Entente Cordiale.

Cambrai, Nov. 12, 1914.

Title: Wounded and a Prisoner of War, by an Exchanged Officer

Author: Malcolm V. Hay

Release date: June 10, 2014 [eBook #45931]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Wounded and a Prisoner of War, by Malcolm V. (Malcolm Vivian) Hay

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/woundedandprison00haym |

BY

AN EXCHANGED OFFICER

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

William Blackwood and Sons

Edinburgh and London

1916

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | THE FIRST TEN DAYS | 1 |

| II. | THE RETREAT | 47 |

| III. | CAMBRAI | 83 |

| IV. | LE NUMÉRO 106 | 117 |

| V. | STORIES FROM LE NUMÉRO 106 | 158 |

| VI. | CAMBRAI TO WÜRZBURG | 188 |

| VII. | WÜRZBURG | 231 |

| VIII. | WÜRZBURG TO ENGLAND | 285 |

| ENTENTE CORDIALE, CAMBRAI, NOV. 12, 1914. | Frontispiece | |

| TAISNIÈRES-EN-TERACHE, AUGUST 16, 1914. | Facing p. | 4 |

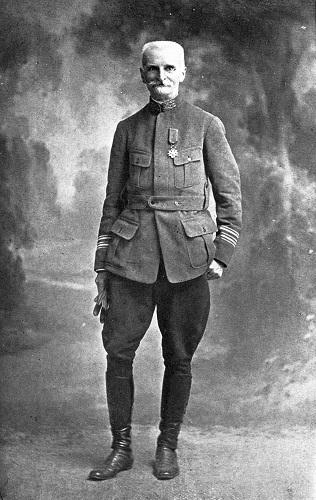

| LE COLONEL FAMÉCHON | " | 84 |

| DOCTEUR DEBU, CHIRURGIEN-EN-CHEF, HÔPITAL CIVIL, CAMBRAI | " | 90 |

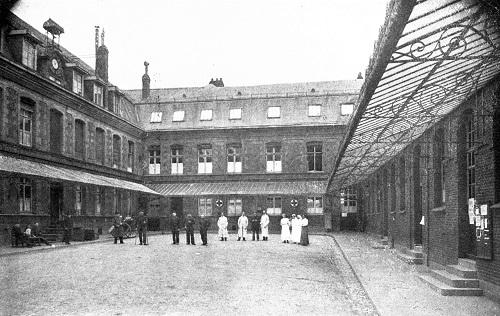

| L'HÔPITAL "106" | " | 118 |

| M. VAMPOUILLE IN THE SALLE CINQ | " | 122 |

| GENERAL OBERARZT SCHMIDT, KÖNIGLICHE ERSTE BAYRISCHE RESERVE CORPS | " | 138 |

| TAKEN AT L'HÔPITAL, NOTRE DAME, CAMBRAI, OCTOBER 1914 | " | 148 |

| GERMANY AT HOME! A MEMBER OF THE MEDICAL STAFF AT CAMBRAI | " | 150 |

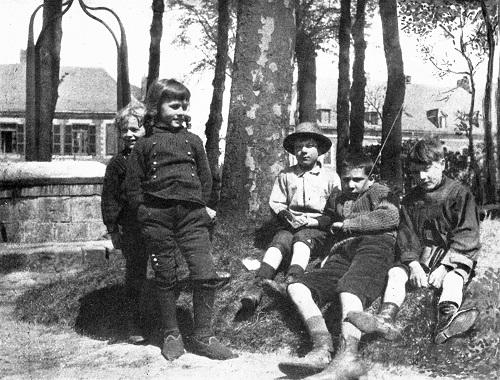

| FOUNDLINGS FROM LA BASSÉE. Photo taken at Cambrai. |

" | 160 |

| BRITISH SOLDIERS AT THE "106" | " | 166 |

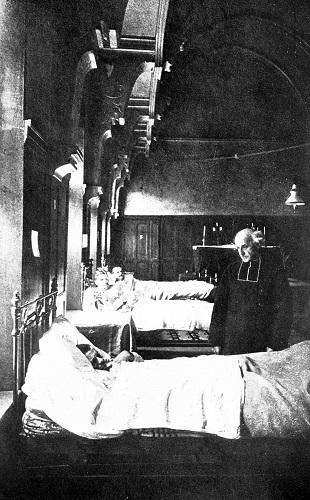

| A WARD AT THE "106" | " | 180 |

| M. LE VICAIRE-GÉNÉRAL | " | 184 |

| FESTUNG MARIENBERG | " | 230 |

| THE COURTYARD AND CHAPEL, FESTUNG MARIENBERG | " | 236 |

| FESTUNG MARIENBERG—ENTRANCE TO INNER COURTYARD | " | 284 |

Wounded and a Prisoner

of War.

Already on the shore side the skyline showed oddly-shaped shadows growing grey in the first movement of dawn. From the quay a single lamp threw its scarce light on the careful evolutions of the ship, and from the darkness beyond a voice roared in the still night instructing the pilot with inappropriate oaths and words not known to respectable dictionaries. There is not much room to spare for a troop-ship to turn in the narrow harbour, and by the time we got alongside the night was past.

The few pedestrians abroad in the streets of Boulogne at this early hour stood watching what must to them have seemed a strange procession. As the pipes were heard all down the steep, narrow street, there was a head at every window, and much waving of flags and cheering—"Vive l'Angleterre!"

The way through the town is long and steep. The sun made its heat felt as we neared the top of the hill and passed long lines of market carts waiting for examination outside the Bureau de l'Octroi. Half a mile farther on, beyond the last few straggling houses, there is a signpost pointing to the Camp St Martin. Here, in a large field, to the left of the road, stood four lines of tents of the familiar pattern. The ground was fresh and clean, for we were first in the field. From the Camp St Martin a beautiful view is obtained over the sea, whence the breeze is always refreshing even on the hottest morning of the summer.

The country round Boulogne is steeply undulating pasture-land, hedged and timbered like a typical English countryside. From the Camp St Martin the lighthouse of Etaples can be seen, a white splash where the coast-line disappears over the horizon; and on such a day as this, when the haze of the sun's heat makes all distant objects indistinct, even the most powerful lens will not show more of the English coast than just a shadow that mixes with the blur of sea and sky.

The streets of Boulogne were busy all that day with marching troops. At the quayside, transports arrived from hour to hour and unloaded their unusual cargo. From a point on the shore where Lyon and I were bathing close to the harbour entrance, we could see far out to sea a large ship, escorted by a destroyer. As the ship came nearer, her three decks appeared black with innumerable dots as if covered by an enormous swarm of bees, and when she passed the narrow entrance of the harbour we could see the khaki uniform and hear the sound of cheering. Cheering crowds lined the passage of our troops, but it seemed to me that the people showed little agitation or excitement, and that anxiety was the prevailing sentiment.

News from the front there was none. No one knew where the front was. The "Evening Paper," a single sheet, printed in large characters on one side only, confined itself to recording that Liége still held out, and that General French had gone to Paris.

The battalion paraded at 10 A.M. next morning at the Camp St Martin for inspection by a French General. In all armies the ritual of inspection is much the same, but on this occasion the ceremony had a special interest from the fact that never before in history had a British regiment been inspected by a French General on the soil of France. The General was accompanied by two French Staff Officers, one of whom was acting as interpreter, and from the scrap of talk which reached my ear as they went past, it seemed that conversation was proceeding with difficulty. "En hiver ça doit être terriblement froid," remarked the General. "Demandez leur donc"—this to the interpreter—"si les hommes portent des culottes en hiver"!

Leaving St Martin's Camp late on Sunday evening, entraining in the dark at Boulogne, the long day in the heavy, slow-moving train before we reached our detraining station at Aulnois, were experiences which then held all the interest and excitement of novelty. From Aulnois to the village of Taisnières-en-Terache is a pleasant walk of an hour through a country of high hedges enclosing orchards and heavy pasture-land. The sunlight was already fading as we left the station, and when at last our journey's end was reached it was pitch dark.

M. le Maire had plenty of straw, the accommodation was sufficient, and billeting arrangements were soon completed.

Taisnières-en-Terache.

August 16, 1914.

Our host, a fine-looking old man, tall and broad with large limbs, abnormally large hands, and something of a Scotch shrewdness in the look of his eye, had served in 1870 in a regiment of Cuirassiers, and showed us the Commemoration medal which had been granted recently by the French Government to survivors of the campaign. We sat down in his parlour about nine o'clock to a very welcome meal, and at the conclusion various toasts were drunk in the very excellent wine of which our host had provided a bottle apiece for us.

A sentry stood on the road outside the farmyard gate, where, fortunately, there was not much chance of his getting anything to do. His orders were to challenge any party that might come along the road, and not to let them proceed unless they could show the necessary pass. These passes were issued at the Mairie to all the inhabitants of the commune, and no one was allowed out after dark except for a definite purpose and at a stated hour which was to be marked on the pass. So it was fortunate that no one did pass along that night, as a nocturnal interview between our bewildered sentry and a belated French pedestrian would undoubtedly have aroused the whole company, and I might have been hauled out of bed in the early hours of morning to act as interpreter.

The next day, the 17th, Trotter and I were ordered to go off to St Hilaire, about ten miles distant, to arrange billets for the battalion. We started off on horseback in the cool of the morning, glad of the chance to see something of the country and to escape the daily dusty route-march.

St Hilaire is a picturesque village situated on the side of a hill overlooking a large tract of country, with a fine view of Avesnes, the chef lieu d'arrondissement. In the absence of the Maire the selection of billets was rendered very difficult, as many of the principal houses in the village were locked up, and no one could tell us if they would be available. After much perspiring and chattering in the hot sun, the distribution of accommodation for men and horses and the chalking up of numbers at every house was finally accomplished, in spite of the fact that at each house-door stood a generous citizen who insisted on our drinking mutual healths in cider, beer, and curious liqueurs.

By the time we reached Taisnières it was getting dark, and we were held up on the outskirts of the village by a sentry belonging to the Royal Scots, who would not let us in without the password. Neither of us had the least idea what it was, and the situation was saved by the appearance of a N.C.O., who at once let us through.

On reporting at headquarters we found that orders had been changed, and our destination was to be not St Hilaire after all, but a village farther north called St Aubin. And so the day's work was wasted.

At St Aubin there was no difficulty about billets. The Maire had everything made ready, so that when the battalion arrived, tired and hungry after an early start and a dusty ten-mile walk, it was not long before dinners were cooking in the farmyards, and much scrubbing and cleaning of equipment was in progress all down the village street.

The money for paying out the troops had been sent in 20-franc notes, presumably through some error on the part of the paymaster, so that the notes had to be taken to the nearest bank and exchanged for the newly issued 5-franc notes. The adjutant asked me to get a conveyance of some kind in the village, and to proceed to Avesnes, where the Sous-préfet, who had been warned of my arrival, would give all facilities for changing the money. A large bag of English silver which had been collected from the men was also to be taken that it might be exchanged for French money. A fat innkeeper offered to drive me into Avesnes, and after many delays and much conversation our "equipage" was ready. Captain Picton-Warlow, who had appointed himself escort to the expedition, looked with some dismay at the dilapidated conveyance. The horse was of the heavy-jointed, heavy-bellied variety that seems always to go more slowly than any living thing. The cart is hard to describe, although of a kind not easy to forget once one had been in it for a drive. The body, shaped like a half-circle balanced on springs, was supposed to hold three people. The equilibrium, we found, was maintained by the passengers accommodating their position to the slope of the road. The driver addressed the horse as "Cocotte," and we were off, creating much amusement through the village—Picton-Warlow, big and tall, perched up alongside the driver, trying with some appearance of dignity to maintain his balance and that of the cart.

Seven kilometres is more than four miles and less than five, and although that is the distance from St Aubin to Avesnes, we managed to spend over an hour on the road. Cocotte, being weak in the forelegs, was not allowed to trot downhill, and could not be expected to do more than crawl uphill with "trois grands gaillards comme nous sommes," said our conductor. On level ground we advanced ("elle fait du chemin quand même cette pauvre bête") at a cumbersome trot. An endeavour to get more speed out of the driver by explaining that we had to be in Avesnes in time to change some money before the banks closed met with no success. "The banks at Avesnes have been closed for three days," said he; but if the Messieurs wanted change, what need to go so far as Avesnes when he himself was able and willing to provide "la monnaie" for a hundred, two hundred, even a thousand francs. However, we required far more than our good friend could supply, and besides, there was the expectant Sous-préfet, who should not be disappointed, so on we jogged. Avesnes came in sight long before we got there, as the town lies in a valley. Our horse and driver, equally frightened at the steepness of the hill, proceeded with exasperating caution. Half-way down the hill tramcars and slippery pavements reduced our rate of progress still further, until the jogging of the strangely balanced cart turned into a soothing rhythmic sweep from side to side.

"Halte! Qui vive!" Our challenger, un brave père de famille de l'armée territoriale, would not let us pass without a long gossip, his interest being chiefly centred in "le kilt." The horse having been wakened up, we proceeded at a decorous pace through the town and stopped outside the Café de la Paix. On the way through the streets we had attracted a certain amount of attention, and as we neared the café the nucleus of a fair-sized procession began to accumulate. After our descent from the cart the procession became a rapidly swelling crowd. Telling our driver to remain at the café to wait orders, I asked where the Sous-préfet could be found. Monsieur le Sous-préfet was not at his bureau, "mais à la Sous-préfecture en haut de la ville; nous allons vous y conduire tout de suite." And up the street we all went, Picton-Warlow most embarrassed and suggesting schemes for the dispersal of the crowd.

The Sous-préfecture, on top of the hill, is a large comfortable-looking villa, surrounded by quite a large garden, palm-trees, and flower-beds, with an imposing stone entrance-gate. Opposite the gateway is an open square, behind us were the curious crowds of Avesnois. In front, to our astonishment, the road was blocked, and two sides of the square filled up by a whole brigade of the British troops. A hurried consultation with Picton-Warlow as to our next move allowed time for the crowd behind to form up on the remaining side of the square in the evident expectation of some interesting military ceremonial. The entrance to the Sous-préfet's house was guarded by an officier de gendarmerie on a black horse. We advanced towards this official, and after mutual salutes requested to see the Sous-préfet. "M. le Sous-préfet was receiving the generals, but would be quite ready to receive us too." As there was no other way of escaping from the crowd except through the gateway, we marched off up to the house, determined to explain the situation to the servant who opened the door, and ask leave to wait until the Sous-préfet should be disengaged. The door was opened by a servant en habit noir, behind him on a table in the hall we could see caps with red tabs and gold lace. "It is about time we were out of this," said Picton-Warlow. The domestic in evening clothes, doubtless thinking we were some kind of generals, said in answer to our request to be allowed to wait that we would be shown in at once. It was useless to explain that this was precisely what we wanted to avoid, and as I could get nothing out of the stupid man but "ces messieurs sont là qui vous attendent," we determined to beat a retreat. However, the obtuse domestic was equally determined that we should not escape. On the right side of the hall in which we stood were two large folding doors. Suddenly, and after the manner of Eastern fairy tales, these huge panelled doors were flung open. The servant had disappeared and we two stood alone, unannounced, on the threshold of a large drawing-room where "ces messieurs" were sitting in conclave. For an instant we stood speechless and motionless, taking in at a glance Madame la Sous-préfete in evening dress seated at the far end of the room, on her right General M., on the other side a brigade-major, two French officers of high rank, and a whole lot of Frenchmen in evening dress with decorations and ribbons, all seated on chairs in a circle, a very small fragile Louis XV. table in the middle. The sudden appearance in the doorway of a kilted subaltern with two money bags slung over his shoulder did not seem to astonish the assembled company, with the exception of General M. and his brigade-major. I looked round for some one to apologise to for our intrusion, and was about to make a polite speech to the lady in evening dress, when a gentleman dressed in black silk, slim and courteous, advanced into the middle of the room. It was M. le Sous-préfet. In the name of France, in the name of the Republic and of the Town Council and citizens of Avesnes, he welcomed us. He went on at some length, dignified as only a Frenchman can be, and most flattering. I began to feel like an ambassador. When the address was completed, I replied to the best of my ability in the same strain, expressing our devotion, &c., to France, the Republic, Avesnes, and our consciousness of the great honour that was being done to us, ending up with an apology for intrusion upon their deliberations, and proposing to retire to the place whence we had come.

But the Sous-préfet would not hear of our leaving; "Quand Messieurs les Ecossais viennent à Avesnes il faut boire le champagne." With these words he led me forward, Picton-Warlow following reluctantly in the rear, and introduced us to Mme. la Sous-préfete. Picton-Warlow, after shaking hands with the gracious lady, took refuge on a chair next the brigade-major, while I was taken to the other end of the circle and introduced to M. le Maire. The money-bags had escaped notice, and I was glad to get rid of them by placing them under my chair. The circle broken by our unexpected arrival now re-formed, and as we sat waiting for the champagne, I was informed by my neighbour the Maire that the gentlemen in evening dress were members of the Conseil Municipal of Avesnes who had been summoned by the Sous-préfet to do honour to General M., whose brigade was to billet in or near the town. Not many minutes passed before the champagne arrived, ready poured out, the glasses carried in on a large tray by the daughter of the house, a self-possessed young lady of perhaps fourteen years of age. Close behind followed a younger brother in bare legs, short socks, and black knickerbocker suit, carrying a dish of cakes and biscuits. With a glass of champagne in each hand, our host crossed over to General M. and pledged a lengthy toast in somewhat similar style to the speech which had been made to me. "I drink," said he, "to the most noble and the most brave, as well as the most celebrated of British Generals." During the delivery of the address General M. looked most uncomfortable, especially when his qualifications and qualities were being enumerated; in reply, he made a very gracious bow to the Sous-préfet, and we sipped healths all round. After the champagne had been drunk the party became more animated, and formed into groups, in each of which was a distinguished guest struggling with unreasonable French genders, and I was presently able to explain quietly to our host the motive of our visit. M. le Sous-préfet had never had any word of such an errand; he said that the banks would be shut for another week, but suggested that the Receveur des Impôts would be able to provide such change as might be required. Meantime Picton-Warlow had been talking to the Brigadier, who had by now realised and was most amused at the situation. When we got up to bid our adieux, I heard the General say—sotto voce—to Picton-Warlow, "For God's sake don't go off and leave us here alone." When I turned round at the door and saluted the assembly there was a distinct twinkle in M.'s eye, and I think the Sous-préfet was not without some slight quiver of the eyelid as he bade us a cordial farewell.

The "Bureau du Receveur" was open, but there was no one about save the caretaker, who informed us that the "patron" had gone off with all his clerks "to see the English march round the town." We directed our steps towards the swelling sound of pipe-and-drum band, and mingled with the crowd lining the main boulevard which encircles the upper part of the town. P. W. made friends with a French soldier who was in charge of a motor-car which was held up within the barrier formed by the circular manœuvre of the Brigade. It appeared from what this man said that the citizens of Avesnes had made great preparations to welcome the men, and that they were so disappointed on hearing that the troops were under orders to march farther north that General M., at the Sous-préfet's request, promised to march his men three times round the town. The whole population had turned out to witness the parade, and there did not seem to be much chance of retrieving the Receveur des Impôts from among the enthusiastic cheering mob that swelled around. Our new-found friend, the French soldier, now took us under his wing. He set a number of his friends to hunt down the line, and several civilians joined in the search, among whom was our burly driver, who had got tired of waiting for us at the café. As we were now seated in the motor-car, and had accepted the owner's kind offer to drive us back to St Aubin, we told our fat driver that his services and that of the horse and cart would not be required. Some one then came running up to say that M. le Receveur des Impôts had been found and was now at the Bureau.

The business of changing the French notes was soon carried through, but the English silver could not be changed, as the rate of exchange was a matter on which discussion might have lasted the whole afternoon.

When M.'s Brigade had finished their last lap we in the motor-car were then able to proceed with our commissions. The first stop was at the chemist's. Picton-Warlow stayed in the car. The chemist greeted me as an old friend, and I presently recognised him to be one of the gentlemen who in evening dress had taken part in the reception at the Sous-préfecture. He was now standing at the back of his shop in the middle of a group of stout, middle-aged, and severely respectable-looking citizens, to whom he was telling the story of the day's adventure. After my arrival the conversation came gradually round to a discussion of the Entente Cordiale, and the alliance Franco-Ecossaise, until I felt that a request to purchase tooth-paste would be almost an indiscretion.

Outside, a crowd had again collected, and Picton-Warlow, sitting unprotected in the back of the car, was an object of respectful yet insistent curiosity. Here was a chance to see "le kilt" at close quarters. The good citizens (and citizenesses too) climbed on to and into the car to see and feel "les jambes nues! mais en hiver ça doit être terrible!"

Picton-Warlow refused to sit in the car at our next stop, and so we went together into "Le Grand Bazar." "Avez-vous des plumes, de l'encre, et du papier à écrire?" "Mais ou, Monsieur, on va vous faire voir cela tout de suite." And we were led round the shop to inspect the trays wherein it is the custom of bazaars to display their stock.

Simple-minded inhabitants of a wild and mountainous region (les Hig-landerrs) are no doubt unaccustomed to the splendour of bazaars, so the shop-girls watched with expectant interest. Picton-Warlow selected the best shaving-brush (this for the Adjutant, whose kit had got lost) out of a tray of very second-rate brushes with nothing of the "Blaireau" about them except the name. "Tiens," said one of the girls, nudging another, "Il s'y connait, le grand! Il a pris le meilleur du premier coup!" "Mais parle donc pas si fort, je te dis que 'l'autre' comprend." While "le grand" was making his purchases, a French reservist, the only other customer in the shop, looked on with absorbing interest. The brave poilu could no longer contain his curiosity, and began to follow "le grand," pretending to take an interest in the pens, ink, and paper. Just as "le grand" was choosing an indelible pencil, the poilu ventured to stretch out a hand and feel the texture of his kilt. "Mais comme ils doivent avoir froid en hiver! Les jambes nues," he said, addressing me; and then as "le grand" turned round, "Pardon, quel rang?" "Capitaine," said I in a solemn voice. The poilu in horror stepped back a pace, saluted "le grand." "Pardon, mon capitaine, je ne savais pas." "L'autre qui comprend," then explained the significance of stars and stripes, and with great difficulty persuaded the abashed and no longer curious soldier that we were not in the least offended at his unintentional breach of discipline.

We had to drive up to the barracks in order that our driver could get his permis de rentrée, and, refusing with regret the hospitality of the officer in charge, we started off for St Aubin, arriving back in time to pay out before night had fallen. Before turning in I went down to the end of the village to settle up with the fat innkeeper; we had a farewell drink of wine, and I paid him five francs, his own price, for the hire of Cocotte and the carriole.

The five officers of D Company were billeted alongside H.Q., who were in the big house. Our tiny cottage consisted of two small rooms adjoining the kitchen, inhabited by an old couple, who, when I came in that evening, were sitting silently over the dying embers of the kitchen fire. The picture of the old man, small of stature and wizened in features, and very poor, is still vivid in my mind. Life had left its mark most distinctly upon him. One could see how from early morning to late at night he had from childhood toiled over the hard earth which had drawn him down, until now his back was bent as if still at labour, even when at rest by the fireside. The two did not speak when I came in, but sat watching the fire. No other light was in the room. An occasional flicker from the hearth lit up the walls of brown-coloured plaster, the clean but badly-laid tiles, an old cupboard of polished walnut, the kitchen table, also old, and black from smoke and much polishing. I asked the old man if he would wake me at four. "Mais oui, Monsieur," he replied, "nous nous coucherons pas, nous autres, nous restons pour garder le feu, et si vous voulez de l'eau chaude demain matin on vous en donnera."

These good Samaritans had provided beds for the five of us, and they were to sit up and watch the fire.

The bedroom next the kitchen contained no furniture save the four beds, each of which was provided with a straw mattress, but no sheets or blankets. Captain Lumsden occupied a tiny room at the back—so small that it was more cupboard than a room. It was here that the old people slept. The bed, which took up nearly the whole space, was covered with clean white sheets and an eider-down quilt, very new looking, as if they were used only on special occasions. Lumsden would have spread his valise on the floor had there been room, as the bed was at least a foot too short for his long limbs.

About an hour before dawn the old man came in with a jug of hot water and a stump of candle. After a very rapid shave, I hurried out into the darkness with a little Chinese lantern bought at the Grand Bazar.

We messed with H.Q. at the auberge just opposite, and thither I went as assistant P.M.C. to make sure breakfast would be ready. The oil-lamps were lit in the long low room, and hot café au lait, with round loaves of bread and fromage de Marolles, had been laid on the table. A large dish of steaming bacon came over from the cook's fire, which was in the orchard behind H.Q. This was the last substantial breakfast that any of us were to get for many a long day.

All the marching had so far been done along pleasant country roads through a country of hedges and orchards, very like central and southern England. But the aspect changed when, shortly after leaving St Aubin, we reached the Route Nationale. The battalion wheeled to the left, and we were marching down one of the chaussées pavées which are a special feature of Belgium and Northern France. The chaussée, or centre of the road, is paved with large uneven cobbles, on a width of eight to ten yards. On each side of the paved roadway a macadamised surface, about three yards broad, slopes away at a steep camber to the well-kept grass accôtement, which would be very nice to walk on were it not for the narrow channels every twenty or thirty yards draining to the deep, clean ditch, which runs outside the line of beautiful trees that flank both sides of the road.

We marched straight through the town of Maubeuge, which was full of French soldiers of the Territorial Reserve. The pavement in the town is atrocious, and made my feet sore; the sun was hotter than ever; the dust, being now largely coal-dust, was more unpleasant than before. We halted for a few minutes just beyond the bridge over the railway, where British troops were unloading guns from long lines of trucks. When I turned from watching the station I found that my platoon had got mixed up with a lot of French reservists, and that an unofficial and very dangerous rifle inspection was taking place, which was fortunately cut short by the order to "Fall in" coming down from the head of the column.

Shortly after crossing the railway the road turns sharply to the right, past an antiquated bastion, reminiscent of Vauban; by the roadside is a finger-post pointing to Belgium. What we saw on rounding the corner was strange, and at first inexplicable: it was as if a tornado had visited the spot. Where a row of cottages had been was now a shapeless mass of ruins. The ground was covered with huge trees lying across each other, the branches fresh and green, the roots broken and torn as if by some high explosive. The French had been clearing a field of fire. Beyond the entanglement of the fallen trees a network of barbed wire was being laid on a depth of some two hundred yards.

About two miles out of the town we passed the trench, of which rumour had reached us at our first billets. At Taisnières we had heard that 15,000 people were digging trenches in front of Maubeuge! The trench, deep and broad, stretched away on both sides of the road as far as the eye could see, and probably encircled the whole of Maubeuge. The road itself was blocked by barbed-wire entanglements, a space being left in the middle wide enough for the passage of a single cart. In a wood some few hundred yards behind the line of defence was a very cleverly-hidden field fortification, in which, no doubt, some of the famous 75 mm. guns were concealed.

All along the road for a distance of several miles men were working hard to clear a field of fire, hacking off branches, cutting off the tops of trees and blowing some up by the roots. A field telephone along the roadside connected these working parties with the observation officer of the battery.

At 2.15, tired, hot and hungry, we entered Joigny la Chaussée, a long straggling village, one side of the road in Belgium, the other in France.

Dinner was a very poor affair that evening—thin, watery soup with slices of bread soaked, omelette stiffened with some ration bacon.

Next morning, while we were having breakfast of café au lait and partly developed omelette, our hostess bewailed lugubriously the prospect of a German invasion, thus showing in the light of subsequent events that she appreciated the military situation far better than we did. "Ils vont tout piller, tout prendre de ce que nous avons, ces sauvages!"

On leaving Joigny la Chaussée we were back again on the highroad, forming part of a long column which was moving in the direction of Mons, distant some ten to twelve miles. Our enemies that morning, just as on the previous day, were dust, cobble-stones, and the sun.

Shortly before midday the battalion halted at a level crossing on the outskirts of Mons, and then turned to the left down a side road which runs along the railway line, opposite a small station. The rest of the column marched on over the railway and through the town.

We spent most of the afternoon waiting by the roadside; the men sat down, some on the road, some in the ditch on the railway side, all thirsty, hot, and hungry. The inhabitants of the locality, a straggling suburb, brought along some loaves and cheese, which did not, however, go far among so many. Then came a woman with two jugs of what looked like wine and water. The first man to reach her, instead of drinking the stuff, washed his mouth with it and spat on to the road, and all those who followed did the same. "They do not seem to like it," said the woman as she passed me with the empty jugs. "C'est pourtant très rafraîchissant, de l'eau sucrée avec un peu de menthe." Peppermint-water does not suit the Scotch palate!

Captain Lumsden and I went off to search for an estaminet to try to get something to eat, and we had not far to go. But the new-found estaminet did not lay itself out to supply anything but thin beer and short drinks. However, we got two pork cutlets and some eggs, and were sitting half-way through this welcome meal when A—— M——, with some other officers, having discovered our retreat, entered and ordered lunch, but with little success. The two pork cutlets and six fried eggs had apparently exhausted the resources of the establishment, and the new-comers had to content themselves with bread and butter, Dutch cheese, and the thin mixture, yellow in colour, slightly bitter to taste, which in this misguided locality is called beer.

On getting back to the road we found that most of the officers had settled down to sleep in the ditch on one side of the road, and most of the men followed their example on the other.

Train-loads of refugees, mostly women and children, were continually passing through the station.

It was nearly four o'clock when at last the order came to fall in. We marched back past the level-crossing and followed the railway line for a short way along a narrow paved road leading to the little village of Hyon, situated on a hill immediately to the right of Mons, where the Chateau de Hyon overlooks the plains and stands out distinctly in the picturesque landscape.

The sun had not long set when the men were settled down in billets, and cooking-pots stood smoking in the village street, where the afterglow of sunset still held off the twilight.

Through the still air came the hum of an aeroplane, which soon was floating over the village, about 2000 feet above our heads, spying out our position—unmolested and unafraid, the first German Taube!

"From the Camp before Mons,

September 26.

Comrade,

I received yours and am glad yourself and your wife are in good health.... Our battalion suffered more than I could wish in the action.... I have received a very bad shot in the head myself, but am in hopes, and please God, I shall recover. I will not pretend to give you an account of the battle, knowing you have better in the prints....

Your assured friend and comrade,

John Hull."

Quoted in the Tatler, Oct. 29, 1709.

The war of 1914 is in many ways an illustration of Alison's remark that battle-grounds have a tendency to repeat themselves, for to a student of Marlborough's campaigns the whole battle-line of Flanders is familiar. In 1709 the confederate armies, British, Dutch, Prussian, under Marlborough, numbering about 95,000 strong, succeeded by rapid marches in cutting off Mons from the French who were marching to its relief. After a most sanguinary battle, which took place on the 11th September, the French were forced to retire.

Between 1709 and 1914 no military comparison is possible owing to the new factors which have entered into the operations of war. Moreover, in 1709 the opposing forces were approximately equal. Still it is interesting to note that in 1709 the French, although beaten and compelled to retire, suffered less, owing to the strength of their position, than the confederate army, and that the French retreat from Mons was accomplished in perfect order.

The aspect of the country stretching northwards beyond the village and woods of Hyon is probably much the same to-day as when Marlborough's troops camped there in the autumn of 1709. From the dominating woods of Hyon the ground slopes very gradually, and is divided into irregular plots of cultivated ground, groups of farm buildings, and patches of woodlands; farther down the valley away to the right are some considerable villages; near at hand on the left lies the town of Mons, partly hidden from view by a piece of rising ground.

On leaving billets at Hyon on Sunday, 23rd August, each company marched out with separate orders to take up the position to which it had been detailed the night before, and it was about 6 A.M. when D company reached the appointed spot on the main road from Mons. There had been rain in the night; the sun was already high, but as yet no summer haze impeded the distant view. Vainly did field-glasses explore the country for some sign of the enemy, and we little imagined that through the far distant woods the Huns were once more descending upon the Hainault. We, resting in the shade of the long avenue of trees, had not yet realised the imminence of great events.

In the days of peace, when soldiering was mostly confined to a manœuvring space on some open heath, and the route-march along the King's highway, the word "battlefield" had lost its meaning, and was a contradiction in terms in its literal sense. Fields were always "out of bounds." Since landing in France we had not yet lost the fear of cultivated ground, and at every halting-place precautions were taken to prevent troops straying off the highway; and when in billets, entrance into orchards, gardens, and fields surrounding the village was strictly forbidden. We had marched along many miles of long straight dusty road between the pleasant trees, and halted many times by a roadside such as this, when nothing but a shallow ditch and the conventions of soldiering in peace time prevented our entry into potential battlefields. The word of command to fall in had for so many years been followed inevitably by a simple "quick march," and so on to the next halt.

Now, with the command "left wheel, quick march," we left the straight road and entered the cultivated fields, marching across a piece of bare stubble, then over some thickly growing beetroot still wet with dew, and again without hindrance, for there was no fence on all the land; across yet another plot of stubble up to the edge of a large cabbage patch, where two sticks were standing freshly cut, and stuck into the ground as if to mark the stand for guns at a cover shoot.

In front the unencumbered ground, cultivated in narrow strips, sloped evenly down to a main road which crossed our front diagonally, and formed an angle on the left, but out of sight, with the road we had just left. At this point the angle of the roads held by C Company on our left flank was hidden from view by a piece of rising ground. On the right flank and at a lower level, No. 14 platoon had already started digging their trench in a stubble field: beyond this, and in the same line, was a plantation of tall trees, with thick undergrowth.

The Route Nationale, with its usual border of poplar-trees, cuts diagonally across the patchwork of roots, stubble, and meadow. The distance at its nearest point to our trench, which is now traced out on the edge of the cabbage field, is just about 400 yards; 50 yards farther down to the right, on the far side of the road, there is a large white house.

Beyond the road the fields carry a heavy crop of beetroot, but there is here no great width of cultivated land. The irregular border of the forest reaches in some places to within four or five hundred yards of the road, forming a barrier to the searching of a field-glass at 1000 yards from our position. Away to the right the valley opens out like a map, with villages dotted here and there among green plantations in the middle distance, and beyond a great rolling stretch of country looking to the naked eye like some large barren heath, but showing in the field-glass the patch-quilt effect of innumerable tiny strips of variegated cultivation.

On such a day as this, when the sun is shining in the distant valley, while thick clouds above shade and tone the light, one can see farther yet to where fields and woods and villages fade together in the blue distance, with here and there a darker tone of shadow, and sometimes the sparkle of sunlight on a distant roof.

There was nothing in all the prospect to give the slightest hint of war. No traffic stirred down the straight avenue of poplars; distant patches of open country away to the right where the sun was shining remained still and deserted. Overhead the clouds had been gathering. The trench was nearly completed, when the rain came suddenly and with almost tropical force, blinding all view of the landscape.

I determined to pass away the time with a visit to the white house by the roadside, and at the same time get a look at our trench from what might soon be the enemy's point of view.

The village on the road and on our flank (half left) consisted of a dozen houses. Every house was shut up. The warm rain poured in torrents, and the village appeared to be deserted. I turned and walked slowly down the road towards the white house.

I can still see in my mind's eye the picture of this roadside inn as I saw it that morning, as none will ever see it again.

The house stood back a little from the road; two steps above the ground-level one entered the estaminet, a large airy room, a long table down the centre covered with a red-and-white check oilcloth. Outside stood a number of iron tables and chairs on each side of a sanded level space for playing bowls or ninepins. Beyond this a garden, or rather series of rose bowers, each with its seat, a green patch of long grass in the centre, and high hedges on the side nearest the road, and on the side nearest the cultivated fields and the woods beyond. In one of the rose bowers in the garden I found a sentry peering through the hedge. I was struck with the air of conviction with which, in answer to my question, he said he had seen nothing. The tone showed how convinced he was that this was simply the old old game of morning manœuvres and finish at lunch-time.

In my own mind such an impression was fast fading. The barricaded silent village up the road had helped to create a sense of impending tragedy. But the mask of make-believe did not quite fall from my eyes until I met the woman of the estaminet, a woman who came out of the white house weeping and complaining aloud, with her children clinging to her skirt. Her words I have never forgotten, though at the time I did not realise the whole meaning they contained, nor that this woman's words were the protest of a nation.

The Germans were close at hand, she said, and would destroy everything. What was to be done, where was she to flee for safety? Her frightened, sobbing voice, and the frightened faces of the children, these were, indeed, the first signs of war! I told her the truth that I knew nothing, and could give no advice as to whether it was safe to stay or flee, and as I left the tidy sanded garden and stepped on to the main road she raised her voice again with prophetic words: "What have we done, we poor people, 'paisible travailleurs'? What have we done that destruction should now fall upon our heads? Qu'est ce que nous avons fait de mal!"

The warm sunshine was pleasant after the rain. Not a sign of life on the long straight road. Four hundred yards away a soldier was still planting cabbages along the top of our parapet. I watched his work for a moment through my field-glasses, and then turned and looked across the road at the thick undergrowth beyond the cultivated ground. If the woman of the estaminet was right, even now those woods might conceal a German scout.

If at the time such a thought passed through my mind, it scarcely obtained a moment's consideration, so difficult it was then to realise the change that had already come upon the world. How incredible it is now that at the last moment of peace the prospect of real fighting could have still seemed so remote.

Somewhere hidden in the memory of all who have taken part in the war there is the remembrance of a moment which marked the first realisation of the great change—the moment when material common things took on in real earnest their military significance, when, with the full comprehension of the mind, a wood became cover for the enemy, a house a possible machine-gun position, and every field a battlefield.

Such an awakening came to me when sitting on the roadside by the White Estaminet. The sound of a horse galloping and the sight of horse and rider, the sweat and mud and the tense face of the rider bending low by the horse's neck, bending as if to avoid bullets. The single rider, perhaps bearing a despatch, followed after a short space by a dozen cavalrymen, not galloping these, but trotting hard down the centre of the road, mud-stained, and also with tense faces. A voice crying out above the rattle of hoofs on the roadway: "Fall back and join H.Q."

Now that the sound of cavalry had passed away the road was quiet again. There was no stir around the white house, no peasants or children to see the soldiers, no stir in the fields and woods beyond.

Behind the closed shutters of the white house the tearful woman of the estaminet listened in terror to the sound of horses' hoofs, and crouched in the silence that followed. I returned slowly across the drenched fields filled with the new realisation that this trench of ours was "the front."

The trench, three feet deep and not much more that eighteen inches broad, formed a gradual curve thirty to forty yards in length, and sheltered three sections of the platoon. The fourth section was entrenched on higher ground a hundred yards back, protecting our left flank.

At some distance to the rear stood a pile of faggots, which we laid out in a straight line and covered with a sprinkling of earth to form a dummy trench.

The dinners were served out and the dixies carried away, still in peace. The quiet fields and woods, with the sun now high in the heavens, seemed to contradict the idea of war. Searching round the edge of every wood, searching in turn each field and road, my field-glasses could find no sign of troops, and nothing disturbed the Sunday morning calm. Then, far away, a mile or more along the border of a wood, I saw the grey uniforms.

A small body of troops, not more than a platoon, showed up very badly against the dark background; even as I looked again they had disappeared among the trees. To the left of the white house, beyond the road and beyond the beetroot fields, the thick brushwood which skirts the cultivated ground becomes more open, and here the sun throws a gleam of light. Here, it seemed, were many shadows. At that moment German snipers, unknown to us, were already lying somewhere on the edge of the wood. The sound of bullets is most alarming when wholly unexpected. Those German scouts must have been using telescopic sights, for they managed to put a couple of bullets between Sergeant Lee and myself. Still more unexpected and infinitely more terrifying was the tremendous explosion from behind, which knocked me into the bottom of the trench, for the moment paralysed with fright.

The battery behind the woods of Hyon had fired its first range-finding shell rather too low, and the shot ricochetted off a tree on the road behind our trenches.

The situation in front of the trenches had not yet changed, as far as one could see, since the first shot was fired. An occasional bullet still flicked by, evidently fired at very long range.

The corner house of the hamlet six to seven hundred yards to our left front was partly hidden from view by a hedge. The cover afforded by this house, the hedge and the ditch which ran alongside it, began to be a cause of anxiety. If the enemy succeeded in obtaining a footing either in the house itself or the ditch behind the hedge, our position would be enfiladed.

One of my men who had been peering over the trench through two cabbage stalks, proclaimed that he saw something crawling along behind this hedge. A prolonged inspection with the field-glasses revealed that the slow-moving, dark-grey body belonged to an old donkey carelessly and lazily grazing along the edge of the ditch. The section of my platoon who were in a small trench to our left rear, being farther away and not provided with very good field-glasses, suddenly opened rapid fire on the hedge and the donkey disappeared from view. This little incident caused great amusement in my trench, the exploit of No. 4 section in successfully despatching the donkey was greeted with roars of laughter and cries of "Bravo the donkey killers," all of which helped to relieve the tension.

It was really the donkey that made the situation normal again. Just before there had been some look of anxiety in men's faces and much unnecessary crouching in the bottom of the trench. Now the men were smoking, watching the shells, arguing as to the height at which they burst over our heads, and scrambling for shrapnel bullets.

The German shells came in bunches; some burst over the road behind, others yet farther away crashed into the woods of Hyon. At the same time the rattle of one of our machine-guns on the left and the sound of rapid rifle fire from the same quarter showed that C Company had found a target, while as yet we peered over our trenches in vain. I will not pretend to give an account of the battle of Mons, "because you have better in the prints," and because my confused recollection of what took place during the rest of the afternoon will not permit of recounting in their due order even events which took place on our small part of the front. The noise of bursting shells, the sound of hard fighting on our left, must have endured for nearly an hour before any attempt was made by the Germans, now swarming in the wood behind the white house, to leave cover and make an attack on our front. From the farthest point of the wood, at a range of 1200 yards, a large body of troops marched out into the open in column, moving across our front to our left flank, evidently for the purpose of reinforcing the attack on C Company.

At 1200 yards rifle fire, even at such a target, is practically useless. It was impossible to resist the temptation to open fire with the hope of breaking up the column formation and thus delaying the reinforcement operations. "No. 1 Section, at 1200 yards, three rounds rapid." I bent over the parapet, glasses fixed on the column. They were not quite clear of the wood and marching along as if on parade.

At the first volley the column halted, some of the men skipped into the wood, and most of them turned and faced in our direction. With the second and third volleys coming in rapid succession they rushed in a body for cover.

All our shots seemed to have gone too high and none found a billet, but the enemy made no further attempt to leave the wood in close formation, but presently advanced along the edge of the wood in single file, marching in the same direction as before, and affording no target at such a distance.

Various descriptions of the battle of Mons speak of the Germans advancing like grey clouds covering the earth, of "massed formation" moving across the open to within close range of our trenches, to be decimated by "murderous fire."

On every extended battle line incidents will occur affording opportunities for picturesque writing, but in the attack and defence of an open position in the days of pre-trench war, excepting always the noise of bursting shells, the hum of bullets and the absence of umpires, the whole affair is a passable imitation of a field-day in peace time.

Our position at Hyon, important because it dominated the line of retreat, was weakly held. We had practically no supports. The German superiority at that part of the line was probably about three to one in guns, and five or more to one in men.

The enemy attacked vigorously, met with an unexpectedly vigorous resistance, hesitated, failed to push their action home, and lost an opportunity which seldom occurred again—an opportunity which has now gone for ever.

With half the determination shown at Verdun the Germans could have captured our position with comparatively trifling loss, turned our flank, and disorganised the preparation for retreat.

The steady hammer of one of our machine-guns and a renewed burst of rapid fire from the rifles of C Company made it clear that an attack on the village was in progress. Then the battery whose first shell had nearly dropped into our trench put their second shot neatly on to the red-tiled house at the left-hand corner of the village.

A shell bursting over a village! Who would pay attention now to such a detail when whole villages are blown into the air all along a thousand miles of battle?

Twenty feet above the red tiles a double flash like the twinkling of a great star, a graceful puff of smoke, soft and snow-white like cotton-wool. In that second the red tiles vanished and nothing of the roof remained but the bare rafters.

Now our guns were searching out the German artillery positions, and sent shell after shell far over our heads on to the distant woods; and now the German shells, outnumbering ours by two or three to one, were bursting all along the woods behind our trenches and behind the main road. The noise of what was after all a very mild bombardment seemed very terrible to our unaccustomed ears!

Still the rattle of a machine-gun on our left; but the bursts of rifle fire were less prolonged and at rarer intervals, so that the pressure of the German attack was apparently relaxing. The surprise of the day came from our right flank.

Here the main road ran across and away diagonally from our line, so that the amount of open ground in front of No. 14 Trench was considerably nearer 600 than 400 yards—the whole distance from this trench to the road being bare pasture-land, with scarcely cover for a rabbit. No. 14 Trench extends to within a few yards of the thick plantation which runs almost parallel with our line. The cover is not much more than two or three acres in extent, and on the far side of the wood the line is carried on by another company.

I was on the point of laying down my glasses, having made a final sweep of the ground, including a look down to No. 14 Trench, when something caught my attention in the plantation, and at that same moment a body of troops in extended order dashed out of the woods and doubled across the open meadow. The sight of these men, coming apparently from behind our own line and making at such speed for the enemy, was so entirely unexpected that, although their uniforms even at the long range seemed unfamiliar, I did not realise they were Germans. A volley from No. 14 Trench put an end to uncertainty. The line broke, each man running for safety at headlong speed; here and there a man, dropping backwards, lay still on the grass.

In the centre of the line the officer, keeping rather behind the rest, stumbled and fell. The two men nearest him stopped, bent down to assist him, looking for a moment anxiously into his face as he lay back on the grass, then quickly turned and ran for cover. A very few seconds more and the remaining racing figures dodged between trees on the main road and found safety.

When the rifle fire ceased, two or three of the grey bodies dotted about the field were seen to move; one or two rose up, staggered a few paces, only to fall at once and lie motionless; other two or three wriggled and crawled away; and one rose up apparently unhurt, running in zigzag fashion, dodging from side to side with sudden cunning, though no further shot was fired.

The German attack now began to press on both flanks—on the left perhaps with less vigour, but on the right an ever-increasing intensity of rifle fire seemed to come almost from behind our trenches; but on neither left nor right could anything be seen of the fighting. The ceaseless tapping of our two machine-guns was anxious hearing during that long afternoon, and in the confusion of bursting shells the sound of busy rifles seemed to be echoing on all sides.

Three German officers stepped out from the edge of the wood behind the white house; they stood out in the open, holding a map and discussing together the plan of attack. The little group seemed amazingly near in the mirror of my field-glass, but afforded too hopelessly small a target for rifle fire at a 1000 yards' range. The conference was, however, cut short by a shell from our faithful battery behind the wood of Hyon. A few minutes later, the officers having skipped back into cover, a long line of the now familiar grey coats advanced slowly about ten yards from the wood and lay down in the beetroot field; an officer, slightly in front of his men, carrying a walking-stick and remaining standing until another shell threw him on to his face with the rest.

Our shells were bursting splendidly beyond the white house, with now and then a shell on what had once been the red-tiled corner house, and now and then a shell into the woods beyond where the German reserves were sheltering.

Two or three lines of supports issued forth from the wood, and the first line pushed close up to the white house; but as long as we could see to shoot, and while our shells were sprinkling the fields with shrapnel, the enemy failed to reach their objective and suffered heavy casualties.

After the sun had set the vigour of the fight was past, and in the twilight few shells were exchanged from wood to wood, although machine-guns still drummed and rifles cracked, keeping the enemy from further advance. And now, far in the distant valley—perhaps fifteen or twenty miles away—the smoke of exploding shells hung in white puffs on the horizon, and the red flame of fire showed here and there a burning village in the wake of the French Army.

General French had by now received the news of the retreat from Charleroi, and the retreat of the British Army was in hasty preparation; but from us all such great doings were hidden.

Although it was now too dark for accurate shooting—for even the road and the white house were fading into the dusk—we had selected a certain number of outstanding marks easily seen in the twilight: a stump of a tree, a low bush, and a low white wall—points which the enemy would have to cross should they attempt to approach the house from the left flank. A remnant of the twilight remained when the Germans left the cover of the beetroot field, and with my field-glasses I could just manage to see when they passed in front of our prearranged targets, to see also the sudden hail of bullets spatter on the road and against the white wall among leaping, dodging shadows. On the right the machine-gun was silent for a space. In front dead silence round the familiar shadows of the white house. Then a voice broke out of the darkness, and a sound as of hammering on wooden doors. What followed, and what atrocious deed was committed in the night, none can ever surely tell.

The voice shouted again, "Frauen und Kinder heraus!" No description can convey the horror of this voice from the dark, the brutal bullying tone carrying to our ears an instant apprehension. More hammering, and then a woman's screams—the brutal voice and piercing screams as of women being dragged along, and the French voice of a man loudly protesting, with always the hard staccato German words of command; then yet another louder shrieking, then three rifle-shots, and a long silence. A long silence, and never more in the night did we hear the man's protesting voice or the terrified shriek of women.

The silence was broken by leaping, crackling flames, and in an instant the white house was a roaring bonfire. Fiercely danced the flames, carrying high into the night their tribute to German efficiency!

During the long silence after the three shots, we had all seen with eyes straining through the darkness, how shadows were at work round the walls, and one shadow on the roof whose errand there was at first a mystery, but was quickly explained in the light of the great blaze which rose up instantaneously from a spark kindled in the darkness of the courtyard.

In the ring of light thrown by the blazing house, the trees on the roadside, the out-houses beyond the courtyard, and even, for a short way, the beetroot fields, showed vividly against the black arch of night. Here, on the fringe of light in uncertain mist of mingled smoke and darkness, it seemed as if men were grouped revelling over the night's work. Now that the roof had fallen in, clouds of smoke hung low over the fields and the red-hot glow gave little light. Only every now and then a flame, shooting high into the thick darkness, threw a momentary gleam on a wider arch and showed the black shadows of men dodging back into the safety of the night.

The work was well and quickly done. The pleasant roadside inn where I had idly wandered in the morning was now a smouldering ruin.

There is no excuse for this ruin of a Belgian home. The burning was deliberate, and carried out with military precision under orders given by the officer in command, serving no conceivable military purpose, and prompted solely by a spirit of wanton destruction.

The story of the three shots in the dark will, perhaps, never be clearly told, but there can be little doubt—there is none in the minds of those who heard—that both the women and the man were brutally murdered.

Nearly a thousand years ago this same land was laid waste by the Huns, who left a memory that has lasted down to the hour of their return, for "it is in memory of the Huns," says an ancient chronicle, "that the province received the name of Hanonia or Hainault," a name which it retains to this day.

Again, after a thousand years, the Huns have risen and left a track in Europe for the memory of many generations.

Captain Picton-Warlow came up and whispered the order to retire. We had lain for many hours in front of our trench with bayonets fixed, expecting an attack at any moment, finding alarm in every shadow and fear in the rustling of night breezes.

There was safety for a time on the main road, and relief in the companionable formation of fours from the isolation and responsibility of trenches.

During the few moments' halt before marching down the road we heard how C Company had suffered heavy casualties. Major Simpson—reported mortally wounded. Lieut. Richmond—killed.

A few hundred yards down the road a machine-gun flashed red in the darkness; just before reaching it we turned down a side road to the right and joined on to the rest of the battalion. Here, by the roadside, close up against a grassy bank, a number of men were resting, some huddled up, others lying quite still. Almost at once the battalion moved on again, leaving the kilted figures by the roadside.

Less than an hour after leaving the main road we halted on a steep hillside meadow. The order was given to lie down, and for the two or three hours of the remaining night the companies slept on the field in column of fours.

The sloping hillside where we had spent the night breaks at its crest and drops steeply down to the village of Nouvelle, and the rich pasture-land with tall poplar-trees in ordered array. Beyond the ground rises suddenly, with patches of cultivation sloping up to the skyline in gentle undulations. Twenty yards below the crest of the hill, three hundred yards from a small plantation, two field-guns lay abandoned in the open. D Company, posted two hundred yards from the village, were scraping into some sort of cover by the roadside, when a well-timed shell burst right between the two guns, followed by half a dozen more along the ridge of the hill. The enemy was ranging the village, and soon two shells burst among the poplar-trees close to our "trenches," now six inches deep into the hard chalk rock.

We left the village just in time. Marching through the empty street between the shuttered houses I caught a glimpse of the two abandoned field-guns, and of a team of horses galloping along the ridge under the blazing shells. The guns were saved, but I never heard if the two gallant riders obtained recognition of their gallant deed.

For several miles our road ran alongside the railway and through open country. Pleasant in the cool morning air, and peaceful until about 9 A.M., when the enemy began to shell the road from the wooded hills on our right flank. The battalion then crossed the railway, and two companies entrenched across a wide stretch of open pasture, facing the direction in which we had been marching, protected from the right to some extent by the railway embankment.

The enemy occupied a position among slag-heaps and factory chimneys about 4000 yards to our front, and as our own guns were only 200 yards behind, the noise of the artillery duel was prodigious. On this occasion the heavy guns from Maubeuge did very useful work. The big shells could actually be seen sailing along like monster torpedoes, and at each explosion among the slag-heaps an enormous cloud of dust rose into the air.

Our trenches possessed few of the desiderata carefully laid down in the Field Service pocket-book. The parapet was far from bullet-proof, the bright yellow clay against the green must have been visible for more than a mile, and the average depth of the trench was certainly not more than a foot. Shells were bursting here and there, sometimes far in front, now far behind, along the railway line and only occasionally over the trench, for the Huns had not yet succeeded in locating our battery. Probably they were somewhat disturbed by the "Jack Johnsons" from Maubeuge. At eleven o'clock our guns retired and we followed suit, each platoon retiring independently. While No. 13 re-formed along a high wall surrounding the woods and garden of a small chateau about a quarter of a mile behind the trench, we had a narrow escape from disaster, as a shell landed just beyond the wall, killing two men and some horses.

We marched to Bavai without further incident, entering the town soon after dark. Here was all the confusion of retreat. Heavy motor-waggons, some French transport, staff officers' cars with blinding headlights, and vehicles of every description obstructed our progress through the town. I remember seeing a London taxi, one of the W.G.'s, loaded with ammunition-boxes.

A mile outside the town we turned into an orchard and bivouacked for the night, first dining on strong tea and a ration biscuit.

There was vigour and cheerfulness in the warm sunrise, and the battalion quickened its step and recovered its usual cheery spirit as we left the woods and entered the open country, marching down a narrow macadamised road, avoiding the horrors of the paved Route National. Later on in the morning, one of the first duels between a British and a German aeroplane took place right over the road. The Taube, at about 4000 feet, was then following our march, having not yet observed, as we had, 7000 to 8000 feet up among the clouds, a tiny speck, gradually growing bigger. Then the Taube took alarm and turned at full speed for the German lines. The speck, now seen to be a British aeroplane, dropped straight down to within a few hundred feet of the German machine, which was circling and dodging at various angles, striving in vain to escape. A puff of smoke from the British machine sent the enemy crashing to the ground.

Along the dusty road, marching in the hot sun with no knowledge of our destination or reason for such incessant toil, halting for short minutes, enough to ease the pack and rest the rifle and then on again, until the alternate marching and halting becomes the whole occupation not only of the body but of the mind—the eye finds no charm in pleasant countryside, and the mind gathers few pictures; the endless road, the choking dust, the unvaried pace in the hot sun.

On again through paved country towns where the hard stones are hot to weary feet, down to peaceful villages in fresh green valleys and up the long steep slope on the far side and again on, now across open country, now through the shade of green woods. Here by the village pond a pedestrian might well sit a while and smoke his pipe, watching the children paddle in the brown water under the shade of ancient trees. Often a glimpse through open doors showed cool tiled kitchens with peasants at the midday meal. Many shops in the village street were closed, with the reason therefor chalked across the shutters, "Fermé pour cause de Mobilisation." At the Mairie, and sometimes at street corners, large yellow posters, still fresh and clean, called reservists to arms in the name of La République.

We found many such towns and villages, with groups of men and women outside the numerous estaminets, offering bottles of beer and wine, or cigarettes; others with large buckets of wine and water. Glasses of wine and water were quickly seized, emptied in a few steps, handed back to some spectator farther down the line, and passed back again to the wine buckets.

There had been some thunder early in the afternoon, and overhead the storm-clouds were lowering.

Another long weary climb along the straight dusty road to reach a large open plateau, where an advance-guard of the 4th Division was entrenching, for during all that day of our long march the 4th Division was detraining, and part of this force took up a position north of Solesmes.

Large drops of rain were falling as we reached the crest of the hill, and soon a smart shower cleaned the road of dust, giving a new coolness to the air and a new vigour to the weary column.

After the long lonely road it was heartening to see the British troops, a mere handful of men, making ready against the vast armies of Germany, whose advance-guard were now hard on our heels.

That afternoon and all that night the 4th Division, newly landed from England, fighting odds of at least ten to one, held off the German advance, and then rejoined the line of battle in the hours between midnight and dawn.

Many months later a prisoner at Würzburg, an officer of the King's Own (4th Division), told me a story of that night's battle. When leaving the village of Bethancourt, fighting every foot along the village street in the darkness of the night, with the Germans pouring in at the far side of the village, Lt. Irvine and Sergeant —— entered a house where one of their men had been carried mortally wounded. They went to an upstairs room where the dying soldier had been carried. Irvine was at the foot of the stairs and Sergeant —— still busied with the wounded soldier, when a violent knocking was heard at the street door. Just as the door burst open and the Germans were pouring in and up the stairs, the Sergeant came unarmed out on to the landing. Sergeant —— was a big powerful man, who had held a heavy-weight boxing championship. Without a moment's hesitation he picked up a big sofa which happened to be close beside him on the landing and crashed it down on the head of the nearest German, breaking his neck and throwing those behind him into a confused mass at the foot of the stairs. Irvine emptied his revolver into the struggling mass, the Sergeant dropped over the banisters, and both escaped unharmed through the back of the house. Sergeant —— was killed in the trenches next morning.

Now that the 4th Division lay between ourselves and the enemy, a halt was made on the slope of a long straight hill, and the cooks began to serve out dinner. It was half-past five. The rain poured heavily. Major Duff and I sat by the roadside comparing notes and searching for a solution of our continued retreat. We knew nothing then of von Kluck's attempt to outflank the French army.

For the first time since we had left Bavai a motor-car came down the road, making in the direction of the 4th Division, and going dead slow, as the tired men lying on both sides of the road left little enough space in the centre. The driver stopped and shared our wet seat on the bank. It was a strange meeting for the three of us. Now Duff and I sought information from this driver friend of ours, a distinguished member of the House of Commons, acting as Intelligence Officer, and this was the answer to our inquiry: "We are drawing the Germans on!"

Three or four shabby cottages and a whitewashed estaminet stand by the roadside on top of the hill, overlooking the valley of the Sambre.

A few miles farther on, where a road branches off from the main road to Cambrai, and curls down the face of a steep hillside, Solesmes, hidden in the valley, shows the top of a church spire. The householders of Solesmes were putting up their shutters as we passed through the town, and less than an hour later shells were bursting over the pleasant valley.

Not many miles away to the left lies Landrecies, which R. L. Stevenson refers to, in 'An Inland Voyage,' as "a point in the great warfaring system of Europe which might on some future day be ranged about with cannon, smoke, and thunder." That evening the prophecy was fulfilled.

Caudry was reached at dusk, and here we heard the welcome news that our billets were close at hand. For two more miles along a narrow road, through the soaking rain, the battalion dragged slowly along. During the long twenty-five miles from Bavai to Caudry, the longest day of the retreat, very few men had fallen out; though all were weary through want of food and sleep, and many feet were blistered and bleeding, every man had kept his pack and greatcoat. The column slept that night crowded under the humble roofs of Audencourt.

In the chill light of dawn trenches were being dug outside the village. The line to be held by the battalion extended as far as Caudry, and the position of No. 13 platoon was about half-way between Audencourt and Caudry, close to a small square-shaped plantation. The rear of my platoon had just cleared the wood when a shell burst overhead, and we had the unpleasant experience of digging trenches under fire.

When at last we were under cover the shelling ceased, having caused no casualties at our end of the line, although some damage had been done up among the leading platoon, now entrenched about 500 yards to our left, their left resting on Caudry.

From information received long afterwards, the explanation of this early morning attack is as follows: German scouts had, on the previous evening, already located our position in the village of Audencourt, and a battery, placed behind Petit Caudry either during the night or very early in the morning, had ranged the little square-shaped wood from the map, and as soon as their observation man, who was probably in the church tower at Bethancourt, saw No. 13 platoon marching past the wood, he signalled to the guns to open fire. (These guns were almost at once driven away by the troops occupying the village of Caudry.)

The ground in front of our trenches slopes gently down to the Route Nationale Caudry—Le Cateau, which at this point runs on an embankment and is lined with fine old poplar-trees. This road was our first-range mark—350 yards.

Beyond the road the ground rises at a fairly steep slope to the village of Bethancourt.

At the edge of the village, on the ridge of the hill, the gate-post of a small paddock was our second-range mark—900 yards. Between the Route Nationale and the village the land is open pasture, so that no accurate ranges could be taken between 400 and 900 yards. The ridge of the hill runs at a slightly decreasing slope down to a small wood; on the right of this is a stubble field, and to the right again, on the far ridge of the hill, are beetroot fields through which a telephone wire runs, the range being 1200 yards. Caudry was on our left, with the houses of Petit Caudry just visible on our left front; on our right the village of Audencourt, with two platoons entrenched strongly. Behind lay open country, stretching back about 400 to 500 yards to the road between Caudry and Audencourt; again beyond that for at least half a mile open country interspersed with small thickets.

For nearly half an hour after the shelling ceased the countryside resumed its usual aspect. First the church tower of Bethancourt, then house by house, the village itself came into the full light of the rising sun, whose rays soon reached our newly dug trench to cheer us with their summer warmth. Captain Lumsden came along to supervise the clearing of a field of fire between our end of the line and the Route Nationale.

Our trench was dug in a stubble field where the corn had just been stooked, and it was now our business to push all the stooks over. This gave occasion for a great display of energy and excitement. When the stooks had been laid low we made a very poor attempt to disguise the newly thrown-up earth by covering the top of the trenches with straw, which only seemed to make our position more conspicuous than ever. The trench was lined with straw, and we cut seats and made various little improvements. Then our guns began to speak.

At the corner of the village of Bethancourt there stands (or stood that morning) a farmhouse. In the adjacent paddock two cows were peacefully browsing. The first shell burst right above them. They plunged and kicked and galloped about, but soon settled down again to graze. Several shells hit the church tower; the fifth or sixth set fire to a large square white house near the church on the right. Our gunners made good practice at the two cows, and shell after shell burst over or near their paddock, from which they finally escaped to gallop clumsily along the ridge of the hill and disappear into the wood, no doubt carrying bits of shrapnel along with them. For at least half an hour our guns had everything to themselves, and it must have been a most unpleasant half-hour for those who were on "the other side of the hill."

About 9 A.M. the German artillery got to work. Many attempts have been made to describe the situation in a trench while an artillery duel is in progress, but really no words can give any idea of the intensity of confusion. On both our flanks machine-guns maintained a steady staccato. All other sounds were sudden and nerve-straining, especially the sudden rush of the large German shell followed by the roar of its explosion in the village of Audencourt, where dust and débris rise like smoke from a volcano, showing the enemy that the target has been hit.