Title: The Usurper: An Episode in Japanese History

Author: Judith Gautier

Translator: Abby Langdon Alger

Release date: September 29, 2014 [eBook #47002]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marc D'Hooghe (Images generously made available by the Internet Archive.)

| I. | THE LEMON GROVE | |

| II. | NAGATO'S WOUND | |

| III. | FEAST OF THE SEA-GOD | |

| IV. | THE SISTER OF THE SUN | |

| V. | THE KNIGHTS OF HEAVEN | |

| VI. | THE FRATERNITY of BLIND MEN | |

| VII. | PERJURY | |

| VIII. | THE CASTLE OF OWARI | |

| IX. | THE TEA-HOUSE | |

| X. | THE TRYST | |

| XI. | THE WARRIOR-QUAILS | |

| XII. | THE WESTERN ORCHARD | |

| XIII. | THE MIKADO'S THIRTY-THREE DINNERS | |

| XIV. | THE HAWKING-PARTY | |

| XV. | THE USURPER | |

| XVI. | THE FISHERMEN OF OSAKA BAY | |

| XVII. | DRAGON-FLY ISLAND | |

| XVIII. | THE PRINCIPALITY OF NAGATO | |

| XIX. | A TOMB | |

| XX. | THE MESSENGERS | |

| XXI. | THE KISAKI | |

| XXII. | THE MIKADO | |

| XXIII. | FATKOURA | |

| XXIV. | THE TREATY OF PEACE | |

| XXV. | CONFIDENCES | |

| XXVI. | THE GREAT THEATRE OF OSAKA | |

| XXVII. | OMITI | |

| XXVIII. | HENCEFORTH MY HOUSE SHALL BE AT PEACE | |

| XXIX. | THE HIGH-PRIESTESS OF THE SUN | |

| XXX. | BATTLES | |

| XXXI. | THE FUNERAL PILE |

Night was nearly gone. All slept in the beautiful bright city of Osaka. The harsh cry of the sentinels, calling one to another on the ramparts, broke the silence, unruffled otherwise save for the distant murmur of the sea as it swept into the bay.

Above the great dark mass formed by the palace and gardens of the Shogun[1] a star was fading slowly. Dawn trembled in the air, and the tree-tops were more plainly outlined against the sky, which grew bluer every moment. Soon a pale glimmer touched the highest branches, slipped between the boughs and their leaves, and filtered downward to the ground. Then, in the gardens of the Prince, alleys thick with brambles displayed their dim perspective; the grass resumed its emerald hue; a tuft of poppies renewed the splendor of its sumptuous flowers, and a snowy flight of steps was faintly visible through the mist, down a distant avenue.

At last, suddenly, the sky grew purple; arrows of light athwart the bushes made every drop of water on the leaves sparkle. A pheasant alighted heavily; a crane shook her white wings, and with a long cry flew slowly upwards; while the earth smoked like a caldron, and the birds loudly hailed the rising sun.

As soon as the divine luminary rose from the horizon, the sound of a gong was heard. It was struck with a monotonous rhythm of overpowering melancholy,—four heavy strokes, four light strokes; four heavy strokes, and so on. It was the salute to the coming day, and the call to morning prayers.

A hearty youthful peal of laughter, which broke forth suddenly, drowned these pious sounds for an instant; and two men appeared, dark against the clear sky, at the top of the snowy staircase. They paused a moment, on the uppermost step, to admire the lovely mass of brambles, ferns, and flowering shrubs which wreathed the balustrade of the staircase. Then they descended slowly through the fantastic shadows cast across the steps by the branches. Reaching the foot of the stairs, they moved quickly aside, that they might not upset a tortoise creeping leisurely along the last step. This tortoise's shell had been gilded, but the gilding was somewhat tarnished by the dampness of the grass. The two men moved down the avenue.

The younger of the pair was scarcely twenty years old, but would have passed for more, from the proud expression of his face, and the easy confidence of his glance. Still, when he laughed, he seemed a child; but he laughed seldom, and a sort of haughty gloom darkened his noble brow. His costume was very simple. Over a robe of gray crape he wore a mantle of blue satin, without any embroidery. He carried an open fan in his hand.

His comrade's dress was, on the contrary, very elegant. His robe was made of a soft white silk, just tinged with blue, suggestive of reflected moonlight. It fell in fine folds to his feet, and was confined at the waist by a girdle of black velvet. The wearer was twenty-four years old; he was a specimen of perfect beauty. The warm pallor of his face, his mockingly sweet eyes, and, above all, the scornful indifference apparent in his whole person, exercised a strange charm. His hand rested on the richly wrought hilt of one of the two swords whose points lifted up the folds of his black velvet cloak, the loose hanging sleeves of which were thrown back over his shoulders.

The two friends were bare-headed; their hair, twisted like a rope, was knotted around the top of their heads.

"But where are you taking me, gracious master?" suddenly cried the older of the two young men.

"This is the third time you have asked that question since we left the palace, Iwakura."

"But you have not answered once, light of my eyes!"

"Well! I want to surprise you. Shut your eyes and give me your hand."

Iwakura obeyed, and his companion led him a few steps across the grass.

"Now look," he said.

Iwakura opened his eyes, and uttered a low cry of astonishment.

Before him stretched a lemon grove in full bloom. Every tree and every shrub seemed covered with hoar-frost; on the topmost twigs the dawn cast tints of rose and gold. Every branch bent beneath its perfumed load; the clusters of flowers hung to the ground, upon which the overburdened boughs trailed. Amid this white wealth which gave forth a delicious odor, a few tender green leaves were occasionally visible.

"See," said the younger man with a smile, "I wanted to share with you, my favorite friend, the pleasure of this marvellous sight before any other eye rested on it. I was here yesterday: the grove was like a thicket of pearls; to-day all the flowers are open."

"These trees remind me of what the poet says of peach-blossoms," said Iwakura; "only here the snow-flakes of butterflies' wings with which the trees are covered have not turned rose-colored in their descent from heaven."

"Ah!" cried the younger man sighing, "would I might plunge into the midst of those flowers as into a bath, and intoxicate myself even unto death with their strong perfume!"

Iwakura, having admired them, made a slightly disappointed grimace.

"Far more beautiful blossoms were about to open in my dream," said he, stifling a yawn. "Master, why did you make me get up so early?"

"Come, Prince of Nagato," said the young man, laying his hand on his comrade's shoulder, "confess. I did not make you get up, for you did not go to bed last night."

"What?" cried Iwakura; "what makes you think so!"

"Your pallor, friend, and your haggard eyes."

"Am I not always so?"

"The dress you wear would be far too elegant for the hour of the cock.[2] And see! the sun has scarcely risen; we have only reached the hour of the rabbit."[3]

"To honor such a master as you, no hour is too early."

"Is it also in my honor, faithless subject, that you appear before me armed? Those two swords, forgotten in your sash, condemn you; you had just returned to the palace when I summoned you."

The guilty youth hung his head, not attempting to defend himself.

"But what ails your arm?" suddenly cried the other, noticing a thin white bandage wound about Iwakura's sleeve.

The latter hid his arm behind him, and held out the other hand.

"Nothing," he said.

But his companion grasped the arm which he concealed. The Prince of Nagato uttered an exclamation of pain.

"You are wounded, eh? One of these days I shall hear that Nagato has been killed in some foolish brawl. What have you been doing now, incorrigible and imprudent fellow?"

"When Hieyas, the regent, comes before you, you will know only too much about it," said the Prince; "you will hear fine things, O illustrious friend, in regard to your unworthy favorite. Methinks I already hear the sound of the terrible voice of the man from whom nothing is hid: 'Fide-Yori, ruler of Japan, son of the great Taiko-Sama, whose memory I revere! grave disorders have this night troubled Osaka.'"

The Prince of Nagato mimicked the voice of Hieyas so well that the young Shogun could not repress a smile.

'And what are these disorders?' you will say. 'Doors broken open, blows, tumults, scandals.' 'Are the authors of these misdeeds known?' 'The leader of the riot is the true criminal, and I know him well.' 'Who is he?' 'Who should it be but the man who takes a share in every adventure, every nocturnal brawl; who, but the Prince of Nagato, the terror of honest families, the dread of peaceful men?' And then you will pardon me, O too merciful man! Hieyas will reproach you with your weakness, dwelling upon it, that this weakness may redound to the injury of the Shogun and the profit of the Regent."

"What if I lose patience at last, Nagato," said the Shogun; "what if I exile you to your own province for a year?"

"I should go, master, without a murmur."

"Yes; and who would be left to love me?" said Fide-Yori, sadly. "I am surrounded by devotion, not by affection like yours. But perhaps I am unjust," he added; "you are the only one I love, and doubtless that is why I think no one loves me but you."

Nagato raised his eyes gratefully to the Prince.

"You feel that you are forgiven, don't you?" said Fide-Yori, smiling. "But try to spare me the Regent's reproaches; you know how painful they are to me. Go and salute him; the hour of his levee is at hand; we will meet again in the council."

"Must I smile upon that ugly creature?" grumbled Nagato.

But he had his dismissal; he saluted the Shogun, and moved away with a sulky air.

Fide-Yori continued his walk along the avenue, but soon returned to the lemon grove. He paused to admire it once more, and plucked a slender twig loaded with flowers. But just then the foliage rustled as if blown by a strong breeze; an abrupt movement stirred the branches, and a young girl appeared among the blossoms.

The Shogun started violently, and almost uttered a cry; he fancied himself the prey to some hallucination.

"Who are you?" he exclaimed; "perhaps the guardian spirit of this grove?"

"Oh, no," said the girl in a trembling voice; "but I am a very bold woman."

She issued from the grove amidst a shower of snowy petals, and knelt on the grass, stretching out her hands to the King.

Fide-Yori bent his head toward her, and gazed curiously at her. She was of exquisite beauty,—small, graceful, apparently weighed down by the amplitude of her robes. It seemed as if their silken weight bore her to her knees. Her large innocent eyes, like the eyes of a child, were timid and full of entreaty; her cheeks, velvety as a butterfly's wings, were tinged with a slight blush, and her small mouth, half open in admiration, revealed teeth white as drops of milk.

"Forgive me," she exclaimed, "forgive me for appearing before you without your express command."

"I forgive you, poor trembling bird," said Fide-Yori, "for had I known you and known your desire, my wish would have been to see you. What can I do for you? Is it in my power to make you happy?"

"Oh, master!" eagerly cried the girl, "with one word you can make me more radiant than Ten-Sio-Dai-Tsin, the daughter of the Sun."

"And what is that word?"

"Swear that you will not go to-morrow to the feast of the God of the Sea."

"Why this oath?" said the Shogun, amazed at this strange request.

"Because," said the young girl, shuddering, "a bridge will give way beneath the King's feet; and when night falls, Japan will be without a ruler."

"I suppose you have discovered a conspiracy?" said Fide-Yori, smiling.

At this incredulous smile the girl turned pale, and her eyes filled with tears.

"O pure disk of light!" she cried, "he does not believe me! All that I have hitherto accomplished is in vain! This is a dreadful obstacle, of which I never dreamed. You hearken to the voice of the cricket which prophesies heat; you listen to the frog who croaks a promise of rain; but a young girl who cries, 'Take care! I have seen the trap! death is on your path!' you pay no heed to her, but plunge headlong into the snare. But it must not be; you must believe me. Shall I kill myself at your feet? My death might be a pledge of my sincerity. Besides, if I have been deceived, what matters it? You can easily absent yourself from the feast. Hear me! I come along way, from a distant province. Alone with the dull anguish of my secret, I outwitted the most subtle spies, I conquered my terrors and overcame my weakness. My father thinks me gone on a pilgrimage to Kioto; and, you see, I am in your city, in the grounds of your palace. And yet the sentinels are watchful, the moats are broad, the walls high. See, my hands are bleeding; I burn with fever. Just now I feared I could not speak, my weary heart throbbed so violently at sight of you and with the joy of saving you. But now I am dizzy, my blood has turned to ice: you do not believe me."

"I believe you, and I swear to obey you," said the king, touched by her accent of despair. "I will not go to the feast of the God of the Sea."

The young girl uttered a cry of delight, and gazed with gratitude at the sun as it rose above the trees.

"But tell me how you discovered this plot," continued the Shogun, "and who are its authors?"

"Oh! do not order me to tell you. The whole edifice of infamy that I overthrow would fall upon my own head."

"So be it, my child; keep your secret. But at least tell me whence comes this great devotion, and why is my life so precious to you?"

The girl slowly raised her eyes to the King, then looked down and blushed, but did not reply. A vague emotion troubled the heart of the Prince. He was silent, and yielded to the sweet sensation. He would fain have remained thus, in silence, amidst these bird songs, these perfumes, beside this kneeling maiden.

"Tell me who you are, you who have saved me from death," he asked at last; "and tell me what reward I can give you worthy of your courage."

"My name is Omiti," said the young girl; "I can tell you nothing more. Give me the flower that you hold in your hand; it is all I would have from you."

Fide-Yori offered her the lemon twig; Omiti seized it, and fled through the grove.

The Shogun stood rooted to the spot for some time, lost in thought, gazing at the turf pressed by the light foot of Omiti.

[1] Lord of the kingdom. This is the same title as Tycoon, but the latter was not created till 1854.

[2] Six hours after noon.

[3] Six o'clock in the morning.

The Prince of Nagato had returned to his palace. He slept stretched out on a pile of fine mats; around him was almost total darkness, for the blinds had been lowered, and large screens spread before the windows. Here and there a black lacquer panel shone in the shadow and reflected dimly, like a dull mirror, the pale face of the Prince as he lay on his cushions.

Nagato had not succeeded in seeing Hieyas: he was told that the Regent was engaged with very important business. Pleased at the chance, the young Prince hurried home to rest for a few hours before the council.

In the chambers adjoining the one in which he slept servants came and went silently, preparing their master's toilette. They walked cautiously, that the floor might not creak, and talked together in low tones.

"Our poor master knows no moderation," said an old woman, scattering drops of perfume over a court cloak. "Continual feasting and nightly revels,—never any rest; he will kill himself."

"Oh, no! pleasure does not kill," said an impudent-looking boy, dressed in gay colors.

"What do you know about it, imp?" replied the woman. "Wouldn't you think the brat spent his life in enjoyment like a lord? Don't talk so boldly about things you know nothing of!"

"Perhaps I know more about them than you do," said the child, making a wry face; "you haven't got married yet, for all your great age and your great beauty."

The woman threw the contents of her flask in the boy's face; but he hid behind the silver disk of a mirror which he was polishing, and the perfume fell to the ground. When the danger was over, out popped his head.

"Will you have me for a husband?" he cried; "you can spare me a few of your years, and between us we'll make but a young couple."

The woman, in her rage, gave a sharp scream.

"Will you be quiet?" said another servant, threatening her with his fist.

"But who could listen to that young scamp without blushing and losing her temper?"

"Blush as much as you like," said the child; "that won't make any noise."

"Come, Loo, be quiet!" said the servant.

Loo shrugged his shoulders and made a face, then went on listlessly rubbing his mirror.

At this instant a man entered the room.

"I must speak to Iwakura, Prince of Nagato," he cried aloud.

All the servants made violent signs to impose silence on the new-comer. Loo rushed towards him and stopped his mouth with the rag with which he was polishing the mirror; but the man pushed him roughly away.

"What does all this mean?" he said. "Are you crazy? I want to speak to the lord whom you serve, the very illustrious daimio who rules over the province of Nagato. Go and tell him, and stop your monkey tricks."

"He is asleep," whispered a servant.

"We cannot wake him," said another.

"He is frightfully tired," said Loo, with his finger on his lip.

"Tired or not, he will rejoice at my coming," said the stranger.

"We were ordered not to wake him until a few moments before the hour for the council," said the old woman.

"I sha'n't take the risk of rousing him," said Loo, drawing his mouth to one side.—

"Nor I," said the old woman.

"I will go myself, if you like," said the messenger; "moreover, the hour of the council is close at hand. I just saw the Prince of Arima on his way to the Hall of a Thousand Mats."

"The Prince of Arima!" cried Loo; "and he is always late!"

"Alas!" said the old woman; "shall we have time to dress our master?"

Loo pushed aside a sliding partition and opened a narrow passage; he then softly entered Nagato's bedroom. It was cool within, and a delicate odor of camphor filled the air.

"Master! master!" said Loo in a loud voice, "the hour has come; and besides there is a messenger here."

"A messenger!" cried Nagato, raising himself on one elbow; "what does he look like?"

"He is dressed like a samurai:[1] he has two-swords in his sash."

"Let him come in at once," said the Prince, in a tone of agitation.

Loo beckoned to the messenger, who prostrated himself on the threshold of the room.

"Approach!" said Nagato.

But the messenger being unable to see in the dark hall, Loo folded back one leaf of a screen which intercepted the light. A broad band of sunshine entered; it lighted up the delicate texture of the matting which covered the wall and glistened on a silver stork with sinuous neck and spread wings, hanging against it.

The messenger approached the Prince and offered him a slender roll of paper wrapped in silk; then he left the room backwards.

Nagato hastily unrolled the paper, and read as follows:

"You have been here, illustrious one, I know it! But why this madness, and why this mystery? I cannot understand your actions. I have received severe reprimands from my sovereign on your account. As you know, I was passing through the gardens, escorting her to her palace, when all at once I saw you leaning against a tree. I could not repress an exclamation, and at my cry she turned towards me and followed the direction of my eyes. 'Ah!' she said, 'it is the sight of Nagato that draws such cries from you. Could you not stifle them, and at least spare me the sight of your immodest conduct?' Then she turned and looked at you several times. The anger in her eyes alarmed me. I dare not appear before her to-morrow, and I send you this message to beg you not to repeat these strange visits, which have such fatal consequences to me. Alas! do you not know that I love you, and need I repeat it? I will be your wife whenever you wish.... But it pleases you to adore me as if I were an idol in the pagoda of the Thirty-three thousand three hundred and thirty-three.[2] If you had not risked your life repeatedly to see me, I should think you were mocking me. I entreat you, expose me to no more such reproofs, and do not forget that I am ready to recognize you as my lord and master, and that to live by your side is my dearest desire."

Nagato smiled and slowly closed the roll; he fixed his eyes upon the streak of light cast on the floor from the window, and seemed lost in deep revery.

Little Loo was greatly disappointed. He had tried to read over his master's shoulder; but the roll was written in Chinese characters, and his knowledge fell short of that. He was quite familiar with the Kata-Kana, and even knew something of Hira-Kana; but unfortunately was entirely ignorant of Chinese writing. To hide his vexation, he went to the window and lifting one corner of the blind, looked out.

"Ah!" he said, "the Prince of Satsuma and the Prince of Aki arrive together, and their followers look askance atone another. Ah! Satsuma takes precedence. Oh! oh! there goes the Regent down the avenue. He glances this way, and laughs when he sees the Prince of Nagato's suite still standing at the door. He would laugh far louder if he knew how little progress my master had made in his toilet."

"Let him laugh, Loo! and come here," said the Prince, who had taken a pencil and roll of paper from his girdle and hastily written a few words. "Run to the palace and give this to the King."

Loo set off as fast as his legs could carry him, pushing and jostling those who came in his way to his utmost.

"And now," said Iwakura, "dress me quickly."

His servants clustered about him, and the Prince was soon arrayed in the broad trailing trousers which make the wearer look as if he were walking on his knees, and the stiff ceremonial mantle, made still more heavy by the crest embroidered on its sleeves. The arms of Nagato consisted of a black bolt surmounting three balls in the form of a pyramid.

The young man, usually so careful of his dress, paid no attention to the work of his servants; he did not even glance at the mirror so well polished by Loo, when the high pointed cap, tied by golden ribbons, was placed on his head.

As soon as his toilette was complete he left the palace; but so great was his abstraction that, instead of getting into the norimono awaiting him in the midst of his escort, he set off on foot, dragging his huge pantaloons in the sand, and exposing himself to the rays of the sun. His suite, terrified at this breach of etiquette, followed in utter disorder, while the spies ordered to watch the actions of the Prince hastened to report this extraordinary occurrence to their various masters.

The ramparts of the royal residence at Osaka, thick, lofty walls flanked at intervals by a semicircular bastion, form a huge square, which encloses several palaces and vast gardens. To the south and west the fortress is sheltered by the city; on the north the river which flows through Osaka widens, and forms an immense moat at the foot of the rampart; on the east, a narrower stream bounds it. On the platform of the walls grows a row of centenarian cedars of a sombre verdure, their level branches projecting horizontally across the battlements. Within, a second wall, preceded by a moat, encloses the parks and palaces reserved for the princes and their families. Between this wall and the ramparts lie the houses of soldiers and officials. A third wall surrounds the private palace of the Shogun, built upon a hill. This building is of simple but noble design. Square towers with roof upon roof rise here and there from the general mass. Marble stair-ways, bordered by slender lacquer railings, and decorated at the foot by bronze monsters or huge pottery vases, lead to the outer galleries. The terrace before the palace is covered with gravel and white sand which reflects back the splendor of the sun.

In the centre of the edifice stands a large, lofty, and magnificently ornate square tower. It supports seven roofs, whose angles are bent upward; on the topmost roof two enormous goldfish[3] writhe and twist, glittering so that they may be seen from every point of the city.

In that part of the palace nearest to this tower is the Hall of a Thousand Mats, the meeting-place for the Council.

The lords arrived from all directions, climbed the hill, and moved towards the central portico of the palace, which opens upon a long gallery loading directly into the Hall of a Thousand Mats.

This lofty, spacious hall is entirely bare of furniture. Movable partitions sliding in grooves intersect it and, when closed, form compartments of various sizes. But the partitions are always opened wide in such a way as to produce agreeable effects of perspective. The panels in one compartment are covered with black lacquer decorated in gold, in another of red lacquer or of Jeseri wood, the veins of which form natural and pleasing designs. Here, the screen, painted by a famous artist, is lined with white satin heavily embroidered with flowers; there, on a dead gold ground, a peach-tree loaded with its pink blossoms spreads its gnarled branches; or perhaps merely an irregular sprinkling of black, red, and white dots oil dark wood dazzles the eye. The mats which cover the floor are snow white, and fringed with silver.

The nobles, with their loose pantaloons falling below their feet, seem to move forward on their knees, and their robes brush the mats with a continuous sound, like the murmur of a waterfall. The spectators, moreover, preserve a religious silence. The Hattamotos, members of an order of nobility, recently instituted by the Regent, crouch in the farthest corners, while the Samurais, of ancient lineage, owners of fiefs and vassals of princes, pass these newly made nobles by, with scornful glances, and come perceptibly closer to the great drawn curtain veiling the platform reserved for the Shogun. The Lords of the Earth, princes supreme in their own provinces, form a wide circle before the throne, leaving a free space for the thirteen members of the Council.

The councillors soon arrive. They salute each other, and exchange a few words in low voices; then take their places.

On the left, presenting their profile to the drawn curtain, are the superior councillors. They are five in number, but only four are present. The nearest to the throne is the Prince of Satsuma, a venerable old man with a long face full of kindness. Next to him is spread the mat of the absentee. Then comes the Prince of Satake, who bites his lip as he carefully arranges the folds of his robe. He is young, dark-skinned, and his jet black eyes twinkle strangely. Next to him is established the Prince of Ouesougi, a fat and listless-looking man. The last is the Prince of Isida, a short, ugly-faced fellow.

The eight inferior councillors crouching opposite the throne are the princes of Arima, Figo, Wakasa, Aki, Tosa, Ise, and Coroda.

A stir is heard in the direction of the entrance, and every head is bent to the ground. The Regent advances into the hall. He moves rapidly, not being embarrassed, like the princes, by the folds of his trailing trousers, and seat's himself, cross-legged, on a pile of mats to the right of the throne.

Hieyas was at this time an old man. His back was slightly bent, but he was broad-shouldered and muscular. His head, entirely shaven, revealed a high forehead, with prominent eyebrows. His thin lips, cruel and obstinate in expression, were deeply marked at the corners with downward wrinkles. His cheek-bones were extremely marked, and his prominent eyes flashed forth abrupt and insincere glances.

As he entered, he cast an evil look, accompanied by a half-smile, towards the vacant place of the Prince of Nagato. But when the curtain rose, the Shogun appeared, leaning with one hand on the shoulder of his youthful councillor.

The Regent frowned.

All the spectators prostrated themselves, pressing their foreheads on the ground. When they rose, the Prince of Nagato had taken his place with the rest.

Fide-Yori seated himself, and motioned to Hieyas that he might speak.

Then the Regent read various unimportant reports,—nominations of magistrates, movements of the troops on the frontier, the change of residence of a governor whose term had expired. Hieyas explained briefly and volubly the reasons which had actuated him. The councillors ran their eyes over the manuscripts, and having no objection to make, acquiesced by a gesture. But soon the Regent folded all these papers and handed them to a secretary stationed near him; then resumed his speech, after first coughing:—

"I called this special meeting to-day," he said, "that its members might share the fears which I have conceived for the tranquillity of the kingdom, on learning that the severe supervision ordered over the European bonzes and such Japanese as have embraced their strange doctrine, are strangely relaxed, and that they have resumed their dangerous intrigues against the public peace. I therefore demand the enforcement of the law decreeing the extermination of all Christians."

A singular uproar arose in the assembly,—a mixture of approval, surprise, cries of horror and of anger.

"Would you witness a renewal of the hideous and bloody scenes whose terror still lingers in our minds?" cried the Prince of Satake with his wonted animation.

"It is odd to affirm that poor people who preach nothing but virtue and concord can disturb the peace of an empire," said Nagato.

"The Daimio speaks well," said the Prince of Satsuma; "it is impossible for the bonzes of Europe to have any effect upon the tranquillity of the kingdom. It is therefore useless to disturb them."

But Hieyas addressed himself directly to Fide-Yori.

"Master," said he, "since no one will share my anxiety, I must inform you that a dreadful rumor is beginning to circulate among the nobles and among the people."

He paused a moment, to add solemnity to his words.

"It is said that he who is still under my guardianship, the future ruler of Japan, our gracious lord, Fide-Yori, has embraced the Christian faith."

An impressive silence followed these words. The spectators exchanged glances which said clearly that they had heard the report, which might have a solid basis.

Fide-Yori took up the word.

"And should a calumny spread by ill-intentioned persons be avenged upon the innocent I I command that the Christians shall not be molested in any way. My father, I regret it, thought it his duty to pursue with his wrath and to exterminate those unhappy men; but I swear, while I live, not one drop of their blood shall be shed."

Hieyas was stupefied by the resolute accent of the young Shogun; for the first time he spoke as a master, and commanded. He bowed in sign of submission, and made no objection. Fide-Yori had attained his majority, and if he was not yet proclaimed Shogun it was because Hieyas was in no haste to lay down his power. He did not, therefore, wish to enter into open strife with his ward. He set the question aside for the time being, and passed to something else.

"I am told," he said, "that a nobleman was attacked and wounded last night on the Kioto road. I do not yet know the name of this noble; but perhaps the Prince of Nagato, who was at Kioto last night, heard something of this adventure?"

"Ah! you know that I was at Kioto," muttered the Prince; "then I understand why there were assassins on my path."

"How could Nagato be at Osaka and at Kioto at one and the same time?" asked the Prince of Satake. "There is nothing talked of this morning but the water-party which he gave last night, and which ended so merrily with a fight between the lords and the sailors from the shore."

"I even got a scratch in the squabble," said Nagato, smiling.

"The Prince traverses in a few hours distances that others would take a day to go over," said Hieyas; "that's all. Only, he does not spare his horses; every time he comes back to the palace, his animal falls down dead."

The Prince of Nagato turned pale, and felt for the sword missing from his girdle.

"I did not suppose that your anxious care extended even to the beasts of the kingdom," said he, with an insolent irony. "I thank you in the name of my dead horses."

The Shogun, full of alarm, cast supplicating glances at Nagato. But it seemed as if the Regent's patience were proof against all trials to-day. He smiled and made no reply.

However, Fide-Yori saw that anger smouldered in his friend's soul; and dreading some fresh outburst, he put an end to the council by withdrawing.

Almost immediately one of the palace guards informed the Prince of Nagato that the Shogun was asking for him. The Prince said a pleasant word to several nobles, bowed to the rest, and left the hall without turning his head in the direction of Hieyas.

When he reached the apartments of the Shogun, he heard a woman's voice, petulant, and at the same time complaining. He caught his own name.

"I have heard all," said the voice,—"your refusal to accede to the wishes of the Regent, whom you suffered to be insulted before your very eyes by the Prince of Nagato, whose impudence is truly incomparable; and the rare patience of Hieyas, who did not take up the insult from respect for you, from pity for him whom you believe to be your friend, in your ignorance of men."

Nagato recognized the speaker as the Shogun's mother, the beautiful and haughty Yodogimi.

"Mother," said the Shogun, "turn your thoughts to embroidery and dress: that is woman's sphere."

Nagato entered hurriedly, that he might not longer be an unsuspected listener.

"My gracious master asked for me," he said. Yodogimi turned and blushed slightly on seeing the Prince, who bowed low before her.

"I have something to say to you," said the Shogun.

"Then I will retire," said Yodogimi bitterly, "and go back to my embroidery."

She crossed the room slowly, rustling her trailing silken robes, and casting as she went out a singular look at Nagato, compounded of coquetry and hate.

"You heard my mother," said Fide-Yori.

"Yes," said Nagato.

"Every one is anxious to detach me from you, my friend: what can be their motive?"

"Your mother is blinded by some calumny," said the Prince; "the others see in me a clear-sighted foe, who can outwit the plots which they contrive against you."

"It was of a plot I wished to speak to you."

"Against your life?"

"Precisely. It was revealed to me in a strange fashion, and I can scarcely credit it; yet I cannot resist a certain feeling of uneasiness. To-morrow, at the feast of the God of the Sea, a bridge will give way beneath me."

"Horrible!" cried Nagato. "Do not go to the feast."

"If I stay away," said Fide-Yori, "I shall never know the truth, for the plot will not be carried out. But if I go to the feast," he added with a smile, "if the conspiracy really exist, the truth would be somewhat difficult of proof."

"To be sure," said Nagato. "Still, our doubts must be set at rest; some means must be found. Is your route fixed?"

"Hieyas has arranged it."

Fide-Yori took a roll of paper from a low table and read:—

"Yedogava Quay, Fishmarket Square, Sycamore Street, seashore. Return by Bamboo Hill and Swallow bridge.

"The wretches!" cried Iwakura; "that is the bridge swung across the valley!"

"The place would be well chosen indeed," said the Shogun.

"It must be that bridge; those crossing the countless city canals would not expose you to death by crumbling under your feet, but at the utmost to a disagreeable bath."

"True," said Fide-Yori; "and from the Swallow bridge I should be hurled upon the rocks."

"Have you full trust in my friendship for you?" asked the Prince of Nagato, after a moment's thought.

"Can you doubt it, Iwakura?" said the Shogun.

"Very well, then. Fear nothing, feign complete ignorance, let them lead the way, and march straight up to the bridge. I have thought of a way to save you, and yet discover the truth."

"I trust myself to you, friend, in perfect confidence."

"Then let me go; I must have time to carry out my scheme."

"Go, Prince; I place my life in your hands untremblingly," said the Shogun.

Nagato hastened away, first saluting the king, who replied by a friendly gesture.

[1] Noble officer in the service of a daimio or prince.

[2] Temple at Kioto containing 33,333 idols.

[3] These fish actually exist, and are valued at an immense sum, many placing it as high as a million dollars.

Next day, from early dawn, the streets of Osaka were full of movement and mirth. The people prepared for the feast, rejoicing in the thought of coming pleasures. Shops, the homes of artisans and citizens, opening full upon the street, afforded a free view of their modest interiors, furnished only with a few beautifully colored screens.

Voices were heard, mixed with bursts of laughter; and now and then some mischievous child struggled out of his mother's arms, while she was trying to dress him in his holiday attire, and frisked, and danced with glee upon the wooden stairs leading from the house to the road. He was then recalled with cries of pretended anger from within, the father's voice was heard, and the child returned to his mother, trembling with impatience.

Sometimes a little one would cry: "Mother, mother! Here comes the procession!"

"Nonsense!" said the mother; "the priests have not even finished dressing yet."

But still she moved towards the front of the house, and, leaning over the light balustrade, gazed into the street.

Carriers, naked save for a strip of stuff knotted round their waists, hastened rapidly by, across their shoulders a bamboo stick, which bent at the tip from the weight of a package of letters. They went in the direction of the Shogun's residence.

Before the barber's shops the crowd was thicker than elsewhere; the boys could not possibly shave all the chins presented, or dress all the heads offered. Customers awaiting their turn chatted gayly outside the door. Some were already dressed in their holiday garb, of bright colors, covered with embroidery. Others, more prudent, naked to the waist, preferred to finish their toilet after their hair was dressed. Vegetable-sellers and fish-merchants moved about through the throng, loudly praising their wares, which they carried in two buckets hanging from a cross piece of wood laid over one shoulder.

On every side people were trimming their houses with pennants, and streamers, and embroidered stuffs covered with Chinese inscriptions in gold on a black or purple ground; lanterns were hung up, and blossoming boughs.

As the morning advanced, the streets became fuller and fuller of merry tumult. Bearers of norimonos, clad in light tunics drawn tightly round their waist, with large shield-shaped hats, shouted to the people to make room. Samurais went by on horseback, preceded by runners, who, with lowered head and arms extended, forced a passage through the crowd. Groups paused to talk, sheltered from the sun by huge parasols, and formed motionless islands in the midst of the surging, billowy sea of promenaders. A doctor hurried by, fanning himself gravely, and followed by his two assistants carrying the medicine-chest.

"Illustrious master, are you not going to the feast!" cried the passers-by.

"Sick men pay no heed to feasts," he answered with a sigh; "and as there are none for them, there can be none for us."

On the banks of Yedogava the excitement was still greater. The river was literally hidden by thousands of vessels; the masts trimmed, the sails still unset, but ready to unfurl, like wings; the hatchways hung with silks and satins; the prows decked with banners whose golden fringe, dipped into the water, glittered in the sun, and stained the azure stream with many-colored ripples.

Bands of young women in brilliant attire came down the snowy steps of the river-banks cut into broad terraces. They entered elegant boats made of camphor-wood, set off by carvings and ornaments of copper, and filled them with flowers, which spread perfumes through the air.

From the top of Kiobassi—that fine bridge which resembles a bent bow—were hung pieces of gauze; crape, and light silk, of the most delicate colors, and covered with inscriptions. A gentle breeze softly stirred these lovely stuffs, which the boats, moving up and down, pushed aside as they passed. In, the distance glistened the tall tower of the palace and the two monstrous goldfish which adorn its pinnacle. At the entrance to the city, to right and left of the river, the two superb bastions looking out to sea displayed on every tower, at each angle of the wall, the national standard, white with a scarlet disk, —an emblem of the sun rising through the morning mists. Scattered pagodas upreared above the trees against the radiant sky their many roofs, curled upward at the edge in Chinese fashion.

The pagoda of Yebis, the divinity of the sea, attracted especial attention upon this day; not that its towers were higher, or its sacred doors more numerous, than those of neighboring temples, but from its gardens was to start the religious procession so eagerly awaited by the crowd.

At last, in the distance, the drum sounded. Every ear was bent to catch the sacred rhythm familiar to all: a few violent blows at regular intervals, then a hasty roll, gradually fading and dying, then again abrupt blows.

A tremendous roar of delight rose from the crowd, who instantly took their places along the houses on either side of the streets through which the procession was to pass.

The Kashiras, district police, rapidly stretched cords from stake to stake, to prevent the throng from trespassing on the main street. The procession had started; it had passed through the Tory, or sacred gateway which stands outside the pagoda of Yebis; and soon it defiled before the impatient multitude.

First came sixteen archers, one behind the other, in two lines, each man at a convenient distance from the other. They wore armor made of plates of black horn fastened together by stitches of red wool. Two swords were thrust through their sashes, barbed arrows extended above their shoulders, and in their hands they held huge bows of black and gold lacquer. Behind them came a body of servants bearing long staffs tufted with silk. Then appeared Tartar musicians, whose advent was announced by a joyous racket. Metallic vibrations of the gong sounded at intervals, mingled with drums beaten vigorously, shuddering cymbals, conch-shells giving out sonorous notes, shrill flute-tones, and blasts of trumpets rending the air, formed such an intensity of noise, that the nearest spectators winked and blinked, and seemed almost blinded.

After the musicians came, borne on a high platform, a gigantic crawfish, ridden by a bonze. Flags of every hue, long and narrow, bearing the arms of the city, and held by boys, swung to and fro about the enormous crustacean. Following, were fifty lancers, wearing round lacquer hats, and carrying on their shoulders a lance trimmed with a red tassel. Two servants led next a splendidly caparisoned horse, whose mane, drawn up above his neck, was braided and arranged like a rich fancy trimming. Standard-bearers marched behind this horse; their banners were blue, and covered with golden characters. Then advanced two great Corean tigers, with open jaws and bloodshot eyes. Children in the crowd screamed with fright; but the tigers were of pasteboard, and men, hidden in their paws, made them move. A monstrous drum, of cylindrical form, followed, borne by two bonzes; a third walked beside it and struck the drum incessantly with his clenched fist.

Finally came seven splendidly dressed young women, who were received with merry applause. These were the most famous and most beautiful courtesans of the town. They walked one after the other majestically, full of pride, each accompanied by a maid, and followed by a man who held a large silken parasol over her. The people, who knew them well, named them as they passed.

"There's the woman with the silver teal!" Two of those birds were embroidered on the large loose-sleeved cloak which she wore over her many dresses, whose collars were folded one above the other upon her breast. The cloak was of green satin, the embroidery of white silk, mixed with silver. The fair one's headdress was stuck full of enormous tortoise-shell pins, forming a semicircle of rays around her face.

"That one there, that is the seaweed woman!"

The beautiful growth, whose silken roots were lost in the embroideries of the cloak, floated out from the stuff and fluttered in the wind.

Then came the beauty with the golden dolphin; the beauty with the almond-blossoms; the beauties with the swan, the peacocks, and the blue monkey. All walked barefooted upon high clogs made of ebony, which increased their apparent height. Their heads bristled with shell-pins, and their faces, skilfully painted, seemed young and charming under the soft shadow of the parasol.

Behind these women marched men bearing willow-branches; then a whole army of priests, carrying on litters, or under pretty canopies with gilded tops, the accessories, ornaments, and furniture of the temple, which was purified during the progress of the procession.

After all these came the shrine of Yebis, the God of the Sea, the indefatigable fisher who spends entire days wrapped in a net, a line in his hand, standing on a rock half submerged in the water. The octagonal roof was covered with blue and silver, bordered with a pearl fringe, and surmounted by a great bird with outspread wings. This shrine, containing the God Yebis invisible within, was borne by fifty bonzes naked to the waist.

Behind, upon a litter, was borne the magnificent fish consecrated to Yebis, the Akama, or scarlet lady,—the favorite dish of all those who are fond of dainty fare. Thirty horsemen armed with pikes ended the procession.

The long train crossed the city, followed by the crowd which gathered in its rear; it reached the suburbs, and after a long march came out upon the sea-shore.

Simultaneously with its arrival, thousands of vessels reached the mouth of Yedogava, which wafted them gently towards the ocean. The sails were spread, the oars bit the water, banners floated on the breeze, while the sun flashed myriad sparkles across the blue, dancing waves.

Fide-Yori also reached the shore by the road that skirts the river bank; he stopped his horse and sat motionless in the midst of his suite, which was but scanty, the Regent being unwilling to eclipse the religious cortége by the royal luxury.

Hieyas himself was carried in a norimono, as were the mother and wife of the Shogun. He declared himself ill.

Fifty soldiers, a few standard-bearers, and two out-runners formed the entire escort.

The arrival of the young Prince divided the attention of the crowd, and the procession of Yebis no longer sufficed to attract every eye. The royal headdress, a sort of oblong golden cap placed upon Fide-Yori's head, made him easily recognizable from a distance.

Soon the religious procession filed slowly before the Shogun. Then the priests with the shrine left the ranks and went close down to the water's edge.

Upon this the fishermen and river boatmen suddenly ran up with cries, bounds, and gambols, and threw themselves upon the bearers of Yebis. They imitated a battle, uttering shouts, which grew more and more shrill. The priests made a feigned resistance; but soon the shrine passed from their shoulders to those of the stout sailors. The latter with howls of joy rushed into the sea and drew their beloved god through the clear waves, while bands of music, stationed on the junks which ploughed the sea, broke into merry melody. At last the sailors returned to land, amidst the cheers of the crowd, who soon scattered, to return in all haste to the town, where many other diversions awaited them,—open-air shows, sales of all sorts, theatrical representations, banquets, and libations of saki. Fide-Yori left the beach in his turn, preceded by the two runners and followed by his train. They entered a cool and charming little valley, and took a road which, by a very gentle slope, led to the summit of the hill. This road was utterly deserted, all access to it having been closed since the evening before.

Fide-Yori thought of the plot, of the bridge which was to give way and hurl him into an abyss. He had dwelt upon it all night with anguish; but beneath this bright sun, amidst this peaceful scene, he could no longer believe in human malice. And yet the path chosen for the return to the palace was strange. "We will take this road to avoid the crowd," said Hieyas; but he had only to close another way to the people, and the King might have gone back to the castle without making this odd circuit.

Fide-Yori looked about for Nagato; he was nowhere to be seen. Since morning the Shogun had twenty times inquired for him. The Prince was not to be found.

Sad forebodings seized upon the young Shogun. He suddenly asked himself why his escort should be so scanty, why he was preceded by two runners only. He looked behind him, and it seemed to him as if the norimono-bearers slackened their pace.

They reached the brow of the hill and soon Swallow bridge appeared at the turn of the road. As his eye fell upon it, Fide-Yori involuntarily reined in his horse; his heart beat violently. The frail bridge, boldly flung from one hill to another, crossed a very deep valley. The river, rapid as a torrent, leaped over the rocks with a dull, continuous noise. But the bridge seemed as usual to rest firmly upon the smooth rocks which jutted out beneath it.

The runners advanced unshrinkingly. If the conspiracy existed, they knew nothing of it. The young King dared not pause; he seemed to hear echoing in his ears Nagato's words: "March fearlessly towards the bridge!"

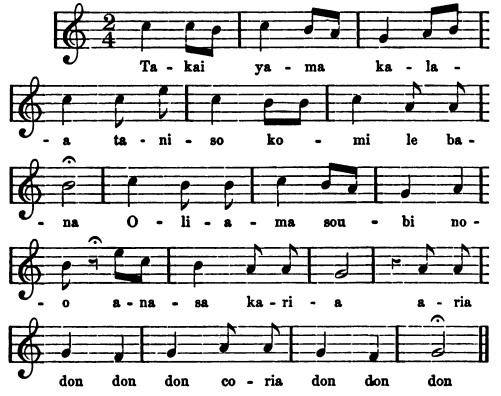

But the beseeching tones of Omiti also thrilled through his mind he recalled the oath which he had uttered. Nagato's silence alarmed him above all else. How many things might occur to foil the Prince's plan! Surrounded by skilful spies who watched his slightest acts, he might have been carried off and prevented from communicating with the King. All these thoughts rushed tumultuously into Fido-Yori's brain, the last supposition making him turn pale. Then, by one of those mental freaks often noted in situations of extreme peril, he suddenly recalled a song which he had sung as a child, to make himself familiar with the chief sounds of the Japanese language. He mechanically repeated it:—

"Color and perfume fade away.

What is there in this world that is permanent?

The day which is passed, vanishes in the gulf of oblivion.

It is like the echo of a dream.

Its absence causes not the slightest distress."

"I learned that when a mere child," murmured the King; "and yet I now shrink and hesitate at the possibility of death."

Ashamed of his weakness, he urged his horse forward. Just then a loud noise was heard on the opposite side of the bridge; and, suddenly turning the corner of the road, angry horses, with flying mane and bloodshot eyes, appeared, dragging behind them a chariot laden with the trunks of trees. They hastened towards the bridge, and their furious feet rang doubly loud upon the wooden flooring.

At the sight of these animals coming towards them Fide-Yori's whole escort uttered cries of terror, the porters dropped their norimonos, the women jumped out of them in alarm, and, gathering up their ample robes, fled hastily away. The runners, whose feet already touched the bridge, turned abruptly, and Fide-Yori instinctively sprang to one side.

But all at once, like a cord which, too tightly stretched, breaks, the bridge gave way with a loud crash; it first bent in the centre, then the two fragments rose suddenly in the air, scattering a shower of pieces on every hand. The horses and the car were plunged into the river, the water dashing in foam to the very brow of the hill. For some moments one animal hung by his harness, struggling above the gulf; but his bonds gave way and he fell. The tumultuous stream quickly bore to the sea horses, floating tree trunks, and all the remnants of the bridge.

"Oh, Omiti!" cried the King, motionless with horror, "you did not deceive me! This then was the fate reserved for me! Had it not been for your devotion, sweet girl, my mangled body would even now be flung from rock to rock."

"Well, master, you possess the knowledge that you wished. What do you think of my team?" cried a voice close beside the King.

The latter turned. He was alone, all his servants had abandoned him; but he saw a head rising from the valley. He recognized Nagato, who quickly climbed the stony elope and stood beside the King.

"Ah, my friend! my brother!" said Fide-Yori, who could not restrain his tears. "What have I ever done to inspire such hatred? Who is the unhappy man whom my life oppresses, and who would fain hurry me from the world?"

"Would you know that wretch?—would you learn the name of the guilty man?" said Nagato with a frown.

"Do you know him, friend? Tell me his name."

"Hieyas!" said Nagato.

It was the warmest hour of the day. All the halls of the palace at Kioto were plunged in cool darkness, thanks to the lowered shades and open screens before the windows.

Kioto is the capital, the sacred city, the residence of a god exiled to earth, the direct descendant of the celestial founders of Japan, the absolute sovereign, the high priest of all the forms of religion practised throughout the kingdom of the rising sun, in fact, the Mikado. The Shogun is only the first among the subjects of the Mikado; but the latter, crushed beneath the weight of his own majesty, blinded by his superhuman splendor, leaves the care of terrestrial affairs to the Shogun, who rules in his stead, while he sits alone, absorbed in the thought of his own sublimity.

In the centre of the palace parks, in one of the pavilions built for the nobles of the court, a woman lay stretched upon the floor which was covered with fine mats. Suddenly she rose upon her elbow and plunged her dainty fingers in the dark masses of her hair. Not far from her, an attendant, crouched on the ground, was playing with a pretty dog of a rare species, which looked like a ball of black and white silk. A koto, or musical instrument with thirteen strings, a writing-case, a roll of paper, a fan, and a box of sweetmeats were scattered over the floor, which no furniture concealed. The walls were made of cedar wood, carved in open work or covered with brilliant paintings enhanced by gold and silver; half-closed panels formed openings through which other halls were visible, and beyond these still other apartments.

"Mistress, you are sad," said the attendant. "Shall I strike the koto-strings, and sing a song to cheer you?"

The mistress shook her head.

"What?" cried the maid, "Fatkoura no longer loves music? Has she then forgotten that she owes the light of day to it? For when the Sun-goddess, enraged with the gods, withdrew into a cavern, it was by letting her hear divine music for the first time that she was led back to heaven!"

Fatkoura uttered a sigh, and made no answer.

"Shall I grind some ink for you? Your paper has long remained as stainless as the snow on Mount Fusi. If you have a grief, cast it into the mould of verse, and you will be rid of it."

"No, Tika; love is not to be got rid of; it is a burning pain, which devours one by day and by night, and never sleeps."

"Unhappy love, perhaps; but you are beloved, mistress!" said Tika, drawing nearer.

"I know not what serpent hidden in the depths of my heart tells me that I am not."

"What!" said Tika in amaze, "has he not revealed his deep passion by a thousand acts of folly? Did he not come but lately, at the risk of his life,—for the wrath of the Kisaki might well prove fatal,—merely to behold you for one instant?"

"Yes; and he vanished without exchanging a single word with me, Tika!" added Fatkoura, seizing the young girl's wrists in a nervous grasp. "He did not even look at me."

"Impossible!" said Tika; "has he not told you that he loved you?"

"He has; and I believed him, because I was so eager to believe. But now I believe him no longer."

"Why?"

"Because if he loved me he would have married me long since, and taken me to his estates."

"But the affection which he bears his master keeps him at the Court of Osaka!"

"So he says; but is that the language of love I What would I nob sacrifice for him!... Alas! I thirst for his presence! His face, so haughty, and yet so gentle, floats before my eyes! I long to fix it, but it escapes me! Ah! if I might but spend a few happy months with him, I would gladly kill myself afterwards, lulling myself to sleep with my love; and my past happiness would be a soft winding-sheet for me."

Fatkoura burst into sobs and hid her face in her hands. Tika strove to console her. She threw her arms around her, and said a thousand affectionate things, but could not succeed in calming her.

Suddenly a noise was heard at the other end of the room, and the little dog began to yelp.

Tika rose quickly and ran out, to prevent any servant from entering and seeing the emotion of her mistress; she soon returned beaming.

"It is he! it is he!" she exclaimed. "He is here; he wishes to see you."

"Do not jest with me, Tika!" said Fatkoura, rising to her feet.

"Here is his card," said the young girl; and she offered a paper to Fatkoura, who read at a glance:—

"Iwakura Teroumoto Mori, Prince of Nagato, entreats the honor of admission to your presence."

"My mirror!" she cried frantically. "I am horrible thus,—my eyes swollen, my hair disordered, dressed in a robe without embroidery! Alas! instead of weeping, I should have foreseen his coming, and busied myself with my toilette from early dawn!"

Tika brought the mirror of burnished metal, round as the full moon, and the box of perfumes and cosmetics.

Fatkoura took a pencil and lengthened her eyes. But her hand trembled, she made too heavy a line; then, wishing to repair the mistake, only succeeded in smearing her whole cheek with black. She clenched her fists with rage, and ground her teeth. Tika came to her aid, and removed the traces of her awkwardness. She placed upon the lower lip a little green paint, which became pink on contact with the skin. To replace the eyebrows, which had been carefully plucked out, she made two large black spots very high upon her forehead; to make the oval of her face longer, she sprinkled a little pink powder on her cheek-bones; then rapidly removed all the apparatus of the toilette, and threw over her mistress's shoulders a superb kirimon. Then she left the hall at full speed.

Fatkoura, trembling violently, stood beside the gotto as it lay on the floor, one hand holding up her mantle heavy with ornament, and eagerly fixed her gaze on the entrance.

At last Nagato appeared. He advanced, placing one hand on the golden hilt of one of his two swords, and, bowing with graceful dignity, said: "Pardon me, fair Fatkoura, if I come like a storm which sweeps across the sky unannounced by any foreboding clouds."

"You are to me like the sun when it rises from the sea," said Fatkoura, "and you are always expected. Stay! but a moment since I wept for your sake. See! my eyes are still red."

"Your eyes are like the evening and the morning stars," said the Prince. "But why did they drown their rays in tears? Can I have given you any cause to grieve?"

"You are here, and I have forgotten the cause of my sorrow," said Fatkoura, smiling; "perhaps I wept because you were far away."

"Why can I not be always here?" cried Nagato, with such an accent of truth that the young woman felt all her fears vanish, and a flash of joy illumined her countenance. Perhaps, however, she mistook the meaning of the Prince's words.

"Come closer," she said, "and rest upon these mats. Tika will serve us with tea and a few delicacies."

"Could I not first send the Kisaki a secret petition of the utmost importance?" asked Nagato. "I seized upon the pretext of this precious missive in order to get away from Osaka," he added, seeing a shadow on Fatkoura's brow.

"The sovereign has been vexed with me since your last appearance; I dare not approach her, or send any of my servants to her."

"And yet this note must be in her hands with the briefest possible delay," said Nagato, with a slight frown.

"What shall we do?" said Fatkoura, whom this trifling mark of distress had not escaped. "Will you come with me to one of my illustrious friends, the noble Iza-Farou No-Kami? She is in favor just now; perhaps she will help us."

"Let us go to her at once," said the Prince.

"Let us go," said Fatkoura with a sigh.

The young woman called Tika, who had remained in the next room, and signed to her to draw a sliding-panel, which opened upon a gallery encircling the pavilion.

"Are you going out, mistress?" said Tika. "Shall I summon your suite?"

"We are going incognito, Tika, to take a walk in the orchard. Really," she added, with her finger on her lips, "we are going to visit the noble Iza-Farou."

The maid bent her head in token of understanding. Fatkoura 'bravely set foot on the balcony, but sprang back hastily with an exclamation.

"It's a furnace," she cried.

Nagato picked up the fail lying upon the floor.

"Courage!" he said; "I will cool the air nearest your face."

Tika took a parasol, which she opened over her mistress's head, and Nagato waved the huge fan. They set out, sheltered at first by the projecting roof. Fatkoura led the way. Now and then she touched her finger-tips to the open-work cedar balustrade, and uttered a baby shriek at its burning contact. The pretty silken-haired dog, who had felt obliged to join the party, followed at a distance, growling, doubtless, remarks upon the madness of a walk at such an hour of the day.

They turned the corner of the house, and found themselves in front of it, at the top of a broad staircase leading to the garden, between two balusters ornamented with copper balls; a third baluster, in the centre of the staircase, divided it into two parts.

In spite of the intolerable heat and the vivid light, whose reflection from the sandy soil fairly blinded them, Fatkoura and the Prince of Nagato pretended to be walking with no other object than to pick a few flowers and admire the charming prospect which lay before them at every step. Although the gardens were deserted, they knew that the eye of the spy was never closed. They made haste to reach a shady alley, and soon arrived at a group of sumptuous pavilions scattered among the trees and connected by covered galleries.

"It is here," said Fatkoura, who, far from looking in the direction of the buildings of which she spoke, was leaning over a little pond filled with water so clear as to be almost invisible.

"Just see that pretty fish!" she said, purposely raising her voice; "I should think he was carved from a block of amber. And that one who looks like a ruby sprinkled with gold! he seems hanging in mid air, the water is so transparent. See, his fins are like black gauze, and his eyes like balls of fire! Decidedly, of all the dwellers in the palace, Iza-Farou has the finest fish."

"What, Fatkoura!" cried a feminine voice from the interior of a pavilion, "are you out at such an hour? Is it because you are a widow that you take so little care of your skin, and let it be destroyed by the sun?"

A blind was half raised, and Iza-Farou thrust out her pretty head, bristling with light tortoise-shell pins.

"Ah!" she said, "the lord of Nagato! You will not pass by my house without honoring me by entering," she added.

"We will come in with pleasure, thanking the fate which led us in this direction," said Fatkoura.

They went up the steps leading to the pavilion, and moved on through the flowers filling the balcony.

Iza-Farou came towards them.

"What had you to tell me?" she said to her friend in a low voice, as she gracefully saluted the Prince.

"I need your help," said Fatkoura; "you know I am in disgrace."

"I know it; shall I sue for your pardon? But can I assure the Queen that you will never again commit the fault which angered her so deeply?" said Iza-Farou, casting a mischievous glance at Nagato.

"I am the only criminal," said the Prince, smiling. "Fatkoura is not responsible for the actions of a madman like me."

"Prince, I think she is proud to be the cause of what you call mad acts; and many are the women who envy her."

"Do not jest with me," said Nagato; "I am sufficiently punished by having drawn down the wrath of her sovereign upon the noble Fatkoura."

"But that is not the question in point," cried Fatkoura. "The Lord of Nagato is bearer of an important message which he wishes to transmit to the Kisaki secretly. He first came to me; but as I cannot approach the Queen just now, I thought of your kind friendship."

"Trust the message to me," said Iza-Farou, turning to the Prince; "in a very few moments it shall be in the hands of our illustrious mistress."

"I am overcome with gratitude," said Nagato, taking from his bosom a white satin wrapper containing the letter.

"Wait here for me; I will return soon."

Iza-Farou took the letter, and ushered her guests into a cool and shady hall, where she left them alone.

"These pavilions communicate with the Kisaki's palace," said Fatkoura; "my noble friend can visit the sovereign without being seen by other eyes. May the gods grant that the messenger bring back a favorable answer, and I may see the cloud which darkens your brow vanish!"

The Prince seemed, in fact, absorbed and anxious; he nibbled the tip of his fan as he paced the room. Fatkoura followed him with her eyes, and her heart involuntarily stood still; she felt a return of the dreadful agony which had so recently wrung tears from her, and which the presence of her beloved had suddenly calmed.

"He does not love me," she murmured in despair; "when his eyes turn towards me, they alarm me by their cold and almost contemptuous expression."

Nagato seemed to have forgotten the presence of the young woman; he leaned against a half-open panel, and seemed lost in a dream, at once sweet and poignant.

The rustle of a dress upon the mats that covered the floor drew him from his revery. Iza-Farou returned; she seemed in haste, and soon appeared at the corner of the gallery. Two young boys, magnificently attired, followed her.

"These are the words of the divine Kisaki," said she, as soon as she was within speaking distance of Nagato: "'Let the suppliant make his request in person.'"

At these words Nagato turned so pale, that Iza-Farou, frightened, thinking that he would faint, rushed towards him, to prevent him from falling.

"Prince," she cried, "be calm! Such a favor is, I know, enough to cause your emotion: but are you not used to all honors?"

"Impossible!" muttered Nagato, in a voice which was scarcely audible; "I cannot appear before her."

"What!" said Iza-Farou, "would you disobey her command?"

"I am not in court-dress," said the Prince.

"She will dispense with ceremony for this time only, the reception being secret. Do not keep her waiting longer."

"So be it; lead the way!" suddenly exclaimed Nagato, who had now apparently conquered his emotion.

"These two pages will conduct you," said Iza-Farou.

Nagato left the room rapidly, preceded by the Kisaki's two servitors; but not so rapidly that he did not hear a stifled cry which broke from the lips of Fatkoura.

After walking for some time, and passing through the various galleries and halls of the palace without paying the slightest heed to them, Nagato came to a great curtain of white satin, embroidered in gold, whose broad folds, silvery in the light, leaden-hued in the shade, lay in ample heaps upon the ground.

The pages drew aside this drapery; the Prince advanced, and the quivering waves of satin fell together again behind him.

The walls of the hall which he entered glittered faintly in the dim light; they gave out flashes of gold, the whiteness of pearls and purple reflections, while an exquisite perfume floated in the air. At the end of the room, beneath curtains fastened back by golden cords, sat the radiant sovereign in the midst of the silken billows of her scarlet robes; the triple plate of gold, insignia of omnipotence, rose above her brow. The Prince grasped the vision with one involuntary look; then, dropping his eyes as if he had gazed upon the sun at noon, he advanced to the centre of the room and fell upon his knees; then slowly his face sank to the ground.

"Iwakura," said the Kisaki, after a long pause, "what you ask of me is serious. I desire certain explanations from your own lips before I prefer your request to the sublime master of the world, the son of the gods, my spouse."

The Prince half rose, and strove to speak, but could not; he felt as if his bosom would burst with the frantic throbbing of his heart. The words died on his lips, and he remained with downcast eyes, pale as death.

"Is it because you think me angry with you that you are so much alarmed?" said the Queen, looking at the Prince for an instant with surprise. "I can forgive you, for your crime is but slight. You love one of my maidens, that is all."

"Nay, I do not love her!" cried Nagato, who, as if he had lost his senses, raised his eyes to his sovereign.

"What matters it to me?" said the Kisaki abruptly. For one second their gaze met; but Nagato closed his guilty eyes, and trembling at his own audacity, awaited its punishment.

But after a pause the Kisaki went on in a quiet voice: "Your letter reveals to me a terrible secret; and if what you imagine is true, the peace of the kingdom may be deeply affected."

"That is why, Divine Sister of the Sun, I had the boldness to beg for your all-powerful intercession," said the Prince, unable completely to master the quiver in his voice. "If you grant my prayer, if I obtain what I ask, great misfortunes may be prevented."

"You know, Iwakura, that the Celestial Mikado is favorable to Hieyas; would he believe in the crime of which you accuse his favorite I and would you be willing to maintain in public the accusation hitherto kept secret?"

"I would maintain it to Hieyas' very face," said Nagato firmly; "he is the instigator of the odious plot which came near costing my young master his life."

"That affirmation would endanger your own life. Have you thought of that?"

"My life is a slight thing," said the Prince. "Besides, the mere fact of my devotion to Fide-Yori is enough to attract the Regent's hatred. I barely escaped assassination by his men a few days ago, on leaving Kioto."

"What, Prince! is that indeed possible?" said the Kisaki.

"I only mention the unimportant fact," continued Nagato, "to show you that this man is familiar with crime, and that he is anxious to rid himself of those who stand in the way of his ambition."

"But how did you escape from the murderers?" asked the Kisaki, who seemed to take a lively interest in the adventure.

"The sharp blade of my sword and the strength of my arm saved my life. But why should you waste your sublime thoughts upon so trifling an incident?"

"Were the assassins numerous?" inquired the Queen, curiously.

"Ten or twelve, perhaps. I killed several of them; then I gave my horse the spurs, and he soon put a sufficient distance between them and me."

"What!" said the Kisaki meditatively, "is the man who has the confidence of my divine spouse so fierce and treacherous? I share your fears, Iwakura, and sad forebodings overwhelm me; but can I persuade the Mikado that our presentiments are not vain? At least I will try to do so, for the good of my people and the salvation of the kingdom. Go, Prince; be at the reception this evening. I shall then have seen the Lord of the World."

The Prince, having prostrated himself, rose, and with his head still bent towards the earth, withdrew backwards from the room. As he reached the satin curtain, he once more almost involuntarily raised his eyes to the sovereign, who followed him with her gaze. But the drapery fell and the adorable vision disappeared.

The pages led Iwakura to one of the palaces reserved for sovereign princes passing through Kioto. Happy to find himself alone, he stretched himself upon a pile of cushions, and, still deeply moved, gave himself up to a delicious revery.

"Ah!" he murmured, "what strange joy fills my soul! I am intoxicated; perhaps it comes from breathing the air that surrounds her! Ah! terrible madness, hopeless longing which causes me such sweet suffering, how much you must be increased by this unexpected interview! Already I had often fled from Osaka; exhausted, like a diver perishing for want of air, I came hither, to gaze upon the palaces which hide her from my sight, or to catch an occasional glimpse of her in the distance as she leaned over a balcony, or paced the garden paths surrounded by her women; and I bore hence a store of happiness. But now I have breathed the perfume which exhales from her person, her voice has caressed my ear, I have heard my name tremble on her lips! Can I now be content with what has hitherto filled up my life? I am lost; my existence is ruined by this impossible love; and yet I am happy. Soon I shall see her again, no longer under the constraint of a political audience, but able to dazzle myself at my ease with her beauty. Shall I have strength to conceal my agitation and my criminal love? Yes, divine sovereign, before thee only my haughty spirit falls prostrate, and my every thought turns towards thee as the mists to the sun. Goddess, I adore thee with awe and respect; but alas! I love thee as well, with a mad tenderness, as if thou wert but a mere woman!"

Night had come; to the heat of the day had succeeded a delicious coolness, and the air was full of perfume from the garden flowers, wet with dew.

The balconies running outside the palace halls in which the evening diversions were to take place, were illuminated, and crowded with guests, who breathed the evening air with delight. The Prince of Nagato ascended the staircase of honor, bordered on either hand by a living balustrade of pretty pages, each holding in his hand a gilded stick, at the end of which hung a round lantern. The Prince passed through the galleries slowly, on account of the crowd; he bowed low when he encountered any high dignitary of the Court, saluted the princes, his equals, in friendly phrase, and approached the throne room.

This hall shone resplendent from the myriad rays of lanterns and of lamps. A joyous uproar filled it as well as the neighboring apartments seen through the widely opened panels.

The maids-of-honor chattered together, and their voices were-blended with the slight rustle of their robes, as they arranged the ample folds. Seated on the right and left of the royal dais, these princesses formed groups, and each group had its hierarchic rank and its especial colors. In one the women were arrayed in pale-blue robes flowered with silver; in another in green, lilac, or pale-yellow gowns.

Upon the dais covered with soft carpets, the Kisaki shone resplendent in the midst of the waves of satin, gauze, and silver brocade formed by her full scarlet and white robes, scintillating with precious stones. The three vertical plates surmounting her diadem looked like three golden sunbeams hovering above her brow.

Certain princesses had mounted the steps to the throne, and, kneeling upon the topmost one, talked merrily with their sovereign; the latter sometimes littered a low laugh, which scandalized some silent old prince, the faithful guardian of the severe rules of etiquette. But the sovereign was so young, not yet twenty years old, that she might readily be pardoned if she sometimes ceased to feel the weight of the crown upon her head; and at her laughter, joy spread on every side, as the songs of the birds break forth with the first rays of the sun.

"The supreme gods be praised!" said one princess in an undertone to her companions, "the sorrow that oppressed our sovereign has passed away at last; she is gayer than ever this evening."

"And in what a clement mood!" said another. "There is Fatkoura restored to favor. She mounts the stops to the throne. The Kisaki has summoned her."

In fact Fatkoura stood upon the last step of the royal dais; but the melancholy expression of her features, her fixed and bewildered gaze, contrasted strangely with the serene and happy look imprinted upon every face. She thanked the Kisaki for granting her pardon; but she did it in a voice so sad and so singularly troubled that the young Queen trembled, and raised her eyes to her former favorite.

"Are you ill?" she asked, surprised at the change in the young woman's features.

"With joy at winning forgiveness, perhaps," stammered Fatkoura.

"You need not remain for the feast if you are not well."

"I thank you," said Fatkoura, bending low, as she moved away and was lost in the crowd.

The notes of a hidden orchestra were soon heard, and the entertainment began.

A curtain was drawn aside in the wall opposite the throne, and revealed a charming landscape.

Mount Fusiyama appeared in the background, rearing its snow-sprinkled peak above a necklace of clouds; the sea, of a deep blue, dotted with a few white sails, lay at the foot of the mountains: a road wound along among trees and thickets of flowering shrubs.