THE GREAT GEYSER BASIN OF THE UPPER YELLOWSTONE.

WONDERS

OF THE

YELLOWSTONE

EDITED BY

JAMES RICHARDSON.

New Edition, with new Map and Illustrations.

NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1886

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1873, by

SCRIBNER, ARMSTRONG & CO.,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Crown of the Continent—Yellowstone Lake—Ancient Volcanic Action—Modern Thermal Phenomena | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Early Explorations—Lewis and Clarke's Expeditions—Trappers' Yarns—Colonel Raynold's Expedition—The Washburn Expedition—Colonel Barlow's Expedition—Dr. Hayden's Geological Survey | 5 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Route from Fort Ellis to Bottlers' Ranch—Fort Ellis—Prospect from the Divide—Snowy Mountain—Trail Creek—Pyramid Mountain—The Bottler Brothers—Yellowstone Valley | 15 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Bottlers' Ranch to Gardiner's River—River Valley—Second Cañon—Cinnabar Mountain—The Devil's Slide—Western [x]Nomenclature—Precious Stones | 21 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Hot Springs of Gardiner's River—Third Cañon—Rapids—Valley of Gardiner's River—Thermal Springs—White Mountain—Hot Springs—Natural Bathing-pools—Diana's Bath—Liberty Cap—Bee-hive—Extinct Geysers—Beautiful Water—Vegetation in Hot Springs—Antiquity of Springs—Classification of Thermal Springs | 27 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Gardiner's River to Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone—Forks of Gardiner's River—Gallatin Mountains—Basaltic Columns—Falls of Gardiner's River—Mountain Prospect—Over the Divide—Agatized Wood—Delightful Climate—Mountain Verdure—Volcanic Ridges—Ravines—Third Cañon of the Yellowstone—Hell-roaring River—Hell-roaring Mountain—East Fork of the Yellowstone—Ancient Springs and Calcareous Deposits—First Bridge over the Yellowstone—Rock Cutting—Tower-creek Cañon—Column Rock—The Devil's Den—Tower Falls—The Devil's Hoof—Mineral Springs—Mouth of Grand Cañon | 43 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Over Mount Washburn to Falls of the Yellowstone—Ascent of Mount Washburn—Extensive View—Steam Puffs—Elephant's Back—Grand Cañon—Yellowstone Basin—The Three Tetons—First View of Yellowstone Lake—Madison Mountains—Gallatin Range—Emigrant Peak—Geological History of the Yellowstone Basin—Ancient Volcanic Action—Descent of Mount Washburn—Hell-broth Springs—The Devil's Caldron—Cascade Creek—The Devil's Den—Crystal Cascade | 61 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Grand Cañon and the Falls of the Yellowstone—Description of Grand Cañon—Descent into the Cañon—History [xi]of Grand Cañon—-Lower Falls—Upper Falls | 78 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| From the Falls to the Lake—River above the Falls—Alum Creek—Boiling Springs—Crater Hill—A Narrow Escape—The Locomotive Jet—Sulphur Springs—Mud Puffs—No Vegetation—Temperature of Springs—Muddy Geyser—Mud Volcano—Mud-sulphur Springs—The Grotto—The Giant's Caldron—Movements of Muddy Geyser | 90 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

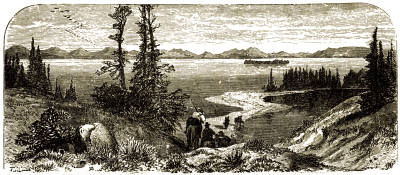

| Yellowstone Lake—Setting of the Lake—Shape of the Lake—Shores of the Lake—Yellowstone Trout—Worms in Trout—Waterfowl—The Guide-bird—Fauna of Yellowstone Basin—Islands in the Lake—The First Explorers | 105 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Around the Yellowstone Lake—Hot Springs of Pelican Creek—Hot Springs of Steam Point—Fire Slashes—Difficult Travelling—Little Invulnerable—Poetry in the Wilderness—Volcanic Peaks—Mounts Langford, Doane, and Stephenson—Brimstone Basin—Alum Creek—Upper Yellowstone—Wind River Mountains—Valley of Upper Yellowstone—The Five Forks—Bridger's Lake—Yellowstone Mountains—Heart Lake—Madison Lake—Mount Sheridan—Flat Mountain—Bridger's "Two Ocean River"—A Companion lost—Lakes and Springs—Hot Springs on the West Shore—Bridge Creek—Dead Springs—The Elephant's Back | 114 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

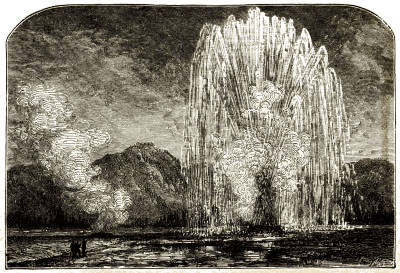

| Upper Geyser Basin—The Grand Geyser Region—Firehole River—Madison Lake—Mountains about the Lake—Cascades—The Geysers—Old Faithful—The Bee-hive—The Giantess—Castle Geyser—Grand Geyser—The Saw-mill—The Comet—The Grotto—The Pyramid—The Punch Bowl—Black Sand Geyser—Riverside Geyser—The Fan—The [xii]Sentinels—Iron Spring Creek—Soda Geyser | 133 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Lower Geyser Basin—Down the Firehole—Prismatic Hot Springs—The Cauldron—Old Spring Basins—The Conch Spring—Horn Geyser—Bath Spring—The Cavern—Mud Springs—Thud Geyser—Fountain Geyser—Mud Pot—Fissure Spring—White Dome Geyser—Bee-hive—Petrifaction—Hot Spring Vegetation—Cold Spring—General View of the Basin—The Twin Buttes—Fall of the Fairies—Rainbow Spring | 162 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

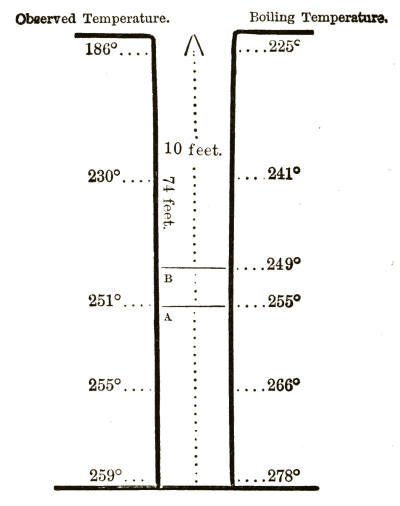

| Natural History of Geysers and other Thermal Springs—Iceland Geysers—History of The Geyser—The Strokr—Eruption of the Geyser—Growth of the Geyser—Mechanism of Geysers—Artificial Geysers—Life and Death of Geysers—Laugs—New Zealand Hot Springs—Te Tarata—Hot Springs of the Waikato—Origin of Mineral Springs—Chemistry of Mineral Springs | 180 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Mr. Everts's Thirty-seven Days of Peril—Lost—Loss of Horse—Midnight Dangers—Starvation—Return to Lake—No Food in the Midst of Plenty—Bessie Lake—Thistle Roots—Hunted by a Lion—Storms—First Fire—Vain Efforts to find Food—Attempt to cross the Mountains—The Lost Shoe—Forest on Fire—Hallucination—Turned back—The Doctor—Physiological Transformations—Descending the River—Loss of Lens—Discovery and Rescue | 199 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Our National Park—The Yellowstone Reservation—Dr. Hayden's Report—Text of Act of Congress—Appointment of Hon. N. P. Langford Superintendent of Park | 250 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| Great Geyser Basin | Front |

| Hot Springs of Gardner's River | 27 |

| Diana's Bath, Gardner's River | 31 |

| Liberty Cap, Gardner's River | 36 |

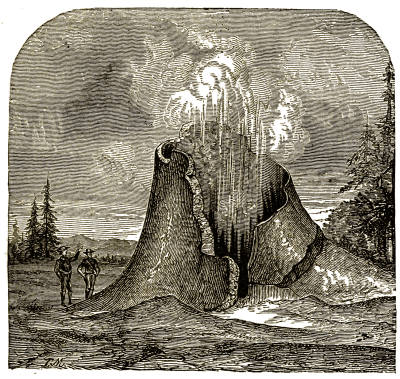

| Extinct Geyser, East Fork of the Yellowstone | 50 |

| The Devil's Hoof | 58 |

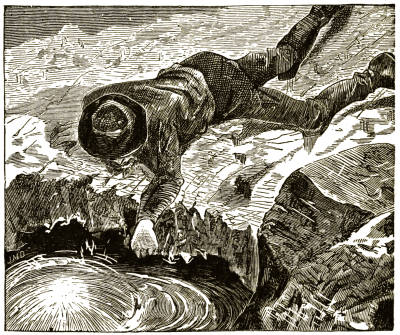

| Getting a Specimen | 72 |

| The Devil's Den | 76 |

| Upper Falls of the Yellowstone | 86 |

| The Mud Volcano | 100 |

| Yellowstone Lake | 106 |

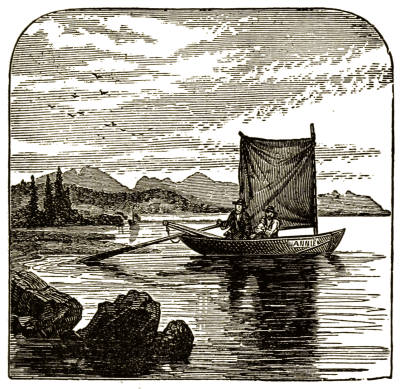

| The First Boat on Yellowstone Lake | 113 |

| Breaking Through | 122 |

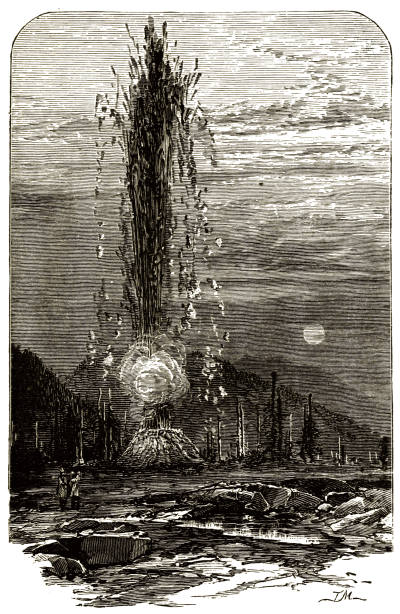

| The Grand Geyser, Firehole Basin | 144 |

| The Giant Geyser | 153 |

| Fan Geyser, Firehole Basin | 158 |

| The Bee-hive | 161 |

| Grand Cañon and Lower Falls of the Yellowstone | 194 |

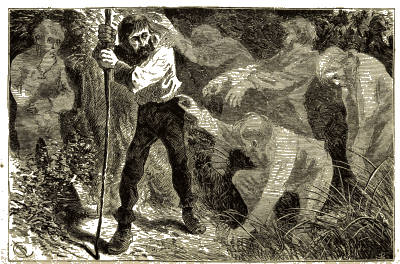

| Imaginary Companions | 236 |

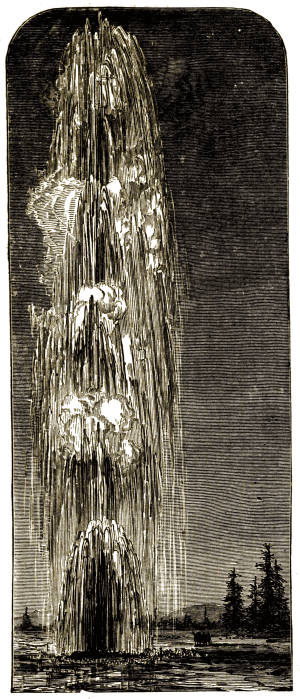

| The Giantess, Firehole Basin | 252 |

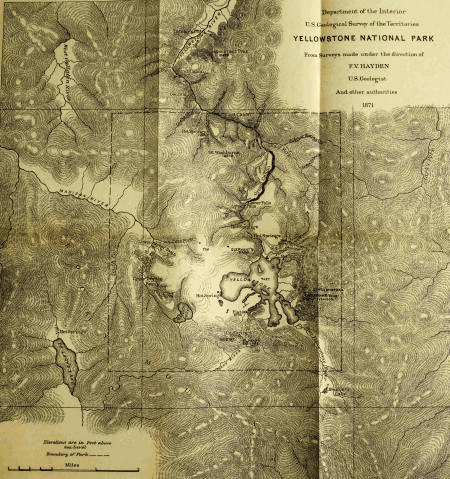

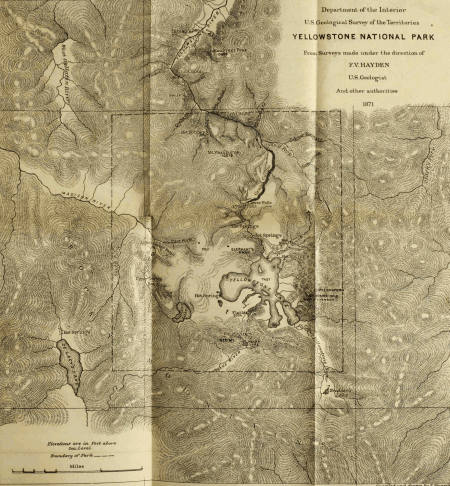

| MAPS. | |

| Hayden's Geological Survey of Yellowstone National Park. | |

CHAPTER I.

THE CROWN OF THE CONTINENT.

In the northwest corner of the Territory of Wyoming, about half way between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Ocean, and in the same latitude as the State of New York, the grand Rocky Mountain system culminates in a knot of peaks and ranges enclosing the most remarkable lake basin in the world. From this point radiate the chief mountain ranges, and three of the longest rivers of the Continent—the Missouri, the Columbia, and the Colorado.

On the south are the Wind River Mountains, a snow-clad barrier which no white man has ever crossed. On the east is the Snowy Mountain Range, and the grand cluster of volcanic peaks between it and Yellowstone Lake. On the west is the main divide of the Rocky Mountains. On the north are the bold peaks of the Gallatin Range,[2] and the parallel ridges which give a northward direction to all the great tributaries of the Missouri from this region.

Set like a gem in the centre of this snow-rimmed crown of the continent, is the loveliest body of fresh water on the globe, its dark-blue surface at an elevation greater than that of the highest clouds that fleck the azure sky of a summer's day, over the tops of the loftiest mountains of the East. Its waters teem with trout, and the primeval forests that cover the surrounding country are crowded with game. But these are the least of its attractions. It is the wildness and grandeur of the enclosing mountain scenery, and still more the curious, beautiful, wonderful and stupendous natural phenomena which characterize the region, that have raised it to sudden fame, and caused it to be set apart by our national government as a grand national play-ground and museum of unparalleled, indeed incomparable, marvels, free to all men for all time.

Evidences of ancient volcanic action on the grandest scale are so abundant and striking throughout the lake basin, that it has been looked upon as the remains of a mammoth crater, forty miles across. It seems, however, to have been rather the focus of a multitude of craters. "It is[3] probable," says the United States geologist, Dr. Hayden, with his usual caution, "that during the Pliocene period the entire country drained by the sources of the Yellowstone and the Columbia was the scene of volcanic activity as great as that of any portion of the globe. It might be called one vast crater, made up of a thousand smaller volcanic vents and fissures, out of which the fluid interior of the earth, fragments of rock and volcanic dust, were poured in unlimited quantities. Hundreds of the nuclei or cones of these volcanic vents are now remaining, some of them rising to a height of 10,000 to 11,000 feet above the sea. Mounts Doane, Longford, Stevenson, and more than a hundred other peaks, may be seen from any high point on either side of the basin, each of which formed a centre of effusion."

All that is left of the terrific forces which threw up these lofty mountains and elevated the entire region to its present altitude, now finds issue in occasional earthquake shocks, and in the innumerable hot springs and geysers, whose description makes up so large a portion of this book of wonders. Nowhere else in the world can the last-named phenomena be witnessed on so grand a scale, in such limitless variety, or amid scenes so marvellous in beauty, so wild and unearthly in savage[4] grandeur, so fascinating in all that awes or attracts the lover of the curious, the wonderful, the magnificent in nature.

CHAPTER II.

FIRST EXPLORATIONS.

In their exploration of the headwaters of the Missouri in the summer of 1805, the heroic Captains Lewis and Clarke discovered and named the three terminal branches of that river—the Jefferson, the Madison, and the Gallatin; then ascending the first named to its springs among the Rocky Mountains, they crossed the lofty ridge of the divide and pursued their investigations along the Columbia to the sea. The following summer they returned, separately exploring the two main branches of the Great River of the Northwest, each perpetuating the name and fame of his brother explorer by calling a river after him. Ascending the southern, or Lewis Fork, Captain Clarke recrossed the mountains to Wisdom River, (a branch of the Jefferson,) then traversed the country of the Jefferson, the Madison and the Gallatin[6] to the Rochejaune, or Yellowstone, which he followed to its junction with the Missouri, where he rejoined Captain Lewis. The map of the country explored by these brave men, makes the source of the Yellowstone a large lake, doubtless from information received from the Indians, but they seem to have heard nothing of the marvels along the upper reaches of the river and around the lake from which it flows.

In later years—especially after the discovery of the Montana gold-mines had drawn to the upper valleys of the Missouri an adventurous, gold-seeking population, who scoured the mountains in all directions—rumors of burning plains, spouting springs, great lakes and other natural wonders, came down from the unknown regions up the Yellowstone. And not content with these, the imagination was freely drawn on, and the treasure valleys of the Arabian Nights were rivalled, if not reproduced. Our over-venturous party, hotly pursued by Indians, escaped, report said, by travelling night after night by the brilliant light of a huge diamond providentially exposed on a mountain. A lost trapper turned up after protracted wandering in this mysterious region, his pockets stuffed with nuggets of gold gathered in a stream which he could never find again. More astounding[7] still was a valley which instantly petrified whatever entered it. Rabbits and sage-hens, even Indians were standing about there, like statuary, among thickets of petrified sage-brush, whose stony branches bore diamonds, rubies, sapphires, emeralds and other gems by the thousand, as large as walnuts. "I tell you, sir," said one who had been there, to Colonel Raynolds, "it is true, for I gathered a quart myself and sent them down the country."

The first earnest attempt to explore the valley of the upper Yellowstone was made in 1859, by Colonel Raynolds, of the Corps of Engineers. His expedition passed entirely around the Yellowstone basin, but could not penetrate it. In his report to the War Department, he says:

"It was my original desire to go from the head of Wind River to the head of the Yellowstone, keeping on the Atlantic slope, thence down the Yellowstone, passing the lake, and across by the Gallatin to the three forks of the Missouri. Bridger said at the outset that this would be impossible, and that it would be necessary to cross over to the headwaters of the Columbia and back again to the Yellowstone. I had not previously believed that crossing the main crest twice would be more easily accomplished than the transit over what was[8] in effect only a spur; but the view from our first camp settled the question adversely to my opinion at once. Directly across our route lies a basaltic ridge, rising not less than 5,000 feet above us, its walls apparently vertical, with no visible pass or even cañon. On the opposite side of this are the headwaters of the Yellowstone. Bridger remarked triumphantly and forcibly on reaching this spot, 'I told you you could not go through. A bird can't fly over that without taking a supply of grub along.' I had no reply to offer, and mentally conceded the accuracy of the information of 'the old man of the mountains.' * * * * *

"After this obstacle had thus forced us over on the western slope of the Rocky Mountains, an effort was made to recross and reach the district in question, but although it was June, the immense body of snow baffled all our exertions, and we were compelled to content ourselves with listening to marvellous tales of burning plains, immense lakes, and boiling springs, without being able to verify these wonders. I know of but two white men who claim to ever have visited this part of the Yellowstone Valley—James Bridger and Robert Meldrum. The narratives of both these men are very remarkable, and Bridger, in one of his recitals, described an immense boiling spring, that is a perfect[9] counterpart of the Geysers of Iceland. As he is uneducated, and had probably never heard of the existence of such natural marvels elsewhere, I have little doubt that he spoke of that which he had actually seen. The burning plains described by these men may be volcanic, or, more probably, burning beds of lignite similar to those on Powder River, which are known to be in a state of ignition.... Had our attempt to enter this district been made a month later in the season, the snow would have mainly disappeared, and there would have been no insurmountable obstacles to overcome.

"I cannot doubt, therefore, that at no very distant day the mysteries of this region will be fully revealed, and though small in extent, I regard the valley of the upper Yellowstone as the most interesting unexplored district of our widely expanded country."

Ten years after Colonel Raynolds's unsuccessful attempt to solve the problem of the Yellowstone, a small party under Messrs. Cook and Folsom ascended the river to the lake, and crossed over the divide into the Geyser Basin of the Madison. No report, we believe, was published of their discoveries. At any rate, the general public were indebted for their first knowledge of the marvels of this region to an expedition organized in the summer of[10] 1870 by some of the officials and leading citizens of Montana. This company, led by General Washburn, the Surveyor-General of the Territory, and accompanied by a small escort of United States cavalry under Lieutenant G. C. Doane, left Fort Ellis toward the latter part of August, and entered the valley of Yellowstone River on the 23d. During the next thirty days they explored the cañons of the Yellowstone and the shores of Yellowstone Lake; then crossing the mountains to the headwaters of the Madison, they visited the geyser region of Firehole River, and ascended that stream to its junction with the Madison, along whose valley they returned to civilization, confident, as their historian wrote, that they had seen "the greatest wonders on the Continent," and "convinced that there was not on the globe another region where, within the same limits, nature had crowded so much of grandeur and majesty, with so much of novelty and wonder."

Mr. Langford's account of this expedition, published in the second volume of Scribner's Monthly, and the report of Lieutenant Doane, printed some time after by the United States Government, (Ex. Doc. No. 51, 41st Congress,) gave to the world the first authentic information of the marvels of this wonderful region. Though their[11] route lay through a terrible wilderness, and most of the party were but amateur explorers at best, only one (Mr. Everts) met with a serious mishap. This gentleman's story of his separation from the company, and his thirty-seven days of suffering and perilous wandering, is one of the most thrilling chapters of adventure ever written.

The path fairly broken, and the romance of the Yellowstone shown to have a substantial basis in reality, it was not long before others were ready to explore more fully the magnificent scenery and the strange and peculiar phenomena described by the adventurers of 1870. As soon as the following season was sufficiently advanced to admit of explorations among the mountains, the Chief Engineer of the Military Department of the Missouri, Brevet Colonel John W. Barlow, set out for a two months' survey of the Yellowstone Basin, under special orders from General Sheridan. His route lay along the river to the lake; thence along the northern shore of the lake to the hot springs on its western bank; thence across the mountains westward to the Geyser Basins of Firehole River, which he ascended to its source in Madison Lake; thence to Heart Lake, the source of Snake River; thence across the mountains to Bridger's Lake, in the valley of the Upper Yellowstone. Descending[12] this stream to where it enters Yellowstone Lake, he returned by the east shore of the lake to Pelican Creek; thence across the country to the Falls of the Yellowstone; thence over the mountains to the East Fork of the Yellowstone, which he followed to its junction with the main stream.

In the meantime, a large and thoroughly-organized scientific party, under Dr. F. V. Hayden, U. S. geologist, were making a systematic survey of the region traversed by Colonel Barlow. The work done by this party is briefly summarized by Dr. Hayden as follows:

"From Fort Ellis, we passed eastward over the divide, between the drainage of the Missouri and Yellowstone, to Bottlers' Ranch. Here we established a permanent camp, leaving all our wagons and a portion of the party. A careful system of meteorological observations was kept at this locality for six weeks. From Bottlers' Ranch we proceeded up the valley of the Yellowstone, surveyed the remarkable hot springs on Gardiner's River, The Grand Cañon, Tower Falls, Upper and Lower Falls of the Yellowstone, thence into the basin proper, prepared charts of all the Hot Spring groups, which were very numerous, and continued up the river to the lake. We then commenced a systematic survey of the lake and its surroundings.[13] Mr. Schönborn, with his assistant, made a careful survey of the lake and the mountains from the shore, and Messrs. Elliott and Carrington surveyed and sketched its shore-lines from the water in a boat. Careful soundings were also made, and the greatest depth was found to be three hundred feet. From the lake I proceeded, with Messrs. Schönborn, Peale, and Elliott to the Firehole Valley, by way of East Fork of the Madison; then ascended the Firehole Valley. We made careful charts of the Lower and Upper Geyser Basin, locating all the principal springs, and determining their temperatures. We then returned over the mountains by way of the head of Firehole River, explored Madison Lake, Heart Lake, etc. After having completed our survey of the lake, we crossed over to the headwaters of the East Fork by way of the valley of Pelican Creek, explored the East Fork to its junction with the main Yellowstone, and thence to Bottlers' Ranch, which we reached on the 28th of August. From this place we passed down the Yellowstone, through the lower cañon, to the mouth of Shield's River, to connect our work with that of Colonel Wm. F. Raynolds, in 1860. From there we returned to Fort Ellis."

It is safe to say that no exploring expedition on[14] this continent ever had a more interesting field of investigation, or ever studied so many grand, curious and wonderful aspects of nature in so short a time.

CHAPTER III.

FORT ELLIS TO BOTTLERS' RANCH.

The Yellowstone tourist leaves the confines of civilization at Fort Ellis. This frontier military post, situated near the head of the beautiful and fertile valley of the East Gallatin, commands the valleys of the Yellowstone and the three forks of the Missouri—the finest and most productive portion of Montana. On the east and north are ranges of hills and mountains which form the divide between the waters of the Yellowstone and the Missouri. On the south and west, the beautiful Valley of the Gallatin. Abundant vegetation, beautiful scenery, streams of pure water flowing down the mountain-sides and across the plains on every hand, and a climate that can hardly be surpassed in any country, combine to make this pleasant station one of the most charming places on the continent.

For the first six miles the road from Fort Ellis[16] to the wonder-land of the Yellowstone Valley follows the general course of the East Gallatin, up steep acclivities and through the defiles of a hilly country to the crest of the divide. The road here takes advantage of a natural pass between hills that rise from six hundred to twelve hundred feet above the road, itself considerably more elevated than the summit of the White Mountains. From the tops of the hills on either side the view is wonderfully fine in every direction. To the west lies the Gallatin Valley, with its cordon of snow-capped peaks, its finely-timbered water courses, and its long, grassy declivities, dotted with the habitations of pioneers, and blooming with the fruits of industry. To the eastward lies the beautiful Valley of the Yellowstone, not yet laid under tribute to man. On the further side of this valley—the bed of an ancient lake—the eye takes in at a glance one of the most symmetrical and remarkable ranges of mountains in all the West. Indeed, Dr. Hayden says, in describing them:

"Several of my party who had visited Europe regarded this range as in no way inferior in beauty to any in that far-famed country. A series of cone-shaped peaks, looking like gigantic pyramids, are grouped along the east side of the valley for thirty or forty miles, with their bald, dark summits covered[17] with perpetual snow, the vegetation growing thinner and smaller as we ascend the almost vertical sides, until, long before reaching the summits, it has entirely disappeared. On all sides deep gorges have been gashed out by aqueous forces cutting through the very core of the mountains, and forming those wonderful gulches which only the hardy and daring miner has ventured to explore. This range, which is called on the maps Snowy Mountains, forms the great water-shed between two portions of the Yellowstone River, above and below the first cañon, and gives origin to some of the most important branches of that river. From the summit of Emigrant Peak, one of the highest of these volcanic cones, one great mass of these basaltic peaks can be seen as far as the eye can reach, rising to the height of 10,000 to 11,000 feet above the sea. Emigrant Peak, the base of which is cut by the Yellowstone River, is 10,629 feet above tide-water, while the valley plain near Bottlers' Ranch, on the opposite side of the river, was found to be 5,925 feet. This splendid group of peaks rises 5,000 feet and upward above the valley of the Yellowstone."

About three miles from the divide the road strikes the valley of Trail Creek, a small-sized trout-stream of great clearness and purity, flowing[18] southeastward to the Yellowstone, between high hills wooded at the summits. Approaching the river, the country becomes more and more volcanic in appearance, masses of basaltic lava cropping out from the high ridges on the right and left. Many of these masses show a perpendicular front of several hundred feet, with projections resembling towers, castles and the like. Several miles away on the right, is Pyramid Mountain, a snow-capped peak. Farther to the south is a long range of mountains, also covered with snow, even in midsummer.

On the left of the valley the foot hills bear abundant verdure, the highest summits being covered with a vigorous growth of pines. Trail Creek enters the Yellowstone about thirty miles from Fort Ellis. Ten miles further up the Yellowstone is Bottlers' Ranch, the last abode of civilized man in this direction.

The Bottler brothers, who have established themselves here, belong to that numerous class of pioneers who are satisfied only when their field of operation is a little in advance of civilization, exposed to privation and danger, yet possessing advantages for hunting, trapping and fishing not enjoyed by men content to dwell in safety. These, however are not their only occupations. They[19] have under cultivation large fields of wheat, potatoes and other crops, possess extensive herds of cattle, and make large quantities of butter, for which they find a ready market in the mining camps of Emigrant Gulch across the river, which at this point is a very rapid stream, about three hundred feet wide and four feet deep on the riffles at low water.

Of this part of the valley Dr. Hayden says: "It is about fifteen miles long, and will average three miles in width; it is well watered, soil fertile, and in every respect one of the most desirable portions of Montana. We may not look for any districts favorable for agriculture in the Yellowstone Valley above the second cañon; but this entire lake basin seems admirably adapted for grazing and for the cultivation of the usual crops of the country. The cereals and the roots have already been produced in abundance, especially wheat and potatoes. The mountains on either side are covered with snow, to a greater or less extent, all the year, which in melting feeds the numerous little streams that flow down the mountain-sides in the Yellowstone. Hundreds of springs flow out of the terraces. One terrace near Bottlers' Ranch gives origin to fifty springs within a mile, and then, all aggregating together in the river bottom, form a[20] large stream. Thus there is the greatest abundance of water for irrigation, or for any of the purposes of settlement. The elevation of the valley at this ranch is 4,925 feet, and this may be regarded as the average in altitude. But a small portion of it is occupied as yet, but the time is not far distant when the valley will be covered with fine farms and the hills with stock. It will always be a region of interest, from the fact that it is probably the upper limit of agricultural effort in the Yellowstone Valley."

CHAPTER IV.

BOTTLERS' RANCH TO GARDINER'S RIVER.

At Bottlers' Ranch the wagon road terminates. For the first ten miles beyond, the trail runs along the west bank of the river through the wildest imaginable scenery of rock, river and mountain. The path is narrow, rocky and uneven, frequently leading over steep hills of considerable height. From the top of one of these, a bold mountain spur coming down to the water's edge, the view up the valley is very fine, embracing the river fringed with cottonwoods, the foot hills covered with luxuriant, many-tinted herbage, and over all the snow-crowned summits of the distant mountains. Above this point the valley opens out to a "bottom" of large extent and great beauty. Across the river the steep lava mountains come close to the stream, their lofty fronts covered with stunted timber. A large portion of the bottom land is subject to overflow by[22] the numerous mountain streams that come in from the right, and bears an abundance of grass, in many places waist high. The river is skirted with shrubbery and cedars, the latter having thick trunks, too short for ordinary lumber, yet of beautiful grain for small cabinet work, and susceptible of exquisite finish.

At the head of this valley is the second cañon of the Yellowstone, granite walls rising on either side to the height of a thousand feet or more, and the river dashing through the narrow gorge with great velocity. Seen from the lofty mountain spur over which the trail is forced to pass, the bright green color of the water, and the numerous ripples, capped with white foam, as the roaring torrent rushes around and over the multitude of rocks that have fallen from above into the channel, present a most picturesque appearance. Above the cañon, which is about a mile in length, the valley widens slightly, then narrows so as to compel the traveller to cross a ridge, on whose summit lies a beautiful lake. Descending to the valley again the road traverses a tract of level bottom land, a mile or two wide, covered with a heavy growth of sage-brush. Throughout all this portion of its course, the Yellowstone is abundantly stocked with trout of the largest variety known this side the Rocky Mountains.

Some ten miles above the second cañon on the edge of the river valley is Cinnabar Mountain, whose weather-beaten side presents one of the most singular freaks of nature in the world. Two parallel vertical walls of rock, fifty feet wide, traverse the mountain from base to summit, and project to the height of three hundred feet for a distance of fifteen hundred feet. The sides are as even as if wrought by line and plumb. The rock between the walls and on either side has been completely worn away. Speaking of this curious formation, Mr. Langford says:

"We had seen many of the capricious works wrought by erosion upon the friable rocks of Montana, but never before upon so majestic a scale. Here an entire mountain-side, by wind and water, had been removed, leaving as the evidences of their protracted toil these vertical projections, which, but for their immensity, might as readily be mistaken for works of art as of nature. Their smooth sides, uniform width and height, and great length, considered in connection with the causes which had wrought their insulation, excited our wonder and admiration. They were all the more curious because of their dissimilarity to any other striking objects in natural scenery that we had ever seen or heard of. In future years, when the wonders of the[24] Yellowstone are incorporated into the family of fashionable resorts, there will be few of its attractions surpassing in interest this marvellous freak of the elements."

According to the observations of Dr. Hayden, the mountain is formed of alternate beds of sandstone, limestone, and quartzites, elevated to a nearly vertical position by those internal forces which acted in ages past to lift the mountain ranges to their present heights. Standing at the base and looking up the sides of the mountain, the geologist could not but be filled with wonder at the convulsions which threw such immense masses of rocks into their present position. Ridge after ridge extends down the steep sides of the mountain like lofty walls, the intervening softer portions having been washed away, leaving the harder layers projecting far above. In one place the rocks incline in every possible direction, and are crushed together in the utmost confusion. Between the walls at one point is a band of bright brick-red clay, which has been mistaken for cinnabar, and hence the name Cinnabar Mountain. The most conspicuous ridge is composed of basalt, which must have been poured out on the surface when all the rocks were in a horizontal position. For reasons best known to himself, one of the first explorers[25] of this region gave these parallel ridges the title of "Devil's Slide."

"The suggestion was unfortunate," writes the historian of the Expedition, "as, with more reason perhaps, but with no better taste, we frequently had occasion to appropriate other portions of the person of his Satanic Majesty, or of his dominion, in signification of the varied marvels we met with. Some little excuse may be found for this in the fact that the old mountaineers and trappers who preceded us had been peculiarly lavish in the use of the infernal vocabulary. Every river and glen and mountain had suggested to their imaginations some fancied resemblance to portions of a region which their pious grandmothers had warned them to avoid. It is common for them, when speaking of this region, to designate portions of its physical features, as "Firehole Prairie,"—the "Devil's Den,"—"Hell Roaring River," etc.—and these names, from a remarkable fitness of things, are not likely to be speedily superseded by others less impressive."

These "impressive" titles stand in curious contrast with the fanciful names bestowed in this region by Capts. Lewis and Clarke,—Wisdom River, Philosophy River, Philanthropy Creek, and the like.

From the Devil's Slide to the mouth of Gardiner's River, twelve miles, the ground rises rapidly, passing[26] from a dead level alkali plain, to a succession of plateaus covered slightly with a sterile soil. Evidences of volcanic action begin to be frequent: old craters converted into small lakes appear here and there, prettily fringed with vegetation, and covered with waterfowl. Scattered over the hills and through the valleys are numerous beautiful specimens of chalcedony and chips of obsidian. Many of the chalcedonies are geodes, in which are crystals of quartz; others contain opal in the centre and agate on the exterior; and still others have on the outside attached crystals of calcite.

CHAPTER V.

HOT SPRINGS OF GARDINER'S RIVER.

Ten miles above the Devil's Slide, Gardiner's River, a mountain torrent twenty yards wide, cuts through a deep and gloomy gorge and enters the Yellowstone at the lower end of the Third Cañon.

At this point the Yellowstone shrinks to half its usual size, losing itself among huge granite[28] boulders, which choke up the stream and create alternate pools and rapids, crowded with trout. Worn into fantastic forms by the washing water, these immense rock masses give an aspect of peculiar wildness to the scenery. But the crowning wonder of this region is the group of hot springs on the slope of a mountain, four miles up the valley of Gardiner's River. The first expedition passed on without seeing them, but they could not escape the vigilance of the scientific company that followed.

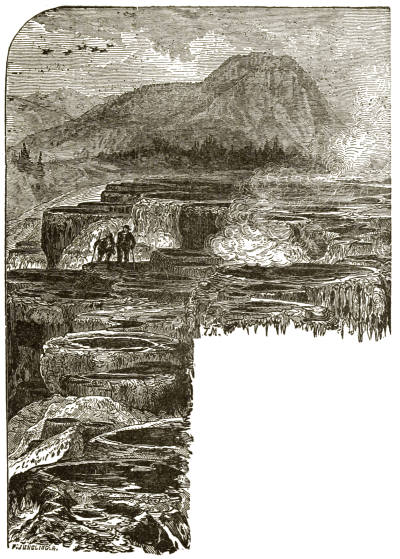

The lower reaches of the valley of Gardiner's River, and the enclosing hillsides, are strewn with volcanic rock, having the appearance of furnace cinder. The tops of the rounded hills are covered with fragments of basalt and conglomerate, whose great variety of sombre colors add much to the appearance of desolation which characterizes the valley. Here and there are stagnant lakes fifty to a hundred yards in diameter, apparently occupying ancient volcanic vents. Crossing a barren, elevated region two miles in extent, and three or four hundred feet above the river-bed, the trail descends abruptly to a low "bottom" covered with a thick calcareous crust, deposited from hot springs, now for the most part dry. At one point, however, a large stream of hot water, six feet wide and two[29] feet deep, flows swiftly from beneath the crust, its exposed portion clearly revealed by rising steam. The quantity of water flowing from this spring is greater than from any other in this region; its temperature ranges from 126° to 132° Fah. A little further above are three or four other springs near the margin of the river. These have nearly circular basins, six to ten feet in diameter, and a temperature not above 120°. Already these springs have become the resort of invalids, who speak highly of the virtues of the waters. A short distance up the hill are abundant remains of springs, which in time past must have been very active. For nearly a mile the steep hill-side is covered with a thick crust of spring deposits, which, though much decomposed and overgrown with pines and cedars, still bear traces of the wonderful forms displayed in the vicinity of the active springs further up the hill. Ascending the hill, Dr. Hayden's party came suddenly and unexpectedly upon these marvellous deposits, which they agreed in pronouncing one of the finest displays of natural architecture in the world. The snowy whiteness of the deposit, which has the form of a frozen cascade, at once suggested the name of White Mountain Hot Spring. The springs now in active operation cover an area of about one square mile,[30] while the rest of the territory, three or four square miles in extent, is occupied by the remains of springs which have ceased to flow. Small streams flow down the sides of the Snowy Mountain in channels lined with oxide of iron of the most delicate tints of red. Others show exquisite shades of yellow, from a deep, bright sulphur, to a dainty cream-color. Still others are stained with shades of green, all these colors as brilliant as the brightest aniline dyes. The water after rising from the spring basin flows down the sides of the declivity, step by step, from one reservoir to another, at each one of them losing a portion of its heat, until it becomes as cool as spring-water. Within five hundred feet of its source Dr. Hayden's party camped for two days by the side of the little stream formed by the aggregated waters of these hot springs, and found the water most excellent for drinking as well as for cooking purposes. It was perfectly clear and tasteless, and harmless in its effects. During their stay here all the members of the party, as well as the soldiers comprising their escort, enjoyed the luxury of bathing in these most elegantly carved natural bathing-pools; and it was easy to select, from the hundreds of reservoirs, water of any desired temperature. These natural basins vary somewhat in size, but many of them are[31] about four by six feet in diameter, and one to four feet in depth. Their margins are beautifully scalloped, and adorned with a natural beadwork of exquisite beauty.

BATHING-POOLS (DIANA'S BATH.)

The level or terrace upon which the principal active springs are located, is about midway up the sides of the mountain, covered with the sediment. Still farther up are the ruins of what must have[32] been at some period more active springs than any at present known. The sides of the mountain for two or three hundred feet in height, are thickly encrusted with calcareous deposit, originally ornamented with elegant sculpturing, like the bathing pools below; but atmospheric agencies, which act readily on the lime, have obliterated all their delicate beauty.

The largest living spring is near the outer margin of the main terrace. Its dimensions are twenty-five feet by forty, and its water so perfectly transparent that one can look down into the beautiful ultramarine depth to the very bottom of the basin. Its sides are ornamented with coral-like forms of a great variety of shades, from pure white to a bright cream yellow, while the blue sky reflected in the transparent water gives an azure tint to the whole which surpasses all art. From various portions of the rim, water flows out in moderate quantities over the sides of the hill. Whenever it gathers into a channel and flows quite swiftly, basins with sides from two to eight feet high are formed with their ornamental designs proportionately coarse; but when the water flows slowly, myriads of little basins are formed, one below another, with a semblance of irregular system. The water holds in solution a great amount of lime,[33] with some soda, alumina and magnesia, which are slowly deposited as the water flows down the sides of the mountain. Underneath the sides of many of the pools are rows of exquisitely-ornamented stalactites, formed by the dripping of the water over the margins. All these springs have one or more centres of ebullition which is constant, though seldom rising more than four or five inches above the surface. The ebullition is due mainly to the emission of carbonic acid gas. The springs in the centre of the main basin are probably all at the boiling point—194° at this elevation. Being inaccessible, however, it is impossible to determine their actual temperature. The hottest that could be reached was 162° Fah. The terrace immediately above the main basin is bordered by a long rounded ridge with a fissure extending its whole length, its interior lined with beautiful crystals of pure sulphur. Only hot vapors and steam issue from this fissure, though the bubbling and gurgling of water far beneath the surface can be distinctly heard. Back of this ridge are several small springs which throw up geyser-like jets of water intermittently to the height of three feet.

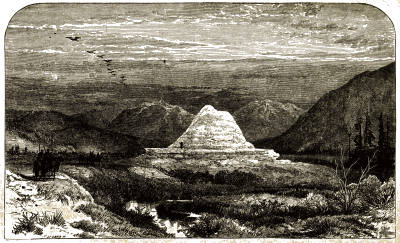

On the west side of this deposit, about one-third of the way up the White Mountain from the river and terrace, where was once the theatre of many[34] active springs, old chimneys or craters are scattered thickly over the surface, and there are several large holes and fissures leading to vast caverns below. The crust gives off a dull hollow sound beneath the tread, and the surface gives indistinct evidence of having been adorned with the beautiful pools or basins already described. At the base of the principal terrace is a large area covered with shallow pools some of them containing water, with all the ornamentations perfect, while others are fast going to decay, and the decomposed sediment is as white as snow. On this sub-terrace is a remarkable cone about 50 feet in height and 20 feet in diameter at the base. Its form has suggested the name of Liberty Cap. It is undoubtedly the remains of an extinct geyser. The water was forced up with considerable power, and probably without intermission, building up its own crater until the pressure beneath was exhausted, and the spring gradually closed itself over at the summit and perished. No water flows from it at the present time. The layers of lime were deposited around the cap like the layers of straw on a thatched roof, or hay on a conical stack. Not far from the Liberty Cap is a smaller cone, called, from its form, the "Bee-hive." These springs are constantly changing their position; some die out, others burst out in new places. On the[35] northwest margin of the main terrace are examples of what have been called oblong mounds. There are several of them in this region, extending in different directions, from fifty to one hundred and fifty yards in length, from six to ten feet high, and from ten to fifteen feet broad at the base. There is in all cases a fissure from one end of the summit to the other, usually from six to ten inches wide, from which steam sometimes issues in considerable quantities, and on walking along the top one can hear the water seething and boiling below like a cauldron. The[36] inner portion of the shell, as far down as can be seen, is lined with a hard, white enamel-like porcelain; in some places beautiful crystals of sulphur have been precipitated from the steam. These mounds have been built up by a kind of oblong fissure-spring in the same way that the cones have been constructed. The water, continually spouting up, deposited sediment around the edges of the fissure until the force was exhausted, and then the calcareous basin was rounded up something like a thatched roof by overlapping layers.

THE LIBERTY CAP.

Near the upper terrace, which is really an old rim, are a number of these extinct, oblong geysers, some of which have been broken down so as to show them to be mere shells or caverns, now the abode of wild animals. Dr. Hayden attempted to enter one of them, and found it full of sticks and bones which had been carried in by wild beasts; and swarms of bats flitted to and fro. Some of the mounds have been worn away so that sections are exposed, showing the great number and thickness of the overlapping layers of sediment. Many mounds are overgrown with pine-trees, which must be at least eighty or a hundred years old. Indeed, the upper part of this mountain appears like a magnificent ruin of a once flourishing village of these unique structures, now fast decomposing, yet beautiful and instructive[37] in their decay. One may now study the layers of deposit, sometimes thousands on a single mound, as he would the rings of growth in a tree. How long a period is required to form one of these mounds, or to build up its beautiful structure, there is no data for determining. On the middle terrace, where the principal portion of the active springs are, some of the pine-trees are buried in sediment apparently to the depth of six or eight feet. All of them are dead at the present time. There is, however, evidence enough around the springs to show that the mineral-water is precipitated with great rapidity. It is probable that all the deposits in the immediate vicinity of the active springs are constantly changing from the margin of the river to the top of the White Mountain and return. The deposits upon the summit are extensive, though now there is very little water issuing from the springs there, and that is of low temperature. Quantities of steam are ever ascending from the springs, and on damp mornings the entire slope of the mountain is enveloped in clouds of vapor.

"But," observes Dr. Hayden, in summing up his account of this indescribable locality, "it is to the wonderful variety of exquisitely delicate colors that this picture owes the main part of its attractiveness. The little orifices from which the hot water issues[38] are beautifully enamelled with the porcelain-like lining, and around the edges a layer of sulphur is precipitated. As the water flows along the valley, it lays down in its course a pavement more beautiful and elaborate in its adornment than art has ever yet conceived. The sulphur and the iron, with the green microscopic vegetation, tint the whole with an illumination of which no decoration-painter has ever dreamed. From the sides of the oblong mound, which is here from 30 to 50 feet high, the water has oozed out at different points, forming small groups of the semicircular, step-like basins.

"Again, if we look at the principal group of springs from the high mound above the middle terrace, we can see the same variety of brilliant coloring. The wonderful transparency of the water surpasses anything of the kind I have ever seen in any other portion of the world. The sky, with the smallest cloud that flits across it, is reflected in its clear depths, and the ultramarine colors, more vivid than the sea, are greatly heightened by the constant gentle vibrations. One can look down into the clear depths and see, with perfect distinctness, the minutest ornament on the inner sides of the basins; and the exquisite beauty of the coloring and the variety of forms baffle any attempt to portray them, either with pen or pencil. And then, too, around the borders[39] of these springs, especially those of rather low temperature, and on the sides and bottoms of the numerous little channels of the streams that flow from these springs, there is a striking variety of the most vivid colors. I can only compare them to our most brilliant aniline dyes—various shades of red, from the brightest scarlet to a bright rose tint; also yellow, from deep-bright sulphur, through all the shades, to light cream-color. There are also various shades of green, from the peculiar vegetation. These springs are also filled with minute vegetable forms, which under the microscope prove to be diatoms, among which Dr. Billings discovers Palmella and Oscillara. There are also in the little streams that flow from the boiling springs great quantities of a fibrous, silky substance, apparently vegetable, which vibrates at the slightest movement of the water, and has the appearance of the finest quality of cashmere wool. When the waters are still these silken masses become incrusted with lime, the delicate vegetable threads disappear, and a fibrous, spongy mass remains, like delicate snow-white coral."

The antiquity of these springs is a question of great interest, yet difficult of solution. When were these immense deposits begun? On the margin of the mountain, high above the present position[40] of the hot springs, is a bed of white, or yellowish white limestone, from fifty to a hundred and fifty feet thick. It is regularly stratified and the jointing is complete. There is a belt a mile long and one fourth of a mile wide, covered with cubical masses of this rock that have fallen down the slope of the mountain. These immense blocks, fifty to one hundred feet in each dimension, appear as if the mass had slowly fallen down as the underlying rocks were worn away. So thickly is this belt covered with these huge masses that it is with the greatest difficulty one can walk across it. It would seem that this bed must at one time have extended over a portion or all of the valley of Gardiner's River. Much of the rock is very compact, and would make beautiful building-stone, on account of its close texture and color, and it could be converted into the whitest of lime. If the rocks are examined, however, over a considerable area, they are found to possess all the varieties of structure of a hot-spring deposit. Some portions are quite spongy, and decompose readily; others are made up of very thin laminæ, regular or wavy; enough to show the origin of the deposit without a doubt. But in what manner was it formed? Dr. Hayden believes that the limestone was precipitated in the bottom of a lake, which was filled with hot-springs,[41] much as the calcareous matter is laid down in the bottom of the ocean at the present time. Indeed, portions of the rock do not differ materially from the recent limestones now forming in the vicinity of the West India Islands. The deposit was evidently laid down on a nearly level surface, with a moderately uniform thickness, and the strata are horizontal. Since this group of strata was formed, the country has been elevated, and the valley of Gardiner's River has been carved out, so that the commencement of the period of activity of these springs must date back to a period merging on, but just prior to, the present geological period—probably at the time of the greatest action of the volcanic forces in this region.

Classed with reference to their chemical constituents, the springs here and elsewhere in the Yellowstone Valley are of two kinds: those in which lime predominates, and those in which silica is most abundant. The springs of Gardiner's River are mainly the former. Where does the lime come from? The geology of the country surrounding the springs shows already that there is underneath the spring deposits, at least a thickness of 1,500 feet, of carboniferous limestone; and if the origin of the heat which so elevates the temperature of the waters of these springs is as deep seated as[42] is generally supposed, the heated waters have ample time and space for dissolving the calcareous rocks through which they flow.

CHAPTER VI.

GARDINER'S RIVER TO GRAND CAÑON.

About a mile above the springs, Gardiner's River separates into three branches—the East, Middle, and West Forks, which rise high up in the mountains, among perpetual snows. They wind their way across a broad plateau covered mostly with a dense growth of pines, but with some broad, open, meadow-like spots, which, seen from some high mountain peak, lend a rare charm to the landscape. After gathering a sufficient supply of water, they commence wearing their channels down into the volcanic rocks, deeper and deeper as they descend. Each one has its water-fall, which would fill an artist with enthusiasm. From the high ridge between the East and Middle Forks a fine view is obtained of the surrounding country.

Far to the southwest are lofty peaks covered with snow, rising to the height of 10,000 feet, and forming[44] a part of the magnificent range of mountains that separates the Yellowstone from the sources of the Gallatin. From this high ridge one can look down into the chasm of the Middle Fork, carved out of the basalt and basaltic conglomerates to the depth of 500 to 800 feet, with nearly vertical sides. In the sides of this cañon, as well as those of the East Fork, splendid examples of basaltic columns are displayed, as perfect as those of the celebrated Fingal's Cave. They usually appear in regular rows, vertical, five and six sided, but far more sharply cut than elsewhere seen in the West, though occasionally the columns are spread out in the form of a fan. Sometimes there are several rows, usually about fifty feet high, one above the other, with conglomerate between.

The cañon is about 500 yards from margin to margin at top, but narrows down until on the bottom it is not more than forty yards wide. At one point the water pours over a declivity of 300 feet or more, forming a most beautiful cascade. The direct fall is over 100 feet. The constant roar of the water is like that of a train of cars in motion. The pines are very dense, usually of moderate size, and among them are many open spaces, covered with stout grass, sometimes with large sage-bushes. Upon the high hills the vegetation is remarkably luxuriant, indicating[45] great fertility of soil, which is usually very thick, and made up mostly of degraded igneous rocks. Above the falls the rows of vertical, basaltic columns continue in the walls of the cañon, and they may well be ranked among the remarkable wonders of this rare wonder-land. The lower portion of the cañon is composed of rather coarse igneous rocks, which have a jointage and a style of weathering like granite. The West Fork rolls over a bed of basalt, which is divided into blocks that give the walls the appearance of mason-work on a gigantic scale. Below the falls the river has cut the sides of the mountain, exposing a vertical section 400 feet high, with the same irregular jointage.

South of the hot springs is a round dome-like mountain, rising 2,100 feet above them, or 8,500 feet above the sea. Its summit commands a prospect from thirty to fifty miles in every direction. To the north and west stands a group of lofty peaks over 10,000 feet above the sea, and covered with huge masses of snow. These peaks form a part of the range that separates the waters of the Gallatin from those of the Yellowstone. Farther on to the southward are the peaks of the head of the Madison, and in the interval one black mass of pine forest, covering high plateaus, with no point rising over 8,500[46] feet above the sea—the whole region being more or less wavy or rolling, interspersed here and there with beautiful lakes a few hundred yards in diameter; and here and there a bright-green grassy valley through which little streams wind their way to the large rivers. In one of these lakes the explorers saw the greatest abundance of yellow water-lily, which blooms in great profusion on the surface of all the mountain lakes of the Yellowstone Basin. On the east side of Gardiner's Cañon, and west of the Yellowstone, is a sort of wave-like series of ridges, with broad, open, grassy interspaces, with many groves of pines. These ridges gradually slope down to the Yellowstone, northeast. Far to the east and north is one jagged mass of volcanic peaks, some of them snow-clad, others bald and desolate to the eye. Far to the south, dimly outlined on the horizon, may be seen the three Tetons and Madison Peak—monarchs of all the region. A grander view could not well be conceived.

Leaving Gardiner's River, Dr. Hayden's party ascended the broad slope of the dividing ridge between that river and the streamlets which flow into the Yellowstone. Immense boulders of massive granite, considerably rounded, are a marked feature of the country about the entrance of the East Fork. One of these, a mass of red feldspathic granite, is[47] twenty-five feet thick and fifty feet long. The high wavy ridge, 9,000 feet above the sea, is composed of beds of steel-gray and brown sandstone and calcareous clay, in which are numerous impressions of deciduous leaves. Vast quantities of silicified wood of great perfection and beauty are scattered all over the surface. In some cases long trees have been turned to agate, the rings of growth as perfectly shown as in recent wood. The soil is very thick, and covered with luxuriant vegetation.

"We were travelling through this region in the latter part of the month of July," writes Dr. Hayden, "and all the vegetation seemed to be in the height of its growth and beauty. The meadows were covered densely with grass and flowers of many varieties, and among the pines were charming groves of poplars, contrasting strongly by their peculiar enlivening foliage with the sombre hue of the pines. The climate was perfect, and in the midst of some of the most remarkable scenery in the world, every hour of our march only increased our enthusiasm.

"The climate during the months of June, July, and August, in this valley, cannot be surpassed in the world for its health-giving powers. The finest of mountain water, fish in the greatest abundance, with a good supply of game of all kinds, fully satisfy the wants of the traveller, and render this valley[48] one of the most attractive places of resort for invalids or pleasure-seekers in America."

From the summit of the ridge the party descended to the valley of the Yellowstone, nearly opposite the mouth of the East Fork of that river. The road was a rough one. During the period of volcanic action in this region, the sedimentary rocks were crumpled into high, sharp, wave-like series of ridges; from innumerable fissures, igneous matter was poured out over the surface cooling into basalt; and from volcanic vents was also thrown out, into the great lake, rock fragments and volcanic dust, which were arranged by the water and cemented into a breccia. Deep into these ridges the little streams have cut their channels, forming what should be called valleys, rather than cañons, with almost vertical sides. These ravines, 500 to 800 feet deep, covered mostly with grass or trees, occur in great numbers, many of them entirely dry at present, but attesting the presence and power, at no very remote period, of aqueous forces compared with which those of the present are utterly insignificant.

Before studying this portion of the Yellowstone Valley, it may be well to retrace our steps to the mouth of Gardiner's River, to explore the Third Cañon of the Yellowstone, so far as possible, and the rest of its interesting valley up to this point.

As already noticed, the country about the mouth of Gardiner's River is desolate and gloomy. The hill-slopes are covered with sage brush, the constant sign of arid soil, and grass is scarce. This is the first poor camping-place on the route. The cañon being impassable, the trail passes to the right, crossing several high mountain-spurs, over which the way is much obstructed by fallen timber, and reaching at last a high rolling plateau. This elevated tract is about thirty miles in extent, with a general declivity to the north. Its surface is an undulating prairie, dotted with groves of pine and aspen. Numerous lakes are scattered throughout its whole extent, and great numbers of springs, which flow down the slopes, are lost in the volume of the Yellowstone. The river breaks through this plateau in a winding cañon over 2,000 feet in depth—the middle cañon of the Yellowstone rolling over volcanic boulders in some places, and in others forming still pools of seemingly fathomless depth. At one point it dashes to and fro, lashed to a white foam on its rocky bed; at another, where a deep basin occurs in the channel, it subsides into a crystal mirror. Numerous small cascades are seen tumbling from the rocky walls at different points and the river appears from the lofty summits a mere ribbon of foam in the immeasurable distance[50] below. Standing on the brink of the chasm the heavy roaring of the imprisoned river comes to the ear only in a sort of hollow, hungry growl, scarcely audible from the depths. Lofty pines on the bank of the stream "dwindle to shrubs in dizziness of distance." Everything beneath, says Lieut. Doane, has a weird and deceptive appearance. The water does not look like water, but like oil. Numerous fish-hawks are seen busily plying their vocation, sailing high above the waters, and yet a thousand feet below the spectator. In the clefts of the rocks down, hundreds of feet down, bald eagles have their eyries, from which one can see them swooping still farther into the depths to rob the ospreys of their hard-earned trout. It is grand, gloomy, and terrible; a solitude peopled with fantastic ideas; an empire of shadows and of turmoil.

The plateau formation is of lava, generally in horizontal layers, as it cooled in a surface flow, yet upheaved in many places into wave-like undulations. Occasionally granite shafts protrude through the strata, forming landmarks of picturesque form. Like dark icebergs stranded in an ocean of green, they rise high above the tops of the trees in wooded districts, or stand out grim and solid on the grassy expanse of the prairies.

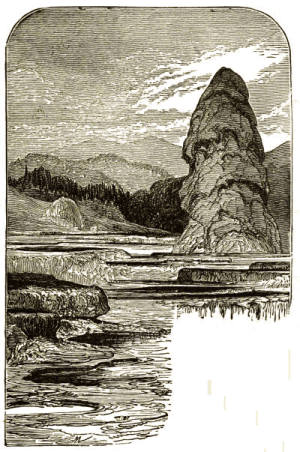

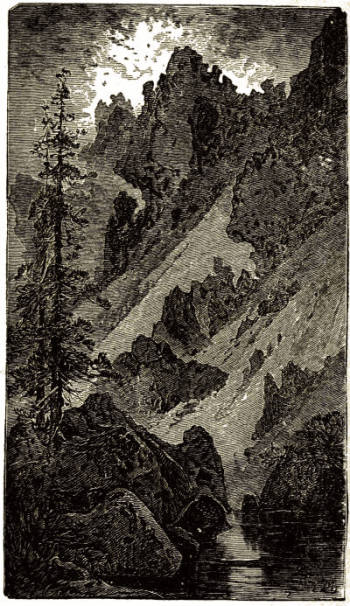

EXTINCT GEYSER, EAST FORK OF THE YELLOWSTONE.

Near the head of the Third Cañon a stream flows into the Yellowstone from the northeast, bearing the sonorous title, Hell-Roaring River. It is quite a large stream, rising high among the mountains, and flowing with tremendous impetuosity down the deep gorges. The mountains on either side come close down to the channel of the Yellowstone, and are among the most rugged in this rugged region. A huge peak of this sort, composed of stratified gneiss, with deep strata of massive red and grey granite, stands at the mouth of Hell-Roaring River, and takes to itself the same imposing name. A short distance above the mouth of Hell Roaring River, the East Fork of the Yellowstone comes in from the southeast. Its sources are high up among the most rugged and inaccessible portions of the basaltic range, several jagged peaks which rise from 10,000 to 11,000 feet above the sea.

"The summits of these high peaks," observes Mr. Hayden, "are all close, compact trachyte, while all around the sides are built up walls of stratified conglomerate. It is plain that all of them are the nuclei of old volcanoes. The trachyte may sometimes be concealed by the conglomerates, but I am inclined to think that each one has formed a centre of effusion. Large quantities of silicified wood are found among the conglomerates, mostly inclosed in the volcanic cement, evidently thrown out of the[52] active craters with the fragments of basalt. My impression is, that when the old volcanoes disgorged their contents into the great lake of waters around, they threw out also portions from the sedimentary formations, and thus the silicified wood comes from the Tertiary or Cretaceous beds, which may have formed the upper part of the walls of the crater. At any rate, these woods belong to the Coal Series of the West, and they are scattered profusely among the conglomerates. Interlaced among the massive beds of volcanic conglomerates are some layers of a light-grey or whitish sandy clay, which show that the whole breccia or conglomerates, with the intercalated layers of clay or sand, were deposited in water like any sedimentary water rocks."

Interesting ruins of ancient springs abound in this valley. Mr. Hayden describes one, a very curious mammiform mound of calcareous deposit, about forty feet high, built up by overlapping layers like those of Liberty Cap on Gardiner's River.

"This cone is a complete ruin. No water issues from it at the present time, and none of the springs in the vicinity are above the ordinary temperature of brook-water; sulphur, alum, and other chemical deposits are abundant. This old ruin is a fine example of the tendency of the cone to close up its[53] summit in its dying stages. The top of the cone is somewhat broken; but it is eighteen feet in diameter at this time, and near the centre there is a hole or chimney two inches in diameter, plainly a steam-vent. This marks the closing history of this spring. The inner portions of this small chimney are lined with white enamel, thickly coated with sulphur, which gives it a sulphur-yellow hue. The base upon which the cone rests varies in thickness. On the east side huge masses have been broken off, exposing a vertical wall twenty feet high, built up of thin horizontal laminæ of limestone. On the west side the wall is not quite as high, perhaps eight or ten feet. It would seem, therefore, that it was at first an overflowing spring, depositing thin horizontal layers until it built up a broad base ten to twenty feet in height; then it gradually became a spouting spring, building up with overlapping layers like the thatch on a house, until it closed itself at the top and ceased."

In the tongue that runs down between the junction of the East Fork and the Yellowstone, there is a singular butte cut off from the main range, which at once attracts the traveller's attention. The basis or lower portion of the butte is granite, while the summit is capped with the modern basalt, and the débris on the sides and at the base is remarkable in[54] quantity, and has very much the appearance of an anthracite coal-heap. This butte will always form a conspicuous landmark, not only on account of its position, but also from its peculiar shape and structure.

Just below the junction of the East Fork the first and only bridge across the Yellowstone was constructed in 1870 for the accommodation of miners bound for the "diggings" on Clark's Fork. It was a work of considerable boldness, as the river is some two hundred feet wide, and flows with great rapidity over its narrow and rocky channel.

A short distance above the bridge, on the west side of the Yellowstone, is a splendid exhibition of black micaceous gneiss, forming a vertical wall on the right side of a little creek, while on the left the entire mass of the hills for miles in extent is composed of the usual igneous rocks. Through these rocks the stream, now not more than four feet wide and six inches deep, has cut a channel from two hundred to four hundred yards wide, through the hardest rocks to a depth varying from five hundred to a thousand feet!

Further up the Yellowstone, on the same side, are a number of wonderful ravines and cañons carved in like manner into the very heart of the mountains. Most conspicuous of these is the[55] Cañon of Tower Greek. Before reaching that stream, however, Column Rock, a noticeable feature in a landscape of great extent and beauty, demands at least a passing notice. Column Cliff would be a more appropriate name, since it extends along the east bank of the river upwards of two miles. Says Mr. Langford, whose observations were made from the west side: "At the distance from which we saw it, we could compare it in appearance to nothing but a section of the Giant's Causeway. It was composed of successive pillars of basalt overlying and underlying a thick stratum of cement and gravel resembling pudding-stone. In both rows, the pillars, standing in close proximity, were each about thirty feet high and from three to five feet in diameter. This interesting object, more from the novelty of its formation and its beautiful surroundings of mountain and river scenery than anything grand or impressive in its appearance, excited our attention, until the gathering shades of evening reminded us of the necessity of selecting a suitable camp."

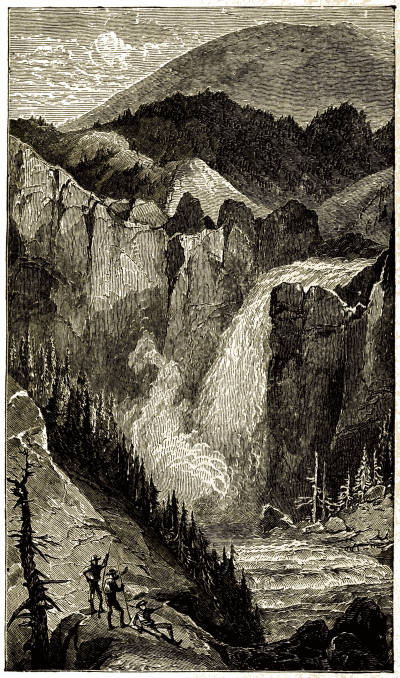

Tower Creek rises in the high divide between the valleys of the Missouri and the Yellowstone, and flows for about ten miles through a cañon so deep and gloomy that it has earned the appellation,[56] "Devil's Den." About two hundred yards above its entrance into the Yellowstone, the stream pours over an abrupt descent of one hundred and fifty-six feet, forming one of the most beautiful falls to be found in any country. These falls are about 260 feet above the level of the Yellowstone at the junction, and are surrounded with columns of volcanic breccia, rising fifty feet above the falls and extending down to the foot, standing like gloomy sentinels, or like gigantic pillars at the entrance of some grand temple. "One could almost imagine," says Dr. Hayden, "that the idea of the Gothic style of architecture had been caught from such carvings of nature."

Speaking of the symmetry of some of these columns, Mr. Langford says:

"Some resemble towers, others the spires of churches, and others still shoot up as lithe and slender as the minarets of a mosque. Some of the loftiest of these formations, standing like sentinels upon the very brink of the fall, are accessible to an expert and adventurous climber. The position attained on one of their narrow summits, amid the uproar of waters and at a height of 250 feet above the boiling chasm, as the writer can affirm, requires a steady head[57] and strong nerves; yet the view which rewards the temerity of the exploit is full of compensations. Below the fall the stream descends in numerous rapids, with frightful velocity, through a gloomy gorge, to its union with the Yellowstone. Its bed is filled with enormous boulders, against which the rushing waters break with great fury.

Many of the capricious formations wrought from the shale excite merriment as well as wonder. Of this kind especially was a huge mass sixty feet in height, which, from its supposed resemblance to the proverbial foot of his Satanic Majesty, we called the "Devil's Hoof." The scenery of mountain, rock, and forest surrounding the falls is very beautiful. Here, too, the hunter and fisherman can indulge their tastes with the certainty of ample reward. As a half-way resort to the greater wonders still farther up the marvellous river, the visitor of future years will find no more delightful resting-place. The name of "Tower Falls," which we gave it, was suggested by some of the most conspicuous features of the scenery."

THE DEVIL'S HOOF.

The sides of the chasm are worn into caverns lined with variously-tinted mosses, nourished by clouds of spray which rise from the cataract; while above, and to the left, a spur from the great plateau rises over all, with a perpendicular front of 400 feet. The fall is accessible both at the brink and at the foot, and fine views can be obtained from either side of the cañon. In appearance it strongly resembles Minnehaha, but is several times as high, and the volume of water is at least eight times as great. In the basin a large petrified log was found imbedded in the débris. "Nothing," says Lieutenant[59] Doane, "can be more chastely beautiful than this lovely cascade, hidden away in the dim light of overshadowing rocks and woods, its very voice hushed to a low murmur, unheard at the distance of a few hundred yards. Thousands might pass by within a half mile and not dream of its existence; but once seen, it passes to the list of most pleasant memories."

Along the Yellowstone, near the mouth of Tower Creek, is a system of small mineral springs distributed for a distance of two miles in the bottom of the deep cañon through which the river runs. Several of these springs have a temperature at the boiling point; many are highly sulphurous, holding, in fact, more sulphur than they can carry in solution, and depositing it in yellowish beds along their courses. Several of them are impregnated with iron, alum, and other substances. Their sulphurous fumes can be detected at the distance of half a mile. The excess of sulphur in the rock-walls of the cañon give a brilliant yellow color to the rocks in many places. The formation is usually very friable, falling with a natural slope to the edge of the stream, but occasionally masses of a more solid nature project from the wall in curious shapes of towers, minarets, and the like; while over all the solid ledge of trap, with its dark and well-defined columns, makes[60] a rich and beautiful border inclosing the pictured rocks below.

This is the mouth of the Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone.

CHAPTER VII.

OVER MOUNT WASHBURN TO THE FALLS OF THE YELLOWSTONE.

The Upper or Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone extends from the mouth of Tower Creek to the foot of the Great Fall, a distance of twenty miles. It is impassable throughout its entire length, and accessible to the water's edge only at few points and by dint of severe labor. The trail ascends the divide between Tower Creek and the Yellowstone, skirting for six or eight miles the cañon of Tower Creek. The ground rises rapidly and is much broken by creek-beds running parallel with the river. Following the highest ridges, the first explorers reached at last a point whence they could overlook the Grand Cañon cleaving the slopes and breaking through the lofty mountain ranges in front. Here they caught their first glimpse of a phenomenon afterwards to become a familiar sight to them. Through the mountain gap formed by the cañon,[62] and on the interior slopes some twenty miles distant, an object appeared which drew a simultaneous expression of wonder from every one in the party. It was a column of steam, rising from the dense woods to the height of several hundred feet. They had all heard fabulous stories of this region, and were somewhat skeptical of appearances. At first it was pronounced a fire in the woods, but presently some one noticed that the vapor rose in regular puffs, as if expelled with a great force. Then conviction was forced upon them. It was, indeed, a great column of steam, puffing away on the lofty mountain side, with a roaring sound, audible at a long distance, even through the heavy forest. A hearty cheer rang out at this discovery, and they pressed onward with renewed enthusiasm.

The highest peak of this ridge was named by the first company who climbed it—Mount Washburn—in honor of their leader. The view from its summit is "grand beyond description;" yet some conception of its grandeur can be formed, let us hope, from the graphic review of its more striking features by Lieutenant Doane.

"Looking northward, the great plateau stretches away from the base of the mountain to the front and left with its innumerable groves and sparkling waters, a variegated landscape of surpassing beauty,[63] bounded on its extreme verge by the cañons of the Yellowstone. The pure atmosphere of this lofty region causes every outline of tree, rock, or lakelet to be visible with wonderful distinctness, and objects twenty miles away appear as if very near at hand. Still further to the left the snowy ranges on the headwaters of Gardiner's River stretch away to the westward, joining those on the head of the Gallatin, and forming, with the Elephant's Back, a continuous chain, bending constantly to the south, the rim of the Yellowstone Basin. On the verge of the horizon appear, like mole-hills in the distance, and far below, the white summits above the Gallatin Valley. These never thaw during the summer months, though several thousand feet lower than where we now stand upon the bare granite, and no snow visible near, save in the depths of shaded ravines. Beyond the plateau to the right front is the deep valley of the East Fork bearing away eastward, and still beyond, ragged volcanic peaks, heaped in inextricable confusion, as far as the limit of vision extends. On the east, close beneath our feet, yawns the immense gulf of the Grand Cañon, cutting away the bases of two mountains in forcing a passage through the range. Its yellow walls divide the landscape nearly in a straight line to the junction of Warm Spring (Tower) Creek below. The[64] ragged edges of the chasm are from two hundred to five hundred yards apart, its depth so profound that the river bed is nowhere visible. No sound reaches the ear from the bottom of the abyss; the sun's rays are reflected on the farther wall and then lost in the darkness below. The mind struggles and then falls back upon itself, despairing in the efforts to grasp by a single thought the idea of its immensity. Beyond, a gentle declivity, sloping from the summit of the broken range, extends to the limit of vision, a wilderness of unbroken pine forest.

"Turning southward, a new and strange scene bursts upon the view. Filling the whole field of vision, and with its boundaries in the verge of the horizon, lies the great volcanic basin of the Yellowstone—nearly circular in form, from fifty to seventy-five miles in diameter; and with a general depression of about 2,000 feet below the summits of the great ranges which form its outer rim. Mount Washburn lies in the point of the circumference, northeast from the centre of the basin; far away in the southwest, the three great Tetons on Snake River fill another space in the circle; connecting these two highest are crescent ranges, one westward and south, past Gardiner's River and the Gallatin, bounding the lower Madison, thence to the[65] Jefferson and by the Snake River range to the Tetons; another eastward and south, a continuous range by the head of Rose Bud, inclosing the sources of the Snake, and joining the Tetons beyond. Between the south and west points, this vast circle is broken through in many places for the passage of the rivers; but a single glance at the interior slopes of the ranges shows that a former complete connection existed, and that the great basin has been one vast crater of a now extinct volcano. The nature of the rocks, the steepness and outline of the interior walls, together with other peculiarities to be mentioned hereafter, render this conclusion a certainty. The lowest point in this great amphitheatre lies directly in front of us, and about eight miles distant: a grassy valley, branching between low ridges, running from the river toward the centre of the basin. A small stream rises in this valley, breaking through the ridges to the west in a deep cañon, and falling into the channel of the Yellowstone, which here bears in a northeast course, flowing in view as far as the confluence of the small stream, thence plunged into the Grand Cañon, and hidden from sight. No falls can be seen, but their location is readily detected by the sudden disappearance of the river; beyond this open valley the basin appears to be filled with a succession of low,[66] converging ridges, heavily timbered, and all of about an equal altitude.