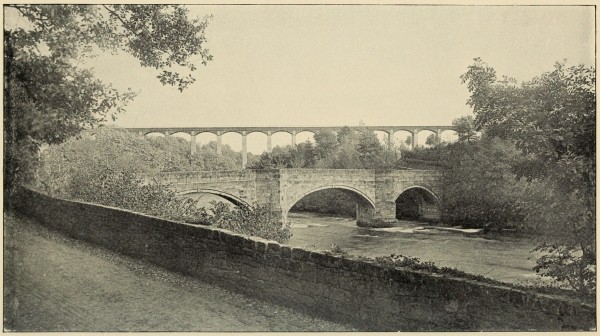

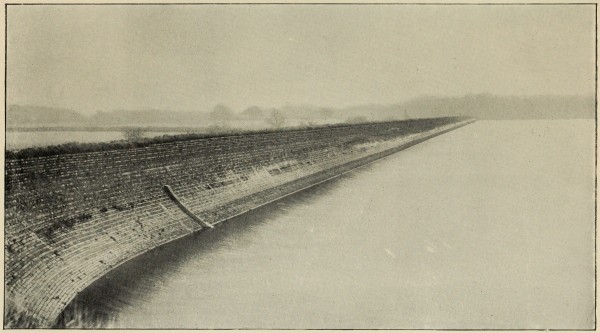

AQUEDUCT AT PONTCYSYLLTE (IN THE DISTANCE).

(Constructed by Telford to carry Ellesmere Canal over River Dee. Opened 1803. Cost £47,000. Length, 1007 feet.)

[Frontispiece.

Title: British Canals: Is their resuscitation practicable?

Author: Edwin A. Pratt

Release date: November 23, 2014 [eBook #47435]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, MWS and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

AQUEDUCT AT PONTCYSYLLTE (IN THE DISTANCE).

(Constructed by Telford to carry Ellesmere Canal over River Dee. Opened 1803. Cost £47,000. Length, 1007 feet.)

[Frontispiece.

BRITISH CANALS:

IS THEIR RESUSCITATION PRACTICABLE?

BY EDWIN A. PRATT

AUTHOR OF "RAILWAYS AND THEIR RATES," "THE ORGANIZATION

OF AGRICULTURE," "THE TRANSITION IN AGRICULTURE," ETC.

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1906

The appointment of a Royal Commission on Canals and Waterways, which first sat to take evidence on March 21, 1906, is an event that should lead to an exhaustive and most useful enquiry into a question which has been much discussed of late years, but on which, as I hope to show, considerable misapprehension in regard to actual facts and conditions has hitherto existed.

Theoretically, there is much to be said in favour of canal restoration, and the advocates thereof have not been backward in the vigorous and frequent ventilation of their ideas. Practically, there are other all-important considerations which ought not to be overlooked, though as to these the British Public have hitherto heard very little. As a matter of detail, also, it is desirable to see whether the theory that the decline of our canals is due to their having been "captured" and "strangled" by the railway companies—a theory which many people seem to believe in as implicitly as they do, say, in the Multiplication Table—is really capable of proof, or whether that decline is not, rather, to be attributed to wholly different causes.

In view of the increased public interest in the general question, it has been suggested to me that [viii]the Appendix on "The British Canal Problem" in my book on "Railways and their Rates," published in the Spring of 1905, should now be issued separately; but I have thought it better to deal with the subject afresh, and at somewhat greater length, in the present work. This I now offer to the world in the hope that, even if the conclusions at which I have arrived are not accepted, due weight will nevertheless be given to the important—if not (as I trust I may add) the interesting—series of facts, concerning the past and present of canals alike at home, on the Continent, and in the United States, which should still represent, I think, a not unacceptable contribution to the present controversy.

EDWIN A. PRATT.

London, April 1906.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | INTRODUCTORY | 1 |

| II. | EARLY DAYS | 12 |

| III. | RAILWAYS TO THE RESCUE | 23 |

| IV. | RAILWAY-CONTROLLED CANALS | 32 |

| V. | THE BIRMINGHAM CANAL AND ITS STORY | 57 |

| VI. | THE TRANSITION IN TRADE | 74 |

| VII. | CONTINENTAL CONDITIONS | 93 |

| VIII. | WATERWAYS IN THE UNITED STATES | 104 |

| IX. | ENGLISH CONDITIONS | 119 |

| X. | CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS | 142 |

| APPENDIX—THE DECLINE IN FREIGHT TRAFFIC ON THE MISSISSIPPI | 151 | |

| INDEX | 157 |

| HALF-TONE ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| AQUEDUCT AT PONTCYSYLLTE (in the distance) | Frontispiece | |

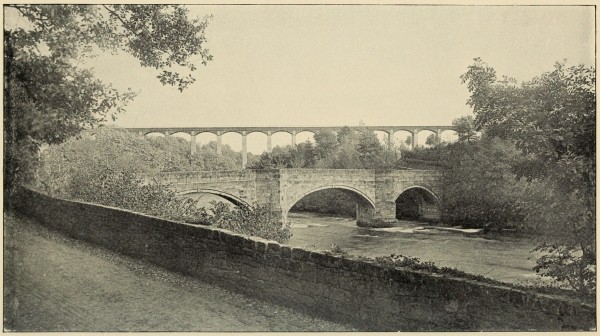

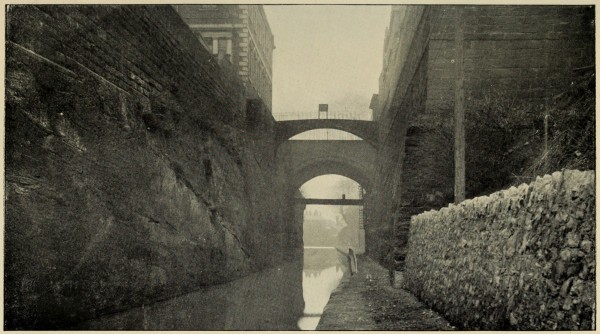

| WHAT CANAL WIDENING WOULD MEAN: COWLEY TUNNEL AND EMBANKMENTS | To face page | 32 |

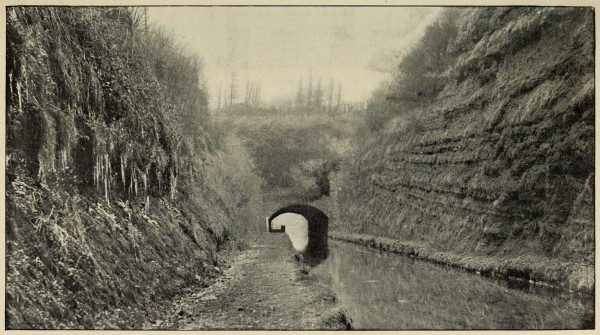

| LOCKS ON THE KENNET AND AVON CANAL AT DEVIZES | " " | 42 |

| WAREHOUSES AND HYDRAULIC CRANES AT ELLESMERE PORT | " " | 48 |

| WHAT CANAL WIDENING WOULD MEAN: SHROPSHIRE UNION CANAL AT CHESTER | " " | 70 |

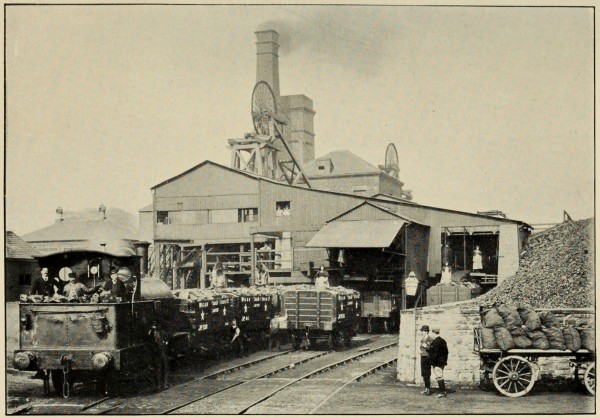

| "FROM PIT TO PORT": PROSPECT PIT, WIGAN | " " | 82 |

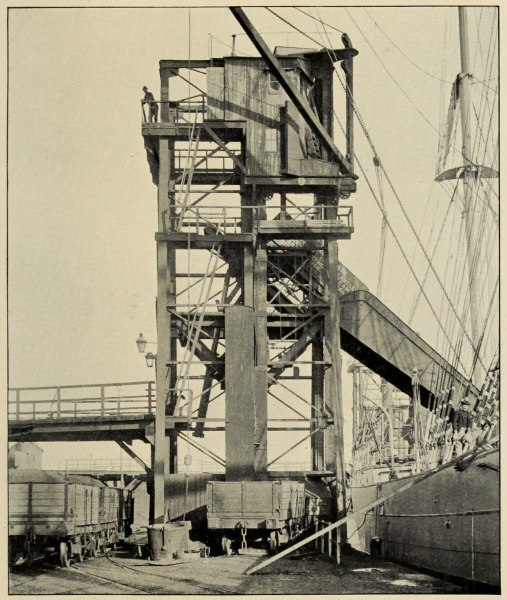

| THE SHIPPING OF COAL: HYDRAULIC TIP ON G.W.R., SWANSEA | " " | 88 |

| A CARGO BOAT ON THE MISSISSIPPI | " " | 110 |

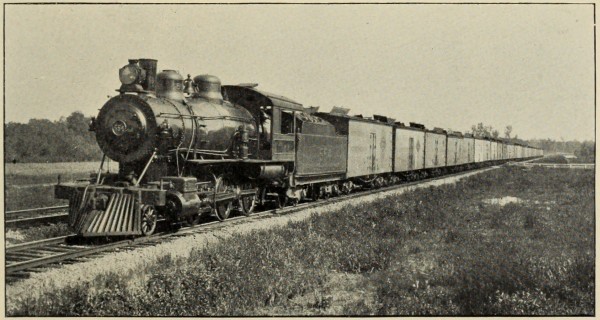

| SUCCESSFUL RIVALS OF MISSISSIPPI CARGO BOATS | " " | 114 |

| WATER SUPPLY FOR CANALS: BELVIDE RESERVOIR, STAFFORDSHIRE | " " | 128 |

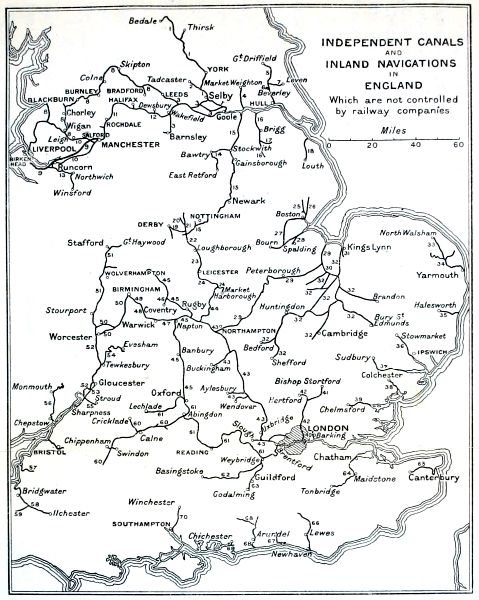

| MAPS AND DIAGRAMS | ||

| INDEPENDENT CANALS AND INLAND NAVIGATIONS | " " | 54 |

| CANALS AND RAILWAYS BETWEEN WOLVERHAMPTON AND BIRMINGHAM | " " | 56 |

| SOME TYPICAL BRITISH CANALS | " " | 98 |

BRITISH CANALS

The movement in favour of resuscitating, if not also of reconstructing, the British canal system, in conjunction with such improvement as may be possible in our natural waterways, is a matter that concerns various interests, and gives rise to a number of more or less complicated problems.

It appeals in the most direct form to the British trader, from the point of view of the possibility of enabling him to secure cheaper transit for his goods. Every one must sympathise with him in that desire, and there is no need whatever for me to stay here to repeat the oft-expressed general reflections as to the important part which cheap transit necessarily plays in the development of trade and commerce. But when from the general one passes to the particular, and begins to consider how these transit questions apply directly to canal revival, one comes at once to a certain element of insincerity in the agitation which has arisen.

There is no reason whatever for doubt that, whereas one section of the traders favouring canal revival would themselves directly benefit therefrom, there [2]is a much larger section who have joined in the movement, not because they have the slightest idea of re-organising their own businesses on a water-transport basis, but simply because they think the existence of improved canals will be a means of compelling the railway companies to grant reductions of their own rates below such point as they now find it necessary to maintain. Individuals of this type, though admitting they would not use the canals themselves, or very little, would have us believe that there are enough of other traders who would patronise them to make them pay. In any case, if only sufficient pressure could be brought to bear on the railway companies to force them to reduce their rates and charges, they would be prepared to regard with perfect equanimity the unremunerative outlay on the canals of a large sum of public money, and be quite indifferent as to who might have to bear the loss so long as they gained what they wanted for themselves.

The subject is, also, one that appeals to engineers. As originally constructed, our British canals included some of the greatest engineering triumphs of their day, and the reconstruction either of these or even of the ordinary canals (especially where the differences of level are exceptionally great), would afford much interesting work for engineers—and, also, to come to commonplace details, would put into circulation a certain number of millions of pounds sterling which might lead some of those engineers, at least, to take a still keener interest in the general situation. There is absolutely no doubt that, from an engineering standpoint, reconstruction, however costly, would present no unsurmountable technical difficulties; but I must confess that when engineers, looking at the [3]problem exclusively from their own point of view, apart from strictly economic and practical considerations, advise canal revival as a means of improving British trade, I am reminded of the famous remark of Sganerelle, in Molière's "L'Amour Médecin"—"Vous êtes orfévre, M. Josse."

The subject strongly appeals, also, to a very large number of patriotic persons who, though having no personal or professional interests to serve, are rightly impressed with the need for everything that is in any way practicable being done to maintain our national welfare, and who may be inclined to assume, from the entirely inadequate facts which, up to the present, have been laid before them as to the real nature and possibilities of our canal system, that great results would follow from a generous expenditure of money on canal resuscitation here, following on the example already set in Continental countries. It is in the highest degree desirable that persons of this class should be enabled to form a clear and definite opinion on the subject in all its bearings, and especially from points of view that may not hitherto have been presented for their consideration.

Then the question is one of very practical interest indeed to the British taxpayer. It seems to be generally assumed by the advocates of canal revival that it is no use depending on private enterprise. England is not yet impoverished, and there is plenty of money still available for investment where a modest return on it can be assured. But capitalists, large or small, are not apparently disposed to risk their own money in the resuscitation of English canals. Their expectation evidently is that the scheme would not pay. In the absence, therefore, of any willingness on the part of shrewd capitalists—ever on the [4]look-out for profitable investments—to touch the business, it is proposed that either the State or the local authorities should take up the matter, and carry it through at the risk, more or less, either of taxpayers or ratepayers.

The Association of Chambers of Commerce, for instance, adopted, by a large majority, the following resolution at its annual meeting, in London, in February 1905:—

"This Association recommends that the improvement and extension of the canal system of the United Kingdom should be carried out by means of a public trust, and, if necessary, in combination with local or district public trusts, and aided by a Government guarantee, and that the Executive Council be requested to take all reasonable measures to secure early legislation upon the subject."

Then Sir John T. Brunner has strongly supported a nationalisation policy. In a letter to The Times he once wrote:

"I submit to you that we might begin with the nationalisation of our canals—some for the most part sadly antiquated—and bring them up to one modern standard gauge, such as the French gauge."

Another party favours municipalisation and the creation of public trusts, a Bill with the latter object in view being promoted in the Session of 1905, though it fell through owing to an informality in procedure.

It would be idle to say that a scheme of canal nationalisation, or even of public trusts with "Government guarantee" (whatever the precise meaning of that term may be) involving millions of public money, could be carried through without affecting [5]the British taxpayer. It is equally idle to say that if only the canal system were taken in hand by the local authorities they would make such a success of it that there would be absolutely no danger of the ratepayers being called upon to make good any deficiency. The experiences that Metropolitan ratepayers, at least, have had as the result of County Council management of the Thames steamboat service would not predispose them to any feeling of confidence in the control of the canal system of the country by local authorities.

At the Manchester meeting of the Association of Chambers of Commerce, in September 1904, Colonel F. N. Tannett Walker (Leeds) said, during the course of a debate on the canal question: "Personally, he was not against big trusts run by local authorities. He knew no more business-like concern in the world than the Mersey Harbour Board, which was a credit to the country as showing what business men, not working for their own selfish profits, but for the good of the community, could do for an undertaking. He would be glad to see the Mersey Boards scattered all over the country." But, even accepting the principle of canal municipalisation, what prospect would there be of Colonel Walker's aspiration being realised? The Mersey Harbour Board is an exceptional body, not necessarily capable of widespread reproduction on the same lines of efficiency. Against what is done in Liverpool may be put, in the case of London, the above-mentioned waste of public money in connection with the control of the Thames steamboat service by the London County Council. If the municipalised canals were to be worked on the same system, or any approach thereto, as these municipalised steamboats, [6]it would be a bad look-out for the ratepayers of the country, whatever benefit might be gained by a small section of the traders.

Then one must remember that the canals, say, from the Midlands to one of the ports, run through various rural districts which would have no interest in the through traffic carried, but might be required, nevertheless, to take a share in the cost and responsibility of keeping their sections of the municipalised waterways in an efficient condition, or in helping to provide an adequate water-supply. It does not follow that such districts—even if they were willing to go to the expense or the trouble involved—would be able to provide representatives on the managing body who would in any way compare, in regard to business capacity, with the members of the Mersey Harbour Board, even if they did so in respect to public spirit, and the sinking of their local interests and prejudices to promote the welfare of manufacturers, say, in Birmingham, and shippers in Liverpool, for neither of whom they felt any direct concern.

Under the best possible conditions as regards municipalisation, it is still impossible to assume that a business so full of complications as the transport services of the country, calling for technical or expert knowledge of the most pronounced type, could be efficiently controlled by individuals who would be essentially amateurs at the business—and amateurs they would still be even if assisted by members of Chambers of Commerce who, however competent as merchants and manufacturers, would not necessarily be thoroughly versed in all these traffic problems. The result could not fail to be disastrous.

I come, at this point, in connection with the possible liability of ratepayers, to just one matter of detail that might be disposed of here. It is certainly one that seems to be worth considering. Assume, for the sake of argument, that, in accordance with the plans now being projected, (1) public trusts were formed by the local authorities for the purpose of acquiring and operating the canals; (2) that these trusts secured possession—on some fair system of compensation—of the canals now owned or controlled by railway companies; (3) that they sought to work the canals in more or less direct competition with the railways; (4) that, after spending large sums of money in improvements, they found it impossible to make the canals pay, or to avoid heavy losses thereon; and (5) that these losses had to be made good by the ratepayers. I am merely assuming that all this might happen, not that it necessarily would. But, admitting that it did, would the railway companies, as ratepayers, be called upon to contribute their share towards making good the losses which had been sustained by the local authorities in carrying on a direct competition with them?

Such a policy as this would be unjust, not alone to the railway shareholders, but also to those traders who had continued to use the railway lines, since it is obvious that the heavier the burdens imposed on the railway companies in the shape of local rates (which already form such substantial items in their "working expenses"), the less will the companies concerned be in a position to grant the concessions they might otherwise be willing to make. Besides, apart from monetary considerations, the principle of the thing would be intolerably unfair, and, if only [8]to avoid an injustice, it would surely be enacted that any possible increase in local rates, due to the failure of particular schemes of canal municipalisation, should fall exclusively on the traders and the general public who were to have been benefited, and in no way on the railway companies against whom the commercially unsuccessful competition had been waged.

This proposition will, I am sure, appeal to that instinct of justice and fair play which every Englishman is (perhaps not always rightly), assumed to possess. But what would happen if it were duly carried out, as it ought to be? Well, in the Chapter on "Taxation of Railways" in my book on "Railways and their Rates," I gave one list showing that in a total of eighty-two parishes a certain British railway company paid an average of 60·25 per cent. of the local rates; while another table showed that in sixteen specified parishes the proportion of local rates paid by the same railway company ranged from 66·9 per cent. to 86·1 per cent. of the total, although in twelve parishes out of the sixteen the company had not even a railway station in the place. But if, in all such parishes as these, the railway companies were very properly excused from having to make good the losses incurred by their municipalised-canal competitors (in addition to such losses as they might have already suffered in meeting the competition), then the full weight of the burden would fall upon that smaller—and, in some cases, that very small—proportion of the general body of ratepayers in the locality concerned.

The above is just a little consideration, en passant, which might be borne in mind by others than those who look at the subject only from a trader's or an engineer's point of view. It will help, also, to [9]strengthen my contention that any ill-advised, or, at least, unsuccessful municipalisation of the canal system of the country might have serious consequences for the general body of the community, who, in the circumstances, would do well to "look before they leap."

But, independently of commercial, engineering, rating and other considerations, there are important matters of principle to be considered. Great Britain is almost the only country in the world where the railway system has been constructed without State or municipal aid—financial or material—of any kind whatever. The canals were built by "private enterprise," and the railways which followed were constructed on the same basis. This was recognised as the national policy, and private investors were allowed to put their money into British railways, throughout successive decades, in the belief and expectation that the same principle would be continued. In other countries the State has (1) provided the funds for constructing or buying up the general railway system; (2) guaranteed payment of interest; or (3) has granted land or made other concessions, as a means of assisting the enterprise. Not only has the State refrained from adopting any such course here, and allowed private investors to bear the full financial risk, but it has imposed on British railways requirements which may certainly have led to their being the best constructed and the most complete of any in the world, but which have, also, combined with the extortions of landowners in the first instance, heavy expenditure on Parliamentary proceedings, etc., to render their construction per mile more costly than those of any other system of railways in the world; while to-day local taxation [10]is being levied upon them at the rate of £5,000,000 per annum, with an annual increment of £250,000.

This heavy expenditure, and these increasingly heavy demands, can only be met out of the rates and charges imposed on those who use the railways; and one of the greatest grievances advanced against the railways, and leading to the agitation for canal revival, is that these rates and charges are higher in Great Britain than in various other countries, where the railways have cost less to build, where State funds have been freely drawn on, and where the State lines may be required to contribute nothing to local taxation. The remedy proposed, however, is not that anything should be done to reduce the burdens imposed on our own railways, so as to place them at least in the position of being able to make further concessions to traders, but that the State should now itself start in the business, in competition, more or less, with the railway companies, in order to provide the traders—if it can—with something cheaper in the way of transport!

Whatever view may be taken of the reasonableness and justice of such a procedure as this, it would, undoubtedly, represent a complete change in national policy, and one that should not be entered upon with undue haste. The logical sequel, for instance, of nationalisation of the canals would be nationalisation of the railways, since it would hardly do for the State to own the one and not the other. Then, of course, the nationalisation of all our ports would have to follow, as the further logical sequel of the State ownership of the means of communication with them, and the consequent suppression of competition. From a Socialist standpoint, the successive steps here mentioned would certainly be approved; but, even [11]if the financial difficulty could be met, the country is hardly ready for all these things at present.

Is it ready, even in principle, for either the nationalisation or the municipalisation of canals alone? And, if ready in principle, if ready to employ public funds to compete with representatives of the private enterprise it has hitherto encouraged, is it still certain that, when millions of pounds sterling have been spent on the revival of our canals, the actual results will in any way justify the heavy expenditure? Are not the physical conditions of our country such that canal construction here presents exceptional drawbacks, and that canal navigation must always be exceptionally slow? Are not both physical and geographical conditions in Great Britain altogether unlike those of most of the Continental countries of whose waterways so much is heard? Are not our commercial conditions equally dissimilar? Is not the comparative neglect of our canals due less to structural or other defects than to complete changes in the whole basis of trading operations in this country—changes that would prevent any general discarding of the quick transit of small and frequent supplies by train, in favour of the delayed delivery of large quantities at longer intervals by water, however much the canals were improved?

These are merely some of the questions and considerations that arise in connection with this most complicated of problems, and it is with the view of enabling the public to appreciate more fully the real nature of the situation, and to gain a clearer knowledge of the facts on which a right solution must be based, that I venture to lay before them the pages that follow.

It seems to be customary with writers on the subject of canals and waterways to begin with the Egyptians, to detail the achievements of the Chinese, to record the doings of the Greeks, and then to pass on to the Romans, before even beginning their account of what has been done in Great Britain. Here, however, I propose to leave alone all this ancient history, which, to my mind, has no more to do with existing conditions in our own country than the system of inland navigation adopted by Noah, or the character of the canals which are supposed to exist in the planet of Mars.

For the purposes of the present work it will suffice if I go no further back than what I would call the "pack-horse period" in the development of transport in England. This was the period immediately preceding the introduction of artificial canals, which had their rise in this country about 1760-70. It preceded, also, the advent of John Loudon McAdam, that great reformer of our roads, whose name has been immortalised in the verb "to macadamise." Born in 1756, it was not until the early days of the nineteenth century that McAdam really started on his beneficent mission, and even then the high-roads of England—and especially of Scotland—were, as a rule, deplorably [13]bad, "being at once loose, rough, and perishable, expensive, tedious and dangerous to travel on, and very costly to repair." Pending those improvements which McAdam brought about, adapting them to the better use of stage-coaches and carriers' waggons, the few roads already existing were practically available—as regards the transport of merchandise—for pack-horses only. Even coal was then carried by pack-horse, the cost working out at about 2s. 6d. per mile for as much as a horse could carry.

It was from these conditions that canals saved the country—long, of course, before the locomotive came into vogue. As it happened, too, it was this very question of coal transport that led to their earliest development. There is quite an element of romance in the story. Francis Egerton, third and last Duke of Bridgewater (born 1736), had an unfortunate love affair in London when he reached the age of twenty-three, and, apparently in disgust with the world, he retired to his Lancashire property, where he found solace to his wounded feelings by devoting himself to the development of the Worsley coal mines. As a boy he had been so feeble-minded that the doubt arose whether he would be capable of managing his own affairs. As a young man disappointed in love, he applied himself to business in a manner so eminently practical that he deservedly became famous as a pioneer of improved transport. He saw that if only the cost of carriage could be reduced, a most valuable market for coal from his Worsley mines could be opened up in Manchester.

It is true that, in this particular instance, the pack-horse had been supplemented by the Mersey and Irwell Navigation, established as the result of Parliamentary powers obtained in 1733. This navigation [14]was conducted almost entirely by natural waterways, but it had many drawbacks and inconveniences, while the freight for general merchandise between Liverpool and Manchester by this route came to 12s. per ton. The Duke's new scheme was one for the construction of an artificial waterway which could be carried over the Irwell at Barton by means of an aqueduct. This idea he got from the aqueduct on the Languedoc Canal, in the south of France.

But the Duke required a practical man to help him, and such a man he found in James Brindley. Born in 1716, Brindley was the son of a small farmer in Derbyshire—a dissolute sort of fellow, who neglected his children, did little or no work, and devoted his chief energies to the then popular sport of bull-baiting. In the circumstances James Brindley's school-teaching was wholly neglected. He could no more have passed an examination in the Sixth Standard than he could have flown over the Irwell with some of his ducal patron's coals. "He remained to the last illiterate, hardly able to write, and quite unable to spell. He did most of his work in his head, without written calculations or drawings, and when he had a puzzling bit of work he would go to bed, and think it out." From the point of view of present day Board School inspectors, and of the worthy magistrates who, with varied moral reflections, remorselessly enforce the principles of compulsory education, such an individual ought to have come to a bad end. But he didn't. He became, instead, "the father of inland navigation."

James Brindley had served his apprenticeship to a millwright, or engineer; he had started a little business as a repairer of old machinery and a maker of new; and he had in various ways given proof of [15]his possession of mechanical skill. The Duke—evidently a reader of men—saw in him the possibility of better things, took him over, and appointed him his right-hand man in constructing the proposed canal. After much active opposition from the proprietors of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation, and also from various landowners and others, the Duke got his first Act, to which the Royal assent was given in 1762, and the work was begun. It presented many difficulties, for the canal had to be carried over streams and bogs, and through tunnels costly to make, and the time came when the Duke's financial resources were almost exhausted. Brindley's wages were not extravagant. They amounted, in fact, to £1 a week—substantially less than the minimum wage that would be paid to-day to a municipal road-sweeper. But the costs of construction were heavy, and the landowners had unduly big ideas of the value of the land compulsorily acquired from them, so that the Duke's steward sometimes had to ride about among the tenantry and borrow a few pounds from one and another in order to pay the week's wages. When the Worsley section had been completed, and had become remunerative, the Duke pledged it to Messrs Child, the London bankers, for £25,000, and with the money thus raised he pushed on with the remainder of the canal, seeing it finally extended to Liverpool in 1772. Altogether he expended on his own canals no less than £220,000; but he lived to derive from them a revenue of £80,000 a year.

The Duke of Bridgewater's schemes gave a great impetus to canal construction in Great Britain, though it was only natural that a good deal of opposition should be raised, as well. About the year 1765 [16]numerous pamphlets were published to show the danger and impolicy of canals. Turnpike trustees were afraid the canals would divert traffic from the roads. Owners of pack-horses fancied that ruin stared them in the face. Thereupon the turnpike trustees and the pack-horse owners sought the further support of the agricultural interests, representing that, when the demand for pack-horses fell off, there would be less need for hay and oats, and the welfare of British agriculture would be prejudiced. So the farmers joined in, and the three parties combined in an effort to arouse the country. Canals, it was said, would involve a great waste of land; they would destroy the breed of draught horses; they would produce noxious or humid vapours; they would encourage pilfering; they would injure old mines and works by allowing of new ones being opened; and they would destroy the coasting trade, and, consequently, "the nursery for seamen."

By arguments such as these the opposition actually checked for some years the carrying out of several important undertakings, including the Trent and Mersey Navigation. But, when once the movement had fairly started, it made rapid progress. James Brindley's energy, down to the time of his death in 1772, was especially indomitable. Having ensured the success of the Bridgewater Canal, he turned his attention to a scheme for linking up the four ports of Liverpool, Hull, Bristol, and London by a system of main waterways, connected by branch canals with leading industrial centres off the chief lines of route. Other projects followed, as it was seen that the earlier ventures were yielding substantial profits, and in 1790 a canal mania began. In 1792 no fewer than eighteen new canals were promoted. In [17]1793 and 1794 the number of canal and navigation Acts passed was forty-five, increasing to eighty-one the total number which had been obtained since 1790. So great was the public anxiety to invest in canals that new ones were projected on all hands, and, though many of them were of a useful type, others were purely speculative, were doomed to failure from the start, and occasioned serious losses to thousands of investors. In certain instances existing canals were granted the right to levy tolls upon new-comers, as compensation for prospective loss of traffic—even when the new canals were to be 4 or 5 miles away—fresh schemes being actually undertaken on this basis.

The canals that paid at all paid well, and the good they conferred on the country in the days of their prosperity is undeniable. Failing, at that time, more efficient means of transport, they played a most important rôle in developing the trade, industries, and commerce of our country at a period especially favourable to national advancement. For half a century, in fact, the canals had everything their own way. They had a monopoly of the transport business—except as regards road traffic—and in various instances they helped their proprietors to make huge profits. But great changes were impending, and these were brought about, at last, with the advent of the locomotive.

The general situation at this period is well shown by the following extracts from an article on "Canals and Rail-roads," published in the Quarterly Review of March 1825:—

"It is true that we, who, in this age, are accustomed to roll along our hard and even roads at the rate of 8 or 9 miles an hour, can hardly imagine the [18]inconveniences which beset our great-grandfathers when they had to undertake a journey—forcing their way through deep miry lanes; fording swollen rivers; obliged to halt for days together when 'the waters were out'; and then crawling along at a pace of 2 or 3 miles an hour, in constant fear of being set down fast in some deep quagmire, of being overturned, breaking down, or swept away by a sudden inundation.

"Such was the travelling condition of our ancestors, until the several turnpike Acts effected a gradual and most favourable change, not only in the state of the roads, but the whole appearance of the country; by increasing the facility of communication, and the transport of many weighty and bulky articles which, before that period, no effort could move from one part of the country to another. The pack-horse was now yoked to the waggon, and stage coaches and post-chaises usurped the place of saddle-horses. Imperfectly as most of these turnpike roads were constructed, and greatly as their repairs were neglected, they were still a prodigious improvement; yet, for the conveyance of heavy merchandise the progress of waggons was slow and their capacity limited. This defect was at length remedied by the opening of canals, an improvement which became, with regard to turnpike roads and waggons, what these had been to deep lanes and pack-horses.[1] But we [19]may apply to projectors the observation of Sheridan, 'Give these fellows a good thing and they never know when to have done with it,' for so vehement became the rage for canal-making that, in a few years, the whole surface of the country was intersected by these inland navigations, and frequently in parts of the island where there was little or no traffic to be conveyed. The consequence was, that a large proportion of them scarcely paid an interest of one per cent., and many nothing at all; while others, judiciously conducted over populous, commercial, and manufacturing districts, have not only amply remunerated the parties concerned, but have contributed in no small degree to the wealth and prosperity of the nation.

"Yet these expensive establishments for facilitating the conveyance of the commercial, manufacturing and agricultural products of the country to their several destinations, excellent and useful as all must acknowledge them to be, are now likely, in their turn, to give way to the old invention of Rail-roads. Nothing now is heard of but rail-roads; the daily papers teem with notices of new lines of them in every direction, and pamphlets and paragraphs are thrown before the public eye, recommending nothing short of making them general throughout the kingdom. Yet, till within these few months past, this old invention, in use a full century before canals, has [20]been suffered, with few exceptions, to act the part only of an auxiliary to canals, in the conveyance of goods to and from the wharfs, and of iron, coals, limestone, and other products of the mines to the nearest place of shipment....

"The powers of the steam-engine, and a growing conviction that our present modes of conveyance, excellent as they are, both require and admit of great improvements, are, no doubt, among the chief reasons that have set the current of speculation in this particular direction."

Dealing with the question of "vested rights," the article warns "the projectors of the intended railroads ... of the necessity of being prepared to meet the most strenuous opposition from the canal proprietors," and proceeds:—

"But, we are free to confess, it does not appear to us that the canal proprietors have the least ground for complaining of a grievance. They embarked their property in what they conceived to be a good speculation, which in some cases was realised far beyond their most sanguine hopes; in others, failed beyond their most desponding calculations. If those that have succeeded should be able to maintain a competition with rail-ways by lowering their charges; what they thus lose will be a fair and unimpeachable gain to the public, and a moderate and just profit will still remain to them; while the others would do well to transfer their interests from a bad concern into one whose superiority must be thus established. Indeed, we understand that this has already been proposed to a very considerable extent, and that the level beds of certain unproductive canals have been offered for the reception of rail-ways.

"There is, however, another ground upon which, in many instances, we have no doubt, the opposition of the canal proprietors may be properly met—we mean, and we state it distinctly, the unquestionable fact, that [21]our trade and manufactures have suffered considerably by the disproportionate rates of charge upon canal conveyance. The immense tonnage of coal, iron, and earthenware, Mr Cumming tells us,[2] 'have enabled one of the canals, passing through these districts (near Birmingham), to pay an annual dividend to the proprietary of £140 upon an original share of £140, and as such has enhanced the value of each share from £140 to £3,200; and another canal in the same district, to pay an annual dividend of £160 upon the original share of £200, and the shares themselves have reached the value of £4,600 each.'

"Nor are these solitary instances. Mr Sandars informs us[3] that, of the only two canals which unite Liverpool with Manchester, the thirty-nine original proprietors of one of them, the Old Quay,[4] have been paid for every other year, for nearly half a century, the total amount of their investment; and that a share in this canal, which cost only £70, has recently been sold for £1,250; and that, with regard to the other, the late Duke of Bridgewater's, there is good reason to believe that the net income has, for the last twenty years, averaged nearly £100,000 per annum!"

In regard, however, to the supersession of canals in general by railways, the writer of the article says:—

"We are not the advocates for visionary projects that interfere with useful establishments; we scout [22]the idea of a general rail-road as altogether impracticable....

"As to those persons who speculate on making rail-ways general throughout the kingdom, and superseding all the canals, all the waggons, mail and stage-coaches, post-chaises, and, in short, every other mode of conveyance by land and water, we deem them and their visionary schemes unworthy of notice."

It is not a little curious to find that, whereas the proposed resuscitation of canals is now being actively supported in various quarters as a means of effecting increased competition with the railways, the railway system itself originally had a most cordial welcome from the traders of this country as a means of relieving them from what had become the intolerable monopoly of the canals and waterways!

It will have been seen that in the article published in the Quarterly Review of March 1825, from which I gave extracts in the last Chapter, reference was made to a "Letter on the Subject of the Projected Rail-road between Liverpool and Manchester," by Mr Joseph Sandars, and published that same year. I have looked up the original "Letter," and found in it some instructive reading. Mr Sandars showed that although, under the Act of Parliament obtained by the Duke of Bridgewater, the tolls to be charged on his canal between Liverpool and Manchester were not to exceed 2s. 6d. per ton, his trustees had, by various exactions, increased them to 5s. 2d. per ton on all goods carried along the canal. They had also got possession of all the available land and warehouses along the canal banks at Manchester, thus monopolising the accommodation, or nearly so, [24]and forcing the traders to keep to the trustees, and not patronise independent carriers. It was, Mr Sandars declared, "the most oppressive and unjust monopoly known to the trade of this country—a monopoly which there is every reason to believe compels the public to pay, in one shape or another, £100,000 more per annum than they ought to pay." The Bridgewater trustees and the proprietors of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation were, he continued, "deaf to all remonstrances, to all entreaties"; they were "actuated solely by a spirit of monopoly and extension," and "the only remedy the public has left is to go to Parliament and ask for a new line of conveyance." But this new line, he said, would have to be a railway. It could not take the form of another canal, as the two existing routes had absorbed all the available water-supply.

In discussing the advantages of a railway over a canal, Mr Sandars continued:—

"It is computed that goods could be carried for considerably less than is now charged, and for one-half of what has been charged, and that they would be conveyed in one-sixth of the time. Canals in summer are often short of water, and in winter are obstructed by frost; a Railway would not have to encounter these impediments."

Mr Sandars further wrote:—

"The distance between Liverpool and Manchester, by the three lines of Water conveyance, is upwards of 50 miles—by a Rail-road it would only be 33. Goods conveyed by the Duke and Old Quay [Mersey and Irwell Navigation] are exposed to storms, the delays from adverse winds, and the risk of damage, during a passage of 18 miles [25]in the tide-way of the Mersey. For days together it frequently happens that when the wind blows very strong, either south or north, their vessels cannot move against it. It is very true that when the winds and tides are favourable they can occasionally effect a passage in fourteen hours; but the average is certainly thirty. However, notwithstanding all the accommodation they can offer, the delays are such that the spinners and dealers are frequently obliged to cart cotton on the public high-road, a distance of 36 miles, for which they pay four times the price which would be charged by a Rail-road, and they are three times as long in getting it to hand. The same observation applies to manufactured goods which are sent by land-carriage daily, and for which the rate paid is five times that which they would be subject to by the Rail-road. This enormous sacrifice is made for two reasons—sometimes because conveyance by water cannot be promptly obtained, but more frequently because speed and certainty as to delivery are of the first importance. Packages of goods sent from Manchester, for immediate shipment at Liverpool, often pay two or three pounds per ton; and yet there are those who assert that the difference of a few hours in speed can be no object. The merchants know better."

In the same year that Mr Sandars issued his "Letter," the merchants of the port of Liverpool addressed a memorial to the Mayor and Common Council of the borough, praying them to support the scheme for the building of a railway, and stating:—

"The merchants of this port have for a long time past experienced very great difficulties and obstructions in the prosecution of their business, in consequence of the high charges on the freight of goods [26]between this town and Manchester, and of the frequent impossibility of obtaining vessels for days together."

It is clear from all this that, however great the benefit which canal transport had conferred, as compared with prior conditions, the canal companies had abused their monopoly in order to secure what were often enormous profits; that the canals themselves, apart from the excessive tolls and charges imposed, failed entirely to meet the requirements of traders; and that the most effective means of obtaining relief was looked for in the provision of railways.

The value to which canal shares had risen at this time is well shown by the following figures, which I take from the Gentleman's Magazine for December, 1824:—

| Canal. | Shares. | Price. | |||

| £ | s. | d. | £ | ||

| Trent and Mersey | 75 | 0 | 0 | 2,200 | |

| Loughborough | 197 | 0 | 0 | 4,600 | |

| Coventry | 44 | 0 | 0 | (and bonus) | 1,300 |

| Oxford (short shares) | 32 | 0 | 0 | " " | 850 |

| Grand Junction | 10 | 0 | 0 | " " | 290 |

| Old Union | 4 | 0 | 0 | 103 | |

| Neath | 15 | 0 | 0 | 400 | |

| Swansea | 11 | 0 | 0 | 250 | |

| Monmouthshire | 10 | 0 | 0 | 245 | |

| Brecknock and Abergavenny | 8 | 0 | 0 | 175 | |

| Staffordshire & Worcestershire | 40 | 0 | 0 | 960 | |

| Birmingham | 12 | 10 | 0 | 350 | |

| Worcester and Birmingham | 1 | 10 | 0 | 56 | |

| Shropshire | 8 | 10 | 0 | 175 | |

| Ellesmere | 3 | 10 | 0 | 102 | |

| Rochdale | 4 | 0 | 0 | 140 | |

| Barnsley | 12 | 0 | 0 | 330 | |

| Lancaster | 1 | 0 | 0 | 45 | |

| Kennet and Avon | 1 | 0 | 0 | 29 | |

These substantial values, and the large dividends that led to them, were due in part, no doubt, to the general improvement in trade which the canals had helped most materially to effect; but they had been greatly swollen by the merciless way in which the traders of those days were exploited by the representatives of the canal interest. As bearing on this point, I might interrupt the course of my narrative to say that in the House of Commons on May 17, 1836, Mr Morrison, member for Ipswich, made a speech in which, as reported by Hansard, he expressed himself "clearly of opinion" that "Parliament should, when it established companies for the formation of canals, railroads, or such like undertakings, invariably reserve to itself the power to make such periodical revisions of the rates and charges as it may, under the then circumstances, deem expedient"; and he proposed a resolution to this effect. He was moved to adopt this course in view of past experiences in connection with the canals, and a desire that there should be no repetition of them in regard to the railways then being very generally promoted. In the course of his speech he said:—

"The history of existing canals, waterways, etc., affords abundant evidence of the evils to which I have been averting. An original share in the Loughborough Canal, for example, which cost £142, 17s. is now selling at about £1,250, and yields a dividend of £90 or £100 a year. The fourth part of a Trent and Mersey Canal share, or £50 of the company's stock, is now fetching £600, and yields a dividend of about £30 a year. And there are various other canals in nearly the same situation."

At the close of the debate which followed, [28]Mr Morrison withdrew his resolution, owing to the announcement that the matter to which he had called attention would be dealt with in a Bill then being framed. It is none the less interesting thus to find that Parliamentary revisions of railway rates were, in the first instance, directly inspired by the extortions practised on the traders by canal companies in the interest of dividends far in excess of any that the railway companies have themselves attempted to pay.

Reverting to the story of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway—the projection of which, as Mr Sandars' "Letter" shows, represented a revolt against "the exorbitant and unjust charges of the water-carriers"—the Bill promoted in its favour was opposed so vigorously by the canal and other interests that £70,000 was spent in the Parliamentary proceedings in getting it through. But it was carried in 1826, and the new line, opened in 1830, was so great a success that it soon began to inspire many similar projects in other directions, while with its opening the building of fresh canals for ordinary inland navigation (as distinct from ship canals) practically ceased.

There is not the slightest doubt that, but for the extreme dissatisfaction of the trading interests in regard alike to the heavy charges and to the shortcomings of the canal system, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway—that precursor of the "railway mania"—would not have been actually constructed until at least several years later. But there were other directions, also, in which the revolt against the then existing conditions was to bring about important developments. In the pack-horse period the collieries of Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire [29]respectively supplied local needs only, the cost of transport by road making it practically impossible to send coal out of the county in which it was raised. With the advent of canals the coal could be taken longer distances, and the canals themselves gained so much from the business that at one time shares in the Loughborough Canal, on which £142 had been paid, rose, as already shown, to £4,600, and were looked upon as being as safe as Consols. But the collapse of a canal from the Leicestershire coal-fields to the town of Leicester placed the coalowners of that county at a disadvantage, and this they overcame, in 1832, by opening the Leicester and Swinnington line of railway. Thereupon the disadvantage was thrown upon the Nottinghamshire coalowners, who could no longer compete with Leicestershire. In fact, the immediate outlook before them was that they would be excluded from their chief markets, that their collieries might have to be closed, and that the mining population would be thrown out of employment.

In their dilemma they appealed to the canal companies, and asked for such a reduction in rates as would enable them to meet the new situation; but the canal companies—wedded to their big dividends—would make only such concessions as were thought by the other side to be totally inadequate. Following on this the Nottinghamshire coalowners met in the parlour of a village inn at Eastwood, in the autumn of 1832, and formally declared that "there remained no other plan for their adoption than to attempt to lay a railway from their collieries to the town of Leicester." The proposal was confirmed by a subsequent meeting, which resolved that "a railway from Pinxton to Leicester is essential to the [30]interests of the coal-trade of this district." Communications were opened with George Stephenson, the services of his son Robert were secured, the "Midland Counties Railway" was duly constructed, and the final outcome of the action thus taken—as the direct result of the attitude of the canal companies—is to be seen in the splendid system known to-day as the Midland Railway.

Once more, I might refer to Mr Charles H. Grinling's "History of the Great Northern Railway," in which, speaking of early conditions, he says:—

"During the winter of 1843-44 a strong desire arose among the landowners and farmers of the eastern counties to secure some of the benefits which other districts were enjoying from the new method of locomotion. One great want of this part of England was that of cheaper fuel, for though there were collieries open at this time in Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, and Derbyshire, the nearest pits with which the eastern counties had practicable transport communication were those of South Yorkshire and Durham, and this was of so circuitous a character that even in places situated on navigable rivers, unserved by a canal, the price of coal often rose as high as 40s. or even 50s. a ton. In remoter places, to which it had to be carted 10, 20, or even 30 miles along bad cross-roads, coal even for house-firing was a positive luxury, quite unattainable by the poorer classes. Moreover, in the most severe weather, when the canals were frozen, the whole system of supply became paralysed, and even the wealthy had not seldom to retreat shivering to bed for lack of fuel."

In this particular instance it was George Hudson, the "Railway King," who was approached, and the [31]first lines were laid of what is now the Great Northern Railway.

So it happened that, when the new form of transport came into vogue, in succession to the canals, it was essentially a case of "Railways to the Rescue."

Both canals and railways were, in their early days, made according to local conditions, and were intended to serve local purposes. In the case of the former the design and dimensions of the canal boat used were influenced by the depth and nature of the estuary or river along which it might require to proceed, and the size of the lock (affecting, again, the size of the boat) might vary according to whether the lock was constructed on a low level, where there was ample water, or on a high level, where economy in the use of water had to be practised. Uniformity under these varying conditions would certainly have been difficult to secure, and, in effect, it was not attempted. The original designers of the canals, in days when the trade of the country was far less than it is now and the general trading conditions very different, probably knew better what they were about than their critics of to-day give them credit for. They realised more completely than most of those critics do what were the limitations of canal construction in a country of hills and dales, and especially in rugged and mountainous districts. They cut their coat, as it were, according to their cloth, and sought to meet the actual needs of the day rather than anticipate the requirements of futurity. From their point of view this was the simplest solution of the problem.

WHAT CANAL WIDENING WOULD MEAN.

(Cowley Tunnel and Embankments, on Shropshire Union Route between Wolverhampton and the Mersey.)

[To face page 32.

But, though the canals thus made suited local conditions, they became unavailable for through traffic, except in boats sufficiently small to pass the smallest lock or the narrowest and shallowest canal en route. Then the lack of uniformity in construction was accompanied by a lack of unity in management. Each and every through route was divided among, as a rule, from four to eight or ten different navigations, and a boat-owner making the journey had to deal separately with each.

The railway companies soon began to rid themselves of their own local limitations. A "Railway Clearing House" was set up in 1847, in the interests of through traffic; groups of small undertakings amalgamated into "great" companies; facilities of a kind unknown before were made available, while the whole system of railway operation was simplified for traders and travellers. The canal companies, however, made no attempt to follow the example thus set. They were certainly in a more difficult position than the railways. They might have amalgamated, and they might have established a Canal Clearing House. These would have been comparatively easy things to do. But any satisfactory linking up of the various canal systems throughout the country would have meant virtual reconstruction, and this may well have been thought a serious proposition in regard, especially, to canals built at a considerable elevation above the sea level, where the water supply was limited, and where, for that reason, some of the smallest locks were to be found. To say the least of it, such a work meant a very large outlay, and at that time practically all [34]the capital available for investment in transport was being absorbed by new railways. These, again, had secured the public confidence which the canals were losing. As Mr Sandars said in his "Letter":—

"Canals have done well for the country, just as high roads and pack-horses had done before canals were established; but the country has now presented to it cheaper and more expeditious means of conveyance, and the attempt to prevent its adoption is utterly hopeless."

All that the canal companies did, in the first instance, was to attempt the very thing which Mr Sandars considered "utterly hopeless." They adopted a policy of blind and narrow-minded hostility. They seemed to think that, if they only fought them vigorously enough, they could drive the railways off the field; and fight them they did, at every possible point. In those days many of the canal companies were still wealthy concerns, and what their opposition might mean has been already shown in the case of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The newcomers had thus to concentrate their efforts and meet the opposition as best they could.

For a time the canal companies clung obstinately to their high tolls and charges, in the hope that they would still be able to pay their big dividends. But, when the superiority of the railways over the waterways became more and more manifest, and when the canal companies saw greater and still greater quantities of traffic being diverted from them by their opponents, in fair competition, they realised the situation at last, and brought down their tolls with a rush. The reductions made were so substantial [35]that they would have been thought incredible a few years previously.

In the result, benefits were gained by all classes of traders, for those who still patronised the canals were charged much more reasonable tolls than they had ever paid before. But even the adoption of this belated policy by the canal companies did not help them very much. The diversion of the stream of traffic to the railways had become too pronounced to be checked by even the most substantial of reductions in canal charges. With the increasing industrial and commercial development of the country it was seen that the new means of transport offered advantages of even greater weight than cost of transport, namely, speed and certainty of delivery. For the average trader it was essentially a case of time meaning money. The canal companies might now reduce their tolls so much that, instead of being substantially in excess of the railway rates, as they were at first, they would fall considerably below; but they still could not offer those other all-important advantages.

As the canal companies found that the struggle was, indeed, "utterly hopeless," some of them adopted new lines of policy. Either they proposed to build railways themselves, or they tried to dispose of their canal property to the newcomers. In some instances the route of a canal, no longer of much value, was really wanted for the route of a proposed railway, and an arrangement was easily made. In others, where the railway promoters did not wish to buy, opposition to their schemes was offered by the canal companies with the idea of forcing them either so to do, or, alternatively, to make such terms with them as would be to the advantage of the canal shareholders.

The tendency in this direction is shown by the extract already given from the Quarterly Review; and I may repeat here the passage in which the writer suggested that some of the canal companies "would do well to transfer their interests from a bad concern into one whose superiority must be thus established," and added: "Indeed, we understand that this has already been proposed to a very considerable extent, and that the level beds of certain unproductive canals have been offered for the reception of rail-ways." This was as early as 1825. Later on the tendency became still more pronounced as pressure was put on the railway companies, or as promoters, in days when plenty of money was available for railway schemes, thought the easiest way to overcome actual or prospective opposition was to buy it off by making the best terms they could. So far, in fact, was the principle recognised that in 1845 Parliament expressly sanctioned the control of canals by railway companies, whether by amalgamation, lease, purchase, or guarantee, and a considerable amount of canal mileage thus came into the possession, or under the control, of railway companies, especially in the years 1845, 1846, and 1847. This sanction was practically repealed by the Railway and Traffic Acts of 1873 and 1888. By that time about one-third of the existing canals had been either voluntarily acquired by, or forced upon, the railway companies. It is obvious, however, that the responsibility for what was done rests with Parliament itself, and that in many cases, probably, the railway companies, instead of being arch-conspirators, anxious to spend their money in killing off moribund competitors, who were generally considered to be on the point of dying a natural death, were, at times, [37]victims of the situation, being practically driven into purchases or guarantees which, had they been perfectly free agents, they might not have cared to touch.

The general position was, perhaps, very fairly indicated by the late Sir James Allport, at one time General Manager of the Midland Railway Company, in the evidence he gave before the Select Committee on Canals in 1883.

"I doubt (he said) if Parliament ever, at that time of day, came to any deliberate decision as to the advisability or otherwise of railways possessing canals; but I presume that they did not do so without the fullest evidence before them, and no doubt canal companies were very anxious to get rid of their property to railways, and they opposed their Bills, and, in the desire to obtain their Bills, railway companies purchased their canals. That, I think, would be found to be the fact, if it were possible to trace them out in every case. I do not believe that the London and North-Western would have bought the Birmingham Canal but for this circumstance. I have no doubt that the Birmingham Canal, when the Stour Valley line was projected, felt that their property was jeopardised, and that it was then that the arrangement was made by which the London and North-Western Railway Company guaranteed them 4 per cent."

The bargains thus effected, either voluntarily or otherwise (and mostly otherwise), were not necessarily to the advantage of the railway companies, who might often have done better for themselves if they had fought out the fight at the time with their antagonists, and left the canal companies to their fate, instead of taking over waterways which have been more or less of a loss to them ever since. [38]Considering the condition into which many of the canals had already drifted, or were then drifting, there is very little room for doubt what their fate would have been if the railway companies had left them severely alone. Indeed, there are various canals whose continued operation to-day, in spite of the losses on their wholly unremunerative traffic, is due exclusively to the fact that they are owned or controlled by railway companies. Independent proprietors, looking to them for dividends, and not under any statutory obligations (as the railway companies are) to keep them going, would long ago have abandoned such canals entirely, and allowed them to be numbered among the derelicts.

As bearing on the facts here narrated, I might mention that, in the course of a discussion at the Institution of Civil Engineers, in November 1905, on a paper read by Mr John Arthur Saner, "Waterways in Great Britain" (reported in the official "Proceedings" of the Institution), Mr James Inglis, General Manager of the Great Western Railway Company, said that "his company owned about 216 miles of canal, not a mile of which had been acquired voluntarily. Many of those canals had been forced on the railway as the price of securing Acts, and some had been obtained by negotiations with the canal companies. The others had been acquired in incidental ways, arising from the fact that the traffic had absolutely disappeared." Mr Inglis further told the story of the Kennet and Avon Canal, which his company maintain at a loss of about £4,000 per annum. The canal, it seems, was constructed in 1794 at a cost of £1,000,000, and at one time paid 5 per cent. The traffic fell off steadily with the extension of the railway system, and in 1846 [39]the canal company, seeing their position was hopeless, applied to Parliament for powers to construct a railway parallel with the canal. Sanction was refused, though the company were authorised to act as common carriers. In 1851 the canal owners approached the Great Western Railway Company, and told them of their intention to seek again for powers to build an opposition railway. The upshot of the matter was that the railway company took over the canal, and agreed to pay the canal company £7,773 a year. This they have done, with a loss to themselves ever since. The rates charged on the canal were successively reduced by the Board of Trade (on appeal being made to that body) to 1¼d., then to 1d., and finally ½d. per ton-mile; but there had never been a sign, Mr Inglis added, that the reduction had any effect in attracting additional traffic.[5]

To ascertain for myself some further details as to the past and present of the Kennet and Avon Navigation, I paid a visit of inspection to the canal in the neighbourhood of Bath, where it enters the River Avon, and also at Devizes, where I saw the remarkable series of locks by means of which the canal reaches the town of Devizes, at an elevation of 425 feet above sea level. In conversation, too, with various authorities, including Mr H. J. Saunders, the Canals Engineer of the Great Western Railway [40]Company, I obtained some interesting facts which throw light on the reasons for the falling off of the traffic along the canal.

Dealing with this last mentioned point first, I learned that much of the former prosperity of the Kennet and Avon Navigation was due to a substantial business then done in the transport of coal from a considerable colliery district in Somersetshire, comprising the Radstock, Camerton, Dunkerton, and Timsbury collieries. This coal was first put on the Somerset Coal Canal, which connected with the Kennet and Avon at Dundas—a point between Bath and Bradford-on-Avon—and, on reaching this junction, it was taken either to towns directly served by the Kennet and Avon (including Bath, Bristol, Bradford, Trowbridge, Devizes, Kintbury, Hungerford, Newbury and Reading) or, leaving the Kennet and Avon at Semmington, it passed over the Wilts and Berks Canal to various places as far as Abingdon. In proportion, however, as the railways developed their superiority as an agent for the effective distribution of coal, the traffic by canal declined more and more, until at last it became non-existent. Of the three canals affected, the Somerset Coal Canal, owned by an independent company, was abandoned, by authority of Parliament, two years ago; the Wilts and Berks, also owned by an independent company, is practically derelict, and the one that to-day survives and is in good working order is the Kennet and Avon, owned by a railway company.

Another branch of local traffic that has left the Kennet and Avon Canal for the railway is represented by the familiar freestone, of which large quantities are despatched from the Bath district. The stone goes away in blocks averaging 5 tons [41]in weight, and ranging up to 10 tons, and at first sight it would appear to be a commodity specially adapted for transport by water. But once more the greater facilities afforded by the railway have led to an almost complete neglect of the canal. Even where the quarries are immediately alongside the waterway (though this is not always the case) horses must be employed to get the blocks down to the canal boat; whereas the blocks can be put straight on to the railway trucks on the sidings which go right into the quarry, no horses being then required. In calculating, therefore, the difference between the canal rate and the railway rate, the purchase and maintenance of horses at the points of embarkation must be added to the former. Then the stone could travel only a certain distance by water, and further cost might have to be incurred in cartage, if not in transferring it from boat to railway truck, after all, for transport to final destination; whereas, once put on a railway truck at the quarry, it could be taken thence, without further trouble, to any town in Great Britain where it was wanted. In this way, again, the Kennet and Avon (except in the case of consignments to Bristol) has practically lost a once important source of revenue.

A certain amount of foreign timber still goes by water from Avonmouth or Bristol to the neighbourhood of Pewsey, and some English-grown timber is taken from Devizes and other points on the canal to Bristol, Reading, and intermediate places; grain is carried from Reading to mills within convenient reach of the canal, and there is also a small traffic in mineral oils and general merchandise, including groceries for shopkeepers in towns along the canal route; but, whereas, in former days a grocer would [42]order 30 tons of sugar from Bristol to be delivered to him by boat at one time, he now orders by post, telegraph, or telephone, very much smaller quantities as he wants them, and these smaller quantities are consigned mainly by train, so that there is less for the canal to carry, even where the sugar still goes by water at all.

Speaking generally, the actual traffic on the Kennet and Avon at the western end would not exceed more than about three or four boats a day, and on the higher levels at the eastern end it would not average one a day. Yet, after walking for some miles along the canal banks at two of its most important points, it was obvious to me that the decline in the traffic could not be attributable to any shortcomings in the canal itself. Not only does the Kennet and Avon deserve to rank as one of the best maintained of any canal in the country, but it still affords all reasonable facilities for such traffic as is available, or seems likely to be offered. Instead of being neglected by the Great Western Railway Company, it is kept in a state of efficiency that could not well be improved upon short of a complete reconstruction, at a very great cost, in the hope of getting an altogether problematical increase of patronage in respect to classes of traffic different from what was contemplated when the canal was originally built.

LOCKS ON THE KENNET AND AVON CANAL AT DEVIZES.

(A difference in level of 239 feet in 2½ miles is overcome by 29 locks. Of these, 17 immediately follow one another in direct line, "pounds" being provided to ensure sufficiency of reserve water to work boats through.)

Photo by Chivers, Devizes.]

[To face page 42.

Within the last year or two the railway company have spent £3,000 or £4,000 on the pumping machinery. The main water supply is derived from a reservoir, about 9 acres in extent, at Crofton, this reservoir being fed partly by two rivulets (which dry up in the summer) and partly by its own springs; and extensive pumping machinery is provided for raising to the summit level the water [43]that passes from the reservoir into the canal at a lower level, the height the water is thus raised being 40 feet. There is also a pumping station at Claverton, near Bath, which raises water from the river Avon. Thanks to these provisions, on no occasion has there been more than a partial stoppage of the canal owing to a lack of water, though in seasons of drought it is necessary to reduce the loading of the boats.

The final ascent to the Devizes level is accomplished by means of twenty-nine locks in a distance of 2½ miles. Of these twenty-nine there are seventeen which immediately follow one another in a direct line, and here it has been necessary to supplement the locks with "pounds" to ensure a sufficiency of reserve water to work the boats through. No one who walks alongside these locks can fail to be impressed alike by the boldness of the original constructors of the canal and by the thoroughness with which they did their work. The walls of the locks are from 3 to 6 feet in thickness, and they seem to have been built to last for all eternity. The same remark applies to the constructed works in general on this canal. For a boat to pass through the twenty-nine locks takes on an average about three hours. The 39½ miles from Bristol to Devizes require at least two full days.

Considerable expenditure is also incurred on the canal in dredging work; though here special difficulties are experienced, inasmuch as the geological formation of the bed of the canal between Bath and Bradford-on-Avon renders steam dredging inadvisable, so that the more expensive and less expeditious system of "dragging" has to be relied on instead.

Altogether it costs the Great Western Railway Company about £1 to earn each 10s. they receive from the canal; and whether or not, considering present day conditions of trade and transport, and the changes that have taken place therein, they would get their money back if they spent still more on the canal, is, to say the least of it, extremely problematical. One fact absolutely certain is that the canal is already capable of carrying a much greater amount of traffic than is actually forthcoming, and that the absence of such traffic is not due to any neglect of the waterway by its present owners. Indeed, I had the positive assurance of Mr Saunders that, in his capacity as Canals Engineer to the Great Western, he had never yet been refused by his Company any expenditure he had recommended as necessary for the efficient maintenance of the canals under his charge. "I believe," he added, "that any money required to be spent for this purpose would be readily granted. I already have power to do anything I consider advisable to keep the canals in proper order; and I say without hesitation that all the canals belonging to the Great Western Railway Company are well maintained, and in no way starved. The decline in the traffic is due to obvious causes which would still remain, no matter what improvements one might seek to carry out."

The story told above may be supplemented by the following extract from the report of the Great Western Railway Company for the half-year ending December 1905, showing expenses and receipts in connection with the various canals controlled by that company:—

GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY CANALS,

for half-year ending 31st December 1905.

| Canal. | To Canal Expenses. | By Canal Traffic. | ||||

| Bridgwater and Taunton | £1,991 | 2 | 8 | £664 | 8 | 9 |

| Grand Western | 197 | 7 | 1 | 119 | 10 | 10 |

| Kennet and Avon | 5,604 | 0 | 9 | 2,034 | 18 | 8 |

| Monmouthshire | 1,557 | 3 | 3 | 886 | 16 | 8 |

| Stourbridge Extension | 450 | 19 | 4 | 765 | 7 | 1 |

| Stratford-upon-Avon | 1,349 | 11 | 3 | 724 | 1 | 4 |

| Swansea | 1,643 | 15 | 7 | 1,386 | 14 | 9 |

| ———————— | ———————— | |||||

| £12,793 | 19 | 11 | £6,581 | 18 | 1 | |

| ———————— | ———————— | |||||

The capital expenditure on these different canals, to the same date, was as follows:—

| Brecon | £61,217 | 19 | 0 |

| Bridgwater and Taunton | 73,989 | 12 | 4 |

| Grand Western | 30,629 | 8 | 7 |

| Kennet and Avon | 209,509 | 19 | 3 |

| Stourbridge Extension | 49,436 | 15 | 0 |

| Stratford-on-Avon | 172,538 | 9 | 7 |

| Swansea | 148,711 | 17 | 6 |

| ——————— | |||

| Total, | £746,034 | 1 | 3 |

These figures give point to the further remark made by Mr Inglis at the meeting of the Institution of Civil Engineers when he said, "It was not to be imagined that the railway companies would willingly have all their canal property lying idle; they would be only too glad if they could see how to use the canals so as to obtain a profit, or even to reduce the loss."

On the same occasion, Mr A. Ross, who also took part in the debate, said he had had charge of a number of railway-owned canals at different times, and he was of opinion there was no foundation [46]for the allegation that railway-owned canals were not properly maintained. His first experience of this kind was with the Sankey Brook and St Helens Canal, one of wide gauge, carrying a first-class traffic, connecting the two great chemical manufacturing towns of St Helens and Widnes, and opening into the Mersey. Early in the seventies the canal became practically a wreck, owing to the mortar on the walls having been destroyed by the chemicals in the water which the manufactories had drained into the canal. In addition, there was an overflow into the Sankey Brook, and in times of flood the water flowed over the meadows, and thousands of acres were rendered barren. Mr Ross continued (I quote from the official report):—

"The London and North-Western Railway Company, who owned the canal, went to great expense in litigation, and obtained an injunction against the manufacturers, and in the result they had to purchase all the meadows outright, as the quickest way of settling the question of compensation. The company rebuilt all the walls and some of the locks. If that canal had not been supported by a powerful corporation like the London and North-Western Railway, it must inevitably have been in ruins now. The next canal he had to do with, the Manchester and Bury Canal, belonging to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company, was almost as unfortunate. The coal workings underneath the canal absolutely wrecked it, compelling the railway company to spend many thousands of pounds in law suits and on restoring the works, and he believed that no independent canal could have survived the expense. Other canals he had had to do with were the Peak Forest, the Macclesfield and the Chesterfield canals, and the Sheffield and South Yorkshire Navigation, which belonged to the old Manchester Sheffield and Lincolnshire [47]Railway. Those canals were maintained in good order, although the traffic was certainly not large."

On the strength of these personal experiences Mr Ross thought that "if a company came forward which was willing to give reasonable compensation, the railway companies would not be difficult to deal with."

The "Shropshire Union" is a railway-controlled canal with an especially instructive history.