Title: The Book of Roses

Author: Francis Parkman

Release date: October 29, 2014 [eBook #47232]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

CHAPTER IV. MISCELLANEOUS OPERATIONS

CHAPTER V. GROUPS and FAMILIES

ROSES MOST APPROVED BY THE BEST CULTIVATORS OF THE PRESENT DAY

IT IS needless to eulogize the Rose. Poets from Anacreon and Sappho, and earlier than they, down to our own times, have sung its praises; and yet the rose of Grecian and of Persian song, the rose of troubadours and minstrels, had no beauties so resplendent as those with which its offspring of the present day embellish our gardens. The "thirty sorts of rose," of which John Parkinson speaks in 1629, have multiplied to thousands. New races have been introduced from China, Persia, Hindostan, and our own country; and these, amalgamated with the older families by the art of the hybridist, have produced still other forms of surpassing variety and beauty. This multiplication and improvement are still in progress. The last two or three years have been prolific beyond precedent in new roses; and, with all regard for old favorites, it cannot be denied, that, while a few of the roses of our forefathers still hold their ground, the greater part are cast into the shade by the brilliant products of this generation.

In the production of new roses, France takes the lead. A host of cultivators great and small—Laffay, Vibert, Verdier, Margottin, Trouillard, Portemer, and numberless others—have devoted themselves to the pleasant art of intermarrying the various families and individual varieties of the rose, and raising from them seedlings whose numbers every year may be counted by hundreds of thousands. Of these, a very few only are held worthy of preservation; and all the rest are consigned to the rubbish heap. The English, too, have of late done much in raising new varieties; though their climate is less favorable than that of France, and their cultivators less active and zealous in the work. Some excellent roses, too, have been produced in America. Our climate is very favorable to the raising of seedlings, and far more might easily be accomplished here.

In France and England, the present rage for roses is intense. It is stimulated by exhibitions, where nurserymen, gardeners, landed gentlemen, and reverend clergymen of the Established Church, meet in friendly competition for the prize. While the French excel all others in the production of new varieties, the English are unsurpassed in the cultivation of varieties already known; and nothing can exceed the beauty and perfection of some of the specimens exhibited at their innumerable rose-shows. If the severity of our climate has its disadvantages, the clearness of our air and the warmth of our summer sun more than counterbalance them; and it is certain that roses can be raised here in as high perfection, to say the very least, as in any part of Europe.

The object of this book is to convey information. The earlier portion will describe the various processes of culture, training, and propagation, both in the open ground and in pots; and this will be followed by an account of the various families and groups of the rose, with descriptions of the best varieties belonging to each. A descriptive list will be added of all the varieties, both of old roses and those most recently introduced, which are held in esteem by the experienced cultivators of the present day. The chapter relating to the classification of roses, their family relations, and the manner in which new races have arisen by combinations of two or more old ones, was suggested by the difficulties of the writer himself at an early period of his rose studies. The want of such explanations, in previous treatises, has left their readers in a state of lamentable perplexity on a subject which might easily have been made sufficiently clear.

Books on the rose, written for the climates of France or England, will, in general, greatly mislead the cultivators here. Extracts will, however, be given from the writings of the best foreign cultivators, in cases where experience has shown that their directions are applicable to the climate of the Northern and Middle States. The writer having been for many years a cultivator of the rose, and having carefully put in practice the methods found successful abroad, is enabled to judge with some confidence of the extent to which they are applicable here, and to point out exceptions and modifications demanded by the nature of our climate.

Among English writers on the rose, the best are Paul, Rivers, and more recently Cranston, together with the vivacious Mr. Radclyffe, a clergyman, a horticulturist, an excellent amateur of the rose, and a very amusing contributor to the "Florist." In France, Deslongchamps and several able contributors to the "Revue Horticole" are the most prominent. From these sources the writer of this book drew the instructions and hints which at first formed the basis of his practice; but he soon found that he must greatly modify it in accordance with American necessities. There was much to be added, much to be discarded, and much to be changed; and the results to which he arrived are given, as compactly as possible, in the following pages.

Jan. 1,1866.

THE ROSE requires high culture. This belle of the parterre, this "queen of flowers," is a lover of rich fare, and refuses to put forth all her beauties on a meagre diet. Roses, indeed, will grow and bloom in any soil; but deficient nourishment will reduce the size of the flowers, and impair the perfection of their form. Of all soils, one of a sandy or gravelly nature is the worst; while, on the other hand, a wet and dense clay is scarcely better. A rich, strong, and somewhat heavy garden loam, abundantly manured, is the soil best adapted to all the strong-growing roses; while those of more delicate growth prefer one pro-portionably lighter.

Yet roses may be grown to perfection in any soil, if the needful pains are taken. We will suppose an extreme case: The grower wishes to plant a bed of roses on a spot where the soil is very poor and sandy. Let him mark out his bed, dig the soil to the depth of eighteen inches? throw out the worst portion of it, and substitute in its place a quantity of strong, heavy loam: rotted sods, if they can be had, will be an excellent addition; and so, also, will decayed leaves. Then add a liberal dressing of old stable manure: that taken from a last year's hot-bod will do admirably. It is scarcely possible to enrich too highly. One-fourth manure to three-fourths soil is not an excessive proportion. Now incorporate the whole thoroughly with a spade, level the top, and your bed is ready.

Again: we will suppose a case, equally bad, but of the opposite character. Here the soil is very wet, cold, and heavy. The first step is to drain it. This may be done thoroughly with tiles, after the approved methods; or, if this is too troublesome or expensive, simpler means may be used, which will, in most situations, prove as effectual. Dig a hole about five feet deep and four feet wide at the lower side of your intended bed of roses: in this hole place an inverted barrel, with the head knocked out; or, what is better, an old oil cask. In the latter case, a hole should be bored in it, near the top, to permit the air to escape. Fill the space around the cask or barrel with stones, and then cover the whole with earth. If your bed is of considerable extent, a drain, laid in stone or tile, should be made under or beside the bed, at the depth of three feet, and so constructed as to lead to the sunken barrel. Throw out, if necessary, a portion of the worst soil of the bed, substituting light loam, rotted leaves, and coarse gritty sand. Then add an abundance of old stable manure, as in the former case.

In the great majority of gardens, however, such pains are superfluous. Any good garden soil, deeply dug, and thoroughly enriched, will grow roses in perfection. Neither manure nor the spade should be spared. Three conditions are indispensable,—sun, air, and exemption from the invasion of the roots of young growing trees. These last are insidious plunderers and thieves, which invade the soil, and rob its lawful occupants of the stores of nutriment provided for them.

A rose planted on the shady side of a grove of elm or maple trees is in one of the worst possible of situations. If, however, the situation is in other respects good, the evil of the invading roots may be cured for a time by digging a trench, three feet deep, between the trees and the bed of roses; thus cutting off the intruders. The trench may then be filled up immediately; but, if the trees are vigorous, it must be dug over again the following year. It is much better to choose, at the outset, an airy, sunny situation, at a reasonable distance from growing trees; but, at the same time, a spot exposed to violent winds should be avoided, as they are very injurious and exhausting.

Roses may be planted either in spring or in autumn. In the Northern States, the severity of the winter demands some protection, when planted in autumn, for all except the old, hardy varieties. Plant as early as possible, that the roots may take some hold on the soil before winter closes. October, for this reason, is better than November. The best protection is earth heaped around the stem to the height of from six inches to a foot. Pine, cedar, or spruce boughs are also excellent. When earth alone is used, the top of the rose is often frost-killed; but this is usually of no consequence, the growth and bloom being only more vigorous for this natural pruning. Dry leaves heaped among or around the roses, and kept down by sticks or pieces of board, or by earth thrown on them, are also good protectors. In spring, plant as early as the soil is in working order; that is to say, as soon as it is dry enough not to adhere in lumps to the spade.

In planting, prune back the straggling roots with a sharp knife, but save as many of the small fibres as possible. If you plant in spring, prune back the stem at least half way to the ground; but, if you plant in autumn, by all means defer this operation till the winter is over. The ground around autumn-planted roses should be trodden down in the spring, since the plant will have been somewhat loosened in its place by the effect of frost; but this treading must not take place until the soil has become free from excessive moisture. Budded roses require a peculiar treatment in planting, which we shall describe when we come to speak of them.

Next to soil and situation, pruning is the most important point of attention to the rose-grower. Long treatises have been written on it, describing in detail different modes applicable to different classes of roses, and confusing the amateur by a multitude of perplexing particulars.

One principle will cover most of the ground: Weaklygrowing roses should be severely pruned: those of vigorous growth should be pruned but little. Or, to speak more precisely, roses should be pruned in inverse proportion to the vigor of their growth.

Much, however, depends on the object at which the grower aims. If he wishes for a profusion of bloom, without regard to the size and perfection of individual flowers, then comparatively little pruning is required. If, on the other hand, he wishes for blooms of the greatest size and perfection, without regard to number, he will prune more closely.

The pruning of any tree or shrub at a time when vegetation is dormant acts as a stimulus to its vital powers. Hence, when it is naturally vigorous, it is urged by close pruning to such a degree of growth, that it has no leisure to bear flowers, developing instead a profusion of leaves and branches. The few flowers which it may produce under such circumstances, will, however, be unusually large.

The most vigorous growers among roses are the climbers, such as the "Boursaults" and the "Prairies."

These require very little pruning: first, because of their vigor; and, secondly, because quantity rather than quality of bloom is asked of them. The old and dry wood should be cut wholly away, leaving the strong young growth to take its place, with no other pruning than a clipping-off of the ends of side-shoots, and a thinning-out of crowded or misshapen branches. In all roses, it is the young, well-ripened wood that bears the finest flowers. Old enfeebled wood, or unripe, soft, and defective young wood, should always be removed.

Next in vigor to the climbers are some of the groups of hardy June roses; such, for example, as those called the Hybrid China roses. These are frequently grown on posts or pillars; in which case they require a special treatment, to be indicated hereafter. We are now supposing them to be grown as bushes in the garden or on the lawn. Cut out the old wood, and the weak, unripe, and sickly shoots, as well as those which interfere with others; then shorten the remaining stems one-third, and cut back the side-shoots to three or four buds. This is on the supposition that a full mass of bloom is required, without much regard to the development of individual flowers. If quality rather than quantity of bloom is the desideratum, the pruning both of the main stems and of the side-shoots must be considerably shorter.

Roses of more moderate growth, including the greater part of the June, Moss, Hybrid Perpetual, and Bourbon roses, require a proportionally closer pruning. The stems may be cut down to half their length, and the side-shoots shortened to two buds. All the weak-growing roses, of whatever class, may be pruned with advantage even more closely than this. Some of the weak-growing Hybrid Perpetuals grow and bloom best when shortened to within four or five buds of the earth. The stronggrowing kinds, on the contrary, if pruned thus severely, would grow with great vigor, but give very few flowers.

The objects of pruning are threefold: first, to invigorate the plant; secondly, to improve its flowers; and, thirdly, to give it shape and proportion. This last object should always be kept in view by the operator. No two stems should be allowed to crowd each other. A mass of matted foliage is both injurious and unsightly. Sun and air should have access to every part of the plant. Six or seven stems are the utmost that should be allowed to remain, even on old established bushes; and these, as before mentioned, should be strong and well ripened, and should also be disposed in such a manner, that, when the buds have grown into shoots and leaves, the bush will have a symmetrical form. In young bushes, three, or even two, good stems are sufficient.

Pruning in summer, when the plant is in active growth, has an effect contrary to that of pruning when it is in a dormant state. Far from increasing its vigor, it weakens it, by depriving it of a portion of its leaves, which are at once its stomach and its lungs. Only two kinds of summer pruning can be recommended. The first consists in the removal of small branches which crowd their neighbors, and interfere with them: the second is confined to the various classes of Perpetual roses, and consists merely in cutting off the faded flowers, together with the shoots on which they grow, to within three or four buds of the main stem. This greatly favors their tendency to bloom again later in the summer.

When old wood is cut away, it should be done cleanly, without leaving a protruding stump. A small saw will sometimes be required for this purpose; though in most cases a knife, or, what is more convenient, a pair of sharp pruning-shears, will be all that the operator requires.

When roses are trained to cover walls, trellises, arches, or pillars, the main stems are encouraged to a strong growth. These form the permanent wood; while the side-shoots, more or less pruned back, furnish the flowers. For arbors, walls, or very tall pillars, the strongest growers are most suitable, such as the Prairie, Boursault, and Ayrshire roses. Enrich the soil strongly, and dig deep and widely. Choose a healthy young rose, and, in planting, cut off all the stems close to the earth. During the season, it will make a number of strong young shoots. In the following spring cut out half of them, leaving the strongest, which are to be secured against the wall, or over the arbor, diverging like a fan or otherwise, as fancy may suggest. The subsequent pruning is designed chiefly to regulate the growth of the rose, encouraging the progress of the long leading shoots until they have reached the required height, and removing side-shoots where they are too thick. Where a vacant space occurs, a strong neighboring shoot may be pruned back in spring to a single eye. This will stimulate it to a vigorous growth, producing a stem which will serve to fill the gap. Of the young shoots, which, more or less, will rise every season from the root, the greater part should be cut away, reserving two or three to take the place of the old original stems when these become weak by age. When these climbing roses are used for pillars, they may either be trained vertically, or wound in a spiral form around the supporting column.

Roses of more moderate growth are often trained to poles or small pillars from six to twelve feet high. Some of the Hybrid China roses are, as before mentioned, well adapted to this use; and even some of the most vigorous Moss roses, such as Princess Adelaide, may be so trained. Where a pole is used, two stems are sufficient. These should be examined, and cut back to the first strong and plump bud, removing the weaker buds always found towards the extremity of a stem. Then let the stems so pruned lie flat on the earth till the buds break into leaf, after which they are to be tied to the pole. If they were tied up immediately, the sap, obeying its natural tendency, would flow upward, expanding the highest bud, and leaving many of those below dormant, so that a portion of the stem would be bare. (The same course of proceeding may be followed with equal advantage in the case of wall and trellis roses.) The highest bud now throws up a strong leading shoot, while the stem below becomes furnished with an abundance of small side-shoots. In the following spring, the leading shoot is to be pruned back to the first strong bud, and the treatment of the previous year repeated. By pursuing this process, the pillar may, in the course of two or three years, be enveloped from the ground to the summit with a mass of leaves and blossoms.

These and all other rose-pruning operations are, in the Northern States, best effected in March, or the end of February; since roses pruned in autumn are apt to be severely injured and sometimes killed by the severity of our winters.

Nothing is more beneficial to roses than a frequent digging and stirring of the soil around them. The surface should never be allowed to become hard, but should be kept light and porous by hoeing or forking several times in the course of the season. A yearly application of manure will be of great advantage. It may be applied in the autumn or in the spring, and forked in around the plants. Cultivators who wish to obtain the finest possible blooms sometimes apply liquid manure early in the summer, immediately after the flower-buds are formed. This penetrates at once to the roots, and takes immediate effect on the growing bud.

The amateur may perhaps draw some useful hints from an experiment made by the writer in cultivating roses, with a view to obtaining the best possible individual flowers. A piece of land about sixty feet long by forty wide was "trenched" throughout to the depth of two feet and a half, and enriched with three layers of manure. The first was placed at eighteen inches from the surface; the second, at about nine inches; and the third was spread on the surface itself, and afterwards dug in. The virgin soil was a dense yellow loam of considerable depth; and, by the operation of "trenching," it was thoroughly mixed and incorporated with the black surface soil. Being too stiff and heavy, a large quantity of sandy road-scrapings was laid on with the surface-dressing of manure. When the ground was prepared, the roses were planted in rows. They consisted of Hardy June, Moss, Hybrid Perpetual, Bourbon, and a few of the more hardy Noisette roses. They were planted early in spring, and cut back at the same time close to the ground. Many of the Perpétuais and Bourbons flowered the first season, and all grew with a remarkable vigor. In November, just before the ground froze, a spadesman, working backward midway between the rows, dug a trench of the depth and width of his spade, throwing the earth in a ridge upon the roots of the roses as he proceeded. This answered a double purpose. The ridge of earth protected the roots and several inches of the stems, while the trench acted as a drain. In the spring, the earth of the ridge was drawn back into the trench with a hoe, and the roses pruned with great severity; some of the weak-growing Perpetuals and Mosses being cut to within two inches of the earth, and all the weak and sickly stems removed altogether. The whole ground was then forked over. The bloom was abundant, and the flowers of uncommon size and symmetry. Had the pruning been less severe, the mass of bloom would have been greater, but the individual flowers by no means of so good quality.

Of budded roses we shall speak hereafter, in treating of propagation. There is one kind, however, which it will be well to notice here. In England and on the Continent, it is a common practice to bud roses on tall stems or standards of the Dog Rose, or other strong stock, sometimes at a height of five feet or more from the ground. The head of bloom thus produced has a very striking effect, especially when the budded rose is of a variety with long slender shoots, adapted to form what is called a "weeper."

In France, standard roses are frequently planted near together in circular or oval beds, the tallest stems being in the centre, and the rest diminishing in regular gradation to the edge of the bed, which is surrounded with dwarf roses. Thus a mound or hill of bloom is produced with a very striking and beautiful effect.

Unfortunately, the severe cold and sudden changes of the Northern States, and especially of New England, are very unfavorable to standard roses. The hot sun scorches and dries the tall, bare stem; and the sharp cold of winter frequently kills, and in almost every case greatly injures, the budded rose at the top. It is only by using great and very troublesome precaution that standards can here be kept in a thriving condition. This may be done most effectually by cutting or loosening the roots on one side, laying the rose flat on the ground, and covering it during winter under a ridge of earth. Some protection of the stem from the hot sun of July and August can hardly be dispensed with.

With regard to the mounds of standard roses first mentioned, it is scarcely worth while to attempt them here; but a very good substitute is within our reach. By choosing roses with a view to their different degrees of vigor,—planting the tall and robust kinds in the middle, and those of more moderate growth in regular gradation around them,—we may imitate the French mounds without the necessity of employing standards. Of course it will require time, and also judicious pruning, to perfect such a bed of roses; but, when this is done, it will be both a beautiful and permanent ornament of the lawn or garden.

A new mode of growing roses, so as to form a tall pyramid instead of a standard, has been recently introduced in England. Instead of inserting buds at the top of the stem only, they are inserted at intervals throughout its whole length, thus clothing it with verdure and flowers. By this means it is effectually protected from the sun, and one of the dangers which in our climate attend standard roses is averted. The following directions are copied from a late number of the "Gardener's Chronicle:"—

"Some strong two-years-old stocks of the Manetti Rose should be planted in November, in a piece of ground well exposed to sun and air. The soil should have dressings of manure, and be stirred to nearly two feet in depth. In the months of July and August of the following year, they will be in a fit state to bud. They should have one bud inserted in each stock close to the ground. The sort to be chosen for this preliminary budding is a very old Hybrid China Rose, called Madame Pisaroni; a rose with a most vigorous and robust habit, which, budded on strong Manet-ti stocks, will often make shoots from six to seven feet in length, and stout and robust in proportion. In the month of February following, the stocks in which are live buds should be all cut down to within six inches of the bud. In May, the buds will begin to shoot vigorously: if there are more shoots than one from each bud, they must be removed, leaving only one, which in June should be supported with a slight stake, or the wind may displace it.

"By the end of August, this shoot ought to be from five to six feet in height, and is then in a proper state for budding to form a pyramid. Some of the most free-growing and beautiful of the Hybrid Perpetual roses should be selected, and budded on these stems in the following manner: Commence about nine inches from the ground, inserting one bud; then on the opposite side of the stock, and at the same distance from the lower bud, insert another; and then at the same distance another and another; so that buds are on all sides of the tree up to about five feet in height, which, in the aggregate, may amount to nine buds. "You will thus have formed the foundation of a pyramid. I need scarcely add that the shoots from the stock must be carefully removed during the growing season, so as to throw all its strength into the buds. It will also be advisable to pinch in the three topmost buds rather severely the first season, or they will, to use a common expression, draw up the sap too rapidly, and thus weaken the lower buds. In the course of a year or two, magnificent pyramids may thus be formed, their stems completely covered with foliage, and far surpassing any thing yet seen in rose culture."

Another new method of culture is put forward in recent French and English journals, and is said to have proved very successful, increasing both the size of the flowers and the period of bloom. I cannot speak of it from trial; but, as it may be found worth an experiment, I extract from the "Florist and Pomologist" the account there given of the process by a Mr. Perry, who was one of the first to practise it. He says,—

"As I have now spoken of the advantages attendant upon this mode of training, I will proceed to explain the method of carrying it out. I will suppose that the plants are well established, and are either on their own roots, or budded low on the Manetti (the former I prefer). The operation of bending and pegging-down should be performed in the month of March, or early in April. All the small growth should be cut clean away, and the ends of the strong shoots cut off to the extent only of a few inches. These shoots should then be carefully bent to the ground, and fastened down by means of strong wooden pegs, sufficiently stout to last the season, and to retain the branches in their proper positions. Care must be taken that the branches do not split off at the base; but the operator will soon perceive which is the best and easiest mode of bending the tree to his wishes. Many shoots will spring up from the base of the plants, too strong to produce summer blooms; but most of them will gratify the cultivator will such noble flowers in the autumn that will delight the heart of any lover of this queen of flowers. These branches will be the groundwork for the next year. I have recently been engaged in cutting all the old wood away which last season did such good duty, and am now furnished with an ample supply of snoots from four to eight feet high, which, if devoid of leaves, would strongly remind me of fine raspberry-canes, and which, by their appearance, promise what they will do for the forthcoming season. I would suggest that these long shoots should now be merely bundled together, and a stake put to each plant, so as to prevent their being injured by the wind. In this state let them remain until the latter end of March, and then proceed as I have before mentioned. I feel convinced, that, when this method of pegging-down and dwarfing stronggrowing roses becomes generally known, many of the justly esteemed and valuable robust show varieties will occupy the position in our flower-gardens they are justly entitled to."

A good soil, a good situation, free air and full sun, joined with good manuring, good pruning, and good subsequent culture, will prevent more diseases than the most skilful practitioner would ever be able to cure. There are certain diseases, however, to which roses, under the best circumstances, are more or less liable. Of these, the most common, and perhaps the worst, is mildew. It consists in the formation on the leaves and stems of û sort of minute fungus, sometimes presenting the appearance of a white frost. Though often thought to be the result of dampness, it frequently appears in the dryest weather. Many of the Bourbon roses, and those of the Hybrid Perpétuais nearest akin to the Bourbons, are peculiarly liable to it. In the greenhouse, the best remedy is sulphur, melted and evaporated at a heat not high enough to cause it to burn. In the open air, the flour of sulphur may be sifted over the diseased plants. English florists use a remedy against mildew and other kinds of fungus, which is highly recommended, but of which I cannot speak from trial. It consists in syringing the plants affected with a solution of two ounces of blue vitriol dissolved in a largo stable bucket of water.

The worst enemies of the rose belong to the insect world. Of these there are four, which, in this part of the country, cause far more mischief than all the rest combined. The first is the aphis, or green fly; the second is the rose-slug, or larva of the saw-fly; the third is the leaf-hopper, sometimes called the thrip; and the fourth is the small beetle, popularly called the rose-bug. The first three are vulnerable, and can be got rid of by using the right means. The slug is a small, green, semi-transparent grub, which appears on the leaves of the rose about the middle of June, eats away their vital part, and leaves nothing but a brown skeleton, till at length the whole bush looks as if burned. The aphis clings to the ends of young shoots, and sucks out their sap. It is prolific beyond belief, and a single one will soon increase to thousands. Both are quickly killed by a solution of whale-oil soap, or a strong decoction of tobacco, which should be applied with a syringe in the morning or evening, as the application of any liquid to the leaves of a plant under the hot sun is always injurious. The same remedy will kill the leaf-hopper, which, being much more agile than the others, is best assailed on a cold day, when its activity is to some degree chilled out of it. Both sides of the leaves should be syringed, and the plant thoroughly saturated with the soap or tobacco-water.

Two thorough and well-timed applications will suffice to destroy the year's crop of slugs.

The rose-bug is endowed with a constitution which defies tobacco and soap; and, though innumerable remedies have been proposed, we know no better plan than to pick them off the bushes by hand, or, watching a time when they are chilled with cold, to shake them off upon a cloth laid on the ground beneath. In either case, sure work should be made of them by scalding or crushing them to death.

The following account of the rose-bug and the slug is from Dr. Harris's work on "Insects Injurious to Vegetation:"—

"The saw-fly of the rose, which, as it does not seem to have been described before, may be called Selandria Rosae, from its favorite plant, so nearly resembles the slug-worm saw-fly as not to be distinguished therefrom except by a practised observer. It is also very much like Selandria barda, Vitis, and pygmaea, but has not the red thorax of these three closely-allied species. It is of a deep and shining black color. The first two pairs of legs are brownish-gray, or dirty white, except the thighs, which are almost entirely black. The hind legs are black, with whitish knees. The wings are smoky and transparent, with dark-brown veins, and a brown spot near the middle of the edge of the first pair. The body of the male is a little more than three-twentieths of an inch long; that of the female, one-fifth of an inch or more; and the wings expand nearly or quite two-fifths of an inch. These saw-flies come out of the ground at various times between the 20th of May and the middle of June, during which period they pair, and lay their eggs. The females do not fly much, and may be seen, during most of the day, resting on the leaves; and, when touched, they draw up their legs, and fall to the ground. The males are now active, fly from one rose-bush to another, and hover around their sluggish partners. The latter, when about to lay their eggs, turn a little on one side, unsheathe their saws, and thrust them obliquely into the skin of the leaf, depositing in each incision thus made a single egg. The young begin to hatch in ten days or a fortnight after the eggs are laid. They may sometimes be found on the leaves as early as the 1st of June, but do not usually appear in considerable numbers till the 20th of the same month. How long they are in coming to maturity, I have not particularly observed; but the period of their existence in the caterpillar state probably does not exceed three weeks. They somewhat resemble young slug-worms in form, but are not quite so convex. They have a small, round, yellowish head, with a black dot on each side of it; and are provided with twenty-two short legs. The body is green above, paler at the sides, and yellowish beneath; and it is soft and almost transparent, like jelly. The skin of the back is transversely wrinkled, and covered with minute elevated points; and there are two small, triple-pointed warts on the edge of the first ring, immediately behind the head.

"The gelatinous and sluggish creatures eat the upper surface of the leaf in large, irregular patches, leaving the veins and the skin beneath untouched; and they are sometimes so thick, that not a leaf on the bushes is spared by them, and the whole foliage looks as if it had been scorched by fire, and drops off soon afterwards. They cast their skins several times, leaving them extended and fastened on the leaves: after the last moulting, they lose their semi-transparent and greenish color, and acquire an opaque yellowish hue. They then leave the rose-bushes; some of them slowly creeping down the stem, and others rolling up and dropping off, especially when the bushes are shaken by the wind. Having reached the ground, they burrow to the depth of an inch or more in the earth, where each one makes for itself a small oval cell of grains of earth, cemented with a little gummy silk. Having finished their transformations, and turned to flies within their cells, they come out of the ground early in August, and lay their eggs for a second brood of young. These, in turn, perform their appointed work of destruction in the autumn: they then go into the ground, make their earthen cells, remain therein throughout the winter, and appear in the winged form in the following spring and summer. During several years past, these pernicious vermin have infested the rose-bushes in the vicinity of Boston, and have proved so injurious to them as to have elicited the attention of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, by whom a premium of one hundred dollars, for the most successful mode of destroying these insects, was offered in the summer of 1840. In the year 1832, I first observed them in the gardens in Cambridge, and then made myself acquainted with their transformations. At that time they had not reached Milton, my former place of residence; and they did not appear in that place till six or seven years later. They now seem to be gradually extending in all directions; and an effectual method for preserving our roses from their attacks has become very desirable to all persons who set any value on this beautiful ornament of our gardens and shrubberies. Showering or syringing the bushes, with a liquor made by mixing with water the juice expressed from tobacco by tobacconists, has been recommended: but some caution is necessary in making this mixture of a proper strength; for, if too strong, it is injurious to plants; and the experiment does not seem, as yet, to have been conducted with sufficient care to insure safety and success. Dusting lime over the plants, when wet with dew, has been tried, and found of some use; but this and all other remedies will probably yield in efficacy to Mr. Haggerston's mixture of whale-oil soap and water, in the proportion of two pounds of the soap to fifteen gallons of water.

"Particular directions, drawn up by Mr. Haggerston himself, for the preparation and use of this simple and cheap application, may be found in the 'Boston Courier' for the 25th of June, 1841, and also in most of our agricultural and horticultural journals of the same time. The utility of this mixture has already been repeatedly mentioned in this treatise, and it may be applied in other cases with advantage. Mr. Haggerston finds that it effectually destroys many kinds of insects; and he particularly mentions plant-lice, red spiders, canker-worms, and a little jumping insect, which has lately been found quite as hurtful to rose-bushes as the slugs or young of the saw-fly. The little insect alluded to has been mistaken for a Thrips, or vinc-frettor: it is, however, a leaf-hopper, or species of Tettiyonia, and is described in a former part of this treatise.

"The rose-chafer, or rose-bug as it is more commonly and incorrectly called, is also a diurnal insect. It is the Melolontha subspinosa of Fabricius, by whom it was first described, and belongs to the modern genus Macrodaclylus of Latreille. Common as this insect is in the vicinity of Boston, it is, or was a few years ago, unknown in the northern and western parts of Massachusetts, in New Hampshire, and in Maine. It may, therefore, be well to give a brief description of it. This beetle measures seven-twentieths of an inch in length. Its body is slender, tapers before and behind, and is entirely covered with very short and close ashen-yellow down; the thorax is long and narrow, angularly widened in the middle of each side, which suggested the name subspinosa, or somewhat spined; the legs are slender, and of a pale-red color; the joints of the feet are tipped with black, and are very long; which caused Latreille to call the genus Macrodactylus: that is, long toe, or long foot.

"The natural history of the rose-chafer, one of the greatest scourges with which our gardens and nurseries have been afflicted, was for a long time involved in mystery, but is at last fully cleared up. The prevalence of this insect on the rose, and its annual appearance coinciding with the blossoming of that flower, have gained for it the popular name by which it is here known. For some time after they were first noticed, rose-bugs appeared to be confined to their favorite, the blossoms of the rose; but within forty years they have prodigiously increased in number, have attacked at random various kinds of plants in swarms, and have become notorious for their extensive and deplorable ravages. The grape-vine, in particular, the cherry, plum, and apple trees, have annually suffered by their depredations: many other fruit-trees and shrubs, garden vegetables and corn, and even the trees of the forest and the grass of the fields, have been laid under contribution by these indiscriminate feeders, by whom leaves, flowers, and fruits are alike consumed. The unexpected arrival of these insects in swarms at their first coming, and their sudden disappearance at the close of their career, are remarkable facts in their history. They come forth from the ground during the second week in June, or about the time of the blossoming of the damask-rose, and remain from thirty to forty days. At the end of this period the males become exhausted, fall to the ground, and perish; while the females enter the earth, lay their eggs, return to the surface, and, after lingering a few days, die also.

"The eggs laid by each female are about thirty in number, and are deposited from one to four inches beneath the surface of the soil: they are nearly globular, whitish, and about one-thirtieth of an inch in diameter, and are hatched twenty days after they are laid. The young larvæ begin to feed on such tender roots as are within their reach. Like other grubs of the Scarabæians, when not eating they lie upon the side, with the body covered, so that the head and tail are nearly in contact: they move with difficulty on a level surface, and are continually falling over on one side or the other. They attain their full size in the autumn, being then nearly three-quarters of an inch long, and about an eighth of an inch in diameter. They are of a yellowish-white color, with a tinge of blue towards the hinder extremity, which is thick, and obtuse or rounded. A few short hairs are scattered on the surface of the body. There are six short legs; namely, a pair to each of the first three rings behind the head: and the latter is covered with a horny shell of a pale rust color. In October they descend below the reach of frost, and pass the winter in a torpid state. In the spring they approach towards the surface, and each one forms for itself a little cell of an oval shape by turning round a great many times, so as to compress the earth, and render the inside of the cavity hard and smooth. Within this cell the grub is transformed to a pupa during the month of May by casting off its skin, which is pushed downwards in folds from the head to the tail. The pupa has somewhat the form of the perfected beetle, but is of a yellowish-white color; its short, stump-like wings, its antennæ, and its legs, are folded upon the breast; and its whole body is enclosed in a thin film, that wraps each part separately. During the month of June, this filmy skin is rent: the included beetle withdraws from its body and its limbs, bursts open its earthen cell, and digs its way to the surface of the ground. Thus the various changes, from the egg to the full development of the perfected beetle, are completed within the space of one year.

"Such being the metamorphoses and habits of these insects, it is evident that we cannot attack them in the egg, the grub, or the pupa state: the enemy in these stages is beyond our reach, and is subject to the control only of the natural but unknown means appointed by the Author of Nature to keep the insect tribes in check. When they have issued from their subterranean retreats, and have congregated upon our vines, trees, and other vegetable productions, in the complete enjoyment of their propensities, we must unite our efforts to seize and crush the invaders. They must indeed be crushed, scalded, or burned, to deprive them of life; for they are not affected by any of the applications usually found destructive to other insects. Experience has proved the utility of gathering them by hand, or of shaking them or brushing them from the plants into tin vessels containing a little water. They should be collected daily during the period of their visitation, and should be committed to the flames, or killed by scalding water. The late John Lowell, Esq., states that, in 1823, he discovered on a solitary apple-tree the rose-bugs 'in vast numbers, such as could not be described, and would not be believed if they were described, or at least none but an ocular witness could conceive of their numbers. Destruction by hand was out of the question,' in this case. He put sheets under the tree, shook them down, and burned them.

"Dr. Green of Mansfield, whose investigations have thrown much light on the history of this insect, proposes protecting plants with millinet, and says that in this way only did he succeed in securing his grape-vines from depredation. His remarks also show the utility of gathering them. 'Eighty-six of these spoilers,' says he, 'were known to infest a single rose-bud, and were crushed with one grasp of the hand.' Suppose, as was probably the case, that one-half of them were females: by this destruction, eight hundred eggs, at least, were prevented from becoming matured. During the time of their prevalence, rose-bugs are sometimes found in immense numbers on the flowers of the common white-weed, or ox-eyed daisy (Chrysanthemum leucanihemum); a worthless plant, which has come to us from Europe, and has been suffered to overrun our pastures and encroach on our mowing-lands. In certain cases, it may become expedient rapidly to mow down the infested white-weed in dry pastures, and consume it, with the sluggish rose-bugs, on the spot.

"Our insect-eating birds undoubtedly devour many of these insects, and deserve to be cherished and protected for their services. Rose-bugs are also eaten greedily by domesticated fowls; and when they become exhausted and fall to the ground, or when they are about to lay their eggs, they are destroyed by moles, insects, and other animals, which lie in wait to seize them. Dr. Green informs us that a species of dragon-fly, or devil's-needle, devours them. He also says that an insect, which he calls the enemy of the cut-worm (probably the larva of a Carabus or predaceous ground-beetle), preys on the grubs of the common dor-bug. In France, the golden ground-beetle (Carabus auratus) devours the female dor, or chafer, at the moment when she is about to deposit her eggs. I have taken one specimen of this fine ground-beetle in Massachusetts; and we have several other kinds equally predaceous, which probably contribute to check the increase of our native Melolonthians."

MANY OF the ever-blooming roses cannot, in our climate, be cultivated in the open air without extreme precaution to protect them from the cold. To grow them most successfully, the aid of glass is necessary. Many of the Hardy Perpetual roses may also be grown with advantage in pots, by which means their bloom may be prolonged into the early winter months, or they may be forced into premature flowering long before their natural season of bloom. The first essential in the pot culture of roses is the preparation of the soil. Those of delicate growth, like most of the China and Tea roses, require a lighter soil than the more robust varieties, like most of the Hardy Perpetuals. A mixture of loam, manure, leaf-mould, and sand, in the proportion of two bushels of loam to one bushel of manure, one bushel of leaf-mould, and half a bushel of sand, makes a good soil for the more delicate roses. For the more robust kinds, the proportion of loam and of manure should be greater. In all cases, the materials should be mixed two or three months before they are wanted for use, and turned over several times to incorporate them thoroughly. They are frequently, however, mixed, and used at once. The best loam is that composed of thoroughly rotted turf. A very skilful English rose-grower, Mr. Rivers, recommends the compact turf shaved from the surface of an old pasture, and roasted and partially charred on a sheet of iron over a moderate fire. I have found no enriching material so good as the sweepings from the floor of a horse-shoer, in which manure is mixed with the shavings of hoofs. It is light and porous, and furnishes, in decomposing, a great quantity of ammonia. For the more delicate roses it is particularly suited, while the stronger kinds will bear manures of a stronger and denser nature. The light black soil from the woods is an excellent substitute for leaf-mould; or, to speak more correctly, it is a natural leaf-mould in the most thorough state of decomposition.

Young and thrifty roses which have been grown during summer may be potted for the house in September. They should be taken up with care, the large straggling roots cut back, and all bruised ends removed with a sharp knife. The ends of the branches should also be cut back. They may then be potted in the compost just described, which should first be sifted through a very coarse sieve. The pots must be well drained with broken crocks placed over the hole at the bottom. Care must be taken that the pot be not too large, as this is very injurious. A sharp stick may be used to compact the soil about the roots; and from half an inch to an inch in depth should be left empty at the top, to assist in thorough watering, which is a point of the first importance.

When the roses are potted, they should be placed in a light cellar or shed, or under a shady wall. They must be well watered, and it is well to syringe them occasionally. In a week or two they will have become established, and may then be removed to a greenhouse without fire, and with plenty of air; care, however, being taken to protect them from frost at night.

The roses so treated are intended for blooming from mid-winter to the end of spring; and we shall soon speak further of them under the head of Forcing.

A great desideratum is the obtaining of roses in the early part of winter. This may be done by growing everblooming roses in pots in the open air during summer, plunging the pot in the earth, and placing a tile or brick beneath it to prevent the egress of roots and the ingress of worms. Towards the end of August, cut off all the flowers and buds, at the same time shortening the flower-stalks to two or three eyes. Then give the roses a supply of manure-water to stimulate their growth. If they are in a thrifty condition, they will form new shoots and flower-buds before the frost sets in; and may then be removed to a cold greenhouse, where they will continue, to flower for several months.

The following is the description given by Mr. Rivers of a practice recently introduced in England, and which seems well worth a trial here, with such modifications as the heat of our sun may require:—

"To have a fine bloom of these roses, or, indeed, of any of the Hybrid Perpetuals, Bourbons, or China roses, in pots towards the end of summer or autumn, take plants from small pots (those struck from cuttings in March or April will do), and put them into six-inch, or even eight-inch pots, using a compost of light turfy loam and rotten manure, equal parts: to a bushel of the compost add half a peck of pounded charcoal, and the same quantity of silver sand; make a hot-bed of sufficient strength, say three to four feet in height, of seasoned dung, so that it is not of a burning heat, in a sunny, exposed situation,' and on this place the pots; then fill up all interstices with sawdust, placing it so as to cover the rims, and to lie on the surface of the mould in the pots about two inches deep. The pots should have a good sound watering before they are thus plunged, and have water daily in dry weather. The bottom heat and full exposure to the sun and air will give the plants a vigor almost beyond belief. This very simple mode of culture is as yet almost unknown. I have circulated among a few friends the above directions; and have no doubt, that, in the hands of skilful gardeners, some extraordinary results may be looked for in the production of specimens of soft-wooded plants. I may add, that, when the heat of the bed declines towards the middle of July, the pots must be removed, some fresh dung added, and the bed remade, again plunging the plants immediately. Towards the end of August, the roots of the plants must be ripened: the pots must, therefore, be gradually lifted out of the saw-dust; i.e., for five or six days, expose them about two inches below their rims; then, after the same lapse of time, a little lower, till the whole of the pot is exposed to the sun and air: they may be then removed to the greenhouse, so as to be sheltered from heavy rain. They will bloom well in the autumn, and be in fine order for early forcing. If plants are required during the summer for exhibition, or any other purpose, care must always be taken to harden or ripen their roots, as above, before they are removed from the hot-bed."

"Forcing" is the very inappropriate name of the process by which roses and other plants are induced to bloom under glass in advance of their natural season. We say that the name is inappropriate, because one of the chief essentials to the success of the process consists in an abstinence from all that is violent or sudden, and in the gentle and graduated application of the stimulus of artificial heat.

Roses may be forced in the greenhouse, but not to advantage, because the conditions of success will be inconsistent with the requirements of many of the other plants. The process is best carried on in a small glass structure made for such purposes, and called a "forcing-pit."

A pit ten or twelve feet long and eight or ten wide will commonly be large enough. It may be of the simplest and cheapest construction. In a dry situation, there is advantage in sinking the lower part of it two or three feet below the surface of the ground. The roses may be placed on beds of earth, or on wooden platforms, so arranged as to bring the top of the plants near the glass; and a sunken path may pass down the middle. The pit may be heated by a stove enclosed with brick-work, and furnished with a flue of brick or tile passing along the front of the pit, and entering the chimney at the farther end. The lights must be movable, or other means provided' for ample ventilation; and if these are such that the air on entering will pass over the heated flues, and thus become warmed in the passage, great advantage will result. A pit may be appended to a greenhouse; in which case it may be heated by hot-water pipes furnished with means of cutting off or letting on the water.

The roses potted for forcing, as directed in the last section, should be kept in a dormant state till the middle of December. A portion of them may then be brought into the pit, and the young shoots pruned back to two or three eyes. The heat at first must be very moderate, not much exceeding forty-five degrees in the daytime: and, throughout the process, the pit should be kept as cool as possible at night; great care, however, being taken that no frost is admitted. With this view, the glass should be covered at sunset with thick mats. Syringe the plants as the buds begin to swell, and lose no opportunity to give air on mild and bright days. Raise the heat gradually till it reaches sixty degrees; which is enough during the winter months, so far as fire-heat is concerned. The heat of the sun will sometimes raise it to seventy or eighty degrees. Syringe every morning; and, if the aphis appears, fumigate with tobacco; then syringe forcibly to wash off the dead insects. As the plants advance in growth, they require plenty of water; and, as the buds begin to swell, manure-water may be applied once or twice. When the buds are ready to open, the pots may be removed to the greenhouse or drawing-room, and another supply put in their place for a second crop of flowers. When the blooms are faded, the flower-stalks may be cut back to two or three eyes, and the plants placed again in the forcing-pit for another crop. This, of course, is applicable to ever-blooming roses only.

The most common and simple way, however, of obtaining roses in winter, is to grow them on rafters in the greenhouse. Some of the Noisette, China, and Tea roses, thus treated, will furnish an abundant supply of excellent flowers. By pruning them at different periods during the summer and autumn, they will be induced to flower in succession; since, with all roses, the time of blooming is, to a great degree, dependent on the time of pruning.

Roses potted in the manner described for forcing may also be brought into bloom in the sunny window of a chamber or drawing-room. They will bloom much better if allowed to remain at rest in a cool cellar for a month or two after potting.

The following is a cheap mode of forcing, described by an English cultivator. The amateur may, perhaps, be disposed to make the experiment.

"Those who wish for the luxury of forced roses at a trifling cost may have them by pursuing the following simple method: Take a common garden frame, large or small, according to the number of roses wanted; raise it on some posts, so that the bottom edge will be about three feet from the ground at the back of the frame, and two feet in front, sloping to the south. If it is two feet deep, this will give a depth of five feet under the lights at the back of the frame, which will admit roses on little stems as well as dwarfs. Grafted or budded plants of any of the Perpetual roses should be potted in October, in a rich compost of equal portions of rotten dung and loam, in pots about eight inches deep and seven inches over, and plunged in the soil at the bottom. The air in the frame may be heated by linings of hot dung; but care must be taken that the dung be turned over two or three times before it is used, otherwise the rank and noxious steam will kill the young and tender shoots: but the hazard of this may be avoided by building a wall of turf, three inches thick, from the ground to the bottom edge of the frame. This will admit the heat through it, and exclude the steam. The Perpetual roses, thus made to bloom early, are really beautiful."

Now, in the way of exciting the reader's emulation, I will mention a few items of the opening flower-show of the Crystal Palace, Sydenham, on the 26th of May, a few years ago. The following specimens of roses, in pots, are chronicled among innumerable others:—

Madame Willeemoz (Tea-scented Rose), seven feet high, with more than a hundred expanded flowers.

Souvenir de la Malmaison (Bourbon Rose), with thirty expanded flowers, the largest more than five inches in diameter.

Paul Pereas (Hybrid Bourbon Rose), six feet high, with nearly a hundred expanded flowers.

Coupe d'Hébé (Hybrid Bourbon Rose), six feet high, covered with a mass of bloom.

These were all raised by Mr. Paul, one of the most skilful of English rose-growers; and were the results of patience, care, and experience. We hold the production of specimens like these a work of art worthy of zealous emulation. Our climate is quite as favorable to their production as that of England; and, when the floricultural art has reached among us the same development, our horticultural shows will, no doubt, boast decorations equally splendid. The plants just mentioned were the productions of a nurseryman; but specimens of roses grown to the highest perfection are every year exhibited in England by amateur cultivators. The competition for prizes, far from being a mere strife for a small sum of money, is an honorable emulation, in which the credit of success is the winner's best reward.

One point cannot be too often urged in respect to horticultural pursuits. Never attempt to do any thing which you are not prepared to do thoroughly. A little done well is far more satisfactory than a great deal done carelessly and superficially. He who raises one perfect and fully developed specimen of a plant is a better horticulturist than he who raises an acre of indifferent specimens. The amateur who has made himself a thorough master of the cultivation of a single species or variety, has, of necessity, acquired a knowledge and skill, which, with very little pains, he may apply to numberless other forms of culture. Learn to produce a first-class specimen of the rose grown in a pot, and you will have no difficulty in successfully applying your observation and experience to a vast variety of plants. We will, therefore, enter into some detail as to the methods of procedure. For many of the specific directions I am indebted to Mr. Paul, the exhibiter of the fine specimens named above, and the author, among other books, of a useful little treatise on the cultivation of roses in pots.

Soil is the point that first demands attention, and directions concerning it have already been given. You have bought a number of young roses, in small pots, in the spring. Be sure that these roses have been in a dormant state during the winter; for, if they have been kept in growth, their vital power is partially exhausted. They may be budded on short stems of the Manetti or other good stock (see the chapter on Budding), or they may be on their own roots. The Tea and China roses are certainly better in the latter condition. Shift them from the small pots into pots a very little larger, without breaking the ball of earth around their roots. Water them well, and plunge them to the edge of the pot in earth, in an open, airy, sunny place. Or they may be set on the surface, provided the spaces between them are well packed with tan, coal-ashes, or swamp-moss. The last is excellent: it holds moisture like a sponge. In every case, the pots should rest on flat bricks, slates, tiles, or inverted pans, in order that worms may be excluded, and that the roots may not be tempted to thrust themselves through the hole. In potting, thorough drainage should be secured by placing broken crocks at the bottom of the pot.

Encourage the growth of the plants by pinching off the flower-buds. The object throughout the summer is to get a few stout well-ripened shoots by autumn. Therefore the pots should not be very close together, since this would deprive the plants of free air and sunlight. Watering must be carefully attended to. Cut out, or pinch off, weak or ill-placed shoots; or, what is better, prevent their growth by rubbing off the buds that threaten to form such. Thus, if several buds are crowded together in one place, rub off all but one or two of them, choosing the strongest for preservation. This is called dis-budding. Those of the plants that grow most vigorously will require to be shifted into still larger pots in July; but this should be done only in cases where it is necessary. As a guide on this point, turn them carefully out of the pots to examine the roots; and, if these are found protruding in great abundance from the ball of earth, larger pots will be required; but, if otherwise, the same one will suffice. Some roses suffer greatly if placed in pots too large for them; and the same is more or less true of all plants.

Late in autumn, when growth has ceased, shift the roses again, if they need it, and place them for wintering in a cellar or cold frame. In the spring, prune them, as directed in the chapter on Pruning. After the rose is pruned, stake out the shoots to as great distances as possible. Indeed, the larger ones should be made to lie almost horizontal: this will cause the buds to "break," or open, regularly along their whole length; whereas, if left upright, a few at the top would break, and the rest remain dormant. As soon as the buds have opened, the shoots may be tied up again. Syringe the opening buds, and water moderately, increasing the amount of moisture as the leaves expand, and watering abundantly during all the period of full activity of growth; that is, during summer and early autumn. An occasional application of manure-water is useful. Watch for insects and mildew, and apply the remedies elsewhere directed. About midsummer, shift those that need it into larger pots; an operation which, if performed with skill, will not check their growth in the least. Continue to disbud and to remove weak and ill-placed shoots, tying out the rest, as they grow, to stakes, in order to bring the plant into a symmetrical form. This form is a matter of taste with the cultivator: it may be a half-globe, a fan, or a pyramid or cone. The last is usually the best; one strong stem being allowed to grow in the centre, and smaller stems trained in gradation around it. None must interfere with their neighbors, and air should have free play through the plant.

You have reached the second autumn, and your plants are now excellent for forcing; but, if you aim at first-class specimens, you must give them, at the least, one season more of growth and training. To this end, keep them dormant through the winter in a cellar or cold frame as before, and prune them early in spring. We will suppose that a pyramidal plant is desired. As soon as they are pruned, draw the lower shoots downwards over the rim of the pot, just beneath which a wire should pass around, to which the shoots are to be tied with strings of bass-matting. The shoots higher up are to be arranged, with the aid of sticks and strings, so as to decrease in circumference till they terminate in a point. Constant care and some judgment are needed throughout the growing season to preserve symmetry of form. Strong shoots must be pinched back, and weak ones encouraged. Both the plant, and the pot that contains it, are, or ought to be, so large by this time, that handling them, especially in the act of shifting, becomes somewhat difficult. In the third, or at farthest in the fourth autumn, you may expect, as the result of your pains, a plant that in its blooming season will make a brilliant contrast with the half-grown and indifferent specimens sometimes exhibited at our horticultural shows.

If you forget every other point of the above directions, keep in mind the following: Drain your pots thoroughly; and, when you water them, be sure that you give water enough to penetrate the whole mass of the earth contained in them. Watering only the surface, and leaving the roots dry, is ruinous.

THERE ARE five modes of propagating the rose,—by layers, by cuttings, by budding, by grafting, and by suckers.

This is perhaps, for the amateur, the most convenient and certain method. The best season for layering is the summer, from the end of June to the end of August; and, for some varieties, even later. The rose which is to be multiplied should be in a condition of vigorous growth.

Loosen and pulverize the soil around it; and, if heavy and adhesive, add a liberal quantity of very old manure mixed with its bulk of sharp sand. The implements needed for the operation are a knife, a trowel, and hooked wooden pegs. Choose a well-ripened shoot of the same season's growth, and strip off the leaves from its base a foot or more up the stalk; but, by all means, suffer the leaves at the end to remain. Bend the shoot gently downward with the left hand, and insert the edge of the knife in its upper or inner side six or eight inches from its base, and immediately below a bud. Cut half way through the stem; then turn the edge of the knife upward, and cautiously slit the stem through the middle, to the length of an inch and a half, thus a tongue of wood, with a bud at its end, will be formed. With the thumb and finger of the left hand raise the upper part of the stem erect, at the same time by a slight twist turning the tongue aside, steadying the stem meanwhile with the right hand. Thus the tongue will be brought to a right angle, or nearly so, with the part of the stem from which it was cut. Hold it in this position with the left hand, while with the trowel you make a slit in the soil just beneath it. Into this insert the tongue and bent part of the stem to a depth not much exceeding two inches. Press the earth firmly round them, and pin them down with one of the hooked pegs. Some operators cut the tongue on the lower or outer side of the stem; but this has a double disadvantage. In the first place, the stem is much more liable to break in being bent; and, in the next place, the tongue is liable to re-unite with the cut part, and thus defeat the operation. When all is finished, the extremity of the shoot should stand out of the ground as nearly upright as possible, and should by no means be cut back,—a mistaken practice in use with some gardeners.

In a favorable season, most of the layers will be well rooted before the frost sets in. If the weather is very dry, there will be many failures. Instead of roots, a hard cellular substance will form in a ball around the tongue. In the dry summer of 1864, the rose-layers were thus "clubbed" with lumps often as large as a hen's egg; but cases like this are rare.

In November, it is better in our severe climate to take up the rooted layers, and keep them during winter in a "cold frame;" that is, a frame constructed like that of a hot-bed, without the heat. Here they should be set closely in light soil to the depth of at least six inches, and covered with boards and matting; or they may be potted in small pots, and placed in a frame or cellar.

Layers may be made in spring from wood of the last season's growth; but laying the young wood during slimmer, as described above, is much to be preferred.

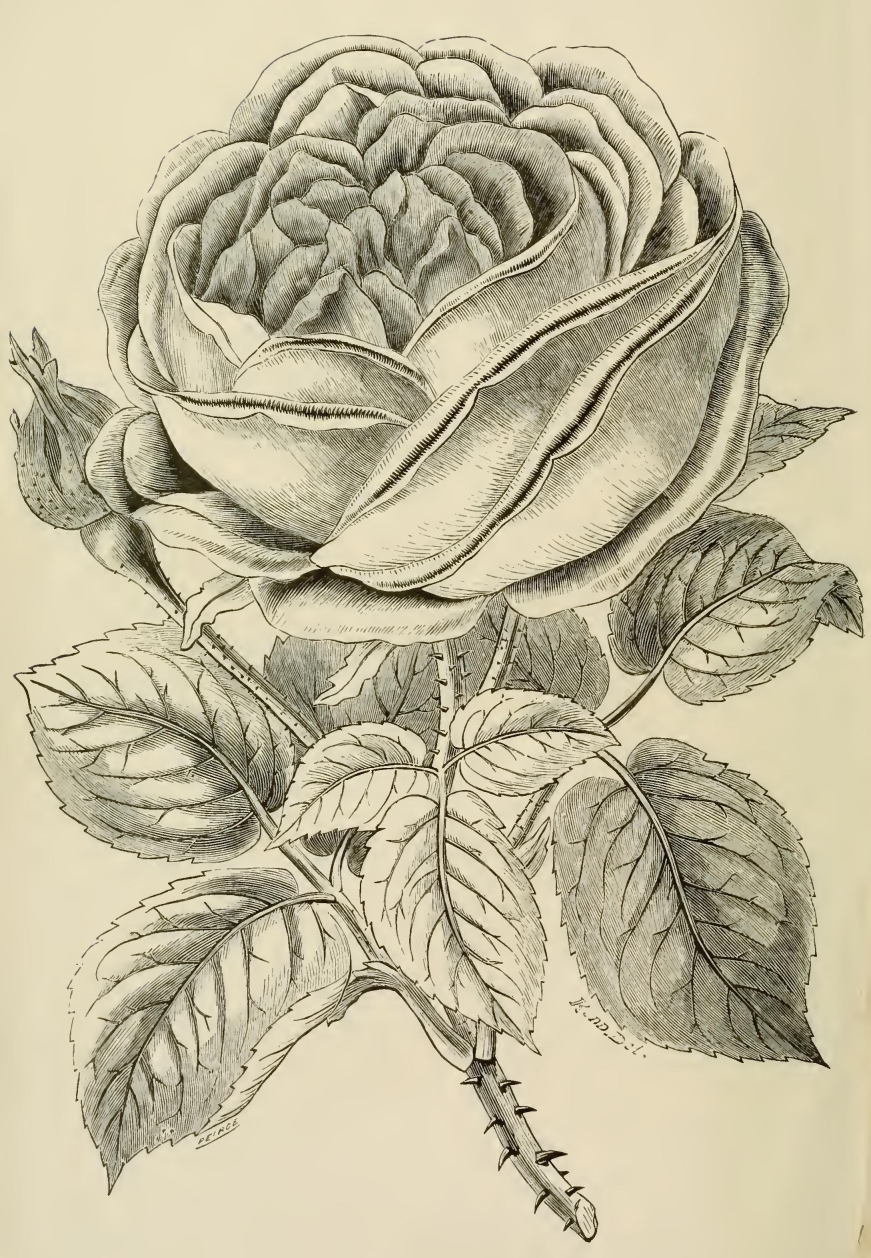

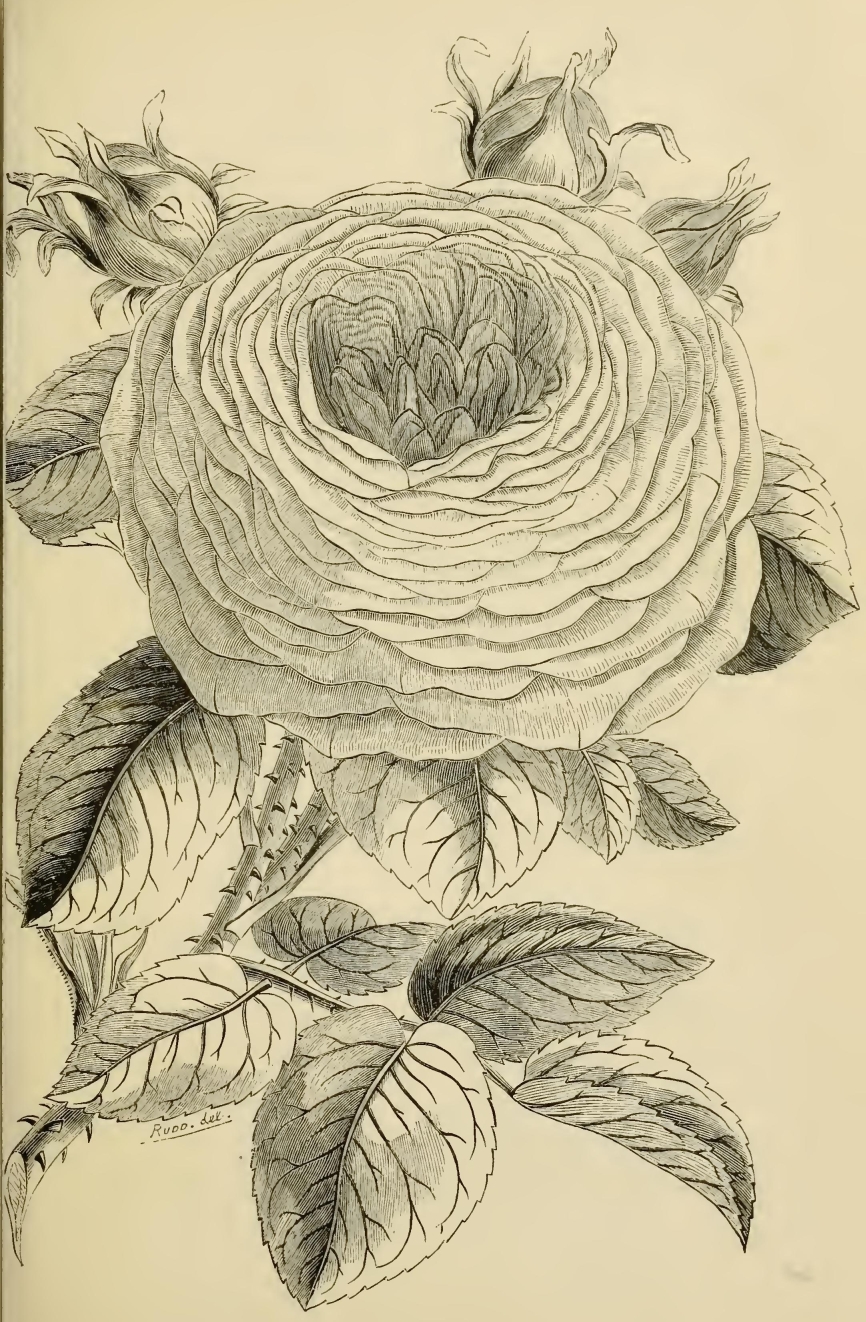

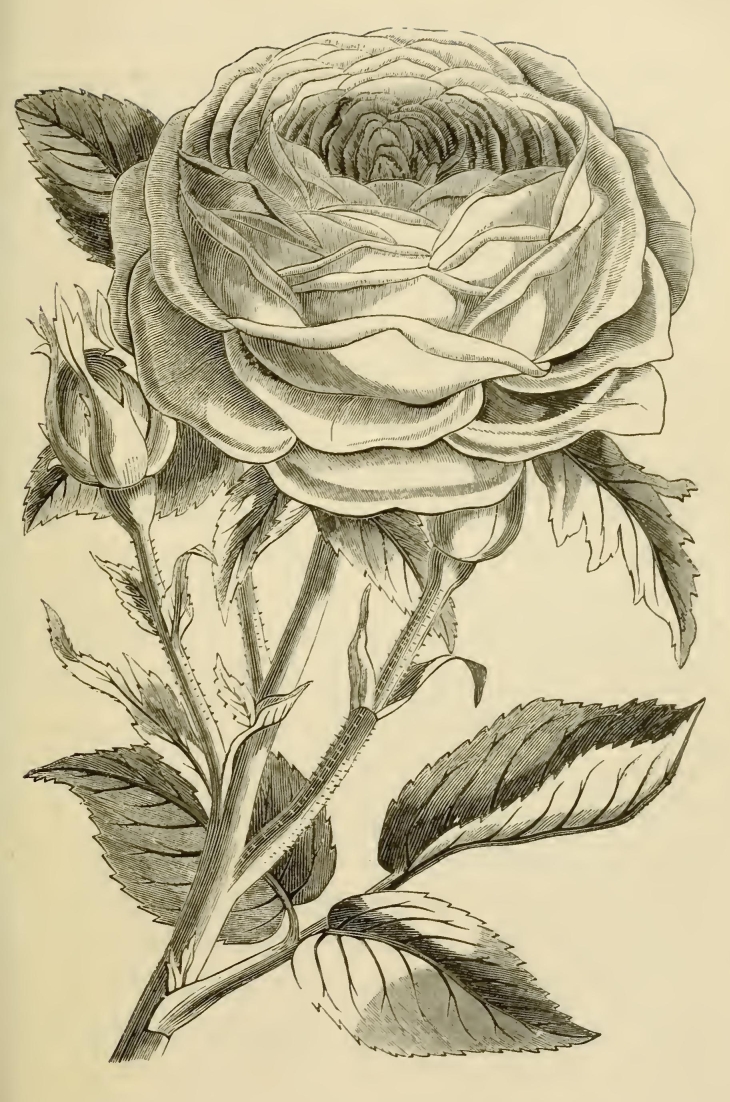

[Ill 0072]

All roses may be propagated by cuttings; but some kinds strike root much more readily than others. The hard-wooded roses, including the entire family of the Hardy June roses, and especially the Mosses, are increased with difficulty by cuttings. The Hybrid Perpétuais root more readily; while the tender ever-blooming roses, including the Teas, Noisettes, and Chinas, are propagated in this way with great ease.

Cuttings may be made from the ripened or the half-ripened wood. In the case of roses, and of nearly all ligneous plants, cuttings made from the ripe wood do not require bottom-heat, and are more likely to be injured than benefited by it. On the other hand, cuttings of the soft or unripe wood strike root with more quickness and certainty if stimulated by the application of a gentle heat from below.

In propagating roses from the ripe wood, the cuttings must be made early in autumn from wood of the same season's growth. The chances of success will be increased if they are taken off close to the old wood with what is called a "heel;" that is, with a very small portion of the old wood attached. The heel should be trimmed smooth with a sharp knife: the cuttings may be six or eight inches long. Strip off any leaves which may still adhere to them, and plant them in rows, at a depth of about five inches, in a cold frame. The soil should be very light, and thoroughly drained: water it, to settle it, around the cuttings. On the approach of frost, they should be protected with boards and mats, giving them air on fine days during winter. In the spring, a white cellular growth called a "callus" will have formed at the heel of each cutting, which, if the process succeeds, will soon emit roots, and become a plant.

Propagation in summer from the half-ripe wood is a better and less uncertain method. In June and July, immediately after the blossoms wither, and before the rose has begun its second growth, cuttings should be made of the flower-stems. Each cutting may contain two or three buds. The lower leaves must be taken off; but the upper leaves must remain. Trim off the stem smoothly with a sharp knife below the lowest bud, and as near to it as possible without injuring it.

If the cuttings are taken off with a heel, as above described, the chance of success will be greater. They may now be inserted at the depth of an inch and a half around the edge of a small pot filled one-third with broken crocks, and the remainder with a mixture of loam, leaf-mould, and sharp sand. Now place them in a frame on the shady side of a hedge or fence, water them to settle the soil, and cover them closely with glass. Sprinkle them lightly every morning and night; and, when moisture gathers on the inner surface of the glass, turn it over, placing the dry side inward. If mould or decay attacks the cuttings, wedge up the glass a little to give them air. In a week or two, they will form a callus; after which they may be removed to a gentle hot-bed, kept moderately close, and shaded from the direct sun. Here they will quickly strike root, and may be potted off singly into small pots.

Another mode of propagation, and a favorite one with nursery-men, is practised early in the spring. In this case, the cuttings are made from forced roses, or roses grown on greenhouse rafters. Some propagators prefer the wood in a very soft state, cutting it even before the flowers are expanded. The cuttings may be placed in pots as in the former case, or in shallow boxes or earthen pans thoroughly drained with broken crocks. The soil should be shallow enough to allow the heel of the cutting to touch the crocks. They are to be placed at once on a moderate bottom-heat, covered closely with glass, and shaded from the direct rays of the noontide sun. Their subsequent treatment is similar to that of summer cuttings. They must be closely watched, and those that show signs of mould or decay at once removed.

After the callus is formed, they will bear more air. When rooted, they should be potted into small pots, and placed on a hot-bed of which the heat is on the decline. Towards the end of May, when the earth is warmed by the sun, they may be turned out of the pots into the open ground, where they will soon make strong plants.

Many American nursery-men strike rose-cuttings in spring, in pure sand, over a hot-bed or a tank of hot water, in the close air of the propagating-house. They must be potted immediately on rooting, as the sand supplies them with nothing to subsist on. We have seen many hundreds rooted in this way with scarcely a single failure.

The management of difficult cuttings requires a certain tact, only to be gained by practice and observation; and the gardener who succeeds in rooting a pot of cuttings of the Moss Rose has some reason to be proud of his success.

With respect to the relative value of roses propagated by the methods above described, the most experienced cultivators are unanimous in the opinion, that those raised from layers and from cuttings of the ripe wood, without artificial heat, are superior in vigor and endurance to those raised from the half-ripe wood with the stimulus of a close heat. Unfortunately, the former method is so slow and uncertain when compared with the latter, that nurserymen rarely employ it to any great extent; and a good choice of roses on their own roots, raised without heat, is sometimes difficult to find.

The following is a mode of propagation not often practised, but which is well worthy of trial, as it is applicable to prunings which are usually thrown away. The extract is from the "Gardener's Chronicle."

"The rose is as easily propagated by means of buds or eyes as the vine. If your correspondent 'X' will take a strong shoot from almost any kind of rose in a dormant state, and with a sharp knife cut it into as many pieces as there are good eyes on the shoots, the pieces not being more than one inch long, taking care to have the eye in the centre of the piece, he will doubtless succeed. One-third of the wood should be cut clean off from end to end at the back of the eye, just as you would prepare a vine eye. In preparing the cutting-pans, it is most essential to put a good quantity of broken potsherds in the bottom, beginning with large pieces, and finishing with others more finely broken: then mix a quantity of good loam, leaf-soil, and sand, in equal proportions; rub it through a fine sieve, and fill the pans to within one inch of the top, pressing down the soil moderately firm. After that, put in the eyes in a leaning or slanting position, pressing them firmly into the soil with the thumb and finger; taking care to keep the thumb on the bottom end of the cutting, to prevent the bark from being injured. After the eyes are put in, give the pan two or three gentle raps on the bench; then put half an inch of silver or clean river sand on the top, water with a fine rose, and plunge the pans in a nice bottom heat of say sixty degrees, covering the surface over with moss to prevent the soil from getting dry: they will not require any more water for a week or ten days. The moss should be carefully removed as soon as the young shoots begin to push through the sand. In three weeks from that time, the roses will be fit for potting off into large sixty-sized pots. They should then be placed in a temperature of seventy degrees, when they will soon repay the care bestowed on them. I, however, prefer grafting on the Manetti stock. I grafted a lot in a dormant state seven weeks ago: they are now nice plants, and will be in bloom by May."—J. Willis, Oulton Park, Cheshire.

This mode of propagation is attended with great advantages and great evils. A new or rare rose may be increased by it more rapidly and surely than by any other means; while roses of feeble growth on their own roots will often grow and bloom vigorously when budded on a strong and congenial stock. On the other hand, the very existence of a budded rose is, in our severe climate, precarious. A hard winter may kill it down to the point of inoculation, and it is then lost past recovery; whereas a rose on its own roots may be killed to the level of the earth, and yet throw up vigorous shoots in the spring. Moreover, a budded rose requires more attention than the cultivator is always willing to bestow on it. An ill-informed or careless amateur will suffer shoots to grow from the roots or stem of the stock; and, as these are always vigorous, they engross all the nourishment, and leave the budded rose to dwindle or die; while its disappointed owner, ignorant of the true condition of things, often congratulates himself on the prosperous growth of his plant. At length he is undeceived by the opening of the buds, and the appearance of a host of insignificant single roses in the place of the Giant of Battles or General Jacqueminot.