Title: The History of the Fifty-ninth Regiment Illinois Volunteers

Author: David Lathrop

Release date: May 1, 2014 [eBook #45558]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

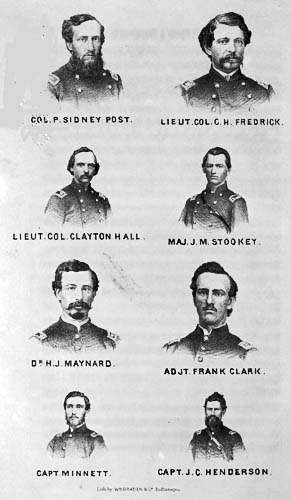

| COL. P. SIDNEY POST. | LIEUT. COL. C. H. FREDRICK. |

| LIEUT. COL. CLAYTON HALL. | MAJ. J. M. STOOKEY. |

| DR. H. J. MAYNARD. | ADJT. FRANK CLARK. |

| CAPT. MINNETT. | CAPT. J. C. HENDERSON. |

| Lith. by Wm. BRADEN & Co. Indianapolis. | |

BY DR. D. LATHROP.

HALL & HUTCHINSON,

PRINTERS AND BINDERS, INDIANAPOLIS, IND.

1865.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight

hundred and sixty-five,

BY DR. DAVID LATHROP,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States, for

the District of Indiana.

HALL & HUTCHINSON, STEREOTYPERS, PRINTERS AND BINDERS.

Early in the month of May, 1861, C. H. Frederick and David McGibbon, two prominent citizens of St. Louis, Mo., called on General Lyon, and proffered to raise a regiment of infantry, to serve for three years, or during the war. C. H. Frederick, having previously served his country in a military capacity, and being familiar with military tactics, was deemed by General Lyon, a very suitable person to engage in the undertaking, and immediately authorized to recruit and organize a regiment, and to have command of the same.

Colonel Frederick, at the breaking out of the rebellion, was engaged in a lucrative business in St. Louis, but at the call of his country he sacrificed his profitable interests, and gave his energies to the preservation of the Union. After an immense amount of difficulty, Colonel Frederick and his co-worker, Major McGibbon, working night and day, succeeded in enlisting enough loyal friends in and around St. Louis, to enable them to accomplish their purpose. By the middle of June three companies, and a nucleus of the fourth, was collected and rendezvoused at the St. Louis arsenal. Captains Hale, Renfrew, Veatch, and Elliott commanding.

About this time Captain S. W. Kelly was induced to become a recruiting officer, to assist in filling up the regiment. By the 24th of June he had recruited seventy men in his own neighborhood, and on that day an election was held, and S. W. Kelly was unanimously elected Captain, John Kelly First Lieutenant, and H. J. Maynard Second Lieutenant. On the 6th day of August, 1861, Captain Kelly numbered on the muster roll of his company, (F,) at the St. Louis Arsenal, seventy-one men; and through his influence three other companies had joined in the organization of the regiment. Captain Stookey, of Belleville, Ill., had recruited a large company of men for the service, and was now induced to join this regiment, thus making nine companies in rendezvous at the Arsenal on the 6th day of August.

As soon as the first three companies were formed, and before they were uniformed, they were sent down to Cape Girardeau, Mo., that place being threatened by the enemy, to assist in building fortifications. As soon as the next three companies were mustered in, and before they were uniformed, they were ordered to Pilot Knob, Mo. Here they underwent great hardship, not having uniforms or blankets, and scarcely anything to make them comfortable. The other three companies on their arrival at St. Louis, were sent with Colonel Frederick up the South-west branch of the Pacific railroad, to protect the bridges, etc., in order to keep that road open for the retreat of General Lyon's army after their defeat at Wilson's Creek, Mo. This work being accomplished, Colonel Frederick returned to St. Louis, and after overcoming many difficulties succeeded in getting the nine companies back to the arsenal. The next thing to be done, was to have them uniformed and drilled. This, also, was perseveringly and successfully attended to by the Colonel and Major McGibbon.

The men and the officers with one or two exceptions, were sadly deficient in a knowledge of military tactics or drills, and Colonel Frederick consequently took upon himself the task of drilling the regiment daily. In a short space of time he succeeded in making them quite well acquainted with company and battalion drills.

About the 1st of September 1861, Colonel Frederick and Major McGibbon, in order to promote the welfare of the regiment and secure good to the Union cause, tendered the command to Captain J. C. Kelton, then A.A.G. for General Fremont. Captain Kelton, after a time, accepted the command with the proviso that Frederick should have the Lieut. Colonelcy, and McGibbon the Majority. This arrangement was speedily confirmed by an election of the officers of the regiment, and the organization became complete,—one company only being required to make a full regiment. Upon Colonel Kelton assuming command, he procured the Tenth Company, viz. Company K, Captain Snyder, of Chicago, Ills., commanding, and this completed the Ninth Missouri, Volunteer Regiment.

Company K, was organized in the city of Chicago in the month of September, 1861. A majority of the men were recruited by Lieutenant Abram J. Davids. It was originally intended as a company of sappers and miners, to be attached to Bissell's Engineer Regiment of the West. At least that was the inducement held out to the men. On the 5th of September the company was not quite full, and its services being needed immediately, forty-five men were taken from the Forty-Second Illinois, (then organizing at Chicago), and enrolled with the company on its muster into service on the 6th day of September, making an aggregate of ninety-seven men. Their camp equipage was drawn on the night of the 6th, and on the morning of the 7th marched under the command of Captain Henry N. Snyder, to the Chicago, Alton and St. Louis depot, and took the cars for St. Louis. They arrived at Illinoistown the evening of the same day, and in the morning crossed the Mississippi, and marched through St. Louis to Benton barracks; they here learned that they were to be attached to the Ninth Regiment Missouri Volunteer Infantry. It caused considerable dissatisfaction in the company, not that they had any objection to the regiment, but they wished to enter the arm of service for which they were recruited. Notwithstanding, there was no disobedience of orders.

On the 2d of September they were armed with Harper's Ferry rifles, and well equipped throughout; no company in the service ever started out better supplied with ordnance and camp equipage. On the afternoon of the 22d of September they left Benton barracks, marched to the depot, and took the cars en route for Jefferson City, where they arrived the next evening. They joined the Ninth Missouri on the following morning, and embarked with them on the steamer War Eagle, September 30th, bound for Boonville.

On the 22d of September, 1861, the regiment was ordered to Jefferson City, Mo., and on the 26th again ordered to Boonville, Mo. After remaining in camp a short time, Colonel Kelton was placed in command of a brigade, under General Pope. The brigade consisted of the Ninth Missouri, Lieut. Colonel Frederick, commanding; Thirty-Seventh Illinois, Colonel Julius White, commanding, and the Fifth Iowa, Colonel Worthington, commanding.

While at the St. Louis Arsenal, two companies under the command of Lieut. Colonel C. H. Frederick, were sent by Colonel F. P. Blair, up the Mississippi river to Howell's Island, where he captured five valuable steamboats from the hands of the rebels, who were about to use them to cross their forces to the south side, to join the rebel General Price. The total value of property thus secured from the hands of the rebels, amounted to two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. He also skirmished over the island in search of a rebel camp, and by this movement it was effectually broken up. Those two companies were composed of picked men from the different companies of the regiment.

HISTORY OF THE FIFTY-NINTH REGIMENT,

ILLINOIS VOLUNTEER INFANTRY.

The Fifty Ninth Illinois Regiment entered the service of the United States, on the 6th day of September, 1861, under the cognomen of Ninth Missouri, at St. Louis, in that State. At that time the State of Illinois had filled her quota of volunteers, and would not receive the services of the patriotic young men who had collected themselves together for the purpose of preserving the glorious Union, then in danger of being severed.

The call of the President for seventy-five thousand volunteers, as well as that for forty-two thousand, had been so speedily filled by men whose business engagements, and perhaps entire want of business, permitted to enter the service without much sacrifice on their part, excluded, for the time being, these noble men from entering the service in the name of their own State. Although disappointed, they were still determined to devote their services to their country in some useful field of labor. Missouri was the most convenient and available State for this purpose, and was willing to accept of their aid, and hence the companies were organized into the Ninth Regiment of Missouri Volunteers, on the 6th of September, 1861.

General Fremont was in command of the department of Missouri, and as soon as the regiment was fully equipped, he ordered that it should report to General Pope, at Jefferson City, Mo. In the best of spirits the men left the old barracks and marched to the river for embarkation. The old and rickety steamer War Eagle lay in waiting, with steam up, to receive them. A very pleasant and lively time was passed in going up, and on their arrival at Jefferson City, a pretty camping ground received them, to await further orders. Here the regiment lay in camp until the 30th of September, when they were again embarked for farther up the river.

At Jefferson City the regiment was joined by a pioneer company of ninety-seven men, and by a squad of twenty men recruited by Captain Kelly, of Company F, who fell into ranks as the regiment was re-embarking on the same old War Eagle, for "up the river."

The embarkation of a regiment, was, at that early day of the war, an exciting scene. Never before had such scenes been witnessed by the citizens of our inland river towns, nor had the men of the regiment ever before exhibited themselves to the gaze of the populace in such a display as they now did. The regiment was first marched in column down to the wharf, and ordered to stack arms. Then, as the way was open, one company at a time was marched to the boat and took quarters as directed. The quarters of each soldier consisted of just room enough to stand, or sit upon his knapsack on the floor, selected somewhere within the region of his own company. The regiment as it marched to the landing, to the time of the fife and drum, attracted the notice of the whole city. Its appearance was really captivating. The uniform being all new and unsoiled, and consisting of a closely fitting jacket of fine gray cloth, and pants of the same material, looked exceedingly neat and pleasing to the eye, and their knapsacks, cartridge boxes and guns, all new, and glistering in the sunshine, caused a sensation indescribable. No regiment has ever entered the service with more éclat than the Ninth Missouri. The men, wagons, horses and mules, all being huddled indiscriminately on board, the bell rang, and the old boat steamed up the turbid Missouri. During the night the boat rounded to at Boonville, Mo., and the regiment went into camp here for fourteen days, for the purpose of collecting supplies and fitting up for a campaign into the interior.

Boonville is a pretty town, of perhaps one thousand inhabitants, and is situated on the right bank of the Missouri River. It seems to be quite a flourishing place, and has something of an inland trade. The country in the vicinity is good and under good cultivation, and the improvements on the adjoining farms are excellent. The land is considerably broken, but very productive. It is a most splendid fruit country. No country in the world can produce larger and finer apples and peaches, than that around Boonville, as the soldiers of the Ninth can testify. It is also a fine grape region and can boast of many fine vineyards. Wine is made here to some extent, as the Ninth can also testify, for they had the pleasure of tasting some of it, as well as having plenty of fruit while in camp here. A majority of the citizens are professedly friends to the cause of the Union, and are disposed to treat the soldier kindly and with hospitality, so long, at least, as the Union army is in the neighborhood. There are some who turn the cold shoulder and show a disposition to insult and annoyance, but they are more numerous in the country than in town, and this is more to our liking than otherwise; for it is but little we need from the citizens in town, but from the country we need mules, horses and forage, and confiscation is now the order of the day.

As soon as the regiment had comfortably arranged camp, a detail was made to go into the country prospecting for contraband stock. There were twelve or fifteen wagons to each regiment to be furnished with mules or horses, at the rate of six to a team. The boys were not many days in finding stock enough to supply the demand, and in doing so they found some amusement for themselves, and received many deep and bitter curses from the owners of the stock.

Some four miles down the river, lived a wealthy old rebel sympathizer, who possessed several mules and some fine horses, which the boys took a fancy to, and concluded they must have. The old gentleman stubbornly refused to give them up, and made threats to shoot any one who attempted to interfere with his property. The prospecting party were too few in number to catch the mules and bring them off, so they started one of their number to camp after reinforcements, while the others remained to guard the stock, and amuse the old secesh with some of their Union arguments. The old man, at first, seemed very uneasy, but after a time quieted himself so as to apparently enjoy the society of the boys very much. Thus time passed until night approached, and supper was announced. The boys partook of the bounties of the table, and again engaged the old gentleman in conversation, and thus the hours went by till bed time. An invitation to retire was proffered them, which they politely refused, preferring rather to bunk it on the floor, where they were, than to indulge the luxury of sheets and feathers. If the old gentleman entertained any suspicions of roguery on the part of the boys, he gave no indications of the fact, but quietly wished them a good night's rest, and withdrew to his own apartment for the night. About three in the morning, the reinforcements arrived from camp, and quietly proceeded to let out and drive the mules off to town, while the boys on guard bridled and saddled four good horses and joined the detachment. Early in the morning, the old farmer presented himself to Colonel Kelton with his complaints. Patiently the Colonel listened to him, and then gave him vouchers for his confiscated property, to be paid if he should prove himself a faithful, good citizen of the United States. Thus, in the course of ten days, was the wagons all supplied with good teams.

Other preparations for a campaign being nearly completed, the regiment was in daily anticipation of a move. The sick were sent to town to be left at hospital. Dr. H. J. Maynard, First Assistant Surgeon of the regiment, was assigned to the duty of fitting up quarters for their reception, and with energy of purpose and goodness of heart he performed the duty. Fifty of the regiment were unfitted to start on the campaign on account of sickness. There were many cases of measles. This disease had attacked some of the boys at Jefferson City; three of whom were left in hospital there. Many of the cases left in charge of Dr. Maynard, were critical, but by his kind care and good treatment, speedily recovered.

The regiment was now in good condition for a march, and the boys all anxious to try the realities of a campaign. The weather was delightful and the roads good. Price and his army was somewhere in the country, and every one desired to be after him. Drilling had been faithfully practiced since coming to Boonville, and the men began to feel like old soldiers in military tactics, and were confident if they could overtake Price he would be defeated, and the war in Missouri would be speedily terminated. Orders finally came to march, and on the morning of the 12th of October, all was hurry and confusion in preparation for the start. Tents were to be struck and the wagons loaded. Knapsacks were to be packed and comfortably fitted to the back; haversacks to be filled with plenty of rations; wild mules to be caught from the corral and hitched to the wagons; and last, though not least, pretty apple girls and wash women to be settled with before leaving. All was accomplished in due time, and about noon the brigade moved out.

Three regiments composed the brigade: the Ninth Missouri, the Fifth Iowa and the Thirty-seventh Illinois—three as good regiments as ever shouldered a musket. Colonel Kelton was in command of the brigade.

While in camp here, two boys who had joined the regiment at St. Louis, deserted, and were never heard of. Their names are now forgotten, as they should be, and they themselves are now perhaps, if living, no more than wandering vagabonds.

On Sunday, the 12th day of October, 1861, the brigade bid adieu to the attractions and comforts of civilized society, for the long period of three years or during the war. Little did they think, as they marched through the streets of Boonville, that it would require three years of sacrifice for the government of the United States to put down so insignificant a rebellion as that which was now raging through its borders. They doubted not of the ability of our armies now in Missouri, to drive Price from the State, and restore peace in a few months. Their confidence in Fremont, in their own commanders and in themselves was unbounded. Their belief that the rebels would not withstand an equal contest, was well founded and did not diminish their ardor or their hopes of a speedy termination of the rebellion. They looked forward to a campaign of a few months duration, and then to a return to their homes, with peace attending them on the way. But how sadly were they to be disappointed! They supposed the policy upon which the war was to be conducted was fully established, and that all there was to do was to whip out the rebels, who were at this time in arms against them. They did not anticipate that time, as it passed, would develop new schemes and new policies until the whole became entirely revolutionized, and magnified into the most terrible rebellion the world ever witnessed. They did not think that while they were going to battle with the enemy in their front, the Government at Washington was changing its policy, so that instead of one they would have ten rebels to fight, and instead of a six months campaign they would have a five years war. They had read the closing words of the President's inaugural address, to-wit: "Physically speaking, we can not separate. We can not remove our respective sections from each other, nor build an impassable wall between them. A husband and wife may be divorced and go out of the presence and beyond the reach of each other; but the different parts of our country can not do this. They can not but remain face to face; and intercourse, either amicable or hostile, must continue between them. Is it possible, then, to make that intercourse more advantageous or more satisfactory after separation than before? Can aliens make treaties easier than friends can make laws? Can treaties be more faithfully enforced between aliens, than laws can among friends? Suppose you go to war; you can not fight always, and when, after much loss on both sides, and no gain on either, you cease fighting, the identical questions, as to terms of intercourse, are again upon you.

"To the extent of my ability I shall take care, as the Constitution itself expressly enjoins upon me, that the laws of the Union be faithfully executed in all the States. Doing this I deem to be only a simple duty on my part. I shall perfectly perform it, so far as is practicable, unless my rightful masters, the American people, shall withhold the requisition, or, in some authoritative manner, direct the contrary. I trust this will not be regarded as a menace, but only as the declared purpose of the Union, that it will constitutionally defend and maintain itself. In doing this there need be no bloodshed or violence, and there shall be none, unless it is forced upon the national authority. The power confided to me will be used to hold, occupy and possess the property and places belonging to the government, and collect the duties and imports. But beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion—no using of force against or among the people anywhere.

"In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government: while I shall have the most solemn one to preserve, protect and defend it." And they had all confidence in the promises of the President, that the "laws of the Union should be faithfully executed in all the States," and that the power confided to him would be used to "hold, occupy and possess the property and places belonging to the government, and collect the duties and imposts; but beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion—no using of force against or among the people anywhere." And they knew that Congress had voted, for the use of the President, one hundred thousand more men, and one hundred million more dollars than he had requested, to make the contest a short and decisive one," and they knew that that number of men was about "one-tenth, of those, of proper age, within the regions where apparently all are willing to engage," and that the "sum is less than a twenty-third part of the value owned by the men who seem ready to devote the whole." Knowing these things, the members of the Ninth Missouri marched out from Boonville with light hearts and heavy knapsacks, without a murmur. They knew that while they were under Fremont, they were entirely able to destroy every vestige of rebellion in Missouri. Over three hundred thousand soldiers, in other fields, were waiting orders from the Federal government, or were in active service; and that sixty odd vessels, with one thousand one hundred and seventy-four guns, were in commission, and twenty-three steam gun boats were on the stocks rapidly approaching completion, if not already completed. That sixty regiments of Federal troops were encamped near Washington, and that every armory in the land was at work night and day. Knowing all these things, why should they not anticipate a speedy termination to their soldier life, and enjoy in anticipation home society once more? Alas, little did they suppose that they themselves were to be the instruments in the hands of the President to work out the "salvation of the Almighty."

It is said that Governor Yates, of Illinois, telegraphed to the President at a certain time, to "call out one million of men, instead of three hundred thousand, that he might make quick work of the rebellion." The President replied: "Hold on Dick; let's wait and see the salvation of the Almighty." Had the President deemed it policy to have adopted Dick's advice, the rebellion might have been quelled, but perhaps the cause would not have been removed; and our good, honest President has not only been aiming to quell the rebellion, but to remove the cause at the same time. Hence the instrumentality of the army in establishing the policy of the administration. As the army progressed in strength and military discipline, so did the views of the administration and people change in regard to what might be accomplished in the destruction of the casus belli. And hence the "military necessities."

The brigade marched a few miles from town and bivouacked for the night. On the 13th and 14th it marched about twenty-eight miles, and went into camp near Syracuse.

The country is here not so broken as at Boonville, and is under good cultivation, with neat and comfortable farm houses and barns dotting the whole landscape.

The regiment lay in camp here on the 15th, and on the morning of the 16th, struck tents and took up the line of march for the rebel army. Price is reported to be about seventy-five miles to the south-west, erecting fortifications.

Since leaving Boonville, some of those who were indisposed on starting, had become so sick as to be unable to proceed, and were consequently taken to Syracuse, and left there to be disposed of by the Medical Director in charge. From Syracuse they were sent to St. Louis, to the hospital.

When leaving camp, the writer being detained until after the regiment had moved, came across a young man who had laid himself down by the road-side to die, as he said. He was taking the measles and was quite sick. The Surgeon of the regiment, Dr. Hazlett, had overlooked, or been deceived in the appearance of this young man at the morning examination, and had ordered him to march with the regiment. This he was unable to do, and would have been left by the road-side if he had not been accidentally discovered. With some difficulty he was conveyed to Syracuse and left in hospital. The commander of his company was subsequently notified of his death in the St. Louis hospital.

From the 16th to the 23d of October, the regiment continued its line of march daily. It moved in a south-western direction, crossing the Pacific railroad at Otterville.

Otterville is a small town on the railroad, near the right bank of the Lamoine river. It numbers from three to five hundred inhabitants, most of whom are very indifferent to the Union cause. No manifestations of rejoicing were shown on the approach of the noble men who were coming to protect them from the ravages of the rebel army; no stars and stripes were spread to the breeze as they came in sight, but every one manifested a coolness which indicated very distinctly in which direction their sympathies lay.

The country still continues to be very good. The farming lands are here under good cultivation and well improved. The soil is productive, and gives liberally into the hands of the cultivator. Every one seems to be prospering but somewhat discouraged at this time, as Price's army made rather heavy draws on their granaries and larders as he passed through here, and the Union army is now claiming a share of what they have left. There is yet an abundance to supply all demands, and no one need to suffer.

The brigade passes through Otterville without halting, and none but a few stragglers have any thing to say to the citizens, either to aggravate or soothe them. The direction taken is towards Warsaw, on the Osage river, where, it is rumored, Price is entrenching.

The routine of a campaign is now fully commenced. Reveille is sounded at five o'clock in the morning—all hands must then turn out to roll call—breakfast is cooked, and at seven the bugle sounds to fall in for the march. Two hours steady march follows, and then a rest of ten minutes, and thus until twelve or fifteen miles is passed over, when, if wood and water is convenient, camp is selected, tents are pitched, supper is provided, retreat is sounded, and all becomes quiet for the night. Thus it was with the Ninth, until their arrival at Warsaw. There is nothing to enliven the monotony of the march but the lively jokes and sallies of wit of the boys, and the change of scenery through which they pass.

The distance from Otterville to Warsaw, by the roads the regiment moved, is perhaps seventy miles, and the face of the country is considerably variegated. For the most part it is a level, unbroken region until you approach the bluffs of the Osage. The land is however rolling and enough diversified with hills and elevated peaks, to make it interesting to the traveler.

On the 23d of October, the regiment went into camp two miles north of Warsaw, to await the construction of a military bridge across the Osage river. The Osage at this point is about three hundred yards wide, with abrupt high banks and a deep swift current, so that it is impossible to cross an army in any other way than by means of a strong substantial bridge.

On the arrival of the division, as many "sappers and miners" and laborers as could be profitably employed, were set to work, and in forty-eight hours the bridge was ready for crossing. It was a very rude structure, but answered every purpose.

At Warsaw other troops came in from other directions, and swelled the forces which were to cross at this point to quite a large army. Some arrived in the morning before the Ninth, and about ten thousand passed the regiment after it had gone into camp. The weather continues delightful, and regiments coming in and passing, with their bright guns and accoutrements, present a splendid and most cheering spectacle.

There was great disappointment manifested by the troops on their arrival here and finding that Price was still on the wing. Here is where madame rumor had strongly entrenched the rebel army, and the boys had confidently expected to have a battle with him at this point. Their chagrin was great when they learned that he had still two or three weeks the start of them towards Arkansas. They were consoled somewhat by a probability that he might stop at Springfield and give them battle. They now felt that after being reinforced by so vast an army as seemed to have joined them here, they could whip the whole southern confederacy, before breakfast, some bright morning, if it could be found. Although disappointed, they were not discouraged, but were very eager for the pursuit to recommence.

While laying here those who could get passes, and some who could not, went over to town, and spent the day in making observations. Warsaw was the first town the boys had any leisure or opportunity to visit since leaving Boonville, and it was quite a treat for them to chat with the citizens, and partake of their hospitalities. A few of them came back to camp pretty blue,—something besides water having been found in Warsaw,—and a few did not return until the next morning, having found some other attractions to detain them.

Although there was quite a number of men reporting to the surgeon at the morning sick call, there were but few serious cases of disease in the regiment at this time. The seeds of the measles had produced its fruits and disappeared, and now the regiment was comparatively healthy. While laying here, news was received of the death of Johnson Kyle, of Company D, at Jefferson City. He was one of the three left there sick with the Measles, when the regiment started for Boonville. His name heads the list of deaths to be recorded by the regiment, after leaving St. Louis. John Burk, of Co. F, very soon followed him, and occupies the second place in that honored list.

On the morning of the 25th of October, the troops commenced crossing the river, and about 11 o'clock, A.M., the Ninth Missouri landed on the opposite shore, and halted an hour for dinner, and for stragglers to come up from Warsaw. Although orders against straggling was very strict, and the punishment threatened, severe, many of the soldiers fell out of ranks, and slipped off to town.

Warsaw is situated on the left bank of the Osage river, and is the largest town passed through since leaving Boonville. There being no towns of any size within many miles of it, it has quite an extended country trade, and boasts of several large stores and business houses of different kinds. The rebels while here, two weeks since, supplied themselves with goods to a large amount, from two or three Union Stores which were in the town. The merchants and citizens here are still undecided as to which cause they should give their influence. They are all, however, willing to be let alone. No demonstrations of satisfaction or the contrary, was manifested while the army remained here.

At 1 o'clock, the bugle sounded, and the line of march was again taken up and continued until the 30th, when the army went into camp for a day or two, at Humansville. The direction from Warsaw to Humansville, is southward, and the fear of the men now was, that the rebels were making for Arkansas. Rumor again had it that they were fortifying somewhere between here and Springfield, Missouri; but the boys did not credit it. Nothing reliable could be obtained of their whereabouts, and Arkansas appeared to be the most inviting place for a fleeing army. At any rate, it was evident that they had so far, fled as fast as they had been pursued.

The country from the Osage to this point is poor, broken and rocky. It seems as though nature intended this as the stone quarry for the universe. Here is stone enough to supply the United States with building material for centuries. The roads are all stone, the hills are solid rock, and the fields are stone. There is very little tillable lands south of the Osage, until within the vicinity of Humansville. There are a few farms, and occasionally a small town, but they are for the most part deserted. The inhabitants, perhaps, have gone south with Price. Quincy, the largest town on the road, is entirely deserted; the citizens all being rebels.

The only incident of note, during the march from the Osage, to Humansville, was the return to the army of Major White and his Prairie Scouts.

On the 30th of September, Price evacuated Lexington, and commenced a retreat to the south. He left a rebel guard there in charge of some Union prisoners. On the 15th of October, Major White, commanding a squadron of cavalry, called Prairie Scouts, with two and twenty men, made a forced march of nearly sixty miles, surprised Lexington, dispersed the rebels, captured sixty or seventy prisoners, took two steam ferry boats, and some other less valuable articles, secured the Union prisoners left there, and with a rebel captured flag, returned by another route to Warsaw, traveling with neither provisions nor transportation, and joining Fremont's forces south of the Osage. As characteristic of the energy of the men whom Gen. Fremont gathered about him, it is worth narrating, that Major White's horses being unshod, he procured some old iron, called for blacksmiths from the ranks, took possession of two unoccupied blacksmith's shop, and in five days made the shoes and shod all his horses. At another time, the cartridges being spoiled by rain, they procured powder and lead, and turning a carpenter's shop into a cartridge factory, made three thousand cartridges. Such men could march, if necessary, without waiting for army wagons and regular equipments. As the Major and his Prairie Scouts proceeded to Head Quarters, they were greeted with cheer after cheer by the soldiers. The rebel flag, being the first they had seen, was a great curiosity to the boys. In contrast with their own loved stars and stripes, it was an insignificant affair. Its stars and bars elicited the scorn and contempt of every one who saw it. The curses bestowed upon it were not loud, but they were deep and came from the heart.

On the 30th of October, the Brigade went into camp, near Humansville. Humansville, is a small town in Hickory County, Mo., and is the only place where any demonstrations were made, in honor of the stars and stripes, between Boonville and Springfield. Here the soldiers of the Union were welcomed by the waiving of flags and the smiles of the women, and the kindly greetings of the citizens generally. A portion of Price's army had passed through this place, some three weeks before, and had carried off all the goods belonging to the merchants, and had mistreated the inhabitants of the town and vicinity to such a degree, that they were heartily tired of their presence, and were rejoiced at the approach of the Federal troops.

The weather continues pleasant, and an opportunity is here offered the boys to wash up their clothing. This was rather an amusing task, as they had not as yet become accustomed to such work. Fires were started along the branches, and by the use of their camp kettles, they managed to hang out quite a respectable lot of clean army linen. Those having money and not being partial to the washing business, had their washing done by the women of the town, at the rate of ten cents per piece.

When going into camp it was thought that, perhaps, several days would be spent here, to allow the men some rest and to ascertain the distance to, and position of the enemy; but about noon of the 31st, orders came to be ready to march at a moment's notice.

The sick of the regiment, had been increasing for the last ten days, to such an extent, that now there was no means of conveying them any farther. Thus far, they had been transported in wagons, but it was now necessary to select such as could not, in a measure, provide for themselves, and leave them behind. The Surgeon, therefore, fitted up the Meeting-house in town, in the best possible manner, and removed the sick to it. A cook, some nurses, and several days rations, were left with them. Poor fellows! they all nearly starved to death before they could get away, and three did die from the effects of disease and want of proper nourishment. After the army left, the patriotism of the ladies and gentlemen of the town, oozed out at their fingers ends, and our sick boys could get nothing from them. One man, John Clemens, of Co. H, who was very sick when taken there, died on the 4th of November. Bromwell Kitchen, of Co. F, soon followed, and Nathaniel B. Westbrook, of Co. A, died on the 20th. The others eventually found their way to the regiment.

At 4 o'clock orders were received to strike tents and move out. An hour was now spent in busy preparation for the march. No one had thought that there would be a move before morning, and all were taken by surprise at the order to march just as night was setting in. Conjectures flew thick and fast through camp, as to what caused the haste in moving. Some supposed that Price was not far away, and that they were going to surprise him by a night attack. Some supposed one thing and some another, but all was wrapped in uncertainty.

At 6 o'clock, the bugle sounded to fall in, and the first night march of the regiment, now commenced. Camp was one and a half miles west of Humansville, and to get to the main road to Springfield, the regiment had to retrace its march back through the town. When therefore it commenced filing off in the direction it had come, the impression prevailed that they were on the retreat. Retreat! retreat, passed along the line, we are on the retreat—what does this mean, was the general inquiry. As soon, however, as they had passed through town, and struck the Springfield road, they found that they were not retreating, but were continuing their old line of march. This pleased them, and with alacrity they moved forward. The moon had not yet made its appearance, and the evening was quite dark. Several of the boys in going over the rough roads, fell and crippled themselves so as to be unable to proceed. The large stones which composed the road, would sometimes form steps of six inches in height, and in stepping, they would fall forward with serious results. The moon now makes her appearance, bright and fair, and the road becomes distinct so that marching becomes easy, and much more rapid progress is made. The march continued till near morning, when the troops bivouacked for a few hours rest.

The bugle again sounds, and the march is continued. At 12 o'clock, a halt is again called, and an order is brought round to lighten baggage. All extra, useless and heavy baggage is ordered to be left, under guard, until brought forward by the wagon train. This is indicative of a forced march, or a going into battle. The latter is not probable, as no enemy is reported near. At 2 o'clock, the regiment moved out in light equipments.

Shortly after starting, a rumor got afloat that Price was really making a stand at Springfield. This news was received with a shout, and a more rapid movement of the troops. From this time until its arrival at Springfield, the regiment had no other than absolutely needful rest. The nearer the approach to Springfield, the more confirmed became the report of the rebel army being in that vicinity. The regiment having made ten or twelve miles this afternoon, went into camp on the banks of a small creek, which happened to run in the right place for their convenience.

Here an incident occurred which came very near terminating the life of one of the boys. He had gone to the creek to wash, and while there, walked out on a small log which projected from the bank over the water. His weight was too great for the support of the log; it gave way and he fell with his back across a log below him, and his head and shoulders into the water. He was badly hurt, and had there been no assistance near by, he would have drowned. He was unable to march for several days, so as to keep up with the regiment. The march from here to Springfield was uninterrupted, and on the night of the 3d of November, the regiment went into camp within easy distance of Springfield.

On the morning of the 5th, the Ninth Missouri found itself encamped on the out skirts of a large army. Fremont had arrived with the greater portion of his army several days before, and driven Price from Springfield, and was now awaiting for the balance of his forces to come up. The Ninth had marched, in the last two days and nights, over fifty miles, to be in time for the anticipated advance, and they were now rejoiced that they had arrived in due season. A more happy set of men than those of the Ninth Missouri, could not have been found in the army. It had been on the march twenty days, with but little prospect of overtaking the enemy. Now the enemy were before them, and their march was perhaps terminated for the present.

On the approach of General Fremont, Price had fallen back to a chosen position, some ten miles south of Springfield, leaving a garrison of three or four hundred men to hold the place, until he could get thoroughly entrenched in his new position, and to give General McCulloch time to join him from below, with his Texas and Arkansas forces.

General Fremont, in order to disperse this rebel garrison and get possession of the town, directed Major Zagonyi, commandant of General Fremont's body guard, to ride forward with a force of about three hundred, to make a reconnaissance, and, if practicable, capture or disperse the rebels, and take possession of the village. Major Zagonyi was a Hungarian officer, drawn to the western service by the fame of Fremont.

He had himself recruited the body guard which he commanded. It consisted of three companies of carefully picked men, armed with light sabers and revolvers. The first company also carried carbines. One hundred and sixty of this guard, with one hundred and forty of Major White's Prairie Scouts, already spoken of, constituted his force. As he advanced, he learned that the rebel guard had been reinforced, and that over two thousand men were ready to receive him. They had also been warned of his approach, and surprise was impossible. Prudence would have dictated that he return for reinforcements.

But Fremont's body guard had been a subject of much ridicule and abuse. He determined to make good its reputation for valor, at least. Perhaps by attacking the enemy in the rear, he might still secure the benefit of a surprise. This advantage he would gain, if possible. A detour of twelve miles around Springfield brought them to the rebel's position, but upon their south flank.

They were strongly posted just west of the village, on the top of a hill, which sloped toward the west. Immediately in their rear was a thick wood, impenetrable by cavalry. Before they came within sight of the enemy, Zagonyi halted his men. Drawing them up in line, he addressed them in the following brief and nervous words:

"Fellow-soldiers, this is your first battle. For our three hundred, the enemy are two thousand. If any of you are sick or tired by the long march, or if any think the number is too great, now is the time to turn back."

He paused; no one was sick or tired. "We must not retreat," he continued. "Our honor, and the honor of our General, and of our country, tell us to go on. I will lead you. We have been called holiday soldiers for the pavements of St. Louis. To-day we will show that we are soldiers for the battle. Your watchword shall be 'Fremont and the Union!' Draw saber! By the right flank—quick trot—march!"

With that shout—"Fremont and the Union!"—upon their lips, their horses pressed into a quick gallop, they turn the corner which brings them in sight of the foe. There is no surprise. In line of battle, protected in the rear by a wood which no cavalry can enter, the rebels stand, forewarned, ready to receive the charge. There is no time to delay—none to draw back. In a moment they have reached the foot of the hill. The rebel fire sweeps over their heads. The Prairie Scouts, by a misunderstanding of orders, become separated from their companions, and fail to join them again. Up the steep hill the hundred and sixty men press upon the two thousand of their foe. Seven guard horses fell upon a space not more than twenty feet square. But nothing can check their wild enthusiasm. They break through the rebel line. They drive the infantry back into the woods. They scatter the hostile cavalry on this side, and on that. They pursue the flying rebels down the hill again, and through the streets of the village.

It seems incredible, yet it is sober history—not romance; in less than three minutes, that body-guard of a hundred and sixty men had utterly routed and scattered an enemy twenty-two hundred strong. Planting the Union flag upon the court house, they retire as night set in, that they may not be surprised in the darkness by new rebel forces. Their loss was sixteen killed and twenty eight wounded, out of the whole three hundred.

This has been pronounced an unnecessary sacrifice. The charge, it is said, was ill judged. But the bravery surely merits the highest commendation, and the success sanctifies the judgment of Zagonyi, which directed the assault. Moreover, we needed the example of this chivalrous dash and daring, to wake up some of our too cautious generals, and to inspire that enthusiasm and that confidence of success, which are essential to great accomplishments. For let it not be forgotten, that this was an expedition, which, in its ultimate results, was designed to sweep the Mississippi to the Gulf.

The ladies of Springfield, thus redeemed from rebel marauders, requested permission to present to their heroic deliver a Union flag. Will it be believed? When this body-guard returned to St. Louis, by peremptory orders from Washington, it was disbanded; the officers retired from service, and the men were denied rations and forage. It was deemed inexpedient that a corps should exist, so enthusiastically devoted to their chivalrous leader. In the order which came for their disbanding, they were condemned for "words spoken at Springfield." Condemned for that war-cry, which inspired to as glorious a charge as was ever made on battle field, "Fremont and the Union."

Zagonyi, in his official report of the battle, says: "Their war-cry, 'Fremont and the Union,' broke forth like thunder. Half of my command charged upon the infantry, and the remainder upon the cavalry, breaking their line at every point. The infantry retired into the thick wood, where it was impossible to follow them. The cavalry fled in all directions through the town. I rallied and charged through the streets, in all directions, about twenty times, returning at last to the court house, where I raised the flag of one of my companies, liberated the prisoners, and united my men, who now amounted to seventy, the rest being scattered or lost.

"From the beginning to the end, the body-guard behaved with the utmost coolness. I have seen battles and cavalry charges before; but I never imagined that a body of men could endure and accomplish so much in the face of such fearful disadvantage. At the cry of 'Fremont and the Union,' which was raised at every charge, they dashed forward repeatedly in perfect order, and with resistless energy. Many of my officers, non-commissioned officers and privates, had three, or even four horses killed under them. Many performed acts of heroism; not one but did his whole duty."

On the 29th of October, General Fremont established his head-quarters at Springfield. From Boonville to Springfield he had invariably marched with the advance of his army. On the 30th, General Ashboth brought up his division, and General Lane, on the same day, appeared with his brigade of Kansas border men, and two hundred mounted Indians and negroes. And on the 2d and 3d of November, General Pope brought up the rear with his command, of which the Ninth Missouri formed a part.

Since leaving Humansville, the health of the regiment continued good. Nearly all the men had been able to march up with the regiment. Those who gave out on the way were given passes by the Surgeon to fall back on the train and ride on the wagons. At this time there was but one ambulance allowed to each regiment, and this was used principally by the Surgeon for his own convenience, to the exclusion of the sick and disabled.

Ambulances had been provided, to move in the rear of the regiments on a march, and to attend them in time of battle for the purpose of transporting those who became disabled on the march, and for hauling the wounded from the battle field; but the Surgeons did not seem to understand it in that light. They took it for granted that ambulances were an especial comfort provided for themselves, and appropriated them accordingly. Many an anxious look is cast at the lazy Doctor, riding in the ambulance, by the sick, sore-footed soldier. Many a sick, weary and worn-out soldier is allowed to fall by the wayside, or to climb on the top of a loaded lumbering old army wagon, and ride with the hot sun pouring his ardent rays upon him, until night, or until the march is ended; while the healthy, robust Surgeon takes his ease in the closely covered and nicely cushioned ambulance.

The Surgeon is allowed two horses for his especial use, and now his lackey, detailed from the ranks, is riding one and leading the other behind the ambulance. The Surgeon has ridden on horse back during the cool of the morning, but now the heat is too oppressive and he retires to the shade of the vehicles, leaving his fat, sleek and magnificently caparisoned charger to be cared for by the unmanly soldier, who prefers being a lackey to wearing the honor and manhood of the man in the ranks.

The staff officers, and those of the line also, are allowed by government eleven dollars per month to pay servants for attending them, but as a general rule, they manage to get a soldier from the ranks to do their work, at the expense of the government, and put the eleven dollars into their own pockets. There are some men who scorn to stoop to such trickery; but it is a notable fact, that there are many, wearing the insignia of high official stations, who take advantage of their oath for the pitiful sum of eleven dollars per month. And it is also a fact, that there are men who have voluntarily taken upon themselves an oath to serve their country as good soldiers, who willingly allow themselves to be placed upon a footing with the veriest colored slaves in the land. The language is not too harsh. A soldier has been seen washing the feet and trimming the toe-nails of his captain, and this not only once, but habitually. The appellation given to him, and those of his calling, was "Toe-Pick."

On the morning of the 5th the regiment moved quarters to within a mile of town, and pitched their tents in regular camp order. The whole country for miles around Springfield was now filled with tents, and soldiers were as thick as ants on an ant hill. The whole army of Fremont was now here, and was said to number seventy-two thousand—or, there was said to be seventy-two thousand rations issued. A more noble looking set of men were never gathered into an army. Filled with enthusiasm and confidence in their leader, this army could not have been defeated by any rebel force brought against it. The men were very anxious for a forward move toward the enemy, and rumor had it that in a day or two the enemy would be met. But, alas! for human calculations. No movement was at this time to be made against the foe; but, instead, an inglorious retreat. Shame, and deathless infamy, attend the instigators of the retrograde movement of this splendid army.

On the 2d day of November General Fremont received notice of his recall to St. Louis to answer charges preferred against him, and of his being superseded in his command by General Hunter. Why was this retrograde movement to be made? Why was General Fremont removed from the command at this most auspicious moment? "Not until the secret political history of the rebellion, which unmasks hearts and exhibits motives, shall be written, can these questions be fully answered."

As soon as the intelligence that General Fremont was superseded by General Hunter spread through the camp, the wildest excitement everywhere prevailed. "Officers and men organized themselves into indignation meetings. Large numbers of officers declared their determination to resign. Whole companies threw down their arms."

General Fremont consecrated all his personal influence, entreating the men to remain, like true patriots, at their posts. He sent immediately to General Hunter the intelligence of his appointment, and, without delay, issued the following beautiful and effective appeal to the army:

"Head-Quarters Western Dep't.,

"Springfield, Mo., Nov. 2d, 1861.

"Soldiers of the Mississippi Army:—Agreeably to orders this day received I take leave of you. Although our army has been of sudden growth, we have grown up together, and I have become familiar with the brave and generous spirits which you bring to the defense of your country, and which makes me anticipate for you a brilliant career. Continue as you have begun, and give to my successor the same cordial and enthusiastic support with which you have encouraged me. Emulate the splendid example which you have already before you, and let me remain, as I am, proud of the noble army which I had thus far labored to bring together. Soldiers, I regret to leave you. Most sincerely I thank you for the regard and confidence you have invariably shown to me. I deeply regret that I shall not have the honor to lead you to the victory which you are just about to win; but I shall claim to share with you in the joy of every triumph, and trust always to be fraternally remembered by my companions in arms.

"J. C. FREMONT,

"Major-General U.S.A."

In the evening, one hundred and ten officers, including every brigadier-general in the army, visited General Fremont in a body. They presented him a written address, full of sympathy and respect, and earnestly urged him to lead them against the enemy. General Fremont replied to the address, that, if General Hunter did not arrive before morning, he would comply with their request. At eight o'clock in the evening he accordingly issued the order of battle. The enemy occupied the same ground as that which they had occupied in the battle of Wilson's Creek. General Lyon's plan of attack was to be substantially followed.

The rebels were to be surrounded. Generals Sigel and Lane were to assail them in the rear, General Ashboth from the east, Generals McKinstry and Pope in front. The attack was to be simultaneous. Every camp was astir with the inspiriting news. Every soldier was full of enthusiasm.

But at midnight General Hunter arrived. General Fremont informed him of the condition of affairs, advised him of his plans, and surrendered the command into his hands. The order for battle was forthwith countermanded, and orders were issued to the army to prepare to turn their backs upon the foe, and retrace their march to St. Louis. The next morning General Fremont and his staff left the camp. As he passed along the soldiers crowded the streets and the roadsides to witness his departure, and, as they returned to their quarters, each one asked himself the question: "Why has Fremont been removed?" No ground for his removal had ever been made known. It was suggested that he was too extravagant in the financial management of his department. But there was no more justice in charging him with extravagance than there would have been any other General in command of a department. "Wherever there is carrion the vultures flock." Wherever there is an opportunity for public plunder corrupt men greedily gather. They abounded in Washington, in New York, in St. Louis; but no definite charges could be made that General Fremont ever participated in any scheme to defraud the Government. The mystery lay in the fact that General Fremont was far in advance of the nation's representatives, either in the field or cabinet. "He realized that the rebels were in earnest. He realized that all attempts at pacification by timidity and concessions to traitors were unavailing, and would but add fuel to the flame. He realized that the only way to stop rebellion was to chastise rebels with the rod of justice." And, realizing these things, he issued the following proclamation, which gave great offense to the more timid officials:

"Head-Quarters Western Dep't.

"St. Louis, Mo., August 31st, 1861.

"Circumstances, in my judgment, of sufficient urgency, render it necessary that the Commanding General of this Department should assume the administrative powers of the State. Its disorganized condition, the helplessness of the civil authority, the total insecurity of life, and the devastation of property by bands of murderers and marauders, who infest nearly every county in the State, and avail themselves of the public misfortunes and the vicinity of a hostile force, to gratify private and neighborhood vengeance, and who find an enemy wherever they find plunder,—finally demand the severest measures to repress the daily increasing crimes and outrages, which are driving off the inhabitants and ruining the State. In this condition, the public safety and the success of our armies require unity of purpose, without let or hindrance, to the prompt administration of affairs.

"In order, therefore, to suppress disorder, to maintain, as far as now practicable, the public peace, and to give security and protection to the persons and property of loyal citizens, I do hereby extend, and declare established, martial law throughout the State of Missouri. The lines of the army of occupation in this State are, for the present, declared to extend from Leavenworth, by way of the posts of Jefferson City, Rolla and Ironton, to Cape Girardeau, on the Mississippi River. All persons who shall be taken with arms in their hands within these lines shall be tried by court martial, and, if found guilty, will be shot. The property, real and personal, of all persons in the State of Missouri who shall take up arms against the United States, and who shall be directly proven to have taken active part with their enemies in the field, is declared to be confiscated to the public use; and their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared free men.

"All persons who shall be proven to have destroyed, after the publication of this order, railroad tracks, bridges or telegraphs, shall suffer the extreme penalty of the law. All persons engaged in treasonable correspondence, in giving or procuring aid to the enemies of the United States, in fomenting tumult, in disturbing the public tranquility, by creating and circulating false reports or incendiary documents, are in their own interest warned that they are exposing themselves to sudden and sure punishment.

"All persons who have been led away from their allegiance are required to return to their homes forthwith; any such absence without sufficient cause will be held to be presumptive evidence against them.

"The object of this declaration is to place in the hands of the military authorities the power to give instantaneous effect to existing laws, and to supply such deficiencies as the conditions of war demand. But it is not intended to suspend the ordinary tribunals of the country, where the law will be administered by the civil officers in the usual manner, and with their customary authority, while the same can be peaceably exercised.

"The Commanding General will labor vigilantly for the public welfare, and in his efforts for their safety, hopes to obtain not only the acquiescence but the active support of the loyal people of the country.

"J. C. FREMONT,

"Major-General Commanding."

"An out-cry from all pro-slavery partisans, in all parts of the country, went up against the man who had first dared to proclaim liberty to the slaves of rebels." A demand was made for his removal. Fair means were not alone used for this end. The most strenuous efforts were secretly made to undermine him in the confidence of the Administration, and by bitter public attacks through the press to rob him of the confidence of the people. And success attended those efforts.

The President, whose duty it was to hold a controlling influence in the councils of the nation, coincided with this intriguing faction against his better judgment, and submitted to this great injustice—injustice both to Fremont and the country. The proclamation of General Fremont was accordingly modified, and Fremont himself deprived of his command.

On the reception of the President's letter, requesting him to modify his proclamation, Fremont replied:

"If," said he, "your better judgment decides that I was wrong in the article respecting the liberation of slaves, I have to ask that you will openly direct me to make the correction. The implied censure will be received as a soldier always should receive the reprimand of his chief. If I were to retract of my own accord it would imply that I myself thought it wrong, and that I had acted without the reflection which the gravity of the point demanded. But I did not. I acted with full deliberation, and with the certain conviction that it was a measure right and necessary, and I think so still."

General Fremont submitted to the modification, which was to confine the confiscation and liberation of only such slaves as had been actually employed by the rebels in military service. If they worked the guns they were to be free. If they only raised the cotton which enabled the rebels to buy the guns they were not to be free, but to be returned to their masters if they should escape to our lines in search of freedom. But this did not satisfy those who were even more anxious to treat the rebels with conciliation and have Fremont removed and his influence destroyed, than to strike the rebellion with heavy blows. Let Fremont be removed at all hazards. He was removed, and his army was recalled from Springfield, and in less than six months another army under General Curtis, pursuing the same plan which General Fremont had formed, and governed by the very policy recommended in his proclamation, marched over the same ground, under much more adverse circumstances, and met the enemy only after a tedious pursuit of one hundred and twenty miles farther off than the fall before.

On the morning of the 4th of November Abraham C. Coats, of Company C, was brought into the regimental hospital in an entirely unconscious condition. He was taken in the night with what was supposed to be a congestive chill. Every means known to the Surgeon was resorted to to restore him to consciousness and preserve his life, but all were unavailing. He never spoke after being brought in, and died about noon of the next day. A post mortem examination revealed nothing to indicate the cause of his death.

Several of the boys were taken sick while in camp here, and when the regiment marched they were loaded into an army wagon to be transported to wherever the regiment might be destined. One of these died in the wagon the second night after leaving Springfield and was buried by the roadside. The others, after eight days' torture, arrived, more dead than alive, at Syracuse, where they remained in hospital all winter.

On the morning of the 9th of November, with sad hearts and elongated countenances, the Ninth Missouri Volunteers took up the line of march, which they had so lately spun out in such glorious anticipations, to wind it back to the very place from whence they had started one month before.

The weather still continued fine, but the roads had become so awful dusty, that suffocation threatened to be the fate of every one who traveled them. There had been no rain since leaving Boonville. Water was becoming scarce, excepting in the larger streams; although Missouri is usually abundantly supplied with that refreshing element. Abundant crystal streams of purest water; springs bubbling from many a creviced rock and wells of unfailing depths, are met with every where in southern Missouri.

The regiment followed its old line of march, until after crossing the Osage, when it took the most direct road to Otterville. From Otterville it continued down the railroad to Syracuse, where it arrived on the 17th of November, having marched from Springfield in eight days, without rest. In its devious course from Boonville to Springfield, and from Springfield to Syracuse, the regiment had marched over three hundred miles.

On arriving at Syracuse, it bivouacked on a common in town, in anticipation of taking the cars in a day or two for St. Louis. Rumor had it, that the troops were all going to St. Louis, either to go into winter quarters or to be sent South. No one thought of wintering at Syracuse.

There was no enemy within one hundred and fifty miles of this place, and a necessity for stopping here did not exist. Yet, in this vicinity were they destined to lay in idleness for three long months.

As the regiment passed Warsaw, on its return, some of the boys, who had learned the working of the wires on their previous visit, again slipped from the ranks and succeeded in getting their canteens filled with the ardent. Two of these, on coming into camp just in the dusk of the evening, caused quite a sensation. They had been "hale fellows well met," until whisky had got advantage of their better judgment, when they agreed to disagree, and the one using the breech of his gun, as the strongest argument he could think of, knocked the other over the head with so severe a blow as to cause insensibility. A crowd was soon collected, and the belligerent one was placed under guard, while the defunct was hurried to the hospital, to be placed in hands of the Surgeon. On examination, the Surgeon discovered something of a cut on the scalp, which was bleeding pretty freely; and having a little too much of the ardent in his own hat to see single, he pronounced the man mortally wounded, with a fractured skull.

After having the bruise dressed, the Surgeon retired to his own quarters, leaving the impression that the man would not live through the night; in fact he gave it as his opinion, that he was in articuls mortis at this moment.

The commander of the regiment placed the one who gave the death-blow, under double guard, binding his hands and feet so as there should be no possibility of escape. By and by all retired to their quarters, and none, except the guard and the watchers by the side of the dying man, were awake in camp. The man lay very quiet until about eleven o'clock, when he was observed to draw a very heavy and prolonged inspiration. Soon another followed, and his eyes opened. For a moment they wandered restlessly over the tent, and then he sprung to his feet.

"Well! where the hell am I? What does this mean? Say, what is the meaning of this? Is this the hospital? How is it that I am here? I'm not sick. There is nothing the matter with me; where is my quarters, say, I am not going to stay here, that's certain!" and off he started like a quarter horse for his company.

The mystery was, that he was very much intoxicated when he was hit, and the blow only set him into a most profound drunken slumber. Early the next morning the Colonel released the prisoner, and the Surgeon passed the joke in good spirits, although his reputation in prognosis was somewhat impaired by the incident.

On the arrival of the regiment at Syracuse it was discovered that about fifty of the men were on the sick list. Some were quite sick from the effects of the continued jolting they had suffered in the wagons, while others were only worn down by hard marching.

The Surgeon immediately took possession of the Planter House, a deserted hotel in town, and established his hospital in it. Straw was procured, and the men were as comfortably placed upon it over the floor as circumstances would admit.

On the morning of the 18th the regiment was moved out two miles from town, and went into regular camp.

As the men were marching through the town the rain descended in torrents, wetting them thoroughly. This was the first rain seen since leaving Boonville, and was received in high glee.

Visions of St. Louis now began to grow dim in the eyes of some of the men, although many still believed that they were only waiting transportation. The Surgeon delayed, from day to day, making any provisions for the comfort of the sick, expecting orders to ship them for St. Louis. But orders never came, and it became a fixed fact that the regiment was to winter here.

Newspapers were brought to Syracuse daily, and something of what was going on in the world could be learned from them. During the last month a newspaper had not been seen in the regiment. Some of the officers would occasionally get a paper, but the soldiers never. From these it was ascertained that the war was still progressing, and that the rebellion was assuming a magnitude of unexpected dimensions.

Many of the soldiers were led to believe, by their withdrawal from Springfield, that their services would not much longer be required in the field, and that they would soon be allowed to go home, but on reading the papers they lay aside all such pleasing ideas.

The weather was now becoming quite cool, and tents were more carefully pitched than usual—ditches were dug, and embankments thrown up, to keep the cold winds from blowing in under them. Good warm blankets were issued, and a new suit of clothing provided, so that, so far as possible, suffering might be prevented. Plenty of wood was provided, and on cold days large fires were burning in front of every tent. At night pans of living coals were taken into the tents as substitutes for stoves. Thus they managed to keep quite comfortable. Army rations were in abundance, and the citizens were liberal in their supply of cakes, pies and apples, at a moderate compensation, and sometimes without any pay whatever. Occasionally one would come into camp more greedy of gain than his neighbor, or, perhaps, tinctured a little with secession proclivities; in such cases "confiscation" was the word, and his load would soon disappear, without his being any the richer.

The sick men, who were left at Boonville under the care of Doctor Maynard, now joined the regiment. Without an exception, the kind care and judicious treatment of this excellent Surgeon had restored all to good health, and they joined the regiment in good spirits, and were welcomed most cordially by their comrades.

About the 10th of December the regiment broke camp here and moved out to the bottoms of the Lamoine river. The object of the move was the erection of fortifications for the defense of the railroad bridge across the Lamoine. Their camp was selected on some swamp-bottom lands on the left bank of the river. The boys were immediately set to work cutting the trees and cleaning off the grounds, while details were sent off to work on the fortifications on the opposite bank of the river.

On the morning of the 14th marching orders were issued for the next day, and on the 15th, through a heavy snow storm, they marched to Sedalia, twenty-five miles distant. The roads were bad, and the marching very heavy, yet most of the men came into camp with the regiment. They were marched out for the purpose of cutting off recruits and a large supply train going to Price's army. When they arrived at Sedalia the work was being accomplished by another portion of the Division. A part of Davis' Division had taken another route, and had succeeded in overtaking and capturing some seventy wagons and one thousand one hundred prisoners, among whom was the son of the old General. The Ninth Missouri consequently had nothing to do but march back to its camp on the Lamoine. This it was two days in accomplishing. Thus marching fifty miles in three days. Thus making in all, since leaving Boonville, fully four hundred miles. Here the regiment remained until the 25th of January, 1862.

When the regiment removed from Syracuse to the Lamoine, the Surgeon, Doctor Hazlett, went with them, leaving sixty sick men at Syracuse in charge of the Hospital Steward, without having made any preparations yet for their comfort. The building was very well calculated for an hospital, but needed renovating very badly, and should have had bunks built for the patients to lay on; but nothing of the kind had been attended to; and now, to attend to the wants of sixty sick men, only one nurse, one cook and the Steward, were to be had. Many of the men were desperately sick, and should have had better care taken of them; but, fortunately, only two cases proved fatal after the Surgeon left—Henry Rue, of Company F, on the 1st day of January, 1862, and John Rule, of Company D, on the 28th of the same month. Two also died while the Surgeon was in attendance—Boston Cherrington, of Company A, and McClenning, of Company E. At the Lamoine, Phillip Shindola, of Company B, James Edwards, Company C, George W. Lewis and William St. George, Company B, and William S. Gore, Company F, were taken sick, and died in January, 1862.

The living at the Hospital consisted of beef, pilot-bread, sugar and coffee or tea.

There was an hospital fund of money, accumulated by the commutation of rations belonging to sick men; but, as with the ambulances, the Surgeons are sometimes dishonest enough to appropriate this fund to their own use. The cooking facilities about the hospital consisted in a camp-kettle, (holding about five gallons,) for coffee or tea, and one of the same size for boiling beef, and a log fire out of doors. With these facilities the cook prepared the rations for sixty sick soldiers for over two months, rain, snow or shine, as the case might be.

The manner of feeding the patients was thus: The kettle of coffee and soup is brought into the center of the room where the sick are, and tin-cups are filled and handed round, and a "shingle" (pilot cracker) is handed at the same time, with a piece of boiled beef on it. If the patient has had money he has perhaps provided himself with a biscuit or piece of light bread, purchased of some citizen. The men set around over the floor on their straw pallets, and eat, some swearing at the coffee, and some cursing the soup, and all making some remark or other about the fare. One, for instance, would like some potatoes or chicken soup; one some bread and milk, one some corn bread, and another would fancy mush and milk. Sometimes these things could be procured by paying their own money for them, and thus there would be a feast. Poor fellows! They deserve better things than these, but it is impossible for the Steward and attendants to provide anything more suitable. May God forgive those who should look after these things for neglecting their duty, or for being dishonest.

The soldier in camp lives very similar to this: Messes are formed from the occupants of one tent, perhaps numbering four or five, or more; the rations are drawn, and all cooked in the same vessels. A small camp-kettle supplies them with coffee, and a larger one with boiled beef, bean-soup, etc. Then, with tin-cups, tin-plates, knives and forks, they pitch in, each one helping himself until he is satisfied. While eating he either stands or sits on the ground, as he may elect. Thus they live day after day and month after month and no variety unless they buy and pay for it them selves. Many of them do spend all their wages in buying something to eat. It is amusing to look through the streets of Syracuse, and see the soldiers buying the luxuries that the farmers' wives bring to town to sell. Here are several wagons, surrounded by soldiers, buying and trying to buy, sausage meat, fresh pork, chickens, butter, eggs, pies, cakes, corn-bread, milk, apples, etc. The argus eyes of the ladies are kept busy, or else they make small profits. While many are honestly paying for what they get, others are playing confiscation, and dishonestly getting what they do not pay for. Pies and cakes are in great demand; and such pies! The pie-crust is made by wetting some flour with water until it becomes pasty, some sour apples are then wrapped up in it, and it is then dried in a moderately heated oven. When it is sufficiently done it can't be broken, but must be twisted asunder and swallowed in mass; yet the soldiers pay a quarter for such pies, and consider them a luxury.

The first case of bushwhacking known to the regiment occurred at Syracuse. A boy belonging to the Eighth Indiana Regiment was on his way to join his regiment, and stopping at the hospital to ascertain where he would find it, was induced to stay a day or two before going farther. The day following he walked out into the brush, about one hundred yards from the hospital, and was shot down by some unseen hand. The report of the gun was heard at the hospital, and in a few moments the body was found, laying on the snow, in a dying condition. There was an inch or two of snow on the ground, and it was thought the murderer might be found by his foot-prints in the snow. Several of the boys from the hospital started immediately in pursuit. The afternoon was spent in following foot marks through the woods, but nothing definite was ever learned of who committed the murder. One of the scouts reported on his return that "the scoundrel would never shoot another soldier," intimating that he had overtaken and shot the bushwhacker; but credit was not given to his story.