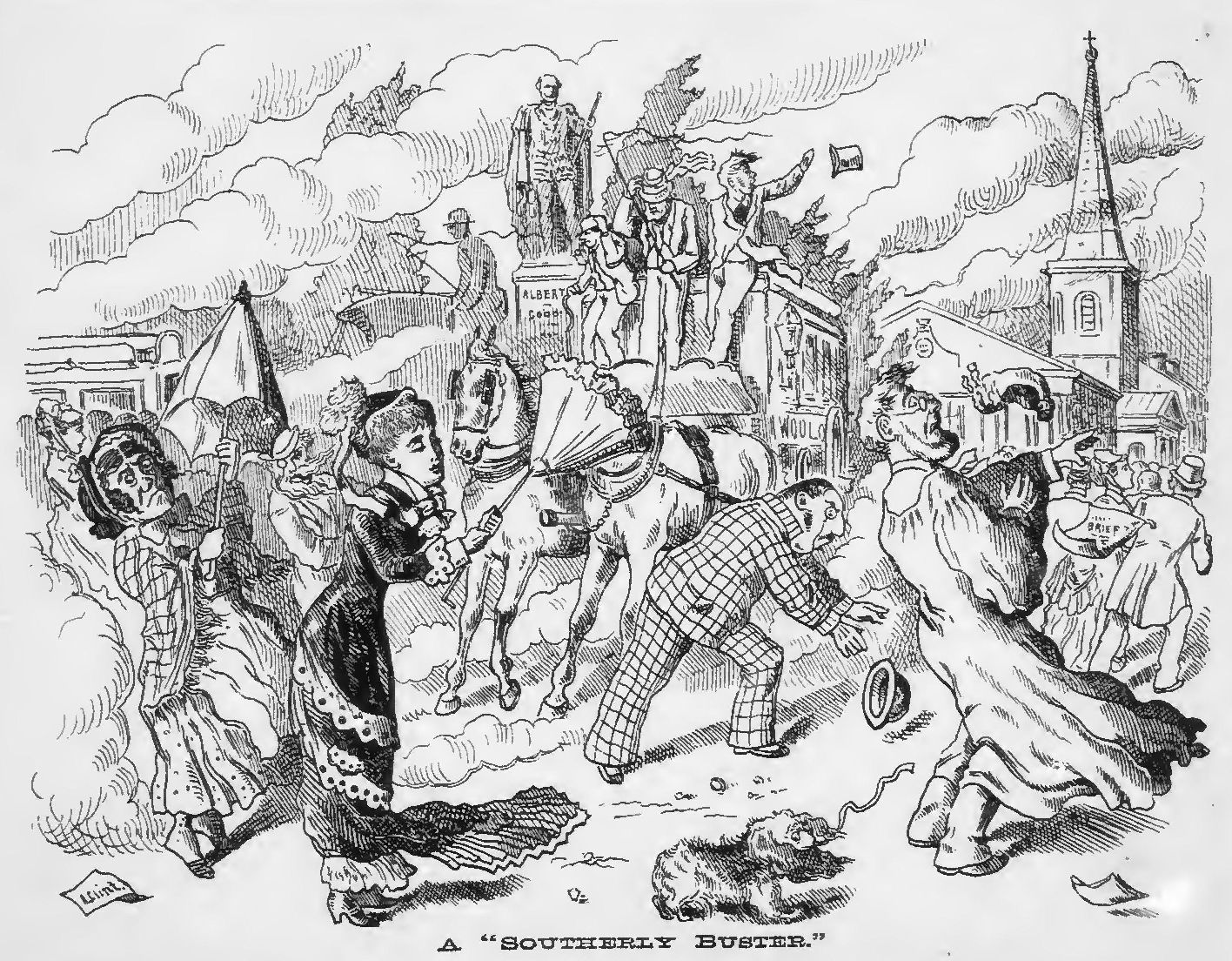

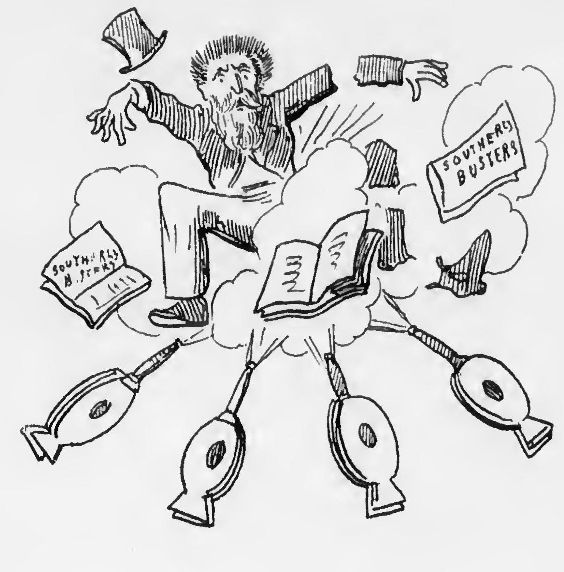

Title: Southerly Busters

Author: George Herbert Gibson

Illustrator: Alfred Clint

Montagu Scott

Release date: April 14, 2014 [eBook #45391]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

Many of these Scraps were originally contributed by the Author to "The Town and Country Journal," "Sydney Punch," "The Illustrated Sydney News," and other Australian newspapers and magazines.

CONTENTS

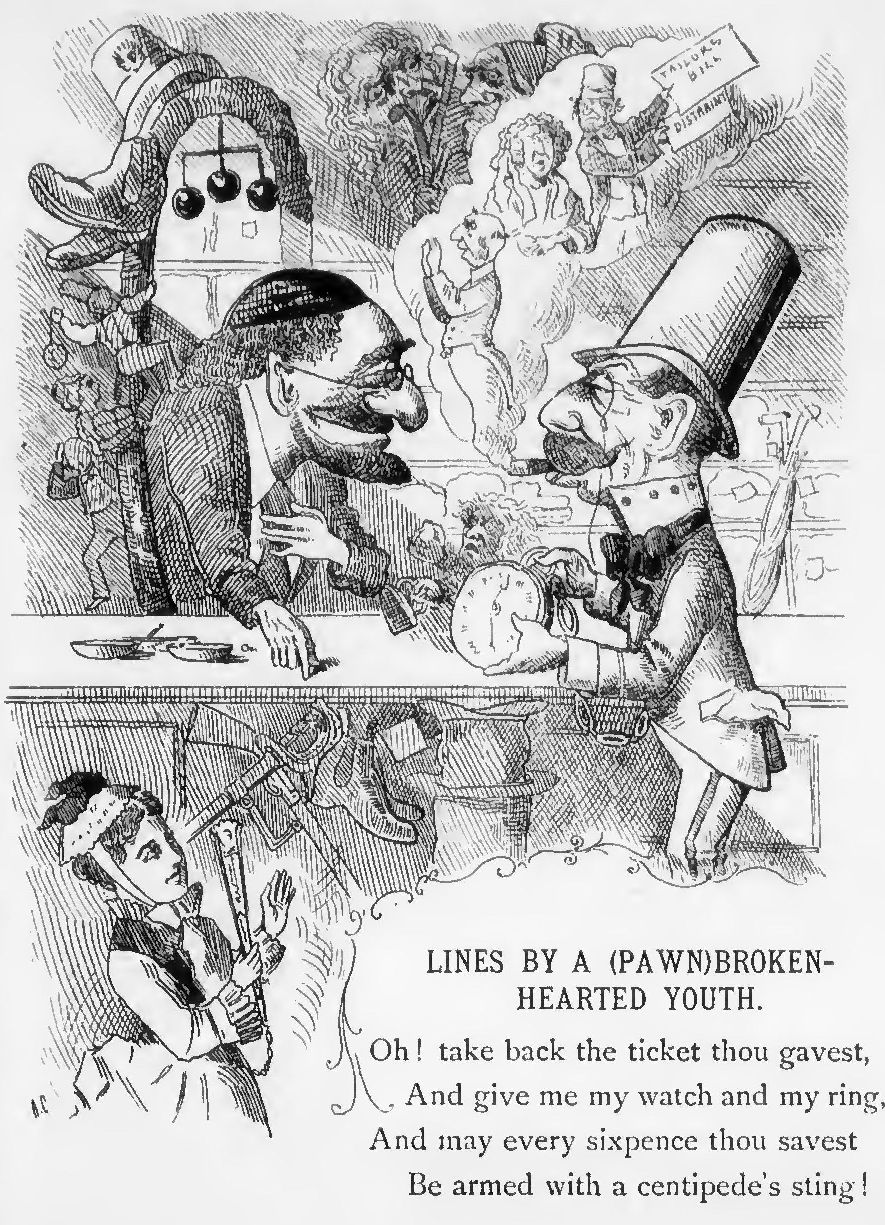

LINES BY A (PAWN)BROKEN-HEARTED YOUTH.

MORAL PHILOSOPHY FOR LITTLE FOLKS.

SUPERNATURAL REVELATIONS OF A FANCY-GOODS MAN,

EPITAPH ON A CONVIVIAL SHEARER.

A CANDIDATE FOR AN EARLY GRAVE.

THE OYSTERMEN'S AND FISHMONGERS' PIC-NIC.

a. "Billy," a tin pot for making tea in.

b. Young gentlemen getting their "colonial experience" in the bush are called "jackeroos" by the station-hands. The term is seldom heard except in the remote "back-blocks" of the interior.

c. It was formerly the practice of squatters to give a ration of flour, mutton, and, occasionally, tea and sugar, to all persons travelling ostensibly in search of work. The custom, however, as might have been expected, became frightfully abused by loafers, and has of late fallen into disuse, to the intense disgust of the tramping fraternity in general.

d. The Yanko is a noted sheep-station in the Murrumbidge district (the Paradise of loafers), where travellers were, and, I believe, still are, feasted at the expense of the owners, on a scale of great magnificence, and somewhat mistaken liberality.

e. The utterly refined and unsophisticated reader is informed that to "whip the cat" signifies, in nautical parlance, to weep or lament.

I AM assured that something in the way of an apologetic preface is always expected from a "new-chum" author who has had the hardihood to jump his Pegasus over the paddock fence (so to speak), and drop, uninvited, into the field of letters; and so, having induced a publisher, in a moment of weakness, to bring me before the public, it behoves me to conciliate that long-suffering body by conforming to all established rules. I am aware that my excuse for inflicting this work on mankind is somewhat "thin" but, such as it is, I will proceed to state it, as a "plea in bar" against all active and offensive expressions of indignation on the part of outraged humanity.

Having "got me some ideas," as Mr Emmett says in the character of "Fritz," and feeling the necessity for inflicting them on somebody imminent, I tried their effect on my own immediate circle of friends. It was not satisfactory. They listened, indeed, for a while, thinking that I was suffering from a slight mental derangement which would be best treated by judicious humouring. Some even affected to be entertained, and laughed (what a hollow mockery of merriment it was! ) at atrocious puns; but I could see the look of hate steal over countenances which had hitherto beamed on me with interest and affection, and was not deceived.

I saw that friendship would not long survive such a test and desisted; but it was too late. They perceived I had what Artemus Ward calls the "poetry disease;" feared that it might be infectious; knew that it was an insufferable bore to the afflicted party's circle of acquaintances; and—forgot to visit me.

When their familiar knocks no longer resounded on the door of my lodging in ———— street, and their familiar footsteps ceased to crush the cockroaches on the dark and winding staircase leading to my apartment, I bethought me of that institution which I had always heard alluded to as the "kind and generous public." Here, I thought (for I was unsophisticated), is the very friend I am in need of, which will receive me with its thousand arms, laugh with me with its thousand mouths, weep with me with its thousand eyes, and whose thousand hearts will beat in unison with mine whether my mood be one of sadness or of joy; behave itself, in fact, like a species of benevolent and sympathetic Hydra, shorn of its terrors, and fit to take part in the innocent and arcadian recreations of the millenium, when the (literary) lion shall lie down with the critic, and newspapers shall not lie any more—even for money.

During my hunt for that all essential auxiliary, a publisher, without whom the first step on the road to literary distinction (or extinction) cannot be taken, I learnt a few plain truths about my hydra-headed friend; amongst others that he was not to be hoodwinked, and would neither laugh, weep, nor sympathise unless he saw good and sufficient cause. I am in consequence not quite so sanguine as I was. However, I have gone too far to recede, and have concluded to throw myself on the bosom or bosoms of that animal and take my chances of annihilation.

One of my unsympathising friends assured me the other day that my book would certainly send anyone to sleep who should attempt its perusal. I gave him a ballad to read, and watched him anxiously while he skimmed a page or two. He did not sleep—not he, but a raging thirst overcame him at the fourteenth verse, and he begged me to send for a jug of "half-and-half" with such earnestness that a new and dreadful apprehension filled my breast. If this was to be the effect of my work on the Public at large, I should empty the Temperance Hall, and fill the Inebriate Asylum in six months! As I had hitherto prided myself that my work was entirely free from any immoral tendency, I earnestly hoped that his organization was a peculiar one, and that its effect on him was exceptional, and not; likely to happen again.

Sleep, indeed! Would that these pages might be found to possess the subtle power of inducing "tired Nature's sweet restorer" to visit the weary eyelids of knocked-up humanity; that they might become a domestic necessity, like Winslows "soothing-syrup," and "a blessing to mothers;" that the critic—pausing midway in a burst of scathing invective against their literary and metrical deficiencies—overcome by their drowsy influence—might sink in dreamless slumber, and wake to sing in praise of their narcotic properties, and chaunt their merits as a soporific.

In conclusion, I would fain ask thee, gentlest of gentle readers, to look with leniency on the many defects and shortcomings of this volume, and to remember that the writer was long, if not an outcast, a homeless wanderer among the saltbush plains and and sandhills of Australia, and the kauri and pouriri forests of New Zealand; that, for seven years, the prototypes of "Ancient Bill," hereinafter mentioned, were his associates; and that, if these experiences have enabled him to touch with some degree of accuracy on matters relating to the Bush, they have at the same time militated against the cultivation of those refinements of style and language which commend the modern author to his reader, and which are Only to be acquired in the civilized atmosphere of a city.

N.B.—I desire here to thank my friend, Mr. Henry Wise, of Sydney, to whom I am indebted for the design which adorns the cover of the book.

I beheld a shadow dodging, on the pavement 'neath my

lodging,

'Neath my unpretending lodging—opposite the very door:

"'Tis that prodigal," I muttered, "who enjoys the second

floor—

He it is, and nothing more."

Answering my thoughts, I stated, "'Tis the artist that's located

Here, returning home belated, seeking entrance at the door—

Coming back from where he's revelled, and, like me, with locks

dishevelled,

Wits besotted and bedevilled, oft I've seen him so before;

'Tis no rare unknown occurrence, but a customed thing of

yore—

Jones it is, and nothing more."

Certain then 'twas no illusion, "Sir," I said, in some

confusion,

"Pardon my abrupt intrusion—Mr. Jones, we've met before;

Potent drinks have o'er me bubbled, and the fact is I was

troubled,

For your form seemed strangely doubled, and my brain is sick

and sore—

Let us seek my room and cupboard, and its mystery explore—

There is gin, if nothing more."

Deep into the darkness glaring, I beheld a radiance flaring,

And a pair of eyes were staring—eyes I'd never seen before—

And, my fear and dread enhancing, towards me came a form

advancing,

And the rays of light were dancing from a lantern which it

bore—

'Twas a regulation bull's-eye—"'Tis a (something) Trap," I

swore —

"'Tis a Trap, and nothing more."

Glittering with the P. C. button, redolent of recent mutton,

(Fitting raiment for a glutton) was the garment which he

wore;

And his vast colossal figure, in the pride of manly vigour,

Looming larger, looming bigger, came betwixt me and the

door—

Cutting off my hopes of entrance to my home at number four—

Stood, and stared, and nothing more.

And his features, grimly smiling, calm, unmoved, (intensely

riling)

I betake me to reviling, and a stream of chaff outpour—

"Say, thou grim and stately brother, has thy fond and doting

mother

Got at home like thee another? Art thou really one of four?

Did she, did she sell the mangle? Tell me truly, I implore!"

Quoth the Peeler, "Hold your jawr!"

Long I stood there fiercely glaring, most profanely cursing,

swearing— .

And my right arm I was baring, meaning thus the Trap to

floor—

Straight he grabbed me by the collar, said 'twas worse than

vain to holler,

That his person I must foller to the gloomy prison door;

"'Tell me, Robert," said I sadly, "must I go the Bench

before?"

Quoth the Peeler, "'Tis the lawr!"

"Shall I be with felons banded, by the 'beak' be reprimanded,

And with infamy be branded?—thou art versed in prison

lore—

Say not, Robert, that my bread will 'ere be earned upon the

tread-mill,

That a filthy prison bed will echo to my fevered snore—

Ever echo to the music of my wild unearthly snore!"

Quoth the Peeler, "'Tis the lawr!"

Thought on thought of bitter sadness, dissipating hope and

gladness,

Goading me to worse than madness, crowded on me by the

score;

Ne'er before incarcerated, how that Peeler's form I hated,

Cries for freedom, unabated—'wrenched from out my bosom's

core'—

Broke upon the midnight stillness, "Robert, set me free

once more!"

Quoth the Peeler, "Never more!"

Never since the days of Julian was there such a mass

herculean

Clad in garments so cerulean, with so little brains in store;

And I cursed his name, and number, and his form as useless

lumber

Only fit to snore and slumber on a greasy kitchen floor—

On the slime bespattered boarding of a greasy kitchen floor—

Fit for this and nothing more!

And my heart was heavy loaded with a sorrow which

corroded,

And my expletives exploded with a deep and muffled roar;

But a sudden inspiration checked the clammy perspiration

That 'till now, without cessation, streaming ran from every pore,

And what checked the perspiration that ran streaming from

each pore

Was a thought, and nothing more.

In my pocket was a shilling! Could that giant form be

willing,

Tempted by the hope of swilling beer, to set me free once

more?

Tempted by the lust of riches, and the silver shilling

which is

In the pocket in my breeches, and my liberty restore?

Hastily that garment searching, from its depths I fiercely tore

But a 'Bob,' and nothing more.

Wrenched it from my trousers' pocket,

While his eye within the socket gleamed and sparkled like a

rocket,

Grimly rolled, and gloated o'er,

Glared upon me—vainly mining in my pockets' depths—

repining

That its worn and threadbare lining

IT should press, ah! never more.

Said I, while the coin revealing, "Robert, I've a tender

feeling

For the Force there's no concealing, and thy manly form

adore;

Thee I ne'er to hurt or slay meant; take, oh! take this

humble payment—

Take thy grasp from off my raiment, and thy person from

my door;

Though I like thee past expression, though I venerate the

corps,

Fain I'd bid thee 'Au revoir!'

And I view with approbation that official's hesitation,

For his carnal inclination with his duty was at war;

But that Peeler, though he muttered, knew which side his

bread was buttered,

But a word or two he uttered, and his choking grasp fore-

bore—

And he, when his clutching fingers from their choking grasp

forebore,

Vanished, and was seen no more.

Oft at night when I'm returning, and the foot-path scarce

discerning—

Whiskey-fumes within me burning like a molten reservoir—

In imagination kneeling, oft in fancy I'm appealing

To the kind and manly feeling of that giant Trap once more—

To the tender kindly feeling of the Trap I saw before—

Vanished now for ever more!

Oh! take back the ticket thou gavest,

And give me my watch and my ring,

And may every sixpence thou savest

Be armed with a centipede's sting!

O ! uncle, I never expected

Such grief would result from my calls,

When, hard-up, depressed, and dejected,

I came to the Three Golden Balls.

I noticed thy free invitation—

Enticing (though brief)—"Money Lent

I came to thee, oh, my relation,

For succour, for mine was all spent.

Thine int'rest in me was affecting—

I noticed a tear in thine eye,

Without for a moment suspecting

How int'rest would tell by and bye.

It's true I'd been doing the heavy,

And going a trifle too fast;

I've been a most dutiful 'nevvy,'—

But, uncle, I know thee at last;

I brought thee a gun, and a pistol,

And borrowed a couple of pound,

Then exit, and cheerfully whistle

In time to my heart's happy bound.

I thought thee a regular "trimmer,"

I thought thee a generous man;

I drank to thy health in a brimmer,

And pretty nigh emptied the can.

I went with a mob "to do evil,"

I laughed, and I danced, and I sang;

Bid sorrow fly off to the Devil,

And care and depression go hang.

I looked on the vintage that's ruby,

I "looked on the wine" that "is red,"

But 'twasn't mere looking o'erthrew me,

Or made it get into my head.

In spite of the Israelite's warning,

In spite of what Solomon said,

You may look from the dusk to the dawning,

And still toddle sober to bed.

Away with such hollow pretences!

It wasn't from watching the cup

I lost the control of my senses,

Or, falling, I couldn't get up.

Destruction again was before me,

And empty once more was my purse,

But thoughts of mine uncle came o'er me,

And withered my half-uttered curse.

I thought that the mines of Australia

I'd found in the meanest of men,

And, smoking a fearful "regalia,"

I sought thine iniquitous den.

My walk, though a little unsteady,

Was dignity tempered with grace;

I playfully asked for the "ready,"

And smiled in thy villainous face.

I brought thee my best Sunday beaver,

And gorgeous habiliments new;

My watch—such a fine English lever!—

I left, unbeliever, with you.

I brought thee a coat—such a vestment!

'Twas newly constructed by Poole;

I've found it a losing investment—

Oh! how could I be such a fool?

I told thee I hadn't a "stiver;"

I said I'd been "cutting it fat,"

And coolly demanded a "fiver,"—

How thou must have chuckled at that!

Thou wee can'st remember the morning

Succeeding thy Sabbath, thou Jew!

When cursing the year I was born in,

I felt the first turn of the screw.

And, hope from my bosom departing,

Like dew from the rays of the sun,

My wits the sad news were imparting

How I'd been deluded and done.

And, borne on the telegraph wire,

A message came swiftly to me;

It said that my grey-headed sire

Was pining his offspring to see.

How face my infuriate father—

My property mortgaged and gone?

For darkly his anger will gather;

I've hardly a rag to put on.

Thine int'rest I cannot repay thee,

And gone are my coat and my hat;

Thou hast all my duds—I could slay thee!

Oh! how could I be such a flat?

I brought thee each gift of my mother,

Each gift of my generous aunt;

The pistol belonged to my brother—

I'd like to restore it, but can't:

For, uncle, thy fingers are sticky,

And, if the sad truth be confessed,

Thy heart is as false as the "dicky,"

Which covers my sorrowful breast.

I've managed the needful to borrow,

My watch and my ring to redeem;

I hope that the sight of my sorrow

May cause thee a horrible dream.

'Twere joy should I hear that the pistol

Had burst in thy villainous hand—

While smoking the "bird's eye" of Bristol,

My breast would dilate and expand.

I leave thee, for vain is resistance,

And little thou heedest my slang,

But I'd barter ten years of existence

For power to cause thee a pang.

O! had I the wand of a wizard,

A Nemesis cruel I'd bribe

To torture that Israelite's gizzard,

And caution the rest of his tribe.

O! ye who are fond of excitement,

Ye students of Med'cine and Law,

Be warned by this awful indictment,

And never give Moses your paw!

From Moses who spoiled the Egyptian,

To Moses who buys your old clo',

They're all of the self-same description—

They take, but they never let go.

Ye sons of the Man on the Barrel

(That's Bacchus)—ye "Monks of the Screw!"

Don't mortgage your wearing apparel,

Or have any truck with a Jew;

But take to cold water and virtue,

And never, whatever befalls,

Let any false logic convert you

To visit the "Three Golden Balls."

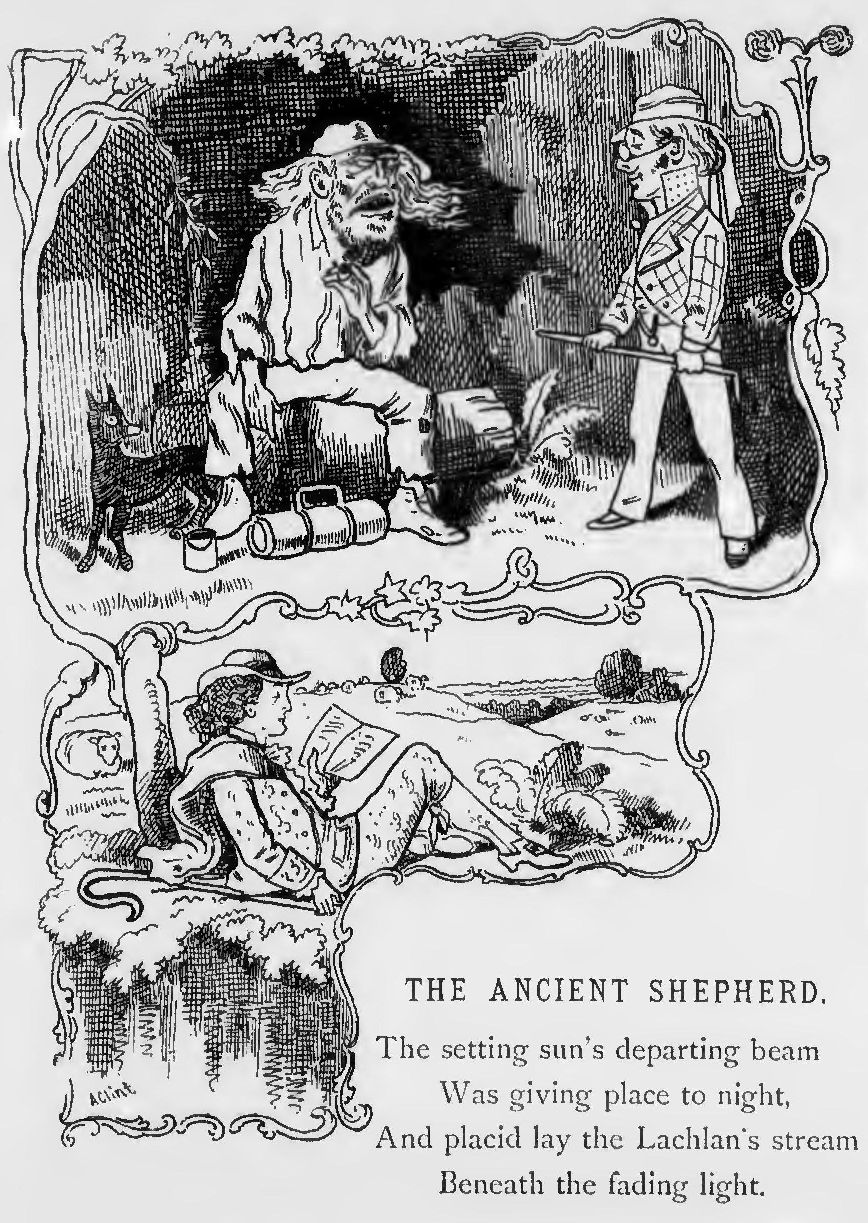

The shadows of the River Gums

Were stretching long and black,

As, far from Sydney's busy hum,

I trod the narrow track.

I watched the coming twilight spread,

And thought on many a plan;

I saw an object on ahead—

It seemed to be a man.

A venerable party sat

Upon a fallen log;

Upon him was a battered hat,

And near him was a dog.

The look that o'er his features hung

Was anything but sweet;

His swag and "billy"a lay among

The grass beneath his feet.

And white and withered was his hair,

And white and wan his face;

I'd rather not have ipet the pair

In such a lonely place.

I thought misfortune's heavy hand

Had done what it could do;

Despair seemed branded on the man,

And on the dingo too.

A hungry look that dingo wore—

He must have wanted prog—

I think I never saw before

So lean and lank a dog.

I said—"Old man, I fear that you

Are down upon your luck;

You very much resemble, too,

A pig that has been stuck."

His answer wasn't quite distinct—

(I'm sure it wasn't true):

He said I was (at least, I think,)

"A"—something—"jackeroo!"

He said he didn't want my chaff,

And (with an angry stamp)

Declared I made too free by half

"A-rushing of his camp."

I begged him to be calm, and not

Apologise to me;

He told me I might "go to pot"

(Wherever that may be);

And growled a muttered curse or two

Expressive of his views

Of men and things, and squatters too,

New chums and jackeroos.

But economical he was

With his melodious voice;

I think the reason was because

His epithets were choice.

I said—"Old man, I fain would know

The cause of thy distress;

What sorrows cloud thine aged brow

I cannot even guess.

"There's anguish on thy wrinkled face,

And passion in thine eye,

Expressing anything but grace,

But why, old man, oh! why?

"A sympathising friend you'll find

In me, old man, d'ye see?

So if you've aught upon your mind

Just pour it into me."

He gravely shook his grizzled head

I rather touched him there—

And something indistinct he said

(I think he meant to swear).

He made a gesture with his hand,

He saw I meant him well;

He said he was a shepherd, and

"A takin' of a spell."

He said he was an ill-used bird,

And squatters they might be ———

(He used a very naughty word

Commencing with a D.)

I'd read of shepherds in the lore

Of Thessaly and Greece,

And had a china one at home

Upon the mantelpiece.

I'd read about their loves and hates,

As hot as Yankee stoves,

And how they broke each other's pates

In fair Arcadian groves;

But nothing in my ancient friend

Was like Arcadian types:

No fleecy flocks had he to tend,

No crook or shepherds' pipes.

No shepherdess was near at hand,

And, if there were, I guessed

She'd never suffer that old man

To take her to his breast!

No raven locks had he to fall,

And didn't seem to me

To be the sort of thing at all

A shepherd ought to be.

I thought of all the history.

I'd studied when a boy—

Of Paris and Ænone, and

The siege of ancient Troy.

I thought, could Helen contemplate

This party on the log,

She would the race of shepherds' hate

Like Brahmins hate a dog.

It seemed a very certain thing

That, since the world began,

No shepherd ever was like him,

From Paris down to Pan.

I said—"Old man, you've settled now

Another dream of youth;

I always understood, I vow,

Mythology was truth

"Until I saw thy bandy legs

And sorrow-laden brow,

But, sure as ever eggs is eggs,

I cannot think so now.

"For, an a shepherd thou should'st be,

Then very sure am I

The man who wrote mythology

Was guilty of a lie.

"But never mind, old man," I said,

"To sorrow we are born,

So tell us why thine aged head

Is bended and forlorn?"

With face as hard as Silas Wegg's

He said, "Young man, here goes."

He lit his pipe, and crossed his legs,

And told me all his woes.

He said he'd just been "lammin'-down"

A flock of maiden-ewes,

And then he'd had a trip to town

To gather up the news;

But while in Bathurst's busy streets

He got upon the spree,

And publicans was awful cheats

For soon "lamm'd down" was he.

He said he'd "busted up his cheque"

(What's that, I'd like to know?)

And now his happiness was wrecked,

To work he'd got to go.

He'd known the time, not long ago,

When half the year he'd spend

In idleness, and comfort too,

A-camping in a "bend."

No need to tread the weary track,

Or work his strength away;

He lay extended on his back

Each happy summer day.

When sun-set comes and day-light flags,

And dusky looms the scrub,

He'd bundle up his ration-bags

And toddle for his grub,

And to some station-store he'd go

And get the traveller's dower—

"A pint o' dust"—that was his low

Expression meaning flour;

But now he couldn't cadge about,

For squatters wasn't game

To give their tea and sugar out

To every tramp that came.

The country's strength, he thought, was gone,

Or going very fast,

And feeding tramps now ranked among

The glories of the past.

He'd seen the "Yanko" in its pride,

When every night a host

Of hungry tramps at supper tried

For who could eat the most.

A squatter then had feelin's strong

And tender in his breast,

And if a trav'ller came along

He'd ask him in to rest.

"But squatters now!"——he stamped the soil,

And muttered in his beard,

He wished they'd got a whopping boil

For every sheep they sheared!

His language got so very bad—

It couldn't well be worse,

For every second word he had

Now seemed to be a curse.

And shaking was his withered hand

With passion, not with age—

I never thought so old a man

Could get in such a rage.

His eyes seemed starting from his head,

They glared in such a way;

And half the wicked words he said

I shouldn't like to say;

But from his language I inferred

There wasn't one in three,

Of squatters worth that little word

Commencing with a "D."

Alas! for my poetic lore,

I fear it was astray,

It never said that shepherds swore,

Or talked in such a way.

The knotted cordage of his brow

Was tightened in a frown—

He seemed the sort of party, now,

To burn a wool-shed down.

He told me, further, and his voice

Grew very plaintive here,

That now he'd got to make the choice

And work, or give up beer!

From heavy toil he'd always found

'Twas healthiest to keep,

And mostly stuck to cadgin' round,

And lookin' after sheep.

But shepherdin' was nearly "cooked"—

I think he meant to say

That shepherds' prospects didn't look

In quite a hopeful way.

A new career he must begin,

(And fresh it roused his ire)

For squatters they was fencin' in

With that infernal wire;

And sheep was paddocked everywhere—

'Twas like them squatters' cheek!—

And shepherds now, for all they'd care,

Might go to Cooper's Creek.

He said he couldn't use an axe,

And wouldn't if he could;

He'd see 'em blistered on their backs

'Fore he'd go choppin' wood;

That nappin' stones, or shovellin',

Warn't good enough for he,

And work it was a cussed thing

As didn't ought to be.

He'd known the Lachlan, man and boy,

For close on forty year,

But now they'd pisoned every joy,

He thought it time to clear.

They gave him sorrow's bitter cup,

And filled his heart with woe,

And now at last his back was up,

He felt he ought to go.

He'd heard of regions far away

Across the barren plains,

Where shepherds might be blythe and gay

And bust the squatters' chains.

To reach that land he meant to try,

He didn't care a cuss,

If 'twasn't any better, why,

It couldn't be much wuss.

Amongst the blacks, though old and grey,

Existence he'd begin,

And give his ancient hand away

In marriage to a "gin."

He really was so old and grim,

The thought was in my mind,

That any gin to marry him

Would have to be stone blind.

'Twould make an undertaker smile:

What tickled me was this,

The thought of such an ancient file

Indulging in a kiss!

And, if it's true, as Shakespeare said,

That equal justice whirls,

He ought to think of Nick instead

Of thinking of the girls.

Then drooped his grim and aged head,

And closed that glaring eye,

And not another word he said

.Except a grunt or sigh.

More lean he looks and still more lank

Such changes o'er him pass,

And down his ancient body sank

In slumber on the grass.

I thought, old chap, you're wearing out,

And not the sort of coon

To lead a blushing bride about,

Or spend a honeymoon;

Or if, indeed, there were a bride

For such a withered stick,

With such a tough and wrinkled hide,

That bride should be old Nick.

As streaks of faintish light began

To mark the coming day,

I left that grim and aged man

And slowly stole away.

And when the winter nights are rough,

And shrieking is the wind,

Or when I've eaten too much duff

And dreams afflict my mind,

I see that lean and withered hand,

And, 'mid the gloom of night,

I see the face of that old man,

And horrid is the sight:

While on my head in agony

Up rises every hair,

I see again his glaring eye—

In fancy hear him swear.

At breakfast time, when I come down

To take that pleasant meal,

With pallid face, and haggard frown,

Into my place I steal;

And when they say I'm far from bright,

The truth I dare not tell:

I say I've passed a sleepless night,

And don't feel very well.

Oh! Mother, say, for I long to know,

Where doth the tree of Freedom grow,

And strike its roots in the heart of man

As deep and far as the famed banyan?

Is it 'mid those groups in the Southern Seas,

In the Coral Isles, or the far Fijis,

Where the restless billows seeth and toss

'Neath the gleaming light of the Southern Cross?

"Not there—not there, my child."

Then tell me, mother, can it be where

The cry of "Liberty" rends the air?

Where grow the maize and the maple tree,

In the fertile "bottoms" of Tennessee?

Or is it up where the north winds roar,

Away by the fair Canadian shore,

Where the Indians shriek with insane halloos—

As drunk as owls in their bark canoes?

"Not there—not there, my child."

Or is it back in the Western States,

Where Colt's revolver rules the fates,

And Judges lounge in a liquor shop

While Dean and Adams's pistols pop?

Where Justice is but a shrivelled ghost

As deaf and blind as a stockyard post,

And License sits upon Freedom's chair—

Oh, say, dear mother, can it be there?

"Not there—not there, my child."

Is it on the banks of the wild Paroo,

Where the emu stalks, and the kangaroo

Bounds o'er the sand-hills free and light,

And the dingo howls through the sultry night;

Where the native gathers the nardoo-seed

For his frugal meal; and the centipede—

While the worn-out traveller lies inert,

Invades the folds of his flannel shirt?

"Not there—not there, my child."

Is it where yon death-like stillness reigns

O'er the vast expanse of the salt-bush plains,

Where the shepherd leaveth his Leicester ewes

For the firm embrace of his noon-tide snooze,

And the most enchanting visions come

To his thirsty spirit of Queensland rum,

While the sun rays strike through his garments scant—

Is it there, dear mother, this wond'rous plant?

"Not there—not there, my child."

Or Southward, down where our brethren hold

Those keys of power, rich mines of gold—

That land of rumour and vague reports,

Alluvial diggings, and reefs of quartz—

Where brokers give you the straightest "tip,"

And let in in the way of "scrip;"

Where all men vapour, and vaunt, and boast,

And manhood suffrage rules the roast?

"Not there—not there, my child."

Is it where the blasts of the simoom fan,

The blazing valleys of Hindustan;

Where the Dervish howls, and their dupes are fleeced

By the swarth Parsee, and the Brahmin priest;

Where men believe in their toddy-bowls,

And the transmigration of human souls,

And the monkeys battle with countless fleas

On the twisted boughs of the tamarind trees?

"Not there—not there, my child."

Or is it more to the northward, more

Toward the ice-bound rivers of Labrador,

Where the glittering curtain of gleaming snow

Enshrouds the home of the Esquimaux;

Or further still to the north, away

Where the bones of the Artic heroes lay

Long, long on the icy surface bare,

To bleach and dry in the frosty air?

"Not there—not there, my child."

Then is it, mother, among the trees

That shade the paths in the Tuilleries,

Where the students walk with the pale grisettes,

And scent the air with their cigarettes?

Or doth it bloom in that atmosphere

Of mild tobacco and lager beer,

Where gutteral curses mingle too

With the croupiers patter of "faites votre jeu?"

"Not there—not there, my child."

"Boy, 'tis a plant that loves to blow

Where the fading rays of the sunset go;

Up where the sun-light never sets,

And angels tootle their flageolets;

Up through the fleecy clouds, and far

Beyond the track of the farthest star,

Where the silvery echoes catch no tone

Of a simmering sinner's stifling groan:

'Tis there—'tis there, my child!"

Countless sheep and countless cattle

O'er his vast enclosures roam;

But you heard no children prattle

'Round that squatter's hearth and home.

Older grew that squatter, older,

Solitary and alone,

And they said his heart was colder

Than a granite pavin'-stone.

Other squatters livin handy,

Wot had daughters in their prime.

For that squatter "shouted" brandy

In the Township many a time;

And those gals kept introdoocin'

In their toilets every art

With the object of sedoocin'

That old sinner's stony heart.

Thus they often made exposures

Of their ankles, I'll be bound,

When they, in his vast enclosures,

Met that squatter ridin' round.

Their advances he rejected,

Scornin' both their hands and hearts,

'Till one day a cove selected

Forty acres in those parts.

And that stalwart free-selector

Had the handsomest of gals;

Conduct couldn't be correcter

Than his youngest daughter Sal's.

Prettily her head she tosses—

Loves a thing she don't regard;

Rides the most owdacious hosses

Wot was ever in a yard.

She was lithe and she was limber—

Farmers daughter every inch—

Not averse to sawin' timber

With her father at a pinch.

In remotest dells and dingles,

Where most gals would be afraid,

There she went a-splittin shingles,

Pretty tidy work she made.

And that free selector's daughter,

Driving of her father's cart,

Made the very wildest slaughter

In that wealthy squatter's heart.

He proposed, and wasn't blighted,

Took her to his residence,

With his bride he was delighted

For she saved him much expense.

Older grew that aged squatter,

White and grizzly grew his pate,

'Till his weak rheumatic trotters

Couldn't bear their owner's weight.

Then he grew more helpless, 'till he

Couldn't wash and couldn't shave,

And one evening cold and chilly

He was carried to his grave.

Then that free selector's daughter

Came right slap "out of her shell;"

Calm and grave as folks had thought her,

She becomes a howling swell.

To the neighb'ring township drove she

In her chariot and pair,

Splendid dreams and visions wove she

While she braided up her hair.

She peruses Sydney papers,

Sees a paragraph which tells

Her benighted soul the capers

Cut down there by nobs and swells;

Then she couldn't stop contented

In a region such as this,

While the atmosphere she scented

Of the great metropolis.

Her intention she imparted

To the neighbours round about;

Packed her duds, farewell'd, and started,

And for Sydney she set out.

Now her pantin' bosom hankers

Spicily her form to deck,

So she sought her husband's bankers

And she drew a heavy cheque.

She, of course, in dress a part spent,

Satins, sables, silk and grebe,

And she took some swell apartments

Situated near the Glebe.

With the very highest classes

In her heart she longed to jine—

Her opinion placed the masses

Lower in the scale than swine.

But she found it wasn't easy

Climbin' up ambition's slope;

Slippy was the road, and greasy,

To the summit of her hope.

If into a "set" she wriggled,

She'd capsize some social rule,

Then those parties mostly giggled,

Loadin' her with ridicule.

Many an awkward solecism—

Many a breach of etiquette,

(Though she knew her catechism)

Often made her eyelids wet.

Her plebeian early trainin'

Was a precious pull-back then,

Which prevented her from gainin'

Footin' with the "upper ten."

Strugglin' after social fame was

Simply killin' her out-right,

So she settled that the game was

Hardly worth the candle-light.

Things got worse and things got worser,

'Till she had a vision strange,

The forerunner and precurser

Of a most decided change.

In a dream she saw the station

Where her father now was boss,

And his usual occupation

Was to ride a spavined hoss.

Round inspectin' every shepherd

With his penetratin' sight,

And those underlings got peppered

If he found things wasn't right.

When she saw her grey-haired sire

"Knockin' round" among the sheep,

For her home a strong desire

Made her yell out in her sleep.

Then she saw herself in fancy

In her strange fantastic dream,

With her elder sister Nancy,

Yokin up the bullock team.

Up out of her sleep she started,

And the tears came to her eyes;

She was almost broken-hearted,

To her waitin' maid's surprise.

She was sad and penitential,

Like the Prodigal of old,

So she got a piece of pencil

And her state of mind she told

To her grey and aged father

In that far outlandish place;

And she told him that she'd rather

Like to see his wrinkled face.

Then that quondam free-selector

Shed the biggest tears of joy;

When he knew he might expect her

His was bliss without alloy.

Home came Sarah, just as one fine

Day in May was near its close,

And the fadin' rays of sunshine

Glinted oil her father's nose.

She beheld it glowing brightly;

Filial yearning was intense;

So she made a rush and lightly

Cleared the four-foot paddock fence.

Hugged he her in fond embraces;

Kissed she him with many a kiss;

And she busted her stay-laces

In an ecstasy of bliss.

Then she wept with sorrow, thinkin',

From the colour of his face,

That her parent had been drinkin',

Which was probably the case.

But he, when he found his coat all

Wet with many a filial tear,

Took a solemn pledge tee-total

To abstain from rum and beer.

Then she went and sought her sisters,

Judy, Nancy, and the rest;

On their faces she raised blisters

With the kisses she impressed.

And she once more con amore

"Cottoned " to the calves and sheep,

Likewise for her parent hoary

She professed affection deep.

Lavished on him fond caresses,

Stuck to him like cobbler's-wax,

Cut up all her stylish dresses

Into garments for the blacks.

All her talents were befitted

To a rough-and-tumble life,

And from sheep to sheep she flitted

When the "scab" and "fluke" were rife.

Sarah's heart was soft and tender,

Her repentance was complete,

Never sighed she more for splendour,

For the "Block" or George's-street.

Many a "back-block" lady-killer,

Many a wealthy squatter's son,

Wanted her to "douse the wilier,"

But she wasn't to be won.

For that free-selector's daughter

Said, when settled in her home,

She'd be (somethinged) if they caught Her

Venturin' again to roam.

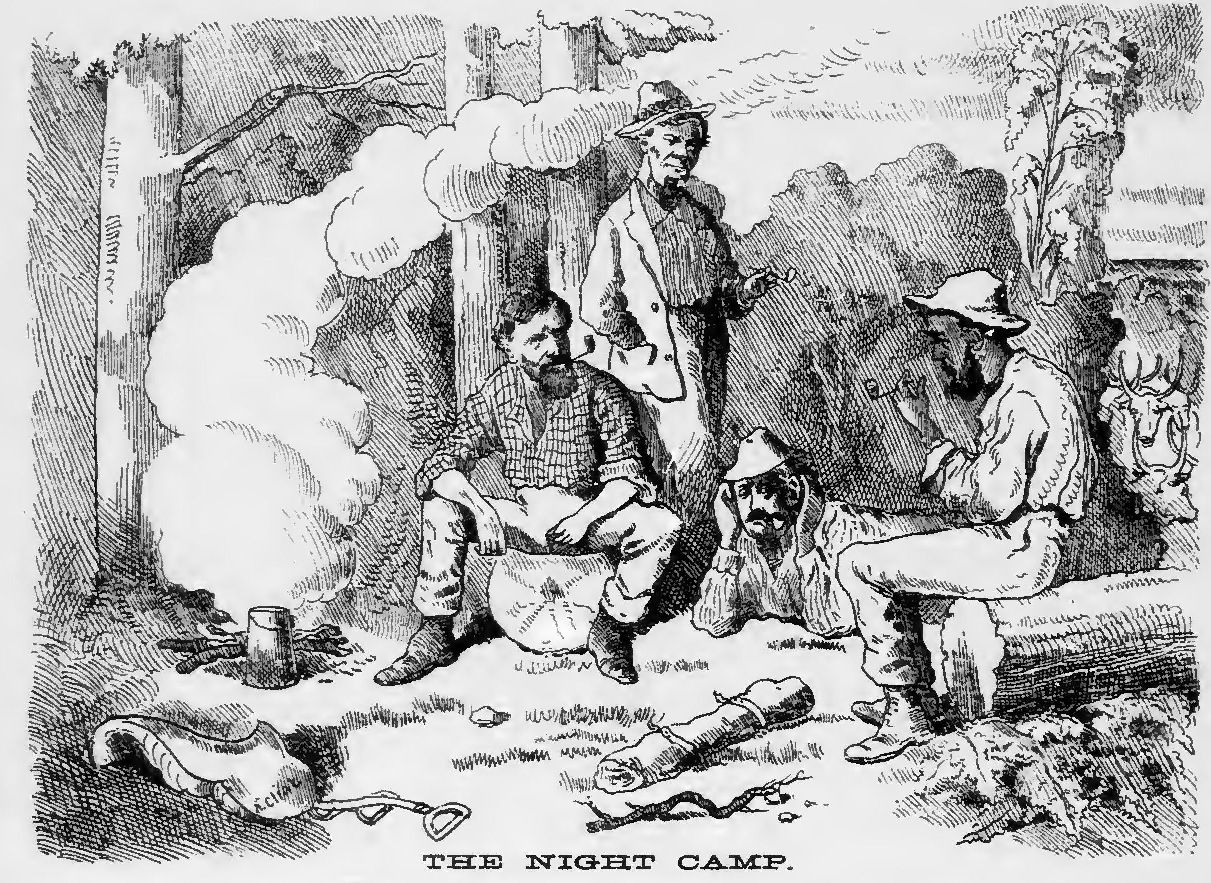

The song goes round, we yarn and chaff,

And cheerily the bushman's laugh

Rolls through the forest glade.

The hobbled horses feed around,

We hear the horse-bell's tinkling sound;

The sand beneath their feet is ground,

As in the creek they wade.

We hear them crunch the juicy grass—

The water gleams like polished glass,

Beneath the moon's bright ray.

Mosquitos form in solid cloud—

They sting and sing, both sharp and loud;

Around the prostrate forms they crowd,

And keep repose at bay.

We watch the stars shine over head,

And lounge upon the bushman's bed—

A blanket on the ground.

Each feels himself Dame Nature's guest,

Our heads upon our saddles rest;

At length, with weariness oppressed,

We sink in sleep profound.

We sleep as only weary ones

Among hard-handed labour's sons,

With minds at rest from debts and duns—

As only these can do—

Until the daylight's first faint streak

Has lightly touched the distant peak,

And o'er us where the branches creak,

Is slowly creeping through.

Reluctantly with sleep we strive,

And hear the call to "look alive"!

We soon desert the camp.

The horses caught and blankets rolled,

The "Super's" brief instructions told—

We mount, and scarce our steeds can hold,

Impatiently they stamp.

We ford the creek and need no bridge,

And climb a steep and scrubby ridge,

And then, boys, there's a sight!—

The "gully," by the sun unkist,

Beneath lies rolled in gleaming mist

And flowing waves of light;

As yet untouched by noon-tide heat,

Like rocks where broken waters meet,

'Tis wrapped as by a winding sheet

In billows fleecy white.

Onward, and soon the sun's fierce rays

Will dissipate the morning haze—

He soars in fiery pomp.

We skirt the shallow "clay-pan's" marge,

Force "lignum" thickets, dense and large,

And often-times we briskly charge

Some dark "Yapunya-swamp."

We gather first a quiet lot,

Then off again with hurried trot

Upon our toilsome tramp.

Each gully, range, and hill we beat,

Charge every horned thing we meet—

With ringing shout and gallop fleet—

And "run" then "on the camp."

The shaggy herd increases fast;

We know by lengthened shadows cast

Time too has galloped hard;

'Twill try our powers, howe'er we strive,

This most rebellious mob to drive,

E're night-fall, to the yard.

The order comes,—"Each to his place!"

And homeward now at length we face.

The frightened monsters roar;

Some tear the unresisting ground,

And some with frantic rush and bound

(Half maddened by the stockwhip's sound)

Each other fiercely gore!

We spread along the scattered line,

Some on the "wings," and some behind,

And steer them as we can.

There's but one pass through yonder hill;

To guide them there will need some skill,

And try both horse and man.

Some hidden object checks them there;

The leaders snuff the wind, and glare,

Then bellowing with their tails in air,

Swerve madly to the right.

A stockman hears our voices ring;

With easy stretch and supple spring,

His horse bears down along their wing,

The living mass he wheels:

Too close he presses; at the sight

One "breaks" and bellows with affright;

Dick swoops upon him, like a kite;

The cutting thong he deals;

It falls with heavy sounding thwack—

Such din those mountain gullies black

Have scarce or never heard.

He knows his work, that well-trained hack,

Nor heeds the stockwhip's echoing crack,

And sullenly the bull turns back,

To join the hurrying herd.

"Look out!" a warning voice has said,

"There's 'Mulga,' boys, and right ahead!"

And now begins the rub;

From some their garments will be stripped,

And saddle-flaps and "knee-pads" ripped,

And horses' feet in holes be tripped,

Before they clear the scrub.

You, stockmen from the Murray's side,

Who through the "Mallee" boldly ride,

Beware the "mulga-stake!"

'Tis strong and tough as bullock-hide,

Nor will, like "mallee," turn aside;

But, in its savage, sylvan pride,

Will neither bend nor break!

Once through the scrub, we don't care how

Things go; we've got them steadied now

And haven't lost a beast—

And, far as ranges human eye,

The plains are level as a die—

Our toil has nearly ceased.

The Sun goes down, the day-light fails,

But now we near the Stockyard rails—

We've one sharp struggle more.

One half the mob have never been

(Forced from those gullies cool and green)

In "branding-yard" before!

We jam them at the open space;

They ring around, and fear to face

The widely open gate.

Whips crack, and voices shout in vain;

The cattle "ring," and strive again

To force a passage to the plain.

Impatiently we wait,

Till one old charger glares around,

And snuffing cautiously the ground

Stalks through between the posts.

With lowered heads the others "bore"

And jam, and squeeze, and blindly gore;

And with a hollow muttered roar

Pour in those horned hosts!

Those posts are fourteen inches through—

They creak, and groan, and tremble too,

Before that pouring rush!

They're in at last, the gates are shut;

And falls o'er paddock, yard, and hut,

A calm nocturnal hush.

In youth he met with sad rebuffs,

Hard, hard was William's lot,

And most unnecessary cuffs

And kicks he often got.

At length one night both dark and black

A window he got through,

And with fresh weals upon his back

He joined a whaler's crew.

He learnt to "hand," and "reef," and steer,

And knew the compass pat;

He learnt to honour and revere

The boatswain and his "cat."

He went to every coral isle

Down in the Southern seas,

Where dark-eyed beauties beam and smile

Beneath the bread-fruit trees.

His foot was firm upon the deck

As Norval's on his heath;

He dared the tempest and the wreck

For whale and walrus teeth.

He braved Pacific foam and spray,

For oil and bêche-le-mer,

Till he grew ugly, old, and grey,

An ancient mariner.

His face got red, and blue, and pink

With grog and weather stains;

He looked much like the missin link

When in the mizen chains.

Bill Blubber's gone, and he'll be missed

By all on British soil;

Be aisy now and hold your whist,

He'll go no more for Hoyle!

No more he'll see the billows curl

In north Atlantic gales;

No more the keen harpoon he'll hurl

At spermaceti whales.

Ah! never more he'll heave the log—

A harsh decree was Fate's;

He took an over-dose of grog

When up in Be(e)hring Straits.

Death blew a bitter blast and chill

Which struck his sails aback,

And round the corse of Workhouse Bill

They wound a Union Jack.

A "longing, lingering look" they cast,

Then sewed him in a bag,

And half way up the lofty mast

They hoist the drooping flag.

His mess-mates crossways tossed the yards,

Askew they hung the sails,

Eschewed tobacco, rum, and cards,

And filled the ship with wails

The grief-struck skipper drank some grog,

Of solace he had need,

And made an entry in the log

No livin' soul could read.

And then a ghastly laugh he laughed

His spirits to exhalt,

And then he called the boatswain aft

And mustered every salt

The whalers gave one final howl,

And cursed their hard, hard lucks;

They came, and though the wind was foul,

They wore their whitest ducks.

The captain—kindest, best of men—

Strove hard his breath to catch;

(Crouched like an incubating hen,

Upon the after-hatch).

He said as how the time was come

To Bill to say good-bye;

And tears of water and of rum,

Stood in each manly eye.

Said he, "My lads, dispel this gloom,

"Bid grief and sorrow halt;

"For if the sea must be his tomb,

"D'ye see it aint his f(v)ault.

"' Tis true we'll never see his like

"At 'cutting in' a whale—

"At usin knife an' marlin-spike,

"But blubber won't avail.

"Soh! steady lads, belay all that!

"'Vast heaving sobs and sighs;

"Don't never go to 'whip the cat'

"For William, bless his eyes!

"I knew him lads when first he shipped,

"And this is certain, that

"Though William by the 'cat ' was whipped,

"He never 'whipped the cat!"

The skipper read the service through,

And snivelled in his sleeve,

While calm and still, old work'us Bill

Awaits the final heave.

He had no spicy hearse and three,

No gay funereal car;

But, at the word, souse in the sea

They pitch that luckless tar.

Short-handed then those whalemen toil

Upon their oily cruise,

And many and many a cruse of oil

For want of Bill they lose.

The mate and captain in despair

His cruel fate deplore;

His mess-mates swore they never were

In such a mess before.

The crew, who had a bitter cup

To drink with their salt-horse,

When next they hauled the mainsel up,

Bewailed his missin corse. *

* Mizen-course o' course.

Alas! his corpse had downward sunk,

His soul hath upward sped,

And Will hath left a sailor's 'bunk'

To share an oyster's bed.

We hope his resting place will suit—

We trust he's happy now—

Laid where the pigs can never root,

Lulled by the ocean's sough.

This Christmas-eve? This stifling night?

The leaves upon the trees?

The temperature by Farenheit

Some ninety odd degrees?

Ah me! my thoughts were off at score

To Christmases I've passed,

Before upon this Southern shore

My weary lot was cast.

To Christmases of ice and snow,

And stormy nights and dark;

To holly-boughs and mistletoe,

And skating in the Park

To vast yule-logs and yellow fogs

Of the vanished days of yore—

To the keen white frost, and the home that's lost,

The home that's mine no more.

'Twas passing nice through snow and ice

To drive to distant "hops,"

But here, alas! the only ice

Is in the bars and shops!

I've Christmased since those palmy days

In many a varied spot,

And suffered many a weary phase

Of Christmas cold and hot.

When cherished hopes were stricken down-

Hopes born but to be lost—

And when the world's chill blighting frown

Seemed colder than the frost.

'Tis hard to watch—when from within

The heart all hope has flown—

The old year out, the new year in,

Unfriended and alone

When whispers seem to rise and tell

Of scenes you used to know—

You almost hear the very bells

You heard so long ago.

I've Christmased in a leaky tub

Where briny billows roll,

And Christmased in the Mulga scrub

Beside a water-hole.

With ague in my aching joints,

And in my quivering bones;

My bed, the rough uneven points

Of sharp and jaggèd stones.

Where life a weary burden was

With all the varied breeds

Of creeping things with pointed stings,

And snakes, and centipedes.

'Twas not a happy Christmas that:

How can one happy be

With bull-dog ants inside your hat,

And black ants in your tea?

Australian child, what cans't thou know

Of Christmas in its prime?

Not flower-wreathed, but wreathed in snow,

As in yon northern clime.

Thou hast not seen the vales and dells

Arrayed in gleaming white,

Nor heard the sledge's silver bells

Go tinkling through the night.

For thee no glittering snow-storm whirls;

Thou hast instead of this

Only the dust-storm's eddying swirls—

The hot-wind's scalding kiss!

What can'st thou know of frozen lakes,

Or Hyde—that Park divine?

For, though by no means lacking snakes,

Thou hast no "Serpentine."

Thou hast not panted, yearned to cut

Strange figures out with skates,

Nor practised in the water-butt,

Nor heard those dismal "waits."

For thee no "waits" lugubrious voice

Breaks forth in plaintive wail;

Rejoice, Australian child, rejoice!

That balances the scale.

I see in fancy once again

The London streets at night—

Trafalgar square, St. Martin's Lane—

Each well remembered sight.

Past twelve! and Nature's winding-sheet

Is over street and square,

And silently now fall the feet,

Of those who linger there.

I see a wretch with hunger bold

(An Ishmaelite 'mong men)

Crawl from some hovel dark and cold—

Some foul polluted den—

A wretch who never learnt to pray,

And wearily he drags

His life along from day to day

In wretchedness and rags.

I see a wandering carriage lamp

Glide silently and slow;

The night-policeman's heavy tramp

Is muffled by the snow.

I hear the mournful chaunt ascend

('Tis meaningless to you)

"We're frozen out, hard-working men,

We've got no work to do!"

All, all the many sounds and sights

Come trooping through my brain

Of London streets, and winter nights,

And pleasure mixed with pain.

Be happy you who have a home,

Be happy while you may,

For sorrow's ever quick to come,

And slow to pass away.

Your churches and your dwellings deck

With ferns and flowers fair;

I would not breathe a word to check

The mirth I cannot share.

For, though my barque's a shattered hull,

And I could be at best

But like the famed Egyptian skull,

A mirth-destroying guest,

I would not play the cynic's part,

Nor at thy pleasure sneer—

I wish thee, Reader, from my heart,

A happy, glad New year.

Some years ago I chanced upon a magazine article containing a dissertation upon a now almost obsolete kind of versification, much affected by Ben Jonson and some of the last century poets, in which the first two or three lines of each verse ask a question, and the echo of the concluding words gives an answer more or less appropriate. An amusing example was given in the article above mentioned, which was equally rough on the great violinist of the past and his audience, thus:

"What are they who pay six guineas

To hear a string of Paganini's?"

(Echo) "Pack 'o ninnies!"

I read this and a few other examples, and was straightway stricken with a desire to emulate this eccentric and somewhat difficult species of versification, and now with considerable diffidence, and a choking prayer for mercy at the hands of the critic, I lay my attempt before the reader. The following echo-verses are not on any account whatever to be understood as reflecting on the present or any past Government of this Colony. They are merely to be taken as shadowing forth a state of things possible in the remote future.

Our land hath peace, prosperity, and rhino,

And Legislators true, and staunch, and tried—

What trait have they, that is not pure—divine oh?

(Echo interposing) "I know!"

What is it, if thus closely thou hast pried?

"Pride!"

If thus into their hearts thou hast been prying,

Thy version of the matter prithee paint;

Tell us, I pray, on what are they relying?

"Lying!"

I thought their honour was without a taint—

"Taint!"

Have they forgotten all their former glories?

Their virtue—what hath chanced its growth to stunt?

Oh! wherefore should they change their ancient mores?

"More ease!"

What weapon makes the sword of Justice blunt?

"Blunt!" *

* Coin

Thou would'st not speak thus, wert thou now before 'em:

Why do I heed, why listen to thy tale?

Can'st purchase, then, the honour of the Forum?

For Rum!"

And what would blind Dame Justice with her scale?

"Ale!"

Beware! the fame of Senators thou'rt crushing!

Too flippantly thou givest each retort.

What are they doing while for their shame I'm blushing?

"Lushing!"

And drinking?—pray continue thy report—

Port

Curse on these seeds of death, and those who sow them

But there's another thing I'd fain be told—

What of the masses, the canaille below them?

"B-low them!"

Thou flippant one! how is the mob consoled?

"Sold!"

Now, by stout Alexander's sword, or

Rather by his Holiness the Pope!

By what means keep they matters in this order?

"Sawder!"

With what do they sustain the people's hope?

"Soap!"

Take they indeed no passing thought, no care or

Heed of what for safety should be done?

What brought about this modern Reign of Terror?

"Error!"

Is there no hope for thee, my land, mine own?

"None!"

Base love of liquor, ease, and lucre, this it

Is which coileth round her, link on link;

Dark is her hope, e'en as the grave we visit!

"Is it?"

Of what black illustration can I think?

"Ink!"

Alas my country! shall I not undeceive her?

Shall I not strike one patriotic blow?

I'd help her had I but the means, the lever—

"Leave her!"

May we not hope? speak Echo, thou must know—

"No!"

Then shall be heard—when, round us slowly creeping,

Shall come this adverse blast to fill our sails—

Instead of mirth, while hope aside 'tis sweeping—

"Weeping!"

Instead of songs of praise in New South Wales—

"Wails!"

THE following ballad suggested itself to the Author while in the remote interior and suffering from a severe attack of indigestion, he having rashly partaken of some damper made by a remorseless and inexperienced new-chum. Those who do not know what ponderous fare this particular species of bush-luxury is when ill-made may possibly think the sub-joined incidents a little over-drawn. If a somewhat gloomy atmosphere be found pervading the narrative, it is to be attributed to the fact that all the horrors of dyspepsia shadowed the Author's soul at the time it was written, and, if further extenuation be required, it may be stated that he had previously been going through a course of gloomy and marrow-freezing literature, commencing with Edgar Poe's "Raven," and winding up with the crowning atrocity (or albatrossity) which saddened the declining years of Coleridge's Ancient Mariner.

The squatter kings of New South Wales—

The squatter kings who reign

O'er rocky hill, and scrubby ridge,

O'er swamp, and salt-bush plain—

Fenced in their runs, and coves applied

For shepherding in vain.

The squatters said that closed should be

To tramps each station-store;

That parties on the "cadging suit"

Should ne'er have succour more;

And when Bill the shepherd heard the same

He bowed his neck and swore.

Now, though that ancient shepherd felt

So mad he couldn't speak,

No sighs escape his breast, no tears

From out his eyelids leak,

But he swore upon the human race

A black revenge to wreak.

He brooded long, and a fiendish light

Lit up the face of Bill;

He saw the way to work on men

A dark and grievous ill,

And place them far beyond the aid

Of senna, salts, or pill.

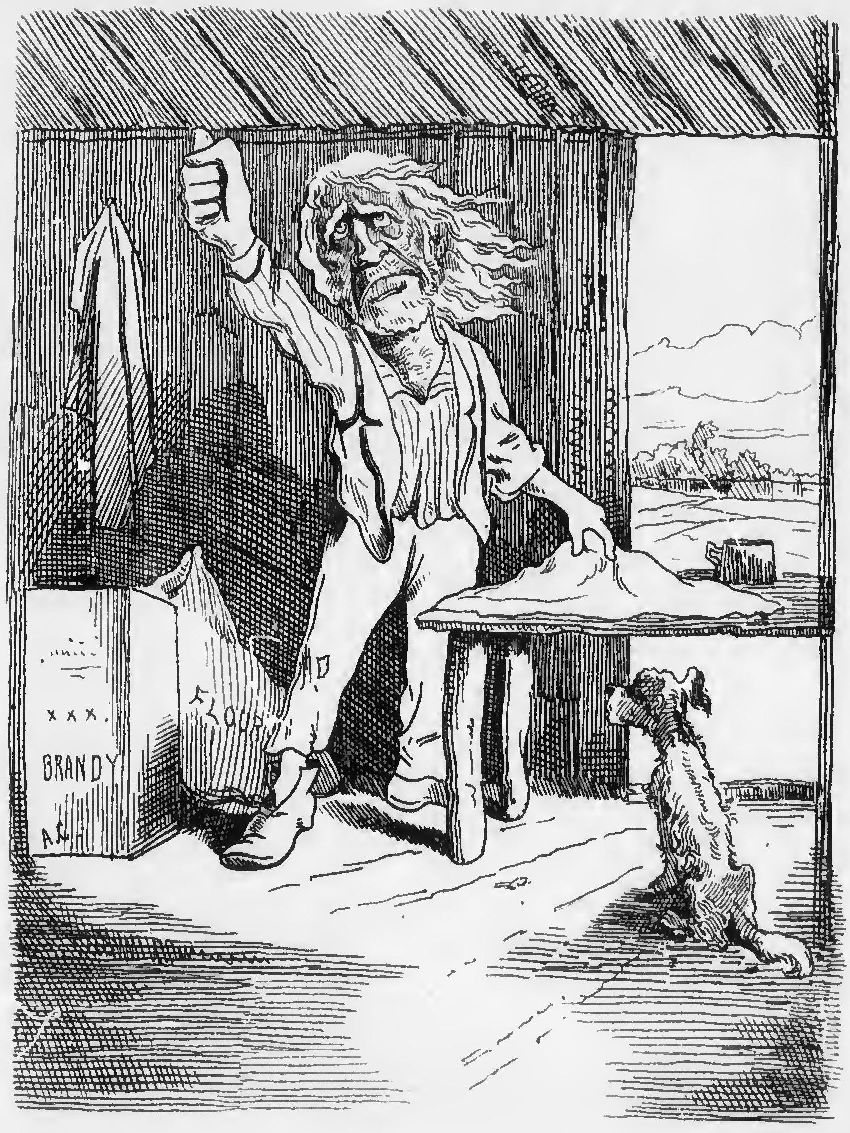

He hied him to his lonely hut

By a deep dark, lakelet's shore;

He passed beneath its lowly roof—

He shut and locked the door;

And he emptied out his flour bag

Upon the hard clay floor.

Awhile he eyed the mighty mound

With dark, malignant zeal,

And then, a shovel having found,

"Their fates," said he, "I'll seal";

And he made a "damper" broad and round

As a Roman chariot-wheel.

He soddened it with water drawn

From out that black lagoon,

And he smiled to think that those who ate

A piece of it would soon

Be where they'd neither see the light

Of sun, nor stars, nor moon.

For when that damper came to be

Dug from its glowing bed,

Its fell specific gravity

Was far o'er gold or lead,

And a look of satisfaction o'er

That shepherd's features spread.

The shepherd sat by the gloomy shore

Of the black and dark lagoon;

His face was lit, and his elf-locks hoar

By the rays of the rising moon.

His hand was clenched, and his visage wore

A deadly frown and black,

And his eye-balls glare, for a stranger fair

Is wending down the track.

The shepherd hath bidden the stranger halt

With courtesy and zeal,

And hath welcomed him to his low roof-tree,

And a share of his evening meal.

As the fare he pressed on his hungry guest,

And thought of its deadly weight,

With savage glee he smiled for he

Imagined his after fate.

The stranger hath eaten his fill I ween

Of that fell and gruesome cake,

And hath hied him away in the moon-light's sheen

For a stroll by the deep, dark lake;

For he thought he'd lave each stalwart limb

In the wavelet's curling crest,

And take a dive and a pleasant swim

'Ere he laid him down to rest.

The coat that covered his ample chest

On the lakelet's marge he threw;

His hat, his boots, and his flannel-vest,

And his moleskin trowsers too.

He hummed a tune, and he paused awhile

To hear the night-owl sing;

His ears were cocked, and his palms were locked,

Prepared for the final spring.

An unsuspecting look he cast

At the objects on the shore—

A splash! a thud! and beneath the flood

He sank to rise no more!

The shepherd saw from his lonely hut

The dread catastrophé;

A notch on a withered stick he cut—

"That's number one," said he,

"But, if I live 'till to-morrow's sun

"Shall gild the blue-gum tree,

"With more, I'll stake my soul, that cake

"Of mine will disagree."

Then down he sat by his lonely hut

That stood by the lonely track,

To the lakelet nigh, and a horse came by

With a horse-man on his back.

And lean and lank was the traveller's frame

That sat on that horse's crup:

'Twas long I ween since the wight had seen

The ghost of a bite or sup.

"Oh! give me food!" to the shepherd old

With plaintive cry he cried;

A mildewed crust or a pint o'dust *

Or a mutton cutlet fried.

"In sooth in evil case am I,

Fatigue and hunger too

Have played the deuce with my gastric juice,

It's 'got no work to do.'

"I've come o'er ridges of burning sand

That gasp for the cooling rain,

Where the orb of day with his blinding ray

Glares down on the salt-bush plain

* Flour.

"O'er steaming valley, lagoon, and marsh

Where the Sun strikes down 'till, phew!

The very eels in the water feels

A foretaste of a stew.

"I hungered long 'till my wasting form

Was a hideous sight to view;

But fit on a settler's fence to sit

To scare the cockatoo.

"My hair grew rank, and my eyeballs sank

'Till—wasted, withered, and thin—

The ends and points of my jarring joints

Stuck out through my parched up skin.

"Shrunk limb and thew, 'till at length I grew

As thin as a gum-tree rail;

At the horrid sight of my hideous plight

Each settler's face turned pale:

"And as I travelled the mulga scrubs,

And forced a passage through

I scared the soul of the native black

A gathering his 'nardoo.'

"On snake or lizard I'd fain have fed,

But piteous was my plight,

And the whole of the brute creation fled

In horror at the sight.

"Scrub turkeys, emus, I appall;

Their eggs I longed to poach,

But they collared their eggs, their nests and all,

And fled at my approach!

"And the possums 'streaked' it up the trees,

And frightened the young gallârs,

And all the hairs on the native-bears

Stood stiff as iron bars!"

The shepherd came from his low roof-tree

And gazed at the shrunken wight;

He gave him welcome courteously,

And jested at his plight.

He led the traveller 'neath his roof,

And gazed in his wan, worn face,

Where want was writ, and he bid him sit

On an empty 'three-star' case.

And a smile of evil import played

On the face of ancient Bill

As some of the damper down he laid,

And bid him take his fill.

With mute thanksgiving in his breast

The food the stranger tore;

Piece after piece he closely pressed

Down on the piece before.

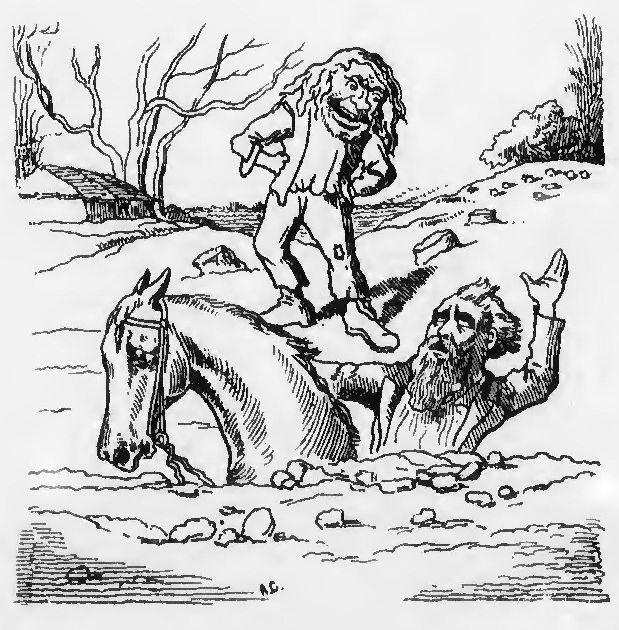

And then—his heart fresh buoyed with hope—

Essayed to mount his steed,

But the horse shut flat as an opera-hat

With the weight of his master's feed;

And horse and man sunk through the sod

Some sixty feet or less!

No crust, I swear, of the Earth could bear

The weight of the gruesome mess!

Then the shepherd grinned with a grizzly grin

As he notched his stick again;

The night passed by and the sun rose high

And glared on the salt-bush plain.

Two "gins" set forth in a bark canoe

To traverse the gloomy lake,

And he bid them take enough for two,

For lunch, of the deadly cake.

Enough for two! 'twas enough I ween

To settle the hash of four,

For the barque o'er-flowed with the crushing load—

They sank to rise no more.

And ever his fiendish lust for blood—

His thirst for vengeance grows;

In sport he threw a crumb or two

To the hawks and carrion crows;

And as they helpless, fluttering lay,

His eldrich laughter rings;

One crumb to bear through the lambent air

Was past the power of wings.

Beside his door he sat 'till noon

When a bullock-team came by;

The echoes 'round with the whips resound,

And the drivers' cheery cry.

Upon the dray a piece he threw

No bigger than your hand,

Of the cursed thing, 'twas enough to bring

The bullocks to a stand.

And, though they bend their sinewy necks

'Till red with their crimson gore,

And fiercely strain yoke, pole, and chain

With savage, muttering roar,

The wheels sank down to the axle-tree—

Through the hard baked clay they tore,

And a single jot from out that spot

They shifted never more.

Then the shepherd called to the drivers, "Ho!

My frugal meal partake."

And, though they ate but a crumb or two

Of the fell, unholy cake,

Down, down they sank on the scorching track,

Immovable and prone,

And steel blue ants crawled up their pants

And ate them to the bone!

For days by his lonely hut sat Bill,

The hut to the lakelet nigh,

And he wrought his dark revengeful will

On each traveller that came by.

And he eats nor drinks meat, bread, nor gruel,

Nor washes, nor combs, nor shaves,

But he yelled, and he danced a wild pas seul

O'er each of his victims' graves.

Three weeks passed by, but his end was nigh—

His day was near its close,

For rumour whispered his horrid deeds,

And in arms the settlers rose.

They came, hinds, shepherds, and shearers too,

And squatters of high degree;

His hands they tied, and his case they tried

'Neath the shade of a blue gum tree.

They sentence passed, and they gripped him fast,

Though to tear their flesh he tried;

His teeth he ground, but his limbs they bound

With thongs of a wild bull's hide.

They laid him down on a "bull-dog's" nest,

For the bull-dog ants to sting;

On his withered chest they pile the rest

Of the damnèd cursèd thing.

They gather round and they stir the ground

'Till the insects swarm again,

And the echoes wake by the gloomy lake

With his cry of rage and pain.

O'er his writhing form the insects swarm—

O'er arm, o'er foot, and leg;

The damper pressed on his heaving chest,

And he couldn't move a peg.

'Till eve he lay in the scorching heat,

And the rays of the blinding sun,

Then the black-ants came and they soon complete

What the bull-dogs have begun.

'Tis o'er at last, and his spirit passed

With a yell of fiendish hate,

And down by the shore of that black lagoon,

Where his victims met their fate—

Where the "bunyip" glides, and the inky tides

Lip, lap on the gloomy shore,

And the loathsome snake of the swamp abides,

He wanders ever more.

And when the shadows of darkness fall

(As hinds and stock-men tell)

The plains around with his howls resound,

And his fierce, blood-curdling yell.

The kangaroos come forth at night

To feed o'er his lonely grave,

And above his bones with disma' tones

The dingos shriek and rave.

And when drovers camp with a wild-mob there

They shiver with affright,

And quake with dread if they hear his tread

In the gloom of the ebon night!

I feel that any reader who has been long-suffering enough to accompany me thus far must be craving earnestly for a change of some sort, even though it but take the form of an oasis of indifferent prose in a monotonous Sahara of verse; I want it myself, and I know that the reader must yearn for it, even as the bushman who has sojourned long among the flesh-pots of remote sheep and cattle stations yearneth after the pumpkins and cabbages of the Mongolian market gardener. I am, therefore, going to write about social evils; not because I think I can say anything particularly original or striking about them, but because I must have a subject, and I know the craving of the Colonial mind after practical ones. I commence diffidently, however; not on account of the barrenness of the theme—oh! dear no—it is its very fruitfulness which baffles me; its magnitude that appals me; its comprehensiveness which gets over me; and my inability to deal with it in such limited space which "knocks me into a cocked-hat".

Even as I write, things which may be legitimately called social evils rise up before me in spectral array, like Banquo's issue, in sufficient numbers to stretch not only to the "crack of doom,"—wherever that mysterious fissure may be—but a considerable distance beyond it.

Unfortunately, too, each one, like the progeny of that philoprogenitive Scotchman, "bears a glass which shows me many more," until I am as much flabbergasted as Macbeth himself, and am compelled to take a glass of something myself to soothe my disordered nerves.

If every one were permitted to give his notion of what constitutes a social evil my difficulties would be still more augmented, and the schedule swelled considerably. I know men who would put their wives down in the list as a matter of course; and others, fathers of families, who would include children. Few married men would omit mothers-in-law; most domestics would include work and masters and mistresses; and hardly anybody would exclude tax-gatherers. Fortunately, however, these well-meaning, but mistaken reformers, will have to take back seats on the present occasion, and leave me to touch on a few, at least, of what are legitimate and undeniable social evils.

Look at them, as they drag their mis-shapen forms past us in hideous review! Adulteration of food, political dishonesty, "larrikinism," barbarism on the part of the police, lemonade and gingerbeerism in the stalls of theatres, peppermintlozengism in the dress circle, flunkeyism, itinerant preacherism in the parks—what a subject this last is, by the way, and how beautifully mixed up one's faith becomes after listening to half a dozen park preachers, of different denominations, in succession! After hearing the different views propounded by these self-constituted apostles, an intelligent islander from the Pacific would receive the impression that the white man worshipped about seventy or eighty different and distinct gods (a theological complication with which his simple mind would be unable to grapple), and he would probably retire to enjoy the society of his graven image with an increased respect for that bit of carving, and any half-formed inclinations to dissent from the religion of his forefathers quenched for ever.

I have neither space, ability, nor desire to tackle such stupendous subjects as political dishonesty or adulteration. They are so firmly grafted on our social system that nothing short of a literary torpedo could affect them in the slightest degree, but I do feel equal to crushing the boy who sells oranges and lemonade in the pit—who when, in imagination, I am on the "blasted heath" enjoying the society of the weird sisters, or at a Slave Auction in the Southern States, sympathising with the sufferings of the Octoroon, ruthlessly drags me back to nineteenth century common places with his thrice damnable war- cry of "applesorangeslemonadeanabill!" a string of syllables which are in themselves death to romance, and annihilation to sentiment, irrespective of the tone and key in which they are uttered. If for one happy moment I have forgotten that Hamlet is in very truth "a king of shreds and patches," or that Ophelia is a complicated combination of rouge, paste, springs, padding, and pectoral improvers, I maintain that it is playing it particularly rough on me if I am to be recalled to a remembrance of all this by the bloodcurdling shibboleth of these soulless fruit merchants. Can lemonade compensate me for the destruction of the airy castles I have been building? Can ginger-beer steep my senses again in the elysium of romance and sentiment from which they have been thus ruthlessly awakened? Or can an ocean of orange-juice wash away or obliterate the disagreeable consciousness that I am a clerk in a Government office, or a reporter on the staff of a weekly paper, and am neither Claud Melnotte nor "a person of consequence in the 13th century?"—unhesitatingly no! And if, in addition, there be wafted towards me a whiff or two of a highly-flavoured peppermint lozenge from some antique female—on whose head be shame! and on whose false front rest eternal obliquy—my cup of sorrow is full, my enjoyment of the drama is destroyed, the Recording angel has a lively time of it for an hour or so registering execrations, and I am plunged in an abyss of melancholy from which the arm of a Hennessy (the one that holds the battle axe) or a Kinahan can alone rescue me. And here, reader, I must conclude, for your patience is in all probability exhausted, and my washerwoman has called: she is a social evil of the most malignant type.

Little grains of rhubarb,

Spatula'd with skill,

Make the mighty bolus

And the little pill.

Little pence and half-pence,

Hoarded up by stealth,

Make the mighty total

Of the miser's wealth

Little trips to Randwick,

Taking six to three,

Make the out-at-elbows

Seedy swells we see.

Little sprees on oysters,

Bottled stout and ale,

Lead but to the cloisters

Of the gloomy gaol.

Little tracts and tractlets,

Scattered here and there,

Lead the sinner's footsteps

To the house of prayer.

Little bits of paper,

Headed I.O.U.,

Ever draw the Christian

Closer to the Jew.

Little chords and octaves,

Little flats and sharps,

Make the tunes the angels

Play on golden harps.

Little bouts with broom-sticks,

Carving forks and knives,

Make the stirring drama

Of our married lives.

Little flakes of soap-suds,

Glenfield starch, and blue,

Make the saint's white shirt-fronts

And the sinner's too.

Little tiny insects,

Smaller than a flea,

Make the coral inlands

In the southern sea.

Little social falsehoods,

Such as "Not at home,"

Lead to realms of darkness

Where the wicked roam.

Likewise little cuss words

Such as "blast," and "blow,"

Quite as much as wuss words

Fill the place below.

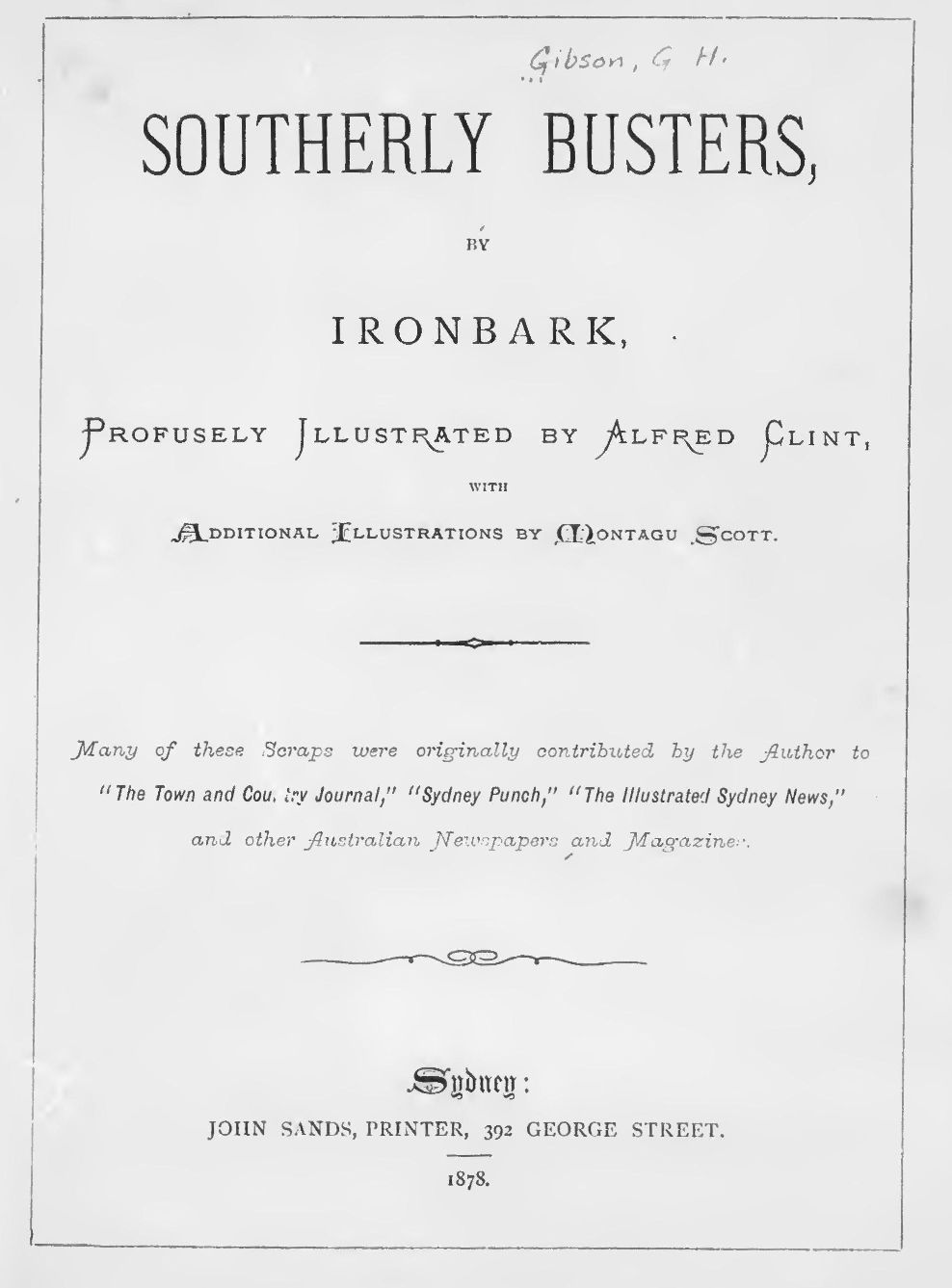

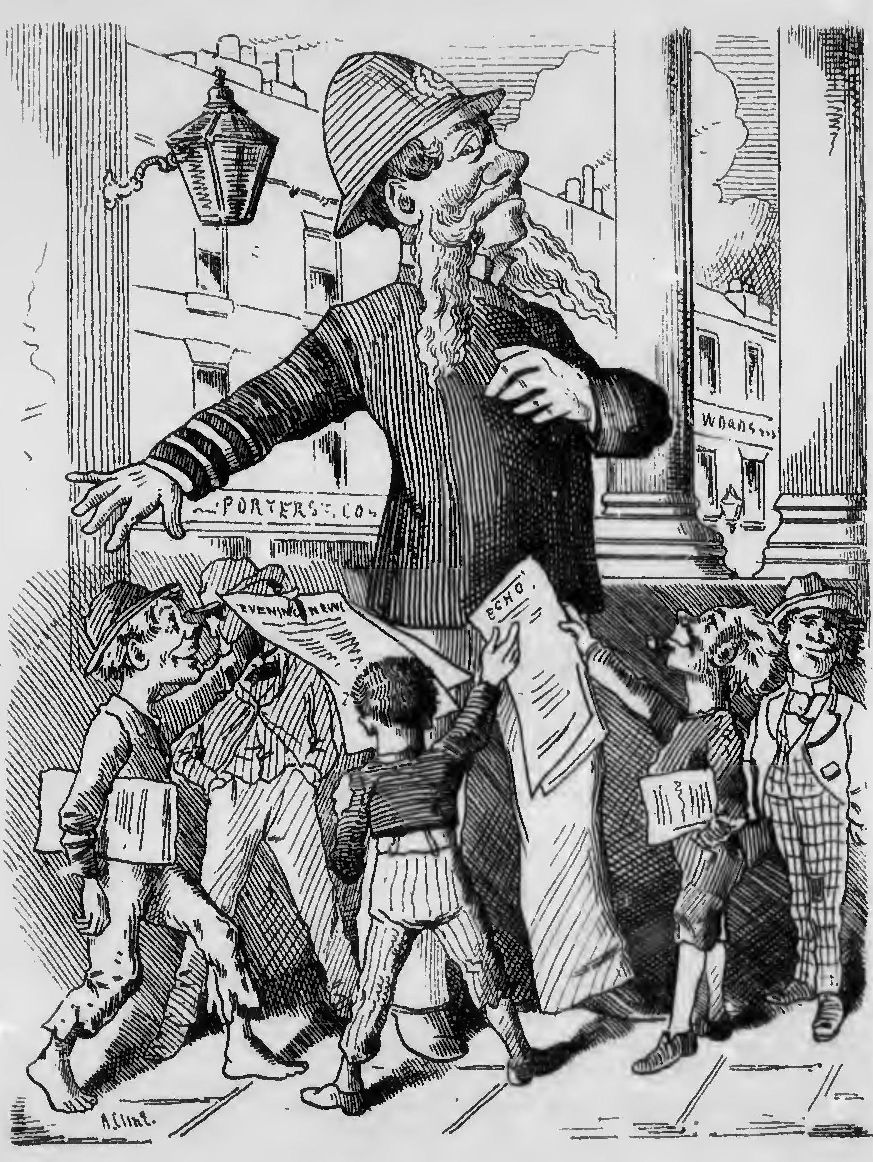

At four one afternoon;

I saw a stately peeler there,

He softly hummed a tune.

The sun-rays lit his buttons bright;

He stalked with stately stride;

It was a fair and goodly sight—

The peeler in his pride

And padded was his manly breast,

Such kingly mien had he,

And such a chest, I thought how blest

That peeler's lot must be.

I noted well his martial air,

And settled that of course

He was the idol of the fair,

The angel of the Force.

No cook or house-maid could resist,

I felt, by any chance,

That dark moustache with cork-screw twist,

That marrow-searching glance.

And o'er each little news-boy's head

He towered like a mast;

His voice, to match that stately tread,

Should shame a trumpet-blast!

I pondered on the matter much

And thought I'd like to be

Escorted to the "dock" by such

A demi-god as he.

I gazed upon his form entranced—

He never noticed me,

For visions through his fancy danced

Of mutton cold for tea.

He knew he hadn't long to stand

'Till—Mary's labours o'er—

She'd lead him gently by the hand

Inside the kitchen door.

Ensconced in some snug vantage-coign

At ease he'd stretch each limb,

And feast on cutlet and sirloin,

Purloined for love of him.

I leant against a scaffold-beam—

I must have had a nap

I think, because I had a dream—

I dreamt I was a 'trap'!