Title: The English and Scottish popular ballads, volume 1 (of 5)

Editor: Francis James Child

Release date: February 20, 2014 [eBook #44969]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Simon Gardner, Katherine Ward, Alicia Williams,

David T. Jones and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net

This book contains material in multiple languages, and numerous examples of archaic, non-standard and dialect forms of English. Therefore no attempts to standardize spelling would be appropriate. The only changes made to the text are to correct typographical errors etc. which are listed at the end of the book. Minor corrections to format or punctuation have been made without comment.

Footnotes have been numbered sequentially throughout the book but are presented at the end of each section or ballad to which they refer.

Unicode characters have been used for special symbols and diacritics in the text. These should appear in the following table:

| ā | macron |

| ă ĭ | breve |

| ć ń ś ẃ | acute accent |

| Č č ĕ Ř ř š Š ž | caron/hacek |

| ȝ | yogh |

| ł | l with stroke (in Polish etc.) |

| Œ œ | oe-ligature |

| ş | s with cedilla |

| † | dagger used to represent upright cross symbol |

Greek symbols are also rendered with Unicode characters, but a Latin transliteration is provided in the "hover-text".

Note that [a'] and ['s] denote editorial insertions of contracted forms: e.g. on page 299 [a'] is an editorial insertion of "a'" (for "all"); on page 309 ['s] is an editorial insertion of "'s" (for "has"?).

[Pg i]

THE ENGLISH AND SCOTTISH

POPULAR BALLADS

EDITED BY

FRANCIS JAMES CHILD

IN FIVE VOLUMES

VOLUME I

NEW YORK

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

This Dover edition, first published in 1965, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the work originally published by Houghton, Mifflin and Company, as follows:

This edition also contains as an appendix to Part X an essay by Walter Morris Hart entitled "Professor Child and the Ballad," reprinted in toto from Vol. XXI, No. 4, 1906 [New Series Vol. XIV, No. 4] of the Publications of the Modern Language Association of America.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-24347

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc. 180 Varick Street New York, N.Y. 10014

To

FREDERICK J. FURNIVALL, ESQ.

OF LONDON

My Dear Furnivall:

Without the Percy MS. no one would pretend to make a collection of the English Ballads, and but for you that manuscript would still, I think, be beyond reach of man, yet exposed to destructive chances. Through your exertions and personal sacrifices, directly, the famous and precious folio has been printed; and, indirectly, in consequence of the same, it has been transferred to a place where it is safe, and open to inspection. This is only one of a hundred reasons which I have for asking you to accept the dedication of this book from

Your grateful friend and fellow-student,

F. J. Child.

Cambridge, Mass., December 1, 1882.

It was my wish not to begin to print The English and Scottish Popular Ballads until this unrestricted title should be justified by my having at command every valuable copy of every known ballad. A continuous effort to accomplish this object has been making for some nine or ten years, and many have joined in it. By correspondence, and by an extensive diffusion of printed circulars, I have tried to stimulate collection from tradition in Scotland, Canada, and the United States, and no becoming means has been left unemployed to obtain possession of unsunned treasures locked up in writing. The gathering from tradition has been, as ought perhaps to have been foreseen at this late day, meagre, and generally of indifferent quality. Materials in the hands of former editors have, in some cases, been lost beyond recovery, and very probably have lighted fires, like that large cantle of the Percy manuscript, maxime deflendus! Access to several manuscript collections has not yet been secured. But what is still lacking is believed to bear no great proportion to what is in hand, and may soon come in, besides: meanwhile, the uncertainties of the world forbid a longer delay to publish so much as has been got together.

Of hitherto unused materials, much the most important is a large collection of ballads made by Motherwell. For leave to take a copy of this I am deeply indebted to the present possessor, Mr Malcolm Colquhoun Thomson, of Glasgow, who even allowed the manuscript to be sent to London, and to be retained several months, for my accommodation. Mr J. Wylie Guild, of Glasgow, also permitted the use of a note-book of Motherwell's which supplements the great manuscript, and this my unwearied friend, Mr James Barclay Murdoch, to whose solicitation I owe both, himself transcribed with the most scrupulous accuracy. No other good office, asked or unasked, has Mr Murdoch spared.

Next in extent to the Motherwell collections come those of the late Mr Kinloch. These he freely placed at my disposal, and Mr William Macmath, of Edinburgh, made during Mr Kinloch's life an exquisite copy of the larger part of them, enriched with notes from Mr Kinloch's papers, and sent it to me across the water. After Mr Kinloch's death his collections were acquired by Harvard College Library, still through the agency of Mr Macmath, who has from the beginning rendered a highly valued assistance, not less by his suggestions and communications than by his zealous mediation.

No Scottish ballads are superior in kind to those recited in the last century by Mrs Brown, of Falkland. Of these there are, or were, three sets. One formerly owned by Robert Jamieson, the fullest of the three, was lent me, to keep as long as I required, by my honored friend the late Mr David Laing, who also secured for me copies of several ballads of Mrs Brown which are found in an Abbotsford manuscript, and gave me a transcript of the Glenriddell manuscript. The two others were written down for William Tytler and[Pg viii] Alexander Fraser Tytler respectively, the former of these consisting of a portion of the Jamieson texts revised. These having for some time been lost sight of, Miss Mary Fraser Tytler, with a graciousness which I have reason to believe hereditary in the name, made search for them, recovered the one which had been obtained by Lord Woodhouselee, and copied it for me with her own hand. The same lady furnished me with another collection which had been made by a member of the family.

For later transcriptions from Scottish tradition I am indebted to Mr J. F. Campbell of Islay, whose edition and rendering of the racy West Highland Tales is marked by the rarest appreciation of the popular genius; to Mrs A. F. Murison, formerly of Old Deer, who undertook a quest for ballads in her native place on my behalf; to Mr Alexander Laing, of Newburgh-upon-Tay; to Mr James Gibb, of Joppa, who has given me a full score; to Mr David Louden, of Morham, Haddington; to the late Dr John Hill Burton and Miss Ella Burton; to Dr Thomas Davidson.

The late Mr Robert White, of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, allowed me to look through his collections in 1873, and subsequently made me a copy of such things as I needed, and his ready kindness has been continued by Mrs Andrews, his sister, and by Miss Andrews, his niece, who has taken a great deal of trouble on my account.

In the south of the mother-island my reliance has, of necessity, been chiefly upon libraries. The British Museum possesses, besides early copies of some of the older ballads, the Percy MS., Herd's MSS and Buchan's, and the Roxburgh broadsides. The library of the University of Cambridge affords one or two things of first-rate importance, and for these I am beholden to the accomplished librarian, Mr Henry Bradshaw, and to Professor Skeat. I have also to thank the Rev. F. Gunton, Dean, and the other authorities of Magdalen College, Cambridge, for permitting collations of Pepys ballads, most obligingly made for me by Mr Arthur S. B. Miller. Many things were required from the Bodleian library, and these were looked out for me, and scrupulously copied or collated, by Mr George Parker.

Texts of traditional ballads have been communicated to me in America by Mr W. W. Newell, of New York, who is soon to give us an interesting collection of Children's Games traditional in America; by Dr Huntington, Bishop of Central New York; Mr G. C. Mahon, of Ann Arbor, Michigan; Miss Margaret Reburn, of New Albion, Iowa; Miss Perine, of Baltimore; Mrs Augustus Lowell, Mrs L. F. Wesselhoeft, Mrs. Edward Atkinson, of Boston; Mrs Cushing, of Cambridge; Miss Ellen Marston, of New Bedford; Mrs Moncrieff, of London, Ontario.

Acknowledgments not well despatched in a phrase are due to many others who have promoted my objects: to Mr Furnivall, for doing for me everything which I could have done for myself had I lived in England; to that master of old songs and music, Mr William Chappell, very specially; to Mr J. Payne Collier; Mr Norval Clyne, of Aberdeen; Mr Alexander Young, of Glasgow; Mr Arthur Laurenson, of Lerwick, Shetland; Mr J. Burrell Curtis, of Edinburgh; Dr Vigfusson, of Oxford; Professor Edward Arber, of Birmingham; the Rev. J. Percival, Mr Francis Fry, Mr J. F. Nicholls, of Bristol; Professor George Stephens, of Copenhagen; Mr R. Bergström, of the Royal Library, Stockholm; Mr W. R. S. Ralston, Mr William Henry Husk, Miss Lucy Toulmin Smith, Mr A. F. Murison, of London; Professor Sophocles; Mr W. G. Medlicott, of Longmeadow; to Mr M. Heilprin, of New York, Mme de Maltchycé, of Boston, and Rabbi Dr Cohn, for indispensable translations from Polish and Hungarian; to Mr James Russell Lowell, Minister of the United States at London; to Professor Charles Eliot Norton, for such "pains and benefits" as I could ask only of a life-long friend.

In the editing of these ballads I have closely followed the plan of Grundtvig's Old Popular Ballads of Denmark, a work which will be prized highest by those who have used it most, and which leaves nothing to be desired but its completion. The author is as much at home in English as in Danish tradition, and whenever he takes up a ballad which is common to both nations nothing remains to be done but to supply what has come to light since the time of his writing. But besides the assistance which I have derived from his book, I have enjoyed the advantage of Professor Grundtvig's criticism and advice, and have received from him unprinted Danish texts, and other aid in many ways.

Such further explanations as to the plan and conduct of the work as may be desirable can be more conveniently given by and by. I may say here that textual points which may seem to be neglected will be considered in an intended Glossary, with which will be given a full account of Sources, and such indexes of Titles and Matters as will make it easy to find everything that the book may contain.

With renewed thanks to all helpers, and helpers' helpers, I would invoke the largest coöperation for the correction of errors and the supplying of deficiencies. To forestall a misunderstanding which has often occurred, I beg to say that every traditional version of a popular ballad is desired, no matter how many texts of the same may have been printed already.

F. J. Child.

[December, 1882.]

I have again to express my obligations and my gratitude to many who have aided in the collecting and editing of these Ballads.

To Sir Hugh Hume Campbell, for the use of two considerable manuscript volumes of Scottish Ballads.

To Mr Allardyce, of Edinburgh, for a copy of the Skene Ballads, and for a generous permission to print such as I required, in advance of a possible publication on his part.

To Mr Mansfield, of Edinburgh, for the use of the Pitcairn manuscripts.

To Mrs Robertson, for the use of Note-Books of the late Dr Joseph Robertson, and to Mr Murdoch, of Glasgow, Mr Lugton, of Kelso, Mrs Alexander Forbes, of Edinburgh, and Messrs G. L. Kittredge and G. M. Richardson, former students of Harvard College, for various communications.

To Dr Reinhold Köhler's unrivalled knowledge of popular fiction, and his equal liberality, I am indebted for valuable notes, which will be found in the Additions at the end of this volume.

The help of my friend Dr Theodor Vetter has enabled me to explore portions of the Slavic ballad-field which otherwise must have been neglected.

Professors D. Silvan Evans, John Rhys, Paul Meyer, and T. Frederick Crane have lent me a ready assistance in literary emergencies.

The interest and coöperation of Mr Furnivall and Mr Macmath have been continued to me without stint or weariness.

It is impossible, while recalling and acknowledging acts of courtesy, good will, and friendship, not to allude, with one word of deep personal grief, to the irreparable loss which all who are concerned with the study of popular tradition have experienced in the death of Svend Grundtvig.

F. J. C.

June, 1884.

| VOLUME I | |||

| ballad | page | ||

| Biographical Sketch of Professor Child | xvii | ||

| 1. | Riddles Wisely Expounded | 1 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 484; II, 495; III, 496; IV, 439; V, 205, 283.) | |||

| 2. | The Elfin Knight | 6 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 484; II, 495; III, 496; IV, 439; V, 205, 284.) | |||

| 3. | The Fause Knight Upon the Road | 20 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 485; II, 496; III, 496; IV, 440.) | |||

| 4. | Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight | 22 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 485; II, 496; III, 496; IV, 440; V, 206, 285.) | |||

| 5. | Gil Brenton | 62 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 489; II, 498; III, 497; IV, 442; V, 207, 285.) | |||

| 6. | Willie's Lady | 81 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 498; III, 497; V, 207, 285.) | |||

| 7. | Earl Brand | 88 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 489; II, 498; III, 497; IV, 443; V, 207, 285.) | |||

| 8. | Erlinton | 106 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 498; IV, 445.) | |||

| 9. | The Fair Flower of Northumberland | 111 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 493; II, 498; III, 499; V, 207.) | |||

| 10. | The Twa Sisters | 118 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 493; II, 498; III, 499; IV, 447; V, 208, 286.) | |||

| 11. | The Cruel Brother | 141 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 496; II, 498; III, 499; IV, 449; V, 208, 286.) | |||

| 12. | Lord Randal | 151 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 498; II, 498; III, 499; IV, 449; V, 208, 286.) | |||

| 13. | Edward | 167 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 501; II, 499; III, 499; V, 209, 287.) | |||

| 14. | Babylon; or, The Bonnie Banks o Fordie | 170 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 501; II, 499; III, 499; IV, 450; V, 209, 287.) | |||

| 15. | Leesome Brand | 177 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 501; II, 499; III, 500; IV, 450; V, 209, 287.) | |||

| 16. | Sheath and Knife | 185 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 499; III, 500; IV, 450; V, 210.) | |||

| 17. | Hind Horn | 187 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 502; II, 499; III, 501; IV, 450; V, 210, 287.) | |||

| 18. | Sir Lionel | 208 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 500; IV, 451.) | |||

| 19. | King Orfeo | 215 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 500; III, 502; IV, 451; V, 211.) | |||

| 20. | The Cruel Mother | 218 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 504; II, 500; III, 502; IV, 451; V, 211, 287.) | |||

| 21. | The Maid and the Palmer (The Samaritan Woman) | 228[Pg xii] | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 501; III, 502; IV, 451; V, 212, 288.) | |||

| 22. | St. Stephen and Herod | 233 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 505; II, 501; III, 502; IV, 451; V, 212, 288.) | |||

| 23. | Judas | 242 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 288.) | |||

| 24. | Bonnie Annie | 244 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 452.) | |||

| 25. | Willie's Lyke-Wake | 247 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 506; II, 502; III, 503; IV, 453; V, 212, 289.) | |||

| 26. | The Three Ravens | 253 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 454; V, 212.) | |||

| 27. | The Whummil Bore | 255 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 212.) | |||

| 28. | Burd Ellen and Young Tamlane | 256 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 507; III, 503.) | |||

| 29. | The Boy and the Mantle | 257 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 507; II, 502; III, 503; IV, 454; V, 212, 289.) | |||

| 30. | King Arthur and King Cornwall | 274 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 507; II, 502; III, 503; V, 289.) | |||

| 31. | The Marriage of Sir Gawain | 288 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 507; II, 502; IV, 454; V, 213, 289.) | |||

| 32. | King Henry | 297 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 502; IV, 454; V, 289.) | |||

| 33. | Kempy Kay | 300 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 213, 289.) | |||

| 34. | Kemp Owyne | 306 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 502; III, 504; IV, 454; V, 213, 290.) | |||

| 35. | Allison Gross | 313 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 504; V, 214.) | |||

| 36. | The Laily Worm and the Machrel of the Sea | 315 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 214, 290.) | |||

| 37. | Thomas Rymer | 317 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 505; III, 504; IV, 454, 290.) | |||

| 38. | The Wee Wee Man | 329 | |

| 39. | Tam Lin | 335 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 507; II, 505; III, 504; IV, 455; V, 215, 290.) | |||

| 40. | The Queen of Elfan's Nourice | 358 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 505; III, 505; IV, 459; V, 215, 290.) | |||

| 41. | Hind Etin | 360 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 508; II, 506; III, 506; IV, 459; V, 215.) | |||

| 42. | Clerk Colvill | 371 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 506; III, 506; IV, 459; V, 215, 290.) | |||

| 43. | The Broomfield Hill | 390 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 508; II, 506; III, 506; IV, 459, 290.) | |||

| 44. | The Twa Magicians | 399 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 506; III, 506; IV, 459; V, 216, 290.) | |||

| 45. | King John and the Bishop | 403 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: I, 508; II, 506; IV, 459; V, 216, 291.) | |||

| 46. | Captain Wedderburn's Courtship | 414[Pg xiii] | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 507; III, 507; IV, 459; V, 216, 291.) | |||

| 47. | Proud Lady Margaret | 425 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 460; V, 291.) | |||

| 48. | Young Andrew | 432 | |

| 49. | The Twa Brothers | 435 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 507; III, 507; IV, 460; V, 217, 291.) | |||

| 50. | The Bonny Hind | 444 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 218.) | |||

| 51. | Lizie Wan | 447 | |

| 52. | The King's Dochter Lady Jean | 450 | |

| 53. | Young Beichan | 454 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 508; III, 507; IV, 460; V, 218, 291.) | |||

| Additions and Corrections | 484 | ||

| VOLUME II | |||

| 54. | The Cherry-Tree Carol | 1 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 509; V, 220.) | |||

| 55. | The Carnal and the Crane | 7 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 509; III, 507; IV. 462; V, 220.) | |||

| 56. | Dives and Lazarus | 10 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 510; III, 507; IV, 462; V, 220, 292.) | |||

| 57. | Brown Robyn's Confession | 13 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 510; III, 508; IV, 462; V, 220, 292.) | |||

| 58. | Sir Patrick Spens | 17 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 510; V, 220.) | |||

| 59. | Sir Aldingar | 33 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 510; III, 508; IV, 463; V, 292.) | |||

| 60. | King Estmere | 49 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 510; III, 508; IV, 463.) | |||

| 61. | Sir Cawline | 56 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 511; III, 508; IV, 463.) | |||

| 62. | Fair Annie | 63 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 511; IV, 463; V, 220.) | |||

| 63. | Child Waters | 83 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 511; III, 508; IV, 463; V, 220.) | |||

| 64. | Fair Janet | 100 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 508; IV, 464; V, 222, 292.) | |||

| 65. | Lady Maisry | 112 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 508; IV, 466; V, 222, 292.) | |||

| 66. | Lord Ingram and Chiel Wyet | 126 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 511; III, 508; V, 223, 292.) | |||

| 67. | Glasgerion | 136 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 511; III, 509; IV, 468; V, 293.) | |||

| 68. | Young Hunting | 142 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 512; III, 509; IV, 468; V, 223.) | |||

| 69. | Clerk Saunders | 156 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 512; III, 509; IV, 468; V, 223, 293.) | |||

| 70. | Willie and Lady Maisry | 167 | |

| 71. | The Bent Sae Brown | 170[Pg xiv] | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 509; IV, 469; V, 223.) | |||

| 72. | The Clerks's Twa Sons o Owsenford | 173 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 512; III, 509; IV, 469; V, 293.) | |||

| 73. | Lord Thomas and Fair Annet | 179 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 512; III, 509; IV, 469; V, 223, 293.) | |||

| 74. | Fair Margaret and Sweet William | 199 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 224, 293.) | |||

| 75. | Lord Lovel | 204 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 512; III, 510; IV, 471; V, 225, 294.) | |||

| 76. | The Lass of Roch Royal | 213 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 510; IV, 471; V, 225, 294.) | |||

| 77. | Sweet William's Ghost | 226 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 512; IV, 474; V, 225, 294.) | |||

| 78. | The Unquiet Grave | 234 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 512; III, 512; IV, 474; V, 225, 294.) | |||

| 79. | The Wife of Usher's Well | 238 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 513; V, 294.) | |||

| 80. | Old Robin of Portingale | 240 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 513; III, 514; IV, 476; V, 225, 295.) | |||

| 81. | Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard | 242 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 513; IV, 476; V, 225.) | |||

| 82. | The Bonny Birdy | 260 | |

| 83. | Child Maurice | 263 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 514; IV, 478.) | |||

| 84. | Bonny Barbara Allan | 276 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 514.) | |||

| 85. | Lady Alice | 279 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 514; V, 225.) | |||

| 86. | Young Benjie | 281 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 478.) | |||

| 87. | Prince Robert | 284 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 295.) | |||

| 88. | Young Johnstone | 288 | |

| 89. | Fause Foodrage | 296 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 513; III, 515; IV, 479.) | |||

| 90. | Jellon Grame | 302 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 513; III, 515; IV, 479; V, 226, 295.) | |||

| 91. | Fair Mary of Wallington | 309 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 513; III, 515; IV, 479; V, 227.) | |||

| 92. | Bonny Bee Hom | 317 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 229.) | |||

| 93. | Lamkin | 320 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 513; III, 515; IV, 480; V, 229, 295.) | |||

| 94. | Young Waters | 342 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 516.) | |||

| 95. | The Maid Freed from the Gallows | 346 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 514; III, 516; IV, 481; V, 231, 296.) | |||

| 96. | The Gay Goshawk | 355 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 517; IV, 482; V, 234, 296.) | |||

| 97. | Brown Robin | 368[Pg xv] | |

| 98. | Brown Adam | 373 | |

| 99. | Johnie Scot | 377 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 486; V, 234.) | |||

| 100. | Willie o Winsbury | 398 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: II, 514; III, 517; IV, 491; V, 296.) | |||

| 101. | Willie o Douglas Dale | 406 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 517; V, 235.) | |||

| 102. | Willie and Earl Richard's Daughter | 412 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 518.) | |||

| 103. | Rose the Red and White Lily | 415 | |

| 104. | Prince Heathen | 424 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 296.) | |||

| 105. | The Bailiff's Daughter of Islington | 426 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 518; V, 237.) | |||

| 106. | The Famous Flower of Serving-Men | 428 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 518; IV, 492.) | |||

| 107. | Will Stewart and John | 432 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 237.) | |||

| 108. | Christopher White | 439 | |

| 109. | Tom Potts | 441 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 518.) | |||

| 110. | The Knight and Shepherd's Daughter | 457 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 492; V, 237.) | |||

| 111. | Crow and Pie | 478 | |

| 112. | The Baffled Knight | 479 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 518; IV, 495; V, 239, 296.) | |||

| 113. | The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry | 494 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 518; IV, 495.) | |||

| Additions and Corrections | 495 | ||

| VOLUME III | |||

| 114. | Johnie Cock | 1 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 495.) | |||

| 115. | Robyn and Gandeleyn | 12 | |

| 116. | Adam Bell, Clim of the Clough, and William of Cloudesly | 14 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 518; IV, 496; V, 297.) | |||

| 117. | A Gest of Robyn Hode | 39 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 519; IV, 496; V, 240, 297.) | |||

| 118. | Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne | 89 | |

| 119. | Robin Hood and the Monk | 94 | |

| 120. | Robin Hood's Death | 102 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 240, 297.) | |||

| 121. | Robin Hood and the Potter | 108 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 497.) | |||

| 122. | Robin Hood and the Butcher | 115 | |

| 123. | Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar | 120 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 297.) | |||

| 124. | The Jolly Pinder of Wakefield | 129[Pg xvi] | |

| 125. | Robin Hood and Little John | 133 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 297.) | |||

| 126. | Robin Hood and the Tanner | 137 | |

| 127. | Robin Hood and the Tinker | 140 | |

| 128. | Robin Hood newly Revived | 144 | |

| 129. | Robin Hood and the Prince of Aragon | 147 | |

| 130. | Robin Hood and the Scotchman | 150 | |

| 131. | Robin Hood and the Ranger | 152 | |

| 132. | The Bold Pedlar and Robin Hood | 154 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 240.) | |||

| 133. | Robin Hood and the Beggar, I | 155 | |

| 134. | Robin Hood and the Beggar, II | 158 | |

| 135. | Robin Hood and the Shepherd | 165 | |

| 136. | Robin Hood's Delight | 168 | |

| 137. | Robin Hood and the Pedlars | 170 | |

| 138. | Robin Hood and Allen a Dale | 172 | |

| 139. | Robin Hood's Progress to Nottingham | 175 | |

| 140. | Robin Hood rescuing Three Squires | 177 | |

| 141. | Robin Hood rescuing Will Stutly | 185 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 497.) | |||

| 142. | Little John a Begging | 188 | |

| 143. | Robin Hood and the Bishop | 191 | |

| 144. | Robin Hood and the Bishop of Hereford | 193 | |

| 145. | Robin Hood and Queen Katherine | 196 | |

| 146. | Robin Hood's Chase | 205 | |

| 147. | Robin Hood's Golden Prize | 208 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 519.) | |||

| 148. | The Noble Fisherman, or, Robin Hood's Preferment | 211 | |

| 149. | Robin Hood's Birth, Breeding, Valor and Marriage | 214 | |

| 150. | Robin Hood and Maid Marian | 218 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 519.) | |||

| 151. | The King's Disguise, and Friendship with Robin Hood | 220 | |

| 152. | Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow | 223 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 241.) | |||

| 153. | Robin Hood and the Valiant Knight | 225 | |

| 154. | A True Tale of Robin Hood | 227 | |

| 155. | Sir Hugh, or, The Jew's Daughter | 233 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 519; IV, 497; V, 241, 297.) | |||

| 156. | Queen Eleanor's Confession | 257 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 498; V, 241, 297.) | |||

| 157. | Gude Wallace | 265 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 242.) | |||

| 158. | Hugh Spencer's Feats in France | 275 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 499; V, 243.) | |||

| 159. | Durham Field | 282 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 297.)[Pg xvii] | |||

| 160. | The Knight of Liddesdale | 288 | |

| 161. | The Battle of Otterburn | 289 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 520; IV, 499; V, 243, 297.) | |||

| 162. | The Hunting of the Cheviot | 303 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 502; V, 244, 297.) | |||

| 163. | The Battle of Harlaw | 316 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 245.) | |||

| 164. | King Henry Fifth's Conquest of France | 320 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 245.) | |||

| 165. | Sir John Butler | 327 | |

| 166. | The Rose of England | 331 | |

| 167. | Sir Andrew Barton | 334 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 502; V, 245.) | |||

| 168. | Flodden Field | 351 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 507; V, 298.) | |||

| 169. | Johnie Armstrong | 362 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 520; IV, 507; V, 298.) | |||

| 170. | The Death of Queen Jane | 372 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 245, 298.) | |||

| 171. | Thomas Cromwell | 377 | |

| 172. | Musselburgh Field | 378 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 507.) | |||

| 173. | Mary Hamilton | 379 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 507; V, 246, 298.) | |||

| 174. | Earl Bothwell | 399 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 247.) | |||

| 175. | The Rising in the North | 401 | |

| 176. | Northumberland betrayed by Douglas | 408 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 299.) | |||

| 177. | The Earl of Westmoreland | 416 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 299.) | |||

| 178. | Captain Car, or, Edom o Gordon | 423 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 520; IV, 513; V, 247, 299.) | |||

| 179. | Rookhope Ryde | 439 | |

| 180. | King James and Brown | 442 | |

| 181. | The Bonny Earl of Murray | 447 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 515.) | |||

| 182. | The Laird o Logie | 449 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 520; IV, 515; V, 299.) | |||

| 183. | Willie Macintosh | 456 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 516.) | |||

| 184. | The Lads of Wamphray | 458 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: III, 520.) | |||

| 185. | Dick o the Cow | 461 | |

| 186. | Kinmont Willie | 469 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 516.) | |||

| 187. | Jock o the Side | 475 | |

| 188. | Archie o Cawfield | 484 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 516.) | |||

| Additions and Corrections | 496 | ||

| VOLUME IV | [Pg xviii] | ||

| 189. | Hobie Noble | 1 | |

| 190. | Jamie Telfer of the Fair Dodhead | 4 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 518; V, 249, 300.) | |||

| 191. | Hughie Grame | 8 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 518; V, 300.) | |||

| 192. | The Lochmaben Harper | 16 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 300.) | |||

| 193. | The Death of Parcy Reed | 24 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 520.) | |||

| 194. | The Laird of Wariston | 28 | |

| 195. | Lord Maxwell's Last Goodnight | 34 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 251.) | |||

| 196. | The Fire of Frendraught | 39 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 521; V, 251, 301.) | |||

| 197. | James Grant | 49 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 251.) | |||

| 198. | Bonny John Seton | 51 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 251.) | |||

| 199. | The Bonnie House o Airlie | 54 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 252.) | |||

| 200. | The Gypsy Laddie | 61 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 522; V, 252, 301.) | |||

| 201. | Bessy Bell and Mary Gray | 75 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 522; V, 253.) | |||

| 202. | The Battle of Philiphaugh | 77 | |

| 203. | The Baron of Brackley | 79 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 522; V, 253.) | |||

| 204. | Jamie Douglas | 90 | |

| 205. | Loudon Hill, or, Drumclog | 105 | |

| 206. | Bothwell Bridge | 108 | |

| 207. | Lord Delamere | 110 | |

| 208. | Lord Derwentwater | 115 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 522; V, 254.) | |||

| 209. | Geordie | 123 | |

| 210. | Bonnie James Campbell | 142 | |

| 211. | Bewick and Graham | 144 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 522.) | |||

| 212. | The Duke of Athole's Nurse | 150 | |

| 213. | Sir James the Rose | 155 | |

| 214. | The Braes o Yarrow | 160 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 522; V, 255.) | |||

| 215. | Rare Willie Drowned in Yarrow, or, The Water o Gamrie | 178 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 256.) | |||

| 216. | The Mother's Malison, or, Clyde's Water | 185 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 256, 301.) | |||

| 217. | The Broom of Cowdenknows | 191 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 523; V, 257.) | |||

| 218. | The False Lover won back | 209 | |

| 219. | The Gardener | 212[Pg xix] | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 258.) | |||

| 220. | The Bonny Lass of Anglesey | 214 | |

| 221. | Katharine Jaffray | 216 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 523; V, 260.) | |||

| 222. | Bonny Baby Livingston | 231 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 523; V, 261.) | |||

| 223. | Eppie Morrie | 239 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 262.) | |||

| 224. | The Lady of Arngosk | 241 | |

| 225. | Rob Roy | 243 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 523; V, 262.) | |||

| 226. | Lizie Lindsay | 255 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 524; V, 264.) | |||

| 227. | Bonny Lizie Baillie | 266 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 265.) | |||

| 228. | Glasgow Peggie | 270 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 266.) | |||

| 229. | Earl Crawford | 276 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 301.) | |||

| 230. | The Slaughter of the Laird of Mellerstain | 281 | |

| 231. | The Earl of Errol | 282 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 267.) | |||

| 232. | Richie Story | 291 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 270.) | |||

| 233. | Andrew Lammie | 300 | |

| 234. | Charlie MacPherson | 308 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 301.) | |||

| 235. | The Earl of Aboyne | 311 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 270, 301.) | |||

| 236. | The Laird o Drum | 322 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 272.) | |||

| 237. | The Duke of Gordon's Daughter | 332 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 273.) | |||

| 238. | Glenlogie, or, Jean o Bethelnie | 338 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 273, 302.) | |||

| 239. | Lord Saltoun and Auchanachie | 347 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 273.) | |||

| 240. | The Rantin Laddie | 351 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 274.) | |||

| 241. | The Baron o Leys | 355 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 275.) | |||

| 242. | The Coble o Cargill | 358 | |

| 243. | James Harris (The Dæmon Lover) | 360 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 524.) | |||

| 244. | James Hatley | 370 | |

| 245. | Young Allan | 375 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 275.) | |||

| 246. | Redesdale and Wise William | 383 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 276.) | |||

| 247. | Lady Elspat | 387[Pg xx] | |

| 248. | The Grey Cock, or, Saw you my Father? | 389 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 302.) | |||

| 249. | Auld Matrons | 391 | |

| 250. | Henry Martyn | 393 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 302.) | |||

| 251. | Lang Johnny More | 396 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: IV, 524.) | |||

| 252. | The Kitchie-Boy | 400 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 277.) | |||

| 253. | Thomas o Yonderdale | 409 | |

| 254. | Lord William, or, Lord Lundy | 411 | |

| 255. | Willie's Fatal Visit | 415 | |

| 256. | Alison and Willie | 416 | |

| 257. | Burd Isabel and Earl Patrick | 417 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 278.) | |||

| 258. | Broughty Wa's | 423 | |

| 259. | Lord Thomas Stuart | 425 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 279.) | |||

| 260. | Lord Thomas and Lady Margaret | 426 | |

| 261. | Lady Isabel | 429 | |

| 262. | Lord Livingston | 431 | |

| 263. | The New-Slain Knight | 434 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 279.) | |||

| 264. | The White Fisher | 435 | |

| 265. | The Knight's Ghost | 437 | |

| Additions and Corrections | 439 | ||

| VOLUME V | |||

| 266. | John Thomson and the Turk | 1 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 279.) | |||

| 267. | The Heir of Linne | 11 | |

| 268. | The Twa Knights | 21 | |

| 269. | Lady Diamond | 29 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 303.) | |||

| 270. | The Earl of Mar's Daughter | 38 | |

| 271. | The Lord of Lorn and the False Steward | 42 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 280.) | |||

| 272. | The Suffolk Miracle | 58 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 303.) | |||

| 273. | King Edward the Fourth and a Tanner of Tamworth | 67 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 303.) | |||

| 274. | Our Goodman | 88 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 281, 303.) | |||

| 275. | Get up and bar the Door | 96 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 281, 304.) | |||

| 276. | The Friar in the Well | 100 | |

| 277. | The Wife Wrapt in Wether's Skin | 104[Pg xxi] | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 304.) | |||

| 278. | The Farmer's Curst Wife | 107 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 305.) | |||

| 279. | The Jolly Beggar | 109 | |

| 280. | The Beggar-Laddie | 116 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 305.) | |||

| 281. | The Keach I the Creel | 121 | |

| 282. | Jock the Leg and the Merry Merchant | 126 | |

| 283. | The Crafty Farmer | 128 | |

| 284. | John Dory | 131 | |

| 285. | The George Aloe and the Sweepstake | 133 | |

| 286. | The Sweet Trinity (The Golden Vanity) | 135 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 305.) | |||

| 287. | Captain Ward and the Rainbow | 143 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 305.) | |||

| 288. | The Young Earl of Essex's Victory over the Emperor of Germany | 145 | |

| 289. | The Mermaid | 148 | |

| 290. | The Wylie Wife of the Hie Toun Hie | 153 | |

| 291. | Child Owlet | 156 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 305.) | |||

| 292. | The West-Country Damosel's Complaint | 157 | |

| 293. | John of Hazelgreen | 159 | |

| 294. | Dugall Quin | 165 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 305.) | |||

| 295. | The Brown Girl | 166 | |

| 296. | Walter Lesly | 168 | |

| 297. | Earl Rothes | 170 | |

| 298. | Young Peggy | 171 | |

| 299. | Trooper and Maid | 172 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 306.) | |||

| 300. | Blancheflour and Jellyflorice | 175 | |

| 301. | The Queen of Scotland | 176 | |

| 302. | Young Bearwell | 178 | |

| 303. | The Holy Nunnery | 179 | |

| 304. | Young Ronald | 181 | |

| 305. | The Outlaw Murray | 185 | |

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 307.) | |||

| Fragments | 201 | ||

| (Additions and Corrections: V, 307.) | |||

| Additions and Corrections | 205, 283 | ||

| Glossary | 309 | ||

| Sources of the Texts | 397 | ||

| Index of Published Airs | 405 | ||

| Ballad Airs from Manuscript: | |||

| 3. The Fause Knight upon the Road | 411 | ||

| 9. The Fair Flower of Northumberland | 411 | ||

| 10. The Twa Sisters | 411 | ||

| 11. The Cruel Brother | 412[Pg xxii] | ||

| 12. Lord Randal | 412 | ||

| 17. Hind Horn | 413 | ||

| 20. The Cruel Mother | 413 | ||

| 40. The Queen of Elfan's Nourice | 413 | ||

| 42. Clerk Colvill | 414 | ||

| 46. Captain Wedderburn's Courtship | 414 | ||

| 47. Proud Lady Margaret | 414 | ||

| 53. Young Beichan | 415 | ||

| 58. Sir Patrick Spens | 415 | ||

| 61. Sir Colin | 415 | ||

| 63. Child Waters | 415 | ||

| 68. Young Hunting | 416 | ||

| 75. Lord Lovel | 416 | ||

| 77. Sweet William's Ghost | 416 | ||

| 84. Bonny Barbara Allan | 416 | ||

| 89. Fause Foodrage | 416 | ||

| 95. The Maid freed from the Gallows | 417 | ||

| 97. Brown Robin | 417 | ||

| 98. Brown Adam | 417 | ||

| 99. Johnie Scot | 418 | ||

| 100. Willie o Winsbury | 418 | ||

| 106. The Famous Flower of Serving-Men | 418 | ||

| 144. Johnie Cock | 419 | ||

| 157. Gudo Wallace | 419 | ||

| 161. The Battle of Otterburn | 419 | ||

| 163. The Battle of Harlaw | 419 | ||

| 164. King Henry Fifth's Conquest of France | 420 | ||

| 169. Johnie Armstrong | 420 | ||

| 173. Mary Hamilton | 421 | ||

| 182. The Laird o Logie | 421 | ||

| 222. Bonny Baby Livingston | 421 | ||

| 226. Lizie Lindsay | 421 | ||

| 228. Glasgow Peggie | 422 | ||

| 235. The Earl of Aboyne | 422 | ||

| 247. Lady Elspat | 422 | ||

| 250. Andrew Bartin | 423 | ||

| 256. Alison and Willie | 423 | ||

| 258. Broughty Wa's | 423 | ||

| 278. The Farmer's Curst Wife | 423 | ||

| 281. The Keach i the Creel | 424 | ||

| 286. The Sweet Trinity | 424 | ||

| 299. Trooper and Maid | 424 | ||

| Index of Ballad Titles | 425 | ||

| Titles of Collections of Ballads, or Books containing Ballads, which are very briefly cited in this work | 455 | ||

| Index of Matters and Literature | 469 | ||

| Bibliography | 503 | ||

| Corrections to be made in the Print | 567 | ||

| Appendix: Professor Child and the Ballad | 571 | ||

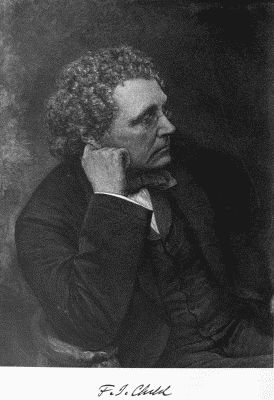

Francis James Child was born in Boston on the first day of February, 1825. He was the third in a family of eight children. His father was a sailmaker, "one of that class of intelligent and independent mechanics," writes Professor Norton, "which has had a large share in determining the character of our democratic community, as of old the same class had in Athens and in Florence." The boy attended the public schools, as a matter of course; and, his parents having no thought of sending him to college, he went, in due time, not to the Latin School, but to the English High School of his native town. At that time the head master of the Boston Latin School was Mr Epes Sargent Dixwell, who is still living, at a ripe old age, one of the most respected citizens of Cambridge. Mr Dixwell had a keen eye for scholarly possibilities in boys, and, falling in with young Francis Child, was immediately struck with his extraordinary mental ability. At his suggestion, the boy was transferred to the Latin School, where he entered upon the regular preparation for admission to Harvard College. His delight in his new studies was unbounded, and the freshness of it never faded from his memory. "He speedily caught up with the boys who had already made considerable progress in Greek and Latin, and soon took the first place here, as he had done in the schools which he had previously attended." Mr Dixwell strongly advised his father to permit him to continue his studies, and made arrangements by which his college expenses should be provided for. The money Professor Child repaid, with interest, as soon as his means allowed. His gratitude to Mr. Dixwell and the friendship between them lasted through his life.

In 1842 Mr Child entered Harvard College. The intellectual condition of the college at that time and the undergraduate career of Mr Child have been admirably described by his classmate and lifelong friend, Professor Norton, in a passage which must be quoted in full[1]:—

"Harvard was then still a comparatively small institution, with no claims to the title of University; but she had her traditions of good learning as an inspiration for the studious youth, and still better she had teachers who were examples of devotion to intellectual pursuits, and who cared for those ends the attainment of which makes life worth living. Josiah Quincy was approaching the close of his term of service as President of the College, and stood before the eyes of the students as the type of a great public servant, embodying the spirit of patriotism, of integrity, and of fidelity in the discharge of whatever duty he might be called to perform. Among the Professors were Walker, Felton, Peirce, Channing, Beck, and Longfellow, men of utmost variety of temperament, but each an instructor who secured the respect no less than the gratitude of his pupils.

"The class to which Child belonged numbered hardly over sixty. The prescribed course of study which was then the rule brought all the members of the class together in recitations and lectures, and every man soon knew the relative standing of each of his fellows. Child at once took the lead and kept it. His excellence was not confined to any[Pg xxiv] one special branch of study; he was equally superior in all. He was the best in the classics, he was Peirce's favorite in mathematics, he wrote better English than any of his classmates. His intellectual interests were wider than theirs, he was a great reader, and his tastes in reading were mature. He read for amusement as well as for learning, but he did not waste his time or dissipate his mental energies over worthless or pernicious books. He made good use of the social no less than of the intellectual opportunities which college life affords, and became as great a favorite with his classmates as he had been with his schoolfellows.

"The close of his college course was marked by the exceptional distinction of his being chosen by his classmates as their Orator, and by his having the first part at Commencement as the highest scholar in the class. His class oration was remarkable for its maturity of thought and of style. Its manliness of spirit, its simple directness of presentation of the true objects of life, and of the motives by which the educated man, whatever might be his chosen career, should be inspired, together with the serious and eloquent earnestness with which it was delivered, gave to his discourse peculiar impressiveness and effect."

Graduating with the degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1846, Mr Child immediately entered the service of the college, in which he continued till the day of his death. From 1846 to 1848 he was tutor in mathematics. In 1848 he was transferred, at his own request, to a tutorship in history and political economy, to which were annexed certain duties of instruction in English. In 1849 he obtained leave of absence for travel and study in Europe. He remained in Europe for about two years, returning, late in 1851, to receive an appointment to the Boylston Professorship of Rhetoric and Oratory, then falling vacant by the resignation of Professor Edward T. Channing.

The tutorships which Mr Child had held were not entirely in accordance with his tastes, which had always led him in the direction of literary and linguistic study. The faculty of the college was small, however, and it was not always possible to assign an instructor to the department that would have been most to his mind. But the governors of the institution were glad to secure the services of so promising a scholar; and Mr Child, whose preference for an academic career was decided, had felt that it was wise to accept such positions as the college could offer, leaving exacter adjustments to time and circumstances. Meantime he had devoted his whole leisure to the pursuit of his favorite studies. His first fruits were a volume entitled Four Old Plays[2] published in 1848, when he was but twenty-three years old. This was a remarkably competent performance. The texts are edited with judgment and accuracy; the introduction shows literary discrimination as well as sound scholarship, and the glossary and brief notes are thoroughly good. There are no signs of immaturity in the book, and it is still valued by students of our early drama.

The leave of absence granted to Mr Child in 1849 came at a most favorable moment. His health had suffered from close application to work, and a change of climate had been advised by his physicians. His intellectual and scholarly development, too, had reached that stage in which foreign study and travel were certain to be most stimulating and fruitful. He was amazingly apt, and two years of opportunity meant much more to him than to most men. He returned to take up the duties of his new office a trained and mature scholar, at home in the best methods and traditions of German universities, yet with no sacrifice of his individuality and intellectual independence.

While in Germany Mr Child studied at Berlin and Göttingen, giving his time mostly[Pg xxv] to Germanic philology, then cultivated with extraordinary vigor and success. The hour was singularly propitious. In the three or four decades preceding Mr Child's residence in Europe, Germanic philology (in the wider sense) had passed from the stage of "romantic" dilettantism into the condition of a well-organized and strenuous scientific discipline, but the freshness and vivacity of the first half of the century had not vanished. Scholars, however severe, looked through the form and strove to comprehend the spirit. The ideals of erudition and of a large humanity were not even suspected of incompatibility. The imagination was still invoked as the guide and illuminator of learning. The bond between antiquity and mediævalism and between the Middle Ages and our own century was never lost from sight. It was certainly fortunate for American scholarship that at precisely this juncture a young man of Mr Child's ardent love of learning, strong individuality, and broad intellectual sympathies was brought into close contact with all that was most quickening in German university life. He attended lectures on classical antiquity and philosophy, as well as on Germanic philology; but it was not so much by direct instruction that he profited as by the inspiration which he derived from the spirit and the ideals of foreign scholars, young and old. His own greatest contribution to learning, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, may even, in a very real sense, be regarded as the fruit of these years in Germany. Throughout his life he kept a picture of William and James Grimm on the mantel over his study fireplace.

Mr Child wrote no "dissertation," and returned to Cambridge without having attempted to secure a doctor's degree. Never eager for such distinctions, he had been unwilling to subject himself to the restrictions on his plan of study which candidacy for the doctorate would have imposed. Three years after, however, in 1854, he was surprised and gratified to receive from the University of Göttingen the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, accompanied by a special tribute of respect from that institution. Subsequently he received the degree of LL. D. from Harvard (in 1884) and that of L. H. D. from Columbia (in 1887); but the Göttingen Ph. D., coming as it did at the outset of his career, was in a high degree auspicious.

The Boylston Professorship of Rhetoric and Oratory, to which, as has been already mentioned, Mr Child succeeded on his return to America toward the end of 1851, was no sinecure. In addition to academic instruction of the ordinary kind, the duties of the chair included the superintendence and criticism of a great quantity of written work, in the nature of essays and set compositions prepared by students of all degrees of ability. For twenty-five years Mr Child performed these duties with characteristic punctuality and devotion, though with increasing distaste for the drudgery which they involved. Meantime a great change had come over Harvard: it had developed from a provincial college into a national seminary of learning, and the introduction of the "elective system"—corresponding to the "Lernfreiheit" of Germany—had enabled it to become a university in the proper sense of the word. One result of the important reform just referred to was the establishment of a Professorship of English, entirely distinct from the old chair of Rhetoric. This took place on May 8, 1876, and on the 20th of the next month Mr Child was transferred to the new professorship. His duties as an instructor were now thoroughly congenial, and he continued to perform them with unabated vigor to the end. In the onerous details of administrative and advisory work, inseparable, according to our exacting American system, from the position of a university professor, he was equally faithful and untiring. For thirty years he acted as secretary of the Library Council, and in all that time he was absent from but three meetings. As chairman of the Department of English and of the Division of Modern Languages, and as a member of many important committees, he was ever prodigal of time and effort. How steadily he attended to the regular duties of the class-room, his pupils, for fifty years, are[Pg xxvi] the best witnesses. They, too, will best understand the satisfaction he felt that, in the fiftieth year of his teaching, he was not absent from a single lecture. No man was ever less a formalist; yet the most formal of natures could not, in the strictest observance of punctilio, have surpassed the regularity with which he discharged, as it were spontaneously, the multifarious duties of his position.

Throughout his service as professor of rhetoric, Mr Child, hampered though he was by the requirements of his laborious office, had pursued with unquenchable ardor the study of the English language and literature, particularly in their older forms, and in these subjects he had become an authority of the first rank long before the establishment of the English chair enabled him to arrange his university teaching in accordance with his tastes. Soon after he returned from Germany he undertook the general editorial supervision of a series of the 'British Poets,' published at Boston in 1853 and several following years, and extending to some hundred and fifty volumes. Out of this grew, in one way or another, his three most important contributions to learning: his edition of Spenser, his Observations on the Language of Chaucer and Gower, and his English and Scottish Popular Ballads.

Mr Child's Spenser appeared in 1855.[3] Originally intended, as he says in the preface, as little more than a reprint of the edition published in 1839 under the superintendence of Mr George Hillard, the book grew upon his hands until it had become something quite different from its predecessor. Securing access to old copies of most of Spenser's poems, Mr Child subjected the text to a careful revision, which left little to be done in this regard. His Life of Spenser was far better than any previous biography, and his notes, though brief, were marked by a philological exactness to which former editions could not pretend. Altogether, though meant for the general reader and therefore sparingly annotated, Mr Child's volumes remain, after forty years, the best edition of Spenser in existence.

The plan of the 'British Poets' originally contemplated an edition of Chaucer, which Mr Child was to prepare. Becoming convinced, however, that the time was not ripe for such a work, he abandoned this project, and to the end of his life he never found time to resume it. Thomas Wright's print of the Canterbury Tales[4] from the Harleian MS. 7334 had, however, put into his hands a reasonably faithful reproduction of an old text, and he turned his attention to a minute study of Chaucer's language. The outcome was the publication, in the Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences for 1863, of the great treatise to which Mr Child gave the modest title of Observations on the Language of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. It is difficult, at the present day, to imagine the state of Chaucer philology at the moment when this paper appeared. Scarcely anything, we may say, was known of Chaucer's grammar and metre in a sure and scientific way. Indeed, the difficulties to be solved had not even been clearly formulated. Further, the accessible mass of evidence on Anglo-Saxon and Middle English was, in comparison with the stores now at the easy command of every tyro, almost insignificant. Yet, in this brief treatise, Mr Child not only defined the problems, but provided for most of them a solution which the researches of younger scholars have only served to substantiate. He also gave a perfect model of the method proper to such inquiries—a method simple, laborious, and exact. The Observations were subsequently rearranged and condensed, with Professor Child's permission, by Mr A. J. Ellis for his work On Early English Pronunciation; but only those who have studied them in their original form can appreciate their merit fully. "It ought never to be forgotten," writes Pro[Pg xxvii]fessor Skeat, "that the only full and almost complete solution of the question of the right scansion of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales is due to what Mr Ellis rightly terms 'the wonderful industry, acuteness, and accuracy of Professor Child.'" Had he produced nothing else, this work, with its pendant, the Observations on Gower,[5] would have assured him a high place among those very few scholars who have permanently settled important problems of linguistic science.

Mr Child's crowning work, however, was the edition of the English and Scottish Popular Ballads, which the reader now has before him. The history of this is the history of more than half a lifetime.

The idea of the present work grew out of Mr Child's editorial labors on the series of the 'British Poets,' already referred to. For this he prepared a collection in eight small volumes (1857-58) called English and Scottish Ballads.[6] This was marked by the beginnings of that method of comparative study which is carried out to its ultimate issues in the volumes of the present collection. The book circulated widely, and was at once admitted to supersede all previous attempts in the same field. To Mr Child, however, it was but the starting-point for further researches. He soon formed the plan of a much more extensive collection on an altogether different model. This was to include every obtainable version of every extant English or Scottish ballad, with the fullest possible discussion of related songs or stories in the "popular" literature of all nations. To this enterprise he resolved, if need were, to devote the rest of his life. His first care was to secure trustworthy texts. In his earlier collection he had been forced to depend almost entirely on printed books. No progress, he was convinced, could be made till recourse could be had to manuscripts, and in particular to the Percy MS. Accordingly he directed his most earnest efforts to securing the publication of the entire contents of the famous folio. The Percy MS. was at Ecton Hall, in the possession of the Bishop's descendants, who would permit no one even to examine it. Two attempts were made by Dr Furnivall, at Mr Child's instance, to induce the owners to allow the manuscript to be printed,—one as early as 1860 or 1861, the other in 1864,—but without avail. A third attempt was more successful, and in 1867-68 the long-secluded folio was made the common property of scholars in an edition prepared by Professor Hales and Dr Furnivall.[7]

The publication of the Percy MS. not only put a large amount of trustworthy material at the disposal of Mr Child; it exposed the full enormity of Bishop Percy's sins against popular tradition. Some shadow of suspicion inevitably fell on all other ballad collections. It was more than ever clear to Mr Child that he could not safely take anything at second hand, and he determined not to print a line of his projected work till he had exhausted every effort to get hold of whatever manuscript material might be in existence. His efforts in this direction continued through many years. A number of manuscripts were in private hands; of some the whereabouts was not known; of others the existence was not suspected. But Mr Child was untiring. He was cordially assisted by various scholars, antiquaries, and private gentlemen, to whose coöperation ample testimony is borne in the Advertisements prefixed to the volumes in the present work. Some manuscripts were secured[Pg xxviii] for the Library of Harvard University—notably Bishop Percy's Papers, the Kinloch MSS, and the Harris MS.,[8]—and of others careful copies were made, which became the property of the same library. In all these operations the indispensable good offices of Mr William Macmath, of Edinburgh, deserve particular mention. For a long series of years his services were always at Mr Child's disposal. His self-sacrifice and generosity appear to have been equalled only by his perseverance and wonderful accuracy. But for him the manuscript basis of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads would have been far less strong than it is.

Gradually, then, the manuscript materials came in, until at last, in 1882, Mr Child felt justified in beginning to print. Other important documents were, however, discovered or made accessible as time went on. Especially noteworthy was the great find at Abbotsford (see the Advertisement to Part VIII). In 1877 Dr David Laing procured, "not without difficulty," leave to prepare for Mr Child a copy of the single manuscript of ballads then known to remain in the library at Abbotsford. This MS., entitled "Scottish Songs," was so inconsiderable, in proportion to the accumulations which Sir Walter Scott had made in preparing his Border Minstrelsy, that further search seemed to be imperatively necessary. In 1890 permission to make such a search, and to use the results, was given by the Honorable Mrs Maxwell-Scott. The investigation, made by Mr Macmath, yielded a rich harvest of ballads, which were utilized in Parts VII-IX. To dwell upon the details would be endless. The reader may see a list of the manuscript sources at pp. 397 ff. of the fifth volume; and, if he will observe how scattered they were, he will have no difficulty in believing that it required years, labor, and much delicate negotiation to bring them all together. One manuscript remained undiscoverable, William Tytler's Brown MS., but there is no reason to believe that this contained anything of consequence that is not otherwise known.[9]

Meanwhile, concurrently with the toil of amassing, collating, and arranging texts, went on the far more arduous labor of comparative study of the ballads of all nations; for, in accordance with Mr Child's plan it was requisite to determine, in the fullest manner, the history and foreign relations of every piece included in his collection. To this end he devoted much time and unwearied diligence to forming, in the Library of the University, a special collection of "Folk-lore," particularly of ballads, romances, and Märchen. This priceless collection, the formation of which must be looked on as one of Mr Child's most striking services to the university, numbers some 7000 volumes. But these figures by no means represent the richness of the Library in the departments concerned, or the services of Mr Child in this particular. Mediæval literature in all its phases was his province, and thousands of volumes classified in other departments of the University Library bear testimony to his vigilance in ordering books, and his astonishing bibliographical knowledge. Very few books are cited in the present collection which are not to be found on the shelves of this Library.

In addition, Mr Child made an effort to stimulate the collection of such remains of the traditional ballad as still live on the lips of the people in this country and in the British Islands. The harvest was, in his opinion, rather scanty; yet, if all the versions thus recovered from tradition were enumerated, the number would not be found inconsiderable. Enough was done, at all events, to make it clear that little or nothing of value remains to be recovered in this way.

To readers familiar with such studies, no comment is necessary, and to those who are unfamiliar with them, no form of statement can convey even a faint impression of the industry, the learning, the acumen, and the literary skill which these processes required. In writing the history of a single ballad, Mr Child was sometimes forced to examine[Pg xxix] hundreds of books in perhaps a dozen different languages. But his industry was unflagging, his sagacity was scarcely ever at fault, and his linguistic and literary knowledge seemed to have no bounds. He spared no pains to perfect his work in every detail, and his success was commensurate with his efforts. In the Advertisement to the Ninth Part (1894), he was able to report that the three hundred and five numbers of his collection comprised the whole extant mass of this traditional material, with the possible exception of a single ballad.[10]

In June, 1896, Mr Child concluded his fiftieth year of service as a teacher in Harvard College. He was at this time hard at work on the Tenth and final Part, which was to contain a glossary, various indexes, a bibliography, and an elaborate introduction on the general subject. For years he had allowed himself scarcely any respite from work, and, in spite of the uncertain condition of his health,—or perhaps in consequence of it,—he continued to work at high pressure throughout the summer. At the end of August he discovered that he was seriously ill. He died at Boston on the 11th day of September. He had finished his great work except for the introduction and the general bibliography. The bibliography was in preparation by another hand and has since been completed. The introduction, however, no other scholar had the hardihood to undertake. A few pages of manuscript,—the last thing written by his pen,—almost illegible, were found among his papers to show that he had actually begun the composition of this essay, and many sheets of excerpts testified to the time he had spent in refreshing his memory as to the opinions of his predecessors, but he had left no collectanea that could be utilized in supplying the Introduction itself. He was accustomed to carry much of his material in his memory till the moment of composition arrived, and this habit accounts for the fact that there are no jottings of opinions and no sketch of precisely what line of argument he intended to take.

Mr Child's sudden death was felt as a bitter personal loss, not only by an unusually large circle of attached friends in both hemispheres, but by very many scholars who knew him through his works alone. He was one of the few learned men to whom the old title of "Master" was justly due and freely accorded. With astonishing erudition, which nothing seemed to have escaped, he united an infectious enthusiasm and a power of lucid and fruitful exposition that made him one of the greatest of teachers, and a warmth and openness of heart that won the affection of all who knew him. In most men, however complex their characters, one can distinguish the qualities of the heart, in some degree, from the qualities of the head. In Professor Child no such distinction was possible, for all the elements of his many-sided nature were fused in his marked and powerful individuality. In his case, the scholar and the man cannot be separated. His life and his learning were one; his work was the expression of himself.

As an investigator Professor Child was at once the inspiration and the despair of his disciples. Nothing could surpass the scientific exactness of his methods and the unwearied diligence with which he conducted his researches. No possible source of information could elude him; no book or manuscript was too voluminous or too unpromising for him to examine on the chance of its containing some fact that might correct or supplement his material, even in the minutest point. Yet these qualities of enthusiastic accuracy and thoroughness, admirable as they undoubtedly were, by no means dominated him. They were always at the command of the higher qualities of his genius,—sagacity, acumen, and a kind of sympathetic and imaginative power in which he stood almost alone among recent scholars. No detail of language or tradition or archæology was to him a mere lifeless fact; it was transmuted into something vital, and became a part of that universal humanity which always moved him wherever he found it, whether in the pages of a mediæval[Pg xxx] chronicle, or in the stammering accents of a late and vulgarly distorted ballad, or in the faces of the street boys who begged roses from his garden. No man ever felt a keener interest in his kind, and no scholar ever brought this interest into more vivifying contact with the technicalities of his special studies. The exuberance of this large humanity pervades his edition of the English and Scottish ballads. Even in his last years, when the languor of uncertain health sometimes got the better, for a season, of the spirit with which he commonly worked, some fresh bit of genuine poetry in a ballad, some fine trait of pure nature in a stray folk-tale, would, in an instant, bring back the full flush of that enthusiasm which he must have felt when the possibilities of his achievement first presented themselves to his mind in early manhood. For such a nature there was no old age.

From this ready sympathy came that rare faculty—seldom possessed by scholars—which made Professor Child peculiarly fit for his greatest task. Few persons understand the difficulties of ballad investigation. In no field of literature have the forger and the manipulator worked with greater vigor and success. From Percy's day to our own it has been thought an innocent device to publish a bit of one's own versifying, now and then, as an "old ballad" or an "ancient song." Often, too, a late stall-copy of a ballad, getting into oral circulation, has been innocently furnished to collectors as traditional matter. Mere learning will not guide an editor through these perplexities. What is needed is, in addition, a complete understanding of the "popular" genius, a sympathetic recognition of the traits that characterize oral literature wherever and in whatever degree they exist. This faculty, which even the folk has not retained, and which collectors living in ballad-singing and tale-telling times have often failed to acquire, was vouchsafed by nature herself to this sedentary scholar. In reality a kind of instinct, it had been so cultivated by long and loving study of the traditional literature of all nations that it had become wonderfully swift in its operations and almost infallible. A forged or retouched piece could not deceive him for a moment; he detected the slightest jar in the genuine ballad tone. He speaks in one place of certain writers "who would have been all the better historians for a little reading of romances." He was himself the better interpreter of the poetry of art for this keen sympathy with the poetry of nature.

Constant association with the spirit of the folk did its part in maintaining, under the stress of unremitting study and research, that freshness and buoyancy of mind which was the wonder of all who met Professor Child for the first time, and the perpetual delight of his friends and associates. It is impossible to describe the charm of his familiar conversation. There was endless variety without effort. His peculiar humor, taking shape in a thousand felicities of thought and phrase that fell casually and as it were inevitably from his lips, exhilarated without reaction or fatigue. His lightest words were full of fruitful suggestion. Sudden strains of melancholy or high seriousness were followed, in a moment, by flashes of gaiety almost boyish. And pervading it all one felt the attraction of his personality and the goodness of his heart.

Professor Child's humor was not only one of his most striking characteristics as a man; it was of constant service to his scholarly researches. Keenly alive to any incongruity in thought or fact, and the least self-conscious of men, he scrutinized his own nascent theories with the same humorous shrewdness with which he looked at the ideas of others. It is impossible to think of him as the sponsor of some hypotheses which men of equal eminence have advanced and defended with passion; and, even if his goodness of nature had not prevented it, his sense of the ridiculous would not have suffered him to engage in the absurdities of philological polemics. In the interpretation of literature, his humor stood him in good stead, keeping his native sensibility under due control, so that it never degenerated into sentimentalism. It made him a marvelous interpreter of Chaucer, whose spirit he had caught to a degree attained by no other scholar or critic.

To younger scholars Professor Child was an influence at once stimulating and benignant. To confer with him was always to be stirred to greater effort, but, at the same time, the serenity of his devotion to learning chastened the petulance of immature ambition in others. The talk might be quite concrete, even definitely practical,—it might deal with indifferent matters; but, in some way, there was an irradiation of the master's nature that dispelled all unworthy feelings. In the presence of his noble modesty the bustle of self-assertion was quieted and the petty spirit of pedantic wrangling could not assert itself. However severe his criticism, there were no personalities in it. He could not be other than outspoken,—concealment and shuffling were abhorrent to him,—yet such was his kindliness that his frankest judgments never wounded; even his reproofs left no sting. With his large charity was associated, as its necessary complement in a strong character, a capacity for righteous indignation. "He is almost the only man I know," said one in his lifetime, "who thinks no evil." There could be no truer word. Yet when he was confronted with injury or oppression, none could stand against the anger of this just man. His unselfishness did not suffer him to see offences against himself, but wrong done to another roused him in an instant to protesting action.

Professor Child's publications, despite their magnitude and importance, are no adequate measure either of his acquirements or of his influence. He printed nothing about Shakspere, for example, yet he was the peer of any Shaksperian, past or present, in knowledge and interpretative power. As a Chaucer scholar he had no superior, in this country or in Europe: his published work was confined, as we have seen, to questions of language, but no one had a wider or closer acquaintance with the whole subject. An edition of Chaucer from his hand would have been priceless. His acquaintance with letters was not confined to special authors or centuries. He was at home in modern European literature and profoundly versed in that of the Middle Ages. In his immediate territory,—English,—his knowledge, linguistic and literary, covered all periods, and was alike exact and thorough. His taste and judgment were exquisite, and he enlightened every subject which he touched. As a writer, he was master of a singularly felicitous style, full of individuality and charm. Had his time not been occupied in other ways, he would have made the most delightful of essayists.

Fortunately, Professor Child's courses of instruction in the university—particularly those on Chaucer and Shakspere—gave him an opportunity to impart to a constantly increasing circle of pupils the choicest fruits of his life of thought and study. In his later years he had the satisfaction to see grow up about him a school of young specialists who can have no higher ambition than to be worthy of their master. But his teaching was not limited to these,—it included all sorts and conditions of college students; and none, not even the idle and incompetent, could fail to catch something of his spirit. One thing may be safely asserted: no university teacher was ever more beloved.

And with this may fitly close too slight a tribute to the memory of a great scholar and a good man. Many things remain unsaid. His gracious family life, his civic virtues, his patriotism, his bounty to the poor,—all must be passed by with a bare mention, which yet will signify much to those who knew him. In all ways he lived worthily, and he died having attained worthy ends.

G. L. Kittredge.

[1] C. E. Norton, 'Francis James Child,' in the Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, XXXII, 334, 335; reprinted, with some additions, in the Harvard Graduates' Magazine, VI, 161-169 (Boston, 1897). I have used this biographical sketch freely in my brief account of Professor Child's boyhood.

[2] Four Old Plays | Three Interludes: Thersytes Jack Jugler | and Heywoods Pardoner and Frere: | and Jocasta a Tragedy | by Gascoigne and | Kinwelmarsh | with an | Introduction and Notes | Cambridge | George Nichols | MDCCCXLVIII. The editor's name does not appear in the title-page, but the Preface is signed with the initials F. J. C. Jocasta was printed from Steevens's copy of the first edition of Garcoigne's Posies, which had come into Mr Child's possession.

[3] The Poetical Works of Edmund Spenser. The text carefully revised, and illustrated with notes, original and selected, by Francis J. Child. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1855. 5 vols.

[4] The Canterbury Tales of Geoffrey Chaucer. A new text, with illustrative notes. Edited by Thomas Wright. London, printed for the Percy Society, 1847-51. 3 vols.