[i]

HISTORY

OF

THE ZULU WAR.

[ii]

[iii]

[iv]

[v]

HISTORY OF THE ZULU WAR.

| Stereoscopic Co |

Copyright. |

(Facsimile of his Signature on the last Draft drawn by him

through the Standard Bank on Messrs. Rothschild & Co.)

HISTORY

OF

THE ZULU WAR.

BY

A. WILMOT, F.R.G.S.

LONDON:

RICHARDSON AND BEST, PATERNOSTER ROW;

AND

A. WHITE AND CO.,

"SOUTH AFRICAN MAIL" OFFICE, 17, BLOMFIELD STREET.

CAPE OF GOOD HOPE:

TO BE HAD OF ALL BOOKSELLERS THROUGHOUT THE COLONY.

1880.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

PREFATORY NOTE.

The salient features and the principal events of the Zulu

war are referred to in this volume. Long and uninteresting

details respecting minor operations are omitted, and an

attempt is made to furnish a readable book, which gives

a fair view of the causes, origin, and progress of the war.

It must be borne in mind that South African Kafir wars

constitute one tragedy in various acts. The Zulu campaigns

are merely last links of a chain. The war with Cetywayo

is identical in principle with those waged with Gaika,

T'Slambie, Dingaan, Kreli, and Sandilli. The tide of

savagery has been periodically rolled back, and it was either

necessary that this should be done, or that white men

should abandon Southern Africa. The fatuous policy of

Lord Glenelg caused the wars of 1846 and 1852, and there

is in essence no difference between it and the policy

advocated by the opponents of Sir Bartle Frere. In order

not to load this introductory note with lengthy observations,

a paper will be found in the Appendix treating upon this

subject.[1]

[vi]

Blue Books and correspondents' letters necessarily form

the principal authorities. The preliminary portion of the

book has been really requisite, and it is hoped that it will

be found not the least interesting portion of the volume.

No doubt, in the first connected narrative of the Zulu war,

many omissions and inaccuracies may be discovered, but

every effort has been made to collect the truth from the

most reliable authorities, and to tell it without fear, favour,

or prejudice.

Port Elizabeth,

25th September, 1879.

[vii]

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. |

| PAGE |

| Early History of the Zulu Nation and of Natal |

1 |

| |

| CHAPTER II. |

| Native Policy in Natal—Laws, Customs, and Religion of the

Zulus |

21 |

| |

| CHAPTER III. |

| Events preliminary to Zulu War—Commencement of Hostilities |

34 |

| |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| Lord Chelmsford's Plans—The Battle of Isandhlwana—The

Heroic Defence of Rorke's Drift—Panic in the Colony—Request

for Reinforcements—Reply from the Queen—The

Ministry—Sir Bartle Frere—Lord Chelmsford |

50 |

| |

| CHAPTER V. |

| Pearson's Column—March to Ekowe—Battle of Inyezane—Ekowe—Zulu

Army—Wood's Column—Reinforcements

from England—The Colonists—The Navy |

71 |

| |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| The Zlobane Mountain—Piet Uys—The Battle of Kambula—The

Intombe Disaster—Battle of Ghinghelovo—Relief of Ekowe |

91 |

| [viii] |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| The Services of Native Contingents—Lord Chelmsford and

Sir H. Bulwer—Review of the Campaign—Difficulties

of Transport—Immense Delay—Burying the Dead at

Isandhlwana |

112 |

| |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

| Sir Bartle Frere's Policy—Censure of the Home Government—Slow

Operations—Affair of the 5th of June—The

Prince Imperial—His Arrival—Services—Character—Death—Court-Martial—Funeral

Rites and Embarkation of the Body of the Prince Imperial |

140 |

| |

| CHAPTER IX. |

| The Policy of Sir Bartle Frere—Slow Advance of the

British Columns—Appointment and Arrival of Sir Garnet

Wolseley—Battle of Ulundi—Resignation and Departure

of Lord Chelmsford |

170 |

| |

| CHAPTER X. |

| Lord Chelmsford's Policy—Promptness and Decision of Sir

Garnet Wolseley—The Hunt and Capture of Cetywayo—Departure

from Natal—The Last of the Zulu Kings

a Prisoner in the Castle of Cape Town—Great Meeting

with Zulu Chiefs—Sir G. Wolseley's Speech—Settlement

of the Country—End of the War |

203 |

| |

| Appendix |

213 |

[ix]

[x]

[1]

HISTORY OF THE ZULU WAR.

CHAPTER I.

EARLY HISTORY OF THE ZULU NATION AND OF NATAL.

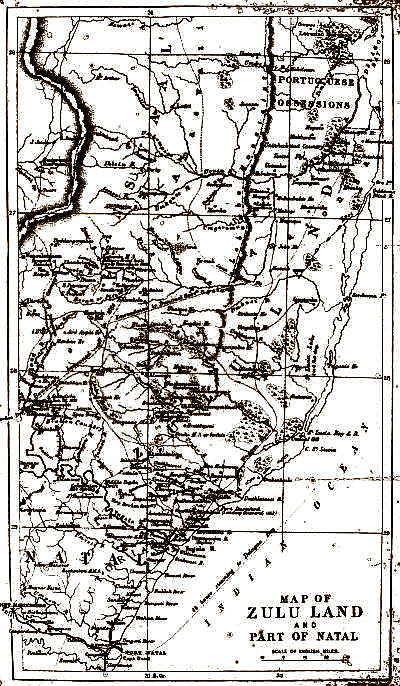

Two different races met in Southern Africa about the

middle of the seventeenth century. One had migrated

from the centre of the continent; the other sent out settlers

from one of the most civilized and prosperous countries

of Europe. These races were the Kafirs and the Dutch.

The former arrived at the banks of the Great Fish River

about the same time that Surgeon Van Riebeek landed on

the shores of Table Bay for the purpose of establishing "a

place of refreshment for the outward and homeward bound

fleets of the chartered Dutch East India Company."

The progress of the new colony was so gradual and slow

that it was not until the nineteenth century that Kafir

irruptions were effectually checked, and then the British

Government had assumed sovereignty over the Cape of

Good Hope. Different causes, to which it is not necessary

to refer, made the descendants of the Dutch settlers so[2]

dissatisfied with our rule that a portion of them, in the

year 1837, passed into that easterly portion of Southern

Africa styled Natal. There they came in contact with the

bravest and best-organized portion of the great Kafir race.

The Ama-Zulus were originally a small and despised

tribe. They were "tobacco sellers," or pedlars, and carried

on this occupation at the beginning of the present century

in the country between the Black and White Umvolosi

rivers. In contradistinction to the nature of their employment,

and as an emblem of the ambition of the people,

the name they gave themselves was one of the proudest

they could have chosen, as "the Zulus" in the Kafir

tongue signifies "the Celestials." At an early period in

this century a great leader arose among them, who became

the Genghis Khan of Southern Africa. This chief was

fitly named "Utskaka"—"Chaka," or "Break of Day;" and

it was in consequence of his efforts and of his success that

a new era commenced for his countrymen.

Chaka and his army.

Chaka was never defeated, and never fled before a foe.

Having ascended the throne by means of the murder of

his uncle, he proceeded at once to convert a nation of

pedlars into a nation of warriors. Immense care was

taken with military training, and the weapon by means

of which the Roman soldiers conquered the world was

adopted for the use of the army. The short sword, or

stabbing assegai, was supplied, with the command that

each warrior should carry but one, and either bring it

back from the battle-field or be put to death as a coward.

Marriage was forbidden, although the gratification of[3]

brutal lust was allowed. No warrior could have a wife

or child to imbue him with any tender sentiment. The

practice of circumcision, although one of the most ancient

and important rites, was abandoned, so that everything,

no matter how sacred or how important, was sacrificed

in order to create invincible legions. The army consisted

of three divisions. The first was composed of veterans,

styled "amadoda," or men; the second of youths, "ebuto;"

and the third of "ezibuto," or carriers. It was in the last

division that conquered enemies were frequently enrolled.

The king was the commander-in-chief, and under him were

the principal indunas, or ministers of state. Each regiment

was at least 1500 strong, and was led by a captain,

who had under him numerous subalterns. Military kraals

were scattered over the country, generally of an oval shape,

and of large dimensions. Reviews took place at the great

place of the king, where songs, dances, and chivalrous

games were all made use of to increase the military

enthusiasm of the warriors. When war was determined

upon, extreme secrecy was observed, spies were sent out,

and the usual incantations and sacrifices performed by the

priest or witch-doctor. A herald, dressed in the skins of

wild beasts, so as to present a terrific appearance, then

was sent to the army, and cried with a loud voice, "Maiku-puke!"—"Go

up!" An inspiring oration was delivered by

the king, and they went forth to conquer or to die, fifty

thousand well-organized, determined savages, giving no

quarter, slaying men, women, children, and even domestic

animals. Thus has a warrior described the onset of one of[4]

these savage armies:—"The Matabele lions raised the

shout of death, and fell upon their victims. It was the

shout of victory. Their hissing and hollow groans told

their progress among the dead. A few moments laid

hundreds on the ground. The clash of shields was the

signal of triumph. They entered the town with the roar

of the lion; they pillaged and fired the houses, speared

the mothers, and cast their infants to the flames. They

slaughtered cattle; they danced and sang till the dawn of

day; they ascended and killed till their hands were weary

of the spear."

Chaka not only led his army in person, but was accustomed

himself to seize the first victim, and to kill him with

his spear. After subduing the petty tribes around, he bore

his victorious arms further, and carried fire and sword

along the slopes of the Drakenberg Mountains. One of his

greatest conquests was over the Undwandwa people, and

this was followed by the destruction of the Umtetwas. An

attack was then made upon the brave Amaquabi, who

occupied both sides of the Tugela river, which forms the

present boundary of Natal. Merciless slaughters followed

victory, and the tide of conquest only ceased on the banks

of the Umsimvoboo.

In the year 1828, Lieutenant Farewell, Mr. H. Fynn,

and a few others, were permitted to visit Chaka, who then

resided at a distance of about 150 miles in a north-north-east

direction from D'Urban, Port Natal. The Englishmen

were received by the mighty Zulu potentate with great ceremony.

Nine thousand armed warriors stood around, and[5]

the despotic character of the monarch was reflected in the

servile submission with which he was treated by his subjects.

Chaka munificently granted a large tract of country

to Mr. H. Fynn, and subsequently conferred a similar

favour upon Lieutenant King. These grants—and all

grants of this nature—were, strictly speaking, mere feudal

investitures, paramount rights being retained by the

monarch. The first European settlement in Natal was

thus formed. An act of treason on the part of one of

Chaka's greatest lieutenants alienated him from his native

land, and became the means of carrying fire and sword

north of the Drakenberg Mountains as far as Bamangwato.

Moselekatsi, whom Captain Harris styles the "Lion of

the North," was this lieutenant. Wherever he moved destruction

and death marked his path, and he soon succeeded

in rearing another cruel military despotism over the graves

of those whom he had conquered.

Assassination of Chaka.

The last army of Chaka which went forth to destroy

was itself destroyed by one of those strange judgments

which bear analogy to that inflicted on the hosts of Sennacherib.

A nation dwelling close to the Palula river had

to be conquered, but before this place was reached a frightful

disease, styled "blood sickness," broke out, and was so

fatal in its results that only a few men of the great army

were able to return to tell the tale. Scarcely had this

event occurred, when the tyrant was himself assassinated.

Chaka was seated peacefully in his kraal, near the Umvoti

river, surrounded by his councillors and principal officers,

when a band of desperate men, headed by his brother[6]

Dingaan, rushed among them, and each, seizing his victim,

plunged a spear into his heart. Thus perished the Napoleon

of the Zulu race, by the hand of his own nearest

relative, and at a moment when he did not suspect treachery

or dream of any insurrection against his well-consolidated

power.

Dingaan—"poor fellow!"—was no doubt secretly

encouraged by a large portion of the Zulu people. A

number of the principal captains and friends of the late

monarch fled, and several were put to death. The new

capital was removed from the Umvati river to the White

Umvolosi river, distant 45 miles in a direct line from the

sea, and about 160 miles from D'Urban. The favour that

had been extended by Chaka to the few Englishmen who

arrived in Natal with Mr. H. Fynn was a sufficient reason

for the adoption by his successor of an exactly opposite

policy. An army of 3000 men was sent to D'Urban,

and the few English settlers escaped with the utmost

difficulty. Every vestige of property was destroyed.

Quietness was, however, restored in a few years afterwards,

and in the year 1833 Dingaan sent down spies to find out

what progress had been made by the intruders.

Captain Allen Gardiner arrived in 1835, and proceeded

to the great place of the king. This missionary traveller

mentions incidentally that, according to treaty, he brought

back several men who had fled from the cruel despotism of

the Zulu monarch. These captives fully calculated upon

being put to death. Captain Gardiner pleaded for them,

and was able to assure them that the king had promised[7]

to spare their lives. Nowha, one of the unfortunate

prisoners, mournfully replied, "They are killing us

now;" and they were all cruelly tortured to death by

starvation.[2]

Dingaan and the Boers.

In consequence of various causes, among which discontent

with British rule requires prominent mention, a

number of Dutch farmers left the Cape Colony in 1835,

and, under the command of Pieter Retief, crossed the Drakensberg

Mountains in 1837, and entered Natal. Their

leader proceeded to Dingaan's capital, for the purpose of

negotiating a treaty of peace and obtaining a formal

cession of territory. In the last week of January, 1838,

Pieter Retief, accompanied by seventy picked horsemen,

crossed the Buffalo river, and on the 2nd of February

arrived at Dingaan's kraal. The Zulu monarch fixed the

4th of February as the day for signing a formal cession of

an immense district in Natal to the emigrant Boers. The

necessary document, drawn out by the Rev. Mr. Owen,

missionary, with Dingaan, was duly signed, and business

having been satisfactorily concluded, the Dutchmen were

invited into the king's kraal to take leave of Dingaan. As

requested, Retief and his followers left their arms outside.

The Zulu monarch, surrounded by his favourite regiments,

conversed in the most friendly manner, and while a

"stirrup cup" of maize beer was in course of being

drunk, suddenly cried out, "Bulala matagati!"—"Kill

the wizards!" These words were the signal for a cruel[8]

massacre. More than 3000 savages beat to death, with

knobkerries, the unfortunate Dutchmen who had been

weak enough to trust to Zulu promises and Zulu honesty.

The corpses of the slaughtered men were dragged out of

the kraal to an adjacent hillock, and there allowed to

become the prey of wolves and vultures.

Dingaan looked upon the massacre of the farmers who

had vainly trusted to his honour as only a commencement

of hostilities. Ten regiments were immediately ordered

out to exterminate all the Dutch emigrants. While these

people were, without suspicion, waiting for the return of

their husbands and relatives, a Zulu army crawled up to

their nearest camp, near the Blaauwkrantz river, close to

the present commemorative town of Weenen, or "Weeping."

A sudden surprise at the dawn of day was effected, and

then ensued the barbarous murder in cold blood of every

man, woman, and child. Other detachments surprised

other parties, and few escaped. The destroying army

moved swiftly southward and towards the sea. Wherever

the "laager" plan was adopted, it was successful; and at

"Necht Laager," on the Bushmans river, a few determined

men succeeded in defending themselves against an

overwhelming force of savages. The engagement lasted

all day, but when the farmers' ammunition was nearly

exhausted, the fire from a 3-pounder, rigged at the back

of one of the waggons, killed several Zulu chiefs, and

caused a precipitate retreat. The men who were afterwards

able to visit the principal scenes of slaughter discovered

frightful scenes of horror and misery. Waggons[9]

were demolished, and by their ruins lay the corpses of

men, women, and children abandoned to the wild beasts.

Among the heaps of dead found at Weenen two young girls

were picked out, one of whom had been pierced by nineteen

assegai stabs, and the other by twenty-one. Both

survived, although they remained cripples for life. It is

estimated that in one week 600 white settlers were

sacrificed as victims to the savage treachery of Dingaan.

Slaughter of English.

Vengeance was determined upon by the Dutch emigrants,

and a party of 400, having placed themselves

under the command of Piet Uys and of Hendrik Potgieter,

advanced from the Klip River Division against

Dingaan. This took place in April, 1838; but unfortunately,

shortly before, a party of Englishmen from

D'Urban, with 700 friendly Zulus, having crossed the

Tugela river near its mouth and destroyed a native town,

the army of Dingaan, which had been kept in reserve,

suddenly surrounded them and killed nearly every European.[3]

The conquerors followed up their success as far

as D'Urban, and forced the few white people then resident

there to take refuge on board a vessel named the Comet,

fortunately lying at anchor in the bay. Dingaan, with his

principal forces, watched the Dutch emigrants, and learned

that Piet Uys and Hendrik Potgieter had placed themselves

at the head of 400 men, with the object of invading

Zululand. The wily savage allowed the Dutchmen to

advance to a place closed in between two hills, within a[10]

few miles of his capital, and thence led them to a valley,

where a desperate hand-to-hand combat took place. The

farmers had been accustomed to fight by firing from horseback,

and then falling back rapidly to reload. They were

so hemmed in by their position, that this mode of procedure

was impossible, and they were at last, in desperation, compelled

to concentrate their fire on one portion of the Zulu

host. They then charged through the gap thus made,

and escaped. Unfortunately, Piet Uys did not succeed in

cutting his way through, and died with his son, fighting

bravely against terrible odds. After this disastrous engagement,

the Boers were so disheartened that hostilities were

for some time suspended. They were renewed in August,

1838, when Dingaan attacked the Dutch in their laagers,

but was in all cases repulsed with loss. Towards the

close of that year, an army of 10,000 Zulus attacked the

Dutch farmers in a strongly intrenched position at the

Umslatoos river. The engagement took place on Sunday,

the 16th of December. For three hours overwhelming

masses of natives endeavoured to force the emigrant camp,

until Pretorius, finding that ammunition was beginning

to fail, ordered 200 men to sally forth on horseback,

and take the enemy in flank. This manœuvre was successful,

and the forces of Dingaan were compelled to fly,

after leaving a large number on the field.[4] After this

decisive battle 5000 head of cattle were captured, and an

advance was made to the hillock where lay the mortal[11]

remains of Retief and the brave men who perished with

him. A frightful and ghastly spectacle was beheld:

broken skulls, on which could be seen the marks of the

knobkerries and stones with which they had been fractured,

bones of legs and arms, and, strange to say, the skeleton

of Retief, recognizable by a leathern pouch or bandoleer, in

which was found the deed signed by Dingaan, resigning

to the emigrant farmers "the place called Port Natal,

together with all the land annexed; that is to say, from

the Tugela to the Umzimvoboo river, and from the sea

to the north, as far as the land may be useful and in my

possession."

Arrival of Major Charteris.

On the return of the emigrant Boers from this very

successful attack on the Zulus, they were surprised to find

that a small detachment of Highlanders, under the

command of Major Charteris had taken possession of the

Bay of Natal. This was done by order of Sir George

Napier, Governor of the Cape Colony, from a desire[5] "to

put an end to the unwarranted occupation of parts of the

territories belonging to the natives by certain emigrants of

the Cape Colony, being subjects of his Majesty." No

conflict, however, took place at this time. The Dutch were

busily employed during the year 1839 in laying out the

towns of Pietermaritzburg[6] and D'Urban, as well as in

appointing landrosts or magistrates, and establishing regulations

for the government of the country. Dingaan frequently

sent in ambassadors charged with messages of[12]

peace, but it was soon discovered that this was merely a

plan for carrying out a system of espionage.

A brother of Dingaan, named Panda, who had been

generally looked upon with contempt as a mere sensualist

who was undisposed for the fatigues of warfare, became an

object of jealousy to the king, in consequence of a large

party among the Zulus, who were tired of constant fighting

and bloodshed, showing some disposition to prefer him

to his brother. An attempt to capture and kill Panda

was followed by his flight across the Tugela into Natal,

and his application to the Dutch emigrant farmers for assistance.

Such an opportunity was gladly seized upon;

and in the next year (1840) an army of Panda's, 4000

strong, was joined by 400 mounted farmers, under the

command of Andries Pretorius. While the forces were

mustering in Pietermaritzburg, an ambassador from

Dingaan, named Tamboosa, arrived, bringing proposals for

peace. Upon being seized and questioned, this messenger

admitted that one of the objects of his mission was to

obtain every possible information, with a view of reporting

it to his master. This, however, by no means justified the

blunder and crime committed by the Dutch farmers, who

put Tamboosa to death, and would not even listen to his

prayer for mercy on behalf of his young attendant, who

suffered with him. Scarcely was this execution over when

the armies of Dingaan and Panda met in battle. In this

fierce encounter two regiments were entirely destroyed, and

the fortune of the day declared in favour of Panda, merely

in consequence of a portion of his brother's army deserting[13]

in his favour. The Dutch farmers vigorously followed up

this success, and forced Dingaan to take shelter among a

small tribe close to Delagoa Bay, who killed him in order

to secure the favour of his conquerors.

Panda proclaimed king.

On the 14th of February, 1840, and on the banks of the

Umvolosi river, the emigrant Boers proclaimed Panda

king of the Zulu people, and at the same time declared that

their own sovereignty extended from St. Lucia Bay to the

Umzimvoboo (St. John's). Shortly previous to this date,

Sir George Napier had ordered the British garrison to

abandon D'Urban, and Captain Jervis, who held the local

command, said, on the occasion of his departure, that he

wished the inhabitants peace and happiness, hoping that

they would cultivate these beautiful regions in quiet and

prosperity, "ever regardful of the rights of the people

whose country you have adopted, and whose home you

have made your own." We cannot be surprised that, under

all the circumstances, the emigrant Boers looked upon

Natal as rightfully their country, and that the British

Government had even abandoned it in their favour. Having

assisted in conquering Dingaan, and placed Panda upon

the throne, there was no reason to fear native aggressions.

No fewer than 36,000 head of cattle were given in by the

new monarch as an indemnity, so that the Boers were

able to settle down not only in peace, but with considerable

additional means at their disposal.

The government adopted by this society of farmers

was of an exceedingly ill-concerted character, and soon

proved to be essentially anarchic and unworkable. The[14]

legislative, executive, and judicial powers were centred

in a Volksraad of twenty-four members, who were required

to assemble every three months at Pietermaritzburg. All

the members performed their duties gratuitously, but

landrosts, each of whom enjoyed a salary of £100 per

annum, were appointed at the chief town, as well as

at D'Urban and Weenen. Two or three members of

the Volksraad, who happened to live near Pietermaritzburg,

formed what was styled the Commissie Raad, to

whom executive functions requiring immediate despatch

were entrusted; but whatever they did had to be submitted

for approval to the entire Volksraad. Besides,

a federal bond of union existed with the Winburg, Caledon,

and Madder districts of the Orange Free State, from which

places delegates were sent. The acts of the Commissie

Raad, as well as those of the permanent officials, were so

assailed in the Volksraad, and such personal and offensive

attacks were indulged in by this body, that good government

became impossible; and so little was law respected,

that Judge Cloete informs us that when he arrived as

Commissioner in 1843, the landrost of Pietermaritzburg

informed him that a judgment which he had passed several

months before, against a respectable inhabitant living only

a few miles from that town, ordering him to return cattle

which he had illegally withheld from a Hottentot, was still

a dead letter, as the defendant had openly declared he

would shoot the first messenger of the law who should

dare to come on his premises.

The English and the Boers.

The Volksraad of the Boers had applied to the Governor[15]

of the Cape Colony for acknowledgment and recognition

of the State as free and independent, and Sir George Napier

had returned an answer by no means unfavourable, but

their conduct soon made it evident that it would be impossible

to grant their petition. Stock was stolen from

Natal farmers towards the end of the year 1840, and armed

burghers, under Andries Pretorius, were instructed to pursue

the thieves. Traces of cattle, supposed to be those stolen,

were followed to some kraals of the Amabaka tribe, and

without any delay these people were attacked, several

killed, 3000 head of cattle and 250 sheep and goats carried

off. At the same time seventeen children were seized—in

fact, captured as slaves. The conduct of Pretorius was

approved by the Volksraad, but Sir George Napier found

himself obliged to reprobate it in the strongest language.

British troops were immediately sent to the Umgasi river,

between the Kei and the Umzimvoboo, and his Excellency

declined any further intercourse with the emigrant Boers,

unless they distinctly acknowledged that they were subjects

of the Queen of England. Although the Home Government

was at that time very reluctant to extend its colonial

possessions, a despatch was sent to Sir George Napier, in

which he was informed that her Majesty could not acknowledge

the independence of her own subjects, but that the

trade of the emigrant Boers would be placed upon the same

footing as that of any other British settlement, upon their

receiving a military force to exclude the interference with

the country by any other European power. It was then

within the option of the Boers to secure all the substantial[16]

advantages of self government; but as in the Transvaal

now, so in Natal at the period in question—obstinate folly

animated the councils of the people, and an ultimatum was

sent, stating their intention "to remain on the same footing

as heretofore." Upon this, Sir George Napier issued

a proclamation, in which it was stated that as the emigrant

farmers had refused to be recognised or treated as British

subjects, and had recently passed a resolution by which all

Kafirs inhabiting Natal were to be removed, without their

consent, into the country of Faku (Pondoland), military

occupation of the colony would be resumed. Shortly

afterwards, the troops stationed at the Umgazi camp were

ordered to march to Natal. This small force, consisting of

250 men, besides a small party of the Cape corps and two

field-pieces, arrived safely at D'Urban, and a few days

afterwards the brig Pilot came to anchor in the bay, bringing

them stores and provisions, as well as two 18-pounders

and ammunition. This vessel was soon afterwards followed

by the schooner Mazeppa.

The Volksraad of the emigrant Boers was astonished

and indignant at the military occupation of D'Urban, and

more than 300 men, under Andries Pretorius, were immediately

ordered out. The capture of some cattle, and

the receipt of a letter ordering him to quit Natal, so enraged

the commander of the small English force, that

he led a night attack against the Dutch camp at Congella.

So ill managed, however, was the expedition, that Captain

Smith was repulsed and his guns captured. Out of 140 men

whom he led in this unfortunate affray no fewer than[17]

103 were killed, wounded, and missing. He then saw that

his little force was reduced to extremities, but exerted himself

most indefatigably and perseveringly to resist to the

last. A fortification something similar in character to a

laager was formed at D'Urban, by means of the numerous

waggons in the camp, with the requisite trenches and mounds.

The Dutch Boers fortunately allowed the time in which

they should have taken advantage of their victory to pass

by, and soon saw that, in consequence of their inertness,

a conquest which in the first instance would have been easy

was now converted into a siege. In the mean time Captain

Smith was able to send off for assistance to the Cape Colony.

Richard King, then living in a hut at D'Urban, volunteered

to carry the despatches. Mr. G. C. Cato conveyed him and

his horses across the channel to the Bluff, and then he

rode off, leading a spare horse, and before daybreak

succeeded in passing the Umcomas river. There he was

safe from the danger of pursuit, but had to face the perils

of crossing two hundred rivers, and of traversing a wild

country inhabited by savages. Upon this slender thread

hung the destinies of the British in Natal.

The English besieged.

Encouraged by their success, the Boers overpowered

the detachment of British troops stationed at the Point,

and took most of the English residents prisoners to Pietermaritzburg.[7]

Then all their efforts were directed against

the fort, in which Captain Smith had been able to mount[18]

an 18-pounder and to secure provisions and ammunition.

The farmers, who had three field-pieces, carried on a heavy

cannonade for three days, and when they had exhausted

their ammunition, turned the siege into a rigorous blockade.

Two sorties made by the garrison were unavailing, and at

last the rations were reduced to the smallest quantity sufficient

to sustain life; dried horseflesh became the principal

article of food, and the utmost anxiety prevailed as to the

success of Richard King, and the arrival of reinforcements

from the Cape Colony. Many a time eyes were strained

for some sign of assistance; at last, on the night of the

24th of June, they saw, with inexpressible relief, the rockets

and blue lights which announced that a vessel with reinforcements

had arrived.

Dick King had succeeded. After a ride of many

hundreds of miles over trackless, unknown, and savage

regions, he had safely reached the Cape Colony. It was

on the ninth day after he left the Bluff at Natal that he

arrived, almost exhausted, in Graham's Town. Colonel

Hare, the Lieutenant-Governor of the Eastern Province,

immediately sent the grenadier company of the 27th Regiment,

in the schooner Conch, from Port Elizabeth, and

when Sir George Napier heard the news in Cape Town,

he lost no time in persuading Admiral Percy to despatch

the flagship Southampton, with the 25th Regiment on board,

under the command of Colonel Cloete. The ship of war

arrived at Natal only one day after the Conch. A landing

was immediately effected with very trifling loss; the Boer

force was driven back to the Congella. A gale of wind[19]

drove the Southampton to sea, and supplies became so

scarce that Colonel Cloete was obliged to obtain the services

of Zulus to secure cattle. Some of these killed two Dutch

farmers, and this gave occasion to a panic among the

Boers, who precipitately fled to Pietermaritzburg.

Dismay of the Boers.

Amidst great consternation and great confusion, a

meeting of the Volksraad was held in the church at Pietermaritzburg,

when recriminations, quarrelling, and loud

talking occupied the entire Sunday. At last it was resolved

to propose terms of peace to Colonel Cloete; but the

ignorance and simplicity of the Boers were displayed by

their holding out as a threat the succour they might receive

from the King of Holland, to whom letters had some time

previously been sent by the hands of a trader named

Smellekamp. After negotiations, Colonel Cloete granted

an amnesty to all except four ringleaders, and Natal was

peaceably once more under the rule of the British Crown.

These transactions took place in 1842; and in the following

year the Honourable Henry Cloete, afterwards a Judge

of the Supreme Court of the Cape Colony, was sent to Natal

as her Majesty's Commissioner, with ample authority to

inaugurate a settled system of government, and to put an

end to the anarchy and confusion which prevailed. By

the exercise of great tact and judgment he was successful.

A powerful radical faction in the Volksraad opposed submission

in the most outrageous and foolish manner. They

even adopted a plan to assassinate the leading members of

the peace party; but Andries Pretorius, one of the latter,

and a wise, true friend of his adopted country, having discovered[20]

the plot, exposed it publicly, and brought its

authors to shame. Judge Cloete tells us that this patriot

addressed the meeting in a strain of impassioned extemporaneous

eloquence not unworthy of Cicero when denouncing

Cataline, and turned the tide so powerfully

against the would-be assassins as to entirely defeat their

plot. Entire submission to the British Government

followed. Major Smith was succeeded by Colonel Boys, of

the 45th Regiment, as military commandant, and his

Honour Martin West, resident magistrate of Graham's

Town, was appointed the first Lieutenant-Governor of

Natal.

[21]

CHAPTER II.

NATIVE POLICY IN NATAL. LAWS, CUSTOMS, AND

RELIGION OF THE ZULUS.

The protection of the natives was the professed object of

the British Government in taking possession of Natal. The

conquests of Chaka had driven no fewer than 100,000

fugitives to the westward of the Tugela river, and how to

rule this vast and fast increasing number of natives soon

became a problem fraught both with difficulty and danger.

Mr. Theophilus Shepstone, son of a Wesleyan missionary,

thoroughly conversant with the Kafir language, customs,

manners, and habits, was appointed to take charge of the

numerous natives of Natal. His policy can be very briefly

described. It was to keep all the coloured races entirely

distinct from the white population. They were collected

in locations, and governed by their own laws, through

their own chiefs, under Mr. Shepstone as the great chief.

Large tracts of country, rugged and mountainous, were set

apart for the various tribes, and there, in an Italian

climate, and in the lap of a most productive and generous

soil, they increased and multiplied. Christianity and real[22]

civilization were ignored, and a most dangerous imperium in

imperio created. The wretched refugees who fled from the

Zulu tyrant found their lot in Natal incomparably more

happy than in the precarious existence of former days.

Their easy, savage, sensuous life made them useless

citizens, and when labour was required for the sugar

plantations on the coast, it had to be obtained from India.

However smoothly and well the native policy seemed to

work, it soon became very evident that the 20,000 white

people of Natal were really seated on a political volcano.

Three hundred thousand heathen savages of an alien race

had the power to rise and destroy them at any moment,

and it was impossible to be sure that they might not at any

time have the inclination. All the checks which religion

and civilization place on men had been deliberately cast

aside. No doubt the Zulu monarch was feared; but there

can be no doubt also that if the dread paramount ruler of

the Zulu race had at any time crossed the Tugela as a

conqueror, tens of thousands of his own race in the colony

would have joined him out of fear, and hastened to prove

their loyalty by the massacre of every white inhabitant of

Natal. This is no fanciful idea, but sober earnest fact.[8]

The Shepstone native policy.

There was no difficulty at first in subjecting to proper

control the broken, dispirited bands of refugees, who sought

shelter, food, and protection in Natal; and if right methods[23]

had been adopted, one of the finest races of the African

continent would have been raised from a state of loathsome

degradation to one of civilization—saved from heathenism

themselves to become coadjutors with the white races in

raising the country to real prosperity. In place of this,

the cruel slavery of polygamy was permitted, which allows

the men to live in independent idleness by means of the

severe drudgery of their oppressed wives. Grossly impure

and inhuman laws and practices, including the vile superstitions

of witchcraft, were tolerated and allowed. No

country could advance under such circumstances, and the

colony of Natal, therefore, remains at the present day what

it has always been—immeasurably behind the Cape of

Good Hope; a land of samples in which nothing really

succeeds, and where sugar, which forms its principal

export, is even now a doubtful experiment, on which labour

imported from India at enormous cost has to be employed;

a lovely country, whose fertility is almost as great as its

beauty, but cursed by a most unchristian, wicked, and

foolish system of government, so far as the great bulk of

the population is concerned. It would have been very easy

at the outset to establish comparatively small locations,

presided over by British magistrates, who would have

administered justice according to British law. If, in addition,

title-deeds had been given in such a manner as to

give individual rights, then, in the words of the Rev. W. C.

Holden,[9] the large number of natives within the colony

might have been converted into men who would take a real[24]

interest in the country and soil, for the defence of which

they would fight and die. They would have become a strong

wall of defence against the Zulu on the east, and the

Amaxosa on the west, instead of a source of continual

danger and alarm.[10] Slavery was abolished everywhere

throughout the British dominions, with the one exception

of Natal. There 50,000 women were sold for wives

to the highest bidder, as horses, cattle, and goods at an

auction mart, under the special sanction and special

arrangement of the Queen's Government.

Before proceeding further, it is necessary to pass briefly

in review the laws, manners, and customs of the Zulu race.

Without a knowledge of this subject it will be perfectly

impossible to appreciate the policy of Sir Bartle Frere, or

to understand either the real causes of the war, or of many

events in its progress. We have seen that Chaka, the Zulu

conqueror, formed a great military nation. His successors

were specially warriors, and as the people chose similar

weapons to those with which the ancient Romans conquered

the world, so, like that people, were they fully animated with

the feeling that virtus, or the highest possible merit, consisted

in bravery in the field of battle. The Boers despised

the enemy, and hundreds of their bravest men fell victims.

Almost about the same time, the English settlers at[25]

D'Urban made the same mistake, and 2000 of their Kafir

allies, as well as several of their own number, were slaughtered

and left to be devoured by beasts of prey on the

hills of Zululand. History repeats itself: Lord Chelmsford

made the same mistake, which was expiated in the blood

of hundreds of British soldiers on the field of Isandhlwana.

Zulu customs.

Among the Zulus every female child is so much property,

and in this respect treated exactly like a chattel or

beast of burden. Her life is one of the grossest degradation

and slavery. When she has reached the age of puberty

disgusting ceremonies are performed, and there is no idea

or appreciation of chastity. The most brutal lust is not

only tolerated, but actually enforced by law. When a girl

is married, she is merely sold to the highest bidder, entirely

without reference to her own consent, and then becomes

the slave of her husband, for whom she has to labour in the

field and perform menial work. The day after the party of

a bride has arrived at her owner's hut, the peculiar ceremony

takes place of the woman being allowed and enjoined

to tax her powers to the utmost to use abusive language to

her lord. She pours every insulting and provoking epithet

she can think of upon him, this being the last time in

which she is permitted to act and speak independently.

At last she takes a certain feather out of her head, by

means of which the act of marriage, or rather of going into

slavery, becomes complete. Mr. Holden speaks of the great

obscenity at "marriage" celebrations, and remarks that

"no respectable pages can be defiled with a description of

what then takes place, especially in connection with the[26]

marriage of men of rank and chiefs. There is full licence

given to wholesale debauchery, and both men and women

glory in their shame."[11] It is impossible to pursue this

subject further. This is certain, that the very grossest and

most filthy obscenities and immoralities are absolutely enjoined

and required by Zulu law and custom. Marriage

is entirely a misnomer. To quote from an excellent authority,

"No word corresponding to the Saxon word 'wife'

is found in the Zulu language. The term most nearly

approaching to it is umkake, and its correlatives umkako and

umkami, which means his she or female. The man owns his

wives as truly, according to native law, as he does his spear

or his goat, and he speaks of them accordingly." The owner

of the woman says, "I have paid so many cattle for you;

therefore you are my slave, my dog, and your proper place

is under my feet." One of these poor slaves, when seen

standing by a load far too great for her strength, was asked

if she could carry it. She stood up and ingenuously remarked,

"If I were a man I could not, but I am a woman."

There is no slavery in the world more sad or deplorable

than that to which the poor women of the Zulu nation are

subjected.[12]

Religion of the Zulus.

Spiritualism is the religion of the Zulu, and witchcraft

is the machinery by means of which it is practised. Only

a very vague idea exists about a Supreme Being, and the[27]

definite national faith embraces only a belief in the influence

of the spirits of deceased ancestors. The ghosts

of departed chiefs and warriors are specially respected and

feared. It is to these spirits that they attribute all the

power given by Christians to God, and the witch-doctors

are the mediums or priests of the worship. A knowledge

of subtle and powerful vegetable poisons exists, and so

common is the practice of secret poisoning that universal

safeguards are used against it. Every one who gives food

to another takes a part himself, in proof that it contains

no poison. Besides deadly drugs, there is what is styled

the "ubuti," or bewitching matter, which is supposed to be

deposited in some secret place, and to be made the instrument

of evil by means of supernatural agency. The

"isanusi," or witch-doctors, are the go-betweens, whose duty

it is to discover and to avert evil. These men fill the

threefold office of doctors, priests, and soothsayers. They

heal diseases, offer sacrifices, and exercise the art of

divination. As they are assumed to have full power over

the invisible world, their influence is enormous, and is

readily taken advantage of by chiefs and powerful men, for

the purpose of destroying enemies and promoting schemes

of war and plunder. A youth who aspires to be enrolled

among the isanusi gives early signs of being destined for

the office. He dreams of the spirits of the departed chiefs

of his people, sees visions, falls into fits of frenzy; he

catches snakes and twists them round his person, seeks

out medicinal roots, and goes for instruction to experienced

isanusi. At last what is called a "change in the moon"[28]

takes place within him; he becomes a medium fitted to

hold converse with spirits, and is able to communicate

with them. One of the greatest authorities who has ever

lived with and studied the Kafir races—Mr. Warner—says,

"It is impossible to suppose that these priests are not,

to a considerable extent, self-deceived, as well as the deceivers

of others; and there is no difficulty, to one who

believes the Bible to be a divine revelation, in supposing

that they are also to a certain extent under Satanic influence;

for the idolatrous and heathen nations of the

earth are declared in the inspired volume to be, in a

peculiar manner, under the influence and power of the

devil."

Witch doctors.

Every illness and misfortune is supposed to be caused

by witchcraft. It usually happens that the suspected

person is a rich man, or some one on whom it is thought

desirable to wreak vengeance. The people of the kraal and

neighbourhood go in a body to the isanusi, who, before

their arrival, foretells their approach, and makes other

revelations, frequently so extraordinary that the Rev.

Mr. Holden,[13] who is thoroughly conversant with the subject,

states that there is much greater difficulty in explaining

these phenomena by ordinary means than by supernatural

interposition. The whole company, on arrival, sit down

and salute the witch-doctor; they are then told to beat

the ground with their sticks, and while this is in course

of being done, he repeatedly shouts out, "Yeswa!"—"He

is here!" He discloses secrets about the accused, and at[29]

last, fixing his eyes upon the doomed one, charges him

with the crime. Generally the isanusi succeeds in selecting

the suspected person; but if he fail, a circle is formed, and

a wild, frenzied dance performed, amidst most frightful

gesticulations and cries. Among the Zulus, not only is the

unfortunate person killed whom the witch-doctor declares

guilty, but his wife and children are murdered, and his

property seized. Among the Amaxosa Kafirs, the most

frightful tortures are used to induce the unfortunate victim

to confess.[14] It is difficult to appreciate adequately the

enormous power of the witch-doctors. It was in 1857 that

Umhlakaza was made a willing tool in the hands of Kreli,

Sandilli, and Umhala for the purpose of a war of extermination

against the whites. It was prophesied that if the

people destroyed their cattle and corn, the whole would

rise again with vast increase, and that their enemies

would be utterly destroyed. Sir George Grey had taken

every precaution, and war was therefore made impossible.

Like the witches in "Macbeth," the prophet had merely

lured on his victims to destruction. Having burned their

ships, by destroying all their resources there was no escape,[30]

and, in spite of the humane exertions of the colonists,

70,000 human beings perished of famine in a land of

plenty. It will thus be seen how an entire people can

easily be induced to embark in the most desperate

undertakings by the skilful use of the superstitious

means at the disposal of their chiefs. Sacrifices of

beasts are offered by the priests, according to prescribed

rules. These are made to the spirits of the departed.

A hut is sacredly cleaned and set apart, in which the

sacrifice is shut up during the night, in order that

the "isituta," or spirits, may drink in its flavour. On

the next day the place is opened, and the meat devoured

by the people. All sacrifices, with trifling exceptions, must

be offered by priests. The blood is never spilt, but caught

in a vessel, and it is necessary to burn the bones. The

frenzy or inspired madness characteristic of the priests

of the ancient oracles is commonly assumed by the priests

of the Zulu spiritualists, and many of their ceremonies are

occult, and have never been made known to Europeans.

Great military rite.

The Zulu government is thoroughly despotic. The will

of the tyrant is law, and he has unlimited power of life or

death. We have seen that Chaka sacrificed everything to

military power, and in order to succeed, banished even

circumcision, and refused to allow his warriors to marry.

Women's love and children's tenderness were forbidden to

the stern soldiers of the new empire. Medicines composed

of various plants and roots were used to purify the body and

make it strong, and ordinarily sacrifices were offered for

the same purpose. The great national sacrifice to make[31]

the army invulnerable is styled "ukukufula," when flesh

is cut off the shoulder of a living beast and roasted on

a fire into which certain charms have been thrown. Each

man bites off a mouthful, and passes on the meat to the

next, while the priest makes incisions in parts of their bodies,

into which he inserts the powdered charcoal of the charms.

The poor animal is left in torture all this time, and is not

killed until the ceremonies are ended. A decoction is also

prepared from medicinal roots, and sprinkled by means of

the tail of an ox over the bodies of the warriors. All this is

designed to make the Zulus either invulnerable, or to enable

them, if they do fall in battle, to join triumphantly the

heroes of their race in the spirit world. The three great

divisions of the army already referred to, comprising

"men," "young men," and "carriers," were sub-divided

into regiments with a proper staff of officers. The Zulu

strength is in attack, when with ferocious yells they

throw themselves with undaunted bravery upon their

enemy. Two horns advance and endeavour to flank the

foe, while the main body follows quickly to their support.

Virtus—military bravery—is their summum bonum, and

death is the immediate penalty of any form of cowardice.

Extreme cunning and dissimulation are considered essential

qualifications of a general, so that to lure a foe into ambush,

or to deceive him by illusory promises or messages

of peace, are considered proofs of wisdom and ability.

Honour, humanity, and generosity are perfectly unknown,

and merely considered signs of weakness. When an enemy

is defeated, prisoners are never taken, and those not killed[32]

in the heat of battle are cruelly tortured and mutilated,

with every mark of indignity and contempt. Women and

children are not spared, and the most cruel destruction of

the most cruel northern barbarians, who devastated Europe,

pales before the complete and effectual ruin which marks

the progress of a Zulu conqueror.

Sir Bartle Frere.

In times of peace the army remains at military kraals,

and is occasionally called up to the great place of the king

for review. It is always in a state of readiness, and burning

for employment. War is the pastime, glory, and wish

of the men, who eagerly desire to wash their spears in

blood, that they may obtain the only glory for which they

care to live, and secure that plunder which can enable

them to acquire wives and cattle. Nothing could be more

dangerous, or a more awful threat to a colony, than an

army of this description under the orders of a despotic

savage, without the slightest principle, and urged on to

fight by all the traditions and ideas of his race. Let it be

remembered also that the country of Natal was once owned

by the Zulus, and that, while held by a garrison of only

20,000 whites, there were no fewer than 300,000 savage

heathen inhabitants in it of similar colour, race, and religion

to the people of Cetywayo. Once let the flood-gates

be lifted and a conquering "invulnerable" army enter

Natal, nothing could prevent the general rising of the vast

masses of natives within that colony. If that had occurred,

British dominion would have set in an ocean of blood, and

every white man, woman, and child in the settlement must

have been slaughtered. It was one wise, good man who[33]

averted that catastrophe, and his name was Bartle Frere.

Slowly, but most certainly, will the mists of prejudice be

lifted from the minds of the English people, and they will

learn to know that the policy they so much vilified saved

the British name from dishonour, and the British people

and British interests in South Africa from destruction.

[34]

CHAPTER III.

EVENTS PRELIMINARY TO ZULU WAR—COMMENCEMENT

OF HOSTILITIES.

The Transvaal in danger.

Thirty-six years had elapsed since the eventful ride of

Dick King from D'Urban to Graham's Town. The British

colony of Natal had grown slowly. Immigrants arrived;

a representative Constitution was granted. During this

period numbers of people of Dutch extraction formed settlements

in the Orange Free State and Transvaal Republic.

The British Government in the first instance established

sovereignty over the former country, but abandoned it on

the 23rd of February, 1854. The Republic commenced from

that date. So far as the Transvaal is concerned, Potgieter

established the town of Potchefstroom in 1839, and soon after

enormous territory, extending from the Vaal to the Limpopo,

came under the dominion of the South African Republic.

The first session of Volksraad was held in 1848, and it was

in 1852 that Pretorius succeeded in obtaining the treaty

at Sand river, by means of which the independence of

the Republic was recognized by the British Crown. One

of the first Acts of the Volksraad was to repeal a former

resolution fixing their southern boundary at the twentyfifth[35]

degree of south latitude, because the Volksraad has

no means of determining where the said degree of south

latitude is. Amongst the people civilization made slow

progress. "Not many years ago," wrote Mr. Thomas

Baines in his valuable work on the Gold Regions of South

Africa, "their own Surveyor-General was mobbed for using

a theodolite in the streets of Potchefstroom instead of

stepping off the distance like the Veldt Valkt miester of

the good old times." Sir Arthur Cunynghame, in his

recent narrative, gives us yet more amusing and striking

illustrations of the utter simplicity and ignorance of the

Boers. As was to be expected under the circumstances,

the Government was extremely narrow and objectionable;

in proof of which it is only necessary to state that no

Englishman or German was allowed to possess landed

property, it was forbidden to discover or work minerals,

while slavery really existed, and was practised under what

was styled the Apprentice Law, passed in 1856.[15] In spite

of the discovery of gold-fields at Pilgrim's Rest, the country

became insolvent, wars with the natives took place, and

at last such a state of insolvency and danger was attained

that the British Government found it imperatively necessary

to intervene. The Zulus, under Cetywayo, intended

to overrun the country, and this would have threatened

all British South Africa. The northern territory of the

State had already been abandoned to the natives; the

Government was powerless, and all confidence in it had[36]

fled; commerce was destroyed, and the country was bankrupt.

Under these circumstances, Sir Theophilus Shepstone,

on the 12th of April, 1877, found himself imperatively

obliged to place the Transvaal territory under the protection

of the British flag.

In Natal, under the administration of Sir Benjamin

Pine, during the year 1873, a rebellion broke out on the

part of a chief named Langalibalele, which was only prevented

from becoming a general war by the admirably

prompt action of the local Government. The philanthropic

societies in England, with Bishop Colenso, championed the

cause of this rebel, and Sir B. Pine was, in consequence

of their exertions, recalled. Sir Garnet Wolseley, who

succeeded that officer, says, "Langalibalele, as I am informed

by all classes here, official and non-official (a small

knot of men of extreme views excepted), is regarded by the

native population at large as a chief who, having defied

the authorities, and in doing so occasioned the murder

of two white men, is now suffering for that conduct. In

their opinion his attempts to brave the Government have

been checkmated, and his banishment from the colony,

regarded as a lenient punishment by the natives at large,

cannot fail to be a serious warning to all other Kafir chiefs,

not only in Natal but in the whole of South Africa, to

avoid imitating his example."[16]

Sir Garnet Wolseley effected an important change in

the colonial legislature, by adding eight nominee members

to the Council, which previously consisted of five ex-officio[37]

and fifteen elected members. The annexation of the Transvaal

followed; and, speaking of this, Sir Benjamin Pine

says that "the strong ground taken in defence of the

measure is that its hostilities with the native tribes seriously

imperilled the peace of our colonies—that it was, in fact,

a next-door neighbour's house in flames, which might any

moment set ours on fire. In this respect, the ground for

annexing the Transvaal Republic was very much stronger

than that which justified our taking possession of Natal.

The latter country did not at that time touch our boundary

at any point. It was a house several streets off."

Diamonds and guns.

The discovery of diamonds in South Africa, in 1867,

exercised by degrees an enormous influence upon the

attitude of the natives throughout Southern Africa. When

the success of the dry diggings at the New Rush caused the

formation of Kimberley, that town became the centre of

an enormous gun trade. From north and east, thousands of

Kafirs of various tribes flocked to a place where they could

obtain, for the reward of their labour, the means of exterminating

the hated white man in South Africa. The

Gealekas under Kreli, the Gaikas of Sandilli, as well as

the Zulus beyond Natal, were not slow to seize such an

opportunity. For years the trade continued, and the

weapons purchased were soon used against the Government

which permitted their sale. Wars were waged upon the

eastern and northern borders of the Cape Colony during

1877, 1878, and 1879. Sir Benjamin Pine, with some

fancy and a great deal of truth, styles the diamond of the

Kimberley mines the bloodstone of South Africa. As[38]

the Zulu system makes war a necessity constantly thirsted

for by the army, advantage was taken of the easy opportunity

of getting firearms afforded by the inconceivable

blindness and fatuity of the British Government. In the

year 1877, Cetywayo had quite made up his mind for a

deadly conflict with the white man. Guns were purchased,

preparations were made, and the army crouched like a

tiger in its lair, ready to spring.

Since the first establishment of the colony of Natal,

and of the Transvaal Republic, the Governments of these

countries had the Zulu military power suspended, like the

sword of Damocles, as a perpetual threat over their heads.

Of course, by the annexation of the latter State in 1877, all

its responsibilities devolved upon her Majesty's Government.

Cetywayo, the son of Panda, succeeded his father in the

year 1872, and it formed part of Sir T. Shepstone's policy

to conciliate and please him in every possible manner.

That officer went so far as to attend his coronation, which

was celebrated with the grandest forms of savage ceremonial.[17]

At the same time a number of promises and

engagements were received from the king. All this was,

of course, merely a solemn farce. The descendant of

Dingaan, who first signed a deed giving Natal to the Dutch,

and then murdered in cold blood the men who had trusted

to his honour, was not likely to depart from the traditions

and policy of his race. Dissimulation, fraud, and cunning

are characteristic qualities of every Zulu ruler, and Cetywayo[39]

excelled in them all. The Government of Natal was

lulled into security, while Bishop Colenso and the well-meaning

but profoundly ignorant men who form the self-styled

philanthropical societies in England have, even up

to the present moment, been completely hoodwinked and

deceived. Sir Bartle Frere, writing of Cetywayo's solemn

promises, says, "None of these promises have been since

fulfilled; the cruelties and barbarisms which deformed the

internal administration of Zululand in Panda's reign have

been aggravated during the reign of Cetywayo, and his

relations with his neighbours have been conducted in a

spirit fatal to peace and security beyond the Zulu border."[18]

Natal in danger.

The well-organized and peculiarly formidable military

power of the Zulus was still further consolidated and

strengthened by Cetywayo, so that a standing menace and

threat of a very serious nature existed against both Natal

and the Transvaal. Nothing can better prove the danger

than the fact that the Zulu monarch formally and repeatedly

requested the consent of the British Government

to wars of aggression, which he proposed for the ostensible

purpose of initiating his young soldiers in bloodshed, and

reviving the system of unprovoked territorial aggression

which had been so successfully carried out by the model

and demi-god of the nation—Chaka.

A large tract of land on the western boundary of Zululand,

between the Buffalo and Pongolo rivers, which had

long formed part of the Transvaal, was claimed by the

Zulus, and they had requested the Natal Government to[40]

arbitrate in this matter. Eventually a Commission was

appointed, which decided that Cetywayo's cession of a tract

of land relied on by the Transvaal claim was promised

when he was only heir apparent, and that the cession had

not been subsequently formally ratified by his father Panda,

nor by the great council of the Zulu nation; therefore the

country in question had never ceased to belong to them.

Private rights of bonâ fide settlers, which could not in justice

be abrogated, were confirmed, but otherwise the sovereignty

of the territory was ceded to the Zulus. Since his installation

the tone of Cetywayo had become entirely altered.

When a remonstrance was sent against a barbarous murder

of young women by the king, replies of extreme insolence

were sent to the Natal Government, and the opportunity

was taken to state that no responsibility was admitted;

at the same time, the solemn installation promises were

distinctly denied, and Cetywayo affirmed his intention of

shedding blood in future on a much greater scale. In

the latter part of July, 1878, the Zulu chief Sirayo entered

British territory, carried off two women—British subjects—and

forcibly put them to death. Redress was demanded,

but not given.

On the 11th of December, 1878, a final message was

sent to Cetywayo, in which the reasonable and just demands

of the Government were summarized. He was called upon

to give up the offenders who had violated British territory,

and to effect various reforms in the administration of his

government, in accordance with the solemn promises made

at his installation. A few informal messages made and[41]

retracted only served to show the cunning and deceit of

Cetywayo, and it was clear to demonstration that the Zulu

potentate and the Zulu army had determined upon war.

Hostile attitude of the Zulus.

The High Commissioner writes (30th September) to

the Imperial Government:—"It is difficult to give any

adequate idea of the strength of evidence of the state of

feeling. Zulu regiments are reported as moving about on

unusual and special errands, several of them organizing

royal hunts on a great scale in parts of the country where

little game is to be expected, and where the obvious object

is to guard the border against attack. The hunters are said

to have received orders to follow any game they may rouse

across the border, which it appears is, according to Zulu

custom, a recognized mode of provoking or declaring war.

Unusual bodies of armed men are stated to watch all drifts

and roads leading into Zululand, and these guards are

occasionally reported as warning off Natal natives from

entering the Zulu territory, accompanying the warning

with contemptuous intimation that orders have been given

to kill all Natalions if they trespass across the border.

Zulu subjects came hastily into Natal to reclaim cattle

which they had sent hither to graze, giving as their reason

that Zululand is so disturbed that they know not what will

happen. Serious alarm is expressed because three large

ships have been seen on the coast making for Delagoa Bay,

and great irritation is expressed by Zulus at the stoppage

of the supplies of arms and ammunition they used to

receive through that port.

"The reports first received of raids into Natal territory[42]

by large bodies of armed men, who dragged two refugee

women out of the huts of British subjects, with expressions

of contemptuous disregard for what the English Government

might think, or say, or do, and the murders of the

women directly they were on the other side of the boundary

line, appear to be confirmed in every particular.

"There seems to be no doubt that the parties were

headed by two sons of Sirayo. This chief lives near the

Natal border, and was well known as extremely anti-English

in his feelings. Until quite lately he was so little in favour

with Cetywayo, that he had not for some time attended to

any summons to the royal kraal. He was nevertheless

appointed by Cetywayo to represent him at the Boundary

Commission. Partly, it was said, on account of his rank

and influence and known antipathy to Europeans, and

partly because he could not refuse to attend at the royal

kraal to give an account of his stewardship, he did so

attend, and in the absence of the prime minister, was

appointed to act for him, a proceeding which, considering

his known anti-English feeling, is regarded as significant.

"It is to be remembered that the facts, of which a brief

summary is here given, have been sifted from a mass of

very alarming rumours, current during the month, which

his Excellency the Lieutenant-Governor considered more

doubtful, or unworthy of credit, but which are circulated

in a manner to increase agitation and excitement on both

sides of the border."

Firmness of Sir Bartle Frere.

The only question remained—Were we to allow the

enemy to wait for a favourable opportunity and attack[43]

us at an advantage, or protect Natal and British South

Africa by a policy of firmness and consistency? The

latter alternative was chosen by her Majesty's High

Commissioner; and on the 4th of January, 1879, Sir

Bartle Frere placed in the hands of Lieutenant-General

Lord Chelmsford, commanding in South Africa, the further

enforcement of all demands.[19] There can be no doubt

whatever that this course was the only possible one consistent

with the safety of Natal and British South Africa.

Cetywayo had been long preparing for war, and had most

fully determined upon it, urged on by the irrepressible

warlike organization and the army, which thirsted for an

opportunity of exertion and could not safely be balked.

Self-preservation and self-defence rendered it absolutely

necessary that an army should enter Zululand.

[44]

Early in January, 1879, four columns crossed the

Tugela. The line of advance described a crescent, of

which one horn rested on Luneberg, or the Pongolo, and

the other, or base, terminated at the lower drift of the

Tugela, close to the sea. Colonel Pearson was in command

of the first column, whose centre was an intrenched camp

on the summit of a bluff directly overlooking the Tugela

river.

It consisted of—

Regular infantry.—1500, comprising eight companies of

the Buffs under Colonel Parnell, and six companies of the

99th under Colonel Welman.

Royal Engineers.—One company, with two 7-pounder

guns, under Lieutenant Lloyd.

Naval Brigade.—200 blue jackets and marines, under

Captain Campbell, from H.M.S. Active and Tenedos, with

three Gatling guns.

Mounted infantry.—200 of Captain Barrow's.

Mounted volunteers.—200 belonging to the D'Urban

Mounted Rifles (Captain W. Shepstone); Alexander

Mounted Rifles (Captain Arbuthnot); Victoria Mounted

Rifles (Captain Sauer); Stanger Mounted Rifles (Captain

Addison); the Natal Hussars (Captain Norton). To all this

must be added a native contingent of 2000, under Major

Graves, and two companies of the 99th, posted at Stanger

and D'Urban. This was the coast column.

The second column was planted at a commanding

position called Krantz Kop, inaccessible except on the

Natal side. It comprised 3300 natives, with 200 European[45]

officers, supported by two rocket tubes under Lieutenant

Russell, R.E., and 250 mounted natives.

Lord Chelmsford's advance.

The head-quarters of the third column was at Helpmakaar,

situated on high and open ground commanding

an extensive prospect. The depôts were at Grey Town and

Ladysmith. This column was exceptionally strong, and consisted

of seven companies of the 1-24th, and eight of the

2-24th; six 7-pounder guns with special Kaffrarian carriages;

a squadron of mounted infantry under Captain

Browne; the Natal Mounted Police, 150 strong; the Natal

Carbineers (Captain Shepstone); the Buffalo Border Guard

(Captain Robson); the Newcastle Mounted Rifles (Captain

Bradstreet); 2000 of the Native Contingent, 2nd Regiment,

under Commandant Lonsdale, and 2000 natives under

Colonel Glyn. General Lord Chelmsford, commander-in-chief,

accompanied the column.

The fourth column had Utrecht as its base, and rested

its line on the Blood river, thus covering the disputed

Transvaal border. It comprised the 13th and 90th Regiments,

six guns, Buller's Light Horse, and a number of

natives. It consisted of about 2000 well-seasoned, reliable

men, exclusive of the natives, and was under the command

of Colonel Evelyn Wood, V.C.

On the 10th of January, 1879, the full period expired

for the Zulu king to meet the demands of her Majesty's

High Commissioner. On the 11th of January No. 3

column, under Colonel Glyn, crossed the Buffalo river

into Zululand. Heavy rains had made the roads very bad,

and caused the Tugela to rise so much that a barrel-raft, a[46]

pont, and a boat had to be made use of for the passage of

the troops. No opposition whatever was made by the

enemy. In the mean time the fourth column, under

Colonel Wood, had been halted at Bemba's Kop, distant

about thirty-five miles from Rorke's Drift.

On the 11th of January, Lord Chelmsford, with the bulk

of the mounted men of No. 3 column, met Colonel Wood

with his "irregulars" about twenty miles from Rorke's

Drift, and was completely satisfied with the efficiency of the

latter force, and attributed the satisfactory state of Wood's

column to its commander's energy and military knowledge.[20]

Burning of Sirayo's kraal.

On the 12th of January, Lord Chelmsford wrote: "We

have had our first fight to-day. I ordered the whole force

out this morning to reconnoitre the road along which we

shall eventually have to pass. In passing by the Nkudu

hill, we noticed that some herds of cattle had been driven

up close under the krantz where one of Sirayo's strongholds

was said to be. I ordered Colonel Glyn, with four

companies 1-24th, and the 1-3rd Native Contingent, to

work up under the krantz in skirmishing order. On the

approach of this force near the krantz, fire was opened

upon them out of the caves, and the fight commenced. It

lasted about half an hour, and ended in our obtaining

possession of all the caves and all the cattle. Colonel

Degacher, who had been sent for from camp when we found

that the krantz was occupied by the enemy, came up[47]

towards the end of the affair with half-battalion 2-24th,

and about 400 of the 2-3rd Native Contingent. This force

went forward to Sirayo's own kraal, which is situated under

a very steep krantz filled with caves. The British soldiers