away," cried Toby, holding up the almost empty bag, which a short time previous had been so well filled with silver.

"Stubbs—thrown—the—money—away?" repeated Ben, with a pause between each word, as if he could not understand that which he himself was saying.

"Yes," sobbed Toby, as he shook out the remaining contents of the bag; "there's only half a dollar, an' all the rest is gone."

"The rest gone?" again repeated Ben. "But how come the monkey to have the money?"

"He tried to get at it out in the woods, an' I s'pose the moment I got asleep he felt for it in my pockets. This is all there is left, an' he threw away some just as I woke up."

Again Toby held the bag up where Ben could see it, and again his grief broke out anew.

Ben could say nothing; he realized the whole situation: that the monkey had got at the money bag while Toby was sleeping, that in his play he had thrown it away piece by piece; and he knew that that small amount of silver represented liberty in the boy's eyes. He felt that there was nothing he could say which would assuage Toby's grief, and he remained silent.

"Don't you s'pose we could go back an' get it?" asked the boy, after the intensity of his grief had somewhat subsided.

"No, Toby, it's gone," replied Ben, sorrowfully. "You couldn't find it if it was daylight, an' you don't stand a ghost of a chance now in the dark. Don't take on so, my boy. I'll see if we can't make it up to you in some way."

Toby gave no heed to this last remark of Ben's. He hugged the monkey convulsively to his breast, as if he would seek consolation from the very one who had wrought the ruin, and rocking himself to and fro, he said, in a voice full of tears and sorrow:

"Oh, Mr. Stubbs, why did you do it?—why did you do it? That money would have got us away from this hateful place, an' we'd gone back to Uncle Dan'l's, where we'd have been so happy, you an' me. An' now it's all gone—all gone. What made you, Mr. Stubbs, what made you do such a bad, cruel thing? Oh, what made you?"

"Don't, Toby—don't take on so," said Ben, soothingly; "there wasn't so very much money there, after all, an' you'll soon get as much more."

"But it won't be for a good while, an' we could have been in the good old home long before I can get so much again."

"That's true, my boy; but you must kinder brace up, an' not give way so about it. Perhaps I can fix it so the fellers will make it up to you. Give Stubbs a good poundin', an perhaps that'll make you feel better."

"That won't bring back my money, an' I don't want to whip him," cried Toby, hugging his pet the closer because of this suggestion. "I know what it is to get a whippin', an' I wouldn't whip a dog, much less Mr. Stubbs, who didn't know any better."

"Then you must try to take it like a man," said Ben, who could think of no other plan by which the boy might soothe his feelings. "It hain't half so bad as it might be, an' you must try to keep a stiff upper lip, even if it does seem hard at first."

This keeping a stiff upper lip in the face of all the trouble he was having was all very well to talk about, but Toby could not reduce it to practice, or, at least, not so soon after he knew of his loss, and he continued to rock the monkey back and forth, to whisper in his ear now and then, and to cry as if his heart was breaking, for nearly an hour.

Ben tried, in his rough, honest way, to comfort him, but without success, and it was not until the boy's grief had spent itself that he would listen to any reasoning.

All this time the monkey had remained perfectly quiet, submitting to Toby's squeezing without making any effort to get away, and behaving as if he knew he had done wrong, and was trying to atone for it. He looked up into the boy's face every now and then with such a penitent expression, that Toby finally assured him of forgiveness, and begged him not to feel so badly.

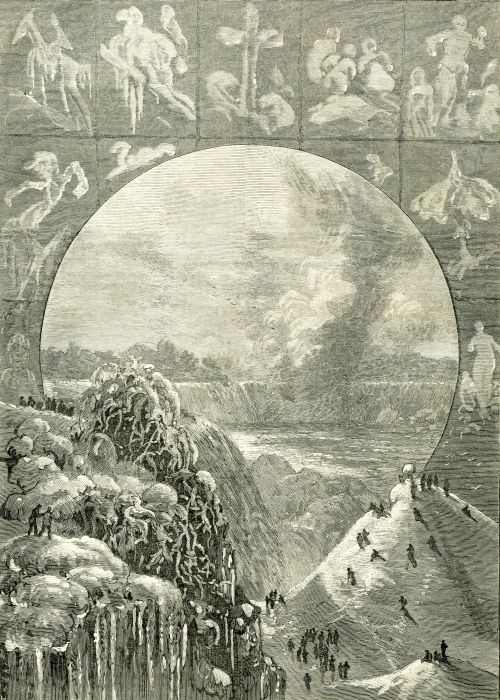

In the whole world there is probably no more beautiful ice scenery than that surrounding our own Falls of Niagara during a severe winter such as the one just passed. A few weeks ago one of our artists visited Niagara in order to make sketches that might convey to the readers of Young People some idea of this wonderful scenery, and on the next page you may see the result of his labor.

Many of you have been to Niagara in summer, and know what a mass of boiling, seething foam the river is just below the Falls. Now it is all quiet, covered many feet thick with great cakes of ice that have plunged over the cataract, and become frozen into one vast solid mass which forms the famous ice bridge of which so much is written. As these great blocks of ice are of every conceivable shape, and are piled one on top of another in every imaginable position, this ice bridge is by no means an easy one to cross.

One of the most remarkable features of this Niagara winter scenery is the great ice mountain that rises grand and white in front of each fall for two-thirds of its height. These ice mountains are formed by the spray from the Falls, which freezes the instant it touches a solid body; and thus, as long as the cold weather lasts, the ice mountains are constantly growing higher and thicker.

The boys living in the village of Niagara, or who visit the Falls in winter, climb these ice mountains by means of foot-holes chopped in the ice with hatchets, and upon reaching the top, sit down and slide to the bottom.

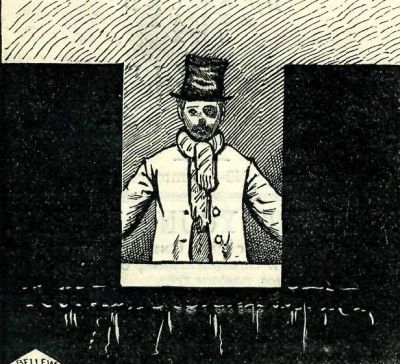

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

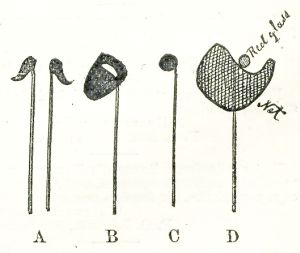

The spray of which the ice mountains is formed, and of which the air near the Falls is filled, freezes so quickly whenever it touches anything, that while our artist was making his sketches it covered his pencil with a thick coating of ice until it looked like this (Fig. 1), and after he had held his sketch-book closed in his hand for a minute, it presented this appearance (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

He himself was so incased in white ice that he looked like a Santa Claus. Icicles hung from his beard, his mustache, his eyelashes, and from every point of his clothing, until he found he could only stand within reach of the spray for a few minutes at a time, or he would be weighed down and rooted to the spot by the rapidly accumulating ice.

The ice formed from the spray is not clear and glittering, but is of the purest white, like the frosting on wedding cake, only much whiter, and as it covers the branches and twigs of the trees in Prospect Park, and on the islands near the Falls, the effect is wonderfully beautiful. Glistening in the bright sunlight, these forests of ice are more like beautiful dreams of fairy-land than anything ever seen; and under the light of a full moon the scene is weird and ghostly, but beautiful beyond description.

On Luna Island, which divides the American Fall, every stone, stump, and bush has been covered with ice until it forms a grotesque figure in white. Some of these figures our artist has transferred to his paper, and named "Ice Goblins." The branches of the trees, beneath which visitors must walk, are so laden with these "Goblins" that they frequently break beneath the weight, and great pieces of ice rattle down about one's ears in the most unpleasant manner.

ICE GOBLINS AND WINTER SCENERY AT NIAGARA.—Drawn by W. H.

Gibson.—[See Page 279.]

ICE GOBLINS AND WINTER SCENERY AT NIAGARA.—Drawn by W. H.

Gibson.—[See Page 279.]

The otter is the aquatic member of the great weasel family, and plays the same part in lakes and rivers as his mischievous cousin in the forests. It is found in all parts of the world—on tropical islands throughout South America, and in the cold sea-coasts of Kamtchatka and Alaska. Eleven different varieties are mentioned by naturalists.

One of these, the sea-otter, haunts the rocky shores of the coasts and islands of Behring Sea and the Northern Pacific. Its habits are like those of the seal, and its soft, glossy black fur is very much prized, especially in China, where a trimming of otter fur is worn by high officials as a mark of rank.

The sea-otter is a very fond mother, and will fight vigorously in defense of its baby. If attacked when on shore, it will seize the baby in its mouth as a cat would seize a kitten, and scurry into the water as fast as possible, for once among the dashing waves it is safe, and will gambol and frolic gleefully with its rescued offspring. The sea-otter often sleeps on its back on the surface of the sea, and hunters mention having seen the baby lying on the breast of its sleeping mother, closely infolded by her fore-paws, while the waves formed a rocking, tossing cradle.

The sea-otter is the largest member of its family, but the prettiest and most playful of the tribe is the fish-otter, which is pictured in the accompanying engraving feeding its little ones with a fresh fish just caught in the pool by this most skillful of fishers. This otter is from two to three feet long, with a thick furry tail twelve to sixteen inches in length. It has very short legs, and stands not more than a foot high. Its paws are webbed for swimming, as its natural home is the water, but on land it can travel over the ground with great rapidity. It has small, prominent eyes, and little round ears, which are almost hidden in its soft brown fur.

The fish-otter is like a school-boy in its fondness for sliding down hill. Wherever there are bands of otters, slides are found worn on the slopes leading down to the shores of ponds and rivers, in the snow in the winter, and in the soft mud in the summer. Troops of otters have often been seen amusing themselves in this odd fashion. They slide lying on the ground, with the fore-feet bent backward, and push themselves forward with the hind-feet. When the slide is well worn and slippery, these funny little beasts go down with great velocity, and seem to take as much pleasure in their frolicsome antics as if they were a crowd of boys and girls.

The fish-otter lives around fresh-water lakes and rivers in Canada, in certain localities of South America, and in many wild portions of the United States and Europe. It is a famous fisherman. It can dive and stay under water a long time, and it swims so swiftly and so silently that even the quick-darting fish can rarely escape its sharp little teeth. If its prey be small, the otter lifts its head above the surface of the water, and easily bites off the choice morsels, but if the capture be a salmon or a good-sized trout, the otter swims ashore with it, and makes a leisurely repast on the grassy bank. Only the delicate parts of the fish are eaten by this dainty fisherman. When fish are not plenty, it will often attack ducks and other water-birds, like a weasel, sucking only the blood. The keeper of a park near Stuttgart at one time missed many beautiful ducks from a rare collection which had been domiciled on the banks of a water-course. All efforts to discover the thief were in vain. Night after night the keeper stood guard, gun in hand, and in spite of constant cries of alarm from the nests along the shore, no foe could be discovered. At length the keeper saw a dark object appear suddenly above the water. He fired,[Pg 282] but saw nothing more. Taking a boat, he rowed over to the spot where the object had disappeared, and with a boat-hook drew to the surface a soft mass, which proved to be a large otter, mortally wounded. From that time the ducks were left undisturbed.

The nest of the fish-otter is a very snug hiding-place. The entrance is through a hole in the bank about three feet under water. From this hole an excavated passageway leads up four or five feet, and ends in a little chamber warmly lined with moss and soft grasses. From this chamber a small tunnel goes to the top of the ground above, thus securing ventilation and plenty of fresh air. In this snug chamber the little otters are born. For the first ten days they are blind, but when their eyes are once open, they grow rapidly, and in about two months are lively and strong enough to accompany their mother on her fishing excursions.

Young otters are sometimes taken from the nest and brought up on bread and milk. They make the most affectionate pets imaginable. A story is told of a lady who had a pet otter that was so attached to its mistress as to follow her everywhere. It would frolic with her in the most amusing fashion, climbing up on to her shoulder, and rubbing its soft fur against her cheek. If it was sleepy, it would climb up her dress and curl up in her lap like a pet cat; and although its mistress's clothing always bore the marks of its sharp little teeth and claws, it remained for a long time a favored pet in the household.

Tame otters are often taught to catch fish for their masters, and many instances are recorded where pet otters have been valued by hunters as highly as their dogs, and have rendered quite as valuable service in supplying the table with dainties.

The Chinese make great use of the otter as a fisherman, and train it so skillfully for this purpose that it will mind the commands of its master as quickly as a well-trained dog.

The fish-otter was well known to the ancient Greeks and Romans, and was the subject of many wonderful fables and superstitions in olden times.

"Oh, mother! not for a whole week!" Patty's brown eyes were wide with doubt and surprise.

"Why, child, you just said never, and a week's a good deal short of that," answered busy little Mrs. Keniston, tucking another stick into the fire, with an odd little gleam, either from the fire-light or some inward amusement, dancing round the corners of her mouth. She was used to Patty's nevers, and a little tired of them.

Patty went to the window, and drummed on the pane, and stared rather forlornly into the small yard, where red-haired Job Twitchett was jumping up and down, jerking the handle of the old blue pump. He stuck out his tongue at her and winked one eye, but she was too abstracted to notice this customary beginning of hostilities. It was all very well to quarrel with Matty Monroe, and vow never to speak to her again (Matty was real mean to stay away from the spring, just because Kez King had said she might drop in that afternoon; she had no business to break her promise, and she had promised Patty, certain sure, that she would come and bring Rosinella and the tea set with her), but to be forbidden to speak to her for a week was quite another thing. Why, Sir Leon was to have married Rosinella before the week was out!

There was a great commotion in the yard. Job was setting Pug at Tabby. "Hi! look at yer old cat!" he shouted, starting a war-dance on the platform of the clothes-drier, and pointing derisively to poor pussy, who stood on the wood-shed roof, with her tail the size of a hearth-brush. But even this attack on her favorite could not dispel Patty's melancholy. She just glanced out to see that Tabby was really out of reach, and then went slowly up stairs to her little room in the attic to find Sir Leon.

Sir Leon was a doll. He was a very splendid doll, with brown eyes and hair, a black velvet cap with a long white feather, a silken cloak, and slashed trousers reaching only to the knee, like a knight of olden times. He even had long gray stockings, and—crowning glory!—a pair of top-boots made of chamois leather. Cousin Evelyn had dressed him for Patty's birthday, and Cousin Evelyn came from New York, and could do anything.

Patty picked him up, and looked fiercely in his amiable waxen countenance.

"I don't care a snap for your whiskers!" she exclaimed, hotly, giving him a vicious little shake. "I don't believe but what Cousin Evelyn just stuck 'em on herself; and it's my opinion you were made for a girl, Sir Leon de Montmorenci."

And at the thought of that dreadful possibility, and Matty Monroe's faithlessness, she sat down on the boot-box and cried.

Next morning Mrs. Keniston was rolling out pie-crust in the kitchen, when Patty entered slowly, with a kind of dubious brightness in her face, and curled up in a big chair by the table, with her head on her hand. A pencil and some paper projected from her apron pocket.

"Well, Patty," said Mrs. Keniston, cheerily, "what kind of turn-overs shall it be?"

"Mamma," responded Patty, soberly, "did you ever have any love-letters?"

Mrs. Keniston paused, with rolling-pin upraised in astonishment.

"No. Yes. Of course. What ever put it into your head to ask such questions, child? There, take that, and go and get your little pie board, and roll it out smoothly, and I'll let you bake some dolly's pies. Don't worry your silly head about love-letters yet awhile, my dear."

"But did you?" persisted Patty. "Because I want to write one—at least Sir Leon does—and we don't know how to begin. How did yours begin?"

"I think my first began, 'My dear Miss Holliwell,'" said Mrs. Keniston, laughing. "Ask papa. He'll know."

"Did it?" inquired Patty, rather doubtfully. "Why, when Mr. Cope wrote to you to borrow that book, he began, 'My dear Mrs. Keniston,' and his couldn't be a love-letter, you know, because you're married to papa, and he's engaged to Miss Dover. I don't think that sounds lovery enough."

However, she took out her pencil, and began to write, spelling over each word noiselessly to herself as she put it down.

"Who is your letter to, Patty?" asked her mother at last, as she folded it up with a sigh of relief, and wrote an address on the back.

"Why," said Patty, rather falteringly, "it's from Sir Leon to Rosinella. That isn't the same as if I wrote to Matty, is it? Because, you know, Sir Leon's a man, and I'm not, and Matty—well, Matty isn't Rosinella. Matty never was Queen of Beauty at a tournament the way Rosinella was when we had one in the orchard the day after Cousin Evelyn told us Ivanhoe. And it isn't Matty's trousseau we're making; it's Rosinella's. And Rosinella has golden hair, and Matty has auburn. And—I may send it, mayn't I?"

"Yes, indeed, you may," said Mrs. Keniston, laughing much more than was necessary, Patty thought. "May I see it?"

Patty handed it across the table, with a glance of mingled pride and apprehension, and this is what Mrs. Keniston read:

"My dear Miss Rosinella, Aingle of my Life,—I do miss you very much indeed and o how I wish we could see each other before wensday which is such a long way of but I supose we cant becourse Patty Kenistons mother says she mussnt speak to Matty Monroe till then becourse they quareled. I hope they will never quarel again dont you?

"Patty Keniston says she wont. She has been very lonely without Matty and wonders if she has finished your wedding dress which she hopes she has becourse she wants us to be marryed wensday anyhow in her dollshouse. She is going to have a reall frosted wedding cake for us and hopes Matty will bring over some rasberry vinneger for wine to drink helths with the way they allways used to do you know. O how I do want to see you and be marryed. Anser this soon and write a long letter for I am dying to hear from you my own presious Rosinella.

"Ever your loving knite

"Sir Leon der Montmorensy."

Mrs. Keniston laughed until she cried, and had to wipe her tears with her apron; but all she said, when she gave back the letter, was, "Oh, Patty! Patty! of all the children—"

Of course the postman was late next morning; but when he came, he was in remarkably good-humor, and wore a smile that creased his whole countenance as Patty danced up to him, asking, excitedly, "A letter for me? a letter for me?"

But he only chuckled, and shook his head for answer, and then said, slowly, "Wa'al, no, little gal; I'm sorry ter disapp'int yer, but ther' ain't," adding, with a twinkle, "Does anybody by the name of Montmorenci live hereabouts?"

"Oh, it's my letter! it's my letter!" screamed Patty. "Do give it to me, Mr. Skinner."

"Couldn't posserbly, little gal. 'Tain't yours, yer see. It's d'rected ter 'Sir Leon de Montmorenci, Knight.' That ain't your name, ye know," said Mr. Skinner, producing a tiny envelope.

"Oh yes, it is! I mean, it's my doll's!" shouted Patty; and seizing the precious letter, she ran into the house with it, and left Mr. Skinner still chuckling to himself with a hearty enjoyment of the little girl's delight.

Here is the letter:

"My dear Sir Leon,—Many thanks for your kind letter. I am quite ready to be married. Matty made my wedding dress yesterday. It is of white satin a piece left over from her Mothers and trimmed with white lace. I have a lovely vail. Matty says she will bring the raspberry vinegar" ("She's spelled it different from what I did," thought Patty; "guess she asked Lida") "and some crullers. And now I have an idear. Let us have a tellegraph. You ask Patty Keniston to come to the gate post at nine to-morrow and Matty will meet her with her end of the string. I think it is nice to live next door. Tell Patty Matty won't speak to her so she needent be afraid to come. I think your letter was lovely. I cannot make one half so nice but then your the gentleman and Im the lady so anyway it wouldent be propper. I love you. Tell Patty to be sure and come. Ever your faithfull ladilove,

"Rosinella Saint Hilaire."

"How splendid!" said Patty. "We can write all the time, then. I may, mayn't I, mother?"

Mrs. Keniston nodded. She was trying on a dress, and her mouth was full of pins.

And after that it wasn't hard at all. The telegraph was such a blessing! But still, when the week came to an end, Patty and Matty flew into each other's arms as if they had been separated for a year.

"Oh, Matty!" said Patty, and "Oh, Patty!" said Matty, and "Hi!" said Job Twitchett, bobbing his head over the fence, "yer'll fight agen in a fortnit."

"Go away, you bad boy," said Patty, facing him fiercely. "We shall NEVER fight again!"

And though Job repeated "Hi!" and snapped his fingers, they didn't—for a whole month.

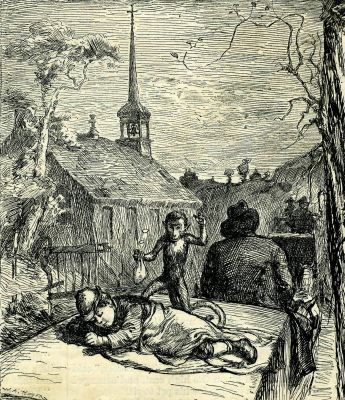

"So you are Phil's good friend Lisa?" said Miss Rachel Schuyler, sitting in her cool white wrapper in the dusk of this warm May evening. "I want to hear more about Phil. The dear child has quite won my heart, he looks so like a friend of mine whom I have not seen for many years. How are you related to him, and who were his parents?"

"I am not related to him at all, Miss Schuyler."

"No?"—in some surprise. "Why, then, have you the care and charge of him?"

LISA RELATES PHIL'S HISTORY TO MISS SCHUYLER.

LISA RELATES PHIL'S HISTORY TO MISS SCHUYLER.

"I was brought up in his mother's family as seamstress, and went to live with her when she married Mr. Randolph, and—"

"Who did you say? What Mr. Randolph?"

"Mr. Peyton Randolph."

Miss Rachel seemed much overcome, but she controlled herself, and hurriedly said, "Go on."

"There was no intercourse between the families after the marriage, for Mrs. Randolph was poor, and they all had been opposed to her. I suppose you do not care to hear all the details—how they went abroad, and Mr. Randolph died there; and while they were absent, their house was burned; and there was no one to take care of Phil but me, for Phil had been too sick to go with his father and mother; and Mrs. Randolph did not live long after her return. I nursed them both, Phil and his mother; and when she was gone, I came on to the city, thinking I could do better here, but I have found it hard, very hard, with no friends. Still, I have pretty steady work now as shop-woman, though I can not do all that I would like to do for Phil."

Miss Schuyler was crying.

"Lisa, you good woman, how glad I am I have found you! Phil's father was the dearest friend I ever had."

"Phil's mother gave the child to me, Miss Schuyler."

"Don't be alarmed; I do not wish to separate you. How can I ever thank you enough for telling me all this? And what a noble, generous creature you are, to be toiling and suffering for a child no way related to you, and who must have friends fully able to care for him if they would!"

"I love him as if he were my own. Sometimes I have thought I ought to try and see if any of his relatives would help us, but I can not bear to, and so we have just worried along as we could. But Phil needs a doctor and medicine, and more than I can give him."

"He shall have all he needs, and you too," said Miss Schuyler, warmly.

At this Lisa broke down, the kind words were so welcome. And the two women cried together; but not long, for Miss Schuyler rose and got Lisa some refreshing drink, and made her take off her bonnet and quiet herself, and then said:

"Now we must plan a change for Phil, and see how soon it can be accomplished. And you must leave that tiresome shop, and I will give you plenty of work to do. See, here are some things I bought to-day that I shall have to wear this summer."

She opened the packages—soft sheer lawn and delicate cambric that gave Lisa a thrill of pleasure just to touch once more, for she loved her work. "I shall be so glad to sew again, and I wish I had some of my work to show you."

"Oh, I know you will do it nicely. I am going out of[Pg 284] town in a few days, and I want you and Phil to go with me. Do you think you can?"

"I am a little afraid," said Lisa, hesitating, "that we are not fit to; and yet—"

"I will see to all that. Now I suppose you can not leave Phil alone much longer—besides, there is a shower coming. To-morrow I will bring a doctor to visit the dear boy, and we will see what can be done;" and she put a roll of money in Lisa's hand, assuring her that she should be as independent as she pleased after a while, and repay her, but that now she needed help, and should have it, and that henceforth Phil was to be theirs in partnership.

Lisa hurried away with a light heart. She had indeed toiled and suffered, striven early and late, for the child of her affections, and this timely assistance was a source of great joy.

She was too happy to heed the dashing shower which was now falling. Herself she had never thought of, and her dear Phil now was to be helped, to be cheered, perhaps to be made strong and well, and able to do all that his poor weak hands had tried to do so ineffectually.

She opened the door softly when she reached her room. A little shiver of sweet sad sounds came from the wind harp. She lighted a candle, and looked into the pale face of the sleeping child as he lay in an attitude of weariness and exhaustion, with hands falling apart, and a feverish flush on his thin cheeks.

"My poor Phil! I hope help has not come too late," she whispered, as she began her preparations for his more comfortable repose.

The next day Miss Schuyler came, as she had promised, and brought a physician—a good, kind surgeon—who examined Phil, and pulled this joint and that joint, and touched him here and there, and found out where the pain was, and what caused it, and said nice funny little things to make him laugh, and told him he hoped to make him a strong boy yet. And then they whispered a little about him, and Joe was sent for, and a carriage came, and Phil was wrapped in a blanket, and laid on pillows, and taken out for a drive alone with Miss Schuyler, who chatted with him, and got him more flowers; and when they came back there was a nice dinner on a tray, and ice-cream for his dessert, and Joe was to stay with him until Lisa came home; and before Lisa came, there was a nice new trunk brought in, and several large parcels. And Phil thought he had never seen such a day of happiness. After his dinner and a nap, and while Joe sat and played on his violin, Phil sketched and made a lovely little picture of flowers and fairies, in his own simple fashion, to give to Miss Schuyler. And then Lisa came home, and the parcels were opened; and there were nice new dresses for Lisa, and a pretty, thin shawl, and a new bonnet; and for Phil there was a comfortable flannel gown, and soft slippers, and fine handkerchiefs and stockings; and Phil found a little parcel too for Joe with a bright bandana in it, and the old man was very happy.

"It seems like Christmas," said Joe.

Phil thought he had never seen quite such a Christmas, and said,

"It seems more like fairy-land, and I only hope it will not all fade away and come to an end, like a bubble bursting."

"To me," said Lisa, "it is God's own goodness that has done it all, for it was He who gave Miss Schuyler her warm, kind heart."

"And, Joe," said Phil, "we are to go in the country, and you are to go with us; is not that nice?"

"Very nice, Phil. I'm glad Miss Rachel's found out your father was her friend."

Then Joe took up his violin again, and played "Home, Sweet Home," and "Auld Lang Syne"; and Phil fancied the violin was a bird, and sang of its own free-will, and thinking this reminded him how soon he would hear the dear wild birds in the woods, and he wondered if the fairies would come to him there.

Then Joe went home, and Lisa had errands to do, and again she put the wind harp in the window, and left Phil alone, keeping very still in expectation of another visit from his fairy friend.

Here comes the train;

We watch it from the bars;

Who will stop the engine

And put us in the cars?

It fell of itself,

The lazy ball,

And you needn't tell me

I let it fall!

Perhaps it was tired,

Like me and you,

And wanted to rest

A minute or two.

Little Miss Bessie

Has a new muff,

And fur gloves to keep her

Hands warm enough.

Mamma will let her

Run in the snow,

No matter how keenly

The wind may blow.

Little Mary gave a feast,

And seven guests invited;

In the garden it was laid,

And every one delighted.

They had cups of milk for tea,

And lots of cake and candy;

The sparrows thought 'twas jolly fun

To have a feast so handy.

When the crumbs were cleared away,

They danced and cut up capers;

And not a word about the feast

Was printed in the papers.

We give notice that in future no more offers for exchange of birds' eggs will be printed in the Post-office Box. During last summer we repeatedly endeavored to impress upon the minds of our readers that only one egg should be taken from each nest; but even this will, in many cases, cause anxiety to the mother-bird, and as the nesting season again approaches, we think best to request our boys and girls to leave the nests entirely undisturbed. The robbery and destruction of birds' nests by boys, in their eagerness to obtain eggs, have driven away thousands of song-birds from many parts of the country, and the new game-laws of this State will contain a very strict prohibition of this cruel practice, enforced by a heavy penalty.

We believe that our decision in this matter will meet with the hearty approval of every one of our young readers, and the sweet warbling of the birds on sunny summer mornings will amply repay them for the loss of a few eggs from their collections.

St. Louis, Missouri.

I am nine years old. I take Young People, and I am so pleased with it! I am very much interested in "Toby Tyler."

I am a good rider on a bicycle, and I can ride a horse well, too. I have a beautiful pony. She is sorrel, with silver mane and tail. Her name is Dolly, and when I call she always answers, and looks at me with her big brown eyes. She can almost talk. Dolly is full of mischief. She can untie her halter, take down a bar, open the oat bin, and help herself. She is as plump as a seal. I sometimes drive her in a little phaeton, and she is a good stepper on the road. I do hope every little boy who has a pony gives it as good care as I do mine.

I save every copy of Young People, and by-and-by I will give them to some poor child who can not take it.

Joe W. L. G.

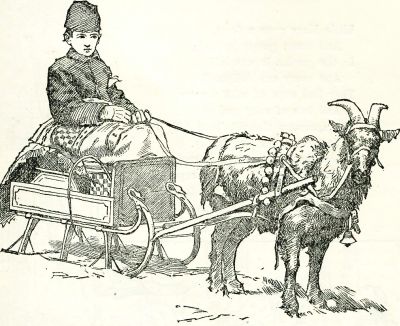

Perhaps some of our readers will remember a letter from Harry C. H., of Lansingburg, New York, published in the Post-office Box of No. 66. It described his black goat Dan, which he drives, harnessed, with a set of silver-plated harness, to a wagon or sleigh. Thinking you might be pleased to make the acquaintance of Harry and Dan, the Editor of Young People sent for their photograph, and here they are, silver-plated harness, bells, red box cutter, fur robe, and all—a very neat-looking turn-out. Don't you think so?

Jacksonville, Florida.

I live in an orange grove in Florida, the "Land of Flowers."

Florida has a great many ponds and marshes, with lots of fish in them, and it has a great deal of wire-grass and pine timber.

I have been up the great Oklawaha River, but I did not care for anything except the Silver Springs, which were very beautiful indeed. The water was so clear I could see trout, pike, and other large fish swimming about forty feet below the surface.

I have just begun to take Young People. Mamma gave it to my brother and myself for a Christmas present.

I go to school, and I have the best teacher that anybody ever had.

Lewis.

Mount Pleasant Academy, Sing Sing, New York.

I have taken Young People from the beginning, and I like it very much. Some of the other boys in this school take it, and they all think it is the best paper published. We all like "The Moral Pirates" the best of all the stories, and "Toby Tyler" the next. We have not had very good coasting nor skating lately, on account of the weather, but if it grows cold, and snows some more, we will have it.

I am collecting stamps, but all my duplicates are easy ones, and I have not enough to exchange yet.

I think the editor must work pretty hard to make the paper so nice for us to read.

Now I must stop writing, and study my Bible lesson.

Louis F. R.

Warrensburg, Missouri.

One week ago I had a letter to the Post-office Box nearly finished, and we were very happy, but just as night was coming on, mamma got a telegram from Colorado, nine hundred and ninety miles away, saying that our dear papa had died that morning. How dark the world did look! I used to write to him in mamma's letters, and he would write to me and my little brother about little tame bears and antelopes, and the funny prairie-dogs, and how high the mountains looked with their white caps of snow. He was so far across the mountains that the rivers ran toward the Pacific. Papa was shot and mortally wounded by some Mexicans. He was brought home to be buried, which was a great comfort to mamma.

Mamma likes the historical stories in Young People, and she hunts up more about the principal characters mentioned, and tells me about them. Was the "tiny tot" in the story of Prince Charlie the Duke of York, after whom the State and city of New York was named?

Harry D. S.

Yes, the "tiny tot" was the Duke of York, and on the death of his brother became James II., King of England. The name of New York city was changed from New Amsterdam to New York in 1664, Charles II. having, in violation of all national courtesy, granted the colony of New Netherlands to his brother James, then Duke of York.

Brooklyn, E. D., Long Island.

We have a very nice club, which is called the "Young Girls' Reading Club." We meet every other week at the different girls' houses, and we read the works of Longfellow, Tennyson, Whittier, and other poets. There are six members in our club. I am the treasurer, for we collect dues, just like "grown-up" clubs. We have to pay ten cents initiation fee, and after that five cents a week. There is a one-cent fine for violation of the rules, of which there are five. We are sure to make money, for the girls often break the rules.

Anna G. H.

Brooklyn, Long Island.

I send the Young Chemists' Club the simplest way of making chlorine gas, which is useful in many experiments: Mix one part oxide of manganese and two parts hydrochloric acid in a retort; heat gently over a spirit-lamp, when a greenish vapor will be seen to rise, which may be collected over warm water at the mouth of the retort. Care should be taken, however, not to inhale it, as it is a powerful poison, and a rag saturated with alcohol and ammonia should frequently be waved about to purify the atmosphere.

G. F. L.

This correspondent and many others have requested us to give the address of the president of the Young Chemists' Club, as they desire to correspond on scientific subjects. This we can not do unless authorized by the officers of the club. If Charles H. W., the president, desires to communicate with these young chemical students, he will kindly send a letter to that effect to the Post-office Box.

Vevay, Indiana.

I am so anxious about Toby Tyler! I do hope he won't get killed or die, but go back safe to his good uncle. I wanted to send him my dollar to help him, but mamma said I had better not. I am so sorry for him!

I have commenced studying German since the holidays. My teacher says I will soon overtake the class that began in September. I like it the best of all my studies.

Bertie M. A.

Brooklyn, Long Island.

We used to have an alligator. We fed it on raw meat. We kept it in a tub, and it used to jump out and run after grandpa when he had on red slippers. One day it got out of the tub, and ran down the steps into the kitchen, and jumped into my aunt's lap. Soon after that we sent it away.

M. Ella S.

Pasadena, California.

I am sick, and can not go to school, so I thought I would write to the Post-office Box. I have an orange-tree my father gave me about three years ago, and now it has more than a hundred oranges on it.

I had Young People as a birthday present from my mother. I think it is a nice present, because it lasts all the year.

Carlos P.

We have a little Home Literary Society which entertains us one evening every week, and I wish to inquire if Ida B. D. would kindly write to me in reference to the play acted during the holidays by the Silver Crescent Dramatic Club of San Francisco, California, of which she is the secretary.

Clara A. Hooper,

Rockport, Spencer County, Ind.

Emporia, Kansas.

On January 28 we celebrated Kansas Day, it being twenty years since Kansas was admitted to the Union as a State. The celebration was at the High School. The room was decorated with red, white, and blue, and a picture of John Brown was hung under two flags. The Kansas motto was over the door, and the coat of arms was drawn on the blackboard. Each pupil studied about some county, and they all sung "John Brown's Body," "Call to Kansas," and "The Star-spangled Banner." Essays were read on the history, products, schools, etc., of Kansas, and "The Kansas Emigrant" and other pieces were read by the scholars. It is just splendid to have Kansas Day.

Maud B.

Detroit, Michigan, February 8, 1881.

I have received so many letters for exchange of postmarks that I can not possibly answer them all right away. Correspondents will please take notice.

Harry W. Quimby.

Duluth, Minnesota.

I have received many boxes of specimens and curiosities from unknown persons. I receive the box, but there is no name on it, and no postal card referring to it, and often when there is a postal, there is no name even on that. Now those persons, no doubt, are disappointed at receiving no acknowledgment, but it is entirely their own fault, for whenever any one sends me specimens, accompanied by the name and address, he is sure to receive a box in return.

If all who have sent things to me, and have received no answer, will send me a postal describing the package or box they have sent, I will send a box of specimens in return.

Horace H. Mitchell.

The above letter is only one among many of the same character which we receive daily. We print it to impress, if possible, upon the minds of careless boys and girls the great importance of giving their full name and address, by the omission of which they cause trouble, not alone to themselves and their correspondents, but also to the Post-office Box.

I think Young People gets better and better. I am very much interested in the story of "Toby Tyler." I used to think it would be great fun to travel with a circus, but now I don't think it would be any fun at all.

I would be glad to exchange Lake Superior agates for star-fishes. I am nine years old.

J. Edwards Woodbridge,

Duluth, St. Louis County, Minn.

I am commencing a collection of stamps, and I will exchange a large piece of lead ore for forty stamps. I am eleven years old.

Newton Compton,

Care of Rev. J. M. Compton,

Rural Grove, Montgomery County, N. Y.

The following exchanges are also desired by correspondents:

A Lester saw in running order, for a self-inking press.

Edgar Garnan,

10 Highland Street, Roxbury, Mass.

Postmarks, sea-shells, marble from Vermont and Nova Scotia, flint from France, and other minerals, for postmarks, stamps, Indian relics, Lake Superior agates, shells, or other curiosities.

Raymond C. Morey,

Swanton, Franklin County, Vt.

Choice varieties of flower seeds, for peacock coal, petrified wood, shells, sea-mosses, coral, agates, or[Pg 287] minerals. Correspondents will please mark specimens.

Anna Favre,

Ontario, Story County, Iowa.

Postage stamps.

Shelton A. Hibbs,

505 North Eighteenth Street, Philadelphia, Penn.

Choice sea-shells for Mexican garnets.

Emma K. Chattle, care of Dr. T. G. Chattle,

Long Branch, N. J.

Foreign postage stamps.

Arthur T. Smith,

Westminster, Carroll County, Md.

Ten postmarks, for five foreign stamps, except English or Canadian.

M. F. Cooper,

Evans Mills, Jefferson County, N. Y.

Stones or earth from Ohio, for the same from any other State, or for autographs of renowned persons.

Walter Olmsted,

104 Brownell Street, Cleveland, Ohio.

Postage and revenue stamps and postmarks, for postage stamps.

Charles L. Hollingshead,

72 Grant Place, Chicago, Ill.

Amethyst from Grand Menan, New Brunswick, for foreign postage stamps.

Harlow Clark,

Hastings, Minn.

West Indian and other foreign stamps, for old Cuban (issues previous to 1875) and old Spanish stamps.

Percival G. Burgess,

55 Atlantic Street, Portland, Maine.

Minerals and stamps.

Walter S. Besse,

P. O. Box 235, New Bedford, Mass.

Stones from Massachusetts, for stones or curiosities from other States.

Robert W. Wales,

South Framingham, Mass.

An Austrian coin of 1859 and a Canadian half-penny, for twenty-five different kinds of stamps.

William Krummel,

167 Loth Street, Cincinnati, Ohio.

A stone from New York State, for one from any other State or Territory except Colorado.

Locke Stimpson,

Mineville, Essex County, N. Y.

Postmarks.

Will M. Edwards,

Noblesville, Hamilton County, Ind.

Ten postmarks, for one postage stamp. Stamps from South America, Turkey, or Greece preferred.

William T. Plumb,

Constableville, Lewis County, N. Y.

Foreign postage stamps and United States revenue stamps, for others.

A Reader of "Young People,"

P. O. Box 8, Newton Centre, Mass.

Red shells from Buzzard's Bay, postage stamps, mostly from South America, and American and foreign postmarks, for foreign postage stamps.

Walter S. Crane,

P. O. Box 474, Brookline, Mass.

Seven African stamps (no duplicates), for two Indian arrow-heads.

William G. Flanagan,

Johnstown, Cambria County, Penn.

Thirty postmarks, for five foreign postage stamps.

Clifton B. Gates,

Ellington, Chautauqua County, N. Y.

Petrified wood, for Indian relics and foreign postage stamps.

B. Pease,

279 East Fifth Street, St. Paul, Minn.

A stone from the Mammoth Cave, or stamps, for shells, ocean curiosities, or minerals.

Dellie Porter,

Russellville, Logan County, Ky.

Indian arrow-heads, for foreign postage stamps or shells.

William and Jennie Otterson,

Bennet Creek (viâ Mountain Home), Idaho Ter.

Postmarks, stamps, coins, and minerals, for stamps, coins, and minerals.

George F. Breckenwood,

Bay City, Mich.

Stamps and sea-shells, for minerals, Indian relics, or coins.

C. H. Whitlock,

P. O. Box 485, Ithaca, N. Y.

R. O. C.—The city of Santa Fe, in New Mexico, is the oldest in the United States.

"Inquisitive Joe."—The first narrow-gauge railroad was that leading from collieries either in Wales or the north of England, upon which point authorities differ. The gauge of four feet eight and a half inches is supposed to have been determined by the width of axle of the colliery wagons, and, once adopted, to have been applied to new roads built in other localities for passenger traffic.—It is supposed that the Chinese were the first to mine coal, and also from time immemorial to collect gas from it for purposes of illumination. Their method of working mines was very primitive, and is but little improved up to the present time. It is supposed that coal was used in Great Britain previous to the Roman invasion, but was probably collected only at the outcrops of the coal seams. In 1259 a charter was granted to the freemen of Newcastle to "dig for cole," by the King, Henry III., and from this time coal mining was an extensive industry. In France and Belgium, coal was also mined for fuel at a very early period. The Greeks and Romans were evidently acquainted with coal as fuel, but are supposed to have made little or no use of it.

Michael G. S.—There were two obelisks on the site of the ancient port of Alexandria, known as Cleopatra's Needles, one erect, the other fallen. The fallen one was taken to England in 1877, and the obelisk formerly erect is now placed in the Central Park of New York city.

John C.—Cockroaches, often called Croton-bugs in New York city, will devour anything they can find in the domestic store-room. They will also eat woollen cloth. They will exist a long time without food, as did the specimen you imprisoned in a bottle. Had you fed your bug with crumbs of bread or cake, he would have eaten greedily. The species of cockroaches which is found in houses in all maritime towns is supposed to be an emigrant from Asia, from which country it spread to Europe, and afterward came to America, where it has made itself thoroughly at home, to the great annoyance of many housewives, who battle in vain against the ravaging hordes of these disgusting insects.