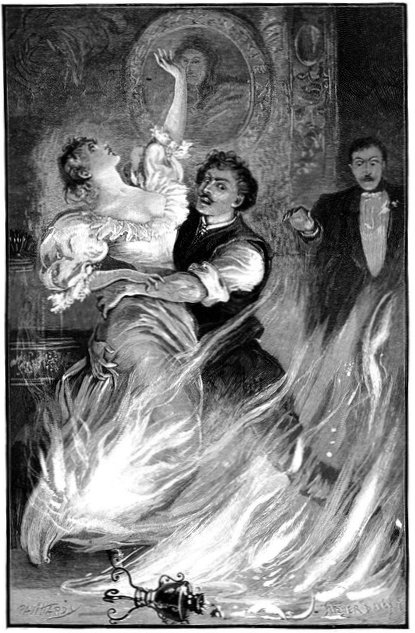

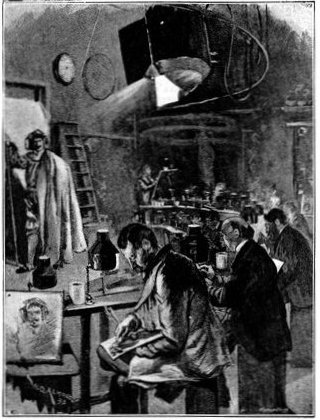

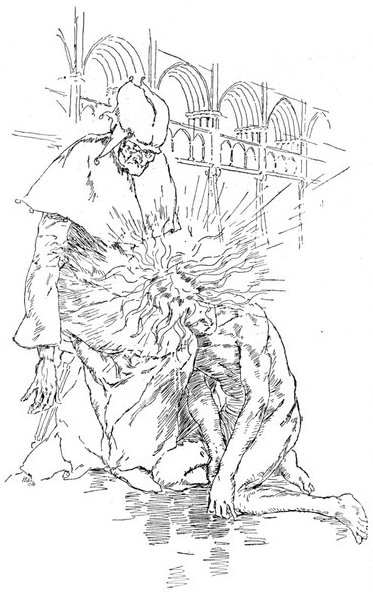

"HE RUSHED THROUGH THE POOL OF BLAZING OIL."

(See page 456.)

Title: The Strand Magazine, Vol. 07, Issue 41, May, 1894

Author: Various

Editor: George Newnes

Release date: November 17, 2014 [eBook #47376]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Jonathan Ingram and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

EDITED BY GEORGE NEWNES

Vol VII., Issue 41.

May, 1894

Antonio's Englishman

Zig-zags at the Zoo

Stories From the Diary of a Doctor.

From Behind the Speaker's Chair.

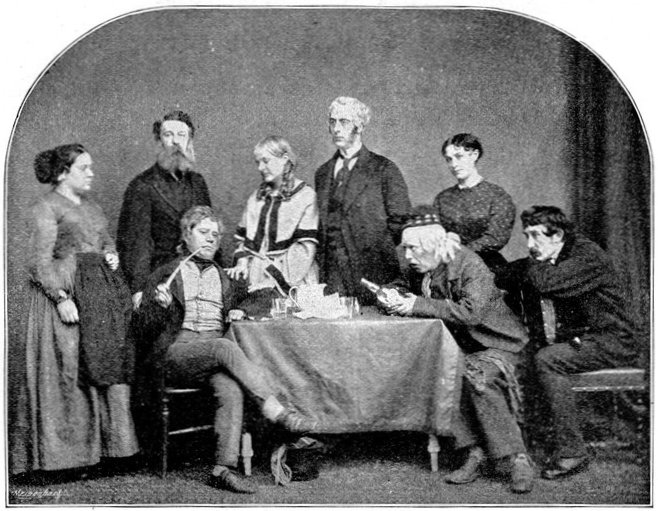

A Bohemian Artists' Club.

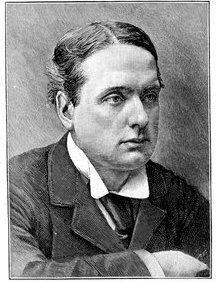

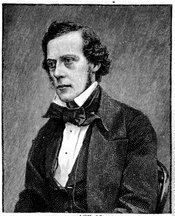

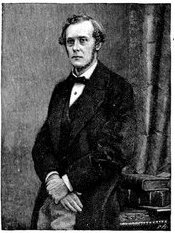

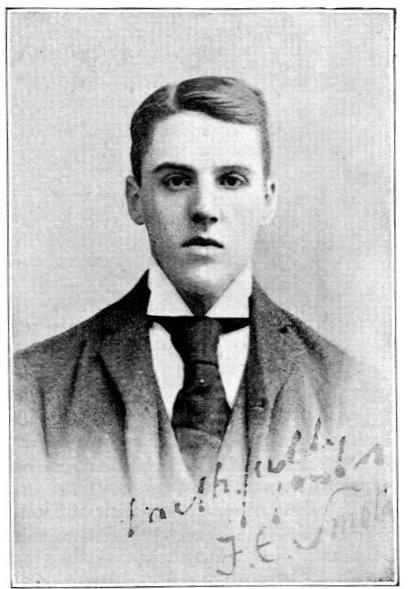

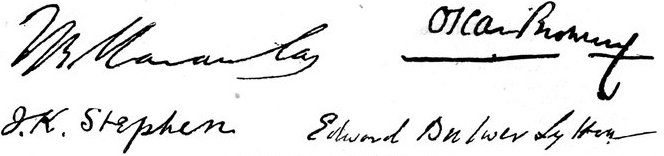

Portraits of Celebrities at Different Times of their Lives.

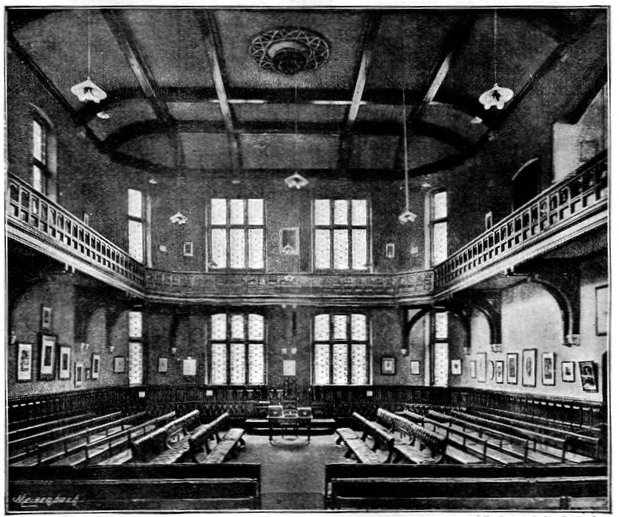

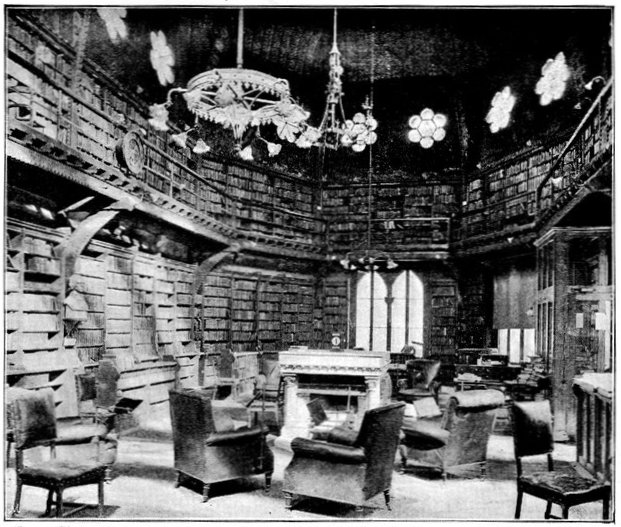

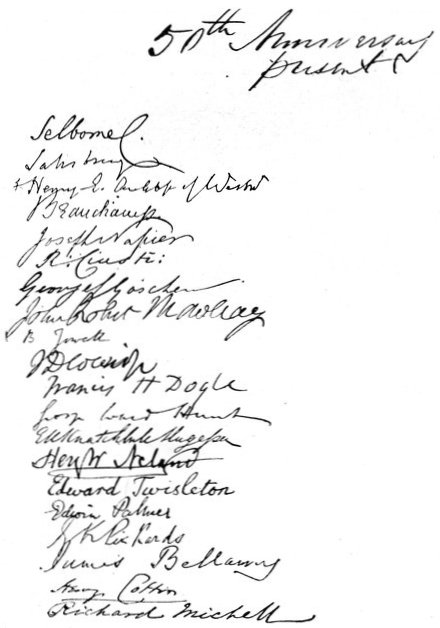

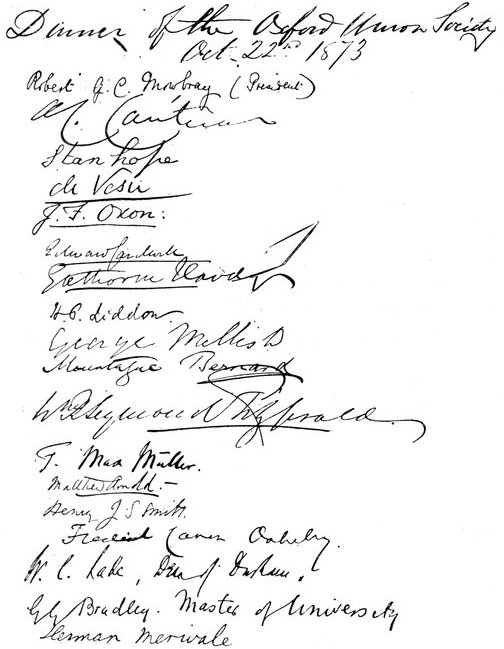

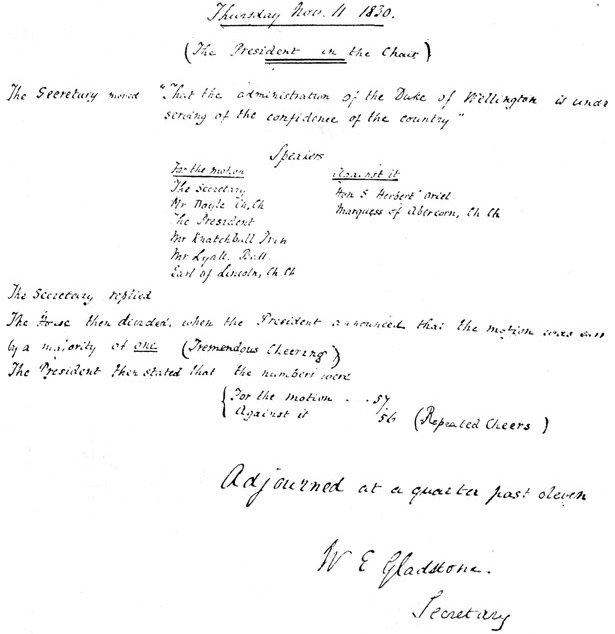

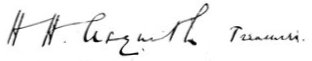

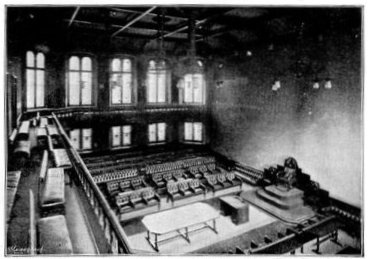

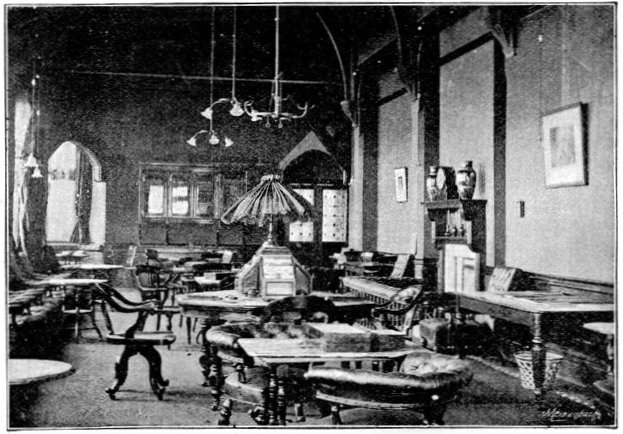

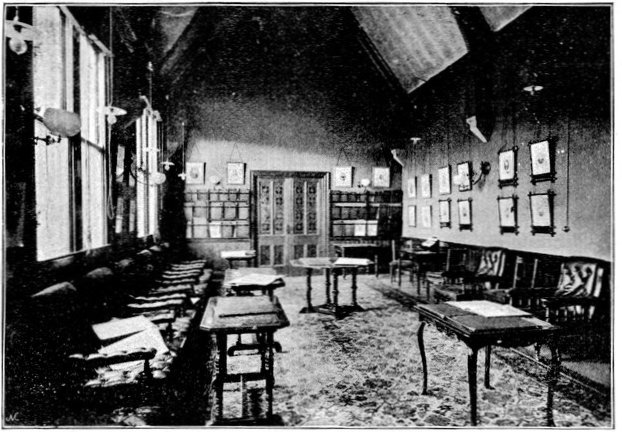

The Oxford and Cambridge Union Societies.

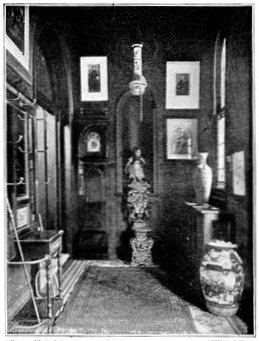

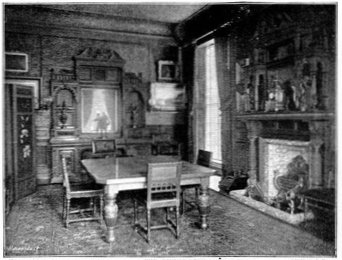

Illustrated Interviews.

Martin Hewitt, Investigator.

Beauties:—Children.

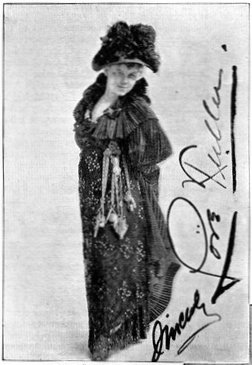

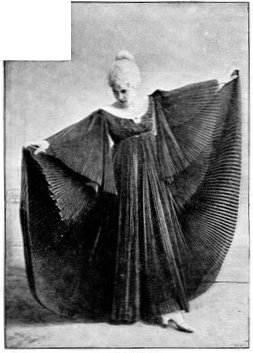

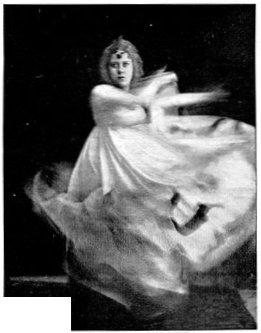

Löie Fuller—The Inventor of the Serpentine Dance.

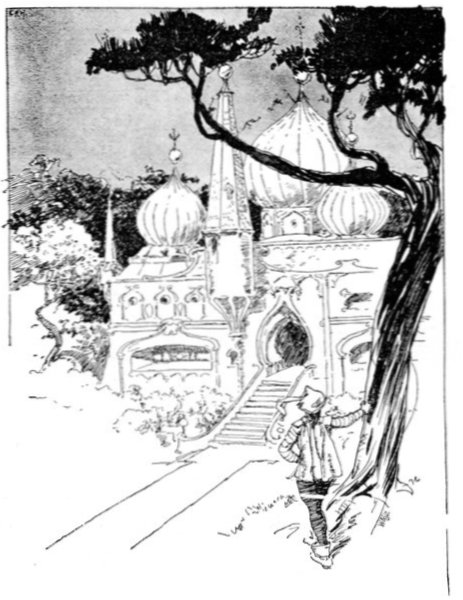

The Three Gold Hairs of Old Vsevede

The Queer Side of Things.

Transcriber's Notes

"HE RUSHED THROUGH THE POOL OF BLAZING OIL."

(See page 456.)

Antonio was young, handsome, and a gondolier. He lacked but two things; a gondola of his own, and an Englishman. He was too poor to buy a gondola, and though he occasionally hired an old and extremely dilapidated one, and trusted to his handsome face to enable him to capture a party of foreign ladies, his profits had to be divided with the owner of the gondola, and were thus painfully small. The traghetto brought him in a few francs per month, and he picked up other small sums by serving as second oar, whenever tourists could be convinced that a second oar was necessary. Still, Antonio was desperately poor, and he and his young wife were often uncomfortably hungry.

Now, if the Madonna would only send him an Englishman, even if it were only for a single year, Antonio could easily save enough money to buy himself a beautiful gondola, besides living in the lap of luxury. His brother Spiro had owned an Englishman for only seven months and a half, and already he was a capitalist, with his own gondola, and, figure it to yourself!—with four hundred francs in the savings bank! And Spiro had done nothing to deserve this blessing, for he was notoriously an unbeliever, and never went inside a church except when he was escorting English ladies, when, of course, he prayed with fervour at the most conspicuous shrine, which was worth at least ten extra soldi of buona mano. Whereas, Antonio was deeply religious, and at least once a year gave a wax candle to the Blessed Virgin of Santa Maria Zobenigo. "But patience!" said Antonio daily to himself. "Some day the Madonna will grow weary, and will say, 'Give that Antonio an Englishman, so that I can have a little peace and quiet.' And then the Englishman will appear, and Antonio's fortune will be made."

Of course Antonio knew of every foreigner who came to Venice with the intention of making a prolonged stay. There is no detective police in the world that can be compared with the Venetian gondolier in learning the ways and purposes of tourists. To know all about the foreigner is at once his business and his capital. The Englishman who comes to Venice and determines to spend six months or a year in that enchanted city, may reach this decision on a Saturday night and mention it to no living soul. Yet by the following Monday morning all the gondoliers in Venice know that there is an Englishman to be striven for, and they have even settled in their own minds precisely what apartment he will probably hire. How they arrive at this knowledge it is not for me to say. There are mysteries in the Venice of to-day, as there were in the Venice of the Ten and of the Three.

Now, it fell out that one day Antonio learned that an Englishman and his wife, a young couple, who had every appearance of sweet temper and scant knowledge of the world, had arrived at the Albergo Luna, and had told the porter that they intended to take a house and live forever in Venice. The porter was an intimate friend of Antonio, and had been promised a handsome commission on any foreigner whom he might place in Antonio's hands. Within an hour after receiving the precious information, Antonio had put on his best shirt, had said ten Aves at lightning speed, had promised the Blessed[Pg 452] Virgin two half-pound wax candles in case he should land this desirable Englishman, and was back again at the Luna and waiting to waylay his prey.

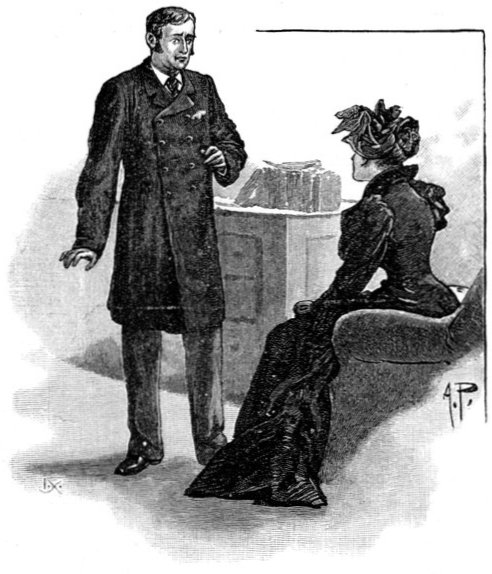

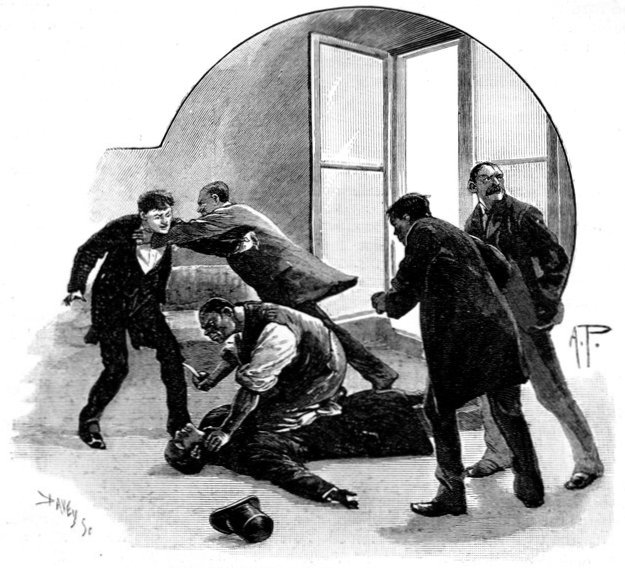

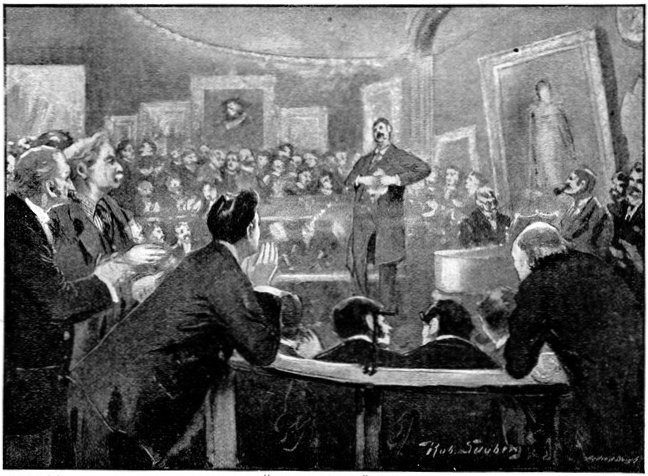

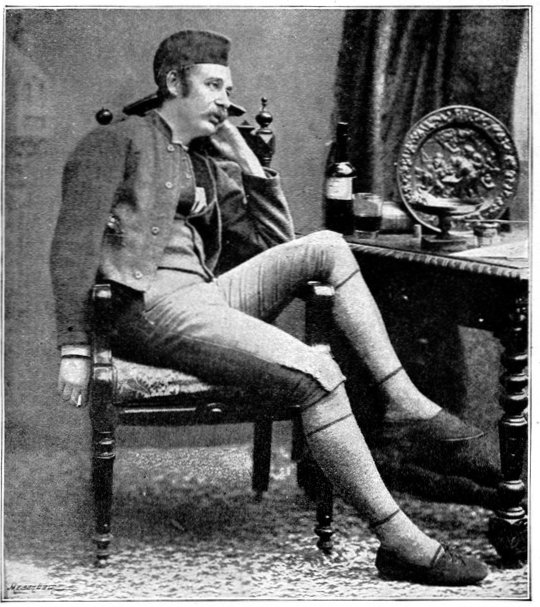

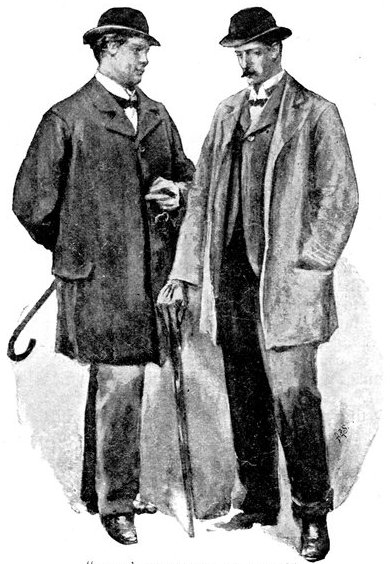

"THE PORTER PRESENTED ANTONIO."

The porter presented Antonio, and asserted that, as a combination of professional skill and moral beauty, Antonio was simply unique. Mr. Mildmay, the Englishman in question, was pleased with Antonio's clean shirt, and Mrs. Mildmay was captivated by his chestnut curls, and the frank, innocent expression of the young fellow's face. He was hired on the spot, with the new gondola which he professed to own, for 150 francs per month, including his board. He was to bring his gondola and his recommendations to the hotel to be inspected that afternoon, and was to begin his duties on the following day, the Mildmays having already secured an apartment in advance of their arrival in Venice.

The long-hoped-for fortune had arrived at last. "He is a man of excellent heart, the paron," said Antonio to the porter. "He will be as wax in my hands: already I love him and the sweet parona. You shall have your share of him, my Zuane. No one can say that I am not a just man."

Antonio hurried at once from the hotel with a note from the porter to a dealer in gondolas, certifying that the bearer had secured a most eligible Englishman. He had to pay a heavy price for the hire by the month of a nearly new gondola, but the payments were to form part of the purchase-money, and Antonio did not grudge the price. Then he stopped at his house to show the new gondola to his wife, and tell her the blessed news, and then, armed with his baptismal certificate, and an old letter from a notary, informing him that the funeral expenses of his father must be paid or serious consequences would follow, he returned to the hotel.

The Mildmays were satisfied with the gondola, and with Antonio's recommendations; for they could not read Italian handwriting, and when Antonio informed them that the notary's letter was a certificate that he was the most honest man in Venice, and that it had been given him by a German Prince whom he had served ten years, they were not in a position to contradict the assertion. Moreover, they were already half in love with the handsome and happy face of their gondolier, and would have taken him without any recommendation at all, sooner than have taken an old and ugly gondolier with the recommendation of the British Consul and the resident chaplain. The next day Antonio entered upon his duties, and began the joyous task of making hay[Pg 453] while the sun of the Englishman shone on him.

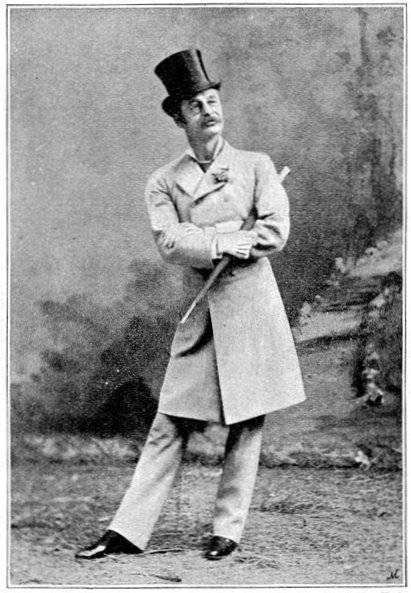

"HE SHOWED THE NEW GONDOLA TO HIS WIFE."

The gondolier in private service in Venice does many things wholly unconnected with his boat. He usually waits on his master's table; he polishes the concrete floors, and he is sent on every variety of errand. Antonio was tireless, respectful, and cheerful, and the Mildmays agreed that he was an ideal servant. Of course they responded to his suggestion that he needed a livery, and he was soon furnished at their expense with a handsome suit of heavy blue cloth, a picturesque hat, a silk sash, and an overcoat. He looked very handsome in his new dress, and the difference between what he paid the tailor and what he charged his master provided his wife and his little boy with their entire wardrobe for the coming winter.

Venice is a cold city after the winter fogs begin, and when Antonio advised the Mildmays to lay in their entire stock of firewood in September instead of waiting until the price should be higher, they said to one another what a comfort it was to have a servant who really looked after their interests. So Antonio was commissioned to buy the wood, and he bought it. He made a handsome commission on the transaction, and, in addition, he had about one-fifth of the whole amount of wood delivered at his own residence. It is true that this was not quite enough to provide him fuel for the entire winter, but the deficiency could easily be remedied by simply carrying home three or four sticks under his coat every night, and Antonio was not a man who shrank from any honest labour when the good of his family was in view.

About ten days after the arrival of his Englishman, Antonio informed him that the gondola needed to go to the squero to have its bottom cleaned, at a cost of ten francs. This, however, he insisted upon paying out of his own pocket, because the foulness of the bottom had been incurred before he entered Mr. Mildmay's service. This scrupulous display of honesty still further convinced the Englishman that he had the pearl of gondoliers, and when the next day Antonio asked him to give him as a loan, to be deducted from his future wages, fifty francs, wherewith to make certain essential but wholly unintelligible repairs to the gondola, Mr. Mildmay was of his wife's opinion that it would be a shame to require the poor man ever to repay it.

The first thing that shook the Mildmays' confidence in Antonio was a little incident in connection with a chicken. They had had a pair of roast fowls for dinner and had eaten only one, intending to have the other served cold for luncheon the next day. When late in the evening Mrs. Mildmay accidentally discovered Antonio in the act of going out of the house with the cold fowl stuffed under his coat, she demanded an explanation. "It is true, parona," said Antonio, "that I took the fowl. And why? Because all the evening I had seen you and the paron sitting together in such love and happiness that my heart bled for poor Antonio, who has no happy fireside at which to sit. And so I said to myself, 'Antonio! surely you deserve a[Pg 454] little happiness as well as these good and noble people! Take the cold fowl, and eat it with love and gratitude in your heart!'"

"TAKE THE COLD FOWL, AND EAT IT."

Mrs. Mildmay could not scold him after this defence, and she simply contented herself with telling him that he might keep the fowl for this time, but that such a method of equalizing the benefits of fortune must not occur again. Antonio promised both her and himself that it should not, and though he continued to keep his wife's table fully supplied from that of the Mildmays, the latter never again found him in possession of surreptitious chickens.

One day Antonio found a gold piece, twenty francs in fact, on the floor of his gondola. He knew it must have been dropped by the paron, and he promptly brought it to him. "How wrong I was," said Mrs. Mildmay, "to doubt the poor fellow because of that affair of the chicken. No one would ever have been the wiser if he had kept that twenty-franc piece, but he brought it to us like an honest man." For once she was right in believing Antonio to be honest. Nothing could have induced him to sully his soul and hands by unlawfully detaining his master's money. He was determined to make all the money out of his providential Englishman that he could make in ways that every gondolier knows to be perfectly legitimate, but he was no thief, and Mr. Mildmay could fearlessly have trusted him with all the money in his purse.

Antonio was now one of the happiest men in Venice, but one morning he came to Mr. Mildmay with a face of pathetic sadness, and asked for a day's holiday. "It is not for pleasure that I ask it," he said; "my only pleasure is to serve the best of masters. But my little boy is dead, and is to be buried to-day. I should like to go with the coffin to San Michele."

Mr. Mildmay was unspeakably touched by the man's sorrow and the quiet heroism with which he bore it. He gave him the day's holiday and fifty francs towards the funeral expenses of his child. When Antonio appeared in the morning, quiet, sad, but scrupulously anxious to do his whole duty, the Mildmays felt that they really loved the silent and stricken man.

Misfortune seemed suddenly to have run amuck at Antonio. A week after the death of his child, he announced in his usual quiet way that his wife was dead. It was very sudden, so he said. He did not know exactly what was the disease, but he thought it was rheumatism. The Mildmays thought it strange that rheumatism should have carried off a woman only twenty-two years old, but strange things happen in Venice, and the climate is unquestionably damp. Antonio only asked for half a holiday to attend the funeral, and he added that unless the paron could advance him two hundred francs of his wages, he should be unable to save his wife from being buried in the common ditch. Of course, this could never be permitted, and Antonio received the two hundred francs, and Mrs. Mildmay told her husband that if he should think of deducting it from the unhappy man's wages, she could never respect him again.

For a time the darts of death spared the household of Antonio. The gondola made its alleged monthly visit to the squero to have its bottom cleaned at Mr. Mildmay's expense, and the amount of repairs and paint which[Pg 455] it needed did seem unexpectedly large. But Antonio was not foolishly grasping. So long as he doubled his wages by tradesmen's commissions, and by little devices connected with the keeping of the gondola, he felt that he was combining thrift with prudence. He made, however, one serious mistake, of which he afterwards repented when it was too late. Instead of giving the Madonna the two wax candles which he had promised her, he gave her two stearine candles, trusting that she would not notice the difference. It was not in keeping with his honest and religious character, and there were times when the recollection of it made him feel uneasy.

As the winter wore on Antonio's devotion to his employers never slackened. Beyond the commissions which it is but just and right that the faithful gondolier should exact from those dogs of tradesmen, even if they did charge the same commissions in his master's bills, he was tireless in protecting the Mildmays from imposition. He was never too tired to do anything that he was asked to do, and although, when his brother Spiro was temporarily out of employment, Antonio discovered that there was nearly always too much wind to render it safe to take the gondola out with a single oarsman, and that he would therefore furnish a second oarsman in the person of Spiro at his master's expense, he never intimated that he was not ready to row hour after hour while the Mildmays explored the city and the lagoon. Mr. Mildmay was fascinated by the narrow Venetian streets, and spent hours exploring alone every part of the city. He was probably perfectly safe in so doing, for highway robbery and crimes of violence are almost unknown in Venice; but for all that he was always, though without his knowledge, accompanied on his walking excursions by the stealthy and unsuspected Antonio, who kept out of sight, but in readiness to come to his assistance should the necessity arise.

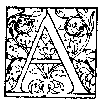

Toward spring Antonio thought it best to have his wife's mother die, but to his surprise Mr. Mildmay did not offer to pay the old lady's funeral expenses. He drew the line at mothers-in-law, and Antonio received only his half-holiday to accompany the corpse to the cemetery. This miscarriage made Antonio think more than ever of that failure to keep his promise to the Madonna in the matter of the wax candles, and he sometimes wondered if she were capable of carrying her resentment so far as to take his Englishman from him.

"ANTONIO WONDERED."

There is gas in Venice, but the judicious householder does not use it, save when he desires to enshroud his rooms in a twilight gloom. If he wishes a light strong enough to read by, he burns petroleum. It was, of course, Antonio who supplied the petroleum to the Mildmay household, and equally of course, he bought the poorest quality and charged for the dearest. Now, in spite of all the care which a timid person may lavish on a lamp burning cheap petroleum, it is nearly certain sooner or later to accomplish its mission of setting somebody or something on fire, and Antonio's petroleum, which was rather more explosive than gunpowder, unaccountably spared the inmates of the casa Mildmay until late in the month of March, when it suddenly asserted itself.

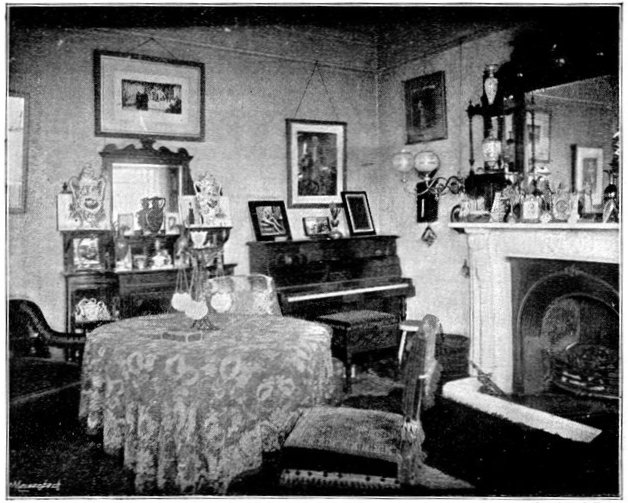

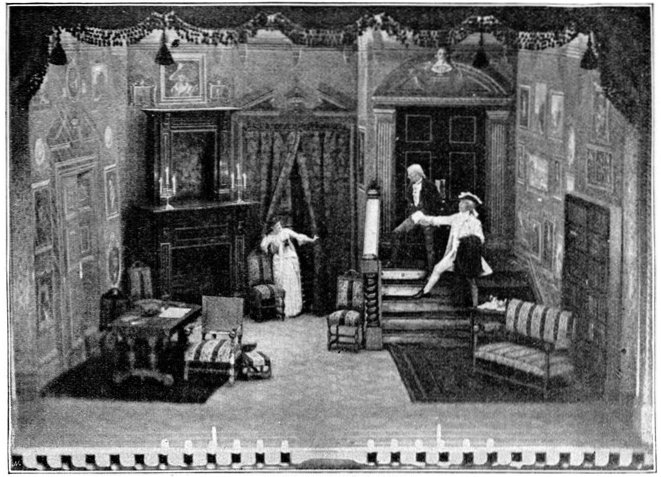

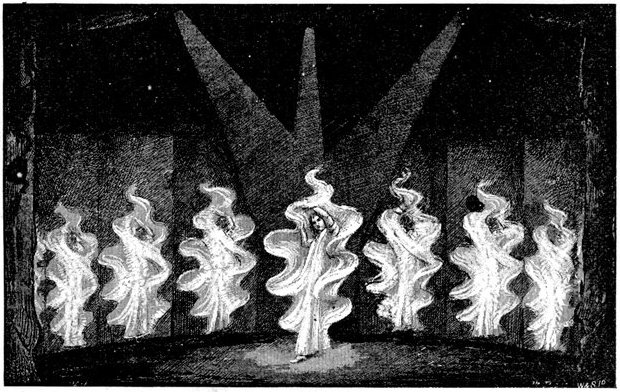

It happened in this way. One evening Mrs. Mildmay took a lamp in her hand, and started to cross the wide and slippery floor of her drawing-room. The rug on which[Pg 456] she trod moved under her, and she came near falling. In the effort to save herself she dropped the lamp. It broke, and in an instant she was in a blaze.

Antonio was in the ante-room. The door was open and he saw the accident. He sprang to Mrs. Mildmay's assistance. He did not attempt to avoid the flames, but rushed directly through the pool of blazing oil, burning his feet and ankles horribly. He seized Mrs. Mildmay, and tore away her dress with his bare hands. He had nothing to wrap around her, for he was wearing no coat at the time, but he clasped her close in his arms, and smothered the flames that had caught her petticoat by pressing her against his bosom. She escaped with nothing worse than a slightly burned finger, but Antonio's hands, arms, feet and ankles were burned to the bone. By this time Mr. Mildmay, who had been in his study, heard his wife calling for help, and made his appearance.

Antonio asked the parona's permission to sit down for a moment, and then fainted away. The cook was called and sent for the doctor. She met Antonio's brother in the calle, close to the house, and sent him upstairs. With his help Antonio was carried to Mrs. Mildmay's bedroom, and laid on the bed, and before the doctor came the wounded man had regained consciousness, and had thanked the Mildmays for their care of him.

The doctor, after dressing the wounds, said that the man might very probably recover. But Antonio announced that he was about to die, on hearing which decision the doctor changed his mind.

"When a Venetian of the lower class gives up, and says he is going to die," said the doctor, "no medical science can save him. Your man will die before morning, if he has really lost all hope. There! he says he wants a priest; you might as well order his coffin at once. I can do nothing to save him."

"Paron," said Antonio, presently, "would you, in your great goodness, permit my wife to come to see me for the last time?"

"You shall have anything you want, my brave fellow," replied Mr. Mildmay, "but I thought your wife was dead."

"I was mistaken about it," said Antonio. "It was her twin sister who died, and they were so much alike that their own mother could not tell them apart. No, my poor wife is still alive. May she bring my little boy with her?"

"Tell her to bring anybody you may want to see," replied his master, "but I certainly thought your little boy was buried last January."

"The paron is mistaken, if he will pardon me for saying so. It was my little girl who died. Was it not so, Spiro?"

Spiro confirmed Antonio's statement, like a loyal brother who is afraid of no fraternal lie, and Mr. Mildmay had not the heart to trouble the sufferer with any more suggested doubts of his veracity.

Antonio was duly confessed, and received absolution. "Did you tell the father about the candles?" whispered Spiro after the priest had gone.

"I thought," answered Antonio, "that perhaps the Madonna had not yet noticed that they were not wax, and that it would not be wise to tell her of it, just as one is going where she is."

In the early morning Antonio died. His family, and Mr. and Mrs. Mildmay, were at his bedside. He died bravely, with the smile of an innocent little child on his face. "I have served the dear paron faithfully," he said, just as he died. "I know he will take care of my wife and child. And he will take Spiro as his gondolier."

Mr. Mildmay religiously carried out Antonio's dying request. He installed Spiro in the place of the dead man, and he settled an annuity on Zanze, the disconsolate widow. He gave Antonio a grave all to himself in San Michele, and a beautiful white marble tombstone, with the epitaph, "Brave, Faithful, and Honest." He came to know somewhat later how Antonio had enriched himself at his expense, but he said to his wife: "After all, my dear, Antonio was strictly honest according to his own code. I think I have known some Englishmen of unblemished reputation, whose honesty, according to the English code, could not be compared with that of the poor boy who gave his life for yours."

W. L. Alden.

Whence has arisen the notion that monkeys are happy creatures? Probably from the inadequate fact that they pull one another's tails and run away. But a being may be mischievous without being happy. Many mischievous boys are never happy: possibly because the laws of Nature won't permit of half the mischief they are anxious to accomplish. Still, the monkey, at any rate in a state of freedom, is looked upon as a typically happy creature. "And watch the gay monkey on high," says[Pg 458] Bret Harte; and Mr. Kipling addresses the monkey as "a gleesome, fleasome thou," which latter looks like an attempt to make an admissible adjective pass in an unwarranted brother. I have seen monkeys fleasome, treesome, freesome, keysome (opposite adjectives these, you will perceive on reflection), and disagreesome, but cannot call to mind one that looked in the least gleesome. Everything that runs up a fence or swings on a rope is not necessarily jolly, much as the action would appear to justify the belief. Many a human creature has stormed a fence with a lively desire to attain the dogless side, but no noticeable amount of jollity; and a man escaping from fire by a rope wastes no time in unseasonable hilarity, dangle he never so quaintly. Look at their faces; look also at the monkey's face. If a monkey grin, it is with rage; his more ordinary expression of countenance is one of melancholy reflection—of sad anxiety. His most waggish tricks are performed with an air of hopeless dejection. Now, this may be due to any one of three causes, or even to a mixture of them. It may be that, like the boy, he dolorously reflects that, after all, mischief has its limits; that you cannot, so to speak, snatch the wig of the man in the moon, upset the Milky Way, or pull the tail of the Great Bear. Or it may be that a constant life of practical jokes, and of watchfulness to avert them, is a wearying and a saddening thing after all. Or it may be that every ape, meditating on his latest iniquity, tries for ever to look as though it were the other monkey.

RATHER SHY.

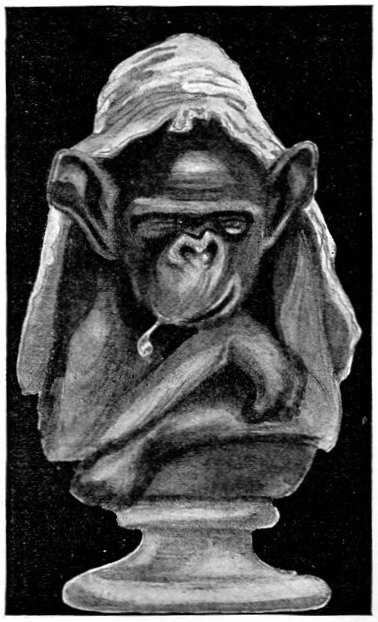

With many people, to speak of the Zoo monkeys is to speak of Sally. Poor Sally! Who would not weep for Sally? For Sally is dead and hath not left her peer. A perversion of Milton is excusable in the circumstances. Why is there no memorial of Sally? "Is the spot marked with no colossal bust?" as they say on invitations to bachelor small-hour revels. There should, at least, be a memorial inscription to Sally.

Sally, when first she came here in 1883, was a modest and, indeed, rather a shy chimpanzee. A few years of elementary education, however, quite changed Sally's character, for she learnt to count up to five, and to be rather impudent. Wonderfully uniform are the results of elementary education.

SALLY ON A BUST.

The chimpanzees, orang-outangs, and such near relatives of humanity are kept, when they are alive to keep, in the sloths' house. Such as are there chiefly occupy their time in dying. It seems to be the only really serious pursuit they ever take to. Sudden death is so popular among them,[Pg 459] that it is quite impossible to know how many are there at any particular time without having them all under the eye at the moment. A favourite "sell" among them is for a chimpanzee or orang to become a little educated and interesting, then wait till some regular visitor invites all his friends to inspect the phenomenon, and die just before they arrive at the door. This appears to be considered a most amusing practical joke by the dead monkey, and is much persevered in.

A STAGE IRISHMAN.

Sally was a black-faced chimpanzee. The white-faced kind is more common, and in the days of its extreme youth much more like a stage Irishman, except that his black hair gives him the appearance of wearing dress trousers very much frayed at the ankles.

A DECEPTIVE BRAIN-PAN.

WHAT WILL HE BECOME?

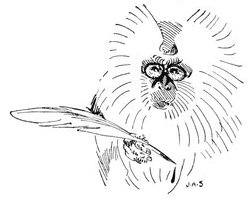

The orang-outang is less intellectual as a rule than the chimpanzee; but he has a deceptive appearance of brain-pan—an illusory height of forehead—that earns undeserved respect. Many a man has conducted a successful business with credit on the strength of a reputation as easily earned. With the orang as with the chimpanzee, it is in infancy that he presents the most decently human appearance. But even then he is a low, blackguard sort of baby—worse than the precocious baby of the Bab Ballad could possibly have been. He should have a pipe for a feeding-bottle and a betting-book to learn his letters from. These anthropoid apes come with such suddenness and die with such uncertainty that I cannot say whether there are any in the Zoo now or not—I haven't been there since yesterday. But wanderoos there are, I feel safe in saying, and Gibbons. The wanderoo is a pretty monkey, and usually gentle. He has a grave, learned, and reverend aspect as viewed from the front, and this is doubtless why, in India, his is supposed to be a higher caste, respected and feared by other monkeys. That same wig, however, that looks so venerable in the forefront view, is but a slatternly tangle in profile, like unto the chevelure of a dowdy kitchenmaid. But a wanderoo, well taught, and of good-temper, is as clean and quaint a pet as you may desire, and as delicate as the poet's gazelle, with its incurable habit of dying. The same may be said of the Gibbon. In this climate he Declines and Falls[Pg 460] on the smallest excuse, although, perhaps, not quite so readily as the chimpanzee, who may almost be said to Decline and Fall professionally, like Mr. Wegg.

GRAVE AND LEARNED.

The Diana monkey, too, makes a pleasant pet, and is not so confirmed a dier as some. The Diana monkey here is over in the large monkey-house, in the middle of the Gardens. Her name is Jessie, and her beard is most venerable and patriarchal. But just outside the eastern door of the big house, John, the Tcheli monkey, occupies his separate mansion. John is a notable and a choleric character. He dislikes being made the object of vulgar curiosity, and is apt to repel an inspection of his premises with a handful of sawdust. Any unflattering remark on his personal appearance will provoke a wild dance about his cage and a threatening spar through the wires. But once threaten him with a policeman—do as much as mention the word, in fact—and John becomes a furious Bedlamite, with the activity of a cracker and the intentions of dynamite. Against floor, walls, ceiling, and wires he bounces incontinent, flinging sawdust and language that Professor Garner would probably translate with hyphens and asterisks. John is the most easily provoked monkey I know, and the quaintest in his rage. He is also the hardiest monkey in the world, being capable of enjoying a temperature of ten degrees below zero; but there is a suitable penalty provided in the by-laws for any person so lost to decency as to suggest that this Tcheli monkey is a very Tcheli monkey indeed. For John's benefit I would suggest an extra heap of sawdust on Bank Holidays. On an occasion of that sort it is little less than cruelty to keep him short of ammunition.

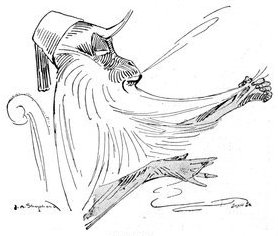

DOWDY.

THE DIANA.

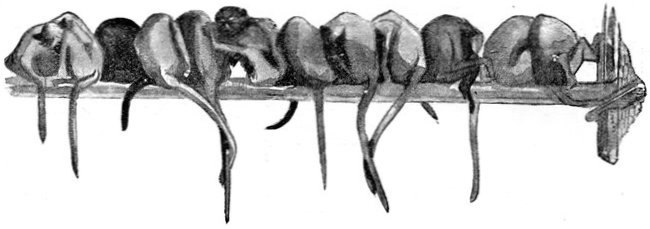

Of the big monkey-house, who remembers more than a nightmare of tails, paws, and chatterings? Here are monkeys with beards, monkeys with none, big monkeys, little monkeys, monkeys with blue faces, monkeys who would appear to have escaped into the grounds at some time and to have sat on freshly painted seats; all thieving from visitors and each other,[Pg 461] pulling tails, swinging, turning somersaults, with faces expressive of unutterable dolor and weariness of the world. The wizen, careworn face of the average monkey appeals to me as does that of the elderly and rheumatic circus-clown, when his paint has washed off. The monkey, I am convinced, is as sick of his regulation jokes as is the clown of his. But he has a comic reputation to keep up, and he does it, though every mechanical joke is a weariness and a sorrow to the flesh. "There is somebody's tail hanging from a perch," reflects the monkey, looking lugubriously across the cage. "I am a joker, and several human creatures are looking at me, and preparing to laugh; consequently, I must pull that tail, though I would prefer to stay where I am, especially as it belongs to a big monkey, who will do something unpleasant if he catches me." And with an inward groan he executes the time-honoured joke and bolts for his life. It is a sad affliction to be born a wag by virtue of species. There is one monkey here who for some weeks displayed a most astonishing reluctance to snatch things through the wires, and a total disinclination to assist or share in the thefts of his friends by "passing on" or dividing. For some time I supposed him to be a moral monkey strayed from a Sunday-school book, and afflicted with an uncomfortable virtue. But afterwards I found that his conscientiousness was wholly due to his having recently grabbed a cigar by the hot end, and imbibed thereby a suspicion of the temperature of everything. Beware especially, in this house, of the paws of Marie, the Barbary ape. She has a long reach, and quickness enough to catch a bullet shot Poole-fashion—softly. Only Jungbluth, her keeper, can venture on familiarities, and him she takes by the eyebrows, gently stroking and smoothing them.

IS IT CONSCIENTIOUSNESS?

SOMETHING LIKE A MOUSTACHE.

Behind the large room Jungbluth keeps sick monkeys, delicate monkeys, tiny monkeys, and curious monkeys, who have no room outside. Here is a beautiful moustache monkey, segregated because of a slight cold, and at liberty to train his moustache without interference, if only it would grow sufficiently long. Watch the light fur under the chin of a moustache monkey; it is tinted with a delicate cobalt blue, a colour that would seem impossible, except in feathers.

NERVES.

But the little marmosets and the Pinche monkey, all in a cage together, are chiefly interesting here. The[Pg 462] Pinche monkey is badly afflicted with nerves, and, as he is undisputed chief of the community, the marmosets have to be careful how they sneeze, or cough, or blink, or his indignation may be aroused. So that the whole performance in this cage is a sort of eccentric knockabout act, by the celebrated Marmosetti Eccentric Quartette. Marmoset No. 1 ventures on a gentle twitter, and the rest join in the song. Promptly the irritated Pinche bounds from his inmost lair, and the songsters are scattered. Everybody doesn't know, by-the-bye, that the marmoset is consumed with an eternal ambition to be a singing bird, and practises his notes with hopeless perseverance. Another thing that many seem to be ignorant of, even some who keep marmosets as pets, is that a marmoset's chief food should consist of insects. In a state of freedom he also eats small birds; but for a pet, cockroaches and bluebottles will probably be found, as a dietary, preferable in some respects to humming-birds and canaries.

ENTER.

ENTER ALSO.

THE MARMOSETTI TROUP.

EXIT.

SOLILOQUY.

Among the sick in this place is a spider monkey. Mind, I say he is there. To-morrow, or in five minutes, he will probably be somewhere else, for that is the nature of a monkey. Sickening, recovering, dying, snatching, jumping, tail-pulling, bonnet-despoiling, everything a monkey does is done in a hurry. This particular spider monkey has two or three names, as Jerry, Tops, and Billy, whereunto he answers[Pg 463] indifferently; but I prefer to call him Coincidence, because of his long arms, and he answers as well to that name as to another. He came in here because of a severe attack of horizontal bar in the stomach. I have never seen a monkey fall, and, for that reason, wish I had seen the attack, as a curiosity. For, by some accident, unparalleled in monkey history, Coincidence managed to miss his hold, and fell on his digestive department across a perch. He is a long, thread-papery sort of monkey, and it took a little time to convince him that he wasn't broken in half. When at last he understood that there was still only one of him, he set himself to such a doleful groaning and rubbing and turning up of the eyes, that Jungbluth put him on the sick list at once. But it took a very few hours to make him forget his troubles; and, indeed, I have some suspicion that the whole thing was a dodge to secure a comfortable holiday in hospital. That certainly is the opinion of Coincidence's friend, the Negro monkey, as his face will tell you, if you but ask him the question. It may interest those who already know that Coincidence has a long arm, to know also that he has but four fingers to each hand and no thumb; it is a part of his system. His tail is another part of his system, and you mustn't touch it. There is no more affable and friendly monkey alive than Coincidence, although he is a little timid; but once touch his tail (it is long, like everything else belonging to Coincidence), and you lose his friendship for ever. He instantly complains to Jungbluth, and points you out unmistakably for expulsion.

COINCIDENCE.

SPIDERS.

ON THE SICK LIST.

"COINCIDENCE? HE'S ALL RIGHT."

It is this house that witnesses most excitement on Bank Holidays. Who would be a monkey in a cage set in the midst of a Bank Holiday crowd? I wouldn't, certainly, if there were a respectable situation available as a slug in some distant flower pot, or a lobster at the bottom of the sea. Is a monkey[Pg 464] morally responsible for anything he may do under the provocation of a Bank Holiday crowd? Is he not rather justified in the possession of all the bonnets and ostrich feathers he can grab by way of solatium? Bank Holiday is the dies iræ of these monkeys, and then is Professor Garner avenged. The Professor shut himself in an aluminium cage, and the cage littered about Africa for some time, an object of interest to independent monkeys—a sort of free freak show. Here the monkeys, secure in their cage, study the exterior freaks, collecting specimens of their plumage, whiskers, spectacles, and back hair. But it is hard work—and savage.

RECOVERING.

It takes even a cageful of monkeys a few days to recover from a Bank Holiday, and for those few days trade is slack indeed. At such times it is possible to observe the singular natural phenomenon of a monkey in a state of comparative rest. But he is more doleful than ever.

DIES IRÆ.

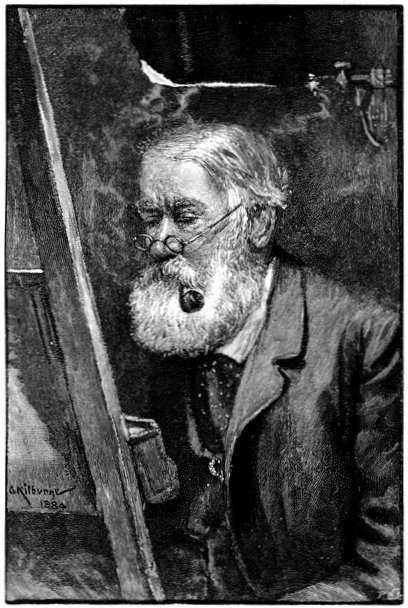

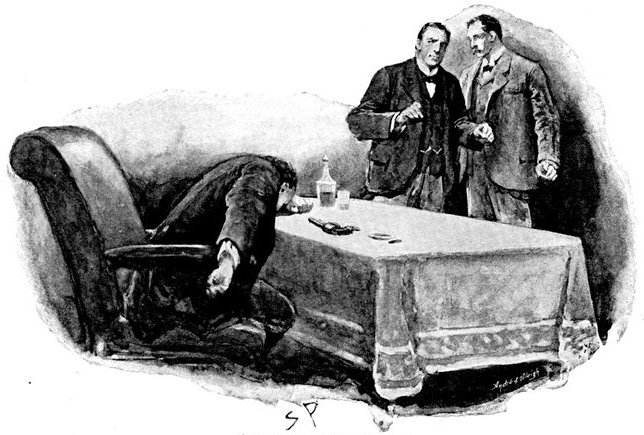

By the Authors of "The Medicine Lady."

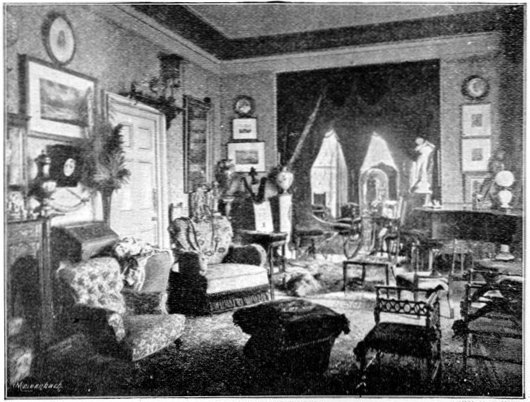

On a certain evening in the winter of the year before last, I was sent for in a hurry to see a young man at a private hotel in the vicinity of Harley Street. I found my patient to be suffering from a violent attack of delirium tremens. He was very ill, and for a day or two his life was in danger. I engaged good nurses to attend him, and sat up with him myself for the greater part of two nights. The terrible malady took a favourable turn, the well-known painful symptoms abated. I persevered with the usual remedies to insure sleep, and saw that he was given plenty of nourishment, and about a week after his seizure Tollemache was fairly convalescent. I went to visit him one evening before he left his room. He was seated in a great armchair before the fire, his pipe was near him on the mantelpiece, and a number of Harper's Magazine lay open, and face downwards, on a table by his side. He had not yet parted with his nurse, but the man left the room when I appeared.

"I wish you'd give me the pleasure of your company for half an hour or so," said Tollemache, in a wistful sort of voice.

I found I could spare the time, and sat down willingly in a chair at the side of the hearth. He looked at me with a faint dawning of pleasure in his sunken eyes.

"What can I order for you?" he asked. "Brandy-and-soda and cigars? I'll join you in a weed, if you like."

I declined either to smoke or drink, and tried to draw the young man into a light conversation.

As I did so, finding my efforts, I must confess, but poorly responded to, I watched my patient closely. Hitherto he had merely been my patient. My mission had been to drag him back by cart-ropes if necessary from the edge of the valley of death. He was now completely out of danger, and although indulgence in the vice to which he was addicted would undoubtedly cause a repetition of the attack, there was at present nothing to render me medically anxious about him. For the first time, therefore, I gave Wilfred Tollemache the critical attention which it was my wont to bestow on those who were to be my friends.

He was not more than twenty-three or twenty-four years of age—a big, rather bony fellow, loosely built. He had heavy brows, his eyes were deeply set, his lips were a little tremulous and wanting in firmness, his skin was flabby. He had a very sweet and pleasant smile, however, and notwithstanding the weakness caused by his terrible infirmity, I saw at once that there were enough good points in him to make it worth any man's while to try to set him on his legs once more.

I drew the conversation round to his personal history, and found that he was willing enough to confide in me.

He was an American by birth, but had spent so much time in Europe, and in England in particular, that no very strong traces of his nationality were apparent in his bearing and manner. He was an only son, and had unlimited wealth at his command.

"How old are you?" I asked.

"Twenty-three, my last birthday."

"In short," I said, rising as I spoke, standing before the hearth, and looking down at him, "no man has brighter prospects than you—you have youth, money, and I doubt not, from the build of your head, an abundant supply of brains. In short, you can do anything you like with your life."

He gave a hollow sort of laugh, and poking the ashes out of his pipe, prepared to fill it again.

"I wouldn't talk cant, if I were you," he said.

"What do you mean?" I asked.

"Well, that sort of speech of yours would befit a parson."

"Pardon me," I rejoined, "I but express the sentiments of any man who values moral worth, and looks upon life as a great responsibility to be accounted for."

He fidgeted uneasily in his chair. He was in no mood for any further advice, and I prepared to leave him.

"You will be well enough to go out to-morrow," I said, as I bade him good-bye.

He scarcely replied to me. I saw that he was in the depths of that depression which generally follows attacks like his. I said a word or two to the nurse at leaving, and went away.

It seemed unlikely that I should see much more of Tollemache; he would be well in a few days and able to go where he pleased;[Pg 466] one more visit would probably be the last I should be obliged to make to him. He evidently did not respond to my overtures in the direction of moral suasion, and, much occupied with other matters, I had almost passed him from my mind. Two days after that evening, however, I received a short note from him; it ran as follows:—

"Will you come and see me as a friend? I'm like a bear with a sore head, but I promise not to be uncivil.

"Yours sincerely,

"Wilfred Tollemache."

I sent a reply by my man to say that I would have much pleasure in visiting him about nine o'clock that evening. I arrived at Mercer's Hotel at the hour named. Tollemache received me in a private sitting-room. Bottles containing wines and liqueurs were on the table. There was a box of cigars and pipes.

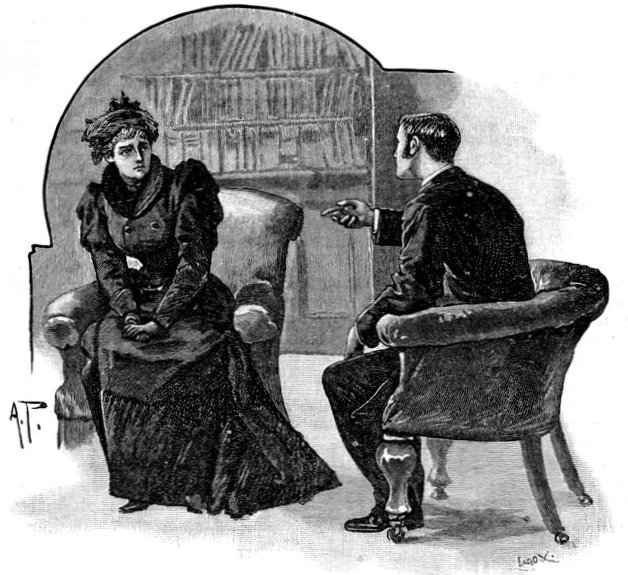

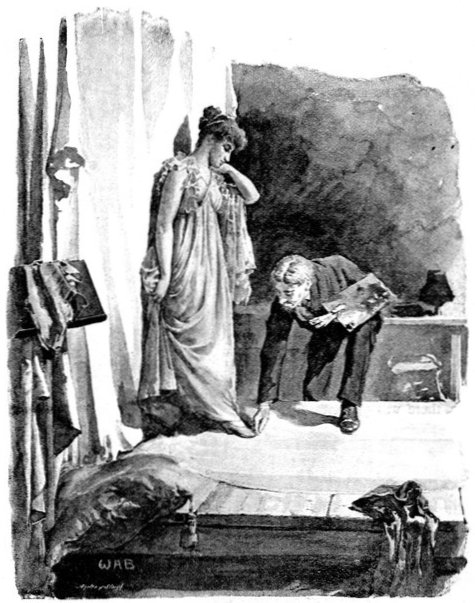

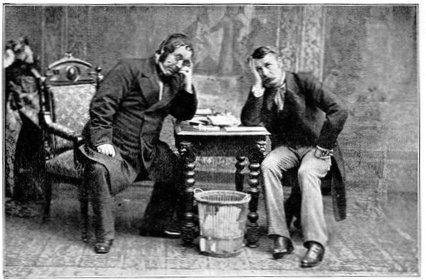

"I BADE HIM GOOD-BYE."

"You have not begun that again?" I could not help saying, glancing significantly at the spirits as I spoke.

"No," he said, with a grim sort of smile, "I have no craving at present—if I had, I should indulge. These refreshments are at your service. At present I drink nothing stronger or more harmful than soda-water."

"That is right," I said, heartily. Then I seated myself in a chair and lit a cigar, while Tollemache filled a pipe.

"It is very good of you to give up some of your valuable time to a worthless chap like me," he said.

There was a strange mingling of gratitude and despair in the words which aroused my sympathy.

"It was good of you to send for me," I rejoined. "Frankly, I take an interest in you, but I thought I had scared you the other night. Well, I promise not to transgress again."

"But I want you to transgress again," said Tollemache. "The fact is, I have sent for you to-night to give you my confidence. You know the condition you found me in?"

I nodded.

"I was in a bad way, wasn't I?"

"Very bad."

"Near death—eh?"

"Yes."

"The next attack will prove fatal most likely?"

"Most likely."

Tollemache applied a match to his pipe—he leant back in his chair and inhaled the narcotic deeply—a thin curl of blue smoke ascended into the air. He suddenly removed the pipe from his mouth.

"Twenty-three years of age," he said, aloud, "the only son of a millionaire—a dipsomaniac! Craving comes on about every three to four months. Have had delirium tremens twice—doctor says third attack will kill. A gloomy prospect mine, eh, Halifax?"

"You must not sentimentalize over it," I said; "you have got to face it and trample on the enemy. No man of twenty-three with a frame like yours and a brain like yours need be conquered by a vice."

"You know nothing about it," he[Pg 467] responded, roughly. "When it comes on me it has the strength of a demon. It shakes my life to the foundations. My strength goes. I am like Samson shorn of his locks."

"There is not the least doubt," I replied, "that the next time the attack comes on, you will have to make a desperate fight to conquer it. You must be helped from outside, for the fearful craving for drink which men like you possess is a form of disease, and is closely allied to insanity. How often do you say the craving seizes you?"

"From three to four times a year—in the intervals I don't care if I never touch a drop of strong drink."

"You ought never to touch wine, or strong drink of any kind; your frame does not need it, and with your peculiar bias it only acts as fuel to the hidden fire."

"You want me to be a teetotaler?" responded Tollemache. "I never will. I'll take no obligatory vow. Fifty vows would not keep me from rushing over the precipice when the demon is on me."

"I don't want you to take a vow against drink," I said, "as you say you would break it when the attack comes on. But if you are willing to fight the thing next time, I wish to say that all the medical skill I possess is at your service. I have a spare room in my house. Will you be my guest shortly before the time comes? You are warned of its approach, surely, by certain symptoms?"

"Yes, I have bad dreams; I am restless and nervous; I am consumed by thirst. These are but the preliminary symptoms. The full passion, as a rule, wakens up suddenly, and I am, in short, as a man possessed."

Tollemache looked deeply excited as he spoke. He had forgotten his pipe, which lay on the table near. Now he sprang to his feet.

"Halifax," he said; "I am the wretched victim of a demon—I often wish that I were dead!"

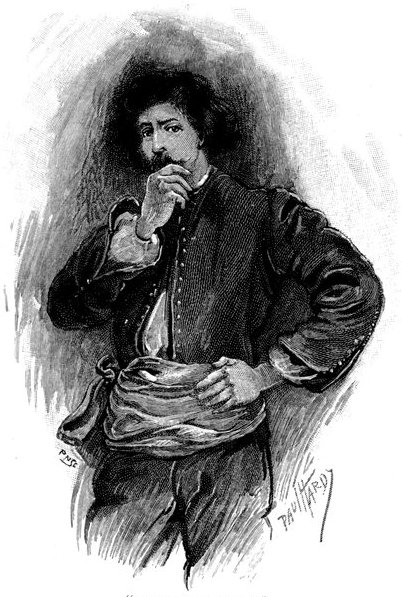

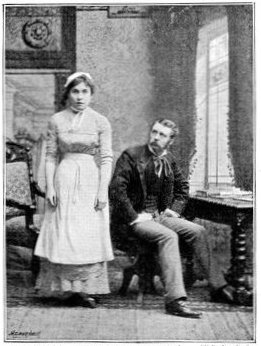

"I AM THE WRETCHED VICTIM OF A DEMON."

"You must fight the thing next time," I said. "It will be an awful struggle, I don't pretend to deny that; but I believe that you and I together will be a match for the enemy."

"It's awfully good of you to take me up—'pon my word it is."

"Well, is it a bargain?" I said.

"If you'll have it so."

"You must consider yourself my patient," I continued, "and obey me implicitly from this moment. It is most important that in the intervals of the attacks your health should be built up. I should recommend you to go to Switzerland, to take a sea voyage, or to do anything else which will completely brace the system. You should also cultivate your intellectual qualities, by really arduous study for a couple of hours daily."

"The thing I like best is music."

"Very well, study the theory of music. Don't weaken yourself over the sentimental parts. If you are really musical, and have taken it up as a pastime, work at the drudgery part for the next couple of months as if your bread depended on it. This exercise will put your brain into a healthy condition, and help to banish morbid thoughts. Then you must take plenty of exercise. If you go to Switzerland, you must do all the walking and the tobogganing which the weather will permit. If you go into the country, you must ride for so many hours daily. In short, it is your duty to get your body into training condition in order to fight your deadly enemy with any chance of success."

I spoke purposely in a light, matter-of-fact tone, and saw to my satisfaction that Tollemache was impressed by my words—he seemed interested, a shadow of hope flitted across his face, and his view of his own position was undoubtedly more healthy.

"Above all things, cultivate faith in your own self," I continued.

"No man had ever a stronger reason for wishing to conquer the foe," he said, suddenly. "Let me show you this."

He took a morocco case out of his pocket, opened it, and put it into my hand. It contained, as I expected, the photograph of a girl. She was dark-eyed, young, with a bright, expectant, noble type of face.

"She is waiting for me in New York," he said. "I won't tell you her name. I have not dared to look at the face for weeks and weeks. She has promised to marry me when I have abstained for a year. I am not worthy of her. I shall never win her. Give me the case." He shut it up without glancing once at the picture, and replaced it in his breast pocket.

"Now you know everything," he said.

"Yes."

Soon afterwards I left him.

Tollemache obeyed my directions. The very next evening a note in his handwriting was given to me. It contained the simple information that he was off to Switzerland by the night mail, and would not be back in England for a couple of months.

I did not forget him during his absence. His face, with its curious mingling of weakness and power, of pathetic soul-longings and strong animalism, often rose before me.

One evening towards the end of March I was in my consulting-room looking up some notes when Tollemache was announced. He came in, looking fresh and bronzed. There was brightness in his eyes and a healthy firmness round his lips. He held himself erect. He certainly was a very fine-looking young fellow.

"Well," he said, "here I am—I promised to come back, and I have kept my word. Are you ready for me?"

"Quite ready, as a friend," I replied, giving him a hearty shake of the hand; "but surely you don't need me as a doctor? Why, my dear fellow, you are in splendid case."

He sat down in the nearest chair.

"Granted," he replied. "Your prescription worked wonders. I can sleep well, and eat well. I am a good climber. My muscles are in first-class order. I used to be a famous boxer in New York, and I should not be afraid to indulge in that pastime now. Yes, I am in capital health; nevertheless," here he dropped his voice to a whisper, "the premonitory symptoms of the next attack have begun."

I could not help starting.

"They have begun," he continued: "the thirst, the sense of uneasiness, the bad dreams."

"Well," I replied, as cheerfully as I could, "you are just in the condition to make a brave and successful fight. I have carefully studied cases like yours in your absence, and I am equipped to help you at all points. You must expect a bad fortnight. At the end of that time you will be on terra firma and will be practically safe. Now, will you come and stay with me?—you know I have placed a bedroom at your disposal."

"Thanks, but it is not necessary for me to do that yet. I will go to my old quarters at Mercer's Hotel, and will give you my word of honour to come here the first moment that I feel my self-control quite going."

"I would rather you came here at once."

"It is not necessary, I assure you. These symptoms may vanish again completely for a time, and although they will inevitably return, and the deadly thing must be fought out to the bitter end, yet a long interval may elapse before this takes place. I promised you to come to England the moment the first unpropitious symptom appeared. I shall be in your vicinity at Mercer's, and can get your assistance at any moment; but it is unfair to take possession of your spare room at this early date."

I could not urge the matter any farther. Helpful as I wished to be to this young man, I knew that he must virtually cure himself. I could not take his free will from him. I gave him some directions, therefore, which I hoped might be useful: begged of him to fill up all his time with work and amusement, and promised to go to him the first moment he sent for me.

He said he would call me in as soon as ever he found his symptoms growing worse, and went away with a look of courage and resolution on his face.

I felt sure that he was thinking of the girl whose photograph he held near his heart. Was he ever likely to win her? She was not a milk-and-water maiden, I felt convinced. There was steel as well as fire in those eyes. If she ever consented to become Tollemache's wife, she would undoubtedly keep him straight—but she was no fool. She knew the uselessness of throwing herself away on a drunkard.

Tollemache came to see me on the Monday of a certain week. On the following Thursday morning, just after I had finished seeing the last of my patients, my servant brought me a letter from him.

"This should have been handed to you yesterday," he said. "It had slipped under a paper in the letter-box. The housemaid has only just discovered it."

I opened it quickly. It contained these words:—

"Dear Halifax,—The demon gains ascendency over me, but I still hold him in check. Can you dine with me to-night at half-past seven? "Yours sincerely,

"Wilfred Tollemache."

The letter was dated Wednesday morning. I should have received it twenty-four hours ago. Smothering a vexed exclamation, I rushed off to Mercer's Hotel.

I asked for Tollemache, but was told by one of the waiters that he was out. I reflected for a moment and then inquired for the manager.

He came out into the entrance-hall in answer to my wish to see him, and invited me to come with him into his private sitting-room.

"What can I do for you, Dr. Halifax?" he asked.

"Well, not much," I answered, "unless you can give me some particulars with regard to Mr. Tollemache."

"He is not in, doctor. He went out last night, between nine and ten o'clock, and has not yet returned."

"I am anxious about him," I said. "I don't think he is quite well."

"As you mention the fact, doctor, I am bound to agree with you. Mr. Tollemache came in between six and seven last night in a very excited condition. He ran up to his rooms, where he had ordered dinner for two, and then came down to the bureau to know if any note or message had been left for him. I gathered from him that he expected to hear from you, sir."

"IN A VERY EXCITED CONDITION."

"I am more vexed than I can express," I replied. "He wrote yesterday morning asking me to dine with him, and through a mistake the letter never got into my possession until twenty-four hours after it was written."

"Poor young gentleman," replied the manager, "then that accounts for the worry he seemed to be in. He couldn't rest, but was up and down, watching, as I gather now, for your arrival, doctor. He left the house soon after nine o'clock without touching his dinner, and has not since returned."

"Have you the least idea where he is?" I asked.

"No, sir, not the faintest; Mr. Tollemache has left all his things about and has not paid his bill, so of course he's safe to come back, and may do so at any moment. Shall I send you word when he arrives?"

"Yes, pray do," I answered. "Let me know the moment you get any tidings about him."

I then went away.

The manager had strict orders to give me the earliest information with regard to the poor fellow, and there was now nothing whatever for me to do but to try to banish him from my mind.

The next morning I went at an early hour to Mercer's to make inquiries. The manager came himself into the entrance-hall to see me.

"There's been no news, sir," he said, shaking his head: "not a line or a message of any sort. I hope no harm has happened to the poor gentleman. It seems a pity you shouldn't have got the letter, doctor, he seemed in a cruel way about your not turning up."

"Yes, it was a sad mistake," I answered, "but we must trust that no disaster has occurred. If Mr. Tollemache were quite well, I should not, of course, trouble my head over the matter."

"He was far from being that," said a waiter who came up at this moment. "Did you tell the doctor, sir, about the lady who called yesterday?" continued the man, addressing the manager.

"No, I had almost forgotten," he replied. "A lady in deep mourning—young, I should say, but she kept her veil down—arrived here last evening about eight o'clock and asked for Mr. Tollemache. I said he was out, and asked if she would wish her name to be left. She seemed to think for a moment and then said 'No,' that it didn't matter. She said she would come again, when she hoped to see him."

In his intercourse with me, Tollemache had never spoken of any lady but one, and her photograph he kept in his breast pocket. I wondered if this girl could possibly have been to see him, and, acting on the conjecture that the visitor might be she, I spoke.

"If the lady happens to call again," I said, "you may mention to her that I am Mr. Tollemache's medical man, and that I will see her with pleasure if she likes to come to my house in Harley Street." I then further impressed upon the manager the necessity of letting me know the moment any tidings came of Tollemache, and went away.

Nothing fresh occurred that evening, but the next morning, just when I had seen the last of my patients, a lady's card was put into my hand. I read the name on it, "Miss Beatrice Sinclair." A kind of premonition told me that Beatrice Sinclair had something to do with Tollemache. I desired my servant to admit her at once.

The next moment a tall girl, in very deep mourning, with a crape veil over her face, entered the room. She bowed to me, but did not speak for nearly half a minute. I motioned her to seat herself. She did so, putting up her hand at the same moment to remove her veil. I could not help starting when I saw her face. I bent suddenly forward and said, impulsively:—

"I know what you have come about—you are anxious about Wilfred Tollemache."

She looked at me in unfeigned surprise, and a flood of colour rushed to her pale cheeks. She was a handsome girl—her eyes were dark, her mouth tender and beautiful. There was strength about her face—her chin was very firm. Yes, I had seen those features before—or, rather, a faithful representation of them. Beatrice Sinclair had a face not easily forgotten.

"If this girl is Tollemache's good angel, there is undoubtedly hope for him," I murmured.

"I COULD NOT HELP STARTING WHEN I SAW HER FACE."

Meanwhile, the astonished look on her face gave way to speech.

"How can you possibly know me?" she said. "I have never seen you until this moment."

"I am Tollemache's doctor, and once he told me about you," I said. "On that occasion, too, he showed me your photograph."

Miss Sinclair rose in excitement from her seat. She had all the indescribable grace of a well-bred American girl.

"The fact of your knowing something about me makes matters much easier," she said. "May I tell you my story in a very few words?"

"Certainly."

"My name, as you know, is Beatrice Sinclair. I am an American, and have spent the greater part of my life in New York. I am an only child, and my father, who was a general in the American army, died only a week ago. It is three years since I engaged myself provisionally to Wilfred Tollemache. We had known each other from childhood. He spoke of his attachment to me; he also told me"—here she hesitated and her voice trembled—"of," she continued, raising her eyes, "a fearful vice which was gaining the mastery over him. You know to what I allude. Wilfred was fast becoming a dipsomaniac. I would not give him up, but neither would I marry a man addicted to so terrible a failing. I talked to my father about it, and we agreed that if Wilfred abstained from drink for a year, I might marry him. He left us—that is three years ago. He has not written to me since, nor have I heard of him. I grew restless at last, for I—I have never ceased to love him. I have had bad dreams about him, and it seems to me that his redemption has been placed in my hands. I induced my father to bring me to Europe and finally to London. We arrived in London three weeks ago, and took up our quarters at the Métrôpole. We employed a clever detective to find out Wilfred Tollemache's whereabouts. A week ago this man brought us the information that he had rooms at Mercer's Hotel. Alas! on that day, also, my father died suddenly. I am now alone in the world. Two evenings ago I went to Mercer's Hotel to inquire for Mr. Tollemache. He was not in, and I went away. I returned to the hotel again this morning. Your message was given to me, and I came on to you at once. The manager of the hotel told me that you were Mr. Tollemache's medical man. If he needed the services of a doctor he must have been ill. Has he been ill? Can you tell me anything about him?"

"I can tell you a good deal about him. Won't you sit down?"

She dropped into a chair immediately, clasping her hands in her lap; her eyes were fixed on my face.

"You are right in your conjecture," I said. "Tollemache has been ill."

"Is he alive?"

"As far as I can tell, yes."

Her lips quivered.

"Don't you know where he is now?" she asked.

"I deeply regret that I do not," I answered.

She looked at me again with great eagerness.

"I know that you will tell me the truth," she continued, almost in a whisper. "I owe it to my dead father not to go against his wishes now. What was the nature of Mr. Tollemache's illness?"

"Delirium tremens," I replied, firmly.

Miss Sinclair's face grew the colour of death.

"I might have guessed it," she said. "I hoped, but my hope was vain. He has not fought—he has not struggled—he has not conquered."

"You are mistaken," I answered; "Tollemache has both fought and struggled, but up to the present he has certainly won no victory. Let me tell you what I know about him."

I then briefly related the story of our acquaintance. I concealed nothing, dwelling fully on the terrible nature of poor Tollemache's malady. I described to Miss Sinclair the depression, the despair, the overpowering moral weakness which accompanies the indulgence in this fearful vice. In short, I lifted the curtain, as I felt it was my duty to do, and showed the poor girl a true picture of the man to whom she had given her heart.

"Is there no hope for him?" she asked, when I had finished speaking.

"You are the only hope," I replied. "The last rock to which he clings is your affection for him. He was prepared to make a desperate fight when the next craving for drink assailed him. You were the motive which made him willing to undergo the agony of such a struggle. I look upon the passion for drink as a distinct disease: in short, as a species of insanity. I was prepared to see Tollemache through the next attack. If he endured the torture without once giving way to the craving for drink, he would certainly be on the high road to recovery. I meant to have him in my own house. In short, hopeless as his case seemed, I had every hope of him."

I paused here.

"Yes?" said Miss Sinclair. "I see that you are good and kind. Why do you stop? Why isn't Wilfred Tollemache here?"

"My dear young lady," I replied, "the best-laid plans are liable to mishap. Three days ago, Tollemache wrote to me telling me that he was in the grip of the enemy, and asking me to come to him at once. Most unfortunately, that letter was not put into my hands until twenty-four hours after it should have been delivered. I was not able to keep[Pg 472] the appointment which Tollemache had made with me, as I knew nothing about it until long after the appointed hour. The poor fellow left the hotel that night, and has not since returned."

"IS THERE NO HOPE?"

"And you know nothing about him?"

"Nothing."

I rose as I spoke. Miss Sinclair looked at me.

"Have you no plan to suggest?" she asked.

"No," I said, "there is nothing for us to do but to wait. I will not conceal from you that I am anxious, but at the same time my anxiety may be groundless. Tollemache may return to Mercer's at any moment. As soon as ever he does, you may be sure that I will communicate with you."

I had scarcely said these words before my servant came in with a note.

"From Mercer's Hotel, sir," he said, "and the messenger is waiting."

"I will send an answer in a moment," I said.

The man withdrew—Miss Sinclair came close to me.

"Open that letter quickly," she said, in an imperative voice. "It is from the hotel. He may be there even now."

I tore open the envelope. There was a line from the manager within.

"Dear Sir,—I send you the enclosed. I propose to forward the dressing-case at once by a commissionaire."

The enclosed was a telegram. The following were its brief contents:—

"Send me my dressing-case immediately by a private messenger.—Wilfred Tollemache."

An address was given in full beneath:—

"The Cedars, 110, Harvey Road, Balham."

I knew that Miss Sinclair was looking over my shoulder as I read. I turned and faced her.

Her eyes were blazing with a curious mixture of joy, excitement, and fear.

"Let us go to him," she exclaimed; "let us go to him at once. Let us take him the dressing-case."

I folded up the telegram and put it into my pocket.

Then I crossed the room and rang the bell. When my servant appeared, I gave him the following message:—

"Tell the messenger from Mercer's," I said, "that I will be round immediately, and tell him to ask the manager to do nothing until I come."

My servant withdrew and Miss Sinclair moved impatiently towards the door.

"Let us go," she said: "there is not a moment to lose. Let us take the dressing-case ourselves."

"I will take it," I replied; "you must not come."

"Why?" she asked, keen remonstrance in her tone.

"Because I can do better without you," I replied, firmly.

"I do not believe it," she answered.

"I cannot allow you to come with me," I[Pg 473] said. "You must accept this decision as final. You have had patience for three years; exercise it a little longer, and—God knows, perhaps you may be rewarded. Anyhow, you must trust me to do the best I can for Tollemache. Go back to the Métrôpole. I will let you know as soon as I have any news. You will, I am sure, trust me?"

"Oh, fully," she replied, tears suddenly filling her lovely eyes. "But remember that I love him—I love him with a very deep love."

There was something noble in the way she made this emphatic statement. I took her hand and led her from the room. A moment later she had left me, and I was hurrying on foot to Mercer's Hotel.

The manager was waiting for me in the hall. He had the dressing-case in his hand.

"Shall I send this by a commissionaire?" he asked.

"No," I replied, "I should prefer to take it myself. Tell the porter to call a hansom for me immediately."

The man looked immensely relieved.

"That is good of you, doctor," he said; "the fact is, I don't like the sound of that address."

"Nor do I," I replied.

"Do you know, Dr. Halifax, that the young lady—Miss Sinclair, she called herself—came here again this morning?"

"I have just seen her," I answered.

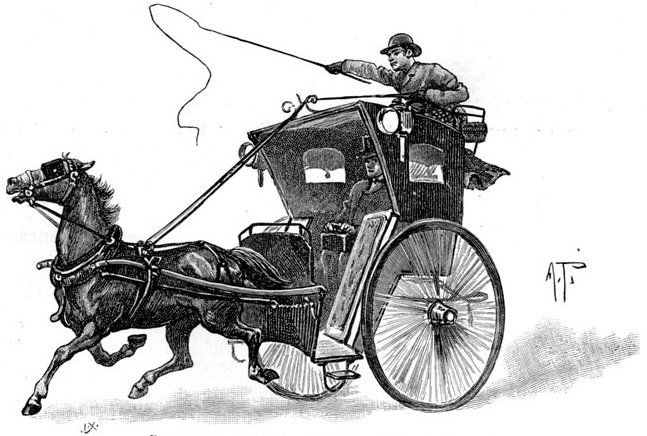

The hall porter now came to tell me that the hansom was at the door. A moment later I was driving to Balham, the dressing-case on my knee.

"A MOMENT LATER I WAS DRIVING TO BALHAM."

From Mercer's Hotel to this suburb is a distance of several miles, but fortunately the horse was fresh and we got over the ground quickly. As I drove along my meditations were full of strange apprehensions.

Tollemache had now been absent from Mercer's Hotel for two days and three nights. What kind of place was Harvey Road? What kind of house was 110? Why did Tollemache want his dressing-case? And why, if he did want it, could not he fetch it himself? The case had been a favourite of his—it had been a present from his mother, who was now dead. He had shown it to me one evening, and had expatiated with pride on its unique character. It was a sort of multum in parvo, containing many pockets and drawers not ordinarily found in a dressing-case. I recalled to mind the evening when Tollemache had brought it out of his adjacent bedroom and opened it for my benefit. All its accoutrements were heavily mounted in richly embossed silver. There was a special flap into which his cheque-book fitted admirably. Under the flap was a drawer, which he pulled open and regaled my astonished eyes with a quantity of loose diamonds and rubies which lay in the bottom.

"I picked up the diamonds in Cape Town," he said, "and the rubies in Ceylon. One or two of the latter are, I know, of exceptional value, and when I bought them I hoped that they might be of use——"

Here he broke off abruptly, coloured, sighed, and slipped the drawer back into its place.

It was easy to guess where his thoughts were.

Now that I had seen Miss Sinclair, I felt that I could better understand poor Tollemache. Such a girl was worth a hard fight to win. No wonder Tollemache hated himself when he felt his own want of moral strength, and knew that the prize of such a love as hers might never be his.

I knew well that the delay in the delivery of the note was terribly against the poor fellow's chance of recovery, and as I drove quickly to Balham,[Pg 474] my uneasiness grew greater and greater. Was he already in the clutches of his foe when he sent that telegram? I felt sure that he was not in immediate need of cash, as he had mentioned to me incidentally in our last interview that he had drawn a large sum from his bank as soon as ever he arrived in England.

We arrived at Balham in about an hour, but my driver had some difficulty in finding Harvey Road.

At last, after skirting Tooting Bee Common we met a policeman who was able to acquaint us with its locality. We entered a long, straggling, slummy-looking road, and after a time pulled up at 110. It was a tall house, with broken and dirty Venetian blinds. The hall door was almost destitute of paint. A balcony ran round the windows of the first floor.

I did not like the look of the house, and it suddenly occurred to me that I would not run the risk of bringing the dressing-case into it.

I had noticed the name of a respectable chemist over a shop in the High Street, a good mile away, and desired the driver to go back there at once.

He did so. I entered the shop, carrying the case in my hand. I gave the chemist my card, and asked him if he would oblige me by taking care of the dressing-case for an hour. He promised civilly to do what I asked, and I stepped once more into the hansom and told the man to drive back as fast as he could to 110, Harvey Road.

He obeyed my instructions. The moment the hansom drew up at the door, I sprang out and spoke to the driver.

"I want you to remain here," I said. "Don't on any account leave this door until I come out. I don't like the look of the house."

The man gave it a glance of quick interrogation. He did not say anything, but the expression of his eyes showed me plainly that he confirmed my opinion.

"I think you understand me," I said. "Stay here until you see me again, and if I require you to fetch a policeman, be as quick about it as you can."

The man nodded, and I ran up the broken steps of 110.

The door possessed no knocker, but there was a bell at the side.

I had to pull it twice before it was answered; then a slatternly and tawdrily dressed servant put in an appearance. Her face was dirty. She had pinned a cap in hot haste on her frowzy head of red hair, and was struggling to tie an apron as she opened the door.

"Is Mr. Tollemache in?" I asked. "I wish to see him at once."

The girl's face became watchful and secretive—she placed herself between me and the hall.

"There's a gentleman upstairs," she said; "but you can't see him, he's ill."

"Oh, yes, I can," I answered. "I am his doctor—let me pass, please. Mr. Tollemache has telegraphed for his dressing-case, and I have replied to the telegram."

"Oh, if you have brought the parcel, you can go up," she said, in a voice of great relief. "I know they're expecting a parcel. You'll find 'em all on the first floor. Door just opposite the stairs—you can't miss it."

I pushed past her and ran up the stairs. They were narrow and dark. The carpet on which I trod felt greasy.

I flung open the door the girl had indicated, and found myself in a good-sized sitting-room. It faced the street, and the window had a balcony outside it.

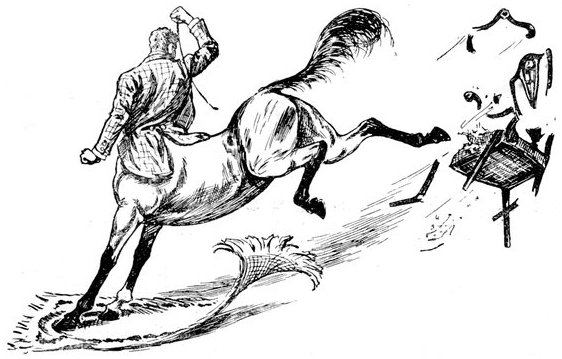

Seated by a centre table drawn rather near this window were three men, with the most diabolical faces I have ever looked at. One of them was busily engaged trying to copy poor Tollemache's signature, which was scrawled on a half sheet of paper in front of him—the other two were eagerly watching his attempts. Tollemache himself lay in a dead drunken sleep on the sofa behind them.

My entrance was so unexpected that none of the men were prepared for me. I stepped straight up to the table, quickly grabbed the two sheets of paper, crushed them up in my hand, and thrust them into my pocket.

"I have come to fetch Mr. Tollemache away," I said.

The men were so absolutely astonished at my action and my words, that they did not speak at all for a moment. They all three jumped from their seats at the table and stood facing me. The noise they made pushing back their chairs aroused Tollemache, who, seeing me, tottered to his feet and came towards me with a shambling, uneasy gait.

"Hullo, Halifax, old man, how are you?" he gasped, with a drunken smile. "What are you doing here? We're all having a ripping time: lots of champagne; but I've lost my watch and chain and all my money—three hundred pounds—I've telegraphed for my cheque-book, though. Glad you've come, old boy—'pon my word I am. Want[Pg 475] to go away with you, although we have had a ripping time, yes, awfully ripping."

"You shall come," I said. "Sit down first for a moment."

I pushed him back with some force on to the sofa and turned to one of the men, who now came up and asked me my business.

"What are you doing here?" he inquired. "We don't want you—you had better get out of this as fast as you can. You have no business here, so get out."

"Yes, I have business here," I replied. "I have come for this man," here I went up to Tollemache and laid my hand on his shoulder. "I am his doctor and he is under my charge. I don't leave here without him, and, what is more," I added, "I don't leave here without his property either. You must give me back his watch and chain and the three hundred pounds you have robbed him of. Now you understand what I want?"

"We'll see about that," said one of the men, significantly. He left the room as he spoke.

During his absence, the other men stood perfectly quiet, eyeing me with furtive and stealthy glances.

Poor Tollemache sat upright on the sofa, blinking with his heavy eyes. Sometimes he tried to rise, but always sank back again on his seat. During the whole time he kept muttering to himself:—

"Yes, good fellows these: jolly time, champagne, all the rest, but I'm robbed; this is a thieves' den. Don't leave me alone, Halifax. Want to go. You undershtand. Watch and chain gone, and all my money; three hundred in notes and gold. Yes, three hundred. Won't let me go till I give 'em my cheque-book; telegraphed for cheque-book in dressing-case. You undershtand, yes. Don't leave me, old boy."

"It will be all right," I said. "Stay quiet."

The position was one of extreme danger for both of us. There was nothing whatever for it but to carry matters with a cool hand and not to show a vestige of fear. I glanced round me and observed the position of the room. The sofa on which Tollemache was sitting was close to the window. This window had French doors, which opened on to the balcony. I edged close to it.

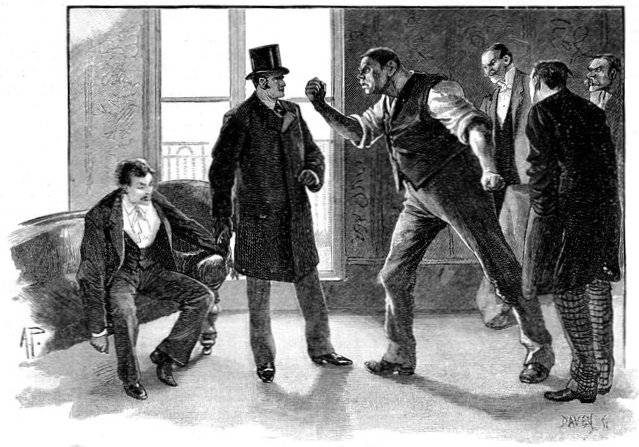

I did not do this a moment too soon. The man who had left the room now returned with a ruffian of gigantic build, who came up to me at once with a menacing attitude.

"WHO ARE YOU?"

"Who are you?" he said, shaking his brawny fist in my face. "We don't want you here—get out of this room at once, or it will be the worse for you. We won't 'ave you a-interfering with our friends. This gent 'ave come 'ere of his own free will. We like him, and 'e's 'eartily welcome to stay as long as 'e wants to. You'd best go, ef you value your life."

While he was speaking I suddenly flung my hand behind me, and turning the handle of the French window threw it open.

I stepped on to the balcony and called to the cabman: "Stay where you are," I said, "I may want you in a moment." Then I entered the room again.

"I don't wish to waste words on you," I said, addressing the burly man. "I have come for Mr. Tollemache, and I don't mean to leave the house without him. He comes away with me the moment you return his watch and chain, and the three hundred pounds you have stolen from him. If you don't fetch that watch and chain, and that money, I shall send the cabman who is waiting for me outside, and who knows me, for the police. You are best acquainted with what sort of house this is, and with what sort of game you are up to. It is for you to say how near the wind you are sailing. If you wish the police to find out, they can be here in a minute or two. If not, give me the money and the watch and chain. I give you two minutes to make your choice."

Here I took out my watch and looked at it steadily.

I stepped again on to the balcony.

"Cabby," I shouted, "if I am not with you in three minutes from now, go and bring a couple of policemen here as quickly as ever you can."

The cabman did not speak, but he took out his watch and looked at it.

I re-entered the room.

"Now you know my mind," I said. "I give you two minutes to decide how to act. If Mr. Tollemache and I are not standing on the pavement in three minutes from now, the police will come and search this house. It is for you to decide whether you wish them to do so or not."

I was glad to see that my words had an effect upon the biggest of the ruffians. He looked at his companions, who glanced back at him apprehensively. One of them edged near me and tried to peer over my shoulder to see if the cabman were really there.

Tollemache went on mumbling and muttering on the sofa. I stood with my back to the window, my watch in my hand, marking the time.

"Time's up," I said, suddenly replacing the watch. "Now, what do you mean to do?"

"We'd best oblige the gent, don't yer think so, Bill?" said one of the men to his chief.

"We'll see about that," said the chief. He came close to me again.

"Now, look you 'ere," he said, "you'd best go out quiet, and no mischief will come. The gent 'ere 'e give us the watch and chain and the money, being old pals of his as he picked up in New York City."

"That's a lie," shouted Tollemache.

"Stay quiet," I said to him.

Then I turned to the ruffian, whose hot breath I felt on my cheek.

"We do not leave here," I said, "without the watch and chain and the money. My mind is quite made up. When I go, this gentleman goes, and we neither of us go without his property."

These words of mine were almost drowned by the heavy noise of an approaching dray. It lumbered past the window. As it did so, I stepped on to the balcony to acquaint the cabman with the fact that the three minutes were up.

I looked down into the street, and could not help starting—the cab had vanished.

I turned round quickly.

The big man had also stepped upon the balcony—he gave me an evil glance. Suddenly seizing me by the collar, he dragged me back into the room.

"You ere a humbug, you ere," he said, "wid yer bloomin' cabs—there ain't no cab there—no, nor never wor. Ef you don't go in one way you go in another. It ain't our fault ef things ain't quite agreeable. Come along, Sam, lend a 'and."

The next moment the ruffian had laid me flat on my back on the floor, and was kneeling on my chest.

Tollemache tottered from the sofa, and made a vain struggle to get the brute away.

"You get out of this," the fellow thundered at him. "I'll make an end of you, too, ef you don't look out."

He fumbled in his pocket and took out a huge clasp-knife.

I closed my eyes, feeling sure that my last hour had come. At this moment, however, the rapidly approaching sound of cab wheels was distinctly audible. A cab drove frantically up and stopped at the door.

The four ruffians who were clustered round me all heard it, and the big man took his knee off my chest.

Quick as thought I found my feet again, and before anyone could prevent me, leaped out on to the balcony. Two policemen were standing on the steps of the house—one of them had the bell-pull in his hand and was just about to sound a thundering peal.

"Stop," I shouted to him; "don't ring for a moment—stay where you are."[Pg 477] Then I turned and faced the group in the room.

"I FELT SURE THAT MY LAST HOUR HAD COME."