Title: Egyptian Birds

Author: Charles Whymper

Release date: September 9, 2014 [eBook #46825]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text.

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol ![]() will bring up a larger version of the illustration.

will bring up a larger version of the illustration.

Egyptian Birds.

Foreword.

List of Illustrations.

The Griffon Vulture, The Egyptian Vulture, The Kestrel, The Parasitic Kite or Egyptian Kite, White Owl, Screech Owl, The Little Owl, Egyptian Eagle Owl, The Hoopoe, The Kingfisher, Black and White Kingfisher, The Little Green Bee-eater, The Swallows, White Wagtail, The Crested Lark, The White-rumped Chat, Rosy-vented Chat, The Blue-throated Warbler, The Reed Warbler, The Sparrow, The Desert Bullfinch or Trumpeter Finch, Hooded Crow, Egyptian Turtle-dove or Palm Dove, Senegal Sand-grouse, Sand Partridge, The Quail, Cream-coloured Courser, The Green Plover or Lapwing, Spur-winged Plover, Black-headed Plover, Little Ringed-plover, The Snipe, The Woodcock, The Painted Snipe, The Avocet, The Sacred Ibis, The Crane, The Spoonbill, The Storks, The White Stork, The Black Stork, The Shoebill or Whale-headed Stork, The Common Heron, Buff-backed Heron, The Night Heron, The Flamingo, Green-backed Gallinule, The Coot, The Egyptian Goose, Pintail-duck, The Shoveller Duck, The Teal, The White Pelican, The Cormorant, Lesser Black-backed Gull, The Black-headed Gull.

List of Birds.

Index:

A,

B,

C,

D,

E,

F,

G,

H,

I,

J,

K,

L,

M,

N,

O,

P,

Q,

R,

S,

T,

V,

W.

(etext transcriber's note)

EGYPTIAN BIRDS

IN THE SAME SERIES.

EGYPT

PAINTED AND DESCRIBED BY

R. TALBOT KELLY

R.I., R.B.A., F.R.G.S., F.Z.S.

Containing 75 Full-page Illustrations in

Colour.

Price 20s. net.

(Post free, price 20s. 6d.)

Published by

A. & C. BLACK, Soho Square, LONDON, W.

| AGENTS | |

| America | The Macmillan Company |

| 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York | |

| Australasia | The Oxford University Press |

| 205 Flinders Lane, Melbourne | |

| Canada | The Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd. |

| 27 Richmond Street West, Toronto | |

| India | Macmillan & Company, Ltd. |

| Macmillan Building, Bombay | |

| 309 Bow Bazaar Street, Calcutta |

BY

CHARLES WHYMPER

LONDON

ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK

1909

DEDICATED TO

His Highness The Khedive

IN GRATEFUL RECOGNITION

OF MUCH PERSONAL KINDNESS AND INTEREST

SHOWN TO

THE AUTHOR

THE question is so often asked, “What is the name of that bird?” that the author has tried in plainest fashion to answer such questions. The scientific man will find little that is new in these pages; they are not meant for him—they are alone meant for the wayfaring man who, travelling this ancient Egypt, wishes to learn something of the birds he sees.

C. W.

Houghton, Huntingdonshire,

1909.

| Coot | Frontispiece | |

FACING PAGE | ||

| Birds in Mid-air | ||

| A View on the Nile near Minieh | ||

| Griffon Vulture | ||

| Egyptian Vulture | ||

| Egyptian Kite | ||

| Kites in Flight | ||

| Barn-Owl | ||

| Little Owl | ||

| Egyptian Eagle Owl | ||

| Hoopoe | ||

| Common Kingfisher | ||

| Black and White Kingfisher | ||

| Little Green Bee-Eater | ||

| Common Swallow and Egyptian Swallow | ||

| Pale Crag Swallow | ||

| White Wagtail | ||

| Crested Lark | ||

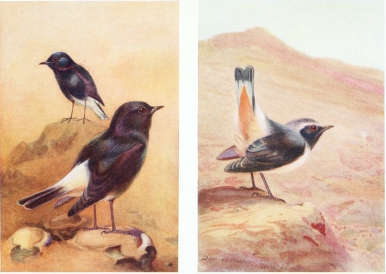

| White-rumped Chat and Rosy Chat | ||

| Blue-throated Warbler | ||

| Reed Warbler | ||

| Sparrow | ||

| Desert Bullfinch or Trumpeter Finch{x} | ||

| Hooded Crow | ||

| Egyptian Palm Doves | ||

| Sand-Grouse | ||

| Hey’s Sand-Partridge | ||

| Quail | ||

| Cream-coloured Courser | ||

| Green Plover or Lapwing | ||

| Spur-winged Plover | ||

| Black-headed Plover | ||

| Ringed Plover | ||

| Common Snipe | ||

| Painted Snipe | ||

| Avocet | ||

| Sacred Ibis and Papyrus | ||

| Cranes | ||

| Spoonbills | ||

| Black Stork | ||

| Shoebill Stork | ||

| Herons | ||

| Buff-backed Heron | ||

| Night Heron | ||

| Flamingo | ||

| Studies of Gallinule | ||

| Egyptian Geese | ||

| Pintail, Teal, and Shoveller Duck | ||

| White Pelicans | ||

| Cormorants | ||

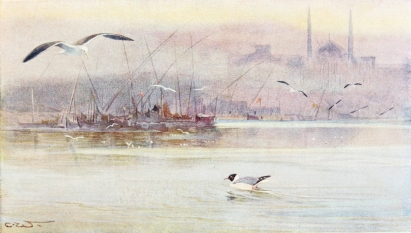

| Lesser Black-backed Gull and Black-headed Gull |

Also eleven line drawings in the text.

PLINY declares that it was by watching the flight of birds in general, and of the Kite in particular, that men first conceived the idea of steering their boats and ships with a tail or rudder, for, says he, “these birds by the turning and steering by their tails showed in the air what was needful to be done in the deep.” Nowhere can the aerial movements of birds be better studied than on the Nile, and as one’s eye becomes trained it is just by the varying individual methods of flight that one is often able to identify the particular species of birds. This is to the most casual observer self-evident in those birds that fly close, near, or over one’s head; but it is astonishing how, as the eye gets trained, even a faint speck high up in mid-air can be absolutely identified by some peculiarity of shape and movement. On Plate 2 are some half-dozen different birds depicted as in flight, to assist the reader to identify the birds he will frequently see.

No. 1 is the ordinary Kite of Egypt. Seen as soon as one lands at Alexandria or Port Said:{2} it is with us everywhere. Its most distinctive characteristics are the forked shape of its tail, and its familiarity with man, the latter leading it to have no sort of fear of flying near one, so near that its yellow beak and ever-restless eye, as it turns its head this way or that, can easily be seen, whilst its tail, moving in sympathy, sweeps it round to right or left.

No. 2 is the Kestrel, or Windhover of England. As this hawk is not a devourer of carrion, but feeds on mice, lizards, beetles, and other living things, it does not usually come so near the habitations of men, and is rarely seen in the centre of cities, but on the outskirts of towns and up the country it is common enough. When seen hovering with its body hanging in mid-air, with its wings rapidly beating above its head as shown, there should be no difficulty in recognising it. Again, when flying low its rich brown-red plumage and sharp-pointed wings should be noted, and if seen dashing into some cleft of ruined masonry or rocky cliff-side it can often be identified by the incessant, penetrating, squeaky call of the young in the nest, for by the time most visitors are in the country, i.e. March and April, it has its young nearly fully fledged.

No. 3 is a Peregrine Falcon. In general shape{3} this is typical of all the falcons, and gives a characteristic attitude in its rushing downward swoop. The head is blunt and sunk into the shoulders, the wings are stiff, rigid, pointed and powerful, the tail straight and firm.

Nos. 4 and 5 are Vultures shown flying farther away from the spectator’s eye, and consequently on a smaller scale. The black and white of the adult Egyptian Vulture, No. 4, is such a distinctive characteristic that recognition is easy, but in the case of the young bird the plumage is dirty brown and grey with faint dark streaks on it, and at that stage might be confused with Griffon Vultures, if it were not for its smaller size. In flying, the way it tucks its head in so that only its bill seems visible, and the very small tail in proportion to the wing area, are the outstanding peculiarities of this, and indeed all Vultures.

No. 5 shows a distant group of Griffons, purposely placed at a distance, as on the small space of a page, if they were brought as near the eye as the other birds, they would completely cover the whole space, for they have an enormous span of wing. Note how small the tail is, and how the head is practically invisible.

Nos. 6 and 7 are of different orders of birds{4} altogether, one being a Stork, the other the Heron. The Storks fly with outstretched neck, whilst all of the great family of Herons fly with their neck doubled up and the head rather tucked back towards the shoulders.

If these seven characteristic diagrammatic pictures of birds are once really learnt, it will enable the most ordinary observer not only to know those particular six birds, but the whole families, meaning many scores of birds of which these are chosen as representatives. The eyesight of some may need help in the form of a good field-glass. What is a good field-glass each individual must discover for him or herself, since the good glass is the one that really suits the sight of its owner. Some of the most noted glasses of to-day are not, anyhow to myself, of as much use as an old-fashioned one that I have had for years, and with which I am able at once to “get on” to the object I wish to observe. This is a most important detail, because birds are rarely still or quiet for long. When flying, this is particularly the case, and the simpler the glass and its mechanism the quicker you are on the object,—and this when, perhaps, you have only a matter of seconds for your observation is of first importance. As I do not wish either to{5} embark on a libel action on the one side, or act as an advertiser of any maker, not even of the maker of my own glass, I praise or blame none, but suggest with all earnestness to every one who desires to really enjoy the study of bird life on the Nile or in their own country, without fail to get a glass that suits them, and which they can handle with lightning speed. I dwell on this because I have met so many having most expensive modern glasses who say they cannot find any pleasure in using them on birds, and I generally find that it is owing to the small field that their glasses cover. Sometimes these glasses are of quite extraordinary power, so that I have heard a man declare he could see a fly crawling over a carved face on the tip-top of some far-away temple, but that type of glass is not what is wanted for rough and ready quick field work, and it is of no more use than the three-feet long telescope still beloved by the Scotch stalkers. Birds rarely if ever allow time for one to lie down on one’s back, and with help of stout stick and the top of knee make a firm stand on which to place the glass and get the range. Over twenty-five years ago I wrote on “Nature through a Field-glass,”[1] and although since then one has had to alter{6} one’s views on so many different points, I do not think I would wish to alter one single word in the claim made for the value of this aid to Nature study. So many birds are such small objects, that ten or fifteen paces away they are mere spots, and very difficult to recognise, as the detail of their plumage at that distance is lost, and all you can say is, that it is some small bird, but with a glass you can have it brought up to your very eye, you can see the arrangement of the masses of the feathers, and note even the ever lifting and falling of its little crest, as it goes creeping and stealthily gliding through the twigs and bushes after its insect food.

[1] In The Art Journal.

Egypt certainly is singularly fortunate in that birds here are far tamer than we find them at home, and so admit of a closer inspection; but even so, I should have been, times without number, utterly at a loss to exactly identify certain birds if it were not for my trusty glasses. There are some occasions where, owing to the extraordinary tameness of birds, no glasses are needed, and I recommend to all bird enthusiasts the ground within the areas under the control of the Antiquities Department. No guns are allowed there, as they are up and down the Nile, and the{7} birds know it. One of my favourite places of observation was at the Sacred Lake at Karnac. By the courtesy of Mr. Weigall, Chief Inspector of Antiquities, Upper Egypt, I was allowed to sleep in a disused building by the water-side, and by that means enjoyed opportunities, which fall to the lot of few, of studying bird life from midnight to early morning, and it is astonishing the number of birds that foregather to that quiet spot. Practically all night through there were sounds of birds coming or going at intervals. The calling of Coots one to another were the commonest sounds during the darkest hours; but at about 3 A.M., when I thought I could discern a little light, I would distinctly hear the “scarpe scarpe” cry of Snipe. A little later the hooting of the Eagle Owl, whom I knew had his nest up on the top of one of the end columns of the great hall, and then gradually from this side, then from that, came an ever-increasing series of calls and pipings, and one could make out flocks of Duck disappearing over the ridge of sand and broken-up masses of masonry. Later, shadowy forms of Greenshank or Plover showed as they went paddling by some faintly lighted-up pool, till at last the sun was up, and crested Larks were running round the banks fearlessly, and blue-throated{8} warblers were hopping about the few bushes at the edge, and ever and anon flitting down to the ground and back again to the leafy shelter.

The question is asked and asked, but no very distinct answer comes, why are the birds so tame in Egypt? I am at a loss to know myself, for the land teems with foxes, jackals, kites, vultures, eagles, falcons, and hawks without end, all with an eye to business, ever circling round ready to devour any unprotected thing they can lay claws upon, and yet this seemingly utter fearlessness of all these mild-natured, defenceless little birds. Further, here in Egypt are perhaps more “demon boys” than are to be found elsewhere, and I hold firmly with the ancient sage, who said “that of all savage beasts the boy is the worst,” so that the tameness of some of Egypt’s birds is one more mystery of this land of mysteries.

In the following pages I have almost entirely spoken of the particular birds pictured in the illustrations. I am quite prepared for the question, however, “But why did you not include such and such a bird?” and my defence can only be the old one of the difficulty of settling various person’s ideas of what should be considered the best{9} representative list of anything—whether it be birds, books, or pretty women. It must also be remembered that Egypt proper—the area alone treated upon in these pages—begins at Alexandria and ends at Assoan, a stretch of country of about 525 miles, whilst the breadth may be anything from fifty miles to less than one. From that area our selection has had to be mainly confined, and it has meant excluding a certain number of very beautiful and interesting forms.

Bird lovers should remember that when the, at first, seemingly rather extortionate demand of 120 piastres is made, before they are given the card which admits them to the temples, tombs, and areas under the control of the Antiquities Department, they are, in a very important way, really helping on the preservation of birds, for, as already has been said, on no ground under the control of the Department are birds allowed to be shot, and as these spots are the very ones in all Egypt most visited, it is very necessary, as amongst the thousands of tourists that are made familiar with the fact that wild duck, snipe, and waders were very tame at these places, there would always be some unsportsmanlike guns, who would seize the opportunity of{10} going to those very places. Then no longer would the hooting of owls be heard in the ruins, no swallows nesting in the rock-hewn tombs, and no coot and wildfowl would ever be seen on the small sheets of water or sacred lakes that adjoin the temples. That all these birds are there means a very great added interest to these places to every one, and to some of us bird enthusiasts the living interest is greater than that which we can whip up for those heavy, severe, architectural achievements, or wild chaotic masses of ruined masonry.

Elsewhere the point of the scarcity of bird life in the hot summer months has been spoken of, but it is also curious to note that there are just about three to five weeks of mid-winter during which there is no migratory wave seemingly going on at all, up or down the Nile valley. No bands, great or small, of birds heading due north or due south are ever to be seen, and the remark is often made on the paucity of bird life, some persons even declaring that it is “a birdless land.” That the native birds are very small in number is true, but the total number of birds, and varieties of birds, that come for a time and pass on is very great. Those that live in temperate climes do, however, have the best of the deal, as it must ever be a greater{11}

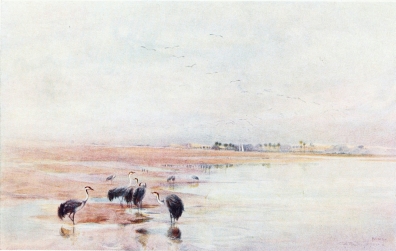

![]()

A VIEW ON THE NILE NEAR MINIEH

possession to have the birds nesting around one than merely passing by in migrating flights, be those flights as amazing as they may. Birds, from whatever reason is not certainly known, do not love the excessively hot or cold areas as breeding-places, but do seem to love the more moderate temperate climes. In Great Britain the number of birds that will and do breed within a very small tract of ground is amazing, and Mr. Kearton tells of a small copse in Hertfordshire in which were the nests, with eggs or young, of nine different species of birds, all within fifty yards of one another; and in another case, within a space of ten yards, were a tit’s, a flycatcher’s, and a wood wren’s nest. In Egypt, the number of birds breeding is not large, and excepting some of the great lakes with their margins of shallow water and swampy reeds, there are few places that offer any attractions for birds to nest in any numbers. In the groves of palms you do get many doves building in close proximity with kites and crows, and along certain stretches of the Nile banks large colonies of sand-martins build, but with these exceptions the fact remains that this country has not a large list of birds breeding in any numbers. In the great lakes of Lower Egypt and the Fayoum there are, however,{12} enormous areas of some of the best feeding-grounds imaginable for water-fowl, and the fowl know it; nowhere can be seen more variety of duck, and herons, and waders, and shore birds, than at Lake Menzaleh. Elsewhere, I have already referred to my visit in March and April to this little known part of Egypt, and I wish that those who say this is “a birdless land,” would only go and stay a few days at Kantara, Matariya, Damietta or Port Said, and then see if they could still call it “birdless.” The extreme north and east side of the lake is separated only from the Mediterranean by a narrow bank of sand. Its waters are brackish, the Nile contributes but little to its bulk, and the opinion is largely held that if it could be made to contribute more, the food supply for the fish in it would be considerably increased, to the very great benefit of the fish supply of the country. Every village and town on the lake has many fishermen with boats out night and day. They catch a very large quantity, but it is said every year the size of the fish caught is steadily decreasing, and to increase the food-supply for the fish is now the aim of the authorities. This matter does not immediately affect the birds, as they love the small fry, but if Lake Menzaleh were to once lose its value as a supplier of profitable fish food,{13} it might come to pass that some future engineer would turn his attention to this great area of waste water, and turn it into profitable cultivated ground, and then the birds would be driven away here as completely as they were in England when our fens and meres were drained to make good corn land. Therefore, this proposal to let in more Nile water is of much importance to Menzaleh remaining the great stronghold of bird life in Egypt. At present the spectacle it presents of its crowds of birds seen under the almost constant blue sky, is one that all would be very sorry to lose. The Flamingo come as its crowning glory, but the list of birds is long, and Mr. M. J. Nicoll tells how in only one week’s stay, at Gheit-el-Nassara, on the north-west side of the lake, he met with no less than eighty-seven species. The ordinary visitor to Egypt hurries away from Alexandria or Port Said, but any who love Nature ought to leave a few days for places other than the Nile, if they are to obtain anything at all like a complete knowledge of Egyptian Birds.{14}

Head and neck bare of fine feathers, but covered with short white down. Lower part of the neck surrounded by a ruff of long, thin, lance-shaped feathers, generally but not always white; sometimes it is buffish, sometimes rich rufous; wings at shoulders are light greyish brown, getting darker to nearly black on the large flight feathers. Breast and flanks grey, brown under tail-coverts a brighter burnt-sienna tone. Legs dull grey; base of beak yellow. Young birds are generally duller and lighter coloured than adults.

Length, 48 inches, but individuals vary greatly.

THIS is the Vulture so constantly depicted on the monuments of Egypt, and I do not think that any one has ever raised the slightest doubt of its identity; but the same can hardly be said of all the birds thereon figured.

EAGLES, VULTURES, HAWKS

Many different arrangements have been made of the order in which birds should be placed, some placing one, others, another family first, and the wise men are even yet not all agreed, so that the old-time method has been adopted of beginning with the birds of prey, since it is probably the order with which the ordinary reader is most familiar.

Eagles are not common, and though in the complete list of Egyptian birds the names of four are given, it is hardly likely to be a bird seen, whilst Vultures and Kites, and certain Hawks, most certainly will be.

Mr. Howard Carter, whose long connection with the work of the Antiquities of Egypt gives him the right to speak with authority, is now preparing for publication a book on this whole subject of the portrayal of animal life by Egyptian art, which is awaited with great interest, as he has given years of study to this one branch; and though I may venture to say something now and again of the present-day birds, and their pictured presentments in temples or tombs, the reader will do well to wait till Mr. Carter’s book is published before coming to too positive a conclusion on a rather vexed subject. Of the Vulture there is no doubt, but of which of the existing hawks was the model of the Hawk almost as frequently depicted as the Vulture few are agreed, and personally I can arrive at no very satisfactory conclusion.

The Griffon Vulture is common now, and probably always has been. Its usefulness is {16}undeniable, and it practically does no harm. It takes no toll of lambs or kids, and I never have heard of it snatching up the smallest of chickens. Its food is entirely carrion with the addition, possibly, of an occasional lizard or small snake. Vultures and Kites together are the very best of workmen, for the work they undertake they do absolutely thoroughly. No one has to go after them and clear up what they leave half-done, for they never leave anything half-done, be it a dead camel, or ten dead donkeys, or a mass of putrid offal from the shambles. They come; they see; they swallow; and not one speck or scrap of flesh or sinew will be left to-morrow on all those snow-white bones, and not the slightest sign of anything that can putrefy will even stain the ground; all is cleared away, and all corrupting danger gone by the time they have flown. They will remain all night through and the next day, if the job is a big one, and never dream of charging overtime! It is doubtless this that makes the natives of Eastern countries so unspeakably careless, as we think, of all sanitary precautions. They know that they need take no trouble; in a matter of hours, days at most, these winged scavengers will come, save them all bother and trouble, and clear the{17} mess away. It is also this, one is disposed to think, and this alone, that is at the bottom of what to us seems an amazing fact, that they never destroy birds, so that even birds whose travels take them out of Egypt for a season, returning, know that here anyhow they will not be molested, and show themselves familiarly where in other countries they would exhibit the very opposite tendency.

Of late years a change has undoubtedly taken place in some birds owing to the ever-increasing number of visitors, many of whom come with guns determined to get specimens. Birds are not fools, and the great Griffon in particular seems to have learnt that it behoves him to have a care, and distrust the too near approach of the white man who may desire to possess his great wings to mount as trophies: and one has heard of its becoming quite a difficult matter to get within range of these grand birds. Grand birds they are indeed when seen on the wing fairly near. When far up in mid-air they strike your imagination as mysterious, marvellous masters of the air, but see them close enough to make out their very feathers, and then no other word comes to your lips but, “What grand birds!” All the sleepy, dull, heavy look that they have when clumsily{18} walking, half hopping, on the ground, or when sitting huddled up, at once disappears, and you acclaim the Griffon the king of flying things. A sea-gull, a swallow, an eagle, and many another, are all splendid in their graceful mastery over, and use of, the air we live in, but for sheer majesty of dominion I know no equal to the great Griffon Vulture.

One has often seen it on the sand-banks by the river’s side, sitting perhaps, either dozing after a gorge or waiting for the late lamented to reach just that nice point which means dinner-time. Sometimes they mildly squabble amongst themselves; sometimes they advance open-mouthed on some late arrival who comes swooping down with feet and legs stretched out well in front of him. But on the whole, I think, after its flight, its one outstanding virtue is its sociability. We none of us quite like that person who shuns his fellows, and was never known to have any gathering of friends even in simplest social fashion, and with birds there are some of those selfish kinds who prefer to live alone and feed alone, and absolutely resent any attempted sociability. But the Vulture, in spite of his rather forbidding face, is a downright sociable creature. On many a time one has seen Egyptian Vultures feeding with a{19} dozen of their bigger cousins, who, when themselves well fed, have allowed even the despised crows to have some pickings from the feast.

Being tied up to a bank for two or three days during the Hamseen wind, which was blowing a perfect gale right in our teeth, I saw a curious sight of Vultures turning themselves into a sort of coroner’s jury on a dead buffalo. In the centre of a little sheltered bay was the “dear departed,” who was being closely examined and overhauled by a gaunt, sandy-coloured native dog. There he sat like a coroner growling out his observations, whilst the twelve—there were just a dozen Vultures—sat placidly waiting their turn for a closer study of the remains. They sat so long and patiently that one was surprised they did not end the matter in force, drive away the presiding officer, and get to real business, but we left them still waiting and seemingly discussing what was to be the verdict.

Whenever one has been taken to see a Vulture in captivity, either in hotel or other gardens, it has usually been this, the Griffon Vulture, that has been the unhappy captive.{20}

White all over body, wings black, a curious fringe of long feathers round the head; these sometimes get stained a more or less strong yellow; bare parts round eye and beak, yellow. Legs pinky, eyes carmine red, but Shelley says they do not get the full red eye till their fourth year.

Entire length, 27 inches.

THIS vulture, as shown by the above description, is markedly different from the great Griffon Vulture, and there can be no possible mistake in recognising it. From the tail-piece, which is taken from a painting of one on the inside of a wooden outside coffin casing, one can easily see the peculiarities of this bird; and at Deir-el-Bahari there are many painted examples showing the bird more or less in its natural colours, the bright yellow of the bill is shown, and the dark wings are rendered in a dull green. Why they should render one colour by another seems strange, but here again we must wait till Mr. Howard Carter gives us his explanation of this and the many other points he is still patiently working out. The wonderful way in{21}

which the vultures assemble directly there is anything in the way of carrion has been often noticed: they will appear where a moment before there was not one to be seen either on the earth or in the blue vault. And this was at one time regarded as one of the wonders of the bird world; but as is so often the case, more exact knowledge rather reduces the marvellous. The habit of vultures is to fly at a very great height and to keep circling round; each bird practically keeps to one area, another takes a great sweeping circle adjoining; and others all the way round are in the same fashion, ever circling on the look-out. The moment one discerns anything down he swoops; this is instantly observed by the bird on the adjoining beat, and down he rushes; this again is repeated indefinitely, and so in a few minutes a dozen or more vultures may be there at the find where before were none. The circles that each make are frequently very large, perhaps many miles; it can easily be imagined, therefore, what a large area can be covered, and covered most minutely, by, say, half a dozen birds. The young are very different in plumage, being a rather dirty grey-brown all over, with brown eyes, and they retain this peculiarity till their fourth year, when they get{22} the white and black plumage. But they somehow always look untidy birds. This perhaps holds good of all vultures when sitting in repose; their wings seem to be too loose jointed, and they hang their feathers so as to give the impression that they are not firmly fixed in and might fall out, but the moment they spring into the air their wings gain at once a sort of rigidity, and all the sloppy, untidy effect disappears. This bird is certainly more often seen than the preceding, since it is not afraid of the haunts of man; but one is not at all certain that it is really commoner. In all the representations of this as of other birds, the old Egyptian artists have a curious habit of depicting their birds with their legs stretched out too far in front, and looking as if the bird were in danger of falling over backwards.

Once as we were drifting by a bit of sandbank, the river being very low, I remember well an awful-looking, unrecognisable object, dirty, dishevelled, and, as children say, “very bluggy,” coming towards us over the skyline. It more resembled some poor drunk man who had been fighting and had got fearfully knocked about, and what bird it was, if bird at all, we knew not. Well, this dilapidated-looking thing walked slowly down the slope{23} to the water’s edge; then we saw it had been having a real gorge; it was hideously rotund, and had apparently been living inside “the joint” until, sick with repletion, unable to fly, its very feathers clogged with gore, it made its way down to refreshen and clean itself, which when done, to our surprise it turned out to be just a common Egyptian Vulture.

Why the Vultures are featherless on neck and head is told in an old story in Curzon’s Monasteries of the Levant. King Solomon, according to this account, was journeying in the heat of the day. “The fiery beams were beginning to scorch his neck and shoulders when he saw a flock of vultures flying past. ‘O Vultures!’ cried King Solomon, ‘come and fly between me and the sun, and make a shadow with your wings to protect me, for its rays are scorching my neck and face.’ But the Vultures would not, so the King lifted up his voice and cursed them, and told them that as they would not obey, ‘The feathers of your neck shall fall off, and the heat of the sun, and the cold of the winter, and the keenness of the wind, and the beating of the rain, shall fall upon your rebellious necks, which shall not be protected like other birds. And whereas you have hitherto fared{24} delicately, henceforth ye shall eat carrion and feed upon offal; and your race shall be impure till the end of the world.’ And it was done unto the Vultures as King Solomon had said.”

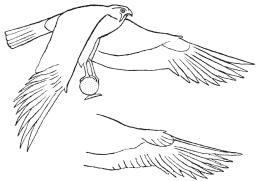

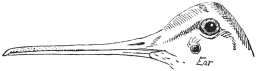

![]()

Figs. 3 and 4.

Drawing from a painting of a Hawk at Karnak, to show the overlap of the

wing feathers.

The male has the upper plumage of head, back, and wings red-brown, spotted and barred with black; under-parts buff with black spots on flanks, and which on breast are smaller and closer together, making long lines. Rump and tail blue-grey, barred with black, one broad bar at end of tail tipped with pure white, base of bill and legs yellow, eyes brown. The female is without the blue-grey, and is more evenly brown all over, with spots and bars on the tail.

Length, 13·5 inches.

THIS is the commonest Hawk, and nests in nearly all the ruins of temples and old buildings up and{26} down the land, and, as already stated, the young are often to be heard when they cannot be seen, calling with their incessant squeaky voice for their devoted parents. The parents are to be seen searching for food, hovering over the fields in the same way that they do at home, for this bird is the familiar Windhover (see Plate II.). The quantity of mice that it consumes is enormous, and of lizards, beetles, and particularly locusts, it also takes toll. So that though it does not do the useful work that the Kites are doing day by day, it still clears the land of what would otherwise be grave scourges.

The Kestrel is one of the birds of which large quantities of mummies have been found, and it was clearly treated with quite sacred rites, lending colour to the views of some that this is the original of the Hawk so frequently pictured and sculptured. This question is one, however, that as doctors disagree upon, it is not for a layman to venture judgment; but several of the best preserved specimens of wall-paintings at Deir-el-Bahari in their drawing suggest much more the shape of a long-legged Sparrow Hawk than the compact Kestrel. The colouring of these pictures is so different, sometimes one part of a bird will be{27} in red, in others it will be green. We are told, however, that this is all right and they both are right; this is something of a mystery and passes my own comprehension. The view is certainly possible that these ancient artists never thought any future race of mankind would come worrying round to know what particular specific kind of bird was meant, they alone desiring to give a rendering of a typical Hawk.

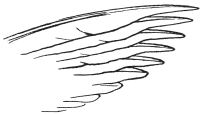

Honestly admiring the fine work of these old artists, I yet retain my own liberty to point out what is wrong, and the accompanying illustrations show a very glaring error which is repeated over and over again, a thousand times, throughout the temples and tombs of the country. Fig. 3 shows the two wings of a painted hawk at Karnak; the right wing shows the outside, the left the inside of the wing. In the right wing the feathers are shown with their front edge lapping over the hind edge of the feather next in front. This gives a certain strength to the whole surface of the wing-area needed for flight, and if that be an accurate representation of the outside of a Hawk’s wing in nature, and it is, then it follows that the inside surface would show the reverse; that is to say, the free edge of each feather would show over-lapping{28} the feather next behind it, as shown in figures Nos. 4 and 5. But Fig. 3 shows how the ancients thought birds should have their feathers placed, back and front, both identical. In all humility, I have once or twice pointed this out to devout Egyptologists, but they pass it over. “A mere convention,” they say; “they always render wings so; worship, worship!”

![]()

Fig. 5.

Drawing of the primary quills of a Hawk, from Nature. Seen from the

under surface to show the overlap of the feathers.

Mr. J. H. Gurney says that Egyptian Kestrels are certainly bolder than the British, and that he has “seen one swoop at a Booted Eagle,” and another “feather a Hooded Crow which ventured too near its nest.” He also draws attention to its size, and I think that it is certainly frequently of smaller dimensions than those at home; indeed, on{29} the score of size, it is not easy to distinguish it from the Lesser Kestrel.

There are two Kestrels in Egypt: the one we have already described, and the Lesser Kestrel, which is like a small edition of the former, with the exception that his back and wings of bright red-brown are without spots, and the breast is only marked with small black spots, while the claws are yellowish white. Its length is 11.5 inches. When seen flying it is well-nigh impossible to identify it from the larger species, and I have heard of cases of men having shot what they thought was the Common Kestrel, and finding to their astonishment that it was the much rarer Lesser Kestrel. Its food consists mainly of insects and beetles, but it varies this stock diet with mice. I have seen it sitting in a cleft of the wall of the Ramaseum and other temples, but it is by no means a common bird. It nests commonly in the ruins and temples, and on the high cliffs, and its young can be oftener heard than seen, as they utter a very penetrating squeak, squeak, squeak call.{30}

Plumage—Head and neck grey; back and wings dark brown, under parts a rufous brown, the edges of the feathers lighter than the centres, which have a dusky streak, whilst the tail is broadly barred. Cere and legs yellow.

THIS Kite, which is seen everywhere, is not the Kite which we have accounts of as being once common in England, and which could be seen long years ago flying round St. Paul’s Cathedral; but it is a true Egyptian native. I have it from men who have lived long in Egypt, through summer as well as winter, that in the really hot months this bird is practically the only feathered fowl one ever does see during those glaring months. There may be other birds left in the country, but you do not see them; they wisely keep out of sight in whatever isolated shaded place they can find. The Kite alone bears the full glare of that broiling sun, ever on the look out for every chance of a mouthful of any decaying nastiness it can secure, and{31}

in this is the secret of its privileged position; unmolested even in the busiest haunts of men, secure in crowded city or up-country village, its services as scavenger are invaluable, and when every other bird has fled it never for a day quits its post or ceases its labours.

We will spare the reader a detailed menu of this omnivorous bird, but all who visit Egypt ought to bless it, as until some enlightened system of sanitation is adopted, this bird, almost unaided, makes the land possible to live in, or to be visited with any safety or pleasure. If it were exterminated as the Kites have been in Great Britain, it is almost impossible to exaggerate what would be the dire results to the health of the newcomers to this old Eastern country. Mercifully there seems no sort of chance of its numbers decreasing. Indeed, in 1908 I saw behind the New Winter Palace Hotel at Luxor, a flock which certainly ran into hundreds; two dead donkeys thrown out behind the walls of the Hotel grounds were the cause of this vast congregation. They never leave a shred of anything more than the bones, picked as clean and white as the paper this is printed on; they tidy it all up, and for days after the main body of birds have left, a stray bird or two comes sweeping down{32} to see if there is any tiny scrap of flesh, or skin, or sinew left hidden away under stone or sand. On several occasions I have seen Kites bathing in the water, so presumably, although they are called unclean birds, they are in reality as cleanly as most. As far as personal observation goes I should call the Swifts and Swallows the dirtiest birds; anyhow they are more infested with odious parasites than any other birds I have handled. Kites build untidy, clumsy nests of sticks; rubbish, rags, and even bits of newspapers are to be sometimes found hanging on the outside: they are generally placed in the upper boughs of some high tree, and in many of the gardens in the centre of squares in Cairo you can watch them bringing food to their squealing young. They breed very early, and often they have a brood hatched by the end of January.

There is something very fascinating in watching their flight, it seems so easy and strong, and from its complete fearlessness it approaches so near the spectator that the movement of the tail as it turns to right or left can be seen acting as a well-directed rudder. As already stated, Pliny says it was observing this that gave man his first idea of how to steer his boats and ships. And{33}

the frequent stooping of the head down to the food it holds in its feet is another interesting action that can be watched clearly without the aid of field-glasses, as it passes close overhead. The tail of the young is not so forked as in the adult, and the general plumage duller coloured all over.

The Black Kite, Milvus migrans, is said to be a very rare bird in Egypt, but I certainly think it is commoner than some imagine. It is very similar in general appearance to the last, and unless seen very near is hard to identify. On 13th January 1908 I was fortunate, however, in seeing some three or four at the river-side at Karnak, beaten down low by a high wind, with completely black beaks and very dark rich black-brown plumage. Mr. Erskine Nicol, who was with me, also noted them. Shelley says, “The general shade of the plumage is blacker. The dark streaks down the centres of feathers on throat and crop are broader than in the Egyptian Kite, and the bill is entirely black.”

Plumage of upper-parts a tawny yellow, mottled, speckled, and pencilled with delicate grey, black and white; face white, as are the under-parts; individuals vary in being lighter or darker; buffish-white on chest, feet pinkish, beak yellowish. Entire length, 13·5 inches.

EITHER of the two last English names are perhaps in this case more suitable than the first, as barns in Egypt are scarce, whilst this owl is common, and is met with in temples and tombs fairly frequently.

In the past it must always have been a common bird, as it is one of the few quite easily identified birds used in hieroglyphics (in spite of which, to my astonishment, in a recent work on Egypt this owl is called the Horned Owl).

The Barn Owl has practically a world-wide range, being found not only in Europe but Africa, Asia, Australia, and America, and though examples from certain localities do show some variation in plumage, it is still always unmistakably the Barn Owl. It{35}

is, however, not met with within the Arctic Circle. At home its food is nearly entirely mice, but in Egypt it has no hedgerows to hunt, no large farmyards and rich granaries, and though it does get some mice it has to take lizards, an occasional small bird, and sometimes fish, or even scraps of carrion.

Of all the owls this has the softest, most silent flight, and this in itself is somewhat uncanny as it quite quietly passes close to you, and then disappears in the gloom, from which a little later may come a terrifying screech as of a strangled infant. There is little room for wonder, then, that all simple folk should have regarded this bird as evil-omened: and the old Scriptures have many references in this spirit when describing places haunted, desolated, the “abode of owls and dragons.” To this day, in our own country, the feeling is evinced most strangely in spite of all our modern education. Very cleverly the early Egyptians caught the most salient feature—the extraordinary large mask-like face—and in some of the wall decorations at Deir-el-Bahari, which are in perfect preservation, it would be well-nigh impossible to improve on them as exact portraits of the Barn Owl. A possible cause of the choice of this bird is that it is one of the best-known species: for of all the{36} owls this one is quite peculiar in its habit of rather courting than flying from the haunts of man; for though it is in the ruins of temples it is also to be found in the thick foliage near villages and towns, and has even been noticed flying about in the very heart of Cairo in the Ezbekeir Gardens, as recorded by Mr. J. H. Gurney in his Rambles of a Naturalist—and the habit of attaching itself to human habitations is universal wherever it is met the world round.

The Barn Owl has a custom which those who suffer from indigestion may well envy, and that is its power of disgorging, after every meal, all the indigestible portions of its dinner in a compact, round, hard pellet, about the size of a nut: and from under some of its roosting-places great basketsfull of these pellets have been collected, and men of science analyzing these have obtained therefrom the most precise information as to the diet of this much-persecuted bird. From such observations the value of its services in our own country were rather tardily recognised. But now that it is established that nine-tenths of its food consists of mice and rats, the law of the land has been invoked to protect it. Lord Lilford writes on the extraordinary appetite of young owls, that{37} “I have seen a young Barn Owl take down nine full-grown mice one after another till the tail of the ninth stuck out of his mouth, and in three hours’ time the young ‘gourmand’ was crying out for more.”

Plumage—A plain greyish-brown with dark markings and spots on the breast; eyes yellow. Entire length, 8·5 inches.

THE Little Owl is a common bird, but it is not, when flying, very owl-like in appearance; and doubtless it is very often seen and not recognised as an owl at all, especially as it flies freely in the daytime, and I have even seen it sitting facing the sun on some wooden trellis-work in a garden at mid-day; and not only once, but morning after morning it could be seen enjoying the warmth. This peculiarity, the very opposite of what we find in most owls, has led to an awkward position in some parts of England—for in certain of the Midland counties this owl is rapidly becoming a perfect scourge. Some distinguished naturalists in Northamptonshire and other counties thought it would be good to introduce this undoubtedly rather fascinating bird from the Continent—where it is common—into the British Isles—where it was very rare—so year after year{39}

they obtained large numbers of these owls, and liberated them in the hope that they would breed and multiply. Their hopes have been more than justified, for they did at once settle down and increase; they passed first from the county they were liberated in to the adjoining county of Huntingdon; then, spreading over that, they extended their area into Cambridgeshire, then on into Suffolk, Essex, Norfolk. Every one was at first delighted, and keepers were given strict injunctions on no account to worry the newcomers; but gradually the keepers’ faces began to get long, and first one and then another reported strange stories of depleted coops shortly after the foster-hen was put out into the open with her family of ten or more young birds. Ornithologists were scandalised at these stories—an owl take a young game-bird: impossible!—but what is impossible in the eyes of men of science has turned out to be a fact, and this charming-looking Little Owl is found to be one of the worst vermin on the whole list which vexes the soul of the game preserver. For it is just this, that at the very time the young pheasants or hand-reared partridges are put out, the Little Owl has its own little family to feed; the foster-mother, the hen, being{40} always kept shut in the coop, the little puff-balls of pheasants, as they are in those early days, run in and out between the bars, and once outside are, of course, without protection. The Owl has noticed this fact, and it may be seen sitting on the top of the coop watching till one of the little birds is conveniently near, and down it swoops and carries it away for its own family’s dinner; this it will repeat time after time till it has cleared off the whole lot. This can only happen, of course, when the young pheasants are very very small—a few days old—and hand-reared, for if they were out and about with their own mother—or in the case of partridges their own father—they would be safe, as neither would allow such an impudent attack to be made without going for the murderous marauder. It has only been after years and years of persistent effort that gamekeepers have been induced to learn that all ordinary owls flying at night-time—when all young birds are safe under their mothers’ wings—are harmless, and that from the good they do in clearing off hundreds of mice and young rats, should be, and must be, protected. They are now protected; but this newcomer arrives—not an ordinary night owl at all—and the whole{41} position is changed, and years of teaching will be thrown to the winds, as it will be hard indeed to persuade the average thick-headed keeper that he was not right all along, and that every owl of every sort ought to be shot at sight and nailed to the pole. So much for benevolent intentions of increasing the variety of a country’s fauna. Nearly always it is best not to interfere with Nature’s order, and the rabbit pest in Australia, and the sparrows in America, are already known to most as illustrations of this fact.

The Little Owl makes a quaint pet, and thrives well in confinement; its antics and poses are really droll, and the big eyes look at you with a seeming deep intelligence. This is the owl, by the way, that by the ancient Greeks, was made sacred to Pallas Athene and used as a symbol of wisdom; furthermore, it was engraved on many of their coins.

In Egypt it is everywhere—in town and country, in ruined temples, dismal tombs, and gardens bright with flowers and sunshine. I have seen it sitting on the upright poles of shadoofs, and on the tops of high stalks of growing maize, and once I saw it, in broad daylight, on the back of a recumbent buffalo.{42}

Plumage a rich buff-brown, with darker markings of black, brown, and grey. Large wing-feathers and tail broadly barred with blackish brown; chin and upper throat white; under-plumage bright golden buff, with blotches and streaks on the flanks; beak black; eyes of most intense flame-like orange. Total length, 20 inches.

THIS name Eagle Owl is almost more imposing than the bird itself, as, though large, it is much smaller than the Eagle Owl of Europe.

It is to be found in some of the very largest of the temples, ruined or otherwise, but, as far as my own knowledge goes, not in many of the smaller buildings. Its principal haunts are the steep cliff-like sides of the hills and mountains.

When staying in the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings, every night regularly as the sun sank behind the ridge, the first weird “Booom” rang out, soon to be answered by another similar call from another part of the hills, and then, soon and silently, there floated past the big dull brown form. Sailing away to the opposite side, with my glasses{43}

I could see it stretch out its legs forward as it settled on to some favourite ledge of rock, and turning its great head round, so that I could see its glorious coloured eyes, would utter a still louder booming challenge. This was so absolutely regular that when working I knew exactly where certain purple-blue shadows would be across the face of the otherwise golden cliff-side, when I heard its first call. Twice I had one in captivity; one died, but the other seemed to recover so well from a damaged wing, that as soon as I had finished the studies needed, I decided to let it go free, and let it out; but, stupefied by confinement, or else because the wing was not really strong enough to make flight easy, it only hopped and walked about in a rather aimless way, and was in danger of being attacked by the dogs of our camp. So I had to catch, and in my arms carry my captive right high up the Deir-el-Bahari cliffs—and any that have been there know what that means—and at a safe place near a cleft I had often seen them at, set it free; neither then, nor during my toil up that cliff was I rewarded by the slightest sign of gratitude; on the contrary, hissing viciously and clawing right and left with its big talons, intent{44} on doing me serious damage, my prisoner strove with me. That was in the evening; very early the next day I went right up the same place, and as there were no feathers or other marks of murder, I sincerely hope the poor bird got safely away to some sheltering cave, there to be welcomed by wife or husband, as the case might be, and regaled with great store of such food as Eagle Owls love. When with me, sardines, scraps of meat, and bits of bony chicken were readily eaten, but a great dislike was shown to being watched at meals.{45}

Head and crest rich rusty orange; the tips of feathers of crest black; the neck and chest rufous changing to a pink hue on breast; wings and tail black with broad white parallel bars; under-parts buff to white; legs brown; beak black; eyes brown. Length, 12 inches.

THE hoop-hoop-hoop cry of this bird is almost as curiously attractive as its varied plumage and magnificent crest. You see it everywhere, and it loves the haunts of man. It is not well to know too much of one’s heroes, and it certainly is well not to know too much of the habits of some of the wild children of the earth and air. The repulsiveness of the menu of the Hoopoe is enough to make one put one’s pen through its name and never mention it. But it is not always feeding, and when walking about in stately fashion on some mud wall, lifting its great circular crown of feathers ever and again, whilst it utters its call-name hoop-hoop-hoopoe, it is so picturesque and charming one has to pass its nasty little peculiarities by. We have to do this frequently with our own unfeathered{46} friends for the good we presume they possess, and there is much that is good in this perky little bird.

Time was, it is said, when the Hoopoe had no crest, and he only got one granted by royal favour. The king of those days was importing a new bride from Asia, and decided to have her met at the port on the Red Sea where she landed, with unusual pomp. His army was to go down and escort her to the royal city, and all the birds of the air were instructed also to wait her arrival and form a flying sunshade with their wings, and fan the air with their pinions, whilst all should fill the heavens with their sweet songs—and thus she should come. The birds agreed, all but the Hoopoe. He objected, he knew something about the lady, and he wouldn’t consent to go. Saying he would rather not, he flew away to a cave in some far-away mountain in the desert. When the king heard of this he was very wroth. Anyhow, he had the culprit sent for, and now the poor Hoopoe is brought before his enraged majesty, but so bravely did he comport himself, and so well did he defend his position, showing that if he did that for which he had conscientious objections, he would suffer grave moral and intellectual damage, and therefore it was with all respect he begged to be excused. His Majesty was so amazed{47}

with his bravery and intelligence that he took from off his own head the royal crown and placed it on the Hoopoe’s, saying, truly thou art a very king amongst birds, and shall for ever be crowned. To show the truth of this story, it is only necessary to come to Egypt, when the most sceptical will be at once converted, as he will see that every single Hoopoe to this day is indeed right royally crowned as no other bird is.[3]

[3] A variation of this story is given by the Hon. Robert Curzon, in his Visits to Monasteries in the Levant. There the Hoopoe was told by the king to go home and consult his spouse, as to what should be the royal gift, and she, like a true feminine, on being questioned, said, “Let us ask for crowns of gold on our heads, that we may be superior to all other birds.” The request was granted, but the king forewarned them that they would see the folly of their request; and all Hoopoes of both sexes strutted about with solid gold crowns, and “the queen of the Hoopoes gave herself airs, and sat upon a twig, and refused to speak to the Merops, her cousin” (bee-eater), but a certain fowler, who set traps and nets for birds, put a broken mirror into his traps. The queen of course went to look into it to the better see herself and her golden crown, and got caught. The value of these solid gold crowns soon led to every man’s hand being against the vain Hoopoes. “Not a Hoopoe could show its head, but it was slain or taken captive, and the days of the Hoopoes were numbered; then their minds were filled with sorrow and dismay.” The king of the Hoopoes went back to the monarch and related their piteous plight, and Solomon said, “Behold, did I not warn thee of thy folly, in desiring to have crowns of gold? Vanity and pride have been thy ruin. But now, that a memorial may remain of the service which thou didst render unto me, your crowns of gold shall be changed into crowns of feathers, that ye may walk unharmed upon the earth.”

The Cairo Zoological Gardens report it as “a fairly numerous visitor in spring and autumn” to the gardens, and of course most know that it is a{48} casual visitor to the British Isles; but there it is at once shot, as soon as seen, and is then mounted by the local taxidermist. Few collections of stuffed birds, however modest, are without examples of British-killed Hoopoes. That it will ever therefore become common with us is impossible, but that it might be a regular visitor is certain, for, as long as there have been any records kept, its appearance in the summer has been noted, and no farther than the Continent it is a regular and honoured visitor. The last Hoopoe I saw in Egypt was on April 6, on Lake Menzaleh; it rose from a mere scrap of an island all soft sand, and headed to the dunes that separate the lake from the Mediterranean, and the last I saw of it, was it still flying with its head pointed to European shores.{49}

General plumage a metallic blue; the under parts, lores, and ear coverts are bright chestnut; throat, white; the top of the head is a greenish turquoise with darker markings; the back is a brilliant cobalt blue shading into darker ultramarine blue on rump and tail; legs, red; eyes, brown. Length 7 inches, but individuals vary much.

IN Egypt this bird is common, and would be commoner if it were not in some parts relentlessly pursued for its brilliant plumes. When at Matariya on Lake Menzaleh I heard that the regular price was a half piastre (or a penny farthing) per skin, and that at that price hundreds were obtained. As we at home are not entirely blameless on this point much must not be said, but it is nevertheless to be regretted, as its brilliant plumage is such a valuable addition to the frequently colourless river scenery. Wherever there is water both in Upper and Lower Egypt this bird will be met with, and in the Luxor district it is really common. It is a bird that loves some particular spot, and clings to some one reach or another, so that where once seen it is highly probable to be seen again. It{50} is said to breed in Egypt, and probably does in localities suited to it.

The food is chiefly fish, and it has often been noted that it swallows such prey, after one or two preparatory blows, head foremost. In flight it hardly seems to move its wings, or they are moved so quickly that the eye does not catch the movement, it seems to pass along smoothly, literally like an arrow. This bird, like so many bright plumaged ones, is no songster, and has only a sort of shrill call note. Both male and female are alike in plumage, but the female has more red on the lower bill.

There is one other Kingfisher that may be met with, the Little Indian Kingfisher, very similar in plumage to the last, but it is a smaller bird and its bill is longer. I do not think I have ever seen it, though I know those who say they have noticed it several times on the rushing water in the Assoan district.{51}

The whole plumage black and white; feathers on top of head form crest; under surface white. In the male two dark bands cross the upper breast, in the female only one; both have some thin lance-shaped black markings on the sides; beak and legs black; eyes brown. Length, 11·5 inches.

THIS is a bird few know till they have been up the Nile; but when they have, they know it well, for it is not at all of a retiring nature, but boldly shows itself, and is very fond of sitting in conspicuous places, on the tops of poles, or on the dahabeah chains. Many seem to find it difficult to understand this is a Kingfisher, since they have a preconceived idea that Kingfishers must all necessarily be bright-plumaged birds, like the preceding species; but the Kingfishers are a very large family, and very various in size and colour. The Australian “Laughing Jackass” is a Kingfisher, and there are many others that possess no very special brilliance of plumage.

This Black and White Kingfisher is a true resident in Egypt, and just about the time we all leave for our homes it sets to work to make one,{52} and digs out a hole in the soft sides of the Nile bank. In some cases it burrows back two to three feet before it widens out the chamber in which the nest is made. I do not know that the bird is in any way persecuted, but it is not beloved of the people, as they accuse it of eating too many of their young fish. Visitors who do not like their muddy Nile fish do not see any great offence in this, but I can quite see the matter from the native’s point of view, and am a little astonished that it has been allowed to increase and multiply as it has. Last year, each evening, something like thirty used to roost on the chain cable of Mr. Davis’s dahabeah, moored just opposite Luxor. Where they all came from was something of a mystery, as, though you would see one now and again on that reach of river, you would never be able to see anything like that number; yet every evening in they used to come, and after a rather excited noisy discussion settled down to roost for the night.

A most interesting thing in this bird is its singular habit of hanging in mid-air, above the water, on the look-out for fish. Although I have said fish, it is certain it must take other creatures than fish, for I have often seen it, not{53}

only hovering over the Sacred Lake at Karnak, but also plunging head foremost down into its waters, and securing some food or other, with which it has at once flown away to some convenient perch and there swallowed it. Now there are no fish in the Karnak Lake, and it is clear that what the Kingfisher goes for must be some variety of its ordinary fishy food, and must be some larvæ or fine fat water-beetle. When hanging thus in mid-air it reminds me a little of our own Windhover or Kestrel, in its quick clapping stroke of wings, whilst its body and tail hang nearly perpendicularly down, till it sees what it wants; then the position of its body alters in a flash, and down it plunges, and is lost for a moment in the splash and spray that it raises by the impact with the water.{54}

The plumage throughout is green, with a black eye-stripe and a black marking in front on chest; legs brown, beak black, eyes crimson, two centre tail-feathers very elongated. Total length, 11 inches.

THERE are three species of Bee-eaters, but this, the Little Green Bee-eater, is chosen because it is resident, and because it must be seen by every one in Upper Egypt. The other two species are both birds of passage through Egypt, and are seldom seen or heard till April or May, when most people have left. This bird is well called the Green Bee-eater since it is green right over every part of its upper plumage, but owing to the shading of parts not in the full light of the sun it often appears as if its head were of burnished gold, and again when it flies, if the light be at all behind it, the transparent outstretched wings look a brilliant orange owing to the under-sides being of that rich warm colour. In habits it will remind any observer of our Fly-catchers at home, for it sits rather humped up on a dead twig, wall, or post till, suddenly observing some passing bee or fly, it{55}

swoops down on its prey and then back again to its perch to enjoy its food. This it will continue to do by the hour together, till, first stretching out one wing and leg, and then the other, it decides to set out for pastures new, and with an easy, long, sweeping flight, rising and then falling, it disappears from view. It is a very tame little bird, and is met with literally everywhere; but it is undoubtedly most fond of the wells with a few trees growing round them, or the gardens or palm-groves. I do not remember to have seen one actually on the ground, in which matter it is similar to all very short-legged birds, and its legs are very short.

It is a melancholy fact to have to record that it is far too often shot by visitors; and worse, sometimes now native boys catch it for the delectation of tourists, and, tying a bit of string round its legs, hold it as if it were perching naturally on their hands. They then offer it to tourists as a tame, pet bird, and I fear the tourist too often buys of them, for otherwise these utterly mercenary little rascals would not indulge in this traffic. Needless to say the poor bird always dies—indeed, is more often than not half-dead when in the boy’s hand, as its half-glazed eye only too plainly shows.{56} One hardly knows how to cure this cruelty, for the humane nearly always rebuke the boy, give him a piastre or two, and liberate the bird, and pass on thinking they have done a good deed. The bird can only flutter feebly away, and the boy of course re-catches it and goes through the same performance with the next kind-hearted, foolish visitor. It is with regret I write it, but I do not in the least now believe in the Egyptian’s love for birds, or anything other than backsheesh. Why the birds are or were so universally tame is not because of their kindliness, but simply because of their apathy. The moment it dawns on them that there is anything to be made out of birds or any other lovely thing they are as brutal as the very worst British hooligan.

I have sometimes seen Bee-eaters in the ruins and temples, and in this connection it is interesting to recall that there is a very good representation of one flying, in the celebrated series of pictures of the expedition to Punt at Deir-el-Bahari, the only case I can remember of a Bee-eater being so represented. It is entirely insectivorous, and is one of the many birds which ought, in this insect-infested country, to be strictly preserved, for it is appalling to think what an unbearable land this would be for us thin-skinned{57} people if the teeming clouds of flies and mosquitoes were not held in some check by these industrious birds, which are all day long steadily trying to reduce their numbers.

By modern naturalists the Common Swift is not placed along with the Swallow, but comes near the Bee-eaters and Nightjars, and I therefore place my notes on this bird at this point.

When I arrived early in October 1907 at Deir-el-Bahari, I saw thousands upon thousands of Swifts flying round in never-ending circles, and all, as far as I was able to identify them, the same Swift that goes shrieking its weird song down every town and village in rural England. Night after night, in the wonderful glow that follows the actual sunset, I used to go to the top of the great cliffs that overhang Queen Hatashu’s temple, where round me raced here, there, and everywhere, these great clouds of birds, sometimes so near me, as I sat quietly hidden in a niche of the rocks, that I could easily have knocked them down with a stick; whilst others were high, high up, circling round. Every now and then so close they came, shrilly shrieking and screaming, one after another, in follow-my-leader fashion, that I felt the cool fanning of the air from their{58} beating wings. In the early morning they were out again, but during the middle of the day they were rarely if ever to be seen. By the end of November there were but few, and when I returned after Christmas there was hardly one to be seen. About the middle of January I saw flocks of them again at Karnak, which is only just on the other side of the river.

Shelley seems to speak of the Common Swift as rare, and he is most probably right, but I have no doubt whatever of the identity of those I saw in the neighbourhood of Thebes at that particular time. The Swift that really breeds here is the Pale Swift, which, instead of being almost black all over like the Common Swift, has a more or less uniform greyish-brown plumage, and is considerably smaller; Shelley says two inches.

In the report of the Giza Zoological Society on the wild birds that have been observed in the gardens, both species of Swifts are noticed as having occurred there, and it is probable that both kinds are spread over the whole of Egypt. Why it is not generally noticed is because, as has been said, it flies out rather late, and keeps to great heights, never within my own experience flying as at home a foot or so above the ground.{59}

The Pale Swift I have often seen, and so close to me that the main difference in plumage to the Common Swift has been definitely noted. I myself have never heard it make the wild shrieking note our own bird makes, but then I have only seen it in the mid-winter months.{60}

| Hirundo rustica | Hirundo savignii | |

| European Common Chimney Swallow | Egyptian |

Upper plumage from forehead to tail, deep metallic steel blue-black; forehead and throat, rich red-brown; a band of the blue borders the red on throat; underparts creamy-white; beak very short and black; eyes, dark brown. Length, 8 inches.

THE above description is of the Common or Chimney Swallow, and if for the creamy-white underparts, you read red-brown underparts, length 7 inches, you have an accurate description of the Egyptian or Oriental Chimney Swallow. As the Egyptian Swallow and our own Common Swallow are so similar in appearance and habits, both are dealt with in this article. With so little difference between the two species, it is not strange that persons seem to find it hard to distinguish the one from the other; but really, if one watches at all carefully, he will soon note if the individual bird has the creamy-white underparts or no, as it is seldom that any swallow flies long without that sideway swerve which shows the wing lifted free above the body. The first date I have noted as{61}

![]()

COMMON SWALLOW AND EGYPTIAN SWALLOW

seeing the Common Swallow was February 1, 1908, at the Mût Lake, Karnak; but I have no doubt that at some parts up or down the river they can be seen all the winter through. After February, day by day, the great hosts of them, all flying with earnest intent due north, makes one of the most interesting sights to English eyes in all Egypt, as one can well believe that some of those very birds will be the first to greet one on his return home in April or May. I have often seen them hawking about over the waters of some small insect-haunted pool in friendly company with their Oriental cousins, and have always marvelled at their leaving a land with its constant sun and amazing wealth of flies and insects, for our own comparatively inclement clime and poor food-supply. In a room I slept in, at the hut at Deir-el-Bahari, there was a swallow’s nest just over my bed, and though it was too early when I was there in January for them to start breeding, on several occasions the Egyptian Swallows came fluttering in through the unglazed windows, just to take a look round and see that all was right for later on. On February 14 I saw two, which were clearly mated birds, on the ground, picking up scraps of twigs and straw, and then rapidly{62} fly away. In a few minutes both were back again, and one seemed to be taking mud, whilst the other kept searching for just the right-sized bit of dry grass or straw; it took up many bits, but they did not seem to satisfy the requirements and were dropped, till just the right-sized piece was forthcoming. So it is clear they must start nesting very early, and pretty certainly will have, as our British bird does, two broods in the season. There is practically little or no difference in the habits of either of these two Swallows—the one might be the other—and though I have watched them long and carefully, I am unable to recall any single peculiarity that our Swallow has from the Egyptian. Both alike have that habit of dipping momentarily into the water, then rising for a short distance, and again fluttering down on to the surface with a slight splash, and both kinds seem to have boundless energy and strength, tearing up and down incessantly by the hour together. So many birds rest in flight by making long sweeping curves with rigidly outstretched wings. Kites and Vultures are great exponents of this power, but the Swallows, though they can do it of course, are nearly all the day careering in headlong flight with restless energy, and the{63}

long journey they take in migration is probably, under fair climatic conditions, nothing at all formidable to them. If, however, they get caught in some storm or blizzard-like gale, it is an altogether different matter, and there are many records of the Mediterranean coast being littered with hundreds of dead bodies of the Swallows that have succumbed and fallen helplessly into the sea. Watching them flying about the river, or above the growing crops, one finds it difficult to picture a more perfectly happy existence—food in abundance, sunshine all day long, and a kindly welcome at roosting time in every house or rough mud-hut—and cheery and grateful it seems for it all, if one may judge by its lively twittering song. No wonder every country has made a special favourite of the Swallow. It is entirely insectivorous, and, as has been said of several other birds, the use that they are in this land of plagues of flies is enormous.

Swallows’ nests, as is well known, are generally placed on some horizontal beam or masonry. Martin’s nests are placed on the perpendicular sides of buildings, and by choice close under the eaves of our broad-roofed houses. Both are built of mud, and the mud is very generally obtained from roadsides{64} or by the river’s edge, but if any of my readers will endeavour to build up a nest with such mud against an upright wall, they will attempt an all but impossible task, for as the curve begins to grow outwards it will with its own weight fall away from the wall. What is it, then, that the Swallows and Martins do to make their nests adhere? If you examine an old last year’s nest and try and break the outer shell, you will find it very tough considering the material it is made of, and the toughening matter is a secretion of saliva. In the case of some species of Swallows this secretion is so great that the whole of the nest is made of that substance alone, with the lining of a few feathers. And it is this nest, cleaned of all foreign matter which is the base of the much-esteemed delicacy known as birdnest soup. Few who have partaken of this luxury are perhaps aware that it is simply solidified saliva.

Of Martins there are two—the House-Martin and the Sand-Martin, both birds common to Great Britain. Of the latter, literally thousands and thousands will be seen nesting in colonies in the mud banks by all who go up and down the river; restless and cheerful, they are one of the welcome sights of the Nile trip, and often for miles at a stretch the whole banks are honeycombed with{65} their nesting holes, and ever and again, moved by some common impulse, hundreds come rushing out and over the boat with noisy twitterings, and then scattering, gradually return in ones and twos to their homes again.{66}

Crown of head and nape dark grey or black, upper plumage delicate grey, wings brownish, some of the feathers edged with white; tail dark-brownish, two outer feathers on each side white; forehead, most of the cheek and under-parts white, black collar, legs and bill black, eyes brown. Length, 7 inches.

I HAVE pictured this particular Wagtail as it is perhaps the commonest of all, but there are several other kinds that at certain seasons might dispute the point and run it very close. It is very similar, superficially, to the familiar Pied Wagtail, but is greyer, less positively black and white, and might well be called the Grey rather than the White Wagtail. In the winter months, in Egypt, at whatever part of the country, north or south, you may be, you will see Wagtails of some sort or another busily chasing flies with ever-restless activity, and the numbers that there must be of this most useful bird is past all computation. Wagtails are peculiar in that they are about the smallest birds that really walk and run. All other{67}

small birds—finches, warblers, and the rest—move by hopping; but Wagtails all run, and hardly ever make any semblance of a hop unless the sudden bound into the air after some passing fly be called a hop. No bird is neater or more graceful in line than this, and I am sadly conscious of how little of its real beauty the drawing gives; the daintiness with which it does everything is singularly beautiful. Though many pass the winter in Egypt some must go farther south, as when the time comes for their return to their northern breeding-places in February and March there is a notable increase in their numbers, and I remember one particular evening in March when the whole cultivated ground round the Ramaseum, Thebes, was literally covered with them, and as darkness came on even more seemed to be dropping in on every side. The next day, when I went to the same place, the bulk had already gone, and there were hardly more than you could see at any time.