Title: Harper's Young People, June 7, 1881

Author: Various

Release date: December 19, 2014 [eBook #47699]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| Vol. II.—No. 84. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | PRICE FOUR CENTS. |

| Tuesday, June 7, 1881. | Copyright, 1881, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

Author of "The Moral Pirates," etc.

The sound of oars could be distinctly heard, and the boys listened breathlessly. The night was so dark that they could see but a little distance from their own vessel, and could only judge of the distance of the invisible row-boat, and the direction in which it was moving, by the sound. As they stood shivering in the cold mist, expecting every moment to be attacked by thieves, they could not be said to be enjoying themselves. They would have given a great deal to have been safe at home and in their warm beds. As they afterward acknowledged, they were a good deal frightened; and there are few men who, in the same circumstances, would not have felt that they were in a very awkward situation.

"You tell us what to do," whispered Tom to the Captain, "and we'll do it."

"If they come, we've got to fight," answered Charley; "for if we were to let them take our boat, we'd starve to death out here in the marshes."

The sound of the oars came nearer and nearer, and presently the boys caught a glimpse of a boat gliding through the water only a few rods away.

"Perhaps they won't see us," Harry whispered in Charley's ear.

At this moment the oars stopped, and a voice said, "Thar's that yacht belonging to them boys that I was telling you I see this mornin' down by Rockaway. Somebody must have piloted 'em, or they couldn't have got through the islands."

"Oh, go on," replied another voice. "We won't get to Amityville in half an hour if you stop to talk."

The oars resumed their regular dip; the row-boat disappeared in the darkness, and in a little while the silence was as complete as if there was no one within a league of the Ghost.

"Now we'll go to sleep again," said Tom, still speaking in a low voice; "though, come to think of it, my turn to watch must have come round by this time."

"It's just ten o'clock," replied Charley. "Well, we're more frightened than hurt; but the thieves may pay us a visit yet. When you call any of us, just remember that if you put your hand on a fellow's forehead, he will wake up cool and sensible; but if you shake him, he'll be very likely to jump, or sing out, or do something of the kind. Good-night all, and don't go to sleep on your watch, Tom."

Harry, Joe, and Charley crept back to their blankets, and prepared to sleep, while Tom, sitting on deck, tried to keep awake. What was very strange was that while Tom, whose duty it was to keep awake, grew horribly sleepy, the other boys, who had a right to go to sleep, found themselves as broad awake as they had ever been in their lives. No one spoke for fear of keeping his neighbor awake; but the frequency with which somebody rolled over, or drew a long and tired breath, showed that there were no sleepy boys in the Ghost's cabin. By-and-by Charley, whose hearing was very sharp, thought that he heard oars once more. Making his way softly on deck, he listened, and found that he was not mistaken. He woke Tom, who was sleeping serenely, and sent him to rouse the other boys; but they had already heard the whispered order of the Captain, and were on deck before they could be called.

"It may be another fisherman going home late," said Charley. "I wish they'd keep better hours, and not rouse people up at midnight. There, I see them. They're coming this way, I think."

A row-boat, approaching by a different channel from that which the fishermen had followed, was now dimly visible. She was rowed by two pair of sculls, and a third man could be seen sitting in the stern-sheets.

"Keep down out of sight, boys," whispered Charley. "Perhaps they'll say something if they think we're asleep."

"There she is; I see her," said one of the men, in a voice loud enough to be heard by the listening boys.

"Them boys are all asleep," said another man. "Row up to her easy, and we can dump 'em on to the meadow before they get waked up."

"Boat ahoy!" called out Charley, springing up. "Who are you, and what do you want?"

"We're the United States frigate Constitution," replied one of the men. "We want to hear you chaps say your catechism." So saying, the men resumed their oars, and rowed toward the Ghost.

"Keep off," cried Charley. "If you come near us, we will fire into you. I give you fair warning."

The men who were rowing stopped for a moment, but the man in the stern, ordering them to row on, fired a pistol, the bullet of which whistled over Tom's head, and made him "duck" in the most polite manner. On came the row-boat, but Charley, who had hastily pointed the gun, scratched a match, and stood sheltering the flame with his hand, and waiting for the sulphur to burn out, as coolly as if he were in his own room. In a few seconds the blue flame was succeeded by the bright glow of the burning wood, and touching the match to the priming, Charley stepped hastily back, while the explosion that followed sounded to the excited boys like the roar of a thirty-two-pounder.

One or two of the marbles hit the row-boat, for the rattle made by them was distinctly heard; but most of Charley's canister-shot flew over the heads of the men without touching them. They were, however, thoroughly alarmed, and putting the boat around, rowed rapidly away. Charley had dropped on his knees the instant after he had fired, and was now reloading with the utmost haste, ramming down a handful of nails that he drew from his pocket, where he had kept them in reserve, wrapped in a torn piece of his handkerchief.

"Hurrah!" shouted Harry. "We've beat 'em. I only wish we had sunk their boat."

"That wouldn't have done us any good," said Charley. "If they don't come back again, I shall be entirely satisfied."

"What a bang the old cannon made!" exclaimed Joe. "I wonder if we really hit anybody?"

"If we had, we would have known it," replied Charley. "I think we've frightened them away. They know that every yacht generally carries a gun, and they won't suspect that we hadn't anything but marbles to fire at them. If we do have to fire again, we shall do some mischief, for I've loaded the gun with nails, and they will do twice as much execution as marbles."

Of course nobody thought of trying to go to sleep again; so the crew of the Ghost sat on deck with water-proof blankets over their shoulders, and waited for the renewal of the attack. They grew tired of waiting after a while, and Harry proposed that they should hoist the jib, and with the light west wind that was blowing, try to make their way out from among the islands into the open bay. "We know," added he, "from what the fisherman said that we are in the channel, and we must be nearly out of this wilderness, for don't you remember the man he had with him expected to get to Amityville in half an hour? So let's go on. It will be easier than waiting here all night."

The suggestion was warmly received, and it was not long before the canvas cabin was stowed away, and the Ghost was slowly feeling her way through the darkness. Charley did not venture to hoist the mainsail, for he was afraid of running aground so hard that it would be difficult to get the boat afloat again. Joe stood at the bow, and tried to see as far ahead as possible, while the other boys kept a look-out on all sides for the piratical row-boat. After a little while the channel grew broader, and they were congratulating themselves that they must be nearly out of the archipelago, when once more the dip of oars was heard right astern.

"Haul up that mainsail, the port watch, just as quick as you can," cried the Captain. "The sheet's all slack, and you can get it up. Bring the gun aft here, Joe, and mind you don't drop it overboard."

Had there been more wind, the two boys could not have got up the mainsail with the wind nearly aft; but as it was, they had it up and the sheet trimmed in almost as little time as it takes to tell of it. In the mean time Joe had lugged the cannon aft, and put it on the new "over-hang," or extension, that Charley had added to the boat. He then took the helm for a minute, while Charley primed[Pg 499] the gun, and put his hat carefully on the touch-hole, so as to keep the powder dry.

"Now lie down on the bottom boards, all of you," said the Captain. "If those fellows are after us, they'll probably use their pistols, and there's no use in more than one of us getting hit." Charley himself, like a prudent fellow, managed to dispose the greater part of his body below the wash-board, though he had to keep his head and one arm above the deck.

The Ghost moved much more rapidly now that her mainsail was drawing, but the oars were evidently coming nearer. Before long a pistol-shot was fired, which was evidently meant for the Ghost, although the bullet flew wide of the mark. Charley sailed the boat without feeling the least alarm, for he knew that the chance of his being hit by a pistol-bullet from a boat that was too far off to be in sight was extremely small. But the thieves were steadily gaining on the yacht, and when they finally came in sight, it was plain that they were rowing their very hardest.

Charley rose up, and steadying the tiller between his knees, told Joe to light a match, and keep the flame out of sight until he should call for it. The man in the stern of the row-boat, who was apparently the leader of the gang, called out to him to throw the Ghost up into the wind, or it would be the worse for him. Charley paid no attention to him, but carefully taking the match from Joe, leaned down, aimed the gun, and fired.

The aim was excellent, and luck was also on the side of the Ghost. The load of nails struck the row-boat, which was now not more than forty feet away, full in the bow, and tore a hole in her, scattering a shower of splinters among the men, at least one of whom was wounded, for he cried out, "I'm hit." The rowers instantly dropped their oars, and from the excited exclamations which they made, it was evident that the boat was in danger of sinking.

"Come up, boys," shouted Charley, gayly. "We've beat them this time, sure. They won't fire any more pistols at us to-night."

The boys sprang up, and gave three cheers; but as the last cheer was still ringing in the air, there was a heavy crash, and the enthusiastic boys fell one over another into the bottom of the boat, while a hoarse voice shouted: "Get out of that! What do you mean by running into us?" In their excitement they had allowed the Ghost to run directly into a large oyster sloop that was lying at anchor without any light in her rigging.

Making the Ghost fast to the sloop, Charley climbed on board the latter, and quickly explained to the three men who were on deck how it happened that they were sailing about the bay at two o'clock in the morning.

"So it was you that was firing, was it?" said the captain of the sloop. "Well, now, I want to know! Fired a cannon right slap into 'em, did ye? Well, now, that beats me."

"It beat them too," remarked Joe.

"You didn't kill none of 'em, did ye?"

"No, and I don't think we hurt anybody very much; but we knocked a hole in their boat," said Charley.

"Hope you did. They won't drown, for they're regular wharf rats; but the sheriff'll catch 'em on the meadows to-morrow. How big a ball does that gun of yourn carry?"

"We hadn't any balls, so we fired a lot of nails wrapped up in a handkerchief at them. I shouldn't have thought the nails would have held together, but they did, and I know there was a hole knocked in the boat by the way the men acted."

"They're the same fellows that stole Sam Harris's cat-boat last week; but I guess they won't steal no more—not for the present."

The oystermen who had been awakened by the cannon, and had supposed that it was fired by some steamer that had run ashore on the beach, were now ready to turn in again. The captain of the sloop told the boys to lower their sails, and to make the yacht fast to the sloop's stern.

"You won't be troubled no more to-night, and we'll tow you over to Amityville to-morrow morning, if you want to go there," said the captain. "But you'd better go to sleep, now. There'll be somebody on the look-out on board the sloop, so you needn't be afraid of nothing."

Thanking him heartily, the boys went back to their own vessel, lowered the sails, and making the painter fast to the stern rail of the sloop, prepared to take a morning nap. They did not take the trouble to rig up the canvas cabin, but covered themselves with their water-proof blankets, leaving only their heads exposed to the dew.

"That's the first time I've been under fire," remarked Charley, as he tucked the water-proof around him.

"Weren't you afraid when they fired at you?" asked Joe.

"Yes. I suppose I was; that is, I didn't want to be hit, and I wished I was where nobody would fire pistols at me; but I knew that there wasn't one chance in a hundred that I would be hit."

"I hate this whole fighting business," said Tom. "Last year we had a fight with tramps, and now we've had this fight. Who would ever have thought that peaceable boys, who don't do any mischief or interfere with anybody, would have to have real fights with tramps and pirates? If we'd killed one of those fellows, it would have spoiled all our fun. I couldn't have enjoyed the cruise one bit."

"Well, we didn't kill anybody, and there isn't the least chance that we'll have any more fighting," said Charley.

"We owe our getting out of trouble to-night to you, Charley," said Harry. "If old Admiral Farragut had been here, he couldn't have done better than you did."

"That's so," cried Tom and Joe together.

"Oh, come, now," said Charley, "you're too complimentary. I was Captain, and it was my duty to do what I could to keep the boat from being stolen. Any one of you fellows would have done just the same in my place. Good-night, all. I'll be asleep in three minutes, if you don't talk to me."

He was probably as good as his word; but his companions, who, now that the danger was over, found that they were very tired, were asleep before they had time to calculate whether or not three minutes had come and gone.

The latest of the great African explorers is a young Portuguese officer, Major Serpa Pinto, who in 1877 and 1878 crossed Africa from Benguela, a Portuguese settlement on the west coast, to the mouth of the river Zambezi, on the east coast. His journey was not as long or as hazardous as those made by Cameron and Stanley, and part of it was through a region already explored by Livingstone. Still, Major Pinto saw many wonderful things which other explorers had not seen, and made valuable discoveries concerning the sources of the great rivers Coanza and Zambezi. Many African travellers have heard from the natives stories of a tribe of white Africans, but no one fully believed those stories until Major Pinto actually came into the region where the white Africans live, and saw, as he tells us, quite a number of them.

Not the least remarkable of Major Pinto's exploits was his discovery of a new cure for the rheumatism. One night a terrible thunder-storm began soon after dark. It was by far the worst storm that the Major had ever seen, and such quantities of rain fell that the ground became soaked, and wherever any one trod, the water spurted up as it does from a wet sponge when it is squeezed. The traveller took a severe cold, and in the morning he[Pg 500] found himself suffering from a violent attack of rheumatism. He was unable to move hand or foot, and was consumed by a raging fever. Nevertheless, his men put him on a litter, and carried him on his way, until they came to a broad river just below a cataract.

A CURE FOR RHEUMATISM.

A CURE FOR RHEUMATISM.

The only means of crossing this river was a little worn-out canoe which was so leaky that the natives had to thrust moss into the cracks to keep the water from fairly rushing into it. In the bottom of this canoe, which was only large enough to hold two men, Major Pinto was carefully laid, and then a stout negro undertook to paddle it across the river. The rain had swollen the river so that it was full of whirlpools, that caught the canoe, and whirled it round and round. The negro worked hard with his paddle, but he had no control over the canoe, which was gradually drawn into the rough water at the foot of the cataract. Major Pinto tried to move so that he could look over the side of the canoe, and see the danger which threatened him, but it caused him such agony to move even his little finger, that he was compelled to give up the attempt. Meanwhile the canoe was leaking so that it was nearly half full of water, and the negro, telling his helpless passenger that it was necessary to lighten the frail craft in order to keep it from sinking, jumped out and swam ashore. Major Pinto, thus deserted and left to his fate, fully expected to be drowned. Presently a big wave poured into the canoe, which instantly sank, leaving the Major in the water. To his great surprise, he began to swim vigorously, holding his watch out of the water with one hand. Although a moment before he had not been able to move a muscle, he swam ashore without the least difficulty, and when he landed on the bank his fever had vanished, and he had not a particle of rheumatism left. This was a most astonishing cure, but it probably would not prove successful anywhere except in Central Africa. At all events, it would be hardly safe for an American boy suffering with inflammatory rheumatism to have himself thrown into a deep river.

While living in the country of Bihé—a part of Africa near the sources of the river Coanza—Major Pinto was visited by a magician, who wanted to sell him anointment that would make it impossible for a rifle-bullet to hit him. The magician insisted that if any man were to rub a little of this precious ointment on his body, he would be perfectly safe, no matter how often his enemies might fire at him. As a proof of the power of this ointment, the magician said that the earthen vase which held it had been fired at thousands of times, but that no man could possibly hit it.

Major Pinto said that if he were to shoot at the vase, he rather thought he could hit it, and the magician told him that he might try his very best, but that the powerful ointment would turn his bullet aside. Now the magician did not know that the Major could shoot any better than the natives, and when he placed the vase eighty yards away, he felt certain that the white man could not hit it. Major Pinto took careful aim, fired, and knocked the vase into a thousand pieces. The natives, who had always believed in the power of the ointment, set up a shout when they saw what had happened, and the magician, knowing that his trade in ointment was ruined, slunk away, and never came back to demand payment for his broken vase.

Like all African travellers, Major Pinto had a great deal of trouble with his men, who were all native Africans. They were constantly stealing his property, getting drunk, and running away. He had, however, one faithful man, who was brave, honest, and devoted to his master. This man's name was Augoustino; he saved his master's life on several occasions, and to him is due almost as much credit for the success of the exploration as to Major Pinto himself.

"Tell me, tell me, silver moon,

Which of all the months discloses

Greatest sweetness?" "Dreamy June,

Summer's darling," said the moon,

"Month of roses."

"ZITA," THE GYPSY GIRL.

"ZITA," THE GYPSY GIRL.

"March!" said Spring. Quickly melting, the ice ran away,

And the frost hurried out of the ground,

And the leaves, brown and dry, dropped with Autumn's "good-by,"

With the wind went a-skurrying round.

And from the deep mud in a low, swampy place

A turtle his long neck thrust out,

And winking and blinking his funny round eyes,

He lazily peered all about.

Then he dragged from the mire—like a snail on his back

He bore it—his box-like abode,

And patiently climbed for an hour or more

Up the bank, till he came to the road.

There an old man he met, who was crooked and gray,

And who walked with a stout oaken cane.

Cried the turtle, "Hello! please tell Ned that I'm here,

And am waiting to see him again."

"Who's Ned?" asked the man. "Just examine my top

(I suppose you have learned how to spell),

And a name and some figures he carved with his knife

When we parted, you'll find on my shell."

The old man he stooped with a grunt, for he was

Decidedly lame in each knee.

And he read, "August 1st, 1820—Ned Mott,"

And then chuckled, "Good gracious! that's me."

"You!" the turtle exclaimed. "Why, Ned Mott is a boy

Whose laugh can be heard for a mile;

With hair brown as earth, and with eyes bright as mine—

You! Excuse me, I really must smile."

"I am he." "It can't be." "Yes, it can. Don't you see,

Many years since you saw him have sped?"

"What's years? I know nothing 'bout years, but I know

That you are not rosy-cheeked Ned.

"He's a boy, and he wears a small cap with a peak,

And in summer picks berries called whortle.

Oh! the stupidest thing is a stupid old man."

"You mistake, 'tis a stupid old turtle.

I'm Ned Mott." "You are not." "If I'm not, I'll be shot."

"Then be shot," and he dropped with a thud,

That sleepy, that ancient, that obstinate turtle,

Head-foremost back into the mud.

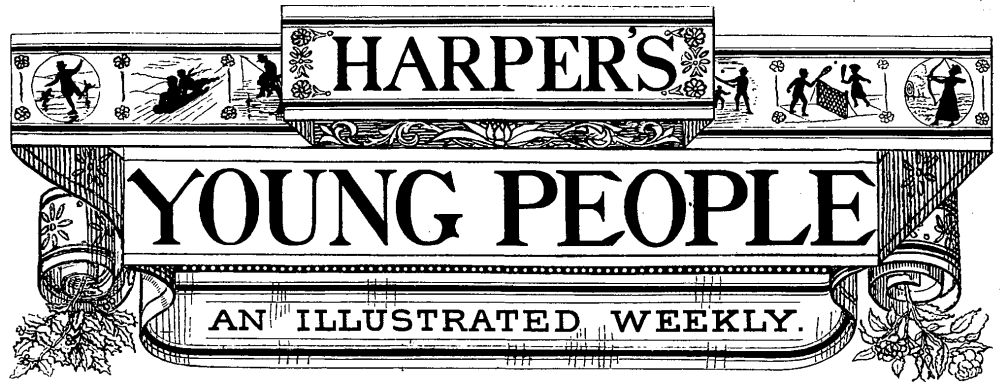

When I say that the game of lawn tennis was invented by an English gentleman some seven or eight years ago, I am quite prepared to hear from some of my readers, whose favorite study is history, that it is much older than that, and was known both in France and England as long ago as the reign of Henry III. And indeed the correction will have much truth in it, for tennis was known even further back than that. People who always want to get at the very beginning of everything claim that the game, or something very like it, was played in the reign of the cruel Emperor Nero, who, you will remember, fiddled while Rome was burning before his eyes. Fiddling, perhaps, was not his only amusement, and it is quite possible that in the interval between one horrible act of cruelty and another, the Emperor indulged in a game of tennis. But Nero is not at all a pleasant person to associate with such a beautiful game, so, if you please, we will leave history to the historians, and see what our modern great-great-grandchild of the old tennis is.

Those of my readers who live in or near large cities will probably know that it is an out-door game played with a racquet and a ball, but for the benefit of those who do not know it, I will give a few hints as to the laying out of the court, and the implements necessary for the game.

First of all, you must have a lawn; not necessarily a perfectly level piece of turf as smooth as a parlor carpet, but a fairly level plot of grass, which a scythe or a mowing-machine can soon put into order. Of course all stones and sticks must be picked up, and if you have a roller at hand, you will improve your lawn greatly by running the roller over it once or twice. When the ground is prepared, get some small pointed sticks and some string, and lay out the "court" according to the[Pg 502] lines on the diagram on this page, stretching the string from one stick to another at the distances marked on the diagram. When this is done, get some whitewash and a brush two inches wide, and mark lines on the grass wherever the string passes over it. Then you may pull up the stakes and the string.

READY TO "SERVE."

READY TO "SERVE."

The broad line across the middle of the diagram is where the net goes. If any one of the party knows how to make a net with a two-inch mesh, so much the better; but most of my readers will prefer to buy one, I think. The net is twenty-four feet long and four feet wide, and is fastened to posts, about five feet high, at each side of the court. The posts are supported on the outer side by "guy-ropes" fastened to stakes driven into the ground, while the strain of the net between the posts supports them on the inner side. And now that the court is marked out, and the net pitched, we have everything ready except the bats and balls.

The bat, or racquet, is a very pretty piece of workmanship, and I dare not venture to hope that the cleverest of my readers could make one, so we will assume that, even if everything else is home-made, the racquet must be bought. And so, indeed, must the balls; but a hollow India rubber ball of about two and a half inches diameter is so well known to all boys that we may dismiss it with the remark that it is as well to have at least two balls at hand in a game, to save time.

The game may be played by either two or four persons. In the latter case each pair will play as partners on each side of the net. The one who strikes the ball first (and this is decided by agreement) is called the "server." Standing with one foot outside the line at the end of the right-hand court, and the other foot inside the court (position marked A in diagram), the server strikes the ball so that it falls in the court diagonally opposite him, just over the net at B, where a player on the other side will be waiting to receive it. After the ball has bounced once, the player must strike it over the net, and it must be returned from one side of the net to the other until some one fails to do so properly. One partner plays in the inner court and the other in the outer one, and after the "service" and the first return, either of the players may return the ball to any part of their opponents' court, according as it pitches nearer to one than to the other. When a player fails to return the ball properly, it counts one for the other side, and the server begins again from his old position, except that he must serve from the left-hand court this time if he served from the right-hand court last.

Counting.—A game consists of four "points." It counts against one side, and in favor of the other,

1. When the server makes two "faults" in succession. (A "fault" is the failure of the server to send the ball into the proper court.)

2. When a player does not return the ball over the net.

3. When a player sends the ball so far that it falls outside the court.

4. When a player allows the ball to strike the ground more than once before he returns it.

When one side has made four points, a new game is begun, but the same side must not "serve" two games in succession, for there is some advantage in the "service," and it would not be fair for one side to have it oftener than the other.

It will often happen that both sides will have made three points at the same time, and when that does happen, the score is called "deuce," and either side has to make two points in succession to win the game. If the server's side makes a point when the score is "deuce," it is called "advantage in," and if the other side then makes a point, their point cancels the other, and the score is set back to "deuce" again. When the other side (not the server's) makes a point after "deuce," it is called "advantage out," and this point may be cancelled by the other side making one, as before. When one side has made two points in succession after "deuce," the game is won. The side which wins six games first wins the "set," and then the players may rest awhile, or choose fresh sides.

All the principal rules of the game are included in the description of the game given above, but if you buy a full tennis set, a little book containing the rules will be included in it.

As I have said, everything but the bats and balls can be made at home, since nothing is required but two posts, five feet high and an inch and three-quarters in thickness, four tent-pegs to fasten the guy-ropes to, and a net.

But even if it is decided to purchase a set, the cost is not very great compared with that of some other games, especially if two or three families club together. A good tennis set, consisting of four bats, four balls, a net, two posts, guy-ropes, four stakes, and a mallet for driving these last into the ground, can be bought for fifteen dollars. The bats alone of this set would cost eight dollars, and the net two dollars. The poles are rather expensive, as they are made each in two pieces so as to pack into a box, the pieces fitting together in a brass socket. Poles without a joint in the middle can easily be made, thus saving four dollars in the cost of the outfit. The guy-ropes, runners, and stakes cost seventy-five cents a set, but these can easily be made. The cost would thus be reduced to eleven dollars, namely, eight dollars for four bats, one dollar for four balls, and two dollars for a net.

Of course players will dress lightly for the game. A flannel suit is the best thing to wear, as it is cool, and prevents the wearer from taking cold easily. Ordinary shoes can generally be worn, but most players prefer canvas shoes with rubber soles of an uneven surface to prevent slipping. For girls—and this is as much a girl's game as a boy's—short dresses of blue flannel, or some other material that is both cool and strong, are recommended; and canvas shoes with rubber soles can be bought, in girls' sizes, at almost any shoe store. English girls wear the "Jersey," shown in the cut on the preceding page, as a tennis costume, and this neat, close-fitting dress is already becoming popular in this country.

Lawn tennis is a game that requires a quick hand and eye, lively movement, and a good temper. There are two things which spoil the game, even among good players. These are lack of interest in the game, so that a player does not play his best all the time, and a show of bad temper. Angry words and solemn sulks are nowhere more out of place than on the tennis lawn.

I don't know if you are acquainted with Johnny McGinnis. Everybody knows his father, for he's been in Congress, though he is a poor man, and sells hay and potatoes, and I heard father say that Mr. McGinnis is the most remarkable man in the country. Well, Johnny is Mr. McGinnis's boy, and he's about my age, and thinks he's tremendously smart; and I used to think so too, but now I don't think quite so much of him. He and I went away to be pirates the other day, and I found out that he will never do for a pirate.

You see, we had both got into difficulties. It wasn't my fault, I am sure, but it's such a painful subject that I won't describe it. I will merely say that after it was all over, I went to see Johnny to tell him that it was no use to put shingles under your coat, for how is that going to do your legs any good, and I tried it because Johnny advised me to. I found that he had just had a painful scene with his father on account of apples; and I must say it served him right, for he had no business to touch them without permission. So I said, "Look here, Johnny, what's the use of our staying at home and being laid onto with switches and our best actions misunderstood and our noblest and holiest emotions held up to ridicule?" That's what I heard a young man say to Sue one day, but it was so beautiful that I said it to Johnny myself.

"Oh, go 'way," said Johnny.

"That's what I say," said I. "Let's go away and be pirates. There's a brook that runs through Deacon Sammis's woods, and it stands to reason that it must run into the Spanish Main, where all the pirates are. Let's run away, and chop down a tree, and make a canoe, and sail down the brook till we get to the Spanish Main, and then we can capture a schooner, and be regular pirates."

"Hurrah!" says Johnny. "We'll do it. Let's run away to-night. I'll take father's hatchet, and the carving-knife, and some provisions, and meet you back of our barn at ten o'clock."

"I'll be there," said I. "Only, if we're going to be pirates, let's be strictly honest. Don't take anything belonging to your father. I've got a hatchet, and a silver knife with my name on it, and I'll save my supper and take it with me."

So that night I watched my chance, and dropped my supper into my handkerchief, and stuffed it into my pocket. When ten o'clock came, I tied up my clothes in a bundle, and took my hatchet and the silver knife and some matches, and slipped out the back door, and met Johnny. He had nothing with him but his supper and a backgammon board and a bag of marbles. We went straight for the woods, and after we'd selected a big tree to cut down, we ate our supper. Just then the moon went under a cloud, and it grew awfully dark. We couldn't see very well how to chop the tree, and after Johnny had cut his fingers, we put off cutting down the tree till morning, and resolved to build a fire. We got a lot of fire-wood, but I dropped the matches, and when we found them again they were so damp that they wouldn't light.

All at once the wind began to blow, and made a dreadful moaning in the woods. Johnny said it was bears, and that though he wanted to be a pirate, he hadn't calculated on having any bears. Then he said it was cold, and so it was, but I told him that it would be warm enough when we got to the Spanish Main, and that pirates ought not to mind a little cold.

Pretty soon it began to rain, and then Johnny began to cry. It just poured down, and the way our teeth chattered was terrible. By-and-by Johnny jumped up, and said he wasn't going to be eaten up by bears and get an awful cold, and he started on a run for home. Of course I wasn't going to be a pirate all alone, for there wouldn't be any fun in that, so I started after him. He must have been dreadfully frightened, for he ran as fast as he could, and as I was in a hurry, I tried to catch up with him. If he hadn't tripped over a root, and I hadn't tripped over him, I don't believe I could have caught him. When I fell on him, you ought to have heard him yell. He thought I was a bear, but any sensible pirate would have known I wasn't.

Johnny left me at his front gate, and said he had made up his mind he wouldn't be a pirate, and that it would be a great deal more fun to be a plumber, and melt lead. I went home, and as the house was locked up, I had to ring the front-door bell. Father came to the door himself, and when he saw me, he said, "Jimmy, what in the world does this mean?" So I told him that Johnny and me had started for the Spanish Main to be pirates, but Johnny had changed his mind up in Deacon Sammis's woods, and that I thought I'd change mine too.

Father had me put to bed, and hot bottles and things put in the bed with me, and before I went to sleep, he came and said: "Good-night, Jimmy. We'll try and have more fun at home, so that there won't be any necessity of your being a pirate." And I said, "Dear father, I'd a good deal rather stay with you, and I'll never be a pirate without your permission."

This is why I say that Johnny McGinnis will never make a good pirate. He's too much afraid of getting wet.

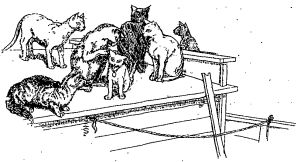

"PETS OF THE FAMILY."—From a Painting by Edwin Douglas.

"PETS OF THE FAMILY."—From a Painting by Edwin Douglas.

A long time ago there lived a young King in the east of Germany, who was so famous for strange adventures and out-of-the-way exploits that the people in those parts talk of him still; and if you turn away from the railway track, and march off with your knapsack through the passes of the "Giant Mountains," you will hear many a curious story about him, and many a strange old song, from the miners and charcoal-burners, whose queer little huts are dotted all over the higher slopes. And if, after three weeks or a month among those grand old forests, and green upland pastures, and shining water-falls, and huge black precipices—sleeping in your plaid under the lee of a big rock, and sharing some charcoal man's fried potatoes beside a pine-log fire—you do not come back with health and strength enough for a dozen, and good old stories enough for a library, it will certainly be your own fault.

This German prince had become King when he was little more than a boy, and hardly fit to manage such a difficult business as taking care of a whole kingdom at once. Indeed, he often wished that the kingdom could take care of itself, and leave him a little more liberty; for he would far rather have been galloping over hedge and ditch on his good horse than wading through piles of musty state papers, and he thought it far better fun to follow the deer up the hills with his gun than to sit perched up on a throne in his crown and robes, with ever so many people coming and making long speeches to him, of which he hardly understood a word.

But, happily for our poor prince, he had one good friend at his court who was never tired of trying to amuse and entertain him. This was an old friend of his father's, called Count Thorn, who had taught him his lessons as a child, and still kept a kind of charge over him now that he was growing to be a man. The Count looked so tall and grand, with his fur-trimmed robe, and high frilled collar, and long gray beard, that he seemed like one of the old portraits in the great dining hall stepping down from its frame. But there was a merry twinkle in his deep dark eyes every now and then which showed that he could enjoy a joke as well as any one, and that he had[Pg 504] a kind heart underneath all.

And so, indeed, he had; and the young King (who was very fond of him, and used to call him "uncle") always ended by doing what the Count told him, although he grumbled a little at times. "Happy as a King?" he would say, when he came back from a long morning in the council chamber: "I believe I'm the least happy man in my kingdom, for I'm the only one who can't do as he likes."

And then the old Count would lay a hand on his shoulder, and say, kindly: "My boy, you weren't made King just to do as you like, and to amuse yourself. You have to think of your people, and try to make them happy; and if you want to be a really great King, such as your father was, that's what you must do." And the young King would laugh, and answer, cheerily, "You're quite right, uncle, and I'll do my best." And after that there would be no more grumbling for a good while, and everything would go on quite comfortably.

Now the King had another favorite besides the Count, and one with whom very few people cared to meddle; for this other favorite was nothing less than a fine young African lion, big enough and strong enough to kill a man with one bite. He and his master might almost be said to have grown up together, for the lion had been given to the King when it was a mere cub and he a mere boy, and it was so tame that it would follow him everywhere like a dog, and eat out of his hand.[Pg 505] At night, when the King went to bed, the lion slept on a mat outside his door; and I promise you there was no fear of any one disturbing him while that sentinel was on duty.

Now the King used jokingly to call this lion his brother, because whenever he flew into a rage (as he very often did), Count Thorn would say, gravely, "My boy, an angry man is no better than a wild beast; and if you choose to be just the same as that lion yonder, we may as well make him King instead of you."

And then the King would pat the lion's huge tawny head, and say, laughingly: "Do you hear that, old fellow? How would you like to have to sit all day with a big crown on, and a heavy robe round you, hearing a lot of fellows make long speeches? I don't think it would suit you at all." And the lion would open its great red mouth and give a long yawn, as much as to say, "I don't think it would."

So long as the beast was only a cub, Count Thorn made no objection to it, and indeed was rather pleased that his pupil had found something to amuse him. But now that the cub had grown into a full-sized lion, with teeth that would crack a man's skull like a nut, and a paw that would beat in an oaken door at one blow, it was a very different thing; and the old Count began to be somewhat anxious. He knew that the lion's savage nature might awake at any moment, and that, if it did, the King would be torn in pieces before a hand could be lifted to save him. The more he thought[Pg 506] of the whole business, the less he liked it; and at last he made up his mind to speak out. So one day he came to the King in his garden, with such a grave face that the young man cried out at once: "Why, uncle, what's the matter? you look as if you were just going to be beheaded."

"My boy," said the Count, gravely, "I want to talk seriously with you."

"Which means that I'm going to get a scolding," observed the King, folding his arms, with such a rueful look that Count Thorn could scarcely help laughing.

"I don't want to scold you," he answered, "but I do want to advise you, and I hope you won't be vexed at a word of counsel from your old friend. My dear boy, that lion of yours is a dangerous pet, and I want you to get rid of him."

"What! get rid of old Max?" cried the King. "You can't mean that, surely, uncle? Why, I couldn't do without him now—he's the oldest friend I've got, except yourself. Besides," he added, slyly, "if I did send him away, what would you do when you wanted to scold me for being passionate, and you had no 'wild beast' to point to?"

"This is no laughing matter," said the Count, shaking his head. "Suppose he were to spring upon you all at once, and seize you in those great jaws of his, what then?"

"As if he'd ever dream of doing anything of the sort!" laughed the King. "Why, he's as tame as any dog, and tamer, too."

"Well, if you won't send him away," urged the Count, "at all events have him chained up, or put in a cage, so that he can do no harm."

"Come, come, uncle," cried the young man, reproachfully, "that's really a little too bad! How long do you think I should live if I were chained or caged up like that? and Max is quite as fond of his liberty as I am of mine. No, no; I'll do anything else you like, but I can't have my poor old lion ill-treated."

In short, let Count Thorn talk as he pleased, the King was not to be persuaded; and like most people who are fond of having their own way, he had to pay dearly for it in the end, as you shall see.

One night, having gone to bed later than usual, he had a strange dream. He thought that he was lying on the bed with his uniform coat on, and that a servant came into the room, and began to brush his sleeve with a hard brush. Presently the man passed from the sleeve to the hand that hung out of it, and rasped the skin with the rough bristles until it grew so painful that the King could bear it no longer, but gave a start and a cry, and—awoke.

For a moment he hardly knew whether he was still dreaming or not. His left hand was hanging over the side of the bed, and something hard and prickly was rasping it and making it painful; but that something was the rough tongue of the lion, which had crept softly into the room (the King having for once forgotten to shut his door), and was licking the outstretched hand, which was just beginning to bleed!

At this taste of fresh blood—the first he had ever had—the beast's fierce nature suddenly awoke. Already his mane was beginning to bristle, and his tail to jerk restlessly to and fro, and his great yellow eyes to flash fire. Bitterly enough, now that it was too late, did the poor King recall his old friend's warning, which he had treated so lightly. He was utterly alone, far from all help, and before him was no longer his tame, affectionate favorite, but a raging beast of prey.

But the young King was as brave a man as ever lived, and even when so suddenly brought face to face with this awful danger, he never flinched. He saw instantly that there was only one thing for him to do, and that it must be done without losing a moment. Never withdrawing his look for a moment from the savage eyes of the beast, or attempting to withdraw the hand which it was licking, he slid the other hand softly up to the bed's head, where his loaded pistols always hung.

Flash! bang! The room was filled with smoke, and as the servants rushed in, they saw the lion dead on the floor, and the King sitting with his face buried in his hands.

So ended all Count Thorn's troubles and anxieties; but somehow he did not appear much pleased after all. In his heart he was sorry for the brave beast that his pupil had loved so long; and when the King looked up from burying his dead favorite among the flowers in his garden, he saw that the old Count's keen gray eyes were as dim as his own.

Clinton was a rosy-cheeked boy, with a pair of dirty hands, and a very stupid head for the nine parts of speech. In fact, as far as his knowledge of grammar went, he was a dunce, and that's a very unpleasant thing to be, especially when one gets a daily thrashing, you know. Well, Clinton was a dunce, and his teacher knew it, and all the school knew it, and he knew it, and he felt very sulky about it on this particular day when I write of him; for he has come out of school with a red, swollen hand, and a pair of red, swollen eyes, though he wouldn't cry about a thrashing, not he—oh no, he is too brave for that.

Now Clinton lived in a nice little house near a nice little village, in which stood the school-house, and when he went home every day he had to go through an open field, and then through a piece of woods. It was about four o'clock on a summer afternoon—he had been kept in again—and the heat had not yet faded away. The sun looked hot and stary through the mist in Clinton's eyes, but its saucy, knowing look put him out, for it seemed to have too much information for a well-balanced sun.

Presently he came to a fresh bit of grass, by such a lordly old tree; so he threw himself down, all breathless and rosier than ever, and folding his inky fingers under his head, he fell to watching a domestic robin up in the tree, and thinking about the detested lessons at the same time.

"Now," said he—for he had a great habit of talking to himself aloud—"what good can there be in a fellow's learning that horrible stuff? I'll never have the faintest idea of what it all means, I'm sure, any more than that round robin up above me."

Whereupon the round robin looked very wise, as if it knew what it knew; but Clinton didn't mind it, but went on talking to himself.

"I was always rather shaky on the subject of fairies, but I'm blest if I wouldn't like to get a glimpse of one this moment, for I don't believe anybody else could help me."

And just then the robin looked down from his nest, and called out, "You're right there."

Clinton glanced up, and to his surprise saw that the lordly old tree had grown into a ragged pair of stairs, and the round robin nodded to him as if it said as plainly as possible, "Come up." So he began climbing up; but as fast as he climbed, it hopped on above him, and the stairs began to grow and grow. But he kept bravely on, for he knew the stairs would stop some time, and he was sure the round robin would, though he was somewhat astonished when he found the stairs making directly for the sun, and he was still more so when, as he came near the brilliant orb of day, he saw its mouth open like a great portcullis, and on its huge upper lip was written in long black letters,

And here the stairs stopped, and he saw the round robin go in with a crowd of gay and festive people; so, when he came up to the top of the stairs, he went in too. And he found himself in a lofty chamber of clouds, and away[Pg 507] up at one end under a great rainbow sat a haughty-looking King, and the gay and festive people ranged themselves on either side of him. By-and-by the King called out in a loud voice:

"Where is little Article, our page?"

Immediately a small boy, in a pair of mighty slippers, who looked like a very little article indeed, stood trembling before the King.

"Come," roared the King, "don't stand loafing about, but run as fast as you can to the royal presence of Queen Noun, and tell her we request her attendance." Whereat the little Article, trembling a great deal, skipped backward to the door, and then ran off as fast as he could. "For how," said the King, trying to get off a poor joke, as kings are apt to—"how could King Verb be merry if the object of his thoughts and the subject of his affections be absent from the throne?"

And this seemed to tickle all the gay and festive people immensely, for they giggled a great deal, and were much annoyed because Clinton did not giggle too, though he could not for the world tell what they were having such fun about. One of them even would have spoken to him, had not his Majesty just then called out lustily to the man at the door, "Admit them instantly, Sir Preposition." And obediently Sir Preposition drew back the curtain, and led forward a lady enveloped in a long thick veil. The King hopped down from his throne, he was in such a hurry, exclaiming, as he went, in a very hoarse voice, "Allow thy lord to rend the midnight cloud, and behold the moon in all her glory." At the same time he lifted up the cloud, as he called it, and disclosed, not the slightest hint of a beauty, but the withered face of a hideous old woman.

Then the King, I am ashamed to say, turned round and shook his fist in the timid little Article's face. "How dare you, minion," shrieked he, "point out this ugly old Aunt Pronoun, placing her instead of the fairest princess living—Soldiers! soldiers!"—here he turned almost blue in the face, and pointed to the puny little Article as if he were a very lion—"soldiers, seize the traitor!" he hissed.

The soldiers were about to obey him, when a piercing scream rung out through the apartment. Everybody looked round to see what had happened; and sure enough, almost next to where Clinton stood, a very spare court lady had fallen into hysterics. "Oh! alas!" cried she, gasping all the while like any fish; "ah me! alack! fiddle-dee-dee! How—can—he—be—so—cruel!" Here she flung herself into somebody's arms, and was dragged from the room.

"Ho! ho!" said the King; "who's that?"

"Lady Interjection," squeaked the little Article, nervously touching his hat.

"Lady Interjection, is it? Well, she'd better stop this kind of business, as it is growing rather dreary. However, that won't hinder our making short work of Aunt Pronoun. Soldiers!"

Again the soldiers marched up in a most decorous way, when a handsome young courtier rushed forward, and threw himself at the feet of the King. "My dear brother-in-law—I mean your Majesty," he exclaimed—"can't you make up your royal mind to spare this dear old party, remembering her infirmities? Oh, do make up your mind to do so, and to spare also my sister, Queen Noun! Call to mind her many pleasing qualities. She is beautiful, charming, graceful, witty, loving, gentle—"

"Stop! stop! Adjective," shouted the King; "you'll drive me mad. Get up and listen to my Lord Adverb, and don't kneel there chattering like a magpie."

Immediately an aged and venerable man approached King Verb. As Adjective departed, he heard him whisper in the Prime Minister's ear, "Do your best to modify him."

The old man nodded sagaciously, and then addressed his sovereign in a low, clear voice: "Your grace will pardon the rashness of an aged man if I say you have acted somewhat hastily. The advice I give you is to think slowly, coolly, deliberately, and wisely, and then act—kindly."

"Excellent!" said the testy monarch, for he had cooled down a great deal. "Let us hear what Aunt Pronoun can say for herself."

The old lady seemed very cross at the way she had been abused. She drew herself up, and made the King wince, she looked at him so hard. "I have nothing, sire, to say for myself," she said, "save that the Queen, on receiving your message, bid me come to you with the news that you have a young prince born to you."

How the people did shout for joy at this announcement, and how the King did smile, you can not imagine. At any rate Clinton couldn't.

"We thank you for this glorious news, Madam Pronoun," said King Verb, "and we beg you to pardon our sudden displeasure. In recompense, we will have to make you the Prince's godmother. Come, what shall his name be?"

Ladies of Pronoun's age are not so easy to make up with; so she looked very injured at first, but by-and-by began smiling. "King Verb," said she, "I was much grieved at your anger, for it was entirely unmerited; but I rejoice at your kindness, and in token of your having taken the Queen and myself again into court favor and your friendship, I will name the young Prince—Conjunction."

"Hurrah!" cried Clinton, he was so mightily pleased; "I see it all now."

"I am glad you do," said his teacher's voice, close beside him; "but you'd better get up now, else you'll take cold. It's pretty near sunset, and you've been sleeping on this grass nearly two hours."

Clinton sat up, rubbed his eyes, and looked about him. There he was in the woods, as natural as life. Could it have been a dream? Ha! what was that? He happens to spy the round robin looking over his nest, and—yes—winking at him. He got up and meekly followed his teacher, never speaking a word. But from that day to this he firmly believes that what he saw was true, and from that day to this I don't believe he ever missed a grammar lesson.

Pretty little Kitty Kimo was sent by her mistress to the cat show, where her silky fur, bright eyes like great yellow daisies, and pink sea-shell-like ears, soon won her a prize, and she came home with a beautiful silver medal hung round her neck by a blue ribbon, and just the proudest little kit in all catdom.

Oh, how Miss Alice petted her, and fed her on chicken and cream for a week afterward! and how all the poor black, white, and gray cats who had not been to the show watched her with envy as she promenaded up and down the fence with the pretty medal glittering on her neck, and turning her vain little head right and left that every one might see it.

"She puts on as many airs as though she had killed a dozen rats," said Tabby Tortoiseshell, a scraggy-looking old cat, who was blind in one eye.

"When she couldn't catch even a mouse to save her life," said Tommy Scratchclaw, a famous hunter and mouser.

"She hissed and spat at me this morning, when I met her in the violet bed," said Pussy Clover, "and then scampered off up the elm-tree to show her tin locket to Dandy Maltese, who presented her with the neck of a sparrow he had just killed on the spot."

"Silly kitten!" sniffed old Granny Grimalkin, taking a pinch of catnip snuff. "Beauty isn't everything. I once won a brass button on a cord by turning door handles and jumping over a cane; but she hasn't done a thing except look as if butter wouldn't melt in her mouth."

"Let us take her medal away, and make her win it back," suggested Sancho Squaller, a powerful black cat, with eyes like buttercups.

"Hurrah! so we will," shouted Tommy Scratchclaw; and all the cats and kits purred a glad assent, and all set up such a mewing and caterwauling, as they discussed how it should be done, that the cook at the corner came rushing out with a broom to drive "those plaguey cats" off the fence.

Kitty Kimo meanwhile, quite unconscious of the plans of her enemies, had enjoyed her sparrow neck exceedingly, and then curled herself up in the shade of a rose-bush for a noon-day nap, and slept so soundly that she never even opened one eye when tiny Topsy Titmouse crept slyly up on her velvety paws, and with her little white teeth gnawed the blue ribbon, and bore off the medal in triumph. Fancy Kitty Kimo's dismay, when she awoke, to see her precious medal shining on the breast of ugly Tabby Tortoiseshell, while all the other cats sat round in a circle, twirling their whiskers and chuckling at the success of their trick.

"Me-ow! me-ow! me-ow!" she wailed. "Oh, give me back my medal, my beautiful medal!"

"Not until you have earned it," replied black Sancho Squaller, with the sternness of a judge.

"What must I do?" she cried.

"Bring us the head of the wicked old rat who steals our meat and milk," said Tommy Scratchclaw, "and you shall have your prize."

And all the cats laughed a scornful "Ha! ha! ha!" for they well knew little Miss Kimo would stand no chance against his ratship, who was as strong as he was bad, and had fought and conquered the most renowned warriors in the block.

So at these words poor Kitty Kimo wailed louder than ever, and gave up her prize for lost, until Dandy Maltese, who sympathized with her, suggested that she should engage, the services of Ratty Terrier, a smart little dog that lived next door.

Now Kitty was rather afraid of Ratty, but she felt that she must make every effort to regain her lost trinket; so taking a wish-bone with her as a peace-offering, she that afternoon ventured to call on Mr. Terrier.

Not being very fond of cats, he showed his teeth at sight of her, and looked rather savage, but she quickly laid the chicken bone before him, and it so gratified him that he listened quite pleasantly to her petition.

"So you want me to kill Mr. Gray Rat for you?" he said. "He is a plucky old fellow, and has given me many a good laugh at the way he snips bits out of the cats' ears; but I think you have been badly treated, and if you will bring me a nice marrow-bone, I'll see what I can do for you."

Kitty looked very doleful at this, but as Ratty turned away, and began snapping at flies, she murmured, "I'll try," and tripped off round the corner to where a fat jolly butcher was chopping up meat.

"Mew, mew, mew," said Kitty, rubbing against his foot.

"Why, little cat, what do you want?" asked the butcher.

"Mew, mew, mew," cried Kitty again; but the butcher did not understand cat language, so she took hold of a big bone that lay on the counter, with her teeth, when he said,

"Oh no, Miss Kitty, you can't have that unless you pay me a penny for it."

This made Kitty very sad. "For where can I get a penny?" she thought, as she walked slowly out of the shop. But just outside she met a monkey who was dancing gayly to the sound of a hand-organ, and for doing so people gave him a great many pennies, which he slipped into his coat pocket. He sat down after a while to rest, and refresh himself with an apple, and then Kitty stole up, and begged:

"Please, Mr. Jack, give me one of your pennies to buy a marrow-bone for Ratty Terrier, and then he will kill the wicked old rat for me, and I shall get back the medal I won at the cat show."

"Chatter, chatter, chatter," said the monkey. "Most of these belong to my master; but I will give you one of mine if you will get me a handful of pea-nuts from yonder stand. I am very fond of them, and they sell very few for a cent."

This stand was kept by a toothless old woman, and Kitty knew it was useless to try and make her understand kitten talk; but she ran across the way, and heard the old lady mumbling to herself, "I'd give a lot of pea-nuts for a few drops of fresh milk to put in my tea."

At these words Kitty purred for joy, and fairly skipped over the ground, for she was acquainted with a goat, who, she thought, would be sure to give her some milk. But when she came to the pasture where the goat was feeding, she found Nanny as selfish as the rest of the world, and not a drop of milk would she give, unless Kitty brought her a head of green lettuce for her supper.

Poor Kitty felt terribly discouraged; but she thought, "I might as well keep on now," and pattered away once more on her tired little paws to a farm on the border of the town, where lay a beautiful field of young lettuce, watched over by a funny old scarecrow in a red waistcoat and shabby hat, who stood there to frighten away the birds that destroyed the delicate leaves.

"He looks rather cross," thought Kitty, as she approached this figure, and her heart went pitapat as she stopped, and began, "Mew! mew!"

"Hey! hey!" cried the scarecrow, whirling round, for he thought it was a cat-bird.

"Please, Mr. Crow, don't scare me," stammered Kitty; "for I am only a kitten; and, oh, do please give me a head of your nice lettuce for Nanny the goat."

"And what will she give you for it?" asked the scarecrow.

"Some milk for the pea-nut woman to put in her tea."

"And what will the pea-nut woman give you?"

"A handful of pea-nuts for Jack the monkey."

"And what will Master Jack give you?"

"A penny to buy a marrow-bone for Ratty Terrier."

"Who will probably bite off your head for your pains."

"Oh no, indeed. He has promised to kill the wicked rat that steals our food for me; and then Tabby and Sancho will give me back the beautiful medal I won at the cat show."

"You are winning it twice, I think; but can you frighten birds?"

"Oh yes, indeed."

"Well, then, just scare away that old crow over there, who has no respect for me, and feasts in the field here under my very eyes, and I will give you a head of lettuce."

"That I will, right gladly," said Kitty; and she rushed the crow with such vigor that he almost choked to death in his fright, and flew away so far that he could never find his way back again.

"Thank you very much," said the scarecrow, when Kitty came back quite breathless from the race, and with her nose as red as a rose-bud. "I can manage all the other birds myself. Now help yourself to a head of lettuce."

Kitty did as she was told; and bidding the old scarecrow, who was so much kinder than he looked, "good-night," hurried away to Nanny the goat, who shook her horns with delight at sight of the fresh young leaves, and gave the kitten some milk in an egg-shell, and also a drink for herself.

The toothless old woman, who had just made up her mind to take her tea clear, was as pleased as she was surprised at the milk pussy brought her, but forgot all about the pea-nuts, until Kitty patted them with her paw. "Oh! Do you want pea-nuts? You shall have them; help yourself to a good handful. You deserve them for being such a smart little cat, and bringing me just what I wanted."

Away went Kitty with her mouth and paws full of nuts, at receiving which the monkey chattered like a whole flock of magpies, and gave her the brightest penny he had in his pocket.

"So you've brought the penny!" exclaimed the butcher, in open-mouthed astonishment, as Kitty laid it in front of him, and seizing the marrow-bone, made off before he could say so much as "Scat!"

"Bow-wow-wow! you deserve a medal, and that's a fact," said Ratty Terrier, wagging his tail at sight of the bone which fairly made his mouth water. And after he had devoured half of it, and hidden the rest in his under-ground store-house, he set out on the promised rat-hunt.

And oh! a fierce battle took place that night, for the old thief fought bravely, and the terrier received many a deep scratch on his saucy little nose, but he came off victor at last, and the rat's head, carefully wrapped in a large leaf, was sent next morning to little Kitty Kimo, who gayly delivered it to the other cats, all of whom rejoiced over the death of their enemy.

"You have well earned your prize at last," said Granny Grimalkin, after Kitty had related her adventures, "for you are as persevering as you are pretty." And Tabby Tortoiseshell herself tied the blue ribbon round Kitty Kimo's neck, while Mademoiselle Catalina Squallita led off in a gay chorus in which all joined, the principal burden of which was, "Me-ow, me-ow-ow, me-ow-ow-ow."

Kitty Kimo was never known to put on airs again, but was always willing to lend her medal to Pussy Clover or Topsy Titmouse to wear to balls or serenades, and she was known far and wide as the Prize Kitten, and the brightest and prettiest cat of the square.

Dedham, Massachusetts.

I am a grandmother, eighty-four years old, and I wish to tell the dear readers of Young People of an episode in the life of my three little grandchildren.

The youngest, a boy, when two years old, had a canary given him. He and two sisters older than he delighted in watching and feeding the little pet, seeing him plunge into his bowl of water to wash, and then sitting on his perch to brush his bright plumage and give them a sweet morning song.

One hot morning his cage was hung out under the portico. The bees, attracted by his sweet food, flew into the cage for some honey to fill the curious cells they had made. The birdie looked upon them as intruders, and probably pecked at them, but the little busy bees, claiming their right to gather honey anywhere in God's wide domain, covered him with stings. Hearing a loud buzzing, we went out to see what had happened. The bird was covered with bees, and before we could rescue it, they had poisoned it so badly that it gasped a few minutes, and died.

When the children found their pet was dead, after gazing very sorrowfully for a while, they got a spade, and without saying a word, took the dead bird and marched slowly to the garden. The sisters dug a grave, and the little boy laid his pet in its last resting-place, and silently covered it with earth.

S. H.

Richmond, Staten Island.

This is the first letter I ever wrote to any paper. I am only seven years old.

Papa has one of the funniest crows you ever saw. He tries to talk. We had to cut his wing, because he used to fly away.

My little sister Lucy, who is almost four years old, sends Young People a picture she drew. It has four kisses on it. We love the Post-office Box best of all.

Hallett S.

I have a garden of my own. I fixed it all myself, and I planted seeds in it. They are coming up nicely.

I went eeling with my little brother Hallett, and we caught enough for dinner.

Willie S.

New Castle, Kentucky.

I live out in the country four miles. I read all the letters in the Post-office Box, and I am so much interested in them! I am reading Robinson Crusoe now, and I like it so much!

We had a very long winter. It snowed fifty or sixty times. We have such nice times in the summer. Sometimes we all go down to Drennon Creek, and take our dinners, and stay all day.

I wrote a composition on Toby Tyler.

Charlie S.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I live here with my aunt, and I go to school. I have not seen my mother or father for two years, but mother is coming soon. My father is Captain of Company H, Eleventh United States Infantry. He is in Montana Territory, at Fort Custer, not far from the place where General Custer was killed by Sitting Bull and his tribe. The fort is on a hill between the Little and Big Horn rivers. Bismarck is the nearest railroad station, but a railroad is going to be built nearer. Then the station will be Big Horn City or Terry's Landing. Big Horn City is a small place, with only one store and a few houses. Terry's Landing is a kind of fort. It has breastworks and a stockade. It is a landing-place for boats, and one company is stationed there. It is near Fort Custer, and every year the company there is changed.

I have the skin of a wild-cat that was killed out in the Big Horn Mountains. It is a great deal bigger than that of an ordinary cat. It measures three feet three inches from head to tail, and fourteen inches round. It has claws like a cat.

William S. G.

Woodbury, New Jersey.

I have two cunning little gray squirrels, named Frisky and Fluff. They are not tame enough to be let out of their cage. The other day somebody left the cage door open, and the window in the room was wide open. When mamma came up stairs, there sat Mr. Frisky on the door-sill, looking very much as if he meant to run away. When he saw mamma, he scampered into his bed, and she locked the cage door pretty quickly. I am only six years old, and my hand is tired writing.

Florence R. H.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I wish to notify correspondents that I have no more stamps to exchange. I have had over one hundred letters to answer, and each day brings more. Several have sent stamps, but no address, so that I can not return them.

Young People must go to all parts of the world, as the answers to my offer of exchange testify.

Madgie B. Rauch.

My old issues of United States stamps are all gone, but I will exchange some green 2-cent revenue stamps, and foreign postage stamps, for 7, 12, 24, 30, or 90 cent stamps of any issue, for coins, stamps from Africa, China, or South or Central America, or for any department stamps except 1, 3, and 6 cent Treasury.

Charles W. Tallman,

P. O. Drawer 5, Hillsdale, Mich.

I have had so many applications for my Sandwich Island stamps that my stock is exhausted.

I will now exchange stamps from Porto Rico, Cuba, Jamaica, Barbadoes, Hong-Kong, Japan, Cape of Good Hope, Egypt, India, Bavaria, and "Thurn und Taxis," for other rare stamps and for coins; South American and African stamps particularly desired. I will also give twenty-five foreign stamps for two good arrow-heads.

Sheppard G. Schermerhorn,

46 West Nineteenth Street, New York City.

I wish to notify correspondents that I have no more postmarks left.

I have a number of Jules Verne's stories in pamphlet form which I would like to exchange. I will give one for a United States cent, date 1840 or 1846, or for a half-cent of any date but 1851. I will send the complete story of A Voyage Around the World for the cents between 1833 and 1837.

Roland Godfrey,

Gardner, Centre P. O., Worcester Co., Mass.

My stock of foreign stamps is exhausted. I will now give ten United States postmarks for five from any foreign country, or from Nevada, Arizona, Idaho, or Washington Territory. I will exchange even for postmarks from other States.

Lawrence B. Jones,

P. O. Box 1036, Wilkesbarre, Penn.

The following correspondents withdraw their names from our exchange list, their stock of shells, ores, stamps, and other things being exhausted: E. P. Snivelly, Columbus, Ohio; Charles R. Crowther, Bridgeport, Conn.; Ned Robinson, Fairfield, Ill.; Walter C. Freeland, Brooklyn, N. Y.; Charles H. Purdy, Jersey City Heights, N. J.; and G. Vasa Edwards, Plattsburgh, N. Y. Exchangers will please take notice.

I would like to exchange fifty foreign stamps, for a star-fish one foot nine inches in circumference. Or one hundred foreign stamps, for fifteen perfect arrow-heads, twelve perfect spear-heads, or two good-sized stone hatchets. Also one hundred and twenty-eight foreign stamps, for a genuine Indian bow and two good arrows. There are no duplicates among my stamps, and some of them are unused. I will also exchange stamps for other Indian relics besides those named above. Correspondents will please give the locality where each curiosity was found.

D. O. L., care of E. A. Moore,

741 Cherry Street, Kansas City, Missouri.

I have just received a large supply of gold ore, and of rock from the Mammoth Cave, which I will exchange for curiosities. I will also exchange petrifactions. I especially desire to obtain the claw of a grizzly bear.

Dellie H. Porter,

Russellville, Logan Co., Ky.

Isaac S. Yerks, Brooklyn, New York, wishes the address of the correspondent who sent him a specimen of gypsum in a parlor-match box.

Paul L. Ford, Brooklyn, New York, wishes the address of the correspondent who sent a stone from Natural Bridge.

Bertha A. Brumagim, Summerdale, New York, has received three unused foreign stamps, and will return used foreign stamps if the correspondent will send address, and the number of stamps wished for.

Any more correspondents wishing to exchange foreign stamps for those from Hong-Kong or Japan, will please address me at Lake Mahopac, Putnam County, New York, instead of 27 East Twenty-second Street, as heretofore. I should like to ask those correspondents who are owing me stamps to send them to my new address as soon as possible.

Harriette B. Woodruff.

I will exchange woods and ores for curiosities, but I do not wish to exchange for stamps any longer. Nearly every correspondent sends me 1, 2, and 3 cent cancelled United States stamps, and wishes woods in return, and I do not think it is fair.

John L. Hanna, 219 East Madison Street,

Fort, Wayne, Allen Co., Ind.

It certainly is not fair to send these common United States stamps, which every boy and girl can obtain by the hundred, and expect anything of value in return. Stamps which are so very common, and are so very easily obtained by every one, can not be considered of any value for exchange. We refer only to the stamps of low denominations in use at the present time. Certain old issues of 1, 2, and 3 cent United States stamps are much more difficult to obtain than many kinds of foreign stamps.

The following exchanges are offered by correspondents:

Amethyst, onyx, carnelian, topaz, moss-agate, blood-stone, sard, garnet, and malachite, for stamps from Buenos Ayres, Bolivia, Uruguay, Paraguay, Ecuador, United States of Colombia, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Hanover, Modena, Philippine Islands, and Azores; or for a genuine Indian bow and arrow, stone hatchet, spear-heads, or arrow-heads.

Willie Brown,

15 South Thirteenth Street, Newark, N. J.

Rock from the Hoosac Tunnel, for Indian relics, shells, minerals, or foreign stamps. Correspondents will please label specimens.

Arthur C. Bouchard,

51 Eagle Street, North Adams, Mass.

Unpolished specimens of pear, cherry, pine, black or white oak, maple, willow, silver-poplar, or horse-chestnut, or a bottle of sand or water from Lake Michigan, for a bottle of water from any river, or soil from any State except Illinois, or tin, silver, copper, or iron ore. Please label specimens.

Max Baird, care of Baird & Bradley,

90 La Salle Street, Chicago, Ill.

Coins, minerals, stamps, fossils, relics of Indians or Mound-Builders, shells, ocean curiosities, pressed flowers, etc, for other specimens.

W. E. Brehmer,

P. O. Box 747, Penn Yan, Yates Co., N. Y.

Varieties of iron ore, for other minerals or curiosities.

Eddie C. Brown, care of E. J. Farnum,

Wellsville, Allegany Co., N. Y.

A Seltz's American Boy's Theatre, with nine different plays, wires for working, in perfect order, cost eight dollars, for a printing-press and type. Please send postal to arrange for exchange before sending package.

C. H. B., Jun.,

34 Clifford Street, Boston, Mass.

Pressed flowers, for Indian arrow-heads.

A. A. Beebe, Falmouth, Barnstable Co., Mass.

Stones from five different States, for minerals, ores, or curiosities of any kind except stamps.

A. L. Clarke,

133 South Shaffer Street, Springfield, Ohio.

A sea-shell, a curious stone, or a piece of forest moss, for five stamps from Asia, or South America or adjacent islands.

J. F. C.,

West Yarmouth, Mass.

Florida moss, silk cocoons, stones from Georgia or North Carolina, and specimens of wood, for gold or silver ore, fossils, or any other curiosity.

Anson Cutts, Eden, Effingham Co., Ga.

Forty-two postmarks or three foreign stamps, for ocean curiosities.

George O. Dawson,

133 East Eleventh Street, Leadville, Col.

Stamps from Jamaica, Cuba, Danish West Indies, France, Australia, and past and present issues of Canada, for stamps from Mexico, Turkey, Persia, Portugal, Newfoundland, and other countries.

T. C. Des Barres, Jun.,

93 Bloor Street East, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Ten postmarks from Ohio (no duplicates), for the same number from Texas, California, Oregon, or Louisiana.

Frankie J. Dick,

P. O. Box 866, Ashtabula, Ohio.

Lava, shells from nearly all parts of the world, and foreign postage stamps, for Indian relics, curious birds' wings; or stuffed birds or animals. Please send list of things you wish to exchange before sending any article.

C. N. Daly,

Bergen Point, N. J.

Minerals, for Indian arrow-heads. United States stamps, for any curiosity.

Walter and H. C. Dickinson,

1004 Madison Avenue, New York City.

Twenty-five foreign stamps (no duplicates), for five coins.

George H. Elder,

99 Broadway, Brooklyn, E. D., N. Y.

Carnelians from Lake Pepin, Minnesota, and stones from the Pacific coast, for Florida moss.

Julia F. Ehrman,

205 East Ohio Street, Chicago, Ill.

Sandwich Island and other rare postage stamps and revenue stamps, for stamps. A 90-cent United States postage stamp, a 30 and 50 cent due stamp, and 7, 10, 24, and 90 cent Treasury stamps especially desired.

Fred W. Flatten,

215 Myrtle Avenue, Brooklyn, N. Y.

A piece of bark of a California tree, a small piece of Scotch pearl, a stone, sand, and soil of Pennsylvania, and three foreign stamps, for a piece of zinc[Pg 511] ore and any five foreign stamps except Canadian, Russian, and English.

Alvin M. Evans,

Care of J. H. Evans, Oil City, Venango Co., Pa.

An ounce of soil from Manitoba, or Canadian postage stamps, for Indian arrow-heads, ores, coins, or rattlesnake rattles.

A. Fergusson,

Drawer 36, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

Rare stamps, for stamps, coins, Indian relics, or any curiosity except postmarks and minerals.

Hulda Faglon,

25 Columbia Street, Brooklyn, N. Y.

Dried willow pussies and pressed violets, for Texas, California, or Florida moss.

Bessie Gleason, West Medford, Mass.

Five-pfennige German stamps, violet issue of 1875, for French stamps issued between 1853 and 1869.

Charles S. Greene,

Rockview Street, Jamaica Plains, Mass.

An illustrated life of Zachariah Chandler, Michigan Senator, for an autograph letter written by any eminent person.

Nellie G.,

P. O. Box 750, Saranac, Ionia Co., Mich.

A piece of coral from Australia, shells from the Mississippi River, petrified wood and bark, gold ore from California, silver ore, minerals, and Indian relics, for a genuine Indian bow or a scroll-saw.

Emil Hartmann,

1818 South Seventh Street, St. Louis, Mo.

Postmarks, for stamps; six varieties of stamps, for one foreign coin; or stamps, for stamps and curiosities.

Jamie D. Heard,

105 Market Street, Pittsburgh, Penn.

Soil from Delaware, for the same from any other State except New York.

Willis H. Hazard,

Delaware College, Newark, Del.

A Brazilian stamp, for a 12 and 15 cent United States; a 3-penny English stamp, for a 30-cent United States.