Title: William Harvey

Author: Sir D'Arcy Power

Release date: August 23, 2014 [eBook #46664]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Neanderthal, Chris Curnow and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Masters of Medicine

| Title. | Author. |

| John Hunter | Stephen Paget |

| William Harvey | D’Arcy Power |

| Edward Jenner | Ernest Hart |

| Sir James Simpson | H. Laing Gordon |

| Hermann von Helmholtz | John G. McKendrick |

| William Stokes | Sir William Stokes |

| Claude Bernard | Michael Foster |

| Sir Benjamin Brodie | Timothy Holmes |

| Thomas Sydenham | J. F. Payne |

| Vesalius | C. Louis Taylor |

| M | |

| asters | |

| of | |

| edicine | |

WILLIAM HARVEY

Art Repro. Co.y Ph. Sc.

Cornelius Jonson Engraved by Hall.

WILLIAM HARVEY.

1578 1657

BY

D’Arcy Power, F.S.A.,

F.R.C.S. Eng.

SURGEON TO THE VICTORIA HOSPITAL FOR CHILDREN,

CHELSEA

LONDON

T. FISHER UNWIN

PATERNOSTER SQUARE

MDCCCXCVII

Copyright by T. Fisher Unwin, 1897, for Great Britain

and Longmans Green & Co. for the

United States of America

To

DR. PHILIP HENRY PYE-SMITH, F.R.S.

IN RECOGNITION OF HIS PROFOUND KNOWLEDGE OF

THE PRINCIPLES ADVOCATED BY HARVEY, AND

IN GRATITUDE FOR MANY KINDNESSES

CONFERRED BY HIM UPON

THE AUTHOR

It is not possible, nor have I attempted in this account of Harvey, to add much that is new. My endeavour has been to give a picture of the man and to explain in his own words, for they are always simple, racy, and untechnical, the discovery which has placed him in the forefront of the Masters of Medicine.

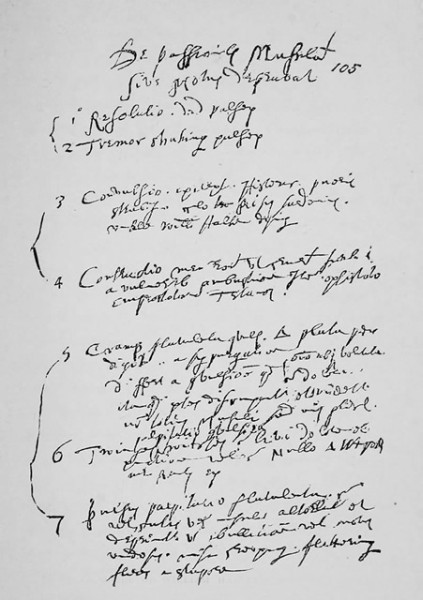

The kindness of Professor George Darwin, F.R.S., and of Professor Villari has introduced me to Professor Carlo Ferraris, the Rector Magnificus, and to Dr. Girardi, the Librarian of the University of Padua. These gentlemen, at my request, have examined afresh the records of the University, and have given me much information about Harvey’s stay there. The Cambridge Archæological Society has laid me under[x] an obligation by allowing me to reproduce the Stemma which still commemorates Harvey’s official connection with the great Italian University. Dr. Norman Moore has read the proof sheets; his kindly criticism and accurate knowledge have added greatly to the value of the work, and he has lent me the block which illustrates the vileness of Harvey’s handwriting.

I have collected in an Appendix a short list of authorities to each chapter that my statements may be verified, for Harvey himself would have been the first to cry out against such a gossiping life as that which Aubrey wrote of him.

D’ARCY POWER.

May 20, 1897.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |||

| I. | HARVEY’S LINEAGE | 1 | |

| II. | EARLY LIFE | 11 | |

| III. | THE LUMLEIAN LECTURES | 39 | |

| IV. | THE ZENITH | 70 | |

| V. | THE CIVIL WAR | 117 | |

| VI. | HARVEY’S LATER YEARS | 141 | |

| VII. | HARVEY’S DEATH, BURIAL, AND EULOGY | 166 | |

| VIII. | HARVEY’S ANATOMICAL WORKS | 188 | |

| IX. | THE TREATISE ON DEVELOPMENT | 238 | |

| APPENDIX | 267 | ||

| INDEX | 271 | ||

WILLIAM HARVEY

The history of the Harvey family begins with Thomas Harvey, father of William, the discoverer of the circulation of the blood. The careful search of interested and competent genealogists has ended in the barren statement that the family is apparently descended from, or is a branch of the same stock as, Sir Walter Hervey, “pepperer,” or member of the ancient guild which afterwards became the important Company of Grocers. Sir Walter was Mayor of London in the year reckoned from the death of Henry III. in November, 1272. It was the noise of the citizens assembled in Westminster Hall clamouring for Hervey’s election as Mayor that disturbed the King’s deathbed.

The lineage would be a noble one if it could be established, for Hervey was no undistinguished Mayor. He was the worthy pupil and successor of Thomas Fitzthomas, one of the great champions in that struggle for liberty which ended in the death of Simon de Montfort, between Evesham and Alcester, but left the kingdom with a Parliament. Hervey’s counsels reconstituted in London the system of civic government, and established it upon its present base; for he assumed as chief of the executive the right to grant charters of incorporation to the craftsmen of the guilds. For a time his efforts were successful, and they wrought him much harm. But his idea survived, and in due season prevailed, for the companies have entirely replaced the guilds not only in London but throughout England.

It would be truly interesting if the first great discoverer in physiology could be shown to be a descendant of this original thinker on municipal government. The statement depends for the present on the fact that both bore for arms “argent, two bars nebulée sable, on a chief of the last three crosses pattée fitchée; with the crest, a dexter hand appaumée proper, over it a crescent inverted argent,” but arms were as often assumed in the reign of Elizabeth as they are in the Victorian era.

Thomas Harvey, the father of William, was born in 1549, and was one of a family of two brothers and three sisters, all of whom left children. Thomas married about 1575 Juliana, the eldest daughter of William Jenkin. His wife died in the following year, probably in childbed, for she left him a daughter, Julian or Gillian, who married Thomas Cullen, of Dover, and died about 1639.

Thomas Harvey married again on the 21st of January, 1576-1577, his second wife being Joane, the daughter of Thomas Halke, or Hawke, who was perhaps a relative of his first wife on her mother’s side. She lived at Hastingleigh, a village about six miles from Ashford in Kent, and to this couple William was born on the 1st of April, 1578, his father being then twenty-nine and his mother twenty-three.

William proved to be the eldest of “a week of sons,” as Fuller quaintly expresses it, “whereof this William was bred to learning, his other brethren being bound apprentices in London, and all at last ended in effect in merchants.” This statement is not strictly true, as only five of the sons became Turkey merchants and there were besides two daughters.

Thomas Harvey was a jurat, or alderman, of Folke[4]stone, where he served the office of mayor in 1600. He lived in a fair stone house, which afterwards became the posthouse. Its site, however, is no longer known, though it is the opinion of those best qualified to judge that it stood at the junction of Church Street with Rendezvous Street.

Thomas Harvey seems to have been a man of more than ordinary intelligence and judgment, for “his sons, who revered, consulted, and implicitly trusted him, made their father the treasurer of their wealth when they got great estates, who, being as skilful to purchase land,” says Fuller, “as they to gain money kept, employed and improved their gainings to their great advantage, so that he survived to see the meanest of them of far greater estate than himself.” To this end he came to London after the death of his wife in 1605, and lived for some time at Hackney, where he died and was buried in June, 1623. His portrait is still to be seen in the central panel in one end wall of the dining-room at Rolls Park, Chigwell, in Essex, which was one of the first estates acquired by his son Eliab. “It is certainly,” says Dr. Willis, “of the time when he lived, and it bears a certain resemblance to some of the likenesses we have of his most distinguished son.”

All that is known of Joan Harvey is on a brass[5] tablet, which still exists to her memory in the parish church at Folkestone. It bears the following record of her virtues, written either by her husband or by William Harvey, her son:—

“A.D. 1605 Nov. 8th died in the 50th. yeare of her age

Joan Wife of Tho. Harvey. Mother of 7 sones & 2 Daughters.

A Godly harmles Woman: A chaste loveinge Wife:

A Charitable qviet Neighbour: A cõfortable frendly Matron:

A provident diligent Hvswyfe: A carefvll tēder-harted Mother.

Deere to her Hvsband: Reverensed of her Children:

Beloved of her Neighbovrs: Elected of God.

Whose Soule rest in Heaven, her body in this Grave:

To her a Happy Advantage: to Hers an Unhappy Loss.”

The children of Thomas and Joan Harvey were—

(1) William, born at Folkestone on the 1st of April, 1578; died at Roehampton, in Surrey, on the 3rd of June, 1657; buried in the “outer vault” of the Harvey Chapel at Hempstead, in Essex.

(2) Sarah, born at Folkestone on the 5th of May, 1580, and died there on the 18th of June, 1591.

(3) John, born at Folkestone on the 12th of November, 1582; servant-in-ordinary, or footman, to James I.—“a post,” says Sir James Paget, “which does not certainly imply that he was in a much lower rank than his brothers. It may have been such a place at Court as is now called by a synonym of more seeming dignity; or, if not, yet he may have received[6] a good salary for the office whilst he discharged its duties by deputy.” Thus Burke in his famous speech on Economical Reform mentions that the king’s turnspit was a member of Parliament.

He received a pension of fifty pounds a year when he resigned his place to Toby Johnson on the 6th of July, 1620. He was a member of Gray’s Inn, and filled several offices of importance, for he was “Castleman” at Sandgate, in Kent, and King’s Receiver for Lincolnshire jointly with his brother Daniel. He sat in Parliament as a member for Hythe, and died unmarried on the 20th of July, 1645.

(4) Thomas was born at Folkestone on the 17th of January, 1584-1585. He married first Elizabeth Exton, about 1613; and, secondly, Elizabeth Parkhurst, on the 10th of May, 1621, and he had children by both marriages. His only surviving son sat as M.P. for Hythe in 1621; he also acted as King’s Receiver for Lincolnshire. Thomas Harvey was a Turkey merchant in St. Laurence Pountney, at the foot of London Bridge. He was perhaps a member of the Grocers’ Company. He died on the 2nd of February, 1622-1623, and was buried in St. Peter-le-Poor.

(5) Daniel, also of Laurence Pountney Hill, a Turkey merchant and member of the Grocers’ Com[7]pany, was born at Folkestone on the 31st of May, 1587. He was King’s Receiver for Lincolnshire jointly with his brother John. He married Elizabeth Kynnersley about 1619, paid a fine rather than serve the office of Sheriff of London at some time before 1640, and died on the 10th of September, 1649. He was a churchwarden of St. Laurence Pountney in 1624-1625, and was buried there; but his later days were spent on his estate at Combe, near Croydon, in Surrey. His fourth son became Sir Daniel Harvey, and was ambassador at Constantinople, where he died in 1672. His daughter Elizabeth married Heneage Finch, the first Earl of Nottingham, and from this marriage are descended the Earls of Winchelsea and Aylesford.

(6) Eliab, also of Laurence Pountney Hill, a Turkey merchant and member of the Grocers’ Company, was born at Folkestone on the 26th of February, 1589-1590. He was the most successful of the merchant brothers, and to his watchful care William owed much of his material wealth; for Aubrey says that “William Harvey took no manner of care about his worldly concerns, but his brother Eliab, who was a very wise and prudent manager, ordered all not only faithfully but better than he could have done for himself.” Eliab had estates at Roehampton, in Surrey,[8] and at Chigwell, in Essex. He built the “Harvey Mortuary Chapel with the outer vault below it” in Hempstead Church, near Saffron Walden. Here he buried his brother William in 1657, and here he was himself buried in 1661. He married Mary West on the 15th of February, 1624-1625, and by her had several children, of whom the eldest at the Restoration became Sir Eliab Harvey.

Walpole writes to Mann about one of his descendants. “Feb. 6, 1780. Within this week there has been a cast at hazard at the Cocoa Tree, the difference of which amounted to an hundred and fourscore thousand pounds. Mr. O’Birne, an Irish gamester, had won £100,000 of a young Mr. Harvey of Chigwell, just started for a midshipman into an estate by his elder brother’s death. O’Birne said, ‘You can never pay me.’ ‘I can,’ said the youth; ‘my estate will sell for the debt.’ ‘No,’ said O’B., ‘I will win ten thousand—you shall throw for the odd ninety.’ They did, and Harvey won.” This midshipman afterwards became Sir Eliab Harvey, G.C.B., in command of the Téméraire at the battle of Trafalgar, and Admiral of the Blue. He sat in the House of Commons for the town of Maldon from 1780 to 1784, and for the county of Essex from 1802 until his death in 1830.[9] With him the male line of the family of Harvey became extinct.

(7) Michael, the twin brother of Matthew, was born at Folkestone on the 25th of September, 1593. He lived in St. Laurence Pountney, and St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate. Like his other brothers he was a Turkey merchant, and perhaps a member of the Grocers’ Company. He married Mary Baker on the 29th of April, 1630, and after her death Mary Millish, about 1635. He had three children by his second wife, and one of his sons died at Bridport in 1685 from wounds received in the service of King James II. Michael Harvey died on the 22nd of January, 1642-1643, and is buried in the church of Great St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate.

(8) Matthew, the twin brother of Michael, and like him a Turkey merchant and perhaps a member of the Grocers’ Company, was born at Folkestone on the 25th of September, 1593. He married Mary Hatley on the 15th of December, 1628, and dying on the 21st of December, 1642, was buried at Croydon. His only child died in her infancy.

(9) Amye, the youngest daughter and last child of Thomas and Joan Harvey, was born at Folkestone on the 26th of December, 1596. She married George[10] Fowke in 1615, and died, leaving issue, at some time after 1645.

Mr. W. Fleming, the assistant librarian, tells me that nine autotype reproductions of the portraits of the Harvey family at Rolls Park (page 4) are now suspended on the left-hand side wall of the hall of the Royal College of Physicians in Pall Mall. They represent (1) Thomas Harvey and his seven sons. (2) William Harvey, probably an enlarged portrait of that in the preceding group. (3) A family group in the dress of the Queen Anne period. (4) Portrait of a lady in the dress of the reign of Queen Elizabeth; in the corner of the picture appears “obiit 25 Maii 1622.” (5), (6) and (7) Portraits of ladies in the dress of the eighteenth century. (8) Portrait of a gentleman in the dress of Charles II.’s time. (9) Portrait of a gentleman in the dress of Queen Anne’s reign.

Very little is known of the early life of William Harvey. His preliminary education was probably carried on in Folkestone, where he learnt the rudiments of knowledge, gaining his first acquaintance with Latin. One of his earliest distinct recollections must have been in the memorable days in July, 1588, when all was bustle and commotion in his native town. The duty of resisting the Spanish Armada in Kent and Sussex fell upon the “Broderield,” or confederation of the Cinque Ports, a body which consisted of the Mayor, two elected Jurats, and two elected Commoners from Hastings, Sandwich, Dover, Romney, Hythe, Winchelsea, and Rye. And as Folkestone for all purposes of defence was intimately allied with Dover, it is not at all unlikely that Thomas Harvey, one of its Jurats, was of its number, or that[12] he was a member of the “Guestling,” which, affiliated with the Broderield, had to fix the number, species, and tonnage of the shipping to be found by each port, a somewhat difficult task, as each port’s share was a movable quantity requiring constant rearrangement. But even with the machinery of the Broderield and the Guestling, it must have needed much activity to raise the £43,000 which the Cinque Ports contributed to set out the handy little squadron of thirteen sail which did its duty under the orders of Lord Henry Seymour in dispersing the remains of the great Spanish fleet. Harvey must have had some remembrance of the turmoil of the period, though it may have been partially effaced by his new experiences at the King’s School, Canterbury, where he was entered for the first time in the same year.

He remained at the King’s School for five years, no doubt coming home for the holidays, some of which must have been spent in watching the constant transport of troops to Spain and Portugal which was so noticeable a feature in the history of the Cinque Ports during the later years of the life of Elizabeth.

His schooling ended, Harvey entered at once as a pensioner, or ordinary student, at Caius College, Cambridge, his surety being George Estey. The[13] record of his entry still exists in the books of the College. It runs: “Gul. Harvey, Filius Thomae Harvey, Yeoman Cantianus, ex oppido Folkeston, educatus in Ludo Literario Cantuar. natus annos 16, admissus pensionarius minor in commeatum scholarium, ultimo die Mai 1593.” (William Harvey, the son of Thomas Harvey, a yeoman of Kent, of the town of Folkestone, educated at the Canterbury Grammar School, aged 16 years, was admitted a lesser pensioner at the scholars’ table on the last day of May, 1593.)

The choice of the college seems to show that Harvey was already destined by his father to follow the medical profession. His habits of minute observation, his fondness for dissection and his love of comparative anatomy had probably shown the bias of his mind from his earliest years. Thirty-six years before Harvey’s entry, Gonville Hall had been refounded as Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, by Dr. Caius, who was long its master. Caius, in addition to his knowledge of Greek, may be said to have introduced the study of practical anatomy into England. His influence obtained for the college the grant of a charter in the sixth year of the reign of Queen Elizabeth, a charter by which the Master and Fellows were allowed to take annually the bodies of two criminals condemned to[14] death and executed in Cambridge or its Castle free of all charges, to be used for the purposes of dissection, with a view to the increase of the knowledge of medicine and to benefit the health of her Majesty’s lieges, without interference on the part of any of her officials. Unfortunately no record has been kept as to the use which the college made of this privilege, nor are there any means of ascertaining whether Harvey did more than follow the ordinary course pursued by students until he graduated as a Bachelor of Arts in 1597. His education, in all probability, had been wholly general thus far, consisting of a sound knowledge of Greek, a very thorough acquaintance with Latin, and some learning in dialectics and physics. He was now to begin his more strictly professional studies, and the year after he had taken his Arts degree at Cambridge found him travelling through France and Germany towards Italy, where he was to study the sciences more nearly akin to medicine, as well as medicine itself.

The great North Italian Universities of Bologna, Padua, Pisa, and Pavia, were then at the height of their renown as centres of mathematics, law, and medicine. Harvey chose to attach himself to Padua, and many reasons probably influenced him in his[15] choice. The University was specially renowned for its anatomical school, rendered famous by the labours of Vesalius, the first and greatest of modern anatomists, and by the work of his successor, Fabricius, born at Aquapendente in 1537. Caius had lectured on Greek in Padua, and some connection between his college at Cambridge and his old University may still have been maintained, though it was now nearly a quarter of a century since his death. The fame of Fabricius and his school was no doubt the chief reason which led Harvey to Padua, but there was an additional reason which led his friends to concur cheerfully in his resolve. Padua was the University town of Venice, and the tolerance which it enjoyed under the protection of the great commercial republic rendered it a much safer place of residence for a Protestant than any of the German Universities, or even than its fellows in Italy. The matriculation registers which have recently been published show how large a number of its medical and law students were drawn from England and the other Protestant countries of Europe, and the English and Scotch “nation” existed in Padua as late as 1738, when the days of mediæval cosmopolitanism were elsewhere rapidly passing away.

The Universities of Europe have always been of two[16] types, the one Magistral, like that of Paris, with which we are best acquainted, for Oxford and Cambridge are modelled on Paris, and the Masters of Arts form the ruling body; the other, the Student Universities, under the control of the undergraduates, of which Bologna was the mother. Hitherto Harvey had been a member of a Magistral University, now he became attached to a University of Students, for Padua was an offshoot of Bologna. Hitherto he had received a general education mainly directed by the Church, now he was to follow a special course of instruction mainly directed by the students themselves, for they had the power of electing their own teachers, and in these points lies the great difference between a University of Masters and a University of Students.

In 1592 there were at Padua two Universities, that of the jurists, and that of the humanists—the Universitas juristarum and the Universitas artistarum. The jurists’ University was the most important, both in numbers and in the rank of its students; the artistarum Universitas consisted of the faculties of divinity, medicine, and philosophy. It was the poorer, and in some points it was actually under the control of the jurists. In each university the students were enrolled according to their nationality into a series of “nations.” [17] Each nation had the power of electing one, and in some cases two, representatives—conciliarii—who formed with the Rectors the executive of the University. The conciliarii, with the consent of one Rector, had the power of convening the congregation or supreme governing body of the University, which consisted of all the students except those poor men who lived “at other’s expense.”

Harvey went to Padua in 1598, but it appears to be impossible to recover any documentary evidence of his matriculation, though it would be interesting to do so, as up to the end of the sixteenth century each entry in the register is accompanied by a note of some physical peculiarity as a means of identifying the student. Thus:—

“D. Henricus Screopeus, Anglus, cum naevo in manu sinistrâ, die nonâ Junii, 1593.” [Mr. Henry Scrope, an Englishman, with a birthmark on his left hand (matriculated), 9 June, 1593.]

“Johannes Cookaeus, anglus, cum cicatrice in articullo medii digiti die dicta.” [John Cook, an Englishman, with a scar over the joint of his middle finger (matriculated) on the same day (9 June, 1593).] And at another time, “Josephus Listirus, anglus, cum parva cicatrice in palpebra dextera.” [Joseph Lister, an[18] Englishman, with a little scar on his right eyebrow (matriculated on the 21st of November, 1598).]

Notwithstanding Harvey entered at Padua in 1598 no record of him has been found before the year 1600, although Professor Carlo Ferraris, the present Rector Magnificus and Dr. Girardi, the Librarian of the University, have, at my request, made a very thorough examination of the archives.

Dr. Andrich published in 1892 a very interesting account of the English and Scotch “nation” at Padua with a list of the various persons belonging to it. This register contains the entry, “D. Gulielmus Ameius, Anglus,” the first in the list of the English students in the Jurist University of Padua for the new century as it heads the year 1600-1601, and a similar entry occurs in 1601-1602. There are also entries about this person which show that at the usual time of election, that is to say, on the 1st of August in the years 1600, 1601, and 1602, he was elected a member of the council (conciliarius) of the English nation in the Jurist University of Padua. His predecessors, colleagues, and successors in the council usually held office for two years. He was therefore either elected earlier into the council, or he was resident in the university for a somewhat longer time than the majority of the students.

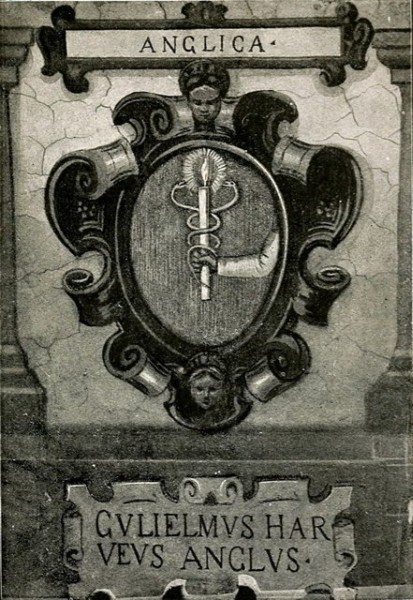

Prof. Ferraris and Dr. Girardi have carefully examined this entry for me, and they assure me that there is no doubt that in the original the word is Arveius and not Ameius and that it refers to William Harvey. They are confirmed in this idea by the discovery of his “Stemma” as a councillor of the English nation for the year 1600. Stemmata are certain tablets erected in the university cloisters and in the hall or “Aula Magna” (which is on the first floor) to commemorate the residence in Padua of many doctors, professors, and students. They are sometimes armorial and sometimes symbolical. In 1892 Professor George Darwin carried an address from the University of Cambridge to that of Padua on the occasion of the tercentenary celebration of the appointment of Galileo to a Professorship in Padua. Professor Darwin then made a careful examination of these monuments so far as they related to Cambridge men, but he was unable to find any memorial of Harvey. Professor Ferraris continued the search, and on the 20th of March, 1893, he wrote to Professor Darwin: “We have succeeded in our search for the arms of Harvey. We have discovered two in the courtyard in the lower cloister. The first is a good deal decayed and the inscription has disap[20]peared; but the second is very well preserved and we have also discovered the inscription under a thin coating of whitewash which it was easy to remove.” The monuments, which are symbolical, though Harvey was a gentleman of coat armour, are situated over the capitals of the columns in the concavity of the roof, one being in the left cloister, the other in the cloister opposite to the great gate of the court of the palace.

The kindness of Professor George Darwin has enabled me to reproduce this “stemma” from a photograph made for the Cambridge Antiquarian Society’s publications. The memorial consists of an oval shield with a florid indented border having a head carved at each end of the oval. The shield shows a right arm which issues from the sinister side of the oval and holds a lighted candle round which two serpents are twined. Traces of the original colouring (a red ground, a white sleeved arm, and green serpents) remained on one of the monuments, and both have now been accurately restored by the Master and Fellows of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. A coloured drawing of the tablet has also been made at the expense of the Royal College of Physicians of London, and is now in their possession. A replica of this drawing was[21] presented by the University Senate of Padua to Gonville and Caius College on the occasion of the dinner given in their hall in June, 1893, to commemorate the admission of Harvey to the college on the 31st of May, 1593.

It appears, therefore, that Harvey was a member of the more aristocratic Universitas Juristarum at Padua, which admitted a few medical and divinity students into its ranks, and that he early attained to the position of conciliarius of his nation. As a conciliarius Harvey must have taken part more than once in one of the most magnificent ceremonials which the university could show—the installation of a new Rector. The office of Rector was biennial, the electors being the past rectors, the councillors, and a great body of special delegates. The voting was by ballot, a Dominican priest acting as the returning officer. The ceremony took place in the Cathedral in the presence of the whole university. Here the Rector elect was solemnly invested with the rectorial hood by one of the doctors, and he was then escorted home in triumph by the whole body of students, who expected to be regaled with a banquet, or at the least with wine and spices. Originally a tilt or tournament was held, at which the new rector was required to[22] provide two hundred spears and two hundred pairs of gloves; but this practice had been discontinued for some time before Harvey came into residence. A remarkable custom, however, remained, which allowed the students to tear the clothes from the back of the newly elected rector, who was then called upon to redeem the pieces at an exorbitant rate. So much license attended the ceremony that a statute was passed in 1552 to restrain “the too horrid and petulant mirth of these occasions,” but it did not venture to abolish the time-honoured custom of the “vestium laceratio.”

To make up for the magnificence of these scenes the Paduan student underwent great hardships. Food was scanty and bad, forms were rough, the windows were mere sheets of linen, which the landlord was bound to renew as occasion required; but to this Harvey was accustomed, for as late as 1598 the rooms of some of the junior fellows at King’s College, Cambridge, were still unprovided with glass. Artificial light was ruinously expensive, and there was an entire absence of any kind of amusement.

The medical session began on St. Luke’s Day in each year, when there was an oration in praise of medicine followed by High Mass and the Litany[23] of the Holy Ghost. The session lasted until the Feast of the Assumption, on August 15th, and in this time the whole human body was twice dissected in public by the professor of Anatomy. The greater part of the work in the university was done between six and eight o’clock in the morning, and some of the lectures were given at daybreak, though Fabricius lectured at the more reasonable hour (horà tres de mane) which corresponded with nine o’clock before noon.

Hieronymus Fabricius was at once a surgeon, an anatomist, and the historian of medicine; and as he was one of the most learned so he was one of the most honoured teachers of his day. Amongst the privileges which the Venetian Senate conferred upon the rector of the University of Padua was the right to wear a robe of purple and gold, whilst upon the resignation of his office he was granted the title for life of Doctor, and was presented with the golden collar of the Order of St. Mark. Fabricius, like the Rector, was honoured with these tokens of regard. He was granted precedence of all the other professors, and in his old age the State awarded him an annual pension of a thousand crowns as a reward for his services. The theatre in which he lectured still exists. It is now an ancient building with circular[24] seats rising almost perpendicularly one above another. The seats are nearly black with age, and they give a most venerable appearance to the small apartment, which is wainscoted with curiously carved oak. The lectures must have been given by candlelight, for the building is so constructed that no daylight can be admitted. But when Harvey was at Padua the theatre was new, and the Government had placed an inscription over the entrance to commemorate the liberality as well as the genius of Fabricius, who had built the former theatre at his own expense. Here Harvey sat assiduously during his stay in Padua, learning charity, perhaps, as well as anatomy from his master; for Fabricius had at home a cabinet set apart for the presents which he had received instead of fees, and over it he had placed the inscription, “Lucri neglecti lucrum.”

Fabricius was more than a teacher to Harvey, for a fast friendship seems to have sprung up between master and pupil. Fabricius—then a man of sixty-one he lived to be eighty-two—was engaged during Harvey’s residence in Padua in perfecting his knowledge of the valves of the veins. The valves had been known and described by Sylvius of Louvilly (1478-1555), that old miser, but prince of lecturers, who[25] warmed himself in the depth of a Parisian winter by playing ball against the wall of his room rather than be at the expense of a fire, and who threatened to close the doors of his class-room until two defaulting students either paid their fees or were expelled by their fellows. But the work of Sylvius had fallen into oblivion and Fabricius rediscovered the valves in 1574. His observations were not published until 1603, when they appeared as a small treatise “de venarum ostiolis.” There is no doubt that he demonstrated their existence to his class, and Harvey knew of the treatise, though it was published a year after he had returned to England. Indeed, when we look at Harvey’s work, much of it appears to be a continuation and an amplification of that done by Fabricius. Both were intensely interested in the phenomena of development; both wrote upon the structure and functions of the skin; both studied the anatomy of the heart, lungs, and blood vessels; both wrote a treatise “de motu locali.” Harvey’s youth, his comparative freedom from the trammels of authority, and his more logical mind, enabled him to outstrip his master and to avoid the errors into which he had fallen. This advance is particularly well seen in connection with the valves of the veins. Fabricius taught that their purpose[26] was to prevent over-distension of the vessels when the blood passed from the larger into the smaller veins (a double error) whilst they were not needed in the arteries because the blood was always in a state of ebb and flow. It was left for Harvey to point out their true use and to indicate their importance as an anatomical proof of the circulation of the blood.

Harvey graduated as Doctor of Medicine at Padua in 1602 in the presence, it is said, of Fortescue, Willoughby, Lister, Mounsell, Fox [disguised in the Records as Vulperinus], and Darcy, some of whom remained his friends throughout life. The eulogistic terms in which his diploma is couched leave no doubt that his abilities had made a deep impression upon the mind of his teachers. By some means it came into the hands of Dr. Osmond Beauvoir, head master of the King’s School, Canterbury, by whom it was presented to the College of Physicians of London on September 30, 1766. The diploma is dated April 25, 1602, and it confers on Harvey the degree of Doctor of Physic, with leave to practise and to teach arts and medicine in every land and seat of learning. It further recites that “he had conducted himself so wonderfully well in the examination, and had shown such skill, memory, and[27] learning that he had far surpassed even the great hopes which his examiners had formed of him. They decided therefore that he was skilful, expert, and most efficiently qualified both in arts and medicine, and to this they put their hands, unanimously, willingly, with complete agreement, and unhesitatingly.”

Armed with so splendid a testimonial Harvey must have returned at once to England, for he obtained the degree of Doctor of Medicine from the University of Cambridge in the same year. The University records of Padua seemed to show that he maintained a somewhat close relationship with his Italian friends for some years afterwards as the following entries appear:—

“1608-9 xxi. julii d. Gulielmus Herui, anglus.

ix-xxx d. Gulielmus Heruy.

30 D. Gulielmus Heruy anglus die xx aug. cons. anglicae electus.”

The entries are given as they stand in Dr. Andrich’s book, “De natione Anglica.” They need further elucidation, for they either refer to some other person of the name of Harvey, or they point to visits made by Harvey in some of his numerous continental journeys. It is somewhat remarkable that all the records are found in the annals of the jurist university[28] when Harvey should have belonged to the humanists. Perhaps the prestige of the dominant University more than compensated for the separation from his colleagues who were studying medicine. Indeed the separation may have been only nominal, for the students of the humanist and jurist universities might have sat side by side in the lecture theatre and in the dissecting room, just as members of the different colleges still do in Oxford. But party distinctions ran high at the time, and there was probably no more social intercourse between the members of the two universities than there is now between the individuals of different corps in a German university.

Soon after his return to England Harvey seems to have taken a house in London, in the parish of St. Martin’s, extra Ludgate, and he lost no time in attaching himself to the College of Physicians. This body had the sole right of licensing physicians to practise in London and within seven miles of the City. Admission to the College was practically confined to graduates in medicine of the English Universities, but those who held a diploma from a foreign university were allowed to enrol themselves if they produced letters testimonial of admission ad eundem at Oxford or Cambridge, and perhaps it was for this[29] reason that Harvey proceeded to qualify himself by taking his M.D. degree at Cambridge. He was admitted a Candidate of the College of Physicians on October 5, 1604, in the stone house, once Linacre’s, in Knightrider Street, the candidates being the members or commonalty of the College from whom its Fellows were chosen.

Harvey married a few weeks after his admission to the College of Physicians. The Registers of St. Sepulchre’s Church are wanting at this time, but the allegation for his marriage licence is still extant. It was issued by the Bishop of London and runs:—

“1604 Nov. 24. William Harvey, Dr. of Physic, Bachelor, 26, of St. Martin’s, Ludgate, and Elizabeth Browne, Maiden, 24, of St. Sepulchre’s, daughter of Lancelot Browne of same, Dr. of Physic who consents; consent also of Thomas Harvey, one of the Jurats of the town of Folston in Kent, father of the said William; at St. Sepulchre’s Newgate.”

Dr. Browne was physician to Queen Elizabeth and to James I. He died the year following the marriage of his daughter.

Harvey’s union was childless, and we know nothing of Mrs. Harvey except that she died before her husband, though she was alive in 1645, when John Harvey died and left her a hundred pounds. She is[30] incidentally mentioned by her husband in the following account of an accomplished parrot, who was Mrs. Harvey’s pet. Through a long life the parrot maintained the masculine character until in one unguarded moment she lost both life and reputation.

“A parrot, a handsome bird and a famous talker, had long been a pet of my wife’s. It was so tame that it wandered freely through the house, called for its mistress when she was abroad, greeted her cheerfully when it found her, answered her call, flew to her, and aiding himself with beak and claws, climbed up her dress to her shoulder, whence it walked down her arm and often settled upon her hand. When ordered to sing or talk, it did as it was bidden even at night and in the dark. Playful and impudent, it would often seat itself in my wife’s lap to have its head scratched and its back stroked, whilst a gentle movement of its wings and a soft murmur witnessed to the pleasure of its soul. I believed all this to proceed from its usual familiarity and love of being noticed, for I always looked upon the creature as a male on account of its skill in talking and singing (for amongst birds the females rarely sing or challenge one another by their notes, and the males alone solace their mates by their tuneful warblings) ... until ... not long[31] after the caressings mentioned, the parrot, which had lived for so many years in health, fell sick, and by and by being seized with repeated attacks of convulsions, died, to our great sorrow, in its mistress’s lap, where it had so often loved to lie. On making a post-mortem examination to discover the cause of death I found an almost complete egg in its oviduct, but it was addled.”

There are no means of knowing how Harvey spent the first few years of his married life in London, though it is certain that he was not idle. He was probably occupied in making those observations on the heart and blood vessels which have since rendered his name famous. Indeed his lectures show an intimate acquaintance with the anatomy of more than sixty kinds of animals, as well as a very thorough knowledge of the structure of the human body, and such knowledge must have cost him years of patient study. At the same time he practised his profession, and won for himself the good opinion of his seniors.

He was elected a Fellow of the College of Physicians, June 5, 1607, and thereupon he sought almost immediately to attach himself to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.

The offices in the hospital at that time were usually granted in reversion—that is to say, a successor was appointed whilst the occupant was still in possession. Following this custom the hospital minutes record that—

“At a Court [of Governors] held on Sunday, the 25th

day of February, Anno Domini 1608-9,

“In presence of Sir John Spencer, Knight, President

(and others).

“Mr.[1] Dr. Harvey

“This day Mr. William Harvey Doctor of Physic made suit for the reversion of the office of the Physician of this house when the same shall be next void and brought the King’s Majesty his letters directed to the Governors of this house in his behalf, and showed forth a testimony of his sufficiency for the same place under the hand of Mr. Doctor Adkynson president of the College of the physicians and diverse other doctors of the auncientest of the said College. It is granted at the contemplation of his Majesty’s letters that the said Mr. Harvey shall have the said office next after the decease or other departure of[33] Mr. Doctor Wilkenson who now holdeth the same with the yearly fee and duties thereunto belonging, so that then he be not found to be otherwise employed, that may let or hinder the charge of the same office, which belongeth thereunto.”

This grant practically gave Harvey the position which is now occupied by an assistant physician, as one who was appointed to succeed to an office in this manner was usually called upon to discharge its duties during the absence or illness of the actual holder. Harvey seems to have carried out his duties with tact and zeal, for Dr. Wilkinson, himself a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, gave him the benefit of his professional experience and remained his friend.

It seems possible that John Harvey’s position at Court enabled him to obtain from the King the letters recommendatory which rendered his brother’s application so successful at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. However this may be, Harvey did not long occupy the subordinate position, for Dr. Wilkinson died late in the summer of 1609, and on August 28 in the same year Harvey offered himself to the House Committee “to execute the office of physician of this house until Michaelmas next, without any recompense[34] for his pains herein, which office Mr. Doctor Wilkinson, late deceased, held. And Mr. Doctor Harvey being asked whether he is not otherwise employed in any other place which may let or hinder the execution of the office of the physician toward the poor of this hospital hath answered that he is not, wherefore it is thought fit by the said governors that he supply the same office until the next Court (of governors). And then Mr. Doctor Harvey to be a suitor for his admittance to the said place according to a grant thereof to him heretofore made.” The form of his election therefore was identical with that which is still followed at the Hospital in cases of an appointment to an uncontested vacancy. The House Committee or smaller body of Governors recommend to the whole body or Court of Governors with whom the actual appointment lies.

Harvey performed his duties as physician’s substitute at the hospital until—

“At a Court [of Governors] held on Sunday the 14th

day of October 1609.

“In presence of Sir John Spencer, Knight, President

(and others).

“Dr. Harvey.

“This day Mr. William Harvey Doctor of Physic[35] is admitted to the office of Physician of this Hospital, which Mr. Dr. Wilkenson, deceased, late held, according to a former grant made to him and the charge of the said office hath been read unto him.”

The charge runs in the following words; it is dated the day of Harvey’s election:—

“October 14, 1609.

“The Charge of the Physician of St. Bartholomew’s

Hospital.

“Physician.

“You are here elected and admitted to be the physician for the Poor of this Hospital, to perform the charge following, That is to say, one day in the week at the least through the year or oftener as need shall require you shall come to this hospital and cause the Hospitaller, Matron, or Porter to call before you in the hall of this hospital such and so many of the poor harboured in this hospital as shall need the counsell and advice of the physician. And you are here required and desired by us, in God his most holy name, that you endeavour yourself to do the best of your knowledge in the profession of physic to the poor then present, or any other of the poor at any time of the week which shall be sent home unto you by the[36] Hospitaller or Matron for your counsel, writing in a book appointed for that purpose such medicines with their compounds and necessaries as appertaineth to the apothecary or this house to be provided and made ready for to be ministered unto the poor, every one in particular according to his disease. You shall not, for favour, lucre, or gain, appoint or write anything for the poor but such good and wholesome things as you shall think with your best advice will do the poor good, without any affection or respect to be had to the apothecary. And you shall take no gift or reward of any of the poor of this house for your counsel. This you will promise to do as you shall answer before God, and as it becometh a faithful physician, whom you chiefly ought to serve in this vocation, is by God called unto and for your negligence herein, if you fail, you shall render account. And so we require you faithfully to promise in God his most holy name to perform this your charge in the hearing of us, with your best endeavour as God shall enable you so long as you shall be physician to the poor of this hospital.”

Dr. Norman Moore says that, as physician, Harvey sat once a week at a table in the hall of the hospital, and that the patients who were brought to him sat by[37] his side on a settle—the apothecary, the steward, and the matron standing by whilst he wrote his prescriptions in a book which was always kept locked. The hall was pulled down about the year 1728, but its spacious fireplace is still remembered because, to maintain the fire in it, Henry III. granted a supply of wood from the Royal Forest at Windsor. The surgeons to the hospital discharged their duties in the wards, but the physician only went into them to visit such patients as were unable to walk.

The office of physician carried with it an official residence rented from the governors of the hospital at such a yearly rent and on such conditions as was agreed upon from time to time. Harvey never availed himself of this official residence, for at the time of his election he was living in Ludgate, where he was within easy reach of the hospital. For some reason, however, it was resolved at a Court of Governors, held under the presidency of Sir Thomas Lowe on July 28, 1614, that Harvey should have this residence, consisting of two houses and a garden in West Smithfield adjoining the hospital. The premises were let on lease at the time of the grant, but the tenure of Harvey or of his successor was to begin at its expiration. The lease did not fall in until 1626,[38] when Harvey, after some consideration, decided not to accept it. It was therefore agreed, on July 7, 1626, that his annual stipend should be increased from £25 to £33 6s. 8d. In these negotiations, as well as in some monetary transactions which he had with the steward of the hospital at the time of his election as physician to the hospital, we seem to see the hand of Eliab, for throughout his life William was notoriously open-handed, indifferent to wealth, and constitutionally incapable of driving a bargain.

Until the year 1745 the teaching of Anatomy in England was vested in a few corporate bodies, and private teaching was discouraged in every possible way, even by fine and imprisonment. The College of Physicians and the Barber Surgeons’ Company had a monopoly of the anatomical teaching in London. In the provinces the fragmentary records of the various guilds of Barber Surgeons show that many of them recognised the value of a knowledge of Anatomy as the foundation of medicine. In the universities there were special facilities for its teaching. But subjects were difficult to procure, and dissection came to be looked upon as part of a legal process so inseparably connected with the death penalty for crime that it was impossible to obtain even the body of a “stranger” for anatomical purposes.

The Act of Parliament which, in 1540, united the Guild of Surgeons with the Company of Barber Surgeons in London especially empowered the masters of the united company to take yearly the bodies of four malefactors who had been condemned and put to death for felony for their “further and better knowledge, instruction, insight, learning, and experience in the science and faculty of surgery.” Queen Elizabeth, following this precedent, granted a similar permission to the College of Physicians in 1565. The Charter allowed the President of the College of Physicians to take one, two, three, or four bodies a year for dissection. The radius from which the supply might be obtained was enlarged, so that persons executed in London, Middlesex, or any county within sixteen miles might be taken by the college servants.

The proviso would appear to be unnecessary, considering the great number of executions which then took place and the small number of bodies which were required, but it probably enabled the subjects to be obtained with greater ease. The executions in London were witnessed by great crowds, who often sided with the friends of the felons, and rendered it impossible for the body to be taken away for dissection. The Charter of James I. enlarged these powers by[41] allowing the College of Physicians to take annually the bodies of six felons executed in London, Middlesex, or Surrey.

Little is known in detail of the manner in which Anatomy was taught by the College of Physicians, but the labours of Mr. Young and Mr. South have given us an accurate picture of the way in which it was carried out by the Barber Surgeons in London. We may be sure that in so conservative an age the methods did not differ greatly at the two institutions, especially as the Barber Surgeons usually enlisted the services of the better trained physicians to teach their members both Anatomy and Surgery.

Anatomy was taught practically in a series of demonstrations upon the body; but as there was no means of preserving the subject, it had to be taught by a general survey rather than in minute detail. The method adopted was the one still followed by the veterinary student. A single body was dissected to show the muscles (this was the muscular lecture); another to show the bones (the osteological lecture); another to show the parts within the head, chest, and abdomen (the visceral lecture). The osteological lecturer was not always identical with the visceral lecturer, nor he with the lecturer upon the muscles,[42] though some great teachers, like Reid and Harvey, gave a course upon each subject.

The Demonstrations usually took place four times a year, and were called Public Anatomies, because the subject was generally a public body—that is to say, it was a felon executed for his misdeeds. There was also an indefinite number of Private Anatomies. The attendance of surgeons at the Public Anatomies was compulsory. The attendance at the Private Anatomies was by invitation. It was illegal for any surgeon to dissect a human body in the City of London, or within a radius of seven miles, without permission of the Barber Surgeons’ Company; and in 1573 the Company’s Records for May 21st contain the minute: “Here was John Deane and appointed to bring in his fine of ten pounds (for having an Anatomy in his house contrary to an order in that behalf) between this and Midsummer next”—an enormously heavy punishment when we remember the relative value of money in those days. Whenever a surgeon wished to dissect a particularly interesting subject, it was termed a Private Anatomy, and it was generally performed at the Hall of the Company after due permission had been asked for and obtained, the surgeon inviting his own friends and pupils, the Company inviting whom it chose.

Every effort was made to insure the punctual attendance at the public or compulsory anatomies, for it was enacted in 1572 that every man of the Company using the mystery or faculty of surgery, be he freeman, foreigner, or alien stranger, shall come unto the Anatomy lecture, being by the beadle warned thereto. And for not keeping their hour, both in the forenoon and also in the afternoon, and being a freeman, shall forfeit and pay at every time fourpence. The foreigner (or one who was not free of the Company) in like manner, and the stranger sixpence. The said fines and forfeits to be employed by the anatomists for their expenses. Excuses were sometimes admitted, for a few years earlier Robert Mudsley “hath licence to be absent from all lecture days without payment of any fine because he hath given over exercising of the art of Surgery and doth occupy only a silk shop and shave.” In later years, the higher the position of the defaulter in the Company, the heavier was his fine for non-attendance; so that the assistants of the Company, who corresponded to the Council of the present Royal College of Surgeons, were fined 3s. 4d. for each lecture they missed.

Every effort was made to render the lectures[44] successful. The best teachers were obtained; they were paid liberally, and each lecturer or reader was himself assisted by two demonstrators. Each course lasted three days—a lecture in the morning, a lecture in the afternoon, and a feast between the two lectures. As the anatomies were a public show, we may feel sure that Pepys attended one, and, as usual, he gives a perfectly straightforward account of the proceedings. He records under the date February 27, 1662-1663: “Up and to my office.... About eleven o’clock Commissioner Pett and I walked to Chyrurgeon’s Hall (we being all invited thither, and promised to dine there), where we were led into the Theatre: and by and by comes the reader Dr. Tearne, with the Master and Company in a very handsome manner: and all being settled, he begun his lecture, this being the second upon the kidneys, ureters, &c., which was very fine; and his discourse being ended, we walked into the Hall, and there being great store of company, we had a fine dinner and good learned company, many Doctors of Phisique, and we used with extraordinary great respect.... After dinner Dr. Scarborough took some of his friends, and I went along with them, to see the body alone, which we did, which was a lusty fellow, a seaman that was hanged for a robbery.[45] I did touch the dead body with my bare hand: it felt cold, but methought it was a very unpleasant sight.... Thence we went into a private room, where I perceive they prepare the bodies, and there were the kidneys, ureters, &c., upon which he read to-day, and Dr. Scarborough, upon my desire and the company’s, did show very clearly the manner of the disease of the stone and the cutting, and all other questions that I could think of.... Thence with great satisfaction to me back to the Company, where I heard good discourse, and so to the afternoon lecture upon the heart and lungs, &c., and that being done we broke up, took leave and back to the office, we two, Sir W. Batten, who dined here also, being gone before.” Pepys’ interest in this particular lecture lay in the fact that he had himself been cut for stone, a disease which seems to have been hereditary in his mother’s family. Dr. Scarborough, who had been the Company’s lecturer for nineteen years, was the friend and pupil of Harvey, whose interest had obtained the post for him. He seems to have been succeeded by Dr. Christopher Terne, assistant physician to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, whose lecture Pepys heard.

The cost of the lectures and demonstrations was[46] defrayed at first by the Corporations, but in course of time, benefactors came forward and bequeathed funds for the purpose. In the year 1579 there was a motion before the Court of the Barber Surgeons’ Company concerning a lecture in surgery “to be had and made in our Hall and of an annuity of ten pounds to be given for the performance thereof yearly by Master Doctor Caldwall, Doctor in phisick; but it was not concluded upon neither was any further speech at that time.” No reference to the proposal occurs subsequently in the minute books, so that the idea was probably abandoned, no doubt upon the ground that it would lead to additional expense which the Company was unprepared to meet. The annuity was only ten pounds a year, and in 1646 the cost of the lectures, including the dinners, amounted to £22 14s. 6d., or without the feasts to £12 14s. 6d. It is now obvious that the Company did a very stupid thing, for in 1581, two years later, Lord Lumley in conjunction with Dr. Caldwell, and at his instance, founded the Lumleian lectureship at the College of Physicians. The surgeons thus lost a noble benefaction which should of right have belonged to them and with which Harvey might still have been associated, for whilst he[47] was lecturing at the College of Physicians, Alexander Reid, his junior in years as well as in standing, was lecturing at the Barber Surgeons’ Hall in Monkwell Street.

The Lumleian lecture was a surgery lecture established at a cost of forty pounds a year, laid as a rent charge upon the lands of Lord Lumley in Essex, and of Dr. Caldwell in Derbyshire.

Its founders were two notable men. Lord Lumley, says Camden, was a person of entire virtue, integrity, and innocence, and in his old age, was a complete pattern of true nobility. His father, the sixth baron, suffered death for high treason, but the son was made a Knight of the Bath two days before the coronation of Queen Mary. He was one of the lords appointed to attend Queen Elizabeth at her accession, in the journey from Hatfield to London, and at the accession of James I. he was made one of the Commissioners for settling the claims at his coronation. He died April 11, 1609, without surviving issue. Dr. Caldwell had enjoyed unique honour at the College of Physicians. He was examined, approved, and admitted a Fellow upon 22nd December, 1559, and upon the same day he was appointed a Censor. He became President in[48] 1570, and was present at the institution of the lecture in 1582. He was then so aged, his white head adding double reverence to his years, that when he attempted to make a Latin oration to the auditors he was compelled to leave it unfinished by reason of his manifold debilities. And in a very short time afterwards the good old doctor fell sick, and as a candle goeth out of itself or a ripe apple falleth from a tree, so departed he out of this world at the Doctors’ Commons, where his usual lodgings were, and was buried on the 6th of June immediately following, in the year 1584, at S. Ben’et’s Church by Paul’s Wharf, at the upper end of the chancel.

The design of the benefaction was a noble one. It was the institution of a lecture on Surgery to be continued perpetually for the common benefit of London and consequently of all England, the like whereof had not been established in any University of Christendom (Bologna and Padua excepted). An attempt had been made to establish such a lectureship at Paris, but the project failed when Francis I. died, on the last day of March, 1547.

The reader of the Lumleian lecture was to be a Doctor of Physic of good practice and knowledge who was to be paid an honest stipend, no less in[49] amount than that received by the Regius Professors of law, divinity, and physic, in the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. The lecturer was enjoined to lecture twice a week throughout the year, to wit on Wednesdays and Fridays, at ten of the clock till eleven. He was to read for three-quarters of an hour in Latin and the other quarter in English “wherein that shall be plainly declared for those that understand not Latin.”

The lecturer was appointed for life and his subjects were so arranged that they recurred in cycles. The first year he was to read the tables of Horatius Morus, an epitome or brief handling of all the whole art of surgery, that is, of swellings, wounds, ulcers, bone-setting, and the healing of broken bones commonly called fractures. He was also to lecture upon certain prescribed works of Galen and Oribasius, and at the end of the year in winter he was directed “to dissect openly in the reading place all the body of man, especially the inward parts for five days together, as well before as after dinner; if the bodies may last so long without annoy.”

The second year he was to read somewhat more advanced works upon surgery and in the winter “to dissect the trunk only of the body, namely, from the[50] head to the lowest part where the members are and to handle the muscles especially. The third year to read of wounds, and in winter to make public dissections of the head only. The fourth year to read of ulcers and to anatomise [or dissect] a leg and an arm for the knowledge of muscles, sinews, arteries, veins, gristles, ligaments, and tendons. The fifth year to read the sixth book of Paulus Aegineta, and in winter to make an anatomy of a skeleton and therewithall to show the use of certain instruments for the setting of bones. The sixth year to read Holerius of the matter of surgery as well as of the medicines for surgeons to use. And the seventh year to begin again and continue still.”

The College of Physicians made every effort to fulfil its trust adequately. Linacre, its founder and first President in 1518, allowed the Fellows to use the front part of his house—the stone house in Knightrider Street, consisting of a parlour below and a chamber above, as a council room and library, and the college continued to use these rooms for some years after his death, the rest of the premises being the property of Merton College, Oxford. At the Institution of the Surgery lecture the Fellows determined to appropriate the sum of a hundred pounds out of their[51] common stock—and this proved to be nearly all the money the College possessed—to enlarge the building and to make it more ornamental and better suited for their meetings and for the attendance at their lectures. The result appears to have been satisfactory, for two years later, it was ordered, on the 13th of March, 1583-1584, that a capacious theatre should be added to the College thus enlarged.

Dr. Richard Forster was appointed the first Lumleian lecturer, and when he died in 1602, William Dunne took his place. Dunne, however, did not live to complete a single cycle of lectures for Thomas Davies was elected in May, 1607. The College then again began to outgrow its accommodation, and as the site did not allow of any further additions to the buildings, a suitable house and premises were bought of the Dean and Chapter of St. Paul’s in Amen Corner, at the end of Paternoster Row. The last meeting of the College in Linacre’s old house in Knightrider Street, took place on the 25th of June, 1614, and its first meeting in Amen Corner was held on the 23rd of August, 1614. Dr. Davies died in the following year, and on the 4th of August, 1615, William Harvey was appointed to the office of Lumleian lecturer, though his[52] predecessor was not buried until August 20th. He continued to occupy this post until his resignation in 1656, when his place was taken by (Sir) Charles Scarborough. The duties of the lecturer, no doubt, had been modified with each fresh appointment, but even in Harvey’s time, there is some evidence to show that the subjects were still considered in a definite order.

Harvey, in all probability, began to lecture at once upon surgery as the more theoretical portion of his subject, but it was not until April, 1616, that he gave his first anatomical lecture. It was a visceral lecture for the terms of the bequest required that it should be upon the inward parts. At this time Harvey was thirty-seven years of age. A man of the lowest stature, round faced, with a complexion like the wainscot; his eyes small, round, very black and full of spirit; his hair as black as a raven and curling; rapid in his utterance, choleric, given to gesture, and used when in discourse with any one, to play unconsciously with the handle of the small dagger he wore by his side.

The MS. notes of his first course of lectures are now in the British Museum. They formed a part of the library of Dr. (afterwards Sir Hans) Sloane,[53] which was acquired under the terms of his will by the nation in 1754. For a time the book was well known and extracts were made from it, then it disappeared and for many years it was mourned as irretrievably lost. But in 1876 it was found again amongst some duplicate printed books which had been set aside, and in the following year it was restored to its place in the Manuscript Department. The notes were reproduced by an autotype process, at the instigation of Sir E. H. Sieveking, and under the supervision of a Committee of the Royal College of Physicians. This facsimile reproduction was published in 1886 with a transcript by Mr. Scott, and an interesting introduction from the pen of Dr. Norman Moore. The original notes are written upon both sides of about a hundred pages of foolscap, which had been reduced to a uniform size of six inches by eight, though the creases on the paper show that they have been further folded so as to occupy a space of about eight inches by two. These leaves have been carefully bound together in leather which presents some pretensions to elegance, but it is clear that the pages were left loose for some years after they were written. There seems to be no doubt that Harvey used the volume in its present form whilst he was lecturing, for three small threads of twine have[54] been attached by sealing wax to the inner side of the cover so that additional notes could be slipped in as they were required. It must be assumed that Harvey did this himself, for he wrote so badly and the notes are so full of abbreviations, interlineations, and alterations, as to render them useless to any one but the author.

The title-page, which is almost illegible, is written in red ink. It runs, “Stat Jove principium, Musae, Jovis omnia plena. Prelectiones Anatomiae Universalis per me Gulielmum Harveium Medicum Londinensem Anatomie et Chirurgie Professorem. Anno Domini 1616. Anno aetatis 37 prelectae Aprili 16, 17, 18. Aristoteles Historia Animalium, lib. i. cap. 16. Hominum partes interiores incertae et incognitae quam ob rem ad caeterorum Animalium partes quarum similes humanae referentes eas contemplare.” The motto prefixed to the title-page that “everything is full of Jove” is an incorrect quotation from the third Eclogue of his favourite author Virgil, of whom he was so enamoured that after reading him for a time he would throw away the book with the exclamation, “He hath a devil.” This particular line appears especially to have struck his fancy, for he quotes it twice in his treatise on development, and he works out the idea which it represents in his fifty-fourth essay.[55] He there shows that he understands it to mean that the finger of God or nature, for with him they are synonymous terms, is manifest in every detail of our structure whether great or small. For he says: “And to none can these attributes be referred save to the Almighty, first cause of all things by whatever this name has been designated—the Divine Mind by Aristotle; the Soul of the Universe by Plato; the Natura Naturans by others; Saturn and Jove by the Gentiles; by ourselves, as is seemly in these days, the Creator and Father of all that is in heaven and earth, on whom all things depend for their being, and at whose will and pleasure all things are and were engendered.” He thus opened his lectures in a broad spirit of religious charity quite foreign to his environment but befitting the position he has been called upon to occupy in the history of science.

These notes of Harvey’s visceral lecture are of especial value to us though they are a mere skeleton of the course—a skeleton which he was accustomed to clothe with facts drawn from his own vast stores of observation, with the theories of all his great predecessors and with the most apposite illustrations. Fortunately they deal with the thorax and its contents so that they show us the exact point which[56] he had reached in connection with his great discovery of the circulation of the blood and the true function of the heart. The notes therefore are interesting reading quite apart from the peculiarities of their style.

Harvey was so good a Latin scholar, and during his stay in Italy had acquired such a perfect colloquial knowledge of the language that it is clear he thought with equal facility in Latin or in English, so that it is immaterial into which language he put his ideas. He uses therefore many abbreviations, and whole sentences are written in a mixture of Latin and English, which always sounds oddly to our unaccustomed ears, and often seems comical. Thus, in speaking of the lungs and their functions, he says, “Soe curst children by eager crying grow black and suffocated non deficiente animali facultate,” and in speaking of the eyes and their uses, he says, “Oculi eodem loco, viz., Nobilissimi supra et ante ad processus eminentes instar capitis in a Lobster ... snayles cornubus tactu pro visu utuntur unde occuli as a Centinell to the Army locis editis anterioribus.” Sometimes he embodies an important experimental observation in this jargon as in the example, “Exempto corde, frogg scipp, eele crawle, dogg Ambulat.”

The more important and original ideas throughout[57] the notes are initialled WH., and this seems to have been Harvey’s constant practice, for it occurs even in the books which he has read and annotated, whilst to other parts of his notes he has appended the sign Δ.

The lectures were partly read and partly oral, and we know from the minute directions laid down by the Barber Surgeons Company the exact manner in which they were given. The “Manual of Anatomy,” published by Alexander Reid in 1634, has a frontispiece showing that the method of lecturing adopted in England was the same as that in use throughout Europe. The body lay upon a table, and as the dissections were done in sight of the audience, the dissecting instruments were close to it. The lecturer, wearing the cap of his doctor’s degree, sate opposite the centre of the table holding in his hand a little wand[2] to indicate the part he mentions, though in many cases the demonstration was made by a second doctor of medicine known as the demonstrator, whilst the lecturer read his remarks. At either end of the table was an assistant—the Masters of the Anatomy—with scalpel in hand ready to expose the different structures, and to clear up any[58] points of difficulty. The audience grouped themselves in the most advantageous positions for seeing and hearing, though in some cases places were assigned to them according to age and rank.

The lecturer upon Anatomy, apart from the fact that he was a Doctor of Physic was a person of considerable importance in the sixteenth century. The greatest care was taken of him, as may be understood from the directions which the Barber Surgeons gave to their Stewards in Anatomy or those members of the Company who were appointed to supervise the arrangements for the lectures. They were ordered “to see and provide that there be every year a mat about the hearth in the Hall that Mr. Doctor be made not to take cold upon his feet, nor other gentlemen that do come and mark the Anatomy to learn knowledge. And further that there be two fine white rods appointed for the Doctor to touch the body where it shall please him; and a wax candle to look into the body, and that there be always for the doctor two aprons to be from the shoulder downwards and two pair of sleeves for his whole arm with tapes, for change for the said Doctor, and not to occupy one Apron and one pair of sleeves every day which is unseemly. And the Masters of the Anatomy that[59] be about the body to have like aprons and sleeves every day both white and clean. That if the Masters of the Anatomy that be about the Doctor do not see these things ordered and that their knives, probes, and other instruments be fair and clean accordingly with Aprons and sleeves, if they do lack any of the said things afore rehearsed he shall forfeit for a fine to the Hall forty shillings.”

The whole business of a public anatomy was conducted with much ceremony, and every detail was regulated by precedent. The exact routine in the Barber Surgeons’ Company is laid down in another series of directions. The clerk or secretary is instructed in his duties in the following words: “So soon as the body is brought in deliver out your tickets which must be first filled up as followeth four sorts:—The first form, to the Surgeons who have served the office of Master you must say: Be pleased to attend &c. with which summons you send another for the Demonstrations: to those below the Chair [i.e., who have not filled the office of Master of the Company] you say: Our Masters desire your Company in your Gown and flat Cap &c. with the like notice for the Demonstrations as you send to the ancient Master Surgeons. To the Barbers, if ancient masters, you[60] say: Be pleased to attend in your Gown only, and if below the Chair, then: Our Masters desire &c. as to the others above, but without the tickets for the demonstrations.

“The body being by the Masters of Anatomy prepared for the lecture (the Beadles having first given the Doctor notice who is to read) and having taken orders from the Master or Upper Warden [of the Company] of the Surgeons’ side concerning the same, you meet the whole Court of Assistance [i.e., the Council] in the Hall Parlour where every gentlemen cloathes himself [i.e., puts on his livery or gown], and then you proceed in form to the Theatre. The Beadles going first, next the Clerk, then the Doctor, and after him the several gentlemen of the Court; and having come therein, the Doctor and the rest of the Company being seated, the Clerk walks up to the Doctor and presents him with a wand and retires without the body of the Court [i.e., the theatre in which the assemblage of the company technically constituted a “court”] until the lecture is over when he then goes up to the Doctor and takes the wand from him with directions when to give notice for the reading in the afternoon which is usually at five precisely, and at one of the clock at noon, which he[61] pronounces with a distinct and audible voice by saying, This Lecture, Gentlemen, will be continued at five of the clock precisely. Having so said he walks out before the Doctor, the rest of the Company following down to the Hall parlour where they all dine, the Doctor pulling off his own robes and putting on the Clerk’s Gown first, which it has always been usual for him to dine in. And after being plentifully regaled they proceed as before until the end of the third day, which being over (the Clerk having first given notice in the forenoon) that the lecture will be continued at five of the clock precisely (at which time the same will be ended) he attends the Doctor in the clothing room where he presents him folded up in a piece of paper the sum of ten pounds, and where afterwards he waits upon the Masters of Anatomy and presents each of them in like manner with the sum of three pounds, which concludes the duty of the Clerk on this account.

“N.B.—The Demonstrator, by order of the Court of Assistants, is allowed to read to his pupils after the public lecture is over for three days and till six of the clock on each day and no longer, after which the remains of the body is decently interred at the expence of the Masters of Anatomy, which usually[62] amounts unto the sum of three pounds seven shillings and fivepence.”

The study of Anatomy seems to have been regarded universally as an exhausting occupation, for throughout Europe it was the custom to present the auditors with wine and spices after each lecture, unless some more substantial refreshment was provided.

Harvey’s lectures at the College of Physicians were probably given with similar ceremony to those just described. His first course was delivered on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, April 16, 17, and 18, 1616. On the following Tuesday, April 23rd, Shakespeare died at Stratford-on-Avon, and on the succeeding Thursday, April 25th, he was buried in the chancel of the parish church.

At the beginning of his lectures Harvey lays down the following excellent canons for his guidance, of which the sixth seems to indicate that he was acquainted with the works of John of Arderne—

1. To show as much as may be at a glance, the whole belly for instance, and afterwards to subdivide the parts according to their position and relations.

2. To point out what is peculiar to the actual body which is being dissected.

3. To supply only by speech what cannot be shown on your own credit and by authority.

4. To cut up as much as may be in the sight of the audience.

5. To enforce the right opinion by remarks drawn from far and near, and to illustrate man by the structure of animals according to the Socratic rule [given by Aristotle and affixed as an extract to the title-page of the lectures[3]]. To bring in points beyond mere anatomy in relation to the causes of diseases, and the general study of nature with the object of correcting mistakes and of elucidating the use and actions of parts for the use of anatomy to the physician is to explain what should be done in disease.

6. Not to praise or dispraise other anatomists, for all did well, and there was some excuse even for those who are in error.

7. Not to dispute with others, or attempt to confute them, except by the most obvious retort, for three days is all too short a time [to complete the work in hand].

8. To state things briefly and plainly, yet not letting anything pass unmentioned which can be seen.

9. Not to speak of anything which can be as well explained without the body or can be read at home.

10. Not to enter into too much detail, or into too minute a dissection, for the time does not permit.