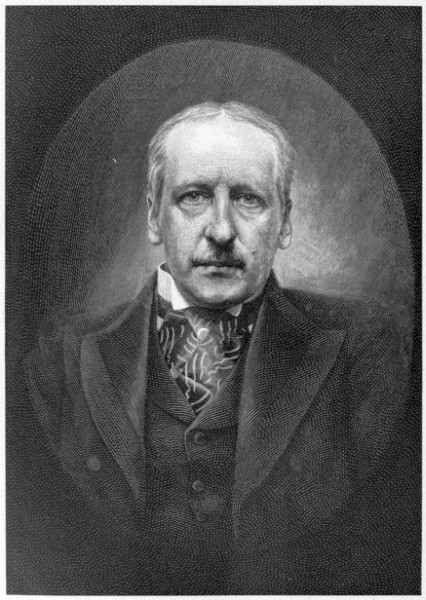

WILLIAM PEPPER.

WILLIAM PEPPER.

Title: Appletons' Popular Science Monthly, October 1899

Author: Various

Editor: William Jay Youmans

Release date: August 28, 2014 [eBook #46710]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Judith Wirawan, Greg Bergquist and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Established by Edward L. Youmans

EDITED BY

WILLIAM JAY YOUMANS

VOL. LV

MAY TO OCTOBER, 1899

NEW YORK

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

1899

Copyright, 1899,

By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY.

WILLIAM PEPPER.

WILLIAM PEPPER.

APPLETONS' POPULAR SCIENCE MONTHLY.

OCTOBER, 1899.

By the Right Reverend HENRY C. POTTER.

The analogies between the life of an individual and that other organism which we call civilized society are as interesting as for any other reason because of their inexhaustible and ever-fresh variety. The wants, the blunders, the growth, the perils of the individual are matched at every step by those other wants and dangers and developments which rise in complexity and in variety as the individual and the social organism rise in intelligence, in numbers, and in wealth. It ought to interest us, if it never has, to consider from how much that is mischievous and dangerous we should be delivered if we could revert from the civilized to the savage state; and it is undoubtedly true that serious minds have sometimes been tempted to question whether civilization is quite worth all that it has cost us in its manifold departures from a simple and more primitive condition.

Such a question may, at any rate, not unnaturally arise when we ask ourselves the question, What, on the whole, is the influence upon manhood—by which I mean, here and for my present purpose, the qualities that make courage, self-reliance, self-respect, industry, initiative—in fact, those independent and aggressive characteristics by which great races, like great men, have climbed up out of earlier obscurity and inferiority into power, leadership, and distinction; what is the influence upon these of conditions which tend, apparently by an inevitable law, to beget or to encourage indolence, inertia, parasitic dependence?

One can not but be moved to such a question by either of two papers which have recently appeared in these pages: I mean that[Pg 722] entitled Abuse of Public Charity, by Comptroller Bird S. Coler; and that by Prof. Franklin H. Giddings, of Columbia University, on Public Charity and Private Vigilance. The community whose capable and efficient servant he is has reason to be thankful that, in the person of a public official intrusted with such large responsibilities, it has a thoughtful and far-seeing student of problems whose grave importance he has so opportunely pointed out. It needs the courage and the knowledge of such a one to affirm that "it is easier for an industrious and shrewd professional beggar to live in luxury in New York than to exist in any other city in the world," which, if any social reformer or minister of religion or mere critic of the social order had said it, would probably have been denounced as an atrabilious and unwarranted exaggeration.

Concerning the comptroller's indictments of certain charitable societies and organizations as expensive mechanisms for the consumption of appropriations or contributions largely spent upon their salaried officials, I am quite willing to recognize the force of Professor Giddings's demurrer to the effect that a so-called charitable society may now and then rightly exist, and expend its income largely, if not wholly, upon the persons whom it employs as its agents, since these agents are the vigilant committees whose office it is to detect, discourage, and expose unworthy objects, whether of public or private charity. But that, besides such agencies, there are constantly called into being wholly spurious organizations, which profess to exist for the relief of certain classes of sufferers or of needy people; that these succeed, sooner or later, in fastening themselves upon the treasury of the city and of the State; and that they are, in a great many cases, monuments of the most impudent and unscrupulous fraud, there can be no smallest doubt.

Well, it may be asked, What are you going to do about it? Will you accept the inevitable evils that march in the rear of all public or private charity, or will you sweep all the various agencies, which have relieved such manifold varieties of human want and alleviated to such an incalculable degree human misery, out of existence? Will you care to contemplate what a great city like New York or London would be if to-morrow you closed the doors of all the hospitals, crèches, homes of the aged, asylums for the crippled, the blind, the insane, and the like, and turned their inmates one and all into the street?

That is certainly a very dramatic alternative to present; but suppose that we look at it a little more closely. And, in order that we may, I shall ask my reader to go back with me, not to that primitive or barbaric era to which I began by referring, but only to a somewhat earlier stage in our own social history, with which[Pg 723] many persons now living are abundantly familiar. One of the interesting and startling contrasts which might be presented to one anxious to impress a stranger with our American progress would be to take only our present century, and group together, out of its statistics, the growth and development, in its manifold varieties, during that period in any city, great or small, of institutional charity. But if such a one were just he would have, first of all, to put upon his canvas some delineation of that situation which, under so many varying conditions and amid such widely dissimilar degrees of privilege or of opportunity, preceded it. I listened the other day to the story of a charming woman, of marked culture and refinement, as she depicted, with unconscious grace and art, the life of a gentlewoman of her own age and class—she was young and fair and keenly sympathetic—on a Southern plantation before the civil war. One got such a new impression of those whom, under other skies and in large ignorance of their personal ministries or sacrifices, we had been wont to picture as indolent, exclusive, indifferent to the sorrow and disease and ignorance that, on a great rice or cotton or sugar plantation in the old days, were all about them; and one learned, with a new sense of reverence for all that is best in womanhood, how, in days that are now gone forever, there were under such conditions the most skillful beneficence and the most untiring sympathies.

But, in the times of which I speak, the service on the plantation for the sick slave (which, an ungracious criticism might have suggested, since a slave was ordinarily a valuable piece of property, had something of a sordid element in it) was matched in communities and under conditions where no such suspicion was possible. No one who knows anything of life in our smaller communities at the beginning of the century can be ignorant of what I mean. There was no village or smallest aggregation of families that had not its Abigail, its "Aunt Hannah," its "Uncle Ben," who, when there was sickness or want or sorrow in a neighbor's house, was always on hand to sympathize and to succor. I do not forget that it is said that, even under our greatly changed conditions, in modern cities this is still true of the very poor and of their kindness and mutual help to one another; and I thank God that I have abundant reason, from personal observation, to know that it is. But, happily, neither great cities nor small are largely made up of the very poor, and the considerations that I am aiming to present to those who will follow me through these pages are not concerned with these. What I am now aiming to get before my readers is that there was a time, and that it was not so very long ago, when that vast institutional charity which exists among us to-day,[Pg 724] and which I believe to be in so many aspects of it so grave a menace to our highest welfare, did not exist, because it had no need to exist. The ordinary American community, East or West, had, as distinguishing it, however small its numbers and narrow its means, two characteristics which our modern systems of institutional charity are widely conspiring to extinguish and destroy. One of these was that resolute endurance of straitness and poverty of which there is so fine and true a portraiture in Miss Wilkins's remarkable story Jerome. I venture to say that the charm of that rare book, to a great many of the most intelligent and appreciative of its readers, lay in the fact that they could match it, or something like it, in their own experience; that they had known silent and proud women, and brave and proud boys, to whom, whatever the hard pinch of want that they knew, to accept a dole was like accepting a blow, and who covered their poverty alike from the eye of inquisitive stranger or kin with a robe of secrecy that was at once impenetrable and all-concealing. Life to them was a battle, and they could lose it, as heroes have lost it on the tented field, without a murmur; but to sue for bread to some other, even if that other were of the same blood, would have smitten them as with the stain of personal dishonor.

And over against such, in the days and among the communities of which I speak, were those whose gift and ministry it was—without an intrusive curiosity, without a vulgar ostentation, without a word or look that implied that they guessed the sore need to which they reached out—yet somehow to discover it, to succor it, and then to help, finest and rarest of all, to hide it.

Now, then, behind such a condition of things there was a sure and wise discernment, even if it was only instinctive, of a profound moral truth, which was this: that you can not help me, nor I you, without risk. For the most sacred thing in either of us is our manhood or womanhood—that thing which differentiates us from any mere mechanism, that thing in us which says, I can, I ought, I will. Take that out of human nature and what is left is not worth considering, save as one might consider any other clever mechanism. But the power to choose, the power to act, and the consciousness that choice and action are to be dominated by something that answers to the instinct of loyalty to God, to self-respect, to the ideals of honor and righteousness—that is what makes life worth living, and any conceivable thing worth seeking or doing. Now, the moment that the question of our mutual relations enters we have to be concerned with the way in which they will act on this power, quality, characteristic—call it what you will—that makes manhood. It is not enough, for example, that my impulse to give you a pint[Pg 725] of gin is a benevolent impulse, if certain tendencies in you make it antecedently probable that a pint of gin will presently convert you from the condition of a rational being into that of a beast. And so of any impulse of mine in the direction of beneficence which, in its gratification, threatens manhood—that is, self-reliance, self-respect, independence, the right and faithful use of powers in me.

And here we come to the problem which lies at the basis of the whole question of charitable relief, for whatever class and in whatever form. The wholesome elements in that earlier situation, to which I have just referred, were threefold, and in our modern situation each one of them is sorely attenuated, if not wholly absent:

1. In the first place, there was a relative uniformity of condition. In other words, at the beginning of the present century in almost all communities, whether industrial or agricultural, the disparities of estate were inconsiderable. There was perhaps the rich man of the village or town, or two or three or half a dozen of them; but they were rich only relatively, and they were marked exceptions. The great majority of the people were of comparatively similar employments and circumstances. Among these there were indeed considerable varieties of task work, but work and wage were not far apart; and, what was of most consequence, a certain large identity of condition brought into it a certain breadth of sympathy and mutual help, out of which came the outstretched hand and the open door for the man who was out of work and was looking for it.

2. Yes, who was looking for it. For here again was a distinguishing note of those earlier days of which I am speaking. Idleness was a distinct discredit, if not dishonor. In communities where everybody had to work, an idler or a loafer was an intolerable impertinence, and was usually made to feel it.

3. And yet, again, there was the vast difference in those days from ours that the industries of the world had not taken on their immensely organized and mechanized characteristics. A mechanic—e. g., out of a job—then could turn his hand to anything that ordinary tools and muscle and intelligence could do. But an ordinary mechanic now must be a skilled mechanician in a highly specialized department, and when he is out of a job there, he is ordinarily out of it all along the line.

I might, as my reader will have anticipated me in recognizing, go on almost indefinitely in this direction; but I have said enough, I trust, to prepare him for the point which I want to make in connection with our modern charities and their mischief. Our modern social order, in a word, has become more complex, more segregated,[Pg 726] more specialized. A whole class of people in cities—those, I mean, of considerable wealth—with a few noble exceptions (which, however, in our greater cities, thank God, are becoming daily less rare), live in profound ignorance of the condition of their fellow-citizens. Now and then, by some sharp reverse in the financial world or some national recurrence of "bad times," they are made aware that large numbers of their neighbors are out of work and starving. And, at all times, they are no less reminded that there is a considerable class—how appallingly large it is growing to be in New York Mr. Coler has told us—who need help, or think they do, and who, at any rate, more or less noisily demand it in the street, at the door, by begging letter, or in a dozen other ways that make the rich man understand why the prayer of Agur was, "Give me neither poverty nor riches."[1]

Well, something must be done, they agree. What shall it be? Shall the State do it, or the Church, or the individual? If only they could, as to that, agree! But it has been one of the most pathetic notes of our heedless and superficial treatment of a great problem that, here, there has not been from the beginning even the smallest pretense of a common purpose or any moderately rational course of action. Undoubtedly it is true that there is no imaginable mechanism that could relieve any one of these agencies from responsibility in the matter of relief to the unfortunate, nor is it desirable that there should be. Sometimes it has been the Church that has undertaken the relief of the poor and sick, sometimes it has been largely left to the individual, and sometimes it has been as largely left to the State. But, in any case, the result has been almost as often as otherwise mischievous, or corrupt and corrupting. For, in fact, the ideal mode of dealing with the problems of sickness, destitution, and disablement should be one in which the common endeavor of the State, the Church, and the individual should be somehow unified and co-ordinated. But, incredible as it ought to be, the history of the best endeavors toward such co-ordination has been a history of large inadequacy and of meager results. As an illustration of this it is enough to point to the history of the Charity Organization Society in New York, which, I presume, is not greatly different from that of similar societies elsewhere. Antecedently it would have seemed probable that such a society, which aims simply to discourage fraud, to relieve genuine want, and to protect the community from being preyed upon by the idle and the vicious, would have the sympathy of that great institution, some of whose teachings are, "If any man will not work, neither shall he eat"; "Stand upright on thy feet";[Pg 727] "Provide things honest in the sight of all men"; "Not slothful in business"; and the like. But, as a matter of fact, such societies have had no more bitter antagonists than the churches, and no more vehement opponents than ministers of religion. In a meeting composed of such persons I have heard one of their number denounce with the most impassioned oratory any agency which undertook, by any mechanism, to intrude into the question of the circumstances, resources, or worthiness of those who were the objects of ecclesiastical almsgiving. Who, he demanded, could know so well as the clergy all the facts needed to enable them wisely and judiciously to assist those worthy and needy brethren who were of their own household of faith? Nothing could sound more plausible or probable; but in a little while it happened that a woman who had for years been a beneficiary of this very pastor died, leaving behind her, among her effects, sundry savings-bank books which showed her to be possessed of some thousands of dollars, which she bequeathed to relatives in a distant land. Still more recently a case of a similar character has occurred in which a still larger amount having been paid over in small sums through a long series of years by a church, the whole, with interest, has been found to have been hoarded, the recipient having been a person entirely capable of self-support, and, as a matter of fact, during the whole period self-supporting, and the large accumulations are at present the subject of a suit in which the church is endeavoring to recover what it not unnaturally regards as its own misappropriated money.

And yet, as any one knows who knows anything of the delicacy, vigilancy, and thoroughness with which a well-organized society conducts its work, any such grotesque and deplorable result would, with a little wise co-operation between the Church and such a society, have been rendered impossible. I know how impatient many good people are of the services of any such association, and we have all heard ad nauseam of their protests against a "spy system which invades the sacred privacy of decent poverty," and the rest; but, in fact, such persons never seem to realize that, in one aspect of it, the Church stands, or, as a matter of common honesty, as the administrator of trust funds, ought to stand, on the same equitable basis, at least, as a life-insurance company. Now, when I seek the benefits of a life-insurance company I am asked certain questions which affect not only my physical resources but my diseases, my ancestry and their diseases, my personal habits, infirmities, and the like. If the company has the right, in the just interests of its other clients, to ask these questions, as administering a large trust, has not the Church, which is also the administrator of a trust no less in the interest of other clients?

[Pg 728]But, indeed, this is the lowest aspect of such a question, and I freely admit it. The title of this paper points to that gravest aspect of it, with which I am now concerned. The largest mischief of indiscriminate almsgiving is not its wanton waste—it is its inevitable and invariable degradation of its objects. I have spoken of the grave antagonism of the Church to wisely organized charity, but it is but the echo of the hostility of the individual, and often of the best and wisest men and women. Elsewhere (but not, I think, in print) I have related an incident in this connection of which one is almost tempted to say ex uno disce omnes. Approaching one day, when I was a pastor in a great city, the door of one of my clerical brethren, I observed a woman leaving it who, though she hastily turned her back upon me, I recognized as a member of my own congregation. On entering my friend's study I said to him:

"I beg your pardon, but was not that Mrs. —— whom I saw leaving your door a moment ago?"

"Yes."

"What was she after, may I ask?"

My friend—now, alas! no longer living—was a man distinguished by singular delicacy and chivalry of character and bearing, and he turned upon me with some surprise and hauteur and said:

"Well, yes, you may ask; but I do not know that, in the matter of the sad and painful circumstances of one of my own parishioners, I am called upon to answer."

"Precisely," I replied; "but, as it happens, she isn't your parishioner."

"What do you mean, sir?" he exclaimed, with some heat. "Do you suppose that I don't know the members of my own flock?"

"On the contrary," I said, "I have no doubt that you know not only them but the members of a great many other flocks, as in the instance of the person who has just left your door, who, as it happens, has been a member of the church of which I am rector for some fifteen years."

The remark and the abundant evidence with which I was able to re-enforce it at last persuaded my friend to institute further inquiries, which resulted in the discovery that the subject of those inquiries maintained similar relations with some seven parishes, from every one of which she was receiving, as a poor widow, a monthly allowance! And yet my reverend brother was one of the most strenuous opponents of any system or society, any challenge or interrogation which, as he said, came between him and his poor. Alas! though in one sense they were his poor, in another[Pg 729] they were as remote from him as if they and he had been living in different hemispheres. With every sympathy for their distresses, he had not come to recognize that, under those complex conditions of our modern life, to which I have already referred, a real knowledge of the classes upon whom need and misfortune and the temptations to vice and idleness press most heavily has become almost a science, in which training, experience, most surely a large faith, but no less surely a large wisdom, are indispensable.

In this work there is undoubtedly a place for institutional charity, and also for that other which is individual. The former affords a sphere for a wise economy, for prompt and immediate treatment or relief, and for the utilization of that higher scientific knowledge and those better scientific methods which the home, and especially the tenement house, can not command. But over against these advantages we are bound always to recognize those inevitable dangers which they bring with them. The existence of an institution, whether hospital, almshouse, or orphanage, to the care of which one may easily dismiss a sick member of the household, or to which one may turn for gratuitous care and treatment, must inevitably act as strong temptations to those who are willing to evade personal obligations that honestly belong to them. In connection with an institution for the treatment of the eye and ear, with which I happen to be officially connected, it was found, not long ago, that the number of patients who sought it for gratuitous treatment was considerably increased by persons who came to the hospital in their own carriages, which they prudently left around the corner, and whose circumstances abundantly justified the belief that they were quite able to pay for the treatment, which, nevertheless, their self-respect did not prevent them from accepting as a dole. Such incidents are symptomatic of a tendency which must inevitably degrade those who yield to it, and which is at once vicious and deteriorating. How widespread it is must be evident to any one who has had the smallest knowledge of the unblushing readiness with which institutional beneficence is utilized in every direction. A young married man in the West, I have been told, wrote to his kindred in the East: "We have had here a glorious revival of religion. Mary and I have been hopefully converted. Father has got very old and helpless, and so we have sent him to the county house." One finds himself speculating with some curiosity what religion it was to which this filial scion was converted. Certainly it could not have been that which is commonly called Christian!

And at the other end of the social scale the situation is often little better. In our greater cities homes have been provided for[Pg 730] the aged, and especially for that most deserving class of gentlewomen who, having been reared in affluence, come to old age, after having struggled to maintain themselves by teaching, needlework, and the like, with broken powers and empty purses. But it has, I am informed, been often impossible to find places for them in institutions especially created for their care, because its lady managers have filled their places with their own worn-out servants, who, having spent their years and strength in their employer's service, are turned over in their old age, with a shrewd frugality which one can not but admire, to be maintained at the cost of other people. It is impossible to confront such instances, and they might be multiplied indefinitely, without recognizing how enormous are the possibilities of mischief even in connection with the most useful institutional charity.

And yet these are not so great as those which no less surely follow, as it is oftenest administered, in the train of individual beneficence. In an unwritten address, not long ago, I mentioned an illustration of this which I have been asked to repeat here. While a rector in a large city parish, I was called upon by a stranger who asked for money, and who, as evidence of his claims upon my consideration, produced a letter from my father, written some twenty-five years before, when he was Bishop of Pennsylvania. The writer had, when this letter was placed in my hands, been dead for some twenty years, but, in a community in which he had been greatly loved and respected, his words had not, even in that lapse of time, lost their power. The letter was a general letter, addressed to no one, and therein lay its mischief. When read, it had in each instance been returned to its bearer, and he soon discovered that he had in it a talisman that would open almost any pocket. He was originally a mechanic who had been temporarily disabled by a fit of sickness; when I saw him, however, he was obviously, and doubtless for years had been, in robust health. But he had discovered that if he were willing to beg he need not work, and he had long before made his choice on the side of ease and indolence. After reading the letter which he produced, and looking at its date and soiled condition, both revealing the long service that it had performed, I said to him, "No, I will not give you anything, but I will pay you ten dollars if you will let me have that letter." It would not be easy to describe the leer of cunning and contempt with which he promptly took it out of my hand, folded it, placed it in his pocketbook, and left the room. He was not so innocent as to surrender his whole capital in trade!

Now, here was a man to whom a well-meaning but inconsiderate act of kindness had been the cause of permanent degradation.[Pg 731] The highest qualities in such a one—manhood, self-respect, frugal and industrious independence—had been practically destroyed, and an act of charity had made of one who was doubtless originally an honest and hard-working young man, a mendicant, a loafer, and a fraud.

And yet for a sincere and self-sacrificing purpose to help our less fortunate fellow-men there were never so many inspiring and encouraging opportunities. Along with the undeniably increasing complexity of our modern life there have arisen those attractive instrumentalities for a genuine beneficence which find their most impressive illustrations in the improvements of the homes of the poor in college settlements, in young men's and young girls' clubs in connection with our mission churches, in the kindergartens and in the cooking schools founded by these and other beneficent agencies, in juvenile societies for teaching handicrafts and encouraging savings, and, best of all, in that resolute purpose to know how the other half live, of which the noble service of Edward Denison in England; of college graduates in England and in America, who have made the college and university settlements their post-graduate courses; of such women here and in Chicago as Miss Jane Addams, and the charming group of gentlewomen living in the House in Henry Street, New York, maintained with such modest munificence by Mr. Jacob Schiff; of such laborious and discerning scrutiny and sympathy as have been shown in the studies and writings of my friend Mr. Jacob Riis—are such noble and enkindling examples.

These and such as these are indicating to us the lines along which our best work for the relief of ignorance and suffering and want may to-day be done, and the more closely they are studied, and the more intimately the classes with which they are concerned are known, the more abundantly they will vindicate themselves. For these latter have in them, far more commonly than we are wont to recognize, those higher instincts of self-respect and of manly and womanly independence that, in serving our fellow-men, we must mainly count upon. There are doubtless instinctive idlers and mendicants among the poor, as, let us not forget, there are chronic idlers, borrowers, "sponges," among the classes at the other end of the social scale. But the same divine image is in our brother man everywhere, and the better, more truly, more closely we know him, the more profoundly we shall realize it. During some six weeks spent, a few years ago, in the most crowded ward in the world, among thousands of people who lived in the narrowest quarter and upon the most scanty wage, I gave six hours every day to receiving anybody and everybody who came to me. During that[Pg 732] time I had visits from dilapidated gentlemen from Albany and Jersey City and Philadelphia and the like, who supposed that I was a credulous fool whose money and himself would be soon parted, and who gave me what they considered many excellent reasons for presenting them with five dollars apiece. But, during that whole period, not one of the many thousands who lived in the crowded tenements all around me, and to hundreds of whom I preached three times a week, asked me for a penny. Not one! They came to me by day and by night, men and women, boys and girls, for counsel, courage, sympathy, admonition, reproof, guidance, and such light as I could give them—but never, one of them, for money. They are my friends to-day, and they know that I am theirs; and, little as that last may mean to the weakest and the worst of them, I believe that, in the case of any man or woman who tries to understand and hearten his fellow, it counts for a thousandfold more than doles, or bread, or institutional relief.

By GEORGE A. DORSEY.

As one approaches the center of Arizona, along the line of the Santa Fé Railroad, whether he come from the east or from the west, his attention is sure to be arrested by several tall, spire-like hills which are silhouetted against the sky to the far north. These peaks are the Moki Buttes, and to the north of them lies the province of Tusayan, the land of the Mokis, or the Hopis, as they prefer to be called. That country to-day contains more of interest to the student of the history of mankind than any other similar-sized area on the American continent. But very few of the great throng that roll by on the Santa Fé trains every year in quest of pleasure, of recreation, of new scenes and strange, stop off at Holbrook or Winslow to take the journey to the Hopis, and very few even know of the existence of these curiously quaint pueblos of this community, which to-day lives pretty much as it did before Columbus set out on his long voyage to the unknown West.

The term pueblo, a Spanish word meaning town, is by long and continued use now almost confined to the clusters of stone and adobe houses which to-day shelter the sedentary Indians of New Mexico and Arizona. Not only are these Indian towns called "pueblos," but we speak of the Indians themselves as the Pueblo Indians, and of the culture of the people—for they all have much in common—as the pueblo culture. This similarity of culture is not due to[Pg 734] unity of race or of language, but is the resultant of a peculiar environment. In recent times, the limits of the pueblo-culture area have contracted to meet the demands of the white man; we know also that before the advent of the Spaniard many once populous districts had been abandoned, and as a result there came to be fewer but larger villages. We know also, both from tradition and from archæological evidence, that in former days the pueblo people inhabited many of the villages of southern Colorado and Utah, and that the Hopis and their kin were numerous in many parts of Arizona. The silent houses of the cliffs, the ruins of central Arizona, and the great crumbling masses of adobe of the Salt and Gila River valleys and in northern Chihuahua are all former habitations of the Pueblo Indian. To-day there are no representatives of these people in Utah or Colorado, while the seven Hopi towns of Tusayan alone remain in Arizona. But there are still many pueblos scattered along the Rio Grande, Jemez, and San Juan Rivers in New Mexico. Alike in culture, we may divide the existing pueblos into four linguistic groups—namely, the Hopis of Arizona, the Zuñis of New Mexico, the Tehuas east of the Rio Grande, and the Queres to the west of the Rio Grande. Of the earlier home of the last three stocks we know but little. The ancestors of the Hopis we know came from different directions—some from the cliff dwellings of the north, others from central Arizona. To-day, however, they form a congeries of clans united and welded into a unit by similarity of purpose and by the more powerful influence of a peculiar environment.

The opinion was held until within a very few years that the Hopis represented a small branch of the Shoshonean division of the Uto-Aztecan stock, but Dr. Fewkes, our greatest authority on the Hopi, has questioned the accuracy of this classification, and it can be stated that the true affinities of the Hopi have not yet been discovered.

The province of Tusayan, or the Moqui Reservation, as it is officially known to-day, contains about four thousand square miles and about two thousand Indians. It is in the northeastern part of Arizona, and its towns are about eighty miles by trail from the railroad. The present inhabitants are grouped in seven pueblos, located on three parallel mesas, or table-lands, which extend southward like stony fingers toward the valley of the Little Colorado River. The first or east mesa contains the pueblos of Walpi, Sitcomovi, and Hano; on the second or middle mesa are Miconinovi, Cipaulovi, and Cuñopavi; and on the third or west mesa stands Oraibi, largest and most ancient of all Hopi pueblos, and in many respects the best preserved and most interesting community in the[Pg 735] world. A community without a church, separated by a broad, deep valley from its nearest neighbor, with but a single white man within twenty miles, removed nearly thirty-five miles from a trading post, isolated, proud, spurning the advances of the Government, Oraibi could maintain its independence if every other community on the earth were blotted out of existence.

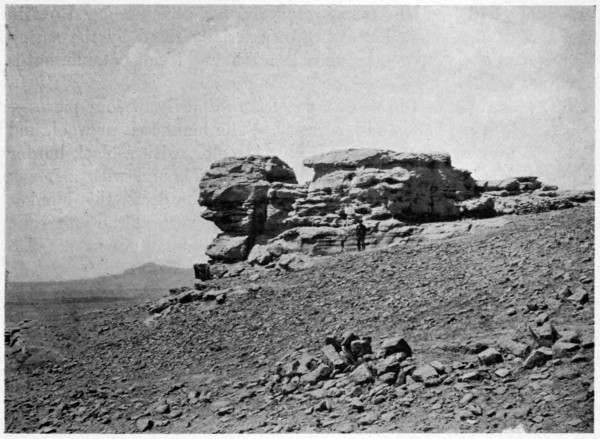

The journey from Winslow to Oraibi is not without great interest. The beautiful snow-capped peaks of the San Francisco Mountain are always in sight far away to the west, and when the eye tires of the rigid and immovable desert their graceful outlines check the often rising feeling of utter helplessness. Then there is a sweep and barrenness of the plain which is impressive and often awe-inspiring, and which at times produces a feeling similar to that created by the sea. Save for the stunted cottonwoods along the Little Colorado River, there is scant vegetation to relieve the bright reds, yellows, and blues of the painted desert over which the sun's heat quivers and dances, revealing here and there mirages of lakes and forests of wonderfully deceptive vividness. Arising out of the plain here and there are brief expanses of table-lands, with the soft under strata crumbled away and the higher strata having fallen down the sides, producing often the appearance of a ruined castle. At the foot of the mesas are clumps of sagebrush and grease wood, while the plain is dotted here and there with patches of cactus and[Pg 736] bright-colored flowers. Foxes and wolves are common enough, and we are rarely out of sight or sound of the coyote, bands of which make night hideous with their shrill, weird cry.

Although the Navajo country proper is to the north and east of Tusayan, their hogans, or thatched-roofed dugouts, are met with here and there along the valley of the river. The Navajos are the Bedouins of America. We often see the women in front of the hogans weaving, or the men along the trail tending their flocks of sheep and goats, for they are great herders and produce large quantities of wool, part of which they exchange to the traders; the remainder the women weave into blankets, which are in general use throughout the Southwest and which find their way through the trade to all parts of the relic-loving world. They raise, in addition, great quantities of beans, which they also send out to the railroad. They are better supplied with ponies than the Hopi, and with them make long journeys, for the Navajos do not live a communal life as do the pueblo people, but are scattered over an extensive territory, each family living alone and being independent of its neighbors.

After a long and tiresome journey of four days we arrive at the foot of the mesa and begin the long, upward climb, for Oraibi is eight hundred feet above the surrounding plain and seven thousand feet above the level of the sea. Just before the crest is reached[Pg 737] the trail for fifty or more feet is simply a path along and up the base of a rocky precipice, its steps worn deep by the never-ending line of Indians passing to and fro. Once upon the summit we have an unobstructed view over the dry, arid, sun-parched valleys for many miles—a view which, in spite of its desolation, is extremely fascinating.

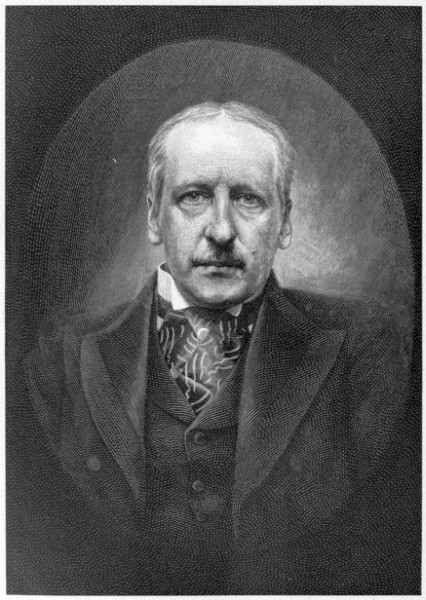

Street Scene, Oraibi.

Street Scene, Oraibi.

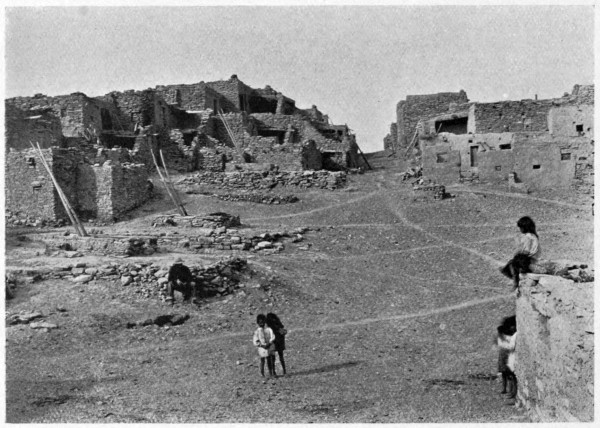

We often speak of this or of that town as the oldest on the continent. But here we are in the streets of a town which antedates all other cities of the United States—a pueblo which occupied this very spot when, in 1540, Coronado halted in Cibola and sent Don Pedro de Tobar on to the west to explore the then unknown desert. Imagine seven rather irregularly parallel streets about two hundred yards long, with here and there a more open spot or plaza, lined on each side with mud-plastered, rough-laid stone houses, and you have Oraibi. The houses rise in the form of terraces to a height of two or three stories. As a rule there is no opening to the ground-floor dwellings save through a small, square hatch in the roof. Leading up to this roof are rude ladders, which in a few rare instances are simply steps cut in a solid log, differing in nowise from those found leading into the chambers of the old cliff ruins of southern Colorado. The roof of the first row or terrace of houses forms a kind of balcony or porch for the second terrace, and so the roof of the second-story houses serves a similar useful purpose for the third-story houses.

Terrace Scene, Streets of Oraibi.

Terrace Scene, Streets of Oraibi.

Two things impress one on entering a Hopi home for the first time—the small size of the rooms, with their low ceilings, and the cleanness of the floors. Both floors and walls are kept fresh and bright by oft-renewed coats of thin plaster, which is always done by the woman, for she owns the house and all within it; she builds it and keeps it in repair. The ceiling is of thatch held up by poles, which in turn rest on larger rafters. Apart from the mealing bins and the piki stones, to be described later, there is no furniture—no table, no chairs, no stools, simply a shelf or two with trays of meal or bread, and near the wall a long pole for clothing, suspended by buckskin thongs from the rafters. Their bed is a sheepskin rug and one or two Navajo blankets spread on the floor wherever there may be a vacant space. In one corner may be a pile of corn stacked up like cordwood, and in another corner melons or squashes and a few sacks of dried peaches or beans. Between the thatch and rafters you will find bows and arrows, spindles, hairpins, digging-sticks, and boomerangs, and from the wall may hang a doll or two, children's playthings. Such is an Oraibi home; but it always seems a happy home, and the traveler is always welcome.

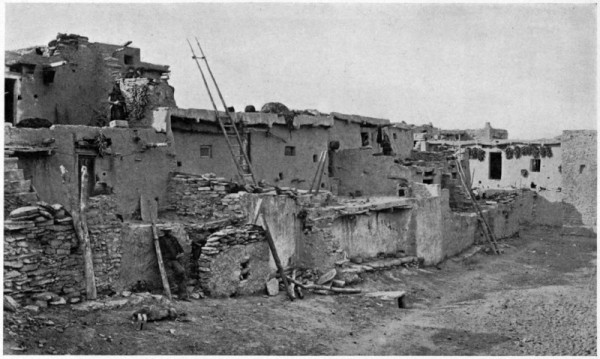

Street Scene, Oraibi.

Street Scene, Oraibi.

A prominent feature of almost every pueblo plaza is a squarish,[Pg 738] boxlike elevation which extends about two feet above the level of the earth and measures about six feet in length, with a two-foot hole in the center, from which projects to a considerable height the posts of a ladder. If you descend this ladder you will find yourself in a subterranean chamber, rectangular in shape, and measuring about twenty-five feet in length by about fifteen feet in breadth, with a height from the floor to the ceiling of about ten feet. This underground room is the kiva, or the estufa of the Spaniards. Here are held all the secret rites of religious ceremonies, and here the men resort to smoke, to gossip, to spin, and weave. The floor, to an extent of two thirds of the entire length, except for a foot-wide space extending around this portion, is excavated still farther to a depth of a foot and a half. The remaining elevated portion is for the spectators, while the banquette around the excavation is used by the less active participants in the ceremonies. Just under the hatchway and in front of the spectators' floor is a depression which is used as a fire hearth. The walls are neatly coated with plaster, and the entire floor is paved with irregularly shaped flat stones fitted together in a rough manner. There is sometimes inserted in the floor, at the end removed from the spectators, a plank with a circular hole about an inch and a half in diameter; this hole is called the sipapu, and symbolizes the opening in the earth through which the ancestors of the Hopi made their entrance into this world. The roof of the kiva is supported by great, heavy beams, which are brought from the San Francisco Mountain with infinite trouble and labor. In Oraibi there are thirteen kivas, each probably in the possession of some society, one of which belongs to women, who there erect their altar in the mamzrouti ceremony. Oraibi has the largest number of kivas of any of the Hopi pueblos; in a single plaza there are no less than four kivas. This plaza is on the west side of the village, and one of the kivas is of special interest, for in it are held the secret rites of the weird snake ceremony. A little to the west of this plaza is a small bit of the mesa, standing apart and separated from the main mesa by a depression. This is known as "Oraibi rock," whence the pueblo takes its name. The etymology of this name "Oraibi" is lost in a misty past, but the rock is still held in great veneration. On it stands a rude shrine, where one may always find sacrificial offerings of prayer-sticks, pipes, sacred meal, cakes, etc.

Oraibi Rock, upon which stands Katcin Kiku, the Principal Oraibi Shrine.

Oraibi Rock, upon which stands Katcin Kiku, the Principal Oraibi Shrine.

The roof of a Hopi house is always of interest. Here we may see corn drying in the sun or loads of fagots ready for use, women dressing their hair or fondling their babies, or groups of children playing or roasting melon seeds in an old broken earthenware vessel which rests on stones over a fire. From the projecting rafters are[Pg 739] ears of corn hung up to dry, or pieces of meat placed there to be out of reach of the dogs, or bunches of yarn just out of the dye pot. When a ceremony is being performed in some one of the plazas the roofs near by present a scene which is animated in the extreme, every square foot of space being occupied by a merry, good-natured throng of young and old. As one looks from one group to another it is impossible not to notice the stunted and dwarfed appearance of the women, which is in marked contrast to that of the men, who are beautifully formed, of medium height, and of well-knit frames. There is not, however, the same powerful ruggedness or splendid development among these pueblo dwellers which we find among the plains Indians, for the days of the Hopi women are spent in carrying water and grinding corn, while the men in summer till their fields and in winter spin and weave.

In considering the routine life of the Hopi it is hard to draw a sharp line between what we may call his regular daily occupations and his religious life, for they are closely interwoven. He is by nature a religionist, and he never forgets his allegiance and obligations to the unseen forces which control and command him.

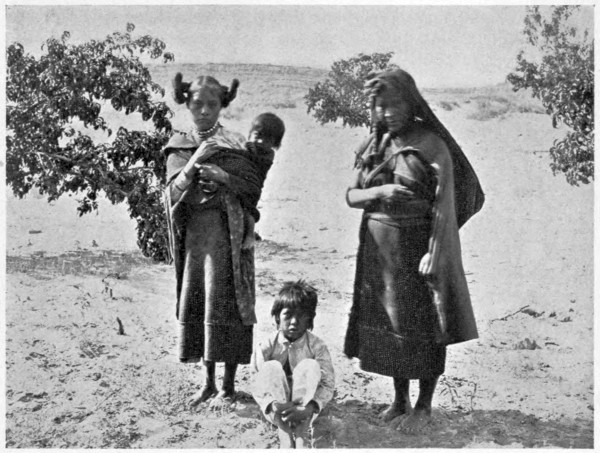

An Oraibi Mother and Children.

An Oraibi Mother and Children.

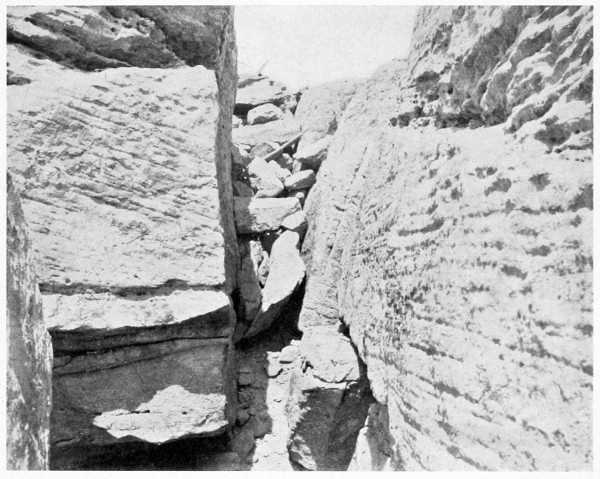

In nothing is the primitiveness or the absence from contamination of the Hopi better revealed than in the children, for here, as elsewhere, is it shown that they are the best conservators of the[Pg 740] habits and customs of ancestral life. What utter savages the little fellows are! Stark naked generally, whether it be summer or winter, dirty from head to foot, their long black hair disheveled and tangled and standing out in every direction, their head often resembling a thick matted bunch of sagebrush. They are never idle; now back of the village behind tiny stone ramparts eagerly watching their horsehair bird snares, or engaged in a sham battle with slings and corncobs, or grouped in threes or fours about a watermelon, eagerly and with much noise gorging themselves to absolute fullness, or down on the side of the mesa playing in the clay pits. A not uncommon sight is that of two or three little fellows trudging off in pursuit of imaginary game, armed with miniature bows and arrows or with boomerangs and digging-sticks. In their disposition toward white visitors they are extremely shy and reticent, but they are also very inquisitive and curious, and, furthermore, they have a sweet tooth, and one only need display a stick of candy to have half the infantile population of the pueblo at his heels for an hour at a time. If perchance one of the little fellows should die, he is not buried in the common cemetery at the foot of the mesa, but he is laid away among the rocks in some one of the innumerable crevices which are to be found on all sides near the top of the mesa, for the Hopis, in common with many other native tribes of America, believe that the souls of departed children do not journey to the spirit land, but are born again.

Grave of Child in Rock Crevice.

Grave of Child in Rock Crevice.

As the girls reach the age of ten or twelve they distinguish themselves by dressing their hair in a manner which is both striking and absolutely unique on the face of the earth. The hair is gathered into two rolls on each side of the head, and then, at a distance of from one to two inches, is wound over a large U-shaped piece of wood into two semicircles, both uniting in appearance to form a single large disk, the diameter of which is sometimes as much as eight inches. After marriage the hair is parted in the middle over the entire head, and is gathered into two queues, one on each side, which are then wound innumerable times by a long hair string beginning a few inches from the head and extending about four inches. The ends of the queues are loose. Hopi maidens are, as a rule, possessed of fine, regular features, slender, lithe, and graceful bodies, and are often beautiful. But with the early marriage comes a daily round of drudgery, which prevents full development and stunts and dwarfs the body. But to old age she is generally patient, cheerful, nor does she often complain. Lines produced by toil and labor may show in her face, but rarely those of worry or discontent. Even long before marriage she has not only learned to help her mother in the care of her younger brothers[Pg 741] and sisters, but she has already trained her back to meet the requirements of the low-placed corn mills. From her tenth year to her last it has been estimated that every Hopi woman spends on an average three hours out of every twenty-four on her knees stooping over a metate, or corn-grinder, for corn forms about ninety per cent of the vegetable food of the Hopis.

In every house you will find, in a corner, a row of two, three, or four square boxlike compartments or bins of thin slabs of sandstone set on edge. Each bin contains a metate set at an angle with its lower edge slightly below the level of the floor. There is a clear space around each stone to permit of a better disposition of the corn and meal. The texture of the metates is graduated from the first to the last, the final one being capable of grinding the finest meal. Accompanying the metate is a crushing or grinding stone about a foot in length and from three to four inches wide. Its under surface is flat, while its upper surface is convex to a slight extent, so as to permit of its being grasped firmly by the thumb and fingers of both hands. The corn is ground between these two stones, the upper one being worked up and down the metate by a motion of the operator not unlike that of a woman washing clothes on a washboard. The favorite position assumed by the woman while working is to sit on her knees, her toes resting against the wall of the house behind her. Of the many colors of corn used by the Hopis, blue is the most common, and corn of this color is ordinarily employed in the making of bread; other colors, however, are used for the piki consumed in ceremonial feasts.

The stone used by the Oraibians for making piki is from a sandstone quarry near Burro Springs. It is about twenty inches long by fourteen broad, and is three inches thick. The upper surface is first dressed by means of stone picks, and is polished by a hard rubbing-stone, and then finally treated with pitch and other ingredients until its surface is as smooth as glass. It is mounted on its two long edges by upright slabs, so that it stands about ten[Pg 742] inches from the level of the floor, the floor itself being usually excavated to a depth of two or three inches beneath the stone. At a height of about four feet above this primitive griddle is a large rectangular hood which is extended above the roof in the form of a chimney made of bottomless pots, one resting on the other. Kneeling in front of the stone and supporting her body with her left arm, the woman coats the stone with the thin batter of corn and water with the fingers of her right hand. After a few seconds' time she lifts the waferlike sheet from the stone and transfers it to a mat which is made for this special purpose. For some time the piki remains soft and pliable, and while in this condition she rolls or folds the sheets according to her custom—some folding, others rolling it. It is a curious sight on the feast days of certain ceremonies to see women gathering from all quarters of the village at an appointed house, each carrying a tray heaped high with rolls of this paper bread.

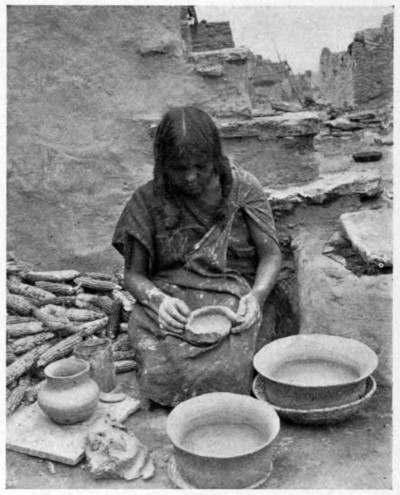

Woman of Oraibi making Coiled Pottery.

Woman of Oraibi making Coiled Pottery.

The Hopis are among the foremost potters in North America, when we take into consideration the fineness of the clays used and the character of the decoration. But in many respects, especially in form, their ware is much inferior to that of the ancient Mexicans and Peruvians. They make pottery to-day as they did hundreds of years ago, but the quality of the work has greatly deteriorated and the earthenware now produced is not to be compared with that found in near-by Hopi ruins. It should be kept in mind, however, that the specimens found in the ancient graves are to a certain extent ceremonial, and consequently better made and more ornate in their decoration than those which were made simply for household purposes. Still, there are a fineness of texture and a delicacy of coloring in the ancient ware which can not now be produced. It is to be noted, also, that the Hopi woman of to-day can not decipher the designs on the earlier pottery, although she often copies them. The demand for earthenware vessels, however, is nearly as great at present as it was in prehistoric days, for you may search the homes of Oraibi for a long time without finding a tin pan or an iron pot. Thus it is that every Hopi woman must be a worker in clay, and one of the occasional sights is that of a woman on her "front porch" surrounded by vessels of all sizes and in varying degrees of completeness. The process of pottery-making is somewhat as follows: After the clay has been worked into a plastic mass she draws out from it a round strip the size of one's finger and about five inches in length. This is coiled flat in the bottom of the tray, and forms the base of the vessel. Other clay strips are kneaded out of the mass, and these are coiled in a gradually increasing spiral, the desired shape and proportion being acquired at the same[Pg 743] time, until the vessel has reached its proper height. The sides of the vessel are then thinned down, and both inside and outside are made smooth by means of small bits of gourds and polishing-stones. The vessel is then ready for a coat of wash, after which it is painted and fired. This method of making pottery is not peculiar to the pueblos, but is found among some of the tribes of South America.

The art of basketry was never brought to a high state among the Hopis, for they confine themselves chiefly to the manufacture of large shallow trays and rough baskets made of the long, pliable leaves of the yucca or of some other fiber. These answer all ordinary domestic requirements. From the reddish-brown branches of a willowlike bush which grows near, the Hopi mother interweaves a cradle board for her children. This cradle is peculiar in its shape, and especially so in its construction, and differs greatly from that in use among the plains Indians. Another singular point to be noted is the fact that this cradle board is not often strapped to the back, but is usually in the arms, or, more often still, is placed on the floor by the side of the mother as she works. The Oraibi mesa, like other table-lands of Tusayan, is destitute of water. The nearest spring is in the valley at the foot of the mesa nearly a mile away. From before sunrise to ten o'clock of every day there is an almost unbroken line of water carriers going and coming from the[Pg 744] spring, bending under the weight of a large jar which they carry on their back by means of a blanket, the ends of which are tied in a knot on their forehead. No wonder these women grow prematurely old. Winter for them, however, has its advantages, for they have an ingenious way of utilizing the snow to save them from the necessity of going down the mesa for water. One of the most extraordinary sights I saw was that of a Hopi woman and her little girl trudging along, each bent almost to the ground under the weight of an immense snowball. These they were carrying home on their backs, enveloped in a blanket. About half a mile from the pueblo, back on the mesa, reservoirs have been scooped out in the soft sandstone, which are often partially filled by the spring rains, but the water soon becomes brackish and is not potable, but is used for washing clothes.

The costume of the woman consists ordinarily of four pieces—a blanket, dress, belt, and moccasins. The blanket is of wool, and is about four feet square. It is blue in color, with a black border on two sides. These two edges are usually bound with a heavy green or yellow woolen thread. To make the dress, this blanket is once folded and is sewn together with red yarn at the long side, except for a space sufficiently large to accommodate one arm. The folded upper border is also sewn for a short space, which rests on one of the shoulders. The other shoulder and both arms are bare, except as they may be partially covered by the blanket. The belt or sash is of black and green stripes, with a red center, ornamented with geometric designs in black; it is about four inches wide, and is long enough to permit of being wound around the waist two or three times. The moccasins are of unpainted buckskin, one side of the top of which terminates in a long, broad strip, which is wound round the leg several times and extends up to the knee, thus forming a thick legging. More than half the time the Hopi woman is barefooted. The girls wear silver earrings, or suspend from the lobe of the ear small rectangular bits of wood, one side of which is covered with a mosaic of turquoise. This custom is of some antiquity, as ear pendants exactly similar to these have been found in the Hopi ruins of Homolobi, on the Little Colorado River.

In addition to this regulation costume, worn on all ordinary occasions, each Hopi woman is supposed to own a bridal costume and two special blankets, which are worn only in ceremonies, and hence need not here be described. The bridal costume consists of a pair of moccasins, two pure white cotton blankets, one large and the other small, both having large tassels of yellow and the black yarn at each corner, and a long, broad, white sash, each end of which terminates in a fringe of balls and long thread. All three garments,[Pg 745] before being used, are covered with a thick coat of kaolin, so that they are quite stiff. With these garments belongs a reed mat sufficiently large to envelop the small blanket and the sash.

So far as I am able to learn, the three pieces of this remarkable costume are never worn except on a single occasion, and at only one other time does the bride formally appear in any of them. About a month after the marriage ceremony has been performed, during which time she has been living with the family of her husband, she completes the marriage ceremony by returning to the house of her mother. This is termed "going home," and this will be her place of abode until she and her husband own a dwelling of their own. For this ceremony she puts on the larger of the two blankets, which reaches almost to the ground and comes up high on the back of the head, covering her ears. The smaller blanket and the sash are rolled up in the mat, and with this in front of her on her two arms she begins her journey "home." This white cotton costume is probably a survival from times which antedate the introduction of wool into the Southwest.

Who makes all these garments, blankets, etc.? Not the women, as you might expect, but the men. A Hopi woman doesn't even make her own moccasins. If you will descend into one of the kivas[Pg 746] on almost any day of the year, except when the secret rites of ceremonies are being held, you will behold an industrious and an interesting scene. You will find a group of men, naked except for a loin cloth, all busy either with the carding combs, the spindle, or the loom; and to me the most interesting of these three operations is that of the spinning of wool. The spindle itself is long and heavy, and the whorl, in the older examples, is a large disk cut from a mountain goat's horn. There is no attempt at decoration, nor do the spindles compare with those found in Peru and other parts of America for neatness and beauty. An unusual feature of the method employed by the Hopi spinner is the manner in which the spindle is held under one foot while he straightens out the thread preparatory to winding it.

For weaving, two kinds of looms are used. One is a frame holding in place a fifteen-inch row of parallel reeds, each about six inches long and perforated in the center. This apparatus is used solely for making belts, sashes, and hair and knee bands. These are not commonly woven in the kiva, but in the open air on the terrace, one end of the warp being fastened to some projecting rafter. The other loom is much larger, and is used for blankets, dresses, and all large garments. It differs in no essential particular from other well-known looms in use by the majority of the aborigines of this continent. The method of suspending the loom is perhaps worth a moment's notice, as in nearly every house and in all kivas special[Pg 747] provision is made for its erection. From the wall near the ceiling project two wooden beams, on which, parallel to the floor, is a long wooden pole, and to this is fastened, by buckskin thongs, the upper part of the loom. Immediately under this pole is a plank, flush with the floor, in which at short intervals are partially covered U-shaped cavities in the wood, through which are passed buckskin thongs which are fastened to the lower pole of the loom. The sets of thongs are long enough to permit of the loom being lowered or raised to a convenient height. While at work the weaver generally squats on the floor in front of his loom, or he occasionally sits on a low, boxlike stool. It is no uncommon sight to see, at certain times of the year, as many as six or eight looms in operation at one time in a single kiva. The men also do all the sewing and embroidering. Practically all the yarn consumed by the Hopis is home-dyed, but the colors now used are almost entirely from aniline dyes and indigo. Cotton is no longer used except in the manufacture of certain ceremonial garments, all others being made of wool. They own their own sheep, which find a scant living in the valleys; for the better protection of the sheep from wolves they also keep large numbers of goats.

Although the men do all the weaving, they do but little of it for themselves. For the greater part of the year their only garment is the loin cloth—a bit of store calico. In addition, they all own a shirt of cheap black or colored calico, which is generally more or less in rags, and a pair of loose, shapeless pantaloons, made often from some old flour sack or bit of white cotton sheeting. It is a rather incongruous sight to see some old Hopi, his thin legs incased in a dirty, ragged pair of flour-sack trousers, on which can still be traced "XXX Flour, Purest and Best."

Neither sex scarifies, tattoos, or paints any part of the body except in ceremonies, when colored paints are used as each ceremony requires. The men often wear large silver earrings, and suspend from their neck as many strands of shell and turquoise beads as their wealth will allow. Some of the younger men wear, in addition, a belt of large silver disks and a shirt and pantaloons of velvet. Most of their silver ornaments, it should be noted, however, have been secured in trade from the Navajos, who are the most expert silversmiths of the Southwest.

When the Hopi isn't spinning or weaving, he is in his kiva praying for rain, or he is in the field keeping the crows from his corn. I was once asked if the Hopis plow with oxen or horses. They use neither; they do not plow. When they plant corn they dig a deep hole in the earth with a long, sharp stick until they reach the moist soil. When the corn is sprouted and has reached[Pg 749] a height of a few inches there is always the possibility of its being blown flat by the wind or overwhelmed in a sand storm. To provide against this the Hopi incloses the exposed parts of his little field with wind-breakers, made by planting in the earth thick rows of stout branches of brush. These hedges even are often overwhelmed by the sand and completely covered up.

And the crows, and the stray horses, and the cattle! Surely the poor Indian must fight very hard for his corn. For nearly two months he never leaves it unguarded, and that he may be comfortable he makes a shelter behind which he can escape the burning rays of the July and August sun. The shelters are occasionally rather pretentious affairs, at times consisting of a thick brush roof, supported by stout rafters which rest on upright posts. More often, however, they simply consist of a row of cottonwood poles, five or six feet high, set upright at a slight angle in the earth.

Although corn is by far the most important vegetable food, the rich though sun-parched soil yields large crops of beans and melons of all kinds.

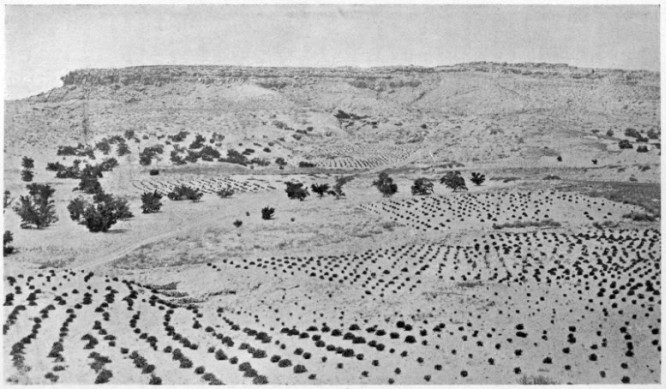

Valley Scene; Fields and Peach Trees. Oraibi on Mesa to the Right.

Valley Scene; Fields and Peach Trees. Oraibi on Mesa to the Right.

Peach orchards also thrive in the sheltered valleys near the mesa, and in the fall great patches of peaches may be seen spread out to dry on the rocks of the mesa to the north of the village. Of both beans and peaches the Hopis generally have large quantities for the outside market, which they take over to the railroad on the backs of burros or ponies.

Before leaving the subject of the daily life of the male portion of Oraibi I have still to mention a curious weapon of which they make occasional use. This is the throwing-stick, or so-called boomerang, which differs only slightly from that used by the aborigines of Australia; the Hopi stick, however is better made, and is ornamented by short red and black lines. This is the weapon of the young men, and with it they work havoc with the rabbits which infest the valleys. But although they have good control over it, as can often be seen on their return from a hunt, they are not able to cause its return as can the Australians. At first thought it seems rather strange that the boomerang should have been evolved by two groups of mankind dwelling in parts of the world so remote, but we must look for the explanation of this phenomenon in the fact that the natural conditions of the two countries have much in common—a generally level, sandy country, with here and there patches of brush, a peculiar condition which would readily yield itself to the development of an equally peculiar and specialized weapon.

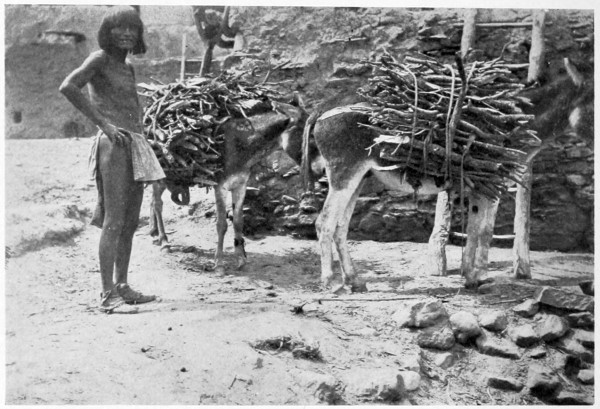

Oraibi Man transporting Firewood with Burros.

Oraibi Man transporting Firewood with Burros.

For fire the Hopi depends almost entirely on the rank growth of brush which is found along the ravines. This suffices to supply[Pg 750] heat to the piki stone and the boiling pot, and enough to keep a fire on the hearth in the kiva. But now and then he must make a distant journey to that part of the mesa where the supply of stunted and scrubby pines and piñons has not already been exhausted; for by custom four kinds of fuel are prescribed for the kivas, and to keep the hearth replenished with these often necessitates long journeys. As the woman bends under her water jar, so the man staggers along under his load of fagots, often carried from a distance of several miles.

By BIRD S. COLER,

COMPTROLLER OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK.

Abuse of municipal charity in New York city has reached a stage where immediate and radical reform is necessary in order to prevent the application of public funds to the payment of subsidies to societies and institutions where professional pauperism is indirectly encouraged and sustained. More than fifty years ago the city began to pay money to private institutions for the support of public charges. The system has grown without check until to-day New York contributes more than three times as much public money to private or semiprivate charities as all the other large cities in the United States combined. The amounts so appropriated in 1898 by some of the chief cities were: Chicago, $2,796; Philadelphia, $151,020; St. Louis, $22,579; Boston, nothing; Baltimore, $227,350; Cincinnati, nothing; New Orleans, $30,110; Pittsburg, nothing; Washington, $194,500; Detroit, $8,081; Milwaukee, nothing; New York city, $3,131,580.51.

No serious attempt has heretofore been made to reform this system of using public funds for the subsidizing of private charities. One reason for this has doubtless been the fact that until recently the local authorities were powerless to avoid or modify the effects of mandatory legislation which has disposed of city moneys without regard to the opinions entertained by the representatives of the local taxpayers. It has always been easier to pass a bill at Albany than to persuade the Board of Estimate and Apportionment of the propriety of bestowing public funds on private charities, and the managers of private charities seeking public assistance have therefore generally proceeded along the line of least resistance. The effect of this system was to make beneficiaries the judges of their own deserts, for the bills presented by them[Pg 751] to the Legislature were usually passed without amendment or modification, and gross inequalities in disbursing public funds have arisen, different institutions receiving different rates of payment for the same class of work.

In 1890 the city paid for the support of prisoners and paupers in city institutions the sum of $1,949,100, and for paupers in private institutions the sum of $1,845,872. In 1898 these figures had increased to $2,334,456 for prisoners and public paupers, and $3,131,580 for paupers in private institutions. Private charity, so called, has prospered at the expense of the city until in some cases it has become a matter of business for profit rather than relief of the needy. The returns made by institutions receiving appropriations in bulk from the city treasury show that many of them are using the public funds for purposes not authorized by the Constitution. The Constitution authorizes payments to be made for "care, support, and maintenance." The reports of a large number of institutions show the money annually obtained from the city carried forward wholly or in part as a surplus. Different uses are made of this surplus, none of them, however, authorized by law or warranted by a proper regard for the interests of the taxpayers. In some cases this surplus is used to pay off mortgage indebtedness, in others for permanent additions to buildings, or for increase of investments and endowment. In one case the manager of an institution frankly explained a remarkable falling off in disbursements (so great that its charitable activities were almost suspended) by stating that it was proposed, by exercising great economy for a number of years, to let the city's annual appropriations accumulate into a respectable building fund. The flagrant nature of this abuse is so apparent that comment is unnecessary.

Appropriations for dependent children have reached enormous proportions. Out of a total of $3,249,623.81 appropriated for private charities in 1899, no less than $2,216,773, or sixty-nine per cent, is for the care and support of children. In no city in the United States will the number of children supported at the public expense compare, in proportion to the population, with the number so cared for in the city of New York. This may be partly accounted for by the extremes of poverty to be met with in the metropolis, especially among the foreign-born population, where the struggle for existence is so severe as to weaken the family ties; partly by the rivalry and competition which have existed between the several institutions devoted to this kind of work; partly by reason of the fact that the rate paid by the city for the care of these children is such as to enable the larger institutions, in all probability, to make a small profit; but, to a considerable extent,[Pg 752] also from an insufficient inspection by public officers for the purpose of ascertaining whether children are the proper subjects of commitment and detention. In the city of New York 50,638 children in private institutions are cared for at the public expense. This is one to every sixty-eight of the estimated population of the city.

So much for the abuse and extent of public charity. Now for the reforming of the system that was fast approaching the condition of a grave scandal. The last Legislature passed a bill placing in the hands of the local Board of Estimate absolute power over all appropriations for charitable purposes, and for the first time in many years reform is possible. The discretion conferred by this act upon the Board of Estimate and Apportionment carries with it a large responsibility. If hereafter the city, in its relation to private charitable institutions, should either, on the one hand, be wasteful of public funds, or, on the other hand, should fail to perform the duties owed by the community to the dependent classes, the blame can not be shifted to the Legislature, but will rest squarely upon the shoulders of the local authorities.

In treating a condition which has been allowed to exist for many years almost without challenge from the local authorities, and which has grown upon the passive or indifferent attitude of the public, sweeping and immediate reforms can be instituted only at the cost of serious temporary injury to certain charitable work of a necessary character. I believe that the best results will be obtained if the city authorities first decide clearly the relations to be established between the city treasury and private charitable institutions, and then move toward that end by gradually conforming the appropriations in the budget to that idea, in such a manner that progress shall be made as rapidly as may be consistent with the desire to avoid crippling excellent charities which have been led to depend for many years upon public assistance. By this, of course, I do not mean to suggest that we should approach the subject with excessive timidity, for the evils that exist have assumed such proportions that a more or less severe use of the pruning knife must be made in dealing with appropriations, else the effect will be scarcely perceptible. I am convinced that ultimately the cause of charity will benefit rather than suffer from this course, for it is a serious objection to the whole subsidy system that it tends to dry up the sources of private benevolence.

In making up the budget for 1900 I shall urge my associates in the Board of Estimate to agree with me to limit the appropriations for charity to actual relief work accomplished. The giving of public money in lump sums to private societies and institutions[Pg 753] for miscellaneous charitable work, of which there is no public or official inspection, should be discontinued at once. It has been the practice for some years past, both in Brooklyn and New York, to donate annually lump sums of money to such organizations. In New York these amounts have been for the most part comparatively small, and principally derived from the Theatrical and Concert-License Fund. In Brooklyn the amounts have been larger, and were obtained originally from the Excise Fund, and later directly from the budget. This practice should be wholly discontinued. The charter itself contains stringent prohibitions against the distribution of outdoor relief by the Department of Public Charities, and the spirit of these provisions would certainly seem to disfavor accomplishing the same result in an indirect manner. Many of these recipients of public funds devote themselves exclusively to outdoor relief, and an examination of the purposes of some of these organizations shows that, however proper these may be as the result of private benevolence, they are extremely improper objects of the public bounty. The immediate and permanent discontinuance of appropriations to all such societies and institutions will correct one of the gravest abuses of the present system. If the persons conducting these miscellaneous charities are really sincere, and believe that they are doing good, they can readily obtain from private sources the funds necessary to carry on the work.

I shall urge that all appropriations to institutions of every kind not controlled by the city be limited to per-capita payment for the support of public charges, and that a system of thorough inspection be at once established to ascertain if present and future inmates are really persons entitled to maintenance at public expense. In addition to this precaution, the comptroller should have full power to withhold payments to any institution after an appropriation has been made if in his judgment, after examination, the money has not been earned. The payment of city money to dispensaries should be discontinued, except in special cases where the work done is clearly a proper charge against the public treasury. No money should be paid for the treatment of dependent persons in any private hospital while there is unoccupied room in the city hospitals.

The city maintains its own hospitals, while at the same time subsidizing private institutions which compete with them. During the last few years great improvements have been made in the city hospitals, but their condition is still capable of considerable further improvement. While sometimes overcrowded, it frequently happens that the city hospitals are not filled to the limits of their capacity, and it would seem as though the city should not[Pg 754] deal with private hospitals except as subsidiary aids or adjuncts to the public institutions. It stands to reason that so long as there are vacant beds in the city hospitals and the city is at the same time subsidizing private hospitals at a cost greater than the expense of caring for patients in its own institutions, a wrong is being done to the taxpayers. If private hospitals are to receive public assistance at all, payments should be made only at some uniform rate, approximately the same as the cost per capita of maintenance in the public institutions.

The gravest problem of public charity is the support and training of dependent children, because that has to do with the making of future citizens of the republic as well as the relief of immediate suffering. This work is entirely in the hands of private societies and institutions. The rearing of large numbers of children in either private or public institutions is in itself an evil—a necessary evil—and likely to continue as long as there is extreme poverty, but still an evil, and not to be fostered by subventions of public money in unnecessary cases, when parents are really able to provide for their support.