Title: Tea and Tea Drinking

Author: Arthur Reade

Release date: July 1, 2014 [eBook #46158]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, MWS and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

BY

ARTHUR READE,

AUTHOR OF "STUDY AND STIMULANTS"

London:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188, FLEET STREET.

1884.

[All rights reserved.]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, LIMITED,

ST. JOHN'S SQUARE.

| Page | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Introduction of Tea | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Cultivation of Tea | 18 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Tea-Meetings | 32 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| How to make Tea | 49 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Tea and Physical Endurance | 66 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Tea as a Stimulant | 79 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Friends and the Foes of Tea | 105 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Tea as a Source of Revenue | 134 |

| Page | |

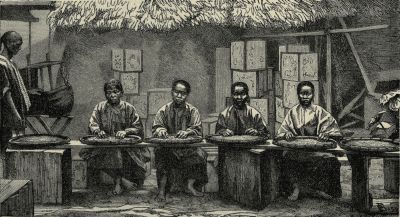

| Sorting Tea in China | Frontispiece |

| A Tea Plantation | 25 |

| Watering a Tea Plantation | 41 |

| Gathering Tea-Leaves | 57 |

| Pressing Tea-Leaves | 73 |

| Pressing Bags of Tea | 89 |

| Drying Tea-Leaves | 108 |

| Sifting Tea | 125 |

| Tea-Tasting in China | 137 |

The question of the influence of tea, as well as that of alcohol and tobacco, has occupied the attention of the author for some time. Apart from its physiological aspect, the subject of tea-drinking is extremely interesting; and in the following pages an attempt has been made to describe its introduction into England, to review the evidence of its friends and foes, and to discuss its influence on mind and health. An account is also given of the origin of tea-meetings, and of the methods of making tea in various countries. Although the book does not claim to be a complete history of tea, yet a very wide range of authors has been consulted to furnish the numerous details which illustrate the usages, the benefits, and the evils (real or imaginary) which surround the habit of tea-drinking.

Introduced by the East India Company—Mrs. Pepys making her first cup of tea—Virtues of tea—Thomas Garway's advertisement—Waller's birthday ode—Tea a rarity in country homes—Introduced into the Quaker School—Extension of tea-drinking—The social tea-table a national delight—England the largest consumer of tea.

"I sent for a cup of tee—a China drink—of which I had never drank before," writes Pepys in his diary of the 25th of September, 1660. It appears, however, that it came into England in 1610; but at ten guineas a pound it could scarcely be expected to make headway. A rather large consignment was, however, received in 1657; this fell into the hands of a thriving London merchant, Mr. [Pg 2]Thomas Garway, who established a house for selling the prepared beverage. Another writer states that tea was introduced by the East India Company early in 1571. Though it may not be possible to fix the exact date, one fact is clear, that it was a costly beverage. Not until 1667 did it find its way into Pepys' own house. "Home," he says, "and there find my wife making of tea, a drink which Mr. Pelling, the potticary, tells her is good for her cold and defluxions." Commenting upon this entry, Charles Knight said, "Mrs. Pepys making her first cup of tea is a subject to be painted. How carefully she metes out the grains of the precious drug which Mr. Pelling, the potticary, has sold her at an enormous price—a crown an ounce at the very least; she has tasted the liquor once before, but then there was sugar in the infusion—a beverage only for the highest. If tea should become fashionable, it will cost in their housekeeping as much as their claret. However, Pepys says the price is coming down, and he produces the handbill of Thomas Garway, in Exchange Alley, which the lady peruses with great satisfaction."

This handbill is an extraordinary production. It is entitled "An exact description of the growth, quality, and virtues of the leaf tea, by Thomas Garway, in Exchange Alley, near the Royal Exchange in London, tobacconist, and seller and retailer of tea and coffee." It sets forth that—

"Tea is generally brought from China, and groweth there upon little shrubs and bushes. The branches whereof are well garnished with white flowers that are yellow within, of the lightness and fashion of sweet-brier, but in smell unlike, bearing thin green leaves about the bigness of scordium, myrtle, or sumack; and is judged to be a kind of sumack. This plant hath been reported to grow wild only, but doth not; for they plant it in the gardens, about four foot distance, and it groweth about four foot high; and of the seeds they maintain and increase their stock. Of this leaf there are divers sorts (though all one shape); some much better than others, the upper leaves excelling the others in fineness, a property almost in all plants; which leaves they gather every day, and drying them in the shade or in iron pans, over a gentle fire, till the humidity be exhausted, then put close up in leaden pots, preserve them for their drink tea, which is used at meals and upon all visits and entertainments in private families, and in the palaces of grandees; and it is averred by a padre of Macao, native of Japan, that the best tea ought to be gathered but by virgins, who are destined for this work. The particular virtues are these; it maketh the body active and lusty; it helpeth the head ache, giddiness and heaviness thereof; it removeth the obstructiveness of the [Pg 4]spleen; it is very good against the stone and gravel, cleaning the kidneys and ureters, being drank with virgin's honey, instead of sugar; it taketh away the difficulty of breathing, opening obstructions; it is good against tipitude, distillations, and cleareth the sight; it removeth lassitude and cleanseth and purifieth acrid humours and a hot liver; it is good against crudities, strengthening the weakness of the ventricle, or stomach, causing good appetite and digestion, and particularly for men of corpulent body, and such as are great eaters of flesh; it vanquisheth heavy dreams, easeth the frame and strengtheneth the memory; it overcometh superfluous sleep, and prevents sleepiness in general, a draught of the infusion being taken; so that, without trouble, whole nights may be spent in study without hurt to the body, in that it moderately healeth and bindeth the mouth of the stomach."

Other remarkable properties are attributed to the Chinese herb; but the extracts we have given sufficiently indicate the efforts made to arrest attention and to induce people to buy tea. As a further inducement, this enterprising dealer assures his readers that whereas tea "hath been sold in the leaf for six pounds, and sometimes for ten pounds the poundweight, the said Thomas hath ten to sell from sixteen to fifty shillings in the pound." This clever puff had the desired effect; for, according to the Diurnal of Thomas Rugge, "There were at this time (1659) a [Pg 5]Turkish drink, to be souled almost in every street, called coffee, and another kind of drink called tea; and also a drink called chocolate, which was a very hearty drink." It was advertised in the public journals. The Mercurius Politicus, of the 30th of September, 1658, sets forth: "That excellent, and by all physicians approved, China drink, called by the Chineans Teha, by other nations Tay, alias Tee, is sold at the 'Sultaness Head' coffee-house, in Sweeting's Rents, by the Royal Exchange, London." It was sold also at "Jonathan's" coffee-house, in Exchange Alley. In her "Bold Strike for a Wife" Mrs. Centlivre laid one of her scenes at "Jonathan's." While the business goes on she makes the coffee boys cry, "Fresh coffee, gentlemen! fresh coffee! Bohea tea, gentlemen!" But the most famous house for tea was Garway's, or, as it appears in "Old and New London," "Garraway's Coffee-house," which was swept away a few years ago in the "march of improvement." For two centuries, however, it had been one of the most celebrated coffee-houses in the city. Defoe mentions it as being frequented about noon by [Pg 6]people of quality who had business in the city, and "the more considerable and wealthy citizens;" but it was also the resort of speculators. Here the South Sea Bubblers met, as well as the lovers of good tea. Dean Swift, in his ballad on the South Sea Bubble, calls 'Change Alley "a narrow sound, though deep as hell;" and describes the wreckers watching for the shipwrecked dead on "Garraway's Cliffs."

But the influence of Royalty did more than anything else to make tea-drinking fashionable. "In 1662," remarks Mr. Montgomery Martin, in a treatise on the 'Past and Present State of the Tea Trade,' published in 1832, "Charles II. married the Princess Catherine of Portugal, who, it was said, was fond of tea, having been accustomed to it in her own country, hence it became fashionable in England." Edmund Waller, in a birthday ode on her Majesty, ascribes the introduction of the herb to the queen, in the following lines:—

Waller is believed to have been the first poet to write in praise of tea, and no doubt his poem did much to promote its use among the rich. In Lord Clarendon's diary, 10th of February, 1688, occurs the following entry:—

"Le Père Couplet supped with me; he is a man of very good conversation. After supper we had tea, which he said was as good as any he had drank in China. The Chinese, who came over with him and Mr. Fraser, supped likewise with us."

In the Tatler, of the 10th of October, 1710, appears the following advertisement:—

"Mr. Favy's 16s. Bohea tea, not much inferior in goodness to the best foreign Bohee tea, is sold by himself only at the 'Bell,' in Gracechurch Street. Note.—The best foreign Bohee is worth 30s. a pound; so that what is sold at 20s. or 21s. must either be faulty tea, or mixed with a proportionate quantity of damaged green or Bohee, the [Pg 8]worst of which will remain black after infusion."

Tea continued a fashionable drink. Dr. Alex. Carlyle, in his "Autobiography," describing the fashionable mode of living at Harrowgate in 1763, wrote:—"The ladies gave afternoon's tea and coffee in their turn, which coming but once in four or six weeks amounted to a trifle." Probably the ladies did not drink so much as their servants, who are reported to have cared more for tea than for ale. In 1755 a visitor from Italy wrote:—"Even the common maid-servants must have their tea twice a day in all the parade of quality; they make it their bargain at first; this very article amounts to as much as the wages of servants in Italy." This demand was a serious tax upon the purses of the rich; for at that time tea was still excessively dear. According to Read's Weekly Journal, or British Gazetteer, of the 27th of April, 1734, the prices were as follows:—

| Green tea | 9s. to 12s. per lb. |

| Congon | 10s. " 12s. " |

| Bohea | 10s. " 12s. " |

| Pekoe | 14s. " 16s. " |

| Imperial | 9s. " 12s. " |

| Hyson | 20s. " 25s. " |

Gradually, however, the prices came down as the consumption increased. In 1740 a grocer, who had a shop at the east corner of Chancery Lane, advertised the finest Caper at 24s. a pound; fine green, 18s.; Hyson, 16s.; and Bohea, 7s. The latter quality was no doubt used in the "Tea-gardens" which at that time had become popular institutions in and around London. The "Mary-le-Bon Gardens" were opened every Sunday evening, when "genteel company were admitted to walk gratis, and were accommodated with coffee, tea, cakes, &c." The quality of the cakes was an important feature at such gardens: "Mr. Trusler's daughter begs leave to inform the nobility and gentry that she intends to make fruit tarts during the fruit season; and hopes to give equal satisfaction as with the rich cakes and almond cheesecakes. The fruit will always be fresh gathered, having great quantities in the garden; and none but loaf-sugar used, and the finest Epping butter." In one respect the "good old times" were better than these. Gone are the "fruit tarts," the "rich cakes," and the fragrant cup of tea from the suburban "Tea-gardens," which rarely supply refreshment [Pg 10]either for man or beast. At any rate, it is a misnomer to call them "Tea-gardens." We think "Beer-gardens" would more accurately indicate their character. Some day, probably, the landlords of "public-houses" and of "tea-gardens," will endeavour to meet the wants and tastes of all persons. At present they utterly ignore the existence of a large class, not necessarily teetotalers, to whom a cup of tea is more cheering than a glass of grog after a long walk from the city.

Among the most famous tea-houses is Twining's in the Strand. It was founded, Mr. E. Walford says, "about the year 1710, by the great-great-grandfather of the present partners, Mr. Thomas Twining, whose portrait, painted by Hogarth, 'kitcat-size,' hangs in the back parlour of the establishment. The house, or houses—for they really are two, though made one practically by internal communication—stand between the Strand and the east side of Devereux Court. The original depôt for the sale of the then scarce and fashionable beverage, tea, stood at the south-west angle of the present premises, on [Pg 11]the site of what had been 'Tom's Coffee-house,' directly opposite the 'Grecian.' A peep into the old books of the firm shows that in the reign of Queen Anne tea was sold by the few houses then in the trade at various prices between twenty and thirty shillings per pound, and that ladies of fashion used to flock to Messrs. Twining's house in Devereux Court, in order to sip the enlivening beverage in their small China cups, for which they paid their shillings, much as now-a-days they sit in their carriages eating ices at the door of Gunter's in Berkeley Square on hot days. The bank was gradually engrafted on the old business, after it had been carried on for more than a century from sire to son, and may be said as a separate institution to date from the commercial panic of 1825."

Although tea was extensively used in London and some of the principal cities, it did not become popular in country houses. "For instance, at Whitby," writes the historian of that town, "tea was very little used a century ago, most of the old men being very much against it; but after the death of the old people it soon came into general use." [Pg 12]Old habits die hard. The stronger beverage of English ale had been so long in use that the old folks could not be induced to relinquish it for a foreign herb. A striking instance of the force of habit is related by Dr. Aikin, in his history of Manchester (1795). "About 1720," he says, "there were not above three or four carriages kept in the town. One of these belonged to Madame ——, in Salford. This respectable old lady was of a social disposition, and could not bring herself to conform to the new-fashioned beverage of tea and coffee; whenever, therefore, she made her afternoon's visit, her friends presented her with a tankard of ale and a pipe of tobacco. A little before this period a country gentleman had married the daughter of a citizen of London; she had been used to tea, and in compliment to her it was introduced by some of her neighbours; but the usual afternoon's entertainment at gentlemen's houses at that time was wet and dry sweetmeats, different sorts of cake, and gingerbread, apples, or other fruits of the season, and a variety of home-made wines." At that time it was the custom for the apprentices to [Pg 13]live with their employers, whose fare was far from liberal; but "somewhat before 1760," remarks Dr. Aikin, "a considerable manufacturer allotted a back parlour with a fire for the use of his apprentices, and gave them tea twice a day. His fees, in consequence, rose higher than had before been known, from 250l. to 300l., and he had three or four apprentices at a time." Tea was evidently a costly beverage, for "water pottage" appears to have been the usual dish provided for apprentices. Those who could afford it, however, drank the Chinese herb. There are many references to tea in "The Private Journal and Literary Remains of John Byrom," a famous Manchester worthy; and these clearly indicate that in the middle of the eighteenth century tea was very generally provided for visitors. But in some towns the older people were much opposed to tea. The prejudice against it was, however, gradually overcome; the young took kindly to it, and the women, especially, found it an agreeable substitute for alcoholic drinks.

Not until 1860 was tea introduced into the Quaker School at Ackworth, where John [Pg 14]Bright received a portion of his early education. When a boy the great orator was unable to endure the Spartan system of training in force there, and after twelve months' experience he was removed to a private school. For breakfast both boys and girls had porridge poured on bread; for dinner little meat, but plenty of pudding. For a third meal no provision seems to have been made. Mr. Henry Thompson, the historian of the school, thus describes the circumstances under which tea was introduced into the school:—

"In the autumn of 1860, Thomas Pumphrey's health having been in a failing condition for some months, he was requested to take a long holiday for the purpose of recruiting it, if possible. On his return, after a three months' absence, learning that the conduct of the children had been everything that he could desire, he devised for them a treat, which was so effectively managed that we believe it is looked upon by those who had the pleasure of participating in it as one of the most delightful occasions of their school-days. He invited the whole family—boys, girls, and teachers—to an evening tea-party. The only room in the establishment in which he could receive so large a concourse of guests was the meeting-house. In response to his kind proposal, willing helpers flew to his aid. The room where all were wont to meet for worship, and rarely for any other purpose, was by nimble and willing fingers transformed, in a few days, into a festive [Pg 15]hall, whose walls and pillars were draped with evergreen festoons and half concealed by bosky bowers, amidst whose foliage stuffed birds perched and wild animals crouched. Amidst the verdant decorations might also be seen emblazoned the names of great patrons of the school and of the five superintendents who for more than eighty years had guided its internal economy. They who witnessed the scene tell us of two wonderful piles of ornamentation which were erected at the entrances to the minister's gallery—the one symbolic of the activities of the physical, the other of the intellectual, moral, and religious life, as its good superintendent would have them to be.... The village having been requisitioned for cups and saucers for this great multitude, the whole school sat down to a genuine, social, English tea table for the first time in its history."

There can be no doubt that milk is better than tea for the young, but tea now forms part of the dietary at almost every school, and we question whether there is a house in England where tea is unknown. Dr. Edward Smith, writing in 1874, said,—

"No one who has lived for half a century can have failed to note the wonderful extension of tea-drinking habits in England, from the time when tea was a coveted and almost unattainable luxury to the labourer's wife, to its use morning, noon, and night by all classes. The caricature of Hogarth, in which a lady and gentleman approach in a very dainty manner, each holding an oriental tea-cup of infantile size, implies more than a satire upon [Pg 16]the porcelain-purchasing habits of the day, and shows that the use of tea was not only the fashion of a select few, but the quantity of the beverage consumed was as small as the tea-cups."

In another chapter we have given some interesting statistics showing the extent of the consumption of this wonderful beverage, which has exercised such an influence for good in this country.

"A curious and not uninstructive work might be written," Dr. Sigmond said in 1839, "upon the singular benefits which have accrued to this country from the preference we have given to the beverage obtained from the tea-plant; above all, those that might be derived from the rich treasures of the vegetable kingdom. It would prove that our national importance has been intimately connected with it, and that much of our present greatness and even the happiness of our social system springs from this unsuspected source. It would show us that our mighty empire in the east, that our maritime superiority, and that our progressive advancement in the arts and the sciences have materially depended upon it. Great indeed are the blessings which have been diffused amongst immense masses of mankind by the cultivation of a shrub whose delicate leaf, passing through a variety of hands, forms an incentive to industry, contributes to health, to national riches, and to domestic happiness. The social tea-table is like the fireside of our country, a national delight; and if it be the scene of domestic converse and agreeable relaxation, it should likewise bid us remember that everything connected with the growth and preparation of this favourite herb should [Pg 17]awaken a higher feeling—that of admiration, love, and gratitude to Him who 'saw everything that He had made, and behold it was very good.'"

Tea is the national drink of China and Japan; and so far back as 1834 Professor Johnston, in his "Chemistry of Common Life," estimated that it was consumed by no less than five hundred millions of men, or more than one-third of the whole human race! Excluding China, England appears to be the largest consumer of tea, as shown in the following table compiled by Mr. Mulhall, and printed in his "Dictionary of Statistics:"—

| Consumption of luxuries per inhabitant per year. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ounces. | ||

| Coffee. | Tea. | |

| United Kingdom | 15 | 72 |

| France | 52 | 1 |

| Germany | 83 | 1 |

| Russia | 3 | 7 |

| Austria | 35 | 1 |

| Italy | 18 | 1 |

| Spain | 4 | 1 |

| Belgium and Holland | 175 | 8 |

| Denmark | 76 | 8 |

| Sweden and Norway | 88 | 2 |

| United States | 115 | 21 |

Description of the tea-plant—Indigenous to China—Introduced into India—Work in a tea-garden—Tea-gatherers in China—A Chinese tea-ballad—How tea is cured—How the value of tea is determined.

The tea-plant formerly occupied a place of honour in every gentleman's green-house; but as it requires much care, and possesses little beauty, it is now rarely seen. Linnæus, the Swedish naturalist, was greatly pleased at a specimen presented to him in 1763, but was unable to keep it alive. Dr. Edward Smith describes the plant as being closely allied to the camellias; but states that the leaf is more pointed, is lance-shaped, and not so thick and hard as that of the camellia. Dr. King Chambers suggests the spending of an afternoon at a classified collection of living [Pg 19]economic plants; such, for instance, as that at the Botanical Gardens, Regent's Park. It is much pleasanter, he points out, to think of tea as connected with the pretty little camellia it comes from, than with blue paper packets, and the despised "grounds" which for ever after acquire an interest in our minds. The tea-plant, although cultivated in various parts of the East, is probably indigenous to China; but is now grown extensively in India. In consequence of the poorness of the quality of the tea imported by the East India Company, and the necessity of avoiding an entire dependence upon China, the Bengal Government appointed in 1834 a committee for the purpose of submitting a plan for the introduction and cultivation of the tea-plant; and a visit to the frontier station of Upper Assam ended in a determination on the part of Government to cultivate tea in that region.[1] In 1840 the [Pg 20]"Assam Company" was formed, and it is claimed for them that they possess the largest tea plantation in the world. Some idea of the progress of tea cultivation in India may be gathered from the following official figures. In 1850 there was one tea-estate, that of the Assam Company, with 1,876 acres under cultivation, yielding 216,000 lbs. In 1870 there were 295 proprietors of tea-estates, with 31,303 acres under cultivation, yielding 6,251,143 lbs. In 1872-73 the area of land held by tea-planters covered 804,582 acres, of which about 75,000 were under cultivation, yielding 14,670,171 lbs. of tea, the average yield per acre being 208 lbs. Every year thousands of acres are being brought under cultivation, and in a short time it seems likely that we shall be independent of China for our supplies of tea. In the year 1879-80 the exports of Indian tea to Great Britain rose to 40,000,000 lbs., [Pg 21]and in the following year to 42,000,000 lbs. In Ceylon, also, a proportionate increase is taking place. The plant appears to be a native of the island. In Percival's "Account of Ceylon," published in 1805, occurs the following paragraph:—

"The tea-plant has been discovered native in the forests of Ceylon. It grows spontaneously in the neighbourhood of Trincomalee and other northern parts of Ceylon.... I have in my possession a letter from an officer in the 80th Regiment, in which he states that he found the real tea-plant in the woods of Ceylon of a quality equal to any that ever grew in China."

A large quantity of tea is now imported from this island, and new plantations, it is reported, are being made every month; day by day more of the primeval forest goes down before the axe of the pioneer, and before another quarter of a century has passed it is anticipated that the teas of our Indian empire will become the most valuable of its products.

The cultivation of tea in India, and the processes to which it is subjected after the leaf is gathered, differ from those of China. [Pg 22]According to Dr. Jameson, the great difficulty of the Indian tea-planter arises from the wonderful fertility of the soil and the strength of the tea-plant. As soon as the plants "flush" the leaf must be plucked, or it deteriorates to such an extent as to become valueless, and at the next "flush" the plant will be found bare of the young leaves. The delay of even a single day may be fatal. The leaf when plucked must be roasted forthwith, or it ferments and becomes valueless, as is also the case in China. There, however, the tea-harvest occurs only four or five times a year, but in India once a fortnight during some seven months of the year. The number of work-people required on a tea-farm may be estimated from the figures given by Dr. Rhind, who says that to manufacture eighty pounds of black tea per day twenty-five tea-gatherers are requisite, and ten driers and sorters; to produce ninety-two pounds of green tea, thirty gatherers and sixteen driers and sorters.

From "A Tea-Planter's Life in Assam" we take the following account of work in a tea-garden:—

"After the soil has been deep-hoed and is quite ready, transplanting from the nursery begins; few men sow the seed at stake. The nursery is made and carefully planted with seed on the first piece of ground that is cleared, so that by the time the remainder of the garden is ready to be planted out the seed has developed into a small plant, with strength enough to stand being transplanted. Holes are prepared at equal distances, into which the young plants are carefully transferred. The greatest caution is exercised in both taking them up and putting them in their new places, that the root shall be neither bent up nor injured in any way. For this work women and children are employed, as it is light, but requires a gentle hand to pat down the earth around the young plant. It speedily accommodates itself to its new circumstances, and thrives wonderfully if the weather is at all propitious. A succession of hot days with no rain has a most disastrous effect on transplants; their heads droop and but a small percentage will be saved, which means that most of the work will have to be done over again. Once started, plenty of cultivation is the only thing required to keep the plant healthy, and it is left undisturbed for a couple of years to increase in size and strength. At the end of the second year, when the cold season has sent the sap down, the pruning knife dispossesses it of its long, straggling top shoots, and reduces it to a height of four feet; every plant is cut to the same level. The third year enables the planter to pluck lightly his first small crop. Year succeeds year, and the crop increases until the eighth or ninth year, when the garden arrives at maturity and yields as much as ever it will. During the rains the gong is beaten at five o'clock every morning, and again at six, thus allowing an hour for those who wish to have something to eat [Pg 24]before commencing the labours of the day. In the cold weather the time for turning out is not so early; even the Eastern sun is lazier, and there is not so much work to get through. Few of the coolies take anything to eat until eleven o'clock, when they are rung in. The leaf plucked by the women is collected and weighed, and most of the men have finished their allotted day's work by this time, so they retire to their huts to eat the morning meal and to pass the remainder of the day in a luxury of idleness. For the ensuing two or three hours there is perfect rest, except for the unfortunate coolies engaged in the tea-house; their work cannot be left, and as fast as the leaf is ready it must be fired off, else it would be completely ruined. At two o'clock the women are turned out again to pluck, and those men who have not finished their hoeing have to return to complete their task. About six o'clock the gong sounds again, the leaf is brought in, weighed, and spread, and outdoor work is over for the day. No change can be made in the tea-house work, which goes on steadily, and if there has been much leaf brought in the day before, firing will very frequently last from daybreak until well into the night, or small hours of the morning."

At present, however, the greater proportion of tea consumed in England comes from China and Japan, which produce no less than 325,000,000 lbs. annually, against 52,000,000 lbs. by India.

India may be the tea-country of the future, but China still supplies nearly all the world. [Pg 25]Millions of acres are devoted to its cultivation, and the late Dr. Wells Williams states that the management of this great branch of industry exhibits some of the best features of Chinese country life. It is only over a portion of each farm that the plant is grown, and its cultivation requires but little attention, compared with rice and vegetables. The most delicate kinds are looked after and cured by priests in their secluded temples among the hills; these have often many acolytes, who aid in preparing small lots to be sold at a high price. But the same authority tells us that the work of [Pg 26]picking the leaves, in the first instance, is such a delicate operation that it cannot be intrusted to women. Female labour is paid so badly that they cannot afford to exercise the gentleness which characterizes their general movements; and when they come upon the scene of operations they make the best of their short harvest.

The second gathering takes place when the foliage is fullest. This season is looked forward to by women and children in the tea-districts as their working time. They run in crowds to the middle-men, who have bargained for the leaves on the plants, or apply to farmers who need help. "They strip the twigs in the most summary manner," remarks Dr. Williams, "and fill their baskets with healthy leaves, as they pick out the sticks and yellow leaves, for they are paid in this manner: fifteen pounds is a good day's work, and fourpence is a day's wages. The time for picking lasts only ten or twelve days. There are curing houses, where families who grow and pick their own leaves bring them for sale at the market rate. The sorting employs many hands, for it is an important point in connection with the purity of the [Pg 27]various descriptions, and much care is taken by dealers, in maintaining the quality of their lots, to have them cured carefully as well as sorted properly."

Like hop-picking in this country, tea-picking is very tedious work, but its monotony is relieved by singing during the live-long day. The songs of the hop-pickers are not generally characterized by loftiness of tone or purity of sentiment, but travellers in China speak highly of the songs of the tea-pickers. For instance, Dr. Williams quotes in his book on "The Middle Kingdom" a ballad of the tea-picker, which he considers one of the best of Chinese ballads, if regard be had to the character of the sentiment and metaphors. One or two verses will give an idea of this charming ballad,—

The method of curing is thus described:—

"When the leaves are brought in to the curers they are thinly spread on shallow trays to dry off all moisture by two or three hours' exposure. Meanwhile the roasting-pans are heating, and when properly warmed some handfuls of leaves are thrown on them, and rapidly moved and shaken up for four or five minutes. The leaves make a slight crackling noise, become moist and flaccid as the juice is expelled, and give off even a sensible vapour. The whole is then poured out upon the rolling-table, when each workman takes up a handful and makes it into a manageable ball, which he rolls back and forth on the rattan table to get rid of the sap and moisture as the leaves are twisted. This operation chafes the hands even with great precaution. The balls are opened and shaken out, and then passed on to other workmen, who go through the same operation till they reach the head-man, who examines the leaves, to see if they have become curled. When properly done, and cooled, they are returned to the iron pans, under which a low charcoal fire is burning in the brickwork which supports them, and there kept in motion by the hand. If they need another rolling on the table it is now given them. An hour or more is spent in this manipulation, when they are dried to a dull-green colour, and can be put away for sifting and sorting. This colour becomes brighter after the exposure in sifting the cured leaves through sieves of various sizes; they are also winnowed to separate the dust, and afterwards sorted into [Pg 29]the various descriptions of green tea. Finally, the finer kinds are again fired three or four times, and the coarser kinds, as Twankay, Hyson, and Hyson-skin, once. The others furnish the young Hyson, gunpowder, imperial, &c. Tea cured in this way is called luh cha, or 'green tea,' by the Chinese, while the other, or black tea, is termed hung cha, or 'red tea,' each name being taken from the tint of the infusion. After the fresh leaves are allowed to lie exposed to the air on the bamboo trays over night or several hours, they are thrown into the air and tossed about and patted till they become soft; a heap is made of these wilted leaves, and left to lie for an hour or more, when they have become moist and dark in colour. They are then thrown on the hot pans for five minutes and rolled on the rattan table, previous to exposure out of doors for three or four hours on sieves, during which time they are turned over and opened out. After this they get a second roasting and rolling, to give them their final curl. When the charcoal fire is ready, a basket, shaped something like an hour-glass, is placed end-wise over it, having a sieve in the middle, on which the leaves are thinly spread. When dried five minutes in this way they undergo another rolling, and are then thrown into a heap, until all the lot has passed over the fire. When this firing is finished, the leaves are opened out and are again thinly spread on the sieve in the basket for a few minutes, which finishes the drying and rolling for most of the heap, and makes the leaves a uniform black. They are now replaced in the basket in greater mass, and pushed against its sides by the hands, in order to allow the heat to come up through the sieve and the vapour to escape; a basket over all retains the heat, but the contents are turned over until perfectly dry and the leaves become uniformly dark."

When this process is completed, every nerve is strained to put the tea into the market quickly, "and in the best possible condition; for, although it is said that the Chinese do not drink it until it is a year old, the value of new tea is superior to that of old; and the longer the duration of a voyage in which a great mass of tea is packed up in a closed hold, the greater the probability that the process of fermentation will be set up. Hence has arisen the great strife to bring the first cargo of the season to England, and the fastest and most skilfully commanded ships are engaged in the trade, both for the profit and honour of success."

Dr. E. Smith, an authority upon the subject, showed that the value of tea is determined in the market by its flavour and body; by the aromatic qualities of its essential oil and the chemical elements of the leaf, rather than by the chemical composition of its juices. Delicacy and fulness of flavour, with a certain body, are the required characteristics of the market. The same authority tells us that the tea-taster prepares his samples from a uniform and very small [Pg 31]quantity, viz. the weight of a new sixpence, and infuses it for five minutes with about four ounces of water in a covered pottery vessel; and in order to prevent injury to his health by repeated tasting, does not swallow the fluid. He must have naturally a sensitive and refined taste, should be always in good health, and able to estimate flavour with the same minuteness at all times.

[1] Russia, also, has become impressed with the importance of growing its own tea; but the efforts of its agriculturists appear to have been unsuccessful. Samples of the produce of the tea-plants which have been acclimatized in Georgia were lately exhibited in the hall of the Agricultural Society of the Caucasus at Tiflis, and appear to have excited considerable interest. The local journals, however, admit that the samples proved to be rather poor in flavour, and that their aroma resembled that of Chinese teas of very inferior quality. It is pleaded, however, that these specimens were grown by a planter of little experience in the Chinese methods of cultivation and preparation, and hopes are entertained of ultimate success.—Manchester Examiner, April 23, 1884.

The teetotalers and tea—Extravagance of ladies—Joseph Livesey—Reformed drunkards as water-carriers—One thousand two hundred persons at one tea-party—How they brewed their tea—How the Anti-Corn-Law League reached the people—Singing the praises of tea—Tea-drinking contests—"Tea-fights"—Hints on tea-meeting fare—Tea as a revolutionary agent.

How did tea-meetings originate? According to a writer in the Newcastle Chronicle, the teetotalers were the first to introduce these popular social gatherings. "Originally started as a medium of raising funds," he says, "they were conducted in a very different style from that so widely adopted at the present day. Our friends knew of no such thing as a contract for the supply of the viands at so much a head, and they had no experience to teach them how many square [Pg 33]yards of bread a pound of butter could be made to cover. Our wives and sweethearts then undertook the purveying and management of our tea-parties. Each took a table accommodating from sixteen to twenty persons, and presided in person. And, oh! what hearty, jolly, comfortable gatherings we used to have in the old Music Hall in Blackett Street, amidst the abundance of singing hinnies, hot wigs, and spice loaf, served up in tempting display, tea of the finest flavour served in the best china from the most elegant of teapots, accompanied with the brightest of spoons, the thickest of cream, and the blandest of smiles! It is much to be regretted that this excess of gratification should have produced an evil which ultimately changed the character of these pleasant assemblies. A spirit of rivalry among the ladies as to who should have the richest and most elegantly-furnished table became so prevalent that their lords and masters were obliged to protest against the excessive expenditure; and thus the ladies, not being allowed to have their own way, declined to take any further share in the [Pg 34]work. This was a great misfortune, as the proceeds considerably augmented the resources of the Temperance Society."

No such fate met these popular gatherings in other towns. They were conducted on a scale of great magnitude, especially in the birthplace of the temperance movement in England, the town of Preston. Here lives Joseph Livesey, the patriarch of the movement, now in his ninety-first year. The third tea-party of the Preston Temperance Society in 1833, at Christmas, is thus described:—

"The range of rooms was most elegantly fitted up for the occasion. The walls were all covered with white cambric, ornamented with rosettes of various colours, and elegantly interspersed with a variety of evergreens. The windows, fifty-six in number, were also festooned and ornamented with considerable taste. The tables, 630 feet in length, were covered with white cambric. At the upper and lower ends of each side-room were mottoes in large characters, 'temperance, sobriety, peace, plenty,' and at the centre of the room connecting the others was displayed in similar characters the motto, 'happiness.' The tables were divided and numbered, and eighty sets of brilliant tea-requisites, to accommodate parties of ten persons each, were placed upon the table, with two candles to each party. A boiler, also capable of containing 200 gallons, was set up in Mr. Halliburton's yard, to heat [Pg 35]water for the occasion, and was managed admirably by those reformed characters. About forty men, principally reformed drunkards, were busily engaged as waiters, water-carriers, &c.; those who waited at the tables wore white aprons, with 'temperance' printed on the front. The tables were loaded with provisions, and plenty seemed to smile upon the guest. A thousand tickets were printed and sold at 6d. and 1s. each, but the whole company admitted is supposed to be about 1200; 820 sat down at once, and the rest were served afterwards. The pleasure and enjoyment which beamed from every countenance would baffle every attempt at description, and the contrast betwixt this company and those where intoxicating liquors are used is an unanswerable argument in favour of temperance associations."

A tea-party at Liverpool, in 1836, was attended by a greater number, and the account shows very clearly that the early temperance gatherings will contrast favourably with the large Blue Ribbon meetings held at the present time:—

"The great room where tea was provided was fitted up in a style of elegance surpassing anything we could have imagined. The platform and the orchestra for the band were most tastefully decorated. The beams and walls of the building were richly ornamented with evergreens and appropriate mottoes. The tables were laid out with tea-equipages interspersed with flower-pots filled with roses. When the parties sat down, in number about 2500, a most imposing sight presented itself. Wealth, beauty, [Pg 36]and intelligence were present; and great numbers of reformed characters respectably clad, with their smiling partners, added no little interest to the scene, which was beyond the power of language to describe."

In 1837 the Isle of Man Temperance Guardian reported a tea-meeting at Leeds, at which nearly 700 persons sat down; another at Bury, where "500 of both sexes sat down." A tea-party at Exeter is thus described:—"The arrangements were very judicious, and nearly 400 made merry with the 'cup that cheers, but not inebriates,' among whom were numbers of highly respectable ladies and citizens of Exeter. This novel feature presented a most interesting and gratifying sight, from the spirit of cordiality and good-feeling which pervaded it, and cannot but have the most beneficial effect upon society." For the benefit of societies which had not adopted this new and successful method of reaching the public, the secretary of the Bristol Society gave the following account of a Christmas tea-party:—"The tables were provided with tea-services, milk, sugar, cakes and bread and butter, and [Pg 37]one waiter appointed to each, who was furnished with a bright, clean tea-kettle, while the tea, which was previously made, stood in a corner of the room in large barrels, with a tap in each, from which each waiter drew his supply as required, and filled the cups when empty, without noise, confusion, or delay." The following receipt for tea-making was given in the Preston Temperance Advocate, of July, 1836:—

"At the tea-parties in Birmingham they made the tea in large tins, about a yard square, and a foot deep, each one containing as much as will serve about 250 persons. The tea is tied loosely in bags, about ¼lb. in each. At the top there is an aperture, into which the boiling water is conveyed by a pipe from the boiler, and at one corner there is a tap, from which the tea when brewed is drawn out. It may be either sweetened or milked, or both, if thought best, while in the tins. Being thus made, it can be carried in teapots, or jugs, where those cannot be had. Capital tea was made at the last festival by this plan."

Considering the high price of tea and of bread at that time, it is scarcely credible that a charge of 9d. per head for men and women, and of 6d. for "youths under fourteen," was found sufficient to defray the cost, as well as to benefit the funds of the Temperance Society. The value of such [Pg 38]gatherings to the temperance movement it is impossible to estimate. Weaned from the use of fiery beverages, the reformed drunkard needed a substitute which would be at once harmless, as well as stimulating. In tea he found exactly what he wanted. He needed, moreover, company of an elevating kind; and in the tea-party he found the craving for the companionship of men and women fully satisfied. It was by this agency chiefly that the converts to teetotalism were kept together and instructed in the principles of total abstinence from all intoxicating liquors; and we are not surprised that the consumption of drink fell off largely in consequence. Dr. J. H. Curtis, writing in 1836, contended that the introduction of tea and coffee into general use had done much towards reducing the consumption of intoxicating drinks; and, although the expenditure upon intoxicating drinks still remains a formidable amount, there can be no doubt that the general use of tea has lessened the consumption of alcohol.

These gatherings continue very popular, but do not draw such large numbers as in the early days of the movement; but it is [Pg 39]open to question whether the time spent upon them might not be more profitably employed. A writer in the Band of Hope Chronicle (January, 1882) calls attention to this aspect of tea-meetings:—"There should be," he contends, "moderation even in tea-drinking, and when we hear of four or five hours at a stretch being spent over this process at public gatherings, as it seems the good folks do in some parts of the Isle of Man, one cannot but feel there is need for improvement. What would be thought if the time were occupied with the consumption of stronger beverages than tea. There would be little prospect of orderliness in the after-proceedings then; so, anyhow, the tea-drinkers have the best of it even when they are at their worst."

The example of the teetotalers was followed by other reformers. The Preston Temperance Advocate, of October, 1837, says:—"A tea-party was held at Salford, in honour of the return of Joseph Brotherton, Esq., M.P., for this town, to which he was invited. It was attended by 1050 persons, nearly 900 of whom were ladies, and the spectacle presented to the eye by such an assemblage was one of [Pg 40]the most pleasing which I have ever witnessed." The Anti-Corn-Law League also adopted similar means of bringing their friends and subscribers together. "On the 23rd of November, 1842," writes Mr. Archibald Prentice, the historian of the movement, "the first of a series of deeply-interesting soirées in Yorkshire, in furtherance of the great object of Corn-Law Repeal, was celebrated in the saloon, beautifully decorated for the occasion, of the Philosophical Hall, Huddersfield. The occasion, says the Leeds Mercury, was one of high importance, not only for the dignity and benevolence of the object contemplated, but for the enthusiastic spirit manifested by the assembly of both sexes, of the first respectability, extensive in number, and intelligent and influential in its character. More than 600 persons sat down to tea, and more than double that number would have been present had it been possible to provide accommodation." Mr. Prentice records many other tea-meetings attended by 600 and 800 persons. "In Manchester," writes Mr. Henry Ashworth, "a number of ladies took up the Corn-Law question, and [Pg 41]held an Anti-Corn-Law tea-party, which was attended by 830 persons."

A hymn was specially composed for use at temperance gatherings, its purport being to show the superiority of tea-meetings over public-house meetings. It consisted of eight verses, and was printed in the Moral Reformer of February, 1833. One verse will give an idea of its character:—

Total abstinence has not yet found much favour among artists, who too often paint the fleeting pleasures of the wine-cup rather than the enduring pleasures of temperance; but in Mr. Collingwood Banks we have an artist who can sing the praises of a cup of tea as well as paint the charms of a fireside tea-table. To him we are indebted for the following song, which ought speedily to become popular among temperance societies:—

"THE CUP FOR ME.

Another hymn in praise of tea was used in Cornwall, and often sung at tea-meetings by the Rev. J. G. Hartley, a minister of the United Methodist Free Churches. The lines possess little poetical merit, but are worth quoting on account of the pleasure with which they have been received by tens of thousands of people, and of their influence in unlocking the pockets of the people when the box went round.

"It has served us many a good turn," writes Mr. Hartley, "and has helped to clear many a chapel-debt." It would be difficult, no doubt, in our day to cite a single case of a tea-party attended by 500 persons; but if large gatherings are fewer, small ones are more frequent. Every chapel, every church, every day-school, every Sunday-school, every religious association has at least four tea-parties a year: and thus not only is a very large amount of tea consumed, but a very [Pg 45]large number of people are brought under good influences.

In rural districts the Christmas tea-party is the event of the year. It is attended by all the lads and lasses in the neighbourhood; by the milkmaids and the ploughmen, who make sad havoc with the cake. Wonderful, also, is the amount of tea consumed. In fact a tea-drinking contest takes place at these annual reunions. At any rate he is the hero of the table who can drink the most.

We have referred to the decreasing popularity of tea-meetings, and believe that one way of reviving the interest in these festivals would be to provide better refreshments, as well as a greater variety. From the Land's End to John O'Groats, the bill of fare is limited to currant-cake and bread and butter of the cheapest kind. In some cases, where the charge is a shilling per head, beef and sandwiches are provided. An announcement of "a knife and fork tea" at a Primitive Methodist Chapel never fails to secure a good attendance of the members and friends. In Lancashire such meetings are not unfrequently called "tea-fights," probably on [Pg 46]account of the scramble for sandwiches which characterizes the proceedings. But neither cake nor sandwich is sufficient to tempt all who are interested in these social entertainments. The promoters would do well to follow the example of the Vegetarian Society, and provide more fruit and substantial bread, both white and brown. In summer all the fruits in season should be placed upon the tables, and in winter stewed fruits. The following hints on "Tea-Meeting Fare," written by the late Mr. R. N. Sheldrick, who was an active missionary agent of the Vegetarian Society, may prove of service to all who cater for tea-meetings:—

"1. Provide good tea, pure, fresh-ground coffee, cocoa, &c. Let the making of these decoctions be superintended by an experienced friend; serve up nice and hot, but without milk or sugar, leaving these to be added or not, according to individual tastes.

"2. Procure a plentiful supply of good whole-meal wheaten (brown) bread, some white bread, some currant-cake—home-baked if possible, without dripping or lard; two or three varieties of Reading biscuits, such as Osborne, tea, picnic, arrowroot, &c.

"3. Purchase from the nearest market sufficient lettuce, kale, celery, cress, and other fresh salads according to season; also provide a liberal supply of figs, muscatels, almonds, nuts, oranges, apples, pears, plums, cherries, [Pg 47]strawberries, peaches, or such other fruit as may be in season.

"4. Take care, whatever arrangement be adopted, not to let these things be hidden away until the latter part of the feast. Fruits should have the place of honour. The plates or baskets of fruit should have convenient positions along the tables with the bread and butter, biscuits, &c.

"5. Place the arrangements under the control of a well-selected committee of ladies, who will see that the tables are tastefully laid out, and that everybody is supplied. Let there be also, if possible, a profusion of fresh-cut flowers."

Tea, it is true, has not yet worked a complete revolution in the habits of the people, but it has done much to lessen intemperance. Dr. Sigmond, writing nearly half a century ago, referred to its influences for good: "Tea has in most instances," he said, "been substituted for fermented or spirituous liquors, and the consequence has been a general improvement in the health and in the morals of a vast number of persons. The tone, the strength, and the vigour of the human body are increased by it; there is a greater capability of enduring fatigue; the mind is rendered more susceptible of the innocent pleasures of life, and of acquiring information. Whole classes of the community [Pg 48]have been rendered sober, careful, and provident. The wasted time that followed upon intemperance kept individuals poor, who are now thriving in the world and exhibiting the results of honest industry. Men have become healthier, happier, and better for the exchange they have made. They have given up a debasing habit for an innocent one. The individuals who were outcasts, miserable, abandoned, have become independent and a blessing to society. Their wives and their children hail them on their return home from their daily labours with their prayers and fondest affections, instead of shunning their presence, fearful of some barbarity, or some outrage against their better feelings; cheerfulness and animation follow upon their slumbers, instead of the wretchedness and remorse which the wakening drunkard ever experiences."

This picture, it will be observed, is a little over-coloured; but, in the main, it will be granted that tea and other similar beverages have done a good deal to displace spirituous and fermented liquors. The use of tea has certainly resulted in great benefit to the health and morals of the people.

The Siamese method of making tea—A three-legged teapot—Advice of a Chinese poet—How tea should be made—How Abernethy made tea for his guests—The "bubbling and loud-hissing urn"—Tate's description of a tea-table—The tea of public institutions—Rev. Dr. Lansdell on Russian tea—The art of tea-making described—The kind of water to be used. The Chinese method of making tea—Invalids' tea—Words to nurses, by Miss Nightingale.

The mode of preparation of tea for the table has always given rise to discussion. Different nations have different methods. In Siam one method was thus described in a book entitled "Relation of the Voyage to Siam by Six Jesuits," which was published in 1685. "In the East they prepare tea in this manner: when the water is well boiled, they pour it upon the tea, which they have put [Pg 50]into an earthen pot, proportionally to what they intend to take (the ordinary proportion is as much as one can take up with the finger and thumb for a pint of water); then they cover the pot until the leaves are sunk to the bottom of it, and afterwards serve it about in china dishes to be drunk as hot as can be, without sugar, or else with a little sugar-candy in the mouth; and upon that tea more boiling water may be poured, and so it may be made to serve twice. These people drink of it several times a day, but do not think it wholesome to take it fasting."

In "Recreative Science" (vol. i., 1821) there appears a very curious note relating to the translation of a Chinese poem. The editor says,—"Kien Lung, the Emperor of the Celestial Empire, which is in the vernacular China, was also a poet, and he has been good enough to give us a receipt also—would that all didactic poetry meddled with what its author understood. The poet Kien did, and he has left the following recipe how to make tea, which, for the benefit of the ladies who study the domestic cookery, is inserted: 'set an old three-legged teapot [Pg 51]over a slow fire; fill it with water of melted snow; boil it just as long as is necessary to turn fish white or lobsters red; pour it on the leaves of choice, in a cup of Youe. Let it remain till the vapour subsides into a thin mist, floating on the surface. Drink this precious liquor at your leisure, and thus drive away the five causes of sorrow.'"

Poets, as everybody knows, are allowed a good deal of licence, and tea-maids may be pardoned if they are sceptical of the value of the advice of the Chinese poet. How, then, should tea be made? First and foremost, remarks Dr. Joseph Pope, it should be remembered that tea is an infusion, not an extract. An old verse runs thus:—

Dr. Pope lays emphasis on the word flows; it does not say soak. There is, he contends, an instantaneous graciousness, a momentary flavour that must be caught if we would rightly enjoy tea. Assuredly Dr. Abernethy, the celebrated surgeon, must be credited [Pg 52]with the possession of this "instantaneous graciousness." "Abernethy," said Dr. Carlyon, in his "Early Years and Late Reflections," "never drank tea himself, but he frequently asked a few friends to come and take tea at his rooms. Upon such occasions, as I infer from what I myself witnessed, his custom was to walk about the room and talk most agreeably upon such topics as he thought likely to interest his company, which did not often consist of more than two or three persons. As soon as the tea-table was set in order, and the boiling water ready for making the infusion, the fragrant herb was taken, not from an ordinary tea-caddy, but from a packet consisting of several envelopes curiously put together, in the centre of which was the tea. Of this he used at first as much as would make a good cup for each of the party; and to meet fresh demands I observed that he invariably put an additional tea-spoonful into the teapot; the excellence of the beverage thus prepared insuring him custom. He had likewise a singular knack of supplying each cup with sugar from a considerable distance, by a jerk [Pg 53]of the hand, which discharged it from the sugar-tongs into the cup with unerring certainty, as he continued his walk around the table, scarcely seeming to stop whilst he performed these and the other requisite evolutions of the entertainment."

If every woman had treated her guests in the same manner, there would have been little outcry against tea. The innovation of a "bubbling and loud-hissing urn" was strongly condemned by Dr. Sigmond, who, writing in 1839, after quoting Cowper, remarked: "Thus sang one of our most admired poets, who was feelingly alive to the charms of social life; but, alas! for the domestic happiness of many of our family circles, this meal has lost its character, and many of those innovations which despotic fashion has introduced have changed one of the most agreeable of our daily enjoyments. It is indeed a question amongst the devotees to the tea-table, whether the bubbling urn has been practically an improvement upon our habits; it has driven from us the old national kettle, once the pride of the fireside. The urn may be fairly called the offspring [Pg 54]of indolence; it has deprived us, too, of many of those felicitous opportunities of which the gallant forefathers of the present race availed themselves to render them amiable in the eyes of the fair sex, when presiding over the distribution

The consequence of this injudicious change is, that one great enjoyment is lost to the tea-drinker—that which consists in having the tea infused in water actually hot, and securing an equal temperature when a fresh supply is required. Such, too, is what those who have preceded us would have called the degeneracy of the period in which we live, that now the tea-making is carried on in the housekeeper's room, or in the kitchen—

What, he asks, can be more delightful than those social days described by Tate, the poet-laureate?

Fortunately for the lovers of the teapot and the kettle, a change in the fashion of making tea is taking place, the "loud-hissing urn" being now confined almost exclusively to a public tea-party and the coffee tavern. The quality of tea and coffee supplied by the latter institution has long been considered the blot upon an otherwise excellent movement. Not too severely did the Daily Telegraph speak a short time ago against the atrocious stuff supplied under the name of tea in public institutions. The editor said,—

"The very look of it is no longer encouraging. It is either a pale, half-chilled, unsatisfactory beverage, or it contains a dark black-brown settlement from over-boiled tea-leaves. The consumption of tea, no doubt, in England is enormous, and we boast to foreigners that we are fond of our tea; the fashion of tea-drinking, owing mainly to our example, has extended to France, once extremely heretical on the point; and yet where is the foreigner to [Pg 56]find a good cup of tea in England? At the railway stations? Very rarely. At the restaurants? Scarcely ever. And at the newly-started tea and coffee palaces, which are to promote sobriety, the great and crying complaint is that the tea and coffee are so poor that the best-intentioned people are forced back to the dangerous public-house, in order to obtain a little stimulant, for it is idle to deny that both tea and coffee are stimulating to the constitution. Everywhere a great reform in tea is required. Once on a time no confectioner, railway-station, or refreshment-house could rival the home-made brew, made under the eye of the mistress of the household, with the kettle on the hob and the ingredients at hand; but now that the good old custom of tea-making is considered unladylike, and the manufacture has been handed over to the servants, the great charm of the beverage has virtually departed. No one can conscientiously say that they like English tea as at present administered, for the very good reason that it is no longer prepared scientifically. The English fashion of drinking tea would be laughed to scorn by the educated Chinaman or the accomplished Russian. Indeed, it is surprising in how few houses a good cup of tea can be obtained now that it has become unfashionable for the mistress of the establishment, not only to preside over her own tea-table, but to have complete sway over that most necessary article, a kettle of boiling water. The Chinese never dream of stewing their tea, as we too often do in England. They do not drown it with milk or cream, or alter its taste with sugar, but lightly pour boiling water on a small portion of the leaves. It is then instantly poured off again, by which the Chinaman obtains only the more volatile and stimulating portion of its principle. The [Pg 57]most delicious of all tea, however, can be tasted in Russia—supposed to import the best of the Chinese leaves, as it imports the best of French champagne."

According to the Rev. Dr. Lansdell, however, the Russians do not pay extravagantly for their tea, "When crossing the Pacific," he says, "I fell in with a tea-merchant homeward bound from China, and from him I gathered that three-fourths of the Russian trade is done in medium and common teas, such as are sold in London in bond from 1s. 2d. [Pg 58]down to 8d. per English pound, exclusive of the home duty. The remaining fourth of their trade includes some of the very best teas grown in the Ning Chou districts—teas which the Russians will have at any price, and for which in a bad year they may have to pay as much as 3s. a pound in China, though in ordinary years they cost from 2s. upwards. The flowery Pekoe, or blossom tea, costs also about 3s. in China." But Dr. Lansdell heard of some kind of yellow tea which cost as much as five guineas a pound, the Emperor of China being supposed to enjoy its monopoly; but a friend of the doctor told him that he did not think it distinguishable from that sold at 5s. a pound.

The excellence of the Russian tea is attributed, in part, to the fact that it is carried overland. "Whilst travelling eastwards," says Dr. Lansdell, "we had frequently met caravans or carts carrying tea. These caravans sometimes reach to upwards of 100 horses; and as they go at walking pace, and when they come to a river are taken over by ferry, it is not matter for surprise that merchandise should be three months in coming [Pg 59]from Irkutsk to Moscow." Whatever the cause, all travellers eulogize the Russians as tea-makers. Dr. Sigmond, for instance, says,—

"My own experience of the excellence of tea in Russia arose out of a curious incident, which occurred to me during a hasty visit I made to that highly-interesting country. Previous to this adventure, I had been in the habit of taking coffee as my ordinary beverage, and was by no means satisfied with it. I had no idea of the prevailing habit of tea-drinking, previous to my arrival, at Moscow. In the course of the afternoon I left my hotel alone, obtaining from my servant a card, with the name of the street, La Rue de Demetrius, written upon it. I wandered about that magnificent citadel, the Kremlin, until dark, and I found myself at some distance from the point from which I started, and I endeavoured to return to it, and asked several persons the way to my street, of which they all appeared ignorant. I therefore got into one of the drotzskies, and intimated to my Cossack driver that I should be enabled to point out my own street. Although we could not understand each other, we did our mutual signs; and with the greatest cheerfulness and good-nature this man drove me through every street, but I could nowhere recognize my hotel. He therefore drove me to his humble abode in the environs; he infused the finest tea that I had ever seen in a peculiarly-shaped saucepan, set it on a stove, and this, when nearly boiled, he poured out; and a more delicious beverage, nor one more acceptable after a hard day's fatigue and anxiety, I have not tasted."

Other travellers refer to the excellence of [Pg 60]tea in Russia. If we could have an improvement in the quality of tea made in England, we feel sure that a decrease in the consumption of intoxicating drinks would result.

Some reform has already taken place at railway-stations. For the reduction of the price of a cup of tea from sixpence to fourpence on the Great Northern Railway the public are indebted to the Hon. Reginald Capel, Chairman of the Refreshment-Rooms and Hotels' Committee of that company. On the Midland Railway, also, a reduction in the price of non-intoxicating beverages has been made. At the present time the coffee taverns stand most in need of reform.

With the object of inducing our tea-makers to reform their methods of tea-making, we quote some important recommendations of leading physicians. Dr. King Chambers, in his valuable manual of "Diet in Health and Disease," remarks that the uses of tea are (1) to give an agreeable flavour to warm water required as a drink; (2) to soothe the nervous system when it is in an uncomfortable state from hunger, fatigue, or mental excitement. The best tea therefore is, he contends, that which [Pg 61]is pleasantest to the taste of the educated consumer, and which contains most of the characteristic sedative principles. As Dr. Poore has pointed out, tannic acid, which is one of the dangers as well as one of the pleasures of tea, is largely present in the common teas used by the poor. "The rich man," he says, "who wishes to avoid an excess of tannic acid in the 'cup that cheers,' does not allow the water to stand on the tea for more than five, or at most eight minutes, and the resulting beverage is aromatic, not too astringent, and wholesome. The poor man or poor woman allows the tea to simmer on the hob for indefinite periods, with the result that a highly astringent and unwholesome beverage is obtained. There can be no doubt that the habit of drinking excessive quantities of strong astringent tea is a not uncommon cause of that atonic dyspepsia, which seems to be the rule rather than the exception among poor women of the class of sempstresses." The late Dr. Edward Smith devoted considerable attention to this subject, and we cannot do better than quote his observations:—"The aim should be to [Pg 62]extract all the aroma and dried juices containing theine, with only so much of the substance of the leaf as may give fulness, or, as it is called, body to the infusion. If the former be defective, the respiratory action of the tea and the agreeableness of the flavour will be lessened, whilst if the latter be in excess there will be a degree of bitterness which will mash the aromatic flavour. As the theine is without flavour, its presence or absence cannot be determined by the taste of the tea. All agree, therefore, that the tea should be cooked in water, and that the water should be at the boiling-point when used; but there is not an agreement as to the duration of the infusing process. If the tea be scented or artificially flavoured, the aroma may be extracted in two minutes, but the proper aromatic oil of the tea requires at least five minutes for its removal. If flavour is to be considered, it is clear that an inferior tea should not be infused so long as a fine tea.

"The kind of water is believed to have great influence over the process; soft water is preferred. The Chinese direction is, 'Take it from a running stream; that from mill-springs [Pg 63]is the best, river-water is the next, and well-water is the worst;' that is to say, take water well mixed with air. Hence avoid hard water, but prefer tap-water or running water to well-water. It is the practice of a good housewife in the country to send to a brook for water to make tea, whilst she will use the well water for drinking." The mode of making tea in China is to put the tea into a cup, to pour hot water upon it, and then to drink the infusion off the leaves. While wandering over the tea-districts of China, Mr. Fortune only once met with sugar and a tea-spoon. "The merchant invited us to drink tea," writes the Rev. Dr. Lansdell, who recently visited the Mongolian frontier at Maimatchin, "and told us that the Chinese use this beverage without sugar or milk three times a day; namely, at rising, at noon, and at seven in the evening. They have substantial meals at nine in the morning and four in the afternoon." Dr. King Chambers considers tea most refreshing to the dyspeptic if made in the Russian fashion, with a slice of lemon on which a little sugar-candy has been sprinkled, instead of milk or cream. One small cup of an evening is [Pg 64]enough. He also gives the following receipt for making invalids' tea:—

"Pour into a small china or earthenware teapot a cup of quite boiling water, empty it out, and while it is still hot and steaming put in the tea and enough boiling water to wet it thoroughly, and set it close to the fire to steam three or four minutes. Then pour in the quantity of water required, boiling from the kettle, and it is ready for use." Miss Nightingale offers a word of advice to nurses upon the amount of tea which should be given. "A great deal too much against tea is," she remarks, "said by wise people, and a great deal too much of it is given to the sick by foolish people. When you see the natural and almost universal craving in English sick for their tea, you cannot but feel that Nature knows what she is about. But a little tea or coffee restores them quite as much as a great deal; and a great deal of tea, and especially of coffee, impairs the little power of digestion they have; yet a nurse, because she sees how one or two cups of tea or coffee restore her patient, thinks three or four cups will do twice as much. This is [Pg 65]not the case at all: it is, however, certain that there is nothing yet discovered which is a substitute to the English patient for his cup of tea."

Tea and dry bread versus porter and beefsteak—Tea for soldiers—Opinion of Professor Parkes—Tea versus spirits—Tea and Tel-el-Kebir—Lord Wolseley's testimony—Pegs and teapots—Temperance in the navy—Drinking the health of her Majesty in a bowl of tea—Cycling and tea-drinking—Mountain-climbing—Tea in the harvest-field—Cold tea as a summer drink.

Tea is not only a valuable stimulant to the mind, but is the most beneficial drink to those engaged in fatiguing work. Dr. Jackson, whom Buckle quotes as an authority, testified in 1845, that even for those who have to go through great fatigues a breakfast of tea and dry bread is more strengthening than one of beefsteak and porter. "I have been," says Dr. Inman, "a careful reader of all those accounts which tell of endurance of prolonged fatigue, and have [Pg 67]been touched with the almost unanimous evidence in favour of vegetable diet and tea as a beverage, that I have determined in every instance where long nursing, as of a fever patient, is required, to recommend nothing stronger than tea for the watcher." In the army, as well as in the hospital, tea is slowly, but surely, supplanting the use of grog. "As an article of diet for soldiers," remarked Professor Parkes, "tea is most useful. The hot infusion, like that of coffee, is potent both against heat and cold; is most useful in great fatigue, especially in hot climates, and also has a great purifying effect on water. Tea is so light, is so easily carried and the infusion is so readily made, that it should form the drink par excellence of the soldier on service. There is also a belief that it lessens the susceptibility to malaria, but the evidence on this point is imperfect."

Admiral Inglefield, writing in January, 1881, strongly commended the use of tea and coffee as heat producers.

"During this almost Arctic weather, and in the midst of these almost Arctic surroundings, permit me as an old Arctic officer to plead for a short hearing in behalf of [Pg 68]those whose lives may still be in jeopardy for want of some practical experience how to take care of themselves. Among the working classes there is an all-prevailing idea that nothing is so effectual to keep out cold as a raw nip of spirits, and this delusion is to their minds justified, because they find the "raw nip" setting the heart, and blood in more rapid motion; and heat being generated while the influence remains, a sensation of warmth is the natural result, but after a short space reaction sets in, and a slower circulation must ensue. In the evidence given before the last Arctic Committee, of which I was a member, all the witnesses were unanimous in the opinion that spirits taken to keep out cold was a fallacy, and that nothing was more effectual than a good fatty diet, and hot tea or coffee as a drink. Seamen who journeyed with me up the shores of Wellington Channel, in the Arctic Regions, after one day's experience of rum-drinking, came to the conclusion that tea, which was the only beverage I used, was much preferable, and they quickly derived great advantage from its use while undergoing hard work and considerable cold. If cabmen, watchmen, railway servants, and those who from the nature of their duties are compelled to expose themselves during this inclement weather could be persuaded to give up entirely the use of spirituous liquors and use hot tea or coffee for a beverage, I can promise that they would be better fortified to withstand the cold, they would experience more lasting comfort, and there would be more shillings to take to their homes on a Saturday night; happily, also, the trial of temperance for a time, to meet the present emergency, might become with some the habit of a life."

The soldiers who captured Tel-el-Kebir [Pg 69]drank nothing but tea. It was served out to them three times a day. The correspondent of the Daily News (12th of September, 1882) wrote, "Sir Garnet Wolseley having ordered that the troops under his command should be allowed daily a triple allowance of tea, extra supplies of that article are being sent out from the commissariat stores to Ismailia. It is stated that the extra issue of tea is very acceptable to the men, who find a decoction of the mild stimulant in their canteen-bottles the most refreshing and invigorating beverage they can carry with them on the march."

Lord Wolseley having been asked for his temperance testimony, replied in an interesting letter, in which he strongly commended the use of tea. "Once during my military career," he says, "it fell to my lot to lead a brigade through a desert country for a distance of over 600 miles. I fed the men as well as I could, but no one, officer or private, had anything stronger than tea to drink during the expedition. The men had peculiarly hard work to do, and they did it well, and without a murmur. We seemed to have [Pg 70]left crime and sickness behind us with the 'grog,' for the conduct of all was most exemplary, and no one was ever ill. I have always attributed much of our success upon that occasion to the fact that no form of intoxicating liquor formed any portion of the daily ration."