Title: The White Shield

Author: Myrtle Reed

Illustrator: Dalton Stevens

Release date: November 17, 2014 [eBook #47385]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Garcia, D Alexander, Moti Ben-Ari and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

STORIES BY

MYRTLE REED

Author of

Lavender and Old Lace

The Master's Violin

Old Rose and Silver

A Weaver of Dreams

Flower of the Dusk

At the Sign of the Jack O'Lantern

The Shadow of Victory

Threads of Grey and Gold

Etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

DALTON STEVENS

New York

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Publishers

Made in the United States of America

By Myrtle Reed:

A Weaver of Dreams

Old Rose and Silver

Lavender and Old Lace

The Master's Violin

Love Letters of a Musician

The Spinster Book

The Shadow of Victory

Sonnets to a Lover

Master of the Vineyard

Flower of the Dusk

At the Sign of the Jack-o'-Lantern

A Spinner in the Sun

Later Love Letters of a Musician

Love Affairs of Literary Men

Myrtle Reed Year Book

This edition is issued under arrangement with the publishers

G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London

| PAGE | |

| Preface | v |

| Morning | vii |

| The White Shield | 3 |

| An International Affair | 21 |

| A Child of Silence | 47 |

| The Dweller in Bohemia | 63 |

| A Minor Chord | 79 |

| The Madonna of the Tambourine | 87 |

| A Mistress of Art | 103 |

| A Rosary of Tears | 119 |

| The Roses and the Song | 141 |

| A Laggard in Love | 151 |

| Träumerei | 169 |

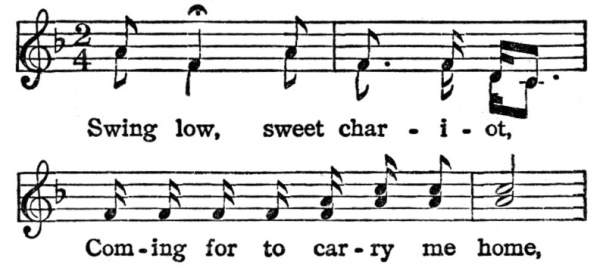

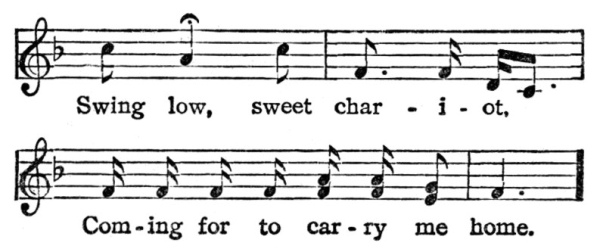

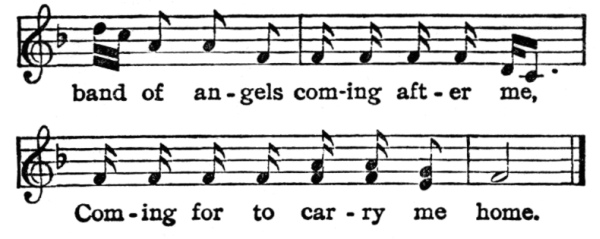

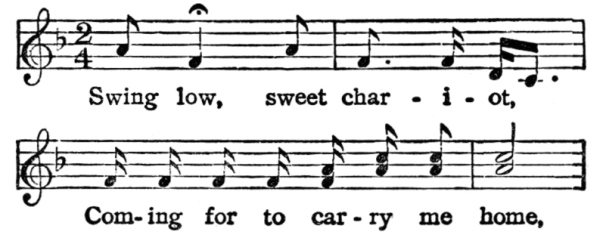

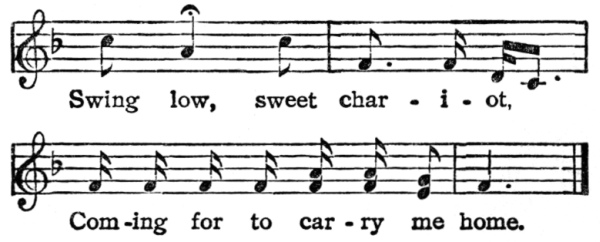

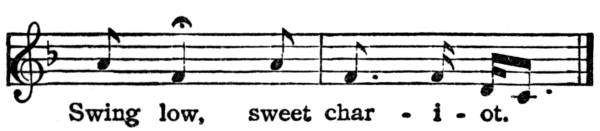

| "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" | 175 |

| The Face of the Master | 189 |

| A Reasonable Courtship | 209[iv] |

| Elmiry Ann's Valentine | 227 |

| The Knighthood of Tony | 247 |

| Her Volunteer | 269 |

| In Reflected Glory | 283 |

| The House Beautiful | 299 |

| From a Human Standpoint | 319 |

The Editor desires to make acknowledgment to the publishers of the following magazines for their courtesy in permitting the use of certain stories in this collection: Munsey's Magazine, The New England Magazine, The Pilgrim, The Smart Set, The Woman's Magazine, The National Magazine, Outing.

The editor takes great pleasure in being able to give to the public another volume from the pen of the lamented author—Myrtle Reed. These fascinating bits of fiction reflect the characteristics of the writer; the same vivid imagination, the quick transition from pathos to humour, the facility of utterance, the wholesome sentiment, the purity of thought, the delicacy of touch, the spontaneous wit which endeared her to friends and to thousands of readers, not only in Europe and America, but also in Australia and South Africa, are here fully represented.

Her mission was largely one of comfort to the suffering and the sorrowing; letters of good cheer went to far-away countries where her personal ministry could reach in no other way, and her writings are rich with sympathy and hope which have poured the oil of gladness into many a wounded spirit.

Pathos is not sadness, but it is rather the sunshine gleaming through a passing cloud, and hence the writings of Myrtle Reed are illumined with the gladsome light of unfailing love. Not only in her books and in letters to troubled souls, but also in her personal records, we find the unfading lines of a deeply devotional nature which was sacredly guarded from the careless observer and seldom discussed even with friends. But in this abiding faith was rooted the brave loyalty and high purpose which not only characterised herself, but also all of her productions.

The beautiful stories here presented have given pleasure to thousands of readers in the magazines in which they first came into print, and it is to the unvarying courtesy of the publishers that we are indebted for the privilege of thus binding the scattered grain into a single golden sheaf.

For the many letters of sincere sympathy which, in response to a formal request, have come from these stranger-friends, the editor is especially grateful.

Chicago, February, 1912.

People said that Joe Hayward's pictures "lacked something." Even the critics, who know everything, were at a loss to find where the deficiency might be. Hayward, himself, worked hard studying the masters, patiently correcting faults in colour and perspective, and succeeding after a fashion. But he felt that art, in its highest and best sense, was utterly beyond him; there was a haunting elusive something which was continually beyond his reach.

Occasionally, when he sold a picture, he would give "a time" to a dozen artist chums from studios near by, as they did, whenever fortune favoured them; after this he would paint again, on and on, with a really tremendous perseverance.

At length, he obtained permission to make an exhibition of his work in a single room at the Art Gallery. The pictures were only ten in number, and some of them[4] were small, but they represented a year's hard work. When he superintended the hanging, on Saturday morning, he was more nearly happy than he had ever been in his life. The placard on the door, "The Hayward Exhibition will open Monday," filled him with pleasure. It was not a conceited feeling of importance, but rather a happy consciousness that he had done his best.

At last he was suited with the arrangement. The men went out with the ladder and wire, and he stood in the centre of the room, contemplating the result. The landscape in the corner might be a little out of drawing, he thought, but the general public would not notice that. And the woman in white, beside it, which he had christened Purity certainly showed to good advantage. He remembered very well the day he had put the finishing touches upon it after the night of revelry in which he had helped Jennings and a dozen other fellows from neighbouring studios to celebrate the sale of Jennings' Study of a Head, and how he had thought, at the time, that he, who spent such nights, had no business to paint a figure like this of Purity.

As he turned to leave the room, he saw a grey gowned young woman, who evidently did not know that the pictures were not as yet upon public view. She passed him as she came in, with a rustle of silken skirts and a cooling odour of violets. Seeing the key of the room in his hand, she turned to him and said: "Pardon me, but can you tell me whose pictures these are?"

"These are Hayward's," he replied.

"Hayward," she repeated after him, as if the name were wholly new to her.

"Hayward is a young artist and of purely local reputation," he explained. "This is his first public exhibition."

She surveyed the collection without any very strong show of pleasure, until he remarked, "You don't seem to think much of his beginning."

She was prompt in her answer: "No, I do not, they seem to lack something."

He sighed inwardly. That old, old, "something." Hayward's pictures all lacked "something" as everybody said of them; but what that something was, his intimates, his fellow artists, were not the kind to know.

"What is it, do you think?" he asked.

"I don't know," she replied slowly. "If one knew the man, one might be able to tell."

For the first time she looked him full in the face. He saw nothing but her eyes, clear and honest, reading him through and through.

"Yes," he answered, "if you knew the man, I think you could tell."

"I'm not at all sure," she laughed, "It's only a fancy of mine."

Drawing a watch from her belt, she looked surprised and turned away. He listened until the silken rustle had completely ceased. Then he, too, went out and on the stair he found a fine handkerchief edged with lace, delicately scented with violet, and minutely marked in the corner: "Constance Grey."

On Sunday night, the studio building where Hayward and others painted glowed with light. The morrow's opening of "The Hayward Exhibition" was being celebrated with "a time" at the expense of the artist. Glasses clinked, and the air was heavy with smoke, two women from a vaudeville theatre, near by made merry upon an impromptu stage.

Everybody seemed to be happy except[7] Hayward. The owner of the handkerchief was in his mind. He felt that those eyes of hers grey, deep, and tender, though they were, might blaze with anger at a scene like this. The handkerchief had no place in such an atmosphere. He went over to his book case, and put it between the leaves of his Tennyson, smiling as he caught the words on the opposite page:

Her handkerchief would feel more at home there, he thought, though as he closed the book, he could not help wondering what she would say if she looked into the room.

A quick eye had followed his movement, and soon afterward its owner, Jennings, took occasion to examine the volume. He waved the handkerchief aloft triumphantly. "Heigho, fellows! Hayward's got a new mark for his clothes! Look here—'Constance Grey'!" Hayward was shaken with mingled shame and anger that he could not explain, even to himself.[8] The words and tone with which he commanded his friend to put the little thing back where he had found it were as hot as they were foolish. For a moment the two men faced each other; then Jennings apologised, and afterward Hayward murmured a sort of apology also. In sparkling champagne they drank to good fellowship again. But the incident was not without a certain subtle effect upon the celebration, and at one o'clock Hayward sat alone with his face buried in his hands, a dainty handkerchief spread out before him, and beside it was the rapidly sketched outline of a face which he had just completed.

He knew now why the action of Jennings had made him so furious. The shaft of light from a woman's eyes, which once strikes deep into the soul of every man, had at last come home to him.

The "opening" was auspicious. Wealth and art alike were well represented. One of his most important pictures was marked "sold" before the evening was over, and everybody congratulated the artist upon his good fortune. In praise of his art, however, very little was said that did not somehow carry in it, perhaps silently, the old drawback—the implication that something[9] was lacking; still exultation ran rife in his veins. There were throngs of beautiful women there and he was the centre of it all.

Toward the end of the evening, a lady who had once sat for a portrait came up to him. She was one of a little group who came in late after a theatre party, but she approached with the air of an old friend.

"Mr. Hayward," she said, "I want you to know my niece."

He followed her into the next room where a young lady sat upon a divan. Her grey eyes were lifted to his face, and then suddenly lowered in confusion.

"Mr. Hayward," she said, "I am so ashamed!" And when he tried to reassure her, she answered: "Let's not talk about it—it's too humiliating!"

So they spoke of other things. He learned that she had come from a distant city to visit relatives, and the aunt invited him to call upon them. Friday afternoon came at last, when Miss Grey and her aunt were at home. Other Fridays followed, and other days which served as well as Fridays. It was seldom that the girl looked him in the face; but when she did so, he felt himself confessed before her—a[10] man with no right to touch even the hem of her garment, yet honouring her with every fibre of his being.

They were much together and Constance took a frank enjoyment in his friendship. He made every effort to please her, and one day they went into the country.

Constance was almost childishly happy, but the seeming perfection of her happiness distressed him when he learned that in a very few days she was to sail for Europe, pass the summer and autumn in travel, and spend the winter in Paris.

At length they sat down under a gnarled oak tree and watched the light upon the river and in the sky. After an embarrassing silence Hayward spoke:

"I think you know the man now,—will you tell me what you think of his pictures?"

She hesitated. "I do not know the man well enough to say, but I will give you my art creed, and let you judge for yourself. I believe that a man's art is neither more nor less than the expression of himself, and that, in order to obtain an exalted expression, his first business is with himself. Wrong living blunts, and eventually destroys, the fundamental sense of right[11] and wrong without which a noble art is impossible. When a man's art is true, it is because he himself is true. The true artist must be a man first, and an artist afterward."

Hayward took her admonition with the meekness becoming his position as her worshipper. The conversation ended with his declaration that he would not paint again until he had something in himself which was worthy of being put into his picture.

"You'll help me, won't you?" he asked.

Her eyes filled. "Indeed I will, if I only can."

He went home with love's fever in his veins. She had promised to help him, and surely there was only one way. He wrote her an ardent note, and an hour later his messenger brought her reply.

"Believe me, I never dreamed of this, and you know what my answer must be; but I do not need to tell you that whatever sincere and honest friendship can offer is already yours.

"With deep regret, I am as ever,

"Constance Grey."

The grim humour of the thing stunned[12] him momentarily and he laughed harshly. Then he flung himself down in a passion of grief. In the morning he took pen and paper again, after a night of sleepless distress.

"You cannot mean what you say. That white womanly soul of yours must wake to love me some day. You have stood between me and the depths, and there has been no shame in the life that I offer you, since you came into it.

"Oh, you perfect thing, you perfect thing, you don't know what you are to me! Constance, let me come!"

The answer was promptly forthcoming:

"I cannot promise what you ask, but you may come and see me if you wish."

Pale with expectancy, Hayward was only the ghost of himself when the servant admitted him. He had waited but a moment when Constance entered the room wearing the gown in which he had first seen her. He rose to meet her, but she came and sat down by his side.

"Listen," she said, "and I will tell you how I feel. I am twenty-five and I have never 'cared.' I do not believe that I[13] ever shall care, for the love that we read of is almost incomprehensible to me. You cannot marry such a woman."

His answer was fervent, his words crowded one upon another in a vehement flood, and his voice was low and hoarse with pent-up emotion, as he implored her to believe in him, trust him, and be his wife,—kneeling at her feet and kissing her hands in abject humility.

It was very hard for her to say what she must, but with an effort she rose and drew away from him.

"I must be true to myself and to you," she said, "and I can say nothing but the old bitter No."

White and wretched, he went away, leaving her white and wretched behind him.

For days and weeks thereafter, Hayward painted busily. Jennings went to see him one afternoon.

"Look here, old fellow," he said, "what's the matter? I know I was ungentlemanly about the handkerchief, but that's no reason why you should cut us all this way. Can't you forget about it?"

"Why, Jennings, old boy, I haven't cut anybody."

"No, but you've tired of us, and you can't hide it. Come down the river with us to-night. The fellows have got a yacht, and we'll have supper on board with plenty of champagne. Won't you come?"

Hayward was seriously tempted. He knew what "the time" would mean—the ecstasy of it and the dull penalties which would follow. But that day by the river came into his memory: a sweet sunlit face, and a woman's voice saying to him: "When a man's art is true, it is because he himself is true."

"Jennings," he said, "do I look like a man who would make good company at a champagne supper? You know what's the matter with me. Why don't you just sensibly drop me?"

Jennings begged, and mocked, and bullied, all in a good-natured way, but his friend was firm. When he went out, Hayward locked the studio door and drew his half finished picture from behind a screen.

"She was right," he said to himself.

Constance sailed. He dreamed of his picture as being hung in the Salon, and of her seeing it there. By and by it was finished, but the artist's strength was gone,[15] and his physician ordered him away from his work.

When he returned, restored to health, the picture was placed on exhibition. Crowds thronged the gallery, columns and pages were written in its praise, and astonishing prices were offered for it, but the picture was not for sale. It, too, crossed the water, and the dream which had comforted him for many months at last came true.

When Constance looked upon Hayward's painting, her heart leaped as if it would leave her breast. White, radiant, and glorified, it was she herself who stood in the centre of the canvas. That self-reliant, fearless pose seemed to radiate infinite calm. Behind her raged the powers of darkness, utterly helpless to pass the line on which she stood. Her face seemed to illumine the shadows around her; her figure was instinct with grace and strength. Below the picture was the name: The White Shield.

The beauty of the conception dawned upon her slowly. Pale and trembling, she stood there, forgetful of the place, and the throng around her. At length she knew what she meant to him; that his art at[16] last rang true because he had loved her enough to be a man for her sake.

She dared not linger before it then, but she came again when the place was empty, and stood before her lover's work, like one in a dream. The fiends in the shadow showed her the might of the temptations he had fought down. She gazed at her own glorified face until her eyes filled with tears. With a great throb which was almost pain, Constance woke to the knowledge that she loved him, even as he loved her—well enough to stand between him and danger till she herself should fall.

The old grey guard, passing through the room, saw her upturned face in that moment of exaltation. It was the same that he saw in the picture above, and he quietly went away to wait until Constance came out, her face flushed and her eyes shining like stars, before he locked the door.

That night the cable trembled with a message to America. It reached Hayward the next morning as he sat reading the daily paper. The envelope fluttered unheeding to the floor, and his face grew tender then radiant as he read the few words which told him that his picture had rewarded his love.

"Wait," he said to the messenger boy. Hurriedly he wrote the answer: "Sailing next steamer"—then, utterly oblivious of the additional expense, he added another word, which must have been very expressive, for Constance turned crimson when it reached her—perhaps because the discerning genius who copies cablegrams in typewriting had put the last word in capitals, thinking that the message came from a Mr. Darling.

The Committee of Literary Extension was holding its first meeting. Five girls sat around a glowing gas log and nibbled daintily at some chocolates which had been sent to the hostess.

"Come, Margaret, you're the chairman of this committee; please tell us what it is all for," suggested Grace Hayes.

"Well, girls, I hardly know how to begin. Most of us in travelling have seen those little huts along the railroad with a little bit of cultivated ground around each one. They are the very embodiment of desolation. I have seen whole families come out to stare at the train as it whirled by, and I have often wondered what place there could be for such people in this beautiful, happy world—why I should have my books and friends and the thousand other things that have been given to me, while other people, and worst of all, other women, have to live lives like that.

"There are boys upon farms, in reform schools, and in little towns who scarcely ever see even a newspaper, and who do not know what a magazine is.

"It is to reach this class of people that this work has been undertaken, and for this purpose our committee has been appointed. Fifteen or twenty magazines and illustrated papers come to us every month—even to the few who are here to-day: perhaps some of you see even more than this. After we have read them, we might send them to these people instead of burning them, and who can tell how many starving minds we may make better, and happier, in this simple way, and with very little effort on our part?"

"Can they read?" It was Grace, an always practical individual, who spoke.

"If they can't, they can learn," responded Miss Stone. "It will be an incentive to their best efforts in every way."

Katherine Bryant leaned forward, her face flushed, and her eyes shining. "Girls," she said, "it's perfectly beautiful. We'll send all of our own magazines and illustrated papers, all we can collect from other sources, and we'll raise money to[23] buy new ones. I don't know of any other way in which we can do so much good."

Plan after plan was suggested, and at last it was decided that the committee should write to a society in Boston which did similar work, and ask for the names and addresses of twenty-five persons who were in need of reading matter. These could be removed from the lists of the Boston society, as the Committee on Literary Extension of the Detroit Young Woman's Club would attend to their needs in future.

In due time the list arrived, with a few particulars opposite each name. The committee was again called together, and the chairman gave each girl five names.

"Katherine dear," she said, "there are some more names in the little note-book that is up-stairs in my desk. They are all boys who have left the reform school. A friend of mine, who is one of the directors, gave them to me, and there are only four or five. Would you mind taking those in addition to your own?"

"Not at all," and Katherine ran up to Margaret's desk.

"Wonder where she keeps her note-book! Oh, here it is, and here is the list."[24] She copied busily. "One, two, three, four; that's all. No, here's another on the next page," and at the end of her slip she wrote: "Robert Ross, Athol, Spink Co., South Dakota." The work was taken up in earnest and many magazines were collected within the next few days. A strict account was kept of everything sent out, and occasionally the girls met to compare notes.

Margaret came home one day and found Mrs. Boyce waiting for her. "My dear," said the lady, "I've lost an address that troubles me, and I think it may have been on the card that I gave you the other day."

"I'll see," replied Margaret, "I copied them all that very afternoon." She took her note-book out of her chatelaine bag and handed it to Mrs. Boyce. "Which one is it?"

The elder lady laughed in a relieved way. "This last one," she answered. "Robert Ross. He's my favourite nephew, off on a shooting trip, and he wants me to write to him. He'd never forgive me, if I didn't. Just give me a card, and I will try not to be so careless again."

Meanwhile Katherine was absorbed in addressing magazines with great vigour.[25] She had found a pile of back numbers in the attic and was trying to divide them properly. The household journals went to a woman in Kansas, fifty miles from a city, others she mailed to a boy of sixteen who was on a farm in Minnesota, and a copy of a popular magazine was addressed to Mr. Robert Ross. At the top of each one she had written, "From Miss Katherine Bryant, Jefferson Ave., Detroit."

A short time afterward, she received a pathetic letter from the woman to whom she had sent the household magazines. "I married for love," she wrote, "and have never been sorry, but I miss many of the things to which I was accustomed in my eastern home. A magazine is an unusual thing upon a Kansas farm, and with all my heart I thank you for the great pleasure you have given a lonely woman."

Mindful of the fact that one of the objects of the committee was to get into correspondence with its beneficiaries, Katherine sat down to write an encouraging note to her and also to others, but before she had finished the postman brought another letter.

It had been mailed in South Dakota. The paper was the white ruled variety, to[26] be found in country stores, but the penmanship was clear and business-like.

"My dear Miss Bryant," the letter began, "I am sure I don't know what good angel possessed you to send me a copy of my favourite magazine, but I am none the less grateful and only too happy to acknowledge it. I am hurt, but the doctor thinks not seriously, and that I shall be all right in a few weeks. The magazine which you so kindly sent has given me the first pleasant day I have had for some time.

"I should be most happy to receive a letter from you, but of course that is too much for a stranger to ask, even though he be ill and alone.

"Sincerely and gratefully yours,

"Robert Ross."

Katherine knit her pretty brows, and read it over again. "It's no queerer than the one I got from the Kansas woman," she decided. "At any rate, they both seem glad to get them and they shall have some more."

She wrote very kindly to Robert Ross, inquiring into the particulars of his injury, and whether or not he lived on a farm. She said he was very fortunate, if he did[27] indeed live in the country, because so many people were pining away and dying in the great cities. The magazine she had sent was one of her own favourites also, and she would send the next number as soon as it came out. In the meantime, she hoped the package of papers she was sending in the same mail would prove acceptable.

Out on the porch of the Athol House, Mr. Ross sat in the sun and reviled creation in general. It was a palatial hotel—for that region—but he seemed unmindful of his advantages.

"Oh, confound it," he groaned, "why couldn't I have shot some other idiot instead of myself? I ought not to be trusted with a gun! Right in the height of the prairie chicken season too, and those other fellows, three of them, off bagging every bit of the game! I hope they won't forget to come back this way, and take me home with them! Emperor, old fellow, it's hard luck. Isn't it?"

The Irish setter, who had been addressed, came and put his cold nose into Mr. Ross's hand. The well-bred dog had refused to desert his wounded master, even for the charms of prairie chickens, and touched by his dumb devotion Ross permitted him to[28] stay. Long conversations were held every day, and Emperor told Ross as plainly as a dog could, that if it hadn't been for that dreadful flesh wound they would be having a fine time in the fields, capturing more game than any other dog and man in the party.

When the landlord returned from the post-office he brought a letter which Emperor carried in triumph to his master. Ross read it in surprise. Who Miss Bryant might be, he did not know, but she wrote a pleasant letter, and it was certainly kind of her to notice him.

He decided that the letter he wrote in acknowledgment of the magazine must have been extremely well done. He thought of the unknown fair one for some time, and then concluded to write again. He was non-committal about himself, fearing to spoil any delusion she might have been labouring under when she sent the magazine.

When Katherine received the second letter, she felt several pricks of conscience. It wasn't a nice thing she was doing, and she knew it. But a person shouldn't let squeamishness interfere with philanthropic work, so she answered promptly.

She drew him into a discussion of an article on "The Desirability of Annexing Canada to the United States," and he criticised it harshly. He forgot to tell her that he was a Canadian by birth and a loyal subject of the King. His point of view was naturally distorted, and she replied with some spirit, dealing very patiently, however, with the frail arguments which he had submitted.

Katherine thought the discussion was a good thing. Anything that would make him think was an unmixed blessing. She fairly glowed as she thought of the mental stimulus she might give to this poor Dakota farmer, who had been hurt in some mysterious way, and her letters grew longer even as they increased in frequency, for Mr. Ross wrote very promptly indeed. She could well understand that, when a cripple had so little to occupy his time in that far away wilderness.

Ross was highly amused. He admired Miss Bryant's letters and wished he might see Miss Bryant herself. A bright idea (as he thought) occurred to him—why not?

With very red cheeks, Miss Katherine read the latest news from Spink County.[30] Her own beautiful Irish setter put his head into her lap, and begged to be petted.

"Go away, Rex, I want to think. The wretch! To ask for my photograph! He evidently doesn't know his place! I'll teach him where it is and then take the name of the impertinent creature off my list!"

She sat down to compose a letter which should make Mr. Robert Ross, alias wretch, squirm in agony. Rex was persistent and put his paw up to shake hands. Katherine turned and looked at him.

"You're a dreadfully nice doggie, but I wish you'd go away and not bother me."

Then an idea came to her which startled her at first, but grew more attractive as she became better acquainted with it. She bent down and whispered to Rex, and he wagged his tail as if he fully understood.

"Yes, Rex, it's got to be done. I'm sorry to sacrifice any of your beauty, but you've got to get your mistress out of a scrape. Come on!" And the willing Rex was escorted into the back yard.

Sooner than he expected, Mr. Ross found a letter at his plate when he limped in to the customary breakfast of black coffee and fried eggs. On this occasion,[31] he omitted the eggs and hastily swallowed the coffee, for the envelope was addressed in familiar style.

It was a very pleasant letter. The writer seemed to meet his advances in a proper spirit, but there was no photograph. "I don't give my pictures to young men, nor old ones either, but I enclose a lock of hair which I have cut off on purpose for you, and I hope you will be pleased with it."

He looked at the enclosure again and again. It was a single silky curl, of a beautiful reddish gold, tied daintily with blue ribbon. He certainly was pleased with it, as she had hoped. "Hair like this and violet eyes," soliloquised Ross. "I must write again without delay." So when the landlord went to the post-office he mailed another letter to Miss Bryant. The first page consisted wholly of raptures.

He began to think that Athol was not so dull a place as he had at first imagined. Those fellows off in the fields shooting prairie chickens were not having any better time than he and Emperor in this thriving town. It was true that Emperor slept most of the time, but magazines, and papers, and letters not only made the[32] time less tedious, but there seemed to be opening up a vista of romance which made the tramping in the stubbly fields look very much less attractive.

While he thought of it, he would read Miss Bryant's letter again. He took it out of the envelope, and the curl fell unnoticed to the floor of what the landlord was pleased to term "the front stoop." Emperor walked over, and seemed interested. His master did not notice him, being absorbed in the letter; at last the dog sniffed uneasily, and then growled, so Ross looked up and was surprised to find him pawing something vigorously. Still Ross did not see what the dog had. "What's the matter with you, old fellow?" Emperor growled again, and bit fiercely at the curl. Its owner rescued it at once, but the dog would not be appeased. He made such a fuss that his master put the letter away. Then Emperor made another attack on the curl, and Ross took it away from him again and examined it closely. A queer look came into his face and a queerer note into his voice. "Emperor, come here. Keep still."

The long golden fringe that made Emperor's tail the thing of beauty that it was,[33] was drawn up on his knee and the curl was laid beside it. There was no doubt at all. It matched exactly. Ross leaned back in his chair with a low whistle. "Well—by—Jove! I wonder if she'll tell me when she writes," he said to himself. With a despairing grin, he remembered his raptures on the subject and decided that Miss Bryant would be very certain to tell him where that "sweet curl" came from!

When the missive from Spink County reached Detroit, Miss Katherine Bryant was a very happy girl. As a rule, it takes very little to make girls happy. For the first time in her life, she longed for a confidant, and unlike most girls, she had none. She took Rex for a long walk and told him all about it. The poor dismantled tail wagged in ecstasy, but his mistress was not sure that he understood the joke in its entirety.

At last she would have her revenge and she took keen delight in answering that letter. "I quite agree with you concerning the beauty of the hair," she wrote. "It came from my beautiful Irish setter, and I am very glad you are pleased with it, though to tell the truth, I should think you utterly heartless if you were not."

Ross sent an elaborate apology for his impertinence, and confessed that he admired her all the more for outwitting him. Inwardly, he wished that Emperor had made his discovery before he had mailed that idiotic letter. His manliness, however, appealed to Katherine and she did not take his name off the list.

In the meantime, the three other men returned to their wounded comrade. They had been very successful and were profuse in their expressions of regret. Ross said nothing of his unknown friend. He felt that it would not be fair to her, and anyhow, when a girl has sent you dog-hair, and you have raved over it, it isn't best to tell of it. He was sure that all the circumstances were in favour of his keeping still about it.

The ugly wound had quite healed when the four men started East together. At St. Paul they separated, Ross and Emperor taking the night train for Detroit and the promised visit to Mrs. Boyce.

She was delighted to see her nephew, and Emperor soon found his way into her good graces. His master took him out for a stroll the same day he arrived, the dog having been long confined in a box-car,[35] and the released captive found his excursion especially refreshing. At a corner, however, he met another Irish setter, also out for a stroll, and the two speedily entered into a violent discussion.

A snarling, rolling, mahogany-coloured ball rolled toward Ross, and a young lady followed, crying at the top of her voice, "Rex! Rex! Come here."

The owner of Emperor rushed into the disturbance with his cane, and succeeded in resolving the ball into its component parts.

Rex, panting and injured, was restored to his agitated mistress, while Emperor chafed at his master's restraining hand.

Apologies were profuse on both sides. "I'm stronger than you," Ross said, "and if you can hold your dog until I get mine out of sight, we shall have no more trouble."

Miss Bryant scolded Rex until his head and tail drooped with shame, and relentlessly kept him at heel all the way home.

At her own gate, she met Margaret Stone, to whom she told the story of her adventure with the handsome stranger, and the other dog, who "looked so much[36] like Rex that his own mother could not have told them apart!"

Margaret's errand was a brief one. Mrs. Boyce was coming over to the Stone mansion with her nephew and she wanted Katherine to come to dinner and stay all night. So Katherine put on her prettiest gown and went over, little thinking what fate had in store for her.

She instantly recognised in Ross the man she had met a few hours before under very different circumstances. He was too much of a gentleman to allude to the occurrence, but she flushed uncomfortably.

Both girls found him an exceedingly pleasant fellow. Katherine had recovered from her embarrassment, and was laughing happily, when Mrs. Boyce began to speak of the Committee on Literary Extension and the good work the girls were doing.

"Do you know, Bob," she went on, "that I nearly lost your address in that way? I gave it to Margaret with the names of some boys from the Reform School. It's a blessed wonder you didn't get magazines and tracts!"

If Robert had been an angel he would not have looked at Katherine, but being merely human he did. Miss Bryant rose[37] in a dignified manner. "Margaret," she said unsteadily, "I must go home."

"Why, Katherine, you were going to stay all night!"

"My—head—aches," she answered.

"Bob," commanded Mrs. Boyce, "you must take Katherine home."

"It's not at all necessary," pleaded Katherine piteously.

"But I insist," repeated Mrs. Boyce with the utmost good will.

Mr. Ross rose. "If Miss Bryant will permit me, I shall be only too glad to accompany her home," he said courteously.

There was nothing to do but submit with the best grace she could assume. Once out of doors, she was the first to break the silence:

"I'm afraid to be out alone—in the city."

"Yes," replied her escort cheerily, "it's a pity you didn't bring your dog!" He could have bitten his tongue out for making such an unlucky speech, but to his surprise Katherine broke down and sobbed hysterically.

Mr. Ross took both her hands in his own. "You are tired and nervous, Miss[38] Bryant, and I beg you to think no more about what has happened. You have no idea how much good you did me out in that miserable little place, and I shall be only too glad to be your friend, if you will let me."

Katherine wiped her eyes: "If you can be my friend, I ought to be very willing to be yours," and just outside of her door Canada and the United States clasped hands in a solemn treaty of peace.

Safely in her own room, the mistress of Rex sat down before the mirror and studied her face attentively. "Katherine Bryant," she said to herself, "you are an idiot! Not foolish, nor silly, nor half witted, nor anything like that—just a plain idiot! He has graduated from the University with high honours, and you, with your miserable little boarding-school education, have instructed him on many subjects. I am thoroughly ashamed of you."

When she finally slept, her dreams were a medley of handsome strangers, mixed with dogs, and reddish-yellow curls tied up with blue ribbons.

Leaning up against the corner lamp-post, Mr. Robert Ross indulged in a spasm of[39] irreverent mirth, but with a great effort he preserved a calm exterior when he again entered the drawing-room of his hostess.

On their way home Mrs. Boyce said: "Bob, why don't you go into business with your uncle and become a good American citizen? We'd love to have you with us, and there is surely a good opening here."

"I'll think about it," he answered, and he did, with the usual result, for it is proverbial that he who hesitates is lost.

Mr. Boyce was quite willing to shift a part of his responsibility to the broad shoulders of his nephew, and an agreement was easily reached. Emperor was quartered in the back yard, where he fretted for a few days and then wreaked his vengeance on sundry grocery boys and milkmen.

When his master went out, the dog usually went along except when Miss Bryant and Rex were to be favoured with a call. If the two dogs met, the customary disturbance ensued. Rex included Ross in his hatred of Emperor, and Emperor was equally hostile toward Miss Bryant.

"Rex," said Katherine, one day, "you are a very nice doggie, but I won't have[40] you treat Mr. Ross with such disrespect. The other night, when we were going out, you had no business to growl when he buttoned my gloves, nor to sniff in that disgusted way at the roses he brought. If you ever do that again, I shall let the dogcatcher take you to the pound!"

The imaginary spectacle of Rex en route to the pound nearly unnerved Katherine, but she felt that she must be severe. Ross punished Emperor with a chain, or with confinement in the back yard, which the dog hated, but where it was necessary to keep him a part of the time, and for a while all went well.

But Ross went away one evening without explaining matters to the sensitive being in the back yard.

Emperor knew well enough where he had gone—knew he was visiting that disagreeable girl who owned that other Irish setter—a very impertinent dog whose manners were so bad that he was a disgrace to the whole setter tribe!

He sulked over his wrongs for an hour or so, and then crawled out through a friendly hole in the fence which he had for some time past been spending his hours of imprisonment in making.

The dining-room of the house on the avenue was lighted by a single gas jet, and the shades were lowered. Miss Bryant and the chafing dish together had evolved a rarebit which made the inner man glow with pleasure.

"Do you remember that awful quarrel we had about annexing Canada to the United States?" asked Robert.

Katherine remembered distinctly.

He went over to her side of the table. "What do you think about it now?"

It was a very ordinary question, but Miss Bryant turned scarlet.

"I—I don't know," she faltered.

He put his arm around her. "I give in," he said; "annexation is the most desirable thing in the world—when shall it take place?"

Katherine raised her head timidly. "Say it, sweetheart," he whispered tenderly.

It happened at this moment that Emperor arrived in search of his master. Rex was sitting on the front steps and declined to take in his card. Then the shrieking, howling barking ball rolled into the vestibule, and Ross made a dash for the door. With considerable effort he got Rex into the back yard, and locked Emperor into[42] the vestibule. Then he went back to Katherine.

He tried to speak lightly, but his voice trembled with earnestness: "Dearest, this entire affair has been coloured, and suggested by, and mixed up with dogs. I think now there will be an interval of peace for at least ten minutes, and I am asking you to marry me."

Rex raised his voice in awful protest, and Emperor replied angrily to the challenge, as he raged back and forth in the vestibule, but Robert heard Katherine's tremulous "Yes" with a throb of joy which even the consciousness of warring elements outside could not lessen. The little figure against his breast shook with something very like a giggle, and Katherine's eyes shining with merriment met his with the question: "What on earth shall we do with the dogs?"

Robert laughed and drew her closer: "It's strictly international, isn't it? Canada and the United States quarrel——"

"And Ireland arbitrates!" said Katherine.

Three months later, in the drawing-room on Jefferson Avenue, to the accompaniment of flowers, lights, and soft music,[43] the treaty was declared permanent. There was a tiny dark coloured footprint on the end of Katherine's train, which no one appeared to notice, and a white silk handkerchief carefully arranged hid from public view a slightly larger spot on the shining linen of the bridegroom, where Emperor had registered his enthusiastic approval of his master's apparel.

But the rest of the committee, in pale green gowns, were bridesmaids, while Emperor and Rex, resplendent in new collars, and having temporarily adjusted their difference as long as they were under guard, had seats of honour among the guests.

At the end of the street stood the little white house which Jack Ward was pleased to call his own. Five years he had lived there, he and Dorothy. How happy they had been! But things seemed to have gone wrong some way, since—since the baby died in the spring. A sob came into Jack's throat, for the little face had haunted him all day.

Never a sound had the baby lips uttered, and the loudest noises had not disturbed his rest. It had seemed almost too much to bear, but they had loved him more, if that were possible, because he was not as other children were. Jack had never been reconciled but Dorothy found a world of consolation in the closing paragraph of a magazine article on the subject:

"And yet we cannot believe these Children of Silence to be unhappy. Mrs. Browning says that 'closed eyes see more[48] truly than ever open do,' and may there not be another world of music for those to whom our own is soundless? In a certain sense they are utterly beyond the pain that life always brings, for never can they hear the cruel words beside which physical hurts sink into utter insignificance. So pity them not, but believe that He knoweth best, and that what seems wrong and bitter is often His truest kindness to His children."

Dorothy read it over and over until she knew it by heart. There was a certain comfort in the thought that he need not suffer—that he need never find what a world of bitterness lies in that one little word—life. And when the hard day came she tried to be thankful, for she knew that he was safer still—tried to see the kindness that had taken him back into the Unknown Silence of which he was the Child.

Jack went up the steps this mild winter evening, whistling softly to himself, and opened the door with his latch-key.

"Where are you, girlie?"

"Up stairs, dear. I'll be down in a minute," and even as she spoke Dorothy came into the room.

In spite of her black gown and the hollows under her eyes, she was a pretty woman. She knew it, and Jack did too. That is he had known, but he had forgotten.

"Here's the evening paper." He tossed it into her lap as she sat down by the window.

"Thank you." She wondered vaguely why Jack did not kiss her as he used to, and then dismissed the thought. She was growing accustomed to that sort of thing.

"How nice of you to come by the early train! I didn't expect you until later."

"There wasn't much going on in town, so I left the office early. Any mail? No? Guess I'll take Jip out for a stroll." The fox-terrier at his feet wagged his tail approvingly. "Want to go, Jip?"

Jip answered decidedly in the affirmative.

"All right, come on," and Dorothy watched the two go down the street with an undefined feeling of pain.

She lit the prettily shaded lamp and tried to read the paper, but the political news, elopements, murders, and suicides lacked interest. She wondered what had come between her and Jack. Something had, there was no question about that;[50] but—well, it would come straight sometime. Perhaps she was morbid and unjust. She couldn't ask him what was the matter without making him angry and she had tried so hard to make him happy.

Jip announced his arrival at the front door with a series of sharp barks and an unmistakable scratch. She opened it as Jack sauntered slowly up the walk and passed her with the remark:

"Dinner ready? I'm as hungry as a bear."

Into the cozy dining-room they went, Jip first, then Jack, then Dorothy. The daintily served meal satisfied the inner man, and he did not notice that she ate but little. She honestly tried to be entertaining, and thought she succeeded fairly well. After dinner he retired into the depths of the evening paper, and Dorothy stitched away at her embroidery.

Suddenly Jack looked at his watch. "Well, it's half past seven, and I've got to go over to Mrs. Brown's and practise a duet with her for to-morrow."

Dorothy trembled, but only said: "Oh, yes, the duet. What is it this time?"

"'Calvary,' I guess, that seems to take the multitude better than anything we[51] sing. No, Jip, not this time. Good-bye, I won't be gone long."

The door slammed, and Dorothy was alone. She put away her embroidery and walked the floor restlessly. Mrs. Brown was a pretty widow, always well dressed, and she sang divinely. Dorothy could not sing a note though she played fairly well, and Jack got into a habit of taking Mrs. Brown new music and going over to sing it with her. An obliging neighbour had called that afternoon and remarked maliciously that Mr. Ward and Mrs. Brown seemed to be very good friends. Dorothy smiled with white lips, and tried to say pleasantly, "Yes, Mrs. Brown is very charming, don't you think so? I am sure that if I were a man I should fall in love with her."

The neighbour rose to go and by way of a parting shot replied: "That seems to be Mr. Ward's idea. Lovely day, isn't it? Come over when you can."

Dorothy was too stunned to reply. She thought seriously of telling Jack, but wisely decided not to. These suburban towns were always gossipy. Jack would think she did not trust him. And now he was at Mrs. Brown's again!

The pain was almost blinding. She went to the window and looked out. The rising moon shone fitfully upon the white signs of sorrow in the little churchyard far to the left.

She threw a shawl over her head and went out. In feverish haste she walked over to the little "God's Acre" where the Child of Silence was buried.

She found the spot and sat down. A thought of Mrs. Browning's ran through her mind:

"Thank God, bless God, all ye who suffer not

More grief than ye can weep for——"

Then someway the tears came, a blessed rush of relief.

"Oh, baby dear," she sobbed, pressing her lips to the cold turf above him, "I wish I were down there beside you, as still and as dreamless as you. You don't know what it means—you never would have known. I'd rather be a stone than a woman with a heart. Do you think that if I could buy death I wouldn't take it and come down there beside you? It hurt me to lose you, but it wasn't the worst. You[53] would have loved me. Oh, my Child of Silence! Come back, come back!"

How long she stayed there she never knew, but the heart pain grew easier after a while. She pressed her lips to the turf again. "Good night, baby dear, good night. I'll come again. You haven't lost your mother even if she has lost you!"

Fred Bennett passed by the unfrequented spot, returning from an errand to that part of town, and he heard the last words. He drew back into the shadow. The slight black figure appeared on the sidewalk a few feet ahead of him and puzzled him not a little. He followed cautiously and finally decided to overtake her. As she heard his step behind her she looked around timidly.

"Mrs. Ward!"

His tone betrayed surprise, and he saw that her eyes were wet and her white, drawn face was tear-stained. She shuddered. A new trouble faced her. How long had he been following her?

He saw her distress and told his lie bravely. "I just came around the corner here."

Her relieved look was worth the sacrifice of his conscientious scruples, he said to himself afterward.

"I may walk home with you, may I not?"

"Certainly."

She took his offered arm and tried to chat pleasantly with her old friend. Soon they reached the gate. She dropped his arm and said good night unsteadily. Bennett could bear it no longer and he took both of her hands in his own.

"Mrs. Ward, you are in trouble. Tell me, perhaps I can help you." She was silent. "Dorothy, you will let me call you so, will you not? You know how much I cared for you in a boy's impulsive fashion, in the old days when we were at school; you know that I am your friend now—as true a friend as a man can be to a woman. Tell me, Dorothy, and let me help you."

There was a rustle of silk on the pavement and her caller of the afternoon swept by without speaking. Already Dorothy knew the story which would be put in circulation on the morrow. Bennett's clasp tightened on her cold fingers. "Tell me, Dorothy, and let me help you!" he said again.

The impulse to tell him grew stronger, and she controlled it with difficulty. "It[55] is nothing, Mr. Bennett, I—I have a headache."

"I see, and you came out for a breath of fresh air. Pardon me. I am sure you will be better in the morning. These cool nights are so bracing. Good night, and God bless you—Dorothy."

Meanwhile Bennett was on his way to Mrs. Brown's cottage. His mind was made up, and he would speak to Jack. He had heard a great deal of idle gossip, and it would probably cost him Jack's friendship, but he would at least have the satisfaction of knowing that he had tried to do something for Dorothy. He rang the bell and Mrs. Brown herself answered it.

"Good evening, Mrs. Brown. No, thank you, I won't come in. Just ask Jack if I may see him a minute on a matter of business."

Ward, hearing his friend's voice, was already at the door.

"I'll be with you in a minute, Fred," he said. "Good night, Mrs. Brown; I am sure we shall get on famously with the duet." And the two men went slowly down the street.

They walked on in silence until Jack said: "Well, Bennett, what is it? You[56] don't call a fellow out like this unless it is something serious."

"It is serious, Jack; it's Dor—it's Mrs. Ward."

"Dorothy? I confess I am as much in the dark as ever."

"It's this way, Jack, she is in trouble."

Ward was silent.

"Jack, you know I'm a friend of yours; I have been ever since I've known you. If you don't take what I am going to say as I mean, you are not the man I think you are."

"Go on, Fred, I understand you. I was only thinking."

"Perhaps you don't know it, but the town is agog with what it is pleased to term your infatuation for Mrs. Brown." Jack smothered a profane exclamation, and Bennett continued. "Dorothy is eating her heart out over the baby. She was in the cemetery to-night sobbing over his grave and talking to him like a mad woman. I came up the back street, and after a little I overtook her and walked home with her. That's how I happen to know. And don't think for a moment that she hasn't heard the gossip. She has, only she is too proud to speak of it. And[57] Jack, old man, I don't believe you've neglected her intentionally, but begin again and show her how much you care for her. Good night."

Bennett left him abruptly, for the old love for Dorothy was strong to-night; not the fitful flaming passion of boyhood, but the deeper, tenderer love of his whole life.

Jack was strangely affected. Dear little Dorothy! He had neglected her. "I don't deserve her," he said to himself, "but I will."

He passed a florist's shop, and a tender thought struck him. He would buy Dorothy some roses. He went in and ordered a box of American Beauties. A stiff silk rustled beside him and he lifted his hat courteously.

"Going home, Mr. Ward? It's early, isn't it?" "But," with scarcely perceptible emphasis, "it's—none—too soon!" Then as her eager eye caught a glimpse of the roses, "Ah, but you men are sly! For Mrs. Brown?"

Jack took his package and responded icily, "No, for Mrs. Ward!" "Cat!" he muttered under his breath as he went out. And that little word in the mouth of a man means a great deal.

He entered the house, and was not surprised to find that Dorothy had retired. She never waited for him now. He took the roses from the box and went up-stairs.

"Hello, Dorothy," as the pale face rose from the pillow in surprise. "I've brought you some roses!" Dorothy actually blushed. Jack hadn't brought her a rose for three years; not since the day the baby was born. He put them in water and came and sat down beside her.

"Dear little girl, your head aches, doesn't it?" He drew her up beside him and put his cool fingers on the throbbing temples. Her heart beat wildly and happy tears filled her eyes as Jack bent down and kissed her tenderly. "My sweetheart! I'm so sorry for the pain."

It was the old lover-like tone and Dorothy looked up.

"Jack," she said, "you do love me, don't you?"

His arms tightened about her. "My darling, I love you better than anything in the world. You are the dearest little woman I ever saw. It isn't much of a heart, dear, but you've got it all. Crying? Why, what is it, sweetheart?"

"The baby," she answered brokenly, and his eyes overflowed too.

"Dorothy, dearest, you know that was best. He wasn't like—" Jack couldn't say the hard words, but Dorothy understood and drew his face down to hers again.

Then she closed her eyes, and Jack held her until she slept. The dawn found his arms around her again, and when the early church bells awoke her from a happy dream she found the reality sweet and beautiful, and the heartache a thing of the past.

The single lamp in "the den" shone in a distant corner with a subdued rosy glow; but there was no need of light other than that which came from the pine knots blazing in the generous fireplace.

On the rug, crouched before the cheerful flame, was a woman, with her elbow on her knee and her chin in the palm of her hand.

There were puzzled little lines in her forehead, and the corners of her mouth drooped a little. Miss Archer was tired, and the firelight, ever kind to those who least need its grace, softened her face into that of a wistful child.

A tap at the door intruded itself into her reverie. "Come," she called. There was a brief silence, then an apologetic masculine cough.

Helen turned suddenly. "Oh, it's you," she cried. "I thought it was the janitor!"

"Sorry you're disappointed," returned[64] Hilliard jovially. "Sit down on the rug again, please,—you've no idea how comfortable you looked,—and I'll join you presently." He was drawing numerous small parcels from the capacious pockets of his coat and placing them upon a convenient chair.

"If one might enquire—" began Helen.

"Certainly, ma'am. There's oysters and crackers and parsley and roquefort, and a few other things I thought we might need. I know you've got curry-powder and celery-salt, and if her gracious ladyship will give me a pitcher, I'll go on a still hunt for cream."

"You've come to supper, then, I take it," said Helen.

"Yes'm. Once in a while, in a newspaper office, some fellow is allowed a few minutes off the paper. Don't know why, I'm sure, but it has now happened to me. I naturally thought of you, and the chafing dish, and the curried oysters you have been known to cook, and——"

Helen laughed merrily. "Your heart's in the old place, isn't it—at the end of your esophagus?"

"That's what it is. My heart moves up into my throat at the mere sight of you."[65] The colour flamed into her cheeks. "Now will you be good?" he continued enquiringly. "Kindly procure for me that pitcher I spoke of."

He whistled happily as he clattered down the uncarpeted stairs, and Helen smiled to herself. "Bohemia has its consolations as well as its trials," she thought. "This would be impossible anywhere else."

After the last scrap of the feast had been finished and the dishes cleared away, Frank glanced at his watch. "I have just an hour and a half," he said, "and I have a great deal to say in it." He placed her in an easy chair before the fire and settled himself on a cushion at her feet, where he could look up into her face.

"'The time has come, the walrus said, to talk of many things,'" quoted Helen lightly.

"Don't be flippant, please."

"Very well, then," she replied, readily adjusting herself to his mood, "what's the trouble?"

"You know," he said in a different tone, "the same old one. Have you nothing to say to me, Helen?"

Her face hardened, ever so slightly, but he saw it and it pained him. "There's no use going over it again," she returned, "but[66] if you insist, I will make my position clear once for all."

"Go on," he answered grimly.

"I'm not a child any longer," Helen began, "I'm a woman, and I want to make the most of my life—to develop every nerve and faculty to its highest and best use. I have no illusions but I have my ideals, and I want to keep them. I want to write—you never can understand how much I want to do it—and I have had a tiny bit of success already. I want to work out my own problems and live my own life, and you want me to marry you and help you live yours. It's no use, Frank," she ended, not unkindly, "I can't do it."

"See here, my little comrade," he returned, "you must think I'm a selfish beast. I'm not asking you to give up your work nor your highest and best development. Isn't there room in your life for love and work too?"

"Love and I parted company long ago," she answered.

"Don't you ever feel the need of it?"

She threw up her head proudly. "No, my work is all-sufficient. There is no joy like creation; no intoxication like success."

"But if you should fail?"

"I shall not fail," she replied confidently. "When you dedicate your whole life to a thing, you simply must have it. The only reason for a failure is that the desire to succeed is not strong enough. I ask no favours—nothing but a fair field. I'm willing to work, and work hard for everything I get, as long as I have the health and courage to work at all."

He looked at her a long time before he spoke again. The firelight lingered upon the soft curves of her throat with a caressing tenderness. Her eyes, deep, dark, and splendid, were shining with unwonted resolution, and her mouth, though set in determined lines, had a womanly sweetness of its own. Around her face, like a halo, gleamed the burnished glory of her hair.

For three long years he had loved her. Helen, with her eyes on things higher than love and happiness, had persistently eluded his wooing. His earnest devotion touched her not a little, but she felt her instinctive sympathy for him to be womanish weakness.

"This is final?" he asked, rising and standing before her.

She rose also. "Yes, please believe me[68]—it must be final; there is no other way. I don't want lovers—I want friends."

"You want me, then, to change my love to friendship?"

"Yes."

"Never to tell you again that I love you?"

"No, never again."

"Very well, we are to be comrades, then?"

She gave him her hand. "Yes, working as best we may, each with the understanding and approval of the other; comrades in Bohemia."

Some trick of her voice, some movement of her hand—those trifles so potent with a man in love—beat down his contending reason. With a catch in his breath, he crushed her roughly to him, kissed her passionately on the mouth, then suddenly released her.

"Women like you don't know what you do," he said harshly. "You hold a man captive with your charm, become so vitally necessary to him that you are nothing less than life, enmesh, ensnare him at every opportunity, then offer him the cold comfort of your friendship!"

He was silent for a breathless instant;[69] then in some measure, his self-control came back. "Pardon me," he said gently, bending over her hand. "I have startled you. It shall not occur again. Good night and good luck—my comrade in Bohemia!"

Helen stood where he had left her until the street door closed and the echo of his footsteps died away. The fire was a smouldering heap of ashes, and the room seemed deathly still. Her cheeks were hot as with a fever, and she trembled like one afraid. It was the first time he had crossed the conventional boundary, and he had said it would be the last, but Love's steel had struck flame from the flint of her maiden soul.

"I wish," she said to herself as she put the room in order, "that I lived on some planet where life wasn't quite so serious."

For his part he was pacing moodily down the street, with his hands in his pockets. Several times he swallowed a persistent lump in his throat. He could understand Helen's ambition, and her revolt against the conventions, but he could not understand her point of view. Even now, he would not admit that she was wholly lost to him. What she had said[70] came back to him with convincing force: "When you dedicate your whole life to a thing, you simply must have it."

"We'll see," he said to himself grimly, "just how true her theory is."

Months passed, and Helen worked hard. She was busy as many trusting souls have been before with "The Great American Novel." She was putting into it all of her brief experience and all of her untried philosophy of life. She was writing of suffering she had never felt, and of love she could not understand.

She saw Frank now and then, at studio teas and semi-Bohemian gatherings, at which the newspaper men were always a welcome feature. There was no trace of the lover in his manner, and she began to doubt his sincerity, as is the way with women.

"So this is Bohemia?" he asked one evening when they met in a studio in the same building as Helen's den.

"Yes,—why not?"

"I was thinking it must be a pretty poor place if this is a fair sample of the inhabitants," he returned easily.

She flushed angrily. "I do not see why you should think so. Here are authors, musicians, poets, painters and playwrights—could one be in better company?"

He paid no attention to her ironical question. "Yes," he continued, "I see the authors. One is a woman—pardon me, a female—who has written a vulgar novel, and gained a little sensational notoriety. The other is a man who paid a fifth-rate publishing house a goodly sum to issue what he calls 'a romance.' The musicians are composers of 'coon songs' even though the African Renaissance has long since waned, and members of theatrical orchestras. The poets have their verses printed in periodicals which 'do not pay for poetry.' The only playwright present has written a vaudeville sketch—and I don't see the painters. Are they painting billboards?"

"Perhaps," said Helen, with exquisite iciness, "since you find us all so far beneath your level, you will have the goodness to withdraw. Your superiority may make us uncomfortable."

Half in amusement, and half in surprise, he left her in a manner which was meant to be coldly formal, and succeeded in being ridiculous.

After a while, Helen went home, dissatisfied[72] with herself, and for the first time dissatisfied with the Bohemia over the threshold of which she had stepped. Always honest, she could not but admit the truth of his criticism. Yet she was wont to judge people by their aspirations rather than by their achievements. "We are all workers," she said to herself, as she brushed her hair. "Every one of those people is aspiring to what is best and highest in art. What if they have failed? Not fame, nor money, but art for art's dear sake. I am proud to be one of them."

In the course of a few weeks the novel was finished, and she subjected it to careful, painstaking revision. She studied each chapter singly, to see if it could not be improved, even in the smallest detail. When the last revision had been made, with infinite patience, she was satisfied. She wanted Frank to read it, but was too proud to make the first overtures towards reconciliation.

The first three publishers returned the manuscript with discouraging promptness. Rejected short stories and verse began to accumulate on her desk. Sunday newspaper specials came home with "return"[73] written in blue pencil across the neatly typed page. Courteous refusal blanks came in almost every mail, and still Helen did not utterly despair. She had put into her work all that was best of her life and strength, and it was inconceivable that she should fail.

Two more publishing houses returned her novel without comment, and with a sort of blind faith, she sent it out again. This time, too, it came back, but with a kindly comment by the reader. "You cannot write until you have lived," was his concluding sentence. Helen sat stiff and still with the letter crumpled in her cold fingers.

Slowly the bitter truth forced itself upon her consciousness. "I have failed," she said aloud, "I have failed—failed—failed." A dry tearless sob almost choked her, and with sudden passionate hatred of herself and her work, she threw her manuscript into the fire. The flames seized it hungrily. Then, someway, the tears came—a blessed rush of relief.

Hilliard found her there when he came at dusk, with a bunch of roses by way of a peace offering. The crumpled letter on the floor and the shrivelled leaves of[74] burned paper in the fireplace afforded him all the explanation he needed. He sat down on the couch beside her and took her trembling hands in his.

The coolness of his touch roused her, and she sighed, burying her tear-stained face in the roses. "I have failed," she said miserably, "I have failed."

He listened without comment to the pitiful little story of hard work and bitter disappointments. "I've given up everything for my art," she said, with a little quiver of the lips, "why shouldn't I succeed in it?"

The temptation to take her in his arms temporarily unmanned him. He left her abruptly and stood upon the hearth rug.

"You are trying to force the issue," he said quietly. "You ar'n't content to be a happy, normal woman, and let art take care of itself. You should touch life at first hand, and you are not living. You are simply associating with a lot of hysterical failures who call themselves 'Bohemians.' Art, if it is art, will develop in whatever circumstances it is placed. Why shouldn't you just be happy and let the work take care of itself? Write the little things that come to you from day to day,[75] and if a great utterance is reserved for you, you cannot but speak it, when the time comes for it to be given to the world."

Helen stared at him for a moment, and then the inner tension snapped. "You are right," she said, sadly, instinctively drawing toward him. "I am forcing the issue."

They stood looking into each other's eyes. Helen saw the strong, self-reliant man who seemed to have fully learned the finest art of all—that of life. She felt that it might be possible to love him, if she could bring herself to yield the dazzling vista of her career. All unknowingly, he had been the dearest thing in the world to her for some little time. Bohemia's glittering gold suddenly became tinsel. There came a great longing to "touch life at first hand."

He saw only the woman he loved, grieved, pained, and troubled; tortured by aspirations she could not as yet attain, and stung by a self-knowledge that came too late. A softer glow came into Helen's face and the lover's blind instinct impelled him toward her with all his soul in his eyes.

"Sweetheart," he said huskily.

Helen stopped him. "No," she said[76] humbly, "I must say it all myself. You are right, and I am wrong. I must live before I am a woman and I must be a woman before I can be an artist. I have cared for you for a long time, but I have been continually fighting against it—I see it all now. I will be content to be a happy woman and let the work take care of itself. Faulty, erring and selfish, I see myself, now, but will you take me just as I am?"

The last smouldering spark of fire had died out and left the room in darkness. Helen's face showing whitely in the shadow was half pleading, and wholly sweet.

Speechless with happiness, he could not move. A thousand things struggled for utterance, but the words would not come. She waited a moment, and then spoke again.

"Have I not humbled myself enough? Is there anything more I can say? I should not blame you if you went away, I know I deserve it all." The old tide of longing surged into the man's pulses again, and broke the spell which lay upon him. With a little cry, he caught her in his arms. She gave her lips to his in that kiss of full surrender which a woman gives but once in her life, then, swinging on silent hinges, the doors of her Bohemia closed forever.

One afternoon before Christmas, a man with bowed head and aimless step walked the crowded streets of a city. The air was clear and cold, the blue sky was dazzlingly beautiful, the sun shone brightly upon his way, yet in his face was unspeakable pain.

His thoughts were with the baby daughter whom he had seen lowered into the snow, only a few hours before. He saw it all,—the folds of the pretty gown, the pink rose in the tiny hands, and the happy smile which the Angel of the Shadow had been powerless to take away.

"You will forget," a friend had said to him.

"Forget," he said to himself again and again. "You can't forget your heart," he had answered, "and mine is out there under the snow."

Through force of habit, he turned down the street on which stood the great church[80] where he played the organ on Sundays and festival days. He hesitated a moment before the massive doorway, then felt in his pocket for the key, unlocked the door and went in. The sun shone through the stained glass windows and filled the old church with glory, but his troubled eyes saw not. He sat down before the instrument he loved so well and touched the keys with trembling fingers. At once, the music came, and to the great heart of the organ which swelled with pity and tenderness, he told his story. Wild and stormy with resentment at first, anger, love, passion, and pain blended together in the outburst which shook the very walls of the church.

"God gives us hearts—and breaks them," he thought and his face grew white with bitterness.

Beside himself with passion, he played on, and on, till the sun sank behind the trees and the afternoon shaded into twilight.

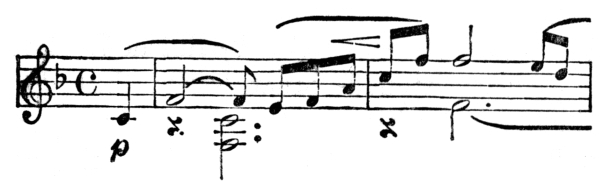

As the shadows filled the church, he accidentally struck a minor chord, plaintive, sweet, almost sad.

He stopped. With that sound a flood of memories came over him—an autumn day in the woods, the trees dropping leaves[81] of crimson and gold, the river flowing at his feet, with the purple asters and goldenrod on its banks, and beside him the fair sweet girl who had made his life a happy one;—and insensibly he drifted into the melody, dreaming, on the saddest day of his life, of the day which had been his happiest.

He remembered the look in her eyes when he had first kissed her. Beautiful eyes they were, brown, soft, and tender, with that inward radiance which comes to a woman only when she looks into the face of the man she loves.

"I will go to her," he whispered, "but not yet, not yet!" And still he played on in that vein of sadness, the sweet influence stealing into his heart till the pain was hushed in peace. Conscious only of a strange sense of uplifting, the music grew stronger as the thought of the future was before him. He was young, talented, he had a wife to live for, and a child—no, not a child—and the tears stole over his cheeks as he again touched the minor chord.

The crescendo came again. The child was safe in the white arms of the snow, and she was hidden away from the sorrows of the earth in the only place where we are ever safe from these—in its heart.

The moon had risen over the hill-tops, and the church was as light as if touched on every side with silver. The organ sounded a strain of exultation in which the minor chord was in some way mingled with the theme. He could face the world now. Any one can die but it takes a hero to live. Something he had read came back to him: "Once to every human being, God gives suffering—the anguish that cuts, burns and stings. The terrible 'one day' always comes and after it our hearts are sometimes cruel and selfish—or sometimes tender as He wishes them to be."

And the strong soul rose above its bitterness, for his "one day" was over, and it could never come again. His strength asserted itself anew as he came down from the organ loft and went toward the door. A little bundle in one of the pews attracted his attention, and he stooped to see what it was. A pale, pinched baby face looked up at him wonderingly, the golden hair shining with celestial glory in the moonlight. The hair, the eyes, the position of the head were much like those of the child he had lost.

Back came the rush of infinite pain—he was not so strong as he had thought—but[83] only for an instant. Hark! was it an echo or his own soul playing upon his quivering heartstrings the minor chord? Again the new strength reasserted itself and into his consciousness rose the higher duty to the living over the love and faith for the lost.

"Was it you played the music?" said the sweet child voice. "I heard it and I comed in!"

"Dear," he said, "where is your home? Are you all alone?"

"Home," she said wonderingly. "Home?"

Without another word, he took the child in his arms and hurried out of the doorway. Along the brilliantly lighted avenue he hastened, till he reached the little cottage in a side street. It was dark within except for the fitful glancings of the moonlight, and he deposited his burden in a big arm-chair while he went in search of his wife.

"Sweetheart," he called, "where are you?"

The sweet face came into the shadow before him, and she laid her hand upon his arm without speaking. He led her to the little waif saying simply: "I have brought you a Christmas gift, dear."

She put out her empty arms and gathered the desolate baby to her breast. The eternal instinct of motherhood swelled up again and for a moment, in the touch of the soft flesh against her own, the tiny grave in the snow seemed only a dream.

"Theodora—Gift of God," he said reverently. Then as the clouds parted, and the moonlight filled every nook and corner of the little room: "Dearest, we cannot forget, but we can be brave, and our Gift of God, shall keep us; shall it be so?"

With a discordant rumble of drums, and the metallic clang of a dozen tambourines, the Salvation Army procession passed down the street. When the leader paused at a busy corner and began to sing, a little knot of people quickly gathered to listen. Some quavering uncertain voices joined in the hymn as the audience increased, then mindful of his opportunity, a tall young man in red and blue uniform began an impassioned exhortation.

George Arnold and his friend Clayton lingered with half humorous tolerance upon the outskirts of the crowd. They were about to turn away when Arnold spoke in a low tone:

"Look at that girl over there."

The sudden flare of the torch-light revealed the only face in the group which could have attracted Arnold's attention. It was that of a girl but little past twenty, who stood by the leader holding a tambourine.[88] She was not beautiful in the accepted sense of the word, but her eyes were deep and lustrous, her mouth sensitive and womanly, and the ugly bonnet could not wholly conceal a wealth of raven hair. Her skin had a delicate pearly clearness, and upon her face was a look of exaltation and purity as though she stood on some distant elevation, far above the pain and tumult of the world.

After a little, the Salvationists made ready to depart, and Arnold and Clayton turned away.