Title: The Birds of Washington (Volume 1 of 2)

Author: William Leon Dawson

John Hooper Bowles

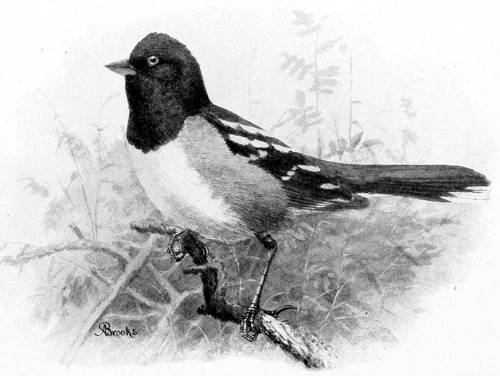

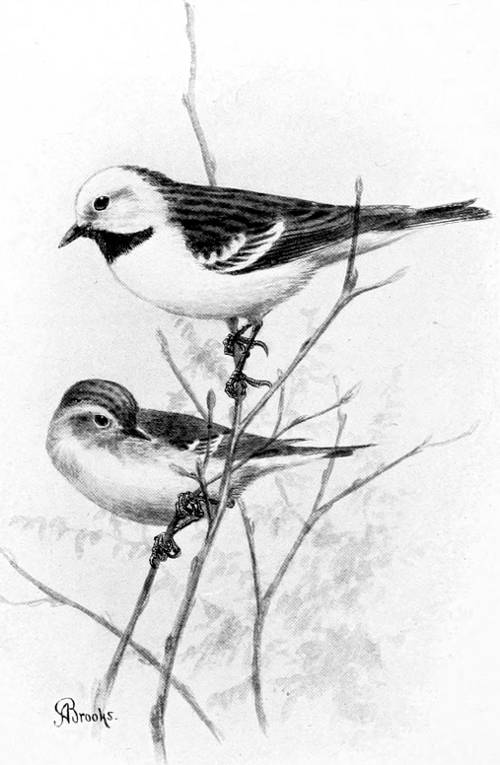

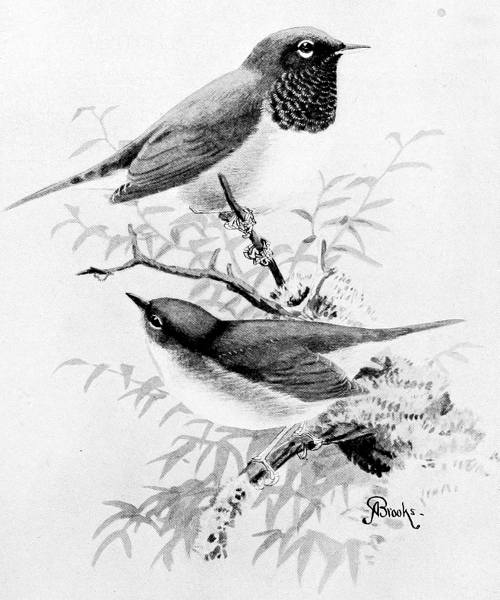

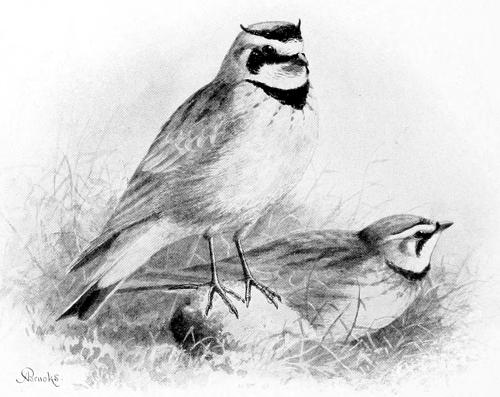

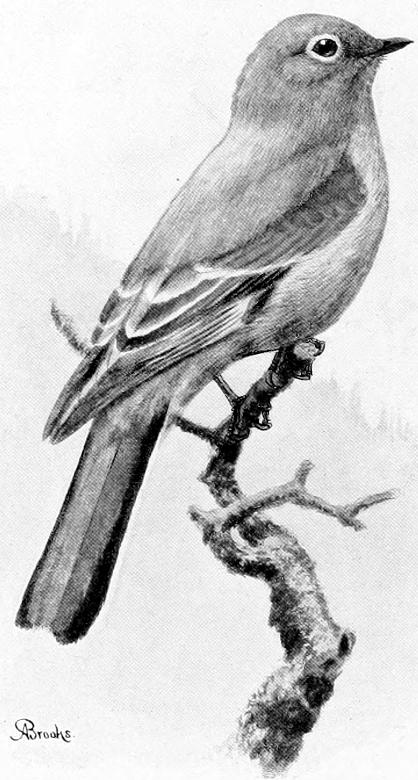

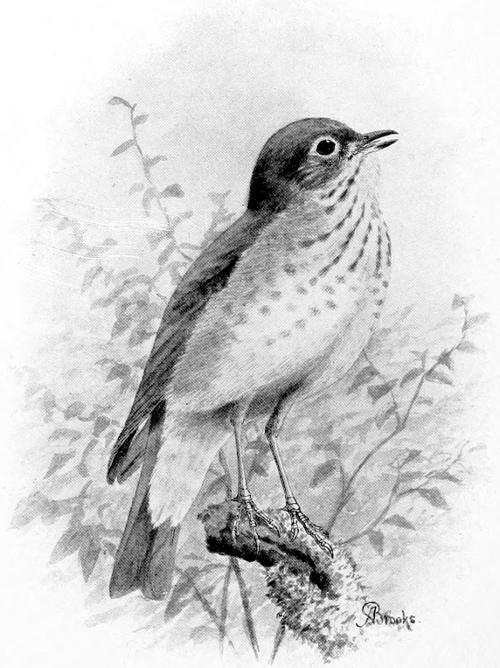

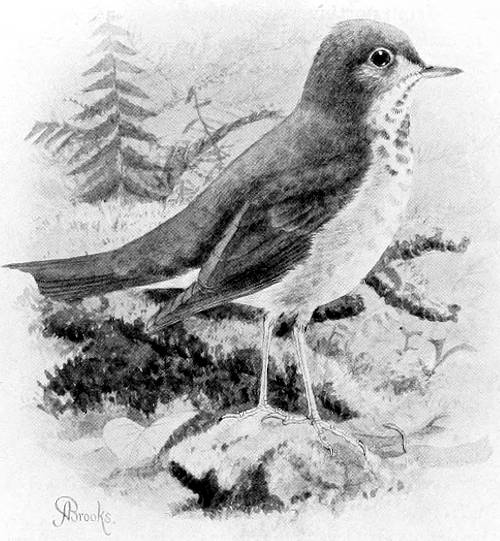

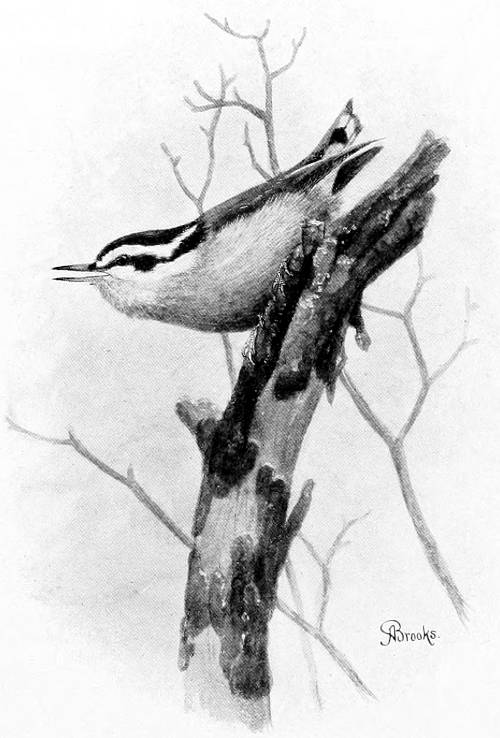

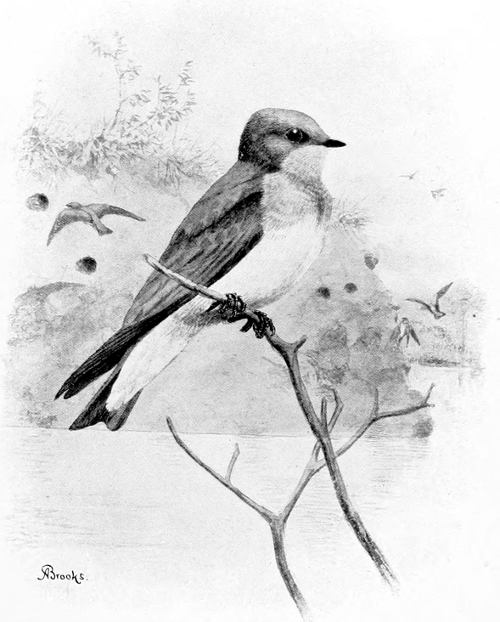

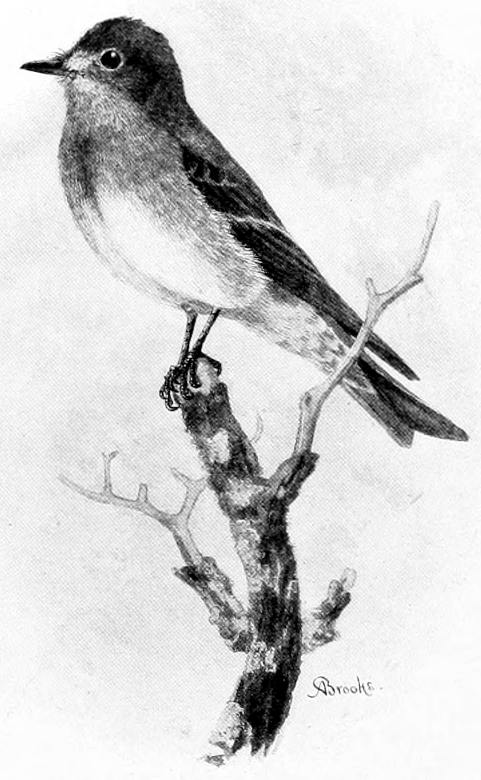

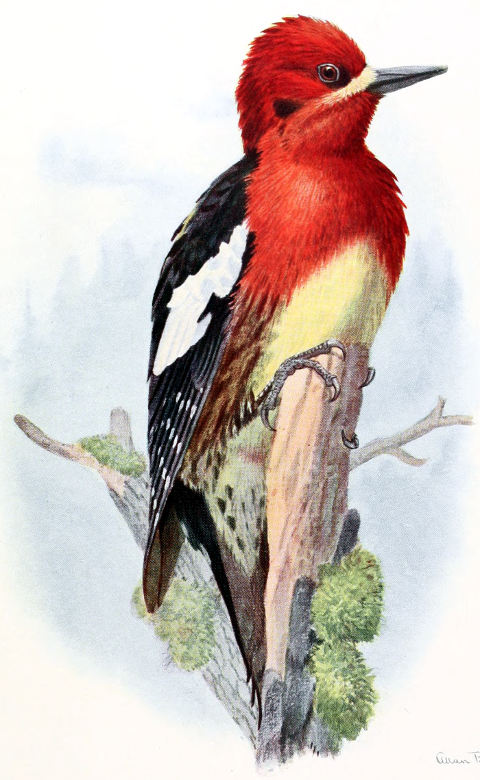

Illustrator: Allan Brooks

Release date: September 3, 2014 [eBook #46764]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness, Stephen Hutcheson, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Of this work in all its editions 1250 copies have been printed and the plates destroyed.

Of the Original Edition 350 copies have been printed and bound, of which this copy is No. 298.

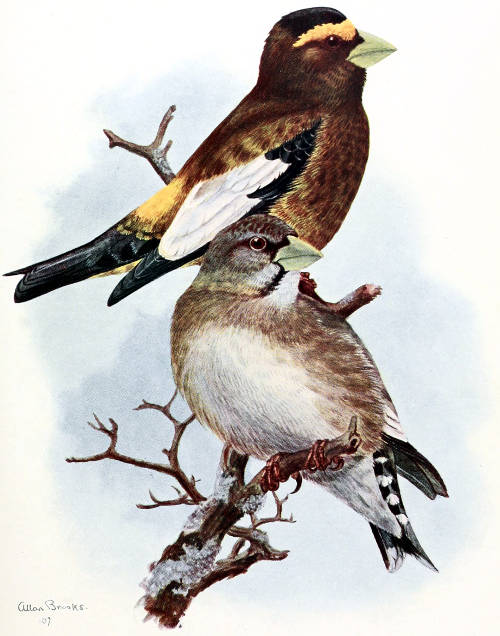

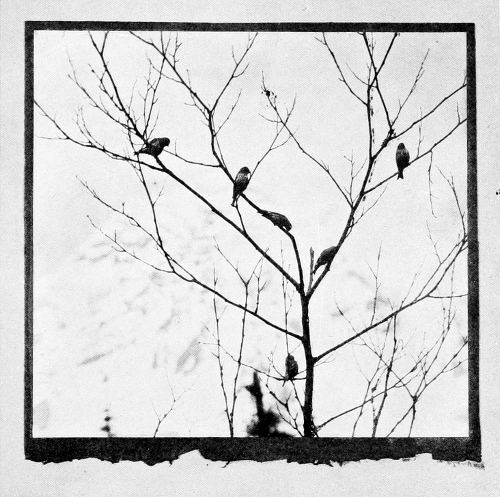

HEPBURN’S LEUCOSTICTE

MALE, ⅚ LIFE SIZE

From a Water-color Painting by Allan Brooks

A COMPLETE, SCIENTIFIC AND POPULAR ACCOUNT OF THE 372 SPECIES OF BIRDS FOUND IN THE STATE

BY

WILLIAM LEON DAWSON, A. M., B. D., of Seattle

AUTHOR OF “THE BIRDS OF OHIO”

ASSISTED BY

JOHN HOOPER BOWLES, of Tacoma

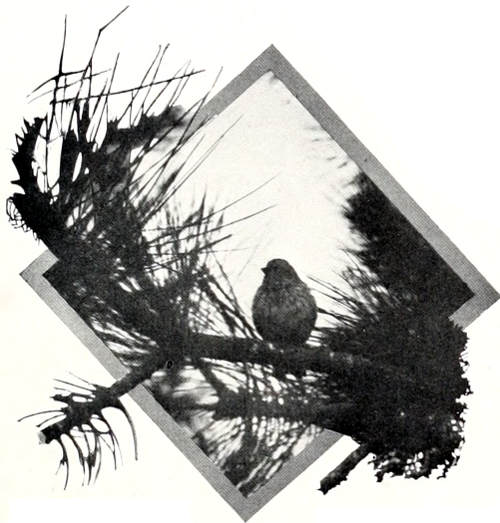

ILLUSTRATED BY MORE THAN 300 ORIGINAL HALF-TONES OF BIRDS IN LIFE, NESTS, EGGS, AND FAVORITE HAUNTS, FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE AUTHOR AND OTHERS.

TOGETHER WITH 40 DRAWINGS IN THE TEXT AND A SERIES OF FULL-PAGE COLOR-PLATES.

BY

ALLAN BROOKS

ORIGINAL EDITION

PRINTED ONLY FOR ADVANCE SUBSCRIBERS.

VOLUME I

SEATTLE

THE OCCIDENTAL PUBLISHING CO.

1909

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Copyright, 1909,

by

William Leon Dawson

Half-tone work chiefly by The Bucher Engraving Company.

Composition and Presswork by The New Franklin Printing Company.

Binding by The Ruggles-Gale Company.

To the

Members

of the

Caurinus Club,

in grateful recognition of their friendly

services, and in expectation that

under their leadership the interests

of ornithology will prosper in

the Pacific Northwest,

this work is respectfully

Dedicated

| INCHES. | |

| Pygmy size | Length up to 5.00 |

| Warbler size | 5.00-6.00 |

| Sparrow size | 6.00-7.50 |

| Chewink size | 7.50-9.00 |

| Robin size | 9.00-12.00 |

| Little Hawk size, Teal size, Tern size | 12.00-16.00 |

| Crow size | 16.00-22.00 |

| Gull size, Brant size | 22.00-30.00 |

| Eagle size, Goose size | 30.00-42.00 |

| Giant size | 42.00 and upward |

Measurements are given in inches and hundredths and in millimeters, the latter enclosed in parentheses.

References under Authorities are to faunal lists, as follows:

| T. | Townsend, Catalog of Birds, Narrative, 1839, pp. 331-336. |

| C&S. | Cooper and Suckley, Rep. Pac. R. R. Surv., Vol. XII., pt. II., 1860, pp. 140-287. |

| L¹. | Lawrence, Birds of Gray’s Harbor, Auk, Jan. 1892, pp. 39-47. |

| L². | Lawrence, Further Notes on Birds of Gray’s Harbor, Auk, Oct. 1892, pp. 352-357. |

| Rh. | Rhoads, Birds Observed in B. C. and Wash., Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila., 1893, pp. 21-65. (Only records referring explicitly to Washington are noted.) |

| D¹. | Dawson, Birds of Okanogan County, Auk, Apr. 1897, pp. 168-182. |

| Sr. | Snyder, Notes on a Few Species, Auk, July 1900, pp. 242-245. |

| Kb. | Kobbé, Birds of Cape Disappointment, Auk, Oct. 1900, pp. 349-358. |

| Ra. | Rathbun, Land Birds of Seattle, Auk, Apr. 1902, pp. 131-141. |

| D². | Dawson, Birds of Yakima County, Wilson Bulletin, June 1902, pp. 59-67. |

| Ss¹. | Snodgrass, Land Birds from Central Wash., Auk, Apr. 1903, pp. 202-209. |

| Ss². | Snodgrass, Land Birds Central and Southeastern Wash., Auk, Apr. 1904, pp. 223-233. |

| Kk. | Keck, Birds of Olympia, Wilson Bulletin, June 1904, pp. 33-37. |

| J. | Johnson, Birds of Cheney, Condor, Jan. 1906, pp. 25-28. |

| B. | Bowles, Birds of Tacoma, Auk, Apr. 1906, pp. 138-148. |

| E. | Edson, Birds of Bellingham Bay Region, Auk, Oct. 1908, pp. 425-439. |

For fuller account of these lists see Bibliography in Vol. II.

References under Specimens are to collections, as follows:

| U. of W. | University of Washington Collection; (U. of W.) indicates lack of locality data. |

| P. | Pullman (State College) Collection. P¹. indicates local specimen. |

| Prov. | Collection Provincial Museum, Victoria, B. C. |

| B. | Collection C. W. & J. H. Bowles. Only Washington specimens are listed. |

| C. | Cantwell Collection. |

| BN. | Collection Bellingham Normal School. |

| E. | Collection J. M. Edson. |

Love of the birds is a natural passion and one which requires neither analysis nor defense. The birds live, we live; and life is sufficient answer unto life. But humanity, unfortunately, has had until recently other less justifiable interests—that of fighting pre-eminent among them—so that out of a gory past only a few shadowy names of bird-lovers emerge, Aristotle, Pliny the Elder, Ælian. Ornithology as a science is modern, at best not over two centuries and a half old, while as a popular pursuit its age is better reckoned by decades. It is, therefore, highly gratifying to those who feel this primal instinct strongly to be able to note the rising tide of interest in their favorite study. Ornithology has received unwonted attention of late, not only in scientific works but also in popular literature, and it has taken at last a deserved place upon the curriculum of many of our colleges and secondary schools.

We of the West are just waking, not too tardily we hope, to a realization of our priceless heritage of friendship in the birds. Our homesteads have been chosen and our rights to them established; now we are looking about us to take account of our situation, to see whether indeed the lines have fallen unto us in pleasant places, and to reckon up the forces which make for happiness, welfare, and peace. And not the least of our resources we find to be the birds of Washington. They are here as economic allies, to bear their part in the distribution of plant life, and to wage with us unceasing warfare against insect and rodent foes, which would threaten the beneficence of that life. They are here, some of them, to supply our larder and to furnish occupation for us in the predatory mood. But above all, they are here to add zest to the enjoyment of life itself; to please the eye by a display of graceful form and piquant color; to stir the depths of human emotion with their marvelous gift of song; to tease the imagination by their exhibitions of flight; or to goad aspiration as they seek in their migrations the mysterious, alluring and ever insatiable Beyond. Indeed, it is scarcely too much to say that we may learn from the birds manners which will correct our own; that is, stimulate us to the full realization in our own lives of that ethical program which their tender domestic relations so clearly foreshadow.

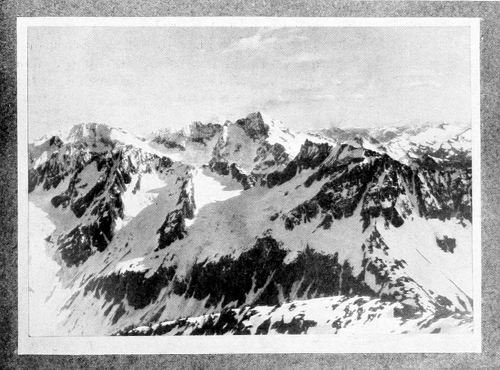

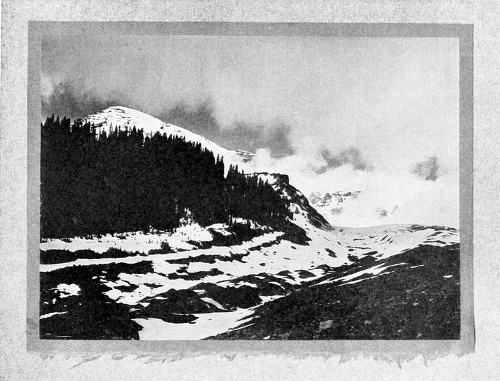

In the matter herein recorded account has of course been taken of nearly all that has been done by other workers, but the literature of the birds of Washington is very meager, being chiefly confined to annotated lists, and the conclusions reached have necessarily been based upon our own experience, comprising some thirteen years residence in the State in the case of Mr. Bowles, and a little more in my own. Field work has been about equally divided between the East-side and the West-side and we have both been able to give practically all our time to this cause during the nesting seasons of the past four years. Parts of several seasons have been spent in the Cascade Mountains, but there remains much to learn of bird-life in the high Cascades, while the conditions existing in the Blue Mountains and in the Olympics are still largely to be inferred. Two practically complete surveys were made of island life along the West Coast, in the summers of 1906 and 1907; and we feel that our nesting sea-birds at least are fairly well understood.

Altho necessarily bulky, these volumes are by no means exhaustive. No attempt has been made to tell all that is known or may be known of a given species. It has been our constant endeavor, however, to present something like a true proportion of interest as between the birds, to exhibit a species as it appears to a Washingtonian. On this account certain prosy fellows have received extended treatment merely because they are ours and have to be reckoned with; while others, more interesting, perhaps, have not been considered at length simply because we are not responsible for them as characteristic birds of Washington. In writing, however, two classes of readers have had to be considered,—first, the Washingtonian who needs to have his interest aroused in the birds of his home State, and second, the serious ornithological student in the East. For the sake of the former we have introduced some familiar matter from other sources, including a previous work[1] of the author’s, and for this we must ask the indulgence of ornithologists. For the sake of the latter we have dilated upon certain points not elsewhere covered in the case of certain Western birds,—matters of abundance, distribution, sub-specific variety, etc., of dubious interest to our local patrons; and for this we must in turn ask their indulgence.

The order of treatment observed in the following pages is substantially the reverse of that long followed by the American Ornithologists’ Union, and is justifiable principally on the ground that it follows a certain order of interest and convenience. Beginning, as it does, with the supposedly highest forms of bird-life, it brings to the fore the most familiar birds, and avoids that rude juxtaposition of the lowest form of one group with the highest of the one above it, which has been the confessed weakness of the A. O. U. arrangement.

The outlines of classification may be found in the Table of Contents to each volume, and a brief synopsis of generic, family, and ordinal characters, in the Analytical Key prepared by Professor Jones. It has not been thought best to give large place to these matters nor to intrude them upon the text, because of the many excellent manuals which already exist giving especial attention to this field.

The nomenclature is chiefly that of the A. O. U. Check-List, Second Edition, revised to include the Fourteenth Supplement, to which reference is made by number. Departures have in a few instances been made, changes sanctioned by Ridgway or Coues, or justified by a consideration of local material. It is, of course, unfortunate that the publication of the Third Edition of the A. O. U. Check-List has been so long delayed, insomuch that it is not even yet available. On this account it has not been deemed worth while to provide in these volumes a separate check-list, based on the A. O. U. order, as had been intended.

Care has been exercised in the selection of the English or vernacular names of the birds, to offer those which on the whole seem best fitted to survive locally. Unnecessary departures from eastern usage have been avoided, and the changes made have been carefully considered. As matter of fact, the English nomenclature has of late been much more stable than the Latin. For instance, no one has any difficulty in tracing the Western Winter Wren thru the literature of the past half century; but the bird referred to has, within the last decade, posed successively under the following scientific names: Troglodytes hiemalis pacificus, Anorthura h. p., Olbiorchilus h. p., and Nannus h. p., and these with the sanction of the A. O. U. Committee—certainly a striking example of how not to secure stability in nomenclature. With such an example before us we may perhaps be pardoned for having in instances failed to note the latest discovery of the name-hunter, but we have humbly tried to follow our agile leaders.

In the preparation of plumage descriptions, the attempt to derive them from local collections was partially abandoned because of the meagerness of the materials offered. If the work had been purely British Columbian, the excellent collection of the Provincial Museum at Victoria would have been nearly sufficient; but there is crying need of a large, well-kept, central collection of skins and mounted birds here in Washington. A creditable showing is being made at Pullman under the energetic leadership of Professor W. T. Shaw, and the State College will always require a representative working collection. The University of Washington, however, is the natural repository for West-side specimens, and perhaps for the official collection of the State, and it is to be devoutly hoped that its present ill-assorted and ill-housed accumulations may early give place to a worthy and complete display of Washington birds. Among private collections that of Mr. J. M. Edson, of Bellingham, is the most notable, representing, as it does, the patient occupation of extra hours for the past eighteen years. I am under obligation to Mr. Edson for a check-list of his collection (comprising entirely local species), as also for a list of the birds of the Museum of the Bellingham Normal School. The small but well-selected assortment of bird-skins belonging to Messrs. C. W. and J. H. Bowles rests in the Ferry Museum in Tacoma. [viii] Here also Mr. Geo. C. Cantwell has left his bird-skins, partly local and partly Alaskan, on view.

Fortunately the task of redescribing the plumage of Washington birds has been rendered less necessary for a work of such scope as ours, thru the appearance of the Fifth Edition of Coues Key,[2] embodying, as it does the ripened conclusions of a uniquely gifted ornithological writer, and above all, by the great definitive work from the hand of Professor Ridgway,[3] now more than half completed. These final works by the masters of our craft render the careful repetition of such effort superfluous, and I have no hesitation in admitting that we are almost as much indebted to them as to local collections, altho a not inconsiderable part of the author’s original work upon plumage description in “The Birds of Ohio” has been utilized, or re-worked, wherever applicable.

In compiling the General Ranges, we wish to acknowledge indebtedness both to the A. O. U. Check-List (2nd Edition) and to the summaries of Ridgway and Coues in the works already mentioned. In the Range in Washington, we have tried to take account of all published records, but have been obliged in most instances to rely upon personal experience, and to express judgments which must vary in accuracy with each individual case.

The final work upon migrations in Washington is still to be done. Our own task has called us hither and yonder each season to such an extent that consecutive work in any one locality has been impossible, and there appears not to be any one in the State who has seriously set himself to record the movements of the birds in chronological order. Success in this line depends upon coöperative work on the part of many widely distributed observers, carried out thru a considerable term of years. It is one of the aims of these volumes to stimulate such endeavor, and the author invites correspondence to the end that such an undertaking may be carried out systematically.

In citing authorities, we have aimed to recall the first publication of each species as a bird of Washington, giving in italics the name originally assigned the bird, if different from the one now used, together with the name of the author in bold-face type. In many instances early references are uncertain, chiefly by reason of failure to distinguish between the two States now separated by the Columbia River, but once comprehended under the name Oregon Territory. Such citations are questioned or bracketed, as are all those which omit or disregard scientific names. The abbreviated references are to standard faunal lists appearing in the columns of “The Auk” and elsewhere, and these are noted more carefully under the head of Bibliography, among the Appendices.

At the outset I wish to explain the peculiar relation which exists between myself and the junior author, Mr. J. H. Bowles. Each of us had long had in mind the thought of preparing a work upon the birds of Washington; but Mr. Bowles, during my residence in Ohio, was the first to undertake the task, and had a book actually half written when I returned to the scene with friendly overtures. Since my plans were rather more extended than his, and since it was necessary that one of us should devote his entire time to the work, Mr. Bowles, with unbounded generosity, placed the result of his labors at my disposal and declared his willingness to further the enterprise under my leadership in every possible way. Except, therefore, in the case of signed articles from his pen, and in most of the unsigned articles on Grouse and Ducks, where our work has been a strict collaboration, the actual writing of the book has fallen to my lot. In practice, therefore, I have found myself under every degree of indebtedness to Mr. Bowles, according as my own materials were abundant or meager, or as his information or mine was more pertinent in a given case.

Mr. Bowles has been as good as his word in the matter of coöperation, and has lavished his time in the quest of new species, or in the discovery of new nests, or in the location of choice subjects for the camera, solely that the book might profit thereby. In several expeditions he has accompanied me. On this account, therefore, the text in its pronouns, “I,” “we,” or “he,” bears witness to a sort of sliding scale of intimacy, which, unless explained, might be puzzling to the casual reader. I am especially indebted to Mr. Bowles for extended material upon the nesting of the birds; and my only regret is that the varying requirements of the task so often compelled me to condense his excellent sketches into the meager sentences which appear under the head “Nesting.” Not infrequently, however, I have thrown a few adjectives into Mr. Bowles’s paragraphs and incorporated them without distinguishing comment, in expectation that our joint indebtedness will hardly excite the curiosity of any disengaged “higher critic” of ornithology. Let me, then, express my very deep gratitude to Mr. Bowles for his generosity and my sincere appreciation of his abilities so imperfectly exhibited, I fear, in the following pages, where I have necessarily usurped the opportunity.

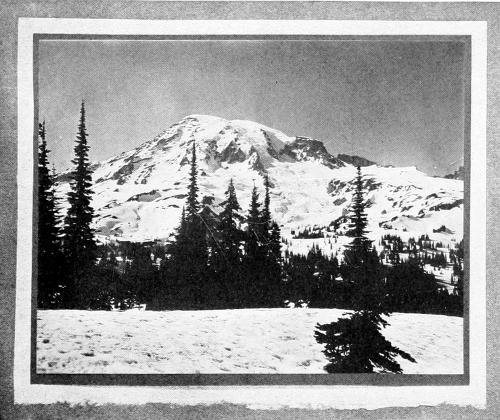

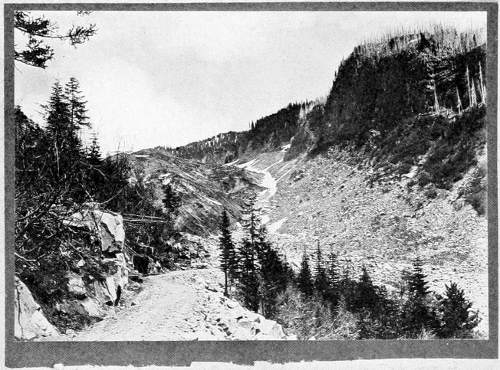

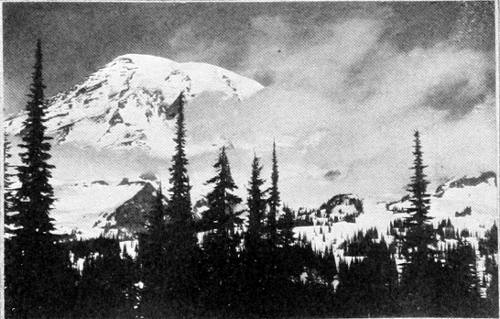

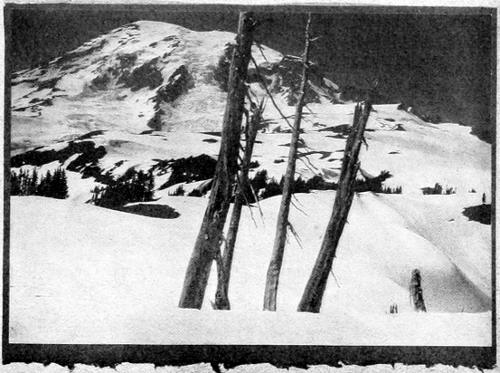

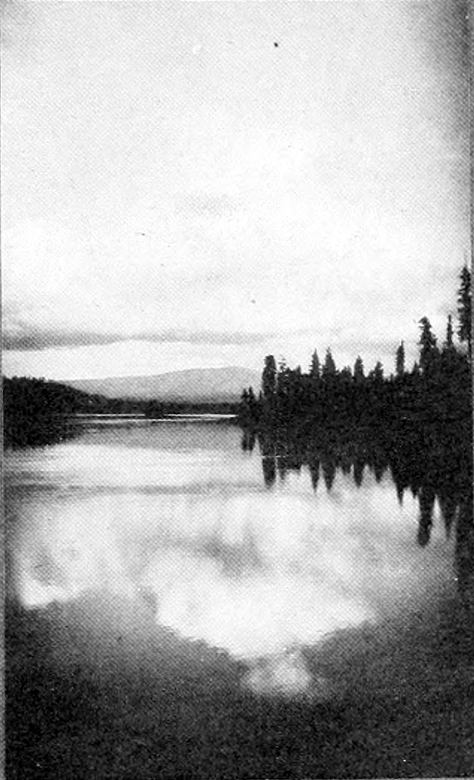

It is matter of regret to the author that the size of these volumes, now considerably in excess of that originally contemplated, has precluded the possibility of an extended physical and climatic survey of Washington. The striking dissimilarity of conditions which obtain as between the eastern side of the State and the western are familiar to its citizens and may be easily inferred by others from a perusal of the following pages. Our State is excelled by none in its diversity of climatic and physiographic features. The ornithologist, therefore, may indulge his proclivities in half a dozen different bird-worlds without once leaving our borders. Especially might the taxonomist, the subspecies-hunter, revel in the minute shades of difference in plumage which characterize the representatives of the same species as they appear in different sections of our State. We have not gone into these matters very carefully, because our interests are rather [x] those of avian psychology, and of the domestic and social relations of the birds,—in short, the life interests.

While the author’s point of view has been that of a bird-lover, some things herein recorded may seem inconsistent with the claim of that title. The fact is that none of us are quite consistent in our attitude toward the bird-world. The interests of sport and the interests of science must sometimes come into conflict with those of sentiment; and if one confesses allegiance to all three at once he will inevitably appear to the partisans of either in a bad light. However, a real principle of unity is found when we come to regard the bird’s value to society. The question then becomes, not, Is this bird worth more to me in my collection or upon my plate than as a living actor in the drama of life? but, In what capacity can this bird best serve the interests of mankind? There can be no doubt that the answer to the latter question is usually and increasingly, As a living bird. Stuffed specimens we need, but only a representative number of them; only a limited few of us are fitted to enjoy the pleasures of the chase, and the objects of our passion are rapidly passing from view anyway; but never while the hearts of men are set on peace, and the minds of men are alert to receive the impressions of the Infinite, will there be too many birds to speak to eye and ear, and to minister to the hidden things of the spirit. The birds belong to the people, not to a clique or a coterie, but to all the people as heirs and stewards of the good things of God.

It is of the esthetic value of the bird that we have tried to speak, not alone in our descriptions but in our pictures. The author has a pleasant conviction, born of desire perhaps, that the bird in art is destined to figure much more largely in future years than heretofore. We have learned something from the Japanese in this regard, but more perhaps from the camera, whose revelations have marvelously justified the conventional conclusions of Japanese decorative art. Nature is ever the nursing mother of Art. While our function in the text has necessarily been interpretative, we have preferred in the pictures to let Nature speak for herself, and we have held ourselves and our artists to the strictest accounting for any retouching or modification of photographs. Except, therefore, as explicitly noted, the half-tones from photographs are faithful presentations of life. If they inspire any with a sense of the beauty of things as they are, or suggest to any the theme for some composition, whether of canvas, fresco, vase, or tile, in things as they might be, then our labor shall not have been in vain.

In this connection we have to congratulate ourselves upon the discovery, virtually in our midst, of such a promising bird-artist as Mr. Allan Brooks. I can testify to the fidelity of his work, as all can to the delicacy and artistic feeling displayed even under the inevitable handicap of half-tone reproduction. My sincerest thanks are due Mr. Brooks for his hearty and generous coöperation in this enterprise; and if our work shall meet with approval, I shall feel that a large measure of credit is due to him.

The joy of work is in the doing of it, while as for credit, or “fame,” that is a mere by-product. He who does not do his work under a sense of privilege is a [xi] hireling, a clock-watcher, and his sufficient as coveted meed is the pay envelope. But those of us who enjoy the work are sufficiently rewarded already. What tho the envelope be empty! We’ve had our fun and—well, yes, we’d do it again, especially if you thought it worth while.

But the chief reward of this labor of love has been the sense of fellowship engendered. The progress of the work under what seemed at times insuperable difficulties has been, nevertheless, a continuous revelation of good will. “Everybody helps” is the motto of the Seattle spirit, and it is just as characteristic of the entire Pacific Northwest. Everybody has helped and the result is a composite achievement, a monument of patience, fidelity, and generosity far other than my own.

I gratefully acknowledge indebtedness to Professor Robert Ridgway for counsel and assistance in determining State records; to Dr. A. K. Fisher for records and for comparison of specimens; to Dr. Chas. W. Richmond for confirmation of records; to Messrs. William L. Finley, Herman T. Bohlman, A. W. Anthony, W. H. Wright, Fred. S. Merrill, Warburton Pike, Walter I. Burton, A. Gordon Bowles, and Walter K. Fisher, for the use of photographs; to Messrs. J. M. Edson, D. E. Brown, A. B. Reagan, E. S. Woodcock, and to a score of others beside for hospitality and for assistance afield; to Samuel Rathbun, Prof. E. S. Meany, Prof. O. B. Johnson, Prof. W. T. Shaw, Miss Adelaide Pollock, and Miss Jennie V. Getty, for generous coöperation and courtesies of many sorts; to Francis Kermode, Esq., for use of the Provincial Museum collections, and to Prof. Trevor Kincaid for similar permission in case of the University of Washington collections. My special thanks are due my friend, Prof. Lynds Jones, the proven comrade of many an ornithological cruise, who upon brief notice and at no little sacrifice has prepared the Analytical Key which accompanies this work.

My wife has rendered invaluable service in preparing manuscript for press, and has shared with me the arduous duties of proof-reading. My father, Rev. W. E. Dawson, of Blaine, has gone over most of the manuscript and has offered many highly esteemed suggestions.

To our patrons and subscribers, whose timely and indulgent support has made this enterprise possible, I offer my sincerest thanks. To the trustees of the Occidental Publishing Company I am under a lasting debt of gratitude, in that they have planned and counselled freely, and in that they have so heartily seconded my efforts to make this work as beautiful as possible with the funds at command.

One’s roll of obligations cannot be reckoned complete without some recognition also of the dumb things, the products of stranger hearts and brains, which have faithfully served their uses in this undertaking: my Warner-and-Swasey binoculars (8-power)—I would not undertake to write a bird-book without them; the Graflex camera, which has taken most of the life portraits; the King canvas boat which has made study of the interior lake life possible;—all deserve honorable mention.

Then there is the physical side of the book itself. One cannot reckon up the [xii] myriad hands that have wrought upon it, engravers, printers, binders, paper-makers, messengers, even the humble goatherds in far-off Armenia, each for a season giving of his best—out of love, I trust. Brothers, I thank you all!

Of the many shortcomings of this work no one could be more sensible than its author. We should all prefer to spend a life-time writing a book, and having written it, to return and do it over again, somewhat otherwise. But book-making is like matrimony, for better or for worse. There is a finality about it which takes the comfort from one’s muttered declaration, “I could do it better another time.” What I have written I have written. I go now to spend a quiet day—with the birds.

William Leon Dawson.

VOL. I.

Description of Species Nos. 1-181

A.O.U. No. 486a. Corvus corax principalis Ridgw.

Synonym.—Formerly called the American Raven.

Description.—Color uniform lustrous black; plumage, especially on breast, scapulars and back, showing steel-blue or purplish iridescence; feathers of the throat long, narrow, pointed, light gray basally; primaries whitening at base. Length two feet or over, female a little smaller; wing 17.00-18.00 (438); tail 10.00 (247); bill 3.20 (76.5); depth of bill at nostril 1.00 (28.5); tarsus 2.68 (68).

Recognition Marks.—Large size,—about twice as big as a Crow; long rounded tail; harsh croaking notes; uniform black coloration. Indistinguishable afield from sinuatus.

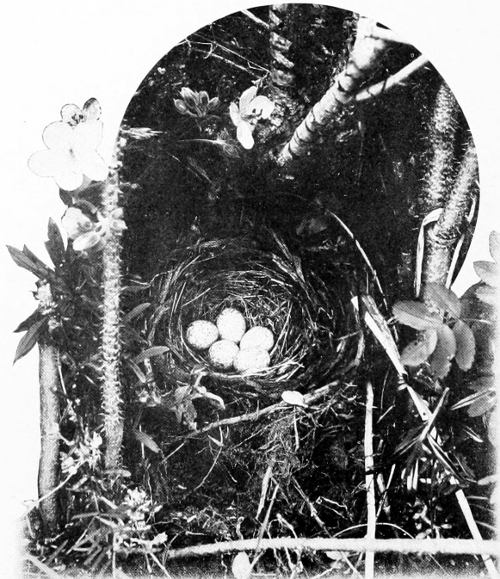

Nesting.—Nest: a large but compact mass of sticks, lined with grass, wool, cow-hair, etc., placed high in fir trees or upon inaccessible cliffs. Eggs: 4-7 (8 of record), usually 5, pale bluish green or olive, spotted, blotched, and dashed with greenish brown and obscure lilac or purple. Av. size, 1.90 × 1.33 (48.26 × 33.78). Season: April 15; one brood.

General Range.—“Arctic and Boreal Provinces of North America; south to Eastern British Provinces, portions of New England, and Atlantic Coast of United States, higher Alleghenies, region of the Great Lakes, western and northern Washington, etc.” (Ridgway).

Range in Washington.—Found sparingly in the Cascade and Olympic Mountains, more commonly along the Pacific Coast.

Migrations.—Resident but wide ranging.

Authorities.—[Lewis and Clark, Hist. Ex. (1814), Ed Biddle: Coues. Vol. II. p. 185.] Corvus carnivorus Bartram, Baird, Rep. Pac. R. R. Surv. IX. 1858, pp. 561, 562, 563. (T). C&S. L¹. D¹(?). B. E.

Specimens.—(U. of. W.) Prov. C.

Altho nowhere abundant, in the sense which obtains among smaller species, nor as widely distributed as some, there is probably no other bird which has attracted such universal attention, or has left so deep an impress upon history and literature as the Raven. Primitive man has always felt the spell of his sombre presence, and the Raven was as deeply imbedded in the folklore of the maritime Grecian tribes as he is today in that of the Makahs and Quillayutes upon our own coast. Korax, the Greek called him, in imitation of his hoarse cry, Kraack, kraack; while the Sanskrit name, Karava, reveals the ancient root from which have sprung both Crow and Raven.

Quick-sighted, cunning, and audacious, this bird of sinister aspect has been invested by peoples of all ages with a mysterious and semi-sacred character. His ominous croakings were thought to have prophetic import, while his preternatural shrewdness has made him, with many, a symbol of divine knowledge. We may not go such lengths, but we are justified in placing this bird at the head of our list; and we must agree with Professor Alfred Newton that the Raven is “the largest of the Birds of the Order Passeres, and probably the most highly developed of all Birds.”

The Raven is a bird of the wilderness; and, in spite of all his cunning, he fares but ill in the presence of breech-loaders and iconoclasts. While it has not been the object of any special persecution in Washington, it seems to share the fate reserved for all who lift their heads above the common level; and it is now nearly confined in its local distribution to the Olympic peninsula; and is nowhere common, save in the vicinity of the Indian villages which still cling to our western shore.

In appearance the Raven presents many points of difference from the Common Crow, especially when contrasted with the dwarf examples of the northwestern race. It is not only larger, but its tail is relatively much longer, and fully rounded. The head, too, is fuller, and the bill proportionately stouter with more rounded culmen. The feathers of the neck are loosely arranged, resulting in an impressive shagginess; and there is a sort of uncouthness about these ancient birds, as compared with the more dapper Crow.

Ravens are unscrupulous in diet, and therefrom has arisen much of the dislike which has attached to them. They not only subsist upon insects, worms, frogs, shellfish, and cast-up offal, but devour the eggs and young of sea-birds; and, when pressed by hunger, do not scruple to attack rabbits, young lambs, or seal pups. In fact, nothing fleshly and edible comes amiss to them. In collecting along the sea-coast I once lost some sandpipers,—which I had not had time to prepare the evening before—because the dark watcher was “up first”. Like the Fish Crow, they hang about the Indian villages to some extent, and dispute with the ubiquitous Indian dog the chance at decayed fish and offal.

NORTHERN RAVEN.

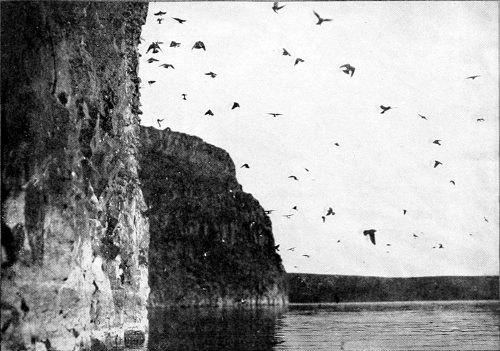

Altho by force of circumstances driven to accept shelter and nesting sites in the dense forests of the western Olympic slope, the Raven is a great lover of the sea-cliffs and of all wild scenery. Stormy days are his especial delight and he soars about in the teeth of the gale, exulting, like Lear, in the tumult: “Blow winds, and crack your cheeks!” The sable bird is rather majestic on the wing, and he soars aloft at times with something of the motion and dignity of the Eagle. But the Corvine character is complex; and its gravest representatives do some astonishingly boyish things. For instance, according to Nelson, they will take sea-urchins high in air and drop them on the cliffs, for no better reason, apparently, than to hear them smash. Or, again, they will catch the luckless urchins in mid-air with all the delight of school-boys at tom-ball.

Nests are to be found midway of sea-cliffs in studiously inaccessible places, or else high in evergreen trees. Eggs, to the number of five or six, are deposited in April; and the young are fed upon the choicest which the (egg) market affords. We shall need to apologize occasionally for the shortcomings of our favorites, and we confess at the outset to shameless inconsistency; for even bird villains are dear to us, if they be not too bad, and especially if their badness be not directed against us. Who would wish to see this bold, black brigand, savage, cunning, and unscrupulous as he is, disappear entirely from our shores? He is the deep shadow of the world’s chiaroscuro; and what were white, pray, without black by which to measure it?

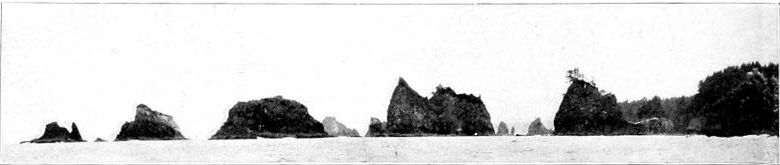

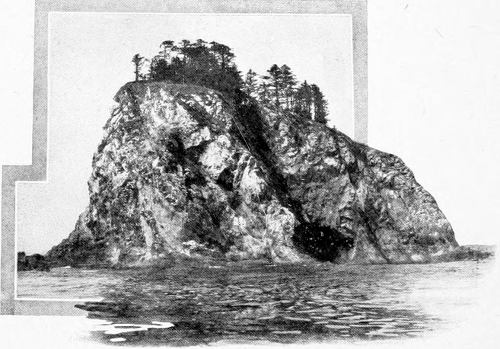

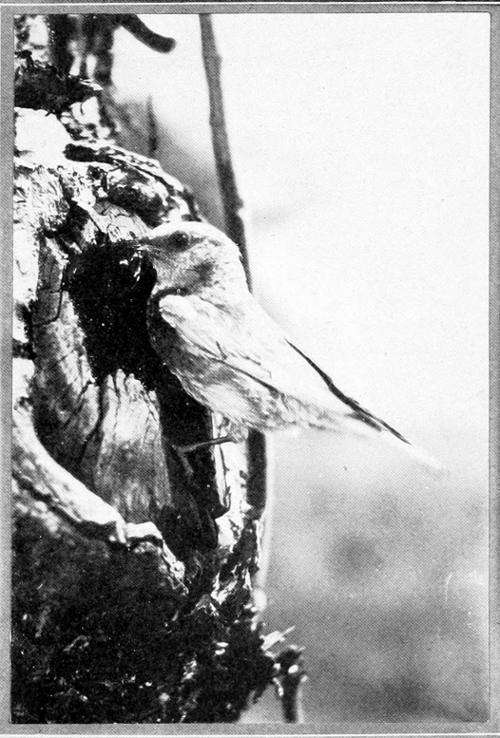

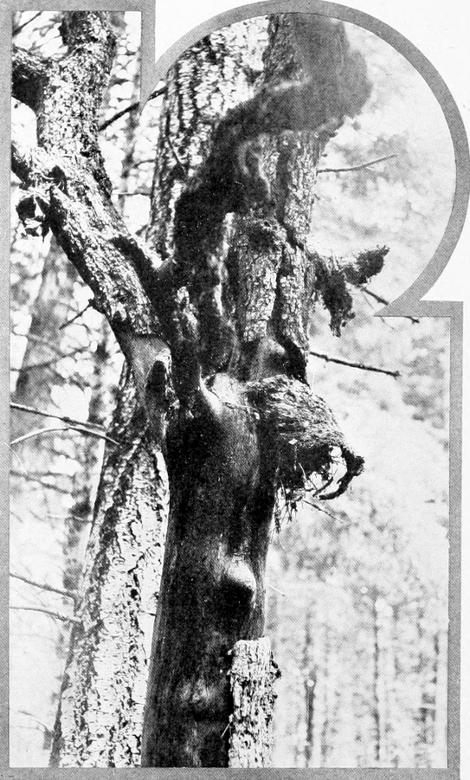

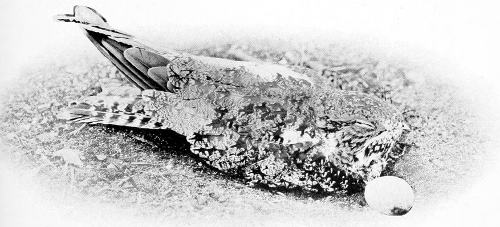

Taken in Clallam County. Photo by the Author.

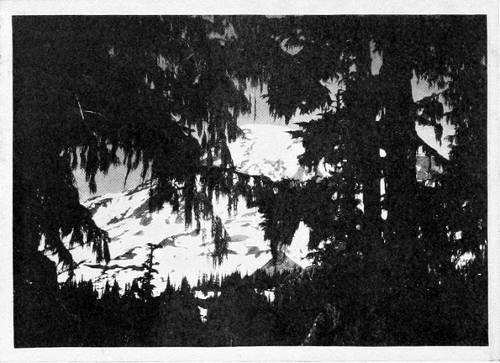

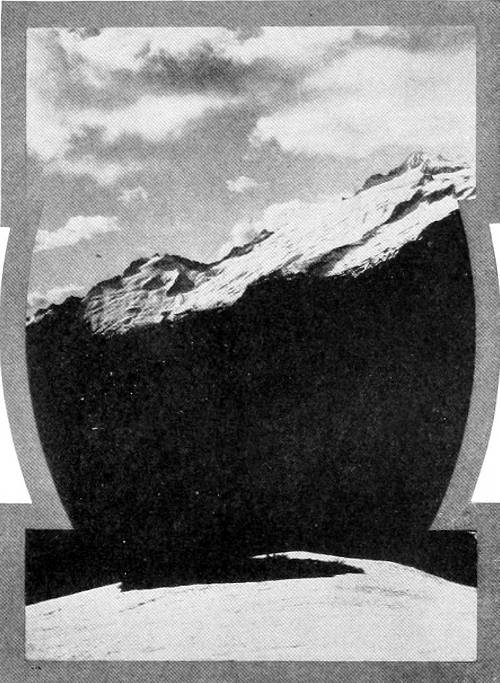

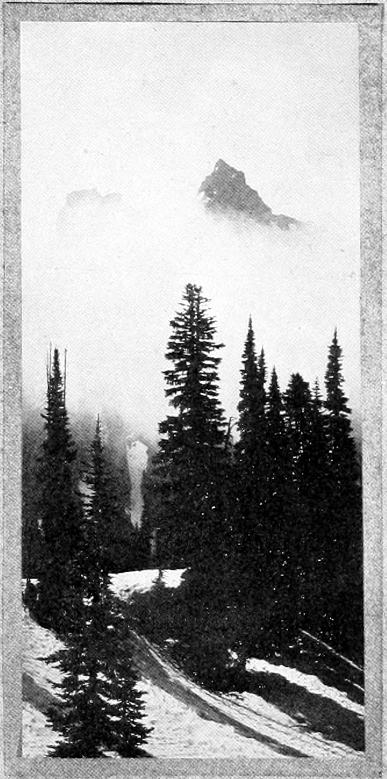

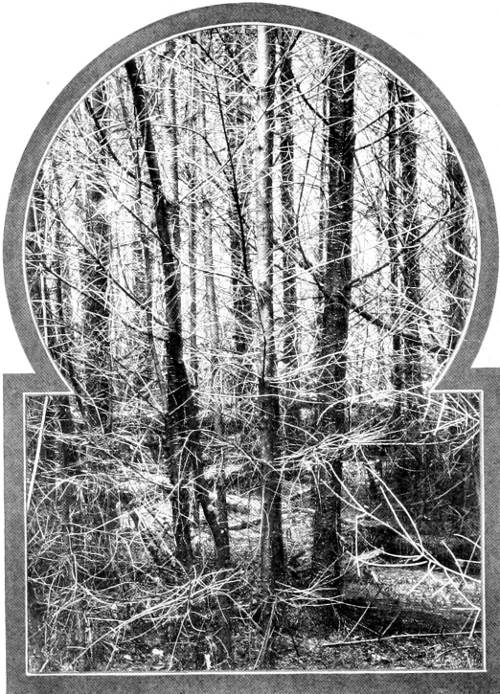

POINT-OF-THE-ARCHES GROUP, A CHARACTERISTIC HAUNT OF THE RAVEN.

A. O. U. No. 486. Corvus corax sinuatus (Wagler).

Synonyms.—American Raven. Southern Raven.

Description.—Like preceding but averaging smaller; bill relatively smaller and narrower; tarsus not so stout. Length up to 26 inches, but averaging less. Culmen 2.85 (72).

Recognition Marks.—As in preceding—distinguishable only by range.

Nesting.—Nest: placed on ledge or in crannies of basalt cliffs, more rarely in pine trees.

General Range.—Western United States chiefly west of the Rocky Mountains; in its northerly extension nearly coincident with the Upper Sonoran life zone, south to Honduras.

Range in Washington.—May be arbitrarily defined as restricted to the East-side, but common only on the treeless plains and in the Blue Mountain region. Resident.

Authorities.—Corvus carnivorus Bart., Cooper and Suckley, Rep. Pac. R. R. Surv. XII. pt. II. 1860, p. 210. Bendire, Life Hist. N. A. Birds, Vol. II. p. 396 f.

It is no mere association of ideas which has made the Raven the bird of ill omen. Black is his wing, and black is his heart, as well. While it may be allowed that he works no direct damage upon the human race, we cannot but share in sympathy the burden of the bird-world which regards him as the bete noir, diabolical in cunning, patient as fate, and relentless in the hour of opportunity.

As I sit on an early May morning by the water’s edge on a lonely island in the Columbia River, all nature seems harmonious and glad. The Meadowlarks are pricking the atmosphere with goads of good cheer in the sage behind; the Dove is pledging his heart’s affection in the cottonwood hard by; the river is singing on the rapids; and my heart is won to follow on that buoyant tide—when suddenly a mother Goose cries out in terror and I leap to my feet to learn the cause. I have not long to wait. Like a death knell comes the guttural croak of the Raven. He has spied upon her, learned her secret, swept in when her precious eggs were uncovered; and he bears one off in triumph,—a feast for his carrion brood. When one has seen this sort of thing a dozen times, and heard the wail of the wild things, the croak of the Raven comes to be fraught with menace, the veritable voice of doom.

To be sure, the Raven is not really worse than his kin, but he is distinguished by a bass voice; and does not the villain in the play always sing bass? Somehow, one never believes the ill he hears of the soulful tenor, even tho he sees him do it; but beware of the bird or man who croaks at low C.

Of all students of bird-life in the West, Captain Bendire has enjoyed the best opportunities for the study of the Raven; and his situation at Camp Harney in eastern Oregon was very similar to such as may be found in the southeastern part of our own State. Of this species, as observed at that point, he says:

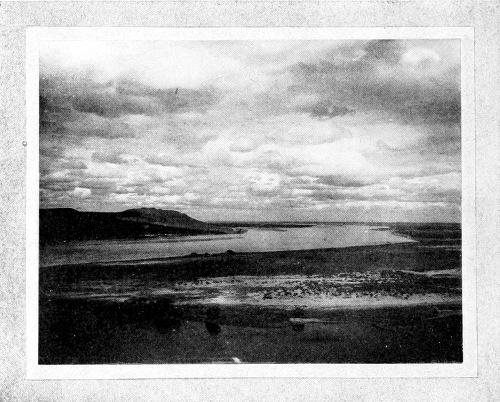

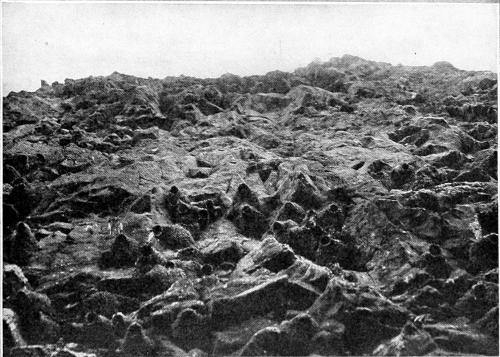

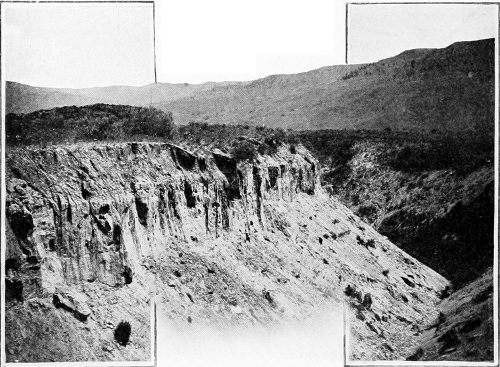

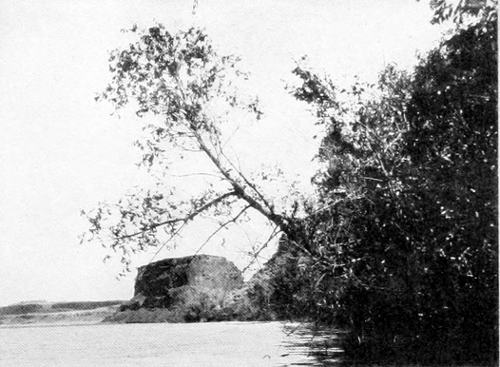

Taken near Wallula. Photo by the Author.

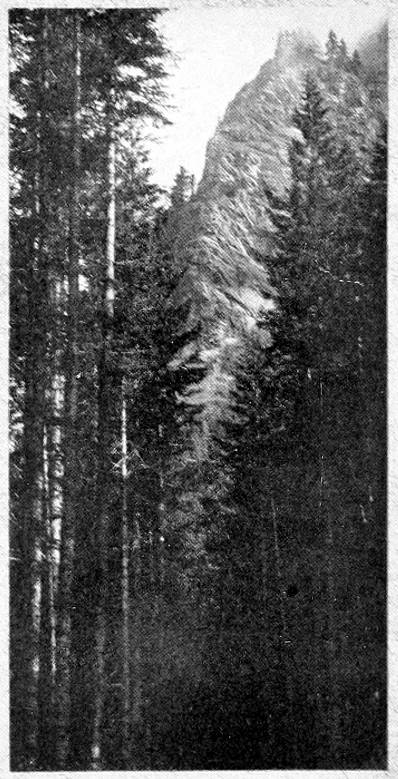

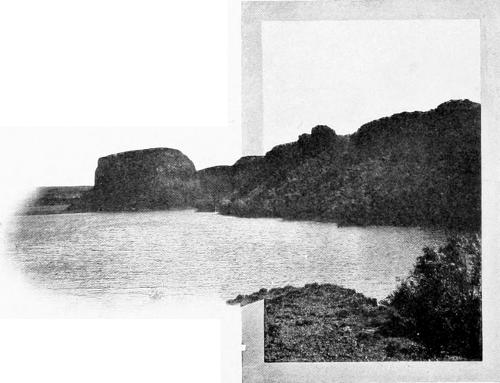

THE RAVEN’S FIEF.

“They are stately and rather sedate-looking birds, remain mated thru life, and are seemingly very much attached to each other, but apparently more unsocial to others of their kind. On the ground their movements are deliberate and dignified; their walk is graceful and seldom varied by hurried hops or jumps. They appear to still better advantage on the wing, especially in winter and early spring, when pairs may be frequently seen playing with each other, performing extraordinary feats in the air, such as somersaults, trying to fly on their backs, etc. At this season they seem to enjoy life most and to give vent to their usually not very exuberant spirits by a series of low chuckling and gurgling notes, evidently indifferent efforts at singing.

“Their ordinary call is a loud Craack-craack, varied sometimes by a deep [7] grunting koerr-koerr, and again by a clucking, a sort of self-satisfied sound, difficult to reproduce on paper; in fact they utter a variety of notes when at ease and undisturbed, among others a metallic sounding klunk, which seems to cost them considerable effort. In places where they are not molested they become reasonably tame, and I have seen Ravens occasionally alight in my yard and feed among the chickens, a thing I have never seen Crows do. * * *

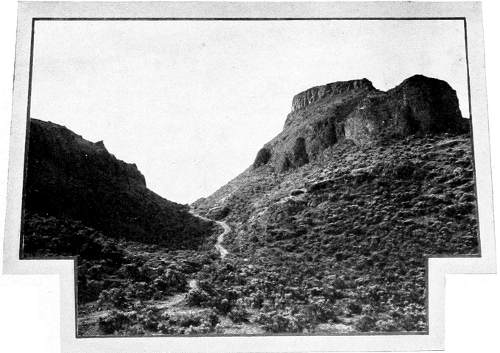

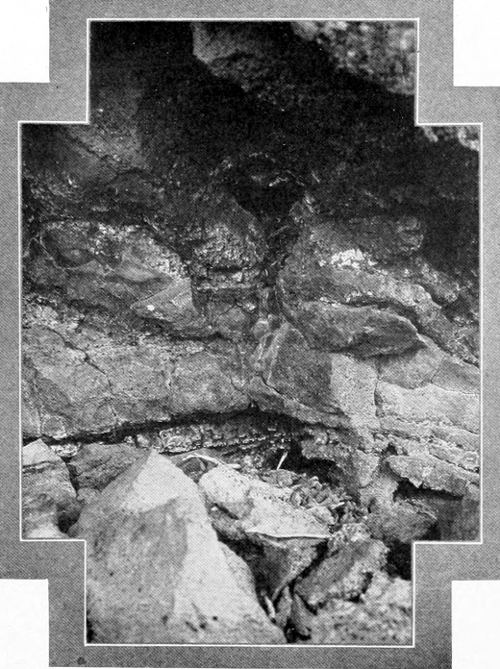

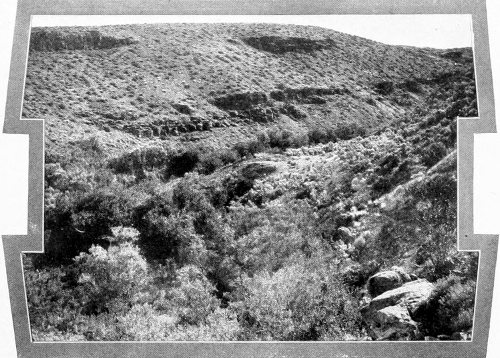

Taken in Walla Walla County. Photo by the Author.

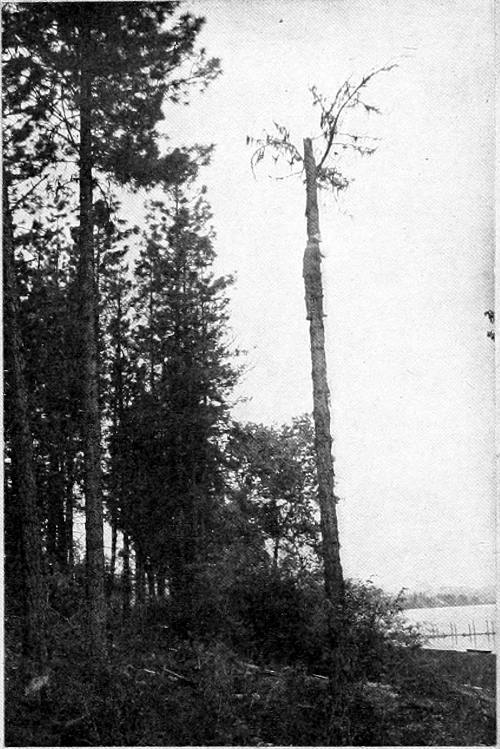

NESTING HAUNT OF THE MEXICAN RAVEN.

“Out of some twenty nests examined only one was placed in a tree. It was in a good sized dead willow, twenty feet from the ground, on an island in Sylvies River, Oregon, and easily reached; it contained five fresh eggs on April 13, 1875. The other nests were placed on cliffs, and, with few exceptions, in positions where they were comparatively secure. Usually the nest could not be seen from above, and it generally took several assistants and strong ropes to get near them, and even then it was frequently impossible to reach the eggs without the aid of a long pole with a dipper attached to the end. A favorite site was a cliff with a southern exposure, where the nest was completely covered from above by a projecting rock.”

Having once chosen a nesting site, the Ravens evince a great attachment for that particular locality; and, rather than desert it, will avoid notice by deferring the nesting season, or by visiting the eggs or young only at night.

We have no records of the taking of Raven’s eggs in Washington, but it [8] does unquestionably breed here. A nest was reported to us on a cliff in the Crab Creek Coulee. While we were unable to visit it in season, we did come upon a family group some weeks later, comprising the two adults and five grown young. This is possibly the northernmost breeding station of the Mexican Raven yet reported.

A. O. U. No. 488b. Corvus brachyrhynchos hesperis (Ridgw.).

Synonyms.—California Crow. Common Crow. American Crow.

Description.—Entire plumage glossy black, for the most part with greenish blue, steel-blue, and purplish reflections; feathers of the neck normal, rounded. Bill and feet black; iris brown. Length 16.00-20.00; wing 12.00 (302); tail 6.70 (170); bill 1.83 (46.5); depth at nostril .65 (16.5). Female averages smaller than male.

Recognition Marks.—Distinguishable from Northwest Crow by larger size and clearer voice.

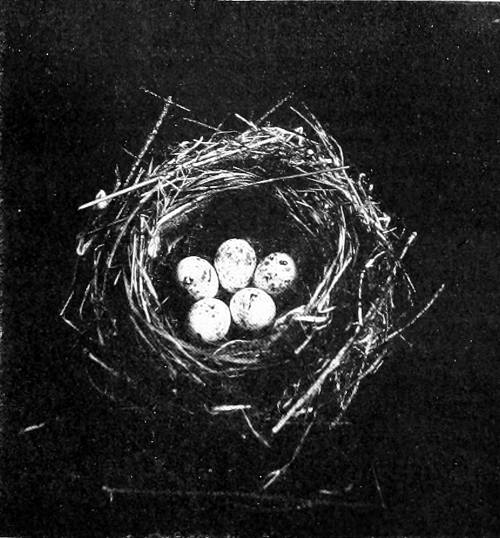

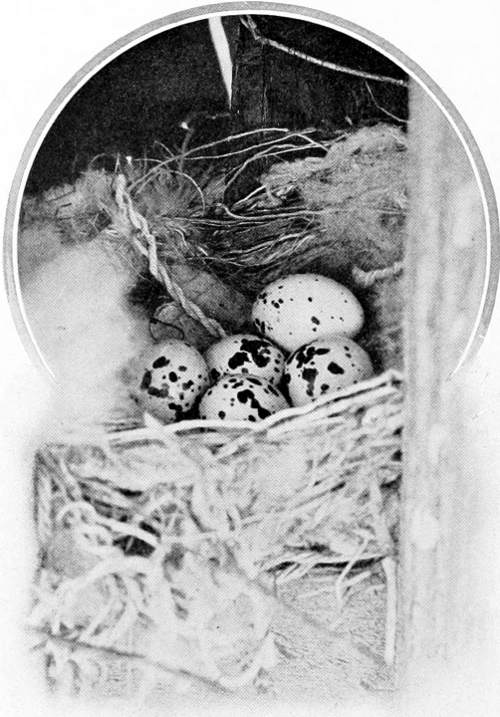

Nesting.—Nest: a neat hemisphere of sticks and twigs carefully lined with bark, roots and trash, and placed 10-60 feet high in trees,—willow, aspen, pine, or fir. Eggs: 4-6, usually 5, same coloring as Raven’s. Occasionally fine markings produce a uniform olive-green, or even olive-brown effect. Av. size 1.66 × 1.16 (42.2 × 29.5). Season: April 15-May 15; one brood.

General Range.—Western United States from Rocky Mts. to Pacific Coast, save shores of northwestern Washington, north in the interior of British Columbia, south to Arizona.

Range in Washington.—Of general distribution along streams and in settled portions of State, save along shores of Puget Sound, the Straits, and the Pacific north of Gray’s Harbor. Not found in the mountains nor the deeper forests, and only locally on the sage-brush plains.

Migrations.—Resident but gregarious and localized in winter. The winter “roosts” break up late in February.

Authorities.—Corvus americanus Aud., Baird, Rep. Pac. R. R. Surv. IX. 1858, 566 (part). Brewster, B. N. O. C. VII. 227. T. C&S. D¹. Kb. Ra. D². Ss¹. Ss². Kk. J. B. E.

Specimens.—BN(?).

While the Raven holds a secure place in mythology and literature, it is the Crow, rather, which is the object of common notice. No landscape is too poor to boast this jetty adornment; and no morning chorus is complete without the distant sub-dominant of his powerful voice, harsh and protesting tho it be.

The dusky bird is a notorious mischief-maker, but he is not quite so black as he has been painted. More than any other bird he has successfully matched his wits against those of man, and his frequent easy victories and consequent [9] boastings are responsible in large measure for the unsavory reputation in which he is held. It is a familiar adage in ebony circles that the proper study of Crow-kind is man, and so well has he pursued this study that he may fairly be said to hold his own in spite of fierce and ingenious persecution. He rejoices in the name of outlaw, and ages of ill-treatment have only served to sharpen his wits and intensify his cunning.

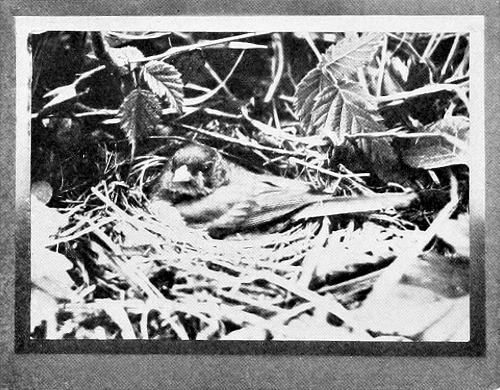

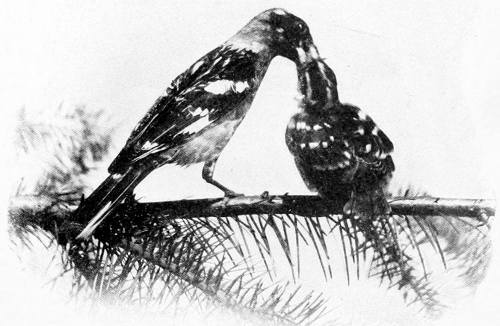

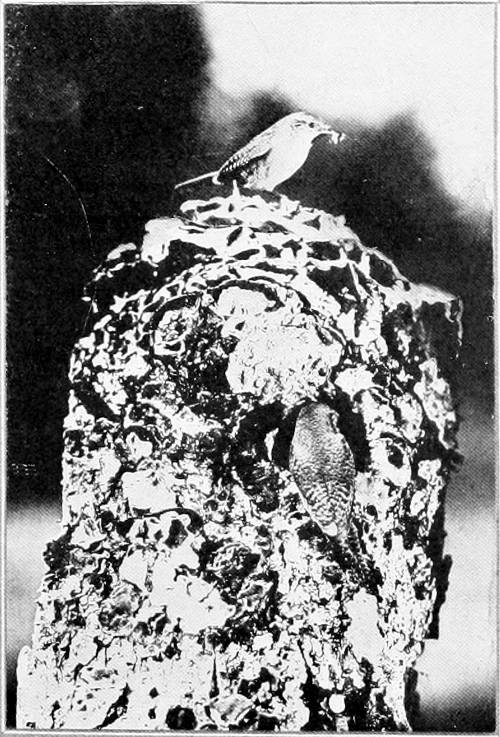

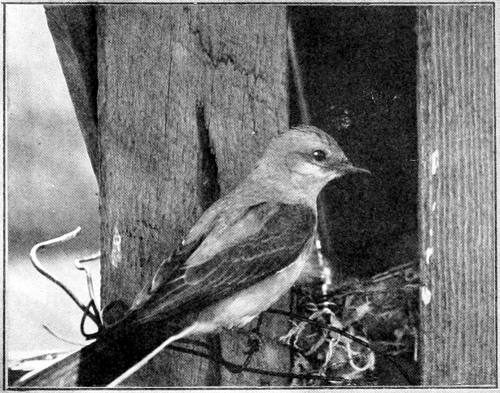

Taken in Oregon. Photo by Bohlman and Finley.

WESTERN CROW AT NEST.

That the warfare waged against him is largely unnecessary, and partly unjust, has been pretty clearly proven of late by scientists who have investigated the Crow’s food habits. It is true that he destroys large numbers of eggs and nestlings, and, if allowed to, that he will occasionally invade the poultry yard—and for such conduct there can be no apology. It is true, also, that some damage is inflicted upon corn in the roasting-ear stage, and that corn left out thru the winter constitutes a staple article of Crow diet. But it is estimated that birds and eggs form only about one-half of one per cent of their total diet; and in the case of grain, certainly they perform conspicuous services in raising the crop. Besides the articles of food mentioned, great [10] quantities of crickets, beetles, grasshoppers, caterpillars, cut-worms, and spiders, are consumed. Frogs, lizards, mice, and snakes also appear occasionally upon the bill of fare. On the whole, therefore, the Crow is not an economic Gorgon, and his destruction need not largely concern the farmer, altho it is always well to teach the bird a proper reverence.

The psychology of the Crow is worthy of a separate treatise. All birds have a certain faculty of direct perception, which we are pleased to call instinct; but the Crow, at least, comes delightfully near to reasoning. It is on account of his phenomenal brightness that a young Crow is among the most interesting of pets. If taken from the nest and well treated, a young Crow can be given such a large measure of freedom as fully to justify the experiment from a humanitarian standpoint. Of course the sure end of such a pet is death by an ignorant neighbor’s gun, but the dear departed is embalmed in memory to such a degree that all Crows are thereafter regarded as upon a higher plane.

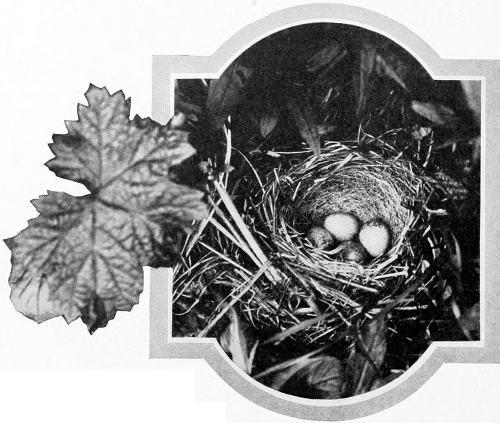

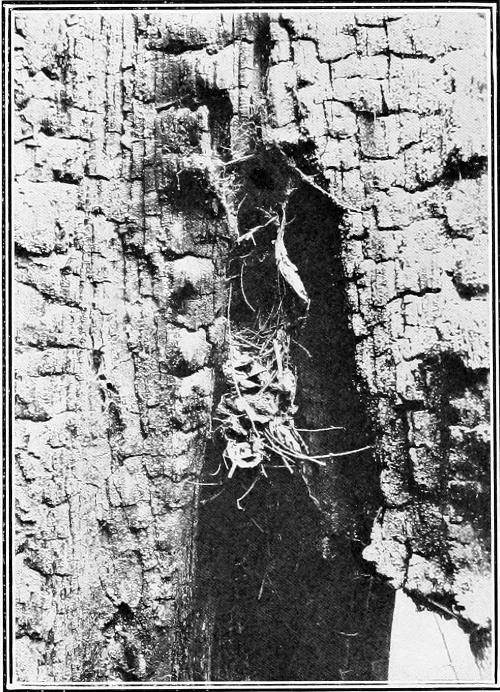

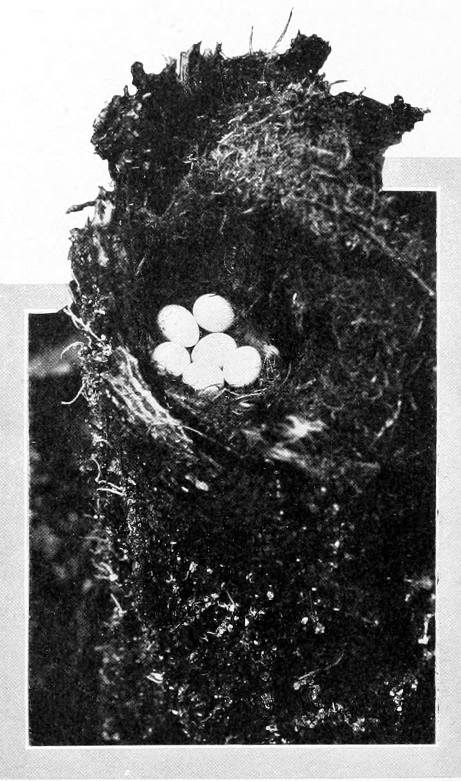

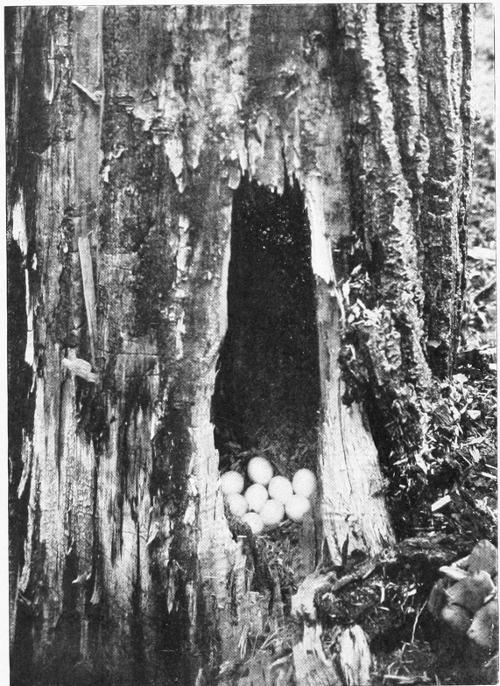

Taken in Benton Co. Photo by the Author.

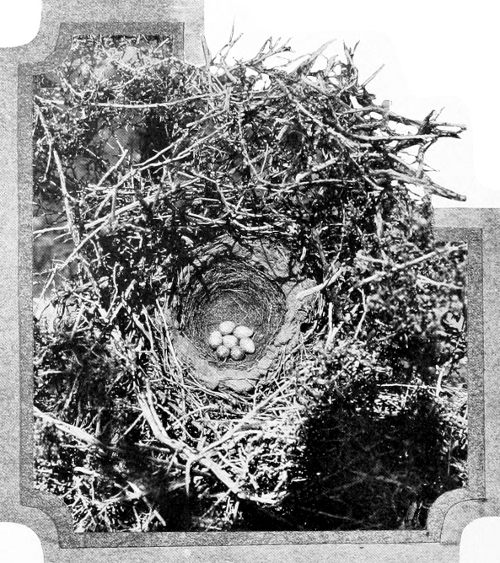

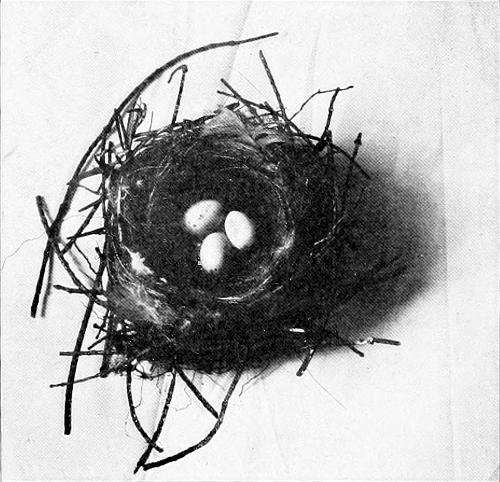

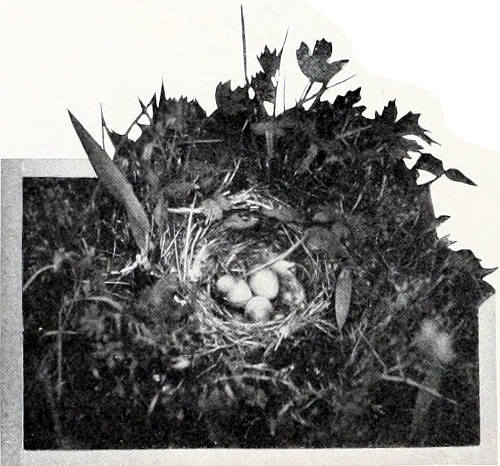

NEST AND EGGS OF WESTERN CROW.

Everyone knows that Crows talk. Their cry is usually represented by a single syllable, caw, but it is capable of many and important modifications. For instance, keraw, keraw, comes from some irritated and apprehensive female, who is trying to smuggle a stick into the grove; kawk-kawk-kawk proclaims sudden danger, and puts the flock into instant commotion; while caw-aw, caw-aw, caw-aw reassures them again. Once in winter when the bird-man, for sport, was mystifying the local bird population by reproducing the notes of the Screech Owl, a company of Crows settled in the tops of neighboring trees, and earnestly discussed the probable nature of the object half-concealed under a camera cloth. Finally, they gave it up and withdrew—as I supposed. It [11] seems that one old fellow was not satisfied, for as I ventured to shift ever so little from my strained position, he set up a derisive Ca-a-a-aw from a branch over my head,—as who should say, “Aw, ye can’t fool me. Y’re just a ma-a-an,” and flapped away in disgust.

Crows attempt certain musical notes as well; and, unless I mistake, the western bird has attained much greater proficiency in these. These notes are deeply guttural, and evidently entail considerable effort on the bird’s part. Hunger-o-ope, hunger-o-ope, one says; and it occurs to me that this is allied to the delary, delary, or springboard cry, of the Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata),—plunging notes they have also been called.

Space fails in which to describe the elaborate structure of Crow society; to tell of the military and pedagogical systems which they enforce; of the courts of justice and penal institutions which they maintain; of the vigilantes who visit vengeance upon evil-minded owls and other offenders; or even of the games which they play,—tag, hide and seek, blind-man’s-buff and pull-away. These things are sufficiently attested by competent observers; we may only spare a word for that most serious business of life, nesting.

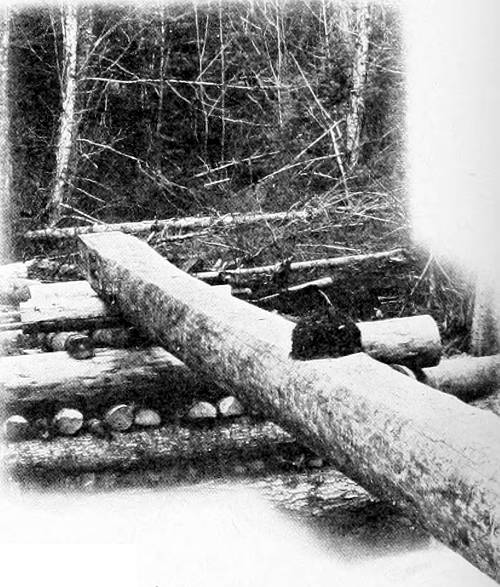

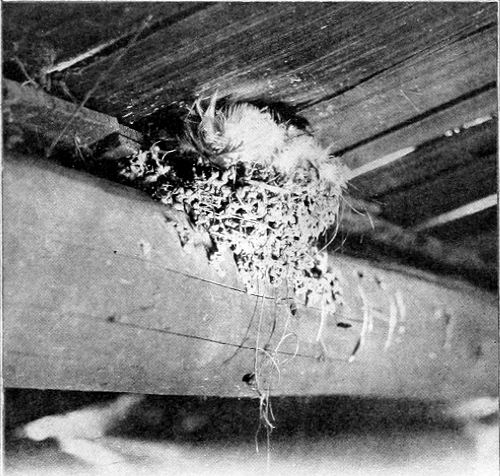

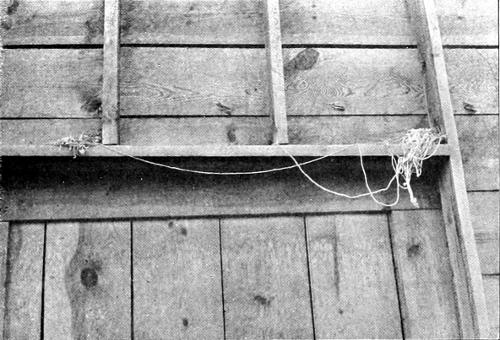

A typical Crow’s nest is a very substantial affair, as our illustration shows. Upon a basis of coarse sticks, a mat of dried leaves, grasses, bark-strips, and dirt, or mud, is impressed. The deep rounded bowl thus formed is carefully lined with the inner bark of the willow or with twine, horse-hair, cow-hair, rabbit-fur, wool, or any other soft substance available. When completed the nesting hollow is seven or eight inches across and three or four deep. The expression “Crow’s nest,” as used to indicate disarray, really arises from the consideration of old nests. Since the birds resort to the same locality year after year, but never use an old nest, the neighboring structures of successive years come to represent every stage of dilapidation.

West of the mountains nests are almost invariably placed well up in fir trees, hard against the trunk, and so escape the common observation. Upon the East-side, however, nests are usually placed in aspen trees or willows; in the former case occurring at heights up to fifty feet, in the latter from ten to twenty feet up. Escape by mere elevation being practically impossible, the Crows resort more or less to out-of-the-way places,—spring draws, river islands, and swampy thickets.

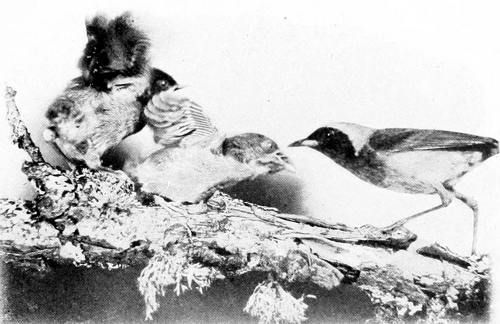

Notwithstanding the fact that the spring season opens much earlier than in the East, the Crows, true to the traditions of a northern latitude, commonly defer nesting till late in April. Fresh eggs may be found by the 20th of April, but more surely on the 1st of May. Incubation lasts from fourteen to eighteen days; and the young, commonly five but sometimes six in number, are born naked and blind.

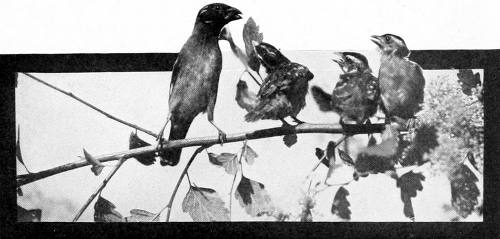

It is when the Crow children are hatched that Nature begins to groan. It is then that birds’ eggs are quoted by the crate; and beetles by the hecatomb [12] are sacrificed daily in a vain effort to satisfy the Gargantuan appetites of these young ebons. I once had the misfortune to pitch camp in a grove of willows which contained a nestful of Crows. The old birds never forgave me, but upbraided me in bitter language from early morn till dewy eve. The youngsters also suffered somewhat, I fear, for as often as a parent bird approached, cawing in a curiously muffled voice, choked with food, and detected me outside the tent, it swallowed its burden without compunction, in order that it might the more forcibly berate me.

If the male happened to discover my out-of-doorness in the absence of his mate, he would rush at her when she hove in sight, in an officious, blustering way, and shout, “Look out there! Keep away! The Rhino is on the rampage again!”

I learned, also, to recognize the appearance of hawks in the offing. At the first sign the Crow, presumably the male, begins to roll out objurgatory gutturals as he hurries forward to meet the intruder. His utterances, freely translated, run somewhat as follows: “That blank, blank Swainson Hawk! I thought I told him to keep away from here. Arrah, there, you slab-sided son of an owl! What are ye doing here? Git out o’ this! (Biff! Biff!) Git, I tell ye! (Biff!) If ever I set eyes on ye again, I’ll feed ye to the coyotes. Git, now!” And all this without the slightest probability that the poor hawk would molest the hideous young pickaninnies if he did discover them. For when was a self-respecting hawk so lost to decency as to be willing to “eat crow”?

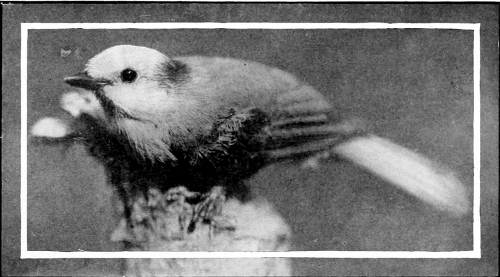

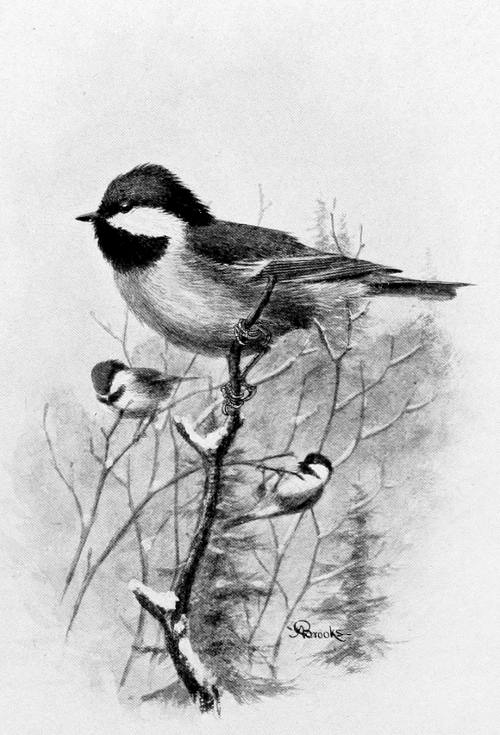

A. O. U. No. 489. Corvus brachyrhynchos caurinus (Baird).

Synonyms.—Fish Crow. Western Fish Crow. Northwest Fish Crow. Puget Sound Crow. Tidewater Crow.

Description.—Similar to C. b. hesperis, but decidedly smaller, with shorter tarsus and relatively smaller feet. Length 15.00-17.00; wing 11.00 (280); tail 6.00 (158); bill 1.80 (46); tarsus 1.95 (50).

Recognition Marks.—An undersized Crow. Voice hoarse and flat as compared with that of the Western Crow. Haunts beaches and sea-girt rocks.

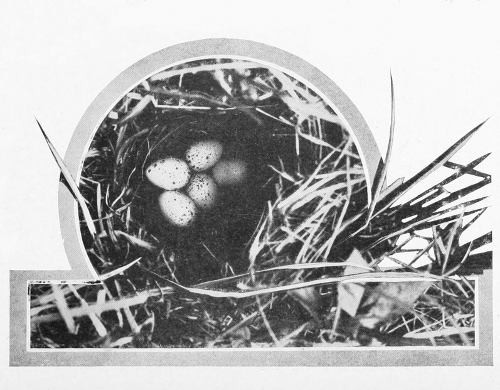

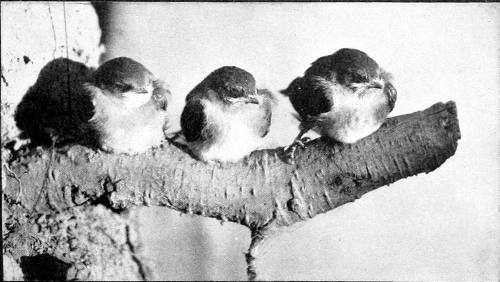

Nesting.—Nest: a compact mass of twigs and bark-strips with occasionally a foundation of mud; lined carefully with fine bark-strips and hair; 4.00 deep and 7.00 across inside; placed 10-20 feet high in orchard or evergreen trees, sometimes in loose colony fashion. Eggs: 4 or 5, indistinguishable in color from those of the [13] Common Crow, but averaging smaller. A typical set averages 1.56 × 1.08 (39.6 × 27.4). Season: April 15-June 1; one brood.

General Range.—American coasts of the North Pacific Ocean and its estuaries from Olympia and the mouth of the Columbia River north at least to the Alaskan peninsula.

Range in Washington.—Shores and islands of Puget Sound, the Straits of Juan de Fuca, and the West Coast (at least as far south as Moclips, presumably to Cape Disappointment). Strictly resident.

Authorities.—[Lewis and Clark, Hist. Ex. (1814), ed. Biddle: Coues, Vol. II. p. 185.] Corvus caurinus Baird, Baird, Rep. Pac. R. R. Surv. IX. June 29, 1858, 569, 570. T. C&S. L¹. Rh. Kb. Ra. Kk. B. E.

Specimens.—U. of W. Prov. E. B.

After lengthy discussion it is pretty well settled that the Crow of the northwestern sea-coasts is merely a dwarfed race of the Corvus brachyrhynchos group; and that it shades perfectly into the prevailing western type, C. b. hesperis, wherever that species occupies adjacent regions. This area of intergradation lies chiefly south and west of Puget Sound, in Washington; for the Crow is ever fond of the half-open country, and does not take kindly to the unmitigated forest depths, save where, as in the case of the Fish Crow, he may find relief upon the broad expanses of shore and tide-flats. The case is quite analogous to that of native man. The larger, more robust types were found in the eastern interior, while those tribes which were confined exclusively to residence upon the sea-shore tended to become dwarfed and stunted; and the region of intergradation lay not chiefly along the western slopes of the Cascades with their crushing weight of tall timber, but in the prairie regions bordering Puget Sound upon the south.

It is impossible, therefore, to pronounce with certainty upon the subspecific identity of Crows seen near shore in Mason, Thurston, Pierce, or even King County; but in Clallam, Jefferson, San Juan, and the other counties of the Northwest, one has no difficulty in recognizing the dwarf race. Not only are these Crows much smaller in point of size, but the voice is weaker, flatter, and more hoarse, as tho affected by an ever-present fog. So marked is this vocal change, that one may note the difference between birds seen along shore in Pierce County and those which frequent the uplands. However,—and this caution must be noted—the upland birds do visit the shore on occasion; and the regular shore dwellers are by no means confined thereto, as are the more typical birds found further north.

The early observers were feeling for these differences, and if Nature did not afford sufficient ground for easy discrimination, imagination could supply the details. The following paragraph from the much quoted work[4] of John Keast Lord is interesting because deliciously untrue.

“The sea-coast is abandoned when the breeding time arrives early in May, when they resort in pairs to the interior; selecting a patch of open prairie, where there are streams and lakes and where the wild crab apple and white-thorn grows, in which they build nests precisely like that of the Magpie, arched over the top with sticks. The bird enters by a hole on one side but leaves by an exit hole in the opposite. The inside is plastered with mud; a few grass stalks strewn loosely on the bottom keep the eggs from rolling. This is so marked a difference to the Barking Crow’s nesting [“Barking Crow” is J. K. L.’s solecism for the Western Crow, C. b. hesperis], as in itself to be a specific distinction. The eggs are lighter in blotching and much smaller. I examined great numbers [! !] of nests at this prairie and on the Columbia, but invariably found that the same habit of doming prevailed. After nesting, they return with the young to the sea-coasts, and remain in large flocks often associated with Barking Crows until nesting time comes again.”—No single point of which has been confirmed by succeeding observers.

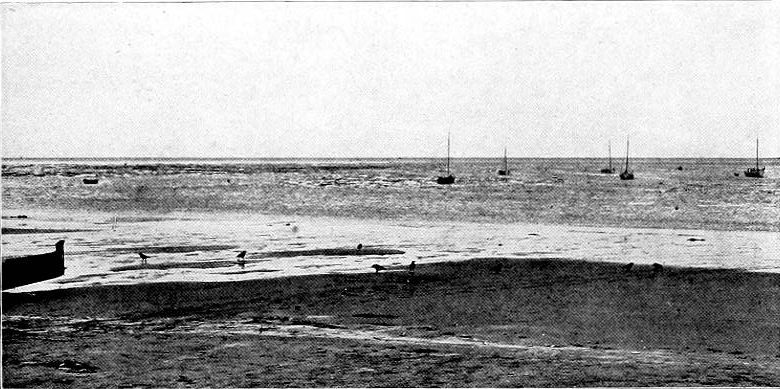

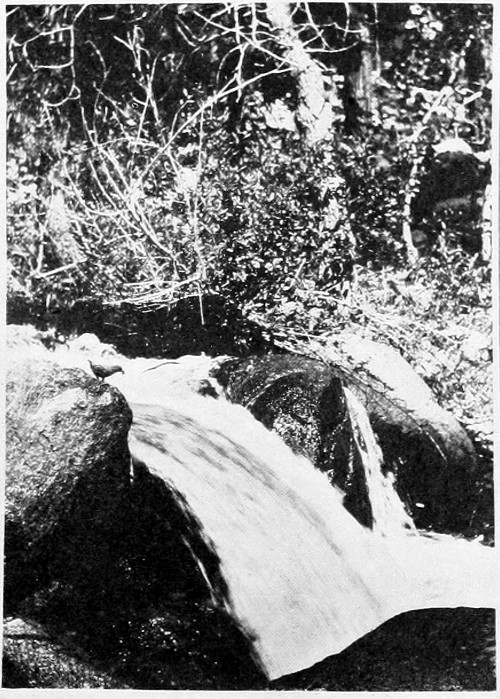

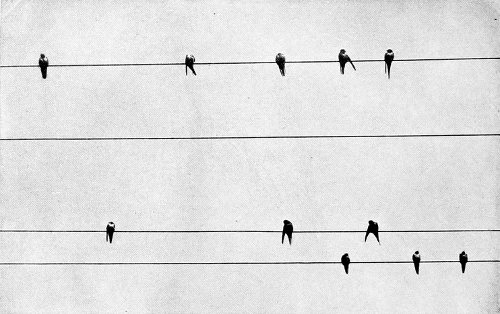

Taken at Neah Bay. Photo by the Author.

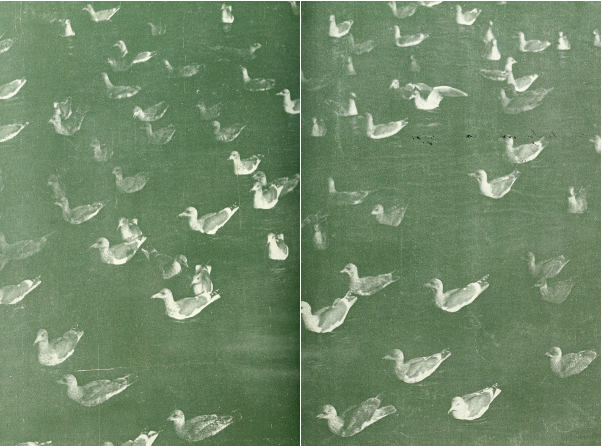

THE PHANTOM CROWS.

Dr. Cooper wrote[5] with exact truthfulness: “This fish-crow frequents the coast and inlets of this Territory in large numbers, and is much more gregarious and familiar than the common Crow. Otherwise it much resembles that bird in habits, being very sagacious, feeding on almost everything animal and vegetable, and having nearly the same cries, differing rather in tone than character. Its chief dependence for food being on the sea, it is generally found along the beach, devouring dead fish and other things brought up by the waves. It is also very fond of oysters, which it breaks by carrying them upward and dropping again on a rock or other hard material. When the tide is full they resort to the fields or dwellings near the shore and devour potatoes and other vegetables, offal, etc. They, like the gulls, perceive the instant of change of the tide, and flocks will then start off together for a favorite feeding ground. They are very troublesome to the Indians, stealing [15] their dried fish and other things, while from superstitious feelings the Indians never kill them but set a child to watch and drive them away. They build in trees near the shore in the same way as the common crow and the young are fledged in May.”

Mr. J. F. Edwards, a pioneer of ’67, tells me that in the early days a small drove of pigs was an essential feature of every well-equipped saw-mill on Puget Sound. The pigs were given the freedom of the premises, slept in the saw dust, and dined behind the mess-house. Between meals they wandered down to the beach and rooted for clams at low tide. The Crows were not slow to learn the advantages of this arrangement and posted themselves promptly in the most commanding and only safe positions; viz., on the backs of the pigs. The pig grunted and squirmed, but Mr. Crow, mindful of the blessings ahead, merely extended a balancing wing and held on. The instant the industrious rooter turned up a clam, the Crow darted down, seized it in his beak and made off; resigning his station to some sable brother, and leaving the porker to reflect discontentedly upon the rapacity of the upper classes. Mr. Edwards declares that he has seen this little comedy enacted, not once, but a hundred times, at Port Madison and at Alberni, V. I.

The Fish Crows have learned from the gulls the delights of sailing the main on driftwood. I have seen numbers of them going out with the tide a mile or more from shore, and once a Crow kept company with three gulls on a float so small that the gulls had continually to strive for position; but the Crow stood undisturbed.

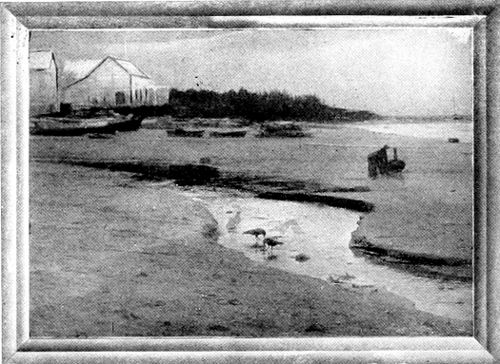

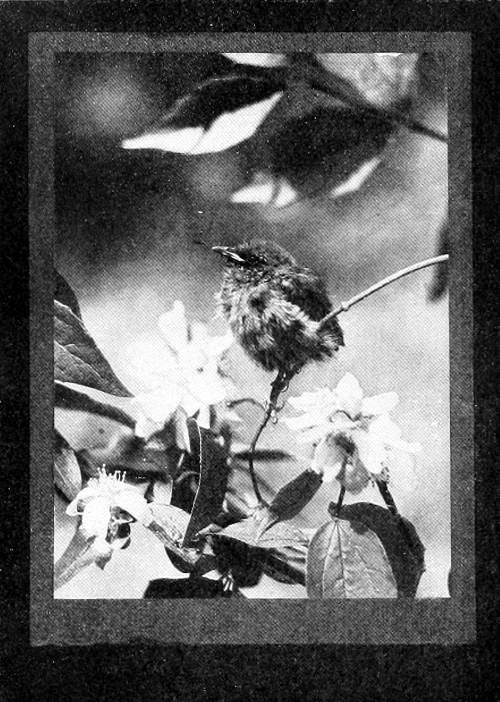

Photo by the Author.

BIRDS AND BOATS AT NEAH BAY.

Speaking of their aquatic tendencies, Mr. A. B. Reagan, of La Push, assures me that he has repeatedly seen them catch smelt in the ocean near shore. These fish become involved in the breakers and may be snatched from above by the dextrous bird without any severe wetting.

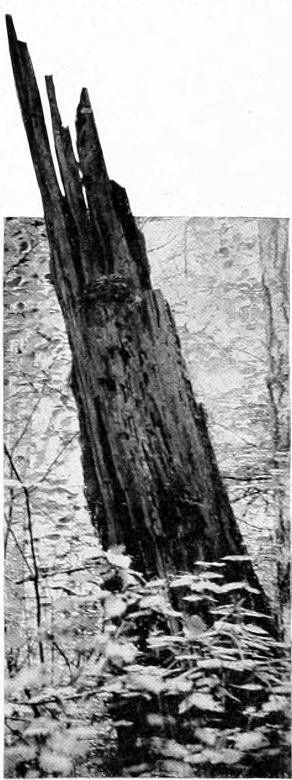

Crows are still the most familiar feature of Indian village life. The Indian, perhaps, no longer cherishes any superstition regarding him, but he is reluctant to banish such a familiar evil. The Quillayutes call the bird Kah-ah-yó: and it is safe to say that fifty pairs of these Fish Crows nest within half a mile of the village of La Push. They nest, indifferently, in the saplings of the coastal thickets, or against the trunks of the larger spruces, and take little pains to escape observation. The birds are, however, becoming quite shy of a gun. Seeing a half dozen of them seated in the tip of a tall spruce in the open woods, I raised my fowling piece to view, whereupon all flew with frantic cries. Indeed it required considerable manœuvering and an ambuscade to secure the single specimen needed.

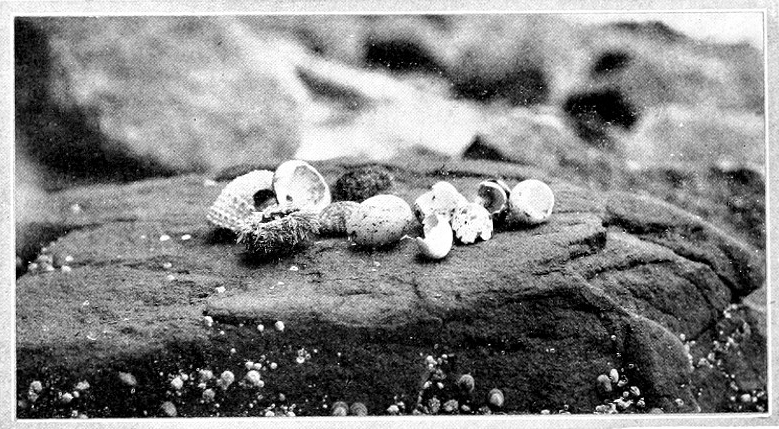

Taken on Waldron Id. Photo by the Author.

THE CROW’S FARE.

At Neah Bay the Fish Crows patrol the beach incessantly and allow very little of the halibut fishers’ largess to float off on the tide. And the Oke-t(c)ope, as the Makahs call the birds, have little fear of the Indians, altho they are very suspicious of a strange white man. I once saw a pretty sight on this beach: a three year old Indian girl chasing the Crows about in childish glee. The birds enjoyed the frolic as much as she, and fell in [17] behind her as fast as she shooed them away in front—came within two or three feet of her, too, and made playful dashes at her chubby legs. But might I be permitted to photograph the scene at, say, fifty yards? Mit nichten! Arragh! To your tents, O Israel!

In so far as this Crow consents to perform the office of scavenger, he is a useful member of society. Nor is his consumption of shell-fish a serious matter. But when we come to consider the quality and extent of his depredations upon colonies of nesting sea-birds, we find that he merits unqualified condemnation. For instance, two of us bird-men once visited the west nesting of Baird Cormorants on Flattop, to obtain photographs. As we retired down the cliff, I picked up a broken shell of a Cormorant’s egg, from which the white, or plasma, was still dripping. As we pulled away from the foot of the cliff a Crow flashed into view, lighted on the edge of a Shag’s nest, seized an egg, and bore it off rapidly into the woods above, where the clamor of expectant young soon told of the disposition that was being made of it. Immediately the marauder was back again, seized the other egg, and was off as before. All this, mind you, in a trice, before we were sufficiently out of range for the Cormorants to reach their nests again, altho they were hastening toward them. Back came the Crow, but the first nest was exhausted; the second had nothing in it; the Shags were on the remainder; moments were precious—he made a dive at a Gull’s nest, but the Gulls made a dive at him; and they too hastened to their eggs.

Subsequent investigation discovered rifled egg-shells all over the island, and it was an easy matter to pick up a hatful for evidence. As he is at Flattop, so he is everywhere, an indefatigable robber of birds’ nests, a sneaking, thieving, hated, black marauder. It is my deliberate conviction that the successful rearing of a nestful of young Crows costs the lives of a hundred sea-birds. The Baird Cormorant is, doubtless, the heaviest loser; and she appears to have no means of redress after the mischief is done, save to lay more eggs,—more eggs to feed more Crows, to steal more eggs, etc.

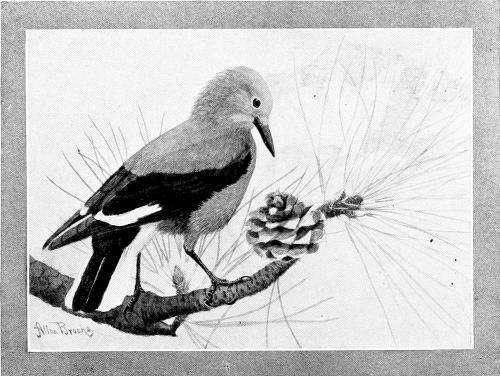

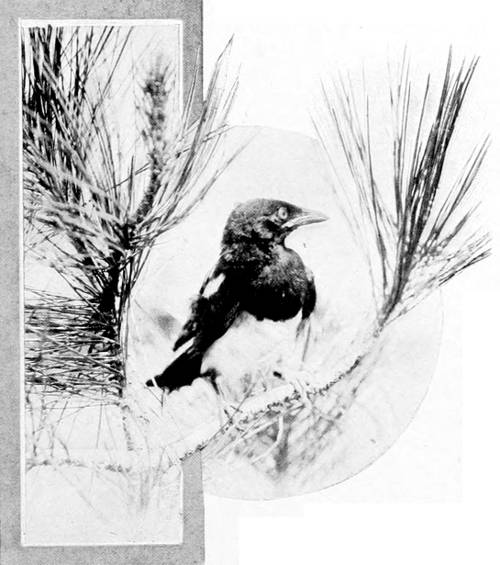

A.O.U. No. 491. Nucifraga columbiana (Wils.).

Synonyms.—Clark’s Crow. Pine Crow. Gray Crow. “Camp Robber.” (Thru confusion with the Gray Jay, Perisoreus sp.).

Description.—Adults: General plumage smoky gray, lightening on head, becoming sordid white on forehead, lores, eyelids, malar region and chin; wings glossy black, the secondaries broadly tipped with white; under tail-coverts and four outermost pairs of rectrices white, the fifth pair with outer web chiefly white and the inner web chiefly black, the remaining (central) pair of rectrices and the upper tail-coverts black; bill and feet black; iris brown. Shade of gray in plumage of adults variable—bluish ash in freshly moulted specimens, darker and browner, or irregularly whitening in worn plumage. Young like adults, but browner. Length 11.00-13.00; wing 7.00-8.00 (192); tail 4.50 (115); bill 1.60 (40.7); tarsus 1.45 (36.8). Female smaller than male.

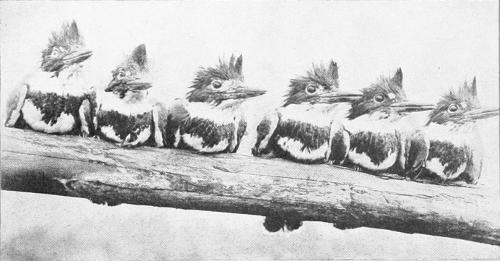

Recognition Marks.—Kingfisher size; gray plumage with abruptly contrasting black-and-white of wings and tail; harsh “char-r” note.

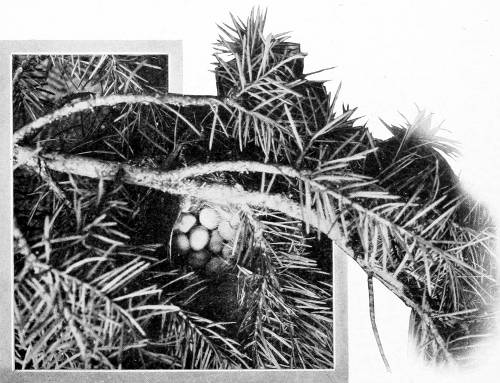

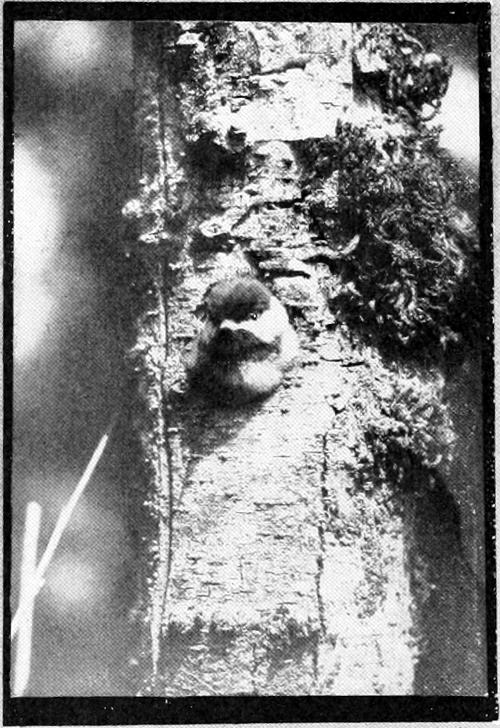

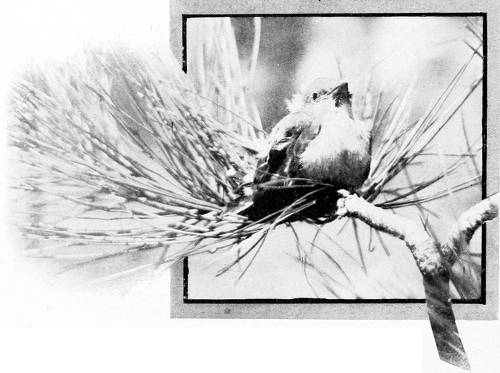

Nesting.—Nest: basally a platform of twigs on which is massed fine strips of bark with a lining of bark and grasses, placed well out on horizontal limb of evergreen tree, 10-50 feet up. Eggs: 2-5, usually 3, pale green sparingly flecked and spotted with lavender and brown chiefly about larger end. Av. size, 1.30 × .91 (33 × 23.1). Season: March 20-April 10; one brood.

General Range.—Western North America in coniferous timber, from Arizona and New Mexico to Alaska; casual east of the Rockies.

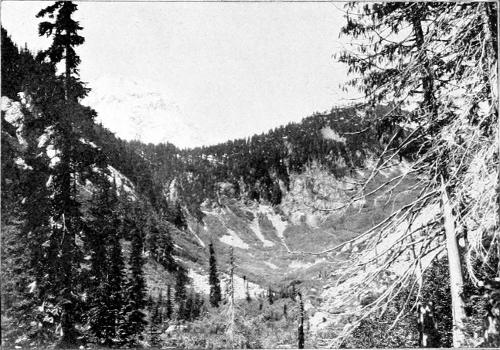

Range in Washington.—Of regular occurrence in the mountains thruout the State. Resident in the main but visits the foothills and lower pine-clad levels of eastern Washington at the close of the nesting season.

Authorities.—Corvus columbianus, Wilson, Am. Orn. iii. 1811, 29. T. C&S. D¹. D². J. E.

Specimens.—(U. of W.). Prov. E. C.

No bird-lover can forget his first encounter with this singular Old-Bird-of-the-Mountains. Ten to one the bird brought the man up standing by a stentorian char’r’r, char’r’r, char’r’r, which led him to search wildly in his memory whether Rocs are credited with voices. If the bird was particularly concerned at the man’s intrusion, he presently revealed himself sitting rather stolidly on a high pine branch, repeating that harsh and deafening cry. The grating voice is decidedly unpleasant at close quarters, and it is quite out of keeping with the unquestioned sobriety of its grizzled owner. A company of Nutcrackers in the distance finds frequent occasion for outcry, and the din is only bearable as it is softened and modified by the re-echoing walls of some pine-clad gulch, or else dissipated by the winds which sweep over the listening glaciers.

CLARK’S NUTCRACKER.

Clark’s Nutcracker is the presiding genius of the East-side slopes and light-forested foothills, as well as of the rugged fastnesses of the central Cordilleras. His presence, during fall and winter, at the lower altitudes depends in large measure upon the pine-cone crop, since pine seeds are his staple, tho by no means his exclusive diet. This black and white and gray “Crow” curiously combines the characteristics of Woodpecker and Jay as well. Like the Lewis Woodpecker, he sometimes hawks at passing insects, eats berries from bushes, or alights on the ground to glean grubs, grasshoppers, and black crickets. In the mountains it shares with the Jays of the Perisoreus group the names “meat-bird” and “camp-robber,” for nothing that is edible comes amiss to this bird, and instances are on record of its having invaded not only the open-air kitchen, but the tent, as well, in search of “supplies.”

Of its favorite food, John Keast Lord says: “Clark’s ‘Crows’ have, like the Cross-bills, to get out the seeds from underneath the scaly coverings constituting the outward side of the fir-cone; nature has not given them [20] crossed mandibles to lever open the scales, but instead, feet and claws, that serve the purpose of hands, and a powerful bill like a small crowbar. To use the crowbar to advantage the cone needs steadying, or it would snap at the stem and fall; to accomplish this one foot clasps it, and the powerful claws hold it firmly, whilst the other foot encircling the branch, supports the bird, either back downward, head downward, on its side, or upright like a woodpecker, the long clasping claws being equal to any emergency; the cone thus fixed and a firm hold maintained on the branch, the seeds are gouged out from under the scales.”

These Nutcrackers are among the earliest and most hardy nesters. They are practically independent of climate, but are found during the nesting months—March, or even late in February, and early April—only where there is a local abundance of pine (or fir) seeds. They are artfully silent at this season, and the impression prevails that they have “gone to the mountains”; or, if in the mountains already, the presence of a dozen feet of snow serves to allay the oölogist’s suspicions.

The nest is a very substantial affair of twigs and bark-strips, heavily lined, as befits a cold season, and placed at any height in a pine or fir tree, without noticeable attempt at concealment. The birds take turns incubating and—again because of the cold season—are very close sitters. Three eggs are usually laid, of about the size and shape of Magpies’ eggs, but much more lightly colored. Incubation, Bendire thinks, lasts sixteen or seventeen days, and the young are fed solely on hulled pine seeds, at the first, presumably, regurgitated.

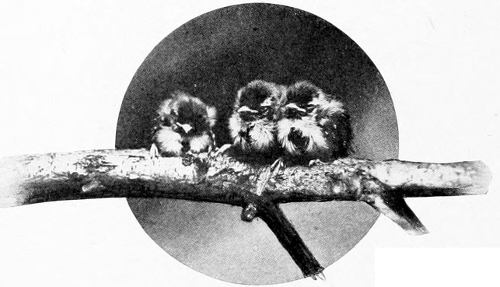

If the Corvine affinities of this bird were nowhere else betrayed, they might be known from the hunger cries of the young. The importunate añh, añh, añh of the expectant bantling, and the subsequent gullú, gullú, gullú of median deglutition (and boundless satisfaction) will always serve to bind the Crow, Magpie, and Nutcracker together in one compact group. When the youngsters are “ready for college,” the reserve of early spring is set aside and the hillsides are made to resound with much practice of that uncanny yell before mentioned. Family groups are gradually obliterated and, along in June, the birds of the foothills begin to retire irregularly to the higher ranges, either to rest up after the exhausting labors of the season, or to revel in midsummer gaiety with scores and hundreds of their fellows.

A. O. U. No. 492. Cyanocephalus cyanocephalus (Maxim.).

Synonyms.—Blue Crow. Maximilian’s Jay. Pine Jay.

Description.—Adults: Plumage dull grayish blue, deepening on crown and nape, brightening on cheeks, paling below posteriorly, streaked and grayish white on chin, throat and chest centrally; bill and feet black; iris brown. Young birds duller, gray rather than blue, except on wings and tail. Length of adult males 11.00-12.00; wing 6.00 (154); tail 4.50 (114); bill 1.42 (36); tarsus 1.50 (38). Female somewhat smaller.

Recognition Marks.—Robin size; blue color; crow-like aspect.

Nesting.—Not supposed to nest in State.

General Range.—Piñon and juniper woods of western United States; north to southern British Columbia (interior), Idaho, etc.; south to Northern Lower California, Arizona, New Mexico, and western Texas; casually along the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mts.

Range in Washington.—One record by Capt. Bendire, Fort Simcoe, Yakima Co., June, 1881, “quite numerous.” Presumably casual at close of nesting season.

Authorities.—[“Maximilian’s Nutcracker,” Johnson, Rep. Gov. W. T. 1884 (1885), 22.] Cyanocephalus cyanocephalus (Wied), Bendire, Life Hist. N. A. Birds, Vol. II. p. 425 (1895).

Specimens.—C.

Captain Bendire who is sole authority for the occurrence of this bird in Washington may best be allowed to speak here from his wide experience:

“The Piñon Jay, locally known as ‘Nutcracker,’ ‘Maximilian’s Jay,’ ‘Blue Crow,’ and as ‘Pinonario’ by the Mexicans, is rather a common resident in suitable localities throughout the southern portions of its range, while in the northern parts it is only a summer visitor, migrating regularly. It is most abundantly found throughout the piñon and cedar-covered foothills abounding between the western slopes of the Rocky Mountains and the eastern bases of the Sierra Nevada and Cascade ranges in California, Nevada, and Oregon.

“It is an eminently sociable species at all times, even during the breeding season, and is usually seen in large compact flocks, moving about from place to place in search of feeding grounds, being on the whole rather restless and erratic in its movements; you may meet with thousands in a place to-day and perhaps to-morrow you will fail to see a single one. It is rarely met with at altitudes of over 9,000 feet in summer, and scarcely ever in [22] the higher coniferous forests; its favorite haunts are the piñon-covered foothills of the minor mountain regions, the sweet and very palatable seeds of these trees furnishing its favorite food during a considerable portion of the year. In summer they feed largely on insects of all kinds, especially grasshoppers, and are quite expert in catching these on the wing; cedar and juniper berries, small seeds of various kinds, and different species of wild berries also enter largely into their bill of fare. A great deal of time is spent on the ground where they move along in compact bodies while feeding, much in the manner of Blackbirds, the rearmost birds rising from time to time, flying over the flock and alighting again in front of the main body; they are rather shy and alert while engaged in feeding. I followed a flock numbering several thousands which was feeding in the open pine forest bordering the Klamath Valley, Oregon, for more than half a mile, trying to get a shot at some of them, but in this I was unsuccessful. They would not allow me to get within range, and finally they became alarmed, took wing, and flew out of sight down the valley. On the next day, September 18, 1882, I saw a still larger flock, which revealed its presence by the noise made; these I headed off, and awaited their approach in a dense clump of small pines in which I had hidden; I had not long to wait and easily secured several specimens. On April 4, 1883, I saw another large flock feeding in the open woods, evidently on their return to their breeding grounds farther north, and by again getting in front of them I secured several fine males. These birds are said to breed in large numbers in the juniper groves near the eastern slopes of the Cascade Mountains, on the head waters of the Des Chutes River, Oregon. I have also seen them in the Yakima Valley, near old Fort Simcoe, in central Washington, in June, 1881, in an oak opening, where they were quite numerous. Their center of abundance, however, is in the piñon or nut-pine belt, which does not extend north of latitude 40°, if so far, and wherever these trees are found in large numbers the Piñon Jay can likewise be looked for with confidence.

“Their call notes are quite variable; some of them are almost as harsh as the ‘chaar’ of the Clarke’s Nutcracker, others partake much of the gabble of the Magpie, and still others resemble more those of the Jays. A shrill, querulous ‘peeh, peeh,’ or ‘whee, whee,’ is their common call note. While feeding on the ground they kept up a constant chattering, which can be heard for quite a distance, and in this way often betray their whereabouts.”

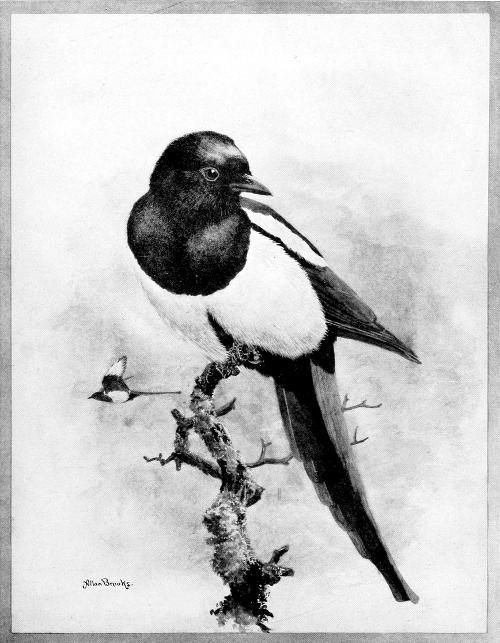

A. O. U. No. 475. Pica pica hudsonia (Sabine).

Synonym.—Black-billed Magpie.

Description.—Adults: Lustrous black with violet, purplish, green, and bronzy iridescence, brightest on wings and tail; an elongated scapular patch pure white; lower breast, upper abdomen, flanks and sides broadly pure white; primaries extensively white on inner web; a broad band on rump with large admixture of white; tail narrowly graduated thru terminal three-fifths; bill and feet black; iris black. Young birds lack iridescence on head and are elsewhere duller; relative length of tail sure index of age in juvenile specimens. Length of adults 15.00-20.00, of which tail 8.00-12.00 (Av. 265); wing 7.85 (200); bill 1.35 (35.); tarsus 1.85 (47).

Recognition Marks.—Black-and-white plumage with long tail unmistakable.

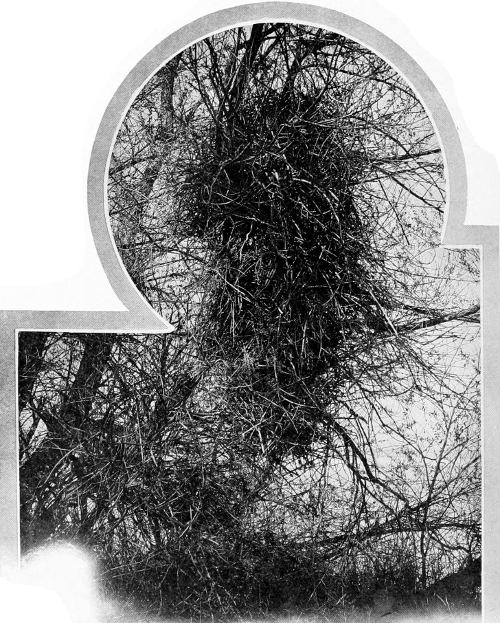

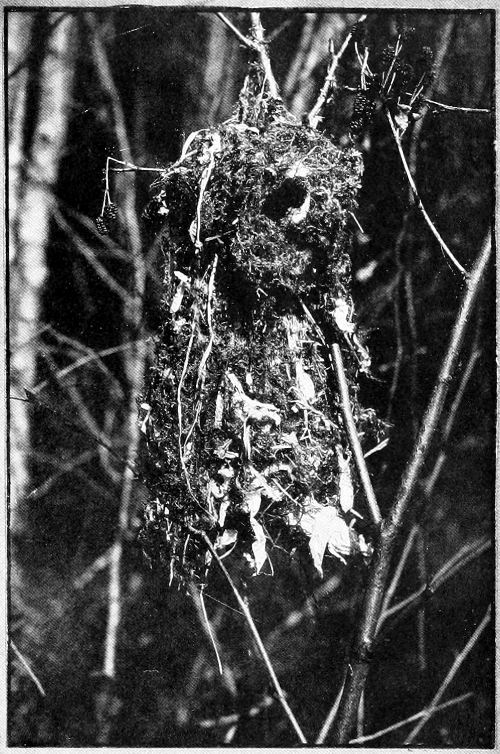

Nesting.—Nest: normally a large sphere of interlaced sticks, “as big as a bushel basket,” placed 5-40 feet high in willow, aspen, grease-wood or pine. The nest proper is a contained hemisphere of mud 8-10 inches across inside, and with walls 1-2 inches in thickness, carefully lined for half its depth with twigs surmounted by a mat of fine rootlets. Eggs: 7 or 8, rarely 10, pale grayish green, quite uniformly freckled and spotted with olive green or olive brown. Occasionally spots nearly confluent in heavy ring about larger end, in which case remainder of egg likely to be less heavily marked than usual. Shape variable, rounded ovate to elongate ovate. Av. size, 1.20 × .88 (30.5 × 22.3). Season: March 20-May 1; one brood.

General Range.—Western North America chiefly in treeless or sparsely timbered areas from southern Arizona, New Mexico, and western Texas north to northwestern Alaska. Straggles eastward to west shore of Hudson Bay, and occurs casually in North Central States, Nebraska, etc. Replaced in California west of the Sierras by Pica nuttalli.

Range in Washington.—Confined to East-side during breeding season, where of nearly universal distribution. Disappears along east slope of Cascades and does not-deeply penetrate the mountain valleys. Migrates regularly but sparingly thru mountain passes to West-side at close of breeding season.

Authorities.—[Lewis and Clark, Hist. Ex. (1814) Ed. Biddle: Coues, Vol. II. p. 185.] Pica hudsonica Bonap., Baird, Rep. Pac. R. R. Surv. IX. pt. II. (1858), 578. T. C&S. Rh. D¹. Ra. D². Ss¹. Ss². J. B. E.

Specimens.—(U. of W.) P. Prov. B. E. BN.

Here is another of those rascals in feathers who keep one alternately grumbling and admiring. As an abstract proposition one would not stake a sou marquee on the virtue of a Magpie; but taken in the concrete, with a sly wink and a saucy tilt of the tail, one will rise to his feet, excitedly shouting, “Go it, Jackity,” and place all his earnings on this pie-bald steed in the race for avian honors. It is impossible to exaggerate this curious contradiction in Magpie nature, and in our resulting attitude towards it. It is much the same with the mischievous small boy. He has surpassed the [24] bounds of legitimate naughtiness, and we take him on the parental knee for well-deserved correction. But the saucy culprit manages to steal a roguish glance at us,—a glance which challenges the remembrance of our own boyish pranks, and bids us ask what difference it will make twenty years after; and it is all off with discipline for that occasion.

The Magpie is indisputably a wretch, a miscreant, a cunning thief, a heartless marauder, a brigand bold—Oh, call him what you will! But, withal, he is such a picturesque villain, that as often as you are stirred with righteous indignation and impelled to punitive slaughter, you fall to wondering if your commission as avenger is properly countersigned, and—shirk the task outright.

The cattle men have it in for him, because the persecutions of the Magpie sometimes prevent scars made by the branding iron from healing; and cases are known in which young stock has died because of malignant sores resulting. This is, of course, a grave misdemeanor; but when the use of fences shall have fully displaced the present custom of branding, we shall probably hear no more of it.

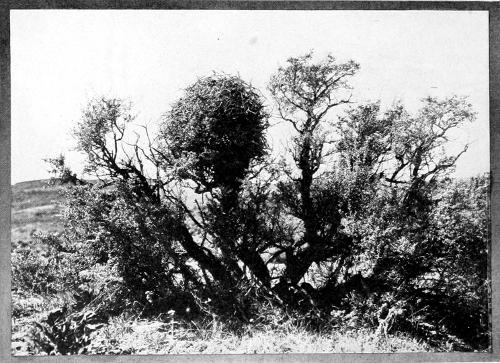

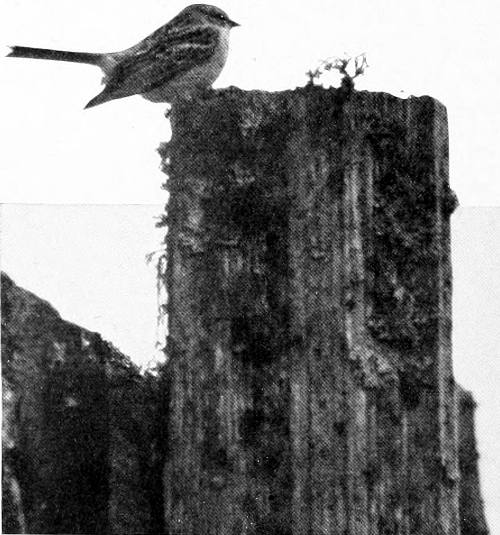

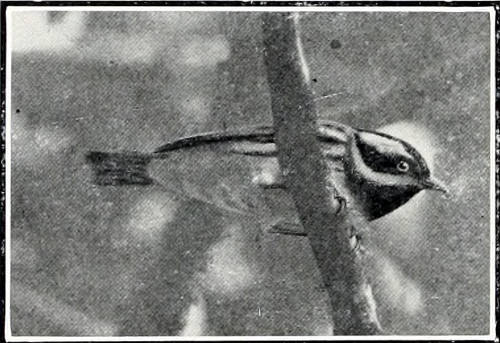

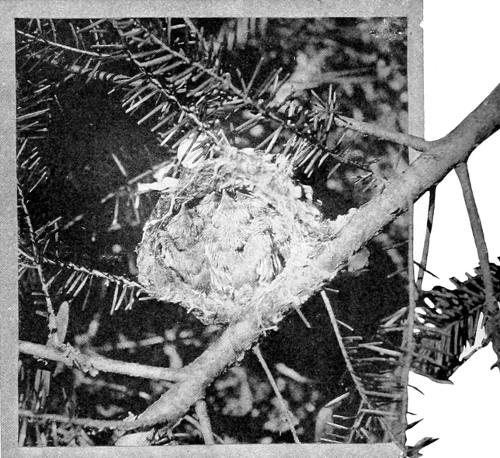

Taken in Yakima County. Photo by the Author.

NEST OF MAGPIE IN GREASEWOOD.

AMERICAN MAGPIE.

Beyond this it is indisputably true that Magpies are professional nest robbers. At times they organize systematic searching parties, and advance thru the sage-brush, poking, prying, spying, and devouring, with the ruthlessness and precision of a pestilence. Not only eggs but young birds are appropriated. I once saw a Magpie seize a half-grown Meadowlark from its nest, carry it to its own domicile, and parcel it out among its clamoring brood. Then, in spite of the best defense the agonized parents could institute, it calmly returned and selected another. Sticks and stones shied by the bird-man merely deferred the doom of the remaining larks. The Magpie was not likely to forget the whereabouts of such easy meat.

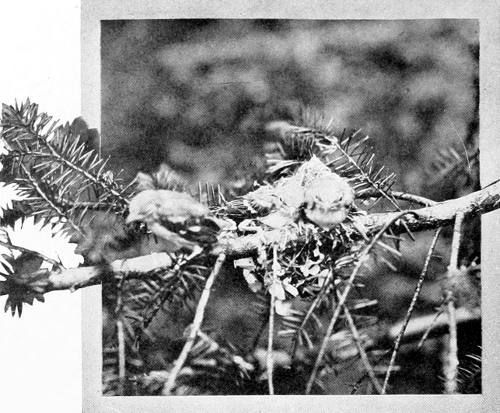

Taken in Yakima County. Photo by the Author.

MAGPIE’S NEST FROM ABOVE.

WITH CANOPY REMOVED. SAME NEST AS IN ILLUSTRATION ON PAGE 24.

Nor is such a connoisseur of eggs likely to overlook the opportunities afforded by a poultry yard. He becomes an adept at purloining eggs, and can make off with his booty with astonishing ease. One early morning, seeing a Magpie fly over the corral with something large and white in his bill, and believing that he had alighted not far beyond, I followed quickly and frightened him from a large hen’s egg, which bore externally the marks [27] of the bird’s bill, but which was unpierced. Of course the only remedy for such a habit is the shot-gun.

To say that Magpies are garrulous would be as trite as to say hens cackle, and the adjective could not be better defined than “talking like a Magpie.” The Magpie is the symbol of loquacity. The very type in which this is printed is small pica; that is small Magpie. Much of this bird’s conversation is undoubtedly unfit for print, but it has always the merit of vivacity. A party of Magpies will keep up a running commentary on current events, now facetious, now vehement, as they move about; while a comparative cessation of the racket means, as likely as not, that some favorite raconteur is holding forth, and that there will be an explosion of riotous laughter when his tale is done. The pie, like Nero, aspires to song; but no sycophant will be found to praise him, for he intersperses his more tuneful musings with chacks and barks and harsh interjections which betray a disordered taste. In modulation and quality, however, the notes sometimes verge upon the human; and it is well known that Magpies can be instructed until they acquire a handsome repertoire of speech.