Title: The Little Lame Prince and His Travelling Cloak

Author: Dinah Maria Mulock Craik

Illustrator: Hope Dunlap

Release date: June 15, 2014 [eBook #45975]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Kiwibrit and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The cover image was produced by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Transcriber's Note:

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible. A number of the original illustrations included internal references (page numbers) and the captions were not clear. These have been removed from the illustrations. The illustrations have been moved to just below or beside the text to which they refer. The captions have been added below the relevant illustration. The illustration with the caption 'The procession had moved on....' was originally spread over two pages. These have been stitched together as a single illustration. A list of Illustrations has been added. Several page numbers will be found to be missing. These pages were blank pages in the original book.

Copyright, 1909, by

Rand-McNally & Company

All rights reserved

Entered at Stationers' Hall

Edition of 1937

Made in U. S. A.

PAGE |

|

| Chapter I | 9 |

| Chapter II | 19 |

| Chapter III | 31 |

| Chapter IV | 43 |

| Chapter V | 53 |

| Chapter VI | 65 |

| Chapter VII | 81 |

| Chapter VIII | 91 |

| Chapter IX | 99 |

| Chapter X | 112 |

| "Take care and don't let the baby fall" | 8 |

| The Little Lame Prince | 9 |

| "All the people in the palace were lovely" | 10 |

| "The poorlittle kitchen maid..." | 11 |

| "The procession had moved on" | 14 |

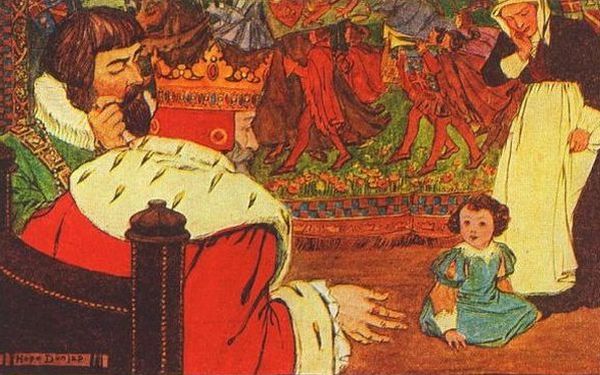

| "How old is his Royal Highness?" | 20 |

| "And in truth they were very fine children, the whole seven of them." | 27 |

| "They made a great show when they rode out together on seven beautiful horses." | 27 |

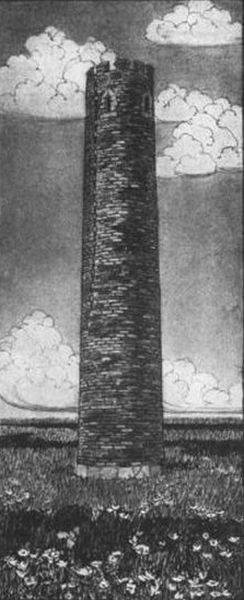

| "One large round tower which rose up in the center of the plain." | 31 |

| "He was rather frightened, and the face, black as it was, looked kindly at him." | 34 |

| "She laid those two tiny hands on his shoulders" | 38 |

| "Prince Dolor had never seen anything like it." | 43 |

| "Even when a little better, he was too weak to enjoy anything," | 45 |

| "By-and-by a few stars came out, first two or three, and then quantities" | 56 |

| "She brought in the supper and lit the candles," | 58 |

| "And they looked at him—as if wondering to meet in mid-air such an extraordinary sort of a bird." | 62 |

| "After a few windings and vagaries, it settled into a respectable stream." | 69 |

| "It was made up of cornfields, pasturefields, lanes, hedges, brooks, and ponds." | 71 |

| "In it were what the Prince had desired to see, a quantity of living creatures," | 71 |

| "The shepherd lad evidently took it for a large bird " | 74 |

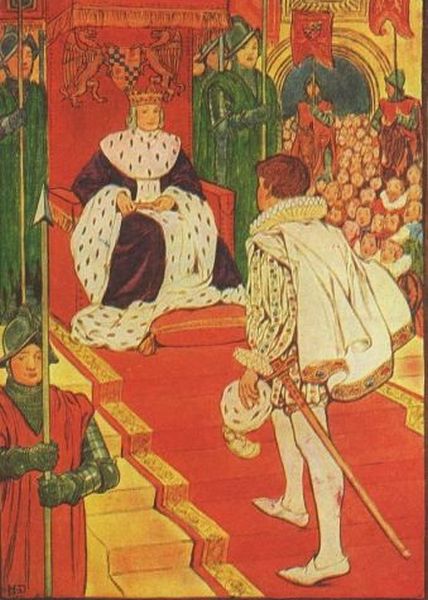

| "You are a king." | 84 |

| "One half the people seemed so happy and busy..." | 89 |

| "while the other half were so wretched and miserable." | 89 |

| "It had terraces and gardens, battlements and towers." | 90 |

| "Its windows looked in all directions," | 90 |

| "She pecked at the tiles with her beak—" | 92 |

| There came pouring a stream of sun-rays | 109 |

| So Prince Dolor quitted his tower...quitted it as the great King of Nomansland. | 111 |

| "When he drove out through the city streets, shouts followed him wherever he went." | 116 |

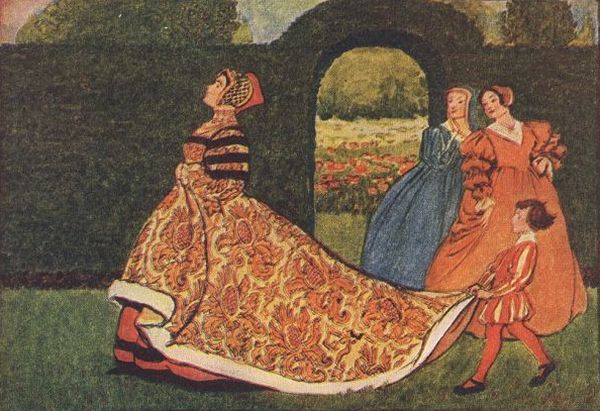

| "But as she was so grand a personage now, any little faults she had did not show." | 118 |

| "All the people....assembled to see the young Prince installed solemnly in his new duties, and undertaking his new vows." |

119 |

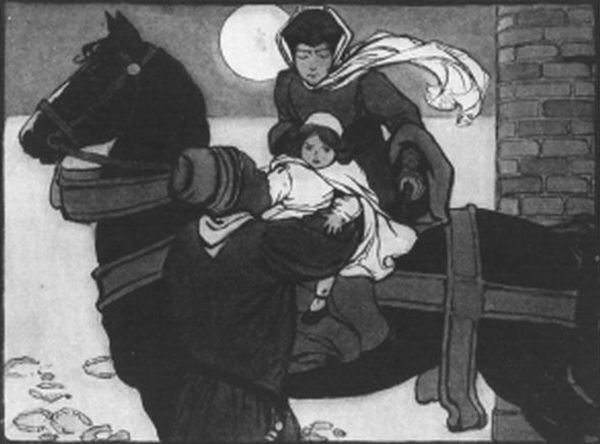

"Take care, don't let the baby fall again."

es, he was the most beautiful Prince that ever was born. Of course, being a prince, people said this: but it was true besides. When he looked at the candle, his eyes had an expression of earnest inquiry quite startling in a new-born baby. His nose—there was not much of it certainly, but what there was seemed an aquiline shape; his complexion was a charming, healthy purple; he was round and fat, straight-limbed and long—in fact, a splendid baby, and everybody was exceedingly proud of him. Especially his father and mother, the King and Queen of Nomansland, who had waited for him during their happy reign of ten years—now made happier than ever, to themselves and their subjects, by the appearance of a son and heir.

The only person who was not quite happy was the king's [Pg 10] brother, the heir-presumptive, who would have been king one day, had the baby not been born. But as his Majesty was very kind to him, and even rather sorry for him—insomuch that at the Queen's request he gave him a dukedom almost as big as a county,—the Crown Prince, as he was called, tried to seem pleased also; and let us hope he succeeded.

The Prince's christening was to be a grand affair. According to the custom of the country, there were chosen for him four-and-twenty godfathers and godmothers, who each had to give him a name, and promise to do their utmost for him. When he came of age, he himself had to choose the name—and the god-father or godmother—that he liked best, for the rest of his days.

Meantime, all was rejoicing. Subscriptions were made among the rich to give pleasure to the poor: dinners in town-halls for the working men; tea-parties in the streets for their wives; and milk and bun feasts for the children in the schoolrooms. For Nomansland, though I cannot point it out in any map, or read of it in any history, was, I believe, much like our own or many another country.

As for the Palace—which was no different from other palaces—it was clean "turned out of the windows," as people say, with the preparations going on. The only quiet place in it was the room which, though the Prince was six weeks old, his mother the Queen had never quitted. Nobody said she was ill, however; it would have been so inconvenient; and as she said nothing about it herself, but lay pale and placid, giving no trouble to anybody, nobody thought much about her. All the world was absorbed in admiring the baby.

"All the people in the palace were lovely

too—or thought themselves so ... from

the ladies-in-waiting down ..."

"The poor little bridesmaid ... in her

pink cotton gown ... though doubtless,

there never was such a pretty girl."

The christening-day came at last, and it was as lovely as the Prince himself. All the people in the palace were lovely too—or thought [Pg 11] themselves so, in the elegant new clothes which the queen, who thought of everybody, had taken care to give them, from the ladies-in-waiting down to the poor little kitchenmaid, who looked at herself in her pink cotton gown, and thought, doubtless, that there never was such a pretty girl as she.

By six in the morning all the royal household had dressed itself in its very best; and then the little Prince was dressed in his best—his magnificent christening-robe; which proceeding his Royal Highness did not like at all, but kicked and screamed like any common baby. When he had a little calmed down, they carried him to be looked at by the Queen his mother, who, though her royal robes had been brought and laid upon the bed, was, as everybody well knew, quite unable to rise and put them on.

She admired her baby very much; kissed and blessed him, and lay looking at him, as she did for hours sometimes, when he was placed beside her fast asleep; then she gave him up with a gentle smile, and saying "she hoped he would be very good, that it would be a very nice christening, and all the guests would enjoy themselves," turned peacefully over on her bed, saying nothing more to anybody. She was a very uncomplaining person—the Queen, and her name was Dolorez.

Everything went on exactly as if she had been present. All, even the King himself, had grown used to her absence, for she was not strong, and for years had not joined in any gaieties. She always did her royal duties, but as to pleasures, they could go on quite well without her, or it seemed so. The company arrived: great and notable persons in this and neighboring countries; also the four-and-twenty godfathers and godmothers, who had been chosen with care, as the people who would be most useful to his Royal Highness, should he ever want [Pg 12] friends, which did not seem likely. What such want could possibly happen to the heir of the powerful monarch of Nomansland?

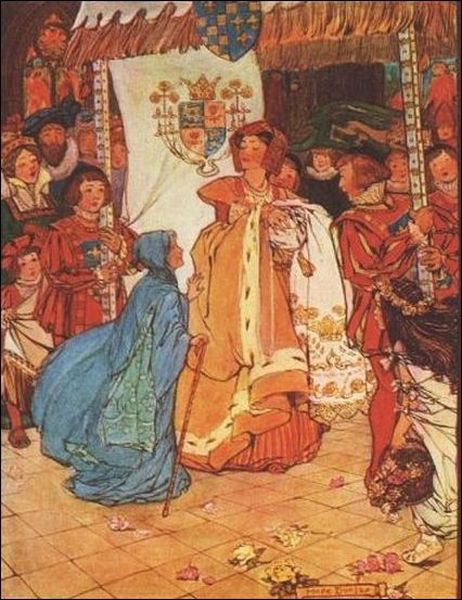

They came, walking two and two, with their coronets on their heads—being dukes and duchesses, prince and princesses, or the like; they all kissed the child, and pronounced the name which each had given him. Then the four-and-twenty names were shouted out with great energy by six heralds, one after the other, and afterwards written down, to be preserved in the state records, in readiness for the next time they were wanted which would be either on his Royal Highness's coronation or his funeral. Soon the ceremony was over, and everybody satisfied; except, perhaps, the little Prince himself, who moaned faintly under his christening robes, which nearly smothered him.

In truth, though very few knew, the Prince in coming to the chapel had met with a slight disaster. His nurse—not his ordinary one, but the state nursemaid, an elegant and fashionable young lady of rank, whose duty it was to carry him to and from the chapel, had been so occupied in arranging her train with one hand, while she held the baby with the other, that she stumbled and let him fall, just at the foot of the marble staircase. To be sure, she contrived to pick him up again the next minute, and the accident was so slight it seemed hardly worth speaking of. Consequently, nobody did speak of it. The baby had turned deadly pale but did not cry, so no person a step or two behind could discover anything wrong; afterwards, even if he had moaned, the silver trumpets were loud enough to drown his voice.

It would have been a pity to let anything trouble such a day of felicity.

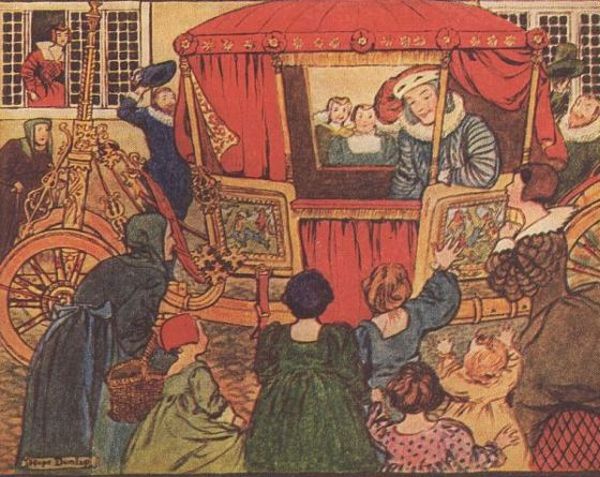

So, after a minute's pause, the procession had moved on. Such a procession! Heralds in blue and silver; pages in crimson and gold; and a troop of little girls in dazzling white, carrying baskets of flowers, which they strewed all the way before the nurse and child,—finally the four-and-twenty godfathers and godmothers, as proud as possible, and so splendid to look at that they would have quite extinguished their small godson—merely a heap of lace and muslin with a baby-face inside—had it not been for a canopy of white satin and ostrich feathers, which was held over him wherever he was carried.

The procession had moved on. Such a procession! Heralds in blue and silver; pages in crimson and gold.

Thus, with the sun shining on them through the painted windows, they stood; the King and his train on one side, the Prince and his attendants on the other, as pretty a sight as ever was seen out of fairyland.

"It's just like fairyland," whispered the eldest little girl to the next eldest, as she shook the last rose out of her basket; "and I think the only thing the Prince wants now is a fairy godmother."

"Does he?" said a shrill but soft and not unpleasant voice behind; and there was seen among the group of children somebody—not a child—yet no bigger than a child: somebody whom nobody had seen before, and who certainly had not been invited, for she had no christening clothes on.

She was a little old woman dressed all in grey: grey gown, grey hooded cloak, of a material excessively fine, and a tint that seemed perpetually changing, like the grey of an evening sky. Her hair was grey and her eyes also; even her complexion had a soft grey shadow over it. But there was nothing unpleasantly old about her, and [Pg 15] her smile was as sweet and childlike as the Prince's own, which stole over his pale little face the instant she came near enough to touch him.

"Take care. Don't let the baby fall again."

The grand young lady nurse started, flushing angrily.

"Who spoke to me? How did anybody know?—I mean, what business has anybody—?" Then, frightened, but still speaking in a much sharper tone than I hope young ladies of rank are in the habit of speaking—"Old woman, you will be kind enough not to say 'the baby,' but 'the Prince.' Keep away; his Royal Highness is just going to sleep."

"Nevertheless, I must kiss him. I am his godmother."

"You!" cried the elegant lady nurse.

"You!!" repeated all the gentlemen and ladies in waiting.

"You!!!" echoed the heralds and pages—and they began to blow the silver trumpets, in order to stop all further conversation.

The Prince's procession formed itself for returning—the King and his train having already moved off towards the palace—but, on the topmost step of the marble stairs, stood, right in front of all, the little old woman clothed in grey.

She stretched herself on tiptoe by the help of her stick, and gave the little Prince three kisses.

"This is intolerable," cried the young lady nurse, wiping the kisses off rapidly with her lace handkerchief. "Such an insult to his Royal Highness. Take yourself out of the way, old woman, or the King shall be informed immediately."

"The King knows nothing of me, more's the pity," replied the old woman with an indifferent air, as if she thought the loss was more on his Majesty's side than hers. "My friend in the palace is the King's wife."

"Kings' wives are called queens," said the lady nurse, with a contemptuous air.

"You are right," replied the old woman. "Nevertheless, I know her Majesty well, and I love her and her child. And—since you dropped him on the marble stairs (this she said in a mysterious whisper, which made the young lady tremble in spite of her anger)—I choose to take him for my own. I am his godmother, ready to help him whenever he wants me."

"You help him!" cried all the group, breaking into shouts of laughter, to which the little old woman paid not the slightest attention. Her soft grey eyes were fixed on the Prince, who seemed to answer to the look, smiling again and again in causeless, aimless fashion, as babies do smile.

"His Majesty must hear of this," said a gentleman-in-waiting.

"His Majesty will hear quite enough news in a minute or two," said the old woman sadly. And again stretching up to the little Prince, she kissed him on the forehead solemnly.

"Be called by a new name which nobody has ever thought of. Be Prince Dolor, in memory of your mother Dolorez."

"In memory of!" Everybody started at the ominous phrase, and also at a most terrible breach of etiquette which the old woman had committed. In Nomansland, neither the king nor the queen were supposed to have any Christian name at all. They dropped it on their coronation-day, and it was never mentioned again till it was engraved on their coffins when they died.

"Old woman, you are exceedingly ill-bred," cried the eldest lady-in-waiting, much horrified. "How you could know the fact passes my comprehension. But even if you did not know it, how dared you presume to hint that her most gracious Majesty is called Dolorez?"

"Was called Dolorez," said the old woman with a tender solemnity.

The first gentleman, called the Gold-stick-in-waiting, raised it to strike her, and all the rest stretched out their hands to seize her; but the grey mantle melted from between their fingers like air; and, before anybody had time to do anything more, there came a heavy, muffled, startling sound.

The great bell of the palace—the bell which was only heard on the death of some of the Royal family, and for as many times as he or she was years old—began to toll. They listened, mute and horror-stricken. Some one counted: One—two—three—four—up to nine and twenty—just the queen's age.

It was, indeed, the Queen. Her Majesty was dead! In the midst of the festivities she had slipped away, out of her new happiness and her old sufferings, neither few nor small. Sending away her women to see the sight—at least, they said afterwards, in excuse, that she had done so, and it was very like her to do it—she had turned with her face to the window, whence one could just see the tops of the distant mountains—the Beautiful Mountains, as they were called—where she was born. So gazing, she had quietly died.

When the little Prince was carried back to his mother's room, there was no mother to kiss him. And, though he did not know it, there would be for him no mother's kiss any more.

As for his Godmother—the little old woman in grey who called herself so—whether she melted into air, like her gown when they touched it, or whether she flew out of the chapel window, or slipped through the doorway among the bewildered crowd, nobody knew—nobody ever thought about her.

Only the nurse, the ordinary homely one, coming out of the Prince's nursery in the middle of the night in search of a cordial to quiet his continual moans, saw, sitting in the doorway, something [Pg 18] which she would have thought a mere shadow, had she not seen shining out of it two eyes, grey and soft and sweet. She put her hand before her own, screaming loudly. When she took them away, the old woman was gone.

Everybody was very kind to the poor little Prince. I think people generally are kind to motherless children, whether princes or peasants. He had a magnificent nursery, and a regular suite of attendants, and was treated with the greatest respect and state. Nobody was allowed to talk to him in silly baby language, or dandle him, or above all to kiss him, though, perhaps, some people did it surreptitiously, for he was such a sweet baby that it was difficult to help it.

It could not be said that the Prince missed his mother; children of his age cannot do that; but somehow after she died everything seemed to go wrong with him. From a beautiful baby he became sickly and pale, seeming to have almost ceased growing, especially in his legs, which had been so fat and strong. But after the day of his christening they withered and shrank; he no longer kicked them out either in passion or play, and when, as he got to be nearly a year old, his nurse tried to make him stand upon them, he only tumbled down.

This happened so many times that at last people began to talk about it. A prince, and not able to stand on his own legs! What a dreadful thing! what a misfortune for the country!

Rather a misfortune to him also, poor little boy! but nobody seemed to think of that. And when, after a while, his health revived, and the old bright look came back to his sweet little face, and his body grew larger and stronger, though still his legs remained the same, people continued to speak of him in whispers, and with grave shakes of the head. Everybody knew, though nobody said it, that something, impossible to guess what, was not quite right with the poor little Prince.

Of course, nobody hinted this to the King his father: it does not do to tell great people anything unpleasant. And besides, his Majesty took very little notice of his son, or of his other affairs, beyond the necessary duties of his kingdom. People had said he would not miss the Queen at all, she having been so long an invalid: but he did. After her death he never was quite the same. He established himself in her empty rooms, the only rooms in the palace whence one could see the Beautiful Mountains, and was often observed looking at them as if he thought she had flown away thither, and that his longing could bring her back again. And by a curious coincidence, which nobody dared to inquire into, he desired that the Prince might be called, not by any of the four-and-twenty grand names given him by his godfathers and godmothers, but by the identical name mentioned by the little old woman in grey,—Dolor, after his mother Dolorez.

Once a week, according to established state custom, the Prince, dressed in his very best, was brought to the King his father for half-an-hour, but his Majesty was generally too ill and too melancholy to pay much heed to the child.

Only once, when he and the Crown Prince, who was exceedingly attentive to his royal brother, were sitting together, with Prince Dolor playing in a corner of the room, dragging himself about with his arms rather than his legs, and sometimes trying feebly to crawl from one chair to another, it seemed to strike the father that all was not right with his son.

"How old is his Royal Highness?" said he suddenly to the nurse.

"Two years, three months, and five days, please your Majesty."

"How old is his Royal Highness?" said he suddenly to the nurse.

"It does not please me," said the King with a sigh. "He ought to be far [Pg 21] more forward than he is now, ought he not, brother? You, who have so many children, must know. Is there not something wrong about him?"

"Oh, no," said the Crown Prince, exchanging meaning looks with the nurse, who did not understand at all, but stood frightened and trembling with the tears in her eyes. "Nothing to make your Majesty at all uneasy. No doubt his Royal Highness will outgrow it in time."

"Outgrow—what?"

"A slight delicacy—ahem!—in the spine; something inherited, perhaps, from his dear mother."

"Ah, she was always delicate; but she was the sweetest woman that ever lived. Come here, my little son."

And as the Prince turned round upon his father a small, sweet, grave face—so like his mother's—his Majesty the King smiled and held out his arms. But when the boy came to him, not running like a boy, but wriggling awkwardly along the floor, the royal countenance clouded over.

"I ought to have been told of this. It is terrible—terrible! And for a prince, too! Send for all the doctors in my kingdom immediately."

They came, and each gave a different opinion, and ordered a different mode of treatment. The only thing they agreed in was what had been pretty well known before: that the prince must have been hurt when he was an infant—let fall, perhaps, so as to injure his spine and lower limbs. Did nobody remember?

No, nobody. Indignantly, all the nurses denied that any such accident had happened, was possible to have happened, until the faithful country nurse recollected that it really had happened, on the day of the christening. For which unluckily good memory all the others scolded her so severely that she had no peace of her life, and soon after, by the influence of the young lady nurse who had carried the baby that fatal day, and who was a sort of connection of the Crown Prince, being his wife's second cousin once removed, the poor woman was pensioned off, and sent to the Beautiful Mountains, from whence she came, with orders to remain there for the rest of her days.

But of all this the King knew nothing, for, indeed, after the first shock of finding out that his son could not walk, and seemed never likely to walk, he interfered very little concerning him. The whole thing was too painful, and his Majesty had never liked painful things. Sometimes he inquired after Prince Dolor, and they told him his Royal Highness was going on as well as could be expected, which really was the case. For after worrying the poor child and perplexing themselves with one remedy after another, the Crown Prince, not wishing to offend any of the differing doctors, had proposed leaving him to nature; and nature, the safest doctor of all, had come to his help, and done her best. He could not walk, it is true; his limbs were [Pg 23] mere useless additions to his body; but the body itself was strong and sound. And his face was the same as ever—just his mother's face, one of the sweetest in the world!

Even the King, indifferent as he was, sometimes looked at the little fellow with sad tenderness, noticing how cleverly he learned to crawl, and swing himself about by his arms, so that in his own awkward way he was as active in motion as most children of his age.

"Poor little man! he does his best, and he is not unhappy; not half so unhappy as I, brother," addressing the Crown Prince, who was more constant than ever in his attendance upon the sick monarch. "If anything should befall me, I have appointed you as Regent. In case of my death, you will take care of my poor little boy?"

"Certainly, certainly; but do not let us imagine any such misfortune. I assure your Majesty—everybody will assure you—that it is not in the least likely."

He knew, however, and everybody knew, that it was likely, and soon after it actually did happen. The King died, as suddenly and quietly as the Queen had done—indeed, in her very room and bed; and Prince Dolor was left without either father or mother—as sad a thing as could happen, even to a Prince.

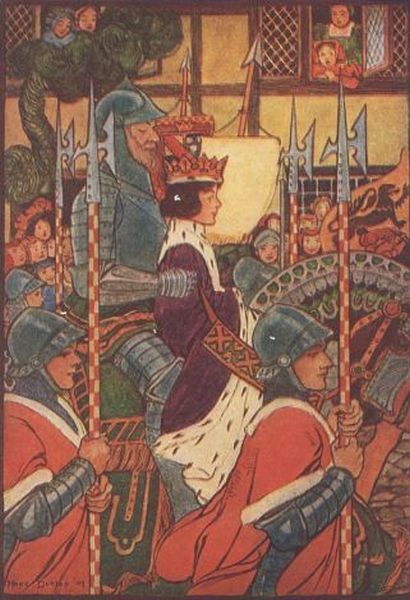

He was more than that now, though. He was a king. In Nomansland, as in other countries, the people were struck with grief one day and revived the next. "The king is dead—long live the king!" was the cry that rang through the nation, and almost before his late Majesty had been laid beside the queen in their splendid mausoleum, crowds came thronging from all parts of the royal palace, eager to see the new monarch.

They did see him—the Prince Regent took care they should—sitting on the floor of the council-chamber, sucking his thumb!

And when one of the gentlemen-in-waiting lifted him up and carried him—fancy, carrying a king!—to the chair of state, and put the crown on his head, he shook it off again, it was so heavy and uncomfortable. Sliding down to the foot of the throne, he began playing with the golden lions that supported it, stroking their paws and putting his tiny fingers into their eyes, and laughing—laughing as if he had at last found something to amuse him.

"There's a fine king for you!" said the first lord-in-waiting, a friend of the Prince Regent's (the Crown Prince that used to be, who, in the deepest mourning, stood silently beside the throne of his young nephew. He was a handsome man, very grand and clever looking). "What a king! who can never stand to receive his subjects, never walk in processions, who, to the last day of his life, will have to be carried about like a baby. Very unfortunate!"

"Exceedingly unfortunate," repeated the second lord. "It is always bad for a nation when its king is a child; but such a child—a permanent cripple, if not worse."

"Let us hope not worse," said the first lord in a very hopeless tone, and looking towards the Regent, who stood erect and pretended to hear nothing. "I have heard that these sort of children with very large heads and great broad foreheads and staring eyes, are——well, well, let us hope for the best and be prepared for the worst. In the meantime——"

"I swear," said the Crown Prince, coming forward and kissing the hilt of his sword—"I swear to perform my duties as regent, to take all care of his Royal Highness—his Majesty, I mean," with a grand bow to the little child, who laughed innocently back again. "And I will do my humble best to govern the country. Still, if the country has the slightest objection——"

But the Crown Prince being generalissimo, and having the whole army at his beck and call, so that he could have begun a civil war in no time; the country had, of course, not the slightest objection.

So the king and queen slept together in peace, and Prince Dolor reigned over the land—that is, his uncle did; and everybody said what a fortunate thing it was for the poor little Prince to have such a clever uncle to take care of him. All things went on as usual; indeed, after the Regent had brought his wife and her seven sons, and established them in the palace, rather better than usual. For they gave such splendid entertainments and made the capital so lively, that trade revived, and the country was said to be more flourishing than it had been for a century.

Whenever the Regent and his sons appeared, they were received with shouts—"Long live the Crown Prince!" "Long live the Royal family!" And, in truth, they were very fine children, the whole seven of them, and made a great show when they rode out together on seven beautiful horses, one height above another, down to the youngest, on his tiny black pony, no bigger than a large dog.

"And, in truth, they were very fine children, the whole seven of them."

"They made a great show when they rode out together on seven beautiful horses."

As for the other child, his Royal Highness Prince Dolor—for somehow people soon ceased to call him his Majesty, which seemed such a ridiculous title for a poor little fellow, a helpless cripple, with only head and trunk, and no legs to speak of—he was seen very seldom by anybody.

Sometimes, people daring enough to peer over the high wall of the palace garden, noticed there, carried in a footman's arms, or drawn in a chair, or left to play on the grass, often with nobody to mind him, a pretty little boy, with a bright intelligent face, and large melancholy eyes—no, not exactly melancholy, for they were his mother's, and she was by no means sad-minded, but thoughtful and dreamy. They rather perplexed people, those childish eyes; they were so exceedingly innocent and yet so penetrating. If anybody did a wrong thing, told a lie for instance, they would turn round with such a grave silent surprise—the child never talked much—that every naughty person in the palace was rather afraid of Prince Dolor.

He could not help it, and perhaps he did not even know it, being no better a child than many other children, but there was something about him which made bad people sorry, and grumbling people ashamed of themselves, and ill-natured people gentle and kind. I suppose, because they were touched to see a poor little fellow who did not in the least know what had befallen him, or what lay before him, living his baby life as happy as the day was long. Thus, whether or not he was good himself, the sight of him and his affliction made other people good, and, above all, made everybody love him. So much so, that his uncle the Regent began to feel a little uncomfortable.

Now, I have nothing to say against uncles in general. They are usually very excellent people, and very convenient to little boys and girls.

Even the "cruel uncle" of "The Babes in the Wood" I believe to be quite an exceptional character. And this "cruel uncle" of whom I am telling was, I hope, an exception too.

He did not mean to be cruel. If anybody had called him so, he would have resented it extremely: he would have said that what he did was done entirely for the good of the country. But he was a man who had been always accustomed to consider himself first and foremost, believing that whatever he wanted was sure to be right, and, therefore, he ought to have it. So he tried to get it, and got it too, as people like him very often do. Whether they enjoy it when they have it, is another question.

Therefore, he went one day to the council-chamber, determined on making a speech and informing the ministers and the country at large that the young King was in failing health, and that it would be advisable to send him for a time to the Beautiful Mountains. Whether he really [Pg 30] meant to do this; or whether it occurred to him afterwards that there would be an easier way of attaining his great desire, the crown of Nomansland, is a point which I cannot decide.

But soon after, when he had obtained an order in council to send the King away—which was done in great state, with a guard of honour composed of two whole regiments of soldiers—the nation learnt, without much surprise, that the poor little Prince—nobody ever called him king now—had gone on a much longer journey than to the Beautiful Mountains.

He had fallen ill on the road and died within a few hours; at least, so declared the physician in attendance, and the nurse who had been sent to take care of him. They brought his coffin back in great state, and buried it in the mausoleum with his parents.

So Prince Dolor was seen no more. The country went into deep mourning for him, and then forgot him, and his uncle reigned in his stead. That illustrious personage accepted his crown with great decorum, and wore it with great dignity, to the last. But whether he enjoyed it or not, there is no evidence to show.

And what of the little lame prince, whom everybody seemed so easily to have forgotten?

Not everybody. There were a few kind souls, mothers of families, who had heard his sad story, and some servants about the palace, who had been familiar with his sweet ways—these many a time sighed and said, "Poor Prince Dolor!" Or, looking at the Beautiful Mountains, which were visible all over Nomansland, though few people ever visited them, "Well, perhaps his Royal Highness is better where he is than even there."

They did not know—indeed, hardly anybody did know—that beyond the mountains, between them and the sea, lay a tract of country, barren, level, bare, except for short stunted grass, and here and there a patch of tiny flowers. Not a bush—not a tree—not a resting-place for bird or beast was in that dreary plain. In summer, the sunshine fell upon it hour after hour with a blinding glare; in winter, the winds and rains swept over it unhindered, and the snow came down, steadily, noiselessly, covering it from end to end in one great white sheet, which lay for days and weeks unmarked by a single footprint.

"One large round tower which rose up

in the center of the plain."

Not a pleasant place to live in—and nobody did live there, apparently. The only sign that human creatures had ever been near the spot, was one large round tower which rose up in the centre of the plain, and might be seen all over it—if there had been anybody to see, which there never was. Rose, right up out of the ground, as if it had grown of itself, like a mushroom. But it was not at all mushroom-like; on the contrary, it was very solidly built. In form, it resembled the Irish round towers, which have puzzled people for so long, nobody being [Pg 32] able to find out when, or by whom, or for what purpose they were made; seemingly for no use at all, like this tower. It was circular, of very firm brickwork, with neither doors nor windows, until near the top, when you could perceive some slits in the wall, through which one might possibly creep in or look out. Its height was nearly a hundred feet high, and it had a battlemented parapet, showing sharp against the sky.

As the plain was quite desolate—almost like a desert, only without sand, and led to nowhere except the still more desolate sea-coast—nobody ever crossed it. Whatever mystery there was about the tower, it and the sky and the plain kept their secret to themselves.

It was a very great secret indeed—a state secret—which none but so clever a man as the present king of Nomansland would ever have thought of. How he carried it out, undiscovered, I cannot tell. People said, long afterwards, that it was by means of a gang of condemned criminals, who were set to work, and executed immediately after they had done, so that nobody knew anything, or in the least suspected the real fact.

And what was the fact? Why, that this tower, which seemed a mere mass of masonry, utterly forsaken and uninhabited, was not so at all. Within twenty feet of the top, some ingenious architect had planned a perfect little house, divided into four rooms—as by drawing a cross within a circle you will see might easily be done. By making skylights, and a few slits in the walls for windows, and raising a peaked roof which was hidden by the parapet, here was a dwelling complete; eighty feet from the ground, and as inaccessible as a rook's nest on the top of a tree.

A charming place to live in! if you once got up there, and never wanted to come down again.

Inside—though nobody could have looked inside except a bird, and hardly even a bird flew past that lonely tower—inside it was furnished with all the comfort and elegance imaginable; with lots of books and toys, and everything that the heart of a child could desire. For its only inhabitant, except a nurse of course, was a poor little solitary child.

One winter night, when all the plain was white with moonlight, there was seen crossing it a great tall black horse, ridden by a man also big and equally black, carrying before him on the saddle a woman and a child. The woman—she had a sad, fierce look, and no wonder, for she was a criminal under sentence of death, but her sentence had been changed to almost as severe a punishment. She was to inhabit the lonely tower with the child, and was allowed to live as long as the child lived—no longer. This, in order that she might take the utmost care [Pg 34] of him; for those who put him there were equally afraid of his dying and of his living. And yet he was only a little gentle boy, with a sweet sleepy smile—he had been very tired with his long journey—and clinging arms, which held tight to the man's neck, for he was rather frightened, and the face, black as it was, looked kindly at him. And he was very helpless, with his poor small shrivelled legs, which could neither stand nor run away—for the little forlorn boy was Prince Dolor.

"He was rather frightened, and the face, black as it was, looked kindly on him."

He had not been dead at all—or buried either. His grand funeral had been a mere pretence: a wax figure having been put in his place, while he himself was spirited away under charge of these two, the condemned woman and the black man. The latter was deaf and dumb, so could neither tell nor repeat anything.

When they reached the foot of the tower, there was light enough to see a huge chain dangling from the parapet, but dangling only half way. The deaf-mute took from his saddle-wallet a sort of ladder, arranged in pieces like a puzzle, fitted it together and lifted it up to meet the chain. Then he mounted to the top of the tower, and slung from it a sort of chair, in which the woman and the child placed themselves and were drawn up, never to come down again as long as they lived. Leaving them there, the man descended the ladder, took it to pieces again and packed it in his pack, mounted the horse, and disappeared across the plain.

Every month they used to watch for him, appearing like a speck in the distance. He fastened his horse to the foot of the tower and climbed it, as before, laden with provisions and many other things. He always saw the Prince, so as to make sure that the child was alive and well, and then went away until the following month.

While his first childhood lasted, Prince Dolor was happy enough. He had every luxury that even a prince could need, and the one thing wanting—love, never having known, he did not miss. His nurse was very kind to him, though she was a wicked woman. But either she had not been quite so wicked as people said, or she grew better through being shut up continually with a little innocent child, who was dependent upon her for every comfort and pleasure of his life.

It was not an unhappy life. There was nobody to tease or ill-use him, and he was never ill. He played about from room to room—there were four rooms—parlour, kitchen, his nurse's bed-room, and his own; learnt to crawl like a fly, and to jump like a frog, and to run about on [Pg 36] all-fours almost as fast as a puppy. In fact, he was very much like a puppy or a kitten, as thoughtless and as merry—scarcely ever cross, though sometimes a little weary. As he grew older, he occasionally liked to be quiet for awhile, and then he would sit at the slits of windows, which were, however, much bigger than they looked from the bottom of the tower,—and watch the sky above and the ground below, with the storms sweeping over and the sunshine coming and going, and the shadows of the clouds running races across the blank plain.

By-and-by he began to learn lessons—not that his nurse had been ordered to teach him, but she did it partly to amuse herself. She was not a stupid woman, and Prince Dolor was by no means a stupid boy; so they got on very well, and his continual entreaty "What can I do? what can you find me to do?" was stopped; at least for an hour or two in the day.

It was a dull life, but he had never known any other; anyhow, he remembered no other; and he did not pity himself at all. Not for a long time, till he grew to be quite a big little boy, and could read easily. Then he suddenly took to books, which the deaf-mute brought him from time to time—books which, not being acquainted with the literature of Nomansland, I cannot describe, but no doubt they were very interesting; and they informed him of everything in the outside world, and filled him with an intense longing to see it.

From this time a change came over the boy. He began to look sad and thin, and to shut himself up for hours without speaking. For his nurse hardly spoke, and whatever questions he asked beyond their ordinary daily life she never answered. She had, indeed, been forbidden, on pain of death, to tell him anything about himself, who he was, or what he might have been. He knew he was Prince Dolor, because she always [Pg 37] addressed him as "my prince," and "your royal highness," but what a prince was he had not the least idea. He had no idea of any thing in the world, except what he found in his books.

He sat one day surrounded by them, having built them up round him like a little castle wall. He had been reading them half the day, but feeling all the while that to read about things which you never can see is like hearing about a beautiful dinner while you are starving. For almost the first time in his life he grew melancholy: his hands fell on his lap; he sat gazing out of the window-slit upon the view outside—the view he had looked at every day of his life, and might look at for endless days more.

Not a very cheerful view—just the plain and the sky—but he liked it. He used to think, if he could only fly out of that window, up to the sky or down to the plain, how nice it would be! Perhaps when he died—his nurse had told him once in anger that he would never leave the tower till he died—he might be able to do this. Not that he understood much what dying meant, but it must be a change, and any change seemed to him a blessing.

"And I wish I had somebody to tell me all about it; about that and many other things; somebody that would be fond of me, like my poor white kitten."

Here the tears came into his eyes, for the boy's one friend, the one interest of his life, had been a little white kitten, which the deaf-mute, kindly smiling, once took out of his pocket and gave him—the only living creature Prince Dolor had ever seen. For four weeks it was his constant plaything and companion, till one moonlight night it took a fancy for wandering, climbed on to the parapet of the tower, dropped over and disappeared. It was not killed, he hoped, for cats have nine lives; indeed, he almost fancied he saw it pick itself up and scamper away, but he never caught sight of it more.

"Yes, I wish I had something better than a kitten—a person, a real live person, who would be fond of me and kind to me. Oh, I want somebody—dreadfully, dreadfully!"

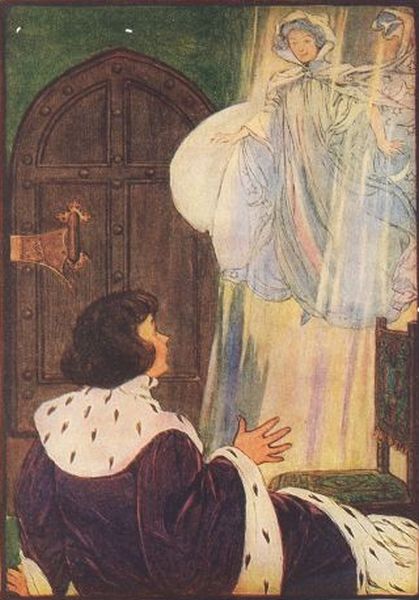

As he spoke, there sounded behind him a slight tap-tap-tap, as of a stick or a cane, and twisting himself round, he saw—what do you think he saw?

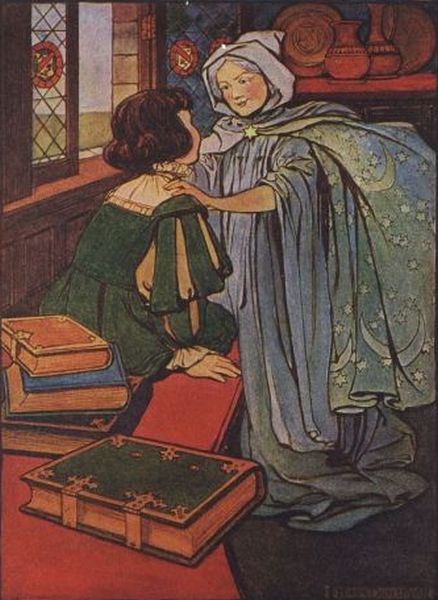

Nothing either frightening or ugly, but still exceedingly curious. A little woman, no bigger than he might himself have been, had his legs grown like those of other children, but she was not a child—she was an old woman. Her hair was grey, and her dress was grey, and there was a grey shadow over her wherever she moved. But she had the sweetest smile, the prettiest hands, and when she spoke it was in the softest voice imaginable.

"My dear little boy,"—and dropping her cane, the only bright and rich thing about her, she laid those two tiny hands on his shoulders—"my own little boy, I could not come to you until you had said you wanted me, but now you do want me, here I am."

"She laid those two tiny hands on his shoulders—

'My own little boy,

I could not come to you until you said you wanted me.'"

"And you are very welcome, madam," replied the Prince, trying to speak politely, as princes always did in books; "and I am exceedingly obliged to you. May I ask who you are? Perhaps my mother?" For he knew that little boys usually had a mother, and had occasionally wondered what had become of his own.

"No," said the visitor, with a tender, half-sad smile, putting back the hair from his forehead, and looking right into his eyes—"No, I am not your mother, though she was a dear friend of mine; and you are as like her as ever you can be."

"Will you tell her to come and see me then?"

"She cannot; but I dare say she knows all about you. And she loves you very much—and so do I; and I want to help you all I can, my poor little boy."

"Why do you call me poor?" asked Prince Dolor in surprise.

The little old woman glanced down on his legs and feet, which he did not know were different from those of other children, and then at his sweet, bright face, which, though he knew not that either, was exceedingly different from many children's faces, which are often so fretful, cross, sullen. Looking at him, instead of sighing, she smiled. "I beg your pardon, my prince," said she.

"Yes, I am a prince, and my name is Dolor; will you tell me yours, madam?"

The little old woman laughed like a chime of silver bells.

"I have not got a name—or rather, I have so many names that I don't know which to choose. However, it was I who gave you yours, and you will belong to me all your days. I am your godmother."

"Hurrah!" cried the little prince; "I am glad I belong to you, for I like you very much. Will you come and play with me?"

So they sat down together, and played. By-and-by they began to talk.

"Are you very dull here?" asked the little old woman.

"Not particularly, thank you, godmother. I have plenty to eat and drink, and my lessons to do, and my books to read—lots of books."

"And you want nothing?"

"Nothing. Yes—perhaps—If you please, godmother, could you bring me just one more thing?"

"What sort of thing?"

"A little boy to play with."

The old woman looked very sad. "Just the thing, alas, which I cannot give you. My child, I cannot alter your lot in any way, but I can help you to bear it."

"Thank you. But why do you talk of bearing it? I have nothing to bear."

"My poor little man!" said the old woman in the very tenderest tone of her tender voice. "Kiss me!"

"What is kissing?" asked the wondering child.

His godmother took him in her arms and embraced him many times. By-and-by he kissed her back again—at first awkwardly and shyly, then with all the strength of his warm little heart.

"You are better to cuddle than even my white kitten, I think. Promise me that you will never go away."

"I must; but I will leave a present behind me—something as good as myself to amuse you—something that will take you wherever you want to go, and show you all that you wish to see."

"What is it?"

"A travelling-cloak."

The Prince's countenance fell. "I don't want a cloak, for I never go out. Sometimes nurse hoists me on to the roof, and carries me round by the parapet; but that is all. I can't walk, you know, as she does."

"The more reason why you should ride; and besides, this travelling-cloak——"

"Hush!—she's coming."

There sounded outside the room door a heavy step and a grumpy voice, and a rattle of plates and dishes.

"It's my nurse, and she is bringing my dinner; but I don't want dinner at all—I only want you. Will her coming drive you away, godmother?"

"Perhaps; but only for a little. Never mind; all the bolts and bars in the world couldn't keep me out. I'd fly in at the window, or down through the chimney. Only wish for me, and I come."

"Thank you," said Prince Dolor, but almost in a whisper, for he was very uneasy at what might happen next. His nurse and his godmother—what would they say to one another? how would they look at one another?—two such different faces: one, harsh-lined, sullen, cross, and sad; the other, sweet and bright and calm as a summer evening before the dark begins.

When the door was flung open, Prince Dolor shut his eyes, trembling all over: opening them again, he saw he need fear nothing; his lovely old godmother had melted away just like the rainbow out of the sky, as he had watched it many a time. Nobody but his nurse was in the room.

"What a muddle your Royal Highness is sitting in," said she sharply. "Such a heap of untidy books; and what's this rubbish?" kicking a little bundle that lay beside them.

"Oh, nothing, nothing—give it me!" cried the prince, and darting after it, he hid it under his pinafore, and then pushed it quickly into his pocket. Rubbish as it was, it was left in the place where she had sat, and might be something belonging to her—his dear, kind godmother, whom already he loved with all his lonely, tender, passionate heart.

It was, though he did not know this, his wonderful travelling-cloak.

And what of the travelling-cloak? What sort of cloak was it, and what good did it do the Prince?

Stay, and I'll tell you all about it.

Outside it was the commonest-looking bundle imaginable—shabby and small; and the instant Prince Dolor touched it, it grew smaller still, dwindling down till he could put it in his trousers pocket, like a handkerchief rolled up into a ball. He did this at once, for fear his nurse should see it, and kept it there all day—all night, too. Till after his next morning's lessons he had no opportunity of examining his treasure.

When he did, it seemed no treasure at all; but a mere piece of cloth—circular in form, dark green in colour, that is, if it had any colour at all, being so worn and shabby, though not dirty. It had a split cut to the centre, forming a round hole for the neck—and that was all its shape; the shape, in fact, of those cloaks which in South America are called ponchos—very simple, but most graceful and convenient.

Prince Dolor had never seen anything like it. In spite of his disappointment he examined it curiously; spread it out on the floor, then arranged it on his shoulders. It felt very warm and comfortable; but it was so exceedingly shabby—the only shabby thing that the Prince had ever seen in his life.

"Prince Dolor had never seen anything like it. In spite of his

disapointment he examined it curiously."

"And what use will it be to me?" said he sadly. "I have no need of outdoor clothes, as I never go out. Why was this given me, I wonder? and what in the world am I to do with it? She must be a rather funny person, this dear godmother of mine."

Nevertheless, because she was his godmother, and had given him the cloak, he folded it carefully and put it away, poor and shabby as it was, hiding it in a safe corner of his toy-cupboard, which his nurse never meddled with. He did not want her to find it, or to laugh at it, or at his godmother—as he felt sure she would, if she knew all.

There it lay, and by-and-by he forgot all about it; nay, I am sorry to say, that, being but a child, and not seeing her again, he almost forgot his sweet old godmother, or thought of her only as he did of the angels or fairies that he read of in his books, and of her visit as if it had been a mere dream of the night.

There were times, certainly, when he recalled her; of early mornings like that morning when she appeared beside him, and late evenings, when the grey twilight reminded him of the colour of her hair and her pretty soft garments; above all, when, waking in the middle of the night, with the stars peering in at his window, or the moonlight shining across his little bed, he would not have been surprised to see her standing beside it, looking at him with those beautiful tender eyes, which seemed to have a pleasantness and comfort in them different from anything he had ever known.

"Even when a little better, he was too weak to enjoy anything, but lay all

day long on his sofa, fidgetting his nurse extremely."

But she never came, and gradually she slipped out of his memory—only a boy's memory, after all; until something happened which made him remember her, and want her as he had never wanted anything before.

Prince Dolor fell ill. He caught—his nurse could not tell how—a complaint common to the people of Nomansland, called the doldrums, as unpleasant as measles or any other of our complaints; and it made him restless, cross, and disagreeable. Even when a little better, he was too weak to enjoy anything, [Pg 46] in her intense terror lest he might die, she fidgetted him still more. At last, seeing he really was getting well, she left him to himself—which he was most glad of, in spite of his dulness and dreariness. There he lay, alone, quite alone.

Now and then an irritable fit came over him, in which he longed to get up and do something, or go somewhere—would have liked to imitate his white kitten—jump down from the tower and run away, taking the chance of whatever might happen.

Only one thing, alas! was likely to happen; for the kitten, he remembered, had four active legs, while he——

"I wonder what my godmother meant when she looked at my legs and sighed so bitterly? I wonder why I can't walk straight and steady like my nurse—only I wouldn't like to have her great noisy, clumping shoes. Still, it would be very nice to move about quickly—perhaps to fly, like a bird, like that string of birds I saw the other day skimming across the sky—one after the other."

These were the passage-birds—the only living creatures that ever crossed the lonely plain; and he had been much interested in them, wondering whence they came and whither they were going.

"How nice it must be to be a bird. If legs are no good, why cannot one have wings? People have wings when they die—perhaps: I wish I was dead, that I do. I am so tired, so tired; and nobody cares for me. Nobody ever did care for me, except perhaps my godmother. Godmother, dear, have you quite forsaken me?"

He stretched himself wearily, gathered himself up, and dropped his head upon his hands; as he did so, he felt somebody kiss him at the back of his neck, and turning, found that he was resting, [Pg 47] not on the sofa-pillows, but on a warm shoulder—that of the little old woman clothed in grey.

How glad he was to see her! How he looked into her kind eyes, and felt her hands, to see if she were all real and alive! then put both his arms round her neck, and kissed her as if he would never have done kissing!

"Stop, stop!" cried she, pretending to be smothered, "I see you have not forgotten my teachings. Kissing is a good thing—in moderation. Only, just let me have breath to speak one word."

"A dozen!" he said.

"Well, then, tell me all that has happened to you since I saw you—or rather, since you saw me, which is a quite different thing."

"Nothing has happened—nothing ever does happen to me," answered the Prince dolefully.

"And are you very dull, my boy?"

"So dull, that I was just thinking whether I could not jump down to the bottom of the tower like my white kitten."

"Don't do that, being not a white kitten."

"I wish I were!—I wish I were anything but what I am!"

"And you can't make yourself any different, nor can I do it either. You must be content to stay just what you are."

The little old woman said this—very firmly, but gently, too—with her arms round his neck, and her lips on his forehead. It was the first time the boy had ever heard any one talk like this, and he looked up in surprise—but not in pain, for her sweet manner softened the hardness of her words.

"Now, my prince—for you are a prince, and must behave as such—let us see what we can do; how much I can do for you, or show you how to do for yourself. Where is your travelling-cloak?"

Prince Dolor blushed extremely. "I—I put it away in the cupboard; I suppose it is there still."

"You have never used it; you dislike it?"

He hesitated, not wishing to be impolite. "Don't you think it's—just a little old and shabby, for a prince?"

The old woman laughed—long and loud, though very sweetly.

"Prince, indeed! Why, if all the princes in the world craved for it, they couldn't get it, unless I gave it them. Old and shabby! It's the most valuable thing imaginable! Very few ever have it; but I thought I would give it to you, because—because you are different from other people."

"Am I?" said the Prince, and looked first with curiosity, then with a sort of anxiety, into his godmother's face, which was sad and grave, with slow tears beginning to steal down.

She touched his poor little legs. "These are not like those of other little boys."

"Indeed!—my nurse never told me that."

"Very likely not. But it is time you were told; and I tell you, because I love you."

"Tell me what, dear godmother?"

"That you will never be able to walk, or run, or jump, or play—that your life will be quite different to most people's lives: but it may be a very happy life for all that. Do not be afraid."

"I am not afraid," said the boy; but he turned very pale, and his lips began to quiver, though he did not actually cry—he was too old for that, and, perhaps, too proud.

Though not wholly comprehending, he began dimly to guess what his godmother meant. He had never seen any real live boys, but he had seen pictures of them; running and jumping; [Pg 49] which he had admired and tried hard to imitate, but always failed. Now he began to understand why he failed, and that he always should fail—that, in fact, he was not like other little boys; and it was of no use his wishing to do as they did, and play as they played, even if he had had them to play with. His was a separate life, in which he must find out new work and new pleasures for himself.

The sense of the inevitable, as grown-up people call it—that we cannot have things as we want them to be, but as they are, and that we must learn to bear them and make the best of them—this lesson, which everybody has to learn soon or late—came, alas! sadly soon, to the poor boy. He fought against it for a while, and then, quite overcome, turned and sobbed bitterly in his godmother's arms.

She comforted him—I do not know how, except that love always comforts; and then she whispered to him, in her sweet, strong, cheerful voice—"Never mind!"

"No, I don't think I do mind—that is, I won't mind," replied he, catching the courage of her tone and speaking like a man, though he was still such a mere boy.

"That is right, my prince!—that is being like a prince. Now we know exactly where we are; let us put our shoulders to the wheel and——"

"We are in Hopeless Tower" (this was its name, if it had a name), "and there is no wheel to put our shoulders to," said the child sadly.

"You little matter-of-fact goose! Well for you that you have a godmother called——"

"What?" he eagerly asked.

"Stuff-and-nonsense."

"Stuff-and-nonsense! What a funny name!"

"Some people give it me, but they are not my most intimate friends. These call me—never mind what," added the old woman, with a soft twinkle in her eyes. "So as you know me, and know me well, you may give me any name you please; it doesn't matter. But I am your godmother, child. I have few godchildren; those I have love me dearly, and find me the greatest blessing in all the world."

"I can well believe it," cried the little lame Prince, and forgot his troubles in looking at her—as her figure dilated, her eyes grew lustrous as stars, her very raiment brightened, and the whole room seemed filled with her beautiful and beneficent presence like light.

He could have looked at her for ever—half in love, half in awe; but she suddenly dwindled down into the little old woman all in grey, and with a malicious twinkle in her eyes, asked for the travelling-cloak.

"Bring it out of the rubbish cupboard, and shake the dust off it, quick!" said she to Prince Dolor, who hung his head, rather ashamed. "Spread it out on the floor, and wait till the split closes and the edges turn up like a rim all round. Then go and open the skylight—mind, I say open the skylight—set yourself down in the middle of it, like a frog on a water-lily leaf; say 'Abracadabra, dum, dum, dum,' and—see what will happen!"

The prince burst into a fit of laughing. It all seemed so exceedingly silly; he wondered that a wise old woman like his godmother should talk such nonsense.

"Stuff-and-nonsense, you mean," said she, answering, to his great alarm, his unspoken thoughts. "Did I not tell you some people called me by that name? Never mind; it doesn't harm me."

And she laughed—her merry laugh—as childlike as if she were the prince's age instead of her own, whatever that might be. She certainly was a most extraordinary old woman.

"Believe me or not, it doesn't matter," said she. "Here is the cloak: when you want to go travelling on it, say Abracadabra, dum, dum, dum; when you want to come back again, say Abracadabra, tum tum ti. That's all; good-bye."

A puff of pleasant air passing by him, and making him feel for the moment quite strong and well, was all the Prince was conscious of. His most extraordinary godmother was gone.

"Really now, how rosy your Royal Highness's cheeks have grown! You seem to have got well already," said the nurse, entering the room.

"I think I have," replied the Prince very gently—he felt kindly and gently even to his grim nurse. "And now let me have my dinner, and go you to your sewing as usual."

The instant she was gone, however, taking with her the plates and dishes, which for the first time since his illness he had satisfactorily cleared, Prince Dolor sprang down from his sofa, and with one or two of his frog-like jumps, not graceful but convenient, he reached the cupboard where he kept his toys, and looked everywhere for his travelling-cloak.

Alas! it was not there.

While he was ill of the doldrums, his nurse, thinking it a good opportunity for putting things to rights, had made a grand clearance of all his "rubbish," as she considered it: his beloved headless horses, broken carts, sheep without feet, and birds without wings—all the treasures of his baby days, which he could not bear to part with. Though he seldom played with them now, he liked just to feel they were there.

They were all gone! and with them the travelling-cloak. [Pg 52] He sat down on the floor, looking at the empty shelves, so beautifully clean and tidy, then burst out sobbing as if his heart would break.

But quietly—always quietly. He never let his nurse hear him cry. She only laughed at him, as he felt she would laugh now.

"And it is all my own fault," he cried. "I ought to have taken better care of my godmother's gift. O, godmother, forgive me! I'll never be so careless again. I don't know what the cloak is exactly, but I am sure it is something precious. Help me to find it again. Oh, don't let it be stolen from me—don't, please!"

"Ha, ha, ha!" laughed a silvery voice. "Why, that travelling-cloak is the one thing in the world which nobody can steal. It is of no use to anybody except the owner. Open your eyes, my prince, and see what you shall see."

His dear old godmother, he thought, had turned eagerly round. But no; he only beheld, lying in a corner of the room, all dust and cobwebs, his precious travelling-cloak.

Prince Dolor darted towards it, tumbling several times on the way,—as he often did tumble, poor boy! and pick himself up again, never complaining. Snatching it to his breast, he hugged and kissed it, cobwebs and all, as if it had been something alive. Then he began unrolling it, wondering each minute what would happen. But what did happen was so curious that I must leave it for another chapter.

If any reader, big or little, should wonder whether there is a meaning in this story, deeper than that of an ordinary fairy tale, I will own that there is. But I have hidden it so carefully that the smaller people, and many larger folk, will never find it out, and meantime the book may be read straight on, like "Cinderella," or "Blue-Beard," or "Hop-o'-my Thumb," for what interest it has, or what amusement it may bring.

Having said this, I return to Prince Dolor, that little lame boy whom many may think so exceedingly to be pitied. But [Pg 54] if you had seen him as he sat patiently untying his wonderful cloak, which was done up in a very tight and perplexing parcel, using skilfully his deft little hands, and knitting his brows with firm determination, while his eyes glistened with pleasure, and energy, and eager anticipation—if you had beheld him thus, you might have changed your opinion.

When we see people suffering or unfortunate, we feel very sorry for them; but when we see them bravely bearing their sufferings, and making the best of their misfortunes, it is quite a different feeling. We respect, we admire them. One can respect and admire even a little child.

When Prince Dolor had patiently untied all the knots, a remarkable thing happened. The cloak began to undo itself. Slowly unfolding, it laid itself down on the carpet, as flat as if it had been ironed; the split joined with a little sharp crick-crack, and the rim turned up all round till it was breast-high; for meantime the cloak had grown and grown, and become quite large enough for one person to sit in it, as comfortable as if in a boat.

The Prince watched it rather anxiously; it was such an extraordinary, not to say a frightening thing. However, he was no coward, but a thorough boy, who, if he had been like other boys, would doubtless have grown up daring and adventurous—a soldier, a sailor, or the like. As it was, he could only show his courage morally, not physically, by being afraid of nothing, and by doing boldly all that it was in his narrow powers to do. And I am not sure but that in this way he showed more real valour than if he had had six pairs of proper legs.

He said to himself, "What a goose I am! As if my dear godmother would ever have given me anything to hurt me. Here goes!"

So, with one of his active leaps, he sprang right into the middle of the cloak, where he squatted down, wrapping his arms tight round his knees, for they shook a little and his heart beat fast. But there he sat, steady and silent, waiting for what might happen next.

Nothing did happen, and he began to think nothing would, and to feel rather disappointed, when he recollected the words he had been told to repeat—"Abracadabra, dum, dum dum!"

He repeated them, laughing all the while, they seemed such nonsense. And then—and then——

Now, I don't expect anybody to believe what I am going to relate, though a good many wise people have believed a good many sillier things. And as seeing's believing, and I never saw it, I cannot be expected implicitly to believe it myself, except in a sort of a way; and yet there is truth in it—for some people.

The cloak rose, slowly and steadily, at first only a few inches, then gradually higher and higher, till it nearly touched the skylight. Prince Dolor's head actually bumped against the glass, or would have done so, had he not crouched down, crying, "Oh, please don't hurt me!" in a most melancholy voice.

Then he suddenly remembered his godmother's express command—"Open the skylight!"

Regaining his courage at once, without a moment's delay, he lifted up his head and began searching for the bolt, the cloak meanwhile remaining perfectly still, balanced in air. But the minute the window was opened, out it sailed—right out into the clear fresh air, with nothing between it and the cloudless blue.

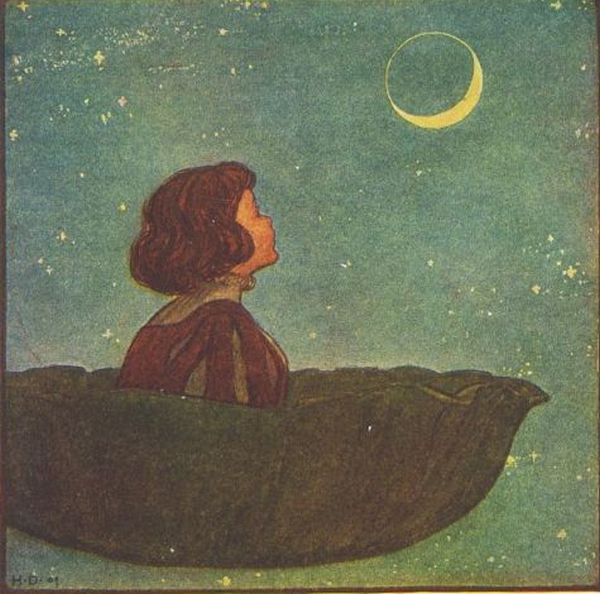

Prince Dolor had never felt any such delicious sensation before! I can understand it. Cannot you? Did you never think, in watching the rooks going home singly or in pairs, oaring their way across the calm evening sky, till they vanish [Pg 56] like black dots in the misty grey, how pleasant it must feel to be up there, quite out of the noise and din of the world, able to hear and see everything down below, yet troubled by nothing and teased by no one—all alone, but perfectly content.

Something like this was the happiness of the little lame Prince when he got out of Hopeless Tower, and found himself for the first time in the pure open air, with the sky above him and the earth below.

True, there was nothing but earth and sky; no houses, no trees, no rivers, mountains, seas—not a beast on the ground, or a bird in the air. But to him even the level plain looked beautiful; and then there was the glorious arch of the sky, with a little young moon sitting in the west like a baby queen. And the evening breeze was so sweet and fresh, it kissed him like his godmother's kisses; and by-and-by a few stars came out, first two or three, and then quantities—quantities! so that, when he began to count them, he was utterly bewildered.

"By-and-by a few stars came out, first two or three, and then quatities!"

By this time, however, the cool breeze had become cold, the mist gathered, and as he had, as he said, no outdoor clothes, poor Prince Dolor was not very comfortable. The dews fell damp on his curls—he began to shiver.

"Perhaps I had better go home," thought he.

But how?—For in his excitement the other words which his godmother had told him to use had slipped his memory. They were only a little different from the first, but in that slight difference all the importance lay. As he repeated his "Abracadabra," trying ever so many other syllables after it, the cloak only went faster and faster, skimming on through the dusky empty air.

The poor little Prince began to feel frightened. What if his wonderful travelling-cloak should keep on thus travelling, perhaps to the world's end, carrying with it a poor, tired, hungry [Pg 57] boy, who, after all, was beginning to think there was something very pleasant in supper and bed?

"Dear godmother," he cried pitifully, "do help me! Tell me just this once and I'll never forget again."

Instantly the words came rushing into his head—"Abracadabra, tum, tum, ti!" Was that it? Ah, yes!—for the cloak began to turn slowly. He repeated the charm again, more distinctly and firmly, when it gave a gentle dip, like a nod of satisfaction, [Pg 58] and immediately started back, as fast as ever, in the direction of the tower.

He reached the skylight, which he found exactly as he had left it, and slipped in, cloak and all, as easily as he had got out. He had scarcely reached the floor, and was still sitting in the middle of his travelling-cloak—like a frog on a water-lily leaf, as his godmother had expressed it—when he heard his nurse's voice outside.

"Bless us! what has become of your Royal Highness all this time? To sit stupidly here at the window till it is quite dark, and leave the skylight open too. Prince! what can you be thinking of? You are the silliest boy I ever knew."

"Am I?" said he absently, and never heeding her crossness; or his only anxiety was lest she might find out anything.

She would have been a very clever person to have done so. The instant Prince Dolor got off it, the cloak folded itself up into the tiniest possible parcel, tied all its own knots, and rolled itself of its own accord into the farthest and darkest corner of the room. If the nurse had seen it, which she didn't, she would have taken it for a mere bundle of rubbish not worth noticing.

Shutting the skylight with an angry bang, she brought in the supper and lit the candles, with her usual unhappy expression of countenance. But Prince Dolor hardly saw it; he only saw, hid in the corner where nobody else would see it, his wonderful travelling-cloak. And though his supper was not particularly nice, he ate it heartily, scarcely hearing a word of his nurse's grumbling, which to-night seemed to have taken the place of her sullen silence.

"She brought in the supper and lit the candles,

with her usual unhappy

expression ... he only saw his wonderful travelling-cloak."

"Poor woman!" he thought, when he paused a minute to listen and look at her, with those quiet, happy eyes, so like his mother's. "Poor woman! she hasn't got a travelling-cloak!"

And when he was left alone at last, and crept into his little bed, where he lay awake a good while, watching what he called his "sky-garden," all planted with stars, like flowers, his chief thought was, "I must be up very early to-morrow morning and get my lessons done, and then I'll go travelling all over the world on my beautiful cloak."

So, next day, he opened his eyes with the sun, and went with a good heart to his lessons. They had hitherto been the chief amusement of his dull life; now, I am afraid, he found them also a little dull. But he tried to be good—I don't say Prince Dolor always was good, but he generally tried to be—and when his mind went wandering after the dark dusty corner where lay his precious treasure, he resolutely called it back again.

"For," he said, "how ashamed my godmother would be of me if I grew up a stupid boy."

But the instant lessons were done, and he was alone in the empty room, he crept across the floor, undid the shabby little bundle, his fingers trembling with eagerness, climbed on the chair, and thence to the table, so as to unbar the skylight—he forgot nothing now—said his magic charm, and was away out of the window, as children say, "in a few minutes less than no time!"

Nobody missed him. He was accustomed to sit so quietly always, that his nurse, though only in the next room, perceived no difference. And besides, she might have gone in and out a dozen times, and it would have been just the same; she never could have found out his absence.

For what do you think the clever godmother did? She took a quantity of moonshine, or some equally convenient material, and made an image, which she set on the window-sill reading, or by the table drawing, where it looked so like Prince Dolor, that any common observer would never have guessed the deception; [Pg 60] and even the boy would have been puzzled to know which was the image and which was himself.

And all this while the happy little fellow was away, floating in the air on his magic cloak, and seeing all sorts of wonderful things—or they seemed wonderful to him, who had hitherto seen nothing at all.

First, there were the flowers that grew on the plain, which, whenever the cloak came near enough, he strained his eyes to look at; they were very tiny, but very beautiful—white saxifrage, and yellow lotus, and ground-thistles, purple and bright, with many others the names of which I do not know. No more did Prince Dolor, though he tried to find them out by recalling any pictures he had seen of them. But he was too far off; and though it was pleasant enough to admire them as brilliant patches of colour, still he would have liked to examine them all. He was, as a little girl I know once said of a playfellow, "a very examining boy."

"I wonder," he thought, "whether I could see better through a pair of glasses like those my nurse reads with, and takes such care of. How I would take care of them too! if only I had a pair!"

Immediately he felt something queer and hard fixing itself on to the bridge of his nose. It was a pair of the prettiest gold spectacles ever seen; and looking downwards, he found that, though ever so high above the ground, he could see every minute blade of grass, every tiny bud and flower—nay, even the insects that walked over them.

"Thank you, thank you!" he cried in a gush of gratitude—to anybody or everybody, but especially to his dear godmother, whom he felt sure had given him this new present. He amused himself with it for ever so long, with his chin pressed on the rim [Pg 61] of the cloak, gazing down upon the grass, every square foot of which was a mine of wonders.

Then, just to rest his eyes, he turned them up to the sky—the blue, bright, empty sky, which he had looked at so often and seen nothing.

Now, surely there was something. A long, black, wavy line, moving on in the distance, not by chance, as the clouds move apparently, but deliberately, as if it were alive. He might have seen it before—he almost thought he had; but then he could not tell what it was. Looking at it through his spectacles, he discovered that it really was alive; being a long string of birds, [Pg 62] flying one after the other, their wings moving steadily and their heads pointed in one direction, as steadily as if each were a little ship, guided invisibly by an unerring helm.

"They must be the passage-birds flying seawards!" cried the boy, who had read a little about them, and had a great talent for putting two and two together and finding out all he could. "Oh, how I should like to see them quite close, and to know where they come from, and whither they are going! How I wish I knew everything in all the world!"

A silly speech for even an "examining" little boy to make; because, as we grow older, the more we know, the more we find out there is to know. And Prince Dolor blushed when he had said it, and hoped nobody had heard him.

Apparently somebody had, however; for the cloak gave a sudden bound forward, and presently he found himself high up in air, in the very middle of that band of ærial travellers, who had no magic cloak to travel on—nothing except their wings. Yet there they were, making their fearless way through the sky.

Prince Dolor looked at them, as one after the other they glided past him; and they looked at him—those pretty swallows, with their changing necks and bright eyes—as if wondering to meet in mid-air such an extraordinary sort of a bird.

"They looked at him ... as if wondering to meet in mid-air

such an

extraordinary sort of bird."

"Oh, I wish I were going with you, you lovely creatures!" cried the boy. "I'm getting so tired of this dull plain, and the dreary and lonely tower. I do so want to see the world! Pretty swallows, dear swallows! tell me what it looks like—the beautiful, wonderful world!"

But the swallows flew past him—steadily, slowly, pursuing their course as if inside each little head had been a mariner's compass, to guide them safe over land and sea, direct to the place where they desired to go.

The boy looked after them with envy. For a long time he followed with his eyes the faint wavy black line as it floated away, sometimes changing its curves a little, but never deviating from its settled course, till it vanished entirely out of sight.

Then he settled himself down in the centre of the cloak, feeling quite sad and lonely.