MR. PUNCH AT THE SEASIDE

MR. PUNCH'S RAILWAY BOOK

MR. PUNCH ON THE CONTINONG

MR. PUNCH'S BOOK OF LOVE

MR. PUNCH AFLOAT

MR. PUNCH IN THE HIGHLANDS

OTHERS TO FOLLOW

Title: Mr. Punch on the Continong

Editor: J. A. Hammerton

Release date: May 20, 2014 [eBook #45700]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Lesley Halamek and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note: Some Illustrations have been moved higher in the book to allow uninterrupted flow of the text. All Page numbers have been retained. Page numbers in round brackets are duplicates of regular page numbers occurring elsewhere, and have been coded accordingly.

PUNCH LIBRARY OF HUMOUR

Edited by J. A. Hammerton

Designed to provide in a series of volumes, each complete in itself, the cream of our national humour, contributed by the masters of comic draughtsmanship and the leading wits of the age to "Punch," from its beginning in 1841 to the present day.

MR. PUNCH ON THE CONTINONG

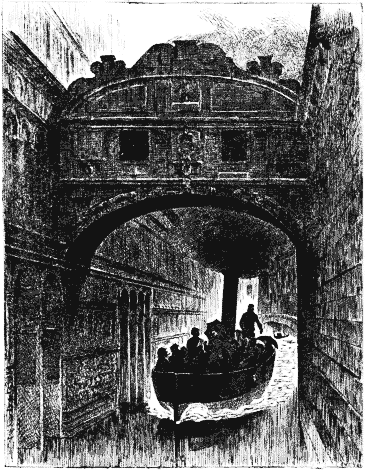

("SIC TRANSIT GLORIA MUNDI")

'Andsome 'Arriet. "Ow my! If it 'yn't that bloomin' old Temple Bar, as they did aw'y with out o' Fleet Street!"

Mr. Belleville (referring to Guide-book). "Now, it 'yn't! It's the fymous Bridge o' Sighs, as Byron went and stood on; 'im as wrote Our Boys, yer know!"

'Andsome 'Arriet. "Well, I never! It 'yn't much of a Size, any'ow!"

Mr. Belleville. "'Ear! 'ear! Fustryte!"

WITH 152 ILLUSTRATIONS

BY

|

PHIL MAY, |

PUBLISHED BY ARRANGEMENT WITH

THE PROPRIETORS OF "PUNCH"

THE AMALGAMATED PRESS, LTD.

Punch Library of Humour

Crown 8vo. 192 pages, fully illustrated, pictorial cover, 1s. net.

MR. PUNCH AT THE SEASIDE

MR. PUNCH'S RAILWAY BOOK

MR. PUNCH ON THE CONTINONG

MR. PUNCH'S BOOK OF LOVE

MR. PUNCH AFLOAT

MR. PUNCH IN THE HIGHLANDS

OTHERS TO FOLLOW

(A Foreword)

Nothing is more calculated to give Englishmen a good conceit of themselves in the matter of international courtesy than a careful examination of the archives of Mr. Punch, such as was necessary in the preparation of the present volume. To anyone familiar with the anti-British attitude of the French comic press before these happier days of the Entente Cordiale, and of the German press at all times, the complete absence of all manner of ill-feeling from Mr. Punch's jokes about our neighbours across the Channel is little short of wonderful. Even in the days when the English people were the unfailing subject for every French satirist when he suffered from an unusual attack of spleen, our national jester seems never to have lost the good-humour with which he has usually surveyed the life of the Continent. Indeed, as the pages here brought [pg 6] together will readily prove, Mr. Punch has seldom, if ever, laid himself open to the charge of insularity in his point of view. Instead of showing a tendency to ridicule our neighbours on the Continent, he has been more inclined to pillory the follies of his own countrymen, and to contrast their behaviour on the Continent rather unfavourably with that of the natives. But, even so, there is nothing in these humorous chronicles of "Mr. Punch on the Continong" which will not amuse equally the travelling or the stay-at-home Briton and the foreigner, since each will find many of his national characteristics "touched off" in a way that is no less kindly than amusing. The fact that a considerable proportion of these pages are from the pen of George Du Maurier, himself a Frenchman by birth, is a reminder that long before the Governments of France and Great Britain had come into their present relationship of intimate friendliness, Mr. Punch had maintained his own Entente Cordiale!

(pg 8)

Scene—Boulevards, Paris

Professional Beggar (whining). "Ayez pitié, mon bon m'sieu. Ayez pitié! J'ai froid—j'ai bien froid!"

Le Bon Monsieur (irritably). "Allez au di——" (suddenly thinking that sunshine might be preferable) "aux Champs Elysées!"

(TWO ASIDES)

Young England. "Rummy style of 'at!"

La Jeune France. "Drôle de chapeau!"

(To a Friendly Adviser)

When starting off on foreign trips,

I've felt secure if someone gave me

Invaluable hints and tips;

Time, trouble, money, these would save me.

I'm off; you've told me all you know.

Forewarned, forearmed, I start, instructed

How much to spend, and where to go;

Yet free, not like some folks "conducted."

Now I shall face, serene and calm,

Those persons, often rather pressing

For little gifts, with outstretched palm.

To some of them I'll give my blessing.

To others—"service" being paid—

Buona mano, pourboire, trinkgeld;

They fancy Englishmen are made

Of money, made of (so they think) geld.

The garçon, ready with each dish,

His brisk "Voilà, monsieur" replying

To anything that one may wish;

His claim admits of no denying.

The portier, who never rests,

Who speaks six languages together

To clamorous, inquiring guests,

On letters, luggage, trains, boats, weather.

The femme de chambre, who fills my bain;

The ouvreuse, where I see the acteur.

A cigarette to chef de train,

A franc to energetic facteur.

I give each cocher what is right;

I know, without profound researches,

What I must pay for each new sight—

Cathedrals, castles, convents, churches.

Or climbing up to see a view,

From campanile, roof, or steeple,

Those verbal tips I had from you

Save money tips to other people.

Save all those florins, marks or francs—

Or pfennige, sous, kreutzer, is it?—

The change they give me at the banks,

According to the towns I visit.

I seem to owe you these, and yet

Will money do? My feeling's deeper.

I'll owe you an eternal debt—

A debt of gratitude, that's cheaper.

The Cleaner (showing tourists round the church). "Voilà le Maître-autel, m'sieu' et 'dame."

British Matron. "Oh, to be sure, yes. You remember, George, we had French beans, à la Maître Autel for dinner yesterday!"

(A Note from One who has all but done it)

Dear Mr. Punch.—Now that so many of my countrymen (the word includes both sexes) patronise Monte Carlo, it is well that they should be provided with an infallible system. Some people think that a lucky pig charm or a piece of Newgate rope produces luck. But this impression is caused by a feeling of superstition—neither more nor less. What one wants in front of the table is a really scientific mathematical system. This I am prepared to give.

Take a Napoleon as a unit, making up your mind to lose up to a certain sum, and do not exceed that sum. Now back the colour twenty consecutive times. Don't double, but simply keep to the unit. When you have lost to the full extent of your limit, double your stake. Keep to this sum for another twenty turns. By this time it is a mathematical certainty that you must either have won—or lost. Of course, if you have won [pg 13] you will be pleased. If you have lost, keep up your heart and double your stakes again. This time you will be backing the colour with a stake four times as large as your original fancy. Again go for twenty turns, and see what comes of it.

Of course, if you still lose it will be unfortunate, but you cannot have everything. And with this truism, I sign myself,

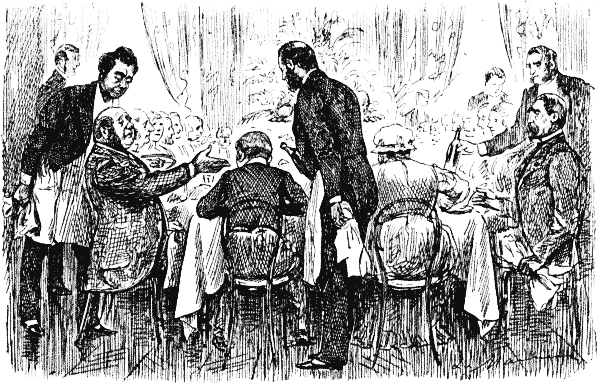

First Foreigner. "This is what they call à la Russe, isn't it!"

Second Foreigner. "Alleroose is it? Well there! I could a' sworn it warn't beef nor mutton."

(By a Dipper in Brittany)

[Apropos of a correspondence in the Daily Graphic]

Mrs. Grundy rules the waves,

With Britons for her slaves—

They're fearful to disport themselves,

Unless the sexes sort themselves

And take their bathing, sadly, for French gaiety depraves (!)

'Tis time no more were seen

The out-of-date "machine";

Away with that monstrosity

Of prudish ponderosity—

Why can't we have the bathing tent or else the trim cabine?

I think we should advance

If we took a hint from France,

And mingled (quite decorously)

On beaches that before us lie

All round our coasts—we do abroad whene'er we get the chance!

O'er here in St. Maló

The thing's quite comme il faut;

Why not in higher latitude?

I can't make out the attitude

Of those who make the British dip so "shocking," dull and slow!

First Tripper (in French Picture Gallery). "What O! 'Erb! What price this?"

Gardien (who quite understands him). "Pardon, M'sieur, eet is not 'Watteau,' and eet is not for sale!"

(pg 19)

On the Appian Way

We are with a guide, voluble after the fashion of guides all the world over, and capable of speaking many languages execrably. His English, no doubt, is typical of the rest. "Datt-e building dere," he says, "is de Barze of Caracalla."

"The what?" says my companion.

"De Barze of Caracalla—vere de ancient Romans bayze demselfs in de water—same as ve go to Casino, zey take a barze, morning, afternoon, ven zey like."

"It must have been a large building," I venture, ineptly.

"In dem dere barze," he retorts, impressively, "sixteen honderd peoples all could chomp in de water same time!"

"Jolly good splash they must have made," says A.

The guide pays no attention, but continues:—

"Dem dere barze not de biggest. In de Barze of Diocletian four tousand peoples all could chomp in de water same time. In all de barze in Rome forrrty tousand could chomp in same time."

"I wonder," says A., "how they got 'em all together and started them jumping?"

"Vell, dey not all chomp togesser every day same peoples, but ven de barze all full den forrrty tousand chomp in same time."

At the Bosco Sacro.

"Now," remarks the guide, "I tell you fonny story—make you laugh. Ven dem eight honderd robbers foundated Rome dey live on a 'ill and dey haf no religion. Den come de King Numa Pompilio: he say 'dey most haf religion,' so he can goffern dem better. Den 'e go to diss bosco, and ven he come back he tell dem robbers he haf seen de Naimp Egeea——"

"The Nymph Egeria," A. intervenes, with superiority.

"Vell, I say de Naimp Egeea. He say he haf seen her, dat she haf appareeted to him, and so dey get deir religion."

A. laughs dubiously.

"Yes," concludes the guide, "dat iss a fonny story."

By the Circus of Maxentius.

"Diss is de Circus of Massenzio. He build 'im ven his son Romulus die. No, diss is not de same Romulus who foundated Rome, but anosser one, a leetle boy, de son of de Emperor Massenzio. He die ven he vos a leetle boy. In dem days it not [pg 20] permitted to make sacrifice of men, so dey build a race-course instead: it is de same ting, for some of de charioteers alvays get dem killed, and Massenzio tink dey go play wiz Romulus."

In the Catacombs.

"Ven de martiri condemnated to dess and dey kill dem, dey safe some drops blood in a leetle bottle and dey put dem bottles in de valls. Dere iss a bit, you see. San Sebastiano 'e vos condemnated to de arrows—dey shotted 'im—and afterward dey smash his head on a column. Dere is de column."

"What was that you were telling us about Caracalla just now?"

"Caracalla he no like 'is brozzer Geta—so he kill 'im. Den he make 'im a god and tell peoples to vorship him, and 'e say 'I did not like my brozzer ven he vos a man, but I like him very moch ven he is a god.' Dat is anosser funny story."

At Boulogne.—Mrs. Sweetly (on her honeymoon). "Isn't it funny, Archibald, to see so many foreigners about? And all talking French!"

Fritz the Waiter (to Lady and Gent just arrived, and a little at sea as to the sort of a kind of a place it is). "Yes, madame, dere is such a lot of Swift people here. More dan half de peoples what is here is Swift."

John Henry Jones thinks he will do a little bit of marketing for himself, and asks the price of tomatoes. With a killing glance and a winning smile, the vendor replies that for him they will be a franc apiece, but that he mustn't mention it. The modest J. H. J. blushes, and buys, in spite of some misgiving that for anybody else they would be about sixpence a dozen.

Scene—A Table d'hôte

Aristocratic English Lady (full of diplomatic relations). "A—can you tell me if there is a resident British Minister here?"

Scotch Tourist. "Well, I'm not just quite sure—but I'm told there's an excellent Presbyterian service every Sunday!"

Wonder if there be an inn upon the Continent where you are furnished gratis with a cake of soap and bed candle.

Wonder how many able-bodied English waiters it would take to do the daily work of half a dozen French ones.

Wonder why it is that Great (and Little) Britons are so constantly heard grumbling at the half a score of dishes in a foreign bill of fare, while at home they have so frequently to feed upon cold mutton.

Wonder what amount of beer a German tourist daily drinks, and how many half-pint glasses a waiter at Vienna can carry at a time without spilling a drop out of them.

Wonder how it is that, although one knows full well that many Paris people are most miserably poor, one never sees such ragged scarecrows in its streets as are visible in London.

Wonder how many successive ages must elapse ere travellers abroad enjoy the luxury of salt-spoons.

Wonder why so many tourists, and particularly ladies, will persist in speaking French, with a true Britannic accent, when the waiter so considerately answers them in English.

Wonder when our foreign friends, who are in most things so ingenious, will direct their ingenuity to the art of drainage coupled with deodorising fluids.

Wonder if there be a watering-place in France where there is no Casino, and where Frenchmen may be seen engaged in any game more active than dominoes or billiards.

Wonder when it will be possible to get through seven courses at a foreign table d'hôte without running any risk of seeing one's fair neighbour either eating with her knife or wiping her plate clean by sopping bread into the gravy.

Wonder what would be the yearly increase of deafness in Great Britain, if our horses all had bells to jangle on their harness, and our drivers all were seized with the mania for whip-cracking, which possesses in such fury all the coachmen on the Continent.

Wonder in what century the historian will relate that a Frenchman was seen walking in the country for amusement.

Wonder why it is that when one calls a Paris waiter, he always answers, "V'la, M'sieu," and then invariably vanishes.

Wonder when Swiss tourists will abstain from buying alpenstocks which they don't know how to use, and which are branded with the names of mountains they would never dare to dream of trying to do more than timidly look up to.

Wonder in what age of progress a sponge-bath will be readily obtainable abroad, in places most remote, and where Britons least do congregate.

Wonder if French ladies, who are as elegant in their manners as they are in their millinery, will ever acquire the habit of eating with their lips shut.

Wonder when it will be possible to travel on the Rhine, without hearing feeble jokelets made about the "rhino."

Mrs. Vanoof (shopping in Paris). "Now let me see what you've got extra special."

Salesman. "Madam, we 'ave some ver' fine Louis treize."

Mr. Vanoof. "Trays, man! What do we want with trays!"

Mrs. Vanoof. "Better try one or two; they're only a louis."]

"Oh—er—pardong, Mossoo—may kelly le shmang kilfoker j'ally poor ally Allycol Militair?"

"Monsieur, je ne comprends pas l'Anglais, malheureusement!"

[Our British Friend is asking for the way to the École Militaire.

(pg 36)

Scene—Public drawing-room of hotel in the Engadine.

The Hon. Mrs. Snobbington (to fair stranger). "English people are so unsociable, and never speak to each other without an introduction. I always make a point of being friendly with people staying at the same hotel. One need never know them afterwards!"

(pg 37)

The Delamere-Browns, who have been spending their honeymoon trip in France, have just taken their seats on the steamer, agreeably conscious of smart clothes and general well-being, when to them enters breathlessly, Françoise, the "bonne" from the hotel, holding on high a very dirty comb with most of its teeth missing.

Françoise (dashing forward with her sweetest smile). "Tiens! J'arrive juste à point! Voilà un peigne que madame a laissé dans sa chambre!" [Tableau!

(pg 40)

Appalling position of Mr. and Mrs. Tompkins, who had a jib horse when the tide was coming in.

(pg 41)

First Compatriot (in Belgian café). "I beg your pardon, sirr. Are ye an Irishman?"

Second Compatriot. "I am!" [Silence.

First Compatriot. "I'd as soon meet a crocodile as an Irishman 'foreign parts. I beg ye'll not address yer conversation to me, sirr!!"

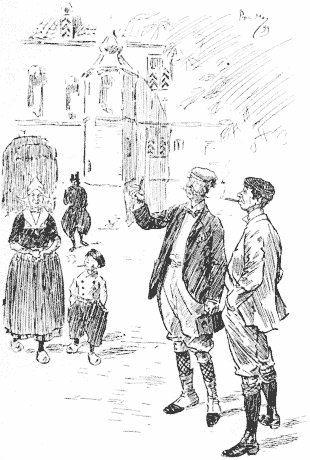

When we came to Amsterdam, we determined, Pashley, Shirtliff and I, that we would take the earliest opportunity of seeing Marken. Wonderful place, by all accounts. Little island, only two miles from mainland, full of absolutely unsophisticated inhabitants. Most of them have never left Marken—no idea of the world beyond it! Everybody contented and equal; costumes quaint; manners simple and dignified. Sort of Arcadia, with dash of Utopia.

And here we are—actually at Marken, just landed by sailing-boat from Monnickendam.

All is peaceful and picturesque. Scattered groups of little black cottages with scarlet roofs, on mounds. Fishermen strolling about in baggy black knickerbockers, woollen stockings, and wooden shoes.

Women and girls all dressed alike, in crimson bodice and embroidered skirt; little cap with one long brown curl dangling coquettishly in front of each ear. Small children—miniature replicas of their elders—wander lovingly, hand in hand. A few urchins dart off at our approach, like startled fawns, and disappear amongst the cottages. Otherwise, our arrival attracts no attention.

The women go on with their outdoor work, cleaning their brilliant brass and copper, washing and hanging out their bright-hued cotton and linen garments, with no more than an occasional shy side-glance at us from under their tow-coloured fringes. "Perfectly unconscious," as Shirtliff observes, enthusiastically, "of how unique and picturesque they are!"

All the more wonderful, because excursion steamers run every day during the season from Amsterdam.

We walk up and down rough steps and along narrow, winding alleys. Shirtliff says he "feels such a bounder, going about staring at everything as if he was at Earl's Court." Thinks the Markeners must hate being treated like a show. We shouldn't like it ourselves!

That may be, but, as Pashley retorts, it's the Markeners' own fault. They shouldn't be so beastly picturesque.

Fine buxom girl approaches, carrying pail. On closer view, not precisely a girl—in fact, a matron of mature years. These long, brown side-curls deceptive at a distance; impression, as she passes, of a kind of Dutch "Little Toddlekins"; view of broad back and extensive tract of fat, bare neck under small cap. She turns round and intimates by expressive pantomime that her cottage is close by, and if we would care to inspect the interior, we are heartily welcome. Uncommonly friendly of her. Pashley and I are inclined to accept, but Shirtliff dubious—we may have misunderstood her. We really can't go crowding in like a parcel of trippers!

Little Toddlekins, however, quite keen about it; [pg 31] sees us hesitate, puts down pail and beckons us on round corner with crooked forefinger, like an elderly Siren. How different this simple, hearty hospitality from the sort of reception foreigners would get from an English fishwife! We can't refuse, or we shall hurt her feelings. "But whatever we do," urges Shirtliff, "we mustn't dream of offering her money. She'd be most tremendously insulted."

Of course, we quite understand that. It would be simply an outrage. We uncover, and enter, apologetically. Inside, [pg 32] an elderly fisherman is sitting by the hearth mending a net; a girl is leaning in graceful, negligent attitude against table by window. Neither of them takes the slightest notice of us, which is embarrassing. Afraid we really are intruding. However, our hostess—good old soul—has a natural tact and kindliness that soon put us at our ease. Shows us everything. Curtained recesses in wall, where they go to bed. "Very curious—so comfortable!" Delft plates and painted shelves and cupboards. "Most decorative!" Caps and bodices worn by females of the family. "Charming; such artistic colour!" School copybooks with children's exercises. "Capital; so neatly written!" What is she trying to make us understand? Oh, in winter, the sea comes in above the level of the wainscot. "Really! How very convenient!" We don't mean this, but we are so anxious to please and be pleased, that our enthusiasm is degenerating into drivel. Girl by the window contemplates us with growing contempt; and no wonder. High time we went.

Little Toddlekins at the end of her tether; looks at us as if to imply that she has done her [pg 33] part. Next move must come from us. Pashley consults us in an undertone. "Perhaps, after all she does expect, eh? What do we think? Would half a gulden—— What?"

Personally, I think it might, but Shirtliff won't hear of it, "Certainly not. On no account! At all events he'll be no party to it. He will simply thank her, shake hands, and walk out." Which he does. I do the same. He may be right, and anyhow, if one of us is to run the risk of offending this matron's delicacy by the offer of a gratuity, Pashley will do it better than I.

Pashley overtakes us presently, looking distinctly uncomfortable. "Did he tip her?" "Yes, he tipped her." "And she flung it after you!" cries Shirtliff, in triumph. "I knew she would! Now I hope you're satisfied!"

"If I am, it's more than she was," says Pashley. "She stuck to it all right, but she let me see it was nothing like what she'd expected for the three of us."

Shirtliff silent but unconvinced. However, as we go on, we see a beckoning forefinger at almost every door and window. Every Markener anxious that we should walk into his little parlour—and pay for the privilege. All of them, as Pashley disgustedly observes, "On the make"; got some treasured heirloom that has been in the family without intermission for six months, and that they would be willing to part with, if pressed, for a consideration. We don't press them; in fact, we are obliged at last to decline their artless invitations—to their unconcealed disgust. Nice people, very, but can't afford to know too many of them.

"At least the children are unspoilt," says Shirtliff, as we come upon a couple of chubby infants, [pg 36] walking solemnly hand in hand as usual. He protests, when Pashley insists on presenting them with a cent, or one-fifth of an English penny, apiece. "Why demoralise them, why instil the love of money into their innocent minds?" Shirtliff wants to know.

He is delighted when they exhibit no sort of [pg 37] emotion on being thus enriched. It shows, he says, that, as yet, they have no conception what money means.

The pair have toddled off towards a gathering [pg 38] of older children, and Pashley, who has brought a Kodak, wonders if he can induce them to stay as they are while he takes a snapshot. Shirtliff protests again. Only spoil them, make them conceited and self-conscious, he maintains.

But the children have seen the Kodak, and are eager to be taken. One of them produces a baby from neighbouring cottage, and they arrange themselves instinctively in effective group by a fence.

Pashley delighted. "Awfully intelligent little beggars!" he says. "They seem to know exactly what I want."

They also know exactly what they want, for the moment they hear the camera click, they make a rush at us, sternly demanding five cents a head for their services.

Shirtliff very severe with them; not one copper shall they have from him; not a matter of pence, but principle, and they had better go away at once. They don't; they hustle him, and some of the taller girls nudge him viciously in the ribs with sharp elbows, as a hint that "an immediate settlement is requested." Pashley and I do the best we can, but we soon come to the end of our Dutch coins. However, no doubt English pennies will—— Not a bit of it! Even the chubby infants don't consider them legal tender here, and reject them with open scorn.

Fancy we have compromised all claims at last. No; Marken infantry still harassing our rear. What more do they want? It appears that we have not paid the baby, which is an important extra on these occasions, and which they carry [pg 41] after us in state as an unsatisfied creditor and a powerful appeal to our consciences. Adult Markeners come out, and seem to be exchanging remarks (with especial reference to Shirtliff, who is regarded as the chief culprit) on the meanness that is capable of bilking an innocent baby.

"What I like about Marken," says Pashley, when we are safely on board our sailing boat, to which we have effected a rather ignominious [pg 42] retreat, "what I like about Marken is the beautiful simplicity and unworldliness of the natives. Didn't that strike you, Shirtliff?"

We gather from Shirtliff's reply that he failed to observe these characteristics.

At Munich.—Mr. Joddletop (to travelling companion at Bierhalle). What they call this larger beer for I'm blessed if I know! Why, it's thinner than the Bass I drink at home!

Mrs. Tripper (examining official notice on the walls of Boulogne). What's that mean, Tripper, "Pas de Calais"?

Tripper (who is proud of his superior acquaintance with a foreign language). It means—"Nothing to do with Calais," my dear. These rival ports are dreadfully jealous of one another!

Very Much Abroad.—Brown. I say, Smith, you've been here before. Tell me where I can get a first dish of Tête de veau?

Smith. Tête de veau? Let's see, that's "calf's head," isn't it? Well, I heard of a place where they ought to have it good, as they call it the Hôtel de Veal.

He. "You climed ze Matterhorn? Zat was a great foot."

She. "Great feat, you mean, count."

He. "Ah! Zen you climed him more as once!"

["The recent complaints of the rudeness shown to English travellers in Switzerland by the natives has been officially denied by the authorities of Lucerne."—Daily Paper.]

You are an idiot, a fool, and a rascal. (Official explanation.) Terms of endearment denoting feeling of the utmost friendship.

Why do you come here? Why don't you stay at home? (Official explanation.) Merely questions asked to stimulate pleasant conversation.

You are a rosbif, a boule dogue, and plum-pudding. (Official interpretation.) Fine names intended to express the greatest possible admiration for British institutions.

If you speak we will knock you down. (Official interpretation.) Merely a kindly expression of concern calculated to produce repose.

You are one brutal, ugly-faced foreigner. (Official interpretation.) A jocular salutation.

You sell your wife at Smithfield—Long live the Boers! (Official interpretation.) A polite attempt to commence a courteous conversation.

Are you English? (Official interpretation.) The highest praise imaginable.

Youthful North Briton (on honeymoon tour, proud of his French). "Gassong! La—le—le—cart——"

Garçon. "Oui, m'sieu', tout de suite!"

Admiring Bride. "Losh! Sandy, what did he say?"

Youthful North Briton (rather taken aback). "Aweel, Jeannie, dear, he kens I'm Scotch, an' he asked me to 'tak' a seat.'"

(pg 46)

(pg 47)

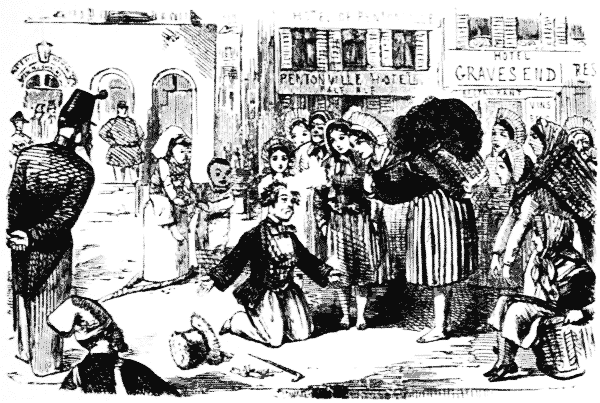

Our friend, 'Arry Belville, is so knocked all of a heap by the beauty of the foreign fish girls, that he offers his 'and and 'art to the lovely Pauline.

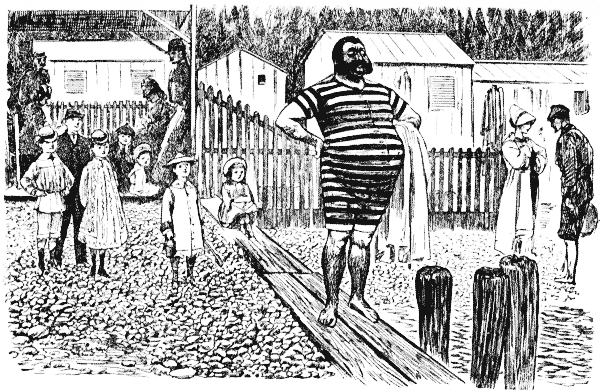

After the bath, the Count and Countess de St. Camembert have a little chat with their friends before dressing; and Monsieur Roucouly, the famous baritone, smokes a quiet cigarette, ere he plunges into the sandy ripple.

Or, The Legend of Lionel

"Newhaven to Dieppe," he cried, but, on the voyage there,

He felt appalling qualms of what the French call mal de mer;

While, when the steward was not near, he struck Byronic attitudes,

And made himself most popular by pretty little platitudes.

And, while he wobbled on the waves, be sure they never slep',

While waiting for their Lionel, the Damsels of Dieppe.

He landed with a jaunty air, but feeling rather weak,

While all the French and English girls cried out "C'est magnifique!"

They reck'd not of his bilious hue, but murmur'd quite ecstatical,

"Blue coat, brass buttons, and straw hat—c'est tout-à-fait piratical!"

He hadn't got his land-legs, and he walked with faltering step,

But still they thought it comme-il-faut, those Damsels of Dieppe.

The Douane found him circled round by all the fairest fair,

The while he said, in lofty tones, he'd nothing to declare;

He turned to one girl who stood near, and softly whisper'd "Fly, O Nell!"

But all the others wildly cried, "Give us a chance, O Lionel!"

And thus he came to shore from all the woes of Father Nep.,

With fatal fascinations for the Damsels of Dieppe.

He went to the Casino, whither mostly people go,

And lost his tin at baccarat and eke petits chevaux;

And still the maidens flocked around, and vowed he was amusing 'em;

And borrowed five-franc pieces, just for fear he should be losing 'em;

And then he'd sandwiches and bocks, which brought on bad dyspep-

-sia for Lionel beloved by Damsels of Dieppe.

As bees will swarm around a hive, the maids of La belle France

Went mad about our Lionel and thirsted for his glance;

In short they were reduced unto a state of used-up coffee lees

By this mild, melancholic, maudlin, mournful Mephistopheles.

He rallied them in French, in which he had the gift of rep-

-artee, and sunnily they smiled, the Damsels of Dieppe.

At last one day he had to go; they came upon the pier;

The French girls sobbed, "Mon cher!" and then the English sighed, "My dear!"

He looked at all the threatening waves, and cried, the while embracing 'em,

(I mean the girls, not waves,) "Oh no! I don't feel quite like facing 'em!"

And all the young things murmured, "Stay, and you will find sweet rep-

aration for the folks at home in Damsels of Dieppe."

And day by day, and year by year, whene'er he sought the sea,

The waves were running mountains high, the wind was blowing free.

At last he died, and o'er his bier his sweethearts sang doxology,

And vowed they saw his ghost, which came from dabbling in psychology.

And to this hour that spook is seen upon the pier. If scep-

tical, ask ancient ladies, once the Damsels of Dieppe.

To Intending Tourists.—"Where shall we go?" All depends on the "coin of 'vantage." Switzerland? Question of money. Motto.—"Point d'argent point de Suisse."

At Interlachen.—Cockney Tourist to Perfect Stranger. Must 'ave been a 'ard frost 'ere last night, sir.

Perfect Stranger (startled). Dear me! Why?

Cockney Tourist. Why, look at the top of that there 'ill, sir (points to the Jung Frau). Ain't it covered with snow!

Smith (meeting the Browns at the station on their return from the Continent). "Delighted to see you back, my boy! But—well, and how did you like Italy?"

Mrs. B. (who is "artistic"). "Oh, charming, you know, the pictures and statues and all that! But Charles had typhoid for six weeks at Feverenze (our hotel was close to that glorious Melfizzi Palazzo, y'know), and after that I caught the Roman fever, and so," &c., &c.

[They think they go to Ramsgate next year.

"Now, then, mossoo, your form is of the manliest beauty, and you are altogether a most attractive object; but you've stood there long enough. So jump in and have done with it!"

Sir G. Midas (to his younger son). "There's a glass o' champagne for yer, 'Enry! Down with it, my lad—and thank 'Eaven you're an Englishman, and can afford to drink it!"

[According to a correspondent of the Times, it is proposed to erect bridges connecting Venice with the mainland.]

One afternoon in the autumn of 1930, when the express from Milan arrived at Venice an Englishman stepped out, handed his luggage ticket to a porter, and said, "Hotel Tiziano."

"Adesso Hotel Moderno, signore," remarked the porter.

"They've changed the name, I suppose. All right. Hotel Moderno, gondola."

"Che cosa, signore?" asked the porter, apparently confused, "gon—, gondo—, non capisco. Hotel Moderno, non è vero?" And he led the way to the outside, where the Englishman perceived a wide, asphalted street. "Ecco là, signore, la stazione sotterranea del Tubo dei Quattro Soldi; ecco qui la tramvia elettrica, e l'omnibus dell' hotel."

"Gondola," repeated the Englishman. The porter stared at him again. Then he shook his head and answered, "Non capisco, signore, non parlo inglese." So the Englishman entered the motor omnibus, started at once, for there were no other travellers, [pg 54] and in a few minutes arrived at the hotel, designed by an American architect and fifteen stories in height. The gorgeous marble and alabaster entrance-hall was entirely deserted.

Having engaged a room, the Englishman asked for a guide. The hall porter, who spoke ten languages fluently and simultaneously, murmured some words into a telephone, and almost immediately a dapper little man presented himself with an obsequious bow.

"I want to go round the principal buildings," said the Englishman. "You speak English, of course."

"Secure, sir," answered the guide, with another bow; "alls the ciceronians speaks her fine language, but her speak I as one English. Lets us go to visit the Grand Central Station of the Tube."

"Oh, no," said the Englishman, "not that sort of thing! I'm not an engineer. I should like to see the Doge's Palace."

"Lo, sir! The Palace is now the Stazione Centrale Elettrica."

"Then it's no good going to see that. I will go to St. Mark's."

"San Marco is shutted, sir. The vibrazione of the elettrical mechanism has done fall the mosaics. The to visit is become too periculous."

"Oh, indeed! Well, we can go up the Grand Canal."

"The Canal Grande, sir, is now the Via Marconi. Is all changed, and covered, as all the olds canals of Venezia, with arches of steel and a street of asfalto. Is fine, fine, è bella, bella, una via maravigliosa"!

"You don't mean to say there isn't a canal left? Where are the gondolas then?"

"An, una gondola! The sir is archeologo. Ebbene! We shalls go to the Museo. There she shall see one gondola, much curious, and old, ah, so old!"

"Not a canal, not a gondola—except in the museum! What is there to see?"

"There is much, sir. There is the Tube of the Four Halfpennies, tutto all' inglese, as at London. He is on the arches of steel below the news streets. There is the bridge from the city to Murano, one span of steel all covered of stone much thin, as the Ponte della Torre, the Bridge of the Tower, at London. Is marvellous, the our bridge! Is one bridge, and not of less not appear to be one bridge, but one castle of the middle age in the middle air. È bellissimo, e anche tutto all' inglese. And then——"

"Stop," cried the Englishman. "Does anybody ever come to your city now? Any artists, for instance?"

"Ah, no, sir! Pittori, scultori, perche? But there are voyagers some time. The month past all the Society of the Engineers of Japan are comed, and the hotels were fulls, and all those sirs were much contenteds and sayed the city was marvellous. She shall go now, sir, to visit the bridge?"

"No," said the Englishman, emphatically, "not I! Let me pay my bill here and your fee, whatever it is, and take me back to the railway station as fast as you can. There are plenty of bridges in London. I am going back there."

At Brussels.—Mrs. Trickleby (pointing to announcement in grocer's window, and spelling it out).

Jambon d' Yorck. What's that mean, Mr. T.?

Mr. T. (who is by way of being a linguist). Why, good Yorkshire preserves, of course. What did you suppose it was—Dundee marmalade?

"These 'ere cigars at three a 'na'penny 'as just as delicate a flavour as them as we pays a penny a piece for at 'ome!"

The Garsong (to Jones and Brown, from Clapham). "But your dinner, gentlemans! He go to make 'imself cold, if you eat 'im not!"

Dear Charlie,—You heard as I'd left good old England agen, I'll be bound.

Not for Parry alone, mate, this time—I've bin doing the Reglar Swiss Round.

Mong Blong, Mare de Glass, and all that, Charlie—guess it's a sight you'd enjoy

To see 'Arry, the Hislington Masher, togged out as a Merry Swiss Boy.

'Tis a bit of a stretch from the "Hangel," a jolly long journey by rail.

But I made myself haffable like; I'd got hup on the toppingest scale;

Shammy-hunter at Ashley's not in it with me, I can tell yer, old chap;

And the way as the passengers stared at me showed I wos fair on the rap.

Talk of hups and downs, Charlie! North Devon I found pooty steep, as you know.

But wot's Lynton roads to the Halps, or the Torrs to that blessed Young Frow?

I got 'andy with halpenstocks, Charlie, and never came much of a spill;

But I think, arter all, that, for comfort, I rayther prefer Primrose 'Ill.

But that's ontry nous, dont cher know; keep my pecker hup proper out 'ere.

'Arry never let on to them Swiss as he felt on the swivel—no fear!

When I slipped down a bloomin' crevassy, I did do a bit of a 'owl,

On them glasheers, to keep your foot fair, you want claws, like a cat on the prowl.

Got arf smothered in snow, and no kid, Charlie—guide swore 'twas all my hown fault,

'Cos I would dance, and sing too-ral-li-ety, arter he'd hordered a halt.

Awful gonophs, them guides, and no herror; they don't know their place not a mite,

And I'm dashed if this cad didn't laugh (with the rest), 'cos I looked sich a sight.

At Ostend.—Biffles (to Tiffles). In this bloomin' country everyone's a prince or a marquis or a baron or a nob of some sort, so I've just shoved you down in the Visitors' Book as Lord Harthur MacOssian, and me as the Dook of FitzDazzlem!

Tiffles. Well, now, that is a lark! What'd our missuses say?

[And what did their "Missuses" say when B. and T., held in pawn by the hotel proprietor (charging aristocratic prices), had to write home to Peckham Rye for considerable advances from the family treasuries?

Passenger from London (as the train runs into the Gare du Nord, Paris). "Oh—er—I say—er—garsong! Kel ay le nomme du set plass?"

Sur la Plage! and here are dresses, shining eyes, and golden tresses,

Which the cynic sometimes guesses are not quite devoid of art;

There's much polyglottic chatter 'mid the folks that group and scatter,

And men fancy that to flatter is to win a maiden's heart.

'Tis a seaside place that's Breton, with the rocks the children get on,

And the ceaseless surges fret on all the silver-shining sand;

Wave and sky could scarce be bluer, and the wily Art-reviewer

Would declare the tone was truer than a seascape from Brett's hand.

And disporting in the waters are the fairest of Eve's daughters,

Each aquatic gambol slaughters the impulsive sons of France,

While they gaze with admiration at the mermaids' emulation,

And the high feats of natation at fair Dinard on the Rance.

There are gay casino dances, where, with Atalanta glances

That ensnare a young man's fancies, come the ladies one by one;

Every look is doubly thrilling in the mazes of quadrilling,

And, like Barkis, we are willing, ere the magic waltz is done.

And at night throng Fashion's forces where the merry little horses

Run their aggravating courses throughout all the Season's height;

Is the sea a play-provoker?—for the bard is not a joker

When he vows the game of poker goeth on from morn till night.

There St. Malo walls are frowning,—'twas immortalised by Browning,

When he wrote the ballad crowning with the laurel Hervé Riel;

With ozone each nerve that braces, pleasant strolls, and pretty faces,

Sure, of all fair seaside places, Breton Dinard bears the bell!

Compensation,—"Ullo, Jones! You in Paris!"

"Yes, I've just run over for a holiday."

"Where's your wife?"

"Couldn't come, poor dear. Had to stop at home on account of the baby!"

"Why, your holiday will be half spoiled!"

"Yes. Mean to stay twice as long, to make up!"

He tries to make a droski-driver understand that he could have gone the same distance in a hansom for less money.

At Paris.—Professed Linguist. Look here! Moi et un otrer Mossoo—a friend of mine—desirong der go par ler seven o'clock train à Cologne. Si nous leaverong the hotel at six o'clock et ung demy, shall nous catcherong le train all right? Comprenny voo? Voo parly Français, don't you? You understand French, eh?

Polite Frenchman (who speaks the English). I understand the French? Ah yase! Sometimes, monsieur!

(Supplementary Facts—omitted from the Times List)

That everything is so much better on the Continent.

That the proverbially polite Frenchman never smokes before ladies in a railway carriage.

That not for worlds would he shut the window in your face and glare at you if you ask for a little air.

That no official ever seen through a pigeon-hole at a post bureau is dyspeptic and insolent.

That sanitary improvements in Italy do not mean typhoid fever.

That where your bed-room walls are of paper, and somebody on one side of you retires in good spirits at two, and somebody else on the other gets up lively at four, you have a refreshing night's rest.

That rambling parties of Cook's tourists add immensely to the national prestige.

That the discovery of what it is you eat in a vol-au-vent at a "diner à trois francs," will please but not surprise you.

That it is such fun being caged-up in a railway waiting-room, and then being allowed to scamper for your life to the carriages.

That perpetual fighting to get into over-crowded hotels, crammed with vulgar specimens of your own fellow-countrymen, is really enjoyable and exhilarating work.

That a couple of journeys across the Channel, especially if it is blowing both ways, are at least always something pleasant to look back upon.

That when you once get home again, England, spite some trivial advantages, being without Belgian postmen, French omnibuses, and Swiss police-regulations, strikes you as almost unendurable.

At Monte Carlo.—Angelina (sentimentally). Look, Edwin, how the dear palms are opening themselves instinctively to the golden air.

Edwin (brutally remembering his losses at the table and the long hotel bill). If you can show me any palm in the place, human or vegetable, which doesn't open itself instinctively to the golden air, I'll eat my hat!

[Angelina sighed profoundly, and Edwin opened his purse strings.

Mrs. Blunderby. "Now, my dear Monty, let me order the luncheon ar-la-Fraingsy. Gassong! I wish to begin—as we always do in Paris, my dears—with some chef-d'œuvres—you understand—some chef-d'œuvres."

[Emile, the waiter, is in despair. It occurs to him, however, presently that the lady probably means "Hors d'œuvres," and acts accordingly.

Not those, along the route prescribed

To see them in a hurry,

Church, palace, gallery, described

By worthy Mr. Murray.

Nor those detailed as well by whom

But Baedeker, the German;

The choir, the nave, the font, the tomb,

The pulpit for the sermon.

No tourist traps which tire you out,

A never-ending worry;

Most interesting things, no doubt,

Described by Mr. Murray.

Nor yet, O gastronomic mind—

In cookery a boss, sage

In recipes—you will not find,

I mean Bologna sausage.

Not beauties, which, perhaps, you class

With your own special curry;

Not beauties, which we must not pass

If led by Mr. Murray.

I sing—alas, how very ill!—

Those beauties of the city,

The praise of whose dark eyes might fill

A much more worthy ditty.

O, Ladies of Bologna, who

The coldest heart might flurry,

I much prefer to study you

Than Baedeker or Murray.

Those guide-book sights no longer please;

Three hours still, tre ore,

I have to lounge and look at these

Bellissime signore.

Then slow express—South Western goes

Much faster into Surrey—

Will take me off to other shows

Described by Mr. Murray.

But still, Signore, there will be,

By your sweet faces smitten,

One Englishman who came to see

What Baedeker has written.

Let Baedeker then see the lot

In frantic hurry-scurry.

I've found some beauties which are not

Described by Mr. Murray.

Overheard at Chamonix.—Stout British Matron (in a broad British accent, to a slim diligence driver). Êtes-vous la diligence?

Driver. Non, madame, mais j'en suis le cocher.

Matron (with conviction). C'est la même chose; gardez pour moi trois places dans votre intérieur demain.

(pg 77)

First Tourist. "I say, old chap, it smells pretty bad about here; it's the river, I suppose?"

Second Tourist. "Yes—Seine Inférieure."

(Scene—Restaurant in Switzerland)

Tourist (to manager, who knows English). "There are two bottles of wine in our bill. We had only one bottle."

Manager. "Ach, he is a new waiter, and zee confounded echo of zee mountain must have deceived zee garçon."

Anxious Tourist. "Since your town has been newly drained, I suppose there is less fever here?"

Hotel-Keeper (reassuringly). "Ach, yes, sir! Ze teefoose (typhus) is now quite ze exception!"

(pg 83)

First Man (tasting beer). "Hullo! I ordered lager. This isn't lager!"

Second Man (tasting). "No; but it's jolly good, all the same!"

Third Man (tasting). "C'est magnifique! mais ce n'est pas lager-r-r!"

Mrs. Ramsbotham, who has been staying at Boulogne for a short time, writes as follows:—

"Bullown-some-Air is, I am informed, not what it used to be, though the smells must be pretty much as always, which is not the scent of rheumatic spices. It's called Bullown-some-Air because if the sea-breeze wasn't too powerful for the smells, living would be impossible. Many of the visitors to the hotels on the Key told me the bedrooms were full of musketeers, who came in when the candle went out, and bit them all over. Such a sight as one poor gentleman was! He reminded me of the Spotted Nobleman at the Agrarian in Westminster. Then, on the Sunday I was there, a day as I had always been given to [pg 77] understand the French were 'tray gay,' there was actually no music, no band, no concert, and in fact no amusement whatever at the Establishmong day Bangs (so called because there's a shooting-gallery next it, where they bang away all day at so much a head), which might as well have been closed, as there was no race-game (of which I had heard so much), no Tom Bowling* (they wouldn't get up a Tom Bowling unless there were nine persons [pg 78] present, which Mr. Hackson says is much the same as when magistrates meet and there isn't a sufficient number to make a jorum), and only one gentleman trying to produce another to play billiards with him.

"There was a theatre open. Not being a Samaritan myself, though as strict as anyone as to my own regular religious diversions at church, I let Mr. Hackson take myself and Lavinia to see The Clogs of Cornwall, which, I think, was the name of the opera, though, as I hadn't a bill, and didn't understand one quarter of what they were saying—not but what I was annoyed by Lavvy and Mr. Hackson always turning round to explain the jokes to me—I confess I did not see what either Cornwall or Clogs had to do with the story. The singing and the acting was worse than anything I'd ever met with at an English seaside theatre, because a place like Bullown ought to have a theatre as good as the one at Brighton. The customs worn by the actors were ugly, and when the lover, who was intended for a sailor—though his dress wasn't at all de rigger—said, confidentially, to the audience, alluding to an unfortunately [pg 80] plain young person who played the part of the Herring, "She is lovely!" there was a loud laugh, or, as Mr. Hackson, who speaks French perfectly, called it, a levy de reedo, all over the house, and this emulating from people who, I always thought, were remarkable for their politeness, was about the rudest thing I ever heard done to a public character in a playhouse.

"The place was hot, and the seats uncomfortable; so that after two acts, which was more like being in a penitentiary than a place of recrimination, we left, and went to our hotel, where, there being nothing more to do than there was anywhere else, Lavinia and myself retired to rest—that is, such rest as the musketeers would allow us. She slept in a back cupboard, called a cabinet de Twilight, because it was so dark and scarcely any veneration, there being no fireplace, and only such a window, as it was healthier to keep shut than open: but she had the advantage over me in not being troubled by any musketeers. There was only one of them in my room, and when I heard him singing away like a couple of gnats, I hid under the bedclothes, and he couldn't find me till I came up [pg 82] again for air, like a fish, and then he bit me on the forehead.

"Next morning we went to breakfast 'à la four sheets' they call it, on account of the size of the table-napkins, at the Rest-wrongs on the pier. The time they kept us! as there was only one gossoon to about twenty persons. The best thing we had there was our own appetite, which we brought with us.

"After this there was nothing doing in the place till dinner-time (called table doat because they're so fond of it), and after that there was a dull concert at the Establishmong, and as Mr. Hackson told us, who went there, a dull dance and poor fireworks at the Artillery Gardens in the Oat Veal. The 'Oat Veal' is French for the high part of the town, but, judging from the smells on and about the Key, I should say that our hotel was situated in quite the highest part of the town.

"Less than a week at Bullown was quite enough and too much for us. If Sunday here were only lively, it would be a nice change from London, or Dover, or Folkestone, or Ramsgate, as I do not know a pleasanter and easier way to go than [pg 83] starting by the London, Chatting and Dover train at 10 A.M. from Victoria or Holborn Viaduct, arriving at Dover at twelve. Then by one of the comfortablest boats I was ever in, called the Inflicter or Invigorator, I couldn't catch which, but Mr. Hackson told me it was Latin for 'unconquered,' which takes you, if it's a fine day and wind and tide favourable, in an hour and a quarter to Callous (or [pg 84] Kally in French), and if you are only going on to Bullown, you have your luggage examined (as if you were a smuggling brigadier!), and you have more than an hour for lunch before you start again. The luncheon at the Kallyous buffy is excellent, and the buffers, who speak English with hardly any accident, are most attentive. Then, when you've finished, you start for Bullown by the 2.45 train, and are at your hotel by 3.30 or thereabouts, which is what I call doing it uxuriously.

"But Bullown, as Mr. Hackson said to me, requires some ongterprenner, which means 'an undertaker,' to look after it, as it has become so deadly-lively. I think this must be a joke of Mr. Hackson's, one of his caramboles, as they call them in French, as what Bullown wants is waking up. As it is now, Bullown is a second-class place, and will soon be a third-class one, which, as Mr. Hackson says, 'Arry and an inferior dummy-mong will have all to themselves.

* We fancy Mrs. R. means "Tombola."

During his recent tour in Switzerland, Tomkins, who is rather nervous, had a most terrifying experience.

O dubious hybrid, what your patronymic

Or pedigree may be, does not much matter;

But if my own attire you mean to mimic,

And flaunt the fact that you, too, have a hatter—

Well then, in self-defence I'll pick with you

A bone or two.

Perchance you have a motive, deep, ulterior,

In donning head-gear borrowed from banditti?

You wish to show an intellect superior,

(And hide a profile which is not too pretty?

Or is it, simply, you prefer to go

Incognito?

A transmigrated Balaam's self you may be,

But still I bar your method of progression;

For while I sit, as helpless as a baby,

And scale each precipice in steep succession,

You scorn the mule-track, and pursue the edge

Of ev'ry ledge.

How can I scan with rapt enthusiasm

These Alpine heights, when balanced à la Blondin,

While you survey with bird's-eye view each chasm?

I cry Eyupp! Avanti!—you respond in

Attempts straightway to improvise a "chute"

For me, you brute!

Basta! per Bacco! I'll no longer straddle

(With cramp in each adductor and extensor)

This seat of torture that they call a saddle!

Va via! in plain English, get thee hence, or——

On second thoughts, to leave unsaid the rest,

I think, were best!

(pg 87)

First Alpine Tourist. "I say, Will, are you asleep?"

Second Tourist. "Asleep? No, I should think not! Hang it, how they bite!"

First Tourist. "Try my dodge. Light your pipe, and blow a cloud under the clothes! They let go directly. There's a lot perched on the foot-bar of my bed now—coughing like mad!"

Tommy (who has just begun learning French, on his first visit to Boulogne). "I say, daddy, did you call that man 'garçon'?"

Daddy (with pride). "Yes, my boy."

Tommy (after reflection). "I say, daddy, what a big garçon he'll be when he's out of jackets and turn-downs, and gets into tails and stick-ups!"

(You may speak to anyone in France, even to a bold gendarme—if you are only decently polite)

"I implore your pardon for having deranged you, mister the gendarme, but might I dare to ask you to have the goodness to do me the honour to indicate to me the way for to render myself to the Street of the Cross of the Little-Fields?"

From a recent letter in the Times it would seem that tourists visiting the hotels on the Rigi have to secure entertainment at the point (or rather the knuckle) of the fist. If the fashion is permitted to become chronic (by the patient endurance of the British public), the diary kept by the visitor to the Rigi is likely to appear in the following form:—

Tuesday, 4 A.M.—Just seen the sun rise. Rather cloudy in the valley, but on the whole magnificent. Will stay until to-morrow, as I am sure the air is excellent.

5 A.M.—Going back to the hotel. The night porter is shouting at me.

8 A.M.—Just finished a three hours' fight with the night porter. He scored "first blood" to my "first knock-down blow." I was able to polish him off in forty-seven rounds, and consequently have an excellent appetite for breakfast.

9 A.M.—After some desperate struggling with half-a-dozen waiters, have secured a cup of coffee and a small plate of cold meat.

12 A.M.—Have been asleep on a bench outside the hotel for the last two hours and a half, recovering from my recent exertions.

1 P.M.—Have fraternised with five English tourists armed with alpenstocks. One of our party has opened negotiations with the hotel-keeper as to the possibility of obtaining some lunch.

2 P.M.—Our ambassador has returned with his coat torn into tatters, and one of his eyes severely bruised.

3 P.M.—By a coup de main we have seized the salle-à-manger, and now are feasting merrily on bread and honey.

4 P.M.—Just driven from our vantage-ground by eight boots, ten waiters, the landlord and auxiliaries from the kitchen.

6 P.M.—Have spent the last two hours in consultation.

7 P.M.—A spy from our party (assuming the character of an English duke) is just leaving us for the front.

8 P.M.—Our spy has just returned, and reports that when he asked for a room the enemy attacked him with brooms and candlesticks.

9 P.M.—Have just matured our plan of attack.

10 P.M.—Glorious news! A triumphant victory! Our party, in single file, made a descent upon the table-d'hôte, seized a large number of hors d'œuvres, and, after an hour's desperate fighting, secured a large room on the top floor, where we are now safely barricaded for the night! Hurrah!

At Dieppe.—Edwin. Awfully jolly here! Awfully jolly band! Awfully jolly waltz! Awfully jolly, isn't it?

Angelina. Quite too awfully nice!

Edwin. Waltz over. Awfully nice moon! Awfully jolly to be a poet, I should think. Say heaps of civil things about the moon, don't you know! Rather jolly, eh? Tennyson, and that sort of thing, don't you know?

Angelina. Yes, isn't he a perfect love?

Edwin. Yes—great fun. Next dance—square. Awfully stupid things—squares, eh? You're not engaged?

Angelina (archly). Not yet!

Edwin. Then let's sit it out.

Once I thought that you could boast

Such a perfect southern sky,

Flecked with summer clouds at most;

Always sunny, always dry,

Warm enough, perhaps, to grill an

Englishman, O muddy Milan!

Now I find you soaking wet,

Underneath an English sky;

Pavements, mediæval yet,

Whence mud splashes ever fly;

And, to make one damp and ill, an

Endless downpour, muddy Milan!

Though you boast such works of art,

Where is that unclouded sky?

Muddy Milan, we must part,

I shall gladly say good-bye,

Pack, and pay my little bill—an

Artless thing—and leave you, Milan.

At Boulogne.—Ted (to 'Arry). What's the meaning of "avis" on those placards?

'Arry. There's a question from a feller as 'as studied Latin with me at the Board School! 'Ave you forgotten all about the black swan? It's a notice about birds, of course!

She. "So, dear baron, you are just come down from the mountains. What lovely views you get there, do you not?"

Herr Baron. "Most lofly!"

She. "And what delicious water they give you to drink there!"

Herr Baron. "Ach, yes. That also haf I seen."

(pg 97)

Mr. Brown. "I say, Maria, what's the meaning of 'Sarner fairy hang,' which I hear you say in all the French shops, when they haven't got what you want—which they never have?"

Mrs. B. "Oh, it only means 'It's of no consequence.'"

Mr. B. "How odd! Now I always say 'Nimport'! But I dare say it comes to the same in the end."

Before the Holidays (an Anticipation)

Really nothing so pleasant as packing. Such fun to see how many things you can get into a portmanteau. Won't take any books as the "Continong" will be enough for amusement.

Capital carriages to Dover. Everything first-rate. Civil guards. Time-table not a dead letter. Splendid boats, smooth sea, and a first-rate buffet at Calais.

Dear Paris! Just the place for the inside of a week. Boulevards full of novelties. Theatres in full swing. Evenings outside the cafés perfect happiness. Splendid!

En route. Swiss scenery, as ever, lovely. Mountains glorious, passes, lakes. Delightful. Nothing can compare with a jaunt through the land of Tell.

Italy—dear old Italy. Oh, the blue sky and the tables d'hôte! What more glorious than the ruins of Rome? What more precious than the pictures of Florence? What more restful than the gondolas of Venice?

And the people even! The French the pink of [pg 97] politeness. The Swiss homely and kindly. The Italians inheriting the nobility of the Cæsars.

And all this to take the place of hard work. Well, it is to come. Bless everybody!

After the Holidays (a Retrospect)

What can be worse than packing? And after [pg 98] all the trouble of shoving things in anywhere, you find you have left half your belongings behind! And of course the books you half read during your weary travels are stopped at the Custom House.

Beastly journey from Paris to Calais, and as for the crossing afterwards—well, as long as I live I shall never forget it!

Dear Paris! Emphatically "dear," with the accent on the expense. Glad to be out of it. Boulevards deserted. Theatres playing "relâche." Cafés deathtraps in the service of the influenza.

En route! Who cares for Switzerland—always the same! Eternal mountains—yet coming up promising year after year! Sloppy passes, misty views. Beastly monotonous. The Cantons played out.

Italy! Who says Italy? Blue sky not equal to Wandsworth. Rome unhealthy. Art treasures at Florence not equal to collection in South Kensington. Mosquitoes at Venice.

And the people! Cheeky French, swindling Swiss, and dirty Italians!

And yet this is all to be supplemented by the same hard work. In the collar again. Oh! hang everybody!

Aunt Fanny. "I do like these French watering-places. The bathing costume is so sensible!"

Hilda. "Oh, yes, auntie! And so becoming!"

(pg 100)

Voice from above. "For heaven's sake be more careful, Smith. Remember, you've got the whiskey!"

Arab (as Mr. and Mrs. Smith appear). "Sh! You vant a guide! I am ze best guide in Alger! For five franc I take you to Arab café vare Inglees not 'lowed. For ten franc I show you ze street vare it is dangerous for ze Inglees for to go. And for twenty franc—sh!—I stand you on ze blace vare ze last Inglees tourist vos got shot!"

[Mr. and Mrs. Smith wish they were back in England.

'Arry Belville. "Yes! I like it extremely. I like the lazy ally sort of feeling. I like sitting at the door of a caffy to smoke my cigar; and above all (onter noo) it's a great comfort to wear one's beard without bein' larfed at!"

Excepting for their money, English tourists are perhaps not highly valued on the Continent. We would therefore offer a few practical suggestions, which, now that the tourist season has returned, will be found, no doubt, invaluable to Britons when abroad:—

1. When you begin inspecting a foreign town or city, it is wise to stalk along the middle of the [pg 100] streets, and make facetious comments on whatever you think funny. Laugh loudly at queer names which you see above shop-windows, especially if their owners, as is frequently the case, are lounging by the doorposts.

2. When you go into a church, strut and stare about as though you were examining a picture exhibition. Display contemptuous [pg 102] pity for the worshippers assembled, and make in a loud voice whatever critical remarks you happen to think proper.

3. If, while you take your walks abroad, you encounter an unfledged and enthusiastic traveller, who daringly attempts to enter into conversation with you, do your best to snub him in recital of his exploits, and render him dissatisfied with his most active feats. Interrupt his narrative with pitying exclamations, such as "Ah, I see! you went by the wrong route;" or, "O, then you just missed the very finest point of view." You may discover, very likely, he has seen much more than you have: but by judicious reticence you may conceal this awkward secret, and render him well-nigh as discontented as yourself.

4. When you are forced to start upon some mountain expedition, let everybody learn what an early bird you are, and awaken them to take a lively interest in your movements. Stamp about your room in your very thickest boots, and, if you have a friend who sleeps a few doors off, keep bellowing down the passage at the tiptop of your voice, although there may be invalids in plenty within earshot.

5. Should you gallantly be acting as a courrier des dames, mind that your lady friends are called an hour sooner than they need to be. A pleasant agitation will be thus caused near their bedrooms. They will amuse those sleeping next them with an incessant small talk, and, as their maid will be dispatched on endless little errands, their door will be heard creaking and banging-to incessantly until they clatter downstairs.

6. When you come into a drawing-room or salon de lecture, make your triumphal entry with all the noise you can, so as to attract the general attention. Keep your hat upon your head and glare fiercely at the quiet people who are reading, as though, like Gessler, you expected them to kneel down and pay homage to it.

7. Should your neighbour at the table d'hôte attempt to broach a conversation with you, turn your deaf ear, if you have one, to his insolent intrusion. If in kindliness of spirit he will still persist in talking, freeze the current of his speech by your iciness of manner, or else awe him into silence by your majesty of bearing.

8. If, despite your English efforts to remain an [pg 106] island, you find yourself invaded by aggressive foes to silence, strive to awe them by the mention of your friend Lord Snobley, or of any other nobleman with whom you may by accident have ever come in contact. For aught they care to know, you may be his Lordship's hairdresser; but the title of a lord is always pleasant hearing in the company of Britons, although benighted foreigners have not such respect for it.

9. Never give yourself the trouble to order wine beforehand for the table d'hôte, but growl and grumble savagely at waiters for not bringing it the instant you have ordered it, even though you happen to have entered the room late, and find a hundred people waiting to be served before you.

10. In all hotels where service is included in the bill, be sure you always give a something extra to the servants. This leads them to expect it as a thing of course, and to be insolent to those who can't so well afford to give it.

Unpleasantly Suggestive Names of "Cure" Places Abroad.—Bad Gastein. Which must be worse than the first day's sniff at Bad-Eggs-la-Chapelle.

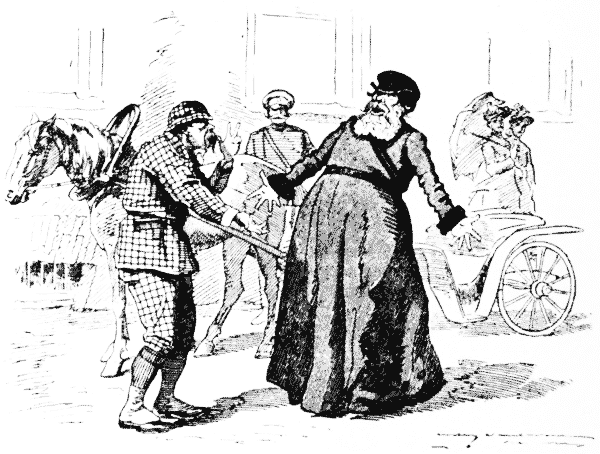

Row in a Belgian estaminet (In three tableaux)

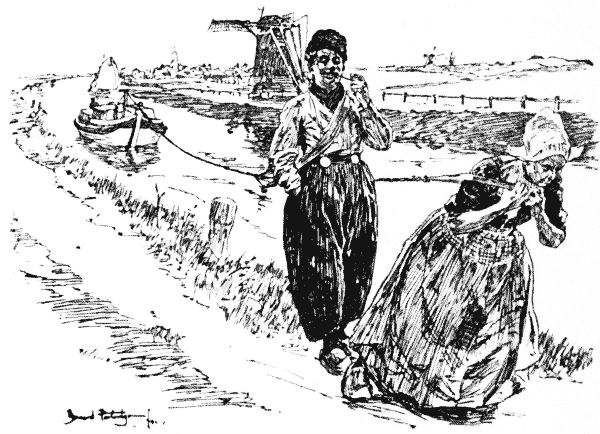

The Dutch peasant is not without his simple notions of chivalry. As we see by the above, he believes in letting the lady have the pull.

Abominable work of man,

Defacing nature where he can

With engineering;

On plain or hill he never fails

To run his execrable rails;

Coals, dirt, smoke, passengers and mails,

At once appearing.

To Alpine summits daily go

The locomotives to and fro.

What desecration!

Where playful kids once blithely skipped,

Where rustic goatherds gaily tripped,

Where clumsy climbers sometimes slipped,

He builds a station.

Up there, where once upon a time

Determined mountaineers would climb

To some far châlet;

Up there, above the carved wood toys,

Above the beggars, and the boys

Who play the Ranz des Vaches—such noise

Down in the Thal, eh?

Up there at sunset, rosy red,

And sunrise—if you're out of bed—

You see the summit,

Majestic, high above the vale.

It is not difficult to scale—

The fattest folk can go by rail

To overcome it.

For nothing, one may often hear,

Is sacred to the engineer;

He's much too clever.

Well, I must hurry on again,

That mountain summit to attain.

Good-bye. I'm going by the train.

I climb it? Never!

At Monte Carlo.—First Briton. One never sees any young girls here.

Second Briton (brutally inclined). No! the ladies are obliged to be trente et quarante to match the tables.

Provincial Tourist (to "Kellner" who offers him sausages). "I say, old feller, any 'osses died about 'ere lately! Chevals morts, you know!!"

[And the worst of it is, that though his compatriots did not laugh,

as he expected, the "vulgarian" wasn't

a bit abashed.

Ostend must be a glorious place. From an advertisement which has appeared in an evening contemporary I gather that "the multitude, anxious to spend an elegant and fashionable sojourn in the country, has rendered itself this year at Ostend. It is a long time since such an opulent clientele has been united in a seaside resort. At the fall of day the vast terraces of the fashionable restaurants, situated along the sea-bank, present a fairy aspect. There is quite a confusion of dazzling costumes upon which sparkle thousand gems, and all this handsome cosmopolitan society passes through the saloons of the Kursaal Club, in which one hears spoken all known languages as at Babel and Monte Carlo, and of which the attractions are identical to those of the latter place." This is the first time I have heard of a similarity to Babel being mentioned as an attraction. But no doubt an opulent clientele has peculiar tastes of its own, especially when its dazzling costumes sparkle with thousand gems.

In a small Belgian town (naturally not Ostend) I once saw the following notice hung over the door of a washerwoman's establishment:—

Anglish linge tooke here from 1 sou

Shert, cols, soaks, sleep-shert, pokets.

I eet my hatt.

The last sentence puzzled me for a long time. Finally I came to the conclusion that it was not intended so much to be a statement of actual fact as an enticement to English people, who would of course take all their washing to a lady commanding so gay and accurate a knowledge of an English catch-phrase.

My third example of English as she is spoke is from a notice issued by an out-of-the-way hotel in Italy, which had changed its management:—

"The nobles and noblesses traveller are beg to tell that the direction of this splendid hotel have bettered himself. And the strangers will also find high comforting luxuries, hot cold water coffee bath and all things of perfect establishment and at prices fixed. Table d'hôte best of Italy France everywere. [pg 113] Onclean linens is quick wash and every journals is buy for readers. Beds hard or soaft at the taste of traveller. Soaps everywere plenty. Very cheaper than other hotel. No mosquits no parrot no rat."

Scene—A table d'hôte abroad.

He. "Parlez-vous Français, mademoiselle?"

She. "No, sir."

He. "Sprechen Sie Deutsch, Fraülein?"

She. "No."

He. "Habla usted Español, señorita?"

She. "No."

He. "Parlate Italiano, signorina?"

She. "No!" (Sighs.)

[Pause.

She. "Do you speak English, sir?"

He. "Hélas! non, mademoiselle!" (Sighs deeply.)

(The extra half-franc)

Aunt Jemima (blue ribbon). "There, coshay. This is pour voomaym—sankont sonteems! But it's a peurmanger, you know—not a pour boire!!"

Intending English visitors to Spa, who may wish to become, temporarily, members of the Cercle des Étrangers, will be pleased with the following courteous circular:—

"M.,—In polite replying of your esteemed letter of the —— I will hasten to send you a statute of the 'Cercle des Étrangers' with a formulary at this annexed.

"Please to send us the formulary back, as soon as possible, the formalities for the reception as member wanting two days time.

"We dare inform you that only those persons are allowed to go into the drawing-rooms of the Casino, which previously have fulfilled the prescribed formalities of admittance.

"Under-signed, having been acquainted with the [pg 116] statutes of the 'Cercle des Étrangers,' wishes to fulfill the prescribed formalities in order to have inlet and therefore gives following indications:"

(Space for particulars as to name, forename, title, or trade, "spot and datum," with signature, here follows; and so this most interesting document concludes.)

Quantity not Quality.—Brown, senior. Well, Fred, what did you see during your trip abroad?

Brown, junior.—Aw—'pon m' word, 'don't know what I saw 'xactly, 'only know I did more by three countries, eight towns, and four mountains, than Smith did in the same time!

The Love of Nature.—First Chappie. Lovely place, Monte Carlo, isn't it! Such beautiful scenery!

Second Chappie. Beautiful!—such splendid air, too!

First Chappie. Splendid!—a—(pause)—let's go into the casino!

[Exeunt to the tables, where they remain for the rest of the day.

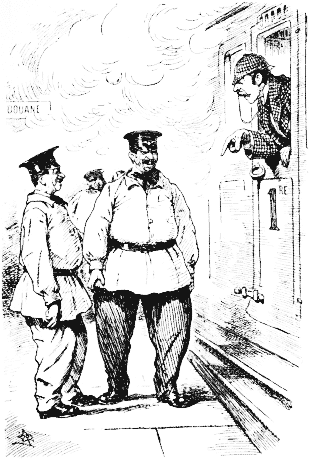

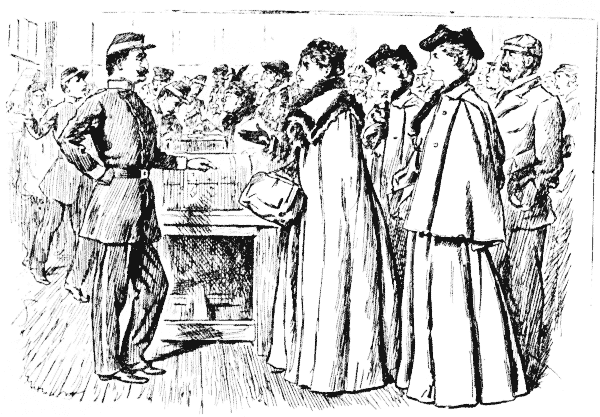

Scene—Bureau of the Chiefs of the Douanes

French Official. "You have passport?"

English Gent. "Nong, mossoo."

Official. "Your name."

Gent. "Belleville."

Official. "Christian nom?"

Gent. "'Arry!"

Official. "Profession?"

Gent. "Banker!"

She. "I wonder what makes the Mediterranean look so blue?"

He. "You'd look blue if you had to wash the shores of Italy!"

Scene—A Café in Paris

Scene—A Café in Paris

London Gent. "Garcong! tas de corfee!"

Garçon. "Bien, m'sieu'—Vould you like to see zee Times?"

London Gent. "Hang the feller! Now, I wonder how the doose he found out I was an Englishman!"

Indignant Anglo-Saxon (to provincial French innkeeper, who is bowing his thanks for the final settlement of his exorbitant and much-disputed account). "Oh, oui, mossoo! pour le matière de ça, je paye! Mais juste vous regardez ici, mon ami! et juste—vous—marquez—mes—mots! Je paye—mais je mette le dans la 'Times!'"

The Long Vacation is drawing to a close, and parents and guardians may like to know how reading tours have aided in advancing the education of their respective scions. Should any doting fathers be interested in the absorption of foreign languages into their sons' systems, the following mems from the diary of a University man, who has just returned from a tour abroad, whither he had gone expressly to perfect himself in European tongues, may be productive of some reflection.

July.

Left Dover for our tour. Met American Colonel X. Y. Zachary at Calais. Glorious brick. Knew French, and talked for us all. Gave us quite a twang, and left us devoted to Yankees.

Put up at Grand Hotel. English waiter. Saved us lots of trouble. Went to English tavern. Excellent beefsteak for dinner. Cheese direct from Cheshire. Went to open-air music hall in the Shongs Eliza, what they call a coffee concert. Two English clowns and a man who sang [pg 120] "Tommy, make Room for your Uncle." English family on both sides of us. Dropped their H's freely. Met two college chums in the yard of the Grand when we came back.

Went out to buy German Dictionary, French Grammar, and Italian Dialogues. Bought a copy of Punch instead—great fun.

Started for Italy. Capital guard with the train: knew English thoroughly. Queen's messenger in the carriage; splendid linguist. What's the use of trying to speak a foreign language, if you don't begin in your cradle!

Arrived at Turin. Met the Larkspur girls at the station. Went everywhere with them. They are all awfully jolly. Quite gorgeous at slang. Must buy that Italian Grammar and Dialogues. Learnt the Italian for "Yes" to-day.

On to Venice. How well our gondolier talks English. Lovely weather for cricket or lawn tennis. Nothing so jolly here. Old bricks, and dirty punts they call gondowlers.

August.

Start for Rome. Fancy a Roman train. What was it? All Gaul, or all the train, was divided in [pg 122] tres partes. Sang comic songs all the way. Bother Rome! it reminds one of Virgil and Horace, and all those nuisances. By the way, we must not forget the Italian Dialogues. Hotel commissioner, such a good fellow. Has lived in the Langham for the last six years. Told us a capital American story. Left the others to go round the monuments while I played a game of billiards with Captain Crawley. By Jingo! he does play well. He never learnt Italian or French, but I have heard he is a Greek. Speaks English like a Briton.

Meant to have begun Italian to-day; but too hot, really. Go back by Vienna and Trieste. Better buy a German Dictionary. Charlie's voice downstairs, by Jove! Hurrah! Off to Vienna. Go over the Tyrol by night. Sleep all the way.

Vienna. Awfully good beer. English parson in same hotel. Knows the governor. Wants me to take him round, and as he hears I am studying German, will I interpret for him? See him further first.

September.

Leave Vienna, to escape parson. The German tongue most attractive when made into sausages. [pg 124] Lingo simply horrible. Couldn't learn it if I tried.

Arrived at Munich. Drove round the English Garden. Nothing English in it except weeds and ourselves. Saw Richard the Third played at the theatre. Call that Shakspeare? Well! I am particularly etcetrad. And in German, too! Why don't they learn English?

Home in time for some partridges. By the way, wonder what became of the "coach" who went out with me? Never bought the grammars and dictionaries, after all. There's nothing like English if you want to be understood.

At Baden-Baden.—Captain Rook. Yes, my dear sir, although they have closed the Public Tables, still, if you really want a little amusement, I think I can introduce you to a very good set indeed. Where they play low, you know—only to pass the time.

Young Mr. Pidgeon. Oh, thank you. I should like it very much indeed. But I am giving you a great deal of trouble?

Captain Rook. Not at all!

Paterfamilias (who will do the parleyvooing himself instead of leaving it to his daughters). "Oh—er—j'ai bezwang d'oon bootail de—de—de——Here, you girls! what's the French for eau de Cologne?"

A correspondent reports the following advertisement, written in chalk on the box of a Swiss shoeblack:—

"English Spoken. American

Understood."

Scene—Boulevard Café.

First Irate Frenchman. Imbécile!

Second I. F. Canaille!!

First I. F. Cochon!!!

Second I. F. Chamberlaing!!!!

"You like Ostende, Monsieur Simpkin?"

"Oh, yes, orfly! It's so 'richurch,' don'tcherknow. Just come up to the 'Curse Hall,' will you?"

(pg 131)

(A very distant Future, let us hope)

Tourist. Can you speak English?

Guide. Yes, sir. I lived in London for many years.

Tourist. It is a very long time since I was in Florence. What is there to see in your city now?

Guide. The city has been entirely improved, sir. There is the new Palazzo Municipale. It is superb.

Tourist. I don't think I should care for that. What else is there?