Title: Deeds of a great railway

A record of the enterprise and achievements of the London and North-Western Railway company during the Great War

Author: G. R. S. Darroch

Author of introduction, etc.: Leopold James Maxse

Release date: May 2, 2014 [eBook #45563]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Terry Jeffress and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The transcriber created the cover image and places it in the public domain.

A RECORD OF THE ENTERPRISE AND ACHIEVEMENTS

OF THE LONDON AND NORTH-WESTERN

RAILWAY COMPANY DURING

THE GREAT WAR

By G. R. S. DARROCH

(CROIX DE GUERRE)

ASSISTANT TO THE CHIEF MECHANICAL ENGINEER L. & N.W.R.

WITH A PREFACE BY

L. J. MAXSE

With Illustrations

"The Railway Executive Committee have

been too modest, the public do not know

what they achieved."—Engineering.

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1920

All rights reserved

Page 120, footnote, for said the Tsar, read said of the Tsar.

" 149, line 22, for Walschaerte valve appertaining, read Walschaerte valve gear appertaining.

" 162, line 23, for mileage of permanent available read mileage of permanent way available.

"Let thy speech be better than silence, or be silent," is a golden and an olden precept, one moreover that may, or may not, impel the aspiring rhetorician to beware the pitfalls which ever and anon threaten to ensnare his footsteps; and in compiling this little work the present Author has not been unmindful of at least two dilemmas with which he has felt himself to be faced; one, the danger of toying with that "little knowledge" which in the course of his professional duties he has been at pains—in fact could hardly fail—to acquire; the other, the debatable policy of presenting to a public, however indulgent, a subject of which, at the moment of writing, and in common with the majority of people, he is heartily tired, namely that of Munitions of War.

Prompted, however, by an ardent and innate love, dating from his earliest school-days, for railway-engines, trains, and everything appertaining thereto—a love, moreover, so compelling that at the romantic age of thirteen he applied for an engine-pass with which joyously to ride home for the holidays, and without which, owing [vi] to a polite but firm refusal, he suffered many a pang of disappointment—feeling, too, that railway enthusiasts, whether amateur or professional, cannot fail to evince a certain degree of interest in the truly amazing rôle enacted during the war by the locomotive departments of the great railway companies of the country, he has ventured to touch upon what may best, perhaps, be termed the "war effort" of the London and North-Western Railway, the premier British line, of which the locomotive G.H.Q. are, as is well known, to be found at Crewe.

In treating this subject, the Author has, as will be seen, refrained as far as possible from wearying the reader with interminable statistics, with technical dissertations descriptive of methods of manufacture, and other tedious prosaics. His aim has been rather to recall the hair-breadth escapes to which the nation was subjected; to show by means of various and authentic extracts from public utterances recorded in the Press of the day, and from recent publications, the necessities which arose contingent upon the trend of military operations and upon the arena of political pantomimes; and to illustrate the manner in which the London and North-Western Railway, predominant amongst the great railway and industrial enterprises of the British Isles, not only was able, but did, rise to the occasion, providing those sorely needed and essential "sinews" of war which were so largely instrumental in extricating the country from an extremely awkward predicament, as well [vii] as from a situation that was both ugly and menacing.

Gratia gratiam parit, but the Author regretfully feels that in the present instance he is debarred from showing, in any practical manner, his appreciation of the kindness of those who have assisted him in his task. Ingratitude is not infrequently held to be the "worst of vices," and undoubtedly "words are but empty thanks"; nevertheless the Author finds it a pleasure as well as a duty to acknowledge his deep sense of indebtedness to those members of the staff at Crewe Works for their spontaneous assistance in regard to information supplied.

He also takes this opportunity of tendering his sincere thanks to the following Editors for their kind permission to reproduce various extracts from the columns of their respective newspapers: The Editors of the Daily Mail, of the Morning Post, of the Pall Mall Gazette, of the Times, of Engineering, of the Engineer, of Modern Transport.

His best thanks are also due to the Managers of the following firms of Publishers, who have been good enough to allow reproductions of extracts from well-known books which, respectively, they have produced: Messrs. Blackwood, "An Airman's Outings," "Contact"; Messrs. Cassell, "The Grand Fleet, 1914-1916," Lord Jellicoe; Messrs. Constable, "1914," Lord French; Messrs. Flammarion, Paris, "Enseignements Psychologiques de la Guerre Européenne," M. Gustav Lebon; Messrs. Hodder & Stoughton, [viii] "Winged Warfare," Captain Bishop, V.C.; Messrs. Hutchinson, "My War Memories, 1914-1918," General Ludendorff.

He is equally indebted to Mr. C. J. Bowen-Cooke, C.B.E., for permission to reproduce extracts from his work "British Locomotives"; also to Mr. L. W. Horne, C.B.E., M.V.O., and his personal staff at Euston, who so kindly supplied statistics in regard to war-time traffic. Last, but not least, are due the Author's thanks to Mr. L. J. Maxse, Editor and Proprietor of the National Review, whose readiness to pen a few prefatory remarks is now most gratefully acknowledged.

Whilst in no way seeking to underrate the intelligence, or to disavow the knowledge, already possessed by those readers who may be sufficiently patient to bear with him, the Author would beg that at least they may not see cause to classify him with those who "wishing to appear wise among fools, among the wise seem foolish."

Crewe, 1920.

The British cannot be accused, even by their bitterest critics, of blowing their own trumpet. Indeed, they fail in the opposite direction, and, as a general rule, carry their modesty to a point when it positively ceases to be a virtue, because it causes credit to go where it is not due. If we are unpopular as a nation—of which we are continually assured, though whether we are more disliked than other nations may be doubted—it is certainly not on account of boasting by our men of action and achievement. Occasionally, it is true, we suffer under the extravagant claims of Talking Men—chiefly politicians—who are possibly inspired by the apprehension that unless they were their own advertisers mankind would remain oblivious and therefore ungrateful as regards the services they are supposed to have rendered.

The events of the Great War will gradually emerge in proper perspective, and things will then seem somewhat different to what they do to-day, when there is a certain and inevitable reaction which both enables pretenders to pose as saviours of Society, and encourages us to [x] overlook much of which we may be legitimately proud because it has demonstrated afresh to a world that was forgetting it that the British are essentially a great people with a genius for everything appertaining to war, however lacking in the supreme art of making durable peace. In that day we shall want to know a great deal more than we do at present concerning the origin of a conflict which has been to some extent obscured by interested parties on both sides of the North Sea who have enveloped the palpitating pre-war crisis in a curtain of misrepresentation. It is common ground that Germany willed the war for which she was super-abundantly prepared, while Great Britain willed peace for which she was no less eager. Not for the first time in our history were we taken completely unawares—neither Government nor public having the faintest inkling of any impending storm, still less that civilisation was on the eve of a cataclysm of which it would feel the effects for more than one century.

As we look back on the Dark Ages of 1914, so graphically recalled by the author of this book, we can only marvel at our blindness and wonder how it could be that so many highly trained observers and experts on current events could entirely ignore a danger that, in the familiar French phrase, "leapt to the eyes." Of this strange phenomenon there has so far been no attempt at any explanation, no amende from those "great wise and eminent men"—not confined to any particular political party—whose [xi] business it should have been to see what stared them in the face, altogether apart from the fact that the Government of the day commanded that abundance of accurate inside information concerning international affairs, which, from generation to generation, is at the service of His Majesty's Ministers. It would be some consolation and compensation for all we have endured during this portentous period were there any guarantee that no such catastrophe could recur because the terrible lesson of 1914 to 1918 had been assimilated by Responsible Statesmen who ask so much from the Community that we are entitled to expect something from them in return.

If we cannot afford to forget the political aspect of that crisis, it is infinitely more agreeable to contemplate the miraculous manner in which "England the Unready" buckled to and transformed herself into the mighty machine whose hammer blows on every element ultimately turned the scale, and with the aid of Allies and Associates converted what at the outset looked like "World Power" for Germany into her "Downfall."

Of the part played by the Fighting Men we know a good deal, and the more we know the more we admire. Of the wonderful organisation largely improvised, that placed and kept vast forces in the field all over the world, we know next to nothing, partly because the more dramatic aspects of the war have naturally attracted the attention of its historians, partly because [xii] those with the necessary knowledge have been too busy re-converting the machine to pacific purposes to be able to write its war record.

In this attractive volume, Mr. Darroch, Assistant to the Chief Mechanical Engineer in the Locomotive Department of the London and North Western Railway Company at Crewe,—who has enjoyed the advantage of two full years' active service overseas,—tells us in so many words how our premier Railway Company "did its bit." Every factor in that great organisation was subordinated to the common object, and the Works at Crewe as urgency arose became a Munitions Department. It is a wonderful and stimulating story—made all the more interesting because the author continually bears in mind that it is part of a still larger whole and breaks what is entirely new ground to the vast majority of the reading public.

There is a desire in some quarters to banish the war as an evil dream—to bury its sacred memories, to forget all about it. If we followed this shallow advice, we should merely prove ourselves to be unworthy of the sublime sacrifice, thanks to which we escaped destruction, besides making a recurrence of danger inevitable. To our author, who is an enthusiast in his calling, this book has been a labour of love, and he has certainly made us all his debtors by this brilliant and entrancing chapter of the history of the London and North-Western.

L. J. MAXSE.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Foreword | v | |

| Preface | ix | |

| I. | Being Mainly Historical | 1 |

| II. | Armoured Trains | 39 |

| III. | Mechanical Miscellanea | 51 |

| IV. | The Graze-Fuse | 75 |

| V. | Care of the Cartridge Case | 83 |

| VI. | Gunnery and Projectiles (Rudimentary Notes and Notions) | 93 |

| VII. | The Crewe Tractor | 127 |

| VIII. | "Hullo! America" | 135 |

| IX. | The Art of Drop-Forging | 139 |

| X. | 1914-1918 Passengers and Goods | 153 |

| XI. | Indispensable | 176 |

| XII. | L'Envoi | 200 |

| APPENDIX A | ||

| The System of Control applied to the Armoured Trains manufactured in Crewe Works | 211 | |

| APPENDIX B | ||

| Explanatory of the Gauge | 212 | |

| APPENDIX C | ||

| The Thread-Miller, and the "Backing-off" Lathe, as applied to Shell Manufacture | 215 | |

| PAGE | ||

| C. J. Bowen-Cooke, Esq., C.B.E., Chief Mechanical Engineer, London and North-Western Railway | Frontispiece | |

| Armoured Train | 45 | |

| Various Types of Artificial Limbs | 68 | |

| The Protector, or Mine-sweeping, Paravane | 70 | |

| Gauges made at Crewe and used for the Manufacture of Graze-Fuses | 78 | |

| Reversible Mechanical Tapping Machine for Fuse Caps Designed at Crewe | 78 | |

| The Graze-Fuse, shewn in section | 80 | |

| Rolling out Dents in 4·5-inch Fired Cartridge Case | 89 | |

| "Patriot."—A Typical Example of the "Claughton" Class of 6´ 6´´, Six Wheels Coupled Express Passenger Engine with Superheated Boiler; Four h.p. Cylinders, 15-3/4´´ bore x 26´´ stroke; Boiler Pressure, 175 lbs. per sq. inch; Maximum Tractive Force, 24,130 lbs.; Weight of Engine and Tender in Working Order, 117 tons | 99 | |

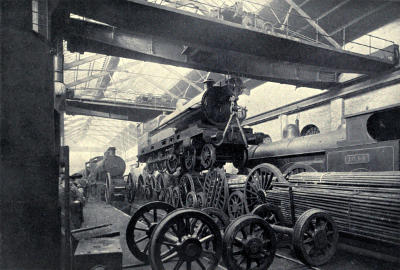

| 6-inch Shell Manufacture in the New Fitting Shop, Crewe Works | 112 | |

| A Crewe Tractor in Road Trim | 130 | |

| A Crewe Tractor as Light-Railway Engine on Active Service | 130 | |

| Limber Hooks: Illustrating Duplex Method of Drop Forging | 145 | |

| [xvi] Trunnion Brackets for 6-inch Howitzer Gun, Drop Forgings | 145 | |

| The 4-ton Drop Hammer | 148 | |

| Naval Gun weighing 68 tons. A Typical Instance of War-time Traffic | 173 | |

| Breakdown Crane and Lifting Tackle for Shipping Small Goods Engines | 178 | |

| An Overseas Locomotive Panel "Severely Wounded" | 178 | |

| Type of Overhead Travelling Crane, Built at Crewe and Supplied to the Overseas "Rearward Services" | 180 | |

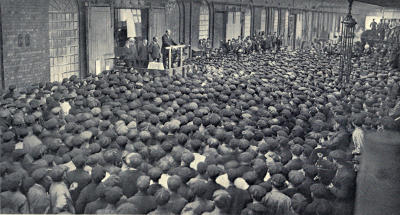

| "We, the Working Men of Crewe, will do all that is Humanly Possible to Increase the Output of Munitions, and Stand by our Comrades in the Trenches" | 186 | |

| London and North-Western Railway War Memorial, Euston | 210 | |

| Manufacture of a Hob-cutter, in "relieving" or "backing-off" lathe | Appendix C | |

"England woke at last, like a giant, from her slumbers,

And she turned to swords her plough-shares, and her pruning hooks to spears,

While she called her sons and bade them

Be the men that God had made them,

Ere they fell away from manhood in the careless idle years."

Thus it was that on that fateful morning of August 5th, 1914, England awoke, awoke to find herself involved in a struggle, the magnitude of which even the most well-informed, the most highly placed in the land, failed utterly, in those early days, to conceive or to grasp; in death-grips with the most formidable and long-since-systematically prepared fighting machine ever organised in the history of the world by master-minds, ruthless and cunning, steeped in the science of war. England awoke, dazed, incredulous, unprepared; in fact, to quote the very words of the Premier, who, when Minister of Munitions, was addressing a meeting at Manchester in the summer of 1915, "We were the worst organised nation in the world for this war." [2]

The worst organised nation! And this, in spite of repeated public utterances and threats coming direct to us from the world-aggressors, as to the import of which there never should, nor indeed could, have been any shadow of doubt.

"Neptune with the trident is a symbol for us that we have new tasks to fulfil ... that trident must be in our fist"; thus the German Emperor at Cologne in 1907. "Germany is strong, and when the hour strikes will know how to draw her sword"; Dr. von Bethmann-Hollweg, in the Reichstag, 1911. Or to burrow further back into the annals of the last century, one recalls a challenge, direct and unmistakable, from the pen of so prominent a leader of German public opinion as Professor Treitshke, "We have reckoned with France and Austria—the reckoning with England has yet to come; it will be the longest and the hardest."

The reckoning came, swiftly and with deadly purpose. Necessity knew no law, Belgian territory was violated, Paris was threatened, the Prussian spear pointing straight at the heart of France.

Unprepared, taken unawares, and, but for the sure shield of defence afforded by her Fleet, well-nigh negligible, England awoke.

Happily, the nation as a whole was sound; though hampered as it was by a Peace-at-any-price section of the Press, and honeycombed though it had become with the burrowings of the "yellow English," that "lecherous crew" who, naturalised or unnaturalised, like snakes in [3] the grass, sought, once the hour had struck, to sell the country of their adoption, the man-in-the-street little knew, and probably never will know with any degree of accuracy, how near England came to "losing her honour, while Europe lost her life."

To reiterate all that was written at the time with the one object of keeping England out of the fray, of making her desert her friends, and of causing her, "after centuries of glorious life, to go down to her grave unwept, unhonoured, and unsung," is naturally beyond the scope of this necessarily brief résumé of the status quo ante. But, lest we forget, lest we relapse once again to our former and innate characteristics of sublime indifference and of complacent laissez-faire, heedless of that oft-repeated warning, "They will cheat you yet, those Junkers! Having won half the world by bloody murder, they are going to win the other half with tears in their eyes, crying for mercy,"1 a cursory glance through one or two of the more glaring and self-condemnatory essays at defection from the one true and only path consistent with the nation's honour and integrity, may not be held amiss.

Literæ scriptæ manent, and so he who runs may still read the remonstrance of a high dignitary of the Church, to wit, the Bishop of Lincoln, as set forth in the Daily News and Leader, August 3rd, 1914—"For England to join in this hideous war would be treason to civilisation, and [4] disaster to our people"; or this reassuring sop from the Archbishop of York on November 21st, 1914—"I have a personal memory of the Emperor very sacred to me." The strange views of a leading daily newspaper are typical of the "Party of dishonour." In its columns in August, 1914, we read, "The question of the integrity of Belgium is one thing; its neutrality is quite another. We shall not easily be convinced ... that the sacrosanctity of Belgian soil from the passage of an invader is worth the sacrifice of so much that mattered so much more to Englishmen." "Cold feet" was an affliction from which the same journal was evidently suffering on the same date, for "from all parts of the kingdom we are hearing of businesses that are about to close down if Great Britain goes to war. It is going to be an appalling catastrophe." In this respect, too, the Parliamentary correspondent of the Daily Chronicle doubtless felt that the spilling of ink was likely to be more profitable than the shedding of blood, as evinced by his inspiring little contribution on August 3rd: "Whatever the outcome of the present tension, I believe the Cabinet have definitely decided not to send our Expeditionary Force abroad. Truth to tell, the issues which have precipitated the conflict which threatens to devastate the whole of Europe are not worth the bones of a single soldier." This policy of "scuttle" must ever remain as shameful as it is unintelligible to the ordinary self-respecting Britisher; but as to the nature of the plea put forward by the Daily News, August 4th, [5] there can be no vestige of doubt: "If we remained neutral we should be, from the commercial point of view, in precisely the same position as the United States. We should be able to trade with all the belligerents (so far as the war allows of trade with them); we should be able to capture the bulk of their trade in neutral markets; we should keep our expenditure down; we should keep out of debt; we should have healthy finances."

It has been said that "each country and each epoch has the Press which it deserves"; but although God may have given us our Press just as He has given us our relations, at least let us thank God that we can choose our Papers just as we can choose our friends.

On "Black Saturday" (August 1st, 1914) the position was literally "touch and go," as may be gathered from the following:—"Powerful City financiers, whom it was my duty to interview this Saturday (August 1st) on the financial situation, ended the Conference with an earnest hope that Britain would keep out of it" (Mr. Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, in an interview with Mr. Henry Beech Needham, Pearson's Magazine, March, 1915).

Clearly, international finance had all but succeeded in winning the day for the Fatherland. S.O.S. must assuredly have been the signal subconsciously sent out by the staunch little minority in the Asquith Cabinet; for when the tide was at its lowest ebb, when England's honour literally hung in the balance, and while Mr. Asquith was [6] still waiting and wobbling, there came Mr. Bonar Law's memorable letter as voicing the opinion of the Government Opposition, and of which the plain, outspoken meaning may be said to have had the effect of definitely turning the scale:—"Dear Mr. Asquith, Lord Lansdowne and I feel it our duty to inform you that in our opinion, as well as in that of all the colleagues whom we have been able to consult, it would be fatal to the honour and security of the United Kingdom to hesitate in supporting France and Russia at the present juncture, and we offer our unhesitating support to the Government in any measures they may consider necessary for that object. Yours very truly, A. Bonar Law."

The tonic effect of this dose of stimulant was as immediate as it was invigorating, for "on Sunday (August 2nd)," as Sir Edward Grey announced the following day in the House of Commons (cp. the Times, August 4th, 1914), "I gave the French ambassador the assurance that if the German Fleet comes into the Channel or through the North Sea to undertake hostile operations against the French coasts or shipping, the British Fleet will give all the protection in its power." Further, although "we have not yet made an engagement to send the Expeditionary Force out of the country" we were not letting the grass grow under our feet, for "the mobilisation of the Fleet has taken place; that of the Army is taking place." All self-respecting Englishmen were able to breathe again; we were at least to be permitted to do our bare [7] duty towards our neighbour; we could, in fact, once again look him in the face. But the Almighty indeed "moves in a mysterious way, His wonders to perform," and it needed the blatant blundering of the bullet-headed Boche, which throughout the prolonged agony has proved one of the greatest assets of the Entente cause, more often than not being instrumental in saving ourselves in spite of ourselves, finally to ensure that we fulfilled our treaty, as well as our moral, obligations. Our erstwhile "checker" of armament expenditure took very good care, subsequently, to remove the possibility of any doubt lingering on this score—"This I know is true.... I would not have been a party to a declaration of war, had Belgium not been invaded, and I think I can say the same thing for most, if not all, of my colleagues.... If Germany had been wise, she would not have set foot on Belgian soil. The Liberal Government then would not have intervened" (Mr. Lloyd George, in an interview with Mr. Harry Beech Needham, Pearson's Magazine, March, 1915).

Wednesday, August 6th, is a day that will remain "momentous in the history of all times," for owing to the incursion within Belgian territory of German troops "His Majesty's Government have declared to the German Government that a state of war exists between Great Britain and Germany as from 11 p.m. on August 4th" (cp. the Times, August 5th, 1914).

Thenceforth eyes became riveted on the North Sea, thoughts centred on Belgium. [8] Liège, the first stumbling-block in the path of the invader, was holding at bay the oncoming enemy hordes, thousands of whom advancing in close formation were made blindly to bite the dust.

Eagerly the newspapers were bought up; every fresh message ticked off on the "tape" was greedily devoured. A French success in Alsace, a German submarine sunk, fighting on the Meuse and in the Vosges, Lorraine invaded by the French—these and other announcements, acting as apperitiffs to whet the appetite, added to the excitement of the hour. Pressure of public opinion had ousted Lord Haldane from the War Office; Kitchener, "with an inflexible will, a heart that never fails at the blackest moments, a spirit that time and again has been proved unconquerable," becoming Secretary of State for War. With the approval of His Majesty the King, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe assumed supreme command of the Home Fleets, Field-Marshal Sir John French was nominated to the command of the British Expeditionary Force. Yet as day succeeded day and little or nothing became visibly apparent, vainly on all hands, but with increasing persistence, was asked the question, "Why did not England move?" Why this inaction, this seeming hesitation? The Fleet had been as if swallowed up by the waters. All was silence everywhere. At midnight on August 12th we were at war with Austria, and although "the general attitude of the nation is what it ever has been in time of trial, sedate, sensible, [9] and self-possessed," the Times of August 15th, anxious, no doubt, to ease the existing tension, openly commented on the fact that "all sorts of absurd and unfounded rumours have been circulated by light-headed and irresponsible individuals," throwing ridicule on "dire reports of mishaps suffered by the Allies, of German victories, of insurrections in the French capital, and even of heavy British casualties by land and sea." Three more days "petered out," however, before all doubts were dispelled, and these "dire reports" shown to be totally void and without foundation. On Tuesday, August 18th, or exactly a fortnight from the declaration of war, it was with mingled feelings of gratitude and of relief that we read in our morning paper, "The following statement was issued last night by the Press Bureau—'The Expeditionary Force, as detailed for foreign service, has been landed on French soil. The embarkation, transportation, and disembarkation of men and stores were alike carried through with the greatest possible precision, and without a single casualty.'"

Only those who had been intimately connected with, or actually concerned in, this the first move in the great drama were aware of the intense amount of activity that had been crowded into the breathless space of those two short weeks. The ordinary man-in-the-street, the strap-hanger, the lady in the stalls, the girl in the taxi, all were purposely kept in the dark; the great British Public knew nothing.

Those of us who happily foresaw the historical [10] interest and value that must surely accrue in the years to come from the preservation of the newspapers of the day may yet ponder in reminiscent mood headlines and paragraphs, descriptive of events and portraying emotions, current and constraining, throughout those August days.

On August 18th, the Times, habitually dignified, lucid and exemplary, touches on the occasion in a vein deserving as it is decorous: "The veil is at last withdrawn from one of the most extraordinary feats in modern history—the dispatch of a large force of armed men across the sea in absolute secrecy. What the nation at large knew it knew only from scraps of gossip that filtered through the foreign Press. From its own Press, from its own Government, it learned nothing; and patiently, gladly, it maintained, of its own accord, the conspiracy of silence." It was true, in fact inevitable, that "every day for many days now mothers have been saying good-bye to sons, and wives to husbands," but "until Britain knew that her troopships had safely crossed that narrow strip of water that might have been the grave of thousands, Britain held her peace." However, "now that we are at last allowed to refer to the dispatch of a British Army to the seat of war, we may heartily congratulate all concerned upon the smooth and easy working of the machinery. The staffs of England and France who prepared the plan of transport, the railway and steamship companies which carried the men, the officers and men who marched silently off without the [11] usual scenes of farewell at home, and last, but not least, the Navy that covered the transports from attack, all deserve very hearty congratulations."

Comparisons are odious, and it is obviously without any desire to detract from the laudable performances of others in the accomplishment of this, "one of the most extraordinary feats in modern history," that reference of a special character is here made to the singularly high state of efficiency obtaining on the great British railway companies, which alone rendered possible so remarkable an achievement as that of marshalling at a moment's notice, and dispatching, the many trains necessary for the conveyance to the different ports of embarkation within the United Kingdom of the four Divisions of all arms and one of Cavalry of which the original British Expeditionary Force was composed.

It is true that on the outbreak of war, the State, at least in name, assumed control of the railways, and this by virtue of an Act of Parliament passed in 1871 (34 and 35 Victoria, c. 86) "for the Regulation of the Regular and Auxiliary Forces of the Crown," section XVI. of which enacted that "When Her Majesty, by order in Council, declares that an emergency has arisen in which it is expedient for the public service that Her Majesty's Government should have control over the railroads of the United Kingdom, or any of them, the Secretary of State may, by warrant under his hand, empower any person or persons named in such warrant to take possession in the name or on behalf of Her Majesty of any [12] railroad in the United Kingdom ... and the directors, officers, and servants of any such railroad shall obey the directions of the Secretary of State as to the user of such railroad ... for Her Majesty's service."

A previous "Act for the better Regulation of Railways, and for the Conveyance of Troops" (5 and 6 Victoriae 30th July, a.d., 1842, cap. LV. section XX.), similarly declares—"Be it enacted, 'That whenever it shall be necessary to move any of the Officers or Soldiers of Her Majesty's Forces of the Line, Ordnance Corps, Marines, Militia, or the Police Force, by any Railway, the Directors thereof shall and are hereby required to permit such Forces respectively with their Baggage, Stores, Arms, Ammunition, and other Necessaries and Things, to be conveyed at the usual Hours of starting, at such Prices or upon such Conditions as may from Time to Time be contracted for between the Secretary at War and such Railway Companies for the Conveyance of such Forces, on the Production of a Route or Order for the Conveyance signed by the proper Authorities."

Hence it will be seen that, always subject to the provisions of the National Defence Act of 1888 (51 and 52 Victoriae, c. 31), which simply ensured that naval and military requirements should take precedence over every other form of traffic on the railways whenever an Order for the embodiment of the Militia was in force, the actual working of the various departments of the different railway companies when war was [13] declared remained, to all intents and purposes, identical with that prevailing in the piping times of peace, that is to say in the hands of the individual "directors, officers and servants" of the respective railways, with the result that in the absence of all attempt at interference on the part of official bureaucracy, "all went merry as a marriage-bell"; staffs worked day and night; confusion was conspicuous by its absence; smoothly, yet unrehearsed, proceeded the unparalleled programme, until the last man had been detrained, the last gun hauled aboard the transport lying in readiness at the quay; and in due course, as has already been mentioned, "the Contemptibles" were landed in France without a single casualty.

Whilst touching lightly upon the evident and praiseworthy preparedness and consequent ability of the great railway companies to deal with "the emergency" the moment it arose, it will perhaps not be uninteresting to inquire briefly into the circumstances dating back to the "fifties" of the last century from which were evolved and brought gradually to a state as nearly approaching perfection as is humanly possible the organisation necessary for the speedy and safe transport of troops by rail in time of war.

History ever repeats itself, and it has invariably been the case that the imminent peril of invasion rather than any grandiose scheme of foreign conquest has been the determining factor in arousing that martial spirit, so prone to lying [14] dormant, but which, handed down to us by our forbears, undoubtedly exists in the fibre of every true-born Britisher, and which has assuredly been the means of raising England to her present pinnacle of greatness.

The three more obviously parallel instances in modern times of the manifestation of this trait so happily characteristic of the nation are to be found, first and foremost perhaps in connection with the present-day world conflict, when in response to the late Lord Kitchener's first appeal for recruits thousands flocked to the colours. Apposite indeed was the following brief insertion to be found in the personal column of the Times, August 26th, 1914: "'Flannelled fools at the wicket and muddied oafs at the goal' have now an opportunity of proving whether Mr. Kipling was wrong." They seized the opportunity in no uncertain manner; incontrovertibly they proved him wrong, "The first hundred thousand," or "Kitchener's mob" as they were affectionately termed, being speedily enrolled, and forming the nucleus of the immense armies which eventually took the field.

Analogous to this effort may be taken the crisis occurring in the middle of the last century, when, in the year 1858, out of what may best be described perhaps as a "storm in a tea-cup," there loomed the threat of invasion by our friends from across the Channel, resulting in a scare the immediate outcome of which was the formation of the Volunteer Force, which quickly reached a total of 150,000 men.

[15] Although this particular crisis must be considered as bearing more directly on present-day matters of interest in view of the fact that the importance of steam-traction by rail relative to warlike operations commenced at that time to make itself felt, the extent to which the nation seemed likely to be imperilled was, nevertheless, scarcely to be compared with the danger that threatened during what may be termed the closing phase of the Napoleonic era, when in the year 1805 massed in camp at Boulogne was the flower of the French Army equipped with quantities of flat-bottomed boats ready for its conveyance across the Channel. To counter this formidable menace was mustered in England a force of 300,000 Volunteers, imbued with the same fervent ardour, the same spirit of intense patriotism and self-sacrifice that has ever been evinced by the country in her hour of peril. How the menace was in fact averted, and the last bid for world-domination by the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte frustrated, is common knowledge, the memorable action off Cap Trafalgar determining once and for all the inviolability of England's shores. "England," exclaimed Pitt, "has saved herself by her courage; she will save Europe by her example."

The average historian of to-day, who mentally is as firmly convinced that the genius of Nelson won the Battle of Trafalgar as he is ocularly certain that the famous admiral's statue dominates Trafalgar Square, will, on the other hand, in all probability deny that the use of steam as [16] a motive force was contemporaneous with the period in which Nelson lived. But although it is somewhat of a far cry from the latter part of the eighteenth century to the "eighteen-fifties" when steam was to become a factor of no mean importance in the waging of modern war, there is, nevertheless, conclusive evidence to show that dating so far back as the "seventeen-seventies" individual efforts of admittedly a most elementary, albeit utterly fascinating, kind were already being made with a view to solving the problem wrapt up in this "water-vapour," and so compelling the elusive energy to be derived therefrom as a motive agency for rendering facile human itinerancy. No sooner had the first self-propelled steam-carriage made its appearance on the road, than speculation became rife as to the range of potentialities lying latent in the then phenomenal invention; well-nigh limitless seemed the vista about to unfold itself to human ambition, and looking back over the past century and a half how strangely prophetic sound these lines from the pen of Erasmus Darwin, who died in 1802!—

"Soon shall thy arm, unconquered steam! afar

Drag the slow barge, or drive the rapid car;

Or, on wide-waving wings expanded, bear

The flying chariot through the field of air!"

Evidently the "Jules Verne" of his day, Erasmus Darwin was physician as well as poet; his ideas, so we are told, were indeed "original and contain the germs of important truths," to which may, in some measure, be attributed the [17] genius of his grandson, the famous Charles R. Darwin, discoverer of natural selection.

It is true the petrol engine has latterly proved its more ready adaptability to the purpose of road locomotion and of aviation, but the fact remains that steam to this day eminently preserves her predominance in the world of ocean and railway travel.

Seldom does one find the evolution of any one particular branch of scientific endeavour traced in so alluring as well as instructive a manner as proves to be the case, when, taking down from the nearest bookshelf that delightful little volume "British Locomotives," one pursues the author, Mr. C. J. Bowen-Cooke (now C.B.E. and Chief Mechanical Engineer of the London and North-Western Railway), with never-abating interest through his treatise on the early history of the modern railway engine. He tells us that "the first self-moving locomotive engine of which there is any authenticated record was made by a Frenchman named Nicholas Charles Cugnot, in the year 1769. It was termed a 'land-carriage,' and was designed to run on ordinary roads." Although we learn that "there are no particulars extant of this, the very first locomotive," this same Cugnot designed and constructed two years later, a larger engine, "which is still preserved in the Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers at Paris." The French are a people ever prone to looking further than their noses, hence the fact that the French Government not unnaturally "took some interest in this notion of a steam land-carriage, [18] and voted a sum of money towards its construction, with the idea that such a machine might prove useful for military purposes." Man proposes, but God disposes, and as luck would have it the vehicle seemed fore-ordained to end its brief career somewhat ingloriously, for after it "had been tried two or three times it overturned in the streets of Paris, and was then locked up in the Arsenal." A lapse of ten or a dozen years supervened before England began looking to her laurels, but "in 1784 Watt took out a patent for a steam-carriage, of which the boiler was to be of wood or thin metal, to be secured by hoops or otherwise to prevent its bursting from the pressure of steam"! It was not long, however, ere the steam road carriage was superseded by a locomotive designed to run on rails, of which the earliest "broods," embracing such "spifflicating" species as the Puffing Billies, Rockets, Planets, etc., and "hatched" from the brains of eminent men such as Stephenson and Trevithick, were necessarily original and quaint to a degree. It is, unfortunately, impossible here to do more than skim the copious wealth of interesting data through which Mr. Bowen-Cooke so admirably pilots us, and which evidently he has spared no pains to collect; suffice it to add that the succeeding years bear unfailing witness to that intense earnestness which, sustaining the early locomotive pioneers unwearying in their well-doing, was so largely instrumental in the attainment of that perfection of which we, their beneficiaries, now in our own season reap the benefit.

[19] It was not until the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830, when the directors of that line offered "a premium of £500 for the most improved locomotive engine," that any real tendency towards modern design and external appearance began to make itself apparent. The stimulus afforded by this offer, however, was rousing in effect, engines becoming gradually larger and more or less powerful, until in the year 1858 Mr. Ramsbottom designed and built for the London and North-Western Railway Company at Crewe an express passenger engine known familiarly as the "seven foot six," in that its single pair of driving wheels measured 7 feet 6 inches in diameter. Bearing the name of "Lady of the Lake" (for, whilst sacrificing perhaps a certain amount of power for speed, it was "certainly one of the prettiest engines ever built"), this engine and others of the same "class" remained in the service of the London and North-Western Railway until quite recently, thus forming a link between the earth-shaking events of the present day and that period of anxious calm, when the scare (to which reference has previously been made) became the occasion in 1858 for centring public opinion on the possibilities of, and the advantages likely to accrue from, transport by rail in time of war.

The Crimean struggle of 1855 had done little enough to enhance England's military prestige, only to be followed, two years later, by the nightmare horrors of the Mutiny.

Throughout the first and second Palmerston [20] Ministries, the reading of the European barometer remained at "stormy," and an attempt in 1858 to assassinate the Emperor Napoleon III., which was believed to have had its origin in England, served as a prelude to the "blowing-off" of a considerable volume of steam, especially when a year later, the war between France and Austria having terminated and the kingdom of Italy being created, the French people found themselves free to devote their then bellicose attentions, as had so frequently been their misguided and regrettable wont, to our insular selves. It is, however, an ill wind that blows nobody any good, and the very fact that the tone, particularly of the military party in France, was violent and aggressive to a degree, had the salutary effect of serving as a mirror in which was accurately reflected our own deplorable unpreparedness for war.

Commenting on the situation, the writer of a leading article in the Times of April 19th, 1859, openly deplores the fact that "the Englishman of the present day has forgotten the use of arms"; not merely this, but "the practice of football or of vying with the toughest waterman on the Thames is of little service to young men when their country is in danger."

Mercifully enough, perhaps, the pernicious sensationalism of the cinema, and the vacant thrills afforded by the scenic railway, were magic lures unknown in those mid-Victorian days, manly and open-air forms of sport already being considered sufficiently derogatory to the inculcation [21] within the minds of the younger generation of that fitting sense of duty, of self-sacrifice, and subservience to discipline.

The opinion was further expressed that "there can be only one true defence of a nation like ours—a large and permanent volunteer force supported by the spirit and patriotism of our young men, and gradually indoctrinating the country with military knowledge," the article concluding with this ominous reminder—"We are the only people in the world who have not such a force in one form or another."

"Si vis pacem, para bellum" was the obvious corollary drawn by all sober-minded people and seriously inclined members of the community, and on the 13th of May, 1859, the Times had "the high gratification of announcing that this necessity (that of home defence) is now recognised by the Government," for "in another portion of our columns will be found a circular addressed by General Peel to the Queen's Lieutenants of counties sanctioning the formation of Volunteer Rifle Corps." At the same time the war in Italy was made to serve the purpose of bringing out in full relief the importance of steam as a novel factor in strategical operations, for we further read (cp. the Times, May 13th, 1859) that "steam—an agency unknown in former contests—renders all operations infinitely more practicable.... Railroads can bring troops to the frontier from all quarters of the kingdom.... It is in steam transport, in fact, that we discover the chief novelty of the war."

[22] Thenceforward matters began to assume practical shape, and in the following year 1860, on September 15th, we come across a reference to the Volunteer movement "which has so signal a success as to produce a costless disciplined army of 150,000 marksmen," springing from "a unanimous feeling of the necessity of preparing for defence." Conspicuous amongst this "costless disciplined army" figure the 1st Middlesex (South Kensington) Engineer Volunteers, "numbering now," as we find, on October 23rd, 1860, "over 500 members," and "daily increasing in strength is making rapid progress in its drills, etc." The 1st Middlesex was evidently the original corps of Engineer Volunteers to be formed, and thus became the precursor of other and similar corps which sprang into being in other parts of the country; a fine example of which (although entirely distinct in that it was the sole Engineer Corps to embody railway engineers) was later to become apparent in the 2nd Cheshire Engineers (Railway) Volunteers.

Formed in January, 1887, the battalion was recruited entirely from amongst the employés of the London and North-Western Railway, comprising firemen, cleaners, boilermakers and riveters, fitters, smiths, platelayers, shunters, and pointsmen. The nominal strength of the establishment was six companies of 100 men each, but in addition 245 men enlisted as a matter of form in the Royal Engineers for one day and were placed in the First Class Army [23] Reserve for six years, forming the Royal Engineer Railway Reserve, and being liable for service at any time. During the South African War 285 officers and men saw service at the front, and the military authorities were not slow to appreciate the invaluable aid rendered by this picked body of men. On the inception of Lord Haldane's scheme of Territorials in 1908, the battalion was embodied therein, and continued as such until March, 1912, when for some inexplicable reason it was finally disbanded.

How valuable an asset from the professional point of view were deemed, originally, these Engineer Corps, may be gathered from the Times of November 23rd, 1860, which congratulates the 1st Middlesex, as being the parent corps, on having been "most successful in obtaining skilled workmen of the class from which are drawn the Royal Engineers. Every member of the corps goes through a course of military engineering in field works, pontooning, etc.," with the result that the Volunteer Engineers "will therefore form a valuable adjunct to the Royal Engineers in the event of their being called into the field."

The ball once started rolling, it was not unnaturally deemed advisable to form some central and representative body of control, and the Times of January 10th, 1865, gives an account of an "interesting ceremony of presenting prizes to the successful competitors of rifle practice of the Queen's Westminster (22nd Middlesex) Rifle Volunteers," when Colonel [24] McMurdo, then Inspector-General of the Volunteer Forces, "who was received with loud and long-continued applause," in the course of a speech referred to the formation of a new corps, "a most important one both for the Volunteer Force and the Regular Army. He would tell the objects of this corps," which would consist of 30 Lieutenant-Colonels, and would enlist other members down to the rank of sergeants:—"In order that the Volunteers and the Army of England should be able to move in large masses from one part of the country to another they would have to depend upon railways. In all the wars of late years—as in the Italian war, the war in Denmark, and in the American war—the railway had been brought into service, to move armies rapidly from place to place, and this new corps, which at present consisted of the most eminent railway engineers and general managers of the great lines, had the task of bringing into a unity of action the whole system of railways of Great Britain; so that if war should visit England, which God forbid, this country would be placed on an equality with countries whose Governments possessed the advantage—if advantage it might be called—of carrying on the business of the railways. And the importance of this they might estimate when he assured them that with the finest army in the world, unless they had a system by which 200,000 men could move upon the railways with order, security, and precision, efficiency and numbers would be of no avail upon the day of battle; and that unless [25] we had order, unless we had certainty in the moving of large masses, the day of battle, which might come, would be to us a day of disaster."

Accorded the title of "The Engineer and Railway Volunteer Staff Corps," this select little group, combining some of the best brains and ability to be found in the engineering and managerial departments of the railways, acted in the capacity of consulting engineers to the Government, from the time of its formation until the year 1896, when a smaller body composed on similar lines and known as the "War Railway Council" was introduced for the purpose of supplementing, and to some extent relieving, the original Railway Staff Corps.

As has already been seen, although in accordance with the provisions of the Act of 1871 the Government would assume control of the railways in the event of "an emergency" arising, the directors, officers, and servants of the different companies would nevertheless be required to "carry on" as usual, and to maintain, each in their several spheres, the actual working of the lines.

The final adjustment of any minor defects that may have been apparent in the rapidly completing chain of organisation was speedily accelerated by the Agadir crisis of 1911, resulting in the inception in the following year of that unique and singularly thorough institution, the Railway Executive Committee, which in turn superseded its immediate predecessor, the War Railway Council.

On the outbreak of the world conflict in [26] August, 1914, and following on an official announcement by the War Office to the effect that Government control would be exercised through this "Executive Committee composed of General Managers of the Railways," Sir Herbert Walker, K.C.B., General Manager of the London and South-Western Railway, who was forthwith appointed Acting-Chairman of the Railway Executive Committee, issued in concise form a further and confirmatory statement, in which he drew attention to the fact that "the control of the railways has been taken over by the Government for the purpose of ensuring that the railways, locomotives, rolling-stock, and staff shall be used as one complete unit in the best interests of the State for the movement of troops, stores, and food supplies.... The staff on each railway will remain under the same control as heretofore, and will receive their instructions through the same channels as in the past."

Indelibly imprinted though the memory of those fateful August days must remain in the minds of every living individual, days brimful of wonderings alternating with doubt, expectancy, ill-foreboding, and occasional delight, coupled with an all-pervading sense of mystery completely enshrouding the movements of our own forces, few indeed were aware of the extent of the task imposed upon the Railway Executive Committee. Yet so swiftly, so silently, was the entire scheme of mobilisation carried through, that it was with a sense bordering on bewilderment [27] and with something akin to a gulp that the public found itself digesting the news of the safe transport and arrival in France of the Expeditionary Force. On the occasion of his first appearance in the House of Lords as Secretary of State for War, the late Lord Kitchener referred in brief, but none the less eulogistic terms, to the successful part played by the railway companies (cp. the Times, August 26th, 1914): "I have to remark that when war was declared mobilisation took place without any hitch whatever. The railway companies in the all-important matter of railway transport facilities have more than justified the complete confidence reposed in them by the War Office, all grades of railway services having laboured with untiring energy and patience. We know how deeply the French people appreciate the prompt assistance we have been able to afford them at the very outset of the war." Nor has Sir John French neglected to record his own appreciation of so signal a performance, for, in describing the events leading up to the concentration of the British Army in France, he writes (cp. "1914," p. 40): "Their reports (i.e. of the corps commanders and their staffs) as to the transport of their troops from their mobilising stations to France were highly satisfactory. The nation owes a deep debt of gratitude to the naval transport service and to all concerned in the embarking of the Expeditionary Force. Every move was carried out exactly to time."

So far so good, it will be opined. Certainly [28] from the chief points of disembarkation, Boulogne and le Havre, there were "roses, roses all the way," surely never before in the annals of warfare have troops from an alien shore been greeted with such galaxy of joy and enthusiasm, though perhaps most touching tribute of all was that of a wayside impression, the figure of an old peasant leaning heavily on his thickly gnarled stick, with cap in hand outstretched, his wan smile and glistening tear-dimmed eye indicating in measure unmistakable the depth and sincerity of his silent gratitude.

"On Friday, August 21st, the British Expeditionary Force," Sir John French tells us, "found itself awaiting its first great trial of strength with the enemy," and the childish display of wrathful indignation evinced by Wilhelm the (would-be) Conqueror, who is credited with having slapped with his gauntlet the face of an all too-zealous staff officer, bearer of so displeasing an item of intelligence, is not devoid of humour. The nursery parallel is complete—"Fe, fi, fo, fum," roared the giant, "I smell the blood of an Englishmen." "Gott im himmel," snarled the Kaiser, "It is my Royal and Imperial command that you concentrate your energies, for the immediate present, upon one single purpose, and that is that you address all your skill and all the valour of my soldiers to exterminate first the treacherous English and walk over General French's contemptible little army." Head-quarters, Aix-la-Chapelle, August 19th, 1914, (cp. the Times, October 1st, 1914).

[29] "Up to that time," however, as Sir John French asseverates in his further reminiscences, "as far as the British forces were concerned, the forwarding of offensive operations had complete possession of our minds.... The highest spirit pervaded all ranks"; in fact "no idea of retreat was in the minds of the leaders of the Allied Armies," who were "full of hope and confidence." In this wise, then, did the Regulars, the flower of the British Army, enter the fray, little dreaming that the entire nation and Empire were to be trained in their wake, or that upwards of four years, instead of so many months, involving sacrifices untold, must elapse ere we were destined to emerge (or perhaps muddle) successfully from out the wood.

For the moment, as it transpired, "nothing came to hand which led us to foresee the crushing superiority of strength which actually confronted us on Sunday, August 23rd"; neither had "Allenby's bold and searching reconnaissance led me (Sir John French) to believe that we were threatened by forces against which we could not make an effective stand." How completely the strength and disposal of the enemy forces had been veiled, no more than a few brief hours sufficed to disclose; disillusion quickly supervened. "Our intelligence ... thought that at least three German corps (roughly 150,000 men)2 were advancing upon us," and following [30] on a severe engagement in the neighbourhood of Charleroi in which the French 80th Corps on our left suffered heavily, a general retirement commenced. Namur had fallen on August 25th, and there was no blinking the truth, it was the Germans who were advancing, not we! Thenceforward, the retreat, the now historic Retreat from Mons, orderly throughout, set in along the whole line of the Allied Armies; of respite there was none, day in day out, 'neath the burning rays of an August sun the enemy pressure increased rather than relaxed.

The following narrative set down by an eye-witness, temporarily en panne during the afternoon and evening of August 27th on the outskirts of the little provincial town of Ham, depicts briefly but with some degree of vividness the tragic nature of the scene that was being enacted. After making some slight preliminary allusion to the pitiable plight of refugees who everywhere helped to block the roads, "there commenced," so the narrative runs, "this other spectacle of which I speak; at first, as it were, a mere trickle, a solitary straggler here, a stray cavalry horseman there, until the trickle grew, grew into a strange and never-ending living stream; for, down the long straight route nationale from Le Cateau, and so away beyond from Mons, they came those 'broken British regiments' that had been 'battling against odds'; men bare-headed, others coatless, gone the very [31] tunic from their backs; tattered, blood-stained, torn; now a small detachment, now a little group; carts and wagons heaped with impedimenta galore, while lying prone on top of all were worn-out men and footsore. And all the time along the roadside fallen-out, limping, hobbling, stumbling, came stragglers, twos and threes, men who for upwards of four days and nights, without repose, had fought and marched and trekked, till sheer exhaustion well-nigh dragged each fellow to the ground. Yet on they kept thus battling 'gainst the numbness of fatigue, that mates more broken than themselves should ease, in measure slight, their sufferings in the bare comfort of thrice-laded carts. All but ashamed to poke the crude curiosity of a camera in the grim path of war-worn warriors such as these, from where I stood, as unobtrusive as could be, I snapped three instantaneous glimpses of this gloriously pitiful review, stamped though it was already ineradicably in the pages of my memory. Twilight fell, and night, and still the stream flowed in and ever onward."

The news in London, heralded by a special Sunday afternoon edition of the Times, came as a bolt from the blue, for not since the announcement of the landing of the Expeditionary Force in France had anything of an authentic nature been received as to its subsequent doings or movements; in fact, as the Times pointed out on August 19th, "the British Expeditionary Force has vanished from sight almost as completely as the British Fleet"; further, as if to complete [32] the nightmare of uncertainty, "British newspaper correspondents are not allowed at the front; ... the suspense thus imposed upon the nation is almost the hardest demand yet made by the authorities,—with some misgivings we hope it may be patiently borne."

The British public, however, in spite of occasional qualms and momentary misgivings, ever confident of success and sure in its inflexible belief that the British Army could hold its own against almost any odds (the prevailing logic being that one Britisher was as good as any three dirty Germans), had bidden Dame Rumour take a back seat in the recesses of its mind.

Incredible then the news that broke the spell: "This is a pitiful story I have to write," so read the message, dated Amiens, August 29th, "and would to God it did not fall to me to write it. But the time for secrecy is past. I write with the Germans advancing incessantly, while all the rest of France believes they are still held near the frontier." What had happened? How could it be true? Sir John French wastes no time in mincing matters:—"The number of our aeroplanes was limited." "The enormous numerical and artillery superiority of the Germans must be remembered." "It (the machine gun) was an arm in which the Germans were particularly well found. They must have had at least six or seven to our one." "It was, moreover, very clear that the Germans had realised that the war was to be one calling for colossal supplies of munitions, supplies indeed [33] upon such a stupendous scale as the world had never before dreamed of, and they also realised the necessity for heavy artillery."

The time for secrecy was past; but how to stem the tide? The situation was, and indeed remained, such that a year later Mr. Lloyd George (then Secretary of State for War) was moved to make this astounding admission in the House of Commons: "The House would be simply appalled to hear of the dangers we had to run last year." And again at a subsequent date when as Minister of Munitions he exclaimed in the House, "I wonder whether it will not be too late. Ah! fatal words on this occasion! Too late in moving here, too late in arriving there, too late in coming to this decision, too late in starting enterprises, too late in preparing. In this war the footsteps of the Allied forces have been dogged by the mocking spectre of 'Too late.'"

In this connection it would be amusing, were it not so utterly tragic, to compare a slightly previous and public utterance from the lips of this same "Saviour of his Country":—"This is the most favourable moment for twenty years to overhaul our expenditure on armaments" (Mr. Lloyd George. Daily Chronicle, January 1st, 1914).

Happily however, "il n'est jamais trop tard pour bien faire," and this good old adage as to it being never too late to mend was perhaps never better exemplified than when, the Army Ordnance authorities having realised that the [34] Government arsenals were in no position to cope fully with the demands likely to be made by the military authorities in the field, that other army of "Contemptibles," the staffs and employés of the great engineering concerns of this country, came forward in a manner unparalleled in the history of modern industry, and forthwith commenced to adapt themselves and their entire available plant to the process of manufacturing munitions of war.

Foremost amongst firms of world-wide repute must be mentioned the great London and North-Western Railway Company, whose Chief Mechanical Engineer, Mr. C. J. Bowen-Cooke, C.B.E., realising from the outset the import of the late Lord Kitchener's forecast as to the probable duration and extent of the war, and in spite of ever-increasing demands on locomotive power which he found himself compelled to meet for military as well as for ordinary civilian purposes, threw himself heart and soul into the problem of adapting the then existing conditions and plant in the Company's locomotive works at Crewe to the requirements of the military authorities.

Forewarned as it was to some extent by the hurricane advance of the Hun, the Government was also forearmed in that it was empowered by the provisions of the Act of 1871 not merely to take over the railroads of the United Kingdom, but, should it be deemed expedient to do so, the plant thereof as well. The Government might even take possession of the plant without the [35] railroad; though how the railways could have been maintained minus their plant, any more than the Fleet could have remained in commission minus its dockyards, is doubtless a problem that was duly considered by those who framed the wording of the Act in the year of grace 1871.

However that may be, as soon as the really desperate nature of the struggle began to dawn upon the Government, and it was seen to be a case of "all or nothing," the then President of the Board of Trade, Mr. Runciman, M.P., was not slow to espy the latent, yet none the less patent, possibilities which surely existed within the practical domain of railway workshops.

In certain circumstances it may be regarded as fortunate that not a few of those happy-go-lucky individuals, whose leaning is towards politics, are gifted with the convenient art of adapting themselves and their views to that particular quarter whence the wind happens to be blowing. "I must honestly confess," as this same Mr. Runciman had expressed himself when in 1907 he was Financial Secretary to the Treasury, "that when I see the armaments expanding it is gall and wormwood to my heart; the huge amount of money spent on the Army is a sore point with every one in the Treasury."

Particularly galling, therefore, must have seemed the rate at which expenditure on armaments was increasing by leaps and bounds in 1914; yet so ingenuous is the manner in which [36] politicians are calmly capable of effecting a complete volte-face, that on October 13th we find Mr. Runciman positively engaged in seeking out the late Sir Guy Calthorp, then General Manager of the London and North-Western Railway, and Mr. Bowen-Cooke, for the purpose of eliciting their views as to the extent to which the railway companies might be relied upon to assist the Government in spending still more huge amounts of money (incidentally thus adding a further dose of wormwood to his heart), especially in regard to the output of artillery.

Without knowing for the moment what actually were the more immediate and pressing requirements of the Government, Mr. Cooke suggested an interview with the late Sir Frederick Donaldson, then Director of Army Ordnance at Woolwich Arsenal, with whom he was personally acquainted; the result being that Sir Frederick was able to point out in detail the difficulties with which he was faced, handing over to Mr. Cooke a number of drawings of gun-carriage chassis, etc., which he (Mr. Cooke) went through, tabulating them in concise form, so that at a forthcoming meeting which had been called at the Railway Clearing House for Tuesday, October 20th, the Chief Mechanical Engineers of the Midland, Great Western, North-Eastern, Great Northern, and Lancashire and Yorkshire Railways who were present should have every facility for noting and deciding what they could best undertake in their respective railway workshops.

[37] The rapid growth of this Government work necessitated arrangements being made for orders to pass through some recognised channel, and in November 1914, an offshoot of the previously-mentioned Railway Executive Committee, consisting of the Chief Mechanical Engineers of the principal railway companies, together with representatives from the War Office, was created, to be called "the Railway War Manufacturers' Sub-Committee."

Briefly the duties of this sub-committee were to consider, to co-ordinate, and to report upon various requests by or through the War Office to the railway companies, to assist in the manufacture of warlike stores and equipment. All applications for work to be done in the railway workshops, either for the War Department or for War Department contractors, were submitted to this committee by one of the War Office members. On receipt of any request the railway members of the committee decided whether the work was such as could be effectively undertaken by the railway companies, and if their decision was favourable, steps were taken to ascertain which companies could and would participate in the work, the amount of work they could undertake to turn out, and the approximate date of delivery. The War Office members decided as to the priority of the various demands made upon the railway companies. The actual order upon the railway companies to carry out any manufacturing work was given to such companies by the Railway Executive Committee.

[38] To detail the manner in which the London and North-Western Railway Company's locomotive Works at Crewe became, in great measure, as it were, a private arsenal subsidiary to the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich is the aspiring theme of the succeeding pages of this narrative.

1. Carl Rosemeier, a German in Switzerland, to the Allies. Cp. Daily Mail, June, 1919.

2. The German army corps of two divisions has 44,000 men, and a combatant strength of 26,900 rifles, 48 machine guns, 1200 sabres, and 144 guns. The German army corps of three divisions is approximately 60,000 strong (cp. the Times, August 29th, 1914).

"The armourers,

With busy hammers closing rivets up,

Give dreadful note of preparation."

Shakespeare.

Actually the first "job" to be undertaken in Crewe Works, with a view to winning the war and kicking the Hun away back across the Rhine whence rudely and ruthlessly he had pushed his unwelcome presence, was the hurried overhaul of a L. & N.W.R. motor delivery van which, destined for immediate service overseas and in conjunction with other and similar vehicles volunteered by such well-known firms as the A. & N. Stores, Bovril, Ltd., Carter Paterson, Harrod's Stores, Sunlight Soap, etc., ad lib., formed the nondescript nucleus, unique and picturesque, but none the less invaluable, of the mammoth columns of W.D. lorries which eventuated in proportion as the Country got into her stride.

Thereafter the "fun" became fast and furious; orders succeeded one another in quick succession, and in ever-increasing numbers, with the result that men who till then had been accustomed to [40] living, moving, and having their being solely and entirely in an atmosphere of cylinders, motion rods, valves, and all the like paraphernalia of locomotive structure, suddenly found themselves "switched over" on to then unknown quantities, such as axle-trees, futchels, wheel-naves, stop-plates, elevating arcs, trunnions, and other attributes of "war's glorious art"; until from bolt shop to wheel shop, fitting and electric shops to boiler shop, foundries to smithy and forge, one and all became absorbed in the tremendous issue which threatened the ordered status, the very vitals, of the civilised communities of the world.

One, if not indeed the, centre of wartime activity within the extensive domain of Crewe Works may be said to have been the mill-shop; for, although of necessity "fed" in respect to integral parts by other—and for the time being subsidiary—shops throughout the Works, it was here that were assembled and completed in readiness for dispatch to that particular theatre of war for which they were destined numerous "jobs" of anything but "Lilliputian" dimensions, and evincing characteristics of exceptional interest and unmistakable merit.

So immersed in munition manufacture did the shop become that, always—even in the everyday humdrum round of peace-time procedure—a source of delight and information to the visitor, professional and amateur alike, entry within its portals perforce assumed the nature of a privilege which Mr. Cooke, bowing to the dictates of [41] D.O.R.A., but none the less regretfully, felt constrained to withhold from all save the few legitimate bearers of either Government or other similar and indisputably genuine credentials.

Employing none but men possessed of considerable technical knowledge conjointly with the highest degree of mechanical skill and ability, the mill shop might, not without reason, be termed a "seat of engineering"; a "siége," that is, not simply productive of new machinery, but responsible for the repair and maintenance within the Works, as well as for the repair throughout the Company's entire so-called "outdoor" system, of a plant of infinite variety, embracing machinery evincing qualities so diverse as are to be found in air-compressors, gas engines, hydraulic capstans, lifts, presses, etc.

Fitly enough, however, in spite of these habitually peaceful proclivities, the soul of the millwright from the very outset of the war became infused with the spirit of Mars, and pride of place should perhaps be accorded the two armoured trains which, during the late autumn and early winter months of 1914-15, claimed the combined energies and ingenuity of those who were called upon to construct them.

Invasion was a bogey which, rightly or wrongly, undoubtedly throughout the whole period of the war never failed to exercise the minds, not only of competent military and naval authorities, but of amateur and would-be "Napoleon-Nelsons" as well, and right up to the spring of 1918, when every available ounce [42] of weight was flung across the Channel to counter what was destined to prove the final and despairing enemy offensive, large forces had been kept at home, if merely as a precautionary measure.

True enough, a certain degree of material damage accompanied not infrequently by a sufficiently heavy toll of human, and usually civilian, life resulted from perennial air raids, and an occasional ballon d'essai smacking of "tip and run" on the part of some small detachment or flying squadron of enemy ships might momentarily upset the resident equilibrium of one or other of our East-coast seaside resorts; but nothing approaching the semblance of any actual or serious attempt at invasion was ever known to occur; in fact, Mr. Lloyd George, when speaking at Bangor in February, 1915, went so far as to "lodge a complaint against the British Navy," which, he reminded his hearers, "does not enable us to realise that Britain is at the present moment waging the most serious war it has ever been engaged in. We do not understand it." There was no disputing the fact, those at home never really understood the war; almost equally self-evident was the truism that they seldom if ever really appreciated to the full the natural beauty and charm of their native shores. It needed the grim reality of the former, and the aching sense of void created by enforced and prolonged absence from the latter, to bring home the unadulterated meaning of each in its true perspective, as may be seen from that poignant [43] little plaint, pencilled from the hell of a front-line trench:—

"The wind comes off the sea, and oh! the air,

I never knew till now that life in old days was so fair,

But now I know it in this filthy rat-infested ditch,

When every shell must kill or spare, and God alone knows which."

Very similar, too, is the strain reflected by the French "poilu," who, drafted out to distant Macedonia, and languishing 'midst the fever-stricken haunts of the mosquito, plagued everlastingly besides by sickening swarms of flies, suddenly exclaims,—"Où est notre France? la chère France, qu'on ne savait pas tant belle et si bonne avant de l'avoir quittée?" From fighting men at the front and from them alone could realistic portrayals of pent-up emotions such as these emanate; they alone were capable of expounding the naked definition of the word "War;" the people at home "do not understand it."

Whether it was by good luck or by good management that "this sweet land of liberty" of ours, England, remained unmolested, immune from the horrors that were being perpetrated just across the narrow dividing line afforded by the waters, within sound of the guns, within range of modern projectile, must be left to the realm of conjecture; although some idea of "the dangers we had to run" may very well be obtained by a perusal of a few of the several and extremely cogent observations which no less an authority than Admiral Viscount Jellicoe has to [44] make on the subject in his notable work "The Grand Fleet, 1914-16."

In comparing the relative strength of Great Britain and Germany he insists that "the lesson of vital importance to be drawn" is that "if this country in the future decides to rely for safety against raids or invasion on the Fleet alone, it is essential that we should possess a considerably greater margin of superiority over a possible enemy in all classes of vessels than we did in August, 1914," and one of the four cardinal points which he cites as being the raison d'être of the Navy is that of preventing "invasion of this country and its overseas dominions." Conditions had, moreover, undergone such a complete change since the Napoleonic era, that whereas one hundred years ago "stress of bad weather was the only obstacle to closely watching enemy ports, now the submarine destroyer and the mine render such dispositions impossible," with the result that "throughout the war the responsibility of the Fleet for the prevention of raids or invasion was a factor which had considerable influence on naval strategy." Thus although, as we learn, certain defined patrol areas in the North Sea were watched on a regular organised plan by our cruiser squadrons, it was not a difficult matter for enemy ships to slip through. For "the North Sea, though small in contrast with the Atlantic, is a big water area of 120,000 square miles in extent," and whilst the Fleet was based at Scapa Flow it was not only impossible to intercept ships, but equally impossible [45] "to ensure that the enemy would be brought to action after such an operation" as that of a raid.

Bearing these considerations in mind, it is not altogether surprising that the military authorities awoke to the fact that the policy of having two strings to one's bow is not usually a bad one; and so, rather than "rely for safety against raids or invasion on the Fleet alone," they bethought themselves of the secondary line of defence which would readily be afforded by armoured trains.