Through the Gates of Old Romance

Through the Gates

of Old Romance

BY W. JAY MILLS

Author of "Historic Houses of New Jersey"

Editor of "Glimpses of Colonial Society and the Life

at Princeton College, 1766-1773"

With Illustrations by John Rae

PHILADELPHIA & LONDON

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

1903

Copyright, 1903

By J. B. Lippincott Company

Published November, 1903

Electrotyped and Printed by

J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia, U. S. A.

TO THE FOUR MANNERS

OF MANNERS HOUSE ON

OLD BARROW STREET

Contents

List of Illustrations

An Unrecorded Philadelphia

Romance the Franklin

Family helped into Flower

An Unrecorded Philadelphia Romance the Franklin Family helped into Flower

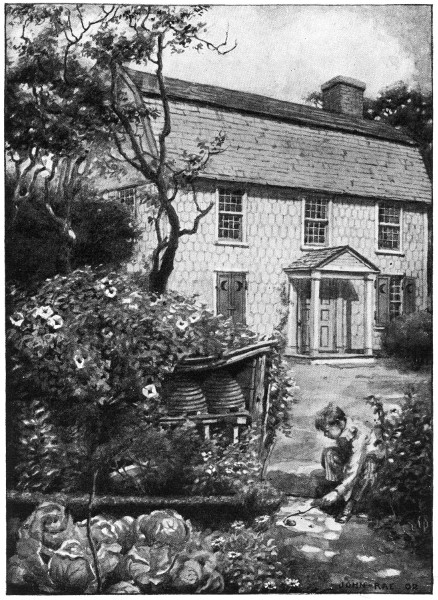

IT was at a musical party given by the great Franklin a few months after he returned from London to Philadelphia, in 1762, that Betsey Shewell first met Benjamin West and entered with him through the ever-swaying gates of Romance. At the time she was known as a belle of the Quaker City, and he is best described by that keen observer of mankind, Doctor Jonathan Morris, as "a young painter of fine parts enjoying[16] his native haunts after the glamour of European capitals."

The modest Franklin house in the heart of the city was at that time a Mecca for the choice spirits of the colonists. Statesmen, scholars, and men of wealth trod the pebbly street to the philosopher's through all hours of the day until long after candle-lighting time. Benjamin Franklin meant many things to many people. It is small wonder that poor Mrs. Franklin often lamented that her "Pappy," as she called her husband, was unhappily affected with a too tender and benevolent disposition, and that all the world claimed the privilege of troubling him with their calamities and distress. But still the lady loved her kind, especially those with good ears, tradition says, and the night that "Pappy" gave this frolic for his buxom daughter Sarah she smiled at the company with broad good-humor. And, knowing this (for otherwise there would have been no party at Franklin's),[17] we can raise the curtain on the scene with impunity, and listen to the ghostly wails of violins, the tinkles of tired spinets, and the long-lost voices of the company.

The night-shutters before the windows of the Franklin parlor are open, for it is the summer time. About the wide, plain room with its few embellishments the guests are grouped in a circle. The host seems to be in a merry mood, and is strumming away on the famous guitar, a knowledge of which he was always ready to impart to his intimate female acquaintances. The ever-laughing Sarah, who seldom sighed for more than the days brought to her, is in her element. She is having a party, and she knows that there is a spicy Madeira punch in the Staffordshire bowl her father purchased as a gift for her mother in England, and a high pyramid of sweet cakes their faithful Abigail made that morn adorns the sideboard. As she flits out into the entry she nudges a girl who is seated by the door, one of a[18] group composed of Mr. and Mrs. Abram Bickley and good Doctor Jonathan Morris. The girl answers her invitation to join her with a wan and unresponsive smile. Her rather piquant face is suffused with sadness, and she pays no heed to the remarks of her companions. It is easy to see that Mrs. Bickley is annoyed by her behavior. Many eyes are focussed on her fine full gown of soft lustring, but she seems unaware of their attention, for the lady is Miss Betsey Shewell, who is indulging herself in a fit of the vapors.

Betsey Shewell had been crossed in love. Like a foolish maid, she had given her heart where it was not wanted, and the object of her affections, Isaac Hunt, a young gentleman from the West Indies, was then paying desperate court to her niece, Mary Shewell, a girl of her own age.

Isaac Hunt, the spoiled heir of an aristocratic Tory family settled at Bridgetown in the Barbadoes, must have been something[19] of an Adonis. His son, the gifted gossiper Leigh Hunt, whom Charles Lamb referred to as "The Indicator" in the famous couplet he addressed to him, wrote of his father, "He was fair and handsome, with delicate features, a small aquiline nose, and blue eyes. To a graceful address he joined a remarkably fine voice, which he modulated with great effect." It was in reading with this voice the poets and other classics that he made conquest of the two girls' hearts.

The image of this fascinating gentleman was constantly haunting Betsey Shewell's mind as she sat moping by the door of Benjamin Franklin's parlor at the close of a summer's day one hundred and forty-one years ago. That very evening she knew he was to ride over from the Red Lion to visit Mary Shewell, then staying with Betsey Bickley at Penn Rhyn, the Bickley country house, five miles below Bristol on the Delaware. He was with his "shy, dark-haired Mary" now, no doubt. Try as she would,[20] it seemed impossible for her to forget him. Her sister Bickley, observing her sad face, began to fidget. She looked at her with disgust and was about to speak, when the sound of the knocker suddenly reverberated through the house, and Sarah, hastening to open the front door, welcomed in a party of belated guests.

"Betsey Shewell! Betsey Shewell!" resounded the voice of the indefatigable Sarah over the babble of feminine tongues in the hall. "Betsey, I want to present to thee Mr. Benjamin West."

The melancholy maid turned round on her clavichord stool, and as she rose to courtesy, the color left her cheeks, for before her stood a youth strangely like her longed-for lover, but of a finer presence. His eyes, hair, and nose were the same, and when he spoke, the tones of his voice—low and tender, like Isaac's—were as balm to her lacerated heart.

It was Jonathan Morris who later in the[21] evening fanned the flame of Miss Shewell's curiosity in regard to the handsome Mr. West. He knew almost every step in the round of the young painter's life. There were many things he told her in regard to his early years passed at Springfield, Delaware County, where he did his first drawings with colors given to him by the Indians. How his rude paintings were the pride of a simple Quaker community and the delight of a mother who believed her son to be predestined for some exalted place in the world.

We can see the girl's bright eyes glisten as she listens to the tale of the day when the youth first left his home to journey to the city and to fame. His father and several neighbors accompanied him part of the way on the Strasburg road, which was then unsafe to travel without the protection of a score of muskets. In those days of pioneer life under King George the way from Springfield township to the City of Brotherly[22] Love was a hazardous one, infested with bands of brigands constantly on the watch for travellers. As he pictures West flying through the forest pursued by outlaws, but at last outwitting them, her eyes stray to the young painter, who is talking with her sister. She views him with mingled emotions. Brave and valiant, he dashes before her on the charger of courage over the rough and rocky places of life. And then the face of Isaac Hunt comes to her mind in the guise of a handsome weakling. Her foolish infatuation for him is flickering and dying. What has he ever done like this man who has risen from a humble environment to a figure of consequence through the force of his own nature? The words of Morris have succeeded in exciting her interest.

West feels her gaze upon him and turns to look at her. She is wonderfully lovely in her shimmering gown. Their eyes meet and he goes to her. The vapors that Doctor Franklin's music could not dispel have vanished,[23] and in their place the lights of love are all aglow for conquest.

Sarah Franklin was the life of her party that night. She even made her mother—good jolly home dame that few Philadelphia fine madams would have anything to do with—sing for the company. Perhaps she sang the quaint song Franklin composed for her some years after his marriage, called "My Plain Country Joan." If she did, she must have lingered with satisfaction over the last verses, in which "Pappy" paid a tribute to her worth:

When the company rose and gathered in a group for the chorus, there were two who stole out into the cool entry. They were Betsey and West, the idealization of her[24] former lover. There he finished for her the story that his early patron had begun. She heard of his life in Italy and the admiration his work excited. Through the great cities of Europe she strayed with him until they came to the small town of Reading, where, in a watchmaker's rose-embowered shop, his brother tinkered over fusees, ratchet wheels, and main-springs. In his words peace lingered along the village street, and she sighed over the charm of it.

When the chairs came the Franklin household stood on the doorstep and wished their guests "good-night and good rest." West helped Miss Shewell into her sister's vehicle, bound for Stephen Shewell's abode on Chestnut Street, where the Bickley party were to pass the night. After the carriers started he followed in the chair's shadow until he neared the alley which led to his lodging-place; there he turned and threw a kiss at it in the darkness. The girl's conquest[25] was complete. The lights of love had burned him.

Betsey, seated by her sister in their slow-moving vehicle, was silent. As they passed the long rows of Cheapside houses, each like its neighbor, some new memory of the evening would come to her. Life seemed an intangible mystery with labyrinths of intricacies. She had found a lover strangely like Isaac Hunt in appearance, and yet so different. As she mounted the steps of her four-poster a little later she almost pitied her niece Mary.

Philadelphia was a gossipy place in the days before the Revolution, and it soon became noised abroad that the young limner West was paying court to Betsey Shewell. The Bickleys had retired to Penn Rhyn, but the maiden still stayed on at her brother Shewell's abode. This brother Shewell was a wealthy man, following the mercantile calling of many of his family. It is a tradition that he desired to marry his sister to[26] a Water Street compatriot over twice her age, and therefore frowned on any gentleman whose admiration was ardent enough to lead him to call upon her. West had visited the fair sister several times before the rumors of their love-affair reached his ears. Returning one night from the Hat Tavern, where he had business with one Widow Cadwell, he fell in with a meddlesome friend of Betsey's who inadvertently told him of the tales that were floating about the town. That a saucy nincompoop of a painter should dare set his eyes on one of the Shewells was a strange thing to this arrogant gentleman whose days were bound with buckram. Nevertheless, he resolved to deal summarily with all parties concerned and sift the matter to the bottom. At first he thought of calling out West, but decided that it would create too much scandal; besides, although the painter's usual demeanor was most peaceable, it was said that while in the Lancaster militia he had become well[27] skilled in the use of his sword. As he rode homeward his anger grew at every rod the horse covered. He scowled at the timorous handmaiden who opened the door of his house. His spurs beat the hard pine-wood floor as he strode through the hall.

The family were seated at the evening repast. Mrs. Shewell, a dainty, fluttering little woman with the air of a shy wood-pigeon, rose to greet him, but fell back in her seat as she saw his face. Betsey glanced at him, too. She did not quail, for she had known her brother longer than his wife. For a moment there was a silence awesome as the void between two thunder-claps. Then fury was let loose upon the room and tore the story of a tender love-affair from a girl's heart.

"Love him, dost thou? Thy chamber, miss, is the place for thee until thy mind mends." The man sputtered as he made to seize the now thoroughly frightened girl.

The dining-room, so peaceful a few minutes[28] before, became a scene of wild confusion. Mrs. Shewell was taken with the hysterics, the frightened handmaiden, having entirely lost her wits, let fall a tray of India ware she was clutching, and in the nearby aviary a pair of Brazilian parrots set up a screeching.

Through the hall and up the stairway Stephen Shewell forced his sister, now grown passive, and thrust her into her chamber, locking the door from the outside. From the landing he called in a loud voice his orders that no one should go to her. The tongues of the household were silent, and quiet came after the storm.

Later in the night, when the hall candles were snuffed out and the stern lord of the mansion had fallen asleep, Mrs. Shewell crept to the girl's door and, unfastening the lock, stole in to give her comfort. The room was dark and the little woman's throat became parched as she imagined all sorts of awful things which might have[29] befallen her sister-in-law. A chair gave an unearthly creak, and she stood still, afraid to move, when Betsey descried her and spoke.

The girl was seated, fully dressed, by the window, gazing on the sleeping city. Mrs. Shewell approached her, and, putting her arms about her neck, wept softly as she thought over the past scene. Betsey kissed her and smiled out at the night. Somewhere off over those dim roofs just touched by a pale moon's light he was sleeping, dreaming of her. Over the silent streets her prayer floated to him, where'er he was: "Oh, Mother Night, fold your tranquil shadows about his couch and guide his wanderings in that wondrous land to pleasant places." Her face was suffused with the joy of love. They might shut her away forever behind closed doors, but they could not destroy the memory of the world she had found with him.

Sarah Franklin was one of the first to[30] hear of Betsey Shewell's incarceration and its cause.

"'Tis hard on the poor maid," she said to her father over their morning dish. "Her love-affairs always run amuck. First 'tis her niece Shewell who runs away with Isaac Hunt, and now 'tis that cock-a-spur of a brother who shuts her away from Mr. West."

Mrs. Franklin was up in arms in an instant. "Pappy" should go at once to get her out. The poor maid was no doubt languishing. Then, too, 'twas well known Mr. West was soon leaving again for foreign countries.

Franklin shook his shaggy head and bent lower over his bowl. "Would you have me carry coals to Newcastle?" he asked. "We must bide our time, for he that stops a little makes an end the sooner."

Sarah smiled, for she knew that when her father waxed proverbial his mind was making a pleasant excursion.

"We must bide our time," he repeated again. Neither Sarah nor her mother spoke, for they knew his mood.

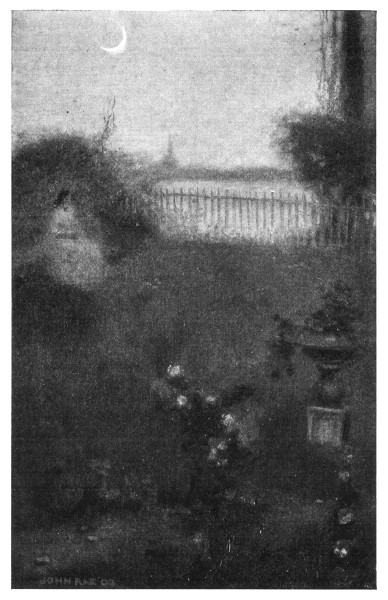

A few hours before the Franklins began their digression on Betsey Shewell's fate a dark-coated figure stood before the Shewell house and threw tiny pebbles at the third-story chamber window where the girl slept. There was no one on the street. The solitary lanternman, who had laid aside his rattle and staff, called out in a husky voice the last "All's well and near morning," and departed. Daylight's eyes were on the verge of opening. Faint streaks of pink were drawn across a sombre sky like tassels bedecking a dull brocade. It was the wonder hour when ghosts are creeping back to their graves and the living are about to awake.

Soon a young girl appeared at the window, opened it, and began to talk softly with the man below. Sweet were the words that the dawn wind caught, for the pair were the lovers Betsey Shewell and Benjamin[32] West. It was in this manner that they sometimes saw each other. Although the window was at too great a height for the youth to clamber up to his ladylove or the lady to descend to him, it still permitted soft vows and protestations. This particular morning West brought the sad news that he had obtained a berth on a vessel leaving port in a fortnight. Could she not in some way escape from her prison? The heart of the girl, so near and yet far away from her lover on the pavement, beat wildly 'neath her quilted night-robe. Vainly she longed for the wings of a bird that she might light by his side. For an instant there was a faint hope, and then it was dashed away.

Below a window casement creaked softly. Stephen Shewell was listening ensconced in the folds of the chintz window-piece. "Would thee, hussy? Would thee?" he murmured. He could hear the voice of West imploring his Betsey to try and fly with him. The old crone who kept his[33] lodging-place in Christ Church Alley would secrete her until the ship left port. "Oh, but to have the impudent fellow by the neck!" In his rage he clenched the soft folds of his worsted damask banyan. He longed for something to throw,—as he ofttimes did at the vermin of the night. Over under the shadow curtains of the bed his wife was waking. From a happy dream the daylight led her eyes to her husband's face leering out of the curtain. Knowing of the stolen meetings, fright overcame the awe of her husband, and she gave one piercing shriek, prolonged and full of anguish. The three actors in the drama each received a shock in a different way. There was a hurry of footsteps in the street below. Windows rattled and opened. Grave night-capped Quakers looked askance at one another from house to house. What was the matter? Inside the third-story window of the Shewell mansion a girl swooned.

When the sun was high a great coach drove away from Shewell's and took the road for the Bickley house, Penn Rhyn, many good leagues from the city. It carried a pallid maid guarded by two stout Quakeresses, servants and aides of Stephen Shewell. The hoyden hussy was wedged between them, disgraced and bound for the sequestered rural shades where impecunious painters were not.

Out into the wooded country the vehicle rolled. At every jolt of the lumbering thing the larger and stouter of the two seized a blunderbuss from an arm-chest, in fear of possible highwaymen. The girl between them gave no heed to their thoughts. Like one only half awake, she gazed out at the country. Each field and fallow they skirted was bearing her farther away from him. The sweet odor of the hay-ricks, the clouds that seemed to be racing with them, the life of the waving trees, and the trilling birds fluttering out of the coverts they[35] brushed, all spoke of him. Each whispered some message, she knew not what.

"He will never find me again," she mused. Tears came to her eyes, and the drops which were not to be kept back fell on the palm of the stouter Quakeress, who was dozing.

The woman opened her sleepy eyes and gazed at her almost compassionately, then closed them again and fell into a deep slumber. The coach was striking level land. Now the other Quakeress was nodding. For a moment the girl was tempted to seize the blunderbuss from its leather bed and jump out into the road. Then fear overcame her, and she, too, sank back and closed her eyes.

It was the ringing of an evening bell tolled in a nearby hamlet which welcomed them into the beautiful roadway leading to Penn Rhyn. That roadway is little changed to-day, but the house itself gazes upon its visitors in new attire. Probably there is no[36] mansion in Pennsylvania that has had a more interesting history than this pile erected early in the eighteenth century by a pompous Bickley from Buckinghamshire. On the estate is the family tomb guarding the dust of many generations of Bickleys—young Bickleys who faded before their perfect bloom, old Bickleys who were glad enough to lay down the thread of life and rest their tired bones on that moss-grown bank. A long procession of men and women bearing a name that they all were proud of, with but one exception. He, Robert Bickley, cursed his name and his father one Christmas night and then threw himself into the Delaware because the stern gentleman had told him never to darken his door in life, owing to an unfortunate marriage. Now, every Christmas eve it is said that he rises from the river, gaunt and slimy, and steals up the path to the house. Sometimes a belated wanderer sees him standing in the moonlight before the great hall door of[37] Penn Rhyn, moaning over his unhappy fate. Again he is heard in the corridors tapping with ghostly fingers at each chamber door for admittance. Promptly on the stroke of twelve weird, unearthly cries fill the house. Then every wakeful sleeper cuddles down low under the bedclothes. Perhaps it is only the wind playing about the chimneys, but the superstitious would have us believe that it is the shade of poor Robert Bickley calling to his young wife and cursing his fate and name.

Twilight, with her many fairy couriers,—the glowworms, fireflies, and velvety night-moths,—was settling over the paths of Penn Rhyn's garden when the two Quakeresses and the girl, stiff from their long journey, alighted before the Bickley door. The Bickleys were overjoyed to see their sister before brother Shewell's letter was delivered by the stoutest of the guards, who still carried the blunderbuss. After Abram Bickley perused the epistle with knitted[38] brow an air of depression fell on the group. "She is to stay in the country, guarded close, for the summer, and the next summer until this painter fellow is filched from her head," he read to his wife.

The figures on the porch, with their background of dim vines and murky bricks, made a night-piece worthy of the brush of Mr. Hogarth. To the girl, tired and distraught, the front of the house seemed to be covered with mocking faces like the masks about the playboard of the Philadelphia theatre. She hated them all with their looks of compassion, scorn, and surprise. The dull-witted Quakeresses were speaking again with her brother-in-law. Their slow-mouthed sentences came to her ears. "I am here like some poor thief awaiting jail," the girl thought, as she looked at them. Then the faces began to fade. She had wandered into a world of fragrant dusk filled with the good-night prayers of closing flowers. She would willingly go to jail for love.[39] There was nothing more beautiful in the world. Each prison bar she would twine with it. Each day and night should be carpeted with it. Her face was raised heavenward to the field of little stars.

In the course of events the world in which the Shewells moved learned that Benjamin West had departed for England, and that Betsey Shewell was secreted in a safe country retreat where it would be impossible for him to find her. Sarah Franklin brought to her father's mind his half promise to aid the lovers.

"We must bide our time," he said. "Haste trips up its own heels." That night he penned a letter to West in London. In a few months an answer came. When "Pappy" showed it to his family one morning, they almost devoured him with kisses.

"Take me with you, father, when you set out for Bickleys," Sarah implored. "I want to be in the plot."

"That you shall," he promised her. "There is much to be done first, though, for we must get at old West."

"'Twill be like the play, and I shall wear my new mourning mitts," Sarah called, pirouetting in glee.

Mrs. Franklin's face was aglow with motherly pride. "Thou shalt wear a new store silk, for the Bickleys be fine feathers at home, I hear."

She glanced at "Pappy" for assent, but he was deep in a newspaper. "I will get it out of him," she said, nodding to the daughter knowingly.

Betsey Shewell, who was practically a prisoner at Penn Rhyn, so closely was she watched, thought often of her lover in the weary run of days. She was only allowed to walk as far as the terrace with one of the family or some saucy maid well aware of her mistress's shortcoming. Her diversions were few, and but for her cousin Betsey Bickley she would have wasted from grief. From[43] her she learned of Isaac Hunt, and her lips curved with scorn at the praise bestowed upon him. Her niece brought the news one day of a letter received by Abram Bickley from over the sea. Both girls wondered at its contents. Could it be from West? A closer watch seemed to be kept over the fair visitor. Many an hour they pondered over it, surmising this and that and wreathing it with sanguine fancies. The suspense was becoming maddening when all hope was dashed to the ground by Abram Bickley, who read the communication to his wife one morning as the four sat in the dreary garden. It was from a London creditor.

Another June was upon the land,—a wet month more like some silly April than the span of days loved for cheer and sunshine. The two Betseys were out in the Bickley garden gathering drenched roses for the want of something better to do. All of a sudden from the sleepy road there came the[44] clatter of wheels and the clink of a slow nag's feet. Then into view loomed a comfortable chaise of the style afterwards known as the "Postmaster-General." The pair nearly dropped their budholders in the momentary excitement. Rising from her seat and waving a kerchief was a girl. The face they knew well.

"Sarah Franklin, I do believe," called Betsey Bickley. "Yes, yes; 'tis her father with the reins."

"Pappy" and his daughter had come on their long-promised visit to the Bickleys. Sarah Franklin was radiant with happiness, and it was easy to see that her father reflected her mood. A sight to behold she was when she descended from the side step. Her gown, the fought-for store silk, was garnished with a multitude of varicolored prim flowers, and its folds tried in vain to cover her Paris shoes with red heels, which, in lieu of paste buckles, owing to "Pappy's" hatred of gewgaws, she had tied with red ribbons.[45] On her head she wore a stiffened pasteboard trimmed with "masqueraded bombazin" and adorned with a waving plume which the wind swayed like the dancer a venturesome manager of the new theatre had put on in the tragedy "The Orphan."

"Oh, you dear Betsey Shewell and Betsey Bickley," she exclaimed, laughingly, as she threw herself alternately in each girl's arms. "My heart thumps at the sight of thee!"

Her father smiled at her actions over his spectacles as he added his greeting.

The noise of the arrival soon brought the whole of the Bickley household to the door.

"'Tis an honor, sir, to see you here," Abram Bickley said, as he helped Benjamin Franklin from his seat.

"There is naught of an honor about it," Sarah Franklin whispered mockingly in Betsey Shewell's ear. "We have come for a play; but keep it to thyself," she added,[46] as if afraid of her words. Then she took off her long black mitts and twirled them in the other's face.

"Won't thee make a sweet actor lady," she said, to the other girl's wonderment, as they walked together.

There were great doings at Penn Rhyn the day the most talked of man in Philadelphia and his daughter arrived. The largest guest chambers were aired, the fattest goose-feather pillows were brought out, and sweet herbs were placed in all the chimney-piece ornaments. Mrs. Bickley prated in a grandiloquent manner to her maids. A statesman on a visit to her abode gave her undisguised pleasure.

The whole house was soon in a bustle. Sarah Franklin, who sat with Betsey Shewell on a bench in one of the fast-drying paths near the doorway, heard many sounds familiar to her housewifely ears. There were the whack and thump of duster and broom. Delicious odors soon[47] began to steal from the kitchen and mingle with the scents of revived flowers.

"There will be a party to-morrow night," she said to her companion.

"A party!" reiterated the other in surprise.

"Yes, a party! Wait and see. 'Tis part of the play I have writ with my father out of our heads." Then she began to hum a tralala. "Tell not a soul," she cautioned, and nothing the other said could get another word out of her.

When the Franklins and their travelling chests were safely in their rooms, Sarah opened her chamber door and went in to her father. "She is closely watched," she said. "Did you hint at a merry-making for to-morrow, father?"

"That I did," he answered. "And now, miss, you must lay your traps well. Tell neither of the maids aught, for women have restive tongues. You are proof of the maxim. Go you to Bet Shewell's room[48] to-morrow and have her show you her finery. Find out her clothes closet, and to-morrow night, when the noise is on, creep to her room and do them up in a bundle. Have them ready to give her when it is time to tell the news. To Bet Bickley say that you have a desire to see the neighborhood gallants, and get her to bid them all for to-morrow night. Her father will let her if he knows it is your hanker. Lay thy plans well. Remember, two heads and a goose make a market. It is a lot of trouble we are going to for young West, and I don't begrudge the turn; but we must not fall out with the Bickleys."

The famous Miss White, of Philadelphia, who lived to a great age, repeating reminiscences of her cousin good Bishop White used often to tell of that sometime gathering given for Benjamin Franklin by the Bickleys at Penn Rhyn. Among the guests she always gave the names of Francis Hopkinson, Doctor Jonathan Morris, and her[49] cousin, who was then a lad. No one ever disputed her, and it is safe to say that the three celebrities were there.

Early in the evening the neighbors began to arrive from nearby country-seats, and the house was soon filled with a great company, for Mrs. Bickley wanted her world to know of the honor being paid her. Along the south walk each of the boxwood grotesques was strung with little Chinese lanterns. A bush cut in the shape of a bird held a green dragon in the mouth. The host had planned for a garden frolic, but a soft rain was falling. A wit suggested that the fair ones don capuchins and repair to the lawn for a water-nymph dance. The drawing-room was filled with the noise of gay badinage and the rustle of silken garments. A female voice in an adjoining room was trilling in languishing strains Mr. Vernon's new Vauxhall-garden song, "Jenny and Chole." Between the notes one could catch the fretful murmur of the rain. Its patter on the catalpa leaves[50] near the windows was like the protestations of some band of elfin children angry at the death of moonlit hours and lost playtimes.

To all observers Franklin was in his gayest mood, and repeated funny tales and made frequent jests; his daughter also laughed with all the gentlemen surrounding her. But in reality their hearts were both heavy. Betsey Shewell was upstairs locked in her chamber, and their long-cherished plan of setting her free seemed worsted, for a servant sat guard by the door.

Outside at the back of the house, hidden by a clump of bushes, the father of Benjamin West was waiting patiently for the lady who was to fly with him to England. Some distance from the Bickley grounds his rowboat that was to bear them to a frigate at Chester was moored to a bank. The night was far advanced and his old limbs were quaking from the cold rain. His eyes, resting on the house, saw a candle flash from[51] an upper window. He knew that it must be a signal.

Sarah Franklin, as soon as she discovered the way the wind blew, began, at her father's instigation, quietly to take goodies from the dining-room up to the servant by the door.

"I can't let you give them to her, miss," the woman said when the girl first approached.

"They are not for Betsey, but for yourself," Sarah answered. "You must be tired watching. I thought you would like some cheer," she added artfully.

Fate aided the conspirator, for it chanced that the woman was a glutton, and she drank eagerly of the huge jug of stiff punch. She was snoring blissfully when Sarah again came up to her. Slipping her hand into the other's apron pocket, she found the door-key. On tiptoe she crept to the door and, turning the lock, opened it a few inches and went in very softly, bolting it on the inside.

A night-lamp was burning on a wall-piece and Betsey Shewell did not shriek, as Sarah feared she might, on her entrance. She was dressed and lying on a sofa listening to the sounds of mirth from below. She had been pondering over Sarah's strange words of the morning and the day before, and their meaning was now dawning on her. The Franklins were going to help her to escape from Penn Rhyn.

The girl, in disordered party finery, seized a candle from a stand, lit it over the lamp, and held it before the window. Betsey Shewell ran to her and began to clutch at her skirts, unnerved at the glorious thoughts of freedom.

"Hist!" the other said, touching her lips. "West's father comes across the lawn."

Both girls had mounted the sill and were motioning to the man below, who was placing a ladder before the window. Betsey began to sob in her excitement.

"I cannot go! I cannot go!" she wailed.

Sarah shook her companion gently as she drew a heavy hooded cape about her head.

"Hush! Hush!" she murmured. "Do you want to wake the woman by the door? Your lover longs for you in London Town and my father and I want to get thee to him. There is no time to stop now for your things," she added. "Part of the play I prated of is ruined, for we did not count on your being shut up here to-night." She was losing her breath and the din downstairs seemed to be lessening. "Go! go!" she said.

For a moment the girls were clasped in each other's arms. "I can ne'er repay your goodness," one of them said. From the other's eyes flashed all manner of sweet wishes.

"Go!" she whispered again hoarsely. "Good that is too late is as good as nothing." She was smiling alone in the darkness.

Off into the night floated the murmur of convivial voices in bibulous cadence. Now the great Franklin was laughing. A watchful[54] ear could catch the patter of faint footsteps.

Outside the room the servant still snored by the door. Sarah passed her safely and replaced the key. No one was ever the wiser for the part she and her father had played in West's life until she told it herself in later years.

Down to the river an old man and a girl stole through the darkness. Off to an unknown land it bore them to bask in the sunshine of a laurel-strewn pathway the painter Benjamin West knew through a long and fruitful life.

Recently one of his old letters to Doctor Jonathan Morris was brought to light, written four years after his marriage to Betsey Shewell, on September 2, 1765, in the church of St. Martin's in the Fields. It breathes of peace and contentment, and when that worthy read it to the Franklin household, there was one who sighed over its sentiments, and another, alas! over the spelling.

"Dear Jonathan,

"Our worthy Friend Thos Goodwin being just about to imbark on his returne to North America I could not let so favorable an opportunity Pass without returning you my thanks for your kind favor to me by Thos Carrington. By him I intended to have answered it but his leaving this place without giving me the least notice if his returne (which he rather promised he would before his departure) has been the ocasion of this omission, which I hope my dear friend will not think an neglect. As I can asshure him his letter gave me that pleasure which may be felt on the meeting of long absent friends, for such was your letter to me. It revived fresh to my memory as tho I had been in the actual enjoyment of the many Pleasing and happy hours I have spent with you in those Rural and inocent juvenal amusements with which America alone abounds my sighs are often intruding and vainely wishing again for those past pleasures which I have there so often experience in those Solitary retreats, or what they people of this side the water call the wilds of America and which is I think a true Image of the following celebrated lines—

"My having had an oppertunity for the last ten years of my life from the vast Toures I have made in visiting the great Capitals in Europe of forming and inlarging my knowledge of Both the world and man and thereby know that true value of America and the Boundless blessings its inhabitance injoy. For without this oppertunity I might have remained in Ignorance of the real Blessings they Injoy and the State of happyness that subsists between them. For it's by comparison we learn to know the true value of all things—And from thence arises its real worth and esteem.

"As this is the part of the world my department in life has fixed me, I have indeavored to accommodate and settle myself in a domestick life with my little Famely which consists of my dear Betsey and her little boy."

The Love-story of the Noted

Nathaniel Moore and "the

Heavenly Ellen," a Belle of

Chambers Street, New York

City

The Love-story of the Noted Nathaniel Moore and "the Heavenly Ellen," a Belle of Chambers Street, New York City

"VERY far away Federal Hall seems to-day as I sit at Aunt's window and gaze out into the street full of chaises and passing pedestrians—The grim stone Pompeys on the garden gates seem to mock at me a simple country girl bound in this hot-bed of fashion for another fortnight—Oh my tenderest Diana how I long for the fresh green of the countryside to give the balm of solitude to my fluttering heart—Ogling and pretty spoken gentlemen New York has in abundance but a girl in[60] my situation no longer cares for a string of gallants—You, my dearest consoler have guessed my secret that he loves me—How can I describe to you his eyes, his hair, his voice, when it is such perfect bliss to pen he loves me...."

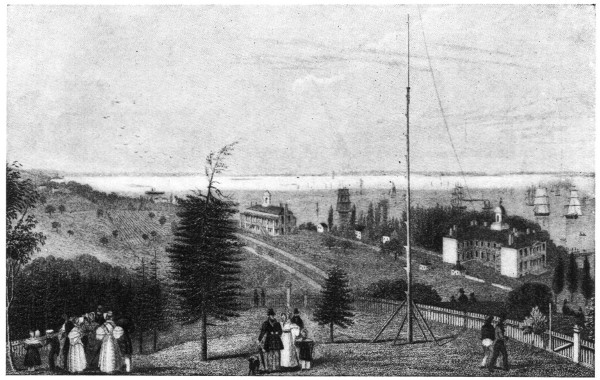

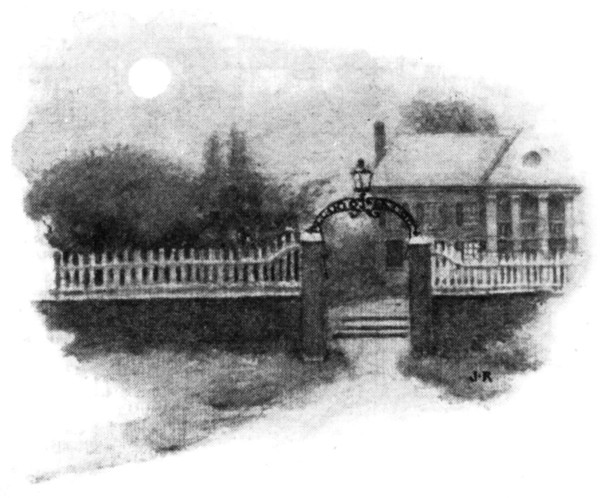

A great red brick mansion in Chambers Street, guarded by two sentinel-like elm-trees and a tall iron fence; a sidewalk filled with the fashionables of Gotham starting for the afternoon Battery promenade; and up behind the eye-like panes of one of the haughty, staring windows a maiden dreaming over her pen. There is the picture. A demure little country Phyllis, visiting her august city relatives for the first time, has found herself in two strange worlds—fashion and love. In the extract taken from her letter written to a home confidante is the key to a forgotten romance of old New York. Love! the key to all the romances since the world began. "He loves me," she writes, the time-worn phrase every true daughter of Eve has hoped to[63] whisper to herself or cry out to the multitudes, and we feel the thrill of those faded but impassioned words as in imagination we open the gates of that old-time mansion and enter into the year of 1807.

New York society, which seems to undergo a complete revision every quarter of a century, has entirely changed since the name of Moore meant as much to the metropolis as that of Biddle to Philadelphia or Carroll to Baltimore. At the time of which I write, when the first numbers of the "Salmagundi Papers" were startling North River aristocrats, fields lay beyond the new St. John's Church, and Canal Street was looked upon by the sagacious as the probable Mecca for retail commerce. Jeremy Cockloft, the younger, gives us a glimpse of the residence portion of the city in "The Stranger at Home, or a Tour of Broadway." "Broadway—great difference in the gentility of streets; a man who resides in Pearl-Street, or Chatham-Row, derives no[64] kind of dignity from his domicile, but place him in a certain part of Broadway—anywhere between the Battery and Wall-Street, and he straightway becomes entitled to figure in the beau monde, and struts as a person of prodigious consequence."

In the new Chambers Street, named after one of Trinity's vestrymen, was the home of Dr. William Moore, then the first physician of old New York. With a wife who was a daughter of Nathaniel Fish, and a brother, the Right Reverend Benjamin Moore, D.D., Bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the State of New York and Rector of Trinity Church, his right to dose the aristocratic element of the city was undisputed. It is small wonder that his morning parlor was generally filled with patients who, tradition says, sometimes literally fought for admission into the inner room and the presence of their "dear gentlemanly doctor."

William Moore was a physician of the old[67] school, and is remembered as wearing a bob-tailed wig and wrist ruffles long after the fashion was obsolete. No doubt this adherence to the costume of a past régime gave him an additional hold over many of his patrons. Legion were the antique dames struggling against the invasion of demoralizing French fashions who derived momentary satisfaction watching him amble to the family pew in Trinity, followed by numerous exponents of that scapegrace, Napoleon's Empire.

Dr. William Moore, of Chambers Street! A long-dead king of pills and potions. How stern looks the old figure in the bottle-green coat the name conjures up! We can hear the voice of Thomas, the negro valet, call out, "Dis way to de Dochtar's sanctum, missy or madam." "Not you thar, ladies," as the circle rises. Many a humble possessor of a backache or a heartache must have trembled before that roomful of Crœsus's children on hearing a summons to the awesome[68] presence. Just over the office a maiden sat one spring afternoon in the glow of a love-dream. She heard the dull murmur below, but her thoughts were too beautiful to heed an interlude so closely allied to pain. Through the garden gates the people passed in and out, and now and then the voice of Thomas would come floating to her with his "Dis way to de Dochtar's sanctum." Little did she imagine, as she bent over her pen, that she would ever be called there and the closing door shut out her love-dream forever.

Two years before Ellen Conover, the girl of the picture, first came to town a youth had journeyed to her home, Federal Hall, in Monmouth County, New Jersey, on a visit. He was Nathaniel Fish Moore, the son of Dr. Moore. The time was a college vacation, for the young man was a student at Columbia, the institution so closely associated with the Moore name. Mrs. Conover née Anna Fish, his mother's twin sister, was[71] proud of her handsome and high-spirited nephew, and encouraged his intimacy with her sons and daughters.

On the outskirts of Marlboro, where Federal Hall lifted its white head above the low stretches of verdant country, Ellen first met the youth who was to be her future lover. When the great coach rounded the turnpike curve with rumbles and groans, and the foam-flecked horses were becoming mere specks in the gray distance, did any of that merry party realize that in the infrangible twilit silence of an early summer's eve two kindred souls had found each other? Up the hilly meadow whose multitude of young green things seem awed at the shadowy approach of night the family trudges, followed by slaves carrying the horse-hair trunks! What a peaceful pastoral scene it is! The spring and all her delicate children are dead, and in her place have come the thousand charms of happier summer. We hear the mother's tender voice, the father's[72] deep tones, and now and then the eager questions of the boy as he helps the maiden through tangles and over stones. The arms of the darkness are encircling them and shutting them away. Soon they will reach that great hall door which no longer guards the welcoming glow of a high-piled hearth. Before it every year the summer comes and goes. The flowers creep up to it, the wind and the rain sigh against it, but the old-time lovers long ago joined the silent company in God's immutable garden of rest.

Freehold, the next town to Marlboro, was the county-seat and the resort of a gentry which closely modelled itself after the country families of England. Racing, hunting, shooting, and fishing then comprised a large part of the sum of existence for the Jersey squire. Every great landowner possessed a small army of slaves, and the wheels of life ran smoothly. Heavy silver flagons were on the oaken sideboards, old port and sherry in Mammy Dinah's[73] cellaret, and a strong box overflowing with gold pieces was secreted somewhere behind the Spectators on the library shelves. On the yellow road creeping out from the court-house stood half a hundred happy Jersey homes—Battle Hill, Violet Bank, Cincinnati Hall, Forman Place, Mount Pleasant Hall, Wassung Vale, Shipley, Harmony Hall, Haven Home, Lover's Port. Only a few of them are left to-day. Mornings spent in following the hounds through dewy coverts, afternoons in spinning or visiting, and evenings in dancing or reading Goldsmith with some favored companion in the englenook by the hall fire composed the daily and nightly curriculum that Ellen Conover and the Jersey girls of her class knew.

It is said that the portrait of Ellen Conover, by the elder Jarvis, in a white empire gown against a dull pink background, was more like a caricature of her than a faithful rendering of her charms. Her eyes were deep blue, her hair of a gold-brown color,[74] and her complexion had that fresh soft tint only to be compared to wild roses. Clement Moore, a son of Bishop Moore, who wrote "'Twas the Night before Christmas," a poem which has delighted so many generations of children, used to dwell with rapture on the beauty of her arms and neck. He was one of the gay young city sparks who looked with favor on the little country girl when she first appeared in town, and lost his heart in the bargain, too, if tradition does not err. This we know, that the Knickerbocker belles were palling upon him at that period, and his muse hurled fiery diatribes at the modish nakedness of his young country-women.

After the stately dinners were over in the Moore mansion, and the hour for stray patients past, the parlors became scenes of revelry. Eight o'clock was then the usual calling time in the city, and when the voice of the old clock had finished welcoming in that portion of the evening dear to feminine[75] hearts, Thomas had answered the knock of many a beau. These were the good old days when jolly Colonel Marinus Willet, the city's mayor, was the model of every smooth-faced buck, and sweet Anne Bankhead, coming to town with her fair tresses arranged in the Paris mode resembling the comb of a rooster, started a fashion which made the fortune of the "Empereur des Barbieres Frizzing Palace on de Brudeway." We know the names of many of the Moore girls' callers. Among the favored were Henry Major, who married Jane Moore on August 2, 1808, in St. John's Church, still standing on Varick Street. Then there was Henry de Rham, who married her sister Maria; John Titus, engaged in business with Mr. Major; John Swartwout, the loyal friend of Colonel Burr; Theodore Frelinghuysen, and many others.

On the Orleans claw-footed sofas, then humiliated by chintz covering depicting the[76] Corsican's bees, the Misses Moore would sit with their swains. There were four of these ponderous pieces of furniture in the large room, so that there was never any danger of crowding. We can picture to ourselves Ellen and her lover taking part in the gayety and longing to be by themselves in some quieter spot. In Monmouth her heart would not tell her that she loved him, but here she had discovered the sweet secret.

How beautiful was their blossoming love-dream! No doubt, after Thomas crept down to the servants' quarters to bed and the hall was deserted, they often stole away from the company, opened the massive mahogany door, and gazed off over the patch of garden into the night. Only the garden knew of their first kisses,—the nesting birds and the drowsy flowers. They always seem to keep an eye open for human lovers. The robins and the bluebirds chirp sadly, and the flowers give forth fragrant sighs just as[77] if they knew that the course of "true love never runs smooth."

Under the little beech-tree, with his arm about her, he told her of the humble home he hoped to rent in Gansevoort Street when she would say "Yes." He would not be dependent on his father. His office down on Nassau Street was no longer always deserted.

"I will bring mammy from the country," she would whisper. "And Ned."

"Yes, dear," he would answer.

"I shall cook the breakfast for you with my own hands every morning."

Little white hands. How he pressed them!

"Isn't it beautiful just to be here together?" her lips would falter, as if afraid of the words.

Poor little old-time lovers! Poor little fluttering hearts! There are steps on the pavement outside the gates, for the watch have started on the weary walk with night.

The Moore girls who decorously occupied the Orleans sofas all through the calling hours soon began to notice the couple who so often left the circle. In the morning at the breakfast-table there were often sly innuendoes that Dr. Moore, absorbed in his Herald, never paid any attention to and Mrs. Moore could not understand. She would have, though, if she had observed the burning roses in a maiden's cheeks and the angry eyes of the youth opposite glaring at his tormentors.

"Oh, girls, did you observe the new moon last night?" Jane Moore would innocently ask. "Ellen, you must have." Then how they would giggle.

"Hush, girls!" Mrs. Moore would say as she poised her Wedgwood coffee-cup and gazed around the table. "Young ladies in your station of life should never laugh so loudly; it is not genteel."

Some of the young fellows who called at the house were not so observing as the Moore[79] girls. Freddy Frelinghuysen used to try and keep the pretty country cousin by his side on one of the sofas when the sparking hour was on. Captain William Montgomery, just home from the West Indies, professed open admiration for a New York maiden who could spin.

"If you will spin me a shirt in an afternoon like the girls in Melrose used to make I will give you the handsomest lace dress to be found in the city," he once said.

"Agreed," she answered. "And if I fail I will give you the finest dress suit a tailor can make."

You may be sure that the proud sister-in-law of a bishop never heard of this wager. The girls kept it a secret.

"It is not anything, after all," Jane said to her sisters. "Ellen not being town bred, it will exonerate her."

Ned did not like the idea very much, but Ellen seemed so delighted at the chance to show her skill that he did not have the heart[80] to dampen her pleasure with a lecture on the improprieties.

"I must remember that she is a bloom of the fresh free countryside, where life is broader and less restrained by convention," he said to himself. So Ellen was left to win her wager with happiness.

One morning Mrs. Moore announced from behind the George III. coffee-urn bearing the arms of the Fish family that she had decided to give a ball. "As the wife of a physician and the sister of a bishop, I feel it my duty to do something for society. Not a bread-and-butter affair like old Mrs. Hone gives; nor should I care to entertain the mob of vulgarians Mrs. Van Pelt does. Something elegant for the representative families, William," she said, giving her spouse's coffee-cup a conciliatory dash of cream.

"Oh, you lovely, lovely mamsey!" the Moore girls chorus. "No, we can't sit still," they cry, heedless of her admonishment.[81] About the table they pirouette and out into the hall, almost knocking over the haughty, stout Miss Rattlebones whom Thomas is leading to the doctor's office.

"Won't it be simply perfect?" they keep asking Ellen. "We will have the waltz,—the new dance so fashionable abroad, you know."

"And 'The Devil among the Tailors' they had at Matilda Hoffman's the other night," Jane added.

"The what? The devil something do I hear you say?" asks Mrs. Moore, rolling her eyes in a horrified fashion. "We will never have that indecent dance in my abode."

What happy days followed Mrs. Moore's announcement, with the hundred things to be planned and finished! Every gallant who shared the Orleans sofas with the Misses Moore during those evenings before the great event was asked whether he preferred white or blue bunting for the parlor ceiling.[82] Did he like the idea of pink roses in the Nast vases on the chimney-piece? Could he imagine the room lighted by five hundred candles? Wasn't it shocking that mother was contemplating serving five kinds of punch? The parlor was becoming a huge question mark and the Moore ball the talk of the city.

Ellen and her lover shared in all the preparations for the affair, but very often they stole out to their trysting-spot of an evening to be alone.

The fateful night before the ball the Argus eyes of Mrs. Moore descried them from her bedroom window seated under their favorite beech-tree. At first she thought the figures were Jane and Mr. Major. Then, blowing out her candle, the cruel spring starlight helped her to make out the forms of Nathaniel and Ellen. Like one fascinated, she watched them. The wind blew the silver leaves of the beech-tree and she learned their secret. He had kissed her.[83] "Oh, it is dreadful!" she whispered to herself, murmuring like one who has received a shock. "They are first cousins. My Nathaniel loves her. I have been blind." The memory of the bantering words passed at table came back to her with a new meaning. Why, only the other day William, her younger son, had told her that Nathaniel was in Brooke's getting the rents of Gansevoort Street houses. The ball had driven everything else from her mind. The affair must be broken off at once. She would seek William.

Doctor Moore was seated by a hickory-wood fire in an adjoining apartment, ensconced in a flowered chintz dressing-gown. The bustle of preparation for the past few days had annoyed him, but the spirit of peace now seemed to have found a place in the wide firelit room. A negress was passing a warming-pan lightly over the lavender-scented sheets of the high four-poster. It was an old-fashioned winter custom that the[84] doctor demanded all through the spring. The air was filled with the dreamy scents of lavender and the pungent odor of the hickory boughs. The fire made the tired man close his eyes, and the ponderous medical treatise dropped to the floor. Morpheus was wooing him when the startling figure of Mrs. Moore, with her nightcap awry and her hair falling over her shoulders, entered the room, bringing him back to the world he was trying to forget. The walls of the old room heard sad things that night. Young hearts that had blossomed out like twin buds on a stem were to be torn asunder. Their little beech-tree in the garden seemed to be aware of impending disaster, and the dreary sighing of its leaves suddenly fell upon the two by the fire. The night was nearly dead.

"Perhaps, after all, Jane, we have been premature with our worrying and there is nothing between them," the weary father said. "I will see Nathaniel in the morning.[85] Now go to bed, dear; you know to-morrow is your ball, and that will bring you many duties."

The mystical to-morrow. Like some wan and beggared guest, it tapped on the panes of the great Moore mansion. The cold starlight had not fulfilled its promise, and the face of the day was old before the world was up to see it. Outside the Moore gates it was all gray mist, and yet many of the household looked at it happily. The cooks sang as they worked over the breakfast by candle-light. In a week's time they had prepared a roomful of good things for the children of pleasure to eat that night.

Thomas chuckled gleefully as he showed his new red-and-gold party livery to the company below stairs. He knew that he was a very handsome nigger, and many a lady's maid would smile at him as she followed her mistress through the hall when the ball commenced. None of the ladies appeared at breakfast, and after the last dish[86] was removed Doctor Moore asked Nathaniel to follow him to the office.

"Nathaniel," the father said, motioning his son to a seat, "your mother saw your conduct in the garden last night with Miss Conover, and I wish to know its meaning."

The young man had refused to be seated, and stood by one of the windows gazing out into the mist. The grayness filled him with a vague intimation of approaching trouble. Ellen's name was its first sense of realization. "I love Miss Conover," he answered, almost unconsciously.

The old physician in the stiff-backed desk-chair knit his brow and pulled his stock up higher about his throat, an action familiar to his patients. He seemed lost in thought. In front of him was his desk covered with medicine phials, but here was a case that no medicine he could give would help.

"My son," he said, and the clock accentuated the huskiness of his voice. "My son, you have no right to love Miss Conover.[87] She is your first cousin, and you can never marry her. It is a hopeless love."

"Other men have married their cousins, sir. There are Jonathan Kortright and Hulda Reid, and Chauncey Prince——"

"Yes, Nathaniel," the doctor's voice interrupted his passionate speech, "the world is full of law-breakers; but it is the edict of God that two of one flesh cannot marry. I should never countenance such a union. Your children would be accursed."

The glowing eyes of the young man were riveted on those older eyes drooping beneath the gray wig. Why didn't he storm and rage as he used to in the old days when a lad in torn nankeens and begrimed face was brought to that desk like a culprit before a tribunal of justice? He could see that his father pitied him. In the next room they were tacking up the wall decorations for the ball, and a monotonous tap, tap was joined to the maddening ticking of the clock.

Suddenly the youth rose to his full height[88] before the old man and caught his weary eyes. "I shall marry her," he said. "I defy you, God, or the devil to stop me!"

The wrinkled, passive face before him seemed dazed and blurred. There was no answer. Oh, how cold and dreary the room looked! Life, after all, held very little. The fire died out in the youth's eyes. "My God, what a hell you have given me!" he cried. There was a knock at the door and the father rose to open it. In the middle of the floor he stopped and went up to his son. Upon the strong young arms he placed his feeble hands. "Be a brave man, my son," he said. "May God help you!"

In her aunt's room overhead Ellen was humming an air she remembered Miss Trelawny singing a week before at the Park, when Nathaniel had given a gay little theatre party to celebrate the winning of Captain Montgomery's gown. It had arrived only that morning from Madame Bouchard's on Cortlandt Street, and the[89] black maid had spread it on a bed where the young ladies could admire it. Very beautiful were its soft folds of Machlin lace.

"You will be more like a partner of the fashionable Madame Moreau than a country girl to-night," Jane Moore told Ellen, as she and her sisters hurried off to deliver some of their mother's orders.

"Watch Ned's eyes, Jane, when he first sees her," Maria whispered, as she closed the bedroom door softly.

Ellen gazed out into the street. The mist was rising. Perhaps, after all, it would be a clear night. Through the gates came a ceaseless stream of flower men and women carrying wicker baskets piled high with early blooms; Fly-Market dealers with bundles of provisions; Mrs. Leach and some of the girls from the Broadway Frozen Cream Parlor to make the sherbets and syllabubs. A group of urchins and older busybodies were standing in the middle of the street gazing up at the windows.

"It would be grand to be rich and give parties like them foine birds," a chimney-sweep's wife remarked to the woman next to her.

"Now, don't ye envy them, miss," her companion replied. "Ye never can tell when ye look at a big house what's hiding behind the velvets afore the windows."

The grim Pompeys on the gates seemed to smile at her logic. And yet, after all, the darkness overhead was breaking away, and from out the sombre clouds the sky was spilling pale new-born sunshine over roofs and steeples and despairing streets.

Those who heard of the glories of the Moore ball in their youth are not likely ever to forget it: the music, the supper, the graciousness of host and hostess, and the company. There was a new Astor piano borrowed from the bishop to mingle its fresh voice with that of the tired Moore spinet and the playing of the Park's four violinists. The people who attended it, whose names[91] were as well known then as the pure tones of Trinity's bells,—Le Roys, Rutgers, Gouverneurs, Beekmans, Jays, de Lanceys, Wilcoxes, Livingstons, Kissams, Kortrights, Clarksons, Schermerhorns, Van Pelts, Clarks, Varicks, Waddingtons, Van Santvoorts, Van Nests, Pells, Kembles, Fairlees, and Waters,—they were the great of 1807.

In the largest parlor, where the Orleans sofas are pushed ignominiously against the wall, youthful New York is whirling about to the strains of the Corporal Listnor waltz. Two belles of the evening the room contains,—Maria Mayo, of Virginia and New Jersey, who married General Winfield Scott, and Matilda Hoffman, the love of gay young Washington Irving. A third, and the most remarked of all that large company,—Ellen Conover,—has just passed through the doorway on the arm of Nathaniel Moore. A handsome couple they make,—she in her lace gown and he in[92] dark plum-colored evening clothes. She is smiling, for she does not see the look of misery in his eyes.

"The stars are out, dear; shall we go into the garden and sit under our own little beech-tree?" she asks.

Our beech-tree! How the words sink into his soul and cut like knives!

"No, Ellen," he answers; "the leaves of the tree, so tender and young, are old and seared for us."

"Why, Nathaniel, how strange you talk!" she says. Then she looks into his white face and begins to understand.

Oh, the anguish of his drawn young face, as he folds her in his arms and tells her to be brave. Into the library she follows him. Her step has lost its buoyancy and the roses have died in her cheeks. A woman's intuition has guessed what he has to tell her. Something has come between them. Softly he closes the door on the lights, the music, and the babble of happy voices.

"Kiss me and never let me speak again, darling," he whispers. But she lets him speak—and break her heart.

Almost a century has passed since the dawn after the Moore ball when a girl stole down the slender staircase of that proud mansion. It was Ellen Conover garbed for a journey. Like the ghost of pleasure, she crept through the trellis-work of faded flowers which adorned the landing and hurried noiselessly over the slippery hall. No one was about but Thomas, who was picking up some of the motto papers and dead flowers strewn over the dining-room floor. Hearing the rustle of a woman's dress, he came to the door of that room and looked out with startled eyes.

"Why, missy, is you going abroad so early?" he asked, incredulously.

"Yes, Tom, I'm going back to Monmouth."

Seeing a question in his eyes, she continued,—

"Aunt will understand. I have left a note by her door."

In her hand she held a square deerskin bag, and the negro, not forgetting his manners in his bewilderment, asked whether he could carry it for her.

"Thanks, Tom," she said, wearily, as he relieved her of the heavy burden. "Colonel Montgomery is to be at the Broadway corner for me. He is going to Englishtown, and has promised to see me home. The Paulus Hook coach passes at seven, you know."

Beside the lyre-shaped hat-rack Ellen paused for a moment. Thomas thought that she was going to faint, but she beckoned for him to go on. Before her was Nathaniel's gray beaver, the one she had liked him in so much. She remembered he wore it that happy day they wandered down to Gansevoort Street to look at their little dream-house. Dear dream-house, that would never be theirs. The wistaria vine that twined so lovingly about the stoop-rail high[95] up to the dormer window would never purple for them. Was he asleep now? She wondered what he would think of her running off in this fashion. "Perhaps it is foolish, but I could never stand seeing him again," she murmured to herself. On the floor were his riding-gloves, swept off the hat-rack by some heedless reveller of the night before. Like one lingering in a dream, she picked them up and tenderly put them in the pocket of her coat. For a moment she stood silent with her hand on the door in the attitude of one listening to a benediction. Outside a soughing wind was sweeping through the deserted street and the dark hall was full of its whispered sighs. Softly she opened the door on the new day, and then, as if speaking to an invisible presence, she said, "May you sometimes think of me as I shall always think of you, dear heart." And the sweetest part of the story is, he was faithful to her memory until death.

A True Picture of the

Last Days of Aaron Burr

A True Picture of the Last Days of Aaron Burr

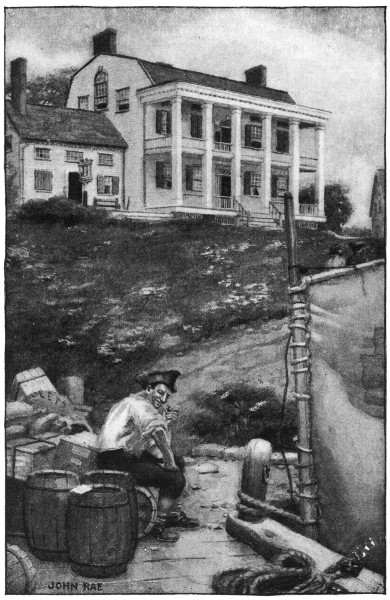

AN old house that has fallen to ruin always has something pathetic about it, but a great hostelry in the clutches of decay, where warmth and cheer have welcomed generations of travellers, is sadder still. In Port Richmond, Staten Island, there is still standing the Richmond Inn, suffering from the weight of many years. Erected before the war of 1812, until 1820 it was the home of the Mersereau family, who owned most of the surrounding land when the place[100] bore the name of Mersereau's Ferry. The Mersereaus were Huguenots, and descended from two brothers who fled with their mother from France to America on the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Richmond Inn rests on the site of an earlier Mersereau mansion,—a witness of the Revolution. During the early part of the last century there were no buildings to shut off the view of the water-front, and its lawn ran down to a bluff overlooking the ferry landing and wharf. There Jed Simonson, a soldier who had fought at Monmouth, received the freight from the Jersey shore and the chance scow bearing Indian luxuries purchased from the hold of some newly-arrived merchantman. Great trees stood guard at the back of the inn like a troop of shadowy sentinels, and through them came sweet scents of the verdant country that rolled away over the British breastworks still covering the nearby hills. On the wide galleries of this haven of rest old sea-captains[103] could always be seen gently dozing as they puffed long pipes in the sunlight, or perchance gazing through spy-glasses at the white sails flecking the harbor. The ocean underwent quick transitions as they rounded Cape Hatteras or struck the Gulf Stream, and the nautical yarns they spun of the "Merry Marys," "Saucy Belles," and "Swift Sallys" were ropes which led to the seamen's true Elysium.

At nightfall the mail-coach often drove up before the door with a load of happy guests and bore others away. Those were the days when social intercourse was a feature of tavern life. "Good-by! Good-by!" a dozen feminine voices would call as the gay party of Southerners departed on their long journey to Baltimore. Toasts of Calverts and St. Marys, tears and kisses and fluttering handkerchiefs before the coach rumbled past the little red general store into the darkness. And then later in the evening, when it was time for the candles,[104] the young people remaining would assemble in the hall for a reel, made merrier by the jingly protests of the gold-legged Clementi piano. It was to this abode that Aaron Burr, world-weary and near death, was brought in 1836.

Aaron Burr, the courageous, was then sunk into an abyss so low that his enemies should have been satisfied. For years he had endured the censure of his fellows, the vituperation of Federalists and anti-Federalists, and the sneers of the populace without a murmur. Like the rock depicted on the old seal with which he used to stamp his letters, his lofty spirit had been unmoved by the winds and waves of public opinion. But now disease and old age had found him, and the spectre every human thing must some day face was his relentless pursuer. Until recently there was one living who remembered his arrival at the old hostelry. How the black stage-driver and a gentleman of the party assisted him up the steps to the[107] door and then up the quaint staircase to the largest guest-room on the second floor. The spot is still shown where stood the ancient curtained bed he occupied. The wide, white carved mantel-piece where his tired eyes must have often rested has not been disturbed, and one of the old window-panes bears the sentence, scratched with a diamond, "All is vanity," which tradition says is his work.

Aaron Burr's career is a strange record of triumphs almost reached; the picture of a proud spirit tortured and frenzied by fate. The story has been handed down from generation to generation in the Edwards family, and is preserved among the papers of the late William Paterson, of Perth Amboy, that when Aaron Burr was an infant in the parsonage on Broad Street, Newark, his mother often prayed that her son should be as a star among men. Her prayer was answered, but not in the way she would have wished. From his mother Burr inherited that morbid sensitiveness which eventually[108] proved his downfall. Esther Edwards never forgot some of the stings she had endured when painting fans in the manner of Watteau for the fashionable women of Boston. Her son always believed that Alexander Hamilton was the cause of his ruin in the eyes of Washington, the loss of the Presidency of the United States, and the constant blackener of his good name by tongue and pen. If the shadow of Hamilton had never crossed the path of Burr, the latter's name might have been glorious for all time.

In the Paterson papers on Princeton College, recently published under the title "Glimpses of Colonial Society and the Life at Princeton College, 1766-1773," we find recorded that "little Burr" was one of the most popular men of his class at "The College of New Jersey." "To see you shine as a Speaker would give great pleasure to your friends in general and to me in particular. You certainly are capable of making a good Speaker, dear Burr," that noble[109] youth, William Paterson, wrote to him when leaving Princeton in 1772. Through Paterson we learn that Burr would go any length to serve a friend, wrote in a lady-like hand, and at sixteen was the admiration of the fair sex of Elizabethtown. This comrade and a few other of the jolly founders of the Cliosophic Society were the subjects of Burr's reminiscences in those last summer days when the sea-air stealing through his windows seemed to give him new life. The horrible nightmare of his later years was forgotten. He was a boy again at the little village of Princeton that his father loved, the sun shone on proud Nassau Hall, the Scotch silversmiths tinkered all day long in the shops lengthening the Main Street, the lights glowed in the tavern, and fair Betsy Stockton was the belle and toast of the College.

Almost every stage of Aaron Burr's life is tinged with melodramatic interest, and it is fitting that the woman who befriended[110] him in his last years should have been the daughter of a British soldier met on the battle-field of Quebec. There Burr saw the gallant Richard Montgomery and his own college-mate, John Macpherson, stain the snow with their blood, and it is a disputed tradition that Burr carried the wounded Montgomery from the field. The name of the generous soul who cared for him after his disastrous marriage with Madame Jumel and subsequent removal from Mrs. Hedden's house in Paulus Hook was Mrs. Joshua Webb. It has been written that she kept a boarding-house in the old Jay mansion, a proud dwelling in New York's history, and sheltered her father's friend at the risk of fortune and reputation. Madame Jumel, towards the close of her life, used to relate that she offered him pecuniary aid at that period, but it was proudly refused.

In his basement room at Mrs. Webb's, propped up in bed by his faithful black servant Kester, or Keaser, as the name is[111] sometimes written, Burr received his old friends. There John Vanderlyn, the youth from Kingston whom he befriended, and who became a famous painter, celebrated for his "Marius," would visit him; there, too, came Judge Ogden Edwards, then residing in the Dongan manor-house at West New Brighton, Colonel Richard Conner, and a few other faithful ones whose names are unrecorded. The portrait of his lost Theodosia, who stands forth in history as the noblest of daughters, hung in front of the bed. Through the window he could obtain glimpses of familiar streets where he had once walked with his wife, Theodosia Prevost, the lovely niece of the eccentric Thomas Bartow, of Amboy. But they were changing. The abode on Maiden Lane, his first New York house, was destroyed, and the larger mansion at the corner of Nassau and Cedar Streets was also gone. Richmond Hill, one of the most beautiful country-seats in New York,[112] where, in her fourteenth year, Theodosia presided over her father's board and conversed with the greatest men of the day, was then covered by Varick Street, and St. John's Park, which was in the beginning of its glory. At the little Maiden Lane house his wife had penned him many of her beautiful letters. Her ghost must have often come before him as he read over the faded epistle written one stormy night after he had left her for New Jersey, in which she outpoured for him her ardent love:

"Thus pensive, surrounded by gloom, thy Theo sat, bewailing thy departure. Every breath of wind whistled terror; every noise at the door was mingled with hope of thy return, and fear of thy perseverance, when Brown arrived with the word—embarked—the wind high and the water rough. Heaven protect my Aaron; preserve him, restore him to his adoring mistress. A tedious hour elapsed, when our son was the joyful messenger of thy safe landing at Paulus Hook. Stiff with cold how must his papa have fared? Yet grateful for his safety[113] I blessed my God. I envied the ground which bore my pilgrim. I pursued each footstep. Love engrossed his mind; his last adieu to Bartow was the most persuasive token. 'Wait till I reach the opposite shore that you may bear the glad tidings to your trembling mother.' O, Aaron, how I thank thee! Love in all its delirium hovers about me; like opium it lulls me to safe repose! Sweet serenity speaks, 'tis my Aaron presides. Surrounding objects check my visionary charm. I fly to my room and give the day to thee."

New York was undergoing a great transition. She was outgrowing her maidenhood, and her swift feet took sure foothold in meadow, swamp, and woodland. To these changes Burr was unconscious. He had known her well and loved her, but when his clear brain grew listless and his eyes lost their fire she cast him out. Soon came the day when he was to look at the familiar sights for the last time. Tears filled his eyes as he gazed from the deck of the primitive steamboat which voyaged twice a day[114] from the Battery to Staten Island. He knew that it was his last farewell, and the calloused heart was melted. In that sad moment his friend must have held his feeble hand. The world had not deprived him of everything—there was something at the last!

When Aaron Burr was brought to the Richmond Inn, the hostelry was kept by Daniel Winant, a man of Dutch descent. He was assisted in his task by two young daughters, who were the life of the little hamlet. Old Port Richmond residents used to tell of their kindness to the famous guest, nursing him devotedly and doing all in their power to shield him from the annoyance of curious strangers who journeyed to the Port to gaze upon him.

Among the guests stopping at the hotel during Burr's last days there was a young man of twenty-four by the name of Olando Buel, from New Preston in Connecticut. The quizzical, genial Olando in his little shop, cutting posies and weeping willows[115] on tombstones or making tall mahogany clocks with wonderful embellishments, still lives in the minds of many of the islanders. In God's acres, which lie north and south and east and west over this isle of the great State of New York, Olando's white blooms cover many and many a green mound. What a great man was Olando, to record the lives of a small army of humanity! Sweet were the emblems he placed over their faded lives. Close to the specimens of his handiwork are older stones on which are figured skulls and other cruel reminders of death; but Olando gave his tired ones the emblems of nature, the never-ceasing resurrection. The elements are sweeping away some of his trees and flowers, it is true, for this youth from New England came to cut tombstones as a travelling apprentice to one Thompson, in the spring before Aaron Burr thought of Staten Island as his last home.

Olando frequently occupied a seat next to Burr on the gallery, and in after-years the[116] interested visitor could always induce him to relate his memories of this time. The favorite among his stories was of Mrs. Webb's arrival at the inn to obtain a last look at the face of her old friend the morning after his death. Olando had prepared the body for its final resting-place the night before and was still in charge of the remains. Mrs. Webb came heavily veiled and accompanied by her small daughter. In the hall they waited until the chamber of death was deserted, and then timidly crossed its threshold. When the passionate tears of this noble woman fell on the withered face of the dead, the heart of her observer was touched, and he gazed on the scene with wet eyes.