Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

Some typographical errors have been corrected;

a list follows the text.

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol  will bring up a larger version of the illustration.

will bring up a larger version of the illustration.

Contents.

List of Illustrations

Index:

A,

B,

C,

D,

E,

F,

G,

H,

I,

J,

K,

L,

M,

N,

O,

P,

Q,

R,

S,

T,

U,

V,

W,

X,

Z

(etext transcriber's note) |

GREECE

COMPANION VOLUMES ILLUSTRATED BY THE SAME ARTIST

THE HOLY LAND

CONTAINING 92 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS,

MOSTLY IN COLOUR

PRICE 20s. NET

OXFORD

CONTAINING 60 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

IN COLOUR

PRICE 20s. NET

EDINBURGH

CONTAINING 60 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

IN COLOUR

PRICE 7s. 6d. NET

Published by

A. & C. BLACK, Soho Square, LONDON, W.

| AGENTS |

| America | The Macmillan Company |

| | 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York |

| Canada | The Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd. |

| | 27 Richmond Street West, Toronto |

| India | Macmillan & Company, Ltd. |

| | Macmillan Building, Bombay |

| | 309 Bow Bazaar Street, Calcutta |

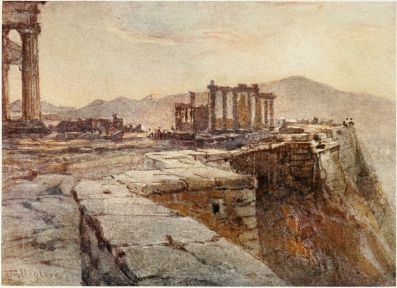

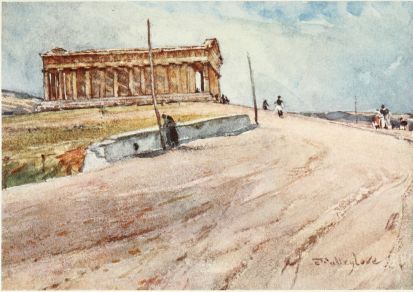

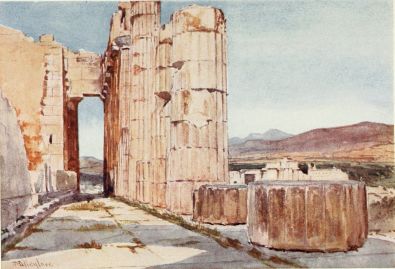

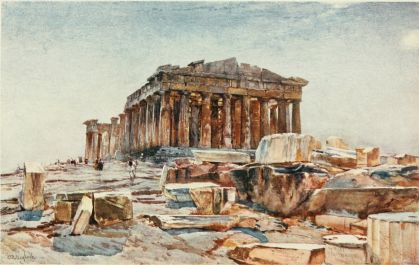

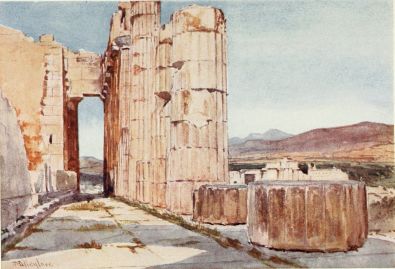

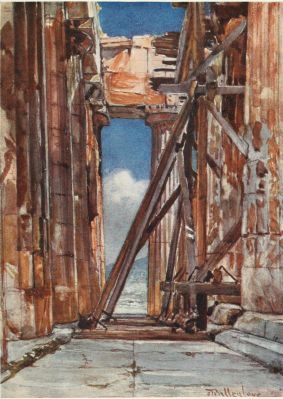

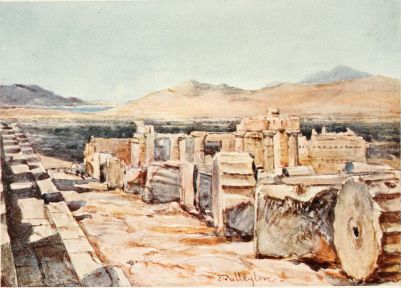

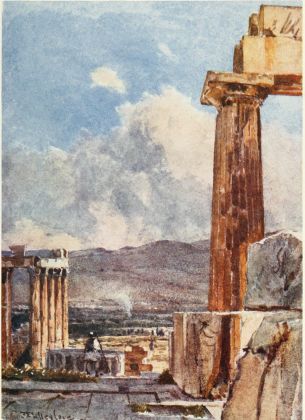

THE PARTHENON FROM THE PROPYLÆA (EARLY MORNING)

THE PARTHENON FROM THE PROPYLÆA (EARLY MORNING)

The pale golden light on the architraves within the Posticum is

reflected from the east side of the west front of the Temple. The

scarped rock to the right is the boundary of the precinct of Artemis

Brauronia. The drum of a column in the right-hand corner of the drawing

represents the southernmost column of the eastern portico of the

Propylæa. For obvious artistic reasons the whole column could not be

included in the drawing. The pedestal before the column is that of the

statue of Athene Hygieia by the sculptor Pyrrhos. Two or three paces in

front of it are the remains of a large free-standing altar.

GREECE · PAINTED BY

JOHN FULLEYLOVE, R.I.

DESCRIBED BY THE REV.

J. A. M‘CLYMONT, M.A., D.D.

PUBLISHED BY A. AND C.

BLACK · LONDON ·MCMVI

{iv}

{v}

Author’s Note

AMONG the authorities consulted by the writer of the Text (who has had

the advantage of a recent visit to Greece) special acknowledgments are

due to Grote’s monumental History of Greece, and to J. G. Frazer’s

lucid and searching Commentary on Pausanias’s Description of Greece.

Aberdeen, April 1906.

{vi}

{vii}

Contents

{ix}

List of Illustrations

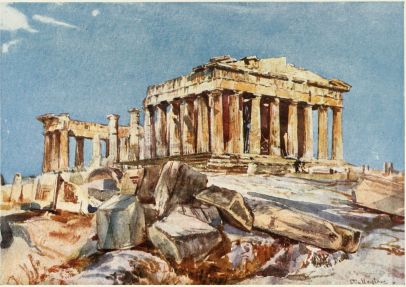

| 1. | The Parthenon from the Propylæa | Frontispiece |

| | | FACING PAGE |

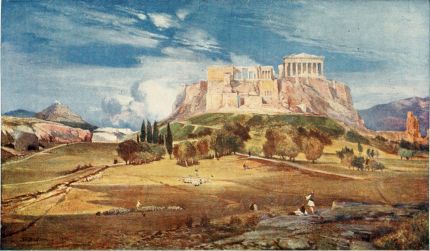

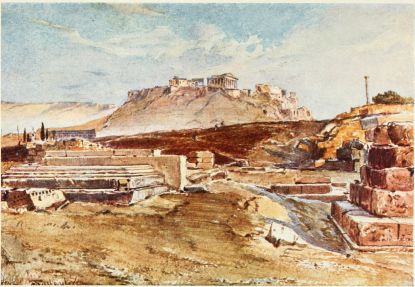

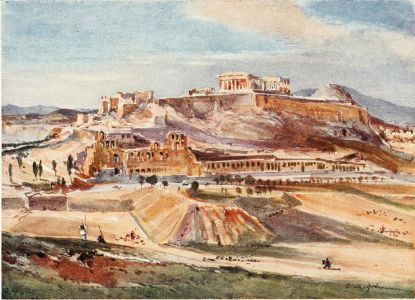

| 2. | The Acropolis from the Site of the Temple of Olympian Zeus | 2 |

| 3. | Corfu. The Old Fort from the West | 8 |

| 4. | Corfu. The Old Fort from the South | 10 |

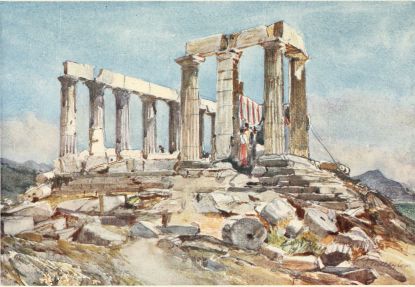

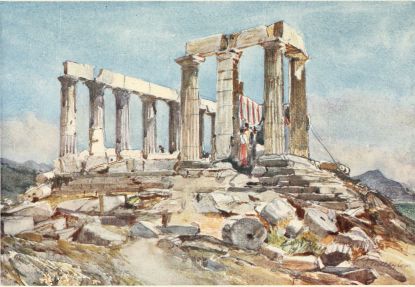

| 5. | The Temple of Athena at Sunium | 14 |

| 6. | Sunset from the North-Eastern Corner of the Acropolis | 16 |

| 7. | Delphi from Itea | 20 |

| 8. | Delphi. The Castalian Gorge and Spring | 24 |

| 9. | Delphi. The Portico of the Athenians | 28 |

| 10. | The Ancient Quarries on Mount Pentelikon | 32 |

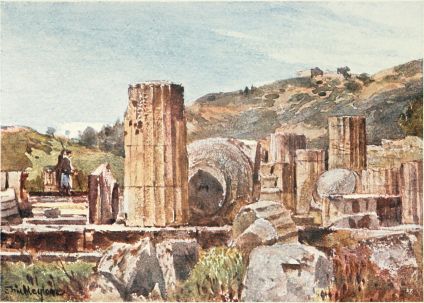

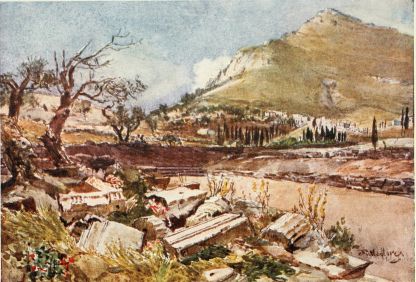

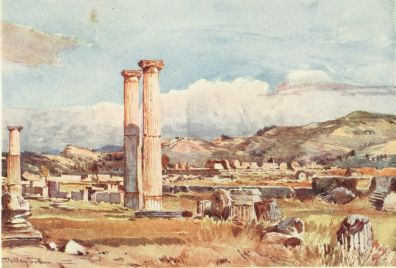

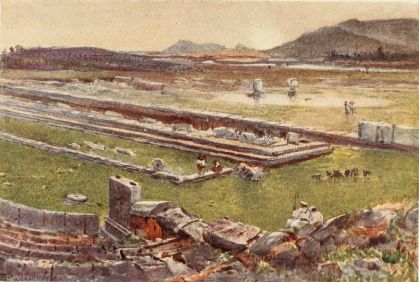

| 11. | Olympia. The base of the Kronos Hill with the remains of the Temple of Hera and the Philippeion | 36 |

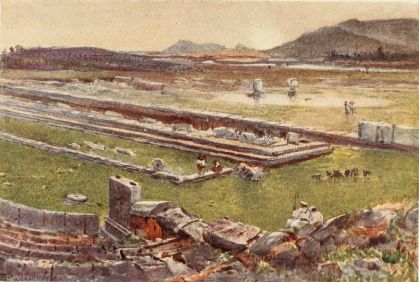

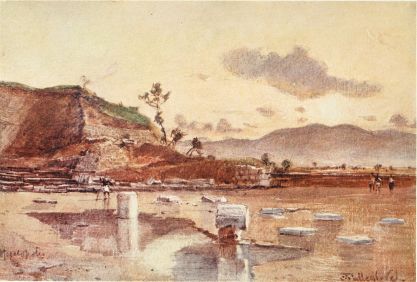

| 12. | Olympia. The Palæstra and remains of the Temple of Zeus | 40 |

| 13. | The Temple of Hera at Olympia | 44 |

| 14. | The Bastion and Temple of Wingless Victory viewed from the ascent to the Propylæa | 48 |

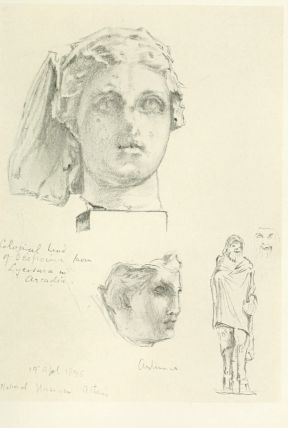

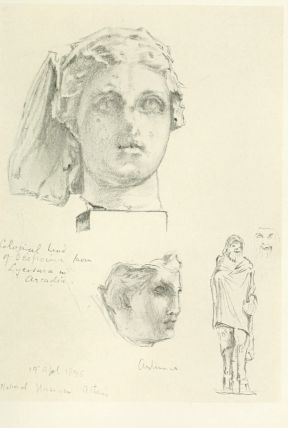

| 15. | Colossal Head of Despoina | 52 |

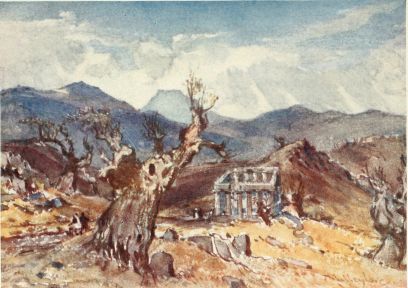

| 16. | The Temple of Apollo at Bassæ in Arcadia, with distant view of Mount Ithome | 54 |

| 17. | Site of Megalopolis in Arcadia | 58 |

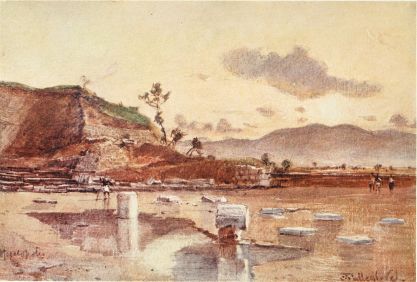

| 18. | Megalopolis in Arcadia{x} | 62 |

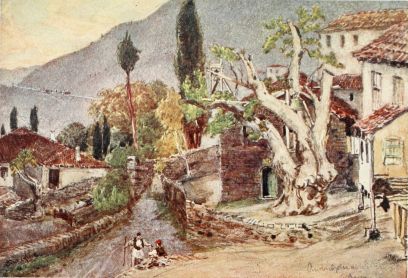

| 19. | Andritsæna. The resting-place for the Temple of Apollo at Bassæ | 66 |

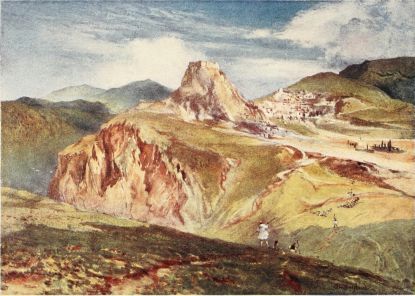

| 20. | The Castle of Karytæna in Arcadia | 70 |

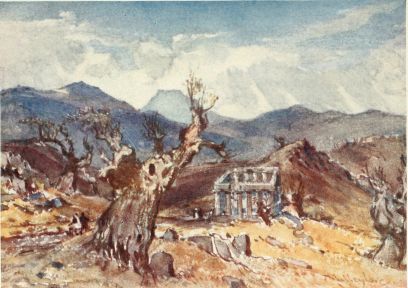

| 21. | Interior of the Temple of Apollo at Bassæ in Arcadia | 72 |

| 22. | The Laconian Gate of Messene | 74 |

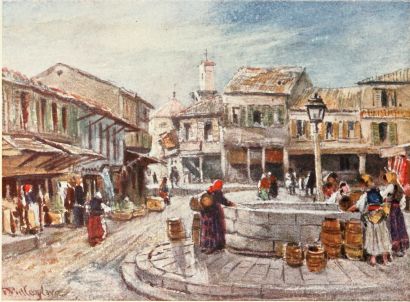

| 23. | Kalamata on the Gulf of Messene | 76 |

| 24. | Mount Ithome from the Stadion of Messene | 80 |

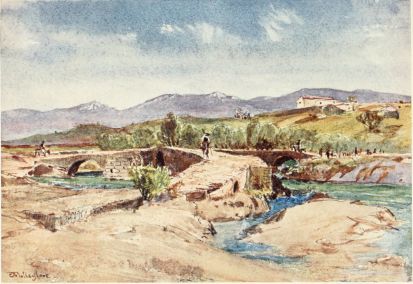

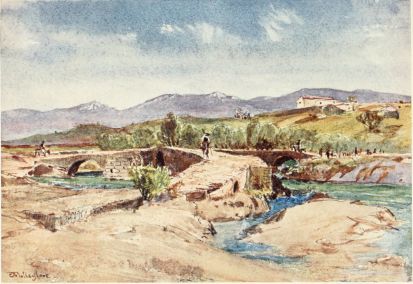

| 25. | Triple Bridge over the Mavrozoumenos River | 84 |

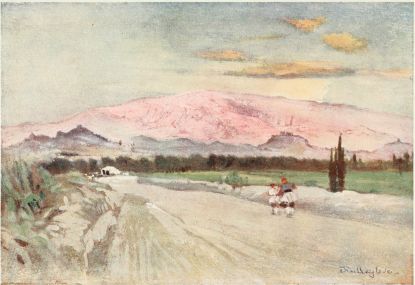

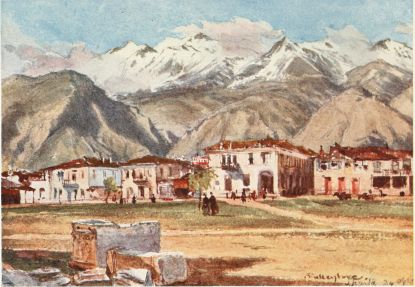

| 26. | Sparta and Mount Taÿgetus | 86 |

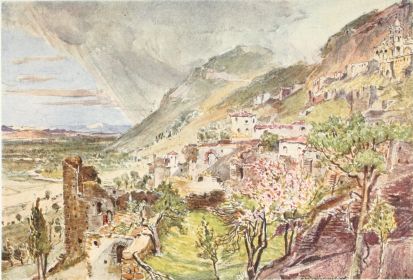

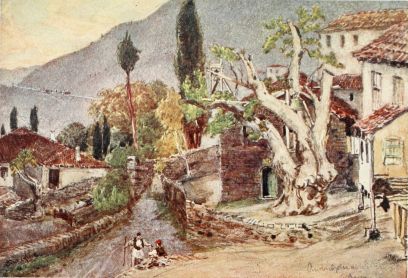

| 27. | Mistra, near Sparta | 90 |

| 28. | Mistra and the Valley of the Eurotas | 92 |

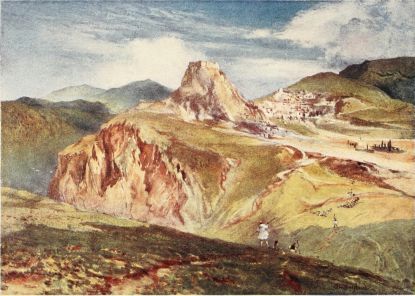

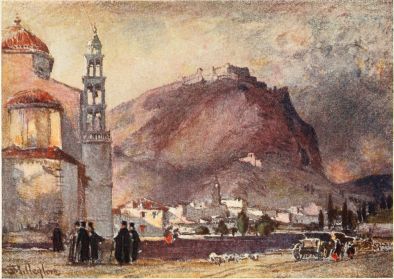

| 29. | Argos and Larissa | 96 |

| 30. | The Acropolis of Mycenæ from South-West, with Mount Elias | 100 |

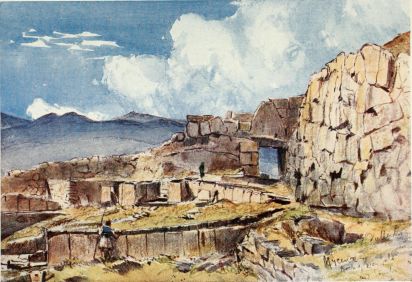

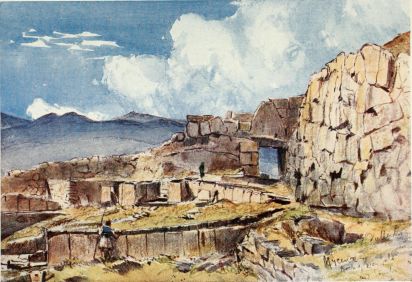

| 31. | Mycenæ, showing the site of the famous discoveries of Schliemann | 104 |

| 32. | Tiryns. The Gate of the Upper Castle | 106 |

| 33. | Nauplia and Tiryns from the Road to Argos | 108 |

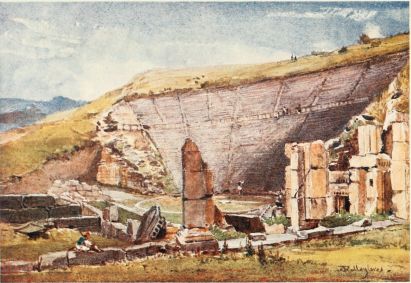

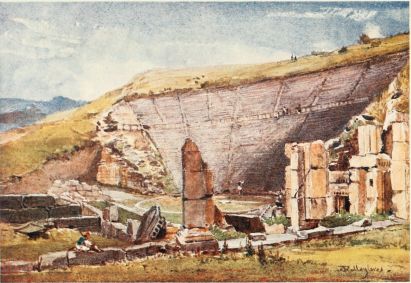

| 34. | The Theatre of Epidaurus | 110 |

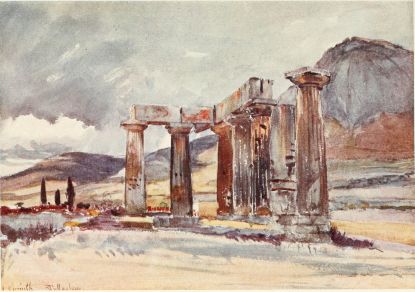

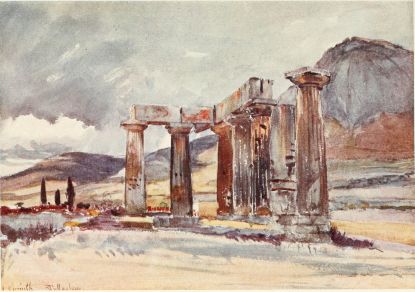

| 35. | The Temple at Corinth | 114 |

| 36. | The Temple of Athena at Sunium from the North | 118 |

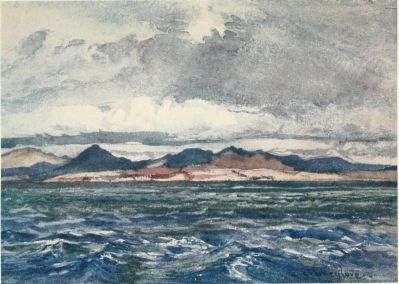

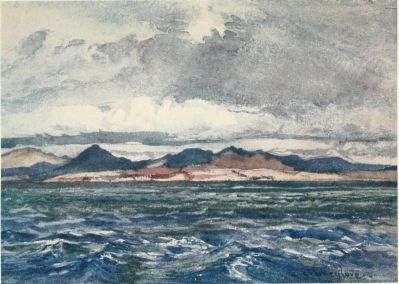

| 37. | Off Cape Matapan | 122 |

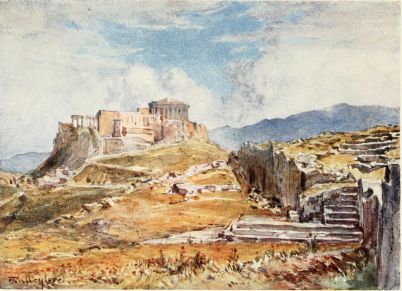

| 38. | The Western End of the Acropolis seen from below the Pnyx | 124 |

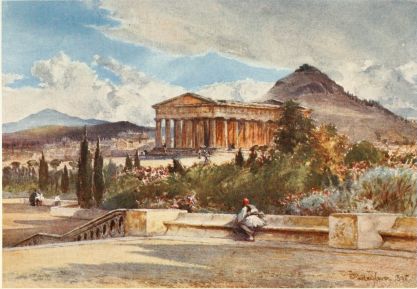

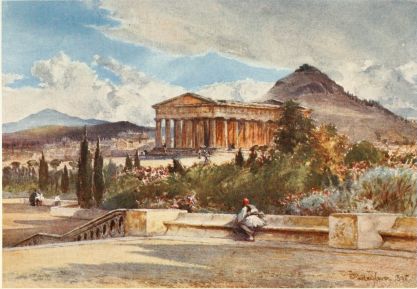

| 39. | The Temple of Theseus from the South-West | 128 |

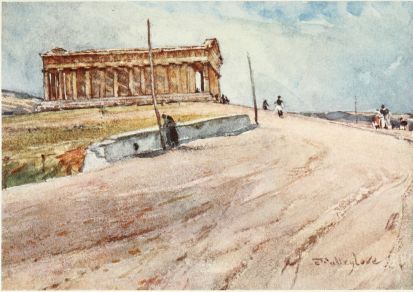

| 40. | The Temple of Theseus from the North-West | 130 |

| 41. | The Areopagus and the Theseum | 132 |

| 42. | The Battle-Field of Marathon from Mount Pentelikon | 136 |

| 43. | The Seaward End of the Plain of Attica looking towards Salamis | 140 |

| 44. | The Temple of Athena on the Island of Ægina | 144 |

| 45. | Vista of the Northern Peristyle of the Parthenon looking westward{xi} | 146 |

| 46. | The Western Portico of the Parthenon from the South | 148 |

| 47. | The Acropolis and the Temple of Olympian Zeus from the Hill Ardettos | 150 |

| 48. | The Parthenon from the Northern End of the Eastern Portico of the Propylæa | 152 |

| 49. | Mount Pentelikon and Lycabettos from the North-Eastern

Angle of the Parthenon | 154 |

| 50. | The Propylæa from the Northern Edge of the Platform of the Parthenon | 156 |

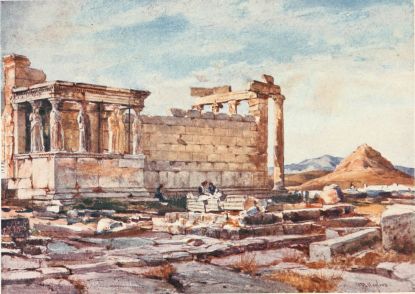

| 51. | The Southern side of the Erechtheum, with the foundations of the earlier Temple of Athena Polias | 158 |

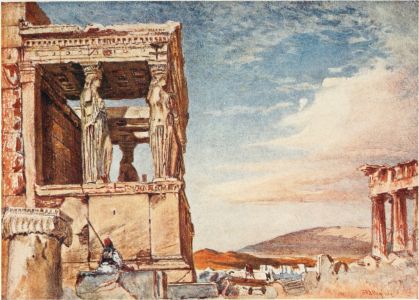

| 52. | The Caryatid Portico of the Erechtheum from the West | 160 |

| 53. | The Northern Portico of the Erechtheum | 162 |

| 54. | The Eastern Portico of the Erechtheum viewed from the Northern Peristyle of the Parthenon | 164 |

| 55. | The Dipylon at Athens | 168 |

| 56. | The Street of Tombs outside the Dipylon at Athens | 172 |

| 57. | Athens from the Road to Eleusis | 174 |

| 58. | Convent of Daphni | 176 |

| 59. | Sacred Way from Athens to Eleusis, looking towards Salamis | 178 |

| 60. | The Great Temple of the Mysteries, Eleusis | 180 |

| 61. | The Hall of the Great Temple of the Mysteries, Eleusis | 182 |

| 62. | The Acropolis from the base of the Philopappus Hill | 184 |

| 63. | The lower part of the Auditorium of the Theatre of Dionysos at Athens | 188 |

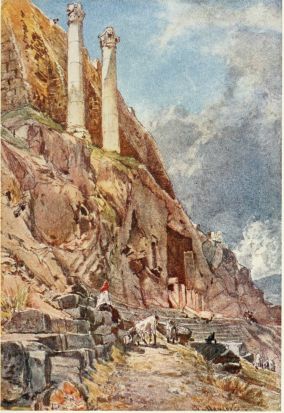

| 64. | The Cavern Chapel on the South Side of the Acropolis | 190 |

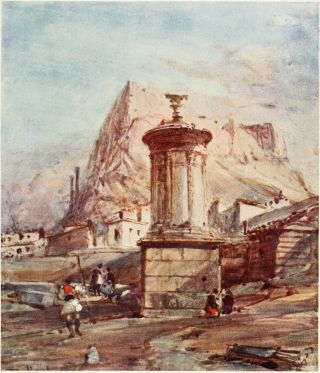

| 65. | The Choragic Monument of Lysicrates | 194 |

| 66. | The Pnyx; or Place of Assembly of the People | 198 |

| 67. | The Acropolis with Kallirrhoè in the Foreground{xii} | 202 |

| 68. | Athens. The Monument of Agrippa and the Pinacotheca | 206 |

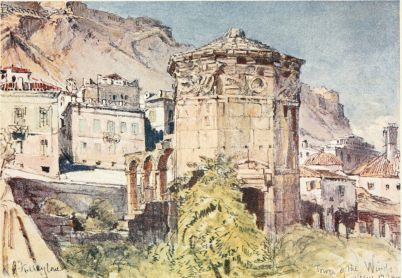

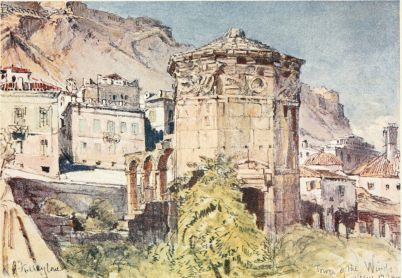

| 69. | The Tower of the Winds | 208 |

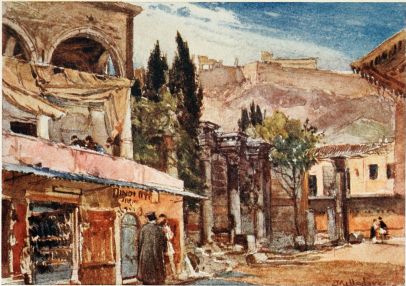

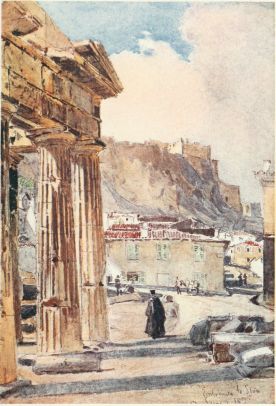

| 70. | The Portico of Athena Archegetis | 210 |

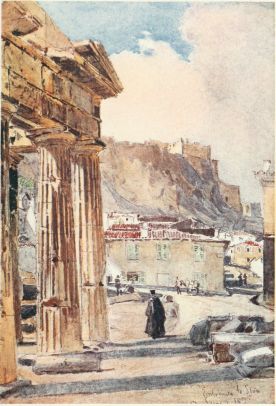

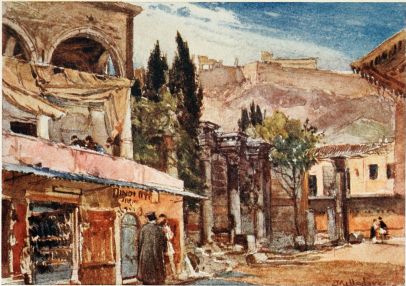

| 71. | The Stoa of Hadrian | 212 |

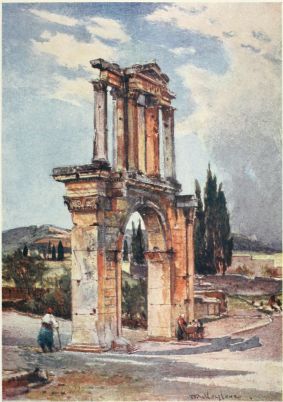

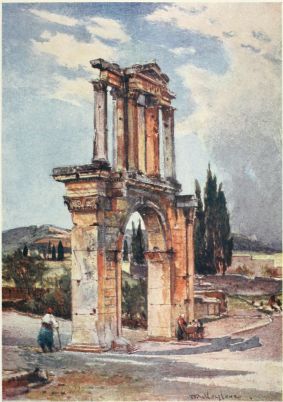

| 72. | The Arch of Hadrian | 216 |

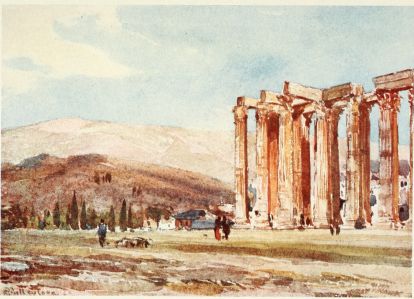

| 73. | Columns of the Temple of Olympian Zeus from the North-West | 220 |

| 74. | The Square in front of the King’s Palace at Athens | 222 |

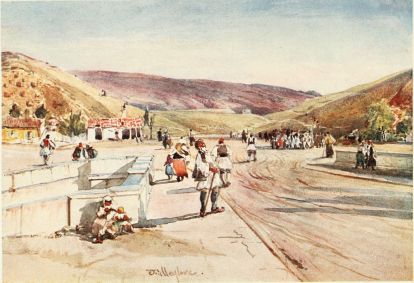

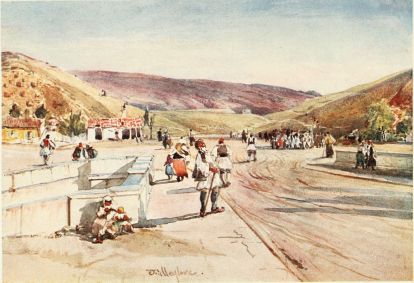

| 75. | The Stadion at Athens | 226 |

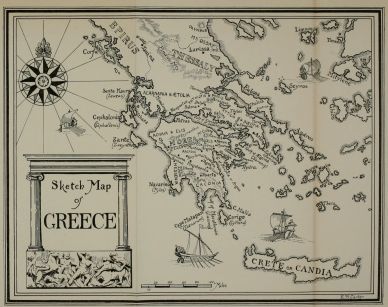

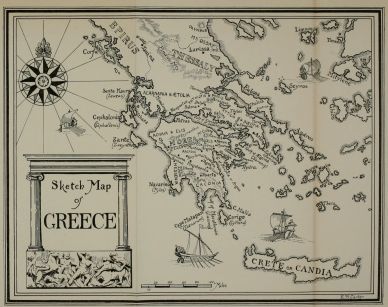

| Sketch Map at end of Volume. |

The Illustrations in this Volume have been engraved and printed in England by

The Hentschel Colourtype, Limited.

{1}

G R E E C E

INTRODUCTORY

MORE perhaps than any other country in Europe, Greece owes its charm to

the traditions of a remote past. It has no lack of fine scenery, and

there is much that is interesting in its modern life; but what chiefly

distinguishes it from other countries is the rich and beautiful

mythology which is reflected in its poetry, its art, and its philosophy,

and was to a large extent the inspiration of its glorious history.

It will not be expected that any attempt should be made in these pages

to give an adequate account of the artistic and architectural creations

which, even in their ruins, form the chief attraction of the country.

For detailed information on these matters, the reader must be left to

consult such guide-books as Baedeker and Murray, or works specially

devoted to archæology or art. The object of the present writer will be

attained if he succeed in providing a congenial intellectual atmosphere

for the scenes and objects to be presented by the artist. For this

purpose it will be necessary, among other things, to recall many of the

ancient{2} legends, as well as the historical events associated with the

places referred to. The history cannot be understood apart from the

mythology, for the latter is a key to the religious faith as well as to

the patriotic sentiment of the nation.

Opinions may differ as to the right interpretation of many of the myths,

but whatever explanation we may be disposed to give of them, whether we

regard them as allegorical, semi-historical, or purely poetical, they

are generally full of human interest, and they were very dear to the

Greeks as the embodiment of their earliest thoughts and cherished

memories. Embalmed in their poetry, consecrated by their temples, and

signalised by many other monuments, the Greek mythology formed for

centuries the chief intellectual wealth of the nation. Even when history

and philosophy had begun to make their influence felt, the old stories,

dramatised by the tragic poets, still continued to fill the imagination

and to occupy the attention of all classes of the people. Though Plato

had a good deal to say against some of them from an ethical point of

view, he did not propose in his ideal Republic to do away with them

altogether, he only wished them to be so corrected and purified as to

promote the interests of a sound morality and a reasonable theology.

An important feature of Greek mythology was its close connection with

the received genealogies. These nearly always terminated, at the upper

end, in a god or a hero, after whom a family or a group of families was

named, with the curious result, to our modern{3}

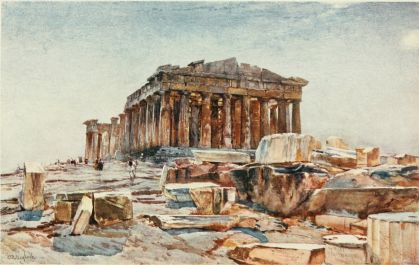

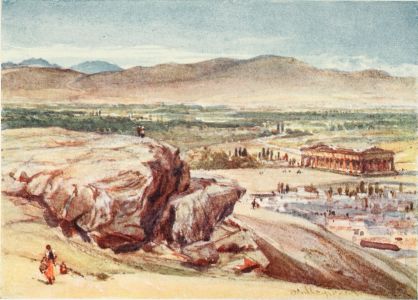

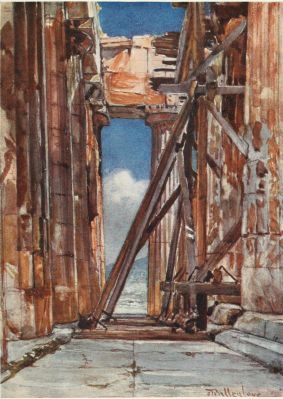

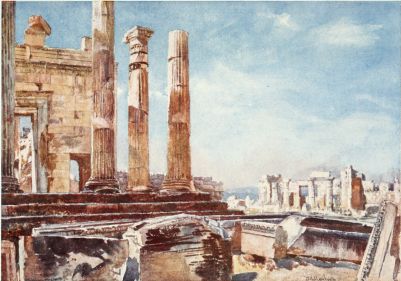

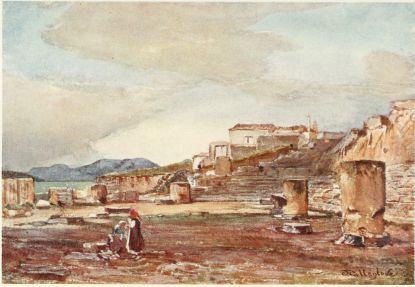

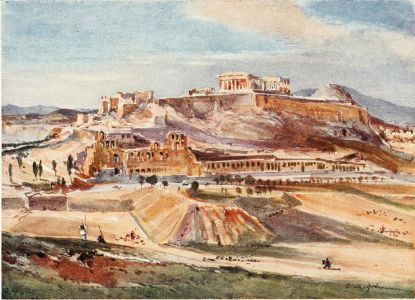

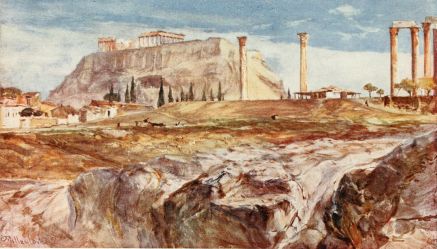

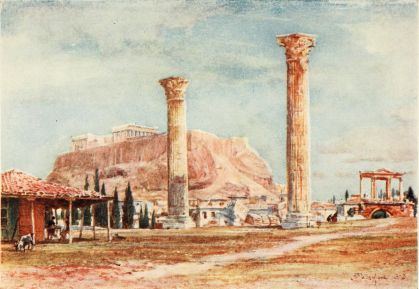

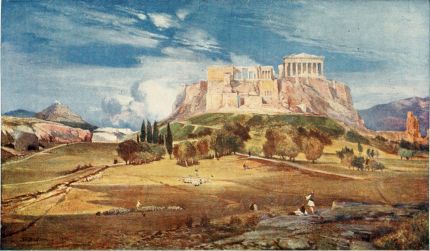

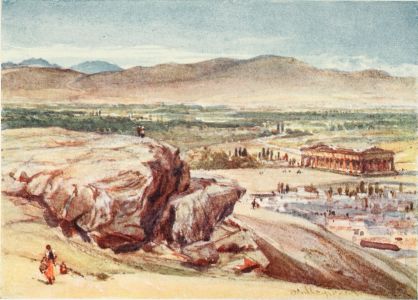

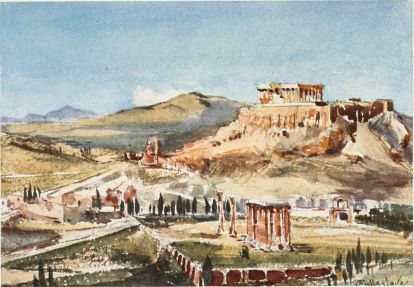

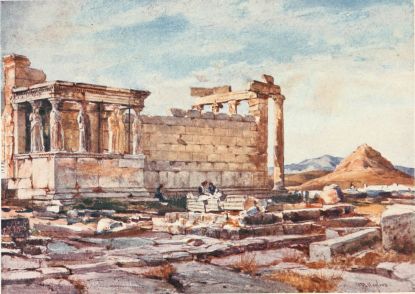

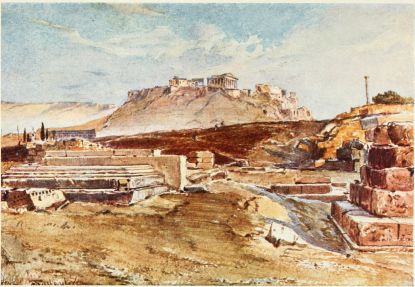

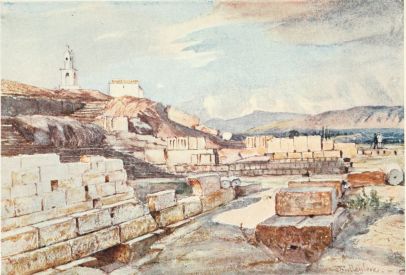

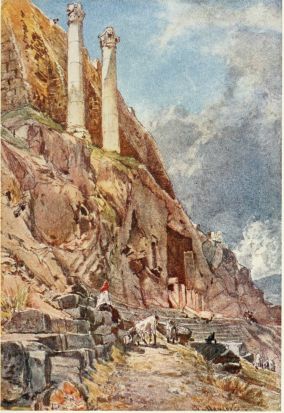

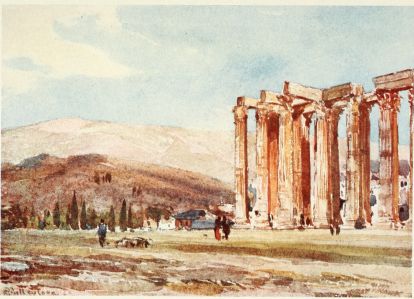

THE ACROPOLIS FROM THE SITE OF THE TEMPLE OF OLYMPIAN

ZEUS

THE ACROPOLIS FROM THE SITE OF THE TEMPLE OF OLYMPIAN

ZEUS

The two detached colossal columns belong to the west end of the southern

peristyle of the Temple. To the right is the Arch of Hadrian. The

striking form of the masses of rock, which constitute the natural

defence of the Acropolis on its eastern side, shows with great effect in

this drawing.

mind, that the shorter the pedigree the more honour it conferred upon

its living representative. The public genealogies were thus an incentive

both to the piety and the pride of the more influential classes, and

they help to account for the reverence in which the ancient mythology

was so long held by such an enlightened nation as the Greeks.

With the exception of Palestine, there is probably no country that can

compare with Greece for the influence it has exerted on the life and

thought of the world, in proportion to its size and population. In area

it was never so large as Scotland, and its population, which is now

under two millions and a half, was probably never much greater.

How far the influence of ancient Greece was due to the racial

characteristics of its inhabitants, which they brought with them from

other parts of the world, and how far to the peculiarities of the

country itself, is a question which it is not easy to determine. To some

extent, no doubt, both causes operated. The inhabitants belonged to a

good stock, the Indo-Germanic, while their geographical position and

surroundings were well fitted to develop a high type of manhood. The

beauty of the scenery, the purity of the atmosphere, the geniality of

the climate, the fertility of the plains and valleys, the grandeur of

the mountains,—more numerous and widespread than in any other part of

Europe of similar extent except Montenegro,—the bracing influence of

the sea, and the commercial advantages afforded by its coasts, which are

more extensive{4} than those of any other country in proportion to its

size, looking in the direction of Europe, Asia, and Africa—all these

things no doubt helped to make the ancient Greeks the great nation that

they were, though their comparative obscurity in modern times shows that

something more is needed to produce a similar effect.

If we would form an adequate conception of the nation’s influence, we

must take into account the numerous Greek colonies which were planted in

Asia Minor and on the southern shore of the Black Sea, on the coast of

Macedonia, along the Hellespont and Bosporus, and also in Sicily and

Italy, where a new Greek world sprang up, which received the name of

Magna Græcia. Hundreds of years before Athens reached the height of

its glory, there was a Greek city in Italy, Cumæ (founded by colonists

from Chalcis and Cymæ in Asia Minor), which held the first place in the

peninsula for wealth and civilisation; while another Greek settlement

was to be found as far west as Marseilles, which had been colonised from

Phocæa in Asia Minor about 600 B.C.

The inhabitants of Greece in this wider sense not only spoke the same

language (whose preservation was largely due to the influence of Homer),

but were also bound together by fellowship in blood, in religion, and in

manners. They were hardly more distinguishable from the rude and

ignorant tribes of Europe than from the more civilised Orientals who

practised human sacrifice, polygamy, and the mutilation of enemies. But

perhaps the most marked characteristic of the{5} Greeks was their love of

local autonomy, and their rooted aversion to anything like imperial

rule, such as prevailed so widely in Asia. Their attachment to an

individual city, as the capital of a small district, was doubtless due

in great measure to the divided nature of the country, which is broken

up by mountains and rivers and arms of the sea into numberless plains

and valleys only a few miles in extent. While this had the effect of

fostering a spirit of independence, combined with a sense of civic

obligation, which helped to develop the energies and capacities of the

individual, the proximity to each other of so many rival states bred a

great amount of jealousy and strife, which frequently led to bloody and

destructive wars. Such disintegrating tendencies were too much even for

the consolidating force of a common language and literature, or of

voluntary confederations for the purpose of worship or amusement.

Occasionally a great national emergency, such as the Persian invasion,

might force the Greeks to join together for the resistance of a common

foe, but it was almost inevitable that sooner or later they should fall

into the hands of a great military power, such as Macedonia, and lose

the civic liberties of which they were so proud. The political decay of

Greece, however, only widened the scope of its influence. As the

dissolution of the Jewish polity was followed by the rapid spread of a

religion which had its roots in the Jewish Scriptures, so the national

degradation of the Greeks led to a still wider diffusion of their

language, their literature, and their civilisation.

{6}

{7}

CHAPTER I

THE IONIAN ISLANDS AND THE “ODYSSEY”

THE first place in Greece on which a traveller from the West usually

sets foot is Corfu, one of the Ionian Islands, which were given up by

Great Britain in 1864 to gratify the patriotic aspirations of the

Greeks. The sacrifice was not without its compensations, as it relieved

Britain from an annual outlay of £100,000, which had been the cost of

administration.

The principal Ionian Islands are five in number, namely, Corfu

(Corcyra), Santa Mauro (Leucas), Ithaca, Cephalonia (Cephallenia), and

Zanté (Zacynthus). They represent a territory of more than 1000 square

miles, with a population of about a quarter of a million, who are mainly

dependent on shipping and on the trade in oil, wine, and currants.

A romantic interest attaches to the promontory of Leucas, which

terminates in what is still known as Sappho’s Leap, in allusion to an

old tradition which tells how the famous poetess, who shares with Alcæus

the chief honours in Æolian lyric poetry, here put an end to her life to

escape from the pangs of unrequited{8} affection. In Zacynthus we have an

illustration of the historical accuracy of Herodotus in the existence of

some curious springs on the south-west, from which the water comes out

mingled with pitch.

From an antiquarian point of view, however, still greater interest

attaches to Corcyra, Ithaca, and Cephallenia, as they have Homeric

associations which carry us back to a still earlier period.

Corfu or Corcyra, although not the largest, is the most populous of the

whole group. It is a beautiful island, with a beautiful situation,

looking out on the blue waters of the Southern Adriatic, with the snowy

mountains of Epirus in the distance. It has two commodious harbours, in

which the shipping of many nations may be seen. The streets of the city

are narrow and old-fashioned, but it has an interesting old fortress

with a handsome esplanade. Near the harbour is the former residence of

the British High Commissioner (an office once held by Mr. Gladstone),

with beautiful public gardens in front of it. The environs of the city

are charming, with orange-groves here and there glowing in the brilliant

sunshine, amid a profusion of roses, geraniums, and other blooms almost

growing wild, with miles on miles of olive-trees in the background.

From the earliest times the island was a place of importance to the

shipping world, as the ancients, in sailing, liked to keep near to land,

and generally put in to shore at night, unless they wished to take

advantage of some favourable breeze which did not{9}

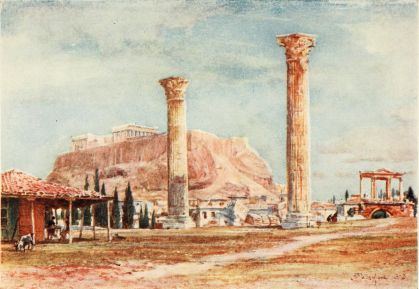

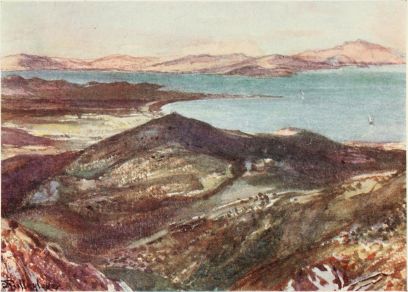

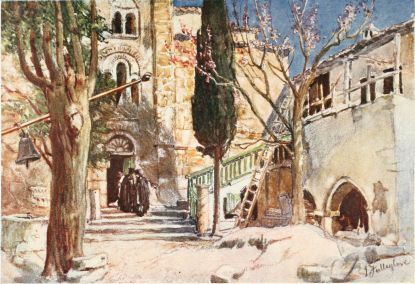

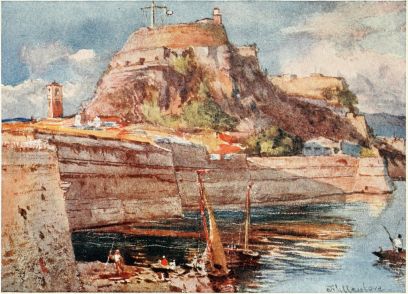

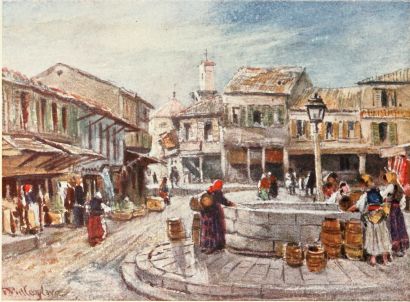

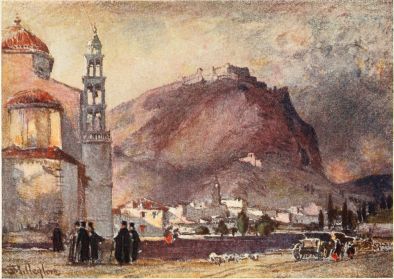

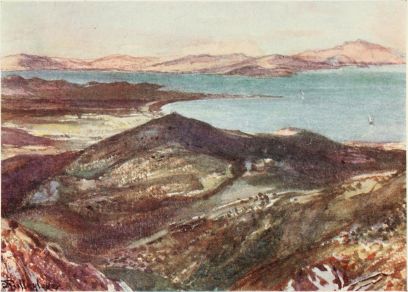

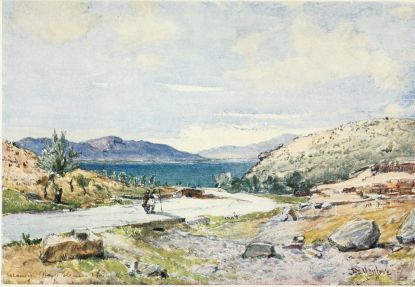

CORFU. THE OLD FORT FROM THE WEST

CORFU. THE OLD FORT FROM THE WEST

To the left the Albanian Mountains.

rise till after sunset. In this way the island afforded convenient

shelter for those who were sailing from the Peloponnesus to Italy, and

facilitated Greek traffic with Epirus. It became the seat of a

Corinthian colony in 734 B.C., when Syracuse was also founded, but it

never showed much sympathy or affection for the mother-city. Indeed, the

first sea-battle we read of in authentic history took place between the

ships of Corinth and Corcyra (c. 665 B.C.), when the latter came off

victorious. Before the Peloponnesian war broke out there were great

complaints on the part of Corinth on account of due respect not being

shown to her representatives at the public festivals in the

daughter-city; and the subsequent action of the latter in putting

herself under the protection of Athens, when she became involved in

difficulties with Corinth and Epidamnus, was largely the cause of the

great war which proved so injurious to the prosperity and power of

Athens. In the course of its early history Corcyra was the scene of some

terrible conflicts and cruel slaughters, almost without a parallel in

any other part of Greece. Since that time it has passed through many

vicissitudes under Roman, Byzantine, Crusading, Venetian, French, and

British rule.

But the greatest interest of the place arises from the tradition which

identifies it with the Phæacian island Scheria, on which Odysseus was

cast after his stormy voyage from the island of Calypso. No remains have

been found of the palace of Alcinous, where Odysseus met with such

generous hospitality, but about two{10} miles from the esplanade at

Canone (One-Gun Battery), near the end of a promontory, we get a view

of the secluded bay or gulf (Lake of Kalikiopoulo) on which the weary

voyager is said to have been cast ashore, at the mouth of a brook

(Cressida), which falls into the lake, and where Nausicaa and her

maidens were amusing themselves after their great washing was over. At a

little distance from the shore lies the rocky islet of Ponticonisi

(“Mouse-Island”), which tradition identifies with the Phæacian ship that

was turned into stone by the wrath of Poseidon, as it was beginning its

homeward voyage to Ithaca with Odysseus on board.

All this local tradition, however, is rejected by a recent explorer, M.

Victor Bérard, who has taken enormous pains to investigate the matter.

He is convinced that the palace of Alcinous and the whole scene

described by Homer in connection with the visit of Odysseus lay on the

western side of the island, near the Convent of Palæocastrizza, and he

concludes from indications in the poem that the Phæacians had come from

the ancient city of Cumæ (Hypereia), driven out by the Œnotrians

(Cyclopes). But whatever view we may take on these points there can be

little doubt that Corfu, which lay as it were on the outskirts of the

ancient Greek world, and not far from Ithaca (to which Odysseus sailed

from it in a night), is the island which Homer had in view when he

described the home of the Phæacians.

Still more interesting, from a Homeric point of{11}

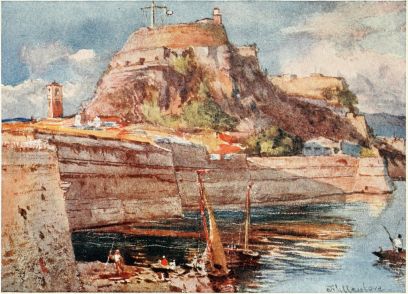

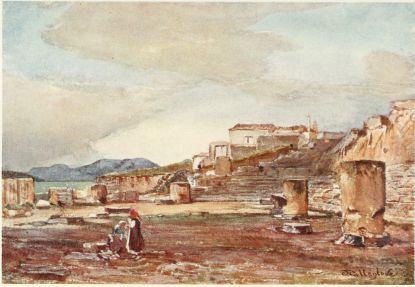

CORFU. THE OLD FORT FROM THE SOUTH

CORFU. THE OLD FORT FROM THE SOUTH

view, is the small island of Ithaca (about 37 square miles in extent),

where the poet locates the home of his wandering hero and his wife

Penelope, the one the early Greek ideal of practical sagacity, as

Achilles is of martial impetuosity, and the other the model of conjugal

devotion, as Nausicaa is of maidenly grace. The identity of the island

has recently been called in question by an eminent archæologist

(Dörpfeld), who regards Leucas as the island referred to in the

Odyssey. But it would require strong evidence to overcome the

presumption in favour of the island which now bears the name of Ithaca,

and which corresponds to the poet’s description as well as we have any

right to expect, considering the want of maps and guide-books at the

time that he wrote. Perhaps its claim may yet receive fuller

confirmation as the result of excavations; but in the meantime it is

interesting to know that a terrace wall built of rough-hewn blocks has

been discovered on the west coast, in the neighbourhood of a port to

which the name Polis (City) is still applied, though there is no modern

town to justify the name.

In this connection some interest also attaches to Cephallenia, the

largest island of the group. There is a little village on its east

coast, called Samos, from which the boat sails to Ithaca, and as an

island called Samé is often mentioned in the Odyssey in connection

with Ithaca, and the subjects of Odysseus are sometimes called

Cephallenians, we are evidently not far from the scenes depicted by the

great poet.

It would scarcely be possible to exaggerate the{12} influence which the

Homeric poetry has exercised on the intellect and imagination of the

Greeks, and it is impossible for any one to enter into the spirit of

Greek history and literature without some acquaintance with it. Homer

has often been called the “Bible of the Greeks,” and there is truth in

the saying both from a religious and a literary point of view. Herodotus

was mistaken when he said that Homer and Hesiod had created the religion

of the Greeks, but they certainly did much to systematise it, and, by

giving Jupiter a place of supremacy among the gods, they paved the way

for the triumph of monotheism.

In course of time Homer came to be regarded by his countrymen as their

chief authority, not only on religious subjects but in almost all

matters of interest to a thoughtful and inquiring mind. The reading and

hearing of his poetry was the chief means of education. It was no

uncommon thing for a boy to be able to recite both the Iliad and the

Odyssey from memory. Classical writers speak of Homer in terms not

only of admiration but of reverence. Æschylus said that he had gathered

up the crumbs from Homer’s table; and Sophocles was so much in sympathy

with the Odyssey that he was spoken of as “the tragic Homer.” There

was, therefore, nothing strange in the sentiment which led Alexander the

Great to carry about with him in his eastern campaigns a copy of Homer,

said to have been edited for him by his old tutor Aristotle, and kept in

a precious Persian casket. About a third of the recently discovered

Egyptian{13} papyri are inscribed with passages from the Iliad and the

Odyssey.

While the oldest poetry of Greece, as of other countries, was probably

of a lyric character, called forth by the joys and sorrows of common

life or by the festive celebration of the seasons, the more stately

epic, dealing with grander themes, and chanted rather than sung, with

occasional accompaniment on the harp, found more favour with princes and

their nobles, and attracted the most gifted authors to its service, till

it reached the high stage of development which we find in the writings

of Homer. These poems may be described as the oldest literature in

existence, but they were doubtless the result of many previous efforts

of a more archaic character, traces of which may be found in the older

bards and legendary themes that are mentioned by Homer himself.

The Iliad and Odyssey show to what a high degree of civilisation and

culture the Hellenic race had attained not much later than 1000 B.C. In

the freeness of their spirit, combined with reverence for law, and in

their vivid portraiture of the different members of the Pantheon, seen

through the medium of a rich and sympathetic humanity, the poems present

a pleasing contrast to all other heathen pictures of things human and

divine. Their language is as admirable as the thought,—so rich and

flexible, entirely free from the crudities that might have been expected

in such primitive literature. Matthew Arnold sums up Homer’s

characteristics from a literary point of view, as rapidity,{14} plainness

of thought, plainness of style, and nobleness. These qualities give the

poet as strong a hold on the sympathies of his readers as he assigns to

the minstrel in the Odyssey, when he makes Eumæus say of his old

master, now returned, but still in disguise: “Even as when a man gazes

on a minstrel whom the gods have taught to sing words of yearning joy to

mortals, and they have a ceaseless desire to hear him as long as he will

sing, even so he charmed me, sitting by me in the halls.”

The controversy which has been going on for more than a hundred years

regarding the authorship of the poems does not much affect their

interest for the general reader. Similar questions were raised more than

two thousand years ago. Even before Plato’s time there had been a

sifting process by which a number of hymns and minor poems formerly

attributed to Homer (as the whole book of Psalms used to be to David)

were found to be the work of unknown authors of a later date. A century

or two later there were Alexandrian critics who denied that the Iliad

and the Odyssey could have come from the same author. But modern

critics have assailed the integrity of the two great poems themselves.

They have based their theories partly on the improbability of such long

poems being composed and transmitted before writing had come into

general use (an argument which has lost its force owing to recent

discoveries of early writing), and partly on the apparent repetitions,

interpolations, and discrepancies, which are supposed to have been{15}

THE TEMPLE OF ATHENA AT SUNIUM (CAPE COLONNA)

THE TEMPLE OF ATHENA AT SUNIUM (CAPE COLONNA)

Distant view over the hills.

due either to the accidents of compilation or to the need for adaptation

to suit the varying tastes of readers in different parts of the Greek

world. Perhaps the strongest proof of composite authorship is to be

found in the different stages of civilisation and religion which are

discernible in different parts of the poetry, and the marked

inconsistencies in certain of the leading characters. It is also very

significant that Mount Olympus, the dwelling of the gods, is at one time

the snow-clad mountain in the north which still bears that name, and in

other and later passages is a bright and gladsome region, free from rain

or snow or stormy wind. It is now generally agreed that the nucleus of

the Iliad was a series of ancient lays concerning Achilles, derived

from Northern Greece, and moulded by Æolic art, while the remainder of

the poem and the bulk of the Odyssey were of a considerably later

date, and came from an Ionic source. The poems as a whole were probably

touched up and put into their present form by some one living on the

coast of Asia Minor (perhaps at Smyrna, the meeting-place of Æolic and

Ionic traditions), who sang of the glories of a by-gone age with the

patriotic pride of a colonial. Whether his name was Homer is a different

question, for it is quite possible the word may have been, as some

maintain, a common term, meaning “compiler.” It is well to remember that

the “blind bard who dwelt in rocky Chios,” so often identified with

Homer since Thucydides set the example, is merely the description

applied to himself by the writer of the Hymn to the Delian{16} Apollo, whom

no one now believes to have been the author of the Iliad or the

Odyssey. We know that the Great Unknown, whoever he may have been, was

succeeded by the Homeridæ of Chios, and these again, by the Rhapsodes or

professional reciters, whom we come across in the pages of Plato and

Xenophon.

Another subject of controversy has been as to whether the Homeric

narratives have a historic basis to rest upon. Some have gone so far as

to doubt whether the Trojan War ever took place; and it has been

suggested that many of the stories in the Iliad are due to solar

myths. But the excavations of Schliemann at Ilium and Mycenæ have rather

discredited such scepticism; and the recent explorer already mentioned

(Bérard), who has sailed over the course which appears to have been

taken by Odysseus,—extending from Troy to Gibraltar,—has found the

topographical and maritime allusions so accurate as to come to the

conclusion that the poet must have had the benefit of some ancient book

of reference, corresponding to the Pilot’s Guide, and drawn up in all

probability by the Phœnicians, who were masters of the Mediterranean

before the Greeks. But while the main thread of the narrative in the

Odyssey may be historical, the poet has worked into it many fanciful

legends, like those to be found in the literature of many nations.

Indeed the story of Odysseus’ adventures as a whole is perhaps no more

historical than the tale of Robinson Crusoe, created by Defoe out of the

experience of Alexander Selkirk on the island of Juan Fernandez.{17}

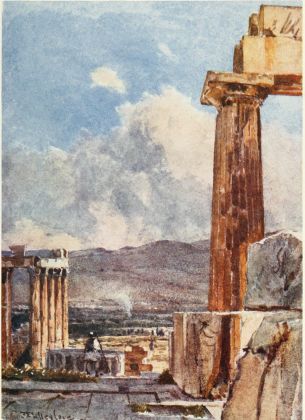

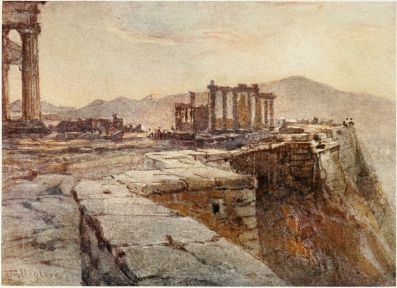

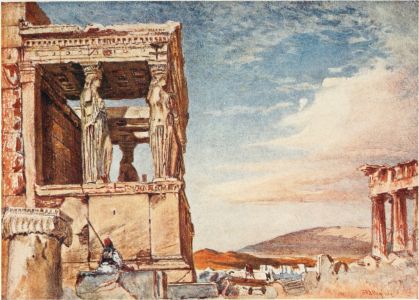

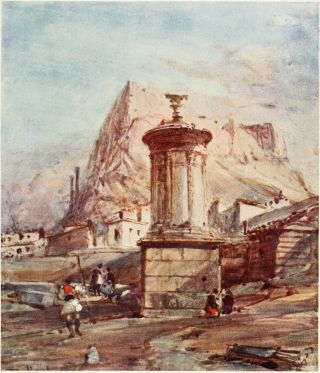

SUNSET FROM THE NORTH-EAST CORNER OF THE ACROPOLIS

SUNSET FROM THE NORTH-EAST CORNER OF THE ACROPOLIS

To the left, a bit of the east front of the Parthenon; to the right, the

precipitous north side of the Acropolis; in the middle distance the

Erechtheum, showing all three of its porticoes; in shadow, between the

Parthenon and the Erechtheum, the upper part of the Propylæa.

No criticism, however, can alter the fact that we have in the Odyssey

some of the most charming pictures of social and domestic life that are

to be found in any literature, touched up with a colouring of the

strangest old-world romance, and deriving lustre from a religion which,

however defective from an ethical point of view, was wedded to an

imagination so rich and powerful as almost to efface in the mind of the

reader the distinction between the natural and the supernatural.{18}

CHAPTER II

DELPHI AND ITS ORACLE

AFTER entering the Gulf of Corinth the first port at which the steamers

touch is Patras, the largest city in the Peloponnesus, with about 40,000

inhabitants,—looking across to Missolonghi on the northern shore, where

Byron died and where his heart is buried. The only notable thing about

Patras in pre-Christian times was its inclusion in the Achæan League,

that last outburst of the Hellenic love of independence. In modern times

it has had the distinction to be the first city to raise the national

flag in the War of Liberation (1821). Its patron saint is St. Andrew,

who has a cathedral dedicated to him, with a crypt in which his bones

are said to have their resting-place. It is a prosperous and well-built

city, with a picturesque country behind it, rich in vines and olives,

and in front of it the inland sea which is the great highway of Greek

commerce. But its chief interest for the traveller is the fact that it

is the place at which arrangements can best be made for visiting Delphi

and Olympia, two of the most attractive spots in Greece.{19}

Delphi is situated on the mainland. To reach it the traveller has to

sail across from Patras to Itea, a small port at the head of the famous

Crisæan Gulf. The drive from Itea to Delphi on a fine April day is one

of the finest in the world. For a few miles you hold northward along the

plain, passing through a long forest of olive trees, with gnarled and

twisted trunks, the fresh leaves glistening in the sun and changing

colour in the breeze, shafts of glowing light shooting through the

branches. In the distance rise hills on hills, crowned by the snowy

summit of Parnassus. But it is not till you leave the plain and turn to

the right, slowly ascending by a zigzag route to the village of Chryso,

the ancient Crisa, that you begin to realise the sublimity of the

surroundings. The solemn grandeur of the mountains is above you. Below

lies the fertile plain, which was dedicated to Apollo and became the

scene of the Pythian Games when they reached their full development. As

you look down, the olive wood presents a new appearance and seems to

wind, like a great river of oil, towards the sea, whose rock-bound

coast, in the opening made by the bay at which you landed, shows the

pink, white, and blue houses of Itea sparkling in the sun. The Gulf of

Corinth, of which you can only catch glimpses now and then, might pass

for a great lake, bordered by the hills of Achaia in the south, and

surmounted in the far distance by the glittering summits of Erymanthus

and Cyllene, which rise to a height of 7000 or 8000 feet. In the course

of the journey you may often{20} come upon a mass of flowers, sometimes

covering the slope on the roadside, sometimes running into the field and

mingling with the ripe corn, which the rustics are reaping with the

old-fashioned hook. The most conspicuous and abundant of all the flowers

is the large scarlet poppy, which might be counted by the thousand, and

often spreads over a great extent of ground. After passing Crisa, almost

the only signs of life we saw on the way were flocks of black goats with

their tinkling bells, and a long string of heavy-laden camels, with

their young ones running by their side, moving along in solemn

procession from the east.

As we approached Delphi, the view presented sterner outlines and a wider

range, embracing the dales and gorges of the Pleistus valley, and the

rugged hills of Cirphis on the south, as well as the mighty range of

Parnassus, with its outlying spurs and precipices. Of these the most

remarkable and the most celebrated are the Phædriadæ or shining peaks,

overshadowing the ancient sanctuary of Apollo, which was for centuries

the religious centre of the Greek world, as the Vatican was to mediæval

Christendom. The world-wide influence exerted by the Delphian oracle is

one of the most interesting facts in all history. It was characteristic

of the Hellenic as compared with the Hebrew mind that the oracle should

hold such a prominent place in the national religion: for it was a

religion dominated by the imagination rather than the conscience. At the

same time it should not be forgotten that, until its decadence, the

oracle was more frequently consulted{21}

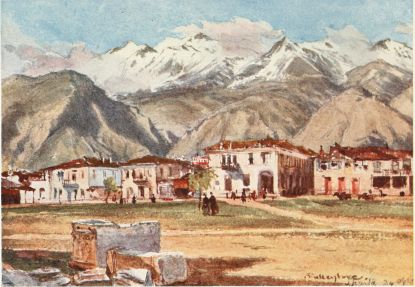

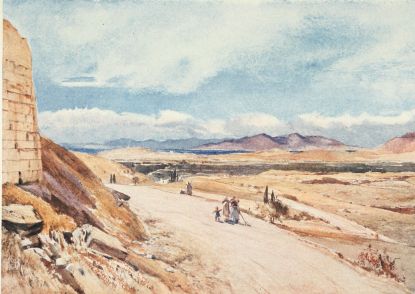

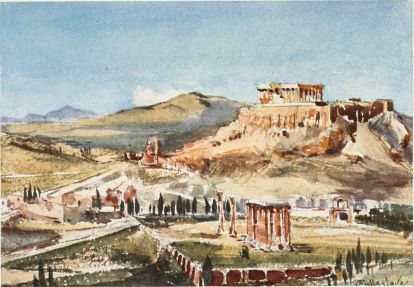

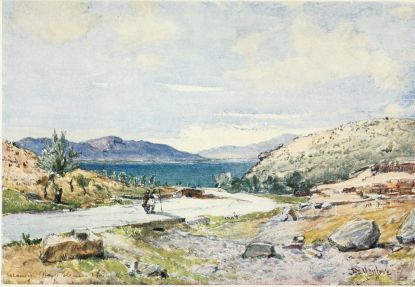

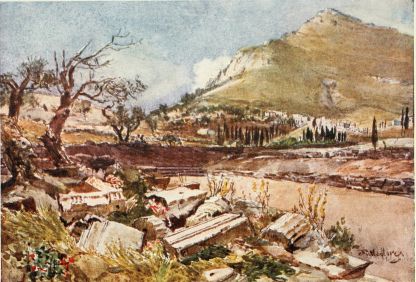

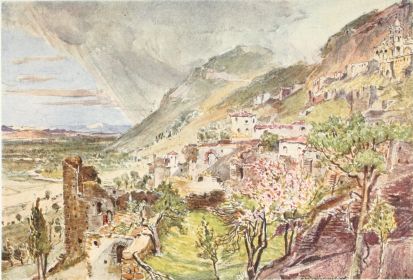

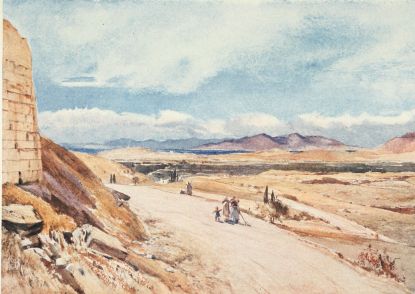

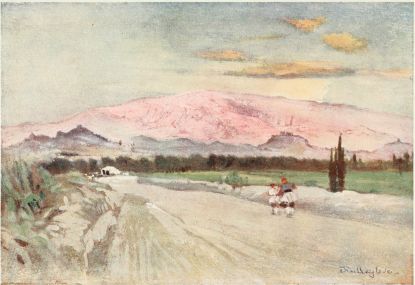

DELPHI FROM ITEA

DELPHI FROM ITEA

This drawing indicates in a general way the position of Delphi with

regard to the plain of Cirrha below and the snowclad summit of Parnassos

above. On the left is the opening of the gorge of the Pleistos. Just

above where it disappears from view, to the right, the new village

called Delphi is visible on the slope of the mountain in front of the

great precipices of the Castalian Gorge. Ancient Delphi lies out of

sight in the hollow immediately behind the new village, and between it

and the Castalian cliffs.

for guidance in the practical affairs of life than merely to gratify

curiosity as to future events. The Delphian oracle originated, no doubt,

in the superstitious awe which the place inspired as the supposed centre

of the earth, possessed of mysterious cavities by which it was believed

possible to hold communication with the dead. In the earliest times it

was connected with the worship of the earth-goddess Gæa or Gē, who

sheltered the dead in her bosom. Later, the presiding deity was Themis,

the goddess of law and order in the natural world. But during the whole

historical period Apollo was the source of inspiration, the god of light

and the highest interpreter of the divine will. During the three winter

months Dionysus reigned, in the absence of Apollo.

The reverence in which the oracle was held, even in the most enlightened

times, was largely due to the wisdom and prudence of the priests—five

in number—who belonged to the noblest Delphian families and held office

for life. They were brought into contact with leading men who came to

consult the oracle from all parts of the Greek-speaking world,—men like

Lycurgus and Solon and Socrates and Xenophon and Alexander the

Great,—and they appear to have been on terms of intimacy with such

national poets as Hesiod and Pindar and Æschylus. Pindar’s iron chair

was carefully preserved in the sacred precincts, and the priest of

Apollo cried nightly as he closed the temple, “Let Pindar the poet go in

unto the supper of the gods.”

The priests put their own interpretations on the{22} ecstatic utterances of

the prophetess, which she delivered in their hearing and in the presence

of the inquirer after she had drunk the holy water, chewed the

laurel-leaf, and mounted the tripod to inhale the narcotic vapour which

arose from the chasm beneath. These interpretations they embodied in

hexameter verses, generally disappointing from a poetical point of view,

considering the auspices under which they were delivered, and frequently

ambiguous in their terms, when it did not seem advisable for the oracle

to commit itself to a definite opinion. One of the best known and most

interesting cases of this sort was the answer given to Crœsus, King

of Sardis, when he was deliberating whether he ought to go to war with

Persia. Before inquiring on so important a point he resolved to test all

the chief oracles, six in number, by asking each of them through a

special messenger to say what he was doing on a specified day, on which

the question was to be put. The oracle that best stood the test was

Delphi, and Crœsus proceeded to ask advice on the momentous question

about which he was so anxious, bestowing on the temple of Apollo at the

same time magnificent gifts of solid gold and silver, and immense

offerings for sacrifice. The answer was that if he went to war with

Persia he would destroy a great empire, which he at once took in a

favourable sense. He was defeated, however, and Cyrus became master of

his city and kingdom, thus fulfilling the oracle in an unexpected sense.

He would have been put to death by his conqueror had it not been that{23}

when he lay bound upon a funeral pile, which had been already kindled,

his exclamations led Cyrus to inquire what he was speaking of, and on

hearing of Solon’s warning as to the instability of human greatness,

which the fallen monarch had been calling to mind, Cyrus gave orders

that Crœsus should be at once released. The flames had taken such

hold of the wood, however, that he would still have perished if Apollo

had not heard his prayers and sent a heavy shower of rain, which

extinguished the fire. The disappointment of his hopes gave such a shock

to Crœsus’ faith that, by the leave of Cyrus, he sent to Delphi the

chains in which he had been bound to the pile, with a message asking if

that was the way in which Apollo treated his faithful votaries. In the

reply he was reminded that Apollo had saved his life, and was told that

he had not been careful enough in his interpretation of the oracle, and

that it had been impossible any longer to avert the doom which rested on

him as the fifth in descent from an ancestor who had incurred the divine

wrath by the murder of his master and the usurpation of his throne.

With one exception—the encouragement which it gave on certain rare

occasions to human sacrifice—the general influence of the oracle was

salutary, from a social and political as well as an ethical point of

view. On the walls of the temple were inscribed some of the sayings of

the wise men of Greece, such as “Know thyself,” “Nothing to excess.” The

oracle did much for the protection of rights where no legal sanction was

available. It checked blood-feuds, and gave its{24} sanction to the

purification and pardon of those who had committed homicide under

extenuating circumstances. It could even dispense with ritual observance

altogether where there was no real guilt. For example, to a good man who

had slain his friend in defending him against robbers, and had fled to

the sanctuary in great distress of mind, its answer was: “Thou didst

slay thy friend striving to save his life; go hence, thou art purer than

thou wert before.” It confirmed the sanctity of oaths. Herodotus gives a

striking instance of its high standard of morality when, in answer to an

inquirer who asked whether by repudiating his oath he might claim a

large sum of money which had been deposited with him, the prophetess

declared that to tempt the god as he had done and to commit the crime

was the same thing, and that the divine judgment would descend on him

and on his house. For “there is a nameless son of Perjury, who has

neither hands nor feet; he pursues swiftly, until he seizes and destroys

the whole race and all the house.” It also rendered good service, as

many inscriptions show, in connection with the emancipation of slaves,

whose deposits it took care of, until a sufficient sum was available for

the purchase of their freedom from their masters, who were interdicted

from making any further claim upon their services. Besides the light and

leading which the oracle afforded to some of the early lawgivers of

Greece, and the wise counsels which it gave on questions of peace or

war, it was specially useful in advising cities on all projects of

colonisation.{25}

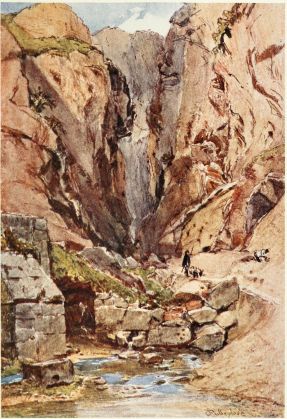

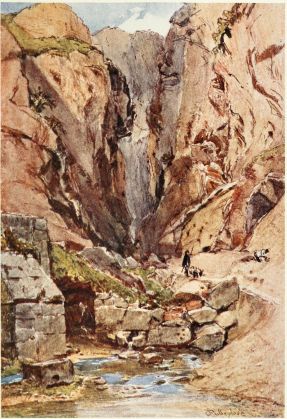

DELPHI, THE CASTALIAN GORGE AND SPRING

DELPHI, THE CASTALIAN GORGE AND SPRING

The scarped vertical face of rock, which may be seen above the figure of

the shepherd, shows the recently excavated site of the Place for the

Lustration of Pilgrims, to which the water of the Castalian spring was

carried by an artificial channel in the rock. The masonry to the left of

the drawing is part of a modern reservoir.

It seems to have been almost the invariable practice for Greeks to

consult the oracle before resolving to plant a colony, so much so that

Delphi is declared to have been “the best-informed agency for emigration

that any State has ever possessed.”

Its prestige declined owing to several causes. The priests were not

always proof against bribery; and when it became known at any time that

they had thus abused their office, it produced a deep feeling of

indignation and distrust. There are several well-attested cases of

corruption, chiefly on the part of Spartans. One of their kings,

Cleomenes, procured the deposition of his brother-king Demaratus by

bringing private influence to bear at Delphi. When the facts of the case

came to light, the prophetess was deposed from her office, and her chief

adviser at Delphi had to take to flight. Another Spartan king,

Pleistoanax, who had been exiled for accepting bribes from Pericles,

succeeded, after eighteen years’ residence in Arcadia (where, for

safety, half of his dwelling-house was within the enclosure of a

temple), in obtaining his recall to Sparta with great honour, owing to

the injunctions to this effect, which were repeatedly given by the

oracle as the result of bribes. Lysander, the great Spartan general,

after he was deprived of his command, concerted a scheme with the

authorities at Delphi for getting himself recognised as king through the

publication of fabricated records, alleged to be of great antiquity, and

only to be opened by a genuine son of Apollo. Such a pretender they

secured, but the{26} scheme broke down owing to the timidity of one of the

conspirators.

Another drawback was that the growing power of rival states rendered it

increasingly difficult for the oracle to hold the balance with any

fairness between them, and at the same time maintain its old and

intimate relations with Sparta. Its dignity was also lowered when,

instead of being open for consultation for a month once a year, more

frequent opportunities were afforded and trivial questions entertained.

But perhaps the most serious difficulty they had to contend with was the

growing intercourse and correspondence of the different cities of

Greece, both with one another and with foreign cities, and the general

spread of knowledge, which tended to impair the reverence in which the

oracle had been held, and deprived its priests of the monopoly of

general information which they seem to have at one time virtually

enjoyed. By the time the Christian era began, the Greek oracles had been

practically superseded by the Chaldæan astrologers; and when Julian the

Apostate in the fourth century tried to revive the glory of Delphi, he

received the answer, “Tell the king the earth has fallen, the beautiful

mansion; no longer has Phœbus a home, nor a prophetic laurel, nor a

font that speaks: gone dry is the talking water.” It was finally

suppressed by the Emperor Theodosius towards the end of the fourth

century.

Like the still older sanctuary of Dodona (where revelations were

supposed to be given through the{27} rustling of a sacred oak), Delphi was,

alternately with Thermopylæ, the seat in historic times of an

Amphictyony or union of states, which existed for the worship of the

deity whose shrine they were pledged to defend, as well as for mutual

friendship and protection. Unfortunately the history of the oracle,

although a national institution, was marked at various times by deadly

strife among the different Hellenic tribes whose interests were

involved. At first the management of the oracle seems to have been in

the hands of the people of Crisa, who were Phocians, but after the

protracted war waged by the Amphictyony against the natives of Cirrha,

the adjacent sea-port, on account of the extortions they practised on

the pilgrims to the shrine and the outrages they sometimes perpetrated

on them, the trust was committed by the federation to the inhabitants of

Delphi, who were of Dorian extraction. Cirrha was laid waste, the whole

Crisæan plain was dedicated to Apollo, and the spoils of Cirrha were

used to establish the Pythian games on a more ambitious footing than had

been possible when they were held in the limited space available at

Delphi.

A second Sacred War, as it was called, broke out in 357 B.C., when the

Amphictyonic Council, after imposing a fine on the Phocians at the

instigation of their enemies the Thebans, which remained unpaid,

proceeded to confiscate their territory. The Phocians offered a long and

desperate resistance, asserting their old right to administer the

affairs of the sanctuary. In the course of the war their leaders had

recourse to the{28} treasures of the temple again and again, melting and

coining the precious metals, and turning the brass and iron into arms.

Altogether they are said to have appropriated no less than £2,300,000,

which was required to keep up their large mercenary army.

The fabulous wealth of the place had often tempted the cupidity of

foreign foes, but on every occasion the god had been found able to

protect himself. When Xerxes sent a detachment of his huge army to

despoil the shrine, his soldiers were thrown into a panic and put

utterly to flight by great rocks tumbling down upon them from the cliffs

of Parnassus in the midst of a terrible thunderstorm. The rocks were

shown to Herodotus in the precincts of the temple of Athena,—perhaps

the same as are still to be seen in the low ground to the south of the

public road. A similar experience is said to have befallen the Gauls

under Brennus about two hundred years afterwards. At an intermediate

date (370 B.C.), when Jason of Pheræ, the powerful ruler of Thessaly,

set out for Delphi with, as it was believed, a hostile intent, under

colour of sacrificing to the god a thousand bulls and ten thousand

sheep, goats, and swine, he was suddenly cut off in the prime of life by

a treacherous band of assassins.

There was yet a third Sacred War, a few years afterwards. The objects of

Amphictyonic wrath on this occasion were not the Phocians but the

Locrians of Amphissa (now Salona), who had taken possession of Cirrha

and repeated the old offence of using part of the consecrated ground for

their own secular purposes.{29}

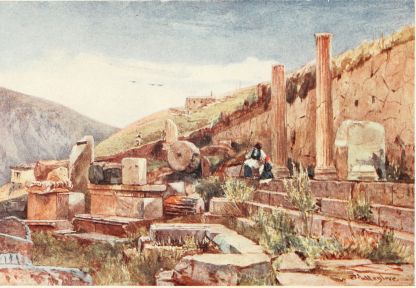

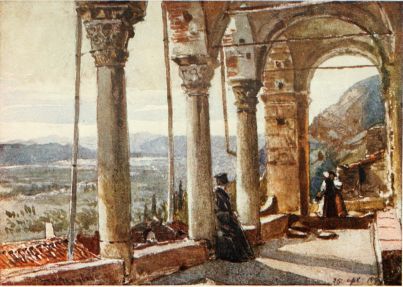

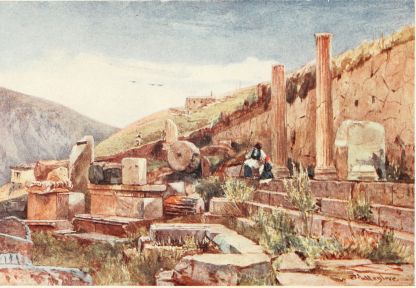

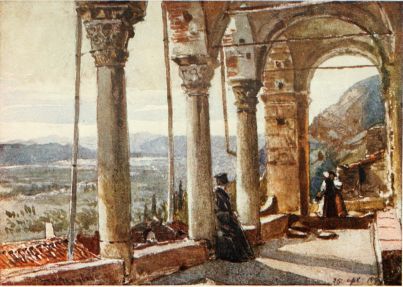

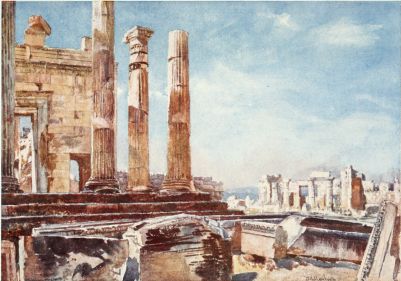

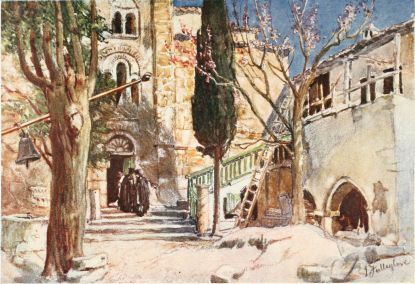

DELPHI. THE PORTICO (STOA) OF THE ATHENIANS

DELPHI. THE PORTICO (STOA) OF THE ATHENIANS

The wall of polygonal masonry to the right is part of the Heleniko, or

terrace wall, of the Great Temple of Apollo. Three marble steps at the

back of the Athenian portico, with two Ionic columns in place, stand in

front of the wall. The “sacred way,” terminating at the east end of the

Great Temple above, passes in front of this portico, and the row of

marble seats along its farther side marks out its course. To the left of

the drawing is seen the mountain slope of Kirphis leading down to the

gorge of the river Pleistos.

The sympathies of Greece were divided in this war, and the final outcome

of the struggle was that Philip of Macedonia, who had been called in to

finish the previous war, and had been admitted a member of the

Amphictyony in place of the dispossessed Phocian tribe, now became

master of Greece by reason of his victory over the combined forces of

Athens and Thebes at the fateful battle of Chæronea in 338 B.C.

Within the past few years French archæologists have done wonderful work

at Delphi. By the removal of the modern village of Castri, the

foundations of the temple and the remains of many of the surrounding

buildings and monuments have been brought to light. As you pass along

the “Sacred Way” you can identify many of the sites mentioned by

Pausanias, in the very order in which he describes them. In most places

the old pavement still remains, with grooves to keep the feet from

slipping. Some of the most precious relics have been removed to the

Museum, where there are also models of many of the most beautiful works

of art that have perished. Among the former is the famous Omphalos or

“Navel-stone,” on which Apollo is often represented as sitting. It

marked the spot at which two eagles met, which had been sent out by

Jupiter from extreme east and west, of equal speed in flight, to

determine the exact centre of the earth. The marble stone which is now

shown, although apparently identical with that seen by Pausanias,—for

it was discovered on the same spot,—may be only an imitation of the

original, like another which has also been recently discovered;{30} and the

golden eagles which stood beside the Omphalos have also disappeared.

The chasm in the temple floor, from which the vapour ascended that was

supposed to inspire the prophetess, cannot now be found, having probably

been filled up somehow; but a little way off there is a rock with a rift

in it, on which the first Sibyl (mentioned by Plutarch) is supposed to

have sat and prophesied. The rift may have been the lurking-place of the

dragon which Apollo shot with his darts, when he came from Delos, the

land of his birth, to inaugurate the ministry of the Cretan travellers,

whom he had enlisted in the service of his new sanctuary. According to

the legend the skin of the dragon was left to rot, giving rise to the

ancient name Pytho, by which Delphi was known in the days of Homer. In

the hymn to the Delphian Apollo the scene of the combat is laid in the

gorge of the Phædriadæ, but the other conjecture is supported by the

proximity to the Sibyl’s rock of an enclosure like a threshing-floor,

which is supposed to be the place where the drama was enacted every

fourth year.

A little way above the temple is an open-air theatre—one of the best

preserved in Greece. It is in the usual horse-shoe form, with its

sloping back, enclosing the sitting accommodation for the spectators,

resting on a rising ground. The stadium is still higher, right under the

cliffs of Parnassus on the north, and shut in by rising grounds on

either side, but commanding a magnificent view to the south over valley

and mountain. It was the ancient scene of the Pythian games, and is{31}

still recognisable as such in almost every feature. Apollo was regarded

as the leader of the Muses, and the Pythian festival was originally a

musical, not an athletic contest. The prize of laurel wreath was given

for the best song in honour of Apollo to the accompaniment of the lyre.

At the conclusion of the first Sacred War, nearly 600 B.C., the chariot

races (which are deprecated in the Homeric hymn) were inaugurated in the

plain beneath. But the higher form of competition still continued,

including even poetry and painting—a distinction of which no other

pagan cult can boast. Deeply interesting as the ruins are from an

archæological point of view, they bring home a sense of the

transitoriness of early glory when one thinks how little remains of the

thousand statues and trophies and votive offerings which once filled the

spot with “the glory that was Greece.” Time has robbed it of the

treasures of art which were to be seen in the days of Pliny, even after

the ravages of Sulla and of Nero. Happily, one of the most interesting

and beautiful of all the monuments has just been restored, namely the

Treasury of the Athenians, which was built of Parian marble in the form

of a small Doric temple, from the spoils taken on the field of Marathon.

It seems to have been overthrown by an earthquake, but almost all the

blocks of which it was constructed have been discovered among the ruins,

and have been fitted together with such skill and success as to

reproduce the old inscriptions engraved upon the walls, including

several hymns to Apollo, with their musical notation.{32} The expense of

the restoration has been mainly borne by the city of Athens.

A few hundred yards to the east is the Castalian spring, in the cleft

between the lofty Phædriadæ. At one time it was believed to confer the

gift of prophecy on those who drank of it; but its rock-hewn basin is

now used by the village women for washing clothes. In ancient times its

water was used for sacred purposes by the prophetess and her attendants

and all who came to consult the oracle. That the purification sought was

not merely that of the body may be inferred from a prophetic utterance

which has been rendered as follows:—

To the pure precincts of Apollo’s portal,

Come, pure in heart, and touch the lustral wave:

One drop sufficeth for the sinless mortal;

All else e’en ocean’s billows cannot lave.

If the traveller pursue his journey a few hours farther to the east,

passing the picturesque little town of Arachova, about 2000 feet above

the sea, he will reach the ancient Cleft or Triple Way, in a scene of

desolate grandeur at the end of a long, deep, narrow valley. It was

there that Œdipus, seeking to escape the destiny which had just been

announced to him by the oracle, and unaware of his true parentage, met

his father Laius, King of Thebes, on his way to Delphi, and in a fit of

anger at the unceremonious way in which he was jostled aside by the

royal charioteer, slew the aged king and all his attendants save one,—a

crime which was the beginning of those many sorrows in his{33}

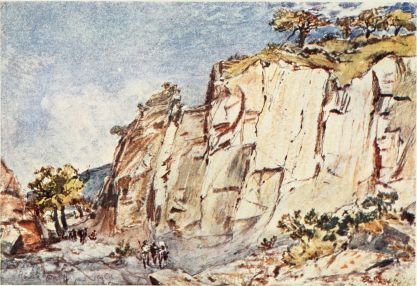

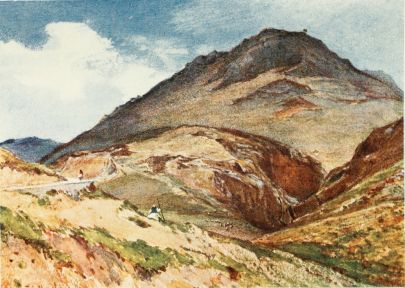

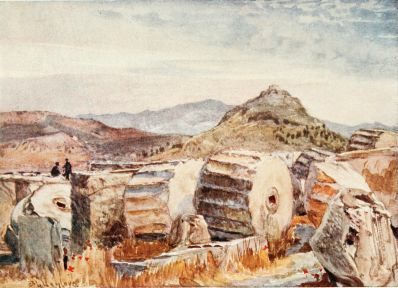

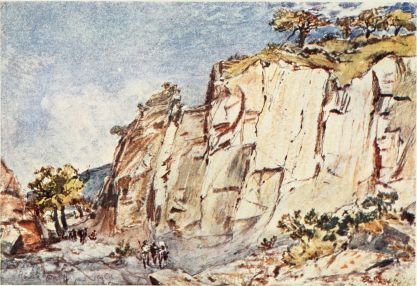

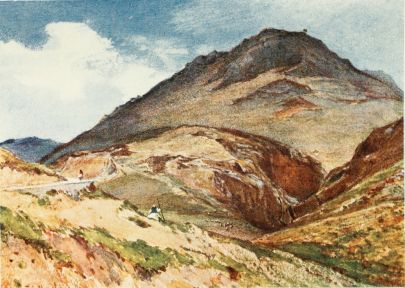

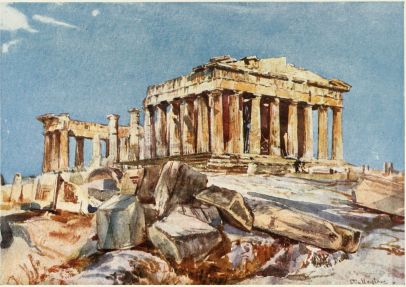

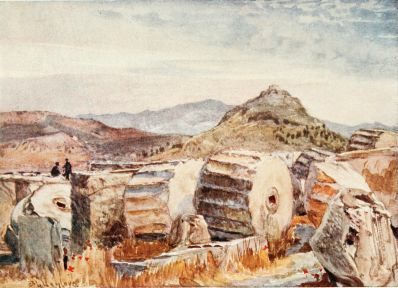

THE ANCIENT QUARRIES ON MOUNT PENTELIKON

THE ANCIENT QUARRIES ON MOUNT PENTELIKON

Of extraordinary interest as the material source of the finest

architecture and sculpture of Ancient Greece.

family history which were to be the theme of some of the greatest of the

Greek tragedies. Pausanias mentions that the tomb of the murdered men,

with unhewn stones heaped upon it, was to be seen at the middle of the

place where the three roads met: the modern traveller finds a monument

with an inscription which tells how Johannes Megas was killed on the

same spot in 1856, in an encounter with a band of brigands, which he was

seeking to extirpate.{34}

CHAPTER III

OLYMPIA AND ITS GAMES

OLYMPIA has been described by an ancient writer as the fairest spot in

Greece. In so describing it, he must have had in view not only the

natural scenery but also the beautiful buildings and statuary with which

it was so richly adorned as the time-honoured seat of the Olympian

games. The scenery is pleasing without being grand, presenting in this

respect a striking contrast to the stern majesty of Delphi. It may be

described as a peaceful and fertile plain, traversed by the river

Alpheus, whose waters Heracles is said to have diverted from their

course to cleanse the Augean stables. On either side, and also at its

western end, the plain is shut in by hills, while far away to the east

the mountains of Arcadia, where the Alpheus has its rise, can be dimly

seen. In the immediate foreground, standing by itself, as if detached

from the low range behind, there is a small conical hill, about 400 feet

high, covered with pines and brushwood, and bearing a name (Cronius)

which calls to mind the primeval deity who was dethroned by his son

Zeus, the presiding god of Olympia.{35} Close to this hill, on the south,

lies the Altis or sacred enclosure, originally a consecrated grove,

which, in course of time, was overspread with altars and temples and

other public buildings.

Thirty years ago there was scarcely any trace of this ancient glory to

be seen. But within the last generation a great work of excavation and

discovery has been carried on by German archæologists, at an expense of

£40,000, generously defrayed by the German Government, on the

understanding that all objects of interest brought to light should be

allowed to remain in Greece. One can form some idea of the labour

involved in the undertaking from the fact that the average depth of the

débris, composed of the clay washed down from the Cronius hill and the

alluvial deposits of the river Cladeus (which joins the Alpheus close to

the Altis on the west), was fully sixteen feet.

Although associated, more than any other spot in Greece, with the

worship of the “father of gods and men,” Olympia seems originally to

have been devoted to the honour of his consort Hera, or possibly of

both. The oldest architectural remains within the enclosure are those of

a temple of Hera, to which Pausanias assigned an earlier date than we

can give to any other sacred ruin in Greece, namely, about 1096 B.C. Its

great antiquity is proved by the resemblance which it bears in some

respects to the architecture of Mycenæ, and also by the fact that the

existing columns (of which thirty-four out of the original forty have

been more or less preserved) were evidently preceded by columns of{36}

wood, one of which, made of oak, was still standing when Pausanias

visited the place in the second century A.D. Wood seems to have been the

material in which the Doric architecture was originally executed; and in

this instance it was only as the wood of each column decayed that it was

replaced with stone, the natural result being that the columns differ

greatly from one another in thickness and style and the nature of their

stone. Some of them must have been substituted for the wooden ones as

early as the seventh century B.C., for their capitals are among the

oldest specimens of Doric architecture that are anywhere to be found.

Pausanias tells us that this temple contained rude images of both Zeus

and Hera; and not far from the spot a head has been discovered, twice as

large as life, which is supposed with great probability to belong to the

latter. It is believed to date from the seventh or sixth century B.C.,

and is made of the same soft stone as the base still remaining, which

could not have lasted so long unless it had been under cover. The eyes

are large, the head is crowned, and the face wears a look of

complacency, without much dignity or refinement. Hera seems to have had

much the same prominence in Olympia as she had in Argolis, where the

family of Pelops was also in the ascendant.

It was only gradually that Zeus obtained general recognition as the

chief deity in the court of Olympus, becoming the centre of the

Pan-Hellenic religion reflected in Homer, which was as powerful a bond

of union among the ancient Greeks as Christianity has{37}

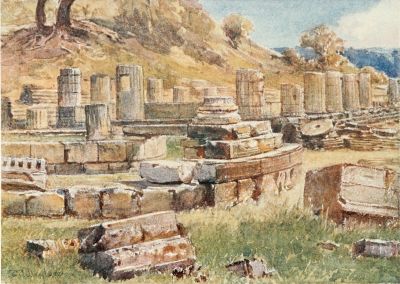

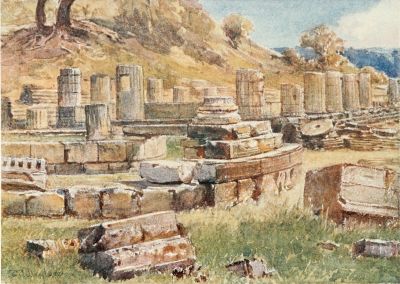

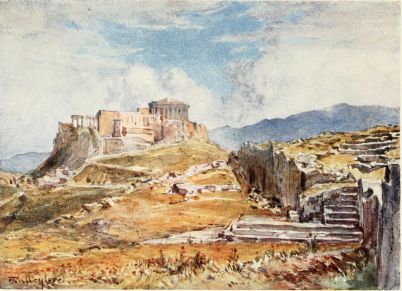

OLYMPIA. THE BASE OF THE KRONOS HILL, WITH THE REMAINS OF

THE TEMPLE OF HERA AND THE PHILIPPEION

OLYMPIA. THE BASE OF THE KRONOS HILL, WITH THE REMAINS OF

THE TEMPLE OF HERA AND THE PHILIPPEION

At the foot of the hill, the columns of the north, south, and west sides

of the Heræon still in situ are clearly shown, and also the cella wall

on the west and south. The remains of the Philippeion, a circular

building erected by Philip II. of Macedon (circ. 336 B.C.), are in the

foreground, to the west of the Heræon. The base of one of the Ionic

columns is in its place, and the marble steps which supported the

colonnade are connected by a slab of marble with the circular

sub-structure of the central mass of the building.

proved to be in modern times in preserving the Greek nationality under

the Turkish Empire. The supremacy which was given to Zeus in theory in

other parts of the country was visibly realised at Olympia, where the

chief sanctuary was a temple dedicated to his worship, more than 200

feet long and about 90 feet wide, surrounded by 134 columns, each of

them about 34 feet high, dating probably from the fifth century B.C. It

was a magnificent edifice, as we may still judge from the appearance of

the columns and the decorations of the pediments and the

frieze—although built of native conglomerate. On the east pediment of

the gable there were twenty-one colossal and imposing figures,

representing those interested in the chariot-race from Pisa to the

isthmus of Corinth, by which Pelops gained the kingdom and the hand of

the king’s daughter; while on the west there was a representation, in a

similar style, of the legendary battle of the Lapiths and the Centaurs.

On the metopes of the frieze the Twelve Labours of Heracles were

depicted, and along the sides of the roof gargoyles projected in the

form of lions’ mouths. Many of these figures have been recovered, mostly

in fragments, and are exhibited in the local museum. In the same place

there is an exquisite statue of Hermes by Praxiteles, which was found

under a covering of clay in front of the very pedestal in the temple of

Hera where Pausanias mentions that he had seen it standing, and also a

Niké of Pæonius, representing the goddess of Victory flying through the

air to execute the behest of Zeus.{38}

But the crowning glory of Olympia, the masterpiece of Pheidias and of

Greek art, is gone beyond recall. It was a colossal image of Jupiter,

made of gold and ivory and ebony, about 40 feet high, and standing on a

pedestal of bluish-black stone in the innermost part of the temple.

Cicero expressed his admiration of it by saying that Pheidias had

designed it not after a living model but after that ideal beauty which

he saw with the inward eye alone. Dīo Chrysostom bore still more

impressive testimony to its entrancing beauty when he said: “Methinks

that if one who is heavy-laden in mind, who has drained the cup of

misfortune and sorrow in life, and whom sweet sleep visits no more, were

to stand before this image, he would forget all the griefs and troubles

that are incident to the life of man.” It is uncertain whether the image

perished in the fire which destroyed the temple in the beginning of the

fifth century A.D., or was carried to Constantinople and consumed in a

conflagration which took place there in 475 A.D.

Near the centre of the Altis has been found the foundation of the great

altar of Zeus (which was made of ashes and rose to a height of 22 feet),

and not far off an ancient altar of Hera, where an immense quantity of

small bronzes and terra-cotta figures has been found. In the same

neighbourhood has been traced the Pelopium, a precinct sacred to the

memory of Pelops, where he was worshipped as a hero with a ritual of a

sad and gloomy nature, directed to a pit as an emblem of the grave, and

more akin to the primitive{39} worship of the Chthonian or infernal gods

than to that of the deities who were enthroned on lofty Olympus.

The fame of Olympia may be said to have rested even more on its games

than on its religious associations, though the secular and sacred were

so bound up with one another, in ancient Greece, that it is scarcely

possible to form a true conception of the one without the other. The

Olympian games held the foremost place among those competitive

exhibitions, which were so illustrative of the spirit of emulation

characteristic of the Greeks, as well as of their ideal of a harmonious

development of body and soul. There were three other foundations of the

same kind: the Pythian, in honour of Apollo, likewise held every four

years; the Nemean (under the care of Argos), every second year, in

honour of Zeus; and the Isthmian (under Corinth), also held every second

year, in honour of Poseidon. The prizes were respectively a wreath of

bay, of pine, and of parsley, a palm-branch being also placed in the

hand of the victor. The prize at Olympia was a wreath of olive, cut with

a golden sickle by a boy, both of whose parents had to be alive—as

among the Gauls the priest had to cut the sacred mistletoe with the same

precious metal. At the three other places just mentioned the games dated

practically from the first quarter of the sixth century B.C. But the

register of victors in the Olympian games went back to 776 B.C., which

is the first definite and reliable date (called the First Olympiad) in

Greek chronology.

The origin of all these gatherings may probably be{40} traced to the

funeral games mentioned in Homer and Hesiod, which were celebrated by a

chief in honour of a departed friend or relative. According to one

account the Olympian games were instituted by Heracles in honour of

Pelops, grandfather of Agamemnon and brother of the ill-fated Niobe, who

had come to Pisa from the Lydian kingdom of his father Tantalus—that

presumptuous guest at the table of the gods whose name is immortalised

for us in the English word which describes the nature of his penal

sufferings. The traditional connection of Olympia with Asia Minor is

borne out by the resemblance of the bronzes above mentioned to early

Phrygian art, as well as by other circumstances; and there is no reason

to doubt that Olympia was at one time in the hands of the Achæans.

The Dorian invasion of the Peloponnesus about 1100 B.C., eighty years

after the fall of Troy, marked a new era in the history of Olympia. The

Heracleids (whose shipbuilding for the voyage across the narrow straits

of the Gulf is still commemorated in the name of the port Naupactus,

on the northern side of the Gulf) are said to have rewarded the Ætolian

exile Oxylus, who acted as their guide (answering to the oracular

description of “a man with three eyes,” whom they were to find—being

one-eyed and riding on a horse with two eyes), by confirming him in the

possession of Elis, which in older times was known as Epeia, and is so

referred to by Homer. For a long time the Eleans and the Pisatans seem

to have superintended the games{41}

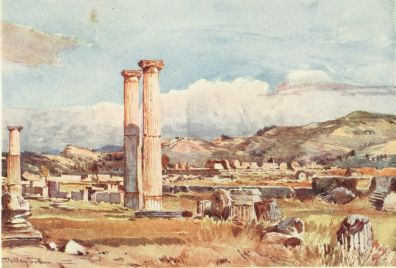

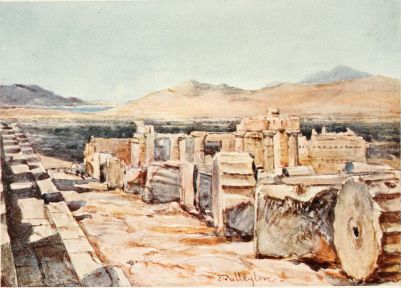

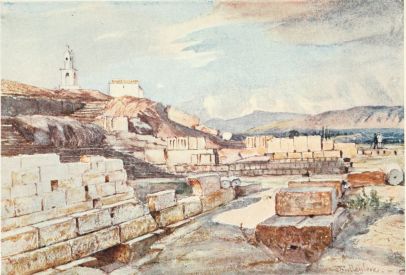

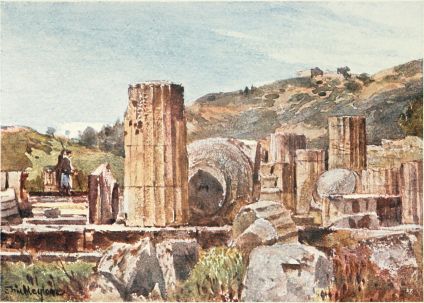

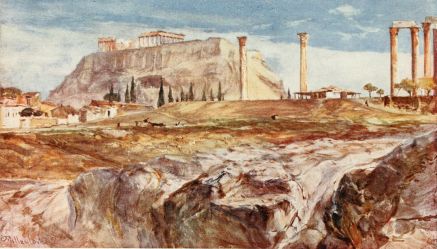

OLYMPIA. THE PALÆSTRA AND REMAINS OF THE TEMPLE OF ZEUS

OLYMPIA. THE PALÆSTRA AND REMAINS OF THE TEMPLE OF ZEUS

This view is taken from the western side of the Palæstra, and the

standing columns in the foreground are part of the southern colonnade of

that building. The platform (Krepidoma) of the great Temple (which was

raised upon a mound and occupied the highest point of the Altis or

sacred enclosure) is in the centre of the drawing. Many of the colossal

drums and other architectural members of the Temple lie scattered about

on the platform. Across the valley of the Alpheios are seen the Phellon

Mountains, topped by splendid masses of cloud. This drawing is a record

of a lovely spring day in the Western Peloponnesus.

jointly, with the support of the Dorian settlement at Sparta, whose

great lawgiver, Lycurgus, was said to have put the institution on a new

footing in concert with Iphitus, the king of Pisatis, the names of both

being inscribed on a famous quoit of which Aristotle speaks. Pausanias

tells us that the towns of Elis and Pisatis appointed sixteen

women—eight from each state—to weave the festal robe (peplos) for

the image of the Olympian Hera. The Pisatans, however, were afterwards

displaced, and in 570 B.C. their city was destroyed, and Elis obtained

the whole right of administration.

The first historic game was a foot-race, and it was only by degrees that

other contests were at various times added. The pentathlon, during

which the Pythian air was played on the flutes in honour of Apollo,

consisted of running, jumping, throwing the disc or quoit, throwing the

javelin, and wrestling. Finally came chariot-racing (in a hippodrome

adjoining the Altis), which, though necessarily confined to men of

wealth, added much to the spectacular attractions of the games.

The competitors had to strip naked for the athletic contests, this being

a characteristic feature of the Greek games, obligatory on all without

distinction of rank. There were games for boys as well as for men, and

the celebrations, which at first were confined to a single day, extended

ultimately to five days. The women had a festival of their own, with

games for girls; but at the ordinary games married women were not

allowed to be present. At the same time there was very little

coarseness{42} or cruelty about them, compared with a Roman gladiatorial

exhibition or a Spanish bull-fight—except in the pancratium, a

combination of wrestling and boxing, in which the combatants were

allowed to get the better of one another by any means in their power,

provided they did not make use of any weapon, which was forbidden in all

the contests. The conflict was sometimes attended with a fatal result.

Pausanias mentions a case of this kind in which a dead man was

proclaimed victor, and crowned with the olive wreath.

The stadium or race-course can be distinctly traced north-east of the

Altis. The two parallel grooves in the stone pavement at the

starting-point, the one a few inches in front of the other, were

evidently intended to give the runner a secure footing. The course was

600 feet long, which became a recognised measure of distance, as the

English furlong was derived from the length of a furrow. But the double

race was soon introduced, which accounts for there being similar grooves

at the other end, where the seats for the judges were, as the start

would then have to be made from that end. In the same place you can also

trace the sockets, about four feet apart, in which were fixed the wooden

posts that marked off the space for each of the runners, who could be

accommodated to the number of twenty.

There is a vaulted entrance to the stadium about a hundred feet high

(one of the oldest examples of such work in cut stone, 350-300 B.C.),

through which none could pass but the judges and heralds, and the

competitors,{43} who must have gone through ten months’ training, and were

lodged during the games at the public expense. Close to this entrance

are still to be seen a large number of pedestals, on which stood at one

time certain brazen images, well fitted to warn competitors against any

infringement of the rules. They were called Zanēs in honour of Zeus, and

they had all been placed there at the expense of persons who had been

convicted of some violation of the rules. Giving or receiving bribes was

the most common offence at Olympia, as it was indeed with the Greeks

generally, even in the more serious game of politics. But there were

others of a different nature. For example, Pausanias tells of a man of

Alexandria who had come too late for the boxing match, and, finding that

another had been adjudged the prize without a contest and was already

wearing the olive wreath, put on the gloves as though for a fight and

rushed at the victor, for which he was sentenced to pay a fine. In

contrast to the penal erection of a statue to Zeus, the winner of a

prize was allowed to put up a statue in commemoration of his victory,

and the third time he thus distinguished himself he was at liberty to

erect an image of himself. In this way Olympia became in course of time

a great school of art as well as a gymnastic arena. In Homer there is no

mention of statues of the gods, not even of wood, and the development of

art in this line during the seventh and sixth centuries was very

remarkable.

Xerxes or one of his princes is said to have expressed his astonishment

that the Greeks should contend so{44} earnestly for the sake of an olive

wreath. But in reality the wreath was only an emblem of the honour

conferred upon the victor. In the days of Solon, before the games had

reached the height of their popularity, a grant of 500 drachms was made