Title: Bird Guide: Water Birds, Game Birds, and Birds of Prey East of the Rockies

Author: Chester A. Reed

Release date: August 6, 2014 [eBook #46516]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Chris Curnow and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

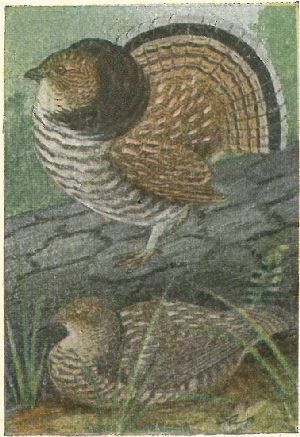

Ruffed Grouse.

BY

CHESTER A. REED

Author of

North American Birds’ Eggs, and, with Frank M. Chapman, of Color Key to North American Birds. Curator in Ornithology, Worcester Natural History Society

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1921

Copyrighted 1906.

Copyrighted, 1910, CHAS. K. REED,

Worcester, Mass.

While strolling through a piece of woodland, or perhaps along the marsh or seashore, we see a bird, a strange bird—one we never saw before. Instantly, our curiosity is aroused, and the question arises, “What is it?” There is the bird! How can we find out what kind it is? The Ornithologist of a few years ago had but one course open to him, that is to shoot the bird, take it home, then pore through pages of descriptions, until one was found to correspond with the specimen. Obviously, such methods cannot be pursued today, both humane and economical reasons prohibiting. We have but one alternative left us: We must make copious notes of all the peculiarities and markings of the bird that is before us. On our return home, we get down our bird books, and there are many excellent ones. After carefully looking through the whole library, we find that, although many of our books are well illustrated, none of them has the picture of what we seek, so we adopt the tactics of the “Old-time” Ornithologist, before mentioned, and pore over pages of text, until finally we know what our bird was. It is for just such emergencies as this—to identify a bird when you see it, and where you see it, that this little pocket “Bird Guide” is prepared. May it be the medium for saving many of today’s seekers for “bird truths” from the many trials and tribulations willingly encountered, and hard and thorny roads gladly traveled by the author in his quest for knowledge of bird ways.

CHESTER A. REED.

Worcester, Mass.

1906.

The study of the birds included in this book is much more difficult than that of the small land birds. Many of the birds are large; some are very rare; all are usually shy and have keen eyesight, trained to see at a distance; in fact, many of them have to depend upon their vigilance for their very existence. Therefore, you will find that the majority of these birds will have to be studied at long range. Sometimes, by exercising care and forethought, you may be able to approach within a few feet of the bird you seek, or induce him to come to you. It is this pitting your wits against the cunning of the birds that furnishes one-half of the interest in their study. Remember that a quick motion will always cause a bird to fly. If you seek a flock of plover on the shore, or a heron in the marsh, try to sneak up behind cover if possible; if not, walk very slowly, and with as little motion as possible, directly towards them; by so doing you often will get near, for a bird is a poor judge of distance, while a single step sideways would cause him to fly. Shore birds can usually be best observed from a small “blind,” near the water’s edge, where they feed. Your powers of observation will be increased about tenfold if you are equipped with a good pair of field glasses; they are practically indispensable to the serious student and add greatly to the pleasures of anyone. Any good glass, that has a wide field of vision and magnifies three or four diameters, is suitable; we can recommend the ones described in the back of this book.

WHAT TO MAKE NOTE OF.—What is the nature of the locality where [7] seen; marsh, shore, woods, etc? If in trees does it sit upright or horizontal? If on the ground, does it run or walk, easily or with difficulty? If in the water, can it swim well, can it dive, does it swim under water, can it fly from the water easily, or does it have to patter over the surface before flying? What does it seem to be eating? Does it have any notes? Does it fly rapidly; with rapid wing beats or not; in a straight line or otherwise? Does it sail, or soar? In flocks or singly? These and hundreds of other questions that may suggest themselves, are of great interest and importance.

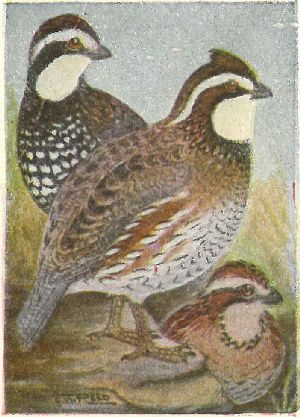

A PLEA TO SPORTSMEN.—Many of the birds shown in this book are Game Birds, that is, birds that the law allows you to shoot at certain seasons of the year. Some of these are still abundant and will be for numbers of years; others are very scarce and if they are further hunted, will become entirely exterminated in two or three years. Bob-whites are very scarce in New England; Prairie Hens are becoming scarce in parts of the west; the small Curlew is practically extinct, while the larger ones are rapidly going. In behalf of all bird lovers, we ask that you refrain from killing those species that you know are rare, and use moderation in the taking of all others. We also ask that you use any influence that may be yours to further laws prohibiting all traffic in birds. The man who makes his living shooting birds will make more, live longer and die happier tilling the soil than by killing God’s creatures. We do not, now, ask you to refrain from hunting entirely, but get your sport at your traps. It takes more skill to break a clay pigeon than to kill a quail.

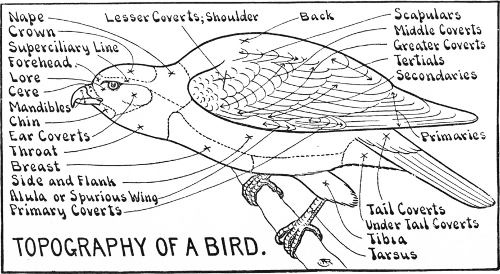

TOPOGRAPHY OF A BIRD

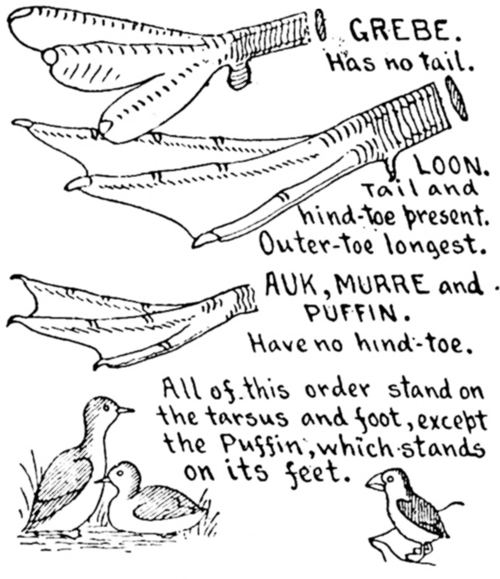

GREBES; Colymbidæ:—Form, duck-like; bill pointed and never flattened; no tail; legs at extreme end of body; each flattened toe with an individual web; wings small. Flies rapidly, but patters along the water before taking wing. Expert divers, using wings as well as feet, to propel them, under water.

LOONS. Family Gaviidæ:—Larger than Grebes; bill long, heavy, and pointed; tail very short; feet webbed like a duck’s, but legs thin and deep; form and habits, grebe-like.

AUKS, MURRES, PUFFINS. Family Alcidæ:—Bills very variable; tail short; usually takes flight when alarmed, instead of diving as do grebes and loons. With the exception of puffins, which stand on their feet, all birds of this order sit upon their whole leg and tail. They are awkward on land; some can hardly walk.

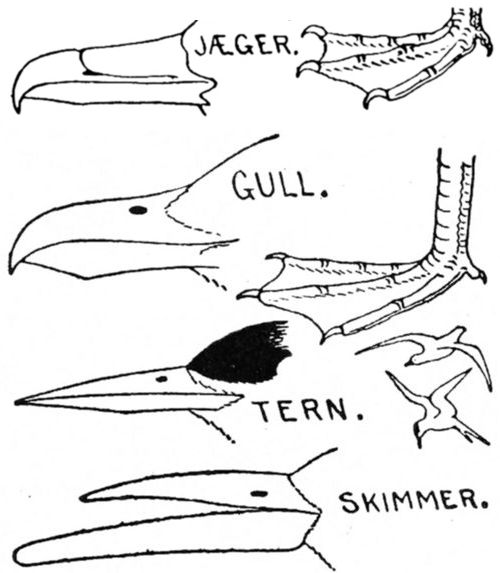

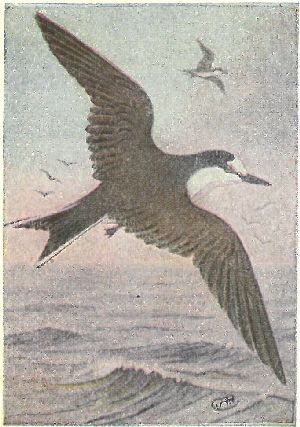

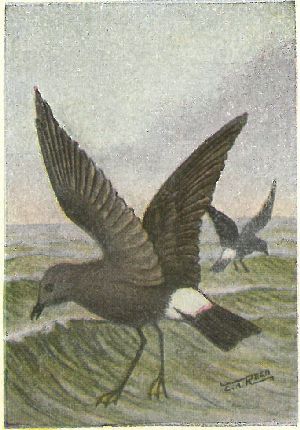

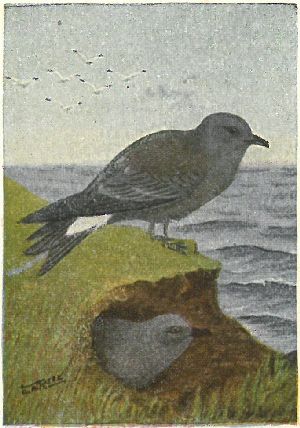

SKUAS, JAEGERS. Family Stercorariidæ:—Marine birds of prey; bill strongly hooked, with long scaly shield, or cere, at the base; claws strong and curved, hawk-like; flight hawk-like; plumage often entirely sooty-black, and always so on the back.

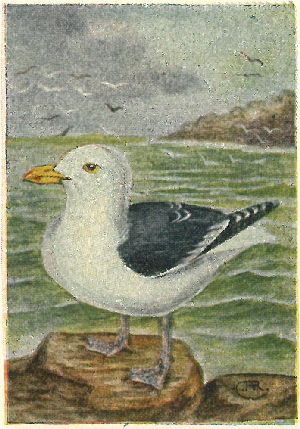

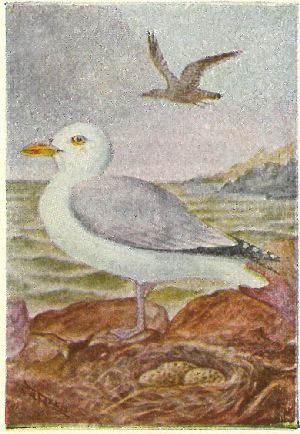

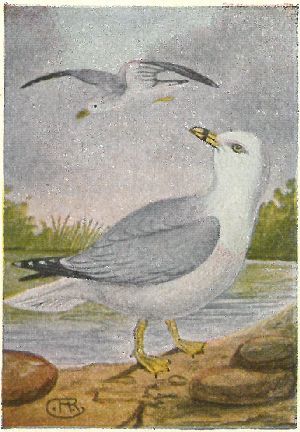

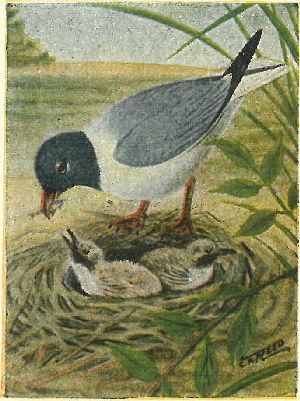

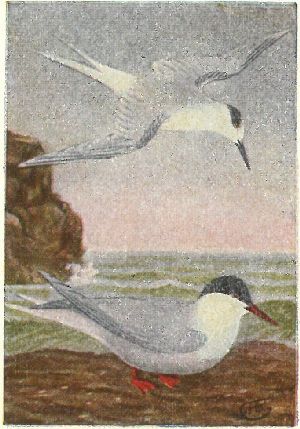

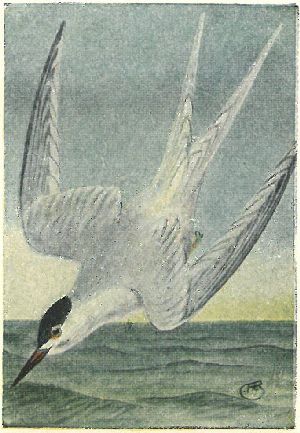

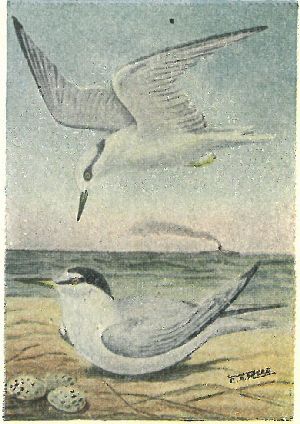

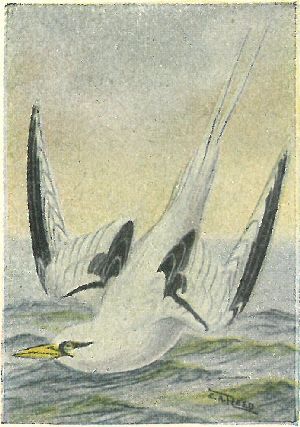

GULLS, TERNS. Family Laridæ:—Gulls have hooked bills, usually yellowish, yellow eyes and pale, webbed feet. Heap, underparts and square tail are white in adults; back, pearl-grey; exceptions are the four small black-headed gulls, which also have reddish legs. Gulls fly with the bill straight in front, and often rest on the water. Terns have forked tails, black caps, and their slender, pointed bills and small webbed feet are usually red. They fly with bill pointed down, and dive upon their prey.

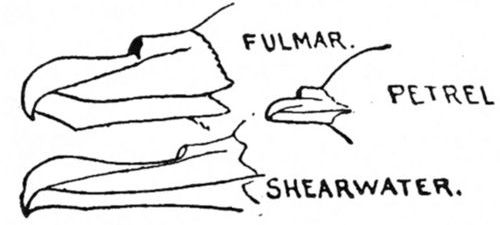

FULMARS, SHEARWATERS, PETRELS. Family Procellariidæ:—Nostrils opening in a tube on top of the hooked bill. Plumage of fulmars, gull-like; shearwaters [11] entirely sooty black, or white below; petrels blackish, with white rumps,—very small birds. All seabirds.

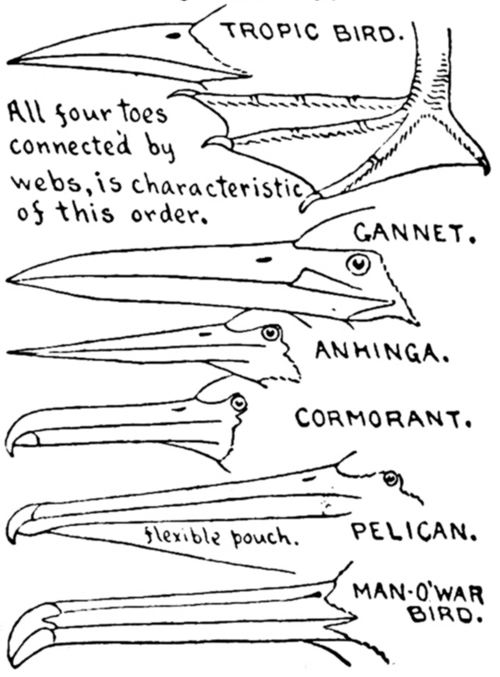

All four toes joined by webs.

TROPIC BIRDS. Family Phaethontidæ:—Bill and form tern-like; middle tail feathers very long.

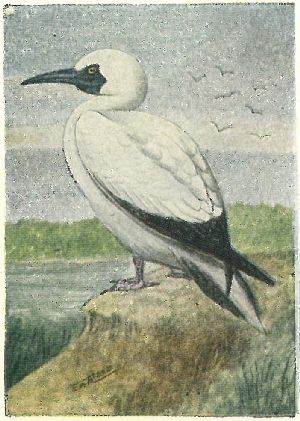

GANNETS. Family Sulidæ:—Bill heavy and pointed; face and small throat pouch, bare.

SKAKE-BIRDS. Family Anhingidæ:—Bill slender and pointed; neck and tail very long, the latter rounded; habits like those of the following.

CORMORANTS. Family Phalacrocoracidæ:—Bill slender, but hooked at the tip; plumage glossy black and brown; eyes green. They use their wings as well as feet when pursuing fish under water.

PELICANS. Family Pelecanidæ:—Bill very long and with a large pouch suspended below.

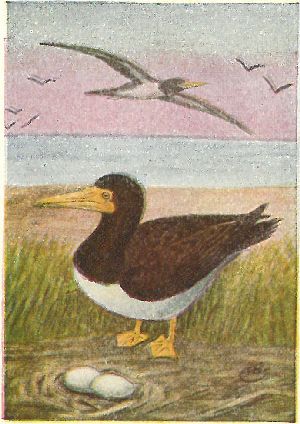

MAN-O’-WAR BIRDS. Family Fregatidæ:—very long and strongly hooked; tail long and forked; wholly maritime, as are all but the preceding three.

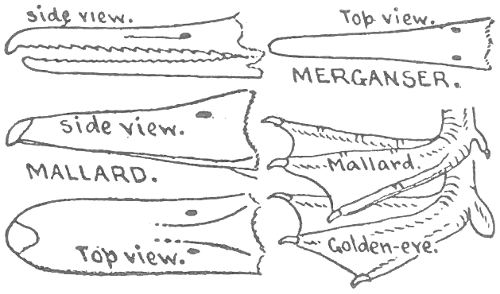

Mergansers, with slender, toothed bills with which to catch the fish they pursue under water.

Other ducks have rather broad bills, more or less resembling those of the domestic duck. Their flight is rapid and direct. River ducks have no web, or flap, on the hind toe; they get their food without going entirely under water, by tipping up. Sea ducks have a broad flap on the hind toe.

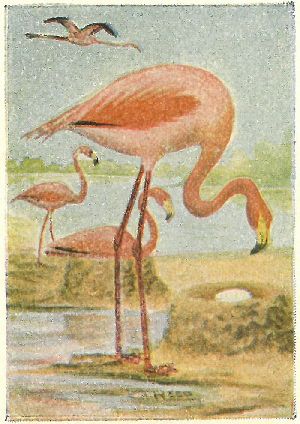

Family Phoenicopteridæ:—Large, long-necked, pink birds with a crooked box-like bill, long legs and webbed feet.

Long-legged, wading birds, with all four toes long, slender and without webs. Usually found about the muddy edges of ponds, lakes or creeks, and less often on the sea shore. Wings large and rounded.

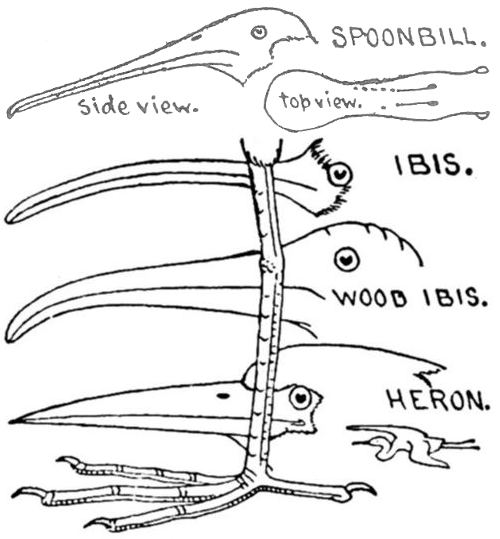

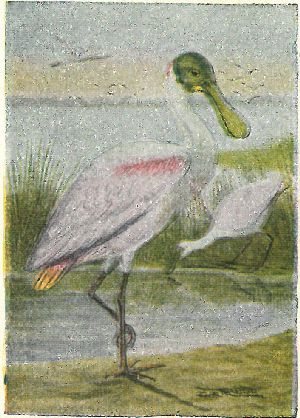

SPOONBILL. Family Plataleidæ:—Bill long, thin and much broadened at the end; head bare.

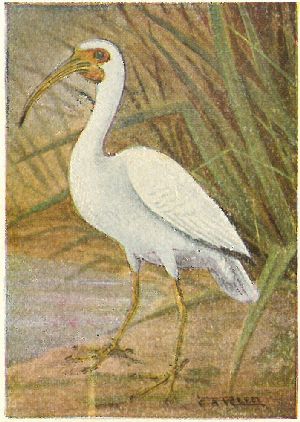

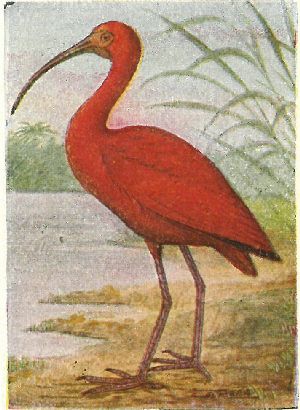

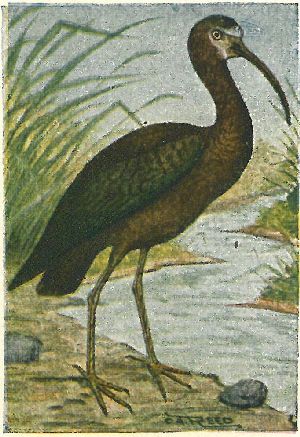

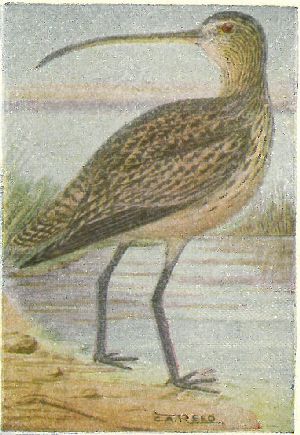

IBISES. Family Ibididæ:—Bill long, slender and curved down. Ibises and Spoonbills fly with the neck fully extended.

STORKS. Family Ciconiidæ:—Bill long, heavy, and curved near the end; head and upper neck bare.

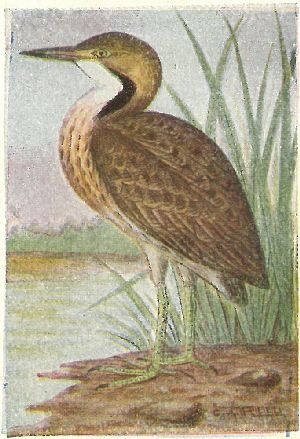

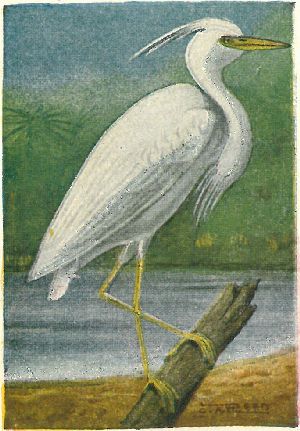

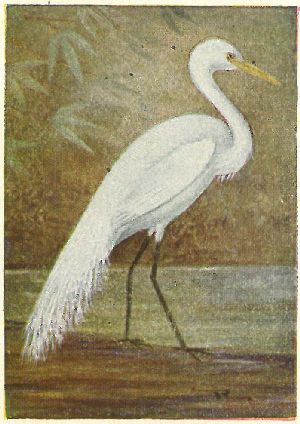

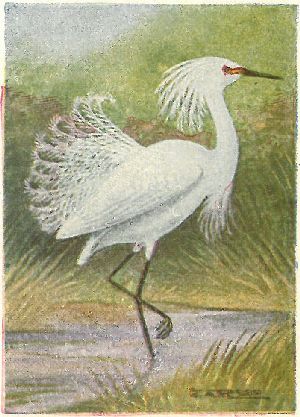

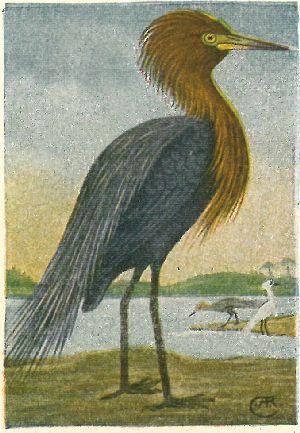

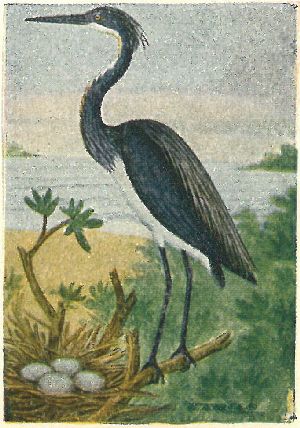

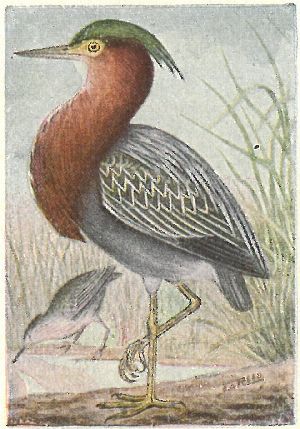

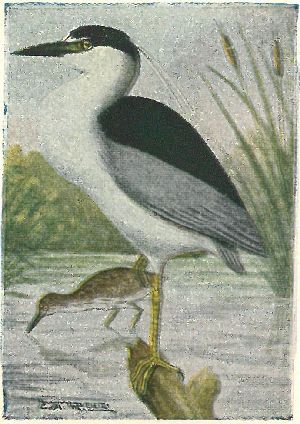

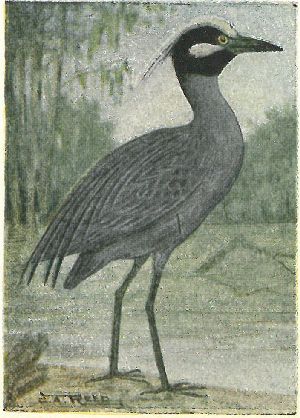

HERONS, BITTERNS, EGRETS. Family Ardeidæ:—Bill long, straight and pointed; head usually crested, and back often with plumes. Herons fly with a fold in the neck, and the back of the head resting against the shoulders.

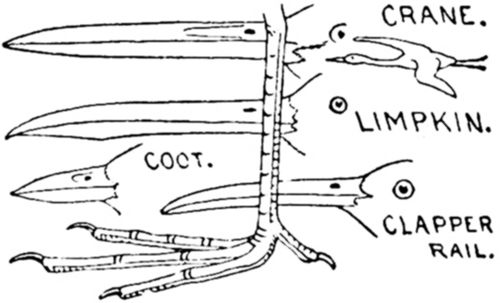

Birds of this order, vary greatly in size and appearance, but all agree in having the hind toe elevated, whereas that of the members of the last order leaves the foot on a level with the front toes; neck extended in flight.

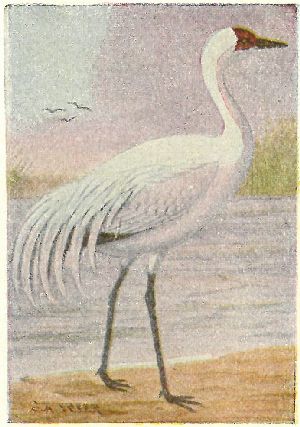

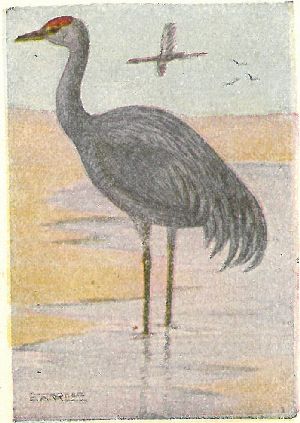

CRANES. Family Grudidæ:—Very large and heron-like, but with plumage close feathered; top of head bare; bill long, slender and obtusely pointed.

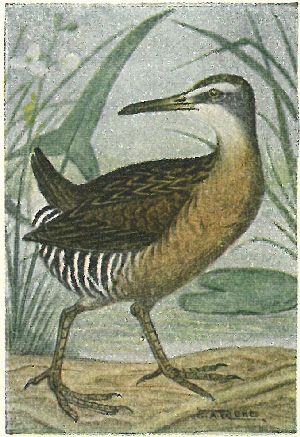

COURLANS. Family Aramidæ:—Size mid-way between the cranes and rails; bill long and slender.

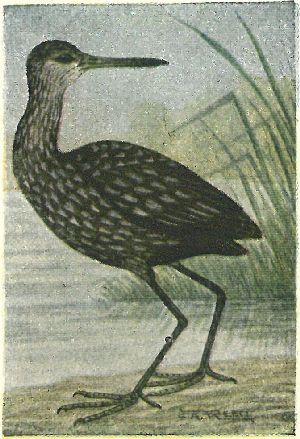

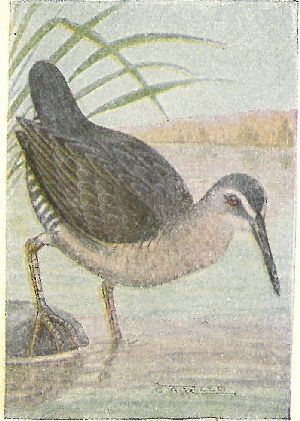

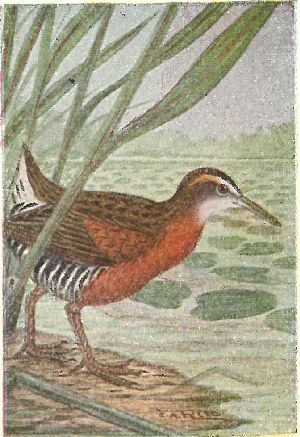

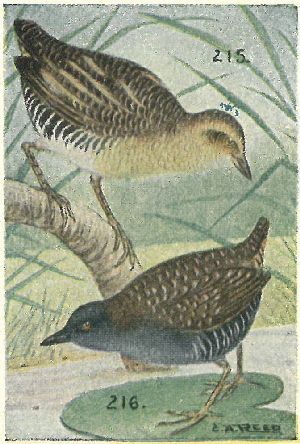

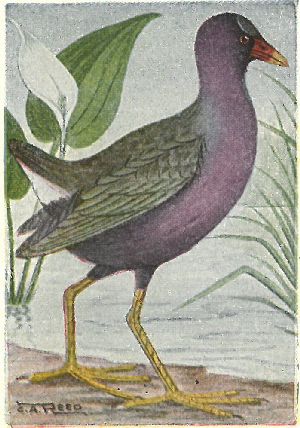

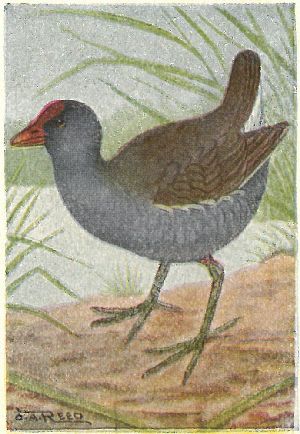

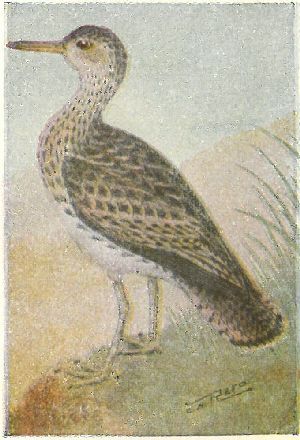

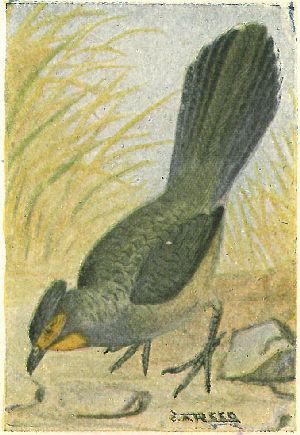

RAILS, ETC. Family Rallidæ:—Bills are variable, but toes and legs long; wings short; flight slow and wavering; marsh skulkers, hiding in rushes. Gallinules have a frontal shield on the forehead, Coots have lobate-webbed feet, short, whitish bills.

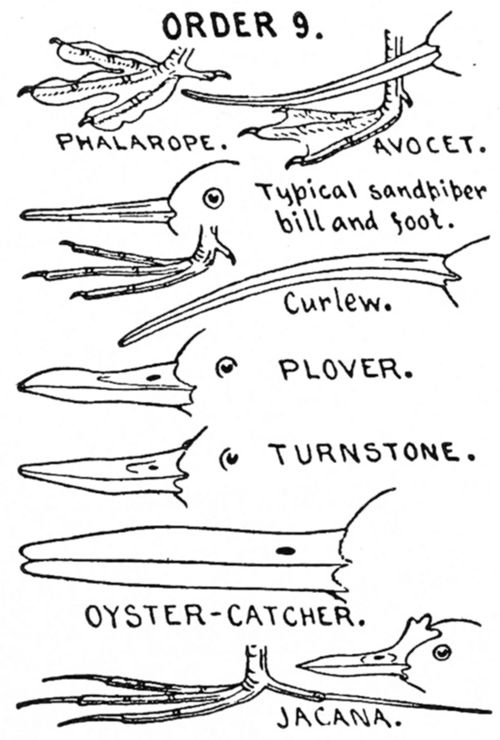

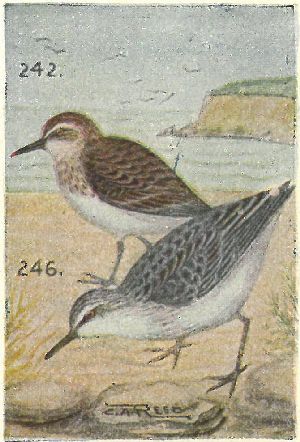

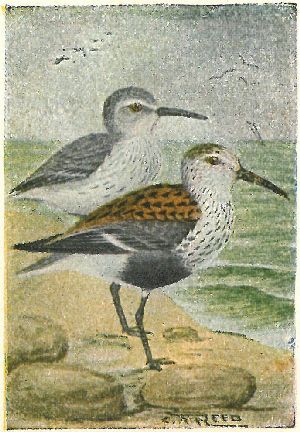

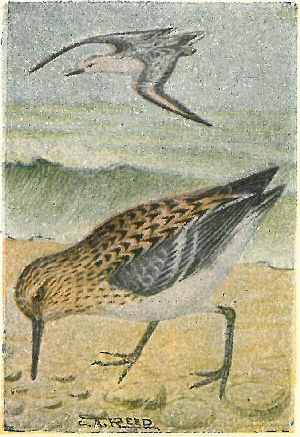

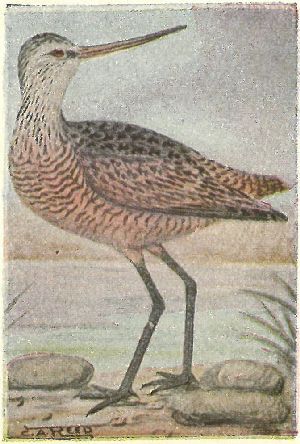

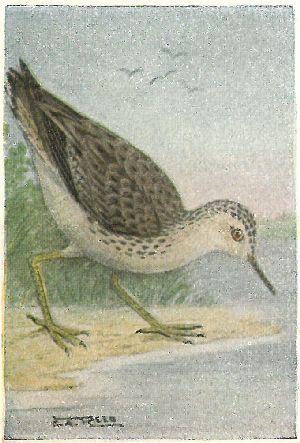

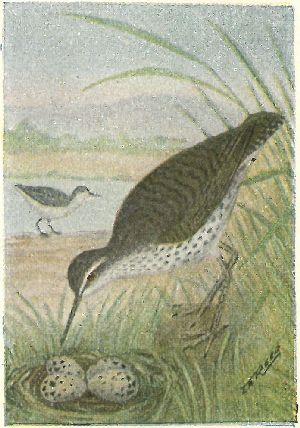

Comparatively small, long legged, slender-billed birds seen running along edges of ponds or beaches.

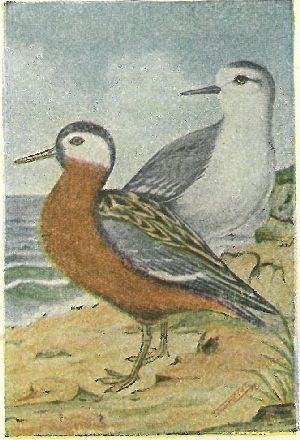

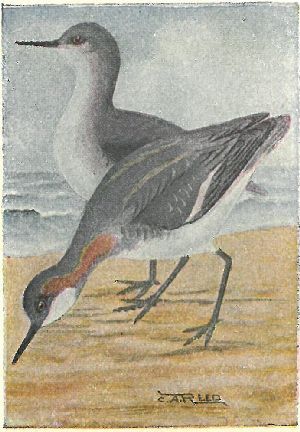

PHALAROPES. Phalaropodidæ.—Toes with lobed webs.

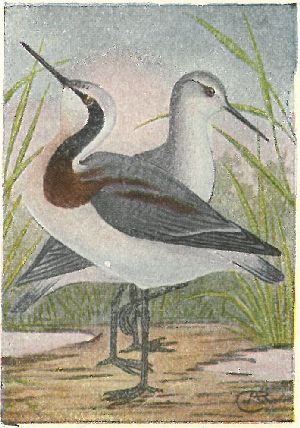

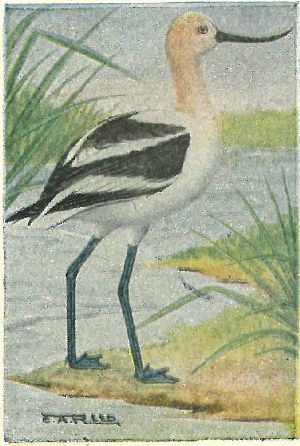

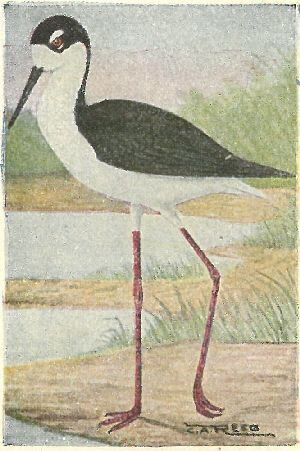

AVOCETS, STILTS. Recurvirostridæ:—Avocet, with slender recurved bill, and webbed feet; stilt, with straight bill, very long legs, toes not webbed.

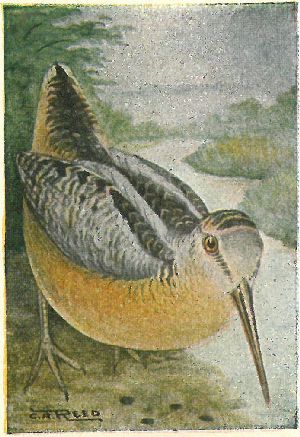

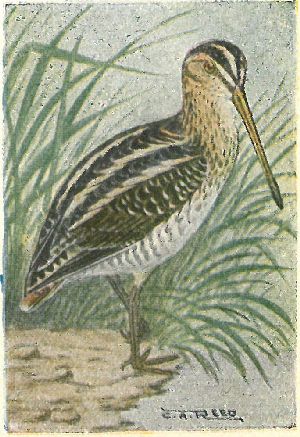

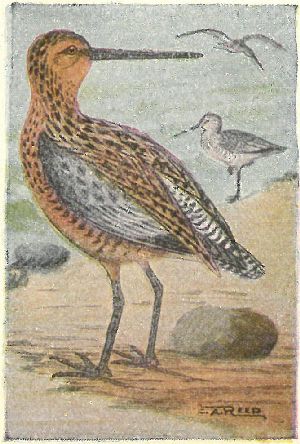

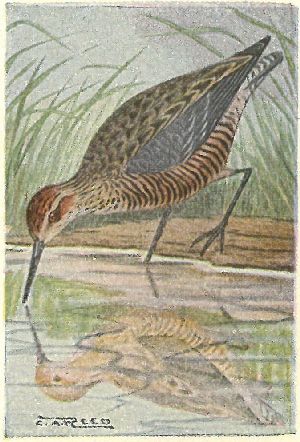

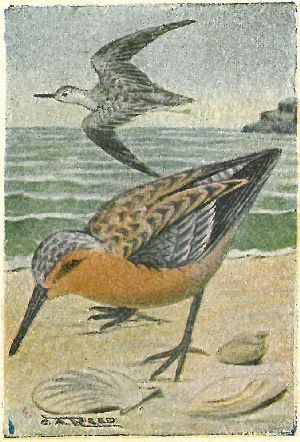

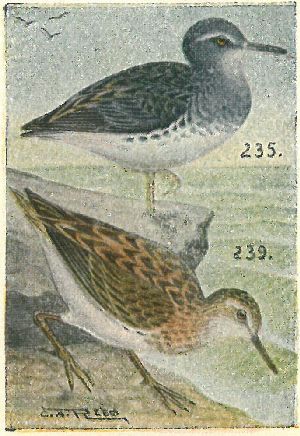

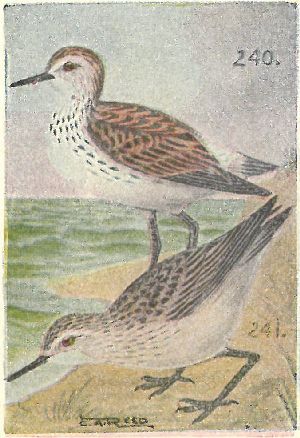

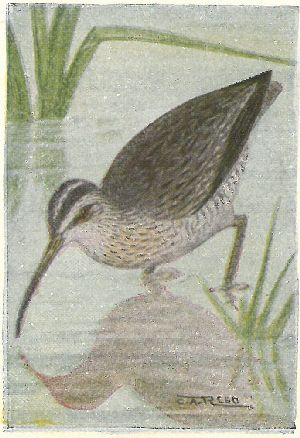

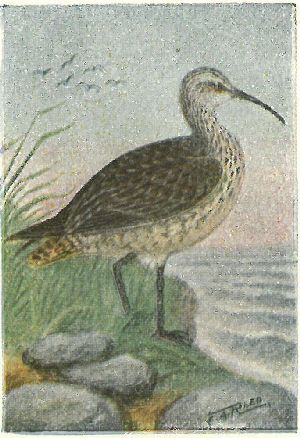

SNIPES, SANDPIPERS, ETC. Family Scolopacidæ:—Bills very variable but slender, and all, except the Woodcock, with long pointed wings; flight usually swift and erratic.

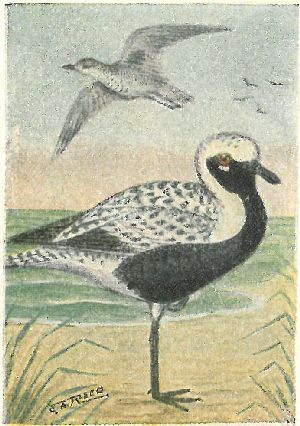

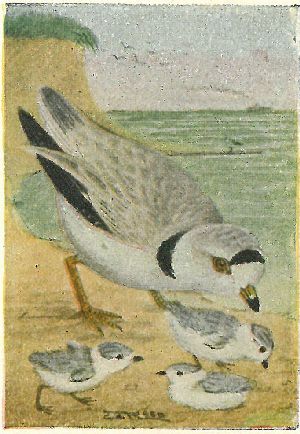

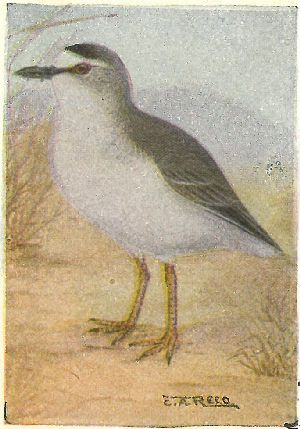

PLOVERS. Family Charadriidæ:—Bill short and stout; three toes.

TURNSTONES. Family Aphrizidæ:—Bill short, stout and slightly up-turned; four toes.

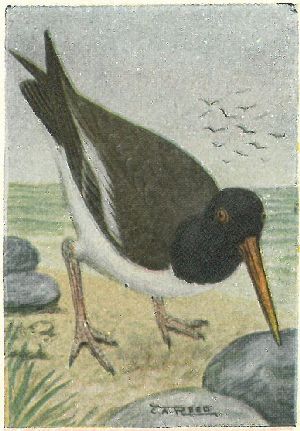

OYSTER-CATCHERS. Family Hæmatopodidæ:—Bill long, heavy and compressed; legs and toes stout; three toes slightly webbed at base.

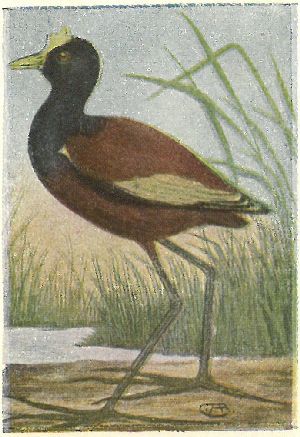

JACANAS. Family Jacanidæ:—Bill with leaf-like shield at the base; legs and toes extremely long and slender; sharp spur on wing.

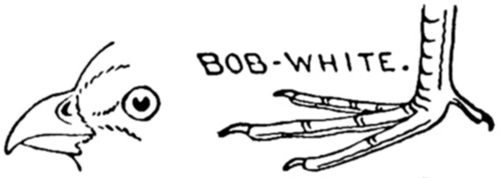

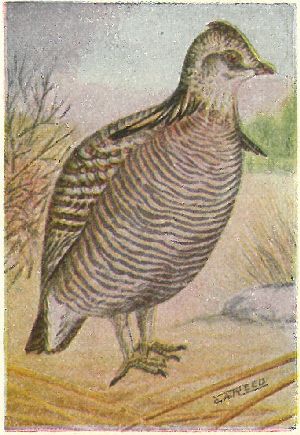

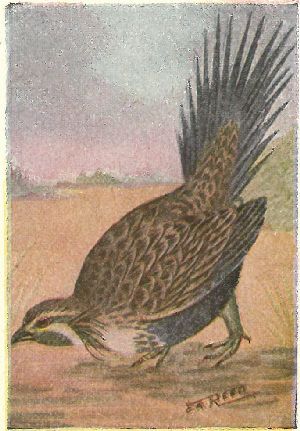

Ground birds of robust form; bill hen-like; wings short and rounded; feet large and strong.

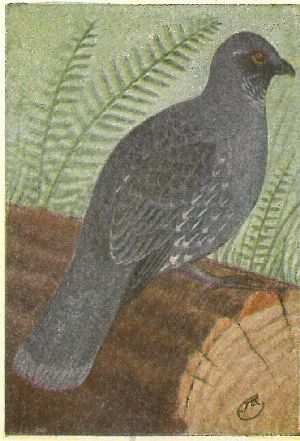

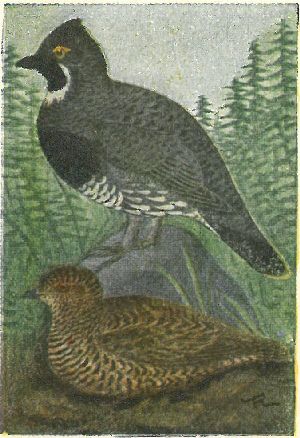

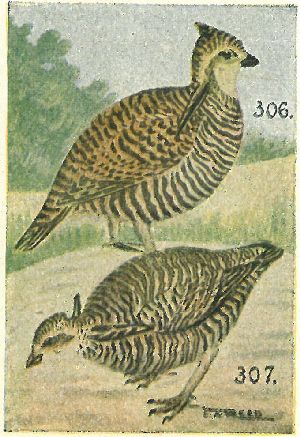

PARTRIDGES, GROUSE. Family Tetraonidæ:—Legs bare in the partridges, feathered in grouse.

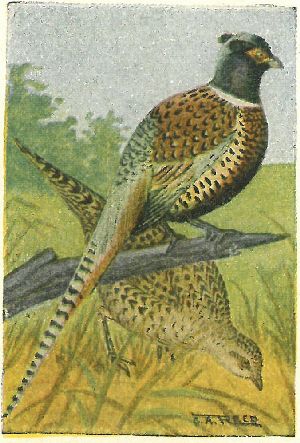

TURKEYS, PHEASANTS. Family Phasianidæ:—Legs often spurred, or head with wattles, etc.

GUANS. Family Cracidæ:—Represented by the Chachalaca of Texas.

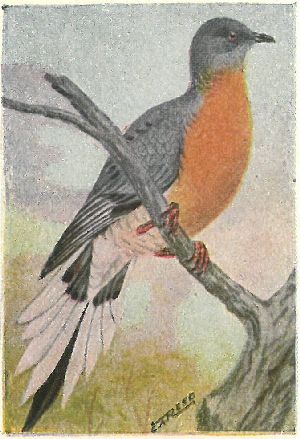

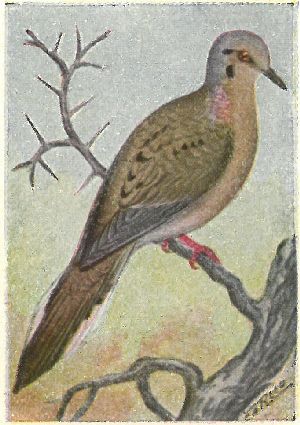

Family Columbidæ:—Bill slender, hard at the tip, and with the nostrils opening in a fleshy membrane at the base. Plumage soft grays and browns.

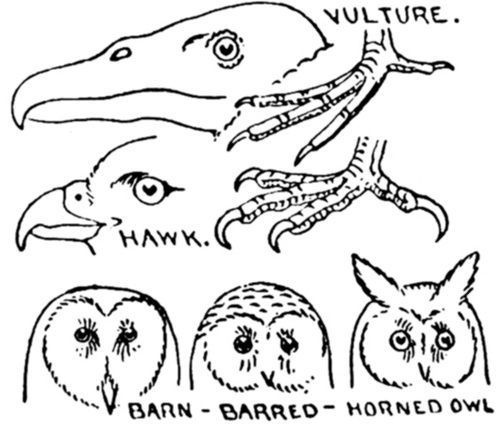

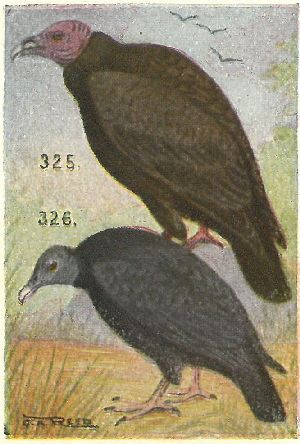

VULTURES. Cathartidæ:—Head bare; feet hen-like.

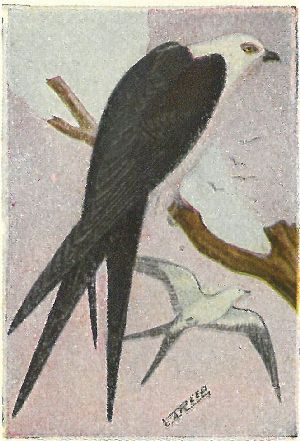

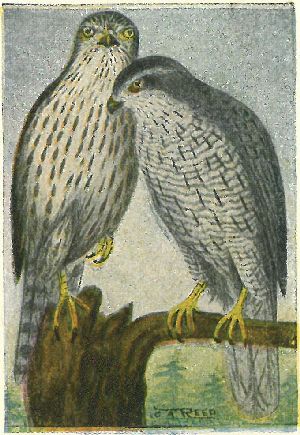

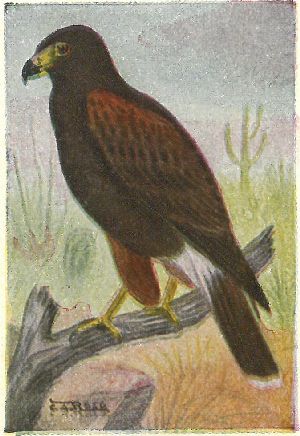

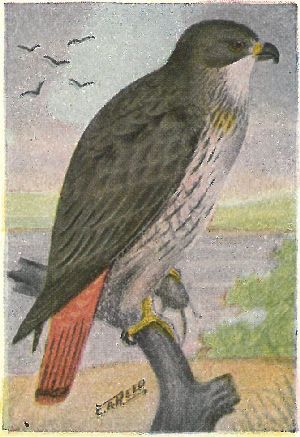

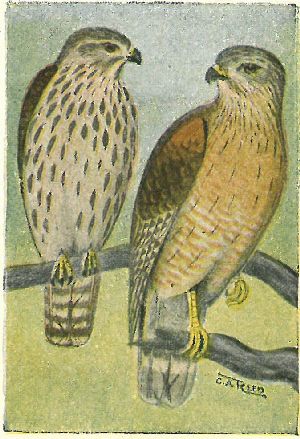

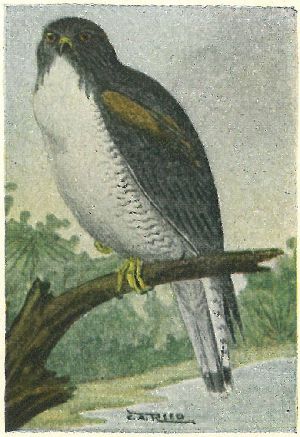

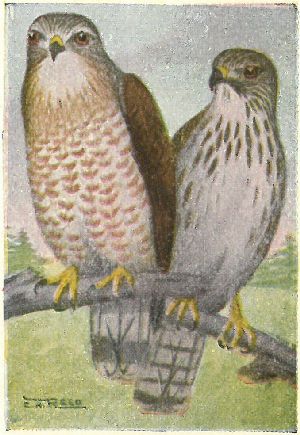

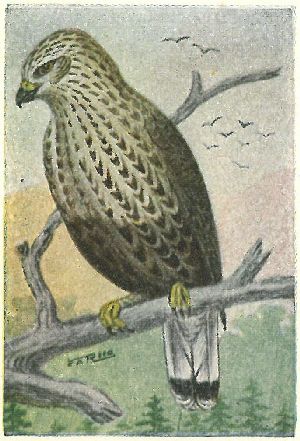

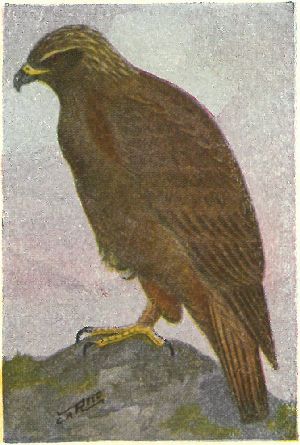

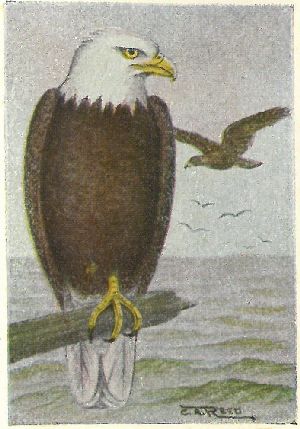

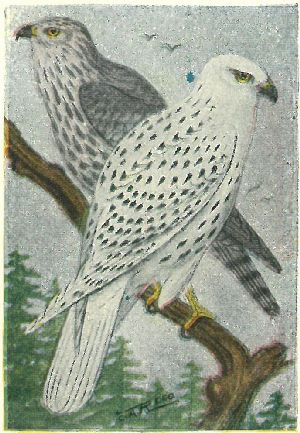

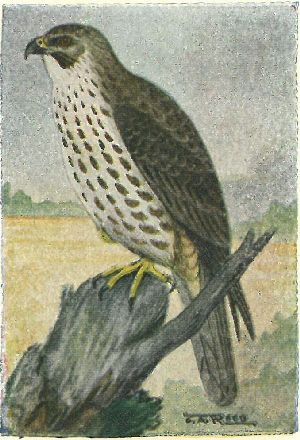

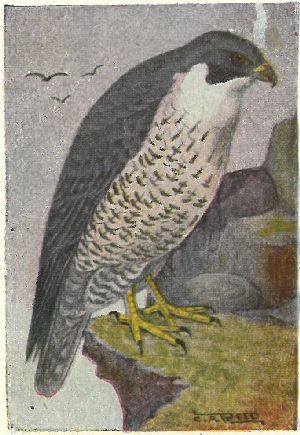

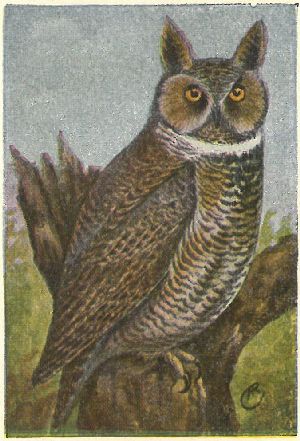

HAWKS, EAGLES. Falconidæ:—Bill and claws strongly hooked; nostrils in a cere at base of bill.

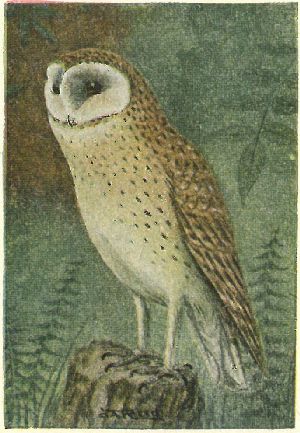

BARN OWLS. Aluconidæ:—Black eyes in triangular facial disc; middle toe-nail serrated.

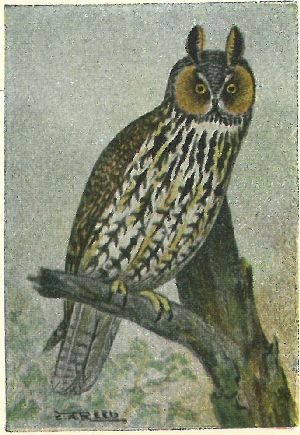

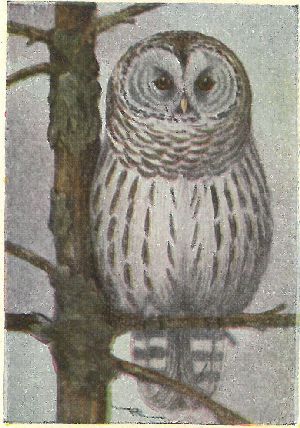

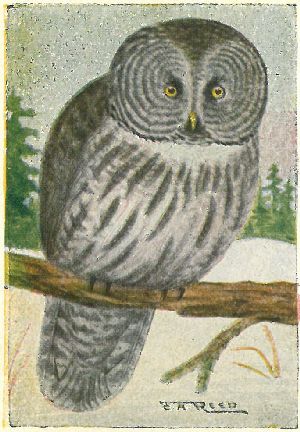

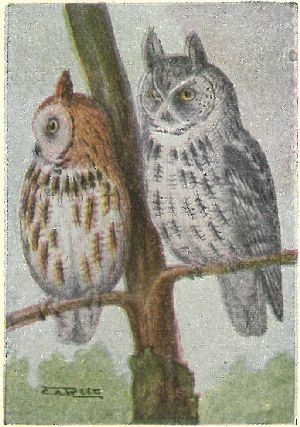

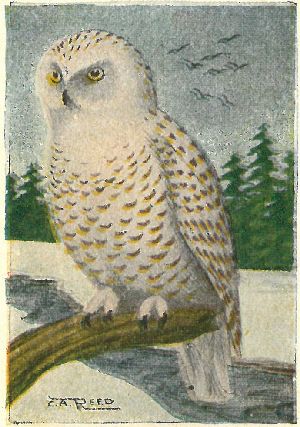

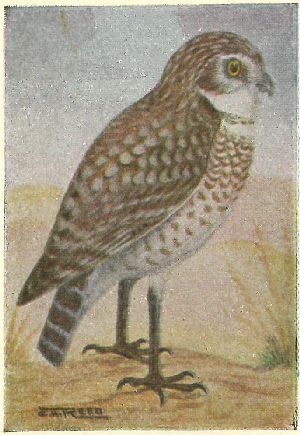

HORNED OWLS, ETC. Bubonidæ:—Facial disc round; some species with ears, others without.

PART 1

Water Birds, Game Birds and Birds of Prey

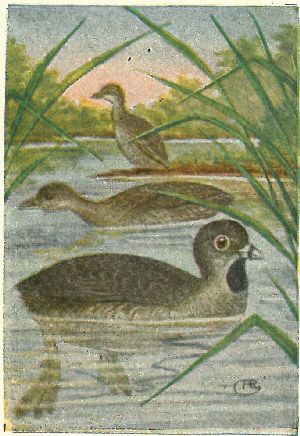

All grebes have lobate-webbed feet, that is each toe has its individual web, being joined to its fellow only for a short distance at the base.

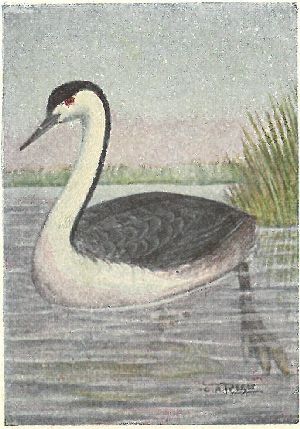

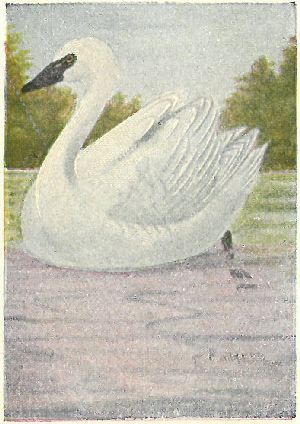

This, the largest of our grebes, is frequently known as the “Swan Grebe” because of its extremely long, thin neck. In summer the back of the neck is black, but in winter it is gray like the back.

Notes.—Loud, quavering and cackling.

Nest.—A floating mass of decayed rushes, sometimes attached to upright stalks. The 2 to 5 eggs are pale, bluish white, usually stained (2.40 × 1.55). They breed in colonies.

Range.—Western North America, from the Dakotas and Manitoba to the Pacific, and north to southern Alaska. Winters in the Pacific coast states and Mexico.

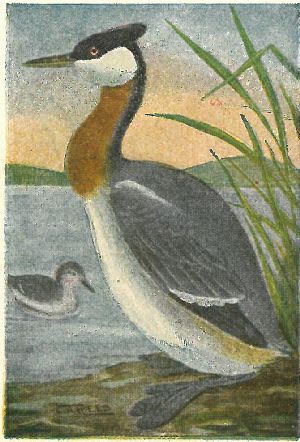

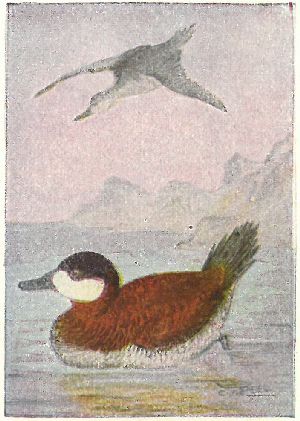

This is next to the Western Grebe in size, both being much larger than any of our others. In summer, they are very handsomely marked with a reddish brown neck, silvery white cheeks and throat, and black crown and crest, but in winter they take on the usual grebe dress of grayish above and glossy white below. Because of their silky appearance and firm texture, grebe breasts of all kinds have been extensively used in the past to adorn hats of women, who were either heedless or ignorant of the wholesale slaughter that was carried on that they might obtain them.

Nest.—Of decayed rushes like that of the last. Not in as large colonies; more often single pairs will be found nesting with other varieties. Their eggs average smaller than those of the last species (2.35 × 1.25).

Range.—North America, breeding most abundantly in the interior of Canada, and to some extent in the Dakotas. Winters in the U. S., chiefly on the coasts.

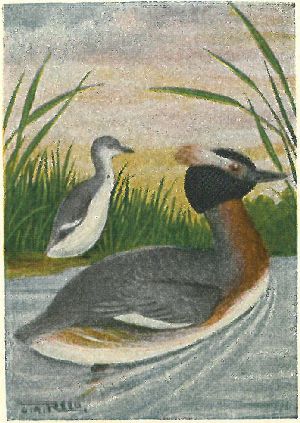

As is usual with grebes, summer brings a remarkable change in the dress of these birds. The black, puffy head is adorned with a pair of buffy white ear tufts and the foreneck is a rich chestnut color. In winter, they are plain gray and white but the secondaries are always largely white, as they are in the two preceding and the following species. The grebe diet consists almost wholly of small fish, which they are very expert at pursuing and catching under water. One that I kept in captivity in a large tank, for a few weeks, would never miss catching the shiners, upon which he was fed, at the first lightning-like dart of his slender neck. They also eat quantities of shell fish, and I doubt if they will refuse any kind of flesh, for they always have a keen appetite.

Nest.—A slovenly built pile of vegetation floating in the “sloughs” of western prairies. The 3 to 7 eggs are usually stained brownish yellow (1.70 × 1.15).

Range.—Breeds from Northern Illinois and So. Dakota northward; winters from northern U. S. to the Gulf of Mexico.

This is a western species rarely found east of the Mississippi. In summer, it differs from the last in having the entire neck black; in winter it can always be distinguished from the Horned Grebe by its slightly upcurved bill, while the upper mandible of the last is convex. In powers of swimming and diving, grebes are not surpassed by any of our water birds. They dive at the flash of a gun and swim long distances before coming to the surface; on this account they are often called “devil divers.” They fly swiftly when once a-wing, but their concave wings are so small that they have to patter over the water with their feet in order to rise.

Nest.—They nest in colonies, often in the same sloughs with Horned and Western Grebes, laying their eggs early in June. The 4 to 7 eggs are dull white, usually stained brownish, and cannot be separated from those of the last.

Range.—Western N. A., breeding from Texas to Manitoba and British Columbia; winters in western U. S. and Mexico.

This is much smaller than any others of our grebes; in breeding plumage it most nearly resembles the following species, but the bill is black and sharply pointed. It has a black patch on the throat, and the crown and back of the head are glossy blue black; in winter, the throat and sides of the head are white.

Nest.—Not different from those of the other grebes. Only comparatively few of them breed in the U. S. but they are common in Mexico and Central America. Their eggs, when first laid, are a pale, chalky, greenish white, but they soon become discolored and stained so that they are a deep brownish, more so than any of the others; from 3 to 6 eggs is a full complement (1.40 × .95).

Range.—Found in the United States, only in the Lower Rio Grande Valley in Southern Texas, and southwards to northern South America.

In any plumage this species cannot be mistaken for others, because of its stout compressed bill and brown iris; all the others have red eyes. In summer the bill is whitish with a black band encircling it; the throat is black; the eye encircled by a whitish ring; the breast and sides are brownish-gray. In winter they are brownish-black above and dull white below, with the breast and sides washed with brown. Young birds have more or less distinct whitish stripes on the head.

Notes.—A loud, ringing “kow-kow-kow-kow (repeated many times and ending in) kow-uh, kow-uh.”

Nest.—Of decayed rushes floating in reed-grown ponds or edges of lakes. The pile is slightly hollowed and, in this, the 5 to 8 eggs are laid; the bottom of the nest is always wet and the eggs are often partly in the water; they are usually covered with a wet mass when the bird is away. Brownish-white (1.70 × 1.15).

Range.—Whole of N. A., breeding locally and usually in pairs or small colonies.

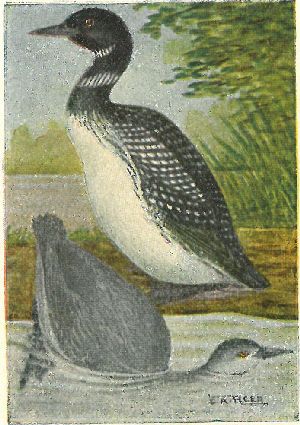

In form, loons resemble large grebes, but their feet are full webbed like those of a duck; they have short, stiff tails and long, heavy, pointed bills. They have no tufts or ruffs in breeding season, but their plumage changes greatly. The common loon is very beautifully and strikingly marked with black and white above, and white below; the head is black, with a crescent across the throat and a ring around the neck. In winter, they are plain gray above and white below.

Loons are fully as expert in diving and swimming as are the grebes. They are usually found in larger, more open bodies of water.

Notes.—A loud, quavering, drawn-out “wah-hoo-o-o.”

Nest.—Sometimes built of sticks, and sometimes simply a hollow in the sand or bank under overhanging bushes, usually on an island. The 2 eggs are brownish with a few black specks (3.50 × 2.25).

Range.—N. A., breeding from northern U. S. northwards; winters from northern U. S. southwards.

This loon lives in the Arctic regions and only rarely is found, in winter, in Northern United States. In summer, it can readily be distinguished from the common loon by the gray crown and hind-neck, as well as by different arrangement of the black and white markings. In winter, they are quite similar to the last species but can be recognized by their smaller size, and can be distinguished from the winter plumaged Red-throated Loon by the absence of any white markings on the back. Like the grebes, loons have to run over the surface of the water in order to take flight, and they are practically helpless when on land. Their flight is very rapid, in a straight line, and their neck is carried at full length in front. This species has red eyes, as do all the other loons.

Nest.—The same as the last species, but the two eggs have more of an olive tint and are smaller (3.10 × 2.00).

Range.—Arctic America, wintering in Canada and occasionally in Northern United States.

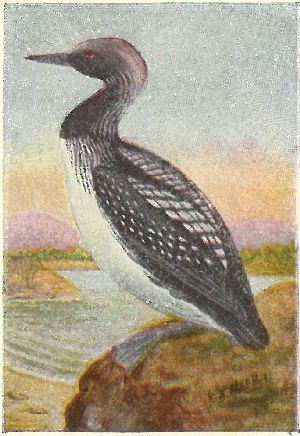

Besides being smaller than the common loon, this species has a more slender bill, which has a slightly up-turned appearance owing to the straight top to the upper mandible; in summer, its back and head are gray, with no white spots, although the back of the head has a few white streaks; there is a large patch of chestnut on the fore-neck; the under parts are white. In winter, it is gray above and white below, but the back is sprinkled with small white spots; at this season it can easily be distinguished from Holbœll Grebe by the absence of any white patch in the wings as well as by the differently shaped feet.

Nest.—A depression in the sand or ground, not more than a foot or two from the water’s edge, so they can slide from their two eggs into their natural element. The eggs, which are laid in June, are olive-brown, specked with black (2.90 × 1.75).

Range.—Breeds from New Brunswick and Manitoba north to the Arctic Ocean; winters throughout the United States.

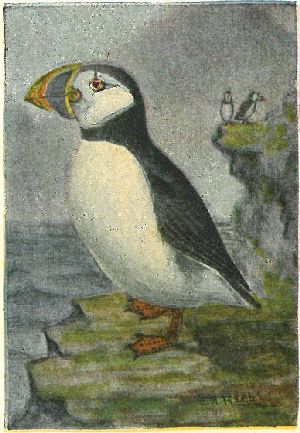

Puffins are grotesque birds, with short legs, stout bodies and very large, thin bills, that of the common Puffin being 2 in. in length and about the same in height; the bill is highly colored with red and yellow, and the feet are red; eyes, white. It will be noticed that the blackish band across the throat does not touch the chin, this distinguishing it from the Horned Puffin of the Pacific coast. Adults in winter shed the greater portion of their bill, lose the little horns that project over the eye, and the face is blackish; they then resemble young birds. They live on rocky shores, the more precipitous the better. They stand erect upon their feet and walk with ease.

Notes.—A low croak.

Nest.—They breed in large colonies on rocky cliffs, laying their single white eggs (2.50 × 1.75) in crevices.

Range.—Breeds from Matinicus Rock, Me., northward; winters south casually to Cape Cod. Large-billed Puffin (F. a. naumanni) is found in the Arctic Ocean.

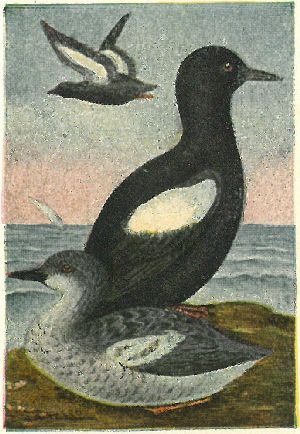

These birds are very abundant about the rocky islands from Maine northward. They may be seen sitting in rows on the edges of the rocks, or pattering along the water as they rise in flight, from its surface, at a boat’s approach. In summer the plumage is entirely black, except the large white patches on the wings; legs red; eyes brown. This species has the bases of the greater coverts black, while they are white in Mandt Guillemot (C. mandtii—No. 28), which is found from Labrador northward. In winter, these birds are mottled gray and white above, and white below, but the patches still show.

Notes.—A shrill, piercing, squealing whistle.

Nest.—Guillemots lay two eggs upon the bare rock or gravel in crevices or under piles of boulders where they are difficult to get at. They are grayish or greenish-white, beautifully and heavily blotched with black and brownish (2.40 × 1.60).

Range.—Breeds on coasts of North Atlantic from Maine northward; winters south to Long Island.

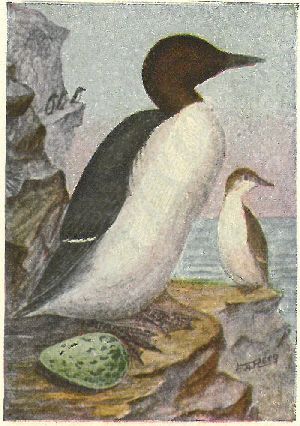

In summer the throat is brownish black, but in winter the throat and sides of head are white; feet blackish bill, long and stout, 1.7 in. long, while that of Brunnich Murre (Uria lomvia—No. 31), is shorter (1.25 in.) and more swollen. The ranges and habits of the two species are the same. Murres are very gregarious, nesting in large colonies on northern cliffs. In summer every ledge available at their nesting resort is lined with these birds, sitting upright on their single eggs.

Notes.—A hoarse imitation of their name “murre.”

Nest.—Their single eggs are laid upon the bare ledges of cliffs. They are pear-shaped to prevent their rolling off when the bird leaves; greenish, gray or white in color, handsomely blotched or lined with blackish (3.40 × 2.00). Their eggs present a greater diversity of coloration and marking than those of any other bird.

Range.—Breeds from the Magdalen Is. northward; winters south to Long Island.

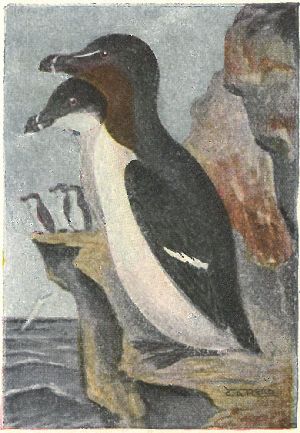

Similar in size and form to the murre, but with a short, deep, thin black bill, crossed by a white line. In summer, with a white line from the eye to top of bill, and with a brownish black throat; in winter, without the white line and with the throat and sides of head white. They nest and live in large colonies, usually in company with murres. Their food, like that of the murres, puffins and guillemots is of fish and shell fish, or marine worms. They get these from the rockweed along the shores or by diving; they are good swimmers, using both their feet and wings to propel them through the water, the same as do the grebes and loons.

Notes.—A hoarse grunt or groan (Chapman).

Nest.—Their single eggs are laid on ledges of cliffs; they are not nearly as pointed at the smaller end, as murre eggs, and are always grayish white in color, marked with blackish blotches (3.1 × 2.00).

Range.—Breeds from the Magdalen Islands northward; winters south to Long Island.

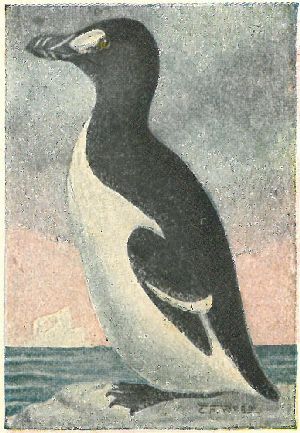

This largest of the auks lived, as far as we have authentic record, until 1844, when it became extinct, largely through the agency of man. Although nearly twice as long a bird as the Razor-billed Auk, their wings were shorter than those of that bird, being only a trifle longer than those of the little Dovekie; they were flightless, but the wings were used to good advantage in swimming. Being in the direct line of travel between the old world and the new, sailors, on passing vessels, killed countless numbers of them for food, and in some cases merely for the love of slaughter. They lived on coasts and islands of the Atlantic from Mass., northwards. There are about seventy mounted birds preserved, of which five or six, as well as some skeletons, are in this country.

Their eggs resemble those of the Razor-bill but, of course, are much larger (5.00 × 3.00). About 70 of these are in existence, six being in this country (Washington, Phila., and four recently purchased by John E. Thayer, of Lancaster, Mass.).

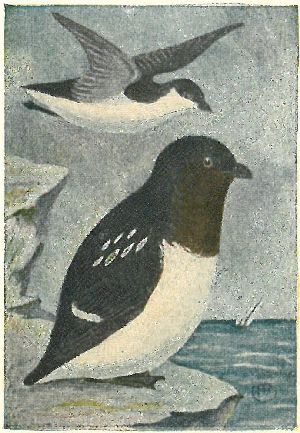

These little auks, called “ice birds” by the fishermen, are very abundant in the far north. In summer, they have a blackish brown throat and breast, but they are never seen in the United States or southern parts of the British possessions in that plumage. In winter, their throats and sides of the head are white as well as the rest of their upper parts. At all seasons the edges of the scapulars and tips of the secondaries are white, as are usually spots on each eyelid. Even in winter, they are only casually found on our coast, for they keep well out at sea. Occasionally they are blown inland by storms and found with their feet frozen fast in the ice of some of our ponds or lakes.

Nest.—They lay single pale greenish blue eggs, placing them in crevices of sea cliffs; size 1.80 × 1.25.

Range.—Breeds on islands in the Arctic Ocean and on the coasts of Northern Greenland; winters south to Long Island and casually farther.

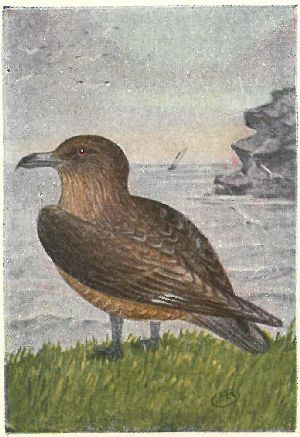

These large birds are the most powerful and audacious pirates among the sea fowl of northern waters. Their whole form is indicative of strength; form robust, feet strong, and bill large, powerful and hooked. Their plumage is of a nearly uniform blackish-brown, with white shafts to the wing feathers and a white patch at the base of the primaries.

Nest.—They do not nest in large colonies, only a single or a few pairs breeding in the same locality. Their nests are hollows in the ground, a short distance back from the rocky shores. The two eggs that they lay are olive brown, spotted with blackish (2.75 × 1.90).

Range.—North Atlantic coasts, chiefly on the Old World side, breeding from the Shetland Islands and possibly Greenland, northwards. They are only rarely found on our coasts even in winter, but have been taken as far south as New York.

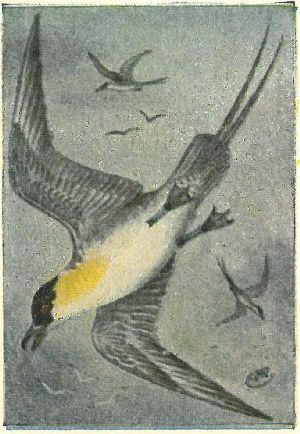

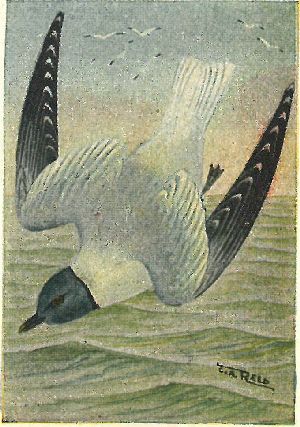

Jaegers are more slender in form than the Skuas, but like them are piratical in their habits, preying chiefly upon terns. Off Chatham, Mass., I have often watched them in pursuit of the graceful terns, but, excellent fliers as the latter birds are, they were always overtaken and forced to drop the fish that they carried, and the jaeger would rarely miss catching it as it fell. This species has two color phases independent of sex or age. In the light plumage the top of the head is black; rest of the upper parts and the under tail coverts brownish black; underparts and bases of primaries, white. Dark phase,—Entirely blackish brown except the white shafts to wing feathers and bases Of primaries. In any plumage they can be distinguished from the other species by the rounded, lengthened central tail feathers.

Nest.—A hollow in the ground in marshy places. The two eggs are olive brown spotted with black.

Range.—Northern hemisphere, breeding north of the Arctic Circle; winter from Mass. southward.

Two phases of color, both similar to those of the last, but the central pair of tail feathers are pointed and project about 4 in. beyond the others; bill 1.4 in. long, with the nostril nearest the end. All jaegers have grayish blue legs with black feet, and brown eyes. They are called “Jiddy hawks” by fishermen, who often feed them fish liver. Their flight is like that of a hawk. The nesting habits and range are the same as the next.

Like the last species, but with the pointed central tail feathers projecting 8 or 10 in. and with a shorter bill (1.15 in.) and the nostril about midway of its length. It is less often found in the dark phase.

Notes.—Shrill wailing whistles.

Nest.—Nest and eggs like those of the Pomarine Jaeger.

Range.—Arctic regions, wintering south to Florida.

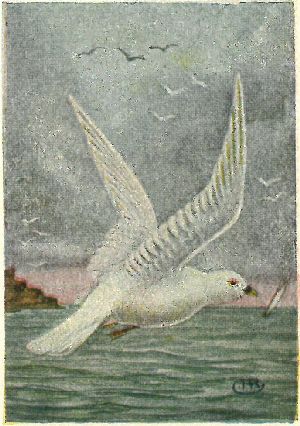

Entirely pure white with the shafts of the primaries yellowish; bill dark at base and yellow at tip; eyes brown, surrounded by a narrow red ring; feet black. Young birds are spotted with brown on the head, tips of wing and tail. This beautiful “Snow Gull,” as it is called by whalers, is abundant at its breeding ground in the Arctic regions, but is rarely seen as far south as the United States. It breeds the farthest north of any of the gulls except Ross Gull.

Nest.—Of grasses and seaweed, usually on ledges of cliffs, but occasionally on the ground farther inland. The three eggs, laid in June, are grayish-buff, marked with brown and black (2.30 × 1.70).

Range.—Breeds only north of the Arctic Circle, and winters south to New Brunswick and British Columbia; casually to Long Island and the Great Lakes.

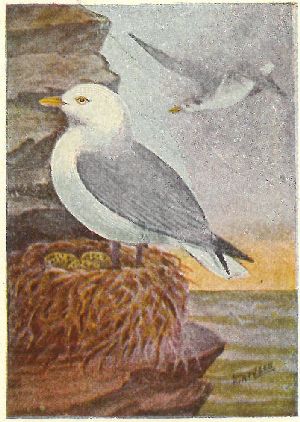

In summer, with plumage white, except the gray back and wings, and solid black tips to the primaries; in winter, the sides and back of the head are washed with the color of the back; young birds are like winter adults but have a dusky spot back of the eye; feet blackish, bill yellow in adults and black in young birds. Kittiwakes are very abundant in their northern breeding ground, and are common off the New England coast in winter. They usually keep well out at sea, often hovering around fishing boats to pick up refuse that is thrown overboard. They can easily be identified by their small size, the distinct black tip to the wings and their black feet.

Notes.—“Keet-a-wake, keet-a-wake.”

Nest.—A pile of small sticks, grass and weeds, placed on ledges of sea cliffs. The 3 or 4 eggs are olive gray, with black markings (2.20 × 1.70).

Range.—Breeds from the Gulf of St. Lawrence north to the Arctic Circle; winters south to Long Island and casually farther.

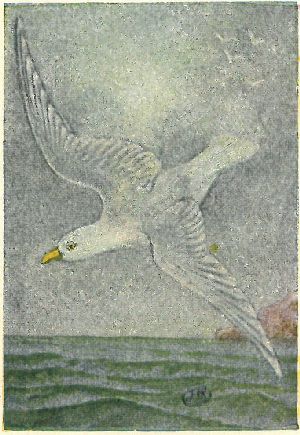

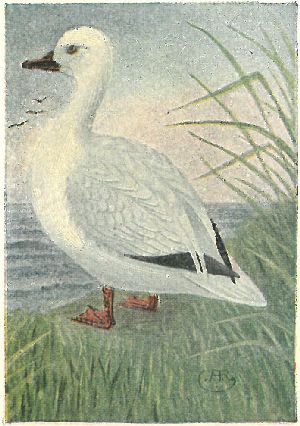

Plumage white with a pearl gray mantle; no black in the plumage, the primaries being white or grayish; bill and eye yellow, the former with a red spot at the end of the lower mandible; feet flesh color. In winter, the head is slightly streaked with brownish. Young birds are mottled grayish brown and white, of varying shades, but always lighter than the young of the Herring Gull. Some specimens are very beautiful, being entirely white, with a few spots of brownish on the back, resembling the markings of a light-colored Snowy Owl. This species is one of the largest and most powerful of the gull family, only surpassed by the Great Black-backed Gull.

Nest.—Usually a bulky structure of grasses, seaweed and moss placed on the ground; the two or three eggs are brownish gray with brown and black spots (3. × 2.20).

Range.—Breeds from Labrador and Hudson Bay northward; winters south to New England, the Great Lakes and Calif.

Plumage exactly like that of the Glaucus Gull but the birds are smaller and are found farther north.

Range.—Breeds in Greenland and winters south to Northern New England and the Great Lakes.

Plumage very similar to that of the Iceland and Glaucus Gulls, but with the primaries conspicuously gray, with white tips. As usual with the gull family, this species feeds largely, during the nesting season upon eggs and young of other sea birds. They seem to have a special liking for Cormorant eggs, and these ungainly creatures have to sit on their nests very closely to prevent being robbed.

Range.—Breeds about the mouth of Hudson Bay; winters south to Long Island.

Largest and most powerful of our gulls. Adults in summer have the head, tail and underparts white, back slaty black, eyes and bill yellow, with a red spot near the tip of the lower mandible; feet flesh color; primaries tipped with white. In winter, the head is streaked with dusky. Young birds are mottled with dusky brown above, and streaked with the same below. These birds are very rapacious, and besides feeding upon refuse, fish and shellfish, devour, during the summer season, a great many eggs and young of other sea birds; this habit is common to nearly all the larger gulls.

Notes.—A laughing “ha-ha” and a harsh “keouw.”

Nest.—Either hollows on the ground or masses of weeds and drift, hollowed out to receive the three grayish brown eggs, spotted with blackish and lilac (3. × 2.15).

Range.—These gulls breed from Newfoundland northward, being most abundant on the Labrador coast. In winter they are found as far south as the Carolinas, usually in company with Herring Gulls.

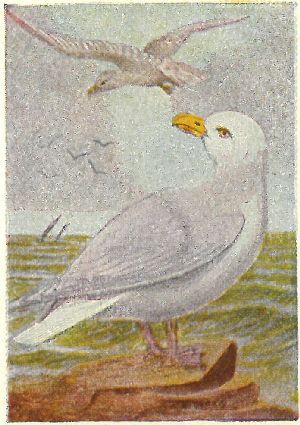

Adults in summer, white, with gray mantle, and black primaries tipped with white. In winter, the head and neck are streaked below with grayish brown. Bills of adults, yellow with red spot on lower mandible; eye yellow; feet flesh color; bill of young, flesh color with a blackish tip. These are the most abundant of the larger gulls and the best known because of their southerly distribution. Several of the smaller Maine islands have colonies of thousands of birds each, and in winter great numbers of them are seen in all the harbors along our seacoast. Young gulls are born covered with down, and can run swiftly and swim well.

Notes.—“Cack-cack-cack” and very noisy squawkings when disturbed at their breeding grounds.

Nest.—A hollow in the ground, or a heap of weeds and trash. The three eggs are olive-gray, spotted with black (2.8 × 1.7).

Range.—Breeds from Maine, the Great Lakes and Dakotas northward; winters south to the Gulf of Mexico.

Adults in summer.—White with pearl gray mantle; ends of outer primaries black with white tips; eye yellow; feet and bill greenish-yellow, the latter crossed by a black band near the tip. In winter, the head and neck are streaked with grayish. Young birds are mottled brownish-gray above, and the tail has a band of blackish near the end.

The adults can be distinguished from the Kittiwakes, which most closely resemble them, by the yellowish feet and white tips to the black primaries.

Nest.—In hollows in the ground, usually in grass. The two or three eggs are gray or brownish gray, strongly marked with black (2.80 × 1.75). They breed in large colonies, often in company with other gulls and terns.

Range.—Whole or North America, breeding from Newfoundland, Dakota and British Columbia northwards, most abundantly in the interior; winters from Northern United States southward.

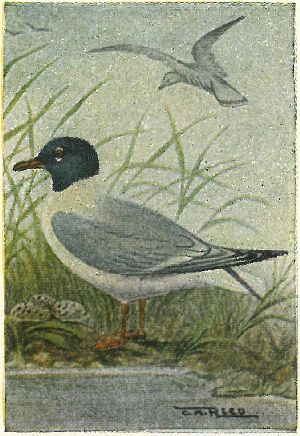

Largest of the black-headed gulls. Bill and feet carmine-red; primaries wholly black or only with slight white tips; eye brown; in breeding season, with the underparts tinged with pinkish. In winter, without the black hood, the head being tinged with grayish, and the bill and feet dusky. Young birds are like winter adults with the back more or less mixed with brownish and the tail crossed by a black band. The most southerly distributed of our eastern gulls, its northern breeding place being on the southern shore of Mass.

Notes.—Strange cackling laughter; hence their name.

Nest.—Heaps of rubbish and weeds on the ground in wet marshes. The 3 to 5 eggs are gray or olive-gray with black spots (2.25 × 1.60).

Range.—Breeds from the Gulf of Mexico north to Mass., and in the interior to Ohio, but most abundantly on the South Atlantic coast. Winters from the Carolinas to Northern South America.

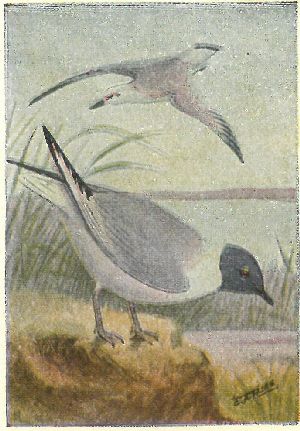

Adult in summer.—Hood dark; mantle lighter than the last species; primaries gray with black ends broadly tipped with white; underparts rosy; bill and feet red, the former dark toward the tip, and more slender than that of the Laughing Gull. In winter, the plumage changes the same as that of the last but the color of the primaries and the shape of the bill will always identify this species. These gulls are strictly birds of the interior, nesting on low marshy islands in ponds or sloughs, often in company with grebes, upon whose eggs they subsist to a great extent.

Notes.—Similar to those of the last species.

Nest.—A mass of weeds, etc., on the ground in marshes, often partly floating in the water. The eggs are similar to those of the Laughing Gull but the markings are usually in the form of zigzag lines as well as spots (2.25 × 1.60).

Range.—Interior of North America, breeding from Iowa and the Dakotas north to Middle Canada; winters from the Gulf States southward.

Adult in summer.—Hood lighter gray and not as extensive as in the last two species; bill slender and black; feet coral red; primaries white with black tips and outer web of first one; mantle paler than either of the last. In winter, the head is white with gray spots back of the eyes. Young birds have the back mixed with brownish and the tail with a band of black near the tip, but the bill and primaries always separate this species in any plumage from the other black-headed gulls. These little gulls are one of the most beautiful and graceful of the family, but they are rarely found in the U. S. with the dark hood.

Nest.—Of weeds and grass on the ground, but not in the watery situations chosen by the preceding species. The three eggs are olive-brown, marked with blackish (1.90 × 1.30).

Range.—Breeds in the interior from Hudson Bay and Northern Manitoba northward. Winters from Maine, the Great Lakes and British Columbia southward.

Bill short and slender; tail wedge-shaped. Adults in summer.—With no hood, but with narrow black collar; mantle light pearl; primaries wholly white with the exception of a blackish outer web to the first one; feet coral red, and underparts tinged with rosy in the nesting season. In winter, with no black collar nor pink underparts, and with blackish spot before the eye. Young mixed with blackish above, and with a black band across the tip of the tail; feet black; easily distinguished, when in the hand, by the very small bill, and the wedge shaped tail. This gull has the most northern distribution of any known bird, except, possibly, the Knot. Its breeding grounds were first reported by Nansen in 1896, in Franz Josef Land. It is one of the rarest birds in collections.

Range.—Polar regions, south in winter to Point Barrow, Alaska, and Disco Bay, Greenland.

Tail slightly forked; bill small and black, tipped with yellow. Adults in summer.—Head with a slaty-gray hood, edged with a black ring around the neck; outer primaries black, with white tips, and edge of shoulder black; feet blackish; eye ring orange red. In winter, without the hood or collar, but the head is tinged with gray on the ears and nape. Young birds most nearly resemble those of the Bonaparte Gull, but the primaries are blackish, and the tail slightly forked. This species is very abundant within the Arctic Circle, but is not as boreal as the last.

Nest.—In depressions in the ground, usually lined with grass; the three eggs are olive-brown, marked with deeper brown and black (1.75 × 1.25).

Range.—Breeds from northern Alaska and the islands about the mouth of Hudson Bay northwards; winters south on the Atlantic coast to Maine and rarely New York.

Differs from all other terns in the shape of its black bill, which is stout, but with the upper mandible not hooked nor curved, as in the gulls. Tail forked about 1.5 in. Adults have the crown black in summer, while in winter the head is white, with the nape and spot in front of eye, black mixed with white. Young birds are similar to winter adults but have the back feathers margined with brownish, and the neck streaked with gray. This species is found only on our South Atlantic and Gulf coasts, and is not abundant anywhere.

Notes.—A high, thin, somewhat reedy “tee-tee-tee,” sometimes suggesting a weak voiced katydid (Chapman).

Nest.—A slight, unlined depression in the short marsh grass or on the beaches. The three eggs are olive gray, spotted with black and brown (1.80 × 1.30).

Range.—Breeds in Texas and along the Gulf and South Atlantic coasts to Virginia; later, may wander north to New England; winters south of the U. S.

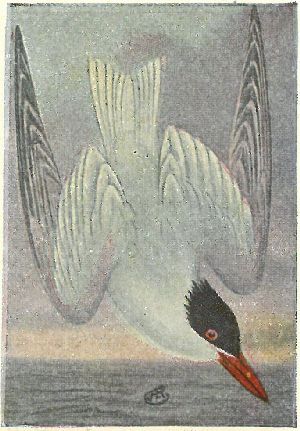

Largest of our terns. Bill heavy and bright red; head crested; tail forked about 1.5 in.; eyes brown. Adults in summer have the crown and occipital crest glossy black. Winter adults and young birds have the crown mixed with white, and the latter are also blotched with blackish on wings and tail.

Nest.—The 2 or 3 buffy, spotted eggs are laid in hollows in the sand. Size 2.60 × 1.75.

Range.—Breeds locally along the South Atlantic coast and in the interior to Great Slave Lake.

Similar to the last, but smaller; bill more slender; tail forked 3.5 in.

Nest.—A hollow in the sand. The 2 or 3 eggs are creamy buff, with distinct blackish-brown spots (2.60 × 1.70).

Range.—Breeds in the Gulf States and north to Virginia and Calif.; winters south of the U. S.

Head crested; bill and feet blackish, the former with a yellow tip. Adults have the crown glossy black. Young birds, and winter adults, have the crown mixed with white, and the former have blackish markings on the wings; tail forked 2.75 in. Like the majority of terns, these breed in immense colonies.

Nest.—Their two or three eggs are deposited in slight hollows in the sand. They are cream colored, boldly spotted with blackish brown (2.10 × 1.40).

Range.—Breeds on the Florida Keys, Bahamas and the West Indies; later may stray north as far as New England; winters south of the United States.

This is a rare South American species, described by Audubon as having occurred in New Jersey and New York. It has the form of the Forster Tern, a bright yellow bill and no black crown, but a black line through the eye to the ears.

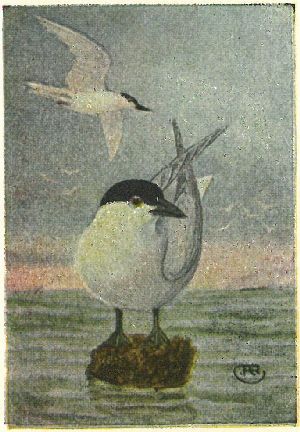

No crest on this or any of the following terns. Tail forked 4 in.; below pure white. In summer, with bill and feet orange red; crown black. In winter, the crown is white, but there is a blackish patch about the eyes, and the bill and feet are dark. These beautiful birds are often known as “Sea Swallows,” because of their similarity in form and flight to those well known land birds. They are the embodiment of grace as they dart about high in the air, bill pointed downward, alert and ready to dart down upon any small fish or eel that may attract their fancy. They usually get their food by plunging.

Notes.—A sharp, twanging “cack.”

Nest.—A hollow in the ground, in which the 3 eggs are laid in June. Eggs whitish, greenish or brownish, variously marked with brown, black and lavender (1.80 × 1.30).

Range.—Breeds in the interior, north to Manitoba, and on the coasts to Virginia and Calif. Winters from the Gulf States southward.

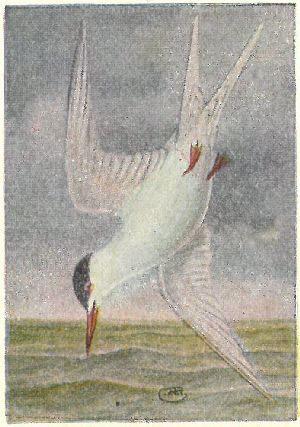

Mantle darker than that of any of the similar terns; washed with grayish below; bill and feet bright red, the former shading to black on the tip; tail less deeply forked (3.1 in.); edge of outer primaries and outer tail feathers, blackish. Changes in winter correspond to those of the last. Young birds have the feathers on the back margined with brownish.

Note.—An energetic “tee-arr, tee-arr.”

Nest.—The three eggs are laid in a slight hollow on the sandy beach.

Range.—Breeds locally from the Gulf States to Greenland and Hudson Bay; winters south of the U. S.

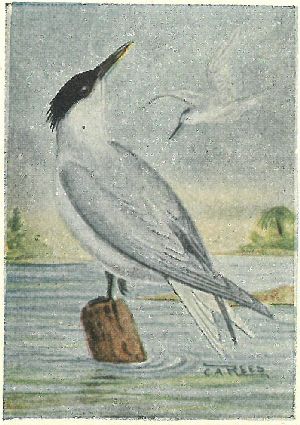

Similar to the Common Tern, but tail longer (forked 4.5 in.) and bill wholly red. In winter, bill and feet dark, as are those of the others.

Range.—Breeds from Mass. northwards; winters in the south.

This species is the most gracefully formed of the terns. The tail is 7.5 in. long, forked to a depth of 5.25 in. In summer, the bill is blackish, changing to red only at the base. The underparts are a beautiful rosy tint in the breeding season; tail entirely white; feet red. In winter the usual changes occur, and young birds have dusky edges to the feathers of the back and wings. Terns are now becoming more abundant on our coast, their slaughter and persecution for millinery purposes fortunately having been stopped in time to prevent their extinction.

They feed chiefly upon small fish and marine insects, and often gather about fishing boats, waiting for an opportunity to dive after any bit that may be thrown overboard.

Notes.—A harsh “cack” and “tee-arr,” like that of the common Tern.

Nest.—Eggs like those of the similar terns.

Range.—Breeds on the Atlantic coast north to Mass.; winters south of the U. S.

Smallest of our terns. Adult in summer.—Crown, nape, and line through the eye, black; forehead and line above the eye, white; bill and feet yellow, the former black at the tip. In winter, the crown is white, the blackish being restricted to the nape and about the eyes.

These pretty little sea swallows were abundant both on the coast and in the interior but are yearly becoming more scarce especially on the Atlantic coast. They are very aggressive when anyone approaches their nesting grounds and will continually dash down at you as they utter their sharp cries of disapproval.

Notes.—A sharp, metallic clattering “cheep, cheep.”

Nest.—Two or three eggs are laid upon the bare sand. They are buffy-gray, sharply specked with blackish (1.25 × .95).

Range.—Breeds north to Mass., the Great Lakes and Calif.; winters south of the United States.

Adult in summer.—Above sooty-black, except the white outer tail feathers. Crown, line through the eye, bill and feet, black; forehead and underparts white; eye red. Young birds are smoky slate color all over, with the tail feathers, and some on the back and breast, tipped with whitish. This is the “egg bird” of tropical countries, thousands of their eggs being taken for food.

Note.—A nasal “ker-wacky-wak” (Chapman).

Nest.—A single egg deposited in a hollow in the sand; it is creamy-white, spotted with blackish-brown.

Range.—Tropical countries; breeds north to the Florida Keys and islands in the Gulf of Mexico; sometimes wanders north to New England.

Similar to the last, but the back and wings much lighter, and the white of the forehead extends over the eyes; nape whitish.

Range.—Breeds north to the Bahamas.

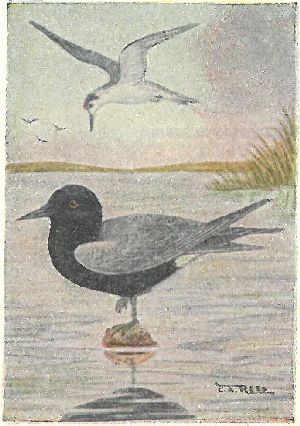

Adults in summer with the head, neck and underparts, black; back, wings and tail, dark gray; eyes brown. In winter, the forehead, neck and underparts are white; nape and patch back of eye blackish.

In summer these little terns are found only in the interior, where they nest about marshy ponds. They are very pugnacious and will sometimes touch an intruder with their wings as they dart past. As usual with the family, they nest in colonies.

Notes.—A sharp “peek.” (Chapman).

Nest.—A pile of weeds and trash in sloughs on the prairies, or about the edges of marshy lakes, the nests often being surrounded by, and partly floating in the water. The three eggs are very dark colored, having an olive-brown or greenish background, blotched with black (1.35 × .95).

Range.—Breeds in the interior from middle U. S. north to Alaska and Hudson Bay; winters south of the U. S., migrating along the Atlantic coast as well as in the interior.

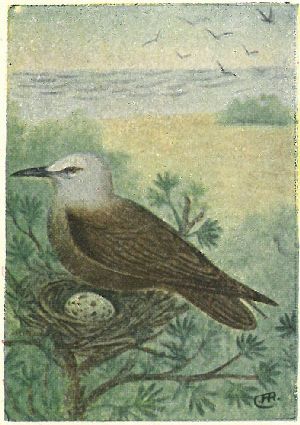

Adults with the crown silvery-white, the rest of the plumage being sooty-brown; the bill, feet and line to the eye are black. The plumage of these beautiful birds is very soft and pleasing to the eye. They look to be gentle and confiding, and a closer acquaintance shows that they are. They will frequently allow themselves to be touched with the hand before they leave their nests. They are abundant in some of the Bahaman and West Indian Islands, where they nest in company with other species.

Notes.—A hoarse reedy “cack” increasing to a guttural “k-r-r-r-r-r-r-r.” (Chapman).

Nest.—Of sticks and grasses, placed at low elevations in the tops of trees and bushes, or upon the ground. The single egg that they lay is buffy, spotted with black and brown (2.00 × 1.30).

Range.—Breeds north to the Bahamas and on Bird Key near Key West; rarely wanders on the Atlantic coast to South Carolina.

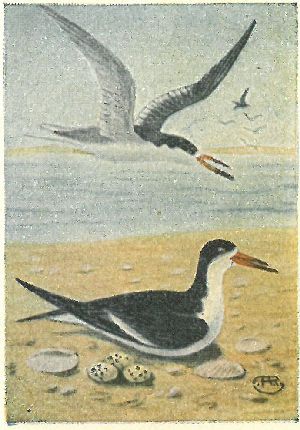

These strange birds are not apt to be mistaken for any other. They are locally abundant on the South Atlantic coast as far north as Virginia. Their flight is swift and more direct than that of terns; they fly in compact flocks, in long sweeps over the water, feeding by dropping their long, thin mandible beneath the surface and gathering in everything edible that comes in their path.

Notes.—Baying like a pack of hounds.

Nest.—Their 3 or 4 eggs are deposited in hollows in the sandy beaches. They are creamy-white, beautifully marked with blackish-brown and gray (1.75 × 1.30).

Range.—Breeds on the Gulf coast and on the Atlantic coast to New Jersey; after nesting, they occasionally wander northward as far as Nova Scotia; winters from the Gulf States southwards.

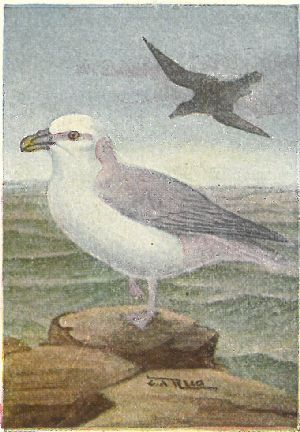

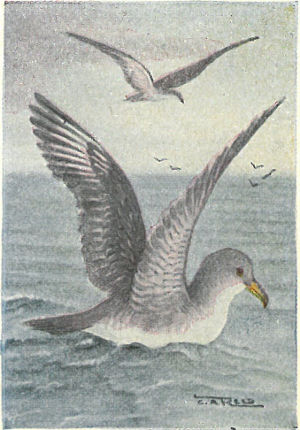

Bill short and stout, compared to that of the shearwaters, strongly hooked at the tip and with the nostrils opening out of a single tube, prominently located on the top of the bill. They have two color phases, the light one being gull-like, but the tail is gray like the mantle; eyes brown; bill and feet yellowish. In the dark phase they are uniformly gray above and below. These plumages appear to be independent of sex or age. They are extremely abundant at some of their breeding grounds in the far north. The birds are constant companions of the whalers, and feed largely upon blubber that is thrown overboard.

Nest.—Their single white eggs are laid upon bare ledges of sea cliffs (2.90 × 2.00).

Range.—Breeds in the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans from Labrador and northern Scotland northward; winters south regularly.

This rare bird is found off the coast of New England and in Long Island Sound from July to September. It is slightly larger than the similar Greater Shearwater, the back and head are lighter in color, the entire underparts are white, and the bill is yellowish. Its nesting habits and eggs are unknown, but they are supposed to breed in the Antarctic regions.

The majority of specimens that have been taken have been found off Chatham, Mass.

This small shearwater, except in point of size, is quite similar to the following, but the under parts are white, except the under tail coverts which are sooty; the back and head are somewhat lighter too. They nest in abundance on some of the Bahaman and West Indian Islands, and can usually be met with off the South Atlantic coast in summer.

Their eggs, which are pure white (2.00 × 1.35), are deposited at the end of burrows dug by the birds.

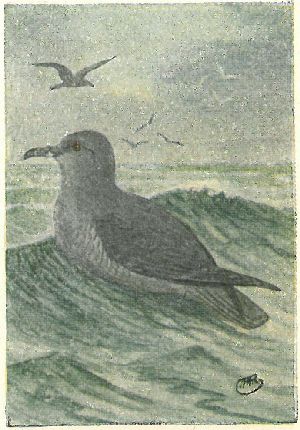

Entire upper parts, top and sides of head, bill and feet, grayish or brownish-black; middle of belly and under tail coverts dusky. This species is the most abundant of the shearwaters found off our coast. They are constant attendants of the fishermen when they are at work, and at other times are usually to be seen flying low over the water, or resting in large bodies upon its surface. Their flight is peculiar and distinctive,—three flaps of the wings then a short sail, repeated over and over. Possibly this habit is acquired by their swooping down into the troughs of waves, then flapping to clear the next crest. They are very greedy and continually quarreling among themselves in order to get the lion’s share of the food. They are called “Haglets” by the fishermen.

Notes.—Harsh, discordant squawks when feeding.

Nest.—While the habits of these birds are well known their breeding places are yet a mystery.

Range.—Whole North Atlantic coast in summer.

Sooty grayish-black all over except the under wing coverts, which are whitish; eye brown, bill and feet black. A few of these may usually be seen with flocks of the Greater Shearwaters, and sometimes a flock composed entirely of this variety will be encountered. They are expert swimmers on the surface of the water, but I have never seen one dive. Their food is almost if not wholly composed of oily refuse gathered from the surface of the water. In order to take flight, they paddle along the water a few steps; it is difficult for them to rise, except against the wind. If you sail upon them from the windward, they go squawking and pattering over the water in all directions, and can frequently be caught in nets. They are very tame, and will sometimes take food offered them, from the hand.

Notes.—Guttural squawks like those of the large species.

Range.—North Atlantic coast in summer.

Smallest of our petrels, and darker than either the Leach or Wilson; tail square; upper tail coverts white, tipped with black.

This species is rare on the coasts of this country, but is common on the shores of the old world. It is the original “Mother Cary’s Chicken.” They nest abundantly on the shores of Europe and the British Isles.

Their single white eggs, deposited at the end of burrows, are dull white with a faint wreath of brown dots.

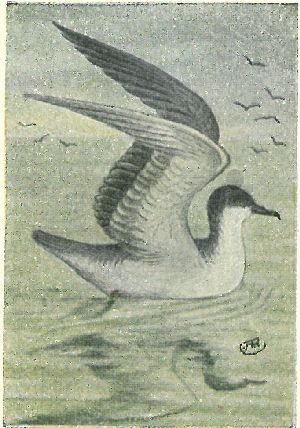

Tail square at end; coverts white, not tipped with black; legs long, with yellow webs. This species is very abundant on our Atlantic coast from July to Sept., spending the summer here after having nested in the Kerguelen Is. in February. Their upper parts are much more darker than those of Leach Petrel.

Their note is a weak twittering “keet-keet.”

Tail forked; tail coverts white, not tipped with black; legs much shorter than those of Wilson Petrel, which is the only other common species on our eastern coasts. Leach Petrel is a very abundant breeding bird on Maine islands and northward. Some of the soft peaty banks of islands are honeycombed with entrances to their burrows, which extend back, near the surface of the ground, for two or three feet, and terminate in an enlarged chamber. Here one of the birds is always found during the period of incubation, and sometimes both birds, but one is usually at sea feeding during the daytime, returning at night to relieve its mate. All petrels and their eggs have a peculiar, characteristic and oppressive odor.

Notes.—A weak clucking.

Nest.—Single egg at end of burrow; white with a very faint ring of brown dots around the large end.

Range.—Breeds northward from Maine; winters to Virginia.

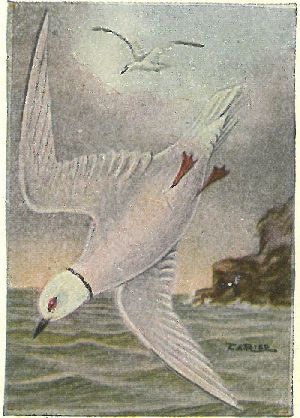

Form tern-like, but with the central tail feathers much lengthened (about 18 in.); legs short and not very strong; all four toes connected by webs.

These beautiful creatures fly with the ease and grace of a tern, but with more rapid beating of the wings. They are strong and capable of protracted flight, often being found hundreds of miles from land. They feed upon small fish which they capture by diving upon from a height above the water, and upon snails, etc., that they get from the beaches and ledges. They are very buoyant, and sit high in the water with their tails elevated to keep them from getting wet.

Nest.—A mass of weeds and seaweed placed upon rocky ledges. The single egg that they lay is creamy, so thickly sprinkled and dotted with purplish brown as to obscure the ground color (2.10 × 1.45).

Range.—Breeds north to the Bahamas and Bermudas.

Bill, face and naked throat pouch, slaty-blue; eye yellow; feet reddish. Plumage white except the primaries, secondaries and other tail feathers, which are black. Young birds are streaked above with gray and brownish, and are dull white below. Boobies are birds of wide distribution in the Tropics, this species being rarely seen in southern Florida, but quite abundant on some of the West Indian islands. Owing to the numerous air cells beneath their skin, they are very buoyant and can ride the waves with ease during severe storms. They secure their prey, which is chiefly fish, by plunging after it.

Nest.—Their one or two eggs are laid usually upon the bare ground on low islands, or sometimes in weed-lined hollows. The eggs are pure white, covered with a thick chalky deposit (2.50 × 1.70).

Range.—Breeds north to the Bahamas and the Gulf of California; sometimes strays to Florida.

This species, commonly called the Brown Booby, is brownish black with the exception of a white breast and underparts. Young birds are entirely brownish black; bill and feet greenish yellow; eye white. They are one of the most abundant breeding birds upon many of the Bahaman and West Indian Islands. They have great powers of flight and dart about with the speed of arrows, carrying their long bill and neck at full length before them. They are awkward walkers, and, owing to their buoyancy, it is difficult for them to swim under water, but they are unerring in securing their prey by plunging upon it from a height.

Nest.—They breed in colonies of thousands, laying their two eggs upon the bare sand or rocks. The eggs are chalky white, more or less nest stained (2.40 × 1.60).

Range.—Breeds in the Bahamas and West Indies; wanders north casually to the Carolinas.

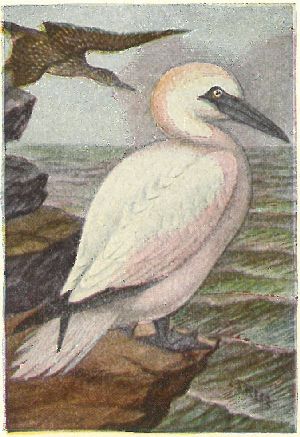

Primaries black; rest of plumage white; back of head tinged with straw color; bill and feet bluish black. Young grayish or brownish black, mottled above and streaked below. This species is the largest and most northerly distributed of the gannet family. Thousands upon thousands of them breed upon high rocky islets off the British coast. The only known nesting places used by them in this country are Bird Rock and Bonaventure Island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence; in these places they nest by thousands, their rough piles of seaweed touching each other in long rows on the narrow ledges.

Notes.—A harsh “gor-r-r-rok.” (Chapman).

Range.—North Atlantic, breeding, on the American side, only on islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Winters along the whole United States coast, floating in large flocks out at sea, and rarely coming on land.

Adult male with a glossy greenish-black head, neck and underparts, the neck being covered behind, in breeding season, with numerous filamentous, whitish plumes. Female and young with neck and breast fawn color in front. Eyes red, face greenish and gular pouch orange. Middle tail feathers curiously crimped. These peculiar birds spend their lives within the recesses of swamps, the more dismal and impenetrable, the better. They perch on limbs overhanging the water and dive after fish, frogs, lizards, etc., that pass beneath, from which they get one of their names, American Darter. They swim with the body submerged, with only their serpent-like head and neck visible; hence they are called Snake-birds.

Nest.—Of sticks and leaves in bushes or trees over water, large colonies of them nesting in the same swamp. The 3 to 5 eggs are bluish, covered with a chalky deposit (2.25 × 1.35).

Range.—Breeds north to the Carolinas and Ill. Winters in Gulf States.

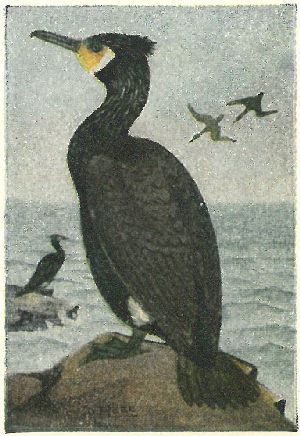

Largest of our cormorants; tail with 14 feathers. Adults with glossy black head, neck and underparts; in breeding season with white plumes on the neck and a white patch on the flanks. Young with throat and belly white, rest of underparts mixed brown with black. Cormorants feed chiefly upon fish which they pursue and catch under water. They were formerly extensively, and are now to a less extent, used by the Chinese to catch fish for them, a ring being placed around their neck to prevent their swallowing their prey.

Nest.—Made of seaweed and sticks on narrow ledges of rocky islets or sea cliffs, this species being entirely maritime. The four eggs are greenish-white, covered with a chalky deposit (2.50 × 1.40).

Range.—Breeds from Nova Scotia and Newfoundland north to Labrador and Greenland; winters south to the middle states.

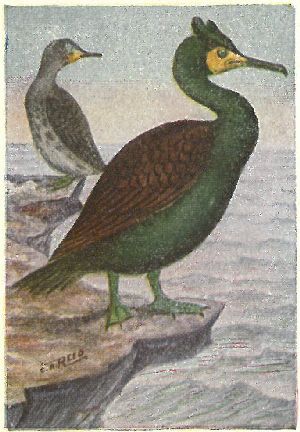

Tail with 12 feathers; distinguished from the last species in any plumage by the shape of the gular sac; on the common Cormorant the feathers on the throat extend forward to a point, making the hind end of the pouch heart-shaped, while in the present species it is convex. In breeding plumage, this species has a tuft of black feathers on either side of the head. The throat pouch is orange yellow; eyes green. These cormorants are found to some extent along the Atlantic coast, in summer, from Maine northward, but they are chiefly birds of the interior, being particularly abundant in Manitoba.

Nest.—On ledges on the coast, and on the ground in the interior, or in trees. The nests are made of sticks and weeds, shallow, shabby platforms holding 3 or 4 eggs. The eggs are bluish-green and chalky.

Range.—Breeds from Maine, on the coast, Minnesota northward; locally in North Carolina. Winters in the Gulf States. 120a., Fla. Cormorant, found in the South Atlantic and Gulf States, is smaller.

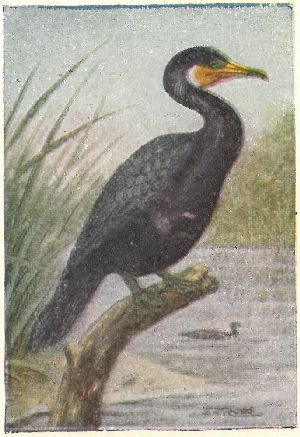

Adults with feathers bordering on the gular sac, white. In breeding plumage, the sides of head and neck have tufts of filmy white feathers, eyes green, as they are in all cormorants. All cormorants are expert swimmers and fishermen. They never plunge for their prey, but pursue and catch it under water, the same as do the grebes. When perching, they sit erect with their neck bent in the form of a letter S. They fly with their necks outstretched, and with rather slow wing beats. They are very gregarious and nest in large colonies, this species always being found in swamps or heavy shrubbery, surrounding bodies of water.

Nest.—Usually in trees overhanging the water, or upon the ground, in either case being made of sticks and weeds. The 3 to 5 eggs are bluish-green, covered with a chalky deposit (2.25 × 1.35).

Range.—Breeds north to the extreme southern boundary of the United States; wanders north casually to Ill. in summer.

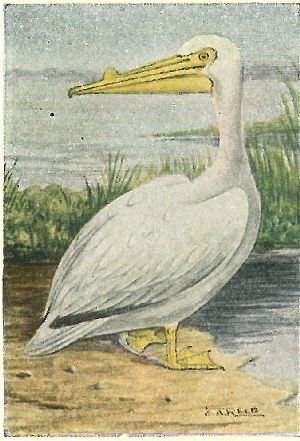

White with black primaries. Eye white; bill and feet yellow, the former in the breeding season being adorned with a thin upright knob about midway on the top of the upper mandible. The large pouch, with which pelicans are armed, is used as a dip net to secure their food, which consists of small fish. The White Pelican scoops up fish as he swims along the surface of the water; when he has his pouch partially filled, he tilts his head, contracts the pouch, thereby squeezing the water out of the sides of his mouth, and swallows his fish.

Nest.—Of sticks and weeds on the ground on islands or shores of inland lakes. They breed in colonies, and lay their eggs in June. The two or three eggs are pure white (3.45 × 2.30).

Range.—Breeds in the interior from Utah and Minn. northward. Winters on the Gulf coast and in Florida; rare on the Atlantic coast.

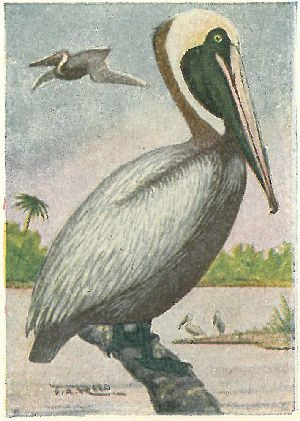

Pouch greenish; eye white; back of neck in breeding season, rich velvety brown; at other seasons the whole head is white. These pelicans nest abundantly on some of the islands on the Gulf coast of the U. S., on Pelican Island on the east coast of Florida, and sometimes on the coast of Georgia and South Carolina. Like the White Pelican, this species lives chiefly upon small fish, but they procure them in a different manner. They are continually circling about at a low elevation above the water and, upon sighting a school of fish, will plunge headfirst into it, securing as many as possible.

Nest.—Either on the ground or in low trees, in the latter case being more bulky than in the former; composed of sticks and weeds. The three to five eggs that they lay are pure white with the chalky covering common to eggs of birds belonging to this order.

Range.—Breeds on the Gulf coast, and on the South Atlantic, north to South Carolina; later may casually stray to New England; winters on the South Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

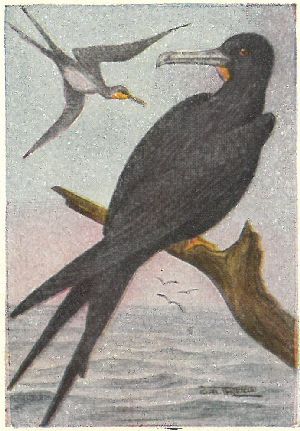

Eye brown; bill long, comparatively slender, and flesh, colored; gular sac orange; feet small and weak, with the four toes joined by webs. Frigate birds are strictly maritime; they nest in large colonies and usually travel in large companies. In expanse of wing compared to size of body they are unequalled by any other bird, and in power of flight they are only surpassed, possibly, by the albatrosses. They can walk only with difficulty and are very poor swimmers, owing to their small feet and long tail, but they are complete masters of the air and delight to soar at great heights. Their food of small fish is secured by plunging, or preying upon other sea birds.

Nest.—A low, frail platform of sticks in the tops of bushes or low trees. They lay but a single white egg in March or April; size 2.80 × 1.90.

Breeds in the Bahamas, West Indies, Lower California and possibly on some of the Florida Keys.

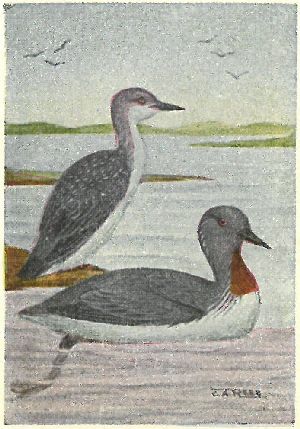

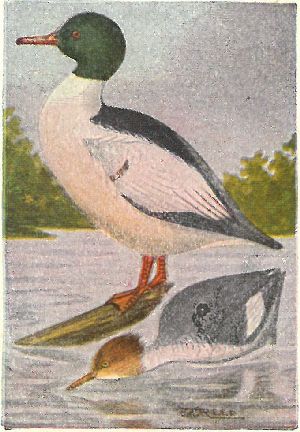

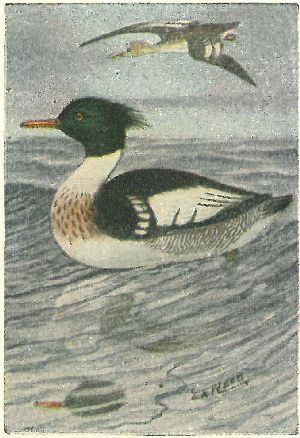

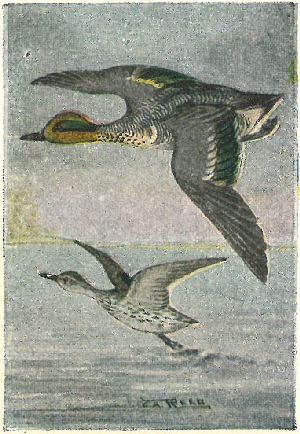

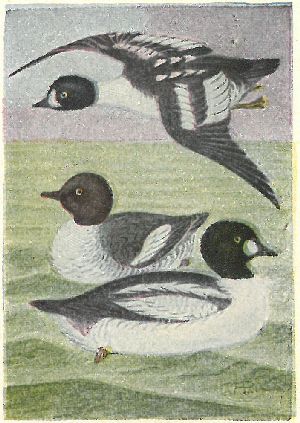

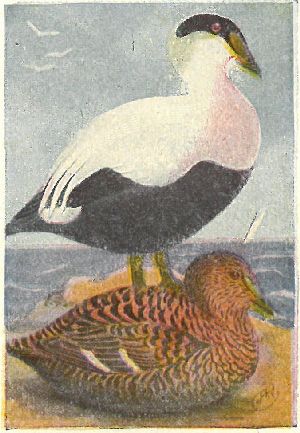

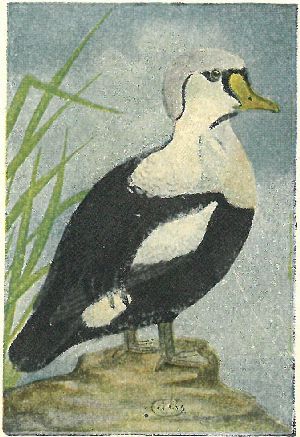

Bill, feet and eye red in male, the former with a black stripe along the top; plumage black and white, with a greenish-black head; no crest. Female gray and white, with brown head, crested; chin white; eye yellow. These birds have the bill long, not flattened, but edged with sharp teeth to grasp the fish, upon which they live to a great extent. They are exceptionally good swimmers for members of this family, and can chase and catch their fish, using their wings to aid their legs in propelling them through the water.

Nest.—In holes of trees, cavities among the rocks, or less often on the ground. The nest is made of leaves and grasses and lined with downy feathers from the breast of the female. The 6 to 9 eggs are creamy-buff (2.7 × 1.75); June.

Range.—Whole of North America. Breeds from New Brunswick, North Dakota and California, northward. Winters from the northern boundary of the U.S. south to the Gulf of Mexico.

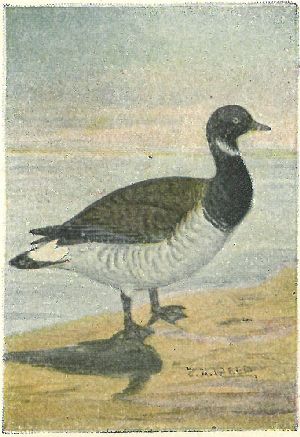

Eye, bill and feet red, like those of the last species, but the head is crested on the male, as well as the female, and a band across his breast is mixed rusty and black streaks. The female has not as brightly colored a head as the female of the American Merganser, and the throat is not pure white. They can be distinguished in any plumage, from the fact that the nostril is nearer the eye than it is the tip of the bill, while that of the last species is located midway between the eye and the tip of the bill. This is the species that is most often found in salt water. It is also found inland but not as commonly as the last.

Notes.—A low croak.

Nest.—On the ground, concealed in tufts of long grass or overhanging rocks. Their 5 to 10 eggs are olive buff in color (2.50 × 1.70); June, July.

Range.—Breeds from Maine and Ill., northward; winters throughout the United States.

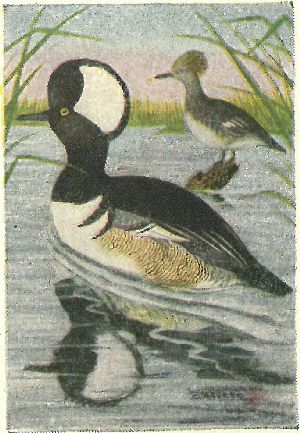

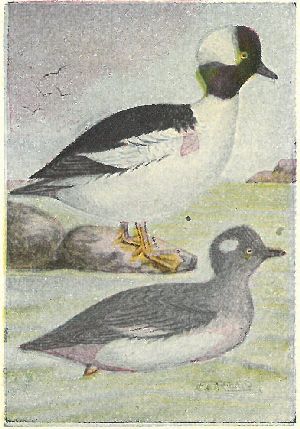

Bill short compared to those of other mergansers, and black. It is not apt to be mistaken for any other duck, because of its small size and the large crest with which both sexes are adorned, that of the male being black with a large, white patch, and that of the female plain brown.

The male has the power of raising or lowering his crest; when excited he will at times repeatedly open and shut it like a fan. When at a distance on the water, the male might possibly be mistaken for the Buffle-head, as that species also has white on the head, but its back also is largely white. Both male and female have yellow eyes.

Notes.—Low, muttered croakings.

Nest.—In holes of trees on the banks of, or near, streams or lakes. The bottom of the cavity is lined with grasses and down, and on this they lay 8 to 12 grayish white eggs (2.15 × 1.70); May, June.

Range.—Breeds locally throughout the U. S., but most abundantly north of our borders; winters in the South.

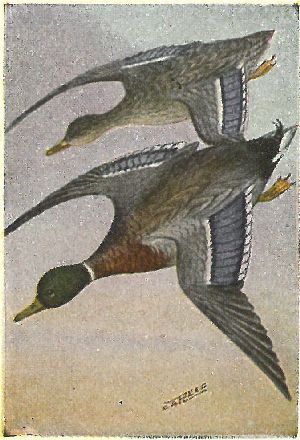

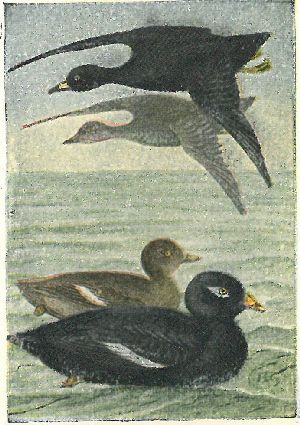

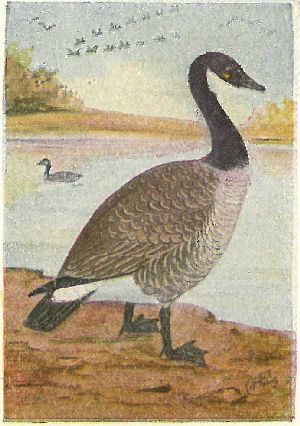

Male.—Head, green; speculum purplish-blue; bill olive-green; legs orange; eyes brown. The female most closely resembles the Black Duck but is lighter colored, more brownish, and the speculum, or wing patch, is always bordered with white. This species is one of the handsomest and most valuable of ducks. It is the cogener of the domestic ducks, and is largely used as a table bird.

Their food consists chiefly of mollusks and tender grasses. These they usually get in shallow water by “tipping up,” that is, reaching the bottom without going entirely under water. They also visit meadows and the edges of grain and rice fields for food.

Notes.—A nasal “quack,” often rapidly repeated when they are feeding.

Nest.—Of grass, lined with downy feathers, concealed in tufts of grass near the water’s edge. The 6 to 10 eggs are buffy or olive-greenish (2.25 × l.65).

Range.—Breeds from the northern tier of states northward; winters in southern half of the U.S.

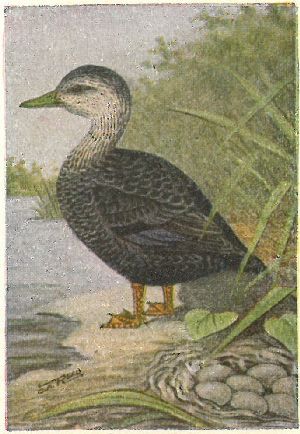

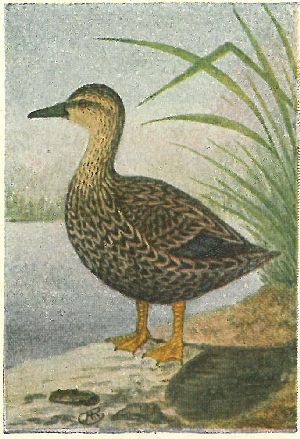

General plumage mottled blackish, the feathers having lighter edges; throat, buffy, streaked with blackish; crown and line through eye, nearly solid blackish; speculum bluish-purple, with no white; bill greenish-black; legs brownish. Black Ducks breed locally in pairs, throughout northern United States and southern Canada. This is the species most often seen in New England. When in flight, it can usually be recognized by the dark colored underparts and the white lining to the wings. Its habits are just like those of the Mallard, with which it is closely related.

Notes.—A “quack,” like that of the Mallard.

Nest.—Placed on the ground, not far distant from the water’s edge; made of grass and feathers; the 6 to 10 eggs are buff-colored (2.30 × 1.70); May, June.

Range.—Breeds locally from N. Y. and Iowa northward; winters south to the Gulf.

Much lighter than the Black Duck, all the feathers being broadly margined with buffy; throat nearly clear buffy without markings. The habits of this species, which is restricted to Florida and the Gulf coast to Louisiana, are the same as those of the northern Black Duck.

Notes.—Precisely like those of the Mallard.

Nest.—Of grass and down, on the ground, the eggs being like those of the Black Duck but averaging a trifle smaller (2.15 × 1.50); April.

Range.—Florida and the Gulf coast to La.; resident. 134a., Mottled Duck (A. f. maculosa), is very similar to the Florida species, but is mottled with black on the belly, instead of streaked. It is found on the coast of Texas and north to Kansas.

Male with chestnut wing coverts and white speculum; lining of wings white; eyes brown. The female is similar, but the back and wings are brownish-gray and the speculum gray and white. A rather rare migrant in New England, common in the Middle States and abundant west of the Mississippi. They are usually found in meadows and grain fields bordering marshes or lakes. As is usual with ducks, these do most of their feeding early in the morning or after dusk, and spend the greater part of the day in sleeping. They are of the most active and noisy of ducks, which accounts for their Latin name “streperus,” meaning noisy.

Notes.—A rapid, shrill quacking.

Nest.—Feather-lined hollows in the ground, concealed by patches of weeds or tall grass. Eggs 7 to 10, creamy buff color (2.10 × 1.60); May, June.

Range.—Northern Hemisphere; breeds in northern United States, except the eastern portion, and in Canada; winters along the South Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

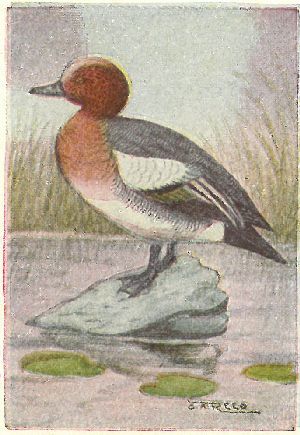

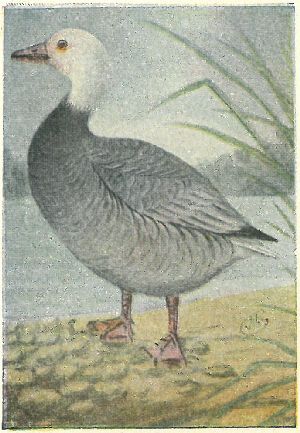

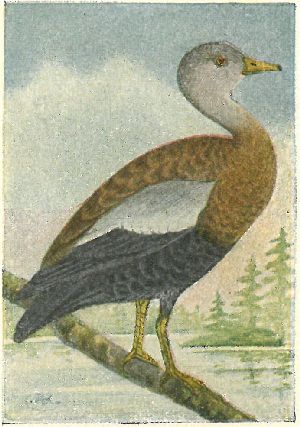

Crown buffy; head reddish brown; wing coverts white; speculum green. Female with blackish speculum, and a pale, rusty head, neck, breast and sides, streaked or barred with blackish. The Widgeon is an Old World duck that rarely, and accidentally, strays to our Atlantic or Pacific coasts. It breeds in America only in the Aleutian Islands. Its habits are the same as the next species, our American Widgeon.

In the Old World it is regarded as one of the best of table ducks. Its food consists of marine and freshwater insects, small shell-fish, seaweed and grass. Its nidification is just like that of the Baldpate.

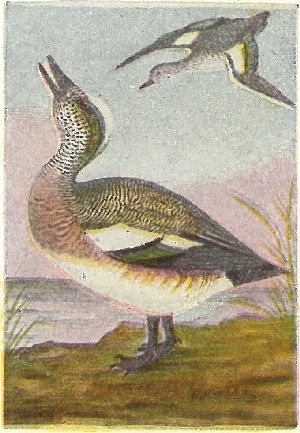

Wing coverts and top of head white; rest of head and neck finely specked with black; speculum and broad stripe back of eye, green; female, similar but with the whole head specked, and with no green on the ears. They can usually be identified at a distance by the absence of any dark areas, and when flying by the whiteness of the underparts. Baldpates are common and well known birds throughout North America, where they are called by a great variety of names, most of which refer to the bald appearance of the top of the head, owing to the white feathers. Their food consists of mollusks, insects, grain, and tender shoots of grass; their flesh is, consequently, very palatable and they are much sought as table birds.

Notes.—A shrill, clear whistle.

Nest.—Of grass, lined with feathers from the breast of the female; situated on the ground in tall grass near the water’s edge. 8 to 10 buff eggs (2.15 × 1.50); June.

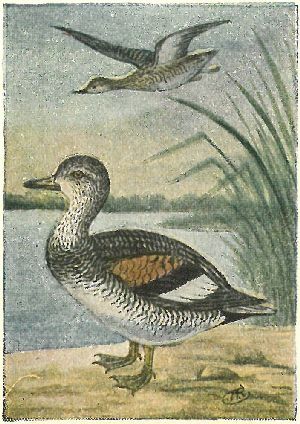

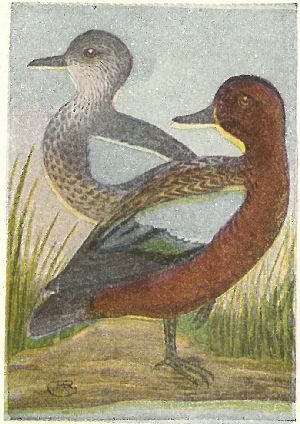

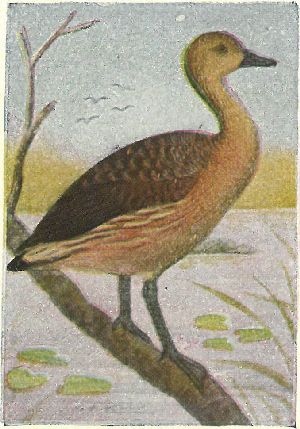

Head reddish-brown; speculum and large patch back of eye, green; a white crescent in front of wing. Female with the head and neck whitish, finely streaked with dusky; wings as in male. These ducks are abundant in most parts of the United States, but are rather uncommon in New England. They are usually seen in flocks of ten or a dozen, and often a single bird, or two or three, may be found with a flock of Mallards. They frequent ponds, marshes and rush-grown shores of creeks, rivers or lakes, feeding upon shellfish, insects, aquatic plants and seeds.

Notes.—Shrill, piping whistles, rapidly repeated.

Nest.—On the ground under the shelter of tall grass; it is made of weeds and grass, and lined with feathers. They lay from 5 to 9 eggs, buffy (1.85 × 1.25); May, June.

Range.—Breeds from the northern tier of states northward; winters from Va., Ill. and British Columbia, southward.

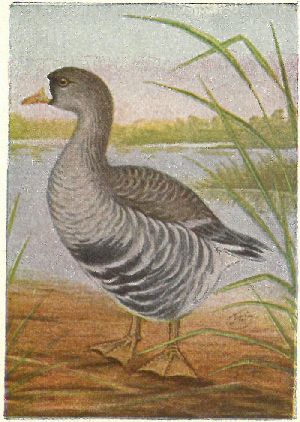

Male.—Head gray, with a white crescent in front of the eye; underparts buffy, heavily spotted with black; wing coverts blue; speculum green. Female similar to the female Green-winged Teal, but with blue wing coverts. Teal can easily be distinguished from other ducks by their small size; the present species can usually be separated from the last, by the darker underparts, the longer neck and smaller head. Their flight is very rapid; it probably appears to be more rapid than that of other ducks because of the much smaller size of the Teal. They usually fly in compact lines and when ready to alight, do so very precipitously.

Notes.—A weak, but rapidly uttered quacking.

Nest.—Made of weeds, placed in tall grass bordering marshes or ponds. 6 to 10 buffy eggs are laid during May or June (1.90 × 1.30).

Range.—Breeds from Maine, Ohio and Kansas northward; winters in the lower half of eastern United States.

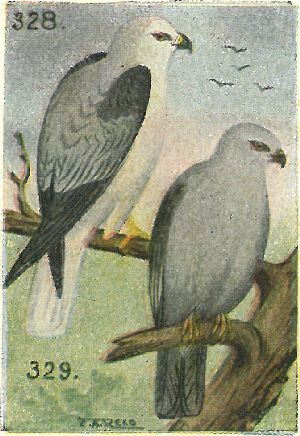

Male with the whole head, neck and underparts bright cinnamon; wings as in the Blue-winged species. Female similar to the female Blue-wing, but more rusty below, and the throat is tinted or quite dark, while that of the last species is usually light. These beautiful birds are very abundant west of the Rocky Mountains, but are of only casual or accidental occurrence east of the Mississippi Valley and sometimes Southern Florida. Their favorite nesting places are in fields of tall grass or clover, in close proximity to marshes or ponds.

Nest.—Compactly woven of grasses and lined with down; they lay from eight to as many as thirteen buffy white eggs, size 1.85 × 1.35; May, June.

Range.—Breeds in Western United States and British Columbia. Occurs rarely in the Mississippi Valley, Southern Texas and Florida.

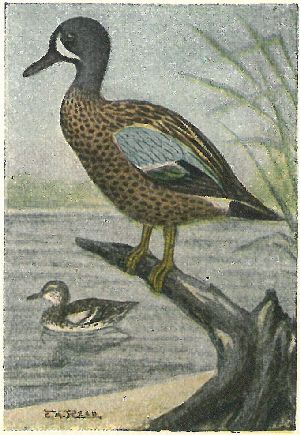

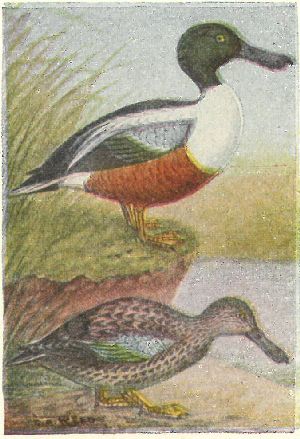

Bill long, and much broader at the tip than at the base; head and speculum green; belly reddish-brown; breast and back, white; wing coverts, pale blue; eye yellow; feet orange. Female with head, neck and underparts, brownish-yellow, specked or streaked with dusky; wings as in the male, but not as brightly colored. Easily recognized in any plumage by the large, broad bill. If it were not for this large and ungainly shaped bill, this species might be classed as one of our most beautiful ducks, when in full plumage, which is only during the breeding season; at other seasons the head of the male is largely mixed with blackish.

Nest.—Of fine grasses and weeds, lined with feathers; they lay 6 to 10 grayish eggs (2.10 × 1.50); May.

Range.—Whole of the northern hemisphere. Breeds in America, from Minnesota and Dakota northwards, and locally farther south; winters on the South Atlantic and Gulf coasts; rare during migrations on the North Atlantic coast.

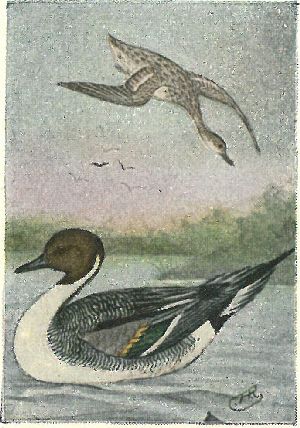

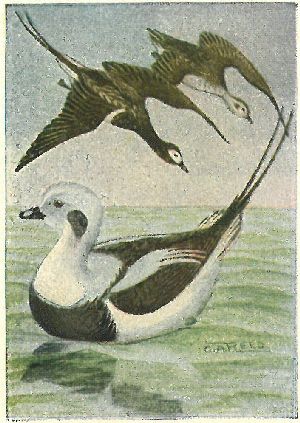

Tail pointed, and, in the male, with the two central feathers considerably lengthened; neck unusually long and slender for a duck; form more slender than that of other ducks. Male with brownish head and stripe down back of neck; back and sides barred with black and white; speculum green, bordered with white or buff. Female mottled brownish, buffy and black, but to be known by the sharply pointed tail feathers and long neck; speculum brownish. These ducks are strong swimmers and good fliers, but poor divers; they get their food the same as does the Mallard by “tipping up,” their long neck enabling them to feed in comparatively deep water. They are quite timid and lurk in the tall grass of the marshes during the daytime, feeding chiefly after dark.

Notes.—Quacks like those of the Mallard.

Nest.—On the ground, and like that of other ducks, well lined with feathers; 6 to 12 eggs (2.20 × 1.50).

Range.—Breeds from Ill. and Iowa northward; winters in southern half of the U. S.

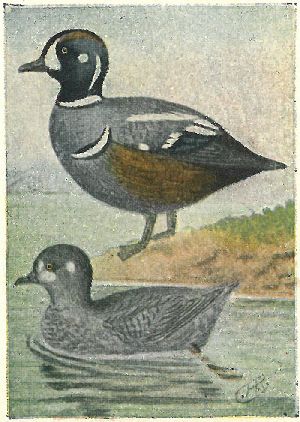

Head crested in both sexes, the feathers being especially lengthened on the nape. No other American duck that can possibly be mistaken for them. The male Wood Duck is the most beautiful of the family, in this or any other country, its only rival being the gaily colored Mandarin, of China. In summer, they may be found about the edges of clear ponds or lakes, especially those located in woods remote from human habitations. They are very local in their distribution and only one or two pairs will be found in a locality. In most parts of their range they are rapidly diminishing in numbers.

Notes.—A soft whistled “peet, peet” and a squawky danger-note like “hoo-eek, hoo-eek.”

Nest.—In the hollow of a tree usually near the water’s edge. The bottom is lined with soft downy feathers, and 8 to 15 buffy eggs are laid (2.00 × 1.50).

Range.—Whole of the United States and southern Canada, breeding locally throughout the range. Winters in southern half of the U. S.

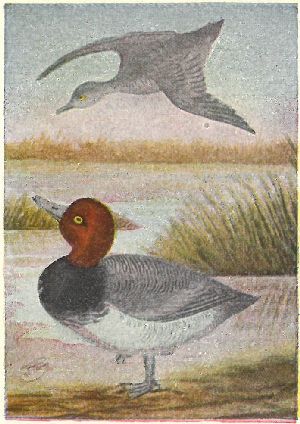

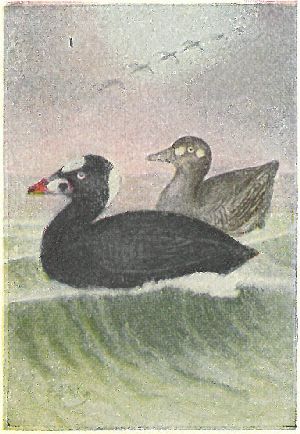

Note the shape of the bill of this species, as compared to that of the similarly colored Canvas-back. The male Redhead has a bluish bill with a black tip, and his back is much darker than that of the Canvas-back; eye yellow. The female has the throat white and the back plain grayish-brown, without bars. Redheads dive and swim with great agility; they feed largely upon water plants and mollusks which they get from the bottom of ponds, or along the seashore. They breed very abundantly in the sloughs of the prairies in the Northwest.

Notes.—A hollow, rapid croaking.

Nest.—Of grasses, lined with feathers, in marshes. Their 6 to 12 eggs are buffy white (2.40 × 1.70); May, June.

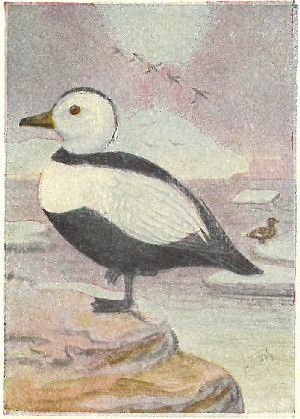

Range.—Breeds chiefly in the interior, from Minnesota and Dakota northward, and to a lesser degree north from Maine. Winters in southern part of the U. S.