|

Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

Some typographical errors have been corrected;

a list follows the text.

The illustrations

have been moved from mid-paragraph for ease of reading.

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol  will bring up a larger version of the image.

will bring up a larger version of the image.

(etext transcriber's note) |

LATER QUEENS OF THE

FRENCH STAGE

Sophie Arnould

Painted by J. B. Greuze (Wallace Collection)

LATER QUEENS OF

THE FRENCH STAGE

BY

H. NOEL WILLIAMS

AUTHOR OF “QUEENS OF THE FRENCH STAGE,” “MADAME RÉCAMIER

AND HER FRIENDS,” “MADAME DE POMPADOUR,” “MADAME

DE MONTESPAN,” “MADAME DU BARRY,” ETC.

LONDON AND NEW YORK

H A R P E R & B R O T H E R S

45 ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1906

TO

A. M. BROADLEY

CONTENTS

| PAGE |

| I. | SOPHIE ARNOULD | I |

| II. | MADEMOISELLE GUIMARD | 99 |

| III. | MADEMOISELLE RAUCOURT | 143 |

| IV. | MADAME DUGAZON | 195 |

| V. | MADEMOISELLE CONTAT | 223 |

| VI. | MADAME SAINT-HUBERTY | 263 |

| | INDEX:

A,

B,

C,

D,

E,

F,

G,

H,

I,

J,

L,

M,

N,

O,

P,

Q,

R,

S,

T,

V,

W,

X,

Z | 345 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Sophie Arnould (Photogravure) | Frontispiece |

| | After the painting by Greuze in the Wallace Collection at Hertford House |

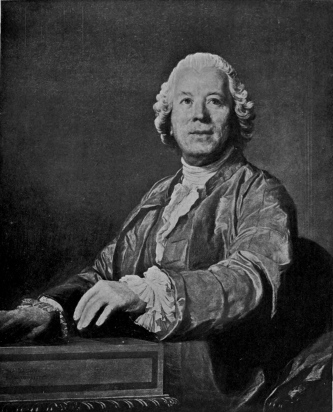

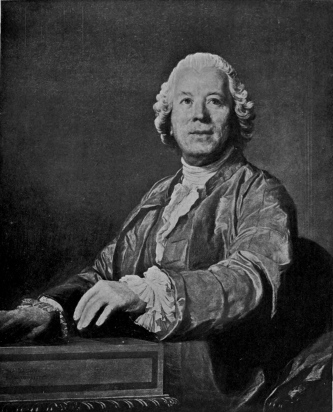

| Gluck | To face page 56 |

| | After the painting by N. F. Duplessis |

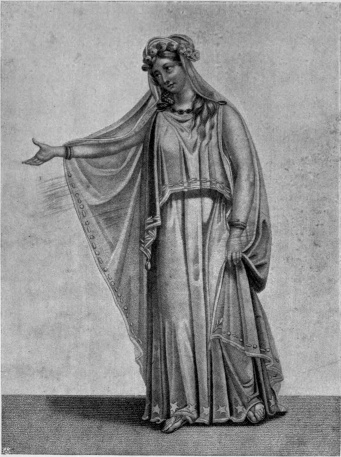

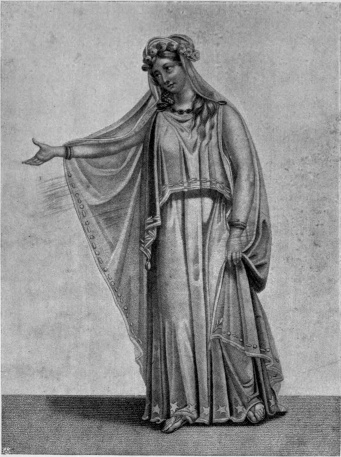

| Sophie Arnould | " 72 |

| | From an engraving by Prud’hon after the drawing by Cœuré |

| Marie Madeleine Guimard | " 112 |

| | From an engraving by Gervais after the painting by Boucher |

| Mlle. Raucourt | " 160 |

| | From an engraving by Ruotte after the painting by Gros, in the collection of Mr. A. M. Broadley |

| Madame Dugazon | " 202 |

| | From an engraving by Monsaldi after the painting by Jean Baptiste Isabey |

| Louise Contat | " 240 |

| | After the painting by Dutertre |

| Madame Saint-Huberty | " 288 |

| | From an engraving by Colinet after the painting by Le Moine |

{1}

{2}

{3}

LATER QUEENS OF THE

FRENCH STAGE

I

SOPHIE ARNOULD

IN her unpublished Mémoires,[1] which she began, but never completed,

and only a few pages of which—possibly all that she wrote—have been

preserved, Sophie Arnould tells us that she was born in 1745, “in the

same alcove in which Admiral Coligny had been assassinated two hundred

years before.” As a matter of fact, the celebrated singer was born on

February 14, 1745, and it was not until some years after her birth that

her parents removed to the Hôtel de Ponthieu, Rue Béthisy, then known as

the Rue des Fossés-Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois.[2]

Sophie’s parents belonged to the upper bourgeoisie, and at the time

of her birth appear to have been in {4}comfortable circumstances. Her

father, Jean Arnould, was a worthy man, whose worldly ambitions were

limited to securing a comfortable competence, retiring from business,

and purchasing some Government or municipal office and the social

distinction which went with it. Her mother, however, had received an

excellent education, “which, joined to her natural intelligence,” says

Sophie, “rendered her in society the most amiable and interesting of

women.” She affected literary society and numbered among her friends and

acquaintances Voltaire, Fontenelle, who, a few days before his death,

called to show her the manuscript of one of the great Corneille’s

tragedies, Piron, the Comte de Caylus, Moncrif, the Abbé (afterwards the

Cardinal) de Bernis, Diderot, and d’Alembert.

So impressed was Madame Arnould by the conversation of these

celebrities, that she determined to make her little girl a prodigy of

learning. Sophie’s education began almost as soon as she was out of her

cradle. She was precocious and learned quickly. At four, she declares,

she could read; at seven she wrote better than at the time of penning

her Mémoires, and at the same age could read music at sight without

any difficulty. The infant prodigy was petted and spoiled to the top of

her bent, “dressed up in silk and satin, with marcasite necklace and

flowers in her hair.”

When the child was four or five years old she attracted the attention of

the Princess of Modena, wife of the Prince de Conti, from whom, however,

she was separated.{5} Madame de Conti, lonely and bored, without husband,

lover, child, or occupation, took a violent fancy to Sophie, and begged

Madame Arnould to let her have the little girl to live with her. Madame

Arnould consented, and Sophie became the plaything of the eccentric

princess, “who dragged her about everywhere as she might have her little

dog,” now nursing her on her knee, now setting her down to the

harpsichord, now taking her visiting in her carriage, now summoning her

to her salon to amuse her guests, and anon, if she happened to be in an

ill-humour, turning her out into the ante-chamber to play with the

yawning lackeys.

No pains were spared with Sophie’s education, and the best masters of

the day were engaged to teach her all the arts and accomplishments.

Before she was twelve, she could both write and speak her own language

correctly—a rare accomplishment in those days outside literary

circles,[3] and was familiar with Latin or Italian; while she could sing

like a professional.

Her musical talents were not destined to remain long hidden. When the

time for her first communion drew near, she was placed in the Ursuline

Convent at Saint-Denis, the supérieure of which was a fellow

townswoman and friend of Madame Arnould. Here she sang in the choir, and

with such astonishing success that Court and town flocked to hear her,

and Voltaire, from his retreat at Ferney, wrote to his little friend a

letter congratulating her on her twofold success as a vocalist and a

first communicant; an epistle which Madame Arnould, who did not share

the Patriarch’s views on matters of religion,{6} promptly committed to the

fire, although the Duc de Nivernais begged for a copy on his knees. On

leaving Saint-Denis, Sophie returned to live with Madame de Conti, who,

delighted by the notice which she had attracted, provided her with the

most celebrated music-masters to be found in France: Balbatre gave her

lessons on the harpsichord, and the famous Jéliotte—Jéliotte, the pride

of the Opera!—Jéliotte, “the happy and discreet conqueror of all the

fair ladies in Paris!”—condescended to sing with her. Sophie proved

herself worthy of her teachers.

It was then the fashion, among ladies of rank, to do penance during Lent

by retiring to one of the many convents in Paris or its neighbourhood.

Some of the visitors were, of course, sincerely desirous of benefiting

by the services, the conversation of the nuns, and the opportunities for

meditation which these peaceful abodes afforded; but to the majority the

practice would appear to have been regarded merely as a kind of rest

cure. There was nothing at all austere or conventual about the life for

such as these. They rose late, walked in the gardens, dined on plain but

well-cooked food, received visits from their friends, attended a service

or two, supped, and retired early to bed; and if their souls did not

greatly benefit, the early hours and simple fare worked wonders with

their complexions. They had, too, an opportunity of listening to some

very beautiful singing; for, during Holy Week, the convents vied with

one another in engaging the finest voices of the Opera to reinforce

their choirs, and the services of such singers as Jéliotte, Chassé, and

Mlles. Fel, Chevalier, and Anna Tonelli were always in great request.

At the beginning of Holy Week 1757, Madame de{7} Conti, who, as became an

Italian princess, was very strict in her observance of Lent, arrived at

the Abbey of Panthémont, where she found the community in a state of

consternation. The convent in question had not deemed it necessary to

enlist the services of any of the stars of the Opera, as it numbered

among its inmates a nun with an exceptionally beautiful voice. But alas!

she had suddenly been taken ill, and it was feared that it would be

impossible to replace her. Half fashionable Paris would be coming on

Holy Wednesday to hear the Tenebræ sung, and there would be no one

capable of singing it. The abbess fell upon Madame de Conti’s neck and

wept tears of mortification.

The princess bade her not despair, told her of the talent of her little

protégée, and suggested that she should be sent for; a proposal to

which the grateful abbess readily consented.

Holy Wednesday came, and with it a great crowd of visitors. At the

beginning of the service Sophie was a little nervous, but quickly

recovered her presence of mind, and sang so divinely that her hearers

were enraptured, and some, in spite of the solemnity of the place, could

not refrain from applause. The following day there was not a vacant seat

in the church; while on Good Friday the doors were literally besieged,

and more than two hundred carriages were turned back. Those who had

succeeded in gaining admission had every reason to congratulate

themselves on their good fortune, for Sophie sang the Miserere of

Lalande, and with such exquisite pathos that there was scarcely a dry

eye in the congregation.[4]

Paris was as delighted as if it had found a new fashion.{8} All the

Faubourg Saint-Germain wended its way to the Hôtel de Conti to

congratulate the princess upon the possession of this little wonder with

her angelic voice. The Court was scarcely less interested and, finally,

the Queen, the pious Marie Leczinska, who lived in a little world of her

own and seldom troubled herself about what was happening in the one

outside, expressed a desire to see Sophie.

“On your account,” remarked Madame de Conti to the radiant girl, “her

Majesty condescends to remember my existence.” (The said Majesty did not

approve of ladies who lived apart from their husbands.) Nevertheless,

the Queen had to be obeyed, and so the princess, who was proud of her

protégée and, in truth, far from displeased with so striking a tribute

to her discernment, ordered her coach and set out for Versailles.

On reaching the Château, Madame de Conti and Sophie were conducted to

Marie Leczinska’s apartments, where the Queen almost immediately joined

them. Her Majesty smiled very graciously upon the girl, and kissed her

forehead, murmuring: “She is indeed very pretty!” Then several

portfolios of music were put before her, and she was bidden to choose

what she would like to sing, and not to be afraid; a somewhat

unnecessary exhortation, since never was there a more self-possessed

young person. Sophie, quite undismayed by the presence of her royal

auditor, forthwith assailed a very difficult piece, and had scarcely

finished when the Queen, who was herself a musician of no mean

attainments, remarked to Madame de Conti: “I should like to have her,

cousin; you will give her up to me, will you not?” meaning that she

wished to make her one of her Musicians of the Chamber. Afterwards

refreshments{9} were brought in, and the Queen, having complimented the

young singer and bestowed upon her a friendly pat with her fan, took her

departure.

But there was another Queen of France: Madame de Pompadour, to wit, who

had already expressed a wish to hear Sophie sing; a wish which could no

more be ignored than that of Marie Leczinska. On the morrow of the

interview with the Queen, Madame du Hausset, the favourite’s femme de

chambre, presented herself at the Hôtel de Conti, bearing a letter from

her mistress to the princess, requesting the loan of little Mlle.

Arnould till the evening.

This request caused Madame de Conti considerable embarrassment. What one

called then “les grandes convenances” forbade her to present Sophie to

both the crowned and the uncrowned Queen of France. On the other hand, a

refusal would mortally offend the latter, who was an extremely awkward

person to offend, as a great many people, from Princes of the Blood and

Ministers of State to ballad-mongers, had found to their cost. The poor

lady was at a loss what to do.

Finally, she sought refuge in a compromise. Sophie should go to

Versailles again, but, on this occasion, not in her patroness’s company,

but in that of her mother. So Madame Arnould was sent for and told to

take her daughter, as from Madame de Conti, to the favourite; and the

princess congratulated herself on having emerged with credit from a very

embarrassing situation.

Madame de Pompadour received her visitor very graciously, and remarked

that “mother and daughter were the very picture of one another,” after

which, saying that the King had sent for her, and that she would return

in a few minutes, she left them to themselves.{10} In the room in which

they sat were two magnificent harpsichords, one of which had been

decorated with charming pictures by Boucher. This instrument attracted

Sophie’s attention, and, while Madame de Pompadour was absent, she

stepped up to it, ran her fingers over the keys, and began to sing. The

marchioness, returning at that moment, listened entranced to the girl’s

singing until she had finished, when she exclaimed: “My dear child, le

bon Dieu has made you for the theatre; you were born, formed as one

ought to be for it: you will not tremble before the public.”

Then their hostess conducted them through her apartments, where Sophie

appears to have been particularly struck by the favourite’s sumptuous

bed, with its green and gold hangings and gold fringes, raised, like a

throne, upon a daïs, and enclosed within a semi-circular balustrade of

gold and marble, the exact counter-part, in fact, of the Queen’s own

couch. The marchioness begged her to sing again, and, delighted with her

sweet voice, smilingly inquired who were her masters; to change

countenance, however, when she heard their names, for they were the same

whom she had engaged for her idolised little daughter, Alexandrine

d’Étoiles, who had died some years before.

As Sophie and her mother were taking their leave, Madame de Pompadour

drew the latter aside, and said in a low voice: “If the Queen should ask

for your daughter for the music of the Chamber, do not have the

imprudence to consent. The King goes from time to time to these little

family concerts, and, instead of giving this child to the Queen, you

will have made a present of her to the King.” Then she turned to Sophie,

and, having examined the lines in the girl’s{11} forehead and hand, said to

her gravely: “You will make a charming princess!”

A few days after these visits, Madame Arnould received a communication

from the Gentlemen of the Chamber to the effect that her Majesty had

deigned to admit the demoiselle Sophie Arnould into her private company

of musicians and singers, at a salary of one hundred louis; Madame

Arnould received a similar appointment, at the same salary as her

daughter.

Hardly had the good lady had time to master the contents of this

document, when there came a second of a much less welcome nature. It was

a lettre de cachet, informing her that by the express order of the

King, the demoiselle Sophie Arnould was attached to his Majesty’s

company of musicians, and, in particular, to his theatre of the Opera.

On reading this, the poor mother burst into tears. She had no objection

to her daughter singing before the virtuous Marie Leczinska, but the

Opera was a very different matter. No young girl could hope to preserve

her virtue for long at the Académie Royale de Musique, the rules of

which emancipated its members from parental control. Rather than see her

child ruined, she resolved to consign her to a convent, and,

accordingly, hurried off to Madame de Conti to implore her assistance.

Madame de Conti promised to do all in her power to save Sophie from the

danger which threatened her, and took the girl to her friend the Abbess

of Panthémont. “I bring you,” said she, “this young girl, of whom the

Gentlemen of the Chamber wish to make an actress; a decision which does

not meet with my approval. Conceal her for me in some little corner of{12}

your convent, until I have had an opportunity of speaking to the King.”

To which the discreet abbess replied: “Princess, salvation is possible

in every profession. I cannot bring myself to thwart the wishes of the

King, to whom I owe my abbey. Go and see the abbesses of Saint-Antoine

and Val-de-Grâce: perhaps, in this matter, they will have more courage

than myself.”

Madame de Conti tried Saint-Antoine and Val-de-Grâce; but at both she

received the same answer as at Panthémont; and was reluctantly forced to

the conclusion that further attempts in the same direction offered but

very small prospect of success.

There remained, however, another way of escape: marriage. Sophie had an

admirer—a devoted and, what was more to the point, an eligible

admirer—a certain Chevalier de Malézieux, who asked nothing better than

to give her the protection of his name. In his day, M. de Malézieux had

been a noted vainqueur de dames, but that day, alas! was long past,

and though he strove manfully to repair the ravages of time by the aid

of an ingenious toilette, the only result of his efforts was to give him

the appearance of a majestic ruin.

Madame de Conti had, at first, regarded this veteran dandy’s attentions

to her protégée with scant favour, and, meeting the old gentleman one

day at the Arnoulds’ house, charitably related for his benefit the story

of a prince of her own family, who had imprudently contracted a marriage

at the age of eighty, and had died the same night. Still, a day or two

later, she told Sophie that she might do worse than take charge of the

chevalier and his infirmities, provided that he would agree to settle

his whole fortune upon her; and after the arrival{13} of the lettre de

cachet from Versailles, and her abortive attempts to secure the girl’s

admission to a convent, actually proposed to send for M. de Malézieux,

and have the marriage celebrated there and then.

Madame Arnould, however, did not altogether approve of such haste, while

Sophie shed tears enough to melt the heart of the sternest parent; and

the matter, therefore, remained in abeyance. Nevertheless, the

chevalier, encouraged by Madame de Conti, pressed his suit with ardour,

dyed his eyebrows, rouged his cheeks, “shaved twice a day,” and, one

fine morning, presented himself at the Arnoulds’ house, bearing the

draft of a marriage-contract, in which the whole of his property,

amounting to some 40,000 livres a year, was settled upon Sophie.

The prospect of so advantageous a settlement in life for her daughter

was a temptation greater than any self-respecting mother could be

expected to resist, and though M. Arnould declined to force the girl

into a marriage which was distasteful to her, his wife lost no

opportunity of sounding the praises of M. de Malézieux—or rather of M.

de Malézieux’s income—in Sophie’s reluctant ear. That young lady,

however, only pouted, and when her antiquated admirer strove to soften

her heart towards him by citing the example of Madame de Maintenon, who,

when a young and beautiful girl, no older than Sophie herself, had

espoused the crippled poet Scarron, replied, laughing: “I will make a

similar marriage to-morrow, on condition that my husband will begin by

being a cripple, and end by being a king.”[5]

And so poor M. de Malézieux’s contract was never{14} signed, and no

alternative now remained for Madame Arnould but to allow Sophie to enter

the Opera, trusting that, for some time to come, her services would only

be required for the Concerts of Sacred Music which were given during

Lent. This hope, however, was not realised, for the directors of the

Opera happened to be just at that time on the look-out for some novelty

to divert the attention of their patrons from the mediocrity of the

pieces with which they had lately been provided, and, accordingly, on

December 15, 1757, the young singer was called upon to make her first

bow to the public.

It was a very modest début—merely the singing of an air introduced

into an opera-ballet by Mouret, entitled Les Amours des Dieux.[6]

Nevertheless, restricted as were the girl’s opportunities on this

occasion, she quickly became a public favourite; indeed, the eagerness

to see and hear her was so great that on the evenings on which she

appeared, the doors of the theatre were besieged, and Fréron

sarcastically observed that “he doubted whether people would give

themselves so much trouble to enter Paradise.”

“Mlle. Arnould,” says the Mercure de France of the following January,

which was but the feeble echo of the enthusiasm of the public,

“continues her début in Les Amours des Dieux, with great and

well-deserved success. She attracts the public to such an extent that

the Thursday has become the most brilliant day at the Opera, altogether

effacing the Friday. The second air which she sings affords her more

scope for the display of her talent than the first. She possesses at

once a charming{15} face, a beautiful voice, and warmth of sentiment. She

is full of expression and of soul. Her voice is not only tender, but

passionate. In a word, she has received all the gifts of Nature, and, in

order to perfect them, she receives all the resources of Art.”

At the beginning of the New Year, Sophie appeared in a second piece,

called La Provençale, in which she confirmed the favourable impression

she had created in Les Amours des Dieux. “Mlle. Arnould,” says the

Mercure, “sang the Provençale with the ingenuous charm of her age.

In this rôle she had only one important song. It is the monologue (‘Mer

paisible’...), into which she threw all the expression that it

demanded. The crowded houses which have followed it up to Lent are

proofs of the pleasure which she gives the public.”

In the following April the young actress reaped the reward of her

success by receiving her first important part, that of Venus in Énée et

Lavinie, a tragic opera in five acts by Fontenelle, music by

Dauvergne.[7] The confidence reposed in her was not misplaced, and she

received as much applause as she had previously obtained in ariettas and

pastorals. Such was her success indeed that she was speedily promoted to

the principal rôle, and the admiring critic of the Mercure, who had

already spoken in high terms of the new singer’s rendering of Venus,

consecrated to her the following article:

“On Tuesday, April 13, Mlle. Arnould played the{16} rôle of Lavinie for the

first time. Her success was complete. The tragic indeed seems to be the

genre most suited to her. It is, at any rate, that in which she has

appeared to most advantage. Her gestures are noble without arrogance and

expressive without grimaces. Her acting is vivacious and animated, and

yet never departs from the natural. This excellent actress has already

partially corrected herself of a kind of slowness, which is only

suitable to the arietta. Bad examples had led her astray. We invite her

to pay heed to no one but herself, if she wishes to approach nearer and

nearer to perfection.”

“So great a success renders it almost needless for us to observe that

Mlle. Arnould has retained this rôle; that she has brought back the

public to the Opera; finally, that she has adorned Énée et Lavinie

with an appearance of novelty.”

Some months later the Mercure returns to the subject of Énée et

Lavinie, and observes that Mlle. Arnould played the latter part “with

that intelligence, that dignity, those natural and touching graces which

enchant the public.” “Happily,” continues the critic, “she has depended

upon her own impulses before allowing herself to be intimidated by all

the little prejudices of the art. Model as a débutante, she reanimates

the lyric stage and appears to communicate her soul to those who have

the modesty and the talent to imitate her.”

Towards the end of June of that year, Sophie created a trio of small

parts in an opera-ballet in three acts, entitled Les Fêtes de

Paphos.[8] Collé, that most exacting{17} of critics, is very severe on

this piece, but, at the same time, has nothing but praise for Sophie,

who appears to have covered herself with glory. “At the first

representation,” he writes, “the music of this ballet was thought

pitiable, and it would not have survived six, if it had not been for a

young actress who made her first appearance this winter, and who, in

four months, has become the queen of the theatre. Never have I seen

combined in the same actress more grace, more truth of sentiment,

dignity of expression, intelligence, and fire. Never have I seen grief

more charmingly expressed. She can depict the deepest horror without her

countenance losing one feature of its beauty. She would be twice as

great an actress as Mlle. Le Maure,[9] if she only possessed two-thirds

of her voice, and Mlle. Le Maure will always be regarded as a great

artiste. I speak of Mlle. Sophie Arnould, who is not yet nineteen years

old.”[10]

The voice of Sophie Arnould was very far from being a powerful one.

“Nature,” she says in her Mémoires, “had seconded this taste [the

taste for music] with a tolerably agreeable voice, weak but sonorous,

though not extremely so. But it was sound and well-balanced,{18} so that,

with a clear pronunciation and without any defect save a slight lisp,

which could hardly be considered a fault, not a word of what I sang was

lost, even in the most spacious buildings.”

She might have added, without fear of contradiction, that her voice was

infinitely sweet and that she possessed the gift of imparting to it

wonderful pathos and expression. “She brought to harmony, emotion, to

the song, compassion, to the play of the voice, sentiment. She charmed

the ear and touched the heart. All the domain of the tender drama, all

the graces of terror, were hers. She possessed the cry, and the tears,

and the sigh, and the caresses of the pathetic.... What art, what

genius, must there have been to wrest so many harmonies from a

contemptible voice, a feeble throat.”[11]

Another important factor in Sophie’s success is to be found in the fact

that she was not only a great singer, but an accomplished actress, which

great singers rarely are. When Madame Arnould had found that she had no

alternative but to allow her daughter to enter the Opera, she had, like

a sensible woman, decided that, since to the Opera Sophie must go,

nothing which could possibly make for her success in her profession

should be neglected, and had sent her to take lessons in singing from

Mlle. Fel, and in acting from Mlle. Clairon. The girl had not failed to

benefit by the teaching of the famous tragédienne, and her command of

facial expression and the dignity and grace of her movements would have

reflected credit on a veteran member of the Comédie-Française, while for

a débutante of the lyric stage they were little short of

extraordinary.

And yet, with all her vocal and histrionic talents,{19} it may be doubted

whether Sophie would so speedily have attained the dazzling position in

the estimation of both the public and the critics which was now hers,

had she not been fortunate enough to possess physical attractions of a

high order. If we are to judge of her appearance solely by her portraits

by La Tour and Greuze, she must have been a very pretty woman. In the

former, which the excellent engraving by Bourgeois de la Richardière has

helped to popularise, Sophie is depicted at the moment when she is about

to sing. Her lips are parted; her eyes, fine and full of expression, and

surmounted by arched eyebrows, are turned imploringly heavenward; while

her face, which is oval in shape, with small and regular features, wears

a look at once charming and pathetic. In the Greuze portrait—now in the

Wallace Collection at Hertford House—the actress is dressed in white,

with a large black hat decorated with a white plume. Her elbow rests on

a chair, her chin on the back of her hand; her expression is nonchalant

and slightly ennuyé.

These portraits, as we have already remarked, are those of a very pretty

woman; but it should be added that the pen-portraits which some of her

contemporaries have left of Sophie are not altogether in accord with the

crayon of La Tour or the brush of Greuze—nor yet with the description

which the lady gives us of her own charms[12]—and we are, therefore,

inclined to think that both artists have rather idealised their subject,

a practice not uncommon with portrait-painters{20} in the eighteenth

century or, for that matter, in much later times. Collé and Grimm, it is

true, both speak of Sophie as beautiful, though without condescending to

particulars; but, on the other hand, Madame Vigée Lebrun asserts that

the beauty of her face was spoiled by her mouth, while one of the

inspectors of the Lieutenant of Police describes her skin as “black and

dry.” That curious work L’Espion anglais confirms the artist and the

inspector: “To tell the truth, there is nothing remarkable about her;

her face is long and thin; she has a villainously ugly mouth, prominent

teeth, standing out from the gums, and a black and greasy skin.” The

writer adds, however, that she possessed “two fine eyes,” a feature

which also impressed Madame Lebrun, who says that they gave their owner

“a piquant look,” and were “indicative of the wit which had made her

celebrated.”

But two fine eyes, as one of her biographers very justly observes, count

for much, especially when animated by the intelligence, the feeling, and

the passion which belonged to Sophie; and no sooner did she appear upon

the stage than a host of soupirants gathered about her. For some

months, however, they sighed in vain. The guardian of the Golden Fleece

was not more vigilant or more awe-inspiring than Madame Arnould. Every

evening she escorted her daughter to the theatre, remained in her

dressing-room while the mysteries of her toilette were being performed,

accompanied her to the corner of the stage, and then waited in the wings

until the young actress made her exit, when she again took charge of

her. She seemed to have as many eyes as Argus himself. If an admirer

bolder than the rest ventured to approach Sophie, before he had uttered

half a dozen words down{21} would swoop the watchful mother, with a

freezing: “Allons! laissez la petite en repos, s’il vous plait,

Monsieur!” before which the luckless gallant fled incontinently. If a

poulet were despatched, it was invariably intercepted and returned to

the sender, with a message which made him feel supremely foolish. “She

is not a woman at all,” exclaimed the indignant Duc de Fronsac, after

one of these rebuffs; “she is a veritable watch-dog!”

But even the most intelligent of watch-dogs cannot always discriminate

between friend and foe. The danger came from a quarter whence the poor

mother least expected it. She herself admitted the wolf into the

sheepfold.

For some time past, matters had not gone well with the Arnoulds; M.

Arnould had become involved in some disastrous speculations, which had

swallowed up the greater part of his fortune, and a long and serious

illness had made further inroads upon his resources. Accordingly, about

the time that Sophie made her début at the Opera, he removed from the

Rue du Louvre to the Hôtel de Lisieux, Rue

Fossés-Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, and converted his new residence into

an inn, where “persons from the provinces were accommodated at thirty

sols a night.”[13] To this inn there came, one fine day in the spring of

1758, a handsome young man of about five and twenty, who informed the

Arnoulds that his name was Dorval, that he was an artist by profession,

and that he had just arrived from Normandy, to study painting and get a

play produced. M. Dorval was a model guest. He never grumbled about his

food or his wine, never questioned the amount of his bills, never

returned home{22} with an unsteady gait or accompanied by undesirable

acquaintances, as did so many young provincials who aspired to imitate

the vices of the fine gentlemen of the capital. And then he was so

ingenuous, so friendly, and had such charming manners. He knew nothing

of the ways of Paris, he said, but, morbleu! he had heard that it was

a terribly wicked place and full of snares and pitfalls for unwary

youth. Would M. Arnould do him the favour of taking care of his purse?

Would Madame have the complaisance to do the same for his lace? Ah! it

was indeed a fortunate hour which had led him to the Hôtel de Lisieux!

The good people might have thought it a little singular that a young man

with so well-filled a purse and such fine lace should have selected so

unpretentious a hostelry as theirs for a lengthy stay; also that,

although he never looked askance at the menus of the Hôtel de Lisieux,

he was constantly receiving hampers containing fish, game, truffles, and

choice wines, which, he said, came from his fond parents in Normandy,

and begged his hosts and their daughter to share with him. But M. Dorval

quite disarmed suspicion—if any existed—by reading the letters he

received from home to the sympathetic Madame Arnould, and, besides,

innkeepers have more important matters requiring their attention than

the investigation of the private affairs of their guests, particularly

those who give no trouble, pay regularly, and are so agreeable and

open-handed as was this young Norman.

M. Dorval overwhelmed Madame Arnould with attention; he had literary

tastes, and recognised in her a kindred soul. To Sophie he was also

attentive, though not more so than good-breeding required. In a short

time he had become quite a friend of the family,{23} dining and supping

with them, escorting the ladies to the Opera and home again at the

conclusion of the performance, and spending the rest of the evening in

their company. One night, after playing a couple of games of backgammon

with M. Arnould, Dorval pleaded an insupportable headache and retired to

his modest apartment. Soon afterwards a man in a lackey’s livery entered

the house by means of a false key, knocked at his door, and informed him

that all was ready. Dorval emerged from his room, and was joined by

Sophie. The pair crept noiselessly down the stairs, across the courtyard

and into the street, at the corner of which a coach was awaiting them.

Dorval helped the girl in and took his seat beside her; the driver

cracked his whip; the coach rolled away. Sophie was carried off!

Terrible was the consternation at the Hôtel de Lisieux the following

morning. Madame Arnould was like one distraught; M. Arnould, who had not

yet fully recovered from his recent illness, had a serious relapse. As

for the Chevalier de Malézieux, when the news was communicated to him he

took to his bed and never left it again, dying of grief—or, perhaps, of

wounded vanity. In Paris, nothing else was talked of but the elopement

of the queen of the Opera, and many were the wagers made about the

identity of the fortunate individual who had borne away the coveted

prize. All uncertainty was soon at an end. Two days later a letter was

brought to the Hôtel de Lisieux, signed Louis, Comte de

Brancas-Lauraguais, in which the writer offered his apologies to M. and

Madame Arnould for the deception he had been obliged to practise upon

them, and concluded by a formal promise to espouse their daughter—if he

should ever become a widower!{24}

Madame Arnould dried her tears; M. Arnould’s illness took a favourable

turn. Since Sophie had been carried off, it was at least some

consolation to learn that her abductor was a man of rank and wealth, and

not a mere middle-class libertine; one, too, who, without doubt, was

only prevented from giving his name and all that went with it to the

object of his affection by the unfortunate circumstance that he was

already provided with a wife. The worthy pair quite forgot their

disgrace as they thought of the brilliant future which awaited their

daughter, when the earth should have closed over poor, delicate Madame

de Lauraguais—she lived till 1793, and her career was ended by the

guillotine—and the count’s father, the old Duc de Lauraguais, should

have gone the way of all flesh. Why, if the Fates were kind, ere many

months had passed Sophie might be a countess—nay, a duchess! And so

when, in due course, the prodigal daughter came, in a magnificent coach,

to pay a visit of courtesy to her parents, she found, instead of tears

and reproaches, caresses and pardon. Such was the moral code of the year

of grace 1758!

Louis Léon Félicité de Brancas, Comte de Lauraguais, the first lover of

Sophie Arnould, was a singular creature. “He has all possible talents

and all possible eccentricities,” wrote Voltaire, while Collé describes

him as “the most serious fool in the kingdom.” His conceit was

stupendous, his extravagance unbounded, his energy and versatility truly

astonishing; he dabbled in everything and confidently believed that he

excelled in whatever he might choose to undertake. Now he was composing

tragedies intended to eclipse the masterpieces of Corneille and Racine;

now making experiments in{25} chemistry or anatomy which were to completely

revolutionise those sciences; anon writing treatises in favour of

inoculation, or endeavouring to bring about reforms in the theatre,[14]

or riding in horse-races.[15] The violence with which he advocated his

own views and his unsparing denunciations of all who ventured to differ

from him, no matter how highly placed they might be, were perpetually

bringing him into collision with the authorities, and he was several

times exiled or imprisoned, only to resume his eccentric career the

moment his punishment was at an end. The stories about him are

numberless.

On one occasion he wrote a comedy, entitled La Cour du Roi Pétaud, and

coaxed his unsuspecting father to persuade the Comte de Saint-Florentin,

the Minister of the King’s Household, to direct the Comédie-Italienne to

produce it. The order was on the point of being{26} sent, when one of

Saint-Florentin’s secretaries, happening to glance through the play,

discovered, to his horror, that it was nothing less than a clever and

biting satire on certain idiosyncrasies of his Most Christian Majesty

Louis XV. himself, which, had it been represented, would most certainly

have entailed banishment or the Bastille on all concerned in its

production.[16]

On another, he appeared, at four o’clock in the morning, at the lodging

of two poor but talented young chemists, hustled them into a coach which

was in waiting, and carried them off to Sèvres, where he had a little

house, in which he was in the habit of conducting his chemical

experiments. Leading his companions to the laboratory, he addressed them

as follows: “Messieurs, I wish you to make certain experiments; you will

not leave this house until they are completed. Adieu; I shall return a

week hence; you will find here everything you require; the servants have

orders to attend to your wants; set to work.” So saying, he locked them

in and went{27} away. When he returned, the young chemists communicated to

him the result of their labours, a discovery of some little importance,

upon which he offered them a sum of money if they would agree to

surrender to him the credit of having made it. “You,” said he, “have

genius, and you want money. I have money, and I want genius. Let us

strike a bargain. You shall have clothes to wear, and the glory shall be

mine.” The young chemists consented, and Lauraguais went about boasting

everywhere of the discovery he had made; and such, says Diderot, who

tells the story, was his conceit that he soon succeeded in persuading

himself that it was he to whom the credit really belonged, and that the

young men had done nothing, except render him some merely mechanical

assistance.[17]

A third story of this extraordinary man is even more amusing than the

preceding one. He appears to have had a theory that it would be possible

for a person to support life entirely on a diet of forced fruit,

provided that they were kept in the same temperature as was required for

the production of what they consumed. He, therefore, persuaded one of

his mistresses to allow herself to be shut up in a green-house and fed

upon grapes, pine-apples, and so forth. This regimen, as may be

supposed, did not agree with the lady, who soon declared that she was

starving. “Ungrateful girl!” exclaimed the disgusted count. “Can you

complain of not having sufficient to eat—a trivial matter at

best—while you are thus abundantly supplied with the luxuries that

every one longs for?”

So eccentric a character as Lauraguais was hardly calculated to make any

woman happy, whether wife{28} or mistress, and Sophie declared long

afterwards that the count “had given her two million kisses and caused

her to shed four million tears.” Nevertheless, the liaison was a

tolerably long one, and, for the first three years, in the course of

which the actress presented her lover with two children, we are assured

that they were a most affectionate couple. By the police-reports of the

time, Sophie is represented as an extravagant, grasping and avaricious

woman, who cared for the count only so long as he was able and willing

to gratify her innumerable caprices. Extravagant she no doubt was, but

in regard to the other and graver charge, she would appear to have been

maligned, that is to say, if we are to place any reliance in the

following anecdote related by Diderot:

“For some days past a rumour has been current that Mlle. Arnould is

dead, but it requires confirmation. In the meanwhile, the Abbé Raynal

has made me her funeral oration, by relating to me some fragments of a

conversation which passed between her and Madame Portail [the wife of a

president of the Parliament of Paris], in which, it appears, the latter

played the part of a wanton, and the little actress that of an honest

woman:

“ ‘Is it possible, Mademoiselle, that you have no diamonds?’

“ ‘No, Madame, nor do I think them necessary for a little bourgeoise of

the Rue du Four.’

“ ‘Then, I presume, you have an allowance?’

“ ‘An allowance! Why should I have that, Madame? M. de Lauraguais has a

wife, children, a position to maintain, and I do not see that I could

honourably accept the smallest part of a fortune which legitimately

belongs to others.{29}’

“ ‘Oh, par ma foi! If I were in your place, I should leave him.’

“ ‘That may be, but he likes me, and I like him. It may have been

imprudent to take him, but, since I have done so, I shall keep him.’

“I do not recollect the remainder of the conversation, but I have an

idea that it was as dishonourable on the part of the president’s wife as

honourable on the part of the actress.”[18]

If Lauraguais really was so generous a protector as the police-reports

and those writers who accept them would have us believe, it is certainly

rather surprising to find on November 13, 1759, when the count’s passion

for his mistress was undoubtedly at a very high temperature, the sieur

Jean Baptiste Delamarre, tipstaff to the Châtelet de Paris, acting on

behalf of the sieur Jean Baptiste Desper, perruquier, requiring the

attendance of a commissary of police to witness an execution upon the

goods of the demoiselle Madeleine Sophie Arnould, residing on the first

floor of a house in the Rue de Richelieu. The said demoiselle, it

appeared, had, twelve months before, taken the apartment in question, on

a lease for three, six, or nine years, at an annual rental of 2400

livres; but the perruquier had not as yet seen any part of that sum. The

goods seized were left in the charge of one Chevalier, fruiterer of the

Rue Traversière, parish of Saint-Roch, from whom, we may presume, Sophie

or Lauraguais subsequently redeemed them.[19]

After her elopement with the Comte de Lauraguais,{30} Sophie became more

than ever the idol of the public, and, for the next few years, might

without exaggeration have parodied the famous mot of le Grand

Monarque and exclaimed: “L’Opéra, c’est moi!” Never, declared both

public and critics, had the heroines of lyrical tragedy: the Psychés,

the Proserpines, the Thisbés, the Iphises, and the Cléopâtres, found so

worthy a representative, and, no matter how insipid the opera which

related the story of their woes might happen to be, the young singer was

always sure of an enthusiastic reception. The patrons of the

Palais-Royal seemed indeed as if they could not have enough of her; the

directors, who owed to her popularity their increased receipts, were at

her feet; every one adored her, or pretended to do so, and every one

trembled before her epigrams.

For side by side with her reputation as a singer and actress, Sophie was

building up another reputation, and one which was to endure long after

her stage triumphs had been forgotten: that of a diseur de bons mots,

and of bons mots of a peculiarly caustic kind. Few indeed were the

wits of her time—and they were plentiful enough in the eighteenth

century—who cared to cross swords with her, and such was the dread

which her sharp tongue inspired that people imagined they detected a

sarcasm lurking even in her most innocent remark, as the following

incident will show.

It was the custom of the Royal Family of France to dine in public (au

grand couvert) on certain days of the week, and any respectably dressed

person was permitted to view his Most Christian King partaking of his

soup or his venison. In the days of Louis XIV., who, if his

sister-in-law, the Princess Palatine, is to be believed, was in the

habit of disposing at a single meal of as much{31} as would suffice an

ordinary person for at least three,[20] a dinner au grand couvert must

have been a spectacle worth going a long way to see; but as “the

Well-Beloved” had no pretensions to emulate the gastronomic feats of his

predecessor, the ceremony was now shorn of much of its former interest.

Sophie, who had never yet enjoyed a near view of her sovereign,

expressed one day a desire to attend one of these dinners, and a noble

admirer, accordingly, conducted her to Versailles and into the Salon de

Grand Couvert, where he placed her exactly opposite the King. His

Majesty was in the act of raising his glass to his lips when he caught

her eye. At the same moment Sophie remarked, half-involuntarily, to her

companion: “The King drinks!” Louis, who had heard much of the young

lady’s biting wit, was apparently under the impression that these simple

words were intended as a covert jest at his expense, and became so

embarrassed that every one present noticed it. Finally, he motioned to

Sophie to withdraw, which she did, reflecting that a reputation as a wit

sometimes has its drawbacks.

To appreciate the witticisms of Sophie Arnould as they deserve, they

must be read in the language in which they were uttered, for, when

translated, the point of many of them—plays upon names and so forth—is

lost. Not a few, too, of her most pungent sayings will scarcely bear

reproduction in a modern work, for her wit was essentially the wit of

the coulisses, whose frequenters were seldom at any pains to curb

their tongues, even{32} in the presence of the highest in the land.

Fortunately, however, there still remain a considerable number of mots

which may be rendered into English with tolerable fidelity and without

injuring the susceptibilities of even the most fastidious of readers.

Sophie was an inveterate punster, a form of wit more appreciated in the

eighteenth century than it is to-day. Here is one, however, which most

of us will find it hard not to forgive.

The Duc de Bouillon became so enamoured of the charms of a young singer

named Mlle. Laguerre that, in the course of three months, he was

reported to have squandered upon her no less a sum than 800,000 livres.

This prodigality greatly exasperated the creditors of the duke, who

complained to the King himself, with the result that the infatuated

nobleman received orders to retire to his country-seat. A few days

later, some one, meeting Sophie, happened to inquire after the health of

Mlle. Laguerre. “I do not know how she is at present,” was the reply;

“but for the last month the poor child has been living entirely on soup

(bouillon).”

This same Mlle. Laguerre created the principal rôle in Piccini’s

Iphigénie en Tauride, produced on January 22, 1781. At the first

performance she sang admirably and contributed largely to the

enthusiastic reception it received; but on the second evening her

efforts were but too obviously inspired by wine. “Mon Dieu!” exclaimed

Sophie. “This is not Iphigenia in Tauris; it is Iphigenia in Champagne!”

Mlle. Laguerre was only one among many of Sophie’s colleagues to suffer

from the sharpness of that lady’s tongue. She was particularly severe

upon the famous danseuse Mlle. Guimard, the subject of our next

sketch,{33} whose many wealthy conquests would appear to have excited her

jealousy. Mlle. Guimard, though the very embodiment of grace and

elegance upon the stage, was slender almost to attenuation, and Sophie

dubbed her “la squelette des Grâces.” Seeing her one evening

performing a pas de trois with two male dancers, she declared that it

put her in mind of a couple of dogs quarrelling over a bone. On another

occasion, when the danseuse’s well-known liaison with Jarente,

Bishop of Orléans, the holder of the feuille of benefices, happened to

be the subject of conversation, she remarked: “I cannot conceive why

that little silk-worm is so thin; she lives upon such a good leaf

(feuille).”

Another butt of her sarcasm was Mlle. Beaumesnil, who, after gallantries

innumerable, married a singer of the Opera, named Belcourt. By that time

her charms were on the wane, and, making a virtue of necessity, she

became a model wife. One day, some one speaking of her early career,

observed that she had then been like a weather-cock, veering round to a

new lover every day. “Just so,” answered Sophie, “and very like a

weather-cock in this also, that she did not become fixed till she was

rusty.”

But Sophie was very far from confining her witticism to her comrades of

the Opera; no one was safe from her shafts. When the intriguing old Duc

de la Vauguyon, the Dauphin’s governor, who had done his best to sow

dissension between that prince and Marie Antoinette, died, he was

regretted by no one. The day after his death, the opera of Castor et

Pollux was played. In this piece there was a ballet of devils, which on

this particular evening went all wrong, whereupon Sophie observed that

the devils were so much upset by M. de{34} la Vauguyon’s arrival among them

that their heads were turned.

M. de Boynes, who succeeded the Duc de Choiseul-Praslin as Minister of

Marine, in 1760, was an honest and well-meaning man, but entirely

ignorant of the duties of that important post. One evening he appeared

at the Opera, where the scene on the stage represented a ship on a

stormy sea. “Oh, how fortunate!” exclaimed Sophie. “He has come here to

get some idea of the Navy.”

Better perhaps was her remark about the Abbé Terrai, the detested

Comptroller-General of Finance, whose expedients for raising money

excited so much indignation in the last years of Louis XV. The abbé, who

suffered from a defective circulation, was seen, one bitter winter’s

day, with his hands hidden in a huge muff. “What need has he of a muff?”

asked the actress. “Are not his hands always in our pockets?”

The Ministers, indeed, seem to have been very favourite objects of

Sophie’s sarcasm. On being shown a snuff-box, with the head of the Duc

de Choiseul on one side, and that of Sully, the great Minister of Henri

IV. on the other, she exclaimed: “Tiens! they have put the receipts

and the expenses together.”

The liaison between Sophie and the Comte de Lauraguais was, as might

be expected, from the singular character of the latter, not untroubled

by storms. The count, though honestly attached to his mistress, was

jealous, suspicious, headstrong, and passionate, always full of some new

and frequently wild project or other, with which he expected her to

sympathise, while the slightest opposition to his wishes was sufficient

to throw{35} him into such paroxysms of rage that it was dangerous to

approach him.[21] At times, he led poor Sophie a terrible life, and over

and over again she was on the point of leaving him. At last, in the

autumn of 1761, after their irregular union had lasted about three

years, it came temporarily to a close.

Lauraguais had written a tragedy on the not very novel subject of

Iphigenia in Tauris.[22] He had dedicated it to Voltaire, and, so soon

as it was completed, set out for Ferney, to read it to the Patriarch. It

would appear that, for some time past, the count’s vagaries had been

more than usually difficult to endure—possibly the labours of

composition had not been without their effect upon his temper. Any way,

Sophie resolved to profit by this moment of liberty, and no sooner had

her tyrannical lover left Paris, than she ordered her coach—a present{36}

from the absent Lauraguais—threw into it pell-mell everything portable

that she had ever received from him: jewellery, plate, lace, porcelain,

and so forth, placed the two children whom she had borne him on the top,

and despatched the whole cargo to the Hôtel de Lauraguais, Rue de Lille,

with a note for Madame de Lauraguais, in which she stated that “having

resolved to recover her freedom, she did not wish to retain anything

which might serve to remind her of her unhappy love-affair.”[23] Madame

de Lauraguais, who was a good and long-suffering woman, accepted the

children, “regretting very much that they were not her own,” but sent

back the coach and the rest of its contents.

At the same time, Sophie wrote to Ferney the following letter:

“Monsieur, mon cher ami,—You have written a very fine tragedy, so

fine that I can no more understand it than your other proceedings. You

have gone to Geneva, to receive a crown of the laurels of Parnassus from

the hands of M. de Voltaire, leaving me alone and abandoned to myself. I

profit by my liberty, that liberty so precious to philosophers, to leave

you. Do not take it ill that I am weary of living with a madman who

dissected his{37} coachman, and who wished to act as my accoucheur, with

the intention of dissecting me also. Allow me, therefore, to remove

myself out of reach of your philosophic bistoury.”[24]

When the Comte de Lauraguais received the aforegoing epistle he was so

overcome that he clutched his valet by the shoulder, exclaiming:

“Support me, Fabien; this blow is more than I can bear!” Then, bidding a

hasty adieu to Voltaire, he posted off to Paris and tried, by promises,

threats, and every means he could think of, to induce his mistress to

return to him. All his efforts were, however, fruitless, and soon

afterwards Sophie placed the comble upon his misery by “coming to an

arrangement” with M. Bertin, a wealthy financier.[25]

The gallantry of the eighteenth century, it should be understood, had

its etiquette, which was strictly observed by all who wished to be

thought men of honour. Before even approaching Sophie on the matter, M.

Bertin wrote to the Comte de Lauraguais, to inform him that, having been

given to understand that all was at end between the count and Mlle.

Arnould, he proposed to take the lady in question under his protection,

if she were willing to honour him by accepting it. Sophie{38} consented, on

certain conditions; Lauraguais sorrowfully withdrew, and M. Bertin gave

a supper-party, at which he formally presented Mlle. Arnould to his

friends.

M. Bertin was not only rich and generous, but easy-going, good-tempered,

and practical; in fact, the very antithesis of his erratic predecessor.

He had lately been cruelly deceived by Mlle. Hus, a star of the

Comédie-Française, his admiration for whom is said to have cost him

something like a million livres, and his heart positively yearned for

sympathy and affection. But alas! Sophie had none to give him. It was in

vain that he paid her debts; that he provided a handsome dowry for one

of her sisters; that he commissioned a celebrated coachbuilder of the

singular name of Antechrist to construct for her an equipage which was

the envy and admiration of all the ladies in Paris; that he loaded her

with diamonds. The actress soon decided that poor M. Bertin was dull,

wearisome, altogether insupportable, and began to look about for fresh

conquests.

She had not far to look. So soon as it was known that the adorable Mlle.

Arnould was no longer inaccessible, all the admirers whom the jealous

transports of Lauraguais had kept at a respectful distance flocked

around her, and Sophie, having broken with the man who had possessed her

heart, threw scruples to the winds, and bestowed her favours upon

several gallants, varying in social position—or, at least, so M. de

Sartines’s inspectors reported—from the Prince de Conti to a handsome

young friseur, who called daily to dress the lady’s hair.

But, in spite of these “passades” and the lavish generosity wherewith

her titular protector sought to gain her affections, love for Lauraguais

still smouldered{39} in Sophie’s breast, and, at the beginning of the

following year, only a few days after the enamoured M. Bertin had

bestowed upon her the sum of 12,000 livres, by way of a New Year’s gift,

all Paris was astonished to hear that she had thrown over the financier

and returned to the count.

At first, the public was inclined to applaud what it was pleased to

consider the rare disinterestedness of the lady in preferring a

comparatively poor admirer to an exceptionally wealthy one. But when it

became known that poor Bertin’s brief reign had cost him over 100,000

livres, exclusive of the New Year’s gift mentioned above, it veered

round, and Bachaumont reports that the general impression was that the

financier had been very hardly treated. He himself expresses the opinion

that the favoured lover was in honour bound to indemnify the abandoned

one for the very large sums he had expended on the capricious Sophie,

and that, as this had not been done, Mlle. Arnould must be held to have

gained the affection of tender and susceptible hearts on false

pretences, and must therefore—morally at least—“be relegated to the

crowd of women from whom she had been drawn.”[26]

It is only fair to Lauraguais to say that, very soon after this was

written, he gave the lie to the rumour that Sophie’s liaison with

Bertin had been nothing but an ingenious speculation on the part of that

lady, by refunding to his discomfited rival all that he had disbursed on

her behalf, so that, in the end, the financier “lost nothing except the

most charming woman in Paris.”

The second stage of the liaison between Sophie and{40} Lauraguais was not

less stormy than the first; in fact, it might quite as appropriately be

called a renewal of hostilities as a renewal of love. A week or two of

bliss, and then their quarrels recommenced, more frequent and more

violent than before. After what had passed, the count felt that he had

the right to be suspicious, and he took the fullest advantage of it.

Almost every day there were angry accusations, indignant denials, bitter

reproaches, and floods of tears, followed by apologies, vows of

amendment, and reconciliation. Never was there a more singular pair of

lovers. They seem to have been perpetually separating and coming

together again, for, though life with one another was intolerable, they

were even more unhappy apart; while if any misfortune happened to befall

either of them, however strained their relations at the time might be,

all grievances were straightway forgotten. An instance of this occurred

towards the end of the following year.

The practice of inoculation for the small-pox, which had been introduced

into England by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu early in the eighteenth

century, had hitherto made but little progress in France,

notwithstanding the fact that it had had several distinguished

advocates, including Voltaire and Jean Jacques Rousseau. Towards the

year 1763, however, a strong movement in its favour took place, in

consequence of which the Parliament of Paris, on the requisition of the

Advocate-General, Joly de Fleury, passed a decree prohibiting

inoculation until the Faculties of Medicine and Theology should have

pronounced a definite opinion on the subject.

The decree roused the indignation of Lauraguais, who was one of the

warmest supporters of the innovation,{41} and his indignation vented itself

in a Mémoire sur l’inoculation, wherein M. Joly de Fleury was very

roughly handled. This memoir he read before the Académie des Sciences,

of which he was a member, and demanded permission to print it. The

Academy at first demurred, but ultimately gave its consent, on the

understanding that the references to the Advocate-General should be

expunged. Apparently this condition was not observed, for the

publication of the memoir was followed by an acrimonious correspondence,

ending with a lettre de cachet, which directed that M. le Comte de

Lauraguais should be conveyed to Metz and imprisoned in the citadel

during his Majesty’s pleasure.[27]

On learning of the arrest of her lover, Sophie was in despair. She

closed her salon and put on mourning. The few friends who were permitted

to intrude upon her sorrow found her dissolved in tears, and went about

declaring that nothing so pathetic had ever been seen before. The Abbé

de Voisenon wrote to the imprisoned count, describing in touching

language the actress’s grief, and felicitating him on having found a

faithful mistress at the Opera; a piece of good fortune, said the abbé,

so remarkable that it ought to go far to console him for his captivity:

“Ne te plains pas de ton malheur,

Du cœur de La Vallière il te fournit la preuve,

On assure qu’Arnould se souvient d’être veuve

Et que de sa constance elle fait son bonheur.”

Lauraguais’s family and friends did everything in their power to procure

his release; but both Louis XV. and Choiseul had come to regard that

nobleman as a{42} public nuisance, and turned a deaf ear to their appeals.

And so the count remained for some four months at Metz, and might have

remained a good deal longer, had not a fortunate chance enabled Sophie

to intervene on his behalf.

On November 2, the opera of Dardanus was played before the Court, at

Fontainebleau, Sophie taking the part of the heroine Iphise, one of her

most successful impersonations. On this occasion she appears to have

surpassed herself, and even the bored King was moved to something like

admiration. Profiting by the impression she had created, without waiting

to doff the robes of Iphise, she begged for a few minutes’ conversation

with the Duc de Choiseul, and, throwing herself at his feet, besought

him to release her lover. “The heart of the gallant and all-powerful

Minister was touched, and he had not the courage to refuse to this

beautiful and tearful Iphise the return of her Dardanus.”[28]

Lauraguais returned more infatuated than ever. Gratitude had redoubled

his love for his mistress; never had she appeared to him more adorable.

Declaring that it was his intention to consecrate to her alone the

liberty which he owed to her, he installed himself at Sophie’s house, as

in the early days of their liaison, and refused even to see his

unfortunate wife, whom he unjustly suspected of having been a trifle

lukewarm in her efforts to obtain his release. This was a little too

much for the endurance even of that long-suffering lady, and,{43} soon

afterwards, she sought and obtained a judicial separation.

His few months’ imprisonment at Metz would appear to have exercised a

chastening effect upon the volatile count, as, for the next three or

four years, though quarrels were still of frequent occurrence, there was

no open rupture between the lovers. During this period, two more

children were born to them: a son, Antoine Constant, who subsequently

entered the army, rose to be colonel of a regiment of cuirassiers, and

was killed at the battle of Wagram; and a daughter, Alexandrine Sophie,

of whom we shall have something to say later on.

Perhaps the comparative harmony which now reigned between this singular

pair was the result of a tacit understanding that they should forgive

and forget. At any rate, they were very far from being all in all to one

another during these years. Some doubt seems to have existed as to

whether Alexandrine Sophie, born March 7, 1767, had not the right to

claim an even more illustrious descent than that of the Brancas; for,

though M. de Lauraguais recognised the child as his, the assiduous

attentions paid by the Prince de Conti to her mother rendered it quite

possible that she had royal blood in her veins. On his side, the count

indulged in several “passades,” one of which, with a certain Mlle.

Robbi, a colleague of Sophie, threatened to develop into a more

permanent connection. Finally, in the spring of 1768, the union was

again dissolved, Lauraguais being, on this occasion, the one to sever

the knot.

On February 26 of that year, a young German danseuse, Mlle. Heinel by

name, who had already achieved a reputation in Vienna, made her

appearance at the Opera, and created a great sensation. “Mlle. Heinel,”

says{44} Grimm, “afflicted with seventeen or eighteen years, two large,

expressive eyes, and two well-shaped legs, which support a very pretty

face and figure, has arrived from Vienna and made her début at the

Opera in the danse noble. She displays a precision, a sureness, an

aplomb, and a dignity of bearing comparable to the great Vestris. The

connoisseurs of dancing pretend that, in two or three years, Mlle.

Heinel will be the first danseuse in Europe, and the connoisseurs of

charms are disputing the glory of ruining themselves for her.”[29]

In a letter written some months later, Grimm becomes quite ecstatic over

the beauty and talent of his young compatriot:

“Her grace and dignity make of her a celestial creature. To see her, I

do not say dance, but merely walk across the stage, is alone worth the

money that one pays at the door of the Opera.”[30]

The charms of this “celestial creature” proved{45} more than the

susceptible heart of M. de Lauraguais could withstand, and we read in

the Mémoires secrets, under date March 28, 1768:

“Her (Mlle. Heinel’s) attractions have so captivated M. le Comte de

Lauraguais as to cause him to forget those of Mlle. Arnoux (sic). He has

given her, as a wedding-present à l’Allemand, 30,000 livres, 20,000

livres to a brother, to whom she is much attached, an exquisite set of

furniture, a coach, and so forth. It is computed that the première

cost this magnificent nobleman 100,000 livres.”

Sophie appears to have been anything but heart-broken at the desertion

of her eccentric lover—probably she was as anxious to be rid of him,

for a season, as he was to leave her—and, less than a year later, we

find her corresponding with him in the friendliest manner. By that time

the count had had more than enough of the society of Mlle. Heinel,

concerning whom Sophie has many spiteful things to say. She herself, she

informs him—perhaps with a view of exciting his jealousy—is receiving

great attention from the Prince de Conti, who often invites her,

together with other past, present, and potential members of his

seraglio,[31] to his box at the Opera, where he invariably greets her

with a kiss upon the chin.[32]

{46}

Sophie’s life at this period affords us very little that is edifying to

contemplate, and much that is the reverse. Her apartment in the Rue du

Dauphin was the rendezvous of many wits and men of letters: Marmontel,

Crébillon fils, Dorat, Voisenon, and the Abbé Arnaud; but it was also

frequented by nearly all the fashionable libertines of the day, and “her

table was an altar of free life and free love.” “Foreign Ambassadors

covered her with diamonds, Serene Highnesses threw themselves at her

feet, dukes and peers sent her carriages, and Princes of the Blood

deigned to have children by her.”[33] Unlike the majority of her

colleagues, who clung tenaciously to the few poor shreds of reputation

that were left them, Sophie appears to have been perfectly indifferent

to public opinion, and jested cynically with comparative strangers on

the depraved life she was leading.

In the spring of 1770, we find her accepting a new amant en titre, in

the person of Charles Alexander Marc Marcellin d’Alsace, Prince d’Hénin

et du Saint-Empire. The Prince d’Hénin was a dull, pompous man,

nicknamed, by a play on his title, “le prince des nains,” who seems to

have taken the actress under his protection merely because it was the

mode in those days to keep a mistress, and the more notorious the lady,

the greater the distinction she conferred upon her lover. His chief

recommendations, so far as Sophie was concerned, were that he was very

rich and disposed to allow her to do{47} pretty much as she pleased, so

long as the admirers whom he chanced to encounter on his visits to her

house behaved towards him with the deference which he considered due to

his exalted rank.

Her apartment in the Rue du Dauphin not being large enough to

accommodate all the distinguished persons who desired to pay homage to

her, Sophie, about this time, removed to a more commodious one in the

Rue des Petits-Champs. This, in its turn, becoming too small for her

requirements, she made up her mind to have an hôtel built, and selected

a site in the Chaussée-d’Antin, immediately adjoining the hôtel of Mlle.

Guimard—the “Temple of Terpsichore,” as it was called—the erection of

which had half-ruined more than one of the adorers of “la squelette des

Grâces.”

In the Bibliothèque Nationale may be seen a drawing of the façade of the

proposed house, and plans of the rez-de-chaussée and the first and

second floors. The drawing of the façade bears the following

inscription:

“Façade of a projected house for Mlle. Arnould in the Chaussée-d’Antin.

The house to be constructed side by side with that of Mlle. Guimard, and

to be of the same dimensions.—Bélanger.”

On the portico, which is supported by two Doric columns, may be seen the

figure of the Muse Euterpe, with the features of Sophie Arnould. The

plan of the second floor is inscribed: “Plan of the second floor of

Mlle. Arnould’s projected house, in which there are to be four small

rooms for the accommodation of the children.”

This palace never got beyond the paper stage, for Sophie fell in love

with the architect and the architect with her, in consequence of which,

we may presume,{48} the Prince d’Hénin, or whatever wealthy admirer was to

have defrayed the expenses, declined to have anything further to do with

the scheme.

François Joseph Bélanger, the architect in question, was a charming man.

He was then about thirty years of age, handsome, good-tempered, witty,

and one of the most rising members of his profession.[34] Sophie loved

him dearly—for a time at least—though this did not prevent her

indulging in various passing fancies. Once, when he was temporarily out

of favour, she sent him his congé, and, at the same time, wrote to an

actor named Florence, inviting him to take the vacant place in her

affections. Bélanger, however, happening to call at her house at a time

when she was not at home, found the two letters on her desk, read them,

and promptly changed the envelopes. The result was that Florence

received the congé, instead of the avowal of love, and naturally

became very cold in his manner towards Sophie, who, deeply mortified,

turned for consolation to her faithful architect.

At one time a rumour was current that Sophie was about to become Madame

Bélanger, and, when questioned on the matter, the lady replied: “What

would you have? So many people are endeavouring to destroy my reputation

that I need some one who can restore it. I could not make a better

choice, since I have selected an architect!” The marriage, however, did

not take place, though that would not appear to have been the fault of

Bélanger.{49} Notwithstanding the fact that a lady with so romantic a past,

and three fine children to prevent people forgetting it, was hardly the

kind of wife for a rising professional man, the architect would have

been only too willing to regularise their connection. But Sophie had no

mind to marry any one who was unable to satisfy all her caprices; and it

is probable that the rumour referred to was started and circulated by

her with the object of giving the lie to another, which was occasioning

her intense annoyance.[35]

Sophie’s insolence and pride in this the heyday of her prosperity knew

no bounds. She insulted the Lieutenant of Police and was, in

consequence, placed under arrest for twenty-four hours; she made biting

epigrams about Ministers and other distinguished persons, which, no

doubt, duly reached her victims’ ears; she behaved with such “unexampled

audacity” and “essential want of respect” towards Madame du Barry, on

the occasion of a performance before the Court, at Fontainebleau, that,

but for the intervention of the injured lady—the most sweet-tempered

left-hand queen who ever degraded a throne—she would have spent the

next six months as a prisoner in the Hôpital,[36] and she drove the

unfortunate directors of the Opera to the verge of distraction with her

whims and caprices.

The race of prime donne is proverbially a capricious{50} one; the

profession of an impresario one of the most trying which can fall to the