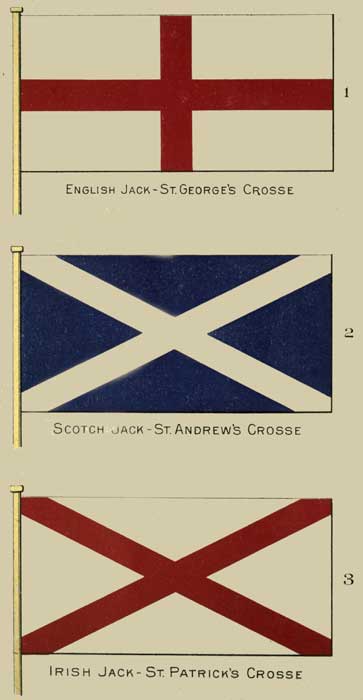

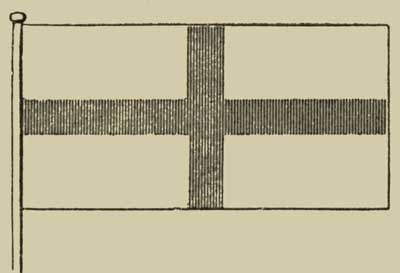

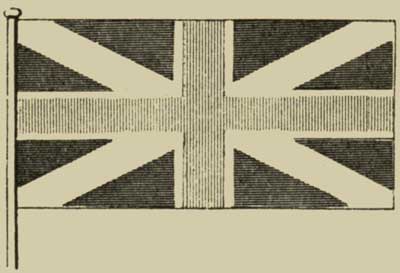

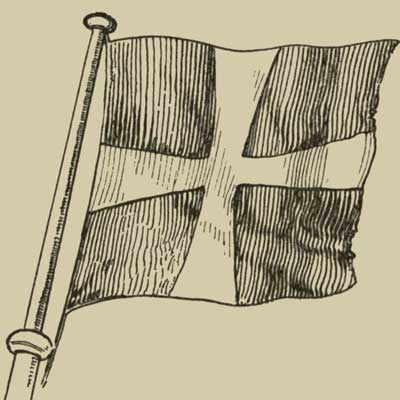

| 1 English Jack—St. George's Crosse |

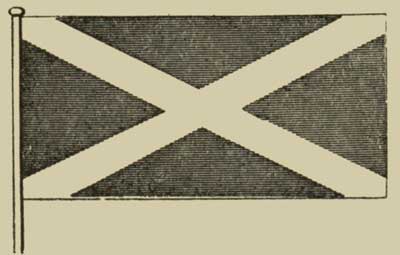

| 2 Scotch Jack—St. Andrew's Crosse |

| 3 Irish Jack—St. Patrick's Crosse |

Title: History of the Union Jack and Flags of the Empire

Author: Barlow Cumberland

Release date: April 26, 2014 [eBook #45498]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Their Origin, Proportions and Meanings as tracing the Constitutional Development of the British Realm, and with References to other National Ensigns

BY BARLOW CUMBERLAND, M.A.

Past President of the National Club, and of the Sons of England, Toronto; President of the Ontario Historical Society, Canada

With Illustrations and Nine Coloured Plates

THIRD EDITION, REVISED AND EXTENDED, WITH INDEX

TORONTO WILLIAM BRIGGS Booksellers' Row, Richmond Street West 1909 Copyright, Canada, 1909, by BARLOW CUMBERLAND.

TO THE FLAG ITSELF THIS STORY OF THE

Union Jack

IS DEDICATED WITH MUCH RESPECT BY ONE OF ITS SONS.

PLATE I.

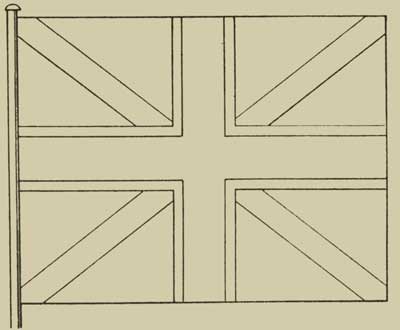

| 1 English Jack—St. George's Crosse |

| 2 Scotch Jack—St. Andrew's Crosse |

| 3 Irish Jack—St. Patrick's Crosse |

This history of the Union Jack grew out of a paper principally intended to inform my boys of how the Union Jack of our Empire grew into its present form, and how the colours and groupings of its parts are connected with our government and history, so that through this knowledge the flag itself might speak to them in a way it had not done before.

A search for further information, extended over many varied fields, gathered together facts that had previously been separated, and grouped them into consecutive order; thus the story grew, and having developed into a lecture, was afterwards, at the suggestion of others, launched upon its public way.

The chapters on the history of the Jacks in the Thirteen American Colonies and in the United States are also new ground and may be of novel interest to not a few. The added information on the proper proportions of our Union Jack, and the directions and reasons for the proper making of its parts, may serve to correct some of the unhappy errors which now exist and may interest all in the observation and study of flags.

An Index has been added, and a record of the "Diamond Anthem" is also appended.

I would acknowledge the criticisms and kindly assistance of many, particularly of Mr. James Bain, Public Librarian of Toronto, who opened out to me the valuable collection in his library; of Mr. J. G. Colmer, C.M.G., Secretary to the Canadian High Commissioner, London, who assisted in obtaining material in England; and of Mr. W. Laird Clowes, Sir James Le Moine, Sir J. G. Bourinot and Dr. J. G. Hodgins, Historiographer of Ontario, who have made many valuable and effective suggestions.

Toronto, October 1, 1900.

The celebration of EMPIRE DAY and of other National and Historic Anniversaries, accompanied by appropriate addresses, has greatly developed at home and abroad. The instructing value of Flags as the visible evidences of the progressive periods of National history, and the concentration of patriotic remembrance, having become more appreciated, have led, no doubt, to the request for a re-issue of this book, which had been for some time out of print.

For such purposes, and as an assistance to Readers and Teachers, the material has been practically recast and new matter incorporated, so that with the collations in the Index the phases of the various portions of the Flags, both of the British and other nationalities, may be more conveniently traced and connected.

Much additional information, particularly in the designing and creation of the Flags, has been sought out and, with additional illustrations, recorded with a view that the intentions expressed in their forms may be more clearly evidenced, their meanings realized, and their connection with Constitutional movements developed.

The suggestions and assistance of many correspondents, to this end, has been much availed of and is thankfully acknowledged.

During the interval since the last issue the Liberties and Methods of the British Constitution have still further expanded. Additional Daughter-Parliaments in the Dominions over-seas have been empowered, and their Union Flags created. To these, as also added information on other Ensigns, is due the addition to the Title.

The references in stating the progress of our National Flag are, of necessity, much condensed, but the writer trusts that with the instructing aid and narrations of its exponents, the information here put together may be found of help in causing the study of Flags, and the stories which they voice, to be of increasing interest, and their Union Jack and Ensigns more intimately known to our youth as the living emblems of our British History and Union.

Port Hope, September, 1909.

| Chapter | Page | |

| A Poem—The Union Jack | 11 | |

| Notes on Flags | 12 | |

| I. | Emblems and Flags | 13 |

| II. | The Origins of National Flags | 21 |

| III. | The Origin of the Jacks | 32 |

| IV. | The English Jack | 41 |

| V. | The Supremacy of the English Jack | 53 |

| VI. | The Scottish Jack | 64 |

| VII. | The "Additional" Union Jack of James I. | 71 |

| VIII. | The English Jack Restored | 81 |

| IX. | The Evolution of the Red Ensign | 92 |

| X. | The Sovereignty of the Seas—The Fight for the Flag | 102 |

| XI. | The Sovereignty of the Seas—The Fight for the Trade | 111 |

| XII. | The Union Jack of Queen Anne, 1707 | 118 |

| XIII. | The Two-Crossed Jack in Canada | 132 |

| XIV. | The Irish Jack | 140 |

| XV. | The Jacks in the Thirteen Colonies of North America | 153 |

| XVI. | The Union Flags of the United States | 170 |

| XVII. | The Jack and Parliamentary Union in Britain | 182 |

| XVIII. | The Jack and Parliamentary Union in Canada | 189 |

| XIX. | The Union Jack of George III., 1801 | 199 |

| XX. | The Lessons of the Crosses | 215 |

| XXI. | The Proportions of the Crosses | 222 |

| XXII. | Under the Three Crosses in Canada | 235 |

| XXIII. | The Flag of Freedom | 243 |

| XXIV. | The Flag of Liberty | 253 |

| XXV. | The Union Jack as a Single Flag | 264 |

| XXVI. | The Jacks in Red, White and Blue Ensigns | 272 |

| XXVII. | The Union Ensigns of the British Empire | 280 |

| Appendix A. | The Maple Leaf Emblem | 295 |

| Appendix B. | Letters from the Private Secretary of His Majesty King Edward VII. | 298 |

| Appendix C. | Canadian War Medals | 299 |

| Appendix D. | A Record of the "Diamond Anthem" | 300 |

| Index | 313 |

| No. | Page | |

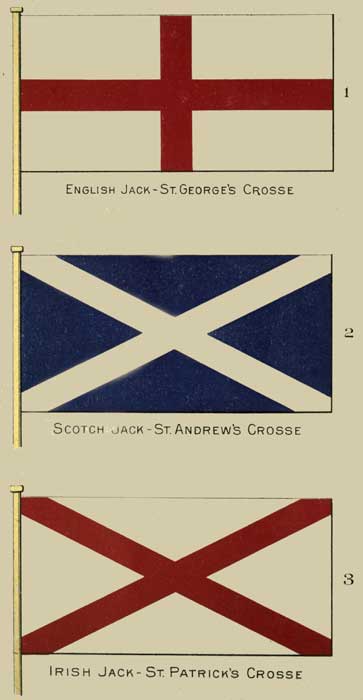

| 1. | Assyrian Emblems | 15 |

| 2. | Eagle Emblems | 16 |

| 3. | Tortoise Totem | 18 |

| 4. | Wolf Totem | 18 |

| 5. | The Hawaiian Ensig | 30 |

| 6. | A Red Cross Knight | 35 |

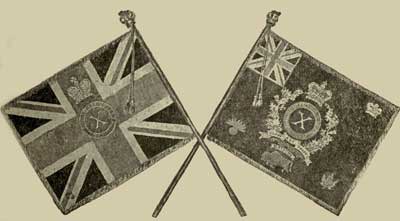

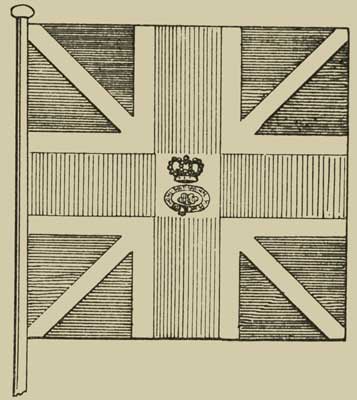

| 7. | Colours of 10th Royal Grenadiers, Canada | 39 |

| 8. | St. George's Jack | 41 |

| 9. | The Borough Seal of Lyme Regis, 1284 | 46 |

| 10. | Brass in Elsing Church, 1347 | 49 |

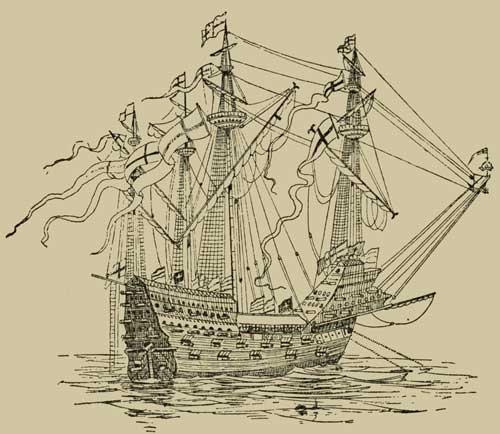

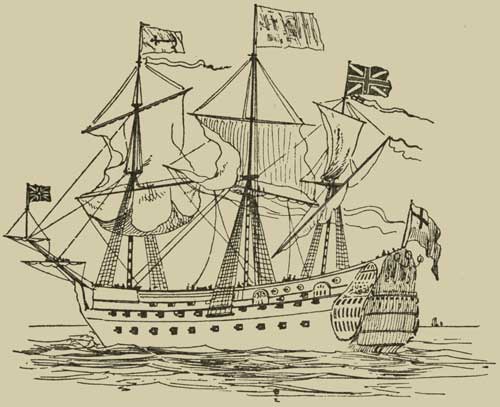

| 11. | The Henri Grace à Dieu, 1515 | 60 |

| 12. | St. Andrew's Jack | 64 |

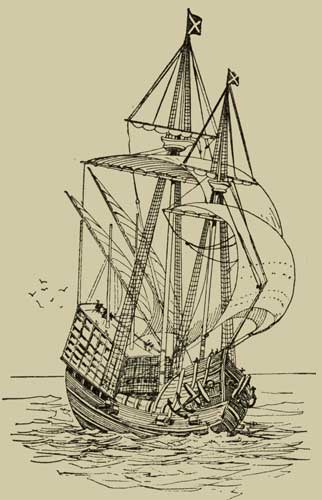

| 13. | Scotch "Talle Shippe," 16th Century | 67 |

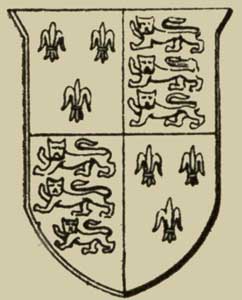

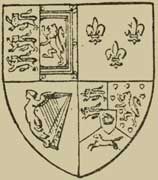

| 14. | Royal Arms of England, Henry V., 1413, to Elizabeth | 71 |

| 15. | Royal Arms of James I., 1603 | 72 |

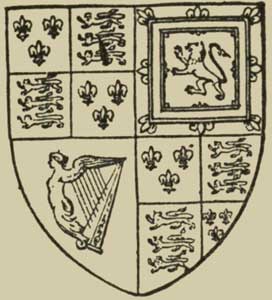

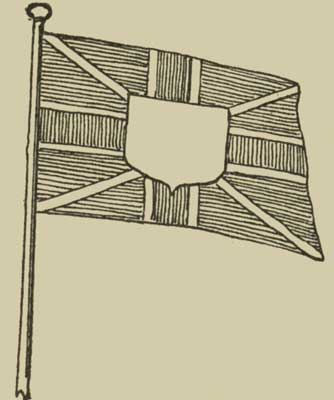

| 16. | Jack of James I., 1606 | 74 |

| 17. | The Sovereign of the Seas, 1637 | 85 |

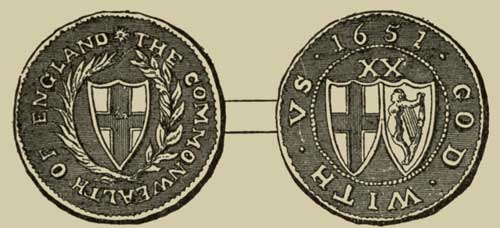

| 18. | Commonwealth Twenty-Shilling Piece | 87 |

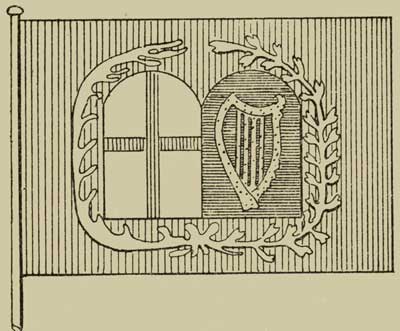

| 19. | Commonwealth Boat Flag | 88 |

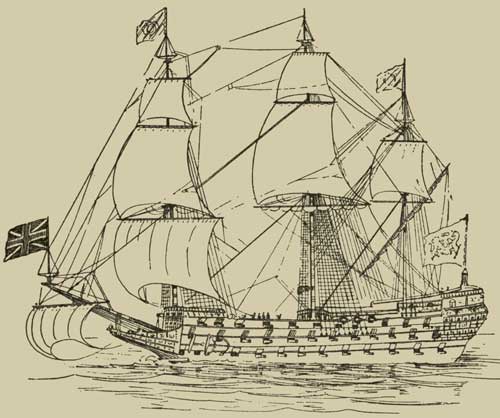

| 20. | The Naseby. Charles II. | 95 |

| 21. | Medal of Charles II., 1665 | 98 |

| 22. | Whip-lash Pennant, British Navy | 108 |

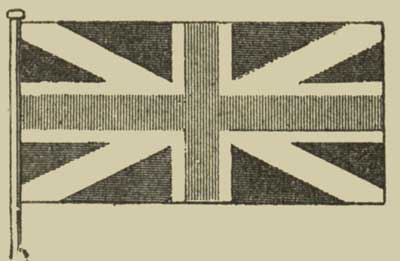

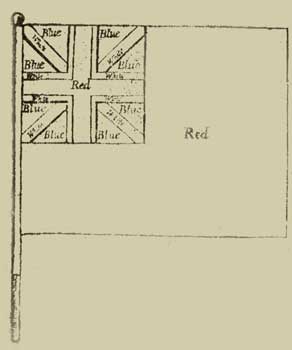

| 23. | Union Jack of Anne, 1707 | 118 |

| 24. | Draft "C," Union Jack, 1707 | 121 |

| 25. | The Red Ensign in "The Margent," 1707 | 125 |

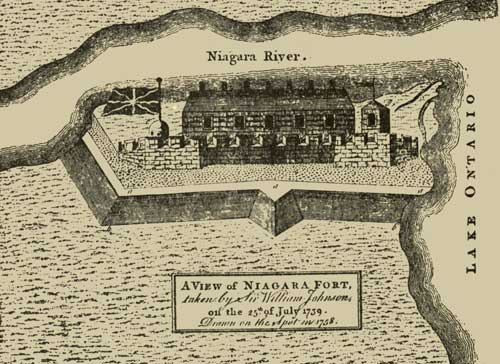

| 26. | Fort Niagara, 1759 | 128 |

| 27. | The Assault at Wolfe's Cove, Quebec, 1759 | 130 |

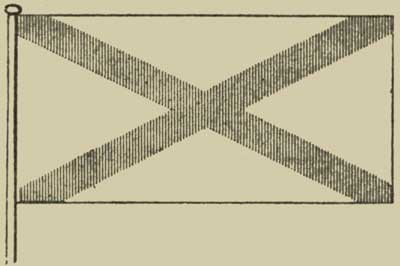

| 28. | St. Patrick's Jack | 141 |

| 29. | Labarum of Constantine | 142 |

| 30. | Harp of Hibernia | 143 |

| 31. | Seal of Carrickfergus, 1605 | 148 |

| 32. | Royal Arms of Queen Victoria[Pg 8] | 148 |

| 33. | Medal of Queen's First Visit to Ireland | 149 |

| 34. | The Throne of Queen Victoria in the House of Lords, 1900 | 150 |

| 35. | Arms of the Fitzgeralds | 151 |

| 36. | Medal of Louis XIV., "Kebeca Liberata," 1690 | 165 |

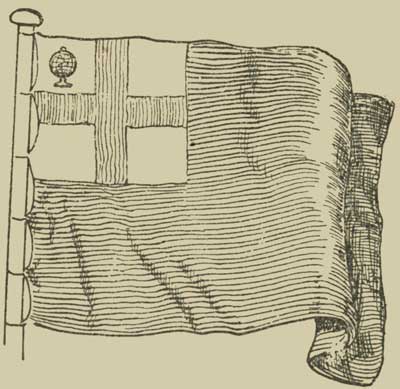

| 37. | New England Ensign | 166 |

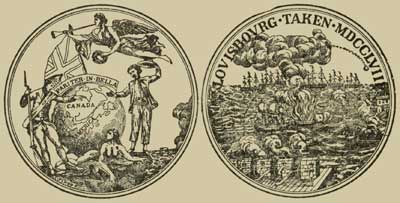

| 38. | The Louisbourg Medal, 1758 | 168 |

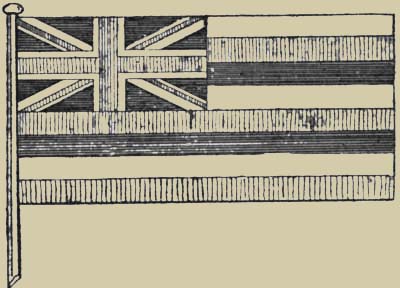

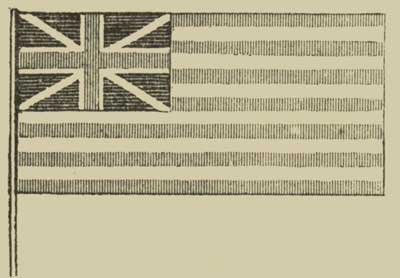

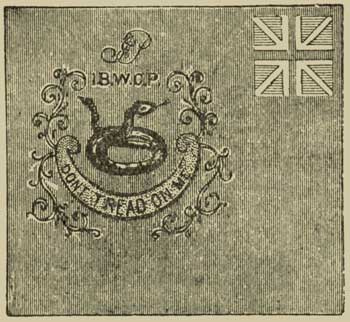

| 39. | The First Union Flag, 1776 | 174 |

| 40. | The Pennsylvania Flag, 1776 | 176 |

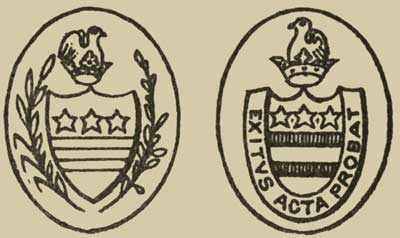

| 41. | Arms of the Washington Family | 177 |

| 42. | Washington's Book-Plate | 178 |

| 43. | Washington's Seals | 179 |

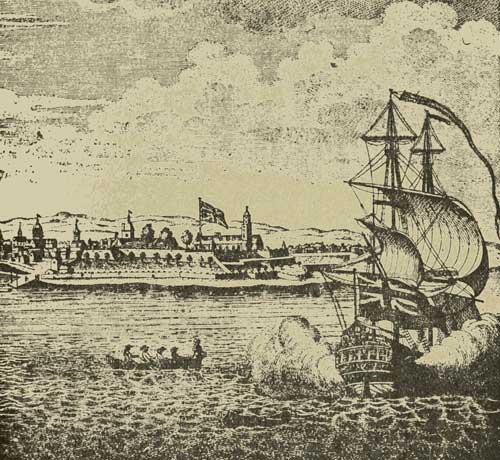

| 44. | Fort George and the Port of New York in 1770 | 187 |

| 45. | Royal Arms of George II. | 190 |

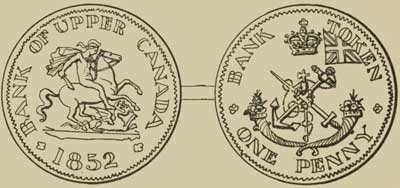

| 46. | The Great Seal of Upper Canada, 1792 | 195 |

| 47. | Upper Canada Penny | 198 |

| 48. | Draft "C" of Union Jack, 1800 | 200 |

| 49. | Royal Arms of George III., 1801 | 202 |

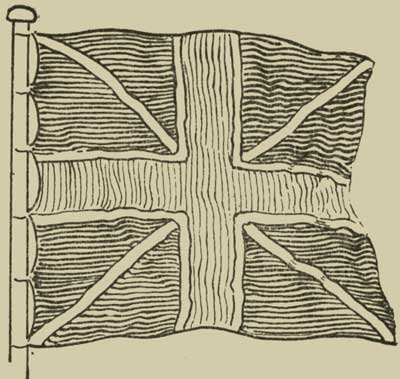

| 50. | Union Jack of George III., 1801 | 203 |

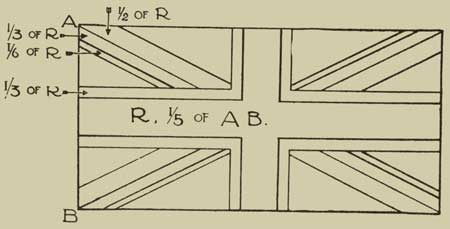

| 51. | Outline Jack—The Proper Proportions of the Crosses | 209 |

| 52. | The Union Jack and Shackleton at Farthest South | 213 |

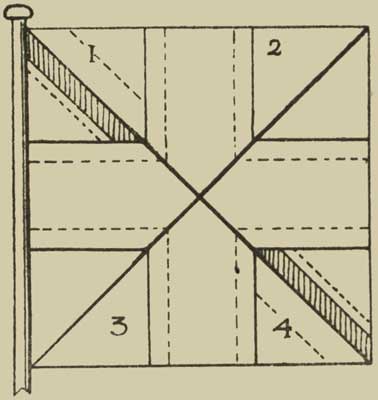

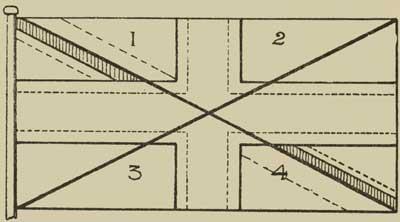

| 53. | Square Union Jack | 219 |

| 54. | Oblong Union Jack | 220 |

| 55. | Flag of a French Caravel, 16th Century | 223 |

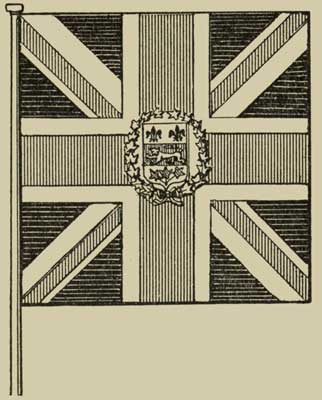

| 56. | The Colonial Jack, 1701 | 226 |

| 57. | Jack of England, 1711 | 227 |

| 58. | Jack in Carolina, 1739 | 228 |

| 59. | The Combat between La Surveillante and the Quebec, 1779 | 229 |

| 60. | Ensign of 7th Royal Fusiliers, 1775 | 230 |

| 61. | "King's Colour," 1781 | 231 |

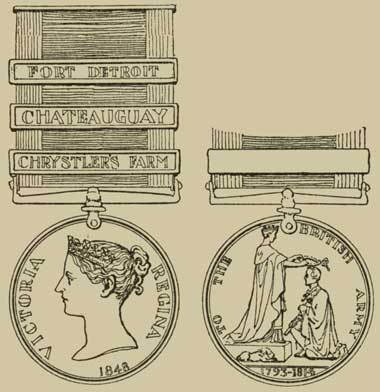

| 62. | The War Medal, 1793-1814 | 236 |

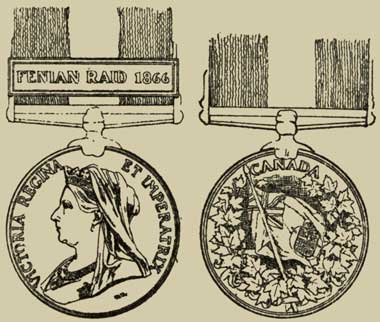

| 63. | The Service Medal, Canada, 1866-1870 | 237 |

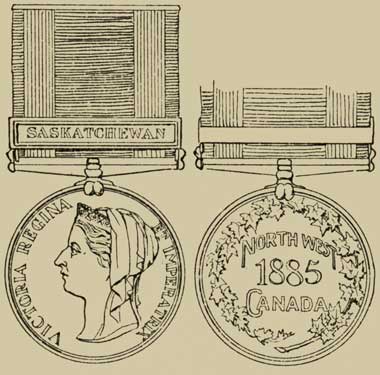

| 64. | The North-West Canada Medal, 1885 | 240 |

| 65. | Flag of the Governor-General of Canada | 259 |

| 66. | Flag of the Lieutenant-Governor of Quebec | 260 |

| 67. | Australian Emblems | 283 |

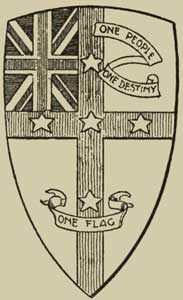

| 68. | Australian Federation Badge | 287 |

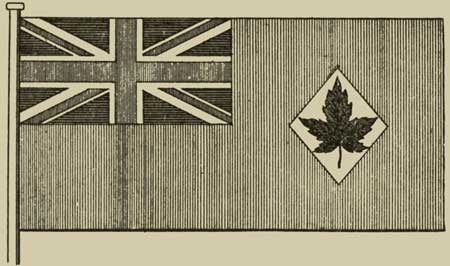

| 69. | Suggested Canadian Union Ensign | 297 |

| Page | ||

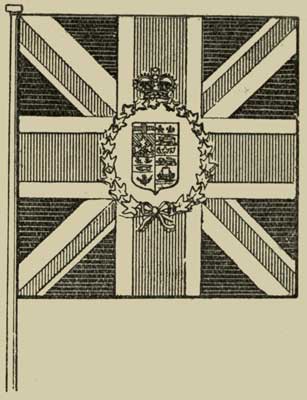

| Plate I. | Frontispiece | |

| 1. English Jack—St. George's Crosse. | ||

| 2. Scottish Jack—St. Andrew's Crosse. | ||

| 3. Irish Jack—St. Patrick's Crosse. | ||

| Plate II. | 22 | |

| 1. Germany. | ||

| 2. Italy. | ||

| 3. Greece. | ||

| 4. Hawaii. | ||

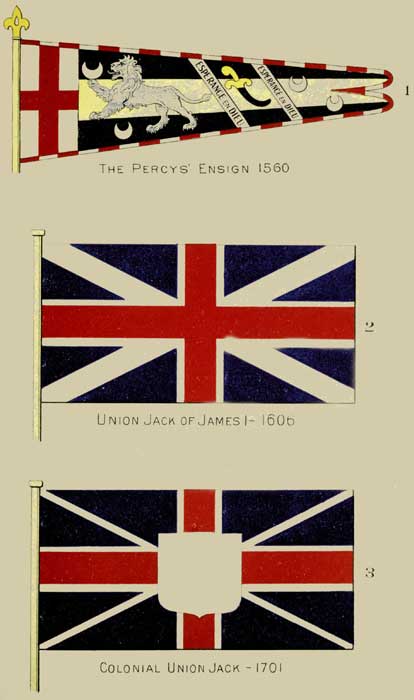

| Plate III. | 76 | |

| 1. The Percys' Ensign, 1560. | ||

| 2. Union Jack of James I., 1606. | ||

| 3. Colonial Union Jack, 1701. | ||

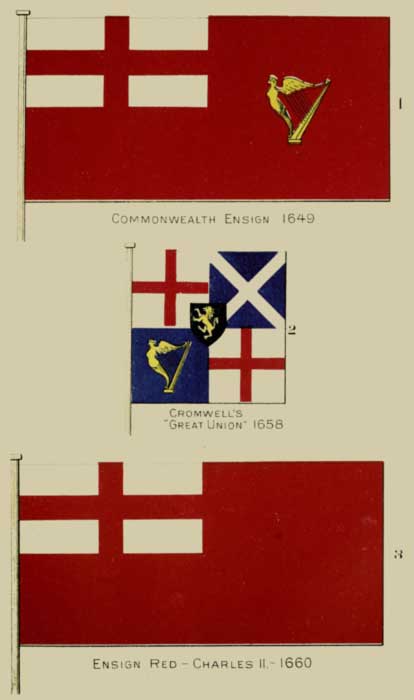

| Plate IV. | 92 | |

| 1. Commonwealth Ensign, 1648. | ||

| 2. Cromwell's "Great Union," 1658. | ||

| 3. Ensign Red—Charles II., 1660. | ||

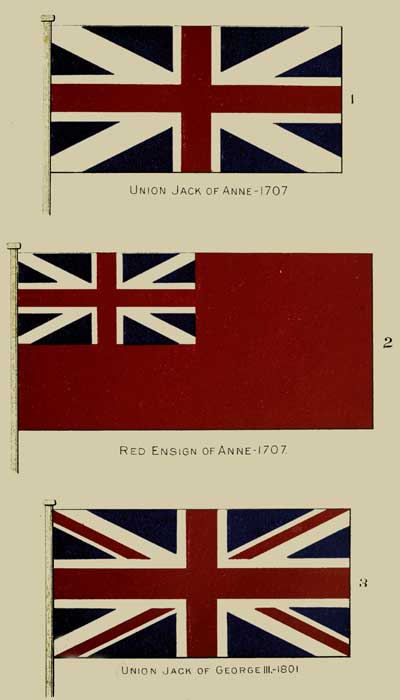

| Plate V. | 118 | |

| 1. Union Jack of Anne, 1707. | ||

| 2. Red Ensign of Anne, 1707. | ||

| 3. Union Jack of George III., 1801. | ||

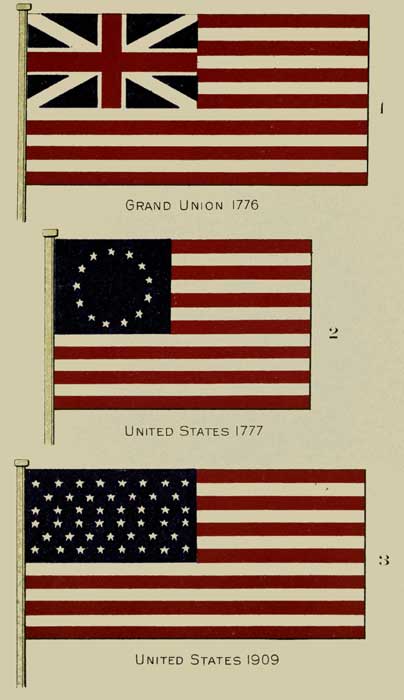

| Plate VI. | 174 | |

| 1. Grand Union, 1776. | ||

| 2. United States, 1777. | ||

| 3. United States, 1909. | ||

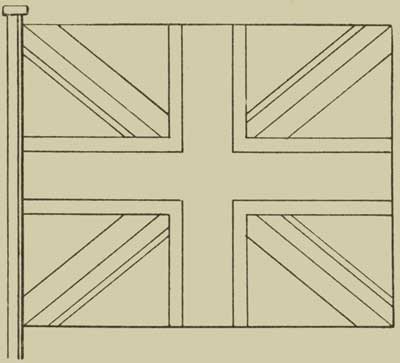

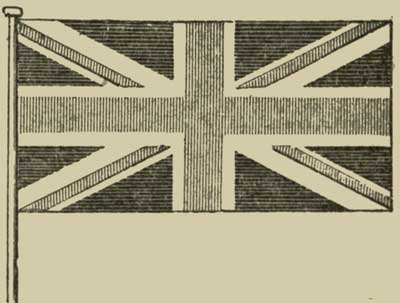

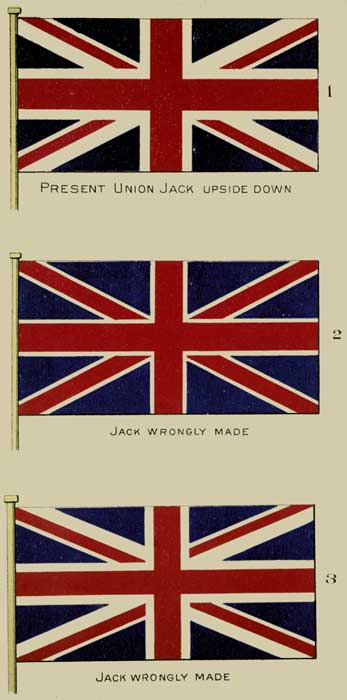

| Plate VII. | 218 | |

| 1. Present Union Jack upside down. | ||

| 2. Jack wrongly made. | ||

| 2. Jack wrongly made. | ||

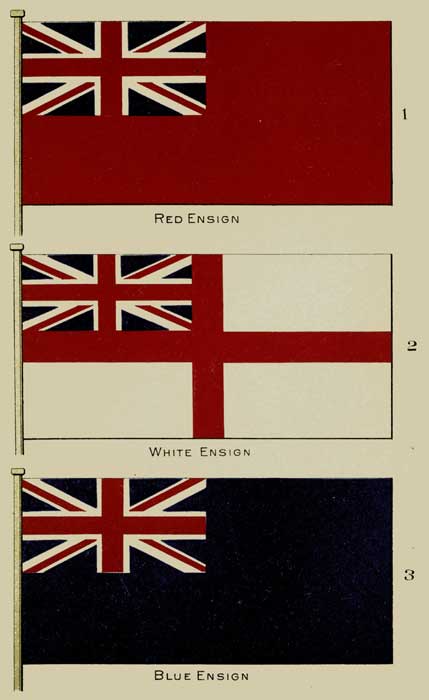

| Plate VIII. | 272 | |

| 1. Red Ensign. | ||

| 2. White Ensign. | ||

| 3. Blue Ensign. | ||

| Plate IX. | 280 | |

| 1. Canadian Union Ensign. | ||

| 2. Australian Union Ensign. | ||

| 3. New Zealand Union Ensign. |

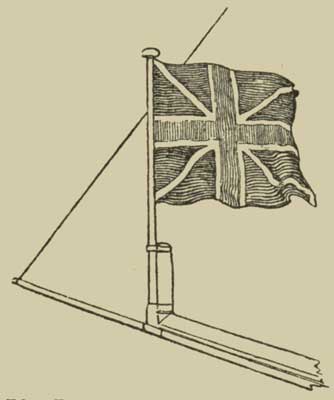

NAMES OF PARTS.

Particular names are given to the several parts of a flag.

The part next the flagstaff, or width, Is called the "hoist."

The outer part, or length, is termed the "fly," and also the "field."

These parts are further divided into "quarters," or "cantons": two "next the staff," two "in the fly."

These descriptive terms should be noted, as they will be in constant use in the pages which follow.

USAGE.

A flag at half-mast is a sign of mourning.

A flag reversed is a signal of distress.

The lowering of a flag is a signal of surrender.

The raising of the victors' flag in its place is a signal of capture.

The nationality of a country is shown by its flag.

The nationality of a vessel is made known by the flag she flies at the stern.

To hoist the flag of one nation under that of another nation, on the same flag-staff, is to show it disrespect.

EMBLEMS AND FLAGS.

There is an instinct in the human race which delights in the flying of flags—a sentiment which appears to be inborn, causing men to become enthusiastic about a significant emblem raised in the air, whether as the insignia of descent, or as a symbol of race, or of nationality; something which, being held aloft before the sight of other men, declares, at a glance, the side to which the bearer belongs, and serves as a rallying point for those who think with him.

The child chortles at a piece of riband waved before him; a boy marches with head erect and martial stride as bearer of the banner at the head of his mimic battalion; the man, at duty's call, rallies to his national standard, and leaving home and all, stakes his life for it in his country's cause; and when the battle of life is closing and steps are homeward bound, the gray-beard, lifting his heart-filled eyes, blesses[Pg 14] the day that brings him back within sight of his native flag.

At all ages and in all times has it been the same. The deeper we go into the records of the past the more evidence do we find that man, however varied his race or primitive his condition, however cultured his surroundings or rude his methods, has universally displayed this innate characteristic instinct of delighting and glorifying in some personal or national emblem.

To search for and discover the emblems which they bore thus discloses to us the eras of a people's history, and, therefore, it is that the study of a nation's flag is something more than a mere passing interest, and becomes one of real educational value, meriting our closest investigation, for the study of Flags is really the tracing of History by sight.

In ancient Africa, explorations among the sculptured antiquities on the Nile have brought to light a series of national and religious emblem-standards, which had meaning and use among the Egyptians long before history had a written record. The fans and hieroglyphic standards of the Pharaohs are the index to their dynasties.

The Israelites, at the time of the Exodus, had their distinctive emblems, and in the Book of Numbers (ch. ii. 2), it is related how Moses directed that in their journeyings, "Every man of the children of Israel shall pitch by his own standard, with the ensign of their father's house."

So it came that to every Jewish child, in all the subsequent centuries, the emblem on the standard of his tribe recalled the history and the trials of his[Pg 15] ancestors and fortified his faith in the God of their Deliverance.

From the lost cities of Nineveh have been unearthed the ensign of the great Assyrian race, the "Twin Bull" (1), sign of their imperial might, and the records of their warriors are thus identified.

In Europe in later times there were few parts of the continent which did not become acquainted with the metal ensigns of the great Roman Empire. The formidable Legions of their armies, issuing from the centre of the realm, carried the Imperial Eagle at their head, and setting it in triumph over many a subjugated state, established its supremacy among the peoples as a sign of the all-conquering power of their mighty Empire. To this eagle of the Roman legions may be traced back the crop of eagle emblems (2), which are borne by so many of the nationalities of Europe at the present day. The golden eagle of the French battalions, the black eagle of Prussia, the white eagle of Poland, and the double-headed[Pg 16] eagles of Austria and Russia, whose two heads typify claim to sovereignty over both the ancient Eastern and Western sections of the Roman Empire, are all descendants from the Imperial Eagle of ancient Rome.

| Austrian. | Roman. | Russian. |

| Prussian. | French. |

As these nationalities of modern Europe have successively arisen and developed into their separate existence, the emblem of their ancient subjugation has been raised by them as the emblem of their power, just as the Cross, which was once the emblem[Pg 17] of the degradation and death of the Christ, has been accepted as the signal and glory of the nations which have come under the Christian sway.

As on the Eastern, so also on the Western hemisphere. On all continents the rainbow in the heavens is a perpetual memorial of the covenant made between God and man—the sign that behind the wonders of nature dwells the still more wonderful First Cause and Author of them all. The Peruvians, far back in the centuries of existence on the continent of South America, had preserved a tradition of a great event which, although it had taken place on another hemisphere, yet had been, by some means, transmitted to theirs, and, tracing from it the story of their national origin, they carried this emblem as sign of the lineage which they claimed as being, as they called themselves, "The Children of the Skies." Thus it was that under the standard of a "Rainbow" the armies of the Incas of Peru valiantly resisted the invasions of Pizzaro when, in the sixteenth century, the South American Continent came under the domination of Spain.

National emblems were borne farther north on the Northern continent by another nation, even yet more ancient than the Peruvians. Embedded in the ruins of buried cities of the Aztecs, in Mexico, are found the memorials of a constructive and artistic people, whose emblem of the "Eagle with outstretched wings," repeated with patriotic iteration in the stone carvings of their buildings, has thus come down to us the mute declarant of their national aspirations. The nation itself as a power has long since passed[Pg 18] away, but the outlines of their emblem still preserve the ideals of the vanished race.

A living instance of much interest also evidences the adherence to national emblems among the earlier inhabitants of North America. Long before the invading Europeans first landed on the shores of the North Atlantic coasts, the nomad Red Indian, as he travelled from place to place through the fastnesses of the forests, along the shores of the great lakes, over the plains of vast central prairies, or amid the mountains that crown the Pacific slope, everywhere attested the story of his descent by the "Totem" of his family. This sign of the Tortoise (3), the Wolf (4), the Bear, or the Fish, painted or embroidered on his trappings or carved upon his weapons, was displayed as evidence of his origin, and whether he came as a friend or advanced as a foe, its presence nerved him to maintain the reputation of his family and the honour of his tribe.

To-day the Red Man slowly yields to the ever-advancing march of the dominant and civilizing white; his means of sustenance by the chase, or of livelihood by his skill as a trapper, have been destroyed. The Indian tribes are, under the Indian treaties, required to remain within large blocks of territory called "Reserves," so that now in his poverty he is maintained upon these "reservations" solely by the dole of the[Pg 19] peoples by whom his native country has been absorbed; yet, though so changed in their circumstances, his descendants still cling with resolute fortitude and pathetic eagerness to these ancient insignia of their native worth. These rudely-formed emblems, in outline and shape mainly taken from the animals and birds of the plain and forest, are the memorials in his decadence of the long past days when his forefathers were the undisputed monarchs of all the wilds and possessors of its widest domains. They are the Indian patents of nobility, and thus are clung to with all the pride of ancient race.

This Instinct in man to attach a national meaning to some vital emblem, and to display it as evidence of his patriotic fervour, is thus found to be all-pervading. The accuracy of its form may not be exact—it may, indeed, be well-nigh indistinguishable in its outlines—but whenever it be raised aloft, the halo of patriotic meaning, with which memory has illumined it, is answered by the flutterings of the bearer's heart; self is lost in inspiring recollection; clanship, absorbing the individual, enfolds him as one of a mighty whole, and the race-blood that is deep within him springs quick into action, obedient to the stirring call.

The fervour of this manifestation was eloquently expressed by Lord Dufferin in narrating some incidents which had occurred during one of his official tours through Canada, when Governor-General of the country, the greatest daughter-nation among the children of the Union Jack:

"Wherever I have gone, in crowded cities, in the remote hamlets, the affection of the people for their[Pg 20] Sovereign has been blazoned forth against the summer sky by every device which art could fashion or ingenuity invent. Even in the wilds and deserts of the land, the most secluded and untutored settler would hoist some cloth or rag above his shanty, and startle the solitude of the forest with a shot from his rusty firelock and a lusty cheer from himself and his children in glad allegiance to his country's Queen. Even the Indian in his forest and on his reserve would marshal forth his picturesque symbols of fidelity in grateful recognition of a Government that never broke a treaty or falsified its plighted word to the Red Man, or failed to evince for the ancient children of the soil a wise and conscientious solicitude."[1]

Of all emblems, a Flag is the one which is universally accepted among men as the incarnation of their intensest sentiment, and when uplifted above them, concentrates in itself the annals of a nation and all the traditions of an empire.

A country's flag becomes, therefore, of additional value to its people in proportion as its symbolism is better understood and its story is more fully known. Its combinations should be studied, its story unfolded—for in itself a flag is nothing, but in its meaning it is everything.

So long, then, as pride of race and nation exists among men, so long will a waving flag command all that is strongest within them, and stir their national instincts to their utmost heights.

THE ORIGINS OF NATIONAL FLAGS.

With such natural emotions stirring within the breasts of its people, one can appreciate the fervid interest taken by each nation in its own national flag, and understand how it comes that the associations which cluster about its folds are so ardently treasured up.

Flags would at first sight appear to be but gaudy things, displaying contrasts of colour or variations of shape or design, according to the mood or the fancy of some enterprising flagmaker. This, no doubt, is the case with many signalling or mercantile flags. On the other hand, there is, in not a few of the flags known as "national flags," some particular combination of form or of colourings which, if they were but known, indicates the reason for their origin, or which marks some historic memory. There has been, perhaps, some notable occasion on which they were first displayed, or they may have been formed by the joining together of separate designs united at some eventful epoch, to signalize a victorious cause, or to perpetuate the memory of a great event. These great stories of the past are thus brought to mind and told anew by the coloured folds each time they are spread open by the breeze; for of most national flags it can be said, as was said by an American orator[3] of his[Pg 22] own, "It is a piece of bunting lifted in the air, but it speaks sublimity, and every part has a voice." It is to see these colours and hear these voices in the British national flags that is our present undertaking.

Before tracing the history of our British Union Jack, some instances may be briefly mentioned in which associations connected with the history of some other nations are displayed in the designs of their national flags.

The colours of the German national banner are black, white and red (Pl. II., fig. 1). Since 1870, when, at the conclusion of the French war, the united German Empire was formed, this has been the general Standard for all the states and principalities that were then brought into imperial union; although each of these lesser states continues to have, in addition, its own particular flag. This banner of United Germany introduced once more the old German colours, which had been displayed from 1184 until the time when, in 1806, the empire was broken up by Napoleon I. Tradition is extant that these colours had their origin as a national emblem at the time of the crowning of Frederic I. (Barbarossa) in 1152, as ruler of the countries which are now largely included in Germany. On this occasion the pathway to the cathedral at Aix-la-Chapelle was laid with a carpeting of black, gold and red, and the story goes that after the ceremony this carpet was cut by the people into strips which they then displayed as flags. Thus by the repetition of these historic colours in their ensign the present union of the German Empire is connected with the early history of more than seven centuries before.

PLATE II.

| 1 GERMANY | 2 ITALY |

| 3 GREECE | 4 HAWAIIAN |

| 5 CHAMPLAIN 1608 | 6 FRENCH from 1794 |

The national ensign of United Italy (Pl. II. , fig. 2) is a flag having three parallel vertical stripes, green, white and red, the green being next the flagstaff. Upon the central white stripe there is shown a red shield, having upon it a white cross. This national flag was adopted in 1870, after the Italian peoples had risen against their separate rulers, and the previously separated principalities and kingdoms had, under the leadership of Garibaldi, been consolidated into one united kingdom under Victor Emmanuel, the then reigning king of Sardinia. The red shield here displayed on the centre of the Italian flag designates the arms of the House of Savoy, to which the Royal House of Sardinia belonged, and which had been gained by the following ancient and honourable event:

The island of Rhodes, an Italian colony in the Eastern Mediterranean, had, in 1311, been in deadly peril from the attacks of the Turks. In their extremity the then Duke of Savoy came to the aid of the Knights Hospitallers of St. John, who were defending the island, and with his help they were able to make a successful resistance. In record and acknowledgment of this great service the Knights of St. John granted to the House of Savoy the privilege of wearing upon their royal arms the white cross on a red shield, which was the badge of their order of St. John.

So it happened when, nearly six centuries afterwards, the Sardinians again came to the aid of their southern brethren, and the King of Sardinia was crowned as ruler over the new united Italian kingdom,[Pg 24] the old emblem won in defence of ancient liberties was further perpetuated on the banner of the new kingdom of liberated and united Italy.

The colours of the Greek flag preserve the memory of a dynasty. In 1828, the Greeks, after rising in successful rebellion, had freed their land from Mohammedan domination and the power of the Sultan of Turkey. The several States formed themselves into one united kingdom, and seeking a king from among the royal houses of Europe, obtained, in 1832, Otho I., a scion of the ruling house of Bavaria. The dynasty at that time set upon the throne of Greece has since been changed, the Bavarian having parted company with the kingdom in 1861. The throne was then offered to Prince Alfred of England, but declined by him. The present king, chosen in 1863, after the withdrawal of his predecessor, is a member of the Royal House of Denmark; yet, notwithstanding this change in the reigning family, the white Greek Cross upon a light blue ground in the upper quarter, and the four alternate stripes of white on a light blue ground in the field, which form the national flag of Greece (Pl. II. , fig. 3), still preserve the blue and white colours of Bavaria, from whence the Greeks had obtained their first king.

The Tri-colour as displayed by the present Republic in France (Pl. II. II., fig. 6) has been credited with widely differing explanations of its origin, as its plain colours of blue, white and red admit of many different interpretations.

One story of its origin is, that its colours represent those of the three flags which had been carried in suc[Pg 25]cession in the early centuries of the nation. The early kings of France carried the plain blue banner of St. Martin. To this succeeded, in A.D. 1124, the flaming red flag, or Oriflamme, of St. Denis, to be afterwards superseded, in the fifteenth century, by the white "Cornette Blanche," the personal banner of the heroic Joan of Arc.

It was under this royal white flag (Pl. II., fig. 5), bearing upon it the lilies of ancient France, that Cartier, in 1534, had sailed up the St. Lawrence, and Champlain, in 1608, had founded Quebec. Under this flag Canada was colonized; to it belonged the glories of the Jesuit Fathers and Dollard; with it La Salle and Marquette explored the far West, planting three fleur-de-lis as the sign of their discoveries. Under it Frontenac, Montcalm and Levis[4] achieved their renown, and all the annals of early Canada are contained under its régime until, in 1759, after the assault by Wolfe, it was exchanged, at the cession of Quebec, for the British Union Flag.

The tri-colour of Republican France was never carried by the forefathers of the French Canadians of the Province of Quebec, nor has it any connection with the French history of Canada. In fact, it did not make its appearance as an emblem until the time of the revolution in France in 1789, or thirty years after the original French régime in Canada had closed its eventful period.

More detailed evidence of the origin of this flag states that the creation of the tri-colour arose from the incident that, when the revolutionary militia were first assembled in the city of Paris, at the revolution of 1789, they had adopted blue and red, which were the ancient colours of the city of Paris, for the colours of their cockade; between these they placed the white of the soldiery of the Bourbon régime, who afterwards joined their forces, and thus they had combined the blue, white and red in the "tri-colour" as their revolutionary signal.[5]

Whether or not its colours record those of the three ancient monarchical periods, or those of the revolution, the tri-colour as a French ensign for use by the people of France, as their national flag both on land and sea, was not regularly established until a still later period, in 1794. Then it was that the Republican Convention passed the first decree[6] authorizing an ensign and directing that the French national flag (Pl. II. , fig. 6) shall be formed of the three colours placed vertically in equal bands—that next the staff being blue, the centre white, and the fly red.

This was the flag under which Napoleon I. won his greatest victories, both as General and Emperor; but whatever glories may have been won for it by France, yet many years before it had been even designed, or the prowess of Napoleon's armies had created its renown, the French Canadian had been fighting under the Union Jack as his patriotic ensign and[Pg 27] adding to the history of its valiant glory by victory won by himself in defence of his own Canadian home.[7] When in Canada the tri-colour is seen flying it is raised solely out of compliment and courtesy to the French-speaking friends in modern France. The fact that the tri-colour has received any acceptance with the French-speaking Canadian may have arisen from the reason that, side by side with the Union Jack, it had participated in all the struggles and glories of the Crimea, when the two flags, the tri-colour and the Union Jack, were raised together above Sebastopol.

It is interesting to note how it is stated to have first arrived.[8] The Canadiens-Français being, by lineage and temperament, Monarchists, had shown no regard or liking for the early Revolutionary and Republican emblem, and had never raised it in Canada.

In 1853, under Victoria and Napoleon III., an entente cordiale had been established between England and France, and in that same year arrangements had been completed with the Allan Line to build new steamers and perform a regular service direct between Liverpool and Montreal. Actuated, no doubt, by the prevailing fervour, they had selected as the distinguishing, or "house," flag of their line one of the same shape and colours as the French flag, but with the broad bands reversed, the red being next the mast instead of the blue as in the French ensign.

In the spring of 1854, as their first steamer was[Pg 28] seen entering the St. Lawrence, this flag so nearly resembled the French ensign as to cause surprise to be expressed. "What," said the older heads, "the flag of the Revolution on an English ship!" It was a novel sight, but great were the rejoicings over the establishment of the new line.

Their second ship came in dressed with many French and English flags, for war had been declared by the alliance of England and France against Russia, this being the first announcement in Canada, for there were no telegraph cables in those days.

Following this came the exploits of the allied armies in the Crimea, bringing with them the consequent profusion and intertwining of the English and French flags with which ships and business buildings were decorated to celebrate their combined victories.

Such was the entry of the tri-colour into Canada, not being introduced by the Canadians, speaking French, but by their English friends.

A quaint suggestion has been made to the writer by no less an authority than Sir James Le Moine, the historian of Quebec: "The French Canadian is very partial to display, but is primarily economical. While the simple colours of the tri-colour can be conveniently made by the most inexperienced, the details of the Union Jack are very difficult to cut and to correctly sew together. The bonne mère can easily provide out of her household treasures the materials for the one, but she must purchase the other, and this, therefore, is the reason why the tri-colour is so frequently seen in French-speaking Quebec."

The tri-colour, having never been the flag of his[Pg 29] forefathers, carries neither allegiance nor loyalty to the French Canadian. His people have never fought under it, while many a gallant French Canadian son has poured out his blood for the Union Jack at home in defence of Canada or upon foreign shores in service in the British armies. It has never brought him liberty or protection as has his Union Jack, which has been his British flag for a century and a half, and for more than a quarter of a century before the tri-colour of the European French ever came into existence.

Another flag—although it has ceased to be a national flag, and is now the flag of a possession of the United States—should yet be mentioned by reason of the history which was told in its folds.

The Hawaiian national ensign (5) was at first composed of nine horizontal stripes of equal width, alternating white, red and blue, the top stripe being white and the bottom blue.[9]

Afterwards the lowest stripe was taken off and the new flag (Pl. II. , fig. 4) adopted, in which there are eight stripes, the bottom stripe being red and the British Union Jack placed in the upper corner.

The Sandwich Islands, made known to the world mainly by the tragic death of Captain Cook, in 1778, and now known as the Hawaiian Islands, had been fused into a single monarchy by the impetuous valour of King Kamehama, who, in 1794, admitted Christian missionaries to his kingdom. Its existence as an independent monarchy was thereafter maintained and was recognized by the great powers.

Internal difficulties having arisen in the kingdom and an insult been given to a British consul, the islands were ceded and the sovereignty offered to Great Britain in 1843, when, on 12th February, the Union Jack was raised on all the islands, the understanding being that the natives were to be under the protection of the flag of Great Britain, and internal order to be guaranteed pending the final disposition which might be arrived at in England between the representatives of the Hawaiians and the British Government.[10]

The British did not accept the proffered transfer of the islands, but returned the sovereignty to the native government, which was thereafter to continue as an independent monarchy under the protection of Great Britain; and by an accompanying treaty all British manufactures and produce were to be admitted duty free. On July 31st, 1843, the British flag was lowered and the new Hawaiian ensign raised[Pg 31] in its place.[11] It was in recognition of this event that the Union Jack was placed in the Hawaiian ensign.

In the same year France and England agreed never to take possession of the islands either by protectorate or in any other form.

The natives steadily decreased in number and in power, and the trade and commerce of the islands had passed almost entirely into American hands.

Dissensions had afterwards arisen under the subsequent native sovereigns, and in 1893 the Queen, Liliuokalani, was deposed by a revolution, and a republican government formed under President Dole, an American citizen.

Cession of the islands was offered in 1896 to the American Government and was refused, but in 1898 the islands were finally annexed to the United States and the American ensign raised; but the Hawaiian flag, with its Union Jack in the upper corner, continued as a local flag, and was so displayed on June 14th, 1900, at the inauguration of President Dole as Governor of the new-formed "Territory of Hawaii," among the Territories of the United States.

These instances of the origin of some of the national flags of other nations show how history is interwoven in their folds, and how they perpetuate the memories of past days or of the men who have dominated vital occasions. A singularly similar origin is associated with the creation of the Stars and Stripes, the ensign of the United States of North America (Pl. VI. , fig. 3), which is treated of in Chapter XVI.

THE ORIGIN OF THE JACKS.

It is quite evident, then, that national flags are not merely a haphazard patchwork of coloured bunting, nor by any means "meaningless things." Their combinations have a history, and, in many cases, tell a story; but of all the national flags there is none that bears upon its folds so interesting a story, nor has its history so plainly written in its parts and colourings, as has our British "Union Jack."

Our present enterprise is to search out whence it got its name, how it was built up into its present form, and what is the meaning of each of its several parts. This is not only an enquiry of deepest interest, but is of practical and educational value, for to trace the story of the successive combinations of our national flags is to follow the history of the British race.

The flags of other nations have mostly derived their origin from association with some dominant personage, or with a particular epoch. They are, as a rule, the signal of a dynasty or the record of some revolution; but our British Union Jack records in its folds the steady and continuous growth of a great nation, and traces, by the changes made in it during centuries of adventure and progress, and by the flags in which it has been successively combined, the[Pg 33] gradual extension of its union and methods of Constitutional Government over a world-wide Empire.

The origin of the name "Union Jack" has given rise to considerable conjecture and much interesting surmise; in the proclamation of Charles I., 1634, it is called the "Union Flagge"; in the treaty of peace made with the Dutch in 1674, in the reign of Charles II., it is mentioned as "His Majesty of Great Britain's flag or Jack," and in the proclamation of Queen Anne, in 1707, as "Our Jack, commonly called the Union Jack."

The most generally quoted suggestion given for the origin of the name is that it was acquired from the fact that the first proclamation which authorized a flag, in which the national crosses of England and Scotland were for the first time combined, was issued by James VI. of Scotland, after he had become James I. of England, and that as King James frequently signed his name in the French manner as "Jacques," this was abbreviated into "Jac," and thus his new flag came to be called a "Jack."

The derivation suggested is ingenious and interesting, but cannot be accepted as correct, for the simple reason that there were "Jacks" long before the time and reign of James I., and that their prior origin may be clearly traced.

In the earliest days of chivalry, long before the time of the Norman conquest of England, both the knights on horseback and the men on foot of the armies in the field wore a surcoat or "Jacque" (whence our word "Jacket"), extending over the body from the neck to the thighs, bearing upon it the[Pg 34] blazon or sign either of their lord or of their nationality. Numberless examples of these are to be seen in early illuminated manuscripts, or on monuments erected in many cathedrals and sanctuaries.

In the time of the Crusaders, during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, when the Christian nations of Europe were combined together to rescue Jerusalem and the Holy Land from the rule of the Mohammedan, the warrior pilgrims, recruited from the different countries, wore crosses of different shapes and colours upon their surcoats, to indicate the nationalities to which they belonged, and to evidence the holy cause in which they were engaged. It was from wearing these crosses that they gained their name of "Crusaders," or cross-bearers.

The cross worn by each of the nationalities was of a different colour—that of France being red; Flanders, green; Germany, black, and Italy, yellow.

In the earlier crusades the cross worn by the English was white, but in later expeditions the red cross of St. George was adopted and worn upon the Jacque as the sign of the English, in the same way as shown in the accompanying knightly figure (6).

The continuing use of this St. George cross, and the reason for wearing it as an identification of English forces is well shown in the following extracts from the "Ordnaunces," issued to the army with which Richard II. of England invaded Scotland in 1386:

"... Also that everi man of what estate, condicion or nation thei be of, so that he be of oure partie, bere a signe of the[Pg 35][Pg 36] armes of Saint George, large, bothe before and behynde upon parell, that yf he be slayne or wounded to deth, he that has so doon to hym shall not be putte to deth for defaulte of the crosse that he lacketh, and that non enemy do here the same token or crosse of Saint George, notwithstanding yf he be prisoner upon payne of deth."[12]

A fuller understanding is afforded of the character of this "parell," as also of the early adoption of its name by references to it given in 1415:

"At those days the yoemen had their lymmes at lybertie, and their jackes were longe and easy to shote in."[13]

The sailors of the "Cinque Ports" of Hastings, Sandwich, Hythe, Romney and Dover, on the east of England, to which Winchelsea and Rye were subsequently added, and by whose municipalities, in consideration of certain privileges granted them, the royal navies were in early days principally manned, are recorded to have worn as their uniform, in 1513, "a cote of whyte cotyn, with a red crosse and the armes of ye Ports underneathe."

In the time of Queen Mary the continuation of the custom is further evidenced by entries in a contemporary diary of 1588:

"... The x day of January hevy news came to London that the French had won Cales (Calais), the whyche was the[Pg 37] hevest tydings to England that ever was herd of.

"The xj day of January the Cete of London took up a thousand men and made them whytt cotes and red crosses and every ward of London found men.

"The xviij day of May there was sent to the shyppes men in whytt cotes and red crosses, and gones to the Queen's shyppes."[14]

These "surcoats" or "Jacques" came in time to be known as the "Jacks" of the various nationalities they represented, and it was from the raising of one of these upon a lance or staff at the bow of a ship, in order that the nationality of those on board might be made known, that a single flag bearing on it only the cross of St. George, or the cross of St. Andrew, came to be known as a "Jack." From this origin, too, the small flag-pole at the bow of a ship is still called the "Jack-staff," and similarly the short flag-pole at the stern of vessels, upon which the distinguishing Ensign of the nationality of the ship is displayed, is called the "Ensign-staff."

This custom of wearing the national Jack at the bow had not only been early established by usage, but had also been officially recognized. On the great seal of the first Lord Admiral of England, in 1409, under Henry IV., a one-masted galley is shown.[15] At the stern of the ship is the Royal Standard of the King, and at the bow a staff bearing on it the square banner or Jack of St. George, the sign of England.

Another instance of the use of these national Jacks as a sign of national union is to be noted.

During the feudal period of European history, when armed forces were called into the field, each of the nobles and leaders, as in duty bound, furnished to the cause his quota of men equipped with complete armament. These troops bore upon their arms and banners the heraldic device or coat-of-arms of their own liege lord, as a sign of "the company to which they belonged"; and in such way the particular locality from which they came, and the leadership under which they were marshalled could at once be recognized.

The Sovereigns also in their turn displayed the banner of the kingdom over which each reigned, such as the fleur-de-lis for France, the cross of St. George for England, the cross of St. Andrew for Scotland; and this banner of the king formed the ensign under which the combined forces of the royal adherents and their supporters served.

As the forces collected together came to be more the national army of the nation and less the personal adherents of their chief, it was provided in England that the liege lord of each local force should bear on his banner the cross of St. George, as well as his own coat-of-arms, the ordinance being:

"Every Standard, or Guydhome, is to hang in the chiefe the crosse of St. George and to conteyne the crest or supporter and devise of the owner."[16]

An excellent example of this is given in the standard or ensign of the forces of the Earls of Percy in the sixteenth century (Pl. III. , fig. 1). In the chief is the red cross of St. George, as the sign of allegiance to King and nation; in the fly is the crest of the Percys, a blue lion with other insignia, and their motto, "Esperance en Dieu," the signs of their liege lord and local country.

This flag declared its bearers to be the men of the Percy contingent, Englishmen, and soldiers of the King.

A survival of this ancient custom exists to this day in our British military service, both in the Colonial and Imperial forces. Rifle regiments do not carry "colours," but all infantry regiments are entitled,[Pg 40] upon receiving the royal warrant, to carry two flags, which are called "Colours" (7).

The "First," or "King's Colour," is the plain "Union Jack," in sign of allegiance to the Sovereign, and upon this, in the centre, is the number or designation of the regiment, surmounted by a royal crown. The "Second," or "Regimental Colour," has a small Union Jack in the upper corner. The body of the flag is of the local colour of the facings of the regiment. If the facings are blue, as in all "Royal" regiments, the flag is blue; if they are white, then the flag is white, having on it a large St. George's cross in addition to the small Union Jack in the upper corner. On the body of this colour are embroidered the regimental badge, the names of actions in which it has taken part, and any distinctive emblems indicating the special history of the regiment itself, and in territorial regiments the locality from which they are recruited. In this way both the national and local methods of distinction are to-day preserved and displayed in the same way as they were in original times; the Union Jack of the present day having been substituted for the St. George's cross of the first period.

Such, then, was the origin of the name Jack, and it is from the combination of the three national "Jacks" of England, Scotland and Ireland, at successive periods in their history, into one flag, that the well-known "Union Jack" of our British nation has gradually grown into its present form.

THE ENGLISH JACK.

A.D. 1194-1606.

The original leader and dominant partner in the three kingdoms, which have been the cradle of the British race throughout the world, was England, and it is her flag which forms the groundwork upon which our Union Flag has been built up.

The English Jack (Pl I. , fig. 1) is described in simple language as a white flag having upon it a plain red cross.

This is the banner of St. George (8), the patron saint of England, and in heraldic language is described as "Argent, a cross gules" (on silver-white a plain red cross).

The great Christian hero, St. George, is stated by those who have made most intimate search into his legend and history[17] to have been descended from a noble Cappadocian Christian family, and to have been beheaded for his faith on the 23rd April, A.D.[Pg 42] 303, during the persecution of the Christians by the Emperor Diocletian. The anniversary of that day is for that reason celebrated as St. George's Day. He was a soldier of highest renown, a knight of purest honour, and many exploits of his heroism and courage are narrated in ancient prose and poetry.

About three miles north along the shore of the Mediterranean, from the city of Beyrut (Beyrout), there was in the time of the Crusaders, and still remains, an ancient grotto cut into the rock, and famous as being the traditional place where the gallant knight St. George,

was reputed to have performed one of his most doughty deeds, and had "redeemed the King's daughter out of the fiery jaws of a dreadful dragon.[19]

The memory of St. George has always been greatly revered in the East, particularly by the Christian Greek Church, by which he was acclaimed as the "Victorious One," the "Champion Knight of Christendom," and early accepted as the protector saint of soldiers and sailors. One of the first churches erected by Constantine the Great, about A.D. 313, and many other Eastern churches, were dedicated to him.

It is to be noted, however, that St. George has never been canonized by the Roman Church, nor his name placed in her calendar of sacred saints. His name, like those of St. Christopher, St. Sebastian and[Pg 43] St. Nicholas, was only included in a list issued in A.D. 494, by Pope Gelasius, as being among those "whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose actions are known only to God.[20]

The form of his cross is that known as the Greek Cross, the four arms being at right angles to each other, and in this form is displayed in the upper corner of the national Greek ensign, in this case as a white cross on a blue ground. (Pl II., fig. 3.)

This Greek religious connection has also caused the adoption of the cross of St. George in the insignia of other nations. The Czar of Russia is not only the "Autocrat of the People of the Empire of all the Russias," but he is also the "Supreme Head of the Orthodox Faith," which in Russia is represented by the Greek Church. His Imperial Standard is a yellow flag upon which is displayed a black two-headed eagle bearing upon its breast a red shield on which is emblazoned in white the figure of St. George slaying a dragon. This same colouring, white on red, is followed in the decoration of the Order of St. George, which is the second order of knighthood in Russia, and in the white cross of St. George, as shown in the official flags of the Russian ambassadors.

On the royal arms of Austria the black two-headed eagle bears on its breast a shield with a red ground having on it a white St. George's cross.

The insignia of eight nations bear the Greek cross of the St. George shape, but in four different colours on grounds of three different colours:

| Greece | a | white | cross | on a | blue | ground. |

| Russia | a | " | " | " | red | " |

| Austria | a | " | " | " | " | " |

| Denmark | a | " | " | " | " | " |

| Switzerland | a | " | " | " | " | " |

| Norway | a | blue | " | " | " | " |

| Sweden | a | yellow | " | " | blue | " |

| England | a | red | " | " | white | " |

England is, however, the only nation which has adopted the Red cross of St. George as its special national ensign.

The cry of "St. George for Merrie England" has re-echoed through so many centuries that his place as the patron saint of the kingdom is firmly established. Wherever ships have sailed, there the red cross of St. George has been carried by the sailor-nation who chose him as their hero.

The incident from which came his adoption as patron saint is thus narrated in the early chronicles. In 1190, Richard I., Cœur de Lion, of England, had joined the French, Germans and Franks in the third great crusade to the Holy Land; but while the other nations proceeded overland to the seat of war, Richard built and engaged a great fleet, in which he conveyed his English troops to Palestine by sea. His armament consisted of "254 talle shippes and about three score galliots." Sailing down the eastern shore with these and arriving off the coast, he won a gallant sea-fight over the Saracens near Beyrut, and the grotto of St. George, and by this victory intercepted the reinforcements which their ships were carrying to the[Pg 45] relief of Acre, at that time being besieged by the combined armies of the Crusaders.

St. George, the redresser of wrongs, the protector of women, the model of Christian chivalry, and the tutelary saint of England, was not a seafaring hero, nor himself connected with the sea, but it was after and in memory of their sailors' victory near the scene of his exploits that the seafaring nation adopted him as their patron saint.

The red cross emblem of St. George is stated by the chroniclers to have been at once thereafter adopted by Richard I., who immediately placed himself and his army under the especial protection of the Saint, raised his banner at their head, and is reported to have introduced the emblem into England itself after his return in 1194. Further evidence of its introduction and its continued use is given by the record that in 1222 St. George's Day was ordered to be kept as a holiday in England.[21]

Some aver that the emblem was not generally accepted until under Edward I., in 1274. This prince, before his accession to the throne, had served in the last Crusades, and during that time had visited the scene of the victory and the grotto of the Saint. It is pointed out that this visit of Prince Edward to Palestine coincided with the change made in their badge by the English Order of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem from an eight-pointed Maltese cross to a straight white Greek cross, and that at the time of this change came the appearance upon the English banners of the St. George's cross, but of the[Pg 46] English national colour red,[22] therefore they deduce that the further employment of the emblem as the national flag was then additionally authorized by Edward I.

From this last date (1274) onward the St. George's cross and the legend of "St. George and the Dragon" in England are, at all events, in plain evidence. An early instance is that found in the borough of Lyme[Pg 47] Regis, in Dorset, to which Edward I., in 1284, granted its first charter of incorporation and its official seal. A photo reproduction of a wax impression of this borough seal (9), taken from an old "Toll lease" is here given. The flag of St. George is seen at the mast-head, and below it the Royal Standard of Richard I., with its three lions for England, carried by Edward in Palestine during the lifetime of his father. At the bow of the ship is the figure of the Saint represented in the act of slaying the dragon, and having on his shield the St. George's cross.

The religious and Christian attributes of St. George are commemorated on the seal by the representation of the Crucifixion and by the Saint, the head of whose spear is a St. George's cross, being shown as in angel form. The sea tradition of his adoption is also sustained by the characteristic introduction of the "galley" into the design.

Around the edge of the seal is the rude lettering of the inscription in Latin: "Sigillum: Comune: De: Lim" ("The common seal of Lyme"). Near the top may be seen the "star and crescent" badge[Pg 48] of Richard I., adopted by him as a record of his naval victory, and which is still used as an "admiralty badge" upon the epaulettes of admirals of the British navy.

This seal of Lyme Regis is said to be the earliest representation of St. George and the dragon known in England.

The same form of cross was placed by Edward I., in 1294, upon the monumental crosses which he raised at Cheapside, Charing Cross and other places, in memory of his loved Queen Eleanor, to mark the spots at which her body rested during the funeral procession when her remains were carried from Lincoln through Northampton to London.

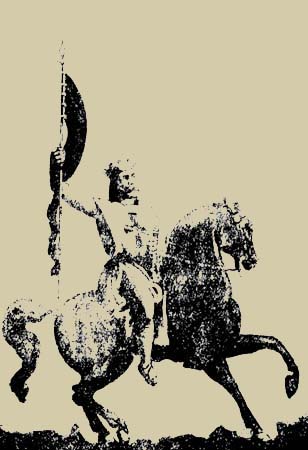

Another instance of a later date is found on a "sepulchral brass" (10), placed to the memory of Sir Hugh Hastings in Elsing Church, Norfolk, and dated 1347.

These plates of engraved brass, inserted in the stone coverings of so many graves in the interior of the churches in England, are most interesting examples of early memorial art. The figure of the deceased is usually drawn in full length upon them in lines cut deeply into the metal, and is accompanied by an inscription setting forth his deeds and his name.

In the upper part of the architectural tracery surrounding the figure on the brass in question is a circle 8-1/4 inches in diameter, in which the figure of St. George is as shown. The Saint here appears as a knight, clad in full armour and mounted upon horseback, representing him in his character as the leader of chivalry and knightly manhood. A further de[Pg 49]velopment of the attribute of manly vigour will be noted in that, instead of being shown as piercing, as previously, the fiery dragon of the ancient legend, he is now represented as slaying the equally typical two-legged demon of vice. This representation still further exemplifies the teaching and allegory of the emblem of "St. George and the Dragon."

St. George represents the Principle of Good, the Dragon the Principle of Evil. It is the contest be[Pg 50]tween virtue and vice, in which the knight by his virtues prevails—a splendid emblem for a Christian people.

This photo reproduction is from a "rubbing" in black lead recently taken from the brass, and shows, so far as the reduced scale will permit, the St. George's crosses upon the surcoat and shield of the knight and the trappings of his horse.

In 1350, on St. George's Day, the "most noble Order of the Garter" was instituted by Edward III., with magnificent ceremony in the St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle. This is the highest order of knighthood in the kingdom. Its jewel, called "The George," is a representation of St. George and the Dragon, and in the centre of the "Star" of the Order is the red cross of St. George.

So onward through all the centuries, and now St. George is the acclaimed patron saint of England and all Englishmen.

It was under this red cross banner of St. George that Richard I., the Lion-hearted, after proving their seamanship in victory and giving his men their battle-cry, "Saint George—forward!"[24] showed the mettle of his English Crusaders in the battles of the Holy Land, and led them to the walls of Jerusalem. With it the fleets of Edward I. claimed and maintained the "lordship of the Narrow Seas." Under this single red cross flag the ships of England won the epochal naval victory of Sluys, where the English bowman shot his feathered shafts from shipboard as blithely as when afterwards on land the[Pg 51] French battlefields resounded to the cry of "England and St. George," when the undying glories of Cressy and Poictiers were achieved, and again at Agincourt when Henry V. led on his men to victory. Under it, too, Cabot discovered Cape Breton, Drake sailed around the world, Frobisher sought the Northwest passage, Raleigh founded Virginia, and the navy of Elizabeth carried confusion into the ill-fated Spanish Armada.

This is a "glory roll" which justifies the name of England as "Mistress of the Seas." Her patron saint was won as a record of naval victory. With this red cross flag of St. George flying above them, her English sailors swept the seas around their white-cliffed coasts, and made the ships of all other nations do obeisance to it. With it they penetrated distant oceans, and planted it on previously unknown lands as signs of the sovereignty of their king, making the power of England and England's flag known throughout the circle of the world.

All this was done before the time when the sister-nations had joined their flags with hers, and it is a just tribute to the seafaring prowess of the English people, and to the victories won by the English Jack, that the single St. George's cross is in the British fleets the Admiral's Flag, and flies as his badge of rank; that it is in the Command Pennant of all captains and officers in command of ships, and that the English red cross flag is the groundwork of the White Ensign of the British navy (Pl. VIII., fig. 2). This is the "distinction flag" of the British navy, allowed to be carried only by His Majesty's ships-of-war, and[Pg 52] restricted, except by special grant, solely to those bearing the Royal commission.[25]

Thus has the memory of Richard I. and his men been preserved, and all honour done to the "Mariners of England," the sons of St. George, whose single red cross flag, the English Jack, has worthily won the poet's praise:

THE SUPREMACY OF THE ENGLISH JACK.

A.D. 871-1606.

While it is true that flags and banners had grown up on land from the necessity of having some means of identifying the knights and nobles, whose faces were encased and hidden from sight within their helmets, yet it was at sea that they attained to their greatest estimation. There the flag upon the mast became the ensign of the nation to which the vessel belonged, and formed the very embodiment of its power. To fly the flag was an act of defiance, to lower it an evidence of submission, and thus the motions of these little coloured cloths at sea became of highest importance.

The supremacy of one nation over another was measured most readily by the precedence which its flag received from the ships of other nationalities. National pride, therefore, became involved in the question of the supremacy of the flag at sea, and in this contest the English were not behindhand in taking their share, for the supremacy of the sea meant to England something more than the mere precedence of her flag. It meant that no other power should be allowed to surpass her as a naval power; not that she desired to carry strife against their coun[Pg 54]tries, but esteemed it more for the protection of her own shores at home, and the preservation of peace along the confines of her island seas.

This faith in the maintenance of the Supremacy of the Seas remains potent to this present day, as is shown by the demand of the British people that their navy shall be maintained at a two-power standard, and so be equal in strength to the navies of any other two of the nations which sail the oceans. It is no new ardour, nor the outcome of any modern development or exigency, but is the outgrowth of the determination of the nation from its earliest days to maintain the supremacy of its flag, and is strengthened by the lessons learned in those centuries.

Alfred the Great of England (871-901) was the first to establish any supremacy for the English flag, and to him is attributed the first gathering together of a Royal navy, the creation of an efficient force at sea being a portion of that sea-policy which he so early declared, and which has ever since been the ruling guide of the English people. The true defence of England lay, Alfred considered, in maintaining a fleet at sea of sufficient power to stretch out afar, rather than in trusting to fortifications for effective land resistance when the enemy had reached her shores; that it was better to beat the enemy at sea before he has a chance to land, and thus to forestall invasion before it came too near—a policy which in these days of steam is simply being reproduced by the creation of "Dreadnoughts," swift and strong, to hit hard on distant seas. The bulwarks of England were considered in his time, as they are still considered, to[Pg 55] be her ships at sea rather than the parapets of her forts on land.

Introducing galleys longer and faster than those of the Danes,[28] Alfred kept his enemies at a respectful distance, and, dwelling secure under the protection of his fleet, was thus enabled to devote himself with untrammelled energy to the establishment of the internal government of his kingdom.

His successors followed up his ideas, and under Athelstane (901) the creation of an English merchant navy was also developed. Every inducement was offered to merchants who should engage in maritime ventures. Among other decrees then made was one that, "if a merchant so thrives that he pass thrice over the wide seas in his own craft he was henceforth a Thane righte worthie."[29] Thus honours were to be won as well as wealth, and in pursuit of both the merchants of England extended their energies to wider traffic on the seas.

King Edgar (973-75), by virtue of his navy, won and assumed the title of "Supreme Lord and Governor of the Ocean lying around about Britain." Thus did the English flag, carried by its navies, sail the seas. But Harold, the last of the Saxon kings, instead of maintaining his ships in equipment and fitness to protect his shores, allowed them, for want of adequate[Pg 56] provisions, to be dispersed from their station behind the Isle of Wight, and so, forgetting the teachings of Alfred, left his southern coasts unguarded and let the Norman invader have opportunity to land, an opportunity which was promptly seized.

The Norman monarchs of England held in their turn to the supremacy which the early Saxon kings had claimed for her flag at sea.

When the conquest of England, in 1066, had been completely effected by the Norman forces, the shores on each side of the "narrow seas" between England and Normandy were combined under the rule of William the Conqueror, communication by water increased between the two portions of his realm, and the maritime interests of the people were greatly extended and established.

Richard I. showed England to the other nations, during the Crusades, as a strong maritime power. King John followed in his footsteps, and in 1200, the second year of his reign, issued his declaration directing that ships of all other nations must honour his Royal flag:

"If any lieutenant of the King's fleet in any naval expedition, do meet with on the sea any ship or vessels, laden or unladen, that will not vail and lower their sails at the command of the Lieutenant of the King or the King's Admiral, but shall fight with them of the fleet, such, if taken, shall be reported as enemies, and the vessels and goods shall be seized and forfeited as the goods of enemies."

The supremacy which King John thus claimed, his successors afterwards maintained and extended, so that under Edward I., Spain, Germany, Holland, Denmark, and Norway, being all the other nations, except France, which bordered on the adjacent seas, joined in according to England "possession of the sovereignty of the English seas and the Isles therein,"[30] together with admission of the right which the English had of maintaining sovereign guard over these seas, and over all the ships of other Dominions, as well as their own, which might be passing through them.

Edward II. was given, in 1320, the title of "Lord of the Seas."[31]

Edward III., himself a sailor-king and commander of his fleets, was fully imbued with the force of the Alfred maxim, so that when invasion threatened England he said, "he deemed it better with a strong hand to go seek the enemy in his own country than wait ignobly at home for the threatened danger."[32] Putting his maxim into action he led his fleet across the Channel, and his victory over the French fleet at Sluys, off Flanders, on the 24th June, 1340, was the Trafalgar of its day, and the resulting supremacy of the English Jack on the narrow seas enabled him to land his forces on the foreign shores, when he subsequently invaded France to establish his claim to the French throne.

The prowess of himself and of his seamen in their[Pg 58] victory over the French and Spanish fleets won for Edward the proud title of "King of the Seas," in token of which he was represented upon his gold coinage standing in a ship "full royally apparelled."[33]

During the Wars of the Roses less attention was given by the nation to maritime matters, and while the English were so busily engaged in fighting amongst themselves, the Dutch of the Netherlands, under the Duke of Burgundy, developed a large carrying trade, and so increased their fleets that, in 1485, at the accession of Henry VII., they had become a formidable shipping rival of England, and were a thorn in the side of France. Over the ships of the French the Dutch so lorded it on the narrow seas that, to quote Philip de Commines, their

"navy was so mighty and strong, that no man durst stir in these narrow seas for fear of it making war upon the King of France's subjects and threatening them everywhere."

Two flags, the striped standard of the Dutch and the red cross Jack of the English, were now rivalling each other on the adjacent seas and on the Atlantic. The contest for the supremacy which had begun was continued for nearly two hundred years thereafter.

In the time of Henry VII. more attention was given to merchant shipping and foreign adventure. Cabot carried the English flag across the Atlantic under the license which he and his associates received from Henry VII., empowering them

"to seek out and find whatsoever isles, countries, regions, or provinces of the heathen and infidels, whatsoever they might be; and set up his banner on every isle or mainland by them newly found."

With this authority for its exploits the red cross of St. George was planted, in 1497, on the shores of Newfoundland and Florida, and the English Jack thus first carried into America formed the foundation for the subsequent British claim to sovereignty over all the intervening coasts along the Atlantic.

Under Henry VIII. England began to bestir herself in making provision for a regular navy. A drawing in the Pepysian Library gives the details of the Henri Grace à Dieu (11), built in 1515 by order of Henry VIII., which was the greatest warship up to that time built in England, and has been termed the "parent of the British Navy." At the four mastheads fly St. George's ensigns, and from the bowsprit end and from each of the round tops upon the lower masts are long streamers with the St. George's cross, very similar in form to the naval pennants of the present day. The castellated building at the bow, and the hooks with which the yards are armed, tell of the derivation of the nautical terms "forecastle" and "yard arm" still in use.

With such improved armament the cross of St. George continued to ruffle its way on the narrow seas, and widened the scope of its domain.

The supremacy claimed for the English Jack never lost anything at the hands of its bearers, and an event which occurred in the reign of Queen Mary gives a[Pg 60] vivid picture of the boldness of the sea-dogs by whom it was carried, and of how they held their own over any rival craft:

(From the Pepysian collection.)

The Spanish fleet, of one hundred and sixty sail, was escorting Philip II., of Spain, when coming to his marriage with the English Queen, in 1554. It was met off Southampton by the English fleet, of twenty-eight sail, under Lord William Howard, who was then "Lord High Admiral in the narrow seas." The Spanish fleet, with their King on board, was fly[Pg 61]ing the Royal flag of Spain, and was proceeding to pass the English ships without paying the customary honours. The English admiral promptly fired a shot into the Spanish admiral's ship, and the whole fleet was obliged to strike their colours and lower their topsails in homage to the English flag. Not until this salute had been properly done would Howard permit his own squadron to salute the Spanish King.[34]

Under Elizabeth seamanship mightily increased. Her merchant fleets, from being mere coasters, extended their ventures to far distant voyages, in some of which the Queen herself was said to have had an interest; and while before her time soldiers had exceeded seamen in numbers, the positions were now reversed.

The defeat of the Spanish Armada, in 1588, was one of the crowning achievements of the supremacy of the English Jack, yet it would almost seem as though the glorious flag had, in the never-to-be-forgotten action of the undaunted Revenge, kept for the closing years of its single cross period the grandest of all the many strifes in which it had been engaged.

England and Spain were then at open war. The English fleet, consisting of six Queen's ships, six victuallers of London, and two or three pinnaces, was riding at anchor near the island of Flores, in the Azores, waiting for the coming of the Spanish fleet, which was expected to pass on its way from the West Indies, where it had wintered the preceding year. On the 1st September, 1591, the enemy came in sight,[Pg 62] numbering fifty-three sail, "the first time since the great Armada that the King of Spain had shown himself so strong at sea."[35]

The English had been refitting their equipment, the sick had all been sent on shore, and their ships were not in readiness to meet so overwhelming an armament. On the approach of the Spaniards, and to save the fleet from being penned in by them along the coast, five of the English ships slipped their cables, and together with the consorts sailed out to sea. Sir Richard Grenville, in the Revenge, was left behind to collect the men on shore and bring off the sick, and so, after having done this duty, came out alone to meet the enemy, which was marshalled in long extended line outside the port. He might have sailed around their wing, but this would have been an admission of inferiority, and, bold to recklessness, he thrust his little ship right through the centre of their line. Rather than strike his flag, he withstood the onset of all the Spanish fleet, which closed in succession around him, and thus this century of the red cross Jack closed with a sea-fight worthy of its story, and one which has been preserved by a Poet Laureate in undying verse, whose lines ought to be known by every British boy:

In such way, audacious in victory and unconquered in defeat, the English sailors, beneath their English Jack, held for the mastery of the oceans from Alfred to Elizabeth, and laid the foundations of that maritime spirit which still holds for Great Britain the proud supremacy of the seas.

THE SCOTTISH JACK.

From a very early period St. Andrew has been esteemed as the patron saint of Scotland, and held in veneration quite as strong as that entertained in England for St. George. The "saltire," or diagonal cross of St. Andrew (12), shaped like the letter X is attributed to the tradition that the saint, considering himself unworthy to be crucified on a cross of the same shape as that on which his Saviour had suffered, had, by his own choice, been crucified with legs and arms extended upon a cross of this shape, and, therefore, it has been accepted as the emblem of his martyrdom.

The "Scottish Jack" (Pl I., fig. 2) is a white oblong cross upon a blue ground. This is the banner of St. Andrew (12), and in heraldic language is described as "Azure, a saltire argent" (on azure blue, a silver-white saltire).

How St. Andrew came to be adopted as the patron saint of Scotland is a subject of much varying conjecture. It is said that in the early centuries, about A.D. 370, some relics of the apostle St. Andrew were[Pg 65] being brought to Scotland by some Greek monks, and although the vessel carrying them was wrecked and became a total loss, the sacred bones were brought safe to shore at the port in the County of Fife, still called St. Andrews, where a church was erected to his memory.

The most favoured tradition as to the date of his authorized adoption as a patron saint is that it occurred in A.D. 987, when Hungus, king of the Picts, was being attacked by Athelstane, the king of the West Saxons,[37] Achaius, king of the Scots, with 10,000 of his Scottish subjects, came to the relief of Hungus, and the two kings joined their forces to repel the Southern invaders. The Scottish leaders, face to face with so formidable a foe, were passing the night in prayer to God and St. Andrew, when upon the background of the blue sky there appeared, formed in white clouds, the figure of the white cross of the martyr saint. Reanimated by this answering sign, the Scottish soldiers entered the fray with enthusiastic valour, and beset the English with such ardour as to drive them in confusion from the field, leaving their king, Athelstane, behind them dead among the slain. Since that time the white saltire cross, upon a blue ground, the banner of St. Andrew, has been carried by the Scots as their national ensign.