Title: The Camp-life of the Third Regiment

Author: Robert Thomas Kerlin

Release date: July 27, 2014 [eBook #46430]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographic errors have been corrected.

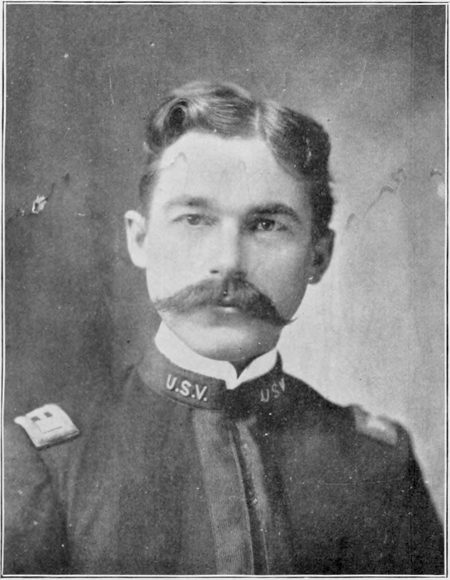

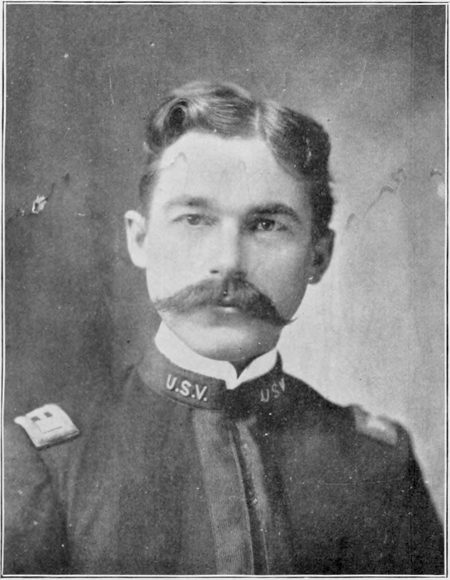

CHAPLAIN ROBERT T. KERLIN.

To the brave, true, and generous-hearted boys, my comrades and friends, of the Third Missouri Volunteers, who offered their lives for country in the cause of humanity.

BY

Chaplain Robert T. Kerlin.

1898.

HUDSON-KIMBERLY PUB. CO.

KANSAS CITY, MO.

What is camp-life like? What did we do? How did we fare? What scenes, incidents, and episodes occurred? These are questions everyone wishes answered by somebody who "saw it all." If one cannot paint, one should have the dramatic skill of a Schiller to render all this picturesque manner of life worthily vivid to the reader. How rich it is in its free manifestations of human nature! No restraint here upon one's being and seeming to be what he is. The qualities, good and bad, of our common humanity, therefore, appear unrestrained by the conventionalities, undisguised by the false glosses of civil society. All here has reverted to primitive conditions.

Enter the camp with me, if you will, and we shall watch together this moving panorama of soldier life; we shall see and hear and feel what as visions and impressions will remain with us forever—and not painfully so altogether, either on account of the evils or the hardships, for everywhere the good is more than the evil and the hardships are endured as by brave soldiers. If your heart be sound and good, as the examining surgeon assured me mine was; if you appreciate the immense significance of this national uprising in arms in the cause of humanity; and if you assume, as you rightly should, that this high motive has mainly influenced these men to enlist and offer their lives—then the scenes of the army shall be to you unforgettable evidences of the life energies awakened and the ideals vivified of a people hitherto supposed to be hopelessly materialistic in their thoughts and mercenary in their ways.

The contents of this little book, with the exception of two brief chapters, are letters that were written in camp from time to time and published in different newspapers. It is thought best to present them just as they originally appeared, believing they will thereby most faithfully and vividly bring the characteristics of camp-life before the reader.

Robert T. Kerlin, Chaplain.

| Page | ||

| Dedication | 3 | |

| Preface | 7 | |

| Valedictory | 9 | |

| Letters from Camp: | ||

| I. | Panoramic View | 11 |

| II. | Ole Virginny; Fun in Camp | 20 |

| III. | A Little More Fun; Some Trouble | 25 |

| IV. | Various Things—All Interesting | 31 |

| V. | Joy and Sorrow; A Little Sermon | 39 |

| VI. | The Thoroughfare March and Encampment in the Slough of Despond | 47 |

| Significance of the War | 53 | |

| Chronology | 57 | |

| List of the Dead | 58 | |

Much more remains for the historian, whoever he shall be, of the Third Regiment yet to relate, which things, some pleasant and forever memorable, some unpleasant and perhaps unforgettable, shall here not be so much as suggested. The writer's inclinations are all toward quietude and harmony; his limitations, besides, are imperative in forbidding. At Thoroughfare Gap he fell sick of a fever and was hors de combat during the subsequent encampment there and at Middletown, Pa. He has, therefore, been unable to detail from first-hand knowledge the later and less pleasing experiences of the regiment. The facts, by all concerned, are too well known to require a further exposé. When he believed that his pen could be of genuine service to the regiment, he wrote without thought of fear or favor; he would again so write did the circumstances seem to him to require it; that is, if justice to any demanded it and good should be accomplished by it. By these principles let us ever be guided.

The war is over; so let the sweet-smelling incense of comradeship and fraternity rise on a common altar of Peace.

And now the Chaplain, in bidding his comrades farewell, would make his final words to them worthy of their remembrance, safe for their guidance, and strong for their support to the very end of life. For six months in camp he sought to be their moral guide, their spiritual pastor, and their faithful ministrant in every need of body, mind, and heart. He would still be their counsellor, their friend and helper. As when in camp opportunity could be found he talked to them of the Way of Life, warned them against vice as destructive, encouraged and exhorted them to virtue as only safe and wise, and tried to bring high and pure influences into their lives, so now at parting he would seek to give them a message of friendship, a token of perpetual comradeship in spirit, and would make known to them his great solicitude for their individual welfare, temporal and eternal. Again, and for the last time probably, he would entreat them to be[Pg 10] courageous in the days of peace and in civic duties as they were in times of war and in the exactions of a military camp. Having faith in the boys, believing them to be his friends and prizing their friendship as his abundant reward for all he sought to do for them, he would now say, out of a heart of anxiety that each one of them may prosper in peaceful life and as a brave soldier come to the end of his earthly career victorious in all manner of virtue: Be strong and of good courage; be fearless champions of all that is right, true, and good; espouse and maintain the cause of the just, of the weak, and of the oppressed; resist the proud and the cruel; be an uncompromising foe of evil in all its forms; cherish for yourselves high and worthy ideals; strengthen your wills and gather moral force by manly resistance of wrong and by high achievement of good; strive against bad habits—conquer them if you are brave and wise, else they will conquer you; be loyal to what you have known from childhood to be the wise teachings of all good men. Finally, soldiers, follow Him who dared to die, alone, forsaken, upon the Cross of Calvary, that He might bring truth, love, mercy, righteousness, redemption to mankind. Follow Him! Follow Him!

For a week, in Camp Alger, the boys of the Third have been clearing a forest, digging wells, building kitchen arbors and adobe furnaces, spading and raking about the tents and making themselves beds and other household conveniences out of the materials afforded by the forest primeval. From where I am now sitting, underneath the tall pines, in front of my tent, which a squad are putting in order, you can see a string of boys moving in this way or that, bearing logs from the clearing, or carrying a long pole toward the companies' quarters; while in the valley beyond the tents the Third New York is drilling to the music of bugle and drum, and a forest of oak trees rises beyond. Camp Alger occupies an old Virginia plantation of 1500 acres, about ten miles from Washington. But it is not under garden-like cultivation, as the name and location might suggest. It is a wilderness, with here and there a narrow winding road and a small open field. The various regiments—some twenty odd—are located in this vast, uncared-for estate, just where open space can be found or made. Ours was placed to the west of those already in the ground when we came, and assigned a little field of about 10 acres in extent. The Third New York is encamped along the north side of this field, while we are along the west, and both regiments use it for exercise. The old manor house lies south of us about half a mile. The newer part of the house was built early in this century of brick brought from England, while the older part belongs to the last century, and is built of wood. It is, of course, a historic place, and the lady of the manor told me many interesting things concerning the country around. One of the smooth, sandy roads winding through the estate was made by Washington; another is called "Gallows' Lane," because, during the civil war, so many Union pickets met their fate there at the hands of Col. Mosby's men.

The Third does not have so many visitors at Camp Alger as it had at Jefferson Barracks, and the "producer," that is, the young lady who brings a box of dainties to her soldier laddie, is conspicuously absent. Still, we have not been wholly neglected. Several Missourians living in Washington, among them some congressmen, have visited us. They speak of our regiment in the highest terms of praise, and promise to use their influence to get us early to the front. As for ourselves, having a good opinion of our rank, we expect to be among the first on Cuban soil.

I do not know what impression the newspaper accounts of the Third have made upon your minds, but the impression everywhere made by the boys themselves has been extremely favorable. Every one I talked with in St. Louis, spoke in highest praise of the gentlemanly behavior of the Third—in contrast, I am sorry to say, to some other regiments. And it was so all along our journey eastward. Wherever we stopped any length of time, as at Louisville, Cincinnati and Parkersburg, the papers spoke in the most commendatory terms of our men. We were at Parkersburg nearly a whole day, and "took in" the town. The dailies of that place each gave us a column write-up that made us feel proud of the standard of conduct maintained by our regiment.

If a spectacular, dramatic representation of the Third Regiment in Camp Alger could be put upon the stage it would be more than the success of the season. I suggest this as an opportunity for any Missourian whose aspirations tend toward the dramatic in literature. The writer would have only to be a faithful copyist with enough of the artist's sense and imaginative faculty to select the characteristic and telling features, and present them on a thread of romance. Let me just go about with him a day and show him what he could work into a fine spectacular performance.

First, the general scene shall be a vast wilderness of pines, cedars, oaks and chestnuts, and other forest trees, with a tangled undergrowth of vines, ferns, mosses, blackberry bushes, shrub honeysuckle, laurel and other flowering plants; narrow, sandy roads, worn deep into the red soil by a century of travel, wind through this wilderness; and here and there as they lead, in their windings, over hill and vale, through deep shades, crossing now and then a clear,[Pg 13] rippling stream to which thrushes sing and where mosses and ferns cluster thickly to the water's edge, there should appear in the great forest a little open field, whose yellow soil lies broken into furrows only in strips, indicating to what extent farming had been carried when the government laid hold upon the vast old estate for an army camp.

The Third Regiment shall be placed at the western edge of a small field that opens in the midst of a wilderness and slopes gently southward and eastward toward spring-fed streams that are hidden by shrubbery and fringed by many ferns. The time shall be a day in June, and the action shall open with the rising of the sun. From the higher ground, where the staff officers' tents are situated at the extreme west side under the towering oaks and pines, we shall watch the sun appear above the wooded hill to the east and drive away the white mist in the vale below, while the wild birds, the robins and thrushes, are greeting the dawn with happy lays. The mess fires beyond the tents are started, and in the still air of morning their columns of smoke rise and outspread tall and graceful.

Hark! The bugle sounds the first call. How it thrills the very soul and makes you feel all the grand opportunity of the new day, awakening the old hope never dead, and kindling enthusiasm for life's enterprises ever new! Who would not waken to hear it, however sweet his morning slumbers might be to him? waken to hear, though he should turn over upon his canvas cot and float away into dreamland again with the inspiring notes still echoing through his soul. But if he lies awake he will hear from one quarter "Dixie," it may be, played by the band of some other regiment; shortly afterward, "The Star-Spangled Banner" by another, and then the drum corps of our New York neighbors will make sleep utterly impossible. Then follows our full bugle corps, with revéille proper:

Then the camp is as alive as a swarm of bees, with a similar hum and buzz of mingled noises. A thousand soldiers in a half-hour's time have dressed, performed their simple toilet—a close-shorn head in many instances enabling a towel to render adequate service as comb and brush, and formed into company lines to respond with a lusty "Here!" to the call of their names—soon after to be swinging their guns or clapping their hands in calisthenic drills.

The bugle-call to mess is not so musical, and, put into words, is not so poetical, as some of the others, but it serves the intended purpose. It goes as follows:

After morning mess you may see a variety of scenes characteristic of camp life. You will see a "fatigue" squad lined up before the Sergeant Major's tent to receive orders for duty around headquarters. They will rake the yard and roll up the side-curtains of the tents, clear away some brush, or make some improvement in our sylvan settlement. Here and there in officers' tents you will see the various school assembled—schools for every rank from major of battalion to the non-commissioned officers. And they will study their little blue-backed "Drill Regulations" as diligently as in days gone by they studied their blue-backed spellers.

At 9 o'clock, say, a battalion marches out of camp to take exercise in the field. While it is performing its evolutions you may[Pg 15] perhaps see a skirmishing squad break from the edge of the forest somewhere about, and, with a terrifying yell, make a sudden attack upon the enemy. Across that young peach orchard yonder to our south you will see another company advance by repeated short swift runs and sudden stops, falling each time flat upon the ground to fire, thus driving the foe from the field and winning the day against fearful odds. At 11:30, thirsty, perspiring and dust-begrimed, they come hastily into camp, clash their guns down and look for all the world as though they had just come back from the war. They have met the Spaniards in the field and "routed them and scouted them, nor lost a single man."

When distinguished visitors come to our camp our regimental band comes up to do them honor, and they play, as only this band can, to the delight of all who cover the hillslopes of Camp Alger within hearing. "Ben Bolt," "Margery," "The Merry American," "The Stars and Stripes Forever," and other favorites are finely rendered, but most beautiful of all is their hunting song, with its bugle echo and imitation of the chase resounding through the woods:

And then the barking of the dogs and noise of the pursuers and the capture of the quarry.

At 6:30 we have dress parade. Our stage manager may not be able to present this effectively. He would require the services of an entire university corps of students as "supes." The three battalions of four companies each, preceded by the band and bugle corps, march, after some field movements, before the mounted staff. This is the most imposing warlike spectacle to be exhibited.

After this the boys are free. Soon their tents, viewed from headquarters, will present a diversified and interesting scene. Three hundred white canvas houses, dimly lit within by tallow candles, the mess fires glowing underneath their arbors beyond, white-aproned cooks moving about them, and everywhere groups of boys engaged[Pg 16] in all manner of amusement in the several company lanes—this is the picture—a sort of Midway Plaisance.

We shall place some of these scenes before you upon the stage. There will be no order or formality, but a jolly, free-for-all. Everybody knows, however, who can entertain and what everybody can do, though the amount and variety of artistic talent among these thousand boys is something surprising. We shall first have a mandolin and guitar duet, and this will bring a small group together. B—— B—— will then be called for, and he will increase the crowd. Taking the guitar in hand he will sing some comic darky songs in his inimitable way. "The Warmest Baby in the Bunch" will be called for, then a half dozen others all at once. The medley of titles of popular songs will take the crowd best. C—— will then do some whistling. You will think a mocking bird is in camp. Such chirping, warbling and piping you will say you never heard, except, possibly, from thrushes, robins and mocking birds. Then D—— will be called for. D—— is an Irishman, a true son of Erin. He has been with Barnum as a clown, and now has chosen the army for its freer life. D—— is a splendid fellow. I count him as one of my best friends. Our acquaintance came about in this way:

One evening at Jefferson Barracks, before many of the boys in his company came to recognize me, dressed as I was in citizen's clothes, I joined a promiscuous crowd in their lane where they were having an impromptu entertainment. "The Girl I Left Behind Me," "The Old Oaken Bucket," and other songs that appeal tenderly to the universal heart, had been sung, and that, too, remarkably well. D—— was called for. He placed one foot upon a pine box lying in the center of the circle and started out upon a song that for its pathos touched each heart. In fact, D—— was in a pathetic way that evening. What was our astonishment and chagrin when D—— turned about fierce as a jungle cat, and began swearing like a mule driver. What had happened to evoke such wrath and malediction? A half mile away some boys were greeting the 4th, just then arriving, with vociferous cheering; near by some boys of a neighboring company were thrumming quietly upon a guitar and a mandolin. D—— explained, mainly in words which not even Kipling was ever realistic enough to string together, that he never could begin doing anything[Pg 17] without those "curs" in the neighboring company starting up some noise. D—— was not in the rest of the evening's performance. No amount of persuasion could induce him to proceed. D—— was really not in a happy mood. And though you could not consider his resentment as at all just, anybody would have sympathized with him and have tried to reason away his delusion. But in vain. A few days after I saw D—— by daylight; he recognized me and we had a pleasant little chat. He was all right. Again I saw him, and he had a patch on his face. The "farm house," just outside the reservation, had got the best of D——. Still he and the chaplain are good friends, for D—— has a good heart.

So D—— comes upon the stage and sings, making some fine local hits. Now his song will make you weep, because you can't laugh any more, then another will make you cry for the world of pathos in it, and, as you must think, in his heart, too. If you have a heart yourself to appreciate and sympathize with every brother man you will feel, deep down in it like saying, "God bless you, D——, and give you joy."

Then H——, tall, gaunt, sallow and dry, will recite "St. Peter at the Gate;" S—— will render "The Picture on the Barroom Floor;" N—— will perform on the flute; a half-dozen couples will give a cake-walk, the ladies being distinguished by a handkerchief tied over the head and a poncho around the waist, and better walking you must admit you never saw. Then regretfully we hear the bugle sound tattoo; in fifteen minutes "quarters" will sound, and, in yet another quarter of an hour, "taps."

Some sacred songs are now called for. The chaplain has been present at all the performance, and his interest and delight have been unfeigned. It may be some boy has let slip a word he wouldn't have spoken if the light had been bright, revealing the chaplain.

It may be a hot drop of tallow has fallen upon the hand of some fellow and burnt it while he was intently listening to a song; then he may have spoken hastily. He afterward comes and asks the chaplain's pardon. The whole affair—the various performances and the conduct of the boys, courteous, free and jolly, has been gratifying to the chaplain, and he tells them so, adding a word of encouragement and of counsel. All the boys now want to sing the favorite[Pg 18] song of the camp. We, perhaps, have sung "Rock of Ages," "Yield Not to Temptation," and other old familiar hymns, for they like these best. But now they want to sing, "Nearer My God to Thee," which, because it is best of all, we have put off to the last. Then, with a brief prayer, it may be, for God's blessing upon the soldier boys, and for His protection and guidance, the chaplain dismisses them, while, with heads bowed in reverence, under the stars, heaven's solemn peace seems to have descended upon them.

Then the most beautiful of all the bugle calls sounds out into the stillness of the night. It is "taps." How melodiously it invites to sweet and peaceful rest. The words but feebly suggest the mellow notes of the bugle:

Many things that would be interesting features in a spectacular performance would have to be left out, I fear. You could not, for example, present upon the stage our last Sunday morning's 8 o'clock service. But what pertaining to the whole camp could be more important from any point of view? The marching of the company squads in almost full, though voluntary attendance, to the grove, and taking an easy position on the grass about the improvised pulpit beneath the tall forest trees, the inspiring music, the respectful, unbroken and solemn attention given to the sermon, the profound impression, deepened by the response given by some who came forward to witness before all to their acceptance of the Savior Christ and their purpose to follow Him, then the evening service of song, at which still others, with the like courageous and noble decision make choice of the true way of life—this, taken along with the fact that the boys of this regiment are manly, high-spirited and well-behaved, would be impressive, though only suggested by words.

A true presentation of the Third would, I think, give assurance to many a mother, sister and sweetheart, anxious and prayerful for the welfare of her soldier boy. She would see, for the most part, a sturdy, generous-hearted, gentlemanly, though sun-embrowned and[Pg 19] rollicking body of young men—respectful to citizens and officers, kind, though sometimes rough to one another, eager for "fun or trouble," which means a campaign anywhere against the Spaniards, and stirred generally by a noble motive that enables them to endure hardships like a good soldier.

If the friends of these boys care to know how their present pastor feels about the whole matter he can put it in one sentence, which he hopes will give assurance to anxious hearts. Well, then, he takes a hopeful view of every situation, he has faith in the better and nobler qualities of human nature, and to these, by one means and another, always makes his appeal. He enjoys camp life, though fully aware of all the evils he has to oppose. He enjoys his pastoral work—call it not work—his friendly comradeship, with the boys. He is hopeful, he is encouraged by results, and always encouraging. He is thankful to Almighty God for the true and generous responses these noble-hearted soldier boys make to the good influences he seeks to bring into their lives. May their loved and loving ones at home write them letters of good cheer and good counsel, and encourage them to be as brave in championing the cross of Christ as they certainly will be in fighting for the flag of their country.

It is reported in camp that the New Yorkers, the first night after our arrival and encampment near them, slept on their guns, with bayonets ready for defense. They supposed that of course we were cowboys and toughs, coming as we did from the Indian village at the mouth of the Kaw. As a matter of fact, however, the West, in the rural districts especially, is further removed from primitive condition than the East, whether that be New England or Virginia. These Virginia homesteads indeed are old; but they have reverted, as it were, to nature's dominion, and are covered with a second growth of timber and a tangle of blackberry vines. Here and there you will see a little meadow white with daisies and fringed with wild roses, or a cultivated field with potatoes, corn or wheat growing in it; but how different does the yellow, stony soil, and the scanty growth thereon, appear from what one sees in Missouri. And you will see them plowing with a single horse or mule and the old single-shovel plow. Eastern Virginia is like another world to one of us Westerners. To-day a party of us explored the country hereabouts. First we went to an old homestead about two miles south of our camp to see some old Canton chinaware and colonial furniture which I discovered some days ago. It was the possession of the family of Masons—one of the F. F. Vs. They showed us a gold-hilted sword that was used by Gen. John Mason in the war of 1812. They had old mirrors, sideboards and tables; old hand-made blue china, over a century old; candelabra that in their day cost from $50 to $75, and now, by age, are much enhanced in value; a grandfather's clock that stood on the floor and reached the ceiling, and kept time for the first generation of the republic; and old high-post bedsteads, in which the great-grandparents of many a Missouri boy now at Camp Alger, may have slept. A picture of this old homestead[Pg 21] would be interesting to Westerners if it could be faithfully rendered. The old, deep-cut, yellow road winds around the north slope of the hill southward of the house a few hundred yards. From this the road leading to the house goes down across a small, sparkling stream well fed by springs which you can see here and there in the green slopes of the hills. The house stands under a deep shade of lofty and wide-spreading chestnuts. It is painted white, of course. All of these Virginia houses are so painted or whitewashed. The outhouses are numerous, and likewise exhibit a liberal use of whitewash and white paint. The spring house—that's never wanting on one of these homesteads—the smoke house, the lumber house—which is usually built of logs and was once doubtless a negro cabin—hen house, barns, etc., all looking clean and bright and beautiful in their green setting.

From the Mason homestead we went to an old mill which I had found out when some days ago I visited the outposts. The old mill has not ground any corn, I presume, for a generation. Its mossy roof threatens to tumble in; the old wooden water wheel is falling to ruin, its wooden cogs are fast disappearing. It is a century and a half old. The lady in whose family the mill has always been, and who now lives near it, where her parents, grandparents and great-grandparents before her lived, related to us to-day that Washington, when a young man, came along while they were building the stone foundation and said: "Boys, what are you building here? An Indian fort?" When told that it was a mill, he said it would serve them also as a fort and refuge against the Indians. The nails that now but feebly hold the decaying boards to the massive timbers of the frame were hand-made. Visitors esteem these, or a wooden cog, or some other old iron or piece of wood, as a valuable souvenir. The dwelling house of the owner stands on the steep hillside a few steps away. As you climb up to it you pass the whitewashed spring house, the old ash hopper, the old-fashioned bee hives, all in the midst of blossoming shrubbery, and come to a door under the large-timbered but cozy old veranda, and look into a low ceilinged room of which the whitewashed joists are unhewn logs. While we enjoy the fresh milk and strawberry pies they set[Pg 22] before us, we use our eyes, looking with delight about us upon the old-time things.

It can rain as hard here as at Jefferson Barracks. The night after our arrival, and before the tents were ditched, it rained cats and dogs. The quarters of several companies were inundated—it was easy to get a bath, plunge or shower. One boy sat in his tent perched up on a box with his shoes by the side of him, while the waters swirled around. A shoe was accidentally knocked off and was being hurried away—he makes a run and a splash for it, and returns successful—to find the box with the other shoe swept away into the darkness. He took it philosophically, telling his friends next day that he "went to sleep in the army and woke in the navy."

To-night we were given a free entertainment in Company G lane. It consisted mostly of dancing. First we had the old Virginia reel, and it was given in grand style. The fiddling brought back the scenes of the country picnic and Fourth of July of our boyhood. There was one musical feature, however, that was new. One of the boys, with a lead pencil in each hand, sat by the fiddler and thumped on the strings and produced all the effects of a banjo perfectly. Then they gave us a cake-walk. There were some half-dozen couples that entered the contest. The ladies wore blue-checked handkerchiefs on their heads and poncho skirts. Do not believe any report saying that the boys of the Third are discontented and unhappy. Go down through the company lanes any evening and see what they are doing. You will see a great many writing, some reading, some playing cards, but most of them will be engaged in some out-door amusement. Their amusements are continually varying. At St. Louis it was "leap-frog;" now it is "tug-of-war." "Cock fighting" and "bull fighting" are also amusements, and are said to be very entertaining. We are invited to see some of this to-morrow evening. Of course, the fighting is all between the boys, and when they represent the chickens—as the thing has been described to me—they are so fixed that they tumble all over themselves at the lightest touch. You will hear a great many funny things said, it doesn't matter what the boys are doing. A circus is not more delightful.

Mascots of every imaginable sort—pigs, chickens, cats, dogs, rabbits, terrapins, goats, small boys—are a special feature of camp[Pg 23] life. Odd characters, too, are quite as common. I will tell you of one—a "character"—that belongs to Company E. He must have been picked up, I think, as a sort of mascot. He imitates a pig in all its swinish habits of grunting, squealing, and being unclean.

At Jefferson Barracks a dozen times a day I looked up to see where that pig was. You could not help thinking one was in camp and was very hungry at that. His face, when you saw him, confirmed the deception. A hungry pig following a pail of buttermilk after one taste is not more piggish than this poor boy. On a recent evening, when I was present at a mixed entertainment, consisting of mandolin and guitar music, singing, reciting, etc., "Piggy," as he calls himself, attempted to play his rôle, coming out and getting down in the center of the circle, but he didn't take. The boys were plainly tired of him and called him down. He strongly suggested the court fool of the middle ages. This is the best that could be said of him, an object of extreme pity. What now, after this boy has so long aspired only to amuse people by playing so abject a rôle, at which he has learned to succeed so perfectly—what yet are his human possibilities? Well, that night after singing, his captain invited me in to sit with him awhile, and I referred to this boy, whereupon he related this incident of him. He said that a few days before the "pig" had sent for him to come to the guard house, where, for some misdemeanor, he had been incarcerated, and shoot him. The captain found him all broken up—the human was asserting itself in tears—for man is not only the animal that laughs, but the animal that weeps also; and this particular one was proving himself by his tears a man. The boy said: "Captain, I want you to take me out and shoot me. I would rather you would just kill me than to treat me the way you do." The captain was astonished and asked what he meant. He replied: "Why, you didn't speak to me this morning when I spoke; you just ignored me as if I was nobody. I would rather you'd take me out and shoot me." His captain then explained to him that it was an army rule not to speak to any one in disgrace, and so gave the poor boy relief. The human sense of self-respect was not extinct, but when awakened, was even very strong in this deluded, ignorant boy; which is another confirmation of my fundamental doctrine and principal of action. There are two[Pg 24] things I have supreme faith in: The first is human nature, and the second is Christ's method of dealing with it. These two faiths must not be separated, if they are to remain true and practicable. Only Christ's way of approaching and appealing to men calls forth the good that is in them. To have faith in Christ, that is, in His way and His doctrine, implies, on the other hand, faith in humanity. Whoever will follow Christ's method and show His spirit, His tact, faith and love will find human nature nine parts good to one part evil and responsive in kind to every appeal. To awaken the good that is in every man, is the true work of salvation, and that is done in but one way—that is Christ's. Lowell expressed it all in these words:

The kind of treatment we receive at the hands of others is, in the main, the reflection of our own deeds and thoughts.

"Guard mounting" is the most ceremonious feature of the daily routine of the camp. It occurs at 1 o'clock each day, and occupies almost an hour. The entire band and bugle corps make the ceremony beautiful and impressive, for all the time that the inspection is in process the band plays its patriotic airs and the bugles sound their calls and marches. The old guard, which has been on duty for twenty-four hours, is relieved, and a new guard assembled upon the parade, and after each has undergone thorough inspection, and the officers in command have made report in formal military manner, the new guard, preceded by the blaring bugles, goes to the guard house to be instructed in general and special orders, and thence detailed to their several posts. The guard is composed of details from each of the twelve companies, in numbers according to the requirements of the camp. Our camp at present, with twenty odd posts, requires above seventy men and officers. There is a captain in general command as officer of the day, a lieutenant who is officer of the guard, a sergeant, and a corporal for each of the three reliefs, for the entire sentry force is divided into three parties, each serving in turn two hours and resting four. While, therefore, there is a circuit of outposts extending around all Camp Alger, yet each particular regiment thus has its own circuit of sentinels, who by day and by night pace their beat and challenge those who pass the lines either way, determining whether, according to orders, the passers-by have a right to proceed. A few nights since, in company with the officers of the guard, I made the circuit of our own posts, in order to learn by actual experience how they performed their duties. It may be asked, Why is guard mounting attended with so much of "the pomp and circumstance of war?" So I asked, and the answer from[Pg 26] a "regular" army officer was this: "Why, there is no more serious responsibility laid upon any one than upon the sentinels. The safety of the entire camp depends upon their faithfulness. This ceremony is designed to impress them with a sense of the immense responsibility resting upon them."

A funny thing happened in the Third New York shortly after our arrival here. The officer of the guard, on his round giving instructions, passed by a raw guard and told him that the countersign would now be discontinued. After awhile the officer on his way back was challenged by this guard and asked for the countersign. You can imagine that the officer was somewhat surprised at this. But the guard was firm, and insisted that he should give the countersign or stay outside the lines. "Why," protested the officer, "I just now told you there was no countersign." "You told me," rejoined the innocent and faithful-minded guard, "you told me the countersign would be 'discontinued.'"

These boys joke at every situation. While cutting cedar boughs to make himself a bed the next morning after arriving here, a boy returned my greeting with the proverb: "Yes, a gambler's life; one day the turkey, the next day the feathers." It sounded like a proverb, but for all I know it was original and new.

The guard house suggests some good stories I heard two evenings ago, when I stopped in to see who was there. I found about twenty boys, the most of whom were in for over-staying their leave in the city or for going without leave. But one who called himself a Dutchman was in, as he related, on the following score: The officers of the day and of the guard were on a round of inspection. When they approached his post he called, "Halt, who goes there?" The answer came, "Officers." He sends off straightway for the corporal of the guard. Of course he should have said, "Advance and be recognized." They told him this, and his reply cost him a few dollars and a few days in the guard house. It was, "All officers look alike in the dark to me. I wouldn't advance the Lord Cromwell unless I could see him."

The relation of his experience started the boys to telling stories, and for an hour we had a pleasant time. One story was of a sentinel, who, having halted a man and received to his query, "Who goes[Pg 27] there?" the answer, "A friend with a bottle," commanded, "Advance, uncork the bottle, and let it be recognized!" It was said that the guard was unable to more than half-way recognize the bottle and so sent for the corporal who satisfied himself entirely as to the other half. The "moonshine" about here, it may be remarked, is called "two-step"—presumably because after taking a dram of it a fellow doesn't take more than two steps without tumbling. Another story equally well represents phases of camp life. The sentry posts of Camp Alger are usually in pretty stumpy places. One night one of the officers, just about the time a sentinel called out, "Who goes there?" having stumped his toe, exclaimed, "Jesus Christ!" The guard, according to one version, said, "Advance and be recognized!" According to another version, he called for the corporal to turn out the chaplain! That seemed to him to be the appropriate thing to do. On another occasion when an officer exclaimed, "the devil," a similar call was made for the chaplain to turn out and meet his satanic majesty, who had arrived in camp.

If you would find out what is going on in camp, go some time to the guard house when a large crowd has been "run in," not for any very heinous offense, but for something which they try to justify themselves in, and say they would do again. The crowd will be lively and good hearted, and will have nothing to do but to tell and hear stories. One story on any particular phase of camp life will be a starter; then they follow fast. And the boys will be glad you came if you have chatted with them in a free and sociable way, and will give you a hearty invitation back again.[A]

Last night I accompanied Capt. C——, the commanding officer of the guard, around the sentry circuit of the camp. In the evening I was at the guard house, where two prisoners were immured for a little difficulty they had had, and the captain asked me if I would[Pg 28] not like to make this round with him. Wishing to know all about it, I met him at 10:30 and we went out through the dark. We were halted by every one of the fifteen sentinels. "Halt! Who goes there?" "Friends," I would answer, or, "Officers of the camp." "Advance one and be recognized," would be the sentry's response. Then I would advance, and at the bayonet's point stand till he recognized me or said he could not, and I told him who I was. Then I told my companion to advance, while the guard held his gun at port. The sentries made a great many mistakes, as might be expected. Sometimes they said simply, "Advance," instead of "Advance one;" then we both advanced. The captain thereupon showed him the danger of that. Sometimes I was permitted, when ordered to advance, to go right up to the sentry without his drawing down his gun upon me. The captain would then show him how he exposed himself by that error. Thus he instructed each of the sentinels on duty. One of the "rookies" the other day made a funny blunder. A general instruction to the sentinel is "to walk his post in a military manner, and to salute all commissioned officers and all standards and colors uncased." Wishing to get it fixed firmly in his mind, this guard kept repeating it over and over to himself. The result was that at last he got the word "millinery" hopelessly substituted for "military" and in spite of himself would say "colored officers" instead of "commissioned officers." The officer of the guard found him in this confusion of words—and left him so.

The army is a good school. The average American youth, to render him a good citizen, needs just the lessons of obedience and respect for authority he gets here. My chief study is human nature under the conditions of camp life and under the diverse manifestations inevitably presented in military life. The guard house and the court room afford an opportunity to become acquainted with some classes and specimens of humanity. One evening last week I was retained as advocate for the defense of two accused of cursing their officers. The trial is not conducted as in a civil court, but according to the following manner in the "field court." The lieutenant colonel constitutes the court, and, having summoned the accused before him, reads the charges and proceeds to the investigation. The advocate for the accused has but[Pg 29] a limited opportunity of displaying either his ability or smartness. He can ask only such questions as his client requests shall be asked, and he addresses them not to the witness directly, but to the judge, who puts them to the witness.

In the first case in which I was advocate for the accused, the charge was drawn up in the following prescribed and regular manner:

Charge—Disrespect toward his commanding officer, in violation of the twentieth article of war.

Specification—In that A—— B——, Company ——, United States Infantry, did use vile, abusive and threatening language toward his captain. (Place and date.)

One of the boys was fined $1 and the other $2. The fines go to the Soldiers' Home fund. Two days later I was called on to save one of these boys from being tried on a charge of violating the twenty-second article of war, which reads as follows:

"Any officer or soldier who begins, excites, causes or joins in any meeting or sedition in any troop, etc., shall suffer death or such other punishment as a court-martial may direct."

The colonel read the offender this article and gave him a warning he will perhaps remember.

The lieutenant colonel's tent and mine are side by side, and the proceedings of his court are, therefore, under my observation. The cases, since pay-day especially, have been frequent, "two-step moonshine" having been boot-legged into camp. Some of the boys on outpost duty, thought it would be fun to have some fine spring chickens they found at a farm house. The chickens cost them about $5 apiece. A number of boys over-stayed their leave of absence in the city. They, too, pay for their fun.

Human frailty and freakish love of liberty, more than wilful meanness, appear in the conduct of those brought to trial. And, in most cases, the ancient proverb is illustrated: "He that sinneth against me (says wisdom) wrongeth his own soul."

Our first funeral occurred last Sunday. The circumstances of the case rendered it pathetic in the extreme to whoever paused to reflect. The contrast between the man's mournful career and his honored burial could not have been greater. He died a drunkard's[Pg 30] death. He was laid to rest in the National Cemetery of Arlington, by nature one of the grandest, by associations one of the most famous spots in our whole country. But three days an enlisted man, he was buried with military honors. He was a wrecked and ruined man; he had no relative, not a close friend near him in the hour of his death, but the entire company of which he had so lately become a member, marched ten miles through dust and extreme heat to escort his body to his grave among the great of earth. The bugler, who sounded "taps" for the battleship Maine and for Gen. Grant, and other illustrious dead, sounded the sweet and mellow notes above his mournful tomb, bidding peace and repose to his spirit. What words could be spoken for one of so sad a fate? How much of pathos in it all! How much call for human sympathy, and what warning!

The feeling of comradeship and fraternity is more nobly and powerfully manifested among soldiers than among any other class of men I know of. Their spirit of generosity toward one another is not less strong than is their sense of justice. These, I would say, are the most marked characteristics of the soldier: Feeling of comradeship, spirit of generosity and sense of justice. As for the last, being a fighter by profession, he comes to entertain a high sense of honor, and is called upon to maintain his rights and stand up for his cause. Of course, there is code of laws for army life, which, although unwritten, are none the less strict. There is, therefore, no school of character better than the camp. It, indeed, ruins many. So does every occupation and every environment. But those who set themselves strongly against the evils of this way of life acquire a strength and nobleness which are not possible under less strenuous and trying conditions. It is, therefore, a school for character excelling any other. But greater tact and wisdom and stronger personal influence are required here than elsewhere to direct the sentiments and determine the character of those under training. Good music, good literature, good addresses and entertainments, and good, thoughtful treatment in general are influences that go far toward making good soldiers and good men.

[A] The boys made merry over every situation and joked and jollied one another under all circumstances. A lady visiting the camp at Fairmount Park happened, in passing, to see a nice-looking boy in the guard house, and with surprise stopped and asked, "Why, what have they put you in here for?" The poor boy blushed and began to stammer; a comrade standing by took in the situation and promptly replied, "For playing baseball on Sunday, madame!"

Huckleberries are ripe in the wilderness around Camp Alger, and many boys from Missouri are getting their first taste of the berry immortalized in the name of Tom Sawyer's adventurous friend. Dewberries also find many a nook in the woods and the fallow fields, where of mornings they gleam fresh and black on their low running vines. But most abundant of all are the blackberries. The vines were in blossom when we were at Jefferson Barracks, and we thought we should like to be there—if not at Porto Rico or Manila—when the berries should be ripe; but we find them more abundant around our present camp and of a fine, large growth. Joaquin Miller advised the Virginians to "plow up their dogs and plant vineyards." Were I a Virginian I should present to view such a field as Solomon said belonged to the sluggard, "Lo, it was all grown over with thorns."

There can hardly be a better berry-growing region anywhere than among these old, yellow hills, in sight of the nation's capital. All kinds of berries of a fine quality grow well here by nature, which proves that soil and season are congenial. Under cultivation, as here and there you may see them, the yield is large and the quality excellent. The boys on their visits to the "ole swimmin' hole" usually get not only plenty of good fresh country milk, but scatter through the woods and get a taste of some kind of berries, or quickly buy out any vender they may chance to meet.

The "ole swimmin' hole" is in Accotink Creek, above Tobin's mill. It is just such a place as every one of us was familiar with in boyhood. At the bend of the creek the water deepens, and the old sycamores, leaning half-way across the stream, cast a cooling shade. One aged trunk, with broad limbs, slants up from the water's edge[Pg 32] to the deepest place, as if it had at some time said to itself, "Now, I'll make this an ideal swimming hole by furnishing the boys a place to plunge from." And so here is where the "immortal boy," since before George Washington surveyed the estate of Lord Fairfax, has spent such happy hours as live in the memory of the man forever.

The most prolonged and thorough bath the boys have taken was when they were out last week on their three days' march. Having pitched their flies—small tents just large enough for two men to creep under and sleep with their feet sticking out—officers and men make for the little stream like thirsty oxen on the plains. After a long and dusty march could they desire anything more delightful than what was offered by the cool depths of "Difficult Run?" The bountiful heavens, doubtless with the best intentions, sent them also a shower-bath. And such an one as it was! We thought it could rain at Jefferson Barracks. It doesn't rain so frequently here, but when it does rain it leaves nothing more to be asked for in that line.

The little stream was lashed into a fury, and the boys had to dive to keep from getting wet through. It rains on and on, and pours ever harder. It doesn't matter if the bathers do think they have enough—they get more. And where, meanwhile, are their clothes they would fain put on dry? They are taking a swim, too, and the dust of the hills far away is being thoroughly beaten out of them. Imagine the scene. The features of the picture, if you were to sketch it with Hogarth lines, would be high green hills rising steeply on either side; a narrow, winding valley, through which wanders the little stream; on the west bank of this rivulet, occupying the whole width of the vale and sloping up to meet the low pines on the western hills, some 2,000 toy-like tents, known in soldiers' parlance as "dog-tents" and "flies;" torrents of rain; in the spray and mist of mingling waters an indefinite number of indistinct forms appearing somewhat like the interminable line of royal ghosts in Macbeth. There was no complaint in camp of dry weather for twenty-four hours. D——, of Company C, had the opportunity of his life presented him, for he is an expert with the pencil, his talent amounting almost to genius.

Skirmishing in the woods and out-marches to the Potomac occupied the following day. For discipline the troops behaved with[Pg 33] such caution and vigilance as they would observe in the enemy's country. And in the enemy's country, indeed, they were. That night, just after call to quarters had sounded and quiet had settled down upon the populous village of nomads, the order was passed through camp for every man to be ready to repel a sudden night attack, as a regiment of cavalry had been discovered in the neighborhood by the scouts. You might then have heard a hum of excitement and bustle of preparation, while a thousand bayonets clanked in their sockets and the boys placed their guns by their sides. As for the chaplain, he lay awake straining to catch every challenge and response in the most distant sentry lines, and expecting every moment to hear the blood-chilling yell of the on-rushing enemy as their horses should dash into our camp. The first thing he realized was a quick jerk given to his booted foot sticking from under his "fly," and then the words, "Up, Chaplain, the cavalry's coming." A red streak lay along the eastern sky above the hills; there was a low hum in camp, which was gradually increasing. Lieut.-Col. W——'s good-natured laugh said that it was all a joke, and the chaplain, without having to wait to dress, went off grumbling to the creek to wash his face and get ready for 4 o'clock breakfast. The enemy, for reasons sufficient to themselves, failed to carry out their programme.

Before sunrise the entire Third Regiment, leading the Third Brigade, having broken camp, was formed along the winding road that trails up the hillsides from the little valley, and was ready for the command "Forward." Before the dew had yet wholly vanished from the clover, and before the ripening blackberries had lost their morning coolness, we marched into the old camp led by the band playing "Dixie." We had marched about twelve miles in three hours and forty-five minutes, and only three men had to be brought in in the ambulances. It was remarked by some one that we went so fast we could not read the signs in Dunn Loring. Capt. S——'s funny man said it was because the chaplain was in front and he was leading them in "the straight and narrow way." Most of the officers marched with the men, and all enjoyed their morning walk.

There is no monotony in camp life. There is routine, of course, but many diversions and incidents, and something is [Pg 34]continually happening. Last night in the small hours an order came from corps headquarters for a check-roll to be taken in every regiment instantly. For a few minutes just before midnight the whole camp was in a stir. "What was it for?" everybody was asking of everybody else. "Chesapeake Bay is full of Spanish gunboats, and they want us at once," said one of the sergeants to his men in hurrying them up. It became known this morning that a few hundred soldiers had been raising Cain at Falls Church, and Gen. Graham wanted to find out who they were. Hence this order for a check-roll. Two cavalry regiments were sent out to run in the hilarious lads, but they were only partially successful. The rest of the stampeders are reported to be in Baltimore and Philadelphia, and no one knows where else. The explanation is that the entire Sixth Pennsylvania took French leave for the Fourth.

The other evening, while I was singing with Company E, where my friend D—— belongs (whom, by the way, I wronged by intimating that the patch on his face was there as the sign of a good time passed at the "farm house," it being there, as he informs me, only to cover a boil), while we were singing some sacred songs after D—— had executed a fine jig on a foot-square board and the company's quartette has sung, "The bull-dog on the bank and the bullfrog in the pool," etc., a quick command was given for the company to "fall in" with their guns. They didn't wait for the benediction, and I fell in with them to go "where duty or danger called them." They were rushed in double-quick time into the officers' lane and halted. Then the cause of it all was whispered about. An obnoxious "shack" had been smashed into and the regiment was called out to capture those committing the deed. What happened? We met a crowd, surrounded by an armed posse, coming from that quarter and going rapidly toward the guard house. An investigation there revealed the startling fact that every one of the forty-odd boys surrounded and put under arrest at the canteen was utterly innocent. Every wrong-doer, of course, is innocent till proved guilty; but in the case of this crowd it soon became evident that innocence was indeed injured. They were nearly all "rookies"—that's the word for recruits. How could "rookies" be mixed up so largely in such an affair? A mistake has been made, that is plain.[Pg 35] When the uproar occurred there had been a rush of the "rookies" to the spot to see what was going on; the raiders had fled and escaped, of course, and the "rookies" were hustled in. They learned a lesson early. A picture of them lined up two-deep and frightened by the menacing interrogatories of Col. Gross, while a flickering candle was thrust in the face of each one to discover who he was, and bristling bayonets stood around them; the disappointment of the officers as their mistake and failure became more and more apparent, the fright of the "rookies" as they stood there in the uncertain light and their old clothes, the glad expression of relief when they were ordered to be dismissed—this, too, would be a picture.

Evenings in camp, both among officers and men, are delightfully spent in such amusements as I have already described, in various kinds of farcical entertainments and in story-telling. The Irish element in the regiment is sufficiently prominent to keep everybody happy. A lady friend of our of Celtic stock visits us occasionally from Washington, and makes her visits memorable by the good Irish stories she tells. The other evening when she was here, and there was a lull in the conversation, she suddenly exclaimed, "Oh, do you remember the last time I was out here?" "Why, of course, we do," everybody replied. "Well," said she, "forget that and remember the Maine!" Whereupon the laughing and the story-telling began anew.

If a number of first-class romances do not grow out of the exchange of compliments between the soldier boys and the girls who crowded to the trains to see them on their way here, the postmaster of the Third will be much disappointed. Half of the mail sometimes is addressed to or comes from the numerous places where buttons were traded for bouquets, and sigh was given for sigh, and names were hastily exchanged, as the train sped away. All sorts of souvenirs are sent to Parkersburg, Athens, Cincinnati, and other places, where the senders knew not a soul before their journey through them. Unique methods of meeting the emergencies of army life are sometimes devised. One lad, having no paper, but a clean, white collar, for which he no longer has any use, fills it with a tender message, folds it in an envelope, and so gratifies his wish to communicate with the girl he left behind, while he gives her a souvenir she will cherish long and tell the story of many years after[Pg 36] the war is over, and their grandchildren, perhaps, are gathered about their knees. Another boy has neither paper nor envelope, so he writes upon his cuff, links it together, stamps it, and so sends a message of romantic love to one, it may be, whose fond eyes and fascinating face he saw in some crowd in a strange place. If the chaplain does not have some work to do growing out of all this romance, the postmaster is no prophet, and both of them will be disappointed.

Rhymers and song-makers are not wanting. A letter left camp yesterday directed in the following poetical style:

Another letter was addressed by means of the same jingle—the name only being different. In this I regret to discover evidence that some young man is richer in sweethearts than in poetic devices.

A hardtack was addressed and sent without any envelope, bearing this rhymed message:

The most difficult problem in camp, as the situation appears to one concerned in the perpetual welfare of the men as citizen-soldiers, is to provide for their mental needs. Let me make ample provision for them in this respect and I will guarantee a good morality. Much of the time of the soldier in camp is necessarily unemployed—how shall he occupy himself? Idleness is the devil's great opportunity. The men of the Third have generally been accustomed to books,[Pg 37] magazines and papers—only one man in the entire regiment could not sign his name and he is now dead. The desire for mental employment is, therefore, strong. If it can be met with good literature—as it must be met by some means—it will be far less likely to go out in unprofitable and perilous ways. We have made a good beginning in the way of ministering to the mental and moral needs of the men, having erected a tent 40 feet square and furnished it with tables and seats, and organ and song books, writing material, and magazines and papers. Its capacity, however, is altogether inadequate; it is not an uncommon thing to see it filled, and as many more sitting on the logs around it. We had a dedicatory service last Sunday morning, at which I spoke of the manifold and liberal uses to which it would be put and led the minds of the attentive audience from the meaning of the ceremony and of the ancient tabernacle in the wilderness to thoughts of the dedication and high uses of the true temple of God, which is man himself. Five enlisted men came forward to enlist under the banner of the cross and dedicate themselves to the cause of Christ.

I know these soldiers, and I know that their action is the result of sober thought and manly decision.

I have employed three or four details in building what they termed a "meetin' house." The first time I used a guard-house gang—about twenty boys in for over-staying their leave in Washington after pay-day. They kept up their waggery while bearing logs and building seats and sang, "There'll come a time, we pray, when we'll not have to build a church each day."

There are a half-dozen fellows in the guard house to-day. I just now promised them, to their delight, to take them out to-morrow and work them. They were glad to get out of the "cooler" on any terms. Yesterday I had a volunteer squad—not convicts—helping me "snake" logs with mule teams to our new meeting grounds by the tabernacle. Many provocations, of course, arose—mules, stumpy roads, contrary logs, pestiferous knots, etc. But when I saw some fellow getting wrathy over a justly provoking situation and [Pg 38]struggling with his righteous indignation, I spoke a timely word—sometimes too late—just to refresh his mind with the fact that he was working on a "meetin' house," and with and for the parson. Then we all had a laugh and worked on without cussin'.

These boys are now reading my letters. Half of them will read, or, gathered about in their company lanes, will hear read, this letter. As their friend who would not have them let this evil habit fix itself upon them, I would entreat them to guard themselves against profanity.

Last Saturday I received an interesting packet of letters from someone in St. Louis, who signed herself simply "R. S. M." The idea was so unique and feminine, and the letters gave so much amusement to the boys that I will tell you something about it. There were ten sealed envelopes in the packet accompanied by a note to myself, explaining the object to be to give a little amusement to the boys, and to help fill up a few minutes with "something unusual." Each letter bore a different address, some common name being selected, such as "Mr. Smith," "Mr. Jones," and so on. The inscriptions on the backs of the envelopes were the interesting exterior feature. One was addressed in this manner:

"When this you see, remember me."

"A valentine for a dyspeptic member of Company C."

Then on the back was the following:

Another was addressed, "For a good boy who may open this July 26, '98." On the back of this was written:

"From Illinois and California—A spray of the giant redwood tree, and a spray of the old fashioned 'yarb' our grandmothers used."

Another said on the back: "Just to let you know that some one thinks of the Missouri boys and wants to help them pass a minute away opening a curious envelope."

So they ran. The merriment occasioned by the distribution of these envelopes, as that addressed "to one who feels himself to be very young," was delivered to a bald-headed fellow, and the one addressed "to a good child," was delivered to one whom common acclamation pronounced to be worse than Peck's Bad Boy, would have gratified the sender with a vision such as she could hardly have expected.

A rhyme contained in the one addressed "to a dyspeptic," ran as follows:

Thanks to this thoughtful, gracious lady! She may never know how much good her little plan for cheering the boys has done and will do. She may remain hidden under the initials "R. S. M." But be sure such kind hearts and ingenious hands as hers make this old world brighter and better to live in. It is such little, delicate, thoughtful, feminine acts that bless our lives and do more good ofttimes than books and sermons.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy of St. Louis, the same day, sent us three dozen night shirts for our boys in the hospital. This was a most useful gift and amply supplies our regiment in this respect. We are awaiting with delight the fulfillment of their promise, made through their secretary, Mrs. W. P. Howard, to send us one hundred "sewing kits." These are not the first gifts to prove their patriotism and womanly sympathy for the soldier boys these Daughters of the Confederacy have sent us. Their [Pg 41]ministration to the needs of the regiment began at Jefferson Barracks and has continued, with larger promises of future help.

The Soldiers' Relief Society of Kansas City, of which Mrs. A. W. Childs is president, has also sent many boxes of useful articles to be distributed to the soldiers. I was enabled this afternoon, by the provision of this society, to answer the call of the hospital steward for sheets by taking them two dozen white, clean ones, that surely will make the cot of pain more tolerable. At first, during even those days of extreme heat, you might have seen many a sick fellow lying in the hospital in his blue flannel field shirt. Now all is white and delightful to see, relieving the eye that must needs look upon suffering.

A few evenings ago, as I stood in front of headquarters with a reverend old gentleman, who had served as chaplain in the Civil War, watching together and commenting upon the varied scene before us, the galloping orderlies as they bore messages this way and that; the jolting heavy lumber wagons, drawn each by four mules, hauling rations for the regiments; the manifold activities of the soldiers, some carrying water in their large black buckets from the deep and excellent well the government bored for us; some with large boxes of rubbish which they were bearing, each box on two poles, toward the dumps; a crowd reading, writing and playing games in the Y. M. C. A. tent, while a half dozen boys on one side, among the logs under the great chestnut trees, were pitching rubber rings at pegs in an inclined board, and a like number on the other side were engaged in the old-fashioned farmers' Sunday game of pitching horseshoes, and the band, down in the little plain beyond the tents, was playing its beautiful strains while the guard was being mounted; there passed across this scene of many activities, an object frequently enough seen here, but never seen without its painful suggestiveness—it was the ambulance with the Red Cross upon its ground of blue. And the man of many years and large experience made a remark I shall not forget. "The Red Cross," said he, "is the sign of the highest outcome of our civilization. We had no such society as this in the Civil War. We had no such hospital system as you have. There is nothing, I repeat, that better represents the spirit of Christian civilization than the Red Cross."

While, therefore, as the vehicle thus marked rolled hastily by, giving its momentary pang of sympathy for some hurt or stricken comrade, its triumphant suggestion was of the mission of mercy unexampled in ages past, so supremely Christ-like.

That night, in one of the hospital tents, we sat by the bedside of his dying son. Through the long, slow hours, he upon one side and I upon the other, we watched the heaving breast of pain and the suffering face, and inquired of each other by looks, in the dim light, if there was yet hope for the strong, young soldier to win the battle he was contending in so bravely.

In the still evening air, from twenty hillsides, the mellow notes of the bugle bade good-night and peaceful sleep to the weary soldiers—and we thought eternal rest to the soul of the one we were so anxiously watching. Slowly the stars, however, went round in their courses and looked down—how calm and distant and seemingly all indifferent, upon the bowed head of the aged father as, toward morning, I could hear his regular, though feeble tread up and down outside. And then, as the bright sun rose, and the smoke from the campfires drifted off down the vales, making such a scene of idyllic beauty; then all the hills and valleys echoed with the sound of revéille calling to action, awakening to new hope and the new day's new opportunities. But not for one soldier was all this—his pulse of life beat too low. Till noon he lingered on wrestling with the last enemy, and, as the sun began to slope toward the west, his light on earth went out. In the prime of his years, one of the strongest among his comrades, after ten days of suffering, he passed away—Corporal John B. McNair, a soldier of his country, whose courage was shown not upon the field of carnage where the trumpet and flag inspire on to the deadly charge and heroic deed, but only in a battle where he fought alone, with nothing to inspire, nothing but now and then the kind look or word of comrades to cheer. But he died his country's defender in the cause of humanity. His will be a soldier's reward in heaven. It was last Saturday that, near the great and renowned, we laid him to rest in the beautiful grounds of Arlington.

Sunday morning, the 24th of July, after the regular preaching service, Company D, with a considerable number from other [Pg 43]companies, met in the Y. M. C. A. tent to hold memorial services for Richard Maloy, who died two days before at Fort Myer, from where his remains were sent home for burial. Circumstances made the services nobly impressive. When the president's call for troops was first made, Richard and his brother Charles were at home with their widowed mother in Kansas City. Dick—so was he called by his friends—Dick said to his mother, "Mother, I will go." She replied, "One cannot go, my son, without the other." "Then," said Charles, the younger of the two, "I will go also." So they joined the Third Regiment and went out with their mother's blessing upon them. The rigor of army duty was too severe for their immature bodies. One day Charles, just after the return from the hard practice march, was assigned to outpost duty. Dick said his brother couldn't stand it, and applied to the sergeant to be put on in his place. The substitution was made. It killed Dick.

At the conclusion of the memorial, one of his comrades came to me with an open Testament in his hand, and, with breast choked with emotion, pointed with his finger to the passage: "Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends." That was enough; it told everything.

As for the mother, some said the sudden news would kill her. It did not. When her boys left home for the war it was then that she made her sacrifice and proved her high-minded maternity that could let the larger love of country and of mankind rise superior to the love of her own flesh and blood. She keeps up the traditions of antiquity. Sparta had not nobler women. Such mothers, who bless their parting sons and bid them go, can receive them, living or dead, comforted and exalted with pride that they were stirred by noble impulses and offered their lives in the cause of humanity. We never know the celestial quantities our every-day earth-born acquaintances possess until the hour of supreme need comes to evoke them.

The problem of taking care of an army's sick is indeed no easy one. Our army is still experimenting, or rather, it might be said, improving its system with some phases of the matter yet under discussion. The regimental hospital has been done away with, so that what was the hospital of the regiment is now only a medical [Pg 44]dispensary. Here, in response to the sick call at 6:15 every morning, you may see a crowd of soldiers, from 50 to 100 in number, lined up waiting to receive in turn their capsules and pills. Two long pine trees in front of our dispensary furnish acceptable seats to the weakened boys. In addition to medicines there is little else left of all the complete and excellent equipment the Third started out with, except a half-dozen or so litters, which are used for taking up the sick out of their tents or carrying them off the field to the dispensary until the ambulances can carry them to the division hospital. There never having been any brigade hospitals, there are in Camp Alger only division hospitals—first, second and third.

The Second Division hospital, where, as we belong to this division, our sick are cared for, is organized with thorough system. In general command there is some one of the regimental chief surgeons or brigade surgeons. Then there is a full corps of officers with various ranks and duties. There is a property officer with the rank of lieutenant, and so they run. The chief steward has under him four other stewards and about 220 nurses, there being 24 nurses from each regiment permanently detailed to this service. They are organized with captain, lieutenants, and sergeants, very much like a company, and have regular litter drills daily. There are three general wards, each making a white canvas hall-like chamber nearly 50 paces in length, and three special wards, of which one is for measles and another for critical ailments, and another for surgical cases. In a very serious case, two special nurses are called in and assigned wholly to its care.

The whole number of inmates from the nine regiments constituting our division—that is, about 11,700 men—has run on a daily average from 60 to 80. The more critical cases, where it is practicable or advisable, are removed to the Fort Myer hospital by the side of Arlington. The hospital, situated centrally with reference to the various regiments to which it belongs, now constitutes, with its numerous wards, its various officers' quarters, its kitchen and mess tents, and the large number of tents necessary for the nurses and stewards, a little camp all by itself. Around it its own guards keep up their regular tread, and down toward the general corral, where scores of government wagons and government mules[Pg 45] stand at feeding time, stand the dozen covered ambulances that go night and day on their faithful missions.

On Monday, of this week, the Third underwent inspection by the general inspection officer, Major Brown, of the Fourth Cavalry. Every man in the regiment, and all the quarters and accoutrements, came under the trained and uncompromising eye. At 8 a.m. the several companies were called in battalions to the parade ground, where the soldiers, each with his usual equipment of gun, knapsack, haversack, field-tent, and canteen, stood under the already hot sun to be examined. Then, after disburdening themselves, they were called out again to execute the movements which the inspector might require of them. Some phase of the inspection continued until late in the afternoon, when, beginning at 6 o'clock, the entire regiment passed in review before General Davis, division commander, and his staff. The fine showing we made elicited round after round of cheering from our New York neighbors, and, at the conclusion, high commendation from the reviewing general.

I will conclude with the presentation of another character. I had frequently heard of J——, of Company K, and desired to make his acquaintance. I was sitting on the band seats by our tall flagless flagpole, watching the effects of the sunrise and of the first bugle calls. I noticed some one advancing toward me from the direction of Company K, at the extreme north side of the camp. It might have been seen that, as he came on with grave and measured tread, the eyes of all his comrades were upon him. But it was equally apparent that he for his part disregarded everything. He came up, but spoke not a word and seemed to be aware of no presence or beholding eye. Then he gravely unrolled a cambric flag of the enormous and graceful proportions of 8 inches long by 12 inches broad, and, attaching it to the rope, hoisted it to the top of the pole, while his comrades loudly cheered and laughed at the joke—to all of which he was utterly oblivious—returning with as much gravity as he came. And the toy flag there floated where he raised it aloft, "frenetic," as Browning says, "to be free." This fellow's large-featured, benignant, Scottish face, with its fringe of hair entirely encircling it, spoke full plainly of a big, jolly, generous heart. The boys all call him "Honest Bill." The day we were[Pg 46] going out on our practice march J—— thought he didn't want to go. In fact, he preferred to stay in the guard house. This was his scheme: He goes down to the line of guards, is challenged, makes a dash through, but returns and gives himself up. Quite successful! His large kindly face beams happiness. What does his captain do? Nothing but send him along on the march with the penalty of some days in the guard house hanging over his devoted head. This was enough to try any flesh and blood, and almost enough to provoke even a soldier to swear at his ill luck. I think J—— triumphantly resisted the evil one. When he returned to camp on the third day, a wiser and seemingly no less happy man, he threw down from his strong back not only his own burden of soldierly equipment, but the packs of two of his comrades also who had grown faint in the long march.

So I know J——. Who, from this, doesn't know J——? His heart, sure, is as big as his back is broad, and his nature as open as his face, which shines like a harvest moon. God bless all such comrades.

[There has been considerable said about the mistreatment of volunteer soldiers now in the service of the government, and much of the talk of suffering and want in the camps has been discredited because of its seeming ridiculousness. Americans are not ready to believe that the heads of the departments would permit the brave men to undergo the trials and sufferings that have been so graphically pictured by the newspapers, and the more conservative here put these idle rumors aside as the work of sensation-mongers.

Now a minister of the gospel, a man who is at the front with the soldiers, administering to them spiritual assistance and pointing them, in their dark hours of distress, to a brighter future, has raised his voice, and in words that sink deep into the heart and make the breast of men shudder, he tells us that our boys are being murdered; that the brave sons of Missouri are being cut down like grass before the scythe, through the neglect and tyranny of officers in the army who are supposed to look after their comfort.

Rev. R. T. Kerlin, chaplain of the Third Missouri Regiment, writes from Thoroughfare Gap, Va., to a brother minister at St. Louis, telling him of these things. Dr. Kerlin comes from Clay County, and the people of this city and this State know him.