Title: The Lives of the Saints, Volume 01 (of 16): January

Author: S. Baring-Gould

Release date: September 24, 2014 [eBook #46947]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Matthias Grammel, Greg Bergquist and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

THE

REV. S. BARING-GOULD

SIXTEEN VOLUMES

VOLUME THE FIRST

THE

Lives of the Saints

BY THE

REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A.

New Edition in 16 Volumes

Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of

English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints,

and a full Index to the Entire Work

ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS

VOLUME THE FIRST

January

LONDON

JOHN C. NIMMO

14 KING WILLIAM STREET, STRAND

MDCCCXCVII

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

he Lives of the Saints, which I have begun, is an undertaking, of whose difficulty few can have any idea. Let it be remembered, that there were Saints in every century, for eighteen hundred years; that their Acts are interwoven with the profane history of their times, and that the history, not of one nation only, but of almost every nation under the sun; that the records of these lives are sometimes fragmentary, sometimes mere hints to be culled out of secular history; that authentic records have sometimes suffered interpolation, and that some records are forgeries; that the profane history with which the lives of the Saints is mixed up is often dark and hard to be read; and then some idea may be formed of the difficulty of this undertaking.

After having had to free the Acts of a martyr from a late accretion of fable, and to decide whether the passion took place under—say Decius or Diocletian, Claudius the Elder, or Claudius the younger,—the writer of a hagiology is hurried into Byzantine politics, and has to collect the thread of a saintly confessor's [Pg vi] life from the tangle of political and ecclesiastical intrigue, in that chaotic period when emperors rose and fell, and patriarchs succeeded each other with bewildering rapidity. And thence he is, by a step, landed in the romance world of Irish hagiology, where the footing is as insecure as on the dark bogs of the Emerald Isle. Thence he strides into the midst of the wreck of Charlemagne's empire, to gather among the splinters of history a few poor mean notices of those holy ones living then, whose names have survived, but whose acts are all but lost. And then the scene changes, and he treads the cool cloister of a mediæval abbey, to glean materials for a memoir of some peaceful recluse, which may reflect the crystalline purity of the life without being wholly colourless of incident.

And then, maybe, he has to stand in the glare of the great conflagration of the sixteenth century, and mark some pure soul passing unscathed through the fire, like the lamp in Abraham's vision.

That one man can do justice to this task is not to be expected. When Bellarmine heard of the undertaking of Rosweydus, he asked "What is this man's age? does he expect to live two hundred years?" But for the work of the Bollandists, it would have been an impossibility for me to undertake this task. But even with this great storehouse open, the work to be got through is enormous. Bollandus began January with two folios in double columns, close print, of 1200 pages each. As he and his coadjutors proceeded, fresh materials came in, and February occupies three volumes. May swelled into seven folios, September [Pg vii] into eight, and October into ten. It was begun in 1643, and the fifty-seventh volume appeared in 1861.

The labour of reading, digesting, and selecting from this library is enormous. With so much material it is hard to decide what to omit, but such a decision must be made, for the two volumes of January have to be crushed into one, not a tenth of the size of one of Bollandus, and the ten volumes for October must suffer compression to an hundredth degree, so as to occupy the same dimensions. I had two courses open to me. One to give a brief outline, bare of incident, of the life of every Saint; the other to diminish the number of lives, and present them to the reader in greater fulness, and with some colour. I have adopted this latter course, but I have omitted no Saint of great historical interest. I have been compelled to put aside a great number of lesser known saintly religious, whose eventless lives flowed uniformly in prayer, vigil, and mortification.

In writing the lives of the Saints, I have used my discretion, also, in relating only those miracles which are most remarkable, either for being fairly well authenticated, or for their intrinsic beauty or quaintness, or because they are often represented in art, and are therefore of interest to the archæologist. That errors in judgment, and historical inaccuracies, have crept into this volume, and may find their way into those that succeed, is, I fear, inevitable. All I can promise is, that I have used my best endeavours to be accurate, having had recourse to all such modern critical works as have been accessible to me, for the determining of dates, and the estimation of authorities.

Believing that in some three thousand and six hundred memoirs of men, many of whose lives closely resembled each other, it would be impossible for me to avoid a monotony of style which would become as tedious to the reader as vexatious to myself, I have occasionally admitted the lives of certain Saints by other writers, thereby giving a little freshness to the book, where there could not fail otherwise to have been aridity; but I have, I believe, in no case, inserted a life by another pen, without verifying the authorities.

At the head of every article the authority for the life is stated, to which the reader is referred for fuller details. The editions of these authorities are not given, as it would have greatly extended the notices, and such information can readily be obtained from that invaluable guide to the historian of the Middle Ages, Potthast: Bibliotheca Historica Medii Ævi, Berlin, 1862; the second part of which is devoted to the Saints.

I have no wish that my work should be regarded as intended to supplant that of Alban Butler. My line is somewhat different from his. He confined his attention to the historical outlines of the saintly lives, and he rarely filled them in with anecdote. Yet it is the little details of a man's life that give it character, and impress themselves on the memory. People forget the age and parentage of S. Gertrude, but they remember the mouse running up her staff.

A priest of the Anglican Church, I have undertaken to write a book which I hope and trust will be welcome to Roman and Anglican Catholics, alike. It would have been unseemly to have carried prejudice, impertinent [Pg ix] to have obtruded sectarianism, into a work like this. I have been called to tread holy ground, and kneel in the midst of the great company of the blessed; and the only fitting attitude of the mind for such a place, and such society, is reverence. In reading the miracles recorded of the Saints, of which the number is infinite, the proper spirit to observe is, not doubt, but discrimination. Because much is certainly apocryphal in these accounts, we must not therefore reject what may be true. The present age, in its vehement naturalism, places itself, as it were, outside of the circle of spiritual phenomena, and is as likely to deny the supernatural agency in a marvel, as a mediæval was liable to attribute a natural phenomenon to spiritual causes. In such cases we must consider the evidence and its worth or worthlessness. It may be that, in God's dealings with men, at a time when natural means of cure were unattainable, the supernatural should abound, but that when the science of medicine became perfected, and the natural was rendered available to all, the supernatural should, to some extent, at least, be withdrawn.

Of the Martyrologies referred to, it may be as well to mention the dates of the most important. That of Ado is of the ninth century, Bede's of the eighth;[1] there are several bearing the name of S. Jerome, which differ from one another, they are forms of the ancient Roman Martyrology. The Martyrology of Notker (D. 912), of Rabanus Maurus (D. 856), of Usuardus (875), of Wandalbert (circ. 881). The general catalogue of the Saints by Ferrarius was [Pg x] published in 1625, the Martyrology of Maurolycus was composed in 1450, and published 1568. The modern Roman Martyrology is based on that of Usuardus. It is impossible, in the limited space available for a preface, to say all that is necessary on the various Kalendars, and Martyrologies, that exist, also on the mode in which some of the Saints have received apotheosis. Comparatively few Saints have received formal canonization at Rome; popular veneration was regarded as sufficient in the mediæval period, before order and system were introduced; thus there are many obscure Saints, famous in their own localities, and perhaps entered in the kalendar of the diocese, whose claims to their title have never been authoritatively inquired into, and decided upon. There is also great confusion in the monastic kalendars in appropriating titles to those commemorated; here a holy one is called "the Venerable," there "the Blessed," and in another "Saint." With regard also to the estimation of authorities, the notes of genuineness of the Acts of the martyrs, the tests whereby apocryphal lives and interpolations may be detected, I should have been glad to have been able to make observations. But this is a matter which there is not space to enter upon here.

The author cannot dismiss the work without expressing a hope that it may be found to meet a want which he believes has long been felt; for English literature is sadly deficient in the department of hagiology.

[1] This only exists in an interpolated condition.

martyrology means, properly, a list of witnesses. The martyrologies are catalogues in which are to be found the names of the Saints, with the days and places of their deaths, and generally with the distinctive character of their sanctity, and with an historic summary of their lives. The name is incorrect if we use the word "martyr" in its restricted sense as a witness unto death. "Hagiology" would be more suitable, as a martyrology includes the names of many Saints who were not martyrs. But the term "Martyrology" was given to this catalogue at an early age, when it was customary to commemorate only those who were properly martyrs, having suffered death in testimony to their faith; but it is not unsuitable if we regard as martyrs all those who by their lives have testified to the truth, as indeed we are justified in doing.

In the primitive Church it was customary for the [Pg xii] Holy Eucharist to be celebrated on the anniversary of the death of a martyr—if possible, on his tomb. Where in one diocese there were several martyrs, as, for instance, in that of Cæsarea, there were many days in the year on which these commemorations were made, and the Church—say that of Cæsarea—drew up a calendar with the days marked on which these festivals occurred.

In his "Church History," Eusebius quotes a letter from the Church of Smyrna, in which, after giving an account of the martyrdom of their bishop, S. Polycarp, the disciple of S. John the Divine, the Smyrnians observe: "Our subtle enemy, the devil, did his utmost that we should not take away the body, as many of us anxiously wished. It was suggested that we should desert our crucified Master, and begin to worship Polycarp. Fools! who knew not that we can never desert Christ, who died for the salvation of all men, nor worship any other. Him we adore as the Son of God; but we show respect to the martyrs, as His disciples and followers. The centurion, therefore, caused the body to be burned; we then gathered his bones, more precious than pearls, and more tried than gold, and buried them. In this place, God willing, we will meet, and celebrate with joy and gladness the birthday of this martyr, as well in memory of those who have been crowned before, as by his example to prepare and strengthen others for the combat."[2]

S. Polycarp suffered in the year 166; he had been ordained Bishop of Smyrna by S. John in 96. This passage is extremely interesting, for it shows us, in the age following that of the apostles, the Church already keeping the festivals of martyrs, and, as we may conclude from the words of the letter, over the tombs of the martyrs. In this the Church was following the pattern shown to S. John in vision; for he heard the cry of the souls of the martyrs reposing under the altar in heaven. Guided, doubtless, by this, the Church erected altars over the bodies of saints. Among the early Christian writers there are two, S. Paulinus of Nola, and Prudentius, whose testimony is of intrinsic value, not only from its being curiously interesting, but because it is so full and unequivocal as to the fact of the tombs of the martyrs being used as altars.[3] In one of his letters to Severus, S. Paulinus encloses some verses of his own composition, which were to be inscribed over the altar under which was deposited the body of S. Clavus, of whom the venerable prelate says:

Before describing the basilica of Nola, the Saint proceeds to give a sketch of another but a smaller church, which he had just erected in the town of Fondi. After furnishing some details about this latter edifice, he says, "The sacred ashes—some of the blessed relics of the apostles and martyrs—shall consecrate this little basilica also in the name of Christ, the Saint of saints, the Martyr of martyrs, and the Lord of lords."[5] For this church two inscriptions were composed by Paulinus: one, to accompany the painting with which he had adorned the apse; the other, to announce that portions of the relics of the Apostle S. Andrew, of the Evangelist S. Luke, and of S. Nazarius, and other martyrs, were deposited under the altar. His verses may be thus rendered:

Prudentius visited not only the more celebrated churches in Spain built over the bodies of the martyrs, he being a Spaniard by birth, but he also visited those of Italy and Rome on a journey made in 405. During his residence in the capital of Christianity, the poet frequented the catacombs; and he has bequeathed to us a valuable record of what he there saw. In his hymn in honour of S. Hippolytus, he tells us that he visited the sepulchral chapel in which were deposited the remains of the martyr; and, after having described the entrance into the cemetery, and the frescoes that adorned it, he adds:

In his other hymns, Prudentius bears the most unequivocal testimony to the practice, even then a long time in use, of depositing the relics of the Saints immediately under the altar. It is unnecessary to quote more. The assertions of ancient writers on this point have been several times verified. The bodies of the martyrs have been discovered under the high altars of the churches dedicated to God in their memory. The body of S. Martina, together with those of two other martyrs, SS. Concordens and Epiphanius, were found in 1624 under the high altar of the ancient church near the Roman Forum, which bears the name of the Saint. The body of S. Agnes, and that of another virgin martyr, were also ascertained to be under the high altar of her church, denominated Fuori delle Mura. These, however, had all been removed from the Catacombs into Rome, within the walls.

Now this fact being established, as well as that of the annual commemoration of the Saint reposing in the church, it follows that it became necessary for a Church to draw up calendars marking those days in the year which were consecrated to the memory of martyrs whose relics were preserved in it; for instance, in the Church of Fondi, which contained relics of S. Andrew, S. Luke, S. Nazarius, and others, the Holy Eucharist would be celebrated over the relics on the day of S. Andrew, on that of S. Luke, on that of S. Nazarius, and so on; and it would be necessary for the Church to have a calendar of the days thus set apart.

In the first centuries of the Church, not only the Saints whose bodies reposed in the church, but also the dead of the congregation were commemorated.

When a Roman Consul was elected, on entering on his office he distributed among his friends certain presents, called diptychs. These diptychs were folding tablets of ivory or boxwood, sometimes of silver, connected together by hinges, so that they could be shut or opened like a book. The exterior surface was richly carved, and generally bore a portrait of the Consul who gave them away. Upon the inner surface was written an epistle which accompanied the present, or a panegyric on himself. They were reminders to friends, given much as a Christmas card is now sent. The diptych speedily came into use in the Church. As the Consul on his elevation sent one to his friends to remind them of his exaltation, so, on a death in the congregation, a diptych was sent to the priest as a reminder of the dead who desired the prayers of the faithful. At first, no doubt, there was a pack of these little memorials, each bearing the name of the person who desired to be remembered at the altar. But, for convenience, one double tablet was after a while employed instead of a number, and all the names of those who were to be commemorated were written in this book. From the ancient liturgies we gather that it was the office of the deacon to rehearse aloud, to the people and the priest, this catalogue registered in the public diptychs. In the "Ecclesiastical Hierarchy," attributed to S. Dionysius the Areopagite, but really of a later date, the end of the fifth century, the author says of the ceremonies of the Eucharist, that [Pg xvii] after the kiss of peace, "When all have reciprocally saluted one another, there is made the mystic recitation of the sacred tablets."[7] In the Liturgy of S. Mark we have this, "The deacon reads the diptychs (or catalogue) of the dead. The priest then bowing down prays: To the souls of all these, O Sovereign Lord our God, grant repose in Thy holy tabernacle, in Thy kingdom, bestowing on them the good things promised and prepared by Thee," etc.

It is obvious that after a while the number of names continually swelling would become too great to be recited at once. It became necessary, therefore, to take some names on one day, others on another. And this originated the Necrologium, or catalogue of the dead. The custom of reading the diptychs has ceased to be observed in the Roman Liturgy, though we find it indicated there by the "Oratio supra Diptycha." At present, when the celebrating priest arrives at that part of the Canon called the "Memento," he secretly commemorates those for whose souls he more particularly wishes to pray.

But, in addition to the diptychs of those for whom the priest and congregation were desired to pray, there was the catalogue of the Martyrs and Saints for whom the Church thanked God. For instance, in the modern Roman Mass, in the Canon we have this commemoration: "Joining in communion with, and reverencing, in the first place, the memory of the glorious and ever-virgin Mary, Mother of our God and Lord Jesus Christ; as also of Thy blessed apostles and martyrs, Peter and Paul, Andrew, James, John, Thomas, James, Philip, Bartholomew, Matthew, Simon and Thaddæus; Linus, Cletus, Clement, Xystus, Cornelius, Cyprian, Laurence, Chrysogonus, John and Paul, Cosmas and Damian, and of all Thy Saints," etc. This is obviously a mere fragment of a commemoration of the Blessed Virgin, of the apostles, and then of the special Roman martyrs. The catalogue of the Saints to be remembered was long; there were hundreds of martyrs at Rome alone, and their names were written down on sacred diptychs especially appropriated to this purpose. Such an inscription was equivalent to the present ceremony of canonization. The term canonization itself tells the history of the process. It is derived from that part of the Mass called the Canon, in which occurs that memorial already quoted. On the day when the Pope, after a scrutinizing examination into the sanctity of a servant of God, formally inscribes him among the Saints, he adds his name at the end of those already enumerated in the Canon, after "Cosmas and Damian," and immediately reads Mass, adding this name at this place. Formerly every bishop could and did canonize—that is, add the name of any local Saint or martyr worthy of commemoration in his diocese.

When the list became long, it was found impracticable to commemorate all nominatim at once, and the Saints were named on their special days. Thus, out of one set of diptychs grew the Necrologium, and out of the other the Martyrology.

The Church took pains to collect and commit to writing the acts of the martyrs. This is not to be wondered at; for the martyrs are the heroes of [Pg xix] Christianity, and as the world has her historians to record the achievements of the warriors who have gained renown in conflict for power, so the Church had her officers to record the victories that her sons won over the world and Satan. The Saints are the elect children of the spouse of Christ, the precious fruit of her body; they are her crown of glory. And when these dear children quit her to reap their eternal reward, the mother retains precious memorials of them, and holds up their example to her other children to encourage them to follow their glorious traces.

The first to institute an order of scribes to take down the acts of the martyrs was S. Clement, the disciple of S. Peter, as we are told by Pope S. Damasus, in the "Liber Pontificale."[8] According to this tradition, S. Clement appointed seven notaries, men of approved character and learning, to collect in the city of Rome, each in his own region of the city, the acts of the martyrs who suffered in it. To add to the guarantee of good faith, Pope S. Fabian[9] placed these seven notaries under the control of the seven subdeacons, who with the seven deacons were placed over the fourteen cardinal regions of the city of Rome. Moreover, the Roman Pontiffs obtained the acts of martyrs who had suffered in other churches. These acts were the procès verbal of their trial, with the names of the judges under whom they were sentenced, and an account of the death endured. The acts of S. Philip of Heraclea, SS. Hilary and Tatian, and [Pg xx] SS. Peter, Paul, Andrew, and Dionysia, are examples of such acts. Other acts were those written by eye-witnesses, sometimes friends of the martyrs; those of the martyrs, SS. Perpetua, Felicitas, and their companions are instances. The first part of these was written by S. Perpetua herself, and reaches to the eve of her martyrdom; then another confessor in the same prison took the pen and added to the eve of his death, and the whole was concluded by an eye-witness of their passion. Other acts again were written by those who, if not eye-witnesses, were able, from being contemporaries and on the spot, to gather reliable information; such are the narratives of the martyrs of Palestine by Eusebius, Bishop of Cæsarea. Unfortunately, comparatively few of the acts of the martyrs have come down to us in their genuine freshness; and the Church of Rome, which set the example in appointing notaries to record the facts, has been most careless about preserving these records unadulterated; so that even the acts of some of her own bishops and martyrs, S. Alexander, and S. Marcellinus, and S. Callixtus, are romances devoid of all stamp of truth.

Tertullian[10] says that on the natal days, that is, on the days of martyrdom of the Saints who have suffered for Christ, "We keep an annual commemoration." It is easy to see how this usage necessitated the drawing up of lists in which were inscribed not only the names of the martyrs, and the place of their decease, but also a few words relative to their conflict, so that the people might associate their names with their victories, [Pg xxi]and the names might not become, in time, to them empty sounds. S. Cyprian was absent from Carthage when the persecution was raging there, but he wrote to his clergy, "Note the days of their death, that we may celebrate their commemorations along with the memorials of the martyrs."[11] S. Augustine says,[12] "The Christian people celebrate the memory of the martyrs with religious solemnity, both to excite to imitation, and that they may become fellows in their merits and be assisted by their prayers."

Adrian I. quotes the 13th Canon of the African Church and the 47th of the third Carthaginian Council, in a letter to Charlemagne, in which he says, "The Sacred Canons approved of the passions of the Holy Martyrs being read in Church when their anniversary days were being celebrated."

The names of the martyrs to be commemorated were announced on the eve. By degrees other names besides those of martyrs were introduced into the Martyrologies, as those of faithful servants of God whose lives were deserving of imitation, but who had not suffered to the death in testimony to the truth. Thus we have confessors, or those who endured hardships for Christ, doctors, or teachers of the Church, virgins, widows, bishops and abbots, and even penitents.

The Martyrologies may be divided into two series, the ancient and the modern. We need only concern ourselves with the Ancient Martyrologies.

The first to draw up a tolerably full Martyrology was Eusebius the historian, Bishop of Cæsarea in Palestine, and he did this at the request of the Emperor Constantine. In this Martyrology he noted all the martyrs of whom he had received an authentic account on the days of their suffering, with the names of the judges who sentenced them, the places where they suffered, and the nature of their sufferings. Eusebius wrote about a.d. 320, but there were collections of the sort already extant, as we may learn from the words of S. Cyprian already quoted, who in his instructions to his clergy ordered them to compile what was practically a Martyrology of the Carthaginian Church.

We have not got the Greek Martyrology of Eusebius, but we have the Latin version made by S. Jerome. Bede says of this, "Jerome was not the author, but the translator of this book; Eusebius is said to have been the author."

But even this Latin version has not come down to us in its original form. There are numerous copies, purporting to be the Martyrology of S. Jerome, still extant, but hardly two of them agree. The copies have been amplified. The occasion of S. Jerome making his translation was as follows. At the Council of Milan, held in 390, the presiding Bishop, Gregory of Cordova, read out daily on the eve, as usual, the lists of martyrs whose anniversary was to be celebrated on the morrow. As a good number of those present knew nothing of the martyrs thus commemorated, they wrote by the hands of Chromatius, Bishop of Aquileja, and Heliodorus, Bishop of Altino, to S. Jerome, then at Bethlehem, to request him to draw up for their use a Martyrology [Pg xxiii] out of the collection made by Eusebius of Cæsarea.

To this S. Jerome answered by letter, stating that he had got the passions of the martyrs written by Eusebius, and that he would gladly execute what was asked of him. With this letter he sent the Martyrology, with the name of a martyr to every day in the year except the first of January.[13] Unfortunately, as already said, we have not got a copy of the Martyrology unamended and unenlarged.

Next in importance to the Martyrology of Jerome comes the "Martyrologium Romanum Parvum," mentioned by S. Gregory the Great, who sent a copy of it to the Bishop of Aquileja. Ado, Bishop of Vienne, saw this; it was lent him for a few days, and he made a transcript with his own hand, as he tells us in the preface to his own Martyrology, and it served him as the basis for his work.

Baronius was unable to discover a copy, though he made inquiry for it, in the libraries of Italy; but it was discovered by Rosweydus, the learned Bollandist, and published by him in 1613.

S. Gregory the Great, in his 29th Epistle, says, "We have the names of nearly all the martyrs with their passions set down on their several days, collected into one volume, and we celebrate the Mass daily in their honour."

Cassiodorus, in his "Institution of Divine Lessons," says, "Read constantly the passions of the martyrs, which among other places you will find in the letter of S. Jerome to Chromatius and Heliodorus; they flourished over the whole earth, and provoked to imitation; you will be led thereby to the heavenly kingdom."

Next in importance to the Martyrology of Jerome and the little Roman Martyrology, comes that of the Venerable Bede. In the catalogue of his own works that he drew up, he says, "I wrote a Martyrology of the natal days of the holy martyrs, in which I took care to set down all I could find, not only on their several days, but I also gave the sort of conflict they underwent, and under what judge they conquered the world."

If we compare this Martyrology with the Acts of the Martyrs, we see at once that Bede took his account from them verbatim, merely condensing the narrative.

The Martyrology of Bede was written about 720; Drepanius Florus, a priest of Lyons, who died 860, added to it considerably, and most of the copies of Bede's Martyrology that we have are those enlarged by Florus.

The next martyrologist was Usuardus, monk of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, who died in 876. He wrote his Martyrology at the request of Charles the Bald, who was dissatisfied with the Martyrologies of Jerome and of Bede because they were too short in their narratives, and also because several days in the calendar were left blank. This account, which Usuardus gives in his preface, does not tally with the words of the epistle attributed to S. Jerome that precedes his Martyrology; and leads to the suspicion [Pg xxv] that this portion of the epistle, at least, is not genuine. Usuardus certainly used the Hieronyman Martyrology as the basis of his work, and this has caused his work to be designated the larger Hieronyman Martyrology. This work of Usuardus was so full, that it displaced the earlier Martyrologies in a great many churches. The best edition of the Martyrology of Usuardus is that of Solerius, Antwerp, 1714-1717.

Usuardus was followed by Wandelbert, monk of Prum, who died in 870. Wandelbert followed the Martyrologies of SS. Jerome and Bede, as amplified by Florus, and wrote the notices of the martyrs in hexameter Latin verses. This monument of patience is composed of about 360 metrical pieces, of which each contains the life of the Saint commemorated on the day. To these, which form the bulk of the work, are prefixed others of less importance, prefaces, dedicatory epistles to Lothair, preliminary discourses on the importance of the Martyrology, on the knowledge of times and seasons, months and days, etc. Although Wandelbert wrote for the most part in hexameters, he abandoned them occasionally for lyric metres, which he managed with less facility. D'Achéry published this Martyrology in his "Spicilegium," but the edition is a bad one.

The next martyrologist is Ado, Bishop of Vienne, who has been already mentioned in connection with the "Martyrologium Parvum." Ado was born about the year 800, and died in 875. In his preface, Ado says: "For this work of noting on their proper days the nativities of the Saints, which are generally found [Pg xxvi] confusedly in calendars, I have made use of a venerable and very ancient Martyrology, at Aquileja, sent to a certain holy bishop by the Roman Pontiff, and this was lent me, when at Ravenna, for a few days by a certain religious brother. This I diligently copied, and thought to place it at the head of my work. I have, however, inserted the passions of the Saints somewhat longer in this Martyrology, for the use of the infirm brothers, and those less able to get at books, that they may be able to read out of a little book a compendium to the praise of God and the memory of the martyrs, instead of overhauling a host of big volumes with much labour." The best edition of Ado's Martyrology is that by Geo. Rhodigini, published at Rome, 1740.

There have been many later Martyrologies, but these are of far inferior importance, and need not be here enumerated. In the East, the Greeks had anciently their collections. That of Eusebius probably formed the basis of later Menologies. In the Horology are contained calendars of the Saints for every day with prayers; this portion of the Horology is called the Menology.

The Menology is divided into months, and contains the lives of the Saints, in abridgment, for each day, or the simple commemoration of those whose acts are extant. The Menology of the Greeks is, therefore, much the same as the Latin Martyrology, and there are almost as many Menologies as there are Martyrologies. The principal is that of the Emperor Basil II. (d. 1025), published by Ughelli in his "Italia Sacra." The larger Menologies are entitled "Synaxaria," because [Pg xxvii] they were read in the churches on days of assembly. These lives are very long, and the Menology contains the substance in a condensed form.

The modern Roman Martyrology was drawn up by order of Pope Gregory XIII., who appointed for the purpose eight commissaries, amongst whom was Baronius. It leaves much to be desired, as it bristles with inaccuracies. A fresh edition was issued with some corrections by Benedict XIV. It demands a careful revision. Many of its inaccuracies have been pointed out in the course of this work.

It is impossible to dismiss the subject of Martyrologies without a word on the "Acta Sanctorum" of the Bollandists. This magnificent collection of Lives of the Saints is arranged on the principle of the Synaxarium, or Martyrology—that is to say, the Saints are not given in their chronological order, but as they appear in the calendar.

Heribert Resweidus, of Utrecht, was a learned Jesuit father, born in 1563, who died 1629. In 1607 he published the "Fasti sanctorum quorum vitæ manuscriptæ in Belgio," a book containing the plan of a vast work on the lives of all the Saints, which he desired to undertake. In 1613 he published "Notes on the old Roman Martyrology," which he was the first to discover. In 1615 he brought out the "Lives of the Hermits," and in 1619 another work on the "Eremites of Palestine and Egypt." In 1626 he published the "Lives of the Virgin Saints." He died before the great work for which he had collected, and to which he had devoted his time and thoughts, was begun. But the project was not allowed to drop. It was taken [Pg xxviii] up by John Bollandus, another Jesuit; with him were associated two other fathers of the same order, Henschenius and Papebrock, and in 1643 appeared the January volumes, two in number. In 1648 the three volumes of the February Saints issued from the press. Bollandus died in 1665, and the March volumes, three in number, edited by Henschenius and Papebrock, appeared in 1668. As the work proceeded, material came in in abundance, and the work grew under their hands. May was represented by seven volumes; so also June, July, and August. The compilation is not yet complete. At present, this huge work consists of about sixty folio volumes, which bring the student down to within three days of the end of the month of October; but a large store of material is being utilized in order to complete that month forthwith, and further stores have been accumulated towards the Lives of the Saints for November and December, about 4000 of such biographies being still to be actually written. Moreover, the earlier volumes are very incomplete, and at least the months of January to April need rewriting.

The principle on which the Bollandists have worked is an excellent one. They have not themselves written the lives of the Saints, but they publish every scrap of record, and all the ancient acts and lives of the Saints that are extant. The work is a storehouse of historical materials. To these materials the editors prefix an introductory essay on the value and genuineness of the material, and on the chronology of the Saint's life. They have done their work conscientiously and well. Only occasionally have they [Pg xxix] omitted acts or portions of lives which they have regarded as mythical or unedifying. These omissions are to be regretted, as they would have been instructive.

Another valuable repository of the lives of Saints is Mabillon's "Collection of the Acts of the Saints of the Order of S. Benedict," in nine volumes, published 1668-1701. The arrangement in this collection is by centuries. Theodoric Ruinart, in 1689, published the Acts of the Martyrs, but not a complete series; he selected only those which he regarded as genuine.

With regard to England there is a Martyrology of Christ Church, Canterbury, written in the thirteenth century, and now in the British Museum (Arundell MSS., No. 68); also a Martyrology written between 1220 and 1224, from the south-west of England; this also is in the British Museum (MSS. Reg. 2, A. xiii.). A Saxon Martyrology, incomplete, is among the Harleian MSS. (2785) in the same museum. It dates from the fourteenth century. There is a transcript among the Sloane MSS. (4938), of a Martyrology of North English origin, but this also is incomplete. There are others, later, of less value. The most interesting is "The Martiloge in Englysshe, after the use of the chirche of Salisbury," printed by Wynkyn de Worde in 1526, reissued by the "Henry Bradshaw Society" in 1893. To these Martyrologies must be added the "Legenda" of John of Tynemouth, a.d. 1350; that of Capgrave, a.d. 1450, his "Nova Legenda," printed in 1516; Whitford's "Martyrology," 1526; Wilson's "Martyrologue," 1st edition, 1608, 2nd edition, 1640; and Bishop Challoner's "Memorial of Ancient British [Pg xxx] Piety," 1761. Recently the Rev. Richard Stanton, Priest of the Oratory, London, has issued an invaluable "Martyrology of England and Wales," 1887.

Scottish Kalendars have been reprinted and commented on, and brief lives of the Saints given by the late Bishop Forbes of Brechin, in "Kalendars of Scottish Saints," Edinburgh, 1872.

Unhappily little is known of the Welsh and Cornish and some local English Saints, but it is my purpose to add such information as can be gathered concerning them.

S. BARING-GOULD.

January 1897.

[2] Euseb., "Hist. Eccl.," lib. iv., cap. xv.

[3] S. Paulinus was born a.d. 353, and elected Bishop of Nola a.d. 409. Prudentius was born a.d. 348.

[4] Ep. xii., ad Severum, "His holy bones 'neath lasting altars rest."

[5] Ep. xii., ad Severum.

[6] Hymn xi.

[7] "Eccl. Hierarch.," cap. iii.

[8] S. Damasus was born a.d. 304, and died a.d. 384.

[9] He died a.d. 250; see Ep. i.

[10] Born a.d. 160, died a.d. 245.

[11] Ep. xxxvii.

[12] Lib. xx., contra Faustum, cap. xxi.

[13] The copies of these letters prefixed to the Martyrology vary greatly, and their authenticity has been questioned; but the circumstance is probably true.

A | ||

| page | ||

| S. | Adalhardt | 34 |

| " | Adelelm | 461 |

| " | Adrian | 128 |

| " | Aelred | 176 |

| " | Agatho | 137 |

| " | Agnes | 317 |

| " | Aidan | 467 |

| " | Aldegund | 460 |

| " | Aldric | 96 |

| " | Alexander Acœmetus | 228 |

| SS. | Anastasius and comp. | 334 |

| B. | Angela of Foligni | 63 |

| S. | Anteros | 38 |

| " | Anthony | 249 |

| " | Apollinaris Synclet | 70 |

| " | Apollo | 372 |

| " | Arcadius | 162 |

| SS. | Archelaa and others | 278 |

| S. | Artemas | 370 |

| " | Asclas | 346 |

| " | Athanasius | 38 |

| " | Atticus | 100 |

| " | Audifax | 285 |

| " | Augurius | 312 |

B | ||

| S. | Babylus | 361 |

| " | Baldwin | 112 |

| " | Balthazar | 148 |

| " | Barsas of Edessa | 460 |

| " | Bassian of Lodi | 268 |

| " | Bathild | 394 |

| " | Benedict Biscop | 167 |

| " | Bertilia | 51 |

| SS. | Blaithmac and comp. | 289 |

| S. | Brithwald | 131 |

| [Pg xxxii]

C | ||

| S. | Cadoc | 363 |

| " | Cæsaria | 167 |

| " | Canute Lavard | 97 |

| " | Cedd | 91 |

| " | Ceolwulf | 236 |

| " | Charlemagne | 437 |

| " | Christiana | 146 |

| Circumcision, The | 1 | |

| S. | Clement of Ancyra | 347 |

| " | Concord | 3 |

| Conversion of S. Paul | 370 | |

| S. | Cyriacus | 163 |

| " | Cyril, Alexandria | 418 |

| " | Cyrinus | 44 |

| SS. | Cyrus, John, and others | 465 |

D | ||

| S. | Dafrosa | 57 |

| " | Datius | 210 |

| " | Deicolus | 280 |

| " | Devota | 399 |

| " | Domitian | 136 |

E | ||

| S. | Egwin | 160 |

| SS. | Elvan and Mydwyn | 5 |

| Epiphany, The | 82 | |

| S. | Erminold | 86 |

| " | Eulogius | 312 |

| " | Euthymius | 305 |

| " | Eutropius | 163 |

F | ||

| S. | Fabian | 299 |

| " | Fechin | 310 |

| " | Felix | 199 |

| " | Fillan | 127 |

| " | Francis of Sales | 443 |

| " | Frodobert | 112 |

| " | Fructuosus | 312 |

| " | Fulgentius | 10 |

| " | Fursey | 243 |

G | ||

| S. | Gaudentius | 334 |

| " | Genoveva | 46 |

| " | Genulph | 247 |

| " | Gerlach | 81 |

| " | Germanicus | 284 |

| " | Gildas | 440 |

| " | Gonsalvo | 142 |

| " | Gordius | 42 |

| B. | Gotfried | 194 |

| S. | Gregory of Langres | 58 |

| " | Gudula | 115 |

H | ||

| S. | Habakkuk | 285 |

| " | Henry | 245 |

| SS. | Hermylus and Stratonicus | 179 |

| S. | Hilary | 182 |

| " | Honoratus | 240 |

| " | Hyacintha | 462 |

| " | Hyginus | 149 |

I | ||

| S. | Isidore | 228 |

J | ||

| S. | James (Tarantaise) | 242 |

| " | James the Penitent | 433 |

| " | John the Almsgiver | 348 |

| " | John the Calybite | 233 |

| " | John Chrysostom | 400 |

| " | John of Therouanne | 415 |

| " | Julian of Le Mans | 398 |

| SS. | Julian and comp. | 121 |

| S. | Justina | 133 |

| SS. | Juventine and Maximus | 371 |

K | ||

| [Pg xxxiii] S. | Kentigern | 187 |

L | ||

| S. | Launomar | 287 |

| " | Laurence Justiniani | 119 |

| " | Leobard | 278 |

| " | Lucian of Antioch | 88 |

| " | Lucian of Beauvais | 99 |

| " | Lupus of Châlons | 413 |

M | ||

| S. | Macarius, Alexandria | 28 |

| " | Macarius, Egypt | 221 |

| " | Macedonius | 362 |

| " | Macra | 85 |

| " | Macrina | 202 |

| " | Marcella | 466 |

| " | Marcellus | 238 |

| " | Marcian | 134 |

| " | Marciana | 120 |

| " | Mares | 374 |

| SS. | Maris and others | 285 |

| S. | Martha | 285 |

| SS. | Martyrs at Lichfield | 28 |

| " | Martyrs in the Thebaid | 65 |

| S. | Maurus | 234 |

| " | Maximus | 371 |

| " | Meinrad | 321 |

| " | Melanius | 85 |

| " | Melas | 239 |

| " | Melor | 44 |

| " | Mildgytha | 273 |

| " | Mochua or Cronan | 20 |

| " | Mochua or Cuan | 19 |

| " | Mosentius | 163 |

N | ||

| S. | Nicanor | 133 |

O | ||

| S. | Odilo | 20 |

| B. | Ordorico | 211 |

| S. | Oringa | 146 |

P | ||

| S. | Palæmon | 149 |

| " | Palladius | 417 |

| " | Patiens | 100 |

| " | Patroclus | 315 |

| " | Paul | 215 |

| " | Paula | 384 |

| SS. | Paul and comp. | 277 |

| S. | Paulinus | 436 |

| " | Pega | 118 |

| " | Peter Balsam | 39 |

| " | Peter Nolasco | 470 |

| " | Peter of Canterbury | 86 |

| " | Peter of Sebaste | 125 |

| " | Peter's Chair | 275 |

| " | Pharaildis | 60 |

| " | Polycarp | 378 |

| " | Poppo | 375 |

| " | Præjectus | 375 |

| " | Primus | 44 |

| " | Prisca | 276 |

| " | Priscilla | 238 |

R | ||

| S. | Raymund | 357 |

| " | Rigobert | 61 |

| " | Rumon | 57 |

S | ||

| S. | Sabine | 273 |

| SS. | Sabinian and Sabina | 439 |

| S. | Salvius | 160 |

| SS. | Satyrus and others | 163 |

| S. | Sebastian | 300 |

| " | Serapion | 470 |

| " | Sethrida | 138 |

| " | Severinus | 101 |

| " | Silvester | 36 |

| " | Simeon Stylites | 72 |

| " | Simeon the Old | 383 |

| SS. | Speusippus and others | 246 |

| [Pg xxxiv] S. | Sulpicius Severus | 442 |

| S. | Susanna | 278 |

| " | Syncletica | 67 |

T | ||

| S. | Telemachus | 7 |

| " | Telesphorus | 65 |

| " | Thecla | 278 |

| SS. | Thecla and Justina | 133 |

| S. | Theodoric | 414 |

| " | Theodosius | 151 |

| SS. | Theodulus & comp. | 202 |

| " | Theognis & comp. | 44 |

| S. | Theoritgitha | 397 |

| SS. | Thyrsus and comp. | 416 |

| " | Tigris and Eutropius | 163 |

| S. | Timothy | 359 |

| " | Titus | 53 |

| " | Tyllo | 94 |

U | ||

| S. | Ulphia | 468 |

V | ||

| S. | Valentine | 90 |

| " | Valerius of Trèves | 439 |

| " | Valerius (Saragossa) | 417 |

| " | Veronica of Milan | 196 |

| " | Vincent | 331 |

| " | Vitalis | 156 |

W | ||

| B. | Walter of Bierbeeke | 341 |

| S. | William (Bourges) | 139 |

| " | Wulsin | 118 |

| " | Wulstan | 290 |

X | ||

| SS. | Xenophon and Mary | 389 |

| " | XXXVIII Monks, in Ionia | 175 |

Z | ||

| SS. | Zosimus and Athanasius | 38 |

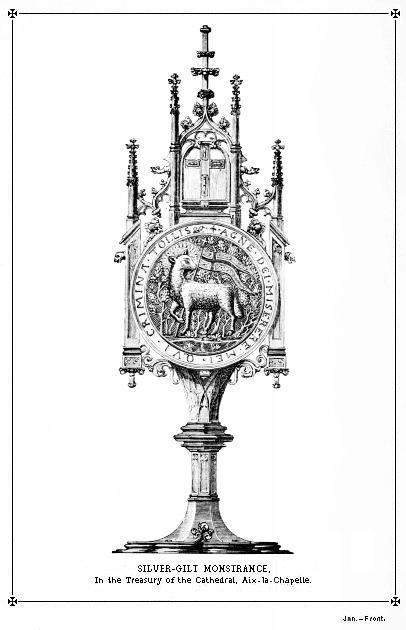

| Silver-gilt Monstrance | Frontispiece | |||

| In the Treasury of the Cathedral, Aix-la-Chapelle. | ||||

| The Circumcision of Christ | to face p. 1 | |||

| From the grand Vienna edition of the "Missale Romanum." | ||||

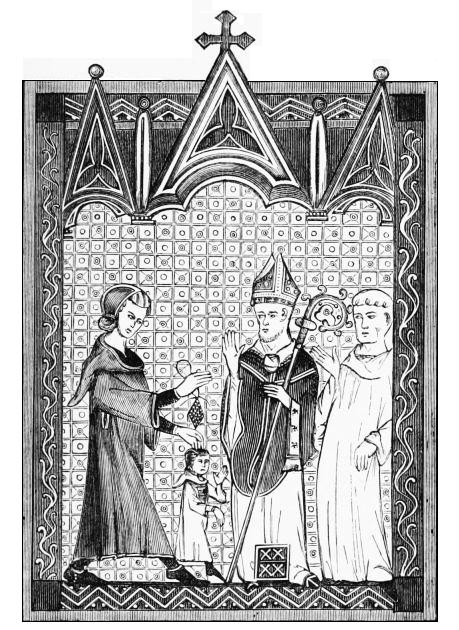

| Oblation of an Infant to a Religious Community | on p. 37 | |||

| S. Genoveva | to face p. 48 | |||

|

From "Caractéristiques des Saints dans l'Art populaire énumérées et expliquées," par le P. Ch. Cahier, de la Compagnie de Jesus. 4to. Paris, 1867. |

||||

| S. Simeon Stylites | to face p. 72 | |||

| From Hone's "Everyday Book." | ||||

| The Epiphany | to face p. 82 | |||

| From the Vienna Missal. | ||||

| Worshippers at the Shrine of a Saint | on p. 87 | |||

| Seal of the City of Brussels | on p. 98 | |||

| S. Genoveva | on p. 132 | |||

| S. Egwin, Bp. of Worcester | to face p. 160 | |||

| After Cahier. | ||||

| [Pg xxxvi] | ||||

| S. Aelred, Ab. of Rievaux | to face p. 176 | |||

| From a Design by A. Welby Pugin. | ||||

| S. Odilo | on p. 178 | |||

| S. Hilary Baptizing S. Martin of Tours | to face p. 184 | |||

|

From a Window, dated 1528, in the Church of S. Florentin, Yonne.. |

||||

| The Three Children in the Fiery Furnace | 184 | |||

| From the Catacombs. | ||||

| Seal of Robert Wishart, Bp. of Glasgow, 1272-1316 | on p. 198 | |||

| Hermit Saints—S. Anthony | on p. 214 | |||

| Hermit Saint | to face p. 216 | |||

| From a Drawing by A. Welby Pugin. | ||||

| S. Ceolwulf (?) | on p. 237 | |||

| S. Honoré | to face p. 240 | |||

| After Cahier. | ||||

| S. Anthony tortured by Demons | to face p. 252 | |||

| From the Design by Martin Schonguer. | ||||

| The Chair of S. Peter in the Vatican | on p. 274 | |||

| S. Peter's Commission, "Feed my Flock" | to face p. 274 | |||

| The Apostolic Succession | to face p. 274 | |||

| Baptism and Confirmation | on p. 283 | |||

| From a Painting in the Catacombs. | ||||

| S. Wulstan, Bp. of Worcester | to face p. 296 | |||

| From a Design by A. Welby Pugin. | ||||

| [Pg xxxvii] | ||||

| SS. Fabian and Sebastian | on p. 298 | |||

| S. Sebastian | to face p. 304 | |||

| From a Drawing by Lucas Schraudolf. | ||||

| The Peacock as a Christian Emblem | on p. 311 | |||

| S. Agnes | to face p. 316 | |||

| From the Vienna Missal. | ||||

| The Virgin Appearing to S. Ildephonsus | to face p. 356 | |||

| After a Painting by Murillo in the Museum at Madrid. | ||||

| S. Timothy | to face p. 360 | |||

| From a Window of the Eleventh Century at Neuweiler. | ||||

| S. Paul | on p. 369 | |||

| After a Bronze in Christian Museum in the Vatican. | ||||

| The Conversion of St. Paul | to face p. 370 | |||

| After the Cartoon by Raphael. | ||||

| Alpha and Omega; the First and the Last | on p. 377 | |||

| SS. Paula, Prisca, and Paul | to face p. 384 | |||

| S. Cyril of Alexandria | to face p. 424 | |||

| After the Picture by Dominichino (or Dominiquin) in the Church of Grotta Ferrata, Rome. | ||||

| S. Cyril of Alexandria | to face p. 432 | |||

| After Cahier. | ||||

| Charlemagne and S. Louis | to face p. 436 | |||

| After a Picture in the Palais de Justice, Paris. | ||||

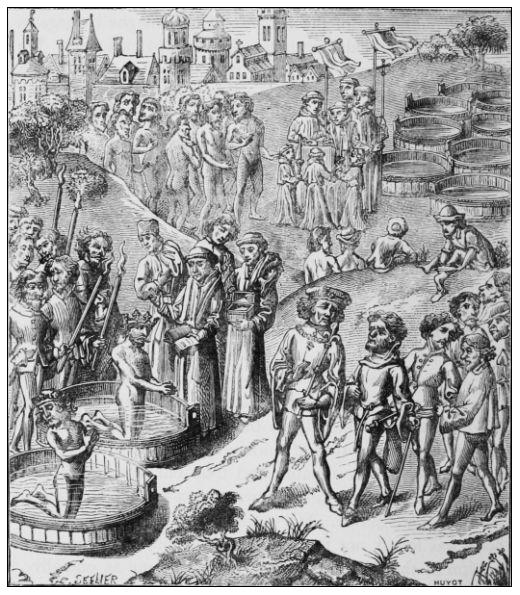

| Baptism of Vanquished Saxons by Command of Charlemagne | on p. 438 | |||

| From a Miniature of the 15th Century in the Burgundy Library at Brussels. | ||||

| [Pg xxxviii] | ||||

| S. Francis of Sales | to face p. 448 | |||

| S. Aldegund | to face p. 460 | |||

| After Cahier. | ||||

| Virgin in Crescent | on p. 464 | |||

| After Albert Dürer. | ||||

| S. Marcella | to face p. 466 | |||

| After an Engraving of the Seventeenth Century. | ||||

| S. Ulphia | to face p. 468 | |||

| From Cahier. | ||||

| S. Peter Nolasco | to face p. 470 | |||

| From Cahier. | ||||

The Feast of the Circumcision of our Lord Jesus Christ.

S. Gaspar, one of the Magi.

S. Concord, P. M., at Spoleto, in Umbria, circ. a.d. 175.

SS. Elvan, B., and Mydwyn, in England, circ. a.d. 198.

S. Martina, V. M., at Rome, a.d. 235.

S. Paracodius, B. of Vienne, a.d. 239.

S. Severus, M., at Ravenna, a.d. 304.

S. Telemachus, M., at Rome, a.d. 404.

S. Fulgentius, B. C. of Ruspe, in N. Africa, a.d. 533.

S. Mochua, or Cuan, Ab. in Ireland, 6th cent.

S. Mochua, or Cronan, Ab. of Balla, in Ireland, 7th cent.

S. Eugendus, Ab. of Condate, in the Jura, a.d. 581.

S. Fanchea, or Fain, V. Abss., of Rosairthir, in Ireland, 6th cent.

S. Clare, Ab. of Vienne, circ. a.d. 660.

S. William, Ab. S. Benignus, at Dijon, a.d. 1031.

S. Odilo, Ab. Cluny, a.d. 1049.

his festival is celebrated by the Church in order to commemorate the obedience of our Lord in fulfilling all righteousness, which is one branch of the meritorious cause of our redemption, and by that means abrogating the severe injunctions of the Mosaic law, and placing us under the grace of the Gospel.

God gave to Abraham the command to circumcise all male children on the eighth day after birth, and this rite was to be the seal of covenant with Him, a token that, through shedding of the blood of One to come, remission of the [Pg 2] original sin inherited from Adam could alone be obtained. It was also to point out that the Jews were cut off, and separate, from the other nations. By circumcision, a Jew belonged to the covenant, was consecrated to the service of God, and undertook to believe the truths revealed by Him to His elect people, and to hold the commandments to which He required obedience. Thus, this outward sign admitted him to true worship of God, true knowledge of God, and true obedience to God's moral law. Circumcision looked forward to Christ, who, by His blood, remits sin. Consequently, as a rite pointing to Him who was to come, it is abolished, and its place is taken by baptism, which also is a sign of covenant with God, admitting to true worship, true knowledge, and true obedience. But baptism is more than a covenant, and therefore more than was circumcision. It is a Sacrament; that is, a channel of grace. By baptism, supernatural power, or grace, is given to the child, whereby it obtains that which by nature it could not have. Circumcision admitted to covenant, but conferred no grace. Baptism admits to covenant, and confers grace. By circumcision, a child was made a member of God's own peculiar people. By baptism, the same is done; but God's own people is now not one nation, but the whole Catholic Church. Christ underwent circumcision, not because He had inherited the sin of Adam, but because He came to fulfil all righteousness, to accomplish the law, and for the letter to give the spirit.

It was, probably, the extravagances committed among the heathen at the kalends of January, upon which this day fell, that hindered the Church for some ages from proposing it as an universal set festival. The writings of the Fathers are full of invectives against the idolatrous profanations of this day, which concluded the riotous feasts in honour of Saturn, and was dedicated to Janus and Strena, or Strenua, a goddess [Pg 3] supposed to preside over those presents which were sent to, and received from, one another on the first day of the year, and which were called after her, strenæ; a name which is still preserved in the étrennes, or gifts, which it is customary in France to make on New Year's Day.

But, when the danger of the heathen abuses was removed, by the establishment of Christianity in the Roman empire, this festival began to be observed; and the mystery of our Blessed Lord's Circumcision is explained in several ancient homilies of the fifth century. It was, however, spoken of in earlier times as the Octave of the Nativity, and the earliest mention of it as the Circumcision is towards the end of the eleventh century, shortly before the time of S. Bernard, who also has a sermon upon it. In the Ambrosian Missal, used at Milan, the services of the day contain special cautions against idolatry. In a Gallican Lectionary, which is supposed to be as old as the seventh century, are special lessons "In Circumcisione Domini." Ivo, of Chartres, in 1090, speaks of the observance of this day in the French Church. The Greek Church also has a special commemoration of the Circumcision.

(about 175.)

[S. Concord is mentioned in all the Latin Martyrologies. His festival is celebrated at Bispal, in the diocese of Gerona, in Spain, where his body is said to be preserved, on the 2nd Jan. His translation is commemorated on the 4th July. The following is an abridgment of his genuine Acts.]

In the reign of the Emperor Marcus Antoninus, there raged a violent persecution in the city of Rome. At that time there dwelt in Rome a sub-deacon, named Concordius, whose father was priest of S. Pastor's, Cordianus by name. [Pg 4] Concord was brought up by his father in the fear of God, and in the study of Holy Scripture, and he was consecrated sub-deacon by S. Pius, Bishop of Rome. Concord and his father fasted and prayed, and served the Lord instantly in the person of His poor. When the persecution waxed sore, said Concord to his father, "My lord, send me away, I pray thee, to S. Eutyches, that I may dwell with him a few days, until this tyranny be overpast." His father answered, "My son, it is better to stay here that we may be crowned." But Concord said, "Let me go, that I may be crowned where Christ shall bid me be crowned." Then his father sent him away, and Eutyches received him with great joy. With him Concord dwelt for a season, fervent in prayer. And many sick came to them, and were healed in the name of Jesus Christ.

Then, hearing the fame of them, Torquatus, governor of Umbria, residing at Spoleto, sent and had Concord brought before him. To him he said, "What is thy name?" He answered, "I am a Christian." Then, said the Governor, "I asked concerning thee, and not about thy Christ." S. Concord replied, "I have said that I am a Christian, and Christ I confess." The Governor ordered: "Sacrifice to the immortal gods, and I will be to thee a father, and will obtain for thee favour at the hands of the Emperor, and he will exalt thee to be priest of the gods." S. Concord said, "Harken unto me, and sacrifice to the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt escape eternal misery." Then the governor ordered him to be beaten with clubs, and to be cast into prison.

Then, at night, there came to him the blessed Eutyches, with S. Anthymius, the bishop; for Anthymius was a friend of the governor; and he obtained permission of Torquatus to take Concord home with him for a few days. And during these days he ordained him priest, and they watched together in prayer.

And after a time, the governor sent and brought him before him once more and said to him, "What hast thou decided on for thy salvation?" Then Concord said, "Christ is my salvation, to whom daily I offer the sacrifice of praise." Then he was condemned to be hung upon the little horse; and, with a glad countenance, he cried, "Glory be to Thee, Lord Jesus Christ!"

After this torment he was cast into prison, with irons on his hands and neck. And blessed Concord began to sing praise to God in his dungeon, and he said, "Glory be to God on high, and in earth peace to men of good will." Then, that same night, the angel of the Lord stood by him, and said, "Fear not to play the man, I shall be with thee."

And when three days had passed, the governor sent two of his officers, at night, to him with a small image of Jupiter. And they said, "Hear what the governor has ordered; sacrifice to Jupiter or lose thy head." Then the blessed Concord spat in the face of the idol, and said, "Glory be to Thee, Lord Jesus Christ." Then one of the officers smote off his head in the prison. Afterwards, two clerks and certain religious men carried away his body, and buried it not far from the city of Spoleto, where many waters flow forth.

(about 198.)

[Mentioned in English Martyrologies, and by Ferrarius in his General Catalogue of the Saints. The evidence for these Saints is purely traditional; the first written record of them was by Gildas, a.d. 560, but his account is lost. It is referred to by Matthew of Westminster.]

Saint Elvan of Avalon, or Glastonbury, was brought up in that school erroneously said to have been founded by S. Joseph of Arimathea. He vehemently preached the truth [Pg 6] before Lucius, a British king, and was mightily assisted by S. Mydwyn of Wales (Meduinus), a man of great learning. Lucius despatched Elvan and Mydwyn to Rome, on an embassy to Pope Eleutherius, in 179, who consecrated Elvan bishop, and appointed Mydwyn teacher. He gave them, as companions, two Roman clerks, Faganus and Deruvianus; or, according to some, Fugatius and Damianus. They returned with these to King Lucius, who was obedient to the word of God, and received baptism along with many of his princes and nobles. Elvan became the second archbishop of London. He and Mydwyn were buried at Avalon. S. Patrick is said to have found there an ancient account of the acts of the Apostles, and of Fugatius and Damianus, written by the hand of S. Mydwyn. Matthew of Westminster gives the following account of the conversion of Lucius, under the year 185:—"About the same time, Lucius, king of the Britons, directed letters to Eleutherius, entreating him that he would make him a Christian. And the blessed pontiff, having ascertained the devotion of the king, sent to him some religious teachers; namely, Faganus and Deruvianus, to convert the king to Christ, and wash him in the holy font. And when that had been done, then the different nations ran to baptism, following the example of the king, so that in a short time there were no infidels found in the island."

There is a considerable amount of exaggeration in this account of Matthew of Westminster, which must not be passed over. Lucius is known in the Welsh triads by the name of Lleurwg, or Lleufer Mawr, which means "The great Luminary," and this has been Latinized into Lucius, from Lux, light. He was king of a portion of South Wales only. The Welsh authorities make no mention of the alleged mission to Rome, though, that such a mission should have been sent, is extremely probable. Some accounts say [Pg 7] that Medwy and Elfan were Britons, and that Dyfan and Ffagan (Deruvianus and Faganus) were Roman priests. But both these names are British, consequently we may conjecture that they were of British origin, but resided then at Rome.

Four churches near Llandaf bore the names of Lleurwg (Lucius), Dyfan, Ffagan, and Medwy, which confirms the belief in the existence of these Saints, and indicates the scene of their labours. Matthew of Westminster adds:—"A.D. 185. The blessed priests, Faganus and Deruvianus, returned to Rome, and easily prevailed on the most blessed Pope that all that they had done should be confirmed. And when it had been, then the before-mentioned teachers returned to Britain, with a great many more, by whose teaching the nation of the Britons was soon founded in the faith of Christ, and became eminent as a Christian people. And their names and actions are found in the book that Gildas the historian wrote, concerning the victory of Aurelius Ambrosius."

Geoffrey, of Monmouth, who, unsupported, is thoroughly untrustworthy, mentions the same circumstance, on the authority of the treatise of Gildas, now lost. The embassy to Rome shall be spoken of at length, under the title of S. Lucius, December 11th. See also Nennius, § 22; Bede's Eccles. Hist. i. 4; and the Liber Landavensis, p. 65.

(about 404.)

The following account of the martrydom of S. Telemachus is given by Theodoret, in his Ecclesiastical History, book v., chap. 26:—"Honorius, who had received the empire of Europe, abolished the ancient exhibitions of gladiators in Rome on the following occasion:—A certain man, named Telemachus, who had embraced a monastic life, [Pg 8] came from the East to Rome at a time when these cruel spectacles were being exhibited. After gazing upon the combat from the amphitheatre, he descended into the arena, and tried to separate the gladiators. The bloodthirsty spectators, possessed by the devil, who delights in the shedding of blood, were irritated at the interruption of their savage sports, and stoned him who had occasioned the cessation. On being apprised of this circumstance, the admirable Emperor numbered him with the victorious martyrs, and abolished these iniquitous spectacles."

For centuries the wholesale murders of the gladiatorial shows had lasted through the Roman empire. Human beings, in the prime of youth and health, captives or slaves, condemned malefactors, and even free-born men, who hired themselves out to death, had been trained to destroy each other in the amphitheatre for the amusement, not merely of the Roman mob, but of the Roman ladies. Thousands, sometimes in a single day, had been

"Butchered to make a Roman holiday."

The training of gladiators had become a science. By their weapons, and their armour, and their modes of fighting, they had been distinguished into regular classes, of which the antiquaries count up full eighteen: Andabatæ, who wore helmets, without any opening for the eyes, so that they were obliged to fight blindfold, and thus excited the mirth of the spectators; Hoplomachi, who fought in a complete suit of armour; Mirmillones, who had the image of a fish upon their helmets, and fought in armour, with a short sword, matched usually against the Retiarii, who fought without armour, and whose weapons were a casting-net and a trident. These, and other species of fighters, were drilled and fed in "families" by lanistæ, or regular trainers, who let them out to persons wishing to exhibit a show. Women, [Pg 9] even high-born ladies, had been seized in former times with the madness of fighting, and, as shameless as cruel, had gone down into the arena, to delight with their own wounds and their own gore, the eyes of the Roman people.

And these things were done, and done too often under the auspices of the gods, and at their most sacred festivals. So deliberate and organized a system of wholesale butchery has never perhaps existed on this earth before or since, not even in the worship of those Mexican gods, whose idols Cortez and his soldiers found fed with human hearts, and the walls of their temples crusted with human gore. Gradually the spirit of the Gospel had been triumphing over this abomination. Ever since the time of Tertullian, in the second century, Christian preachers and writers had lifted up their voice in the name of humanity. Towards the end of the third century, the Emperors themselves had so far yielded to the voice of reason, as to forbid, by edicts, the gladiatorial fights. But the public opinion of the mob, in most of the great cities, had been too strong both for Saints and for Emperors. S. Augustine himself tells us of the horrible joy which he, in his youth, had seen come over the vast ring of flushed faces at these horrid sights. The weak Emperor Honorius bethought himself of celebrating once more the heathen festival of the Secular Games, and formally to allow therein an exhibition of gladiators. But, in the midst of that show, sprang down into the arena of the Colosseum of Rome, this monk Telemachus, some said from Nitria, some from Phrygia, and with his own hands parted the combatants, in the name of Christ and God. The mob, baulked for a moment of their pleasure, sprang on him, and stoned him to death. But the crime was followed by a sudden revulsion of feeling. By an edict of the Emperor, the gladiatorial sports were forbidden for ever; and the Colosseum, thenceforth useless, crumbled slowly away into that vast [Pg 10] ruin which remains unto this day, purified, as men well said, from the blood of tens of thousands, by the blood of this true and noble martyr.[14]

(a.d. 533.)

[Roman Martyrology and nearly all the Latin Martyrologies. His life was written by one of his disciples, and addressed to his successor, Felicianus. Many of his writings are extant.]

Fulgentius belonged to an honourable senatorial family of Carthage, which had, however, lost its position with the invasion of the Vandals into Northern Africa. His father, Claudius, who had been unjustly deprived of his house in Carthage, to give it to the Arian priest, retired to an estate belonging to him at Telepte, a city of the province of Byzacene. And here, about thirty years after the barbarians had dismembered Africa from the Roman empire, in the year 468, was born Fulgentius. Shortly after this his father died, and the education of the child devolved wholly on his mother, Mariana. It has been often observed that great men have had great mothers. Mariana was a woman of singular intelligence and piety. She carefully taught her son to speak Greek with ease and good accent, and made him learn by heart Homer, Menander, and other famous poets of antiquity. At the same time, she did not neglect his religious education, and the youth grew up obedient and modest. She early committed to him the government of the house, and servants, and estate; and his prudence in these matters made his reputation early, and he was appointed procurator of the province.

But it was not long before he grew weary of the world; and the love of God drew him on into other paths. He found great delight in religious reading, and gave more time to prayer. He was in the habit of frequenting monasteries, and he much wondered to see in the monks no signs of weariness, though they were deprived of all the relaxations and pleasures which the world provides. Then, under the excuse that his labours of office required that he should take occasional repose, he retired at intervals from business, and devoted himself to prayer and meditation, and reduced the abundance of food with which he was served. At length, moved by a sermon of S. Augustine on the thirty-sixth Psalm, he resolved on embracing the religious life.

There was at that time a certain bishop, Faustus by name, who had been driven, together with other orthodox bishops, from their sees, by Huneric, the Arian king. Faustus had erected a monastery in Byzacene. To him Fulgentius betook himself, and asked to be admitted into the monastery. But the Bishop repelled him saying, "Why, my son, dost thou seek to deceive the servants of God? Then wilt thou be a monk when thou hast learned to despise luxurious food and sumptuous array. Live as a layman less delicately, and then I shall believe in thy vocation." But the young man caught the hand of him who urged him to depart, and, kissing it said, "He who gave the desire is mighty to enable me to fulfil it. Suffer me to tread in thy footsteps, my father!" Then, with much hesitation, Faustus suffered the youth to remain, saying, "Perhaps my fears are unfounded. Thou must be proved some days."

The news that Fulgentius had become a monk spread far and wide. His mother, in transports of grief, ran to the monastery, crying out, "Faustus! restore to me my son, and to the people their governor. The Church always protects widows; why then dost thou rob me, a desolate widow, of my child?" Faustus in vain endeavoured to calm her. [Pg 12] She desired to see her son, but he refused to give permission. Fulgentius, from within, could hear his mother's cries. This was to him a severe temptation, for he loved her dearly.

Shortly after, he made over his estate to his mother, to be discretionally disposed of, by her, in favour of his brother Claudius, when he should arrive at a proper age. He practised severe mortification of his appetite, totally abstaining from oil and everything savoury, and his fasting produced a severe illness, from which, however, he recovered, and his constitution adapted itself to his life of abstinence.

Persecution again breaking out, Faustus was obliged to leave his monastery, and Fulgentius, at his advice, took refuge in another, which was governed by the Abbot Felix, who had been his friend in the world, and who became now his brother in religion. Felix rejoiced to see his friend once more, and he insisted on exalting him to be abbot along with himself. Fulgentius long refused, but in vain; and the monks were ruled by these two abbots living in holy charity, Felix attending to the discipline and the bodily necessities of the brethren, Fulgentius instructing them in the divine love. Thus they divided the authority between them for six years, and no contradictions took place between them; each being always ready to comply with the will of the other.

In the year 499, the country being ravaged by the Numidians, the two abbots were obliged to fly to Sicca Veneria, a city of the proconsular province of Africa. Here they were seized by orders of an Arian priest, and commanded to be scourged. Felix, seeing the executioners seize first on Fulgentius, exclaimed, "Spare my brother, who is not sufficiently strong to endure your blows, lest he die under them, and strike me instead." Felix having been scourged, Fulgentius was next beaten. His pupil [Pg 13] says, "Blessed Fulgentius, a man of delicate body, and of noble birth, was scarce able to endure the pain of the repeated blows, and, as he afterwards told us, hoping to soothe the violence of the priest, or distract it awhile, that he might recover himself a little, he cried out, 'I will say something if I am permitted.'" The priest ordered the blows to cease, expecting to hear a recantation. But Fulgentius, with much eloquence, began a narration of his travels; and after the priest had listened awhile, finding this was all he was about to hear, he commanded the executioners to continue their beating of Fulgentius. After that, the two abbots, naked and bruised, were driven away. Before being brought before the Arian priest, Felix had thrown away a few coins he possessed; and his captors, not observing this, after they were released, he and Fulgentius returned to the spot and recovered them all again. The Arian bishop, whose relations were acquainted with the family of Fulgentius, was much annoyed at this proceeding of the priest, and severely reprimanded him. He also urged Fulgentius to bring an action against him, but the confessor declined, partly because a Christian should never seek revenge, partly also because he was unwilling to plead before a bishop who denied the divinity of the Lord Jesus Christ. Fulgentius, resolving to visit the deserts of Egypt, renowned for the sanctity of the solitaries who dwelt there, went on board a ship for Alexandria, but the vessel touching at Sicily, S. Eulalius, abbot at Syracuse, diverted him from his intention, assuring him that "a perfidious dissension had severed this country from the communion of S. Peter. All these monks, whose marvellous abstinence is noised abroad, have not got with you the Sacrament of the Altar in common;" meaning that Egypt was full of heretics. Fulgentius visited Rome in the latter part of the year 500, during the entry of Theodoric. "Oh," said he, "how beautiful must the [Pg 14] heavenly Jerusalem be, if earthly Rome be so glorious." A short time after, Fulgentius returned home, and built himself a cell on the sea-shore, where he spent his time in prayer, reading and writing, and in making mats and umbrellas of palm leaves.

At this time the Vandal heretic, King Thrasimund, having forbidden the consecration of Catholic bishops, many sees were destitute of pastors, and the faithful were reduced to great distress. Faustus, the bishop, had ordained Fulgentius priest, on his return to Byzacene, and now, many places demanded him as their bishop. Fulgentius, fearing this responsibility, hid himself; but in a time of such trial and difficulty the Lord had need of him, and He called him to shepherd His flock in a marvellous manner. There was a city named Ruspe, then destitute of a bishop, for an influential deacon therein, named Felix, whose brother was a friend of the procurator, desired the office for himself. But the people, disapproving his ambition, made choice unanimously of Fulgentius, of whom they knew only by report; and upon the primate Victor, bishop of Carthage, giving his consent that the neighbouring bishops should consecrate him, several people of Ruspe betook themselves to the cell of Fulgentius, and by force compelled him to consent to be ordained. Thus, he might say, in the words of the prophet, "A people whom I have not known shall serve me."

The deacon, Felix, taking advantage of the illegality of the proceeding, determined to oppose the entrance of S. Fulgentius by force, and occupied the road by which he presumed the bishop would enter Ruspe. By some means the people went out to meet him another way, and brought him into the Cathedral, where he was installed, whilst the deacon, Felix, was still awaiting his arrival in the road. Then he celebrated the Divine Mysteries, with great solemnity, and [Pg 15] communicated all the people. And when Felix, the deacon, heard this, he was abashed, and refrained from further opposition. Fulgentius received him with great sweetness and charity, and afterwards ordained him priest.

As bishop, S. Fulgentius lived like a monk; he fed on the coarsest food, and dressed himself in the plainest garb, not wearing the orarium, which it was customary for bishops to put upon them. He would not wear a cloak (casula) of gay colour, but one very plain, and beneath it a blackish, or milk-coloured habit (pallium), girded about him. Whatever might be the weather, in the monastery he wore this habit alone, and when he slept, he never loosed his girdle. "In the tunic in which he slept, in that did he sacrifice; he may be said, in time of sacrifice, to have changed his heart rather than his habit."[15]

His great love for a recluse life induced him to build a monastery near his house at Ruspe, which he designed to place under the direction of his old friend, the Abbot Felix. But before the building could be completed, King Thrasimund ordered the banishment of the Catholic bishops to Sardinia. Accordingly, S. Fulgentius and other prelates, sixty in all, were carried into exile, and during their banishment they were provided yearly with provisions and money by the liberality of Symmachus, Bishop of Rome. A letter of this Pope to them is still extant, in which he encourages them, and comforts them. S. Fulgentius, during his retirement, composed several treatises for the confirmation of the faith of the orthodox in Africa. King Thrasimund, desirous [Pg 16] of seeing him, sent for him, and appointed him lodgings in Carthage. The king drew up a set of ten objections to the Catholic faith, and required Fulgentius to answer them. The Saint immediately complied with his request, and his answer had such effect, that the king, when he sent him new objections, ordered that the answers should be read to himself alone. He then addressed to Thrasimund a confutation of Arianism, which we have under the title of "Three Books to King Thrasimund." The prince was pleased with the work, and granted him permission to reside at Carthage; till, upon repeated complaints from the Arian bishops, of the success of his preaching, which threatened, they said, the total conversion of the city to the faith in the Consubstantial, he was sent back to Sardinia, in 520. He was sent on board one stormy night, that he might be taken away without the knowledge of the people, but the wind being contrary, the vessel was driven into port again in the morning, and the news having spread that the bishop was about to be taken from them, the people crowded to say farewell, and he was enabled to go to a church, celebrate, and communicate all the faithful. Being ready to go on board when the wind shifted, he said to a Catholic, whom he saw weeping, "Grieve not, I shall shortly return, and the true faith of Christ will flourish again in this realm, with full liberty to profess it; but divulge not this secret to any."

The event confirmed the truth of the prediction. Thrasimund died in 523, and was succeeded by Hilderic, who gave orders for the restoration of the orthodox bishops to their sees, and that liberty of worship should be accorded to the Catholics.