Title: Mesopotamian Archaeology

Author: Percy S. P. Handcock

Release date: March 26, 2014 [eBook #45229]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Delphine Lettau, Turgut Dincer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

Some names with different spellings have not been

corrected as these spellings are possibly alternate

spellings for the same person or location.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHÆOLOGY OF BABYLONIA AND ASSYRIA. BY PERCY S. P. HANDCOCK, M.A. WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS, ALSO MAPS

LONDON: MACMILLAN AND CO. LTD., AND PHILIP LEE WARNER, ST. MARTIN’S STREET. MDCCCCXII

DEDICATED TO

A. M. LORD

IN RECOGNITION

OF MANY ACTS OF FRIENDSHIP

IN every department of science the theories of yesterday are perpetually being displaced by the empirical facts of to-day, though the ascertainment of these facts is frequently the indirect outcome of the theories which the facts themselves dissipate. Hence it is that the works of the greatest scholars and experts have no finality, they are but stepping-stones towards the goal of perfect knowledge. Since the publications of Layard, Rawlinson, Botta and Place much new material has been made accessible for the reconstruction of the historic past of the Babylonians and Assyrians, and we are consequently able to fill in many gaps in the picture so admirably, and as far as it went, so faithfully drawn by the pioneers in the field of excavation and research. This work, which owes its origin to a suggestion made by Dr. Wallis Budge, represents an endeavour on the part of the writer to give a brief account of the civilization of ancient Babylonia and Assyria in the light of this new material.

It is hoped that the infinitude of activities and pursuits which go to make up the civilization of any country will justify the writer’s treatment of so many subjects in a single volume. It will be observed that space allotted to the consideration of the different arts and crafts varies on the one hand according to the relative importance of the part each played in the life of the people, and on the other hand according to the amount of material available for the study of the particular subject.

No effort has been spared to make the chapters on Architecture, Sculpture and Metallurgy as comprehensive as the limitations of the volume permit, while forPg viii the sake of those who desire to pursue the study of any of the subjects dealt with in this book, and to work up the sketch into a picture, a short bibliography is given at the end.

It has not been thought desirable to amass a vast number of references in the footnotes, and the writer is thereby debarred from acknowledging his indebtedness to the works of other writers on all occasions as he would like to have done.

In addition to the chapters which deal expressly with the cultural evolution of the dwellers in Mesopotamia, two chapters are devoted to the consideration of the Cuneiform writing—its pictorial origin, the history of its decipherment, and the literature of which it is the vehicle, while another chapter is occupied with a historical review of the excavations. The short chronological summary at the end obviously makes not the slightest pretension to even being a comprehensive summary; it merely purports to give the general chronological order of some of the better known rulers and kings of Babylonia and Assyria to whom allusion is made in this volume, together with a notice of some of the more significant land-marks in the history of the two countries.

The writer’s thanks are due to the Trustees of the British Museum for permission to photograph some of the objects in the Babylonian and Assyrian Collections, and to Dr. Wallis Budge for facilities and encouragement in carrying out the work; to the University of Chicago Press for allowing him to reproduce illustrations from the American Journal of Semitic Languages and also diagrams from Harper’s Memorial Volumes; to M. Ernest Leroux for permitting him to make use of some of the plates contained in the monumental works of De Sarzec and Heuzey, and to M. Ch. Eggimann of the “Libraire Centrale d’art et d’architecture ancienne maison Morel,” for his very kind permission to reproduce two of the plates contained in Dieulafoy, L’ArtPg ix Antique de la Perse. He is similarly indebted to the Deutsche-Orient Gesellschaft for allowing him to make an autotype copy of one of the plates in Andrae’s Der Anu-Adad Tempel. He further desires to acknowledge the generosity of Prof. H. V. Hilprecht in allowing him to make use of many of the illustrations contained in his numerous publications, and also of Dr. Fisher for permitting him to reproduce some of the photographs contained in his magnificently illustrated work on the excavations at Nippur. He is very sensible of his indebtedness to these two gentlemen, as also to M. Leroux and the Deutsche-Orient Gesellschaft, for the photographs of excavations in progress are obviously of a unique character and admit of no repetition; he further desires to express his obligations to Dr. W. Hayes Ward for his most kind permission to copy a number of seal-impressions and other illustrations contained in his recently published work—Cylinder-Seals of Western Asia. Lastly, he welcomes the opportunity of acknowledging the kindness of Mr. Mansell for allowing him to publish many photographs of objects in the British Museum and the Louvre contained in his incomparable collection, and for in other ways facilitating the illustration of this volume. Most of the plans and drawings used for this volume are the work of Miss E. K. Reader, who has performed her task with her usual skill.

P. S. P. H.

March, 1912.

ERRATA ET CORRIGENDA

p. 6, l. 3, for 2500 B.C. read 2400 B.C. p. 6, l. 18, for 2500 B.C. read 2400 B.C. p. 43, l. 7 from foot,read both French and English explorers p. 62, l. 2, for considerable read much p. 89, l. 5, for ± read — p. 110, l. 2, for 2500 B.C. read 2400 B.C. p. 125, l. 7 from foot, for or read and p. 130, l. 23, for 2400 B.C. read 2350 B.C. p. 155, l. 31, for having read have p. 235, l. 9 from foot, for Sumu-la-ilu read Sumu-ilu p. 247, l. 1, for 2500 B.C. read 2400 B.C. p. 249, l. 35, after crudeness read these heads The reference numbers as printed on Plates VII to XI are inaccurate, and should be altered as follows, in agreement with the List of Illustrations and the references in the text:—

Present number

and positionCorrect number

and positionZiggurat of Ashur-naṣir-pal VII Facing p. 64 VIII Facing p. 78 Inscriptions on Clay VIIIFaci”ng p.78 IXFaci”ng p.106 Ruined Mounds and Court of Men IXFaci”g p.106 XFaci”ng p.132 Water Conduit, Nippur XFaci”g p.132 XIFaci”ng p.138 Excavations in Temple Court XIFaci”g p.138 VIIFaci”ing p.64

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Introduction— | |

| (a) Land and People | 1 | |

| (b) Sketch of Babylonian and Assyrian History | 28 | |

| II. | Excavations | 40 |

| III. | Decipherment of the Cuneiform Inscriptions | 85 |

| IV. | Cuneiform Inscriptions | 95 |

| V. | Architecture | 119 |

| VI. | Sculpture | 181 |

| VII. | Metallurgy | 242 |

| VIII. | Painting | 270 |

| IX. | Cylinder-Seals | 284 |

| X. | Shell-Engraving and Ivory-work | 309 |

| XI. | Terra-cotta Figures and Reliefs | 317 |

| XII. | Stoneware and Pottery | 325 |

| XIII. | Dress, Military Accoutrements, etc. | 337 |

| XIV. | Life, Manners, Customs, Law, Religion | 364 |

| Short Bibliography | 406 | |

List of the more important Kings and Rulers and a Brief Chronological Summary |

408 | |

| Index | 411 | |

| PLATE IN COLOURS | ||

| PLATE | ||

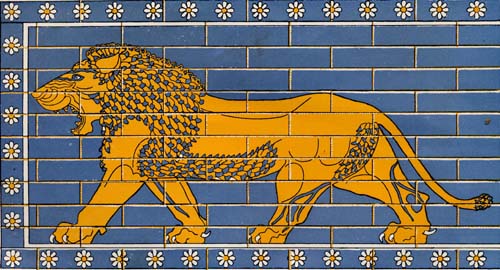

| I. | Coloured Lion at Khorsabad | Frontispiece |

| PLATES IN HALF-TONE | ||

| FACING PAGE | ||

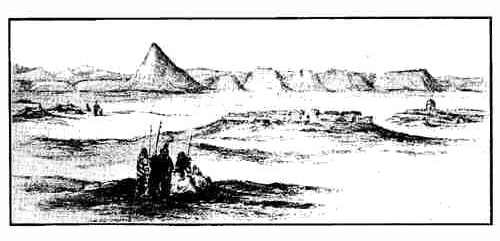

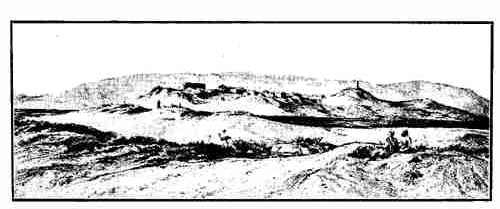

| II. | Kouyunjik and Nebi Yûnus (two views) | 42 |

| Nimrûd (Calah) | 42 | |

| Khorsabad | 42 | |

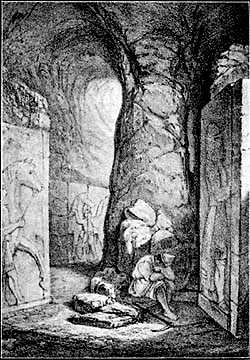

| III. | Excavations at Nimrûd (Calah) in Ashur-naṣir-pal’s Palace |

44 |

| IV. | “Fish-God,” and Entrance Passage, Kouyunjik | 48 |

| V. | Doorway at Tellô, erected by Gudea | 54 |

South-eastern façade of Ur-Ninâ’s building at Tellô |

54 | |

| VI. | Remains of a Stele in a building under that of Ur-Ninâ |

58 |

| The Well of Eannatum | 58 | |

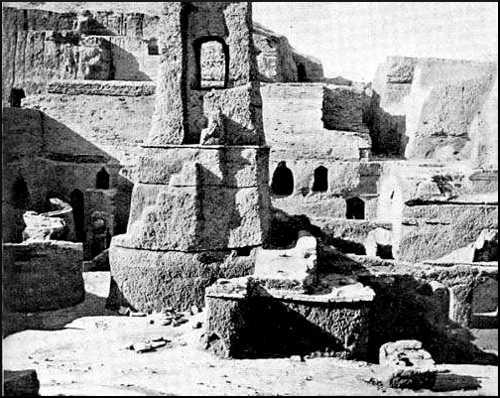

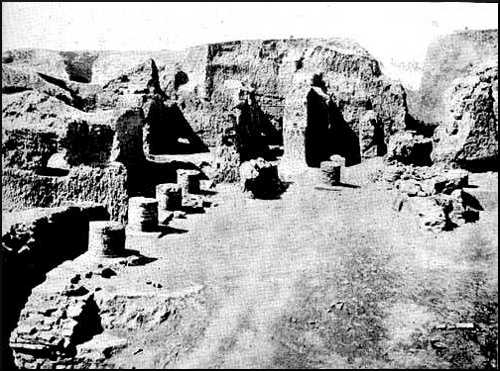

| VII. | Excavations In the Temple Court: Nippur | 64 |

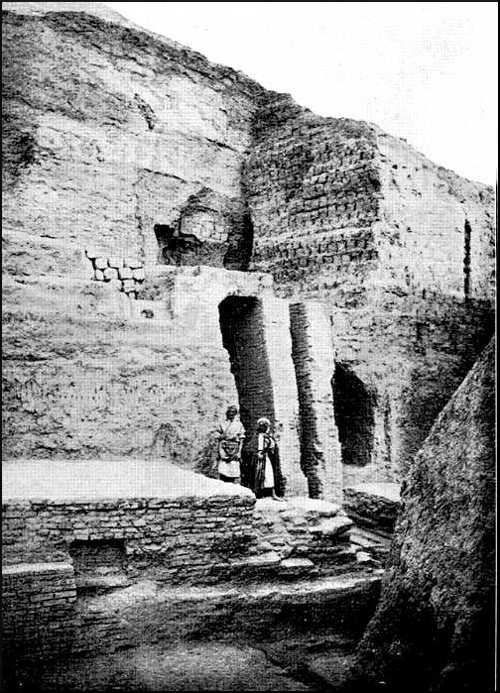

| VIII. | The Ziggurat and Palace of Ashur-naṣir-pal, Ashur | 78 |

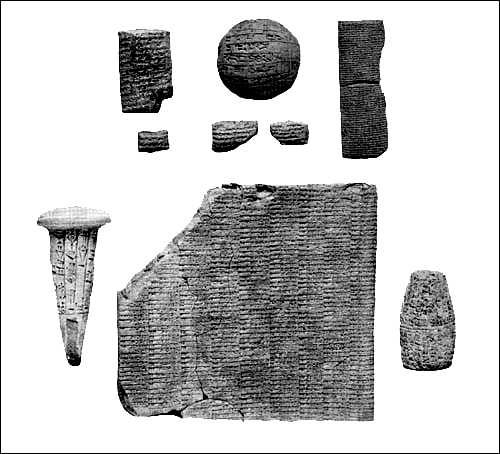

| IX. | Inscriptions on clay illustrating the sizes and shapes of the Tablets, etc., used by the Babylonians and Assyrians |

106 |

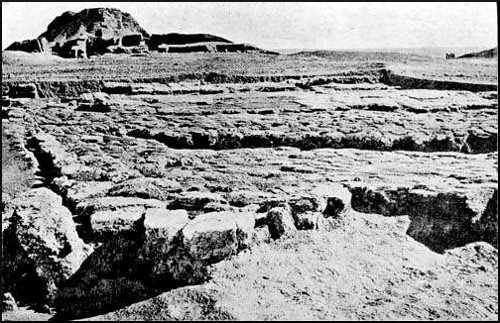

| X. | The Ruined Mounds of Nippur | 132 |

| Court of the Men from the North-East, Nippur | 132 | |

| XI. | Water Conduit of Ur-Engur, Nippur | 138 |

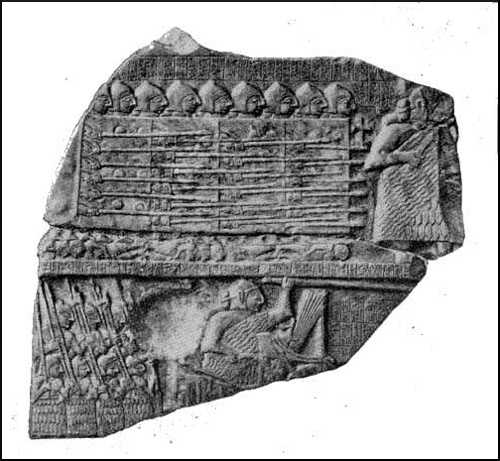

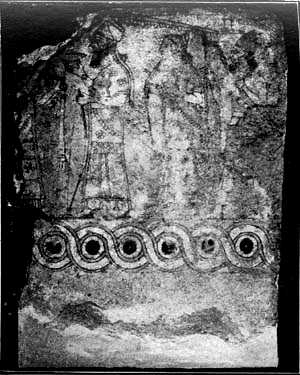

| XII. | Portion of the “Vulture Stele” of Eannatum, Patesi of Lagash |

186 |

| XIII. | Stele of Victory of Narâm-Sin | 192 |

| XIV. | Stele engraved with Khammurabi’s Code of Laws |

198 |

| The Sun-God Tablet | 198 | |

| XV. | Bas-relief of Ashur-naṣir-pal | 202 |

| Pg xivXVI. | Bas-reliefs of Ashur-naṣir-pal (four subjects) | 204 |

| XVII. | Siege of a City by battering-ram and archers | 206 |

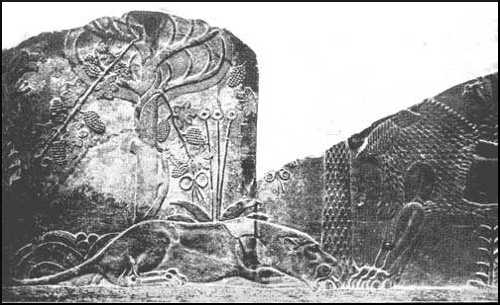

| XVIII. | Ashur-bani-pal’s Hunting Scenes: Lion and lioness in a garden |

218 |

| XIX. | Ashur-bani-pal’s Hunting Scenes (two subjects) | 218 |

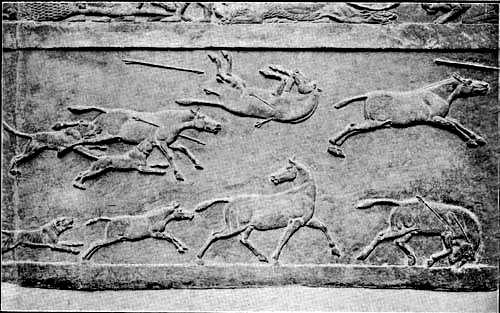

| XX. | Ashur-bani-pal’s Hunting Scenes: Hunting wild asses with dogs |

220 |

Ashur-bani-pal pouring out a libation over dead lions |

220 | |

| XXI. | Ashur-bani-pal reclining at meat | 222 |

| Musicians and Attendants | 222 | |

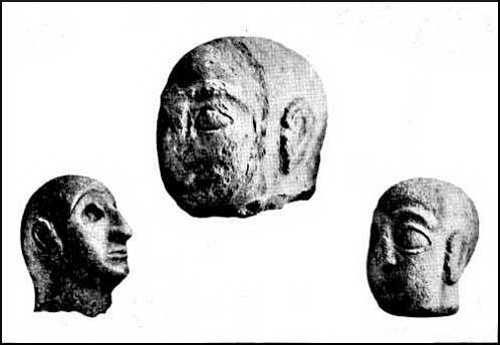

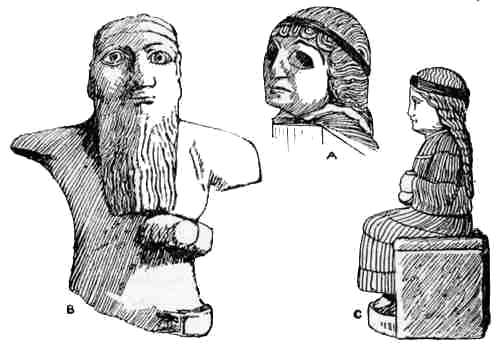

| XXII. | Limestone figure of an early Sumerian | 224 |

| Three archaic stone heads | 224 | |

| XXIII. | Head and two diorite statues of Gudea; upper part of female statuette |

228 |

| XXIV. | Statues of Nebo and Ashur-naṣir-pal; torso of a woman |

230 |

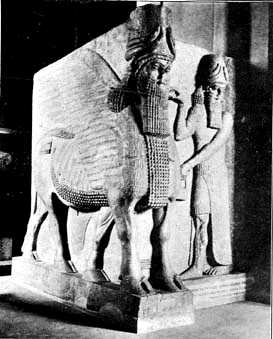

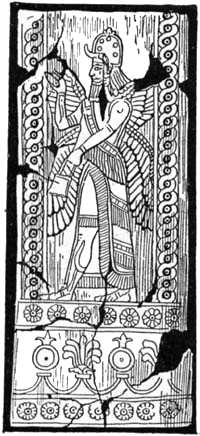

| XXV. | Winged man-headed genii | 236 |

| XXVI. | Stone lion of Ashur-naṣir-pal | 238 |

| XXVII. | The Kasr lion | 240 |

| XXVIII. | Miscellaneous objects of bronze, from Nimrûd |

254 |

| XXIX. | Bronze bowl, from Nimrûd | 256 |

| XXX. | Decorated arch at Khorsabad | 278 |

| XXXI. | Glazed bricks | 282 |

| XXXII. | Ivory panels, from Nimrûd | 314 |

| XXXIII. | Pottery, from Nimrûd and Nineveh | 334 |

| FIGURE | PAGE |

| 1. Pictographs | 97 |

| 2. Pictographs | 99 |

| 3. Late Babylonian “squeeze” of an early inscription | 117 |

| 4. Brick-stamp of Narâm-Sin | 117 |

| 5. Clay covering of the “Sun-Tablet” | 117 |

| 6. Restoration of the temple at Nippur | 137 |

| 7. Restoration of the Anu-Adad temple at Ashur | 144 |

| Pg xv8. Restoration of Sargon’s palace at Khorsabad | 151 |

| 9. Domed roofs in Assyria | 155 |

| 10, 11. Terra-cotta drains | 159 |

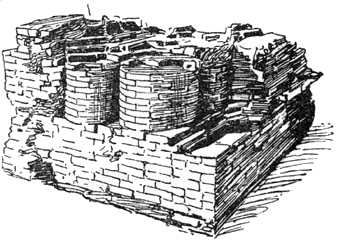

| 12. Columnar piers at Tellô | 161 |

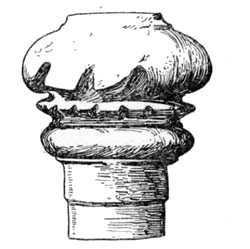

| 13. Large column capital; small column capital | 165 |

| 14. Columns (various) | 166 |

| 15. Early arch at Nippur | 170 |

| 16. Early arch at Tellô | 170 |

| 17. Corbelled arch at Nippur | 173 |

| 18. Round arch at Babylon | 173 |

| 19-22. Arched drains at Khorsabad | 174 |

| 23. Burial-vault at Ashur | 176 |

| 24. Burial-vault at Ur (Muḳeyyer) | 176 |

| 24a. Ziggurat on Assyrian bas-relief | 180 |

| 24b. Ziggurat at Khorsabad | 180 |

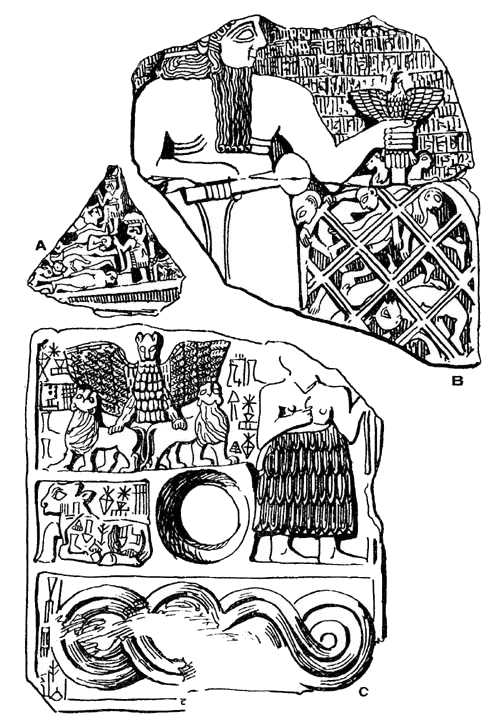

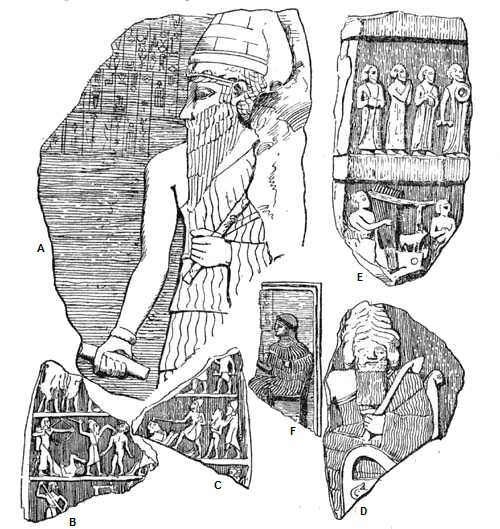

| 25. Six early bas-reliefs | 182 |

| 26. Stele of Ur-Ninâ and mace-head of Mesilim | 185 |

27. Two fragments of the “Vulture Stele”; little sculptured block (Entemena’s reign) | 189 |

| 28. Five bas-reliefs, including one of Narâm-Sin | 194 |

| 29. Bas-relief of Sargon, king of Assyria | 209 |

| 30. Bas-relief of Sennacherib; removal of stone bull | 213 |

| 31. Sennacherib at Lachish | 215 |

| 32. Statue of Esar, king of Adab | 223 |

| 33. Early stone statue of a woman | 224 |

34. Statue of Manishtusu; seated figure of a woman; head of a woman | 225 |

| 35. Seated figure of Shalmaneser II | 231 |

36. Stone lion-head; figure of a dog; stone figure of a human-headed bull inlaid with shell | 234 |

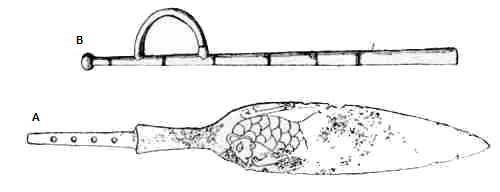

| 37. Copper spear-head; hollow copper tube | 243 |

| 38. Early copper figures | 245 |

39. Copper figures of Basket-bearers; copper figure of Gudea | 247 |

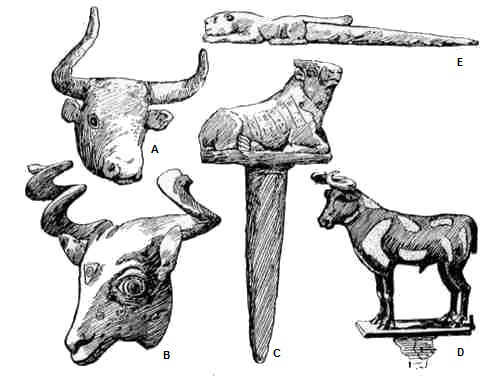

| 40. Figures and heads of animals in copper and bronze | 250 |

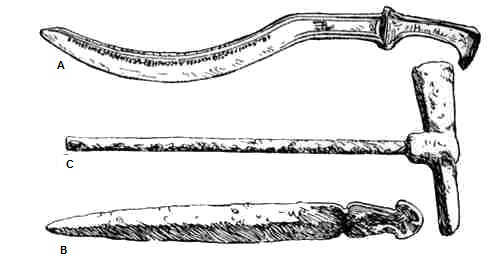

| 41. Two Assyrian swords; an Assyrian axe | 254 |

| 42. Bronze dish | 257 |

| Pg xvi43, 44. Bronze gate-bands | 259, 260 |

| 45. Silver vase of Entemena | 265 |

| 46. Coloured clay relief lion from Babylon | 274 |

47. Coloured bull at Babylon; coloured bull at Nimrûd (Calah) | 275 |

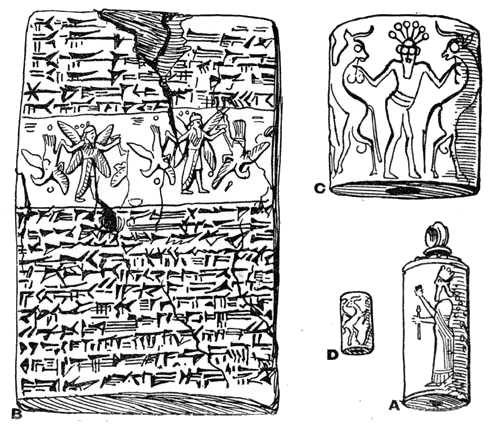

48. Three cylinder seals; clay tablet bearing a seal-impression | 285 |

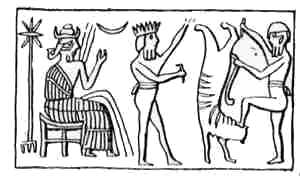

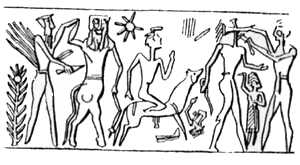

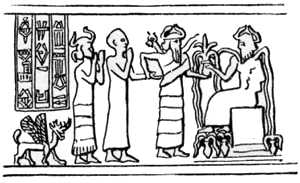

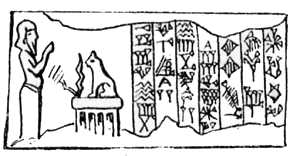

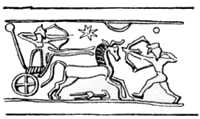

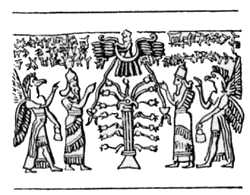

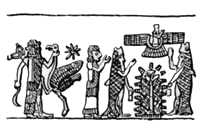

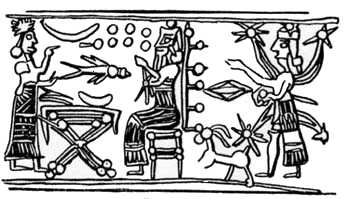

| 49-77. Impressions from cylinder-seals | 289-307 |

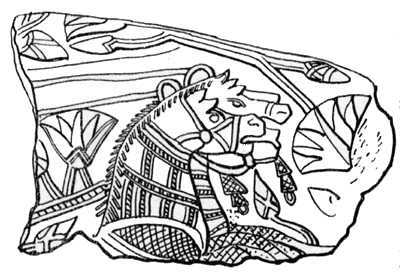

| 78-83. Engravings on shells | 310-312 |

| 84. Carved ivory panel from Nimrûd | 314 |

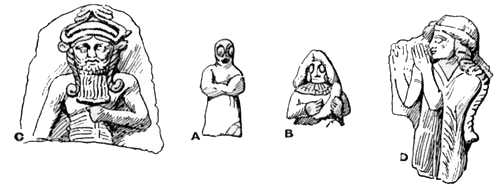

| 85. Early terra-cotta figures | 318 |

| 86. Terra-cotta figures of later date | 320 |

| 87. Terra-cotta figure of a dog | 323 |

| 88. Terra-cotta plaque showing dog with attendant | 323 |

| 89. Stone vase of Narâm-Sin | 328 |

| 90. Decorated stone vase of Gudea | 328 |

91. Three stone vessels, one of which bears an inscription of Sennacherib, and another the name of Xerxes; small glass vessel of Sargon | 330 |

| 92, 93. Two early clay pots from Nippur | 332 |

| 94. Boomerang-shaped weapons | 342 |

| 95. Assyrian jewellery | 348 |

| 96, 97. Combs | 349 |

98, 99. Foot-spearman and Foot-archers of the first Assyrian period | 350 |

| 100-102. Archers in the reign of Sargon | 351 |

| 103-105. Archers in the reign of Sennacherib | 352 |

| 106, 107. Assyrian cavalry | 354, 355 |

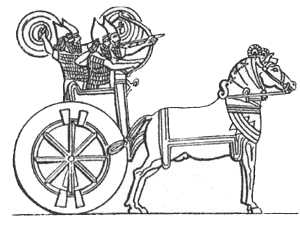

| 108. Assyrian chariotry | 356 |

| 109. Assyrian helmets and head-gears | 357 |

| 110. Assyrian weapons of offence | 358 |

| 111. Battering-rams and shields | 360 |

| 112. Naval equipment of the Assyrians | 362 |

| 113-115. Babylonian emblems | 396-398 |

| MAPS | |

| (1) Mesopotamia, (2) Babylonia | Folder at end |

Mesopotamian Archæology

THE Mesopotamian civilization shares with the Egyptian civilization the honour of being one of the two earliest civilizations in the world, and although M. J. de Morgan’s excavations at Susa the ruined capital of ancient Elam, have brought to light the elements of an advanced civilization which perhaps even antedates that of Mesopotamia, it must be remembered that the Sumerians who, so far as our present knowledge goes, were the first to introduce the arts of life and all that they bring with them, into the low-lying valley of the Tigris and Euphrates, probably themselves emigrated from the Elamite plateau on the east of the Tigris; at all events the Sumerians expressed both “mountain” and “country” by the same writing-sign, the two apparently being synonymous from their point of view; in support of this theory of a mountain-home for the Sumerians, we may perhaps further explain the temple-towers, the characteristic feature of most of the religious edifices in Mesopotamia, as a conscious or unconscious imitation in bricks and mortar of the hills and ridges of their native-land, due to an innate aversion to the dead-level monotony of the Babylonian plain, while it is also a significant fact that in the earliest period Shamash the Sun-god is represented with one foot resting on a mountain, Pg 2 or else standing between two mountains. However this may be, the history of the Elamites was intimately wrapped up with that of the dwellers on the other side of the Tigris, from the earliest times down to the sack of Susa by Ashur-bani-pal, king of Assyria, in the seventh century. Both peoples adopted the cuneiform system of writing, so-called owing to the wedge-shaped formation of the characters, the wedges being due to the material used in later times for all writing purposes—the clay of their native soil—: both spoke an agglutinative, as opposed to an inflexional language like our own, and both inherited a similar culture.

A further, and in its way a more convincing argument in support of the mountain-origin theory is afforded by the early art of the Sumerians. On the most primitive seal cylinders1 we find trees and animals whose home is in the mountains, and which certainly were not native to the low-lying plain of Babylonia. The cypress and the cedar-tree are only found in mountainous districts, but a tree which must be identified with one or the other of them is represented on the early seal cylinders; it is of course true that ancient Sumerian rulers fetched cedar wood from the mountains for their building operations, and therefore the presence of such a tree on cylinder seals merely argues a certain acquaintance with the tree, but Ceteris paribus it is more reasonable to suppose that the material earthly objects depicted, were those with which the people were entirely familiar and not those with which they were merely casually acquainted. Again, on the early cylinders the mountain bull, known as the Bison bonasus, assumes the rôle played in later times by the lowland water-buffalo. This occurs with such persistent regularity that the inference that the home of the Sumerians in those days was in the mountains is almost inevitable. Again, as Ward points out, the composite man-bull Ea-bani, the Pg 3 companion of Gilgamesh, has always the body of a bison, never that of a buffalo. So too the frequent occurrence of the ibex, the oryx, and the deer with branching horns, all argues in the same direction, for the natural home of all these animals lay in the mountains.

The Mesopotamian valley may, for the immediate purpose of this book, be divided into two halves, a dividing-line being roughly drawn between the two rivers just above Abû Habba (Sippar); the northern half embraces the land occupied by the Assyrians, and the southern half that occupied by the Babylonians. The precise date at which Assyria was colonized by Babylonia is not known, but to the first known native2 king of Assyria, Irishum, we may assign an approximate date of 2000 B.C. Babylonia proper is an alluvial plain the limits of which on the east and west are the mountains of Persia and the table-land of Arabia respectively. This valley has been gradually formed at the expense of the sea’s domain, for in the remote past the Persian Gulf swept over the whole plain at least as far northward as the city of Babylon where sea-shells have been found, and probably a good deal further. It owes its formation to the silt brought down by the two rivers and deposited at the mouth of the Gulf: the amount of land thus yearly reclaimed from the sea in early times is not known, but as Spasinus Chorax the modern Mohammerah, which is now some forty-seven miles inland, was situated on the sea-coast in the time of Alexander, we know that the conquest of the land over the sea has been progressing since his time at the rate of 115 feet yearly.

Thus the physical characteristics of the country in which Babylonian civilization was developed, if it was not actually the place of its origin, form a close parallel to those of Lower Egypt; in Egypt however Pg 4such evidence as there is, would indicate the South, or Upper Egypt as the earliest scene of civilization, the North being conquered by the Mesniu (Metal-users) of the South, not only in the battle-field but also in culture and civilization. Both countries have but a small sea-board where their rivers find an outlet, the Nile into the Mediterranean, and the Tigris and Euphrates into the Persian Gulf; both countries had emerged and were yearly emerging out of the sea, for it is certain that at one time the Mediterranean penetrated as far south as Esneh, while as already mentioned, the Persian Gulf extended at least as far as Babylon; we are accordingly not surprised to find in both the Babylonian and Egyptian cosmologies a tradition which told of the creation of the world out of a primæval mass of water, though this idea looms less conspicuously in the Egyptian than in the Babylonian and Hebrew cosmologies. Both countries also were visited by a yearly inundation which, while it brought no small amount of devastation in its train, at the same time deposited the mud so essential to the enrichment of the soil, the desolation being checked or at least mitigated in either country by an elaborate system of irrigation canals, which same canals were in the summer-time the means of conveying the life-giving water to the dry and thirsty land. Both Babylonia and Egypt enjoy a warm climate, though Egypt is much more dry and therefore healthier, and the corresponding dryness of its soil has preserved the tangible evidences of its ancient history in a far more perfect condition than the marsh-country of Lower Mesopotamia; and lastly the climate of Egypt is not subject to the same violent changes of temperature incidental to the seasons in the Valley of the Euphrates.

The evidence of any racial connection between the earliest known inhabitants of the two countries is very precarious; as regards their art, their customs and their language, the Sumerians on the one hand, and the pre-dynastic Pg 5and early dynastic Egyptians on the other, show a complete independence of each other; both countries were probably invaded at an early period of their histories by the Semites, who in the case of Mesopotamia completely supplanted their predecessors of different stock, but who were at the same time themselves absorbed by the higher civilization of the Sumerians to which they were the destined heirs, and to the further development of which they themselves were to contribute so largely; but at what period or periods the Semites swept over Egypt and the north coast of Africa, impressing their indelible and unmistakable stamp upon the foundation-structure of the Egyptian and Libyan languages is not known; whenever it was, we can safely assume that their advent took place in prehistoric days, for the hieroglyphs and probably also the language of the dynastic Egyptians were the natural development of the language and crude picture-signs of their predecessors, and the theory of a violent break in the continuity of early Egyptian civilization at the commencement of the first dynasty is daily becoming more untenable. We are similarly unable to assign any definite date to the arrival of the Semites in the Mesopotamian Valley, though the Neo-Babylonian King Nabonidus gives us a traditional date for Shar-Gâni-sharri3 (Sargon) and his son Narâm-Sin, kings of Agade, who, so far as we know, established the first Semitic empire in the country. There were indeed Semitic Kings of Kish before the time of Shar-Gâni-sharri, but the extent of their sway was clearly very limited compared with the far-reaching empire of the rulers of Agade. But there are reasons for doubting the accuracy of the traditional date of 3750 B.C. which Nabonidus assigns to Narâm-Sin, the chief reason being the extraordinary gap in the yieldings of Babylonian excavations between Pg 6the time of Shar-Gâni-sharri and Narâm-Sin, and that of Gudea, the priest-king of Lagash in Southern Babylonia, who reigned about 2400 B.C.; that is to say, concerning a period of about 1300 years the excavations have afforded us practically no information whatever, while both at the beginning and at the close of that period, we have abundant evidence of the civilization and history of the inhabitants of Babylonia; secondly, the style of art characteristic of the time of Gudea and the kings of Ur, as also the style of writing found in their inscriptions, presuppose no such long interval between the time of Sargon and their own day. But there are yet other considerations which are even more potent, and which deserve greater attention than has been up to the present accorded to them, depending as they do upon the stratification of the ruined mounds themselves. Now it is a very significant fact that the architectural remains of Ur-Engur (circ. 2400 B.C.) at Nippur, are found immediately above those of Narâm-Sin, for such an arrangement is hardly conceivable if a period of some thirteen hundred years separated these two rulers. Again, the excavations carried on by Dr. Banks for the University of Chicago at Bismâya have been productive of similar evidence, for immediately below the ruined ziggurat of Dungi, Ur-Engur’s successor on the throne of Ur, large square bricks of the size and shape characteristic of the time of Shar-Gâni-sharri were discovered, while among the bricks a strip of gold inscribed with the name of Narâm-Sin was also brought to light. The evidence afforded by the excavations on these two sites would thus appear to be exceedingly strong against the traditional date recorded by Nabonidus.4

It is therefore tempting to reason that that long silent period, the silence of which cannot be adequately accounted for, had no existence at all, that Nabonidus’ statement is therefore to be discredited, and that Shar-Gâni-sharri Pg 7and Narâm-Sin probably lived and reigned more than a thousand years later, i.e. about 2650 B.C. On the other hand it is important to remember that the Babylonians were astronomers and mathematicians of no mean order, and that they exercised the greatest possible care in calculating dates, that moreover Nabonidus was a king of Babylonia, and therefore “a priori” likely to be in possession of reliable traditions, if any existed, and further, that he lived 2500 years nearer to the time than we do. The inscription of Nabonidus in question was found in the mound of Sippar near Agade. It says:—“The foundation corner-stone of the temple E-ulba in the town of the eternal fire (Agade) had not been seen since the times before Sargon King of Babylonia and his son Narâm-Sin.... The cylinder of Narâm-Sin, son of Sargon, whom for 3200 years, no king among his predecessors had seen, Shamash the great lord of Sippara hath revealed to him.” Thus according to Nabonidus, Narâm-Sin lived about 3750 B.C. The archæological evidence is however so strong in this particular case, both negatively in regard to the absence of any tangible evidence of the long interval in question, and positively in regard to the stratification of the mounds containing the relics of these two kings and also in regard to the similarity between the earlier sculptures and inscriptions of Shar-Gâni-sharri and Narâm-Sin and those belonging to the latter half of the third millennium B.C., that we are no longer able to maintain the implicit confidence in the historical accuracy of Nabonidus which early scholars once had.

From the inscriptions of Shar-Gâni-sharri and Narâm-Sin that have been brought to light, we gather that the authors of these inscriptions were Semites, in other words we learn that the empire of Agade was a Semitic Empire, and since they extended their empire over all Western Asia, the Sumerian power located more in the south must have proportionately dwindled. But Pg 8their Sumerian predecessors had established their influence and power in Mesopotamia for a long and indefinite time before this date, for Sumerian inscriptions which are almost certainly to be assigned to the pre-Sargonic period give us the names of a large number of early kings and rulers of Babylonia; their early date is shown by the writing of these inscriptions which bear a more archaic stamp than those of Shar-Gâni-sharri and Narâm-Sin. For just as uninscribed sculptures are relatively dateable by the style of art to which they conform, so that it is possible to provisionally say that this sculpture or cylinder-seal is older than that, because it presents a more archaic and less finished style of art, so is it possible to approximately date un-named and un-dated inscriptions by the style of writing adopted in those inscriptions. We thus have two means at our disposal by which we can assign uninscribed monuments of an early period to their relatively correct places in the evolution of art and culture; on the one hand the stratum of the ruined mound in which the object in question has been found can often itself be relatively dated by actually inscribed monuments found either in the stratum itself, or in the stratum immediately above or below; or failing these, by the depth at which the stratum lies below the top of the mound, though this latter alone is a poor criterion owing to the fact that such accumulation will obviously vary in different places. The value of all such evidence however depends on whether or not the strata have been disturbed, as is often unfortunately the case.

The reason why the ruins of Mesopotamian cities have assumed the form of mounds lies in the fact that a conquering chief demolished the clay walls and buildings of his vanquished foe, but instead of clearing the débris away, he built on the top of it; for his new building operations the new-comer often utilized part of the old material, hence the uncertainty of a date assigned to an object, based on the mere assumption that such object Pg 9belongs to the stratum in which it has ultimately found itself, without other corroborative evidence. On the other hand we are in these days always able to apply the purely archæological test, which depends upon a close examination of the style of art or the mode of writing.

Some of these pre-Sargonic rulers already alluded to can be arranged in strictly chronological order, i.e. the rulers of the city of Lagash, one of the earliest centres of Sumerian civilization in Babylonia. Lagash lies fifteen hours’ journey north of Ur and two hours’ east of Warka (the ancient Erech), and it is Lagash which has provided us with more material for our study of early Sumerian life and culture than any other city in the Euphrates valley.

The order of the early pre-Sargonic rulers of Lagash is as follows: Ur-Ninâ, apparently the founder of the dynasty, inasmuch as he bestows no royal title on his father or grandfather, and his successors traced themselves back to him; Akurgal, Eannatum, Enannatum I, Entemena, Enannatum II, Enetarzi, Enlitarzi, Lugal-anda, and Urukagina. But though their chronological order is certain, the length of their reigns is unknown, and their dates can only be approximately ascertained, and even these approximate and relative dates depend entirely on the date of Shar-Gâni-sharri. Assuming the latter’s date to have been about 2650 B.C., Ur-Ninâ’s date would be roughly about 3000 B.C. Ur-Ninâ the first member of the dynasty has left us a number of his sculptures and stelæ, but there are other nameless works of art discovered either in the neighbourhood or actually in Lagash itself which present a less developed form of art, and where inscriptions are concerned, a more archaic style of writing, while in certain cases the monuments in question were actually discovered in the strata underneath the building of Ur-Ninâ, and with these the history of Mesopotamian art and of the civilization to which it bears such eloquent testimony commences.

The race to which the Sumerians belonged is not known, but the fact that their language being agglutinative and not inflexional, was therefore neither Aryan nor Semitic, but at least and in this respect akin to the Mongolian languages, of which Turkish, Finnish, Chinese and Japanese are the most illustrious examples to-day, has led certain scholars to seek a connection between some of the Sumerian roots and certain Chinese words, it must however be admitted that this supposed connection is rather hypothetical at present. Further efforts have also been made by Lacouperie and others to establish parallels between Chinese art and culture and those of the Sumerians, but the evidence is not very convincing.

As the surface-soil of Babylonia did not originate there, but was brought down by the rivers and deposited by them as their currents lost impetus in approaching the sea, and were thus unable to carry their burden further, it is well to trace this soil to its original source. Both the Euphrates and the Tigris rise in the mountains of Armenia,5 the geological formation of which is chiefly granite, gneiss and other feldspathic rocks. These rocks were gradually decomposed by the rains, their detritus being hurried rapidly down-stream; the rivers in the course of their career travel through a variety of geological formations including limestone, sandstone and quartz, all of which contribute something to the silt which is destined to form part of the delta’s soil; the latter being composed mainly of chalk, sand, and clay, is extremely fertile, which won for it a reputation testified to even by the classical writers: thus Herodotus who Pg 11flourished in the seventh century B.C. tells us (I, 293) that “of all the countries that we know, there is none which is so fruitful in grain. It makes no pretension indeed, of growing the olive, the vine, or any other trees of the kind; but in grain it is so fruitful as to yield commonly two hundredfold, and when the production is greatest even three hundredfold. The blade of the wheat-plant and barley is often four fingers in breadth. As for millet and the sesame, I shall not say to what height they grow, though within my own knowledge, for I am not ignorant that what I have already written concerning the fruitfulness of Babylonia, must seem incredible to those who have never visited the country.... Palm trees grow in great numbers over the whole of the flat country, mostly of the kind that bears fruit, and this fruit supplies them with bread, wine and honey.” However exaggerated this account may be, all ancient writers agree in ascribing to Babylonian soil a fertility and productivity surpassing that of any other country with which they were acquainted.

But the present state of the country is very different from what it was, neglect of cultivation having reduced it once more to a desert waste, or, in the immediate neighbourhood of the rivers, to a pestiferous marsh. The rivers have furthermore varied their courses time and again, though this remark applies more to the sluggish stream of the Euphrates with its low banks, than to the more swiftly flowing Tigris whose current is confined by higher banks, and whose course has consequently undergone less change. At the present time, great efforts are being made to make amends for the neglect to which the once fertile plain of Babylonia has so long been subject, and in the early part of last year (1911) the firm of Sir John Jackson (Limited), contractors and engineers, secured the contract for the building of a great dam at the head of the Hindiyah Canal: this latter is a channel for which the Euphrates has forsaken its own Pg 12bed, and consequently the Euphrates’ bed upon whose banks the city of Babylon lies, is in summer-time perfectly dry, all the water flowing down the Hindiyah Canal except at the time of the inundation. Thus it is that the population have practically ceased to attempt the cultivation of the Euphrates’ banks, and have for the most part migrated across country to this canal. The latter however, being quite inadequate for the burden thus thrust upon it by the undivided waters of the Euphrates, has become badly water-logged, and much good land has become swamp. The Turks have been endeavouring for a long time to erect a dam which would drive back part of the water into the bed of the river, and thus at the same time make the regulation of the flow in the canal a possibility, but they have not attained their object. The engineers of Sir William Willcocks were successful in filling up the space between the two arms of the barrage, but the dam was almost immediately breached at another point. When however the scheme now in hand is duly realized, the banks of the Euphrates will once again be dotted with the fertility of bygone days, while the district dependent for its prosperity upon the conditions of the Hindiyah Canal will be similarly improved.

By the side of these rivers flourished the acacia, the pomegranate and the poplar, but the tree which stood the Babylonians in best stead, was the date-palm, from the sap of which they made sugar and also a fermented liquor, while its fibrous barks served for ropes, and its wood, being at the same time light and strong, was extensively used as a building material. So many and so divers were the uses which the date-palm served, that the Babylonians had a popular song6 in which they celebrated the three hundred and sixty benefits of this invaluable tree. The important part which it played in the life of the early Pg 13Sumerian population is indicated by the epithet applied by Entemena to the goddess Ninâ, whom he addresses as the lady “who makes the dates grow,” while various amphora-shaped vats, and also a kind of oval basin evidently used in the manufacture or preservation of date-wine were discovered by De Sarzec at Tellô.

The date-tree finds a place on the Assyrian bas-reliefs, but it must be confessed that the artistic products of the Babylonians and Assyrians do not afford us so much information as might be expected regarding the flora and fauna of the country. Vines and palms are of frequent occurrence on the later bas-reliefs, while oaks and terebinths were also known, for Esarhaddon uses them as material in his building operations at Babylon, and cedar trees were regularly procured for the same purpose.

Of the various trees represented on early seals, hardly any can be identified with any degree of certainty, the date-palm perhaps being excepted: the reed of the marshes appears fairly soon, but the fig-tree on the other hand occurs only in later times, which accords with Herodotus’ intimation that they were not grown in Mesopotamia in his day; this notwithstanding, they must have been known and presumably cultivated sufficiently early, for amongst the offerings made by Gudea (2450 B.C.) to the goddess Bau, figs are enumerated, while the olive-tree must also have been known at an early date, for objects in clay in the form of an olive belonging to the time of Urukagina are still extant.

The Lotus is sometimes engraved on a seal, always in the hand of a god, and with other Egyptian elements it is frequently found on the ivories and bronze dishes from Nimrûd.

Millet and other cereals have been the subject of artistic delineation; flowers of a nondescript character appear in later times, though the conventional designs Pg 14of the rosettes, so familiar in Assyrian art, an example of which is to be found in Pl. XXX, without doubt owed its origin to an actual attempt to reproduce a living flower, while ivy only occurs on a late Græco-Egyptian cylinder, and on a Syro-Hittite cylinder we find a representation of the thistle.

Reeds are found more often than any other tree or plant, alike on cylinder-seals and bas-reliefs. They were in great demand for the construction of huts and light boats, but the clay of their native soil furnished an all-availing and all-abundant material for the building operations of their palaces, temples and houses; its possibilities were recognized at a very early date, and were made use of accordingly. Stone is practically unknown in the low-lying plain of Babylonia,and when required, it had to be quarried far away in the mountains and transported at great cost and labour, hence it was comparatively seldom used for artistic or decorative effects pure and simple, but was rather employed where the desire for durability rendered it necessary; for this reason the stone used in Babylonia is generally basalt, diorite, dolerite or some other hard stone of volcanic origin. In Assyria on the other hand, both alabaster and various kinds of limestone were easily procurable, and were used largely for building purposes, while they both, also, adapted themselves readily to the chisel of the sculptor whose duty it was to record the chief events of the king’s reign in pictorial form upon the walls of his palace.

Of the cereals, wheat, barley, vetches and millet were the most important, and they all grew in large quantities, while as regards domestic animals—horses, oxen, sheep, pigs, goats, asses and dogs were the most familiar; upon the bas-reliefs from Kouyunjik, one of the mounds representing the ancient Nineveh (the other being Nebi Yûnus (“Prophet Jonah”), so-called by the natives, owing to their belief that the prophet Jonah was buried Pg 15there), camels are to be found, while they also form part of the tribute brought by tributary princes to Shalmaneser II King of Assyria 860-825 B.C., and are represented accordingly on the bronze gates from Balâwât and on the so-called Black Obelisk, principally famous for its representation of Jehu and his tribute-bearers. The camels represented here belong to the double-humped Bactrian breed, which have less staying-power than the single-humped dromedaries of Arabia and Africa. In Babylonia at the present day, these last-named are a most important means of locomotion, but in the hilly country of Assyria, they are of less use, owing to their tendency to slip on any but the flattest of grounds. There is apparently only one isolated occurrence of a camel on a cylinder-seal, and that belongs to the Persian period. The Assyrian word used for “camel” is probably of Arabic origin, and Arabia was doubtless the home of the camel. As for horses, oxen, sheep, goats and dogs, they are constantly represented in Assyrian art. The horse being native to Asia, was in all probability domesticated in Mesopotamia earlier than in Egypt; very early evidence of its existence in Mesopotamia was thought to be afforded by an archaic seal-cylinder, now in the Metropolitan Museum of New York, in which a god is represented driving a four-wheeled chariot, in contrast to the Assyrian war-chariots which were two-wheeled; the chariot is drawn by an animal of uncertain character, which Ward originally regarded as a horse, but in view of a representation of a bull drawing a chariot, found on an early Assyrian seal which he dates about 2000 B.C., it is clear that the bull was used to draw chariots in early times, and Ward accordingly regards the ambiguous animal alluded to, as also a bull. The Sumerian name for the horse was “the ass of the mountains,” an indication that the animal was first known to them in its wild state: we find it figured on one of Nebuchadnezzar Pg 16I’s boundary stone (circ. 1120 B.C.), but it was certainly known in the valley much earlier. The Hyksos, or shepherd-kings from Asia introduced the horse into Egypt about 1700 B.C., while mention is made of horses in a letter from Burraburiash the king of Babylon to Amenḥetep, king of Egypt about 1400 B.C.

An extremely early fragment from Nippur (cf. Fig. 25, E) published by Hilprecht and quoted and reproduced by Ward,7 shows us a horned animal dragging a plough, which Ward thinks may be a gazelle or an antelope; if the latter be the case, we may perhaps infer that an animal of that species was used for draft purposes before the bull, and certainly before the horse. However that may be, in later days the horse seems to have been reserved for the battle-field and the chase. The Assyrian soldiers both rode them and harnessed them to their war-chariots, and it is worth noticing how much more successful the Assyrian sculptors were in their representations of the horse than the Egyptians. The horses on the bas-reliefs apparently belong to a smaller, shorter and more thick-set breed than Arabs, and the breed is still supposed to be extant in Kurdistan. The Assyrians do not seem to have been in the habit of endowing the horse with wings or with a human head, as they sometimes did the bull and the lion, though some of the Pehlevi8 seals and rings of later days (A.D. 226-632) show figures of winged horses.

The Ox with “long upright and bent horns” seems to have been domesticated from the very earliest period, and it is represented on cylinder-seals which by their inscriptions show that they belong to the early period when the line-writing had not as yet been supplanted by its later off-shoot cuneiform, while on one of these early seals (cf. Fig. 63) the god himself is depicted riding on one of these bulls; it is however to be observed that the Pg 17bull plays a less conspicuous part in the artistic representations of Mesopotamia than in those of Egypt, where the tombs so often exhibit the daily scenes of agricultural life. Only very rarely is the bull represented on cylinder-seals or sculptures as a sacrificial victim, the best example being afforded by a fragment of the Vulture Stele of Eannatum; the same king informs us elsewhere that he sacrificed bulls to the sun-god in Larsa, and a bull-calf to En-lil, the lord of Nippur, who is better known under the Semitic name of Bêl, a name which however he never bore;9 if however the bull were used but seldom in sacrificial worship, there is no doubt that he was regarded throughout Mesopotamian history as the embodiment of, and therefore the natural symbol for strength and fertility, while the winged bulls of Sargon (cf. Pl. XXV) are the most familiar and perhaps the most characteristic monuments of Assyrian art.

The Mule was used as a beast of burden; carts were drawn by mules, and women and children were borne by them, while they were used for carrying merchandise, and for menial work of every kind; they are occasionally seen on Assyrian bas-reliefs and form one of the subjects of Ashur-bani-pal’s famous Hunting Scenes, where they are in charge of the king’s servants.

The Sheep was domesticated from the earliest times, but representations of the goat are more common; in Fig. 62 we have an extremely archaic seal on which a man is seen driving a goat followed by two sheep. A further example of the goat and sheep is found on the early stone relief seen in Fig. 25, F.

The Goat is of frequent occurrence both on seals and also in bas-reliefs. The goat was, as far as we can tell, the most commonly used sacrificial victim, the worshipper often being represented as bringing a goat in his arms. (For an early example of a goat in Babylonian art, cf. the copper goat’s head from Fâra, 40, B.) Fig. Pg 18The beard is sometimes clearly delineated,10 thereby showing it to be a goat and not an antelope, while both the sheep and goat are well represented on the bronze gate-sheaths from Balâwât. Though the sheep however does not appear to have assumed so important a part as the goat in sacrificial worship, it played a far more conspicuous rôle in augury, and innumerable omens were deduced from an inspection of the various parts of its liver.

The Ass was known from the earliest period, both the wild ass, which Ashur-bani-pal seems to have been so fond of hunting (cf. Pl. XX), and also the domesticated ass. Ward has only found one example of its early representation on cylinder-seals, but the god Nin-girsu’s chariot on the famous Vulture Stele is drawn by an ass, and the fact that Urukagina, one of the kings of the First Dynasty of Lagash, enacted that if a good ass was foaled in the stable of one of the king’s subjects, the king could only purchase it by offering a fair price, and that even then he could not compel the owner to part with it, shows that the ass was in common use in his day.

The Dog finds a place on some of the earliest seals from Babylonia, and is especially common on those representing the legend of Etana and the Eagle (cf. Fig. 62): he also appears on the later Babylonian seals, and is of very frequent occurrence in the Assyrian bas-reliefs.

Here they are seen employed in the chase (cf. Pl. XX). The Assyrian hounds apparently resembled mastiffs, and according to Layard the breed is still extant in Tibet though not in Mesopotamia. We have another good reproduction of a dog on a terra-cotta plaque found by Sir H. Rawlinson at Birs-Nimrûd (cf. Fig. 88), while Ashur-bani-pal has left us a number of clay models of his dogs, made in one piece like the colossal bulls, but Pg 19rather crude in workmanship. Though we thus know little about the breeds of dogs with which the Assyrians and Babylonians were familiar, we at all events know, that they were acquainted with dogs of various colours, for they derived omens from piebald dogs, yellow dogs, black dogs, white dogs and the rest.

The Gazelle was known in Mesopotamia from an early day, and he sometimes appears to take the place of the goat as a victim for sacrifice.

The Antelope is often found represented on early cylinder-seals, and apparently it was occasionally yoked to the plough, as may be seen from an early stone relief from Nippur,11 but it is not always easy to distinguish between the antelope and the goat in Babylonian art.

The Ibex is similarly liable to be confused with the mountain sheep, owing to the shape of their horns, but where correctly depicted, it has a beard. A good and very early example of the Ibex is to be found engraved on a fragment of shell belonging to the earliest Sumerian period (cf. Louvre Cat. No. 222).

The Boar was not often figured, but was without doubt sufficiently common as it is to-day; it is found on an extremely archaic seal (cf. Fig. 54), and numbers of little swine are repeated in four registers on a later cylinder-seal, while on other seals, the huntsman is seen spearing a boar, and lastly a sow with her young are represented on one of the wall-reliefs from Sennacherib’s palace at Kouyunjik. It is interesting to note that as early as the time of Khammurabi12 pork was a highly valued food, so much so that it frequently formed part of the temple offerings, and Ungnad calls attention to one case where a certain maleficent person stole one of the temple-pigs and paid a heavy penalty for so doing, while in the official lists of the provisions for the temple, various parts of the pig are specifically enumerated, Pg 20while from the inspection of pigs favourable and unfavourable omens were derived.

The Rabbit or Hare is rarely found in early sculptures or engravings, but it occurs on the later so-called Syro-Hittite cylinders, and is occasionally portrayed on the Assyrian bas-reliefs.13

The Oryx, the Mountain-Sheep, the Stag, the Tortoise, the Porcupine, the Monkey, all occur occasionally on the cylinders, while as regards the monkey, he forms part of the tribute brought by subject peoples to Shalmaneser II on the Black Obelisk, and is also similarly depicted on the bas-reliefs which adorned the walls of Ashur-naṣir-pal’s palace at Nimrûd, in both of which latter, the monkeys represented appear to belong to an Indian species, and were clearly novelties in the eyes of the Assyrians, who no doubt valued them accordingly.

There are solitary instances of the Fox, the Frog and the Bear, but none of the foregoing play what may be called an important part in the history of the country’s art. The Lion and the Serpent occupy a prominent position in artistic representations, and were undoubtedly familiar and formidable entities in real life, while the majesty of the former and the subtlety of the latter were alone sufficient to obtain for them a place in the mythological and heraldic symbolism of the dwellers of Mesopotamia. The lion was known everywhere, in highlands and lowlands alike, while he still haunts the low marsh country of Babylonia. On the cylinder-seals he generally appears engaged in deadly combat with Gilgamesh, the hero of Babylonian folk-lore, or his friend Ea-bani who of course on all occasions worsts him; he is figured in clay and stone from the earliest (cf. Fig. 26, B) to the latest times, he is embroidered on garments, and decorates scabbards, while he plays an all-important part in the heraldic device of the ancient city of Lagash, which is Pg 21composed of an eagle with outspread wings, clutching two lions facing in opposite directions (cf. Fig. 27), doubtless emblematic of the dominion exercised by the king of Lagash over the peoples of the East and West respectively. He enjoys the doubtful honour of being the peculiar object of the Assyrian King’s attention in later days, and afforded him the sport which he loved above all others (cf. Pl. XIX); individual kings slew great numbers, and Tukulti-Ninib I (1275 B.C.), to take a single example, places it on record that he slew some 920 lions, just as Amenḥetep III king of Egypt similarly boasts that he killed 102 lions in the first ten years of his reign. Originally no doubt lions were sufficiently plentiful, but as their numbers were thinned, it became necessary to capture and preserve them in cages till they were required for the royal hunt (cf. Pl. XXVII). The lion is sometimes reproduced in colossal size, and endowed with wings and the head of a man, in which capacity, stationed at the portals of the King’s palace, his vocation is to ward off the advances of malevolent and maleficent demons, while at other times, he is less fully equipped, and is provided only with a head, bust and hands of a man. Always a creature of weight in more ways than one, his body is not unfittingly adapted to the requirements of the scales; a considerable number of bronze lion-weights have come down to us, the workmanship of which was probably Phœnician (as was also the ivory work of the Assyrian empire), while the weight represented by each lion was inscribed in Phœnician characters. Sometimes again the hollow bronze head of a lion formed the ornate fitting of the end of a chariot-pole. As a general rule, the lion emblematized the King’s enemies, hence it is that, whenever he is seen engaged in conflict, he is always overpowered either by sheer bodily strength as in the case of Gilgamesh, or transfixed by an arrow, speared, or stabbed as we see him so frequently on the bas-reliefs of Assyrian Pg 22palaces. But lions were probably domesticated now and again as they are to-day. On Sir Henry Layard’s first visit to Hillah, he was presented with two lions by Osman Pasha; one of these, he tells us, was a well-known frequenter of the bazaars, the butcher-shops of which he was in the habit of regularly looting, but apart from this amiable little vagary, he appears to have been fairly well-behaved. In his description of the animal, Layard says that he was “taller and larger than a St. Bernard dog, and like the lion generally found on the banks of the rivers of Mesopotamia was without the dark and shaggy mane of the African species.” He further informs us that he had however, seen lions with a long black mane on the river Karûn, which river flows into the Gulf not far from Moḥammerah in the extreme south of Babylonia; but lions of either class are very rarely seen in Mesopotamia to-day, and these as a rule, only at a distance.

The serpent played a smaller part in Mesopotamian art than the lion, but at least from some points of view, a not less significant one. Two serpents entwined round a pole form the centre of the device engraved on the famous cup (cf. Fig. 90) dedicated by Gudea, patesi or priest-king of Lagash about 2450 B.C., to his god Nin-gish-zi-da, who was apparently emblematized by serpents, and on either side of the entwined reptiles, are two winged and serpent-headed monsters, while in a few cylinder-seals of the older period, we find a bearded god whose body consists of a serpent’s coil. In this connection we may compare the device on a cylinder-seal of the same Gudea (cf. Fig. 64), where the intermediary god who is introducing the patesi to a seated deity, whom Ward believes with some reason to be Ea, is characterized by serpents rising from his shoulders.

But the most familiar example of the serpent in Babylonian mythological representation is that of the seal on which two beings, perhaps divine, perhaps human, are Pg 23seated on either side of a tree, and behind one of the two an erect serpent is figured; this seal owes its fame to the opinion held by earlier scholars that this scene represents the pictorial counterpart in Babylonia of the Hebrew tradition of the Fall.

Judging from the representations of snakes found on vases, boundary-stones, cylinder-seals and elsewhere, the snakes prevalent in Mesopotamia at the time when these monuments were prepared, must have been of considerable size, while we know from the literature that some of these snakes were poisonous. The Assyrian kings further make mention of the prevalence of snakes in some of the countries whither they conducted expeditions, or which were subject to them, thus Esarhaddon for example tells us that the land of Bazu swarmed with snakes and scorpions like grasshoppers.

Among other beasts familiar to the inhabitants of Mesopotamia may be mentioned, the Bison (“rimu”) an animal of the mountains and forests, which plays a conspicuous part in the story of Gilgamesh; the old pictograph for the bison consists of the head of an ox in which were inclosed the three diagonal wedges which together signify “mountain,” and thus indicate the place of its origin. Various species of the bovine race have been identified on the cylinder-seals of Babylonia, showing that at the time of the making of the seals, the memory of their existence and probably the actuality of their presence were still felt and known. The buffalo which haunts the swamps of Southern Babylonia often occurs on cylinder-seals belonging to the time of Shar-Gâni-sharri and his successors, and is found engraved on fragments of shell belonging to the earliest Sumerian period. Layard tells us that these ugly animals which thrive in the marshes to-day supply the Arabs with large quantities of milk and butter; they are normally managed with ease, but they have a peculiar antipathy to the smell of soap, and in consequence the odour of freshly-washed Pg 24clothes is apt to irritate them in no small degree. The wild-bull was assiduously hunted by the Sargonid Assyrian kings, among whom we may especially mention Ashur-naṣir-pal in this connection. (For a graphic illustration of that king’s exploits in the chase cf. Pl. XVI). After the Sargonids, the bull-hunt appears no longer as one of the principal royal sports, possibly owing to the relentlessness with which these animals had been hunted down by the kings of that dynasty. In the jungles, at all events in Layard’s day, lions, leopards, lynxes, wild-cats, jackals, hyenas, wolves, deer, porcupines and boars still abounded, while hyenas are sufficiently common to-day.

The Leopard is occasionally figured on the more archaic seals, but seldom on those of later date, it is distinguished specifically by its spots; a good example of the leopard is afforded by an archaic seal much earlier than the time of Shar-Gâni-sharri.14 It will thus be seen that the artistic and literary bequests of Mesopotamia have aided us in no small degree in our endeavour to get a general idea as to the animal-world of that country in bygone days. Such however has been the case, only to a very limited extent in regard to birds, where colour is a more determining factor in their infinite variations than form and shape: here it was that the Egyptian shone forth in all his native genius, and succeeded in vividly depicting so many different kinds of birds upon the walls of his tombs by the aid of his brush and colours. In Assyria and Babylonia, on the other hand, where the artistic genius of the people can never really be said to have used colours alone as the mode of its expression, the only birds frequently found, are the eagle and the vulture,—the eagle as the emblem of sovereign royalty, the vulture as the ever-ready devourer of the remains of slaughtered foes—though without doubt a great variety of birds haunted the plains and marshes as they do to-day.

Pg 25The Eagle, the royal bird par excellence, is the embodiment of kingly rule in the heraldic arms of Lagash as early as the time of her first dynasty, and by the time of Gudea (2450 B.C.) the double-headed eagle, generally characteristic of Hittite art, has made its appearance. It is upon the eagle’s pinions that Etana seeks unsuccessfully to ascend to Heaven, which legend is pictorially represented (cf. Fig. 62) on various archaic seals. In course of time the eagle becomes the aerial support of Ashur, the god from whom Assyria derived its name, and lends its form to the winged disc, which, as M. Heuzey well says, is a “yet more mysterious emblem of divinity”; the Assyrians further deemed it worthy to receive the honour of being united with the body of a man, the composite creature thus produced being accredited with powers more than those enjoyed by mere men, and apparently partaking of a semi-divine character, while on other occasions we see its wings applied to the human-headed body of a bull (cf. Pl. XXV) or a lion, the combined effect of which must have been such as to stagger the boldest of subterranean demons.

The long and bare-necked Vulture is not of frequent occurrence in Mesopotamian art, while on cylinder-seals, it only occurs on those known as Syro-Hittite. The birds of prey from which the “Vulture-stele” derives its name, no doubt are intended to represent vultures; as also are the birds depicted on the bas-reliefs which adorned the walls of Ashur-bani-pal’s palace at Nineveh,15 for in either case they are busily engaged in carrying off the sharply severed limbs and heads of fallen foes.

The Ostrich only appears in Mesopotamian art at a late period, though in Elam rows of ostriches are found depicted on early pottery, closely and inexplicably resembling the familiar ostriches on the pre-dynastic pottery of ancient Egypt. It sometimes however assumes Pg 26a conspicuous position in the embroidery of an Assyrian king’s robe and is found also on a chalcedony seal in Paris.16

The Stork, which in winter time feeds in the Babylonian marshes, occurs on the cylinder-seals, but in some cases it is difficult to determine the bird figured; the Crane and the Bustard both appear to be represented, while we have an undoubted instance of the Swan in a soft serpentine seal which Ward regards as early Assyrian.17 The Cock is confined or practically confined to cylinder-seals of the Persian period.

Ducks are known to have existed by the discovery of stone and marble weights in the form of ducks, one of which is inscribed with the name of Nabû-shum, and another with that of Erba-Marduk.

Doves were used and appreciated from the earliest times, for Eannatum informs us that he offered four doves in sacrifice to the god Enzu, while Swallows and Ravens abounded, for in the Deluge-story, both the swallow and raven as well as the dove are sent forth by Ṣit-napishtim to ascertain how far the waters were abated.18

Locusts are found on one or two seals, and also appear as articles of diet on the Assyrian bas-reliefs (cf. Layard, Series II, Pl. 9), where they are seen strung up on a stick, while the scorpion is of frequent occurrence on the cylinder-seals, and is found on some of the earliest.

Fishes figure alike on seals and on palace walls, but their presence generally seems due to the artist’s desire to remove all doubt from the spectator’s mind with regard to the water, of the success of his reproduction Pg 27of which he is by no means too sanguine. We have one humorous episode in fish-life depicted on the walls of Sennacherib’s palace at Kouyunjik, where a crab is seen effectually pressing its nippers into the body of a luckless fish, while it also occurs once on a cylinder-seal.

Fish were undoubtedly used for food from the earliest times; thus Eannatum records that he presented certain fish as offering to his gods, while one of the reforms introduced by Urukagina, a king of the First Dynasty of Lagash, was the deprivation from office of the extortionate fishery inspectors. The marshes still abound in fish, some of which attain to a considerable size; they are for the most part barbel or carp, their flesh although coarse affording a regular supply of food to the Arabs.

It was not unnatural or unfitting that in a country which had been created and was yearly being created out of and at the expense of the sea, and in which the principal means of transit were the rivers and the canals, the fish as the lord of the waters should fulfil an important place in the mythological and religious conceptions entertained by the inhabitants of that country: thus it was that the god Ea of Eridu, one of the most famous and most important of the Babylonian gods, and the Oannes of the Greeks, who according to one account was the creator of the world, was represented in the form of a fish.

But it is necessary to avoid falling into the danger of assuming that all the animals, birds, fish and trees, either figured on monuments or mentioned in the literature of antiquity, belonged to the fauna or flora of Mesopotamia at the time when these engravings and sculptures were executed; the only absolutely certain and equally obvious inference is that the existence of such fauna or flora was known, while the degree of familiarity of the artist with the specimen in question may, with a good deal of reservation and allowance for the crudeness of Pg 28early art, be inferred from the comparative accuracy with which he has reproduced it, and also the frequency of its occurrence on contemporaneous works of art. With regard to the evidence of the literature, unfortunately in many cases there is some uncertainty as to the identification of the animals and plants alluded to, and furthermore, many of the animals represented pictorially on the monuments or alluded to in the literature form part of the tribute brought by subject states, the precise locality of which, to complicate matters yet further, is often uncertain. Sometimes, as in the case of the horse (cf. p. 15), the early ideographic form of writing teaches us something about the origin of the object mentioned, while the appearance of an animal or tree in early Mesopotamian art, and the existence of the same tree or animal in Mesopotamia to-day is good argument for including it among the ancient fauna and flora of the country. Again with exceptions it may be assumed that animals offered and accepted as tribute by the kings of Babylonia and Assyria were utilized in some way other than merely being afforded accommodation in a zoological gardens, in which connection we may perhaps fairly infer that kings of Assyria who accepted camels from vassal chiefs found use for them as a means of transit, though in the rough country of Assyria itself the camel would not be of great use any more than to-day, owing to the tendency of camels to slip on rough ground, and the consequently practical necessity of confining their use to flat sandy ground, such as is found in Babylonia, where they are seen by the thousand to-day.

In the early days of Babylonian history, the country was divided up into a number of small principalities or city-states, and the practical realization of the approved Pg 29truism that “unity is strength” was only attained at a later date. In this respect also, the early history of Babylonian civilization presents a parallel to that of ancient Egypt, where we find the country similarly apportioned out into a series of districts or nomes, which in course of time tended to amalgamate and in fact crystallized into a northern and a southern kingdom. But in Egypt the process of unification was carried a step further, and at about the time of the First Dynasty, the inhabitants of Egypt owed allegiance to one lord and one lord only—the king of the north and the south, his dual sovereignty being emblematized by his assumption of the crown of the north, and the crown of the south.

It is of course impossible to fix the date of the first appearance of the Sumerians in Babylonia, but the sites of their earliest known settlements were all situated in Sumer or Southern Babylonia, their principal cities being Ur, Erech, Nippur, Larsa, Eridu, Lagash and Umma. It is equally impossible to give anything in the nature of a definite date for the occupation of Northern Babylonia or Akkad by the Semites, suffice it to say that at the earliest period of which historical records have been brought to light, there appears to be evidence of the presence of Semites or Akkadians in Akkad alongside of the Sumerians in Sumer. The principal centres of Semitic occupation were the city of Akkad or Agade, Babylon, Borsippa (Birs-Nimrûd), Cutha, Opis, Sippar and Kish.

The city of Kish became an influential factor in Babylonian politics from the most ancient times.

Thus a certain Mesilim, king of Kish, whose inscribed mace-head was discovered at Tellô (Lagash),19 informs us that he had dedicated the same to the god Nin-girsu, during the patesiate of Lugal-shar-engur at Lagash, and that he had further restored the temple of this same god. Nothing further is known regarding Pg 30this patesi of Lagash, but Mesilim reigned at Kish at a very early date, for Entemena of Lagash commences his historical sketch of the relationship which had existed between his own city and that of Umma with the period of Mesilim.

Now the racial origin of Mesilim is a matter of doubt, but there is no doubt as to the Semitic origin of Sharru-Gi, Manishtusu and Urumush, later kings of Kish, whose reigns must be assigned to the pre-Sargonic period, and it is perhaps therefore reasonable to suppose that the earlier Mesilim was also a Semite. If that be the case, the mace-head of this ruler contains evidence that the early Sumerian city of Lagash was at one time under the domination of Semites, and conclusively proves that—so far as documentary evidence is concerned—Sumerians and Semites existed side by side in Babylonia from the earliest period of Mesopotamian civilization.

Some time after, Lagash succeeded in asserting her independence, and many of her subsequent rulers style themselves “kings.” The First Dynasty of Lagash which was seemingly founded by Ur-Ninâ established themselves securely for some considerable time, but the reign of Urukagina saw the end of the dynasty, and the capture and sack of the city by Lugal-zaggisi, a ruler of the neighbouring city of Umma.

The limits of Lugal-zaggisi’s empire included Ur, Erech, Larsa and Nippur, and he was undoubtedly one of the most powerful rulers of his day. Other pre-Sargonic kings whose power was specifically associated with Erech and Ur, were Lugal-kigub-nidudu and Lugal-kisalsi, but the extent of their sway cannot be estimated with any degree of certainty.

In the time immediately preceding the establishment of the empire of Shar-Gâni-sharri and Narâm-Sin, the rallying point of the Semitic forces of Akkad seems to have been the city of Kish, the conquests of whose three Pg 31kings Sharru-Gi Manishtusu and Urumush prepared the way for their successors at Agade. Thus both Manishtusu and Urumush seem to have extended their power southward into the land of Sumer, while both these kings warred successfully against Elam.

The empire of Shar-Gâni-sharri and Narâm-Sin was however destined to entirely eclipse that of their forerunners, for it not only embraced Mesopotamia north and south, but also Syria and Palestine, and was in fact the first Babylonian empire worthy of the name.

Meanwhile the power of the Sumerians in the south had received a temporary check, and the patesis of Lagash, and other Sumerian centres at the time, clearly ruled on sufferance and not on the strength of rights which they were prepared to assert successfully in the battle-field.

But on the accession of Gudea about 2450 B.C., the momentarily smoking flame of Sumerian influence in Babylonia was kindled anew, and a strong anti-Semitic wave set in. This wave does not seem to have been characterized by a series of wars or battles, for the records of Gudea, the most powerful ruler among the later patesis of Lagash, seldom refer to anything in the nature of military achievements, but the extensiveness of his building operations testifies to the abundance of resources at his command, while the names of the countries which he laid under contribution for building-materials conclusively prove that the influence exercised by Lagash during the reign of Gudea was considerable. The list of the places from which he derived wood and stone includes the mountains in Arabia and on the Syrian coast, while he obtained copper from the mines in the Elamite territory east of the Tigris.

But the importance of Lagash was soon to pass away, and Ur became the dominating power in Babylonia. The dynasty of Ur (circ. 2400 B.C.), which lasted close on 120 years, was founded by Ur-Engur. He included Pg 32the whole of Southern Babylonia within his sphere of influence, while in the north, he has left evidence of his architectural undertakings at Nippur; hence he styled himself the “King of Sumer and Akkad,” but the fact that his son and successor Dungi found it necessary to reduce Babylon indicates that his authority in Akkad was not unquestioned. Dungi reigned 58 years, during which he reduced the whole of Babylonia beneath his sway, and apparently annexed the greater part of Elam. So firmly had he established his control over Elam, that we find the capital of that country (Susa) still retained by his successors, though frequent expeditions had to be undertaken to maintain the “status quo.”

The dynasty of Ur would appear to have been brought to an end by an invasion of Elamites; at all events Ibi-Sin, the last king of Ur, was carried away by the Elamites, and the rule in Babylonia then passed to the city of Isin. The dynasty of Isin lasted some 225 years, during which Babylonia enjoyed great prosperity.

In the latter part of the first half of this period the power in Babylonia seems to have passed temporarily into the hands of Gungunu, king of Ur and Larsa, who laid claim to rule over the whole of Sumer and Akkad, but his supremacy was of short duration, and Isin soon recovered her position as the paramount power in Babylonia.

Meanwhile the Semitic element in the north was gradually regaining its ascendency, and finally asserted itself as a concrete fact in the establishment of a dynasty by Sumu-abu, at the city of Babylon itself, about 2000 B.C.

At about this time the Elamites established themselves in Southern Babylonia at Ur and Larsa under Kudur-Mabuk and his sons Arad-Sin and Rîm-Sin, and during the earlier part of the dynasty exercised a suzerainty over the whole of that region. Subsequently Rîm-Sin met with a severe defeat at the hands of Khammurabi, Pg 33the most illustrious king of the dynasty and the Amraphel of the Book of Genesis, while he met with his death at the hands of Samsu-iluna, Khammurabi’s successor. With the death of Rîm-Sin Elamite power in Babylonia came to an end.

Khammurabi consolidated the power of Babylon, and extended his influence on all sides, but his chief title to fame depends upon his codification of Babylonian law. But Babylon’s supremacy in the south was soon to be successfully challenged by Iluma-ilu who founded a kingdom on the shores of the Persian Gulf, and inaugurated the so-called “Second Dynasty” of the lists of the kings.

Iluma-ilu was a contemporary of Samsu-iluna, whose attacks he twice repelled. Abêshu’, the successor of Samsu-iluna on the throne of Babylon, similarly tried to reduce the rebellious “Country of the Sea” beneath his sway, but without success, and from this time on, Southern Babylonia was ruled over by the kings of the “Country of the Sea.”

But Samsu-iluna had another foe to contend with, besides the southern rebels, a foe moreover ultimately destined to subjugate the whole of Babylonia, under whose rule she was governed for several centuries.

The Kassites were a warlike people whose home lay on the east of the Tigris, and to the north of Elam, and they apparently commenced raiding Babylonian territory in the reign of Samsu-iluna, though they do not seem to have materially affected the Babylonian power. About a century later however, the dynasty of Babylon was brought to an end by an invasion of the Hittites of Cappadocia who sacked the city, destroyed the temple of the great city-god, Marduk, and carried off his statue as a trophy. The Hittite conquest must have paved the way for the invasion of the Kassites who established themselves securely on the throne of Babylon for a very long period. At first their sphere of influence would Pg 34appear to have been confined to the northern half of the plain, but later on they extended their power to the Country of the Sea.

Meanwhile, Assyria in Northern Mesopotamia had emerged as a separate and independent kingdom, and already the signs of her future greatness were visible on the horizon.

The date of the colonization of Assyria is not known, but in any case it must have been before the time of Khammurabi, for the country bore the name of “Assyria” in his time, and was embraced within the limits of his empire. The struggle for supremacy finally ended in a victory for the northerners who under their king Tukulti-Ninib (circ. 1275 B.C.) effected the conquest of Babylonia. In addition to his title “King of Assyria,” Tukulti-Ninib styled himself “King of Karduniash (i.e. Babylon), King of Sumer and Akkad.” From that date down to the destruction of Nineveh (circ. 606 B.C.), and the foundation of the short-lived Neo-Babylonian empire by Nabopolassar, Babylonia takes a subsidiary place in the political history of Western Asia.

The immediate successors of Tukulti-Ninib I appear to have been perpetually engaged in war with the Babylonians, who at no period of their history readily submitted to the Assyrian yoke. Tiglath-Pileser I’s accession to the throne about 1100 B.C. inaugurated a new period in the history of Assyrian expansion. Some of the mountain-tribes who had owed allegiance to former Assyrian monarchs had revolted, and Tiglath-Pileser made it his business to crush them. The northern Moschians who sixty years previously had been the vassals of Assyria, had under the leadership of five kings invaded the territory of Commagene, but they were effectively reduced by Tiglath-Pileser, and the land of Commagene was conquered “throughout its whole extent.”

Various other tribes in the north, of whom the Nairi Pg 35would appear to have been the most important, were similarly brought beneath the Assyrian sway.

In a campaign against Babylonia he was also successful for the moment, and effected the reduction of Babylon, Sippar, Opis and other cities in Lower Mesopotamia. But his triumph here was short-lived, and the Assyrians were expelled by Marduk-nadin-akhê, the king of Babylon, who further invaded Assyria, and carried off the statues of some of the Assyrian gods.

Ashur-bêl-kala, the son and successor of Tiglath-Pileser I, retrieved the fortunes of the Assyrian arms in the south, and forced Marduk-shapik-zêrim the successor of Marduk-nadin-akhê to sue for peace.