Title: The adventures of Captain Mago; or, a Phoenician expedition, B.C. 1000

Author: David-Léon Cahun

Illustrator: Paul Philippoteaux

Translator: Ellen E. Frewer

Release date: December 7, 2014 [eBook #47582]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ramon Pajares, Shaun Pinder and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

OR

A Phœnician Expedition

B.C. 1000

BY

LÉON CAHUN

ILLUSTRATED BY P. PHILIPPOTEAUX, AND TRANSLATED FROM

THE FRENCH BY ELLEN E. FREWER

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1889

TROW'S

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY,

NEW YORK.

The following pages pretend to no original or scientific research. It is their object to present, in a popular form, a picture of the world as it was a thousand years before the Christian Era, and to exhibit, mainly for the young, a summary of that varied information which is contained in books, many of which by their high price and exclusively technical character are generally unattainable.

It would only have encumbered the fictitious narrative, which is the vehicle for conveying the instruction that is designed, to crowd every page with references; but it may be alleged, once for all, that for every statement which relates to the history of the period, and especially to the history of the Phœnicians, ample authority might be quoted from some one or other of the valuable books which have been consulted.

Of the most important of these a list is here appended:—

1. F. C. Movers. Das Phönizische Alterthum.

2. Renan. Mission en Phénicie.

3. Daux. Recherches sur les Emporia phéniciens dans le Zeugis et le Byzacium.

4. Nathan Davis. Carthage and her Remains.

5. Wilkinson. Manners and Customs of Ancient Egyptians.

6. Hœckh. Kreta.

7. Grote. History of Greece.

8. Mommsen. Geschichte der Römischen Republik (Introduction and Chap. I.).

9. Bourguignat. Monuments mégalithiques du nord de l'Afrique.

10. Fergusson. Rude Stone Monuments.

11. Broca and A. Bertrand. Celtes, Gaulois et Francs.

12. Abbé Bargès. Interprétation d'une inscription phénicienne trouvée à Marseille.

13. Layard. Nineveh and its Remains.

14. Botta. Fouilles de Babylone.

15. Reuss. New translation of the Bible, in course of publication.

A few foot-notes are subjoined by way of illustration of what might have been carried on throughout the volume; and an Appendix will be found at the end, containing some explanation of topics which the continuity of the fiction necessarily left somewhat obscure.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I.— | WHY BODMILCAR, THE TYRIAN SAILOR, HATES HANNO, THE SIDONIAN SCRIBE | 1 |

| II.— | THE SACRIFICE TO ASHTORETH | 19 |

| III.— | CHAMAI RECOGNISED BY THE ATTENDANT OF THE SLAVE | 44 |

| IV.— | KING DAVID | 61 |

| V.— | PHARAOH ARRIVES TOO LATE | 76 |

| VI.— | CRETE AND THE CRETANS | 98 |

| VII.— | CHRYSEIS PREFERS HANNO TO A KING | 112 |

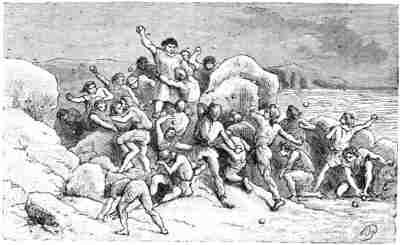

| VIII.— | AN AFFAIR WITH THE PHOCIANS | 132 |

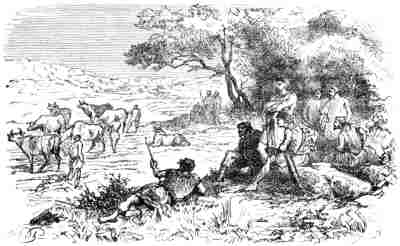

| IX.— | THE LAND OF OXEN | 148 |

| X.— | GISGO THE EARLESS RECOVERS HIS EARS | 166 |

| XI.— | OUR HEADS ARE IN PERIL | 175 |

| XII.— | I CONSULT THE ORACLE | 196 |

| XIII.— | THE SILVER MINES OF TARSHISH | 207 |

| XIV.— | AN AMBUSCADE | 219 |

| XV.— | JUDGE GEBAL DISTINGUISHES HIMSELF | 234 |

| XVI.— | PERILS OF THE OCEAN | 243 |

| XVII.— | [Pg vi]JONO, THE GOD OF THE SUOMI | 260 |

| XVIII.— | JONAH WAXES AMBITIOUS | 277 |

| XIX.— | BODMILCAR AGAIN | 287 |

| XX.— | THE WORLD UPSIDE DOWN | 295 |

| XXI.— | THE QUEEN OF SHEBA | 307 |

| XXII.— | BELESYS FINDS BICHRI SOMEWHAT HEAVY | 314 |

| XXIII.— | WE SETTLE OUR ACCOUNTS WITH BODMILCAR | 327 |

And Thirty-six smaller Text Illustrations.

I am Captain Mago, and Hiram,[1] King of Tyre, was well aware that my experience as a sailor was very great. It was in the third year of his reign that he summoned me to his presence from Sidon,[2] the city of fishermen, and the metropolis of the Phœnicians. He had already been told of my long voyages; how I had visited Malta; how I had traded to Bozrah,[3] the city founded by the Sidonians, but now called Carthada[4] by the Tyrians; and how I had reached the remote Gades in the land of Tarshish.[5]

The star of Sidon was now on the wane. The ships of Tyre were fast occupying the sea, and her caravans were covering the land. A monarchy had been established by the Tyrians, and their king, with the suffects[6] as his coadjutors, was holding sway over all the other cities of Phœnicia. The fortunes of Tyre were thus in the ascendant: sailors and merchants from Sidon, Gebal, Arvad and Byblos were continually enlisting themselves in the service of her powerful corporations.

When I had made my obeisance to King Hiram, he informed me that his friend and ally, David, King of the Jews, was collecting materials for the erection of a temple to his god Adonai (or our Lord) in the city of Jerusalem, and that he was desirous of making his own royal contribution to assist him. Accordingly he submitted to me that at his expense I should fit out a sufficient fleet, and should undertake a voyage to Tarshish, in order to procure a supply of silver, and any other rare or valuable commodity which that land could yield, to provide embellishment for the sumptuous edifice.

Anxious as I was already to revisit Tarshish and the lands of the West, I entered most eagerly into the proposal of the King, assuring him that I should require no longer time for preparation than what was absolutely necessary to equip the ships and collect the crews.

It was still two months before the Feast of Spring, an annual festival that marked the re-opening of navigation. This was an interval sufficient for my purpose, for as the King directed me to call first at Joppa, and to proceed thence to Jerusalem to receive King David's instructions, I had no need for the present to concern myself about anything further than my ships and sailors, knowing that I could safely trust to the fertile and martial land of Judæa to provide me with provisions and soldiers.

The King was highly gratified at my ready acquiescence in his proposition. He instructed his treasurer to hand over to me at once a thousand silver shekels[7] to meet preliminary expenses, and gave orders to the authorities at the arsenal to allow me to select whatever wood, hemp, or copper I might require.

I took my leave of the King and rejoined Hanno my scribe and Himilco my pilot, the latter of whom had been my constant associate on my previous voyages. They were sitting on the side-bench at the great gate of the palace, [Pg 3] and had been impatiently awaiting my return, mutually speculating upon the reason that had induced the King to send for us from Sidon, and naturally conjecturing that it must relate to some future enterprise and adventure. At the first glimpse of my excited countenance, revealing my delight, Hanno exclaimed:

"Welcome back, master; surely the King has granted you some eager longing of your heart!"

"True; and what do you suppose it is?" I asked.

"Perhaps a new ship to replace the one you lost in the Great Syrtes; and perhaps a good freight into the bargain. No son of Sidon could covet more than this."

"Yes, Hanno; this, and more beside," I answered. "But our good fortune at once demands our vows; let us hasten to the temple of Ashtoreth,[8] and there let us render our thanks to the goddess, and sue for her protection and her favour to guard our vessels as we sail to Joppa. To Joppa we go; and onwards thence to Tarshish!"

"Tarshish!" echoed the voice of Himilco, with a cry of ecstasy; and as he spoke he raised up his sole remaining eye towards the skies; he had lost the other in a naval fight. "Tarshish," he said again: "O ye gods, that rule the destinies of ships! ye stars,[9] that so oft have fixed my gaze in my weary watch on deck! here I offer to you six shekels on the spot; 'tis all my means allow. But take me to Tarshish, and vouchsafe that I may come across the villain whose lance took out my eye, so that I may make him feel the point of my Chalcidian sword below his ribs, and I vow that I will offer you in sacrifice an ox, a noble ox, finer than Apis, the god of the idiot Egyptians."

Hanno was less demonstrative. "For my part," he said, "I shall be satisfied if I can barter enough of the vile wine of Judæa, and the cheap ware of Sidon, to get a good return [Pg 4] of pure white silver. I shall only be too pleased to build myself a mansion upon the sea-shore where I can enjoy my pleasure-boat as it glides along with its purple sails, and so to pass my days in ease and luxury."

"Remember, however," I replied, "that before you can get your lordly mansion, we shall again and again have to sleep under the open sky of the cheerless West; and before you arrive at all your luxury, you will have to put up with many a coarse and meagre meal."

"All the more pleasant will be the retrospect," rejoined Hanno; "and when we come to recline upon our costly couches it will be a double joy to dwell upon our adventures, and relate them to our listening guests."

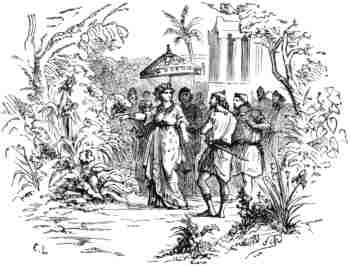

Conversation of this character engaged us till we reached the cypress-grove, from which the temple of Ashtoreth upreared its silver-plated roof. The setting sun was all aglow, and cast its slanting rays upon the fabric, illuminating alike the heavy gilding and the radiant colours of the supporting pillars. Flocks of consecrated doves fluttered in the sacred grove, alighting ever and again upon the gilded rods that connected one pillar with another. Groups of girls were frequently met, dressed in white, embroidered with purple and silver, either hastening, pomegranates in their hands, to make a votive offering at the shrine, or sauntering leisurely in the sacred gardens. Ever and again, as the temple-doors were opened, there was caught the distant melody of the sistra, flutes, and tambourines, upon which the priests and priestesses were celebrating the honour of their goddess. Such were the sounds, the modulated measures of the music mingled with the soft cooings of the doves and the joyous laughter of the heedless maidens, that combined to make a mysterious murmur that could not fail to impress the minds of such as us, rough mariners unaccustomed to anything more harmonious than the groanings of the waves, the creaking of our ships, and the howling of the wind.

I went with Himilco to consult the tariff of the sacrifices, which was exhibited, engraven on a tablet and affixed to the feet of a huge marble dove at the right-hand entrance to the precincts of the temple. As my own offering, I selected some fruit and cakes, the value of which did not exceed a shekel, and was just turning back to call Hanno, when I encountered a man in a dirty and threadbare sailor's coat, who was hurrying along, muttering bitter curses as he went.

"Help me, Baal Chamaim, Lord of the heavens!" I involuntarily exclaimed; "is not this Bodmilcar, the Tyrian?"

The man paused, and recognised me in a moment; and we exchanged the warmest greetings.

Bodmilcar, whom I had thus unexpectedly met, had been one of my oldest associates. Many a time, alike in expeditions of war and commerce, he had commanded a vessel by my side. He was likewise already acquainted with Himilco, who consequently shared my surprise and regret at meeting him in so miserable a plight.

"What ill fate has brought you to this?" was my impatient inquiry. "At Tyre you used to be the owner of a couple of gaouls[10] and four good galleys; what has happened? What has brought it about that you should be here in nothing better than a ragged kitonet?"[11]

"Moloch's[12] heaviest curses be upon the Chaldeans!" ejaculated Bodmilcar. "May their cock-head Nergal[13] torture and burn and roast them all! My story is soon told. I had a cargo of slaves. A finer cargo was never under weigh. The hold of my Tyrian gaoul carried Caucasian men as strong as oxen, and Grecian girls as lissome as reeds; there were Syrians who could cook, or play, or dress the hair; there were peasants from Judæa [Pg 6] who could train the vine or cultivate the field. Their value was untold."

"And tell me, friend Bodmilcar," I inquired, "where are they now? Did they not yield you the countless shekels on which you reckoned?"

"Now! where are they now?" shrieked out the excited man; "they are every one upon their way to some cursed city of the Chaldeans, on the other side of Rehoboth. Instead of shekels I have got plenty of kicks and plenty of bruises, of which I shall carry the marks on my body for a long time to come. The naval suffect gave me a few zeraas,[14] just to relieve my distress, and had it not been for that, I should not have had a morsel of bread to keep life in me. It is now three days since I arrived in Tyre, and to get here I have been continually walking, till my feet are so swollen I can hardly move."

"You mean you have walked here?" said Himilco, compassionately. "But surely you might have found a boat of some sort to bring you?"

"Boat!" growled Bodmilcar, almost angrily; "when did boats begin to journey overland? Did I not tell you I came from Rehoboth in the land of those cursed Chaldeans? But hear me out, and you will sympathise with my misfortune. I started first of all along the coast, buying slaves from the Philistines, and corn and oil from the Jews. I went across to Greece, and made some profitable dealings there. I chanced upon a few wretched little Ionian barques, and secured some plunder so. Then I conceived the project of going through the straits, and I succeeded beyond my hopes in getting iron, and, what is more, in getting slaves from Caucasus. My fortune was made. I was proceeding home, when just as we neared the Phasis, on the Chalybean coast, some alien gods—for sure I am that neither Melkarth nor Moloch would so have dealt with a Tyrian sailor—some alien gods, I say, sent down a frightful storm. With the utmost peril I contrived to save [Pg 7] my crew and all my human cargo; but the bulk of my goods was gone, and my poor vessels were shattered hopelessly. There was but one resource; I had no alternative but to convey my salvage in the best way I could across Armenia and Chaldea by land, consoling myself with the expectation of finding a market for the slaves along the road. But once again the gods were cruelly adverse. We were attacked by a troop of Chaldeans; fifty armed men could not protect a gang of four hundred slaves, who, miserable wretches as they were, could not be induced by blows or prayers to lift up a hand in their own defence. The result was that we were very soon overpowered, and that, together with all my party, I was made a prisoner. The Chaldeans proposed to sell us to the King of Nineveh, and I had the pleasure of finding myself part and parcel of my own cargo."

"But, anyhow, here you are. How did you contrive to get out of your dilemma?" I asked my old comrade.

Bodmilcar raised the skirt of his patched and greasy kitonet, and displayed a long knife with an ivory handle hanging from his belt.

"They forgot to search me," he said, "and omitted to bind me. The very first night on which there was no moonlight I was entertaining a couple of rascals who had charge of me, by telling them wonderful tales about Libyan serpents, and about the men of Tarshish who had mouths in the middle of their chests, and eyes at the tips of their fingers; openmouthed, they were lost in amazement at the lies I was pouring into their ears, and were entirely off their guard. I seized my opportunity; and having first thrust my knife into the belly of one of them, I cut the throat of the other and made my escape. I took to my heels, and, Moloch be praised! the rascals failed to find a trace of me. But now that I am here, the gods only know what is to become of me. If I fail to get service as a pilot, I must enter as a common sailor in some Tyrian ship."

"No need of that, Bodmilcar," I exclaimed; "you have [Pg 8] made your appearance just at a lucky moment. All praise to Ashtoreth! you are just the man I want. I have a commission from the King to fit out ships for Tarshish; I am captain of the expedition, and here at once I can appoint you my second in command. My pilot is Himilco; and here is Hanno, my scribe; we are on our way to the temple of the goddess, and are going in her presence to draw up the covenants."

"Joy, joy, dear Mago!" ejaculated Bodmilcar; "may the gods be gracious to you, and repay your goodness! I shall not regret my disaster at the hands of the Chaldeans, if it ends in a voyage to Tarshish with you. Only let Melkarth vouchsafe us a good ship, and with Himilco to guide our course, we cannot fail to prosper, even though our voyage be to the remotest confines of the world."

Hanno, who meanwhile had joined us, took out from his girdle some ink and some reeds, with a little stone to sharpen them, and having seated himself upon the temple steps, proceeded to draw up the articles which appointed me admiral of the expedition, Bodmilcar vice-admiral, and Himilco pilot-in-chief. Himilco and myself both affixed our seals to the document, and Bodmilcar was proceeding to do so likewise, feeling mechanically for his seal, which he remembered afterwards that the Chaldeans had stolen. I gave him twenty shekels to buy another, and to provide him with a new outfit of clothes. Then, with Himilco, I proceeded to make my oblation of fruits and cakes to Ashtoreth; and in the highest spirits we made our way to the harbour, where our light vessel, the Gadita, was awaiting us.

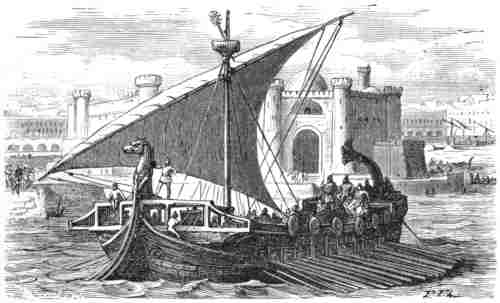

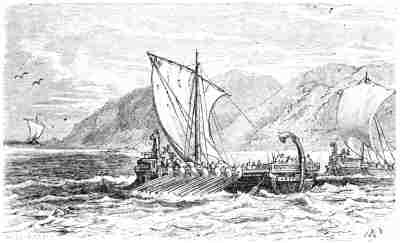

Early next morning we set vigorously to work. I drew out the plans of my vessels upon papyrus sheets. My own Gadita was to be kept as a light vessel; but I resolved to have a large gaoul constructed as a transport to carry the merchandise, and two barques to act as tenders to the gaoul, which would draw too much water to approach very near the shore. As an escorting convoy I chose two large [Pg 9] double-decked galleys,[15] manned by fifty oarsmen, similar to those recently invented at Sidon. At this period, the Tyrians had three of these galleys in port; they were very rapid in their course, and drew very little water; they were armed with strong beaks at the prow; were worked both by oars and sails, and were adapted either for war or commerce.

I determined to use cedar for the keel and sides of my vessel, and oak from Bashan, in Judæa, for the masts and yards. I discarded the ancient method of making my sails of Galilean reeds or papyrus-fibre, preferring to have them woven out of our excellent Phœnician hemp, which the people of Arvad and Tyre are skilful in twisting into a very substantial texture. It was of the same material that I resolved to make my ropes.

As I was going through the arsenal, and wondering at the accumulated mass of copper, I espied a little store of the beautiful white tin obtained from the Celts in the distant islands of the far north-west. Previously to my own voyage those islands had been all but unknown, and I believe that I may say that my own investigation of them has conferred as great a benefit upon the Phœnicians as they had reaped two hundred years before by the discovery of the silver mines of Tarshish.

The sight of the copper determined me upon carrying out a plan which I had for some time been contemplating. It occurred to me that if the keel and flanks under water were protected with copper in the same way as the prows had hitherto been, the solidity of the vessel would be greatly increased, and the wood would be far less liable to decay. Accordingly, I made up my mind to protect the prows of the galleys with a hard alloy of copper and tin, and to sheathe the keels and flanks of all the four vessels with plates of wrought copper. The copper of Cyprus I rejected as being too soft and spongy for my purpose, and that [Pg 10] of Libanus as far too brittle; but the firm yet ductile Cilician metal suited me admirably, and Khelesh-baal, the renowned Tyrian founder, set to work at once to forge me some large sheets, three cubits[16] long by two wide.

The King had placed 200 workmen at my disposal; and, in order that I might better superintend their operations, I took a lodging with my three friends in a house at the corner of the Street of Caulkers, just opposite the arsenal, and there from my window upon the fourth floor I could well overlook the men working in the docks below. I directed Hanno to make out a list of the goods we should require for barter, and he and Himilco chiefly busied themselves in collecting the things together; whilst Bodmilcar, with two of my sailors, kept perambulating the neighbourhood of the harbour, succeeding tolerably well in securing recruits for my crew from amongst the seamen who were loitering about the quays, with tilted hats, looking out for employment.

On the first day of the month Nisan,[17] just four weeks after I had undertaken my commission, I returned home for my evening meal, and found my companions in hot dispute.

"How now!" I cried, on entering the room; "what's this? What is the meaning of this angry contention?"

"I am telling Bodmilcar," said Hanno, "that he has about as much brains as a bullock, and about as much elegance as a Bactrian camel."

"And am I to endure this insolence from a young stripling?" cried Bodmilcar, angrily; "am I to put up with it from a fresh-water lubber, who will cry like a baby at the first gust of wind, and implore us to put him on shore again? He has lived among women and scribblers till he has no more pluck in him than a garden-tortoise."

"I confess," rejoined Hanno, sarcastically, "that I have not had your experience; I have not had the advantage of being pounced upon by the Chaldeans, or of being thrashed by my own slaves. But let me say, I am twenty, and that I hope the first time you find me funking the sea, you [Pg 11] will pitch me overboard like an old sandal. Anyhow, I have had a voyage as far as Chittim;[18] I have been amongst the Ionians, and can speak their language ten times better than any one among you."

"Talk to me about the Ionians," shouted Bodmilcar in a fury, "and I will break every bone in your precious skin."

And, as he spoke, he laid his hand upon his knife; but Hanno, without flinching for a moment, caught up a large pitcher that was standing on the table.

"Steady, steady!" interposed Himilco, "or you will be spilling all the nectar;"[19] and whilst I laid a firm grasp upon Bodmilcar's arm, he rescued the pitcher, and deposited it safely in the corner of the room.

Then addressing myself to the two excited combatants, I said: "Now then, I cannot permit this altercation; you are both under my orders, and you must both submit; conduct yourselves amicably, or it shall be the worse for him that disturbs the peace. But what is the meaning of this chatter about the Ionians?"

Hanno held out his hand to me, in token of submission, expressed his regret for having given offence to Bodmilcar, and assured me that he had only spoken in jest.

"You see now," I said to Bodmilcar, "Hanno is not your subordinate, and you are bound to treat him as your equal. However, what is it that he has said to offend you so grievously?"

Bodmilcar seemed abashed; he stood twirling his beard, and without raising his eyes, said:

"Amongst the slaves that the Chaldeans captured, there was one Ionian girl that I thought to make my wife. I spoke of her to Hanno, but he only jeered me; he told me that the girl had gone off with the Chaldeans of her own accord, merely to get out of reach of me; and his provocation made me angry."

"Nay, nay," said Hanno: "I did not want to make him angry; it was a thoughtless joke; he was somewhat old, I said, for so young a bride, and Ionian girls generally like the perfume of flowers and the fragrance of sweet spices better than the smell of tar."

"It was wrong of you," I said, as sternly as I could, though I really felt inclined to laugh.

To my suggestion that they should make up their quarrel with mutual pledges over a cup of wine, Hanno eagerly responded, "With all my heart, and Ashtoreth give me my deserts if ever wilfully I offend his grey hairs again;" but Bodmilcar took the proffered hand coldly, and with evident constraint.

Seeing that all immediate peril of a smash was over, Himilco brought forward his pitcher again from its place of safety. I heard nothing more of the disagreement; but I could not help noticing that Bodmilcar was never again the same in his demeanour towards Hanno, and that he did not speak to him any more than he could avoid.

About a week later, as I was in the arsenal for the purpose of selecting the ropes for the rigging, Himilco came running to me to inform me that one of the King's servants had arrived with a message that was to be delivered to myself. I went to meet the messenger. He was a tall Syrian eunuch with frizzled hair and painted face, arrayed in a long embroidered robe, and wearing large gold earrings after the fashion of his country. He held a long cane surmounted by a golden pomegranate, and spoke with a languid lisp.

"Are you Captain Mago, the King's naval officer?" he asked, as he eyed me from head to foot.

Receiving my reply, he continued: "I am Hazael, of the royal household; here on my finger you may see the signet which empowers me to exercise my authority. The purpose of my visit is to inspect the vessels you are building; but specially my object is to give instructions that proper accommodation shall be provided for myself, [Pg 13] and for a slave that I have to conduct from my master to Pharaoh, King of Egypt. Two proper berths must be prepared; and the King's orders are that you are to remit us to Egypt after you have visited Jerusalem."

"As to your directions about berths," I replied, utterly astonished at his cool effrontery, "you must permit me to remind you that on board ship the captain, with his pilot under him, invariably allots the place for every passenger."

"Be it so," rejoined the eunuch; "yet it is imperative that separate apartments, tapestried and carpeted suitably, should be provided for myself and for the royal slave. Impossible for us to live in contact with the rough and tarry seamen."

I felt a strong inclination to let Hazael experience how he relished lying full length upon a heap of rubbish that was close at hand; but I controlled my indignation and said:

"I will contrive something. I will either make a partition in a corner of the hold, or put up a cabin of planks upon [Pg 14] the deck; but whatever is done must not interfere with the working of the ship. When I have made the provision in space, I leave you to fit and furnish as you please; but mark you this, your curtains and carpets will be ruined in the first tempest that we get. However, that is your concern, not mine."

"Each of the cabins," complacently continued the eunuch, "must be twelve cubits by six; there must be six benches of sandal-wood and ivory; the bedsteads must be inlaid; the windows must be framed and fitted perfectly."

"Fitted!" I rejoined: "have I not told you already that you may furnish and adorn the cabins as you will: their size, their position must rest with me: in such matters my authority is supreme. You may tell your royal master from me that adequate accommodation shall be provided, but that with my arrangements no one is at liberty to interfere."

The eunuch looked aghast at my temerity; but he seemed somehow to comprehend that I was not to be trifled with. He muttered a few words to the effect that I had better see that everything was duly done, and without a word or gesture of leave-taking, turned on his heel and sauntered leisurely away. I watched him for a moment, and turning to Himilco, who had been near enough to overhear the conversation, I said:

"Unless I reckon badly, that fellow will give us some trouble before we have done with him."

"Ah, no; I'll take care of that," said Himilco. "Sooner than the painted hound should interfere with us too much, I'd have a rope to his heels, and he should dangle, head in the water, all the way from Joppa to Tarshish. 'Tis not for us to permit ourselves to be treated like dogs."

"No," said I; "but maybe, all will go well; Moloch will be our guardian; and once at sea we shall not fail to secure the protection of our Ashtoreth. To tell you the truth, I am really far more apprehensive about Hanno's pranks with Bodmilcar."

"We must hope for the best," replied Himilco. "Bodmilcar will be on board the gaoul, and we will contrive for Hanno to come with us in one of the galleys."

"True," I assented; "it is indispensable that they should be separated. But with regard to this eunuch's requirements; I hardly see whether it will be better to provide the cabins in the gaoul, as being the more roomy, or to have them under my own supervision. Plague upon the slave and eunuch both!"

At that moment Hanno come up, with his roll of papyrus in his hand, and caught the tenor of our conversation.

"A slave and an eunuch to go!" he exclaimed. "Surely the charge of them ought to fall to my lot. Such duties ever belong to a scribe. Besides, I have made some progress in the studies of a magician; and better even than a magician I could humour their fancies, and understand their likes and dislikes."

I expressed my opinion that they would have enough of magicians in Egypt whither they were going, and resolved that I would keep them under my own eye.

"There's an end then to all my pretty scheme of teaching them calligraphy, rhetoric, and what not," said Hanno, smiling. "I must fall back, I see, upon my own accounts."

He unfolded his roll, and submitted to me his reckoning of the amount that would be requisite to pay our sailors and our oarsmen, at the same time handing me his statement of the sums that had already been expended in the purchase of the goods for barter.

The outlay far exceeded the golden talent, the thousand shekels, which the King had advanced. He had, however, commissioned me to spare no expense, and had promised to meet all reasonable demands, so that I felt no uneasiness, but sent Hanno straight to the palace to exhibit the accounts and to ask for a further grant. The request was most generously met.

Meanwhile, Himilco and I continued to employ ourselves [Pg 16] in having planks of fir from Senir[20] fitted to the flanks of our vessels, and in rigging our heavy masts of oak with yard-arms of cedar.

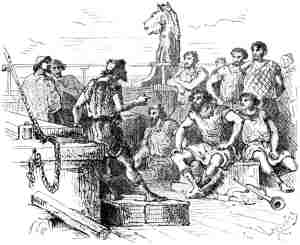

Our work progressed to our entire satisfaction. The Gadita was repaired and entirely refitted; the figure-head, an immense horse, was illuminated with dazzling enamel eyes; the sides of the vessel were painted red upon a black ground; and twelve shields of bronze, each glowing in the centre with a polished copper boss, were hung outside.

After everything had been completed, I obtained permission for the Gadita to be conducted with great ceremony, to the music of trumpets and cymbals, into the basin of the harbour. For the occasion the naval suffect lent me a large purple sail, reserved expressly for state festivities; twelve armed sailors, lance in hand, stood behind the shields of bronze; and twenty-two oarsmen, plying their oars in regular cadence, made the ship glide swiftly through the water. Gisgo, the helmsman, from his station in the stern, deftly wielded the tiller, according to the directions of Himilco, whose place was at the prow. Bodmilcar, Hanno, and myself were upon the poop. We were all of us in state attire, and were conscious of a keen enjoyment of the admiring gaze of the crowds of sailors who thronged, not only the adjacent quays, but the terraces of the arsenal and of the admiralty palace, and watched our manœuvres. The naval suffect was himself one of the spectators; he was seated at the grand entrance of the palace, just above the flight of steps that led down to his official wharf. So pleased he was with the appearance of the Gadita, that he invited all the officers to sup with him in the evening, and sent a sheep, a large jar of wine, two baskets of bread, a supply of figs and raisins, and twelve cheeses, for the entertainment of our sailors.

Arrived at the palace, we passed up the narrow staircases and dim corridors of the eastern tower, and found ourselves in a large round room with a lofty dome, from the centre [Pg 17] of which there hung a polished copper lamp. The suffect paid us many compliments; and, on learning that we should be ready for our outfit within ten days, he gave me permission to go next morning and to choose whatever arms would be requisite for the expedition.

After our entertainment we embarked from the suffect's private wharf, intending to return, all of us, to our own quarters on shore; but all at once Bodmilcar declared himself so enamoured of the Gadita, that he resolved to sleep alone on board. As our boat was silently threading its way along the canal that intersected the mainland, cutting off an island by its course, Hanno commenced singing in a foreign language. My attention was arrested, and I asked him what language it was. He replied that it was Ionian, and expressed his surprise that I did not understand it.

"No," I answered; "it is strange to me. I have sailed but rarely along those coasts. But haven't you done with the Ionians yet?"

"Oh, Bodmilcar is not here to get in a rage, and we have not got the slave amongst us to be affected by any songs of mine."

"The slave!" I exclaimed with wonder. "I did not imagine that the slave would care for your songs. Is she an Ionian?"

Hanno laughed, and made me no answer; but after a while he yielded to my persuasion, and made me acquainted with all he knew.

"Hazael the eunuch," he said, "is a chattering fool. When I went to the palace I saw him, and wormed out of him that the slave in question had been brought from some Chaldean merchants, and that she had been originally carried away from her own country by a Tyrian pirate, so that the whole truth was not hard to guess."

"Not a word of this," I said; "not a word to Bodmilcar. More than ever it makes me resolve to have both eunuch and slave on board my own galley; otherwise I foresee there [Pg 18] will be no end of mischief. Neither you nor Himilco must breathe a syllable until we have seen our unwelcome passengers securely landed at their destination."

Each promised faithfully to preserve the strictest reticence: Hanno, for his part, vehemently asseverating that if a word upon the matter should escape him, he would forthwith cut off his tongue, and devote himself to Horus, the Egyptian god of silence.

As we now reached our lodging, the conversation dropped, and for the next few days we were far too much engaged in active duties to think any further of what had transpired.

I gave my own personal superintendence to the weaving of all the sails, which were made strictly after the directions prescribed by the goddess Tannat.[21] I saw that my ropes were well twisted and thoroughly tarred; and I arranged the benches for my oarsmen with such compactness that there was only an interval of a hand's breadth between the seat of the rower on the upper tier and the head of the man in the tier below.

To give extra strength to the masts and yards, I had them bound at regular distances with bands of ox-hide, and finally I had the entire hulls plated with sheets of copper, fastened together with bolts of bronze.

Never had prouder ships been launched upon the Great Sea.[22]

Two days before the great spring festival which celebrated the re-opening of navigation, and which was observed as a national holiday, our ships were ready in the stocks, and in the course of three hours were launched without difficulty.

The two galleys were each seventy-two ordinary cubits (or sixty-two sacred cubits) long by seventeen wide. The gaoul, with its keel of one solid piece of cedar, was sixty-seven cubits in length by twenty in width; it had three decks and, as I have said, two tiers of rowers; the decks were four cubits apart, and were raised fore and aft, so as to make the elevation sixteen cubits above the water, whilst in the centre it did not exceed twelve cubits. The galleys, when carrying their full burden, and the double line of oarsmen, stood each eight cubits above the water-line. Each contained space enough to take 150 sailors and 50 rowers; but hitherto I had only engaged 200 seamen, expecting that I should be able to enlist the services of 100 soldiers and archers who would be willing to take a share of the working of the vessel. The number of the crew of the gaoul was complete; the Gadita had likewise her full complement of thirty-seven men, and the barques their crews of eight. These two small craft were to be kept constantly in tow, and would consequently be in no need of a pilot; but each of the larger vessels was provided with two pilots, one at the prow, one at the stern, Himilco being pilot-in-chief. At the top of every mast, there was a look-out [Pg 20] place, constructed of fir-wood from Senir, for the purpose of sheltering the man on watch. The apertures for the oars were arranged at equal distances along the sides; and all the vessels, after they had been caulked and tarred, were made to correspond with the Gadita by being painted black with red lines. Hanno had drawn up a document for each of the captains, containing the names of the respective crews, and a complete list of every piece of spare rigging on board, with a register of the place where every article was stored. All the arms, the bedding, the cooking-utensils, the water-barrels, had their positions carefully recorded, and in the crew's quarters between decks, each seaman and rower had his berth distinctly marked with his own name. The cabin under the raised deck at the stern was reserved for the use of the captain and pilots, whilst that under the prow was set apart for the officers of the crew, and the captains of the men-at-arms. On all the vessels the arrangements were identical, with the exception that at the stern of the galley which I had chosen for myself I had ordered a boarded cabin to be erected, divided into two compartments by a partition, and lighted by two small windows, for the especial use of the eunuch and the King's slave under his charge.

Hanno was extremely interested in the selection of good and appropriate names for the ships. At his wish, the gaoul, which was under the command of Bodmilcar, and numbered a large proportion of Tyrians amongst its crew, was named after Melkarth, the god of Tyre. One of the galleys was named the Dagon, being placed under the protection of the Philistine god of fish; whilst the one on which we ourselves were about to embark was dedicated to the Sidonian goddess Ashtoreth, to whom we were personally bound by an especial reverence. Associated with these divinities, of course it was out of all character that the Gadita should retain her previous name; accordingly, at Himilco's request, and in consideration that she was to sail at the head of the squadron, we gave her the designation of [Pg 21] the Cabiros. Bodachmon, the high priest of Ashtoreth, undertook to present us with images of the various deities to be kept on board the ships which were severally dedicated to them.

Bodmilcar was assigned the command of the Melkarth, and her attendant barques; Hasdrubal, a Sidonian, was appointed to the charge of the Dagon; and the Cabiros was confided to the care of Hamilcar, another Sidonian, a bold and experienced seaman.

On board the Ashtoreth, my flag-ship, I took for my personal staff Hanno as scribe, Himilco as head pilot, and Hannibal of Arvad (whom I knew to be a strong, brave man) as commander of my men-at-arms.

Fore and aft of each of the ships Hannibal placed two machines of his own invention for hurling stones and darts, and called "scorpions;" thus, with the exception of the Cabiros, which being small could only carry two, every vessel was provided with four of these powerful engines.

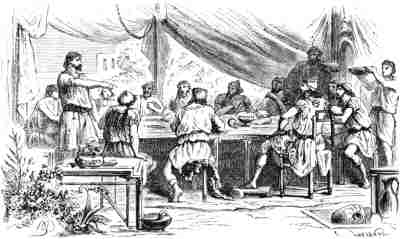

We worked hard throughout the greater part of the night and all the following morning in packing and stowing the freight of our little fleet as it lay in the inner basin of the trade harbour, and the Cabiros joined us to receive her portion of the cargo and provisions. Towards the middle of the day we found time for rest and refreshment. Anticipating our departure on the morrow, several of us met for a frugal meal in a tent that had been erected for our accommodation on one of the quays. The three captains, the commander of my men-at-arms, the chief pilot, and myself, had just seated ourselves at the table, when the curtain that covered the entrance was drawn aside by one of the sailors, and Hazael the eunuch was announced.

Hazael entered with his usual lazy saunter; behind him was a train of six slaves carrying baskets, boxes, and bundles, and accompanied by a workman with a hammer and a variety of tools. Outside, mounted on white asses, were two women, one of them closely veiled; the face of the other was uncovered, and by her red skull-cap with [Pg 22] its gold band and dependent white veil, as well as by her frizzled hair and prominent features, I recognised her at once as a daughter of Israel.

"We have come," said the eunuch, without pretence of courteous salutation, "to take possession of our berths, and to stow away our baggage."

Hanno started to his feet. I laid my hand upon his arm, and asked him what he was about to do.

"To stow away the baggage for them," he replied; adding, "unless, captain, you forbid me."

"Better for you," I continued, "to remain where you are; I have other business for you to do. This falls best to Himilco's duty. Go, Himilco," I said, turning to the pilot, "go and assist Hazael to arrange his property and see to the accommodation of the women."

Himilco emptied his glass, and, not without a longing glance towards the jar of wine round which we were sitting, left the tent. Hanno, who had fallen back to his seat with an assumed air of indifference, now asked:

"And what is the business for which you want me?"

"You must go," I answered, "to the temple of Ashtoreth [Pg 23] to prepare for our sacrifice to-morrow: you must procure us some birds to take with us on board our ships; in stormy weather they will show us which way lies the land: you must find the naval suffect, and deliver him a list of all the crews, and a catalogue of all the cargoes; most of all, you must wait upon the royal treasurer and furnish him with an abstract of all accounts. Is not all this enough for you to do?"

"No time, I see, then, for me to lose," said Hanno, with impetuous eagerness; and snatching up his papyrus roll, he ran hastily away. It was my impression, as I caught sight of him through the half-opened curtain of the tent, that he turned, not in the direction of the temple, but towards the harbour-basin; however, when he came back in the evening all his commissions had been fully and faithfully executed, and I thought no more of the matter.

On his return he was accompanied by one of the officials of the temple, carrying on his head some large bird-cages made of palm-wicker. Hanno himself held a smaller cage, containing four pigeons of a rarer sort, a beautiful shot plumage glittering gaily on their breasts.

"If these birds don't bring us good luck," he said, "I am sure no others will; they come straight from the temple of Ashtoreth, and were handed over to me by the priestess herself, who made me promise that they should be prized according to their worth."

Each of the captains selected his proper share of the birds, with the exception of Bodmilcar, who contemptuously refused.

"Don't the birds suit you?" said Hanno; "what's the matter with them?"

"I want no pigeons," retorted Bodmilcar; "ravens are the birds for me, and I have taken enough of them on board already."

Hanno turned his back; but Himilco, who had witnessed what was passing, remarked:

"Fortunate for the passengers that they will not be on board the Melkarth. Far more congenial, I should think, the cooing of doves than the croaking of ravens, to the ears of an Ionian!"

"Ionian!" ejaculated Bodmilcar, turning pale, "is the slave an Ionian?"

In an instant I gave Himilco a sharp dig below the ribs to recall him to his senses, and as quickly he clapped his finger on his forehead, pretending to recollect himself: "No, no; not an Ionian; I mean a Lydian." And turning round to me he asked me whether he was right.

I made a sort of a gesture which I hoped would satisfy Bodmilcar, but he was manifestly still agitated; he made no further remark, but shortly afterwards quitted the room, mumbling unintelligibly as he went. As soon as his back was fairly turned, Hanno, who had been seated quietly arranging his papyrus leaves, rose from his seat, and advancing towards the door, made a low and solemn bow, a proceeding on his part that caused Himilco to burst into a roar of laughter.

"Our friend Bodmilcar," remarked Hannibal, "seems to be rather a morose sort of gentleman."

"Nothing of the sort, I assure you," said Hanno, satirically; "I hardly know a man of a brighter and more genial temperament; however, I confess that we may thank our stars that we have not to sail in the same ship with him."

Hannibal smiled, in token of assent.

Time to retire for the night had now arrived. We indulged in a parting glass, in recognition of our mutual hopes for the successful issue of the enterprise before us, and with no little emotion, parted to seek the repose which should prepare us for the ceremonial of the morrow.

Early in the morning I repaired to the arsenal, but not too soon to find the crews assembled each round its own captain. Hannibal had been successful in collecting together all the archers and the men-at-arms. Every [Pg 25] captain was attended by his own trumpeter, in a scarlet tunic, the trumpeter of the military captain being distinguished by the magnitude of his trumpet, which was double the size of the others.

With effective precision Hannibal had arranged his soldiers in their ranks. The first rank was composed of twenty archers in white tunics, their heads covered with white linen caps, which were encircled by a band of leather studded with nails, and of which the ends hung down behind. They all wore scarlet waistbands, in which were inserted ivory-handled broadswords; their quivers were attached to a belt of ox-hide, that passed over the shoulder, and was ornamented with a profusion of copper studs. In his hand every one carried his long Chaldean bow, the upper extremity of which was carved to represent a goose's head. Next behind the archers were two ranks of armed men, twenty in each rank: they wore cuirasses composed of small plates of polished copper, and had helmets of the same material. Their tunics were scarlet, and hung below the cuirasses; on the left of their belts was a strong Chalcidian sword, and on the right an ivory-hilted dagger; one hand carried a large circular shield, ornamented in the centre with a deep-red copper figure of the sun; the other hand bore a lance, furnished with a long sharp point of bronze.

Hannibal stood at the head of his troop. He wore a Lydian helmet, surmounted with a silver crest, which was further adorned with a scarlet plume. The image of the sun in the middle of his shield was likewise silver, and around that was a circle of the eleven planets. His sword-handle was carved into the figure of a lion, the lion's head forming the guard. Like all the rest of the company he commanded, his feet and legs were protected by leather greaves or gaiters, laced up the front, and turned upwards at the point in the Jewish fashion. He no sooner saw me approaching than he unsheathed his sword, and his trumpeter sounded three blasts, an example which was [Pg 26] followed by the other trumpeters, all blowing in unison, after which the captains and pilots advanced and made me a general salute.

Our seamen were provided with neither belts, shields, nor helmets, but carried large cutlasses below their kitonets; they wore pointed caps that covered the nape of the neck, similar to those that are constantly seen at Sidon. Hannibal proposed that they should be drawn up and drilled like the soldiers, but I did not acquiesce in his suggestion; I preferred allowing them to rove about at their pleasure, knowing that they could be drilled far better on board ship, after they had been regularly assigned their proper place and duties.

Hanno and Himilco, who had gone by my directions to see that everything was in readiness for the sacrificial rites, now joined us. They were accompanied by two men, each leading a superb bullock covered with purple housings, and with their horns decorated by fillets of embroidery, to which were attached little bells, which tinkled as they moved. Close in their rear followed my slave, carrying on his head a large basket of pomegranates, covered with a napkin embroidered with silver.

After he had stationed our four trumpeters in couples behind his own, Hannibal gave me to understand that he was only waiting for me to give the signal to march. No sooner had I signified my permission, than he shouted out the word of command, and the archers and men-at-arms doubled file and faced about with an alertness that elicited universal commendation. The trumpeters led the way with a flourish that was well-nigh deafening; the archers followed two and two; then came Hannibal at the head of his warriors, all shouldering their lances. My own place was the next; and I marched on, supported by Hanno and Himilco, and immediately followed by my slave and the two men who were in charge of the oxen devoted as victims for the altar; whilst behind us were the four troops of sailors, not marching in any special order, but [Pg 27] each headed by its own captain and pilots. This irregular company brought up the rear.

The thoroughfares along which we passed were decorated gaily. In honour of the great yearly festival of Melkarth, which attracted the mass of all the surrounding population, they were profusely hung with coloured canvas of many a hue, and floating streamers of linen, dyed with the richest shades of purple, orange, green, and vermilion were interspersed amongst waving branches of palms and massy boughs of cedar. Each separate window was a separate centre of display. The people, in holiday attire, were wending their way in crowds in the direction of the island upon which stands the temple of Melkarth, but they stood aside in every portico to allow us to proceed; they were eager in their inquiries as to the meaning and purpose of our formal progress through the streets; and when they understood that we were marching to the shrine of the goddess Ashtoreth to make our sacrifice, and to intreat her favour upon an expedition to Tarshish which we were about to make, they rent the air with their boisterous acclamations. Men expressed their wonder at the concourse of our sailors and the quality of our oxen; women admired our attire and the carriage of our officers, being especially lavish in their praise of Hanno; the children ran after the procession, attracted equally by the glittering crest in Hannibal's helmet, by the glowing red of the trumpeters' tunics, and the swelling notes of their martial music. Every one was unanimous in declaring that never before had so magnificent a retinue left a Phœnician city on a distant enterprise.

As we passed along beneath the sycamines in front of the King's palace, the vast concourse that had assembled in readiness for the royal procession parted asunder to allow us room to pass, and the King's trumpeter and musicians, who were stationed at the gateway, broke out into strains of welcome. A messenger was observed hurrying down from the palace, and it was soon known that he came [Pg 28] with orders for us to halt. Hannibal immediately made his men face about; the sailors, as it were involuntarily, turned towards the palace, and I myself, with Hanno and Himilco, advanced in the direction of the window at which the King is accustomed to show himself to his people, and which is easily distinguishable from the others by the gilding and tapestried hangings with which it is decorated. Meanwhile our trumpeters had taken up the strains of the royal march in concert with the King's musicians, and the melody was re-echoed by various bands in other quarters of the palace-yard.

Only a short time elapsed before the King presented himself at the window. An attendant, gorgeously attired, held over the King's head a purple canopy embroidered with gold and richly jewelled; behind him could be seen the glittering helmets and cuirasses of his body-guard. Without a word of preface, he called me forth by name; and having prostrated myself to the earth in deep obeisance, in another moment I was standing with folded arms before him awaiting his commands.

He spoke to this effect:

"Mago! content I am with the preparation you have made. Well pleased I am with the way in which you have collected your seamen and equipped your warriors in behalf of my friend, my royal ally, King David. You quit these realms for the distant shores of Tarshish. May our guardian gods protect you! Hazael will deliver you the letters signed by my own hand, which you are to present to the various sovereigns who are my allies; to him I have further intrusted the papyrus roll on which my instructions are inscribed. Onwards now, fulfil your oblations to your goddess Ashtoreth. I go to render my sacrifice to our great Melkarth; but when I have discharged my vows, my purpose is to be myself a witness of your departure, and you shall not fail to have still further tokens of my favour."

Again I prostrated myself before the King, who then [Pg 29] retired, leaving me to proceed upon my way, still heralded by the trumpets and greeted by the continuous acclamations of the people. We had hardly turned away, when the great gate of the palace was thrown open, and, headed by a band composed of trumpets, sistra, tambourines, and flutes, there issued the grand procession on its way to the island upon which rose the columns of the temple of Melkarth, the supreme deity of Tyre.

We had hardly reached the limit of the royal court-yard, when Bodmilcar, who had quickened his pace to overtake me, came to my side and said mysteriously,

"Melkarth is a great god!"

"Assuredly!" I said, but did not in the least comprehend his meaning.

"A great god is Melkarth of the Tyrians," he repeated. "Melkarth requires greater sacrifices than Ashtoreth: his sacrifices are large as Moloch's; and they are going to offer him some children to-day."

I assented, yet still failed to see his purpose; but after a little hesitation, he said:

"Might it be permitted me to take my Tyrians and to join the worship of our own Melkarth?"

The discovery of his intention vexed me exceedingly; it was mortifying to myself to see the number of my own retinue diminished, or to allow the dignity of our own observances to Ashtoreth to be curtailed; but I felt that I had no alternative than to comply with his request to make his sacrifice to the god of his peculiar veneration. Reluctantly I gave him my assent, and when we reached the steep street that led up to the elevated groves of "Baaltis-Ashtoreth,"[23] I saw that, instead of continuing with us, he dropped out of our line and joined himself with about thirty of our sailors to a procession that was conducting a chariot, resplendent with gold, and surmounted by a canopy ornamented with plumes of ostrich-feathers. This chariot was conveying the children that [Pg 30] were to be offered as the victims of the sacrifice. To welcome the addition to the throng, the shouts of the populace and the clang of the cymbals burst forth with redoubled vehemence.

"How I hate that sacrificing of children!" said Hanno to me.

"Yes;" I concurred, "but if Moloch and Melkarth demand it, what can be said?"

"With all due reverence for Moloch and Melkarth," he continued, "I cannot but rejoice that Ashtoreth of Sidon makes no such request."

We had now turned into the pathway through the grove that winds up to the temple of Baaltis. By far the greater proportion of the temple-officials were absent, having gone to join the general celebration of the city in honour of Melkarth; only six priests and four priestesses remained. Seen through the hazy glow of the rising sun, the grove and temple looked surprisingly lovely, and one could hardly help being conscious of some feeling of regret at having to leave such charming scenes. But amidst all the fascination of the prospect, I realised how a perpetual residence in such an abode would make a man effeminate, and unfit him for peril and adventure; and proudly I recalled the recollection that apart from the enterprise of her sons, Phœnicia could have known no luxury: it was her commerce that had brought her wealth; and had it not been for their bold and undaunted navigation, the people might have seen their shores the prey of invading kings.

Hanno had manifestly been under a like influence, and had been following a kindred train of thought.

"Yes," he said, as if uttering aloud the conclusion of his own reflections; "yes, even if Pharaoh, Melek-David,[24] the Chaldeans and Assyrians all were to concentrate their hosts and fall on us Phœnicians, we could betake ourselves to our ships and brave them on the seas. Aye, though [Pg 31] they should drive us out from our own domain, build ships, and encounter us upon the ocean where the supremacy has hitherto all of late been ours, yet we have Chittim, Utica, Carthage, Tarshish to fall back upon; the whole world is ours!"

"True," I replied; "in a sense, the world is ours: but it is nothing except our own undaunted perseverance that has made it so. We have had no kings to lead us on to vanquish neighbouring states; we have had no generals to gain us victories and acquire us power; but depending only on our native resources, trusting simply to our own courage, and relying on the good protection of our gods, we have traversed regions that were unexplored, and discovered wealth that was unknown. And now, none dares to assail us; we command the respect of all. None too proud to ask our aid, none too independent to own our service. Who procures Melek-David his choicest timber, his silver and gold? Who provides Pharaoh with balm, his jewels, his copper and his tin? From whom does the Assyrian seek his purple and glass, his ivory and embroidery? Who is the great purveyor of every luxury for every prince and magnate of the world? A Tyrian may well be proud when he claims all this for the mariners of Sidon and the merchant-princes of Phœnicia."

Stirred to emotion by my enthusiasm, Himilco took up the strain: "Yes; great and deservedly great is Tyre's renown. May her spirit of adventure never flag! For my part, give me but the favour of Cabiros for my guiding star, and I would not exchange my peaked sea-cap and ragged kitonet for the tiara sparkling with its fleur-de-lys,[25] and the mantle gorgeous with embroidered work that grace the King of Nineveh!"

Whilst we were thus indulging the spirit of our national pride, the priests within had been lighting the altar-fires and preparing the sacrificial basins, some of which they filled with water, leaving the rest empty. Hannibal had [Pg 32] drawn up his men in order upon the temple-steps, making an imposing array: he had just put them in the form of a crescent, of which the archers in double file at the top were the extremities, the centre being made by the men-at-arms, four deep, and below, an avenue was left for the progress of myself and my companions, the oxen being conducted into the temple by an entrance at the back.

On our approach, our trumpeters gave a loud flourish, which was answered by the flutes and instruments within. The high priest advanced towards us and, in sonorous tones, exclaimed:

"Let Mago, the Sidonian, the son of Maherbaal, now draw near. Commander of the expedition, he comes to present himself before the goddess. Let him now approach, and all his followers attend him!"

Obedient to the summons, I ascended the steps, followed immediately by my slaves; Hanno and Hannibal were on my right hand; Hasdrubal, Hamilcar and Himilco on my left; behind us was the general throng of sailors and of oarsmen. At a sign from Hannibal, the soldiers shouldered their bows and lances, and having faced about, entered the temple by the two side doors, and completely lined the edifice.

An official proclaimed silence. "Order!" he shouted; "Mago, son of Maherbaal, makes an offering for his people."

It was the work of but a short time to bring in the oxen, and have them slain and quartered, and while this was being done my slave distributed amongst us the pomegranates he had brought. The high priest with much formality presented me with the shoulder of one of the victims, upon which, according to rule, I laid a purse containing six shekels of coined money. The officiating priest accepted the offering, and while he was proclaiming my liberality aloud, the sacerdotal scribe was inscribing the names of myself and my captains, together with the amount of my donation, in the temple register. The chief priest then took the breasts of the victims and placed them upon the altar, whence the smoke ascended high towards [Pg 33] the round window in the dome. The black stone at Sidon is the true goddess, but here at Tyre, Ashtoreth is merely represented by a statue. Standing with his face towards this, the priest made his invocation and chanted some prayers to music, which gradually died away into perfect silence.

During the time that these ceremonies were proceeding, the remaining portions of the oxen were being steeped in the lavers, after which they were thrown into great caldrons, part to be boiled over the chafing-dishes in the temple-kitchen, and part to be cooked in the open air of the sacred groves. The sailors lent their ready assistance in kindling the fires and superintending the boilers.

The chief priest next handed me one of the bullock's breasts. I raised it on high with both hands before the goddess, and delivered it back to the priest, who turned it round three times, as if solemnly dedicating it to the deity on my behalf. Hanno went through a corresponding ceremony with the other breast, which was turned round seven times in behalf of us all.

I had given the scribe five shekels to provide us with bread for the entertainment, and in the name of the captains, pilots, and sailors, Hamilcar gave him eight shekels, a part to provide us with wine, a part as a free tribute to the goddess. He entered the several sums upon the registers, and the officiating priest again made a public announcement of our liberality. One after another we prostrated ourselves before the image of the goddess, the high priest made a short final invocation, and full of joy we withdrew from the temple to the adjacent grove. At a sign from Hannibal, the soldiers, who had stood mute and motionless throughout the ceremony, fell out of their ranks, and rushing in wild confusion, mingled with the sailors to assist them in preparing the banquet.

I took my seat at the foot of a noble cypress, and Hanno, Hannibal, and Gisgo, placed themselves as my supporters on either hand, Himilco charging himself with the duty of [Pg 34] superintending the filling of a large earthenware vase with wine. My slave arranged the drinking-cups by placing mine (which had a lion's head at its mouth) in the centre, and disposing those of the captains in order round it. Hannibal's cup was of plated copper, with a stem and two handles, and embossed with flowers and bunches of grapes. Having done this, the slave went away, and returned ushering in two soldiers, who carried a huge caldron; they let the caldron down heavily on the ground, their cuirasses rattling again with their exertion. The lid of the caldron was at once removed; a large basket of bread had been handed round preparatory to the repast, and each man having brought out the wooden knife and spoon that he carried at his waist, the whole of us set ourselves to enjoy an abundant meal.

When the wine-cups had been distributed and charged, I rose from my seat, and raising my cup on high, drank to the health and welfare of the whole assembly.

"A goodly draught is this!" said Hannibal, when he had drained his cup to the very dregs; "it is the wine of my own city Arvad; it gives life and strength to those that drink it; hence Arvad's wide renown for wits and warriors."

"And Arvad's warriors," I said, turning to the captain, "deserve their fame. By-the-by, have your wide wanderings by sea and land ever taken you into Judæa before? Thither it is, you know, that we first direct our course."

"Truly, yes;" replied Hannibal, with his mouth full; "this very sword that I am wearing, and this purple shoulder-belt, were presents from Joab, the general and cousin of the King. I commanded twenty archers under him at the battle of Gebah, when the Philistines were defeated at the mulberry groves. Nor was that the only time. I was garrisoned for a year or more at Hamath, with the troops of Nahari, Joab's armour-bearer, one of David's thirty-seven mighty men. It was on returning thence that I had the command of the soldiers on board [Pg 35] the ship of our friend Hasdrubal here, at the time when the galleys of Sidon were sent to engage the Cilician fleet."

"Aye, I have heard of that expedition," said Himilco; "at that time we were far away at Gades."

"And we," broke in Hamilcar, "were in the service of Pharaoh, sailing along the coast of Ethiopia, beyond the Sea of Reeds.[26] What splendid shells were there, containing precious pearls! and one great fish there was that could swallow a man entire!"

At this moment one of the young priestesses approached our party, and handed Hanno a small packet, carefully wrapped in linen.

"This," she said to him, "is the image of Baaltis. Over it I have burnt the costliest perfumes; I have anointed it with the rarest ointments; I have laid it before the goddess, who has graciously accepted it. To you, Sidonian, I now entrust it, and may it bring good fortune to yourself and all who share your enterprise."

The high priest came in person to deliver us the other images of the gods, that of Melkarth alone excepted, which Bodmilcar himself was to convey from the temple to which he had separately gone.

The priestess offered to accompany us to our ships, that she might sprinkle the images on board before we took our departure.

Himilco craved permission to carry the image of the Cabiros down to the quay before resigning it to the keeping of the captain.

"How about your vow of twenty shekels and a bullock that you made to the Cabiri?" I asked him, as we rose to go.

"That will have to wait," he answered, "till I have come across that Tarshish rascal who deprived me of my eye. The patient gods, I have no doubt, will give me credit, and not require me to pay at once, or in advance."

Meantime Hanno had been uncovering his image of Ashtoreth, and was standing holding it in both hands and [Pg 36] gazing at it with the profoundest admiration. It was an alabaster figure, with a necklace of three rows of gold beads and a pointed cap, beneath which flowed ample masses of wavy hair.

"I, too," said Hanno, "have made a vow to my goddess, but she has promised to abide my time, and to tarry till my expectations and my longings are fulfilled;" and as he spoke, he stooped and kissed the face of the image. I know not whether it was imagination on my part, but I certainly thought the cypresses around gave a soft yet perceptible rustle in response to his words. Perhaps the priestess observed it also, for she smiled on me, and laid her hand on Hanno's shoulder.

"But now, Captain Mago," she cried, "let us start. The time for embarkation is at hand, and the goddess pronounces that it is a favourable hour. Come, let us proceed!"

"To your ships, men; to your ships!" I shouted; and turning for a moment towards the temple, said, "Farewell, Baaltis, Queen of Heaven: to-night thou shalt behold us on the waters of the Great Sea!"

Hannibal, who had resumed his helmet, made a signal to the trumpeters to summon the soldiers and sailors. Hanno and the priestess came on one side of me; Himilco, carrying the image of his god, took his place on the other, and in the same order in which it had come, our cortége wended its way along the decorated streets down towards the port. The roads adjacent to the harbour and all the quays were so densely thronged, that it was only with considerable difficulty that we could force our way along. Every nation seemed to make its contribution to the crowd: besides the native Phœnicians, there were Syrians in their fringed and bordered robes; Chaldeans with their frizzled beards; and Jews in their short tunics and long gaiters, with panther-skins thrown across their shoulders. Again, there were Lydians with bands around their foreheads; Egyptians, some with shorn heads, and some with enormous wigs; Chalybeans, wild in aspect, and half naked; and [Pg 37] men of Caucasus, gigantic in size and strength. Many a far distant land had sent its sons to our Phœnician cities as the headquarters and the home of industry and commerce; Arabs and Midianites were here looking with astonishment at the height of the houses, and bewildered at the multitude of the population; whilst the Scythians of Thogarma, their legs strap-bound, moved with heavy strides, and looked around amazed, perplexed at the absence alike of horses and of chariots from the narrow streets.

The air was filled with songs and shouts of many a different tongue; the people jostled one another in their eagerness to catch a sight of whatever company came last in view. Every band of musicians enlisted its own admirers; every troop of priests attracted the closest scrutiny. Every regiment with its painted shield excited a perpetual interest; and as our own procession, with its trumpeters and soldiers and promiscuous groups of sailors, could not fail to draw a large and curious concourse, it was in the midst of a veritable whirl that we passed the arsenal and made our way to the reserved quay, where our ships, poops inward to the shore, had been left under the care of a few sailors.

Bodmilcar and the eunuch had arrived before us, and were standing in eager conversation on the gangway that led to the poop of the Melkarth. As soon as they observed us, they stopped abruptly, and Bodmilcar whistled for his sailors, whilst the eunuch advanced to meet me.

"Is all your baggage duly stowed on board?" I asked Hazael.

"It is," he answered; "but it disappoints me much that our berths have not been made upon this larger ship; here we might have far more space and comfort: however, it matters little; at the first point we touch we can make a change. Bodmilcar thinks it will be best we should."

"It cannot be," I said; "the King's slave has been entrusted to myself, and under my supervision she must [Pg 38] be. The Melkarth is a transport, and the captain of a transport has no concern with passengers. I must hear no more of this. Do I understand aright that you have letters for me from the King?"

Without one word in reply, the eunuch handed me a box of sandal-wood, which I opened, and found it to contain several sheets of papyrus, on which were written various instructions to myself.

I was about to give orders to my trumpeter to proclaim silence, but before the words were out of my mouth, Bodmilcar rushed forward and threw himself into my arms.

"I have been sacrificing to Melkarth," he exclaimed; "I have paid my vows to my god, and I must unburden my conscience. I wish to ask pardon of any and of all to whom I have shown insolence or ill-temper."

Without hesitation, Hanno offered him his hand, assuring him that he fully forgave everything that had happened in the past, and that, forgetting all previous quarrels, for the future he would show him all proper deference, and yield to his authority. Pleased with this open reconciliation, I expressed my satisfaction that we were able thus to set out with so universal a spirit of harmony and of concord.

In the meanwhile the captains had severally collected their crews, and Hannibal had told off his men-at-arms, reserving ten archers and ten soldiers for our own ship. The priestess then, with the accustomed solemnities, presented each vessel with the image of its own peculiar divinity.

Before we started, our host, with whom we had been sojourning, accompanied by his wife and son, forced his way through the guards that had been keeping the inclosure, and came in haste to me.

"Mago, dear friend," he said, "I could not suffer you to go without seeing you once more. Here are cakes, and here is a basket of dried grapes; but, most of all, here are two goat-skins of genuine nectar. Accept them from me in [Pg 39] token of my good-will. Farewell, and the gods grant you a prosperous voyage!"

"Farewell, honest pilot," said my host's wife to Himilco; "for you I have brought this goat-skin of Byblos, because I know there is no wine you like so well."

"Thanks, good hostess, many thanks," replied Himilco; "to me there is no wine that can compare with the rich and luxurious produce of Phœnicia. I shall not forget your bounty, and if only our star shall favour us, and the Cabiros shall safely bring us home again, I promise to bring you such a gift as shall make the Tyrian women die with envy."

The son, a youth of about sixteen, was devotedly attached to Hanno, and only with the greatest difficulty could be dissuaded from accompanying him upon his voyage. As a farewell gift, he had brought his friend a large packet of the choicest reeds for writing; and the two parted with mutual expressions of affection.

Amongst those present there was yet another whom I regarded with the profoundest reverence, and whose knowledge was accounted as little short of divine. This was an aged priest, named Sanchoniathon,[27] the historian and chronicler of past events; although no traveller himself, he had acquired the fullest information concerning well-nigh every country of the world.

Addressing himself to me, he said: "Mago, my son, Hanno your scribe has undertaken to transmit to me, in writing, an account of whatever he may see rare or wonderful in the far-off lands to which you go; his genius seems bright and quick, but his youth renders him wild and unstable as a kid. Is it too much to ask of you that you will urge him on to keep his word?"

"To gratify you, my father," said Hanno, "I will do all I can to control the caprices and irregularities of my youth. My own indebtedness to you is great. I trust that I may [Pg 40] not forget the lessons you have taught me; and if I can render any aid in enabling you to keep the Phœnicians informed of the wonders of the world, I shall be ready to show myself a pupil worthy of my master."

The aged Sanchoniathon then gave us his blessing. He had scarcely concluded his benediction when the priestess of Ashtoreth came by, returning from the ships. As she passed Hanno I distinctly heard her say in an undertone:

"She is as good as she is beautiful!"

"Hush!" he murmured; "I must forget her! Happy Pharaoh!"

Everything being reported ready, I ordered the trumpeters to sound the signal for departure, and we proceeded to embark. The first man to step on board was old Gisgo, the pilot of the Cabiros, commonly known as Gisgo the Celt, and perhaps still more frequently spoken of as Gisgo the Earless. He had been eight times on a voyage to the Rhone, and the story went that on one of his visits there he had married a Celtic wife, with yellow hair, who was still awaiting him in her native forests; on another occasion he had been taken prisoner by the Siculians, who had cut off both his ears. Having mounted the poop, the old man waved his cap and shouted cheerily:

"Mariners, mariners all! quick and ready! quick on board! rulers of the ocean! sons of Ashtoreth! listen to your captain's call. Tyrians and Sidonians! To sea! to sea! and long live Captain Mago!"

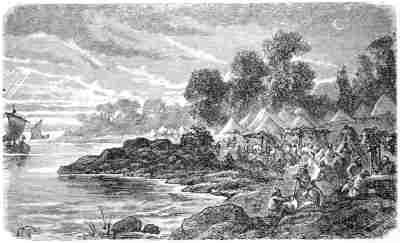

The men all hastened to their several ships, and as soon as I had taken my station on the raised bench of the poop of the Ashtoreth, my standard was hoisted as the signal of departure, the gangways were removed, the boathooks were driven vigorously towards the facing of the quay, and we were on our way.

The Cabiros, with its twenty-two oarsmen, took the lead; next came the Ashtoreth; the Dagon towed the Melkarth, which was too large to hoist a sail in port. Our little squadron floated on past the numerous ships that lined [Pg 41] the quays, making its way through crowds of boats that darted to and fro, conveying the countless visitors to the island where the feast of Melkarth was still in course of celebration. Our trumpeters continued to blow, our oars rose and fell in regular cadence, and the voices of thousands of spectators kept up a perpetual acclamation.

From my own position I could overlook the decks of all the other vessels. Hanno was at my side, and Himilco stood at the bow giving his orders to the helmsman. Hannibal had made his warriors hang their shields over the ship's sides; every one had betaken himself to his proper post, Hazael the eunuch being no exception, as he had retired to the privacy of his own cabin.

Passing the mouth of the trade-harbour, with its two watch-towers, we entered the canal that led to the island; it was covered with boats decorated with holiday-trappings; above it rose the palace of the naval suffect, its terraces all decked with coloured hangings, and thronged with a motley crowd. Beyond again, in the centre of the island, I could see the dome of the temple of Melkarth, the blue smoke of [Pg 42] the sacrifices rising high above its ochred roof. I could even hear the uproarious clanging of the cymbals and the other instruments within.