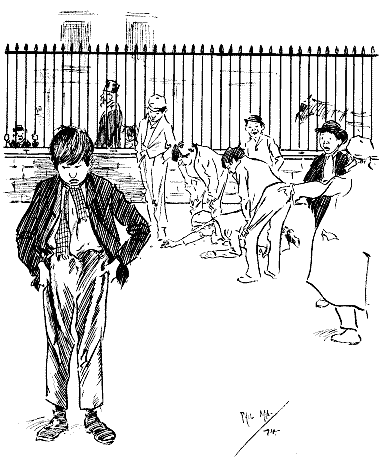

DE GUSTIBUS.

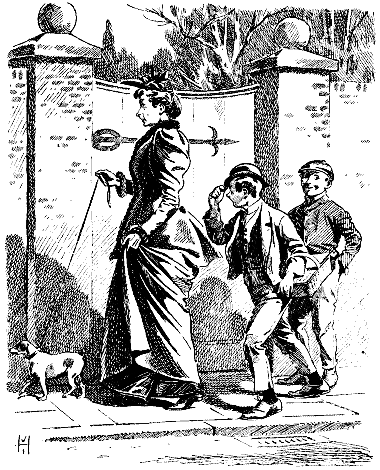

"See 'er, as just parst us? That's Miss Selina Devereux, as sings at the North London Tivoli. She's the pootiest Gal in Camden Town, that little Tart is!"

"Git along with yer! She's got a Chest like a Shillin' Rabbit!"

Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 107, December 15th, 1894

Author: Various

Editor: F. C. Burnand

Release date: August 14, 2014 [eBook #46584]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Punch, or the London Charivari, Malcolm Farmer,

Lesley Halamek, and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net

"See 'er, as just parst us? That's Miss Selina Devereux, as sings at the North London Tivoli. She's the pootiest Gal in Camden Town, that little Tart is!"

"Git along with yer! She's got a Chest like a Shillin' Rabbit!"

The following communications have found their way into the Editor's box at 85, Fleet Street, and are published that their writers may claim them. As most of the signatures were more or less illegible, it has been considered advisable to suppress them, to prevent the possibility of mistakes. The only exception that has been made to this rule is in the case of the last letter, wherein seemingly is summed up the moral of the controversy.

Communication No. 1, dated Tuesday.

Is it not time, considering that there is nothing of particular interest attracting public attention, that a protest should be raised against the "Society" plays which occupy the stages of some of our best theatres? You see I pave the way to my gentle reproof by buttering up vested interests. To do this the better, I will say something nice about "our most capable actors," and write "I remember Buckstone, and Sothern, the Bancrofts, and, aye, Mr. Tree himself." This will prove that there is no malice in my suggestions.

Let me describe the piece to which, in the dead season of the year, I object. The plot is centred in the love for each other of a partially-reclaimed lady and an opium-drinking gentleman; I might use stronger expressions, but I know your paper is intended for the family rather than the dress-circle, and my language is therefore modulated to meet the modest requirements of the case. Take it from me, Sir, that the story of these two individuals is nauseous and degrading. I say that its unravelling should not be foisted on the public in a modern play. But that you may not consider my impressions libellous, I add that the piece is finely staged, and in parts well written. For all that, I cannot imagine why the manager, with his lofty ideas of the function of a theatre as a medium of education, has permitted himself to produce it. And if that observation does not draw the manager in question, my name is not X. Y. Z.

Communication No. 2, dated Wednesday.

Your anonymous contributor "of London" (mark the sarcasm!) was right in imagining that I would be drawn. I consider it my duty to Mr. Henry Arthur Jones to say something about his "accustomed combative geniality," and to Mr. Haddon Chambers to refer to his "cheery stoicism." I will also allude to Mr. Pinero, but as he is not writing for my theatre just now, merely record my conviction that he will be able to survive the sneers against The Second Mrs. Tanqueray—"a play which has made a deep and lasting impression on the thinking public." And when I write "lasting," I am the more obliging, as I assume the rôle of a prophet. It will be "lasting," I am sure. The "thinking public," of course, are those admirable and intellectual persons who fill the stalls and boxes of my theatre, and the stalls and boxes of kindred establishments.

And, while I am talking of "thinking," let me insist that the criticism of the piece by the anonymous one "of London" (mark the irony!) is not a personal matter, but a question that affects the freedom of the thinking community. This is a generation that has outgrown "the skirts of the young lady of fifteen"; and it behoves all to understand the meaning of that apt sentence, and to regard with a jealous eye any attempt to crib, cabin, and confine the development of contemporary thought. "Crib, cabin, and confine" is also good, and entirely worthy of your serious consideration. At a time when the stalls are 10s. 6d., and the family-circle available to those who will not run to gold, is a literary dandy (in whose stained forefinger I seem to detect the sign of an old journalistic hand) to pass a vote of censure on Shakspeare because, forsooth, Hamlet was not forgotten? I trust not. And shall the public (mark you the intellectual, the praiseworthy—in a word, the "thinking public") be debarred from taking their piece in their favourite theatre because, forsooth, there is an interesting correspondence in newspapers in the dullest season of the decrepit old year? Again—I trust not.

Communication No. 3—once more dated Wednesday.

I beg to ask your permission, as an old playgoer, to see myself in print. I do not pretend to be able to write myself, but an eminent littérateur, in a recent number of a popular monthly magazine, has done good service by enforcing the untruthful character of the "problem" pieces recently presented to the public audiences. I have not the ability to comment on this unpleasant phase of the histrionic profession, so merely observe (with a recollection of an old-world story) "them's my sentiments."

Communication No. 4, dated Thursday.

No doubt this letter will reach you with many others, with signatures anonymous and otherwise. Being a bit spiteful I will confine myself to five lines in the hope of gaining insertion. Are not pieces with "girls with a past" played out? Then why slay the slain? I am sure healthier work will now be submitted to the public. And when that happy time arrives there will be found on my bookshelves certain brown-paper-covered tomes that are waiting the inspection of every actor-manager in London. Need I say more? You yourself, Sir, will practically answer the question.

Communication No. 5, dated Friday.

Permit me to keep the ball a rolling. Why is the "young lady of fifteen" to be alone protected? Are not the boys and girls of an older growth to be also preserved from contamination? What is to be done for that large class of playgoers who have entered their second childhood?

Communication No. 6, dated Saturday.

Now that a piece at present being played at a West-End theatre has been well advertised for a whole week in the more largely-read columns of a most influential daily paper, it is to be sincerely hoped that Box and Cox are satisfied.

"With kind regards"—'tis good to see your writing

Even on meagre correspondence-cards,

But would more matter you had been inditing

With kind regards!

Below you add that you are "mine sincerely,"

I wonder if in those two words you wrote

A sweet confession that you care—or merely

The usual ending to a friendly note?

I wonder if that week you still remember,

The shooting lunches and round games of cards,

Our walks and talks that wonderful September—

I wonder what you meant by "kind regards"!

With kind regards, and eyes that, reading, soften

I read your note, most blessed among cards,

And think of you—I dare not say how often—

With kind regards.

Appropriate.—The Command of the Sea, by Wilkinson Shaw. The author will be hereafter known as "Sea-Shaw."

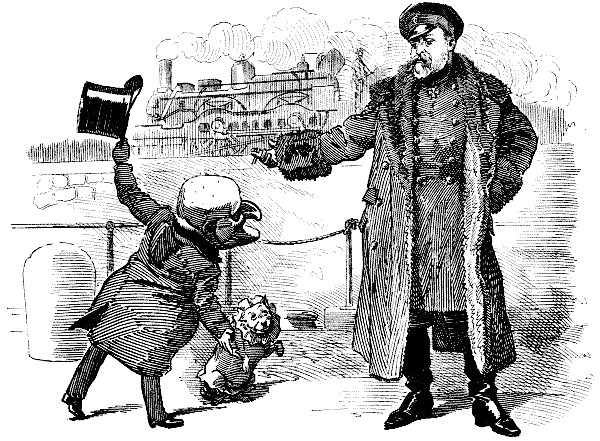

Mr Punch. "Well, Sir, and what found you in Muscovy?"

Prince of Wales (quoting Shakspeare). "'Nothing but Peace, and gentle Visitation'!"

Desperate Position of Messrs. Duffer and Phunk, who are rival aspirants for the hand of Miss Di.

Miss Di (unable to get her Horse to face the water as a jump). "Oh, do please, one of you, just try if that Place is fordable!"

[N.B.—Said "Place" is reported to be a good twelve feet deep BEFORE you come to the mud.

(A Dramatic Scene, with Suggestions from Shakspeare.)

Scene.—A British Quay. Enter The Visible Prince (like the King and his companions in "Love's Labour's Lost") "in Russian habits" but bearing a true British face, not masked. To him enters the most loyal and loving of his subjects and sage counsellors, Mr. Punch.

Mr. Punch (joyously). "All hail the pleasantest Prince upon the earth!"

Prince (gaily.) "Behaviour, what wert thou, till this man show'd thee?"

Mr. Punch. Well capped, my Prince!

Prince. Be you the same, good friend!

"Your bonnet to its right use; 'tis for the head,"

(As Hamlet said), and "'tis indifferent cold."

Mr. Punch. "It is a nipping and an eager air"—

As not unusual in our Isle's December!

Prince. "The air bites shrewdly; it is very cold."

I feel it, Punch, through all my Russian sables,

Though I'm from Muscovy.

Mr. Punch. What met you there, Sir?

Prince (promptly). "Nothing but peace, and gentle visitation!"

Mr. Punch (applauding). Most aptly quoted, Sir! The happiest "lift,"

From him the ever applicable bard,

I've met this many a moon.

Prince. Glad to be back

To English shores—and you—for all the love

I leave behind, and all the cold I come to.

Mr. Punch. Not in our hearts, my Prince, not in our hearts!

Prince. Nay, that I'll swear. Witness your presence here,

This chilling day. "How many weary steps

Of many weary miles you have o'ergone!"

Mr. Punch. "We number nothing that we spend for you:

Our duty is so rich, so infinite,

That we may do it still without account."

When you "vouchsafe the sunshine of your face."

Prince (laughing). Punch, know you all the Swan?

Mr. Punch. E'en as the Swan

Knows all his Punch, which is his favourite reading

In the Elysian Fields; and one good turn

Deserves another! But, my Albert Edward,

"What did the Russian whisper in your ear?"

Prince. Punchius, "He swore that he did hold me dear

As precious eyesight, and did value me

Above this world; adding thereto, moreover,

That he would ever live our England's lover."

Mr. Punch. "God give thee joy of him! The noble Tsar

Most honourably will uphold his word"

As I doubt not. I'm happy o' your visit.

"But what, Sir, purpose they to visit us?"

Prince. "They do, they do, and all apparel'd thus

Like Muscovites, or Russians, as I dress.

Their purpose is to parle, to court, to dance.

And every one his love-feat will advance."

Mr. Punch. As you have done, my Prince, at sorrow's flood

Taking the tide of frank affection, like

A skilled and trusty pilot. Such a Prince,

Good faith, is worth a dozen diplomats

And many full-armed legions.

Prince. May it prove so!

Mr. Punch. Well, let them come! "Disguis'd like Muscovites"

(As Rosaline said) we'll know them still as friends;

And they'll find here, as you there found, my Prince,

"Nothing but peace, and gentle visitation!!!" *

[Exeunt together.

* Love's Labour's Lost, Act V., Scene 2.

A TEMPEST in a teapot stands, one knows,

For noisy nothing in the realms of prose.

But what is that to the prodigious pother

When Minor Poets pulverise each other?

"Birds in their little nests agree,"—all right!

Bards in their little books fall out and fight.

The birds of which the pious rhymster sings

Sure were not "singing birds"—those angry things!

Who prune themselves and peck each other frightfully.

Alas that warblers should contend so spitefully.

All—save the cynic—mourn the Muse's loss,

When Gosse snubs Gale, or Gale be-blizzards Gosse!

(A Story in Scenes.)

PAST XXIV.—THE HAPPY DISPATCH.

"Perhaps it was right to dissemble your love, but——"

Scene XXXV.—The Morning Room. Time—About 1 P.M.

Undershell (to himself, alone). I'm rather sorry that that Miss Spelwane couldn't stay. She's a trifle angular—but clever. It was distinctly sharp of her to see through that fellow Spurrell from the first, and lay such an ingenious little trap for him. And she has a great feeling for Literature—knows my verses by heart, I discovered, quite accidentally. All the same, I wish she hadn't intercepted those snowdrops. Now I shall have to go out and pick some more. (Sounds outside in the entrance hall.) Too late—they've got back from church!

Mrs. Brooke-Chatteris (entering with Lady Rhoda, Sir Rupert, and Bearpark). Such a nice, plain, simple service—I'm positively ravenous!

Lady Rhoda. Struck me some of those chubby choir-boys wanted smackin'. What a business it seems to get the servants properly into their pew; as bad as boxin' a string of hunters! As for you, Archie, the way you fidgeted durin' the sermon was down right disgraceful!... So there you are, Mr. Blair; not been to Church; but I forgot—p'raps you're a Dissenter, or somethin'?

Und. (annoyed). Only, Lady Rhoda, in the sense that I have hitherto failed to discover any form of creed that commands my intellectual assent.

Lady Rhoda (unimpressed). I expect you haven't tried. Are you a—what d'ye call it?—a Lacedemoniac?

Und. (with lofty tolerance). I presume you mean a "Laodicean." No, I should rather describe myself as a Deist.

Archie (in a surly undertone). What's a Deast when he's at home? If he'd said a Beast now! (Aloud, as Pilliner enters with Captain Thicknesse.) Hullo, why here's Thicknesse! So you haven't gone after all, then?

Captain Thicknesse. What an observant young beggar you are, Bearpark! Nothin' escapes you. No, I haven't. (To Sir Rupert, rather sheepishly.) Fact is, Sir, I—I somehow just missed the train, and—and—thought I might as well come back, instead of waitin' about, don't you know.

Sir Rupert (heartily). Why, of course, my dear boy, of course! Never have forgiven you if you hadn't. Great nuisance for you, though. Hope you blew the fool of a man up; he ought to have been round in plenty of time.

Capt. Thick. Not the groom's fault, Sir. I kept him waitin' a bit, and—and we had to stop to shift the seat and that, and so——

Und. (to himself). Great blundering booby! Can't he see nobody wants him here! As if he hadn't bored poor Lady Maisie enough at breakfast! Ah, well, I must come to her rescue once more, I suppose!

Sir Rup. Half an hour to lunch! Anybody like to come round to the stables? I'm going to see how my wife's horse Deerfoot is getting on. Fond of horses, eh, Mr.—a—Undershell? Care to come with us?

Und. (to himself). I've seen quite enough of that beast already! (Aloud, with some asperity.) You must really excuse me, Sir Rupert. I am at one with Mr. Ruskin—I detest horses.

Sir Rup. Ah? Pity. We're rather fond of 'em here. But we can't expect a poet to be a sportsman, eh?

Und. For my own poor part, I confess I look forward to a day, not far distant, when the spread of civilisation will have abolished every form of so-called Sport.

Sir Rup. Do you, though? (After conquering a choke with difficulty.) Allow me to hope that you will continue to enjoy the pleasures of anticipation as long as possible. (To the rest.) Well, are you coming?

[All except Undershell follow their host out.

Und. (alone, to himself). If they think I'm going to be patronised, or suppress my honest convictions——! Now I'll go and pick those—— (Lady Maisie enters from the Conservatory.) Ah, Lady Maisie, I have been trying to find you. I had plucked a few snowdrops, which I promised myself the pleasure of presenting to you. Unfortunately they—er—failed to reach their destination.

Lady Maisie (distantly). Thanks, Mr. Blair; I am only sorry you should have given yourself such unnecessary trouble.

Und. (detaining her, as she seemed about to pass on). I have another piece of intelligence which you may hear less—er—philosophically, Lady Maisie. Your bête noire has returned.

Lady Maisie (with lifted eyebrows). My bête noire, Mr. Blair?

Und. Why affect not to understand? I have an infallible instinct in all matters concerning you, and, sweetly tolerant as you are, I instantly divined what an insufferable nuisance you found our military friend, Captain Thicknesse.

Lady Maisie. There are limits even to my tolerance, Mr. Blair. I admit I find some people insufferable—but Captain Thicknesse is not one of them.

Und. Then appearances are deceptive indeed. Come, Lady Maisie, surely you can trust Me!

[Lady Cantire enters.

Lady Cantire (in her most awful tones). Maisie, my dear, I appear to have interrupted an interview of a somewhat confidential character. If so, pray let me know it, and I will go elsewhere.

Lady Maisie (calmly). Not in the very least, Mamma. Mr. Blair was merely trying to prepare me for the fact that Captain Thicknesse has come back; which was quite needless, as I happen to have heard it already from his own lips.

Lady Cant. Captain Thicknesse come back! (To Undershell.) I wish to speak to my daughter. May I ask you to leave us?

Und. With pleasure, Lady Cantire. (To himself, as he retires.) What a consummate actress that girl is! And what a coquette!

Lady Cant. (after a silence). Maisie, what does all this mean? No nonsense now! What brought Gerald Thicknesse back?

Lady Maisie. I suppose the dog-cart, Mamma. He missed his train, you know. I don't think he minds—much.

Lady Cant. Let me tell you this, my dear. It is a great deal more than you deserve after—— How long has he come back for?

Lady Maisie. Only a few hours; but—but from things he said, I fancy he would stay on longer—if Aunt Albinia asked him.

Lady Cant. Then we may consider that settled; he stays. (Lady Culverin appears.) Here is your Aunt. You had better leave us, my dear.

Somewhat Later; the Party have Assembled for Lunch.

Sir Rup. (to his wife). Well, my dear, I've seen that young Spurrell (smart fellow he is too, thoroughly up in his business), and you'll be glad to hear he can't find anything seriously wrong with Deerfoot.

Und. (in the background, to himself). No more could I, for that matter!

Sir Rup. He's clear it isn't navicular, which Adams was afraid of, and he thinks, with care and rest, you know, the horse will be as fit as a fiddle in a very few days.

Und. (to himself). Just exactly what I told them; but the fools wouldn't believe me!

Lady Culverin. Oh, Rupert, I am so glad. How clever of that nice Mr. Spurrell! I was afraid my poor Deerfoot would have to be shot.

Und. (to himself). She may thank me that he wasn't. And this other fellow gets all the credit for it. How like Life!

Lady Maisie. And, Uncle Rupert, how about—about Phillipson, you know? Is it all right?

Sir Rup. Phillipson? Oh, why, 'pon my word, my dear, didn't think of asking.

Lady Rhoda. But I did, Maisie. And they met this mornin', and it's all settled, and they're as happy as they can be. Except that he's on the look out for a mysterious stranger, who disappeared last night, after tryin' to make desperate love to her. He is determined, if he can find him, to give him a piece of his mind.

[Undershell disguises his extreme uneasiness.

Pilliner. And the whole of a horsewhip. He invited my opinion of it as an implement of castigation. Kind of thing, you know, that would impart "proficiency in the trois temps, as danced in the most select circles," in a single lesson to a lame bear.

Und. (to himself). I don't stir a step out of this house while I'm here, that's all!

Sir Rup. Ha-ha! Athletic young chap that. Glad to see him in the field next Tuesday. By the way, Albinia, you've heard how Thicknesse here contrived to miss his train this morning? Our gain, of course; but still we must manage to get you back to Aldershot to-night, my boy, or you'll get called over the coals by your Colonel when you do put in an appearance, hey? Now, let's see; what train ought you to catch?

[He takes up "Bradshaw" from a writing-table.

Lady Cant. (possessing herself of the volume). Allow me, Rupert, my eyes are better than yours. I will look out his trains for him. (After consulting various pages.) Just as I thought! Quite impossible for him to reach North Camp to-night now. There isn't a train till six, and that gets to town just too late for him to drive across to Waterloo and catch the last Aldershot train. So there's no more to be said.

[She puts "Bradshaw" away.

Capt. Thick. (with undisguised relief). Oh, well, dessay they won't kick up much of a row if I don't get back till to-morrow,—or the day after, if it comes to that.

Und. (to himself). It shan't come to that—if I can prevent it! Lady Maisie is quite in despair, I can see. (Aloud.) Indeed? I was—a—not aware that discipline was quite so lax as that in the British Army. And surely officers should set an example of——

[He finds that his intervention has produced a distinct sensation, and, taking up the discarded "Bradshaw," becomes engrossed in its study.

Capt. Thick. (ignoring him completely). It's like this, Lady Culverin. Somehow I—I muddled up the dates, don't you know. Mean to say, got it into my head to-day was the 20th, instead of only the 18th. (Lamely.) That's how it was.

Lady Culv. Delightful, my dear Gerald. Then we shall keep you here till Tuesday, of course!

Und. (looking up from "Bradshaw," impulsively). Lady Culverin, I see there's a very good train which leaves Shuntingbridge at 3.15 this afternoon, and gets——

[The rest regard him with unaffected surprise and disapproval.

Lady Cant. (raising her glasses). Upon my word, Mr. Blair! If you will kindly leave Captain Thicknesse to make his own arrangements——!

Lady Maisie (interposing hastily). But, Mamma, you must have misunderstood Mr. Blair! As if he would dream of——. He was merely mentioning the train he wishes to go by himself. Weren't you, Mr. Blair?

Und. (blinking and gasping). I—eh? Just so, that—that was my intention, certainly. (To himself.) Does she at all realise what this will cost her?

Lady Culv. My dear Mr. Blair, I—I'd no notion we were to lose you so soon; but if you're really quite sure you must go——

Lady Cant. (sharply). Really, Albinia, we must give him credit for knowing his own mind. He tells you he is obliged to go!

Lady Culv. Then of course we must let you do exactly as you please. (All, except Miss Spelwane, breathe more freely; Tredwell appears.) Oh, lunch, is it, Tredwell? Very well. By-the-bye, see that some one packs Mr. Undershell's things for him, and tell them to send the dogcart round after lunch in time to catch the 3.15 from Shuntingbridge.

Pill. (sotto voce, to Archie). And let us pray that the cart is properly balanced before starting, this time!

Miss Spelwane (to herself, piqued). Going already! I wish I had never touched his ridiculous snowdrops!

Lady Culv. Well, shall we go in to lunch, everybody?

[They move in irregular order towards the Dining Hall.

Und. (in an undertone to Lady Maisie, as they follow last). Lady Maisie, I—er—this is just a little unexpected. I confess I don't quite understand your precise motive in suggesting so—so hasty a departure.

Lady Maisie (without looking at him). Don't you, Mr. Blair? Perhaps—when you come to think over it all quietly—you will.

[She passes on, leaving him perplexed.

Und. (to himself). Shall I? I certainly can't say I do just——Why, yes, I do! That bully Spurrell with his beastly horsewhip! She dreads an encounter between us—and I should much prefer to avoid it myself. Yes, that's it, of course; she is willing to sacrifice anything rather than endanger my personal safety! What unselfish angels some women are! Even that sneering fellow Drysdale will be impressed when I tell him this.... Yes, it's best that I should go—I see that now. I don't so much mind leaving. Without any false humility, I can hardly avoid seeing that, even in the short time I have been among these people, I have produced a decided impression. And there is at least one—perhaps two—who will miss me when I am gone.

[He goes into the Dining Hall, with restored equanimity.

THE END.

I have bin a having quite a long tork with a most respecful looking Gent who tells me he is a reel County Counsellor, and that they has a Gildhall of their own at Charing Cross, where they meets ewery week, the same as the Common Counsellors does at their reel Gildhall in the Citty, and that they has quite made up their minds to make the two Gildhalls into one and have them both for theirselves, and that that will be what they calls Hunifikashun, which means everything for them and not nothink for nobody else.

Not content with what they have got allreddy they means to have all the Citty Perlice, and the Manshun House, and all the Citty's Money, and the rite to all the Tems Water, and to the Lord Mare and Sherryfs Carridges, and to the Old Bayley, and to more other things than I can manage to remember! And he really speaks of all these warious matters jest as if he was quite in ernest, and acshally expected as it woud all be done by the next Parlement when they met next year! And when he found as I reelly didn't beleeve a word of his wunderful stories, he acshally arsked me to go with him to their Gildhall at Charing Cross, and there he put me in a nice seat, and then I heard em all torking away, jest as if they were quite in ernest, all about the many wunderful things as they was about to do soon! Oh, I wunders how long it will be before any on em reelly happens? Not in my life time I'll be bound, nor most likely in nobody elses! Did any reesonable man, woman or child ever hear such a pack of nonsense? To acshally defraud the grand old Citty of Lundon, that is only jest about seven hunderd year old, of all their priwileges and all their rites and all their money! and then I shoud like to know what is to become of me, and the duzzens like me? Nice lots of Lord Mares and Alldermen these County Counsellors woud make! Why I acshally douts whether they coud even manage to make up a decent lot of Common Counselmen under at least a year.

There was one thing as I heard them squabling about while I was there, and that was the nessessity of having some more lunatic asylums, which did not much surprise me, as I shoud think they will soon want a pretty good number for theirselves, if they continnes to go on as they are going.

Brown told me a rayther funny story about the dredful solemnity of these wunderful County Counsellors. He says they have by sum means or other got the right of insistin that there shall be no fun in the theaters, and no warking about between the hacts; and that the publick got so disgusted with the silly regerlations, that in many cases they left off going to them for ewer so long; but they are better now, and will most likely soon go back to their old armless jokes.

(From some hitherto Unpublished Correspondence.)

["Photographs of ladies' feet are now taken in New York as souvenirs for their admirers."—Globe, Dec. 6.]

... It is real kind of you, dearest, to mail your own laddie those half-dozen lovely photographs, or should I call them footographs? I can't say right here which I like best—they're all just fetching, anyway. You bet, I'll treasure them some! I'll wear the midget profile as a chest-protector right along, and put the full-foot vignette under my pillow nights. And the three-quarter platino shall go on my chimney rack—there's a considerable saucy look about the big toe which I'm mashed on horrid. I guess you won't see such a number-one instep as yours any time on these effete old London side-walks. To look at the Britishers' foot-cases in Piccadilly makes me tired, when I think of you any. I'll send views of mine soon in exchange, but I reckon the naked truth might give you fits, so I'll just sit with my rubbers on, and get the camera-man to map you off a walking likeness of my right daisy-crusher. (My left is a trifle out of focus.) Kind regards to you, Poppa....

Miss Maud. "Won't you sing something, Mr. Green?"

The Curate. "I haven't brought my Music. But, if you know the Accompaniment, and would play it, I think I could sing 'The Brigand's Revenge'!"

["It is impossible, we fear, to escape from the conclusion that there is a substantial basis of fact for the rumours ... of atrocities perpetrated by Turkish troops on the Christian inhabitants of Armenia.... By one of the Articles of the Treaty of Berlin the Porte undertook 'to carry out without delay the improvements and reforms demanded by local requirements in the provinces inhabited by the Armenians, and to guarantee their security against the Circassians and the Kurds.'"—"Times" Leader, December 4.]

Again! Is there nothing can humanise ever

The heart of Islam, that red-ravening wolf?

Will bonds of convention and treaty bridge never

Between Turk and Christian the broadening gulf?

Will no lesson teach, and will no promise tether,

The Ottoman hordes when let loose on the foe?

Must slaughter, and rapine, and outrage together,

The old vile triumvirate, fetterless go?

Time's fool seems the Turk, stern, unteachable, savage,

The fiercest fool-fighter on history's roll.

All indolent rest or undisciplined ravage.

The varnish of manner soaks not to his soul.

Red Man of the Orient, ruthless, untamable,

Neighbour, by fortune, in nothing near kin.

Humanity's brotherhood surely is blameable,

Leaving him free from Law's bondage to win!

In sheer self-defence we must muzzle and shackle

This wolf of the world; snatch its poor prostrate prey

From its crimsoning fangs. The old cynical cackle

Of "coffee-house babble" is silent to-day;

And a weapon's at hand, too long left there unlifted,

That Law and that Justice alike now commend

To the grip of Europa. Be murder short-shrifted

And bestial outrage meet summary end!

Not again must hot Islamite hate be permitted

In chase of creed-vengeance the East to embroil;

Not again must its prey fall unaided, unpitied,

The Gallio's mock, and the miscreant's spoil.

There hangs the good Berlin-blade, consecrated

By common agreement to Justice's work!

Be its blow not this time, as aforetime, belated!

Let Europe not bleed for the sin of the Turk!

New Parish-Council Version.

(By a Landlord and Lover of the Good Old Times.)

[At Merton, Surrey, where Mr. William Morris has his factory, a blacksmith was highest of the fifteen successful candidates for the Parish Council, the vicar being eighth.]

Over the vicar, top o' the tree,

The Village Blacksmith stands;

The smith a mighty man is he,

With power in his strong hands;

And his victory well may stir alarms

In Squire-Parsonic bands.

The Squire looks black, his face is long,—

"Vicar not in the van?

Oh! things are going to the doose

As fast as e'er they can!

The blacksmith with his grimy face

Has proved to be best man.

"Week in, week out, he'll spout and fight!

We shall hear him bluff and blow.

He'll vote the good old times all wrong,

The good old fashions slow;

And won't he run the rates right up,

And keep tithe-charges low?

"He'll have his finger in the School,

He'll open wide its door;

He'll keep the Voluntaries starved,

And let the School-Board score.

And he'll want baths and washhouses

And villas for the poor!

"Then he may 'go for' the Old Church,

And rouse the village boys

To listen, not to Parson's drone,

But Agitation's voice,

And 'stead o' singing in the choir

He'll swell Rad ranters' noise.

"'Twill sound to him like Wisdom's voice,

Preaching of Paradise,

As though the thing were at his door;

Plumbed with Progressive lies,

He'll think his hard, rough hand will wipe

The Squire's and Parson's eyes.

"Broiling—orating—borrowing,

Swelling the rates, he goes.

Reform's raw task he will begin,

But who shall see it close?

Church will be robbed, and Land be sold.

Farewell old-time repose!

"'Tis thanks to you, my loud Rad friends,

These lessons you have taught!

By folly from the flaming forge

Our fortunes must be wrought.

And won't there be a blessed mess

Before the fight is fought!"

(By her Husband.)

As I'm daily jolted down

On the early bus to town,

Through the yellow fog and brown,

O'er the stones,

I inhale the tawny air,

And I deem it ether rare,

For my soul is full of fair

Mary Jones.

Fellow-passengers are fain

To abuse the wind and rain,

And the weather, they complain,

Chills their bones:

But I laugh at snow and sleet

As I bump upon my seat,

For I'm thinking of my sweet

Mary Jones.

With a lightsome heart and gay

To the Bank I wend my way.

Where I calculate all day

Debts and loans;

Though anon my fancies flee

From the rows of £ s. d.,

And they wander off to thee,

Mary Jones.

And I cannot blame their taste,

Though a little time they waste

For my Mary would have graced

Monarchs' thrones.

What are pounds and pence to her?—

No. I cannot but concur

With their choice when they prefer

Mary Jones.

Then I hurry home to tea,

And I pass an A. B. C.,

Where I purchase two or three

Cakes and scones:

For I love the smiles that rise

In your laughing hazel eyes

When I offer you my prize,

Mary Jones.

And when tea is cleared away,

And you kindle me my clay,

As I listen to your gay

Dulcet tones,

Then I sometimes wonder who

In the world's the best to do?—

'Gad, it's either I or you,

Mary Jones!

"Askin' yer pardon, Miss, but might that 'ere little Dog's Tail ha' been cut off or druv' in?"

It surely should not be allowed,

The Modern Society Play,

That dreadfully shocking Kate Cloud,

That bad Mrs. P. Tanqueray.

That's what said

X. Y. Z.

It elevates everyone,

The Modern Society Play,

You stupid old son of a gun.

Replied, bursting into the fray,

Fearless, free,

H. B. Tree.

Why make such a clamour? Oh, blow

The Modern Society Play!

As nothing compels you to go,

X. Y. Z., you can just stop away;

Don't you see?

So say we.

"I shall be all right again soon, I'll be bound!" as a dilapidated First Edition observed.

[Yale v. Princeton University. "Before the game commenced an Inspector of police, who was on the ground, addressed the two teams, and cautioned them against violent play. This warning is without precedent in the history of the University contests."—Reuter.]

Scene—Queen's Club. Oxford and Cambridge

Football Match. Teams undergoing

modern torture of ordeal by photograph.

Enter Police-Inspector, rampant,

supported by two Peelers proper. He

"addresses the two teams":—

I'm an Inspector bold, yet wary,

So, gents, you must all take care,

For I'm here to boss this battle,

And see that you all fight fair.

Now fisting, and scragging, and hacking,

Are all fair enough, we say,

But if gents exceed the limits

Of legitimate violent play,

We'll run them in, we'll run them in,

As sure as we're standing here,

We'll run them in, we'll run them in,

For the Peeler knows no fear!

Of course you may fight each other,

But you mustn't attack the crowd,

For we can't have unlimited bloodshed,

And weapons are not allowed.

So, gents, I must kindly ask you

To enter the field without

Your bludgeons and knives and pistols,

Or else, beyond all doubt,

We'll run you in, &c., &c.

[Teams join in chorus. Exit Inspector to look after ambulance arrangements.

The Lord's Day Observance Society

Would make us all pinks of propriety—

All models of mental sobriety,

That is Stiggins and Chadband combined.

They gain, doubtless, some notoriety

By such overwhelming anxiety

To force on us their sort of piety

Of a most puritanical kind.

This Sunday at Home mental diet, I

Dislike, I would rather not try it; I

Suggest that, by way of variety.

Their own business now they should mind.

How to Make Life Happy.—An Infallible Recipe:—Add fifty-nine to the latter half of it. *** Solution will be given next week.

First Boy (much interested in the game of Buttons). "'As 'e lost?"

Second Ditto. "Yes; 'e lost all them Buttons what 'e won off Tommy Crowther yesterday, an' then 'e cut all the Buttons off 'is Clothes, and 'es lost them too!"

Kelt and Salted.—It may be true, as you have heard, that Mr. Standish O'Grady intends to supplement his series of Ossianic stories, Finn and his Companions, by a work entitled Fin an' Haddock. But, we confess, the story seems a little fishy.

A Brummagem Spoon.—You are quite wrong. The creation of the character of Rip Van Winkle was, in point of time, far anterior to the invention of the Self-working Noiseless Screw. Mr. Chamberlain's playful application of the term to Lord Hartington did not imply any proprietorship in the article. The right hon. gentleman was under the impression that he had come across the character in the course of his reading of Dickens' Christmas stories, and, wanting to say something nice of his noble friend, he just mentioned it. It led to some misunderstanding at the time, but has now been forgotten. See our answer to "Three Cows and an Acre" in the Christmas Number.

Residuary Legatee.—Certainly you may recover, especially if you can get A. to refund the money. Don't hesitate to sue. We make a practice of never accepting fees. The 6s. 8d. you enclosed (in stamps, postal order preferable) we shall, at the first opportunity, place in the Poor Box.

Perplexed.—What do you mean by asking us to tell you "If a herring and a-half costs three hapence, how much will a dozen run you in for?" This is just one of those simple problems you can solve for yourself on reference to an ordinary book of arithmetic. Do you suppose we sit here to save the time of idle persons? Our mission is to supply information drawn from authorities not accessible to the average subscriber.

Algernon and Sibyl.—Consult Sir George Lewis, Ely Place, Holborn, E.C. We never advise on delicate subjects such as yours. It is impossible for us to reply to correspondents through the post. Our motto is Audi altem parterem. As the lady may not be familiar with the dead languages, we may perhaps do well to translate. Freely rendered, it means, "We desire that all parties (altem parterem) may hear and profit by our advice."

One-who-has-had-no-rest-to-speak-of-for-fifteen-years-owing-to-neuralgic- pains-and-a-next-door-neighbour-who-plays-the-piano-night-and-day.—No.

Beyond the Dreams of Avarice.—Your record of an incident in the early life of Mr. W. Astor is very interesting. "Musing by the waters of the mighty Hudson he," you say, "conceived the ambition of becoming one of the richest men in the world." It is pleasing to know that his recent entrance upon journalistic enterprise is likely to realise his boyhood's dream.

Advertisement Agent.—There is, we fear, no opening for you in this direction. "Silonio" is not the name of a new shaving soap, as you surmise. It is the title of honour given by the delegates of a remote but respectable African race to a great and good British statesman. Its literal translation into the English tongue is, we are informed, "Open-mouthed."

A Subscriber for Seventy Years.—Your poem, commencing,

Diggle Diggle den,

How is Brother Benn?

Really, Mr. Riley,

Ain't you rather wily?

is perhaps a little monotonous in its interrogative form. But it is not without merit, especially from one of your advanced age. A fatal objection is that it should be out of date. The School-Board Elections, we are glad to say, were completed a fortnight ago. Try again—for some other paper.

[Professor Huxley, at the anniversary meeting of the Royal Society, suggested that in the future imaginative speaking at their dinners might be stimulated by the drinking of liquid oxygen, bien frappé.]

Air—"Take hence the Bowl!"

Take hence the bowl; though beaming

Brightly as bowl e'er shone,

With Fizz sublimely creaming,

Or Port or Zoedone.

There is a new potation

To warm the hearts of men,

And wake imagination—

In Liquid Oxygen!

Each cup I drain, bien frappé,

My tongue pat talk can teach;

It helps to make me happy

In after-dinner speech.

At banquet, or at gala,

I match such mighty men

As Gladstone, Carr, or Sala,

On Liquid Oxygen!

A fig for Mumm or Massio,

Falernian and such fudge;

(Thin stuff those tipples classic

If I am any judge.)

But burning thoughts come o'er me

And fire my tongue, or pen,

When I've a bowl before me

Of Liquid Oxygen!

When fun needs stimulation,

Or fancy fails in fire;

When lags the long oration,

Or tongues postprandial tire;

Then take the tip Huxleyan,

And one long swig,—and then

You'll promptly raise a pæan

To Liquid Oxygen!

"There is nothing in Italy more beautiful to me than the coast-road between Genoa and Spezia." Remember these words of Dickens, in his Pictures from Italy, as I start from Pisa to see that lovely coast, and the Mediterranean, for the first time.

Pisa is sleepy, but the railway officials are wide awake. The man who sells me my ticket "forgets" one lira. This answers capitally with innocent old ladies from England or Germany. The old lady counts her change, and if she has carefully ascertained the fare by reading the price marked on her ticket, she finds at once that there is a halfpenny wanting. She never learns that this is the Government tax. "If you please," she begins; or, "Bitte," and then she goes off into—not hysterics, but French, and murmurs, "Seevooplay, je pongse vous devays avoir donnay moi un sou—er—er—more, vous comprenny?" or, "Il y a encore—er—er—fünfzig, vous savay, à moi à payer." Then the official answers, also in French, "Ah nong, Madame, ceci est la taxe doo gouvernemang sul biglietto, capisce?"

Whereupon the old lady is so agitated by the thought that she has wrongfully accused him of stealing a soldo, that she never notices that he has withheld a lira. If she counts her money later in the day, she will blame those nasty lira notes, which stick together so, that she must have given two somewhere instead of one. But the railway clerk is also prepared for any more exacting stranger, and holds the extra note ready for him. The clerk at Pisa does so, handing it to me, without a word of objection or explanation, as soon as I ask for it. The system is as perfect as it is simple. Having obtained my change, I start for the Mediterranean.

(By the Right Hon. the Author of "The Platitudes of Life," M.P., F.R.S., D.C.L., LL.D.)

Chapter I.—De Omnibus Rebus.

"Ars longa, vita brevis;"1 and indeed "man wants but little here below, nor wants that little long."2 An oriental writer has told us that "all flesh is grass," to which a Scots poet3 has replied, that "A man's a man for a' that." There is a Greek aphorism, not sufficiently well known, which says γνῶθι σεαυτόν. This has been ably rendered by Pope in the words "Know thyself."4 Proverbially "piety begins at home," but it is wrong to deduce from this that education ends when we leave school; "it goes on through life."5

Books are an educational force. They "have often been compared to friends,"6 whom we "never cut."7 They "are better than all the tarts and toys in the world."8 It is not generally known that "English literature is the inheritance of the English race,"9 on whose Empire, by the way, "the sun never sets." We even have "books in the running brooks," as the Bard of Avon10 tells us; so that not only "he that runs," but he that swims, "may read."

"Knowledge for the million,"11 is the "fin de siècle"12 cry of the hour. But "life is real, life is earnest,"13 and we have no time to study original thinkers such as Confucius and Tupper. "Altiora Peto"14 is a saying for the leisured class only. The mass must get its wisdom second-hand and concentrated. If "reading maketh a full man,"15 this kind of reading maketh a man to burst. Hence the "sad in sweet"16 of the book of quoted platitudes. Yet, of course, "there are great ways of borrowing. Genius borrows nobly."17 And it is well to have "the courage of" other people's "opinions."

But reading is not all. You must "use your head."18 And you must, and can, keep it too. For a good man's head is not like a seed-cake that passes in the using. And, again, remember the proverb that "manners makyth man"; though this is not the true cause of the over-population of our islands. In social life much will depend on the way in which you behave to others. "Never lose your temper, and if you do, at any rate hold your tongue, and try not to show it"19—except, one may add, to a doctor.

Many people cannot say "No!" Others early learn to say "No!" when asked to do disagreeable things. "Mens sana in corpore sano." If the last word is pronounced Say No, this constitutes a word-play. There are some bad word-plays in Shakspeare. I disapprove of humour, new or old.

"No man who knows what his income is, and what he is spending, will run into extravagance."20 Plutarch tells us of a man whose income was £500, and he spent £5000 a year knowingly. This must have been an exceptional case. There is an obscure dictum that "money is the root of all evil." "Gold! gold!"21 said an ill-known poet, and, on the other hand, "Hail, independence!"22 said another. "If thou art rich, thou'rt poor"23 is on the face of it an untruth.

1 "Principia Latina."

2 Goldsmith.

3 Burns.

4 "Essay on Man."

5 Lubbock.

6 Lubbock.

7 "Punch."

8 Macaulay.

9 Lubbock.

10 Shakspeare.

11 Calverley.

12 Oscar Wilde.

13 Longfellow.

14 Lawrence Oliphant.

15 Bacon.

16 Browning.

17 Emerson.

18 Lubbock.

19 Lubbock.

20 Lubbock.

21 Park Benjamin.

22 Churchill.

23 Shakspeare.

Professor Erasmus Scoles (of Epipsychidion Villa, St. John's Wood). "Can you tell me, Constable, whether there are any more—er—Atlantes to come up to-night?"

D. 134. "Any More 'ow Much?"

When the century, growing a little bit mellow,

Produces carnations outrageously green;

When you notice a delicate, dairy-like yellow

Adorn the pale face of the best margarine;

When canaries, all warranted excellent singers,

Are sold in the street for a shilling apiece,

But at home all the yellow comes off on your fingers,

Substrata of brown making daily increase;

When a lady you happen to meet on a Monday

With hair that is grey, and with cheeks that are old,

Appears shortly after, the following Sunday,

With rosy complexion, and tresses of gold;

When a nursemaid has one of the worst scarlet-fevers,

Or merely, it may be, a fit of the blues;

When you're offered "Old Masters" as black as coal-heavers,

Or shirts of quite "fast" unwashoutable hues;

When a blue ribbon's equally known as denoting

Teetotal fanatics, a Rad, or a Tory—

In these and like cases too num'rous for quoting

Remember old Virgil, "Ne crede colori."

VI.—Preparing for the Poll.

When I do a thing, I like to do it properly, for even my worst enemies, who call me a fool, admit that I'm a thorough fool. I have accordingly lost no time in getting to work at my electoral campaign. I commenced at a great disadvantage. The other seven candidates were electioneering for a week before the Parish Meeting, and the result was that they all polled three times as many votes as I did. That has happened once. I don't intend that it shall happen more than once.

The first move I made was to cover my house with placards. I noticed that in a recent election Mr. Athelston Riley had pursued these tactics with great success, so I plastered the whole of the walls with "Winkins for Mudford"—"Vote for Winkins,"—but thereby hangs a tale. I gave my instructions to the local printer, and told him where they were to be posted, directing him to do it in the twilight, so that the whole effect might dawn once and for ever upon an astonished village in the morning. He did it, but unfortunately he didn't keep a proof-reader. I noticed next day, before I went out, that all the school-children looked up at the house and giggled. I thought it was merely the inappreciativeness of the youthful mind. There I was wrong. It was the fact that the children knew how to spell that caused the mischief. My house was covered with appeals to "Wote for Vinkins!" It did not take long to get new bills printed, but I am not disposed to deny I was a trifle disconcerted by this false start.

I am now hard at work canvassing. My wife flatly declines to help, and I'm afraid to suggest the girls should take the field in support of their father. I tried to secure the services of the vicar's two daughters, but he only wrote rather a stiff note to say that he thought they would have quite enough to do in advocating his claims. I am not always at one with the clergy, but for once I agree with him. I have succeeded, however, in getting Miss Phill Burtt to help me. Her full name is, of course, Phyllis; but it's always called and spelt "Phill"—I could never understand why. She's a most delightful girl, and is worth, at least, a hundred votes to me. As I explained once before, she has an extraordinary habit of calling all the villagers "idiots"—of course, I mean to her friends (such as myself), not to the villagers themselves. I asked her one day why, if she thought them idiots, she was kind enough to take the trouble to canvass them. "Well, you see," she said with a charming smile that was all her own; "I'm asking them to vote for you." At the time I thought this was a pretty saying, prettily said. I even told it with some amount of pride to my wife just to show her that there were people who did not sympathise with her haughty indifference. Curiously enough my wife only laughed consumedly. When she had recovered, I asked her why she laughed. "Do you really mean to say, Timothy," was her reply, "that you don't see what she meant?"

"Well, though it may seem idiotic...." I said, and was going to add, "I don't," but before I said that, I did see what she (Phyllis, of course, I mean) might have meant. Yet I hope she didn't. Miss Burtt has only one drawback as a canvasser. She is so ridiculously scrupulous, I came across an old woman the other day who was quite deaf to my appeals. Whilst I reasoned with her, I found out how kind Phyllis was to her. "Miss Phill, she's really good to us poor people. I'd vote for her if she was standing." I left, having produced no impression. A day or two after I met Miss Phill Burtt, and asked her to go and canvass the old woman; I felt sure she could secure her vote. Will it be believed that she wouldn't? She said it would be really undue influence if she did. How strange that even the nicest of women are so strangely unpractical at times! Another woman she refused to see because she never called upon her at ordinary times. Still, with all her faults, Miss Burtt is a tower of strength, and as I see her daily going about, canvass book in hand, my hopes rise higher and higher.

Sir Philip Sidney was, as all the world knows, "a veray parfit gentil knight." Possibility of this presupposition of knowledge is fortunate, since Miss Anna M. Stoddart's account of this heroic figure is not, my Baronite sorrowfully says, likely to convey any adequate idea of its personality. Mr. Fox Bourne and Mr. Addington Symonds have written biographies of the Elizabethan soldier, in which he boldly stands forth. Miss Stoddart modestly says her object is "in no way to compete with" these standard works. But why write at all? The marvel is, as Dr. Johnson did not exactly say in illustration of an argument respecting another feminine achievement, not that the work should not have been well done, but that it possibly could be done with such wooden effect. If Miss Stoddart had taken a sheet of paper and with her pair of scissors cut out the figure of a man, writing across it "This is Philip Sidney," she would have conveyed quite as clear and moving a picture of the man as is found in the 111 pages of her book. But then, Mr. Blackwood would not have published the scrap of paper, and we should not have had the charming portrait of Sidney, or the sketches of Penshurst by Margaret L. Huggins which adorn the daintily got-up volume.

My Baronitess writes:—S. Baring Gould turns into delightful English prose some of the ancient Icelandic Sagas, or songs, and shows us how Grettir the Outlaw was a Grettir man than was generally supposed by anyone who had never heard very much about him. When he departed, was he very much Re-grettir'd by all who knew him?

Messrs. Macmillan offer My New Home, provided by Mrs. Molesworth, which many of the little "new" women would like to see. Illustrated by L. Leslie Brooke: "Brooke" suggests "water colours,"—a new idea for next Christmas.

Sou'-wester and Sword, by Hugh St. Leger. A nautical and military combination. The Sou'wester of a tar is not at all at sea when, after a pleasant little shipwreck, he joins the forces at Suakim. The winner of this St. Leger was a rank outsider, with the odds against him, but he wins the day by "throstling" (a new word) a few Soudanese; who must have seemed quite forty to one!

A cousin, especially a Colonial, is such a very pleasant indistinct sort of relative, that he is bound to be a hero of romance, though perhaps a cousin at hand is worth two in the bush; at least, so thinks the heroine in My Cousin from Australia, by Evelyn Everett Green (Hutchinson & Co.); whilst the one whom she should have wed was of course a wicked Baronet (does one often meet a good Baronet in fiction?), who tries to upset his successful rival by giving him a tip over an agreeably high cliff. It is a Christmas story, and so the "tip" is just at the right time. How it ends——You'll see.

Black and White has gone in for a shilling's worth of the truly wonderful in The Dream Club, by Barrie Pain and Eden Philpotts. It is quite an after-turkey, plum-pudding, mince-pie dinner story. How authors and artists must have suffered, judging, at least, by the delightful nightmare illustrations. And the picture-lady of the cover—ahem!—she has evidently forgotten that she is supposed to be "out" at Christmas.

Between the boards of Lothar Meggendorfer's moveable toy-books (H. Grevel & Co.) lies genuine fun. The Scenes of the Life of a Masher are simply irresistible. Little ones will be delighted with The Transformation Scenes, besides, there is Charming Variety with a Party of Six. These books are a good tip for a Christmas gift for the representatives of Tommy and Harry.

Had G. W. Appleton's The Co-Respondent—an attractive title—been in the form of a short magazine story, it would probably have been amusing from first to last. Now it is only amusing at first. Good idea all the same. The old quotation about "Sir Hubert Stanley" is brought in, and, of course, incorrectly. It is not "Praise from Sir Hubert Stanley," but "approbation." However, as it is said by a light-hearted girl of a very modern type, it may be assumed that the misquotation is intentional.

Missing or damaged punctuation has been repaired.

Page 279: 'beariny' corrected to 'bearing'.

"Enter The Visible Prince (like the King and his companions in "Love's Labour's Lost") "in Russian habits" but bearing a true British face, not masked."

Page 286: 'neigbbour' corrected to 'neighbour'.

"and-a-next-door-neighbour-who-plays-the-piano-night-and-day."