Title: The Pansy Magazine, July 1886

Author: Various

Editor: Pansy

Release date: April 16, 2014 [eBook #45409]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

|

GOLD MEDAL, PARIS, 1878.

BAKER'S Breakfast Cocoa. Warranted absolutely pure Cocoa, from which the excess of Oil has been removed. It has three times the strength of Cocoa mixed with Starch, Arrowroot or Sugar, and is therefore far more economical, costing less than one cent a cup. It is delicious, nourishing, strengthening, easily digested, and admirably adapted for invalids as well as for persons in health.

——————

Sold by Grocers everywhere. ——————

W. BAKER & CO., Dorchester, Mass.

|

|

GOLD MEDAL, PARIS, 1878.

BAKER'S Vanilla Chocolate, Like all our chocolates, is prepared

with the greatest care, and

consists of a superior quality of

cocoa and sugar, flavored with

pure vanilla bean. Served as a

drink, or eaten dry as confectionery,

it is a delicious article,

and is highly recommended by

tourists.

——————

Sold by Grocers everywhere. ——————

W. BAKER & CO., Dorchester, Mass.

|

| A warm iron passed over the back of these PAPERS TRANSFERS the Pattern to a Fabric. Designs in Crewels, Embroidery, Braiding, and Initial Letters. New book bound in cloth, showing all Briggs & Co.'s latest Patterns, sent on receipt of 25 cents. Use Briggs & Co.'s Silk Crewels and Filling Silk, specially shaded for these patterns.

104 Franklin St.,

New York. Retail by the leading Zephyr Wool Stores. |

Greatest inducements ever offered. Now's your time to get up orders for our celebrated Teas and Coffees and secure a beautiful Gold Band or Moss Rose China Tea Set, or Handsome Decorated Gold Band Moss Rose Dinner Set, or Gold Band Moss Decorated Toilet Set. For full particulars address

A practical machine. For information Address

| HEADQUARTERS | FOR LADIES' FANCY WORK. |

We will send you our 15-c. Fancy Work Book (new 1886 edition), for 3 two-cent stamps. A Felt Tidy and Imported Silk to work it, for 20 cents. A Fringed linen Tidy and Embroidery Cotton to work it, for 16c., Florence "Waste" Embroidery Silk, 25c. per package. Illustrated Circulars Free. J. F. Ingalls, Lynn, Mass.

It has been the positive means of saving many lives where no other food would be retained. Its basis is Sugar of Milk, the most important element of mothers' milk.

It contains no unchanged starch and no Cane Sugar, and therefore does not cause sour stomach, irritation, or irregular bowels.

It is the Most Nourishing, the Most Palatable, the Most Economical, of all Prepared Foods.

Sold by Druggists—25 cts., 50 cts., $1.00. Send for pamphlet giving important medical opinions on the nutrition of Infants and Invalids.

We will send six copies of "The Household Primer," "Household Receipt Book," and "Household Game Book," to every subscriber who will agree to distribute all but one of each among friends.

The British Government awarded a Medal for this article October, 1885.

AGENTS WANTED.

| SAMPLES FREE! |

CANDY! | Send $1, $2, $3, or $5 for retail box by Express of the best Candies in America, put up in elegant boxes, and strictly pure. Suitable for presents. Express charges light. Refers to all Chicago. Try it once. Address

C. F. GUNTHER, Confectioner, 78 Madison Street, Chicago. |

"Agreed!" shouted the boys. "What shall we call ourselves?"

"The Do-Nothing Club," some one suggested; "we aren't going to do anything, only have all the fun we can."

"We can have that for our motto," said one of the boys.

"Well, we only have a few minutes before the bell will ring: let's elect officers."

So Will tore a few pages out of his note-book, and after some officers had been nominated, each one wrote the names of those he wanted, on his slip. The results were just being announced when the school-bell rang.

"The first meeting of the Do-Nothing Club will be held in our yard to-morrow afternoon," called Will Post, who had been elected president of the new organization.

So the next afternoon, immediately after school, ten boys wended their way through the back gate of Mr. Post's yard, and seated themselves on the woodpile.

"I know where we will go," said Will, "right out in the orchard in the boughs of those two gnarly old apple-trees that just touch." Everyone thought this a splendid plan, so soon the ten boys were in different places in the two great apple-trees in the orchard.

"Has any one a suggestion to make as to the first adventure of the Do-Nothing Club?" said the president, by way of opening the meeting.

"I have," said George Shaw, the treasurer of the club. "You know Mr. Clay's pasture?"

"Yes!" they all said.

"Well, it's just chock-full of daisies and wild strawberries, and I move that next Saturday we ask him if we can get some daisies, and each take a big basket and get it most full of strawberries with a few daisies on top, to make it look all right, you know;" and George chuckled.

"I think it is a splendid plan, worthy of our honorable treasurer," said President Post. A vote was taken, which was almost unanimous in favor of George's proposition, although there were a few demurs made at first on the ground of it's not being "quite honest."

"Honest!" sneered Will, "as if it wasn't all right to refresh ourselves in a big meadow, with what's there, free as grass!" So the objections were silenced, and the meeting adjourned.

Now it so happened that Mr. Post's orchard and Mr. Clay's farm were only separated by a high board fence. Close by this fence grew quite a little coarse grass, and as Mr. Clay thought it took too much room, on this very afternoon on which the Do-Nothing Club held their first meeting, he had taken his scythe and spade, and had gone to cut and dig up the offending material. The day was very hot, and he grew so tired and warm that he determined to lie down in the shade by the fence for a few minutes. But while lying there, he fell into a little doze, and was only awakened by the laughter of the boys as they climbed up the trees, getting seated for the meeting. He lay awake for a few moments, trying to make up his mind to arise, and consequently heard the conversation in the apple-tree, in which he became not a little interested.

Just here I must stop and explain that Mr. Clay knew his meadow was very productive of wild strawberries, and had said to his son, a few days before the time at which my story begins:

"James, there will probably be a quantity of strawberries in the meadow this summer, and if you pick them, you can sell them at a good price, which will bring you considerable spending money. Do you want to try it?"

"Yes, indeed!" had been the reply, and so it was planned that in about a week James should pick his strawberries, and have the money for his "very own."

To go back now to the new club, I may say that the next Friday afternoon (after the apple-tree meeting) the ten boys appeared at Mr. Clay's door.[275]

"Mr. Clay," said the president, "we've formed a new club lately—the Do-Nothing Club, of which I'm the president, and George is treasurer. We decided that the first thing we'd do would be to pick some daisies out of your meadow, that is, if you would let us. You don't use them for anything, do you?"

"Not at all," said the gentleman, heartily; "you are perfectly welcome to pick just as many as you want. But don't step on any more wild strawberries than you can help."

"We'll be careful," said Will, so he nodded good-morning, and the club marched away. "Indeed we won't step on them," he added, when they were out of hearing, "we want the use of them, and it won't do to destroy them."

So bright and early the next morning the club marched to Mr. Clay's meadow, each member armed with a basket, with a good-sized pail inside. They were to fill the pails with berries, and completely cover them with daisies. They worked hard all the morning. About ten o'clock James Clay said to his father, "I guess I'll go out and help. They must be having great fun."

"No, my boy," said Mr. Clay, with a twinkle in his eye, "I would rather not."

When the town clock struck one, the boys had searched the meadow so thoroughly that there was hardly a berry in it, and their pails were nearly all full! Then they went into the woods back of the meadow to rest and take their fill of the fresh fruit. Now you who have no idea of the capacity of boys' stomachs, especially for berries, would hardly believe me if I should state the exact amount that those boys devoured! So I will not give it. Suffice it to say that there were some which they had to throw away, having no place to put them for safe-keeping, and not daring to share them with anyone, for in that case, as Will said, "the cat would be out of the bag." So it came to pass that the rapid river which flowed through Snyvylville could have told, if it had chosen, how one part of it was dyed as red as blood that afternoon, and how it looked as if some awful deed had been done there, until the strawberries were all washed down stream.

On Saturday evening, divers little girls went about the streets of Snyvyville with pails of wild strawberries, and the mothers or fathers of every one of the members of the Do-Nothing Club, happened to buy some of them for the Sunday dinner. But in each family there was great amazement because the boy or boys thereof would eat no berries, and because each boy had the headache and stomachache all day. "I don't believe it was good for you to be out in the sun so long," said Mrs. Post to Will, as she put a fresh cloth dipped in ice-water, on his head. He made no reply, for he knew that it was not the exposure to the sun that gave him the headache, but—quarts of wild strawberries! Too much of a good thing is worse than none at all.

"James dear," said Mrs. Clay to her husband on Saturday evening, after James, Jr., had gone to bed, "I don't believe it will be wise for Jamie to pick all those berries out in the meadow. Couldn't you get somebody to pick them, at two cents a quart? That would leave him quite a good deal of money. The sun is so hot, I am afraid he would get sunstruck."

"I think that will be all right," said Mr. Clay, looking earnestly at his newspaper; "I don't suppose you would mind at all if the person we hired did get sunstruck?"

His wife laughed, but turned again to her mending, and said no more.

On Monday afternoon Mr. Clay went out to continue the work of banishing the aforesaid offensive grass from the face of the earth, but lay down again as he saw, through a crack in the fence, the Do-Nothing Club wending its way toward the apple-trees where it was to meet to talk over the success of the strawberry plan.

"Twenty quarts!" ejaculated George Shaw, "that was pretty good. I hardly thought there would be so many. Wasn't my plan splendid, though, Will—oh! I beg your pardon, Mr. President?"

"Fine!" said the president; "all that you planned for was, anyhow, for I don't suppose you calculated for ten headaches and ten stomachaches, as well as ten pails of berries, did you? As nearly as I can find out, the other members of the club have suffered in these ways, like myself."

There was a good deal more talk; they decided[276] what should be their password, and a great many other private matters. They would have been very much disgusted, I am certain, if they had guessed that Mr. Clay was intently listening to everything that was said. Their motto was to be "Fragi Agrestes," because, as John Clower, the only Latin student of the club, announced, that meant "wild strawberries." Of course that was to be used as the password, too. The seal was to be a leaf of that plant, while the color of the club was to be red.

When they went home, Mr. Clay got up and went to work again, but he didn't work as well as usual, for he had a plan in which he was more interested than he was in demolishing the grass. When he got home he sat down and wrote some sort of a letter which he sealed with a piece of red sealing-wax, and a button which he had found in his wife's button-box.

Thus it happened that on Tuesday morning, when George Shaw went to the post-office to get the mail, he found a big yellow envelope addressed to him. It had a red seal, on which there was stamped the outline of a strawberry leaf. He looked at it in amazement, for the writing was strange. He found the document inside to be sealed with the same seal. I will give you a copy of it:

| The Snyvylville Do-Nothing Club | Dr, |

| To James Clay. | |

| To—— | |

| 20 qts. wild strawberries, at .15 | $3.00 |

| Pay for picking the same, at .02 | .40 |

| Balance | $2.60 |

| Rec'd Payment, | |

| July, 1879. | Cr. |

George stopped on the street in perfect amazement! Then rushed to school, for the last bell was ringing.

At recess, he called a meeting of the club, and showed them the document he had received.

Then there were grave faces and anxious discussions. How could Mr. Clay have found them out?

At last the president said:

"Well, we'll just have to pay him; there is no help for it. Every one of the club must hand over twenty-six cents for his share. Here's another thing we didn't plan for in the strawberry idea. For my part, I wish 'Fragi Agrestes' had never been invented."

The club marched that very afternoon, in a body, to Mr. Clay's house to pay their bill. No willing delegate was found to represent them. Once there, the president had to make the speech.

"We've brought you your money, Mr. Clay. We can't imagine how you found us out; but we hadn't the least notion of stealing! Somehow it never entered our heads that it could be stealing, to help ourselves to wild strawberries. I never thought of such a thing until I saw your bill. There it is. Will you please receipt it? And we'll promise you we won't be likely to get caught in such a scrape again."

"Thank you," said the farmer, putting the money in his pocket, and taking up a pen to receipt the bill. "Boys, I'm not so anxious for money that I had to have my pay for the berries you stole. But I thought it would teach you a lesson; so I sent the bill to the treasurer. And now I want to advise you to take a new name for your club, for you won't prosper under the present one. When you aren't planning to do anything but have fun, you'll get into mischief.

"I'm agreed," said Will; "and I'll resign. I have an idea. Suppose you be our president, Mr. Clay?"

"I!" laughed the farmer.

"Good for you, Will," said the boys. "That's a first-class idea. Will you do it, Mr. Clay?"

"Well," said Mr. Clay, after a moment's consideration, "I don't know but I'll accept. It is quite an honor. President of the Snyvyville Do-Something Club!" and he laughed again.

I wish I had time to tell you the story of the new club! Under Mr. Clay's presidency, they prospered; and became proud of their club. True to their name, they "did" many things[277] which were for their good, not only, but for the good of others.

Some day I may write out their story, or a piece of it.

They grew to be very fond of their president, as well as very proud of his schemes.

The Do-Nothing Club had but one report in the note-book of their secretary:

Resolved, That the Snyvyville Do-Nothing Club change its name to the "Do-Something Club," as it has not prospered under the former title, but has been the cause of ten headaches, ten stomachaches, and the loss of two dollars and sixty cents, to the members thereof.

(Signed) James Powell, Sec'y.

The Club still kept its motto, "Fragi Agrestes," for they thought that "wild strawberries" had taught them a lesson they would not soon forget.

One thing I know, that whereas I was blind, now I see.

I am the good Shepherd; the good Shepherd giveth his life for the sheep.

Our friend Lazarus sleepeth, but I go that I may awake him out of sleep.

Jesus said unto her, I am the resurrection and the life.

"Grandma," said Marion, with almost a shade of reproach in her voice, "did you truly have miracles done for you?"

"I thought so, child, and I don't know but I thought pretty near right. They were the dear Lord's loving kindnesses and tender mercies to a naughty child; and those are miracles enough[278] for reasonable people. I'll tell you the story, and see what you think about it.

"It was the afternoon before the Fourth, and everybody in our house was very busy. There was to be a great celebration the next day, the largest which had ever been in that part of the world. The speaker was to stop at our house, and several of the leading men were coming to take supper with him, and in the evening there was to be fireworks, great wonderful fire balls, such as we don't see now-days, and fine doings of all sorts.

"By the middle of the afternoon, mother began to look very tired. I can seem to see her face now, as she stood looking at the sideboard with its rows of shining dishes. 'That drawer ought to be cleared out,' said she, 'and fixed for the changes of knives, and forks, and spoons, but I don't know who can do it; everybody's hands are full and it is full of all sorts of things.' She wasn't speaking to anybody in particular, just talking low, to herself. I was only a little girl eight years old, and not supposed to notice all that was going on. But I heard it, and decided then and there, that as soon as my mother went out I would set to work at that drawer myself. And I did. It was a hard drawer to clear out; one of those places where in a hurried time things get put that don't belong, and you don't exactly know where they do belong. I worked away at it faithfully, until my back ached with stooping, and every nerve in my body seemed to be on the jump. Over in the corner sat my grandfather, talking with an old friend of his. They did not notice me, but I heard snatches of their talk, about the grand doings which were to be on the next day, and it seemed to me I could hardly wait. My work was almost done, and I was busy with the thought of how pleased mother would be, when I took up a long delicate glass bottle filled with some liquid. The glass was so thin I tried to look through it; as I held it up against the light, my hands must have been trembling with weariness and eagerness, for somehow, I never could understand how, that bottle slipped from me and shivered to bits on the hard floor! The liquid spilled over my hands and spattered on my face and eyes, and in an instant they began to burn as though they were in a flame of fire! To make matters worse, I clapped both hands, all wet as they were, right on my eyes. This made the pain more dreadful than ever. It all happened in a moment of time: the scream, and mother running, and grandfather springing up, and me tumbling over against mother, and hearing her say with a groan: 'Oh Ruthie, Ruthie! she has put out her eyes!'

"Then for a few blessed minutes I was free from pain; I fainted dead away for the first time in my life! The faint didn't last long; the pain in my eyes was too great. Oh! it was a dreadful time. Father went hurrying after the doctor, and mother tried cold water, and milk, and bran-water, and everything else she could think of, to relieve my suffering."

"But, Grandma, what was it? What had you done?" interrupted Marion, her face pale with sympathy.

"There was some dreadful liquid in the bottle, dear, that had burned grandma's eyes, and her skin, wherever it touched, and the doctor was afraid my eyes were put out. Mother said afterwards that she knew he thought so, by the look on his face, and by his refusing to answer her questions.

"He put something on, at last, which relieved the pain a little, then my eyes were bandaged, and I was put to bed. My dear mother, when she stooped down to kiss me after everything was done, did not forget to whisper that I was a dear little girl to try to help mother, and that the drawer looked beautiful.

"I sat up to the supper table that very night, but with bandaged eyes that ached a good deal, and every one at the table wore a sober face; I could tell, by the sound of their voices. I don't know whether father just happened to read those verses at family worship, that night, or whether the trouble made him think of them. However it was, he read the story of the blind man who was cured; and who, when the people questioned and questioned him, could give only this answer: 'One thing I know, that whereas I was blind, now I see.'

"Father's voice trembled over the word 'blind,' and mother cried; I could feel her tears dropping on my hand. But I did not shed a tear; my heart was full of a great thought. Jesus had cured that blind man with a touch,[279] and my Bible verse the Sunday before, had been 'Jesus Christ, the same yesterday, to-day, and forever.' Why couldn't he cure people in just the same way now? Why didn't he? Perhaps he did, only I had never heard of it. Father's prayer made the thought all the stronger. He asked the Lord to bless their little girl, and, if it was possible, to take away the fear which was gnawing at their hearts. He didn't think I would understand. Mother did not know she had screamed out that I had put out my eyes. But I heard her. I knew all about it. I remembered the time when the dog slipped his chain and came and saved me; I thought God sent him; and God could in some way cure me now. Every waking minute that night I prayed to him to cure me. The first thing I did in the morning was to pray the same prayer. I will not deny that I thought about the beautiful fire balls, and all the wonders of the evening, and I asked God, since he could do it just as well, to cure me quick, so I could see all the lovely things.

"Well, children," Grandma dropped her knitting, and, leaning forward, folded her soft white hands over her knee in an impressive way she had, and looked her attentive little audience squarely in the face, "I don't know how it was; I don't pretend to explain it, never have, but when the doctor came that morning, and said he must take off the bandages to bathe my eyes, and warned me that the light would hurt very much, and I must try to be brave, and told my mother that when he saw my eyes, he could give her an idea of how many months I would have to wear the bandage, and when everything was ready, and mother had me in her arms, and father sat the other side, and held my hand, and the doctor unpinned the bandage, I looked straight at father with two eyes that did not even wink, and said: 'Father, they don't hurt a bit; not a single bit.'

"Why, we had almost as much of a time then as he had had the night before! That doctor couldn't seem to believe it; he was determined my eyes should burn, and sure that I could not see father's face. But I saw everything as plain as I do this minute. And my eyes did not hurt at all. I continued to see all day; and at night saw the fire balls, and laughed and made merry with the rest. The happiest girl, I do believe, that ever sat down to a Fourth of July feast. I believed that the dear Lord had touched my eyes and cured them."

"But, Grandma," said skeptical Ralph, "do you really think it was so? Don't you suppose the stuff in the bottle was weaker than they thought, and the doctor's medicine, and the night's sleep, cured your eyes?"

"I don't know," said Grandma, taking up her knitting again; "all I know, is this: the stuff burned so that I thought for a minute the whole of me was on fire; and when I came out of my faint, and tried to look up at mother, I couldn't see a thing! And they all believed that if my eyesight was not quite gone, it would be months and months before I could see again; and never, so well as before. And I know that in the morning when the bandage was taken off, I could see a good deal better than I can now, and my eyes never ached a bit from it afterwards. It is a little piece of the old story. Grandma can't explain it, couldn't then; 'One thing I knew; that whereas I was blind, now I see.'"

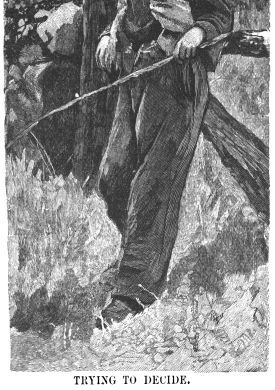

There had been a great deal to do to get ready. Hours and even days had been spent in planning. It astonished both these young people to discover how many things there were to think of, and get ready for, and guard against, before one could go into business. There was a time when with each new day, new perplexities arose. During those days Jerry had spent a good deal of his leisure in fishing; both because at the Smiths, and also at the Deckers, fish were highly prized, but also because, as he confided to Nettie, "a fellow could somehow think a great deal better when his fingers were at work, and when it was still everywhere about him."

There were times, however, when his solitude was disturbed. There had been one day in particular when something happened about which he did not tell Nettie. He was in his fishing suit, which though clean and whole was not exactly the style of dress which a boy would wear to a party, and he stood leaning against a rail fence, rod in hand, trying to decide whether he should try his luck on that side, or jump across the logs to a shadier spot; trying also to decide just how they could manage to get another lamp to stand on the reading table, when he heard voices under the trees just back of him.

They were whispering in that sort of penetrating whisper that floats so far in the open air, and which some, girls, particularly, do not seem to know can be heard a few feet away. Jerry could hear distinctly; in fact unless he stopped his ears with his hands he could not help hearing.

And the old rule, that listeners never hear any good of themselves, applied here.

"There's that Jerry who lives at Smiths," said whisperer number one, "do look what a fright; I guess he has borrowed a pair of Job Smith's overalls! Isn't it a shame that such a nice-looking boy is deserted in that way, and left to run with all sorts of people?"

"I heard that he wasn't deserted; that his father was only staying out West, or down South, or somewhere for awhile."

"Oh! that's a likely story," said whisperer number one, her voice unconsciously growing louder. "Just as if any father who was anybody, would leave a boy at Job Smith's for months, and never come near him. I think it is real mean; they say the Smiths keep him at work all the while, fishing; he about supports them, and the Deckers too, with fish and things."

At this point the amused listener nearly forgot himself and whistled.

"Oh well, that's as good a way as any to spend his time; he knows enough to catch fish and do such things, and when he is old enough, I suppose he will learn a trade; but I must say I think he is a nice-looking fellow."

"He would be, if he dressed decently. The boys like him real well; they say he is smart; and I shouldn't wonder if he was; his eyes twinkle as though he might be. If he wouldn't keep running with that Decker girl all the time, he might be noticed now and then."

At this point came up a third young miss who spoke louder. Jerry recognized her voice at once as belonging to Lorena Barstow. "Girls, what are you doing here? Why, there is that Irish boy; I wonder if he wouldn't sell us some fish? They say he is very anxious to earn money; I should think he would be, to get himself some decent clothes. Or maybe he wants to make his dear Nan a present."

Then followed a laugh which was quickly hushed, lest the victim might hear. But the victim had heard, and looked more than amused; his eyes flashed with a new idea.

"Much obliged, Miss Lorena," he said softly, nodding his head. "If I don't act on your hint,[283] it will be because I am not so bright as you give me credit for being."

Then the first whisperer took up the story:

"Say, girls, I heard that Ermina did really mean to invite him to her candy pull, and the Decker girl too; she says they both belong to the Sunday-school, and she is going to invite all the boys and girls of that age in the school, and her mother thinks it would not be nice to leave them out. You know the Farleys are real queer about some things."

Lorena Barstow flamed into a voice which was almost loud. "Then I say let's just not speak a word to either of them the whole evening. Ermina Farley need not think that because she lives in a grand house, and her father has so much money, she can rule us all. I for one, don't mean to associate with a drunkard's daughter, and I won't be made to, by the Farleys or anybody else."

"Her father isn't a drunkard now. Why, don't you know he has joined the church? And last Wednesday night they say he was in prayer meeting."

"Oh, yes, and what does that amount to? My father says it won't last six weeks; he says drunkards are not to be trusted; they never reform. And what if he does? That doesn't make Nan Decker anything but a dowdy, not fit for us girls to go with; and as for that Irish boy! Why doesn't Ermina go down on Paddy Lane and invite the whole tribe of Irish if she is so fond of them?"

"Hush, Lora, Ermina will hear you."

Sure enough at that moment came Ermina, springing briskly over logs and underbrush. "Have I kept you waiting?" she asked gayly. "The moss was so lovely back there; I wanted to carry the whole of it home to mother. Why, girls, there is that boy who sits across from us in Sabbath-school.

"How do you do?" she said pleasantly, for at that moment Jerry turned and came toward them, lifting his hat as politely as though it was in the latest shape and style.

"Have you had good luck in fishing?"

"Very good for this side; the fish are not so plenty here generally as they are further up. I heard you speaking of fish, Miss Barstow, and wondering whether I would not supply your people? I should be very glad to do so, occasionally; I am a pretty successful fellow so far as fishing goes."

You should have seen the cheeks of the whisperers then! Ermina looked at them, perplexed for a moment, then seeing they answered only with blushes and silence she spoke: "Mamma would be very glad to get some; she was saying yesterday she wished she knew some one of whom she could get fish as soon as they were caught. Have you some to-day for sale?"

"Three beauties which I would like nothing better than to sell, for I am in special need of the money just now."

"Very well," said Ermina promptly, "I am sure mamma will like them; could you carry them down now? I am on my way home and could show you where to go."

"Ermina Farley!" remonstrated Lorena Barstow in a low shocked tone, but Ermina only said: "Good-by, girls, I shall expect you early on Thursday evening," and walked briskly down the path toward the road, with Jerry beside her, swinging his fish. If the girls could have seen his eyes just then, they would have been sure that they twinkled.

They had a pleasant walk, and Ermina did actually invite him to her candy-pull on Thursday evening; not only that, but she asked if he would take an invitation from her to Nettie Decker. "She lives next door to you, I think," said Ermina, "I would like very much to have her come; I think she is so pleasant and unselfish. It is just a few boys and girls of our age, in the Sunday-school."

How glad Jerry was that she had invited them! He had been so afraid that her courage would not be equal to it. Glad was he also to be able to say, frankly, that both he and Nettie had an engagement for Thursday evening; he would be sure to give Nettie the invitation, but he knew she could not come. Of course she could not, he said to himself; "Isn't that our opening evening?" But all the same it was very nice in Ermina Farley to have invited them.

"Here is another lamp for the table," said Jerry gayly, as he rushed into the new room an hour later and tossed down a shining silver dollar. He had exchanged the fish for it.[284] Then he sat down and told part of their story to Nettie. About the whisperers, however, he kept silent. What was the use in telling that?

But from them he had gotten another idea. "Look here, Nettie, some evening we'll have a candy-pull, early, with just a few to help, and sell it cheap to customers."

So now they stood together in the room to see if there was another thing to be done before the opening. A row of shelves planed and fitted by Norm were ranged two thirds of the way up the room and on them were displayed tempting pans of ginger cookies, doughnuts, molasses cookies, and soft gingerbread. Sandwiches made of good bread, and nice slices of ham, were shut into the corner cupboard to keep from drying; there was also a plate of cheese which was a present from Mrs. Smith. She had sent it in with the explanation that it would be a blessing to her if that cheese could get eaten by somebody; she bought it once, a purpose as a treat for Job, and it seemed it wasn't the kind he liked, and none of the rest of them liked any kind, so there it had stood on the shelf eying her for days. There was to be coffee; Nettie had planned for that. "Because," she explained, "they all drink beer; and things to eat, can never take the place of things to drink."

It had been a difficult matter to get the materials together for this beginning. All the money which came in from the "little old grandmothers," as well as that which Jerry contributed, had been spent in flour, and sugar, and eggs and milk. Nettie was amazed and dismayed to find how much even soft gingerbread cost, when every pan of it had to be counted in money. A good deal of arithmetic had been spent on the question: How low can we possibly sell this, and not actually lose money by it? Of course some allowance had to be made for waste. "We'll have to name it waste," explained Nettie with an anxious face, "because it won't bring in any money; but of course not a scrap of it will be wasted; but what is left over and gets too dry to sell, we shall have to eat."

Jerry shook his head. "We must sell it," he said with the air of a financier. Then he went away thoughtfully to consult Mrs. Job, and came back triumphant. She would take for a week at half price, all the stale cake they might have left. "That means gingercake," he explained, "she says the cookies and things will keep for weeks, without getting too old."

"Sure enough!" said radiant Nettie, "I did not think of that."

There were other things to think of; some of them greatly perplexed Jerry; he had to catch many fish before they were thought out. Then he came with his views to Nettie.

"See here, do you understand about this firm business; it must be you and me, you know?"

Nettie's bright face clouded. "Why, I thought," she said, speaking slowly, "I thought you said, or you meant—I mean I thought it was to help Norm; and that he would be a partner."

Jerry shook his head. "Can't do it," he said decidedly. "Look here, Nettie, we'll get into trouble right away if we take in a partner. He believes in drinking beer, and smoking cigarettes, and doing things of that sort; now if he as a partner introduces anything of the kind, what are we to do?"

"Sure enough!" the tone expressed conviction, but not relief. "Then what are we to do, Jerry? I don't see how we are going to help Norm any."

"I do; quite as well as though he was a partner. Norm is a good-natured fellow; he likes to help people. I think he likes to do things for others better than for himself. If we explain to him that we want to go into this business, and that you can't wait on customers, because you are a girl, and it wouldn't be the thing, and I can't, because it is in your house, and I promised my father I would spend my evenings at home, and write a piece of a letter to him every evening; and ask him to come to the rescue and keep the room open, and sell the things for us, don't you believe he will be twice as likely to do it as though we made him as young as ourselves, and tried to be his equals?"

Then Nettie's face was bright. "What a contriver you are!" she said admiringly. "I think that will do just splendidly."

She was right, it did. Norm might have curled his lip and said "pooh" to the scheme, had he been placed on an equality; for he was[285] getting to the age when to be considered young, or childish, is a crime in a boy's eyes. But to be appealed to as one who could help the "young fry" out of their dilemma, and at the same time provide himself with a very pleasant place to stay, and very congenial employment while he stayed, was quite to Norm's mind.

And as it was an affair of the children's, he made no suggestions about beer or cigars; it is true he thought of them, but he thought at once that neither Nettie or Jerry would probably have anything to do with them, and as he had no dignity to sustain, he decided to not even mention the matter. These two planned really better than they knew in appealing to Norm for help. His curious pride would never have allowed him to say to a boy, "We keep cakes and coffee for sale at our house; come in and try them." But it was entirely within the line of his ideas of respectability to say: "What do you think those two young ones over at our house have thought up next? They have opened an eating-house, cakes and things such as my sister can make, and coffee, dirt cheap. I've promised to run the thing for them in the evening for awhile; I suppose you'll patronize them?"

And the boys, who would have sneered at his setting himself up in business, answered: "What, the little chap who lives at Smith's? And your little sister! Ho! what a notion! I don't know but it is a bright one, though, as sure as you live. There isn't a spot in this town where a fellow can get a decent bite unless he pays his week's wages for it; boys, let's go around and see what the little chaps are about."

The very first evening was a success.

Nettie had assured herself that she must not be disappointed if no one came, at first.

"You see, it is a new thing," she explained to her mother, "of course it will take them a little while to get acquainted with it; if nobody at all comes to-night, I shall not be disappointed. Shall you, Jerry?"

"Why, yes," said Jerry, "I should; because I know of one boy who is coming, and is going to have a ginger-snap and a glass of milk. And that is little Ted Locker who lives down the lane; they about starve that boy. I shall like to see him get something good. He has three cents and I assured him he could get a brimming glass of milk and a ginger-snap for that. He was as delighted as possible."

"Poor fellow!" said Nettie, "I mean to tell Norm to let him have two snaps, wouldn't you?"

And Jerry agreed, not stopping to explain that he had furnished the three cents with which Ted was to treat his poor little stomach. So the work began in benevolence.

Still Nettie was anxious, not to say nervous.

"You will have to eat soft gingerbread at your house, for breakfast, dinner and supper, I am afraid," she said to Jerry with a half laugh, as they stood looking at it. "I don't know why I made four tins of it; I seemed to get in a gale when I was making it."

"Never you fear," said Jerry, cheerily. "I'll be willing to eat such gingerbread as that three times a day for a week. Between you and me," lowering his voice, "Sarah Ann can't make very good gingerbread; when we get such a run of custom that we have none left over to sell, I wish you'd teach her how."

I do not know that any member of the two households could be said to be more interested in the new enterprise than Mr. Decker. He helped set up the shelves, and he made a little corner shelf on purpose for the lamp, and he watched the entire preparations with an interest which warmed Nettie's heart. I haven't said anything about Mr. Decker during these days, because I found it hard to say. You are acquainted with him as a sour-faced, unreasonable, beer-drinking man; when suddenly he became a man who said "Good morning" when he came into the room, and who sat down smooth shaven, and with quiet eyes and smile to his breakfast, and spoke gently to Susie when she tipped her cup of water over, and kissed little Sate when he lifted her to her seat, and waited for Mrs. Decker to bring the coffee pot, then bowed his head and in clear tones asked a blessing on the food, how am I to describe him to you? The change was something which even Mrs. Decker who watched him every minute he was in the house and thought of him all day long, could not get accustomed to. It astonished her so to think that she, Mrs. Decker, lived in a house where there was a prayer made every night and morning, and where each evening after supper Nettie read a few verses in the Bible, and her father prayed; that every time she passed her own mother's Bible which had been brought out of its hiding-place in an old trunk, she said, under her breath, "Thank the Lord." No, she did not understand it, the marvelous change which had come over her husband. She had known him as a kind man; he had been that when she married him, and for a few months afterwards.

She had heard him speak pleasantly to Norm, and show him much attention; he had done it before they were married, and for awhile afterwards; but there was a look in his face, and a sound in his voice now, such as she had never seen nor heard before.

"It isn't Decker," she said in a burst of confidence to Nettie. "He is just as good as he can be; and I don't know anything in the world he ain't willing to do for me, or for any of us; and it is beautiful, the whole of it; but it is all new. I used to think if the man I married could only come back to me I should be perfectly happy; but I don't know this man at all; he seems to me sometimes most like an angel."

Probably you would have laughed at this. Joe Decker did not look in the least like the picture you have in your mind of an angel; but perhaps if you had known him only a few weeks before, as Mrs. Decker did, and could have seen the wonderful change in him which she saw, the contrast might even have suggested angels.

Nettie understood it. She struggled with her timidity and her ignorance of just what ought to be said; then she made her earnest reply:

"Mother, I'll tell you the difference. Father prays, and when people pray, you know, and mean it, as he does, they get to looking very different."

But Mrs. Decker did not pray.

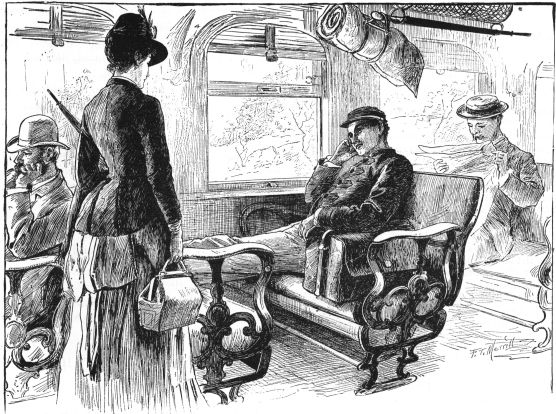

We make a great many stops. "Fourteenth street," shouts the man at the gate, and there is a rush of people to get off, and a rush of people to get on, and away we go; and in almost less time than it takes to get our breath, Twenty-third street, or some other, is shouted, and we stop again.

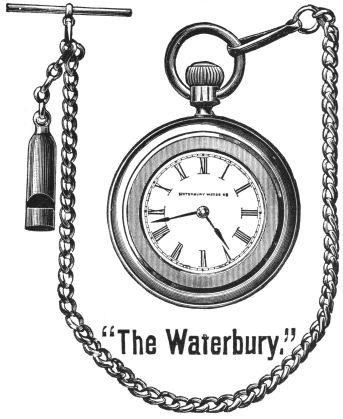

At last Forty-second street is called, and we hurry off; everybody in New York is in a hurry. Yet we have reached a quiet place; the New York Central Depot. "A railroad depot a quiet place!" That astonishes you, does it? Still it is the truth; I am not sure but you would think yourself in a great public library, where people move quietly, and speak low. There is no rush, nor bustle; and the room which we have entered is so large that there can hardly be a crowd, even when many people are there. Many doors line one side, and large clock-faces are set over them; but they keep curious time; no two are alike. If you watch, however, you will discover that the doors and the clocks are all named. One is "N. Y. C. & H. R." another is "N. Y. & N. H." and another is—something else.

The hands of the clock point to the hour and moment that the next train on that particular road will be ready to leave the depot. All we have to do is to look for the name of the road on which we want to travel, and then study the clock over the door. Here is ours, "N. Y. & N. H." We have still fifteen minutes. Before that time, the door is quietly opened, and a man whose duty it is to see that we, by no possibility, make a blunder and board the wrong train, takes his station behind it, and looks carefully at our tickets as we pass; we are seated and away.

The train moves very rapidly, and the sensation is pleasant. No rocking motion, and not nearly so much noise as we sometimes find. We chat together pleasantly, without the feeling that we are talking in a locomotive boiler, where work is going on. We make frequent stops at pleasant villages, where green fields stretch out, on either side, and where the air is sweet with the breath of flowers. One name is called which makes us stretch our necks from the open windows to get as good a view as we can. This is New Haven, "the city of elms," and the seat of Yale College. It is a beautiful city; we can be sure of that, even from the depot view. But we have not time to linger. Some day we will stop there, and take a walk around the college. Now we must make all speed to our destination. At last we hear the name: "Ansonia." And we seize our wraps, and satchels, and umbrellas, and lunch boxes, and make haste. What a pretty village! And what a strange one! The river cuts it in two; makes another village on the other side, which, after all, is the same village, or looks like it. There are many trees, hiding nice old-fashioned houses, near which we get glimpses of many flowers. But the buildings which most attract us to-day are not dwelling houses; unless indeed a race of giants live in them. They are so large! Manufactories? Yes, you have guessed it; the State of Connecticut, you know, is famous for its industry. We have spent so much time in getting here, that we will not be able to stay long in the great building to-day. Still, let us stop a few minutes before this queer machine; it is apparently eating wire. What a stomach it must have! Long coils of fine wire rush into its mouth with such speed that one can hardly see the process. How fast it eats! Such large mouthfuls as it takes! about eight inches of wire at a bite. Now what? No, it doesn't swallow the wire, it simply bites it off, and sends it on. Not far, for as the wire is scurrying by a corner, some one of the wicked people who dwell in this machine, seizes it and bends it double! Poor thing! But as you would naturally expect, it hurries the faster now. Not two inches away, it meets another[291] enemy who in sheer ill humor, apparently, seizes it and in an instant of time has given it such a pinch that its right side is all crinkled; it will bear the marks of that grasp all its life! It scuds on, without a groan, intent apparently on getting out of that country as soon as possible. But no, it is seized again, and the two ends of its poor body are rubbed hastily and mercilessly against a rough surface, until they are like needles for sharpness. It takes but a second, and then the wicked sprite seems to have had revenge enough, and lets the poor wire pass. There is a little open place for which the wire is evidently making; it hopes to slip down there out of sight—hurry! almost there! Alas no, one more sprite reaches out a long finger, and gives that horrid pinch to the other side! "Maimed for life!" the poor wire groans, and at last, at last, having suffered a life-time of torture, so it thinks, though really its whole journey has not taken more than half a minute, it drops breathless and exhausted into the box below. Let us go around and look at it, poor thing! Why, how it shines! And what a merry company it has gotten among! Not alone any more; literally millions of friends of the same outward appearance as itself. "Hairpins!" you exclaim. Yes, indeed; hairpins for the million. Can it be possible that the world will ever want them all? But how pretty they are; and how smooth and fine their points are! Besides, those horrible pinches which we thought were simply vents for ill-humor, were to put those convenient crinkles into the pins, and help them perform their duty in life. In short, the dabs, and pinches, and grindings, hard as they were to bear, were the very things which shaped a mere bit of wire into a useful member of society.

And, when one thinks of it, what a bit of time it took—this preparation—compared with the time which they will now spend in usefulness! No wonder the hairpins in the great box shone brightly when at last they began to understand it all. The question is, little Pansy Blossoms, can you and I, as we stand looking at them, and thinking of all this, learn a lesson which will apply to our human rubs, and pinches, and sharp places? If this be so, then we shall be well repaid for going, and seeing, and thinking.

He quietly resolved to try. But how to get an eaglet was the question. Day after day he would go alone and examine the rocks to see if there was not some way of getting to the nest. There seemed to be none. It was a ledge, almost smooth, and one hundred feet high where the nest was. No ladder would reach it, and if he should go around and climb to the top, he would not be near, as it was many feet down.

One night as he lay thinking the thing over, a thought struck him. "I will go to the top, fasten a rope and let myself down and capture one and climb up again."

In the morning he was a bit wiser and said: "Now if something should happen while I am down there pocketing a young eagle, I might need both hands; in that case how could I climb up? I'll tell the secret to John and Joe Grimes." So they went around to the top of the ledge where they could look over down to the nest.

The old eagle was gone; but there were the five children, talking together at a great rate, not thinking who were near by listening to their conversation and about to knock at their door.

The next moment as they looked up they saw a man coming down by a rope fastened about his body. He seized one and was being drawn up when suddenly the Mother Eagle seeing from far away in the sky an enemy enter her home, and, coming like a flash, dashed upon the robber and would have torn his eyes out; but he fought desperately with his long, sharp knife.

One of his blows almost severed the rope. John and Joe, however, tugged bravely at the other end and their friend with his prize was soon safe but panting at their feet. It is said that when he saw how nearly he came to cutting the rope in two and falling a hundred feet, his hair became instantly white from terror.

The young eagle was taken home and tenderly[292] raised and became as tame as any fowl in the barnyard. It grew to immense size—would fly away out of sight among the clouds, but always return at meal-time and behave like any respectable person. He thought much of his friends; not so much of his friends' enemies. And he had his way of showing his friendship.

And now you need not be surprised to be told about the queer things that the eagle, "Old Abe," did in the War of the Rebellion in 1861-65; how he actually went South with a Western regiment in which were some of his friends, and during battles would fly high and hover over his favorite regiment to cheer it on!

After the battle he would come down and walk among the soldiers and line with them.

The war over, he came back with his regiment and was received like any loyal soldier, with great honor; and his State appropriated a sum to maintain him comfortably in his after years.

There are over thirty references in the Bible to eagles. They are remarkable. A concordance can point them all out. Hunt them up.

Her trunk was on the little front porch waiting for Farmer Dodds, whenever, with his fat white horse and rattling spring wagon he should make his appearance coming over the hill.

Rose seated herself on the trunk, and lightly tapping her heels against the side, looked off in a dreamy way toward the dusty road that wound down from among tree-covered hills, on its way past their own white cottage with rose-vines climbing over the small square windows, and so prettily set down in the midst of an old-fashioned garden, with a broad, straight path leading from the gate to the porch, and at that season bordered with asters of all colors.

Farmer Dodds was not in sight, and Rose, now turning toward the left, followed with her eyes the line of the road, where, having left the slope of hill behind, it struck out across the level. Stubble fields down there were yellow, the green of the meadows was turning into a soft pale brown, and far off the horizon was like a rising mist of purple.

"Aunt Alice," said Rose, stopping the tapping of her heels, "some way the sunshine down yonder looks almost as if you could take it in your hands."

"Tangible light?" said Miss Alice, coming to the porch to look abroad.

"What's that?" asked Rose.

"Why, just the opposite of 'darkness that could be felt', I think."

"Is it?" said Rose gravely. "But, aunt Alice," she continued, "I wonder what I'll do without you here to ask questions of. And how will I ever get along without the Saturday afternoon talks—I've got so used to them, you know. I'll just be awfully lonesome."

"We'll have to plan a way to help that," returned her aunt. "Let me see—how would you like to write a letter to me on the first Saturday? Only you must be careful to write what you would be most apt to talk about if I were here."[293]

"Oh! I'd like to do that," interrupted Rose.

"And then," continued Miss Alice, "I could have a little packet for you at the post-office. Perhaps grandma would let you ride to town with Mr. Dodds, when he goes for his mail, and you could have the pleasure of getting the packet yourself."

"That's a splendid idea!" cried Rose. "But what will you put in the packet?"

"I don't know yet," replied her aunt. "That will depend upon the letter you write to me. It may be some trifling present, or perhaps a single Bible verse, such as I often give you on Saturday evening. But of one thing you may be sure, there will be something in it that will be a true answer to your letter."

While they were talking Mr. Dodds' wagon had come rattling up to the gate. Immediately everything was in a bustle. Grandma came out to see the trunk lifted into the wagon—aunt Alice found that she had left her gloves upstairs and must go after them at the last minute—and there came Priscilla Carter running up the road with a great bunch of bitter-sweet, which Miss Alice was to take to a friend. Rose thought it was delightful, and kept skipping up and down the path, wishing all the time that she were aunt Alice, with a new trunk and going to have a trip on the cars. But at last good-bys were said, the wagon rattled and jingled off, and Mrs. Harrison, Rose and Priscilla were left standing quietly by the white picket gate in the pleasant autumn sunshine.

When Saturday afternoon came around Rose asked her grandmother for pen and ink. Then drawing a square writing-table out to the porch, where it was shady, she began the task of writing a letter that would tell all that had been going on since her aunt went away. Mrs. Harrison was sitting by the window sewing, and for nearly an hour there was no sound save the scratching of her little granddaughter's pen, or[294] now and then a question from her as to how a word should be spelled.

But by and by Rose threw down her pen and pushed her chair noisily back, exclaiming as she did so:

"Well, grandma, I declare! I've got it done at last! Wouldn't you like me to read it to you?"

"Of course, dearie, I should like it very much," answered Mrs. Harrison, glancing up from her sewing.

So Rose sat down on the doorstep and began to read as follows:

Dear Aunt Alice:

I started to school Tuesday, and I'm awfully sorry I was not there the first day, for my seat isn't one bit nice. I'd a great deal rather have the one Altie Crawford is in. She can look out the window and see everybody drive by. There's a real hateful girl sits just behind me too. She is always twisting my curls around her finger; or if she isn't doing that, why, she is borrowing my white-handled knife—the one Mr. Dodds gave me. Miss Milton has a new blue dress. Priscilla took her a great big bunch of white chrysanthemums to put in her belt, and she looked lovely. She is the meanest teacher, though, that I ever had. She won't listen to a word you say to her, and she makes me lend my eraser to everybody in school.

I don't think that's one bit nice of her, and its most worn out, too! She just does it because it is a pretty one. There's a new boy named Robert Wilkie, just started to school, and Miss Milton pets him to death. She is always holding him up for an example, but I think he don't know his lessons any better than the rest of us. I told the girls that you were going to send me a packet, and they were all as excited trying to guess what would be in it!

I've been trying to be real good, and I help grandma wash the dishes most every day, especially when she looks tired. Last evening I got supper all by myself. I fried potato cakes. The edges were a speck jagged, but they were just as brown and nice!

Now I'll have to stop. I've thought and thought, but there isn't anything else to write about. I wonder what you'll put in the packet. I told Priscilla I most thought it would be a ribbon. She's crazy to see what is in it.

Your loving niece,

Rose.

P. S. Priscilla says she can't bear that new boy either. Miss Milton sent her love to you.

"I think that is quite a nice letter," said Mrs. Harrison, when Rose had come to the end. "But however your aunt is to answer it is more than I can guess."

"Don't it seem a long time to wait until Saturday?" said Rose as she folded the letter carefully and put it in an envelope which she brought to her grandmother to address.

"The more patiently you wait the shorter the time will seem," returned Mrs. Harrison.

Rose did wait patiently and cheerfully, and on Saturday afternoon it was a happy girl who rode home beside Farmer Dodds in the spring wagon.

As they drew near the white picket gate she saw Priscilla sitting on the horseblock.

"Have you got it?" cried Priscilla, jumping down, and running to meet the wagon.

For answer Rose held up a square package wrapped in white paper.

"I don't know yet what is in it," said Rose when they drew nearer, "for grandma told me not to open it until I got home. It feels flat, and then there's something round, like a stick of candy, only its pretty large."

The white horse had come to a decided stop by this time and Priscilla held out her hand for the package, while Rose clambered down from the wagon.

"I thank you for the ride, Mr. Dodds," said she, when she reached the ground, "and I'll tell you what is in my packet the next time you come by."

"All right," replied Mr. Dodds, with a sort of merry chuckle, "but be a leetle careful how ye open it. It might be candy, and it might be red pepper."

So saying, he drove off uphill.

"There might be something you wouldn't like," suggested Priscilla, looking a little doubtfully at the package.

"O pshaw!" retorted Rose; "I know better than that. Let's get the scissors."

About one hundred and forty years ago, near the city of Philadelphia, a boy named Benjamin Rush was growing up. It is said of him that as he advanced from childhood to boyhood his love of study was unusual, amounting to a passion. He graduated from Princeton College when only fifteen years old, and with high honors. He began the study of medicine in Philadelphia, but went abroad to complete his medical education and studied under the first physicians in Edinburgh, London and Paris; thus the best opportunities for gaining knowledge of his chosen profession were added to natural abilities and the spirit of research. He became a practising physician in Philadelphia, and was soon after chosen professor of chemistry in a medical college in the same city. While he is now at the distance of a century, best known as one who struck the first blow for temperance reform, yet it is interesting to know that when in 1776, he was a member of the Provincial Assembly of Pennsylvania, he was the mover of the first resolution to consider the expediency of a Declaration of Independence on the part of the American Colonies. He was made chairman of a committee appointed to consider the matter. Afterwards he was a member of the Continental Congress, and was one of the devoted band who in Independence Hall affixed their names to the immortal document which cut the colonies loose from their moorings and swung them out upon a sea of blood, to bring them at last into the harbor of freedom and independence. As was said of him at the meeting in Philadelphia, last year: "He was a great controlling force in all that pertained to the successful struggle of the colonies for national independence." We are told that "He was one of the most active, original and famous men of his times; an enthusiast, a philanthropist, a man of immense grasp in the work-day world, as well as a polished scholar, and a scientist of the most exact methods."

He was interested in educational enterprises; he wrote upon epidemic diseases, and won great honor for himself, so that the kings of other lands bestowed upon him the medals which they are wont to give to those whom they desire to honor. And now let me quote again from one who appreciates the character of this truly great man:

"This matchless physician, eminent scholar and pure patriot blent all his wise rare gifts in one tribute and cast them at the feet of his Master. He was a devout Christian."

At length his soul was stirred within him as he witnessed the increasing evils of intemperance, and he wrote and published his celebrated essay upon "The Effects of ardent Spirits upon the Human Body and Mind, with an account of the means of preventing them, and of the remedies for curing them." This is said to have been the first temperance treatise ever published—the beginning of a temperance literature. One hundred years ago, just one pamphlet of less than fifty pages; now, whole libraries of bound books, besides scores upon scores of pamphlets, leaflets and many periodicals devoted exclusively to the cause of temperance! and nearly three quarters of a century after this good man had gone to his rest, men and women from all over the land thronged the city of his birth "To recount the victories won in the war—and to strike glad hands of fellowship."

And now what made Doctor Rush great? What is the best thing said of him?

Sarah Margaret Fuller was a native of Cambridgeport, Mass. Very early in life she gave promise of the brilliant literary career which she afterwards ran. She was a fine scholar even in childhood, especially in the languages, and in general literature. Her education was carried on in private. After she entered her teens, she became a teacher of the languages in classes in Boston, and in Mr. Alcott's school, and was at one time the principal of a school in Providence. While she was a contributor to the Tribune, she was a member of the family of Horace Greeley. Her views of life were modelled after the philosophy of Ralph Waldo Emerson, and about the year 1839, or 1840, she gave a series of lectures, or talks, though I believe they were called conversazioni, especially for ladies, the object being the propagation of then somewhat novel ideas. She also became the editor of a paper. She wrote much, and with considerable brilliancy. Her "Summer on the Lakes" gives pictures of the Lake Superior region. Her "Woman in the Nineteenth Century" has to do with some phases of the "Woman's Rights Question." In 1846 she went abroad, and married, in Rome, a nobleman, Giovanni Angelo Ossoli. But she bore the name and the title attached to it only a few years. For when she was returning to America, accompanied by her husband, both lost their lives in a shipwreck. She was a woman of strong passions, indeed it has been said of her that "She was noted for her eccentricities and her ungovernable passions." Not just what I would wish to be written of any of my young friends of The Pansy. It is a sad thing when a great and gifted woman misses the happiness of a quiet spirit.

Wilfred's voice was harsh and unpleasant, and he looked at St. George in a way decidedly disagreeable.

George Edward went on whittling.

"Allen, it's no use to pretend that I'm not in an awful scrape by that little affair over at Sachem Hill. Goodness! why don't you speak to a chap?"

"I've nothing to say," observed St. George, proceeding with his work.

"Your tongue is ready enough generally," retorted Wilfred in a temper. "Now, if it suits you to be an oyster, it don't me. I'd rather you'd preach, infinitely."

"I don't do that," cried St. George, throwing down knife and stick, and turning a countenance by no means saintly upon his visitor. "You sha'n't stand there and throw that at me," he declared in a heat.

"I didn't say you did," said Wilfred coolly, "I only said I'd rather you would. So go on."

"It's none of my business what you do," cried St. George, "I'm not going to say a word about it."

"Confound you!" cried Wilfred irritably, flinging his long figure on the bench amongst the shavings, and pushing aside the tools that lay in the way. "Well, hear me, then—I'm in for it, and no mistake. Father is so angry just because I didn't report in time that night, that he threatens to pack me off to boarding-school. In fact, it's as good as decided, and I go next week. Now, you've got the whole."

He threw himself down to the floor as abruptly, plunged his hands in his pockets, and walked to the window.

St. George stood aghast, looking after him.

"Did your mother say so?" he asked at length, hoping, from his knowledge of the Bangs family, that a reprieve might yet arrive from the true head of affairs there.

"Yes," said Wilfred gloomily, "she's worse than father about it, and determined that he sha'n't give in." St. George looked pityingly at him.

"Well, it can't be helped," he said, longing to bestow something better.

"Of course it can't," cried Wilfred, whirling around; "a plague upon you for saying that."

"You wanted me to say something," contributed St. George.

"I know it. But why don't you say 'I told you so,' or, 'If you hadn't been a first-class idiot you'd have dropped that last confounded skate!' Then I could fight you. As it is now, there isn't anything to strike against."

"I'm as sorry as you are," said St. George dubiously, overlooking his ill-success in the matter of conversationally pleasing his friend; "whatever shall I do without you?" There was such genuine regret in his voice and manner, that Wilfred forgot his irritation, and began to look mollified.

"We've had awful good times," he said, coming up to the work-bench again.

"I should think we had," declared St. George in that hearty way of his that made all the boys willing to call him "capital."

"And it's perfectly horrid to begin again with new boys, I tell you. I'd rather run away to sea!" Wilfred's courage failing him once more, he looked the picture of despair.

St. George seeing it, left his own part of the trouble, and turned comforter:

"We're in for it, so all that is left is to face the music."

"Only half-yearly vacations," threw in Wilfred.

St. George's face fell.

"And no boxes from home allowed."

St. George had no words of comfort.

"And no extra 'outs' ever given for good behavior. If there were, I'd set up for a saint," added the victim savagely.

St. George was still silent.

"And all letters must pass through preceptor's hands. Oh! I've seen the bill," said Wilfred in the depths, "besides hearing father and mother read it a good half dozen times. It's just as bad as it can be—a regular old hole of a prison, is Doctor Gowan's Select School for Boys," throwing into his voice as much animosity as he was capable of.[299]

St. George indulged in one or two uneasy turns about the room—his workshop, made out of a part of the generous garret that crowned the old house.

Was not this a terrible punishment indeed for a boy's misdemeanor? Too terrible, it seemed to him, and he felt a growing bitterness in his heart toward the parents who could plan and carry it out, and thus mar, not only the happiness of their own son, but that of a large circle of boys who were to lose a jolly companion.

But at last conscience spoke: "You are wrong. You know that Wilfred has done many things of late that have tried the patience of his father, his mother, and his teachers. You know that they have borne with his increasing unfaithfulness—that they have labored with the boy, hoping and praying for better things. You know they take this course feeling it best for him, and while it is hard for him and for you, it must be borne, realizing it to be the result of the boy's own course. You know all this, now give the case the justice in your own mind that is its due."

St. George turned around and frankly put out his hand.

"It's right you go," he said quite simply, "we'll all try to get along till vacation, old boy."

Wilfred, finding no pity forthcoming, put his hand within the brown palm, waiting for it.

"Keep the rest of the chums together," he begged.

"I'll do my best."

"And remember, we're to go to the same college."

"All right."

"And chum it there."

"All right."

"And I wish," Wilfred looked steadily into the blue eyes gazing into his, "I hadn't done it—dallied over those old skates—but minded father."

St. George bit his lip, but yet he would not preach.

"I'll give you my word it's the last time I'll ever get caught that way."

The blue eyes leaped into sudden fire, and Wilfred's hand was wrung hard.

"All right, old fellow."

Mr. Dalton, the father of the boy who was the host of the evening, stood behind his son's chair looking on and smiling at their eagerness. Presently he said, during a pause in the game;

"Well, boys, you do well; you certainly have a number of interesting facts and dates fastened in your memories, but it occurs to me to wonder if you know anything more than the mere fact. For instance, take this question which is the first that comes to mind, 'What two remarkable events in the reign of Charles the Second?' and the answer, 'The Great Plague and Fire in London.' Now what more do you know of those events?"

Fred Dalton looked up quickly. "I know a little about the Fire, but I do not know about the Plague. I suppose that there was a sort of epidemic raged in London at that time."

"And it must have raged extensively or it would not have been called the Great Plague, and have got into history," said Will Ely.

"You are both very good at supposing," said Mr. Dalton, laughing, "but it is sometimes better to know about a thing than to guess at it."

"I have read an account of the Plague," said Fred Smith. "It raged several months, all one summer, and one third of the people of the city died. Great numbers fled from the city, and so many died that they could not have any burial service, but just buried them in a great pit in the night. They built great bonfires in the streets hoping that the fire and smoke would prevent the spread of the disease, but heavy rains put out the fires. It was a dreadful time!"

"Indeed it was," said Mr. Dalton; "the accounts of it are harrowing. And now what do you know of the Great Fire, Fred?"

"I know that it started in a baker's shop near London Bridge, and that it burned over about five sixths of the city. It burned three days[300] and nights. It was in September, after a very hot and dry summer, so that the houses built of wood were in a well-seasoned state, and made first-rate kindling wood. And then there was a wind that fanned the fire and carried sparks and cinders a long distance, so that new fires kept breaking out in different parts of the city. It is said that there were two hundred thousand people who lost their homes, and that the streets leading out of the city were barricaded with broken-down wagons which the people flying from the fire had overloaded with their goods."

"It was a terrible calamity," said Mr. Dalton; "but like many another it proved a blessing, for the new London was much better built."

"Was the fire set by bad men, or was it an accident?" asked one of the boys.

"Without doubt it was set accidentally, though many people thought otherwise. A monument was erected near the place where the fire started in memory of those who lost their lives in that terrible time, and there was an inscription upon the monument charging the Papists with the crime, but this unjust accusation was afterwards removed by the order of the public authorities. But I will not hinder your game any longer."

"We like this sort of hindering," said one of the boys. "It makes it more interesting."

Mr. Dalton soon returned to say, "Boys, there is a 'Great Fire' in the kitchen, and a pan of corn waiting to be popped, and a Bridget there who does not think boys a 'Great Plague.'"

In less than half a minute there were no boys sitting around that table!

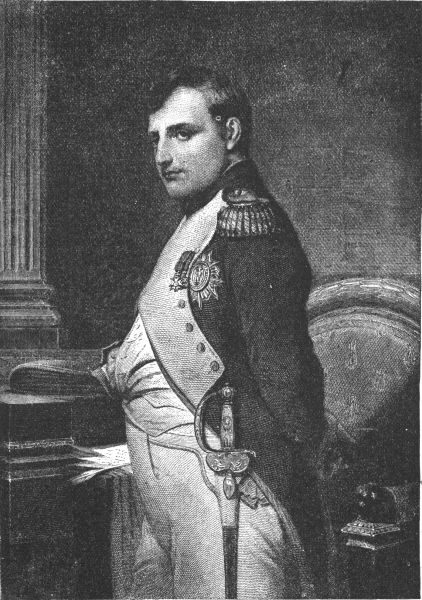

All Europe seemed draped in the weeds of mourning during the years of his power and greatness. I have often thought his reflections must have been sad indeed, when, during the last five years of his life, he was a weary exile on the little gum-tree island of St. Helena, with only a few friends around him, and subjected to great unkindness from the governor of the island.

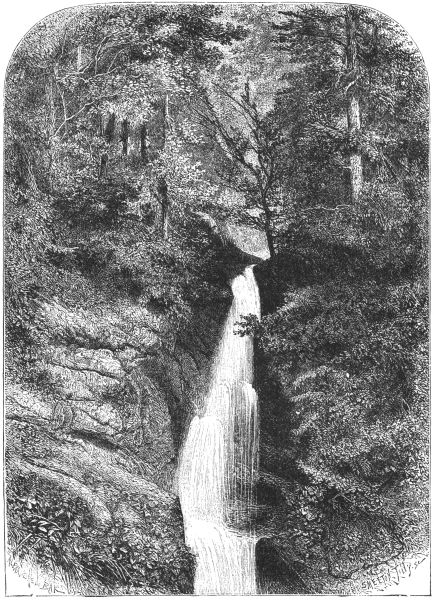

St. Helena is an island in the South Atlantic Ocean, belonging to the British. It acquired celebrity from being the place of Napoleon's banishment. From the ocean it has the appearance of a lofty pyramidal mass of a dark-gray color, rising abruptly from out its depths.

But on approaching, a number of openings are discovered, forming the mouths of narrow valleys or ravines, leading gradually up to a central plateau. On these, at all openings where a landing might be effected, military works have been erected for the purpose of making it secure.

What a contrast does his life there present, to the time when great continents trembled before the power of his triumphant armies.

Napoleon Bonaparte was born in Corsica, 1769, and died at St. Helena, 1821, where he was buried beneath a weeping willow, for nineteen years, when France demanded his remains, and gave such a funeral as few perhaps have ever witnessed.

If any of the Pansies live near a river or lake, and are accustomed to row over the clear, shining surface, they can enter heartily into this most delightful of games. I should first seriously recommend that father or big brother John be invited to take charge of the boat, or if there are not enough big brothers to go around so that every boat can be under trusty guidance, there always is a big cousin or an uncle, or perchance a paid boatman who is competent to assume such a responsibility.

This being all arranged, the fun of trimming the small craft begins. Let each boatload keep all matters secret, so that the grand surprises that come out when the Carnival takes place, may form one of the pleasantest features of the occasion.

Get Chinese lanterns, fasten a pole at either end of row-boat, low enough so that the boats can pass safely under bridges if necessary. Two poles at either end are pretty when decorated with gay lanterns. Pass strings from one pole to another, and across from bow to stern. Hang on these bright bits of tinsel, silver, or any other trifle that will sparkle in the moonlight. Put tinsel or silver bands around top of oars above the hands—and a band around the rower's arms, and around caps. Let the girls wear white, with bright colors, and fancy hats or jaunty caps, carrying garlands.

When all is ready, the forward boat must carry one who rings a bell as the signal to start, also if possible some boys who can play on flutes or horns. There should be sweet voices on all the boats that can sing by a preconcerted plan, something in unison. As the boat sweeps around curves, and dips into bays, and shallows, one could never witness a prettier sight than the carnival presents. It is a regular game of "Follow my Leader" on the water. There must be complete obedience to the one who is leading, great good-nature, and a positive determination on the part of every child who enters into the sport to try his or her best to make all the others enjoy it.

After sailing around and around, singing and playing until tired, the Carnival ends with tying the boats fast, and "following the Leader" over the fields home, dropping the flowers at the doors of those who were not able to take part in the sport.

May you enjoy this Carnival of the Boats, dear Pansies, making it a bright spot in the lives of many, and a memory to gladden the heart.

Paper made of cotton rags was in use, 1000; that of linen rags, in 1170; the manufactory, introduced into England, at Dartford, 1588.

"He described it briefly and simply, but it would fill a volume of beautiful meaning.

"His family dog had made the acquaintance of a neighbor's child on the other side of the street.

"While lying on the door-stone, he had noticed this little thing sometimes at the chamber window, and sometimes on the pavement, in a little carriage.

"During one of his walks on that side of the street, he met the baby, and looked over the rim of the carriage, as a loving dog can look, straight into a pair of baby eyes, and said, 'Good morning!' as well as he could.

"Little by little, day by day and week by week, this companionship went on growing with the growth and strengthening with the strength of the little one. The dog, doubtless because his master had no young child of his own, came at last to transfer frequently his watch and ward to the door-stone on the other side of the street, and to follow as a guard of honor to the baby's carriage on its daily airings. He gave himself up to all the peltings, and little rude rompings, and rough and tumblings of those baby hands.

"One day, as the dog lay in watch by the door-stone, the child, peeping out of the window above, lost its balance, and fell on the stone pavement below. It was taken up quite dead! The red drops of the young life had bespattered the feet and face of the dog as he sprang to the rescue. His heart died out within him in one long, whining howl of grief. From that moment he refused to eat. He refused to be comforted by his master's voice and by his master's home. Day by day and night by night he lay upon the spot where the child fell.

"This was the neighbor's errand. He told it in a few simple words. He had come to my friend, the druggist, for a prescription for his dog—something to bring back his appetite."