Title: Notes on Collecting and Preserving Natural-History Objects

Editor: J. E. Taylor

Contributor: Robert Braithwaite

John B. Bridgman

James Britten

James Buckman

James M. Crombie

Edward Fenton Elwin

W. H. Grattann

H. Guard Knaggs

E. C. Rye

Worthington George Smith

Thomas Southwell

Ralph Tate

Release date: March 9, 2014 [eBook #45084]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Tom Cosmas and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

COLLECTING AND PRESERVING.

NOTES ON COLLECTING AND PRESERVING NATURAL-HISTORY OBJECTS.

BY

J. E. Taylor, F.L.S., F.G.S.

E. F. Elwin.

Thos. Southwell, F.Z.S.

Dr. Knaggs.

E. C. Rye, F.Z.S.

J. B. Bridgman.

Professor Ralph Tate, F.G.S.

Jas. Britten, F.L.S.

Professor Buckman, F.G.S.

Dr. Braithwaite, F.L.S.

Worthington G. Smith, F.L.S.

Rev. Jas. Crombie, F.L.S.

W. H. Grattann.

EDITED BY

J. E. TAYLOR, PhD., F.L.S., F.G.S., &c.

NEW EDITION.

LONDON:

W. H. ALLEN & CO., 13 WATERLOO PLACE. S.W.

1883.

(All rights reserved.)

The following Essays were originally contributed to the pages of 'Science-Gossip,' by the various writers whose names they bear. From the constant queries relating to subjects of this kind, it was deemed advisable to furnish young or intending naturalists with such trustworthy information as would enable them to save time, and gain by the experience of others. For this purpose, the articles have been collected in their present portable form as a Handbook for beginners.

May, 1876.

| PAGE | ||

Preface |

v | |

CHAPTER I. |

||

| Geological Specimens, by J. E. Taylor, F.L.S., F.G.S. | 1 | |

CHAPTER II. |

||

| Bones, by E. F. Elwin | 16 | |

CHAPTER III. |

||

| Birds' Eggs, by T. Southwell, F.Z.S. | 27 | |

CHAPTER IV. |

||

| Butterflies and Moths, by Dr. Knaggs | 44 | |

CHAPTER V. |

||

| Beetles, by E. C. Rye, F.Z.S. | 67 | |

CHAPTER VI. |

||

| Hymenoptera, by J. B. Bridgman | 95 | |

CHAPTER VII. |

||

| Land and Freshwater Shells, by Professor Ralph Tate, F.G.S. | 102 | |

CHAPTER VIII. |

||

| Flowering Plants and Ferns, by J. Britten, F.L.S. (First Part) | 117 | |

CHAPTER IX. |

||

| Flowering Plants and Ferns, by J. Britten, F.L.S. (Second Part) | 131 | |

CHAPTER X. |

||

| Grasses, &c., by Professor Buckman, F.G.S | 139 | |

CHAPTER XI. |

||

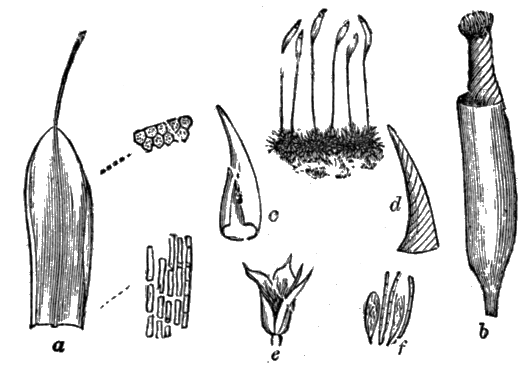

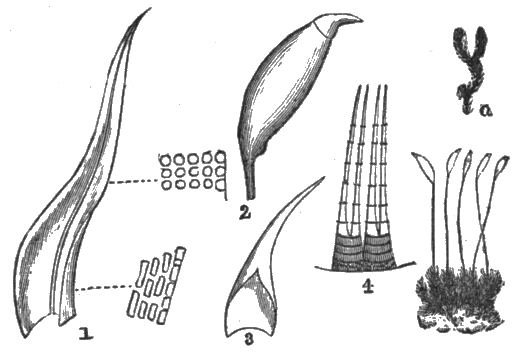

| Mosses, by Dr. Braithwaite, F.L.S | 145 | |

CHAPTER XII. |

||

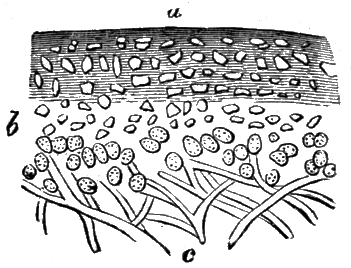

| Fungi, by Worthington G. Smith, F.L.S | 159 | |

CHAPTER XIII. |

||

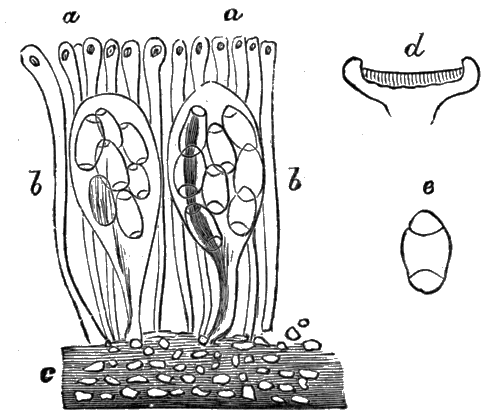

| Lichens, by Rev. James Crombie, F.L.S | 181 | |

CHAPTER XIV. |

||

| Seaweeds, by W. H. Grattann | 195 | |

Index |

209 | |

COLLECTING AND PRESERVING.

I.

GEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS.

By J. E. Taylor, F.L.S., F.G.S.

The great end of natural-history reading should be the development of a love for the objects dwelt upon, and a desire to know more about them. This can only be brought about by such practical acquaintance as collecting and preserving them induces. At the same time we should be sorry to see our young readers degenerate into mere collectors! It is a great mistake to suppose, that because you have a full cabinet of butterflies, moths, or beetles, therefore you are a good entomologist; or that you may lay claim to a distinguished position as a geologist, on account of drawers full of fossils and minerals. But this is a mistake into which young naturalists frequently fall. We have seen people with decided tastes for these studies never get beyond the mere collecting. In that case they stand on a par with [2] collectors of postage-stamps. Nor is there much gained, even if you become acquainted with English, or even Latin, names of natural-history objects. Many people can catalogue them glibly, and never make a slip, and yet they are practically ignorant of the real knowledge which clusters round each object, and its relation to others. Both Latin and English names are useful and even necessary; but when you have simply learnt them, and nothing more, how much wiser are you than before? No, let the learning of names be the alphabet of science—the means by which you can acquire a further knowledge of its mysteries. It would be just as reasonable to set up for a literary man on the strength of accurately knowing the alphabet, as to imagine you are a scientific man the moment you have learned by heart a few scores of Latin names of plants, fossils, or insects! Let each object represent so much knowledge, to which the very mention of its name will immediately conjure up a crowd of associations, relationships, and intimate acquaintances, and you will then see what a store of real knowledge may be represented in a carefully-arranged cabinet.

The heading of the present articles will have indicated the subject chosen for brief treatment. We shall never forget the influence left by reading such charming and suggestive books as Mantell's [3] 'Medals of Creation,' many years ago. Our mind had been prepared for the enthusiasm which this little book produced by the perusal of Page's 'Introductory Text-book,' Phillips's 'Guide to Geology,' and several others of a similar character. But we know of none which impels a young student to go into the field and hammer out fossils for himself, like Dr. Mantell's works. It is impossible not to catch the enthusiasm of his nature. The first place we sallied out to, on our maiden geological trip, was a heap of coal-shale, near a pit's mouth, in the neighbourhood of Manchester. Our only weapon was a common house hammer, for we then knew nothing of the technical forms which geological fancy so often assumes. We had passed that same heap of coal-shale hundreds of times, without suspecting it to be anything more than everybody else considered it viz. a heap of rubbish. Why that particular spot was selected, we cannot now say. We had seen illustrations of carboniferous plants, shells, &c., in books, but we seemed to imagine their discovery could only be effected by scientific men, and that it required a good deal of knowledge before one should attempt to find them. Suffice it to say we made the pilgrimage to the coal-shale heap in pretty much the same mind as we should expect to get the head prize in some fine-art drawing. The humble hammer was [4] put into use, for a brief time without much effect, as we could hardly have commenced on a more barren kind of shale than we had chanced to hit upon. We imagined we could perceive traces of leaves and slender stems, but were afraid to trust our eyes. At any rate, there was nothing definite enough to raise our enthusiasm. But by-and-by, as the hammer kept cleaving open the thin leaf-like layers of shale, there appeared a large portion of that most beautiful of all fossil plants, the Lepidodendron. Those who are familiar with this object, with its lozenge-shaped markings running spirally up the stem, will readily understand the outburst of pleasure which escaped our lips! That was the first real fossil—a pleasure quite equivalent to that of landing the first salmon. How carefully was it wrapped in paper, and carried home in the pocket! There never was, and never will be, another fossil in the world as beautiful as that insignificant fragment of Lepidodendron.

We have seen a good many converts made to geology in a similar manner, since first we laid open to the light this silent memorial of ages which have passed away. Let a man have ever so slight acquaintance with geology, and give him the chance of hammering out a fossil for himself, and the odds are you thereby make him a geologist for life. There is something almost romantic in the idea that you [5] are looking for the first time, and have yourself disentombed the remains of creatures which probably lived scores of millions of years ago! We would strongly advise our readers, therefore, not to fall into the error of supposing that fossil-hunting belongs to highly-trained geologists. On the contrary, it is by fossil-hunting alone that you can ever hope to be a geologist yourself. Another mistake often made, is that of supposing these rich and interesting geological localities are at a distance. It seems so hard to suppose, after reading about typical sections, &c., that under your very feet, in the fields where you have so often played, there occur geological phenomena of no less interest. But it is actually surprising what evidences of our earth's great antiquity, in the shape of fossils, &c., may be studied and obtained in the most out-of-the-way and insignificant places.

You say you have no rocks in your neighbourhood—nothing but barren sands, or beds of brick-earth or clay. Well, go to some section of the latter, exposed, perhaps, in some tarn or stagnant pond in a turnip-field. You examine the sides, and what do you see? Nothing, but here and there a boulder-stone sticking out. Well, be content with that. You said you had no rocks in your neighbourhood; how, then, has that boulder, which is a rounded fragment of a rock broken off from somewhere—how [6] has it come there? Here is a poser at once. Examine it, and you will perhaps see that its hard surface is polished or scratched, and then you remember the theory of icebergs, and feel astonished to think that you hold in your hand an undeniable proof of the truth of that theory. Those very scratchings could have been produced in no other way; that foreign fragment of a rock now only to be found on some distant mountain-side could have been conveyed in no other manner. Not content with the exterior examination, you break the boulder-stone open, when you may chance to find it is a portion of silurian, carboniferous or oolitic limestone, and that it contains fossils belonging to one of those formations. Here is a find—an object with a double interest turning up where you never expected to discover the slightest geological incident! You examine other boulders, and find in them general evidences of ice-action in their present re-deposition, and most instructive lessons as to the nature of rocks of various formations, from the granite and trap series to the fossiliferous deposits. In fact, there is no place like one of these old boulder-pits for making oneself acquainted with petrology, or the nature of stones.

And now, as to the tools necessary to the young geologist. First of all, he cannot take too few! It is a great mistake to imagine that a full set of scientific instruments makes a scientific man. The following hammers, intended for different purposes, ought to be procured. Fig. 1 is an exceedingly useful weapon, and one we commonly use, to the exclusion of all others. It is handy for breaking off fragments of rock for examination; and, if fossils be included in them, for trimming the specimens for cabinet purposes. As a rule, however, field geologists are always divided over the merits of their hammers, some preferring one shape and some another. Fig. 2 is generally used for breaking up hard rocks, for which the bevel-shaped head is peculiarly adapted. It is usually much heavier than the rest, and is seldom used except for specific purposes. If our readers are inclined to study sections of boulder clay, and wish to extract the rounded and angular boulder from its stiff matrix, they cannot do better than use a hammer like Fig. 3. This is sometimes called the "Platypus" [8] pick. Both ends can be used, and the pick end is also good for working on soft rocks, like chalk. A little practice in the field will teach the student how to use these tools, and when, much better than we can describe on paper. The hammers can be obtained from any Scientific instrument manufacturer, or from any of the dealers in geological specimens. We have found that the best hammers for usage, however, were to be made out of an old file, softened and well welded, rolled, and then hammered into a solid mass. If properly tempered a hammer made in this fashion will last you your life.

So much for the rougher weapons of geological strife. Next, be sure and provide yourself with thick-soled shoes or boots. Geological study will take you into a good many queer places, wet and dry, rough and smooth, and it is absolutely necessary to be prepared for the worst. Patent leather boots and kid gloves are rarely worn by practical geologists. [9] And we have heard it remarked at the British Association meetings, that they could always tell which members belonged to the Geological Section by their thick-soled boots. A similar remark applies to clothes. The student need not dress for the quarry as he would for the dining room. Good, strong, serviceable material ought to be their basis.

Secondly, as to the student's comforts and necessaries. These are generally the last thing an ardent naturalist thinks about. For ourselves, however, we give him ample leave to provide himself with pipe and tobacco, should his tastes lie in that direction. We never enjoyed a pipe half so much as when solitarily disinterring organic remains which had slumbered in the heart of the rock for myriads of ages. As to the beer, we can vouch that it never tastes anything like so good as during a geological excursion.

We have found the leathern bags sold for school-book purposes to be as handy to deposit specimens in, during a journey, as anything else. They have the merit of being cheap, are strong, and easily carried. If not large enough, then get a strong, coarse linen haversack, like that worn by volunteers on a field day. Paper, cotton wadding (not wool), sawdust for fragments of larger fossils, intended to [10] be repaired at home, wooden pill-boxes, and a few boxes, which may be obtained from any practical naturalist, with glass tops, are sufficient "stock-in-trade" for the young geologist. The wadding does not adhere to the specimens as wool does, and the glass-topped boxes are useful, as it is not then necessary to open a box and disinter a delicate fossil from its matrix in order to look at it. Add a good strong pocket lens, such as may be bought for half-a-crown, and your equipment will be complete. If you intend to study any particular district, get the sheets published by the Geological Survey. These will give you, on a large scale, the minute geology of the neighbourhood, the succession of rocks, faults, outcrops, &c. In fact, you may save yourself a world of trouble by thus preparing yourself a week or so before you make your geological excursion. The pith of these remarks applies with equal force if you purpose, first of all, to examine the neighbourhood in which you live. Don't do so until you have read all that has been written about it, and examined all the available maps and sections. This advice however, applies more particularly to geological examination of strata. If you are bent chiefly on palæontological investigation, that is, on the study of fossils, perhaps it will be best just to read any [11] published remarks you may have access to, and then boldly take the field for yourself. In addition to a hammer, we would advise the young student to take a good narrow-pointed steel chisel, and a putty-knife. The former is very useful for working round, and eventually obtaining, any fossil that may have been weathered into relief. The latter is equally serviceable for clayey rocks or shales.

In arranging the spoils of these excursions for the cabinet, a little care and taste are required. We will suppose you to possess one of those many-drawered cabinets which can now be obtained so cheaply. Begin at the bottom, so that the lowest drawers represent the lowest-seated and oldest rocks, and the uppermost the most recent. If possible, have an additional cabinet for local geology, and never forget that the first duty of a collector is to have his own district well represented! A compass of a few miles will, in most cases, enable him to get a store of fossils or minerals which cannot well be obtained elsewhere. Supposing he is desirous of having the geological systems well represented, he can always do so by the insertion of such paragraphs as those which appear in the Exchange columns of 'Science Gossip.' It is by well and thoroughly [12] working separate localities in this fashion that the science of geology is best advanced. You hear a good deal about the "missing links," and it is an accepted fact that we, perhaps, do not know a tithe of the organic remains that formerly enjoyed life. Who knows, therefore, but that if you exhaust your district by the assiduous collection of fossils, you may not come across such new forms as may settle many moot points in ancient and modern natural history? The genuine love of geological study is always pretty fairly manifested in a student's cabinet. Science, like charity, begins at home. It impels a man to seek and explain that which is nearest to him, before he attempts the elucidation of what really lies in another man's territory!

It is not necessary that the student should waste time in the field about naming or trying to remember the names of fossils, &c., on the spot. That can be best done at home, and the pleasure of "collecting" can thus be spun to its longest length. Box them, pack them well (or all your labour is lost), and name them at home. Or supposing you do not possess books which can assist you in nomenclature, carry your fossils or minerals, just as you found them, to the nearest and best local museum, where you will be sure to see the majority of them in their proper places and with their proper names. [13] Copy these, and when you arrange your specimens in the cabinet, either get printed cards with the following headings—

(which can always be obtained at a cheap rate from the London dealers), or else set to work and copy them yourself in a good plain hand, so that there is no mistaking what you write. As far as possible, in each drawer or drawers representing a geological formation, arrange your specimens in natural-history order—the lowest organisms first, gradually ascending to the higher. By doing so, you present geological and zoological relationship, so that they can be taken in at a glance. You further make yourself acquainted with the relations of the fossils in a way you never would have done, had you been content to huddle them together in any fashion, so that you had them all together. Glass-topped boxes, again, are very useful in the cabinet, especially for delicate or fragile fossils, as people are so ready to take them in their hands when they are shown, little thinking how soon a cherished rarity may be [14] destroyed, never to be replaced. Pasteboard trays, made of stiff green paper, squared by the student according to size, can also be so arranged as that the drawer may be entirely filled, and so the danger of shaking the contents about may be removed. Each tray of fossils ought to have the above-mentioned label fastened down in such a way as that it cannot by accident get changed by removal.

The spring and summer time are fast approaching, and we know of nothing that will so much assist in their rational enjoyment as the adoption of some study in natural science. Botany, entomology, ornithology, geology, are all health-affording, nature-loving pursuits. We have passed some of the very happiest moments of our lives in solitary quarries, or on green hill-sides,

"The world forgetting, by the world forgot!"

There, amid the wreck of former creations, and with the glory of the present one around us, we have yielded to the delicious sense of reverie, such as can only be begotten under such circumstances. The shady side of the quarry has screened us from solar heat, and, whilst the air has been melodious with a thousand voices, we have made personal acquaintance with the numerous objects of God's [15] creation, animals and plants. How apt are the thoughts of the poet Crabbe, and how well do they convey the feeling of the young geologist in such places:

II.

BONES.

By Edward Fentone Elwin, Caius College.

Why is it that the students of Osteology are so few in number? It is a branch of science which offers a wide field for original research, and one in which at every step one's interest must get more and more engrossed. It is a branch of science in which a sufficient portion of its elements may be rapidly learned, in order to set the student fairly on his road. The barriers which surround it are few: that is to say, the technical barriers are few. Many people who want to occupy themselves with scientific study are deterred, because of the feeling that there are so many laborious preliminaries to be gone through before they can begin to take any real pleasure in the pursuit. Now, in Osteology it is true that a wide and really almost unexplored field lies open before one, but the equipments necessary to fit one for one's journey are easily attained. The first step is to get thoroughly acquainted with some one typical specimen, as a standard of comparison for all future work. It matters little what species is taken; [17] whichever comes most convenient. Some familiar mammal of fair size is the best. The dog is as good as any, and easy to obtain. There ought never to be any real difficulty in getting a suitable specimen. If expense is no object, the simplest way is to get a preparation, set up so as readily to take to pieces, at any of the bone-preservers' shops in London. One like this costs only a moderate sum, and is, of course, the least trouble, although the manner in which professionals prepare their bones is not altogether satisfactory. But we may regard this as something in the light of a luxury; and it is not hard to prepare one's own specimens, provided we do not mind a little manipulation with unsavoury objects. I have given hints as to the best method by which this may be done in various pages of 'Science-Gossip.'[A] Of course, as one's work gets on, one needs further specimens, but I do not think that anyone who keeps his eyes open need be at a loss in this matter. I have picked up several admirable bones ready cleaned by the wind and weather, and many slightly damaged ones may be got at naturalists' shops for small sums, which are almost as good as the perfect ones for an observer's purposes. Even single and isolated bones are often very instructive.

[A] 'Science-Gossip' for 1873, p. 39; for 1874, p. 226.

But the first main point is that of getting the [18] forms, peculiarities, names, and positions of the bones of one skeleton fully impressed on the student's mind. As to the books which are to help him to do this, it is very hard to know what to recommend. As far as I know, there is no really luminous book on osteology in existence. So far as learning the names and peculiarities of the bones, nothing could be better or more to the purpose than Flower's 'Osteology of the Mammalia'; but this treats only of one class, and does not get beyond technical description. The first and second volumes of Owen's 'Comparative Anatomy of Vertebrates' fill the gap the best of any, and yet these are by no means what we really want. There is a good deal about bones in Huxley's 'Anatomy of Vertebrated Animals,' but in such a fragmentary and scattered form as to be of little use. The fact is, the field is yet open for an Osteological Manual. Much has been written on the subject. Pages of precise and accurate description, beautiful and artistic sheets of plates of bones without number, can be seen in any scientific library. But this is only half the matter. We want to advance a step farther. It is the relation between structure and function which needs working out.

When a new bone finds its way into the student's hands, he observes some peculiarity in shape or [19] structure in which it differs from the bones he is already acquainted with; the question naturally occurs to him, Why does this bone assume one shape in one animal, and in another is modified into a different form? He may look in vain in his books for an answer to his query. And yet it is points like these which, in my opinion, make up the true science of Osteology. It is through careful, constant, and intelligent observation, that these enigmas are to be solved. Observation, indoors and out; close attention to the habits of the animal in question, on the one hand, and careful consideration of its anatomical peculiarities, on the other.

Let me give an instance of this, first of all taking it as an axiom that everything has been done with a purpose. Take, then, the skull of a crocodile. What do we find? The orbits of the eyes, the nasal orifice, the passages leading to the auditory apparatus, all situated on a plane, along the upper flattened surface of the head. What, then, is the cause of this? Palpably to allow the crocodile to remain submerged in the water, with its nose, eyes, and ears just above the surface to warn him of the approach of enemies or prey, and the rest of his carcase securely hidden beneath the waters.

Take another instance. Observe the habits of a mole. With what rapidity it burrows underground, [20] shovelling away the earth with its fore feet. Then look at its skeleton. We find just what we should have expected. The bones of its fore legs of astounding strength and breadth, furnished with deep grooves, which, together with its sternum or breastbone, which is furnished with a keel almost like that of the sternum of a bird, afford attachment to the powerful muscles. Its hind legs, being simply needed for locomotion, are of the normal size. So, also, with the birds. The size of the keel of the sternum varies in proportion to the powers of flight which each species requires, for it is to the broad surfaces of the sternum that the great wing-muscles are attached. Take the skeleton of a hummingbird, which spends its life almost upon the wing. We find there a keel of so vast a size, that the remainder of the skeleton is reduced to insignificance in comparison. Of course, these instances that I have given are all of the most obvious nature, but they serve to show my meaning; and the same line of reasoning can, I am sure, be extended to all the more minute points in osteological structure.

In these researches, one is soon struck by the fact that in the modifications in various bones, or sets of bones, in accordance with the habits of each animal, the original type is never departed from, only modified. See, for example, the paddle of a [21] whale. More like the fin of a fish in general appearance, and yet the same set of bones which are found in the arm of a man, are again found in an adapted form in the paddle of the whale. So, also, the fore leg of a horse preserves the same general plan. What is generally called its knee is in reality its wrist. It is there that we find the little group of bones which forms the carpus. All below it answers to our hand—a hand consisting of one finger.

Take even a wider instance. Compare the arm of a man and the wing of a bird. Still greater adaptations have taken place, and yet the plan remains the same. We still find the clavicle or collar-bone, the scapula or shoulder-blade, the humerus, ulna, and radius, answering to the same bones of our arm, a small carpus or wrist, and finally the phalanges or fingers, simplified and lengthened and anchylosed to form but one series of bone, with the exception of a rudimentary thumb. It is not uncommon to find a rudimentary bone like this which in some allied species is fully developed. The leg of the horse again gives us a very striking example of this. There is, so to speak, only a single finger, but we find, one on each side of this single finger, two small bones, commonly known only as splint-bones. These are the rudimentary [22] traces of the same finger-bones, which in the rhinoceros are fully developed.

Now Osteology abounds in wonderful forms of structure like these. It is a study pregnant with pleasurable results, and is a real profitable study, and one in which each fresh student may do real solid work. It is all the little facts observed by naturalists from time to time all over the world, which on being collected together form the nucleus of knowledge; for indeed all the scientific knowledge which we possess is little more than a nucleus, with which we are supplied. The mere collector of curious objects in no way furthers science. Plenty of people have amassed beautiful collections of insects interesting in their way, but of very transient interest if it goes no farther. The collector possibly knows nothing at all of the wonderful internal structure of the animals he preserves. His insects are to him simply a mosaic—a collection of pretty works of art. So also the shell-collector—for I cannot call such a one as I describe a conchologist—has often, I believe, the most vague ideas of what kind of animals they were that dwelt in the cases he so carefully treasures, and his collection is consequently of a dubious worth to him. Now, to those who study the anatomy of the mollusc as well as its shell, such a collection is full of the [23] deepest interest. He has learnt from his dissections that the habits of every variety of mollusc are accompanied by a variety of structure, which occasions a variety in the shape of the case which envelopes it. It all blends together, and forms a harmonious whole. With a real love for science, as doubtless some of these collectors have, one is sorry to see so much time and money wasted on a pursuit which in their hands yields no fruit of any worth. The work of the mere collector can only be classed with that of the compiler of a stamp-album. Whereas, collections of natural objects, combined with intelligent study, are invaluable and almost indispensable to the naturalist.

In Mr. Chivers's note on Preserving Animals, No. 117 of 'Science-Gossip,' the following passage occurs:—"The skeleton must be put in an airy place to dry, but not in the sun or near the fire, as that will turn the bones a bad colour." I cannot comprehend how this idea should have arisen. Perhaps the most indispensable assistant to the skeleton preparer is that very sun which Mr. Chivers warns him against. The bleaching power of the rays of a hot summer sun is astounding, and bones of the most inferior colour can rapidly be turned to a beautiful white by this means. It is for want of time and care in following out this method that the professional [24] skeleton preparers in London resort to the aid of lime, which, although it makes them white, is terribly detrimental to the bones themselves. In a smoky city like London, the principle of sun-bleaching would be hard to follow; but so great is its value, that more than once I have had valuable specimens sent down to me in the country, by a comparative anatomist in London, to undergo a course of sun-bleaching; and a specimen which I have received stained and blotched, I have returned of a beautiful uniform white, a change entirely due to that sun which we are told to beware of.

The question, How are skeletons to be prepared? is one which is repeatedly asked. People desire a method by which with little trouble the flesh may be removed from a specimen, and a beautiful skeleton of ivory whiteness left standing in its natural position. I can assure all such inquirers that this cannot be accomplished by any method at all. The art of preparing bones is a long, elaborate, and difficult one, and he who wishes to become a proficient in it must be alike regardless to the most unpleasant odours, and to handling the most repulsive objects. Mr. Chivers's receipt for the maceration of specimens is about the best which one could have, only I should not advise so frequent a change of the water. What is needed is as rapid a decomposition of the flesh as [25] is possible, and then the cleaning of the skeleton just before the harder ligaments have also dissolved. But this requires very careful watching, and with the utmost pains it is almost impossible to get a skeleton entirely connected by its own ligaments.

Another point which must be taken into consideration is this: What use is to be made of the specimens after they are prepared? Are they for purposes of real study, or simply as curious objects to look at? If the latter is the purpose, I must confess I do not think they are worth the trouble of preparing. If the former is the object for which they are intended, then I think no care or pains are thrown away. But for the real student of Osteology the separated bones, as a rule, are far more valuable than those which are connected. He needs one or two set up for purposes of reference, but the great bulk of his specimens should be separate bones. Osteology is one of the most delightful branches of comparative anatomy, and one not very hard to master. Let anyone try the experiment by getting together a few bones—and those from the rabbit or the partridge we have had for dinner are by no means to be despised—and then, by purchasing Flower's 'Osteology of the Mammalia,' which is a cheap and first-rate book, he will learn what the study of the skeleton really is. And then let him [26] be on the look-out for specimens of all kinds on all occasions, bringing home all suitable objects he meets with in his walks, however unsavoury they may be, and he will be astonished to find how many specimens he will get together in the course of a year. I have now myself upwards of seventy skulls of various kinds, with often the rest of the skeleton as well, the greater part of which were gradually collected, by keeping constantly on the watch for them, within a year and a half.

III.

BIRDS' EGGS.

By Thomas Southwell, F.Z.S., etc.

I can imagine no branch of natural history more fascinating in its nature, or more calculated to attract the attention of the young, than the study of the nests and eggs of birds; the beauty of the structure of the one, and of the form and colour of the others, cannot fail to excite wonder and admiration; and the interest thus excited, if rightly directed, may, and indeed has, in many instances, led to the development of that passionate love for all nature's works, that careful and patient spirit of investigation, and that deep love for truth which should all be characteristics of the true naturalist. Who can look back upon the days, perhaps long passed away, when as a school-boy he wandered through the woods and fields, almost every step unfolding to him some new wonder, some fresh beauty—glimpses of a world of wonders only waiting to be explored—who can look back to such a time without feeling that in those wanderings there dawned upon his mind a source of happiness which in its purity and intensity ranks [28] high amongst those earthly pleasures we are permitted to enjoy, and which has influenced him for good in all the changes which have since come upon him, lightening the captivity of the sick room, and adding fresh brightness to the enjoyments of health.

Between the true naturalist and the mere "collector" there is a wide gap, and I trust that none for whom I am writing will allow themselves to drift into the latter class; the incalculable mischief wrought by those who assist in the extermination of rare and local species by buying up every egg of a certain species which can be obtained, for the mere purpose of exchange, cannot be too much deprecated, and I hope that none of my readers will be so guilty; to them the pleasures of watching the nesting habits of the bird, the diligent search and the successful find are unknown; the eggs in such a cabinet are mere egg-shells, and not objects pregnant with interest, recalling many a happy ramble, and many a hardly-earned reward in the discovery of facts and habits before unknown. Every naturalist must be more or less a collector, but the naturalist should always be careful of drifting into the collector, his note-book and his telescope should be his constant and harmless companions.

When the writer first commenced his collection, the mode of preparing the specimens for the cabinet was very rude indeed, and the method of arranging [29] equally bad; he is sorry to say the popular books upon the subject which he has seen do not present any very great improvement; in giving the results of his own experience, and the plan pursued by the most distinguished oologists of the day, who have kindly allowed him to explain the methods they adopt, he will, he trusts, save not only much useless labour, but many valuable specimens.

Before saying a word as to preparing specimens for the cabinet, I wish to impress upon the young oologist the absolute necessity for using the greatest care and diligence in order satisfactorily to identify, beyond possibility of doubt, every specimen, before he admits it to his collection. Without such precautions, what might otherwise be a valuable collection is absolutely worthless; and it is better to have a small collection of authentic specimens than a much larger one, the history of which is not perfectly satisfactory; in fact, it is a good rule to banish from the cabinet every egg which is open to the slightest doubt. There are some eggs which, when mixed, the most experienced oologist will find it impossible to separate with certainty, and which cannot be identified when once they are removed from the nest.

The difficulties in the way of authentication are by no means slight, but space will not allow me to dwell upon them; the most ready means, however, [30] is that of watching the old bird to the nest, although even in this, as the collector will find by experience, there is a certain liability to error. In collecting abroad it will be found absolutely necessary (however reluctant we may be to sacrifice life) to procure one of the parents with the nest and eggs. As we are writing for beginners at home, we trust such a measure will rarely be necessary; but that an accurate knowledge of the appearance of the bird, its nesting habits, the situation, and the materials of which the nest is composed, will be found amply sufficient to identify the eggs of our familiar birds. This knowledge of course is only to be obtained by patient and long observation; but it is just by such means that the student obtains the practical insight into the habits and peculiarities of the objects of his study, together with the careful and exact method of recording his observations, which eventually enables him to take his place amongst the more severely scientific naturalists whom he desires to emulate.

I will first describe the tools required, and then proceed to the mode of using them.

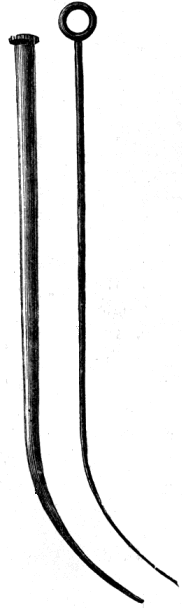

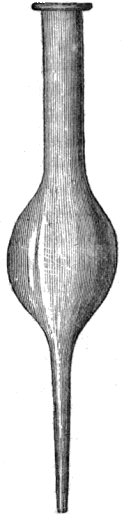

Figs. 4 and 5 are drills used for making the hole in the side of the egg, from which the contents are discharged by means of the blowpipe, Fig. 6. Fig. 4 has a steel point, brass ferrule, and ebony handle, and may be used for eggs up to the size of the wood-pigeon's; Fig. 5 is all steel, the handle octagonal, to give a firm hold to the fingers in turning it, and may be used for eggs from the size of the wood-pigeon's upwards. The points of both are finely cut like the teeth of a file, as shown in the woodcut. The blowpipe, Fig. 6, is about 51/2 inches in length (measured along the curve), and is made of German silver, which from its cleanliness, lightness, and freedom from corrosion, will be found the most suitable: it should be light and tapering, and with a ring at the upper end to prevent it from slipping out of the mouth when used. A piece of thin wire, Fig. 7, should be kept in the tube when not in use, to prevent it from becoming stopped up by any foreign substance. A common jeweller's blowpipe may be used for large eggs, such as those of gulls and ducks. Fig. 8 is a small glass bulb-tube, which may be used for sucking out the contents of very delicate eggs, and other purposes, which will be explained hereafter. The small drill and blowpipe may be carried inside the cover of the note-books.

|

|

| Fig. 6 & 7. German-silver Blowpipe. Wire for unstopping ditto. |

Fig. 8. Glass Bulb-tube, for sucking eggs. |

The sooner a fresh egg is emptied of its contents after it is taken from the nest the better. This should be done by making a hole in the side with the drill (choosing the side which is least conspicuously marked) by working it gently backwards and forwards between the forefinger and thumb, and taking great care not to press too heavily, or the egg will burst with the outward pressure of the drill: a very small hole will generally be found sufficient. When this is done, take the egg in the left hand with the hole downwards, introduce the blowpipe, by blowing gently through which, the contents may soon be forced out. Water should then be introduced by means of a syringe or the bulb-tube, which may be filled and blown into the egg. After shaking, blow the water out again by means of the blowpipe; repeat this till the egg is free from any remains of the yolk or white: should the egg not be quite fresh, it will require more washing. Care should be taken to wet the surface of the egg as little as possible. After washing the interior, lay the egg, with the hole downwards, on a pad of blotting-paper to drain till it is quite dry. Should the eggs be much incubated, I should recommend that the old birds be left to complete their labour [34] of love; but a valuable egg may be made available by carefully cutting a piece out of the side, extracting the young one, and, after replacing the piece of shell with strong gum-water, covering the join with a slip of very thin silk-paper, which may be tinted so as to resemble the egg, and will scarcely be noticed. This is a very rough way of proceeding, however, compared with Professor Newton's plan of gumming several thicknesses of fine paper over the side of the egg to strengthen it, through which the hole is drilled: the young chick is then cut into small pieces by means of suitable instruments, and the pieces removed with others:[B] the paper is then damped and removed from the egg.

[B] "Suggestions for forming Collections of Birds' Eggs." By Professor Newton. Written for the Smithsonian Institution of Washington, and republished by Newman, 9, Devonshire Street, Bishopsgate.

The old plan of making two holes in the side of the egg is very objectionable: a hole at each end is still worse. Many eggs would be completely spoiled by washing; none improved. There is no necessity for washing at all, except such as are very filthy, and these eggs (which you may be sure are not fresh) are not such as should be willingly accepted as specimens: a little dirt only adds to the natural appearance of the egg; washing in most cases certainly [35] does not. Never use varnish to the shell; it imparts a gloss which is not natural: all eggs should not have a polished appearance like those of the Woodpecker. Should the yolk be dried to the side of the egg, a solution of carbonate of soda should be introduced: let it remain till the contents are softened, then blow out and wash well. Great care must be taken not to allow the solution to come in contact with the outside of the egg. Having blown the egg, and allowed the inside to become quite dry, procure some thin silk-paper gummed on one side, and with a harness-maker's punch cut out a number of little tickets suitable to the size of the hole in the egg, moisten one of these, and place it with the gum side downwards over the hole, so as to quite cover it; cover the ticket with a coat of varnish, which will render it air-tight and prevent its being affected by moisture. The egg thus treated will have all the appearance of a perfect specimen, and if kept from the light will suffer very little from fading.

The note-book has been mentioned. This should be a constant companion; nothing should be left to memory. When an egg is taken, a temporary pencil number should at once be placed upon it, and this number should correspond with the number attached to an entry in the note-book, describing the nest (if not removed), its situation, number of eggs, day of [36] month, and any other particular of interest. When the egg is ready for the cabinet, as much of this information (certainly, name, date, and locality) should be indelibly marked upon it as conveniently can be done (neatly, of course, and on the under side); also the number referring to the collector's general list of his collection, into which the important parts of the entry from the note-book should be copied. Never trust to gummed labels, which are always liable to come off; by writing the necessary particulars upon the egg itself there can be no confusion or mistake. Most collectors have their own plan of cataloguing their collection. I have adopted the following, which I find to answer very well. Obtain a blank paper book the size of common letter-paper, rule a horizontal line across the centre of each page, and make a complete list of British birds, placing only two names on each page, one at the head of each division, prefixing a progressive number to each name: this number is to agree with that marked on the egg of the species named. Then follow the locality whence the egg came, by whom taken (if not by myself), or how it came into my possession, with any other particular worthy of note. With all eggs received in exchange or otherwise, this note should, if possible, be obtained in the handwriting of the person from whom they are received, [37] and the slip on which it is written be affixed in the book under the number. When specimens of the eggs of the same species are obtained from various localities, those from each locality should be distinguished by a letter prefixed to the number. The plan will be better understood by referring to the following extract:

62. Great Sedge-warbler (Sylvia turtoides, Meyer).

62. Received of ——, from the cabinet of Mr. ——.

a62. Taken by ——, a servant of ——, on the banks of the river Tougreep, near Valkenswaard, in the south of Holland, on the 9th of June, 1855. The birds may be heard a long way off by their incessant "Kara, Kara, Kara." A few years ago not one was to be found near Valkenswaard.

A. B——

b62. Bought at Antwerp in August, 1865.

———

118. Mealy Red-pole (Fringilla borealis, Tem.).

118. Nyborg, at the head of Mæsk Fjord (one of the two branches into which Varanger Fjord divides), East Finmark, Norway, July, 1855. The birds were very plentiful, and only one species seen, which appears quite identical with that which visits England every winter.

C. D. E——

By means of these entries, and the corresponding number on the egg, mistakes are impossible, and the name and history of each egg would be quite as well known to a stranger as to the possessor. It needs not to be said that this catalogue is replete with the [38] deepest interest to its compiler. In it he sees the record of many a holiday trip and many a successful find. Some of the entries in my own register—the earliest date back five-and-twenty years—are memorials of companions long since dead, or separated by rolling oceans, but on whose early friendship it is a pleasure to dwell.

Nothing can be more vexatious and disappointing than the receipt of a box of valuable eggs in a smashed or injured condition from want of care or knowledge of the proper method of packing. A simple method is recommended by Professor Newton, which, from experience, I can confidently recommend:—Roll each egg in tow, wool, or some elastic material, and pack them closely in a stout box, leaving no vacant place for them to shake; or a layer of soft material may be placed at the bottom of the box, and upon it a layer of eggs, each one wrapped loosely in old newspaper; upon this another layer of wool or moss, then again eggs, and packing alternately until the box is quite full. Bran, sawdust, &c., should never be used; and it should be ascertained that the box is quite filled, so that no shaking or settlement can occur.

Almost every collector has his own plan for constructing his cabinet, and displaying his collection. [39] The beginner, if left to himself, will find it a matter of no small difficulty, and many will be the changes before he arrives at one at all satisfactory. Mr. Osbert Salvin has invented a plan which I think as near perfection as it is possible to arrive at, and through his kindness I am enabled to give a brief description of it. In the first place, his cabinets are so constructed that the drawers, of different depths, are interchangeable. This is effected by placing the runners, which carry the drawers, at a fixed distance from each other and making the depth of each drawer a multiple of the distance between the runners. For example: if the runners are three-quarters of an inch off each other, then let the drawers be 1-1/2, 2-1/4, 3, 3-3/4, 4-1/2, &c., inches deep. All these drawers will be perfectly interchangeable, and a drawer deep enough to hold an ostrich's egg can in a few moments be placed amongst those containing warblers': every requirement of expansion and rearrangement will be vastly facilitated, involving none of those radical changes so worrying to a collector.[C] Mr. Salvin's plan of arranging the eggs is equally simple, and admits of any amount of change with very little trouble. Each drawer is divided longitudinally by [40] thin slips of wood into three or more parts, about 4 to 6 inches across, as may be convenient; a number of sliding stages are then constructed of cardboard, by cutting the cardboard half through, at exactly the width of the partition, and bending the sides down to raise the stage to the required height. A section of one of these stages will be seen in Fig. 9, and the arrangement in the drawer at Fig. 10. A number of oval holes are then to be cut by hand, or with a wadding-punch of suitable size (altered in shape by hammering), and a thin layer of cotton-wool gummed on the upper surface of the stage: the holes, of course, should be suitable in size to the egg they are intended to receive. Between these stages sliding partitions must be placed: these should be made of just sufficient height that the horizontal part may fit closely on the wool, as shown at Fig. 9. These partitions should be made of thin wood for the [41] upright part, along which a horizontal strip of cardboard is to be fastened with glue, on which is to be placed a label bearing the name of the species of egg displayed on the stage, as seen in Fig. 10. All this will be better understood by referring to the figures.

[C] Of course, cabinets thus constructed will be found equally convenient for collections of bird-skins, fossils, &c.

Fig. 9 represents a longitudinal section of one of [42] the stages in its place, with the ends of the two next; 1, showing the cardboard stage; 2, the cotton-wool; 3, the sliding partition; and 4, the horizontal slip of cardboard to carry the label.

Fig. 10 represents one of the drawers on Mr. Salvin's plan: it is divided into three parts (1, 2, 3) by fixed partitions. No. 1 is represented empty; No. 2 with the specimens arranged; No. 3 with two stages and two of the movable partitions.

This may appear very complicated at first sight, but a few trials will be sufficient to master the details, and the result will be very beautiful if neatly carried out. The eggs are well shown, not liable to fall out of their places, and it is very little trouble to alter the arrangement, every part being movable. Each drawer should be covered by a sheet of glass to exclude dust.

Mr. Salvin's cabinet is an excellent one for holding the nests of birds, which should be removed with as little damage as possible, and placed in the drawers, under cover of glass. Great care must be taken to keep them free from moth, to which they are very liable; for this purpose they should be dressed with the solution of corrosive sublimate.

The young collector should remember that what is worth doing at all is worth doing well, and that the care bestowed upon his cabinet is not labour in [43] vain; habits of exactness and precision of arrangement are absolutely necessary if he would make the best use of the materials which come in his way; and, above all, never let him degenerate into the mere collector: his collection should be for use, and not merely ornamental.

IV.

BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS.

By Dr. Henry Knaggs.

The collector of Lepidoptera who aspires to success must read the book of nature as he runs. If he have not the wit to note and turn to account each little fact which may come under his observation, neither he nor science will be the better for his collecting. He should, whenever he makes a capture, know the reason why, or he will never make a successful hunter. He should be ever on the alert: his motto, nunquam dormio.

Some collect for profit, others for pastime; but the aim of our readers, I take it, is not only to acquire a collection of really good specimens, but also at the same time to improve their minds; and the best way of effecting this purpose is to hunt the perfect insect, not so much for itself as for the sake of the golden eggs, which, with proper care and attention, will in due course yield the most satisfactory results in the shape of bred specimens.

This being the case, and space being limited, it [45] seems best to simply touch upon the preliminary stages of insect existence, pointing out as we go those methods of collecting and preserving which experience has shown to be the most successful.

There can be no doubt but that egg-hunting is a very profitable occupation, and far more remunerative than most people dream of, particularly as a means of acquiring the Sphinges, Bombyces, and Pseudo-bombyces. Eggs, speaking generally, are to be found on the plants to which the various species are attached; and a knowledge of the time during which the species remains in the egg state, as well as the appearance of the eggs as deposited in nature, should if possible be acquired previous to proceeding to hunt. The most practical way of ascertaining the food and time is to watch the parent insect in the act of depositing her ova; but when the plant has been thus discovered, the best way is to capture her, and induce her to lay at our home. When eggs are inconspicuous, of small dimensions, or artfully concealed, the use of a magnifying glass is invaluable.

Eggs may be preserved by plunging them in boiling water or piercing them with a very fine needle, or they may have their contents squeezed out and be refilled by means of a fine blowpipe, with [46] some coagulable tinted fluid; but the shells themselves, after the escape of the larvæ, form, when mounted, beautiful objects for the microscope.

The three most successful plans of obtaining caterpillars are searching, beating, and sweeping. The first requires good eyesight and a certain amount of preparatory knowledge; the others are a sort of happy-go-lucky way of collecting, useful enough and profitable in their way, but affording a very limited scope for the exercise of the wits. In searching for larvæ, the chief thing is to observe the indications of their presence. A mutilated leaf, a roughened bark, a tumid twig, a sickly plant, an unexpanded bud, an abortive flower, or a windfall fruit, should at once set us thinking as to the cause; or, again, the webs, the silken threads, the burrowings and trails, or the cast-off skins of larvæ, may first call our attention to their proximity. Of course, larvæ may be found on almost all plants, as well as in the bark, stems, or wood of many; but the collector should fortify himself with a knowledge of what each plant is likely to produce, and hunt accordingly; for though indiscriminate collecting may sometimes be successful, it does not tend to improve the intellectual powers.

Beating is the more applicable method of working trees and bushes. It is carried out by jarring the [47] larvæ from their positions by the aid of a stick or pole, in such a manner that they will fall into an inverted umbrella, or net; or a sheet may be spread beneath for their reception. Sweeping with a strong net, passed from side to side with a mower-like movement, is better adapted for working low ground-herbage. The umbrella net, shown in Fig. 11, is, perhaps, the best for the purpose. It is constructed by hinging two lengths of jack-spring on two pieces of brass, and adapting them to the stick of the net, the upper piece of brass being fixed, the lower movable.

When captured, larvæ should be transferred to [48] chip boxes, or else to finely and freely perforated tins, the latter better preserving the food. A very handy box for the purpose is formed by fitting a second lid on to the bottom of a chip box, and then cutting from the second lid and bottom a hole, as shown in Fig. 12 (2); larvæ may then be inserted through the hole; but when the lid is shifted round, and the holes are not opposite, of course there will be no opening, as in Fig. 12 (1), and the contents are secured from escape.

Larva preserving is carried out by first killing, and then squeezing and extracting the contents through the anal orifice by means of a crochet hook.

When this has been done, the skin is inflated, but not to such an extent as to distend the segments, and is kept thus inflated while it is being dried in a heated metal chamber. Afterwards, if the colours are observed to have faded, they may be cautiously restored by the application of paint. These objects, mounted on suitable artificial leaves, are then ready for the cabinet.

Chrysalis collecting is conducted according to the situation of the object sought. Some are to be [49] found in the chinks of bark or under loose bark, which may be detached by means of a powerful lever. Some are suspended from trees, bushes, copings, hanging head downwards, or girded by silken threads to low plants or walls; others are to be found in the stems or trunks of their food-plants; many are concealed in cocoons of more or less perfect construction, others again amongst fallen leaves, but the majority are to be met with under the surface of the ground; in which case we shall have to dig for them by the aid of a trowel or broad chisel. The best situations for subterranean pupæ are open park-like fields, borders of streams, open spaces in fir woods, and they are usually situated within a foot or so of the tree trunks, at the depth of two or three inches, though sometimes considerably deeper. Of course both larvæ and pupæ of aquatic species will have to be sought for in their element, among the plants they frequent.

Chrysalis preserving is a simple matter: the pupæ may be killed by plunging them into hot water or by baking; frequently, however, we find that the natural polish disappears with death, and this may be restored by varnishing. It is advisable that the cocoons also, where practicable, should be preserved, to give a notion of their appearance in nature.

Moths and butterflies may be sought for at rest or on the wing. They may be disturbed from their hiding places or they may be attracted by various alluring baits.

At rest on stems of grasses and other plants butterflies may be taken on dull, sunless days; but it requires some experience to detect a butterfly with its wings raised up over its back: the little "Blues" may thus be freely boxed in their localities. Again, such butterflies as hybernate may be found in old sheds and outhouses, or under stacks.

Moths may be taken at rest on tree trunks, palings, and walls, or amongst foliage and ground herbage. Some species are to be freely captured in this way after their evening flight is over. Of course, for evening work, a lantern to assist our vision will be indispensable.

On the wing, some butterflies are exceedingly active, others comparatively sluggish; some fly high, others low. In hunting them, the chief points to be remembered are not to alarm, but rather cautiously to stalk our game, and strike, when we have an opportunity, with precision. It is important also to avoid throwing a shadow over them, and it is a good plan to get to windward of them—anything like flurry will be fatal to success.

Moths which fly by day may be chased in the [51] same manner, but some may be observed disporting themselves round trees; these must be watched, and netted as they now and then descend. Others fly at a very low altitude, and are only brought into the field of vision by our assumption of the recumbent position. At night again, though we watch for anything stirring the air, among the trees or the herbage, our tactics are somewhat modified; for, if the insect be of whitish colour, we should so place ourselves that its form will stand boldly out against a mass of dark foliage, whereas, if it be dingy in hue, we must take the sky for our background.

Disturbing insects, and thus causing them to start forth, and so render themselves visible, is another method of collecting. This is carried out in various ways.

First, the occupants of high trees may be expelled by jarring the trunk with a heavily loaded mallet, or by thwacking the trunk with a long hazel stick; but a sharp look-out must be kept, for some sham death, and fall plump down, while others make off as fast as they can. Other plans are to pelt the trees with stones, or pump on them with a powerful garden engine, or beat them with a long pole; and of all tress the most profitable for this purpose is the yew; though firs, oaks, beeches, and other trees are not to be despised.

For beating bushes there is nothing better than a walking-stick, and for low herbage a long switch passed quickly from side to side with a tapping movement is best adapted. The tenants of tree trunks may be disturbed by brushing the surface with a leafy little bough, or, better still, by the use of a strong fan, with which a powerful blast may be driven, the net being held in such a position as to intercept such insects as are blown off.

Thatch-beating in the autumn is a very profitable employment, particularly in the matter of Depressariæ. Sweeping need only be mentioned here, for moths collected by the process are anything but perfect insects.

There are various methods of attracting moths and butterflies. The first is effected by confining a virgin female in a muslin cage, the frame of which may be very readily formed by bending three pieces of cane into circles, and fixing these together at right angles, as shown in Fig. 13. When this baited cage is placed in a favourable position, and the weather is propitious for the flight of the males, the latter will, in some cases, congregate, and may be freely captured.

Then, the food-plant of the species is an attraction [53] at which we stand the best chance of procuring impregnated females.

Various kinds of blooms possess alluring qualities for insects: of these, sallow and ivy are the greatest favourites with collectors. They should be worked after dusk by means of a lantern and net; but the combination of a lantern fixed to a long stick, with a shallow net beneath and a little in advance of it, as shown in the cut, is the apparatus best adapted for the purpose; the object of the net being to intercept any insects which may happen to fall under the stimulus of light. These attractions should be first well searched over, and afterwards, a sheet (split if necessary) having been carefully spread below the bushes, a gentle shaking should be administered. Besides these blossoms, heather, ragwort, bugloss, [54] catchfly, bramble, various grasses, and a vast number of other flowers, are wonderfully attractive. In working patches of bloom we should remain stationary and strike as the visitors arrive. Again, over-ripe fruit, the juicy buds of certain trees, sap exuding from wounds in trees, are all more or less attractive. The secretion of aphides, commonly called honeydew, observable in hot seasons on the leaves of nettles and various other plants and trees, is also well worth attention, and is at times very productive of insects.

Sugaring is the next attraction, and a very important one it is. "Sugar" may be prepared by boiling up equal quantities of coarse "foots" sugar and treacle in a sufficient quantity of stale beer, a small quantity of rum being added previous to use, and also, if considered advisable, a flavouring of jargonelle pears, anise-seed, or ginger-grass. This mixture should be applied by means of a small paint brush to the trunks of trees, to foliage, flowers, tufts of grass, or indeed to any object which may present a suitable surface; for in some localities we are put to shift to know where to spread our sweets. This operation should be performed just before dusk, and soon afterwards the baited spots should be visited and, by the aid of a lantern gently turned on them, examined, a net being held beneath the while. The [55] best form of net for the purpose is formed by socketing two paragon wires into a Y-piece and connecting their diverging extremities by a piece of catgut, as shown in Fig. 15. The catgut, being flexible, will adapt itself (see the dotted line) to the surface of a tree trunk when pressed against it. With regard to insects captured at sugar, they are usually remarkably quiet, and may be boxed without difficulty, and, with a few exceptions, may be conveyed home in the boxes, care being taken to let each have a separate apartment. The boxes should be strengthened with strips of linen pasted round the joints, as shown in Fig. 16, otherwise accidents may occur, particularly on wet evenings or on rough ground. The skittish [56] individuals may be best captured by means of the sugaring drum, of which a cut is given in Fig. 17. This apparatus consists of a cylinder, one end of which is covered with gauze, the other provided with a circular valve, which works in a slit. For use, the valve is opened and the cylinder placed over the insect, which naturally flies towards the gauze; then the valve is closed, the corked piston, shown at the upper part of the cut, placed against it, the valve re-opened, the piston pushed up to the gauze, the insect pinned through the gauze, and the piston withdrawn with the insect transfixed to it.

Light is another most profitable means of attracting. The simplest way is to place a powerful moderator lamp upon a table in front of an open window which faces a good locality, and then wait net in hand for our visitors, which usually make their appearance late in the evening, and continue to arrive until the small hours. Those who prefer it can use the American moth-trap, which is self-acting, detaining such insects as may enter its portals, or those who can afford the space may fit up a room on the same principle. Street lamps are very profitable certain localities, and amply reward the collector who perseveringly and minutely examines them. The apparatus depicted in Fig. 18 is very useful for taking off such insects as may be on the glass of the lamp: it consists of a cyanide bottle attached by a ferrule to the end of a sufficiently long stick. When placed over an insect, [58] stupefaction is quickly produced. A net of the shape represented in Fig. 19 is also very useful for getting at the various parts of the lamp.

The best methods of stupefying and killing insects on the field is the cyanide bottle, prepared by placing alternate layers of cyanide of potassium and blotting-paper in the bottom of a wide-mouthed bottle, the mouth of which is accurately stopped with a cover, which is better for the purpose than a bung. The chloroform bottle, which is generally made with a little nipple, through which the fluid flows slowly out, and covered with a screw-tap, as in the cut 20, is also handy. The chloroform should be dropped over perforations in the box containing our patient, these perforations having been previously made by a few stabs of a penknife. After the fluid is dropped, our thumb should cover it, when the vapour will quickly enter, and the inmate speedily become insensible. Afterwards the coup de grâce may be given to the insect by pricking it under the thorax with the nib of a steel pen dipped in a saturated solution of oxalic [59] acid. If we are smokers, a puff of tobacco may be blown into the box with like result. If we are destitute of any apparatus, and brimstone lucifers for the purpose of suffocating our captures under an inverted tumbler cannot be obtained at some roadside inn, we must fall back on the barbarous practice of pinching the thoraces of such as cannot be carried home in boxes. At home we shall find the laurel jar and ammonia bottle the most useful. The former is made by partially filling a large wide-mouthed bottle or jar with cut and bruised dry leaves of young laurel: if any dampness hang about them, we shall have the mortification of seeing our specimens become mildewed. The latter consists in adding a few lumps of carbonate of ammonia, or some drops of strong liquid ammonia, on a sponge, to the bottle in which our captures, with each box lid slightly opened, have been placed. But it must be borne well in mind, firstly, that ammonia is injurious to the colours of most green insects; and secondly, that if the specimens be not well aired after having been thus killed, the pins with which they are transfixed will become brittle and break. Insects should be left in the ammonia for several hours, and are then in the most delightful condition for setting out.

To pin an insect properly is a most important [60] procedure. The moth, if of moderate dimensions may be rested or held between the thumb and fore finger of the left hand, while the corresponding digits of the right hand operate by steadily pushing a pin through the thorax, bringing it out between the hind pair of coxæ until sufficient of the pin is exposed beneath to steady the insect in the cabinet The direction of the pin should be perpendicular when the insect is viewed from the front, as in Fig. 21; but a lateral view should show the pin slightly slanting forwards, as in Fig. 22. Pins made for the purpose in numerous sizes are sold by Mr. Cooke, of New Oxford Street.

Setting out moths and butterflies is an operation which, if skilfully performed, adds much to the beauty of the future specimens. The method of setting most popular is carried out by means of saddles and braces. These so-called saddles are pieces of cork rounded as in the sectional figure, a groove being cut out for the reception of the bodies of the insects: they are generally strengthened by a strip of wood, upon which they are glued. Braces are wedge-shaped pieces of card or thick note-paper, the thick end strengthened, if necessary, with a disc of card fixed by shoemakers' paste, and pierced with a pin through it, as shown in Fig. 24. The mode of application of these appliances is beautifully shown in Fig. 26[D]. But before these straps can be applied, the wings must first be got into position by means of the setting needle and setting bristle, which are thus manipulated (the setting bristle, by the way, being formed by fixing a cat's whisker and a pin into a piece of cork, at [62] the angle shown in Fig. 25):—After the insect is straightly pinned upon the saddle, and the legs, antennæ, and, if necessary, the tongue, got into position, the left fore-wing is to be pushed or tilted into its place by means of the setting needle, which is merely a darning needle with a handle; and simultaneously it is to be held down by the bristle; then a small brace should be applied to the costa of [63] the fore wing. Next the hind wing should in like manner be adjusted, and as many braces as are considered necessary to keep the wings in their place should be added. Lastly, the right side of the insect should be treated in a similar way.

A very useful mode of setting, invaluable when we are destitute of saddles, is known as "four-strap" setting, and is well explained in Fig. 27. In this case the lower straps are first put into such a position, that when the insect is placed over them the middle of each of the costæ will rest upon them; then the wings are got into position, and the second pair of straps are applied over the wings, the latter retaining their position through the elasticity of their costæ: two more straps are generally added to secure the outer borders of the wings, as shown [64] in the drawing; but these, though advantageous, are not absolutely necessary. The saddles, with their contents, should be kept in a drying house, which is a box adapted for their reception, and freely ventilated, until the specimens are thoroughly dry, when the latter may be cautiously removed, and transferred to the collection.

To preserve our collection from decay, considerable care and attention is necessary. In the first place no insect which is in the least degree suspected of being affected by mites, or mould, or grease, should on any account be admitted to our collections. It is best to be on the safe side and submit every insect received from correspondents, whether mity or not, to quarantine, by which is meant their detention for a few weeks in a box the atmosphere of which is impregnated with some vapour destructive to insect life; such as that of benzole. Our own specimens we should kyanize by touching the bodies of each with a camel's-hair brush dipped in a solution of bichloride of mercury of the strength six grains to the ounce of spirits of wine,—no stronger.

As for mould, it is best destroyed by the application of phænic or carbolic acid, mixed with three parts of ether or spirit. As preventives, the specimens should be kyanized as above. Caution in the [65] use of laurel as a killing agent must be exercised, and the collection must be kept in a dry room.

Grease may be removed by soaking the insects in pure rectified naphtha or benzole, even by boiling them in it if necessary. When the bodies only are greasy, they may be broken off, numbered, and treated as above. After the grease is thoroughly softened, the insects should be covered up in powdered pipeclay or French chalk, which may be subsequently removed by means of a small sable brush. As a precaution against grease, it is advisable to remove the contents of the abdomina by slitting up the latter beneath with a finely pointed pair of scissors before they are thoroughly dry, and packing the cavities with cotton wool. The males, especially of such species as have internal feeding larvæ, should be thus treated.

Some prefer to keep their collections in well-made store boxes, which possess many advantages over the cabinet; for example, they may be kept like books in a bookcase, the upright position rendering the contents less liable to the attacks of mites; they are more readily referred to, and are more portable, and they admit of our gradually expanding our collections to any extent. Cabinets, on the other hand, are preferred by many, for the reasons that they are compact and generally form a handsome article [66] of furniture; moreover, good cabinets are made entirely of mahogany, which is the best wood for the purpose; deal, and other woods containing resinous matter, having a decidedly injurious effect on the specimens. As a preservative, there is, after all, perhaps nothing better than camphor; but it should be used sparingly, or its tendency will be to cause greasiness of the specimens.

V.

BEETLES.

By E. C. Rye, F.Z.S., etc.

The general rules, so ably expounded by Dr. Knaggs in his instructions for collecting Lepidoptera, as to constant alertness and making "the reason why" the starting-point of investigation, apply with equal force to the collector of Coleoptera, and need not be here recapitulated. But they do not, in the instance of the latter, require generally to be observed, except as to the perfect state of beetles; for, owing to the hidden earlier conditions of life of most of those insects, and to the long period during which these conditions exist, it is but seldom that the pursuit of rearing them, so universally and profitably adopted by the Lepidopterist, is found of much use to the collector of beetles. And this is very much to be regretted; because, in the majority of cases, if the latter succeed in rearing a beetle from its earliest stage, and keep proper notes of its appearance and habits, he will probably be adding to the general stock of knowledge, as the lives of comparatively few, even of the commonest species, are recorded from the beginning. It may be, also, in addition [68] to the reasons above mentioned, for the usual want of success attending the rearing of beetle larvæ, that the fact of bred specimens being frequently (from the artificial conditions attending their development, and from their not being allowed that length of time which, in a state of nature, they require after their final change before they are ready to take an active part in their last stage of life) not nearly so good as those taken at large, militates considerably against the more general use of this method of adding to a collection. In this respect, of course, the Lepidopterist is actuated by precisely opposite motives; as for him, a bred specimen is immeasurably superior to one captured. And the fact of so few beetle larvæ being known at all, or, if known, only to the possessor of somewhat rare books, renders it very likely that a mere collector, finding a considerable expenditure of patience and trouble result in the rearing of a species of which he could at any time readily procure any number of specimens, may very probably abandon rearing for the future.

These observations, however, are not in the least intended to dissuade anyone from breeding or endeavouring to breed beetles. On the contrary, it is obvious from them that it is precisely by attending to these earlier stages that the earnest student (novice or expert) has the most chance of distinguishing [69] himself, on account of the more open field for discovery. And in the instance of many small, and especially gregarious, beetles, breeding from the larvæ is frequently very easy, if only the substances (fungus, rotten wood, roots, stems of plants, &c.) containing them be carefully left in precisely the state as when found, and be exposed to the same atmospheric or other important conditions. In fact, to ensure success and good specimens, it is best that in their early stages beetles should be "let alone severely."

It may be here observed that we have been lately in this country indebted to the minute observations and great tact of some of our best students of Micro-Lepidoptera (in which branch of entomology we are second to none in Europe) for some most interesting additions to our knowledge of habits, and for long series of beetles usually rare in collections.