Title: McClure's Magazine, Vol. XXXI, September 1908, No. 5

Author: Various

Release date: June 10, 2014 [eBook #45924]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Kiwibrit and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

For convenience, a Table of Contents and List of Illustrations have been added to this version.

[Translator's Note.] The suppressed memoirs of General Kuropatkin are in four bulky volumes and contain, in the aggregate, about 600,000 words. The first three volumes are devoted, mainly, to a detailed review of the three great battles of the Russo-Japanese war—Liao-yang, the Sha-ho, and Mukden—from the standpoint of modern military science. The fourth volume, which is entitled "Summing up of the War," covers a very wide field, dealing partly with Russia's national problems, her military history, and her policy in Asia, and partly with the causes of the late war, the rise of Japan as a military power, and the reasons for the overwhelming defeat of Russia's armies in the Far East.

Copyright, 1908, by The S. S. McClure Co. All rights reserved

PAGE |

|

| THE MILITARY AND POLITICAL MEMOIRS OF GENERAL KUROPATKIN. | 483 |

| THE SECRET CAUSES OF THE WAR WITH JAPAN. By General Kuropatkin. |

486 |

| THE ROYAL TIMBER COMPANY. | 497 |

| THE AMERICANIZING OF ANDRÉ FRANÇOIS. By Stella Wynne Herron. |

500 |

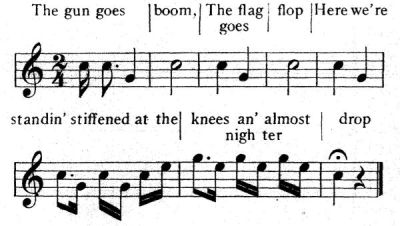

| AIN'T YOU GWINE TO COME? by Edmund Vance Cooke. | 509 |

| JUNGLE BLOOD By Elmore Elliott Peake. | 510 |

| "THE HOUSE OF MUSIC" by Gertrude Hall | 528 |

| VERSES by A. E. Housman. | 542 |

| MY ELECTION TO THE SENATE by Carl Schurz | 543 |

| A CAVALRY PEGASUS by Will Adams. | 557 |

| FROM LEWIS CAROLL TO BERNARD SHAW by Ellen Terry. | 565 |

| IN THE SHADOW OF THE SCAFFOLD by Harry Grahame. | 577 |

| THE BURIED ANCHOR by Perceval Gibbon. | 590 |

| A FOOTPATH MORALITY by Louise Imogen Guiney. | 596 |

| TAFT AND LABOR by George W. Alger. | 597 |

| FOOTNOTES. | 602 |

| Nicholas II., The Tsar of Russia and The Tsarevitch | 483 |

| State Councillor Alexander Mikhailovich Bezobrazoff | 484 |

| Admiral Alexeieff | 485 |

| Sergius de Witte | 486 |

| Two Views of Port Arthur | 488 |

| Taken at the Time of the War | 489 |

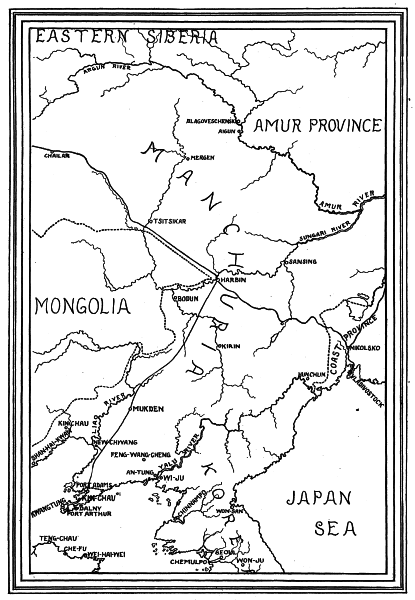

| Map Showing Field of the Operations that led to the War between Russia and Japan |

493 |

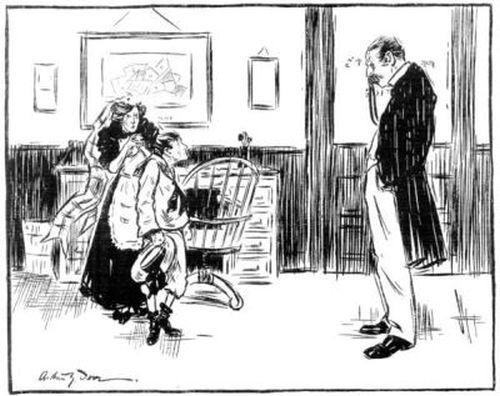

| "'I'd be glad to do it as a favor,' he said." | 502 |

| "'I cannot fight this peasant—I am a gentleman'."” | 504 |

| "'It was of a suddenness, said Angélique blushing" | 505 |

| "That fight will long be remembered in the annals of the gang. | 506 |

| "An admiring concourse of small boys followed at a respectful distance. | 508 |

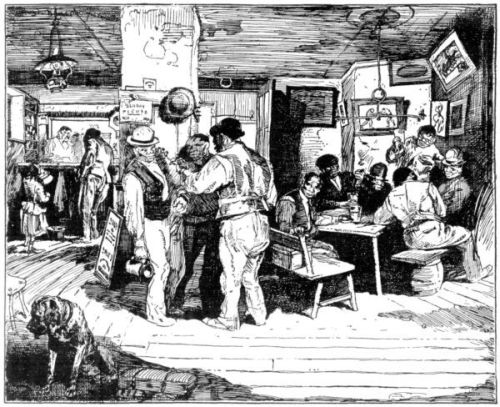

| "Most of the hotel negroes spent this recess in an adjacent dive." | 512 |

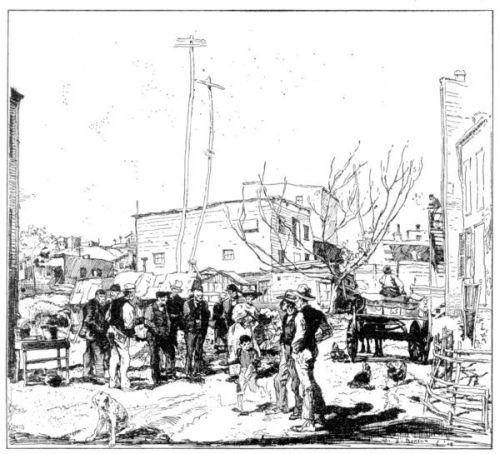

| "It was into this atmosphere that the student took his way" | 515 |

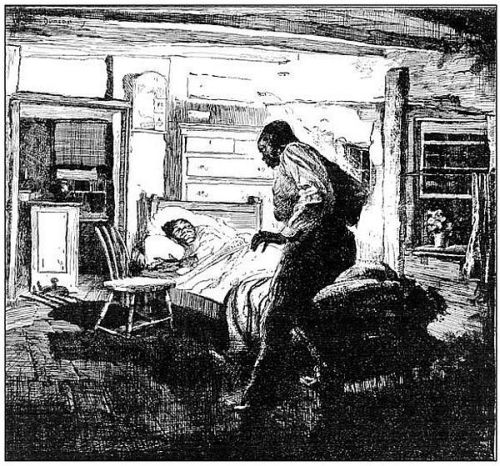

| "Heah's an ole devil i used to wrastle with,' he exclaimed shrilly" | 517 |

| "Old benjy continued to blink silently" | 519 |

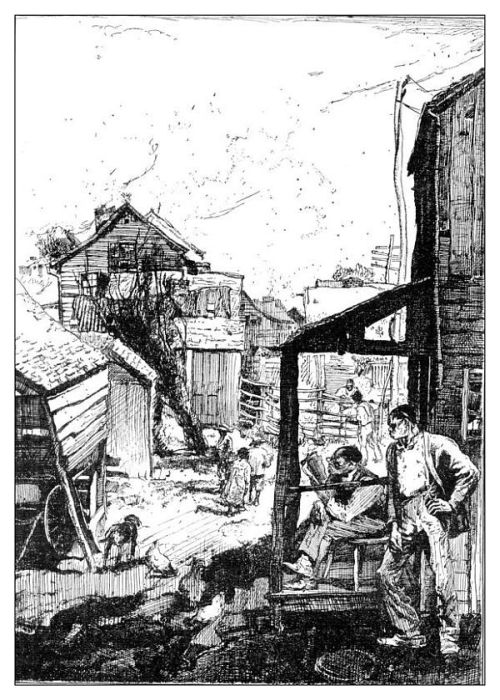

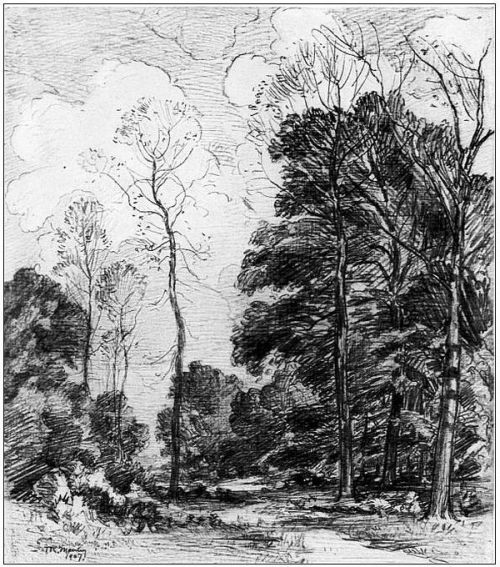

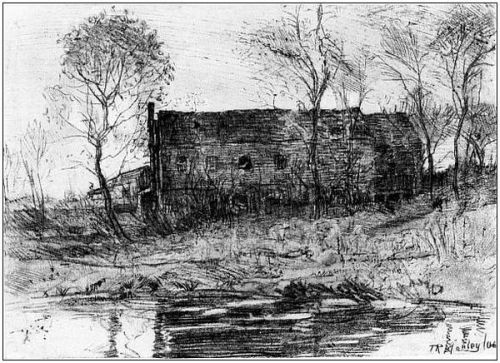

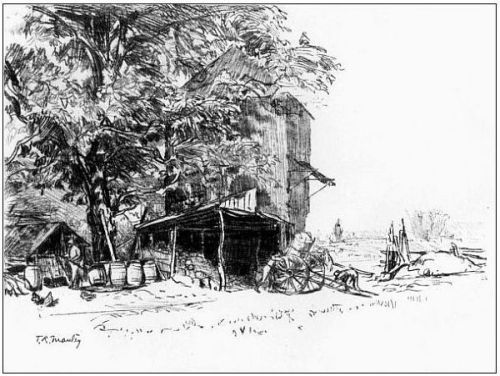

| Four Drawings by Thomas R. Manley: | 523 |

| 1. Drawing. | 523 |

| 2. Drawing. | 524 |

| 3. Drawing. | 525 |

| 4. Drawing. | 526 |

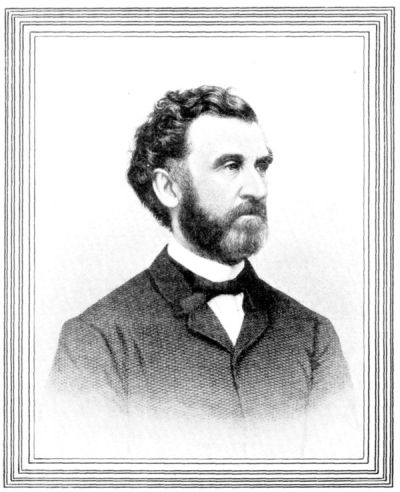

| Dr. Emil Preetorius | 544 |

| Schuyler Colfax | 544 |

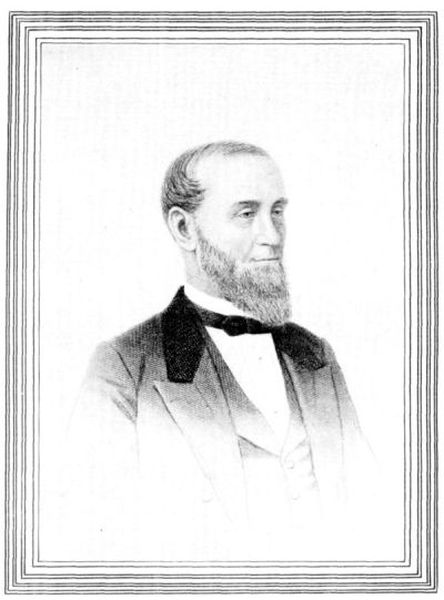

| Ulysses S. Grant | 545 |

| Francis Preston Blair | 546 |

| Horatio Seymour | 546 |

| John B. Henderson | 547 |

| Senator Charles D. Drake | 548 |

| Alexander T. Stewart | 550 |

| "'Are you interested in poetry, sir?' he said" | 558 |

| "'He used language to me, sir, and i am hiss sergeant'" | 559 |

| [No caption] "And so he continued his recital." | 560 |

| [No caption] Miss Cora? | 561 |

| William Ewart Gladstone. | 567 |

| Lord Randolph Churchill. | 567 |

| The Princess of Wales. | 568 |

| Melba as Marguerite in "Faust". | 569 |

| Mrs. Craigie (John Oliver Hobbes). | 569 |

| C. L. Dodgson (Lewis Carroll). | 570 |

| J. M. Barrrie. | 571 |

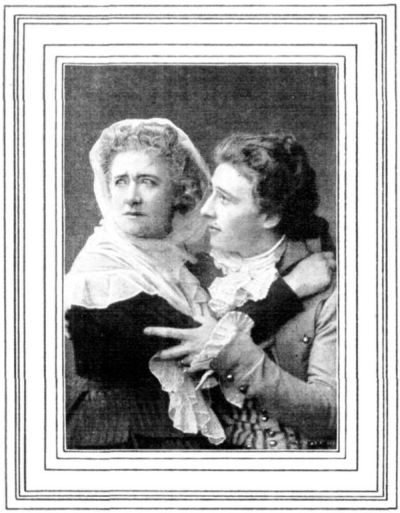

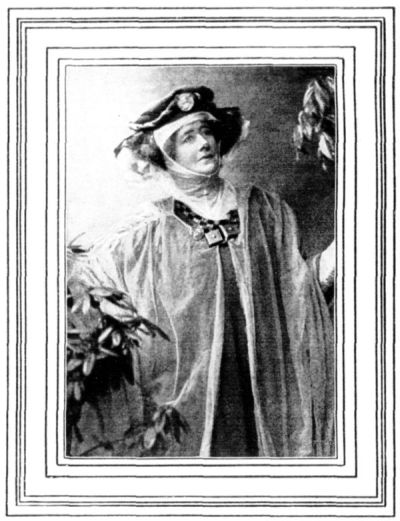

| Ellen Terry and her son, Gordon Craig, in "The Dead Heart". | 572 |

| Ellen Terry as Mistress Page in "Merry Wives of Windsor". | 572 |

| Ellen Terry as Lady Cecily Waynflete in "Captain Brassbound's Conversion". |

573 |

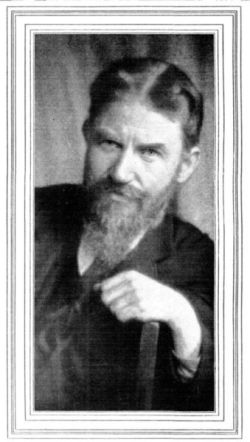

| George Bernard Shaw. | 574 |

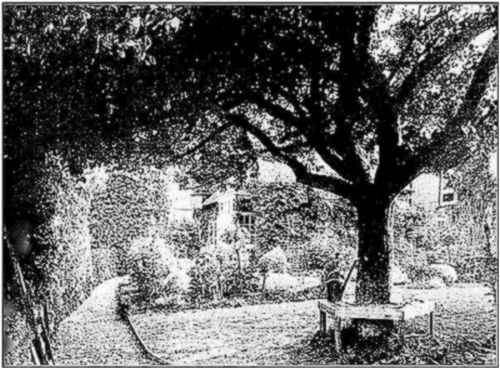

| Miss Terry's Garden at Winchelsea; from a Photograph given by her to Miss Evelyn Smalley. |

575 |

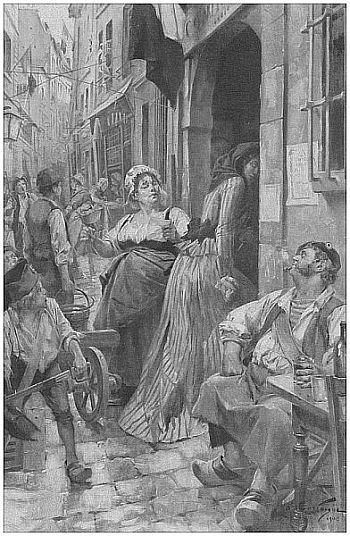

| "Terrible tales of bloodshed and injustice reached the little sun-kissed village of Caen". |

578 |

| "At last, toward evening, she forced her way in". | 580 |

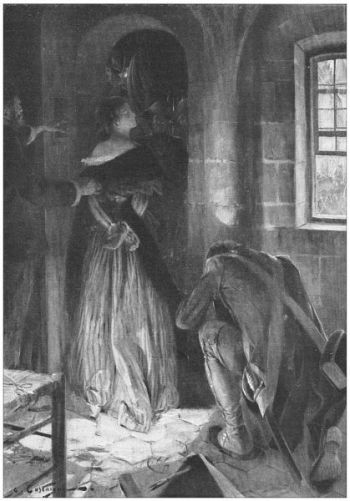

| "'I kiss the tips of your wings,' he said". | 582 |

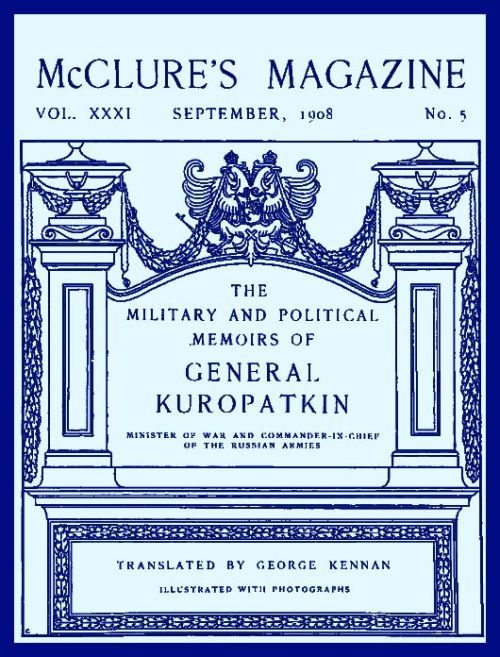

STATE COUNCILLOR ALEXANDER MIKHAILOVICH BEZOBRAZOFF

WHO ACQUIRED HIS EXTRAORDINARY POWER IN THE FAR EAST BY MEANS OF HIS KOREAN TIMBER COMPANY, AN ENTERPRISE IN WHICH HE INTERESTED THE TSAR OF RUSSIA TO THE EXTENT OF 2,000,000 RUBLES. RATHER THAN SACRIFICE THE FAMILY INVESTMENT IN THIS ENTERPRISE, THE TSAR ALLOWED RUSSIA TO BE DRAGGED INTO A WAR WITH JAPAN

I have chosen, as the subject for this article, General Kuropatkin's narrative of the events which preceded the rupture with Japan, in February, 1904, and which may be regarded, historically, as the causes of the war that ensued. It contains many new facts, and throws a flood of light upon Russian governmental methods, upon Russia's Asiatic policy, and upon the character of the monarch who now sits on the Russian throne.

Kuropatkin begins this part of his work with a review of Russia's policy and territorial acquisitions in the Far East, which may be briefly summarized as follows: The question of obtaining an outlet on the Pacific Ocean was theoretically considered in Russia long ago; and the conclusion reached was that, in view of the sparseness of Russia's population east of Lake Baikal, and the insignificance of her commerce, foreign and domestic, in that part of the world, the task of getting access to the Pacific, which might involve a serious struggle, ought not to be imposed upon the existing generation. An outlet was not needed at that time, and it is not needed yet. The Russian War Department, moreover, has always regarded with apprehension, and as far as possible combatted, the opinion that "Russia is the most western of Asiatic states, not the most eastern of European," and that all her future lies beyond the Urals.

Prior to the Japanese-Chinese war, nobody questioned that the trans-Siberian railway should follow a route inside of Russian territory; but the weakness shown by China in 1894-5 suggested a new project, namely, to carry the road through Manchuria and thus shorten it by five hundred versts. General Dukhovski, governor-general of the Pri-Amur and commander of the forces in that territory, opposed this project, and pointed out that a line crossing the boundaries of China would not connect the Pri-Amur with European Russia securely, and would benefit the Chinese rather than the Russian population. His opinion was not approved, and this railroad, which had for Russia such immense importance, was carried through a foreign country. This change of route, which proved to be so unfortunate, was the first striking proof of the fact that Russia, in the Far East, had begun a policy of energetic action. The occupation of Port Arthur, the foundation of Dalny, the construction of the southern branch of the railway, the formation of a commercial fleet on the Pacific, and the timber enterprise of State Councillor Bezobrazoff on the Yalu River in northern Korea, were all links of one and the same chain, which was to unite permanently the destinies of Russia and the destinies of the Far East—and thus bring gain to Russia.

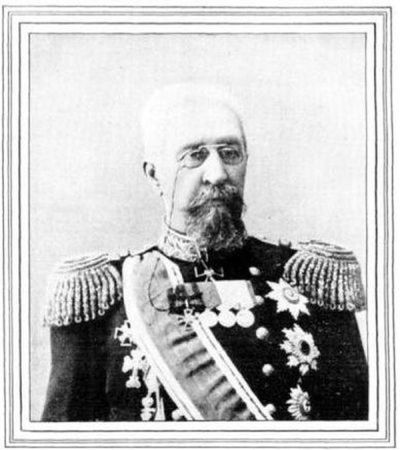

ADMIRAL ALEXEIEFF

WHO SECRETLY SUPPORTED BEZOBRAZOFF IN HIS EFFORTS TO DELAY THE EVACUATION OF SOUTHERN MANCHURIA AND TO BRING THE RUSSIAN ARMS INTO KOREA FOR THE EXPLOITATION OF HIS TIMBER ENTERPRISE. IN RETURN FOR ALEXEIEFF'S SERVICES, BEZOBRAZOFF USED HIS INFLUENCE WITH THE TSAR TO GET ALEXEIEFF APPOINTED VICEROY

"There is a prevalent opinion," says Kuropatkin, "that if we had confined ourselves to the construction of the main trans-Siberian road, even though we built a part of it through northern Manchuria, there would have been no war; that the war was caused by our occupation of Port Arthur and Mukden, and, more particularly, by the Bezobrazoff timber enterprise in Korea. There is also an opinion, held by others, that the building of the main line through northern Manchuria should be regarded not merely as the first of our active enterprises in the Far East, but as the basis and foundation of them all, because if we had carried the road along the Amur, through our own territory, we should never have thought of occupying the southern part of Manchuria and the province of Kwang-tung."

After reviewing the Boxer uprising, the occupation of Manchuria by Russian troops for the protection of the railway, and the treaty agreement with China to evacuate southern Manchuria by April 8, 1903, and northern Manchuria within six months thereafter, General Kuropatkin, who was at that time Minister of War, begins his narrative of later events as follows:

Prior to the conclusion of the treaty with China, in April, 1902, there was a difference of opinion between the commander of Kwang-tung (Admiral Alexeieff) and myself, as to the expediency of evacuating Manchuria, and the importance to us of the southern part of that country. I believed that occupation of southern Manchuria would bring us no profit, but, on the contrary, would involve us in trouble with Japan on one side, through our nearness to Korea, and with China on the other, through our possession of Mukden. I therefore regarded the speedy evacuation of southern Manchuria and Mukden as a matter of extreme necessity. Admiral Alexeieff, on the other hand, as the commander of Kwang-tung, had reason to contend that occupation of southern Manchuria was important because it insured the safety of railroad communication between Kwang-tung and Russia.

This difference of opinion, however, ended with the ratification of the Russo-Chinese treaty of March 26, 1902 (April 8, N. S.). By the terms of that convention, our troops—with the exception of those guarding the railway—were to be removed, within specified periods, from all parts of Manchuria, southern as well as northern. This settlement of the question, was a great relief to the War Department, because it held out the hope of a "return to the West" in our military affairs. In the first period of six months, we were to evacuate the western part of southern Manchuria, from Shan-hai-kuan to the river Liao; and this we punctually did. In the second period of six months, we were to remove our troops from the rest of the province of Mukden, including the cities of Mukden and Yinkow (New Chwang).

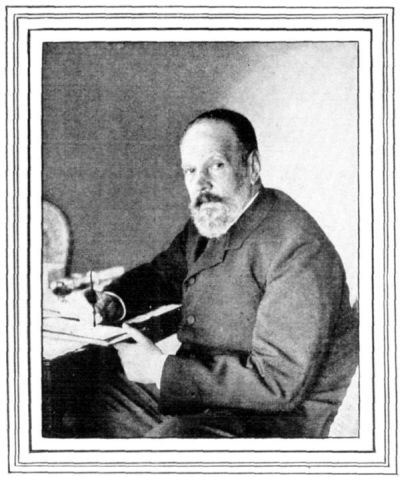

SERGIUS DE WITTE

FORMER RUSSIAN MINISTER OF FINANCE, WHO BUILT UP EXTENSIVE RUSSIAN INTERESTS IN MANCHURIA, AND CREATED THE PORT OF DALNY, AN ACT WHICH KUROPATKIN CLAIMS TO HAVE WEAKENED THE STRENGTH OF PORT ARTHUR

The War Department regarded the agreement to evacuate the province of Mukden with approval, and made energetic preparations to carry it into effect. Barracks for the soldiers to be withdrawn were hastily erected between Blagovestchensk and Vladivostok, in the Pri-Amur country; plans of transportation were drawn up and approved; the movement of troops had begun; and Mukden had actually been evacuated; when, suddenly, everything was stopped by order of Admiral Alexeieff, the commander of Kwang-tung, whose reasons for taking such action have not, to this day, been sufficiently cleared up.[1] It is definitely known, however, that the change in policy which stopped the withdrawal of troops from southern Manchuria corresponded in time with the first visit to the Far East of State Councillor Bezobrazoff, retired. Mukden, which we had already evacuated, was6 reoccupied, as was also the city of Yinkow (New Chwang). The Yalu timber enterprise assumed more importance than ever, and in order [487] to give support to it, and to our other undertakings in northern Korea, Admiral Alexeieff, commander of Kwang-tung, sent a force of cavalry with field guns to Feng-wang-cheng.[2] Thus, instead of completing the evacuation of southern Manchuria, we moved into parts of it that we had never before occupied. At the same time, we allowed operations in connection with the Korean timber enterprise to go on, despite the fact that the promoters of this enterprise, contrary to instructions from St. Petersburg, were striving to give it a political and military character.

There is good reason to affirm that the unexpected change of policy that put a stop to the evacuation of the province of Mukden was an event of immense importance. So long as we held to our intention of withdrawing all our troops from Manchuria (except the railway guard and a small force at Kharbin), and so long as we refrained from invading Korea with our enterprises, there was little danger of a break with Japan; but we were brought alarmingly nearer to a rupture with that Power when, contrary to our agreement with China, we left our troops in southern Manchuria, and when, in the promotion of our timber enterprise, we entered northern Korea. The uncertainty, moreover, with regard to our intentions, alarmed not only China and Japan, but even England, America, and other Powers.

COUNT LAMSDORFF

FORMER RUSSIAN MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS, WHO COÖPERATED WITH WITTE AND KUROPATKIN IN TRYING TO PREVENT WAR WITH JAPAN

In the early part of 1903, our situation in the Far East became very much involved. The interests of the Pri-Amur were thrown completely into the background, and General Dukhovski, the military commander and governor-general of that territory, was wholly ignored in the consideration and decision of the most important questions of Far Eastern policy. Meanwhile, in Manchuria—on Chinese territory—enterprises involving many millions of rubles were undertaken and carried on by virtue of authority that was wholly special. The Minister of Finance (M. Witte) was building and managing there a railroad about two thousand versts in length; he had the direction of a whole army corps of railway guards; he was trying to increase the economic importance of the railway by running in connection with it a fleet of sea-going steamers; he had on the Manchurian rivers a flotilla of smaller vessels, some of which carried guns and gunners; and in military matters he was so independent of the War Department that, without consulting the latter, he even selected and purchased abroad the artillery for the railway guard. Vladivostok, as a terminus, no longer seemed to satisfy the requirements of an international transit line, so, regardless of the fact that the province of Kwang-tung was subject to the authority of the provincial commander, M. Witte, without consulting either the latter or the Minister of War, located and created therein the spacious port of Dalny. The enormous sums of money spent there only lessened the importance and weakened the strength of Port Arthur, because it was necessary either to fortify Dalny, or prepare to have it seized by an enemy and used as a base of operations against us—a thing that afterward happened. Finally, the Minister of Finance managed the affairs of the Russo-Chinese Bank, and had at Peking, Seoul, and other points, his own agents (in Peking, Pokotiloff).

It thus appears that in 1903 M. Witte controlled or directed in the Far East not only railroads, but corps of troops, a fleet of commercial steamers, armed river boats, the port of Dalny, and the Russo-Chinese Bank. At the same time, Bezobrazoff and his company were developing their enterprises in Manchuria and Korea, and promoting, by every possible means, their [488] timber speculation on the Yalu. One incredible scheme of Bezobrazoff followed another; and in the summer of 1903 there was submitted to me for examination a project of his which provided for the immediate concentration in southern Manchuria of an army of 70,000 men. His aim was to utilize the timber company as a means of creating a sort of "screen," or barrier against a possible attack upon us by the Japanese, and in 1902-1903 his activity, and that of his adherents, assumed a very alarming form. Among the requests that he made of Admiral Alexeieff were, to send into Korean territory six hundred soldiers in civilian dress; to organize for service in the same locality a force of three thousand Khunkhuzes[3]; to give the agents of the timber company the support of four companies of chasseurs (six hundred mounted riflemen) to be stationed at Shakhedze, on the Yalu; and to occupy Feng-wang-cheng with a body of troops capable of acting independently. Admiral Alexeieff denied some of these requests, but, unfortunately, he consented to station one company of chasseurs (one hundred and fifty mounted riflemen) at Shakhedze, and to send a regiment of Cossack cavalry, with field guns, to Feng-wang-cheng. These measures were particularly serious and injurious to us, for the reason that they were taken at the very time when we were under obligations to evacuate the province of Mukden altogether.

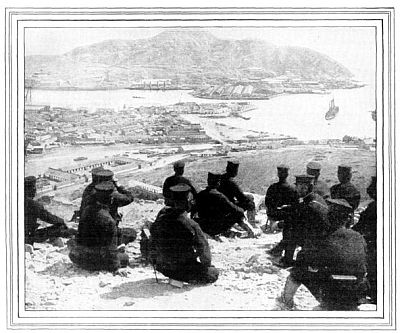

Copyright, 1905, by Underwood & Underwood

TWO VIEWS OF PORT ARTHUR

LOOKING ACROSS THE OLD TOWN OF PORT ARTHUR AND ACROSS THE NAVAL BASIS, FROM A HIGH HILL TO THE NORTH OF THE CITY

The Ministers of Finance, Foreign Affairs, and War (Witte, Lamsdorff and Kuropatkin) all recognized the danger that would threaten us if we continued to defer fulfilment of our promise to evacuate Manchuria, and, more especially, if we failed to put an end to Bezobrazoff's activity in Korea. These three Ministers, therefore, procured the appointment of a special council, which assembled in St. Petersburg on the 5th of April, 1903 (April 18, N. S.), and took into consideration certain propositions which Bezobrazoff had made to its members separately in writing. These propositions had for their object the strengthening of Russia's strategic position in the basin of the Yalu. All three of the Ministers above designated expressed themselves firmly and definitely in opposition to Bezobrazoff's proposals, and all agreed that if his enterprise on the Yalu were to be sustained, it must be upon a strictly commercial basis. The Minister of Finance showed conclusively that, for the next five or ten years, Russia's task in the Far East must be to tranquilize the country and bring to completion the work already undertaken there. He said, furthermore, that although the views of the different departments of the Government were not always precisely the same, there had never been—so far as the Ministers of War, Foreign Affairs, and Finance were concerned—any conflict of action. The Minister of Foreign Affairs pointed out, particularly, the danger involved in Bezobrazoff's proposal to stop the withdrawal of troops from Manchuria.

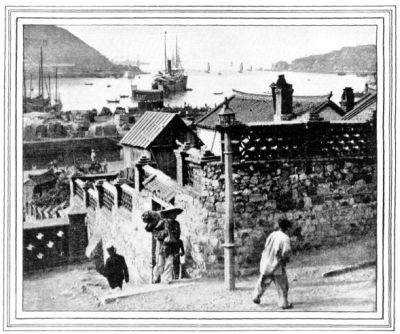

Copyright, 1905, by Underwood & Underwood

TAKEN AT THE TIME OF THE WAR

ON THE TERRACE JUST ABOVE THE WHARVES. THE HIGH PROMONTORY AT THE LEFT IS PART OF THE GOLDEN HILL, WHERE THERE ARE IMMENSELY STRONG FORTIFICATIONS, AND WHERE THE RUSSIANS MAINTAINED AN IMPORTANT SIGNAL STATION UNTIL STOESSEL's SURRENDER

It pleased His Imperial Majesty to say, after he had listened to these expressions of opinion, that war with Japan was extremely undesirable, and that we must endeavor to restore in Manchuria a state of tranquillity. The company formed for the purpose of exploiting the timber on the river Yalu must be a strictly commercial organization, must admit foreigners who desired to participate, and must exclude all ranks of the army. I was then ordered to proceed to the Far East, for the purpose of acquainting myself, on the ground, with our needs, and ascertaining what the state of mind was in Japan. In the latter country, where I met with the most cordial and kind-hearted reception, I became convinced that the Government desired to avoid a rupture with Russia, but that it would be necessary [490] for us to act in a perfectly definite way in Manchuria, and to refrain from interference in the affairs of Korea. If we should go on with the adventure of Bezobrazoff & Co., we should be threatened with conflict. These conclusions I telegraphed to St. Petersburg. After my departure from that city, however, the danger of a rupture with Japan, on account of Korea, had increased considerably—especially when, on the 7th of May, 1903 (May 20, N. S.), the Minister of Finance announced that "after having had an explanation from State Councillor Bezobrazoff, he (the Minister) was not in disagreement with him, so far as the essence of the matter was concerned."

In the council that was held at Port Arthur, when I arrived there, Admiral Alexeieff, Lessar,[4] Pavloff,[5] and I cordially agreed that the Yalu enterprise should have a purely commercial character, and I said, furthermore, that, in my opinion, it ought to be abandoned altogether. I brought about the recall of several army officers who were taking part in it, and suggested to Lieutenant Colonel Madritoff, who was managing the military and political side of it, that he either resign his commission or give up employment which, in my judgment, was not suitable for an officer wearing the uniform of the General Staff. He chose the former alternative.

In view of the repeated assurances given me by Admiral Alexeieff that he was wholly opposed to Bezobrazoff's schemes; that he was holding them back with all his strength; and that he was a convinced advocate of a peaceful Russo-Japanese agreement, I left Port Arthur for St. Petersburg, in July, 1903 (O. S.), fully believing that the avoidance of a rupture with Japan was a matter entirely within our control. The results of my visit to the Far East were embodied in a special report to the Emperor, submitted July 24th, 1903 (August 6, N. S.), in which, with absolute frankness, I expressed the opinion that if we did not put an end to the uncertain state of affairs in Manchuria, and to the adventurous activity of Bezobrazoff in Korea, we must expect a rupture with Japan. Copies of this report were sent to the Minister of Foreign Affairs and the Minister of Finance, and met with their approval.

By some means unknown to me, this report was given publicity; and on the 11th of June, 1905 (June 24, N. S.), the newspaper Razsvet printed an article, by one Roslavleff, entitled "Which is the Greater?" the object of which was to prove that I must be included among the persons responsible for the rupture with Japan, because, through fear of Bezobrazoff, I signed the minutes of the Port Arthur council which put the Yalu enterprise under the protection of Russian troops and thus stopped the evacuation of Manchuria.[6] This article has been reprinted by many Russian and foreign journals, and there has never been any refutation of the misstatements that it contains with regard to my alleged action in signing certain fantastic minutes. M. Roslavleff quotes from my report to the Emperor the following sentences and paragraphs:

"Our actions in the basin of the Yalu and our behavior in Manchuria have excited in Japan a feeling of hostility to us, which, upon our taking any incautious step, may lead to war.... State Secretary Bezobrazoff's plan of operations, if carried out, will inevitably lead to a violation of the agreement that we made with China on the 26th of March, 1902 (April 8, N. S.), and will also cause, inevitably, complications with Japan.... The activity of State Secretary Bezobrazoff, toward the end of last year and at the beginning of this, has practically brought about already a violation of the treaty with China and a breach with Japan.... At the request of Bezobrazoff, Admiral Alexeieff sent a force of chasseurs to Shakhedze (on the Yalu) and kept a body of troops in Feng-wang-cheng. These measures put a stop to the evacuation of the province of Mukden.... Among other participants in the Yalu enterprise who have given trouble to Admiral Alexeieff is Actual State Councillor Balasheff, who has a disposition quite as warlike as that of Bezobrazoff. If Admiral Alexeieff had not succeeded in intercepting a dispatch from Balasheff to Captain Bodisco, with regard to 'catching all the Japanese,' 'punishing them publicly,' and 'taking action with volleys,' there would have been a bloody episode on the Yalu before this time.[7] Unfortunately, it is liable to happen any day, even now.... During my stay in Japan, I had an opportunity to see with what nervous apprehension the people regarded our activity on the Yalu, how they exaggerated our intentions, and how they were preparing to defend, with arms, their Korean interests. Our active operations there [491] have convinced them that Russia is now about to proceed to the second part of her Far Eastern program—that, having swallowed Manchuria, she is getting ready to gulp down Korea. The excitement in Japan is such that if Admiral Alexeieff had not shown wise caution—if he had allowed all the proposals of Bezobrazoff to go through—we should probably be at war with Japan now. There is no reason whatever to suppose that a few officers and soldiers, cutting timber on the Yalu, will be of any use in a war with Japan. Their value is trifling in comparison with the danger that the timber enterprise creates by keeping up the excitement among the Japanese people.... Suffice it to say that, in the opinion of Admiral Alexeieff, and of our ministers in Peking, Seoul, and Tokio, the timber enterprise may be the cause of war; and in this opinion I fully concur."

After quoting the above sentences and paragraphs from my report, M. Roslavleff says: "Thus warmly, eloquently, and shrewdly did Kuropatkin condemn the Yalu adventure, and thus clearly did he see, on the political horizon, the ruinous consequences that it would have for Russia. But why did not this bold and clear-sighted accuser protest against the decision of the Port Arthur council? Why, after making a few caustic remarks about Bezobrazoff, did he sign the minutes of the council which put the Yalu adventure under the protection of Russian troops, and thus stopped the evacuation of Manchuria? Why? Simply because, at that time, everybody was afraid of Bezobrazoff."

Such accusations, which have had wide publicity, require an explanation.

The council held at Port Arthur, in June, 1903, was called for the purpose of finding, if possible, some means of settling the Manchurian question without lowering the dignity of Russia. There were present at this council, in addition to Admiral Alexeieff and myself, Actual State Councillor Lessar, Russian minister in China; Chamberlain Pavloff, Russian minister in Seoul; Major General Vogak; State Councillor Bezobrazoff; and M. Plançon, an officer of the diplomatic service. We were all acquainted with the will of the Emperor that our enterprises in the Far East should not lead to war, and we had to devise means of carrying the Imperial will into effect. With regard to such means there were differences of opinion; but upon fundamental questions there was complete agreement. Among such fundamental questions were:

1. The Manchurian question.

On the 20th of June (July 3, N. S.) the council expressed its judgment with regard to this question as follows: "In view of the extraordinary difficulties and enormous administrative expenses that the annexation of Manchuria would involve, all the members of the council agree that it is, in principle, undesirable; and this conclusion applies not only to Manchuria as a whole, but also to its northern part."

2. The Korean question.

On the 19th of June (July 2, N. S.) the council decided that the occupation of the whole of Korea, or even of the northern part, would be unprofitable to Russia, and therefore undesirable. Our activity in the basin of the Yalu, moreover, might give Japan reason to fear a seizure by us of the northern part of the peninsula. On the 24th of June (July 7, N. S.) the council invited Actual State Councillor Balasheff and Lieutenant Colonel Madritoff, of the General Staff, to appear before it, and explain the status of the Yalu enterprise. From their testimony it appeared that the business was legally organized, the company holding permits from the Chinese authorities to cut timber on the northern side of the Yalu, and a concession from the Korean Government covering the southern side. Although the enterprise lost, to some extent, its provocative character, after the conclusions of the St. Petersburg council of April 5, 1903 (April 18, N. S.) became known in the province of Kwang-tung, its operations could not yet be regarded as purely commercial. Its affairs were managed by Lieutenant Colonel Madritoff, of the General Staff, although that officer was not officially in service.

After consideration of all the facts presented, the members of the council came to the conclusion that "although the Russian Timber Company really appears to be a commercial organization, its employment of officers of the active military service to do work that has military importance undoubtedly gives to it a politico-military aspect." The council, therefore, acknowledged the necessity of "taking measures, at once, to give the enterprise an exclusively commercial character, to exclude from it officers of the regular army, and to commit the management of the timber business to persons not employed in the service of the Empire." On the 24th of June (July 7, N. S.) these conclusions were signed by all the members of the council, including State Councillor Bezobrazoff.

It is evident, from the facts above set forth, that the statement in which M. Roslavleff charges the members of the council with signing minutes of proceedings that gave the Bezobrazoff adventure a place among useful imperial enterprises is fiction. Upon what it was based we do not know. The duty of immediately carrying into effect the conclusions of the council rested upon Admiral Alexeieff, by virtue of the authority given to him. The thing that he had [492] to do, first of all, and that he was fully empowered to do, was to recall our force from Feng-wang-cheng and the company of chasseurs from the Yalu. Why this was not done I do not know. Personally, I did not allow Lieutenant Colonel Madritoff to continue his connection with the timber company as an officer of the General Staff, and I may add that he and other officers who associated themselves with the enterprise did so without consulting me.

But no matter how effective might be the measures taken by Admiral Alexeieff to give the Yalu enterprise a purely commercial character, I still feared that this undertaking, which had obtained world-wide notoriety, would continue to have important political significance. In my report of July 24, 1903 (August 6, N. S.), which was presented to the Emperor upon my return from Japan, I therefore expressed the opinion that an end should be put to the operations of the timber company, and that the whole enterprise should be sold to foreigners.

The thought that our interests in Korea, which were of trifling importance, might bring us into conflict with Japan, caused me incessant anxiety during my stay in the latter country. On the 13th of June, 1903 (June 26, N. S.), when I was passing through the Inland Sea, on my way to Nagasaki, I wrote in my diary:

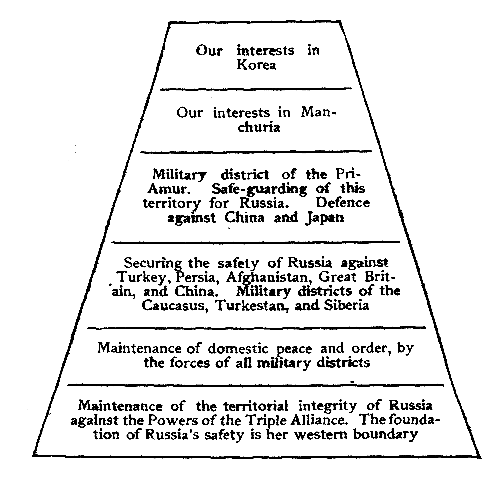

"If I were asked to express an opinion, from a military point of view, with regard to the comparative importance of Russian interests in different parts of the Empire, and upon different frontiers, I should put my judgment into the form of a pyramidal diagram, placing the least important of our interests at the top and the most important at the bottom, as follows:

"This diagram shows clearly where the principal energies of the Ministry of War should hereafter be concentrated, and what direction, in future, should be given to Russia's main powers and resources. The interests that lie at the foundation of our position as a nation are: (1) the defence of the territorial integrity of the Empire against the Powers of the Triple Alliance; and (2) employment of the forces of all our military districts for the preservation of internal peace and order. These are our principal tasks, and in comparison with them all the others have secondary importance. The diagram shows, furthermore, that our interests in the Pri-Amur region must be regarded as more important than our interests in Manchuria, and that the latter must take precedence of our interests in Korea. I am afraid, however, that, for a time at least, our national activity will be based on affairs in the Far East, and, if so, the pyramid will have to be turned bottom side up and made to stand on its narrow Korean top. But such a structure on such a foundation will fall. Columbus solved the problem of making an egg stand on its end by breaking the egg. Must we, in order to make our pyramid stand on its narrow Korean end, break the Russian Empire?"

Upon my return from Japan, I showed the above diagram to M. Witte, who agreed that it was correct.

The establishment of the Viceroyalty in the Far East was for me a complete surprise. On the 2nd of August, 1903 (August 15, N. S.) I asked the Emperor to relieve me from duty as Minister of War, and after the great manœuvers I was granted an indefinite leave of absence, of which I availed myself with the expectation that my place would be filled by the appointment of some other person.

In September, 1903 (O. S.) the state of affairs in the Far East began to be alarming, and Admiral Alexeieff was definitely ordered to take all necessary measures to avoid war. The Emperor expressed his will to this effect with firmness, and did not limit or restrict in any way the concessions that should be made in order to avert a rupture with Japan. All that had to be done was to find a method of making such concessions that should be as little injurious as possible to Russian interests. During my stay in Japan, I became satisfied that the Japanese Government was disposed to consider Japanese and Korean affairs calmly, with a view to arriving at an agreement upon the basis of mutual concessions.

MAP SHOWING FIELD OF THE OPERATIONS THAT LED TO THE WAR BETWEEN RUSSIA AND JAPAN

In view of the alarming situation in the Far East, I cut short my leave of absence, and, in reporting to the Emperor for duty, I gave this threatening state of affairs as my reason for returning. The Emperor, on the 10th of October, 1903 (October 23, N. S.), made the following marginal note upon my letter: "The alarm in the Far East is apparently beginning to subside." In October I recommended that the garrison of Vladivostok be strengthened, but permission to reinforce it was not given. Meanwhile, there was really no reëstablishment of tranquillity in the Far East, and our relations with Japan and China were becoming more and more involved.

On the 15th of October, 1903 (October 28, N. S.) I presented to the Emperor a special report on the Manchurian question, in which I showed that, in order to avoid complications with China and a rupture with Japan, we must put an end to our military occupation of southern Manchuria, and confine our activity and our administrative supervision to the northern part of that territory. My report was, in part, as follows:

"If we do not touch the boundary of Korea, and do not place garrisons between that boundary and the railway, we shall really convince the Japanese that we have no intention of first taking Manchuria and then seizing Korea. In all probability, they will then confine themselves to the peaceful promotion of their interests in the peninsula, and will neither take possession of it with troops, nor greatly increase the strength of their army at home. This will relieve us of the necessity of strengthening our forces in the Far East, and of supporting the heavy burden of an armed peace—even should there be no war. If, on the other hand, we annex southern Manchuria, all the questions that now trouble two nations and threaten to bring about an armed conflict will assume a still more critical aspect. Our temporary occupation of certain points between the railway and Korea will become permanent; our attention will be more and more attracted to the Korean frontier; and our attitude will confirm the suspicion of the Japanese that Russia intends to seize the peninsula.

"That our occupation of southern Manchuria will lead to Japanese occupation of southern Korea there can be no doubt. Beyond that, all is dark. One thing, however, is certain, and that is that if Japan takes this step, she will be compelled to increase rapidly her military strength, and we, in turn, shall respond by enlarging our Far Eastern force. Thus two nations whose interests are so different that they would seem destined to live in peace will begin a contest in which each will try to surpass the other in military resources and power. And we Russians shall do this at the expense of our fighting readiness in the West; at the sacrifice of the interest of our native population; and for the sake of portions of Korea which, so far as Russia is concerned, have no serious importance. If, moreover, other Powers take part in this rivalry, the struggle for military supremacy is liable to change, at any moment, into a deadly conflict, which may not only retard, for a long time, the peaceful development of our Far Eastern possessions, but check the growth and progress of the whole Empire.

Japan a Dangerous and Warlike Enemy

"Even if we should defeat Japan on the mainland (in Korea and Manchuria) we could not destroy her, nor obtain decisive results, without carrying the war into her territory. That, of course, would not be impossible, but to invade a country where there is a warlike population of forty-seven millions, and where even the women participate in wars of national defence, would be a serious undertaking, even for a Power as mighty as Russia. And if we do not destroy Japan utterly—if we do not deprive her of the right and the power to maintain a navy—she will wait until we are engaged in war in the West, and will then avail herself of the opportunity to attack us, either alone, or in coöperation with our Western enemies.

"It must not be forgotten that Japan can not only put quickly into the field, in Korea or Manchuria, a well organized and well trained army of from 150,000 to 180,000 men, but can do this without drawing at all heavily upon her population. If we take the German ratio of regular troops to population, namely, one per cent, we shall see that Japan, with her forty-seven millions of people, can maintain a force of 400,000 soldiers in time of peace, and 1,000,000 in time of war. And we must bear in mind the fact that, even if we reduce this estimate by two thirds, Japan, in a comparatively short time, will be able to oppose us in Korea, and march into Manchuria, with a regular army of from 300,000 to 350,000 men. If we make it our aim to annex Manchuria, we shall be compelled to increase our military strength to such an extent that, with our Far Eastern force alone, we can withstand the Japanese attack in the annexed territory."

From the above lines it will be seen how seriously the War Department regarded such an antagonist as Japan, and how much anxiety it felt concerning possible complications with that Power on account of Korea. At the time when this report was presented, and later, in November, [495] the negotiations that Admiral Alexeieff was carrying on with Japan not only made no progress, but became more critical, the Admiral still believing that to show a yielding disposition would only make matters worse.

Insignificance of Russia's Eastern Interests

Bearing in mind the clearly expressed will of the Emperor that all necessary measures should be taken to avoid war, and not expecting favorable results from Alexeieff's negotiations, I presented to His Majesty, on the 26th of November, 1903 (December 9, N. S.) a second report on the Manchurian question, in which I proposed that we return Port Arthur and the province of Kwang-tung to China, securing, in lieu thereof, certain special rights in the northern part of Manchuria. In substance, this proposition was that we admit the untimeliness of our attempt to get an outlet on the Pacific and abandon it altogether. The sacrifice might seem a grievous one to make, but I showed the necessity for it by presenting two important considerations. In the first place, by surrendering Port Arthur (which had been taken away from the Japanese) and by giving up southern Manchuria (with the Yalu enterprise), we should escape the danger of a rupture with Japan and China. In the second place, we should avoid the possibility of internal disturbances in European Russia. A war with Japan would be extremely unpopular, and would increase the feeling of dissatisfaction with the ruling authorities. My report was, in part, as follows:

"The economic interests of Russia in the Far East are extremely insignificant. We have as yet, thank God, no over-production in manufactures, because even our domestic markets are not yet glutted. There may be some export of articles from our factories and foundries, but it is largely due to artificial encouragement and will cease—or nearly cease—when such encouragement is withheld. Russia, therefore, has not yet grown up to the melancholy necessity of waging war in order to get markets for her products. As for our other interests in the Far East, the success or failure of a few coal or timber enterprises in Manchuria and Korea is not a matter of sufficient importance to make it worth while for Russia to run the risk of war on their account.

"The railway lines that we have built through Manchuria do not change the situation, and the hope that these lines will have world-wide importance, as avenues of international commerce, is not likely, in the near future, to be realized. Travelers, the mails, tea, and possibly some other merchandise, will go over them, but the great masses of heavy international freight which, alone, can give world-wide importance to a railway, will go by sea, simply because they cannot bear railway charges. Such is not the case, however, with local freight to supply local needs. This the roads—and especially the southern branch—will carry more and more, deriving from it most of their revenue, and, at the same time, stimulating the growth of the country, and, in southern Manchuria particularly, benefiting the Chinese population. But if we do not take special measures to direct even local freight to Dalny, that port is likely to suffer from the competition of Yinkow (New Chwang). Port Arthur has no value for Russia as the defence and terminus of a railway, unless that railway is part of an international transit route. The southern branch of the Eastern Chinese road has only—or chiefly—local importance, and, from an economic point of view, Russia does not need to protect it by means so costly as the fortifications of Port Arthur, a fleet of warships, and a garrison of 30,000 soldiers.

"It thus appears that the retention of a position of an aggressive character in Kwang-tung is no more supported by economic than it is by political and military considerations. What, then, are the aims that may involve us in war with Japan and China? Are such aims important enough to justify the great sacrifices that war will demand? The Russian people are powerful, and their faith in Divine Providence, as well as their devotion to their Tsar and their country, is unshaken. We may trust, therefore, that if Russia is destined to undergo the trial of war at the beginning of the twentieth century, she will come out of it with victory and glory. But she will have to make terrible sacrifices—sacrifices that may long retard the natural growth of the Empire.

"In the wars that we waged in the early years of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, the enemy invaded our territory, and we fought for the existence of Russia—marched forth in defence of our country and died for faith, Tsar, and Fatherland. If, in the early years of the twentieth century, war breaks out as the result of controverted questions arising in the Far East, the Russian people and the Russian army will execute the will of their Monarch with as much devotion and self-sacrifice as ever, and will give up their lives and their property for the sake of attaining complete victory; but they will have no intelligent comprehension of the objects for which the war is waged. For that reason there will be no such exaltation of spirit—no such outburst of patriotism—as that which accompanied the wars [496] that we fought either in self-defence or for objects dear to the hearts of the people.

"We are now living through a critical period. Internal enemies, aiming at the destruction of the dearest and most sacred foundations of our life, are invading even the ranks of our army. Large groups of the population have become dissatisfied, or mentally unsettled, and disorders of various sorts—mostly created by a revolutionary propaganda—are increasing in frequency. Cases in which troops have to be called out to deal with such disorders are much more common than they were even a short time ago. We must hope, however, that this evil has not yet taken deep root in Russian soil, and that by strict and wise measures it may be eradicated.

"If Russia were attacked from without, the people, with patriotic fervor, would undoubtedly repudiate the false teaching of the revolutionary propaganda, and show themselves as ready to answer the call of their revered Monarch, and to defend their Tsar and country, as they were in the early years of the eighteenth and particularly in the nineteenth century. If, however, they are asked to make great sacrifices in order to carry on a war whose objects are not clearly understood by them, the leaders of the anti-Government party will take advantage of the opportunity to spread sedition. Thus there will be introduced a new factor which, if we decide on war in the Far East, we must take into account.

"The sacrifices and dangers that we have experienced, or that we anticipate, as results of the position we have taken in the Far East, ought to be a warning to us when we dream of getting an outlet on the unfreezing waters of the Indian Ocean at Chahbar. It is already evident that the English are preparing to meet us there. The building of a railroad across the whole of Persia, and the establishment of a port at Chahbar, with fortifications, a fleet, etc., will simply be a repetition of our experience with the Eastern Chinese Railway and Port Arthur. In the place of Port Arthur, we shall have Chahbar, and instead of war with Japan, we shall have a still more unnecessary and still more terrible war with Great Britain.

"In view of the considerations above set forth, the questions arise: Ought we not to avoid the present danger at Port Arthur, as well as the future danger in Persia? Ought we not to return Kwang-tung, Port Arthur, and Dalny to China, give up the southern branch of the Eastern Chinese Railway, and get from China, in place of it, certain rights in northern Manchuria and a sum of, say, 250,000,000 rubles as reimbursement for expenses incurred by us in connection with the railway and Port Arthur?" Further on in my report I considered fully the advantages and disadvantages of such a decision, and set forth the principal advantages as follows: "(1) We shall escape the necessity of fighting Japan on account of Korea, and China on account of Mukden. (2) We shall be able to reëstablish friendly relations with both Japan and China. (3) We shall give peace and tranquillity, not only to Russia, but to the whole world."

Copies of this report were sent to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Minister of Finance, and Admiral Alexeieff. Unfortunately, my views were not approved, and meanwhile the negotiations with Japan dragged along and became more and more involved. The future historian, who will have access to all the documents, may be able, from study of them, to determine why the will of the Russian Monarch to avoid war with Japan was not carried into effect by his principal co-workers. At present, it is only possible to say, unconditionally, that although neither the Emperor nor Russia desired war, we did not succeed in escaping it. The reason for the failure of the negotiations is evidently to be found in our ignorance of Japan's readiness for war, and her determination to support her contentions with armed force. We ourselves were not ready to fight, and resolved that it should not come to fighting. We made demands, but we had no intention of using weapons to enforce them—and, it may be added, they were not worth going to war about. We always thought, moreover, that the question whether there should be war or peace depended upon us, and we wholly overlooked Japan's stubborn determination to enforce demands that had for her such vital importance, and also her reliance upon our military unreadiness. Thus the negotiations were carried on by the respective parties under unequal conditions.

Then, too, our position was made worse by the form that Admiral Alexeieff gave to the negotiations intrusted to him. References were made that offended Japanese pride, and the whole correspondence became strained and difficult as a result of the Admiral's unfamiliarity with diplomatic procedure and his lack of competent staff assistance. He proceeded, moreover, upon the mistaken assumption that, in such a negotiation, it was necessary to display inflexibility and tenacity. His idea was that one concession, if made, would inevitably lead to another, and that a yielding policy would be more likely, in the end, to bring about a rupture with Japan than a policy of firmness. On the 25th of January, 1904 (February 6, N. S.) [497] diplomatic relations were broken off by the Japanese, and a few days later war began.

My opinions with regard to the relative importance of the tasks set before the War Department of Russia made me a convinced opponent of an active Asiatic policy.

1. Recognizing our military unreadiness on our western frontier, and taking into account also the urgent need of devoting our resources to the work of internal reorganization and reform, I thought that a rupture with Japan would be a national calamity, and I did everything in my power to prevent it. Throughout my long service in Asia, I was an advocate of an agreement with Great Britain there, and I was satisfied that there might also be a peaceable delimitation of spheres of influence in the Far East between Russia and Japan.

2. I regarded the building of the main line of the trans-Siberian railway through Manchuria as a mistake. The decision to adopt that route was made without my participation (I was then commander of the trans-Caspian territory); but it was contrary to the judgment of the War Department's representative in the Far East—General Dukhovski.

3. The occupation of Port Arthur took place before I became Minister of War, and I had nothing to do with it. I regard it as not only a mistake, but a fatal mistake. By thus acquiring, prematurely, an extremely inconvenient outlet on the Pacific, we broke up our good understanding with China and made an enemy of Japan.

4. I was always opposed to the timber enterprise on the Yalu, because I foresaw that it might bring about a rupture with Japan. I therefore took all possible measures to have it made an exclusively commercial affair, or to have it suppressed altogether.

5. So far as the Manchurian question is concerned, I made a sharp distinction between the comparative importance to us of northern Manchuria and southern Manchuria. At first, I was in favor of removing our troops as quickly as possible from both; but after the Boxer uprising, in 1900, I recognized the necessity of keeping on the railway at Kharbin three or four battalions of infantry, a battery, and a hundred Cossacks, as a reserve for the boundary guard.

6. When our position in the Far East became difficult, and there seemed to be danger of a rupture with Japan, I was in favor of decisive measures, and proposed that we avert war by admitting the untimeliness of our attempt to get an outlet on the Pacific; by restoring Port Arthur and Kwang-tung to China; and by selling the southern branch of the Chinese Eastern Railway.

When Adjutant General Daniloff returned from Japan, he told me that, at the farewell dinner given him there, General Terauchi, the Japanese Minister of War, said that General Kuropatkin and he had done everything in their power to avert war. And yet, even now, I sometimes ask myself doubtfully, "Did I do everything that was within the bounds of possibility to prevent it?" The strong desire of the Emperor to avoid war with Japan was well known to me, as it was to his other co-workers, and yet we, who stood nearest to him, were unable to execute his will.

[Editor's Note.]—Among the first questions suggested by General Kuropatkin's narrative and the editorials, reports, and official proceedings that he quotes, are: Who was State Councillor Bezobrazoff? How did he acquire the extraordinary power that he evidently exercised in the Far East? Why was "everybody"—including the Minister of War—"afraid of him"? Why did even the Viceroy respond to his calls for troops, and why was his Korean timber company allowed to drag Russia into a war with Japan, against the opposition and resistance, apparently, of the Tsar, the Viceroy, the Minister of War, the Minister of Finance, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Port Arthur council, and the diplomatic representatives of Russia in Peking, Tokio, and Seoul?

No replies to these questions can be found in General Kuropatkin's record of the events that preceded the rupture with Japan, but convincing answers are furnished by certain confidential documents found in the archives of Port Arthur and published, just after the close of the war, in the liberal Russian review Osvobozhdenie at Stuttgart.[8] Whether General Kuropatkin was aware of the existence of these documents or not, I am unable to say; but as they throw a strong side-light on his narrative, I shall append them thereto, and tell briefly, in connection with them, the story of the Yalu timber enterprise, as it is related in St. Petersburg.

In the year 1898, a Vladivostok merchant named Briner obtained from the Korean Government, upon extremely favorable terms, a [498] concession for a timber company that should have authority to exploit the great forest wealth of the upper Yalu River.[9] As Briner was a promoter and speculator, who had little means and less influence, he was unable to organize his company, and in 1902 he sold his concession to Alexander Mikhailovich Bezobrazoff, another Russian promoter and speculator, who had held the rank of State Councillor in the Tsar's civil service, and who was high in the favor of some of the Grand Dukes in St. Petersburg.

Bezobrazoff, who seems to have been a most fluent and persuasive talker, as well as a man of fine personal presence and bearing, soon interested his Grand Ducal friends in the fabulous wealth of the Far East generally, and in the extraordinary value of the Korean timber concession especially. They all took stock in his enterprise, and one of them, with a view to getting the strongest possible support for it, presented him to the Tsar. Bezobrazoff made upon Nicholas II. an extraordinarily favorable impression and, in the course of a few months, acquired an influence over him that nothing afterward seemed able to shake. That the Tsar became financially interested in Bezobrazoff's timber company is certain; and it is currently reported in St. Petersburg that the Emperor and the Empress Dowager, together, put into the enterprise several million rubles. This report may, or may not, be trustworthy; but the appended telegram (No. 5) sent by Rear Admiral Abaza, of the Tsar's suite, to Bezobrazoff, in November, 1903, indicates that the Emperor was interested in the Yalu enterprise to the extent, at least, of the two million rubles mentioned. Bezobrazoff's "Company," in fact, seems to have consisted of the Tsar, the Grand Dukes, certain favored noblemen of the Court, Viceroy Alexeieff, probably, and the Empress Dowager possibly. Bezobrazoff had made them all see golden visions of wealth to be amassed, power to be attained, and glory to be won, in the Far East, for themselves and the Fatherland. It was this known influence of Bezobrazoff with the Tsar that made "everybody" in the Far East "afraid of him"; that enabled him to enlist in the service of the timber company even officers of the Russian General Staff; that caused Alexeieff to respond to his call for troops to garrison Feng-wang-cheng and Shakhedze; and that finally changed Russia's policy in the Far East and stopped the withdrawal of troops from southern Manchuria.

General Kuropatkin says that the Russian evacuation of the province of Mukden "was suddenly stopped by an order of Admiral Alexeieff, whose reasons for taking such action have not, to this day, been sufficiently cleared up." The following telegram from Lieutenant Colonel Madritoff of the Russian General Staff to Rear Admiral Abaza, the Tsar's personal representative in St. Petersburg, may throw some light on the subject.

(No. 1.)

To Admiral Abaza,

House No. 50, Fifth Line,

Vassili Ostroff, St. Petersburg.Our enterprises in East meet constantly with opposition from Dzan-Dzun of Mukden and Taotai of Feng-wang-cheng. Russian officer-merchants have been sent East to make reconnoissance and examine places on Yalu. They are accompanied by Khunkhuzes whom I have hired. The Dzan-Dzun, feeling that he is soon to be freed from guardianship of Russians, has become awfully impudent, and has even gone so far as to order Yuan to begin hostile operations against Russian merchants and Chinese accompanying them, and to put latter under arrest. Thanks to timely measures taken by Admiral, this order has not been carried out; but very fact shows that Chinese rulers of Manchuria are giving themselves free rein, and, of course, after we evacuate Manchuria, their impudence, and their opposition to Russian interests, will have no limit. Admiral (Alexeieff) took it upon himself to order that Mukden and Yinkow (New Chwang) be not evacuated. [10] To-day it has been decided to hold Yinkow, but, unfortunately, to move the troops out of Mukden. After evacuation of Mukden, state of affairs, so far as our enterprises are concerned, will be very, very much worse which, of course, is not desirable. [10] To-morrow I go to the Yalu myself.

Signed)

Madritoff.

Shortly before Lieutenant Colonel Madritoff sent this telegram to Admiral Abaza, Bezobrazoff, who had been several months in the Far East, started for St. Petersburg, with the intention, evidently, of seeing the Tsar and persuading him to order, definitely, a suspension of the evacuation of the province of Mukden, for the reason that "it would inevitably result in the liquidation of the affairs of the timber company." From a point on the road he sent back to Madritoff the following telegram, which bears date of March 26, 1903 (April 8, N. S.)—the very day when the evacuation of the province of Mukden should have been completed, in accordance with the Russo-Chinese agreement of March 26 (April 8, N. S.), 1902:

(No. 2.)

To Madritoff,

Port Arthur.

There will be an understanding attitude toward the affair after I make my first report. I am only afraid of being too late, as I shall not get there until the 3rd (April 16, N. S.) and the Master (Khozain) leaves for Moscow on the 4th (April 17, N. S.). I will do all that is possible and shall insist on manifestation of energy in one form or another. Keep me advised and don't get discouraged. There will soon be an end of the misunderstanding.

(Signed)

Bezobrazoff.

On April 11, 1903 (April 24, N. S.), Bezobrazoff sent Madritoff from St. Petersburg a telegram written, evidently, after he had made his first "report" to "the Master." It was as follows:

To Madritoff,,

Port Arthur.

Everything with me is all right. I hope to get my views adopted in full as conditions imposed by existing situation and force of circumstances. I hope that if they ask the opinion of the Admiral (Alexeieff), he, I am convinced (sic), will give me his support. That will enable me to put many things into his hands.

(Signed)

Bezobrazoff.

General Kuropatkin says that Admiral Alexeieff gave him "repeated assurances that he was wholly opposed to Bezobrazoff's schemes, and that he was holding them back with all his strength"; but the Admiral was evidently playing a double part. While pretending to be in full sympathy with Kuropatkin's hostility to the Yalu enterprise, he was supporting Bezobrazoff's efforts to promote that enterprise, Bezobrazoff rewarded him, and fulfilled his promise to "put many things into his hands" by getting him appointed Viceroy. Kuropatkin says that this appointment was a "complete surprise to him," and it naturally would be, because the Tsar acted on the advice of Bezobrazoff, von Plehve, Alexeieff, and Abaza, and not on the advice of Kuropatkin, Witte, and Lamsdorff. It will be noticed that von Plehve—the powerful Minister of the Interior—is never once mentioned by name in Kuropatkin's narrative. Everything seems to indicate that von Plehve formed an alliance with Bezobrazoff, and that, together, they brought about the dismissal of Witte, who ceased to be Minister of Finance on the 16th of August, 1903 (August 29, N. S.). Anticipating this result of his efforts, and filled with triumph at the prospect opening before him, Bezobrazoff wrote Lieutenant Colonel Madritoff, on the 12th of August, 1903 (August 25, N. S.), as follows:

(No. 4.)

The great saw-mill and the principal trade in timber will be transferred to Dalny, and this in copartnership with the Ministry of Finance. The Manchurian Steamship Line will have all our ocean freight, amounting to twenty-five million feet of timber, and the business will become international (mirovava). From this you will understand how I selected my base and my operating lines.

In view of the complete defeat of such clear-sighted statesmen and sane counsellors as Kuropatkin, [499] Witte, and Lamsdorff, there can be no doubt that Bezobrazoff's "base and operating lines" were well "selected."

The document that shows most clearly the interest of the Tsar in the Yalu timber enterprise is a telegram sent to Bezobrazoff at Port Arthur, in November, 1903, by Rear Admiral Abaza, who was then Director of the Special Committee on Far Eastern Affairs, over which the Tsar presided, and who acted as the latter's personal representative in all dealings with Bezobrazoff and the timber company. In the original of this telegram, significant words, such as "Witte," "Emperor," "millions," "garrison," "reinforcement," etc., were in cipher; but when Bezobrazoff read it, he (or possibly his private secretary) interlined the equivalents of the cipher words, and also, in one place, a query as to the significance of "artels"—did it mean chasseurs, or artillery? The following copy was made from the interlined original:

(No. 5.)

From Petersburg, Nov. 14-27, 1903.

To Bezobrazoff,

Port Arthur.

Witte has told the Emperor that you have already spent the whole of the two millions. Your telegram with regard to expenditures has made it possible for me to report on this disgusting slander and, at the same time, contradict it. Remember that the Master counts on your not touching a ruble more than the three hundred without permission in every case. Yesterday I reported again your ideas with regard to the reinforcement of the garrison and also with regard to the artels (chasseurs or artillery?) in the basin. The Emperor directed me to reply that he takes all that you say into consideration and that, in principle, he approves. In connection with this, the Emperor again confirmed his order that the Admiral telegraph directly to him. He expects a telegram soon, and immediately upon the receipt of the Admiral's statement, arrangements will be made with regard to the reinforcement of the garrison, and, at the same time, with regard to the chasseurs in the basin. In the course of the conversation, the Emperor expressed the fullest confidence in you.

Signed)

Abaza.

General Kuropatkin refers, again and again, to the Tsar's "clearly expressed desire that war should be avoided," and he regrets that His Imperial Majesty's "co-workers" "were unable to execute his will." It is more than likely that Nicholas II. did wish to avoid war—if he could do so without impairing the value of the family investment in the Korean timber company—but from the above telegram it appears that, as late as November 27, 1903—only seventy days before the rupture with Japan—he was still disregarding the sane and judicious advice of Kuropatkin, was still expressing "the fullest confidence" in Bezobrazoff, and was still ordering troops to the valley of the Yalu.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY ARTHUR G. DOVE

I wonder," said Andrew F. Biron, manager of the White Star Mine, to his sister, as he watched, with drawn brows, André François, immaculate in a white flannel suit, bare-kneed and sailor-hatted, go down the street attended by the ministering Angélique, "what Providence had against me when it picked me for the father of Andrew François?"

"He is certainly the strangest child I have ever known," answered his sister irrelevantly, "and I have had experience with a good many—an old maid always does, you know."

"What he needs is to mix up with the other boys—to become Americanized. There is too much European varnish on him. It needs to be rubbed off so that the real boy underneath will show through."

"He needs something," assented his sister shortly, for she had looked with none too gracious an eye upon the advent of André François and his bonne, the volatile Angélique. "He thinks of nothing except how he is dressed—a miniature fop! He is now ten years old and he is absolutely helpless. He seems never to have learned to do anything for himself. There is no manliness nor independence in him—nothing but a head full of foolish, old-world notions about what is due a gentleman of his standing. As for Angélique, one moment she runs his errands and the next bullies him. Who ever heard of a big boy of ten with a nurse, anyway?" Miss Biron stopped a moment to catch her breath, then continued:

"To be frank with you, Andrew, I think you have been little less than criminal to take so little interest in him as to leave him for eight years in an environment of which you knew nothing. You should have had him home immediately after your wife's death, and not have waited until his grandmother died and the responsibility of your son was literally forced upon you."

"The responsibility of his son." All through a busy morning at the office the phrase remained subconsciously in Mr. Biron's mind. At noon hour, when the work slackened up, he set himself to face and thresh it out, for it was his policy to face and thresh out at the first opportunity any difficulty which confronted him.

For half an hour he paced his office, his hands thrust hard down into his pockets, in his mouth a black, unlighted cigar of the stogie species, upon which he chewed with all the concentrated violence which he would have liked to expend upon the problem in hand. His son—how well he remembered the little two-year-old codger, with his serious blue eyes and his fleece of yellow hair, whom he had taken tight in his arms and told not to forget his daddy, as he bid goodby on the steamer to his pretty, pale French wife going back on a visit to her native land.

After her death, little André François had at once found snug quarters in the home of his aristocratic Parisian grandmother, Madame Fouchette, a grand dame of the old régime. She wrote and begged to keep him. She said he would be placed in a good school—the best, indeed, in France—where, as a rule, none except the sons of noblemen were admitted. Year after year had drifted by, and the busy mine-manager in Colorado, occupied with a thousand and one matters of daily importance, had sent a monthly check of generous figure, together with a quarter-page of hurriedly type-written, kindly words, accompanied at Christmas, and at what he approximately made out to be André François' birthday, by a great miscellaneous box of toys. He religiously selected these as his wife had advised him to select them on that first Christmas—for he instinctively [501] mistrusted his own judgment in such matters—and varied them only in the matter of quantity, which he increased each year in allowance for the boy's growth.

Perhaps it was because he always pictured him as a tyro of two, unsteady on his legs, principally experimental in his speech, that he was so unprepared for the real André François, the above, plus eight formative years of growth in the French capital, an aristocratic grandmother's idolatry, and the training of a school where, "as a rule, only the sons of noblemen were received."

Mr. Biron recalled with a rueful smile that first meeting with his son and heir. André François, self-possessed, slim, and aristocratic, cultivating already the airs and graces of the young boulevardier, greeted the manager of the White Star with a careful—for he was none too sure of where the accent fell in his mother-tongue——

"I am delighted, my father," and kissed him ceremoniously, first on one cheek, then on the other. After which he devoted himself to directing Angélique—who had been his bonne ever since his mother's death and in whose care he had come across the ocean—in the disposal of his four trunks. Madame Fouchette, during her life, had spared neither time nor attention in providing André François with as many new suits and caps as his blue-blooded playmates.

The little raw town of fifteen hundred inhabitants, still half mining-camp, was not prepared for the youthful scion of the Old World, and regarded him as a huge joke. As for Angélique, in her high heels and infinitesimal aprons, with her coquettish airs and her showers of exclamations, nothing like her had ever been seen, except in an overnight show, where the traditional French maid, between a song and dance, whisked imaginary dust off parlor chairs.

At school André François was under a double disadvantage. In the class-room, he not only knew more than any other boy, but frequently and authoritatively corrected the teacher. In the yard his white flannel sailor suit, with its embroidered anchor and immense soft, red silk bow in front, his jaunty round sailor hat and dainty shoes—it had become the mode in Paris at that time to follow the English style in children's dress—were regarded with derisive and hostile looks by the sturdy blue-and- brown-overalled town boys. Indeed, the little transplanted Parisian, as he stood in line with his fellows, looked very much like a lonely orchid in a bunch of dusty field-flowers.

In the yard André François did not shine. His attitude was marked in the eyes of the indigenous youth by a supercilious stupidity. He neither knew nor cared for baseball, football, or any of the lesser sports which excite young America at playtime. He had, indeed, at first extended tentative invitations to a chosen few of his class-mates to engage in a fencing bout, but, finding that art entirely unknown, he contented himself, during recess, with sitting on the bench and reading from a French book, over the top of which he sometimes stared at his hot, excited school-mates with insolent superiority.

They returned his contempt with full measure. One and all looked upon André François as a special brand of "Dago"—under which general head they classified all things Latin—protected from their scorn and patriotism by an arbitrary higher power in the form of a father who was a mine manager.

André François, in turn, confided to his father that nobody but ignorant peasants, with whom no gentleman could associate, attended the school.

So matters stood without a change in either direction two weeks after André François' arrival in town. No change of environment seemed strong enough to move him from his accustomed ways of thought. Every morning he started out for school at a quarter of nine followed by the omnipresent Angélique. Every afternoon he returned at three o'clock, still followed by Angélique.

"Angélique! A nurse! A bonne!" As the manager of the White Star thought of her, he nearly bit the cigar, upon which he was chewing, in half. All the militant Americanism in him rose in revolt. He remembered his own bare-footed, swaggering youth, independent as the wind, insolent as a king. And now his son——. He stopped short in his pacing and stared wrathfully out into the street, which, like all the streets of the town, ended abruptly, without any preliminary slopes, in a sheer wall of rock which went up and up and up into a rugged mountain peak.

It chanced that school had just let out for the noon hour, and down the middle of the street, whistling to the full of his lungs, swinging in a circle around his head a long leather strap with a blue calico-covered book at the end for a weight, swaggered a sturdy specimen of young America. Mr. Biron gazed at him with an envious eye and sighed. Then a thought, sudden and sharp, popped into his head. He hesitated for a moment. But why not? Anything was worth trying.

The manager of the White Star was a man of action, so, without wasting further time in debate with himself, he beat a loud tattoo with his knuckles on the window glass. The whistling stopped.

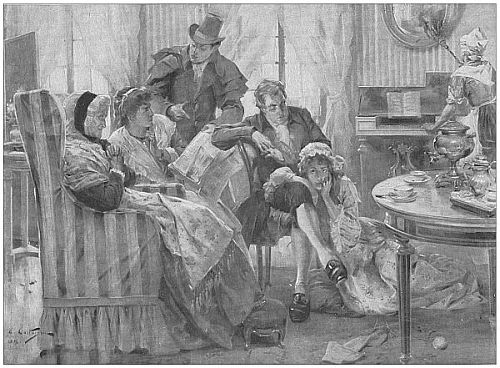

"'I'D BE GLAD TO DO IT AS A FAVOR,' HE SAID"

He crooked his finger and motioned, and the deed was done. A moment later the ground-glass door opened, and a chunky, red-haired boy, with a belligerent eye, stood expectantly before him. The newcomer placed himself so that the big iron office safe furnished a background for him, and as he stood there with his feet wide apart, his hands in his pockets, he seemed as solidly planted as it. A shaft of noonday sunlight, coming through a side window, struck his hair and made a rubescent halo around his freckled face. The manager of the White Star looked him up and down, and the boy eyed him back look for look. At length Mr. Biron cleared his throat.

"What is your name, my lad?" he asked.

"James Joseph McCarthy," answered the boy, in the same quick, phonographic monotone that he had used on his first day at school, when the teacher had asked him the same question.

"Ah, yes—do you know my son, Andrew Francis Biron?"

"Sure. Most everybody knows Andray Franswa."

"And what do you think of—er—André François?"

The boy looked at him searchingly. "You oughter know—he's your kid," he said tersely.

"I know what I think," said Mr. Biron, "but I want to know what you think. That's what I brought you in for. I want to get some data on the subject."

The boy ran his hand through his hair, and his brow puckered, as he struggled to find a phrase by which to sum up his impression of André François. Then he said:

"Ah, gee——" he made an abortive effort, out of regard for parental feelings, to mitigate the vast contempt in his voice, "he's just a darn sissy."

"Um—I see. Are there any more sissies in town?"

"Nope. Not now. There uster be one onest, about a year ago, but he's all right now. We licked him till he got all right."

"And do you intend to lick André François until he gets all right?"

The scion of the McCarthys looked at him suspiciously for a moment, but seeing in his face rather a desire for honest information than the guile of a parent, he answered:

"Nope. Nobody dast to touch him."

"Why?" asked Mr. Biron with a gleam of hope, "would he fight?"

"Who? Him? Him fight? I guess not. It's cause you're his dad. My dad, he said that if I dast to lay a finger on Andray Franswa, he'd skin me alive—an' the rest o' the kids, their dads told 'em the same thing."

"I see," said the manager of the White Star, and he saw also that a certain disadvantage went with being the employer of nearly every man in the town.

He took a thoughtful turn around the office, for his conscience gave him a twinge at the critical moment, then stopped abruptly in front of James Joseph and took from his pocket a bright, new silver dollar.

"See this, Jimmie?" he asked, balancing it seductively on the tip of his index finger, "I will give you this, and further, I will see that no complaint is made to your father—if you lick André François."

Each of Jimmie's eyes grew as big and as round as the dollar.

"Sure? D' yer mean it? Gee, that'd be fine. There's goin' to be a circus next week in Briggs' lot, and us fellows is savin' up. Say—is that what you just said on the dead square?"

"On the dead square," said André François' father solemnly.

Jimmie held out his hand for the dollar. "Sure," he said, "I'll lick Andray Franswa. I'll lay low till that crazy Angélique is out of the way. Burbank, the assayer's assistant, is soft on her, and she stops to talk to him every afternoon, an' Andray Franswa walks as far as from school to the assayer's office alone. I'll get him then. I'm boss o' the gang, an' I kin lick fine. Onest I licked a kid an' he wasn't able to be out fer a week."

"Wait," said Mr. Biron, a little alarmed at the enthusiasm he had invoked. "Remember—you are acting under orders, and your orders are not to hurt him. Just roll him around in the mud good and plenty—and, Jimmie, spoil that white sailor suit."

Jimmie's eyes filled with fellow feeling. For the first time during the interview he and the White Star manager were equals.

"I guess you was a pretty nice kid yourself onest," he said, "an' I know how you must feel 'bout Andray Franswa."

He hesitated a moment, his face twitched with a fierce internal struggle, then he thrust out his arm straight from the shoulder and handed back to Mr. Biron the price of his service.

"I—I'd be glad to do it as a favor," he said.

"Thank you," said André François' father gravely, and he took and pocketed the dollar.

As Jimmie was about to leave the office he put out a detaining hand.

"Oh, by the way," he remarked, with elaborate casuality, "you said something of a circus in Briggs' lot—I can't get away myself, at present, but if you'd take this and go, and let me know if there is anything good, you'd oblige me greatly."

Jimmie McCarthy left the office of the White Star with his ethics and his honor satisfied, and with a dollar in the pocket of his blue overalls.

Thus was enacted the preliminary part of the plot to Americanize André François, fils.