THE AMERICAN SPORTSMAN'S LIBRARY

EDITED BY

CASPAR WHITNEY

RIDING AND DRIVING

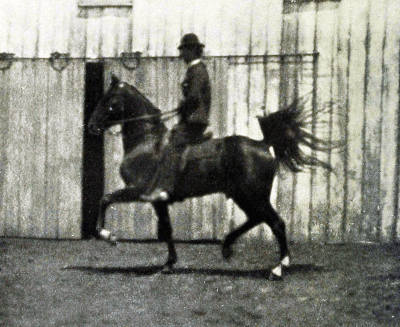

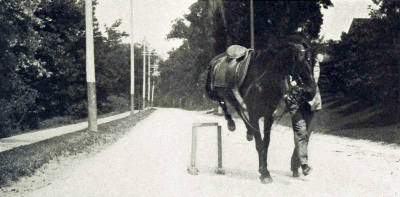

The Gallop-change from Right to Left. The horse, having been in gallop right, has just gone into air from the right fore leg. The right hind leg was then planted, which will be followed in turn by the left hind leg, then the right fore leg, and lastly the left fore leg, from which the horse will go into air; the change from gallop right to gallop left having been made without disorder or a false step.

RIDING AND DRIVING

RIDING

BY

EDWARD L. ANDERSON

AUTHOR OF "MODERN HORSEMANSHIP," "CURB, SNAFFLE, AND

SPUR," ETC., ETC.

DRIVING

HINTS ON THE HISTORY, HOUSING, HARNESSING

AND HANDLING OF THE HORSE

BY

PRICE COLLIER

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd.

1905

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1905.

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published April, 1905.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

CONTENTS

RIDING

By EDWARD L. ANDERSON

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Breeding the Saddle-horse | 3 |

| II. | Handling the Young Horse | 20 |

| III. | The Purchase, the Care, and the Sale of the Saddle-horse | 30 |

| IV. | Some Saddle-horse Stock Farms | 47 |

| V. | The Saddle—The Bridle—How To Mount | 54 |

| VI. | The Seat—General Horsemanship | 64 |

| VII. | American Horsemanship—Our Cavalry | 78 |

| VIII. | How to Ride—The Snaffle-bridle—The Walk and the Trot—Shying—The Cunning of the Horse—Sulking—Rearing—Defeating the Horse | 85 |

| IX. | What Training will do for a Horse—The Forms of Collection | 103 |

| X. | The Spur | 109 |

| XI. | Some Work on Foot—The Suppling | 112 |

| XII. | The Curb-and-Snaffle Bridle—Guiding by the Rein against the Neck—Croup about Forehand—Upon Two Paths | 121 |

| XIII. | The Gallop, and the Gallop Change—Wheel in the Gallop—Pirouette Turn—Halt in the Gallop | 127 |

| [vi]XIV. | Backing | 135 |

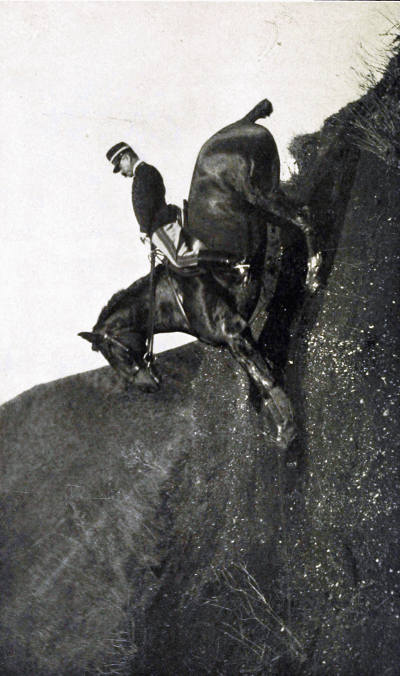

| XV. | Jumping | 138 |

| XVI. | General Remarks | 147 |

DRIVING

By PRICE COLLIER

| Introduction | I | |

| I. | Economic Value of the Horse | 159 |

| II. | The Natural History of the Horse | 169 |

| III. | The Early Days of the Horse in America | 179 |

| IV. | Points of the Horse | 195 |

| V. | The Stable | 211 |

| VI. | Feeding and Stable Management | 225 |

| VII. | First Aid to the Injured | 239 |

| VIII. | Shoeing | 251 |

| IX. | Harness | 259 |

| X. | The American Horse | 284 |

| XI. | A Chapter of Little Things | 300 |

| XII. | Driving One Horse | 315 |

| XIII. | Driving a Pair | 333 |

| XIV. | Driving Four | 353 |

| XV. | The Tandem | 392 |

| XVI. | Driving Tandem. By T. Suffern Tailer | 401 |

| Bibliography | 427 | |

| Index | 429 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

RIDING

By EDWARD L. ANDERSON

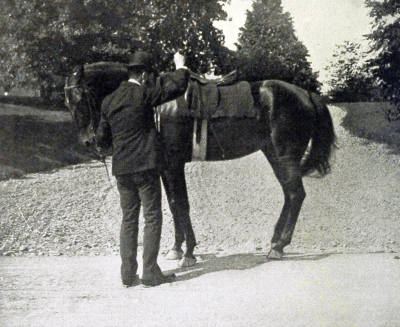

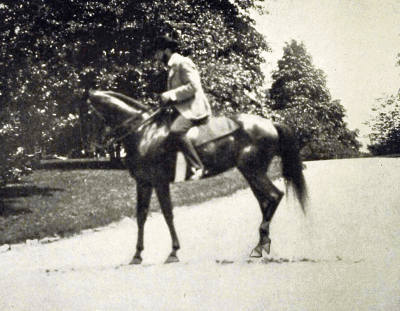

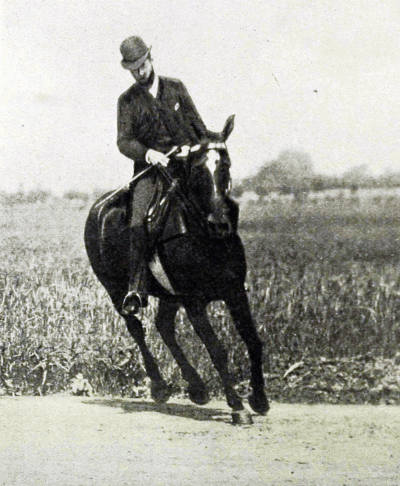

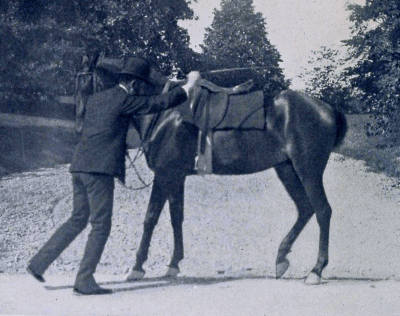

| The Gallop-change from Right to Left. The horse, having been in gallop right, has just gone into air from the right fore leg. The right hind leg was then planted, which will be followed in turn by the left hind leg, then the right fore leg, and lastly the left fore leg, from which the horse will go into air; the change from gallop right to gallop left having been made without disorder or a false step | Frontispiece | |

| FIGURE | FACING PAGE | |

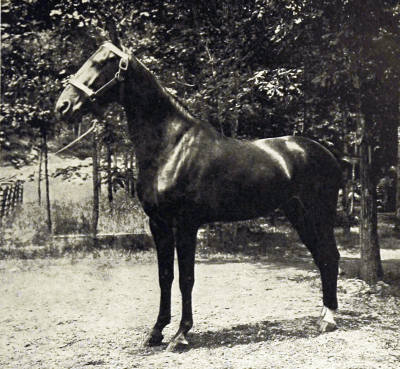

| 1. | Race-horse in Training. Photograph by R. H. Cox | 5 |

| 2. | Dick Wells. Holder of the world's record for one mile. Photograph by R. H. Cox. | 5 |

| 3. | Thoroughbred Mare, L'Indienne. Property of Major David Castleman. Photograph by the author | 7 |

| 4. | Cayuse. Photograph by W. G. Walker | 7 |

| 5. | Abayan Koheilan. Arab stallion, bred by Amasi Hamdani, Smyri, Sheik of the District of Nagd. Property of Sutherland Stock Farm, Cobourg, Canada | 7 |

| 6. | Norwegian Fiord Stallion. Imported by the author | 9 |

| 7. | Mafeking, 16.2, by Temple out of a Mare by Judge Curtis. The property of Colin Campbell, Esq., Manor House, St. Hilaire, Quebec, Canada. This splendid animal has been hunted for three seasons with the Montreal Fox Hounds. He shows great power and quality, and is master of any riding weight | 9 |

| 8. | Prize-winning Charger. Property of Major Castleman. Photograph by the author | 9 |

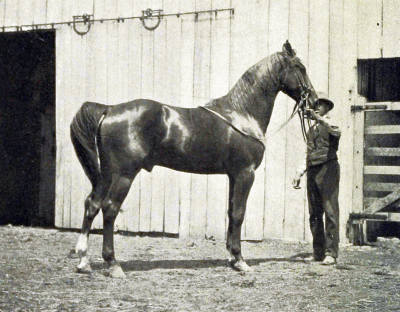

| 9. | [viii]Morgan Stallion, Meteor. Property of Mr. H. P. Crane. Photograph by Schreiber & Sons | 9 |

| 10. | Mademoiselle Guerra on Rubis, a Trakhene Stallion | 10 |

| 11. | Highland Denmark. Property of Gay Brothers, Pisgah, Kentucky. The sire of more prize winners in saddle classes than any other stallion in America. Photograph by the author | 10 |

| 12. | Brood Mare, Dorothy. Owned by General Castleman. This mare has a record of first prize in nearly seventy show rings | 12 |

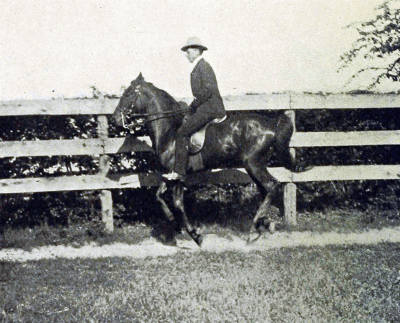

| 13. | Cecil Palmer, American Saddle-horse, Racking. Owned and ridden by Major David Castleman. Photograph by the author | 12 |

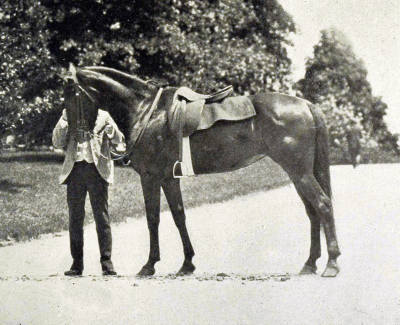

| 14. | The Cavesson. Photograph by the author | 23 |

| 15. | The Horse goes about the Man at the Full Length of the Cavesson Rein. Photograph by the author | 23 |

| 16. | Elevating the Head of the Horse with the Snaffle-bit. Photograph by M. F. A. | 26 |

| 17. | Dropping the Head and Suppling the Jaw. Photograph by M. F. A. | 26 |

| 18. | Bending Head with Snaffle. Photograph by M. F. A. | 28 |

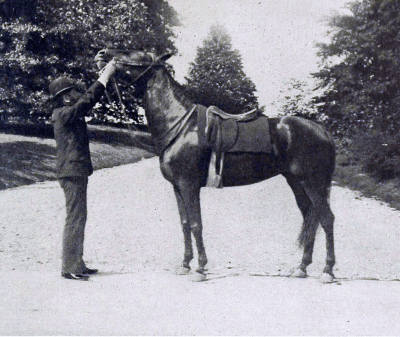

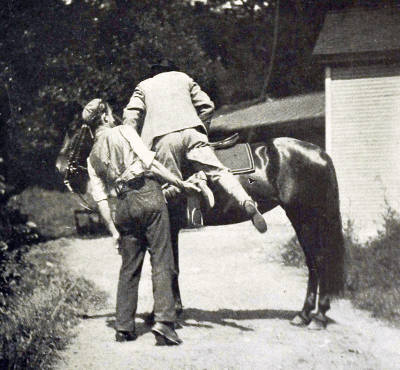

| 19. | A Leg Up. Photograph by M. F. A. | 28 |

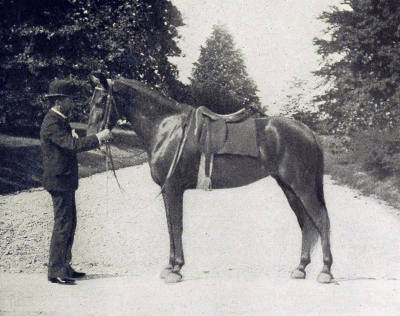

| 20. | Silvana. An English half-bred mare, imported by the author. Photograph by M. F. A. | 37 |

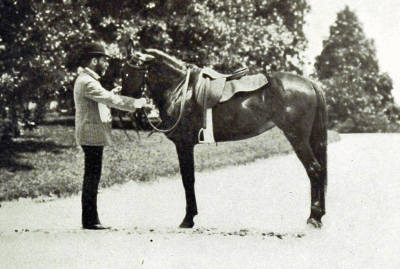

| 21. | Montgomery Chief, Champion Saddle Stallion of America. Property of Ball Brothers, Versailles, Kentucky. Photograph by the author | 37 |

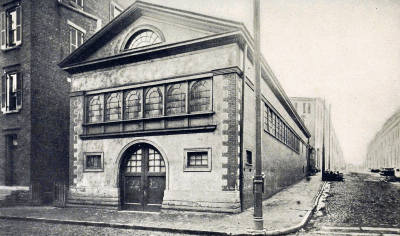

| 22. | Riding-house of the Author | 44 |

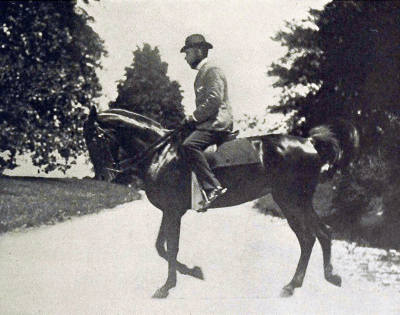

| 23. | Garrard. Two years old. Owned and ridden by Major David Castleman. Photograph by the author | 51 |

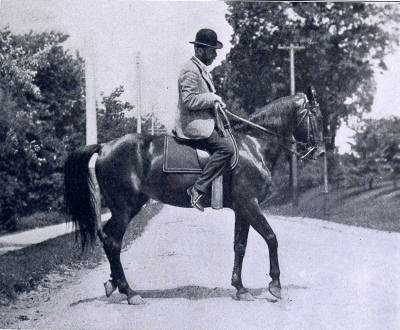

| 24. | Carbonel. Four years old. Owned and ridden by Major David Castleman. Photograph by the author | 51 |

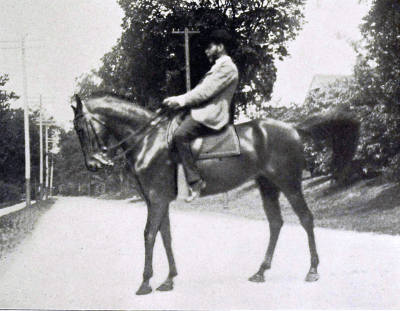

| 25. | High Lassie. Two years old. Owned by Gay Brothers, Pisgah, Kentucky. Photograph by the author | 53 |

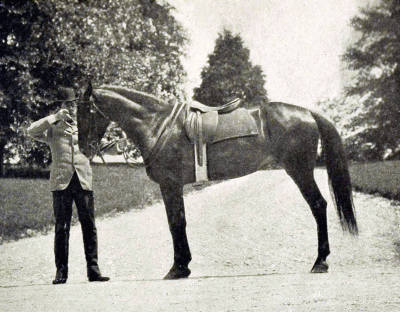

| 26. | Mares and Foals. Gay Brothers. Photograph by the author | 53 |

| 27. | Stirling Chief. Property of Colonel J. T. Woodford, Mt. Stirling, Kentucky. Photograph by the author | 55 |

| 28. | [ix]Stirling Chief in the Trot. Photograph by the author | 55 |

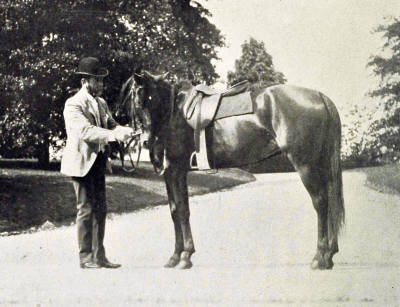

| 29. | Double Bridle Fitted. Photograph by the author | 58 |

| 30. | Mounting with Stirrups. Photograph by M. F. A. | 58 |

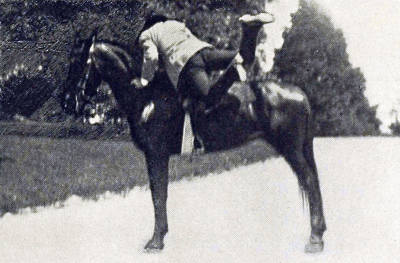

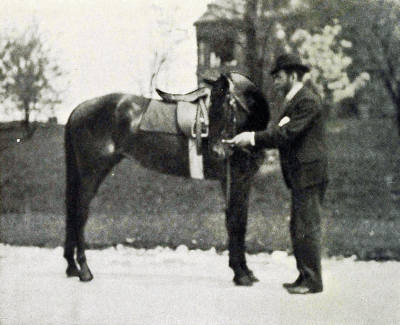

| 31. | Mounting without Stirrups. Photograph by M. F. A. | 60 |

| 32. | Mounting without Stirrups. Photograph by M. F. A. | 60 |

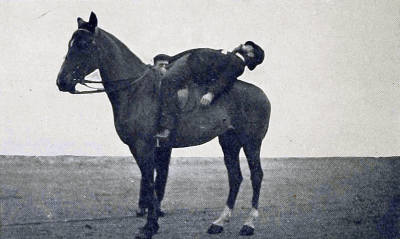

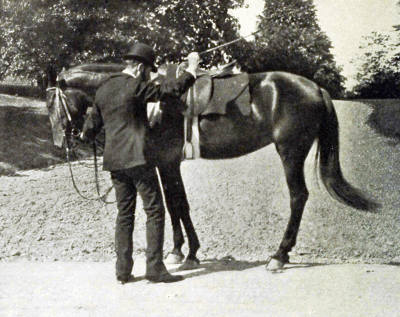

| 33. | Dismounting without Stirrups. Photograph by M. F. A. | 60 |

| 34. | Jockey Seat. Photograph by R. H. Cox | 62 |

| 35. | Pointing the Knees above the Crest of the Horse. Photograph by M. F. A. | 62 |

| 36. | Dropping the Knees to take the Seat without Stirrups. Photograph by M. F. A. |

65 |

| 37. | The Seat. Photograph by M. F. A. | 65 |

| 38. | Leaning Back. Photograph by M. F. A. | 65 |

| 39. | German Cavalry. Photograph by O. Anschutz | 67 |

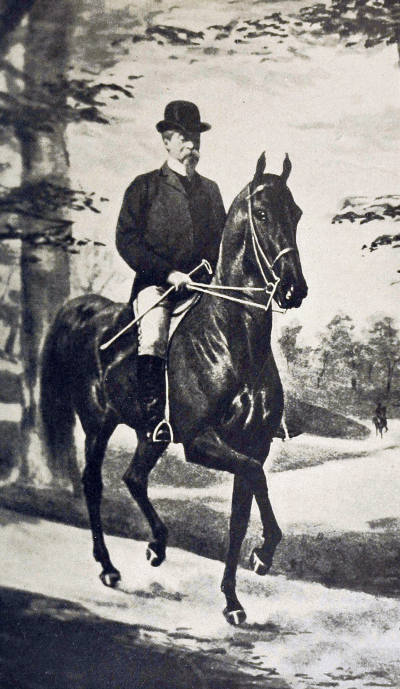

| 40. | Monsieur Leon de Gisbert. Photograph by the author | 69 |

| 41. | Monsieur H. L. de Bussigny. Formerly an officer of the French Army | 69 |

| 42. | Chasseurs d'Afrique | 71 |

| 43. | Spahis. Arabs in the Algerian army of France | 71 |

| 44. | A French Officer. Good man and good horse | 73 |

| 45. | French Officers | 73 |

| 46. | Italian Officers. The horsemanship here exhibited is above criticism. Courtesy of the Goerz Co. | 73 |

| 47. | Italian Officers | 73 |

| 48. | An Italian Officer. The pose of the horse proves the truth of the photograph | 73 |

| 49. | Trooper Royal Horse Guards. Photograph by F. G. O. Stuart | 76 |

| 50. | Scots Grays. Tent Pegging. Photograph by F. G. O. Stuart | 76 |

| 51. | General Castleman | 78 |

| 52. | Mr. C. Elmer Railey | 80 |

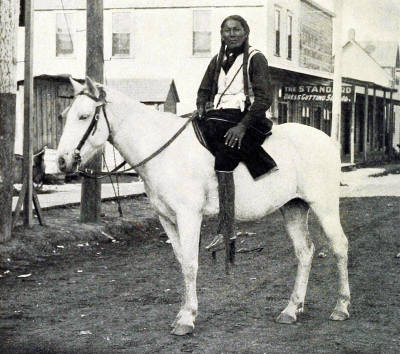

| 53. | A Rider of the Plains. Photograph by W. G. Walker | 80 |

| 54. | Colonel W. F. Cody, "Buffalo Bill." Photograph by Stacy | 83 |

| 55. | An American Horseman | 83 |

| 56. | Troopers of the Fourth and the Eighth Cavalry, United States Army. Photograph by the author | 85 |

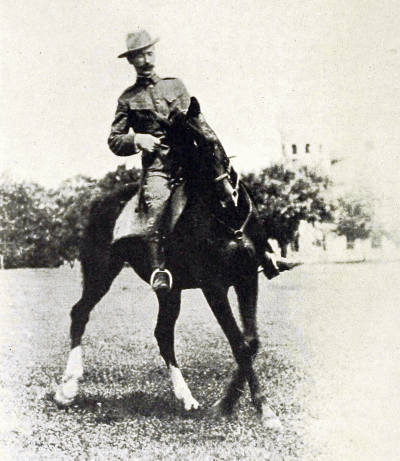

| 57. | [x]Captain W. C. Short. Instructor of Riding at Fort Riley. Photograph by the author | 85 |

| 58. | Three Officers at Fort Riley. Photograph by the author | 87 |

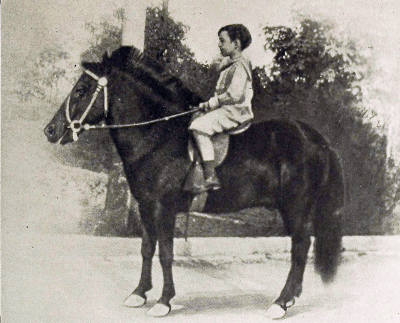

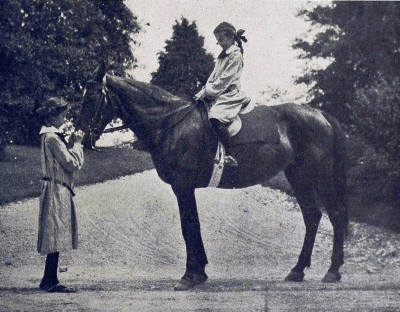

| 59. | The Small Pony is but a Toy. Photograph by Mary Woods | 90 |

| 60. | Up to Ten or Twelve Years of Age Girls should ride in the Cross Saddle to learn the Effects of the Aids. Photograph by the author | 90 |

| 61. | The Alertness of In Hand. Photograph by R. H. Cox | 92 |

| 62. | In Hand in Walk. Photograph by M. F. A. | 92 |

| 63. | United Halt, between Heels and Hand. Photograph by M. F. A. | 94 |

| 64. | In Hand in Trot. Photograph by M. F. A. | 94 |

| 65. | Preventing the Horse rearing by bending the Croup to One Side. Photograph by M. F. A. | 97 |

| 66. | Rearing with Extended Fore Legs. Photograph by Walker | 97 |

| 67. | Major H. L. Ripley, Eighth Cavalry, United States Army. Horse rearing with bent fore legs | 101 |

| 68. | Rolling up a Restive Horse | 101 |

| 69. | Closely United. Photograph by M. F. A. | 102 |

| 70. | Half-halt. Photograph by M. F. A. | 102 |

| 71. | The Scratch of the Spur. Photograph by M. F. A. | 108 |

| 72. | Halt with the Spurs. Photograph by M. F. A. | 108 |

| 73. | Direct Flexion of the Jaw. The snaffle holds the head up. The curb-bit, with the reins drawn toward the chest of the horse, induces the animal to yield the jaw, when the tension upon the reins is released and the animal so rewarded for its obedience. Photograph by M. F. A. | 112 |

| 74. | The Result of the Direct Flexion of the Jaw. Photograph by M. F. A. | 112 |

| 75. | Bending Head and Neck with the Curb-bit. Photograph by M. F. A. |

115 |

| 76. | Bending Head and Neck with the Curb-bit. Photograph by M. F. A. |

115 |

| 77. | Carrying the Hind Legs under the Body. Photograph by M. F. A. | 117 |

| 78. | [xi]Croup about Forehand, to the Right. Photograph by M. F. A. |

117 |

| 79. | Croup about Forehand, to the Right. The left fore leg the pivot. The head bent toward the advancing croup. Photograph by M. F. A. | 119 |

| 80. | In Hand in Place. Photograph by H. S. | 119 |

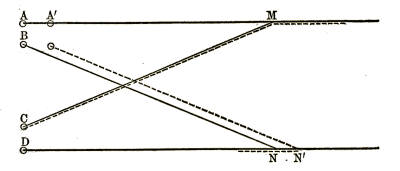

| 81. | The Indirect Indication of the Curb-bit. To turn the horse to the right by bringing the left rein against the neck of the horse. The rider's hand carried over to the right, the thumb pointing to the right shoulder | 122 |

| 82. | The Indirect Indication of the Curb-bit. To turn the horse to the left. The rider's hand is carried over to the left, the thumb pointing to the ground over the left shoulder of the horse | 122 |

| 83. | Reversed Pirouette, to the Left. The hind quarters are carried to the left, about the right fore leg as pivot, the head bent to the left | 124 |

| 84. | Passing on Two Paths to the Right. The forehand slightly in advance of the croup. The head of the horse slightly bent in the direction of progress | 124 |

| 85. | The Gallop. The horse in air | 126 |

| 86. | The Hind Legs are committed to a Certain Stride in the Gallop before the Horse goes into Air | 126 |

| 87. | Gallop Right. The change must be begun by the hind legs as soon as they are free from the ground. The last seven photographs by M. F. A. | 126 |

| 88. | The Wheel in the Gallop. In two paths, the hind feet on a small inner circle |

131 |

| 89. | The Pirouette Wheel. The inner hind leg remains in place as a pivot | 131 |

| 90. | Backing. Taking advantage of the impulse produced by the whip tap to carry the mass to the rear. Photograph by M. F. A. | 135 |

| 91. | Backing. The same principles are observed. Photograph by M. F. A. | 135 |

| 92. | Jumping In Hand. Photograph by M. F. A. | 138 |

| 93. | The Narrow Hurdle. Photograph by M. F. A. | 138 |

| 94. | Jumping In Hand. Photograph by M. F. A. | 138 |

| 95. | Jumping a Narrow Hurdle. Photograph by M. F. A. | 142 |

| 96. | [xii]Jumping a Narrow Hurdle. Photograph by M. F. A. | 142 |

| 97. | Hurdle-racing. Photograph by R. H. Cox | 151 |

| 98. | Thistledown. Four years old. Property of Mr. A. E. Ash brook. Record of seven feet one and three-quarters inches. Photograph by E. N. Williams | 151 |

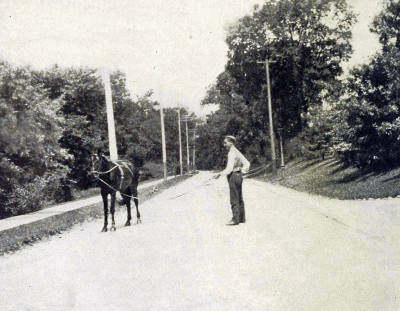

| 99. | Denny Racking. Property of Mr. J. S. Neane. Photograph by the author | 154 |

| 100. | Denny at the Running Walk. Photograph by the author | 154 |

| 101. | Casting a Horse without Apparatus. Photograph by M.F.A. | 154 |

DRIVING

By PRICE COLLIER

| PLATE | ||

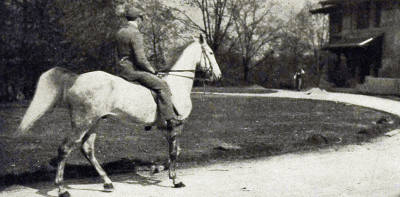

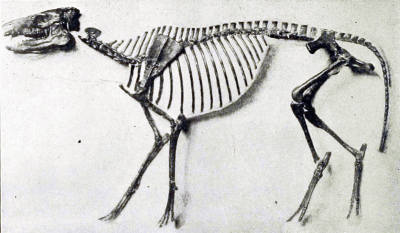

| I. | Protorohippus | 167 |

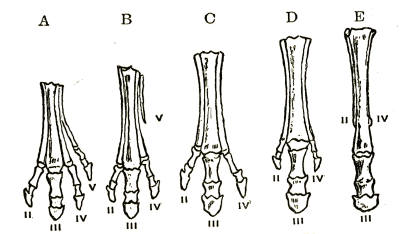

| II. | Development of Horse's Foot From Toes to One | 167 |

| III. | Neohipparion | 170 |

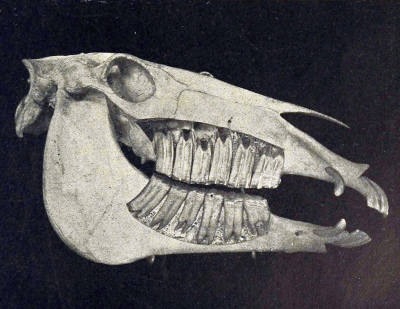

| IV. | Skull of Horse Eight Years Old | 170 |

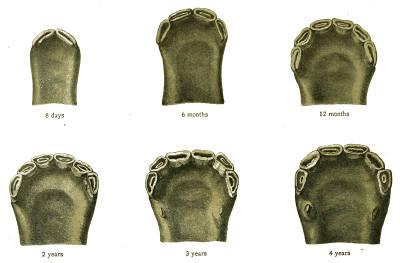

| V. | Teeth of Horse | 195 |

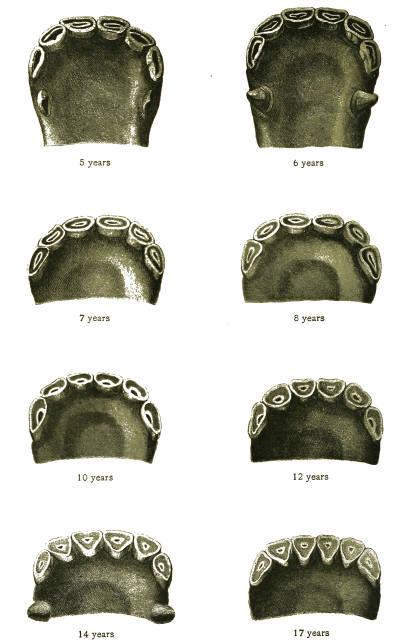

| VI. | Teeth of Horse | 197 |

| VII. | Polo Pony | 199 |

| VIII. | Light-harness Horse | 199 |

| IX. | Harness Type | 202 |

| X. | Flying Cloud, Harness Type | 202 |

| XI. | Children's Pony | 204 |

| XII. | Children's Pony | 204 |

| XIII. | Good Shoulders, Legs, and Feet | 206 |

| XIV. | Heavy-harness Types | 206 |

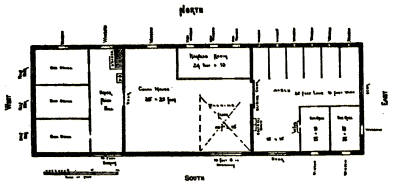

| XV. | Stable Plan | 219 |

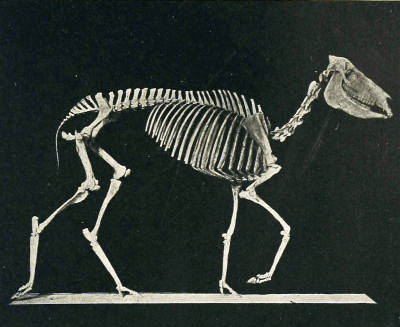

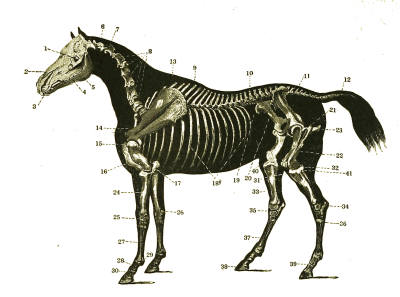

| XVI. | Skeleton of the Horse | 245 |

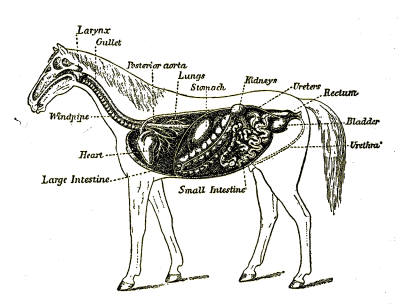

| XVII. | Internal Parts of the Horse | 245 |

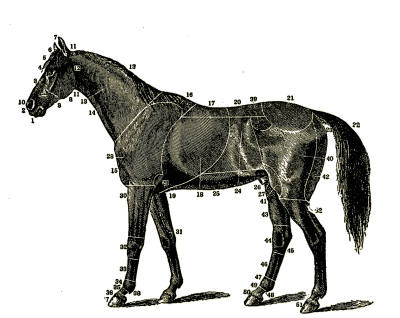

| XVIII. | External Parts of the Horse | 252 |

| XIX. | Foot of the Horse | 252 |

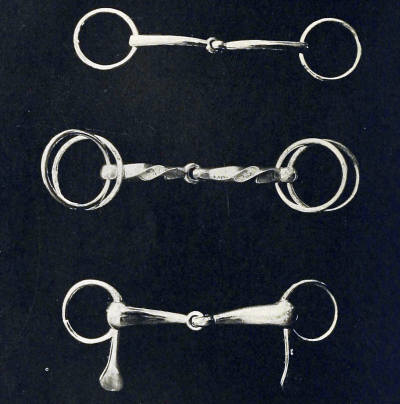

| XX. | Bridoon Bit; Double-ring Snaffle-bit; Half-cheek Jointed Snaffle-bit | 261 |

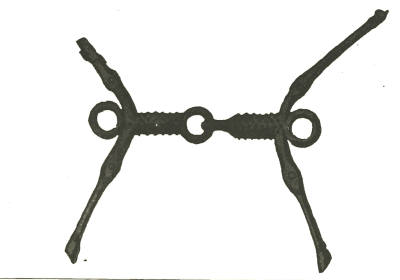

| [xiii]XXI. | Bit found on Acropolis; date, 500 b.c. | 261 |

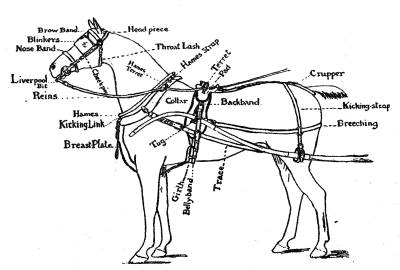

| XXII. | Single Harness | 263 |

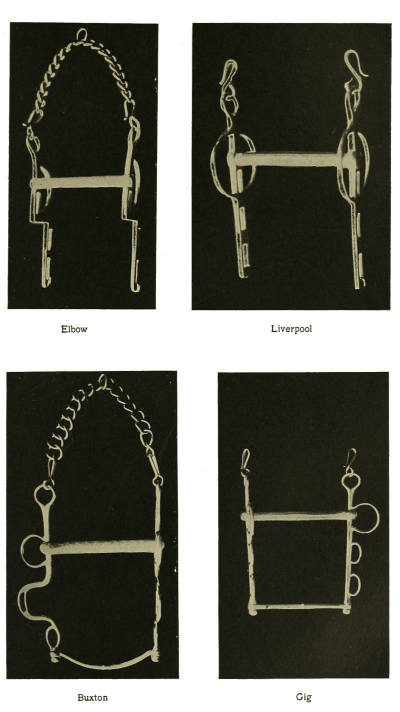

| XXIII. | Elbow-bit; Liverpool Bit; Buxton Bit; Gig-bit | 266 |

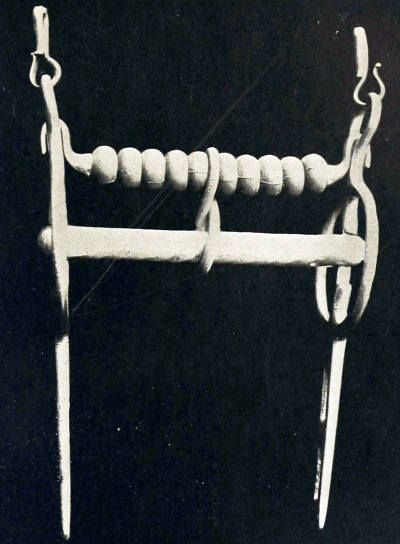

| XXIV. | Swale's Patent Bit | 268 |

| XXV. | Brush Burr | 268 |

| XXVI. | Plain Burr | 268 |

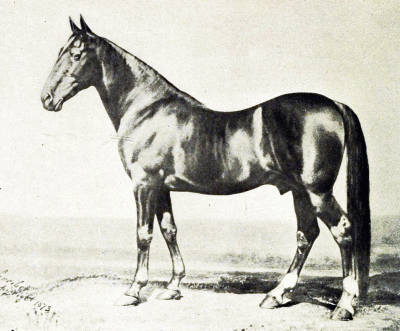

| XXVII. | Hambletonian | 293 |

| XXVIII. | George Wilkes | 293 |

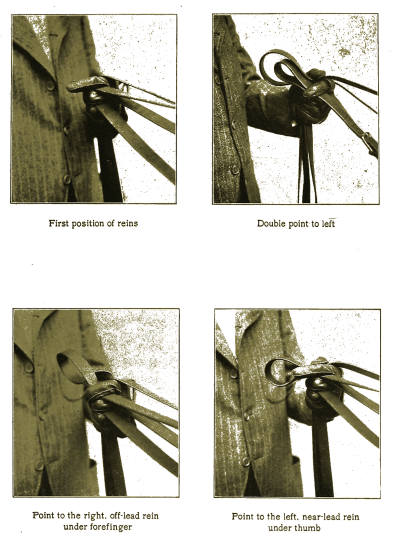

| XXIX. | Driving a Pair | 341 |

| XXX. | Driving a Pair | 348 |

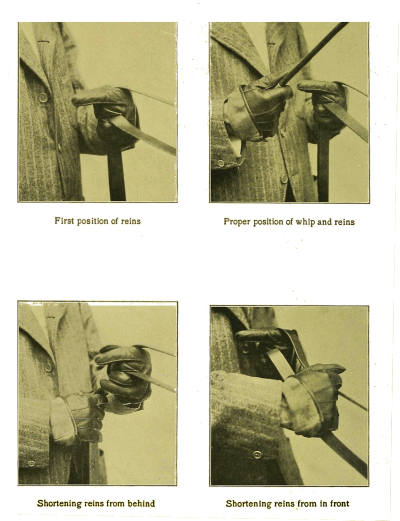

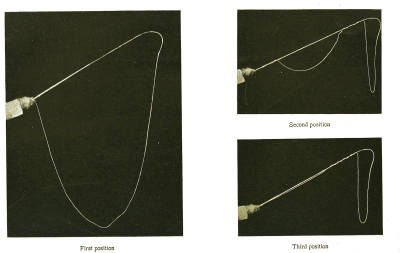

| XXXI. | Positions of Whip | 357 |

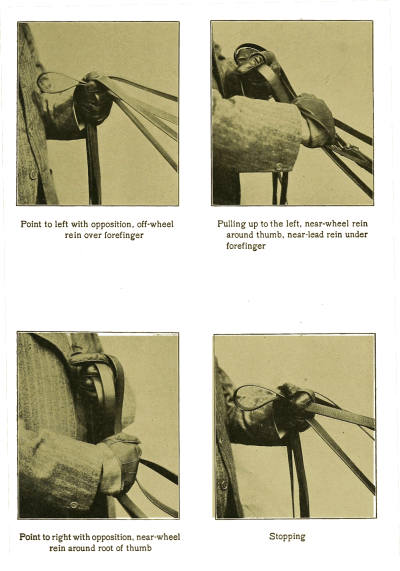

| XXXII. | Driving Four | 364 |

| XXXIII. | Pony Tandem | 391 |

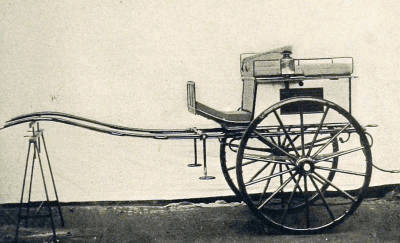

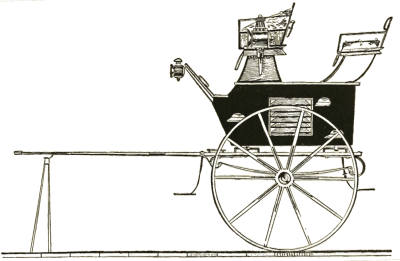

| XXXIV. | Tandem Dog-cart | 394 |

| XXXV. | High and Dangerous Cocking-cart | 394 |

| XXXVI. | Tandem of Mr. McCandless | 404 |

| XXXVII. | Tandem of Mr. T. Suffern Tailer | 404 |

RIDING

By EDWARD L. ANDERSON

RIDING

CHAPTER I

BREEDING THE SADDLE-HORSE

The thoroughbred is universally recognized as the finest type of the horse, excelling all other races in beauty, in stamina, in courage, and in speed; and, further, it is capable in the highest degree of transmitting to its posterity these valuable qualities. Indeed, the greatest virtue possessed by this noble animal lies in its power of producing, upon inferior breeds, horses admirably adapted to many useful purposes for which the blooded animal itself is not fitted.

In England and upon the continent the thoroughbred is held in high esteem for the saddle; but, as General Basil Duke justly remarks, it has not that agility so desirable in a riding-horse, and because of its low action and extended stride it is often wanting in sureness of foot, and in America we prefer to ride the half-breed with better action. Occasionally the thoroughbred is found that fills the requirements of the most exacting rider, and the author has had at least six blood-horses that[4] were excellent under the saddle. One of these, represented by a photograph in a previous work, in a gallop about a lance held in the rider's hand, gave sufficient proof of quickness and suppleness. However, it is admitted on all hands that the horse which most nearly approaches the thoroughbred, and yet possesses the necessary qualities which the superior animal lacks, will be the best for riding purposes.

Although every thoroughbred traces its ancestry in the direct male line to the Byerly Turk, 1690, the Darley Arabian, circa 1700, or the Godolphin Barb, circa 1725, and "it is impossible to find an English race-horse which does not combine the blood of all three," the experience of modern horsemen points to the fact that the blood-horse is as near to the Eastern horse as we should go with the stallion in breeding for the race-course or for ennobling baser strains.

In view of the great influence that these three horses had almost immediately upon English breeds, this present exclusion of the Eastern stallion is striking; but it means simply that the race-horse of our day has more admirable qualities to transmit than the sire of any other blood.

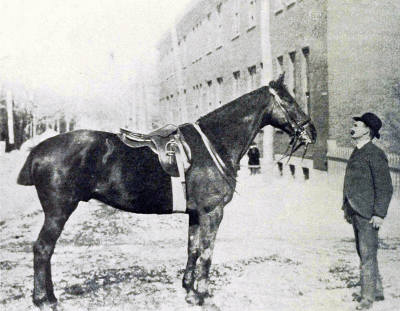

FIG. 1.—RACE-HORSE IN TRAINING

FIG. 2.—DICK WELLS. HOLDER OF THE RECORD FOR ONE MILE

The Bedouin Arabian of the Nejd district, supposed to be the purest strain of the race and the fountainhead of all the Eastern breeds, has become degenerate during the past two hundred years; too often horses of this royal blood are found undersized, calf-kneed, and deficient in many points. Notwithstanding the virtues that such animals may yet be able to transmit, I venture to say that the disdained "Arab" of Turkey, Persia, Egypt, and even that of Europe, as well as the so-called Barb, are better and more useful horses, and it is from these impure races that nearly all of the Eastern blood has come that has found its way into the crosses of European horses during the past hundred years or more. Indeed, if we may believe the statements of the partisans of the Eastern horse, but very little of the best Arab blood has been introduced into Europe.

The Darley Arabian, the ancestor of the best strains in the world, was doubtless of pure desert blood. His color, form, and other characteristics have always satisfied horsemen that his lineage could not be questioned.

In crosses of thoroughbred strains and desert blood the stallion should be of the former race; but in bringing Eastern blood into inferior breeds the blood of the latter should be represented by the mare. All good crosses are apt to produce better riding-horses than those of a direct race.

From the fossil remains found in various parts of the world it is certain that the horse appeared in many places during a certain geological period, and survived where the conditions were favorable.

But whether Western Asia is or is not the home of the horse, he was doubtless domesticated there in very early times, and it was from Syria that the Egyptians received their horses through their Bedouin conquerors. The horses of the Babylonians probably came from Persia, and the original source of all these may have been Central Asia, from which last-named region the animal also passed into Europe, if the horse were not indigenous to some of the countries in which history finds it. We learn that Sargon I. (3800 b.c.) rode in his chariot more than two thousand years before there is an exhibition of the horse in the Egyptian sculptures or proof of its existence in Syria, and his kingdom of Akkad bordered upon Persia, giving a strong presumption that the desert horse came from the last-named region, through Babylonian hands. It seems, after an examination of the representations upon the monuments, that the Eastern horse has changed but little during thousands of years. Taking a copy of one of the sculptures of the palace of Ashur-bani-pal, supposed to have been executed about the middle of the seventh century before our era, and assuming that the bare-headed men were 5 feet 8 inches in height, I found that the horses would stand about 14½ hands—very near the normal size of the desert horse of our day. The horses of ancient Greece must have been starvelings from some Northern clime, for the animals on the Parthenon frieze are but a trifle over 12 hands in height, and are the prototypes of the Norwegian Fiord pony—a fixed type of a very valuable small horse.

FIG. 3.—THOROUGHBRED BROOD-MARE

FIG. 4.—CAYUSE

FIG. 5.—DESERT-BRED ARAB STALLION

The horse was found in Britain from the earliest historical times, and new blood was introduced by the Romans, by the Normans, and under many of the successors of William the Conqueror. The Turkish horse and the barb, it is understood, were imported long before the reign of James I., when Markham's Arabian, said to be the first of pure desert blood, was brought into the country; but from that time many horses were introduced from the East, of strains more or less pure. The Eastern horse was the foundation upon which the Englishman reared the thoroughbred, but we must not lose sight of the skill of the builder nor of the material furnished by native stock. The desert strains furnished beauty, courage, and stamina; the native blood gave size, stride, and many other good qualities; the English breeder combined all these and produced what no other nation has approached, the incomparable thoroughbred.

We accept the thoroughbred as we find him. No man can say exactly how he was produced. The great Eclipse (1764) has upward of a dozen mares in his short pedigree (he was fourth[8] in descent from the Darley Arabian) whose breeding is unknown and which were doubtless native mares, for already the descendants of Eastern horses were known and noted. What is true of the breeding of Eclipse is true of many of his contemporaries who played prominent parts in the studs of their day.

For more than one hundred years no desert-bred stallion has had any marked influence upon the race-horse directly through a thoroughbred mare. In the first decade of the last century a barb stallion bred to a barb mare produced Sultana, who brought forth the granddam of Berthune to Sir Archy. Berthune was much sought after as a sire for riding-horses; besides this barb blood he had strains of Diomed and of Saltram in his veins, all of which were desirable for saddle-horses.

Breeds of animals deteriorate rapidly through lack of nourishment and from in-and-in breeding. It is questionable whether a degenerate race may be restored, within measurable time, by the use of any appreciable amount of its own blood; it is certainly bad policy to found a breed upon poor stock. The better plan would be to form the desired type from new strains. One hundred years ago Lewis and Clark found upon the plains of the Northwest "horses of an excellent race, lofty, elegantly formed, and durable," but one could hardly hope to replace such animals from the cayuse ponies, their descendants, without the introduction of superior blood in such quantities as practically to obliterate the inferior.

FIG. 6.—NORWEGIAN FIORD STALLION

FIG. 7.—HEAVY-WEIGHT HUNTER

FIG. 8.—CHARGER

FIG. 9.—MORGAN STALLION

Some of the range horses of Washington and of Oregon are fairly good animals, and these have more or less of the bronco blood, but all that can be said of the influence of the wild horse is that its descendants can "rustle" for a living where an Eastern horse would starve, and the same thing can be said of the donkey. Admitting that for certain purposes inferior blood must sometimes be introduced for domestic purposes, the better the breeding the better the horse will be. Bon sang bon chien.

The mustang of the southern central plains maintains many of the good qualities of its Spanish ancestors, and is a valuable horse for certain purposes, but we need not consider this animal in breeding for the saddle when we have so many other strains infinitely superior. Polo and cow ponies are not within our intent.

Types and families of horses are produced either by careful "selection and exclusion," or by the chances of environment In the first manner was brought about the thoroughbred, the Percheron, the Orloff, the Trakhene, the Denmark, and every other race or family of real value.

All over the world isolated groups of horses[10] may be found which have become types by an accidental seclusion, and these from various causes are usually undersized and often ill-formed. Such are the mustang and its cousins on the plains, many breeds in Eastern Asia, the Norwegian Fiord pony, the Icelander, the Shetlander, etc., the last-named three being, it is supposed, degenerates of pure desert descent from animals taken north from Constantinople by the returned Varangians in the eleventh century.

In breeding for the saddle, or for any other purpose, the mare should be nearly of the type the breeder desires to obtain, and she should be of strong frame, perfectly sound, of healthy stock, and with a good disposition. If her pedigree be known, the stallion, well-bred or thoroughbred, should be selected from a strain which has been proved to have an affinity with that of the mare. The mingling of certain strains is almost as certain to produce certain results—not, be it understood, everything that may be desired—as does the mixing of chosen colors on the palette. That is to say, size, form, action, and disposition may ordinarily be foretold by the mating between families that are known to nick. The stallion should be no larger than the mare, of a family in which there is no suspicion of transmissible disease, and of good temper, and it certainly should not be lacking in the slightest degree in any point where the mare is not fully developed. The mare might be the stronger animal, the stallion the more highly finished.

FIG. 10.—TRAKHENE STALLION

FIG. 11.—TYPICAL DENMARK STALLION

Where the mare's pedigree is unknown, and the matter is purely an experiment, or where she is undoubtedly of base breeding, the stallion, while of superior blood, should not vary greatly from her type. Peculiarities in either parent are almost certain to be found in an exaggerated form in the foal.

It would be difficult to imagine a better horse, for any conceivable purpose except racing, than a first-rate heavy-weight hunter; yet he may be called an accident, as there is no such breed, and his full brother may be relegated to the coach or even to the plough. The large head and convex face almost invariably found in the weight carrier, and in the "high-jumper," are derived from the coarse blood which gives them size and power; but these features are indications of that courage and resolution which give them value—characteristics which in animals of wholly cold blood are usually exhibited in obstinacy. Indeed, while the English horse, each in its class, has no superior, Great Britain has no type or family of saddle animals such as our Denmark, unless one except cobs and ponies.

Of course, where two animals of the same or of similar strains, and bearing a close resemblance to[12] each other, are mated, the type will be reproduced with much greater certainty than where various strains are for the first time brought together; but even in good matches a foal may show some undesirable feature derived from a remote ancestor. Some marks or characteristics of a progenitor reappear at almost incredible distances from their sources. That Boston's progeny should be subject to blindness, or that Cruiser's descendants should be vicious, or that the offspring of whistlers should prove defective in their wind, are reasonable expectations; but that the black spots on the haunches of Eclipse should be repeated upon his descendants of our day, as is doubtless the case, exhibits an influence that is marvellous. Stockwell (1849) and many others of Eclipse's descendants had those ancestral marks, but Stockwell had many strains of Eclipse blood through Waxy, Gohanna, and other progenitors. When a chestnut thoroughbred shows white hairs through its coat, that peculiarity is ascribed to Venison (1833) blood, if by chance that stallion's name may be found in its pedigree.

FIG. 12.—BROOD-MARE OF SADDLE STRAINS

FIG. 13.—CECIL PALMER RACKING

Where undesirable qualities appear in the products of crosses in breeding for a type, they are bred out in breeding up, or the failures are permitted to die out. It is not probable that any one who was desirous of breeding a horse suitable for the saddle would select a very inferior mare, for, even though her pedigree were unknown, the qualities which suggested her selection would prove her something better. It cannot be denied that occasionally a literal half-breed, by a thoroughbred on common stock, turns out a good animal, and such a cross is often the foundation of valuable types; but the chances are too remote to induce one to try the experiment solely for the produce of the first cross. It is rarely the case that a horse may be found in a gentleman's stable that has not either a liberal, direct infusion of thoroughbred strains, or is not itself a representative of some family which owes its distinction to the blood-horse.

I am schooling a pretty little mare, picked up by chance, for the illustrations of the chapters on riding and training. I believe that Daphne is out of a Morgan mare by a Hambletonian stallion, and that her symmetry comes from the dam. It is greatly to be regretted that the so-called Morgans have been so neglected that it is not easy to find horses with enough of the blood to entitle them to bear the family name. The Morgan, although rather a small horse, was an admirable animal, good in build, in constitution, in action, and in temperament, and its blood combined well with that of the old Canadian pacing stock (of which the original Copperbottom was[14] an example), with Messenger strains, and with those of some other trotting families.

At the Trakhene stud in Germany a distinct breed has been obtained by the admixture of thoroughbred and Eastern blood. How long it took and how many crosses were made to establish the type I cannot say, but it is understood that in the first crosses the stallions were of English blood, the mares of desert strains. These Trakhene horses, usually black or chestnut, are very beautiful animals—large, symmetrical, and of proud bearing. They are sometimes used as chargers by the German emperor and his officers, and in this country they are somewhat familiar as liberty horses in the circus ring. It is said that the Trakhene is not clever upon his feet and that he is not safe in easy paces, which is likely enough, for both the blood-horse and the Arab are stumblers in the walk and in the trot.

In the province of Ontario, Canada, and in the states of Maine and New York, very fine horses are bred for various purposes; and from among these are found good hacks and the animals best suited to the hunting-field that America affords. These Northern horses have good constitutions and, it is thought, better feet than those found beyond the Alleghanies, and the best examples fill the demands of the most critical horseman; but in none of the Northern states can it be said[15] that a breed or family exists that produces a type of hack or hunter, while in the Blue Grass region south of the Ohio we find the Denmarks splendidly developed in every point and with a natural grace and elasticity that make them most desirable for the saddle.

For quite a century the riding-horses of Kentucky have been celebrated in song and story. In the days when bridle-paths were the chief means of intercommunication throughout this state, the pioneer made his journeys as easy as possible by selecting and by breeding saddle-horses with smooth gaits, the rack and the running walk. These movements had been known in the far East and in Latin countries from time immemorial, but it remained for the Kentuckian to perfect them.

Some fifty odd years since a stallion called Denmark was introduced into Kentucky, and from him there has descended a type of saddle-horse which is everywhere held in esteem, for the Denmark horse of to-day has no superior for beauty of form, for docility, for graceful movements and, indeed, for every good quality which should be found in a riding animal. Denmark had been successful on the race-course; he was by imported Hedgeford, and if it be true that there was a stain upon the lineage of his dam, there had been a very successful cross, for the great[16] majority of the saddle-horses of Kentucky boast Denmark as an ancestor. More than nine-tenths of this family trace to the founder's son, Gaines's Denmark, whose dam was by Cockspur, and, probably, out of a pacing mare.

The American Saddle-horse Breeders' Association has undertaken to improve the riding-horses of this country by the formation of a register and by the selection of foundation stallions whose progeny under certain conditions shall be eligible for registry. Their primary object is to encourage the breeding of the gaited saddle-horse, that is, the animal which, from inherited instincts or natural adaptability, may readily be taught to rack, to pace, to go in the running walk and in the fox-trot; but at the same time General Castleman, Colonel Nall, and the other gentlemen engaged with them, are exercising great influence for good upon the horse of the three simpler gaits.

The pedigrees of the foundation sires of this register show many strains of the blood of Saltram and of Diomed, a fair share of that of the Canadian pacer, and enough, doubtless, of that of the Morgan. A fabric woven of such threads must prove of national importance; for, although the registry is open to all horses which can show five saddle-gaits, it should be remembered that such an exhibition is almost a certain proof of the[17] desired breeding and is a certain proof of quality. We may, then, hope for a typical American saddle-horse,—a race that shall have no superior, representatives of which shall be found wherever the horse flourishes.

I am no advocate for any paces other than the walk, the trot, and the gallop, these being the only movements in which the rider can obtain immediate and precise control over the actions of the horse. The riding-horse must be managed by reins and heels; no motions or signs are so exacting, so unmistakable in their demands, and it is impossible readily to obtain movements from a horse that is confused by eight or even five gaits, particularly when some of these gaits require an extension of the animal's forces incompatible with the union required in quick turns and in immediate obedience. It must, however, be acknowledged that the rack, the running walk, and the fox-trot have had a beneficial influence upon the Kentucky saddle-horse. In the first place, these paces required selection in the breeding, and, secondly, the discipline implied by the training, through many generations, has had its effect upon the tempers and dispositions of these splendid animals.

A brood mare should always be well nourished, but not over fed, and, from the time it is able to eat, the foal should have its share of oats as well[18] as of succulent, nutritious grasses, and of sound hay when grazing is impracticable. Our cavalry officers, and horsemen in general, bear testimony to the endurance of animals bred in Kentucky. This vigor is due to the rich blue-grass pastures and to the liberal feeding of the mare and her offspring.

It would appear, upon first viewing the subject, that a horse bred upon rough pasture-land would be more sure of foot than one bred on smooth plains; but that is not always the case. It is true that the animal bred on uneven ground learns to look after itself, and becomes very clever on its feet when obstacles exist, but mountain-bred horses are often stumblers on level roads, in the walk and in the trot. The fact is, that sureness of foot depends upon the manner in which the horse extends and plants its feet, moderate action being the safest, either extremes of high or low action, of short or long strides, militating against the animal's agility. The reason that horses stumble ten times in the walk to once in the trot is because in the first-named pace the pointed toe is usually carried along close to the ground before the fore foot is planted. When the rider unites the horse, this defective action is obviated. During the past twenty years I have taken thousands of photographs of the moving horse in studying the question of action, and I am satisfied[19] that the horse which plants its fore foot with the front of the hoof vertical will stumble; that the horse which straightens its joints and brings the heel to the ground first will travel insecurely and slip on greasy surfaces. I had an example of the last-named in my stable, and the animal several times "turned turtle," as I might have anticipated. Fair action, with fairly bent joints which bring the feet about flat to the ground, the hind legs well under the mass, is the safest form in which the horse moves.

CHAPTER II

HANDLING THE YOUNG HORSE

Before the horse can be taught obedience to the bit and spur it must go through a preliminary course of handling, by which the man obtains mastery over the animal. This work is usually called "breaking-in," and it is a matter of regret that it is almost always conducted in an unnecessarily harsh and rough manner, with the result that many horses are made vicious, or are in other ways spoiled, through the ignorance and cruelty of those who have charge of their early education.

A lively colt is shy, suspicious, and curious, easily amused, and as easily bored; by recognizing these characteristics and conducting his work with reference to them, the trainer will find success easy and agreeable. After the man has gained the confidence of the animal, he will find that the young horse takes great interest in lessons that are varied and not too long continued, and there need be no resistances aroused on the part of the pupil. Except in the very rare cases of animals that are naturally vicious, and such[21] are insane, the training of a horse may be carried on without friction. The faults and vices in a horse usually arise from the efforts of the nervous animal to avoid injudicious restraints before it has been taught by easy steps to yield instinctively to the demands of its trainer. Later misconduct is almost always due to want of firmness and decisive action on the part of the rider. The horse is incapable of that real affection for man such as the dog evinces toward the worst of masters; it is of low intelligence, the boldest of them being subject to panics, but there are few which lack a low craft that enables them to take advantage of every slip or mistake the man may make. A sufficient amount of work and careful treatment will keep a sane horse steady, but when at all fresh most horses are untrustworthy if the man's control be lost. I do not find it necessary to punish my horses; the whip, spur, and reins are employed to convey demands; a harsh word answers every requirement for correction, and the animal cannot resent it as it may the blows of the whip or the stroke of the spur. The photographs of a number of these animals in my various works in almost every possible movement prove how exact is the obedience they render under this course of treatment. When some old favorite refuses to walk into a coal-pit, or voluntarily turns up some well-known road, the fond[22] owner is too apt to confuse instinct or habit with brilliant mental operations, and place too much faith in its good inclinations; but the fact is that in handling this animal we must neglect its will and obtain control over its movement by cultivating the instinctive muscular actions which follow the application of the hand and heel. I have a great admiration for the horse, for its beauty, for its usefulness, for its many excellent qualities, but I do not permit this sentiment to blind me to its shortcomings. Some horses are so good that they inspire an affection which they cannot reciprocate. Since I began this book I lost Silvana, a well-bred English mare which I had owned for eighteen years. She was a very beautiful animal, of high spirit, exact in all the movements of the manège, and of so kind a disposition that she was never guilty of mutinous or disorderly conduct.

Regardless of the treatment it has received previously, the young horse should be "broken to ride," when strong enough to bear the weight of a rider, by some method similar to that which follows.

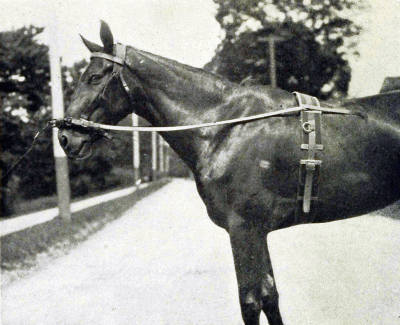

FIG. 14.—THE CAVESSON

FIG. 15.—LONGEING ON THE CAVESSON

But first I wish to say a word about casting the horse, by what is usually called "The Rarey System." Many people believe that to throw the horse is a sure cure for every vice and spirit of resistance. The fact is that a horse is confused, surprised, and humiliated at finding itself helpless, and casting does give the man temporary control which is often a most important matter, and may be the beginning of the establishment of discipline; but mastering the horse permanently cannot be accomplished in a moment, and unless it be necessary to employ the straps in the handling of a violent animal I should advise against it. Vices, faults, and tricks may be remedied only by careful training. I teach many of my horses to lie down, but, as I shall explain later, I do not employ any straps or apparatus.

The first step in breaking-in is to give some lessons on the cavesson. This is a head-collar with a metal nose-band, upon the front and each side of which are stout rings. To the front ring a leather longe line fifteen feet long will be fastened, and from the side rings straps will be buckled to the girth or surcingle at such lengths as will prevent the horse extending its nose so that the face is much beyond the perpendicular. The horse thus fitted should be led to some retired spot where there is level ground enough for a circle of about forty feet. At first the man, walking at the shoulder of the horse, should lead it on the circumference of the circle, to the right and to the left, taking a short hold of the longe line and being careful that the animal does not get so far ahead of him as to have a straight pull forward which may drag him from his feet. From time[24] to time the man will bring the horse to a halt, and require it to stand quite still, making much of it by caresses and kind words, picking up the feet and stroking it gently with the whiphandle all over its body and legs, so that it will not be alarmed at his future motions, and then continuing the progress on the circle. Gradually the length of the hold on the longe line will be increased, until the horse goes about the man at the full length of the strap. In these exercises, also, the horse should frequently be brought to a stop, always on the circumference of the circle, and it should be worked equally to either hand. The lessons should be given twice every day, at first for about fifteen minutes each, and increasing the time until a lesson shall be of three-quarters of an hour's duration. Colored rugs, wheelbarrows, open umbrellas, paper, and other similar objects at which a horse might shy should be placed near the path until the horse is so accustomed to them that it will take no notice. Under no circumstances should the horse be punished, and the man should exercise great care that he does nothing to make the animal fear him. When the horse will go quietly about the man in the walk and in the very slow trot (it should never be permitted to go rapidly), the surcingle may be replaced by the saddle, lightly girthed and the stirrups looped up, the side-lines of the cavesson being[25] removed. Then, at the end of each lesson on the cavesson, that instrument should be replaced by a light snaffle-bridle. The man, facing the head of the horse, should take a snaffle-rein in each hand and make gentle vibrations toward its chest, so that he will give the bit a light feeling on the bars of the mouth. Occasionally he will elevate the head of the horse by extending his arms upward to their full length, then gently bring the head of the horse to a natural height, or to that height which he judges will be the best in which the trained horse should carry it, drawing the reins toward the animal's chest until its face is perpendicular, and no farther, and playing with the bit in light vibrations until the horse takes up the play and gives a supple jaw. He will also bend the head of the horse to the right and to the left, the face vertical, and bring it back to the proper position by the reins, not accepting any voluntary movement from the horse, and endeavoring to obtain always an elastic resistance from its mouth. The head of the horse will also be depressed by the snaffle-reins, until it nearly touches the ground, and then be lifted to the natural height. All of these movements are of high importance, and all of them tend to develop the muscles of the neck and chest; but the elevation of the head and its return to the right height, face vertical, jaw supple, but not flaccid, produces the best[26] results in bitting and should be more frequently practised than the others. If, in these lessons, the horse draws back, it must be made to come to the man; no good results can be obtained from a retreating animal.

Upon some occasion, after the longeing and bitting lesson has been given, when there is no high wind to irritate the horse and the animal seems to be composed, the man should have "a leg up" and quietly drop into the saddle, having first taken a lock of mane in his left hand and with the right, in which the reins should be, grasping the pommel, thumb under the throat of the pommel. He should then let the horse walk off for a few steps, having a very slight tension upon the reins, and quietly dismount. If, as is very unlikely, for the horse will be taken by surprise, though not frightened, the animal makes a jump or a plunge, the rider must maintain his seat, keep up the head of the horse, and dismount when the animal has become quiet. The horse will not rear at this stage; that is an accomplishment it learns from bad hands, and it is probable that it will be perfectly quiet. Each day the riding lesson will be lengthened, and the rider will gradually obtain some control over its movements by the reins and accustom it to bear the pressure of his legs against its sides. The longeing will now be employed to give such exercise as is needed to keep the animal from being too fresh; and when the riding lessons give sufficient work, the longe may be dispensed with, to be resumed if the horse falls into bad habits. But the bitting exercises, previously described, should be occasionally reverted to as long as the horse is used under the saddle.

FIG. 16.—ELEVATION OF THE HEAD WITH SNAFFLE

FIG. 17.—DROPPING HEAD AND SUPPLING JAW

But one more thing is necessary before the horse is ready for the higher training which will be described later, and this desideratum is to confirm the horse in the habit of facing the bit, that is, to go forward against a light tension upon the reins; for without this the rider will have little or no government over its movements, as the bit must have some resistance, slight though it should be, upon which to enforce his demands. Whenever a rider finds that his hand has nothing to work against, that the horse has loosened its hold on the bit and refuses to face it, he may be almost certain that he has an old offender to manage and that mischief is meant, and will follow unless he can force the horse up into the bridle.

The horse may best be taught to face the bit in a slow but brisk trot. The animal must not be started off too abruptly, but the forward movement should begin in a walk; and this is a rule that should always be followed, even though it be for a few steps, unless some good reason for doing otherwise exists. The impulse for the trot and[28] its continuance may be induced by a pressure of the rider's legs against the sides of the horse, or by light taps of the whip delivered just back of the girths.

FIG. 18.—BENDING HEAD WITH SNAFFLE

FIG. 19.—A LEG UP

In a measured, regular trot the horse should be ridden in straight lines, and in circles, first of large, and afterward of decreased, diameters, the pace being maintained by demanding impulses from the hind quarters, the hand taking a light but steady tension upon the reins. No effort will be made to induce the horse to pull against the hand, but the man should endeavor to get just that resistance by which he may direct the animal. It does not really matter if the jaw of the horse does get a little rigid; that can be softened by the bitting exercises and by future lessons, but the horse must go into the bridle. In turning to either hand the inside rein will direct the movement, the outer rein measuring and controlling the effect of the other; the outside leg of the rider will make an increased pressure as the turn is being made to keep the croup of the horse on the path taken by the forehand. On approaching the turn the horse will be slightly collected between hand and heel, and as soon as the horse enters upon the new direction it will be put straight and the aids will act as before. To bring it to a halt, the legs of the rider will close against the sides of the horse; he will then lean back slightly and raise his hand until the horse comes to a walk, and in the same manner he will bring it to a stop. The hand will then release the tension upon the reins and the legs be withdrawn from the sides of the horse. To go forward, the rider will first close his legs against the sides of the horse and meet the impulses so procured by such a tension upon the reins as will induce the horse to go forward in a walk. So, to demand the trot, the increased impulses will first be demanded from the croup, to be met and measured by the hand. It is an invariable rule, at this stage and in every stage, that in going forward, backward, or to either side, the rider's legs will act before the hand to procure the desired impulses.

CHAPTER III

THE PURCHASE, THE CARE, AND THE SALE OF THE SADDLE-HORSE

Whether it has been procured by rapine, purchase, gift, or devise, the owner of a really good saddle-horse has something from which he may derive much pleasure and satisfaction. Nor is such an animal so rare as the late Edmund Tattersall suggested, when he gave it as his opinion that a man might have one good horse in his lifetime, but certainly no more. Almost any horse of good temper, safe action, and sufficient strength may be made pleasant to ride. Alidor was a small cart-horse, low at the shoulder, with a rigid jaw and a coarse head, but he became a charming hack, and I employed him for the photographs of the first edition of "Modern Horsemanship." I bought him as a three-year-old, as an experiment; and when he was four the breeder came to see him and gave me a written statement that, so great were the changes made in appearance and action by the calisthenics of his education, the animal could hardly be recognized.

Of course a man on the lookout for a horse[31] will make an offer for a desirable animal wherever it may be found, but the most satisfactory mode of procedure is to go to some reputable dealer. I have bought horses from dealers in many parts of this country and in England, France, Germany, and other parts of Europe, and I have found them desirous of pleasing and as honest as their neighbors. I once bought a little horse from a trader in Frankfort-on-the-Main, who told me that I was getting a good bargain, and that in case I ever wished to dispose of it he would like to have a refusal. When I was ready to sell, I sent word to the dealer that a friend had offered me a fair advance over the price I had paid, and to my surprise he appeared and without remonstrance gave me the amount my friend had named. I need hardly say the horse was a good one, so I had been well treated all round.

Much of the friction between purchaser and dealer is usually due to the manner in which the former conducts his part of the bargain. It is not agreeable to a fair-minded man to be approached as though he were a swindler, to be offered one-half of the price he has set on his property, and then perhaps to have a sound horse returned because the buyer did not know what he wanted. I do not wish to be understood as saying that all dealers are honest; I have seen too many who would not go straight; but it is reasonable[32] to suppose that most men in a large way of business, who have reputations for honest dealings to maintain, will "do right" by a customer.

It is a mistake for an ignorant purchaser to take a knowing friend with him for protection; this will, in the eyes of the dealer, relieve him in a great measure of responsibility. If the friend is really a good judge, it is far better to let him act alone, when he will be considered a client and not an interloper trying to "crab" a sale, and therefore free to deceive himself and his companion.

Some dealers will not give a warranty of soundness, and a warranty is too often the cause of disputes and of actions at law to make it advisable either to give or to demand one. A veterinary examination and a short trial must suffice. Sometimes the seller requires that the trial shall take place from his yards, to avoid the risk of injury to valuable animals and that blackmail so commonly levied by head grooms and stablemen. In cases where the dealer objected to sending his horse to another's stables, the author has been in the habit of offering a fair sum of money for the privilege, the amount to go on the price of the horse should the sale be effected; and this proposal has usually been acceptable.

Where a trial has been allowed, or even where the purchase has been made, if an indifferent[33] horseman, recognizing his deficiencies, wishes to assure himself of the wisdom of the step he is taking, let him place a cold saddle upon the horse when it is fresh, and immediately mount and go upon the road.

If the animal does not buck or shy, and goes fairly well, albeit a little gay, it is a prize not to be disdained. Many horses, even with stall courage, will go quietly if the saddle be warmed by half an hour's contact with their backs, but will plunge or buck if the rider mounts a saddle freshly girthed. If a fresh horse will stand the ordeal of a cold panel, it will not be apt to misbehave under other trials.

Of course the confident rider will make his essay as soon as the horse comes into his possession, and if the new purchase does not come up to his expectations, he will hope that his skill may remedy the faults he discovers.

To go to the breeder implies a journey, to find often only young horses that are not thoroughly trained and almost always unused to the sights and sounds of traffic, many of which are fearsome to a country-bred horse. On the other hand, on such a visit, the prospective purchaser has a better opportunity of examining the animals offered for sale, and from a knowledge of the pedigrees and an examination of the progenitors he will be able to form some idea of what may be expected[34] in the way of temperament and development; and it will be a satisfaction to have a fixed price, although it may not be a low one. Some of the breeders in Kentucky, Illinois, and Missouri, and perhaps in other parts of the country, do not send their stock to market until the animals are thoroughly and admirably trained; and for a man who purposes "making" his own horse, nothing better could be found than one of the highly bred youngsters from the Blue Grass region. In the following chapter a few of the stock farms devoted to the breeding of high-class saddle-horses are described.

There remains, as sources of supply, the auction, the friend who has a good horse which he is willing to dispose of, and "the stable of the gentleman who is breaking up his establishment previously to a European trip."

It has now become a custom to send very valuable high-class horses to the auction block, and if a man is looking for something that has already proved its superiority in the show-ring, he may often find it his property by nodding to the auctioneer. But, aside from the fact that such an animal has probably reached its climax, and that the same experienced care is demanded to maintain its condition, it is not advisable for a man to purchase such a horse except for exhibition purposes. In the hands of a poor or even[35] of a moderately good horseman, the animal will rapidly deteriorate, for it will be trained beyond his skill; and no rider who wishes to have a comfortable mount should acquire a horse that has had an education beyond the stage of being really "quiet to ride," for he may then bring the animal up to his requirements, whatever may be the measure of his dexterity. As for the inferior grades of horses offered under the hammer, it is better to leave them to experts. Neither the horse of a friend, nor that offered by the coper who hires a private stable from which to entrap the unwary, is to be recommended. Such dealings bring sorrow.

The Ideal Saddle-horse! Any man with a trained eye and ear should be able to recognize it among a herd of others. Its satin robe should be of a chestnut, bay, or brown color, with a silver star on the forehead. It should have a fine, thin mane, and a tail just heavy enough to set off the haunches. It should be of a stature of no more than 15½ hands at the withers, never more than an inch less than that height; of symmetrical form,—if anything appears to be wrong, it is wrong,—with a broad, flat forehead, a face neither concave nor convex, a small muzzle with nostrils that can dilate until they show the fire within, while soft hazel eyes beam forth brightly and kindly. Its pointed ears, beautiful in form,[36] are set far apart, and by their motions express the moods of the vivacious animal. The legs, well muscled above, clean and hard below the knees, are truly placed under the mass, the drivers capable of propelling the weight of horse and man with vigor,—the fore legs giving no suggestion that the body is leaning forward, the hind legs having no appearance of buttressing up the body. The crest is marked, but not too strongly, and the muscles below it play like shadows as the animal proudly arches its tapering neck, which buries itself in broadly divergent jaws. The shoulder slopes rearward in such a manner as to make the back seem shorter than it really is, while the gentle dip of the saddle-place invites one to mount. Its ability to speed under weight is evidenced by a deep, broad chest, its muscular thighs, its well covered limbs, and the strong spine which ends in a dock fairly carried from a nearly level croup. The hoofs are of exactly the right size, the slope conforming to that of the springy pasterns, pointing straight forward, and with level bearings. Its paces should be smooth, even, and regular, four rhythmic beats in the walk, three in the controlled gallop, two in the trot, while the action should only be high enough for safe and graceful movements, the stride not long enough to affect the animal's agility. The temper should "be bold, be bold but not too bold," unaccustomed objects arousing the horse's curiosity rather than its fears, while this mettle is dominated by the rider's hand as it ever finds just that tension upon the reins that it would meet in bending the end of a willow branch.

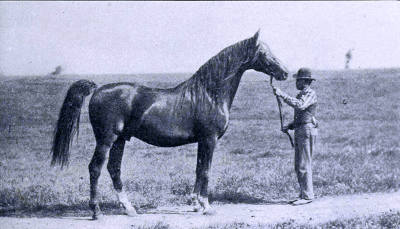

FIG. 20.—SILVANA

FIG. 21.—MONTGOMERY CHIEF

While skill in horsemanship and the possession of a good horse are to be highly considered, all the pleasures of riding are not confined to the expert with his splendid mount. Many men who are never able to attain even tolerable proficiency in the art get a great amount of recreation and satisfaction in the exercise. The author has a friend who, late in life, and when his figure had developed beyond the stage where a secure seat might be practicable, was accustomed to place himself on the back of a quiet pacing-mare, in one of those saddles with a towering horn on the pommel and a fair-sized parapet on the cantle. Thus equipped, he passed many happy hours in going wherever the steady but headstrong Belle was inclined. When the mare brought forth some three-cornered progeny from registered sires, her owner's delight was unbounded, for he was then a breeder as well as a horseman.

No estimate can be made of the real value of a riding-horse, or what a horse for a specific purpose should cost; these depend on the man and the horse. A really satisfactory, confidential[38] animal is worth whatever the man feels that he is able to pay, "even to half his realm." A horse that costs no more than a hundred dollars at four or five years old may be made by care and training of great intrinsic value; while other animals, whose beauty and striking action have sold them for thousands of dollars, may be dear at any price. A good horse should bring a fair price, but the purchaser should be certain that he is paying for the horse, and not for the privilege of seeing it well ridden by an expert. Except where horses are bred in such numbers that the cost of the keep of each is much reduced, there will be very little change coming to the breeder out of the few hundred dollars that he gets for a four-year-old of some quality. The exceptional colt which brings an exceptional price puts up the average of profit, but it is to the dealer that the long price usually goes.

When one sees the wretched cabins, called boxes, hot in summer, draughty in winter, in which horses are kept on many of the breeding farms, and even on some of the race-courses, it is a matter of wonder that health and condition of the stock can be maintained under such circumstances. Exposure to the inclemency of the weather, however, is better than the pampering which city horses usually find in close and overheated stables.

The stable should be reasonably warm in winter and as cool in summer as may be, thoroughly ventilated, without draughts, and with good drainage. The light should be admitted from the rear of the stalls; certainly a horse should not stand facing a near window on a level with its head. A gangway should be in the front of the stalls as well as in the rear, and the horse should be fed through an opening about sixteen inches wide in the front of the stall. This narrow opening will be beneficial to the sight of the horse, and the animal cannot fight its neighbors. For more than half a century the home stable of the author has had such an arrangement, which proved perfectly satisfactory. In that stable there were two rows of stalls facing a middle gangway.

Except for sick or weary horses, the stall is better than the loose box; in the former, stable discipline is better kept up. In a loose box an idle horse is apt to become too playful, and horse-play too often degenerates into something worse, such as biting and kicking.

The floor of the stable should be of hard bricks, or of some combination of asphalt. The drainage should be to the rear of the stalls, with a very slight slope. If the drains are made under the horse, the slopes are multiplied and the inclines are greater than in the length of the stalls. Always the horse should have an abundance of dry[40] straw, and for the night this should be renewed or rearranged, so that the animal shall have a soft, dry bed. The food should be varied, the quantity depending upon the size of the horse, the work demanded of it, and its appetite and digestion. For a horse 15½ hands high, the size in which agility and sufficient strength are usually found, ten to twelve pounds of oats and the same quantity of hay should be given daily in three portions, when in hard work. When the horse is merely exercised, four or five pounds of oats and six pounds of hay will be sufficient. When it is found that a horse does not clean out its manger, the feed should be reduced. In addition to the oats and hay, the horse should have a few carrots two or three times a week, occasionally an apple, and a steamed mash of bran and crushed oats about once a week, as an aperient, given preferably on the eve of some day of rest. During the spring and summer the animal should have a handful of fresh grass, not clover, every day; but not more than a good handful, for a larger quantity might bring on some intestinal trouble, whereas the titbit is greatly appreciated and is highly beneficial. These dainties will be received with a good grace from the master and will encourage friendly relations between horse and man. Salt should be given in very small quantities two or three times[41] a week, and the horse should have a frequent supply of pure, unchilled water, given some time before meals; if it is offered four or five times a day, it will not be too often.

The horse should be out of the stable, except in very inclement weather, for at least two hours every day; eight hours of slow work, with a halt for rest and refreshment after the first three hours, is not too much for a horse in good condition.

During the Civil War, General John Morgan, after two weeks of severe campaigning, marched his cavalry command, without dismounting, a distance of ninety-four miles in about thirty-five hours. Many of the horses of Kentucky breeding performed this work without flinching, and were called upon to do further duty without respite. Notwithstanding the vigor with which General Morgan conducted this raid into Ohio, he was overtaken by General Hobson after twenty-one days of hard marching, in which a distance of about seven hundred and fifty miles was covered. On a previous occasion General Morgan marched his cavalry ninety miles in about twenty-five hours. Under somewhat similar circumstances the "exigencies of the service" have on occasion required the author to remain in the saddle, with but momentary dismounting, if any, for from sixteen to eighteen hours, sometimes riding at the gallop, and the horse, a thoroughbred by Albion,[42] never exhibited distress. Nor will he ever forget that, on the first day of January, 1863, he rode a little mustang from daylight until midnight, without leaving the saddle, except when the horse fell, twice upon a frosty hillside and once on a bit of corduroy road. But such demands upon the endurance of a horse, and, if I may say it, of the man, are not unusual in active military service.

A horse should never be struck or otherwise punished in the stable, and the first exhibition of cruelty on the part of the groom should be the cause of his dismissal.

The currycomb should be used only for cleaning the brush, and never should be applied to the skin of the horse; but so great is the temptation to use it on a mud-covered animal that it is better to abolish the instrument. A whalebone mud brush, a strong straw brush, a smoothing brush, a soft cotton cloth, and several good sponges, together with some wisps of clean straw, should be the only articles of the toilet.

The face and nostrils, the dock, and other hairless parts of the horse should be washed daily; but, except to cleanse sores or for wet bandages, water should never be put upon the legs of the horse. Tight bandages are permissible only when applied by a skilled groom, or under the orders of a veterinary surgeon. Massage, rubbing the legs of the horse with the hand[43] downward, should take the place of bandages except when support is really needed, and then the advice of the professional should be called.

When a horse comes in from a hard day's work, covered with mud, dry serge bandages may be loosely put on the legs while the other parts of the body are receiving the services of the rubber. By the time that the body of the horse is clean the mud upon the legs will have dried, and, the bandages being removed, the dirt may easily be brushed out, a good hand-rubbing following. The hoofs should then be cleaned out and washed, and the horse be placed in its stall knee-deep in straw. Should a horse be brought in late and really "done up" by its work, it will be better to give it a pail of warm gruel, rub dry the saddle-place, and turn it into a warm box-stall at once, without annoying it with the brushing and handling that would be necessary to clean it thoroughly. No weary horse, no matter how dirty it may be, has ever been the worse for a few hours of complete rest under such circumstances, for the quiet will be of far more importance than the dressing. But this course should be followed only under the directions of the master, who should always see that his overworked horses get the attention they require, if he does not superintend the general stable work from time to time as he should.

When the hairs of the tail require cleaning, it is well to use plenty of unchilled water, pretty well saturated with salt, washing the dock also with the solution; and this should be used whenever the horse shows a disposition to rub its tail against the side of the stall The horse should be dressed in some covered place that is shut off from the stalls; and the owner should, occasionally at least, look in on his horses when they are being dressed and at feeding time; and should he find that he is not master of his own stables, he should change his groom or give over keeping horses.

This page is being written while the thermometer is playing about zero and a cold north wind is blustering round the corners of the house, which state of affairs suggests that, when it can be afforded, it is expedient to have a covered ride in which horses may be exercised and trained in stormy weather. An area 35 feet by 70 feet is quite large enough for twelve or more horses, and the many turns and bends required by the limited space will improve the horses therein exercised in every particular. Then the otherwise weary days of winter may be made enjoyable to the horseman by musical rides, for many pretty and intricate figures may be formed by ten or twelve riders. My riding-house is 28 feet by 60, and it is quite large enough for my purposes, as I always work my horses singly and without an attendant. In London I saw Corradini training a manège horse in the gangway of a stable, behind a row of stalls; he had a space of about 8 feet by 30. I believe that the horse was never galloped until it was ridden in public in the circus ring, but the schooling it had received made it fit for any movement.

FIG. 22.—RIDING-HOUSE OF THE AUTHOR

A little study and a little experience should teach a man much regarding the shoeing of his horse. If the animal has true and level action, it should have light irons all round. If it shambles, or if the stride is too confined, the weight of the shoes should be increased. The upper surface of the iron, which comes next to the hoof, should be flat; the lower surface may be bevelled from the outside, or have a groove in which the holes for the nails are punched. The hind shoes should have very small calks, the toes being correspondingly thickened to give a level bearing. Only so much of the crust or wall of the hoof should be removed as will give the foot a level bearing, keeping the toe straight and the face of the hoof with the slope which conforms to that of the pastern. The bars at the heels should not be cut away, except upon the recommendation of a veterinary, and the frog and sole should have nothing removed from them beyond the loose flakes that show themselves as those parts are[46] renewed. The shoe should then be made to fit the prepared hoof, and fastened by no more than five nails, three on the outside quarter, two on the inside, the protruding ends of the nails being cut off and the exposed points clinched. The outer wall of the hoof must not be rasped or scraped.

Turned-in toes or toes turned out may be produced by bad shoeing, or, when natural malformations, be mitigated more or less by good work, a glance at the foot showing what is required in each case. So brushing, interfering, overreaching, forging, bowed tendons, and many other disorders may be produced or prevented. No horse should be sent to the forge unattended unless the smith is a master of his craft, a white blackbird. For ice-covered roads and for slippery asphalt streets, I have found no shoes equal to Dryden's rubber pads.

When it is no longer advisable to retain a horse, it will usually be found that a satisfactory sale is even more difficult than a satisfactory purchase. The saying "first loss is best" applies in this case with force. If a dealer will not take the animal, it is better to send it to the auction block than to hold on indefinitely for a chance buyer. If the seller desires to keep in touch with the horse and to be kept informed of its future, he will give a warranty.

CHAPTER IV

SOME SADDLE-HORSE STOCK FARMS

With Lexington, Kentucky, as a centre one may, with a radius of thirty miles, describe a circumference which will embrace more fine horses than any area of like extent upon the globe. Here is the home of the American saddle-horse, a well-bred animal that has no superior for pleasure riding. There were good saddle-horses in Kentucky before Denmark, Hedgeford's celebrated son, made his appearance; but it was largely to the influence of this stallion upon suitable stocks that the superb animals now under consideration owe their existence, for few, if any, of these horses are without some strains of Denmark blood, even a slight infusion seeming to have great effect. From Kentucky these saddle-horses have found their way into Illinois, Missouri, Tennessee, and other states, and have always met with appreciation for their excellent qualities.

The grazing region of central Kentucky has a gently undulating surface, watered with pretty streams and artificial lakes; on every hand are[48] groves of noble trees in sufficient number to diversify the landscape; and a carpet of rich green turf is spread over the ground, even where the shade is most dense. The climate, the nutritious food, and the intelligent care of man have made these pastures celebrated the world over for the character of the domestic animals they produce.

Within short railway journeys of Lexington, through a lovely, smiling country, are a number of stock farms devoted to the breeding of riding-horses; for, although the stupidity of "the market" demands that these animals shall be quiet to drive, they are bred on purely saddle-horse lines, and the breeder hopes that no animal leaving his hands will ever be called upon to look through a collar. I have known of one case where a farmer asked the privilege of taking back a very fine animal at the purchase price rather than see it put to harness work.

A soldier throughout two wars, an active and efficient park commissioner in Louisville, the city of his adoption, a man of extensive travel and one prominent in many affairs, General John B. Castleman has felt it his duty, as well as his pleasure, to give much time and attention to the improvement of the saddle-horse. Emily, winner of the first premium over mares of any age at the Columbian Exposition, Dorothy, with a clear[49] record in seventy show rings, Matilda, who met defeat but once in fifty competitions, and many other fine animals were reared by this gentleman. Some years since General Castleman removed his breeding establishment to Clifton Farm, Mercer County, and he has recently placed it in the hands of his son, Major David Castleman. Here, upon a range of eight hundred acres, may be found horses of only the most select strains, bred upon lines which have been proved true after years of study and experiment. At the head of the stud is Cecil Palmer, a splendid animal, of perfect paces, and in whose pedigree may be found the names of Denmark, Cockspur, Whip, Gray Eagle, Vermont Black Hawk, and other horses whose blood is in the best representatives of the saddle-animal.

The horses of Clifton Farm are broken to ride at two years of age, and their education is carried on very slowly and most carefully. The foal almost invariably takes naturally to "the five gaits," but no effort is made to force the animal into any particular pace; and if the influence of some remote trotting ancestor exhibits itself in an indisposition to take the rack or the running walk, the animal is not required to accept such accomplishments. The writer saw Major Castleman ride Garrard, a two-year-old, in the slow gallop (or canter), the complacency, tempo, and[50] action of which would have been creditable to a park hack of mature years and careful training. Indeed, the docility of these riding-horses, observed everywhere in a rather thorough tour, was remarkable.

A ride of fifteen or twenty minutes from Lexington, upon the Southern railway, will bring the visitor to Pisgah, where he will find the establishment of the Gay Brothers, the largest farm devoted to the rearing of saddle-horses in this country. Here about three hundred choice animals have the freedom of nearly one thousand acres of blue-grass pasture. At the head of the stud is Highland Denmark, a true type of his family, the sire of more prize winners and fine foals than any stallion in the state. At the Louisville Horse Show, in 1903, the descendants of this horse gained first honors in the classes for two-year-olds, for three-year-olds, for four-year-olds, for the best registered saddle-horse, and for the championship ($1000 value). He is the sire of Motto and of Elsa, well known throughout the country. Highland Denmark is a magnificent animal, 16 hands in height, of splendid form and graceful movements, docile in temper, and, although he runs loose and "has not had a stable door shut in his face" for five years, his beautiful dark bay coat shines like satin. No stock that the writer saw in Kentucky was in better condition than that of the Gay Brothers, the foals of the present year being particularly strong and active.

FIG. 23.—GARRARD, TWO YEARS OLD

FIG. 24.—CARBONEL, FOUR YEARS OLD

The Gay Brothers break their horses to saddle at two years of age; at three years of age their education is enlarged; and at four they are ready for purchasers, and none of them remain on hand unless retained for some specific purpose. So great is the demand for horses of this class, that breeders could readily dispose of more than double the numbers they can furnish, and dealers and other purchasers find it difficult to obtain very desirable horses of four years and upward. Some dealers buy weanlings and yearlings to make sure of the produce of certain well-known mares, and it is by no means a rare case that a foal makes its appearance in the world, the property of some one other than the breeder who has anticipated its birth.