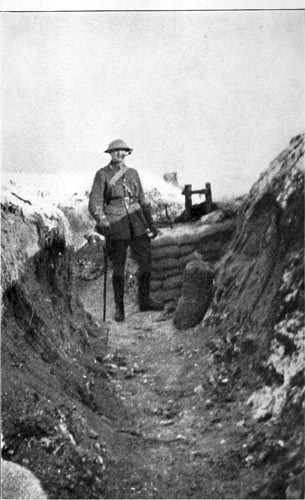

Captain Trounce.

Title: Fighting the Boche Underground

Author: H. D. Trounce

Release date: September 2, 2014 [eBook #46757]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Brian Coe and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries (https://archive.org/details/toronto)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Fighting the Boche Underground, by Harry Davis Trounce

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries. See https://archive.org/details/fightingbocheun00trou |

FIGHTING THE BOCHE UNDERGROUND

BY

H. D. TROUNCE

FORMERLY OF THE ROYAL BRITISH ENGINEERS

NOW CAPTAIN OF ENGINEERS, U.S.A.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND DIAGRAMS

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1918

Copyright, 1918, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

Published October, 1918

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | INTRODUCTORY | 1 |

| II. | TO THE FRONT | 12 |

| III. | UNDERGROUND | 27 |

| IV. | CRATER FIGHTING | 44 |

| V. | TUNNELLING IN THE VIMY RIDGE TRENCHES | 61 |

| VI. | CHALK CAVERNS AND TRENCH MORTARS | 78 |

| VII. | AROUND THE VIMY RIDGE | 97 |

| VIII. | THE SOMME SHOW | 115 |

| IX. | THE BATTLE OF THE ANCRE | 127 |

| X. | THE RETREAT OF ARRAS | 142 |

| XI. | THE BATTLE OF ARRAS | 162 |

| XII. | THE HINDENBURG LINE | 176 |

| XIII. | THE PSYCHOLOGY OF FEAR | 199 |

| XIV. | SOME PRINCIPLES OF MINING | 207 |

| Captain Trounce | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Breathing-apparatus necessary in going into "gassy" galleries | 50 |

| Sector near Neuville-St.-Vaast, Vimy Ridge trenches, April 3, 1916 | 64 |

| The same sector, Vimy Ridge trenches, May 16, 1916 | 66 |

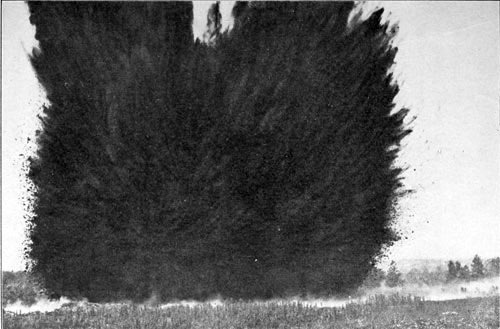

| Explosion of a mine | 80 |

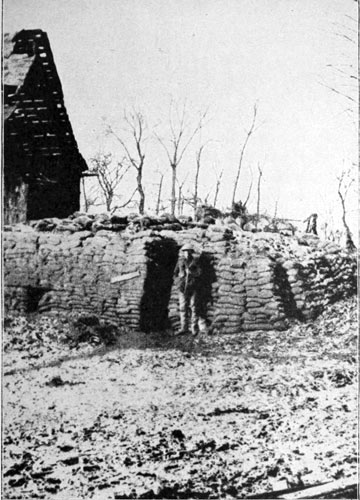

| A cellar, protected by sand-bags, in the village of Hebuterne used as a shelter by engineer officers | 130 |

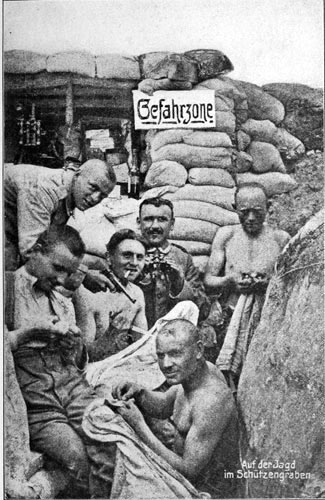

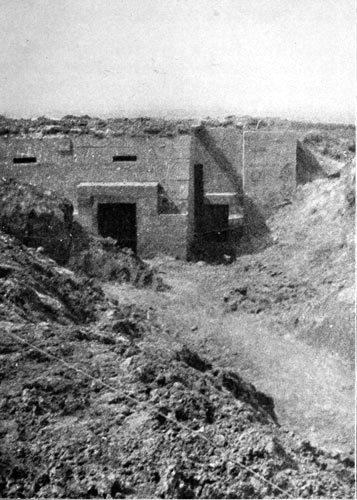

| In a German trench | 156 |

| View from rear of a typical German reinforced concrete machine-gun emplacement. Taken on the Hindenburg line south of Arras | 178 |

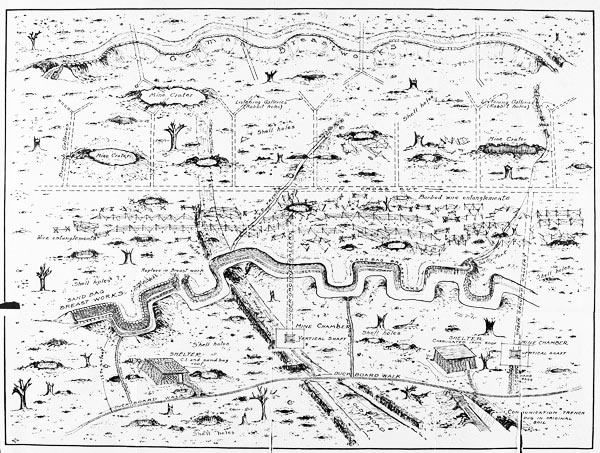

| Rough sketch illustrating breastworks and systems of underground galleries | At end of volume |

It has been frequently suggested to me that I write of my experiences at the front. As one of the advance-guard of the American army who participated in the great struggle for freedom long before the United States espoused the cause of the Allies, I am more than willing to do this, owing to my strong desire that the public should know something of the constant fighting which is going on underneath as well as on the surface and above the ground of the trenches both in France and elsewhere, especially if, by so doing, I can help the people at large more fully to appreciate the importance of the work and the unflinching devotion of that branch of the army which but seldom finds itself singled out for the bestowal of special honors or for the expression of public approbation.

This narrative will be mainly concerned with the engineers and sappers who are so quietly and unostentatiously undergoing extraordinary hardships and dangers in their hazardous work below the ground, in order that their comrades of the infantry may occupy them above, safe, at any rate, from underground attack. In no species of land warfare is a cool head and clear brain, combined with decisive and energetic action and determined courage, more required than in the conduct of these military mining operations.

The value of mines and of similar contrivances of the engineer is partly psychological. Though hundreds of men only may be put out of action by their use, thousands of valuable fighting men suffer mentally from the knowledge or from the mere suspicion that their trenches are undermined by the enemy. Such a suspicion causes the strain on their morale to be very severe and their usefulness to be correspondingly diminished.

The men engaged in this work do not receive that inspiration and access of courage which comes from above-ground activity and which enkindles and stimulates enthusiasm, as in a blood-stirring charge. This trench tunnelling and mine laying requires a different form of bravery: that unemotional courage which results from strong self-control, determination, and perseverance of purpose. The personnel of these engineer-mining regiments usually work in twos and threes, or in small groups, cramped in narrow galleries, sometimes 20, sometimes 200, feet below the surface; and often immediately under or beyond the enemy's front trenches. On numerous occasions they silently force their way underground, despite great difficulties and risk, to within a few feet of the enemy sappers, hardly daring to breathe. A cough, a stumble, or a clumsy touch only are necessary to alarm the enemy, cause them to fire their charge, and thus send another party of opposing soldier miners to the "Valhalla" of modern fighting men. In this war, enormous charges of the highest and deadliest explosives known to man are used. Instant annihilation follows the slightest mistake or carelessness in handling such frightful compounds. Always is there excitement in abundance, but its outward manifestation is of necessity determinedly suppressed. No struggle with a living and resourceful enemy comes to stimulate the soldier mining engineer; only a ghostly adversary has he to contend with, one who is both unresponsive and invisible until the final instant.

No part of such work can be hurried. Underground surveys are calmly and efficiently made, huge mine charges deliberately and quietly placed, electrical connections carefully tested, and at the precise moment fired with terrific detonation and damage. The earth is shaken for miles around, trenches are entirely buried with the débris, while companies of men are engulfed, and immense mine-craters formed.

During the progress of this war there has been a constant increase in the number of engineering troops and development in engineer equipment. While the organization of the German troops at the outset of the war included large numbers of engineer soldiers specially trained for military purposes, the number of engineer units in the British forces as well as those of our other allies was comparatively small.

The training of engineer troops among the Allies for use in trench warfare was extremely limited; their work was confined generally to the operations of open warfare.

Trench warfare changed the whole course of events and rendered necessary wide and sweeping changes in organization, training, and equipment. It has been often stated that this is a war of engineers, and it is certainly true. Engineers and engineering problems are found in every branch of the service.

Instead of being a small and comparatively unimportant corps in our great army machine, they are now of the first importance, and no operations of any magnitude are undertaken without including the necessary engineer forces.

In almost every instance careful liaison or co-operation must be effected with the infantry or other arms concerned in the operations.

I can hardly begin to enumerate the different activities of engineers in trench and open warfare. Some of the most important work done by them in this trench warfare includes the construction, repair, and general maintenance of all trenches (assisted by the infantry); the building of all mined dugouts and shelters of all descriptions; the construction of all strong points and emplacements, machine-gun posts, trench-mortar posts, artillery gun-pits, snipers' posts, O.P.'s, or artillery observation-posts, and so on; all demolition work, such as the firing of large charges of high explosives in mines under the enemy's positions, the destruction of enemy strong points, etc.; the building and maintenance of all roads; the construction and destruction of all bridges, construction and operation of light and heavy railroads, and many other duties too numerous to mention.

It is a work of alternate construction and destruction. The sapper must be a real soldier as well as an engineer. With the possible exception of some of the troops on lines of communication, and some railway, harbor, and other special units, they are all combatant troops, and are so rated and recognized. Many thousands of them are on constant trench work and other thousands on work close up, where they are continually shelled and exposed to fire.

The training of the majority of engineers includes the same methods of offense and defense as the infantry, and well it is that it does so. Almost every day on the western front they are called on to accompany the infantry "over the top," or on a raid on enemy trenches; to destroy enemy defenses; or to consolidate captured trenches; or again to "man the parapet" in holding off enemy attacks until infantry reinforcements can come through the usual "barrage." These things happen every day in the trenches, and the engineer soldier would be at a serious disadvantage if he had not been trained in the use of rifle, bomb, and bayonet. No one has a stronger admiration for the infantry than I have, and every one must take off his hat to these "pucca" (real) fighting men, but the fact remains that the sappers who have continual trench duty are subject to the same constant trench fire as the infantry are every day—the only real difference is that they seldom get a chance to "hit" back. They have their work to do, and seldom have a chance to return the compliment and "strafe the Hun," except in self-defense.

Strategists are pretty well agreed that the main successes of the war must be won by sheer hard trench fighting, and continued until the Germans will not be able to pay the cost in lives and munitions.

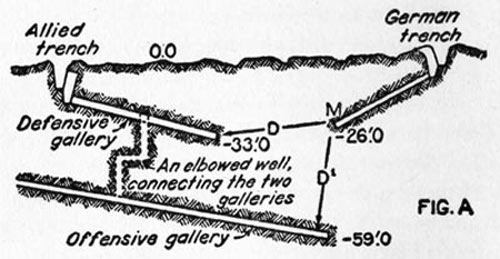

In this underground warfare the work of the engineers whose business it is to protect the infantry from enemy attacks below ground is both serious and interesting. At the headquarters of the mining regiment a note is opened from the Brigade Staff: "Enemy mining suspected at K 24 b 18—request immediate investigation." An experienced mining officer is at once detailed to proceed to the area in question and report on the situation.

At times it is a question of nerves on the part of some lonely sentry, but quite as often it develops that the enemy are mining in the immediate vicinity. Measures to commence counter-mining are at once started.

Then the game of wits below ground begins. Mine-shafts are sunk and small narrow galleries driven at a depth which the engineers hope will bring them underneath the German attack galleries. From day to day and even from hour to hour when they are within striking distance careful and constant listening below ground is undertaken, both friend and foe endeavoring to make progress as silently as possible.

In a regular mine system all manner of ruses are adopted to keep the enemy guessing as to the exact locality of each of their tunnels: false noises in distant or higher galleries; plain working of pick and shovel in others; meanwhile they are silently and speedily making progress in the genuine tunnels to the real objective.

Often we delay the laying of our charges of high explosive until we are within two or three feet of the enemy gallery and can even hear the enemy miners talking. On three occasions I have heard them talking very plainly, and listened for hours to them working on, quite unconscious of their danger. It was always a source of annoyance to me that I could understand so little German. At other times, and this has happened more than once in the clay soil of Flanders, we have broken into enemy galleries and fought them with automatic pistols, bombs, and portable charges of high explosives.

As a means of offensive warfare, mining has taken an important part, particularly in the launching of infantry attacks and night raids.

The battle of Messines Ridge in July, 1916, was started by firing at the "Zero" hour some 19 mines, spread over a front of several kilometres. In these 19 mines the aggregate of the total high explosive used and fired at the same instant was a few thousand short of 1,000,000 pounds. Some of the individual charges were nearly 100,000 pounds each, and had been laid ready for firing for over twelve months. Some idea of the frightful force and power of these charges may be obtained when it is remembered that each of the "Mills" bombs, or hand-grenades carried by British soldiers, contains one quarter of 1 pound, or 4 ounces, only of this explosive. As a result of this terrific blow the Germans retreated for over a half-mile on the entire front mined, and the initial objectives of the British were captured with astonishingly low casualties.

In counter-mining, when the enemy are met below ground in crossing under No Man's Land, it is the usual practice of the Allies to explode a charge or mine which they call a "camouflet." The camouflet totally destroys the enemy's gallery, but does not break the surface. The common and the overcharged mine always blow a deep and wide cone-shaped crater. Large charges of explosive blow craters several hundred feet in diameter and well over 100 feet in depth.

In almost every sector of the western front in France where the trenches are close together, (that is, from 20 or 30 up to 200 yards apart), these mine-craters are found in No Man's Land. In sectors where mining has been very active, mine-craters are so common that they intersect each other. The "blowing" of a crater in No Man's Land at night and the immediate occupation and consolidation of it by the infantry and engineers is a wonderfully stirring affair. The strain on the morale of the infantry occupying sectors which are known to be mined is a terrible one, especially if they have no engineers to combat the stealthy attack. For the hundreds who are killed, buried, or injured from enemy mines there are thousands who suffer a mental strain from the mere suspicion of their existence.

Trench mining now, I am glad to add, is not the menace that it was in 1915 and 1916, but when the good-weather offensives cease and the usual winter trench warfare is renewed, mining will probably make its reappearance.

Being of British parentage and birth, most of my earlier life was spent in England. On coming of age, I left England for Canada, and after a few months there decided to study mining engineering in the United States. I attended a Western college, the Colorado School of Mines, leaving there in 1910 to practise my profession as a civil and mining engineer in California, where I took out my final papers as an American citizen several years before the war.

By reason of my birth my sympathies were naturally much aroused in the earlier part of the great struggle, and the fact that my brother had joined the Canadian forces directly after war had been declared, and the subsequent injury and death in battle of several British cousins, infantry officers, early in the war, preyed on my mind to such an extent that I left my home and practice in California in October, 1915, proceeded to New York, and from there to London. I applied for a commission in the Royal Engineers. No unnecessary questions were asked as to my nationality. I proved my engineering experience, and within two weeks was ordered to report to the officer commanding an officers' training-corps in London to commence training.

It may be of interest to note here that I was then in much the same frame of mind as many of our soldiers are now—generally afraid that the war would be over before they reached the trenches. I was first offered a commission in a field-engineering company of the Royal Engineers, but informed at the same time that it would be necessary for me to put in three or four months' preliminary training in England before I could get over to France.

This did not appeal to me. I was also of the opinion at the time that the war would probably be over before long; and later, by inquiry, elicited the fact that mining engineers were in immediate and great demand on account of very active enemy fighting underground in France. I found out later that a number of British mining engineers, coming back to England from India, Africa, and various parts of the globe to enlist in their country's cause, had applied to the War Office for commissions, and had been accepted at once, given three days to arrange their private affairs, obtain their uniforms and active service-kits, and report to the companies they were posted to in the front-line trenches. Certainly the red tape was cut here.

In less than three weeks I received my commission as second lieutenant, with orders to leave the O.T.C. and proceed to Chatham, to the R.E. Barracks, in company with several other mining officers, for a few days' further training preparatory to proceeding overseas. The British Government makes a grant of approximately $250 to all officers when commissioned in order that they may supply themselves with uniforms and kit. These were soon obtained, and we were then instructed to hold ourselves in readiness to sail at any minute. We were first under orders to sail on Christmas morning, much to my disgust, as it was my first Christmas in England for many years, but we did not finally leave until New Year's eve, when we were taken by troop-train to Southampton, and embarked the same day.

On disembarking in Rouen we were all marched up to the various infantry and other camps established there some four or five kilometres out of the town. Together with several other engineer officers, I was assigned to an infantry camp for a few days' infantry training whilst awaiting orders to proceed up the line. Life in these camps is far from unpleasant, although the training is severe and exacting. The city of Rouen is an extremely interesting one, and numerous amusements were provided by the British and French authorities for the troops who are always coming and going from these base camps. As the scene of the martyrdom of the famous French saint Jeanne d'Arc, it is well known to all the world.

At the first officers' parade, at Rouen after I arrived in France, we were all informed by the camp adjutant that cameras were forbidden and that any man who had a camera in his possession after twenty-four hours would be court-martialled. I had one—a small vest-pocket-kodak—but after this order decided to send it back to a friend in England. Some six months later I was fortunate enough to secure a small kodak in one of the villages behind the lines and managed to get the few pictures which illustrate this account.

There are, necessarily, a large number of military-base and training camps established by the British in France, and the camps at Rouen seem to have been used mainly for reinforcement troops and returned casualties. I met one officer of infantry here who was returning to his regiment in a few days and who had just been reported "fit for duty" again after his third wound! Even early in 1916 this was not uncommon.

In the light of subsequent experience, I am more inclined to condole with the poor fellows who have borne the brunt of the struggle and escaped for long periods without being wounded.

Even the poor chaps who are fatally wounded seldom realize the fact at first, and are only conscious of sudden relief in the thought that they will be away from the trenches for a while. I have seen this instanced many times. In May, 1916, I was sharing a dugout with another officer in the trenches near the Vimy Ridge. R.'s orderly, W., was returning with a message, and as he nearly reached the dugout he was caught by a heavy trench mortar and one of his legs blown off. He was also hit in several other places. We sent for "stretcher-bearers at the double," the usual call when casualties happen in the trenches, and R. promptly fixed him up as best he could with one of the field-bandages we always carried in our blouses. Poor W., one of the finest lads I have ever known, not realizing fully the fatal nature of his wounds, remarked cheerfully: "Blime, I ain't 'alf-crocked now for the rest of my days." We agreed with him, but pretended to envy his certainty of a "blighty." He was carried off to the nearest regimental aid-post, about a quarter of a mile down the nearest communication-trench, but the poor chap never left it, dying within a couple of hours.

At Rouen we received the usual training given to all combatant officers and men reporting there. This included daily lectures and practice in the following subjects: Bomb-throwing, machine-guns and their operation, infantry close and extended order drill, trench mortars and their use, gas lectures, etc., interspersed with long-route marches, sham fights and manœuvres, trench reliefs day and night, and practice and lectures on all the varied forms of frightfulness then indulged in by the opposing armies. The bomb-throwing was most fascinating. At that time the British were using eight or ten varieties of bombs, from the old handle-bombs with streamers attached, to the cricket-ball bomb, which one had to light from a brassard on the arm. I had never even seen a bomb before, and always associated them with the playful humor of the now back-number anarchist. Without any preliminary practice, we were detailed to throw these "live" bombs. My heart was in my mouth as we approached the bombing-trenches, but I very carefully watched the operations of the other fellows, and listened attentively to the very matter-of-fact and callous British corporal instructors. My nerves, however, were in fair shape, and I threw every type without any disastrous consequences, though my heart was certainly working overtime.

While writing of bombs, I want to sound a note of warning to those of our boys who will have this form of amusement in store for them. In these days the throwing of "dummy" bombs always precedes the training with live ones, and this is wise and natural, careful habits being formed in this way which eliminate largely the fatal accidents which have happened so often in the early training of British and French units. The one essential is calmness. Nearly all troops who are highly disciplined have this calmness bred into them, and very useful and necessary it is for almost any operation in modern warfare. A "jumpy" soldier, or one whose nerves are not in the best of shape, very frequently knocks his arm against the parados whilst throwing a bomb, drops it in the trench, fails to throw it clear of the parapet ahead, and in other ways not only seriously endangers his own life but those of his comrades practising with him.

The training at these base camps is made as realistic as possible, one feature being the passage through "gassed" galleries or chambers of all officers and men who report at the camps. The chambers are filled with the strongest and deadliest of gases, chlorine, phosgene, bromine, and other gases being used in more concentrated form than one encounters in the regular attacks. All this and other training gives men the confidence necessary to face bravely the fighting ahead of them.

After six days at Rouen I was posted to my company, and ordered to "go up the line."

Our billet, it developed, was in the village of Sailly-sur-la-Lys, two miles from the front-line trenches opposite Fromelles, and a little south of Armentières, incidentally the scene of very heavy fighting in 1914 and recent operations.

I was fortunate enough to get for a billet a small room off the kitchen of a Flemish farm-house in the village. Our mess, a rough wooden hut, was just across the street, and after proceeding there to meet my company officers, we had a very excellent dinner of a couple of chickens obtained in some mysterious way by our mess corporal. During dinner I was more or less entertained with stories of that day's events as related by the other men, one man describing how a German sniper had put a bullet through his cap during the afternoon in the trenches. (It was not until six months after this that we were supplied with steel helmets.) Another man told how an aerial bomb dropped from an enemy plane had landed within a few yards of him on a road several miles back. I thought the object was to string newcomers like R. and myself, but found out later that it was all part of the usual days' programme.

The next morning my section commander suggested that I ride up with him to inspect our work in the front line. It was taken for granted that I could ride an English motorcycle, and although I was familiar enough with our American varieties, I surely had my troubles with this one. The slipperiness of the metalled and paved roads in this part of Flanders increased my uneasiness. I broke down several times on a very unhealthy road, shelled with annoying regularity by the Boches, much to the disgust of Captain P., who, however, good-naturedly helped me out on each occasion. We all had our troubles in riding motorcycles on the roads in Flanders and France, especially on the pavé or granite-block paving which is so common. When it's wet, and that means most of the time, about the only way to prevent skidding is to open your throttle for all it's worth and travel as fast as you can. One morning, during my first week, I had some six, more or less, painful falls within a mile in riding up. After the last one, I was so mad that I flung the remains of the machine into the ditch on the side of the road and proceeded to walk the rest of the way up. In a short time, though, we got the hang of the machine and could ride anywhere day or night. As a matter of fact, we never lingered on the roads going in and out of the trenches. Most of the metalled or flint roads of Flanders had a ditch on either side, into which we took occasional headers. One had to ride carefully and fast. A motorcycle with the throttle wide open helps to drown the noise of enemy shells bursting in one's vicinity.

Many wild rides I remember, especially at night when, of course, no lights could be used within three or four miles of the front line; and candor compels me to confess that occasionally we would take an extra "whiskey and soda"—the standard British drink—at the mess before leaving in order to give us a little extra Dutch courage. It was always effective; we didn't care much what shell-holes we hit, or how many mud-baths we obtained. To resume, after much trouble Captain P. and I arrived at the advanced material billet, which is always situated within a few hundred yards of the entrance to the communication-trenches, and, leaving our machines here, we started up the trench.

This sector of the trenches, opposite Fromelles, at that time would have been described by veterans in trench fighting as a quiet sector, but I cannot say that it appeared particularly quiet to me that day.

My first impressions under fire were quite complex, but I distinctly recall the fact that I was more scared by the firing of our own artillery than by the comparatively few shells of the enemy which burst in our vicinity. So many things were happening around me in which I was so intensely interested that my curiosity got somewhat the better of my fears, and only when bullets whistled very close, or shells burst fairly near, was I much worried. My second day in the trenches was quite different. I had started to come out alone a few minutes before "stand to," or "stand to arms," as it is officially termed, that is, just before dusk; and as I was making for the communication-trench to go out I was nearly scared out of my wits by a "strafe" which started as a preliminary to a raid which occurred a few minutes later. This raid was not on my immediate front, but about a quarter of a mile farther south, opposite Laventie, and was staged by the Irish Guards. The abrupt change from more or less intermittent fire between the trenches to a violent and constant bombardment from every machine-gun, trench-mortar, rifle-grenade, and other weapon in the trenches, joined at the same time by the howitzers and guns from one to three miles back of the lines, combined to make me feel as though "hell had broken loose," and I made for the nearest dugout with as much assumption of dignity and speed as any near-soldier could effectively combine. It was only then that I fully realized that there was a war on.

I have been in numerous bombardments of this nature preceding night raids since that time, and they are always peculiarly violent, but I never recall any occasion on which I was more badly scared. It was rather curious, too, because nearly all the fire was from our own trenches at first, and the German retaliation did not come until some time after; but all our trench-mortars and other shells from the back just skimmed our parapets so closely that they certainly "put the wind up" me in more senses than one. One's first raid, anyhow, is calculated to be more exciting than a pink tea-party. "Put the wind up" is a term which requires some explanation. The Tommies use it on every occasion when a man shows fear; they say he is "windy" or "has the wind up," until now it is an essential part of the trench language.

Enemy rifle and machine-gun fire was very heavy and we had our share of casualties in this way. One of our advanced billets, Two Tree Farm, was an unhealthy spot. The Boche had several rifles trained on the entrance to this old ruin and the bullets whistled by about shoulder-high regularly through the night across this spot. It was not a favorite place for nightly gossip. We had built a wooden track from near here right up to the front line and would each night tram up our timber and supplies on this light track. We had plenty of grief when our trolleys would slip off the rails and into a foot or two of mud alongside. At one of these times I was going up with supplies and the enemy were getting us taped nicely with their machine-gun fire. Several attached infantrymen were working with us. One lad who was working particularly hard came around to the back to give us an extra hand in getting the car on the track again, and dropped quietly into the mud without a sound with a bullet through his head. We used to figure on two or three casualties a night on this tram. On going in or out we had to walk from Two Tree Farm over a stretch of level ground about a quarter of a mile before we entered V.C. Avenue, the communication-trench. This was not a pleasant walk on account of the absence of cover and the rain of machine-gun and rifle fire which swept this area.

The trenches in Flanders consist, in the front line at least, of sand-bag breastworks, and are not regular trenches at all. The country is so flat that it would be impossible to drain properly a series of trenches cut in the original soil. As a result of the lack of drainage, the consequent difficulties and hardships can be well understood. Each night the enemy would tear big holes in our breastworks in the front line, and we would have to duck and run past them on the following day, and at night repair them again, under their machine-gun fire. The fact that their snipers and machine-gunners had the gap well taped in the daytime didn't add to our pleasure in repairing them at night.

The trenches on our company front here, which included underground galleries emanating from about 16 different shafts, or mine-heads, on about a half-mile front, averaged from 70 to 120 yards distance from the enemy. As the water-level was about 25 feet, the underground tunnels were shallow, mostly about 20 feet in depth. Many of our mines would be entirely flooded out, and it was only by constant and energetic work on the hand-pumps that we kept the water down in the existing galleries. It was a common thing for us to have to wade in rubber hip-boots through tunnels with over a foot of water in them. We worked in these mines twenty-four hours of the day, Sundays and holidays—in fact, no one knew when a Sunday came around, every day being the same in the trenches. Every officer and non-commissioned officer knows the date, however, as numerous and elaborate progress and other reports were furnished to the staff daily. The "padres," or chaplains, sometimes reminded us of the fact that Sundays do occur when we were out in billets back of the line. We worked usually three shifts of eight hours each, and all of our timber and tools, the latter of the most primitive kind, rendered necessary under the unusual circumstances, were brought up at night by company trucks to our advanced billets, which were situated about a mile behind the front line, and close to the entrance of communication-trenches.

The enemy had started his underground mining operations several months before they were discovered by the British and had caused many casualties in the ranks of the infantry; in fact this was the case everywhere on the western front, both in the British and French lines. The Hun has a text-book rule which enjoins him to start underground operations from any trenches which are not farther than 100 metres from the enemy, and in many cases where the distance exceeded this, or where he wished to specially defend any observation-posts, machine-gun posts, or strong points of tactical advantage, he would commence mining from trenches still farther distant.

Handicapped as were the British and French from this cause, they have succeeded by energetic and daring work since that time in more than outmatching the enemy below ground, until now mining beneath the trenches no longer consists, as it did then, in almost exclusively defensive operations. Of its use as an offensive measure, the launching of the attack in the battle of Messines last year serves as an excellent illustration.

In our part of the line at Fromelles, however, at that time the Germans had succeeded in exploding many mines with disastrous effect under our trenches, with the resulting loss of life of many infantrymen and some engineers, and in our early operations they gave us much cause for concern. They "blew," that is, exploded mines, under several of our shaft-houses or mine-shafts whilst the latter were under construction, and destroyed several of our galleries before we could get within striking distance of them. When I joined the company, many of our shafts had been constructed and a considerable footage of galleries completed. In this work below ground in clay it was necessary, of course, to be as quiet as possible so that the Germans could not locate our exact position. Of the fact that we were engaged in counter-mining, and that they were mining also, every one on both sides of No Man's Land was aware, but the point was to keep the Hun guessing as to our exact whereabouts while we discovered all we could about his. Many devices were employed both by the enemy and ourselves to try and fool the other. Our lives and the lives of the men on top depended on our success in outwitting them. Silence below ground was absolutely essential, and every possible precaution to secure this was rigorously insisted on. When we approached, as we often did, in these clay galleries, to within three or four feet, before firing our mines, the men underground would work without boots, often without lights; blankets would be hung at different places along the galleries to drown noise; the floors of the tunnels covered with sand-bags; all timbering done by wedging, no nails being allowed in construction, screws being used instead, and any and every other device thought of to prevent noise adopted.

On many occasions, and particularly when engaged in loading a mine-charge (work always done by the officers), connecting up the detonators or electric leads necessary, etc., when within a few feet of the enemy, and when at the same time we could hear them plainly at work, and were convinced they were employed, by the sound, on the same errand as ourselves; namely, laying a charge of high explosives with which to blow us to eternity, some crazy sapper would fail to stifle a cough or subdue some throat trouble. We always felt inclined to brain these chaps with anything handy, although, poor fellows, they were doing their best to be quiet. Luck certainly was with us on these occasions, and not in one instance in our work in Flanders did the Germans succeed in blowing us when we had more than one or two men underground at the time. How we escaped I don't know. I am sure it was only by the exercise of great care and good judgment, a lot of luck and a kind Providence. Farther south in the chalk country of France everybody below was killed by the resulting concussion, or poisonous gas, which developed on several occasions when the enemy caught us.

The "jumpiness" which all new troops are subject to at first had its influence on us, as on the troops above ground; and in the month or two previous to my joining the company sometimes a mine had been fired when probably by delaying it a little longer we might have secured more satisfactory results in damage and casualties to the enemy. That condition, however, wore off and we very seldom blew any mine unless we had the most certain evidence that we could get a good toll of Germans. We would frequently hold our mines for several days or a week or two, and when the listeners reported that the enemy could be heard in sufficient number in their tunnels just near our charges, we would connect our double set of electric leads to dynamo exploders or blasting-machines, push the handles home hard, and lift them to a higher sphere of operations.

Our galleries in the clay were for the most part from four and a half to five feet in height and from thirty inches to three feet in width, with numerous listening-tunnels, or "rabbit-holes," in size three feet by two, leading off them as we approached the enemy lines.

It was our practice to build a rough mine-chamber or shelter, constructed of walls of sand-bags filled with clay with a few corner-posts of wood, and to cover this shelter with a sheet or two of corrugated iron and sometimes a layer of sand-bags.

These chambers were built usually at from ten to twenty feet back of the sand-bag breastworks which formed our only protection from enemy fire. From these so-called mine-chambers we sank vertical telescope-shafts, sometimes using case-timbers, and sometimes collar-sets with logging or spiling driven in behind. In Flanders, where only these surface shelters can be built, we would usually construct a dugout alongside or connected with a mine-chamber. In the trenches farther south we used the deep dugouts, twenty or thirty feet deep, and often started our systems of tunnels or galleries from them.

Much difficulty was experienced in sinking these shafts. On account of the shallow water, level pumps were resorted to at once, often two or three being necessary to keep the water down. With constant pumping and digging we attained depths of from twenty to twenty-five feet below the surface. At the bottom of the shaft we put in sumps from which to pump the water, and then proceeded to drive our galleries ahead. For the smaller tunnels we used two-inch case-timbers or small timber-sets and excavated the clay with small, specially constructed shovels which we called "grafting-tools."

The man in the face would lie with his back across a plank stretcher placed across the nearest timber set, and would work the grafting-tool with his heel, whilst a second man would very carefully shovel the dirt into sand-bags, and pass them when filled to the man behind him. The latter would in turn pass the sand-bags along to other men as far as the foot of the shaft, when the bags would be attached to a rope and hauled to the surface by means of a rough prospector's windlass.

As the work progressed we would often screw wooden rails to the floors of galleries, and then use small rubber-tired trolleys or cars to move our sand-bags from the face.

During the cold, damp winter of 1915-1916 we could always get warmed up by going below. In the chalk-mines in the succeeding summer it was also quite pleasant to go below and cool off. The men working underground were certainly lucky in this respect. Down below, the rumble of the shelling overhead could be very distinctly heard, and it interfered much with our effective listening to enemy mining operations. It was a great relief sometimes though to get away from the ear-splitting Kr-r-r-umps all around.

In the "rabbit-holes" we were, of course, obliged to crawl on our hands and knees, and would spend many long hours listening to enemy work, which we heard close to us in these "rabbit-holes" most of the time.

Despite all attempts, it was impossible to keep these holes dry. I can remember several occasions when I was so thoroughly dead beat and "all in" that for a few minutes I dozed or slept whilst listening, incidentally lying in several inches of water, and only a few feet from the enemy's work. It was necessary for us to have experienced "listeners" to keep in touch at all times with the progress of enemy work whilst our own was going on, and naturally the officers on duty had to do a large part of this to satisfy themselves. Regular reports were kept in the dugouts on the surface as to the enemy's activity in every direction, and these were carefully studied and plotted on maps by all subalterns when relieving. Our dugouts, as they were called, although they differed very much from the more or less elaborate dugouts which we now use farther south in France, were really only splinter-proof shelters, and consisted of walls of sand-bags with a sheet of corrugated iron on top, and one or two rows of sand-bags on that. A direct hit of any kind was fatal to all occupants. Many hours have I spent in those dugouts with trench mortars and shells dropping all around, and wondering whether their next mortar was going to crack our "egg-shell" of a shelter. However, when things got too hot, we had a big advantage over the infantry in the fact that we could suddenly recollect at these times some very important work twenty feet below ground in our mines which demanded our immediate attention. Like the infantry, though, we were of a rather fatalistic turn of mind, and usually trusted to our luck. One of the half-dozen men who came over to the trenches from England with me was unfortunate enough to be caught in a dugout of this description the very first time he entered the trenches, a mile or two down the line from us, when a "rum-jar" landed on it. Another officer with him at the time was killed, and several men also, but he got off with a bad head wound which sent him back to an English hospital for a few months. Near us was an infantry company headquarters' dugout and we would go there for a little change from time to time. When fate was kind to us we would share some very decent meals together, usually the contents of some one's parcels from England.

These meals were not served in "Palais Royal" style, and often fingers were employed in lieu of forks, but nevertheless we had some merry times. Humor and tragedy touch elbows in the trenches. A man is laughing one minute—the next he is lying dead with a bullet crashed through his heart or brain; or what is more usual and worse to the survivors, with his body so mutilated that it is difficult to find enough of his pitiful remains to bury. So it was with us. We would wear that anxious look occasionally when Fritz would lob over some form of frightfulness which landed very close to us; but it seldom disturbed us for long. One night I had accepted an invitation to dinner with some friends of a very famous old British regiment, the Rifle Brigade, who were garrisoning the trenches we were in. The company commander was a young man about twenty-three, one of the very finest types of the old British regular army officer, and we had been very good friends. Friendships are made quickly under such circumstances. We had "blown" a mine the previous evening, and it was the duty of the infantry here to wire the crater formed by the explosion. The mine had been blown as a defensive measure in preventing the wily Hun from coming closer to this point underground and was located about midway between the trenches in No Man's Land. While we were at dinner, a runner reported that one of Captain G.'s corporals had been wounded while finishing some work on the wire.

Notwithstanding the fact that even at this time orders were in effect that no infantry company commander should go into No Man's Land unless in emergency or on a regular attack, my gallant friend, Captain G., at once got up from dinner and said he was going out to bring his corporal in. We endeavored to dissuade him, and suggested the usual course of sending out the company's stretcher-bearers to get the man in. He would not listen, but hurried out. Climbing over the slimy parapet he attempted to reach the wounded corporal, but was shot through the head just as he reached the edge of the crater. Two stretcher-bearers at once went out and were also shot in a minute or two. Two of his subalterns then very cautiously proceeded to go out through one of the cunningly devised "sally ports" which issue at frequent intervals from the breastworks out to No Man's Land, recovered the bodies, and brought in the wounded corporal. The loss of this fine officer made a great impression on me at the time, but so many incidents of a similar nature were constantly happening that one becomes callous in time without sensing it. I only know that if one gave way to his feelings his nerves would shortly break, and his usefulness would be ended—a somewhat brutal philosophy, but necessary in a war such as this that the German fiends have forced upon us.

By night we would get rid of our spoil or clay from the underground workings, dumping them from sand-bags or gunny sacks into shell-holes, mine-craters, abandoned trenches, depressions in the ground, behind hedges, and in other places offering some concealment from enemy observation. This work was all done under the enemy's machine-gun and rifle fire. Both we and the Boche would fire the "Very" or star lights at more or less regular intervals during the night; the enemy much more frequently than we; and the parties or individuals working on top would have to be very careful when they happened to come within the range of these ghostly silver flares. Usually it was sufficient if one kept quite still, but where trenches are very close and the light drops behind you and throws your figure into relief, the wise course is to immediately drop flat and remain motionless. It isn't quite so easy as one might imagine to stand still on these occasions; but it is quite effective. Any movement of a soldier is spotted in an instant, and at once every sniper and machine-gun operator, constantly on the alert on the enemy parapet, opens fire. One night I was working with my men on top in this way disposing of our sand-bags, and I noticed an infantry officer with a party of four men placing sand-bags on top of a dugout near us. An enemy "Very" light flashed over and behind us, throwing all of our figures into relief. We dropped pronto, as did the men with the infantry officer, but he, poor chap, then only three days in the trenches, was too slow, and got a bullet square through his head. It is strange to note the confidence with which men will work on top of the trenches at night after a little experience. At first it seems impossible that the enemy machine-guns can miss you in their frequent and thorough traverse or sweeps of the lines opposite them, but you gradually gain confidence and find that, unless you expose yourself carelessly by moving when their lights go up in your neighborhood, you usually get off scot-free.

There are many complaints of the monotony of trench life, and certainly some of them are well founded, but in our work there was not much room for monotony.

During my first month or two I was intensely interested in every weapon that the British were using, and whenever a machine-gun, trench-mortar, grenade, or sniper officer was about to start a "shoot" in my sector, I was invariably invited to witness the affair and learned to operate them all in time, much to my satisfaction. My particular delight consisted in using a Vickers machine-gun at night in traversing up and down the enemy's communication-trenches. I guess we soon acquire bloodthirstiness; at any rate, one develops without conscious effort an instinct to "strafe the Hun," not only on general principles, but particularly to avenge the loss of comrades. The artillerymen share this feeling; the F.O.O., or forward observing officers, for each artillery battery, can be found prowling around the trenches at all times, searching the enemy's lines with their powerful field-glasses for targets, and continually discussing the possibilities of new ones with the infantry and engineers in the lines; and at nearly all times lamenting the fact that they can get nothing to shoot at.

While we were here they sent us a bantam division to relieve the old division. These little fellows, hardly a man of them being over five feet two inches in height, were certainly not short of pluck. Nearly all of their officers by way of contrast were exceptionally big men, all over six feet. It was very amusing to see the bantams climbing on to their fire-steps and building up sand-bags to step on so they could see well over the parapet. It's a useful thing, anyway, to be short in trench warfare. You don't have to duck so much.

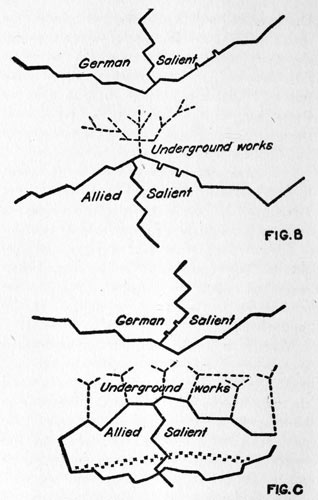

As it was a rare day for us in Flanders when the enemy or ourselves did not "blow" a mine, we were always on our toes. Except in cases of sudden emergency we informed the infantry of our intention to fire a mine, and gave them the time necessary to withdraw their men to points of safety. Often we would blow a mine at night in cooperation with the infantry so that they might at once rush out and "consolidate" the crater, or the nearest lip or rim of the crater. Certain positions in No Man's Land were particularly desirable on account of their strategic value; sometimes for the purpose of enfilading the enemy's trenches by occupying one rim of the crater; or perhaps for the obtaining of better observation-points, or for any other reason. The consolidation of these craters is a wonderfully stirring business. A little explanation of a crater might help.

The engineers fire large charges of high explosives from underground galleries, at a depth of anything from 20 to 200 feet, with the result that a huge hole is blown in the ground in the shape of an inverted cone, like the average shell-hole, but very much wider and deeper. No Man's Land in front of us, where the trenches are close, is pitted with great numbers of these craters, some blown by the Germans and some by us. The craters vary from the small ones, about 70 or 80 feet in diameter and 12 to 20 feet deep, to larger ones to such dimensions as 300 feet in diameter and up to 120 or 130 feet deep. The size, of course, depends on the charge of high explosives used, the depth of the mine-galleries, and the soil one springs the mine in.

The enemy is usually just as concerned with the consolidation of the rim or lip of the crater on their side as we are with ours, and a battle royal for their occupation results. Machine-guns on both sides concentrate fire on the crater almost before the débris from the explosion have had time to fall. It is a weird and wonderful sight. From a fairly calm night, usually with only desultory fire going on, the thunderclap comes. Before firing, which is usually done electrically, the engineers calculate the exact diameter of the crater to be formed, and the previous night the infantry or engineers will have completed a trench forward from the front-line or "jumping-off" trench, to an intersection with the rim of the proposed crater. Directly the charge has been fired, they rush out through this trench and hastily throw up breastworks on the lip of the crater formed. The machine-gunners take up proper offensive and defensive positions; the bombers, usually at the head and the flank of the "throw-up," or lip, erect the wire screens necessary for their temporary protection; the "wire" men place their barbed wire around the portion to be consolidated; and all ranks dig themselves in as fast as they can, later bringing up such timber or other material as they can to strengthen the positions. When it is planned to hold the whole of the crater, the "wire" men completely encircle it with entanglements, and the Lewis gunners and bombers make such changes in disposition as are necessary. This represents the usual procedure when a crater is blown in No Man's Land. Thousands of these craters are so exploded.

On numerous other occasions, when we have penetrated below the surface with our underground galleries under and across No Man's Land to below the Germans' front-line trenches (and in many cases we go as far as their support lines without being discovered), our little affairs are accompanied by infantry raids. Pandemonium reigns supreme at these times, and nothing can be likened to the noise and apparent confusion in which these usually very successful raids are conducted. We fire our mines under their trenches and the infantry raiding-parties immediately cross and clean up any Germans we might have missed with our attentions. As a result of our noiseless work below in the clay, we would occasionally break through into each other's galleries.

Perhaps you would be interested in an underground fight which we had with the Boche in one of our galleries twenty feet below the surface under these trenches. Some two weeks before this we had successfully blown a mine, and two days later had discovered and worked through the broken German gallery we had destroyed. Passing through this gallery, we continued our silent work in the clay, and about fifty feet farther turned off to the left in order to strike what we thought would be the enemy's main defensive gallery. Our miners who were working at this face hurriedly sent up word one morning to our dugout on top, just off the shaft-house, that they had broken into the German gallery with a small hole in the clay. All men working underground had standing orders that if this occurred at any time they should at once put out their candles, observe strict silence, plug up the hole with clay, and report forthwith to the officer on duty. Warning all men to leave the near-by workings below, the officer on duty hurried down to the spot, stopped long enough in our main gallery to make up a mobile, or portable, charge of thirty pounds of guncotton from our magazine, which we had established there for just such emergencies, then proceeded with the utmost care to the gallery mentioned. Lieutenant G. had connected up a dry guncotton primer to the charge, inserted a detonator attached to a short piece of safety-fuse, which latter would burn for about two minutes before detonating the charge. The men had noticed and heard three, certainly, and probably more, Germans at work in their gallery, which was lighted with electric light. Lieutenant G., accompanied by another officer, very carefully withdrew the clay plug, enlarged the hole, slid the box containing the charge into the enemy gallery, lit the fuse, and swiftly and quietly withdrew from the scene. He reached safely the main gallery, quite a distance from the charge, in time to hear the explosion. He then climbed quickly to the top to escape the resulting fatal gases developed by the detonation of the high explosives.

I arrived on the scene a few minutes later and my section commander asked me if I was "game enough," as he described it, to go below with a sapper to investigate the damage done and see how many Germans we had accounted for. I was very willing; so Doherty, the sapper mentioned, and myself equipped ourselves with the "Proto" oxygen breathing-apparatus necessary in going into "gassy" galleries, then descended, carrying also the usual canary in a cage to test the air. The canary soon toppled off his perch and fell dead to the floor of his cage. Canaries and white mice are used in large numbers to detect the presence of poisonous gases below, and, being very susceptible to bad air, are soon killed. [It is a curious sight to see these canaries hung up outside dugouts in all trenches where mining operations are conducted.] Both Doherty and I had previously been trained in the use of the oxygen apparatus, and were quite confident of its ability to take care of the carbon monoxide so that it would not affect our lungs. Before we reached the enemy gallery, I stopped long enough to pick up and carry with me the air-hose, and this I left later in the enemy's workings so that our men on top could pump good air in and allow others down in a short time to resume the offensive. We reached the gallery, found the remains of three Boches that "G." had "sent west" with his charge of guncotton, then proceeded to investigate the damage done. As the enemy gallery was very closely timbered, we had only broken down a portion of it with the charge employed. On entering their gallery, I had carefully searched for and cut all wires that I found there. This was a regular practice with us, the object being to sever all electric leads, wires, or fuses which the enemy may have left connected to a charge or mine already laid.

On breaking into any of these galleries the officer in charge usually enlarges the holes in the clay until he can put his arm through; feels around until he finds any wires, and promptly cuts them with his pliers. Such operations of necessity must be done in darkness and without sound, and one's heart is working like a pump-handle. I was agreeably surprised to find that no Germans had summoned courage enough to investigate matters as we were doing; Doherty, however, did not share my sentiments, and gave me the impression as best he could, enveloped in the oxygen apparatus as he was, that he distinctly regretted their lack of sand. We were both armed with electric-torches and revolvers, but we were not keen on using them oftener than necessary, and so advertising our presence. After leaving the air-hose and noting results, I picked up the cap of one of the defunct Germans, and we came out, or rather crawled out. Our progress was mostly in the form of a crawl, and the steel oxygen cylinders knocking against the timber sets in the narrow galleries as we proceeded did not improve our tempers.

We arrived safely back to the surface and I made my report. After pumping air into the gallery for about an hour, we all went below again, and my section commander and Lieutenant G. crawled through to examine conditions in the enemy's gallery, while I was engaged in the magazine in opening boxes of guncotton and getting more primers and detonators ready for action. Captain B., the section commander, came back presently and informed me that he and G. had been slightly gassed during their investigation of the enemy tunnel, but had not met any Boche; he had decided on making up some raiding-parties, would arm them with mobile charges; attempt to explore the German gallery and mine system, and, if possible, try and destroy their shaft. The difficulties of proceeding farther into the German galleries, now that the enemy was thoroughly aroused, were pretty large, but we agreed with him that it was up to us to get them somehow if we had a possible chance. We made up three of these parties at once; each composed of one officer, one non-commissioned officer, and two sappers; each party armed with revolvers and a mobile charge of thirty pounds of guncotton, the latter being carried in boxes. Each of the sappers provided himself with a couple of Mills bombs, their confidence in these useful little articles on all occasions being quite touching.

It was arranged that Captain B. should station himself at the junction of our gallery with that of the Boche, and if our plans looked like coming "unstuck" he would blow his whistle hard. On this signal we would all hustle back to our own galleries and shaft-head as quickly as possible. "The plans of mice and men gang aft agley" and our luck was not good on this stunt. The other two officers were senior to me and, as usual in such circumstances, resolutely insisted on their right to take their parties in first. It was rather an exceptional affair, our breaking into an enemy gallery, as in most cases either the enemy or ourselves would have fired their mines when within striking distance of each other, so all the men were very keen on it. In my own case, I was so keyed up with excitement that I entirely forgot a bad toothache that I had—resulting from an abscess under a large molar—and these things are usually pretty difficult to forget, even in the trenches. Well, the first two parties passed quietly into the enemy's gallery; and just as I was about to lead my own party in, Captain B. blew his signal whistle, and, according to instructions, I took myself and party back to our own shaft-head, followed soon by the men of the other parties; last of all by the other two officers, who had entered the enemy gallery first. Our plan had come "unstuck." It developed that the first two parties had managed to get in a short distance before meeting any opposition, but that the Boches had then opened fire on them, and they had stopped just long enough to return a few revolver shots, set light to the fuses on their two mobile charges, and run for it. Altogether this last attempt had not been very successful, though we fortunately had no casualties.

I was again asked to go below with Doherty in breathing-apparatus and see what effect the firing of these two last charges had made on the gallery. We did so, but found no living Germans prowling round in the tunnel. We left the air-hose this time farther up their more or less destroyed workings, and reported that, after pumping, we could get down soon again to resume operations. For the time we posted six sappers and a non-commissioned officer near the enemy's entrance to cover any endeavor on the part of the latter to get through into our galleries. They did not attempt to do so; in fact, they didn't seem to care much about going near the place—which fact perhaps proved fortunate for D. and myself, though I knew that fine little Irishman was aching for a scrap with them.

In an hour or so, when the poisonous gas had again been blown out and fresh air pumped in, Lieutenant G. and I, being rather concerned over the possibility of the enemy trying to pump in gas on our men below ground, decided to go in on our own initiative and see what we could do. We proceeded below, armed each with revolver and torch, and were followed by another officer, Lieutenant B., carrying a mobile charge, and a sapper with a second. We walked and crawled very quietly and cautiously until we reached a point about 150 feet up the enemy gallery; here I suggested to G. that it would be decidedly unwise to try to get any farther; the electric lights still alight in the gallery were just a few feet ahead of us, and we could distinguish the sounds of whispering and stealthy walking very near. In crawling in we had, of course, used our torches as little as possible. If I had not persuaded G. as to the wisdom of my advice, I believe he would have attempted to go right up to the German shaft-head. I walked back a little way along the gallery, signalled Lieutenant B. and the sapper to hand me the guncotton charges; then instructed them to clear out.

We decided to fire the charges at this point; so after collecting, with great care to avoid noise, a number of sand-bags filled with clay which the Germans had left in this gallery, we used these for tamping the charge and G. lit the fuse while I covered the gallery with my revolver. G. said "hold on a minute while I get a souvenir," and promptly grabbed a five-foot length of three-inch air-pipe which the Germans used in their work, while I picked up a few empty multicolored sand-bags of the kind favored by the Boche miner.

The shortness of our safety-fuse was also a strong factor in preventing us from going farther. It would burn about two minutes, and in these two minutes we had to crawl and squirm through some very awkward sections in the galleries. In two places there was only room enough for our bodies to scrape through. The timber and clay had been destroyed in several places, and it was difficult at these spots to get through without bringing in some more timber sets or invite clay falls which would have imprisoned us with the charge. Death as the result of an overdose of carbon monoxide is not so bad, as one just drops into a gentle and insidious sleep from which you fail to wake; but the concussion resulting from the detonation of the charge is not such a pleasant affair. We fortunately reached a spot of comparative safety just in time to hear the detonation of the charges. Afterward we climbed to the surface.

I went below again after a half-hour had elapsed; this time without the oxygen apparatus, as I was physically too weak to carry its forty pounds again. Another sapper went down with me, wearing the Proto apparatus, and I leading with a rope around me in case I should be gassed and have to be pulled out. The lad who came with me was not of the same stuff as D.; once, whilst I was crawling ahead of him, I knelt on a piece of broken timber; it made a sharp noise, much like the crack of a revolver, and this rather disconcerted him. He soon recovered, however. No Germans were in evidence. If there were any in their tunnels they were mighty quiet.

This was a busy day for me. I must have had that "rabbit's foot" around my neck in going down first after the charges three times and coming out with a whole skin. We could not quite reach the advanced spot where we had fired the gallery; although near enough. I was gassed a little on this trip. Some two hours later, having prepared a large charge of guncotton, we went below and laid it. During the process, the enemy, gathering their courage, had come back to their gallery and, having cleared some of the débris away, fired a number of shots at our fellows whilst they were loading. We fired the mine in the usual way, by means of blasting machine from our dugout. This dugout was built with an entrance leading off to the mine shaft. We thought our troubles were over for a while anyhow, and four of our men carelessly remained in the dugout, talking and smoking for some ten minutes or so after firing. One of them happened to look up around the dugout, and noticed that all the canaries which we kept there at night, in some four cages, had toppled from their perches and were lying with their feet sticking in the air. With one bound they reached the dugout entrance and fresh air, realizing that the poisonous gas must have come up the shaft before penetrating to the dugout. Poor Captain B. was rather badly gassed and was carried away on a stretcher. He recovered, however, after a few days at the nearest C.C.S. Am glad to record that Lieutenant G. received the Military Cross for his share in these operations, and Captain B. the D.S.O.

On many occasions the British Tunnelling Companies have outwitted the cunning Hun. Here is one instance. The British miners broke into an enemy's gallery in clay and struck the tamping of a charge they had laid and were holding ready to fire. This tamping consisted of clay bags built up in galleries back of the charge in order to confine and intensify the explosion. Working through the tamping, the sappers reached a mine charge of about 4,000 pounds of westphalite, one of the various German high explosives. Carefully extracting this, they connected up the enemy's leads to one of their blasting caps to insure non-detection for electric continuity, and then withdrew. What the Hun mining officer said and felt, when he attempted to fire his mine, may be left to the imagination.

In April, 1916, we were relieved of our work in Flanders, and ordered to move down to trenches some thirty miles farther south, to the chalk country of Artois. The new trenches were near Neuville-St.-Vaast, and about a half-mile south of the famous Vimy Ridge. The British at that time had just taken over another portion of the French line extending down as far as Péronne, in the Somme district and the infantry holding our part of the line at Neuville-St.-Vaast had relieved the French infantry only a few weeks previously. We were to relieve the French Territorial sappers. Mighty glad they must have been to hand this troublesome sector over to us, but no evidence of this was to be seen in their characteristic casual and matter-of-fact attitude. We moved down in the usual way. The A.S.C. (Army Service Corps) furnished us with thirteen buses to take our men down, while the officers rode down in advance on motorcycles. I was detailed to take charge of the convoy of buses, and accompanied them on a motorcycle. Our fellows were all in high spirits at the prospects of a change, and the stops were many. The natural consequence was that I had my troubles in keeping the men from patronizing too liberally the many inviting estaminets on the road down.

After having spent several months in so-called rest-billets pretty close to the line and shelled regularly, we were all immensely pleased to find that our new rest-camp was to be situated in a very pretty little village named Berles, near Aubigny, and some eight miles from the firing-line. This camp, of course, was only intended as a rest-camp, and billets for only a quarter to a third of the company were necessary, as this represented the number of men who would be on rest at any one time. We soon made acquaintance with our advance billets, and these were close enough, being only a mile behind. Captain M. had preceded us to Berles as the billeting officer. The officer who talks French best is usually the man for this job, and he always does very well for himself when it comes to picking his own billet, having first choice. Incidentally it may be remarked the man who talks French well always has the edge on the other fellows. The usual old-fashioned and picturesque farm-house furnished us with a room for a mess. We looked out from this mess-room on to the inevitable midden which is a feature of all the French farm-houses in this part of the world. The buildings of these farms are always arranged in the form of a square, with the house on one side, and barns, stables, and granaries on the other three sides all enclosing a yard in the middle of which is invariably a very filthy pool. The manure from the stables is brought out and dumped into this yard and in addition everything else in the way of refuse from the house. Needless to say, the atmosphere around these middens on warm days in summer might have been healthy, but was certainly not pleasant.

We had been sent down to take over the underground mining at these trenches to meet what the Third Army termed "an urgent situation." It was well described. The fact of the matter was that the Germans had by extraordinary underground activity succeeded in forcing the French and British to abandon the majority of their advanced trenches in this neighborhood. No Man's Land looked like the view one gets of a full moon as seen through very strong telescopes with its numerous craters and shell-holes.

Sector near Neuville-St.-Vaast, Vimy Ridge trenches, April 3, 1916.

View taken from an airplane, showing the British and German front-line trenches and mine craters.

The aeroplane photograph shows the state of affairs when we reached the trenches. The pock-marked appearance of the ground will be noticed. All the smaller marks are shell-craters and the larger or real craters those formed by mine explosions. Note also how the Germans and British have run saps or trenches out to them from their front lines. The Germans had blown mine after mine, sometimes as often as 2 or 3 a day on less than a 500-yard front, until they had succeeded in making life decidedly unpleasant for the poor infantrymen holding these trenches. Whole platoons of men at a time had been engulfed in these terrific mine explosions, which were being blown at all hours, but principally at night. Things were so bad that, when we arrived, the most advanced trenches were practically abandoned, only being held by a few isolated groups of bombing sentries and Lewis gunners for a few hours at a time. The later aeroplane pictures show the state of affairs some six weeks later. By the beginning of July approximately twenty more craters had been fired by the Germans and ourselves in No Man's Land and the trenches adjacent. Unfortunately, I was unable to obtain an aeroplane picture taken at that time. There was an observation-line ahead of the firing-trench; most of our mine-entrances started from this most advanced line of trenches. On some occasions we were left alone underground without any one on top, that is, without any infantry. When this happened we usually posted our own sentries. One night when it happened that no sentries had been posted in one of our trenches, the Huns came over on a short and sharp raid, and actually occupied for a few minutes the trench above us under which we were working, while we continued our work quite placidly below, not knowing what was happening on top. The Jocks, bombing their way through from the firing-line, very soon took care of them, though some Huns got away in the dark.

With the exception of my experience during the Somme offensive, I have never seen anywhere more corpses in the trenches than here. They were so numerous that one could not cut out a new trench thirty feet in length without unearthing as many bodies. All of them were six months old, and the summer was coming on. The barbed wire in No Man's Land was not a pleasant sight. Bodies were tangled up with it everywhere, and the wire in many places was supporting bodies, or at least skeletons, still covered with their tattered uniforms. This was a gruesome sight to us when working at night on top—ghastly and pitiful. During the day the air was heavy with the sickening smell. The only way we could improve matters at all was by smoking hard. Quicklime was provided, but not used in sufficient quantities. I always felt sorry for the few men I ran across who did not smoke. When we first walked up the trenches we would notice what were apparently boots sticking out of the sides of the trenches. On closer examination we would find that there were feet still in them. One particularly callous old Scotch sergeant of ours who used to lose himself frequently adopted the habit of chalking direction signs on these boots.

The same sector, Vimy Ridge trenches, May 16, 1916.

The same points can be easily identified on both pictures. The new mine craters show up plainly.

Some of the dugouts were pretty bad too; we were not inclined to be too particular, but on occasions when it was just a little too strong we would organize search-parties to discover and remove the usual source of the trouble.

Enemy aeroplanes were very active in this sector, and the Boche fliers evidently had sharp eyes when it came to detecting new dugout or mine construction. It was necessary to camouflage all our spoil very carefully, otherwise we could always rely on these spots being shelled or trench-mortared quickly. There was much flying on moonlight nights. Searchlights back of our lines would pick out the enemy planes, and the "archies" at once get very busy. Usually we did not pay much attention to enemy planes, but they had a way of intruding themselves at times which was decidedly disagreeable. They would sometimes rudely interrupt our games of cards in the mess back at our billets. One night they dropped five bombs in quick succession which landed within twenty yards of our Nissen hut, the usual corrugated-iron structure. It was not often that we could afford the time and material for dugouts at our back camps, and as a result the shelling and aeroplane bombing generally was watched with much interest. The flying men at the front are not "fair-weather" aviators. They go up under almost all conditions of weather. Some wonderful flying is seen. All the loops, etc., seem of small account in comparison with the daring nose dives, side slips, and falls of both British and enemy planes. Most men get the flying fever. I applied for transfer to the flying corps in May, 1916, and was passed by the examining officer in the field, but fortunately, perhaps, for myself, my application was turned down by the corps, engineer officers being somewhat scarce at the time.

Souvenirs of German bombs, trench mortars, etc., were much in demand, and some of us were foolish enough to take the detonators and charges out of "dud" T.M.'s, etc. I did this on several occasions, but not without taking every precaution possible to insure against accidents. "Dud" shells are those which have for some reason not exploded because of defective fuse or some mistake in firing. I brought back with me several duds which happened to fall near me and did not explode. Some of the infantry seemed to think that it was a favorite pastime of the engineers to extract the detonators from these duds, and we would often take them out for them, but were at last obliged in self-defense to abandon such a dangerous vocation. I would not handle a dud shell now for a million dollars.

The difficulties of obtaining baths in these trenches at that time were many. The poor infantry would be occupying the front and reserve trenches for a month or six weeks at a time, and it was impossible for them to obtain a bath during this whole time. This hurt more than anything else. We were a little more fortunate in the engineers, and could average a kind of bath about once a week when lucky. Our efforts to get a decent bath with about a half-pint of water were most amusing. Water was very scarce. The rats and beetles in the trenches were large and active and did not add to our pleasure. At night the rats come into their own, and when times were quiet we would pull off some interesting rat hunts and incidentally get some good revolver practice.

Our dugouts in the Vimy Ridge were fairly safe, and after we had been below for a short time, and especially when there was a heavy trench-mortar "strafe" directed in the trenches above, it was not much fun coming out of them. Your heart would be in your mouth as you came up the steps and emerged into the blackness of the trench above. After a few minutes in the trench, however, one would get used to it.