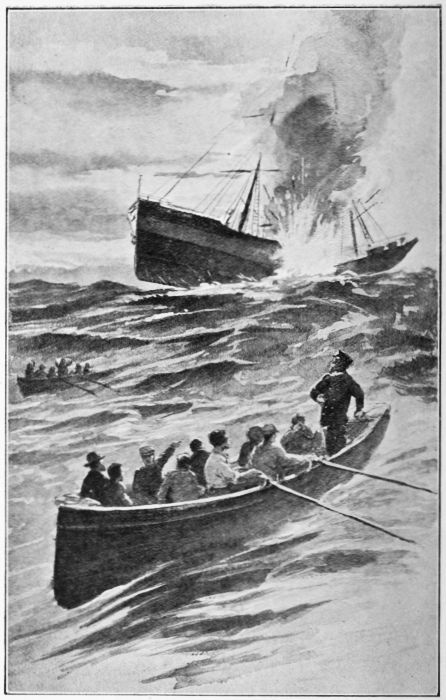

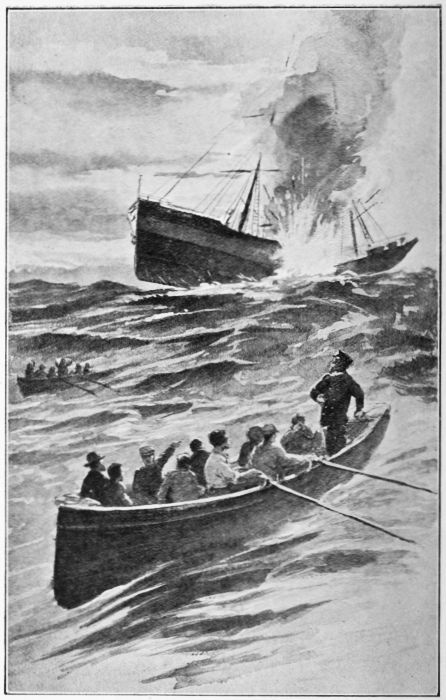

A groan burst from the white lips of the men as the seething

ruin that had been their home for so many weeks disappeared slowly

from view (p. 43).

A groan burst from the white lips of the men as the seething

ruin that had been their home for so many weeks disappeared slowly

from view (p. 43).

Title: Ralph Denham's Adventures in Burma: A Tale of the Burmese Jungle

Author: G. Norway

Release date: May 26, 2014 [eBook #45774]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Matthias Grammel, sp1nd and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

A groan burst from the white lips of the men as the seething

ruin that had been their home for so many weeks disappeared slowly

from view (p. 43).

A groan burst from the white lips of the men as the seething

ruin that had been their home for so many weeks disappeared slowly

from view (p. 43).

Ralph Denham's

Adventures in Burma

A TALE OF THE BURMESE JUNGLE

BY

G. NORWAY

AUTHOR OF "TREGARTHEN," "A DANGEROUS CONSPIRATOR,"

"LOSS OF JOHN HUMBLE," ETC.

LONDON

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & CO., LTD.

Printed in great britain by purnell and sons

paulton, somerset, england

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | RALPH STARTS UPON HIS VOYAGE | 7 |

| II. | A GALE | 19 |

| III. | FIRE AT SEA | 33 |

| IV. | THE RAFT | 44 |

| V. | ADRIFT ON THE OCEAN | 52 |

| VI. | THE DENHAMS AT HOME | 60 |

| VII. | MOULMEIN | 69 |

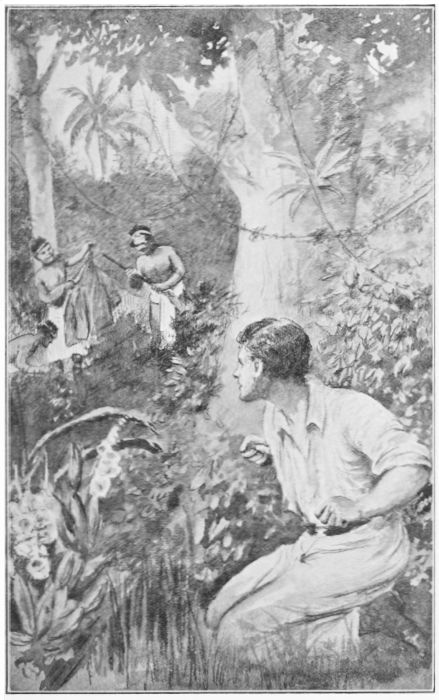

| VIII. | KIRKE ESCAPES | 78 |

| IX. | NEWS FROM RALPH | 87 |

| X. | THE LEOPARD | 96 |

| XI. | WHAT BEFELL KIRKE AFTER HIS ESCAPE | 104 |

| XII. | THE KAREN VILLAGE | 113 |

| XIII. | THE MAN-EATER | 122 |

| XIV. | TATTOOING | 132 |

| XV. | THE OLD MEN'S FAITH | 141 |

| XVI. | BIG GAME | 149 |

| XVII. | THE JUNGLE FIRE | 157 |

| XVIII. | THE DACOIT'S HEAD | 166 |

| XIX. | LOST IN THE JUNGLE | 175 |

| XX. | JUNGLE THIEVES | 184 |

| XXI. | THE RAPIDS | 196 |

| XXII. | KIRKE AND DENHAM MEET | 204 |

| XXIII. | FIGHT WITH DACOITS | 213 |

| XXIV. | THE DACOITS BURN THE VILLAGE | 222 |

| XXV. | DESPERATION | 229 |

| XXVI. | SUNSHINE'S HEROISM | 239 |

| XXVII. | CONCLUSION | 248 |

Mrs. Denham sat in her parlour, a two years old baby boy asleep upon her lap, and an anxious, mournful expression upon her face. She wore the dress of a widow,—a dress so new in its folds that it was evidently but a short time since the Dread Messenger had paused at her threshold to bear away its master and bread-winner.

The room was a shabby one; the fire but a handful of dusty ashes; rain fell without in the dreary street; it was growing dusk, and a soul-depressing cry of "Want chee-e-ep? Do ye want chee-e-eps?" arose ever and anon, as the ragged Irish chip boy wandered up and down.

It was a street of cheap houses in the suburbs of Liverpool, where the misery of poor gentility is perhaps more without alloy than in any other town.

But the door burst open, and a bright-faced, rosy, blue-eyed boy entered, with the freshness of out-of-doors upon him.

"All alone, mother?" said he. "Where's Agnes? Where are the little ones? Why, what a scurvy fire you have! let me cheer it up a little."

He began piling lumps of coal upon the embers in a scientific manner, to which a blaze quickly responded; when he swept up the hearth, and uttered an exclamation of satisfaction as he bent to kiss his mother's face.

"It requires a man to make up a fire," said he. "Where are all the others?"

"Agnes is giving the little ones their tea in the kitchen," replied Mrs. Denham. "I asked her to keep them out of the way for a while, because I want to talk to you, Ralph dear."

"All right, mother mine, fire away," said the boy, throwing himself down on the hearthrug, and resting one arm upon her knee.

"Ralph dear," resumed she, "your uncle Sam has come home; he has been here this afternoon."

"Uncle Sam? How jolly! When did the Pelican come in, mother? I did not know that she was even off Holyhead."

"The Pelican was docked last night, dear, upon the evening tide," said she; "and your uncle has been here a long time this afternoon."

"Was he not very sorry to hear about father?" asked Ralph in a low voice.

"Yes, dear; but he was prepared for the news by my last letter. He is a very kind brother; he has been giving my affairs his careful consideration all the way home, and has already offered some prospect of help; but this depends upon you, Ralph."

"Upon me, mother? I would be so proud to help. You may reckon upon me; but what can I do?"

"What it is a bitter pill for me to swallow, my boy, yet it would be such a help that I do not know how to refuse it."

"What is it, mother?"

"It is for you to go out to Burma, dear. When my last letter reached him, and he knew of your father's hopeless state of health, Uncle Sam secured for you the chance of a situation in a rice firm in Rangoon. He says that there would be a salary at once, upon which you could live with care, and which would soon improve into something much better, and into a position from which, in a few years, you might help one of your brothers. It is not in the house of Herford Brothers,—I wish it were,—but, as he sails for them, he will often see you, and bring us home news of you. It would not be as if you went to quite a strange place, where you would know nobody; and, Ralph, it would be an immense relief even to have your keep off my hands just at present. Dear Agnes maintains herself by her teaching; Lisa's scholarship provides for her education; and if you, my darling boy, were not here we might double up closer and spare another room for a second lodger, which would be a great help to me. But I do not know how to part with you, Ralph, my boy,—my dear, dear boy!"

The poor lady bent her face down upon the curly, tousled head at her knee, and wept sorrowfully.

Ralph passed his arm round her neck in silence, for tumultuous emotion choked him, and he could not speak at first. There had been a time, not so long before, when he would have been wild with delight at the thought of leaving school, going abroad, seeing new countries, being independent. But recent events had sobered his spirits and made him more thoughtful.

He pondered the scheme now without excitement or selfish pleasure; he tried to think whether it would be well for his mother were he to leave her. It seemed to him that it would be so.

"Mother," said he, "it is not as if Agnes were not older than I. Agnes is seventeen, and a companion to you, [Pg 10] while I am not old enough to take father's place with Jack and Reggie. They would not attend to me nor obey me."

"No, dear."

"Then when father was dying he bade me do my best to help you, and I promised that I would. If this is the best for you, mother, I must do it."

There was a manly ring in his voice as he said this, echoing so plainly the sound of the voice that was gone, that his mother almost felt as if it were her husband speaking to her in her son.

They sat silent for a long time, hand clasped in hand; then the sleeping child awoke, and recalled Mrs. Denham to her busy life.

"Uncle Sam is coming back to supper, and wants to talk to you about this," said she.

"I will go out for a walk, to think it all over, if you don't mind, mother; I will come in again by supper time," said the boy.

"Do, dear; it is not a plan that should be carried out in a hurry," said she. And Ralph took up his cap and went out.

He strolled aimlessly up one street, down another, his hands in his pockets and eyes fixed on the ground; then, with sudden determination, he changed his purposeless steps towards the town, and steadily pursued his road to meet his uncle.

So rapidly did he walk now, that he reached the lodging to which Captain Rogers always repaired when on shore just as he was emerging from the door.

"Halloa, my son!" called out the sailor in Cornish accents, "whither so fast?"

"I came to meet you, uncle. Mother has been telling me of your plan for me, and I wanted to talk to you about it while we could be alone."

"Ay, that's right. Men can settle things between themselves better than when there is a lot of soft-hearted women by, to cry over the Lord knows what. You are 'most a man now, Ralph. How you have grown since I've been away! How old are you now?"

"Fifteen, uncle. Fifteen and a half."

"Too old to be lopping about at your mother's apron strings. Old enough to be of some use and good, are you not?"

"Is this plan of use, uncle? Do you really think it would be good for mother?"

"Well, sonnie, to speak the plain truth I don't see no other way in which you are half as likely to keep off her hands. They are full enough, Ralph, without a great hearty fellow like you to be eating her out of house and home."

"That is so, uncle."

"I think that the Herfords would give you a free voyage out. I believe that I could work it so that they would. If they will, you cost her nothing more from this time. Agnes is a sensible maid, she can look after your mother better than you can. I will pay her rent for her, and take Jack to sea with me as soon as he is old enough; and then with a lodger or two, and the bit of money that she has, she may do fairly well. Be a man, Ralph, and do your part."

"I will, uncle, God helping me."

"Well said. But now, look here, there must be no chopping and changing; no crying out that you are homesick, or don't like it, and want to come back again. If you make up your mind to go, there must be some expense incurred for your outfit; and I'll not help unless you give me your word of honour that this shall be all that you mean to cost us. If I launch you, you must sail away on your own account, and make the best of matters however they may turn out. Do you understand me?"

"Yes, uncle. Is it necessary to give my answer now, this evening, or may I sleep upon it?"

"I don't mind your sleeping upon it, as you call it, but I must have your answer almost at once, because I must see Mr. Herford about your passage, and your kit must be got ready."

"I will tell you to-morrow, uncle."

"Mind you do. Mr. Herford goes from home at the end of the week, and I don't know how long he may be away. It would hurry everything up too closely to wait till he returns, when all the Pelican's cargo will be in course of loading, and everything else to settle."

Captain Rogers had intended to make the evening pleasant to his sister and her young folks, but fate was too strong for him on that occasion. Mrs. Denham's eyes were full of tears, and she kept silence as the only way to prevent their overflow. Agnes was little better, and the repressed agitation of their elders checked all the younger ones' chatter.

He went away early; but Ralph would not talk to any of them even when his uncle had left them. He went to his room, and spent the night in thinking, thinking, thinking; trying to make out what his father would have wished,—what was best for his mother,—where his strongest duty lay.

At last he took to prayer; and, for the first time in his young life, really sought help and counsel from his Father in heaven. Such seeking is never unanswered; he slept, woke up clear in his mind as to what he ought to do, and told his uncle that he would go.

"You decide rightly," said his uncle. "People cannot very often do just what they would like best. If I could, I would have got you a start in life nearer home, so that your mother might keep you to be a comfort to her; but she [Pg 13] will not mind so much when you are once gone, and you will sooner be of real use to her and to your brothers in this way than in any other which any of us can command. But, remember, you must take life as it comes, and work hard for yourself once you are started."

"I will, uncle, God helping me."

"Well said, my boy."

After that, all was hurry to prepare him for this important change in his life; his mother cried incessantly; his sister Agnes went about with red eyes, which could scarcely see the stitches that she set in his clothes; his uncle drove him about hither and thither; there was no time to think until the adieux were all made, and they had been towed out of dock.

The Pelican of the North was a barque-rigged, three-masted vessel, laden with coal for Moulmein; and the day was bright when she dropped down the river Mersey. The crew were in good spirits, for the weather, which had been extremely dull and wet for some weeks, cleared up suddenly on the day of sailing. The chilly wind had veered into a balmy quarter, the drenching rain ceased, the sun broke out, and all the little tossing waves seemed to be dancing with joy to see its beams sparkling upon their crests. Great masses of clouds were driving away, farther and farther, overhead, losing their heavy grey colour, and fast becoming soft and snowy white; while the flocks of seagulls, swooping about upon widespread pinions high in the air, might be imagined to be fleecy morsels detached from them on their course, so pure and silvery was their plumage.

Ralph stood by the capstan, looking back to the fort and lighthouse on the New Brighton Point with mixed feelings.

He had never been farther away from home than this before; he was now setting off for an unknown life in a [Pg 14] new country, among strangers, to make his own way as best he could.

He was pleased with his independence, with the thought that he was thus helping his mother; but he had not imagined how love for his home would tug at his heart-strings. It was not until he had felt his mother's farewell kiss, and heard her choked voice blessing him for the last time; it was not until his dearly-loved companion-sister Agnes had sobbed her good-bye on his shoulder; not till he had put the pretty baby back into his nurse's arms, and thought what a great boy he would be before he should, in all probability, see him again,—that he realised how far away he was going, and going alone.

But Ralph owned plenty of pluck; he meant to be brave, and to get on in his new career, so he gulped down these thoughts, and turned to brighter considerations.

His uncle had secured for him a free passage out to Rangoon by entering him as apprentice upon the ship's books.

This is an arrangement occasionally made, by favour, in merchant ships not registered for carrying passengers. The so-called apprentice would hold rather an anomalous position, being expected to do a little light work, particularly while in port, but messing with the captain at sea.

A hardy lad would have little of which to complain in the light of the great pecuniary advantage to himself, but it would depend largely upon his own tact, and also much upon the characters of the regular apprentices and the mates, as to whether he were, or were not, thoroughly comfortable upon a long voyage.

Captain Rogers had another passenger upon this occasion, a Mr. Gilchrist.

Mr. Augustus Herford, the head of the firm of Herford Brothers, to which the Pelican of the North belonged, was devoted to his garden; and orchids were his reigning [Pg 15] hobby. The craze for these flowers was then in its infancy, many varieties being unknown at that time which have since become common. Burma was comparatively little explored, nor were its forests and jungles haunted by collectors as they have been of late years.

Mr. Gilchrist was a self-made man, an enthusiast in his profession as gardener, but more capable than rich. He had educated himself, studied at Kew, mastered much of the science of horticulture,—but lacked capital, and wanted to marry. When, therefore, Mr. Augustus Herford offered him advantageous terms if he would go to Burma and collect orchids for him, he accepted the commission with eagerness, knowing well that, if he succeeded, his prosperity upon his return would be assured.

Mr. Herford was rich; he spared no expense over microscopes, books, collecting boxes, and all the properties for the expedition, and gave him a free passage out.

The Pelican of the North was bound for Moulmein with coal,—would then go to Rangoon in ballast, and return laden with rice. She was towed as far as to the floating lightship; there the steam-tug cast off, and the voyage was fairly begun.

By that time Mr. Gilchrist was down upon his marrow-bones, most horribly sick. He was a delicate man, and suffered terribly. Ralph was also ill, but his uncle encouraged him to struggle against the malady, and the other apprentices ridiculed him so unmercifully as a land-lubber, that he made every effort to keep up, and this with good effect, for he was soon upon his feet again, with a furious appetite even for salt junk and fat pork.

Then, in his good-nature, feeling heartily for a fellow-sufferer, he began to wait upon Mr. Gilchrist, nursing him and tending him well.

It would have been better for this gentleman had he [Pg 16] possessed the same strong reasons for exertion as his young companion; he would perhaps have suffered less. As it was, he was ill for nearly a fortnight; and, the weather being uncertain, Captain Rogers and the mates were glad to be relieved from the necessity of attending upon him, having quite enough to do with sailing the ship.

By degrees Mr. Gilchrist recovered; and, grateful for Ralph's care of him, he then lent him books, talked to him about them, encouraging him to learn many things and improve himself.

Captain Rogers was pleased that his nephew should receive such notice from so clever a man. He had not much education himself outside of his own business, but was shrewd, and entertained a great respect for what he called "book learning."

"It is very kind of you, Gilchrist," said he one evening, sitting with his passenger over their coffee,—"It is very kind of you to indoctrinate that lad as you are doing. It has been hard upon him to be cast upon his beam ends so early in life. His father was a well-read man, and might have given him good schooling had he lived, but my poor sister could not afford it when she was left with so many of them."

"It is an amusement," replied Mr. Gilchrist. "It helps me to pass the time pleasantly, I assure you. I like the boy much, he is very intelligent."

"He is a good sort of fellow," said the captain. "I hope he will get on. But we must be careful not to set him up too much, so as to make the other apprentices jealous of him. I have my doubts of that Kirke. I hate your gentlemen apprentices; they are always more trouble than profit. That one is not worth his salt."

"Is he a gentleman's son, then?"

"Aye. His father is a friend of my boss; the lad is sent [Pg 17] to sea because they can do nothing with him at home, but I wish they had put him in any other ship than this one."

"Is it usual for a gentleman to send his son to sea in the merchant service?" asked Mr. Gilchrist.

"I wish it either were more usual or less," replied the captain. "I hate having them. It always means stupidity, idleness or scampishness; and, whichever it may be, they are no good. If a lad cannot keep his own natural position in life it does not prevent him from having big ideas of himself after coming down to another; and if he gets into ugly scrapes as a gentleman, he will get into uglier ones when the restraint upon him is less."

"You have much experience in boys and men, Rogers."

"Ah! I have—with a certain class of boys and men. Now and then one finds a lad who can work with his hands when he cannot with his head, and who tries to do his best; but good seamen need to use their brains as well as other folks if they are to get on. Such youngsters come to us too late. Their friends don't send them until they have tried everything else and failed. The hardships of our life fall five times as heavily upon them as upon a lad who belongs to a hardier class and has begun earlier. Kirke is not one of that sort; I misdoubt me but what there will be trouble with him before this voyage is over."

"Well, the weather seems to have taken up a better humour at last. We seem to have got out of that circle of squalls through which we have been making our way."

"Yes," said the captain. "We are coming in for a quieter season, if it only lasts. I wish the voyage was over, though. My wife took up a superstitious notion that we should have trouble over it. She had a dream or something which impressed her with that idea; and though I laughed at her, I cannot forget it altogether. Do you believe in warnings and presentiments?"

"I suppose there are few men who could say with truth that they disbelieve in them entirely, but I have seen so many come to nought that I do not entertain much faith in them."

"Ah! well," said the captain, finishing his cup, and rising to leave the cabin, "I suppose I am an old fool to heed such things. I don't see where mischief is to crop up unless through that lad, and he may turn out better than I fear. Good-night, Mr. Gilchrist."

"Good-night."

It was of little use for Captain Rogers to trouble himself in the hope of avoiding jealousy of Ralph on the part of the other apprentices, for the feeling was already rife on the part of Kirke.

That ill-conditioned young man despised everyone on board for not being men of good family, as he himself was, though he was more conscious of his good birth than careful to prove himself a gentleman by his conduct. He could not see why he should be made to work, and the son of a merchant's book-keeper, a lad whose mother let lodgings for her support, should be cockered up in the captain's cabin, reading and writing at his ease, practically exempt from hard toil.

Ralph had not enjoyed a tenth part of the educational advantages which Kirke had thrown away, and was anxious to improve himself now that a chance of doing so was presented.

Mr. Gilchrist was teaching him mathematics and French, lending him books upon botany and natural history, especially such as treated of the country for which he was bound, and also a few volumes of history and travels. He taught him much by conversation upon these subjects; and Ralph, feeling that he had one foot planted upon the social ladder, earnestly desiring to rise higher, flung [Pg 20] himself enthusiastically into these studies as a means for so doing. His uncle did not demand much manual labour from him; he performed that cheerfully, but saw no reason why, his allotted task being done, he should occupy his own time in saving Kirke from doing his share of duty.

There was no great good-feeling between these lads; and Harry Jackson, the third apprentice, was a weak, ordinary sort of boy, who admired Kirke for his adventitious graces, and had become completely his tool.

The three boys all slept in part of a deckhouse amidships, a place divided between the galley and the apprentices' cabin. The ship being an old one, there were no berths for the youngsters, who slept in hammocks slung up at night, and taken down in the morning, rolled up, and stowed away to make room for their meals and accommodation through the day.

Ralph breakfasted with the other two apprentices, their hours being earlier than those of his uncle's cabin. After this meal, he did what work was expected from him, and liked to be clean and ready by the time when Mr. Gilchrist could attend to him in the poop, where chiefly he spent the remainder of the day.

One morning Ralph awoke suddenly, experiencing a very disagreeable shock. The time-honoured joke of letting his hammock down at the head had been played upon him, and Kirke lay comfortably on his own bed squirting water all over him.

"Have done, Kirke!" he cried angrily. "How would you like to be served so?"

"Try it on if you dare," retorted Kirke, aiming a stream of water right into his face. "I only wish you would try it on, just once, and you would see. Get up! You must swab the decks to-day, I did it yesterday."

"Drop that squirt, I tell you!" roared Ralph, as his shirt [Pg 21] was made dripping wet, and a fresh supply of water was drawn into the tube from the basin which Kirke held between his knees.

Kirke's only reply was another jet, which streamed down Ralph's back.

Ralph sprang upon his tormentor, and a struggle took place for possession of the squirt. The tin basin was upset all over the bedclothes, but Denham flung it away and seized hold of the squirt.

Indignation gave him superior strength, he wrenched the instrument out of Kirke's hands, and Kirke drove his clenched fist, straight from his shoulder, into Ralph's face and hit him in the eye.

Fireworks flashed before his vision, and he proceeded to revenge himself in a fair fight; but Jackson ran screaming out of the cabin upon seeing Ralph pitch Kirke out of his hammock as a preliminary, and called to the mate on the watch.

"Mr. Denham is fighting Mr. Kirke," cried he, "and has upset a basin of water all over him in his hammock."

The mate came in.

"Now, my lads," commanded he, "just you understand that I'll allow no rowdy work of that sort. Shut up at once, both of you."

It was the voice of authority, and Ralph scorned to tell tales, so he desisted, pulled a dry shirt out of his chest, and went on deck as soon as he could.

Being a good-natured lad, his anger had then cooled down, and he began to swab the deck, thinking that it would act as a peace-offering to give Kirke the help voluntarily.

Kirke came out slowly and moodily, but did not begin to work on his part. He stood with his hands in his pockets, a sneer conquering the lowering gloom on his face.

"I am glad you know your place at last," said he, as Ralph came near him. "I'll teach you a little more before I have done with you."

Ralph bit his lip to force down an angry reply. He did not want to quarrel with anyone, as that might give his uncle trouble, but it was as much as he could do to keep silence.

At this moment the captain himself stepped out.

"Ralph!" shouted he. "Have you seen my three-foot rule? I can't find it."

"I know where it is," replied he. "I'll fetch it."

"What are you swabbing the deck for?" asked his uncle. "Why are you not doing your own work, Kirke? I'll have no shirking. Set to at once! Ralph, I want you in my cabin."

Kirke had no option but to take up the bucket and begin the menial work which he hated so fiercely.

"Mr. Gilchrist is not well," said the captain. "I hope he is not in for an attack of dysentery, but he is certainly very poorly. I have persuaded him to lie still, and I wish you would put yourself tidy and come and attend to him. Go to the storehouse and get out some brandy for him. Here are the keys. I am wanted on deck to see about twenty things all at once."

Ralph hastened to obey. The ship was victualled upon teetotal principles, but a little spirit was kept for cases of emergency or illness. None had been used hitherto upon this voyage, and the decanters were empty.

Ralph opened the locker where the bottles were stored, took out some brandy, filled one of the little decanters which stood in a silver case, and hurried with it to the invalid's cabin, leaving everything open in the storeroom, for the moment, from his haste to relieve his friend.

Mr. Gilchrist was very unwell indeed. He said that he [Pg 23] was subject to these attacks at times; he did not believe that this was dysentery, he had taken a chill and should be better soon.

Ralph procured some hot water and prepared the cordial for him, but he was sick at once after taking it; he shivered violently, his teeth chattering in his head. This frightened his young nurse very much, for they were now in latitudes where the heat was great; no doctor was on board, and he knew little about illness.

However, the patient was better after a time, the sickness ceased, the headache was lessened, a gentle perspiration broke out, and he fell asleep.

Ralph ventured to steal softly away, and went to lock up the spirit bottles in the storeroom. There he found, to his surprise, that not only the one which he had opened was quite empty, but one of brandy and one of rum were missing.

He called his uncle, who, holding strong opinions upon the subject of temperance, was very angry. He made a strict investigation into the matter, but failed to discover the culprit. The bottles were gone—vanished; nobody would confess to knowing anything about them.

Captain Rogers was very uneasy in his secret mind, for appearances were against Ralph. No one else had been trusted with the keys, and the spirit could not have gone without hands. He knew very little personally about his nephew, being so much at sea himself. He only saw him at long intervals, and in the presence of others; he seemed a steady boy then, and Rogers liked him, but this was the first chance he had met with upon which he could have gone wrong, in this manner, to his uncle's knowledge. With this doubt about him, the captain spoke very sharply to Ralph as to his carelessness in leaving the locker open.

Mr. Gilchrist took Ralph's part. He said that he must have smelt the liquor upon the boy's breath had he drunk it, but the captain knew that about Ralph's family history which he did not choose to talk about.

Ralph called himself a strict teetotaler, which the captain was not; but the elder Denham had been a drunkard, and had died from the consequence of his excesses. Had the madness broken out in his son? Did he inherit it in his blood? Had it taken that worst of all forms—secret drinking? He knew what his sister had suffered from her husband's conduct; was the same thing to begin all over again in the person of her son?

For two days the captain was miserable from this unspoken fear. Ralph had all the appearance of truth and honesty; Mr. Gilchrist was strongly in favour of his innocence; but the mate remarked that nobody but Mr. Denham had been trusted with the keys of the locker, not even the cook or the cook's mate, who, between them, discharged the functions of steward.

For two wretched, suspicious, anxious days did this doubt cark at the captain's heart. Then was little Harry Jackson found drunk—drunk as a lord—late one evening when off his watch.

Fresh investigations were set on foot, and it appeared that Kirke had given the boy some liquor as a bribe for silence regarding his own potations, of which Jackson could not fail to know as they shared the same cabin. Denham had not slept there since Mr. Gilchrist's illness, for he was still unwell, though better; and Ralph had begged to be allowed a bed upon the floor of his cabin, so as to attend upon him if necessary through the night.

Taking advantage of his absence, Kirke had been enjoying himself, after his own fashion, with the stolen spirits, and inducing Harry to join him so as to ensure his silence.

The elder lad's head could already stand copious libations, but that of the younger one could not, and the very means adopted to secure safety led to detection.

The captain, deeply annoyed with himself for suspecting his own nephew, highly wrathful for the trouble thus caused to him, punished Kirke all the more severely, to give him, as he said, "a lesson which he would not forget in a hurry." Ralph tried to beg him off, but his uncle was in a rage and refused to listen to him.

Kirke might have had all the blood of all the Howards running in his veins so great was his anger at his punishment, and he vowed to himself to abscond from the ship as soon as it touched shore, nor ever to run the risk of such ignominy again.

Things were very uncomfortable after this event for Denham. His annoyance while it was pending had been great, it had made him positively unhappy. He felt himself to blame for carelessness in leaving the locker open; he was indignant that the real culprit should cast the onus upon him, knowing him to be perfectly innocent; and he thought that his uncle should have trusted him better. At least he should have spared his own nephew from the charge of dishonesty.

He could not be as friendly as before with either Kirke or Jackson, and felt very lonely.

Mr. Gilchrist continued to be very unwell, unable to talk to him as usual. He had to pursue his studies without help; difficulties beset him; and the other apprentices made themselves extremely disagreeable, keeping up a constant system of petty persecution which rendered life in their cabin almost unendurable, yet of which he scorned to complain to the captain, each separate annoyance being so trivial.

Besides this, the wind increased in strength, and so severe [Pg 26] a gale from the westward set in that the Pelican had to scud before it under bare poles.

For two days there was cause for considerable anxiety, then the mercury rose, a calm clear night succeeded, followed by a bright sunny morning.

"I hope the gale is over," said Ralph, coming into the deckhouse and greeting the other lads cheerfully.

"I daresay you do," growled Kirke. "Counter-jumpers and land-lubbers funk a capful of wind mightily."

"I think we have had rather more than a capful these last two days," replied Ralph, ignoring the insulting language.

"You manage to shirk all the trouble it causes, anyway. I don't see that you need complain," said Kirke with a sneer.

Ralph was silent. He finished his breakfast quickly and went out.

The men were letting all the reefs out of the topsails, and getting the top-gallant yards across, in hopes of a fine day in which to make the most of the favourable gale.

It was a bright, bustling scene, and Ralph was amused by looking on.

The old carpenter stood by him. This man and the sailmaker both came from the same country village in Cornwall where Captain Rogers and Ralph's mother had been born. They always sailed with the captain, if possible, from clannish attachment to him; and loved a chat with Ralph from the same feeling.

"Nice day, Wills," said the boy.

"'Ees, zur, but it won't last," said the carpenter.

and he pointed to the drifting clouds.

"That is it, is it?" said Ralph. "Are we not having rather a bad voyage, Wills? Do ships always have so much bad weather as we are meeting with?"

"No, zur, but uz sailed on a Vriday."

"What could that have to do with it, Wills? Why should that bring bad luck?"

"Can't zay, zur, but it du."

"You Cornishmen are always superstitious, aren't you?"

"Doan't knaw, your honour, as we'm more so than others. 'Tis no use to fly in the face of Providence ef He've given we the gumption to zee more'n other volks."

"Did you ever see the Flying Dutchman in these latitudes, Wills?"

"No, zur, I can't zay as I have zeed 'un, but 'tain't given to every chield to do so. I've zeed Jack Harry's Lights, though, and we wor wrecked then, too."

"Where was that?" asked Ralph with interest.

"Close to home, it wor. We heerd the bells of the old church-tower a-calling the volks to evening service all the time we was clinging to the maintop, and the gear flying in ribbons about our faces, a-lashing uz like whips, and all of uz as worn't fast tied to the mast swept away by the sea that awful Sunday night. Jim Pascoe wor lashed aside of me, and 'Sam,' zays he, 'I wonder whether my old mawther be a-praying for me at this minute, up to church.' It didn't save he even ef she wor, for a big sea rose up, and came thundering down on uz, and he got the full heft of it right upon him, so that it beat the last spunk of life out of him then and there. There wor but six of uz, out of twenty-one, brought ashore that time alive; and there wor but life, and that wor all, among some of we."

"How dreadful!" cried Ralph. "What did you think about while you stood there all that time?"

"I doan't knaw as I did think much, at all. Zemmed as [Pg 28] ef all thought wor beat out of uz. But they there seamen as wor drownded then answer to their names still on a stormy night when the wind blows strong from the west upon thiccee rocks."

"Answer to their names?"

"Ay. You may hear the roll called out, and they men answer 'Here' as plain as you can wish, at midnight, in the heft of a storm."

"Do you really believe that? Did you ever hear it, Wills?"

"Well I can't zay as ever I actually heerd 'un call them, but I knaws they as has; and why for no', Maister Ralph. Perhaps 'ee'll believe I, and find that I speak truth, when I tell 'ee this voyage is doomed to be unfortunate because we set sail on a Vriday. I telled captain it would be, but he wouldn't wait for Sunday though I did beg and pray 'un to do so."

"I can't see what difference two days could make. It would not have saved us the weather we had two days since, nor will it make any difference in whatever may come two days hence."

"Theer's a-many things as 'ee be too young to onnerstand yet, Maister Denham."

"But 'ee did ought to pay heed to 'un, maister," put in Osborn, "because 'ee be Cornish the same as we."

"I have never been in Cornwall, though, Osborn."

"No, I du knaw thiccee, more's the pity," replied the man. "But uz du mind your ma, when hur wor a mighty pretty little maid, a-dancing and a-singing about 'long shore, and a-chattering so gay. Uz du all come from the same place, zur, and we'm proud to knaw 'ee, and to have 'ee on board, ef it be but for the trip. 'Tis one and all to home, 'ee knaweth, zur."

"Yes," laughed Ralph. "I am proud enough of my [Pg 29] Cornish blood, and would like to know more of the good old county, though I fear it will be long before I shall have the chance. You know I am going to Rangoon, to push my way and try to help my mother. She does not dance nor sing much in these days. She has a lot of trouble."

"So we've heerd, zur. Poor little Miss Amy, we be main sorry to think of it. Ef Wills or me can ever be of any service to 'ee, zur, 'ee must look out for uz when the Pelican comes to Rangoon. We shall always stick to cap'n, zur, as we've done for many a day. Uz b'ain't likely to leave 'un to be sarved by any old trade picked up out of the slums."

"That is well; and if I can help either of you at any time, you may depend upon me. It is a bargain between us," said Ralph, laughing.

The appearance of fine weather was delusive, for the bright sunshine changed within a few hours to fog and rain. The wind sprang up again, and the captain was forced to order the mainsail to be hauled in, the topsails close reefed, and the top-gallant yards struck.

The mercury fell, the gale increased in force, and the sea ran extremely high. There was a sharp frost in the night, with snow, and the storm was as furious as ever next morning.

The hatches had to be battened down, and it was dreadful for Mr. Gilchrist and Ralph, wholly inexperienced in nautical matters, unable to see or understand what was going on, or what degree of danger there was, to hear the raging of the elements, while they were in the dark with nothing to distract their thoughts.

There they were, Mr. Gilchrist in his berth, coughing incessantly, and Ralph sitting beside him, listening to the tramp of hurried feet and the shouting voices overhead. [Pg 30] The great sea would strike the poor labouring vessel with a force that caused it to shudder in every straining timber; it would seem to be tossed on high, and then plunge into fathomless deeps, as if sinking to the very bottom of the sea. Tons of water came, ever and anon, rushing overhead. Did this mean that their last hour had arrived? Were they to be drowned in this awful darkness, like rats in a hole? Were they never to see God's light of day again, or look once more over the fair expanse of sea and sky?

They grasped each other's hands at these times, for touch was the only comfort which companionship could give. They could not talk,—awe paralysed speech.

Then the volumes of water seemed to drain off in descending streams through the scupper-holes, and voices would be heard again, and a few sentences of prayer would break from Mr. Gilchrist's lips.

This lasted for two days, awful days for these poor prisoners; but the wind was in their favour, and blew them on their way, though a little too far southwards, and it moderated in course of time.

The captain had the dead-lights removed, the hatches raised, and came down to see how his passengers had fared.

"I never could have believed that light and air would be so welcome," said Ralph; "and it is but a Scotch mist yet, no pleasant sunshine."

"No," replied the captain, "but you will soon have enough of sunshine now. Perhaps you may even have too much of it one of these days. We have lost poor little Jackson," continued he, turning to Mr. Gilchrist.

"What! the boy apprentice?" asked he.

"Ay, poor child! Washed overboard in the night, and one of the seamen yesterday morning. We could not help [Pg 31] either of them, the sea was running so high. Would you like to come up for a bit and see the waves for yourself now?"

But Mr. Gilchrist declined. He dreaded bringing on one of his paroxysms of cough more than the closeness and confinement of the cabin; but Ralph, shocked by his uncle's announcement, was eager to go on deck.

He was not used to death, and it was very awful to him to think that, while he sat in comparative safety below, yet fearing for his own death every moment, this boy, so much younger than himself, had passed suddenly through a watery grave to the portals of that unknown world where he must meet his God.

Where was he now? What could he be doing? He seemed as unfit for a spiritual life as anyone whom Ralph had ever met. A mere troublesome naughty boy, of the most ordinary type; rough, dirty, hungry,—a boy who could laugh at a coarse joke, use bad words, shirk his work whenever he had the chance, and who did nothing except idle play in his leisure time.

What could he be doing among white-robed angels, among the spirits of good men made perfect, among cherubim and seraphim, with their pure eyes, around the Father's throne? Yet had God taken him.

The mysteries of life and death came home, in a vivid light, to Ralph's soul, as he stood holding on to a rope, and gazing down on that boiling sea, whence he dreaded, every moment, to see his young companion's white face looking up at him.

Kirke came by, and Denham's good heart prompted him to turn round and offer him his hand. Little Jackson had run after Kirke like a dog, admired, followed, idolised him, and Ralph thought he must be as much impressed as himself by this awful event.

So he put out his hand, saying—

"Oh, Kirke, I am so sorry to hear about Jackson!"

"Bother you and your sorrow! I wish it had been you," replied Kirke rudely.

Ralph turned away in silence. He, too, almost wished it had been himself, not that he felt more fit to go, but that the heartlessness of this fellow struck a chill to his heart.

But Kirke was not so heedless of the event as he tried to seem, nor so wholly ungrateful for Ralph's sympathy as he chose to appear. This was the first blow which had struck home to him, and in his pride and sullen humour he was trying to resist its softening influence. Not for the world would he have displayed any better feeling at that time, though it was not altogether absent from his heart.

After this painful episode was over, amidst a succession of calms, varied by light south-west breezes, changing gradually more and more to the east, the Pelican of the North crossed the line, and proceeded upon her way in pleasant weather.

Ralph would have enjoyed this time much but for the pest of cockroaches which now swarmed over them and their belongings. These disgusting insects were of two sorts, one of which had always been troublesome from the first, but were now supplemented by a second, not seen much except by night, but which crawled about then in such immense numbers, through the hours of darkness, as to do great damage. They ran over the cabin floors, up the walls, were shaken out in showers from the rigging when a sail was unfurled; they honeycombed the biscuit, they were found in the boots and shoes, and made life a burden to young Denham, who entertained a particular aversion to creeping insects.

"How I wish we could find anything which would rid us of these beastly things?" sighed he one day to Mr. Gilchrist, when the vermin had been seized with a literary fureur, and eaten out the ink from some notes which he had been at considerable pains to compile from a book of natural history. "Last night I thought we must have [Pg 34] some spiritualist on board, or ghosts, or something uncanny. I was wakened up by the noise as if everything in the cabin had taken to dancing about in a frolic, till I discovered it was nothing but thousands of these horrid creatures crawling and rustling about. Some nights I verily believe that they will eat us up bodily."

Mr. Gilchrist laughed.

"Never mind," said he, "we shall be in cooler latitudes soon, and they will become more torpid, and go back to their holes again. We are nearing the Cape."

"Shall we touch at the Cape? Shall we see the Table Mountain, sir, do you think?"

"I rather fancy not. From what the captain said the other day, I believe that there are currents there which are apt to be trying to a heavily-laden ship such as ours. Squalls are very prevalent in rounding the Cape, and I think he will give it a wide berth. We do not need water, nor have we any particular reason for delaying the voyage by putting in at Cape Town."

"We must be near land, I should think, for there are so many birds about now. Some of them are birds that I never saw before."

"Albatrosses to wit? You do not want to shoot one, do you, and share the fate of the Ancient Mariner?"

"No, not quite that, though if everyone who had done so were to be exposed to a similar fate there would be a good many phantom ships careering about the high-seas. Lots of the ships that come into Liverpool have their skins, or their bills, or something on board. I have an albatross' bill at home that a sailor gave me. I have a lot of things fastened up about the walls of my room. It is easy to get foreign curiosities in Liverpool, but I left all mine as a legacy to my sister Agnes, and promised to look out for more when I got [Pg 35] to Rangoon, and met with any chance of sending them home to her."

"It will be a good plan. If you have any ready in time I will take them back for you, and call to see your mother to tell her how you are getting on, what sort of lodgings you have, and all about you."

"That will be very kind, sir. In that case I will try to shoot one of those birds, for they are quite new to me. They are of a blue colour in part, with a black streak across the top of the wings."

"Those are blue petrels, I believe; birds which are only found in southern seas. We will try to preserve the skins of one or two with carbolic powder, though I fear that your friends the cockroaches will get at them."

"Ugh! Don't call them my friends! You should have seen the third mate, Mr. Kershaw, teasing the cook yesterday. Cook came up in the evening for a breath of air, and was leaning over the side looking down at the 'sea on fire' as they call it—it was splendid late last night. Mr. Kershaw came up to him and looked at him very earnestly, first on one side and then on the other, as if he saw something queer about him. Cook began to squirm about uncomfortably.

"'What is it, Mr. Kershaw?' asked he. 'Is there anything wrong about me?'

"'Oh no, my good fellow, no,' said the mate. 'It only struck me that cockroaches are a peculiar kind of pets, but it is every man's own business if he chooses to let them sleep in the folds of his shirt. Do you always keep them there?'

"'Where, where?' called out the cook, all in a hurry. 'Cockroaches on my shirt? Where?'

"He was trying to see over his shoulder in an impossible kind of way; he put his hands up to his neck and down to [Pg 36] his waist at the back; he shuddered, and shook himself, but could not find them; and it was not likely that he could, for there were none there to be found.

"Mr. Kershaw was pretending to help him, poking at him up and down his back.

"'Oh, I thought I had them then!—there, under your arm,—no, down your leg. Dear me! how very active they are. What remarkably fine specimens! They seem to be quite tame; how much you must know about them to live with them like this, quite in the style of a happy family. They really seem to love you. I should not like to keep them about myself though, in this manner. Do you always have them upon your own person, my friend?'

"At last the cook twigged the joke, for we were all laughing so, but he was quite cross about it, and flung away muttering something about fools, and wishing to knock Mr. Kershaw's head off for him."

Ralph could not help laughing again at the remembrance of the scene, and Mr. Gilchrist joined in his merriment.

But soon there was no more time for jokes or laughter, stern reality claimed all their attention.

Mr. Gilchrist was sitting one day upon a lounging-chair, beneath the shade of an awning, when the captain approached him with anxiety plainly imprinted on his face.

"How now, Rogers?" said he; "your face is as long as from here to there!"

"And with good reason too," replied the captain; "I fear that a terrible calamity has come upon us."

"Why, my good fellow, what can be going to happen now?" cried Gilchrist, alarmed in his turn.

"Fire," said Rogers laconically, but with grave emphasis.

"Fire!" exclaimed both Gilchrist and Ralph at the same instant, staring around them in perplexity upon the [Pg 37] placid sea, the sunny sky, the swelling sails, the pennon idly fluttering on the breeze. "Fire! Where? How?"

For all answer the captain pointed to a few slender spiral coils of smoke, issuing from the seams of the deck where the caulking had worn away.

Mr. Gilchrist looked aghast.

"Do you mean the cargo?" he asked fearfully.

"Even so," said the captain. "It may be only heating from water reaching it during the storm. We are going to open the hatches and see if we can put it out, but I fear that the mischief was done when we loaded the coal. It was such wet weather while we were taking it on board. Gilchrist," said he, lowering his voice, "if there is anything particularly valuable among your things, put it up in small compass, and be ready for the worst in case we have to take to the boats."

"Do you anticipate such a thing?"

"It is always well to be prepared."

Mr. Gilchrist had many things—books, maps, scientific instruments, collecting cases, a costly binocular microscope with all its appliances, and other articles, nothing having been spared for his equipment; but in the shock of this surprise he forgot them all, and, springing from his chair, hurried to the scene of action.

The whole crew gathered hastily around to know the worst, and gazed with blanched faces at each other as the hatches were carefully raised.

A universal cry of horror escaped them, when such a cloud of steam and smoke, with so sulphureous a stench, rushed out, upon vent being given to the hold, that they were driven back gasping for air.

"Good Heavens!" cried Mr. Gilchrist, "there are two thousand tons of coal down there! The Lord have mercy upon us!"

"How far are we from land?" asked Ralph.

"I do not know. I suppose that it depends greatly on the wind for calculating the length of time it will take us to reach it. I believe the captain hoped to make Moulmein in about a week or ten days more."

"Where is that hose?" thundered the captain. "Bring it here at once. Douche the hold well. Mellish, we must try to jettison the cargo, and make room for water enough to reach down the hold."

"Right you are, sir!" cried the first mate. "Who volunteers?"

The hardiest men among the crew pressed forward. Two parties were quickly told off, one to relieve the other. The men flew to the pumps and hose; all was excitement and hurry—not a soul of them flinched.

"Here, give me hold of a bucket," cried Mr. Gilchrist, taking his place in a line of men hauling up sea-water to supplement the volumes from the hose.

Ralph rushed to assist at the pumps. Streams of water poured down the hold; volumes of steam arose, hissing, through the hatchways. It was long before the bravest of the men could descend, no one could have breathed in such an atmosphere; and when two leapt into the chasm at last, they had immediately to be drawn up again, fainting, scorched, choked with the sulphureous fumes.

They were laid on the deck, buckets of water dashed upon them, and they came, gasping, to themselves.

"'Tis of no use, mates," said they. "The mouth of hell itself could be no fiercer."

It was indeed like looking down the crater of a volcano to glance into that awful depth—the fire had got complete hold of the coal.

"We must take to the boats, sir," said Mellish.

"Not yet," replied the captain. "We have no security [Pg 39] yet from that cyclone,—did boats fall into its clutches, there is no chance for them. We may skirt it in the barque by God's providence; it blows from the west'ard quarter, and its tail may help us towards the mainland quicker than boats would take us. Batten down the hatches, but leave the hose room for entrance, and keep up the water as much as we can. Provision the boats, and have everything ready to man them quickly when all hope is over; but we stick to the old girl to the last gasp."

There were two large boats, both capable of holding ten or twelve men; two smaller ones, which could accommodate six or eight each; and the captain's gig, usually manned by a similar number.

It would require the whole five to receive all the crew, for it consisted of twenty seamen, an apprentice, Ralph, a cook, sailmaker, carpenter, boatswain, three mates and the captain,—thirty souls besides Mr. Gilchrist. Even with all the five boats there would be but little space to save much of their possessions, but there was the less demand for this as the men, taking fright at the state of the cargo, refused to go below even for their own kits. Indeed, the stench of sulphur, and rapid spread of the smother, justified them in their fears.

The cook's galley and the storehouses were on deck, the latter in the poop, close by the captain's cabin, and the former amidships; it was therefore easy to store the boats with a sufficiency of provision and water, and Captain Rogers proceeded to tell off the men for each.

He himself must be the last to leave the ship; and equally, of course, must Mr. Gilchrist be considered among the first. He must go in the first boat, commanded by Mellish; eight seamen, Kirke, and the carpenter would form its complement. But Mr. Gilchrist refused.

"No," said he. "I am an interloper here, it is right [Pg 40] that I should come last, and leave these poor fellows to have first chance of their lives. Put a married man in my place, there is no one dependent upon me at home."

"Nay," said Captain Rogers, "you are my charge, I must see you safe first."

"My good fellow," replied Mr. Gilchrist with determination, "do not waste time in arguing; I go with you."

"And I too, uncle," said Ralph. "Do not ask me to part from you."

"For you, boy," replied the captain, "right and good, you are as my own, and ought to take risks with me; but for you, Gilchrist, think better of it."

"Now, Rogers," said Mr. Gilchrist, "why waste time? Don't you know when a man has made up his mind?"

There was indeed a general perception that time was short, the men worked with all their might, and the boats were stored rapidly. The three mates and the boatswain were each to command one; the coxswains were selected from the best of the seamen, and every man was given his place, to which he was at once to repair upon a given signal.

Was it wise to wait longer before embarking in them? A dead calm had fallen, an ominous stillness pervaded the atmosphere, no breeze, not the faintest sigh, was there to swell the sails, and a brassy sky in the west received the sinking sun.

And the little coils of smoke grew larger, they writhed up from crack and cranny like snakes, and span and twisted, puffed and swelled, with horrible sportiveness.

The men worked in silence, casting fearful glances on this side and that, as they trod those decks which formed so slight a protection for them from the fiery chasm beneath. They gathered in groups as the night fell with the rapidity of those latitudes, but they did not talk.

In the quiet they could hear little slippings of the coal, little reports now and then, and they fancied that a sullen roar might be distinguished, now gathering volume, then dying away.

The night was very dark,—was it the looming storm or the furnace beneath them which made the air so oppressive and close? Nothing could be done without light, and the suspense was horrible. Every now and then the captain, holding a lantern low, swept the decks, examining to see whether the smoke had increased or lessened. There appeared to be but little difference, but such change as there was lay in the direction of increase.

Thicker and thicker grew the gloom, blacker and blacker the night, heavier and heavier the sultry air. Then a faint moaning was heard among the shrouds, a hissing on the surface of the water, and the cyclone broke upon them with a cry as of demons rejoicing over their prey.

The vessel gave a shudder like a living creature, then bounded forwards, heeling over from force of the wind in the most perilous manner; every cord straining, every sail swollen to its utmost tension.

It was but the edge of the cyclone, but even that gave them enough to do. The sea boiled around them; great waves tossed the devoted ship on their crests, and buried it in their trough, driving it onward with fury all but unmanageable.

Then rose up a wall of water above their heads, it dashed down upon the decks, and rushed out from the scuppers in foaming streams; and in the next instant the mainsail was torn from its holdings, the mast gave way with an awful rending and crash, and beat about to this side and that, to the peril of all around.

"The boats! the boats!" shrieked the men.

"Take to the boats!" shouted Rogers.

They sprang to the davits to loosen the boats, and the howling wind took the gear in its teeth and wrenched its supports from their hold, whirling the two first boats away as if they had been feathers.

Floods of water poured over the decks, making their way plentifully down into the hold through a thousand clefts opened by the straining timbers, and the steam rose in thicker and hotter clouds as they washed away.

Then a lull came,—were they out of the line of the cyclone?

"Cut the ropes of the starboard boats," cried the captain. "We can hold out no longer. 'Tis life or death."

Again was the effort made,—again did failure greet the devoted men; the smaller boat was swamped at once. Better fortune served them over the others; the large one and the captain's gig were lowered safely, and the men crowded into them with headlong speed, many throwing themselves into the seething water in their haste, some to be hauled on board by their comrades, and more than one to be swept out of sight for ever.

Hardly could the united efforts of the captain, mates, and Mr. Gilchrist control the panic: they stood, silent and firm, with set teeth and blanched faces, as the seamen crushed past them and dropped over the side, only endeavouring to withhold them so as to give each his fair chance of escape. Minutes were like hours; the crowd lessened,—cries and shouts for haste rose up from the thronged boats. Captain Rogers turned, caught Ralph by the arm and swung him over the side; Mr. Gilchrist slipped down a rope and was hauled in; Mellish leapt; the captain stood alone, the last of all.

He looked hurriedly around—all were gone, his duty done, and he too threw himself into the gig.

So hampered were the rowers by the mass of living [Pg 43] creatures crushed into so small a space, that they could hardly manage their oars; the boats were weighted down to the water's edge, and had not the storm spent its fury in that last awful burst, all hope of living in such a sea would have been futile.

But the hand of Providence was over them; they shook down into something like order, and rowed away from the doomed ship with all the expedition they could raise; and not one moment too soon; for, hardly were they at a safe distance, when, with an awful roar,—a splitting and crashing of timbers,—an explosion like the crack of doom itself,—the deck was forced upwards, its planks tossed high in air, as if they were chips, by the pillar of white steam that rose exultingly into the sky; great tongues of flame shot rapidly up through it, crimson and orange among rolling volumes of smoke; and the rising sun paled before the glowing fiery mass that reddened the waters far and wide ere it sank into their bosom, leaving its débris of burnt and blackened wastry floating idly on its surface.

A groan burst from the white lips of the men as the seething ruin that had been their home for so many weeks disappeared slowly from their gaze.

What were the occupants of the boats to do? What would become of them? Twenty-six men in boats only meant to accommodate eighteen at most, and these with but little food or water, no change of clothes, few comforts of any kind, an insufficiency even of necessaries,—and they were within the tropics.

The sun rose up in fierce majesty, and blazed down upon them like fire itself. Some had no hats, and suffered terribly from this cause. The sea was like molten metal heaving close around them; the crowd impeded all proper use of the oars or sailing gear. Of this last the captain's gig had none.

The men looked at each other with haggard eyes, despair in their faces. It would require but a slight touch to make them abandon themselves to hopelessness, losing heart altogether, and becoming demoralised.

They must be induced to do something, to strike a blow for their own salvation, or all would be lost.

Rogers was the right man in the right place here. Out broke his cheerful voice—

"Three cheers for the last of the old Pelican, my boys! She dies gloriously after all. No ship-breaker's yard for the gallant old girl!"

He led the cheers, which were echoed but faintly.

"'Tis well," pursued he; "'tis a crowning mercy that we are in the current which sets into the Barogna Flats. It will bear us along softly and well, barring any more cyclones, but it is not likely that we shall have another of those wild customers now. It has swept over for the time, anyhow."

"Will you not make for Diamond Island, sir?" asked Mellish, the first mate.

"By all means," said the captain, "if we are able to make for anything. But, my good fellow," dropping his voice, "we must take our chance of getting anywhere. In this crowd we cannot hold out long, neither can we pick and choose our course. We can practically only drift, and keep up our hearts."

"We are nearly sure to be met by some ship going into Rangoon," said Mellish, speaking with more certainty than he felt.

"There is a light on the Krishna Shoal, if we could reach that," said Kershaw, the third mate. "I was in Rangoon on my first voyage, and remember it; a thing like the devil on three sticks instead of two."

A laugh followed this description of the lighthouse which all the old salts knew.

"Ay, my lad," said the captain cheerily, "we'll make for your three-legged devil, and let him take the hindmost."

"Zur," said old Wills, touching his forelock, "there'm a lot of spars and timbers afloat, would it not be best to try and draw enough in to make a catamaran, like az we used to be teached to make for a pinch when I wor in the navy?"

"A catamaran!" exclaimed young Kershaw. "Why, man, what good would that be so far to sea? You may see them by the dozen off shore, but how do you propose to make one here?"

"From timber-heads and greenhorn, zur," replied the old fellow very demurely.

"Do you think you can?" asked Rogers, who was thinking too intently to have noticed this byplay. "The boats are of such different sizes."

"'Twon't be a fust-class affair, your honour," replied Wills. "Not az if we had her blessed Majesty's resources to hand; but Osborn here, he du knaw what I mean so well az any, and I daresay there's others too."

"Ay!" cried two or three.

"'Twould give more elbow-room d'ye zee, zur."

"It would," said the captain; "but you could not do it unless the boats were nearer of a size, I am convinced."

"Maybe not, sir," said Mr. Mellish, "but there seem to be a lot of casks among the wreckage. If we could haul in half a dozen oil hogsheads, and put them three of a side, we might contrive what would relieve both boats considerably. Then we might leave the big boat to keep that company, and push ahead with the gig to fetch help."

"Right you be, zur," said Wills.

There was a coil of rope in the large boat, they made a running noose in it, and endeavoured to fling it over some of the coveted casks; but the difficulty was enormous, partly from want of room in which to work, and partly from the danger that floating wreckage might swamp their boat, and so destroy their only chance of life.

Some spars and staves were collected, suitable to the purpose, but the sea was much agitated from the recent cyclone, and the difficulty of approaching the hogsheads was apparently insurmountable. The things might have been alive and spiteful, so persistently did they elude every wile.

Just when the men, utterly disheartened, were inclined to abandon the effort as hopeless, the noose caught, [Pg 47] apparently more by haphazard than by skill, and a hogshead of oil was drawn alongside.

In their excitement the men nearly upset the boat, and Rogers had to repress them sternly.

"Have a care, men, have a care! look at the sharks all about us. You don't want to fatten them, do ye?"

"Broach that cask," cried one among them. "Let the ile out, 'twill calm the sea."

"Ay!" said Rogers, "let it out."

Another hogshead was brought in now, and, strange to say, the oil being emptied did make the water smoother as far as it reached around them.

While the men in one boat redoubled their efforts to obtain more of these casks, old Wills and his mate Osborn connected the two empty ones by a spar laid across and firmly affixed to each end. They did this at the imminent risk of their lives, for it was necessary to get upon the spar, in a kneeling position, so as to secure the ropes firmly, and any slip into the sea would probably have been followed by a rush of white light to the spot, and the disappearance of the man, or at least of one of his members.

Those in the boats watched anxiously the while, crying out now and then, "'Ware shark!"

As these alarms were half of them false ones, the old fellows became too well accustomed to them for more than a passing glance from their work, which became safer for them as the casks were firmly fastened.

In the meantime a third cask was obtained, but it seemed all but impossible to attach a fourth. There was one within approachable distance, but it bobbed a little farther off with each effort to cast the noose over it. Seeing the impunity which had attended the efforts of Wills and Osborn, a man called Whittingham, a strong active young daredevil, got [Pg 48] upon the spar, and made his careful way out to its far end, rope in hand, coiled up, ready for a cast.

He worked himself astride the spar with considerable difficulty, for the thing was up in the air at one moment, so that the lookers-on expected to see him flung backwards into the sea; then down the length would plunge, as if about to bury itself in some great green cavern, into which he must go headlong.

It was like riding a kicking horse, but the hardy fellow kept his hold, reached the hogshead farthest from the boat, flung the coil, and it fell short though actually touching the cask.

Reclaiming the length of cord, Whittingham, in defiance of all prudence, flung himself into the boiling sea and swam towards the coveted object.

"Come back, man! Come back!" shouted the captain.

"A shark! A shark!" roared the sailors.

Whittingham paid no heed, he reached the cask and got the rope around it. He had a cord passed round his waist, and prepared to be hauled back by it, when his awful shriek rent the air, and a groan burst from the white lips of his comrades.

A huge shark had rushed swiftly up, and taken the poor fellow's legs off at his middle. The sea was crimsoned with his blood, as his head was seen turned, with an agonised expression, at sight of the certain death come upon him. In another minute the tension of the strong hands relaxed, and the man's upper half also disappeared from sight.

Ralph hid his face, trembling with horror.

But the men knew well that this was the fate which awaited them all did the boats capsize before rescue arrived, and they redoubled their efforts to help themselves.

The fatal cask was drawn in, reddened still with the lifeblood of poor Whittingham, which had splashed all over it, [Pg 49] and it enabled Wills and his assistants to construct a sort of oblong frame, supported at each corner by the buoyant empty vessels. Pieces of wood were laid athwart, the short way of the raft, which became safer with each fresh plank as it was affixed.

The chief difficulty was to obtain the wherewithal for making these planks and timbers secure. There was but very little rope, and only such nails as clung to the riven timbers, with a few which Wills, like all carpenters, happened to have in his pocket. The spars and planks were irregular in length and thickness, neither was it possible to rig up even a cord run around the raft, or any manner of bulwark wherewith to increase its safety.

It could not be navigated by any means, but it could be towed at the stern of the larger boat, and serve to reduce the crush of people there, so as give free scope either to step the mast and sail her, or for the men to use their oars.

Both boats being thus relieved, the captain's gig would then row away, with a light complement of men, and try to make Diamond Island, upon which a pilot station was well known to exist; or the Krishna Shoal, where it was probable that help might be either obtained or signalled for by those in the lightship.

With help of the current this was possible, provided the weather remained calm.

The question now arose as to who should be transferred to the raft,—who could best be spared from the boats.

Mellish must remain in command of the large boat, with Kershaw. The second mate must go with the captain. The four officers must be thus divided to ensure a head in case of accident to either one among them.

The crew of the captain's gig must also be retained. They were picked men, and the most likely to hold out in case of long-continued exertion or another gale of wind.

"Uncle," said Ralph, "I will go on the raft. I cannot help in the boat, I do not know enough, but I can make room for a better man."

"You are right, my boy," said the captain a little huskily. "You are a plucky chap, and your mother shall hear of this if any of us live."

"I go on the raft, equally of course," said Mr. Gilchrist firmly.

"Let we go, maister," proposed Wills, usually spokesman for himself and Osborn. "Uz will keep an eye on the young 'un, ef it be only because he'm Miss Amy's chield."

The captain grasped the old fellow's hand in silence, and two of the ordinary seamen, of less use than the A.B.'s, were added to the little gimcrack craft's crew.

The biscuit was apportioned out to each as far as it went, and the gig parted company from its fellows. When nearly out of sight, the men lifted their oars in the air as a farewell greeting, and the fast gathering shades of night engulfed them.

Their companions, both in the boat and on the raft, watched their disappearance in silence. They were exhausted with the emotions of the last few days, and the heavy work of the last twenty-four hours. Little could be done through the night but wait for the dawn. They set a watch, and each tried to get some rest in turn.

There had been a question as to whether Kirke should not have gone on the raft. It would have been fitter for him to have done so than for Mr. Gilchrist, who, always delicate, had recently been so ill. He was a guest, if not a passenger, and should have had the best place.

He had, however, settled the question for himself, allowing no demur, and the men were grateful to him for so doing. Most of them were married men, with young children or other helpless ones dependent upon them. The safety of [Pg 51] the raft was bound up in the safety of the boat. If anything happened to swamp the boat, the raft was doomed to share the same fate; whereas, were the raft lost, those in the boat still had a chance. Those who could work the oars and sails best were the right men to remain in it.

But Kirke was not one of these; neither his strength nor his knowledge made him as useful as an O.S. would have been, but he claimed his place in the boat as an officer, and there was no time for debate. Captain Rogers let it pass,—perhaps he had his own private reasons for so doing.

The men owned no reasons, public or private, for keeping this much disliked young man among them; they would far rather have had Ralph of the two; and thought that Mr. Gilchrist should have been kept in the best place.

They murmured; they made remarks to each other aimed at the selfish apprentice, and which he perfectly understood; while Kershaw openly taunted him with selfishness and cowardice.

Kirke maintained a dogged silence, but his brow became more lowering, and his mouth more set in a kind of vicious sullenness every moment.

So night fell.

Night fell over the shipwrecked men, a strange one for the denizens of the raft.

There, at least, was peace, and a hearty determination to make the best of their position.

They had some sailcloth and a boat cloak. The men arranged the packages, which had been turned out to disencumber the boat, so as to make a tolerably comfortable back; they laid down a couple of planks close together, rolled up the sailcloth into a kind of cushion above them, and placed Mr. Gilchrist upon it, wrapped in the cloak.

That gentleman would gladly have shared these accommodations among some of them, but the men would not hear of it.

"Lord love you, zur," said Osborn, "there's enough for one, but two wouldn't zay thank'ee for a part. We'm used to roughing it. 'Tis fine and cool after all the heat and pother to-day."

Ralph, upon whom his friend urged his wishes more strongly, only laughed. He seated himself upon one leg on a packing-case, the other foot dangling; he crossed his arms on the head of the biscuit-barrel against which Mr. Gilchrist leaned, half-sitting, and, burying his face upon them, said he should sleep like a top there, for he was so tired he could not keep his eyes open.

The sailors squatted down, finding such ease as was possible, and quiet fell over all. The night was a dark one, and very still; there was not a breath of wind to fill the sail in the boat, half the men there were getting what repose they could, and the others trusted more to the current than to their oars through the darkness. Silence had fallen upon all there as well as on the raft.

But Mr. Gilchrist could not sleep. He was a nervous, excitable man, and the new and excessively perilous position in which he found himself precluded all possibility of sleep. His senses seemed rather to be preternaturally acute, and he could not even close his eyes.

The lapping of the sea against the raft, the occasional gleam of something swiftly passing, and which he believed to be a shark accompanying the crazy little craft,—for what purpose he shuddered to think,—the occasional sounds which reached him from the boat, all kept him awake.

He lay, half-reclining, with his face towards the boat, which was full in his view. He could faintly see the oars dipping into the water, keeping way on the boat, and Kershaw's slim figure holding the tiller ropes. Presently he saw the one set of men relieved by the other, he smiled to observe the mate's long arms tossed out, evidently accompanying a portentous yawn, and then he was replaced by a shorter, broader back, which Mr. Gilchrist knew must belong to Kirke.

A sort of half-doze succeeded for a short time, then Ralph changed his position, which startled him into wakefulness once more, and discontented tones reached him from the boat.

"What are you about? Steer straight. You will tip us all over. What's the fellow doing?"

"Dropped my cap overboard. I was not going to lose it. Shut up!"

A few more murmurs, then all was still again; but, was he mistaken? did his eyes, unaccustomed to judge of objects in the darkness, deceive him, or were they farther from the boat than before?

He peered anxiously into the gloom, and felt certain that the motion of the raft was changed. There was less ripple against its prow.

"Wills," said he softly to the old carpenter, who lay full length within reach of his hand,—"Wills, there is something wrong."

The man was on the alert instantaneously.

"Zur?" he asked.

"I fear we have parted the towline," said Mr Gilchrist.

Wills cautiously moved to where the rope had been fastened—it hung loose, there was no tension upon it, and he hauled it in hand over hand.

"My God!" he cried, "we are lost!"

They shouted to the men in the boat, but the distance was widening every moment between them. Kirke did not seem to hear, to understand. The men clamoured, the first mate arose, took the helm, and tried to turn her head so as to row back, but the darkness was greater than ever. Those in the raft could no longer distinguish the boat, what chance therefore existed of those in the boat seeing the raft, which lay so much lower in the water?