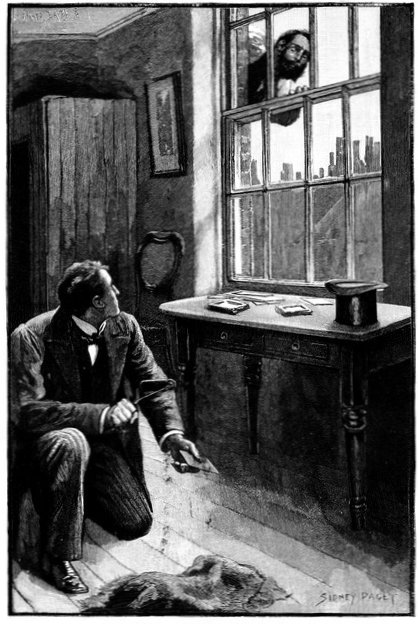

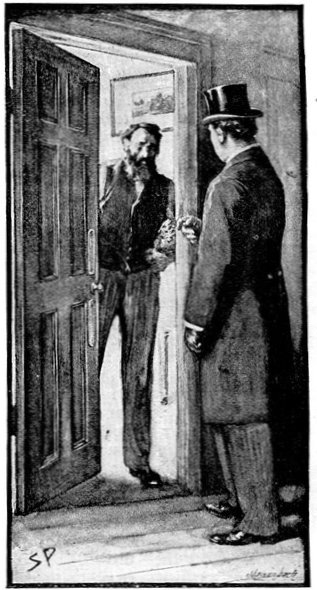

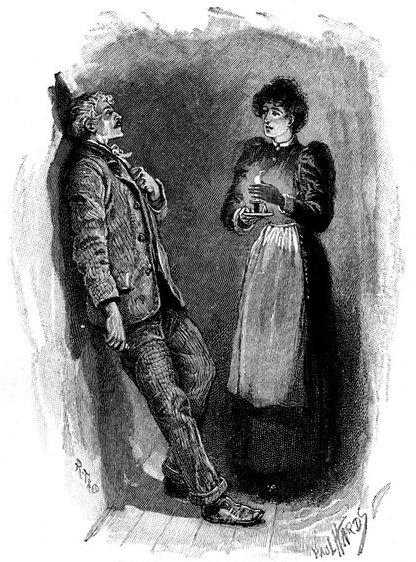

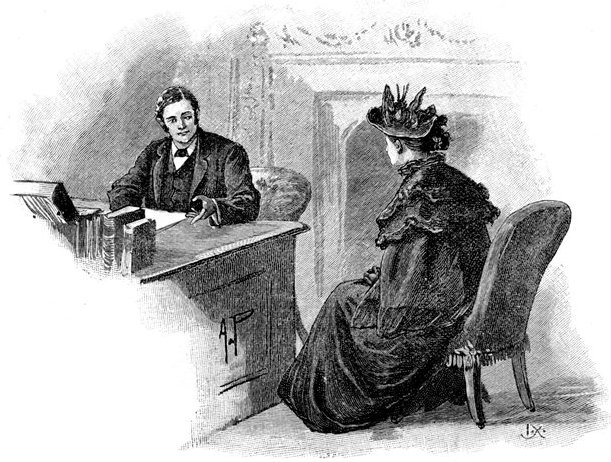

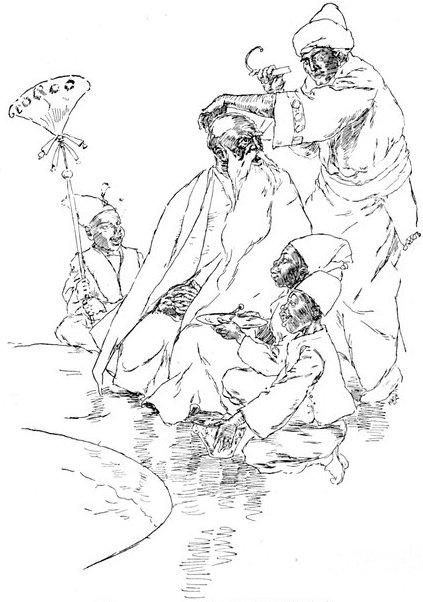

"MIRSKY WAS STARING STRAIGHT AT ME."

(See page 571.)

Title: The Strand Magazine, Vol. 07, Issue 42, June, 1894

Author: Various

Editor: George Newnes

Release date: November 17, 2014 [eBook #47377]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Jonathan Ingram and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

EDITED BY GEORGE NEWNES

Vol VII., Issue 42.

June, 1894

Martin Hewitt, Investigator.

Illustrated Interviews.

The Queen's Yacht.

Light.

Zig-zags at the Zoo.

Stories from the Diary of a Doctor.

Portraits of Celebrities at Different Times of their Lives.

Crimes and Criminals.

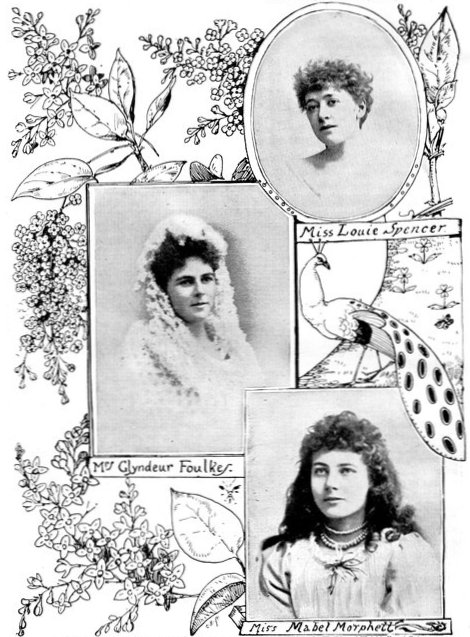

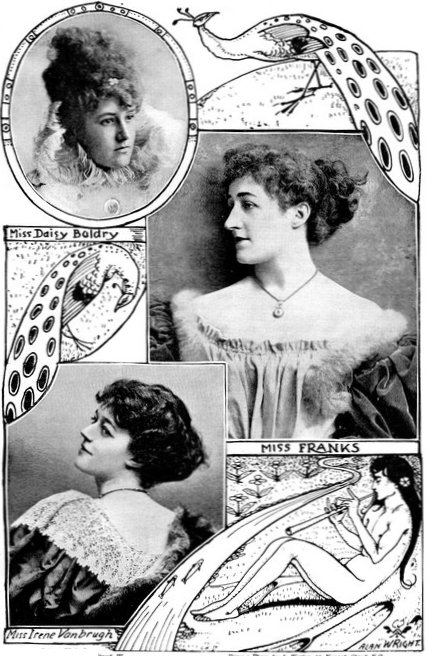

Beauties.

Count Ferdinand de Lesseps.

Some Interesting Pictures.

From Behind the Speaker's Chair.

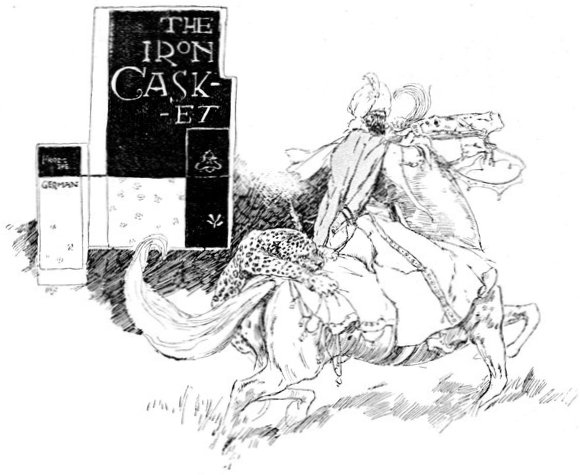

The Iron Casket.

The Queer Side of Things.

Pal's Puzzle Page.

Index.

Transcriber's Notes.

"MIRSKY WAS STARING STRAIGHT AT ME."

(See page 571.)

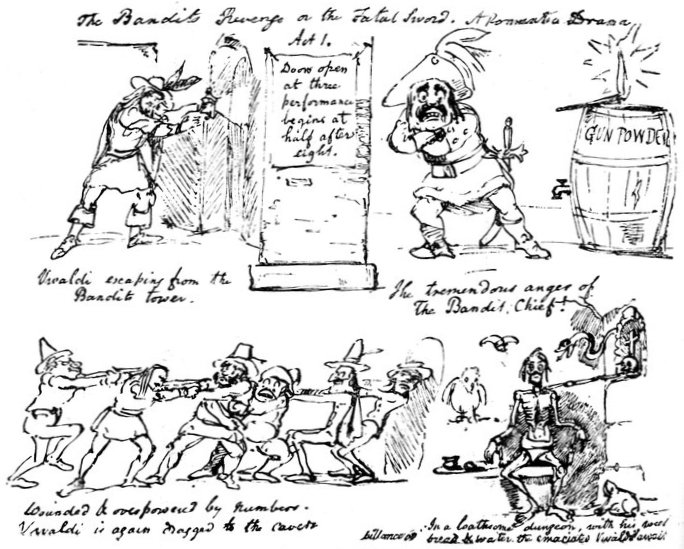

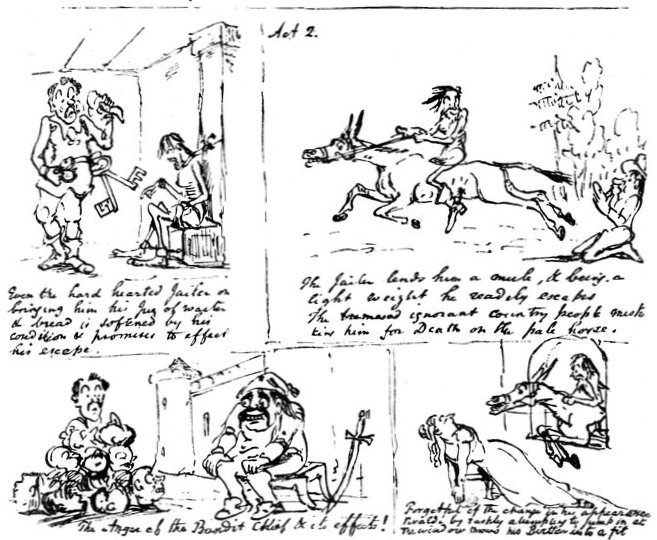

By Arthur Morrison.

Hewitt was very apt, in conversation, to dwell upon the many curious chances and coincidences that he had observed, not only in connection with his own cases, but also in matters dealt with by the official police, with whom he was on terms of pretty regular and, indeed, friendly acquaintanceship. He has told me many an anecdote of singular happenings to Scotland Yard officials with whom he has exchanged experiences. Of Inspector Nettings, for instance, who spent many weary months in a search for a man wanted by the American Government, and in the end found, by the merest accident (a misdirected call), that the man had been lodging next door to himself the whole of the time; just as ignorant, of course, as was the inspector himself as to the enemy at the other side of the party-wall. Also of another inspector, whose name I cannot recall, who, having been given rather meagre and insufficient details of a man whom he anticipated having great difficulty in finding, went straight down the stairs of the office where he had received instructions, and actually fell over the man near the door, where he had stooped down to tie his shoe-lace! There were cases, too, in which, when a great and notorious crime had been committed and various persons had been arrested on suspicion, some were found among them who had long been badly wanted for some other crime altogether. Many criminals had met their deserts by venturing out of their own particular line of crime into another: often a man who got into trouble over something comparatively small, found himself in for a startlingly larger trouble, the result of some previous misdeed that otherwise would have gone unpunished. The rouble note-forger, Mirsky, might never have been handed over to the Russian authorities had he confined his genius to forgery alone. It was generally supposed at the time of his extradition that he had communicated with the Russian Embassy, with a view to giving himself up—a foolish proceeding on his part, it would seem, since his whereabouts, indeed, even his identity as the forger, had not been suspected. He had communicated with the Russian Embassy, it is true, but for quite a different purpose, as Martin Hewitt well understood at the time. What that purpose was is now for the first time published.

The time was half-past one in the afternoon, and Hewitt sat in his inner office examining and comparing the handwriting of two letters by the aid of a large lens. He put down the lens and glanced at the clock on the mantelpiece with a premonition of lunch; and as he did so his clerk quietly entered the room with one of those printed slips which were kept for the announcement of unknown visitors. It was filled up in a hasty and almost illegible hand thus:—

Name of visitor: F. Graham Dixon.

Address: Chancery Lane.

Business: Private and urgent.

"Show Mr. Dixon in," said Martin Hewitt.

Mr. Dixon was a gaunt, worn-looking man of fifty or so, well although rather carelessly dressed, and carrying in his strong though drawn face and dullish eyes the look that characterizes the life-long strenuous brain-worker. He leaned forward anxiously in the chair which Hewitt offered him, and told his story with a great deal of very natural agitation.

"You may possibly have heard, Mr. Hewitt—I know there are rumours—of the new locomotive torpedo which the Government is about adopting; it is, in fact, the Dixon torpedo, my own invention; and in every respect—not merely in my own opinion, but in that of the Government experts—by far the most efficient and certain yet produced. It will travel at least four hundred yards farther than any torpedo now made, with perfect accuracy of aim (a very great desideratum, let me tell you), and will carry an unprecedentedly heavy charge. There are other advantages, speed, simple discharge, and so forth, that I needn't bother you about. The machine is the result of many years of work and disappointment, and its design has only been arrived at by a careful balancing of principles and means, which are expressed on the only four existing sets of drawings. The whole thing, I need hardly tell you, is a profound secret, and you may judge of my present state of mind when I tell you that one set of drawings has been stolen."

"From your house?"

"From my office, in Chancery Lane, this morning. The four sets of drawings were distributed thus: Two were at the Admiralty Office, one being a finished set on thick paper, and the other a set of tracings therefrom; and the other two were at my own office, one being a pencilled set, uncoloured—a sort of finished draft, you understand—and the other a set of tracings similar to those at the Admiralty. It is this last set that has gone. The two sets were kept together in one drawer in my room. Both were there at ten this morning, of that I am sure, for I had to go to that very drawer for something else, when I first arrived. But at twelve the tracings had vanished."

"You suspect somebody, probably?"

"I cannot. It is a most extraordinary thing. Nobody has left the office (except myself, and then only to come to you) since ten this morning, and there has been no visitor. And yet the drawings are gone!"

"But have you searched the place?"

"Of course I have. It was twelve o'clock when I first discovered my loss, and I have been turning the place upside down ever since—I and my assistants. Every drawer has been emptied, every desk and table turned over, the very carpet and linoleum have been taken up, but there is not a sign of the drawings. My men even insisted on turning all their pockets inside out, although I never for a moment suspected either of them, and it would take a pretty big pocket to hold the drawings, doubled up as small as they might be."

"You say your men—there are two, I understand—had neither left the office?"

"Neither; and they are both staying in now. Worsfold suggested that it would be more satisfactory if they did not leave till something was done towards clearing the mystery up, and although, as I have said, I don't suspect either in the least, I acquiesced."

"Just so. Now—I am assuming that you wish me to undertake the recovery of these drawings?"

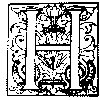

"YOU WISH ME TO UNDERTAKE THE RECOVERY OF THESE DRAWINGS?"

The engineer nodded hastily.

"Very good; I will go round to your office. But first perhaps you can tell me something about your assistants; something it might be awkward to tell me in their presence, you know. Mr. Worsfold, for instance?"

"He is my draughtsman—a very excellent and intelligent man, a very smart man, indeed, and, I feel sure, quite beyond suspicion. He has prepared many important drawings for me (he has been with me nearly ten years now), and I have always found him trustworthy. But, of course, the temptation in this case would be enormous. Still, I cannot suspect Worsfold. Indeed, how can I suspect anybody in the circumstances?"

"The other, now?"

"His name's Ritter. He is merely a tracer, not a fully skilled draughtsman. He is quite a decent young fellow, and I have had him two years. I don't consider him particularly smart, or he would have learned a little more of his business by this time. But I don't see the least reason to suspect him. As I said before, I can't reasonably suspect anybody."

"Very well; we will get to Chancery Lane now, if you please, and you can tell me more as we go."

"I have a cab waiting. What else can I tell you?"

"I understand the position to be succinctly this: the drawings were in the office when you arrived. Nobody came out, and nobody went in; and yet they vanished. Is that so?"

"That is so. When I say that absolutely[Pg 565] nobody came in, of course I except the postman. He brought a couple of letters during the morning. I mean that absolutely nobody came past the barrier in the outer office—the usual thing, you know, like a counter, with a frame of ground glass over it."

"I quite understand that. But I think you said that the drawings were in a drawer in your own room—not the outer office, where the draughtsmen are, I presume?"

"That is the case. It is an inner room, or, rather, a room parallel with the other, and communicating with it; just as your own room is, which we have just left."

"But then, you say you never left your office, and yet the drawings vanished—apparently by some unseen agency—while you were there, in the room?"

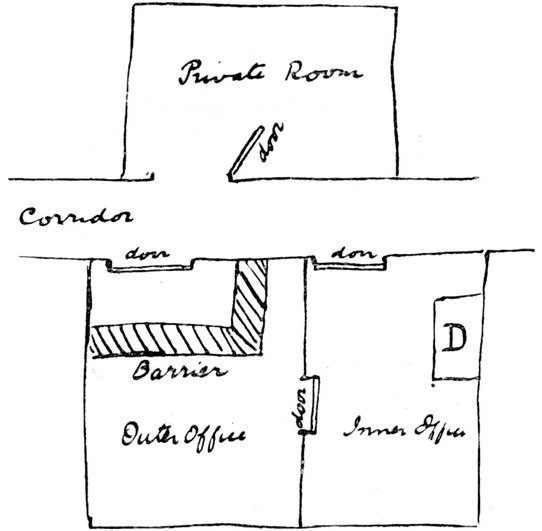

"Let me explain more clearly." The cab was bowling smoothly along the Strand, and the engineer took out a pocket-book and pencil. "I fear," he proceeded, "that I am a little confused in my explanation—I am naturally rather agitated. As you will see presently, my offices consist of three rooms, two at one side of a corridor, and the other opposite: thus." He made a rapid pencil sketch.

"In the outer office my men usually work. In the inner office I work myself. These rooms communicate, as you see, by a door. Our ordinary way in and out of the place is by the door of the outer office leading into the corridor, and we first pass through the usual lifting flap in the barrier. The door leading from the inner office to the corridor is always kept locked on the inside, and I don't suppose I unlock it once in three months. It has not been unlocked all the morning. The drawer in which the missing drawings were kept, and in which I saw them at ten o'clock this morning, is at the place marked D—it is a large chest of shallow drawers, in which the plans lie flat."

"I quite understand. Then there is the private room opposite. What of that?"

"That is a sort of private sitting-room that I rarely use, except for business interviews of a very private nature. When I said I never left my office I did not mean that I never stirred out of the inner office. I was about in one room and another, both the outer and the inner offices, and once I went into the private room for five minutes, but nobody came either in or out of any of the rooms at that time, for the door of the private room was wide open and I was standing at the book-case (I had gone to consult a book), just inside the door, with a full view of the doors opposite. Indeed, Worsfold was at the door of the outer office most of the short time. He came to ask me a question."

"Well," Hewitt replied, "it all comes to the simple first statement. You know that nobody left the place or arrived, except the postman, who couldn't get near the drawings, and yet the drawings went. Is this your office?"

The cab had stopped before a large stone building. Mr. Dixon alighted and led the way to the first floor. Hewitt took a casual glance round each of the three rooms. There was a sort of door in the frame of ground glass over the barrier, to admit of speech with visitors. This door Hewitt pushed wide open, and left so.

He and the engineer went into the inner office. "Would you like to ask Worsfold and Ritter any questions?" Mr. Dixon inquired.

"Presently. Those are their coats, I take it, hanging just to the right of the outer office door, over the umbrella stand?"

"Yes, those are all their things—coats, hats, stick, and umbrella."

"And those coats were searched, you say?"

"Yes."

"And this is the drawer—thoroughly searched, of course?"

"Oh, certainly, every drawer was taken out and turned over."

"Well, of course, I must assume you made no mistake in your hunt. Now tell me, did[Pg 566] anybody know where these plans were, beyond yourself and your two men?"

"I WAS STANDING AT THE BOOKCASE."

"As far as I can tell, not a soul."

"You don't keep an office-boy?"

"No. There would be nothing for him to do except to post a letter now and again, which Ritter does quite well for."

"As you are quite sure that the drawings were there at ten o'clock, perhaps the thing scarcely matters. But I may as well know if your men have keys of the office?"

"Neither. I have patent locks to each door and I keep all the keys myself. If Worsfold or Ritter arrive before me in the morning, they have to wait to be let in; and I am always present myself when the rooms are cleaned. I have not neglected precautions, you see."

"No. I suppose the object of the theft—assuming it is a theft—is pretty plain: the thief would offer the drawings for sale to some foreign Government?"

"Of course. They would probably command a great sum. I have been looking, as I need hardly tell you, to that invention to secure me a very large fortune, and I shall be ruined, indeed, if the design is taken abroad. I am under the strictest engagements to secrecy with the Admiralty, and not only should I lose all my labour, but I should lose all the confidence reposed in me at headquarters should, in fact, be subject to penalties for breach of contract, and my career stopped for ever. I cannot tell you what a serious business this is for me. If you cannot help me, the consequences will be terrible. Bad for the service of the country, too, of course."

"Of course. Now tell me this. It would, I take it, be necessary for the thief to exhibit these drawings to anybody anxious to buy the secret—I mean, he couldn't describe the invention by word of mouth?"

"Oh, no, that would be impossible. The drawings are of the most complicated description, and full of figures upon which the whole thing depends. Indeed, one would have to be a skilled expert properly to appreciate the design at all. Various principles of hydrostatics, chemistry, electricity, and pneumatics are most delicately manipulated and adjusted, and the smallest error or omission in any part would upset the whole. No, the drawings are necessary to the thing, and they are gone."

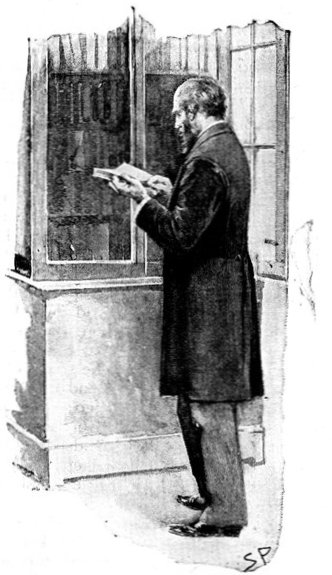

At this moment the door of the outer office was heard to open, and somebody entered. The door between the two offices was ajar, and Hewitt could see right through to the glass door left open over the barrier, and into the space beyond. A well-dressed, dark, bushy-bearded man stood there carrying a hand-bag, which he placed on the ledge before him. Hewitt raised his hand to enjoin silence. The man spoke in a rather high-pitched voice and with a slight accent. "Is Mr. Dixon now within?" he asked.

"He is engaged," answered one of the draughtsmen; "very particularly engaged. I'm afraid you won't be able to see him this afternoon. Can I give him any message?"

"This is two—the second time I have come to-day. Not two hours ago Mr. Dixon himself tells me to call again. I have a very important—very excellent steam-packing to show him that is very cheap and the best of the market." The man tapped his bag. "I have just taken orders from the largest railway companies. Cannot I see him, for one second only? I will not detain him."

"Really, I'm sure you can't this afternoon—he isn't seeing anybody. But if you'll leave your name——"

"My name is Hunter; but what the good of that? He ask me to call a little later and I come, and now he is engaged. It is a very great pity." And the man snatched up his bag and walking-stick and stalked off indignantly.

Hewitt stood still, gazing through the small aperture in the doorway.

"You'd scarcely expect a man with such a name as Hunter to talk with that accent, would you?" he observed, musingly. "It isn't a French accent, nor a German; but it seems foreign. You don't happen to know him, I suppose?"

"No, I don't. He called here about half-past twelve, just while we were in the middle of our search and I was frantic over the loss of the drawings. I was in the outer office myself, and told him to call later. I have lots of such agents here, anxious to sell all sorts of engineering appliances. But what will you do now? Shall you see my men?"

"I think," said Hewitt, rising, "I think I'll get you to question them yourself."

"Myself?"

"Yes, I have a reason. Will you trust me with the key of the private room opposite? I will go over there for a little, while you talk to your men in this room. Bring them in here and shut the door—I can look after the office from across the corridor, you know. Ask them each to detail his exact movements about the office this morning, and get them to recall each visitor who has been here from the beginning of the week. I'll let you know the reason of this later. Come across to me in a few minutes."

Hewitt took the key and passed through the outer office into the corridor.

Ten minutes later, Mr. Dixon, having questioned his draughtsmen, followed him. He found Hewitt standing before the table in the private room, on which lay several drawings on tracing-paper.

"See here, Mr. Dixon," said Hewitt, "I think these are the drawings you are anxious about?"

"MY NAME IS HUNTER."

The engineer sprang toward them with a cry of delight. "Why, yes, yes," he exclaimed, turning them over, "every one of them. But where—how—they must have been in the place after all, then? What a fool I have been!"

Hewitt shook his head. "I'm afraid you're not quite so lucky as you think, Mr. Dixon," he said. "These drawings have most certainly been out of the house for a little while. Never mind how—we'll talk of that after. There is no time to lose. Tell me, how long would it take a good draughtsman to copy them?"

"They couldn't possibly be traced over properly in less than two or two and a half long days of very hard work," Dixon replied, with eagerness.

"Ah! then, it is as I feared. These tracings have been photographed, Mr. Dixon, and our task is one of every possible difficulty. If they had been copied in the ordinary way, one might hope to get hold of the copy. But photography upsets everything. Copies can be multiplied with such amazing facility that, once the thief gets a decent start, it is almost hopeless to checkmate him. The only chance is to get at the negatives before copies are taken. I must act at once; and I fear, between ourselves, it may be necessary for me to step very distinctly over the line of the law in the matter. You see, to get at those negatives may involve something very like housebreaking. There must be no delay—no waiting for legal procedure—or the mischief is done. Indeed, I very much question whether you have any legal remedy, strictly speaking."

"Mr. Hewitt, I implore you, do what you can. I need not say that all I have is at your disposal. I will guarantee to hold you harmless for anything that may happen. But do, I entreat you, do everything possible. Think of what the consequences may be!"

"Well, yes, so I do," Hewitt remarked, with a smile. "The consequences to me, if I were charged with housebreaking, might be something that no amount of guarantee could mitigate. However, I will do what I can, if only from patriotic motives. Now, I must see your tracer, Ritter. He is the traitor in the camp."

"Ritter? But how?"

"Never mind that now. You are upset and agitated, and had better not know more than necessary for a little while, in case you say or do something unguarded. With Ritter I must take a deep course; what I don't know I must appear to know, and that will seem more likely to him if I disclaim acquaintance with what I do know. But first put these tracings safely away out of sight."

Dixon slipped them behind his book-case.

"Now," Hewitt pursued, "call Mr. Worsfold and give him something to do that will keep him in the inner office across the way, and tell him to send Ritter here."

Mr. Dixon called his chief draughtsman and requested him to put in order the drawings in the drawers of the inner room that had been disarranged by the search, and to send Ritter, as Hewitt had suggested.

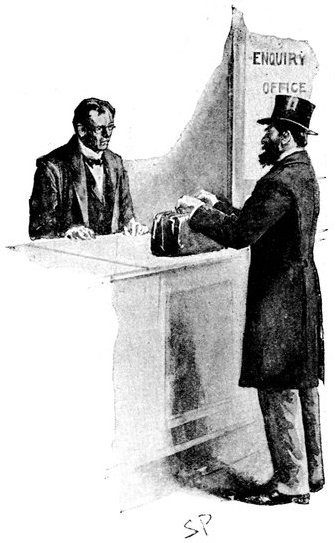

Ritter walked into the private room, with an air of respectful attention. He was a puffy-faced, unhealthy-looking young man, with very small eyes and a loose, mobile mouth.

"SIT DOWN, MR. RITTER."

"Sit down, Mr. Ritter," Hewitt said, in a stern voice. "Your recent transactions with your friend, Mr. Hunter, are well known both to Mr. Dixon and myself."

Ritter, who had at first leaned easily back in his chair, started forward at this, and paled.

"You are surprised, I observe; but you should be more careful in your movements out of doors if you do not wish your acquaintances to be known. Mr. Hunter, I believe, has the drawings which Mr. Dixon has lost, and, if so, I am certain that you have given them to him. That, you know, is theft, for which the law provides a severe penalty."

Ritter broke down completely and turned appealingly to Mr. Dixon:—

"Oh, sir," he pleaded, "it isn't so bad, I assure you. I was tempted, I confess, and hid the drawings; but they are still in the office, and I can give them to you—really, I can."

"Indeed?" Hewitt went on. "Then, in that case, perhaps you'd better get them at once. Just go and fetch them in—we won't trouble to observe your hiding-place. I'll only keep this door open, to be sure you don't lose your way, you know—down the stairs, for instance."

The wretched Ritter, with hanging head, slunk into the office opposite. Presently he reappeared, looking, if possible, ghastlier than before. He looked irresolutely down the corridor, as if meditating a run for it, but Hewitt stepped toward him and motioned him back to the private room.

"You mustn't try any more of that sort of humbug," Hewitt said, with increased severity. "The drawings are gone, and you have stolen them—you know that well enough. Now attend to me. If you received your deserts, Mr. Dixon would send for a policeman this moment, and have you hauled off to the gaol that is your proper place. But, unfortunately, your accomplice, who calls himself Hunter—but who has other names beside that, as I happen to know—has the drawings, and it is absolutely[Pg 569] necessary that these should be recovered. I am afraid that it will be necessary, therefore, to come to some arrangement with this scoundrel—to square him, in fact. Now, just take that pen and paper, and write to your confederate as I dictate. You know the alternative if you cause any difficulty."

Ritter reached tremblingly for the pen.

"Address him in your usual way," Hewitt proceeded. "Say this: 'There has been an alteration in the plans.' Have you got that? 'There has been an alteration in the plans. I shall be alone here at six o'clock. Please come, without fail.' Have you got it? Very well, sign it, and address the envelope. He must come here, and then we may arrange matters. In the meantime, you will remain in the inner office opposite."

The note was written, and Martin Hewitt, without glancing at the address, thrust it into his pocket. When Ritter was safely in the inner office, however, he drew it out and read the address. "I see," he observed, "he uses the same name, Hunter; 27, Little Carton Street, Westminster, is the address, and there I shall go at once with the note. If the man comes here, I think you had better lock him in with Ritter, and send for a policeman—it may at least frighten him. My object is, of course, to get the man away, and then, if possible, to invade his house, in some way or another, and steal or smash his negatives if they are there and to be found. Stay here, in any case, till I return. And don't forget to lock up those tracings."

It was about six o'clock when Hewitt returned, alone, but with a smiling face that told of good fortune at first sight.

"First, Mr. Dixon," he said, as he dropped into an easy chair in the private room, "let me ease your mind by the information that I have been most extraordinarily lucky—in fact, I think you have no further cause for anxiety. Here are the negatives. They were not all quite dry when I—well, what?—stole them, I suppose I must say; so that they have stuck together a bit, and probably the films are damaged. But you don't mind that, I suppose?"

He laid a small parcel, wrapped in newspaper, on the table. The engineer hastily tore away the paper and took up five or six glass photographic negatives, of the half-plate size, which were damp, and stuck together by the gelatine films, in couples. He held them, one after another, up to the light of the window, and glanced through them. Then, with a great sigh of relief, he placed them on the hearth and pounded them to dust and fragments with the poker.

For a few seconds neither spoke. Then Dixon, flinging himself into a chair, said:—

"Mr. Hewitt, I can't express my obligation to you. What would have happened if you had failed I prefer not to think of. But what shall we do with Ritter now? The other man hasn't been here yet, by-the-bye."

"No—the fact is, I didn't deliver the letter. The worthy gentleman saved me a world of trouble by taking himself out of the way." Hewitt laughed. "I'm afraid he has rather got himself into a mess by trying two kinds of theft at once, and you may not be sorry to hear that his attempt on your torpedo plans is likely to bring him a dose of penal servitude for something else. I'll tell you what has happened.

"Little Carton Street, Westminster, I found to be a seedy sort of place—one of those old streets that have seen much better days. A good many people seem to live in each house—they are fairly large houses, by the way—and there is quite a company of bell-handles on each doorpost—all down the side, like organ-stops. A barber had possession of the ground-floor front of No. 27 for trade purposes, so to him I went. 'Can you tell me,' I said, 'where in this house I can find Mr. Hunter?' He looked doubtful, so I went on: 'His friend will do, you know—I can't think of his name; foreign gentleman, dark, with a bushy beard.'

"The barber understood at once. 'Oh, that's Mirsky, I expect,' he said. 'Now I come to think of it, he has had letters addressed to Hunter once or twice—I've took 'em in. Top floor back.'

"This was good, so far. I had got at 'Mr. Hunter's' other alias. So, by way of possessing him with the idea that I knew all about him, I determined to ask for him as Mirsky, before handing over the letter addressed to him as Hunter. A little bluff of that sort is invaluable at the right time. At the top floor back I stopped at the door and tried to open it at once, but it was locked. I could hear somebody scuttling about within, as though carrying things about, and I knocked again. In a little while the door opened about a foot, and there stood Mr. Hunter—or Mirsky, as you like—the man who, in the character of a traveller in steam-packing, came here twice to-day. He was in his shirt sleeves and cuddled something under his arm, hastily covered with a spotted pocket-handkerchief.

"'I have called to see M. Mirsky,' I said, 'with a confidential letter ——.'

"'Oh, yas, yas,' he answered, hastily; 'I know—I know. Excuse me one minute.' And he rushed off downstairs with his parcel.

"Here was a noble chance. For a moment I thought of following him, in case there might be anything interesting in the parcel. But I had to decide in a moment, and I decided on trying the room. I slipped inside the door, and, finding the key on the inside, locked it. It was a confused sort of room, with a little iron bedstead in one corner and a sort of rough boarded inclosure in another. This I rightly conjectured to be the photographic darkroom, and made for it at once.

"There was plenty of light within when the door was left open, and I made at once for the drying-rack that was fastened over the sink. There were a number of negatives in it, and I began hastily examining them one after another. In the middle of this, our friend Mirsky returned and tried the door. He rattled violently at the handle and pushed. Then he called.

"At this moment I had come upon the first of the negatives you have just smashed. The fixing and washing had evidently only lately been completed, and the negative was drying on the rack. I seized it, of course, and the others which stood by it.

"'Who are you, there, inside?' Mirsky shouted indignantly from the landing. 'Why for you go in my room like that? Open this door at once, or I call the police!'

"I took no notice. I had got the full number of negatives, one for each drawing, but I was not by any means sure that he had not taken an extra set; so I went on hunting down the rack. There were no more, so I set to work to turn out all the undeveloped plates. It was quite possible, you see, that the other set, if it existed, had not yet been developed.

"I HAVE CALLED TO SEE M. MIRSKY."

"Mirsky changed his tune. After a little more banging and shouting, I could hear him kneel down and try the keyhole. I had left the key there, so that he could see nothing. But he began talking softly and rapidly through the hole in a foreign language. I did not know it in the least, but I believe it was Russian. What had led him to believe I understood Russian I could not at the time imagine, though I have a notion now. I went on ruining his stock of plates. I found several boxes, apparently of new plates, but, as there was no means of telling whether they were really unused or were merely undeveloped, but with the chemical impress of your drawings on them, I dragged every one ruthlessly from its hiding-place and laid it out in the full glare of the sunlight—destroying it thereby, of course, whether it was unused or not.

"Mirsky left off talking, and I heard him quietly sneaking off. Perhaps his conscience was not sufficiently clear to warrant an appeal to the police, but it seemed to me rather probable at the time that that was what he was going for. So I hurried on with my work. I found three dark slides—the parts that carry the plates in the back of the camera, you know—one of them fixed in the camera itself. These I opened, and exposed the plates to ruination as before. I suppose nobody ever did so much devastation in a photographic studio in ten minutes as I managed.

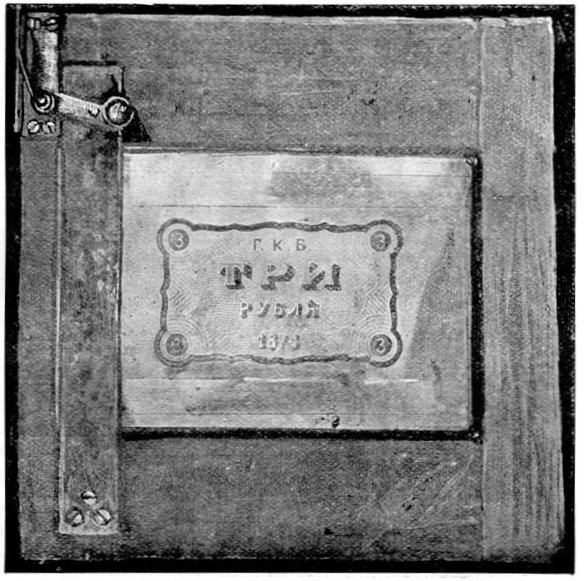

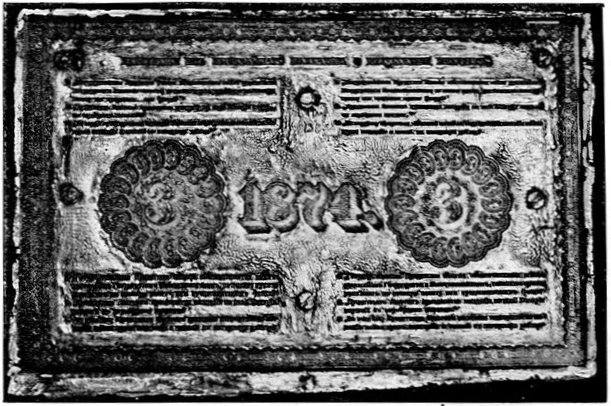

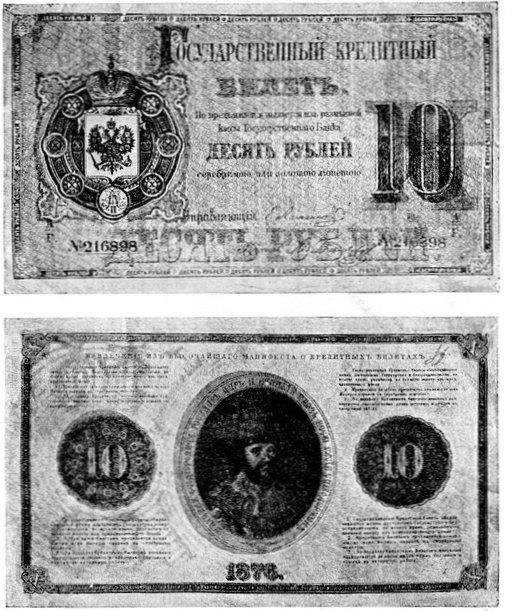

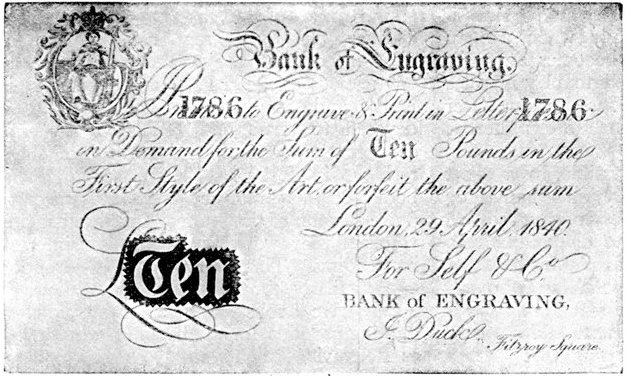

"I had spoilt every plate I could find and had the developed negatives safely in my pocket, when I happened to glance at a porcelain washing-well under the sink. There was one negative in that, and I took it up. It was not a negative of a drawing[Pg 571] of yours, but of a Russian twenty-rouble note!

"HE BEGAN TALKING SOFTLY AND RAPIDLY."

"This was a discovery. The only possible reason any man could have for photographing a bank-note was the manufacture of an etched plate for the production of forged copies. I was almost as pleased as I had been at the discovery of your negatives. He might bring the police now as soon as he liked; I could turn the tables on him completely. I began to hunt about for anything else relating to this negative.

"I found an inking-roller, some old pieces of blanket (used in printing from plates), and in a corner on the floor, heaped over with newspapers and rubbish, a small copying-press. There was also a dish of acid, but not an etched plate or a printed note to be seen. I was looking at the press, with the negative in one hand and the inking-roller in the other, when I became conscious of a shadow across the window. I looked up quickly, and there was Mirsky, hanging over from some ledge or projection to the side of the window, and staring straight at me, with a look of unmistakable terror and apprehension.

"The face vanished immediately. I had to move a table to get at the window, and by the time I had opened it, there was no sign or sound of the rightful tenant of the room. I had no doubt now of his reason for carrying a parcel downstairs. He probably mistook me for another visitor he was expecting, and, knowing he must take this visitor into his room, threw the papers and rubbish over the press, and put up his plates and papers in a bundle and secreted them somewhere downstairs, lest his occupation should be observed.

"Plainly, my duty now was to communicate with the police. So, by the help of my friend the barber downstairs, a messenger was found and a note sent over to Scotland Yard. I awaited, of course, for the arrival of the police, and occupied the interval in another look round—finding nothing important, however. When the official detective arrived he recognised at once the importance of the case. A large number of forged Russian notes have been put into circulation on the Continent lately, it seems, and it was suspected that they came from London. The Russian Government have been sending urgent messages to the police here on the subject.

"Of course I said nothing about your business; but while I was talking with the Scotland Yard man a letter was left by a messenger, addressed to Mirsky. The letter will be examined, of course, by the proper authorities, but I was not a little interested to perceive that the envelope bore the Russian Imperial arms above the words, 'Russian Embassy.' Now, why should Mirsky communicate with the Russian Embassy? Certainly not to let the officials know that he was carrying on a very extensive and lucrative business in the manufacture of spurious Russian notes. I think it is rather more than possible that he wrote—probably before he actually got your drawings—to say that he could sell information of the highest importance, and that this letter was a reply. Further, I think it quite possible that, when I asked for him by his Russian name and spoke of 'a confidential letter,' he at once concluded that I had come from the Embassy in answer to his letter. That would account for his addressing me in Russian through the keyhole; and, of course, an official from the Russian Embassy would be the very last person[Pg 572] in the world whom he would like to observe any indications of his little etching experiments. But anyhow, be that as it may," Hewitt concluded, "your drawings are safe now, and if once Mirsky is caught—and I think it likely, for a man in his shirt-sleeves, with scarcely any start and, perhaps, no money about him, hasn't a great chance to get away—if he is caught, I say, he will probably get something handsome at St. Petersburg in the way of imprisonment, or Siberia, or what-not; so that you will be amply avenged."

"Yes, but I don't at all understand this business of the drawings even now. How in the world were they taken out of the place, and how in the world did you find it out?"

"Nothing could be simpler; and yet the plan was rather ingenious. I'll tell you exactly how the thing revealed itself to me. From your original description of the case, many people would consider that an impossibility had been performed. Nobody had gone out and nobody had come in, and yet the drawings had been taken away. But an impossibility is an impossibility after all, and as drawings don't run away of themselves, plainly somebody had taken them, unaccountable as it might seem. Now, as they were in your inner office, the only people who could have got at them beside yourself were your assistants, so that it was pretty clear that one of them, at least, had something to do with the business. You told me that Worsfold was an excellent and intelligent draughtsman. Well, if such a man as that meditated treachery, he would probably be able to carry away the design in his head—at any rate, a little at a time—and would be under no necessity to run the risk of stealing a set of the drawings. But Ritter, you remarked, was an inferior sort of man, 'not particularly smart,' I think, were your words—only a mechanical sort of tracer. He would be unlikely to be able to carry in his head the complicated details of such designs as yours, and, being in a subordinate position, and continually overlooked, he would find it impossible to make copies of the plans in the office. So that, to begin with, I thought I saw the most probable path to start on.

"When I looked round the rooms I pushed open the glass door of the barrier and left the door to the inner office ajar, in order to be able to see anything that might happen in any part of the place, without actually expecting any definite development. While we were talking, as it happened, our friend Mirsky (or Hunter—as you please) came into the outer office, and my attention was instantly called to him by the first thing he did. Did you notice anything peculiar yourself?"

"No, really I can't say I did. He seemed to behave much as any traveller or agent might."

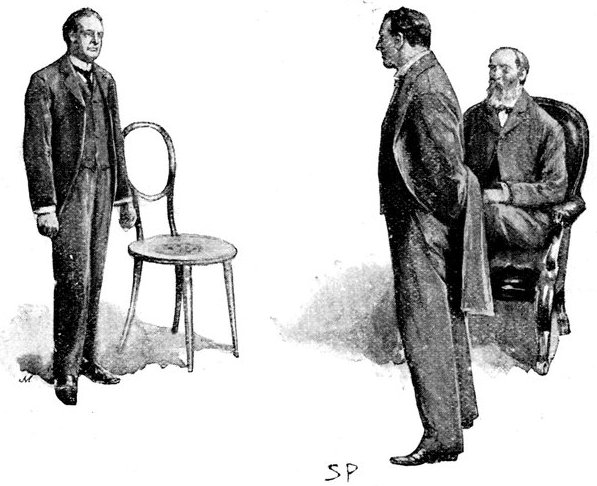

"Well, what I noticed was the fact that as soon as he entered the place he put his walking-stick into the umbrella stand, over there by the door, close by where he stood; a most unusual thing for a casual caller to do, before even knowing whether you were in. This made me watch him closely. I perceived, with increased interest, that the stick was exactly of the same kind and pattern as one already standing there; also a curious thing. I kept my eyes carefully on those sticks, and was all the more interested and edified to see, when he left, that he took the other stick—not the one he came with—from the stand, and carried it away, leaving his own behind. I might have followed him, but I decided that more could be learnt by staying—as, in fact, proved to be the case. This, by-the-bye, is the stick he carried away with him. I took the liberty of fetching it back from Westminster, because I conceive it to be Ritter's property."

Hewitt produced the stick. It was an ordinary, thick Malacca cane, with a buckhorn handle and a silver band. Hewitt bent it across his knee, and laid it on the table.

"Yes," Dixon answered, "that is Ritter's stick. I think I have often seen it in the stand. But what in the world——"

"One moment; I'll just fetch the stick Mirsky left behind." And Hewitt stepped across the corridor.

He returned with another stick, apparently an exact facsimile of the other, and placed it by the side of the other.

"When your assistants went into the inner room, I carried this stick off for a minute or two. I knew it was not Worsfold's, because there was an umbrella there with his initial on the handle. Look at this."

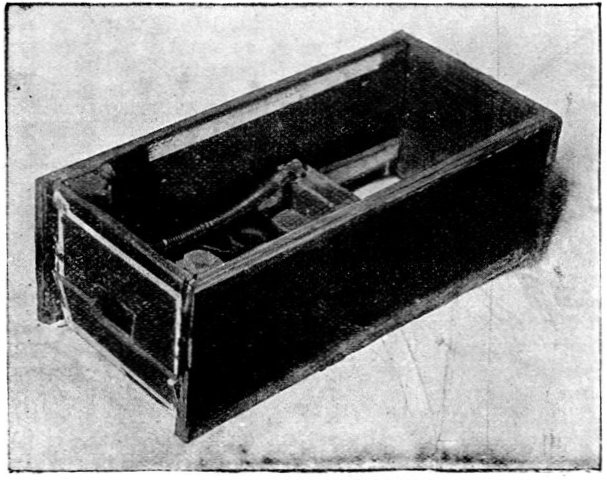

Martin Hewitt gave the handle a twist, and rapidly unscrewed it from the top. Then it was seen that the stick was a mere tube of very thin metal, painted to appear like a Malacca cane.

"It was plain at once that this was no Malacca cane—it wouldn't bend. Inside it I found your tracings, rolled up tightly. You can get a marvellous quantity of thin tracing-paper into a small compass by tight rolling."

"And this—this was the way they were[Pg 573] brought back!" the engineer exclaimed. "I see that, clearly. But how did they get away? That's as mysterious as ever."

"HEWITT PRODUCED THE STICK."

"Not a bit of it. See here. Mirsky gets hold of Ritter, and they agree to get your drawings and photograph them. Ritter is to let his confederate have the drawings, and Mirsky is to bring them back as soon as possible, so that they shan't be missed for a moment. Ritter habitually carries this Malacca cane, and the cunning of Mirsky at once suggests that this tube should be made in outward facsimile. This morning, Mirsky keeps the actual stick and Ritter comes to the office with the tube. He seizes the first opportunity—probably when you were in this private room, and Worsfold was talking to you from the corridor—to get at the tracings, roll them up tightly, and put them in the tube, putting the tube back into the umbrella stand. At half-past twelve, or whenever it was, Mirsky turns up for the first time with the actual stick and exchanges them, just as he afterwards did when he brought the drawings back."

"Yes, but Mirsky came half an hour after they were—oh, yes, I see. What a fool I was! I was forgetting. Of course, when I first missed the tracings they were in this walking-stick, safe enough, and I was tearing my hair out within arm's reach of them!"

"Precisely. And Mirsky took them away before your very eyes. I expect Ritter was in a rare funk when he found that the drawings were missed. He calculated, no doubt, on your not wanting them for the hour or two they would be out of the office."

"How lucky that it struck me to jot a pencil-note on one of them! I might easily have made my note somewhere else, and then I should never have known that they had been away."

"Yes, they didn't give you any too much time to miss them. Well, I think the rest's pretty clear. I brought the tracings in here, screwed up the sham stick and put it back. You identified the tracings and found none missing, and then my course was pretty clear, though it looked difficult. I knew you would be very naturally indignant with Ritter, so, as I wanted to manage him myself, I told you nothing of what he had actually done, for fear that, in your agitated state, you might burst out with something that would spoil my game. To Ritter I pretended to know nothing of the return of the drawings or how they had been stolen—the only things I did know with certainty. But I did pretend to know all about Mirsky—or Hunter—when, as a matter of fact, I knew nothing at all, except that he probably went under more than one name. That put Ritter into my[Pg 574] hands completely. When he found the game was up he began with a lying confession. Believing that the tracings were still in the stick and that we knew nothing of their return, he said that they had not been away, and that he would fetch them—as I had expected he would. I let him go for them alone, and when he returned, utterly broken up by the discovery that they were not there, I had him altogether at my mercy. You see, if he had known that the drawings were all the time behind your book-case, he might have brazened it out, sworn that the drawings had been there all the time, and we could have done nothing with him. We couldn't have sufficiently frightened him by a threat of prosecution for theft, because there the things were, in your possession, to his knowledge.

"As it was, he answered the helm capitally: gave us Mirsky's address on the envelope, and wrote the letter that was to have got him out of the way while I committed burglary, if that disgraceful expedient had not been rendered unnecessary. On the whole, the case has gone very well."

"It has gone marvellously well, thanks to yourself. But what shall I do with Ritter?"

"Here's his stick—knock him downstairs with it, if you like. I should keep the tube, if I were you, as a memento. I don't suppose the respectable Mirsky will ever call to ask for it. But I should certainly kick Ritter out of doors—or out of window, if you like—without delay."

"KNOCK HIM DOWNSTAIRS."

Mirsky was caught, and after two remands at the police-court was extradited on the charge of forging Russian notes. It came out that he had written to the Embassy, as Hewitt had surmised, stating that he had certain valuable information to offer, and the letter which Hewitt had seen delivered was an acknowledgment, and a request for more definite particulars. This was what gave rise to the impression that Mirsky had himself informed the Russian authorities of his forgeries. His real intent was very different, but was never guessed.

"I wonder," Hewitt has once or twice observed, "whether, after all, it would not have paid the Russian authorities better on the whole if I had never investigated Mirsky's little note-factory. The Dixon torpedo was worth a good many twenty-rouble notes."

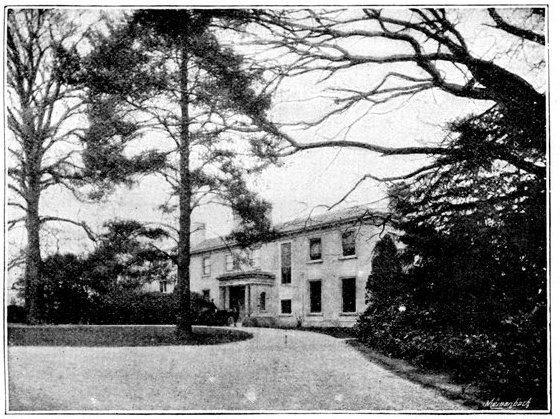

ARLINGTON MANOR

From a Photo by Elliott & Fry.

It would be difficult indeed to single out a more pleasant method of passing a couple of days than with Sir Francis Jeune, Lady Jeune, and their children. It was in the early days of spring that I had this privilege, when, for a brief time, Sir Francis was free from the trials and tribulations of the law, and, together with his family, was enjoying the rest afforded by a short sojourn at his charming house in Berkshire. About a couple of miles from Newbury—rich in reminiscence of the troublesome times associated with the Cromwellian régime—is Arlington Manor. It is a substantially-built country mansion—built of a peculiar species of Bath stone—and no matter from which of its four sides you view the outlook, it is "as fair as fair can be." From one side you can here and there catch sight of a streak of blue sky through a forest of fir trees; from another is a grand stretch of meadows, from which you may often hear the voice of young Francis Christian Seaforth Jeune—Sir Francis's son, who had for his godmother the Princess Christian, and is proud of the fact that he was entered for Harrow before he was four days old—shouting out "Well hit!" at a particularly good drive of the ball by the butler, who happens to be a capital cricketer. Perhaps, however, the view from the veranda is the finest. The lawn is immediately before you; a little series of valleys and hills rise and fall until all is lost in the blue line of hills miles away. It is an ideal spot, and one which must be peculiarly interesting to Sir Francis, owing to its being in the centre of a piece of country closely allied with a period of history in which he is so deeply read. Around the house golf links have been recently laid out. Sir Francis said that I should have been at Arlington and seen a match between Sir Evelyn Wood, Mr. Lockwood, and himself. "The General was the best player," he added, "or, perhaps, I should say, the least bad."

It was on this veranda—with the glorious scene before us—that I met Sir Francis and Lady Jeune. Lady Jeune's two daughters—Miss Madeline Stanley and Miss Dorothy Stanley—were enjoying their first game of croquet of the year. Lady Jeune has been twice married, her first husband being Mr. John Stanley, a brother of Lord Stanley of Alderley. After a time the two young girls joined us. I am well aware that this paper is[Pg 576] to be devoted to Sir Francis and Lady Jeune, but it is impossible to stay one's pen at this point from chronicling an impression formed regarding two of the brightest of sisters. It happened that during my stay at Newbury there was a gymnastic display in the town given by some young women of the class connected with the People's Palace—young women, doubtless, for the most part who know what it is to work, and work hard, for their living. They were entertained to tea at Arlington Manor. The anxiety of the Misses Stanley to make them happy was intense—nothing was forced about it, but all heart-born. I judged Lady Jeune's daughters from the semi-whispered invitations I could not help hearing to many of these young women to "Be sure and come and see us in London, won't you?"—repeated in one case, I know, half-a-dozen times. It is to be hoped that this expression will convey the full meaning with which it struck me.

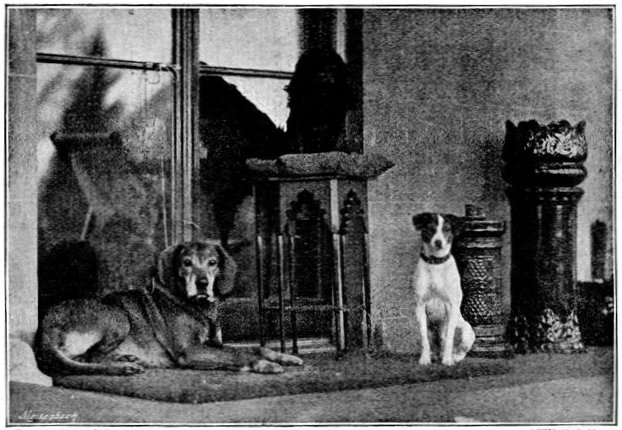

THE DOGS.

From a Photo by Elliott & Fry.

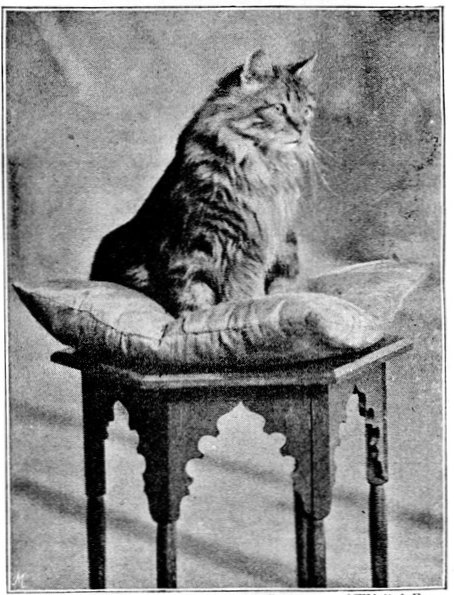

The interior of Arlington Manor is charmingly comfortable. Entering from the veranda—you will probably be followed by one of the quartette of dogs, and even "Randolph," the cat, who has the remarkable feasting record of thirty chickens in a fortnight to be placed to his credit!—you are in the billiard-room. Amongst the engravings of more modern days are those after Sir Joshua Reynolds, Long, and Briton Riviere; but the most noticeable is certainly a very fine set of Hogarth's "Marriage à la Mode." Sir Francis Jeune is a great admirer of Hogarth. Here, too, hangs his card of membership of the Athenæum Club, forming a perfect collection of autographs of as many of the most distinguished men of the day as could possibly get their names on the card which was to "back" Sir Francis's candidature. A huge volume here may be examined with interest. It contains no fewer than seven hundred letters of congratulation which its owner received—and faithfully answered every one—when he was appointed to the judicial vacancy in the Probate, Divorce, and Admiralty Division occasioned by the elevation of Sir James Hannen to the House of Lords. A smaller one is treasured which holds similar letters when Sir Francis was made President of the Division.

"RANDOLPH".

From a Photo by Elliott & Fry.

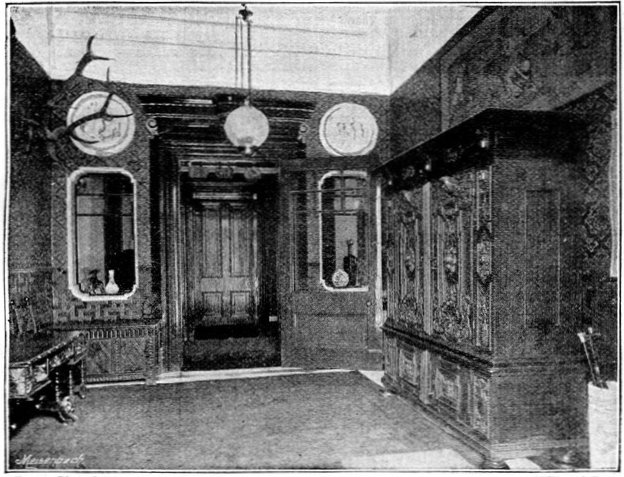

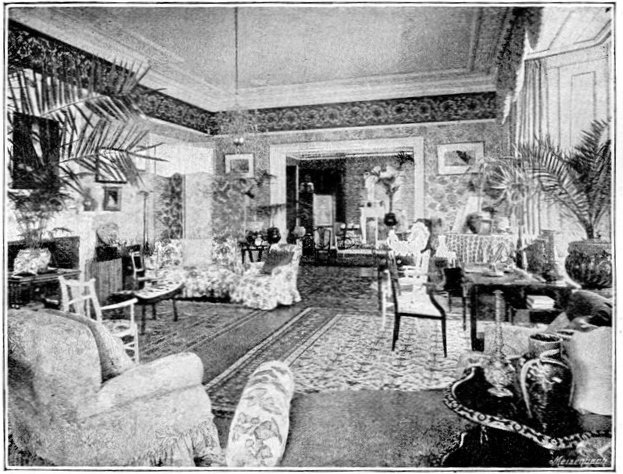

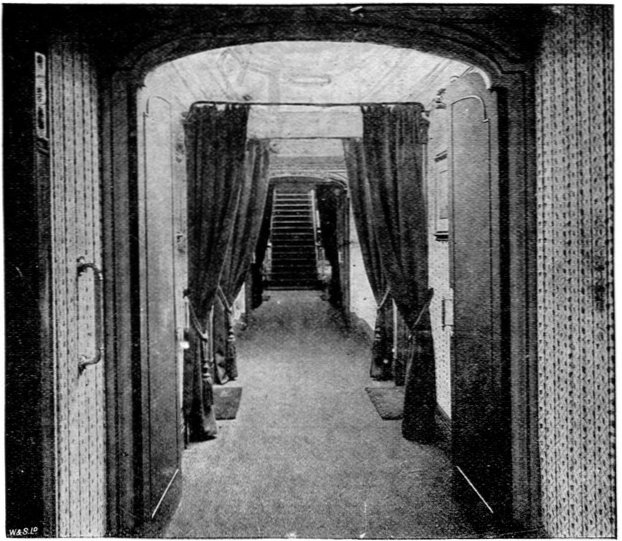

The hall—the entrance to which finds room for a magnificently carved oak cabinet—is very much like the gangway of a ship which leads to the saloon cabins. Indeed, it was constructed on this principle. A[Pg 577] former occupier of Arlington Manor being unable to get out of doors, and being nautically inclined, was wont to walk this hall and imagine he was on board. The first apartment on the right is the drawing-room. It is filled with flowers and portrait reminiscences of friends, whilst its pictures are admirable. There are two very fine pieces of mountain scenery by Lady Canning, a Prout, Loppe—and the old Dutch school is represented. Three pictures, however, are specially interesting. One is a grand Michiel van Mierevelt of Hugo Grotius, and given by him to Oliver Cromwell. It has only been in three or four hands, and was in the possession of an uncle of Sir Francis at the age of ninety-four, and he received it when quite young. It owes its exceptionally fine state of preservation to the fact that it has never been touched by the cleaner—it actually hung in one spot for over sixty years. The other two pictures are over the mantelpieces. One is a copy—the original being at Brahan Castle—of Lady Jeune's great-great-grandmother a daughter of Baron D'Aguilars, and, therefore, a Spanish Jewess, and the other is of Lady Jeune herself, by Miss Thompson.

THE OUTER HALL.

From a Photo by Elliot & Fry.

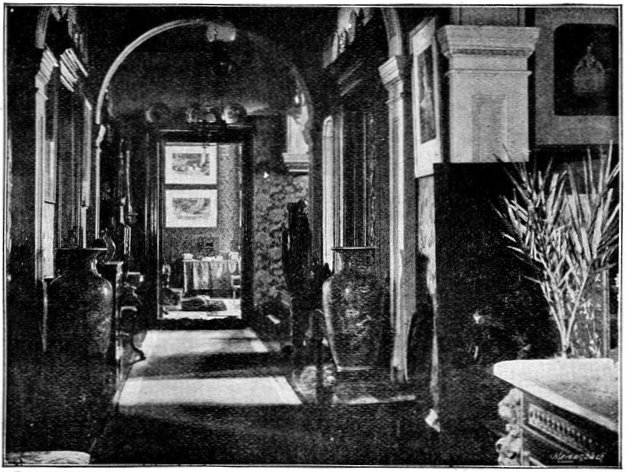

THE INNER HALL.

From a Photo by Elliot & Fry.

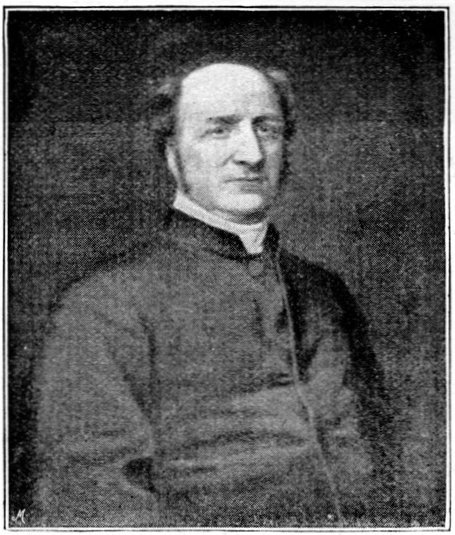

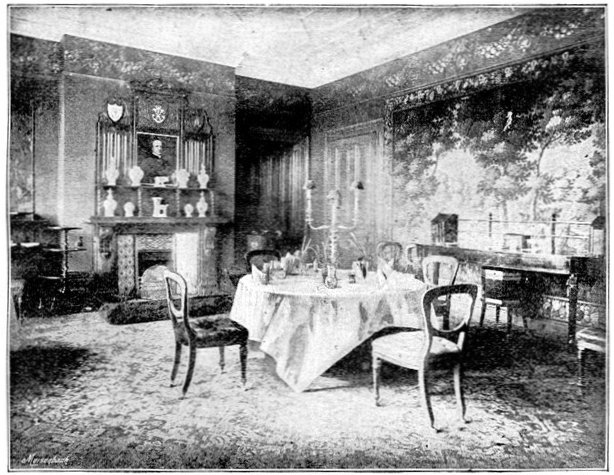

The dining-room is hung with some exquisite tapestry, and in the centre of the oaken mantel-board is a painting of the late Bishop of Peterborough, Sir Francis Jeune's father. Sir Francis's own room upstairs is a very pleasant corner of the house. On a table—in very official-looking boxes, and, indeed, the only suggestion of judicial duties about the place—are the various patents granted to the President, and also those belonging to his father—who was Dean of[Pg 578] Jersey, as well as filling the Episcopal See of Peterborough. Sir Francis merrily points out that the writ accompanying the patent making him a judge expresses in legal phraseology an invitation to pretermit all other business and go to Parliament.

THE DRAWING ROOM.

From a Photo by Elliott & Fry.

"But they wouldn't let me in if I went there," he said.

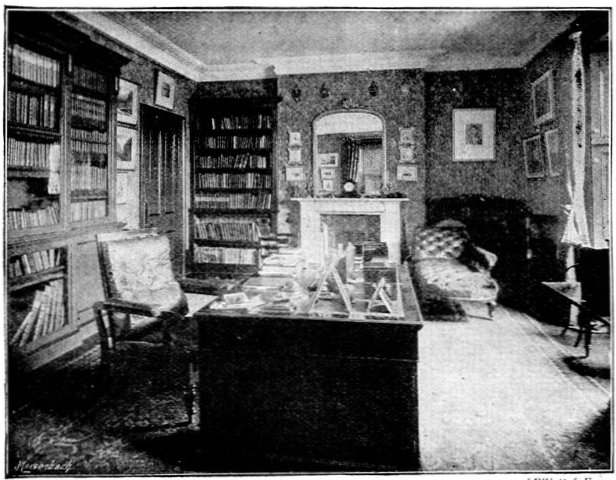

There are a number of beautiful studies by Raphael here. Near the window is a book-case containing many of the prizes Sir Francis won at school and college. We look at them together. Sir Francis takes down from one of the shelves a small volume of "Dodd's Beauties of Shakespeare." It was given to him by Sir George Cornwall Lewis on the occasion of his tenth birthday.

"I value it," said Sir Francis, "because good nature is not a quality generally attributed to Sir George Cornwall Lewis."

There is much, very much, more to look at inside Arlington Manor—and one would like to refer at greater length to its many interior beauties; but the desire to take full advantage of the pleasant opportunity of having a talk with Sir Francis Jeune—and later on with Lady Jeune—leads one to hurry away from the apartments within and settle down in one of the wicker chairs on the veranda and listen to the quietly told story, and the impressive observations of the President of the Probate, Divorce, and Admiralty Division—at his country home.

Sir Francis Jeune is tall—his bearing is erect and stately. His hair is just turning grey—there is never a pleasant twinkle missing out of the immediate vicinity of his eyes. To watch Sir Francis in his court and to observe him in his home results in a conviction that his geniality and justness are as thorough and thoughtful in the one place as in the other. His temperament never seems to alter—he is always kind. He talks enthusiastically and generously about others—particularly his court officials—and quietly and modestly about himself. He has ideas, strong ideas, regarding the law's true administration and the best means of adapting it to the benefit of the public. But all his views are submitted gracefully—he never seeks to cram you with them or to say: "That's it, who can dispute what I say?" I have sat in his court and listened—I have occupied one of the wicker chairs on the veranda in front of the Hampshire Downs and listened, too. It has all amounted to the same thing. He is thoughtful and kind towards all men, both in his actions towards them and his ideas regarding them.

His first words to me, when we settled down to talk, were gratifying indeed.

"I have only been interviewed once before," he said, "and that was only on a small question."

"It is a big one now, Sir Francis—your life."

"Well, it was whilst my father was Dean of Jersey that I was born—on the 17th March, 1843. Though my early years were passed in the atmosphere of the Church, I was never clerically inclined. I was always intended for the Bar, and perhaps it was owing to my parentage that I acquired a practice in ecclesiastical law almost as soon as I was called. My first school was at Mr. Powle's, at Blackheath; then I went to Mr. Penrose's, at Exmouth. It was a school where most Devonshire county boys went—Sir Redvers[Pg 579] Buller left a year before I went, though I was there with his brother. We were admirably taught, and this was the reason why I was placed as high as I could be when I went to Harrow. There I remained for five years—four of which I passed under Dr. Vaughan and the other under Dr. Butler.

"Dr. Vaughan was a man with a most gentle manner and a soft, deliberate voice, and I never saw him agitated. But he was as firm as iron, and a complete specimen of the pussy cat who could always show its claws when disturbed. He was polite to a degree—even, I believe, when flogging a boy!"

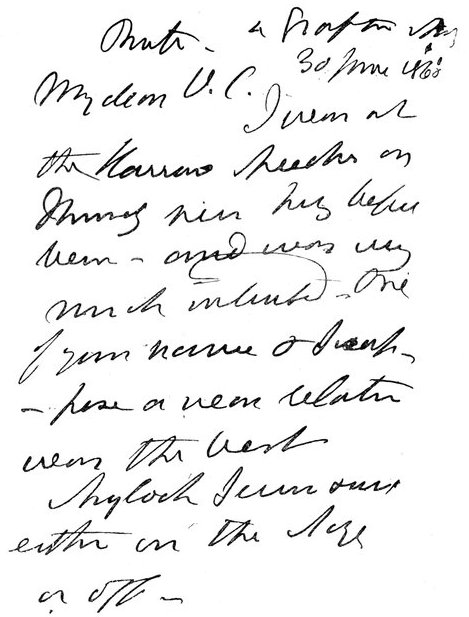

Sir Francis went into the house, and returned very shortly with another volume of letters which he preserves. He turned over the pages, and at last found the one he wanted. It was on blue paper, and the writing was very bad, but its contents were good. It was a letter from the great Lord Brougham to Sir Francis's father, and it told how Brougham had been to Harrow on Speech Day, and seen one of the best Shylocks on or off the stage played by the President in embryo.

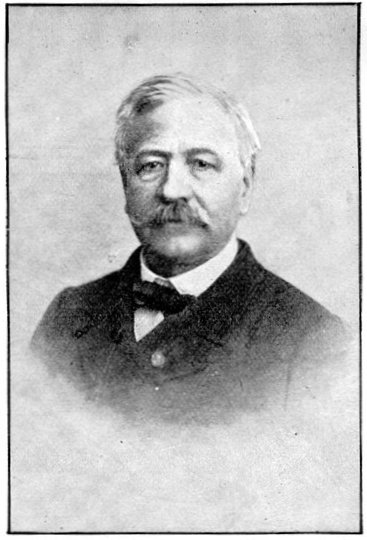

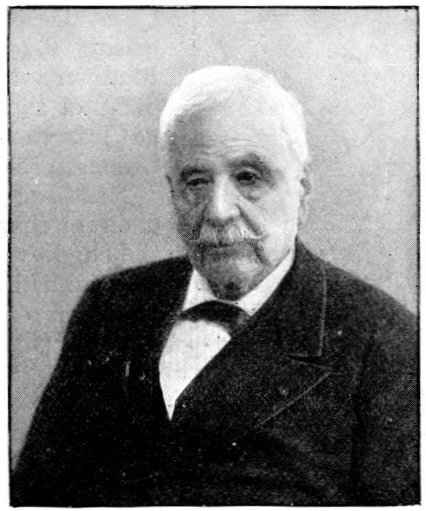

SIR FRANCIS JEUNE'S FATHER.

From a Painting.

Young Jeune did well at Harrow, and he is remembered there to-day, for on every successive advancement in life that has befallen him, the Harrow boys have had a holiday—and not a few either. Young Jeune got many prizes, and crowned his Harrow days by winning the Balliol Scholarship. He matriculated the day on which the Prince Consort was buried. He was at Balliol when Jowett was in his prime.

"He had very strong characteristics," continued Sir Francis, "and his extreme love for Boswell's 'Life of Johnson' was remarkable. He knew it better than any man, and was always quoting it. I remember just before I went up for my final he asked me if I was nervous. I told him rather so. He said:—

"'Never mind—you'll do in the schools better than what you think. Remember the story of Dr. Dodd and Dr. Johnson. When Dr. Dodd was in prison he preached a very fine sermon on the Sunday before he was hanged. People went to Johnson and told him they believed he had written it. 'Depend upon it, sir,' said Johnson to one of them, 'depend upon it that a man's faculties are considerably quickened when he is going to be hanged!'"

THE DINING-ROOM.

From a Photo by Elliott & Fry.

THE STUDY.

From a Photo by Elliot & Fry.

Sir Francis did brilliantly at Oxford, gaining both the Stanhope Prize and Arnold Prize. The former gave occasion to an intensely interesting letter from Dean Stanley. Again the volume of letters was consulted, and a few pages further on from Lord Brougham's note was the missive. Sir Francis opened his Stanhope essay with Matthew Arnold's words:—

"I rejoice to see it," said Dr. Arnold, as he stood on one of the arches of the Birmingham railway, and saw the train pass on through the distant hedgerows—"I rejoice to see it, and to think that feudality is gone for ever. It is so great a blessing to think that any one evil is really extinct."

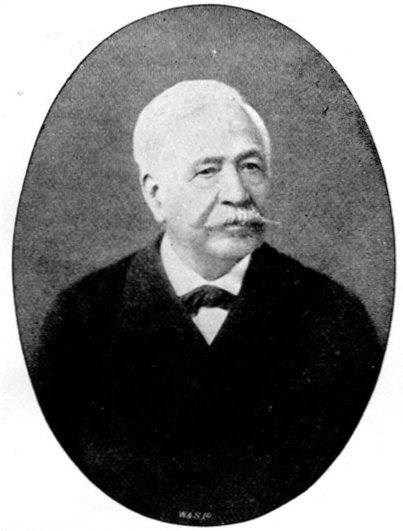

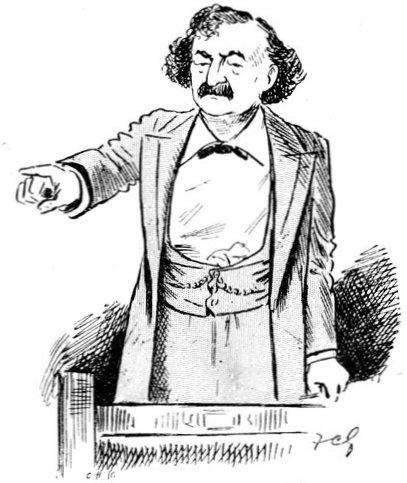

SIR FRANCIS JUENE.

From a Sketch by Harry Furniss.

And this was a most generous, though undoubtedly well-deserved, tribute from Stanley—saying that it was he to whom these words of Dr. Arnold were first addressed.

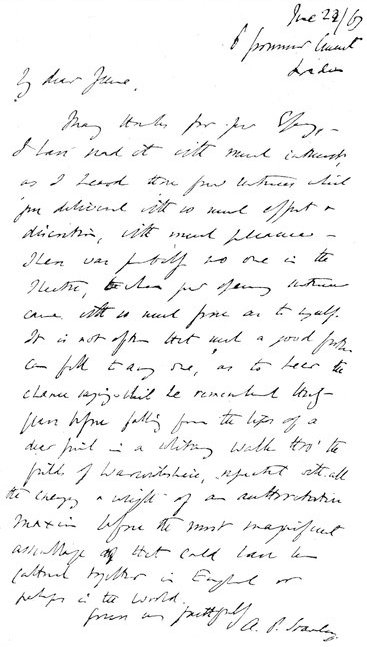

Here is the letter:—

"June 22nd, 1863.

"6, Grosvenor Crescent, London.

"My dear Jeune,—Many thanks for your essay. I have read it with much interest, as I heard those few sentences which you delivered with so much effect and discretion with much pleasure. There was probably no one in the theatre to whom your opening sentences came with so much force as to myself. It is not often that such a good fortune can fall to anyone as to hear the chance sayings which he remembered thirty years before falling from the lips of a dear friend, in a solitary walk through the fields of Warwickshire, repeated with all the energy and weight of an authoritative maxim before the most magnificent assemblage that could have been gathered together in England or perhaps in the world.

"Yours very faithfully,

"A. P. Stanley."

"I left Oxford when I was twenty-one," said Sir Francis, "and proceeded to London immediately and began to study law. Acting under the advice of Lord Westbury, I began by reading in a conveyancer's chambers. I went to Mr. Ebenezer Charles, brother of the present Mr. Justice Charles, a most accomplished lawyer; and happily in the same chambers was Mr. James, afterwards Lord Justice James. James was a brilliant man—but lazy, physically not intellectually, and the pupils had full leave to read his briefs, and tell him their contents and the authorities. His remarks were worth anything to a student. My other legal masters were the great pleaders, Mr. Bullen[Pg 581] and the present Mr. Justice Wills. I was called to the Bar in 1868, but previous to that I went for a year into a solicitor's office, the firm of Baxter, Rose, and Norton. That was worth a great deal to me—the experience gained there was perfectly invaluable. As soon as I was called I was engaged in one very big lawsuit that ran into several years; almost all the great lawyers of the day were connected with it. In that way I not only had excellent employment during my first four years at the Bar, but also made the acquaintance of many eminent barristers."

SIR FRANCIS JEUNE.

From a Photo by Elliott & Fry.

Sir Francis Jeune was for twenty-three years at the Bar, and, when made a judge in 1891, was raised to the Bench with a record that he had been associated with many kinds of legal cases. He participated in much ecclesiastical work—sometimes on one side, and sometimes on the other—when "Ritual" raged strong in the land. He had experience in bankruptcy proceedings, Common Law, Probate and Divorce, and considerable Parliamentary practice fell to his lot.

He did much Privy Council work.

"I frequently held briefs for the Government of Canada, whose general retainer I held, and also other briefs from Canada," said Sir Francis, "and one of these gave rise to a dramatic incident. I was instructed to apply to the Privy Council for leave to appeal on account of some technical flaws in a trial for murder in Canada—the man having been convicted. Whilst I was arguing and hoping to make a good impression on the Court, a telegram was put into my hands. It read: 'So-and-so (the criminal) was hanged by order of the Governor-General at nine o'clock this morning'! It did not seem necessary to continue the argument after that. I recollect my point: it was that the case had never been sent before a grand jury!

"Ballantine! Yes. I was on several occasions associated with him. He was the most brilliant cross-examiner I ever heard—I don't say the best, for he never knew his brief. But his tact and readiness were extraordinary. I remember a divorce suit in which the husband petitioned against the wife. Ballantine and I appeared for the petitioner. The evidence was very much in favour of the wife as given by her maid—a very modest, unassuming girl. It came to Ballantine's turn to cross-examine.

"'What shall I ask her?' he said to me.

"At that moment somebody at the back of the court—I never found out who—whispered to me: 'She had an illegitimate child while in her late mistress's service!'

"I whispered this on to Ballantine, adding that I knew of no ground whatever for the imputation. He got up—and something like the following took place:

"Ballantine: 'I believe something serious happened whilst you were in your late mistress's service?'

"Maid: 'Yes, sir.'

"'Something very serious?'

"'Yes, sir.'

"'I believe you left?'

"'Yes, sir.'

"'When you left, did she mention it to your new mistress?'

"'No, sir.'

"'If she had done so, do you think you would have got your present situation?'

"'No, sir.'

"'If she were to mention it, do you think your mistress would keep you?'

"'No, sir.'

"Ballantine sat down. Sir John Karslake, for the respondent, thought it best not to re-examine, and Lord Hannen, in summing up, remarked that no doubt there might be something in the matter to which Serjeant Ballantine had referred, which might induce the girl to desire to stand well with her mistress, and Sir John Karslake had not felt inclined to re[Pg 582]-examine! We won our case. The real truth, I believe, was that something—some article or the other—had been lost, and the girl was supposed to have been implicated in it.

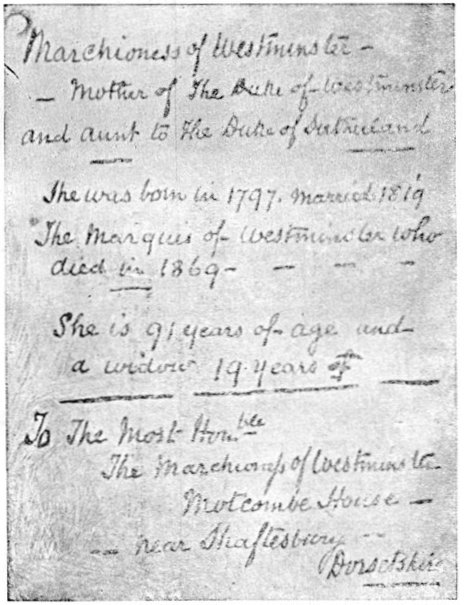

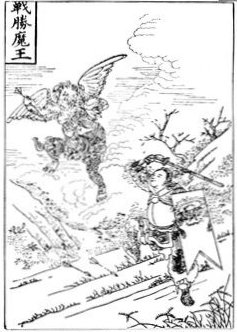

LORD BROUGHAM'S LETTER.

"I have had doubts since whether the tactics were perfectly defensible—but you see the skill. Absolutely nothing was risked, because it would have been easy to retreat if the first answer had been unfavourable. A blundering advocate would have blurted out the offensive suggestion, got an indignant negative, set the judge and jury against him, and been considered a brute.

"Now," suddenly exclaimed Sir Francis, "are you good for a walk to Donnington Castle—we can just do it before luncheon?"

So we started, looking in at the stables on our way, to admire Queen, a purchase of Lady Jeune's, who, by-the-bye, is a capital judge of horseflesh; and Cardinal, so named, as it was bought during the run of "Richelieu" at the Lyceum; the riding ponies of the young ladies, Sir Francis's cob, and a Devonshire pony, recently given to Sir Francis's son by Lord Portsmouth. We stood for a moment at the animals' burying-ground—[Pg 583]about a couple of hundred yards from the house. The greensward round the stones put up to the memory of Fox, a dog who died on July 2, 1892, and poor old Tim, who breathed her last on April 13, 1893, was covered with primroses. Poor old Tim. She was a favourite white cat, whom Sir Francis had had for fifteen years. She died very peacefully in the end. She always waited for her master at the top of the stairs, and, when her days were numbered, just lay down—under Sir Francis's chair in the dining-room—and died.

DEAN STANLEY'S LETTER.

We talked on many things on our way to the famous old castle.

The Ballantine incident led me to ask Sir Francis if he thought counsel were generally fair. "Yes; emphatically yes," he replied. "I have known leading counsel, over and over again, resist great pressure to put forward points they knew were not sound, and to adopt courses of which they did not approve. You will never get law for nothing. I strongly suspect it is as cheap now as ever it will be. It is a great thing to have got rid of technicalities to the extent to which this has been accomplished. The public owe much to Lord Esher's presidency of the Court of Appeal in this matter. You ask me if purely family cases could not be settled at the dining-room table or over the fire. I don't think it possible. No feelings are so bitter as family feelings, and I think it is quite impossible that these matters should often be settled without the decision of a court of law. They often are settled when the cases get into court, because no litigant ever knows the weakness and strength of his case or of his opponent's case until it is in his counsel's[Pg 584] hands, when he quickly becomes acquainted with the real situation."

PETS' BURIAL GROUND.

From a Photo by Elliott & Fry.

"And divorce, Sir Francis?"

"The Divorce Court as we have it now has been in existence since 1857, and in proportion to the population, the number of divorces has not increased. I see a French legal writer of eminence has recently said that the French had in five years after their Divorce Act as many cases as we in thirty after ours. Even allowing for the difference between the laws of the two countries, it is not unsatisfactory as a comparison. Divorce in this country is a far easier thing than is popularly supposed. If a man can prove he does not get a pound a week, he is entitled to a divorce free, and there are always counsel who are kind enough to conduct his case for him. If he does not get counsel, the judge has often to pose as such, which is perhaps rather hard on the judge. Only about 5 per cent. of the divorce cases come from the upper classes—the remainder from the middle, lower, and frequently the pauper classes. The public hear very little of them—they are only interested in cases where the parties concerned are known and the interests at stake are big. But, to my mind, every divorce case in itself is sensational—be they rich or poor concerned—sensational because it is so severely serious. A divorce court should be and is the most serious of courts. If a person laughs, it is not so much the usher who puts it down as the public in the gallery themselves!"

Sir Francis said that he frequently gets through twenty cases of divorce a day, and sometimes sixty probate and divorce summonses and motions. He knows the points of each case—more particularly in the latter—they have been prepared for him by the registrar, and when a counsel rises and starts what promises to be a long discussion, the judge courteously stops him and requests him to argue the one main point. A judge's work is very much misunderstood by the public. When the Court rises at four, he frequently spends a couple of hours in getting ready his notes for summing up, which may come at any time if a case collapses. He must often spend the intervening days between Friday and Monday in "looking into the case."

"And do you think the present divorce laws are satisfactory?" I asked.

"Yes," he replied, thoughtfully, "fairly so. Of course it is said that men and women should be in exactly the same position, as is the case in Scotland; but there is much to be said for our law. One matter does, I think, require alteration. As the law stands, if a woman gets a divorce from her husband and she is given the custody of the children, the man need only keep them until they are sixteen. In many classes of society children require to be educated and maintained till much later, and it is frequently a great tax on the woman."

"And the Press—would you have divorce cases suppressed in the newspapers?"

"I am perfectly satisfied with the Press. Their discretion is admirable, and I have never felt disposed seriously to disapprove of a newspaper for over-reporting. The Press is the voice of the country. Justice is a public thing, and the administration of justice should be given all publicity. If this were not done, how would the public ever know that litigants were getting their rights? Newspaper reports to-day are pretty much as they should be."

We arrived at Donnington, and Sir Francis enthusiastically went over all the part the[Pg 585] old pile had played in the long-ago days of rebellion.

We reached the house again, and entered it with a hearty laugh, for Sir Francis had just told a story which would tend to prove that you will never shape the divorce laws to suit everybody. A Frenchman applied for a divorce, but he had no witnesses. He got them the next day, and his application was granted. A few days afterwards Sir Francis received a letter from him, asking if it would not be possible to curtail the necessary six months in order to make the decree absolute, as the Frenchman had come across a very charming widow with money, and he was afraid that the lady might not be willing to wait six months.

"He made a strong appeal to my sympathies," said Sir Francis, "and I did sympathize, but I could not help him."

It was a very happy evening at Arlington Manor after dinner. Lady Jeune afforded me the opportunity I sought. Few women are better known in the charitable world than Lady Jeune, but it is only when one has met her that one realizes how very practical she is in her deeds of kindness. With a head of perfect silver hair, and keen, bright eyes, she just fixes them on you and says exactly what she thinks. There is nothing hesitating about her—she always appears to know what is best and acts up to it; what will succeed, and it does.

"My childhood," said Lady Jeune, "was passed in Scotland. I was brought up very homely, in a very strict way, with two sisters and a brother. I never came to London until I was eighteen. I cannot tell you how I came to do the things that you suggest I do. I think, perhaps, I drifted into them—but I have always been deeply interested in my own sex, and for the last thirteen or fourteen years particularly so."

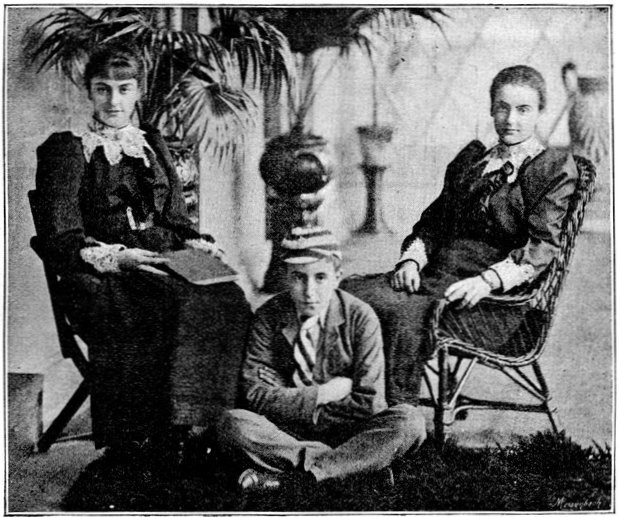

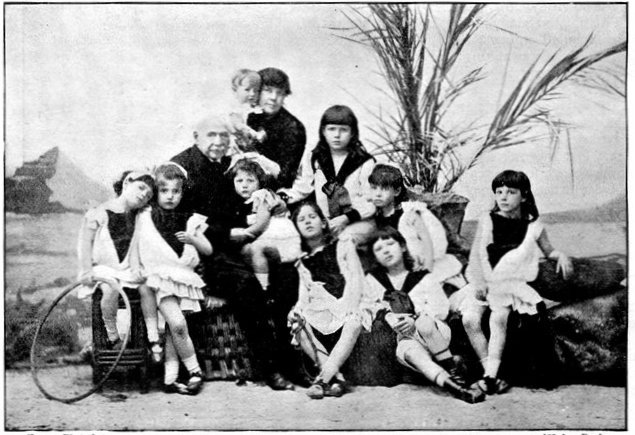

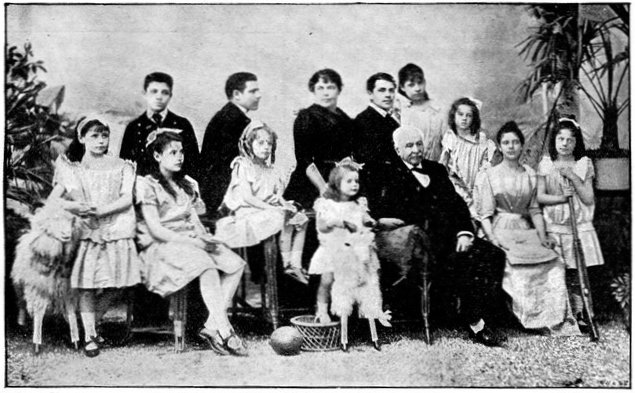

MISS MADELINE STANLEY. MASTER F. C. S. JEUNE. MISS DOROTHY STANLEY.

From a Photo by Elliott & Fry.

"And children?" I hinted.

"Yes, and the little ones, too. My Holiday Fund? Oh, yes. It is about eight years old. Mr. Labouchere had some money given him, and I told him if he would let me have it I would take up the work. I began with £500, and have had as much as £1,800 to spend in the summer months. We board the children out in Essex, Berkshire, Oxfordshire—in fact, in places within easy distance of London, and where the pure, free air is sure. I am a manager of two groups of schools in the poorest parts of London—Shoreditch and Bethnal Green—so that I have a very good choice of really poor, deserving children, to whom the country meadows is like a peep into Heaven. I make no distinction as far as denominations go. Last year I sent away 1,200 children."

Lady Jeune is also interested in factory girls and tired mothers, whilst her Rescue Home in the North of London contains a large laundry business.

I gathered much of the greatest interest from Lady Jeune. The "Revolt of the Daughters" question mystifies her. There is always a certain proportion of young women who don't get on at home, and an outside remedy will never be found. It must be found—if it can be found—in the home[Pg 586] itself. The woman of to-day is a very different sort of person from what she was twenty-five or thirty years ago. The girl of to-day may be more interesting, but she is certainly not so fresh—she knows too much, attempts too much. Twenty-five years ago a woman had no opinions until she was married. Girls of to-day start in their teens, and Lady Jeune thinks they do themselves more harm than good. You cannot have enough athletics for Lady Jeune—that is why the girls of 1894 are so much better grown, taller, and "finer animals," than were those of years ago; but she questions if their children will be equally good-looking and physically developed. The rapidity of life and excitement which many women lead must tell on them. She regards woman's too great love for amusement as being at the bottom of the cause of so many unhappy married homes. Why are there not more real friendships between man and wife? Let that be so, and the home would be home for both. She is a firm advocate of technical education.

"I believe in bigger girls being taught in class," said Lady Jeune; "it does a girl good to work with other girls. Boys? Let every boy be taught a trade at school—his father's trade for choice. Opportunity—as it is to-day—is levelled for all, and whether the boy is the son of a duke or the son of a working-man—a Board school boy—their opportunities and chances of real and true success in life are more equal than formerly."

"Then how would you meet the wants of your surplus boy population, Lady Jeune," I asked—-"the lads of the slums, whose family motto is 'No work, and plenty of it'?"

"Either by emigration, or by some scheme such as the idea of the Gordon Boys' Home carried out on a small scale, which would enable them after training to become soldiers or sailors," replied Lady Jeune.

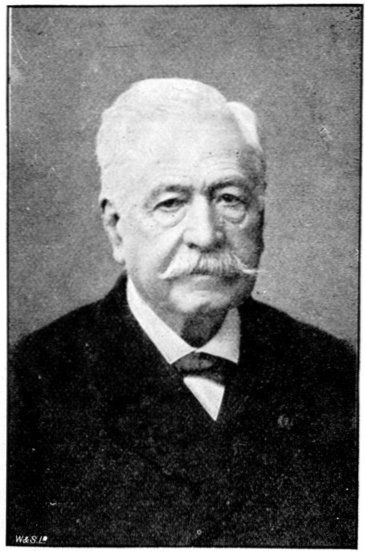

LADY JEUNE.

From a Photo by Elliott & Fry.

It was during the walk back over the fields from Donnington Castle that Sir Francis Jeune paid a magnificent tribute to the abilities of the late Lord Hannen—both as a lawyer and a man. On my return to town the following evening the newspaper placards had the announcement of Lord Hannen's death!

[Pg 587]Harry How.

By Mrs. M. Griffith.

(By special permission of Her Majesty the Queen.)

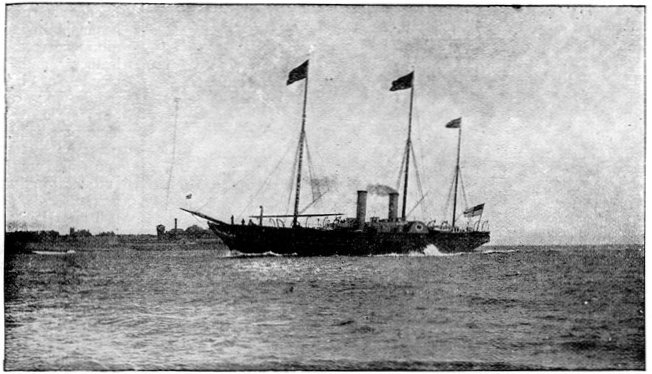

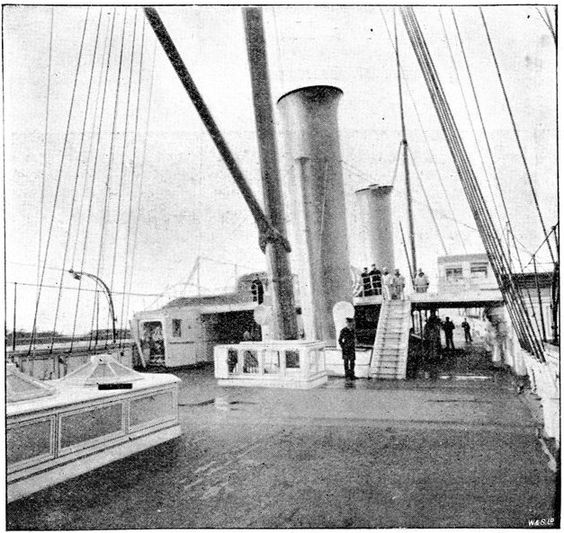

THE "VICTORIA AND ALBERT."

From a Photo by G. West & Son, Southsea.

The Victoria and Albert is a paddle vessel of 2,470 tons, built by Her Majesty's Government and launched from Pembroke Dock in 1855. Her dimensions are: extreme length, 336ft. 4in.; breadth of deck, 40ft.; displacement in tons, when deep, 2,390 tons.

Her engines make twenty-one revolutions a minute, and are supplied by four boilers, with six furnaces to each. It takes about six tons of coal to get up steam, and about three tons an hour to keep her at full speed. Highest indicated horse-power, 2,400.

Her Majesty the Queen made her first cruise in her on July 12th, 1855.

What will first strike any visitor going on board the Victoria and Albert is the utter lack of luxury and magnificence of decoration and furniture in the Royal apartments. The most perfect simplicity, combined with good taste, prevails everywhere. It would be well for those who complain of the cost of our Royal yachts to compare them with those of other nations, and note the difference.

The deck is covered with linoleum, over which red carpeting is laid when the Queen is on board; and plenty of lounges and cushions laid about and many plants, which contrast pleasantly with the white and gold with which the vessel is painted. She is lit electrically throughout, having forty-two accumulating cells. She carries two brass guns (six pounders) for signalling only. There is a pretty little five o'clock tea cabin on deck, which has a hood coming down from the doorway, as a protection from the wind. There is also a miniature armoury, lamp-room, chart-room, and a number of lockers for signalling-flags.

All the Royal apartments have the floors covered with red and black Brussels carpet, in small coral pattern; the walls hung with rosebud chintz, box pleated; the doors of bird's-eye maple, with handles of iron, and fittings heavily electro-plated. Her Majesty's bedroom has a brass bedstead screwed into sockets in the floor, bed furniture of rosebud chintz lined with green silk, canopy to match, green silk blinds, and plain white muslin curtains with goffered frills, mahogany furniture, chintz-covered. Dressing-room: mahogany furniture, covered with green leather, writing and dressing table combined; the walls covered with maps and charts on spring rollers.

The wardrobe-room, in which Her Majesty's dresser sleeps, is furnished in a similar style;[Pg 588] and here I saw a boat cloak of blue embossed velvet, lined with scarlet cloth, and another made entirely of scarlet cloth and with the "Star" on the front, which once belonged to George IV., but is now sometimes worn by the Queen.

THE DECK.

From a Photograph.

In the Princess Royal's room—as it is still called—the furniture is of maple, an electric light pendant hangs over the toilet table, the walls are a pale salmon colour, and the cornice a shell pattern in white and gold, the ceiling done in imitation of plaster.

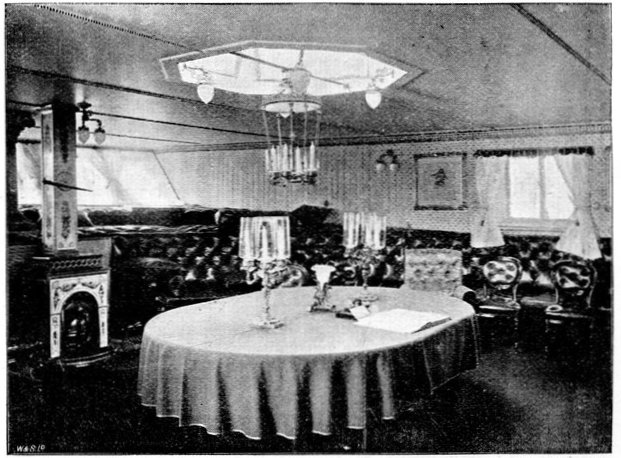

THE PAVILION.

From a Photo by Symonds & Co., Portsmouth.

The cabin which was formerly occupied by the Prince of Wales and Duke of Edinburgh contains two little brass bedsteads, maple furniture, decorated with the Prince of Wales' Feathers; and the Tutor's cabin opens out of it.

The pavilion, or breakfast-room, has mahogany furniture covered in leather, and a couple of large saddle-bag easy chairs, a very handsome painted porcelain stove, and frilled muslin curtains to all the parts.

The dining-room is furnished in a similar way, but the walls are hung with charts and portraits of the former captains of the vessel, who were as follows: (1) Lord Adolphus Fitzclarence, (2) Sir Joseph Denman, (3) George Henry Seymour, C.B., (4) His Serene Highness Prince of Leiningen, (5) Captain Hugh Campbell, and (6) Captain Frank Thompson. A very handsome candelabrum is of nautical[Pg 589] design, and the brass coal scuttle is fashioned like a nautilus shell; walls, salmon; and cornice, white and gold, in "Rose, Shamrock, and Thistle" design.

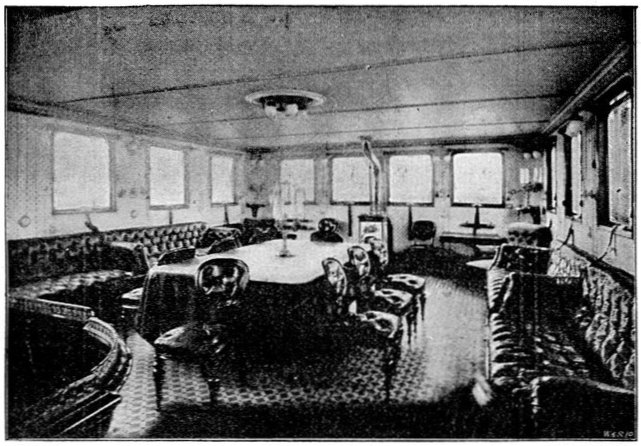

THE DINING-ROOM.

From a Photograph.

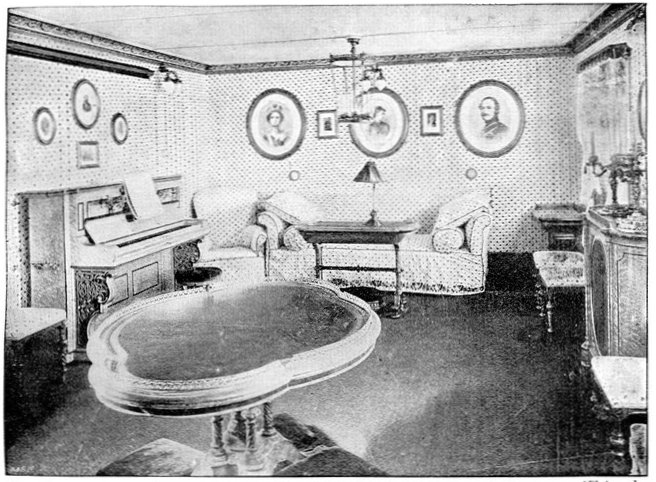

Her Majesty's drawing-room is 26 ft. by 18 ft. 6 in. The walls chintz-covered, and hung with portraits of the Royal Family in oval gilt frames, in the same design as the cornice; the furniture of bird's-eye maple; the coverings, all of chintz, to match the walls. Two large sofas, one at each end of the room; two or three easy chairs, the others high-backed; an "Erard" piano, book-case and cabinet combined, writing-table, occasional tables, and an oval centre table, comprise the whole of the furniture. I noticed a very handsome reading-lamp of copper and brass, for electric light, with a portable connection, so that it can be used in any part of the room. The bells have also the same contrivance. The two chandeliers, for six candles each, are of the same design as the one in the dining-room.

THE DRAWING-ROOM.

From a Photograph.