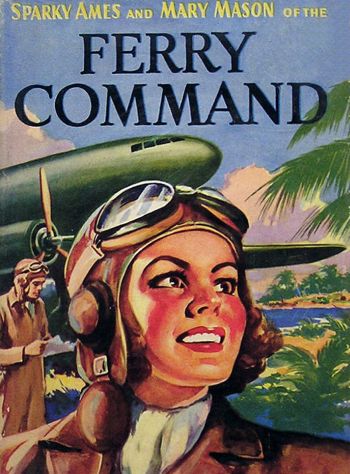

Title: Sparky Ames of the Ferry Command

Author: Roy J. Snell

Illustrator: Erwin L. Hess

Release date: December 27, 2014 [eBook #47793]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Rick Morris, Rod Crawford,

Dave Morgan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net

FIGHTERS FOR FREEDOM Series

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Flight of the Lone Star | 11 |

| II | Savages and the Night | 21 |

| III | Battling a Spy | 35 |

| IV | The Big Hop | 47 |

| V | The Lady in Black | 61 |

| VI | Mysterious Moslem | 72 |

| VII | Battling at Close Quarters | 84 |

| VIII | Desert Battles | 95 |

| IX | A Roll of Papyrus | 109 |

| X | Two Can Hide in a Cloud | 120 |

| XI | The Tumbling Donkey | 130 |

| XII | Sealed Orders | 145 |

| XIII | Snake Charmer | 157 |

| XIV | The Cast Assembles | 163 |

| XV | Burma Detour | 179 |

| XVI | “Me Got Machine Gun!” | 192 |

| XVII | In Swift Pursuit | 204 |

| XVIII | Where Are They? | 215 |

| XIX | St. Elmo’s Fire | 225 |

| XX | Deep Secrets Revealed | 235 |

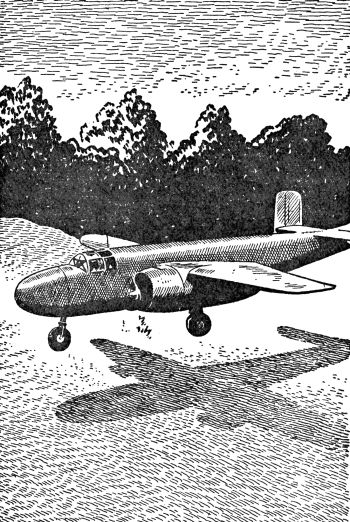

A Formation of Four-Motored Planes Passed Over

The air above the Brazilian jungles along the dark waters of the Rio Branco in northern Brazil was full of sound. The roar and thunder of many motors beat down upon the sea of waving treetops until it seemed to stir them into animated life. A formation of great, four-motored planes was passing over.

Two natives in a small dugout on the river dropped their paddles into their wooden canoe, then sat staring upward. The river’s current swept them beneath the branches of a dead mango tree. One of them reached up to snap off a brittle branch.

Breaking pieces from this branch he placed them, one by one, in the bottom of the canoe. When there were thirty-eight pieces, he stopped to sit as if in a trance watching those great, man-made birds go sweeping on.

Presently his companion grunted, then pointed at the sky upstream. The first native again looked skyward, then placed two more sticks with the others, making forty in all. Then he drawled a few native words that in our language mean:

“One of these big birds is very sick.”

This native was old. He had lived long beneath the overhanging treetops. He knew the ways of birds and men, but not of airplanes. For all that, he was right. One of these flying things of metal was sick, very sick.

Even as he said the words, there came a sudden burst of thunder, and the larger of the two planes, the one that was not “sick,” a ship so well formed—sleek and beautiful—that a native’s eyes shone at sight of it, pulled away from its slow, sick companion and went speeding along over the forest that lined the downsweep of the river.

“Gone,” said the native. “Now this one will die.” His eyes shone with a new light. Once on the Rio Negro, he had seen one of these man-made birds. There had been much on that plane that he had coveted. And now—

These last two planes were not bombers, but transport planes. It was quite evident that the speeding plane had not deserted its companion, for, in a short time, it came roaring back and a girl’s voice speaking into a radio said:

“There’s a rather large clearing about fifty miles down. Think you can make it?”

“We’ll have to try,” came in a man’s strong, even tone. “We’re on one motor now. The other is cutting out on me. Can’t tell how soon it will quit dead.”

“We’ll tag along,” came in the girl’s voice. “If you make it—”

“If we get that far, we’ll try a landing,” was the answer.

“And if anything goes wrong—”

“You’ll fly right on.” The man’s voice was harsh, insistent. “Remember! Secret—”

“Don’t say it, Sparky!” The girl’s voice rose sharp as an alarmed bird’s. “Don’t say it!”

“All right! All right!” the man’s voice grumbled into the tropical air. “Then I won’t say it. All the same—”

“All the same, if you go down there we’re coming right down after you,” the girl insisted. “You know what our orders were, to fly in pairs. If one plane is disabled, its mate must go to the rescue. All other planes must go straight on. We’re on a mission of destruction. That’s all we know. It’s urgent. We must go through!”

“Okay, sister, that’s why you should fly right on.”

“But we won’t.” The girl spoke quietly. “If you crack up, we’ll be right down. This ship has control. I can land her on a dime.”

“But don’t forget—”

“I never forget,” the girl snapped. “Now go on down there and try your luck. It’s all that’s left to do.”

“What’d he mean—secret?” The blonde-haired girl who sat in the co-pilot seat beside the girl who had carried on that spirited conversation, drawled, “What secret?”

“Sorry, Janet,” was the slow reply. “You’ve heard of military secrets, I suppose?”

“For Pete’s sake, Mary Mason! Yes! Of course, I have, but I don’t see—”

“This is one of them.” Mary Mason, the little girl who piloted a big plane, favored her with a smile.

After that, save for the slow drone of motors, there was quiet in the cabin, a tense sort of calm, such as comes before a storm. After a time the blonde-haired Janet said:

“Sparky’s motors didn’t stop all by themselves.”

“Of course they didn’t. Sparky’s too good a pilot for that.”

“He sure is. It’s the work of the enemy. That’s what it is. He knows. He’s after us, after you and Sparky, Don and me. He’s got us coming down in a jungle and we’re only just out of good, old U.S.A. And think of the dizzy miles still ahead of us! And the enemy dogging our luck all the way!”

“I thought of him before I started,” Mary replied quietly. “Let him do his worst. We’ll win, you’ll see!”

For the swift, powerful twin-motored transport plane flown by Mary Mason, the distance to that native clearing on the Rio Branco was just a jump, but she did not jump. Instead she followed doggedly on behind her limping companion. And as she followed, she found time to think. Those were long, long thoughts.

She was a member of the WAFS, Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron, this slender girl with the flashing black eyes and trigger-quick fingers. For six wintry months she had flown planes from east to west, from north to south, and all the way back again. Sometimes these planes were transport planes or bombers with comfortable, heated cabins. More often they were open-seated trainers or fighters. She flew them in wind, rain, and snow. Mile after weary mile in lonely solitude she had gone roaring through the night sky to arrive at last at her destination only to be ushered aboard an airways plane and hurried back again.

“It was hard,” she said to Janet Janes, her companion.

“Sure it was,” the other girl agreed. “Looks as if this would be harder.”

“Perhaps,” Mary answered. “But just think! In the past two days it’s been San Francisco to Denver, to Chicago, to Miami!”

“To Caracas, and then to the heart of a jungle where headhunters beat on hollow logs inviting their friends to a feast.” Janet laughed in spite of herself.

“This will be just a pause,” Mary insisted stoutly. “After that it will be Para, to Dakar in Africa, Dakar to Egypt and the pyramids, Egypt to Persia—”

“Under the Persian moon,” Janet sang softly.

And then:

“Watch!” Mary exclaimed. “There’s the clearing. Sparky has spotted it. He’s preparing to circle. He’s going down!”

Suddenly Mary set her motors thundering. After climbing steeply she leveled off to stare down at the clearing.

“He didn’t go down, not yet,” Janet informed her.

“No. There are people running from that row of native huts. He’d hit them.”

“They’re like ants coming from an ant hill. They don’t seem important.”

“Oh! But they are!” Mary exclaimed. “Every human life is important. Besides, if Sparky killed just one of them, our lives wouldn’t be worth a penny. We’re in the wilds.”

“Probably not a white man within a hundred miles.”

“Or perhaps a thousand.”

“I wish we might go on.” A suggestion of strain crept into Janet’s voice.

“Oh! But we can’t.” Mary’s plane was circling slowly now.

“Of course we couldn’t go on,” she told herself. “Not even if Sparky insisted.”

Through her racing mind whirled memories of other days, those bad days of winter convoy in America. There had been only twenty-five of them, twenty-five WAFS, and so much work to do. Always, on her return from a long, hard trip, muddy, chilled through and half-starved, if he chanced to be in, she had found Sparky waiting in his car to whisk her away to her barracks and after that to a glorious hot meal. “Thick, juicy steaks, French fries, lemon pie, and barrels of hot coffee,” she whispered.

And now Sparky was down there below her in his disabled plane waiting, waiting for the last darting spot to glide from those huts into the bush that lay beyond. No, they could not go on. “Not even for the secret—” she spoke aloud, then checked herself just in time.

“He can’t climb,” she said to Janet. “He can only circle. And if his other motor quits he may go crashing straight down!”

“There!” Janet breathed. “Now there’s no one!”

“Yes, just one more.”

A very small black spot, moving, oh, so slowly, went weaving this way, then that, toward the forest.

“A child!” Mary exclaimed. “How Sparky would hate hitting a child!”

“Now!” Janet breathed.

“No,” Mary groaned. “One more, a smaller one.”

It seemed an eternity before this last child had reached safety.

Of a sudden the plane beneath them lunged downward.

“There they go!” Janet gasped while Mary’s clutching fingers fairly bit into the stick.

But no, Sparky’s plane seemed to shudder. No doubt his motor had quit, then gone on again.

“Why doesn’t he go down?” Mary groaned. “Here, take the plane!” She gave Janet her place. “Just circle slowly.”

With long, swift strides she reached the plane’s door. There she braced herself, then stood watching the plane below.

“He’s going down,” she whispered.

It was true. Circling slowly, cautiously, Sparky nursed his disabled plane at last into a smooth glide that brought him swiftly down.

“He’s out too far,” she groaned. “He’s afraid there’s just one more native child.

“There!” she exclaimed. “He’s down!”

She saw the big plane bump hard, then bump—bump again. It did not heel over, but went gliding straight on.

“He made it!” she screamed aloud. “Oh! Glory!”

Bright hopes sped through her mind. The defective motors would soon be repaired. Before the natives returned they would once again rise high above the jungle and speed away to rejoin their convoy. She had begun to feel dreadfully lonesome away from all that thundering flight. At Para, they would be united and then—

Her thoughts broke off. Her lips parted in a scream that did not come. Of a sudden the ship down there on the ground, gliding forward, had whirled half about. Its right wing crumpled; it turned toward the black waters of the river. After gliding forward half the distance to those threatening waters, it came to a sudden halt, then crumpled into a heap.

With lips parted she kept her eyes glued upon the plane. Would it be set on fire? A slow smoke rose, but no flames.

A figure came tumbling from the plane. “One more!” she whispered. “Just one more!”

The figure that had appeared remained motionless for a space of seconds. Then he leaped forward to re-enter the wreck.

“One of them is hurt,” she called to Janet. “Keep circling.”

It was true, for soon the single figure appeared once more, this time bearing a limp burden.

“Janet,” Mary exclaimed as she resumed control of the plane, “we’re going down!”

“This,” said Janet, “is a large plane. Larger than Sparky’s.”

“And easier to control. This,” said Mary proudly, “is the Lone Star, the only plane of its kind in the world!”

“It’s almost priceless,” Janet agreed.

“Yes, and its cargo is really priceless,” Mary might have added, but did not for that was her military secret, hers and Sparky’s. The C.O. had told just that to her before they took off.

“I am putting it on your plane,” the C.O. had said, “because your Lone Star is the fastest, strongest, most dependable transport plane we have in our outfit. And I have given the plane to you because other than two pilots that cannot be spared, you are the only one who knows her and can take her safely through.”

This, she realized, had been high praise. Hers was a grave responsibility, but Sparky, her good pal, was down there. Was he the one who had been injured? She had no way of knowing.

“I’m going down,” she repeated softly.

As the big plane circled, drifting slowly down, Mary leaned over to say in a deep, impressive voice:

“Janet, if we crash, and there’s a spark of life in you, get out quick and run, crawl, anything. Get away fast.”

“Who wouldn’t?” Janet stared. “If the ship gets on fire the gas tanks will explode and—”

“It’s worse than that,” Mary confided. “This ship is mined.”

“Mined!” Janet stared.

“It certainly is! And by our own people. This is one ship our enemies will never take apart piece by piece, nor its cargo either. In case of a crash, it will be torn to ribbons.”

“That—why, that’s terrible,” Janet’s voice was husky.

“Not as bad as it seems,” was the slow reply. “Only fire will set off the explosives. Bumping won’t do it. There’s a fuse, too. I know right where it is. No, they’ll never get the Lone Star or her cargo. And there’s nothing they’d like half as much to do. But they won’t get her. Never! Never.

“And now,” she breathed. “Here we go!”

As her ship glided down, even in this moment when her own fate seemed to hang in the balance, on the walls of Mary’s mind was painted a picture that would not soon be erased. It was as if her first glimpse of a tropical jungle, the waving palms, the slow, rolling black river, the native huts, the sloping hillside all bathed in a beautiful sunset, had been painted there by some great artist.

And then her ship’s landing wheels touched the broad, hard-trodden path of the natives. Coming in closer to the natives’ shacks she had avoided the treacherous hillside and suddenly, there she was. Graceful as a plover with wings outspread the Lone Star came to rest.

“We made it!” Mary gave vent to a heavy sigh of relief. “But now!” She was up and away in the same breath, for the solving of one difficult problem had only served to bring her closer to another. There had been two men in the bomber when it crashed, Sparky Ames and Don Nelson. One had been injured. Which one? And how badly? She had to know.

“I’m going over there!” she exclaimed as she leaped from the plane, at the same time pointing up the hill.

“Okay. I’ll watch this plane,” Janet said.

“Yes, I think that’s wise. You never can tell.”

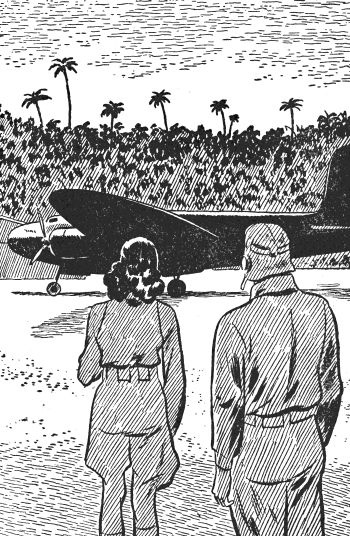

The Lone Star Came to Rest at the Foot of the Hill

Mary cast an apprehensive glance at the long row of native houses. “Homes of a hundred people,” she thought. “Perfectly wild natives.” But now nothing stirred there.

With long, quick strides she made her way where one man bent over the prostrate form of another.

When she was half way there she saw the kneeling man turn his head. Then she knew.

“Oh! Sparky!” she exclaimed. “You’re safe!”

“Sure! What’d you think?” The tall, strongly built young man with black, kinky hair grinned.

“I—I didn’t know.” She was closer now. “It would have been terrible if you had been seriously injured, you know.” Her voice dropped. “Secret cargo!”

“Yes, I know.”

“But Don!” she exclaimed. “Is he badly injured?” She was standing beside Sparky now.

“I can’t tell yet,” was the slow answer. “I have the courage to hope not. He got a bang on the head. That knocked him out. I’ve felt him over pretty carefully. No bones broken is my guess. But he keeps groaning. His hand comes up to his chest. Got a cracked rib or two I shouldn’t wonder.”

“That’s bad, isn’t it?”

“Bad enough, but it might be worse. Anyway, our plane can never be repaired. Not here it can’t.”

“And how will you ever get it out?”

“That’s it,” he agreed. “Looks as if we’re stuck—at least, our plane is. Guess we’ll have to go it alone, Mary, just you and I. It’s the way the Chief would want it.” His voice went husky. “That secret cargo must go through at all cost. Those were the orders. How do you feel about that?”

“How would you feel about going over the top somewhere in Africa?” she challenged.

“I wouldn’t think. I’d just go, same as any other soldier does.”

“It’s the same with me now,” she replied soberly. “I—am a soldier, too. Well, perhaps not quite, but I’m serving in a soldier’s plane, a mighty good one, too. Any man in my shoes would have to have had five hundred hours in the air.”

“And so where duty calls or danger—” he quoted.

“I shall always hope to be there,” she saluted. “But look!” she exclaimed. “Don is trying to sit up. He must not do that!”

“No! No! Old man! Not yet!” Once again Sparky was at his comrade’s side gently pushing him down.

“Wh—where am I? Who—what happened?” came in thick tones.

“You’re here and we’re here. Sparky and Mary,” said Sparky.

“Oh! Then it—it’s all right.” The injured man settled back.

“I’ll go get some pneumatic pillows,” Mary volunteered.

“Yes, and something hot to drink,” Sparky suggested. “That will help a lot.” Mary was away.

When Don had fully recovered consciousness and had been made as comfortable as possible, they gathered around him for a council of war.

“It’s getting dark,” said Sparky. “In another quarter of an hour it will be darker than a stack of black cats. In this land the dawn comes up like thunder, and the sun blinks out in the same way.”

“And there’s no moon,” said Janet.

“All of which means we’re here for the night,” said Mary. “Sparky,” her voice seemed a little strained. “What kind of a country is this?”

“Good head-hunting country,” Sparky laughed.

“No, but really, we’ve got to face facts,” Mary insisted.

“Truth is,” said Sparky, “I don’t know about the upper waters of the Amazon, or the people who live here. Do the rest of you?”

There came a chorus of “no”s.

“All right, then we’ll be prepared for the worst and hope for the best.”

“They scattered fast enough when they saw us coming down,” Don volunteered.

“That was natural,” said Sparky. “It is also natural to suppose that, in the end, they’ll defend their homes. They may come back in the night. There are two loose machine guns in each plane. The Major had them put there for just such a time as this.”

“And for the time when we’ll be over battle zones,” Mary added. “We may be attacked—”

“Just now we’re in a jungle, so we’ll limber up the guns,” said Sparky. “How about you ladies fixing up a little chow?”

“Sure, oh, sure! We’ll do that!” was the quick response.

By the time Sparky had two guns set up in the Lone Star, which he figured might, in the event of an attack in force, be used as a fort, and had dragged the other guns to the spot, a short distance away, which they had chosen as a camp site, darkness had fallen and the girls had coffee brewing over a cheerful fire.

“Say! This is great!” Sparky exclaimed. “I’ve always wanted to go camping but never had time!”

“Well,” Don drawled, “You’ve got about ten hours now with nothing else to do but camp.”

“Unless we’re attacked,” Janet supplemented with a shudder.

“Why bring that up?” Mary laughed. “Dinner is about ready to serve. Let’s make it a date.”

“A date it is,” Sparky agreed.

Their grub box contained a little more than iron rations. Sweet potatoes and sausages each served from a can, big, round white crackers, a square of butter and, aromatic coffee with real sugar and canned cream, made up the bulk of their satisfying meal. Dessert was little wild bananas, and huge, over-ripe grapefruit that were sweet as oranges. These came from the edge of the jungle.

“Um,” Janet breathed. “That was really a feast.”

“Yes, and listen!” Mary exclaimed low, “What was that? Really something different!”

A low rolling sound had come drifting in out of the night.

“A native drum!” was Sparky’s instant answer.

As they listened from farther away came the answer.

“Talking drums,” Mary whispered. “I never expected to hear them.”

She was hearing them all the same and, coming as they did out of the night with the low murmur of the dark, rushing river as their accompaniment, they sounded weird indeed. Now came a roar close at hand, tom-tom-tom sharp and clear, and now from far away with the booms blended into one long roar.

“Night in the jungle,” Mary whispered.

“Crawl into your ship and forget it,” Sparky suggested. “We’ll be here in the morning.”

“Oh! I never could do that,” Janet exclaimed.

“All right,” said Sparky. “Then you girls keep the first watch and I’ll sleep. But first we’ll fix Don up as comfortable as we can.”

It was Don whose eyes first closed in slumber. With soft pneumatic cushions under him and a mosquito canopy to protect him and a soothing capsule to allay his pain, he was asleep before the others could arrange for the watches of the night.

Just as Sparky crept away to the Lone Star for three winks a bright golden moon came rolling along the fringe of the forest.

“Oh! That’s better!” Janet exclaimed.

Was it? It was not long before every shadow cast by the moon appeared to move and the darkened grass houses seemed alive with people.

“Ghosts,” Mary whispered. “Ghosts of native men and women who lived here long before we were born.”

“Be still!” Janet whispered. “I heard a voice. It was somewhere down the river. Listen!”

As they listened a voice seemed to ask: “Why? why? why?”

“That,” Mary laughed low. “That’s a big, old tree frog. He lives in a pool of green water in a hollow tree, way up high. I read about it once. If you drink the water he lives in you’ll go crazy.”

“I think you might,” Janet whispered. “What do you suppose he wants to know with his eternal ‘why’?”

“Perhaps he wants to know why we are here, why my father is out somewhere in Africa.”

“And why my two brothers are in Australia,” said Janet. “Do you know the answer?”

“No,” said Mary. “At least not all the answer. I only know that we must keep on being here, and in Africa, Egypt, Syria, India, China, wherever we’re sent until this terrible war is over and all our loved ones can come home again.”

“Yes, that’s right. But, Mary, you know we were volunteers. We didn’t have to join up. And above all, we didn’t have to go on this long, long trip so far from home.”

This Mary knew was true. They had, in truth, volunteered twice. Joining the WAFS was purely on a voluntary basis. Once they were in they were expected to ferry planes from place to place in their own country. But a sudden, urgent call had come from China for forty planes, all but two of them bombers. There were not enough men available so volunteers were called from among the women.

“All of us volunteered, except those who had children,” Janet said, thinking aloud.

“Who wouldn’t? It’s what I’ve always wanted most.” Mary’s voice rose a little. “When Sparky used to come in after a week’s absence and say, ‘Hello, sister, I’m just back from Russia,’ I was burned up with envy. The next week it would be Africa, and after that London, and there we were plowing through the sky to Kansas City, Des Moines or Peoria. And now,” she breathed, “we are on our way to China by way of Africa, India, and all the rest.”

“We!” Janet exclaimed. “Do they expect just you and me to fly the Atlantic, alone?”

“Why not?” Mary asked, teasingly. “Oh, well—” she added, “Sparky told me tonight that he and I would go on alone.”

“Nice going,” Janet’s tone was a trifle cold.

“Oh, Janet!” Mary put out a hand. “Don’t look at it that way. There’s something aboard the Lone Star that just has to go through. I wish I could tell you what it is. I can’t because I don’t know. Naturally, it’s better that a man pilot the plane, one who has flown the Atlantic many times. It would be natural, too, that Don should go if he were able, but—”

“Oh, sure!” Janet was her old, friendly self again. “I understand. We’ll have to get Don to a hospital somewhere and I’ll stay to see him through.”

“Yes, and you may get to China yet, both of you.”

“Oh, China,” Janet yawned. “Just now I’d love to find myself on Broadway in little, old New York, with a run to Denver waiting for me in the morning. It’s a funny world, isn’t it?”

“It certainly is,” Mary agreed.

At one A.M. Sparky climbed down from the Lone Star’s cabin. “Go on up there and sleep,” was his gruff but kindly order. “We’ve got a tough day ahead.”

They obeyed. While Janet wrapped herself up in blankets, Mary spread out an eiderdown robe her father had once brought from the far North, and they were soon fast asleep.

Three hours later, just as the moon was nearing the crest of the ridge, lying off to the west, Mary crept down from the plane to join Sparky in his vigil.

“Don still asleep?” she asked.

“Sure is. He’s lucky to be able to sleep.”

“Perhaps he’s not so badly injured after all.”

“Bad enough,” Sparky sighed. “We’ll have to get him over to the hospital at Para. Then you and I’ll have to hop the little channel that lies between South America and Africa. Your cargo must go through.”

“Secret cargo!” she whispered. “Wonder what it could be.”

“Some new weapons for destroying Japs perhaps. A new type of sub-machine gun, or just a badly needed medicine for the soldiers up there in Burma. They say it’s plenty bad up there this time of year. Anyway, that secret cargo must go through.”

“‘Ours’ not to reason why—‘ours’ but to do and die,” she parodied.

“Who knows!” His voice sounded solemn in the stillness of the night. “The enemy has our number. I’ve been looking at my motors. They’ve been tampered with, emery dust in the pistons or something.”

“But where could that have happened!” she exclaimed.

“Caracas!”

“But there were soldiers guarding every plane.”

“Soldiers of foreign lands are sometimes traitors. So, too, are mechanics who tune up the motors. We’ll have to be on our guard every moment. This time we were over the land. The next it may be the sea.”

“We’ll watch,” she vowed. “Day and night. Night and day.”

“But it’s all so strange,” she mused after a time. “Why should there be a sudden demand for so many big planes in China?”

“There are rumors of a plan to bomb Tokio.”

“Oh! I’d like to be in on that!”

“Wouldn’t we all! But it’s just a rumor. I’ve heard that we are to attack Burma from two sides.”

“Try to re-capture the Burma Road?”

“Yes.”

“That would be glorious!”

“Then I’ve heard the Japs are going after Russia and that these bombers are for our Russian allies. All these are rumors. We may never know the truth. That’s the way it is in war.”

For a time after that nothing but the low rush of the river and the croaking of the ‘Why’ frog disturbed the silence of the jungle. Then, suddenly, Mary whispered:

“Listen!”

“Singing,” Sparky whispered back after a tense moment. “Natives on the river.”

“The moon has gone behind the hills. They’re coming back. The natives are coming.”

“Yes, and let them come,” Sparky rattled his sub-machine gun. “If they’re peaceful, things will be all right. If not—” He rattled the gun once more. “This is war. The Lone Star and her secret cargo must go through!”

After that for some time they sat there in silence listening to the wild native chant that, with every movement, grew louder.

Then, suddenly, the dark waters of the river came all alight. The long canoes had turned a bend of the river. In each canoe were a dozen torches held aloft. Mary counted nine canoes in all. To her heightened imagination each canoe seemed a hundred feet in length.

“Do they come like that when they want to fight?” she asked gripping Sparky’s arm hard.

“Who knows?” was the brief reply.

For a time Sparky and Mary sat in the dark silently watching the torch-lit procession of great canoes. To Mary it was a fascinating and fearsome spectacle.

Suddenly Sparky let out a low exclamation. “Thunderation!”

At that he jumped from the log on which he had been sitting to kick at their half-burned-out campfire until the coals glowed red again. Then, gathering up an armful of dry-as-tinder leaves, he threw them on the coals.

For a space of seconds a column of dense smoke rose straight toward the stars. Then, as the whole mass burst into flames, all about them, the native huts, the airplanes, and the jungle at their backs stood out in bold relief.

“Sparky!” Mary exclaimed, shrinking back. “Why did you do that?”

“I’ll meet any man half way,” was the reply. “That is, anyone but Hitler’s mob and those dirty, little Japs.”

“But those men are savages!”

“Who knows? What’s a savage anyway,” Sparky’s voice sounded strange. “Every man is a human being. Those are men. Brazil is our ally at war and this is Brazil. When men come to you singing and waving torches, you just must meet them half way.”

By this time the dugout canoes were pulling up to the shore. The chant had ceased. In its place was only the murmur of voices. The torches still flamed.

Soon a procession came moving like a great, twisting, glowing serpent toward the campfire.

“Sparky!” Mary crowded close. “It’s too much. I can’t stand it!”

“Steady, girl!” Sparky’s voice was calm. His hands still gripped the tommy-gun.

As the procession came closer, they saw that most of the natives were all but naked, that some carried rifles and others spears and that they were led by a little man wearing striped trousers, a bright jacket and a sword. They did not pause until, as if in a high-school drill, they had ranged themselves in three semicircular rows before the fire. The little man stood at the center and three steps before them.

Mary tried to think what one swing of Sparky’s spitting tommy-gun would do to those rows and shuddered.

At last the little man spoke. His words came in slow, precise English.

“You are from the United States?”

Sparky and Mary Watched the Natives Come Closer

“That’s right, pardner,” Sparky agreed.

“The United States and Brazil are united against a common enemy.”

“Right again.”

“As our ally I salute you.” The little man’s hand shot up in a salute.

Thrilled to her fingertips, Mary managed to join Sparky in a salute.

The little man spoke a single word in a strange tongue and instantly the circle of natives dropped to their knees in a position of ease.

“Just like that,” Mary whispered. She wanted terribly to cry.

With a courteous gesture the little man invited Mary and Sparky to resume their positions on the log. Then he sat down at Sparky’s side.

“I,” he said, “am Doctor Salazar. I have studied in your country. Being not unskilled in the medical profession and also possessed of an interest in native life, I was sent to this place that I might make friends of the natives. This, you will see, I’ve done.”

“You are wonderful,” Mary exclaimed. “And you are a doctor.”

“Yes, that is my profession.”

“One member of our party has been injured, how seriously we can’t tell,” Sparky explained.

“I am at your service. Shall we have a look at this man?”

They rose and walked over to Don’s side. He had been sleeping but now stared at them with questioning eyes.

“We have brought you a doctor,” said Mary.

“And not a medicine man either,” Sparky laughed.

With practised fingers the little man went over Don from head to toe. “No bones broken,” was his diagnosis. “Probably three ribs cracked. When his chest is taped up, he can be moved.”

“Good! We’ll take him to Para in the morning.”

“In that large plane, I suppose,” said the doctor.

“Yes.”

“And the other plane?” asked the doctor.

“If your men will help us, we can load the motors in our good plane,” said Sparky.

“It shall be done. You are Americans. I am an American. We all are Americans.”

“You’re right. We all are!” Mary exclaimed.

“The motors shall go,” said the doctor. “But that which remains?”

Sparky shrugged. “In a war there will always be losses.”

“My men and I can take it in pieces. We shall float it to the Rio Negro. There it can be put on a steamer. It should be in Para perhaps in two weeks. So there you are.” The doctor made another bow.

“Indeed, you are wonderful!” Mary exclaimed.

“It is all for the great cause. Speed the victory.” The doctor clicked his heels and saluted.

The salute was returned in good measure.

And so it was arranged. Scarcely had the red of dawn disappeared from the sky when the Lone Star rose to greet the sun, then began winging its way toward the far-away city of Para.

Four hours later, far above the clouds, they flew across the broad waters of the Para river at its mouth, then began circling down to the city of Para.

First to catch Mary’s eye was the city’s ancient fortifications. As they circled lower she caught the gleam of the cathedral’s roof. The governor’s palace and other public buildings stood out from among the royal palms. Last but not least were the hundreds of homes, each with its lovely little garden surrounded by palms.

The broad public garden caught her eye, then the airport. So they came circling down to ask for and receive permission to land.

As soon as they were down an ambulance was called and Don, with Janet in attendance, was whisked away to the hospital.

“I’m staying with the ship,” Sparky said to Mary.

“Sure,” Mary agreed. “Can’t take any chances this time.”

“That’s right. Besides there’s a lot to be done. The motors from my ship must be unloaded and arrangements made for the repairing and assembling of the other plane when it arrives—if it does,” Sparky added gloomily.

“Oh! It will!” Mary exclaimed. “I’d trust that little doctor with my life.”

“Okay. We’ll hope for it,” Sparky agreed. “You just hop out somewhere and get yourself a good, square meal.”

“One good Brazilian feed,” she laughed.

“That’s it. One dinner in every land. That’s our motto.”

“I’ll bring you a dinner on a tray, buy tray, dishes, and all. When we get going you can eat the food and throw the dishes into the sea.”

“We’ll be taking off in just a couple of hours, if I can get our papers all cleared up, so don’t admire the scenery too long.”

“Don’t worry. I’ll be right back.”

Even at this strange corner of the world the war was much in evidence. Soldiers were all over the field. Army planes from many lands came and went. At the gate stood two guards. A smile and her uniform were all the passes she needed.

Not so the youth in tattered clothes who stood outside the gate, gazing in at Mary’s big plane.

“That’s some plane you’ve got.” He tipped his seedy hat.

“You’re an American, too.” She smiled.

“Yes—I—guess so. At least I used to be.” He did not smile. “Now, well, I guess you’d say I’m sort of a tropical tramp. Been down here for five years.”

“But,” his voice rose, “Boy! That plane of yours. Must be the best there is!”

“Ever do any flying?” she asked. She should be going on but this boy interested her.

“Sure—I’ve flown quite a bit, here and in U.S.A., too.”

“Why don’t you join up?”

“Your outfit?” He grinned broadly. “You’re a girl.”

“Oh, but there are a lot more men than women flying for the Ferry Command.”

“But then,” her voice dropped, “they probably wouldn’t take you.”

“Why?” His shoulders squared.

“That’s just it,” was the quick reply. “You’re too fit. They’d want you for combat duty. You can’t make our outfit unless you’re too old for combat or there’s something a little wrong with you. Sparky, my fellow-pilot, has a hole in his eardrum. Combat wouldn’t take him, but Ferry did.”

“But say!” She gave him a good, square look. “Why don’t you ship back to U.S.A. and get into a uniform? Afraid to go back?”

“No, just ashamed. I ran away. My mother’s a peach. She really is.”

“Go back and sign up. Get into uniform, then breeze back home. You’ll make a hit.”

“Well, I—”

He broke short off to leap sideways, take three flying steps, then swing his arm to knock something from a stranger’s hand. Without knowing why, Mary followed on the run. It was lucky that she did, for the angry man flashed a knife. He slashed at the boy once and drew blood. His second blow, better aimed, might have been fatal had not Mary done a flying leap to knock his arm high in the air and send the knife flying away.

Instantly they were surrounded by soldiers. The youth and the man were seized. Two soldiers stepped toward Mary.

“What eez zis all about?” one asked.

“I—I really don’t know,” was her faltering answer.

The soldier looked at her in astonishment. “You might have been keeled. Now you say, ‘I know nothing.’”

“It’s a fact for all that.” She smiled in spite of herself. “I—I do things like that sometimes.”

“I’ll tell you what it’s about,” the boy broke in, holding up a bloody arm. “That man,” he pointed to the stranger, “is a spy. He was taking pictures of that big plane. That’s an American plane and I’m an American. He can’t get by with that!”

“Good for you!” The words were on Mary’s lips. She did not say them. Instead she bent down and picked up something black that gave off a bright gleam. “He’s telling the truth,” she said in as quiet a tone as she could command. “Here’s the proof, his camera. That boy knocked it from his hand.”

“It’s a lie!” the man snarled. “I never saw the thing before!”

“It’s one of those costly miniature cameras,” Mary went on. “It takes a hundred pictures as easy as firing a machine gun. And sometimes it’s twice as deadly.” She handed it to the soldier. “Have the film developed. The pictures will speak for themselves.”

“It’s a lie,” the man growled, trying to break away.

“He calls himself Joe Stevens now,” said the boy, swabbing his bleeding arm with a soiled handkerchief. “I knew him in Manos. That was before we entered the war. He was a rubber trader then. They called him Schnieder.”

“We’ll look into this,” said the officer.

To Mary he said, “This boy needs attention. There’s a Red Cross first-aid station up that way a block.”

“I’ll have him fixed up,” said Mary.

“And will you vouch for his return to the station at the airport gate?”

“Absolutely.”

“Come on then,” the soldier spoke to Stevens who had once been Schnieder, then they marched away.

“It’s nothing,” the boy said, hiding his hand. “I’ll fix it.”

“No,” said Mary. “We’re going to the first-aid station. Then you’re going to take me to some place where I can get a swell dinner.”

“Oh, so that’s how it is?” His face lit up. “Come on, then, let’s go.”

An hour later, with his arm neatly bandaged, the boy sat opposite her, smiling. The grand dinner he had promised was coming to an end. It had been all she had dreamed of and more. They were having their black coffee and ice cream.

Taking a pencil from her purse she wrote on a card then handed it to him. “That,” she said, “is my permanent address. I’m going on a rather long journey. I may not come back. We never know. But if I do, I’d like to have something nice waiting for me. Send me your picture when you get in uniform, won’t you?”

“Well, I—” He swallowed hard. “Yes, I will, if I make it.” That was all he said.

At the airport gate he put out a hand for a good stout handclasp.

“Ships that pass in the night.” His voice was husky.

“Yes,” she replied quickly. “Fighting ships that are going to put things to rights in this old world of ours.” At that she turned to march away.

“By the way,” he called after her. “Just in case you might like to know, my name’s Jerry Sikes—”

“Thanks, Jerry.” She smiled. Then without thinking she added, “I’ll be seeing you.”

One more hour passed. Just as they were ready to take off, Mary brought Sparky his dinner on a tray.

“It’s paid for, tray and all,” she said.

“Good! Then, let’s go.” He led the way into the cabin. “They say it brings good luck if you throw your dishes into the sea,” he laughed.

Mary did not laugh. One word Sparky had spoken stuck in her mind.

“Luck,” she whispered to herself. “We may need it, all kinds of luck.” She could not quite forget that they had already lost one plane. Just now she had visions of herself on a rubber raft in mid-Atlantic, casting a line in the vain hope of catching a fish.

Shaking herself free from these disturbing thoughts, Mary checked the No. 1 card Sparky handed her and said, “It’s okay,” then watched him check his gas.

Working together like the well-trained team that they were, they threw on a switch here to release it, then snapped on another there, only to reach for one more switch. Mary nodded to the mechanic waiting outside. He nodded back, then held up a fire bottle. One engine coughed, then the other. Mary reached for two small levers, Sparky eased the throttle back to one thousand, then nodded to the mechanic. The mechanic removed the chocks from before their wheels. Sparky eased his plane slowly down the runway. They picked up speed. Faster—faster—faster they sped and then that magic word, “up,” and they were away.

They were not off for Africa, not yet. Their way led along the coast toward Natal, the jumping off place.

Sometimes they were far out over the sea and then again the beauty of tropical forests lay beneath them. It was a glorious trip.

Just at sunset a white spot appeared before them and Mary knew that this lap of their journey was nearing its end.

“There are good American mechanics at Natal,” Sparky said. “They’ll give the old ship a real going over. We’ll get a few hours of good, sound sleep. And then—”

“We’ll be off.” Mary thrilled to the tips of her toes. “Off for the Old World. We’re going abroad, Sparky! Just think! Really going abroad!”

“It’s just another trip for me,” Sparky laughed low. “But if you get a kick out of it, that’s just fine.”

“Get a kick out of it!” she exclaimed. “Of course I will. If the time ever comes when I no longer get a kick out of things, I’ll be ready to die.”

“Guess you’re right at that,” Sparky agreed. “But then, what’s a thrill to you may be just another headache for someone else. I, too, have my big moments.”

“Let me know when you have one?” she asked.

“I might, at that,” he agreed.

“There’s a good little hotel run just for American women at Natal,” he said. “Run by an old lady called Aunt Polly.”

“Aunt Polly—sounds like a parrot,” Mary laughed.

“She’s got one, too,” said Sparky. “She keeps a nice place. I’ll run over there soon’s we land.

“Set your alarm, for I’ll be after you at two A.M. We’ll not sleep going over so don’t lie awake thinking. Hit the pillow fast and hard. That’s my motto.”

“Fast and hard it shall be,” Mary agreed.

At that they began circling for a landing.

At 2:15 that night they had breakfast sitting on stools in a little all-night stand.

“Lots of coffee and plenty of oatmeal with cream,” was Mary’s order.

“And good, brown toast with well-done bacon,” Sparky added.

“Nervous?” he asked as her fingers shook a bit.

“Yes.”

“That’s fine. I wouldn’t give a plugged nickel for a partner that didn’t have nerves. It’s part of our equipment. Keeps us on our toes. But you’re not scared?”

“Just a little.”

“Don’t be!” He grinned. “It’s only a step.”

“Pretty long step.” She smiled back at him.

“Eighteen hundred miles, plus, and water under us all the way. What could be sweeter? And we’ll be flying out to meet the dawn.”

“Oh, Sparky!” she exclaimed. “That does sound swell! I never did like night. Just to think that we’re hurrying away to meet the sun that is just popping along to meet us! That sure is something.”

The food was excellent so she ordered a lunch “to go” and, producing a gallon thermos bottle, ordered it filled with coffee.

“That,” said Sparky, “will be frozen solid. We’re going to be flying up there among the stars.”

“Oh, no, it won’t,” she gave him a sly smile. “There are some advantages in having a gal for a co-pilot. One of the advantages is a hot lunch half way across.”

“Tasting is believing.” He was a skeptic.

“Wait and see.”

“I’ll wait.”

Ten minutes later they were at the airport and with their arrival a burden seemed to fall upon Mary’s slender shoulders. She had started out light-heartedly enough to do, with her companion, Janet, what no woman of the Ferry Command had ever done before, to ferry a big ship half way round the world. What was more, their ship was to carry a light cargo of vital war equipment. Now her companion was gone. Sparky had taken her place. They had started out forty planes strong. Now one plane was out of action and thirty-eight were a full day ahead of them.

“We’ll have to go it alone,” she said, speaking half to herself and half to Sparky.

“That’s it,” Sparky agreed. “The Fates have arranged that.”

“We’ll Have to Go It Alone,” Said Mary

“And our cargo is priceless. That’s what the Major said.”

“Priceless,” he agreed. “It’s quite as important that it should arrive safely as, well perhaps, as it is for all those big bombers ahead of us to go through.

“But, Mary,” his voice changed, “don’t think of it that way. You’ll tighten up if you do. That might prove fatal. You have to be relaxed, flexible, ready for anything. That’s how you have to be.”

“I—I’ll try to forget that cargo,” she agreed.

“Well,” he breathed, “here’s our ship all primed up and rarin’ to go. Come on. Let’s climb up.”

Once again he handed her the “Form One” card. This time she studied it with supreme care. It told her that the engines were in perfect order, that the tubes of carbon dioxide snow for fire prevention were full as were their oxygen tubes, and that fuel and oil supply were at their maximum.

When she had studied the card, she nodded to Sparky, and at once, he began thumbing the oil gage.

“Do you always check your oil supply?” she asked.

“Always,” was the emphatic reply, “regardless of the report on the card, test your fuel. If you want to keep on living, you’ll always do that. Men are human. An attendant may read your report, note that your No. 1 tank is short a hundred gallons, record that he is putting that amount in, then discover that he has but fifty gallons to spare. He forgets to record the change and—”

“Right out over an endless forest your engine coughs and dies. No gas—I see,” she replied soberly.

“Gas and oil okay,” Sparky murmured. Then in silence he flipped on the ignition and gas, set the electric primer going, counted five, allowed it to snap off, then nodded to his mechanic. The mechanic grinned as he held up a carbon-dioxide fire extinguisher.

“That’s one more thing,” Sparky warned. “Don’t ever start twin motors unless someone is near with the fire bottle. And don’t you let me do it!”

“Is that so bad?” Mary asked.

“Worst in the world,” Sparky exploded. “If one motor fails to start popping, you’ll have a fire in your exhaust pipe.... A fire bottle will put it out in a hurry. But if there’s no fire bottle your ship will go up in smoke. A fire of high octane gas is something to think about!”

He started the energizing wheel going, waited a space of seconds, then threw on the fuel-booster switch. First the right engine began coughing. Mary worked her two levers that enriched the fuel mixture. Sparky eased his throttle back to one thousand, then nodded to the mechanic. The mechanic removed the chocks from before the wheels, and the big ship started to move.

“We’re off!” Mary thought with a little choking sensation at her throat.

Sparky cursed some small, foreign plane that, taxiing across the field, caused him to swing sharply to the right.

“Looks like he did that on purpose,” said Mary.

“May have, at that,” was the reply. “There are some Hitler sympathizers down this way.

“Well,” he sighed ten seconds later. “I fooled him. Now the runway’s clear, so here we go.” The powerful motors roared in unison. They rose sharply toward the stars. Ten minutes later they were out over the blue-black sea and still slowly climbing.

“The sea is so black,” Mary thought. “The sky is all filled with night. Hours of this! How can I bear it?”

Then, as a sense of real joy, the feeling that must come to a night-flying bird, passed over her, she whispered, “But we’re rushing east to meet the dawn.”

“Get on your oxygen mask,” Sparky commanded, crashing into her dream. “We’re going up where there isn’t any weather and mighty little air.”

Their masks were attached by rubber tubes to pipes running from the oxygen storage tanks. When Mary had pulled on her mask she sighed, “Ah! That’s great! Isn’t it wonderful that they should mould our masks to fit our faces!”

“It’s a grand idea,” Sparky agreed, “but you’ll get tired enough of it before we greet that dawn of yours. We’re going up to twenty thousand feet and stay there for hours. We’ll make better time that way and there’ll be no bumps. You can even sleep if you want to.”

“Sleep!” Mary’s voice rose. “I’d never do that. Suppose you fell asleep, or—or something happened to you!”

“I never get sleepy and nothing ever happens.” Sparky settled back in his place. “Talk when you feel like it,” he drawled. “I like the sound of your voice.”

“Oh, you do,” Mary laughed.

They climbed to twenty thousand feet. It seemed to Mary that she could feel the intense cold creeping through their cabin’s walls and her four-inch-thick suit of wool, leather and fur. But this, she knew, was pure imagination.

As they zoomed along through the blue with the black ocean far below and the stars apparently scattered all about them, she felt very little desire to talk. She just wanted to think.

Her mind went back to childhood days. Happy days they had been, those days with her father. School shut out much of this. And then had come college. College vacations found her flying, first with her father, then alone. She had learned about airplane engines from the ground up and had even become an expert with a machine gun.

“That,” she told herself, “was Providence, a dress rehearsal for war.”

As if he had been reading her thoughts, Sparky said, “Mary, there were a dozen or more who volunteered for this job you’re doing now. I wouldn’t want you to think I don’t like your work. I do. You’re swell, but how come they picked on you? You’re about the youngest of the lot.”

“That’s right,” Mary agreed, “but I’ve had more hours of solo flight than any of them. Fifteen hundred, to be exact.”

“Fifteen hundred?” Sparky whistled. “Practically flew from your cradle!”

“Nope—started when I was sixteen. You see, Dad is as much at home in the air as on the ground.”

“And you take after him?”

“Sure. Why not? What’s more, I know a lot about airplane engines and machine guns.”

“Handy man with tools, eh?” Sparky drawled.

“Try me.” Mary did not laugh. “Who knows? This job of ours may call for all the tricks we know before it’s done.”

“Guess that’s right,” Sparky agreed. “And I sure am glad you’re on the job.”

After that they once more lapsed into silence. The miles and the stars flew by. There were times when Mary was plagued by the illusion that somehow their ship had stopped traveling, that they were there, suspended in space, their motors roaring, but taking them nowhere. At such times she felt an all but over-powering desire to scream, for her overwrought imagination was telling her that the motors would roar on until the fuel was gone, then they would crash into the sea.

At times she felt drowsy, at others she was so wide awake that she wanted to leave her seat for a walk. This she knew was not entirely impossible since a bottle of oxygen attached to her tube and slung over her shoulder would give her freedom of movement. But this would call for more exertion than she felt like, and she lapsed back into sleepiness.

Then, little by little, she found herself drifting into a light and hilarious mood. She wanted to sing. She did hum little snatches of funny songs she knew. “The Bear Went Over The Mountain,” “The Old Gray Mare, She Ain’t What She Used To Be,” and “Clementine.”

From time to time Sparky looked at her and growled into his mask.

“Oh, Sparky,” she cried at last, “I’m tired of this mask. Can’t I take it off?”

She meant this only as a joke but Sparky roared, “For heaven’s sake! No! You wouldn’t last half a moment.”

Nothing daunted, she told him a rather long, funny story.

“Is that supposed to be a joke?” he growled. “If so, where’s the point?”

She began to realize that something was wrong.

“Either Sparky has turned into a terrible crab or I’m plain crazy,” she told herself half in despair.

From hilarity she went into gloomy foreboding. Then, of a sudden, she sprang out of both. She knew what had happened. Both she and Sparky were drunk on oxygen. They had been up high too long. They should drop to lower levels at once. But how was she ever to make Sparky see this? In the morose mood of a partially intoxicated man, he would perhaps resist all her suggestions.

After a moment’s thought she believed she had the very idea. “Sparky,” she said, “I’m hungry.”

“Suck your thumb, like a bear,” he growled.

“The coffee’s hot, a whole gallon of it.”

“It’s frozen solid. I told you it would be. Know what the temperature outside is? Thirty-five below.”

“Yes, I know, but that coffee’s still hot.”

“How come?”

“That’s my secret.”

“Then keep it.”

“I’ll bet you five dollars it’s hot, yes, and the bottle of soup, too.”

“You got five dollars?”

“Sure I have.”

“All—all right, it’s a bet.”

“Sure it is. Do come on down to five thousand feet and I’ll show you.”

“Okay, here we go. But I get the five.”

They started down. Anxiously Mary watched the recording gage. Twenty thousand, fifteen thousand, ten, eight—she opened a ventilator, then another. At five thousand they leveled off. When at last the air was changed, they dragged off their masks.

“Whew!” Sparky breathed deeply. “That’s great!”

“You don’t know half of it,” said Mary.

“Where’s your hot coffee?”

“I’ll get it.” She did. When the cork was removed steam rose from the bottle.

“Well, I’ll be!” Sparky exclaimed. “You win! How do you do it?”

“Little electric heat, that’s all.” She pointed at the connections at the base of the thermos bottle.

“Say!” Sparky beamed. “From now on, you and I travel together.”

“At least for some little time,” she agreed with a wise smile.

It was a grand little lunch they enjoyed there above the black waters of the Atlantic. Mary flew the ship while Sparky drank hot coffee and soup, and munched hot cheese sandwiches. Then he took the controls while she carried on with the lunch box.

But when it was all over and they began once more to climb, weighty problems once more bore down upon Mary’s tired brain. Would they again climb high and fly too far, then become oxygen-drunk again? She hated to ask Sparky and yet—

Thousands of weary miles lay ahead, miles where danger lurked all the way. Then, too, there was their precious cargo. Would it reach its destination safely?

“It must,” she whispered. She reached for her mask and then Sparky spoke.

“Forget the mask,” Sparky was saying. “We’ve got loads of gas. Dawn will soon be here. We’ll stay five thousand feet. Go back and get a little rest.”

Reluctantly she obeyed. Having wrapped herself in the eiderdown robe, she fell fast asleep. But not for long. She awoke with a start from a disturbing dream to find an eerie light shining down upon her.

“The ship’s on fire!” she thought tumbling out of her robe.

She sprang to a window to whisper, “We have met the dawn.”

It was true. The sun, a red disk, rolled along the horizon. The sea and the sky were all ablaze with light.

“Sparky!” she exclaimed. “It’s wonderful!”

“Is it?” he asked sleepily. “Just another sunrise. That’s all it seems to be. But look, Mary, you’ve been a peach. I suppose I should apologize for being gruff with you back there when we were way up high.”

“Oh, no!” Mary exclaimed. “Don’t ever apologize. Your friends don’t demand it, your enemies don’t deserve it. Besides I never quarrel with people when they’re drunk.” A teasing smile played about the corners of her mouth.

“Who’s been drunk?” He shot her a quick look. “You think I’m crazy? I’m not a drinking man, but if I were, I’d be plain mad if I drank before a trip like this.”

“Oh! So you weren’t drunk?” She threw back her head for a good laugh. “You were all the same.”

“What!” Sparky seemed ready to leave the controls to crown her.

“Yes, you were drunk and so was I. I was happy and you were sad. That’s how people get when they are drunk.”

“Say, are you crazy?”

“No, Sparky, I’m not.” She laughed again. “We were having an oxygen drunk. It might have been dangerous. I realized the danger just in time. Too much oxygen, too long, that’s all.”

“Too much oxygen, too long,” he repeated after her. “I’ve heard of that happening but just think of an oldtimer like me getting caught with it!”

“The bigger they are the harder they fall.” She favored him with a good laugh. “But it’s not really strange,” she added soberly. “Our trip, this far, has been a hard one. You’ve worked long hours. You were too tired to think. I was fresh. That made all the difference. And just for that, how would you like to crawl back for a few winks?”

“Don’t mind if I do.” He offered her the controls. “But promise me that if anything unusual occurs, seaplanes show up, or anything like that, you’ll call me.”

“I’ll call you,” she agreed.

Sparky’s sleep was long and peaceful. Never had Mary enjoyed herself half so much as on that morning guiding the big ship through the blue sky over a sea as dark and mysterious as death.

An hour passed, two, three hours. Sometimes she wondered in a vague sort of way about their secret cargo. Would it go through safely and would she be with the ship to its journey’s end? Just then none of these things appeared to matter much. It was good to live. That, for the moment, was enough.

There was a spring-like warmth in the air, and a faint fragrance as of flowers. They were going against a mild off-shore breeze.

Once she spotted dark dots on the ocean far below. There were twenty-four, a convoy. It must, she told herself, be an American convoy. She wanted terribly to drop down low and dip a wing in salute but, this, she knew, would never do. Some enemy sub might see that dip and know that the convoy lay beneath her. They would close in and then—

No—it would never do, so she drove straight on toward the rising sun.

At last a long, low, gray-green cloud appeared on the horizon before her. Or was it a cloud? Breathing softly she waited and watched. The long, narrow line widened. It seemed to take form. Some spots were higher, some strips greener than others. At last she whispered excitedly:

“It’s land! Land! Africa! I’ll soon be abroad. The long hop is nearing its end.” She wanted to shout for joy, to scream, but this she knew was not expected of the co-pilot of a big ship so all she said was:

“Sparky! Sparky! Wake up! We’re nearing land, and I don’t know the way to that secret airfield.”

“What—what?” Sparky groaned sleepily. “It can’t be land. I just stretched out here a minute ago.”

“Yes, I know.” Mary laughed for sheer joy. “It’s land all the same. I think I see a camel. Come and see.”

Sparky came forward rubbing his eyes. Adjusting his glasses he took a good look.

“Can’t make out your camel,” he drawled, “but that white spot off to the right is Dakar, all right. Good girl! You hit it right on the nose. Give me the controls and I’ll have you eating fried camel steak and dates before the hour is up.”

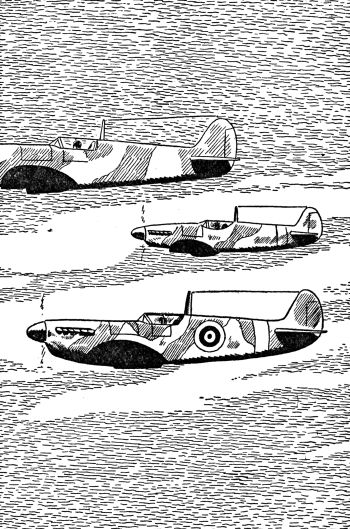

They did just that. Coming down on an airfield fringed with palms, they were given a cordial greeting by a dozen good American soldiers. To a man, they stared at Mary, then grinning, saluted.

Soldiers Greeted Them at the Secret Airfield

“Jeepers, boys!” one of them exclaimed. “An honest-to-goodness lady of the Ferry Command.”

“If they all come like this one, make ’em all ladies from now on,” his buddy chipped in.

“It’s nice to see you all.” Mary put on her best smile. “I only wish I could be with you for a week.”

“Make it two! Make it for the duration!” came in a chorus.

“Two hours,” was Sparky’s pronouncement. “Give our ship the once-over, will you, while we motor in for some chow?”

“Oh, sure, we’ll fix her up fine,” a big sergeant grinned. “But you’ll have to do your own searching for stowaways.”

“And be sure you look well!” the lieutenant in charge added. “I’m short-handed. Can’t spare a man.”

An army jeep appeared and they were whisked away to a small city of low, white buildings, gleaming streets, and many camels.

“My!” Mary exclaimed. “It’s hot!”

“Sure!” said Sparky. “This is Africa.”

“The scene shifts so fast I can’t keep up,” Mary said, fanning herself.

“It won’t be bad in here,” said Sparky, motioning her to enter a long, low eating place. “It’s more than half American, patronized mostly by our people. They run a sort of concession and get real food supplies from America.”

The place was all open screened windows. There was a breeze from the sea. The food was good, even to the coffee.

“Just think of taking off in two hours!” Mary exclaimed. “I’d like to make it two weeks.”

“Sure,” Sparky grinned. “Great place for a gal. Hundred American soldiers to pick from.”

“Sparky! Forget it!” She was half inclined to be angry. “What I mean is, I’d like really to see these places we visit, not go to it hop-skip-jump. It—it seems such a waste.”

“That’s right,” Sparky agreed. “After the war we’ll do it all over—take a whole year for it.”

“Will we?” she asked.

“Who knows?” He spoke slowly. “We may be dead. This is war.”

Sparky hurried through the meal, then excused himself. “Gotta see about our papers,” he explained. “Be back in 'bout half an hour. Get yourself another cup of java and wait here in the shade.”

Hardly had Sparky disappeared when a tall, distinguished-looking young woman entered. She was dressed in a striking manner, all in black, yet it was not the black of mourning for she wore much bright costume jewelry.

The place was fairly empty, a native couple in one corner and two doughboys in another.

“Do you mind?” The woman indicated the chair Sparky had left. “One sees so few women here.”

Mary did not mind. The woman, who spoke with a French accent, took a seat, then ordered cakes and sour wine.

“You are from America?” the woman suggested. Mary nodded.

“A lady soldier?” Mary shook her head.

“But your uniform?”

“In America many women wear uniforms. We like them.” Mary smiled. “I happen to be a member of the Ferry Command.”

“And you flew a big plane all the way! How wonderful! Shall there be many more of you?”

“No—I—” Mary broke off. She had been about to say, “I may be the only one. Mine is a special mission.”

“What a fool I am,” she thought.

“I came for the ride really,” she said, covering up deftly. “My father is over here somewhere.”

“Ah! You brave Americans!” the woman exclaimed. “They saved my country, France, in the last war and now—”

“Now you expect us to do it again,” Mary wanted to say. “And over here you are divided. You don’t really know what you want.”

She did not say this, nor did the woman finish, for at that moment a bright-eyed young woman in khaki entered the place and walked straight to their table to ask:

“Are you Mary Mason?”

“Yes.” Mary stood up.

“I’ve been asked to speak to you—that, that is I have a message for you.” The girl seemed embarrassed. “Perhaps—”

“No! No!” The French woman was on her feet. “I have urgent business. I was about to go. It is good to have seen you—” She bowed to Mary and was gone.

“Will you forgive me.” The girl in khaki dropped into a seat. “I just had to do it. I never saw that woman before. She may be all right. You never know. Over here half the people are for us, the other half against. You dare trust no one. You didn’t—” She hesitated.

“I didn’t tell her a thing worth knowing.” Mary smiled. “Will you have a cup of coffee?”

“Oh, sure!” The other girl’s face beamed. “Real American girls are so rare here.”

“You are a WAC?” Mary suggested.

“Yes, of course. There are very few of us here now, but there will be more and more.” Her voice dropped. “That’s the sort of things they want to know,” she confided in a whisper.

They talked, sipped coffee, and munched cakes until Sparky hurried into the place.

“All set!” he exclaimed. “Our outfit is still far ahead of us. Got to get going.”

After Mary had introduced Lucy Merriman, the WAC, they were on their way.

“I’ll be seeing you,” Mary called back. Then she added in an undertone, “I wonder.”

As she climbed into the car, she caught a glimpse of the tall French woman. She was talking to a small man with a round face.

“That’s a queer-looking pair,” said Sparky. “Lady of quality and a beggar Arab.”

“He looks like a Jap,” Mary gave the fellow a sharp look. She would know him if she saw him again. “Besides,” she added, “he can’t be quite a beggar. He’s got a camel.”

“You meet all types here,” Sparky replied absently. “It’s the strangest country you ever may hope to see. We’ve sure got to watch our step. By rights we should fly square across the desert. But with our cargo,” his voice dropped, “it’s too risky.”

“So we’ll go northeast?” Mary suggested.

“That’s right.”

“That takes us into fighting country?”

“Yes—sort of—”

The car started, returning them to the airfield.

“There’s a secret airport, on an oasis,” Sparky told Mary. “That’ll be our first stop. After that we hit Egypt and another secret spot. Egypt is safe enough. It’s those miles in between.” His brow wrinkled in a frown. “But we’ll make it.”

To Mary the next lap in their long journey will always remain a blank, but the oasis at which they arrived will stand out vividly in her memory.

The reason for the blank was quite simple, for, as soon as they were safely in the air, Sparky said:

“Mary, you look tired. I know you are tough as a hickory limb and you’ve got all kinds of grit—”

“Oh, thanks, Sparky,” she grinned. “I’m glad you’ve got my number.”

“Got your number!” Sparky exploded. “Of course I have and just now you need sleep. That secret cargo of ours won’t wait and so—”

“Sparky! Tell me what our secret cargo is,” she begged.

“Will you stop interrupting me?” he stormed. “How do I know what it is? That’s a military secret. All I know is that China needs all the help we can bring her, every bit! And that this cargo of ours is of the greatest importance. I shouldn’t wonder,” his voice dropped as if he were afraid someone were listening, “I shouldn’t wonder if the enemy knows it’s important. I got a warning to be on my guard not an hour ago, and that goes for you as well. This is a dangerous land. It’s all full of Italians, wild natives, and even a few traitorous Frenchmen that would sell us out for a dime or kill us just for fun.

“And so—” He paused for breath.

“And so—” Mary prompted.

“Let’s see, where was I?” Sparky pulled back the stick to climb a bit. “Oh, yes! And so we’ve just got to keep right on flying. Mighty little time for sleep. I had a dandy rest before we hit Africa. Now it’s your turn. I’ll do this lap. You just crawl back there, roll up in your robe, and sleep.”

All too willingly Mary rolled up in her robe and slept. When she awoke they were circling for a landing at one of the most fascinating spots she had ever known.

Looking down upon it, as they were, from ten thousand feet, it seemed a green carpet on an endless gray floor.

“An oasis!” Mary whispered. “How beautiful!”

“Yes, and I shouldn’t wonder if those dark, moving spots over there on the grasslands were giraffes or maybe elephants.”

“Yes, and there’s a camel caravan just coming in,” Mary exclaimed. “How long it is. Must be fifty camels. And the shadows seem darker than the camels. Oh! I wish we could stay a week!”

“Well, we can’t,” Sparky warned. “Few hours at best. Our right engine isn’t acting properly. Has to be tuned up for this desert air, I guess. That’ll give you a breathing spell. Make the most of it.”

The camel shadows on the desert were long. The sun was almost down when at last their plane came to rest on that long, narrow runway there in the desert.

Here again they found good American soldiers and mechanics. And Mary once more found herself creating a sensation!

“Hey, fellas!” one boy with bulging eyes shouted. “It’s a lady, a lady pilot, right out here just a mile beyond nowhere!”

“Joe! Hey, Jerry! You! Tom!” another called. “Come and see it. We got lions an’ elephants, zebras, giraffes, and aardvarks, but this one is different! Come a-running! See if you can name it.” He looked at Mary and laughed happily.

They were grand boys, all of them, and those who were not on duty showed her the time of her life. They hurried her off to mess where they feasted her on ripe figs, bananas, strawberries, and all manner of African delicacies.

Then one of them said, “Come on! We’ll show you something you’ll never forget.”

“How long will it take?” she demurred.

“Only an hour or two.”

“I’ll have to ask Sparky about that.”

Mary Found Herself Creating a Sensation

She found Sparky perspiring and covered with grease as he worked with the mechanics tuning up the engine.

“Two hours,” was his short reply. “Be back in two hours if you want to fly with me.”

“We’ll be back in an hour!” a boy from Indiana exclaimed.

“Sure! Sure!” they all agreed. “Come on. What are we waiting for? Let’s go.”

And so away they all marched to the shelter where the jeeps were kept.

It was while on this march that Mary received a sudden shock. As they hurried along, they met a woman dressed as a Moslem woman always is. She wore a long, flowing robe and her face, save for her eyes, was covered with a veil. Yet there seemed to be something very familiar about the tall, erect figure and the brisk, springing walk.

“Jeepers! I never saw her before!” a boy whispered.

At the same time Mary was thinking. “I must have seen her somewhere. But how could I—”

Just then the dark eyes shining out from behind the veil gave her a sharp, penetrating look. In her shock Mary stumbled and nearly fell.

“Can she be the woman who asked me questions in that eating place, way back there in the little city by the sea?” she asked herself. And then, “How could it be?”

“Oh!” she exclaimed, stopping short. “I can’t go with you boys. I must not!”

“Aw, come on!” a boy from Texas begged. “You’ll never see a thing like it again.”

“We won’t be gone an hour.”

“Sure! Sure! You must come!”

They were such nice boys and she knew so well what it must mean to be escorting a real American girl in such a place, that she yielded and came along.

“And yet, I shouldn’t do it,” she told herself.

Before they were gone she received a second shock. Just as they were all piling into the car, a small man and a camel came shambling down the road.

“Can he be the little man I saw at the port?” she asked herself. It gave her a shock to think that this little man and the woman in black had somehow made their way here before them. This thought, as far as the little man was concerned, was short-lived. When he had come closer she saw that he was shorter than the other man, that his face was rounder, and there was a scar across his left cheek. She heaved a sigh on making this discovery, but her relief was not to be of long duration.

And so they rattled away, nine boys and a lady, the first they had seen in many a day.

“I shouldn’t have come,” Mary whispered to herself once again. Had she but known it, she was to be thinking that very thought hours later, and with regrets.

Darkness had come. Switching on the lights, they went bumping over the sand ridges.

“Rides just like that big ship of yours, doesn’t it?” said the boy from Kentucky.

“Exactly,” said Mary, giggling like a kid. She was happy but some sprite seemed to whisper, “Not for long.”

After rattling along for a while with the lights on, they snapped the lights off, but rattled straight on.

A dark bulk loomed up before them. Shutting off the gas, they, all but the driver, piled out and began to push.

“Such crazy business,” Mary whispered.

“Wait and see,” came back to her.

At last they came to a halt. The dark bulk was closer now. Mary made out the forms of palm trees. One of the boys was dragging something. Strange sounds came from before them, low grunts, splashes, then a loud trumpet-like sound that made Mary jump.

“Say! What is this?” she whispered.

Someone snapped on a spot light connected by a wire to the car. Then she knew, for there before her, like a set in a museum was a water hole and in the water, belly-deep, stood all manner of creatures, ugly rhinoceros, graceful gazelles, ungainly giraffes, huge elephants and who could say what else.

“Are they really alive?” she asked in an awed whisper.

“Sure! What do you think?” The boy at her side laughed. “We got ’em trained now. You should have seen ’em the first time!”

“Yes, an’ heard ’em,” another laughed low. “They spilled all the water getting out.”

“It’s about all the fun we have way out here,” one boy added with a touch of sorrow. “Oh, gee! Why don’t you stay with us?”

“I’d love to,” said Mary, “but I’ve got a job to do. There’s a war on, you know.”

“And don’t we know it,” the boy whispered. “One night we were bombed. Two boys were killed and three went to the hospital. Gee! Just think of dying way out here!”

Mary was thinking.

By and by she whispered, “We’d better go back.”

Without a word they turned about to go shuffling back to the car. “Thanks a lot for coming with us,” one of the boys shouted when they unloaded at the airport.

“Sure! Sure!” they shouted. “Hope you come this way again!”

“I’ll be seeing you,” she called. Then with a lump in her throat she walked to the plane where the men were just replacing the motor.

Did she see a shadow dart away from the other wing of the plane? It was too dark really to know. “Probably a sneaking old jackal,” she told herself.

“Sparky,” she said as they soared aloft some time later, “I’m going to resign from this job of mine.”

“And then what?” Sparky asked in surprise.

“Then I’m going from place to place in all these lonely spots cheering up the boys.”

“That,” said Sparky, “would be a noble purpose, but just now you’re bound to this big plane and me. And you’ll not leave us for a long time, not till the journey’s end.”

“Not till the journey’s end,” she repeated softly. And how soon would the end come? Who could tell? Perhaps tonight. One never knew. She shuddered a little, then turned her attention to the work of the hour.

That night Mary did not sleep. Sparky had first call on a time for rest and he surely needed it. He told her to call him in two hours.

“But I won’t,” she told herself. “Not if all goes well. Something tells me I won’t sleep if I have the chance.” She found herself haunted by a sense of impending doom. The tall French woman, all in black, and the stately Moslem lady were constantly being blended on the pictured walls of her mind. And after that, with the slow sleepy tread of the desert, came the two little men and their camels. They too seemed part of the same picture, but just how, she could not tell.

“What foolishness!” she whispered. “Lie down, you ghosts.” But they would not. They continued to haunt her.

She gave herself over to glimpses of the desert and the night. There was a glorious moon. The desert beneath her was full of haunting shadows. For the most part they were shadows of sandy hills, but at times they loomed dark and large.

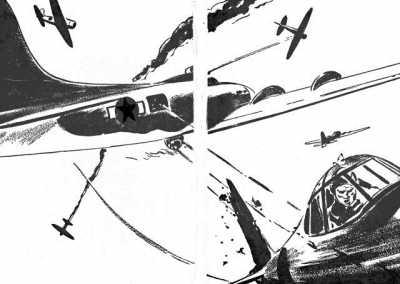

“Oases,” she told herself. “Wonder if friend or foe live here—” Sparky had told her that this night they were to fly over dangerous country. Little pockets of enemy resistance here had not been crushed. She was to keep a sharp lookout and if she sighted a plane, was to call him at once.

“We can outclimb and outfly most enemy fighters,” he had said. “But we must not let them get the drop on us.”

So, with eyes and ears alert, she rode on through the night.

All went well. She called Sparky in three hours. He scolded her for waiting so long.

“It was the spell of the desert at night,” she told him. “Seems as if I could fly on and on forever. And just think! We may never pass this way again!”

“Life is like that, so why bother?” was the reply. She went back for her turn at resting, but did not sleep.

Was it the spell of the desert night that kept her awake? Who can say? At least she did not sleep, just lay there, wrapped in her robe, staring into the darkness, listening to the roar of the motors and thinking, thinking.

Her father was somewhere in Africa. She knew that and no more. It would seem strange to pass over him in the night and not to see him at all. Yet, that might happen. There was no time for looking around, no time for anything. They must go on and on.

When two hours had passed, she was back at Sparky’s side asking for the controls.

“I can’t sleep,” she explained. “Flying over the desert is fascinating. You don’t care a whoop about it.”

“That’s right.”

“Then why not let me have a chance at it?”

“Sure! Why not?” He yielded the controls.

As she took over, the words of an old song were running through her mind:

“Dance, gypsies; sing, gypsies; dance while you may.”