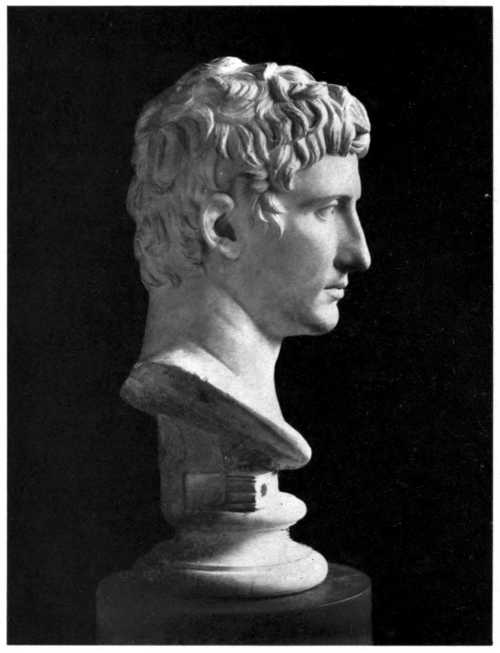

AUGUSTUS.

Bust in the Museum of Fine Arts. Boston.

Title: A History of Roman Literature

Author: Harold North Fowler

Release date: February 22, 2014 [eBook #44975]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Turgut Dincer, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, A History of Roman Literature, by Harold North Fowler

TWENTIETH CENTURY TEXT-BOOKS

BY

HAROLD N. FOWLER, Ph.D.

PROFESSOR IN THE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN

OF WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY

NEW YORK AND LONDON

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Copyright, 1903

By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

PRINTED AT THE APPLETON PRESS,

NEW YORK, U. S. A.

This book is intended primarily for use as a text-book in schools and colleges. I have therefore given more dates and more details about the lives of authors than are in themselves important, because dates are convenient aids to memory, as they enable the learner to connect his new knowledge with historical facts he may have learned before, while biographical details help to endow authors with something of concrete personality, to which the learner can attach what he learns of their literary and intellectual activity.

Extracts from Latin authors are given, with few exceptions, in English translation. I considered the advisability of giving them in Latin, but concluded that extracts in Latin would probably not be read by most young readers, and would therefore do less good than even imperfect translations. Moreover, the texts of the most important works are sure to be at hand in the schools, and books of selections, such as Cruttwell and Banton’s Specimens of Roman Literature, Tyrrell’s Anthology of Latin Poetry, and Gudeman’s Latin Literature of the Empire, are readily accessible. I am responsible for all translations not accredited to some other translator. In making my translations, I have employed blank verse to represent Latin hexameters; but the selections from the Æneid are given in Conington’s rhymed version, and in some other cases I have used translations of hexameters into metres other than blank verse.

In writing of the origin of Roman comedy, I have not mentioned the dramatic satura. Prof. George L. Hendrickson has pointed out (in the American Journal of Philology, vol. xv, pp. 1-30) that the dramatic satura never really existed, but was invented in Roman literary history because Aristotle, whose account of the origin of comedy was closely followed by the Roman writers, found the origin of Greek comedy in the satyr-drama.

The greater part of the book is naturally taken up with the extant literary works and their authors; but I have devoted some space to the lives and works of authors whose writings are lost. This I have done, not because I believe that the reader should burden his memory with useless details, but partly in order that this book may be of use as a book of reference, and partly because the mention of some of the lost works and their authors may impress upon the reader the fact that something is known of many writers whose works have survived, if at all, only in detached fragments. Not a few of these writers were important in their day, and exercised no little influence upon the progress of literature. Of the whole mass of Roman literary production only a small part—though fortunately in great measure the best part—now exists, and it is only by remembering how much has been lost that the modern reader can appreciate the continuity of Roman literature.

The literature of the third, fourth, and fifth centuries after Christ is treated less fully than that of the earlier times, but its importance to later European civilization has been so great that a summary treatment of it should be included even in a book of such limited scope as this.

The Bibliography will, I hope, be found useful. It is by no means exhaustive, but may serve as a guide to those who have not access to libraries. The purpose of the Chronological Table is not so much to serve as a finding-list of dates as to show at a glance what authors were living and working at any given time. In the Index the names of all Latin writers mentioned in the book are to be found, together with references to numerous topics and to some of the more important historical persons.

Besides the works of the Roman authors, I have consulted the general works mentioned in the Bibliography and numerous other books and special articles. I have made most use of Teuffel’s History of Roman Literature, Schanz’s Römische Litteraturgeschichte, and Mackail’s admirable Latin Literature.

My thanks are due to my colleague, Prof. Samuel Ball Platner, who read the book in manuscript and made many valuable suggestions, and to Professor Perrin, who read not only the manuscript, but also the proof, and suggested not a few desirable changes.

Harold N. Fowler.

Cleveland, Ohio.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I.— | Introduction—Early Roman literature—Tragedy | 1 |

| II.— | Comedy | 17 |

| III.— | Early prose—The Scipionic Circle—Lucilius | 32 |

| IV.— | Lucretius | 47 |

| V.— | Catullus—Minor poets | 56 |

| VI.— | Cicero | 65 |

| VII.— | Cæsar—Sallust—Other prose writers | 83 |

| VIII.— | The patrons of literature—Virgil | 97 |

| IX.— | Horace | 114 |

| X.— | Tibullus—Propertius—The lesser poets | 128 |

| XI.— | Ovid | 143 |

| XII.— | Livy—Other Augustan prose writers | 156 |

| XIII.— | Tiberius to Vespasian | 169 |

| XIV.— | The Flavian emperors—The silver age | 194 |

| XV.— | Nerva and Trajan | 211 |

| XVI.— | The emperors after Trajan—Suetonius—Other writers | 226 |

| XVII.— | Literary innovations | 235 |

| XVIII.— | Early Christian writers | 244 |

| XIX.— | Pagan literature of the third century | 253 |

| XX.— | The fourth and fifth centuries | 259 |

| XXI.— | Conclusion | 278 |

| Appendix I.—Bibliography | 285 | |

| Appendix II.—Chronological table | 297 | |

| Index | 303 | |

| FACING PAGE |

|

| Augustus, bust in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, | Frontispiece |

| Cicero, bust in the Vatican Museum, Rome | 65 |

| Cæsar, bust in the Museum at Naples | 83 |

| Virgil and two Muses, mosaic in the Bardo Museum, Tunis | 113 |

INTRODUCTION—EARLY ROMAN LITERATURE—TRAGEDY

Importance of Roman literature—The Romans a practical people—The Latin language—Political purpose of Roman writings—Divisions of Roman literature—Elements of a native Roman literature—Appius Claudius Cæcus—Imitation of Greek literature—L. Livius Andronicus, about 284 to about 204 B. C.—Gnæus Nævius, about 270-199 B. C.—Q. Ennius, 239-169 B. C.—His Tragedies—The Annales—M. Pacuvius, 220 to about 130 B. C.—L. Accius, 170 to after 100 B. C.—The Decay of Tragedy—The Roman theatre, actors and costumes.

Importance of Roman literature. Roman literature, while it lacks the brilliant originality and the delicate beauty which characterize the works of the great Greek writers, is still one of the great literatures of the world, and it possesses an importance for us which is even greater than its intrinsic merits (great as they are) would naturally give it. In the first place, Roman literature has preserved to us, in Latin translations and adaptations, many important remains of Greek literature which would otherwise have been lost, and in the second place, the political power of the Romans, embracing nearly the whole known world, made the Latin language the most widely spread of all languages, and thus caused Latin literature to be read in all lands and to influence the literary development of all the peoples of Europe.

The Romans were a practical race, not gifted with much poetic imagination, but with great ability to organize their state and their army and to accomplish whatever they determined to do. The Romans practical. They had come into Italy with a number of related tribes from the north and had settled in a place on the bank of the Tiber, where they were exposed to attacks from the Etruscans and other neighbors. They were thus forced from the beginning to fortify their city, and live close together within the walls. This made the early development of a form of city government both natural and necessary, and turned the Roman mind toward political organization. Attention to political and military affairs. At the same time, the attacks of external enemies forced the Romans to pay attention to the organization and support of an army. So, from the time of the foundation of their city by the Tiber, the Romans turned their attention primarily to politics and war. The effect upon their language and literature is clearly seen. Their language is akin to Greek, and like Greek is one of the Indo-European family of languages, to which English and the other most important languages of Europe belong. The Latin language. It started with the same material as Greek, but while Greek developed constantly more variety, more delicacy, and more flexibility, Latin is fixed and rigid, a language adapted to laws and commands rather than to the lighter and more graceful kinds of utterance. Circumstances, aided no doubt by the natural bent of their minds, tended to make the Romans political, military, and practical, rather than artistic.

Roman literature, as might be expected after what has just been said, is often not the spontaneous outpouring of literary genius, but the means by which some practical ends or purposes are to be attained. Almost from first to last, the writings of Roman authors have a political purpose, and the influence of political events upon the literature[Pg 3] is most marked. Political purpose of Roman writings. Even those kinds of Roman literature which seem at first sight to have the least connection with political matters have nevertheless a political purpose. Plays were written to enhance the splendor of public festivals provided by office holders who were at the same time office seekers and hoped to win the favor of the people by successful entertainments; history was written to teach the proper methods of action for future use or (sometimes) to add to the influence of living leaders of the state by calling to mind the great deeds of their ancestors; epic and lyric poems were composed to glorify important persons at Rome, or at least to prove the right of Rome to the foremost place among the nations by giving her a literature worthy to rank with that of the Greeks.

The development of Roman literature is closely connected with political events, and its three great divisions correspond to the divisions of Roman political history. Divisions of Roman literature. The first or Republican Period extends from the beginning of Roman literature after the first Punic war (240 B. C.) to the battle of Actium in 31 B. C. The second or Augustan Period, from 31 B. C. to 14 A. D., is the period in which the institutions of the republic were transformed to serve the purposes of the monarchy. The “Golden Age” of Roman literature comprises the last part of the Republican Period and the whole Augustan Period, from 81 B. C. to 14 A. D. The third or Imperial Period lasts from 14 A. D. to the beginning of the Middle Ages. The first part of this period, from 14 to 117 A. D., is called the “Silver Age.” In the first period the Romans learn to imitate Greek literature and develop their language until it is capable of fine literary treatment, and in the latter part of this time they produce some of their greatest works, especially in prose. The second period, made illustrious by Horace and Virgil, is the time when[Pg 4] Roman poetry reaches its greatest height. The third period is a time of decline, sometimes rapid, sometimes retarded for a while, during which Roman literature shows few great works and many of very slight literary value. Throughout the first and second periods, and even for the most part in the third period, Latin literature is produced almost entirely at Rome, is affected by changes in the city, and reflects the sentiments of the city population. It is therefore proper to speak of Roman literature, rather than Latin literature, for that which interests us is the literature of the city by the Tiber and of the civilization with which the city is identified, rather than works written in the Latin language.

The beginning of a real literature at Rome was made by a foreigner of Greek birth, and naturally took the form of an imitation of Greek works. Elements of native Roman literature. This would undoubtedly have been the case, even if the first professional author had been a native Roman, for the Romans had for some time been in close touch with the Greeks of Italy, and Greek literature presented itself to them as a finished product, calling for their admiration and inciting them to imitate it. Nevertheless there were in existence at Rome in early times materials from which a native literature might have arisen if the Greek influence had not been so strong as to prevent their development. The early Romans sang songs at weddings and at harvest festivals, chanted hymns to the gods, and were familiar with rude popular performances which might have given rise to a native drama. The words of such songs and performances were of course, for the most part at least, rhythmical, but few if any of them were committed to writing until much later times. The art of writing was, however, known to the Romans as early as the sixth century B. C., for the Greek colonies on the coast of Italy must have had trade connections with the Romans at a very early time, and wri[Pg 5]ting was thoroughly familiar to the Greeks by the time Rome was two centuries old.

From early times the Romans kept lists of officials, records of prodigies, lists of the dies fasti, i.e., of the days on which it was lawful to conduct public business, and other simple records. The twelve tables of the laws are said to have been written in 451 and 450 B. C., and these had some influence on Roman prose, for they were the first attempt at connected prose in the Latin language. No doubt other laws and probably also treaties were written in Latin and preserved at an early date. Funeral orations called for some practise in oratory, but probably not for careful preparation, and certainly not for composition in writing in the early days of Rome. Appius Claudius Cæcus. The first Roman speech known to have been written out for publication is the speech delivered in 280 B. C., by the aged Appius Claudius Cæcus, in which he urged the rejection of the terms of peace offered by Pyrrhus. This speech was known and read at Rome for two centuries after the death of its author. A collection of sayings or proverbs was also current under the name of Claudius, and he was actively interested in adapting more perfectly to the Latin language the alphabet which the Romans had received from the Greeks, and in fixing the spelling of Latin words.

All this is, however, not so much literature as the material from which literature might have developed if Rome had been removed from the sphere of Greek influence. Since that was not the case, these first steps toward a national literature led to nothing, though they show that the Romans had some originality, and help us to understand some of the peculiarities of Roman literature as distinguished from its Greek prototype. Still Roman literature is a literature of imitation, and the beginning of it was made by a Greek named Andronicus, who was brought to Rome after the capture of Tarentum in

272 B. C. when he was still a boy. At Rome he was the slave of M. Livius Salinator, whose children he instructed in Greek and Latin. When set free, he took the name of Lucius Livius Andronicus, and continued to teach. L. Livius Andronicus. As there were no Latin books which he could use in teaching, he conceived the idea of translating Homer’s Odyssey into Latin, thereby making the beginning of Latin literature. His translation of the Odyssey was rude and imperfect. Andronicus made no attempt to reproduce in Latin the hexameter verse of Homer, but employed the native Saturnian verse (see page 7), probably because it seemed to him better fitted to the Latin language than the more stately hexameter. After the first Punic war, at the Ludi Romani in 240 B. C., Andronicus produced and put upon the stage Latin translations of a Greek tragedy and a Greek comedy. In these and his later dramas he retained the iambic and trochaic metres of the originals, and his example was followed by his successors. He also composed hymns for public occasions. Of his works only a few fragments are preserved, hardly more than enough to show that they had little real literary merit. But he had made a beginning, and long before his death, which took place about 204 B. C., his successors were advancing along the lines he had marked out.

Gnæus Nævius, a freeborn citizen of a Latin city in Campania, was the first native Latin poet of importance. Gnæus Nævius. He was a soldier in the first Punic war, at the end of which, while still a young man, he came to Rome, where he devoted himself to poetry. He was a man of independent spirit, not hesitating to attack in his comedies and other verses the most powerful Romans, especially the great family of the Metelli. For many years he maintained his position, but at last the Metelli brought about his imprisonment and banishment, and he died in exile in 199 B. C., at about[Pg 7] seventy years of age. His dramatic works were numerous, both tragedies and comedies, for the most part translations and adaptations from the Greek, but alongside of these he produced also plays based upon Roman legends. These were called fabulæ prætextæ or prætextatæ, “plays of the purple stripe,” because the characters wore Roman costumes. In one of these plays, the Romulus (or in two, if the Lupus or “Wolf” is not the Romulus under another title), he dramatized the story of Romulus and Remus, and in another, the Clastidium, the defeat (in 222 B. C.) of the Insubrians by M. Claudius Marcellus and Cn. Cornelius Scipio. In his later years he turned to epic poetry and wrote in Saturnian verse the history of the first Punic war, introduced by an account of the legendary history of Rome from the departure of Æneas for Italy after the fall of Troy. This poem was read and admired for many years, and parts of it were imitated by Virgil in the Æneid. Nævius also wrote other poems, called Satires, on various subjects, partly, but not entirely, in Saturnian metre. Of all these works only inconsiderable fragments remain. They show, however, that Nævius was a poet of real power, and that with him the Latin language was beginning to develop some fitness for literary use. His epitaph, preserved by Aulus Gellius, will serve not only to show the stiff and monotonous rhythm of the Saturnian verse, but also, since it was probably written by Nævius himself, to exhibit his proud consciousness of superiority:

Nævius had a right to be proud. He had made literature a real force at Rome, able to contend with the great men of the city; he had invented the drama with Roman characters, and had written the first national epic poem. In doing all this he had at the same time added to the richness and grace of the still rude Latin language. But great as were the merits of Nævius, he was surpassed in every way by his successor.

Quintus Ennius, a poet of surprising versatility and power, was born at Rudiæ, in Calabria, in 239 B. C. Quintus Ennius. While he was serving in the Roman army in Sardinia, in 204 B. C., he met with M. Porcius Cato, who took him home to Rome. Here Ennius gave lessons in Greek and translated Greek plays for the Roman stage. He became acquainted with several prominent Romans, among them the elder Scipio Africanus, went to Ætolia as a member of the staff of M. Fulvius Nobilior, and obtained full Roman citizenship in 184 B. C. His death was brought on by the gout in 169 B. C.

Various works of Ennius. The works of Ennius were many and various, including tragedies, comedies, a great epic poem, a metrical treatise on natural philosophy, a translation of the work of Euhemerus, in which he explained the nature of the gods and declared that they are merely famous men of old times,1 a poem on food and cooking, a series of Precepts, epigrams (in which the elegiac distich was used for the first time in Latin), and satires. His most important works were his tragedies and his great epic, the Annales.

The tragedies were, like those of Nævius, translations of the works of the great Greek tragedians and their less great, but equally popular, successors. His dramatic works. The titles and [Pg 9]some fragments of twenty-two of these plays are preserved, from which it is evident that Ennius sometimes translated exactly and sometimes freely, while he allowed himself at other times to depart from his Greek original even to the extent of changing the plot more or less. For the most part, however, the invention of the plot, the delineation of character, and the poetic imagery of his plays were due to the Greek dramatists whose works he presented in Latin form. To Ennius himself belong the skillful use of the Latin language, the ability to express in a new language the thoughts rather than the words of the Greek poets, and also such changes as were necessary to make the Greek tragedies appeal more strongly to a Roman audience. It is impossible to tell from the fragments just what changes were made, but the popularity of the plays, which continued long after the death of Ennius, proves that the changes attained their object and pleased the audience. The titles of two fabulæ prætextæ by Ennius are known, the Sabine Women, a dramatic presentation of the legend of the Rape of the Sabines, and Ambracia, a play celebrating the capture of Ambracia by M. Fulvius Nobilior. His comedies seem to have been neither numerous nor especially successful.

The Annales. The most important work of Ennius is his great epic in eighteen books, the Annales, in which he told the legendary and actual history of the Romans from the arrival of Æneas in Italy to his own time. In this work, as in his tragedies, he may be said to have followed in the way pointed out by Nævius, but the Annales mark an immense advance beyond the Bellum Punicum of Nævius. The monotonous and unpolished Saturnian metre could not, even in the most skillful hands, attain the dignity or the melodious cadences appropriate to great epic poems. Ennius therefore gave up the native Italian metre and wrote his[Pg 10] epic in hexameter verse in imitation of Homer. This was no easy matter, for the laws of the verse as it existed in Greek could not be applied without change to Latin, but Ennius modified them in some particulars and thus fixed the form of the Latin hexameter, at the same time establishing in great part the rules of Latin prosody. Only about six hundred lines of the Annales remain, and many of these are detached from their context, yet from these we can see that Ennius had much poetic imagination, great skill in the use of words, and great dignity of diction. The line At tuba terribili sonitu taratantara dixit shows at once his ability to make the sound of his words imitate the sound he wishes to describe (in this case that of a trumpet) and his liking for alliteration. This last quality is found in many Roman poets, but in none more frequently than Ennius.

The Annales continued to be read and admired even after the time of Virgil, though the Æneid soon took rank as the greatest Roman epic. Some of the lines of Ennius breathe the true Roman spirit of military pride and civic rectitude, as

or

or

Among the existing fragments are several which seem to have suggested to Virgil some of the passages in the Æneid, and there is no doubt that Virgil found Ennius worthy of imitation.

We may learn something of the character of Ennius from a passage of the Annales in which he is said,5 on the authority of the grammarian L. Ælius Stilo, to be describing himself: “A man of such a nature that no thought ever prompts him to do a bad deed either carelessly or maliciously; a learned, faithful, pleasant man, eloquent, contented and happy, witty, speaking fit words in season, courteous, and of few words, possessing much ancient buried lore; a man whom old age made wise in customs old and new and in the laws of many ancients, both gods and men; one who knew when to speak and when to be silent.”

Ennius was the first great epic poet at Rome. After him epic poetry was neglected, until it was taken up again a hundred years later. Continued production of tragedies, but not of epics. Tragedy, however the other branch of literature in which Ennius chiefly excelled, was cultivated without interruption, for it had become usual to produce tragedies at the chief festivals of the city and on other public occasions, and new plays were therefore constantly in demand. But as gladiatorial shows grew more frequent and more magnificent, tragedy declined in popularity, though tragedies continued to be written, and even acted. The development of Roman tragedy is, however, contained within a few generations, the professional authors of tragedies about whom we have any information are few, and their works are lost, with the exception of such fragments as have happened to be quoted by later writers. It is therefore best to continue the account of Roman tragedy now, even at the sacrifice of strict chronological order.

The successor of Ennius as a writer of tragedies was his nephew, Marcus Pacuvius, who was born at Brundusium in 220 B. C., but spent most of his life at Rome. Marcus Pacuvius. As an old [Pg 12]man he returned to southern Italy, and died at Tarentum about 130 B. C. He was a painter, as well as a writer of tragedies, and it may be due to his activity as a painter that his plays were comparatively few. The titles of twelve tragedies are known, in addition to one fabula prætexta, the Paulus, written in honor of the victory of L. Æmilius Paulus over King Perseus in the battle of Pydna (168 B. C.). These plays are all lost, and the existing fragments (about 400 lines) are unsatisfactory. Cicero considered Pacuvius the greatest Roman tragic writer, and Horace speaks of him as “learned.” Probably this epithet refers to his careful use of language as well as to his knowledge of the less popular legends of Greek mythology. The extant fragments show more ease and grace of style than do those of Ennius, and great richness of vocabulary. Some of the words used are not found elsewhere, and seem to have been invented by Pacuvius himself; at any rate they did not come into ordinary use. Of the real dramatic ability of Pacuvius we can not judge, but his literary skill is evident even from the poor fragments we have. We may therefore believe that Cicero’s favorable judgment of him was in some measure justified.

The last important writer of tragedies, and probably the greatest of all, was Lucius Accius, of Pisaurum, in Umbria. Lucius Accius. He was born in 170 B. C., and one of his first tragedies was produced in 140 B. C., when Pacuvius produced one of his last. Accius lived to a great age, but the date of his death is not known. Cicero, as a young man, was well acquainted with him, and used to listen to his stories of his own early years. The shortness of the life of Roman tragedy, and the rapidity with which Roman literature developed, may be seen by observing that Cicero, the, great master of Latin prose, knew Accius, whose birth took place only thirty-four years after the death of Livius Andronicus.[Pg 13] Of the plays of Accius somewhat more than 700 lines are preserved, and about fifty titles are known. The fragments are for the most part detached lines, but some are long enough to let us see that the poet had a vigorous and graceful style, and a vivid imagination. Like most of his predecessors, Accius wrote various minor poems, and was interested in the development of the Latin language. He proposed a number of innovations, including some changes in the alphabet, but these last were not adopted by others. Besides his tragedies translated from the Greek, he wrote at least two fabulæ prætextæ, the Brutus, in which he dramatized the tale of the expulsion of the Tarquins, and Æneadæ, glorifying the death of Publius Decius Mus at the battle of Sentinum in 295 B. C. Even in his regular tragedies he departed occasionally from the original Greek so far as to show his own power of invention, though these plays were for the most part mere free translations. One of the longer fragments,6 in which a shepherd, who has never seen a ship before, describes the coming of the Argo, may give some idea of Accius’s skill in description:

So great a mass glides on, roaring from the deep with vast sound and breath, rolls the waves before it, and stirs up the whirlpools mightily. It rushes gliding forward, scatters and blows back the sea. Now you might think a broken cloud was rolling on, now that a lofty rock, torn off, was being swept along by winds or hurricanes, or that eddying whirlwinds were rising as the waves rush together; or that the sea was stirring up some confused heaps of earth, or that perhaps Triton with his trident overturning the cavern down below, in the billowy tide, was raising from the deep a rocky mass to heaven.

With Accius, Roman tragedy reaches its height. Contemporary with him were C. Titius and C. Julius Cæsar Strabo (died 87 B. C.), both of whom were orators as well [Pg 14]as tragic poets. Of their works only slight traces remain. Decay of tragedy. After this time tragedies were written by literary men as a pastime, or for the entertainment of their friends, and some of their plays were actually performed. The Emperor Augustus began a play entitled Ajax, Ovid wrote a Medea, and Varius (about 74-14 B. C.) was famous for his Thyestes, but none of these works has left more than a mere trace of its existence. The tragedies of Seneca (about 1-65 A. D.) were rather literary exercises than productions for the stage. With the growth of prose literature, especially of oratory, on the one hand, and the increased splendor of the gladiatorial shows on the other, tragedy ceased to be a living branch of Roman literature.

Before passing on to the treatment of comedy, it would be well to try to picture to ourselves the Roman theatre and the manner of producing a play. The Roman theatre. In the early days of Livius Andronicus there was no permanent theatre building, and the spectators stood up during the performance, but, as time went on, arrangements for seating the audience were made, and finally, in 55 B. C., a stone theatre was erected. Stone theatres had long been in use in Greece, and in course of time they came to be built in all the large cities of the Roman empire. The Roman theatre differed somewhat from the Greek theatre, though resembling it in its general appearance. The stage. The Roman stage was about three or four feet high, and long and wide enough to give room for several actors, usually not more than four or five at a time, one or two musicians, a chorus of indefinite number, and as many supernumeraries as might be needed. These last were sometimes very numerous, when kings appeared with their body-guards, or generals led their armies or their hosts of prisoners upon the stage. At the back of the stage was a building, usually three stories high, representing a palace. In the middle was a door leading into the royal apartments, and two other doors, one at each side, led to the rooms for guests. At each end of the stage was a door, the one at the right leading to the forum, the other to the country or the harbor. Changes of scene were imperfectly made by changing parts of the decoration. In comedies, the background represented not a palace, but a private house or a street of houses.

In front of the stage was the semicircular orchestra or arena, in which distinguished persons had their seats. The orchestra and the cavea. This semicircle was flat and level. The front of the stage formed the diameter. From the curve of the orchestra rose the cavea, consisting of seats in semicircular rows, rising from the orchestra at an angle sufficient to enable those who sat in any row to see over those who sat in front of them. The theatre had no roof, but in the luxurious times of the empire, and even before the end of the republic, a covering of canvas or silk was stretched like a tent between the spectators and the sun.

In the early days of the Roman drama, the actors did not wear masks, but before the end of the republic masks were introduced. Masks and costumes. These were useful in the large theatres of the time, as they added to the volume of the actor’s voice, and since the expression of the actor’s face could be seen by only a small proportion of the spectators, little was lost by hiding it with a mask. The masks themselves were carefully made, and were appropriate to the different characters. The costumes were conventional, kings wearing long robes and holding sceptres in their left hands, all tragic actors wearing boots with thick soles to raise them above the stature of the chorus, and all comic actors wearing low shoes without heels. The actors were, as a rule at least, slaves, but the profits of the profession were so great that a successful actor can have had but little difficulty in buying his freedom.

In Roman tragedies, as in their Greek originals, the dialogue was carried on in simple metres, mostly trochaic and iambic, and a chorus of trained singers sang between the acts, but probably took little part in the action of the play. Dialogue and song. The songs of the chorus were composed in more elaborate metres than the dialogue, and were sung to the accompaniment of the flute. In Roman comedy there was no chorus, but parts of the play were sung as solos or duets. These were called cantica, while the dialogue parts of the comedy were called diverbia.

Plays were performed at Rome on various occasions when the people were to be entertained, and the ædiles and other officials and public men vied with each other in showing their wealth and in courting popularity. Brilliancy of dramatic performances. We must, therefore, imagine, that when a play was performed in the latter part of the republican period the actors, chorus, and supernumeraries were dressed in the richest and most gorgeous costumes, and everything possible was done to add to the spectacular effect of the performance, while the audience, excited by the scene and the action, lost no opportunity of cheering their favorite actors, or hissing those who failed to please.

COMEDY

Comedy imported—Plautus, about 254 to 184 B. C.—Plots of Roman comedies—Extant plays of Plautus—Degree of originality in Plautus—Statius Cæcilius, birth unknown, death about 165 B. C.—Other comic writers—Terence, about 190 to 159 B. C.—Plays of Terence—Plautus and Terence compared—Turpilius, died 103 B. C.—Fabula togata—Titinius, about 150 B. C. (?)—Titus Quinctius Atta, died 77 B. C.—Lucius Afranius, born about 150 B. C.—Fescennine verses—Fabulæ Atellanæ—Pomponius and Novius, about 90 B. C.—Mimes—Decimus Laberius and Publilius Syrus, about 50 B. C.

Comedy, like tragedy, was an imported product, not an original growth, at Rome. Comedy an imported product. There had, to be sure, been improvised dialogues of more or less dramatic nature even before Livius Andronicus, but these, about which a few words will be said later, have nothing to do with the origin of Roman comedy, which is an imitation of the new Attic comedy as it existed at Athens after the time of Alexander the Great, being at its best from about 320 to about 280 B. C. No plays of the new Attic comedy are preserved in the original Greek, but there are fragments which supplement the knowledge we derive from the Latin imitations. The poets of the new comedy, Menander, Philemon, Diphilus, and others, avoided historical and political subjects and drew their comedies from private life, finding in petty intrigues, interesting situations, and unexpected complications, some compensation for the general meagreness of the plot. This kind of play was [Pg 18] called at Rome fabula palliata because the actors wore the pallium, or Greek costume. Another kind of comedy, in which Roman characters and scenes were represented, though even in this kind of plays the plots were derived from Greek originals, was called fabula togata, because the actors wore the Roman toga. Of this latter kind of plays only a few fragments are preserved, and it seems never to have been so popular as the fabula palliata.

Livius Andronicus, Ennius, and Pacuvius, all produced comedies at Rome, as did other writers of tragedies, but of these works only scanty fragments remain. Three writers, Plautus, Cæcilius, and Terence, devoted themselves exclusively to comedy, and it is from the extant plays of the eldest and the youngest of these, Plautus and Terence, that most of our knowledge of Roman comedy is derived.

Titus Maccius Plautus (Flatfoot) was born at Sarsina, a town of Umbria, about 254 B. C. T. Maccius Plautus. He went to Rome while still a boy, and seems to have earned so much as a servant or assistant of actors, that he was able to leave the city and engage in trade at some other place. His business venture was a failure; he lost his money, and returned to Rome, where he hired himself out to a miller, in whose service he was when he wrote his first three plays. His first appearance with a play was probably about 224 B. C. Further details of his life are unknown. He died in 184 B. C., at the age of about seventy years. He was, therefore, a younger contemporary of Livius Andronicus and Nævius, but older than Ennius and Pacuvius.

Of the plays of Plautus twenty are extant, besides extensive fragments of another. His total production is said to have been one hundred and thirty plays, though some of these were probably wrongly ascribed to him. The plots of his plays, as of those of Terence, are usually[Pg 19] founded upon a love affair between a young man of good family and a girl of low position and doubtful character. The plots and characters of Roman comedies. The young man is aided by his servant or a parasite, but his father is opposed to his having anything to do with the girl. The girl’s mother or mistress usually aids the lovers, but often has to be won over by money, which the young man and his servant have to get from his father. Sometimes the characters mentioned are duplicated, and we have two pairs of lovers, two irate fathers, two cunning slaves, etc. Other typical characters are the procurer, the parasite, the boastful soldier, and a few more, who help to bring about amusing situations, and serve as the butt of many jokes. In the end, the lovers are usually united, and the girl turns out to be of good birth, often the long-lost daughter of one of the older men in the play. Sometimes other plots are chosen, as in the Amphitruo, which is founded on the story that Jupiter, when he visited Alcmene, used to take the form of her husband Amphitryon, and the fun of the play is caused by the confusion between the real husband and the disguised god. In a few plays the plot is less decidedly a love plot, but, as a general rule, the Roman comedies had love stories for their foundation. There is, however, room for considerable variety, as may be seen by a brief sketch of the contents of the extant plays of Plautus.

The Amphitruo, bringing the “Father of gods and men” into comic confusion with a mortal, and under very suspicious circumstances at that, is a burlesque, full of rather broad fun and amusing situations, perhaps the most interesting of all Latin comedies. The extant plays of Plautus. In the Asinaria, the Casina, and the Mercator, father and son are rivals for the affection of the same girl. Of these three, the Casina is the worst in its indecency, while the other two lack interest. These plays, however, like all the comedies of Plautus, are full[Pg 20] of animal spirits, plays on words, and clever dialogue. The Aulularia, or Pot of Gold, has a plot of little interest, but is famous for the brilliant and lifelike presentation of the chief character, the old miser Euclio. The Captivi, one of the best of the plays, has for its subject the friendship between a master and his slave. There are no female characters, and the piece is entirely free from the coarseness and immorality which disfigure most of the others. The Trinummus, or Three-penny Piece, has also friendship, not love, as its leading motive, though it ends with a betrothal. This play also is free from coarseness, and gives an attractive picture of the good old days when friend was true to friend. The Curculio is interesting chiefly through the cleverness of the parasite, who succeeds in making the rival of his employer furnish the money needed to obtain the girl. The Epidicus, the Mostellaria, and the Persa, also owe their interest to the tricks and rascalities of the parasite or the valet. The Cistellaria, only part of which is preserved, contains a love affair, but has for its chief interest the recognition between a father and his long-lost daughter. The Vidularia, too, which exists only in fragments, leads up to a recognition, this time between a father and his son. The Miles Gloriosus, a play of very ordinary plot, is distinguished for the somewhat exaggerated and farcical portrait of the braggart soldier. So the Pseudolus is a piece of character drawing, in which the perjured go-between, Ballio, is the one important figure. In the Bacchides the plot is more intricate and interesting, and the execution more brilliant, but the life depicted is that of loose women and immoral men. The Stichus has little plot, but several attractive scenes. Two women, whose husbands have disappeared, remain faithful to them, and are rewarded by having them return with great wealth. The Pœnulus is chiefly interesting on account of passages in the Cartha[Pg 21]ginian language, which have for centuries attracted the attention of linguists. In the Truculentus, a countryman comes to the city and changes his rustic manners for city polish. The scenes are witty and effective, but the plot is weak. In the Menæchmi, twin brothers come to the town of Epidamnum, and their likeness to each other causes most laughable confusion. This is the original of Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors and many other modern plays of similar plot. The Rudens, or Cable, has for its subject the restoration of a long-lost daughter to her father and her union with her lover, but is distinguished from the other plays of Plautus by the evident love of nature and the fresh breath of the sea and open air that breathe through it, making it one of the most attractive of his comedies.

How much of the plots of these plays can be attributed to Plautus himself it is hard to tell. Degree of originality in Plautus. In some instances nearly all the details seem to be Greek, and probably the plays in which this is the case are simply free translations with just enough changes to make them easily understood at Rome. In other cases, as in the Stichus, the play as we have it seems to be made up of scenes only loosely strung together, arranged apparently rather for a Roman audience which cared chiefly for spectacular effect and stage by-play than for a Greek audience accustomed to weigh and criticize the excellence of the plot. In some instances, too, the Latin play is known to be made up of scenes taken from two Greek plays and put together in order to produce a single piece of more action than either of the originals. The importance of the work of the Latin playwright varies therefore considerably. There are, however, numerous passages containing references to details of Roman life, which must be in great measure original with the Roman writer; there are many plays on Latin words which could not be introduced in a mere translation from[Pg 22] a foreign language; and in other respects also the comedies show Roman rather than Greek qualities. We must therefore attribute to Plautus a considerable share of originality, and the metrical form of his plays is naturally due to him alone.

The following passage, whatever it may owe to the Greek original, doubtless owes part of its unusual liveliness to Plautus:7

Sceparnio. But, O Palæmon, holy companion of Neptune, who art said to be a sharer in the labors of Hercules, what’s that I see? Two shipwrecked women. Dæmones.What do you see? Scep. I see two women folk sitting all alone in a boat. How the poor things are tossed about! Ah! ha! Bully for that! The current has turned the boat from the rock to the shore. No pilot could have done it better. I think I never saw bigger waves. They are safe, if they have escaped those billows. Now, now’s the danger! Oh! It has thrown one of them out. But she’s in shallow water; she’ll swim out easily. Whew! Do you see how the water threw that other one out? She’s come up again; she’s coming this way. She’s safe!

A second passage8 will give an idea of the style of some of the dialogue of Plautus. The speakers are a boy, Pægnium, and a maid-servant, Sophoclidisca:

Sophoclidisca. Pægnium, darling boy, good day. How do you do? How’s your health? Pægnium. Bantering talk. Sophoclidisca, the gods bless me! Soph. How about me? Pæg. That’s as the gods choose; but if they do as you deserve, they’ll hate you and hurt you. Soph. Stop your bad talk. Pæg. When I talk as you deserve, my talk is good, not bad. Soph. What are you doing? Pæg. I’m standing opposite and looking at you, a bad woman. Soph. Surely I never knew a worse boy than you. Pæg. What do I do that’s bad, or to whom do I say anything bad? Soph. To whomever you get a chance. Pæg. No man ever thought so. Soph. But many know that it is so. Pæg. Ah! Soph. Bah! Pæg. You judge other people’s characters by your own nature. Soph. I confess I am as a pimp’s maid [Pg 23]should be. Pæg. I’ve heard enough. Soph. What about you? Do you confess you’re as I say? Pæg. I’d confess if I were so. Soph. Go off now. You’re too much for me. Pæg. Then you go off now. Soph. Tell me this: where are you going? Pæg. Where are you going? Soph. You tell; I asked first. Pæg. But you’ll find out last. Soph. I’m not going far from here. Pæg. And I’m not going far, either. Soph. Where are you going, then, scamp? Pæg. Unless I hear first from you, you’ll never know what you ask. Soph. I declare you’ll never find out to-day, unless I hear first from you. Pæg. Is that so? Soph. Yes, it is. Pæg. You’re bad. Soph. You’re a scamp. Pæg. I’ve a right to be. Soph. And I’ve just as good a right. Pæg. What’s that you say? Have you made up your mind not to tell where you’re going, you wretch? Soph. How about you? Have you determined to conceal where you’re bound for, you scoundrel? Pæg. Hang it, you answer like with like. Go away now, since it’s settled so. I don’t care to know. Good-by.

Statius Cæcilius, an Insubrian by birth, probably came to Rome as a slave—that is, a captive—at some time not far from 200 B. C. Statius Cæcilius. Here he became a writer of comedies, was set free by his master, and lived in the same house with Ennius. He died about 165 B. C. The titles of some forty plays by Cæcilius are known; but the extant fragments are too short to afford much information as to his style, his ability, or the contents of his plays. As many of the titles of his pieces are known also as titles of plays by Menander, it is clear that Cæcilius presented plays of the Greek new comedy in Latin form. Other writers of comedies. He appears to have followed the Greek originals rather more closely than Plautus, and to have cultivated elegance of style rather than brilliant dialogue. Other comic writers of the same time were Trabea, Atilius, Aquilius, Licinius Imbrex, and Luscius Lanuvinus, of whose works few fragments exist, and who are mentioned here merely to show that there were writers of comedies at Rome between Plautus and Terence. No one of them, however, seems to [Pg 24] have possessed the originality and exuberant wit of Plautus, or to have attained the elegance and polish of Terence.

Publius Terentius Afer, called Terence in English, was born at Carthage and brought to Rome as a slave. P. Terentius Afer. He can not have come as a captive to Rome, for his birth took place between the second and third Punic wars, at a time when the Romans were waging no war in Africa. He was the slave of the senator Terentius Lucanus, by whom he was carefully educated and soon set free. From him he derived his name Terentius, and he was called Afer on account of his African origin. He became intimate with Scipio Africanus the younger, his friend Lælius, and others of the most cultivated and prominent men of Rome. It was even said by some that the plays of Terence were really written by Scipio, while others thought Lælius was their author. This goes to prove that Terence was intimate with Scipio, Lælius, and the rest, and may be regarded as an indication of his age; for if he was much older than Scipio he would hardly have been charged with passing off Scipio’s work as his own. If he was of the same age as Scipio he was born in 185 B. C., and in that case was only nineteen years old when the Andria, his first play, was produced in 166. It is therefore likely that he was a few years older than Scipio, and was born about 190 B. C. After he had produced six comedies he went to Greece in 160 B. C. to study, and died in the next year either on his way back to Rome or in Greece. His popularity with the most cultivated men of Rome testifies to his good breeding and agreeable manners. Suetonius tells us that he was of moderate height, slender figure, and dark complexion, that he had a daughter who was afterwards married to a Roman knight, and that he left property amounting to twenty acres. The six plays of Terence are all preserved to us, together with the dates of the first performance of each.

The Andria, produced at the Ludi Megalenses, 166 B. C., is adapted from the Andria of Menander, with additions from his Perinthia. The Andria. A young man, Pamphilus, is in love with a girl from Andros, but his father, Simo, has arranged a marriage for him with the daughter of a neighbor, Chremes. Pamphilus’s servant, Davus, succeeds in breaking off the match, and the girl from Andros is finally found to be a daughter of Chremes. Pamphilus and his beloved are united, and a second young man comes forward to marry the other daughter.

The Hecyra (Mother-in-law), first produced at the Ludi Megalenses, 165 B. C., is adapted from the Greek of Apollodorus. The Hecyra. Pamphilus is a young man who has recently married Philumena, for whom he has no affection. He goes on a journey to attend to some property, and Philumena returns to her mother. Upon Pamphilus’s return, a child born to Philumena in his absence is shown to be his, and he and Philumena are reconciled. This play was unsuccessful, and deservedly so, as it is the least interesting Latin comedy extant.

The Heauton-Timorumenos (Self-tormentor), after Menander’s play of the same title, was produced at the Ludi Megalenses in 163 B. C. The Heauton-Timorumenos. Menedemus has by his harshness driven his son Clinias, who is in love with Antiphila, to take service in a foreign army. He therefore torments himself on account of remorse, and he confides his troubles to his friend Chremes, whose son, Clitipho, is in love with Bacchis. When Clinias comes back from the wars, he and Clitipho get Chremes to receive Antiphila and Bacchis in his house, in the belief that Clinias is in love with Bacchis, and that Antiphila is her servant. Finally Antiphila is found to be the daughter of Chremes and is betrothed to Clinias. Clitipho gives up the spendthrift Bacchis. The comic personage of the play is the slave Syrus, who helps the young men to get the money they[Pg 26] need. The character of Chremes is well drawn, but the action of the play is weak.

The Eunuchus, produced at the Ludi Megalenses in 161 B. C., is adapted from the “Eunuch” of Menander, with additions from the “Flatterer” of the same author. The Eunuchus. The plot is complicated and interesting, involving a love affair between Thais and Phædria, who has a soldier as his rival, and a second love affair between Pamphila, who had been brought up as foster sister to Thais, and Phædria’s brother, Chærea. In order to approach Pamphila, Chærea disguises himself as a eunuch. In the end Pamphila’s brother Chremes appears, proclaims her free birth, and sanctions her marriage to Chærea. The characters are well drawn, Chærea, perhaps, the best of all, and the action is amusing.

The Phormio, first performed at the Ludi Romani, in 161 B. C., is adapted from the Greek of Apollodorus. The Phormio. Two brothers, Chremes and Demipho, have gone on a journey, leaving their two sons, Phædria and Antipho, in charge of a slave, Geta. Antipho marries a poor girl named Phanium, from Lesbos, and Phædria falls in love with a slave girl, whose owner sells her to some one else, but agrees to give her to Phædria if he brings the sum of thirty minæ in one day. The two fathers return, and the parasite, Phormio, from whom the play takes its name, now has to get the money for Phædria and to secure the consent of Demipho to the marriage of Antipho and Phanium. He gets the money from Demipho by telling him that he will himself marry Phanium for thirty minæ, but just at the right moment Phanium is found to be the daughter of Chremes, and her marriage with Antipho is accepted by all parties. The plot is well carried out, and the two old men and their sons are well portrayed.

The Adelphœ (Brothers), after Menander’s play of the same name, with additions from a play by Diphilus[Pg 27] was first performed at the funeral games of Æmilius Paulus, in 160 B. C. The Adelphœ. Demea had two sons, and gave his brother, Micio, one of them, named Æschinus, keeping the other, Ctesipho, himself. Micio is a bachelor, and treats Æschinus with the greatest indulgence, whereas Demea is very strict toward Ctesipho, but the result is about the same. Ctesipho falls in love with a harpist, whom Æschinus, to please his brother, carries off from her master. Æschinus himself is engaged in an affair with the daughter of a poor widow. The girl is, however, of good Attic parentage, and Æschinus has promised to marry her. In the end this marriage takes place, Ctesipho gets his harpist and Micio is persuaded to marry the widow.

The plays of Terence are written in a style far more advanced, more refined, and more artistic than those of Plautus, but they show much less originality, wit, and vigor. Terence and Plautus compared. Plautus wrote at a time when Greek culture was already known to the Romans, but when it was less thoroughly appreciated than later, and he wrote not for any one class of Romans, but for the people. The language of Plautus is therefore the language of every-day life as it was spoken by the average Roman; his wit is of the kind that appealed to ordinary men, and his plays have much action, that the common man might enjoy them. Plautus took Greek plays and made them over to suit the average Roman. The position of Terence was different. In his day a cultivated class of Romans existed, who knew Greek literature well, who admired and loved Greek culture, but were none the less patriotic Romans. These men wished to introduce all that was best in Greece into Rome. So far as literature was concerned, they wished to make Latin literature as much like Greek literature as possible, and therefore encouraged imitation rather than originality,[Pg 28] purity and grace of language rather than vigor of thought or expression. These were the men among whom Terence lived, and whose taste influenced him most. His plays contain few indications that they are written for a Roman audience (except, of course, that they are written in Latin), but are Greek in their refinement of language, gentle humor, and polished excellence of detail. There is less variety of metre than in the plays of Plautus, as, indeed, there is less variety of any kind, for Terence relies for his effect, not upon variety, but upon finished elegance. He is the earliest Latin author who tries to equal the Greeks in stylistic refinement, and few of those who came after him were as successful as he.

Many of the qualities of the style of Terence are lost in translation; but something of the air of ease, naturalness, and good humor that pervades his plays is seen in the short scene in the Phormio, in which Demipho asks Nausistrata, the wife of Chremes, to persuade Phanium to marry Phormio.9

Demipho. Come then, Nausistrata, with your usual good nature make her feel kindly toward us, so that she may do of her own accord what must be done. Nausistrata. I will. De. You’ll be aiding me now with your good offices, just as you helped me a while ago with your purse. Na. You’re quite welcome; and upon my word, it’s my husband’s fault that I can do less than I might well do. De. Why, how is that? Na. Because he takes wretched care of my father’s honest savings; he used regularly to get two talents from those estates. How much better one man is than another! De. Two talents, do you say? Na. Yes, two talents, and when prices were much lower than now. De. Whew! Na. What do you think of that? De. Oh, of course— Na. I wish I’d been born a man, I’d soon show you— De. Oh, yes, I’m sure. Na. The way— De. Pray do save yourself up for her, lest she may wear you out; she’s young, you know. Na. I’ll do as you tell me. But there’s my husband coming out of your house.

The comedies of Plautus and Terence have served as the originals for almost countless plays in later times, and through them the Greek comedy has survived until our own day. Turpilius. There were other Latin writers of comedies derived from the Greek after Terence, most noted of whom was Turpilius, who died in 103 B. C., but of their works, which were unimportant, little remains. Of the fabula togata, Roman comedy in Roman dress, little need be said. It never attained great popularity, and it lasted but a comparatively short time. Fabula togata. Titinius, Atta, Afranius. The first writer of comedies of this sort was Titinius. About one hundred and eighty lines of fragments and fifteen titles of his plays are preserved, from which we can learn little about the quality of his works. He seems to have written a little later than Terence. Titus Quinctius Atta has left to us the titles of eleven plays and about twenty-five lines of fragments. Little is known of him except the date of his death, 77 B. C. Lucius Afranius, the last and most important writer of this kind of comedies, was born probably not far from 150 B. C. Forty-two titles and more than four hundred lines of fragments now remain to attest his activity. The scenes of the plays are laid in the smaller towns of Italy, and the characters belong for the most part to the lower social classes. In these respects Afranius seems to have differed little from Titinius and Atta, but his plays had apparently less local color than theirs, and thus approached more nearly the character of the fabula palliata as developed by Terence.

Three other kinds of dramatic composition deserve brief mention, though little now remains of them and their literary importance was never very great. Fescennine Verses. The Fescennine Verses, named from the town of Fescennium in Etruria, were originally sung at rustic festivals and weddings and consisted of jokes and sarcasms directed by the country folk at each other. [Pg 30] Fabulæ Atellanæ. They never became regular stage performances, and gradually lost their dramatic qualities, until they were nothing more than wedding songs. The Fabulæ Atellanæ, named from the Oscan town of Atella, in Campania, had some sort of plot, carried out with more or less dramatic unity. The characters were conventional—Maccus, the fool, Pappus, the old man, Bucco, the talker and liar, Dossenus, the clever man and boaster, and the like—and the whole performance was a popular burlesque comedy, somewhat like our Punch and Judy. This sort of performance was introduced at Rome after the conquest of Campania, in 211 B. C., and Roman youths of good family took the parts for amusement. Somewhat later, the custom arose of performing an Atellan piece at the end of a tragedy. The performers were now regular actors, and presently the Fabulæ Atellanæ became a regular branch of literature, the chief writers of which were Lucius Pomponius, from Bononia, and Novius, both of whom flourished in the time of Sulla, about 90 B. C. Few fragments of their works remain. The Atellan plays continued to be performed even after the beginning of the empire, but the words became less and less important, and the performance became mere pantomime. Mimes. Another kind of burlesque performance was the Mime, which was introduced into Rome from the Greek cities of Italy and Sicily. It had less consistent plots than comedy, and was more popular in its character. Though doubtless introduced at Rome as early as comedy itself, it hardly appears as a branch of literature until about the time of Cicero, when mimes serve as afterpieces at tragic performances. In imperial times mimes were performed independently. The chief authors of mimes were Decimus Laberius (105-43 B. C.), a Roman knight, and Publilius Syrus, a slave from Antioch, both belonging to the time of Cæsar, about the middle of the first century B. C. No mimes are extant, nor is their[Pg 31] loss to be greatly regretted, for their humor was generally coarse, their plots often indecent, and their literary qualities of a low order. Some of the fragments of the mimes of Laberius show, however, considerable merit, and in those of Publilius so many sensible precepts and wise utterances were embodied that a collection of his sayings was made, part of which is preserved to us.

EARLY PROSE-THE SCIPIONIC CIRCLE—LUCILIUS

Greek influence upon Roman prose—Fabius Pictor, 216 B. C.—Cincius Alimentus, 210 B. C.—Cato, 234-149 B. C.—Cato’s works—Orators—Jurists—Latin annalists—Scipio Africanus the younger, 185-129 B. C.—The Scipionic circle—Lucilius, 180(?)-126 B. C.—Satire—Satires of Lucilius—Literature in the fifty years before Cicero—Poetry—History—Learned works—General writers—Jurists—Oratory—Rhetoric addressed to Herennius—Great development of prose in this period.

Tragedy and comedy began, reached their full development, and decayed in the short period of a century and a half between the first play of Livius Andronicus and the death of Accius. It was therefore advisable to give a connected account of dramatic literature at Rome for this entire period, and to reserve for separate treatment the beginnings of prose literature, which, though less rapid in its growth, had a far longer life and was a much truer expression of the national genius.

The rudiments of a strictly native prose literature, the twelve tables of the laws, the various lists and records, and the speeches delivered on public and private occasions, mark the lines along which Roman prose was destined to advance—history, jurisprudence, and eloquence. Greek influence upon Roman prose. But Roman prose, like Roman poetry, came under the influence of Greek literature as soon as the Romans began to pay any attention to literary style. It was when the conquest of southern Italy brought Rome into closer contact than before with the cities of Magna Græcia that Livius [Pg 33] Andronicus was brought to Rome, and it was in the years immediately after the first Punic war that he produced the first Latin plays in imitation of Greek originals. To about the same or a little later time belong the earliest Roman prose writers. Some of these men, regarding the Latin language as too imperfect for use in prose literature, wrote in Greek, recording the events of Roman history for the enlightenment of foreigners and of educated Romans. Q. Fabius Pictor. Such was Quintus Fabius Pictor, a man of much distinction at Rome, who was sent by the state to consult the oracle at Delphi after the battle of Cannæ in 216 B. C. He wrote in Greek prose a history of Rome from the days of Æneas to his own times, selecting the same subject chosen by his contemporary Ennius for his Annales in Latin verse. This work of Fabius Pictor was very soon translated into Latin, and remained one of the chief sources from which later historians, such as Livy, derived their information. L. Cincius Alimentus. Lucius Cincius Alimentus, who was prætor in command of a Roman army in the second Punic war, wrote Roman history in Greek prose, as did also Publius Cornelius Scipio, the son of the elder Africanus, Aulus Postumius Albinus, and Gaius Acilius, about the middle of the second century B. C. Their works, being in Greek, had little direct influence on Latin literature, but show how powerful the Greek influence was among the cultivated men at Rome in the years following the second Punic war. Greek influence. This influence was not confined to literature, but affected dress, manners, ways of thinking—in short, all sides of life—especially among the upper classes. The Greeks of this time were no longer the hardy citizen-soldiers of the old days of Marathon and Thermopylæ, but were now distinguished for culture, refinement, and scholarship, too often accompanied by effeminacy, luxury, and dishonesty. Not by any means all the[Pg 34] Romans were ready to profit by contact with Greek civilization, with its mixture of good and bad qualities, and there was naturally a party at Rome which opposed everything Greek, and wished to preserve the old Roman simplicity. The most important man of this party was Cato.

Marcus Porcius Cato was born at Tusculum, in 234 B. C., and died in 149 B. C. Throughout his life he was active in public affairs. M. Porcius Cato. He was quæstor (204 B. C.), ædile (199 B. C.), consul (195 B. C.), and censor (184 B. C.), and in all his offices showed his honesty, efficiency, singleness of purpose, and sincere, though somewhat narrow-minded, patriotism. He believed that the influence of Greek art, literature, philosophy, and ways of life was bad, though in his old age he learned the Greek language, and studied Greek literature. In a letter to his son, he says: “I shall speak about those Greeks in their proper place, son Marcus, and tell what I discovered at Athens, and that it is good to look into their literature, but not to learn it thoroughly. I shall convince you that their race is most worthless and unteachable.”10

Cato was opposed to the prevailing tendencies in literature—the tendencies which were destined to prevail—but in spite of that he was one of the most productive literary men of his time. Cato as an orator. His active political life gave him many occasions for public speaking, in the senate or before the people, and he spoke often in courts of law, either in suits of his own or as an advocate for others. One hundred and fifty of his speeches existed in Cicero’s, time, and some, at least, were read and admired long after Cicero. About eighty scattered fragments now exist, some of which belong to political, others to legal speeches. These show vigor [Pg 35]and terseness of expression, a sort of dry humor, and straightforward freedom of speech, but no elegance of style.

Cato’s most important work was the Origines, in seven books, the first Roman history in Latin prose. In style and method this work was very uneven. The Origines. Sometimes events were narrated in brief, annalistic fashion, at other times Cato devoted much space to details. One book, from which the whole work derived its name, told of the origins and early history of the various towns of Italy. The work treated of Roman and Italian history from the earliest times to Cato’s own day, and in the latter part Cato took pains to give his own actions at least as much prominence as was their due, even inserting in his narrative the speeches he had delivered on various occasions. In the form of letters to his son, Cato composed treatises on agriculture, the care of health, eloquence, and the art of war. He also wrote a series of rules of conduct in verse, and made a collection of wise and witty sayings.

Of all his works the only one extant is a treatise On Agriculture. Born and brought up in the small town of Tusculum, and full of admiration for the simple virtues of the early Romans, Cato saw with deep disapproval the tendency of the men of his own day to give up agriculture for commercial and financial occupations. The treatise On Agriculture. “It would sometimes be better to seek gain by commerce, if it were not so dangerous; and likewise by money-lending, if it were so honorable. For our ancestors held this matter thus, and put it in the laws in this way, that a thief be punished by a double fine, a money-lender by a fourfold one. From this one can see how much worse citizen they considered a money-lender than a thief. And when they praised a good man, it was a good farmer, a good colonist. They thought that a man was most amply praised who was praised in this[Pg 36] way. Now I think a merchant is energetic and diligent in seeking gain; but, as I said above, he is exposed to danger and ruin. But from farmers both the bravest men and most energetic soldiers arise, and the business they follow is most pious and surest, and least exposed to envy; and those who are occupied in that pursuit are least given to evil thoughts.”11 In other parts of the book Cato gives in short, simple sentences, practical rules to be followed by the farmer. “Be sure to do everything early. For this is the way with farming: if you do one thing late, you will do all the work late.” This style of short, sharp sentences, is characteristic of Cato. He despises all appearance of literary polish, as if he wished to show that the arts of elegance cultivated by most other Roman writers were unnecessary and undesirable.

Cato was one of the most famous orators of his time, but his competitors were many, among them some of the most noted men of Rome. Other orators. Most of these orators were men of natural ability, whose eloquence was trained in the school of public life and owed its effect in great measure to the weight of the speaker’s dignity or the glory of his deeds. Their speeches are lost, and the reputation they had survives only to remind us that during and after the second Punic war Roman eloquence was growing in power, preparing, as it were, for the brilliant oratory of the Gracchi in the second half of the second century B. C., and the superb productions of Cicero in the century to follow. Among orators of Cato’s time should be mentioned Quintus Fabius Maximus Cunctator, five times consul, censor, and dictator, the conqueror of Hannibal, then Quintus Cæcilius Metellus, consul in 206 B. C., Marcus Cornelius Cethegus (died in 196 B. C.), Publius Licinius Crassus (died 183 B. C.), and Scipio Africanus the elder (died 183 B. C.).

In the field of jurisprudence there was considerable activity in the days of Cato. Jurists. Publius Ælius (consul 201, died 174 B. C.) and his brother Sextus (consul 198 B. C.) published the most systematic work on jurisprudence. This work was called Tripertita, and was for centuries regarded with reverence as the beginning from which grew the great system of Roman law. Scipio Nasica (consul 191 B. C.), Lucius Acilius, Quintus Fabius Labeo (consul 183 B. C.), and Cato’s son (born about 192, died in 152 B. C.) were all distinguished jurists whose interpretation of the Twelve Tables and whose wisdom in regard to legal matters are mentioned with praise by later writers. Their writings have perished, but the results of their studies were incorporated in the later works on Roman law.

The annalists who wrote in Greek, such as Fabius Pictor, were followed, soon after the middle of the second century B. C., by several writers whose works differed from theirs chiefly by being written in Latin. Latin annalists. They derived their general views and methods, as well as some of their facts, from earlier Greek historians, such as Ephorus and Timæus. The first of these Latin annalists was Lucius Cassius Hemina, who wrote a history of Rome to his own time. Somewhat more important was Lucius Calpurnius Piso Frugi, who was consul in 133 B. C. His annals covered the same ground as those of Hemina, and are said to have been written in an artless, somewhat rude style. A similar lack of elegance seems to have belonged to the works of the other annalists of this time. Evidently the Romans had not yet learned to write artistic prose. Yet this is the period when, under the guidance of Greek teachers, the Romans were paying more attention than ever before to grammar and rhetoric, purity of language, and nicety of expression.

The man about whom the best literary life of the city[Pg 38] centred was Scipio Africanus the younger, who lived from 185 to 129 B. C. Scipio. He was the son of the distinguished Lucius Æmilius Paulus, whose victory at Pydna, in 168 B. C., had destroyed the last foreign power capable of making serious resistance to the Roman legions, and he had been adopted by the son of the elder Scipio Africanus. He was himself a distinguished soldier, for as a simple officer (tribunus militum) he had saved the Roman army in Africa, after which he had been made consul and commander of the army which brought the third Punic war to a close by the capture and destruction of Carthage (146 B. C.). It might have been expected that he would take an active part in the government, especially as in his time the state needed the help of her best citizens. But Scipio seems to have felt that the internal troubles, which beset the state now that all external dangers were over, were too serious to be cured. He used his influence for good wherever he was able, but made no systematic attempt to correct the abuses of the government, which led at last to the revolutionary disorders of the days of the Gracchi (133-121 B. C.). Instead of being a party leader, he occupied a position somewhat apart from the aristocratic and the popular parties, lending his influence and his eloquence to the causes that seemed to him good, and in this way preserving a reputation for independence and good judgment. His patriotism was undoubted, and his influence as great as that of any man in Rome.

Scipio had been carefully educated, and employed his leisure in literary and intellectual pursuits. The Scipionic circle. He was not an author himself, except in so far as he published his speeches, which were much admired, but he loved to be surrounded by men of letters, to profit by their conversation, and lend them the support of his social position and influence. His somewhat older friend, Gaius Lælius, who was consul in[Pg 39] 140 B. C., shared his literary tastes, though he, too, refrained from publishing other works than speeches. From 167 to 150 B. C. a thousand Greeks of prominent position in their native country were kept as hostages in Italy. Among these was the historian Polybius, who was assigned a residence in Rome, and who became a member of the circle of literary friends who surrounded Scipio and Lælius. The Stoic philosopher Panætius, who afterward became the head of the Stoic school, was another Greek belonging to the Scipionic circle. The influence of Panætius upon Roman philosophy was great, as was that of Polybius upon the writing of Roman history. But Latin writers also gathered about Scipio. Among them were Terence (see page 24), the most polished writer of comedies; Hemina and Piso, the annalists; Gaius Fannius, a nephew of Lælius, who was consul in 122 B. C., and achieved distinction as an orator, besides writing a history of Rome; Sempronius Asellio, whose history of his own times was continued at least to 91 B. C.; Lucius Furius Philus, consul in 136 B. C., orator and jurist, and many others. Among them all, the most original genius was the father of Roman satire, Gaius Lucilius.

Lucilius was born, probably in 180 B. C., at Suessa Aurunca, in Campania. Gaius Lucilius. He was a member of a wealthy equestrian family, and when he went to live at Rome he kept himself free from the cares of business as well as of politics, devoting himself to social life and to literature. He lived as a wealthy bachelor, not holding himself aloof from the pleasures of the capital, but not indulging in excesses. Most of his life was passed in the city, but in 134 B. C. he followed Scipio to the war in Spain, and in 126 B. C., when all who were not Roman citizens were obliged to leave Rome, he made a journey to Sicily, from which he did not return until 124 B. C. He died at Naples in 103 B. C.[Pg 40]

The name satire, (satura) may be derived from the lanx satura, a dish full of all sorts of fruits, and as applied to poems by Ennius (see p. 8), designates poems of mixed contents. Satire. Perhaps all the poems of Ennius, except his dramas and his great epic, may have been classed together as satires. At any rate, Lucilius is the first writer who gave to satire the definite character it has possessed ever since his time. He made his poems the vehicle for the expression of sharp and biting attacks upon persons, institutions, and customs of his day, for genial and humorous remarks about the failings of his neighbors, and for much information about himself. Ever since Lucilius, satire has been at once sharp and humorous, bitter and sweet. This kind of poetry, which takes the form of dialogue, familiar conversation, or letters, is not Greek, but is the invention of him who must be regarded as the most original of all Roman poets.

The Satires of Lucilius were contained in thirty books, each book containing several satires. The Satires of Lucilius. The subjects treated were of all sorts—the faults and foibles of individuals, the defects of works of literature, the ridiculous imitation of Greek manners and dress, the absurdities of Greek mythology, the folly of expensive dinner parties, the author’s journey to Sicily, Latin grammar, the proper spelling of Latin words, and Scipio’s journey to Egypt and Asia. The personality of the writer, his mode of life, and his views on all subjects were so clearly brought before his readers that the Satires were a complete autobiography. They were written for the most part in hexameters, the metre which was adopted by all later Roman satirists, but some of them were in iambic senarii and trochaic septenarii, others in elegiacs.12 They were not written at one [Pg 41]time, but their composition was continued at intervals through many years, for Lucilius was not a professional poet, but a man of letters who expressed himself in verse whenever he felt inclined. His form of expression was unconventional, resembling conversation (in fact he called the poems sermones, “conversations”), with free use of dialogue. Careful literary finish was not attempted, and Horace, whose satires are imitations of those of Lucilius, blames the older poet for carelessness. But the easy and [Pg 42]natural tone of the poems must have more than made up for any lack of polish.