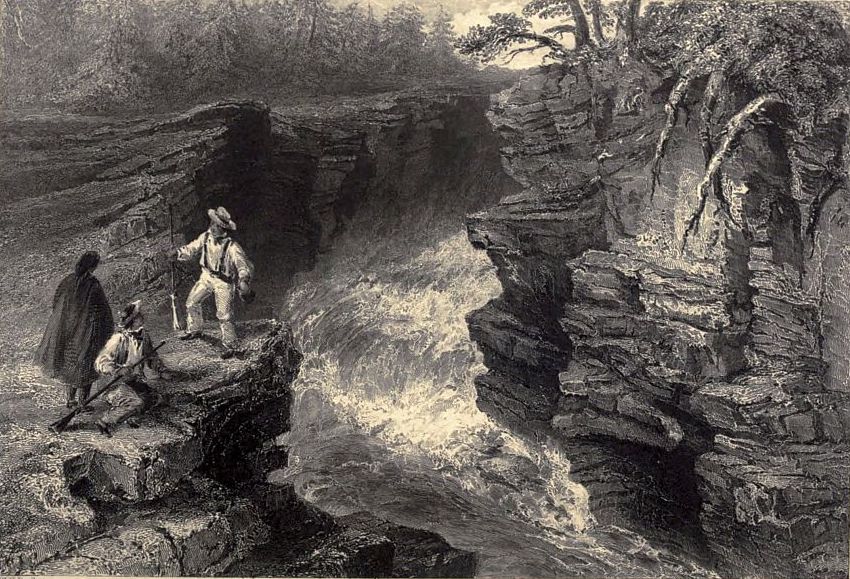

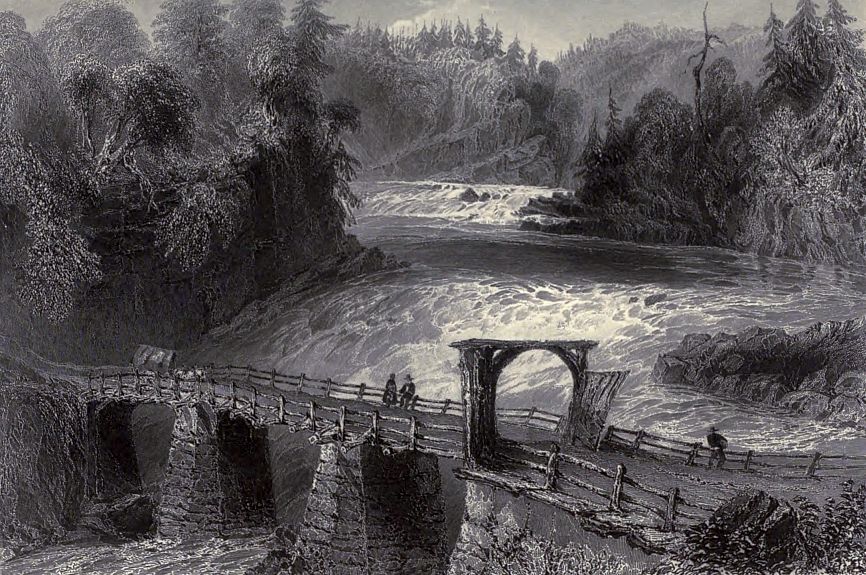

The Chaudière Falls, near Quebec.

Title: Canadian Scenery, Volume 1 (of 2)

Author: Nathaniel Parker Willis

Illustrator: W. H. Bartlett

Release date: December 17, 2014 [eBook #47690]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marcia Brooks, Cindy Beyer, Ross Cooling and

the Project Gutenberg team at

http://www.pgdpcanada.net

The Chaudière Falls, near Quebec.

CANADIAN SCENERY

ILLUSTRATED.

FROM DRAWINGS BY W. H. BARTLETT.

THE LITERARY DEPARTMENT BY

N. P. WILLIS, ESQ.

AUTHOR OF “PENCILLINGS BY THE WAY,” “INKLINGS OF ADVENTURE,” ETC.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

VIRTUE & CO., CITY ROAD AND IVY LANE.

CONTENTS

LIST OF THE ENGRAVINGS.

VOL. I.

Canoe-building at Papper’s Island

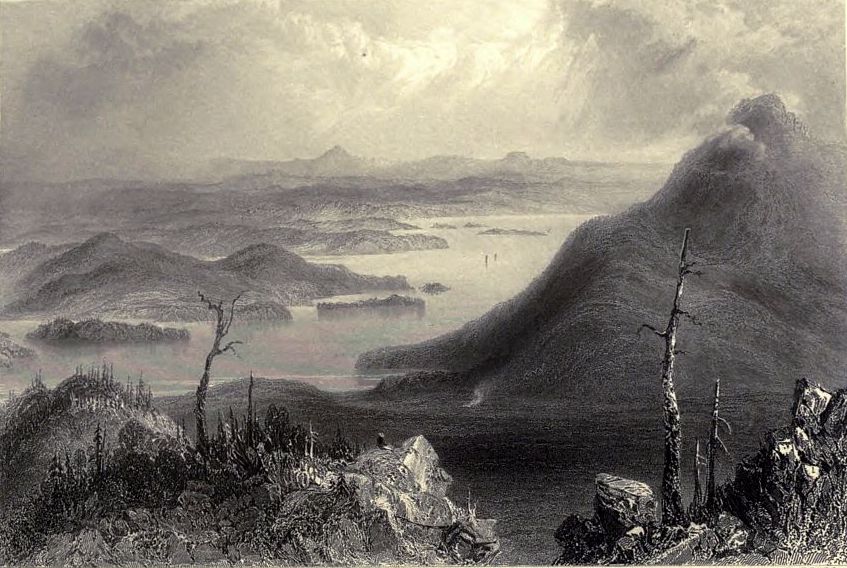

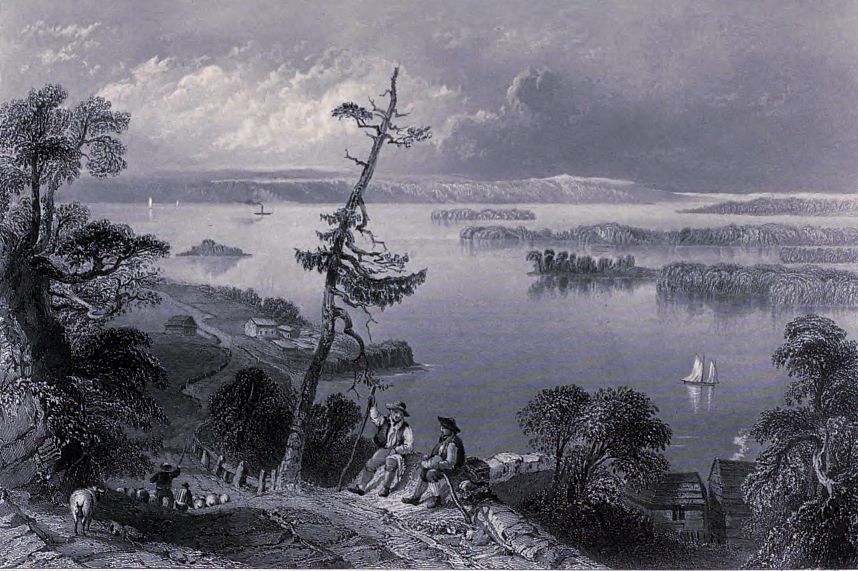

View across the Boundary Line, from the Sugar Loaf

Long Sault Rapid, on the St. Lawrence

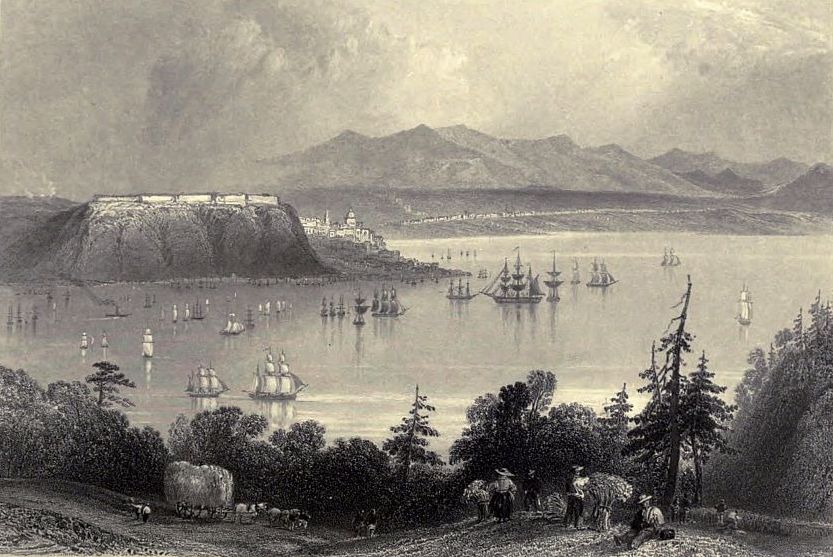

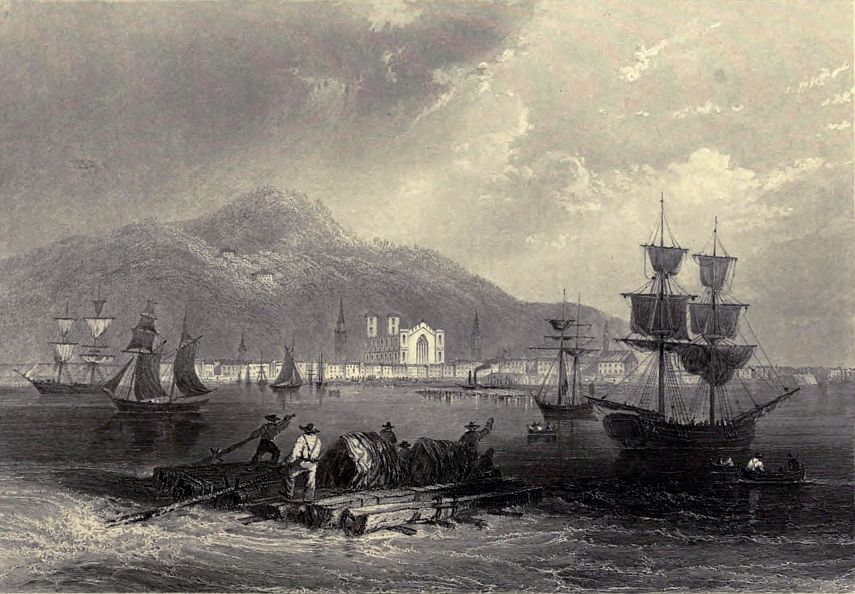

Quebec, from the opposite shore of the St. Lawrence

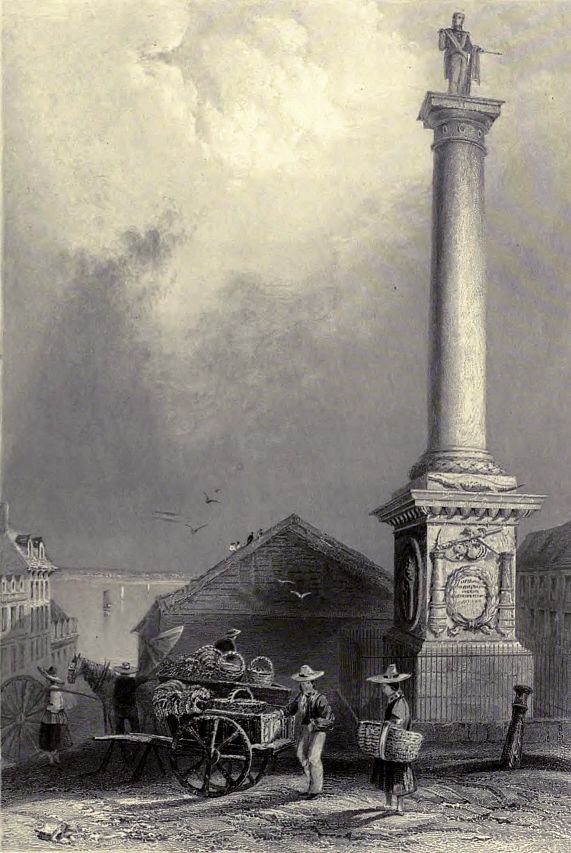

Monument to Wolfe and Montcalm, Quebec

The Plains of Abraham, near Quebec

Les Marches Naturelles, near Quebec

General Brock’s Monument, above Queenston

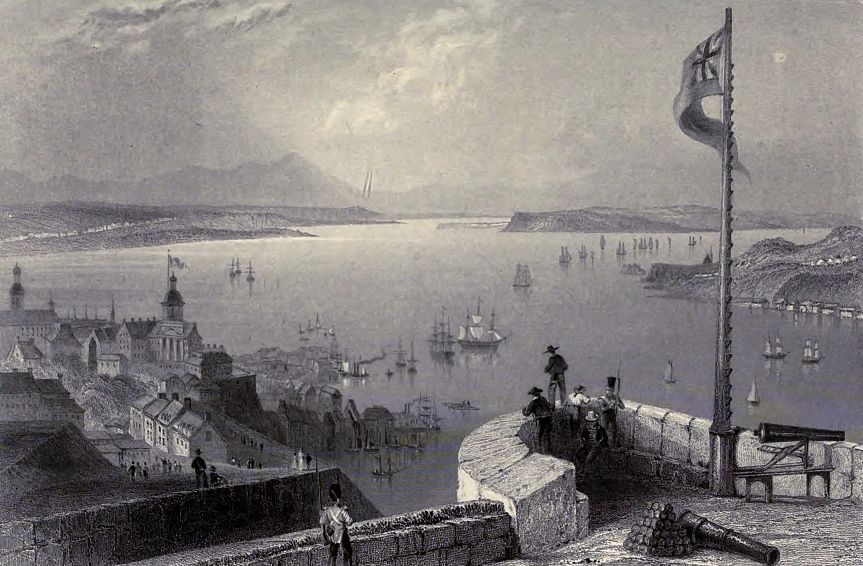

View from the Citadel of Kingston

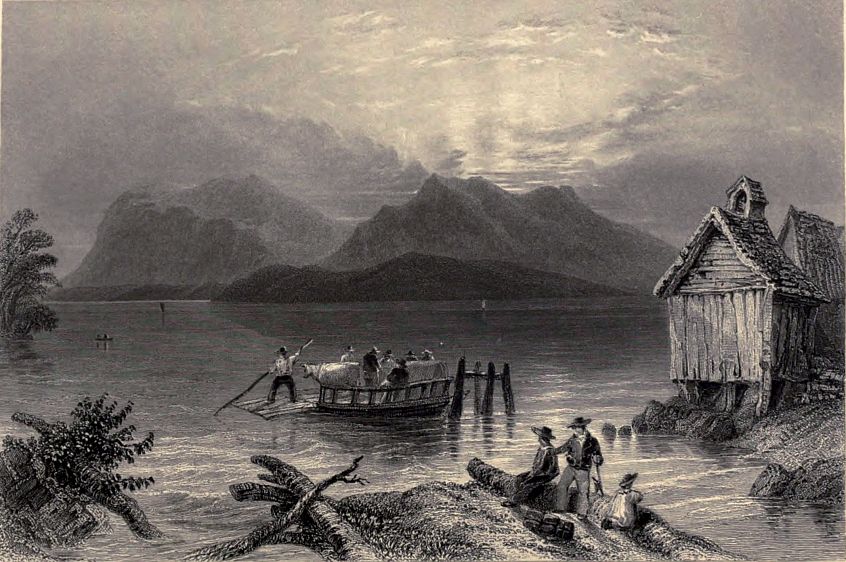

Copp’s Ferry, near Georgeville

The Banks of the River Niagara

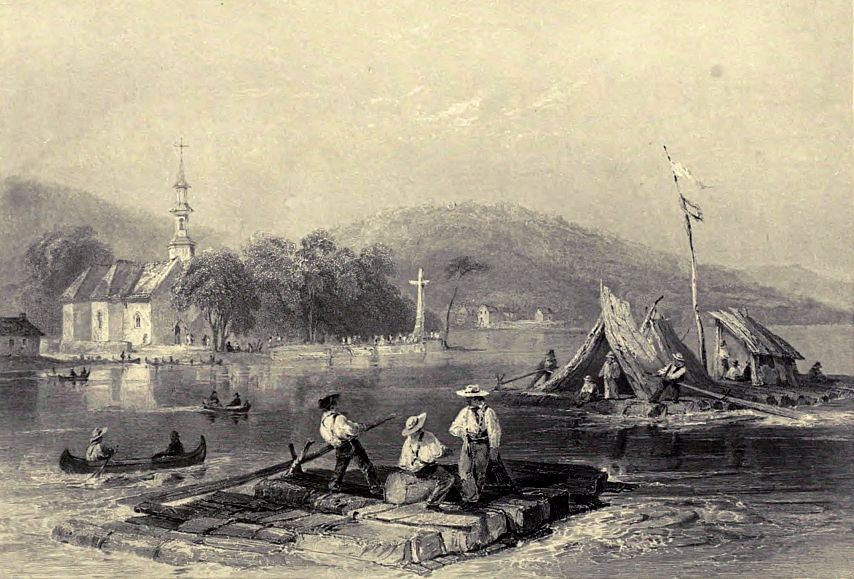

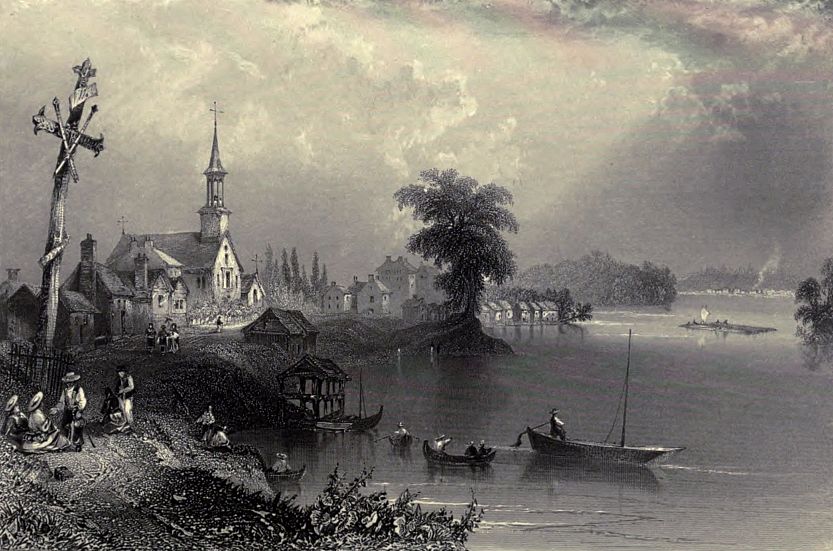

Village of Lorette, near Quebec

Junction of the St. Francis and Magog Rivers

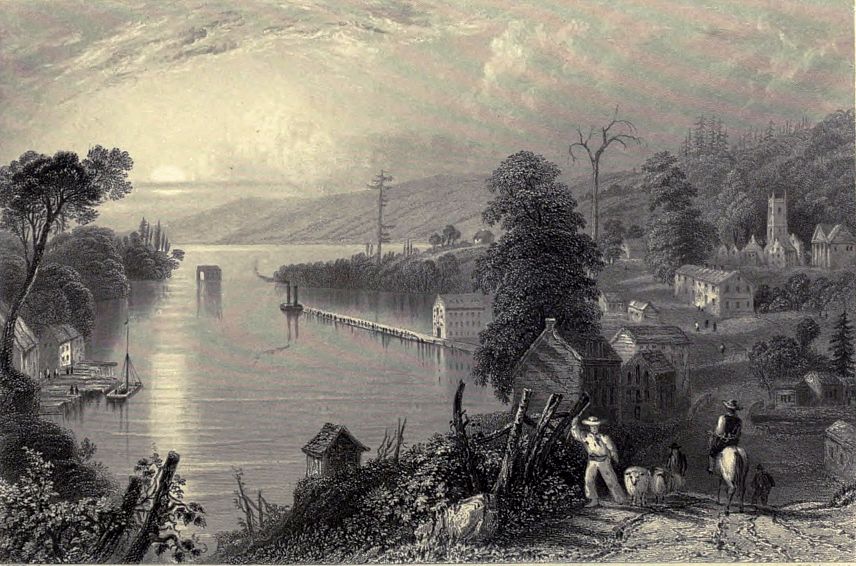

Scene among the Thousand Isles

Rapids, on the approach to the Village of Cedars

Prescott, from Ogdensburg Harbour

Village of Cedars, River St. Lawrence

Montreal, from the St. Lawrence

Raft in a Squall on Lake St. Peter

The Three Rivers, River St. Lawrence

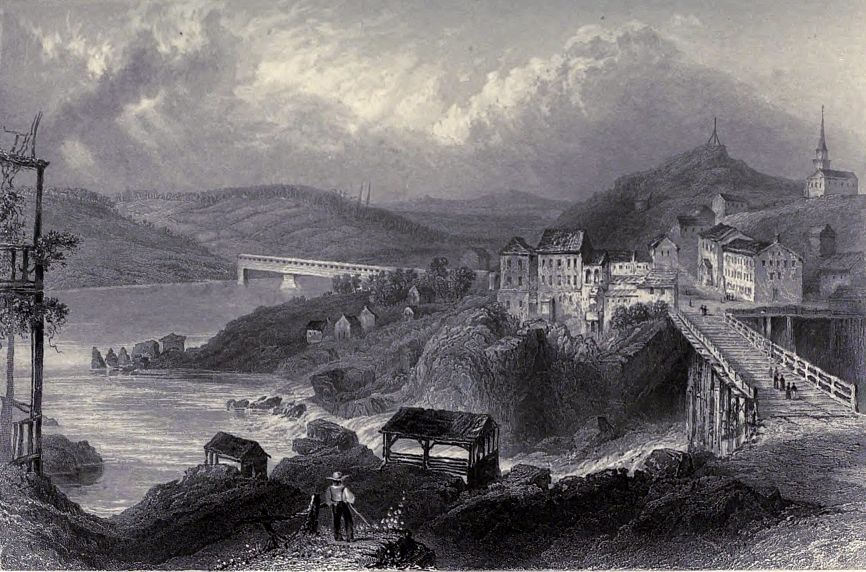

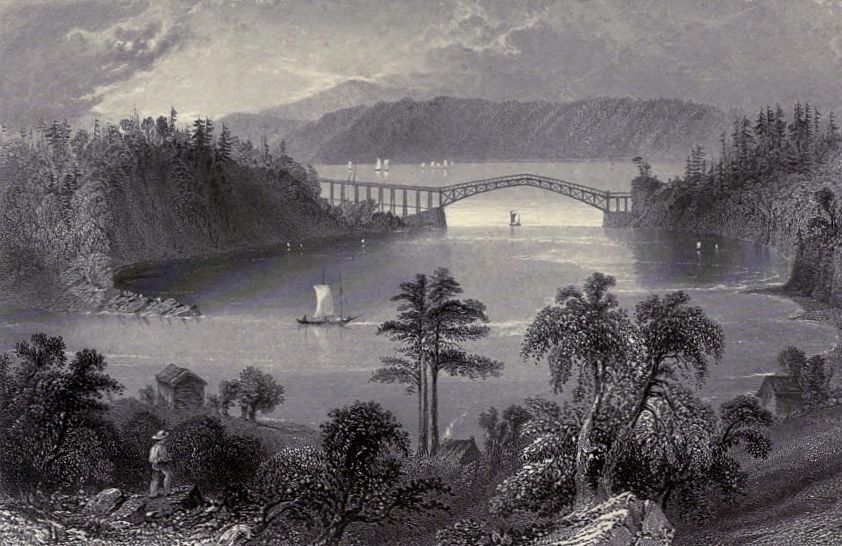

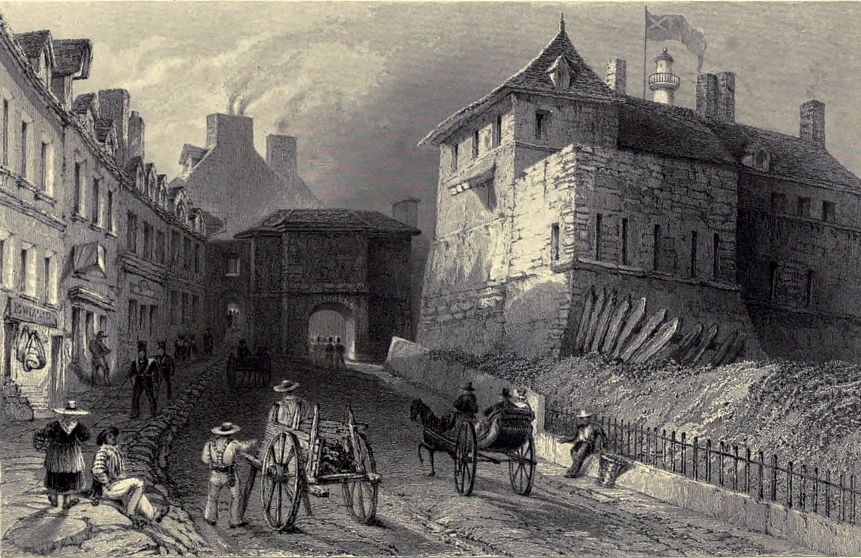

The Chaudière Bridge, near Quebec

The Chaudière Falls, near Quebec

Raft on the St. Lawrence, Cape Sante

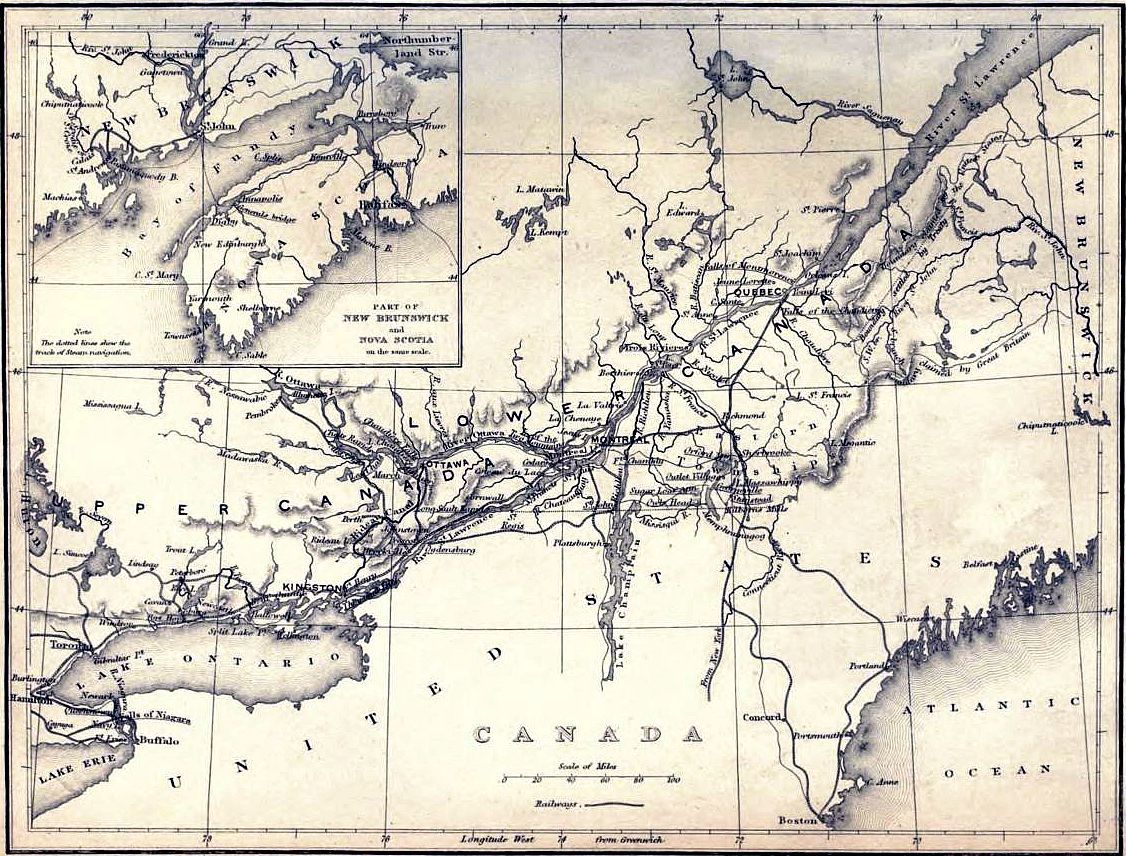

The Map

The name of this magnificent link in the colonial chain with which England has encircled the world, is a matter of considerable doubt.[1] It has been dignified with some research and ingenuity, however, and we can record the result, leaving the choice of solutions to the reader. Hennepin thus unfolds his idea of its origin:—“Les Espagnols ont fait la première découverte du Canada. Ayant mis pied à terre, ils n’y trouvèrent rien de considérable. Cette raison les obligea d’abandonner ce pays, qu’ils appellèrent il Capo di Nada, c’est-à-dire le Cap de Rien (or Cape Nothing), d’où est venu par corruption le nom de Canada.”

La Potherie corroborates this statement, with this difference, that he attributes the Spaniards’ idea of the nothingness of the country to its being covered with snow. He says also that the Indians, on the arrival of Jacques Cartier, frequently pronounced these words: Aca nada (nothing here), which is a very plausible derivation. The words were taught them probably by the Spaniards, who had visited the Baie des Chaleurs, and pronounced them because they found no gold or silver mines.

Our own opinion, however, is, that the word Canada is derived from the word Kanata, which, in Iroquois, signifies a collection of huts. By so unpromising an appellation, is known a province containing upwards of 350,000 square miles, which offer to the agriculturist almost measureless fields of pasture and tillage—to the manufacturer, an incalculable extension of the home market for the disposal of his wares—to the merchant and mariner, vast marts for profitable traffic in every product with which nature has bounteously enriched the earth—to the capitalist, an almost interminable extent for the profitable investment of funds—and to the industrious, skilful, and intelligent emigrant, a field where every species of mental ingenuity and manual labour may be developed and brought into action with advantage to the whole family of man.

The first query that occurs to the reader’s mind in taking up any book on Canada, is, What was the real character of the aboriginal inhabitant, and how far and in what manner has he receded before the advancing step of the white man? Before touching on the history of the civilization of the country, the condition of its savage owners should be well understood.

In their physical character, the American savage is considered by Blumenbach as forming a particular variety in the human species, differing, though not very widely, from the Mongolian. Believing that the New World was peopled from the Old, and considering that the Mongol race was situated nearest the point where Asia and America come almost into contact, we are inclined to ascribe these variations merely to a change of circumstances. The face is broad and flat, with high cheek bones; more rounded and arched, however, than in the allied type, without having the visage expanded to the same breadth. The forehead is generally low; the eyes deep, small, and black; the nose rather diminutive, but prominent, with wide nostrils; and the mouth large, with somewhat thick lips. The stature, which varies remarkably throughout the continent, is, in the quarter of which we treat, generally above the middle size. This property, however, is confined to the men, the females being usually below that standard—a fact which may be confidently ascribed to the oppressive drudgery they are compelled to undergo. The limbs, in both sexes, are well proportioned, and few instances of deformity ever occur.

The colour of the skin in the American is generally described as red, or copper-coloured; or, according to Mr. Lawrence’s more precise definition, “it is an obscure orange or rusty-iron colour, not unlike the bark of the cinnamon tree.” Although we believe that climate is the chief cause of the diversities in human colour, yet it is certain that all savages are dark-tinted. This peculiarity may be accounted for by their constant exposure to the inclemency of the seasons, to sun, air, and tempests; and the same cause, in civilized countries, produces a similar effect on sailors, as well as on those who work constantly in the fields. In the Old World, the intermediate tints between white and black are generally varieties of brown and yellow. The red tint is considered characteristic of the New World. We must, however, observe that the traveller Adair, who lived upwards of thirty years among the Indians, positively asserts that it is produced artificially; that in the oil, grease, and other unctuous substances with which they keep their skin constantly smeared, there is dissolved the juice of a root which gradually tinges it of this colour. He states that a white man, who spent some years with the natives and adorned himself in their manner, completely acquired it. Charlevoix seems also to lean to the same opinion. Weld, though rather inclined to dissent from it, admits that such a notion was adopted by missionaries and others who had resided long in the country. It is certain that the inhabitants glory in this colour, and regard Europeans who have it not as nondescript beings, not fully entitled to the name of men. It may be noticed also, that this tint is by no means so universal as is commonly supposed. Humboldt declares that the idea of its general prevalence could never have arisen in equinoctial America, or been suggested by the view of the natives in that region; yet these provinces include by far the larger part of the aboriginal population. The people of Nootka Sound and other districts of the north-western coast are nearly as white as Europeans; which may be ascribed, we think, to their ample clothing and spacious habitations. Thus the red nations appear limited to the eastern tribes of North America, among whom generally prevails the custom of painting or smearing the skin with that favourite colour. We are not prepared to express a decided opinion on this subject; but it obviously requires a closer investigation than it has yet received.

The hair is another particular in which the races of mankind remarkably differ. The ruder classes are generally defective, either in the abundance or quality of that graceful appendage; and the hair of the Americans, like that of their allied type the Mongols, is coarse, black, thin, but strong, and growing to a great length. Like the latter also, by a curious coincidence, most of them remove it from every part of the head with the exception of a tuft on the crown, which they cherish with much care. The circumstance, however, which has excited the greatest attention, is the absence of beard, apparently entire among all the people of the New World. The early travellers viewed it as a natural deficiency; whence Robertson and other eminent writers have even inferred the existence of something peculiarly feeble in their whole frame. But the assertion, with all the inferences founded upon it, so far as relates to the North American tribes, has been completely refuted by recent observation. The original growth has been found nearly, if not wholly, as ample as that of the Europeans; but the moment it appears, every trace is studiously obliterated. This is effected by the aged females, originally with a species of clam-shell, but now by means of spiral pieces of brass wire supplied by the traders. With these an old squaw will, in a few minutes, reduce the chin to a state of complete smoothness; and slight applications during the year, clear away such straggling hairs as happen to sprout. It is only among old men, who become careless of their appearance, that the beard begins to be perceptible. A late English traveller strongly recommends to his countrymen a practice, which, though scarcely accordant with our ideas of manly dignity, would, at the expense of a few minutes’ pain, save them much daily trouble. The Indians have probably adopted this usage, as it removes an obstacle to the fantastic painting of the face, which they value so highly. A full beard, at all events, when it was first seen on their French visitors, is said to have been viewed with peculiar antipathy, and to have greatly enhanced the pleasure with which they killed these foreigners.

The comparative physical strength of savage and civilized nations has been a subject of controversy. A general impression has obtained that the former, inured to simple and active habits, acquire a decided superiority; but experience appears to have proved that this conclusion is ill-founded. On the field of battle, when a struggle takes place between man and man, the savage is usually worsted. In sportive exercises, such as wrestling, he is most frequently thrown, and in leaping comes short of his antagonist. Even in walking or running, if for a short distance, he is left behind; but in these last movements, he possesses a power of perseverance and continued exertion to which there is scarcely any parallel. An individual has been known to travel nearly eighty miles a day, and arrive at his destination without any symptoms of fatigue. These long journeys, also, are frequently performed without any refreshment, and even having their shoulders loaded with heavy burdens, their power of supporting which is truly wonderful. For about twelve miles, indeed, a strong European will keep a-head of the Indian, but then he begins to flag; while the other, proceeding with unaltered speed, outstrips him considerably. Even powerful animals cannot equal them in this respect. Many of their civilized adversaries, when overcome in war, and fleeing before them on swift horses, have, after a long chase, been overtaken and scalped.

Having thus given a view of the persons of the American Aborigines, we may proceed to consider the manner in which they are clothed and ornamented. This last object might have been expected to have been a very secondary one, among tribes whose means of subsistence are so very scanty and precarious; but so far is this from being the case, that there is scarcely any pursuit which occupies so much of their time and regard. They have availed themselves of European intercourse to procure each a small mirror, in which, from time to time, they view their personal decorations, taking care that every thing shall be in the most perfect order.

Embellishment, however, is not much expended on actual clothing, which is simple, and chiefly arranged with a view to convenience. Instead of shoes they wear what are termed moccasins, consisting of one strip of soft leather wrapped round the foot, and fastened in front and behind. Europeans, walking over hard roads, soon knock these to pieces; but the Indian, tripping over snow or grass, finds them a light and agreeable chaussure. Upwards, to the middle of the thigh, a piece of leather or cloth, tightly fitted to the limb, serves instead of pantaloons, stockings, and boots; it is sometimes sewed on so close as never to be taken off. To a string or girdle round the waist are fastened two aprons, one before and the other at the back, each somewhat more than a foot square; and these are connected by a piece of cloth like a truss, often used also as a capacious pocket. The use of breeches they have always repelled with contempt, as cumbrous and effeminate. As an article of female dress, they would consider them less objectionable; but that the limbs of a warrior should be thus manacled, appears to them utterly preposterous. They were particularly scandalized at seeing an officer have them fastened over the shoulder by braces, and never after gave him any name but Tied-Breech.

The garments now enumerated form the whole of their permanent dress. On occasions of ceremony, indeed, or when exposed to cold, they put over it a short shirt, fastened at the neck and wrists, and above it a long loose robe closed or held together in front. For this purpose they now generally prefer an English blanket. All these articles were originally fabricated from the skins of wild animals; but at present, unless for the moccasins, and sometimes the leggings, European stuffs are preferred. The dress of the female scarcely differs from that of the male, except that the apron reaches down to the knees; and even this is said to have been adopted since their acquaintance with civilized nations. The early French writers relate an amusing anecdote to prove how little dress was considered as making a distinction between the sexes. The Ursuline Nuns, having educated a Huron girl, presented her, on her marriage to one of her countrymen, with a complete and handsome suit of clothes in the Parisian style. They were much surprised, some days after, to see the husband, who had ungenerously seized on the whole of the bride’s attire and arrayed himself in it, parading back and forward in front of the convent, and betraying every symptom of the most extravagant exultation. This was further heightened, when he observed the ladies crowding to the window to see him, and a universal smile spread over their countenances.

These vestments, as already observed, are simple, and adapted only for use. To gratify his passionate love of ornament, the Indian seeks chiefly to load his person with certain glittering appendages. Before the arrival of Europeans, shells and feathers took the lead; but since that period, these commodities have been nearly supplanted by beads, rings, bracelets, and similar toys, which are inserted profusely into various parts of his apparel, particularly the little apron in front. The chiefs usually wear a breastplate ornamented with them; and among all classes, it is an object of the greatest ambition to have the largest possible number suspended from the ear. That organ therefore is not bored, but slit to such an extent that a stick of wax may be passed through the aperture, which is then loaded with all the baubles that can be mustered; and if the weight of these gradually draw down the yielding flap till it rest on the shoulder, and the ornaments themselves cover the breast, the Indian has reached the utmost height of his finery. This, however, is a precarious splendour; the ear becomes more and more unfit to support the burden, when at length some accident, the branch of a tree, or even a twitch by a waggish comrade, lays at his feet all his decorations, with the portion of the flesh to which they were attached. Weld saw very few who had preserved this organ through life. The adjustment of the hair, again, is an object of especial study. As already observed, the greater part is generally eradicated, leaving only a tuft, varying in shape and place according to taste and national custom, but usually encircling the crown. This lock is stuck full of feathers, wings of birds, shells, and every kind of fantastic ornament. The women wear theirs long and flowing, and contrive to collect a considerable number of ornaments for it, as well as for their ears and dress.

But it is upon his skin that the American warrior chiefly lavishes his powers of embellishment. His taste in doing so is very different from ours. “While the European,” says Creuxius, “studies to keep his skin clean, and free from every extraneous substance, the Indian’s aim is that his, by the accumulation of oil, grease, and paint, may shine like that of a roasted pig. Soot scraped from the bottoms of kettles, the juices of herbs having a green, yellow, and above all, a vermilion tint, rendered adhesive by combination with oil and grease, are lavishly employed to adorn his person—or, according to our idea, to render it hideous. Black and red, alternating with stripes, are the favourite tints. Some blacken the face, leaving in the middle a red circle, including the upper lip and tip of the nose; others have a red spot on each ear, or one eye black and the other of a red colour. In war, the black tint is profusely laid on, the others being only employed to heighten its effect, and give to the countenance a terrific expression. M. De Tracy, when Governor of Canada, was told by his Indian allies, that, with his good-humoured face, he would never inspire his enemies with any degree of awe: they besought him to place himself under their brush, when they would soon make him such, that his very aspect would strike terror. The breast, arms, and legs are the seat of more permanent impressions, analogous to the tattooing of the South Sea Islanders. The colours are rather elaborately rubbed in, or fixed by slight incisions with needles and sharp-pointed bones. His guardian spirit, and the animal that forms the symbol of his tribe, are the first objects delineated. After this, every memorable exploit, and particularly the enemies whom he has slain and scalped, are diligently graven on some part of his figure; so that the body of an aged warrior contains the history of his life.

The means of procuring subsistence must always form an important branch of national economy. Writers taking a superficial view of savage life, and seeing how scanty the articles of food are, while the demand is naturally urgent, have assumed that the efforts to attain them must absorb his whole mind, and scarcely leave room for any other thought. But, on the contrary, these are to him very subordinate objects. To perform a round of daily labour, even though insuring the most ample provision for his wants, would be equally contrary to his inclination and supposed dignity. He will not deign to follow any pursuit which does not, at the same time, include enterprise, adventure, and excitement. Hunting, which the higher classes in the civilised parts of the world pursue for mere recreation, is almost the only occupation considered of sufficient importance to engage his attention. It is peculiarly endeared by its resemblance to war, being carried on with the same weapons, and nearly in the same manner. In his native state, the arrow was the favourite and almost exclusive instrument for assailing distant objects; but now the gun has nearly superseded it. The great hunts are rendered more animating, as well as more effectual, from being carried on in large parties, and even by whole tribes. The men are prepared for these by fasting, dreaming, and other superstitious observances, similar to those which we find employed in the anticipation of war. In such expeditions, too, contrivance and skill, as well as boldness and enterprise, are largely employed. Sometimes a circle is formed, when all the animals surrounded by it are pressed closer and closer till they are collected in the centre, and fall under the accumulated weight of weapons. On other occasions, they are driven to the margin of a lake or river, in which if they attempt to take refuge, canoes are ready to intercept them. Elsewhere a space is enclosed by stakes, only a narrow opening being left, which, by clamour and shouts, the game are compelled to enter, and thereby secured. In autumn and spring, when the ice is newly formed and slight, they are pushed upon it, and their legs breaking through, they are easily caught. In winter, when the snow begins to fall, traps are set, in which planks are so arranged, that the animal, in snatching at the bait, is crushed to death. Originally the deer, both for food and clothing, was the most valuable object of chase; but since the trade with Europeans has given such a prominent importance to furs, the beaver has in some degree supplanted it. In attacking this animal, great care is taken to prevent his escape into the water, on which his habitation always borders; and with this view, various kinds of nets and springes are employed. On some occasions, the Indians place themselves on the dyke which encloses his amphibious village. They then make an opening in it, when the inmates, alarmed by seeing the water flowing out, hasten to this barrier, where they encounter their enemies armed with all the instruments of destruction. At other times, when ice covers the surface of the pond, a hole is made, at which the animal comes to respire; he is then drawn out and secured.

The boar is a formidable enemy, which must be assailed by the combined force of the hunters, who are ranged in two rows, armed with bows or muskets: one of them advances and wounds him, and on being furiously pursued, he retreats between the files, followed in the same line by the animal, which is then overwhelmed by their united onset. In killing these quadrupeds, the natives seem to feel a sort of kindness and sympathy for their victim. On vanquishing a beaver or a bear, they celebrate its praises in a song; recounting those good qualities which it will never more be able to display, yet consoling themselves with the useful purposes to which its flesh and skin will be applied.

Of the animals usually tamed and rendered subservient to useful purposes, the Americans have only the dog, that faithful friend to man. Though his services in hunting are valuable, he is treated with no tenderness; but is left to roam about the dwelling, very sparingly supplied with food and shelter. A missionary who resided in a Huron village, represents his life as having been rendered miserable by these animals. At night they laid themselves on his person, for the benefit of the warmth; and whenever his scanty meal was set down, their snouts were always first in the dish. Dog’s flesh is eaten, and has even a peculiar sanctity attached to it: on all solemn festivals it is the principal meat, the use of which on such occasions seems to import some high and mysterious meaning.

But besides the cheering avocations of the chase, other means must be used to ensure the comfort and subsistence of the Indian’s family; all of which, however, are most ungenerously devolved upon the weaker sex. Women, according to Creuxius, serve them as domestics, as tailors, as peasants, and as oxen; and Long does not conceive that any other purposes of their existence are recognised, except those of bearing children and performing hard work. They till the ground, carry wood and water, build huts, make canoes, and fish; in which latter processes, however, and in reaping the harvest, their lords deign to give occasional aid. So habituated are they to such occupations, that when one of them saw a party of English soldiers collecting wood, she exclaimed that it was a shame to see men doing women’s work; and began herself to carry a load.

Through the services of this enslaved portion of the tribe, these savages are enabled to combine, in a certain degree, the agricultural with the hunting state, without any mixture of the pastoral, usually considered as intermediate. Cultivation, however, is limited to small spots in the immediate vicinity of the villages; and these being usually at the distance of sixteen or seventeen miles from each other, it scarcely makes any impression on the immense extent of forest.

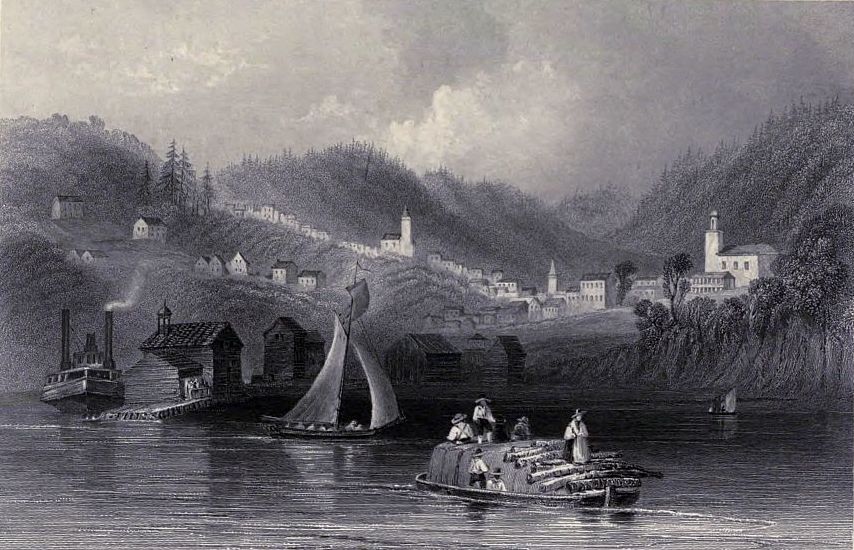

Georgeville.

The women, in the beginning of summer, after having burnt the stubble of the preceding crop, rudely stir the ground with a long crooked piece of wood; they then throw in grain, which is chiefly the coarse but productive species of maize peculiar to the continent. The nations in the south have a considerable variety of fruits; whereas those of Canada appear to have raised only “turnsoles, watermelons, and pompions.” Tobacco used to be grown largely; but that imported by Europeans is now universally preferred, and has become a regular object of trade. The grain, after harvest (which is celebrated by a festival), is lodged in large subterraneous stores lined with bark, where it keeps extremely well. Previous to being placed in these, it is sometimes thrashed; on other occasions, merely the ears are cut off and thrown in.

When first discovered by settlers from Europe, the degrees of culture were found to vary in different tribes. The Algonquins, who were the ruling people previous to the arrival of the French, wholly despised it, and branded as plebeian their neighbours by whom it was practised. In general, the northern clans, and those near the mouth of the St. Lawrence, depended almost solely on hunting and fishing; and when these failed, they were reduced to dreadful extremities, being often obliged to depend on the miserable resource of that species of lichen called tripe de roche.

The maize, when thrashed, is occasionally toasted on the coals, and sometimes made into a coarse kind of unleavened cake. But the most favourite preparation is that called sagamity, a species of pap formed after it has been roasted, bruised, and separated from the husk. It is insipid by itself, but when thrown into the pot along with the produce of the chase, it enriches the soup or stew, one of the principal dishes at their feasts. They never eat victuals raw, but rather over-boiled; nor have they yet been brought to endure French ragouts, salt, pepper, or indeed any species of condiment. A chief, admitted to the Governor’s table, seeing the general use of mustard, was led by curiosity to take a spoonful and put it in his mouth. On feeling its violent effects, he made incredible efforts to conceal them, and escape the ridicule of the company; but severe sneezings, and the tears starting to his eyes, soon betrayed him, and raised a general laugh. He was then shown the manner in which it should be used; but nothing could ever induce him to allow the “boiling yellow,” as he termed it, to enter his lips.

The Indians are capable of extraordinary abstinence from food, in which they can persevere for successive days without complaint or apparent suffering. They even take a pride in long fasts, by which they prepare themselves for any great undertaking. Yet when once set down to a feast, their gluttony is described as enormous, and the capacity of their stomachs almost incredible. They will go from feast to feast, doing honour to each in succession. The chief giving the entertainment does not partake, but with his own hands distributes portions among the guests. On solemn occasions, it is the rule that every thing shall be eaten; nor does this obligation seem to be felt as either burdensome or unpleasant. In their native state, they were not acquainted with any species of intoxicating liquors; their love of ardent spirits being entirely consequent on their intercourse with Europeans.

The habitations of the Indians receive much less attention than the attire, or at least embellishment of their persons. Our countrymen, by common consent, give to them no better appellation than “cabins.” The bark of trees is the chief material both for the houses and boats; they peel it off with considerable skill, sometimes stripping a whole tree in one piece. This coating, spread, not unskilfully, over a framework of poles, and fastened to them by strips of tough rind, forms their dwellings. The shape, according to the owner’s fancy, resembles a tub, a cone, or a cart-shed, the mixture of which gives to the village a confused and chaotic appearance. Light and heat are admitted only by an aperture at the top, through which also the smoke escapes, after filling all the upper part of the mansion. Little inconvenience is felt from this by the natives, who, within doors, never think of any position except sitting or lying; but to Europeans, who must occasionally stand or walk, the abode is thereby rendered almost intolerable; and matters become much worse when rain or snow makes it necessary to close the roof. These structures are sometimes upwards of a hundred feet long; four of them occasionally compose a quadrangle, each open on the inside, and having a common fire in the centre. Formerly, the Iroquois had houses somewhat superior, adorned even with some rude carving; but these were burnt down by the French in successive expeditions, and have never been rebuilt in the same style. The Canadians in this respect seem to be surpassed by the Choktaws, Chickasaws, and other tribes in the south, and even by Sauks in the west, whose mansions Carver describes as constructed of well-hewn planks, neatly jointed, and each capable of containing several families.

In their expeditions, whether for war or hunting, which often lead them through desolate forests, several miles from home, the Indians have the art of rearing, with great expedition, temporary abodes. On arriving at their evening station, a few poles, meeting at top in form of a cone, are in half an hour covered with bark; and having spread a few pine branches within, by way of mattress, they sleep as on beds of down. Like the Esquimaux, they also understand how to convert snow into a material for building; and find it, in the depth of winter, the warmest and most comfortable. A few twigs, plaited together, secure the roof. Europeans in their Indian campaigns, have, in cases of necessity, used with advantage this species of bivouac.

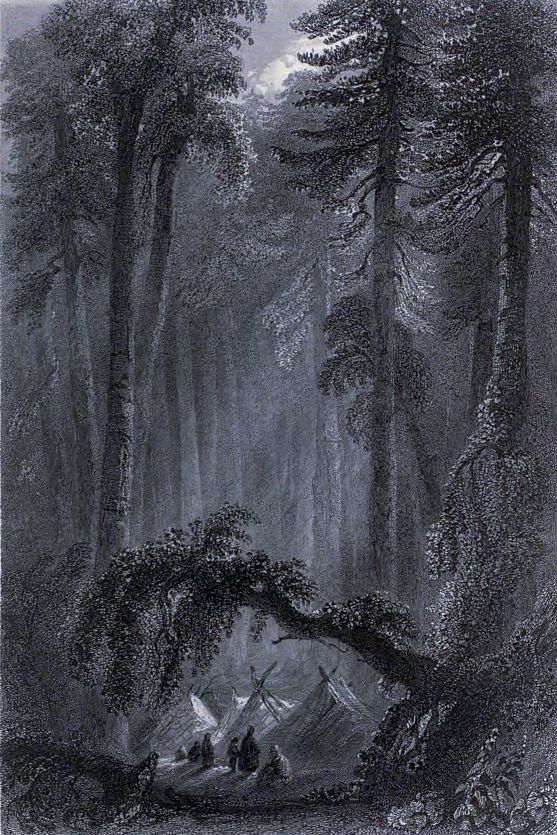

A Forest Scene.

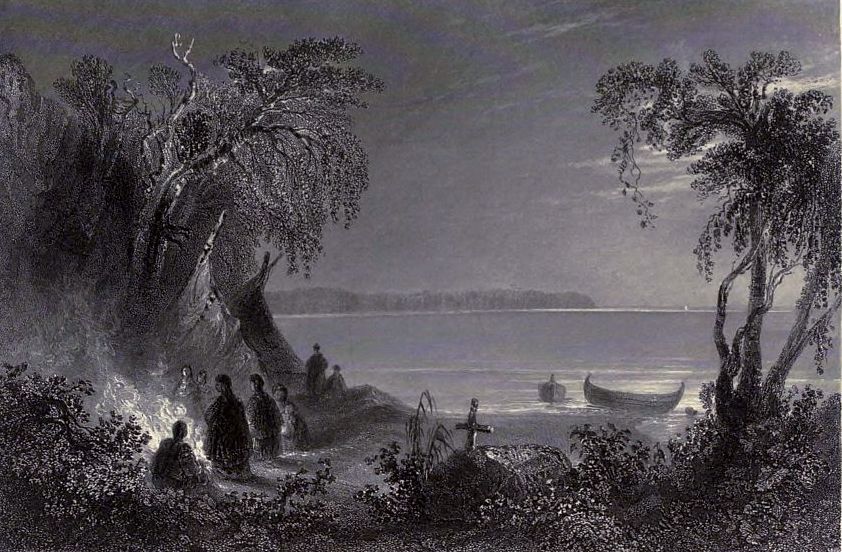

Canoe-building at Papper’s Island.

The furniture in these native huts is exceedingly simple. The chief articles are two or three pots or kettles for boiling their food, with a few wooden plates or spoons. The former, in the absence of metal, with which the inhabitants were unacquainted, were made of coarse earthenware that resisted the fire, and sometimes of a species of soft stone, which could be excavated with their rude hatchets. Nay, in some cases, their kitchen utensils were of wood, and the water made to boil by throwing in heated stones. Since their acquaintance with Europeans, the superiority of iron vessels has been found so decided, that they are now universally preferred. The great kettle or cauldron, employed only on high festivals associated with religion, war, or hunting, attracts even a kind of veneration, and potent chiefs have assumed its name as a title of honour.

Canoes, another fabric which the Indians construct very rudely, are yet adapted with considerable skill to their purpose. These are usually framed of the bark of a single tree, strengthened at the centre with ribs of tough wood. The ends are of bark only; but being curved upwards, are always above water, and thus remain perfectly tight. Our sailors can scarcely believe such nut-shells safe even on the smoothest waters, and see with surprise the natives guiding them amid stormy waves, when their very lightness and buoyancy preserve them from sinking. They have another quality of great advantage in the devious pursuits of the owners; being so extremely light, that they can be easily conveyed on the shoulder from one river or branch of a lake to another. One man, it is said, can carry on his back a canoe in which twelve persons can navigate with safety.

Having taken this minute survey of the physical condition of the Indians, we shall proceed to an examination of their social condition. The fundamental principle of their polity is, the complete independence of every individual, his right to do whatever he pleases, be it good or bad, nay, even though criminal or destructive. When any one announces an intention which is disagreeable to his neighbours, they dare not attempt to check him by reproach or coercion; these would only rivet his determination more strongly. Their only resource is to soothe him, like a spoiled child, by kind words, and especially by gifts. If, notwithstanding, he proceeds to wound or murder any one, the public look on without concern, though revenge is eagerly sought by the kindred of the injured person.

Notwithstanding this impunity, which in countries under the bonds of law, would be followed by the most dreadful consequences, it is somewhat mortifying to the pride of European civilization to learn, that there reigns a degree of tranquillity greater than the strictest police can preserve with us. The Indians are divided into a number of little nations or tribes, fiercely hostile to each other but whose members are bound among themselves by the strictest union. The honour and welfare of the clan supply their ruling principle, and are cherished with an ardour not surpassed in the most brilliant eras of Greek or Roman patriotism.

This national attachment forms a social tie, linking the members to each other, and rendering exceedingly rare, not only deeds of violence, but even personal quarrels; and banishing entirely that coarse and abusive language which is so prevalent among the vulgar in more enlightened communities. This feeling, added to the sentiment of dignity and self-command considered suitable to the character of a warrior, renders their deportment exceedingly pleasing. They are completely free from that false shame which is termed mauvaise honte. When seated at table with Europeans of the highest rank, they retain the most thorough self-possession; and at the same time, by carefully observing the proceedings of the other guests, they avoid all awkwardness in their manners.

The generosity of the Indian in relieving the necessities of others of the tribe, scarcely knows any bounds, and only stops short of an absolute community of goods. No member of a tribe can be in the least danger of starving, if the rest have wherewithal to supply him. Children rendered orphans by the casualties to which savage life is subject, are immediately taken in charge by the nearest relative, and supplied with every thing needful, as abundantly as if they were his own. Nothing gives them a more unfavourable opinion of the French and English, than to see one portion revelling in abundance while the other suffers the extremity of want; but when they are told that for want of these accommodations, men are seized by their fellow-creatures and immured in dungeons, such a degree of barbarism appears to them almost incredible. Whole tribes, when obliged by the vicissitudes of war to seek refuge among their neighbours, are received with unbounded hospitality; habitations and lands are assigned to them, and they are treated by their new friends, in every respect, as part of themselves. It may, however, be observed, that as such an accession of numbers augments the military strength of the tribe, there may be a mixture of policy in this cordial reception.

In consequence of this spirit of order and internal union, the unbounded personal freedom which marks their social condition seldom breaks out into such crimes as would disturb the public peace. Its greatest evil, of which we shall see repeated instances, is, that individuals, actuated by a spirit of revenge or daring enterprise, think themselves justified in surprising and murdering a hated adversary. From this cause, every treaty between the tribes is rendered precarious; though, as each is aware of these lawless propensities, room is left for mutual explanation, so that particular outrages may not involve a general war. This circumstance leads us to notice, that the favourable aspect presented by the interior of these communities can by no means warrant any conclusion as to the superiority of savage life, when compared with civilized man. On the contrary, the most perfect form of government devised by the human being in the state of nature has never been exempted from those feelings of relentless enmity and continual fear with which bordering nations regard each other. These, as will appear in the sequel, often compel to the most direful crimes; but, at present, we shall proceed with our survey of their domestic usages.

Some writers have denied that there exists among the Indians any thing that can properly be termed a matrimonial union. This, however, seems only a prejudice, in consequence of there not being any regular ceremony, as with us. The man, it appears, after having made an arrangement with the parent of his bride, takes her home, and they live in every respect as husband and wife. The mode of courtship among several of the tribes is singular:—the wooer, attended often by several comrades, repairs at midnight to his fair one’s apartment, and there twitches her nose. If she be inclined to listen to his suit, she rises; otherwise she must depart. Though this visit be so very unseasonable, it is said to be rarely accompanied with any impropriety. The missionaries, however, did not think it right to sanction such freedoms in their converts.

The preliminary step is in this manner taken with the lady, but the decision still rests with the father, to whom the suitor now applies. Long has given no unpleasing specimen of the address:—“Father, I love your daughter; will you give her to me, that the small roots of her heart may entangle with mine, so that the strongest wind that blows may never separate them?” He offers at the same time a handsome present, the acceptance of which is considered as sealing the union. Considerable discrepancy prevails in the descriptions, and apparently in the practice, as applied to different tribes; yet, on the whole, great reserve and propriety seem to mark this intercourse.

The young men of the Five Nations valued themselves highly for their correct conduct toward the other sex. Of numerous female captives who fell into their hands during a long series of wars, though some were possessed of great personal beauty, no one had to complain that her honour was exposed to the slightest danger. The girls themselves are not always quite so exemplary; but their failures are viewed with indulgence, and form no obstacle to marriage. Once united by that tie, however, a strict fidelity is expected, and commonly observed. The husband, generally speaking, is not jealous, except when intoxicated; but when his suspicions are really excited regarding the conduct of his partner, he is very indignant, beats her, bites off her nose, and dismisses her in disgrace.

There are occasional instances of a divorce being inflicted without any assigned reason; but such arbitrary proceeding is by no means frequent. As the wife performs the whole of the labour, and furnishes a great part of the subsistence, she is usually considered too valuable a possession to be rashly parted with. In some cases, the domestic drudges become even an object of dispute and competition. A missionary mentions a woman, who, during the absence of her husband, formed a new connexion. Her first partner having returned, without being agitated by any delicate sensibilities, demanded her back. The question was referred to a chief, who could contrive no better scheme than that of placing her at a certain distance from both, and decreeing that he who should first reach her should have her. “Thus,” says he, “the wife fell to him who had the best legs.”

With regard to polygamy, the usual liberty is claimed; and by the chiefs in the west and the south it is indulged to a considerable extent, but among the tribes on the lakes the practice is rare and limited. When it does occur, the man very commonly marries his wife’s sister, and even her whole family, we may suppose, that the household may be thereby rendered more harmonious. The Indian is said never to betray the slightest tenderness towards his wife or children. If he meets them on his return from a distant expedition, he proceeds, without taking the slightest notice, and seats himself in his cabin as if he had not been a day absent. Yet his exertions for their welfare, and the eagerness with which he avenges their wrongs, testify that this apparent apathy springs only from pride, and a fancied sense of decorum. It is equally displayed with regard to his most urgent wants. Though he may have been without food during several days, and enters a neighbour’s house, nothing can make him stoop to ask for a morsel.

The rearing (for it cannot be called the education) of children is chiefly arranged so that it may cost the parents the least possible trouble, in addition to the labour of procuring them subsistence. The father is either engrossed by war and hunting, or resigned to total indolence; while the mother, oppressed by various toils, cannot devote much time to the cares of nurture. The infant, therefore, being fastened with pieces of skin to a board spread with soft moss, is laid on the ground, or suspended to a branch of a tree, where it swings, as in a cradle—an expedient which is so carefully adopted as scarcely ever to be attended with accident. As soon as the creatures are able to crawl on hands and feet, they are allowed to move about every part of the house and vicinity, like a cat or dog. Their favourite resort is the border of the river or lake, to which an Indian village is usually adjacent, and where, in summer, they are seen all day long sporting like fishes. As reason dawns, they enjoy, in the most ample degree, that independence which is held the birthright of the tribe; for, whatever extravagances they may indulge in, the parents never take any steps to restrain or chastise them. The mother only ventures to give her daughter some delicate reproach, or throws water in her face, which is said to produce a powerful effect. The youths, however, without any express instructions, soon imbibe the spirit of their forefathers. Every thing they see, the tales which they hear, inspire them with the ardent desire to become great hunters and warriors. Their first study, their favourite sport, is to bend the bow, to wield the hatchet, and practise all those exercises which are to be their glory in after life. As manhood approaches, they spontaneously assume that serious character, that studied and stately gravity, of which the example has been set by their elders.

The intellectual character of the American savage presents some striking peculiarities. Considering his unfavourable condition, he, of all other human beings, might seem doomed to make the nearest approach to the brute; while, in point of fact, without any aid from letters or study, many of the higher faculties of his mind are developed in a very remarkable degree. He displays a decided superiority over the uninstructed labourer in a civilized community, whose mental energies are benumbed amid the daily round of mechanical occupation. The former spends a great part of his life in arduous enterprises, where much contrivance is requisite, and whence he must often extricate himself by presence of mind and ingenuity. His senses, particularly those of seeing and smelling, have acquired, by practice, an almost preternatural acuteness. He can trace an animal or a foe by indications which, to a European eye, would be wholly imperceptible; and in his wanderings he gathers a minute acquaintance with the geography of the countries which he traverses. He can even draw a rude outline of them, by applying a mixture of charcoal and grease to prepared skins; and on seeing a regular map, he soon understands its construction, and readily finds out places. His facility in discovering the most direct way to spots situated at the distance of hundreds of miles, and known, perhaps, only by the report of his countrymen, is truly astonishing. It has been ascribed by some to a mysterious and supernatural instinct, but it appears to be achieved by merely observing the different aspect of the trees or shrubs, when exposed to the north or south; as also the position of the sun, which he can point out, although hidden by clouds. Even where there is a beaten track, if at all circuitous, he strikes directly through the woods, and reaches his destination by the nearest possible line.

Other faculties of a higher order are developed by the scenes amid which the life of savages is spent. They are divided into a number of little communities, between which are actively carried on all the relations of war, negotiation, treaty, and alliance. As mighty revolutions, observes an eloquent writer, take place in these kingdoms of wood and cities of bark, as in the most powerful civilized states. To increase the influence and extend the possessions of their own tribe—to humble, and, if possible, destroy those hostile to them—are the constant aims of every member of those little commonwealths. For these ends, not only deeds of daring valour are achieved, but schemes are deeply laid, and pursued with the most accurate calculation. There is scarcely a refinement in European diplomacy to which they are strangers. The French once made an attempt to crush the confederacy of the Five Nations, by attacking each in succession; but as they were on their march against the first tribe, they were met by the deputies of the other, who offered their mediation, intimating, that if it were rejected, they would make common cause with the one threatened. That association, also, showed that they completely understood how to employ the hostility, which prevailed between their enemy and the English, for promoting their own aggrandizement. Embassies, announced by the calumet of peace, are constantly passing from one tribe to another.

The same political circumstances develop, in an extraordinary degree, the powers of oratory; for nothing of any importance is transacted without a speech. On every emergency a council of the tribe is called, when the aged and wise hold long deliberations for the public weal. The functions of orator among the Five Nations, had even become a separate profession, held in equal or higher honour than that of the warrior; and each clan appointed the most eloquent of their number to speak for them in the public council. Nay, there was a general orator for the whole confederacy, who could say to the French governor, “Ononthio, lend thine ear—I am the mouth of all the country; you hear all the Iroquois in hearing my word.” Decanesora, their speaker, at a later period, was greatly admired by the English, and his bust was thought to resemble that of Cicero. In their diplomatic discourses, each proposition is prefaced by the delivery of a belt of wampum, of which what follows is understood to be the explanation, and which is to be preserved as a record of the conference. The orator does not express his proposals in words only, but gives to every sentence its appropriate action. If he threatens war, he wildly brandishes the tomahawk; if he solicits alliance, he twines his arms closely with those of the chief whom he addresses; and if he invites friendly intercourse, he assumes all the attitudes of one who is forming a road in the Indian manner, by cutting down the trees, clearing them away, and carefully removing the leaves and branches. To a French writer, who witnessed the delivery of a solemn embassy, it suggested the idea of a company of actors performing on a stage. So expressive are their gestures, that negotiations have been conducted, and alliances concluded between petty states and communities, who understood nothing of one another’s language.

The composition of the Indian orators is studied and elaborate. The language of the Iroquois is even held to be susceptible of an Attic elegance, which few can attain so fully as to escape all criticism. It is figurative in the highest degree, every notion being expressed by images addressed to the senses. Thus, to throw up the hatchet, or to put on the great cauldron, is to begin a war; to throw the hatchet to the sky, is to wage open and terrible war; to take off the cauldron, or to bury the hatchet, is to make peace; to plant the tree of peace on the highest mountain of the earth, is to make a general pacification. To throw a prisoner into the cauldron, is to devote him to torture and death; to take him out, is to pardon and receive him as a member of the community. Ambassadors coming to propose a full and general treaty, say, “We rend the clouds asunder, and drive away all darkness from the heavens, that the sun of peace may shine with brightness over us all.” On another occasion, referring to their own violent conduct, they said, “We are glad that Assarigoa will bury in the pit what is past; let the earth be trodden hard over it; or rather let a strong stream run under the pit to wash away the evil.” They afterwards added, “We now plant a tree, whose top will reach the sun, and its branches spread far abroad; and we shall shelter ourselves under it, and live in peace.” To send the collar underground, is to carry on a secret negotiation; but when expressing a desire that there might be no duplicity or concealment between them and the French, they said, that “they wished to fix the sun in the top of the heaven, immediately above that pole, that it might beat directly down, and leave nothing in obscurity.” In pledging themselves to a firm and steady peace, they declared that they would not only throw down the great war cauldron, and cause all the water to flow out, but would break it in pieces. This disposition to represent every thing by a sensible object extends to matters the most important. One powerful people assumed the appellation of Foxes, while another gloried in that of Cats. Even when the entire nation bore a different appellation, separate fraternities distinguished themselves as the tribe of the Bear, the Tortoise, and the Wolf. They did not disdain a reference even to inanimate things. The Black Cauldron was at one time the chief warrior of the Five Nations; and Red Shoes was a person of distinction, well known to Long the traveller. When the chiefs concluded treaties with Europeans, their signature consisted in a picture, often tolerably well executed, of the beast or object after which they chose to be named.

The absence, among these tribes, of any written or even pictorial mode of recording events, was supplied by the memories of their old men, which were so retentive, that a certain writer calls them living books. Their only remembrancer consisted in the wampum belts, of which one was appropriated to each division of a speech or treaty, and had, seemingly, a powerful effect in calling it to recollection. On the close of the transaction, these were deposited as public documents, to be drawn forth on great occasions, when the orators, and even the old women, could repeat verbatim the passage to which each referred. Europeans were thus enabled to collect information concerning the revolutions of different tribes, for several ages preceding their own arrival.

The earliest visitors of the New World, on seeing among the Indians neither priests, temples, idols, nor sacrifices, represented them as a people wholly destitute of religious opinions. Closer inquiry, however, showed that a belief in the spiritual world, however imperfect, had a commanding influence over almost all their actions. Their creed includes even some lofty and pure conceptions. Under the title of the Great Spirit, the Master of Life, the Maker of Heaven and Earth, they distinctly recognise a supreme ruler of the universe, and an arbiter of their destiny. A party of them, when informed by the missionaries of the existence of a being of infinite power, who had created the heavens and the earth, with one consent exclaimed, “Atahocan! Atahocan!” that being the name of their principal deity. According to Long, the Indians among whom he resided ascribe every event, propitious or unfortunate, to the favour or anger of the Master of Life. They address him for their daily subsistence; they believe him to convey to them presence of mind in battle; and amid tortures, they thank him for inspiring them with courage. Yet, though this one elevated and just conception is deeply graven on their minds, it is combined with others which show all the imperfection of unassisted reason in attempting to think rightly on this great subject. It may even be observed, that the term, rendered into our language, “Great Spirit” does not really convey the idea of an immaterial nature. It imports with them merely some being possessed of lofty and mysterious powers, and in this sense is applied to men, and even to animals. The brute creation, which occupies a prominent place in all their ideas, is often viewed by them as invested, to a great extent, with supernatural powers—an extreme absurdity, which, however, they share with the civilized creeds of Egypt and India.

When the missionaries, on their first arrival, attempted to form an idea of the Indian mythology, it appeared to them extremely complicated, more especially because those who attempted to explain it had no fixed opinions. Each man differed from his neighbour, and at another time from himself; and when the discrepancies were pointed out, no attempt was made to reconcile them. The southern tribes, who had a more settled faith, are described by Adair as intoxicated with spiritual pride, and denouncing even their European allies as “the accursed people.” The native Canadian, on the contrary, is said to have been so little tenacious, that he would at any time renounce all his theological errors for a pipe of tobacco, though, as soon as it was smoked, he immediately relapsed. An idea was found prevalent respecting a certain mystical animal called Meson, or Messessagen, who, when the earth was buried in water, had drawn it up and restored it. Others spoke of a contest between the hare, the fox, the beaver, and the seal, for the empire of the world. Among the principal nations of Canada, the hare is thought to have attained a decided preeminence, and hence the Great Spirit and the Great Hare are sometimes used as synonymous terms. What should have raised this creature to such distinction seems rather unaccountable, unless it were that its extreme swiftness might appear something supernatural. Among the Ottawas alone the heavenly bodies become an object of veneration: the sun appears to rank as their supreme deity.

To dive into the abyss of futurity has always been a favourite object of superstition. It has been attempted by various means, but the Indian seeks it chiefly through his dreams, which always bear with him a sacred character. Before engaging in any high undertaking, especially in hunting or war, the dreams of the principal chiefs are carefully watched, and studiously examined; and according to the interpretation their conduct is guided. A whole nation has been set in motion by the sleeping fancies of a single man. Sometimes a person imagines in his sleep that he has been presented with an article of value by another, who then cannot, without impropriety, leave the omen unfulfilled. When Sir William Johnson, during the American war, was negotiating an alliance with a friendly tribe, the chief confidentially disclosed, that, during his slumbers, he had been favoured with a vision of Sir William bestowing upon him the rich laced coat which formed his full dress. The fulfilment of this revelation was very inconvenient; yet, on being assured that it positively occurred, the English commander found it advisable to resign his uniform. Soon after, however, he unfolded to the Indian a dream with which he had himself been favoured, and in which the former was seen presenting him with a large tract of fertile land, most commodiously situated. The native ruler admitted that, since the vision had been vouchsafed, it must be realized, yet earnestly proposed to cease this mutual dreaming, which he found had turned much to his own disadvantage.

The manitou is an object of peculiar veneration; and the fixing upon this guardian power is not only the most important event in the history of a youth, but even constitutes his initiation into active life. As a preliminary, his face is painted black, and he undergoes a severe fast, which is, if possible, prolonged for eight days. This is preparatory to the dream in which he is to behold the idol destined ever after to afford him aid and protection. In this state of excited expectation, and while every nocturnal vision is carefully watched, there seldom fails to occur to his mind something which, as it makes a deep impression, is pronounced his manitou. Most commonly it is a trifling and even fantastic article; the head, beak, or claw of a bird, the hoof of a cow, or even a piece of wood. However, having undergone a thorough perspiration in one of their vapour-baths, he is laid on his back, and a picture of it is drawn upon his breast by needles of fish-bone dipt in vermilion. A good specimen of the original being produced, it is carefully treasured up; and to it he applies in every emergency, hoping that it will inspire his dreams, and secure to him every kind of good fortune. When, however, notwithstanding every means of propitiating its favour, misfortunes befall him, the manitou is considered as having exposed itself to just and serious reproach. He begins with remonstrances, representing all that has been done for it, the disgrace it incurs by not protecting its votary, and finally, the danger that in case of repeated neglect, it may be discarded for another. Nor is this considered merely as an empty threat; for if the manitou is judged incorrigible, it is thrown away, and by means of a fresh course of fasting, dreaming, sweating, and painting, another is installed, from whom better success may be hoped.

The absence of temples, worship, sacrifices, and all the observances to which superstition prompts the untutored mind, is a remarkable circumstance, and, as we have already remarked, led the early visitors to believe that the Indians were strangers to all religious ideas; yet the missionaries found room to suspect that some of their great feasts, in which every thing presented must be eaten, bore an idolatrous character, and were held in honour of the Great Hare. The Ottawas, whose mythological system seems to have been the most complicated, were wont to keep a regular festival to celebrate the beneficence of the sun; on which occasion, the luminary was told that this service was in return for the good hunting he had procured for his people, and as an encouragement to persevere in his friendly cares. They were also observed to erect an idol in the middle of their town, and sacrifice to it; but such ceremonies were by no means general. On first witnessing christian worship, the only idea suggested by it was that of their asking some temporal good, which was either granted or refused. The missionaries mention two Hurons, who arrived from the woods soon after the congregation had assembled. Standing without, they began to speculate what it was the white men were asking, and then whether they were getting it. As the service continued beyond expectation, it was concluded they were not getting it; and as the devotional duties still proceeded, they admired the perseverance with which this rejected suit was urged. At length, when the vesper hymn began, one of the savages observed to the other—“Listen to them now in despair, crying with all their might.”

The grand doctrine of a life beyond the grave, was, among all the tribes of America, most deeply cherished, and most sincerely believed. They had even formed a distinct idea of the region whither they hoped to be transported, and of the new and happier mode of existence, free from those wars, tortures, and cruelties, which throw so dark a shade over their lot upon earth; yet their conceptions on this subject were by no means either exalted or spiritualized. They expected simply a prolongation of their present life, and enjoyments under more favourable circumstances, and with the same objects, furnishing greater choice and abundance. In that brighter land the sun ever shines unclouded, the forests abound with deer, the lakes and rivers with fish—benefits which are farther enhanced in their imagination by a faithful wife and dutiful children. They do not reach it however, till after a journey of several months, and encountering various obstacles—a broad river, a chain of lofty mountains, and the attack of a furious dog. This favoured country lies far in the west, at the remotest boundary of the earth, which is supposed to terminate in a steep precipice, with the ocean rolling beneath. Sometimes, in the too eager pursuit of game, the spirits fall over, and are converted into fishes. The local position of their paradise appears connected with certain obscure intimations received from their wandering neighbours of the Mississippi, the Rocky Mountains, and the distant shores of the Pacific. This system of belief labours under a great defect, inasmuch as it scarcely connects felicity in the future world with virtuous conduct in the present. The one is held to be simply a continuation of the other; and under this impression, the arms, ornaments, and every thing that had contributed to the welfare of the deceased, are interred along with him. This supposed assurance of a future life, so conformable to their gross habits and conceptions, was found by the missionaries a serious obstacle, when they attempted to allure them by the hope of a destiny, purer and higher, indeed, but less accordant with their untutored conceptions. Upon being told that, in the promised world, they would neither hunt, eat, drink, nor marry a wife, many of them declared that, far from endeavouring to reach such an abode, they would consider their arrival there as the greatest calamity. Mention is made of a Huron girl, whom one of the christian ministers was endeavouring to instruct, and whose first question was, what she would find to eat? The answer being “nothing,” she then asked what she would see? and being informed that she would see the Maker of heaven and earth, she expressed herself much at a loss what she could have to say to him. Many not only reject this destiny for themselves, but were indignant at the efforts made to decoy their children after death into so dreary and comfortless a region.

Another sentiment, congenial with that now described, is most deeply rooted in the mind of the Indians—this is reverence for the dead; with which Chateaubriand, though, perhaps, somewhat hastily, considers them more deeply imbued than any other people. During life they are by no means lavish of their expressions of tenderness; but on the approach of the hour of final separation, it is displayed with extraordinary force. When any member of a family becomes seriously ill, all the resources of magic and medicine are exhausted in order to procure his recovery. When the fatal moment arrives, all the kindred burst into loud lamentations, which continue till some person, possessing the requisite authority, desires them to cease. These expressions of grief, however, are renewed for a considerable time, at sunrise and sunset. After three days the funeral takes place, when all the provisions which the family can procure are expended in a feast, to which the neighbours are generally invited; and, although on all solemn occasions it is required that every thing should be eaten, the relations do not partake. These last cut off their hair, cover their heads, paint their faces of a black colour, and continue long to deny themselves every species of amusement. The deceased is then interred with his arms and ornaments, his face painted, and his person attired in the richest robes which they can furnish. It was the opinion of one of the early missionaries, that the chief object of the Hurons, in their traffic with the French, was to procure materials for honouring their dead; and as a proof of this, many of them have been seen shivering, half naked, in the cold, while their hut contained rich robes to be wrapped round them after their decease. The body is placed in the tomb in an upright posture; and skins are carefully spread round it, so that no part may touch the earth. This, however, is by no means the final ceremony, being followed by another far more solemn and singular. Every eighth, tenth, or twelfth year, according to the custom of the different nations, is celebrated the festival of the dead; and, till then, the souls are supposed to hover round their former tenement, and not to depart for their final abode in the west. On this occasion the people march in procession to the places of interment, open the tombs, and, on beholding the mortal remains of their friends, continue sometime fixed in mournful silence. The women then break out into loud cries, and the party begin to collect the bones, removing every remnant of flesh; the remains are then wrapped in fresh and valuable robes, and conveyed, amid continued lamentation, to the family cabin. A feast is then given, followed during several days by dances, games, and prize combats, to which strangers often repair from a great distance. This mode of celebration certainly accords very ill with the sad occasion; yet the Greek and Roman obsequies were solemnized in a similar manner—nay, in many parts of Scotland, till very recently, they were accompanied by festival, and often by revelry. The relics are then carried to the council-house of the nation, where they are hung for exhibition along the walls, with fresh presents destined to be interred along with them. Sometimes they are even displayed from village to village. At length, being deposited in a pit, previously dug in the earth, and lined with the richest furs, they are finally entombed. Tears and lamentations are again lavished, and during a few days, food is brought to the place. The bones of their fathers are considered by the Indians the strongest ties to their native soil; and when calamity forces them to quit it, these mouldering fragments are, if possible, conveyed along with them.

Under the head of religious rites we may include medicine, which is almost entirely within the domain of superstition. The great warmth of affection which, amid their apparent apathy, the natives cherish for each other, urges them, when their friends are seriously ill, to seek with the utmost eagerness for a remedy; an order of men has thus arisen, entirely different from the rest of society, uniting the characters of priests, physicians, sorcerers, and sages. Nor are they quite strangers to some branches of the healing art: in external hurts or wounds, the cause of which is obvious, they apply various simples of considerable power, chiefly drawn from the vegetable world. Chateaubriand enumerates the ginseng of the Chinese, the sassafras, the three-leaved hedisaron, and a tall shrub called bellis, with decoctions from which they cure wounds and ulcers in a surprising manner. With sharp-pointed bones they scarify inflamed or rheumatic parts; and shells of gourds, filled with combustible matters, serve instead of cupping-glasses. They learned the art of bleeding from the French, but employed it sometimes rashly and fatally, by opening the vein in the forehead. They now understand it better; but their favourite specific in all internal complaints is the vapour-bath. To procure this, a small hut or shed is framed of bark, or branches of trees, covered with skins, and made completely tight on every side, leaving only a small hole through which the patient is admitted. By throwing red hot stones into a pot of water, it is made to boil, and thus emit a warm steam, which, filling the hut, throws the patient into a most profuse perspiration. When he is completely bathed in it, he rushes out, even should it be in the depth of winter, and throws himself into the nearest pond or river; and this exercise, which we should be apt to think sufficient to produce death, is proved by their example, as well as that of the Russians, to be safe and salutary. As a very large proportion of their maladies arise from cold and obstructed perspiration, this remedy is by no means ill chosen. They attach to it, however, a supernatural influence, calling it the sorcerer’s bath, and employ it not only in the cure of diseases, but in opening their minds whenever they are to hold a council on great affairs, or to engage in any important undertaking.

All cases of internal malady, or of obscure origin, are ascribed, without hesitation, to the secret agency of malignant powers, or spirits. The physician, therefore, must then invest himself with his mystic character, and direct all his efforts against these invisible enemies. His proceedings are various, and prompted, seemingly, by a mixture of delusion and imposture. On his first arrival, he begins to sing and dance round the patient, invoking his god with loud cries. Then, pretending to search out the seat of the enchantment, he feels his body all over, till cries seem to indicate the bewitched spot. He then rushes upon it like a madman, or an enraged dog, tears it with his teeth, and often pretends to show a small bone, or other object, which he has extracted, and in which the evil power had been lodged. His disciples, next day, renew the process, and the whole family join in the chorus; so that, setting aside the disease, a frame of iron would appear necessary to withstand the remedies. Another contrivance is, to surround the cabin with men of straw, and wooden masks of the most frightful shapes, in hopes of scaring away the mysterious tormentor. Sometimes a painted image is formed, which the doctor pierces with an arrow, pretending that he has thereby vanquished the evil spirit. On other occasions, he professes to discover a mysterious desire, which exists in the patient unknown to himself, for some particular object; and this, however distant or difficult of attainment, the poor family strain all their efforts to procure. It is alleged, that when the malady appears hopeless, he fixes upon something completely beyond reach, the want of which is then represented as the cause of death. The deep faith reposed in these preposterous remedies caused to the missionaries much difficulty, even with their most intelligent converts. When a mother found one of her children dangerously ill, her pagan neighbours came round, and assured her that if she would allow it to be blown upon, and danced, and howled round in the genuine Indian manner, there would be no doubt of a speedy recovery. They exhorted her to take it into the woods, where the black-robes, as they called the Christian priests, would not be able to find her. The latter could not fully undeceive their disciples, because in that less enlightened age, they themselves were impressed with the notion that the magicians communicated with, and derived aid from the prince of darkness; all they could do, therefore, was to exhort them resolutely to sacrifice any benefit that might be derived from so unholy a source. This, however, was a hard duty; and they record with pride the example of a Huron wife, who, though much attached to her husband, and apparently convinced that he could be cured by this impious process, chose rather to lose him. In other respects, the missionaries suffered from the superstitious creed of the natives, who, even when unconverted, believed them to possess supernatural powers, which it was suspected they sometimes employed to introduce the epidemic diseases with which the country was from time to time afflicted. They exclaimed, it was not the demons that made so many die—it was prayer, images, and baptism; and when a severe pestilential disorder followed the murder of a Frenchman, who fell by their hands, they imagined that the priests were thus avenging the death of their countryman.

We have still to describe the most prominent object of the Indian’s passions and pursuits—his warfare. It is that which presents him under the darkest aspect, effacing almost all his fine qualities, and assimilating his nature to that of fiends. While the most cordial union reigns between the members of each tribe, they have neighbours whom they regard with the deepest enmity, and for whose extermination they continually thirst. The intense excitement which war affords, and the glory which rewards its achievements, probably give the primary impulse; but after hostilities have begun, the feeling which keeps them alive is revenge. Every Indian who falls into the power of an enemy, and suffers the dreadful fate to which the vanquished are doomed, must have his ghost appeased by a victim from that hostile race. Thus every contest generates another, and a more deeply embittered one. Nor are they strangers to those more refined motives which urge civilized nations to take arms—the extension of their boundaries, an object pursued with ardent zeal, and the power of their tribe, which last they seek to promote by incorporating in its ranks the defeated bands of their antagonists. Personal dislike and the love of distinction often impel individuals to make inroads into a hostile territory, even contrary to the general wish; but when war is to be waged by the whole nation, more enlarged views, connected with its interest and aggrandizement, guide the decision. To most savages, however, long-continued peace becomes irksome and unpopular; and the prudence of the aged can with difficulty restrain the fire of the young, who thirst for adventure.

As soon as the determination has been formed, the war-chief, to whom the voice of the nation assigns the supremacy, enters on a course of solemn preparation. This consists not, however, in providing arms or supplies for the campaign; for these are comprised in the personal resources of each individual: he devotes himself to observances which are meant to propitiate or learn the will of the Great Spirit, who, when considered as presiding over the destinies of war, is named Areskoui. He begins by marching three times round his winter-house, spreading the great bloody flag, variegated with deep tints of black. As soon as the young warriors see this signal of death, they crowd around, listening to the oration by which he summons them to the field. “Comrades!” he exclaims, “the blood of our countrymen is yet unavenged; their bones lie uncovered; their spirits cry to us from the tomb. Youths, arise! anoint your hair, paint your faces, let your songs resound through the forest, and console the dead with the assurance that they shall be avenged. Youths! follow me, while I march through the war-path to surprise our enemies, to eat their flesh, drink their blood, and tear them limb from limb! We shall return triumphant; or, should we fall, this belt will record our valour!” The wampum, that grand symbol of Indian policy, is then thrown on the ground. Many desire to lift it, but this privilege is reserved for some chief of high reputation, judged worthy to fill the post of second in command. The leader now commences his series of mystic observances. He is painted all over black, and enters on a strict fast, never eating, or even sitting down, till after sunset. From time to time he drinks a decoction of consecrated herbs, with a view of giving vivacity to his dreams, which are carefully noted, and submitted to the deliberation of the sages and old men. When a warlike spirit is in the ascendant, it is understood that either their tenor or their interpretation betokens success. The powerful influence of the vapour-bath is also employed. After these solemn preliminaries, a copious application of warm water removes the deep black coating, and he is painted afresh in bright and varied colours, among which red predominates. A huge fire is kindled, whereon is placed the great war cauldron, into which every one present throws something; and if any allies, invited by a belt of wampum and bloody hatchet to devour the flesh and drink the blood of the enemy, have accepted the summons, they send some ingredients to be also cast in. The chief then announces the enterprise by singing a war-song, never sounded but on such occasions; and his example is followed by all the warriors, who join in the military dance, recounting their former exploits, and dilating on those they hope to achieve. They now proceed to arm, suspending the bow and quiver, or more frequently the musket, from the shoulder, the hatchet or tomahawk from the hand, while the scalping-knife is stuck in the girdle. A portion of parched corn, or sagamity, prepared for the purpose, is received from the women, who frequently bear it to a considerable distance. But the most important operation is the collection of the manitous, or guardian spirits, to be placed in a common box, which, like the Hebrew ark, is looked up to as a protecting power.

The females, during these preparations, have been busily negotiating for a supply of captives, on whom to wreak their vengeance, and appease the shades of their fallen kindred; sometimes, also, with the more merciful view of supplying their places. Tenderer feelings arise as the moment approaches when the warriors must depart—perhaps to return no more! and, it may be, to endure the same dreadful fate which they are imprecating on others. The leader having made a short harangue, commences the march, singing his war-song, while the others follow, at intervals sounding the war-whoop. The women accompany them some distance, and when they must separate, they exchange endearing names, and express the most ardent wishes for a triumphant return; while each party receives and gives some object which has been long worn by the other, as a memorial of this tender parting.