Title: The Siberian Overland Route from Peking to Petersburg,

Author: Alexander Michie

Release date: March 18, 2014 [eBook #45167]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel, Julia Neufeld and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

THROUGH THE DESERTS AND STEPPES OF MONGOLIA,

TARTARY, &c.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET.

1864.

The following work has but moderate claims, I fear, to public attention; and it would probably not have seen the light at all but for the urgent request of friends, who think better of it than the author does. It has no pretensions to any higher merit than that of being a plain narrative of the journey, and an impartial record of my own impressions of the people among whom I travelled.

Although some portions of the route have been eloquently described by Huc and others, I am not aware that any continuous account of the whole journey between the capitals of China and Russia has appeared in the English language for nearly a century and a half. Important changes have occurred in that period; and, if I may judge of others by myself, I suspect that many erroneous notions are afloat respecting the conditions of life in these far-off regions, and more especially in Siberia. Observation has modified my own pre-conceived opinions on many of the subjects touched on in the following pages, and I am not without a hope that they will be found to contain some information which may be new to many people in this country.

If I have indulged in irrelevant digressions, I can only say that I have limited myself to those reflections which naturally suggested themselves in the course of my travels; and the subjects I have given most prominence to are simply those which happened to be the most interesting to myself.

My thanks are due to various friends for useful hints, confirming and correcting my own observations; but I am especially indebted for some valuable notes on Siberia, its social phenomena, gold mines, &c., to Edwin E. Bishop, Esq., whose long residence in the country, and perfect acquaintance with the language and customs of the people, constitute him an authority on all matters connected with that part of the world.

22, Berkeley Square,

October 28th, 1864.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Shanghai to Tientsin. | |

| PAGE | |

John Bell—"Overland" routes—Peking a sealed book—Jesuits—Opening of China—Chinese jealousy of Mongolia—Errors of British policy—Their results—Preparations for journey—Leave Shanghae—Yang-tse-kiang—Changes in its channel—Elevation of the delta—Chinese records of inundations—The Nanzing—Shantung promontory in a fog—Chinese coasters—Advantages of steam—Our fellow-passengers—Peiho river—Intricate navigation—Sailors in China—Tientsin—New settlement—Municipal council—Improvements—Trade—Beggars—Health—Sand-storms—Gambling | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Tientsin to Peking. | |

Modes of travelling—Carts, horses, boats—Filthy banks of the Peiho—Voyage to Tungchow—Our boat's crew—Chinese distances—Traffic on the Peiho—Temple at Tungchow—Mercantile priests—Ride to Peking—Millet—Eight-mile bridge—Resting place—Tombs—Filial piety—Cemeteries—Old statues—Water communication into Peking—Grain supply | 23 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Peking. | |

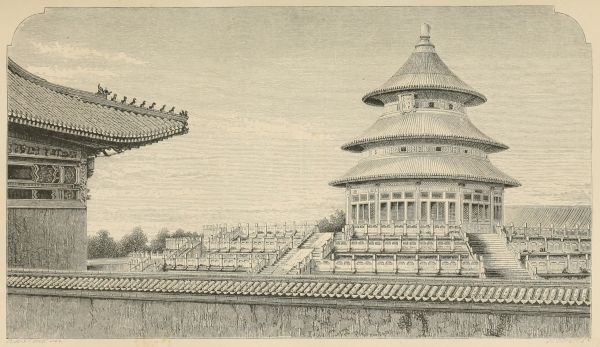

Walls of Peking—Dust and dirt—Street obstructions—The model inn—Restaurant—Our boon companions—Peking customs—Rule of thumb—British legation—Confucian temple—Kienloong's pavilion—Lama temple—Mongol chants—Roman and Bhuddist analogies—Mongols and Chinese—Hospitality of lay brother—Observatory—Street cries—Temple of Heaven—Theatres—European residents—Medical mission under Dr. Lockhart—Chinese jealousy of Mongolia—Russian diplomacy—Reckoning with our host—Ice—Paper-money | 32 |

| [vi]CHAPTER IV. | |

| Peking to Chan-kia-kow. | |

Return to Tungchow—Disappointment—Priest conciliated by Russian language—Back to Peking—Negotiations—Ma-foo's peculation—Chinese honesty and knavery—Loading the caravan—Mule-litters—Leave Peking—Sha-ho—Cotton plant—Nankow—Crowded inn—Difficult pass—Inner "great wall"—Cha-tow—Chinese Mahommedans—Religious toleration—Christians in disfavour—Change of scene—Hwai-lai—Ruins of bridge—Bed of old river—Road traffic—Watch-towers—Chi-ming-i—Legend of monastery—the Yang-ho—Pass—Shan-shui-pu—Coal—Suen-wha-fu—Ride to Chan-kia-kow | 56 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Chan-kia-kow. | |

Arrival at Chan-kia-kow—Focus of Trade—Mixed population—Wealth—Mongols—Russians—Name of Kalgan—Chinese friends—Russian hospitality—Disappointment—Proposed excursion to Bain-tolochoi—Camels at last procured—Noetzli returns to Tientsin—The pass—Mountains—Great Wall—The horse-fair—Dealers—Ox-carts—Transport of wood from Urga—Shoeing smiths—Our Russian host arrives—The "Samovar"—Tea-drinking in Russia—Change of temperature—Elevation of Chan-kia-kow—Preparations for the desert—Cabbages—Warm boots—Camels arrive—Leave Chan-kia-kow—The pass—Superiority of mules, &c., over camels | 72 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Mongolia. | |

Leave China—Mishap in the pass—Steep ascent—Chinese perseverance—Agricultural invasion—Our first encampment—Cold night—Pastoral scene—Introduction to the Mongols—The land of tents—Our conductors—Order of march—Mongol chants—The lama—Slow travelling—Pony "Dolonor"—Night travelling—Our Mongols' tent—Argols—Visitors—Mongol instinct—Camels quick feeders—Sport—Antelopes—Lame camels—Scant pastures—Endurance of Mongols—Disturbed sleep—Optical illusions—"Yourt," Mongol tent—Domestic arrangements—Etiquette—Mongol furniture—Sand-grouse—Track—Wind and rain—A wretched night—Comfortless encampment—Camels breaking down—The camel seasons—No population—No grass—Mingan | 83 |

| [vii]CHAPTER VII. | |

| Mongolia—continued. | |

Visitors at Mingan—Trading—Scene with a drunken Mongol—Good horsemen—Bad on foot—Knowledge of money—Runaway pony—A polite shepherd—Gunshandak—Wild onions—Halt—Expert butcher—Mongol sheep, extraordinary tails—A Mongol feast—Effects of diet—Taste for fat explained—Mongol fasts—Our cooking arrangements—Camel ailings—Maggots—Rough treatment—Ponies falling off—Live in hopes—Dogs—The harvest moon—Waiting for Kitat—Lamas and their inhabitants—Resume the march—Meet caravan—Stony roads—Disturbed sleep—Gurush—Negotiations at Kutul-usu—Salt plains—Sporting lama—Ulan-Khada—Trees—Reach Tsagan-tuguruk—Lamas and black men—Small temple—Musical failure—Our new acquaintances—Horse-dealing—Greed of Mongols—Fond of drink—A theft—The incantation—Kitat returns—Camel lost—Vexatious delay—Start from Tsagan-tuguruk | 102 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Mongolia—continued. | |

Marshes—Camels dislike water—Chinese caravan—Travellers' tales—Taryagi—Looking for cattle in the dark—Butyn-tala—An addition to our party—Russian courier—Water-fowl—Bad water—Kicking camel—Pass of Ulin-dhabha—Mongols shifting quarters—Slip 'tween the cup and the lip—Mountains—The north wind—Guntu-gulu—An accident—Medical treatment—Protuberant ears—Marmots—Ice—Dark night—Bain-ula—Living, not travelling—Charm of desert life—Young pilgrim—Grand scenery—Steep descent—Obon—Horror of evil spirits—Mongol and Chinese notions of devils—Dread of rain—A wet encampment—Snow—The White Mountains—The Bactrian camel—Capability of enduring cold—Job's comforters—Woods appear—The yak—Change of fuel | 122 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Urga to Kiachta. | |

Maimachin in sight—A snow storm—Hasty encampment—Tolla in flood—Delay—Intercourse with Mongols—The night watches—Tellig's family—Rough night—Scene at the Tolla—Crossing the river—the "Kitat" redivivus—His hospitality—How Mongols clean their cups—Maimachin—The Russian consulate—Russian ambition—Its prospects—The Urga, or camp—Kuren—Fine situation—Buildings—[viii]Horse-shoeing—Hawkers—The lamaseries—An ascetic—The Lama-king—Relations between Chinese emperors and the Lama power—Urga and Kara Korum—Historical associations—Prester John and Genghis Khan—Leave Urga—Slippery paths—More delays—The pass—A snow storm—Fine scenery—Rich country—Another bugbear—The Boro valley—Cultivation—Khara-gol—The pass—Lama courier—Shara-gol—Winter quarters—The transmigration—Iro-gol—Forced march—Kiachta in sight | 141 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Mongols—Historical Notes. | |

Early history of Huns—Wars with China—Dispersion—Appear in Europe—Attila—His career—And death—Turks—Mixture of races—Consanguinity of Huns and Mongols—Genghis—His conquests—Divisions of his empire—Timour—A Mahommedan—His wars—And cruelties—Baber—The Great Mogul in India—Dispersion of tribes—Modern divisions of the Mongols—Warlike habits—Religions—The causes of their success in war considered—Their heroes—Their characters—And military talents—Superstition—Use of omens—Destructiveness and butcheries of the Huns and Mongols—Antagonistic traits of character—Depraved moral instincts—Necessity of culture to develop human feelings—Flesh-eating not brutalising—Dehumanising tendency of war—Military qualities of pastoral peoples—Dormant enthusiasm of the Mongols | 166 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Mongols—Physical and Mental Characteristics. | |

Physical characteristics—Meanness—Indolence—Failure in agriculture—Hospitality—Its origin—Pilfering—Honesty—Drunkenness—Smoking—Ir'chi or Kumiss—Morality—Of lamas—Women fond of ornaments—Decency of dress—Physique—Low muscular energy—A wrestling match—Bad legs—Bow-legged—Its causes—Complexions—Eyes—Absence of beard—Comparison with Chinese and Japanese—Effect of habits on physical development—Animal instincts in nomads—Supply the place of artificial appliances—Permanence of types of character—Uniformity in primitive peoples—Causes that influence colour of skin—Mongol powers of endurance—Low mental capacity—Its causes—Superstition produced by their habits—Predisposed to spiritual thraldom—The lamas and their practices—Prayers—Knaveries of lamas—Vagabond lamas—The spread of Bhuddism—Superior to Shamanism—Shaman rites—Political result of Bhuddism—The Mongol kings—Serfs | 185 |

| [ix]CHAPTER XII. | |

| Kiachta. | |

Approach Kiachta—Maimachin—Chinese elegance—The frontier—Russian eagle—The commissary of the frontier—"Times" newspaper—Kiachta—Troitskosarfsk—Meet a countryman—Part from our Mongols—Their programme—A Russian bath—Siberian refinement—Streets and pavement—Russian conveyances—Aversion to exercise—Semi-civilisation—Etiquette—Mixture of peoples—Wealth of Russian merchants—Narrow commercial views—The Chinese of Maimachin—Domestic habits—Russian and Chinese characters compared—Chinese more civilised than the Russians—The Custom-house—Liberal measures—Our droshky—Situation of Kiachta—Supplies—Population—Hay-market—Fish—The garden—Domestic gardening—Climate salubrious—Construction of houses—Stoves—Russian meals—Commercial importance of Kiachta—Inundation of the Selenga—Travelling impracticable—Money-changing—New travelling appointments—Tarantass—Passports—Danger of delay—Prepare to start—First difficulty—Siberian horses—Post-bell | 203 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Kiachta to the Baikal. | |

Leave Troitskosarfsk—Hilly roads—Bouriats—The first post-station—Agreeable surprise—Another stoppage—A night on the hill-side—Hire another carriage—Reach the Selenga—The ferry—Selenginsk—A gallery of art—Cultivation—Verchne Udinsk—Effects of the inundation—Slough of despond—Fine scenery—A dangerous road—A press of travellers—Favour shown us—Angry Poles—Ilyensk—An obsequious postmaster—Tidy post-house—A night at Ilyensk—Treachery suspected—Roads destroyed—Difficult travelling—An old Pole—Baikal lake—Station at Pasoilské—A night scene—The Selenga river—And valley—Agriculture—Cattle, sheep, pigs, dogs | 223 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Lake Baikal to Irkutsk. | |

Morning scene at Pasoilské—Better late than never—Victimised—Russian junks—Primitive navigators—Storms on the Baikal—Scene at the shipping port—Religious ceremony—A polite officer—Inconvenience of the Baikal route—Engineering enterprise—More delay—Fares by the Baikal steamer—Crowing and crouching—The embarkation—[x]The General Karsakof—A naval curiosity—The lake—Its depth—And area—The "Holy Sea"—The passage—Terra firma—Custom-house delay—Fine country—Good roads—Hotels Amoor and Metzgyr | 234 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Irkutsk. | |

In sight of Irkutsk—Handsome town—Wrong hotel—Bad accommodation—Suffocation—Bad attendance—The cuisine—Venerable eggs—Billiards—Meet a friend—Beauties of Irkutsk—Milliners—Bakers—Tobacconists—Prison—Convicts—Benevolence of old ladies—Equipages—Libraries—Theatre—Population—Governor—Generalship—The levée—Governing responsibilities—Importance of commerce—Manufactures insignificant—Education—Attractions of Siberia—Society—Polish exiles—The Decembrists—The sentence of banishment—Its hereditary effect—Low standing of merchants—Discomforts of travelling—Engage a servant—The prodigal—A mistake—Early winter—The Angara—Floating-bridge—Parting view of Irkutsk | 246 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Irkutsk to Krasnoyarsk. | |

Leave Irkutsk—Roads and rivers—Capacity for sleep—Bridges—Break-neck travelling—Endurance of Russian ponies—Verst-posts—Appalling distances—Irregular feeding—Tea versus grog—River Birusa—Boundary of Irkutsk and Yenisei—Stoppage—The telegraph wires—Improved roads—River Kan—The ferrymen—Kansk—A new companion—Prisoner of war—Advantages and disadvantages of travelling in company—Improved cultivation—A snow-storm—Cold wind—Absurd arrangement of stations—The river Yenisei—Mishap at the ferry—The approach to Krasnoyarsk—The town—Population—Hotel—Travellers' accounts—Confusion at the station—The black-book—The courier service | 262 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Krasnoyarsk to Tomsk. | |

Sledges—Sulky yemschiks—Progress to Achinsk—Limit of Eastern Siberia—Game—The Chulim—Difficult ferry—Government of Tomsk—Bad roads again—Job's comforters—Mariinsk—An accident—And another—Resources of a yemschik—A drive through a forest—Ishimskaya—A day too late—A sporting Pole—Disappointment—Annoying delay—[xi]Freezing river—A cold bath—Sledge travelling—A night scene—Early birds—Arrive in Tomsk—Our lodging—Religion of Russians—Scruples of a murderer—Population and situation of Tomsk—Fire Insurance—Climate of Tomsk—Supply of water—Carefulness and hardiness—Skating—Demure little boys—An extinct species—The gold diggings—The Siberian tribes | 273 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Tomsk to Omsk. | |

Refitting—The optician—The feather-pillow question—A friend in need—A dilemma—Schwartz's folly—Old Barnaul leaves us—We leave Tomsk—A weary night—A Russian dormitory—Construction of houses—Cross the Tom—And the Ob—Enter the Baraba steppe—Kolivan—The telegraph—The ladies of Baraba—Game—Windmills—A frozen marsh—Kainsk—Reach Oms—Outbreaks on the Kirghis steppe—Russian aggression—Its effects on different tribes | 290 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Omsk to Ochansk. | |

Leave Omsk—Recruiting—Cross the Irtish—Tukalinsk—Yalootorofsk—Reach Tumen—Improved posting—Snowroads—Ekaterineburg—Mint—Precious stones—Iron works—Englishmen in Siberia—Iron mines—Fish trade—A recruiting scene—Temperature rising—Game—The Urals—Disappointing—A new companion—The boundary between Europe and Asia—Yermak the Cossack—Discovery and conquest of Siberia—Reach Perm—Too late again—Progress of inland navigation—Facilities for application of steam—Water routes of Siberia—Railways—Tatars—Cross the Kama to Ochansk—Dissolving view of snow roads | 305 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Russian and Siberian Peasantry. | |

Siberian and Russian peasantry—The contrast—Freedom and slavery—Origin of Siberian peasants—Their means of advancement—Exiles—Two classes—Their offences and punishments—Privileges after release—Liberality of the government—Its object—Extent of forest—One serf-proprietor in Siberia—Exemptions from conscription—Rigour of the climate on the Lena and Yenisei—Settlers on Angara exempted from taxes—Improvement of Siberian peasants—A bright future—Amalgamation of classes—Slavery demoralising to masters—The emancipation of the serfs—Its results | 320 |

| [xii]CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Kazan.—Polish Exiles. | |

Road to Kazan—Polish prisoners—Arrive at Kazan—More croaking—Temptations to delay—Sell our sledge—View of Kazan—The ferry at the Volga—Ice-boats and icebergs—The military—Tatars—Polish exiles—Kindly treated by their escort—Erroneous ideas on this subject—The distribution of exiles in Siberia—Their life there—The Polish insurrection—Its objects—Imprudence—Consequences—Success would have been a second failure | 331 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Kazan to Petersburg. | |

A day lost—The moujik's opportunity—Return to Kazan—Hotel "Ryazin"—Grease and butter—Evening entertainment—Try again—The ferry—A term of endearment—Ferrymen's devotions—A Jew publican—"Pour boire"—Villages and churches—The road to Nijni—Penance—A savage—A miserable night—Reach Nijni—"Sweet is pleasure after pain"—The great fair—Nijni under a cloud—Delights of railway travelling—A contrast—Reach Moscow—Portable gas—Foundling hospital—The Moscow and Petersburg railway—Grandeur of Petersburg—Late season—Current topics—Iron-clads—The currency—Effects of Crimean war—Russian loyalty—Alexander II. as a reformer—Leave Petersburg | 343 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Russia and China. | |

Earlier intercourse—Analogies and contrasts—Progress of Russia and decadence of China—Permanence of Chinese institutions—Arrogance justified—Not really bigoted—Changes enforced by recent events—The rebellion—Fallacious views in parliament—British interest in China—A bright future—Railways—Telegraphs—Machinery and other improvements—Resources to be developed—Free cities | 357 |

| Postscript | 401 |

| page | |

| Pagoda and Gardens of the Emperor's Summer Palace, Yuen-Min-Yuen. (From a Photograph by Beato) | Frontispiece. |

| Tomb at the Depot. Peking. (From a Photograph by Beato) | Vignette. |

| Tung Chow Pagoda. (From a Photograph by Beato) | 27 |

| Walls of Peking. (From a Photograph by Beato) | 32 |

| Pavilion of the Summer Palace of Yuen-Min-Yuen. (From a Photograph by Beato) | 37 |

| Thibetian Monument in Lama Temple. Peking. (From a Photograph by Beato) | 42 |

| Great Temple of Heaven. Peking. (From a Photograph by Beato) | 48 |

| Part of the Emperor's Palace, Yuen-Min-Yuen. Destroyed 1860. (From a Photograph by Beato) | 55 |

| The Nankow Pass | 63 |

| Halt in the Desert of Gobi | 104 |

| Fording the Tolla near Urga | 147 |

| View of Ekaterinburg. Siberia. (From a Russian Photograph). | 307 |

The charming narrative of John Bell, of Antermony, who, in the reign of Peter the Great, travelled from Petersburg to Peking in the suite of a Russian ambassador, inspired me with a longing desire to visit Siberia and other little-known regions through which he passed. Having occasion to return to England, after a somewhat protracted residence on the coast of China, an opportunity presented itself of travelling through the north of China, Mongolia, and Siberia, on my homeward journey. This is, indeed, the real "overland route" from China, and it may as properly be styled "maritime," as the mail route per P. & O. steamers "overland." The so-called overland route has, however, strong temptations for a person eager to get home. There is a pleasing simplicity about the manner of it which is a powerful attraction to one who is worn out with sleepless nights in a hot climate. It is but to embark on a steamer; attend as regularly at meal times as your constitution will permit; sleep, or[2] what is the same thing, read, during the intervals; and fill up the blanks by counting the passing hours and surveying your fellow passengers steeped in apoplectic slumbers under the enervating influence of the tropics. The sea route has, moreover, a decided advantage in point of time. In forty-five or fifty days I could have reached England from Shanghae by steamer: the land journey viâ Siberia I could not hope to accomplish in less than ninety days.

But the northern route had strong attractions for me in the kind of vague mystery that invests the geography of strange countries, and the character, manners, and customs of their inhabitants. Ever-recurring novelties might be expected to keep the mind alive; and active travelling would in a great measure relieve the tedium of a long and arduous journey. Of the two, therefore, I preferred the prospect of being frozen in Siberia to being stewed in the Red Sea. The heat of Shanghae in the summer was intense and almost unprecedented, the supply of ice was fast undergoing dissolution, and an escape into colder regions at such a time was more than usually desirable.

A few years ago it would have been about as feasible to travel from China to England by way of the moon as through Peking and Mongolia. Peking was a sealed book, jealously guarded by an arrogant, because an ignorant, government. Little was known of the city of the khans except what the Jesuits had communicated in the last century, and what that prince of travellers, Marco Polo, had handed down from the middle ages. No foreigner dared show his face there, except in the guise of a native, and even then at the risk of being detected and subjected to the greatest indignities. The Jesuits, it is true, in the face of the prohibition, continued to smuggle themselves into China, and even into Peking itself, and their perseverance and tenacity of purpose are entitled to all praise. But they[3] occasionally paid dearly for their temerity, and not unfrequently got themselves and their "Christians" into hot water with the authorities. This received the high-sounding name of "persecution;" and if any one lost his life for meddling in other people's affairs, or interfering with the prerogative of the government, he was honoured with the name of a "martyr." The Jesuits had their day of power in China, and if they had but used it modestly they might still have stood at the elbow of the Emperor. They were tried and found wanting, expelled from Peking, and China was closed against foreigners, not, it must be confessed, without some reason.

All that has been changed again. The curtain has risen once more; foreigners are free to traverse the length and breadth of China, and to spy out the nakedness of the land. The treaty of Tientsin and convention of Peking, ratified in November, 1860, which opened up China to travellers for "business or pleasure," was largely taken advantage of in the following year. In 1861, foreign steamers penetrated by the great river Yang-tsze into the heart of China. Four enterprising foreigners explored the river to a distance of 1800 miles from the sea, and many other excursions were set on foot by foreigners, in regions previously known only through the accounts of Chinese geographers or the partial, imperfect, and in some instances obsolete, descriptions of the older Jesuits.

Mongolia, being within the dominions of the Emperor of China, was included in the passport system; and although the Chinese government has made a feeble attempt to impose restrictions on foreign travellers in that region on the ground that, although Chinese, it is not China, up to the present time no serious obstacles have been placed in the way of free intercourse in Mongolia; nor can the plain language of the treaty be limited in its interpretation, unless[4] the ministers of the treaty powers should voluntarily abandon the privilege now enjoyed. It is devoutly to be hoped that no envoy of Great Britain will again commit the error of waiving rights once granted by the Chinese. However unimportant such abandoned rights may appear, experience has shown that the results are not so. Sir Michael Seymour's war at Canton in 1856-7 could never have occurred if our undoubted right to reside in that city had been insisted on some years previously. Our disaster at the Taku forts in 1859 would have been prevented if the right of our minister to reside in Peking had not, in a weak moment, been waived. What complications have not arisen in Japan, from our consenting to undo half Lord Elgin's treaty and allowing the port of Osaca to remain closed to our merchantmen! We cannot afford to make concessions to Asiatic powers. Give them an inch and they will take an ell: then fleets and armies must be brought into play to recover ground we have lost through sheer wantonness.

Too late to join a party who preceded me, I had some difficulty in finding a companion for the journey, but had the good fortune to make the acquaintance of a young gentleman from Lyons, who purposed going to France by the Siberian route with or without a companion. We at once arranged matters to our mutual satisfaction, and proceeded with the preparations necessary for the journey. Having the advantage of excellent practical advice on this head from gentlemen who had already gone over the ground, we had little difficulty in getting up our outfit. A tent was indispensable for Mongolia, and we got a very commodious one from a French officer. A military cork mattress, with waterproof sheets, proved invaluable in the desert. Our clothing department was inconveniently bulky, because we had to provide both for very hot and very cold weather. The commissariat was liberally supplied, rather overdone, as[5] it turned out, but that was a fault on the safe side. The accounts we heard of the "hungry desert," where nothing grows but mutton, induced us to lay in supplies not only for an ordinary journey across, but for any unforeseen delay we might encounter on the way.

We had first to get to Tientsin, six hundred miles from Shanghae, and two steamers were under despatch for that port. I embarked on board the Nanzing, Captain Morrison, about midnight on the 28th July, 1863. Taking advantage of the bright moon, we steamed cautiously down the river Wong-poo for fourteen miles, past the village of Woosung, "outside the marks," and into the great river Yang-tsze, where we cast anchor for the night. It would be hazardous to attempt the navigation of the estuary of the Yang-tsze, even in bright moonlight. Its banks are so flat as to afford no marks to steer by. The estuary is very wide, but the deep water channel is narrow, with extensive shallows on either side. The upper parts of the Yang-tsze-kiang, where the river narrows to a mile or two in breadth, and flows through a bolder country, are more easy of navigation. In the broad part of the river, near its mouth, the deep water channels have a tendency to shift their positions. The surveys of the river from its mouth to Nanking, made in 1842, were found inapplicable in 1861. Where shallows were marked in 1842, deep water was found in 1861, and dry patches were found where the navigable channels were before. The delta of this noble river is rapidly growing into dry land; the "banks" are fast rising into islands, and the channels of the river becoming more circumscribed. The rapidity with which this process is going on is most remarkable. From a point nearly fifty miles from the mouth of the river it is divided into two great branches, called by hydrographers the north and the south entrances. Twenty years ago extensive shallows lay between, and many a good ship[6] found a final resting-place on these treacherous banks. The most dangerous of these are now above water, and are visible from a distance sufficient to enable the pilot to keep clear of them. In the small river Wang-poo also, at and below the town of Shanghae, the land is gaining considerably on the water. An island has formed and is still growing near the mouth of the Wang-poo, known to pilots as the "middle-ground." Until a very few years ago it was entirely under water. In the year 1855 I was aground on the top of it in a schooner near low water, and the rising tide floated us off easily. The island is now so high as to remain uncovered in the highest spring tides. Thus, in the space of eight years, this island has risen more than twelve, and probably not less than eighteen feet. The formation is extending itself downwards; the tail of the island stretching away under water brought up many vessels in 1862 and 1863, where there was plenty of water a year or two before. On the south shore of the Yang-tsze-kiang the lines of embankment mark the different stages of the aggression of the land on the water. When a dry flat was formed liable to inundations in high tides, an embankment of mud was built for the protection of the inhabitants who settled on the reclaimed land. In process of time more land was made, and another embankment formed. Thus three distinct lines of embankment, several miles inland from the present water line, are to be traced from below Woosung towards Hang-chow Bay, and a very large tract of good arable land has been reclaimed from the river, or, as the Chinese call it, the sea, within comparatively modern times. From the causes we see now in active operation, it is easy to trace the formation of the vast alluvial plain which now supports so many millions of inhabitants.

There are, indeed, intimations in the Chinese records of some of these changes. Islands in the sea are mentioned but a few centuries back, which are now hills in inhabited[7] districts. In the dawn of Chinese history allusions are made to a great flood which desolated the land, and the Emperor Yaou has been immortalised for his achievements in subduing and regulating the waters. Yaou reigned about 2200 B.C., and the rising of the waters in his time has been referred by some to the Noachian deluge. But the Chinese empire at that time extended as far south as the Great River, and included three great valleys. It is not an improbable conjecture therefore that there was a large circumference of debateable land barely reclaimed from the sea. With the imperfect means then at command for keeping out the water it is easy to suppose that an unusually high tide would break down the defences and overflow the flat country. It may also be, of course, that then, as now, the Yellow River caused trouble by arbitrarily changing its course, and the patriotic labours of Yaou may have been limited to damming up that wayward stream, which has been called "China's sorrow." But the chronicles of the great inundation do not appear to have been satisfactorily explained, and it may be said of the annals of the reigns of Yaou and Shun, that the interest which attaches to them is in direct proportion to their obscurity.

A few hours' steaming on the 29th took us out of the turbid waters of the Yang-tsze-kiang, but during the whole of that day we continued in shallow water of a very light sea-green colour. The weather was fine, and though still extremely hot, the fresh sea air soon produced a magical effect on our enfeebled digestion. The voyage was as pleasant as a good ship, a good table, and a courteous commander could make it. On the 30th a thick fog settled down on the water, and on the following morning all eyes were anxiously straining after the Shantung promontory, which was the turning-point of our voyage. By dead reckoning we were close to it, but there is no accounting for the effect of the currents that sweep round this bold headland. The tide rushes into the[8] Gulf of Pecheli by one side of the entrance, and out at the other. But from the conformation of the gulf the tidal currents are subject to disturbances from various causes, of which the direction of the wind is the most potent. A north-westerly wind keeps the tide wave at bay, and drives the water out of the gulf, until its level has been lowered several feet below that of the ocean. Great irregularities in the ebb and flow are occasioned by this; and when the cause ceases to act, the reaction is proportionate to the amount of disturbance; the pent-up waters from without flow in with impetuosity, and the equilibrium is restored.

In the dense fog, our commander could only crawl along cautiously, stopping now and again to listen for the sound of men's voices, or the barking of dogs, take soundings, and watch for any indications of the near vicinity of land. At length, to our great joy, the fog lifted over a recognisable point of the promontory, and immediately settled down again. The glimpse was sufficient however, and the good steamer was at once headed westward, for the mouth of the Peiho river, and bowled along fearlessly on her way. As the sun rose higher the mist was dispersed, and the bold rugged outline of the Shantung coast was unveiled before us. The clear blue water was alive with Chinese coasting craft, small and large, of most picturesque appearance. The heavy, unwieldy junks of northern China lay almost motionless, their widespread sails hanging idly to the mast, for there was just wind enough to ripple the surface of the water in long patches, leaving large spaces of glassy smoothness untouched by the breeze.

The crews of the northern junks are hardy stalwart fellows, inured to labour, and zealous in their work. Their vessels are built very low-sided, to enable them to be propelled by oars when the wind fails them. The crews work cheerily at their oars, both night and day, when necessary,[9] keeping time to the tune of their half-joyous, half-melancholy boat-songs. With all their exertions, however, they drive the shapeless lump but slowly through the water, and one cannot help feeling pity for the poor men, and regret for the waste of so much manual labour. It is to be hoped that this hardy race of seamen will find more fruitful fields wherein to turn their strength to account when foreign vessels and steamers have superseded the time-honoured but extravagant system of navigation in China. This end has, indeed, been already reached to a certain extent. China has been imbued with the progressive spirit of the world, to the great advantage both of themselves and foreigners. The southern coasts swarm with steamers, and the Gulf of Pecheli, in this the third year from the opening of foreign trade in the north, was regularly visited by trading steamers. In all discussions in England on the subject of the development of trade in China, the vast coasting trade is generally overlooked, as a matter in which we have no interest. This is a mistake, however, for foreigners have a considerable share in that trade directly, and their steamers and sailing vessels are employed to a very large extent by the Chinese merchants. All produce is very materially reduced in price to the consumer by the facilities for competition among merchants which improved communication affords, and by the diminution in expenses of carriage, which is the necessary result. The rapidity with which foreign vessels can accomplish their voyages as compared with Chinese junks enables the native trader to make so many more ventures in a given time, that he can afford to take smaller profits than formerly, and yet on the average be no loser. Or even if the average results of the year's trade be less profitable to individuals than before, its benefits are spread over a greater number, and, in the aggregate, suffer no diminution. The general interests of the country have been subserved in an[10] important degree by the extension of the coasting trade, where no disturbing influences have been at work; and the prosperity of the general population cannot fail to react favourably on the mercantile class, through whom the prosperity primarily comes.

Chefoo, the new settlement on the Shantung coast, is frequently a port of call for steamers trading between Shanghae and Tientsin. We did not touch there in the Nanzing, but passed at a distance of twelve miles from the bluff rocky headland from which the settlement takes its name. Before darkness had closed in the view we had reached the Mia-tau group of islands which connect the mountain ranges of Shantung, by a continuous chain, with the Liau-tung promontory at the north of the entrance of the Gulf of Pecheli. There is not much difficulty or danger in getting through these islands even at night, but it is always an object to a navigator to reach them before dark. The course is then clear for the Peiho, and he has a whole night's straight run before him with nothing to look out for.

The Peiho river must be an awkward place to "make," except in clear weather. The land is lower even than that of the valley of the Yang-tsze-kiang; the shoal water runs out a long distance into the gulf; and a dangerous sand spit, partly above, and partly under water, stretches fifty miles out to sea on the north of the approach to the river. On reaching the outer anchorage, where vessels of heavy draught lie, the celebrated Taku forts are dimly visible in the haze of the horizon, and masts may be seen inside the river, but the low land on either side is still invisible. A shoal bar, with a very hard bottom, lies between the outer anchorage and the river, and the Nanzing, drawing less than ten feet, was obliged to anchor outside until the rising tide enabled her to get in.

Our Chinese fellow passengers, who had kept remarkably quiet during the voyage, as is their invariable custom, became animated as we ran in between the Taku forts. They were a motley crowd of all classes of people—mercantile, literary, and military. The students who go to Peking to undergo examinations for literary degrees travel now in great numbers by steamer, and doubtless many who, from want of means, want of time, or from any other cause, might hesitate before undertaking such a long journey by the old land route, are now enabled, by means of the coasting steamers, to accomplish the object so deeply cherished by all Chinese literati. The "plucked" ones, and there are many such in China, can now more easily renew their efforts. Men have been known to repair year after year to the examination-hall from their youth upwards, and get plucked every time,—yet, undaunted by constant failure, they persevere in their vain exertions to the winter of their days. The country that can produce such models of perseverance in a hopeless cause may claim to possess elements of vitality, and the usual proportion of fools.

Among our Chinese passengers was an athlete from Fokien, who was bound to Peking to try his prowess in archery. He was a man of great muscular power, fat, and even corpulent. It is remarkable that the training system adopted for the development of the muscles should produce so much fat. I had not observed this before in the Chinese; indeed, the few feats of strength I have seen performed by them have been by men well proportioned and free from fat. But the Japanese wrestlers, who are carefully trained, are generally fat.

The entrance to the Peiho was, as usual, crowded with native and foreign craft, and so narrow and tortuous is the river that great care is necessary to work a long steamer through without accident. Tientsin is distant from Taku, by the windings of the river, between sixty and seventy miles.[12] By the cart road it is only thirty-six. The Nanzing made good way up the river until darkness compelled her to anchor. In the morning the difficulties of the inland navigation began. The river was actually too small for a steamer over two hundred feet long, the turns were too sharp, the ordinary means of handling a steamer were no longer of any avail,—we hauled round several bad turns by means of anchors passed on shore in the boats, but were at length baffled after running the steamer's nose into cabbage-gardens, breaking down fences, and alarming the villagers, who turned out en masse to watch the iron monster as she struggled to force a passage out of her natural element. Partly out of compassion for the men, who were worn out with the uncongenial toil of trudging knee-deep through heavy mud, planting anchors and picking them up again, and partly from some vague hope of a change of tide in the afternoon, the steamer was brought to anchor and hands piped to dinner.

The crews of steamers on the coast of China are usually of a cosmopolite character, chiefly Malays, with a boat's crew of Chinese, the foreign element being reduced to a minimum comprising the officers and engineers. Asiatic sailors do very well when there are plenty of them, the estimate of their value being two of them to one European. They sail for lower wages, but not low enough to compensate the ship-owner for the additional numbers that are necessary. But the Asiatics are more easily handled than Europeans; their regular "watches" may be broken in upon with impunity; they are easier fed, and less addicted to quarrelling with their bread and butter than Europeans, and more especially Englishmen. But any doubt on the part of a shipmaster as to what crew he will employ, will generally be solved by the sailors themselves, who, if English or American, will desert at every port the vessel touches at.

Having my saddle and bridle handy I landed at a village,[13] and borrowing a horse from the farmers, rode to Tientsin, which was only some eight miles distant by the road. The heat was scorching, but greatly mitigated by the mass of bright green foliage that covered the whole country. The soil though dry and dusty is rich to exuberance, fruit grows in great abundance, and, for China, in great perfection. Apples, pears, peaches, apricots, loquats, grapes, are common everywhere in the north, which may be considered the orchard of China. The waving crops of millet, interspersed with patches of beans, and here and there strips of hemp, fill up a vast green ground dotted thickly with villages and pretty clumps of trees. The houses form a dull contrast to the cheerful aspect of the country. In most of the villages they are constructed of mud and straw, which becomes hard enough to be impervious to rain, but the dull parched colour, the small apertures for doors and windows, and general cheerlessness of exterior painfully oppress the sight. The dust of the roads is also an unfavourable medium through which to view the tame though rich beauties of the country. The north of China is cursed with dust, the roads generally are as bad as the road to Epsom on a "Derby day," when that happy event happens to come off in dry weather.

I got back to the Nanzing in time for the final effort to double the difficult corner. The first attempt was successful, and we steamed on gaily through fields and gardens, washing the banks with the wave formed in our wake, which sometimes broke over the legs of unwary celestials who stood gazing after the steamer in stupid wonder like a cow at a railway train. The Chinese take such mishaps good-naturedly—the spectators are always amused, and the victims themselves when the shock of surprise passes off laugh at the joke. The most serious obstacle to our progress had yet to come, however, the "double," a point where the river bends abruptly like the figure S compressed vertically.[14] Extra caution being used there, the appliances of anchors and warps were efficacious, and we passed the double successfully. The smoke of the Waratah, a steamer that left Shanghae the day before us, and which we had passed at sea, now appeared over the trees close to us. There were several reaches of the river between us, however, and we traced the black column of smoke passing easily round the bends that had caused us such difficulty. The Waratah was gaining on us fast, and late in the evening her black hull appeared under our stern, while the Nanzing was jammed at the last bend of the river, unable either to get round herself or to make room for the smaller vessel. Hours were spent in ineffectual endeavours to proceed—the tantalised Waratah could stand it no longer—the captain thought he saw room to pass us, and came up at full speed between us and the bank. But as the sailors say "night has no eyes" even when the moon is shining, and our friend paid for his temerity by crashing his paddle box against our bow. Time and patience enabled us to reach Tientsin at midnight on the 1st August, after spending half as much time in the Peiho river as the whole sea voyage had occupied. I have said enough, and probably much more than enough, to demonstrate the difficulty of navigating the Peiho river with vessels not adapted to it. No vessel should attempt it that is over one hundred and fifty feet in length, for though the risk of loss from stranding is extremely small, the loss of time to large vessels must be serious.

A marvellous transformation had taken place in Tientsin since my previous visit to it in 1861. At that time the few European merchants who had settled there were confined to the Chinese town, the filthiest and most offensive of all the filthy places wherein celestials love to congregate. Now in 1863, the "settlement," that necessary adjunct of every treaty port in China, had been made over to foreigners, laid[15] out in streets, and a spacious quay and promenade on the river bank formed, faced riverwards with solid masonry, the finest thing of the kind in China, throwing into the shade altogether the famous "bund" at Shanghae. The affairs of the settlement are administered by a thoroughly organised "municipal council" after the example of Shanghae, the "model settlement." The newly opened ports have an immense advantage over the original five in having the experience of nearly twenty years to guide them in all preliminary arrangements. That experience shows first—although the soundness of the deduction has been questioned by some able men—the desirability of securing foreign settlements where merchants, consuls, and missionaries may live in a community of their own entirely distinct from the native towns, within which they may put in operation their own police regulations, lay out streets to their own liking, drain, light, and otherwise improve the settlement, levy and disburse their own municipal taxes, and, in short, conduct their affairs as independent communities. These settlements have the further advantage of being susceptible of defence in times of disturbance with the minimum risk of complication between the treaty powers and the Chinese government. Much of the importance Shanghae has achieved of late years is due to the foreign settlement which, being neutral ground and defensible, has become a city of refuge for swarms of Chinese who had been ousted from their homesteads by the rebels. The cosmopolite character of the Shanghae settlement has entailed various inconveniences, which it is thought might be obviated in the new settlements by keeping the different foreign nationalities distinct. Time has not yet pronounced on the success of this experiment. There will probably be a difficulty in putting it thoroughly in practice; no arbitrary regulations will be able to prevent nationalities from fusing into each other to such an extent as the higher[16] laws of interest and policy may dictate. And it will be impossible in practice to subject a mixed community to the laws of any one power. In the meantime concessions are claimed from the Chinese government by each of the treaty powers separately, and so far they have been granted. Whether the isolation of the various concessions be permanent or not, it secures for them at the outset more unanimity in laying out streets and framing preliminary regulations for their good government hereafter. This is of great importance, and the experience of Shanghae is most valuable in this respect. The narrowness of the streets in the settlement there—twenty-two feet—is a standing reproach on the earlier settlers who, with short-sighted cupidity, clung with tenacity to every inch of land at a time when land was cheap and abundant. This fatal error has been avoided in the recent settlements.

The municipality of Shanghae established under the auspices of Sir Rutherford (then Mr.) Alcock, at that time British consul, has on the whole proved such a success that the same system has been adopted in the new settlements. The legality of the institution has often been questioned, but the creation of some such authority was a necessity at the time, and it has worked so well for ten years that it has not only subsisted, but gathered strength and influence by the unanimous will of the community.

Several fine European houses were already built and inhabited on the Tientsin settlement. The ground had been well raised, so as to keep the new town dry, and ensure it a commanding position. It is about two miles lower down the river than the native town, has a fine open country round it, and plenty of fresh air. It is several degrees cooler in the British settlement than in the Chinese town, and altogether the very best site for the purpose has been selected. The merchants retain their offices in the Chinese town, riding[17] or sailing to and fro every day. This system will probably continue to be practised for some time longer, or perhaps altogether, for the convenience of the Chinese dealers. A small minority of the foreign merchants would compel all to retain their business premises in Tientsin, and nothing less than an almost entire unanimity among them would effect the transfer to the new town.

As a dépôt of trade, Tientsin labours under certain disadvantages; the shallow bar outside, and intricate navigation of the river, prevent any but small craft from trading there. Larger vessels do sometimes, or rather did,—for I fancy the practice is discontinued,—repair to the outer anchorage. But the expense of lighterage, and the detention incurred in loading or discharging at such a distance from the port, are so great as to drive such competitors out of the field. The other drawback to Tientsin is the severe winter, and the early closing of the river by ice. This generally happens before the end of November, and the ice does not break up before February or March.

However, Tientsin is the feeder of a large tract of country containing a large consuming population, and the trade is no doubt destined to increase. Much disappointment has, indeed, been felt that the extraordinary start made, chiefly in the sale of foreign manufactures, in the first year of its existence as a port of foreign trade, has not been followed up. This may be explained, however, by the circumstance that in 1860-61 manufactured goods were extremely depressed by over-supply in the south of China. These goods were introduced into Tientsin, and sold direct to the Chinese there, untaxed by the intermediate profits and charges they formerly had to bear when sold in Shanghae, and thence forwarded by Chinese merchants, in Chinese junks, to Tientsin and the north. Prices in Tientsin soon fell so low that the merchants were tempted into large investments[18] during 1861. The markets of the interior became overstocked, and, before the equilibrium was restored, the cotton famine began to be felt, and prices of goods (the Tientsin trade is chiefly opium and cotton goods) rose so high as to deter purchasers, and in a material degree to reduce the consumption of foreign cottons. Another circumstance also operated adversely to a maintenance of the lively trade that grew up in 1861. There were no exports in Tientsin suitable to any foreign market. The foreign trade was therefore limited to the sale of imports, which were paid for in specie. A heavy drain of bullion was the result, more than the resources of the country could bear for any length of time. This of itself was enough to check the further development of trade; for though the precious metals were merely transferred from one part of the country to another, no counter-balancing power then existed by which they could be circulated back to the districts whence they came. There is no good reason why produce suitable to foreign markets should not be found in Tientsin. Wool and tallow will no doubt be obtainable in considerable quantities in process of time, for the country is full of sheep and cattle, and Tientsin is only six days' journey from the frontier of Mongolia, where flocks and herds monopolise the soil.

I must mention a circumstance connected with the Tientsin trade, which is remarkable among an eminently commercial people like the Chinese. At the opening of the trade, in the end of 1860, the relative values of gold and silver varied fifteen per cent. between Tientsin and Shanghae. Gold was purchased for silver in the north, and shipped to Shanghae, at a large profit, and a good many months elapsed before an equilibrium was established.

In and about Tientsin, as almost everywhere else in China, the population is well affected towards foreigners. The British troops that garrisoned Tientsin from 1860 till 1862[19] left behind them the very best impressions on the inhabitants. Not that these troops were any better than any other well-disciplined troops would have been, but the Chinese had been taught to regard foreigners as a kind of aquatic monsters, cruel and ferocious; so when the horrible picture resolved itself into human beings, civil and courteous in their disposition, honestly paying for all they wanted, of vast consumptive powers in the matter of beef and mutton, fruit and vegetables, and, on the whole, excellent customers, the Chinese took kindly to the estimable invaders, and had cause to regret their departure. Foreign merchants were held in high estimation from the first. The free hospitals for Chinese, set on foot by the army surgeons, not only did a great deal of good in alleviating suffering, but prepared the way for mutual good feeling in the after intercourse between natives and foreigners. It has been questioned whether the Chinese, as a race, are susceptible of gratitude. But, at any rate, the respectable classes are sufficiently charitable themselves to appreciate philanthropy in others; and, in the self-imposed and gratuitous labours of the surgeons for the benefit of the sick poor, they saw an example of pure benevolence, which could not but excite their admiration.

The population of Tientsin is supposed to be about 400,000, residing chiefly in the suburbs, for trade is generally carried on without the walls, not only here, but in all Chinese cities. There is an unusually large proportion of beggars about Tientsin, and loathsome objects they are, as they whine about the streets, half clad, in tatters, starved, and often covered with sores. They never sleep but on the ground. At night, when the streets are quiet, the beggars may be discovered huddled together at every corner and on every door-step. Begging is an institution in China, and to qualify for the craft, men have been said to burn out their own eyes, in order to excite compassion for their blindness. A Chinese[20] householder seldom allows a beggar to go away empty. Charity is cheap; a handful of rice, one copper cash, value the fourth part of a farthing, suffices to induce the disgusting object to move on to the next shop. The beggars have seldom any cause to starve in China, but they do very often, and it is probable they bring diseases on themselves in their efforts to excite pity, which carry them off very rapidly. In winter, especially in the north, they seem to die off like mosquitoes, and no one takes any notice of them except to bury them—for the Chinese don't like to leave dead bodies about the streets. In spring they reappear—not the identical beggars, certainly—but very similar ones, and the ranks of the profession are kept filled.

The wealthier natives of Tientsin, traders and shopkeepers, are fond of good living and gambling. They are robust people, and bear up well against the effects of late hours and gross dissipation. The close, filthy atmosphere in which they live and breathe does not seem to injure their health. Epidemics do make great havoc among them occasionally; one year it is cholera, another year it is small-pox; but the general healthiness of the people does not seem to suffer. The climate is exceedingly dry. Little rain or snow falls; but when it does rain, the whole heavens seem to fall at once, not in torrents, but in sheets of water. The peculiar sand-storms, so common in the north of China, have not as yet been satisfactorily investigated. They often come on after a sultry day. A yellow haze appears in the sky, darkening the sun; then columns of fine dust are seen spinning round in whirlwinds. At that stage every living thing seeks shelter, and those who are afield are lucky if they are not caught in the blinding storm before they reach their houses. But even a closely shut-up house affords but half protection, for the fine powdery dust insinuates itself through the crevices of doors and windows, and is palpably present in your soup and[21] your bread for some time after. The most obvious source whence these sand-storms come, is the great sandy desert of Mongolia, but such an hypothesis is hardly sufficient to account for all the phenomena which accompany the sand-storms. It has been supposed that they are due to some peculiar electrical condition of the atmosphere.

The Chinese are passionately addicted to gambling, and the endless variety of games of chance in common use among them does credit to their ingenuity and invention, for it is not likely that they have learned anything from their neighbours. The respectable merchant, who devotes the hours of daylight assiduously to his business, sparing no labour in adjusting the most trifling items of account, will win or lose thousands of dollars overnight with imperturbable complacency. Every grade of society is imbued with the passion. I have amused myself watching the coolies in the streets of Tientsin gambling for their dinner. The itinerant cooks carry with them, as part of the wonderful epitome of a culinary establishment with which they perambulate the streets, a cylinder of bamboo, containing a number of sticks on which are inscribed certain characters. These mystic symbols are shaken up in the tube, the candidate for hot dumpling draws one, and according to the writing found on it, so does he pay for his repast. So attractive is gambling in any form to the Chinese, that a Tientsin coolie will generally prefer to risk paying double for the remote chance of getting a meal for nothing. On one occasion I volunteered to act as proxy for a hungry coolie who was about to try his luck. The offer was accepted with eagerness, and I was fortunate enough to draw my constituent a dinner for nothing. I was at once put down as a professor of the black art, and literally besieged by a crowd of others, all begging me to do them a similar favour, which, of course, I prudently declined. Had I indeed been successful a second time, the[22] dispenser of the tempting morsels would certainly have protested against my interference as an invasion of his prerogative, which is to win, and not to lose.

The Chinese gamblers are, of course, frequently ruined by the practice. They become desperate after a run of ill luck; every consideration of duty and interest is sunk, and they play for stakes which might have startled even the Russian nobles, who used to gamble for serfs. In the last crisis of all, a dose of opium settles all accounts pertaining to this world.

In games of skill the Chinese are no less accomplished. Dominoes, draughts, chess, and such like, are to be seen in full swing at every tea-house, where the people repair to gossip and while away the evening. The little groups one sees in these places exhibit intense interest in their occupation; the victory is celebrated by the child-like exultation of the winner, and any pair of Chinese draught-players may have sat for Wilkie's celebrated picture.

There are several modes of going from Tientsin to Peking. The most common is in a mule cart, which is not exactly a box, but a board laid on wheels with a blue cotton covering arched over it. The cart is not long enough to enable one to lie down full length, nor is it high enough to enable him to sit upright in the European fashion. It has no springs; the roads are generally as rough as negligence can leave them; it is utterly impossible to keep out the dust; and the covering gives but slight protection from the sun. A ride in a Chinese cart is exquisite torture to a European. It is true that experience teaches those who are so unfortunate as to need it several "dodges" by which to mitigate their sufferings, such as filling the cart entirely with straw, and then squeezing into the middle of it. But then the traveller must have some means of securing the feet to prevent being pitched out bodily, and he must hold on to the frame-work of the side by both hands to break the shock of sudden jerks. With all that he will come off his journey feeling in every bone of his body as if he had been passed through a mangle. That the Chinese do not suffer from such treatment I can only attribute to a deficiency in their nervous system. If they suffered in anything like the same degree that a European does, they would have invented a more comfortable conveyance before the Christian era. But the only improvement in comfort I ever heard of is in the carts made for the great[24] mandarins, which have the wheels placed far back, so that between the axle-tree and the saddle the shafts may have an infinitesimal amount of spring in them.

The next mode of travelling is on horseback, which, if you happen to have your own saddle and bridle, is very pleasant, provided the weather is not too hot or too cold. There are plenty of inns on the road-side where you can rest and refresh yourself; but woe betide the luckless traveller who, like myself, nauseates the Chinese cuisine, should he have neglected to provide himself with a few creature comforts to his own liking.

The weather was excessively hot, and judging that there would be many calls on our stamina before our long journey was done, we prudently husbanded our strength at the outset. We therefore chose the slower but more luxurious (!) means of conveyance by boat up the Peiho river to Tungchow, a walled city twelve miles from Peking. Boat travelling in the north has not been brought to such a state of perfection as in the creek and canal country in Chekiang and Keangsoo. In the latter provinces it is practically the only means of travelling, and though slow, is most comfortable. In the north the boats are a smaller edition of those used for transporting merchandise, the only convenience they have being a moveable roof. In two such craft our party embarked on the night of 5th August, 1861, and at 11 p.m., by moonlight, we languidly shoved off from the filthy banks of the Peiho river, the few friends who were kind enough to see us off, with a refinement of politeness worthy of a Chinaman, refusing a parting glass, knowing that we had none to spare. Our sails were of little assistance, so after threading our way through the fleet of boats that lay anyhow in the first two reaches, our stout crews landed with their towing line, by which means we slowly and painfully ascended the stream. Tientsin, as I have said, is the filthiest of all filthy[25] cities; and the essence of its filth is accumulated on the banks of the river, forming an excellent breakwater, which grows faster than the water can wash it away. The putrid mass is enough, one would think, to breed a plague, and yet the water used by the inhabitants is drawn from this river! It was pleasant, indeed, to escape from this pestilential atmosphere, and to inhale the cool fresh air of the country for an hour or two before turning in, as we reflected on the long and tedious journey we had before us, embracing the whole breadth of the continents of Asia and Europe.

The voyage to Tungchow was monotonous in the extreme. Nothing of the country could be seen; for though the water was high enough at the time to have enabled us to look over the low flat banks, the standing crops effectually shut in our view. Four days were occupied in travelling 400 li. We had engaged double crews, in order that we might proceed night and day without stopping, but it was really hard work for them, and we did not like to press them too much. There is no regular towing path on the banks of the Peiho, and at night the men floundered in the wet mud amongst reeds. A youngster of the crew gave us a great deal of trouble—always shirking his work and complaining of hunger. He was a wag, however, and kept both us and the crew in amusement. I have noticed in nearly all Chinese boat-crews there is a character of this sort, whose business seems to be to work as little as possible himself, and keep up a running fire of wit to beguile the toil of the others. A good story-teller is much valued among them. We had also an old man, whose chief business was to boil rice and vegetables for the others, and to steer the boat. His kitchen duties were no sinecure, for the men did get through an incredible quantity of rice in the course of the day. Rice is a poor thing to work on; it is a fuel quickly consumed, and requires constant renewal.

It is the nature of Chinese boatmen to be constantly asking for money. The custom is to pay about half the fare in advance before starting, and the other half when the journey is completed. But no sooner are you fairly under way, than a polite request is made for money to buy rice. It is in vain you remind them of the dollars you have just paid as a first instalment. That has gone to the owner of the boat, of course, but as for them, the boatmen, they have nothing to eat, and cannot go on. Defeated in your arguments you nevertheless remain firm in your purpose; the morning, noon, and evening meals succeed each other in due course. Every one is to be the last, and is followed by the most touching appeals to your benevolence—they will go down on their knees, they will whine and cry, they will beat frantically on their empty stomachs, and tell you "they are starving" in tones and gestures that ought properly to melt the heart of a stone. It is in vain that you deride their importunity; it is in vain that you reproach them with their improvidence. You sternly order them to their work, but are met by the unanswerable question, how can they work without food? You—if you have gone through the ordeal before—know well that you will have no trouble on this score on the second day out.

Has any one ever tried to arrive at the exact value of a Chinese measure of distance? Their li has no doubt been reduced to so many yards, feet, and inches, equal to about one-third of an English mile, on paper; but on the road it is the vaguest term possible. Ask a countryman how far it is to Chung-dsz, and he will answer after a great deal of prevarication ten li. Walk about that distance and inquire again, and you are told it is fifteen li. This will puzzle you if you are a stranger, but go on another half mile, and you find you are at your destination. In the common acceptation of the word, I am convinced it is more a measure of time[27] than distance, and 100 li is an average day's journey. Our Tientsin boatmen put this very prominently when questioned, as they were nearly every hour of the day, as to how far we still were from Tungchow, one of them answered, "If you travel quick it is about 100 li, but if slow it is well on to 200!"

In the first part of our journey we met with no traffic on the river, but towards Tungchow we passed large fleets of junks bound upwards and a few bound down. John Bell says of this river, "I saw many vessels sailing down the stream towards the south-east. And I was informed there are nine thousand nine hundred and ninety-nine vessels constantly employed on this river; but why confined to such an odd number I could neither learn nor comprehend." I should say that during the 140 years that have elapsed since that was written the fleet is more likely to have been shorn of a few odd thousands than increased by the odd unit.

On the fourth day, as we were panting for breath, with the thermometer standing at 97° Fahr., and with anxious eyes contemplating our almost empty ice-box, the pagoda of Tungchow was descried over the tall reeds on the river bank, and we soon were made fast in front of a temple called Fang-wang-meaou.

At this point the Peiho dwindles away into a very small and shallow stream, and practically Tungchow is the head of the navigation, the shipping port of Peking, and the beginning of the land carriage to the north-west provinces of China.

The Fang-wang-meaou is much used by Russians as a dépôt for their goods in transit from Tientsin and Shanghae to Siberia. We found a considerable quantity of tea stored in the temple waiting for transport. In this temple, therefore, by the favour of the reverend personages who preside[28] over it, we bestowed our impedimenta, and took up our quarters for the night in a wing of the building.

The Bhuddist priests are in the habit of transacting business for strangers, and we therefore entered into negotiation with them to provide us carriage either by mules or camels, from Tungchow to Chan-kia-kow, the frontier town between China and Mongolia. We thought by this arrangement we could ride to Peking, do what we wanted there in the way of getting passports, &c., and return to Tungchow and take our departure thence. This proved a delusion, and lost us some valuable time.

There is nothing remarkable about the city of Tungchow. It is situated on a dead level. From a tower on the wall a view of the country is obtained, including the mountains north of Peking. There is a tall pagoda in the city, but as it has no windows in it, it is useless as a look-out.

I found here two ponies that I had sent from Tientsin, in charge of a Chinese "ma-foo" or groom, who agreed to accompany me as far as Chan-kia-kow. My object was to be independent of the Chinese carts at Peking and on the road, and I looked forward to taking one, if not both, of my ponies a considerable distance into the desert of Mongolia. I strongly recommend this plan to any one travelling in that quarter.

On the 10th of August I rode to Peking, the rest of the party following in carts. This would no doubt be a very pretty ride at another season of the year, but in the month of August the millet crops stand as high as twelve and fifteen feet, completely shutting in the road for nearly the whole distance. At eight li from Tungchow we passed the village and handsome stone bridge of Pa-li-keaou or "eight-mile-bridge," which euphonious name gives a title to a distinguished French general. There are no "high" roads, but many bye-roads, and it is not difficult to lose one's way[29] amongst the standing millet. Many parts of the country are very prettily wooded, and there is a half-way house at a well-shaded part of the road, where you naturally dismount to rest yourself under a mat shed, and indulge yourself with hot tea, than which nothing is more refreshing on a hot day, provided the decoction be not too strong, and is unadulterated by the civilised addition of sugar or milk. You may eat fruit here also if you are not afraid of the consequences (but take care that it is ripe), and some naked urchins will cut fresh grass for your beasts. This little place, like many others of its kind, is a "howf" for many loafers, who seek the cool shade, and sit sipping their boiling tea, and languidly fanning themselves while they listen abstractedly to the conversation of the wayfarers.

As we near Peking we come to some slight undulations, and notice some very pretty places with clumps of old trees about them. These are principally graves of great men, and it is remarkable to observe how much attention is paid by the Chinese to the abodes of their dead. Wealthy people will pass their lives in a dismal hovel, something between a pig-stye and a rabbit-warren, into which the light of day can scarcely penetrate; the floors of earth or brick-paved, or if the party is luxurious, he may have a floor of wood, encrusted with the dirt of a generation. But these same people look forward to being buried under a pretty grove of trees, in a nicely kept enclosure, with carefully cultivated shrubs and flowers growing round. Some of the loveliest spots I have seen in China are tombs, the finest I remember being at the foot of the hill behind the city of Chung-zu, near Foo-shan, on the Yang-tsze-kiang. These tombs, adorned with so much taste and care, were in strange contrast with the general rottenness around. But armies have since been there, and it is probable that the angel of destruction has swept it all away.

I am unable to say from what feeling springs this tender regard for tombs among the Chinese. It may be that they consider the length of time they have to lie in the last resting-place, reasonably demands that more care be bestowed on it than on the earthly tenement of which they have so short a lease. Or it may arise simply out of that strong principle of filial piety so deeply engraven in the Chinese mind, and which leads them to make great sacrifices when required to do honour to the names of their ancestors. From whatever motive it comes, however, this filial piety, which even death does not destroy, is an admirable trait in the Chinese character; and I have even heard divines point to the Chinese nation—the most long-lived community the world has seen—as an illustration of the promise attached to the keeping of the fifth commandment. The greatest consolation a Chinaman can have in the "hour of death" is that he will be buried in a coffin of his own selection, and that he has children or grandchildren to take care of his bones. It is to this end that parents betroth their children when young, and hasten the marriages as soon as the parties are marriageable. To this end also I believe polygamy is allowed by law, or at all events not interdicted. If a Chinaman could have the promise made to him, "Thou shalt never want a man to stand before me," he would live at ease for the rest of his days.

There are no cemeteries in China, that I know of, except where strangers congregate—when they of a family, a district, or even a province, combine to buy a piece of ground to bury their dead in. In hilly countries pretty sites are always selected for tombs. In the thickly settled parts of the country every family buries its own dead in its own bit of ground. Thus, when they sell land for building purposes, negotiations have to be entered into for removing the coffins of many forgotten generations. The bones are carefully gathered up and[31] put into earthenware jars, and labelled. This operation is profanely called "potting ancestors." These jars are then buried somewhere else—of course with great economy of space. A house built on the site of an old grave that is suspected of having been only partially emptied, would remain tenantless for ever, and if the ghosts of the departed did not destroy the house, the owner would be compelled to do so.

But I am getting away from the Peking road. Amongst the tombs of great families, outside the walls of the city, are many old marble colossal sculptures of men and animals. The same figures, in limestone, are common in other parts of the country. These sculptures are all more or less dilapidated; some of the figures are still erect; many have fallen down and got broken; and many have been ploughed in. There is nothing remarkable about the workmanship of these, although the colossal size of some of them is striking. They are interesting as memorials of departed greatness, and record their silent protest against the corruption, decay, and degeneracy that has brought the Chinese empire so low.

Water communicating with the Peiho river goes up to the walls of Peking, but is not navigable. It forms a quiet lagoon, the delight of great flocks of the most beautiful ducks and geese. The streams that run through the city can also be connected with the water outside through the arches in the wall; and I am told the intention of those truly great men, who conceived and executed the grand canal, was to bring the water through the city and into the imperial quarters by navigable canals, so that the grain-junks from Keangsoo, which were to supply the capital with food, might be brought in to the gate of the Emperor's palace. It is not to be wondered at that this scheme should have broken down, considering the engineering difficulties attending it.

Nothing of the city of Peking is visible until you are close under the walls, and then the effect is really imposing. The walls are high, massive, and in good repair. The double gates, with their lofty and large three-storied towers over them, and the general solid appearance, inspire one with some of the admiration which poor old Marco Polo used to evince when speaking of the glories of Kambalic, or the city of the Grand Khan.

Once inside the walls you instinctively exclaim, What a hot, dusty place this is! and you call to mind that that is exactly what everybody told you long before its threshold was polluted by barbarian footsteps. Peking is celebrated for its carts, its heat, and its dust. If it rained much the streets would be a sea of mud.

We pursue our way along the sandy tracks between the city wall and the buildings of the town for a mile or two, then plunge into the labyrinth of streets, crowded, dirty and odoriferous. We are being conducted to an inn which is to be better than any that foreigners have been admitted to before.

In our way we crossed the main street which leads from the imperial city straight to the Temples of Heaven and Earth. This street is very wide, and has been very fine, but now more than half its width is occupied by fruit, toy, and fish stalls. The centre of the street has been cut up by cart-wheels[33] for many centuries, and is full of holes and quagmires, so that the practicable portion of this wide thoroughfare is narrowed down to nothing. So it is with all the wide streets of Peking. They are never made. Filth accumulates incredibly fast; and the wider the street the dirtier it is, because it can hold the more.

At last we arrived at this paragon of inns, and passing through the courtyard, where the horses and mules of travellers were tied up, we threaded our way as far into the interior of the establishment as we could get, and then called the landlord. He pretended to make a great to-do about receiving us, and strongly urged that we would find much better accommodation at the West-end. This was not to be thought of, and we soon installed ourselves in a room—but such a room! and such an inn! and such attendance! and such filth everywhere! I have slept in a good many Chinese inns of all sorts, but the meanest road-side hostelry I have ever seen is a degree better than this swell inn in this fashionable city of Kanbalu. Our room was at the far end of the labyrinthine passages, and was evidently constructed to exclude light and air. It was almost devoid of furniture. We certainly could make shift for sleeping accommodation, for travellers can manage with wonderfully little in that way; but we were miserably off for chairs, the only thing we had to sit upon being small wooden stools on four legs, the seat being about five inches wide.