A NAVAL VENTURE

A Naval Venture

The War Story of an

Armoured Cruiser

BY

FLEET-SURGEON T. T. JEANS, R.N.

Author of "Gunboat and Gun-runner"

"John Graham, Sub-Lieutenant, R.N."

"Ford of H.M.S. Vigilant"

&c.

Illustrated by Frank Gillett, R.I.

BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED

LONDON GLASGOW AND BOMBAY

1917

Preface

In this book I have endeavoured to write a gun-room tale which will give a general impression of the part played by the Royal Navy during the Dardanelles operations, and of gun-room life under these conditions.

In writing it I have been greatly assisted by many shipmates—officers, petty officers, and men—who have been employed away from the ship, on various occasions, either on shore or in steamboats, tugs, or motor-lighters. From their accounts it has been possible to bring into the book descriptions of some interesting incidents and operations which did not come under my personal observation.

My thanks are due, more especially, to Lieutenant H. A. D. Keate, R.N., and to Lieutenant V. E. Kemball, R.N., of this ship, who have read laboriously through the manuscript as it progressed, corrected many errors of fact and detail, and suggested very many improvements to the story as a whole.

T. T. JEANS,

Fleet-Surgeon, R.N.

- H.M.S. SWIFTSURE,

-

27th April, 1916.

Contents

CHAP.

Illustrations

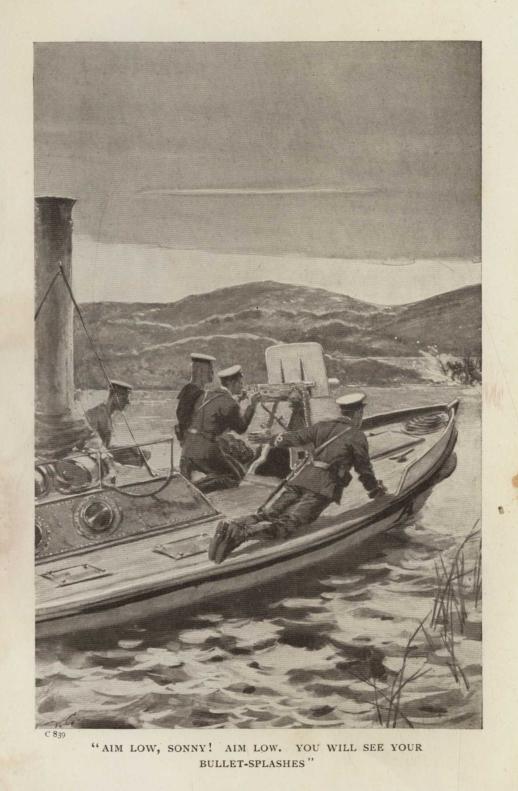

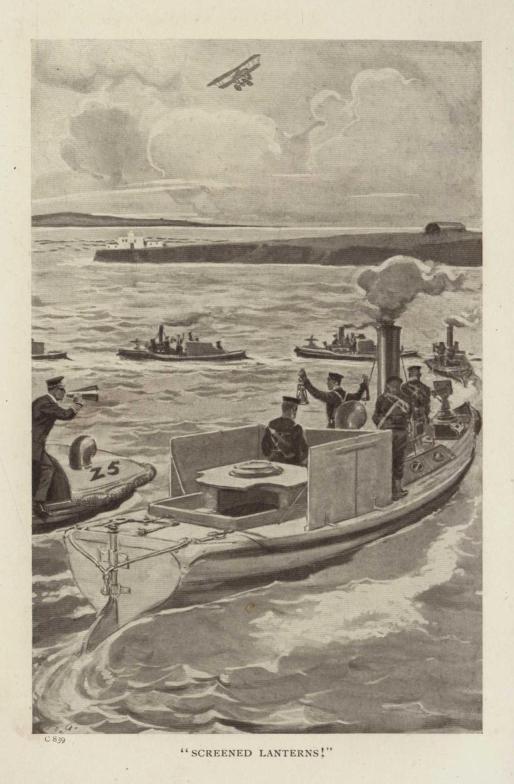

"'Aim low, sonny! Aim low! You will see your bullet-splashes'" . . . Frontispiece

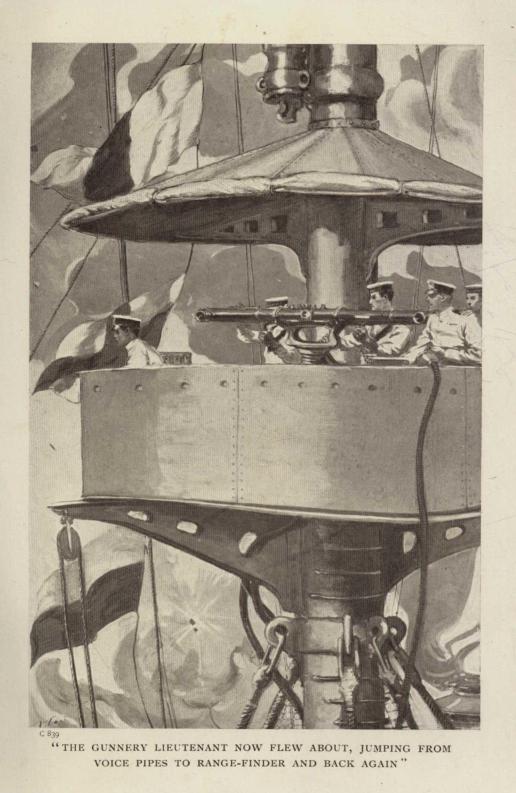

"The Gunnery Lieutenant now flew about, jumping from voice pipes to range-finder and back again"

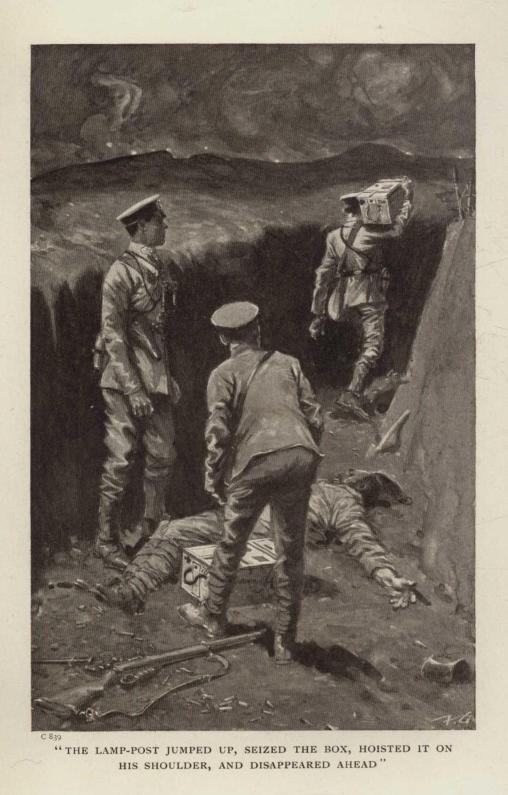

"The Lamp-post jumped up, seized the box, hoisted it on his shoulder, and disappeared ahead"

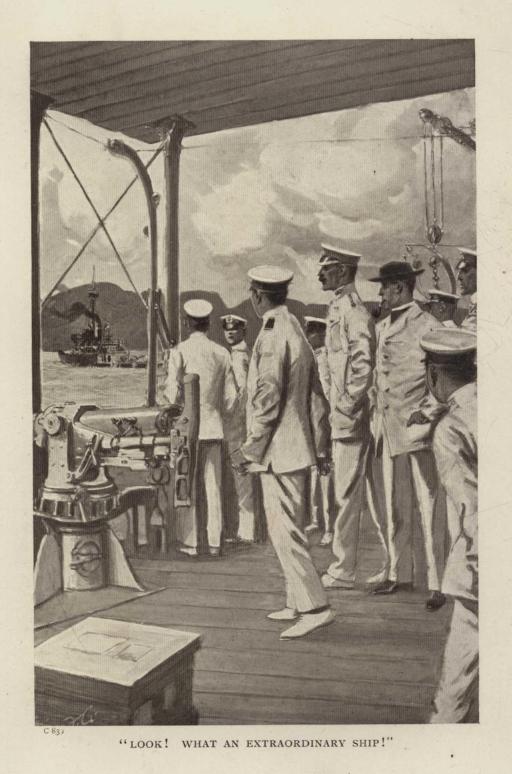

"'Look! what an extraordinary ship!'"

The Gun-room Court Martial on the China Doll

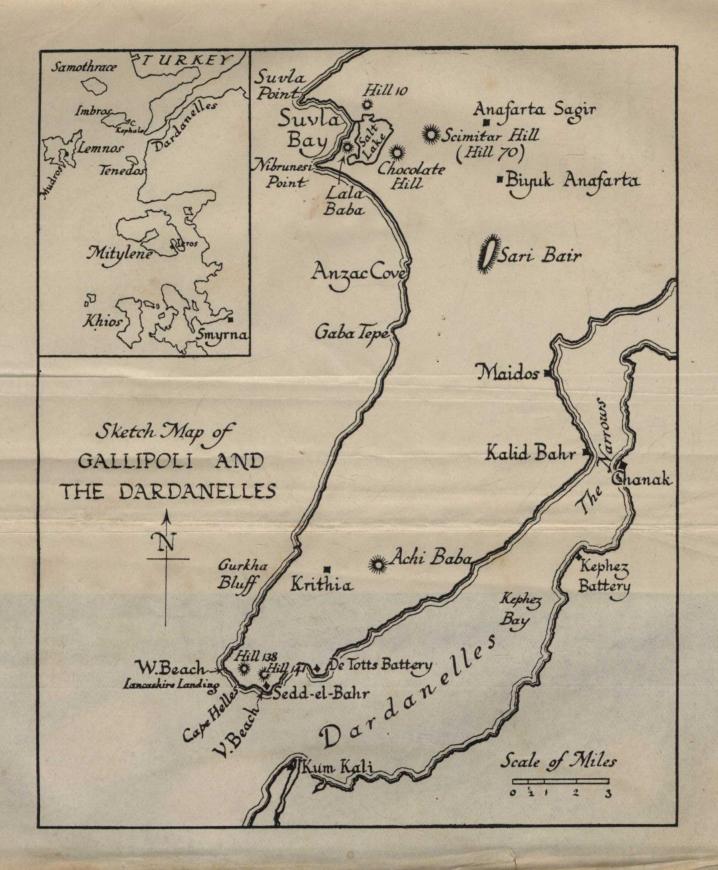

Sketch Map of Gallipoli and the Dardanelles

A NAVAL VENTURE

CHAPTER I

The "Achates" goes to Sea

On one miserably wet and cheerless afternoon of February, 1915, the picket-boat of H.M.S. Achates lay alongside the King's Stairs at Portsmouth Dockyard, whilst her crew, with their boat-hooks, kept her from bumping herself against the lowest steps. The rain trickled down their glistening oilskins, and dark, angry clouds sweeping up from behind Gosport Town on the opposite side of the harbour, and scudding overhead, one after the other, in endless battalions, made it certain that a south-westerly gale was raging in the Channel.

At the top of the steps, with his back to the wind and rain, his feet wide apart, and his hands in his pockets, was the midshipman of the boat, in oilskin, sou'wester, and sea-boots. This was Mr. Vincent Orpen—commonly known as the Orphan—not very tall, but sturdy and broad-shouldered in his bulky oilskins. Between the brim of his dripping sou'wester and his turned-up collar showed a pair of very humorous eyes, a determined-looking nose and mouth, and a pair of large ears reddened by the cold and rain.

He was waiting to take the Captain—Captain Donald Macfarlane—off to Spithead, where the Achates lay, ready for sea, but this absent-minded officer had very probably forgotten the time or place where the boat was to meet him.

Near by, taking shelter in the lee of the signalman's shelter-box, the marine postman and a massive, friendly dockyard policeman were standing with the rain dripping off them.

Presently the midshipman splashed across to them and spoke to the postman.

"The Captain did say King's Stairs; didn't he?"

"King's Stairs at two o'clock, sir; I heard him myself; King's Stairs at two o'clock, and it's now past the half-hour. He was only a-going up to the Admiral's office, he said; just time for me to slip outside to the post office and back again, sir."

Down below, in the picket-boat, Jarvis, the coxswain, an old, bearded petty officer—a Naval Reserve man—was grumbling to one of the crew: "The Cap'n can't never remember nothink—he'll forget hisself one o' these fine days."

"This ain't a fine day," the young A.B.—Plunky Bill—answered cheekily.

"Stow it! I'll give yer 'fine day' when we gets aboard: I knows it ain't. We'll get a fair dusting-down going out to Spithead, and a good many of you youngsters'll wish you'd never come to sea when we gets out in the Channel to-night."

"I 'opes we ain't going back to the mine-bumping 'bizz' in the North Sea, a-waiting for to be terpadoed," Plunky Bill said presently, viciously shoving the picket-boat's dancing stern off the wall with his dripping boat-hook.

"That's about our job," growled Jarvis. "Better blow up yer swimmin'-collar when you gets aboard, and tie it around yer bloomin' neck."

"A precious lot of good they collars be—with sea-boots and oilskins on, and the water as cold as charity."

"Nobody's askin' you to wear it. When you feels you wants to drown, quick, just 'and it over to me—I don't. Dare say you ain't got no one to miss yer; I 'ave—a missus and six kids," growled the coxswain.

Just then the trap hatch of the stokehold flapped up, and out of the small square opening emerged the bare head of the stoker of the picket-boat—an old, grey-headed Naval Reserve man, who actually wore gold spectacles, the effect of which on his coal-begrimed face was very quaint. He looked round him in a patient, dignified manner, and sniffed at the wind and rain.

There was a shout from the top of the steps, and Mr. Orpen, with his hands to his mouth, called down: "Keep out of the rain, Fletcher—don't be an ass!"

The old man did not hear; but one of the boat's crew for'ard bawled out to him: "'Ere, close down yer blooming 'atch—chuck it, grandpa—shut yer face in—the Orphan's a-singing out to yer—'e's nuts on yer 'ealth, 'e is." The old stoker, wiping his rain-spotted spectacles, meekly obeyed, pulled the hatch over his head, and disappeared from view.

Then the postman, with his big, leather letter-bag, clattered down, splashing the puddles on the steps. "The Cap'n's coming at last," he said, and stowed himself away under the fore peak.

Down came Mr. Orpen, jumped aboard, and took the steering-wheel. A moment later, and after him came the tall, gaunt figure of the Captain, the rain trickling off the gold oak-leaves on the peak of his cap, dripping off his long, thin nose and running down his yellowish-red moustache and pointed beard. His greatcoat was glistening with raindrops, and his trousers beneath it were soaked and sticking to his thin shins.

"I forgot to bring my waterproof," he said. "I'm not late, am I?" and nodding cheerfully, he stepped into the boat.

Mr. Orpen saluted. "Shall I carry on, sir?"

The Captain nodded again; Jarvis shouted out orders; the boat's bows were shoved off, the engines thumped, and the picket-boat, starting on her stormy passage to Spithead, bumped the steps with her stern—the last time, had she known it, that she would ever touch England.

The crew dived down below under the fore peak and shut the hatch on top of them, for they knew well what was coming. It came right enough.

Directly the picket-boat left the shelter of the harbour mouth she began to reel and stagger as she steamed along Southsea beach, past the ends of the deserted piers, with the sea on her beam, washing over her and jostling her. Then she turned round the Spit Buoy, and head on to the wind and rain, plunged her way through the short seas, diving and lifting, throwing up clouds of spray which smacked loudly against the oilskins of the midshipman at the wheel and the coxswain hanging on by his side.

As one wave came over the bows, rushed aft along the engine-room sides and swirled round their feet, and its spray, tossed up by the fo'c'sle gun-mounting and by the funnel, covered them from head to foot, Jarvis roared: "Better ease her a bit, sir."

But the Orphan was enjoying himself hugely. He knew the old boat; he knew exactly what she could "stand", and he was not going to ease down until it was absolutely necessary, or until Captain Macfarlane made him; and the Captain was still sitting in the stern-sheets, tugging, absent-mindedly, at his pointed yellow beard, apparently having forgotten where he was, and that if only he went into the cabin he could keep dry.

The picket-boat throbbed and trembled and shook herself, butted into a wave which seemed to bring her up "all standing", swept through it or over it, then charged into another; and as the battered remnants of the waves flung themselves in the Orphan's face and smacked loudly against his oilskins he only grinned, shook his head, and peered ahead from beneath the turned-down brim of his sou'wester.

Jarvis, the coxswain, was not enjoying himself. He hated getting wet—that meant "a bout of rheumatics", and he had a "missus and six kids".

Gradually the picket-boat fought her way out to the black-and-white chequered mass of the Spit Fort, until the four funnels and long, grey hull of the Achates showed through the rain squalls beyond.

A solitary steamboat, on her way ashore, came rushing towards them—a smother of foam, smoke, and spray; and as she staggered past, only a few yards away, with the following seas surging round her stern, Orpen waved a hand to the solitary figure in glistening oilskins at her wheel—a midshipman "pal" of his from another ship—who waved back cheerily and disappeared to leeward as a squall swept down between the two boats.

"A nice little trip he'll have, off, sir—if he don't come back soon," the coxswain shouted when the last wave's spray had run off the brim of his sou'wester and he'd caught his breath. "It's breezin' up every minute, sir!"

Once past the Spit Fort, the picket-boat was in deeper water; the seas became longer, not so steep, and she took them more easily. Orpen needed only one hand now to keep her on her course, and in ten minutes he steered her under the stern of the Achates, and brought her alongside the starboard quarter.

The Captain, dripping with water, jumped on the foot of the ladder as a wave swung the picket-boat's stern close to it. Half-way up the ladder a sudden humorous thought struck him, and, bending down, he called out: "You did not ease down all the time, did you, Mr. Orpen?"

"No, sir," Orpen sang back, grinning with the happiness of everything. He didn't worry in the least—so long as the Captain didn't mind—that he had, by forcing his boat through the seas, wetted him to the skin, and kept him wet for the last twenty minutes.

The officer of the watch shouted "Hook on!" and the picket-boat was hauled ahead under the main derrick, until the big hook dangling from the "purchase" swung above the boat. The crew made the bow and stern lines fast; Fletcher, the old stoker, drew himself up on deck and lowered the funnel, steam roared away from the "escape"; one seaman struggled with the ring of the boat's slings, holding it chest-high; another waited his opportunity, when a wave lifted the picket-boat, to seize the big hook hanging above him; the ring was slipped over it; the midshipman waved his hand and shouted; the slings tautened as the order "up purchase and topping lift" was given; a last wave lopped over the bows, and with a jerk she was hoisted clear of the water and quickly swung inboard.

Up on the quarter-deck the Captain was talking to the Commander—a wiry little man with a weather-beaten face and a grim, hard mouth. "Same old job, sir?" he asked.

The Captain nodded ruefully. "It's all the poor old Achates is fit for."

"You're pretty well soaked, sir. Rather a wet passage off?"

"I forgot to go into the cabin," the Captain laughed.

"We're ready for sea, sir. I shortened in, as you were rather late."

"Was I?" the Captain's eyes twinkled. "Right you are! I'll be up again in a minute. I must get into dry things, or the Fleet Surgeon will be on my tracks"—and he disappeared below.

In half an hour the Achates was under way and steaming out into the Channel and the gale.

This ended her week's "rest"—the second "rest" since the war broke out, six months before. Now she was off again to the North Sea, with its constant gales, its mine-fields, its enemy submarines, and the grim delight of frequent hurried coalings.

It was not a very pleasing prospect.

CHAPTER II

The Gun-room of the "Achates"

Having seen his picket-boat safely landed in her crutches on the booms, the Orphan dived down below to the gun-room to dry himself in front of the blazing stove there.

The gun-room was a long, untidy place on the starboard side of the main-deck, just for'ard of the after 6-inch-gun casemate. A long table, covered with a red cloth, of the usual Service pattern, and rather more than usually torn and stained with grease, occupied most of the deck space, and was now laden with plates, cups and saucers, and, down the middle, in one gorgeous line, tins of jam, loaves of bread, fat pats of butter, and slabs of splendidly indigestible cake.

Long benches, covered with leather cushions, were fixed each side of it, whilst a few chairs, in various stages of decay, were drawn up round the stove and the upset copper coal-box. The after bulkhead of this sumptuous abode was occupied by midshipmen's lockers—rows of them one above the other—and from the half-open locker doors peeped boots and books, woollen helmets, sweaters, and safety waistcoats.

Along the foremost bulkhead was a corticine-covered sideboard with drawers for knives, forks, and spoons, cupboards for bottles, and a cosy gap for a barrel of beer. Above the sideboard, at either end of it, there were two little sliding-doors in the bulkhead, for the plates and food to be passed in from the pantry beyond, and for the dirty plates to be passed out. Between these two sliding-hatches, pictures of beautiful ladies taken from the last Christmas Number of the Sketch had been gummed on to the bare expanse of dirty-white paint, and gave an air of brightness and refinement to an otherwise somewhat depressing interior.

The outer bulkhead—the outer side—the ship's side—had been white—once. Along it were five scuttles, at present closely screwed up, and the tail ends of waves occasionally swished angrily across them. In the spaces between these scuttles, war maps, most of them torn and ragged, had been pasted to the iron-work, and one or two pin-flags still managed to hold fast, though the vast array that had once fluttered across them had long since disappeared.

At each end of the inner bulkhead was a door leading out into the "half-deck", and between them were more lockers, the roaring, smoking stove, its brass chimney, and the upset coal-box. Behind the brass chimney hung a tattered green-baize notice-board on which were pinned a few dusty long-forgotten gun-room orders; whilst from hooks above it hung a cheap alarum clock and five damaged wrist-watches, each in its strap, and each labelled with an official report of the "scrap" during which it had met its honourable fate.

Newspapers and magazines littered untidily the corticine-covered deck; a gramophone box, a couple of greatcoats, and a green cricket bag lay piled in one corner near the lockers; some sextant boxes and two pairs of sea-boots filled another.

Overhead, between the deck beams, wooden battens were fixed, and above them squeezed a motley assortment of greatcoats, golf-bags, cricket pads, and oilskins. Almost anywhere in the gun-room you could put up your hand without looking, and pull down an oilskin or a greatcoat, which, of course, was most convenient, unless you pulled down half a dozen golf-clubs on your head at the same time, when naturally the convenience was not so noticeable.

When the Orphan came in, throwing his wet sou-wester and oilskin into the corner on top of the gramophone box, the only other gun-room officer there was the "China Doll"—the Assistant Clerk. Only just "caught" he was, a very youthful young gentleman of, so far, unblemished reputation, with a pink-and-white face, and a trick of opening and shutting his very big and very blue eyes so exactly like a doll that he had been christened "China Doll" directly he had joined the Honourable Mess.

He was engaged busily toasting bread in front of the stove with the long gun-room toasting-fork, and this was probably his most important duty on board—the duty of making toast for seven-bell tea; the first piece for the Sub-lieutenant, the second for the senior snotty, and the third for that very senior officer—his very senior officer—the Clerk—Uncle Podger.

He had just finished the first piece as the Orphan entered, and looked up, blinking his eyes excitedly.

"What's the news, Orphan? Did the Captain tell you what we're going to do?"

"Late again, China Doll; five minutes after seven bells, and only one piece of toast ready; you'll catch it when the others come along."

In spite of his protests the Orphan grabbed that piece of toast, buttered it and began eating it, standing in front of the stove whilst the China Doll hurriedly began to toast another slice, between the Orphan's legs, and implored him for news of where the ship was going, and what she was to do. But the Orphan was much too busy eating to take any notice; and just as the first slice disappeared and he was licking his fingers, he heard a clattering of sea-boots down the ladder from the deck, and as four dripping snotties poured in, he seized the toasting-fork, pushed the China Doll on one side, and calmly finished toasting the second slice.

These four new-comers were the "Pink Rat", "Bubbles", the "Hun", and Rawlins. The Pink Rat was the senior snotty—a small-sized youngster whom anyone could spot as the Pink Rat, because he had a thin, sharp, ferrety-looking face, very pink complexion, beady eyes, prominent teeth, and long mouse-coloured hair brushed straight back from his forehead and plastered down with grease. Bubbles was half as big again as the Pink Rat, with a fat, red, honest face, creased with continual chuckling, and a fat, red neck which always seemed to swell over his collars. He had something wrong with his nose, and couldn't breathe through it very well, so that when he was laughing—he generally was—he used to throw his head back, open his mouth to breathe, and make the most extraordinary bubbling noises. The Hun, the third to enter, looked a very gentle snotty, very refined and quiet—quiet, that is, compared with the others. He was not big or strong; but when he once was "roused" he would always join the weaker side in a "scrap", and then became so violently excited that whatever he gripped he gripped with all his might—like a wild cat. He had nearly choked Bubbles once; and the Pink Rat never forgot how, at another time, he had nearly pulled out a handful of his hair. He always apologized afterwards. Rawlins, whose proper name was Rawlinson—the last of these four—was a brawny youth with an odd hatchet-shaped head, quite as good-natured as Bubbles, and the least talkative member of the Honourable Mess. He was always willing to look out for a pal's "watch" or boat duty, in itself enough to make anyone very popular.

The Pink Rat, Bubbles, and Rawlins, seeing no toast waiting for them, dashed at the China Doll, charged him into a corner, threw their wet oilskins over him, and fell in a heap on top.

"Toast must be ready!" they yelled as they allowed him to get up.

"I can't make it fast enough when the Orphan's here, alone; look at him—that's his second."

The Orphan had just taken a huge bite out of the new piece; with a rush they threw themselves on him; in the mêlée of feet, legs, and chairs the China Doll captured the toasting-fork, stuck another bit of bread on it, and crouched in front of the fire again.

The general scramble was terminated by the noise of the pantry hatch sliding back, and an enormous, purple-faced marine servant, in his shirt-sleeves, pushed in a big teapot.

"Come along, Barnes, cut us some more bread; open a tin of 'sharks'; where've you put my biscuits?" they called at him.

By this time the third piece of toast was done to a turn; and the Pink Rat, in the absence of the Sub, on watch, was just going to claim it, when in came Uncle Podger—the Clerk—a broad-shouldered, squat youth, with a breezy, cheery countenance, and ruffled hair, who had been promoted to the exalted rank of Clerk exactly three weeks before, and had, therefore, been just a year and three weeks in the Service.

His arrival was greeted with shouts of "Uncle Podger, your minion is slack again at the toast business. The China Doll must be beaten."

The Assistant Clerk dodged the Pink Rat and wriggled free, squealing out that this piece was for the Sub.

"He'll beat me if it isn't ready. He'll be down from the bridge in a minute," he laughed, and took shelter behind his superior officer, explaining that "he'd done one for the Sub, and the Orphan ate that; another for the Pink Rat, and the Orphan had eaten that too; the Sub must have this, mustn't he?"

"Then this is the third," Uncle Podger said with mock gravity. "You were wrong, my young subordinate, very wrong indeed, to give away those other pieces; this one is mine." He gently removed the beautifully browned bread from the prongs of the fork.

"Yes—sir," said the China Doll, dropping his eyelids and pretending to be very humble.

"By the King's Regulations and Gun-room Instructions, there can be no doubt about it, can there?"

"No—sir; no possible doubt whatever—no possible, probable, possible doubt whatever."

The Clerk, glaring majestically at his subordinate officer's familiarity, promptly proceeded to butter and then to eat the slice; whilst the others, crowding round the stove with bits of bread on the ends of knives, tried their best to toast them.

Then the Sub did come in—a man of medium height, shoulders broader than Uncle Podger's, a complexion tanned by exposure to the wind and rain, black hair over a broad forehead, thick black eyebrows over deep-set grey eyes which had a knack of looking through and through anyone he spoke to, a thin Roman nose with a bridge that generally had a bit of the skin off (the remains of his last "scrap"), firm upper lip, a tremendous lower jaw, and a neck like a bull. He came in with his swaggering gait and aggressive shoulders, unbuttoning his dripping oilskin and roaring loudly.

"What ho! without! bring hither the toasted crumpet, the congealed juice of the cow, and we will toy with them anon! Varlets, disrobe me, for I am weary with much watching."

"Hast a savoury dish prepared for me, you pen-driving incubus, you blot on the landscape?" he roared again at the China Doll, who stood with eyes opening and shutting and mouth wide open, watching two of the snotties hauling off the Sub's oilskin.

"Where's my toast?" he roared ferociously.

"Here, sir," and the Assistant Clerk patted the Orphan's stomach, and fled for safety to the ship's office, where he knew he would be safe from instant death, because the Fleet Paymaster, though he would "scrap" with anyone, at any time, anywhere else, would not allow any skylarking there; nor would the stern Chief Writer, whose sanctum it was; and they had to keep friends with the Chief Writer, or never a pen-nib or a piece of blotting-paper would they get when they ran short of these things.

Two more snotties came into the gun-room after the China Doll had escaped.

These were the "Lamp-post" and the "Pimple", the tallest and the shortest in the Mess—the Pimple a little chap with a broad flat face, and a tiny red nose in the middle of it. He was the Navigator's "doggy", and that communicative and ingenious officer was always giving him the latest news—news which he, more often than not, invented himself. The joy of the Pimple's existence was to have some "news" to tell the others. He was a bully in a very small way, and extremely deferential to the Sub and the ward-room officers.

The Lamp-post was a tall, stooping snotty with sloping shoulders; his clothes were always too small for him, and his long thin arms and legs were always in his own way and in that of everyone else. Set him down at a piano and he was marvellous; the joy of his life was to be asked to play the ward-room piano. He could play anything he had ever heard; and inside his aristocratic head were more brains than the rest of the snotties possessed between them, the only one who did not know that being himself.

The whole of the Honourable Mess—with the exception of the escaped China Doll—being now assembled, seven-bell tea pursued its usual course—a cross between a picnic and a dog-fight—until the bugle sounded "man and arm ship", and there was a hurried scramble for oilskins and caps as all, except Uncle Podger, dashed away to their stations.

The ship had now cleared the Isle of Wight and felt the force of the gale. She began to pitch and roll heavily as the heavy seas threw themselves against her starboard bow and rushed along her side.

A minute or two after the "man and arm ship" bugle had sounded, the China Doll strolled jauntily in and started afresh with his afternoon tea.

"When you, Mr. Assistant Clerk, have served as long as I have," commenced Uncle Podger gravely, "you may perhaps learn to realize that cheeking your seniors is punishable by death, or such other punishment as is hereinafter mentioned."

"Pass us the sugar, Podgy, there's a good chap," grinned that very insubordinate officer, as a lurch of the ship threw the sugar-basin into the Clerk's lap.

"Man and arm ship" having passed off satisfactorily, the ship went to "night defence" stations, and the bugle sounded "darken ship".

Barnes, the purple-faced marine servant, still in his shirt-sleeves, came in and solemnly closed down the dead-lights, screwing the steel plates over the glass scuttles, and then proceeded to clear away the debris of seven-bell tea.

Most of the snotties now trooped down from the upper deck to warm themselves round the stove.

CHAPTER III

Ordered to the Mediterranean

Up above, under the fore bridge, the Orphan, looking like an undersized elephant, with all his warm clothes under his oilskins, tramped from port to starboard, and back again round the conning-tower. The crews of his four 6-pounders were clustered round their guns, hunched up in all sorts of winter clothing. Many of them wore their duffel jackets with great gauntleted gloves drawn up over their sleeves, and had already pulled the hoods of their jackets over their heads, giving them the appearance of Eskimo or Arctic explorers; the others were in oilskins padded out with jerseys, jumpers, flannels, and thick vests.

Once issue warm clothing to a bluejacket and never will he leave it off, whatever the temperature, unless he is made to do so.

The chirpy little gunner's mate had reported "all correct, sir, guns cleared away, night-sight circuits switched on, sir, and four rounds a gun ready."

The Orphan had reported himself to the officer of the watch, on the bridge above him, and now had nothing to do, for the best part of two hours, but walk up and down and keep warm.

"They tells me that one of 'em submarines was nosing round these parts two days ago, sir," one of his petty officers said, as he stopped at one gun, looked through the telescope sight, and tested the electric circuit. "It ain't much weather for the poor murdering blighters."

It was not. Darkness was rapidly closing in, and the gale howled angrily out of the west, driving masses of dark rain-clouds and a heavy sea before it.

The Achates dipped her fo'c'sle constantly, and when she lifted and shook herself, the spray shot up far above her bridge screens.

The Orphan and his guns' crews on the wind'ard side would feel the ship quiver as a wave thudded against the casemate below them, and then had just time to duck their heads before millions of icy particles of spray soused viciously over them.

Presently the Orphan took shelter in the lee of the conning-tower and leant moodily against it, thinking of the warmth and gaiety of the dance he had been at the night before, also of a certain little lady in white and blue.

In peace time it is depressing enough to leave a cosy harbour, and face a wild winter's night in the Channel; but in war time the chance of blowing up on a mine and the risk of being torpedoed make the strain very considerable.

For the first night and the first day or two, most people are inclined to be rather "jumpy"; though afterwards this feeling wears off quickly, and one leaves everything to "fate" and ceases to worry.

Only a few days before, Germany had announced to the world the commencement of her submarine blockade of the English coast, so the Channel was probably already swarming with submarines; though even the Orphan, depressed and miserable as he was then, could not have imagined that these submarines had orders to sink merchant ships and mail steamers at sight and without warning, and that a civilized nation had sunk so low, nineteen hundred years after Christ was born into the world, as to plot the whole-sale murder of inoffensive women and children.

But he was miserable enough without knowing that, and opening up his oilskin coat, practised blowing up his safety waistcoat. Then he wondered whether his guns' crews had their swimming-collars with them—as was ordered—and went from gun to gun, dodging the spray, to find out.

It was quite dark now, the foc's'le and the turret below were invisible, and he had to grope his way along to find the guns' crews by hearing them talk or stumbling against them.

One or two of the men had lost their collars; another had burst his trying how big he could blow it; others had left them down below in their kit-bags or lashed in their hammocks.

Plunky Bill, the cheeky A.B. belonging to the picket-boat, was the only one who had his. The gunner's mate explained that "Plunky Bill 'ad a sweet'eart in Portsmouth what was fair gone on 'im, and 'ad made 'im promise to always wear 'is collar".

Plunky Bill evidently thought he had a grievance, and growled out that "'E wasn't going to be bothered with young females, not 'im; a-making 'im look so foolish-like".

"Well, they ain't no use, nohow," the gunner's mate grunted, jerking a thumb towards the heavy sea.

"Any news, sir?" the gunner's mate shouted, when he and the Orphan had regained the lee of the conning-tower, round which solid icy spray swished almost continuously. "The Ruskies are giving it to them Austrians in the neck, proper like, ain't they, sir?"

"Didn't hear any," the miserable Orphan shouted back.

"D'you know where we're off to?" the other asked.

"North Sea again," the Orphan told him.

The gunner's mate had no use for the North Sea—never wanted to see it again, and said so in blood-curdling language.

"What about the Dardanelles, sir?" he asked a moment later. "That's the place I'd like to be in. There's a sight of old 'tubs' gone out there. Any news, sir?"

But the Orphan had heard none, and climbed up on the bridge above to have a yarn with the midshipman of the watch—the Pimple.

He was full of schemes for "ragging" the China Doll.

"Patting your 'tummy', Orphan; that was cheek if you like! and the Sub didn't like it either."

The Pimple was very deferential to the Sub—rather too much so; what the Sub did and what he said made up most of the Pimple's daily existence. "He'd like us to take it out of the China Doll, wouldn't he?"

"Don't be an ass. Let the China Doll alone—it's too beastly wet and cold to bother about him. What about that cake you 'sharked' off the table?" So the Pimple, ever ready to ingratiate himself with anyone, produced a big wedge of gun-room cake out of his greatcoat pocket, and the two of them, crouching under the weather screens, munched away silently.

It was so dark that they could not see the look-out man, who was holding the brim of his sou'wester over his eyes to shield him from the rain and the spray, and trying to pierce the blackness of the stormy night in front of him. Both snotties were startled by a sudden cry from him: "Something a-'ead, sir! on the starboard bow, sir!" Another look-out also spotted something; everyone tried to see it; the officer of the watch dashed to the end of the bridge and peered through his night-glasses; the gunner's mate, down below, could be heard shouting to the guns' crews to "close up"; the breeches of the guns snapped to as they were loaded; and the Orphan, stuffing the remnants of the cake in his pocket, scrambled down the ladder.

"There it is, sir! There! there!—I can see it!' came excitedly out of the darkness. Everyone thought of submarines.

"Just like one, sir!" a signalman bawled to the officer of the watch, who yelled to the Quartermaster "hard-a-port", and rushed into the wheel-house to see that he did it.

At that moment a bobbing light began flickering out of the darkness ahead—a signal lamp.

"It's the challenge, sir," the signalman shouted.

"All right; reply; bring her on her course, Quartermaster. Starboard your helm, hard-a-starboard!" shouted the officer of the watch coolly; and as the Achates' bows swung back again, she swerved past a long, black object down below in the water, with its twittering signal light tossed about like a spark from a chimney on a dark night, and by that faint light they could just see the outline of three funnels before the light was shut off and everything disappeared.

It was only a patrolling destroyer. One could not see her rolling, or the seas breaking over her, but one could realize the horrible discomfort aboard her.

"Poor devils!—a rotten night to be out in—we nearly bumped into her," thought the officer of the watch, jumping to the telephone bell from the Captain's cabin, which was ringing excitedly.

"Nothing, sir; a patrol destroyer; had to alter course to clear her. No, sir, the wind is steady, sir."

It was six o'clock now—four bells clanged below—the first dog-watch was finished, and presently the Pink Rat came up to relieve the Orphan.

"Jolly slack on it!" grumbled the Orphan as he bumped into him and dived down below.

The easiest way aft was along the mess deck—the upper deck was so dark—and as the Orphan passed through one of the stokers' messes he saw Fletcher, the old stoker of his picket-boat, sitting at a mess table, all alone, under an electric light, his face buried in his hands, and a Bible before him.

"What's the matter, Fletcher? you look jolly mouldy," he said, stopping at the end of the table. "What's the matter? Bad news?"

"Yes, sir," he said gently, standing up, one hand pushing his gold spectacles back on his nose, the other marking the place in the book. "A letter from my wife. Our last boy's been killed in France, sir. That's the third; he was a corporal, sir."

His old, refined, tired face looked so abjectly miserable that the Orphan did not know what to say. "Come and get a drink. That'll buck you up," he stuttered.

But Fletcher shook his head. "I'm an abstainer, sir; thank you very much." And the snotty, muttering "I'm sorry", went away along the rest of the noisy, crowded mess deck towards the gun-room.

There was comparative quiet there. The Sub and Uncle Podger were sitting in front of the stove, reading.

"You know old Fletcher—the stoker of my boat; he's frightfully miserable; he's sitting down in his mess looking awful; he's just heard that his last son's been killed; I wish we could do something for him. The letter must have come when I brought off the postman."

"How about a drink?" asked the Sub, scratching his head. "I am sorry."

"Who's that?" asked Uncle Podger; "that old chap with the gold specs?"

The Orphan nodded.

"Fancy having to stick it out—all the misery of it—in a mess deck, with hundreds of chaps cursing and joking all round you," the Sub said. "I don't see what we can do to help him."

"You've got a cabin," Uncle Podger suggested. "Get him down in it; shut him in for an hour. What he wants most is to be alone."

"Right oh!" said the Sub, springing to his feet. "I've got the first watch; he can stay there till 'pipe down';" and he sent Barnes, the purple-faced marine, to find Fletcher and tell him that the Sub-lieutenant wanted him at once in his cabin.

The Sub, swinging his mighty shoulders, stalked down to his cabin, and presently there was a knock outside, and Fletcher peered in. "Yes, sir?"

"I've just heard, Fletcher," the Sub said, holding out his hand. "We are all very sorry; you'd like to be by yourself for a while. Stay here till 'pipe down'; no one shall come near you."

He pushed the old man down in the chair, drew the door across, and went into the gun-room.

A few minutes later the Pimple, who had been to his chest, outside the Sub's cabin, came in.

"Old Fletcher's blubbing like anything," he said. "I heard him."

"Get out of it, you little beast!" roared out the Sub. "Get out of the gun-room till dinnertime. Who told you to go sneaking round?" and Uncle Podger got in a well-judged kick which deposited the miserable Pimple on the deck outside.

The Orphan had the "middle" watch that night, so he turned into his hammock early, and was roughly shaken before it seemed to him that he had been to sleep a minute.

"Still raining?" he grunted to the corporal of the watch who had called him, as he climbed out and hunted round for his clothes.

"Raining and blowing 'orrible!"

He groped his way for'ard, only half awake, stumbling on the unsteady slippery deck-plates, barking his shins against a coaming, and bumping into the rest of the watch as they came up from the lighted mess deck like blind men. He "took over" from the snotty of the first watch, and, as soon as his sleepy eyes had become accustomed to the darkness, began pacing up and down across the narrow deck.

The gale still howled wildly through the fore shrouds, the wet signal halyards still flapped noisily against each other, and the rain still came driving under the bridge; but by this time the Achates had altered course and was running up-Channel, so had the seas on her starboard quarter, and though she was rolling heavily no spray came over her. That was one thing to be thankful for, the Orphan thought, as he looked into the utter blackness ahead of him.

Presently he leant against the conning-tower. But there was nothing for his eyes to rest on, and the screaming of the gale and the roaring of the rushing seas mingling together to make one continual, tumultuous clamour in his ears, lulled him nearly to sleep.

He started—he thought he was dancing with the little lady in white and blue—grinned to himself, and went up on the bridge to have a yarn with Bubbles, who was now the midshipman of the watch; tracked him by his laugh and his snorting noise; doubled up he was, at some yarn the Navigating Lieutenant was telling him—he always laughed long before a yarn came to an end!

"The ass jumped on to the top of the conning-tower—got an arm round the periscope tube, and began banging away at the periscope with a hammer!" the Navigator was shouting as the Orphan came up. (Bubbles threw his head back and roared.) "He'd only got in a few whacks when the old submarine began to dive; down went the conning-tower and the periscope, and the last that was seen of him was a hand and a hammer giving one last whack!"

Bubbles choked and snorted with laughter.

"What was it—a German submarine—was he drowned—did they catch the submarine?" the Orphan asked.

"Yes, they did. It had been badly hit before. We swept for it, and found it three days later, and the brave ass was still clinging to the periscope tube with his feet twisted round the conning-tower rail."

"Who was he?" gasped Bubbles when he could stop laughing.

"No one in particular, only the deck hand of a trawler," the Navigator said, in his cynical way.

Mr. Meredith, the officer of the watch, a tall, good-looking Naval Reserve lieutenant with a weather-beaten face, and rather bald-headed, came up. "It's five bells, you fellows. How about some cocoa? I've got a tin of gingerbreads."

"That's the ticket, old chap!" the Navigator cried, and Bubbles was sent off to make the cocoa and bring it up to the chart-house.

Ten minutes later, the cheery chart-house was filled with the fragrant odour of cocoa, the Navigator's charts had been rolled aside; two were sitting on the table, the other on the settee which was the Navigator's bed at sea, all with steaming cups of cocoa in their hands.

"Where's the 'War Baby'? Go and fetch the War Baby," the Navigator shouted; so off Bubbles went, the light going out as the door slid back, and coming on again as it closed and "made" the electric circuit.

Presently, in came the youngest-looking thing in soldiers anyone ever saw, with a face as pink and white as the China Doll's, and the first buds of a tiny moustache on his upper lip.

"It's perfectly damnable outside," he piped in his girlish voice, as he seized a biscuit and a cup of cocoa.

"Hullo!" sang out the Navigator, as they all heard a knock on a door beneath them; "there's someone banging at the Skipper's door." (The Captain, when at sea, slept in a tiny cabin immediately beneath the chart-house and above the shelter deck.)

They heard the Captain's voice calling "Come in"; and the Navigator, seizing his glasses, and singing out that "the Captain would be up on the bridge in a jiffy—he always does if anyone wakes him," went out, followed by the others.

In a minute the Captain came up, shouting for him.

"Here I am, sir."

He seized the Navigator by the arm excitedly—the Captain was seldom anything but calm—and drew him into the chart-house. "Read this," he said, snapping his jaws together and sticking out his little pointed beard, as the door was closed and the light glared out.

The Navigator read: "Achates is to proceed with dispatch to Malta, calling at Gibraltar for coal if necessary."

"That means the Dardanelles, sir! Finish North Sea, sir?"

Captain Macfarlane looked down at him with twinkling eyes and smiled happily.

In five minutes' time the Achates had ported her helm and was on her new course; the news had flown round the bridge, been bellowed down below to the guns' crews, and shouted down the voice-pipes to the engine-room.

"We're off to Malta!—the Dardanelles!" and everyone who passed the good news added, "Finish North Sea. Thank God!"

The sober, obsolete old Achates seemed to know where she was bound. On her new course she once more faced the gale and the seas, diving and pitching, shaking and trembling, throwing the wild spray crashing against the weather screens, flying over the bridge and pattering against the funnels.

What cared she, or anyone aboard her, however wildly the gale blew!

CHAPTER IV

The Bombardment of Smyrna Forts

The Achates arrived at Gibraltar on the fourth morning out from Spithead, and went alongside the South Mole to coal, just as the warm Mediterranean sun rose above the top of the grand old rock.

The gun-room officers—-everybody, in fact—were in the highest spirits. It was grand to have left behind the dreary, cold English winter, and it was grander still to be on the way to the Dardanelles. Best of all, they could now go to sea without worrying about submarines and mines.

Two days from Gibraltar the daily wireless telegram from England told them that the forts at the entrance to the Dardanelles had been silenced, and that landing-parties were being sent ashore to demolish them.

"Why couldn't they have waited? We shall be too late; we shall miss all the fun," they cried sadly, down in the gun-room; "just come in for the tail end of everything; they'll be up at Constantinople by the time we get there; what sickening rot!"

"If you'd seen as much fighting as I have," Uncle Podger said solemnly—he'd only been a year in the Service, and seen none—"you'd——"

But he wasn't allowed to finish. They shouted:

"Dogs of war! Out, Accountant Branch!" and rolled him and the China Doll on the deck until Barnes banged the trap-door with the porridge-spoon to let them know that breakfast was ready.

At Malta there was another hurried coaling.

It was here they heard that the Bacchante, their chummy ship—a sister ship—the ship which had been next to them in the North Sea patrol—had already passed through Malta bound for the Dardanelles.

It was, of course, the Pimple who heard this first, and who climbed down into a coal lighter alongside to tell the Sub. The Sub, black and grimy, grinned. "We'll get a chance to knock spots out of them at 'soccer', somewhere or other," he said, joyfully rubbing some of the coal-dust on his sleeve over the Pimple's excited and fairly clean face.

"I hope they haven't found out about the sea-gulls," the Pimple said; but the Sub hadn't any more time to talk to him.

The sea-gull incident was rather a sore point with the Bacchante gun-room.

That ship had not yet fired a gun; the Achates had, and the Bacchante snotties were jealous and didn't believe it. All they could find out was that their rival's after 9.2-inch gun had fired at a submarine early one morning.

"What happened?" they would ask. "Did you hit it?"

"Well, we didn't see it again," the Achates gun-room would answer. "We must have hit it."

They always forgot to mention that this submarine had turned out to be a dozen or more sea-gulls sitting close together; and they had told the story so often—of course leaving out the sea-gull part—that they very much hoped that their chummy ship would never get hold of the proper yarn. If once they knew, their legs would be pulled unmercifully.

It would not have mattered so much if one of the Lieutenants or the Commander had made the mistake; but the worst of it was that the Sub had been on watch at the time, so the snotties, the China Doll, and Uncle Podger would have perjured themselves for ever, rather than give away the secret.

At Malta a passenger came on board, a tortoise about eight inches long. Who brought him no one knew, but in a day or two old Fletcher the stoker had adopted him as his own. The old man loved to sit on the boat deck by the hour in the sun, with "Kaiser Bill"—as the men called the tortoise—and feed the ungainly wrinkled brute with bits of cabbage.

Malta was left behind; the weather grew hot; white trousers were ordered to be worn, and were scarce—no one had expected to be sent to a warm climate—but those who had them shared with those who hadn't; the China Doll borrowed a pair, much too big for him, from Uncle Podger; those who had none, and would not borrow, wore their flannel trousers. Of course the Pink Rat turned out in beautifully creased white ducks and spotless shoes; the Pink Rat always carried about with him a very extensive wardrobe, though where he stowed it all, no one could imagine.

But no one bothered about clothes. It was so glorious to be warm again, and to be on their way to "do" something and fire their guns.

"At something better than sea-gulls!" said the Orphan, grinning with delight. "We'll have shells coming all round us; you'll get plenty of them, up in your old foretop, China Doll; you and your range-finder will be blown sky-high in no time. Won't that be fun?"

The China Doll opened and shut his eyes, and simply trembled with excitement.

"The China Doll has his legs blown off!" shouted the Pink Rat—the senior snotty. "First aid on the China Doll!"

With a rush the snotties tumbled him on his back. "Lie still!" they yelled. "Stop kicking—your legs are blown off—you haven't got any!"

"If I haven't got any, you won't feel me kicking!" the China Doll squeaked, lashing out with his feet.

Whilst two ran for a bamboo stretcher, the others captured his legs and tied them together with handkerchiefs and table napkins, so tightly that the victim cried for mercy. The stretcher was brought; they lashed him in it; lashed his arms in, to prevent him grabbing at the furniture and shouting and yelling, ran him aft along the deck to lower him down into the Gunner's store-room, below the armoured deck, where the doctors set up their operating table at "Action" station.

Fortunately for the China Doll the armoured hatch leading down to it was shut down and must not be opened.

On the way back to the gun-room with him, they had to pass the Surgeon's cabin, where Doctor Crayshaw Gordon was sitting, busy censoring letters. Dr. Crayshaw Gordon, R.N.V.R.—in private life he had a big consulting practice in London—hearing the noise and seeing the stretcher, thought there had been an accident, so jumped out of his cabin. "Hello!" he sung out, in his funny chuckling way of talking—fixing his gold eyeglasses on his nose, opening his mouth wide, and pulling nervously at his little pointed tawny beard. "Hello! what's the matter?"

"The China Doll, sir!" they shouted, dropping him on the deck. "Both legs blown off!—he can't kick you, sir, we've lashed him up too tightly."

"It's very painful," the China Doll bleated, all the pink gone out of his face.

Dr. Gordon went down on his knees and began to unlash him.

"Rather too much—too much," he said in his agitated manner, when he found how tightly the handkerchiefs had been fastened, and cried out with alarm when the China Doll's head suddenly dropped back.

"He's fainted, you silly fellows!"

They unbuckled the straps and untied the handkerchiefs in double-quick time.

"Put him on my bunk," Dr. Gordon told them; and, very frightened, they laid him there.

The China Doll's eyes opened, and he looked round not knowing what had happened. "Don't play ass tricks; get out of it; leave him here!" Dr. Gordon ordered gently; and they trooped away, dragging the stretcher along after them—rather sobered for the moment—to get a lecture from the Sub and Uncle Podger when they crowded into the gun-room and told what had happened.

In half an hour the China Doll was back again—none the worse, except that the pink had not all come back in his doll's face—rather pleased with himself than otherwise.

That happened on a Wednesday afternoon. On the Thursday, orders came by wireless for the Achates to rendezvous off the Gulf of Smyrna; and as dawn broke on Friday, the 5th March, she found herself half-way between the islands of Mytilene and Chios.

No one knew what was going to happen except, perhaps, Captain Macfarlane. "And he's probably forgotten," the irrepressible Orphan said.

This young gentleman was on watch with his guns, under the fore bridge, when the rendezvous was reached, and spotted some puffs of smoke rising above the horizon to the north'ard. Presently he saw through his glasses the masts of two battleships.

"What are they?" he asked excitedly of one of his petty officers, who was training a gun in their direction and looking through the telescopic sight.

"I know them, sir!" he cried. "The Swiftsure and Triumph. Look at their cranes—boat cranes—amidships, sir; there can't be any mistaking them, sir."

As the Orphan had never seen them before, he had to take his word for it.

"Trawlers behind 'em, sir—half a dozen or more," the petty officer called out.

In half an hour the very graceful outlines of these two battleships could be seen without glasses—easily distinguished from any other ship in the Navy by their hydraulic cranes for hoisting boats in and out.

The Orphan looked at them with all the more interest, because he knew that they had just come from the Dardanelles, and he peered at them through his glasses to try and discover any shell-marks. They looked as if they had just come out of dockyard hands, and he felt disappointed.

The trawlers followed, like ducklings out for a morning paddle with their father and mother. Very homely they looked.

Signal hoists fluttered and were hauled down, and soon the three big ships, with the little trawlers clustered at a respectful distance, lay with engines stopped.

The Captains of the battleships came across to the Achates, and an R.N.R. Lieutenant—in charge of the trawlers—bobbed alongside in a trawler's dinghy and scrambled on board. All three went below to the Captain's cabin.

It was a perfect morning, the breeze a little chilly, the sea calm, and just beginning to catch the light of the sun as it rose behind the misty, grey mountains of Asia Minor.

The two spotless gigs and the disreputable dinghy lay alongside, and their crews were soon busy answering questions, as the quarter-deck men left off their scrubbing decks and bawled down to know the news, and how things were going, and what was to be done here. "Have you been hit?" was the chief question.

"We got an 8-inch in the quarter-deck," the Swiftsure's boat's crew called up. "Knocked the ward-room about cruel;" and the Triumphs, jealous, told them: "It ain't nothin' compared to Kiao Chau—we got our foretop knocked out bombarding the forts there; a 12-inch shell what did that. It's not near so bad here as what it was out there."

In the hubbub of voices the Commander, splashing out of the battery in his sea-boots, sent the men back to their holystones and squeegees.

The Captains and the R.N.R. Lieutenant went back to their ships and trawlers, and then the three big ships commenced steaming in line ahead up the Gulf of Smyrna, the Achates leading, the Swiftsure astern of her, and the Triumph astern of the Swiftsure. The little trawlers were left behind.

By breakfast-time everyone in the gun-room knew that the forts of Smyrna were to be bombarded. The Navigator's "doggy"—the Pimple—came down bursting with this information. "The Navigator says we shall be in range just after dinner. I heard the Captain tell him they had a big fort there with 9- or 10-inch guns, and a mine-field in front of it—any amount of mines."

"We shall get first smack at them, shan't we?" the others said, beaming. "Our Captain is the senior one, isn't he?" and they hurried through breakfast and clattered up on the quarter-deck to have a look at the land.

By this time the ships were well inside the Gulf of Smyrna, steaming along its southern shore. Green olive-clad hills, rising from the sparkling, sunlit sea, sloped upwards until their sides, becoming barren, towered ragged into the cloudless sky. For two hours they steamed along, until, in front of them, the mountain barrier which circled the head of the Gulf, and sheltered the town of Smyrna itself, loomed ahead fourteen miles away.

The three ships were quite close inshore now, and every officer and man who had no special duties was on deck looking ashore, yarning in the glorious warm sunshine, pointing out villages, eagerly scanning every projecting point of land, and wondering whether the Vali of Smyrna knew they were coming and was prepared.

They were not long in doubt. The tall, aristocratic Major of Marines, soaked in Eastern lore by many years spent among Arabs and Sudanese, suddenly spotted a little pillar of grey smoke rising from the shore. He pointed it out, saying it was a signal, and was much chaffed by the other ward-room officers, until even they realized that he was right, when more curled up from projecting points of land as they steamed past. The news of their approach was being passed along to Smyrna.

"Isn't it exciting? I do feel ripping, inside," the Orphan told the Lamp-post as they both watched the shore and the signals. "Isn't it an adventure? my hat!"

"The Greek galleys and the Roman galleys came along just as we are coming," the learned Lamp-post said excitedly. "I bet the poor galley-slaves' backs were tired before they fetched up!"

"It must have been beastly for them not to be able to see where they were going and not to take part in the fighting."

"They didn't want to," the Lamp-post told him. "Let's come for'ard."

So they went along the boat deck, and from there they soon were able to see a little square shape rising out of the water. It was the fort of Yeni Kali, which commanded the approach to the Bay of Smyrna and the town. It was jutting out on low-lying land from the southern shore of the bay, which here made a broad sweep along the foot of some very high hills.

Up above, on the bridge, the Navigator was pointing out to the Pimple a buoy with a flag on it. "That marks the end of the mine-field. I'll bet anything they've forgotten to remove it, or haven't had time. You see that low ground to the right of it—all covered with bushes and things—they've got batteries somewhere there, and there are more of them half-way up the hills."

The Pimple nervously followed the Navigator's finger as he pointed out the places, and expected every moment that a gun would open fire. He had felt very brave at breakfast when he talked about them, but he was not quite sure whether he was enjoying himself so much as he expected.

The ships stopped engines whilst still out of range, and went to dinner at seven bells. An excited cheery dinner it was, and the mess deck hummed like a wasps' nest, the hoary old grandfathers among the men—and there were many of them—in as high spirits as anybody.

Punctually at half-past twelve Captain Macfarlane went for'ard to the bridge, the ships commenced to go ahead, and the bugles blared out "Action stations"—the ordinary General Quarters bugle without the preliminary two "G" blasts, but what a difference when heard for the first time!

The China Doll, clambering up the fore shrouds to his dizzy perch in the for'ard fire-control top, found his little heart thumping so much that he had to have a "stand easy" half-way up, gripping the ratlines and getting his breath.

Captain Macfarlane—on the bridge—saw him stop, and guessed the reason. He had had much experience of shells coming his way—during the Boer War—and knew how he had hated them, so felt sorry for the youngster.

"A lot depends on you, Mr. Stokes" (that was the China Doll's name), he called up to him encouragingly; and the China Doll was up the rigging like a redshank, tremendously proud and happy, clambered into the top, and began helping the seamen, already there, take the canvas cover off the range-finder and unlash the canvas screens.

The Gunnery-Lieutenant climbed up after him, and snubbed him for asking foolish questions. "Were they going to fire? Who was going to fire? How do I know? You'll know soon enough. Just hang on to those voice-pipes and don't talk."

So for some time the China Doll, humbled again, had nothing to do but look round him. Right ahead was the fort, standing square and bold at the end of the low-lying land. Three miles or so behind it, sloping up the mountains, were the white houses of Smyrna; over to the northern shore, to his left, long heaps lay dazzling in the sun—salt heaps these were; and on the right, the high hills with their concealed batteries. He looked behind at the two ships following astern, and down below at the Achates beneath him, and wondered, if the mast were shot away, whether he would fall clear of her in the water or on top of the boats. The "top" where he was, looked so small from down below, but when he was actually in it, it seemed so big that he thought shells couldn't possibly miss it.

He looked down at the bridge, and saw the Pimple shadowing the tall Navigator as he dodged from side to side of the bridge—they would both go into the conning-tower presently; he saw Mr. Meredith's bald head showing out of the turret on the fo'c'sle, and Rawlinson squeezed his head out too. For a moment he rather wished he could change places with them.

But then the orders came up through the voice-pipes. The Captain wanted the range of the fort. The seaman at the range-finder fumbled about with the thumb-screws and sang out: "One—six—nine—five—o" (the o is sounded as a letter, not as a figure). These were yards. The China Doll shouted down his voice-pipe: "One—six—nine—five—o". Nothing more came up for a quarter of an hour; he noticed how the "top" shook with the vibration of the engines. Then he had to sing down his voice-pipe: "One—five—five—o—o"; another interval; the range came down: "One—four—one—o—o", and the Gunnery-Lieutenant began shouting orders through his voice-pipes about degrees of elevation and the kind of shell to be used.

A bell tinkled close to him, and the red disk showed that the transmitting-room was calling him. Uncle Podger was there, he knew, sitting in the little padded room below the armoured deck and the water-line, with his head almost inside a huge voice-pipe shaped like the end of a gramophone, listening for orders, and waiting to pass them on to the various guns. And it was Uncle Podger's voice which came to him: "What's happening? Are we getting close in? It's beastly hot down here; aren't we going to fire soon?"

Before he could answer, a long signal hoist nearly knocked off his cap, flicking against the side of the "top" as it went up to the mast-head. Down it came again; a corner of a yellow-and-red pendant caught in a voice-pipe; he released it, and saw the signalman haul the flags down, in a gaily coloured heap, on the bridge below him. When he looked astern again, the two ships were spreading out; the vibration of the "top" ceased. He knew that the engines had stopped, and presently all three ships lay in line, with their starboard broadsides turned towards the old fort.

The Gunnery-Lieutenant now flew about, jumping from voice-pipes to range-finder and back again, reporting to the Captain. "Aye, aye, sir!" he shouted, and then called down, "Fore turret!—fore turret! try a ranging shot—common shell—one—four—o—five—o, at the left edge of the fort. Fire when you are ready!"

The China Doll felt funny thrills running up and down his backbone as he watched the fore turret move round, and the long chase of the 9.2-inch gun cock itself in the air. Mr. Meredith's bald head disappeared through the sighting hood. He heard the snap of the breech-block and the cheery sound of "Ready!" Mr. Meredith's head came out of his hood as he gazed at the distant fort through his glasses. He heard the word "Fire!" and at the same moment the fighting-top swayed as if a squall had struck the mast, a great cloud of yellowish smoke blotted out the foc's'le, and the Achates had fired a gun for the second time in the war—on this occasion not at sea-gulls!

In a few seconds a column of water leapt into the air behind the fort—the shell had fallen in the bay beyond. The Gunnery-Lieutenant roared down: "One—three—eight—five—o; fire as soon as you are ready!"

Off went the gun again; another wait, and a black-reddish splash appeared on the face of the fort, and up shot a cloud of dirty smoke. "Hit, sir!"

After that he was too busy to notice anything; he only remembered, later on, that the Turks had not fired back. More signals were hoisted; the Swiftsure and Triumph commenced firing, and in a very short space of time hits were being rapidly made on Yeni Kali fort.

Then the after turret of the Achates opened fire, and with her second round landed a lyddite shell square on one corner of the fort—brick dust and masonry going sky-high.

The Turks did not return the fire.

When, eventually, the bugle sounded the "secure", the China Doll could hardly believe that he had been there for two and a half hours, and at the order to "pack up" he climbed down below, and ran to the gun-room, where Barnes, the big marine, in his shirt-sleeves, was already laying the table for afternoon tea.

The snotties and Uncle Podger came trooping in, jabbering like magpies; the Pink Rat, who was in the after turret, and Rawlinson, who had the foremost one, each claiming that his own gun had made most hits. They both were getting angry—the Pink Rat cool and cynical, Rawlinson's temper getting the better of him.

They seized the China Doll. "You saw; which gun did best?" but the Assistant Clerk was much too wily to take sides, and wriggled away.

They pounced on the Pimple, who had been on the bridge all the time. He, flattered to have his opinion asked, thought that Rawlinson's gun had made more hits.

"That rotten, worn-out pipe of a gun of yours," the Pink Rat sneered, "couldn't hit a haystack at a mile; yours were dropping short all the time!"

"Yours may be the slightly better gun" (it was more modern), "but if you had anything to do with it, it wouldn't hit the Crystal Palace, a hundred yards away," Rawlinson snorted, getting red in the face. "Ours didn't go short."

"Contradiction is no argument," the Pink Rat said loftily; and Rawlinson, who was half as big again as the senior snotty (that was why the Pimple had backed him), would have given him a hiding, had not the Sub come in and stopped them.

"What the dickens does it matter? We've given old Yeni Kali a fair 'beano'; its own mother wouldn't know it. Hurry up with the tea booze; I've to go on watch; out, both of you, if you can't keep quiet!"

Barnes brought in the big teapot, slices of bread and jam and butter disappeared marvellously as they all ate and gabbled. "Why didn't they shoot back?—the mean beggars—I expect we've knocked out all their guns," Rawlinson gurgled with his mouth full. "You didn't, anyway," sneered the Pink Rat.

"I wish we'd gone straight in—don't put your sleeve in my butter—I don't believe those mines would have gone off—wouldn't they?—a bally lot you know about mines—you pig, Pimple, you've taken half that tin of jam—the Captain knows all about them—that's what those trawlers are for—shove across the bread—they'll sweep a passage through them—why didn't they let us fire more of our 6-inch—your old guns, Orphan—they ain't as much good as a sick headache—look at that slice of cake the Pink Rat's cut—put the Pink Rat down for two slices, Barnes, and bring along the teapot."

The Hun put his head in at the door. "Twenty-five minutes past four, sir."

"All right! Curse it! I'm coming," and gulping down what was left of his tea, and grabbing his telescope and cap, the Sub went up to relieve the watch amidst a babel of "Hun! Hun! hold on a jiffy! You were on the bridge all the time; which 9.2 made the most hits? What did the Captain say?"

"The after gun; that's what the Captain said," he told them, and went out again.

"I told you so!" laughed the Pink Rat; and Rawlinson, crestfallen and angry, shouted "that he didn't believe it, and if it was true, that it was all due to the China Doll passing down the wrong ranges".

The poor Assistant Clerk flushed with mortification, and squeaked out: "I know I didn't make any mistake—I just repeated the figures after the Gunnery-Lieutenant—they were right at my end of the voice-pipe."

"Well, don't cry!" Rawlinson growled. "You've got such a silly voice—you can't help it—the figures must have come wrong at our end."

They seized the luckless China Doll, stuck him on a bench at one end of the mess, twisted one of the long white table-cloths into a rope, and made him hold one end, whilst the Orphan held the other to his ear and pretended to listen.

"Now pass the range," they laughed; "try one—five—nine—o—o."

"One—five—nine—o—o," the China Doll called into the end of the table-cloth, not quite certain that he was enjoying himself.

"One—four—seven—six—and a half," repeated the Orphan very solemnly.

"There you are! China! try again!" and they made him give the order. "Train seventeen degrees on the port beam."

The Orphan, thinking hard, shook his head and shouted back "Repeat!"

"Train seventeen degrees on the port beam," the China Doll repeated.

As solemn as a judge, the Orphan sang out, "Tame seven clean fleas in the cream;" and as the poor Assistant Clerk squeaked, "Don't be silly!" there were yells of "He called you silly, Orphan; you aren't going to stand that. Go for him, Orphan. We'll hold him; he shan't hurt you." But Uncle Podger told them all to stop fooling and smooth out the table-cloth. "We can't get things washed properly on board," he said.

CHAPTER V

The "Achates" is Shelled

Next morning, the 6th March—a glorious sunny morning it was—the three ships and the trawlers again moved in towards battered Yeni Kali. The trawlers went ahead to sweep through the mine-field under the protection of the Triumph, whilst the Achates and Swiftsure followed astern.

Breakfast was at seven o'clock—a hurried meal—and everyone bolted down his food in order to get on deck quickly and see the fun.

"Rotten bad form of 'em not to fire at us yesterday," Uncle Podger remarked, emptying half the sugar basin on his porridge. "In all the wars I've been in, we've fired first, then the enemy fired back; we spotted their guns and knocked them out."

"And landed for a picnic afterwards," suggested his neighbour, skilfully bagging the sugar basin.

"Generally," replied the Clerk.

"In the last war I was in," began the China Doll, "we generally asked the enemy to lunch. The Captain said that made them so happy."

"If we're to have breakfast at this silly time," Bubbles chuckled, "I call it a rotten war."

They heard shouts on deck. The half-deck sweeper put his head in to tell them that the Turks were firing, and they all stampeded on deck.

Right ahead, the little trawlers could be seen, in pairs, close in to the old fort and the low-lying land to the right of it. Right on top of the mine-field they were, and spurts of water were splashing up, every other second, among them. Flashes twinkled out from the scrub on the low-lying ground, three, four, five at a time, and the splashes of their shells sprang up, one after the other, between the trawlers.

Everyone held his breath and expected to see a trawler hit, directly.

There was a shout of "The Triumph's started!" A yellowish cloud shot out from her, then another; they shot out all along her broadside, and, right in among the scrub, where the Turkish guns had been firing, burst her 7.5 lyddite shells.

Then splashes began falling close to the Triumph herself—short—short—far over her—right under her stern. "Hit under the fore bridge!" someone shouted. The "Action" bugle blared out in the Achates; officers and men rushed to their stations; and the last thing Uncle Podger and the Lamp-post saw was the trawlers turning round and scuttling back, followed by columns of water leaping up close to them.

Uncle Podger, sedately excited, and the long, thin Lamp-post made their way along the mess deck, pushing through the crowds of men scurrying to and fro; guns' crews squeezing into the casemates and closing the armoured doors behind them; the stoker fire-parties bustling along with their hoses, and the lamp trimmers coming round and lighting the candle lanterns in case the electric light failed.

To get to the "transmitting-room", which was their station, they had to go down the ammunition hoist of "B2" casemate—the for'ard one on the port side of the main deck,—and so many men of the ammunition supply parties had to go down it that there was a squash of men squeezing through the casemate door.

"Early doors, sixpence extra," Uncle Podger grinned, as they waited whilst man after man climbed down the rope-ladder in the hoist. This hoist was simply a steel tube some fifteen feet long, big enough for a broad-shouldered man to crawl through, and the rope ladder dangled down inside it. When the bottom rung of the ladder was reached, there was a jump down of some five feet or so into the "fore cross passage"—a broad space, from side to side across the ship, under the dome of the armoured deck. The magazines were below this fore cross passage, and men standing in them handed up the six-inch cordite charges through open hatches.

Into this space ran the ammunition passages, running aft along each side under the slope of the armoured deck, with the boiler-room bulkheads on the inner sides, and the bulkheads of the lower wing bunkers on the outer. When, as was now the case, the shells in their red canvas bags hung in rows along both these bulkheads, there was precious little room for two people to pass side by side.

The ammunition hoists from all the 6-inch guns, farther aft, opened into these passages, and under each hoist an electric motor and winding drum was placed to run the charges and shells up to the casemate which it "fed". All these spaces and passages were very dimly lighted by electric lights and candle lanterns.

As Uncle Podger and the Lamp-post crawled down the tube and dropped into the "fore cross passage", they were hustled by men dashing out of the ammunition passages, seizing charges and shells from the men standing in the magazine hatches, and dashing back again to their own hoists. These were the "powder-monkeys" of the old days, most of them, now, big bearded men; one, the biggest down there, a man nearly fifty years of age, had been earning five pounds a week, as a diver, before the outbreak of war brought him back to the Navy. And no one was more cheery than he, as he dashed backwards and forwards from his hoist to the magazine, laughing and joking, and wiping the sweat off his face. It was very warm down there, and the smell of sweating men soon made the air heavy.

A bearded ship's corporal came down with the key of the transmitting-room, opened the thick padded wooden door in the bulkhead, and went in. The Fleet-Paymaster and the tall, depressed Fleet-Surgeon followed him down the tube. They scuttled out of the way of the trampling men.

"A nice little place for you to work in, P.M.O.," chuckled the Pay as they wormed themselves into a corner.

"Rats in a trap!" grunted the P.M.O., and drew in his feet and cursed as a seaman trod on them.

The chief sick-berth steward and his assistants had already come down, but vainly looked for a place to stow their surgical dressings. They had to hang them from hooks in the bulkheads.

Uncle Podger and the Lamp-post stood waiting for the Chaplain, the Rev. Horace Gibbons; and when they saw his shoes and scarlet socks dangling from the lower end of the ammunition hoist from "B2" casemate in a helpless, pathetic way, they dashed to his assistance; each seized a foot and guided it to safety on top of a convenient motor-hoist, and as the Padre let go the ladder and jumped feebly, they softened his fall. This was always their first job, for he hated that rope-ladder and that hoist with a deadly hatred, and, most of all, hated falling those last few feet, suddenly dropping, as it were, from heaven, and appearing in an undignified manner among all the men there.

The Lamp-post and Uncle Podger dusted down the little pasty-faced Padre and put his hat on straight.

"Thank you so much! I'm afraid I've broken my pipe in that hoist."

"Hallo, Angel Gabriel!" grinned the Pay, as the three of them passed into the transmitting-room. "Paying a call in the infernal region?"

As they shut the felted door they shut out all the noise.

This transmitting-room was a tiny little place, perhaps fifteen feet long and five wide, with four camp-stools, and rows of telephones and brass indicator boxes with their little red and white figures showing through the slits in them. Voice-pipes, too, everywhere, and in one corner, over a camp-stool—Uncle Podger's camp-stool—projected an enormous brass voice-pipe with a gramophone-shaped end.

Every instrument had its label above it: Conning-tower—After Turret—Starboard 6-inch—Y group—X group—scores of them; and in front of the Padre's camp-stool was a little table, like a school table, with paper lying on it and a pencil chained to it.

"Nothing happened yet, sir," the ship's corporal sang out, as they closed the door and seated themselves on their camp-stools with their backs against the after bulkhead and the door.

Uncle Podger, sitting with his head in his gramophone trumpet, could hear people talking in the conning-tower. "Signal to the Swiftsure to stop engines"—that was Captain Macfarlane's clear, incisive voice; then the Navigator's infectious laugh, "The trawlers are safe, sir; out of range, sir. They've had the fright of their lives, sir."—"Port it is, sir," came the gruff voice of the quartermaster at the wheel. "Steady it is, sir."

He rang up the fore-control top, where the China Doll was perched, and a bell at his side tinkled. "What's going on, China Doll?" he called into his loud-speaking navyphone, giving the mouthpiece a shake.

"Stop that confounded ringing!" it bleated out, in the peculiar nasal tone these navyphones always have. That was the Gunnery-Lieutenant's irritated voice, so Uncle Podger kept silent.

Then he heard, loud and clear through the trumpet mouth: "Transmitting-room! Transmitting-room! Tell the Major and Mr. Meiklejohn" (one of the Lieutenants) "that the port 6-inch will fire first."

"Aye, aye, sir! Port guns will fire first."

He passed on the message to the Lamp-post, and the Lamp-post, who was in charge of the port broadside gun instruments, commenced telephoning to the Major, aft, and Mr. Meiklejohn, up in B1 casemate, above them.

Then more orders came down, rapidly, one after the other; ranges, worked from the foretop, ticked themselves off in the slits of the little brass boxes, were verified, and passed on to the port guns and the turrets.

"Commence with common shell," sounded the trumpet mouth. Uncle Podger repeated it.

"It's showing all right on my dial," the Lamp-post said, a little bothered with so many telephones asking him questions.

"All right, Lampy. Don't lose your wool. Pass it on to the guns."

"What range is showing?" called the trumpet.

"One—two—nine—five—o." "One—two—nine—five—o." "One—two—nine—five—o," the Lamp-post, the Padre, and the ship's corporal told Uncle Podger.

"One—two—nine—five—o," he spoke into his navyphone.

"What range are the guns showing?" asked the trumpet. It was the Gunnery-Lieutenant, anxious to know, at the last moment, whether all the instruments were recording properly.

This meant ringing up each gun, and took time. Presently all the replies were received.

"Y3 shows One—two—nine—o—o, sir," Uncle Podger telephoned. "The others are correct."

"Confound Y3!" he heard the Gunnery-Lieutenant say angrily.

Then the figures in the slits in the brass boxes began to move—the "five" gave way to "o", the "nine" disappeared and "eight" took its place; the range was decreasing. The little labels bearing the types of shell to be used—armour-piercing, common, lyddite—revolved, and came to a standstill with "common" showing.