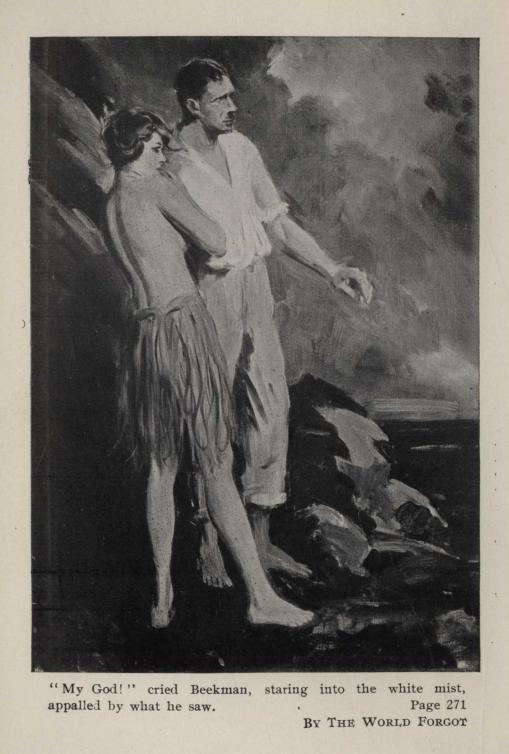

BY THE WORLD FORGOT

By The World

Forgot

A Double Romance of the East and West

By CYRUS TOWNSEND BRADY

With Frontispiece

By CLARENCE F. UNDERWOOD

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Published by arrangement with A. C. McCLURG & COMPANY

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1917

Published September, 1917

Copyrighted in Great Britain

TO

MY GOOD FRIEND AND KINSMAN

JOHN F. BARRETT

CONTENTS

BOOK I

"Ship me somewheres east of Suez"

CHAPTER

I A Clash of Wills and Hearts

II The Stubbornness of Stephanie

III Bill Woywod to the Rescue

IV A Bachelor's Dinner and Its Ending

V The Wedding That Was Not

VI Stephanie Is Glad After All

VII Up Against It Hard

VIII The Anvil Must Take the Pounding

IX The Game and the End

X The Mystery of the Last Words

XI The Triangle Becomes a Quadrilateral

BOOK II

"An' they talks a lot o' lovin',

But wot do they understand?"

XII The Hardest of Confessions

XIII The Search Determined Upon

XIV The Boatswain's Story

BOOK III

"Where there aren't no Ten Commandments"

XV The Spirit of the Island

XVI The Speech of His Forefathers

XVII The House That Was Taboo

XVIII Moonlight Midnight Madness

XIX The Kiss That Was Different

XX The Message of the Past

XXI The Watcher on the Rocks

XXII Twice Saved by Truda

XXIII Truda Comes to His Prison

XXIV "So Farre, So Fast the Eygre Drave"

XXV The Indomitable Ego

BOOK IV

"I've a neater, sweeter maiden,

In a cleaner, greener land"

XXVI In Danger All

XXVII The Speechless Castaways

XXVIII They Comfort Each Other

XXIX The Island Haven

XXX Revelations and Withholdings

XXXI Vi et Armis

BOOK I

"Ship me somewheres east of Suez"

BY THE WORLD FORGOT

CHAPTER I

A CLASH OF WILLS AND HEARTS

"For the last time, will you marry me?"

"No."

"But you don't love him."

"No."

"And you do love me?"

"Yes."

"I don't believe it."

"Would I be here if I did not?"

Now that adverb was rather indefinite. "Here" might have meant the private office, which was bad enough, or his arms, which was worse or better, depending upon the view-point. She could think of nothing better to dispel the reasonable incredulity of the man than to nestle closer to him, if that were possible, and kiss him. It was not a perfunctory kiss, either. It meant something to the woman, and she made it mean something to the man. Indeed, there was fire and passion enough in it to have quickened a pulse in a stone image. It answered its purpose in one way. There could be no real doubt in the man's mind as to the genuineness of that love he had just called in question in his pique at her refusal. The kiss thrilled him with its fervor, but it left him more miserable than ever. It did not plunge him immediately into that condition, however, for he drew her closer to his breast again, and as the struck flint flashes fire he gave her back all that she had given him, and more.

Ordinarily in moments like that it is the woman who first breaks away, but the solution of touch was brought about by the man. He set the girl down somewhat roughly in the chair behind the big desk before which they were standing and turned away. She suffered him thus to dispose of her without explanation. Indeed, she divined the reason which presently came to his lips as he walked up and down the big room, hands in pockets, his brows knitted, a dark frown on his face.

"I can't stand any more of that just now," he said, referring to her caress; "if ever in my life I wanted to think clearly it is now and with you in my arms--Say, for the very last time, will you marry me?"

"I cannot."

"You mean you will not."

"Put it that way if you must. It amounts to the same thing."

"Why can't you, or won't you, then?"

"I've told you a thousand times."

"Assume that I don't know and tell me again."

"What's the use?"

"Well, it gives me another chance to show you how foolish you are, to overrule every absurd argument that you can put forth--"

"Except two."

"What are they?"

"My father and myself."

"Exactly. You have inherited a full measure, excuse me, of his infernal obstinacy."

"Most people call it invincible determination."

"It doesn't make any difference what it's called, it amounts to the same thing."

"I suppose I have."

"Now look at the thing plainly from a practical point of view."

"Is there anything practical in romance, in love, in passions like ours?"

"There is something practical in everything I do and especially in this. I've gone over the thing a thousand times. I'll go over it again once more. You don't love the man you have promised to marry; you do love me. Furthermore, he doesn't love you and I do--Oh, he has a certain affection for you, I'll admit. Nobody could help that, and it's probably growing, too. I suppose in time he will--"

"Love me as you do?"

"Never; no one could do that, but as much as he could love any one. But that isn't the point. For a quixotic scruple, a mistaken idea of honor, an utterly unwarranted conception of a daughter's duty, you are going to marry a man you don't and can't love and--"

"You are very positive. How do you know I can't?"

"I know you love me and I know that a girl like you can't change any more than I can."

"That's the truth," answered the girl with a finality which bespoke extreme youth, and shut off any further discussion of that phase.

"Well, then, you'll be unhappy, I'll be unhappy, and he'll be unhappy."

"I can make him happy."

"No, you can't. If he learns to love you he will miss what I would enjoy. He'll find out the truth and be miserable."

"Your solicitude for his happiness--"

"Nonsense. I tell you I can't bear to give you up, and I won't. I shouldn't be asked to. You made me love you; I didn't intend to."

"It wasn't a difficult task," said the girl smiling faintly for the first time.

"Task? It was no task at all. The first time I saw you I loved you, and now you have lifted me up to heaven only to dash me down to hell."

"Strong language."

"Not strong enough. Seriously, I can't, I won't let you do it."

"You must. I have to. You don't understand. His father gave my father his first start in life."

"Yes, and your father could buy his father twenty times over."

"Perhaps he could, but that doesn't count. Our two fathers have been friends ever since my father came here, a boy without money or friends or anything, to make his fortune, and he made it."

"I wish to God he hadn't and you were as poor as I was when I landed here six years ago. If I could just have you without your millions on any terms I should be happy. It's those millions that come between us."

"Yes, that's so," admitted the girl, recognizing that the man only spoke the truth. "If I were poor it would be quite different. You see father's got pretty much everything out of life that money could buy. He has no ancestry to speak of but he's as proud as a peacock. The friendship between the two families has been maintained. The two old men determined upon this alliance as soon as I was born. My father's heart is set upon it. He has never crossed me in anything. He has been the kindest and most indulgent of men. Next to you I worship him. It would break his heart if I should back out now. Indeed, he is so set upon it that I am sure he would never consent to my marrying you or anybody else. He would disinherit me."

"Let him, let him. I've the best prospects of any broker in New York, and I've already got enough money for us to live on comfortably."

"I gave my word openly, freely," answered the girl. "I wasn't in love with any one then and I liked him as well as any man I had ever met. Now that his father has died, my father is doubly set upon it. I simply must go through with it."

"And as your father sacrificed pretty much everything to build the family fortune, so you are going to sacrifice yourself to add position to it."

"Now that is unworthy of you," said the girl earnestly. "That motive may be my father's but it isn't mine."

"Forgive me," said the man, who knew that the girl spoke even less than the truth.

"I can understand how you feel because I feel desperate myself; but honor, devotion, obedience to a living man, promise to a dead man, his father, who was as fond of me as if I had already been his daughter, all constrain me."

"They don't constrain me," said the man desperately, coming to the opposite side of the big desk and smiting it heavily with his hand. "All that weighs nothing with me. I have a mind to pick you up now and carry you away bodily."

"I wish you could," responded the girl with so much honest simplicity that his heart leaped at the idea, "but you could never get further than the elevator, or, if you went down the stairs, than the street, because my honor would compel me to struggle and protest."

"You wouldn't do that."

"I would. I would have to. For if I didn't there would be no submitting to force majeure. No, my dear boy, it is quite hopeless."

"It isn't. For the last time, will you marry me?"

"As I have answered that appeal a hundred times in the last six months, I cannot."

"Are there any conditions under which you could?"

"Two."

"What are they?"

"What is the use of talking about them? They cannot occur."

"Nevertheless tell me what they are. I've got everything I've ever gone after heretofore. I've got some of your father's perseverance."

"You called it obstinacy a while ago."

"Well, it's perseverance in me. What are your conditions?"

"The consent of two people."

"And who are they?"

"My father and my fiancé."

"I have your own, of course."

"Yes, and you have my heartiest prayer that you may get both. Oh," she went on, throwing up her hands. "I don't think I can stand any more of this. I know what I must do and you must not urge me. These scenes are too much for me."

"Why did you come here, then?" asked the man. "You know I can't be in your presence without appealing to you."

"To show you this," said the girl, drawing a yellow telegram slip from her bag which she had thrown on the desk.

"Is it from him? I had one, too," answered the man, picking it up.

"Of course," said the girl, "since you and he are partners in business. I never thought of that. I should not have come."

"Heaven bless you for having done so. Every moment that I see you makes me more determined. If I could see you all the time and--"

"He'll be here in a month," interrupted the girl. "He wants the wedding to take place immediately and so do I."

"Why this indecent haste?"

"It has been a year since the first postponement and--Oh, what must be must be! I want to get it over and be done with it. I can't stand these scenes any more than you can. Look at me."

The man did more than look. The sight of the piteous appealing figure was more than he could stand. He took her in his arms again.

"I wish to God he had drowned in the South Seas," he said savagely.

"Oh, don't say that. He's your best friend," interposed the girl, laying her hand upon his lips.

"But you are the woman I love, and no friendship shall come between us."

The girl shook her head and drew herself away.

"I must go now. I really can't endure this any longer."

"Very well," said the man, turning to get his hat.

"No," said the girl, "you mustn't come with me."

"As you will," said the other, "but hear me. That wedding is set for thirty days from today?"

"Yes."

"Well, I'll not give you up until you are actually married to him. I'll find some way to stop it, to gain time, to break it off. I swear you shan't marry him if I have to commit murder."

She thought he spoke with the pardonable exaggeration of a lover. She shook her head and bit her lip to keep back the tears.

"Good-bye," she said. "It is no use. We can't help it."

She was gone. But the man was not jesting. He was in a state to conceive anything and to attempt to carry out the wildest and most extravagant proposition. He sat down at his desk to think it over, having told his clerks in the outer office that he was not to be disturbed by any one for any cause.

CHAPTER II

THE STUBBORNNESS OF STEPHANIE

At one point of the triangle stands the beautiful Stephanie Maynard; at another, George Harnash, able and energetic; at the third, Derrick Beekman, who was a dilettante in life. George Harnash is something of a villain, although he does not end as the wicked usually do. Derrick Beekman is the hero, although he does not begin as heroes are expected to do. Stephanie Maynard is just a woman, heroine or not, as shall be determined. Before long the triangle will be expanded into a square by the addition of another woman, also with some decided qualifications for a heroine; but she comes later, not too late, however, to play a deciding part in the double love story into which we are to be plunged.

Of that more anon, as the sixteenth century would put it; and indeed this story of today reaches back into that bygone period for one of its origins. Romance began--where? when? All romances began in the Garden of Eden, but it needs not to trace the development of this one through all the centuries intervening between that period and today. This story, if not its romance, began with an arrangement. The arrangement was entered into between Derrick Beekman senior, since deceased, and John Maynard, still very much alive.

Maynard was a new man in New York, a new man on the street. He was the head of the great Inter-Oceanic Trading Company. The Maynard House flag floated over every sea from the mast heads, or jack staffs, of the Maynard ships. Almost as widely known as the house flag was the Maynard daughter. The house flag was simple but beautiful; the daughter was beautiful but by no means simple. She was a highly specialized product of the nineteenth century. Being the only child of much money, she was everything outwardly and visibly that her father desired her to be, and to make her that he had planned carefully and spent lavishly. With her father's undeniable money and her own undisputed beauty she was a great figure in New York society from the beginning.

No one could have so much of both the desirable attributes mentioned--beauty and money--and go unspoiled in New York--certainly not until age had tempered youth. But Stephanie Maynard was rather an unusual girl. Many of her good qualities were latent but they were there. It was not so much those hidden good qualities but the dazzling outward and visible characteristics that had attracted the attention of old Derrick Beekman.

Beekman had everything that Maynard had not and some few things that Maynard had--in a small measure, at least. For instance, he was a rich man, although his riches could only be spoken of modestly beside Maynard's vast wealth.

But Beekman added to a comfortable fortune an unquestioned social position; old, established, assured. Those who would fain make game of him behind his back--such a thing was scarcely possible to his face--used to say that he traced his descent to every Dutchman that ever rallied around one-legged, obstinate, Peter Stuyvesant and his predecessors. The social approval of the Beekmans--originally, of course, Van Beeckman--was like a lettre de cachet. It immediately imprisoned one in the tightest and most exclusive circle of New York, the social bastille from which the fortunate captive is rarely ever big enough to wish to break out.

Beekman's pride in his ancestry was only matched by his ambitions for his son, like Stephanie Maynard, an only child. If to the position and, as he fancied, the brains of the Beekmans could be allied the fortune and the business acumen of the Maynards, the world itself would be at the feet of the result of such a union. Now Maynard's money bought him most things he wanted but it had not bought and could not buy Beekman and that for which he stood. Maynard's beautiful daughter had to be thrown into the scales.

Maynard had no ancestry in particular. Self-made men usually laugh at the claims of long descent, but secretly they feel differently. Being the Rudolph of Hapsburg of the family is more of a pose or a boast than not. I doubt not that even the great Corsican felt that in his secret heart which he revealed to no one. Maynard's patent of nobility might date from his first battle on the stock exchange, his financial Montenotte, but in his heart of hearts he would rather it had its origin in some old and musty parchment of the past.

Beekman, who was much older than Maynard, had actually helped that young man when he first started out to encounter the world and the flesh and the devil in New York and to beat them down or bring them to heel. A friendship, purely business at first, largely patronizing in the beginning on the one hand, deferentially grateful on the other, had grown up between the somewhat ill-sorted pair. And it had not been broken with passing years.

Maynard, unfortunately for his social aspirations, had married before he had become great. Many men achieve greatness only to find a premature partner an encumbrance to a career. However, Maynard's wife, another social nobody with little but beauty to recommend her, had done her best for her husband by dying before she was either a drag or a help to his fortunes. The two men, each actuated by different motives, which, however, tended to the same end, had arranged the match between the last Beekman and the first Maynard; and that each secretly fancied himself condescending to the other did not stand in the way. The young people had agreeably fallen in with the proposals of the elders, neither of whom was accustomed to be balked or questioned--for old Beekman was as much of an autocrat as Maynard. Filial obedience was indeed a tradition in the Beekman family. There were no traditions at all in the Maynard family, but the same custom obtained with regard to Stephanie.

Young Beekman was good looking, athletic, prominent in society, a graduate of the best university, popular, and generally considered able, although he had accomplished little, having no stimulus thereto, by which to justify that public opinion. He went everywhere, belonged to the best clubs, and was a most eligible suitor. He danced divinely, conversed amusingly, made love gallantly if somewhat perfunctorily, having had abundant practice in all pursuits. For the rest, what little business he transacted was as a broker and business partner of George Harnash, who, for their common good, made the most of the connections to which Beekman could introduce him.

Beekman, who had taken life lightly, indeed, at once recognized the wisdom of his father's rather forcible suggestion that it was time for him to settle down. He saw how the Maynard millions would enhance his social prestige, and if he should be moved to undertake business affairs seriously, as Harnash often urged, would offer a substantial background for his operations.

Stephanie Maynard was beautiful enough to please any man. She was well enough educated and well enough trained for the most fastidious of the fastidious Beekmans. In any real respect she was a fit match for Derrick Beekman, indeed for anybody. There was no society into which she would be introduced that she would not grace.

From a feeling of condescension quite in keeping with his blood young Beekman was rapidly growing more interested in and more fond of his promised wife. Her feelings probably would have developed along the same lines had it not been for George Harnash. He was Beekman's best friend. They had been classmates and roommates at college. Harnash like Beekman was a broker. Indeed the firm of Beekman & Harnash was already well spoken of on the street, especially on account of the ability of the junior partner, who was everywhere regarded as a young man with a brilliant future.

Now Harnash hung, as it were, like Mohammed's coffin, 'twixt heaven and earth. He was not socially assured and unexceptionable as Beekman, but he was much more so than the Maynards. He did not begin with even the modest wealth of the former, but he was rapidly acquiring a fortune and, what is better, winning the respect and admiration of friends and enemies alike by his bold and successful operations. It was generally recognized that Harnash was the more active of the two young partners. Beekman had put in most of the capital, having inherited a reasonable sum from his mother and much more from his father, but Harnash was the guiding spirit of the firm's transactions.

Harnash, who was the exact opposite of Beekman, as fair as the other man was dark, fell wildly in love with Stephanie Maynard. To do him justice, this plunge occurred before definite matrimonial arrangements between the houses of Beekman and Maynard had been entered into. Harnash had not contemplated such a possibility. The two friends were in exceedingly confidential relationship to each other, and Beekman had manifested only a most casual interest in Stephanie Maynard. Harnash, seeing the present hopelessness of his passion, had concealed it from Beekman. Therefore, the announcement casually made by his friend and confirmed the day after by the society papers overwhelmed him.

To do him justice further, while it could not be said that Harnash was oblivious to the fact that the woman he loved was her father's daughter, he would have loved her if she had been a nobody. While he could not be indifferent to the further fact that whoever won her would ultimately command the Maynard millions, George Harnash was so confident of his own ability to succeed that he would have preferred to make his own way and have his wife dependent upon him for everything. However, he was too level headed a New Yorker not to realize that even if he could achieve his ambition the Maynard millions would come in handy.

The thing that made it so hard for Harnash to bear the new situation was the carelessness with which Beekman entered into it. He felt that if the marriage could be prevented it would not materially interfere with the happiness of his friend. Harnash had deliberately set himself to the acquirement of everything he desired. Honorably, lawfully, if he could he would get what he wanted, but get it he would. He found that he had never wanted anything so much as he wanted Stephanie Maynard. Money and position had been his ambitions, but these gave place to a woman. He did not arrive at a determination to take Stephanie Maynard from Derrick Beekman, if he could, without great searchings of heart, but the more he thought about it, the longer he contemplated the possibility of the marriage of the woman he loved to the man he also loved, the more impossible grew the situation.

At first he had put all thought of self out of his mind, or had determined so to do, in order to accept the situation, but he made the mistake of continuing to see Stephanie during the process and when he discovered that she was not indifferent to him he hesitated, wavered, fell. By fair means or foul the engagement must be broken. It could only be accomplished by getting Derrick Beekman out of the way. After that he would wring a consent out of Maynard. To that decision the girl had unconsciously contributed by laying down conditions which, by a curious mental twist, the man felt in honor bound to meet.

Both the elder Beekman and John Maynard were men of firmness and decision. Wedding preparations had gone on apace. The invitations were all but out when Beekman was gathered to his ancestors--there could be no heaven for him where they were not--after an apoplectic stroke. This postponed the wedding and gave George Harnash more time. Now Derrick Beekman had devotedly loved his stern, proud old father, the only near relative he had in the world. He decided to spend the time intervening between that father's sudden and shocking death and his marriage on a yachting cruise to the South Seas. It was characteristic of his feeling for Stephanie Maynard that he had not hesitated to leave her for that long period. The field was thus left entirely to Harnash.

The Maynard-Beekman engagement, of course, had been made public, and Stephanie's other suitors had accepted the situation, but not Harnash. He was a man of great power and persuasiveness and ability and he made love with the same desperate, concentrated energy that he played the business game. He was quite frank about it. He told Stephanie that if she or Beekman or both of them had shown any passion for the other, such as he felt for her, he would have considered himself in honor bound to eliminate himself, but since it would obviously be un mariage de convenance, since both the parties thereto would enter into it lightly and unadvisedly, he was determined to interpose. And there was even in the girl's eyes abundant justification for his action.

No woman wants to be taken as a matter of course. Stephanie Maynard had been widely wooed, more or less all over the world. Although she did not care especially for Derrick Beekman, she resented his somewhat cavalier attitude toward her, and his witty, amusing, but by no means passionately devoted letters, somewhat infrequent, too. Harnash made great progress, yet he came short of complete success.

The Maynards were nobodies socially, that is, their ancestors had been, and they had not yet broken into the most exclusive set, the famous hundred and fifty of New York's best, as they styled themselves to the great amusement of the remaining five million or so, but they came, after all, of a stock possessed of substantial virtues. Stephanie's father was accustomed to boast that his word was his bond, and, unlike many who say that, it really was. People got to know that when old John Maynard said a thing he could be depended upon. If he gave a promise he would keep it even if he ruined himself in the keeping, and his daughter, in that degree, was not unlike him.

Almost a year after his father's death Derrick Beekman sent cablegrams from Honolulu saying he was coming back, and George Harnash and Stephanie awoke from their dream.

"I love you," repeated Stephanie to Harnash in another of the many, not to say continuous, discussions they held after that day at the office. "You can't have any doubt about that, but my word has been passed. I don't dislike Derrick, either. But I'd give anything on earth if I were free."

"And when you were free?"

"You know that I'd marry you in a minute."

"Even if your father forbade?"

"I don't believe he would."

"If he did we would win him over."

"You might as well try to win over a granite mountain. But there's no use talking, I'm not free."

"It's this foolish pride of yours."

"Foolish it may be. I've heard so much about the Beekman word of honor and the Beekman faith that I want to show that the Maynard honor and faith and determination are no less."

"And you are going to sacrifice yourself and me for that shibboleth, are you?"

"I see no other way. Believe me," said the girl, who had resolved to allow no more demonstrations of affection now that it was all settled and her prospective husband was on the way to her, "I seem cold and indifferent to you, but if I let myself go--"

"Oh, Stephanie, please let yourself go again, even if for the last time," pleaded George Harnash, and Stephanie did. When coherent speech was possible he continued: "Well, if Beekman himself releases you or if he withdrew or disappeared or--"

"I don't have to tell you what my answer would be."

"And I've got to be best man at the wedding! I've got to stand by and--"

"Why didn't you speak before?" asked the girl bitterly.

"I was no match for you then. I'm not a match for you now."

"You should have let me be the judge of that."

"But your father?"

"I tell you if I hadn't promised, all the fathers on earth wouldn't make any difference. Now we have lived in a fool's paradise for a year. You're Derrick's friend and you're mine."

"Only your friend?"

"Do I have to tell you again how much I love you? But that must stop now. It should have stopped long ago. You can't come here any more except as Derrick's friend."

"I can't come here at all, then."

"No, I suppose not. And that will be best. Let us put this behind us as a dream of happiness which we will never forget, but from which we awake to find it only a dream."

"It's no dream to me. I will never give you up. I will never cease to try to make it a reality until you are bound to the other man."

They were standing close together as it was, but he took the step that brought him to her side and he swept her to his heart without resistance on her part. She would give her hand to Derrick Beekman, but her heart she could not give, for that was in George Harnash's possession, and when he clasped her in his arms and kissed her, she suffered him. She kissed him back. Her own arms drew him closer. It was a passionate farewell, a burial service for a love that could not go further. It was she who pushed him from her.

"I will never give you up, never," he repeated. "Great as is my regard for Beekman, sometimes I think that I'll kill him at the very foot of the altar to have you."

Stephanie's iron control gave way. She burst into tears, and George Harnash could say nothing to comfort her, but only gritted his teeth as he tore himself away, revolving all sorts of plans to accomplish his own desires.

To him came, with Mephistophelian appositeness, Mr. Bill Woywod.

CHAPTER III

BILL WOYWOD TO THE RESCUE

The three weeks that followed were more fraught with unpleasantness, not to say misery, than any Stephanie Maynard and George Harnash had ever passed. Of the two, Harnash was in the worse case. Stephanie had two things to distract her.

The approaching wedding meant the preparation of a trousseau. What had been got ready the year before would by no means serve for the second attempt at matrimony. Now no matter how deep and passionate a woman's feelings are she can never be indifferent to the preparation of a trousseau. Even death, which looms so horribly before the feminine mind, would be more tolerable if it were accompanied by a similar demand upon her activities. Yet a woman's grief in bereavement is never so deep as to make her careless as to the fit or becomingness of her mourning habiliments. Much more is this true of wedding garments.

Now if these somewhat cynical and slighting remarks be reprehended, nevertheless there is occupation even for the sacrificial victim in the preparation of a trousseau which, were it not so pleasant a pursuit, might even be called labor. The fit of Stephanie's dresses on her beautiful figure was not accomplished without toil, albeit of the submissive sort, on the part of the young lady. That was her first diversion.

For the second relief the girl had a great deal more confidence in her lover's promise than he had himself in his own prowess. Try as he might, plan as he could, he found no way out of the impasse so long as the solution of it was left entirely to him, and the woman was determined to be but a passive instrument.

The obvious course was to go frankly to his friend and lay before him the whole state of affairs in the hope that Beekman himself would cut the Gordian knot by declining the lady's hand. Two considerations prevented that. In the first place, Beekman had confidingly placed his love affair, together with his business affairs, in the hands of his partner. Harnash had not meant to play the traitor but he had been unable to resist the temptation that Stephanie presented, and he simply could not bring himself to make such a bare-faced admission of a breach of trust. Besides, he reasoned shrewdly that even if he did make such a confession it was by no means certain that Derrick Beekman would give up the girl. His letters, since his cable from Hawaii, had rather indicated a strengthening of his affection, and Harnash suspected that the realization that his betrothed was violently desired by someone else would just about develop that affection into a passion which could hardly be withstood.

In the second place, even if Beekman's affection for Harnash would lead him to take the action desired by his friend, there would still be Mr. Maynard to be won over. Harnash had not been associated with Maynard as a broker in various transactions which the older man had engineered, without having formed a sufficiently correct judgment of his character to enable him to forecast absolutely what Maynard's position would be in that emergency. Maynard had a considerable liking and a growing respect for young Harnash. He had casually remarked to his daughter on more than one occasion that Harnash was a young man who would be heard from. Maynard had observed that Harnash strove for many things and generally got what he wanted.

Perhaps that remark, which the poor girl had treasured in her heart, had something to do with her confidence that somehow or other Harnash would work out the problem. But Harnash knew very well how terrible, not to say vindictive, an antagonist and enemy Maynard could be when he was crossed. If Beekman withdrew from the engagement, broke off the marriage, about which there had been sufficient notoriety on account of the first postponement after the older Beekman's death, Maynard's rage would know no bounds. He would assuredly wreak his vengeance upon Beekman, and if Harnash were implicated in any way the punishment would be extended to him.

Harnash knew that Beekman would not have cared a snap of his finger for the older Maynard's wrath. He was not that kind of a man. Nor would he himself have been deterred by the thought of it had he been a little more sure of his position financially. Whatever else he lacked, Harnash had courage to tackle anything or anybody, if there were the faintest prospect of success. But to fight Maynard at that stage in his career was an impossibility. These weighty reasons accordingly decided him that it was useless and indeed impossible to appeal to his friend.

Again, while Harnash was accustomed to stop at nothing to procure his ends, and while he had declared that he would murder Beekman, he knew that although he meant it more than Stephanie supposed, he did not mean it enough to be able to do anything like that. His mind was in a turmoil. He really was fond of Beekman, and if Stephanie and Derrick had been wildly in love with each other Harnash believed that he would have been man enough to have kept out of the way and have fought down his disappointment as best he could. As it was, there was reason and justice in what he urged. Since Stephanie loved him and did not love Beekman, and since Beekman's affection was of a placid nature, the approaching union was horrible.

The wildest schemes and plans ran through his head or were suggested to him after intense thought, only to be rejected. The problem finally narrowed itself down to a question of time. Harnash was a great believer in the function of time in determining events. If he could postpone the marriage again he would have greater opportunity to work and plan. He had enough confidence in himself, backed by Stephanie's undoubted affection, to make him believe that with time he could bring about anything. Therefore he must eliminate Derrick Beekman, temporarily, at least, and he must do it before the wedding. The longer he could keep him away from Stephanie, the better would be his own chance. If even on the eve of the wedding the groom could disappear, the fact would tend greatly to his ultimate advantage, provided Beekman were away long enough.

He concentrated his mind on this proposition. How could he cause Derrick Beekman to disappear the day before his wedding, and how, having spirited him away, could he keep him away long enough to make that disappearance worth while from the Harnash point of view? That was the final form of the problem in its last analysis. How was he to solve it?

He could have Beekman kidnapped, and hold him for ransom in some lonely place in the country. That was a solution which he dismissed almost as soon as he formulated it. The thing was impracticable. He would have to trust too many people. He could never keep him long in confinement. He himself would probably become the victim of continuous blackmail. In the face of rewards that would be offered, his employees would eventually betray him. Sooner or later, unless something happened to Beekman, he would get out. Harnash had plenty of hardihood, but he shivered at the thought of what he would have to meet when Beekman came for an accounting, as sooner or later he would. He would have to find some other way. What way?

Now Harnash's misery was further increased by the fact that Beekman had cabled him to go ahead with the preparations for the wedding. The Beekman yacht had broken down in Honolulu Harbor after that long cruise, and instead of following his telegram straight home, there had been a week of delay. He had explained the situation by cables to Harnash, Stephanie, and her father.

After the yacht, her engines pretty well strained from the year's cruise, had been put in fair shape, ten days had been required for the return passage. Beekman had some business matters to attend to in San Francisco and he did not arrive in New York until a few days before the wedding, which was to take place at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, the Bishop Suffragan and the Dean being the officiating clergymen designate.

It was fortunate in one sense that Beekman had been so delayed, for there was so much for him to do, so many people for him to see, that he had little opportunity for making love to his promised bride, and he had no chance to discern her real feelings any more than he had to find out Harnash's position. He had, indeed, remarked that Stephanie looked terribly worn and strained, and that George Harnash was haggard and spent to an extraordinary degree; but he attributed the one to the excitement of the marriage and the other to the fact that Harnash had been left so long alone to bear the burden of responsibility and decision in the rapidly increasing brokerage business.

When he had swept his unwilling bride-to-be to his heart and kissed her boisterously, he had told her that he would take care of her and see that the roses were brought back to her cheeks after they were married; and after he had shaken Harnash's hand vigorously he had slapped him on the back and declared to him that as soon as the honeymoon was over he would buckle down to work and give him a long vacation. Neither of the recipients of these promises was especially enthusiastic or delighted, but in his joyous breezy fashion Beekman neither saw nor thought anything was amiss.

Never a man essayed to tread the devious paths of matrimony with a more confident assurance or a lighter heart. Nothing could surpass his blindness.

"You see," said Stephanie in a last surreptitious interview with Harnash, "he hasn't the least suspicion. He hugged me like a bear and kissed me like a battering ram," she explained with a little movement of her shoulders singularly expressive of resentment, and even more.

"Damn him," muttered Harnash, under his breath. "He wrung my hand, too, as if I were his best friend."

"Well, you are, aren't you?"

"I was, I am, and I'm going to save him from--"

"From the misfortune of marrying me?"

"I don't see how you can jest under the circumstances."

"George," said the girl, "if I didn't jest I should die. I don't see how I can endure it as it is."

"Stephanie," he repeated, lifting his right hand as if making an oath--as, indeed, he was--"I'm going to take you from him if it is at the foot of the altar."

These were brave words with back of them, as yet, only an intensity of purpose and a determination, but no practical plan. It was Bill Woywod that gave the practical turn to that decision on the part of Harnash.

Now George Harnash came originally from a little down-east town on the Maine coast. That it was his birthplace was not its only claim to honor. It also boasted of the nativity of Bill Woywod. The two had been boyhood friends. Although their several pursuits had separated them widely, the queer friendship still obtained in spite of the wide and ever-widening difference in the characters and stations of the two men.

Running away from school, Bill Woywod had gone down to the sea as his ancestors for two hundred years had done before him. Left to himself, Harnash had completed his high school and college course and had gone down to New York as none of his people had ever done in all the family history. Both men had progressed. Harnash was already well-to-do and approaching brilliant success. He had thrust his feet at least within the portals of society and was holding open the door which he would force widely when he was a little stronger.

Woywod had earned a master's certificate and was now the first mate, technically the mate, of one of the ships of the Inter-Oceanic Trading fleet, in line for first promotion to a master. Woywod was a deep-water sailor. He cared little for steam, and although it was an age in which masts and sails were being withdrawn from the seven seas, he still affected the fast-disappearing wind-jamming branch of the ocean-carrying trade.

Indeed, the last full-rigged ship had been paid off and laid up in ordinary. Just because it was the last wooden sailing ship of the fleet, Maynard, whose fortune had been not a little contributed to by sailing vessels in the preceding century, had refrained from selling her. There was a sentimental streak in the hard old captain of industry, as there is in most men who achieve, and the Susquehanna had not been broken up or otherwise disposed of. On the contrary, every care had been taken of her.

The demands of the great war brought every ocean-carrying ship into service again. The Susquehanna was refitted and commissioned. A retired mariner who had been more or less a failure under steam but whose seamanship was unquestioned was appointed to command. Captain Peleg Fish was one of those old-time sailors to whom moral suasion meant little or nothing. He was Gloucester born, and had served his apprenticeship in the fishing fleet. Thereafter he had been mate on the last of the old American clippers, had commanded a whaler out of New Bedford, and knew a sailing ship from truck to keelson.

He was a man of a hard heart and a heavy hand. His courage was as high as his heart was hard or his hand was heavy. He was also a driver. He drove his ship and he drove his men. He had been a success on the Susquehanna in her time, and because of that he had been able to get crews and keep officers. Quick passages in a well-found ship, and good pay, had offset his proverbial fierceness and brutality. He was now an old man, but sailing masters were scarce. Officers and men were scarce, too, on account of the war, and although the Inter-Oceanic Trading Company had dismissed Captain Fish because of the way he had mishandled the steamer to which they transferred him when they laid up the Susquehanna, yet they were glad to call him into service when they decided again to make use of that vessel.

Grim old Captain Fish made but one condition. He was glad enough to get back to the sea on which he had passed his life on any terms, and doubly rejoiced that he could once more command a wooden sailing ship instead of "an iron pot with a locomotive in her," as he designated his last vessel. That condition was that he should have Bill Woywod for mate. The two had sailed together before. They knew each other, liked each other, worked together hand and glove, for Bill Woywod was a man of the same type as the captain. The captain was getting old, too. He wanted a stouter arm and a quicker eye at his disposal than his own. Besides, Bill hated steam as much as Fish did. He was a natural-born sailor, not a mechanic and engine driver. Among the bucko mates of the past, Bill Woywod would not have yielded second place to anybody. They had to give Woywod a master's pay to get him to ship, but once having agreed to do that, he entered upon his new duties with alacrity.

The Susquehanna was a big full-rigged clipper ship of three thousand tons. Given a favorable wind, she could show her heels to many a tramp steamer or lumbering freighter, and even not a few of the older liners. She was carrying arms and munitions for the Russians and ran between New York and Vladivostok through the Panama Canal.

If there was one person rough, hard-bitten Bill Woywod had an abiding affection for, it was George Harnash. Whenever his ship dropped anchor in New York the first person--and about the only respectable person--he visited was his boyhood friend. To be sure, there was not much congeniality between them. The only tie that bound them was that boyhood friendship, but both of them were men without kith or kin, and they somehow clung to that association. Woywod was proud of his friendship with the rising young broker, and there was a kind of refreshment in the person of the breezy sailor which Harnash greatly enjoyed, especially as the visits of the seaman were not frequent or long enough to pall upon the New Yorker.

Harnash usually took an afternoon and night off when Woywod arrived. They took in the baseball game at the Polo Grounds, dined thereafter at some table d'hote resort which Harnash would never have affected under ordinary circumstances, but which seemed to Woywod the very height of luxury. Then they repaired to some theatre, usually one of the high-kicking variety avowedly designed for the tired business man, which was extremely congenial to the care-free sailor; and not to go further into details it may be alleged that they had a good time together until far in the night or early in the morning, rather. Harnash was usually not a little ashamed next morning; Woywod, never! With sturdy independence Woywod would alternate being host on these occasions. On land and out of his element he was a fairly agreeable companion in his rough, coarse way. It was only on the ship that he became a brute. In the nature of things the devotion, if such it could be called, was all on Woywod's side. It was an aspiration on his part and a condescension on the part of Harnash, however much the latter strove to disguise it.

The Susquehanna had been loaded to her capacity and beyond with war equipment for the Russian Government and was about to take her departure from New York, when Woywod, who had been prevented before by the duties imposed by the necessity of getting the ship ready quickly for her next long voyage, paid his annual or semi-annual visit to his friend. Now these visits had become so thoroughly a matter of custom that Woywod had established the right of entrance. None of the clerks in the outer office would have thought of stopping him, and although Harnash was very strict in requiring respect for the sanctity of his private office Woywod made no hesitation about entering it unceremoniously.

Like all sailors, he moved with cat-like softness and quickness. He opened the door noiselessly and surprised his friend seated at his desk, his face buried in his hands in an attitude of the deepest dejection. Friendship has a discerning power as well as greater passions.

"Why, George, old boy," began Woywod, laying his hand on the other's shoulder, and that touch gave Harnash the first warning that he was not alone, "what's the matter?"

Harnash looked up quickly, rose to his feet as he recognized his visitor, and grasped him by the hand with a warmth he had not shown in years.

"Bill," he explained, "I'm in the deepest trouble that ever fell on a man, and you come like an angel in time to help me."

Harnash must have meant a dark angel, but Woywod knew nothing of that.

"What is it, old man?" he asked. "If it's money you're needin' I got a shot or two in the locker an'--"

"No, it's not money. I'm making more than ever."

"Been buckin' up agin the law an' want a free passage to safety? Well, me an' old man Fish is as thick as peas in a pod, an' the Susquehanna's at your service."

"It's not that, either."

"What in blazes is it, then?"

"A woman."

"Look here, George," said Woywod, "I'm about as rough as they make 'em an' there ain't no man as ever sailed with me that won't endorse that there statement, but I never done no harm to no woman an' if you've been--"

"You're on the wrong tack again, Bill," interposed Harnash, smiling. "It's a woman I love and who loves me."

"Well, I don't reckon I can help you there unless you want me to be best man at the weddin'."

That suggestion struck Harnash as intensely comical, as it well might, but he hastened to add diplomatically:

"I couldn't wish a better man if there were going to be any wedding, but--"

"Do you love a married woman?" asked Woywod, going directly to the point.

"Not exactly."

"What d'ye mean?"

"I'll explain if you'll only give me a chance," answered Harnash, and in as few words as possible he put the sailor in possession of the facts.

"So you want to get rid of the man, do you?" he asked, when the story had been told.

"Yes. I don't want him harmed. I just want him out of the way."

"And you think that I--"

"If you can't help me I don't know who can."

"Look here, George," said Woywod, earnestly. "Is this square an' above board? Are you givin' me the truth?"

"I am."

"An' the gal loves you an' you love her an' she don't love this other chap which she wants to git out of marryin' him?"

"Right."

"Then it's easy."

"I thought you'd find a way."

"It don't take much schemin' for that. Just p'int him out to me an' git him down on the river front some dark night where I can git a hold of him, with a few drinks in him, an' that'll be all there is to it. You won't hear from him until the Susquehanna gits to Vladivostok, an' mebbe not then."

"I don't want any harm to come to him."

"In course not. I'll use him jest as gentle as I do any man on the ship."

"And he must never know that I--"

"He won't know nothin'. When a man gits drunk enough he can't tell what happens. You might tell yer lady friend that this is a little weddin' present I'm makin' to my oldest an' best friend, that is, if you git spliced afore I gits back from Vladivostok."

"I'll surely let her know your part of the transaction. When does the Susquehanna sail?"

"Thursday morning. Tide turns at two o'clock. We'll git out about four."

"You don't touch anywhere?"

"Not a place unless we're druv to it by bad weather or some accident. But if we do git hold of a cable I'll see that he stays safe aboard, in case, which ain't likely, we're obliged to drop anchor in any civilized port."

"Have you got a wireless aboard?"

"Nary wireless. When we take our departure from Fire Island it's up to Cap'n Fish an' me an' the rest of us to bring her in."

"There's no danger?"

"Well, there's always danger in sailin' the seas, but nobody never thinks nothin' about it with a good ship, well officered, well manned an' well found. It's a damn sight safer than the streets of New York with all them automobiles runnin' on the wind an' by the wind an' across the wind an' every other way at the same time. It's as much as a man's life is worth to try to navigate a street. Never mind the danger. We've got to settle a few little details an' then the thing bein' off your mind we can have a royal good time. You ain't got anything on tonight?"

"No engagement that I can't break. If it had been tomorrow, Wednesday, it would have been different because that is the night my friend--"

"Oh, he's a friend of yourn. Why don't you tell--"

"No use, Bill; this is the only way. But because he is a friend of mine I tell you I don't want him to come to any harm or to get any bad treatment."

"If he buckles down to work an' accepts the situation he won't get no bad treatment from me."

This was perfectly honest, for in the brutal school in which he had been trained what he meted out to his men was what he had been taught was right and what he believed they indeed expected, without which indeed discipline could not be maintained and the work of the ship properly done. Harnash had some doubts as to Beekman's ability to buckle down or willingness, rather, but he had to risk something. The two friends put their heads together and the minor details were easily arranged.

"Better tell the gal it's goin' to be all right, hadn't you?" suggested Woywod.

"No," said Harnash, with a truer appreciation of the situation. "I think I'll surprise her."

"It'll be a surprise, all right," laughed the big sailor. "Well, you do your part an' I'll do mine an' if the man does his part he'll come back to find you married an' he can make the best of it. By the way, what's his name?"

"Is it necessary that I should tell you?"

"No, 'tain't necessary an' perhaps on the whole it wouldn't be best. If I don't know his name I can call him a damn liar whatever he says it is, with a clear conscience," went on the sailor blithely and guilelessly, as if conscience really mattered to him.

CHAPTER IV

A BACHELOR'S DINNER AND ITS ENDING

Bachelors' dinners, masculine pre-nuptial festivities, that is, like everything else with which poor humanity deals, may roughly be divided into two kinds, which fall under the generic names of good or bad. Of course, in practice, as in life, goodness often degenerates into badness and badness is sometimes lifted into goodness. Such is the perversity of human nature even at its best that when the declaration is made that Beekman's bachelor dinner was a good one all interest in it is immediately lost! Bad is so much more attractive in literature and in life. Perhaps it may be said that while the dinner had not descended to the unbridled license which sometimes characterized such affairs, and while there were no ladies present in various stages of--shall it be said dress or undress--nevertheless, the young fellows who were present had a delightful time which if not as innocent as the festivities of Stephanie's final entertainment to her lovely attendants, was nevertheless quite what might have been expected from clean, healthy, well-bred young Americans with a reasonable amount of restraint.

The dinner was chosen with fine discrimination and epicurean taste; it was cooked by the best chef, served at the most exclusive club and accompanied by wines with which even the most captious bon vivant could not take issue. Perhaps some of the youngsters drank more than was good for them--which instantly raises the question, how much, or how little, if any, is good for a young man? They broke up at a decently early hour in the morning in much better condition than might have been expected.

Beekman was one of the most temperate of men. He took pride in his athletic prowess and he still kept himself in fine physical trim. A very occasional glass of wine usually limited his indulgence. In this instance, however, under conditions so unusual, he had partaken so much more freely than was his wont--his course being pardonable or otherwise in accordance with the viewpoint--that he was not altogether himself. This was not much more due to the plan of Harnash than to the solicitations of the other friends who found nothing so pleasant on that occasion as drinking to his health, and generally in bumpers. Indeed, not once but many times and oft around the board they pledged him and were pledged in return.

At the insistence of Harnash, Beekman had arranged to spend the night at the former's apartment in Washington Square. Harnash made the point that he was expected to look after him and produce him the next morning in the best trim, therefore he did not wish him to get out of his sight. Accordingly, Beekman had dismissed his own car and when the party broke up about two o'clock in the morning he went away with Harnash in the latter's limousine.

At somebody's suggestion--Beekman could never remember whose, whether it was his or his friend's--they stopped at several places on the way down town for further liquid refreshment of which Beekman partook liberally, Harnash sparingly or not at all. It was not difficult for an adroit man like Harnash, confronted by a rather befuddled man like Beekman, to introduce the infallible knock-out drops, with which he had been provided by Woywod, into the liquor.

As they crossed Twenty-third Street on their way down town Harnash stopped the car. His chauffeur lived on East Twenty-third Street, and Harnash dismissed him, saying he would drive the car down to his private garage back of his residence in Washington Mews himself. There was nothing unusual in this; the chauffeur subsequently testified that he had received the same thoughtful consideration from his employer on many previous occasions. When the chauffeur left the car, the drug had not yet got in its deadly work. Beekman was still all right apparently and the chauffeur subsequently testified that when Beekman bade him good-night he noticed nothing strikingly unusual. Beekman seemed to be himself, although the chauffeur could see that he was slightly under the influence of wine.

By the time the car, driven by Harnash with considerable ostentation and as much notice as possible, for he wanted to attract attention to his arrival, reached the garage, Beekman was absolutely unconscious on the floor of the tonneau, to which he had fallen. Harnash ran the car into the garage, closed the doors with a bang, and ran across the intervening court rapidly and noisily and up to his own apartments. He was ordinarily a considerate young man, and coming in at that hour he would have made as little noise as possible, but on this occasion his conduct was different. He stumbled on the stairs, banged the door behind him, fell over a chair in his room, swore audibly. People subsequently testified that they had heard him coming in and one even saw him, quite alone.

Without pausing an unnecessary moment in the room he made his exit from his apartment by means of the fire escape, and this time not a cat could have moved more silently. Fortunately, the back of the house was in deep shadow and there were no lights adjacent. The shadow of the fence also served him. He reentered the garage, having taken precaution the day before secretly to oil the doors. He dragged his unfortunate friend and companion from the limousine, stripped him of his overcoat and automobile cap, which he put on himself. The coat he had previously worn had differed in every particular from that of Beekman. He removed Beekman's watch and other jewelry and his money, of which he carried a considerable sum. These articles he stowed away in his private locker to which his chauffeur did not have a key. He could remove them to his office safe at his leisure. In Beekman's vest pocket he put a large roll of his own money--he could not steal, though abduction was his intent--and then he lifted him to the floor of his runabout which stood in the garage by the side of the limousine.

He next removed the number plates from the car, replaced them with false ones, and ran the car out of the garage by hand. Every part of it had been oiled so that its movement was absolutely noiseless. Then he shoved the car down the street, which was now deserted, until he got some distance away from the garage. The only really risky part of the enterprise was at that moment. Fortune favored him--or not, as the case may be. At any rate, no one appeared. It was after three o'clock in the morning, the street was deserted, and there was not a policeman in sight. He climbed into the car, started it, and drove off.

He proceeded cautiously at first, seeking unfrequented and narrow streets until he got far enough from the garage to change his going to suit his purpose. After a time he sought the broader streets and passed several people, mostly police officers, but them he now took no care to avoid. He drove near them so that they would notice his general build, which was that of his friend, and the clothes he wore, which were those of his friend, and indeed they testified afterward that they had seen a man dressed as and looking like Beekman, exactly as he had anticipated. He drove past them rapidly so as not to give them time for too close a scrutiny. Also he doubled on his trail often.

When he reached a dark, lonely, and unfrequented block near South Water Street he drew up before the door of a dimly lighted, forbidding looking building, the sign on which indicated that it was a sailors' boarding house. He got out of the car, taking precaution to slip on a false mustache and beard with which he had provided himself, and tapped on a door in a certain way which had been indicated to him. The door was at once opened by a burly, rough, villainous looking individual, the boarding house master, obviously a crimp of the worst class.

"What d'ye want?" he growled out, scrutinizing the newcomer by the aid of a gas jet burning inside the dirty, reeking hall, whose feeble light he supplemented by a flash from an electric torch which really revealed little, since Harnash carefully concealed his already disguised face.

"I have something for Mr. Woywod."

"The mate of the Susquehanna?"

"Yes."

"Well, he told me to receive an' deliver what you got."

"That was our agreement," said Harnash, the little dialogue convincing each man that no doubt was to be entertained of the other.

"Well, where's the goods?"

"In the car."

"Fetch him in."

"He's rather heavy. Perhaps you'll give me a hand."

"Oh, all right," answered the man, putting his electric torch in his pocket.

The two went to the car and the man easily picked up the unconscious Beekman and unaided carried him within the door. Harnash followed. He observed the man glanced at the numbers on the car and was glad that he had taken the precaution to change them. The crimp now dropped the unconscious Beekman in the hallway and turned to Harnash. He found the latter standing quietly, but with an automatic pistol in his hand.

"You needn't be afraid of me," said the man.

"I'm not," answered Harnash. He was ghastly pale and extremely nervous, but not from fear of the crimp. "This is just a matter of precaution."

"Well, what do I git out of this yere job?" asked the man.

"I understand Mr. Woywod will settle with you for that."

"Well, he does, but what I gits from him is the price of a foremast hand, an' 'tain't enough."

The crimp bent over Beekman, flashed the light on him, and pulled out the roll of bills, which he quickly counted.

"It's fair, but I'd ought to git more. This here's a swell job; look at them clo'es."

"They're yours also, if you wish."

"That's somethin', but--"

"It's all you'll get," said Harnash, laying his hand on the door.

The man lifted the torch. Harnash lifted the pistol.

"Just put that torch back in your pocket," he said.

"You're a cool one," laughed the man, but he obeyed the order.

"If it is learned tomorrow that this man has disappeared you'll receive through the United States mail in a plain envelope a hundred dollar bill. If not, you get nothing."

"Suppose I croak him, how'd you know anything about it?"

"Mr. Woywod has arranged to inform me, and he will also put your part of the transaction on record, so if you say a word you'll be laid by the heels and get nothing for your pains. There are a number of things against you, I'm told. The police would be most happy to get you, I know. Just bear that in mind."

The man nodded. He knew when the cards were stacked against him. After all, this did not greatly differ from an ordinary job and he was getting, for him, very well paid for his part of it.

"I got relations with Woywod an' lots of other seafarin' men. My business would be ruined if I played tricks on 'em. You can trust me to keep quiet."

"I thought so," answered Harnash. "Good-night."

He opened the door, stepped outside, closed the door behind him, and waited a moment, but the crimp made no effort to follow him. After all, it was only an every day matter with him. Harnash next drove the car down the street near one of the wharves, where he met Woywod.

"Is it all right, George?" asked the latter.

"All right, Bill. He's at the place you told me to leave him. Can you keep the crimp's mouth shut?"

"Trust me for that," said Woywod confidently. "He's mixed up in too many shady transactions to give anybody any information."

"I'll never forget what you've done for me," said Harnash. "Remember, use him well."

"No fear," laughed his friend as the two shook hands and parted.

Then Harnash drove up the street, waited until he came to a dark alley, turned into it, unobserved, got out of the car, put Beekman's coat and hat into it, donned his own overcoat and cap, which he had brought with him, and still wearing the false mustache and beard changed the numbers on the car, started it, and let it wreck itself against the nearest water hydrant.

It was a long walk up town, even to Washington Square, and he had to go very circumspectly because he did not now wish to be seen by anyone. Again fortune favored him. He gained the garage, crossed the court, mounted the fire escape to his rooms, and sank down, utterly exhausted but triumphant.

His defense was absolutely impregnable. No one could controvert his story. He rehearsed it. He had come home with Beekman after the dinner had terminated. They had had one or two drinks on the way. They had dismissed the chauffeur at Twenty-third Street. When they reached the garage Beekman, moved by some sudden whim, had insisted upon going back to his own apartment up town in Harnash's little roadster. He had been drinking, of course. He was not altogether in possession of his normal faculties, but Harnash was in the same condition and therefore he had not been too insistent. Beekman was as capable of driving the car as Harnash had just showed himself to be. There was nothing he could do to prevent Beekman from going away. He could not even remember, when he was questioned, whether he had tried it or not. At any rate, Beekman had gone away in the roadster and Harnash had gone to bed. So dwellers in the building who heard him come in testified. One who happened to go to the window even had seen him come in. No one had seen or heard him go out. Harnash swore that he had not left the apartment until the next morning.

Beekman, or a man dressed as he was known to be dressed, had been seen by the police officers and others between three or four in the morning, driving through the lower part of the city in a small car the number of which no one had seen. What he was doing in that section of the city no one could imagine. During the course of the morning Harnash's car was found, badly smashed from a collision, lying on its side in a wretched alley off South Water Street. Beekman's overcoat and cap were in the car and that was all there was to it.

No matter what suspicions the crimp might have entertained, he kept his mouth shut and received the day after the one hundred dollar bill in an unmarked envelope which had been mailed at the general postoffice in the afternoon. Even if he had spoken, he could not have thrown much light on the situation. Not even the reward which was offered could tempt him. His business demanded secrecy, absolutely and inviolable, and too many men knew too much about him, which rendered it unsafe for him to open his head. He would not kill the goose that laid the golden egg for him by making further business on the same lines impossible. He really knew nothing, anyway.

The secret was shared between two men, Woywod on the sea and out of communication with New York, and Harnash himself. So long as they kept quiet no one would ever know. Even Beekman himself could not solve the mystery when he returned to New York. It was most ingeniously planned and most brilliantly carried out. Harnash congratulated himself. Stephanie Maynard would certainly be his long before Beekman could prevent it. Still, George Harnash was by no means so happy in the present state of affairs as he had planned and hoped to be. And his trials were not over. He had to meet Stephanie, the wedding party, old John Maynard, the public press, and the public--what would the day bring forth?

CHAPTER V

THE WEDDING THAT WAS NOT

Stephanie Maynard had passed a sleepless night. Her love for George Harnash grew stronger and her abhorrence of the marriage increased in the same degree as the hour drew nearer. Too late she repented of her determination. She wondered why she had not allowed Harnash to take her away and end it all. What, after all, were her father's wishes, or her own promises, or the worldly advantages they would gain, or anything else, compared to love?

Harnash had sent word to her the day before that she was not to give up hope, that something would happen surely, but now the last minute was at hand and nothing had happened. A dozen times she started to call her lover on the telephone and a dozen times she refrained. Finally the hour arrived when the victim must be garlanded for the sacrifice. At least, that is the way she regarded it.

She had not heard a word from her husband-to-be during the morning. Under other circumstances that would have alarmed her, but as it was she was only relieved. The wedding party was assembled at the brand new Maynard mansion on upper Fifth Avenue. Two of the attendants were school friends from other cities and they were guests at the house. The wedding was to be followed by a breakfast and a great reception which the Maynard money and the Beekman position was to make the most wonderful affair of the kind that had ever been given in New York.

With the publicity which modern society courts and welcomes, while it pretends to deprecate it, the papers had published reams about the most private details of the engagement, even to descriptions and pictures of the most intimate under-linen of the bride. Presents of fabulous value, which lost nothing in their description by perfervid pens, were under constant guard in the mansion. Details of police kept back swarms of unaccredited reporters and adventurous sightseers. On the morning of the wedding day the street before the Cathedral was packed with the vulgarly curious long before eleven o'clock. The wedding was to be solemnized at high noon, and was to be the greatest social event which had excited easily aroused and intensely curious New York for a year or more.

The newer members of the exclusive social circle frankly enjoyed it. And such is the contagion of degeneration that the older members, while they affected disdain and annoyance, enjoyed it too. The newspapers had played it up tremendously, and the affair had even achieved the signal triumph of a veiled but well understood cartoon by F. Foster Lincoln, the scourge and satirist of high society, in a recent number of Life.

Everything was ready. The most famous caterer in New York had prepared the most sumptuous wedding breakfast. The most exclusive florist had decorated the church and residence. Society had put on its best clothes, slightly deploring the fact that as it was to be a noon wedding its blooming would be somewhat limited thereby. More tickets had been issued to the Cathedral than even that magnificent edifice could hold and it was filled to its capacity so soon as the doors were opened. The famous choir was in attendance to render a musical program of extraordinary beauty and appropriateness.

As it approached the hour of mid-day the excitement was intense. Women in the crowd were crushed, many fainted. Riot calls had to be sent out and the already strong detachment of police supplemented by reserves. Thus is the holy state of matrimony entered into among the busy rich. With the idle poor it is, fortunately, a simpler affair.

It had been arranged that Derrick Beekman and George Harnash should present themselves at the Maynard mansion not later than eleven o'clock. From there they would drive to the Cathedral in plenty of time to receive the wedding party at the chancel steps. At eleven o'clock a big motor forced its way through the crowd and drew up before the door. From it descended George Harnash alone.

That young man showed the effect of the night he had passed. He was excessively nervous and as gray as the gloves he carried in his hands. He was admitted at once and ushered into the drawing room, which was filled with a dozen young ladies in raiment which even Solomon in all his glory might have envied, who were to make up the wedding party. There also had just arrived the young gentlemen who were to accompany them, who had all been at the bachelor dinner. None of them exhibited any evidence of unusual dissipation. They had slept late and were in excellent condition.

"George, alone!" cried young Van Brunt, who was next in importance to the best man, as Harnash entered the room.

"Where's Beekman?" asked Harnash apparently in great surprise, as he glanced at the little group.

"Not here. You were to bring him. It's time for us to get up to the Cathedral anyway. I'll bet the people are clamoring at the doors now."

"They weren't to be opened till eleven-fifteen," said Grant, one of the fittest members of the party. "It's only eleven now. We've plenty of time."

"Well, you better beat it up now, then. Beekman will be here in a minute, I'm sure," said Harnash. "We'll follow you in half an hour."

As the young men who were to usher left the room the girls fell upon Harnash.

"Mr. Harnash," said Josephine Treadway, who was the maid-of-honor, "will you please tell us where Derrick Beekman is, and why you didn't bring him along?"

"I can't," said Harnash. "As a matter of fact I--"

"You'll tell me, certainly," interposed the voice that he loved.

He turned and found that Stephanie, having completed her toilet, had descended the stair and entered the room. She was whiter than Harnash himself, but her lack of color was infinitely becoming to her in her sumptuous bridal robes, and the adoring young man decided then and there that whatever happened she was worth it.

"Mr. Beekman," continued the girl, "was to be here at eleven o'clock with you. It's after that now and you're here alone. Where is he? Why didn't you bring him?"

"Miss Maynard," said Harnash formally, and in spite of himself he could not prevent his lip from trembling, "I don't know where he is."

"What!" exclaimed the girl, really astonished, as the whole assembly broke into exclamations. Had Harnash accomplished the impossible, as he had threatened?

"I can't find him," went on Harnash. He could scarcely sustain Stephanie's direct and piercing gaze. He forced himself to look at her, however. "I don't know where he is," he repeated.

"But have you searched?"

"Everywhere. I called up his apartment on Park Avenue at ten o'clock. They said he wasn't there and hadn't been there all night. I started my man out at once in a taxicab, jumped into my own car, and I've been everywhere--the office, his clubs--I've even had my secretary and clerks telephone all the hotels on the long chance that he might be at one of them."

"And you haven't found a trace of him? George Harnash--" began Stephanie, but Harnash was too quick for her; he did not allow her to finish.

"You will forgive me," he went on; "I did even more than that in my alarm. I finally notified the police on the chance that he might have been er--er--brought in."

He shot a warning look at Stephanie that checked further inquiries from her.

"Why should he be brought in?" asked Josephine Treadway, who had no reason for not asking the question.

"Why, you see," went on Harnash, "it's desperately hard to tell, and I'd rather die than mention it, but under the circumstances I suppose--"

"Out with it at once," cried Stephanie.

"Well, we had a little dinner last night at--well, never mind where."

"We had a dinner, too," said Josephine.

"Yes, but I imagine ours was--er--different. At any rate, it didn't break up until quite late, or, I should say, early in the morning, and we were not--quite ourselves."

"But Derrick is the most abstemious of men."

"Exactly; so am I, and when that kind go under it's worse than--you understand," he added helplessly.

Stephanie nodded.

"When did you see him last?"

"Why--er--I'll make a clean breast of it."

"Do so, I beg you."

"Well, then, we were right enough when the dinner broke up. Derrick and I left the others to their own devices. He had arranged to spend the night with me. We stopped at one or two places down town, but reached my quarters in Washington Square about two or three o'clock."

Harnash paused and swallowed hard. It was an immensely difficult task to which he had compelled himself, although so far he had told nothing but the truth.

"Go on," said Josephine Treadway impatiently as the pause lengthened.

"He changed his mind after we put the limousine in the garage and insisted on going back to his own rooms."

"Did you let him go?"

"I did."

"Why?"

"Well, Miss Treadway, I couldn't help it, and, to be frank, I didn't try. You see we were neither of us very sure of ourselves and--and--"

"I see."

"He took my runabout, drove off and--that's all."

"Have you found the runabout?"

"Yes, the police found it in an alley near South Water Street, badly smashed. Beekman's overcoat and cap were in the car."

"Do you think he has been hurt?" questioned Stephanie, who had listened breathlessly to the conversation between her lover and her maid-of-honor.

"I'm sure that he can't have been," returned Harnash with definiteness which carried conviction to his questioner, and no one else caught the meaning look he shot at her.

"And that's all?" asked Josephine.

"Absolutely all I can tell you," he replied truthfully, none noticing the equivoke but Stephanie, who of course could not call attention to it.

"You poor girl," said Josephine, gathering Stephanie in her arms.

"It's outrageous. It's horrible," cried the girl, biting her lip to keep back her tears.