Title: Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience

Compiler: Grenville Kleiser

Release date: October 25, 2014 [eBook #47194]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Robert Morse, Anna Whitehead and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

A COLLECTION OF SHORT SELECTIONS,

STORIES AND SKETCHES

FOR ALL OCCASIONS

By

GRENVILLE KLEISER

Author of "How to Speak in Public"

THIRTEENTH EDITION

FUNK & WAGNALLS COMPANY

NEW YORK AND LONDON

Copyright 1908 by

FUNK & WAGNALLS COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

Published March, 1908

In preparing this volume the author has been guided by his own platform experience extending over twelve years. During that time he has given hundreds of public recitals before audiences of almost every description, and in all parts of the country. It may not be considered presumptuous, therefore, for him to offer some practical suggestions on the art of entertaining and holding an audience, and to indicate certain selections which he has found have in themselves the elements of success.

The "encore fiend," as he is sometimes called, is so ubiquitous and insistent that no speaker or reader can afford to ignore him, and, indeed, must prepare for him in advance. To find material that will satisfy him in one or in a dozen of the ordinary books of selections is an almost impossible task. It is only too obvious that many compilations of the kind are put together by persons who have had little or no practical platform experience. In an attempt to remedy this defect this volume has been prepared.

It is believed that the book will be valuable not only to the amateur and the professional reader, speaker, elocutionist, and entertainer, but also to the after-dinner and impromptu speaker, the politician who wants to make a "hit," the business man who wishes to tell a good story and tell it effectively, the school-teacher in arranging her "Friday Afternoon" programs, as well as for reading aloud in the family circle, and for many other occasions.

Providing, as this work does, helpful hints on how to hold an audience, it is hoped that the additional suggestions offered regarding the use of the voice and its modulation, the art of pausing, the development of feeling and energy, the use of gesture and action, the cultivation of the imagination, the committing of selections to memory, and the standing before an audience, while not as elaborate and detailed as found in a regular manual of elocution, will be of practical benefit to those who can not conveniently command the services of a personal instructor.

The author has been greatly assisted in this undertaking not only by the kind permission of publishers and authors to use their copyrighted work, but also by the hearty cooperation of many distinguished platform speakers and readers who have generously contributed successful selections not hitherto published.

The author gratefully acknowledges the special permission granted him by the publishers to print the following copyright selections: "Keep A-goin'!" the Bobbs-Merrill Company, "A Modern Romance," the Publishers of The Smart Set; "The Fool's Prayer," Houghton, Mifflin & Company; "Mammy's Li'l Boy," and "'Späcially Jim," the Century Company; "Counting One Hundred," the Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Company; "At Five O'clock Tea," the Publishers of Lippincott's Magazine.

Grenville Kleiser.

New York City, February, 1908.

| INTRODUCTORY | v | ||

| PART I—HOW TO HOLD AN AUDIENCE | |||

| The Voice | 4 | ||

| The Breath | 6 | ||

| Modulation | 8 | ||

| Pausing | 10 | ||

| Feeling and Energy | 11 | ||

| Gesture and Action | 12 | ||

| Impersonation | 13 | ||

| Articulation and Pronunciation | 13 | ||

| Imagination | 14 | ||

| How to Memorize a Selection | 16 | ||

| Before the Audience | 18 | ||

| PART II—HUMOROUS HITS | |||

| The Train-misser | James Whitcomb Riley | 23 | |

| The Elocutionist's Curfew | W. D. Nesbit | 24 | |

| Melpomenus Jones | Stephen Leacock | 25 | |

| Her Fifteen Minutes | Tom Masson | 28 | |

| The Foxes' Tails | Anonymous | 29 | |

| The Dead Kitten | " | 33 | |

| The Weather Fiend | " | 34 | |

| The Race Question | Paul Laurence Dunbar | 35 | |

| When the Woodbine Turns Red | Anonymous | 38 | |

| Cupid's Casuistry | W. J. Lampton | 39 | |

| When Mah Lady Yawns | Charles T. Grilley | 39 | |

| Watchin' the Sparkin' | Fred Emerson Brooks | 40 | |

| The Way of a Woman | Byron W. King | 42 | |

| The Yacht Club Speech | Anonymous | 43 | |

| Mammy's Li'l' Boy | H. S. Edwards | 44 | |

| Corydon | Thomas Bailey Aldrich | 47 | |

| Gib Him One ub Mine | Daniel Webster Davis | 49 | |

| A Lesson with the Fan | Anonymous | 50 | |

| The Undertow | Carrie Blake Morgan | 51 | |

| Marketing | Anonymous | 52 | |

| A Spring Idyl on "Grass" | Nixon Waterman | 52 | |

| Introducin' the Speecher | Edwin L. Barker | 54 | |

| Counting One Hundred | James M. Bailey | 57 | |

| They Never Quarreled | Anonymous | 58 | |

| Song of the "L" | Grenville Kleiser | 60 | |

| The Village Oracle | J. L. Harbour | 62 | |

| If I Can Be by Her | Benjamin Franklin King | 65 | |

| McCarthy and McManus | Anonymous | 66 | |

| And She Cried | Minna Irving | 68 | |

| Dot Leedle Boy | James Whitcomb Riley | 69 | |

| Mr. Dooley on the Grip | Finlay Peter Dunne | 73 | |

| A Rainy Day Episode | Anonymous | 75 | |

| I Knew He Would Come if I Waited | H. G. Williamson | 76 | |

| Love's Moods and Senses | Anonymous | 77 | |

| A Nocturnal Sketch | Thomas Hood | 78 | |

| Katie's Answer | Anonymous | 79 | |

| "'Späcially Jim" | " | 80 | |

| Agnes, I Love Thee! | " | 81 | |

| The Gorilla | " | 82 | |

| Banging a Sensational Novelist | " | 83 | |

| Hopkins' Last Moments | " | 84 | |

| The Fairies' Tea | " | 85 | |

| Counting Eggs | Anonymous | 86 | |

| The Oatmobile | " | 87 | |

| Almost Beyond Endurance | James Whitcomb Riley | 89 | |

| Proof Positive | Anonymous | 90 | |

| The Irish Philosopher | " | 91 | |

| Belagcholly | " | 93 | |

| A Pantomime Speech | " | 93 | |

| The Original Lamb | " | 95 | |

| When Pa Was a Boy | S. E. Kiser | 95 | |

| The Freckled-faced Girl | Anonymous | 96 | |

| Willie | Max Ehrmann | 98 | |

| Amateur Night | Anonymous | 98 | |

| Bounding the United States | John Fiske | 101 | |

| Der Dog und der Lobster | Anonymous | 102 | |

| He Laughed Last | " | 103 | |

| Norah Murphy and the Spirits | Henry Hatton | 104 | |

| Opie Read | Wallace Bruce Amsbary | 107 | |

| The Village Choir | Anonymous | 108 | |

| Billy of Nebraska | J. W. Bengough | 110 | |

| Dot Lambs Vot Mary Haf Got | Anonymous | 112 | |

| Georga Washingdone | " | 113 | |

| Da 'Mericana Girl | T. A. Daly | 114 | |

| Becky Miller | Anonymous | 115 | |

| Pat and the Mayor | " | 116 | |

| The Wind and the Moon | George MacDonald | 118 | |

| Total Annihilation | Anonymous | 120 | |

| Ups and Downs of Married Life | " | 121 | |

| The Crooked Mouth Family | " | 122 | |

| "Imph-m" | " | 124 | |

| The Usual Way | " | 125 | |

| Nothing Suited Him | " | 126 | |

| A Litte Feller | " | 126 | |

| Robin Tamson's Smiddy | Alexander Rodger | 127 | |

| A Big Mistake | Anonymous | 129 | |

| Lord Dundreary's Letter | " | 131 | |

| Slang Phrases | " | 133 | |

| The Merchant and the Book Agent | " | 134 | |

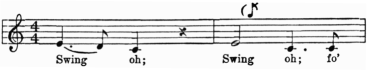

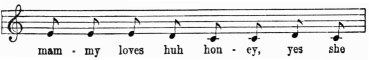

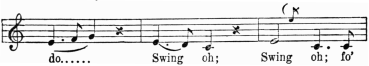

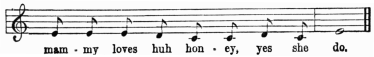

| The Coon's Lullaby | " | 136 | |

| Parody on Barbara Frietchie | " | 137 | |

| Before and After | Charles T. Grilley | 139 | |

| When Greek Meets Greek | Anonymous | 140 | |

| Mr. Potts' Story | Max Adeler | 141 | |

| At Five O'clock Tea | Morris Wade | 143 | |

| Keep A-goin'! | Frank L. Stanton | 145 | |

| A Lover's Quarrel | Cynthia Coles | 146 | |

| Casey at the Bat | Phineas Thayer | 147 | |

| Familiar Lines | Anonymous | 149 | |

| A Friendly Game of Checkers | " | 150 | |

| Modern Romance | Henry M. Blossom, Jr. | 152 | |

| Lullaby | Paul Laurence Dunbar | 153 | |

| The Reason Why | Mary E. Bradley | 154 | |

| How a Bachelor Sews on a Button | Anonymous | 154 | |

| Christopher Columbus | " | 155 | |

| The Fly | " | 156 | |

| The Yarn of the "Nancy Bell" | W. S. Gilbert | 157 | |

| I Tol' Yer So | John L. Heaton | 160 | |

| "You Git Up!" | Joe Kerr | 161 | |

| Presentation of the Trumpet | Anonymous | 162 | |

| Don't Use Big Words | " | 163 | |

| Der Mule Shtood on der Steamboad Deck | " | 164 | |

| The New School Reader | " | 165 | |

| The Poor Was Mad | Charles Battell Loomis | 167 | |

| Lides to Bary Jade | Anonymous | 168 | |

| "Charlie Must not Ring To-night" | Anonymous | 169 | |

| A Short Encore | " | 170 | |

| My Double, and How He Undid Me | Edward Everett Hale | 171 | |

| Romance of a Hammock | Anonymous | 173 | |

| Finnigin to Flannigan | S. W. Gillinan | 175 | |

| An Introduction | Mark Twain | 177 | |

| The Harp of a Thousand Strings | Joshua S. Morris | 177 | |

| The Difficulty of Riming | Anonymous | 179 | |

| So Was I | Joseph Bert Smiley | 181 | |

| The Enchanted Shirt | John Hay | 183 | |

| Deb Oak und der Vine | Charles Follen Adams | 185 | |

| The Ship of Faith | Anonymous | 187 | |

| He Wanted to Know | " | 188 | |

| An Opportunity | " | 190 | |

| Gape-seed | " | 190 | |

| Lariat Bill | " | 192 | |

| The Candidate | Bill Nye | 193 | |

| One Afternoon | Anonymous | 196 | |

| Not In It | " | 198 | |

| A Twilight Idyl | Robert J. Burdette | 199 | |

| Lavery's Hens | Anonymous | 201 | |

| Lisp | " | 202 | |

| They Met by Chance | " | 203 | |

| The Bridegroom's Toast | " | 203 | |

| Rehearsing for Private Theatricals | Stanley Huntley | 204 | |

| The V-a-s-e | James Jeffrey Roche | 206 | |

| Papa and the Boy | J. L. Harbour | 208 | |

| The Obstructive Hat in the Pit | F. Anstey | 210 | |

| Hullo | S. W. Foss | 213 | |

| The Dutchman's Telephone | Anonymous | 214 | |

| Doctor Marigold | Charles Dickens | 216 | |

| The Ruling Passion | William H. Siviter | 219 | |

| The Dutchman's Serenade | Anonymous | 220 | |

| Widow Malone | Charles Lever | 222 | |

| His Leg Shot Off | Anonymous | 224 | |

| The Stuttering Umpire | The Khan | 225 | |

| The Man Who Will Make a Speech | Anonymous | 227 | |

| Carlotta Mia | T. A. Daly | 228 | |

| The Vassar Girl | Wallace Irwin | 229 | |

| A Short Sermon | Anonymous | 231 | |

| A Lancashire Dialectic Sketch | " | 232 | |

| His Blackstonian Circumlocution | " | 233 | |

| Katrina Likes Me Poody Vell | " | 234 | |

| At the Restaurant | " | 235 | |

| A-feared of a Gal | " | 237 | |

| Leaving out the Joke | " | 238 | |

| The Cyclopeedy | Eugene Field | 239 | |

| Echo | John G. Saxe | 244 | |

| Our Railroads | Anonymous | 245 | |

| Wakin' the Young 'Uns | John C. Boss | 247 | |

| Pat's Reason | Anonymous | 249 | |

| Quit Your Foolin' | " | 250 | |

| She Would Be a Mason | James L. Laughton | 251 | |

| Henry the Fifth's Wooing | Shakespeare | 254 | |

| Scene from "The Rivals" | Richard Brinsley Sheridan | 258 | |

| Scenes from "Rip Van Winkle" | As Recited by Burbank | 261 | |

| PART III—SERIOUS HITS | |||

| If We Had the Time | Richard Burton | 267 | |

| The Fool's Prayer | Edward Rowland Sill | 268 | |

| The Eve of Waterloo | Byron | 269 | |

| The Wreck of the Julie Plante | W. H. Drummond | 271 | |

| Father's Way | Eugene Field | 272 | |

| I Am Content | Carmen Sylva Translation | 274 | |

| The Eagle's Song | Richard Mansfield | 275 | |

| Break, Break, Break | Alfred, Lord Tennyson | 277 | |

| Virginius | Macaulay | 277 | |

| The Women of Mumbles Head | Clement Scott | 279 | |

| William Tell and His Boy | William Baine | 282 | |

| Lasca | F. Desprez | 284 | |

| The Volunteer Organist | S. W. Foss | 287 | |

| Life Compared to a Game of Cards | Anonymous | 289 | |

| Old Daddy Turner | " | 290 | |

| The Tramp | " | 292 | |

| The Dandy Fifth | F. H. Gassaway | 293 | |

| On Lincoln | Walt Whitman | 296 | |

| The Little Stowaway | Anonymous | 296 | |

| Saint Crispian's Day | Shakespeare | 299 | |

| The C'rrect Card | George R. Sims | 300 | |

| The Engineer's Story | Rosa H. Thorpe | 303 | |

| The Face Upon the Floor | H. Antoine D'Arcy | 306 | |

| The Funeral of the Flowers | T. De Witt Talmage | 309 | |

| Cato's Soliloquy on Immortality | Joseph Addison | 311 | |

| Opportunity | John J. Ingalls | 312 | |

| Opportunity's Reply | Walter Malone | 312 | |

| The Earl-king | Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe | 313 | |

| Carcassonne | M. E. W. Sherwood | 314 | |

| The Musicians | Anonymous | 315 | |

| On the Rappahannock | " | 317 | |

| Como | Joaquin Miller | 319 | |

| Aux Italiens | Owen Meredith | 322 | |

To hold the interest of an audience and to successfully entertain it—whether from public platform, in fraternal organization, by after-dinner speech, or in the home circle—is a worthy accomplishment. Moreover, the memorizing of selections and rendering them before an audience is one of the best preparations for the larger and more important work of public speaking. Many of our most successful after-dinner speakers depend almost entirely upon their ability to tell a good story.

The art of reciting and story-telling has become so popular in recent years that a wide-spread demand has arisen for books of selections and suggestions for rendering them. Material suitable for encores has been particularly difficult to find. It is thought, therefore, that the present volume, containing as it does a great variety of short numbers, will meet with approval.

There is, perhaps, no talent that is more entertaining and more instructive than that of reciting aloud specimens of prose and poetry, both humorous and serious, from our best writers. Channing says:

"Is there not an amusement, having an affinity with the drama, which might be usefully introduced among us? I mean, Recitation.

"A work of genius, recited by a man of fine taste, enthusiasm, and powers of elocution, is a very pure and high gratification.

"Were this art cultivated and encouraged, great numbers, now insensible to the most beautiful compositions, might be waked up to their excellence and power.

"It is not easy to conceive of a more effectual way of spreading a refined taste through a community. The drama undoubtedly appeals more strongly to the passions than recitation; but the latter brings out the meaning of the author more. Shakespeare, worthily recited, would be better understood than on the stage.

"Recitation, sufficiently varied, so as to include pieces of chaste wit, as well as of pathos, beauty, and sublimity, is adapted to our present intellectual progress."

To recite well, and to be able to hold an audience, one should be trained in the proper use of the voice and body in expression. This requires painstaking study and preparation. It is a mistake to suppose that much can be safely left to impulse and the inspiration of the occasion. With all great artists everything is premeditated, studied, and rehearsed beforehand.

Salvini, the great Italian tragedian, said to the pupils in his art: "Above all, study,—study,—STUDY. All the genius in the world will not help you along with any art, unless you become a hard student. It has taken me years to master a single part."

The voice can be rapidly and even wonderfully developed by practising for a few minutes daily exercises prescribed in any good manual of elocution.[1] Learn to speak in the natural voice. If it is high-pitched, nasal, thin, or unmusical, these defects can be overcome by patient and judicious practise. Do not assume an artificial voice, except in impersonation. Remember that intelligent audiences demand intelligent expression, and will not tolerate the ranting, bombast, and unnatural style of declamation of former days.

Many people speak with half-shut teeth and mouth. Open the mouth and throat freely; liberate all the muscles around the vocal apparatus. Aim to speak with ease, and endeavor to improve the voice in depth, purity, roundness, and flexibility. Daily conversation offers the best opportunity for this practise.

A writer recently said: "Only a very, very few of us Americans speak English as the English do. We have our own 'accent,' as it is called. We are a nervous, eager, strident people. We know it, tho we do not relish having foreigners tell us about it. We speak not mellowly, not with lax tongues and palates, but sharply, shrilly, with hardened mouth and with tones forced back upon the palate. We strangulate two-thirds of our vowels and swallow half the other third. Pure, round, sonorous tones are almost never heard in our daily speech."

Speak from the abdomen. All the effort, all the motive power, should come from the waist and abdominal muscles. These are made to stand the strain that is so often incorrectly put upon the muscles of the throat. Aim at a forward tone; that is, send your voice out to some distant object, imaginary or otherwise, without unduly elevating the pitch. The voice should strike against the hard palate, the hard bony arch just above the upper teeth. Most of the practising should be done on the low pitches.

If there is any serious physical defect of the throat or nose, consult a reliable physician.

Do not overtax the voice. Three periods of ten minutes each are better than an hour's practise at one time. Stop at the first sign of weariness. Do not practise within an hour after eating. Avoid the habitual use of lozenges. There is nothing better for the throat than a gargle of salt and water, used night and morning. Dash cold water on the outside of the throat and rub it vigorously with a coarse towel.

[1] See "How to Speak in Public." a complete manual of elocution, by Grenville Kleiser. Published by Funk & Wagnalls Company. Price, $1.25 net.

The proper management of the breath is an important part of good speaking. Some teachers say the air should be inhaled on all occasions exclusively through the nose. This is practically impossible while in the act of speaking. The aim should be to speak on full lungs as much as possible; therefore a breath must be taken at every opportunity. This is done during the pauses, but often the time is so short that the speaker will find it necessary to use both mouth and nose to get a full supply of air. The breathing should be inaudible.

Practise deep breathing until it becomes an unconscious habit. In taking in the breath the abdomen and chest both expand, and in giving out the breath the abdomen and chest both contract. By this method of respiration the abdomen is used as a kind of "bellows," and the strain is taken entirely off the throat. The breathing should be done without noticeable effort and without raising the shoulders. Whenever possible the breathing should be long and deep. While speaking, endeavor to hold back in the lungs, or reservoir, the supply of air, "feeding" it very gradually to the vocal cords in just the quantity required for a given tone. Reciting aloud, when properly done, is a healthful exercise, and the voice should grow and improve through use; but to speak on half-filled lungs, or from the throat, is distressing and often injurious.

Keep your shoulders well thrown back, head erect, chin level, arms loosely at the sides, and in walking throw the leg out from the hip with easy, confident movement. The weight of the body should be on the ball of the foot, altho the whole foot touches the floor. The breathing should be deep, smooth, and deliberate.

When the breath is not being used in speech, breathe exclusively through the nose. This is particularly desirable during the hours of sleep. As someone has said, if you awake at night and find your mouth open, get up and shut it. A well-known English authority on elocution says that as a golden rule for the preservation of the health, he considers the habit of breathing through the nose invaluable if not imperative. Air, which is the breath of life, has always floating in it also the seeds of death. The nose is a filter and deodorizer, in passing through which the air is cleansed and sent pure into the lungs. The nose warms the air as well as purifies it, and thus prevents it from being breathed in that raw, damp state which is so injurious to those whose lungs are delicate.

Speak immediately upon opening your mouth. Try to turn into pure-toned voice every particle of breath you give out. Replenish the lungs every time you pause. Light gymnastics, brisk walking, running, horseback riding, and other exercise will improve your breathing capacity.

Modulation simply means change of voice. These changes, however, must be intelligent and appropriate to the thought. Monotony—speaking in one tone—must be avoided. The speaker should have the ability to raise or lower the pitch of his voice at will, as well as to vary it in force, intensity, inflection, etc.

Do not confuse "pitch" with "force." Pitch refers to the key of the speaking voice, while force relates to the loudness of the voice. The movement or rate of speaking should be varied to suit the particular thought. It would be ridiculous to describe a horse-race in the slow, measured tones of a funeral procession.

Most of your speaking should be done in the middle and lower registers; but the higher pitches, altho not so often required, must be trained so as to be ready for use. These higher tones are frequently thin and unmusical, but they can be made full and firm through practise.

It is not necessary to study many rules for inflection. The speaker should know in a general way that when the sense is suspended the voice follows this tendency and runs up, and when the sense is completed the voice runs down. In other words, the voice should simply be in agreement with the tendency of the thought, whether it opens up or closes down. The lengths of inflection vary according to the thought and the required emphasis.

For most occasions the speaking should be clear-cut and deliberate. The larger the room or hall, the slower should be the speech, to give the vocal vibrations time to travel. Dwelling on words too long, drawling, or over precision in articulation, is tedious to an audience. The other extreme, undue haste, suggests lack of self-control, and is fatal to successful effort. Of course this does not apply to special selections demanding rapid speech.

There are numerous words in English that represent or at least suggest their meaning in their sound. One who aims to read or recite well should study these effects so as to use them skilfully and with judgment.

The most complete and concise treatment on the subject of expression is perhaps that given in Hamlet's advice to the players when he says:

"Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced it to you—trippingly on the tongue; but if you mouth it, as many of your players do, I had as lief the town crier spoke my lines. Nor do not saw the air too much with your hand, thus; but use all gently: for in the very torrent, tempest, and as I may say whirlwind of your passion, you must acquire and beget a temperance that may give it smoothness. O! it offends me to the soul, to hear a robustious periwig-pated fellow tear a passion to tatters, to very rags, to split the ears of the groundlings; who, for the most part, are capable of nothing but inexplicable dumb-shows, and noise. I would have such a fellow whipped for o'erdoing Termagant; it out-herods Herod: pray you, avoid it....

"Be not too tame neither, but let your own discretion be your tutor: suit the action to the word, the word to the action, with this special observance, that you o'erstep not the modesty of nature; for anything so overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first, and now, was, and is, to hold, as 't were, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time, his form and pressure. Now, this overdone, or come tardy off, tho it make the unskilful laugh, can not but make the judicious grieve; the censure of the which one must, in your allowance, o'erweigh a whole theater of others. O! there be players, that I have seen play—and heard others praise, and that highly—not to speak it profanely, that, neither having the accent of Christians, nor the gait of Christian, pagan, nor man, have so strutted and bellowed, that I have thought some of nature's journeymen had made men, and not made them well, they imitated humanity so abominably."

Words naturally divide themselves into groups according to their meaning. Grammatical pauses indicate the construction of language, while rhetorical pauses mark more particularly the natural divisions in the sense. To jumble words together, or to rattle them off in "rapid-fire" style, is not an entertaining performance. Proper pausing secures economy of the listener's attention, and is as desirable in spoken as in written language.

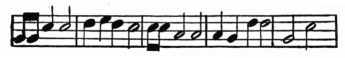

Pauses should vary in frequency and duration. It should be remembered that words are only symbols, and that the speaker should concern himself seriously about the thought which these symbols represent. The concept behind the sign is the important thing. The fine art of pausing can be acquired only after long and faithful study. Then it may become an unconscious habit. An old rime on this subject is worth repeating:

Before you can properly feel what you say you must understand it. Artificial and imitative methods do not produce enduring results. In studying a passage or selection for recitation, the imagination must be kindled, the feelings stimulated, and the mind trained to concentrate upon the thought until it is experienced. This subjective work should always precede the attempt at objective expression. Everything must first be conceived, pictured, and experienced in the mind. When this is done with intelligence, sincerity, and earnestness, there should be little difficulty in giving true and adequate expression to thought.

In all speaking that is worth the while there must be energy, force, and life. The speaker should be wide-awake, alert, palpitating. A speaker—and this applies to the reciter and elocutionist—should be, as someone has said, "an animal galvanic battery on two legs."[2] He must know what he is about. He must be in east.

Make a distinction between loudness and intensity. Often the best effects are produced by suggesting power in reserve rather than giving the fullest outward expression. Intensity in reading or reciting is secured chiefly through concentration and a thorough grasp of the thought. Endeavor to put yourself into your voice. Do not forget that deep, concentrated feeling is never loud. Avoid shouting, ranting, and "tearing a passion to tatters." Go to nature for models. Ask what one would do in real life in uttering the thoughts under consideration.

The emotions must be brought under control by frequent practise. Joy, sorrow, anger, fear, surprize, terror, and other feelings are as colors to the artist and must be made ready for instant use. To quote Richard Mansfield:

"When you are enacting a part, think of your voice as a color, and, as you paint your picture (the character you are painting, the scene you are portraying), mix your colors. You have on your palate a white voice, la voix blanche; a heavenly, ethereal or blue voice, the voice of prayer; a disagreeable, jealous, or yellow voice; a steel-gray voice, for quiet sarcasm; a brown voice of hopelessness; a lurid, red voice of hot rage; a deep, thunderous voice of black; a cheery voice, the color of the green sea that a brisk breeze is crisping; and then there is a pretty little pink voice, and shades of violet—but the subject is endless."

[2] See "Before an Audience," by Nathan Sheppard. Published by Funk & Wagnalls Company. Price, 75 cents.

No better advice can be given upon this subject than to "Suit the action to the word; the word to the action." Unless a gesture in some way helps in the expression and understanding of a thought, it should be omitted. Gesture is not a mere ornament, but a natural and necessary part of true expression. The arms and hands should be trained to perform their work gracefully, promptly, and effectively. If too many gestures are used they lose their force and meaning. Furthermore, too many gestures confuse and annoy the auditor.

Gesture should be practised, preferably before a looking-glass, so thoroughly beforehand as to make it an unconscious act when the speaker comes before his audience.

The correct standing position is to have one foot slightly in advance of the other. The taller the person, the broader should be the base or width between the feet. The body should be erect but not rigid. In repose the arms should drop naturally at the sides. Except in the act of gesticulating do not try to put the hands anywhere, and above all, if a man, not in the pockets.

The aim here should be to lose one's self in the part. To subordinate one's tones, gestures, and manners, and to live the character for the time being, requires no mean ability. Impersonation calls for imagination, insight, concentration, and adaptability. The impersonator must be all at it, and at it all, during the whole time he is impersonating the character.

"To fathom the depths of character," said Macready, the distinguished English actor, "to trace its latent motives, to feel its finest quiverings of emotion, to comprehend the thoughts that are hidden under words, and thus possess one's self of the actual mind of the individual man, is the highest reach of the player's art, and is an achievement that I have discerned but in few. Kean—when under the impulse of his genius he seemed to clutch the whole idea of the man—was an extraordinary instance among those possessing the faculty of impersonation."

Where dialect is used it should be closely studied from life. Stage representations of foreign character are not always trustworthy models.

Articulate and pronounce correctly and distinctly without being pedantic. The organs of articulation—teeth, tongue, lips, and palate—should be trained to rapidly and accurately repeat various sets of elements, until any combination of sounds, no matter how difficult, can be uttered with facility, accuracy, and precision.

A standard dictionary should be consulted whenever there is a doubt either about the meaning or the pronunciation of a word. As to the standard of pronunciation, the speaker should consider at least these three things: (1) authority, (2) custom, and (3) personal taste.

There are many words commonly mispronounced, but only a few can be referred to here: Do not say Toos-day or Chews-day for Tuesday; ur-ride for ride; i-ron for i-urn; wus for was; thun for than; subjict for subject; awf-fiss for off-fiss; fig-ger for figure; to-wards for tords; dook for duke; ketch for catch; day-po for de-po; ab'domen for abdo'men; advertise'ment for adver'tisement; ly'ceum for lyce'um; oc'cult for occult'; often for of'n; sence for since; sujgest for suggest; wownd for woond; wether for whether; sen'ile for se'nile; ad'dress for address'; il'lustrate for illus'trate; ker-own for crown; winder for window; sor for saw; wickud for wicked; ingine for engine; ontil for until.

Words should drop from the mouth like newly-made coins from the mint. Practising on words of several syllables is helpful. Some such as these will serve as examples: "particularly," "unconstitutional," "incompatibility," "unnecessarily," "voluminous," "overwhelmingly," "sesquipedalian," etc.

The ability to make vivid mental pictures of what one recites is of great value to both reader and hearer. Everyone has this faculty to some degree, but few develop it as it should be developed for use in speaking. The clearer the mental picture the speaker has in mind the more vivid will it be to the hearer. Practise making mental images with pictures that appeal strongly to you. Try to see everything in detail. If at first the impressions are obscure, persevere in your practise and substantial results will surely come. Dr. Silas Neff gives a splendid illustration of this kind that can be effectively used for practise:

"A woodman once lived with his family near a shallow stream which flowed between high banks and in the middle of which, opposite his house, was an island. Half a mile up the stream was a dam which supplied water for a saw-mill a hundred yards below. One morning after the father had gone to the mill to work, leaving his wife in the back yard washing some little garments, their two little boys clambered down the bank and waded through the water to the island where they had spent many happy hours in play. About the middle of the forenoon, from some unknown cause, the wall of the dam suddenly gave way, the water plunging through and nearly filling the banks of the stream. The father in the mill heard the noise and looking out saw what had happened. Immediately thinking of his boys he dashed out, hat and coat off, on an awful race down the creek to save their lives. The water after leaving the dam flowed rather slowly for some time and he was soon quite a distance ahead, but he knew that unless he gained very rapidly here, the descent being much greater farther down, the water would overtake his boys before he could reach them. His wife suddenly looked up as the agonizing cries of her husband fell upon her ear. She rushed to the front yard. In quick succession she distinguished the words, 'Get the boys!' The father was a few hundred yards from his home. The water had reached the rapid part of the stream but some distance behind the man. The wife on hearing the words, tho not knowing what was wrong, jumped down the bank and ran through the water, shrieking to the boys. Just as she reached the island they ran to her and, without uttering a word, she took one under each arm and started back as wildly as she came. When half way over she saw her husband dashing out from the edge of the woods and the water not twenty feet behind him. They met at the top of the bank, the father grasped wife and children in his arms and the water passed harmlessly by."[3]

[3] "Talks on Education and Oratory," by Silas S. Neff, Neff College of Oratory, Philadelphia, Pa.

Do not learn a selection simply by rote—that is, by repeating it parrot-like over and over again—but fix it in the mind by a careful and detailed analysis of the thought. As you practise aloud, train your eye to take in as many words as possible, then look away from the book as you recite them aloud. This will give the memory immediate practise and will tend to make it self-reliant.

Having chosen a selection, read it over first in a general way to secure an impression of it in its entirety. Then read it a second time, giving particular attention to each part. Consult a dictionary for the correct meaning and pronunciation of every word about which you are in doubt. Next underline the emphatic words—those which you think best express the most important thoughts. Underscoring one line for emphatic words and two lines for the most emphatic will do for this purpose. Now indicate the various pauses, both grammatical and rhetorical, by drawing short perpendicular lines between the words where they occur. In a general way use one line for a short pause, two lines for a medium pause, and three lines for a long pause. On the margin of the selection you may make other notes, such as the dominant feeling, transitions, changes of rate, force and pitch, special effects, gestures, facial expression, etc.

There is, of course, nothing arbitrary about this work of analysis. Its purpose is to make the student think, to analyze, to be painstaking. The following annotated selection should be carefully considered. Words on which chief emphasis is to be placed are printed in small capitals; those on which less emphasis is to be placed, in italics. It is not intended to be mechanical, but suggestive. After a few selections have been analyzed in this way, pausing and emphasis, and many other elements of expression, will largely take care of themselves.

As you present yourself to your audience, bow slightly and graciously from the waist. Be courteous, but not servile. Avoid haste and familiarity. Be punctilious in dress and deportment, and be prompt in keeping your appointments.

Be sure you have everything ready in advance. If you have to use any properties, such as a table, chair, eye-glass, books, reading-stand, coat, hat, gloves, letters, etc., see that everything is provided and in its place before the time set for your appearance.

Success often depends upon the judicious choice of selections

for the occasion. What will be acceptable to one

audience may not please another. The sentiment and the

length of selections depend upon the time and place where

they are to be given. When an audience expects to be entertained

with humorous rec

itations, to announce in a

sepulchral voice that you will give them a poem of your

own composition, entitled "The Three Corpses," of melancholy

character, is likely to send a chill of disappointment

through them.

Never keep your audience waiting. If an encore is demanded,

return and bow, or if the demand is insistent,

give another number, preferably a short one. Do not be too

eager to give encores; if the applause is not insistent, a

bow will suffice.

"Afterwhiles," copyright 1898, The Bobbs-Merrill Company. Used by special permission of the publishers.

Reprinted from Harper's Magazine, by permission of Harper and Brothers.

Some people find great difficulty in saying good-by when making a call or spending the evening. As the moment draws near when the visitor feels that he is fairly entitled to go away, he rises and says abruptly, "Well, I think——" Then the people say, "Oh, must you go now? Surely it's early yet!" and a pitiful struggle ensues.

I think the saddest case of this kind of thing that I ever knew was that of my poor friend Melpomenus Jones, a curate—such a dear young man and only twenty-three! He simply couldn't get away from people. He was too modest to tell a lie, and too religious to wish to appear rude. Now it happened that he went to call on some friends of his on the very first afternoon of his summer vacation. The next six weeks were entirely his own—absolutely nothing to do. He chatted a while, drank two cups of tea, then braced himself for the effort and said suddenly:

"Well, I think I——"

But the lady of the house said, "Oh, no, Mr. Jones, can't you really stay a little longer?"

Jones was always truthful—"Oh, yes, of course, I—er—can."

"Then please don't go."

He stayed. He drank eleven cups of tea. Night was falling. He rose again.

"Well, now, I think I really——"

"You must go? I thought perhaps you could have stayed to dinner——"

"Oh, well, so I could, you know, if——"

"Then please stay; I'm sure my husband will be delighted."

"All right, I'll stay"; and he sank back into his chair, just full of tea, and miserable.

Father came home. They had dinner. All through the meal Jones sat planning to leave at eight-thirty. All the family wondered whether Mr. Jones was stupid and sulky, or only stupid.

After dinner mother undertook to "draw him out" and showed him photographs. She showed him all the family museum, several gross of them—photos of father's uncle and his wife, and mother's brother and his little boy, and awfully interesting photos of father's uncle's friend in his Bengal uniform, an awfully well-taken photo of father's grandfather's partner's dog, and an awfully wicked one of father as the devil for a fancy-dress ball.

At eight-thirty Jones had examined seventy-one photographs. There were about sixty-nine more that he hadn't. Jones rose.

"I must say good-night now," he pleaded.

"Say good-night! why it's only half-past eight! Have you anything to do?"

"Nothing," he admitted, and muttered something about staying six weeks, and then laughed miserably.

Just then it turned out that the favorite child of the family, such a dear little romp, had hidden Mr. Jones' hat; so father said that he must stay, and invited him to a pipe and a chat. Father had the pipe and gave Jones the chat, and still he stayed. Every moment he meant to take the plunge, but couldn't. Then father began to get very tired of Jones, and fidgeted and finally said, with jocular irony, that Jones had better stay all night—they could give him a shake-down. Jones mistook his meaning and thanked him with tears in his eyes, and father put Jones to bed in the spare-room and curst him heartily.

After breakfast next day, father went off to his work in the city and left Jones playing with the baby, broken-hearted. His nerve was utterly gone. He was meaning to leave all day, but the thing had got on his mind and he simply couldn't. When father came home in the evening he was surprized and chagrined to find Jones still there. He thought to jockey him out with a jest, and said he thought he'd have to charge him for his board, he! he! The unhappy young man stared wildly for a moment, then wrung father's hand, paid him a month's board in advance, and broke down and sobbed like a child.

In the days that followed he was moody and unapproachable. He lived, of course, entirely in the drawing-room, and the lack of air and exercise began to tell sadly on his health. He passed his time in drinking tea and looking at photographs. He would stand for hours together gazing at the photograph of father's uncle's friend in his Bengal uniform—talking to it, sometimes swearing bitterly at it. His mind was visibly failing.

At length the crash came. They carried him up-stairs in a raging delirium of fever. The illness that followed was terrible. He recognized no one, not even father's uncle's friend in his Bengal uniform. At times he would start up from his bed and shriek: "Well, I think I——" and then fall back upon the pillow with a horrible laugh. Then, again, he would leap up and cry: "Another cup of tea and more photographs! More photographs! Hear! Hear!"

At length, after a month of agony, on the last day of his vacation he passed away. They say that when the last moment came, he sat up in bed with a beautiful smile of confidence playing upon his face, and said: "Well—the angels are calling me; I'm afraid I really must go now. Good afternoon."

Reprinted by permission of Life Publishing Company.

Minister—Weel, Sandy, man; and how did ye like the sermon the day?

Precentor—Eh?

Minister—What did you think o' the discourse as a whole?

Precentor—All I was gaun to say was jeest this, that every noo and then in your discoorse the day—I dinna say oftener than noo and then—jeest occasionally—it struck me that there was maybe—frae time to time—jeest a wee bit o' exaggeration.

Minister—Exagger—what, Sir?

Precentor—Weel, maybe that's ower strong a word, I dinna want to offend ye. I mean jeest—amplification, like.

Minister—Exaggeration! amplification! What the deil mischief d'ye mean, Sir?

Precentor—There, there, there! I'll no say anither word. I dinna mean to rouse ye like that. All I meant to say was that you jeest streetched the pint a wee bit.

Minister—Streetched the pint! D'ye mean to say, Sir, that I tell lees?

Precentor—Oh! no, no, no—but I didna gang sae far as a' that.

Minister—Ye went quite far enough, Sir. Sandy, I call upon you, if ever ye should hear me say another word out o' joint, to pull me up there and then.

Precentor—Losh! Sir; but how could I pull ye up i' the kirk?

Minister—Ye can give me sort o' a signal.

Precentor—How could I gie ye a signal i' the kirk?

Minister—Ye could make some kind o' a noise.

Precentor—A noise i' the kirk?

Minister—Ay. Ye're sittin' just down aneath me, ye ken; so ye might just put up your held, and give a bit whustle (whistles), like that.

Precentor—A whustle!

Minister—Ay, a whustle!

Precentor—But would it no be an awfu' sin?

Minister—Hoots, man; doesna the wind whustle on the Sawbbath?

Precentor—Ay; I never thought o' that afore. Yes, the wind whustles.

Minister—Well, just a wee bit soughing whustle like the wind (whistles softly).

Precentor—Well, if there's nae harm in 't, I'll do my best.

So, ultimately, it was agreed between the minister and precentor, that the first word of exaggeration from the pulpit was to elicit the signal from the desk below.

Next Sunday came. Had the minister only stuck to his sermon that day, he would have done very well. But it was his habit, before the sermon, to read a chapter from the Bible, adding such remarks and explanations of his own as he thought necessary. On the present occasion he had chosen one that bristled with difficulties. It was that chapter which describes Samson as catching three hundred foxes, tying them tail to tail, setting firebrands in their midst, starting them among the standing corn of the Philistines, and burning it down. As he closed the description, he shut the book, and commenced the eloocidation as follows:

"My dear freends, I daresay you have been wondering in your minds how it was possible that Samson could catch three hundred foxes.

"Well, then, we are told in the Scriptures that Samson was the strongest man that ever lived. But, we are not told that he was a great runner. But if he catched these three hundred foxes he must have been a great runner, and therefore I contend that we have a perfect right to assume, by all the laws of Logic and Scientific History, that he was the fastest runner that ever was born; and that was how he catched his three hundred foxes!

"But after we get rid of this difficulty, my freends, another crops up—after he has catched his three hundred foxes, how does he manage to keep them all together?

"Now you will please bear in mind, in the first place, that it was foxes that Samson catched. Now we don't catch foxes, as a general rule, in the streets of a toon; therefore it is more than probable that Samson catched them in the country, and if he catched them in the country it is natural to suppose that he 'bided in the country; and if he 'bided in the country it is not unlikely that he lived at a farm-house. Now at farm-houses we have stables and barns, and therefore we may now consider it a settled pint, that as he catched his foxes, one by one, he stapped them into a good-sized barn, and steeked the door and locked it,—here we overcome the second stumbling-block. But no sooner have we done this, than a third rock of offense loups up to fickle us. After he has catched his foxes; after he has got them all snug in the barn under lock and key—how in the world did he tie their tails together? There is a fickler. But it is a great thing for poor, ignorant folk like you, that there has been great and learned men who have been to colleges, and universities, and seats o' learning—the same as mysel', ye ken—and instead o' going into the kirk, like me, they have gone traveling into foreign parts; and they have written books o' their travels; and we can read their books. Now, among other places, some of these learned men have traveled into Canaan, and some into Palestine, and some few into the Holy Land; and these last mentioned travelers tell us, that in these Eastern or Oriental climes, the foxes there are a total different breed o' cattle a'thegither frae our foxes; that they are great, big beasts—and, what's the most astonishing thing about them, and what helps to explain this wonderful feat of Samson's, is, that they've all got most extraordinary long tails; in fact, these Eastern travelers tell us that these foxes' tails are actually forty feet long.

Precentor (whistles).

Minister (somewhat disturbed)—"Oh! I ought to say that there are other travelers, and later travelers than the travelers I've been talking to you about, and they say this statement is rather an exaggeration on the whole, and that these foxes' tails are never more than twenty feet long.

Precentor (whistles).

Minister (disturbed and confused)—"Be—be—before I leave this subject a'thegither, my freends, I may just add that there has been a considerable diversity o' opinion about the length o' these animals' tails. Ye see one man says one thing, and anither, anither; and I've spent a good lot o' learned research in the matter mysel'; and after examining one authority, and anither authority, and putting one authority again the ither, I've come to the conclusion that these foxes' tails, on an average, are seldom more than fifteen and a half feet long.

Precentor (whistles).

Minister (angrily)—"Sandy McDonald, I'll no tak anither inch off o' the beasts' tails, even gin ye should whustle every tooth oot o' your head. Do ye think the foxes o' the Scriptures had na tails at a'?"

One hot day last summer, a young man dressed in thin clothes, entered a Broadway car, and seating himself opposite a stout old gentleman, said, pleasantly:

"Pretty warm, isn't it?"

"What's pretty warm?"

"Why, the weather."

"What weather?"

"Why, this weather."

"Well, how's this different from any other weather?"

"Well, it is warmer."

"How do you know it is?"

"I suppose it is."

"Isn't the weather the same everywhere?"

"Why, no,—no; it's warmer in some places and it's colder in others."

"What makes it warmer in some places than it's colder in others?"

"Why, the sun,—the effect of the sun's heat."

"Makes it colder in some places than it's warmer in others? Never heard of such a thing."

"No, no, no. I didn't mean that. The sun makes it warmer."

"Then what makes it colder?"

"I believe it's the ice."

"What ice?"

"Why, the ice,—the ice,—the ice that was frozen by—by—by the frost."

"Have you ever seen any ice that wasn't frozen?"

"No,—that is, I believe I haven't."

"Then what are you talking about?"

"I was just trying to talk about the weather."

"And what do you know about it,—what do you know about the weather?"

"Well, I thought I knew something, but I see I don't and that's a fact."

"No, sir, I should say you didn't! Yet you come into this car and force yourself upon the attention of a stranger and begin to talk about the weather as tho you owned it, and I find you don't know a solitary thing about the matter you yourself selected for a topic of conversation. You don't know one thing about meteorological conditions, principles, or phenomena; you can't tell me why it is warm in August and cold in December; you don't know why icicles form faster in the sunlight than they do in the shade; you don't know why the earth grows colder as it comes nearer the sun; you can't tell why a man can be sun-struck in the shade; you can't tell me how a cyclone is formed nor how the trade-winds blow; you couldn't find the calm-center of a storm if your life depended on it; you don't know what a sirocco is nor where the southwest monsoon blows; you don't know the average rainfall in the United States for the past and current year; you don't know why the wind dries up the ground more quickly than a hot sun; you don't know why the dew falls at night and dries up in the day; you can't explain the formation of fog; you don't know one solitary thing about the weather and you are just like a thousand and one other people who always begin talking about the weather because they don't know anything else, when, by the Aurora Borealis, they know less about the weather than they do about anything else in the world, sir!"

Scene: Race-track. Enter old colored man, seating himself.

"Oomph, oomph. De work of de devil sho' do p'ospah. How 'do, suh? Des tol'able, thankee, suh. How you come on? Oh, I was des asayin' how de wo'k of de ol' boy do p'ospah. Doesn't I frequent the race-track? No, suh; no, suh. I's Baptis' myse'f an' I 'low hit's all devil's doin's. Wouldn't 'a' be'n hyeah to-day, but I got a boy named Jim dat's long gone in sin an' he gwine ride one dem hosses. Oomph, dat boy! I sut'ny has talked to him and labohed wid him night an' day, but it was allers in vain, an' I's feahed dat de day of his reckonin' is at han'.

"Ain't I nevah been intrusted in racin'? Humph, you don't s'pose I been dead all my life, does you? What you laffin at? Oh, scuse me, scuse me, you unnerstan' what I means. You don' give a ol' man time to splain hisse'f. What I means is dat dey has been days when I walked in de counsels of de ongawdly and set in de seats of sinnahs; and long erbout dem times I did tek most ovahly strong to racin'.

"How long dat been? Oh, dat's way long back, 'fo I got religion, mo'n thuty years ago, dough I got to own I has fell from grace several times sense.

"Yes, suh, I ust to ride. Ki-yi! I nevah furgit de day dat my ol' Mas' Jack put me on 'June Boy,' his black geldin', an' say to me, 'Si,' says he, 'if you don' ride de tail offen Cunnel Scott's mare, "No Quit," I's gwine to larrup you twell you cain't set in de saddle no mo'.' Hyah, hyah. My ol' Mas' was a mighty han' fu' a joke. I knowed he wan't gwine to do nuffin' to me.

"Did I win? Why, whut you spec' I's doin' hyeah ef I hadn' winned? W'y, ef I'd 'a' let dat Scott maih beat my 'June Boy' I'd 'a' drowned myse'f in Bull Skin Crick.

"Yes, suh, I winned; w'y, at de finish I come down dat track lak hit was de Jedgment Day an' I was de las' one up! 'f I didn't race dat maih's tail clean off. I 'low I made hit do a lot o' switchin'. An' aftah dat my wife Mandy she ma'ed me. Hyah, hyah, I ain't bin much on hol'in' de reins sence.

"Sh! dey comin' in to wa'm up. Dat Jim, dat Jim, dat my boy; you nasty, putrid little raskil. Des a hundred an' eight, suh, des a hundred an' eight. Yas, suh, dat's my Jim; I don' know whaih he gits his dev'ment at.

"What's de mattah wid dat boy? Whyn't he hunch hisse'f up on dat saddle right? Jim, Jim, whyn't you limber up, boy; hunch yo'sef up on dat hose lak you belonged to him and knowed you was dah. What I done showed you? De black raskil, goin' out dah tryin' to disgrace his own daddy. Hyeah he come back. Dat's bettah, you scoun'ril.

"Dat's a right smaht-lookin' hoss he's a-ridin', but I ain't a-trustin' dat bay wid de white feet—dat is, not altogethah. She's a favourwright, too; but dey's sumpin' else in dis worl' sides playin' favourwrights. Jim battah had win dis race. His hoss ain't a five to one shot, but I spec's to go way fum hyeah wid money ernuff to mek a donation on de pa'sonage.

"Does I bet? Well, I don' des call hit bettin'; but I resks a little w'en I t'inks I kin he'p de cause. 'Tain't gamblin', o' co'se; I wouldn't gamble fu nothin', dough my ol' Mastah did ust to say dat a hones' gamblah was ez good ez a hones' preachah an' mos' nigh ez skace.

"Look out dah, man, dey's off, dat nasty bay maih wid de white feet leadin' right f'um de pos'. I knowed it! I knowed it! I had my eye on huh all de time. O Jim, Jim, why didn't you git in bettah, way back dah fouf? Dah go de gong! I knowed dat wasn't no staht. Troop back dah, you raskils, hyah, hyah.

"I wush day boy wouldn't do so much jummyin erroun' wid day hoss. Fust t'ing he know he ain't gwine to know whaih he's at.

"Dah, dah dey go ag'in. Hit's a sho' t'ing dis time. Bettah, Jim, bettah. Dey didn't leave you dis time. Hug dat bay maih, hug her close, boy. Don't press dat hoss yit. He holdin' back a lot o' t'ings.

"He's gainin'! doggone my cats, he's gainin'! an' dat hoss o' his'n gwine des ez stiddy ez a rockin'-chair. Jim allus was a good boy.

"Counfound these spec's, I cain't see 'em skacely; huh, you say dey's neck an' neck; now I see 'em! and Jimmy's a-ridin' like—— Huh, huh, I laik to said sumpin'.

"De bay maih's done huh bes', she's done huh bes'! Dey's turned into the stretch an' still see-sawin'. Let him out, Jimmy, let him out! Dat boy done th'owed de reins away. Come on, Jimmy, come on! He's leadin' by a nose. Come on, I tell you, you black rapscallion, come on! Give 'em hell, Jimmy! give 'em hell! Under de wire an'a len'th ahead. Doggone my cats! wake me up wen dat othah hoss comes in.

"No, suh, I ain't gwine stay no longah—I don't app'ove o' racin'; I's gwine 'roun' an' see dis hyeah bookmakah an' den I's gwine dreckly home, suh, dreckly home. I's Baptis' myse'f, an' I don't app'ove o' no sich doin's!"

Reprinted by permission from "The Heart of Happy Hollow," Dodd, Mead & Company, New York.

By permission of Messrs. Forbes & Co., Chicago.

It was the last night before leap-year; it was the last hour before leap-year; in fact, the minute-hand had moved round the dial face of the clock until it registered fifteen minutes of twelve,—fifteen minutes of leap-year. John and Mary were seated in Mary's father's parlor. There was plenty of furniture there but they were using only a limited portion of it. John watched the minute-hand move round the dial face of the clock until, like the finger of destiny, it registered fifteen minutes of twelve,—fifteen minutes of leap-year, when he gasped hard, clutched his coat collar, and said,—

"Mary, in just fifteen minutes, Mary,—fifteen minutes by that clock, Mary,—another year, Mary,—like the six thousand years that have gone before it, Mary,—will have gone into the great Past and be forgotten in oblivion, Mary,—and I want to ask you, Mary,—to-night, Mary,—on this sofa, Mary,—if for the next six thousand years,—Mary!!!——"

"John," she said with a winning smile, "you seem very much excited, John,—can I do anything to help you, John?"

"Just sit still, Mary,—just sit still. In just twelve minutes, Mary,—twelve minutes by this clock, Mary,—like the six thousand clocks that have gone before it, Mary,—will be forgotten, Mary,—and I want to ask this clock, Mary,—to-night, on this sofa, Mary,—if when we've been forgotten six thousand times, Mary,—in oblivion, Mary,—and six thousand sofas, Mary!!——"

"John," she said, more smilingly than ever, "you seem quite nervous; would you like to see father?"

"Not for the world, Mary, not for the world! In just eight minutes, Mary,—eight minutes by that awful clock, we'll be forgotten, Mary,—and I want to ask six thousand fathers, Mary,—if when this sofa, Mary,—has been forgotten six thousand times, Mary,—in six thousand oblivions,—I want to ask six thousand Marys six thousand times, Mary!!!!——"

"John," she said, "you don't seem very well. Would you like a glass of water?"

"Mary,—in just three minutes, Mary,—three minutes by that dreadful clock, Mary,—we'll be forgotten, Mary,—six thousand times,—and I want to ask six thousand sofas, Mary,—if when six thousand oblivions have forgotten six thousand fathers in six thousand years, I want to ask six thousand Marys, six thousand times, Mary!!!!——"

Bang! the clock struck. It was leap-year. The clock struck twelve and Mary turning to John, sweetly said:

"John, it's leap-year; will you marry me?"

"Yes!!!"

Gentlemen, there is no use talking, the way of a woman beats you all.

Mr. Chairman—a—a—a—Mr. Commodore—beg pardon—I assure you that until this moment I had not the remotest expectation that I should be called upon to reply to this toast. (Pauses, turns round, pulls MS. out of pocket and looks at it.) Therefore I must beg of you, Mr. Captain—a—a—Mr. Commatain—a—a—Mr.—Mr. Cappadore—that you will pardon the confused nature of these remarks, being as they must necessarily be altogether impromptu and extempore. (Pauses, turns round and looks at MS.) But Mr. Bos'an—a—a—Mr. Bosadore—I feel—I feel even in these few confused expromptu and intempore—intomptu and exprempore—extemptu and imprempore—exprompore remarks—I feel that I can say in the words of the poet, words of the poet—poet—I feel that I can say in the words of the poet—of the poet—poet, and in these few confused remarks—in the words of the poet—(turns round, looks at MS.)—I feel that I can say in the words of the poet that I feel my heart swell within me. Now Mr. Capasun, Mr. Commasun, why does my heart swell within me—in the few confused—why does my heart swell within me—swell within me—swell within me—what makes my heart swell within me—why does it swell—swell within me? (Turns round and looks at MS.) Why, Mr. Cappadore—look at George Washington—what did he do?—in the few confused——(Strikes dramatic attitude with swelled chest and outstretched arm, preparing for burst of eloquence which will not come.) He—huh—he—huh—he—huh—(turns round and looks at MS.)—he took his stand upon the ship of state—he stood upon the maintopgallant-jib-boomsail and reefed the quivering sail—and when the storms were waging rildly round to wreck his fragile bark, through all the howling tempest he guided her in safety into the harbor of perdition—a—a—a—into the haven of safety. And what did he do then? What did he do then? What did he do then? He—he—he—(looks at MS.)—there he stood. And then his grateful country-men gathered round him—they gathered round George Washington—they placed him on the summit of the cipadel—their capadol—they held him up before the eyes of the assembled world—around his brow they placed a never-dying wreath—and then in thunder tones which all the world might hear——(Flourishes MS. before his face, notices it and sits down in great confusion.)

Reprinted by permission

Shepherd

Pilgrim

Shepherd

Pilgrim

Shepherd

Pilgrim

Shepherd

Pilgrim

Shepherd

Pilgrim

Shepherd

Pilgrim

Shepherd—thoughtfully

Pilgrim—solus

From the Poems of Thomas Bailey Aldrich, Household Edition, by permission of Messrs. Houghton, Mifflin & Co.

A little girl goes to market for her mother.

Butcher.—"Well, little girl, what can I do for you?"

Little Girl.—"How much is chops this morning, mister?"

B.—"Chops, 20 cents a pound, little girl."

L. G.—"Oh! 20 cents a pound for chops; that's awful expensive. How much is steak?"

B.—"Steak is 22 cents a pound."

L. G.—"That's too much! How much is chicken?"

B.—"Chicken is 25 cents a pound" (impatiently).

L. G.—"Oh! 25 cents for chicken. Well my ma don't want any of them!"

B.—"Well, little girl, what do you want?"

L. G.—"Oh, I want an automobile, but my ma wants 5 cents' worth of liver!"

From "A Book of Verses," by permission of Forbes & Co., Chicago.

Introductory Remarks. This selection is a little caricature, introducing two characters. "The Speecher" is one of those young men who has passed through college in one year,—passed through,—and has increasing difficulty in finding a hat large enough to fit his head. His oratorical powers have been praised by his friends, and he never misses an opportunity to exhibit his "great natural talent." "The Chairman" is frequently met in the smaller towns. He has lived there a long time, is acquainted with everybody, makes it a point to form the acquaintance of all newcomers, takes an interest in public affairs, and is often called upon to introduce the speakers who visit the town. His principal weakness is that in the course of his introductory remarks he usually says more than the speaker himself.

The Chairman. (Comes forward to table at center, stands at right, looks nervously at audience, goes to left of table, does not know what to do with hands, returns to right of table, begins in high, nervous voice.) "Gentlemen an' ladies—an' the rest on ye—(goes left of table) I s'pose ye all knowed afore, as per'aps ye do now, that I did not come out to make a speech; but to—to 'nounce the speecher. Now, the speecher has jes come, an' is right in there. (Points with thumb over shoulder to L. and goes R. of table.) I don't know why 'twas they called on me to 'nounce the speecher, unless it is that I've lived here in your midst fer a long while, an' am 'quainted with very nigh every one fer four or five miles about, an' I s'pose that's why they called on me to—to 'nounce the speecher. Now, the speecher is—right in there. (Points L. and goes L.) I s'pose I'm as well calc'lated to 'nounce the speecher as any on ye, an' I s'pose that's why I'm here to—to 'nounce the speecher. Now, the speecher is—right in there. (Points L. and goes R.) You know I've lived here in your midst a long time, an' have allus tuk an active part in all public affairs, an' I s'pose that's why they called on me to—to 'nounce the speecher. Now, the speecher is right in there. (Points L. and goes L.) As I said once afore, I've lived here in your midst fer a long time, an' have allus tuk active part in all public affairs, an' public doin's ginerally. Ye know I was 'pinted tax collector once, an' was road-overseer fer a little while, an' run fer constable of this here township—but I—I didn't git it. (Quickly.) Now, the speecher is—right there. (Points L. and goes R. Wipes forehead with handkerchief.) I jes want to say a word to the young men this evenin'—as I see quite a sprinklin' of 'em here—an' that is that I'd like fer all the young men to grow up an' hold high and honorable offices like I've done. But there, I can't stop any longer, 'cause the speecher is—right in there. (Starts to go, but returns.) Now, I don't want you to think I don't want to talk to ye, fer I do. I do so like to talk to the young men, an' the old men, an' them that are not men. (Smiles.) I love to talk to ye. But, of course, I can't talk to you now, 'cause the speecher is—right in there. (Points L.) But some other time when the speecher's not here—I think there'll be a time afore long—why, I'll talk to you. (Grows confused.) Of course, you know, I'd talk to you now; but—uh—that is—I think there'll be a time afore long—at some other—you know—I—you—the—(desperately) the speecher is right in there. (Rushes to L., stops, and with back to audience, concludes.) I will now interdoose to ye Charles William Albright, of Snigger's Crossroads, a very promisin' young attorney of that place, who will talk to ye. As I said afore, the speecher is right in here. Now, the speecher is right out there." (While standing with back to audience, run fingers through hair to give it a long, scholarly appearance, put on glasses, and take from chair roll of paper and place under arm. To be effective, this paper should be about one foot wide and ten feet long, folded in about five or six-inch folds. At conclusion of chairman's speech, turn and walk to table as the speecher.)

The Speecher. (Walks to table with a strut. Face should have a wise, solemn, self-satisfied expression. Stops at table, surveys the audience with solemn dignity, clears the throat, lays roll of paper on table, takes out handkerchief, clears throat, wipes mouth, smacks lips, lays handkerchief on table, surveys audience again, slowly unrolls paper and lays on table, surveys audience again, clears throat, wipes mouth, smacks lips, poses with one hand on table.) "Ladies—and—gentlemen—and fellow citizens. (Rises on toes and comes back on heels, as practised by some public speakers.) I have fully realized the magnitude of this auspicious occasion, and have brought from out the archives of wisdom one of those bright, extemporaneous subjects, to which, you know, I always do (rising inflection) ample justice. (Rises on toes, clears throat, applies handkerchief to forehead.) The subject for this evening's discussion (very solemn) is coal oil. (Clears throat and looks wise.) Now, the first question that arises is: How do they get it? (In measured tone, on toes, tapping words off on fingers of left hand with forefinger of right hand.) How—do—they—get—it? (Soaringly.) My dear friends, some get it by the pint, and some by the quart. (Clears throat, wipes perspiration from forehead.) But, you say, how do they get it in the first place? (Tragically.) Ah, my dear friends, as Horace Greeley has so fittingly exprest it—that is the question. (Quickly.) But I will explain. When they want to get it they take a great, mammoth auger (imitates) and they bore, and they bore, and they bore, and—(looks at paper quickly)—and they bore! And when they strike the oil it just squirts up. That's how they get it! (Rises on toes, smacks lips and looks wise.) Now, you all know, coal oil is used for a great many things. It is used for medicine, to burn in the lamp, to blow up servant girls when they make a fire with it, and—many other useful things. (Wipes mouth and puts handkerchief in pocket.) The gentlemen in charge will now pass the hat, being careful to lock the door back there so that none of those boys from Squeedunk can get out before they chip in. (Takes paper and rolls it up.) I will say that I expect to deliver another lecture here two weeks from to-night—two weeks from to-night—upon which occasion I would like to see all the children present, as the subject will be of special interest to (rises on toes, closes eyes) the little ones. The subject on that occasion will be 'Will We Bust the Trusts, or Will the Trusts Bust Us?'" (Puts roll of paper under arm and stalks off as if having captured the world.)

As recited by Edwin L. Barker and used by permission.

A Danbury man named Reubens, recently saw a statement that counting one hundred when tempted to speak an angry word would save a man a great deal of trouble. This statement sounded a little singular at first, but the more he read it over the more favorably he became imprest with it, and finally concluded to adopt it.

Next door to Reubens lives a man who made five distinct attempts in a fortnight to secure a dinner of green peas by the first of July, but has been retarded by Reubens' hens. The next morning after Reubens made his resolution, this man found his fifth attempt had been destroyed. Then he called on Reubens. He said:

"What in thunder do you mean by letting your hens tear up my garden?"

Reubens was prompted to call him various names, but he remembered his resolution, put down his rage, and meekly said:

"One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight——"

The mad neighbor, who had been eyeing this answer with suspicion, broke in again:

"Why don't you answer my question, you rascal?"

But still Reubens maintained his equanimity, and went on with the test.

"Nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen——"

The mad neighbor stared harder than ever.

"Seventeen, eighteen, nineteen, twenty, twenty-one——"

"You're a mean thief!" said the mad neighbor, backing toward the fence.

Reubens' face flushed at this charge, but he only said:

"Twenty-two, twenty-three, twenty-four, twenty-five, twenty-six——"

At this figure the neighbor got up on the fence in some haste, but suddenly thinking of his peas, he said:

"You mean, contemptible, old rascal! I could knock your head against my barn and I'll——"

"Twenty-seven, twenty-eight, twenty-nine, thirty, thirty-one, thirty-two, thirty-three——"

Here the neighbor ran for the house, and entering it, violently slammed the door behind him. Reubens did not let up on the enumeration, but stood out there alone in his own yard, and kept on counting, while his burning cheeks and flashing eyes eloquently affirmed his judgment. When he got up into the eighties his wife came out to him in some alarm.

"Why, Reubens, man, what is the matter with you? Do come into the house."

But he didn't stop.

"Eighty-seven, eighty-eight, eighty-nine, ninety, ninety-one, ninety-two——"

Then she came to him, and clung tremblingly to him, but he only turned, looked into her eyes, and said:

"Ninety-three, ninety-four, ninety-five, ninety-six, ninety-seven, ninety-eight, ninety-nine, one hundred! Go into the house, old woman, or I'll bust you!"

They had been married about three weeks, and had just gone to housekeeping. He was starting down town one morning, and she followed him to the door. They had their arms wrapt around each other, and she was saying:

"O Clarence, do you think it possible that the day can ever come when we will part in anger?"

"Why, no, little girl, of course not. What put that foolish idea into my little birdie's head, eh?"

"Oh, nothing, dearest. I was only thinking how perfectly dreadful it would be if one of us should speak harshly to the other."

"Well, don't think of such wicked, utterly impossible things any more. We can never, never, never quarrel."

"I know it, darling. Good-by, you dear old precious, good-by, and—oh, wait a second, Clarence; I've written a note to mamma; can't you run around to the house and leave it for her some time to-day?"

"Why, yes, dearie; if I have time."

"If you have time? O Clarence!"

"What is it, little girlie?"

"Oh, to say 'if you have time' to do almost the very first errand your little wife asks you to do."

"Well, well, I expect to be very busy to-day."

"Too busy to please me? O Clarence, you hurt my feelings so."

"Why, child, I——"

"I'm not a child, I'm a married woman, and I——"

"There, there, my pet. I——"

"No, no, Clarence, if I were your p—p—pet you'd——"

"But, Mabel, do be reasonable."

"O Clarence! don't speak to me so."

"Mable, be sensible, and——"

"Go on, Clarence, go on; break my heart."

"Stuff and nonsense."

"Oh! o—o—o—o—oh!"

"What have I said or done?"

"As if you need ask! But go—hate me if you will, Clarence, I——"

"This is rank nonsense!"

"I'll go back to mamma if you want me to. She loves me, if you don't."

"You must have a brain-storm!"

"Oh! yes, sneer at me, ridicule me, break my poor heart. Perhaps you had better strike me!"

He bangs the door, goes down the steps on the jump, and races off, muttering something about women being the "queerest creatures."

Of course, they'll make it up when he comes home, and they'll have many a little tiff in the years to come, and when they grow old they'll say:

"We've lived together forty-five years, and in all that time have never spoken a cross word to each other!"

Note—The New York elevated cars were so overcrowded at the rush hours of the day that passengers were obliged to ride on engines.

"Why, Mis' Farley, is it really you? It's been so long sence I saw you that I hardly knowed you. Come in an' set down. I was jest a-wishin' some one would come in. I've felt so kind of downsy all mornin'. I reckon like enough it is my stummick. I thought some of goin' to see old Doctor Ball about it, but, la, I know jest what he'd say. He'd look at my tongue an' say, 'Coffee,' an' look cross. He lays half the mis'ry o' the world to coffee. Says it is a rank pizen to most folks, an' that lots o' the folks now wearin' glasses wouldn't need 'em if they'd let coffee alone. Says it works on the ocular nerves an' all that, but I reckon folks here in Granby will go on drinkin' coffee jest the same.

"You won't mind if I keep right on with my work, will you, seein' that it ain't nothin' but sewin' carpet-rags? I've got to send my rags to the weaver this week, or she can't weave my carpet until after she comes home from a visit she 'lows on makin' to her sister over in Zoar. It's just a hit-er-miss strip o' carpet I'm makin' for my small south chamber. I set out to make somethin' kind o' fancy with a twisted strip an' the chain in five colors, but I found I hadn't the right kind of rags to carry it through as I wanted to; so I jest decided on a plain hit-er-miss. I don't use the south chamber no great nohow. It's the room my first husband and his first wife and sev'ral of his kin all died in; so the 'sociations ain't none too cheerin', an' I—I—s'pose you know about Lyddy Baxter losin' her husband last week? No? Well, he's went the way o' the airth, an' Lyddy wore my mournin'-veil an' gloves to the funeral. They're as good as they were the day I follered my two husbands to the grave in 'em. When a body pays two dollars an' sixty-eight cents for a mournin'-veil, it behooves 'em to take keer of it, an' not switch it out wearin' it common as Sally Dodd did hern. If a body happens to marry a second time, as I did, a mournin'-veil may come in handy, jest as mine did.

"Yes, Lyddy's husband did go off real sudden. It was this new-fashioned trouble, the appendysheetus, that tuk him off. They was jest gittin' ready to op'rate on him when he went off jest as easy as a glove. There's three thousand life-insurance; so Lyddy ain't as bereft as some would be. Now, if she'll only have good jedgement when she gits the money, an' not fool it away as Mis' Mack did her husband's life-insurance. He had only a thousand dollars, an' she put half of it on her back before three months, an' put three hundred into a pianny she couldn't play. She said a pianny give a house sech an air. I up an' told her that money would soon be all 'air' if she didn't stop foolin' it away.

"I wouldn't want it told as comin' from me, but I've heerd that it was her that put that advertisement in the paper about a widder with some means wishin' to correspond with a gentleman similarly situated with a view to matrimony. I reckon she had about fifty dollars left at that time. I tried to worm something about it out of the postmaster; for of course he'd know about her mail, but he was as close as a clam-shell. I reckon one has to be kind of discreet if one is postmaster, but he might of known that anything he told me wouldn't go no farther if he didn't want it to. I know when to speak an' when to hold my tongue if anybody in this town does.

"Did you know that Myra Dart was goin' to marry that Rylan chap? It's so. I got it from the best authority. An' she's nine years an' three months an' five days older than him. I looked it up in the town hist'ry. It's a good deal of a reesk for a man to marry a woman that's much older than he is.