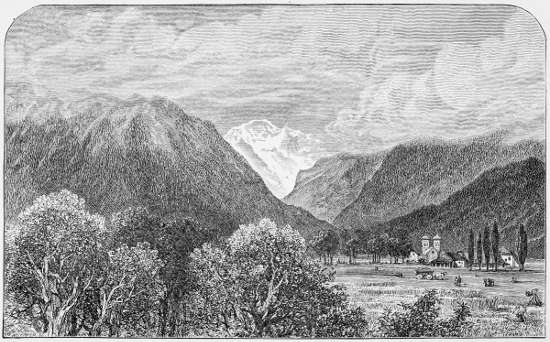

THE JUNGFRAU FROM INTERLAKEN.

Title: Hours of Exercise in the Alps

Author: John Tyndall

Release date: October 27, 2014 [eBook #47209]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Henry Flower and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

HOURS OF EXERCISE.

BY

JOHN TYNDALL, LL.D., F.R.S.,

AUTHOR OF “FRAGMENTS OF SCIENCE FOR UNSCIENTIFIC PEOPLE,” “HEAT

AS A MODE OF MOTION,” ETC., ETC.

NEW YORK:

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY,

72 FIFTH AVENUE.

1896.

Authorized Edition.

A short time ago I published a book of ‘Fragments,’ which might have been called ‘Hours of Exercise in the Attic and the Laboratory’; while this one bears the title of ‘Hours of Exercise in the Alps.’ The two volumes supplement each other, and, taken together, illustrate the mode in which a lover of natural knowledge and of natural scenery chooses to spend his life.

Much as I enjoy the work, I do not think that I could have filled my days and hours in the Alps with clambering alone. The climbing in many cases was the peg on which a thousand other ‘exercises’ were hung. The present volume, however, is for the most part a record of bodily action, written partly to preserve to myself the memory of strong and joyous hours, and partly for the pleasure of those who find exhilaration in descriptions associated with mountain life.

The papers, written during the last ten years, are printed in the order of the incidents to which they relate; and, to render the history more complete, I have, with the permission of their authors, introduced nearly the whole of two articles by Mr. Vaughan Hawkins and Mr. Philip Gossett. The former describes the first assault ever made upon the Matterhorn, the latter an expedition which ended in the death of a renowned and beloved guide.

The ‘Glaciers of the Alps’ being out of print, I can no longer refer to it. Towards the end of the volume, therefore, I have thrown together a few ‘Notes and Comments’ which may be useful to those who desire to possess some knowledge of the phenomena of the ice-world, and of the properties of ice itself. To these are added one or two minor articles, which relate more or less to our British hills and lakes: the volume is closed by an account of a recent voyage to Oran.

I refrain from giving advice, further than to say that the perils of wandering in the High Alps are terribly real, and are only to be met by knowledge, caution, skill, and strength. ‘For rashness, ignorance, or carelessness the mountains leave no margin; and to rashness, ignorance, or carelessness three-fourths of the catastrophes which shock us are[vii] to be traced.’ Those who wish to know something of the precautions to be taken upon the peaks and glaciers cannot do better than consult the excellent little volume lately published by Leslie Stephen, where, under the head of ‘Dangers of Mountaineering,’ this question is discussed.

I would willingly have published this volume without illustrations, and should the reader like those here introduced—two of which were published ten years ago, and the remainder recently executed under the able superintendence of Mr. Whymper—he will have to ascribe his gratification to the initiative of Mr. William Longman, not to me.

I have sometimes tried to trace the genesis of the interest which I take in fine scenery. It cannot be wholly due to my own early associations; for as a boy I loved nature, and hence, to account for that love, I must fall back upon something earlier than my own birth. The forgotten associations of a far-gone ancestry are probably the most potent elements in the feeling. With characteristic penetration, Mr. Herbert Spencer has written of the growth of our appreciation of natural scenery with growing years. But to the associations of the individual himself he adds ‘certain deeper, but now vague, combinations of states, that were organised[viii] in the race during barbarous times, when its pleasurable activities were among the mountains, woods, and waters. Out of these excitations,’ he adds, ‘some of them actual, but most of them nascent, is composed the emotion which a fine landscape produces in us.’ I think this an exceedingly likely proximate hypothesis, and hence infer that those ‘vague and deep combinations organised in barbarous times,’ not to go further back, have come down with considerable force to me. Adding to these inherited feelings the pleasurable present exercise of Mr. Bain’s ‘muscular sense,’ I obtain a somewhat intelligible, though, doubtless, still secondary theory of my delight in the mountains.

The name of a friend whom I taught in his boyhood to handle a theodolite and lay a chain, and who afterwards turned his knowledge to account on the glaciers of the Alps, occurs frequently in the following pages. Of the firmness of a friendship, uninterrupted for an hour, and only strengthened by the weathering of six-and-twenty years, he needs no assurance. Still, for the pleasure it gives myself, I connect this volume with the name of Thomas Archer Hirst.

J. Tyndall.

May 1871.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Lauwinen-Thor | 1 |

| II. | Disaster on the Col du Géant | 18 |

| III. | The Matterhorn—First Assault, with J. J. Bennen as Guide | 27 |

| IV. | Thermometric Stations on Mont Blanc | 53 |

| V. | A Letter from Bâle | 59 |

| Note on the Sound of Agitated Water | 65 | |

| VI. | The Urbachthal and Gauli Glacier | 66 |

| VII. | The Grimsel and the Æggischhorn | 75 |

| Note on Clouds | 82 | |

| VIII. | The Bel Alp | 86 |

| IX. | The Weisshorn | 91 |

| X. | Inspection of the Matterhorn with Bennen | 114 |

| XI. | Over the Moro | 125 |

| XII. | The Old Weissthor | 130 |

| XIII. | Rescue from a Crevasse | 141 |

| XIV. | The Matterhorn—Second Assault, in Company with Bennen | 153 |

| XV. | From Stein to the Grimsel | 166 |

| XVI. | The Oberaarjoch.—Adventure at the Æggischhorn | 174 |

| [x]XVII. | Ascent of the Jungfrau | 180 |

| XVIII. | Death of Bennen on the Haut de Cry | 192 |

| XIX. | Accident on the Piz Morteratsch | 206 |

| XX. | Alpine Sculpture | 219 |

| XXI. | Search on the Matterhorn: a Project | 252 |

| XXII. | The Titlis, Finsteraarschlucht, Petersgrat, and Italian Lakes | 255 |

| XXIII. | Ascent of the Eiger and Passage of the Trift | 265 |

| XXIV. | The Matterhorn--Third and Last Assault | 271 |

| XXV. | Ascent of the Aletschhorn | 295 |

| XXVI. | A Day among the Séracs of the Glacier du Géant Fourteen Years Ago | 318 |

| NOTES ON ICE AND GLACIERS, ETC. | ||

| I. | Observations on the Mer de Glace | 339 |

| II. | Structure and Properties of Ice | 360 |

| III. | Structure of Glaciers | 367 |

| IV. | Helmholtz on Ice and Glaciers | 377 |

| V. | Clouds | 405 |

| VI. | Killarney | 413 |

| VII. | Snowdon in Winter | 421 |

| VIII. | Voyage to Algeria to Observe the Eclipse | 429 |

| The Jungfrau from Interlaken | Frontispiece |

| Ascent of the Lauwinen-Thor | to face page 11 |

| The Weisshorn from the Riffel | „ 91 |

| The Matterhorn (from a drawing by E. W. Cooke, R. A.) | „ 117 |

| Recovery of our Porter | „ 149 |

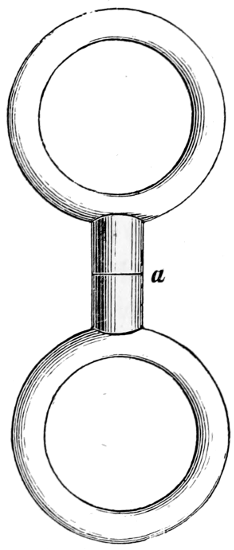

| Johann Joseph Bennen | „ 201 |

| The Gorge of Pfeffers (showing Erosive Action) | „ 219 |

HOURS OF EXERCISE

IN

THE ALPS.

In June 1860 I completed ‘The Glaciers of the Alps,’ which constituted but a fraction of the work executed during the previous autumn and spring. These labours and other matters had wearied and weakened me beyond measure, and to gain a little strength I went to Killarney. The trip was beneficial, but not of permanent benefit. The air of those most lovely lakes was too moist and warm for my temperament, and I longed for that keener air which derives its tone from contact with the Alpine snows. In 1859 I had bidden the Alps farewell, purposing in future to steep my thoughts in the tranquillity of English valleys, and confine my mountain work to occasional excursions in the Scotch Highlands, or amid the Welsh and Cumbrian hills. But in my weariness the mere thought of[2] the snow-peaks and glaciers was an exhilaration; and to the Alps, therefore, I resolved once more to go. I wrote to my former guide, Christian Lauener, desiring him to meet me at Thun on Saturday the 4th of August; and on my way thither I fortunately fell in with Mr. Vaughan Hawkins. He told me of his plans and wishes, which embraced an attack upon the Matterhorn. Infected by his ardour, I gladly closed with the proposition that we should climb together for a time.

Lauener was not to be found at Thun, but in driving from Neuhaus to Interlaken a chaise met us, and swiftly passed; within it I could discern the brown visage of my guide. We pulled up and shouted, the other vehicle stopped, Lauener leaped from it, and came bounding towards me with admirable energy, through the deep and splashing mud. ‘Gott! wie der Kerl springt!’ was the admiring exclamation of my coachman. Lauener is more than six feet high, and mainly a mass of bone; his legs are out of proportion, longer than his trunk; and he wears a short-tail coat, which augments the apparent discrepancy. Those massive levers were now plied with extraordinary vigour to project his body through space; and it was gratifying to be thus assured that the man was in first-rate condition, and fully up to the hardest work.

On Sunday the 5th of August, for the sake of a[3] little training, I ascended the Faulhorn alone. The morning was splendid, but as the day advanced heavy cloud-wreaths swathed the heights. They attained a maximum about two P.M., and afterwards the overladen air cleared itself by intermittent jerks—revealing at times the blue of heaven and the peaks of the mountains; then closing up again, and hiding in their dismal folds the very posts which stood at a distance of ten paces from the hotel door. The effects soon became exceedingly striking, the mutations were so quick and so forcibly antithetical. I lay down upon a seat, and watched the intermittent extinction and generation of the clouds, and the alternate appearance and disappearance of the mountains. More and more the sun swept off the sweltering haze, and the blue sky bent over me in domes of ampler span. At four P.M. no trace of cloud was visible, and a panorama of the Oberland, such I had no idea that the Faulhorn could command, unfolded itself. There was the grand barrier which separated us from the Valais; there were the Jungfrau, Monk and Eiger, the Finsteraarhorn, the Schreckhorn, and the Wetterhorn, lifting their snowy and cloudless crests to heaven, and all so sharp and wildly precipitous that the bare thought of standing on any one of them made me shudder. London was still in my brain, and the vice of Primrose Hill in my muscles.

I disliked the ascent of the Faulhorn exceedingly,[4] and the monotonous pony track which led to the top of it. Once, indeed, I deviated from the road out of pure disgust, and, taking a jumping torrent for my guide and colloquist, was led astray. I now resolved to return to Grindelwald by another route. My host at first threw cold water on the notion, but he afterwards relaxed and admitted that the village might be attained by a more direct way than the ordinary one. He pointed to some rocks, eminences, and trees, which were to serve as landmarks; and stretching his arm in the direction of Grindelwald, I took the bearing of the place, and scampered over slopes of snow to the sunny Alp beyond them. To my left was a mountain stream making soft music by the explosion of its bubbles. I was once tempted aside to climb a rounded eminence, where I lay for an hour watching the augmenting glory of the mountains. The scene at hand was perfectly pastoral; green pastures, dotted with chalets, and covered with cows, which filled the air with the incessant tinkle of their bells. Beyond was the majestic architecture of the Alps, with its capitals and western bastions flushed with the warm light of the lowering sun.

I mightily enjoyed the hour. There was health in the air and hope in the mountains, and with the consciousness of augmenting vigour I quitted my station, and galloped down the Alp. I was soon[5] amid the pinewoods which overhang the valley of Grindelwald, with no guidance save the slope of the mountain, which, at times, was quite precipitous; but the roots of the pines grasping the rocks afforded hand and foot such hold as to render the steepest places the pleasantest of all. I often emerged from the gloom of the trees upon lovely bits of pasture—bright emerald gems set in the bosom of the woods. It appeared to me surprising that nobody had constructed a resting-place on this fine slope. With a fraction of the time necessary to reach the top of the Faulhorn, a position might be secured from which the prospect would vie in point of grandeur with almost any in the Alps; while the ascent from Grindelwald, amid the shade of the festooned trees, would itself be delightful.

Hawkins, who had halted for a day at Thun, had arrived; our guide had prepared a number of stakes, and on Monday morning we mounted our theodolite and proceeded to the Lower Glacier. With some difficulty we established the instrument upon a site whence the glacier could be seen from edge to edge; and across it was fixed in a straight line a series of twelve stakes. We afterwards ascended the glacier till we touched the avalanche-débris of the Heisse Platte. We wandered amid the moulins and crevasses until evening approached, and thus gradually prepared our muscles for more arduous work. On[6] Tuesday a sleety rain filled the entire air, and the glacier was so laden with fog that there was no possibility of our being able to see across it. On Wednesday, happily, the weather brightened, and we executed our measurements; finding, as in all other cases, that the glacier was retarded by its bounding walls, its motion varying from a minimum of thirteen and a half inches to a maximum of twenty-two inches a day. To Mr. Hawkins I am indebted both for the fixing of the stakes and the reduction of the measurements to their diurnal rate.

Previous to leaving England I had agreed to join a party of friends at the Æggischhorn, on Thursday the 9th of August. My plan was, first to measure the motion of the Grindelwald glacier, and afterwards to cross the mountain-wall which separates the canton of Berne from that of Valais, so as to pass from Lauterbrunnen to the Æggischhorn in a single day. How this formidable barrier was to be crossed was a problem, but I did not doubt being able to get over it somehow. On mentioning my wish to Lauener, he agreed to try, and proposed attacking it through the Roththal. In company with his brother Ulrich, he had already spent some time in the Roththal, seeking to scale the Jungfrau from that side. Hawkins had previously, I believe, entertained the thought of assailing the same barrier at the very same place. Having completed our[7] measurements on the Wednesday, we descended to Grindelwald and discharged our bill. We desired to obtain the services of Christian Kaufmann, a guide well acquainted with both the Wetterhorn and the Jungfrau; but on learning our intentions he expressed fears regarding his lungs, and recommended to us his brother, a powerful young man, who had also undergone the discipline of the Wetterhorn. Him we accordingly engaged. We arranged with the landlord of the Bear to have the main mass of our luggage sent to the Æggischhorn by a more easy route. I was loth to part with the theodolite, but Lauener at first grumbled hard against taking it. It was proposed, however, to confine his load to the head of the instrument, while Kaufmann should carry the legs, and I should bear my own knapsack. He yielded. Ulrich Lauener was at Grindelwald when we started for Lauterbrunnen, and on bidding us good-bye he remarked that we were going to attempt an impossibility. He had examined the place which we proposed to assail, and emphatically affirmed that it could not be surmounted. We were both a little chagrined by this gratuitous announcement, and answered him somewhat warmly; for we knew the moral, or rather immoral, effect of such an opinion upon the spirits of our men.

The weather became more serene as we approached Lauterbrunnen. We had a brief evening stroll, but retired to bed before day had quite forsaken the[8] mountains. At two A.M. the candle of Lauener gleamed into our bedrooms, and he pronounced the weather fair. We got up at once, dressed, despatched our hasty breakfast, strapped our things into the smallest possible volume, and between three and four A.M. were on our way. The hidden sun crimsoned faintly the eastern sky, but the valleys were all in peaceful shadow. To our right the Staubbach dangled its hazy veil, while other Bachs of minor note also hung from the beetling rocks, but fell to earth too lightly to produce the faintest murmur. After an hour’s march we deviated to the left, and wound upward through the woods which here cover the slope of the hill.

The dawn cheerfully unlocked the recesses of the mountains, and we soon quitted the gloom of the woods for the bright green Alp. This we breasted, regardless of the path, until we reached the chalets of the Roththal. We did not yet see the particular staircase up which Lauener proposed to lead us, but we inspected minutely the battlements to our right, marking places for future attack in case our present attempt should not be successful. The elastic grass disappeared, and we passed over rough crag and shingle alternately. We reached the base of a ridge of débris, and mounted it. At our right was the glacier of the Roththal, along the lateral moraine of which our route lay.

Just as we touched the snow a spring bubbled from the rocks at our left, spurting its water over stalagmites of ice. We turned towards it, and had each a refreshing draught. Lauener pointed out to us the remains of the hut erected by him and his brother when they attempted the Jungfrau, and from which they were driven by adverse weather. We entered an amphitheatre, grand and beautiful this splendid morning, but doubtless in times of tempest a fit residence for the devils whom popular belief has banished to its crags. The snow for a space was as level as a prairie, but in front of us rose the mighty bulwarks which separated us from the neighbouring canton. To our right were the crags of the Breithorn, to our left the buttresses of the Jungfrau, while between both was an indentation in the mountain-wall, on which all eyes were fixed. From it downwards hung a thread of snow, which was to be our leading-string to the top.

Though very steep, the aspect of the place was by no means terrible: comparing with it my memory of other gulleys in the Chamouni mountains, I imagined that three hours would place us at the top. We not only expected an easy conquest of the barrier, but it was proposed that on reaching the top we should turn to the left, and walk straight to the summit of the Jungfrau. Lauener was hopeful, but not sanguine. We were soon at the foot of[10] the barrier, clambering over mounds of snow. Huge consolidated lumps emerged from the general mass; the snow was evidently that of avalanches which had been shot down the couloir, kneading themselves into vast balls, and piling themselves in heaps upon the plain. The gradient steepened, the snow was hard, and the axe was invoked. Straight up the couloir seemed the most promising route, and we pursued it for an hour, the impression gradually gaining ground that the work would prove heavier than we had anticipated.

We then turned our eyes on the rocks to our right, which seemed practicable, though very steep; we swerved towards them, and worked laboriously upwards for three-quarters of an hour. Mr. Hawkins and the two guides then turned to the left, and regained the snow, leaving me among the crags. They had steps to cut, while I had none, and, consequently, I got rapidly above them. The work becomes ever harder, and rest is unattainable, for there is no resting-place. At every brow I pause; legs and breast are laid against the rough rock, so as to lessen by their friction the strain upon the arms, which are stretched to grasp some protuberance above. Thus I rest, and thus I learn that three days’ training is not sufficient to dislodge London from one’s lungs. Meanwhile my companions are mounting monotonously along the snow. Lauener[11] looks up at me at intervals, and I can clearly mark the expression of his countenance; it is quite spiritless, while that of his companion bears the print of absolute dismay. Three hours have passed and the summit is not sensibly nearer. The men halt and converse together. Lauener at length calls out to me, ‘I think it is impossible.’ The effect of Ulrich’s prediction appears to be cropping out; we expostulate, however, and they move on. After some time they halt again, and reiterate their opinion that the thing cannot be done. They direct our attention to the top of the barrier; light clouds scud swiftly over it, and snow-dust is scattered in the air. There is storm on the heights, which our guides affirm has turned the day against us. I cast about in my mind to meet the difficulty, and enquire whether we might not send one of them back with the theodolite, and thus so lighten our burdens as to be able to proceed. Kaufmann volunteers to take back the theodolite; but this does not seem to please Lauener. There is a pause and hesitation. I remonstrate, while Hawkins calls out ‘Forward!’ Lauener once more doggedly strikes his axe into the snow, and resumes the ascent.

I continued among the rocks, though with less and less confidence in the wisdom of my choice. My knapsack annoyed me excessively; the straps frayed my shoulders, and tied up my muscles.[12] Once or twice I had to get round a protruding face of rock, and then found my bonds very grievous. At length I came to a peculiar piece of cliff, near the base of which was a sharp ridge of snow, and at a height of about five feet above it the rock bulged out, so that a stone dropped from its protuberance would fall beyond the ridge. I had to work along the snow cautiously, squatting down so as to prevent the rock from pushing me too far out. Had I a fair ledge underneath I should have felt perfectly at ease, but on the stability of the snow-wedge I dared not calculate. To retreat was dangerous, to advance useless; for right in front of me was a sheer smooth precipice, which completely extinguished the thought of further rock-work. I examined the place below me, and saw that a slip would be attended with the very worst consequences. To loose myself from the crag and attach myself to the snow was so perilous an operation that I did not attempt it; and at length I ignobly called to Lauener to lend me a hand. A gleam of satisfaction crossed his features as he eyed me on my perch. He manifestly enjoyed being called to the rescue, and exhorted me to keep quite still. He worked up towards me, and in less than half an hour had hold of one of my legs. ‘The place is not so bad after all,’ he remarked, evidently glad to take me down, in more senses than one. I[13] descended in his steps, and rejoined Hawkins upon the snow. From that moment Lauener was a regenerate man; the despair of his visage vanished, and I firmly believe that the triumph he enjoyed, by augmenting his self-respect, was the proximate cause of our subsequent success.

The couloir was a most singular one; it was excessively steep, and along it were two great scars, resembling the deep-cut channels of a mountain stream. They were, indeed, channels cut by the snow-torrents from the heights. We scanned those heights. The view was bounded by a massive cornice, from which the avalanches are periodically let loose.[1] The cornice seemed firm; still we cast about for some piece of rock which might shelter us from the destroyer should he leap from his lair. Apart from the labour of the ascent, which is great, the frequency of avalanches will always render this pass a dangerous one. At 2 P.M. the air became intensely cold. My companion had wisely pocketed a pair of socks, which he drew over his gloves, and found very comforting. My leather gloves, being saturated with wet, were very much the reverse.

The wind was high, and as it passed the crest of the Breithorn its moisture was precipitated and[14] afterwards carried away. The clouds thus generated shone for a time with the lustre of pearls; but as they approached the sun they became suddenly flooded with the most splendid iridescences.[2] At our right now was a vertical wall of brown rock, along the base of which we advanced. At times we were sheltered by it, but not always; for the wind was as fitful as a maniac, and eddying round the corners sometimes shook us forcibly, chilled us to the marrow, and spit frozen dust in our faces. The snow, moreover, adjacent to the rock had been melted and refrozen to a steep slope of compact ice. The men were very weary, the hewing of the steps exhausting, and the footing, particularly on some glazed rocks over which we had to pass, exceedingly insecure. Once on trying to fix my alpenstock I found that it was coated with an enamel of ice, and slipped through my wet gloves. This startled me, for the staff is my sole trust under such circumstances. The crossing of those rocks was a most awkward piece of work; a slip was imminent, and the effects of the consequent glissade not to be calculated. We cleared them, however, and now observed the grey haze creeping down from the peak of the Breithorn to the point at which we were aiming. This, however, was visibly nearer; and, for the first time since we began to climb, Lauener declared that he had good[15] hopes—‘Jetzt habe ich gute Hoffnung.’ Another hour brought us to a place where the gradient slackened suddenly. The real work was done, and ten minutes further wading through the deep snow placed us fairly on the summit of the col.

Looked at from the top the pass will seem very formidable to the best of climbers; to an ordinary eye it would appear simply terrific. We reached the base of the barrier at nine A.M.; we had surmounted it at four; seven hours consequently had been spent upon that tremendous wall. Our view was limited above; clouds were on all the mountains, and the Great Aletsch glacier was hidden by dense fog. With long swinging strides we went down the slope. Several times during our descent the snow coating was perforated, and hidden crevasses revealed. At length we reached the glacier, and plodded along it through the dreary fog. We cleared the ice just at nightfall, passed the Märjelin See, and soon found ourselves in utter darkness on the spurs of the Æggischhorn. We lost the track and wandered for a time bewildered. We sat down to rest, and then learned that Lauener was extremely ill. To quell the pangs of toothache he had chewed a cigar, which after his day’s exertion was too much for him. He soon recovered, however, and we endeavoured to regain the track. In vain. The guides shouted, and[16] after many repetitions we heard a shout in reply. A herdsman approached, and conducted us to some neighbouring chalets, whence he undertook the office of guide. After a time he also found himself in difficulty. We saw distant lights, and Lauener once more pierced the air with his tremendous whoop. We were heard. Lights were sent towards us, and an additional half-hour placed us under the roof of Herr Wellig, the active and intelligent proprietor of the Jungfrau hotel.

After this day’s journey, which was a very hard one, the tide of health set steadily in. I have no remembrance of any further exhibition of the symptoms which had driven me to Switzerland. Each day’s subsequent exercise made both brain and muscles firmer. We remained at the Æggischhorn for several days, occupying ourselves principally with observations and measurements on the Aletsch glacier, and joining together afterwards in that day’s excursion—unparalleled in my experience—which has found in my companion a narrator worthy of its glories. And as we stood upon the savage ledges of the Matterhorn, with the utmost penalty which the laws of falling bodies could inflict at hand, I felt that there were perils at home for intellectual men greater even than those which then surrounded us—foes, moreover, which inspire no manhood by their attacks, but shatter alike the architect and his house[17] by the same slow process of disintegration.[3] After the discipline of the Matterhorn, the fatal slope of the Col du Géant, which I visited a few days afterwards, looked less formidable than it otherwise might have done. From Courmayeur I worked round to Chamouni by Chapieu and the Col de Bonhomme. I attempted to get up Mont Blanc to visit the thermometers which I had planted on the summit a year previously; and succeeded during a brief interval of fair weather in reaching the Grands Mulets. But the gleam which tempted me thus far proved but a temporary truce to the war of elements, and, after remaining twenty hours at the Mulets, I was obliged to beat an inglorious retreat.—Vacation Tourists, 1860.

On the 18th of August, while Mr. Hawkins and I were staying at Breuil, rumours reached us of a grievous disaster which had occurred on the Col du Géant. At first, however, the accounts were so contradictory as to inspire the hope that they might be grossly exaggerated or altogether false. But more definite intelligence soon arrived, and before we quitted Breuil it had been placed beyond a doubt that three Englishmen, with a guide named Tairraz, had perished on the col. On the 21st I saw the brother of Tairraz at Aosta, and learned from the saddened man all that he knew. What I then heard only strengthened my desire to visit the scene of the catastrophe, and obtain by actual contact with the facts truer information than could possibly be conveyed to me by description. On the afternoon of the 22nd I accordingly reached Courmayeur, and being informed that M. Curie, the resident French pastor, had visited the place and made an accurate sketch of it, I immediately called upon him. With the most obliging promptness he[19] placed his sketches in my hands, gave me a written account of the occurrence, and volunteered to accompany me. I gladly accepted this offer, and early on the morning of Thursday the 21st of August we walked up to the pavilion which it had been the aim of the travellers to reach on the day of their death. Wishing to make myself acquainted with the entire line of the fatal glissade, I walked directly from the pavilion to the base of the rocky couloir along which the travellers had been precipitated, and which had been described to me as so dangerous that a chamois-hunter had declined ascending it some days before. At Courmayeur, however, I secured the services of a most intrepid man, who had once made the ascent, and who now expressed his willingness to be my guide. We began our climb at the very bottom of the couloir, while M. Curie, after making a circuit, joined us on the spot where the body of the guide Tairraz had been arrested, and where we found sad evidences of his fate. From this point onward M. Curie shared the dangers of the ascent, until we reached the place where the rocks ended and the fatal snow-slope began. Among the rocks we had frequent and melancholy occasion to assure ourselves that we were on the exact track. We found there a penknife, a small magnetic compass, and many other remnants of the fall.

At the bottom of the snow-slope M. Curie quitted me, urging me not to enter upon the slope, but to take to a stony ridge on the right. No mere inspection, however, could have given me the desired information. I asked my guide whether he feared the snow, and, his reply being negative, we entered upon it together, and ascended it along the furrow which still marked the line of fall. Under the snow, at some distance up the slope, we found a fine new ice-axe, the property of one of the guides. We held on to the track up to the very summit of the col, and as I stood there and scanned the line of my ascent a feeling of augmented sadness took possession of me. There seemed no sufficient reason for this terrible catastrophe. With ordinary care the slip might in the first instance have been avoided, and with a moderate amount of skill and vigour the motion, I am persuaded, might have been arrested soon after it had begun.

Bounding the snow-slope to the left was the ridge along which travellers to Courmayeur usually descend. It is rough, but absolutely without danger. The party were, however, tired when they reached this place, and to avoid the roughness of the ridge they took to the snow. The inclination of the slope above was moderate; it steepened considerably lower down, but its steepest portion did not much exceed forty-five degrees of inclination. At all events, a skilful[21] mountaineer might throw himself prostrate on the slope with perfect reliance on his power to arrest his downward motion.

It is alleged that when the party entered the summit of the col on the Chamouni side the guides proposed to return, but the Englishmen persisted in going forward. One thing alone could justify the proposition thus ascribed to the guides by their friends—a fog so thick as to prevent them from striking the summit of the col at the proper point, and to compel them to pursue their own traces backwards. The only part of the col hitherto regarded as dangerous had been passed, and, unless for the reason assumed, it would have been simply absurd to recross this portion instead of proceeding to Courmayeur. It is alleged that a fog existed; but the summit had been reached, and the weather cleared afterwards. Whether, therefore, the Englishmen refused to return or not on the Montanvert side, it ought in no way to influence our judgment of what occurred on the Courmayeur side, where the weather which prompted the proposal to go back ceased to be blameable.

A statement is also current to the effect that the travellers were carried down by an avalanche. In connection with this point M. Curie writes to me thus: ‘Il paraît qu’à Chamounix on répand le bruit que c’est une avalanche qui a fait périr les[22] voyageurs. C’est là une fausseté que le premier vous saurez démentir sur les lieux.’ I subscribe without hesitation to this opinion of M. Curie. That a considerable quantity of snow was brought down by the rush was probable, but an avalanche properly so called there was not, and it simply leads to misconception to introduce the term at all.

We are now prepared to discuss the accident. The travellers, it is alleged, reached the summit of the col in a state of great exhaustion, and it is certain that such a state would deprive them of the caution and firmness of tread necessary in perilous places. But a knowledge of this ought to have prevented the guides from entering upon the snow-slope at all. We are, moreover, informed that even on the gentler portion of the slope one of the travellers slipped repeatedly. On being thus warned of danger, why did not the guides quit the snow and resort to the ridge? They must have had full confidence in their power to stop the glissade which seemed so imminent, or else they were reckless of the lives they had in charge. At length the fatal slip occurred, where the fallen man, before he could be arrested, gathered sufficient momentum to jerk the man behind him off his feet, the other men were carried away in succession, and in a moment the whole of them were rushing downwards. What efforts were made to check this fearful rush, at what point of the descent the[23] two guides relinquished the rope, which of them gave way first, the public do not know, though this ought to be known. All that is known to the public is that the two men who led and followed the party let go the rope and escaped, while the three Englishmen and Tairraz went to destruction. Tairraz screamed, but, like Englishmen, the others met their doom without a word of exclamation.

At the bottom of the slope a rocky ridge, forming the summit of a precipice, rose slightly above the level of the snow, and over it they were tilted. I do not think a single second’s suffering could have been endured. During the wild rush downwards the bewilderment was too great to permit even of fear, and at the base of the precipice life and feeling ended suddenly together. A steep slope of rocks connected the base of this precipice with the brow of a second one, at the bottom of which the first body was found. Another slope ran from this point to the summit of another ledge, where the second body was arrested, while attached to it by a rope, and quite overhanging the ledge, was the body of the third traveller. The body of the guide Tairraz was precipitated much further, and was much more broken.

The question has been raised whether it was right under the circumstances to tie the men together. I believe it was perfectly right, if only properly done. But the actual arrangement was this: The three[24] Englishmen were connected by a rope tied firmly round the waist of each of them; one end of the rope was held in the hand of the guide who led the party; the other end was similarly held by the hindmost guide, while Tairraz grasped the rope near its middle. Against this mode of attachment I would enter an emphatic protest. It, in all probability, caused the destruction of the unfortunate Russian traveller on the Findelen Glacier last year, and to it I believe is to be ascribed the disastrous issue of the slip on the Col du Géant. Let me show cause for this protest. At a little depth below the surface the snow upon the fatal slope was firm and consolidated, but upon it rested a superficial layer, about ten inches or a foot in depth, partly fresh, and partly disintegrated by the weather. By the proper action of the feet upon such loose snow, its granules are made to unite so as to afford a secure footing; but when a man’s body, presenting a large surface, is thrown prostrate upon a slope covered with such snow, the granules act like friction wheels, offering hardly any resistance to the downward motion.

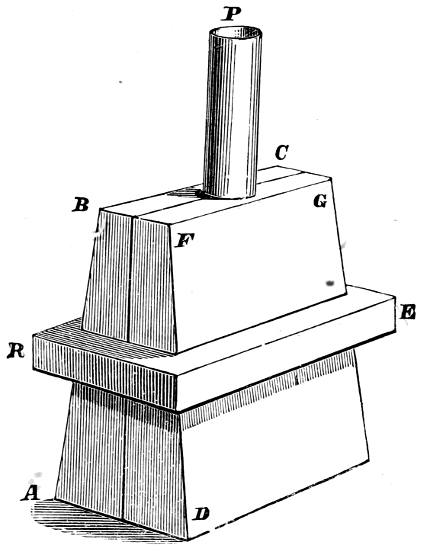

A homely illustration will render intelligible the course of action necessary under such conditions. Suppose a boy placed upon an oilcloth which covers a polished table, and the table tilted to an angle of forty-five degrees. The oilcloth would evidently slide down, carrying the boy along with it, as the[25] loose snow slid over the firm snow on the Col du Géant. But suppose the boy provided with a stick spiked with iron, what ought he to do to check his motion? Evidently drive his spike through the oilcloth and anchor it firmly in the wood underneath. A precisely similar action ought to have been resorted to on the Col du Géant. Each man as he fell ought to have turned promptly on his face, pierced with his armed staff the superficial layer of soft snow, and pressed with both hands the spike into the consolidated mass underneath. He would thus have applied a break, sufficient not only to bring himself to rest, but, if well done, sufficient, I believe, to stop a second person. I do not lightly express this opinion: it is founded on varied experience upon slopes at least as steep as that under consideration.

Consider now the bearing of the mode of attachment above described upon the question of rescue. When the rope is fastened round the guide’s waist, both his arms are free, to drive, in case of necessity, his spiked staff into the snow. But in the case before us, one arm of each guide was virtually powerless; on it was thrown the strain of the falling man in advance, by which it was effectually fettered. But this was not all. When the attached arm receives the jerk, the guide instinctively grasps the rope with the other hand; in doing so, he relinquishes his staff, and thus loses the sheet-anchor of[26] salvation. Such was the case with the two guides who escaped on the day now in question. The one lost his bâton, the other his axe, and they probably had to make an expert use of their legs to save even themselves from destruction. Tairraz was in the midst of the party. Whether it was in his power to rescue himself or not, whether he was caught in the coil of the rope or laid hold of by one of his companions, we can never know. Let us believe that he clung to them loyally, and went with them to death sooner than desert the post of duty.

By F. VAUGHAN HAWKINS, M.A.[4]

The summer and autumn of 1860 will long be remembered in Switzerland as the most ungenial and disastrous season, perhaps, on record; certainly without a parallel since 1834. The local papers were filled with lamentations over ‘der ewige Südwind,’ which overspread the skies with perpetual cloud, and from time to time brought up tremendous storms, the fiercest of which, in the three first days of September, carried away or blocked up for a time, I believe, every pass into Italy except the Bernina. At Andermatt, on the St. Gothard, we were cut off for two days from all communications whatever by water on every side. The whole of the lower Rhone valley was under water. A few weeks later, I found the Splügen, in the gorge above Chiavenna, alto[28]gether gone, remains of the old road being just visible here and there, but no more. In the Valteline, I found the Stelvio road in most imminent danger, gangs of men being posted in the courses of the torrents to divert the boulders, which every moment threatened to overwhelm the bridges on the route. A more unlucky year for glacier expeditions, therefore, could hardly be experienced; and the following pages present in consequence only the narrative of an unfinished campaign, which it is the hope of Tyndall and myself to be able to prosecute to a successful conclusion early next August.

I had fallen in with Professor Tyndall on the Basle Railway, and a joint plan of operations had been partly sketched out between us, to combine to some extent the more especial objects of each—scientific observations on his part; on mine, the exploration of new passes and mountain topography; but the weather sadly interfered with these designs. After some glacier measurements had been accomplished at Grindelwald, a short spell of fair weather enabled us to effect a passage I had long desired to try, from Lauterbrunnen direct to the Æggischhorn by the Roththal, a small and unknown but most striking glacier valley, known to Swiss mythology as the supposed resort of condemned spirits. We scaled, by a seven hours’ perpendicular climb, the vast amphitheatre of rock which bounds the[29] Aletsch basin on this side, and had the satisfaction of falsifying the predictions of Ulrich Lauener, who bade us farewell at Grindelwald with the discouraging assertion that he should see us back again, as it was quite impossible to get over where we were going. As we descended the long reaches of the Aletsch glacier, rain and mist again gathered over us, giving to the scene the appearance of a vast Polar sea, over the surface of which we were travelling, with no horizon visible anywhere except the distant line of level ice. Arrived at the Æggischhorn, the weather became worse than ever; a week elapsed before the measurement of the Aletsch glacier could be completed; and we reluctantly determined to dismiss Bennen, who was in waiting, considering the season too bad for high ascents, and to push on with Christian Lauener to the glaciers about Zinal. Bennen was in great distress. He and I had the previous summer reconnoitred the Matterhorn from various quarters, and he had arrived at the conclusion that we could in all probability (‘ich beinahe behaupte’) reach the top. That year, being only just convalescent from a fever, I had been unable to make the attempt, and thus an opportunity had been lost which may not speedily recur, for the mountain was then (September 1859) almost free from snow. Bennen had set his heart on our making the at[30]tempt in 1860, and great was his disappointment at our proposed departure for Zinal. At the last moment, however, a change of plans occurred. Lauener was unwilling to proceed with us to Zinal: we resolved to give Bennen his chance: the theodolite was packed up and despatched to Geneva, and we set off for Breuil, to try the Matterhorn.

Accessible or not, however, the Mont Cervin is assuredly a different sort of affair from Mont Blanc or Monte Rosa, or any other of the thousand and one summits which nature has kindly opened to man, by leaving one side of them a sloping plain of snow, easy of ascent, till the brink of the precipice is reached which descends on the other side. The square massive lines of terraced crags which fence the Matterhorn, stand up on all sides nearly destitute of snow, and where the snow lies thinly on the rocks it soon melts and is hardened again into smooth glassy ice, which covers the granite slabs like a coat of varnish, and bids defiance to the axe. Every step of the way lies between two precipices, and under toppling crags, which may at any moment bring down on the climber the most formidable of Alpine dangers—a fire of falling stones. The mountain too has a sort of prestige of invincibility which is not without its influence on the mind, and almost leads one to expect to encounter some new[31] and unheard-of source of peril upon it: hence I suppose it is that the dwellers at Zermatt and in Val Tournanche have scarcely been willing to attempt to set foot upon the mountain, and have left the honour of doing so to a native of another district, who, as he has been the first mortal to plant foot on the hitherto untrodden peak, so he will, I hope, have the honour, which he deserves, of being the first to reach the top.

John Joseph Bennen, of Laax, in the Upper Rhine Valley, is a man so remarkable that I cannot resist the desire (especially as he cannot read English) to say a few words about his character. Born within the limits of the German tongue, and living amidst the mountains and glaciers of the Oberland, he belongs by race and character to a class of men of whom the Laueners, Melchior Anderegg, Bortis, Christian Almer, Peter Bohren, are also examples—a type of mountain race, having many of the simple heroic qualities which we associate, whether justly or unjustly, with Teutonic blood, and essentially different from—to my mind, infinitely superior to—the French-speaking, versatile, wily Chamouniard. The names I have mentioned are all those of first-rate men; but Bennen, as (I believe) he surpasses all the rest in the qualities which fit a man for a leader in hazardous expeditions, combining boldness and prudence with an ease and[32] power peculiar to himself, so he has a faculty of conceiving and planning his achievements, a way of concentrating his mind upon an idea, and working out his idea with clearness and decision, which I never observed in any man of the kind, and which makes him, in his way, a sort of Garibaldi. Tyndall, on the day of our expedition, said to him, ‘Sie sind der Garibaldi der Führer, Bennen;’ to which he answered in his simple way, ‘Nicht wahr?’ (‘Am I not?’), an amusing touch of simple vanity, a dash of pardonable bounce, being one of his not least amiable characteristics. Thoroughly sincere and ‘einfach’ in thought and speech, devoted to his friends, without a trace of underhand self-seeking in his relations to his employers, there is an independence about him, a superiority to most of his own class, which makes him, I always fancy, rather an isolated man; though no one can make more friends wherever he goes, or be more pleasant and thoroughly cheerful under all circumstances. But he left his native place, Steinen, he told me, the people there not suiting him; and in Laax, where he now dwells, I guess him to be not perhaps altogether at home. Unmarried, he works quietly most of the year at his trade of a carpenter, unless when he is out alone, or with his friend Bortis (a man seemingly of reserved and uncommunicative disposition, but a splendid mountaineer), in the chase after[33] chamois, of which he is passionately fond, and will tell stories, in his simple and emphatic way, with the greatest enthusiasm. Pious he is, and observant of religious duties, but without a particle of the ‘mountain gloom,’ respecting the prevalence of which among the dwellers in the High Alps Mr. Ruskin discourses poetically, but I am myself rather incredulous. A perfect nature’s gentleman, he is to me the most delightful of companions; and though no ‘theory’ defines our reciprocal obligations as guide and employer, I am sure that no precipice will ever engulf me so long as Bennen is within reach, unless he goes into it also—an event which seems impossible—and I think I can say I would, according to the measure of my capacity, do the same by him. But any one who has watched Bennen skimming along through the mazes of a crevassed glacier, or running like a chamois along the side of slippery ice-covered crags, axe and foot keeping time together, will think that—as Lauener said of his brother Johann, who perished on the Jungfrau, he could never fall—nothing could bring him to grief but an avalanche.[5]

Delayed in our walk from the Æggischhorn by the usual severity of the weather, Tyndall, Bennen, and myself reached Breuil on Saturday, August 18, to make our attempt on the Monday. As we approached the mountain, Bennen’s countenance fell visibly, and he became somewhat gloomy; the mountain was almost white with fresh-fallen snow. ‘Nur der Schnee furcht mich,’ he replied to our enquiries. The change was indeed great from my recollection of the year before; the well-marked, terrace-like lines along the south face, which are so well given in Mr. George Barnard’s picture, were now almost covered up; through the telescope could be seen distinctly huge icicles depending from the crags, the lines of melting snow, and the dark patches which we hoped might spread a great deal faster than they were likely to, during the space of twenty-four hours. There was nothing for it, although our prospects of success were materially diminished by the snow, but to do the best we could. As far as I was concerned, I felt that I should be perfectly satisfied with getting part of the way up on a first trial, which would make one acquainted with the nature of the rocks, dispel the[35] prestige which seemed to hang over the untrodden mountain, and probably suggest ways of shortening the route on another occasion.

We wanted some one to carry the knapsack containing our provisions; and on the recommendation of the landlord at Breuil, we sent for a man, named Carrel, who, we were told, was the best mountaineer in Val Tournanche, and the nephew of M. le Chanoine Carrel, whose acquaintance I once had the honour of making at Aosta. From the latter description I rather expected a young, and perhaps aristocratic-looking personage, and was amused at the entrance of a rough, good-humoured, shaggy-breasted man, between forty and fifty, an ordinary specimen of the peasant class. However, he did his work well, and with great good temper, and seemed ready to go on as long as we chose; though he told me he expected we should end by passing the night somewhere on the mountain, and I don’t think his ideas of our success were ever very sanguine.

We were to start before 3 A.M. on Monday morning, August 20; and the short period for sleep thus left us was somewhat abridged in my own case, not so much by thoughts of the coming expedition, as by the news which had just reached us in a vague, but, unfortunately, only too credible form, of the terrible accident on the Col du Géant a few days before. The account thus reaching us was naturally[36] magnified, and we were as yet ignorant of the names. I could not at night shake off the (totally groundless) idea that a certain dear friend of mine was among them, and that I ought at that moment to be hurrying off to Courmayeur, to mourn and to bury him. In the morning, however, these things are forgotten; we are off, and Carrel pilots us with a lantern across the little stream which runs by Breuil, and up the hills to the left, where in the darkness we seem from the sound to be in the midst of innumerable rills of water, the effects of the late rains. The dark outline of the Matterhorn is just visible against the sky, and measuring with the eye the distance subtended by the height we have to climb, it seems as if success must be possible: so hard is it to imagine all the ups and downs which lie in that short sky-line.

Day soon dawns, and the morning rose-light touches the first peak westward of us; the air is wonderfully calm and still, and for to-day, at all events, we have good weather, without that bitter enemy the north wind; but a certain opaque look in the sky, long streaks of cloud radiating from the south-west horizon up towards the zenith, and the too dark purple of the hills south of Aosta, are signs that the good weather will not be lasting. By five we are crossing the first snow-beds, and now Carrel falls back, and the leader of the day comes to the front: all the day he will be cutting steps, but those[37] compact and powerful limbs of his will show no signs of extra exertion, and to-day he is in particularly good spirits. Carpentering, by the way—not fine turning and planing, but rough out-of-doors work, like Bennen’s—must be no bad practice to keep hand and eye in training during the dead season. We ascend a narrow edge of snow, a cliff some way to the right: the snow is frozen and hard as rock, and arms and legs are worked vigorously. Tyndall calls out to me, to know whether I recollect the ‘conditions:’ i.e. if your feet slip from the steps, turn in a moment on your face, and dig in hard with alpenstock in both hands under your body; by this means you will stop yourself if it is possible. Once on your back, it is all over, unless others can save you: you have lost all chance of helping yourself. In a few minutes we stop, and rope all together, in which state we continued the whole day. The prudence of this some may possibly doubt, as there were certainly places where the chances were greater that if one fell, he would drag down the rest, than that they could assist him; but we were only four, all tolerably sure-footed, and in point of fact I do not recollect a slip or stumble of consequence made by any one of us. Soon the slope lessens for a while, but in front a wall of snow stretches steeply upwards to a gap, which we have to reach, in a kind of recess, flanked by crags of[38] formidable appearance. We turn to the rocks on the left hand. As, to one walking along miry ways, the opposite side of the path seems ever the most inviting, and he continually shifting his course from side to side lengthens his journey with small profit, so in ascending a mountain one is always tempted to diverge from snow to rocks, or vice versâ. Bennen had intended to mount straight up towards the gap, and it is best not to interfere with him; he yields, however, to our suggestions, and we assail the rocks. These, however, are ice-bound, steep, and slippery: hands and knees are at work, and progress is slow. At length we stop upon a ledge where all can stand together, and Carrel proposes to us (for Bennen and he can only communicate by signs, the one knowing only French, the other German) to go on and see whether an easier way can be found still further to the left. Bennen gives an approving nod: he looks with indulgent pity on Carrel, but snubs all remarks of his as to the route. ‘Er weiss gar nichts,’ he says. Carrel takes his axe, and mounts warily, but with good courage; presently he returns, shaking his head. The event is fortunate, for had we gone further to the left, we should have reached the top of the ridge from which, as we afterwards found, there is no passage to the gap, and our day’s work would probably have ended then and there. Bennen now[39] leads to the right, and moves swiftly up from ledge to ledge. Time is getting on, but at length we emerge over the rocks just in face of the gap, and separated from it by a sort of large snow-crater, overhung on the left by the end of the ridge, from which stones fall which have scarred the sides of the crater. The sides are steep, but we curve quickly and silently round them: no stones fall upon us; and now we have reached the narrow neck of snow which forms the actual gap; it is half-past eight, and the first part of our work is done.

By no means the hardest part, however. We stand upon a broad red granite slab, the lowest step of the actual peak of the Matterhorn: no one has stood there before us. The slab forms one end of the edge of snow, surmounted at the other end by some fifty feet of overhanging rock, the end of the ridge. On one side of us is the snow-crater, round which we had been winding; on the other side a scarped and seamed face of snow drops sheer on the north, to what we know is the Zmutt glacier. Some hopes I had entertained of making a pass by this gap, from Breuil to Zermatt, vanish immediately. Above us rise the towers and pinnacles of the Matterhorn, certainly a tremendous array. Actual contact immensely increases one’s impressions of this, the hardest and strongest of all the mountain masses of the Alps; its form is more remarkable than that of[40] other mountains, not by chance, but because it is built of more massive and durable materials, and more solidly put together: nowhere have I seen such astonishing masonry. The broad gneiss blocks are generally smooth and compact, with little appearance of splintering or weathering. Tons of rock, in the shape of boulders, must fall almost daily down its sides, but the amount of these, even in the course of centuries, is as nothing compared with the mass of the mountain; the ordinary processes of disintegration can have little or no effect on it. If one were to follow Mr. Ruskin, in speculating on the manner in which the Alpine peaks can have assumed their present shape, it seems as if such a mass as this can have been blocked out only while rising from the sea, under the action of waves such as beat against the granite headlands of the Land’s End. Once on dry land, it must stand as it does now, apparently for ever.

Two lines of ascent offer, between which we have to choose: one along the middle or dividing ridge, the back-bone of the mountain, at the end of which we stand; the other by an edge some little way to the right: a couloir lies between them. We choose the former, or back-bone ridge; but the other proves to be less serrated, and we shall probably try it on another occasion. As we step from our halting-place, Bennen turns round and addresses us in[41] a few words of exhortation, like the generals in Thucydides. He knows us well enough to be sure that we shall not feel afraid, but every footstep must be planted with the utmost precaution: no fear, ‘wohl immer Achtung.’ Soon our difficulties begin; but I despair of relating the incidents of this part of our route, so numerous and bewildering were the obstacles along it; and the details of each have somewhat faded from the memory. We are immersed in a wilderness of blocks, roofed and festooned with huge plates and stalactites of ice, so large that one is half disposed to seize hold and clamber up them. Round, over, and under them we go: often progress seems impossible; but Bennen, ever in advance, and perched like a bird on some projecting crag, contrives to find a way. Now we crawl singly along a narrow ledge of rock, with a wall on one side, and nothing on the other: there is no hold for hands or alpenstock, and the ledge slopes a little, so that if the nails in our boots hold not, down we shall go: in the middle of it a piece of rock juts out, which we ingeniously duck under, and emerge just under a shower of water, which there is no room to escape from. Presently comes a more extraordinary place: a perfect chimney of rock, cased all over with hard black ice, about an inch thick. The bottom leads out into space, and the top is somewhere in the upper regions: there is[42] absolutely nothing to grasp at, and to this day I cannot understand how a human being could get up or down it unassisted. Bennen, however, rolls up it somehow, like a cat; he is at the top, and beckons Tyndall to advance; my turn comes next; I endeavour to mount by squeezing myself against the sides, but near the top friction suddenly gives way, and down comes my weight upon the rope:—a stout haul from above, and now one knee is upon the edge, and I am safe: Carrel is pulled up after me. After a time, we get off the rocks, and mount a slope of ice, which curves rapidly over for about three yards to our left, and then (apparently) drops at once to the Zmutt glacier. We reach the top of this, and proceed along it, till at last a sort of pinnacle is reached, from which we can survey the line of towers and crags before us up to a point just below the actual top, and we halt to rest a while. Bennen goes on to see whether it be possible to cross over to the other ridge, which seems an easier one. Left to himself, he treads lightly and almost carelessly along. ‘Geb’ Acht, Bennen!’ (Take care of yourself) we shout after him, but needlessly; he stops and moves alternately, peering wistfully about, exactly like a chamois; but soon he returns, and says there is no passage, and we must keep to the ridge we are on.

Three hours had not yet elapsed since we left the[43] gap, and from our present station we could survey the route as far as a point which concealed from us the actual summit, and could see that the difficulties before us were not greater than we had already passed through, and such as time and perseverance would surely conquer. Nevertheless, there is a tide in the affairs of such expeditions, and the impression had been for some time gaining ground with me that the tide on the present occasion had turned against us, and that the time we could prudently allow was not sufficient for us to reach the top that day. Before trial, I had thought it not improbable that the ascent might turn out either impossible or comparatively easy; it was now tolerably clear that it was neither the one nor the other, but an exceedingly long and hard piece of work, which the unparalleled amount of ice made longer and harder than usual. I asked Bennen if he thought there was time enough to reach the top of all: he was evidently unwilling, however, to give up hopes; and Tyndall said he would give no opinion either way; so we again moved on.

At length we came to the base of a mighty knob, huger and uglier than its fellows, to which a little arête of snow served as a sort of drawbridge. I began to fear lest in the ardour of pursuit we might be carried on too long, and Bennen might forget the paramount object of securing our safe[44] retreat. I called out to him that I thought I should stop somewhere here, that if he could go faster alone he might do so, but he must turn in good time. Bennen, however, was already climbing with desperate energy up the sides of the kerb; Tyndall would not be behind him; so I loosed the rope and let them go on. Carrel moved back across the little arête, and sat down, and began to smoke: I remained for a while standing with my back against the knob, and gazed by myself upon the scene around.

As my blood cooled, and the sounds of human footsteps and voices grew fainter, I began to realise the height and the wonderful isolation of our position. The air was preternaturally still; an occasional gust came eddying round the corner of the mountain, but all else seemed strangely rigid and motionless, and out of keeping with the beating heart and moving limbs, the life and activity of man. Those stones and ice have no mercy in them, no sympathy with human adventure; they submit passively to what man can do; but let him go a step too far, let heart or hand fail, mist gather or sun go down, and they will exact the penalty to the uttermost. The feeling of ‘the sublime’ in such cases depends very much, I think, on a certain balance between the forces of nature and man’s ability to cope with them: if they are too weak, the scene[45] fails to impress; if they are too strong for him, what was sublime becomes only terrible. Looking at the Dôme du Goûté or the Zumstein Spitze full in the evening sun, when they glow with an absolutely unearthly loveliness, like a city in the heavens, I have sometimes thought that, place but the spectator alone just now upon those shining heights, with escape before night all but impossible, and he will see no glory in the scene—only the angry eye of the setting sun fixed on dark rocks and dead-white snow.

We had risen seemingly to an immense height above the gap, and the ridge which stretches from the Matterhorn to the Dent d’Érin lay flat below; but the peak still towered behind me, and, measuring our position by the eye along the side of our neighbour of equal height, the Weisshorn, I saw that we must be yet a long way beneath the top. The gap itself, and all traces of the way by which we had ascended, were invisible; I could see only the stone where Carrel sat, and the tops of one or two crags rising from below. The view was, of course, magnificent, and on three sides wholly unimpeded: with one hand I could drop a stone which would descend to Zmutt, with the other to Breuil. In front lay, as in a map, the as yet unexplored peaks to south and west of the Dent d’Érin, the range which separates Val Tournanche from the Valpelline, and the glacier region[46] beyond, called in Ziegler’s map Zardezan, over which a pass, perchance, exists to Zermatt. An illimitable range of blue hills spread far away into Italy.

I walked along the little arête, and sat down; it was only broad enough for the foot, and in perfectly cold blood even this perhaps might have appeared uncomfortable. Turning to look at Tyndall and Bennen, I could not help laughing at the picture of our progress under difficulties. They seemed to have advanced only a few yards. ‘Have you got no further than that yet?’ I called out, for we were all the time within hearing. Their efforts appeared prodigious: scrambling and sprawling among the huge blocks, one fancied they must be moving along some unseen bale of heavy goods instead of only the weight of their own bodies. As I looked, an ominous visitant appeared: down came a fragment of rock, the size of a man’s body, and dashed past me on the couloir, sending the snow flying. For a moment I thought they might have dislodged it; but looking again I saw it had passed over their heads, and come from the crags above. Neither of them, I believe, observed the monster; but Tyndall told me afterwards that a stone, possibly a splinter from it, had hit him in the neck, and nearly choked him. I looked anxiously again, but no more followed. A single shot, as it were, had been fired across our bows; but the ship’s course was already on the point of being put about.

Expecting fully that they would not persevere beyond a few minutes longer, I called out to Tyndall to know how soon they meant to be back. ‘In an hour and a half,’ he replied, whether in jest or earnest, and they disappeared round a projecting corner. A sudden qualm seized me, and for a few minutes I felt extremely uncomfortable: what if the ascent should suddenly become easier, and they should go on, and reach the top without me? I thought of summoning Carrel, and pursuing them; but the worthy man sat quietly, and seemed to have had enough of it. My suspense, however, was not long: after two or three minutes the clatter, which had never entirely ceased, became louder, and their forms again appeared: they were evidently descending. In fact, Bennen had at length turned, and said to Tyndall, ‘Ich denke die Zeit ist zu kurz.’ I was glad that he had gone on as long as he chose, and not been turned back on my responsibility. They had found one part of this last ascent the worst of any, but the way was open thenceforward to the farthest visible point, which can be no long way below the actual top.

It was now just about mid-day, and ample time for the descent, in all probability, was before us; but we resolved not to halt for any length of time till we should reach the gap. Descending, unlike ascending, is generally not so bad as it seems; but in some places here only one can advance at a time, the[48] other carefully holding the rope. ‘Tenez fortement, Carrel, tenez,’ is constantly impressed on the man who brings up the rear. ‘Splendid practice for us, this,’ exclaims Tyndall exultingly, as each successive difficulty is overcome. At length we reach a place whence no egress is possible; we look in vain for traces of the way we had come: it is our friend the ice-coated chimney. Bennen gets down first, in the same mysterious fashion as he got up, and assists us down; presently a shout is heard behind; Carrel is attempting to get down by himself, and has stuck fast; Bennen has to extricate him. We are now getting rapidly lower; soon the difficulties diminish; our gap appears in sight, and once more we reach the broad granite slab beside the narrow col, and breathe more freely.

Two hours have brought us down thus far; but if we are to return by the way we came, three or four hours of hard work are still needed before we arrive at anything like ordinary snow-walking. We hold a consultation. Bennen thinks the rocks, now that the ice is melting in the afternoon sun, will be difficult, and ‘withal somewhat dangerous’ (etwa gefährlich auch). The reader will remark that Bennen uses the word ‘dangerous’ in its legitimate sense. A place is dangerous where a good climber cannot be secure of his footing; a place is not dangerous where a good climber is in no danger of[49] slipping, although to slip may be fatal. We determine to see if it be possible to descend the sides of the snow-crater, on the brink of which we now stand. The crater is portentously steep, deeply lined with fresh snow, which glistens and melts in the powerful sun. The experiment is slightly hazardous, but we resolve to try. The crater appears to narrow gradually to a sort of funnel far down below, through which we expect to issue into the glacier beneath. At the sides of the funnel are rocks, which some one suggests might serve to break our fall, should the snow go down with us, but their tender mercies seem to me doubtful. Cautiously, with steady, balanced tread, we commit ourselves to the slope, distributing the weight of the body over as large a space of snow as possible, by fixing in the pole high up, and the feet far apart, for a slip or stumble now will probably dissolve the adhesion of the fresh, not yet compacted mass, and we shall go down to the bottom in an avalanche. Six paces to the right, then again to the left; we are at the mercy of those overhanging rocks just now, and the recent tracks of stones look rather suspicious; but all is silent, and soon we gain confidence, and congratulate ourselves on an expedient which has saved us hours of time and toil. Just to our right the snow is sliding by, first slowly, then faster; keep well out of the track of it, for underneath is a hard polished surface, and[50] if your foot chance to light there, off you will probably shoot. The snow travels much faster than we do, or have any desire to do; we are like a coach travelling alongside of an express train; in popular phrase, we are going side by side with a small avalanche, though a real avalanche is a very different matter. Soon we come somewhat under the lee of the rocks, and now all risk is over, we are through the funnel, and floundering waist-deep, heedless of crevasses in the comparatively level slopes beyond. We plunge securely down now in the deep snow, where care and caution had been requisite in crossing the frozen surface in the morning; at length we cast off the rope, and are on terra firma.

We shall be at Breuil in unexpectedly good time, before five o’clock; but it is well we are off the mountain early, for clouds and mist are already gathering round the peak, and the weather is about to break. Tyndall rushes rapidly down the slopes, and is lost to view; Bennen and I walk slowly, discussing the results of the day. I am glad to see that he is in high spirits, and confident of our future success. He agrees with me to reach the top will be an exceedingly long day’s work, and that we must allow ten hours at least for the actual peak, six to ascend, four to descend; we must start next time, he says, ‘ganz, ganz früh,’ and manage to reach the gap by seven o’clock. Presently we deviate a little[51] from our downward course; the same thought occupies our minds; we perceive a long low line of roof on the mountain-side, and are not mistaken in supposing that our favourite food will at this hour be found there in abundance. The shepherds on the Italian hills are more hospitable and courteous, I think, than their Swiss brethren: twenty cows are moving their tails contentedly in line under the shed, for Breuil is a rich pasture valley, and in an autumn evening I have counted six herds of from ninety to a hundred each, in separate clusters, like ants, along the stream in the distance. The friendly man, in hoarse but hearty tones, urges us on as we drink; Bennen puts into his hand forty centimes for us both (for we have disposed of no small quantity): but he is with difficulty persuaded to accept so large a sum, and calls after us, ‘C’est trop, c’est trop, messieurs.’ Long may civilisation and half-francs fail of reaching his simple abode; for, alas! the great tourist-world is corrupting the primitive chalet-life of the Alps, and the Alpine man returning to his old haunts, finds a rise in the price even of ‘niedl’ and ‘mascarpa.’

The day after our expedition Bennen and myself recrossed the Théodule in a heavy snow-storm. Tyndall started for Chamouni, for the weather was too bad to justify an indefinite delay at Breuil in the hope of making another attempt that year, and[52] by waiting till another season we were sure of obtaining less unfavourable conditions of snow and ice upon the mountain.—We had enjoyed an exciting and adventurous day, and I myself was not sorry to have something still left to do, while we had the satisfaction of being the first to set foot on this, the most imposing and mightiest giant of the Alps—the ‘inaccessible’ Mont Cervin.—Vacation Tourists, 1860.

The thermometers referred to at p. 17 were placed on Mont Blanc in 1859. I had proposed to the Royal Society some time previously to establish a series of stations between the top and bottom of the mountain, and the council of the society was kind enough to give me its countenance and aid in the undertaking. At Chamouni I had a number of wooden piles shod with iron. The one intended for the summit was twelve feet long and three inches square; the others, each ten feet long, were intended for five stations between the top of the mountain and the bottom of the Glacier de Bossons. Each post was furnished with a small cross-piece, to which a horizontal minimum thermometer might be attached. Six-and-twenty porters were found necessary to carry all the apparatus to the Grands Mulets, whence fourteen of them were immediately sent back. The other twelve, with one exception, reached the summit, whence six of them were sent[54] back. Six therefore remained. In addition to these we had three guides, Auguste Balmat being the principal one; these, with Dr. Frankland and myself, made up eleven persons in all. Though the main object of the expedition was to plant the posts and fix the thermometers, I was very anxious to make some observations on the transparency of the lower strata of the atmosphere to the solar heat-rays. I therefore arranged a series of observations with the Abbé Veuillet, of Chamouni; he was to operate in the valley, while I observed at the top. Our instruments were of the same kind; in this way I hoped to determine the influence of the stratum of air interposed between the top and bottom of the mountain upon the solar radiation.

Wishing to commence the observations at daybreak, I had a tent carried to the summit, where I proposed to spend the night. The tent was ten feet in diameter, and into it the whole eleven of us were packed. The north wind blew rather fiercely over the summit, but we dropped down a few yards to leeward, and thus found shelter. Throughout the night we did not suffer at all from cold, though we had no fire, and the adjacent snow was 15° Cent., or 27° Fahr., below the freezing point of water. We were all however indisposed. I was indeed very unwell when I quitted Chamouni; but had I faltered my party would have melted away. I had[55] frequently cast off illness on previous occasions, and hoped to do so now. But in this I was unsuccessful; my illness was more deep-rooted than ordinary, and it augmented during the entire period of the ascent. Towards morning, however, I became stronger, while with some of my companions the reverse was the case. At daybreak the wind increased in force, and as the fine snow was perfectly dry, it was driven over us in clouds. Had no other obstacle existed, this alone would have been sufficient to render the observations on solar radiation impossible. We were therefore obliged to limit ourselves to the principal object of the expedition—the erection of the post for the thermometers. It was sunk six feet in the snow, while the remaining six feet were exposed to the air. A minimum thermometer was screwed firmly on to the cross-piece of the post; a maximum thermometer was screwed on beneath this, and under this again a wet and dry bulb thermometer. Two minimum thermometers were also placed in the snow—one at a depth of six, and the other at a depth of four feet below the surface—these being intended to give some information as to the depth to which the winter cold penetrates. At each of the other stations we placed a minimum thermometer in the ice or snow, and a maximum and a minimum in the air.